User login

An FP’s guide to exercise counseling for older adults

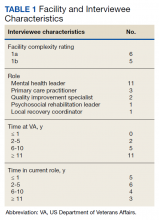

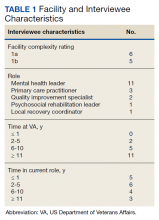

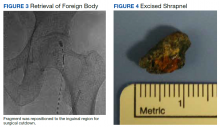

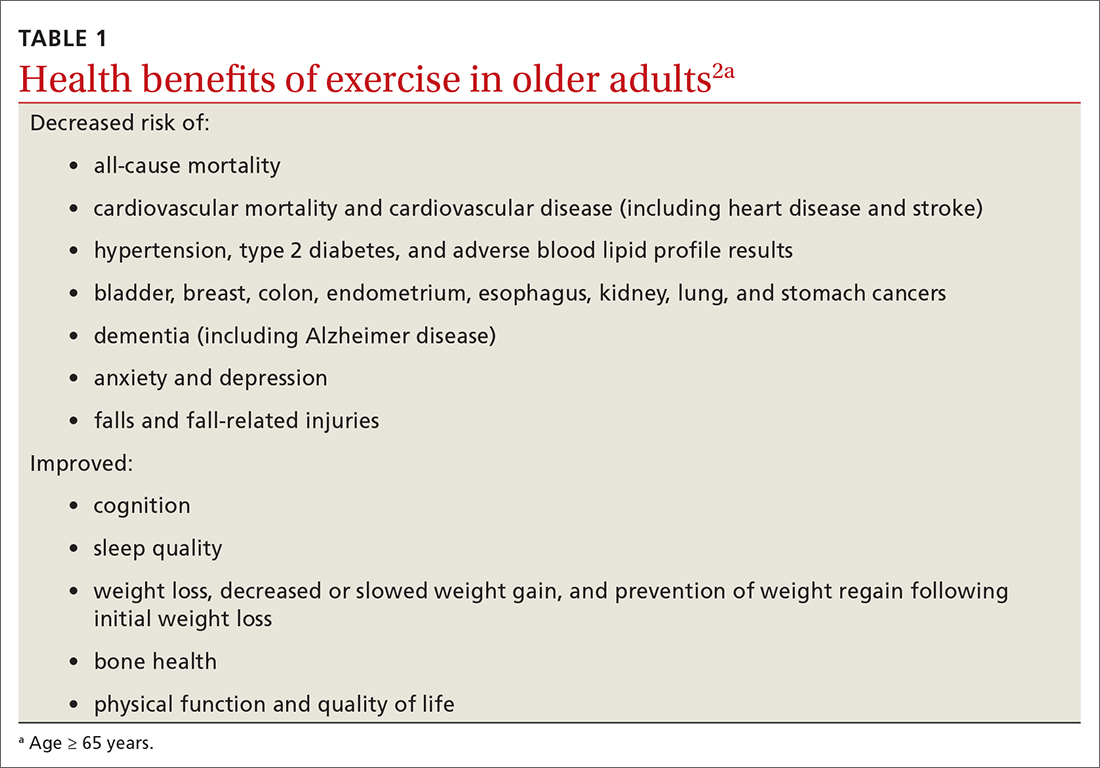

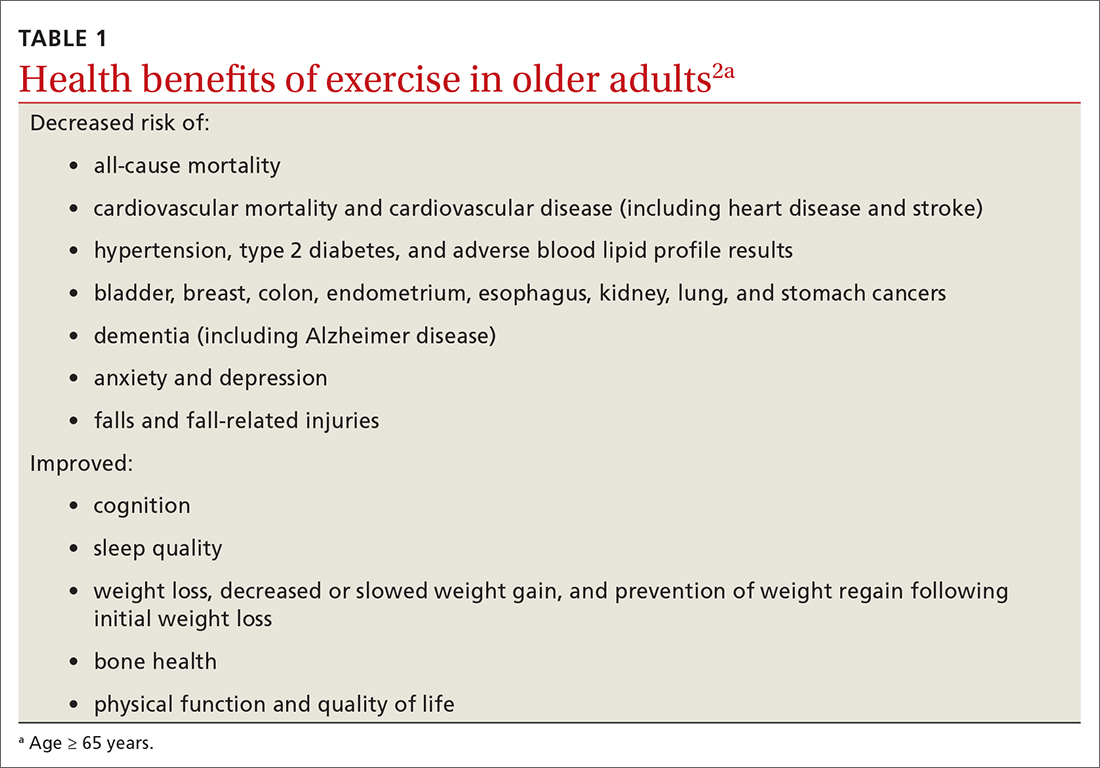

The health benefits of maintaining a physically active lifestyle are vast and irrefutable.1 Physical activity is an important modifiable behavior demonstrated to reduce the risk for many chronic diseases while improving physical function (TABLE 12).3 Physical inactivity increases with age, making older adults (ages ≥ 65 years) the least active age group and the group at greatest risk for inactivity-related health consequences.4-6 Engaging in a physically active lifestyle is especially important for older adults to maintain independence,7 quality of life,8 and the ability to perform activities of daily living.3,9

Prescribe physical activity for older adults

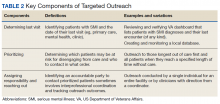

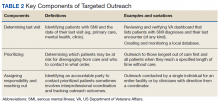

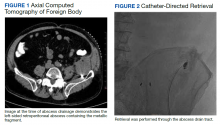

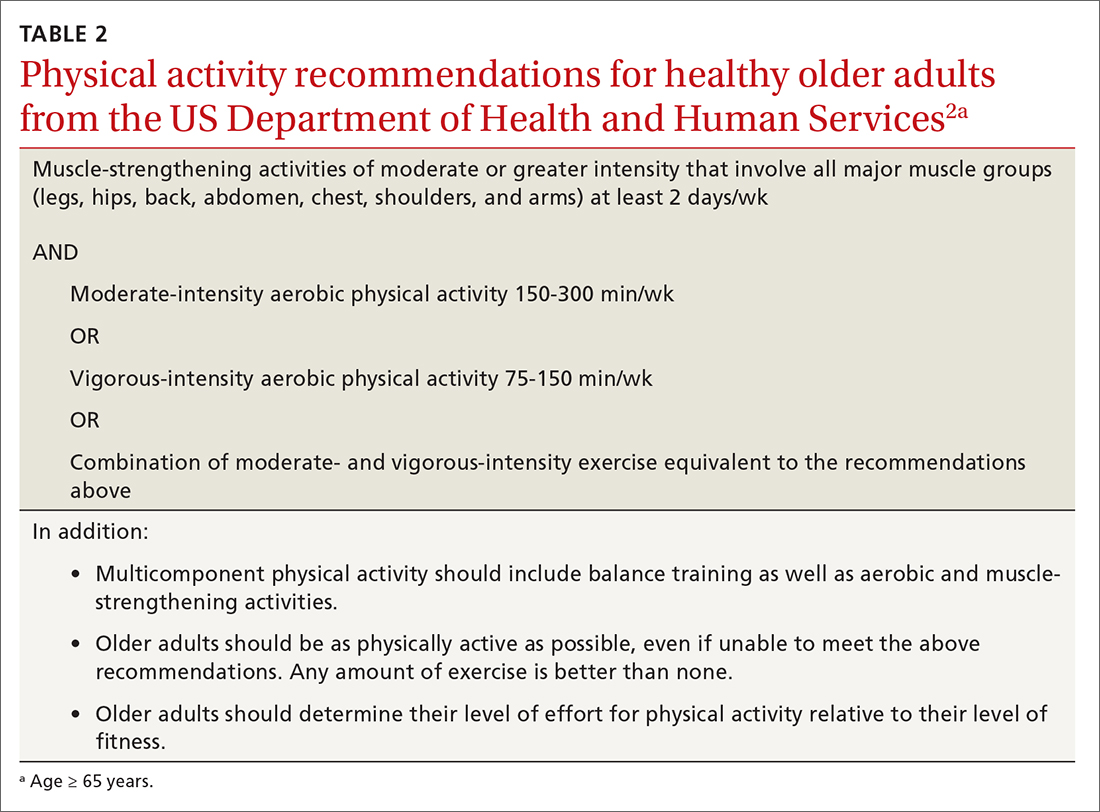

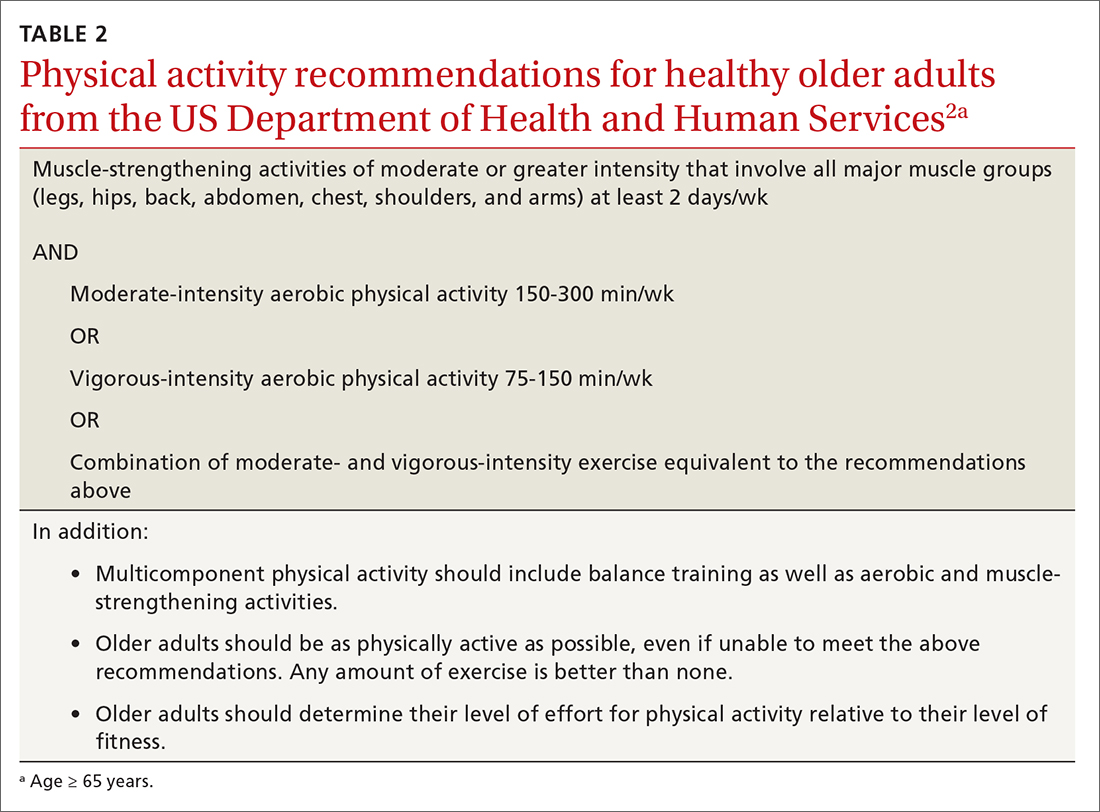

The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend that all healthy adults (including healthy older adults) ideally should perform muscle-strengthening activities of moderate or greater intensity that involve all major muscle groups on 2 or more days per week and either (a) 150 to 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, (b) 75 to 150 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or (c) an equivalent combination, if possible (TABLE 22).3 It is recommended that older adults specifically follow a multicomponent physical activity program that includes balance training, as well as aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities.3 Unfortunately, nearly 80% of older adults do not meet the recommended guidelines for aerobic or muscle-strengthening exercise.3

Identify barriers to exercise

Older adults report several barriers that limit physical activity. Some of the most commonly reported barriers include a lack of motivation, low self-efficacy for being active, physical limitations due to health conditions, inconvenient physical activity locations, boredom with physical activity, and lack of guidance from professionals.10-12 Physical activity programs designed for older adults should specifically target these barriers for maximum effectiveness.

Clinicians also face potential barriers for promoting physical activity among older adults. Screening patients for physical inactivity can be a challenge, given the robust number of clinical preventive services and conversations that are already recommended for older adults. Additionally, screening for physical activity is not a reimbursable service. In July, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) reaffirmed its 2017 recommendation to individualize the decision to offer or refer adults without obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or abnormal blood glucose levels or diabetes to behavioral counseling to promote a healthy diet and physical activity (Grade C rating).13

Treat physical activity as a vital sign

The Exercise is Medicine (EIM) model is based on the principle that physical activity should be treated as a vital sign and discussed during all health care visits. Health care professionals have a unique opportunity to promote physical activity, since more than 80% of US adults see a physician annually. Evidence also suggests clinician advice is associated with patients’ healthy lifestyle behaviors.14,15

EIM is a global health initiative that was established in 2007 and is managed by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). The primary objective of the EIM model is to treat physical activity behavior as a vital sign and include physical activity promotion as a standard of clinical care. In order to achieve this objective, the EIM model recommends health care systems follow 3 simple rules: (1) treat physical activity as a vital sign by measuring physical activity of every patient at every visit, (2) prescribe exercise to those patients who report not meeting the physical activity guidelines, and/or (3) refer inactive patients to evidence-based physical activity resources to receive exercise counseling.16,17

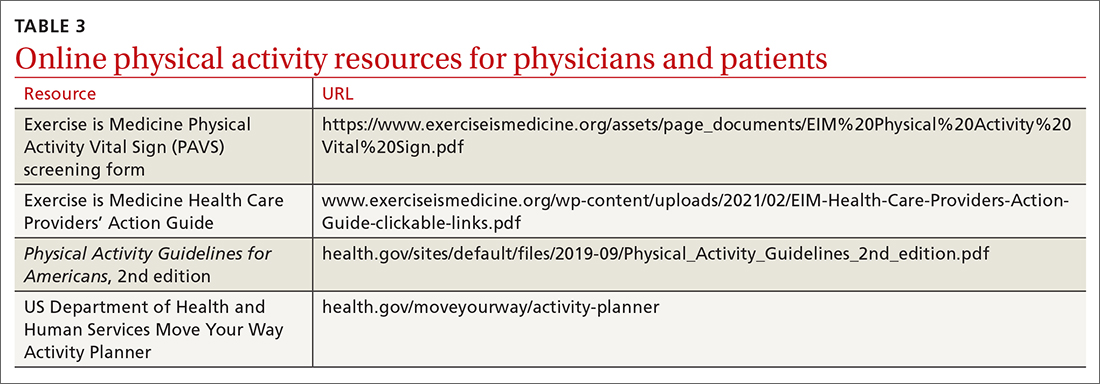

Screen for physical activity using this 2-question self-report

Clinicians may employ multiple tactics to screen patients for their current levels of physical activity. Physical Activity Vital Sign (PAVS) is a 2-item self-report measure developed to briefly assess a patient’s level of physical activity; results can be entered into the patient’s electronic medical record and used to begin a process of referring inactive patients for behavioral counseling.17,18 The PAVS can be administered in less than 1 minute by a medical assistant and/or nursing staff during rooming or intake of patients. The PAVS questions include, “On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity?” and “On average, how many minutes do you engage in physical activity at this level?” The clinician can then multiply the 2 numbers to calculate the patient’s total minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week to determine whether a patient is meeting the recommended physical activity guidelines.16 (For more on the PAVS and other resources, see TABLE 3.)

Continue to: The PAVS has been established...

The PAVS has been established as a valid instrument for detecting patients who may need counseling on physical activity for chronic disease recognition, management, and prevention.17 Furthermore, there is a strong association between PAVS, elevated body mass index, and chronic disease burden.19 Therefore, we recommend that primary care physicians screen their patients for physical activity levels. It has been demonstrated, however, that many primary care visits for older individuals include discussions of diet and physical activity but do not provide recommendations for lifestyle change.19 Thus, exploring ways to counsel patients on lifestyle change in an efficient manner is recommended. It has been demonstrated that counseling and referral from primary care centers can promote increased adherence to physical activity practices.20,21

Determine physical activity readiness

Prior to recommending a physical activity regimen, it is important to evaluate the patient’s readiness to make a change. Various questionnaires—such as the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire—have been developed to determine a patient’s level of readiness, evaluating both psychological and physical factors (www.nasm.org/docs/pdf/parqplus-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=401bf1af_24). Questionnaires also help you to determine whether further medical evaluation prior to beginning an exercise regimen is necessary. It’s important to note that, as is true with any office intervention, patients may be in a precontemplation or contemplation phase and may not be prepared to immediately make changes.

Evaluate risk level

Assess cardiovascular risk. Physicians and patients are often concerned about cardiovascular risk or injury risk during physical activity counseling, which may lead to fewer exercise prescriptions. As a physician, it is important to remember that for most adults, the benefits of exercise will outweigh any potential risks,3 and there is generally a low risk of cardiovascular events related to light to moderate–intensity exercise regimens.2 Additionally, it has been demonstrated that exercise and cardiovascular rehabilitation are highly beneficial for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.22 Given that cardiovascular comorbidities are relatively common in older adults, some older adults will need to undergo risk stratification evaluation prior to initiating an exercise regimen.

Review preparticipation screening guidelines and recommendations

Guidelines can be contradictory regarding the ideal pre-exercise evaluation. In general, the USPSTF recommends against screening with resting or exercise electrocardiography (EKG) to prevent cardiovascular disease events in asymptomatic adults who are at low risk. It also finds insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening with resting or exercise EKG to prevent cardiovascular disease events in asymptomatic adults who are at intermediate or high risk.22

Similarly, the 2020 ACSM Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription reflect that routine exercise testing is not recommended for all older adult patients prior to starting an exercise regimen.17 However, the ACSM does recommend all patients with signs or symptoms of a cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease consult with a clinician for medical risk stratification and potential subsequent testing prior to starting an exercise regimen. If an individual already exercises and is having new/worsening signs or symptoms of a cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease, that patient should cease exercise until medical evaluation is performed. Additionally, ACSM recommends that asymptomatic patients who do not exercise but who have known cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease receive medical evaluation prior to starting an exercise regimen.17

Continue to: Is there evidence of cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease?

Is there evidence of cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease?

Initial screening can be completed by obtaining the patient’s history and conducting a physical examination. Patients reporting chest pain or discomfort (or any anginal equivalent), dyspnea, syncope, orthopnea, lower extremity edema, signs of tachyarrhythmia/bradyarrhythmia, intermittent claudication, exertional fatigue, or new exertional symptoms should all be considered for cardiovascular stress testing. Patients with a diagnosis of renal disease or either type 1 or type 2 diabetes should also be considered for cardiovascular stress testing.

Ready to prescribe exercise? Cover these 4 points

When prescribing any exercise plan for older adults, it is important for clinicians to specify 4 key components: frequency, intensity, time, and type (this can be remembered using the acronym “FITT”).23 A sedentary adult should be encouraged to engage in moderate-intensity exercise, such as walking, for 15 minutes 3 times per week. The key with a sedentary adult is appropriate follow-up to monitor progression and modify activity to help ensure the patient can achieve the goal number of minutes per week. It can be helpful to share the “next step” with the patient, as well (eg, increase to 4 times per week after 2 weeks, or increase by 5 minutes every week). For the intermittent exerciser, a program of moderate exercise, such as using an elliptical, for 30 to 40 minutes 5 times per week is a recommended prescription. FITT components can be tailored to meet individual patient physical readiness.23

Frequency. While the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend a specific frequency of physical activity throughout the week, it is important to remember that some older adults will be unable to meet these recommendations, particularly in the setting of frailty and comorbidities (TABLE 22). In these cases, the guidelines simply recommend that older adults should be as physically active as their abilities and comorbidities allow. Some exercise is better than none, and generally moving more and sitting less will yield health benefits for older adult patients.

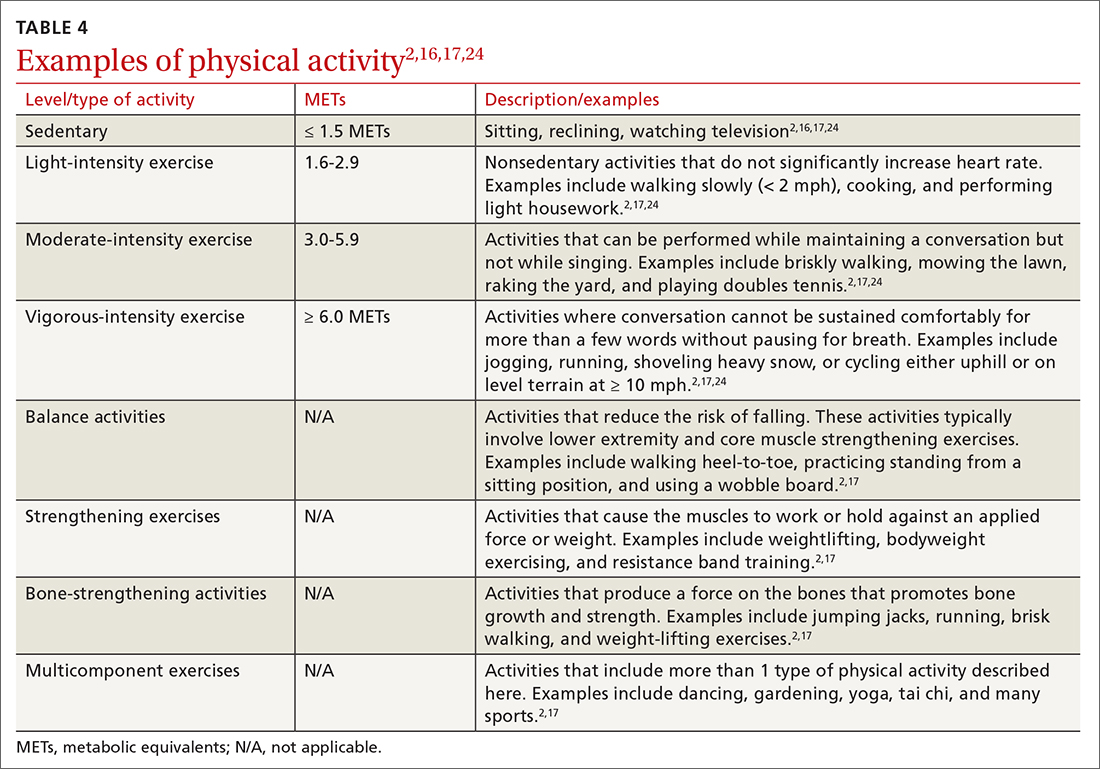

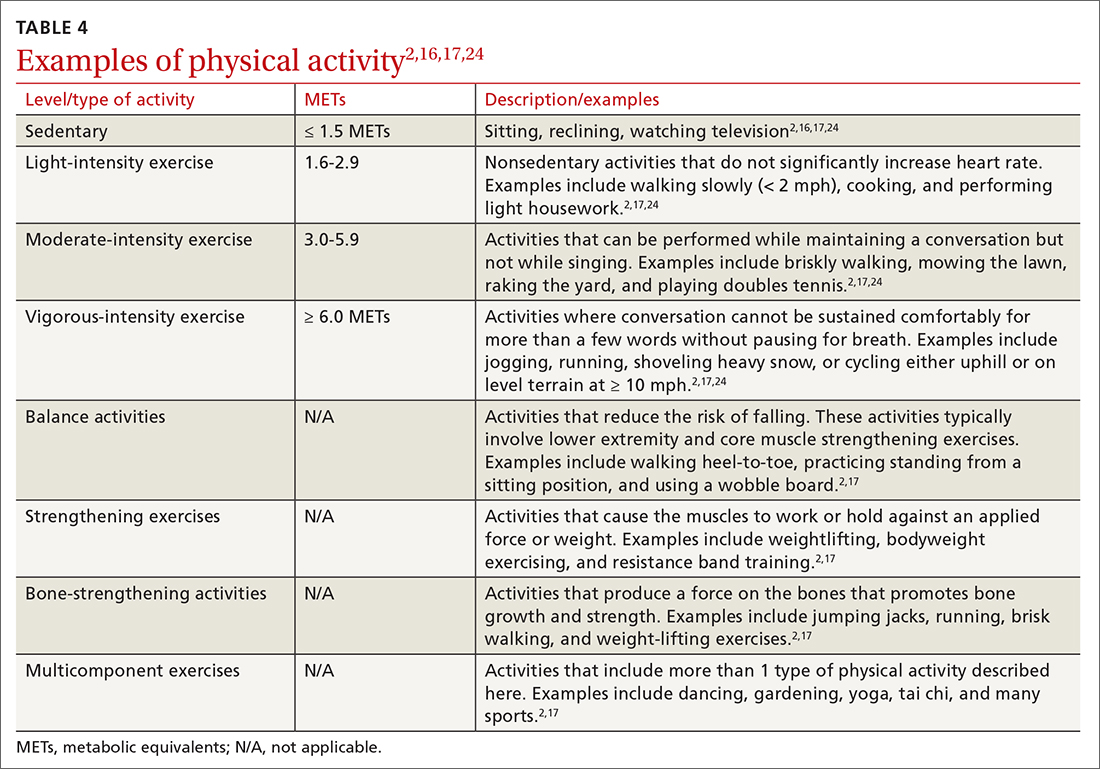

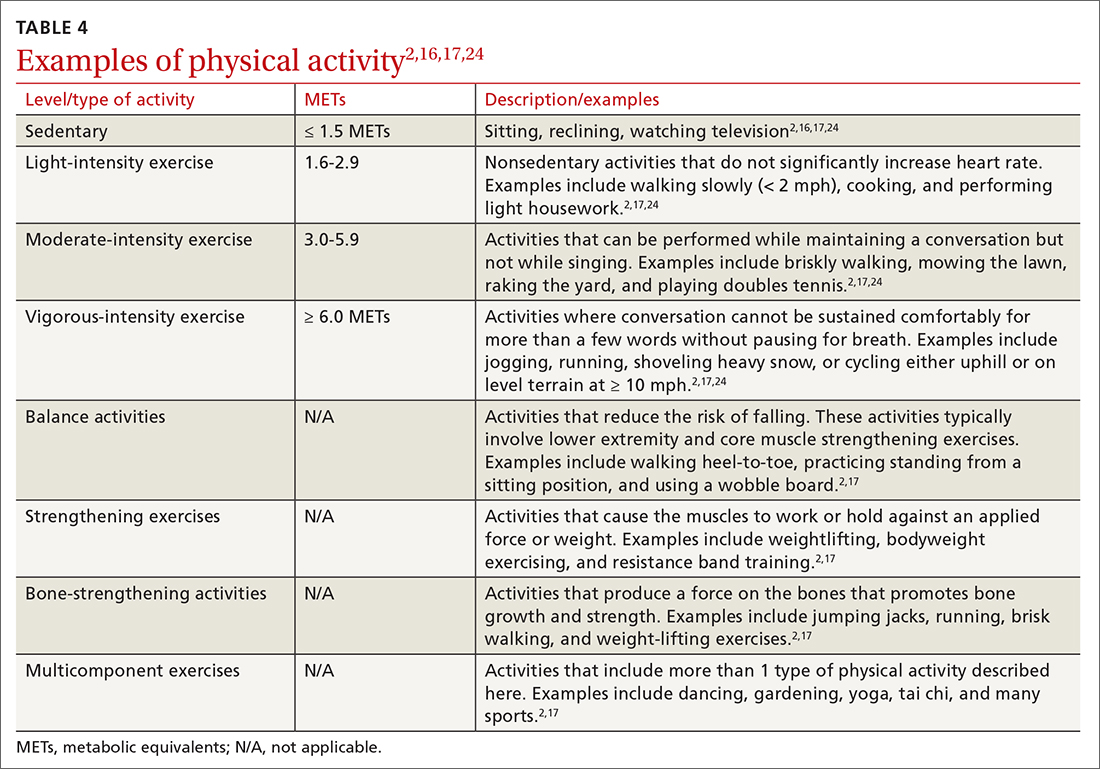

Intensity is a description of how hard an individual is working during physical activity. An older adult’s individual capacity for exercise intensity will depend on many factors, including their comorbidities. An activity’s intensity will be relative to a person’s unique level of fitness. Given this heterogeneity, exercise prescriptions should be tailored to the individual. Light-intensity exercise generally causes a slight increase in pulse and respiratory rate, moderate-intensity exercise causes a noticeable increase in pulse and respiratory rate, and vigorous-intensity exercise causes a significant increase in pulse and respiratory rate (TABLE 42,16,17,24).2

The “talk test” is a simple, practical, and validated test that can help one determine an individual’s capacity for moderate- or vigorous-intensity exercise.23 In general, a person performing vigorous-intensity exercise will be unable to talk comfortably during activity for more than a few words without pausing for breath. Similarly, a person will be able to talk but not sing comfortably during moderate-intensity exercise.3,23

Continue to: Time

Time. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend a specific duration of physical activity throughout the week; however, as with frequency, it is important to remember that duration of exercise is individualized (TABLE 22). Older adults should be as physically active as their abilities and comorbidities allow, and in the setting of frailty, numerous comorbidities, and/or a sedentary lifestyle, it is reasonable to initiate exercise recommendations with shorter durations.

Type of exercise. As noted in the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, recommendations for older adults include multiple types of exercise. In addition to these general exercise recommendations, exercise prescriptions can be individualized to target specific comorbidities (TABLE 22). Weight-bearing, bone-strengthening exercises can benefit patients with disorders of low bone density and possibly those with osteoarthritis.3,23 Patients at increased risk for falls should focus on balance-training options that strengthen the muscles of the back, abdomen, and legs, such as tai chi.3,23 Patients with cardiovascular risk can benefit from moderate- to high-intensity aerobic exercise (although exercise should be performed below anginal threshold in patients with known cardiovascular disease). Patients with type 2 diabetes achieve improved glycemic control when engaging in combined moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and resistance training.7,23

Referral to a physical therapist or sport and exercise medicine specialist can always be considered, particularly for patients with significant neurologic disorders, disability secondary to traumatic injury, or health conditions.3

An improved quality of life. Incorporating physical activity into older adults’ lives can enhance their quality of life. Family physicians are well positioned to counsel older adults on the importance and benefits of exercise and to help them overcome the barriers or resistance to undertaking a change in behavior. Guidelines, recommendations, patient history, and resources provide the support needed to prescribe individualized exercise plans for this distinct population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott T. Larson, MD, 200 Hawkins Drive, Iowa City, IA, 52242; [email protected]

1.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. 2018. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

3. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020-2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854

4. Harvey JA, Chastin SF, Skelton DA. How sedentary are older people? A systematic review of the amount of sedentary behavior. J Aging Phys Act. 2015;23:471-487. doi: 10.1123/japa.2014-0164

5. Yang L, Cao C, Kantor ED, et al. Trends in sedentary behavior among the US population, 2001-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:1587-1597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3636

6. Watson KB, Carlson SA, Gunn JP, et al. Physical inactivity among adults aged 50 years and older—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:954-958. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6536a3

7. Taylor D. Physical activity is medicine for older adults. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:26-32. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131366

8. Marquez DX, Aguinaga S, Vasquez PM, et al. A systematic review of physical activity and quality of life and well-being. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10:1098-1109. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz198

9. Dionigi R. Resistance training and older adults’ beliefs about psychological benefits: the importance of self-efficacy and social interaction. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;29:723-746. doi: 10.1123/jsep.29.6.723

10. Bethancourt HJ, Rosenberg DE, Beatty T, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of physical activity program use among older adults. Clin Med Res. 2014;12:10-20. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2013.1171

11. Strand KA, Francis SL, Margrett JA, et al. Community-based exergaming program increases physical activity and perceived wellness in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2014;22:364-371. doi: 10.1123/japa.2012-0302

12. Franco MR, Tong A, Howard K, et al. Older people’s perspectives on participation in physical activity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1268-1276. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094015

13. US Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral Counseling Interventions to Promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without cardiovascular disease risk factors. July 26, 2022. Accessed August 7, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/healthy-lifestyle-and-physical-activity-for-cvd-prevention-adults-without-known-risk-factors-behavioral-counseling#bootstrap-panel--7

14. Elley CR, Kerse N, Arroll B, et al. Effectiveness of counselling patients on physical activity in general practice: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;326:793. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.793

15. Grandes G, Sanchez A, Sanchez-Pinella RO, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity advice and prescription by physicians in routine primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:694-701. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.23

16. Lobelo F, Young DR, Sallis R, et al. Routine assessment and promotion of physical activity in healthcare settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e495-e522. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000559

17. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2021.

18. Sallis R. Developing healthcare systems to support exercise: exercise as the fifth vital sign. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:473-474. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.083469

19. Bardach SH, Schoenberg NE. The content of diet and physical activity consultations with older adults in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95:319-324. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.03.020

20. Martín-Borràs C, Giné-Garriga M, Puig-Ribera A, et al. A new model of exercise referral scheme in primary care: is the effect on adherence to physical activity sustainable in the long term? A 15-month randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e017211. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017211

21. Stoutenberg M, Shaya GE, Feldman DI, et al. Practical strategies for assessing patient physical activity levels in primary care. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;1:8-15. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.04.006

22. US Preventive Services Task Force. Cardiovascular disease risk: screening with electrocardiography. June 2018. Accessed July 19, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cardiovascular-disease-risk-screening-with-electrocardiography

23. Reed JL, Pipe AL. Practical approaches to prescribing physical activity and monitoring exercise intensity. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:514-522. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.12.024

24. Verschuren O, Mead G, Visser-Meily A. Sedentary behaviour and stroke: foundational knowledge is crucial. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:9-12. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0370

The health benefits of maintaining a physically active lifestyle are vast and irrefutable.1 Physical activity is an important modifiable behavior demonstrated to reduce the risk for many chronic diseases while improving physical function (TABLE 12).3 Physical inactivity increases with age, making older adults (ages ≥ 65 years) the least active age group and the group at greatest risk for inactivity-related health consequences.4-6 Engaging in a physically active lifestyle is especially important for older adults to maintain independence,7 quality of life,8 and the ability to perform activities of daily living.3,9

Prescribe physical activity for older adults

The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend that all healthy adults (including healthy older adults) ideally should perform muscle-strengthening activities of moderate or greater intensity that involve all major muscle groups on 2 or more days per week and either (a) 150 to 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, (b) 75 to 150 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or (c) an equivalent combination, if possible (TABLE 22).3 It is recommended that older adults specifically follow a multicomponent physical activity program that includes balance training, as well as aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities.3 Unfortunately, nearly 80% of older adults do not meet the recommended guidelines for aerobic or muscle-strengthening exercise.3

Identify barriers to exercise

Older adults report several barriers that limit physical activity. Some of the most commonly reported barriers include a lack of motivation, low self-efficacy for being active, physical limitations due to health conditions, inconvenient physical activity locations, boredom with physical activity, and lack of guidance from professionals.10-12 Physical activity programs designed for older adults should specifically target these barriers for maximum effectiveness.

Clinicians also face potential barriers for promoting physical activity among older adults. Screening patients for physical inactivity can be a challenge, given the robust number of clinical preventive services and conversations that are already recommended for older adults. Additionally, screening for physical activity is not a reimbursable service. In July, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) reaffirmed its 2017 recommendation to individualize the decision to offer or refer adults without obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or abnormal blood glucose levels or diabetes to behavioral counseling to promote a healthy diet and physical activity (Grade C rating).13

Treat physical activity as a vital sign

The Exercise is Medicine (EIM) model is based on the principle that physical activity should be treated as a vital sign and discussed during all health care visits. Health care professionals have a unique opportunity to promote physical activity, since more than 80% of US adults see a physician annually. Evidence also suggests clinician advice is associated with patients’ healthy lifestyle behaviors.14,15

EIM is a global health initiative that was established in 2007 and is managed by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). The primary objective of the EIM model is to treat physical activity behavior as a vital sign and include physical activity promotion as a standard of clinical care. In order to achieve this objective, the EIM model recommends health care systems follow 3 simple rules: (1) treat physical activity as a vital sign by measuring physical activity of every patient at every visit, (2) prescribe exercise to those patients who report not meeting the physical activity guidelines, and/or (3) refer inactive patients to evidence-based physical activity resources to receive exercise counseling.16,17

Screen for physical activity using this 2-question self-report

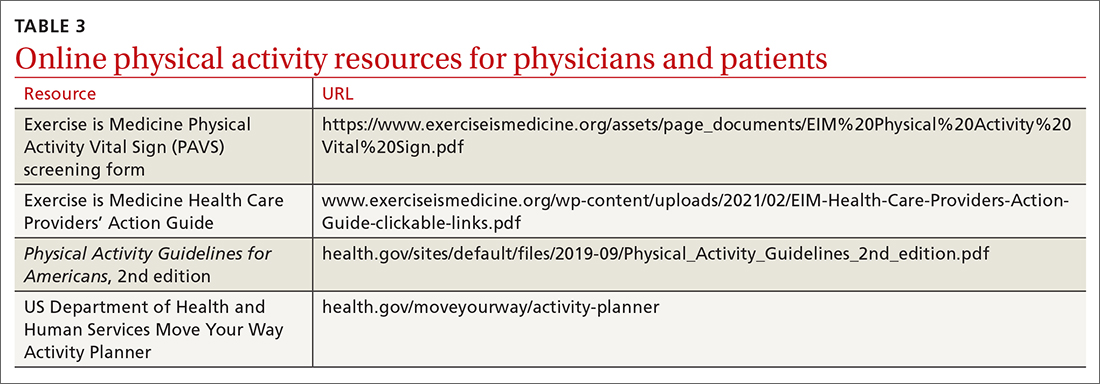

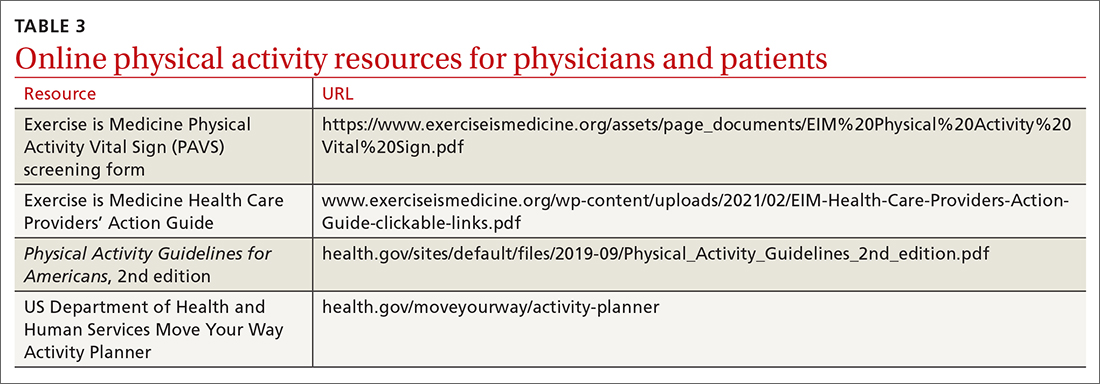

Clinicians may employ multiple tactics to screen patients for their current levels of physical activity. Physical Activity Vital Sign (PAVS) is a 2-item self-report measure developed to briefly assess a patient’s level of physical activity; results can be entered into the patient’s electronic medical record and used to begin a process of referring inactive patients for behavioral counseling.17,18 The PAVS can be administered in less than 1 minute by a medical assistant and/or nursing staff during rooming or intake of patients. The PAVS questions include, “On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity?” and “On average, how many minutes do you engage in physical activity at this level?” The clinician can then multiply the 2 numbers to calculate the patient’s total minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week to determine whether a patient is meeting the recommended physical activity guidelines.16 (For more on the PAVS and other resources, see TABLE 3.)

Continue to: The PAVS has been established...

The PAVS has been established as a valid instrument for detecting patients who may need counseling on physical activity for chronic disease recognition, management, and prevention.17 Furthermore, there is a strong association between PAVS, elevated body mass index, and chronic disease burden.19 Therefore, we recommend that primary care physicians screen their patients for physical activity levels. It has been demonstrated, however, that many primary care visits for older individuals include discussions of diet and physical activity but do not provide recommendations for lifestyle change.19 Thus, exploring ways to counsel patients on lifestyle change in an efficient manner is recommended. It has been demonstrated that counseling and referral from primary care centers can promote increased adherence to physical activity practices.20,21

Determine physical activity readiness

Prior to recommending a physical activity regimen, it is important to evaluate the patient’s readiness to make a change. Various questionnaires—such as the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire—have been developed to determine a patient’s level of readiness, evaluating both psychological and physical factors (www.nasm.org/docs/pdf/parqplus-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=401bf1af_24). Questionnaires also help you to determine whether further medical evaluation prior to beginning an exercise regimen is necessary. It’s important to note that, as is true with any office intervention, patients may be in a precontemplation or contemplation phase and may not be prepared to immediately make changes.

Evaluate risk level

Assess cardiovascular risk. Physicians and patients are often concerned about cardiovascular risk or injury risk during physical activity counseling, which may lead to fewer exercise prescriptions. As a physician, it is important to remember that for most adults, the benefits of exercise will outweigh any potential risks,3 and there is generally a low risk of cardiovascular events related to light to moderate–intensity exercise regimens.2 Additionally, it has been demonstrated that exercise and cardiovascular rehabilitation are highly beneficial for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.22 Given that cardiovascular comorbidities are relatively common in older adults, some older adults will need to undergo risk stratification evaluation prior to initiating an exercise regimen.

Review preparticipation screening guidelines and recommendations

Guidelines can be contradictory regarding the ideal pre-exercise evaluation. In general, the USPSTF recommends against screening with resting or exercise electrocardiography (EKG) to prevent cardiovascular disease events in asymptomatic adults who are at low risk. It also finds insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening with resting or exercise EKG to prevent cardiovascular disease events in asymptomatic adults who are at intermediate or high risk.22

Similarly, the 2020 ACSM Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription reflect that routine exercise testing is not recommended for all older adult patients prior to starting an exercise regimen.17 However, the ACSM does recommend all patients with signs or symptoms of a cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease consult with a clinician for medical risk stratification and potential subsequent testing prior to starting an exercise regimen. If an individual already exercises and is having new/worsening signs or symptoms of a cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease, that patient should cease exercise until medical evaluation is performed. Additionally, ACSM recommends that asymptomatic patients who do not exercise but who have known cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease receive medical evaluation prior to starting an exercise regimen.17

Continue to: Is there evidence of cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease?

Is there evidence of cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease?

Initial screening can be completed by obtaining the patient’s history and conducting a physical examination. Patients reporting chest pain or discomfort (or any anginal equivalent), dyspnea, syncope, orthopnea, lower extremity edema, signs of tachyarrhythmia/bradyarrhythmia, intermittent claudication, exertional fatigue, or new exertional symptoms should all be considered for cardiovascular stress testing. Patients with a diagnosis of renal disease or either type 1 or type 2 diabetes should also be considered for cardiovascular stress testing.

Ready to prescribe exercise? Cover these 4 points

When prescribing any exercise plan for older adults, it is important for clinicians to specify 4 key components: frequency, intensity, time, and type (this can be remembered using the acronym “FITT”).23 A sedentary adult should be encouraged to engage in moderate-intensity exercise, such as walking, for 15 minutes 3 times per week. The key with a sedentary adult is appropriate follow-up to monitor progression and modify activity to help ensure the patient can achieve the goal number of minutes per week. It can be helpful to share the “next step” with the patient, as well (eg, increase to 4 times per week after 2 weeks, or increase by 5 minutes every week). For the intermittent exerciser, a program of moderate exercise, such as using an elliptical, for 30 to 40 minutes 5 times per week is a recommended prescription. FITT components can be tailored to meet individual patient physical readiness.23

Frequency. While the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend a specific frequency of physical activity throughout the week, it is important to remember that some older adults will be unable to meet these recommendations, particularly in the setting of frailty and comorbidities (TABLE 22). In these cases, the guidelines simply recommend that older adults should be as physically active as their abilities and comorbidities allow. Some exercise is better than none, and generally moving more and sitting less will yield health benefits for older adult patients.

Intensity is a description of how hard an individual is working during physical activity. An older adult’s individual capacity for exercise intensity will depend on many factors, including their comorbidities. An activity’s intensity will be relative to a person’s unique level of fitness. Given this heterogeneity, exercise prescriptions should be tailored to the individual. Light-intensity exercise generally causes a slight increase in pulse and respiratory rate, moderate-intensity exercise causes a noticeable increase in pulse and respiratory rate, and vigorous-intensity exercise causes a significant increase in pulse and respiratory rate (TABLE 42,16,17,24).2

The “talk test” is a simple, practical, and validated test that can help one determine an individual’s capacity for moderate- or vigorous-intensity exercise.23 In general, a person performing vigorous-intensity exercise will be unable to talk comfortably during activity for more than a few words without pausing for breath. Similarly, a person will be able to talk but not sing comfortably during moderate-intensity exercise.3,23

Continue to: Time

Time. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend a specific duration of physical activity throughout the week; however, as with frequency, it is important to remember that duration of exercise is individualized (TABLE 22). Older adults should be as physically active as their abilities and comorbidities allow, and in the setting of frailty, numerous comorbidities, and/or a sedentary lifestyle, it is reasonable to initiate exercise recommendations with shorter durations.

Type of exercise. As noted in the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, recommendations for older adults include multiple types of exercise. In addition to these general exercise recommendations, exercise prescriptions can be individualized to target specific comorbidities (TABLE 22). Weight-bearing, bone-strengthening exercises can benefit patients with disorders of low bone density and possibly those with osteoarthritis.3,23 Patients at increased risk for falls should focus on balance-training options that strengthen the muscles of the back, abdomen, and legs, such as tai chi.3,23 Patients with cardiovascular risk can benefit from moderate- to high-intensity aerobic exercise (although exercise should be performed below anginal threshold in patients with known cardiovascular disease). Patients with type 2 diabetes achieve improved glycemic control when engaging in combined moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and resistance training.7,23

Referral to a physical therapist or sport and exercise medicine specialist can always be considered, particularly for patients with significant neurologic disorders, disability secondary to traumatic injury, or health conditions.3

An improved quality of life. Incorporating physical activity into older adults’ lives can enhance their quality of life. Family physicians are well positioned to counsel older adults on the importance and benefits of exercise and to help them overcome the barriers or resistance to undertaking a change in behavior. Guidelines, recommendations, patient history, and resources provide the support needed to prescribe individualized exercise plans for this distinct population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott T. Larson, MD, 200 Hawkins Drive, Iowa City, IA, 52242; [email protected]

The health benefits of maintaining a physically active lifestyle are vast and irrefutable.1 Physical activity is an important modifiable behavior demonstrated to reduce the risk for many chronic diseases while improving physical function (TABLE 12).3 Physical inactivity increases with age, making older adults (ages ≥ 65 years) the least active age group and the group at greatest risk for inactivity-related health consequences.4-6 Engaging in a physically active lifestyle is especially important for older adults to maintain independence,7 quality of life,8 and the ability to perform activities of daily living.3,9

Prescribe physical activity for older adults

The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend that all healthy adults (including healthy older adults) ideally should perform muscle-strengthening activities of moderate or greater intensity that involve all major muscle groups on 2 or more days per week and either (a) 150 to 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, (b) 75 to 150 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or (c) an equivalent combination, if possible (TABLE 22).3 It is recommended that older adults specifically follow a multicomponent physical activity program that includes balance training, as well as aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities.3 Unfortunately, nearly 80% of older adults do not meet the recommended guidelines for aerobic or muscle-strengthening exercise.3

Identify barriers to exercise

Older adults report several barriers that limit physical activity. Some of the most commonly reported barriers include a lack of motivation, low self-efficacy for being active, physical limitations due to health conditions, inconvenient physical activity locations, boredom with physical activity, and lack of guidance from professionals.10-12 Physical activity programs designed for older adults should specifically target these barriers for maximum effectiveness.

Clinicians also face potential barriers for promoting physical activity among older adults. Screening patients for physical inactivity can be a challenge, given the robust number of clinical preventive services and conversations that are already recommended for older adults. Additionally, screening for physical activity is not a reimbursable service. In July, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) reaffirmed its 2017 recommendation to individualize the decision to offer or refer adults without obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or abnormal blood glucose levels or diabetes to behavioral counseling to promote a healthy diet and physical activity (Grade C rating).13

Treat physical activity as a vital sign

The Exercise is Medicine (EIM) model is based on the principle that physical activity should be treated as a vital sign and discussed during all health care visits. Health care professionals have a unique opportunity to promote physical activity, since more than 80% of US adults see a physician annually. Evidence also suggests clinician advice is associated with patients’ healthy lifestyle behaviors.14,15

EIM is a global health initiative that was established in 2007 and is managed by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). The primary objective of the EIM model is to treat physical activity behavior as a vital sign and include physical activity promotion as a standard of clinical care. In order to achieve this objective, the EIM model recommends health care systems follow 3 simple rules: (1) treat physical activity as a vital sign by measuring physical activity of every patient at every visit, (2) prescribe exercise to those patients who report not meeting the physical activity guidelines, and/or (3) refer inactive patients to evidence-based physical activity resources to receive exercise counseling.16,17

Screen for physical activity using this 2-question self-report

Clinicians may employ multiple tactics to screen patients for their current levels of physical activity. Physical Activity Vital Sign (PAVS) is a 2-item self-report measure developed to briefly assess a patient’s level of physical activity; results can be entered into the patient’s electronic medical record and used to begin a process of referring inactive patients for behavioral counseling.17,18 The PAVS can be administered in less than 1 minute by a medical assistant and/or nursing staff during rooming or intake of patients. The PAVS questions include, “On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity?” and “On average, how many minutes do you engage in physical activity at this level?” The clinician can then multiply the 2 numbers to calculate the patient’s total minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week to determine whether a patient is meeting the recommended physical activity guidelines.16 (For more on the PAVS and other resources, see TABLE 3.)

Continue to: The PAVS has been established...

The PAVS has been established as a valid instrument for detecting patients who may need counseling on physical activity for chronic disease recognition, management, and prevention.17 Furthermore, there is a strong association between PAVS, elevated body mass index, and chronic disease burden.19 Therefore, we recommend that primary care physicians screen their patients for physical activity levels. It has been demonstrated, however, that many primary care visits for older individuals include discussions of diet and physical activity but do not provide recommendations for lifestyle change.19 Thus, exploring ways to counsel patients on lifestyle change in an efficient manner is recommended. It has been demonstrated that counseling and referral from primary care centers can promote increased adherence to physical activity practices.20,21

Determine physical activity readiness

Prior to recommending a physical activity regimen, it is important to evaluate the patient’s readiness to make a change. Various questionnaires—such as the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire—have been developed to determine a patient’s level of readiness, evaluating both psychological and physical factors (www.nasm.org/docs/pdf/parqplus-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=401bf1af_24). Questionnaires also help you to determine whether further medical evaluation prior to beginning an exercise regimen is necessary. It’s important to note that, as is true with any office intervention, patients may be in a precontemplation or contemplation phase and may not be prepared to immediately make changes.

Evaluate risk level

Assess cardiovascular risk. Physicians and patients are often concerned about cardiovascular risk or injury risk during physical activity counseling, which may lead to fewer exercise prescriptions. As a physician, it is important to remember that for most adults, the benefits of exercise will outweigh any potential risks,3 and there is generally a low risk of cardiovascular events related to light to moderate–intensity exercise regimens.2 Additionally, it has been demonstrated that exercise and cardiovascular rehabilitation are highly beneficial for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.22 Given that cardiovascular comorbidities are relatively common in older adults, some older adults will need to undergo risk stratification evaluation prior to initiating an exercise regimen.

Review preparticipation screening guidelines and recommendations

Guidelines can be contradictory regarding the ideal pre-exercise evaluation. In general, the USPSTF recommends against screening with resting or exercise electrocardiography (EKG) to prevent cardiovascular disease events in asymptomatic adults who are at low risk. It also finds insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening with resting or exercise EKG to prevent cardiovascular disease events in asymptomatic adults who are at intermediate or high risk.22

Similarly, the 2020 ACSM Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription reflect that routine exercise testing is not recommended for all older adult patients prior to starting an exercise regimen.17 However, the ACSM does recommend all patients with signs or symptoms of a cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease consult with a clinician for medical risk stratification and potential subsequent testing prior to starting an exercise regimen. If an individual already exercises and is having new/worsening signs or symptoms of a cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease, that patient should cease exercise until medical evaluation is performed. Additionally, ACSM recommends that asymptomatic patients who do not exercise but who have known cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease receive medical evaluation prior to starting an exercise regimen.17

Continue to: Is there evidence of cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease?

Is there evidence of cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease?

Initial screening can be completed by obtaining the patient’s history and conducting a physical examination. Patients reporting chest pain or discomfort (or any anginal equivalent), dyspnea, syncope, orthopnea, lower extremity edema, signs of tachyarrhythmia/bradyarrhythmia, intermittent claudication, exertional fatigue, or new exertional symptoms should all be considered for cardiovascular stress testing. Patients with a diagnosis of renal disease or either type 1 or type 2 diabetes should also be considered for cardiovascular stress testing.

Ready to prescribe exercise? Cover these 4 points

When prescribing any exercise plan for older adults, it is important for clinicians to specify 4 key components: frequency, intensity, time, and type (this can be remembered using the acronym “FITT”).23 A sedentary adult should be encouraged to engage in moderate-intensity exercise, such as walking, for 15 minutes 3 times per week. The key with a sedentary adult is appropriate follow-up to monitor progression and modify activity to help ensure the patient can achieve the goal number of minutes per week. It can be helpful to share the “next step” with the patient, as well (eg, increase to 4 times per week after 2 weeks, or increase by 5 minutes every week). For the intermittent exerciser, a program of moderate exercise, such as using an elliptical, for 30 to 40 minutes 5 times per week is a recommended prescription. FITT components can be tailored to meet individual patient physical readiness.23

Frequency. While the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend a specific frequency of physical activity throughout the week, it is important to remember that some older adults will be unable to meet these recommendations, particularly in the setting of frailty and comorbidities (TABLE 22). In these cases, the guidelines simply recommend that older adults should be as physically active as their abilities and comorbidities allow. Some exercise is better than none, and generally moving more and sitting less will yield health benefits for older adult patients.

Intensity is a description of how hard an individual is working during physical activity. An older adult’s individual capacity for exercise intensity will depend on many factors, including their comorbidities. An activity’s intensity will be relative to a person’s unique level of fitness. Given this heterogeneity, exercise prescriptions should be tailored to the individual. Light-intensity exercise generally causes a slight increase in pulse and respiratory rate, moderate-intensity exercise causes a noticeable increase in pulse and respiratory rate, and vigorous-intensity exercise causes a significant increase in pulse and respiratory rate (TABLE 42,16,17,24).2

The “talk test” is a simple, practical, and validated test that can help one determine an individual’s capacity for moderate- or vigorous-intensity exercise.23 In general, a person performing vigorous-intensity exercise will be unable to talk comfortably during activity for more than a few words without pausing for breath. Similarly, a person will be able to talk but not sing comfortably during moderate-intensity exercise.3,23

Continue to: Time

Time. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend a specific duration of physical activity throughout the week; however, as with frequency, it is important to remember that duration of exercise is individualized (TABLE 22). Older adults should be as physically active as their abilities and comorbidities allow, and in the setting of frailty, numerous comorbidities, and/or a sedentary lifestyle, it is reasonable to initiate exercise recommendations with shorter durations.

Type of exercise. As noted in the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, recommendations for older adults include multiple types of exercise. In addition to these general exercise recommendations, exercise prescriptions can be individualized to target specific comorbidities (TABLE 22). Weight-bearing, bone-strengthening exercises can benefit patients with disorders of low bone density and possibly those with osteoarthritis.3,23 Patients at increased risk for falls should focus on balance-training options that strengthen the muscles of the back, abdomen, and legs, such as tai chi.3,23 Patients with cardiovascular risk can benefit from moderate- to high-intensity aerobic exercise (although exercise should be performed below anginal threshold in patients with known cardiovascular disease). Patients with type 2 diabetes achieve improved glycemic control when engaging in combined moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and resistance training.7,23

Referral to a physical therapist or sport and exercise medicine specialist can always be considered, particularly for patients with significant neurologic disorders, disability secondary to traumatic injury, or health conditions.3

An improved quality of life. Incorporating physical activity into older adults’ lives can enhance their quality of life. Family physicians are well positioned to counsel older adults on the importance and benefits of exercise and to help them overcome the barriers or resistance to undertaking a change in behavior. Guidelines, recommendations, patient history, and resources provide the support needed to prescribe individualized exercise plans for this distinct population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott T. Larson, MD, 200 Hawkins Drive, Iowa City, IA, 52242; [email protected]

1.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. 2018. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

3. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020-2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854

4. Harvey JA, Chastin SF, Skelton DA. How sedentary are older people? A systematic review of the amount of sedentary behavior. J Aging Phys Act. 2015;23:471-487. doi: 10.1123/japa.2014-0164

5. Yang L, Cao C, Kantor ED, et al. Trends in sedentary behavior among the US population, 2001-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:1587-1597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3636

6. Watson KB, Carlson SA, Gunn JP, et al. Physical inactivity among adults aged 50 years and older—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:954-958. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6536a3

7. Taylor D. Physical activity is medicine for older adults. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:26-32. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131366

8. Marquez DX, Aguinaga S, Vasquez PM, et al. A systematic review of physical activity and quality of life and well-being. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10:1098-1109. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz198

9. Dionigi R. Resistance training and older adults’ beliefs about psychological benefits: the importance of self-efficacy and social interaction. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;29:723-746. doi: 10.1123/jsep.29.6.723

10. Bethancourt HJ, Rosenberg DE, Beatty T, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of physical activity program use among older adults. Clin Med Res. 2014;12:10-20. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2013.1171

11. Strand KA, Francis SL, Margrett JA, et al. Community-based exergaming program increases physical activity and perceived wellness in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2014;22:364-371. doi: 10.1123/japa.2012-0302

12. Franco MR, Tong A, Howard K, et al. Older people’s perspectives on participation in physical activity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1268-1276. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094015

13. US Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral Counseling Interventions to Promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without cardiovascular disease risk factors. July 26, 2022. Accessed August 7, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/healthy-lifestyle-and-physical-activity-for-cvd-prevention-adults-without-known-risk-factors-behavioral-counseling#bootstrap-panel--7

14. Elley CR, Kerse N, Arroll B, et al. Effectiveness of counselling patients on physical activity in general practice: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;326:793. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.793

15. Grandes G, Sanchez A, Sanchez-Pinella RO, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity advice and prescription by physicians in routine primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:694-701. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.23

16. Lobelo F, Young DR, Sallis R, et al. Routine assessment and promotion of physical activity in healthcare settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e495-e522. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000559

17. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2021.

18. Sallis R. Developing healthcare systems to support exercise: exercise as the fifth vital sign. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:473-474. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.083469

19. Bardach SH, Schoenberg NE. The content of diet and physical activity consultations with older adults in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95:319-324. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.03.020

20. Martín-Borràs C, Giné-Garriga M, Puig-Ribera A, et al. A new model of exercise referral scheme in primary care: is the effect on adherence to physical activity sustainable in the long term? A 15-month randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e017211. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017211

21. Stoutenberg M, Shaya GE, Feldman DI, et al. Practical strategies for assessing patient physical activity levels in primary care. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;1:8-15. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.04.006

22. US Preventive Services Task Force. Cardiovascular disease risk: screening with electrocardiography. June 2018. Accessed July 19, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cardiovascular-disease-risk-screening-with-electrocardiography

23. Reed JL, Pipe AL. Practical approaches to prescribing physical activity and monitoring exercise intensity. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:514-522. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.12.024

24. Verschuren O, Mead G, Visser-Meily A. Sedentary behaviour and stroke: foundational knowledge is crucial. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:9-12. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0370

1.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. 2018. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

3. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020-2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854

4. Harvey JA, Chastin SF, Skelton DA. How sedentary are older people? A systematic review of the amount of sedentary behavior. J Aging Phys Act. 2015;23:471-487. doi: 10.1123/japa.2014-0164

5. Yang L, Cao C, Kantor ED, et al. Trends in sedentary behavior among the US population, 2001-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:1587-1597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3636

6. Watson KB, Carlson SA, Gunn JP, et al. Physical inactivity among adults aged 50 years and older—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:954-958. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6536a3

7. Taylor D. Physical activity is medicine for older adults. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:26-32. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131366

8. Marquez DX, Aguinaga S, Vasquez PM, et al. A systematic review of physical activity and quality of life and well-being. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10:1098-1109. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz198

9. Dionigi R. Resistance training and older adults’ beliefs about psychological benefits: the importance of self-efficacy and social interaction. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;29:723-746. doi: 10.1123/jsep.29.6.723

10. Bethancourt HJ, Rosenberg DE, Beatty T, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of physical activity program use among older adults. Clin Med Res. 2014;12:10-20. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2013.1171

11. Strand KA, Francis SL, Margrett JA, et al. Community-based exergaming program increases physical activity and perceived wellness in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2014;22:364-371. doi: 10.1123/japa.2012-0302

12. Franco MR, Tong A, Howard K, et al. Older people’s perspectives on participation in physical activity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1268-1276. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094015

13. US Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral Counseling Interventions to Promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without cardiovascular disease risk factors. July 26, 2022. Accessed August 7, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/healthy-lifestyle-and-physical-activity-for-cvd-prevention-adults-without-known-risk-factors-behavioral-counseling#bootstrap-panel--7

14. Elley CR, Kerse N, Arroll B, et al. Effectiveness of counselling patients on physical activity in general practice: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;326:793. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.793

15. Grandes G, Sanchez A, Sanchez-Pinella RO, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity advice and prescription by physicians in routine primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:694-701. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.23

16. Lobelo F, Young DR, Sallis R, et al. Routine assessment and promotion of physical activity in healthcare settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e495-e522. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000559

17. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2021.

18. Sallis R. Developing healthcare systems to support exercise: exercise as the fifth vital sign. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:473-474. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.083469

19. Bardach SH, Schoenberg NE. The content of diet and physical activity consultations with older adults in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95:319-324. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.03.020

20. Martín-Borràs C, Giné-Garriga M, Puig-Ribera A, et al. A new model of exercise referral scheme in primary care: is the effect on adherence to physical activity sustainable in the long term? A 15-month randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e017211. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017211

21. Stoutenberg M, Shaya GE, Feldman DI, et al. Practical strategies for assessing patient physical activity levels in primary care. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;1:8-15. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.04.006

22. US Preventive Services Task Force. Cardiovascular disease risk: screening with electrocardiography. June 2018. Accessed July 19, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cardiovascular-disease-risk-screening-with-electrocardiography

23. Reed JL, Pipe AL. Practical approaches to prescribing physical activity and monitoring exercise intensity. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:514-522. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.12.024

24. Verschuren O, Mead G, Visser-Meily A. Sedentary behaviour and stroke: foundational knowledge is crucial. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:9-12. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0370

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Encourage older adults to engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week, OR at least 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week, OR an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity. A

› Recommend older adults perform muscle-strengthening activities involving major muscle groups on 2 or more days per week. A

› Encourage older adults to be as physically active as possible, even when their health conditions and abilities prevent them from reaching their minimum levels of physical activity. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Barriers to System Quality Improvement in Health Care

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; [email protected]

Process improvement in any industry sector aims to increase the efficiency of resource utilization and delivery methods (cost) and the quality of the product (outcomes), with the goal of ultimately achieving continuous development.1 In the health care industry, variation in processes and outcomes along with inefficiency in resource use that result in changes in value (the product of outcomes/costs) are the general targets of quality improvement (QI) efforts employing various implementation methodologies.2 When the ultimate aim is to serve the patient (customer), best clinical practice includes both maintaining high quality (individual care delivery) and controlling costs (efficient care system delivery), leading to optimal delivery (value-based care). High-quality individual care and efficient care delivery are not competing concepts, but when working to improve both health care outcomes and cost, traditional and nontraditional barriers to system QI often arise.3

The possible scenarios after a QI intervention include backsliding (regression to the mean over time), steady-state (minimal fixed improvement that could sustain), and continuous improvement (tangible enhancement after completing the intervention with legacy effect).4 The scalability of results can be considered during the process measurement and the intervention design phases of all QI projects; however, the complex nature of barriers in the health care environment during each level of implementation should be accounted for to prevent failure in the scalability phase.5

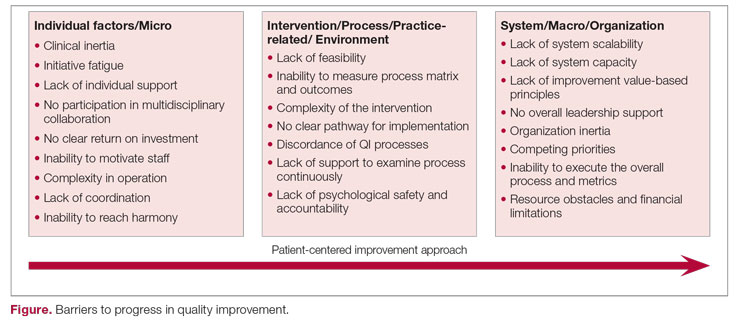

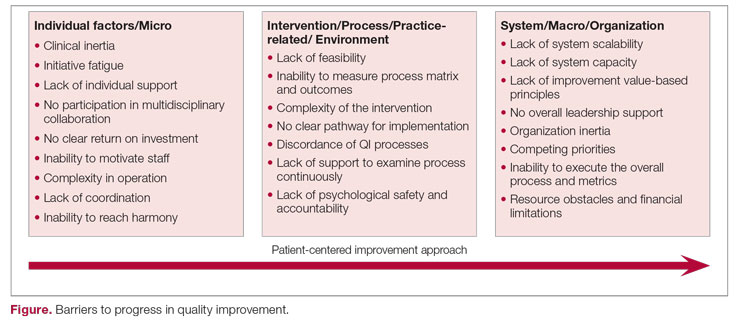

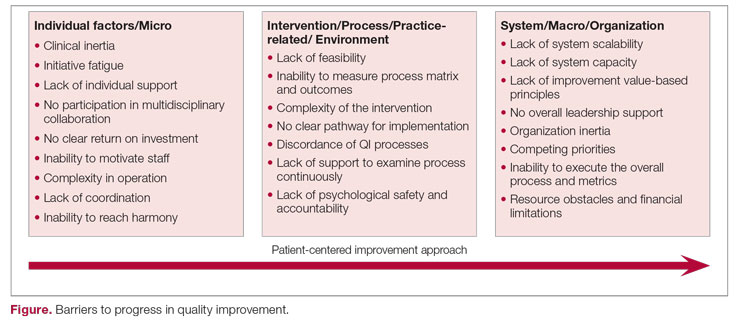

The barriers to optimal QI outcomes leading to continuous improvement are multifactorial and are related to intrinsic and extrinsic factors.6 These factors include 3 fundamental levels: (1) individual level inertia/beliefs, prior personal knowledge, and team-related factors7,8; (2) intervention-related and process-specific barriers and clinical practice obstacles; and (3) organizational level challenges and macro-level and population-level barriers (Figure). The obstacles faced during the implementation phase will likely include 2 of these levels simultaneously, which could add complexity and hinder or prevent the implementation of a tangible successful QI process and eventually lead to backsliding or minimal fixed improvement rather than continuous improvement. Furthermore, a patient-centered approach to QI would contribute to further complexity in design and execution, given the importance of reaching sustainable, meaningful improvement by adding elements of patient’s preferences, caregiver engagement, and the shared decision-making processes.9

Overcoming these multidomain barriers and reaching resilience and sustainability requires thoughtful planning and execution through a multifaceted approach.10 A meaningful start could include addressing the clinical inertia for the individual and the team by promoting open innovation and allowing outside institutional collaborations and ideas through networks.11 On the individual level, encouraging participation and motivating health care workers in QI to reach a multidisciplinary operation approach will lead to harmony in collaboration. Concurrently, the organization should support the QI capability and scalability by removing competing priorities and establishing effective leadership that ensures resource allocation, communicates clear value-based principles, and engenders a psychological safety environment.

A continuous improvement state is the optimal QI target, a target that can be attained by removing obstacles and paving a clear pathway to implementation. Focusing on the 3 levels of barriers will position the organization for meaningful and successful QI phases to achieve continuous improvement.

1. Adesola S, Baines T. Developing and evaluating a methodology for business process improvement. Business Process Manage J. 2005;11(1):37-46. doi:10.1108/14637150510578719

2. Gershon M. Choosing which process improvement methodology to implement. J Appl Business & Economics. 2010;10(5):61-69.

3. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

4. Holweg M, Davies J, De Meyer A, Lawson B, Schmenner RW. Process Theory: The Principles of Operations Management. Oxford University Press; 2018.

5. Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593-624. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00107

6. Solomons NM, Spross JA. Evidence‐based practice barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an integrative review. J Nurs Manage. 2011;19(1):109-120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01144.x

7. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

8. Stevenson K, Baker R, Farooqi A, Sorrie R, Khunti K. Features of primary health care teams associated with successful quality improvement of diabetes care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2001;18(1):21-26. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.1.21

9. What is patient-centered care? NEJM Catalyst. January 1, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559

10. Kilbourne AM, Beck K, Spaeth‐Rublee B, et al. Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: a global perspective. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):30-8. doi:10.1002/wps.20482

11. Huang HC, Lai MC, Lin LH, Chen CT. Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: An open innovation perspective. J Organizational Change Manage. 2013;26(6):977-1002. doi:10.1108/JOCM-04-2012-0047

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; [email protected]

Process improvement in any industry sector aims to increase the efficiency of resource utilization and delivery methods (cost) and the quality of the product (outcomes), with the goal of ultimately achieving continuous development.1 In the health care industry, variation in processes and outcomes along with inefficiency in resource use that result in changes in value (the product of outcomes/costs) are the general targets of quality improvement (QI) efforts employing various implementation methodologies.2 When the ultimate aim is to serve the patient (customer), best clinical practice includes both maintaining high quality (individual care delivery) and controlling costs (efficient care system delivery), leading to optimal delivery (value-based care). High-quality individual care and efficient care delivery are not competing concepts, but when working to improve both health care outcomes and cost, traditional and nontraditional barriers to system QI often arise.3

The possible scenarios after a QI intervention include backsliding (regression to the mean over time), steady-state (minimal fixed improvement that could sustain), and continuous improvement (tangible enhancement after completing the intervention with legacy effect).4 The scalability of results can be considered during the process measurement and the intervention design phases of all QI projects; however, the complex nature of barriers in the health care environment during each level of implementation should be accounted for to prevent failure in the scalability phase.5

The barriers to optimal QI outcomes leading to continuous improvement are multifactorial and are related to intrinsic and extrinsic factors.6 These factors include 3 fundamental levels: (1) individual level inertia/beliefs, prior personal knowledge, and team-related factors7,8; (2) intervention-related and process-specific barriers and clinical practice obstacles; and (3) organizational level challenges and macro-level and population-level barriers (Figure). The obstacles faced during the implementation phase will likely include 2 of these levels simultaneously, which could add complexity and hinder or prevent the implementation of a tangible successful QI process and eventually lead to backsliding or minimal fixed improvement rather than continuous improvement. Furthermore, a patient-centered approach to QI would contribute to further complexity in design and execution, given the importance of reaching sustainable, meaningful improvement by adding elements of patient’s preferences, caregiver engagement, and the shared decision-making processes.9

Overcoming these multidomain barriers and reaching resilience and sustainability requires thoughtful planning and execution through a multifaceted approach.10 A meaningful start could include addressing the clinical inertia for the individual and the team by promoting open innovation and allowing outside institutional collaborations and ideas through networks.11 On the individual level, encouraging participation and motivating health care workers in QI to reach a multidisciplinary operation approach will lead to harmony in collaboration. Concurrently, the organization should support the QI capability and scalability by removing competing priorities and establishing effective leadership that ensures resource allocation, communicates clear value-based principles, and engenders a psychological safety environment.

A continuous improvement state is the optimal QI target, a target that can be attained by removing obstacles and paving a clear pathway to implementation. Focusing on the 3 levels of barriers will position the organization for meaningful and successful QI phases to achieve continuous improvement.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; [email protected]

Process improvement in any industry sector aims to increase the efficiency of resource utilization and delivery methods (cost) and the quality of the product (outcomes), with the goal of ultimately achieving continuous development.1 In the health care industry, variation in processes and outcomes along with inefficiency in resource use that result in changes in value (the product of outcomes/costs) are the general targets of quality improvement (QI) efforts employing various implementation methodologies.2 When the ultimate aim is to serve the patient (customer), best clinical practice includes both maintaining high quality (individual care delivery) and controlling costs (efficient care system delivery), leading to optimal delivery (value-based care). High-quality individual care and efficient care delivery are not competing concepts, but when working to improve both health care outcomes and cost, traditional and nontraditional barriers to system QI often arise.3

The possible scenarios after a QI intervention include backsliding (regression to the mean over time), steady-state (minimal fixed improvement that could sustain), and continuous improvement (tangible enhancement after completing the intervention with legacy effect).4 The scalability of results can be considered during the process measurement and the intervention design phases of all QI projects; however, the complex nature of barriers in the health care environment during each level of implementation should be accounted for to prevent failure in the scalability phase.5

The barriers to optimal QI outcomes leading to continuous improvement are multifactorial and are related to intrinsic and extrinsic factors.6 These factors include 3 fundamental levels: (1) individual level inertia/beliefs, prior personal knowledge, and team-related factors7,8; (2) intervention-related and process-specific barriers and clinical practice obstacles; and (3) organizational level challenges and macro-level and population-level barriers (Figure). The obstacles faced during the implementation phase will likely include 2 of these levels simultaneously, which could add complexity and hinder or prevent the implementation of a tangible successful QI process and eventually lead to backsliding or minimal fixed improvement rather than continuous improvement. Furthermore, a patient-centered approach to QI would contribute to further complexity in design and execution, given the importance of reaching sustainable, meaningful improvement by adding elements of patient’s preferences, caregiver engagement, and the shared decision-making processes.9

Overcoming these multidomain barriers and reaching resilience and sustainability requires thoughtful planning and execution through a multifaceted approach.10 A meaningful start could include addressing the clinical inertia for the individual and the team by promoting open innovation and allowing outside institutional collaborations and ideas through networks.11 On the individual level, encouraging participation and motivating health care workers in QI to reach a multidisciplinary operation approach will lead to harmony in collaboration. Concurrently, the organization should support the QI capability and scalability by removing competing priorities and establishing effective leadership that ensures resource allocation, communicates clear value-based principles, and engenders a psychological safety environment.

A continuous improvement state is the optimal QI target, a target that can be attained by removing obstacles and paving a clear pathway to implementation. Focusing on the 3 levels of barriers will position the organization for meaningful and successful QI phases to achieve continuous improvement.

1. Adesola S, Baines T. Developing and evaluating a methodology for business process improvement. Business Process Manage J. 2005;11(1):37-46. doi:10.1108/14637150510578719

2. Gershon M. Choosing which process improvement methodology to implement. J Appl Business & Economics. 2010;10(5):61-69.

3. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

4. Holweg M, Davies J, De Meyer A, Lawson B, Schmenner RW. Process Theory: The Principles of Operations Management. Oxford University Press; 2018.

5. Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593-624. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00107

6. Solomons NM, Spross JA. Evidence‐based practice barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an integrative review. J Nurs Manage. 2011;19(1):109-120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01144.x

7. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

8. Stevenson K, Baker R, Farooqi A, Sorrie R, Khunti K. Features of primary health care teams associated with successful quality improvement of diabetes care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2001;18(1):21-26. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.1.21

9. What is patient-centered care? NEJM Catalyst. January 1, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559

10. Kilbourne AM, Beck K, Spaeth‐Rublee B, et al. Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: a global perspective. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):30-8. doi:10.1002/wps.20482

11. Huang HC, Lai MC, Lin LH, Chen CT. Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: An open innovation perspective. J Organizational Change Manage. 2013;26(6):977-1002. doi:10.1108/JOCM-04-2012-0047

1. Adesola S, Baines T. Developing and evaluating a methodology for business process improvement. Business Process Manage J. 2005;11(1):37-46. doi:10.1108/14637150510578719

2. Gershon M. Choosing which process improvement methodology to implement. J Appl Business & Economics. 2010;10(5):61-69.

3. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

4. Holweg M, Davies J, De Meyer A, Lawson B, Schmenner RW. Process Theory: The Principles of Operations Management. Oxford University Press; 2018.

5. Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593-624. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00107

6. Solomons NM, Spross JA. Evidence‐based practice barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an integrative review. J Nurs Manage. 2011;19(1):109-120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01144.x

7. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

8. Stevenson K, Baker R, Farooqi A, Sorrie R, Khunti K. Features of primary health care teams associated with successful quality improvement of diabetes care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2001;18(1):21-26. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.1.21

9. What is patient-centered care? NEJM Catalyst. January 1, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559

10. Kilbourne AM, Beck K, Spaeth‐Rublee B, et al. Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: a global perspective. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):30-8. doi:10.1002/wps.20482

11. Huang HC, Lai MC, Lin LH, Chen CT. Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: An open innovation perspective. J Organizational Change Manage. 2013;26(6):977-1002. doi:10.1108/JOCM-04-2012-0047

Reporting Coronary Artery Calcium on Low-Dose Computed Tomography Impacts Statin Management in a Lung Cancer Screening Population

Cigarette smoking is an independent risk factor for lung cancer and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).1-3 The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) demonstrated both lung cancer mortality reduction with the use of surveillance low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) and ASCVD as the most common cause of death among smokers.4,5 ASCVD remains the leading cause of death in the lung cancer screening (LCS) population.2,3 After publication of the NLST results, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) established LCS eligibility among smokers and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services approved payment for annual LDCT in this group.1,6,7

Recently LDCT has been proposed as an adjunct diagnostic tool for detecting coronary artery calcium (CAC), which is independently associated with ASCVD and mortality.8-13 CAC scores have been recommended by the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol treatment guidelines and shown to be cost-effective in guiding statin therapy for patients with borderline to intermediate ASCVD risk.14-16 While CAC is conventionally quantified using electrocardiogram (ECG)-gated CT, these scans are not routinely performed in clinical practice because preventive CAC screening is neither recommended by the USPSTF nor covered by most insurance providers.17,18 LDCT, conversely, is reimbursable and a well-validated ASCVD risk predictor.18,19

In this study, we aimed to determine the validity of LDCT in identifying CAC among the military LCS population and whether it would impact statin recommendations based on 10-year ASCVD risk.

Methods

Participants were recruited from a retrospective cohort of 563 Military Health System (MHS) beneficiaries who received LCS with LDCT at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth (NMCP) in Virginia between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2020. The 2013 USPSTF LCS guidelines were followed as the 2021 guidelines had not been published before the start of the study; thus, eligible participants included adults aged 55 to 80 years with at least a 30-pack-year smoking history and currently smoked or had quit within 15 years from the date of study consent.6,7