User login

Optimizing Narrowband UVB Phototherapy: Is It More Challenging for Your Older Patients?

Even with recent pharmacologic treatment advances, narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy remains a versatile, safe, and efficacious adjunctive or exclusive treatment for multiple dermatologic conditions, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

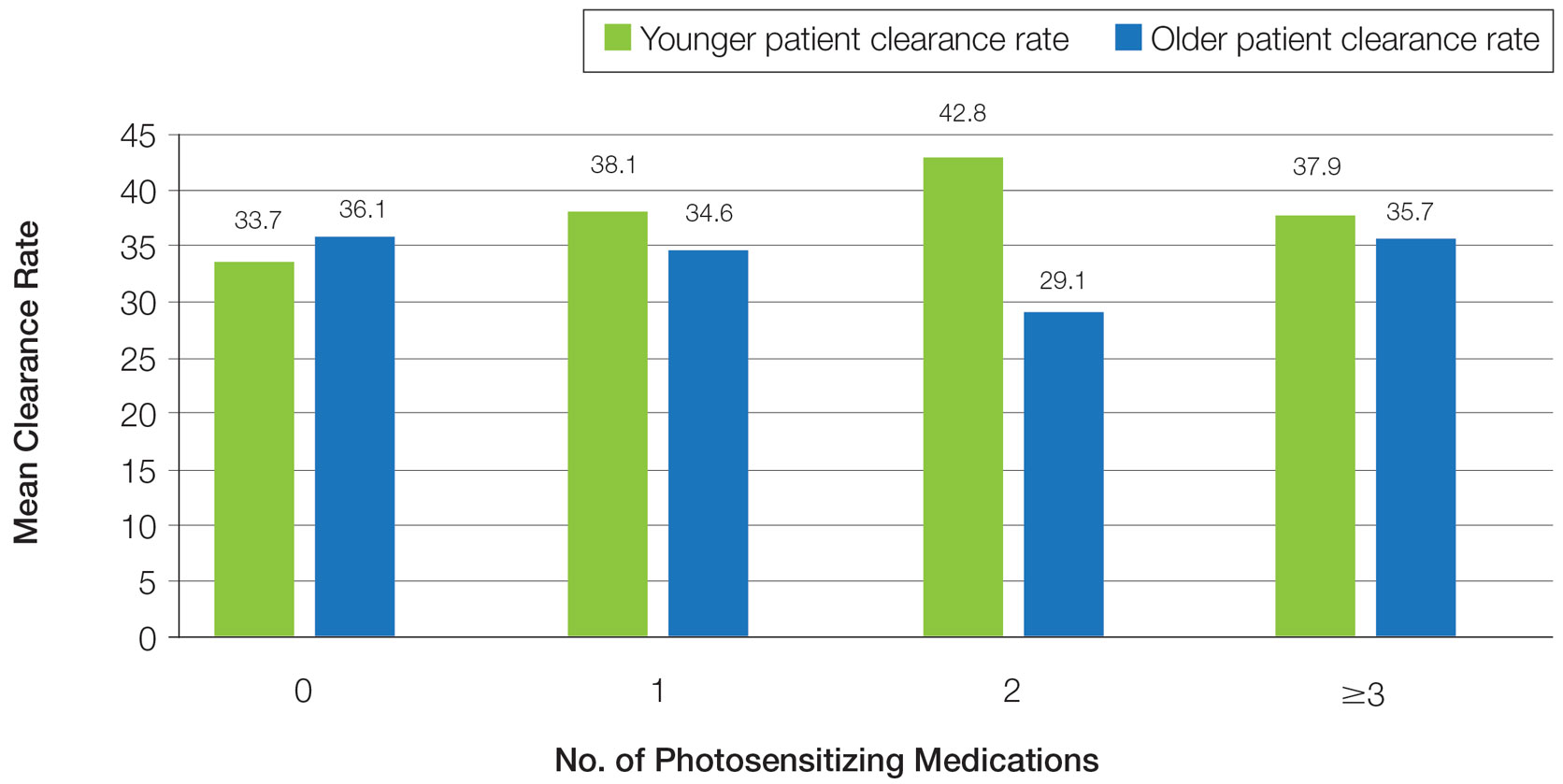

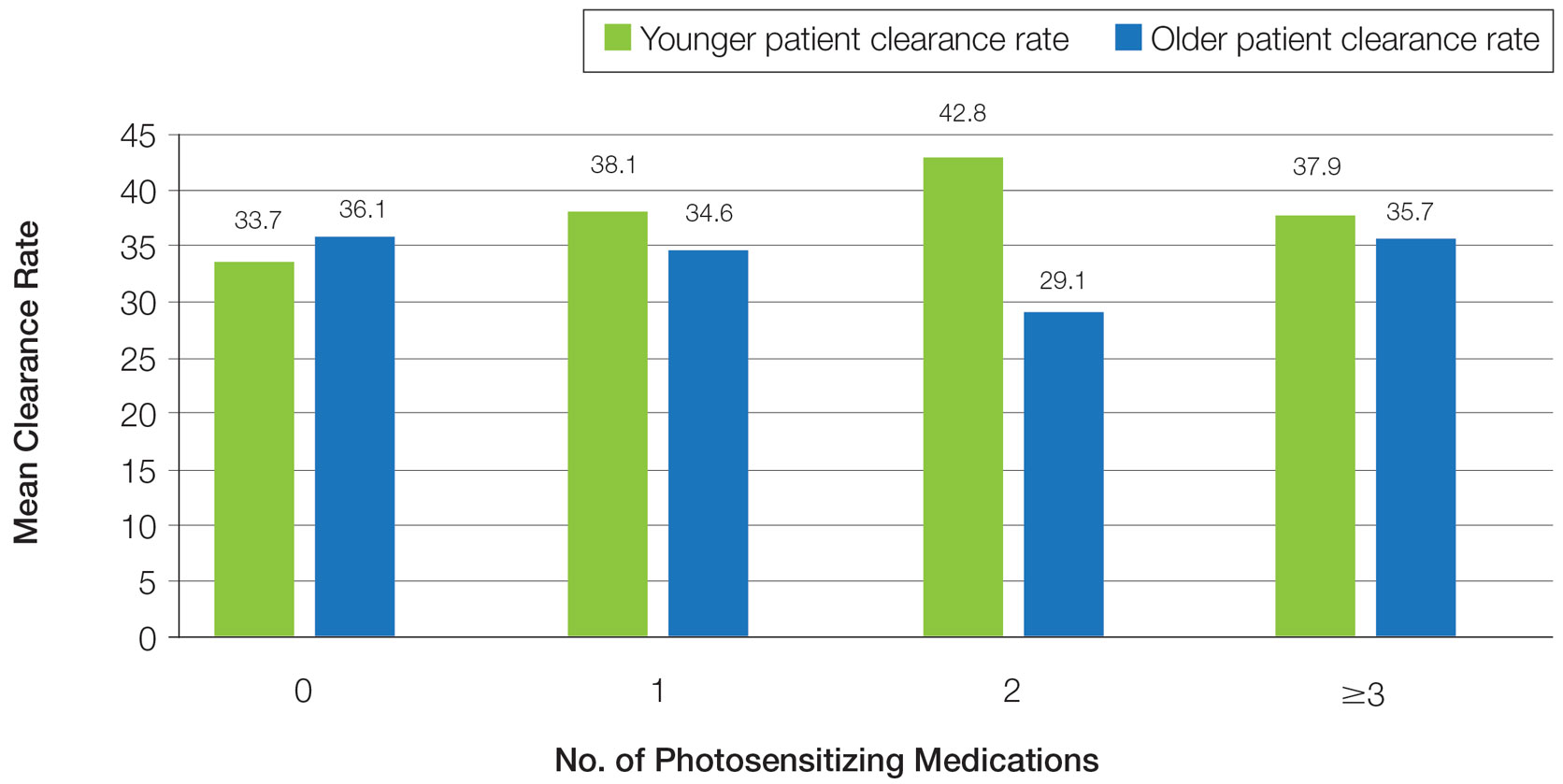

In a prior study, Matthews et al13 reported that 96% (50/52) of patients older than 65 years achieved medium to high levels of clearance with NB-UVB phototherapy. Nonetheless, 2 other findings in this study related to the number of treatments required to achieve clearance (ie, clearance rates) and erythema rates prompted further investigation. The first finding was higher-than-expected clearance rates. Older adults had a clearance rate with a mean of 33 treatments compared to prior studies featuring mean clearance rates of 20 to 28 treatments.7,8,14-16 This finding resembled a study in the United Kingdom17 with a median clearance rate in older adults of 30 treatments. In contrast, the median clearance rate from a study in Turkey18 was 42 treatments in older adults. We hypothesized that more photosensitizing medications used in older vs younger adults prompted more dose adjustments with NB-UVB phototherapy to avoid burning (ie, erythema) at baseline and throughout the treatment course. These dose adjustments may have increased the overall clearance rates. If true, we predicted that younger adults treated with the same protocol would have cleared more quickly, either because of age-related differences or because they likely had fewer comorbidities and therefore fewer medications.

The second finding from Matthews et al13 that warranted further investigation was a higher erythema rate compared to the older adult study from the United Kingdom.17 We hypothesized that potentially greater use of photosensitizing medications in the United States could explain the higher erythema rates. Although medication-induced photosensitivity is less likely with NB-UVB phototherapy than with UVA, certain medications can cause UVB photosensitivity, including thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.8,19,20 Therefore, photosensitizing medication use either at baseline or during a course of NB-UVB phototherapy could increase the risk for erythema. Age-related skin changes also have been considered as a

This retrospective study aimed to determine if NB-UVB phototherapy is equally effective in both older and younger adults treated with the same protocol; to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and clearance rates in both older and younger adults; and to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and erythema rates in older vs younger adults.

Methods

Study Design and Patients—This retrospective cohort study used billing records to identify patients who received NB-UVB phototherapy at 3 different clinical sites within a large US health care system in Washington (Group Health Cooperative, now Kaiser Permanente Washington), serving more than 600,000 patients between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2016. The institutional review board of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute approved this study (IRB 1498087-4). Younger adults were classified as those 64 years or younger and older adults as those 65 years and older at the start of their phototherapy regimen. A power analysis determined that the optimal sample size for this study was 250 patients.

Individuals were excluded if they had fewer than 6 phototherapy treatments; a diagnosis of vitiligo, photosensitivity dermatitis, morphea, or pityriasis rubra pilaris; and/or treatment of the hands or feet only.

Phototherapy Protocol—Using a 48-lamp NB-UVB unit, trained phototherapy nurses provided all treatments following standardized treatment protocols13 based on previously published phototherapy guidelines.24 Nurses determined each patient’s disease clearance level using a 3-point clearance scale (high, medium, low).13 Each patient’s starting dose was determined based on the estimated MED for their skin phototype.

Statistical Analysis—Data were analyzed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp LLC). Univariate analyses were used to examine the data and identify outliers, bad values, and missing data, as well as to calculate descriptive statistics. Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact statistics were used to calculate differences in categorical variables. Linear multivariate regression models and logistic multivariate models were used to examine statistical relationships between variables. Statistical significance was defined as P≤.05.

Results

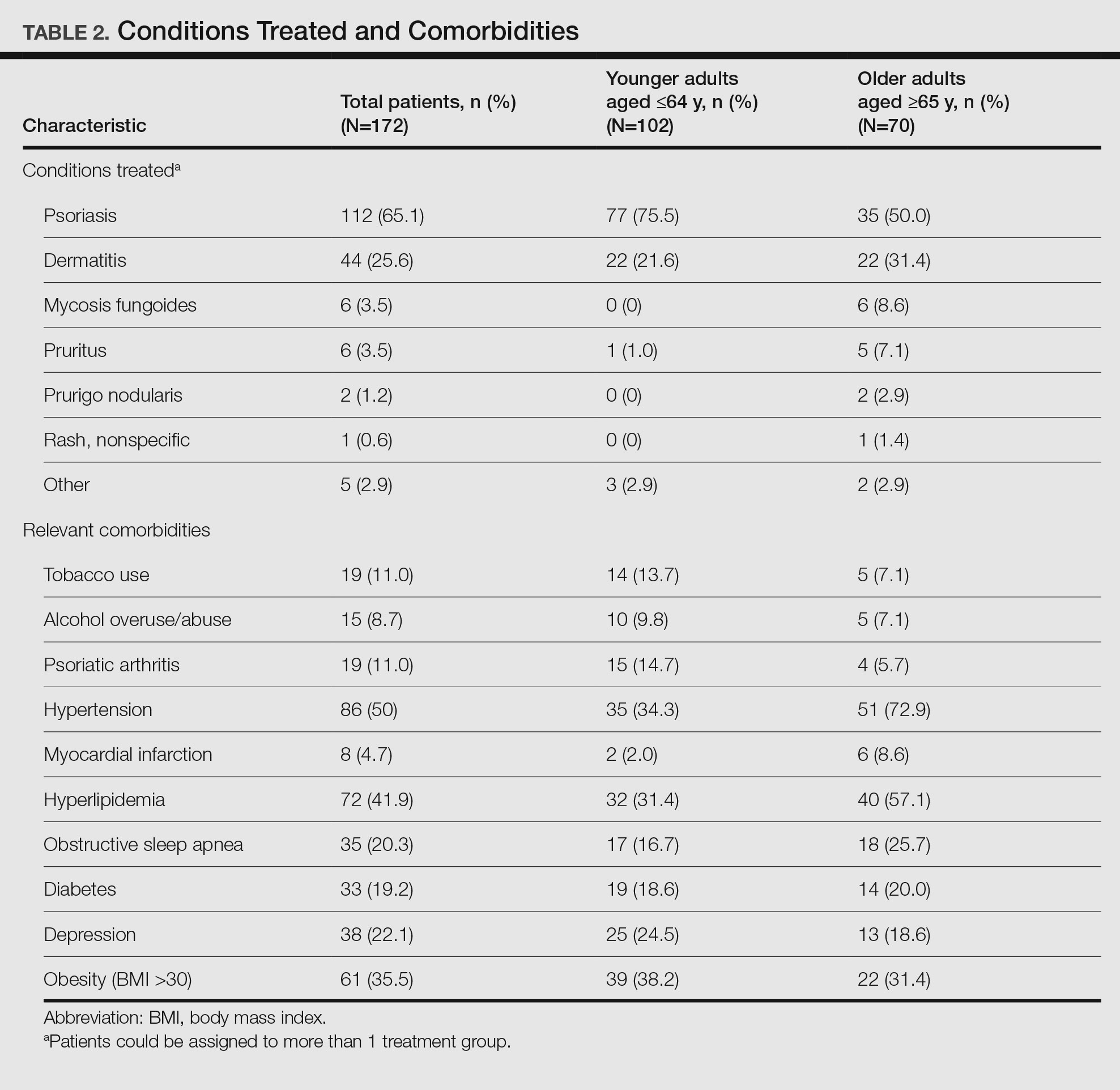

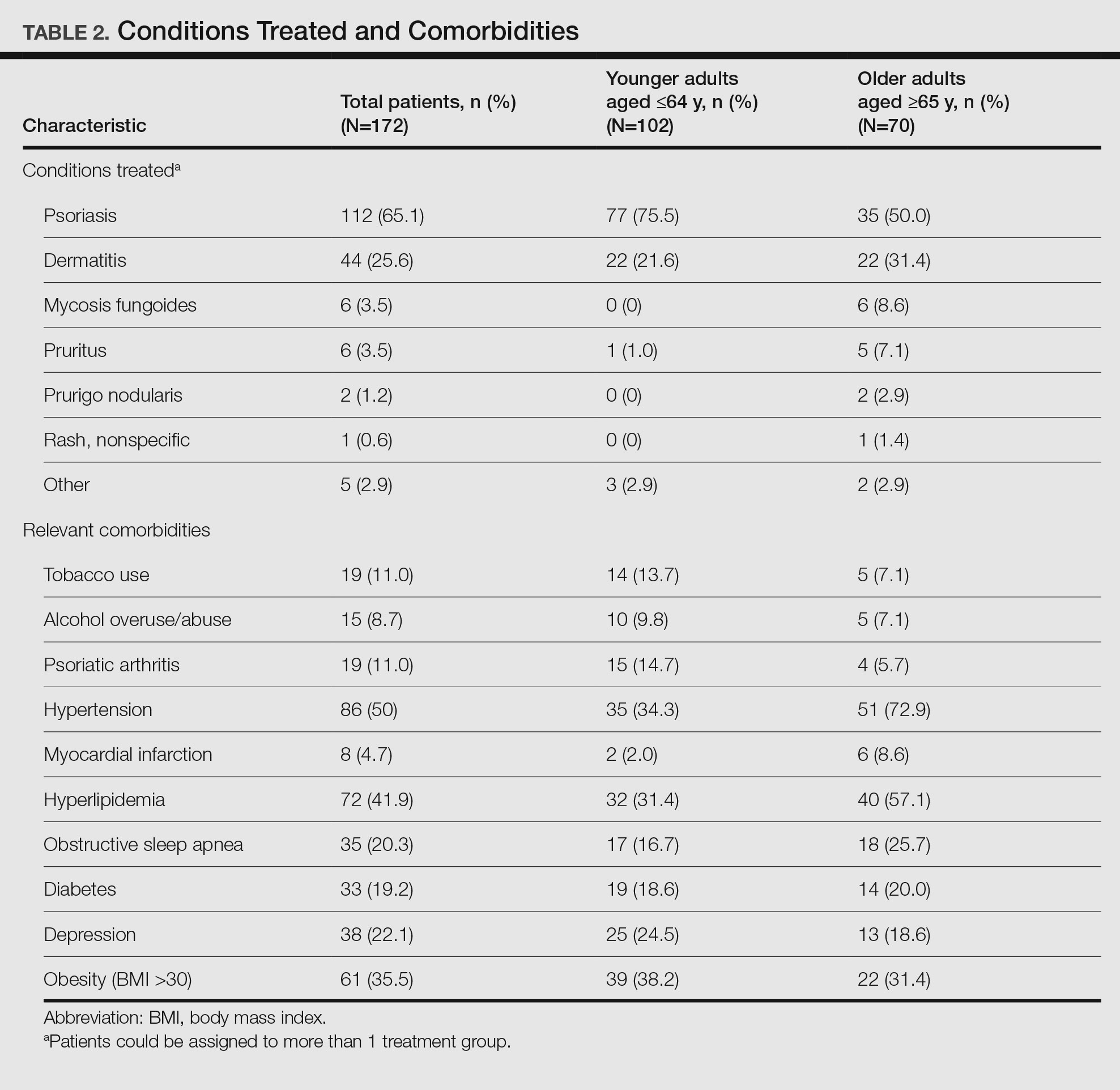

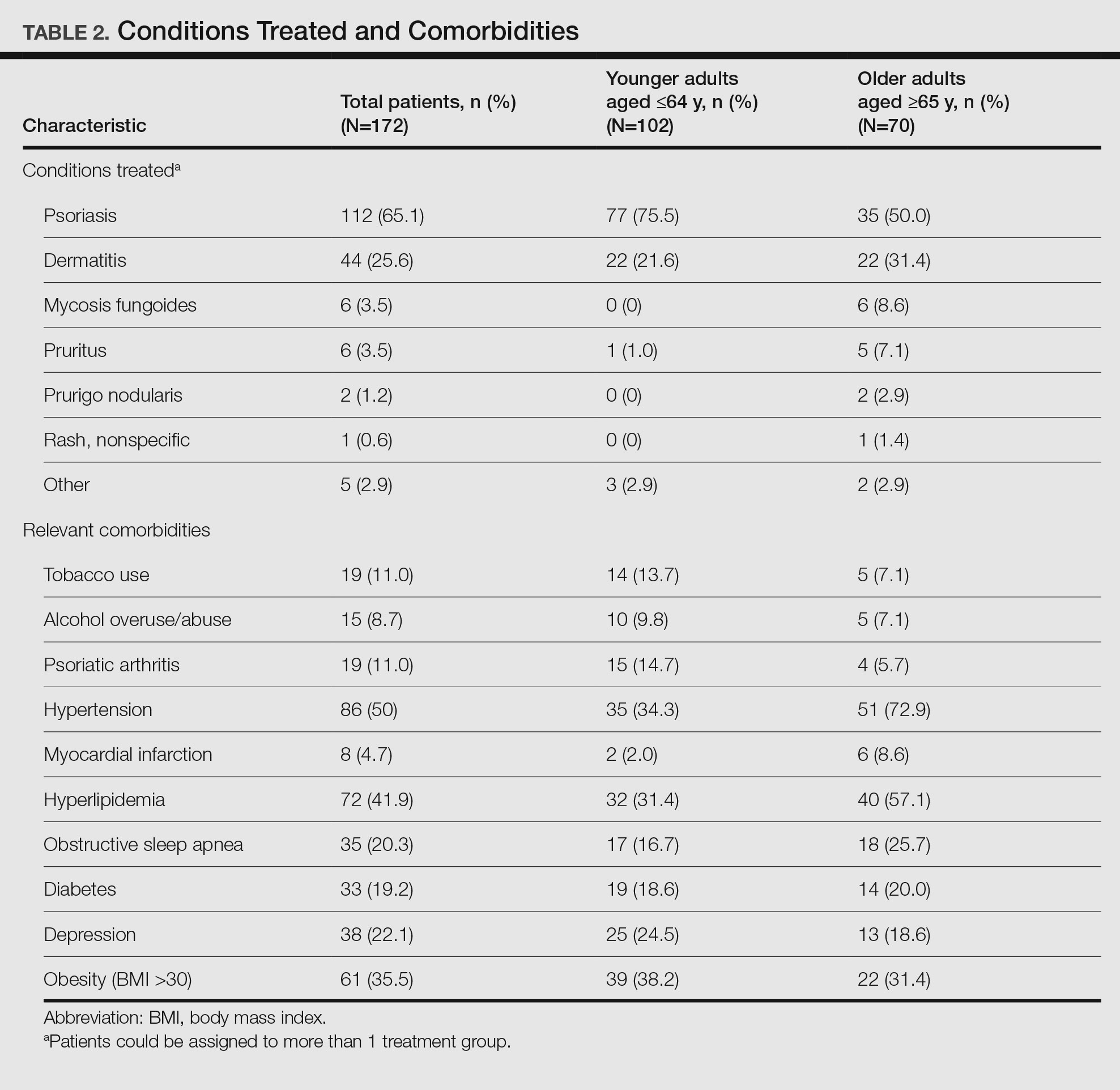

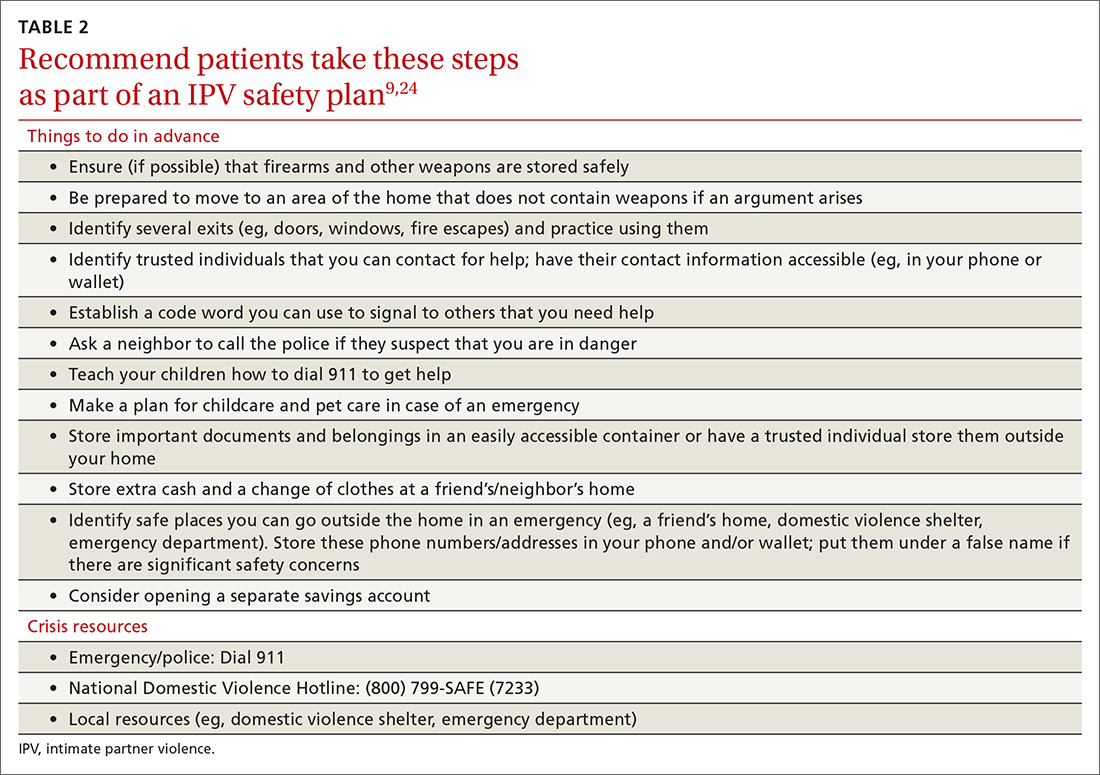

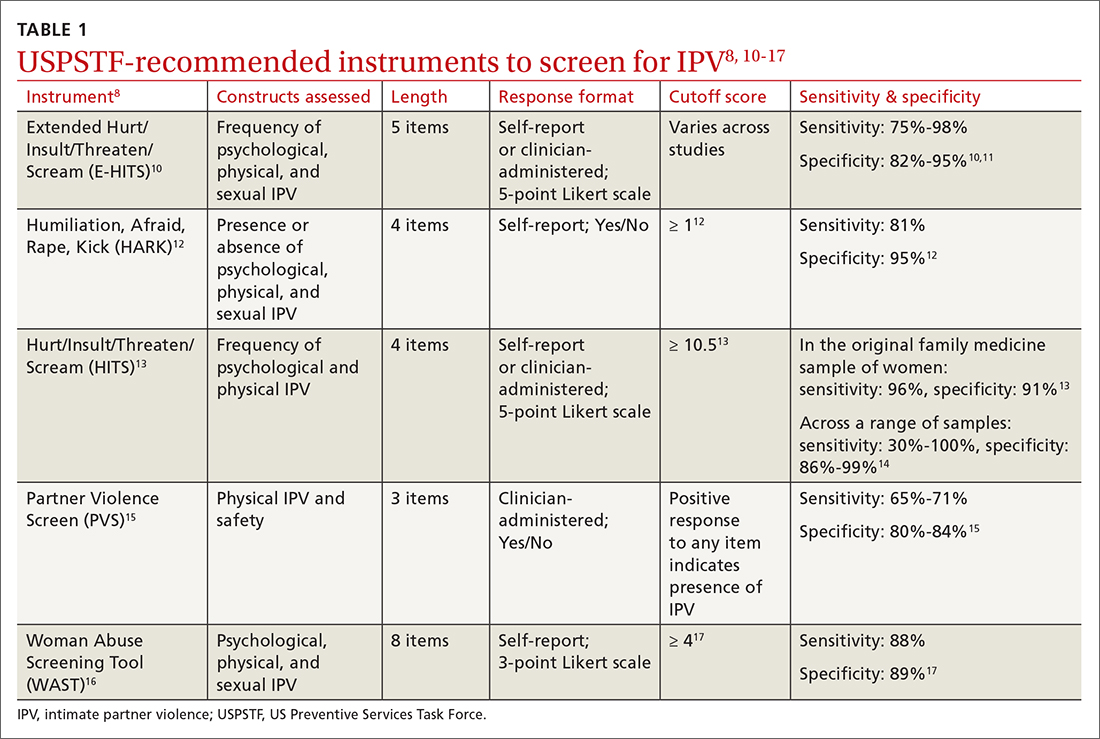

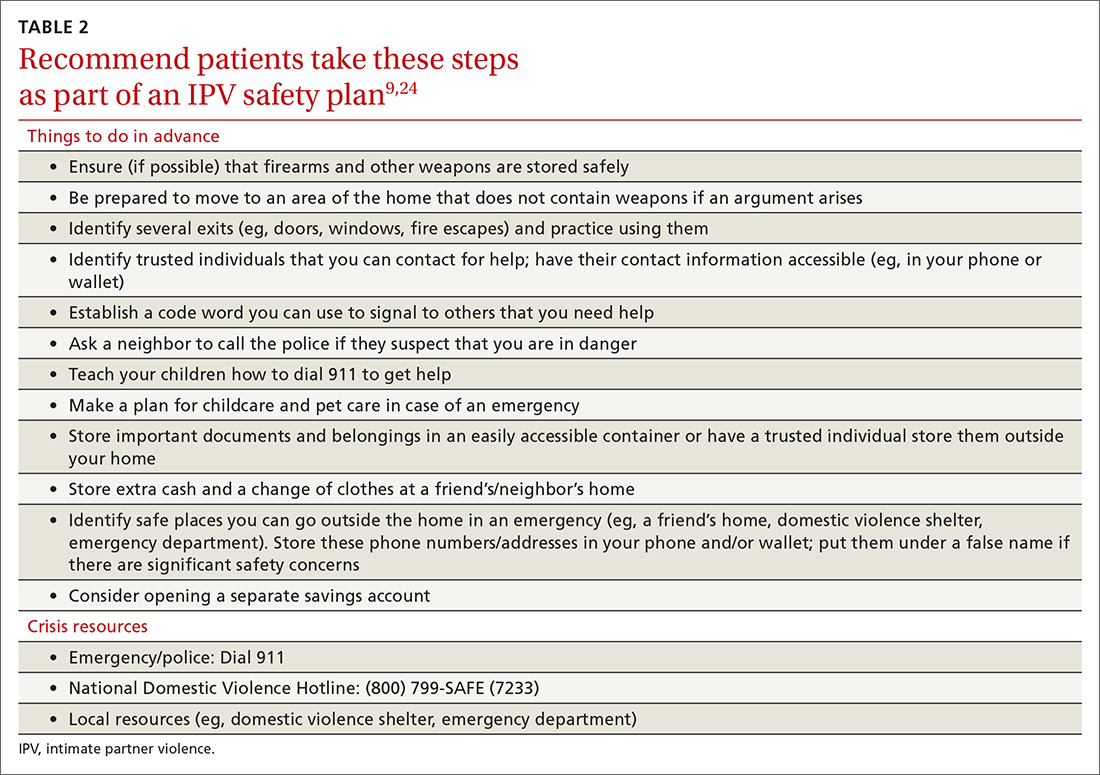

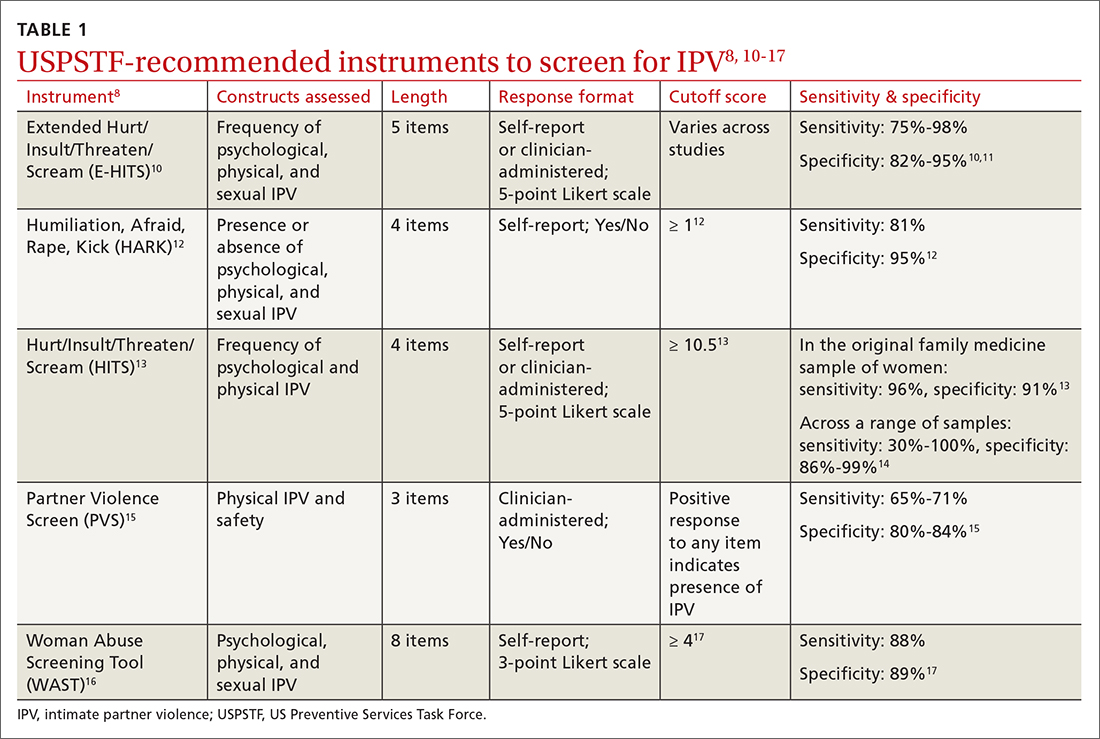

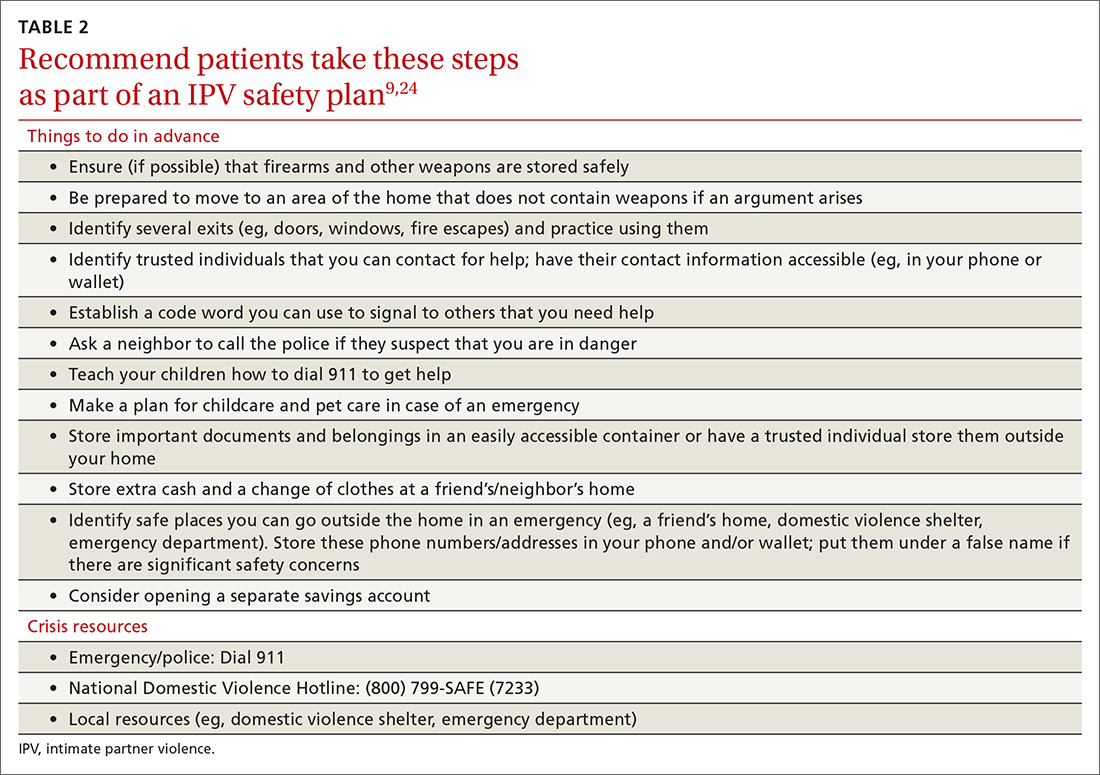

Patient Characteristics—Medical records were reviewed for 172 patients who received phototherapy between 2012 and 2016. Patients ranged in age from 23 to 91 years, with 102 patients 64 years and younger and 70 patients 65 years and older. Tables 1 and 2 outline the patient characteristics and conditions treated.

Phototherapy Effectiveness—

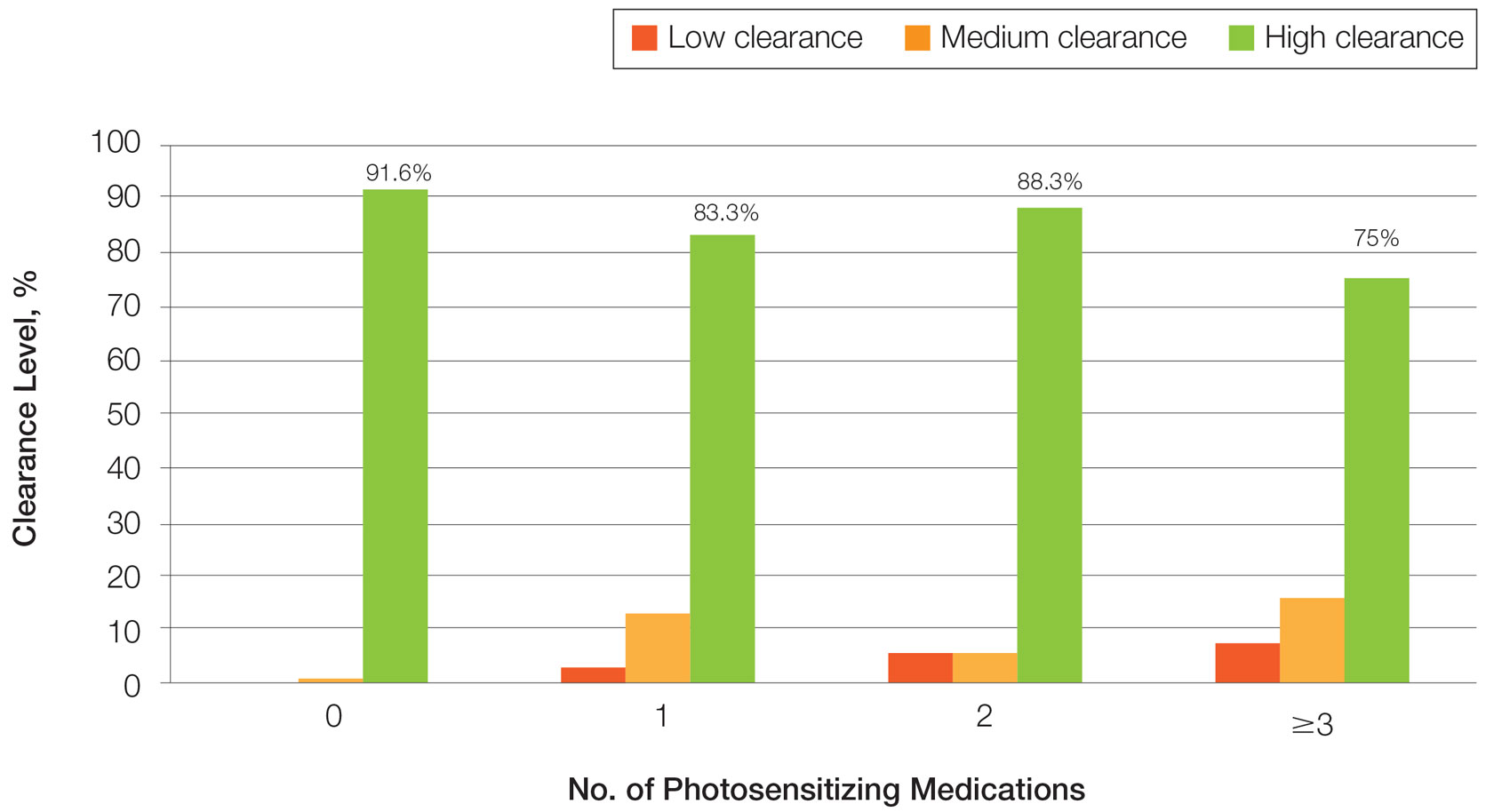

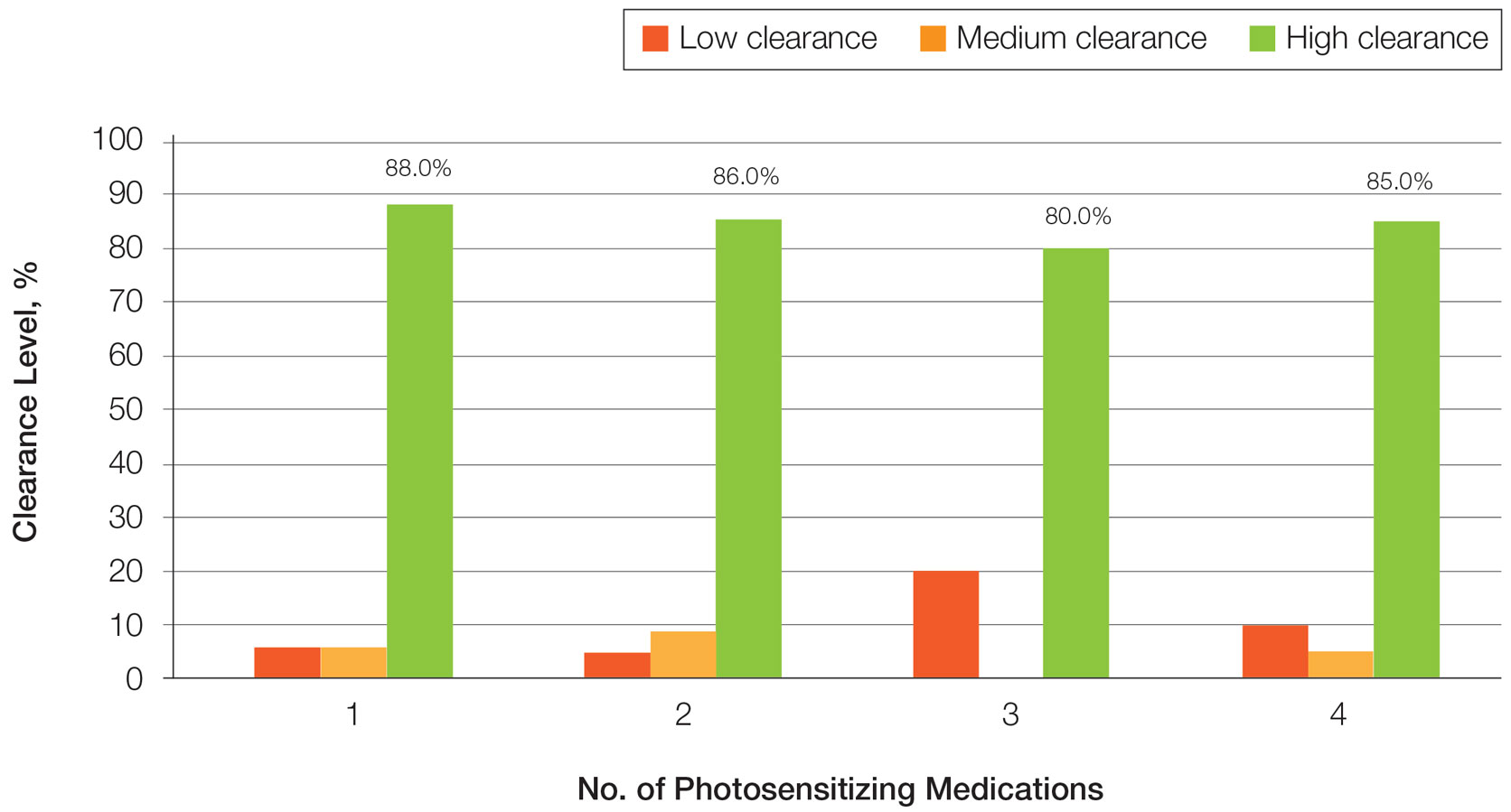

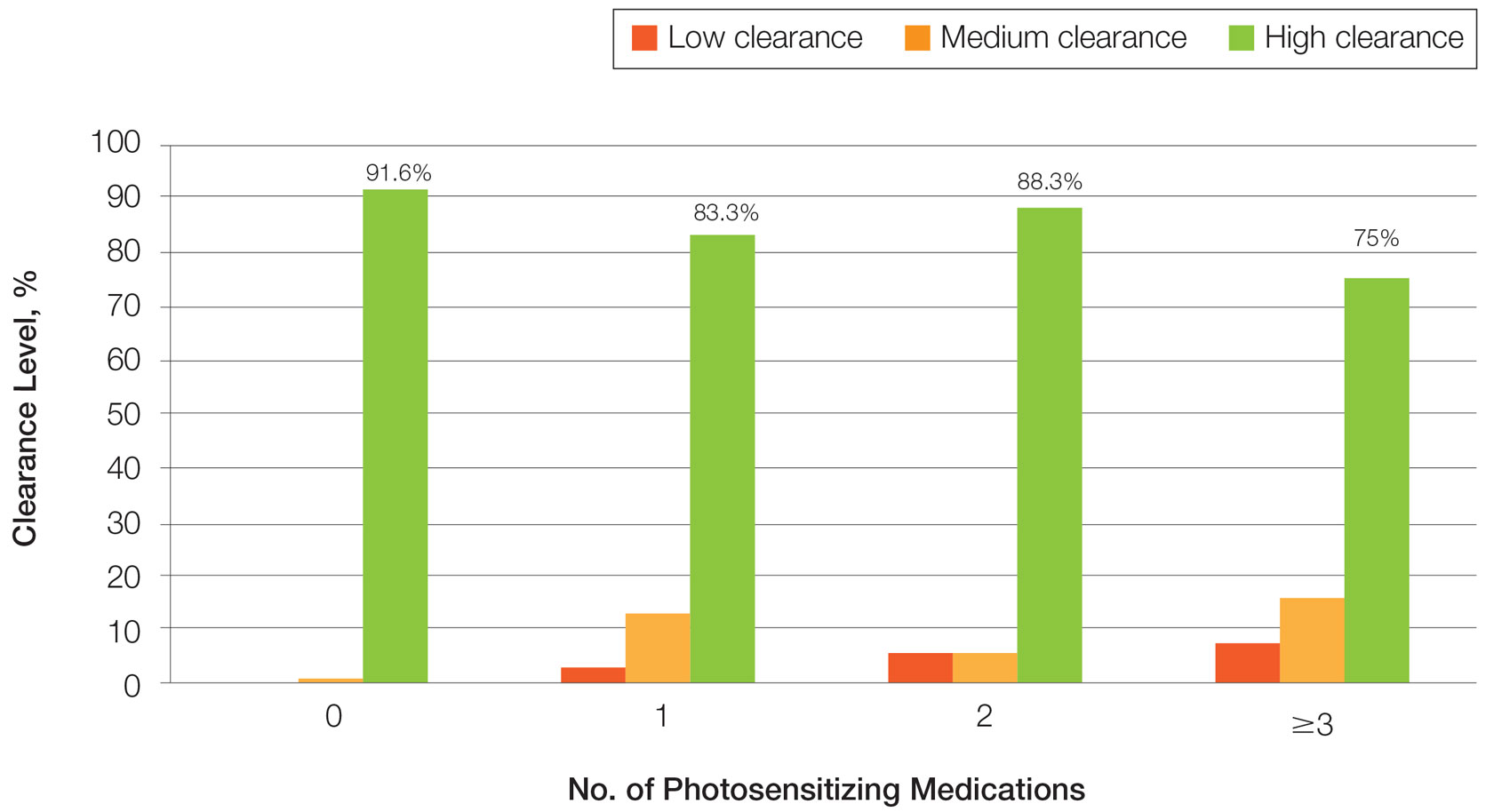

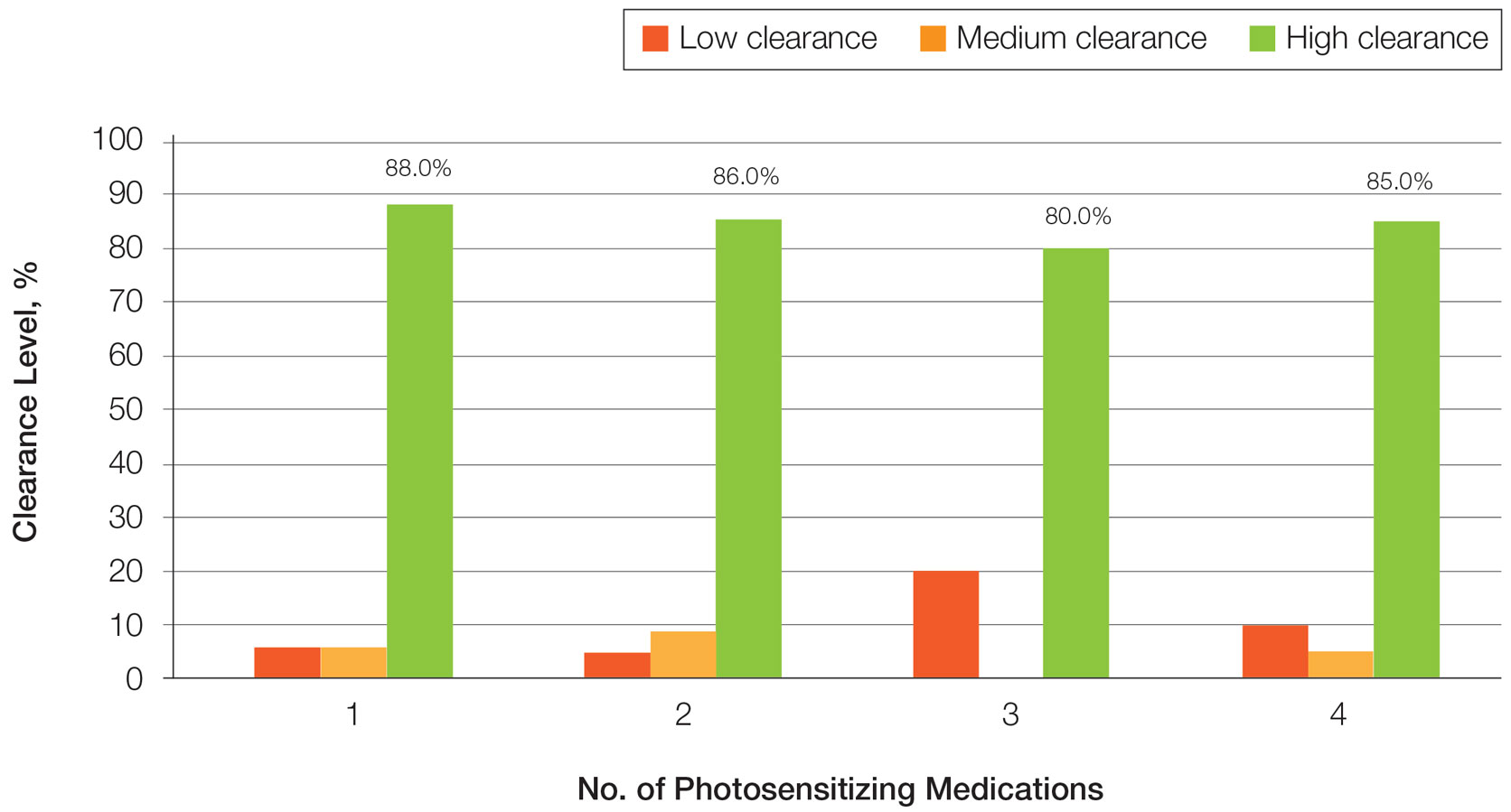

Photosensitizing Medications, Clearance Levels, and Clearance Rates—

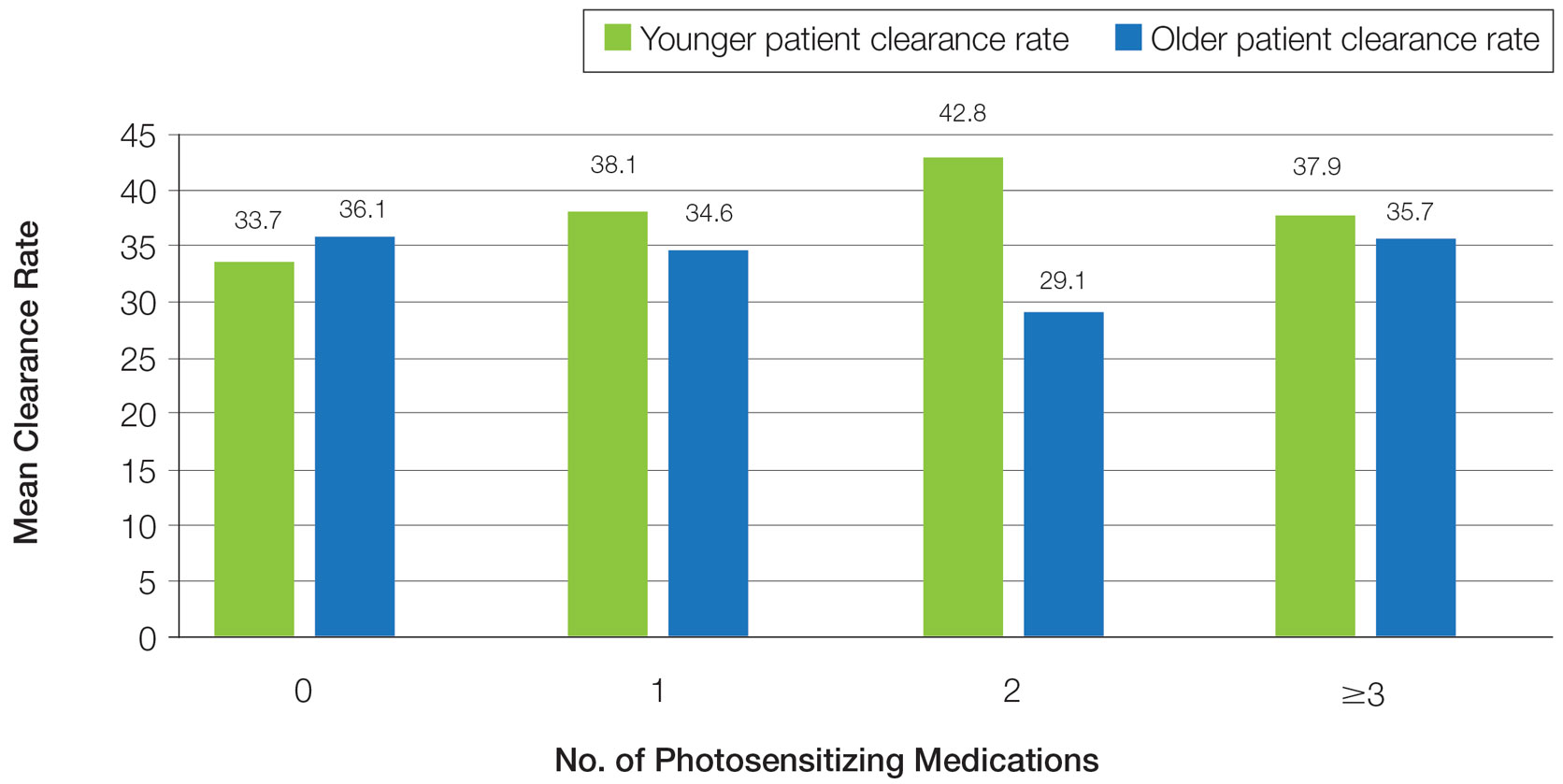

Frequency of Treatments and Clearance Rates—Older adults more consistently completed the recommended frequency of treatments—3 times weekly—compared to younger adults (74.3% vs 58.5%). However, all patients who completed 3 treatments per week required a similar number of treatments to clear (older adults, mean [SD]: 35.7 [21.6]; younger adults, mean [SD]: 34.7 [19.0]; P=.85). Among patients completing 2 or fewer treatments per week, older adults required a mean (SD) of only 31 (9.0) treatments to clear vs 41.5 (21.3) treatments to clear for younger adults, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=.08). However, even those with suboptimal frequency ultimately achieved similar clearance levels.

Photosensitizing Medications and Erythema Rates—

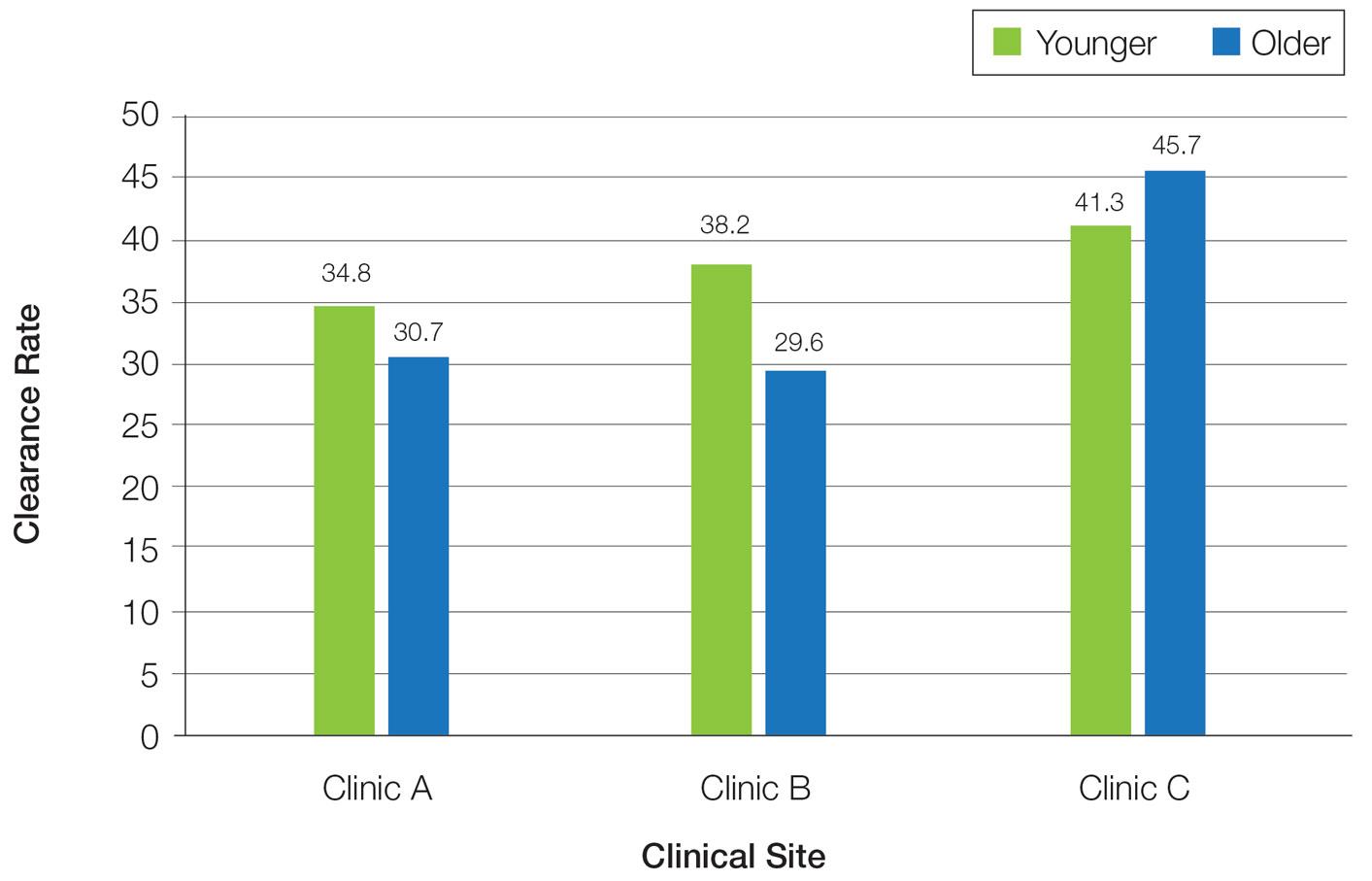

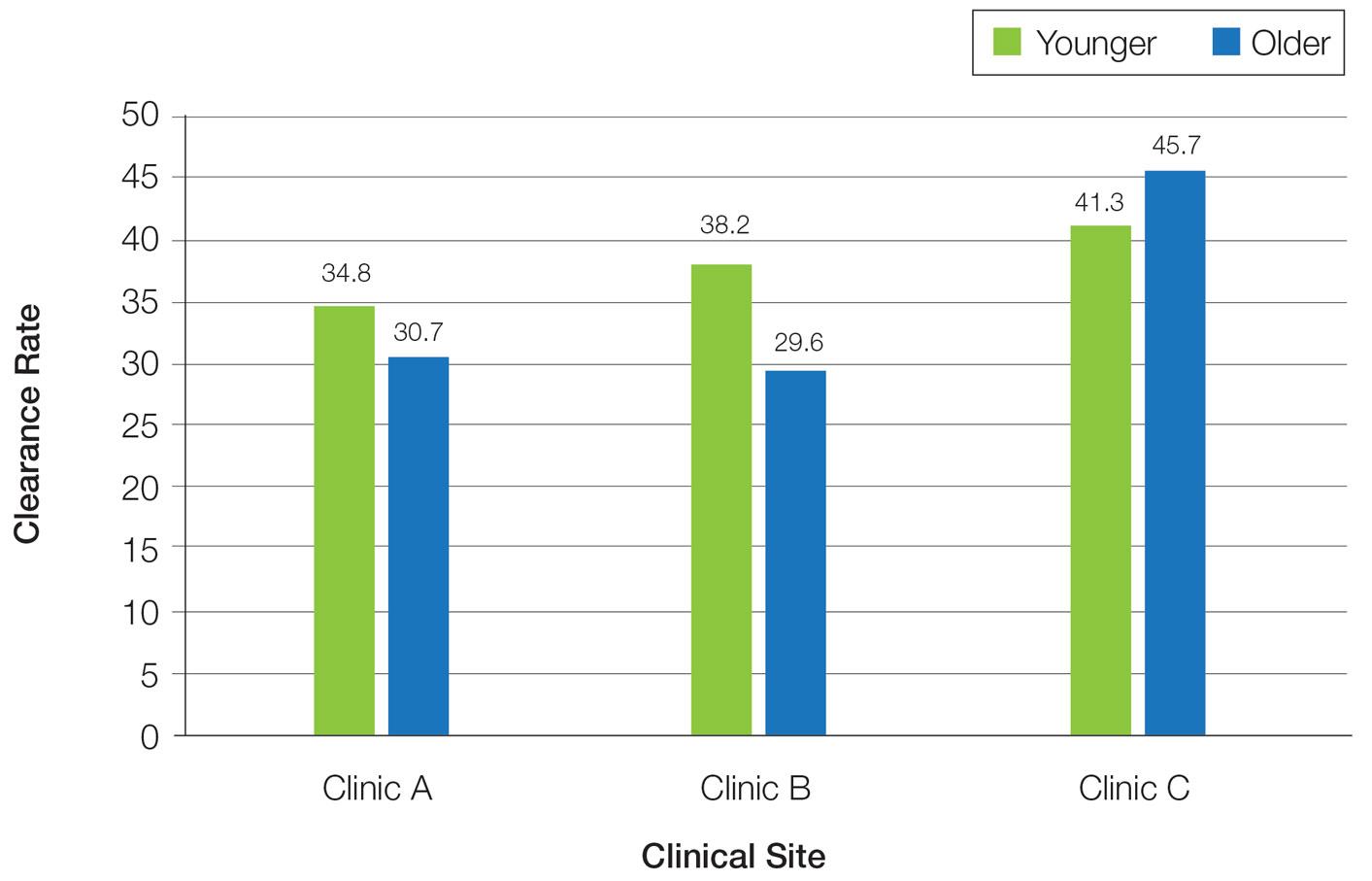

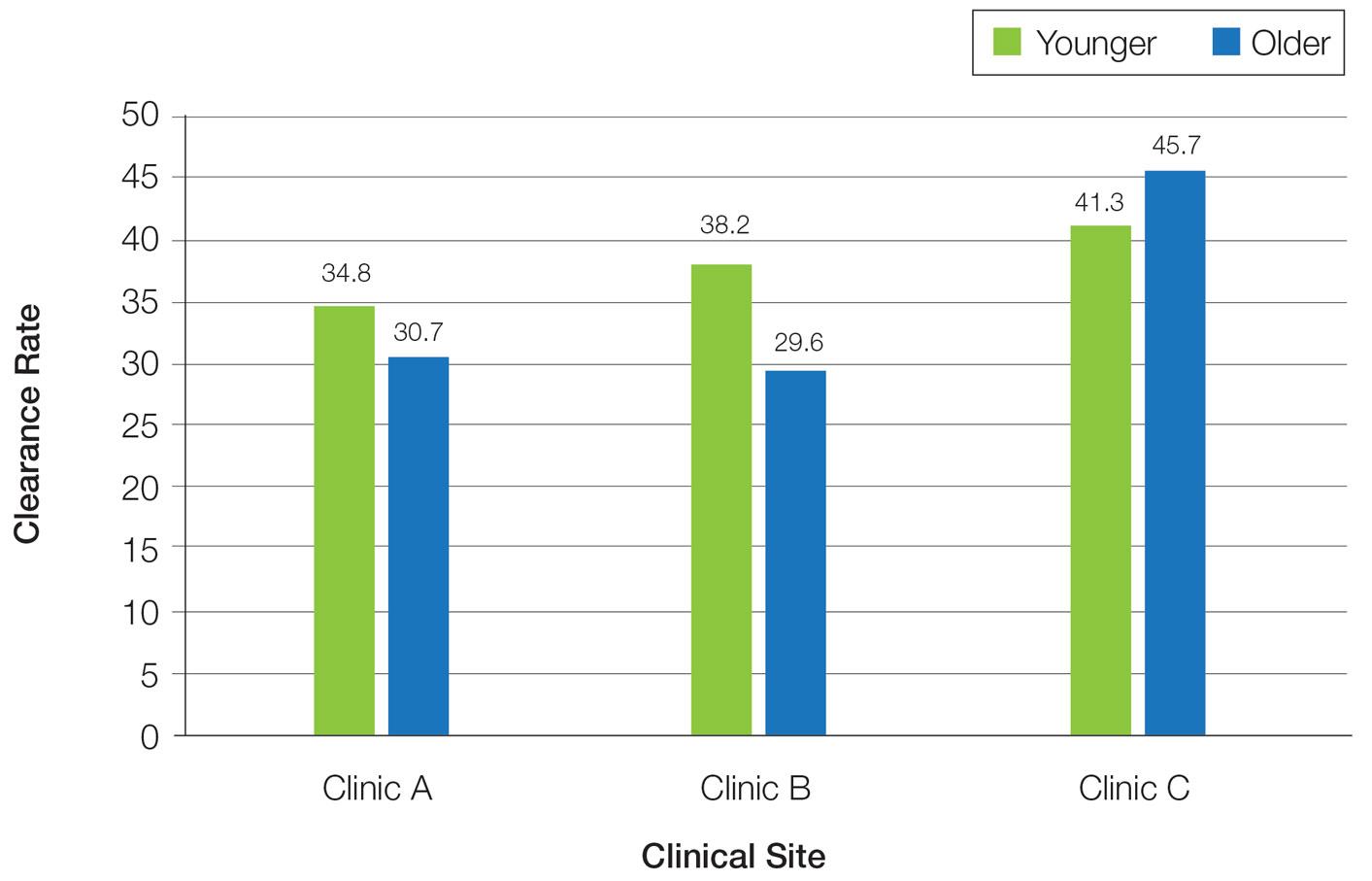

Overall, phototherapy nurses adjusted the starting dose according to the phototype-based protocol an average of 69% of the time for patients on medications with photosensitivity listed as a potential side effect. However, the frequency depended significantly on the clinic (clinic A, 24%; clinic B, 92%; clinic C, 87%)(P≤.001). Nurses across all clinics consistently decreased the treatment dose when patients reported starting new photosensitizing medications. Patients with adjusted starting doses had slightly but not significantly higher clearance rates compared to those without (mean, 37.8 vs 35.5; t(104)=0.58; P=.56).

Comment

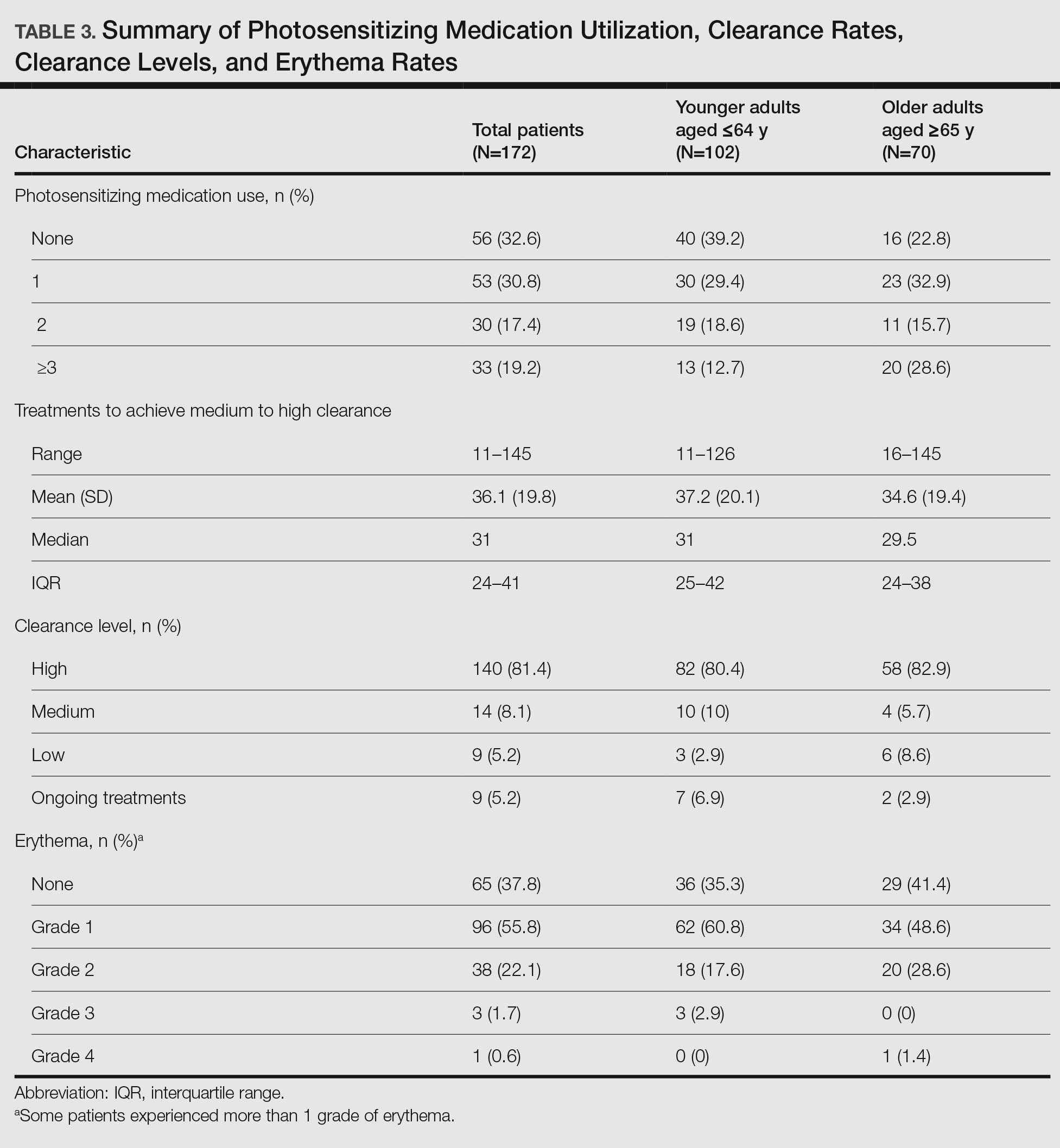

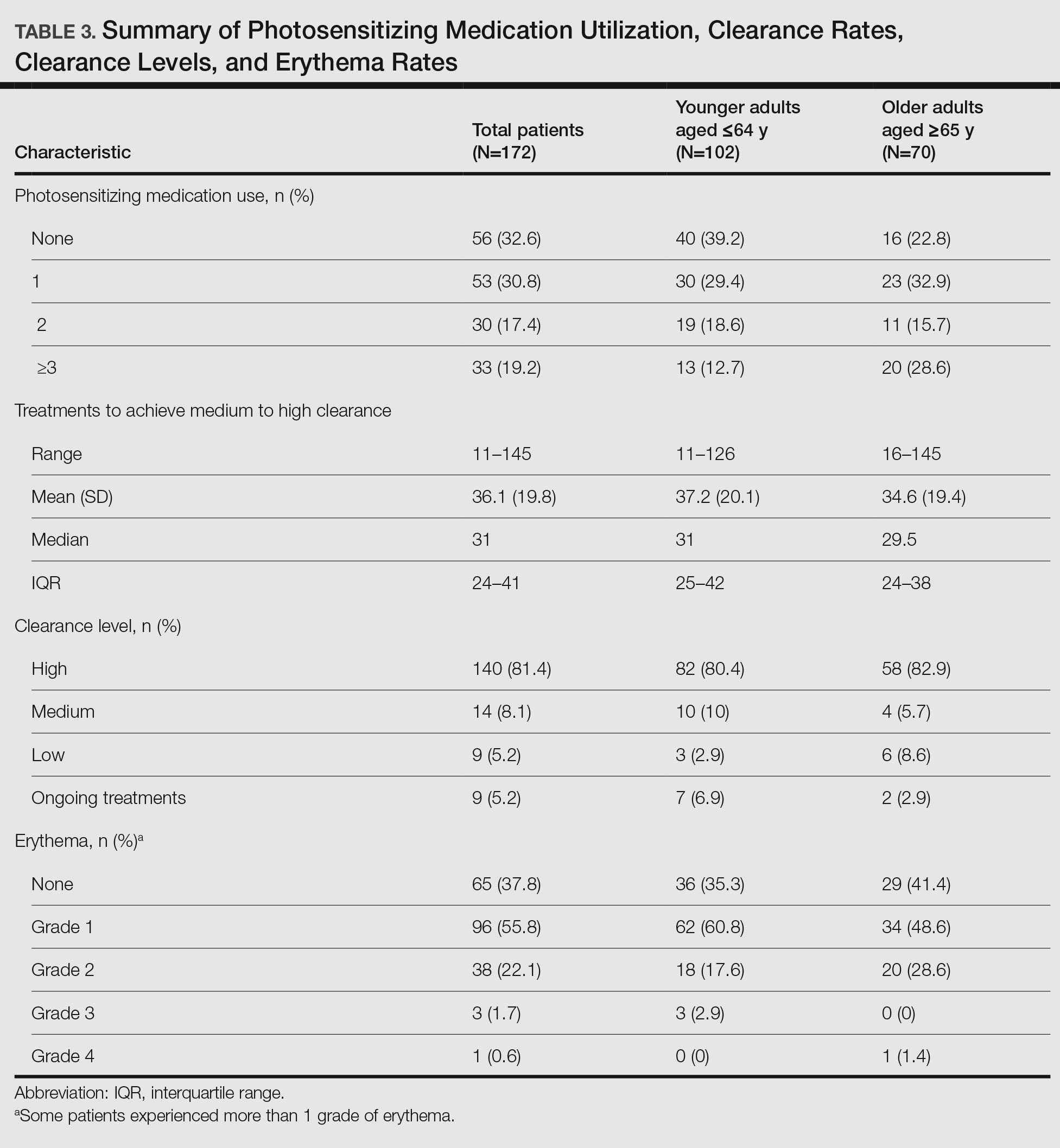

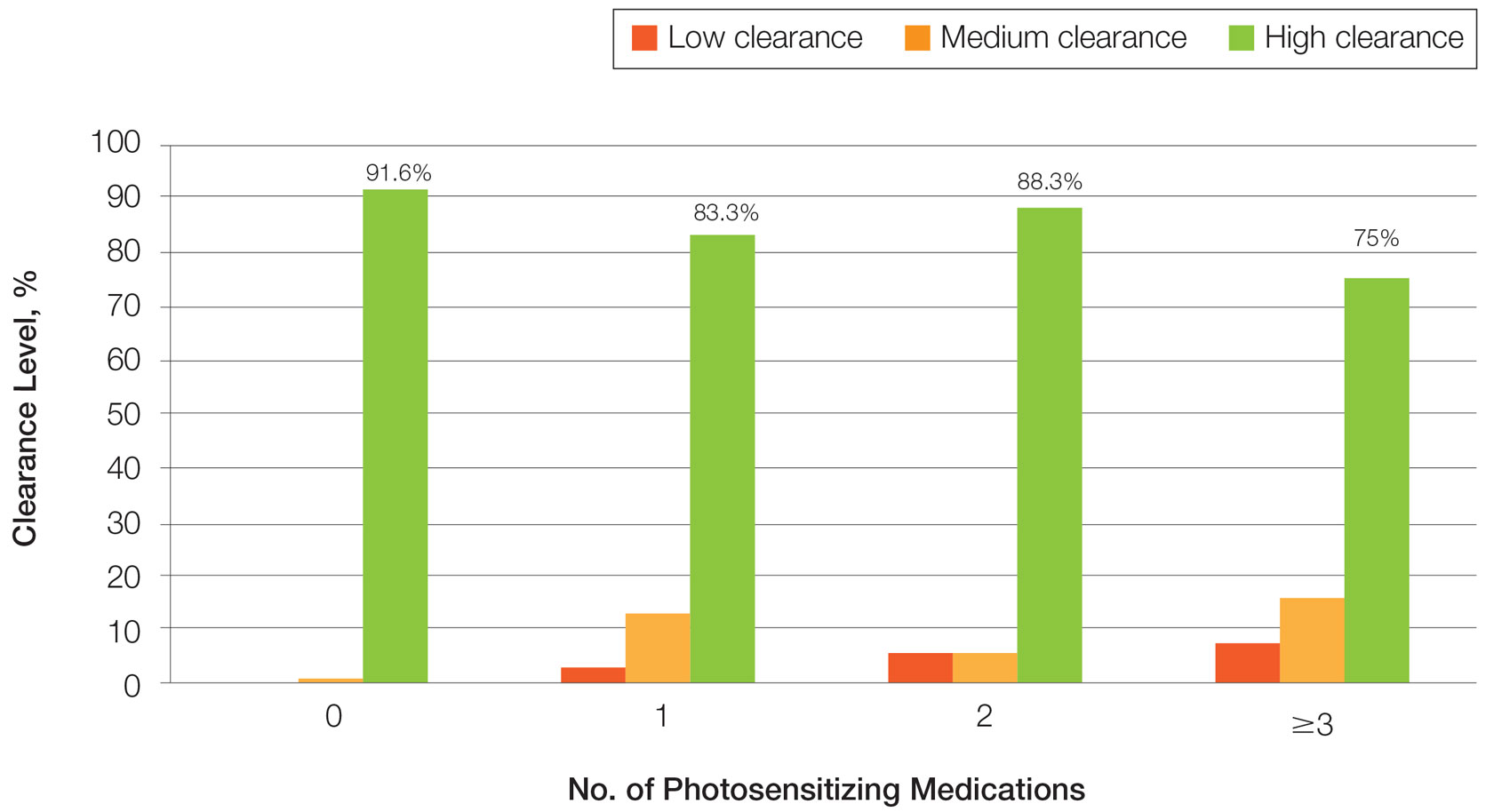

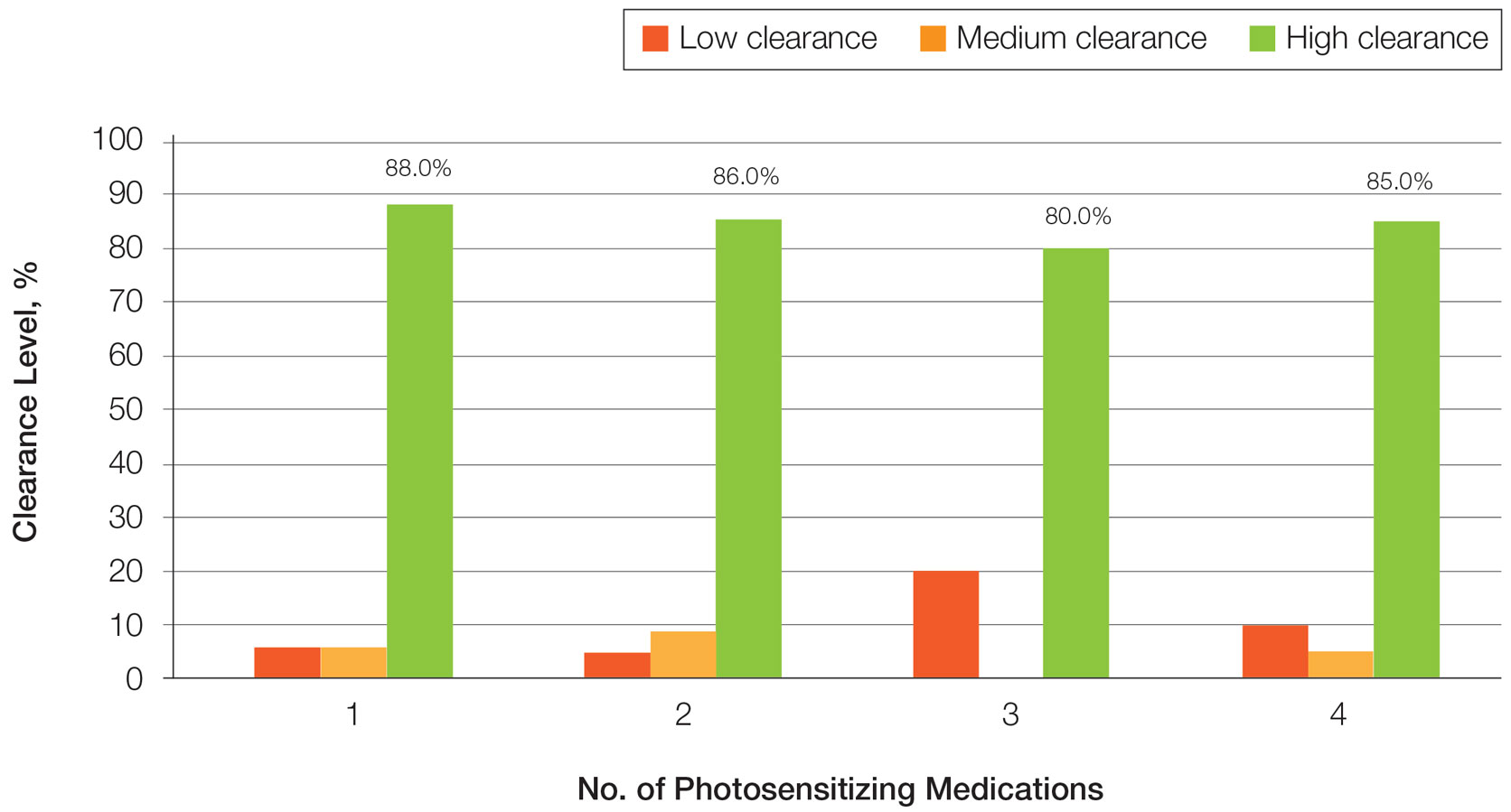

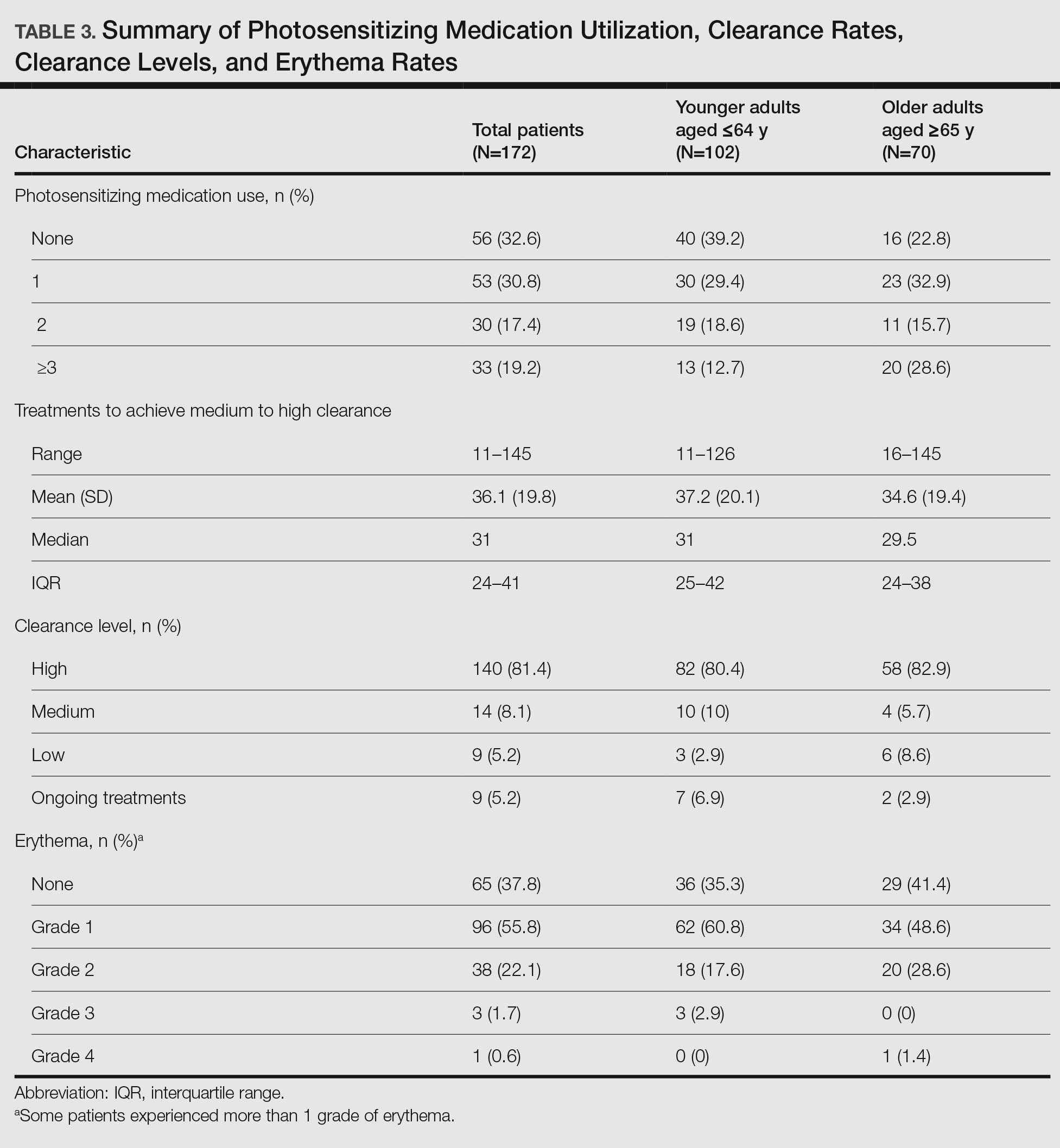

Impact of Photosensitizing Medications on Clearance—Photosensitizing medications and treatment frequency were 2 factors that might explain the slower clearance rates in younger adults. In this study, both groups of patients used similar numbers of photosensitizing medications, but more older adults were taking 3 or more medications (Table 3). We found no statistically significant relationship between taking photosensitizing medications and either the clearance rates or the level of clearance achieved in either age group.

Impact of Treatment Frequency—Weekly treatment frequency also was examined. One prior study demonstrated that treatments 3 times weekly led to a faster clearance time and higher clearance levels compared with twice-weekly treatment.7 When patients completed treatments twice weekly, it took an average of 1.5 times more days to clear, which impacted cost and clinical resource availability. The patients ranged in age from 17 to 80 years, but outcomes in older patients were not described separately.7 Interestingly, our study seemed to find a difference between age groups when the impact of treatment frequency was examined. Older adults completed nearly 4 fewer mean treatments to clear when treating less often, with more than 80% achieving high levels of clearance, whereas the younger adults required almost 7 more treatments to clear when they came in less frequently, with approximately 80% achieving a high level of clearance. As a result, our study found that in both age groups, slowing the treatment frequency extended the treatment time to clearance—more for the younger adults than the older adults—but did not significantly change the percentage of individuals reaching full clearance in either group.

Erythema Rates—There was no association between photosensitizing medications and erythema rates except when patients were taking at least 3 medications. Most medications that listed photosensitivity as a possible side effect did not specify their relevant range of UV radiation; therefore, all such medications were examined during this analysis. Prior research has shown UVB range photosensitizing medications include thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.19 A sensitivity analysis that focused only on these medications found no association between them and any particular grade of erythema. However, patients taking 3 or more of any medications listing photosensitivity as a side effect had an increased risk for grade 2 erythema.

Erythema rates in this study were consistent with a 2013 systematic review that reported 57% of patients with asymptomatic grade 1 erythema.25 In the 2 other comparative older adult studies, erythema rates varied widely: 35% in a study from Turkey18compared to only1.89% in a study from the United Kingdom.17

The starting dose for NB-UVB may drive erythema rates. The current study’s protocols were based on an estimated MED that is subjectively determined by the dermatology provider’s assessment of the patient’s skin sensitivity via examination and questions to the patient about their response to environmental sun exposure (ie, burning and tanning)26 and is frequently used to determine the starting dose and subsequent dose escalation. Certain medications have been found to increase photosensitivity and erythema,20 which can change an individual’s MED. If photosensitizing medications are started prior to or during a course of NB-UVB without a pretreatment MED, they might increase the risk for erythema. This study did not identify specific erythema-inducing medications but did find that taking 3 or more photosensitizing medications was associated with increased episodes of grade 2 erythema. Similarly, Harrop et al8 found that patients who were taking photosensitizing medications were more likely to have grade 2 or higher erythema, despite baseline MED testing, which is an established safety mechanism to reduce the risk and severity of erythema.14,20,27 The authors of a recent study of older adults in Taiwan specifically recommended MED testing due to the unpredictable influence of polypharmacy on MED calculations in this population.28 Therefore, this study’s use of an estimated MED in older adults may have influenced the starting dose as well as the incidence and severity of erythemic events. Age-related skin changes likely are ruled out as a consideration for mild erythema by the similarity of grade 1 erythema rates in both older and younger adults. Other studies have identified differences between the age groups, where older patients experienced more intense erythema in the late phase of UVB treatments.22,23 This phenomenon could increase the risk for a grade 2 erythema, which may correspond with this study’s findings.

Other potential causes of erythema were ruled out during our study, including erythema related to missed treatments and shielding mishaps. Other factors, however, may impact the level of sensitivity each patient has to phototherapy, including genetics, epigenetics, and cumulative sun damage. With NB-UVB, near-erythemogenic doses are optimal to achieve effective treatments but require a delicate balance to achieve, which may be more problematic for older adults, especially those taking several medications.

Study Limitations—Our study design made it difficult to draw conclusions about rarer dermatologic conditions. Some patients received treatments over years that were not included in the study period. Finally, power calculations suggested that our actual sample size was too small, with approximately one-third of the required sample missing.

Practical Implications—The goals of phototherapy are to achieve a high level of disease clearance with the fewest number of treatments possible and minimal side effects.

The extra staff training and patient monitoring required for MED testing likely is to add value and preserve resources if faster clearance rates could be achieved and may warrant further investigation. Phototherapy centers require standardized treatment protocols, diligent well-trained staff, and program monitoring to ensure consistent care to all patients. This study highlighted the ongoing opportunity for health care organizations to conduct evidence-based practice inquiries to continually optimize care for their patients.

- Fernández-Guarino M, Aboin-Gonzalez S, Barchino L, et al. Treatment of moderate and severe adult chronic atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB and the combination of narrow-band UVB/UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:19-23.

- Foerster J, Boswell K, West J, et al. Narrowband UVB treatment is highly effective and causes a strong reduction in the use of steroid and other creams in psoriasis patients in clinical practice. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181813.

- Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, Boms S, et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in skin conditions beyond psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:660-670.

- Ryu HH, Choe YS, Jo S, et al. Remission period in psoriasis after multiple cycles of narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Dermatol. 2014;41:622-627.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

- Tintle S, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Reversal of atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB phototherapy and biomarkers for therapeutic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:583-593.e581-584.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS, Yule S, et al. A randomized, observer-blinded trial of twice vs. three times weekly narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:973-978.

- Harrop G, Dawe RS, Ibbotson S. Are photosensitizing medications associated with increased risk of important erythemal reactions during ultraviolet B phototherapy? Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1184-1185.

- Torres AE, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH, et al. Role of phototherapy in the era of biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:479-485.

- Bukvic´ć Mokos Z, Jovic´ A, Cˇeovic´ R, et al. Therapeutic challenges in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:128-139.

- Di Lernia V, Goldust M. An overview of the efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for psoriasis in the elderly. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:897-903.

- Oliveira C, Torres T. More than skin deep: the systemic nature of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:250-258.

- Matthews S, Pike K, Chien A. Phototherapy: safe and effective for challenging skin conditions in older adults. Cutis. 2021;108:E15-E21.

- Rodríguez-Granados MT, Estany-Gestal A, Pousa-Martínez M, et al. Is it useful to calculate minimal erythema dose before narrowband UV-B phototherapy? Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:852-858.

- Parlak N, Kundakci N, Parlak A, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy starting and incremental dose in patients with psoriasis: comparison of percentage dose and fixed dose protocols. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2015;31:90-97.

- Kleinpenning MM, Smits T, Boezeman J, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B therapy in psoriasis: randomized double-blind comparison of high-dose and low-dose irradiation regimens. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1351-1356.

- Powell JB, Gach JE. Phototherapy in the elderly. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:605-610.

- Bulur I, Erdogan HK, Aksu AE, et al. The efficacy and safety of phototherapy in geriatric patients: a retrospective study. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:33-38.

- Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH. Drug-induced photosensitivity. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:363-368, ix.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS. Photosensitizing drugs may lower the narrow-band ultraviolet B (TL-01) minimal erythema dose. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:389-390.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Gloor M, Scherotzke A. Age dependence of ultraviolet light-induced erythema following narrow-band UVB exposure. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2002;18:121-126.

- Cox NH, Diffey BL, Farr PM. The relationship between chronological age and the erythemal response to ultraviolet B radiation. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:315-319.

- Morrison W. Phototherapy and Photochemotherapy for Skin Disease. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2005.

- Almutawa F, Alnomair N, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of UV-based therapy for psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:87-109.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

- Kwon IH, Kwon HH, Na SJ, et al. Could colorimetric method replace the individual minimal erythemal dose (MED) measurements in determining the initial dose of narrow-band UVB treatment for psoriasis patients with skin phototype III-V? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:494-498.

- Chen WA, Chang CM. The minimal erythema dose of narrowband ultraviolet B in elderly Taiwanese [published online September 1, 2021]. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. doi:10.1111/phpp.12730

Even with recent pharmacologic treatment advances, narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy remains a versatile, safe, and efficacious adjunctive or exclusive treatment for multiple dermatologic conditions, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

In a prior study, Matthews et al13 reported that 96% (50/52) of patients older than 65 years achieved medium to high levels of clearance with NB-UVB phototherapy. Nonetheless, 2 other findings in this study related to the number of treatments required to achieve clearance (ie, clearance rates) and erythema rates prompted further investigation. The first finding was higher-than-expected clearance rates. Older adults had a clearance rate with a mean of 33 treatments compared to prior studies featuring mean clearance rates of 20 to 28 treatments.7,8,14-16 This finding resembled a study in the United Kingdom17 with a median clearance rate in older adults of 30 treatments. In contrast, the median clearance rate from a study in Turkey18 was 42 treatments in older adults. We hypothesized that more photosensitizing medications used in older vs younger adults prompted more dose adjustments with NB-UVB phototherapy to avoid burning (ie, erythema) at baseline and throughout the treatment course. These dose adjustments may have increased the overall clearance rates. If true, we predicted that younger adults treated with the same protocol would have cleared more quickly, either because of age-related differences or because they likely had fewer comorbidities and therefore fewer medications.

The second finding from Matthews et al13 that warranted further investigation was a higher erythema rate compared to the older adult study from the United Kingdom.17 We hypothesized that potentially greater use of photosensitizing medications in the United States could explain the higher erythema rates. Although medication-induced photosensitivity is less likely with NB-UVB phototherapy than with UVA, certain medications can cause UVB photosensitivity, including thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.8,19,20 Therefore, photosensitizing medication use either at baseline or during a course of NB-UVB phototherapy could increase the risk for erythema. Age-related skin changes also have been considered as a

This retrospective study aimed to determine if NB-UVB phototherapy is equally effective in both older and younger adults treated with the same protocol; to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and clearance rates in both older and younger adults; and to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and erythema rates in older vs younger adults.

Methods

Study Design and Patients—This retrospective cohort study used billing records to identify patients who received NB-UVB phototherapy at 3 different clinical sites within a large US health care system in Washington (Group Health Cooperative, now Kaiser Permanente Washington), serving more than 600,000 patients between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2016. The institutional review board of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute approved this study (IRB 1498087-4). Younger adults were classified as those 64 years or younger and older adults as those 65 years and older at the start of their phototherapy regimen. A power analysis determined that the optimal sample size for this study was 250 patients.

Individuals were excluded if they had fewer than 6 phototherapy treatments; a diagnosis of vitiligo, photosensitivity dermatitis, morphea, or pityriasis rubra pilaris; and/or treatment of the hands or feet only.

Phototherapy Protocol—Using a 48-lamp NB-UVB unit, trained phototherapy nurses provided all treatments following standardized treatment protocols13 based on previously published phototherapy guidelines.24 Nurses determined each patient’s disease clearance level using a 3-point clearance scale (high, medium, low).13 Each patient’s starting dose was determined based on the estimated MED for their skin phototype.

Statistical Analysis—Data were analyzed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp LLC). Univariate analyses were used to examine the data and identify outliers, bad values, and missing data, as well as to calculate descriptive statistics. Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact statistics were used to calculate differences in categorical variables. Linear multivariate regression models and logistic multivariate models were used to examine statistical relationships between variables. Statistical significance was defined as P≤.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics—Medical records were reviewed for 172 patients who received phototherapy between 2012 and 2016. Patients ranged in age from 23 to 91 years, with 102 patients 64 years and younger and 70 patients 65 years and older. Tables 1 and 2 outline the patient characteristics and conditions treated.

Phototherapy Effectiveness—

Photosensitizing Medications, Clearance Levels, and Clearance Rates—

Frequency of Treatments and Clearance Rates—Older adults more consistently completed the recommended frequency of treatments—3 times weekly—compared to younger adults (74.3% vs 58.5%). However, all patients who completed 3 treatments per week required a similar number of treatments to clear (older adults, mean [SD]: 35.7 [21.6]; younger adults, mean [SD]: 34.7 [19.0]; P=.85). Among patients completing 2 or fewer treatments per week, older adults required a mean (SD) of only 31 (9.0) treatments to clear vs 41.5 (21.3) treatments to clear for younger adults, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=.08). However, even those with suboptimal frequency ultimately achieved similar clearance levels.

Photosensitizing Medications and Erythema Rates—

Overall, phototherapy nurses adjusted the starting dose according to the phototype-based protocol an average of 69% of the time for patients on medications with photosensitivity listed as a potential side effect. However, the frequency depended significantly on the clinic (clinic A, 24%; clinic B, 92%; clinic C, 87%)(P≤.001). Nurses across all clinics consistently decreased the treatment dose when patients reported starting new photosensitizing medications. Patients with adjusted starting doses had slightly but not significantly higher clearance rates compared to those without (mean, 37.8 vs 35.5; t(104)=0.58; P=.56).

Comment

Impact of Photosensitizing Medications on Clearance—Photosensitizing medications and treatment frequency were 2 factors that might explain the slower clearance rates in younger adults. In this study, both groups of patients used similar numbers of photosensitizing medications, but more older adults were taking 3 or more medications (Table 3). We found no statistically significant relationship between taking photosensitizing medications and either the clearance rates or the level of clearance achieved in either age group.

Impact of Treatment Frequency—Weekly treatment frequency also was examined. One prior study demonstrated that treatments 3 times weekly led to a faster clearance time and higher clearance levels compared with twice-weekly treatment.7 When patients completed treatments twice weekly, it took an average of 1.5 times more days to clear, which impacted cost and clinical resource availability. The patients ranged in age from 17 to 80 years, but outcomes in older patients were not described separately.7 Interestingly, our study seemed to find a difference between age groups when the impact of treatment frequency was examined. Older adults completed nearly 4 fewer mean treatments to clear when treating less often, with more than 80% achieving high levels of clearance, whereas the younger adults required almost 7 more treatments to clear when they came in less frequently, with approximately 80% achieving a high level of clearance. As a result, our study found that in both age groups, slowing the treatment frequency extended the treatment time to clearance—more for the younger adults than the older adults—but did not significantly change the percentage of individuals reaching full clearance in either group.

Erythema Rates—There was no association between photosensitizing medications and erythema rates except when patients were taking at least 3 medications. Most medications that listed photosensitivity as a possible side effect did not specify their relevant range of UV radiation; therefore, all such medications were examined during this analysis. Prior research has shown UVB range photosensitizing medications include thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.19 A sensitivity analysis that focused only on these medications found no association between them and any particular grade of erythema. However, patients taking 3 or more of any medications listing photosensitivity as a side effect had an increased risk for grade 2 erythema.

Erythema rates in this study were consistent with a 2013 systematic review that reported 57% of patients with asymptomatic grade 1 erythema.25 In the 2 other comparative older adult studies, erythema rates varied widely: 35% in a study from Turkey18compared to only1.89% in a study from the United Kingdom.17

The starting dose for NB-UVB may drive erythema rates. The current study’s protocols were based on an estimated MED that is subjectively determined by the dermatology provider’s assessment of the patient’s skin sensitivity via examination and questions to the patient about their response to environmental sun exposure (ie, burning and tanning)26 and is frequently used to determine the starting dose and subsequent dose escalation. Certain medications have been found to increase photosensitivity and erythema,20 which can change an individual’s MED. If photosensitizing medications are started prior to or during a course of NB-UVB without a pretreatment MED, they might increase the risk for erythema. This study did not identify specific erythema-inducing medications but did find that taking 3 or more photosensitizing medications was associated with increased episodes of grade 2 erythema. Similarly, Harrop et al8 found that patients who were taking photosensitizing medications were more likely to have grade 2 or higher erythema, despite baseline MED testing, which is an established safety mechanism to reduce the risk and severity of erythema.14,20,27 The authors of a recent study of older adults in Taiwan specifically recommended MED testing due to the unpredictable influence of polypharmacy on MED calculations in this population.28 Therefore, this study’s use of an estimated MED in older adults may have influenced the starting dose as well as the incidence and severity of erythemic events. Age-related skin changes likely are ruled out as a consideration for mild erythema by the similarity of grade 1 erythema rates in both older and younger adults. Other studies have identified differences between the age groups, where older patients experienced more intense erythema in the late phase of UVB treatments.22,23 This phenomenon could increase the risk for a grade 2 erythema, which may correspond with this study’s findings.

Other potential causes of erythema were ruled out during our study, including erythema related to missed treatments and shielding mishaps. Other factors, however, may impact the level of sensitivity each patient has to phototherapy, including genetics, epigenetics, and cumulative sun damage. With NB-UVB, near-erythemogenic doses are optimal to achieve effective treatments but require a delicate balance to achieve, which may be more problematic for older adults, especially those taking several medications.

Study Limitations—Our study design made it difficult to draw conclusions about rarer dermatologic conditions. Some patients received treatments over years that were not included in the study period. Finally, power calculations suggested that our actual sample size was too small, with approximately one-third of the required sample missing.

Practical Implications—The goals of phototherapy are to achieve a high level of disease clearance with the fewest number of treatments possible and minimal side effects.

The extra staff training and patient monitoring required for MED testing likely is to add value and preserve resources if faster clearance rates could be achieved and may warrant further investigation. Phototherapy centers require standardized treatment protocols, diligent well-trained staff, and program monitoring to ensure consistent care to all patients. This study highlighted the ongoing opportunity for health care organizations to conduct evidence-based practice inquiries to continually optimize care for their patients.

Even with recent pharmacologic treatment advances, narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy remains a versatile, safe, and efficacious adjunctive or exclusive treatment for multiple dermatologic conditions, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

In a prior study, Matthews et al13 reported that 96% (50/52) of patients older than 65 years achieved medium to high levels of clearance with NB-UVB phototherapy. Nonetheless, 2 other findings in this study related to the number of treatments required to achieve clearance (ie, clearance rates) and erythema rates prompted further investigation. The first finding was higher-than-expected clearance rates. Older adults had a clearance rate with a mean of 33 treatments compared to prior studies featuring mean clearance rates of 20 to 28 treatments.7,8,14-16 This finding resembled a study in the United Kingdom17 with a median clearance rate in older adults of 30 treatments. In contrast, the median clearance rate from a study in Turkey18 was 42 treatments in older adults. We hypothesized that more photosensitizing medications used in older vs younger adults prompted more dose adjustments with NB-UVB phototherapy to avoid burning (ie, erythema) at baseline and throughout the treatment course. These dose adjustments may have increased the overall clearance rates. If true, we predicted that younger adults treated with the same protocol would have cleared more quickly, either because of age-related differences or because they likely had fewer comorbidities and therefore fewer medications.

The second finding from Matthews et al13 that warranted further investigation was a higher erythema rate compared to the older adult study from the United Kingdom.17 We hypothesized that potentially greater use of photosensitizing medications in the United States could explain the higher erythema rates. Although medication-induced photosensitivity is less likely with NB-UVB phototherapy than with UVA, certain medications can cause UVB photosensitivity, including thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.8,19,20 Therefore, photosensitizing medication use either at baseline or during a course of NB-UVB phototherapy could increase the risk for erythema. Age-related skin changes also have been considered as a

This retrospective study aimed to determine if NB-UVB phototherapy is equally effective in both older and younger adults treated with the same protocol; to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and clearance rates in both older and younger adults; and to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and erythema rates in older vs younger adults.

Methods

Study Design and Patients—This retrospective cohort study used billing records to identify patients who received NB-UVB phototherapy at 3 different clinical sites within a large US health care system in Washington (Group Health Cooperative, now Kaiser Permanente Washington), serving more than 600,000 patients between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2016. The institutional review board of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute approved this study (IRB 1498087-4). Younger adults were classified as those 64 years or younger and older adults as those 65 years and older at the start of their phototherapy regimen. A power analysis determined that the optimal sample size for this study was 250 patients.

Individuals were excluded if they had fewer than 6 phototherapy treatments; a diagnosis of vitiligo, photosensitivity dermatitis, morphea, or pityriasis rubra pilaris; and/or treatment of the hands or feet only.

Phototherapy Protocol—Using a 48-lamp NB-UVB unit, trained phototherapy nurses provided all treatments following standardized treatment protocols13 based on previously published phototherapy guidelines.24 Nurses determined each patient’s disease clearance level using a 3-point clearance scale (high, medium, low).13 Each patient’s starting dose was determined based on the estimated MED for their skin phototype.

Statistical Analysis—Data were analyzed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp LLC). Univariate analyses were used to examine the data and identify outliers, bad values, and missing data, as well as to calculate descriptive statistics. Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact statistics were used to calculate differences in categorical variables. Linear multivariate regression models and logistic multivariate models were used to examine statistical relationships between variables. Statistical significance was defined as P≤.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics—Medical records were reviewed for 172 patients who received phototherapy between 2012 and 2016. Patients ranged in age from 23 to 91 years, with 102 patients 64 years and younger and 70 patients 65 years and older. Tables 1 and 2 outline the patient characteristics and conditions treated.

Phototherapy Effectiveness—

Photosensitizing Medications, Clearance Levels, and Clearance Rates—

Frequency of Treatments and Clearance Rates—Older adults more consistently completed the recommended frequency of treatments—3 times weekly—compared to younger adults (74.3% vs 58.5%). However, all patients who completed 3 treatments per week required a similar number of treatments to clear (older adults, mean [SD]: 35.7 [21.6]; younger adults, mean [SD]: 34.7 [19.0]; P=.85). Among patients completing 2 or fewer treatments per week, older adults required a mean (SD) of only 31 (9.0) treatments to clear vs 41.5 (21.3) treatments to clear for younger adults, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=.08). However, even those with suboptimal frequency ultimately achieved similar clearance levels.

Photosensitizing Medications and Erythema Rates—

Overall, phototherapy nurses adjusted the starting dose according to the phototype-based protocol an average of 69% of the time for patients on medications with photosensitivity listed as a potential side effect. However, the frequency depended significantly on the clinic (clinic A, 24%; clinic B, 92%; clinic C, 87%)(P≤.001). Nurses across all clinics consistently decreased the treatment dose when patients reported starting new photosensitizing medications. Patients with adjusted starting doses had slightly but not significantly higher clearance rates compared to those without (mean, 37.8 vs 35.5; t(104)=0.58; P=.56).

Comment

Impact of Photosensitizing Medications on Clearance—Photosensitizing medications and treatment frequency were 2 factors that might explain the slower clearance rates in younger adults. In this study, both groups of patients used similar numbers of photosensitizing medications, but more older adults were taking 3 or more medications (Table 3). We found no statistically significant relationship between taking photosensitizing medications and either the clearance rates or the level of clearance achieved in either age group.

Impact of Treatment Frequency—Weekly treatment frequency also was examined. One prior study demonstrated that treatments 3 times weekly led to a faster clearance time and higher clearance levels compared with twice-weekly treatment.7 When patients completed treatments twice weekly, it took an average of 1.5 times more days to clear, which impacted cost and clinical resource availability. The patients ranged in age from 17 to 80 years, but outcomes in older patients were not described separately.7 Interestingly, our study seemed to find a difference between age groups when the impact of treatment frequency was examined. Older adults completed nearly 4 fewer mean treatments to clear when treating less often, with more than 80% achieving high levels of clearance, whereas the younger adults required almost 7 more treatments to clear when they came in less frequently, with approximately 80% achieving a high level of clearance. As a result, our study found that in both age groups, slowing the treatment frequency extended the treatment time to clearance—more for the younger adults than the older adults—but did not significantly change the percentage of individuals reaching full clearance in either group.

Erythema Rates—There was no association between photosensitizing medications and erythema rates except when patients were taking at least 3 medications. Most medications that listed photosensitivity as a possible side effect did not specify their relevant range of UV radiation; therefore, all such medications were examined during this analysis. Prior research has shown UVB range photosensitizing medications include thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.19 A sensitivity analysis that focused only on these medications found no association between them and any particular grade of erythema. However, patients taking 3 or more of any medications listing photosensitivity as a side effect had an increased risk for grade 2 erythema.

Erythema rates in this study were consistent with a 2013 systematic review that reported 57% of patients with asymptomatic grade 1 erythema.25 In the 2 other comparative older adult studies, erythema rates varied widely: 35% in a study from Turkey18compared to only1.89% in a study from the United Kingdom.17

The starting dose for NB-UVB may drive erythema rates. The current study’s protocols were based on an estimated MED that is subjectively determined by the dermatology provider’s assessment of the patient’s skin sensitivity via examination and questions to the patient about their response to environmental sun exposure (ie, burning and tanning)26 and is frequently used to determine the starting dose and subsequent dose escalation. Certain medications have been found to increase photosensitivity and erythema,20 which can change an individual’s MED. If photosensitizing medications are started prior to or during a course of NB-UVB without a pretreatment MED, they might increase the risk for erythema. This study did not identify specific erythema-inducing medications but did find that taking 3 or more photosensitizing medications was associated with increased episodes of grade 2 erythema. Similarly, Harrop et al8 found that patients who were taking photosensitizing medications were more likely to have grade 2 or higher erythema, despite baseline MED testing, which is an established safety mechanism to reduce the risk and severity of erythema.14,20,27 The authors of a recent study of older adults in Taiwan specifically recommended MED testing due to the unpredictable influence of polypharmacy on MED calculations in this population.28 Therefore, this study’s use of an estimated MED in older adults may have influenced the starting dose as well as the incidence and severity of erythemic events. Age-related skin changes likely are ruled out as a consideration for mild erythema by the similarity of grade 1 erythema rates in both older and younger adults. Other studies have identified differences between the age groups, where older patients experienced more intense erythema in the late phase of UVB treatments.22,23 This phenomenon could increase the risk for a grade 2 erythema, which may correspond with this study’s findings.

Other potential causes of erythema were ruled out during our study, including erythema related to missed treatments and shielding mishaps. Other factors, however, may impact the level of sensitivity each patient has to phototherapy, including genetics, epigenetics, and cumulative sun damage. With NB-UVB, near-erythemogenic doses are optimal to achieve effective treatments but require a delicate balance to achieve, which may be more problematic for older adults, especially those taking several medications.

Study Limitations—Our study design made it difficult to draw conclusions about rarer dermatologic conditions. Some patients received treatments over years that were not included in the study period. Finally, power calculations suggested that our actual sample size was too small, with approximately one-third of the required sample missing.

Practical Implications—The goals of phototherapy are to achieve a high level of disease clearance with the fewest number of treatments possible and minimal side effects.

The extra staff training and patient monitoring required for MED testing likely is to add value and preserve resources if faster clearance rates could be achieved and may warrant further investigation. Phototherapy centers require standardized treatment protocols, diligent well-trained staff, and program monitoring to ensure consistent care to all patients. This study highlighted the ongoing opportunity for health care organizations to conduct evidence-based practice inquiries to continually optimize care for their patients.

- Fernández-Guarino M, Aboin-Gonzalez S, Barchino L, et al. Treatment of moderate and severe adult chronic atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB and the combination of narrow-band UVB/UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:19-23.

- Foerster J, Boswell K, West J, et al. Narrowband UVB treatment is highly effective and causes a strong reduction in the use of steroid and other creams in psoriasis patients in clinical practice. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181813.

- Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, Boms S, et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in skin conditions beyond psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:660-670.

- Ryu HH, Choe YS, Jo S, et al. Remission period in psoriasis after multiple cycles of narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Dermatol. 2014;41:622-627.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

- Tintle S, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Reversal of atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB phototherapy and biomarkers for therapeutic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:583-593.e581-584.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS, Yule S, et al. A randomized, observer-blinded trial of twice vs. three times weekly narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:973-978.

- Harrop G, Dawe RS, Ibbotson S. Are photosensitizing medications associated with increased risk of important erythemal reactions during ultraviolet B phototherapy? Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1184-1185.

- Torres AE, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH, et al. Role of phototherapy in the era of biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:479-485.

- Bukvic´ć Mokos Z, Jovic´ A, Cˇeovic´ R, et al. Therapeutic challenges in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:128-139.

- Di Lernia V, Goldust M. An overview of the efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for psoriasis in the elderly. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:897-903.

- Oliveira C, Torres T. More than skin deep: the systemic nature of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:250-258.

- Matthews S, Pike K, Chien A. Phototherapy: safe and effective for challenging skin conditions in older adults. Cutis. 2021;108:E15-E21.

- Rodríguez-Granados MT, Estany-Gestal A, Pousa-Martínez M, et al. Is it useful to calculate minimal erythema dose before narrowband UV-B phototherapy? Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:852-858.

- Parlak N, Kundakci N, Parlak A, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy starting and incremental dose in patients with psoriasis: comparison of percentage dose and fixed dose protocols. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2015;31:90-97.

- Kleinpenning MM, Smits T, Boezeman J, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B therapy in psoriasis: randomized double-blind comparison of high-dose and low-dose irradiation regimens. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1351-1356.

- Powell JB, Gach JE. Phototherapy in the elderly. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:605-610.

- Bulur I, Erdogan HK, Aksu AE, et al. The efficacy and safety of phototherapy in geriatric patients: a retrospective study. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:33-38.

- Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH. Drug-induced photosensitivity. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:363-368, ix.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS. Photosensitizing drugs may lower the narrow-band ultraviolet B (TL-01) minimal erythema dose. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:389-390.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Gloor M, Scherotzke A. Age dependence of ultraviolet light-induced erythema following narrow-band UVB exposure. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2002;18:121-126.

- Cox NH, Diffey BL, Farr PM. The relationship between chronological age and the erythemal response to ultraviolet B radiation. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:315-319.

- Morrison W. Phototherapy and Photochemotherapy for Skin Disease. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2005.

- Almutawa F, Alnomair N, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of UV-based therapy for psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:87-109.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

- Kwon IH, Kwon HH, Na SJ, et al. Could colorimetric method replace the individual minimal erythemal dose (MED) measurements in determining the initial dose of narrow-band UVB treatment for psoriasis patients with skin phototype III-V? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:494-498.

- Chen WA, Chang CM. The minimal erythema dose of narrowband ultraviolet B in elderly Taiwanese [published online September 1, 2021]. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. doi:10.1111/phpp.12730

- Fernández-Guarino M, Aboin-Gonzalez S, Barchino L, et al. Treatment of moderate and severe adult chronic atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB and the combination of narrow-band UVB/UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:19-23.

- Foerster J, Boswell K, West J, et al. Narrowband UVB treatment is highly effective and causes a strong reduction in the use of steroid and other creams in psoriasis patients in clinical practice. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181813.

- Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, Boms S, et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in skin conditions beyond psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:660-670.

- Ryu HH, Choe YS, Jo S, et al. Remission period in psoriasis after multiple cycles of narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Dermatol. 2014;41:622-627.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

- Tintle S, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Reversal of atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB phototherapy and biomarkers for therapeutic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:583-593.e581-584.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS, Yule S, et al. A randomized, observer-blinded trial of twice vs. three times weekly narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:973-978.

- Harrop G, Dawe RS, Ibbotson S. Are photosensitizing medications associated with increased risk of important erythemal reactions during ultraviolet B phototherapy? Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1184-1185.

- Torres AE, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH, et al. Role of phototherapy in the era of biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:479-485.

- Bukvic´ć Mokos Z, Jovic´ A, Cˇeovic´ R, et al. Therapeutic challenges in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:128-139.

- Di Lernia V, Goldust M. An overview of the efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for psoriasis in the elderly. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:897-903.

- Oliveira C, Torres T. More than skin deep: the systemic nature of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:250-258.

- Matthews S, Pike K, Chien A. Phototherapy: safe and effective for challenging skin conditions in older adults. Cutis. 2021;108:E15-E21.

- Rodríguez-Granados MT, Estany-Gestal A, Pousa-Martínez M, et al. Is it useful to calculate minimal erythema dose before narrowband UV-B phototherapy? Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:852-858.

- Parlak N, Kundakci N, Parlak A, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy starting and incremental dose in patients with psoriasis: comparison of percentage dose and fixed dose protocols. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2015;31:90-97.

- Kleinpenning MM, Smits T, Boezeman J, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B therapy in psoriasis: randomized double-blind comparison of high-dose and low-dose irradiation regimens. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1351-1356.

- Powell JB, Gach JE. Phototherapy in the elderly. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:605-610.

- Bulur I, Erdogan HK, Aksu AE, et al. The efficacy and safety of phototherapy in geriatric patients: a retrospective study. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:33-38.

- Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH. Drug-induced photosensitivity. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:363-368, ix.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS. Photosensitizing drugs may lower the narrow-band ultraviolet B (TL-01) minimal erythema dose. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:389-390.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Gloor M, Scherotzke A. Age dependence of ultraviolet light-induced erythema following narrow-band UVB exposure. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2002;18:121-126.

- Cox NH, Diffey BL, Farr PM. The relationship between chronological age and the erythemal response to ultraviolet B radiation. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:315-319.

- Morrison W. Phototherapy and Photochemotherapy for Skin Disease. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2005.

- Almutawa F, Alnomair N, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of UV-based therapy for psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:87-109.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

- Kwon IH, Kwon HH, Na SJ, et al. Could colorimetric method replace the individual minimal erythemal dose (MED) measurements in determining the initial dose of narrow-band UVB treatment for psoriasis patients with skin phototype III-V? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:494-498.

- Chen WA, Chang CM. The minimal erythema dose of narrowband ultraviolet B in elderly Taiwanese [published online September 1, 2021]. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. doi:10.1111/phpp.12730

Practice Points

- Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy remains a safe and efficacious nonpharmacologic treatment for dermatologic conditions in older and younger adults.

- Compared to younger adults, older adults using the same protocols need similar or even fewer treatments to achieve high levels of clearance.

- Individuals taking 3 or more photosensitizing medications, regardless of age, may be at higher risk for substantial erythema with NB-UVB phototherapy.

- Phototherapy program monitoring is important to ensure quality care and investigate opportunities for care optimization.

Polycyclic Scaly Eruption

The Diagnosis: Netherton Syndrome

A punch biopsy from the right lower back supported the clinical diagnosis of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa. The patient underwent genetic testing and was found to have a heterozygous mutation in the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5 gene, SPINK5, that was consistent with a diagnosis of Netherton syndrome.

Netherton syndrome is an autosomal-recessive genodermatosis characterized by a triad of congenital ichthyosis, hair shaft abnormalities, and atopic diatheses.1,2 It affects approximately 1 in 200,000 live births2,3; however, it is considered by many to be underdiagnosed due to the variability in the clinical appearance. Therefore, the incidence of Netherton syndrome may actually be closer 1 in 50,000 live births.1 The manifestations of the disease are caused by a germline mutation in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes the serine protease inhibitor LEKTI.1,2 Dysfunctional LEKTI results in increased proteolytic activity of the lipid-processing enzymes in the stratum corneum, resulting in a disruption in the lipid bilayer.1 Dysfunctional LEKTI also results in a loss of the antiinflammatory and antimicrobial function of the stratum corneum. Clinical features of Netherton syndrome usually present at birth or shortly thereafter.1 Congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, or the continuous peeling of the skin, is a common presentation seen at birth and in the neonatal period.2 As the patient ages, the dermatologic manifestations evolve into serpiginous and circinate, erythematous plaques with a characteristic peripheral, double-edged scaling.1,2 This distinctive finding is termed ichthyosis linearis circumflexa and is pathognomonic for the syndrome.2 Lesions often affect the trunk and extremities and demonstrate an undulating course.1 Because eczematous and lichenified plaques in flexural areas as well as pruritus are common clinical features, this disease often is misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis,1,3 as was the case in our patient.

Patients with Netherton syndrome can present with various hair abnormalities. Trichorrhexis invaginata, known as bamboo hair, is the intussusception of the hair shaft and is characteristic of the disease.3 It develops from a reduced number of disulfide bonds, which results in cortical softening.1 Trichorrhexis invaginata may not be present at birth and often improves with age.1,3 Other hair shaft abnormalities such as pili torti, trichorrhexis nodosa, and helical hair also may be observed in Netherton syndrome.1 Extracutaneous manifestations also are typical. There is immune dysregulation of memory B cells and natural killer cells, which manifests as frequent respiratory and skin infections as well as sepsis.1,2 Patients also may have increased levels of serum IgE and eosinophilia resulting in atopy and allergic reactions to various triggers such as foods.1 The neonatal period also may be complicated by dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, inability to regulate body temperature, and failure to thrive.1,3

When there is an extensive disruption of the skin barrier during the neonatal period, there may be severe electrolyte imbalances and thermoregulatory challenges necessitating treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit. Cutaneous disease can be treated with topical therapies with variable success.1 Topical therapies for symptom management include emollients, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, calcipotriene, and retinoids; however, utmost caution must be employed with these therapies due to the increased risk for systemic absorption resulting from the disturbance of the skin barrier. When therapy with topical tacrolimus is implemented, monitoring of serum drug levels is required.1 Pruritus may be treated symptomatically with oral antihistamines. Intravenous immunoglobulin has been shown to decrease the frequency of infections and improve skin inflammation. Systemic retinoids have unpredictable effects and result in improvement of disease in some patients but exacerbation in others. Phototherapy with narrowband UVB, psoralen plus UVA, UVA1, and balneophototherapy also are effective treatments for cutaneous disease.1 Dupilumab has been shown to decrease pruritus, improve hair abnormalities, and improve skin disease, thereby demonstrating its effectiveness in treating the atopy and ichthyosis in Netherton syndrome.4

The differential diagnosis includes other figurate erythemas including erythema marginatum and erythrokeratodermia variabilis. Erythema marginatum is a cutaneous manifestation of acute rheumatic fever and is characterized by migratory polycyclic erythematous plaques without overlying scale, usually on the trunk and proximal extremities.5 Erythrokeratodermia variabilis is caused by heterozygous mutations in gap junction protein beta 3, GJB3, and gap junction protein beta 4, GJB4, and is characterized by transient geographic and erythematous patches and stable scaly plaques; however, double-edged scaling is not a feature.1 Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive disorder caused by mutations in the zinc transporter SLC39A4. Cutaneous manifestations occur after weaning from breast milk and are characterized by erythematous plaques with erosions, vesicles, and scaling, which characteristically occur in the perioral and perianal locations.6 Neonatal lupus is a form of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Typical skin lesions are erythematous annular plaques with overlying scaling, which may be present at birth and have a predilection for the face and other sun-exposed areas. Lesions generally resolve after clearance of the pathogenic maternal antibodies.7

- Richard G, Ringpfeil F. Ichthyoses, erythrokeratodermas, and related disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:888-923.

- Garza JI, Herz-Ruelas ME, Guerrero-González GA, et al. Netherton syndrome: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB129.

- Heymann W. Appending the appendages: new perspectives on Netherton syndrome and green nail syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:735-736.

- Murase C, Takeichi T, Taki T, et al. Successful dupilumab treatment for ichthyotic and atopic features of Netherton syndrome. J Dermatol Sci. 2021;102:126-129.

- España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:320-331.

- Noguera-Morel L, McLeish Schaefer S, Hivnor C. Nutritional diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:793-809.

- Lee L, Werth V. Lupus erythematosus. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:662-680.

The Diagnosis: Netherton Syndrome

A punch biopsy from the right lower back supported the clinical diagnosis of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa. The patient underwent genetic testing and was found to have a heterozygous mutation in the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5 gene, SPINK5, that was consistent with a diagnosis of Netherton syndrome.

Netherton syndrome is an autosomal-recessive genodermatosis characterized by a triad of congenital ichthyosis, hair shaft abnormalities, and atopic diatheses.1,2 It affects approximately 1 in 200,000 live births2,3; however, it is considered by many to be underdiagnosed due to the variability in the clinical appearance. Therefore, the incidence of Netherton syndrome may actually be closer 1 in 50,000 live births.1 The manifestations of the disease are caused by a germline mutation in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes the serine protease inhibitor LEKTI.1,2 Dysfunctional LEKTI results in increased proteolytic activity of the lipid-processing enzymes in the stratum corneum, resulting in a disruption in the lipid bilayer.1 Dysfunctional LEKTI also results in a loss of the antiinflammatory and antimicrobial function of the stratum corneum. Clinical features of Netherton syndrome usually present at birth or shortly thereafter.1 Congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, or the continuous peeling of the skin, is a common presentation seen at birth and in the neonatal period.2 As the patient ages, the dermatologic manifestations evolve into serpiginous and circinate, erythematous plaques with a characteristic peripheral, double-edged scaling.1,2 This distinctive finding is termed ichthyosis linearis circumflexa and is pathognomonic for the syndrome.2 Lesions often affect the trunk and extremities and demonstrate an undulating course.1 Because eczematous and lichenified plaques in flexural areas as well as pruritus are common clinical features, this disease often is misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis,1,3 as was the case in our patient.

Patients with Netherton syndrome can present with various hair abnormalities. Trichorrhexis invaginata, known as bamboo hair, is the intussusception of the hair shaft and is characteristic of the disease.3 It develops from a reduced number of disulfide bonds, which results in cortical softening.1 Trichorrhexis invaginata may not be present at birth and often improves with age.1,3 Other hair shaft abnormalities such as pili torti, trichorrhexis nodosa, and helical hair also may be observed in Netherton syndrome.1 Extracutaneous manifestations also are typical. There is immune dysregulation of memory B cells and natural killer cells, which manifests as frequent respiratory and skin infections as well as sepsis.1,2 Patients also may have increased levels of serum IgE and eosinophilia resulting in atopy and allergic reactions to various triggers such as foods.1 The neonatal period also may be complicated by dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, inability to regulate body temperature, and failure to thrive.1,3

When there is an extensive disruption of the skin barrier during the neonatal period, there may be severe electrolyte imbalances and thermoregulatory challenges necessitating treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit. Cutaneous disease can be treated with topical therapies with variable success.1 Topical therapies for symptom management include emollients, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, calcipotriene, and retinoids; however, utmost caution must be employed with these therapies due to the increased risk for systemic absorption resulting from the disturbance of the skin barrier. When therapy with topical tacrolimus is implemented, monitoring of serum drug levels is required.1 Pruritus may be treated symptomatically with oral antihistamines. Intravenous immunoglobulin has been shown to decrease the frequency of infections and improve skin inflammation. Systemic retinoids have unpredictable effects and result in improvement of disease in some patients but exacerbation in others. Phototherapy with narrowband UVB, psoralen plus UVA, UVA1, and balneophototherapy also are effective treatments for cutaneous disease.1 Dupilumab has been shown to decrease pruritus, improve hair abnormalities, and improve skin disease, thereby demonstrating its effectiveness in treating the atopy and ichthyosis in Netherton syndrome.4

The differential diagnosis includes other figurate erythemas including erythema marginatum and erythrokeratodermia variabilis. Erythema marginatum is a cutaneous manifestation of acute rheumatic fever and is characterized by migratory polycyclic erythematous plaques without overlying scale, usually on the trunk and proximal extremities.5 Erythrokeratodermia variabilis is caused by heterozygous mutations in gap junction protein beta 3, GJB3, and gap junction protein beta 4, GJB4, and is characterized by transient geographic and erythematous patches and stable scaly plaques; however, double-edged scaling is not a feature.1 Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive disorder caused by mutations in the zinc transporter SLC39A4. Cutaneous manifestations occur after weaning from breast milk and are characterized by erythematous plaques with erosions, vesicles, and scaling, which characteristically occur in the perioral and perianal locations.6 Neonatal lupus is a form of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Typical skin lesions are erythematous annular plaques with overlying scaling, which may be present at birth and have a predilection for the face and other sun-exposed areas. Lesions generally resolve after clearance of the pathogenic maternal antibodies.7

The Diagnosis: Netherton Syndrome

A punch biopsy from the right lower back supported the clinical diagnosis of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa. The patient underwent genetic testing and was found to have a heterozygous mutation in the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5 gene, SPINK5, that was consistent with a diagnosis of Netherton syndrome.

Netherton syndrome is an autosomal-recessive genodermatosis characterized by a triad of congenital ichthyosis, hair shaft abnormalities, and atopic diatheses.1,2 It affects approximately 1 in 200,000 live births2,3; however, it is considered by many to be underdiagnosed due to the variability in the clinical appearance. Therefore, the incidence of Netherton syndrome may actually be closer 1 in 50,000 live births.1 The manifestations of the disease are caused by a germline mutation in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes the serine protease inhibitor LEKTI.1,2 Dysfunctional LEKTI results in increased proteolytic activity of the lipid-processing enzymes in the stratum corneum, resulting in a disruption in the lipid bilayer.1 Dysfunctional LEKTI also results in a loss of the antiinflammatory and antimicrobial function of the stratum corneum. Clinical features of Netherton syndrome usually present at birth or shortly thereafter.1 Congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, or the continuous peeling of the skin, is a common presentation seen at birth and in the neonatal period.2 As the patient ages, the dermatologic manifestations evolve into serpiginous and circinate, erythematous plaques with a characteristic peripheral, double-edged scaling.1,2 This distinctive finding is termed ichthyosis linearis circumflexa and is pathognomonic for the syndrome.2 Lesions often affect the trunk and extremities and demonstrate an undulating course.1 Because eczematous and lichenified plaques in flexural areas as well as pruritus are common clinical features, this disease often is misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis,1,3 as was the case in our patient.

Patients with Netherton syndrome can present with various hair abnormalities. Trichorrhexis invaginata, known as bamboo hair, is the intussusception of the hair shaft and is characteristic of the disease.3 It develops from a reduced number of disulfide bonds, which results in cortical softening.1 Trichorrhexis invaginata may not be present at birth and often improves with age.1,3 Other hair shaft abnormalities such as pili torti, trichorrhexis nodosa, and helical hair also may be observed in Netherton syndrome.1 Extracutaneous manifestations also are typical. There is immune dysregulation of memory B cells and natural killer cells, which manifests as frequent respiratory and skin infections as well as sepsis.1,2 Patients also may have increased levels of serum IgE and eosinophilia resulting in atopy and allergic reactions to various triggers such as foods.1 The neonatal period also may be complicated by dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, inability to regulate body temperature, and failure to thrive.1,3

When there is an extensive disruption of the skin barrier during the neonatal period, there may be severe electrolyte imbalances and thermoregulatory challenges necessitating treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit. Cutaneous disease can be treated with topical therapies with variable success.1 Topical therapies for symptom management include emollients, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, calcipotriene, and retinoids; however, utmost caution must be employed with these therapies due to the increased risk for systemic absorption resulting from the disturbance of the skin barrier. When therapy with topical tacrolimus is implemented, monitoring of serum drug levels is required.1 Pruritus may be treated symptomatically with oral antihistamines. Intravenous immunoglobulin has been shown to decrease the frequency of infections and improve skin inflammation. Systemic retinoids have unpredictable effects and result in improvement of disease in some patients but exacerbation in others. Phototherapy with narrowband UVB, psoralen plus UVA, UVA1, and balneophototherapy also are effective treatments for cutaneous disease.1 Dupilumab has been shown to decrease pruritus, improve hair abnormalities, and improve skin disease, thereby demonstrating its effectiveness in treating the atopy and ichthyosis in Netherton syndrome.4

The differential diagnosis includes other figurate erythemas including erythema marginatum and erythrokeratodermia variabilis. Erythema marginatum is a cutaneous manifestation of acute rheumatic fever and is characterized by migratory polycyclic erythematous plaques without overlying scale, usually on the trunk and proximal extremities.5 Erythrokeratodermia variabilis is caused by heterozygous mutations in gap junction protein beta 3, GJB3, and gap junction protein beta 4, GJB4, and is characterized by transient geographic and erythematous patches and stable scaly plaques; however, double-edged scaling is not a feature.1 Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive disorder caused by mutations in the zinc transporter SLC39A4. Cutaneous manifestations occur after weaning from breast milk and are characterized by erythematous plaques with erosions, vesicles, and scaling, which characteristically occur in the perioral and perianal locations.6 Neonatal lupus is a form of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Typical skin lesions are erythematous annular plaques with overlying scaling, which may be present at birth and have a predilection for the face and other sun-exposed areas. Lesions generally resolve after clearance of the pathogenic maternal antibodies.7

- Richard G, Ringpfeil F. Ichthyoses, erythrokeratodermas, and related disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:888-923.

- Garza JI, Herz-Ruelas ME, Guerrero-González GA, et al. Netherton syndrome: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB129.

- Heymann W. Appending the appendages: new perspectives on Netherton syndrome and green nail syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:735-736.

- Murase C, Takeichi T, Taki T, et al. Successful dupilumab treatment for ichthyotic and atopic features of Netherton syndrome. J Dermatol Sci. 2021;102:126-129.

- España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:320-331.

- Noguera-Morel L, McLeish Schaefer S, Hivnor C. Nutritional diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:793-809.

- Lee L, Werth V. Lupus erythematosus. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:662-680.

- Richard G, Ringpfeil F. Ichthyoses, erythrokeratodermas, and related disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:888-923.

- Garza JI, Herz-Ruelas ME, Guerrero-González GA, et al. Netherton syndrome: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB129.

- Heymann W. Appending the appendages: new perspectives on Netherton syndrome and green nail syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:735-736.

- Murase C, Takeichi T, Taki T, et al. Successful dupilumab treatment for ichthyotic and atopic features of Netherton syndrome. J Dermatol Sci. 2021;102:126-129.

- España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:320-331.

- Noguera-Morel L, McLeish Schaefer S, Hivnor C. Nutritional diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:793-809.

- Lee L, Werth V. Lupus erythematosus. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:662-680.

A 9-year-old boy presented to the dermatology clinic with a scaly eruption distributed throughout the body that had been present since birth. He had been diagnosed with atopic dermatitis by multiple dermatologists prior to the current presentation and had been treated with various topical steroids with minimal improvement. He had no family history of similar eruptions and no personal history of asthma or allergies. Physical examination revealed erythematous, serpiginous, polycyclic plaques with peripheral, double-edged scaling. Decreased hair density of the lateral eyebrows also was observed.

An asymptomatic rash

This patient was given a diagnosis of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CRP) based on the clinical presentation.

CRP is characterized by centrally confluent and peripherally reticulated scaly brown plaques and papules that are cosmetically disfiguring.1 CRP is usually asymptomatic and primarily impacts young adults—especially teenagers.2,3 It affects both males and females and commonly occurs on the trunk.1-3 CRP is believed to be a disorder of keratinization. Malassezia furfur may induce CRP’s hyperproliferative epidermal changes, but systemic treatment that eliminates this organism does not clear CRP.3

A CRP diagnosis is made based on clinical presentation. The eruption usually begins as verrucous papules in the inframammary or epigastric region that enlarge to 4 to 5 mm in diameter and coalesce to form a confluent plaque with a peripheral reticulated pattern. CRP can extend over the back, chest, and abdomen to the neck, shoulders, and gluteal cleft. CRP does not affect the oral mucosa, and rarely involves flexural areas, which differentiates it from the similar looking acanthosis nigricans.2 Although most cases are asymptomatic, mild pruritus may occur.1,2

A skin biopsy is rarely necessary for making a CRP diagnosis, but histopathologic findings include papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, variable acanthosis, follicular plugging, and sparse dermal inflammation.1,3

Systemic antibiotics, most commonly minocycline 100 mg bid for 30 days or doxycycline 100 mg bid for 30 days, are safe and effective for CRP.1,4 Sometimes treatment is extended for as long as 6 months. Although CRP usually responds to minocycline or doxycycline, it is believed that this is the result of these drugs’ anti-inflammatory—rather than antibiotic—properties.1,2,4 Azithromycin is an effective alternative therapy.2,4 There is a high rate of recurrence of CRP in patients after systemic antibiotics are discontinued.2 Uniform responses to treatment and retreatment of flares have solidified the belief that antibiotics are an effective suppressive (if not curative) therapy despite a lack of randomized controlled trials.4

This patient was treated with minocycline 100 mg bid. After 1 month, the rash had improved by 70%. At 3 months, it was completely clear, and treatment was discontinued.

This case was adapted from: Sessums MT, Ward KMH, Brodell R. Cutaneous eruption on chest and back. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:467-468.

1. Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. A study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06955.x

2. Scheinfeld N. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:305-313. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00004

3. Tamraz H, Raffoul M, Kurban M, et al. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: clinical and histopathological study of 10 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e119-e123. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04328.x

4. Jang HS, Oh CK, Cha JH, et al. Six cases of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis alleviated by various antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:652-655. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.112577

This patient was given a diagnosis of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CRP) based on the clinical presentation.

CRP is characterized by centrally confluent and peripherally reticulated scaly brown plaques and papules that are cosmetically disfiguring.1 CRP is usually asymptomatic and primarily impacts young adults—especially teenagers.2,3 It affects both males and females and commonly occurs on the trunk.1-3 CRP is believed to be a disorder of keratinization. Malassezia furfur may induce CRP’s hyperproliferative epidermal changes, but systemic treatment that eliminates this organism does not clear CRP.3

A CRP diagnosis is made based on clinical presentation. The eruption usually begins as verrucous papules in the inframammary or epigastric region that enlarge to 4 to 5 mm in diameter and coalesce to form a confluent plaque with a peripheral reticulated pattern. CRP can extend over the back, chest, and abdomen to the neck, shoulders, and gluteal cleft. CRP does not affect the oral mucosa, and rarely involves flexural areas, which differentiates it from the similar looking acanthosis nigricans.2 Although most cases are asymptomatic, mild pruritus may occur.1,2

A skin biopsy is rarely necessary for making a CRP diagnosis, but histopathologic findings include papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, variable acanthosis, follicular plugging, and sparse dermal inflammation.1,3