User login

Abbreviated Delirium Screening Instruments: Plausible Tool to Improve Delirium Detection in Hospitalized Older Patients

Study 1 Overview (Oberhaus et al)

Objective: To compare the 3-Minute Diagnostic Confusion Assessment Method (3D-CAM) to the long-form Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) in detecting postoperative delirium.

Design: Prospective concurrent comparison of 3D-CAM and CAM evaluations in a cohort of postoperative geriatric patients.

Setting and participants: Eligible participants were patients aged 60 years or older undergoing major elective surgery at Barnes Jewish Hospital (St. Louis, Missouri) who were enrolled in ongoing clinical trials (PODCAST, ENGAGES, SATISFY-SOS) between 2015 and 2018. Surgeries were at least 2 hours in length and required general anesthesia, planned extubation, and a minimum 2-day hospital stay. Investigators were extensively trained in administering 3D-CAM and CAM instruments. Participants were evaluated 2 hours after the end of anesthesia care on the day of surgery, then daily until follow-up was completed per clinical trial protocol or until the participant was determined by CAM to be nondelirious for 3 consecutive days. For each evaluation, both 3D-CAM and CAM assessors approached the participant together, but the evaluation was conducted such that the 3D-CAM assessor was masked to the additional questions ascertained by the long-form CAM assessment. The 3D-CAM or CAM assessor independently scored their respective assessments blinded to the results of the other assessor.

Main outcome measures: Participants were concurrently evaluated for postoperative delirium by both 3D-CAM and long-form CAM assessments. Comparisons between 3D-CAM and CAM scores were made using Cohen κ with repeated measures, generalized linear mixed-effects model, and Bland-Altman analysis.

Main results: Sixteen raters performed 471 concurrent 3D-CAM and CAM assessments in 299 participants (mean [SD] age, 69 [6.5] years). Of these participants, 152 (50.8%) were men, 263 (88.0%) were White, and 211 (70.6%) underwent noncardiac surgery. Both instruments showed good intraclass correlation (0.98 for 3D-CAM, 0.84 for CAM) with good overall agreement (Cohen κ = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58-0.83). The mixed-effects model indicated a significant disagreement between the 3D-CAM and CAM assessments (estimated difference in fixed effect, –0.68; 95% CI, –1.32 to –0.05; P = .04). The Bland-Altman analysis showed that the probability of a delirium diagnosis with the 3D-CAM was more than twice that with the CAM (probability ratio, 2.78; 95% CI, 2.44-3.23).

Conclusion: The high degree of agreement between 3D-CAM and long-form CAM assessments suggests that the former may be a pragmatic and easy-to-administer clinical tool to screen for postoperative delirium in vulnerable older surgical patients.

Study 2 Overview (Shenkin et al)

Objective: To assess the accuracy of the 4 ‘A’s Test (4AT) for delirium detection in the medical inpatient setting and to compare the 4AT to the CAM.

Design: Prospective randomized diagnostic test accuracy study.

Setting and participants: This study was conducted in emergency departments and acute medical wards at 3 UK sites (Edinburgh, Bradford, and Sheffield) and enrolled acute medical patients aged 70 years or older without acute life-threatening illnesses and/or coma. Assessors administering the delirium evaluation were nurses or graduate clinical research associates who underwent systematic training in delirium and delirium assessment. Additional training was provided to those administering the CAM but not to those administering the 4AT as the latter is designed to be administered without special training. First, all participants underwent a reference standard delirium assessment using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) (DSM-IV) criteria to derive a final definitive diagnosis of delirium via expert consensus (1 psychiatrist and 2 geriatricians). Then, the participants were randomized to either the 4AT or the comparator CAM group using computer-generated pseudo-random numbers, stratified by study site, with block allocation. All assessments were performed by pairs of independent assessors blinded to the results of the other assessment.

Main outcome measures: All participants were evaluated by the reference standard (DSM-IV criteria for delirium) and by either 4AT or CAM instruments for delirium. The accuracy of the 4AT instrument was evaluated by comparing its positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity to the reference standard and analyzed via the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. The diagnostic accuracy of 4AT, compared to the CAM, was evaluated by comparing positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity using Fisher’s exact test. The overall performance of 4AT and CAM was summarized using Youden’s Index and the diagnostic odds ratio of sensitivity to specificity.

Results: All 843 individuals enrolled in the study were randomized and 785 were included in the analysis (23 withdrew, 3 lost contact, 32 indeterminate diagnosis, 2 missing outcome). Of the participants analyzed, the mean age was 81.4 [6.4] years, and 12.1% (95/785) had delirium by reference standard assessment, 14.3% (56/392) by 4AT, and 4.7% (18/384) by CAM. The 4AT group had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.84-0.96), a sensitivity of 76% (95% CI, 61%-87%), and a specificity of 94% (95% CI, 92%-97%). In comparison, the CAM group had a sensitivity of 40% (95% CI, 26%-57%) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI, 98%-100%).

Conclusions: The 4AT is a pragmatic screening test for delirium in a medical space that does not require special training to administer. The use of this instrument may help to improve delirium detection as a part of routine clinical care in hospitalized older adults.

Commentary

Delirium is an acute confusional state marked by fluctuating mental status, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. It is exceedingly common in older patients in both surgical and medical settings and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, hospital length of stay, institutionalization, and health care costs. Delirium is frequently underdiagnosed in the hospitalized setting, perhaps due to a combination of its waxing and waning nature and a lack of pragmatic and easily implementable screening tools that can be readily administered by clinicians and nonclinicians alike.1 While the CAM is a well-validated instrument to diagnose delirium, it requires specific training in the rating of each of the cardinal features ascertained through a brief cognitive assessment and takes 5 to 10 minutes to complete. Taken together, given the high patient load for clinicians in the hospital setting, the validation and application of brief delirium screening instruments that can be reliably administered by nonphysicians and nonclinicians may enhance delirium detection in vulnerable patients and consequently improve their outcomes.

In Study 1, Oberhaus et al approach the challenge of underdiagnosing delirium in the postoperative setting by investigating whether the widely accepted long-form CAM and an abbreviated 3-minute version, the 3D-CAM, provide similar delirium detection in older surgical patients. The authors found that both instruments were reliable tests individually (high interrater reliability) and had good overall agreement. However, the 3D-CAM was more likely to yield a positive diagnosis of delirium compared to the long-form CAM, consistent with its purpose as a screening tool with a high sensitivity. It is important to emphasize that the 3D-CAM takes less time to administer, but also requires less extensive training and clinical knowledge than the long-form CAM. Therefore, this instrument meets the prerequisite of a brief screening test that can be rapidly administered by nonclinicians, and if affirmative, followed by a more extensive confirmatory test performed by a clinician. Limitations of this study include a lack of a reference standard structured interview conducted by a physician-rater to better determine the true diagnostic accuracy of both 3D-CAM and CAM assessments, and the use of convenience sampling at a single center, which reduces the generalizability of its findings.

In a similar vein, Shenkin et al in Study 2 attempt to evaluate the utility of the 4AT instrument in diagnosing delirium in older medical inpatients by testing the diagnostic accuracy of the 4AT against a reference standard (ie, DSM-IV–based evaluation by physicians) as well as comparing it to CAM. The 4AT takes less time (~2 minutes) and requires less knowledge and training to administer as compared to the CAM. The study showed that the abbreviated 4AT, compared to CAM, had a higher sensitivity (76% vs 40%) and lower specificity (94% vs 100%) in delirium detection. Thus, akin to the application of 3D-CAM in the postoperative setting, 4AT possesses key characteristics of a brief delirium screening test for older patients in the acute medical setting. In contrast to the Oberhaus et al study, a major strength of this study was the utilization of a reference standard that was validated by expert consensus. This allowed the 4AT and CAM assessments to be compared to a more objective standard, thereby directly testing their diagnostic performance in detecting delirium.

Application for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

The findings from both Study 1 and 2 suggest that using an abbreviated delirium instrument in both surgical and acute medical settings may provide a pragmatic and sensitive method to detect delirium in older patients. The brevity of administration of 3D-CAM (~3 minutes) and 4AT (~2 minutes), combined with their higher sensitivity for detecting delirium compared to CAM, make these instruments potentially effective rapid screening tests for delirium in hospitalized older patients. Importantly, the utilization of such instruments might be a feasible way to mitigate the issue of underdiagnosing delirium in the hospital.

Several additional aspects of these abbreviated delirium instruments increase their suitability for clinical application. Specifically, the 3D-CAM and 4AT require less extensive training and clinical knowledge to both administer and interpret the results than the CAM.2 For instance, a multistage, multiday training for CAM is a key factor in maintaining its diagnostic accuracy.3,4 In contrast, the 3D-CAM requires only a 1- to 2-hour training session, and the 4AT can be administered by a nonclinician without the need for instrument-specific training. Thus, implementation of these instruments can be particularly pragmatic in clinical settings in which the staff involved in delirium screening cannot undergo the substantial training required to administer CAM. Moreover, these abbreviated tests enable nonphysician care team members to assume the role of delirium screener in the hospital. Taken together, the adoption of these abbreviated instruments may facilitate brief screenings of delirium in older patients by caregivers who see them most often—nurses and certified nursing assistants—thereby improving early detection and prevention of delirium-related complications in the hospital.

The feasibility of using abbreviated delirium screening instruments in the hospital setting raises a system implementation question—if these instruments are designed to be administered by those with limited to no training, could nonclinicians, such as hospital volunteers, effectively take on delirium screening roles in the hospital? If volunteers are able to take on this role, the integration of hospital volunteers into the clinical team can greatly expand the capacity for delirium screening in the hospital setting. Further research is warranted to validate the diagnostic accuracy of 3D-CAM and 4AT by nonclinician administrators in order to more broadly adopt this approach to delirium screening.

Practice Points

- Abbreviated delirium screening tools such as 3D-CAM and 4AT may be pragmatic instruments to improve delirium detection in surgical and hospitalized older patients, respectively.

- Further studies are warranted to validate the diagnostic accuracy of 3D-CAM and 4AT by nonclinician administrators in order to more broadly adopt this approach to delirium screening.

Jared Doan, BS, and Fred Ko, MD

Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

1. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24

2. Marcantonio ER, Ngo LH, O’Connor M, et al. 3D-CAM: derivation and validation of a 3-minute diagnostic interview for CAM-defined delirium: a cross-sectional diagnostic test study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):554-561. doi:10.7326/M14-0865

3. Green JR, Smith J, Teale E, et al. Use of the confusion assessment method in multicentre delirium trials: training and standardisation. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):107. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1129-8

4. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method: a systematic review of current usage. Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):823-830. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01674.x

Study 1 Overview (Oberhaus et al)

Objective: To compare the 3-Minute Diagnostic Confusion Assessment Method (3D-CAM) to the long-form Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) in detecting postoperative delirium.

Design: Prospective concurrent comparison of 3D-CAM and CAM evaluations in a cohort of postoperative geriatric patients.

Setting and participants: Eligible participants were patients aged 60 years or older undergoing major elective surgery at Barnes Jewish Hospital (St. Louis, Missouri) who were enrolled in ongoing clinical trials (PODCAST, ENGAGES, SATISFY-SOS) between 2015 and 2018. Surgeries were at least 2 hours in length and required general anesthesia, planned extubation, and a minimum 2-day hospital stay. Investigators were extensively trained in administering 3D-CAM and CAM instruments. Participants were evaluated 2 hours after the end of anesthesia care on the day of surgery, then daily until follow-up was completed per clinical trial protocol or until the participant was determined by CAM to be nondelirious for 3 consecutive days. For each evaluation, both 3D-CAM and CAM assessors approached the participant together, but the evaluation was conducted such that the 3D-CAM assessor was masked to the additional questions ascertained by the long-form CAM assessment. The 3D-CAM or CAM assessor independently scored their respective assessments blinded to the results of the other assessor.

Main outcome measures: Participants were concurrently evaluated for postoperative delirium by both 3D-CAM and long-form CAM assessments. Comparisons between 3D-CAM and CAM scores were made using Cohen κ with repeated measures, generalized linear mixed-effects model, and Bland-Altman analysis.

Main results: Sixteen raters performed 471 concurrent 3D-CAM and CAM assessments in 299 participants (mean [SD] age, 69 [6.5] years). Of these participants, 152 (50.8%) were men, 263 (88.0%) were White, and 211 (70.6%) underwent noncardiac surgery. Both instruments showed good intraclass correlation (0.98 for 3D-CAM, 0.84 for CAM) with good overall agreement (Cohen κ = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58-0.83). The mixed-effects model indicated a significant disagreement between the 3D-CAM and CAM assessments (estimated difference in fixed effect, –0.68; 95% CI, –1.32 to –0.05; P = .04). The Bland-Altman analysis showed that the probability of a delirium diagnosis with the 3D-CAM was more than twice that with the CAM (probability ratio, 2.78; 95% CI, 2.44-3.23).

Conclusion: The high degree of agreement between 3D-CAM and long-form CAM assessments suggests that the former may be a pragmatic and easy-to-administer clinical tool to screen for postoperative delirium in vulnerable older surgical patients.

Study 2 Overview (Shenkin et al)

Objective: To assess the accuracy of the 4 ‘A’s Test (4AT) for delirium detection in the medical inpatient setting and to compare the 4AT to the CAM.

Design: Prospective randomized diagnostic test accuracy study.

Setting and participants: This study was conducted in emergency departments and acute medical wards at 3 UK sites (Edinburgh, Bradford, and Sheffield) and enrolled acute medical patients aged 70 years or older without acute life-threatening illnesses and/or coma. Assessors administering the delirium evaluation were nurses or graduate clinical research associates who underwent systematic training in delirium and delirium assessment. Additional training was provided to those administering the CAM but not to those administering the 4AT as the latter is designed to be administered without special training. First, all participants underwent a reference standard delirium assessment using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) (DSM-IV) criteria to derive a final definitive diagnosis of delirium via expert consensus (1 psychiatrist and 2 geriatricians). Then, the participants were randomized to either the 4AT or the comparator CAM group using computer-generated pseudo-random numbers, stratified by study site, with block allocation. All assessments were performed by pairs of independent assessors blinded to the results of the other assessment.

Main outcome measures: All participants were evaluated by the reference standard (DSM-IV criteria for delirium) and by either 4AT or CAM instruments for delirium. The accuracy of the 4AT instrument was evaluated by comparing its positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity to the reference standard and analyzed via the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. The diagnostic accuracy of 4AT, compared to the CAM, was evaluated by comparing positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity using Fisher’s exact test. The overall performance of 4AT and CAM was summarized using Youden’s Index and the diagnostic odds ratio of sensitivity to specificity.

Results: All 843 individuals enrolled in the study were randomized and 785 were included in the analysis (23 withdrew, 3 lost contact, 32 indeterminate diagnosis, 2 missing outcome). Of the participants analyzed, the mean age was 81.4 [6.4] years, and 12.1% (95/785) had delirium by reference standard assessment, 14.3% (56/392) by 4AT, and 4.7% (18/384) by CAM. The 4AT group had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.84-0.96), a sensitivity of 76% (95% CI, 61%-87%), and a specificity of 94% (95% CI, 92%-97%). In comparison, the CAM group had a sensitivity of 40% (95% CI, 26%-57%) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI, 98%-100%).

Conclusions: The 4AT is a pragmatic screening test for delirium in a medical space that does not require special training to administer. The use of this instrument may help to improve delirium detection as a part of routine clinical care in hospitalized older adults.

Commentary

Delirium is an acute confusional state marked by fluctuating mental status, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. It is exceedingly common in older patients in both surgical and medical settings and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, hospital length of stay, institutionalization, and health care costs. Delirium is frequently underdiagnosed in the hospitalized setting, perhaps due to a combination of its waxing and waning nature and a lack of pragmatic and easily implementable screening tools that can be readily administered by clinicians and nonclinicians alike.1 While the CAM is a well-validated instrument to diagnose delirium, it requires specific training in the rating of each of the cardinal features ascertained through a brief cognitive assessment and takes 5 to 10 minutes to complete. Taken together, given the high patient load for clinicians in the hospital setting, the validation and application of brief delirium screening instruments that can be reliably administered by nonphysicians and nonclinicians may enhance delirium detection in vulnerable patients and consequently improve their outcomes.

In Study 1, Oberhaus et al approach the challenge of underdiagnosing delirium in the postoperative setting by investigating whether the widely accepted long-form CAM and an abbreviated 3-minute version, the 3D-CAM, provide similar delirium detection in older surgical patients. The authors found that both instruments were reliable tests individually (high interrater reliability) and had good overall agreement. However, the 3D-CAM was more likely to yield a positive diagnosis of delirium compared to the long-form CAM, consistent with its purpose as a screening tool with a high sensitivity. It is important to emphasize that the 3D-CAM takes less time to administer, but also requires less extensive training and clinical knowledge than the long-form CAM. Therefore, this instrument meets the prerequisite of a brief screening test that can be rapidly administered by nonclinicians, and if affirmative, followed by a more extensive confirmatory test performed by a clinician. Limitations of this study include a lack of a reference standard structured interview conducted by a physician-rater to better determine the true diagnostic accuracy of both 3D-CAM and CAM assessments, and the use of convenience sampling at a single center, which reduces the generalizability of its findings.

In a similar vein, Shenkin et al in Study 2 attempt to evaluate the utility of the 4AT instrument in diagnosing delirium in older medical inpatients by testing the diagnostic accuracy of the 4AT against a reference standard (ie, DSM-IV–based evaluation by physicians) as well as comparing it to CAM. The 4AT takes less time (~2 minutes) and requires less knowledge and training to administer as compared to the CAM. The study showed that the abbreviated 4AT, compared to CAM, had a higher sensitivity (76% vs 40%) and lower specificity (94% vs 100%) in delirium detection. Thus, akin to the application of 3D-CAM in the postoperative setting, 4AT possesses key characteristics of a brief delirium screening test for older patients in the acute medical setting. In contrast to the Oberhaus et al study, a major strength of this study was the utilization of a reference standard that was validated by expert consensus. This allowed the 4AT and CAM assessments to be compared to a more objective standard, thereby directly testing their diagnostic performance in detecting delirium.

Application for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

The findings from both Study 1 and 2 suggest that using an abbreviated delirium instrument in both surgical and acute medical settings may provide a pragmatic and sensitive method to detect delirium in older patients. The brevity of administration of 3D-CAM (~3 minutes) and 4AT (~2 minutes), combined with their higher sensitivity for detecting delirium compared to CAM, make these instruments potentially effective rapid screening tests for delirium in hospitalized older patients. Importantly, the utilization of such instruments might be a feasible way to mitigate the issue of underdiagnosing delirium in the hospital.

Several additional aspects of these abbreviated delirium instruments increase their suitability for clinical application. Specifically, the 3D-CAM and 4AT require less extensive training and clinical knowledge to both administer and interpret the results than the CAM.2 For instance, a multistage, multiday training for CAM is a key factor in maintaining its diagnostic accuracy.3,4 In contrast, the 3D-CAM requires only a 1- to 2-hour training session, and the 4AT can be administered by a nonclinician without the need for instrument-specific training. Thus, implementation of these instruments can be particularly pragmatic in clinical settings in which the staff involved in delirium screening cannot undergo the substantial training required to administer CAM. Moreover, these abbreviated tests enable nonphysician care team members to assume the role of delirium screener in the hospital. Taken together, the adoption of these abbreviated instruments may facilitate brief screenings of delirium in older patients by caregivers who see them most often—nurses and certified nursing assistants—thereby improving early detection and prevention of delirium-related complications in the hospital.

The feasibility of using abbreviated delirium screening instruments in the hospital setting raises a system implementation question—if these instruments are designed to be administered by those with limited to no training, could nonclinicians, such as hospital volunteers, effectively take on delirium screening roles in the hospital? If volunteers are able to take on this role, the integration of hospital volunteers into the clinical team can greatly expand the capacity for delirium screening in the hospital setting. Further research is warranted to validate the diagnostic accuracy of 3D-CAM and 4AT by nonclinician administrators in order to more broadly adopt this approach to delirium screening.

Practice Points

- Abbreviated delirium screening tools such as 3D-CAM and 4AT may be pragmatic instruments to improve delirium detection in surgical and hospitalized older patients, respectively.

- Further studies are warranted to validate the diagnostic accuracy of 3D-CAM and 4AT by nonclinician administrators in order to more broadly adopt this approach to delirium screening.

Jared Doan, BS, and Fred Ko, MD

Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Study 1 Overview (Oberhaus et al)

Objective: To compare the 3-Minute Diagnostic Confusion Assessment Method (3D-CAM) to the long-form Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) in detecting postoperative delirium.

Design: Prospective concurrent comparison of 3D-CAM and CAM evaluations in a cohort of postoperative geriatric patients.

Setting and participants: Eligible participants were patients aged 60 years or older undergoing major elective surgery at Barnes Jewish Hospital (St. Louis, Missouri) who were enrolled in ongoing clinical trials (PODCAST, ENGAGES, SATISFY-SOS) between 2015 and 2018. Surgeries were at least 2 hours in length and required general anesthesia, planned extubation, and a minimum 2-day hospital stay. Investigators were extensively trained in administering 3D-CAM and CAM instruments. Participants were evaluated 2 hours after the end of anesthesia care on the day of surgery, then daily until follow-up was completed per clinical trial protocol or until the participant was determined by CAM to be nondelirious for 3 consecutive days. For each evaluation, both 3D-CAM and CAM assessors approached the participant together, but the evaluation was conducted such that the 3D-CAM assessor was masked to the additional questions ascertained by the long-form CAM assessment. The 3D-CAM or CAM assessor independently scored their respective assessments blinded to the results of the other assessor.

Main outcome measures: Participants were concurrently evaluated for postoperative delirium by both 3D-CAM and long-form CAM assessments. Comparisons between 3D-CAM and CAM scores were made using Cohen κ with repeated measures, generalized linear mixed-effects model, and Bland-Altman analysis.

Main results: Sixteen raters performed 471 concurrent 3D-CAM and CAM assessments in 299 participants (mean [SD] age, 69 [6.5] years). Of these participants, 152 (50.8%) were men, 263 (88.0%) were White, and 211 (70.6%) underwent noncardiac surgery. Both instruments showed good intraclass correlation (0.98 for 3D-CAM, 0.84 for CAM) with good overall agreement (Cohen κ = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58-0.83). The mixed-effects model indicated a significant disagreement between the 3D-CAM and CAM assessments (estimated difference in fixed effect, –0.68; 95% CI, –1.32 to –0.05; P = .04). The Bland-Altman analysis showed that the probability of a delirium diagnosis with the 3D-CAM was more than twice that with the CAM (probability ratio, 2.78; 95% CI, 2.44-3.23).

Conclusion: The high degree of agreement between 3D-CAM and long-form CAM assessments suggests that the former may be a pragmatic and easy-to-administer clinical tool to screen for postoperative delirium in vulnerable older surgical patients.

Study 2 Overview (Shenkin et al)

Objective: To assess the accuracy of the 4 ‘A’s Test (4AT) for delirium detection in the medical inpatient setting and to compare the 4AT to the CAM.

Design: Prospective randomized diagnostic test accuracy study.

Setting and participants: This study was conducted in emergency departments and acute medical wards at 3 UK sites (Edinburgh, Bradford, and Sheffield) and enrolled acute medical patients aged 70 years or older without acute life-threatening illnesses and/or coma. Assessors administering the delirium evaluation were nurses or graduate clinical research associates who underwent systematic training in delirium and delirium assessment. Additional training was provided to those administering the CAM but not to those administering the 4AT as the latter is designed to be administered without special training. First, all participants underwent a reference standard delirium assessment using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) (DSM-IV) criteria to derive a final definitive diagnosis of delirium via expert consensus (1 psychiatrist and 2 geriatricians). Then, the participants were randomized to either the 4AT or the comparator CAM group using computer-generated pseudo-random numbers, stratified by study site, with block allocation. All assessments were performed by pairs of independent assessors blinded to the results of the other assessment.

Main outcome measures: All participants were evaluated by the reference standard (DSM-IV criteria for delirium) and by either 4AT or CAM instruments for delirium. The accuracy of the 4AT instrument was evaluated by comparing its positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity to the reference standard and analyzed via the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. The diagnostic accuracy of 4AT, compared to the CAM, was evaluated by comparing positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity using Fisher’s exact test. The overall performance of 4AT and CAM was summarized using Youden’s Index and the diagnostic odds ratio of sensitivity to specificity.

Results: All 843 individuals enrolled in the study were randomized and 785 were included in the analysis (23 withdrew, 3 lost contact, 32 indeterminate diagnosis, 2 missing outcome). Of the participants analyzed, the mean age was 81.4 [6.4] years, and 12.1% (95/785) had delirium by reference standard assessment, 14.3% (56/392) by 4AT, and 4.7% (18/384) by CAM. The 4AT group had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.84-0.96), a sensitivity of 76% (95% CI, 61%-87%), and a specificity of 94% (95% CI, 92%-97%). In comparison, the CAM group had a sensitivity of 40% (95% CI, 26%-57%) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI, 98%-100%).

Conclusions: The 4AT is a pragmatic screening test for delirium in a medical space that does not require special training to administer. The use of this instrument may help to improve delirium detection as a part of routine clinical care in hospitalized older adults.

Commentary

Delirium is an acute confusional state marked by fluctuating mental status, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. It is exceedingly common in older patients in both surgical and medical settings and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, hospital length of stay, institutionalization, and health care costs. Delirium is frequently underdiagnosed in the hospitalized setting, perhaps due to a combination of its waxing and waning nature and a lack of pragmatic and easily implementable screening tools that can be readily administered by clinicians and nonclinicians alike.1 While the CAM is a well-validated instrument to diagnose delirium, it requires specific training in the rating of each of the cardinal features ascertained through a brief cognitive assessment and takes 5 to 10 minutes to complete. Taken together, given the high patient load for clinicians in the hospital setting, the validation and application of brief delirium screening instruments that can be reliably administered by nonphysicians and nonclinicians may enhance delirium detection in vulnerable patients and consequently improve their outcomes.

In Study 1, Oberhaus et al approach the challenge of underdiagnosing delirium in the postoperative setting by investigating whether the widely accepted long-form CAM and an abbreviated 3-minute version, the 3D-CAM, provide similar delirium detection in older surgical patients. The authors found that both instruments were reliable tests individually (high interrater reliability) and had good overall agreement. However, the 3D-CAM was more likely to yield a positive diagnosis of delirium compared to the long-form CAM, consistent with its purpose as a screening tool with a high sensitivity. It is important to emphasize that the 3D-CAM takes less time to administer, but also requires less extensive training and clinical knowledge than the long-form CAM. Therefore, this instrument meets the prerequisite of a brief screening test that can be rapidly administered by nonclinicians, and if affirmative, followed by a more extensive confirmatory test performed by a clinician. Limitations of this study include a lack of a reference standard structured interview conducted by a physician-rater to better determine the true diagnostic accuracy of both 3D-CAM and CAM assessments, and the use of convenience sampling at a single center, which reduces the generalizability of its findings.

In a similar vein, Shenkin et al in Study 2 attempt to evaluate the utility of the 4AT instrument in diagnosing delirium in older medical inpatients by testing the diagnostic accuracy of the 4AT against a reference standard (ie, DSM-IV–based evaluation by physicians) as well as comparing it to CAM. The 4AT takes less time (~2 minutes) and requires less knowledge and training to administer as compared to the CAM. The study showed that the abbreviated 4AT, compared to CAM, had a higher sensitivity (76% vs 40%) and lower specificity (94% vs 100%) in delirium detection. Thus, akin to the application of 3D-CAM in the postoperative setting, 4AT possesses key characteristics of a brief delirium screening test for older patients in the acute medical setting. In contrast to the Oberhaus et al study, a major strength of this study was the utilization of a reference standard that was validated by expert consensus. This allowed the 4AT and CAM assessments to be compared to a more objective standard, thereby directly testing their diagnostic performance in detecting delirium.

Application for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

The findings from both Study 1 and 2 suggest that using an abbreviated delirium instrument in both surgical and acute medical settings may provide a pragmatic and sensitive method to detect delirium in older patients. The brevity of administration of 3D-CAM (~3 minutes) and 4AT (~2 minutes), combined with their higher sensitivity for detecting delirium compared to CAM, make these instruments potentially effective rapid screening tests for delirium in hospitalized older patients. Importantly, the utilization of such instruments might be a feasible way to mitigate the issue of underdiagnosing delirium in the hospital.

Several additional aspects of these abbreviated delirium instruments increase their suitability for clinical application. Specifically, the 3D-CAM and 4AT require less extensive training and clinical knowledge to both administer and interpret the results than the CAM.2 For instance, a multistage, multiday training for CAM is a key factor in maintaining its diagnostic accuracy.3,4 In contrast, the 3D-CAM requires only a 1- to 2-hour training session, and the 4AT can be administered by a nonclinician without the need for instrument-specific training. Thus, implementation of these instruments can be particularly pragmatic in clinical settings in which the staff involved in delirium screening cannot undergo the substantial training required to administer CAM. Moreover, these abbreviated tests enable nonphysician care team members to assume the role of delirium screener in the hospital. Taken together, the adoption of these abbreviated instruments may facilitate brief screenings of delirium in older patients by caregivers who see them most often—nurses and certified nursing assistants—thereby improving early detection and prevention of delirium-related complications in the hospital.

The feasibility of using abbreviated delirium screening instruments in the hospital setting raises a system implementation question—if these instruments are designed to be administered by those with limited to no training, could nonclinicians, such as hospital volunteers, effectively take on delirium screening roles in the hospital? If volunteers are able to take on this role, the integration of hospital volunteers into the clinical team can greatly expand the capacity for delirium screening in the hospital setting. Further research is warranted to validate the diagnostic accuracy of 3D-CAM and 4AT by nonclinician administrators in order to more broadly adopt this approach to delirium screening.

Practice Points

- Abbreviated delirium screening tools such as 3D-CAM and 4AT may be pragmatic instruments to improve delirium detection in surgical and hospitalized older patients, respectively.

- Further studies are warranted to validate the diagnostic accuracy of 3D-CAM and 4AT by nonclinician administrators in order to more broadly adopt this approach to delirium screening.

Jared Doan, BS, and Fred Ko, MD

Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

1. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24

2. Marcantonio ER, Ngo LH, O’Connor M, et al. 3D-CAM: derivation and validation of a 3-minute diagnostic interview for CAM-defined delirium: a cross-sectional diagnostic test study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):554-561. doi:10.7326/M14-0865

3. Green JR, Smith J, Teale E, et al. Use of the confusion assessment method in multicentre delirium trials: training and standardisation. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):107. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1129-8

4. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method: a systematic review of current usage. Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):823-830. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01674.x

1. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24

2. Marcantonio ER, Ngo LH, O’Connor M, et al. 3D-CAM: derivation and validation of a 3-minute diagnostic interview for CAM-defined delirium: a cross-sectional diagnostic test study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):554-561. doi:10.7326/M14-0865

3. Green JR, Smith J, Teale E, et al. Use of the confusion assessment method in multicentre delirium trials: training and standardisation. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):107. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1129-8

4. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method: a systematic review of current usage. Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):823-830. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01674.x

VA Launches Virtual Tumor Board

SAN DIEGO – The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) TeleOncology program has rolled out a virtual tumor board that brings medical professionals together to offer insight and guidance about challenging hematology cases. Over the past 6 months the board has held 10 sessions and reviewed about 20 cases. A small survey found that participants think the meetings are beneficial.

“Virtual tumor boards help to connect experts across the country to leverage the expertise within the VA,” he-matologist/oncologist Thomas Rodgers, MD, of the Duke Cancer Institute and Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, told Federal Practitioner in an interview. He is the lead author of a poster about the program that was pre-sented here at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO).

As Dr. Rodgers noted, tumor boards are already in place at some VA centers. However, “they are not available at every VA and often are not set up to cover every cancer type.”

The VA National TeleOncology program created the virtual tumor board program as part of its mission to ex-tend hematology/oncology services across the system. “Cancer care has become increasingly complex. Beyond ad-vancing therapeutics, patient care often involves multiple specialties and medical disciplines,” Dr. Rodgers said. “A tumor board offers a forum for these specialists to communicate with each other in real time, not only to help estab-lish the correct diagnosis and stage of cancer but also to form a consensus on the most fitting treatment option. Think of it as getting all of the people involved in a person’s care in the same room.”

Currently, he said, the virtual tumor boards cover patients with malignant hematology diagnoses such as leuke-mia, multiple myeloma, and lymphomas. “We welcome submissions. If a provider is interested in submitting a case, they can email us and will be provided with a short intake form. Once submitted, we will collect necessary imaging and pathology for review. The provider will then present the patient case on the day of the tumor board.”

Typically, more than 30 medical professionals participate in the virtual tumor boards, Dr. Rodgers said, repre-senting medical oncology/hematology, pathology, radiology, palliative care, pharmacy, social work, and die-tary/nutrition.

According to the poster presented at AVAHO, 9 participants responded to a survey after 4 tumor board sessions. All found the boards to be beneficial or somewhat beneficial, and 55% reported that they were “highly applicable” to their practice.

Pathologist Claudio A. Mosse, MD, PhD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center and VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, praised the virtual tumor board program. “It’s been incredibly useful from my end as a pathologist as it shows me which diagnoses are most challenging for my colleagues,” Dr. Mosse said in an inter-view. “Reviewing and then presenting these challenging cases forces me to go into the published literature to come to a unitary diagnosis based on the patient history, radiology, various laboratory tests, and the biopsy I was asked to review.”

He added that “as a pathologist, I learn so much from the hematologists as they discuss the possible therapeutic options, and that strengthens my ability as a pathologist because I have to understand how one diagnosis versus an-other affects their therapeutic decision tree.”

What’s next for the virtual tumor board program? The next step is to expand to solid tumors, said VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System hematologist/oncologist Vida Almario Passero, MD, MBA, chief medical officer of National TeleOncology, in an interview.

No disclosures were reported.

SAN DIEGO – The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) TeleOncology program has rolled out a virtual tumor board that brings medical professionals together to offer insight and guidance about challenging hematology cases. Over the past 6 months the board has held 10 sessions and reviewed about 20 cases. A small survey found that participants think the meetings are beneficial.

“Virtual tumor boards help to connect experts across the country to leverage the expertise within the VA,” he-matologist/oncologist Thomas Rodgers, MD, of the Duke Cancer Institute and Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, told Federal Practitioner in an interview. He is the lead author of a poster about the program that was pre-sented here at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO).

As Dr. Rodgers noted, tumor boards are already in place at some VA centers. However, “they are not available at every VA and often are not set up to cover every cancer type.”

The VA National TeleOncology program created the virtual tumor board program as part of its mission to ex-tend hematology/oncology services across the system. “Cancer care has become increasingly complex. Beyond ad-vancing therapeutics, patient care often involves multiple specialties and medical disciplines,” Dr. Rodgers said. “A tumor board offers a forum for these specialists to communicate with each other in real time, not only to help estab-lish the correct diagnosis and stage of cancer but also to form a consensus on the most fitting treatment option. Think of it as getting all of the people involved in a person’s care in the same room.”

Currently, he said, the virtual tumor boards cover patients with malignant hematology diagnoses such as leuke-mia, multiple myeloma, and lymphomas. “We welcome submissions. If a provider is interested in submitting a case, they can email us and will be provided with a short intake form. Once submitted, we will collect necessary imaging and pathology for review. The provider will then present the patient case on the day of the tumor board.”

Typically, more than 30 medical professionals participate in the virtual tumor boards, Dr. Rodgers said, repre-senting medical oncology/hematology, pathology, radiology, palliative care, pharmacy, social work, and die-tary/nutrition.

According to the poster presented at AVAHO, 9 participants responded to a survey after 4 tumor board sessions. All found the boards to be beneficial or somewhat beneficial, and 55% reported that they were “highly applicable” to their practice.

Pathologist Claudio A. Mosse, MD, PhD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center and VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, praised the virtual tumor board program. “It’s been incredibly useful from my end as a pathologist as it shows me which diagnoses are most challenging for my colleagues,” Dr. Mosse said in an inter-view. “Reviewing and then presenting these challenging cases forces me to go into the published literature to come to a unitary diagnosis based on the patient history, radiology, various laboratory tests, and the biopsy I was asked to review.”

He added that “as a pathologist, I learn so much from the hematologists as they discuss the possible therapeutic options, and that strengthens my ability as a pathologist because I have to understand how one diagnosis versus an-other affects their therapeutic decision tree.”

What’s next for the virtual tumor board program? The next step is to expand to solid tumors, said VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System hematologist/oncologist Vida Almario Passero, MD, MBA, chief medical officer of National TeleOncology, in an interview.

No disclosures were reported.

SAN DIEGO – The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) TeleOncology program has rolled out a virtual tumor board that brings medical professionals together to offer insight and guidance about challenging hematology cases. Over the past 6 months the board has held 10 sessions and reviewed about 20 cases. A small survey found that participants think the meetings are beneficial.

“Virtual tumor boards help to connect experts across the country to leverage the expertise within the VA,” he-matologist/oncologist Thomas Rodgers, MD, of the Duke Cancer Institute and Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, told Federal Practitioner in an interview. He is the lead author of a poster about the program that was pre-sented here at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO).

As Dr. Rodgers noted, tumor boards are already in place at some VA centers. However, “they are not available at every VA and often are not set up to cover every cancer type.”

The VA National TeleOncology program created the virtual tumor board program as part of its mission to ex-tend hematology/oncology services across the system. “Cancer care has become increasingly complex. Beyond ad-vancing therapeutics, patient care often involves multiple specialties and medical disciplines,” Dr. Rodgers said. “A tumor board offers a forum for these specialists to communicate with each other in real time, not only to help estab-lish the correct diagnosis and stage of cancer but also to form a consensus on the most fitting treatment option. Think of it as getting all of the people involved in a person’s care in the same room.”

Currently, he said, the virtual tumor boards cover patients with malignant hematology diagnoses such as leuke-mia, multiple myeloma, and lymphomas. “We welcome submissions. If a provider is interested in submitting a case, they can email us and will be provided with a short intake form. Once submitted, we will collect necessary imaging and pathology for review. The provider will then present the patient case on the day of the tumor board.”

Typically, more than 30 medical professionals participate in the virtual tumor boards, Dr. Rodgers said, repre-senting medical oncology/hematology, pathology, radiology, palliative care, pharmacy, social work, and die-tary/nutrition.

According to the poster presented at AVAHO, 9 participants responded to a survey after 4 tumor board sessions. All found the boards to be beneficial or somewhat beneficial, and 55% reported that they were “highly applicable” to their practice.

Pathologist Claudio A. Mosse, MD, PhD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center and VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, praised the virtual tumor board program. “It’s been incredibly useful from my end as a pathologist as it shows me which diagnoses are most challenging for my colleagues,” Dr. Mosse said in an inter-view. “Reviewing and then presenting these challenging cases forces me to go into the published literature to come to a unitary diagnosis based on the patient history, radiology, various laboratory tests, and the biopsy I was asked to review.”

He added that “as a pathologist, I learn so much from the hematologists as they discuss the possible therapeutic options, and that strengthens my ability as a pathologist because I have to understand how one diagnosis versus an-other affects their therapeutic decision tree.”

What’s next for the virtual tumor board program? The next step is to expand to solid tumors, said VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System hematologist/oncologist Vida Almario Passero, MD, MBA, chief medical officer of National TeleOncology, in an interview.

No disclosures were reported.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa Overview

Hidradenitis suppurativa

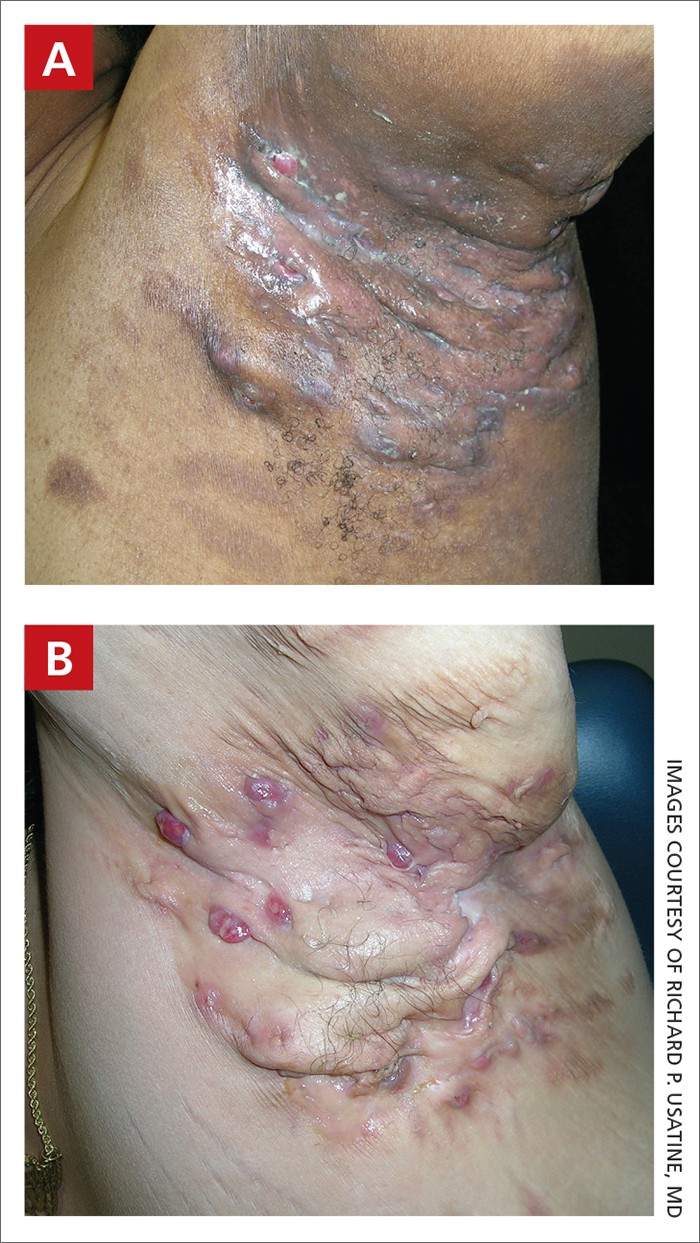

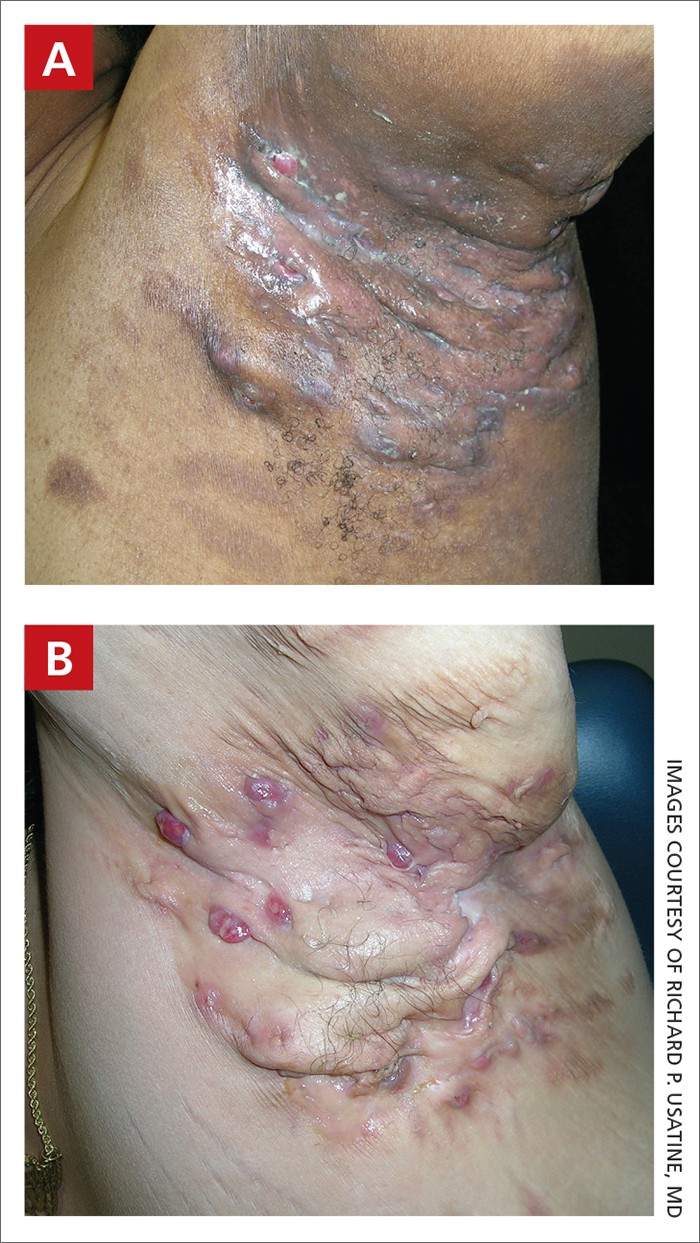

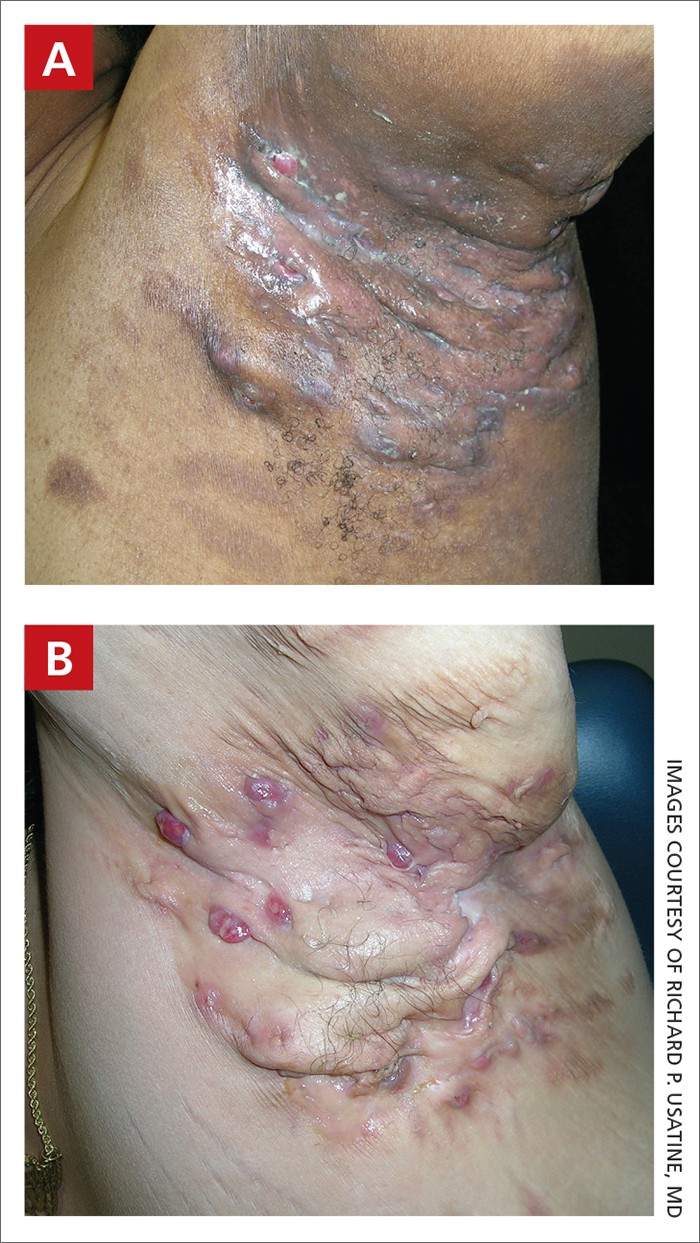

THE COMPARISON

Severe longstanding hidradenitis suppurativa (Hurley stage III) with architectural changes, ropy scarring, granulation tissue, and purulent discharge in the axilla of

A A 35-year-old Black man.

B A 42-year-old Hispanic woman with a light skin tone.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the follicular epithelium that most commonly is found in the axillae and buttocks, as well as the inguinal, perianal, and submammary areas. It is characterized by firm and tender chronic nodules, abscesses complicated by sinus tracts, fistulae, and scarring thought to be related to follicular occlusion. Double-open comedones also may be seen.

The Hurley staging system is widely used to characterize the extent of disease in patients with HS:

- Stage I (mild): nodule(s) and abscess(es) without sinus tracts (tunnels) or scarring;

- Stage II (moderate): recurrent nodule(s) and abscess(es) with a limited number of sinus tracts and/or scarring; and

- Stage III (severe): multiple or extensive sinus tracts, abscesses, and/or scarring across the entire area.

Epidemiology

HS is most common in adults and African American patients. It has a prevalence of 1.3% in African Americans.1 When it occurs in children, it generally develops after the onset of puberty. The incidence is higher in females as well as individuals with a history of smoking and obesity (a higher body mass index).2-5

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The erythema associated with HS may be difficult to see in darker skin tones, but violaceous, dark brown, and gray lesions may be present. When active HS lesions subside, intense hyperpigmentation may be left behind, and in some skin tones a pink or violaceous lesion may be apparent.

Worth noting

HS is disfiguring and has a negative impact on quality of life, including social relationships. Mental health support and screening tools are useful. Pain also is a common concern and may warrant referral to a pain specialist.6 In early disease, HS lesions can be misdiagnosed as an infection that recurs in the same location.

Treatments for HS include oral antibiotics (ie, tetracyclines, rifampin, clindamycin), topical antibiotics, immunosuppressing biologics, metformin, and spironolactone.7 Surgical interventions may be considered earlier in HS management and vary based on the location and severity of the lesions.8

Patients with HS are at risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma in scars, even many years later9; therefore, patients should perform skin checks and be referred to a dermatologist. Squamous cell carcinoma is most commonly found on the buttocks of men with HS and has a poor prognosis.

Health disparity highlight

Although those of African American and African descent have the highest rates of HS,1 the clinical trials for adalimumab (the only biologic approved for HS) enrolled a low number of Black patients.

Thirty HS comorbidities have been identified. Garg et al10 recommended that dermatologists perform examinations for comorbid conditions involving the skin and conduct a simple review of systems for extracutaneous comorbidities. Access to medical care is essential, and health care system barriers affect the ability of some patients to receive adequate continuity of care.

The diagnosis of HS often is delayed due to a lack of knowledge about the condition in the medical community at large and delayed presentation to a dermatologist.

1. Sachdeva M, Shah M, Alavi A. Race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:177-187. doi:10.1177/1203475420972348

2. Zouboulis CC, Goyal M, Byrd AS. Hidradenitis suppurativa in skin of colour. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(suppl 1):27-30. doi:10.1111 /exd.14341

3. Shalom G, Cohen AD. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: what do we know? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:712-713.

4. Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

5. Jemec GB, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S4-S7.

6. Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

7. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

8. Vellaichamy G, Braunberger TL, Nahhas AF, et al. Surgical procedures for hidradenitis suppurativa. Cutis. 2018;102:13-16.

9. Jung JM, Lee KH, Kim Y-J, et al. Assessment of overall and specific cancer risks in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:844-853.

10. Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2021.01.059

THE COMPARISON

Severe longstanding hidradenitis suppurativa (Hurley stage III) with architectural changes, ropy scarring, granulation tissue, and purulent discharge in the axilla of

A A 35-year-old Black man.

B A 42-year-old Hispanic woman with a light skin tone.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the follicular epithelium that most commonly is found in the axillae and buttocks, as well as the inguinal, perianal, and submammary areas. It is characterized by firm and tender chronic nodules, abscesses complicated by sinus tracts, fistulae, and scarring thought to be related to follicular occlusion. Double-open comedones also may be seen.

The Hurley staging system is widely used to characterize the extent of disease in patients with HS:

- Stage I (mild): nodule(s) and abscess(es) without sinus tracts (tunnels) or scarring;

- Stage II (moderate): recurrent nodule(s) and abscess(es) with a limited number of sinus tracts and/or scarring; and

- Stage III (severe): multiple or extensive sinus tracts, abscesses, and/or scarring across the entire area.

Epidemiology

HS is most common in adults and African American patients. It has a prevalence of 1.3% in African Americans.1 When it occurs in children, it generally develops after the onset of puberty. The incidence is higher in females as well as individuals with a history of smoking and obesity (a higher body mass index).2-5

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The erythema associated with HS may be difficult to see in darker skin tones, but violaceous, dark brown, and gray lesions may be present. When active HS lesions subside, intense hyperpigmentation may be left behind, and in some skin tones a pink or violaceous lesion may be apparent.

Worth noting

HS is disfiguring and has a negative impact on quality of life, including social relationships. Mental health support and screening tools are useful. Pain also is a common concern and may warrant referral to a pain specialist.6 In early disease, HS lesions can be misdiagnosed as an infection that recurs in the same location.

Treatments for HS include oral antibiotics (ie, tetracyclines, rifampin, clindamycin), topical antibiotics, immunosuppressing biologics, metformin, and spironolactone.7 Surgical interventions may be considered earlier in HS management and vary based on the location and severity of the lesions.8

Patients with HS are at risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma in scars, even many years later9; therefore, patients should perform skin checks and be referred to a dermatologist. Squamous cell carcinoma is most commonly found on the buttocks of men with HS and has a poor prognosis.

Health disparity highlight

Although those of African American and African descent have the highest rates of HS,1 the clinical trials for adalimumab (the only biologic approved for HS) enrolled a low number of Black patients.

Thirty HS comorbidities have been identified. Garg et al10 recommended that dermatologists perform examinations for comorbid conditions involving the skin and conduct a simple review of systems for extracutaneous comorbidities. Access to medical care is essential, and health care system barriers affect the ability of some patients to receive adequate continuity of care.

The diagnosis of HS often is delayed due to a lack of knowledge about the condition in the medical community at large and delayed presentation to a dermatologist.

THE COMPARISON

Severe longstanding hidradenitis suppurativa (Hurley stage III) with architectural changes, ropy scarring, granulation tissue, and purulent discharge in the axilla of

A A 35-year-old Black man.

B A 42-year-old Hispanic woman with a light skin tone.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the follicular epithelium that most commonly is found in the axillae and buttocks, as well as the inguinal, perianal, and submammary areas. It is characterized by firm and tender chronic nodules, abscesses complicated by sinus tracts, fistulae, and scarring thought to be related to follicular occlusion. Double-open comedones also may be seen.

The Hurley staging system is widely used to characterize the extent of disease in patients with HS:

- Stage I (mild): nodule(s) and abscess(es) without sinus tracts (tunnels) or scarring;

- Stage II (moderate): recurrent nodule(s) and abscess(es) with a limited number of sinus tracts and/or scarring; and

- Stage III (severe): multiple or extensive sinus tracts, abscesses, and/or scarring across the entire area.

Epidemiology

HS is most common in adults and African American patients. It has a prevalence of 1.3% in African Americans.1 When it occurs in children, it generally develops after the onset of puberty. The incidence is higher in females as well as individuals with a history of smoking and obesity (a higher body mass index).2-5

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The erythema associated with HS may be difficult to see in darker skin tones, but violaceous, dark brown, and gray lesions may be present. When active HS lesions subside, intense hyperpigmentation may be left behind, and in some skin tones a pink or violaceous lesion may be apparent.

Worth noting

HS is disfiguring and has a negative impact on quality of life, including social relationships. Mental health support and screening tools are useful. Pain also is a common concern and may warrant referral to a pain specialist.6 In early disease, HS lesions can be misdiagnosed as an infection that recurs in the same location.

Treatments for HS include oral antibiotics (ie, tetracyclines, rifampin, clindamycin), topical antibiotics, immunosuppressing biologics, metformin, and spironolactone.7 Surgical interventions may be considered earlier in HS management and vary based on the location and severity of the lesions.8

Patients with HS are at risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma in scars, even many years later9; therefore, patients should perform skin checks and be referred to a dermatologist. Squamous cell carcinoma is most commonly found on the buttocks of men with HS and has a poor prognosis.

Health disparity highlight

Although those of African American and African descent have the highest rates of HS,1 the clinical trials for adalimumab (the only biologic approved for HS) enrolled a low number of Black patients.

Thirty HS comorbidities have been identified. Garg et al10 recommended that dermatologists perform examinations for comorbid conditions involving the skin and conduct a simple review of systems for extracutaneous comorbidities. Access to medical care is essential, and health care system barriers affect the ability of some patients to receive adequate continuity of care.

The diagnosis of HS often is delayed due to a lack of knowledge about the condition in the medical community at large and delayed presentation to a dermatologist.

1. Sachdeva M, Shah M, Alavi A. Race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:177-187. doi:10.1177/1203475420972348

2. Zouboulis CC, Goyal M, Byrd AS. Hidradenitis suppurativa in skin of colour. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(suppl 1):27-30. doi:10.1111 /exd.14341

3. Shalom G, Cohen AD. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: what do we know? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:712-713.

4. Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

5. Jemec GB, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S4-S7.

6. Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

7. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

8. Vellaichamy G, Braunberger TL, Nahhas AF, et al. Surgical procedures for hidradenitis suppurativa. Cutis. 2018;102:13-16.

9. Jung JM, Lee KH, Kim Y-J, et al. Assessment of overall and specific cancer risks in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:844-853.

10. Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2021.01.059

1. Sachdeva M, Shah M, Alavi A. Race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:177-187. doi:10.1177/1203475420972348

2. Zouboulis CC, Goyal M, Byrd AS. Hidradenitis suppurativa in skin of colour. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(suppl 1):27-30. doi:10.1111 /exd.14341

3. Shalom G, Cohen AD. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: what do we know? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:712-713.

4. Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

5. Jemec GB, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S4-S7.

6. Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

7. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

8. Vellaichamy G, Braunberger TL, Nahhas AF, et al. Surgical procedures for hidradenitis suppurativa. Cutis. 2018;102:13-16.

9. Jung JM, Lee KH, Kim Y-J, et al. Assessment of overall and specific cancer risks in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:844-853.

10. Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2021.01.059

Hidradenitis Suppurativa Pathophysiology

Improving Bone Health in Patients With Advanced Prostate Cancer With the Use of Algorithm-Based Clinical Practice Tool at Salt Lake City VA

Background

The bone health of patients with locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer is at risk both from treatment-related loss of bone density and skeletal-related events from metastasis to bones. Evidence-based guidelines recommend the use of denosumab or zoledronic acid at bone metastasis-indicated dosages in the setting of castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone metastases, and at the osteoporosis-indicated dosages in the hormone-sensitive setting in patients with a significant risk of fragility fracture. For the concerns of jaw osteonecrosis, a dental evaluation is recommended before starting bone modifying agents. The literature review suggests that there is a limited evidence-based practice for bone health with prostate cancer in the real world. Both underdosing and overdosing on bone remodeling therapies place additional risk on bone health. An incomplete dental workup before starting bone modifying agents increases the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Methods

To minimize the deviation from evidencebased guidelines at VA Salt Lake City Health Care, and to provide appropriate bone health care to our patients, we created an algorithm-based clinical practice tool. This order set was incorporated into the electronic medical record system to be used while ordering a bone remodeling agent for prostate cancer. The tool prompts the clinicians to follow the appropriate algorithm in a stepwise manner to ensure a pretreatment dental evaluation and use of the correct dosage of drugs.

Results

We analyzed the data from Sept 2019 to April 2022 following the incorporation of this tool. 0/35 (0%) patients were placed on inappropriate bone modifying agent dosing and dental health was addressed on every patient before initiating treatment. We noted a significant change in the clinician’s practice while prescribing denosumab/zoledronate before and after implementation of this tool (24/41 vs 0/35, P < .00001); and an improvement in pretreatment dental checkups before and after implementation of the tool was noted to be 12/41 vs 0/35 (P < .00001).

Conclusions

We found that incorporating an evidence-based algorithm in the order set while prescribing bone remodeling agents led to a significant improvement in our institutional clinical practice to provide high-quality evidence-based care to our patients with prostate cancer.

Background

The bone health of patients with locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer is at risk both from treatment-related loss of bone density and skeletal-related events from metastasis to bones. Evidence-based guidelines recommend the use of denosumab or zoledronic acid at bone metastasis-indicated dosages in the setting of castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone metastases, and at the osteoporosis-indicated dosages in the hormone-sensitive setting in patients with a significant risk of fragility fracture. For the concerns of jaw osteonecrosis, a dental evaluation is recommended before starting bone modifying agents. The literature review suggests that there is a limited evidence-based practice for bone health with prostate cancer in the real world. Both underdosing and overdosing on bone remodeling therapies place additional risk on bone health. An incomplete dental workup before starting bone modifying agents increases the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Methods

To minimize the deviation from evidencebased guidelines at VA Salt Lake City Health Care, and to provide appropriate bone health care to our patients, we created an algorithm-based clinical practice tool. This order set was incorporated into the electronic medical record system to be used while ordering a bone remodeling agent for prostate cancer. The tool prompts the clinicians to follow the appropriate algorithm in a stepwise manner to ensure a pretreatment dental evaluation and use of the correct dosage of drugs.

Results

We analyzed the data from Sept 2019 to April 2022 following the incorporation of this tool. 0/35 (0%) patients were placed on inappropriate bone modifying agent dosing and dental health was addressed on every patient before initiating treatment. We noted a significant change in the clinician’s practice while prescribing denosumab/zoledronate before and after implementation of this tool (24/41 vs 0/35, P < .00001); and an improvement in pretreatment dental checkups before and after implementation of the tool was noted to be 12/41 vs 0/35 (P < .00001).

Conclusions

We found that incorporating an evidence-based algorithm in the order set while prescribing bone remodeling agents led to a significant improvement in our institutional clinical practice to provide high-quality evidence-based care to our patients with prostate cancer.

Background

The bone health of patients with locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer is at risk both from treatment-related loss of bone density and skeletal-related events from metastasis to bones. Evidence-based guidelines recommend the use of denosumab or zoledronic acid at bone metastasis-indicated dosages in the setting of castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone metastases, and at the osteoporosis-indicated dosages in the hormone-sensitive setting in patients with a significant risk of fragility fracture. For the concerns of jaw osteonecrosis, a dental evaluation is recommended before starting bone modifying agents. The literature review suggests that there is a limited evidence-based practice for bone health with prostate cancer in the real world. Both underdosing and overdosing on bone remodeling therapies place additional risk on bone health. An incomplete dental workup before starting bone modifying agents increases the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Methods

To minimize the deviation from evidencebased guidelines at VA Salt Lake City Health Care, and to provide appropriate bone health care to our patients, we created an algorithm-based clinical practice tool. This order set was incorporated into the electronic medical record system to be used while ordering a bone remodeling agent for prostate cancer. The tool prompts the clinicians to follow the appropriate algorithm in a stepwise manner to ensure a pretreatment dental evaluation and use of the correct dosage of drugs.

Results

We analyzed the data from Sept 2019 to April 2022 following the incorporation of this tool. 0/35 (0%) patients were placed on inappropriate bone modifying agent dosing and dental health was addressed on every patient before initiating treatment. We noted a significant change in the clinician’s practice while prescribing denosumab/zoledronate before and after implementation of this tool (24/41 vs 0/35, P < .00001); and an improvement in pretreatment dental checkups before and after implementation of the tool was noted to be 12/41 vs 0/35 (P < .00001).

Conclusions

We found that incorporating an evidence-based algorithm in the order set while prescribing bone remodeling agents led to a significant improvement in our institutional clinical practice to provide high-quality evidence-based care to our patients with prostate cancer.

Single Institution Retrospective Review of Patterns of Care and Disease Presentation in Female Veterans With Breast Cancer During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Background

Delays in care can impact patient satisfaction and survival outcomes. There are no studies in the literature evaluating the care continuum in veterans with breast cancer. A study of this predominantly African American female veteran population will help us understand barriers to care in this population.

Methods

A retrospective review of 87 patients diagnosed with breast cancer in the year 2021 at the Atlanta VA Medical Center was conducted to assess current care patterns as well as disease characteristics. Patients were included if their initial diagnostic evaluation and therapy for stage I-III breast cancer was at the Atlanta VA. Patients with a history of noncompliance causing delays in care were excluded from analysis. A total of 20 patients were identified for final analysis.

Results

Veterans were predominately African American (85%). Median age was 61 years. Stage at presentation was as follows: stage 1(35%) stage II (30%) and stage III (35%). Receptor status was as follows: hormone receptor positive (35%), Triple negative (35%), and HER-2/neu positive (30%). Genetic testing and genomic assays were completed in 100% of eligible patients per NCCN guidelines. Lumpectomy was performed in 44% of cases and mastectomy in 55% of cases. 40% of cases where mastectomy was performed were done for patient preference alone. Median time for various phases of care were as follows: symptomatic presentation to diagnostic imaging 48 days (range, 7-146), abnormal screening mammogram to diagnostic mammogram 6 days (range, 0-74), diagnostic imaging to diagnostic biopsy 15.5 days (range, 0-43), diagnostic biopsy to initiation of neoadjuvant systemic therapy 22 days (range, 14-31), diagnosis or completion of neoadjuvant systemic therapy to breast cancer surgery 58 days (range, 15-113), and surgery to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy 33 days (range, 14-44).

Conclusions

In comparison to national statistics there was a higher incidence of HER-2/neu positivity (15% vs 30%) and triple negative (12% vs 35%) subtypes, highlighting the need for quicker diagnostic testing. The delay from symptomatic presentation to diagnostic mammogram and biopsy necessitates a response given that high-risk presentations account for 75% of the cases. These findings demonstrate the need for in-house mammography to care for this high-risk minority veteran population.

Background

Delays in care can impact patient satisfaction and survival outcomes. There are no studies in the literature evaluating the care continuum in veterans with breast cancer. A study of this predominantly African American female veteran population will help us understand barriers to care in this population.

Methods

A retrospective review of 87 patients diagnosed with breast cancer in the year 2021 at the Atlanta VA Medical Center was conducted to assess current care patterns as well as disease characteristics. Patients were included if their initial diagnostic evaluation and therapy for stage I-III breast cancer was at the Atlanta VA. Patients with a history of noncompliance causing delays in care were excluded from analysis. A total of 20 patients were identified for final analysis.

Results

Veterans were predominately African American (85%). Median age was 61 years. Stage at presentation was as follows: stage 1(35%) stage II (30%) and stage III (35%). Receptor status was as follows: hormone receptor positive (35%), Triple negative (35%), and HER-2/neu positive (30%). Genetic testing and genomic assays were completed in 100% of eligible patients per NCCN guidelines. Lumpectomy was performed in 44% of cases and mastectomy in 55% of cases. 40% of cases where mastectomy was performed were done for patient preference alone. Median time for various phases of care were as follows: symptomatic presentation to diagnostic imaging 48 days (range, 7-146), abnormal screening mammogram to diagnostic mammogram 6 days (range, 0-74), diagnostic imaging to diagnostic biopsy 15.5 days (range, 0-43), diagnostic biopsy to initiation of neoadjuvant systemic therapy 22 days (range, 14-31), diagnosis or completion of neoadjuvant systemic therapy to breast cancer surgery 58 days (range, 15-113), and surgery to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy 33 days (range, 14-44).

Conclusions