User login

56-year-old man • increased heart rate • weakness • intense sweating • horseradish consumption • Dx?

THE CASE

A 56-year-old physician (CUL) visited a local seafood restaurant, after having fasted since the prior evening. He had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with lisinopril/hydrochlorothiazide.

The physician and his party were seated outside, where the temperature was in the mid-70s. The group ordered oysters on the half shell accompanied by mignonette sauce, cocktail sauce, and horseradish. The physician ate an olive-size amount of horseradish with an oyster. He immediately complained of a sharp burning sensation in his stomach and remarked that the horseradish was significantly stronger than what he was accustomed to. Within 30 seconds, he noted an increased heart rate, weakness, and intense sweating. There was no increase in nasal secretions. Observers noted that he was very pale.

About 5 minutes after eating the horseradish, the physician leaned his head back and briefly lost consciousness. His wife, while supporting his head and checking his pulse, instructed other diners to call for emergency services, at which point the physician regained consciousness and the dispatcher was told that an ambulance was no longer necessary. Within a matter of minutes, all symptoms had abated, except for some mild weakness.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Ten minutes after the event, the physician identified his symptoms as a horseradish-induced vasovagal syncope (VVS), based on a case report published in JAMA in 1988, which his wife found after he asked her to do an Internet search of his symptoms.1

THE DISCUSSION

Horseradish’s active component is isothiocyanate. Horseradish-induced syncope is also called Seder syncope after the Jewish Passover holiday dinner at which observant Jews are required to eat “bitter herbs.”1,2 This type of syncope is thought to occur when horseradish vapors directly irritate the gastric or respiratory tract mucosa.

VVS commonly manifests for the first time at around age 13 years; however, the timing of that first occurrence can vary significantly among individuals (as in this case)

The loss of consciousness may be caused by an emotional trigger (eg, sight of blood, cast removal,8 blood or platelet donations9,10), a painful event (eg, an injection11), an orthostatic trigger12 (eg, prolonged standing), or visceral reflexes such as swallowing.13 In approximately 30% of cases, loss of consciousness is associated with memory loss.14 Loss of consciousness with VVS may be associated with injury in 33% of cases.15

Continue to: The recovery with awareness

The recovery with awareness of time, place, and person may be a feature of VVS, which would differentiate it from seizures and brainstem vascular events. Autonomic prodromal symptoms—including abdominal discomfort, pallor, sweating, and nausea—may precede the loss of consciousness.8

An evolutionary response?

VVS may have developed as a trait through evolution, although modern medicine treats it as a disease. Many potential explanations for VVS as a body defense mechanism have been proposed. Examples include fainting at the sight of blood, which developed during the Old Stone Age—a period with extreme human-to-human violence—or acting like a “possum playing dead” as a tactic designed to confuse an attacker.16

Another theory involves clot production and suggests that VVS-induced hypotension is a defense against bleeding by improving clot formation.17

A psychological defense theory maintains that the fainting and memory loss are designed to prevent a painful or overwhelming experience from being remembered. None of these theories, however, explain orthostatic VVS.18

The brain defense theory could explain all forms of VVS. It postulates that hypotension causes decreased cerebral perfusion, which leads to syncope resulting in the body returning to a more orthostatic position with increased cerebral profusion.19

Continue to: The patient

The patient in this case was able to leave the restaurant on his own volition 30 minutes after the event and resume normal activities. Ten days later, an electrocardiogram was performed, with negative results. In this case, the use of a potassium-wasting diuretic exacerbated the risk of a fluid-deprived state, hypokalemia, and hypotension, possibly contributing to the syncope. The patient has since “gotten back on the horseradish” without ill effect.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consumers and health care providers should be aware of the risks associated with consumption of fresh horseradish and should allow it to rest prior to ingestion to allow some evaporation of its active ingredient. An old case report saved the patient from an unnecessary (and costly) emergency department visit.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Terry J. Hannan, MBBS, FRACP, FACHI, FACMI for his critical review of the manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christoph U. Lehmann, MD, Clinical Informatics Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, TX 75390; [email protected]

1. Rubin HR, Wu AW. The bitter herbs of Seder: more on horseradish horrors. JAMA. 1988;259:1943. doi: 10.1001/jama.259.13.1943b

2. Seder syncope. The Free Dictionary. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Horseradish+Syncope

3. Sheldon RS, Sheldon AG, Connolly SJ, et al. Age of first faint in patients with vasovagal syncope. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:49-54. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00267.x

4. Wallin BG, Sundlöf G. Sympathetic outflow to muscles during vasovagal syncope. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1982;6:287-291. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(82)90001-7

5. Jardine DL, Melton IC, Crozier IG, et al. Decrease in cardiac output and muscle sympathetic activity during vasovagal syncope. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1804-H1809. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00640.2001

6. Waxman MB, Asta JA, Cameron DA. Localization of the reflex pathway responsible for the vasodepressor reaction induced by inferior vena caval occlusion and isoproterenol. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;70:882-889. doi: 10.1139/y92-118

7. Alboni P, Alboni M. Typical vasovagal syncope as a “defense mechanism” for the heart by contrasting sympathetic overactivity. Clin Auton Res. 2017;27:253-261. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0446-2

8. Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2631-2671. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

9. Davies J, MacDonald L, Sivakumar B, et al. Prospective analysis of syncope/pre-syncope in a tertiary paediatric orthopaedic fracture outpatient clinic. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:668-672. doi: 10.1111/ans.16664

10. Almutairi H, Salam M, Batarfi K, et al. Incidence and severity of adverse events among platelet donors: a three-year retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e23648. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023648

11. Coakley A, Bailey A, Tao J, et al. Video education to improve clinical skills in the prevention of and response to vasovagal syncopal episodes. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:186-190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.02.002

12. Thijs RD, Brignole M, Falup-Pecurariu C, et al. Recommendations for tilt table testing and other provocative cardiovascular autonomic tests in conditions that may cause transient loss of consciousness: consensus statement of the European Federation of Autonomic Societies (EFAS) endorsed by the American Autonomic Society (AAS) and the European Academy of Neurology (EAN). Auton Neurosci. 2021;233:102792. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102792

13. Nakagawa S, Hisanaga S, Kondoh H, et al. A case of swallow syncope induced by vagotonic visceral reflex resulting in atrioventricular node suppression. J Electrocardiol. 1987;20:65-69. doi: 10.1016/0022-0736(87)90010-0

14. O’Dwyer C, Bennett K, Langan Y, et al. Amnesia for loss of consciousness is common in vasovagal syncope. Europace. 2011;13:1040-1045. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur069

15. Jorge JG, Raj SR, Teixeira PS, et al. Likelihood of injury due to vasovagal syncope: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2021;23:1092-1099. doi: 10.1093/europace/euab041

16. Bracha HS, Bracha AS, Williams AE, et al. The human fear-circuitry and fear-induced fainting in healthy individuals—the paleolithic-threat hypothesis. Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:238-241. doi: 10.1007/s10286-005-0245-z

17. Diehl RR. Vasovagal syncope and Darwinian fitness. Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:126-129. doi: 10.1007/s10286-005-0244-0

18. Engel CL, Romano J. Studies of syncope; biologic interpretation of vasodepressor syncope. Psychosom Med. 1947;9:288-294. doi: 10.1097/00006842-194709000-00002

19. Blanc JJ, Benditt DG. Vasovagal syncope: hypothesis focusing on its being a clinical feature unique to humans. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:623-629. doi: 10.1111/jce.12945

THE CASE

A 56-year-old physician (CUL) visited a local seafood restaurant, after having fasted since the prior evening. He had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with lisinopril/hydrochlorothiazide.

The physician and his party were seated outside, where the temperature was in the mid-70s. The group ordered oysters on the half shell accompanied by mignonette sauce, cocktail sauce, and horseradish. The physician ate an olive-size amount of horseradish with an oyster. He immediately complained of a sharp burning sensation in his stomach and remarked that the horseradish was significantly stronger than what he was accustomed to. Within 30 seconds, he noted an increased heart rate, weakness, and intense sweating. There was no increase in nasal secretions. Observers noted that he was very pale.

About 5 minutes after eating the horseradish, the physician leaned his head back and briefly lost consciousness. His wife, while supporting his head and checking his pulse, instructed other diners to call for emergency services, at which point the physician regained consciousness and the dispatcher was told that an ambulance was no longer necessary. Within a matter of minutes, all symptoms had abated, except for some mild weakness.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Ten minutes after the event, the physician identified his symptoms as a horseradish-induced vasovagal syncope (VVS), based on a case report published in JAMA in 1988, which his wife found after he asked her to do an Internet search of his symptoms.1

THE DISCUSSION

Horseradish’s active component is isothiocyanate. Horseradish-induced syncope is also called Seder syncope after the Jewish Passover holiday dinner at which observant Jews are required to eat “bitter herbs.”1,2 This type of syncope is thought to occur when horseradish vapors directly irritate the gastric or respiratory tract mucosa.

VVS commonly manifests for the first time at around age 13 years; however, the timing of that first occurrence can vary significantly among individuals (as in this case)

The loss of consciousness may be caused by an emotional trigger (eg, sight of blood, cast removal,8 blood or platelet donations9,10), a painful event (eg, an injection11), an orthostatic trigger12 (eg, prolonged standing), or visceral reflexes such as swallowing.13 In approximately 30% of cases, loss of consciousness is associated with memory loss.14 Loss of consciousness with VVS may be associated with injury in 33% of cases.15

Continue to: The recovery with awareness

The recovery with awareness of time, place, and person may be a feature of VVS, which would differentiate it from seizures and brainstem vascular events. Autonomic prodromal symptoms—including abdominal discomfort, pallor, sweating, and nausea—may precede the loss of consciousness.8

An evolutionary response?

VVS may have developed as a trait through evolution, although modern medicine treats it as a disease. Many potential explanations for VVS as a body defense mechanism have been proposed. Examples include fainting at the sight of blood, which developed during the Old Stone Age—a period with extreme human-to-human violence—or acting like a “possum playing dead” as a tactic designed to confuse an attacker.16

Another theory involves clot production and suggests that VVS-induced hypotension is a defense against bleeding by improving clot formation.17

A psychological defense theory maintains that the fainting and memory loss are designed to prevent a painful or overwhelming experience from being remembered. None of these theories, however, explain orthostatic VVS.18

The brain defense theory could explain all forms of VVS. It postulates that hypotension causes decreased cerebral perfusion, which leads to syncope resulting in the body returning to a more orthostatic position with increased cerebral profusion.19

Continue to: The patient

The patient in this case was able to leave the restaurant on his own volition 30 minutes after the event and resume normal activities. Ten days later, an electrocardiogram was performed, with negative results. In this case, the use of a potassium-wasting diuretic exacerbated the risk of a fluid-deprived state, hypokalemia, and hypotension, possibly contributing to the syncope. The patient has since “gotten back on the horseradish” without ill effect.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consumers and health care providers should be aware of the risks associated with consumption of fresh horseradish and should allow it to rest prior to ingestion to allow some evaporation of its active ingredient. An old case report saved the patient from an unnecessary (and costly) emergency department visit.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Terry J. Hannan, MBBS, FRACP, FACHI, FACMI for his critical review of the manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christoph U. Lehmann, MD, Clinical Informatics Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, TX 75390; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 56-year-old physician (CUL) visited a local seafood restaurant, after having fasted since the prior evening. He had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with lisinopril/hydrochlorothiazide.

The physician and his party were seated outside, where the temperature was in the mid-70s. The group ordered oysters on the half shell accompanied by mignonette sauce, cocktail sauce, and horseradish. The physician ate an olive-size amount of horseradish with an oyster. He immediately complained of a sharp burning sensation in his stomach and remarked that the horseradish was significantly stronger than what he was accustomed to. Within 30 seconds, he noted an increased heart rate, weakness, and intense sweating. There was no increase in nasal secretions. Observers noted that he was very pale.

About 5 minutes after eating the horseradish, the physician leaned his head back and briefly lost consciousness. His wife, while supporting his head and checking his pulse, instructed other diners to call for emergency services, at which point the physician regained consciousness and the dispatcher was told that an ambulance was no longer necessary. Within a matter of minutes, all symptoms had abated, except for some mild weakness.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Ten minutes after the event, the physician identified his symptoms as a horseradish-induced vasovagal syncope (VVS), based on a case report published in JAMA in 1988, which his wife found after he asked her to do an Internet search of his symptoms.1

THE DISCUSSION

Horseradish’s active component is isothiocyanate. Horseradish-induced syncope is also called Seder syncope after the Jewish Passover holiday dinner at which observant Jews are required to eat “bitter herbs.”1,2 This type of syncope is thought to occur when horseradish vapors directly irritate the gastric or respiratory tract mucosa.

VVS commonly manifests for the first time at around age 13 years; however, the timing of that first occurrence can vary significantly among individuals (as in this case)

The loss of consciousness may be caused by an emotional trigger (eg, sight of blood, cast removal,8 blood or platelet donations9,10), a painful event (eg, an injection11), an orthostatic trigger12 (eg, prolonged standing), or visceral reflexes such as swallowing.13 In approximately 30% of cases, loss of consciousness is associated with memory loss.14 Loss of consciousness with VVS may be associated with injury in 33% of cases.15

Continue to: The recovery with awareness

The recovery with awareness of time, place, and person may be a feature of VVS, which would differentiate it from seizures and brainstem vascular events. Autonomic prodromal symptoms—including abdominal discomfort, pallor, sweating, and nausea—may precede the loss of consciousness.8

An evolutionary response?

VVS may have developed as a trait through evolution, although modern medicine treats it as a disease. Many potential explanations for VVS as a body defense mechanism have been proposed. Examples include fainting at the sight of blood, which developed during the Old Stone Age—a period with extreme human-to-human violence—or acting like a “possum playing dead” as a tactic designed to confuse an attacker.16

Another theory involves clot production and suggests that VVS-induced hypotension is a defense against bleeding by improving clot formation.17

A psychological defense theory maintains that the fainting and memory loss are designed to prevent a painful or overwhelming experience from being remembered. None of these theories, however, explain orthostatic VVS.18

The brain defense theory could explain all forms of VVS. It postulates that hypotension causes decreased cerebral perfusion, which leads to syncope resulting in the body returning to a more orthostatic position with increased cerebral profusion.19

Continue to: The patient

The patient in this case was able to leave the restaurant on his own volition 30 minutes after the event and resume normal activities. Ten days later, an electrocardiogram was performed, with negative results. In this case, the use of a potassium-wasting diuretic exacerbated the risk of a fluid-deprived state, hypokalemia, and hypotension, possibly contributing to the syncope. The patient has since “gotten back on the horseradish” without ill effect.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consumers and health care providers should be aware of the risks associated with consumption of fresh horseradish and should allow it to rest prior to ingestion to allow some evaporation of its active ingredient. An old case report saved the patient from an unnecessary (and costly) emergency department visit.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Terry J. Hannan, MBBS, FRACP, FACHI, FACMI for his critical review of the manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christoph U. Lehmann, MD, Clinical Informatics Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, TX 75390; [email protected]

1. Rubin HR, Wu AW. The bitter herbs of Seder: more on horseradish horrors. JAMA. 1988;259:1943. doi: 10.1001/jama.259.13.1943b

2. Seder syncope. The Free Dictionary. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Horseradish+Syncope

3. Sheldon RS, Sheldon AG, Connolly SJ, et al. Age of first faint in patients with vasovagal syncope. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:49-54. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00267.x

4. Wallin BG, Sundlöf G. Sympathetic outflow to muscles during vasovagal syncope. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1982;6:287-291. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(82)90001-7

5. Jardine DL, Melton IC, Crozier IG, et al. Decrease in cardiac output and muscle sympathetic activity during vasovagal syncope. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1804-H1809. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00640.2001

6. Waxman MB, Asta JA, Cameron DA. Localization of the reflex pathway responsible for the vasodepressor reaction induced by inferior vena caval occlusion and isoproterenol. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;70:882-889. doi: 10.1139/y92-118

7. Alboni P, Alboni M. Typical vasovagal syncope as a “defense mechanism” for the heart by contrasting sympathetic overactivity. Clin Auton Res. 2017;27:253-261. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0446-2

8. Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2631-2671. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

9. Davies J, MacDonald L, Sivakumar B, et al. Prospective analysis of syncope/pre-syncope in a tertiary paediatric orthopaedic fracture outpatient clinic. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:668-672. doi: 10.1111/ans.16664

10. Almutairi H, Salam M, Batarfi K, et al. Incidence and severity of adverse events among platelet donors: a three-year retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e23648. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023648

11. Coakley A, Bailey A, Tao J, et al. Video education to improve clinical skills in the prevention of and response to vasovagal syncopal episodes. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:186-190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.02.002

12. Thijs RD, Brignole M, Falup-Pecurariu C, et al. Recommendations for tilt table testing and other provocative cardiovascular autonomic tests in conditions that may cause transient loss of consciousness: consensus statement of the European Federation of Autonomic Societies (EFAS) endorsed by the American Autonomic Society (AAS) and the European Academy of Neurology (EAN). Auton Neurosci. 2021;233:102792. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102792

13. Nakagawa S, Hisanaga S, Kondoh H, et al. A case of swallow syncope induced by vagotonic visceral reflex resulting in atrioventricular node suppression. J Electrocardiol. 1987;20:65-69. doi: 10.1016/0022-0736(87)90010-0

14. O’Dwyer C, Bennett K, Langan Y, et al. Amnesia for loss of consciousness is common in vasovagal syncope. Europace. 2011;13:1040-1045. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur069

15. Jorge JG, Raj SR, Teixeira PS, et al. Likelihood of injury due to vasovagal syncope: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2021;23:1092-1099. doi: 10.1093/europace/euab041

16. Bracha HS, Bracha AS, Williams AE, et al. The human fear-circuitry and fear-induced fainting in healthy individuals—the paleolithic-threat hypothesis. Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:238-241. doi: 10.1007/s10286-005-0245-z

17. Diehl RR. Vasovagal syncope and Darwinian fitness. Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:126-129. doi: 10.1007/s10286-005-0244-0

18. Engel CL, Romano J. Studies of syncope; biologic interpretation of vasodepressor syncope. Psychosom Med. 1947;9:288-294. doi: 10.1097/00006842-194709000-00002

19. Blanc JJ, Benditt DG. Vasovagal syncope: hypothesis focusing on its being a clinical feature unique to humans. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:623-629. doi: 10.1111/jce.12945

1. Rubin HR, Wu AW. The bitter herbs of Seder: more on horseradish horrors. JAMA. 1988;259:1943. doi: 10.1001/jama.259.13.1943b

2. Seder syncope. The Free Dictionary. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Horseradish+Syncope

3. Sheldon RS, Sheldon AG, Connolly SJ, et al. Age of first faint in patients with vasovagal syncope. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:49-54. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00267.x

4. Wallin BG, Sundlöf G. Sympathetic outflow to muscles during vasovagal syncope. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1982;6:287-291. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(82)90001-7

5. Jardine DL, Melton IC, Crozier IG, et al. Decrease in cardiac output and muscle sympathetic activity during vasovagal syncope. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1804-H1809. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00640.2001

6. Waxman MB, Asta JA, Cameron DA. Localization of the reflex pathway responsible for the vasodepressor reaction induced by inferior vena caval occlusion and isoproterenol. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;70:882-889. doi: 10.1139/y92-118

7. Alboni P, Alboni M. Typical vasovagal syncope as a “defense mechanism” for the heart by contrasting sympathetic overactivity. Clin Auton Res. 2017;27:253-261. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0446-2

8. Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2631-2671. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

9. Davies J, MacDonald L, Sivakumar B, et al. Prospective analysis of syncope/pre-syncope in a tertiary paediatric orthopaedic fracture outpatient clinic. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:668-672. doi: 10.1111/ans.16664

10. Almutairi H, Salam M, Batarfi K, et al. Incidence and severity of adverse events among platelet donors: a three-year retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e23648. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023648

11. Coakley A, Bailey A, Tao J, et al. Video education to improve clinical skills in the prevention of and response to vasovagal syncopal episodes. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:186-190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.02.002

12. Thijs RD, Brignole M, Falup-Pecurariu C, et al. Recommendations for tilt table testing and other provocative cardiovascular autonomic tests in conditions that may cause transient loss of consciousness: consensus statement of the European Federation of Autonomic Societies (EFAS) endorsed by the American Autonomic Society (AAS) and the European Academy of Neurology (EAN). Auton Neurosci. 2021;233:102792. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102792

13. Nakagawa S, Hisanaga S, Kondoh H, et al. A case of swallow syncope induced by vagotonic visceral reflex resulting in atrioventricular node suppression. J Electrocardiol. 1987;20:65-69. doi: 10.1016/0022-0736(87)90010-0

14. O’Dwyer C, Bennett K, Langan Y, et al. Amnesia for loss of consciousness is common in vasovagal syncope. Europace. 2011;13:1040-1045. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur069

15. Jorge JG, Raj SR, Teixeira PS, et al. Likelihood of injury due to vasovagal syncope: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2021;23:1092-1099. doi: 10.1093/europace/euab041

16. Bracha HS, Bracha AS, Williams AE, et al. The human fear-circuitry and fear-induced fainting in healthy individuals—the paleolithic-threat hypothesis. Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:238-241. doi: 10.1007/s10286-005-0245-z

17. Diehl RR. Vasovagal syncope and Darwinian fitness. Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:126-129. doi: 10.1007/s10286-005-0244-0

18. Engel CL, Romano J. Studies of syncope; biologic interpretation of vasodepressor syncope. Psychosom Med. 1947;9:288-294. doi: 10.1097/00006842-194709000-00002

19. Blanc JJ, Benditt DG. Vasovagal syncope: hypothesis focusing on its being a clinical feature unique to humans. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:623-629. doi: 10.1111/jce.12945

Noncardiac inpatient has acute hypertension: Treat or not?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 48-year-old man is admitted to your family medicine service for cellulitis after failed outpatient therapy. He has presumed community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection of the left lower extremity and is receiving intravenous (IV) vancomycin. His BP this morning is 176/98 mm Hg, and the reading from the previous shift was 168/94 mm Hg. He is asymptomatic from this elevated BP. Based on protocol, his nurse is asking about treatment in response to the multiple elevated readings. How should you address the patient’s elevated BP, knowing that you will see him for a transition management appointment in 2 weeks?

Elevated BP is common in the adult inpatient setting. Prevalence estimates range from 25% to > 50%. Many factors can contribute to elevated BP in the acute illness setting, such as pain, anxiety, medication withdrawal, and volume status.2,3

Treatment of elevated BP in outpatients is well researched, with evidence-based guidelines for physicians. That is not the case for treatment of asymptomatic elevated BP in the inpatient setting. Most published guidance on inpatient management of acutely elevated BP recommends IV medications, such as hydralazine or labetalol, although there is limited evidence to support such recommendations. There is minimal evidence for outcomes-based benefit in treating acute elevations of inpatient BP, such as reduced myocardial injury or stroke; however, there is some evidence of adverse outcomes, such as hypotension and prolonged hospital stays.4-8

Although the possibility of intensifying antihypertensive therapy for those with known hypertension or those with presumed “new-onset” hypertension could theoretically lead to improved outcomes over the long term, there is little evidence to support this presumption. Rather, there is evidence that intensification of antihypertensive therapy at discharge is linked to short-term harms. This was demonstrated in a propensity-matched veteran cohort that included 4056 hospitalized older adults with hypertension (mean age, 77 years; 3961 men), equally split between those who received antihypertensive intensification at hospital discharge and those who did not. Within 30 days, patients receiving intensification had a higher risk of readmission (number needed to harm [NNH] = 27) and serious adverse events (NNH = 63).9

The current study aimed to put all these pieces together by quantifying the prevalence of hypertension in hospitalized patients, characterizing clinician response to patients’ acutely elevated BP, and comparing both short- and long-term outcomes in patients treated for acute BP elevations while hospitalized vs those who were not. The study also assessed the potential effects of antihypertensive intensification at discharge.

STUDY SUMMARY

Treatment of acute hypertension was associated with end-organ injury

This retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study (N = 22,834) evaluated the electronic health records of all adult patients (age > 18 years) admitted to a medicine service with a noncardiovascular diagnosis over a 1-year period at 10 Cleveland Clinic hospitals, with 1 year of follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria included hospitalization for a cardiovascular diagnosis; admission for a cerebrovascular event or acute coronary syndrome within the previous 30 days; pregnancy; length of stay of less than 2 days or more than 14 days; and lack of outpatient medication data. Patients were propensity-score matched using BP, demographic features, comorbidities, hospital shift, and time since admission. Exposure was defined as administration of IV antihypertensive medication or a new class of oral antihypertensive medication.

Continue to: Outcomes were defined...

Outcomes were defined as a temporal association between acute hypertension treatment and subsequent end-organ damage, such as AKI (serum creatinine increase ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or 1.5 × initial value [Acute Kidney Injury Network definition]), myocardial injury (elevated troponin: > 0.029 ng/mL for troponin T; > 0.045 ng/mL for troponin I), and/or stroke (indicated by discharge diagnosis, with confirmation by chart review). Monitored outcomes included stroke and myocardial infarction (MI) within 30 days of discharge and BP control up to 1 year later.

The 22,834 patients had a mean (SD) age of 65.6 (17.9) years; 12,993 (56.9%) were women, and 15,963 (69.9%) were White. Of the 17,821 (78%) who had at least 1 inpatient hypertensive systolic BP (SBP) episode, defined as an SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg, 5904 (33.1%) received a new treatment. Of those receiving a new treatment, 4378 (74.2%) received only oral treatment, and 1516 (25.7%) received at least 1 dose of IV medication with or without oral dosing.

Using the propensity-matched sample (4520 treated for elevated BP matched to 4520 who were not treated), treated patients had higher rates of AKI (10.3% vs 7.9%; P < .001) and myocardial injury (1.2% vs 0.6%; P = .003). When assessed by SBP, nontreatment of BP was still superior up to an SBP of 199 mm Hg. At an SBP of ≥ 200 mm Hg, there was no difference in rates of AKI or MI between the treatment and nontreatment groups. There was no difference in stroke in either cohort, although the overall numbers were quite low.

Patients with and without antihypertensive intensification at discharge had similar rates of MI (0.1% vs 0.2%; P > .99) and stroke (0.5% vs 0.4%; P > .99) in a matched cohort at 30 days post discharge. At 1 year, BP control in the intensification vs no-intensification groups was nearly the same: maximum SBP was 157.2 mm Hg vs 157.8 mm Hg, respectively (P = .54) and maximum diastolic BP was 86.5 mm Hg vs 86.1 mm Hg, respectively (P = .49).

WHAT’S NEW

Previous research is confirmed in a more diverse population

Whereas previous research showed no benefit to intensification of treatment among hospitalized older male patients, this large, retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study demonstrated the short- and long-term effects of treating acute, asymptomatic BP elevations in a younger, more generalizable population that included women. Regardless of treatment modality, there appeared to be more harm than good from treating these BP elevations.

In addition, the study appears to corroborate previous research showing that intensification of BP treatment at discharge did not lead to better outcomes.9 At the very least, the study makes a reasonable argument that treating acute BP elevations in noncardiac patients in the hospital setting is not beneficial.

CAVEATS

Impact of existing therapy could be underestimated

This study had several important limitations. First, 23% of treated participants were excluded from the propensity analysis without justification from the authors. Additionally, there was no reporting of missing data and how it was managed. The authors’ definition of treatment excluded dose intensification of existing antihypertensive therapy, which would undercount the number of treated patients. However, this could underestimate the actual harms of the acute antihypertensive therapy. The authors also included patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure in the study population, even though they already may have been taking antihypertensive agents.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Potential delays in translating findings to patient care

Although several recent studies have shown the potential benefit of not treating asymptomatic acute BP elevations in inpatients, incorporating that information into electronic health record order sets or clinical decision support, and disseminating it to clinical end users, will take time. In the interim, despite these findings, patients may continue to receive IV or oral medications to treat acute, asymptomatic BP elevations while hospitalized for noncardiac diagnoses.

1. Rastogi R, Sheehan MM, Hu B, et al. Treatment and outcomes of inpatient hypertension among adults with noncardiac admissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:345-352. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7501

2. Jacobs ZG, Najafi N, Fang MC, et al. Reducing unnecessary treatment of asymptomatic elevated blood pressure with intravenous medications on the general internal medicine wards: a quality improvement initiative. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:144-150. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3087

3. Pasik SD, Chiu S, Yang J, et al. Assess before Rx: reducing the overtreatment of asymptomatic blood pressure elevation in the inpatient setting. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:151-156. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3190

4. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, et al. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5:473-477. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.07.002

5. Gauer R. Severe asymptomatic hypertension: evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95:492-500.

6. Lipari M, Moser LR, Petrovitch EA, et al. As-needed intravenous antihypertensive therapy and blood pressure control. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:193-198. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2510

7. Gaynor MF, Wright GC, Vondracek S. Retrospective review of the use of as-needed hydralazine and labetalol for the treatment of acute hypertension in hospitalized medicine patients. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;12:7-15. doi: 10.1177/1753944717746613

8. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:29-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00196.x

9. Anderson TS, Jing B, Auerbach A, et al. Clinical outcomes after intensifying antihypertensive medication regimens among older adults at hospital discharge. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1528-1536. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3007

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 48-year-old man is admitted to your family medicine service for cellulitis after failed outpatient therapy. He has presumed community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection of the left lower extremity and is receiving intravenous (IV) vancomycin. His BP this morning is 176/98 mm Hg, and the reading from the previous shift was 168/94 mm Hg. He is asymptomatic from this elevated BP. Based on protocol, his nurse is asking about treatment in response to the multiple elevated readings. How should you address the patient’s elevated BP, knowing that you will see him for a transition management appointment in 2 weeks?

Elevated BP is common in the adult inpatient setting. Prevalence estimates range from 25% to > 50%. Many factors can contribute to elevated BP in the acute illness setting, such as pain, anxiety, medication withdrawal, and volume status.2,3

Treatment of elevated BP in outpatients is well researched, with evidence-based guidelines for physicians. That is not the case for treatment of asymptomatic elevated BP in the inpatient setting. Most published guidance on inpatient management of acutely elevated BP recommends IV medications, such as hydralazine or labetalol, although there is limited evidence to support such recommendations. There is minimal evidence for outcomes-based benefit in treating acute elevations of inpatient BP, such as reduced myocardial injury or stroke; however, there is some evidence of adverse outcomes, such as hypotension and prolonged hospital stays.4-8

Although the possibility of intensifying antihypertensive therapy for those with known hypertension or those with presumed “new-onset” hypertension could theoretically lead to improved outcomes over the long term, there is little evidence to support this presumption. Rather, there is evidence that intensification of antihypertensive therapy at discharge is linked to short-term harms. This was demonstrated in a propensity-matched veteran cohort that included 4056 hospitalized older adults with hypertension (mean age, 77 years; 3961 men), equally split between those who received antihypertensive intensification at hospital discharge and those who did not. Within 30 days, patients receiving intensification had a higher risk of readmission (number needed to harm [NNH] = 27) and serious adverse events (NNH = 63).9

The current study aimed to put all these pieces together by quantifying the prevalence of hypertension in hospitalized patients, characterizing clinician response to patients’ acutely elevated BP, and comparing both short- and long-term outcomes in patients treated for acute BP elevations while hospitalized vs those who were not. The study also assessed the potential effects of antihypertensive intensification at discharge.

STUDY SUMMARY

Treatment of acute hypertension was associated with end-organ injury

This retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study (N = 22,834) evaluated the electronic health records of all adult patients (age > 18 years) admitted to a medicine service with a noncardiovascular diagnosis over a 1-year period at 10 Cleveland Clinic hospitals, with 1 year of follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria included hospitalization for a cardiovascular diagnosis; admission for a cerebrovascular event or acute coronary syndrome within the previous 30 days; pregnancy; length of stay of less than 2 days or more than 14 days; and lack of outpatient medication data. Patients were propensity-score matched using BP, demographic features, comorbidities, hospital shift, and time since admission. Exposure was defined as administration of IV antihypertensive medication or a new class of oral antihypertensive medication.

Continue to: Outcomes were defined...

Outcomes were defined as a temporal association between acute hypertension treatment and subsequent end-organ damage, such as AKI (serum creatinine increase ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or 1.5 × initial value [Acute Kidney Injury Network definition]), myocardial injury (elevated troponin: > 0.029 ng/mL for troponin T; > 0.045 ng/mL for troponin I), and/or stroke (indicated by discharge diagnosis, with confirmation by chart review). Monitored outcomes included stroke and myocardial infarction (MI) within 30 days of discharge and BP control up to 1 year later.

The 22,834 patients had a mean (SD) age of 65.6 (17.9) years; 12,993 (56.9%) were women, and 15,963 (69.9%) were White. Of the 17,821 (78%) who had at least 1 inpatient hypertensive systolic BP (SBP) episode, defined as an SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg, 5904 (33.1%) received a new treatment. Of those receiving a new treatment, 4378 (74.2%) received only oral treatment, and 1516 (25.7%) received at least 1 dose of IV medication with or without oral dosing.

Using the propensity-matched sample (4520 treated for elevated BP matched to 4520 who were not treated), treated patients had higher rates of AKI (10.3% vs 7.9%; P < .001) and myocardial injury (1.2% vs 0.6%; P = .003). When assessed by SBP, nontreatment of BP was still superior up to an SBP of 199 mm Hg. At an SBP of ≥ 200 mm Hg, there was no difference in rates of AKI or MI between the treatment and nontreatment groups. There was no difference in stroke in either cohort, although the overall numbers were quite low.

Patients with and without antihypertensive intensification at discharge had similar rates of MI (0.1% vs 0.2%; P > .99) and stroke (0.5% vs 0.4%; P > .99) in a matched cohort at 30 days post discharge. At 1 year, BP control in the intensification vs no-intensification groups was nearly the same: maximum SBP was 157.2 mm Hg vs 157.8 mm Hg, respectively (P = .54) and maximum diastolic BP was 86.5 mm Hg vs 86.1 mm Hg, respectively (P = .49).

WHAT’S NEW

Previous research is confirmed in a more diverse population

Whereas previous research showed no benefit to intensification of treatment among hospitalized older male patients, this large, retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study demonstrated the short- and long-term effects of treating acute, asymptomatic BP elevations in a younger, more generalizable population that included women. Regardless of treatment modality, there appeared to be more harm than good from treating these BP elevations.

In addition, the study appears to corroborate previous research showing that intensification of BP treatment at discharge did not lead to better outcomes.9 At the very least, the study makes a reasonable argument that treating acute BP elevations in noncardiac patients in the hospital setting is not beneficial.

CAVEATS

Impact of existing therapy could be underestimated

This study had several important limitations. First, 23% of treated participants were excluded from the propensity analysis without justification from the authors. Additionally, there was no reporting of missing data and how it was managed. The authors’ definition of treatment excluded dose intensification of existing antihypertensive therapy, which would undercount the number of treated patients. However, this could underestimate the actual harms of the acute antihypertensive therapy. The authors also included patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure in the study population, even though they already may have been taking antihypertensive agents.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Potential delays in translating findings to patient care

Although several recent studies have shown the potential benefit of not treating asymptomatic acute BP elevations in inpatients, incorporating that information into electronic health record order sets or clinical decision support, and disseminating it to clinical end users, will take time. In the interim, despite these findings, patients may continue to receive IV or oral medications to treat acute, asymptomatic BP elevations while hospitalized for noncardiac diagnoses.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 48-year-old man is admitted to your family medicine service for cellulitis after failed outpatient therapy. He has presumed community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection of the left lower extremity and is receiving intravenous (IV) vancomycin. His BP this morning is 176/98 mm Hg, and the reading from the previous shift was 168/94 mm Hg. He is asymptomatic from this elevated BP. Based on protocol, his nurse is asking about treatment in response to the multiple elevated readings. How should you address the patient’s elevated BP, knowing that you will see him for a transition management appointment in 2 weeks?

Elevated BP is common in the adult inpatient setting. Prevalence estimates range from 25% to > 50%. Many factors can contribute to elevated BP in the acute illness setting, such as pain, anxiety, medication withdrawal, and volume status.2,3

Treatment of elevated BP in outpatients is well researched, with evidence-based guidelines for physicians. That is not the case for treatment of asymptomatic elevated BP in the inpatient setting. Most published guidance on inpatient management of acutely elevated BP recommends IV medications, such as hydralazine or labetalol, although there is limited evidence to support such recommendations. There is minimal evidence for outcomes-based benefit in treating acute elevations of inpatient BP, such as reduced myocardial injury or stroke; however, there is some evidence of adverse outcomes, such as hypotension and prolonged hospital stays.4-8

Although the possibility of intensifying antihypertensive therapy for those with known hypertension or those with presumed “new-onset” hypertension could theoretically lead to improved outcomes over the long term, there is little evidence to support this presumption. Rather, there is evidence that intensification of antihypertensive therapy at discharge is linked to short-term harms. This was demonstrated in a propensity-matched veteran cohort that included 4056 hospitalized older adults with hypertension (mean age, 77 years; 3961 men), equally split between those who received antihypertensive intensification at hospital discharge and those who did not. Within 30 days, patients receiving intensification had a higher risk of readmission (number needed to harm [NNH] = 27) and serious adverse events (NNH = 63).9

The current study aimed to put all these pieces together by quantifying the prevalence of hypertension in hospitalized patients, characterizing clinician response to patients’ acutely elevated BP, and comparing both short- and long-term outcomes in patients treated for acute BP elevations while hospitalized vs those who were not. The study also assessed the potential effects of antihypertensive intensification at discharge.

STUDY SUMMARY

Treatment of acute hypertension was associated with end-organ injury

This retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study (N = 22,834) evaluated the electronic health records of all adult patients (age > 18 years) admitted to a medicine service with a noncardiovascular diagnosis over a 1-year period at 10 Cleveland Clinic hospitals, with 1 year of follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria included hospitalization for a cardiovascular diagnosis; admission for a cerebrovascular event or acute coronary syndrome within the previous 30 days; pregnancy; length of stay of less than 2 days or more than 14 days; and lack of outpatient medication data. Patients were propensity-score matched using BP, demographic features, comorbidities, hospital shift, and time since admission. Exposure was defined as administration of IV antihypertensive medication or a new class of oral antihypertensive medication.

Continue to: Outcomes were defined...

Outcomes were defined as a temporal association between acute hypertension treatment and subsequent end-organ damage, such as AKI (serum creatinine increase ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or 1.5 × initial value [Acute Kidney Injury Network definition]), myocardial injury (elevated troponin: > 0.029 ng/mL for troponin T; > 0.045 ng/mL for troponin I), and/or stroke (indicated by discharge diagnosis, with confirmation by chart review). Monitored outcomes included stroke and myocardial infarction (MI) within 30 days of discharge and BP control up to 1 year later.

The 22,834 patients had a mean (SD) age of 65.6 (17.9) years; 12,993 (56.9%) were women, and 15,963 (69.9%) were White. Of the 17,821 (78%) who had at least 1 inpatient hypertensive systolic BP (SBP) episode, defined as an SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg, 5904 (33.1%) received a new treatment. Of those receiving a new treatment, 4378 (74.2%) received only oral treatment, and 1516 (25.7%) received at least 1 dose of IV medication with or without oral dosing.

Using the propensity-matched sample (4520 treated for elevated BP matched to 4520 who were not treated), treated patients had higher rates of AKI (10.3% vs 7.9%; P < .001) and myocardial injury (1.2% vs 0.6%; P = .003). When assessed by SBP, nontreatment of BP was still superior up to an SBP of 199 mm Hg. At an SBP of ≥ 200 mm Hg, there was no difference in rates of AKI or MI between the treatment and nontreatment groups. There was no difference in stroke in either cohort, although the overall numbers were quite low.

Patients with and without antihypertensive intensification at discharge had similar rates of MI (0.1% vs 0.2%; P > .99) and stroke (0.5% vs 0.4%; P > .99) in a matched cohort at 30 days post discharge. At 1 year, BP control in the intensification vs no-intensification groups was nearly the same: maximum SBP was 157.2 mm Hg vs 157.8 mm Hg, respectively (P = .54) and maximum diastolic BP was 86.5 mm Hg vs 86.1 mm Hg, respectively (P = .49).

WHAT’S NEW

Previous research is confirmed in a more diverse population

Whereas previous research showed no benefit to intensification of treatment among hospitalized older male patients, this large, retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study demonstrated the short- and long-term effects of treating acute, asymptomatic BP elevations in a younger, more generalizable population that included women. Regardless of treatment modality, there appeared to be more harm than good from treating these BP elevations.

In addition, the study appears to corroborate previous research showing that intensification of BP treatment at discharge did not lead to better outcomes.9 At the very least, the study makes a reasonable argument that treating acute BP elevations in noncardiac patients in the hospital setting is not beneficial.

CAVEATS

Impact of existing therapy could be underestimated

This study had several important limitations. First, 23% of treated participants were excluded from the propensity analysis without justification from the authors. Additionally, there was no reporting of missing data and how it was managed. The authors’ definition of treatment excluded dose intensification of existing antihypertensive therapy, which would undercount the number of treated patients. However, this could underestimate the actual harms of the acute antihypertensive therapy. The authors also included patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure in the study population, even though they already may have been taking antihypertensive agents.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Potential delays in translating findings to patient care

Although several recent studies have shown the potential benefit of not treating asymptomatic acute BP elevations in inpatients, incorporating that information into electronic health record order sets or clinical decision support, and disseminating it to clinical end users, will take time. In the interim, despite these findings, patients may continue to receive IV or oral medications to treat acute, asymptomatic BP elevations while hospitalized for noncardiac diagnoses.

1. Rastogi R, Sheehan MM, Hu B, et al. Treatment and outcomes of inpatient hypertension among adults with noncardiac admissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:345-352. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7501

2. Jacobs ZG, Najafi N, Fang MC, et al. Reducing unnecessary treatment of asymptomatic elevated blood pressure with intravenous medications on the general internal medicine wards: a quality improvement initiative. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:144-150. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3087

3. Pasik SD, Chiu S, Yang J, et al. Assess before Rx: reducing the overtreatment of asymptomatic blood pressure elevation in the inpatient setting. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:151-156. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3190

4. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, et al. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5:473-477. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.07.002

5. Gauer R. Severe asymptomatic hypertension: evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95:492-500.

6. Lipari M, Moser LR, Petrovitch EA, et al. As-needed intravenous antihypertensive therapy and blood pressure control. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:193-198. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2510

7. Gaynor MF, Wright GC, Vondracek S. Retrospective review of the use of as-needed hydralazine and labetalol for the treatment of acute hypertension in hospitalized medicine patients. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;12:7-15. doi: 10.1177/1753944717746613

8. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:29-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00196.x

9. Anderson TS, Jing B, Auerbach A, et al. Clinical outcomes after intensifying antihypertensive medication regimens among older adults at hospital discharge. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1528-1536. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3007

1. Rastogi R, Sheehan MM, Hu B, et al. Treatment and outcomes of inpatient hypertension among adults with noncardiac admissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:345-352. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7501

2. Jacobs ZG, Najafi N, Fang MC, et al. Reducing unnecessary treatment of asymptomatic elevated blood pressure with intravenous medications on the general internal medicine wards: a quality improvement initiative. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:144-150. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3087

3. Pasik SD, Chiu S, Yang J, et al. Assess before Rx: reducing the overtreatment of asymptomatic blood pressure elevation in the inpatient setting. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:151-156. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3190

4. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, et al. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5:473-477. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.07.002

5. Gauer R. Severe asymptomatic hypertension: evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95:492-500.

6. Lipari M, Moser LR, Petrovitch EA, et al. As-needed intravenous antihypertensive therapy and blood pressure control. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:193-198. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2510

7. Gaynor MF, Wright GC, Vondracek S. Retrospective review of the use of as-needed hydralazine and labetalol for the treatment of acute hypertension in hospitalized medicine patients. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;12:7-15. doi: 10.1177/1753944717746613

8. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:29-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00196.x

9. Anderson TS, Jing B, Auerbach A, et al. Clinical outcomes after intensifying antihypertensive medication regimens among older adults at hospital discharge. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1528-1536. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3007

PRACTICE CHANGER

Manage blood pressure (BP) elevations conservatively in patients admitted for noncardiac diagnoses, as acute hypertension treatment may increase the risk for acute kidney injury (AKI) and myocardial injury.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

C: Based on a single, large, retrospective cohort study.1

Rastogi R, Sheehan MM, Hu B, et al. Treatment and outcomes of inpatient hypertension among adults with noncardiac admissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:345-352.

When the public misplaces their trust

Not long ago, the grandmother of my son’s friend died of COVID-19 infection. She was elderly and unvaccinated. Her grandson had no regrets over her unvaccinated status. “Why would she inject poison into her body?” he said, and then expressed a strong opinion that she had died because the hospital physicians refused to give her ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. My son, wisely, did not push the issue.

Soon thereafter, my personal family physician emailed a newsletter to his patients (me included) with 3 important messages: (1) COVID vaccines were available in the office; (2) He was not going to prescribe hydroxychloroquine, no matter how adamantly it was requested; and (3) He warned against threatening him or his staff with lawsuits or violence over refusal to prescribe any unproven medication.

How, as a country, have we come to this? A sizeable portion of the public trusts the advice of quacks, hacks, and political opportunists over that of the nation’s most expert scientists and physicians. The National Institutes of Health maintains a website with up-to-date recommendations on the use of treatments for COVID-19. They assess the existing evidence and make recommendations for or against a wide array of interventions. (They recommend against the use of both ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publishes extensively about the current knowledge on the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Neither agency is part of a “deep state” or conspiracy. They are comprised of some of the nation’s leading scientists, including physicians, trying to protect the public from disease and foster good health.

Sadly, some physicians have been a source of inaccurate vaccine information; some even prescribe ineffective treatments despite the evidence. These physicians are either letting their politics override their good sense or are improperly assessing the scientific literature, or both. Medical licensing agencies, and specialty certification boards, need to find ways to prevent this—ways that can survive judicial scrutiny and allow for legitimate scientific debate.

I have been tempted to just accept the current situation as the inevitable outcome of social media–fueled tribalism. But when we know that the COVID death rate among the unvaccinated is 9 times that of people who have received a booster dose,1 I can’t sit idly and watch the Internet pundits prevail. Instead, I continue to advise and teach my students to have confidence in trustworthy authorities and websites. Mistakes will be made; corrections will be issued. However, this is not evidence of malintent or incompetence, but rather, the scientific process in action.

I tell my students that one of the biggest challenges facing them and society is to figure out how to stop, or at least minimize the effects of, incorrect information, misleading statements, and outright lies in a society that values free speech. Physicians—young and old alike—must remain committed to communicating factual information to a not-always-receptive audience. And I wish my young colleagues luck; I hope that their passion for family medicine and their insights into social media may be just the combination that’s needed to redirect the public’s trust back to where it belongs during a health care crisis.

1. Fleming-Dutra KE. COVID-19 Epidemiology and Vaccination Rates in the United States. Presented to the Authorization Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/02-COVID-Fleming-Dutra-508.pdf

Not long ago, the grandmother of my son’s friend died of COVID-19 infection. She was elderly and unvaccinated. Her grandson had no regrets over her unvaccinated status. “Why would she inject poison into her body?” he said, and then expressed a strong opinion that she had died because the hospital physicians refused to give her ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. My son, wisely, did not push the issue.

Soon thereafter, my personal family physician emailed a newsletter to his patients (me included) with 3 important messages: (1) COVID vaccines were available in the office; (2) He was not going to prescribe hydroxychloroquine, no matter how adamantly it was requested; and (3) He warned against threatening him or his staff with lawsuits or violence over refusal to prescribe any unproven medication.

How, as a country, have we come to this? A sizeable portion of the public trusts the advice of quacks, hacks, and political opportunists over that of the nation’s most expert scientists and physicians. The National Institutes of Health maintains a website with up-to-date recommendations on the use of treatments for COVID-19. They assess the existing evidence and make recommendations for or against a wide array of interventions. (They recommend against the use of both ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publishes extensively about the current knowledge on the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Neither agency is part of a “deep state” or conspiracy. They are comprised of some of the nation’s leading scientists, including physicians, trying to protect the public from disease and foster good health.

Sadly, some physicians have been a source of inaccurate vaccine information; some even prescribe ineffective treatments despite the evidence. These physicians are either letting their politics override their good sense or are improperly assessing the scientific literature, or both. Medical licensing agencies, and specialty certification boards, need to find ways to prevent this—ways that can survive judicial scrutiny and allow for legitimate scientific debate.

I have been tempted to just accept the current situation as the inevitable outcome of social media–fueled tribalism. But when we know that the COVID death rate among the unvaccinated is 9 times that of people who have received a booster dose,1 I can’t sit idly and watch the Internet pundits prevail. Instead, I continue to advise and teach my students to have confidence in trustworthy authorities and websites. Mistakes will be made; corrections will be issued. However, this is not evidence of malintent or incompetence, but rather, the scientific process in action.

I tell my students that one of the biggest challenges facing them and society is to figure out how to stop, or at least minimize the effects of, incorrect information, misleading statements, and outright lies in a society that values free speech. Physicians—young and old alike—must remain committed to communicating factual information to a not-always-receptive audience. And I wish my young colleagues luck; I hope that their passion for family medicine and their insights into social media may be just the combination that’s needed to redirect the public’s trust back to where it belongs during a health care crisis.

Not long ago, the grandmother of my son’s friend died of COVID-19 infection. She was elderly and unvaccinated. Her grandson had no regrets over her unvaccinated status. “Why would she inject poison into her body?” he said, and then expressed a strong opinion that she had died because the hospital physicians refused to give her ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. My son, wisely, did not push the issue.

Soon thereafter, my personal family physician emailed a newsletter to his patients (me included) with 3 important messages: (1) COVID vaccines were available in the office; (2) He was not going to prescribe hydroxychloroquine, no matter how adamantly it was requested; and (3) He warned against threatening him or his staff with lawsuits or violence over refusal to prescribe any unproven medication.

How, as a country, have we come to this? A sizeable portion of the public trusts the advice of quacks, hacks, and political opportunists over that of the nation’s most expert scientists and physicians. The National Institutes of Health maintains a website with up-to-date recommendations on the use of treatments for COVID-19. They assess the existing evidence and make recommendations for or against a wide array of interventions. (They recommend against the use of both ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publishes extensively about the current knowledge on the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Neither agency is part of a “deep state” or conspiracy. They are comprised of some of the nation’s leading scientists, including physicians, trying to protect the public from disease and foster good health.

Sadly, some physicians have been a source of inaccurate vaccine information; some even prescribe ineffective treatments despite the evidence. These physicians are either letting their politics override their good sense or are improperly assessing the scientific literature, or both. Medical licensing agencies, and specialty certification boards, need to find ways to prevent this—ways that can survive judicial scrutiny and allow for legitimate scientific debate.

I have been tempted to just accept the current situation as the inevitable outcome of social media–fueled tribalism. But when we know that the COVID death rate among the unvaccinated is 9 times that of people who have received a booster dose,1 I can’t sit idly and watch the Internet pundits prevail. Instead, I continue to advise and teach my students to have confidence in trustworthy authorities and websites. Mistakes will be made; corrections will be issued. However, this is not evidence of malintent or incompetence, but rather, the scientific process in action.

I tell my students that one of the biggest challenges facing them and society is to figure out how to stop, or at least minimize the effects of, incorrect information, misleading statements, and outright lies in a society that values free speech. Physicians—young and old alike—must remain committed to communicating factual information to a not-always-receptive audience. And I wish my young colleagues luck; I hope that their passion for family medicine and their insights into social media may be just the combination that’s needed to redirect the public’s trust back to where it belongs during a health care crisis.

1. Fleming-Dutra KE. COVID-19 Epidemiology and Vaccination Rates in the United States. Presented to the Authorization Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/02-COVID-Fleming-Dutra-508.pdf

1. Fleming-Dutra KE. COVID-19 Epidemiology and Vaccination Rates in the United States. Presented to the Authorization Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/02-COVID-Fleming-Dutra-508.pdf

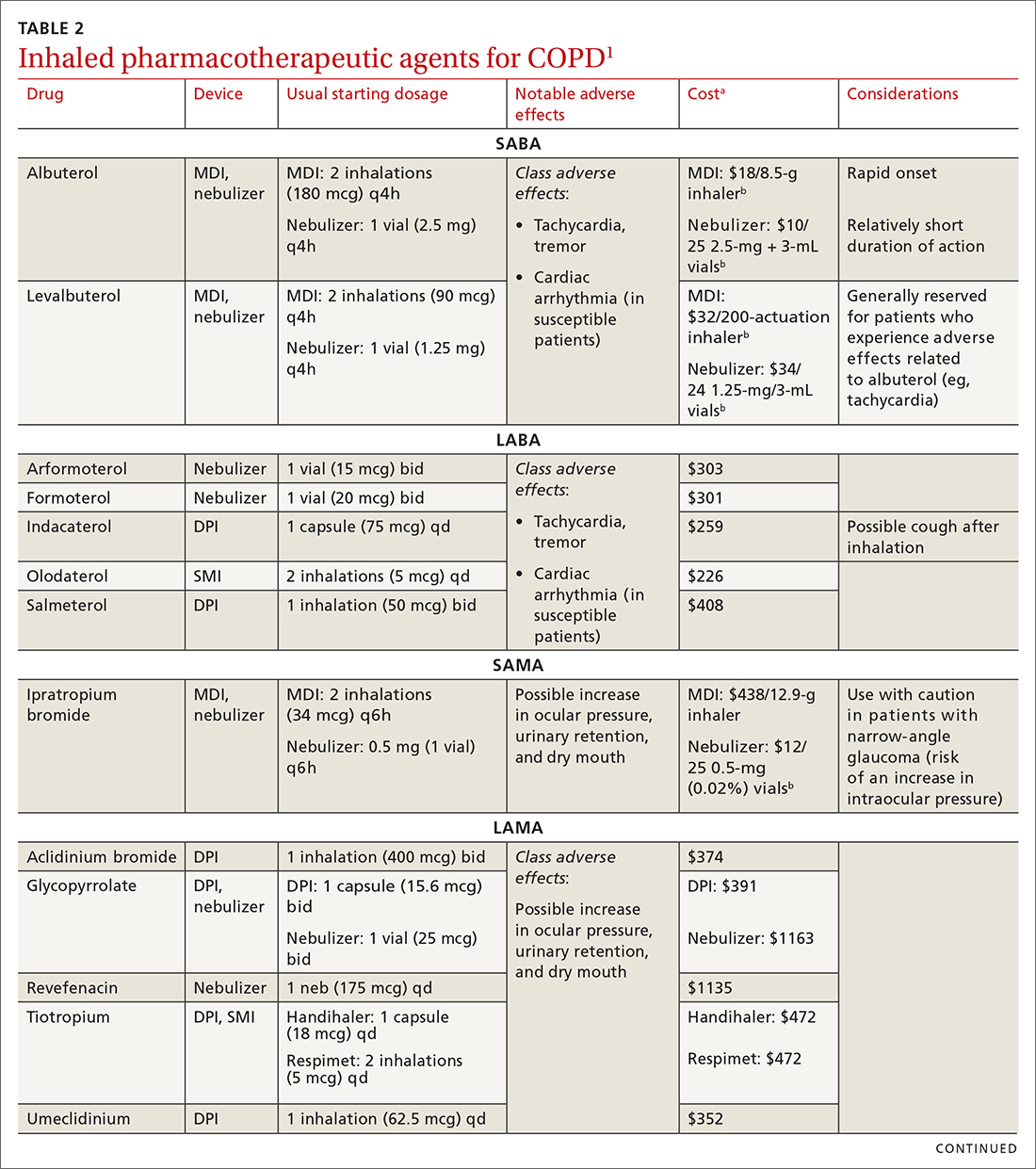

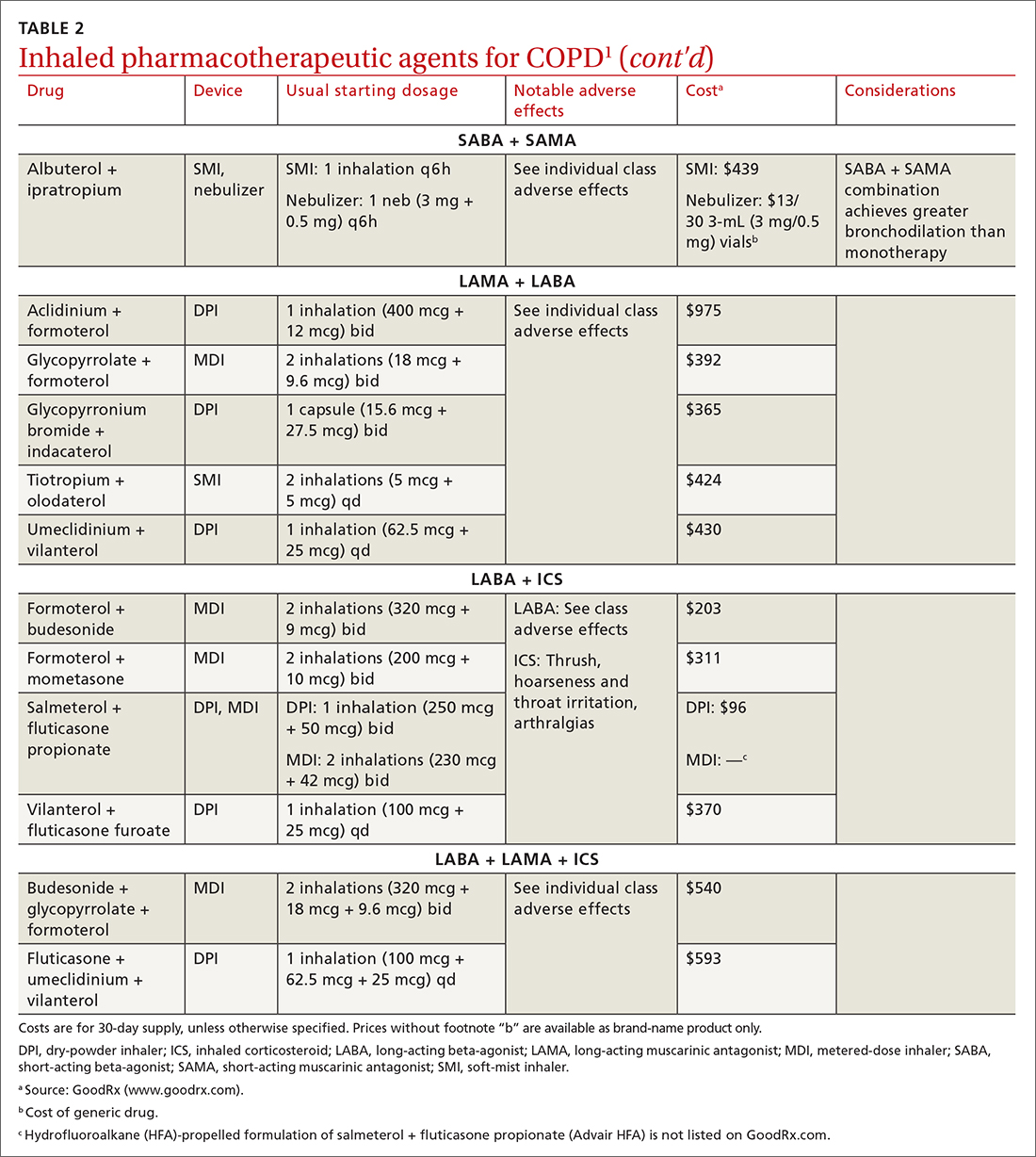

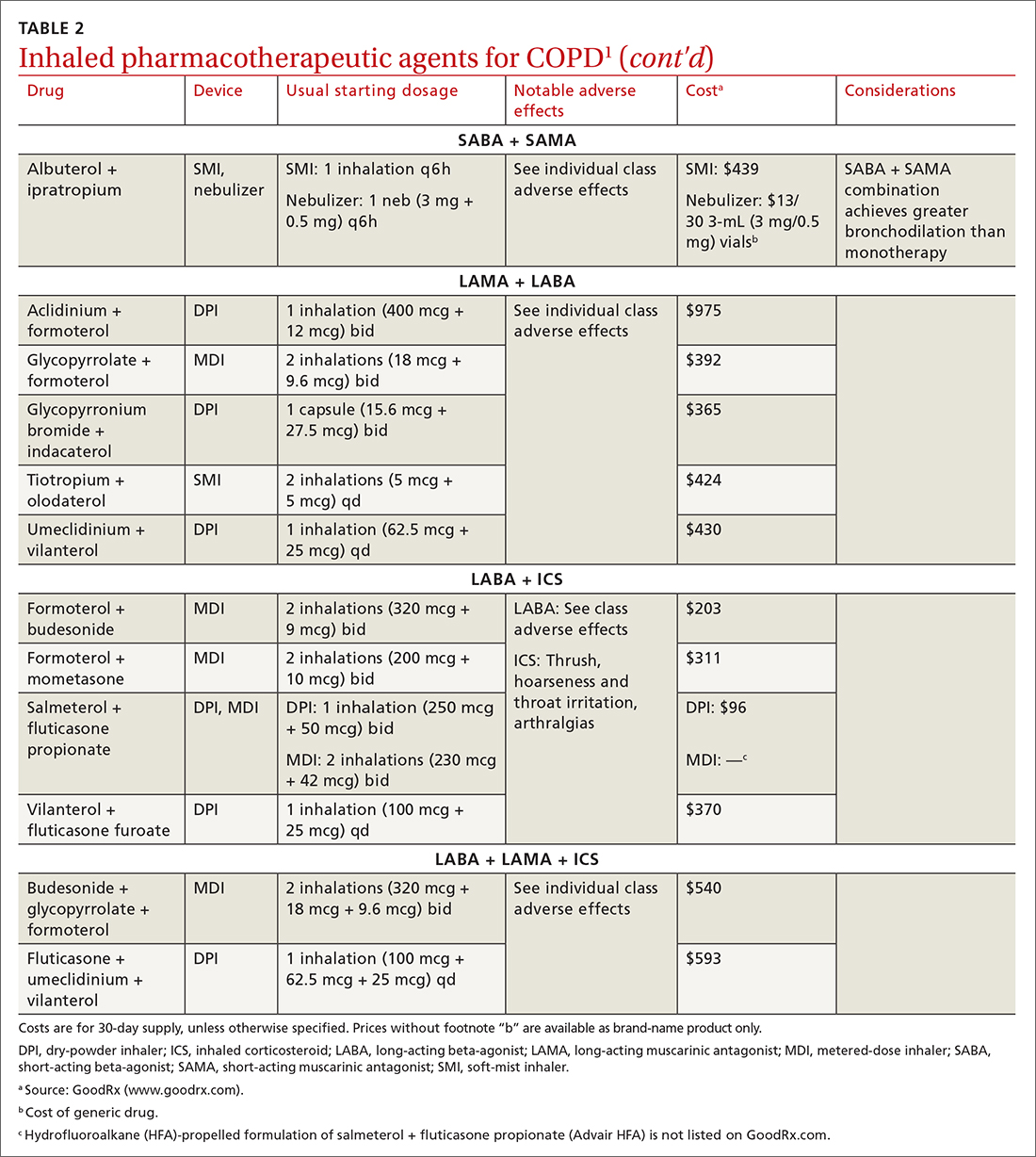

COPD inhaler therapy: A path to success

Managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presents a significant challenge to busy clinicians in many ways, especially when one is approaching the long list of inhaled pharmaceutical agents with an eye toward a cost-effective, patient-centered regimen. Inhaled agents remain expensive, with few available in generic form.

Our primary goal in this article is to detail these agents’ utility, limitations, and relative cost. Specifically, we review why the following considerations are important:

- Choose the right delivery device and drug while considering patient factors.

- Provide patient education through allied health professionals.

- Reduce environmental exposures.

- Rethink the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).

- Understand the role of dual therapy and triple therapy.

There are numerous other treatment modalities for COPD that are recommended in national and international practice guidelines, including vaccination, pulmonary rehabilitation, home visits, phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors, oral glucocorticoids, supplemental oxygen, and ventilatory support.1 Discussion of those modalities is beyond the scope of this review.

Pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy targets

COPD is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation, usually due to airway or alveolar abnormalities, or both, caused by environmental and host factors.2 Sustained lung parenchymal irritation results from exposure to noxious fumes generated by tobacco, pollution, chemicals, and cleaning agents. Host factors include lung immaturity at birth; genetic mutations, such as alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and dysregulation of elastase; and increased reactivity of bronchial smooth muscles, similar to what is seen in asthma.1

Improving ventilation with the intention of relieving dyspnea is the goal of inhaler pharmacotherapy; targets include muscarinic receptors and beta 2-adrenergic receptors that act on bronchial smooth muscle and the autonomic nervous system. Immune modulators, such as corticosteroids, help reduce inflammation around airways.1 Recent pharmacotherapeutic developments include combinations of inhaled medications and expanding options for devices that deliver drugs.

Delivery devices: Options and optimizing their use

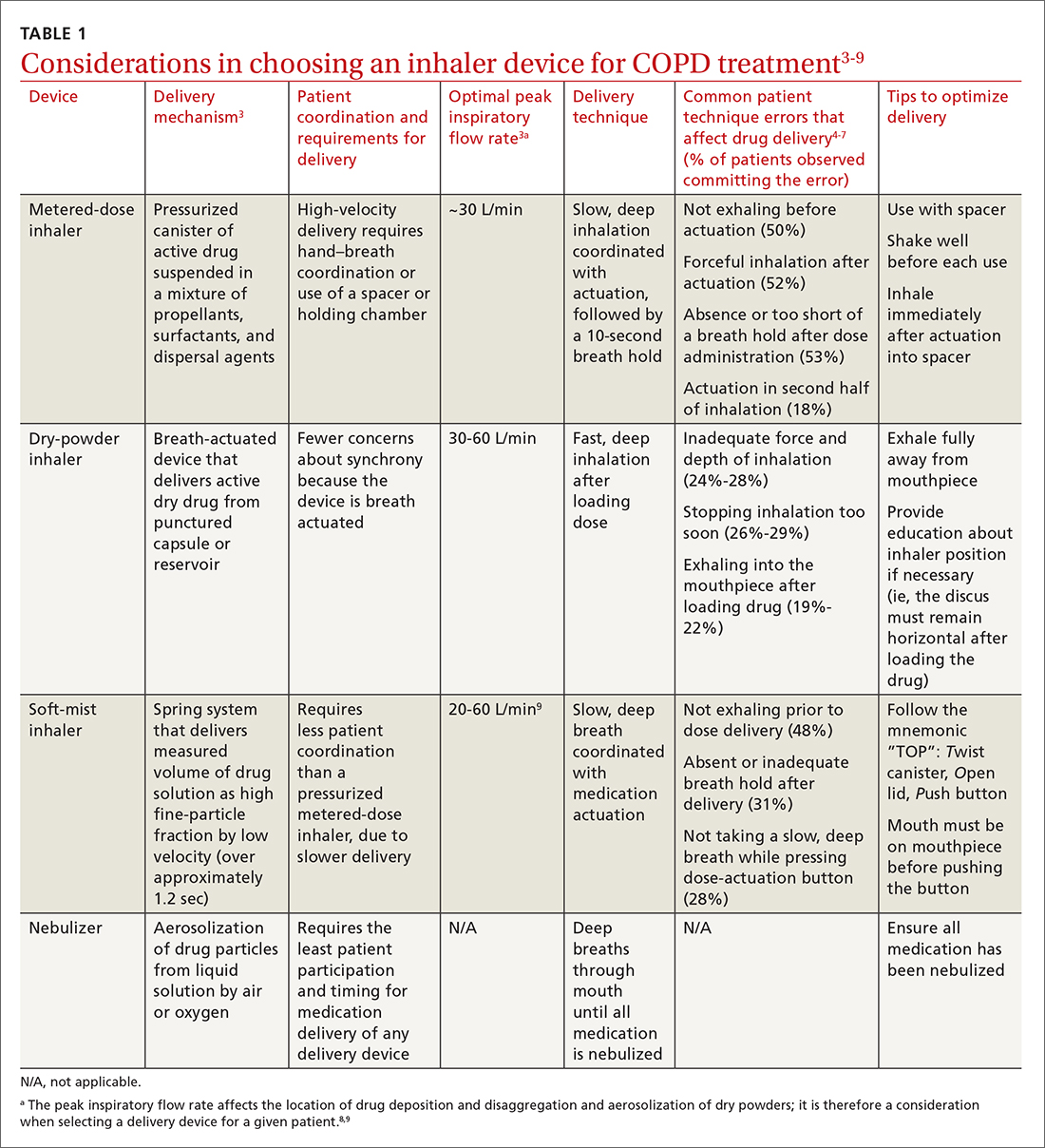

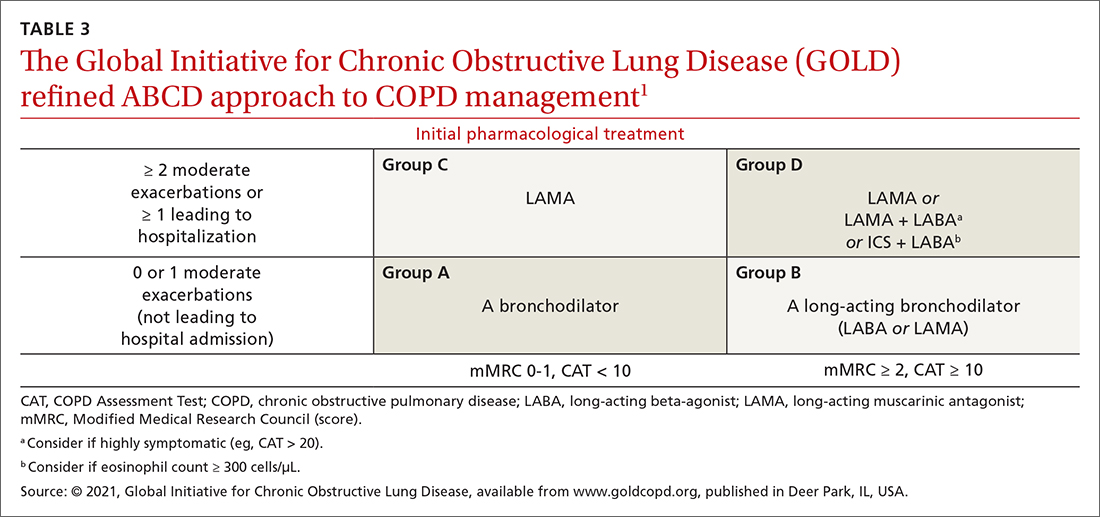

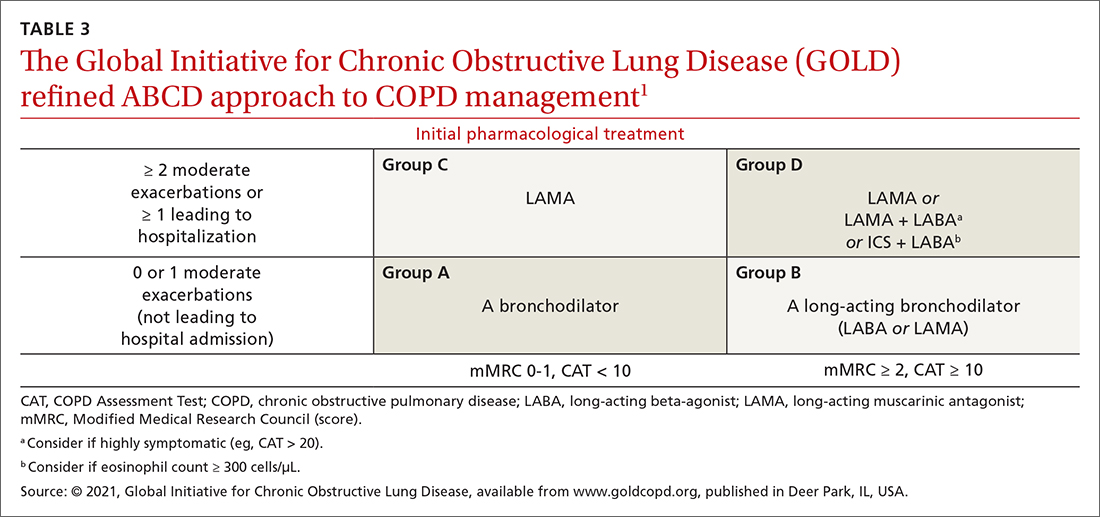

Three principal types of inhaler devices are available: pressurized metered-dose inhalers (MDIs), dry-powder inhalers (DPIs), and soft-mist inhalers (SMIs). These devices, and nebulizers, facilitate medication delivery into the lungs (TABLE 13-9).

Errors in using inhalers affect outcome. Correct inhaler technique is essential for optimal delivery of inhaled medications. Errors in technique when using an inhaled delivery device lead to inadequate drug delivery and are associated with poor outcomes: 90% of patients make errors that are classified as critical (ie, those that reduce drug delivery) or noncritical.2 Critical inhaler errors increase the risk of hospitalization and emergency department visits, and can necessitate a course of oral corticosteroids.10 Many critical errors are device specific; several such errors are described in TABLE 1.3-9

Continue to: Patient education

Patient education is necessary to ensure that drug is delivered to the patient consistently, with the same expectation of effect seen in efficacy studies (which usually provide rigorous inhaler technique training and require demonstration of proficiency).1,2,10 For the busy clinician, a multidisciplinary approach, discussed shortly, can help. Guidelines developed by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommend that inhaler technique be reassessed at every visit and when evaluating treatment response.1TABLE 13-9 provides information on each device type, patient requirements for use, proper technique, common errors in use, and tips for optimizing delivery.

Inhaler education and assessment of technique that is provided to patients in collaboration with a clinical pharmacist, nursing staff, and a respiratory therapist can help alleviate the pressure on a time-constrained primary care physician. Furthermore, pharmacist involvement in the COPD management team meaningfully improves inhaler technique and medication adherence.6,7 Intervention by a pharmacist correlates with a significant reduction in number of exacerbations; an increased likelihood that the patient has a COPD care plan and has received the pneumococcal vaccine; and an improvement in the mean health-related quality of life.11,12

In primary care practices that lack robust multidisciplinary resources, we recommend utilizing virtual resources, such as educational videos, to allow face-to-face or virtual education. A free source of such resources is the COPD Foundation,a a not-for-profit organization funded partly by industry.

Short- and long-acting inhaled medications for COPD

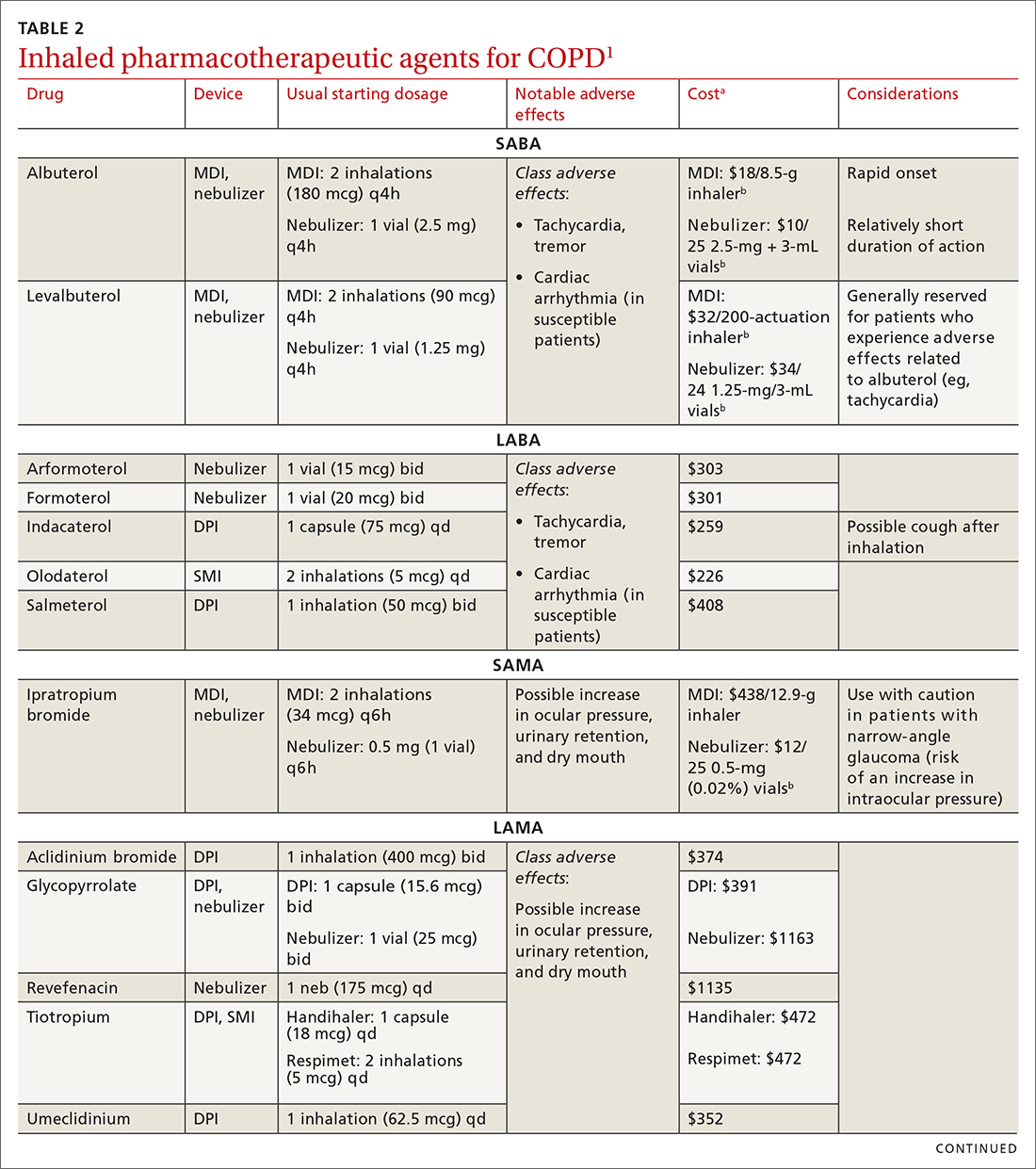

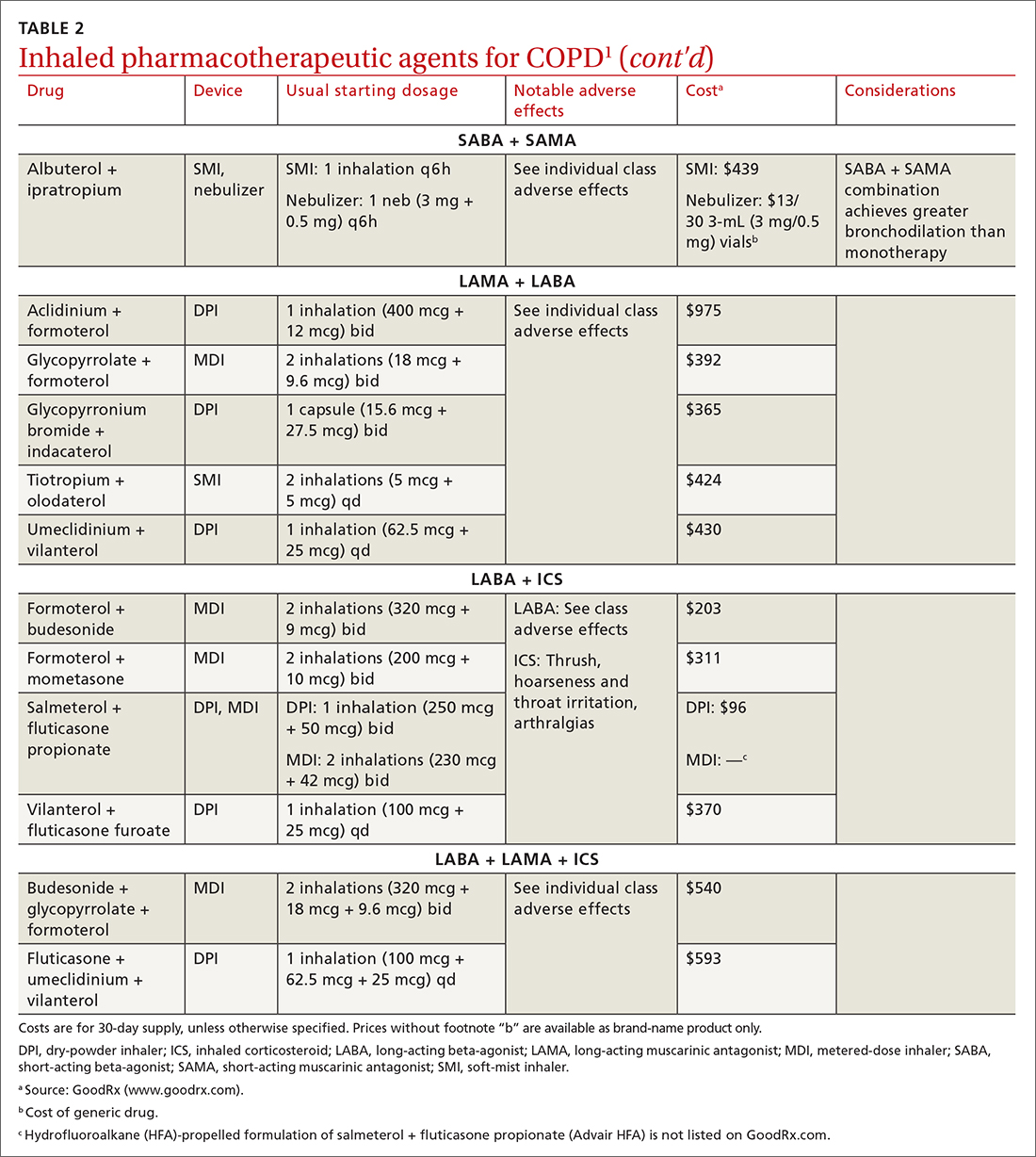

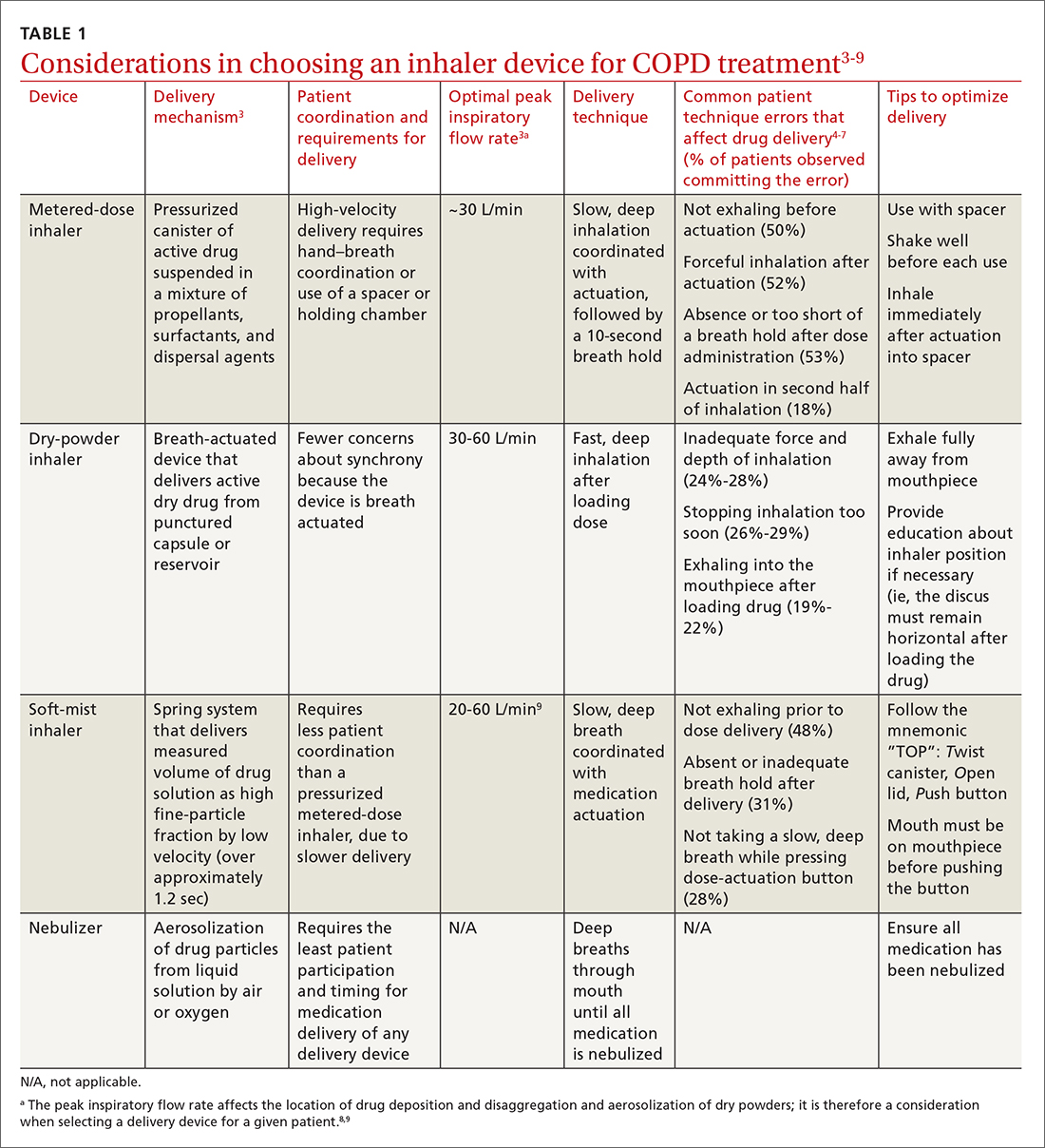

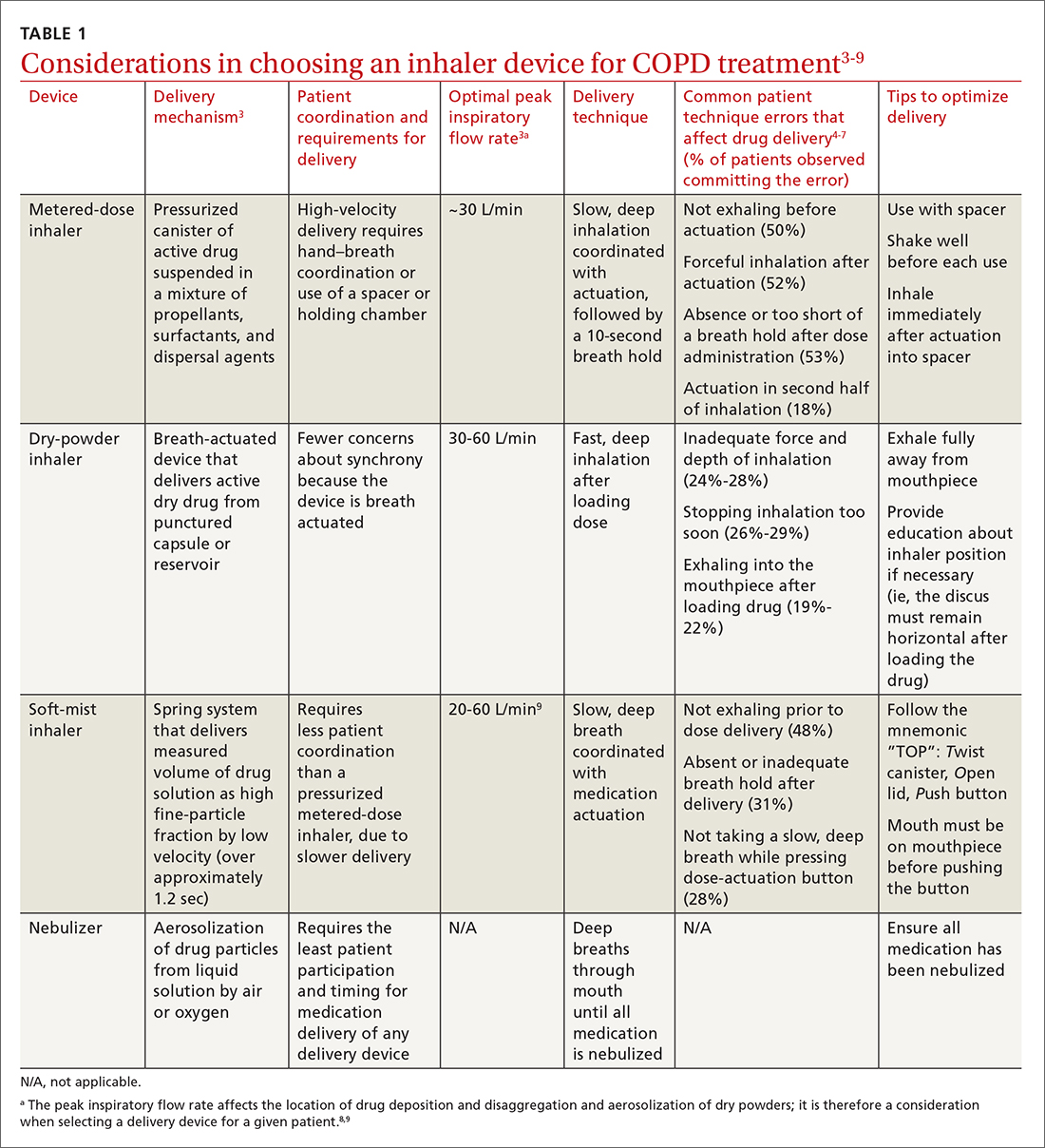

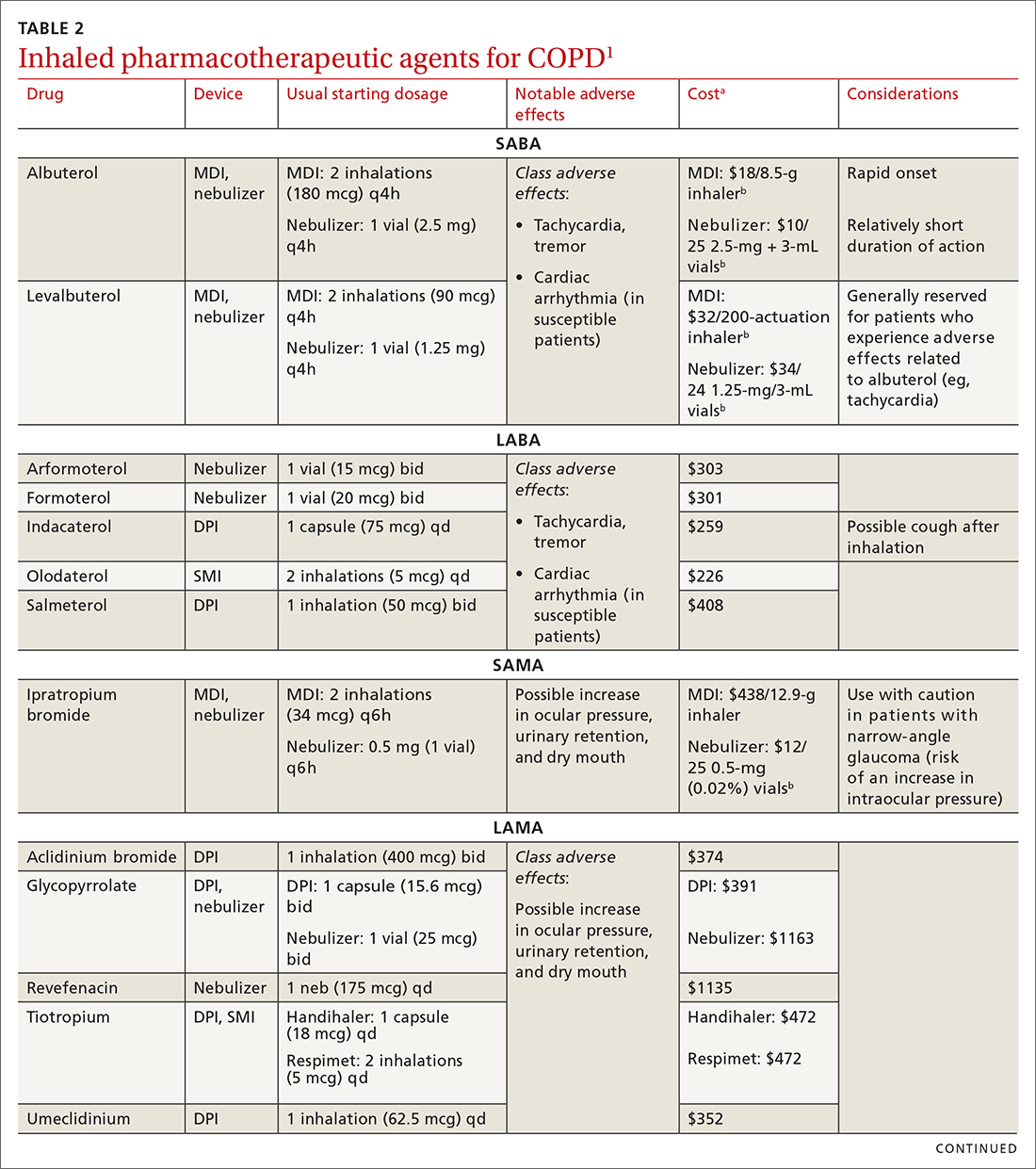

Each class of inhaled medication for treating COPD is discussed broadly in the following sections. TABLE 21 provides details about individual drugs, devices available to deliver them, and starting dosages.

Short-acting agents

These drugs are available in MDI, SMI, and nebulizer delivery devices. When portability and equipment burden are important to the patient, we recommend an MDI over a nebulizer; an MDI is as efficacious as a nebulizer in improving forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and reducing the length of hospital stay for exacerbations.4

Continue to: SABAs

Short-acting beta 2-adrenergic agonists (or beta-agonists [SABAs]). Beta-agonists are typically used to treat exacerbations. They facilitate bronchodilation by upregulating cyclic adenosine monophosphate, preventing smooth-muscle contraction, and reducing dynamic hyperinflation. The effect of a SABA lasts 4 to 6 hours.

In general, SABAs are not recommended for daily use in stable COPD. However, they can be useful, and appropriate, for treating occasional dyspnea and can confer additional symptom improvement when used occasionally along with a long-acting beta 2-adrenergic agonist (or beta-agonist [LABA]; discussed later).1

Albuterol, a commonly used SABA, is less expensive than, and just as effective as, same-class levalbuterol for decreasing breathlessness associated with acute exacerbations. There is no significant difference between the 2 drugs in regard to the incidence of tachycardia or palpitations in patients with cardiovascular disease.13

Although no significant differences have been observed in outcomes when a nebulizer or an MDI is used to administer a SABA, it’s wise to avoid continuous SABA nebulizer therapy, due to the increased risk of disease transmission through the generation of droplets.1,4 Instead, it’s appropriate to use an MDI regimen of 1 to 3 puffs every hour for 2 to 3 hours, followed by 1 to 3 puffs every 2 to 4 hours thereafter, based on the patient’s response.1,4

Short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMAs). Muscarinic antagonists achieve bronchodilation by blocking acetylcholine on muscarinic receptors. We do not specifically recommend SAMAs over SABAs for treating COPD exacerbations in our patients: There is no difference in improvement in FEV1 during an acute exacerbation. Nebulized delivery of a SAMA raises concern for an increase in the risk of acute narrow-angle glaucoma, a risk that can be reduced by using a mask during administration.1,14

Continue to: SABA + SAMA

SABA + SAMA. One combination formulation of the 2 short-term classes of drugs (albuterol [SABA] + ipratropium [SAMA]), US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for every-6-hour dosing, is available for SMI delivery devices and nebulizers. In the setting of a hospitalized patient who requires more frequent bronchodilator dosing, we use albuterol and ipratropium delivered separately (ie, dosed independently), with ipratropium dosed no more frequently than every 4 hours.

Long-acting agents

The mechanisms of long-acting agents are similar to those of their short-acting counterparts. The recommendation is to continue use of a long-acting bronchodilator during exacerbations, when feasible.1

LABA monotherapy reduces exacerbations that result in hospitalization (number needed to treat [NNT] = 39, to prevent 1 hospitalization in an 8-month period).15 Specifically, formoterol at higher dosages reduces exacerbations requiring hospitalization (NNT = 23, to prevent 1 exacerbation in a 6-month to 3-year period).15 Evidence supports better control of symptoms when a LABA is combined with a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA; discussed shortly).1,15

Adverse effects of LABAs include sinus tachycardia, tachyphylaxis, somatic tremors, and, less commonly, hypokalemia—the latter specific to the LABA dosage and concomitant use of a thiazide diuretic. Other adverse effects include a mild decrease in the partial pressure of O2 and, in patients with heart failure, increased oxygen consumption. Although higher dosages are not associated with an increased incidence of nonfatal adverse events, there appears to be no additional benefit to higher dosages in regard to mortality, particularly in patients with stable COPD.1,15

LAMA. Monotherapy with a LAMA reduces the severity of COPD symptoms and reduces the risk of exacerbations and hospitalization (NNT = 58, to prevent 1 hospitalization in a 3 to 48–month period).16 Tiotropium is superior to LABA as monotherapy in (1) reducing exacerbations (NNT = 33, to prevent 1 exacerbation in a 3 to 12–month period) and (2) being associated with a lower rate of all adverse events.17 LAMAs also confer additional benefit when used in combination with agents of other classes, which we discuss in a bit.

Continue to: The most commonly...

The most commonly reported adverse effect of a LAMA is dry mouth. Some patients report developing a bitter metallic taste in the mouth.1

ICSs are not recommended as monotherapy in COPD.1 However, an ICS can be combined with a LABA to reduce the risk of exacerbations in patients with severe COPD (NNT = 22, to prevent 1 exacerbation per year).18 However, this combination increases the risk of pneumonia in this population (number needed to harm [NNH] = 36, to cause 1 case of nonfatal pneumonia per year).18

ICSs increase the incidence of oropharyngeal candidiasis and hoarseness. In addition, ICSs increase the risk of pneumonia in some patients with COPD18—in particular, current smokers, patients ≥ 55 years of age, and patients with a history of pneumonia or exacerbations, a body mass index < 25, or severe COPD symptoms.1,18 ICS therapy does reduce the risk of COPD exacerbations in patients with a history of asthma or with eosinophilia > 300 cells/μL and in those who have a history of hospitalization for COPD exacerbations.19,20

The risk of pneumonia is not equal across all ICS agents. Fluticasone increases the risk of pneumonia (NNH = 23, to cause 1 case of pneumonia in a 22-month period).21 Budesonide showed no statistically significant increase in risk of pneumonia.22 However, further studies on the risk of pneumonia with budesonide are needed because those cited in the Cochrane review21 were much smaller trials, compared to trials of fluticasone, and of low-to-moderate quality. Furthermore, evidence is mixed whether ICS monotherapy in COPD worsens mortality during an 18-month study period.21-23

For these reasons, it’s reasonable to (1) exercise caution when considering the addition of an ICS to LABA therapy and (2) limit such a combination to the setting of severe disease (as discussed already).

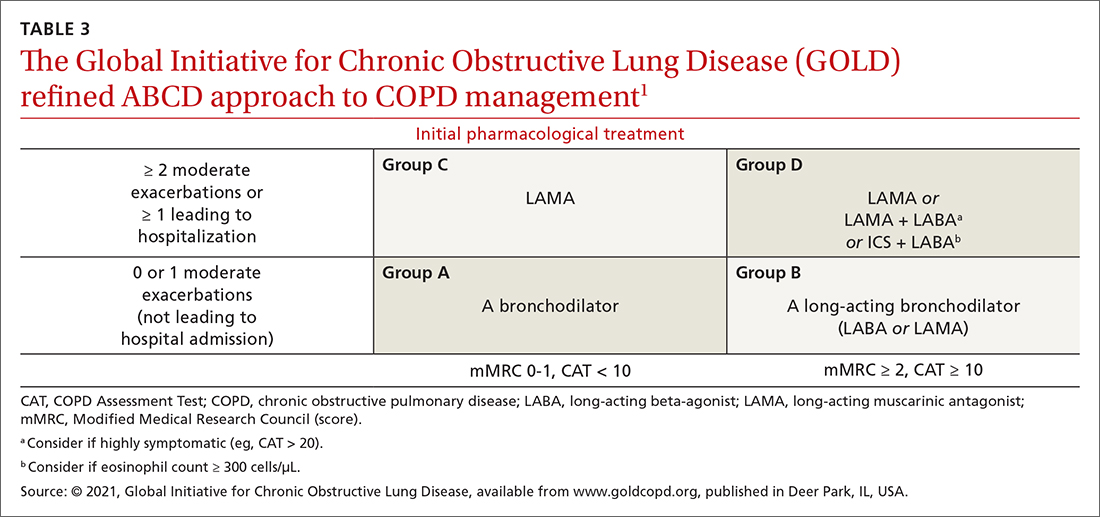

Continue to: LABA + LAMA