User login

Harm Reduction Integration in an Interprofessional Primary Care Training Clinic

Background

Among people who use drugs (PWUD), harm reduction (HR) is an evidence-based low barrier approach to mitigating ongoing substance use risks and is considered a key pillar of the Department of Health and Human Service’s Overdose Prevention Strategy.1 Given the accessibility and continuity, primary care (PC) clinics are optimal sites for education about and provision of HR services.2,3

Aim

- Determining the impact of active and passive methods for HR supply.

- Recognizing the importance of clinician addiction education in the provision of HR services.

Methods

In January 2024, physician and nurse practitioner trainees in the West Haven Veterans Affairs (VA) Center of Education (CoE) in Interprofessional Primary Care received addiction care and HR strategy education. Initially, all patients presenting to the CoE completed a single-item substance use screening. Patients screening positive were offered HR supplies, including fentanyl and xylazine test strips (FTS, XTS), during the encounter (active distribution). Starting October 2024, HR kiosks were implemented in the clinic lobby, offering patients self-serve access to HR supplies (passive distribution). Test strip uptake was tracked through clinical encounter documentation and weekly kiosk inventory.

Results

Between January 2024 and June 2024, 92 FTS and 84 XTS were actively distributed. Upon implementation of the harm reduction kiosk, 253 FTS and 164 XTS were distributed between October 2024 and February 2025. In the CoE, FTS and XTS distribution increased by 275% and 195%, respectively, through passive kiosk distribution relative to active distribution during clinical encounters.

Conclusions

HR kiosk implementation resulted in significantly increased test strip uptake in the CoE, proving passive distribution to be an effective low barrier method of increasing access to HR and substance use disorder (SUD) resources. Although this model may reduce stigma and logistical barriers when presenting for a healthcare encounter, it limits the ability to track and engage patients for more intensive services. While each approach has unique advantages and disadvantages, test strip demand via both methods highlights the significant need for HR resources in PC settings. Continuing education for PC clinicians on low barrier SUD care and HR is critical to optimizing care for this population.

- Haffajee, RL, Sherry, TB, Dubenitz, JM, et al. Overdose prevention strategy. US Department of Health and Human Services (Issue Brief). Published October 27, 2021. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/101936da95b69acb8446a4bad9179cc0/overdose-prevention-strategy.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Advisory: low barrier models of care for substance use disorders. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP23-02-00-005. Published December 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://library.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/advisory-low-barrier-models-of-care-pep23-02-00-005.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Harm Reduction Framework. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2023.

Background

Among people who use drugs (PWUD), harm reduction (HR) is an evidence-based low barrier approach to mitigating ongoing substance use risks and is considered a key pillar of the Department of Health and Human Service’s Overdose Prevention Strategy.1 Given the accessibility and continuity, primary care (PC) clinics are optimal sites for education about and provision of HR services.2,3

Aim

- Determining the impact of active and passive methods for HR supply.

- Recognizing the importance of clinician addiction education in the provision of HR services.

Methods

In January 2024, physician and nurse practitioner trainees in the West Haven Veterans Affairs (VA) Center of Education (CoE) in Interprofessional Primary Care received addiction care and HR strategy education. Initially, all patients presenting to the CoE completed a single-item substance use screening. Patients screening positive were offered HR supplies, including fentanyl and xylazine test strips (FTS, XTS), during the encounter (active distribution). Starting October 2024, HR kiosks were implemented in the clinic lobby, offering patients self-serve access to HR supplies (passive distribution). Test strip uptake was tracked through clinical encounter documentation and weekly kiosk inventory.

Results

Between January 2024 and June 2024, 92 FTS and 84 XTS were actively distributed. Upon implementation of the harm reduction kiosk, 253 FTS and 164 XTS were distributed between October 2024 and February 2025. In the CoE, FTS and XTS distribution increased by 275% and 195%, respectively, through passive kiosk distribution relative to active distribution during clinical encounters.

Conclusions

HR kiosk implementation resulted in significantly increased test strip uptake in the CoE, proving passive distribution to be an effective low barrier method of increasing access to HR and substance use disorder (SUD) resources. Although this model may reduce stigma and logistical barriers when presenting for a healthcare encounter, it limits the ability to track and engage patients for more intensive services. While each approach has unique advantages and disadvantages, test strip demand via both methods highlights the significant need for HR resources in PC settings. Continuing education for PC clinicians on low barrier SUD care and HR is critical to optimizing care for this population.

Background

Among people who use drugs (PWUD), harm reduction (HR) is an evidence-based low barrier approach to mitigating ongoing substance use risks and is considered a key pillar of the Department of Health and Human Service’s Overdose Prevention Strategy.1 Given the accessibility and continuity, primary care (PC) clinics are optimal sites for education about and provision of HR services.2,3

Aim

- Determining the impact of active and passive methods for HR supply.

- Recognizing the importance of clinician addiction education in the provision of HR services.

Methods

In January 2024, physician and nurse practitioner trainees in the West Haven Veterans Affairs (VA) Center of Education (CoE) in Interprofessional Primary Care received addiction care and HR strategy education. Initially, all patients presenting to the CoE completed a single-item substance use screening. Patients screening positive were offered HR supplies, including fentanyl and xylazine test strips (FTS, XTS), during the encounter (active distribution). Starting October 2024, HR kiosks were implemented in the clinic lobby, offering patients self-serve access to HR supplies (passive distribution). Test strip uptake was tracked through clinical encounter documentation and weekly kiosk inventory.

Results

Between January 2024 and June 2024, 92 FTS and 84 XTS were actively distributed. Upon implementation of the harm reduction kiosk, 253 FTS and 164 XTS were distributed between October 2024 and February 2025. In the CoE, FTS and XTS distribution increased by 275% and 195%, respectively, through passive kiosk distribution relative to active distribution during clinical encounters.

Conclusions

HR kiosk implementation resulted in significantly increased test strip uptake in the CoE, proving passive distribution to be an effective low barrier method of increasing access to HR and substance use disorder (SUD) resources. Although this model may reduce stigma and logistical barriers when presenting for a healthcare encounter, it limits the ability to track and engage patients for more intensive services. While each approach has unique advantages and disadvantages, test strip demand via both methods highlights the significant need for HR resources in PC settings. Continuing education for PC clinicians on low barrier SUD care and HR is critical to optimizing care for this population.

- Haffajee, RL, Sherry, TB, Dubenitz, JM, et al. Overdose prevention strategy. US Department of Health and Human Services (Issue Brief). Published October 27, 2021. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/101936da95b69acb8446a4bad9179cc0/overdose-prevention-strategy.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Advisory: low barrier models of care for substance use disorders. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP23-02-00-005. Published December 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://library.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/advisory-low-barrier-models-of-care-pep23-02-00-005.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Harm Reduction Framework. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2023.

- Haffajee, RL, Sherry, TB, Dubenitz, JM, et al. Overdose prevention strategy. US Department of Health and Human Services (Issue Brief). Published October 27, 2021. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/101936da95b69acb8446a4bad9179cc0/overdose-prevention-strategy.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Advisory: low barrier models of care for substance use disorders. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP23-02-00-005. Published December 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://library.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/advisory-low-barrier-models-of-care-pep23-02-00-005.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Harm Reduction Framework. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2023.

Building Trust: Enhancing Rural Women Veterans’ Healthcare Experiences Through Need-Supportive Patient-Centered Communication

Background

Rural women veterans often confront unique healthcare barriers—geographic isolation, gender-related stigma, and limited provider cultural sensitivity that undermine trust and engagement. In response, we co-designed an interprofessional communication curriculum to promote relational, patient-centered care grounded in psychological need support.

Innovation

Anchored in Self Determination Theory (SDT), this curriculum equips nurses and social workers with need-supportive communication strategies that nurture autonomy, competence, and relatedness, integrating two transformative learning methods for enhancing respectful and inclusive listening:

- Cultural humility reflections for veteran-centered care—personal narratives, storytelling, and power-awareness discussions to build lifelong reflective practices.

- Medical improv simulations—adaptive improvisational role plays for healthcare environments fostering presence, adaptability, empathy, trust-building, and real-time responsiveness.

Delivered via a multiday health professions learning lab, the training combines asynchronous workshops with in-person facilitated interactions. Core modules cover SDT foundations, need supportive dialogue, veteran-centered cultural humility, and shared decision-making practices that uplift rural women veterans’ voices. Using Kirkpatrick’s Four Level Model, we assess impact at multiple tiers:

- Reaction: Participant satisfaction and perceived training relevance.

- Learning: Pre/post assessments track SDT knowledge and communication skills gains.

- Behavior: Observe simulations and self-reported changes in communication practices.

- Results: Qualitative satisfaction metrics and care engagement trends among rural women veterans.

Results

A pilot cohort (N = 20) across two rural sites is pending implementation. pre/post surveys will assess any improved confidence in applying need supportive communication and the most effective component in building empathetic presence. Feedback measures will also indicate the significance of combined uses of medical improv and cultural humility on deepened relational capacity and trust.

Discussion

This program operationalizes SDT within healthcare communications, integrating cultural humility and improvisation learning modalities to enhance care quality for rural women veterans, ultimately strengthening provider-patient connections. Using health professions learning lab environments can foster sustained behavioral impacts. Future iterations will expand to additional rural VA sites, co-designing with the voices of women veterans through focus groups.

Background

Rural women veterans often confront unique healthcare barriers—geographic isolation, gender-related stigma, and limited provider cultural sensitivity that undermine trust and engagement. In response, we co-designed an interprofessional communication curriculum to promote relational, patient-centered care grounded in psychological need support.

Innovation

Anchored in Self Determination Theory (SDT), this curriculum equips nurses and social workers with need-supportive communication strategies that nurture autonomy, competence, and relatedness, integrating two transformative learning methods for enhancing respectful and inclusive listening:

- Cultural humility reflections for veteran-centered care—personal narratives, storytelling, and power-awareness discussions to build lifelong reflective practices.

- Medical improv simulations—adaptive improvisational role plays for healthcare environments fostering presence, adaptability, empathy, trust-building, and real-time responsiveness.

Delivered via a multiday health professions learning lab, the training combines asynchronous workshops with in-person facilitated interactions. Core modules cover SDT foundations, need supportive dialogue, veteran-centered cultural humility, and shared decision-making practices that uplift rural women veterans’ voices. Using Kirkpatrick’s Four Level Model, we assess impact at multiple tiers:

- Reaction: Participant satisfaction and perceived training relevance.

- Learning: Pre/post assessments track SDT knowledge and communication skills gains.

- Behavior: Observe simulations and self-reported changes in communication practices.

- Results: Qualitative satisfaction metrics and care engagement trends among rural women veterans.

Results

A pilot cohort (N = 20) across two rural sites is pending implementation. pre/post surveys will assess any improved confidence in applying need supportive communication and the most effective component in building empathetic presence. Feedback measures will also indicate the significance of combined uses of medical improv and cultural humility on deepened relational capacity and trust.

Discussion

This program operationalizes SDT within healthcare communications, integrating cultural humility and improvisation learning modalities to enhance care quality for rural women veterans, ultimately strengthening provider-patient connections. Using health professions learning lab environments can foster sustained behavioral impacts. Future iterations will expand to additional rural VA sites, co-designing with the voices of women veterans through focus groups.

Background

Rural women veterans often confront unique healthcare barriers—geographic isolation, gender-related stigma, and limited provider cultural sensitivity that undermine trust and engagement. In response, we co-designed an interprofessional communication curriculum to promote relational, patient-centered care grounded in psychological need support.

Innovation

Anchored in Self Determination Theory (SDT), this curriculum equips nurses and social workers with need-supportive communication strategies that nurture autonomy, competence, and relatedness, integrating two transformative learning methods for enhancing respectful and inclusive listening:

- Cultural humility reflections for veteran-centered care—personal narratives, storytelling, and power-awareness discussions to build lifelong reflective practices.

- Medical improv simulations—adaptive improvisational role plays for healthcare environments fostering presence, adaptability, empathy, trust-building, and real-time responsiveness.

Delivered via a multiday health professions learning lab, the training combines asynchronous workshops with in-person facilitated interactions. Core modules cover SDT foundations, need supportive dialogue, veteran-centered cultural humility, and shared decision-making practices that uplift rural women veterans’ voices. Using Kirkpatrick’s Four Level Model, we assess impact at multiple tiers:

- Reaction: Participant satisfaction and perceived training relevance.

- Learning: Pre/post assessments track SDT knowledge and communication skills gains.

- Behavior: Observe simulations and self-reported changes in communication practices.

- Results: Qualitative satisfaction metrics and care engagement trends among rural women veterans.

Results

A pilot cohort (N = 20) across two rural sites is pending implementation. pre/post surveys will assess any improved confidence in applying need supportive communication and the most effective component in building empathetic presence. Feedback measures will also indicate the significance of combined uses of medical improv and cultural humility on deepened relational capacity and trust.

Discussion

This program operationalizes SDT within healthcare communications, integrating cultural humility and improvisation learning modalities to enhance care quality for rural women veterans, ultimately strengthening provider-patient connections. Using health professions learning lab environments can foster sustained behavioral impacts. Future iterations will expand to additional rural VA sites, co-designing with the voices of women veterans through focus groups.

Tai Chi Modification and Supplemental Movements Quality Improvement Program

Background

The original program consisted of 12 movements that were to be split up between 3 weeks teaching 4 movements each week. Range of mobility was the main consideration for developing this HPE quality improvement project. Veterans who wanted to participate in Tai Chi were not able to engage in the activity due to the range of movement traditional Tai Chi required.

Innovation

The HPE Quality Improvement program developed a 15-movement warm-up, 12 co-ordinational movements consistent with the original program, 18 supplemental Tai Chi movements that were not included in the original program all of which focus on movements remaining below the shoulders and can be done standing or sitting. Four advanced exercises including “hip over heel” were included to target participants balance if able and to improve their hip strength, knee tendon/ligament strength. Tai Chi loses its potential to increase balance when performed in a sitting position.1 The movements drew upon Fu style Tai Chi and the program developer was given permission from Tommy Kirchoff to use his DVD Healing Exercises. The HPE program consisted of four 30–60-minute weekly sessions of learning the movements with another 4 weekly sessions of demonstrating the movements. Instructors were given written and visual documents to learn from and were evaluated by the developer during the last 4 weeks.

.

Results

Qualitative Data: Instructors notice a difference in how they feel, and appreciate having another option to offer veterans with mobility/standing issues. Patients expressed improvement in mobility relating to bending, arm extension, arm raising, muscle strengthening, hip strengthening and rotation.

Discussion

Future research will want to look at taking measurements before and after patient implementation to determine quantitative data related to balance, strength and range of movement including grip strength, stand up and go, and one-legged stands.

- Skelton DA, Mavroeidi A. How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course, and are there particular ages where MBSBA are most important?. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018;3(2):74-84. Published 2018 Jun 1. doi:10.22540/JFSF-03-074

Background

The original program consisted of 12 movements that were to be split up between 3 weeks teaching 4 movements each week. Range of mobility was the main consideration for developing this HPE quality improvement project. Veterans who wanted to participate in Tai Chi were not able to engage in the activity due to the range of movement traditional Tai Chi required.

Innovation

The HPE Quality Improvement program developed a 15-movement warm-up, 12 co-ordinational movements consistent with the original program, 18 supplemental Tai Chi movements that were not included in the original program all of which focus on movements remaining below the shoulders and can be done standing or sitting. Four advanced exercises including “hip over heel” were included to target participants balance if able and to improve their hip strength, knee tendon/ligament strength. Tai Chi loses its potential to increase balance when performed in a sitting position.1 The movements drew upon Fu style Tai Chi and the program developer was given permission from Tommy Kirchoff to use his DVD Healing Exercises. The HPE program consisted of four 30–60-minute weekly sessions of learning the movements with another 4 weekly sessions of demonstrating the movements. Instructors were given written and visual documents to learn from and were evaluated by the developer during the last 4 weeks.

.

Results

Qualitative Data: Instructors notice a difference in how they feel, and appreciate having another option to offer veterans with mobility/standing issues. Patients expressed improvement in mobility relating to bending, arm extension, arm raising, muscle strengthening, hip strengthening and rotation.

Discussion

Future research will want to look at taking measurements before and after patient implementation to determine quantitative data related to balance, strength and range of movement including grip strength, stand up and go, and one-legged stands.

Background

The original program consisted of 12 movements that were to be split up between 3 weeks teaching 4 movements each week. Range of mobility was the main consideration for developing this HPE quality improvement project. Veterans who wanted to participate in Tai Chi were not able to engage in the activity due to the range of movement traditional Tai Chi required.

Innovation

The HPE Quality Improvement program developed a 15-movement warm-up, 12 co-ordinational movements consistent with the original program, 18 supplemental Tai Chi movements that were not included in the original program all of which focus on movements remaining below the shoulders and can be done standing or sitting. Four advanced exercises including “hip over heel” were included to target participants balance if able and to improve their hip strength, knee tendon/ligament strength. Tai Chi loses its potential to increase balance when performed in a sitting position.1 The movements drew upon Fu style Tai Chi and the program developer was given permission from Tommy Kirchoff to use his DVD Healing Exercises. The HPE program consisted of four 30–60-minute weekly sessions of learning the movements with another 4 weekly sessions of demonstrating the movements. Instructors were given written and visual documents to learn from and were evaluated by the developer during the last 4 weeks.

.

Results

Qualitative Data: Instructors notice a difference in how they feel, and appreciate having another option to offer veterans with mobility/standing issues. Patients expressed improvement in mobility relating to bending, arm extension, arm raising, muscle strengthening, hip strengthening and rotation.

Discussion

Future research will want to look at taking measurements before and after patient implementation to determine quantitative data related to balance, strength and range of movement including grip strength, stand up and go, and one-legged stands.

- Skelton DA, Mavroeidi A. How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course, and are there particular ages where MBSBA are most important?. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018;3(2):74-84. Published 2018 Jun 1. doi:10.22540/JFSF-03-074

- Skelton DA, Mavroeidi A. How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course, and are there particular ages where MBSBA are most important?. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018;3(2):74-84. Published 2018 Jun 1. doi:10.22540/JFSF-03-074

Improving Life-Sustaining Treatment Discussions and Order Quality in a Primary Care Clinic

Background

Veterans Health Administration Directive 1004.03(1) (Advance Care Planning) aims to establish a “system-wide, patient-centered and evidence-based approach to Advance Care Planning.”1 Life-sustaining treatment (LST) orders are documents of patient preference regarding interventions such as mechanical ventilation, CPR, dialysis, artificial nutrition and hydration; and are considered part of an Advance Care Plan. From a bioethics perspective, these orders promote patient autonomy by formalizing patient preferences around LSTs in the medical record, particularly for when a patient lacks capacity and/or cannot make decisions on their own.2 Through consensus building, our team defined vague, inactionable, or incorrectly written LST orders as Potentially Problematic Orders (PPO). PPOs which cause confusion at the bedside or lack clarity around preferences can pose serious risks to patient safety and autonomy by exposing patients to inappropriate initiation or withholding of LSTs. Improving the quality of LST orders and reducing the number of PPOs is a crucial element for safe and effective implementation of Directive 1004.03(1).

Aim

The aim of this quality improvement project was to reduce the number of PPOs in a VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) by 75% by the end of 2025.

Methods

The Model for Improvement was used for this quality improvement project.3 One year of LST orders were audited and thematic analysis identified 7 subtypes of PPO. Some PPO subtypes included clerical errors, potentially mismatched order sets (e.g., Comfort Care order with no associated DNR order) ill-defined or vague orders, and clinically impractical orders (eg, “consents to one shock during CPR”). We defined vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders as the most ethically and clinically challenging given the possibility of confusion or error at the bedside. Initial data were collected from October 2022 to October 2023, and post-intervention data were collected from February 2024 to September 2024. Interventions included process changes (clarifying role responsibility, documentation practices, patient education), regular auditing and feedback from a supervisor, and staff education.

Results

Post-intervention analysis demonstrated that the proportion of PPO remained the same, with 25% of patient charts containing at least one PPO. However, the distribution of PPO in the most ethically and clinically problematic categories (vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders) decreased from 14.7% to <1%.

Conclusions

We successfully reduced the most ethically and clinically challenging PPOs to <1% in our initial intervention. To reduce the overall proportion of PPO, we plan enhancements in process automations, additional physical educational resources, and minor changes in audit criteria. Future projects will aim to address the remaining PPO error types and prepare this project for implementation in other CBOCs.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1004.03(1): Advance care planning. Published December 12, 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11610

- White DB, Curtis JR, Lo B, Luce JM. Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for critically ill patients who lack both decision-making capacity and surrogate decision-makers. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2053-2059. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000227654.38708.C1

- Ogrinc GS, Headrick LA, Barton AJ, Dolansky MA, Madigosky WS, Miltner RS, Hall AG. Fundamentals of Health Care Improvement: A Guide to Improving Your Patients’ Care (4th edition). Joint Commission Resources and Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2022.

Background

Veterans Health Administration Directive 1004.03(1) (Advance Care Planning) aims to establish a “system-wide, patient-centered and evidence-based approach to Advance Care Planning.”1 Life-sustaining treatment (LST) orders are documents of patient preference regarding interventions such as mechanical ventilation, CPR, dialysis, artificial nutrition and hydration; and are considered part of an Advance Care Plan. From a bioethics perspective, these orders promote patient autonomy by formalizing patient preferences around LSTs in the medical record, particularly for when a patient lacks capacity and/or cannot make decisions on their own.2 Through consensus building, our team defined vague, inactionable, or incorrectly written LST orders as Potentially Problematic Orders (PPO). PPOs which cause confusion at the bedside or lack clarity around preferences can pose serious risks to patient safety and autonomy by exposing patients to inappropriate initiation or withholding of LSTs. Improving the quality of LST orders and reducing the number of PPOs is a crucial element for safe and effective implementation of Directive 1004.03(1).

Aim

The aim of this quality improvement project was to reduce the number of PPOs in a VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) by 75% by the end of 2025.

Methods

The Model for Improvement was used for this quality improvement project.3 One year of LST orders were audited and thematic analysis identified 7 subtypes of PPO. Some PPO subtypes included clerical errors, potentially mismatched order sets (e.g., Comfort Care order with no associated DNR order) ill-defined or vague orders, and clinically impractical orders (eg, “consents to one shock during CPR”). We defined vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders as the most ethically and clinically challenging given the possibility of confusion or error at the bedside. Initial data were collected from October 2022 to October 2023, and post-intervention data were collected from February 2024 to September 2024. Interventions included process changes (clarifying role responsibility, documentation practices, patient education), regular auditing and feedback from a supervisor, and staff education.

Results

Post-intervention analysis demonstrated that the proportion of PPO remained the same, with 25% of patient charts containing at least one PPO. However, the distribution of PPO in the most ethically and clinically problematic categories (vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders) decreased from 14.7% to <1%.

Conclusions

We successfully reduced the most ethically and clinically challenging PPOs to <1% in our initial intervention. To reduce the overall proportion of PPO, we plan enhancements in process automations, additional physical educational resources, and minor changes in audit criteria. Future projects will aim to address the remaining PPO error types and prepare this project for implementation in other CBOCs.

Background

Veterans Health Administration Directive 1004.03(1) (Advance Care Planning) aims to establish a “system-wide, patient-centered and evidence-based approach to Advance Care Planning.”1 Life-sustaining treatment (LST) orders are documents of patient preference regarding interventions such as mechanical ventilation, CPR, dialysis, artificial nutrition and hydration; and are considered part of an Advance Care Plan. From a bioethics perspective, these orders promote patient autonomy by formalizing patient preferences around LSTs in the medical record, particularly for when a patient lacks capacity and/or cannot make decisions on their own.2 Through consensus building, our team defined vague, inactionable, or incorrectly written LST orders as Potentially Problematic Orders (PPO). PPOs which cause confusion at the bedside or lack clarity around preferences can pose serious risks to patient safety and autonomy by exposing patients to inappropriate initiation or withholding of LSTs. Improving the quality of LST orders and reducing the number of PPOs is a crucial element for safe and effective implementation of Directive 1004.03(1).

Aim

The aim of this quality improvement project was to reduce the number of PPOs in a VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) by 75% by the end of 2025.

Methods

The Model for Improvement was used for this quality improvement project.3 One year of LST orders were audited and thematic analysis identified 7 subtypes of PPO. Some PPO subtypes included clerical errors, potentially mismatched order sets (e.g., Comfort Care order with no associated DNR order) ill-defined or vague orders, and clinically impractical orders (eg, “consents to one shock during CPR”). We defined vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders as the most ethically and clinically challenging given the possibility of confusion or error at the bedside. Initial data were collected from October 2022 to October 2023, and post-intervention data were collected from February 2024 to September 2024. Interventions included process changes (clarifying role responsibility, documentation practices, patient education), regular auditing and feedback from a supervisor, and staff education.

Results

Post-intervention analysis demonstrated that the proportion of PPO remained the same, with 25% of patient charts containing at least one PPO. However, the distribution of PPO in the most ethically and clinically problematic categories (vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders) decreased from 14.7% to <1%.

Conclusions

We successfully reduced the most ethically and clinically challenging PPOs to <1% in our initial intervention. To reduce the overall proportion of PPO, we plan enhancements in process automations, additional physical educational resources, and minor changes in audit criteria. Future projects will aim to address the remaining PPO error types and prepare this project for implementation in other CBOCs.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1004.03(1): Advance care planning. Published December 12, 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11610

- White DB, Curtis JR, Lo B, Luce JM. Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for critically ill patients who lack both decision-making capacity and surrogate decision-makers. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2053-2059. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000227654.38708.C1

- Ogrinc GS, Headrick LA, Barton AJ, Dolansky MA, Madigosky WS, Miltner RS, Hall AG. Fundamentals of Health Care Improvement: A Guide to Improving Your Patients’ Care (4th edition). Joint Commission Resources and Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2022.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1004.03(1): Advance care planning. Published December 12, 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11610

- White DB, Curtis JR, Lo B, Luce JM. Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for critically ill patients who lack both decision-making capacity and surrogate decision-makers. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2053-2059. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000227654.38708.C1

- Ogrinc GS, Headrick LA, Barton AJ, Dolansky MA, Madigosky WS, Miltner RS, Hall AG. Fundamentals of Health Care Improvement: A Guide to Improving Your Patients’ Care (4th edition). Joint Commission Resources and Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2022.

A Health Educator’s Primer to Cost-Effectiveness in Health Professions Education

Background

Cost-effectiveness (CE) evaluations, for existing and anticipated programs, are common in healthcare, but are rarely used in health professions education (HPE). A systematic review of HPE literature found not only few examples of CE evaluations, but also unclear and inconsistent methodology.1 One proposed reason HPE has been slow to adopt CE evaluations is uncertainty over terminology and how to adapt this methodology to HPE.2 CE evaluations present further challenges for HPE since educational outcomes are often not easily monetized. However, given the reality of constrained budgets and limited resources, CE evaluations can be a powerful tool for educators to strengthen arguments for proposed innovations, and for scholars seeking to conduct rigorous work that sustains critical review.

Innovation

This project aims to make CE evaluations more understandable to HPE educators, using a one-page infographic and glossary. This will provide a primer, operationalizing the steps involved in CE evaluations and addressing why and when CE evaluations might be considered in HPE. To improve comprehension, this is being developed collaboratively with health professions educators and an economist. This infographic will be submitted for publication, as a resource to facilitate educators’ scholarly work and conversations with fiscal administrators.

Results

The infographic includes 1) an overview of CE evaluations, 2) information about inputs required for CE evaluations, 3) guidance on interpreting results, 4) a glossary of key terminology, and 5) considerations for why educators might consider this type of analysis. A final draft will be pilot tested with a focus group to assess interdisciplinary accessibility.

Discussion

Discussions between health professions educators and an economist on this infographic uncovered concepts that were poorly understood or defined differently across disciplines, determining specific knowledge gaps and misunderstandings. For example, facilitating conversation between educators and economists highlighted key terms that were a source of misunderstanding. These were then added to the glossary, creating a shared vocabulary. This also helped clarify the steps and information necessary for conducting CE evaluations in HPE, particularly the issue of perspective choice for the analysis (educator, patient, learner, etc.). Overall, this collaboration aimed at making CE evaluations more approachable and understandable for HPE professionals through this infographic.

- Foo J, Cook DA, Walsh K, et al. Cost evaluations in health professions education: a systematic review of methods and reporting quality. Med Educ. 2019;53(12):1196-1208. doi:10.1111/medu.13936

- Maloney S, Reeves S, Rivers G, Ilic D, Foo J, Walsh K. The Prato Statement on cost and value in professional and interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(1):1-4. doi:10.1080/13561820.2016.1257255

Background

Cost-effectiveness (CE) evaluations, for existing and anticipated programs, are common in healthcare, but are rarely used in health professions education (HPE). A systematic review of HPE literature found not only few examples of CE evaluations, but also unclear and inconsistent methodology.1 One proposed reason HPE has been slow to adopt CE evaluations is uncertainty over terminology and how to adapt this methodology to HPE.2 CE evaluations present further challenges for HPE since educational outcomes are often not easily monetized. However, given the reality of constrained budgets and limited resources, CE evaluations can be a powerful tool for educators to strengthen arguments for proposed innovations, and for scholars seeking to conduct rigorous work that sustains critical review.

Innovation

This project aims to make CE evaluations more understandable to HPE educators, using a one-page infographic and glossary. This will provide a primer, operationalizing the steps involved in CE evaluations and addressing why and when CE evaluations might be considered in HPE. To improve comprehension, this is being developed collaboratively with health professions educators and an economist. This infographic will be submitted for publication, as a resource to facilitate educators’ scholarly work and conversations with fiscal administrators.

Results

The infographic includes 1) an overview of CE evaluations, 2) information about inputs required for CE evaluations, 3) guidance on interpreting results, 4) a glossary of key terminology, and 5) considerations for why educators might consider this type of analysis. A final draft will be pilot tested with a focus group to assess interdisciplinary accessibility.

Discussion

Discussions between health professions educators and an economist on this infographic uncovered concepts that were poorly understood or defined differently across disciplines, determining specific knowledge gaps and misunderstandings. For example, facilitating conversation between educators and economists highlighted key terms that were a source of misunderstanding. These were then added to the glossary, creating a shared vocabulary. This also helped clarify the steps and information necessary for conducting CE evaluations in HPE, particularly the issue of perspective choice for the analysis (educator, patient, learner, etc.). Overall, this collaboration aimed at making CE evaluations more approachable and understandable for HPE professionals through this infographic.

Background

Cost-effectiveness (CE) evaluations, for existing and anticipated programs, are common in healthcare, but are rarely used in health professions education (HPE). A systematic review of HPE literature found not only few examples of CE evaluations, but also unclear and inconsistent methodology.1 One proposed reason HPE has been slow to adopt CE evaluations is uncertainty over terminology and how to adapt this methodology to HPE.2 CE evaluations present further challenges for HPE since educational outcomes are often not easily monetized. However, given the reality of constrained budgets and limited resources, CE evaluations can be a powerful tool for educators to strengthen arguments for proposed innovations, and for scholars seeking to conduct rigorous work that sustains critical review.

Innovation

This project aims to make CE evaluations more understandable to HPE educators, using a one-page infographic and glossary. This will provide a primer, operationalizing the steps involved in CE evaluations and addressing why and when CE evaluations might be considered in HPE. To improve comprehension, this is being developed collaboratively with health professions educators and an economist. This infographic will be submitted for publication, as a resource to facilitate educators’ scholarly work and conversations with fiscal administrators.

Results

The infographic includes 1) an overview of CE evaluations, 2) information about inputs required for CE evaluations, 3) guidance on interpreting results, 4) a glossary of key terminology, and 5) considerations for why educators might consider this type of analysis. A final draft will be pilot tested with a focus group to assess interdisciplinary accessibility.

Discussion

Discussions between health professions educators and an economist on this infographic uncovered concepts that were poorly understood or defined differently across disciplines, determining specific knowledge gaps and misunderstandings. For example, facilitating conversation between educators and economists highlighted key terms that were a source of misunderstanding. These were then added to the glossary, creating a shared vocabulary. This also helped clarify the steps and information necessary for conducting CE evaluations in HPE, particularly the issue of perspective choice for the analysis (educator, patient, learner, etc.). Overall, this collaboration aimed at making CE evaluations more approachable and understandable for HPE professionals through this infographic.

- Foo J, Cook DA, Walsh K, et al. Cost evaluations in health professions education: a systematic review of methods and reporting quality. Med Educ. 2019;53(12):1196-1208. doi:10.1111/medu.13936

- Maloney S, Reeves S, Rivers G, Ilic D, Foo J, Walsh K. The Prato Statement on cost and value in professional and interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(1):1-4. doi:10.1080/13561820.2016.1257255

- Foo J, Cook DA, Walsh K, et al. Cost evaluations in health professions education: a systematic review of methods and reporting quality. Med Educ. 2019;53(12):1196-1208. doi:10.1111/medu.13936

- Maloney S, Reeves S, Rivers G, Ilic D, Foo J, Walsh K. The Prato Statement on cost and value in professional and interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(1):1-4. doi:10.1080/13561820.2016.1257255

Interview Tips for Dermatology Applicants From Dr. Scott Worswick

What qualities are dermatology programs looking for that may be different from 5 years ago?

DR. WORSWICK: Every dermatology residency program is different, and as a result, each program is looking for different qualities in its applicants. Overall, I don’t think there has been a huge change in what programs are generally looking for, though. While each program may have a particular trait it values more than another, in general, programs are looking to find residents who will be competent and caring doctors, who work well in teams, and who could be future leaders in our field.

What are common mistakes you see in dermatology residency interviews, and how can applicants avoid them?

DR. WORSWICK: Most dermatology applicants are highly accomplished and empathic soon-to-be physicians, so I haven’t found a lot of “mistakes” from this incredible group of people that we have the privilege of interviewing. From time to time, an applicant will lie in an interview, usually out of a desire to appear to be a certain way, and occasionally, they may be nervous and stumble over their words. The former is a really big problem when it happens, and I would recommend that applicants be honest in all their encounters. The latter is not a major problem, and in some cases, might be avoided by lots of practice in advance.

What types of questions do you recommend applicants ask their interviewers to demonstrate genuine interest in the program?

DR. WORSWICK: Because of the signaling system, I think that programs assume interest at baseline once an applicant has sent the signal. So, “demonstrating interest” is generally not something I would recommend to applicants during the interview day. It is important for applicants to determine on interview day if a program is a fit for them, so applicants should showcase their unique strengths and skills and find out about what makes any given program different from another. The match generally works well and gets applicants into a program that closely aligns with their strengths and interests. So, think of interview day as your time to figure out how good a fit a program is for you, and not the other way around.

How can applicants who feel they don't have standout research or leadership credentials differentiate themselves in the interview?

DR. WORSWICK: While leadership, and less so research experience, is a trait valued highly by most if not all dermatology programs, it is only a part of what an applicant can offer a program. Most programs employ holistic review and consider several factors, probably most commonly grades in medical school, leadership experience, mentorship, teaching, volunteering, Step 2 scores, and letters of recommendation. Any given applicant does not need to excel in all of these. If an applicant has not done a lot of research, they may not match into a research-heavy program, but it doesn’t mean they won’t match. They should determine in which areas they shine and signal the programs that align with those interests/strengths.

How should applicants discuss nontraditional experiences in a way that adds value rather than raising red flags?

DR. WORSWICK: In general, my recommendation would be to explain what happened leading up to the change or challenge so that someone reading the application clearly understands the circumstances of the experience, then add value to the description by explaining what was learned and how this might relate to the applicant being a dermatology resident. For example, if a resident took time off for financial reasons and had to work as a medical assitant for a year, a concise description that explains the need for the leave (financial) as well as what value was gained (a year of hands-on patient care experience that validated their choice of going into medicine) could be very helpful.

What qualities are dermatology programs looking for that may be different from 5 years ago?

DR. WORSWICK: Every dermatology residency program is different, and as a result, each program is looking for different qualities in its applicants. Overall, I don’t think there has been a huge change in what programs are generally looking for, though. While each program may have a particular trait it values more than another, in general, programs are looking to find residents who will be competent and caring doctors, who work well in teams, and who could be future leaders in our field.

What are common mistakes you see in dermatology residency interviews, and how can applicants avoid them?

DR. WORSWICK: Most dermatology applicants are highly accomplished and empathic soon-to-be physicians, so I haven’t found a lot of “mistakes” from this incredible group of people that we have the privilege of interviewing. From time to time, an applicant will lie in an interview, usually out of a desire to appear to be a certain way, and occasionally, they may be nervous and stumble over their words. The former is a really big problem when it happens, and I would recommend that applicants be honest in all their encounters. The latter is not a major problem, and in some cases, might be avoided by lots of practice in advance.

What types of questions do you recommend applicants ask their interviewers to demonstrate genuine interest in the program?

DR. WORSWICK: Because of the signaling system, I think that programs assume interest at baseline once an applicant has sent the signal. So, “demonstrating interest” is generally not something I would recommend to applicants during the interview day. It is important for applicants to determine on interview day if a program is a fit for them, so applicants should showcase their unique strengths and skills and find out about what makes any given program different from another. The match generally works well and gets applicants into a program that closely aligns with their strengths and interests. So, think of interview day as your time to figure out how good a fit a program is for you, and not the other way around.

How can applicants who feel they don't have standout research or leadership credentials differentiate themselves in the interview?

DR. WORSWICK: While leadership, and less so research experience, is a trait valued highly by most if not all dermatology programs, it is only a part of what an applicant can offer a program. Most programs employ holistic review and consider several factors, probably most commonly grades in medical school, leadership experience, mentorship, teaching, volunteering, Step 2 scores, and letters of recommendation. Any given applicant does not need to excel in all of these. If an applicant has not done a lot of research, they may not match into a research-heavy program, but it doesn’t mean they won’t match. They should determine in which areas they shine and signal the programs that align with those interests/strengths.

How should applicants discuss nontraditional experiences in a way that adds value rather than raising red flags?

DR. WORSWICK: In general, my recommendation would be to explain what happened leading up to the change or challenge so that someone reading the application clearly understands the circumstances of the experience, then add value to the description by explaining what was learned and how this might relate to the applicant being a dermatology resident. For example, if a resident took time off for financial reasons and had to work as a medical assitant for a year, a concise description that explains the need for the leave (financial) as well as what value was gained (a year of hands-on patient care experience that validated their choice of going into medicine) could be very helpful.

What qualities are dermatology programs looking for that may be different from 5 years ago?

DR. WORSWICK: Every dermatology residency program is different, and as a result, each program is looking for different qualities in its applicants. Overall, I don’t think there has been a huge change in what programs are generally looking for, though. While each program may have a particular trait it values more than another, in general, programs are looking to find residents who will be competent and caring doctors, who work well in teams, and who could be future leaders in our field.

What are common mistakes you see in dermatology residency interviews, and how can applicants avoid them?

DR. WORSWICK: Most dermatology applicants are highly accomplished and empathic soon-to-be physicians, so I haven’t found a lot of “mistakes” from this incredible group of people that we have the privilege of interviewing. From time to time, an applicant will lie in an interview, usually out of a desire to appear to be a certain way, and occasionally, they may be nervous and stumble over their words. The former is a really big problem when it happens, and I would recommend that applicants be honest in all their encounters. The latter is not a major problem, and in some cases, might be avoided by lots of practice in advance.

What types of questions do you recommend applicants ask their interviewers to demonstrate genuine interest in the program?

DR. WORSWICK: Because of the signaling system, I think that programs assume interest at baseline once an applicant has sent the signal. So, “demonstrating interest” is generally not something I would recommend to applicants during the interview day. It is important for applicants to determine on interview day if a program is a fit for them, so applicants should showcase their unique strengths and skills and find out about what makes any given program different from another. The match generally works well and gets applicants into a program that closely aligns with their strengths and interests. So, think of interview day as your time to figure out how good a fit a program is for you, and not the other way around.

How can applicants who feel they don't have standout research or leadership credentials differentiate themselves in the interview?

DR. WORSWICK: While leadership, and less so research experience, is a trait valued highly by most if not all dermatology programs, it is only a part of what an applicant can offer a program. Most programs employ holistic review and consider several factors, probably most commonly grades in medical school, leadership experience, mentorship, teaching, volunteering, Step 2 scores, and letters of recommendation. Any given applicant does not need to excel in all of these. If an applicant has not done a lot of research, they may not match into a research-heavy program, but it doesn’t mean they won’t match. They should determine in which areas they shine and signal the programs that align with those interests/strengths.

How should applicants discuss nontraditional experiences in a way that adds value rather than raising red flags?

DR. WORSWICK: In general, my recommendation would be to explain what happened leading up to the change or challenge so that someone reading the application clearly understands the circumstances of the experience, then add value to the description by explaining what was learned and how this might relate to the applicant being a dermatology resident. For example, if a resident took time off for financial reasons and had to work as a medical assitant for a year, a concise description that explains the need for the leave (financial) as well as what value was gained (a year of hands-on patient care experience that validated their choice of going into medicine) could be very helpful.

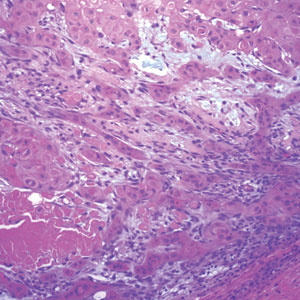

Management of Facial Hair in Women

Facial hair growth in women is complex and multifaceted. It is not a disease but rather a part of normal anatomy or a symptom influenced by an underlying condition such as hypertrichosis, a hormonal imbalance (eg, hirsutism due to polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]), mechanical factors such as pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) from shaving, and perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormonal shifts. Additionally, normal facial hair patterns can vary substantially based on genetics, ethnicity, and cultural background. Some populations may naturally have more visible vellus or terminal hairs on the face, which are entirely physiologic rather than indicative of an underlying disorder. Despite this, societal expectations and beauty standards across many cultures dictate that facial hair in women is undesirable, often associating hair-free skin with femininity and attractiveness. This perception drives many women to seek treatment—not necessarily for medical reasons, but due to social pressure and aesthetic preferences.

Hypertrichosis, whether congenital or acquired, refers to excessive hair growth that is not androgen dependent and can appear on any site of the body. Causes include genetic predisposition, porphyria, thyroid disorders, internal malignancies, malnutrition, anorexia nervosa, or use of medications such as cyclosporine, prednisolone, and phenytoin.1 Hirsutism, by contrast, is characterized by the growth of terminal hairs in women at androgen-dependent sites such as the face, neck, and upper chest, where coarse hair typically grows in men.2 This condition often is associated with excess androgens produced by the ovaries or adrenal glands, most commonly due to PCOS although genetic factors may contribute.

Before initiating treatment, a thorough history and physical examination are essential to determine the underlying cause of conditions associated with facial hair growth in women. Clinicians should assess for signs of hyperandrogenism, menstrual irregularities, virilization, medication use, and family history. In cases of a suspected endocrine disorder, further laboratory evaluation may be warranted to guide appropriate management. While each cause of facial hair growth in women has unique management considerations, the shared impact on psychosocial well-being and adherence to grooming standards in the US military warrants an all-encompassing yet targeted approach. This comprehensive review discusses management options for women with facial hair in the military based on a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE conducted in November 2024 using combinations of the following search terms: hirsutism, facial hair, pseudofolliculitis barbae, women, female, military, grooming standards, hyperandrogenism, and hair removal.

Treatment Modalities

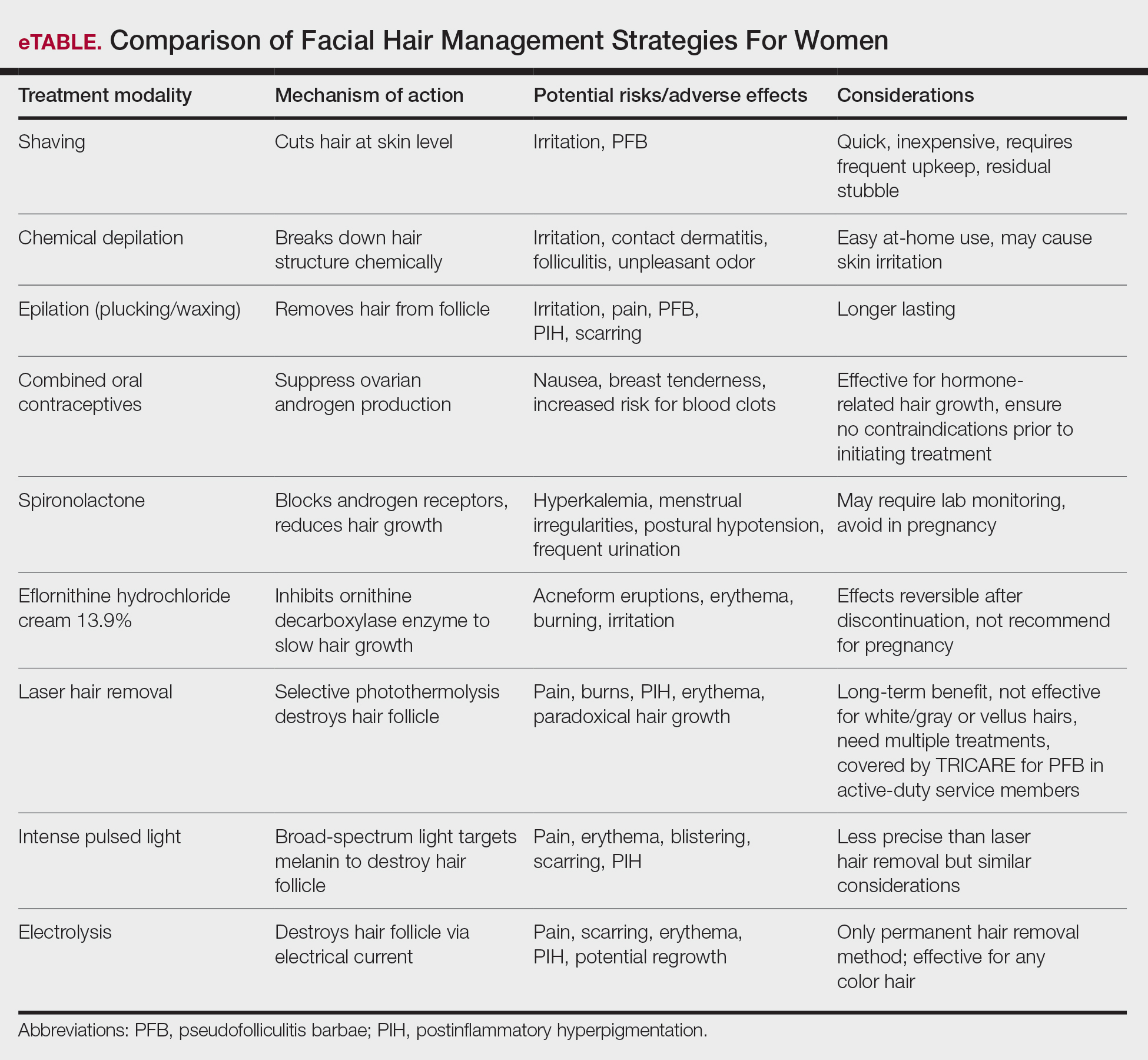

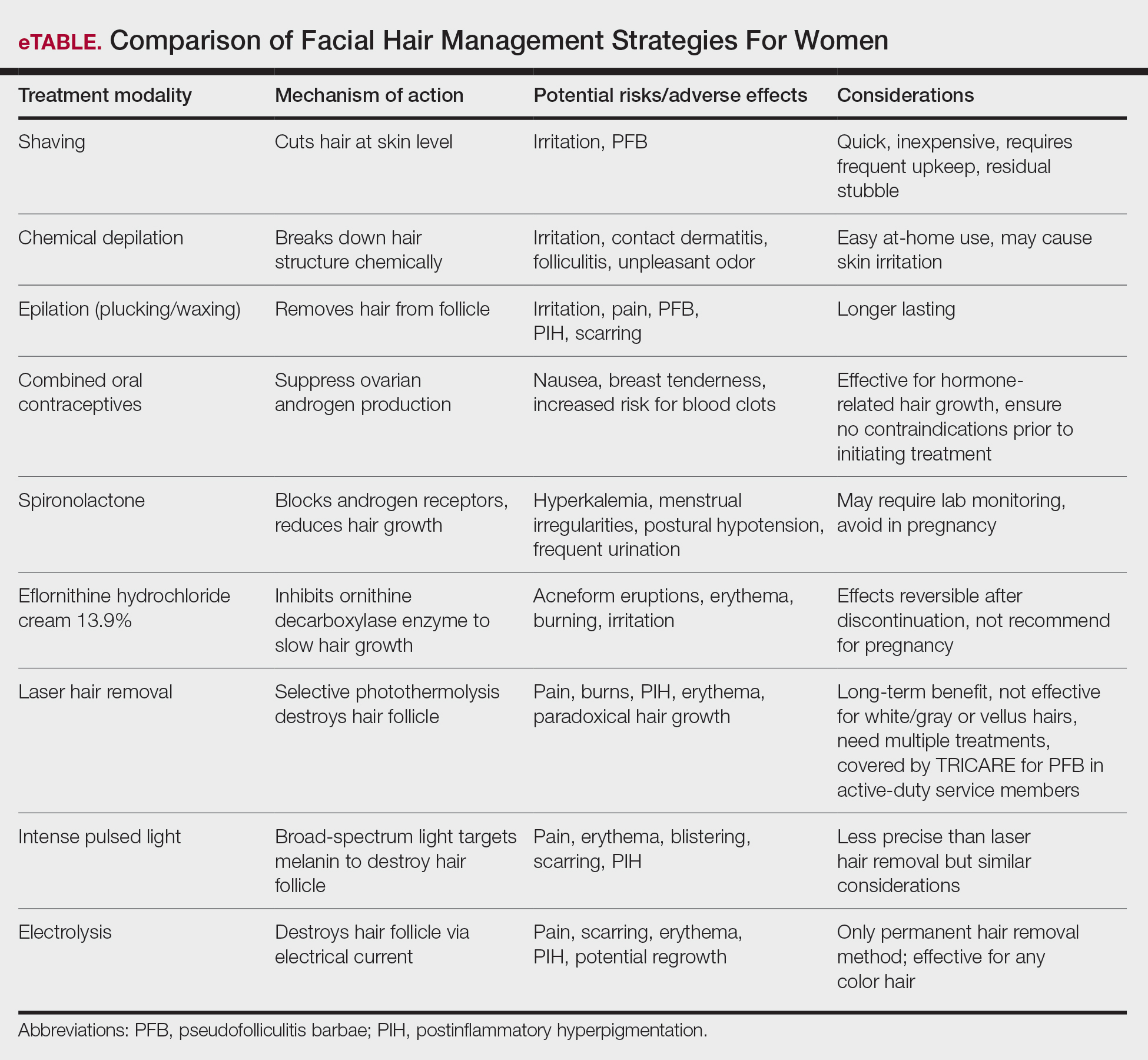

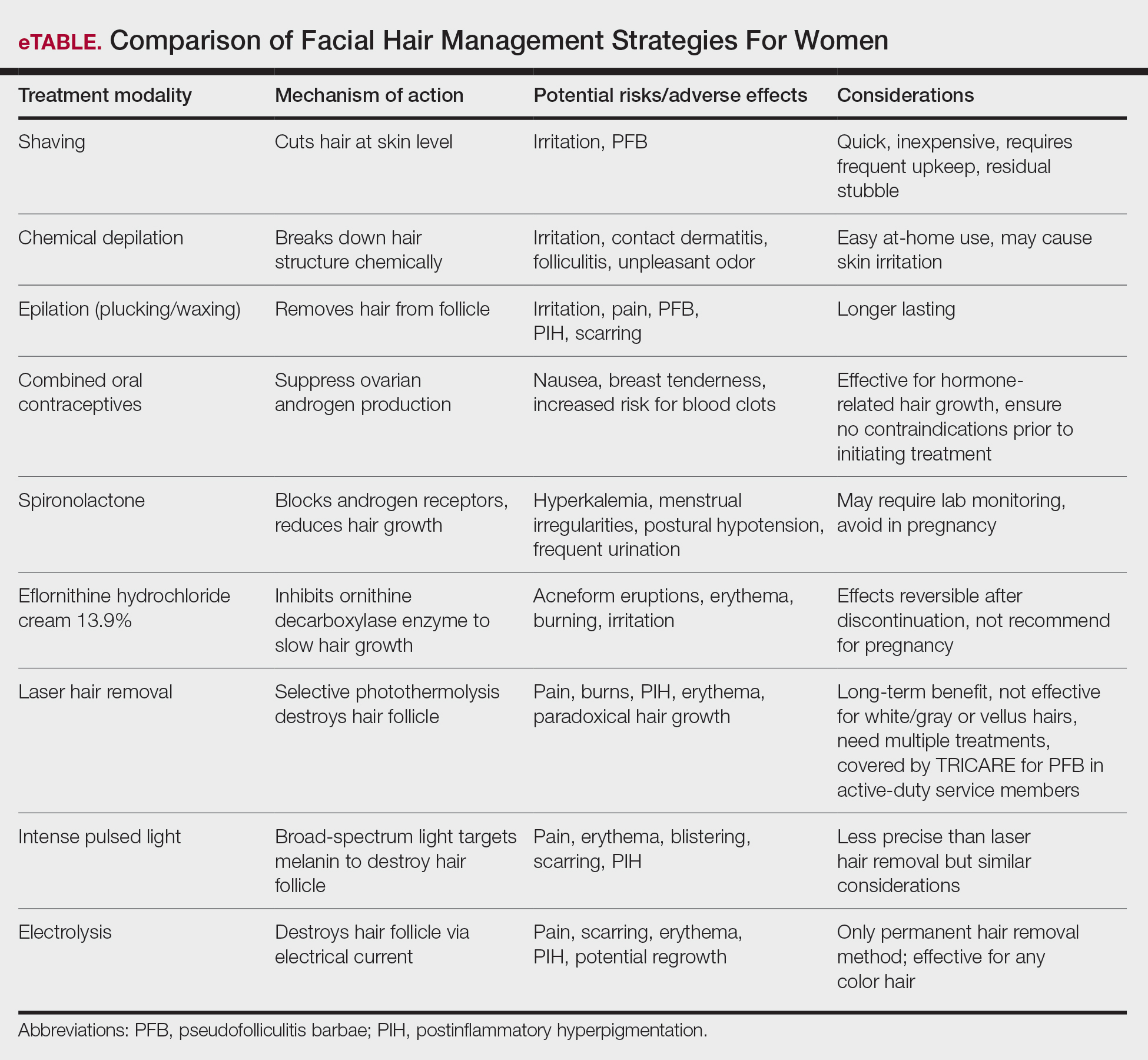

The available treatment modalities, including their mechanisms, potential risks, and considerations are summarized in the eTable.

Mechanical—Shaving remains one of the most widely utilized methods of hair removal in women due to its accessibility and ease of use. It does not disrupt the anagen phase of the hair growth cycle, making it a temporary method that requires frequent repetition (often daily), particularly for individuals with rapid hair growth. The belief that shaving causes hair to grow back thicker or faster is a common misconception. Shaving does not alter the thickness or growth rate of hair; instead, it leaves a blunt tip, making the hair feel coarser or appear thicker than uncut hair.3 Despite its relative convenience, shaving can lead to skin irritation due to mechanical trauma. Potential complications include PFB, superficial abrasions known more broadly as shaving irritation, and an increased risk for infections such as bacterial or fungal folliculitis.4

Chemical depilation, which uses thioglycolates mixed with alkali compounds, disrupts disulfide bonds in the hair, effectively breaking down the shaft without affecting the bulb. The depilatory requires application to the skin for approximately 3 to 15 minutes depending on the specific formulation and the thickness or texture of the hair. While it is a cost-effective option that easily can be done at home, the chemicals involved may trigger irritant contact dermatitis or folliculitis and produce an unpleasant odor from hydrogen disulfide gas.5 They also can lead to PFB.

Epilation removes the entire hair shaft and bulb, with results lasting approximately 6 weeks.6 Methods range from using tweezers to pluck single hairs and devices that simultaneously remove multiple hairs to hot or cold waxing, which use resin to grip and remove hair. Threading is a technique that uses twisted thread to remove the hair at the follicle level; this method may not alter hair growth unless performed during the anagen phase, during which repeated plucking can damage the matrix and potentially lead to permanent hair reduction.5 Common adverse effects include pain during removal, burns from waxing, folliculitis, PFB, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and scarring, particularly when multiple hairs are removed at once.

Pharmacologic—Pharmacologic therapy commonly is used to manage hirsutism and typically begins with a trial of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) containing estrogen and progestin, which are considered the first-line option unless contraindicated.7 If response to COC monotherapy is inadequate, an antiandrogen such as spironolactone may be added. Combination therapy with a COC and an antiandrogen generally is reserved for severe cases or patients who previously have shown suboptimal response to COCs alone.7 Patients should be counseled to discontinue antiandrogen therapy if they become pregnant due to the risk for fetal undervirilization observed in animal studies.8,9 Typical dosing of spironolactone, a competitive inhibitor of 5-α-reductase and androgen receptors, ranges from 100 mg to 200 mg daily.10 Reported adverse effects include polyuria, postural hypotension, menstrual irregularities, hyperkalemia, and potential liver dysfunction. Although spironolactone has demonstrated tumorigenic effects in animal studies, no such effects have been observed in humans.11

Eflornithine hydrochloride cream 13.9% is the first topical prescription medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for reduction of unwanted facial hair in women.12 It works by irreversibly blocking the activity of ornithine decarboxylase, an enzyme involved in the rate-limiting step of polyamine synthesis, which is essential for hair growth. In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial evaluating its effectiveness and safety, twice-daily application for 24 weeks resulted in a clinically meaningful reduction in hair length and density (measured as surface area) compared with the control group.13 When eflornithine hydrochloride cream 13.9% is discontinued, hair growth gradually returns to baseline. Studies have shown that hair regrowth typically begins within 8 weeks after treatment is stopped; within several months, hair returns to pretreatment levels.14 Adverse effects of eflornithine hydrochloride cream generally are mild and may include local irritation and acneform eruptions. In a randomized bilateral vehicle-controlled trial of 31 women, both eflornithine and vehicle creams were well tolerated, with 1 patient reporting mild tingling with eflornithine that resolved with continued use for 7 days.15

Procedural—Photoepilation therapies widely are considered by dermatologists to be among the most effective methods for reducing unwanted hair.16 Laser hair removal employs selective photothermolysis, a principle by which specific wavelengths of light target melanin in hair follicles. This method results in localized thermal damage, destroying hair follicles and reducing regrowth. Wavelengths between 600 and 1100 nm are most effective for hair removal; widely used devices include the ruby (694 nm), alexandrite (755 nm), diode (800-810 nm), and long-pulsed Nd:YAG lasers (1064 nm). Cooling mechanisms such as cryogen spray or contact cooling often are employed to minimize epidermal damage and lessen patient discomfort.

The hair matrix is most responsive to laser treatment during the anagen phase, necessitating multiple sessions to ensure all hairs are treated during this optimal growth stage. Generally, 4 to 6 sessions spaced at intervals of 4 to 6 weeks are required to achieve satisfactory results.17 Matching the laser wavelength to the absorption properties of melanin—the target chromophore—enables selective destruction of melanin-rich hair follicles while minimizing damage to surrounding skin.

The ideal laser wavelength primarily affects melanin concentrated in the hair bulb, leading to follicular destruction while reducing the risk for unintended depigmentation of the epidermis; however, competing structures in the skin (eg, epidermal pigment) also can absorb laser energy, diminishing treatment efficacy and increasing the risk for adverse effects. Shorter wavelengths are effective for lighter skin types, while longer wavelengths such as the Nd:YAG laser are safer for individuals with darker skin types as they bypass melanin in the epidermis.

It is important to note that laser hair removal is ineffective for white and gray hairs due to the lack of melanin. As a result, alternative methods such as electrolysis, which does not rely on pigment, may be more appropriate for permanent hair removal in individuals with nonpigmented hairs. Research indicates that combining topical eflornithine with alexandrite or Nd:YAG lasers improves outcomes for reducing unwanted facial hair.18

In military settings, laser hair removal is utilized for specific conditions such as PFB in male service members to assist with the reduction of hair and mitigation of symptoms.19 The majority of military dermatology clinics have devices for laser hair removal; however, dermatology services are not available at many military treatment facilities, and dermatologic care may be provided by the local civilian dermatologists. That said, laser therapy is covered in the civilian sector for active-duty service members with PFB of the face and neck under certain criteria. These include a documented safety risk in environments requiring respiratory protection, failure of conservative treatments, and evaluation by a military dermatologist who confirms the necessity of civilian-provided laser therapy when it is unavailable at a military facility.20 While such policies demonstrate the military’s recognition of laser therapy as a viable solution for certain grooming-related conditions, many are unaware that the existing laser hair removal policy also applies to women. Increasing awareness of this coverage could help female service members access treatment options that align with both medical and professional grooming needs.

Intense pulsed light (IPL) systems are nonlaser devices that emit broad-spectrum light in the 590- to 1200-nm range. They utilize a flash lamp to achieve thermal damage. Filters are used to narrow the wavelength range based on the specific target. Intense pulsed light devices are less precise than lasers but remain effective for hair reduction. In addition to hair removal, IPL devices are employed in the treatment of pigmented and vascular lesions. Common adverse effects of both laser and IPL hair removal include transient erythema, perifollicular edema, and pigmentary changes, especially in patients with darker skin types. Rare complications include blistering, scarring, and paradoxical hair stimulation in which untreated areas develop increased hair growth.

Electrolysis is recognized as the only method of truly permanent hair removal and is effective for all hair colors.21 However, the variability in technique among practitioners often leads to inconsistent results, with some patients experiencing hair regrowth. Galvanic electrolysis involves inserting a fine needle into the hair follicle and applying an electrical current to destroy the it and the rapidly dividing cells of the matrix.22 The introduction of thermolytic electrolysis, which uses a high-frequency alternating current (commonly 13.56 MHz or 27.12 MHz), has enhanced efficiency by creating heat at the needle tip to destroy the follicle. This approach is faster and now is commonly combined with galvanic electrolysis.23 While no controlled clinical trials directly compare these methods, many patients experience permanent hair removal, with approximately 15% to 25% regrowth within 6 months.22,24

Alternative Options—Home-use laser and light-based devices have become increasingly popular for managing unwanted hair due to their affordability and convenience, with most devices priced less than $1000.25 These devices utilize various technologies, including lasers (808 nm), IPL, or combinations of IPL and radiofrequency.26 Despite their accessibility, peer-reviewed research on their safety profile and effectiveness is limited, as existing data primarily come from industry-funded, uncontrolled studies with short follow-up durations—making it difficult to assess long-term outcomes.25

Psychosocial Impact

A 2023 study of active-duty female service members with PCOS highlighted the unique challenges they face while managing symptoms such as facial hair within the constraints of military service.27 Although the study focused on PCOS, the findings shed light on how facial hair specifically impacts the psychological well-being of servicewomen. Participants described facial hair as one of the most visible and stigmatizing symptoms, often leading to feelings of embarrassment and diminished confidence. Participants also highlighted the professional implications of facial hair, with some describing feelings of scrutiny and judgment from peers and leadership in public. These challenges can be more pronounced in deployments or field exercises where hygiene resources are limited. The lack of access not only affects self-perception but also can hinder the ability of servicewomen to meet implicit expectations for grooming and appearance.27 There is a notable gap in research examining the impact of facial hair on military servicewomen. Given the unique environmental challenges and professional expectations, further investigation is warranted to better understand how facial hair affects women and to optimize treatment approaches in this population.

Final Thoughts

Limited awareness and understanding of facial hair in woman contribute to stigma, often leaving affected individuals to navigate challenges in isolation. Given the impact on confidence, professional appearance, and adherence to military grooming standards, it is essential for health care practitioners to recognize and address facial hair in women. Importantly, laser hair removal is covered by TRICARE for active-duty female service members with PFB, yet many remain unaware of this benefit. Increased awareness of available mechanical, pharmacologic, and procedural treatment options allows for tailored management, ensuring that women receive appropriate medical care.

Wendelin DS, Pope DN, Mallory SB. Hypertrichosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:161-181. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.100

Blume-Peytavi U, Hahn S. Medical treatment of hirsutism. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:329-339. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00215.x

Kang CN, Shah M, Lynde C, et al. Hair removal practices: a literature review. Skin Therapy Lett. 2021;26:6-11.

Matheson E, Bain J. Hirsutism in women. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:168-175.

Shenenberger DW, Utecht LM. Removal of unwanted facial hair. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1907-1911.

Johnson E, Ebling FJ. The effect of plucking hairs during different phases of the follicular cycle. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1964;12:465-474.

Martin KA, Anderson RR, Chang RJ, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hirsutism in premenopausal women: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1233-1257. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00241

Barrionuevo P, Nabhan M, Altayar O, et al. Treatment options for hirsutism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1258-1264. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-02052

Alesi S, Forslund M, Melin J, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-androgens in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. EClinicalMedicine. Published online August 9, 2023. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102162

Escobar-Morreale HF, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of hirsutism: a consensus statement. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:146-170.

Hussein RS, Abdelbasset WK. Updates on hirsutism: a narrative review. Int J Biomedicine. 2022;12:193-198. doi:10.21103/Article12(2)_RA4

Shapiro J, Lui H. Vaniqa—eflornithine 13.9% cream. Skin Therapy Lett. 2001;6:1-5.

Wolf JE Jr, Shander D, Huber F, et al. Randomized, double-blind clinical evaluation of the efficacy and safety of topical eflornithine HCl 13.9% cream in the treatment of women with facial hair. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:94-98. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.03079.x

Balfour JA, McClellan K. Topical eflornithine. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:197-202. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102030-00009

Hamzavi I, Tan E, Shapiro J, et al. A randomized bilateral vehicle-controlled study of eflornithine cream combined with laser treatment versus laser treatment alone for facial hirsutism in women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:54-59. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.025

Goldberg DJ. Laser hair removal. In: Goldberg DJ, ed. Laser Dermatology: Pearls and Problems. Blackwell; 2008.

Hussain M, Polnikorn N, Goldberg DJ. Laser-assisted hair removal in Asian skin: efficacy, complications, and the effect of single versus multiple treatments. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:249-254. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29059.x

Smith SR, Piacquadio DJ, Beger B, et al. Eflornithine cream combined with laser therapy in the management of unwanted facial hair growth in women: a randomized trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1237-1243. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32282.x

Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302. doi:10.12788/cutis.0907

TRICARE Operations Manual 6010.59-M. Supplemental Health Care Program (SHCP)—Chapter 17. Contractor Responsibilities. Military Health System and Defense Health Agency website. Revised November 5, 2021. Accessed February 13, 2024. https://manuals.health.mil/pages/DisplayManualHtmlFile/2022-08-31/AsOf/TO15/C17S3.html

Yanes DA, Smith P, Avram MM. A review of best practices for gender-affirming laser hair removal. Dermatol Surg. 2024;50:S201-S204. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000004441

Wagner RF Jr, Tomich JM, Grande DJ. Electrolysis and thermolysis for permanent hair removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:441-449. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70062-x

Olsen EA. Methods of hair removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:143-157. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70181-7

Kligman AM, Peters L. Histologic changes of human hair follicles after electrolysis: a comparison of two methods. Cutis. 1984;34:169-176.

Hession MT, Markova A, Graber EM. A review of hand-held, home-use cosmetic laser and light devices. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:307-320. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000283

Wheeland RG. Permanent hair reduction with a home-use diode laser: safety and effectiveness 1 year after eight treatments. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:550-557. doi:10.1002/lsm.22051

Hopkins D, Walker SC, Wilson C, et al. The experience of living with polycystic ovary syndrome in the military. Mil Med. 2024;189:E188-E197. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad241

Facial hair growth in women is complex and multifaceted. It is not a disease but rather a part of normal anatomy or a symptom influenced by an underlying condition such as hypertrichosis, a hormonal imbalance (eg, hirsutism due to polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]), mechanical factors such as pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) from shaving, and perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormonal shifts. Additionally, normal facial hair patterns can vary substantially based on genetics, ethnicity, and cultural background. Some populations may naturally have more visible vellus or terminal hairs on the face, which are entirely physiologic rather than indicative of an underlying disorder. Despite this, societal expectations and beauty standards across many cultures dictate that facial hair in women is undesirable, often associating hair-free skin with femininity and attractiveness. This perception drives many women to seek treatment—not necessarily for medical reasons, but due to social pressure and aesthetic preferences.

Hypertrichosis, whether congenital or acquired, refers to excessive hair growth that is not androgen dependent and can appear on any site of the body. Causes include genetic predisposition, porphyria, thyroid disorders, internal malignancies, malnutrition, anorexia nervosa, or use of medications such as cyclosporine, prednisolone, and phenytoin.1 Hirsutism, by contrast, is characterized by the growth of terminal hairs in women at androgen-dependent sites such as the face, neck, and upper chest, where coarse hair typically grows in men.2 This condition often is associated with excess androgens produced by the ovaries or adrenal glands, most commonly due to PCOS although genetic factors may contribute.

Before initiating treatment, a thorough history and physical examination are essential to determine the underlying cause of conditions associated with facial hair growth in women. Clinicians should assess for signs of hyperandrogenism, menstrual irregularities, virilization, medication use, and family history. In cases of a suspected endocrine disorder, further laboratory evaluation may be warranted to guide appropriate management. While each cause of facial hair growth in women has unique management considerations, the shared impact on psychosocial well-being and adherence to grooming standards in the US military warrants an all-encompassing yet targeted approach. This comprehensive review discusses management options for women with facial hair in the military based on a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE conducted in November 2024 using combinations of the following search terms: hirsutism, facial hair, pseudofolliculitis barbae, women, female, military, grooming standards, hyperandrogenism, and hair removal.

Treatment Modalities