User login

Older diabetes drugs linked to dementia risk -- one lower, one higher

a new observational study in patients with type 2 diabetes suggests.

The data, obtained from nationwide electronic medical records from the Department of Veterans Affairs, yielded a 22% lower risk of dementia with TZD monotherapy and a 12% elevated risk with sulfonylurea monotherapy, compared with metformin monotherapy. The apparent protective effects of TZDs were greater among individuals with overweight or obesity.

“Our findings provide additional information to aid clinicians’ selection of [glucose-lowering medications] for patients with mild or moderate type 2 diabetes and [who] are at high risk of dementia,” Xin Tang and colleagues wrote in their article, published online in BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care.

The results “add substantially to the literature concerning the effects of [glucose-lowering medications] on dementia where previous findings have been inconsistent. Studies with a follow-up time of less than 3 years have mainly reported null associations, while studies with longer a follow-up time typically yielded protective findings. With a mean follow-up time of 6.8 years, we had a sufficient duration to detect treatment differences,” the investigators wrote.

“Supplementing [a] sulfonylurea with either metformin or [a] TZD may partially offset its prodementia effects. These findings may help inform medication selection for elderly patients with T2D at high risk of dementia,” they added.

Randomized trials needed to determine cause and effect

Ivan Koychev, PhD, a senior clinical researcher in the department of psychiatry at the University of Oxford (England), told the UK Science Media Centre: “This is a large, well-conducted real-world data study that highlights the importance of checking whether already prescribed medications may be useful for preventing dementia.”

The findings regarding TZDs, also known as glitazones, are in line with existing literature suggesting dementia protection with other drugs prescribed for type 2 diabetes that weren’t examined in the current study, such as newer agents like glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, Dr. Koychev said.

“The main limitations of this study is that following the initial 2-year period the authors were interested in, the participants may have been prescribed one of the other type 2 diabetes drugs [GLP-1 agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors] that have been found to reduce dementia risk, thus potentially making the direct glitazone [TZD] effect more difficult to discern,” Dr. Koychev noted.

And, he pointed out that the study design limits attribution of causality. “It is also important to note that people with type 2 diabetes do run a higher risk of both dementia and cognitive deficits and that these medications are only prescribed in these patients, so all this data is from this patient group rather than the general population.”

James Connell, PhD, head of translational science at Alzheimer’s Research UK, agreed. “While this observational study found that those with type 2 diabetes taking thiazolidinedione had a lower dementia risk than those on the most common medication for type 2 diabetes, it only shows an association between taking the drug and dementia risk and not a causal relationship.

“Double-blind and placebo-controlled clinical trials are needed to see whether the drug [TDZ] could help lower dementia risk in people with and without diabetes. Anyone with any questions about what treatments they are receiving should speak to their doctor,” he told the UK Science Media Centre.

Opposite effects of sulfonylureas, TZDs versus metformin

The study authors analyzed 559,106 VA patients with type 2 diabetes who initiated glucose-lowering medication during 2001-2017 and took it for at least a year. They were aged 60 years or older and did not have dementia at baseline. Most were White (76.8%) and male (96.9%), two-thirds (63.1%) had obesity, and mean hemoglobin A1c was 6.8%.

Overall, 31,125 developed all-cause dementia. The incidence rate was 8.2 cases per 1,000 person-years, ranging from 6.2 cases per 1,000 person-years among those taking metformin monotherapy to 13.4 cases per 1,000 person-years in those taking both sulfonylurea and a TZD.

Compared with metformin monotherapy, the hazard ratio for all-cause dementia for sulfonylurea monotherapy was a significant 1.12. The increased risk was also seen for vascular dementia, with an HR of 1.14.

In contrast, TZD monotherapy was associated with a significantly lower risk for all-cause dementia (HR, 0.78), as well as for Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 0.89) and vascular dementia (HR, 0.43), compared with metformin monotherapy.

The combination of metformin and TZD also lowered the risk of all-cause dementia, while regimens including sulfonylureas raised the risks for all-cause and vascular dementia.

Most of the results didn’t change significantly when the drug exposure window was extended to 2 years.

Effects more pronounced in those with obesity

The protective 1-year effects of TZD monotherapy and of metformin plus TZD, compared with metformin alone, were more significant among participants aged 75 or younger and with a body mass index above 25 kg/m2, compared with those who were older than 75 years and with normal BMIs, respectively.

On the other hand, the greater risk for dementia incurred with sulfonylureas was further increased among those with higher BMI.

This research was partially funded by grants from the National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Koychev is chief investigator for a trial, sponsored by Oxford University and funded by Novo Nordisk, testing whether the GLP-1 agonist semaglutide reduces the risk for dementia in aging adults.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a new observational study in patients with type 2 diabetes suggests.

The data, obtained from nationwide electronic medical records from the Department of Veterans Affairs, yielded a 22% lower risk of dementia with TZD monotherapy and a 12% elevated risk with sulfonylurea monotherapy, compared with metformin monotherapy. The apparent protective effects of TZDs were greater among individuals with overweight or obesity.

“Our findings provide additional information to aid clinicians’ selection of [glucose-lowering medications] for patients with mild or moderate type 2 diabetes and [who] are at high risk of dementia,” Xin Tang and colleagues wrote in their article, published online in BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care.

The results “add substantially to the literature concerning the effects of [glucose-lowering medications] on dementia where previous findings have been inconsistent. Studies with a follow-up time of less than 3 years have mainly reported null associations, while studies with longer a follow-up time typically yielded protective findings. With a mean follow-up time of 6.8 years, we had a sufficient duration to detect treatment differences,” the investigators wrote.

“Supplementing [a] sulfonylurea with either metformin or [a] TZD may partially offset its prodementia effects. These findings may help inform medication selection for elderly patients with T2D at high risk of dementia,” they added.

Randomized trials needed to determine cause and effect

Ivan Koychev, PhD, a senior clinical researcher in the department of psychiatry at the University of Oxford (England), told the UK Science Media Centre: “This is a large, well-conducted real-world data study that highlights the importance of checking whether already prescribed medications may be useful for preventing dementia.”

The findings regarding TZDs, also known as glitazones, are in line with existing literature suggesting dementia protection with other drugs prescribed for type 2 diabetes that weren’t examined in the current study, such as newer agents like glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, Dr. Koychev said.

“The main limitations of this study is that following the initial 2-year period the authors were interested in, the participants may have been prescribed one of the other type 2 diabetes drugs [GLP-1 agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors] that have been found to reduce dementia risk, thus potentially making the direct glitazone [TZD] effect more difficult to discern,” Dr. Koychev noted.

And, he pointed out that the study design limits attribution of causality. “It is also important to note that people with type 2 diabetes do run a higher risk of both dementia and cognitive deficits and that these medications are only prescribed in these patients, so all this data is from this patient group rather than the general population.”

James Connell, PhD, head of translational science at Alzheimer’s Research UK, agreed. “While this observational study found that those with type 2 diabetes taking thiazolidinedione had a lower dementia risk than those on the most common medication for type 2 diabetes, it only shows an association between taking the drug and dementia risk and not a causal relationship.

“Double-blind and placebo-controlled clinical trials are needed to see whether the drug [TDZ] could help lower dementia risk in people with and without diabetes. Anyone with any questions about what treatments they are receiving should speak to their doctor,” he told the UK Science Media Centre.

Opposite effects of sulfonylureas, TZDs versus metformin

The study authors analyzed 559,106 VA patients with type 2 diabetes who initiated glucose-lowering medication during 2001-2017 and took it for at least a year. They were aged 60 years or older and did not have dementia at baseline. Most were White (76.8%) and male (96.9%), two-thirds (63.1%) had obesity, and mean hemoglobin A1c was 6.8%.

Overall, 31,125 developed all-cause dementia. The incidence rate was 8.2 cases per 1,000 person-years, ranging from 6.2 cases per 1,000 person-years among those taking metformin monotherapy to 13.4 cases per 1,000 person-years in those taking both sulfonylurea and a TZD.

Compared with metformin monotherapy, the hazard ratio for all-cause dementia for sulfonylurea monotherapy was a significant 1.12. The increased risk was also seen for vascular dementia, with an HR of 1.14.

In contrast, TZD monotherapy was associated with a significantly lower risk for all-cause dementia (HR, 0.78), as well as for Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 0.89) and vascular dementia (HR, 0.43), compared with metformin monotherapy.

The combination of metformin and TZD also lowered the risk of all-cause dementia, while regimens including sulfonylureas raised the risks for all-cause and vascular dementia.

Most of the results didn’t change significantly when the drug exposure window was extended to 2 years.

Effects more pronounced in those with obesity

The protective 1-year effects of TZD monotherapy and of metformin plus TZD, compared with metformin alone, were more significant among participants aged 75 or younger and with a body mass index above 25 kg/m2, compared with those who were older than 75 years and with normal BMIs, respectively.

On the other hand, the greater risk for dementia incurred with sulfonylureas was further increased among those with higher BMI.

This research was partially funded by grants from the National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Koychev is chief investigator for a trial, sponsored by Oxford University and funded by Novo Nordisk, testing whether the GLP-1 agonist semaglutide reduces the risk for dementia in aging adults.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a new observational study in patients with type 2 diabetes suggests.

The data, obtained from nationwide electronic medical records from the Department of Veterans Affairs, yielded a 22% lower risk of dementia with TZD monotherapy and a 12% elevated risk with sulfonylurea monotherapy, compared with metformin monotherapy. The apparent protective effects of TZDs were greater among individuals with overweight or obesity.

“Our findings provide additional information to aid clinicians’ selection of [glucose-lowering medications] for patients with mild or moderate type 2 diabetes and [who] are at high risk of dementia,” Xin Tang and colleagues wrote in their article, published online in BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care.

The results “add substantially to the literature concerning the effects of [glucose-lowering medications] on dementia where previous findings have been inconsistent. Studies with a follow-up time of less than 3 years have mainly reported null associations, while studies with longer a follow-up time typically yielded protective findings. With a mean follow-up time of 6.8 years, we had a sufficient duration to detect treatment differences,” the investigators wrote.

“Supplementing [a] sulfonylurea with either metformin or [a] TZD may partially offset its prodementia effects. These findings may help inform medication selection for elderly patients with T2D at high risk of dementia,” they added.

Randomized trials needed to determine cause and effect

Ivan Koychev, PhD, a senior clinical researcher in the department of psychiatry at the University of Oxford (England), told the UK Science Media Centre: “This is a large, well-conducted real-world data study that highlights the importance of checking whether already prescribed medications may be useful for preventing dementia.”

The findings regarding TZDs, also known as glitazones, are in line with existing literature suggesting dementia protection with other drugs prescribed for type 2 diabetes that weren’t examined in the current study, such as newer agents like glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, Dr. Koychev said.

“The main limitations of this study is that following the initial 2-year period the authors were interested in, the participants may have been prescribed one of the other type 2 diabetes drugs [GLP-1 agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors] that have been found to reduce dementia risk, thus potentially making the direct glitazone [TZD] effect more difficult to discern,” Dr. Koychev noted.

And, he pointed out that the study design limits attribution of causality. “It is also important to note that people with type 2 diabetes do run a higher risk of both dementia and cognitive deficits and that these medications are only prescribed in these patients, so all this data is from this patient group rather than the general population.”

James Connell, PhD, head of translational science at Alzheimer’s Research UK, agreed. “While this observational study found that those with type 2 diabetes taking thiazolidinedione had a lower dementia risk than those on the most common medication for type 2 diabetes, it only shows an association between taking the drug and dementia risk and not a causal relationship.

“Double-blind and placebo-controlled clinical trials are needed to see whether the drug [TDZ] could help lower dementia risk in people with and without diabetes. Anyone with any questions about what treatments they are receiving should speak to their doctor,” he told the UK Science Media Centre.

Opposite effects of sulfonylureas, TZDs versus metformin

The study authors analyzed 559,106 VA patients with type 2 diabetes who initiated glucose-lowering medication during 2001-2017 and took it for at least a year. They were aged 60 years or older and did not have dementia at baseline. Most were White (76.8%) and male (96.9%), two-thirds (63.1%) had obesity, and mean hemoglobin A1c was 6.8%.

Overall, 31,125 developed all-cause dementia. The incidence rate was 8.2 cases per 1,000 person-years, ranging from 6.2 cases per 1,000 person-years among those taking metformin monotherapy to 13.4 cases per 1,000 person-years in those taking both sulfonylurea and a TZD.

Compared with metformin monotherapy, the hazard ratio for all-cause dementia for sulfonylurea monotherapy was a significant 1.12. The increased risk was also seen for vascular dementia, with an HR of 1.14.

In contrast, TZD monotherapy was associated with a significantly lower risk for all-cause dementia (HR, 0.78), as well as for Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 0.89) and vascular dementia (HR, 0.43), compared with metformin monotherapy.

The combination of metformin and TZD also lowered the risk of all-cause dementia, while regimens including sulfonylureas raised the risks for all-cause and vascular dementia.

Most of the results didn’t change significantly when the drug exposure window was extended to 2 years.

Effects more pronounced in those with obesity

The protective 1-year effects of TZD monotherapy and of metformin plus TZD, compared with metformin alone, were more significant among participants aged 75 or younger and with a body mass index above 25 kg/m2, compared with those who were older than 75 years and with normal BMIs, respectively.

On the other hand, the greater risk for dementia incurred with sulfonylureas was further increased among those with higher BMI.

This research was partially funded by grants from the National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Koychev is chief investigator for a trial, sponsored by Oxford University and funded by Novo Nordisk, testing whether the GLP-1 agonist semaglutide reduces the risk for dementia in aging adults.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ OPEN DIABETES RESEARCH & CARE

Psychedelics and the Military: What a Long, Strange Trip It’s Been

In 2019 the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency invested $27 million in the Focused Pharma program to develop new, more efficacious, rapid-acting drugs, including hallucinogens.1 While Focused Pharma does not include human studies, the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) newly launched psychedelics program research does include clinical trials.2 When I read of these ambitious projects, I recalled 2 prescient memories from my youth.

The first memory was of a dinner table conversation between my father, then chief of pediatrics at a military hospital, and one of my older brothers, a burgeoning hippie. My father mentioned that the military was doing research on lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and my brother asked whether he could bring some home for my brother to try. My father looked up from the dinner table with incredulity and in an ironic monotone replied, “No you would not qualify for the research, you are not in the Army.”

The second was about 10 years later, when I visited the state psychiatric hospital where my father directed the adolescent ward. I saw a group of young adults watching test patterns on an old-fashioned television set. When I asked my father what was wrong with them, he shook his head and said, “Too much LSD.”

Albert Hoffman was a Sandoz chemist when in 1938 he serendipitously developed LSD while working on a fungus that grew on grain. LSD’s psychoactive properties were not discovered until 1943. About a decade later, as the Cold War chilled international relations, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) began conducting experiments on military personnel in the MKUltra program using LSD, electroshock, hypnosis, and other techniques to develop a mind control program before its rivals did.3

Beginning in the 1950s, the US government collaborated with pharmaceutical companies and research universities to develop LSD as part of a campaign of psychological warfare. Though planned to be used against enemies, the program instead exploited US service members to develop hallucinogens as a form of chemical warfare that could render enemy troops mentally incapacitated. That psychiatrists, who then (as now) led much of this research, raised a host of ethical concerns about dual roles, disclosure, and duty.4

Government investigations and academic studies have shown that even soldiers who volunteered for the research were not given adequate information about the nature of the experiments and the potential adverse effects, such as persisting flashbacks. The military’s research on LSD ended in 1963, not because of the unethical aspects of the research, but because the effects of LSD were so unpredictable that the drug could not be effectively weaponized. Like Tuskegee and other research abuses of the time, when the MKUltra program was exposed, there were congressional investigations.5 Later studies found that many of the active-duty research subjects experienced a plethora of lasting and serious psychiatric symptoms. VHA practitioners had to put back together many of these broken service members. This program was rife with violations of research ethics and human rights, and those abuses tainted the field of hallucinogenic research in US Department of Defense (DoD) and VHA circles for decades.5 These research abuses, in part, have led to hallucinogens being categorized as Schedule I controlled substances, effectively blocking federal funding for research until recently.

LSD, Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine), and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA), popularly known as psychedelics, are again receiving attention. However, the current investigations into psychedelics are vastly different—scientifically and ethically. The most important difference is that the context and leadership of these studies is not national security—it is health care.

The goal of this new wave of psychedelic research is not mind control or brain alteration, but liberation of the mind from cycles of rumination and trauma and empowerment to change patterns of self-destruction to affirmation of life. The impetus for this research is not international espionage but to find better treatments for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder, severe substance use disorders, and treatment-resistant depression that contribute to unquantifiable mental pain, psychosocial dysfunction, and an epidemic of suicide among military service members and veterans.6 Though we have some effective treatments for these often combat-inflicted maladies—primarily evidence-based psychotherapies—yet these treatments are not tolerable or safe, fast-acting, or long-lasting enough to succor each and every troubled soul. The success of ketamine, a dissociative drug, in relieving the most distressing service-connected psychiatric diagnoses has provided a proof of concept to reinvigorate the moribund hallucinogenic research idea.7

This dark chapter in US military research is a cautionary tale. The often quoted and more often ignored advice of the Spanish American philosopher George Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” should serve as the guiding principle of the new hallucinogenic research.8 Human subjects’ protections have exponentially improved since the days of the secret LSD project even for active-duty personnel. The Common Rule governs that all research participants are given adequate information that includes whatever is known about the risks and benefits of the research.10 Participants must provide full and free informed consent to enroll in these clinical trials, a consent that encompasses the right to withdraw from the research at any time without jeopardizing their careers, benefits, or ongoing health care.10

These rules, though, can be bent, broken, avoided, or worked around. Only the moral integrity of study personnel, administrators, oversight agencies, research compliance officers, and most important, principal investigators can assure that the rules are upheld and the rights they guarantee are respected.9 It would be a tragic shame if the promised hope for the relief of psychic pain went unrealized due to media hype, shared desperation of clinicians and patients, and conflicts of interests that today are more likely to come from profit-driven pharmaceutical companies than national security agencies. And for all of us in federal practice, remembering the sordid past forays with LSD can redeem the present research so future service members and veterans and the clinicians who care for them have better balms to heal the wounds of war.

1. US Department of Defense, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Structure-guided drug design could yield fast-acting remedies for complex neuropsychiatric conditions. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2019-09-11#

2. Londono E. After six-decade hiatus, experimental psychedelic therapy returns to the VA. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/24/us/politics/psychedelic-therapy-veterans.html

3. Disbennett B. ‘This is the happy warrior, this is he:’ an analysis of CIA and military testing of LSD on non-consenting U.S. service-members and recovery through the VA disability system. Tennessee J Race, Gender, Social Justice. 2015;3(2):1-32. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2416478

4. Smith H. James Ketchum, who conducted mind-altering experiments on soldiers dies at 87. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/james-ketchum-who-conducted-mind-altering-experiments-on-soldiers-dies-at-87/2019/06/04/7b5ad322-86cc-11e9-a491-25df61c78dc4_story.html

5. Ross CA. LSD experiments by the United States Army. Hist Psychiatry. 2017;28(4):427-442. doi:10.1177/0957154X17717678

6. Albott CS, Lim KO, Forbes MK, et al. Efficacy, safety, and durability of repeated ketamine infusions of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and treatment resistant depression. Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3): 17m11634. doi:10.4088/JCP.17m11634

7. Shawler IC, Jordan CH, Jackson CA. Veteran and military mental health issues. Stat Pearls. Updated May 23, 2022. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572092/#_NBK572092_pubdet_

8. Santayana G. The Life of Reason. 1905. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15000/15000-h/15000-h.htm

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1200.05(2). Requirements for the protection of human subjects in research. Amended January 8, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=8171

10. US Department of Defense, Military Health System. Research protections. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.health.mil/About-MHS/OASDHA/Defense-Health-Agency/Research-and-Engineering/Research-Protections

In 2019 the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency invested $27 million in the Focused Pharma program to develop new, more efficacious, rapid-acting drugs, including hallucinogens.1 While Focused Pharma does not include human studies, the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) newly launched psychedelics program research does include clinical trials.2 When I read of these ambitious projects, I recalled 2 prescient memories from my youth.

The first memory was of a dinner table conversation between my father, then chief of pediatrics at a military hospital, and one of my older brothers, a burgeoning hippie. My father mentioned that the military was doing research on lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and my brother asked whether he could bring some home for my brother to try. My father looked up from the dinner table with incredulity and in an ironic monotone replied, “No you would not qualify for the research, you are not in the Army.”

The second was about 10 years later, when I visited the state psychiatric hospital where my father directed the adolescent ward. I saw a group of young adults watching test patterns on an old-fashioned television set. When I asked my father what was wrong with them, he shook his head and said, “Too much LSD.”

Albert Hoffman was a Sandoz chemist when in 1938 he serendipitously developed LSD while working on a fungus that grew on grain. LSD’s psychoactive properties were not discovered until 1943. About a decade later, as the Cold War chilled international relations, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) began conducting experiments on military personnel in the MKUltra program using LSD, electroshock, hypnosis, and other techniques to develop a mind control program before its rivals did.3

Beginning in the 1950s, the US government collaborated with pharmaceutical companies and research universities to develop LSD as part of a campaign of psychological warfare. Though planned to be used against enemies, the program instead exploited US service members to develop hallucinogens as a form of chemical warfare that could render enemy troops mentally incapacitated. That psychiatrists, who then (as now) led much of this research, raised a host of ethical concerns about dual roles, disclosure, and duty.4

Government investigations and academic studies have shown that even soldiers who volunteered for the research were not given adequate information about the nature of the experiments and the potential adverse effects, such as persisting flashbacks. The military’s research on LSD ended in 1963, not because of the unethical aspects of the research, but because the effects of LSD were so unpredictable that the drug could not be effectively weaponized. Like Tuskegee and other research abuses of the time, when the MKUltra program was exposed, there were congressional investigations.5 Later studies found that many of the active-duty research subjects experienced a plethora of lasting and serious psychiatric symptoms. VHA practitioners had to put back together many of these broken service members. This program was rife with violations of research ethics and human rights, and those abuses tainted the field of hallucinogenic research in US Department of Defense (DoD) and VHA circles for decades.5 These research abuses, in part, have led to hallucinogens being categorized as Schedule I controlled substances, effectively blocking federal funding for research until recently.

LSD, Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine), and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA), popularly known as psychedelics, are again receiving attention. However, the current investigations into psychedelics are vastly different—scientifically and ethically. The most important difference is that the context and leadership of these studies is not national security—it is health care.

The goal of this new wave of psychedelic research is not mind control or brain alteration, but liberation of the mind from cycles of rumination and trauma and empowerment to change patterns of self-destruction to affirmation of life. The impetus for this research is not international espionage but to find better treatments for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder, severe substance use disorders, and treatment-resistant depression that contribute to unquantifiable mental pain, psychosocial dysfunction, and an epidemic of suicide among military service members and veterans.6 Though we have some effective treatments for these often combat-inflicted maladies—primarily evidence-based psychotherapies—yet these treatments are not tolerable or safe, fast-acting, or long-lasting enough to succor each and every troubled soul. The success of ketamine, a dissociative drug, in relieving the most distressing service-connected psychiatric diagnoses has provided a proof of concept to reinvigorate the moribund hallucinogenic research idea.7

This dark chapter in US military research is a cautionary tale. The often quoted and more often ignored advice of the Spanish American philosopher George Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” should serve as the guiding principle of the new hallucinogenic research.8 Human subjects’ protections have exponentially improved since the days of the secret LSD project even for active-duty personnel. The Common Rule governs that all research participants are given adequate information that includes whatever is known about the risks and benefits of the research.10 Participants must provide full and free informed consent to enroll in these clinical trials, a consent that encompasses the right to withdraw from the research at any time without jeopardizing their careers, benefits, or ongoing health care.10

These rules, though, can be bent, broken, avoided, or worked around. Only the moral integrity of study personnel, administrators, oversight agencies, research compliance officers, and most important, principal investigators can assure that the rules are upheld and the rights they guarantee are respected.9 It would be a tragic shame if the promised hope for the relief of psychic pain went unrealized due to media hype, shared desperation of clinicians and patients, and conflicts of interests that today are more likely to come from profit-driven pharmaceutical companies than national security agencies. And for all of us in federal practice, remembering the sordid past forays with LSD can redeem the present research so future service members and veterans and the clinicians who care for them have better balms to heal the wounds of war.

In 2019 the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency invested $27 million in the Focused Pharma program to develop new, more efficacious, rapid-acting drugs, including hallucinogens.1 While Focused Pharma does not include human studies, the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) newly launched psychedelics program research does include clinical trials.2 When I read of these ambitious projects, I recalled 2 prescient memories from my youth.

The first memory was of a dinner table conversation between my father, then chief of pediatrics at a military hospital, and one of my older brothers, a burgeoning hippie. My father mentioned that the military was doing research on lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and my brother asked whether he could bring some home for my brother to try. My father looked up from the dinner table with incredulity and in an ironic monotone replied, “No you would not qualify for the research, you are not in the Army.”

The second was about 10 years later, when I visited the state psychiatric hospital where my father directed the adolescent ward. I saw a group of young adults watching test patterns on an old-fashioned television set. When I asked my father what was wrong with them, he shook his head and said, “Too much LSD.”

Albert Hoffman was a Sandoz chemist when in 1938 he serendipitously developed LSD while working on a fungus that grew on grain. LSD’s psychoactive properties were not discovered until 1943. About a decade later, as the Cold War chilled international relations, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) began conducting experiments on military personnel in the MKUltra program using LSD, electroshock, hypnosis, and other techniques to develop a mind control program before its rivals did.3

Beginning in the 1950s, the US government collaborated with pharmaceutical companies and research universities to develop LSD as part of a campaign of psychological warfare. Though planned to be used against enemies, the program instead exploited US service members to develop hallucinogens as a form of chemical warfare that could render enemy troops mentally incapacitated. That psychiatrists, who then (as now) led much of this research, raised a host of ethical concerns about dual roles, disclosure, and duty.4

Government investigations and academic studies have shown that even soldiers who volunteered for the research were not given adequate information about the nature of the experiments and the potential adverse effects, such as persisting flashbacks. The military’s research on LSD ended in 1963, not because of the unethical aspects of the research, but because the effects of LSD were so unpredictable that the drug could not be effectively weaponized. Like Tuskegee and other research abuses of the time, when the MKUltra program was exposed, there were congressional investigations.5 Later studies found that many of the active-duty research subjects experienced a plethora of lasting and serious psychiatric symptoms. VHA practitioners had to put back together many of these broken service members. This program was rife with violations of research ethics and human rights, and those abuses tainted the field of hallucinogenic research in US Department of Defense (DoD) and VHA circles for decades.5 These research abuses, in part, have led to hallucinogens being categorized as Schedule I controlled substances, effectively blocking federal funding for research until recently.

LSD, Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine), and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA), popularly known as psychedelics, are again receiving attention. However, the current investigations into psychedelics are vastly different—scientifically and ethically. The most important difference is that the context and leadership of these studies is not national security—it is health care.

The goal of this new wave of psychedelic research is not mind control or brain alteration, but liberation of the mind from cycles of rumination and trauma and empowerment to change patterns of self-destruction to affirmation of life. The impetus for this research is not international espionage but to find better treatments for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder, severe substance use disorders, and treatment-resistant depression that contribute to unquantifiable mental pain, psychosocial dysfunction, and an epidemic of suicide among military service members and veterans.6 Though we have some effective treatments for these often combat-inflicted maladies—primarily evidence-based psychotherapies—yet these treatments are not tolerable or safe, fast-acting, or long-lasting enough to succor each and every troubled soul. The success of ketamine, a dissociative drug, in relieving the most distressing service-connected psychiatric diagnoses has provided a proof of concept to reinvigorate the moribund hallucinogenic research idea.7

This dark chapter in US military research is a cautionary tale. The often quoted and more often ignored advice of the Spanish American philosopher George Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” should serve as the guiding principle of the new hallucinogenic research.8 Human subjects’ protections have exponentially improved since the days of the secret LSD project even for active-duty personnel. The Common Rule governs that all research participants are given adequate information that includes whatever is known about the risks and benefits of the research.10 Participants must provide full and free informed consent to enroll in these clinical trials, a consent that encompasses the right to withdraw from the research at any time without jeopardizing their careers, benefits, or ongoing health care.10

These rules, though, can be bent, broken, avoided, or worked around. Only the moral integrity of study personnel, administrators, oversight agencies, research compliance officers, and most important, principal investigators can assure that the rules are upheld and the rights they guarantee are respected.9 It would be a tragic shame if the promised hope for the relief of psychic pain went unrealized due to media hype, shared desperation of clinicians and patients, and conflicts of interests that today are more likely to come from profit-driven pharmaceutical companies than national security agencies. And for all of us in federal practice, remembering the sordid past forays with LSD can redeem the present research so future service members and veterans and the clinicians who care for them have better balms to heal the wounds of war.

1. US Department of Defense, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Structure-guided drug design could yield fast-acting remedies for complex neuropsychiatric conditions. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2019-09-11#

2. Londono E. After six-decade hiatus, experimental psychedelic therapy returns to the VA. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/24/us/politics/psychedelic-therapy-veterans.html

3. Disbennett B. ‘This is the happy warrior, this is he:’ an analysis of CIA and military testing of LSD on non-consenting U.S. service-members and recovery through the VA disability system. Tennessee J Race, Gender, Social Justice. 2015;3(2):1-32. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2416478

4. Smith H. James Ketchum, who conducted mind-altering experiments on soldiers dies at 87. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/james-ketchum-who-conducted-mind-altering-experiments-on-soldiers-dies-at-87/2019/06/04/7b5ad322-86cc-11e9-a491-25df61c78dc4_story.html

5. Ross CA. LSD experiments by the United States Army. Hist Psychiatry. 2017;28(4):427-442. doi:10.1177/0957154X17717678

6. Albott CS, Lim KO, Forbes MK, et al. Efficacy, safety, and durability of repeated ketamine infusions of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and treatment resistant depression. Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3): 17m11634. doi:10.4088/JCP.17m11634

7. Shawler IC, Jordan CH, Jackson CA. Veteran and military mental health issues. Stat Pearls. Updated May 23, 2022. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572092/#_NBK572092_pubdet_

8. Santayana G. The Life of Reason. 1905. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15000/15000-h/15000-h.htm

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1200.05(2). Requirements for the protection of human subjects in research. Amended January 8, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=8171

10. US Department of Defense, Military Health System. Research protections. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.health.mil/About-MHS/OASDHA/Defense-Health-Agency/Research-and-Engineering/Research-Protections

1. US Department of Defense, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Structure-guided drug design could yield fast-acting remedies for complex neuropsychiatric conditions. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2019-09-11#

2. Londono E. After six-decade hiatus, experimental psychedelic therapy returns to the VA. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/24/us/politics/psychedelic-therapy-veterans.html

3. Disbennett B. ‘This is the happy warrior, this is he:’ an analysis of CIA and military testing of LSD on non-consenting U.S. service-members and recovery through the VA disability system. Tennessee J Race, Gender, Social Justice. 2015;3(2):1-32. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2416478

4. Smith H. James Ketchum, who conducted mind-altering experiments on soldiers dies at 87. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/james-ketchum-who-conducted-mind-altering-experiments-on-soldiers-dies-at-87/2019/06/04/7b5ad322-86cc-11e9-a491-25df61c78dc4_story.html

5. Ross CA. LSD experiments by the United States Army. Hist Psychiatry. 2017;28(4):427-442. doi:10.1177/0957154X17717678

6. Albott CS, Lim KO, Forbes MK, et al. Efficacy, safety, and durability of repeated ketamine infusions of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and treatment resistant depression. Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3): 17m11634. doi:10.4088/JCP.17m11634

7. Shawler IC, Jordan CH, Jackson CA. Veteran and military mental health issues. Stat Pearls. Updated May 23, 2022. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572092/#_NBK572092_pubdet_

8. Santayana G. The Life of Reason. 1905. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15000/15000-h/15000-h.htm

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1200.05(2). Requirements for the protection of human subjects in research. Amended January 8, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=8171

10. US Department of Defense, Military Health System. Research protections. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.health.mil/About-MHS/OASDHA/Defense-Health-Agency/Research-and-Engineering/Research-Protections

Soccer player with painful toe

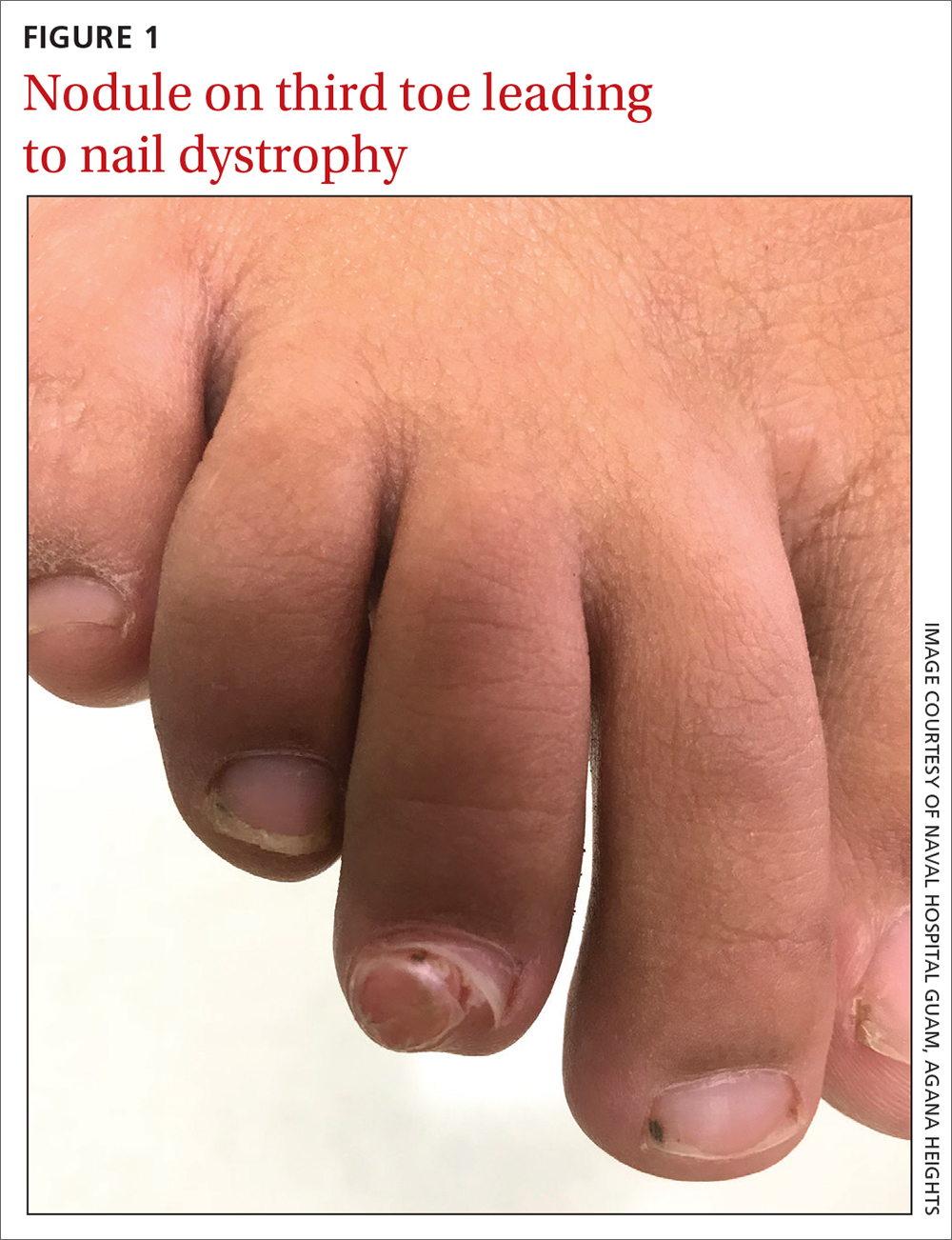

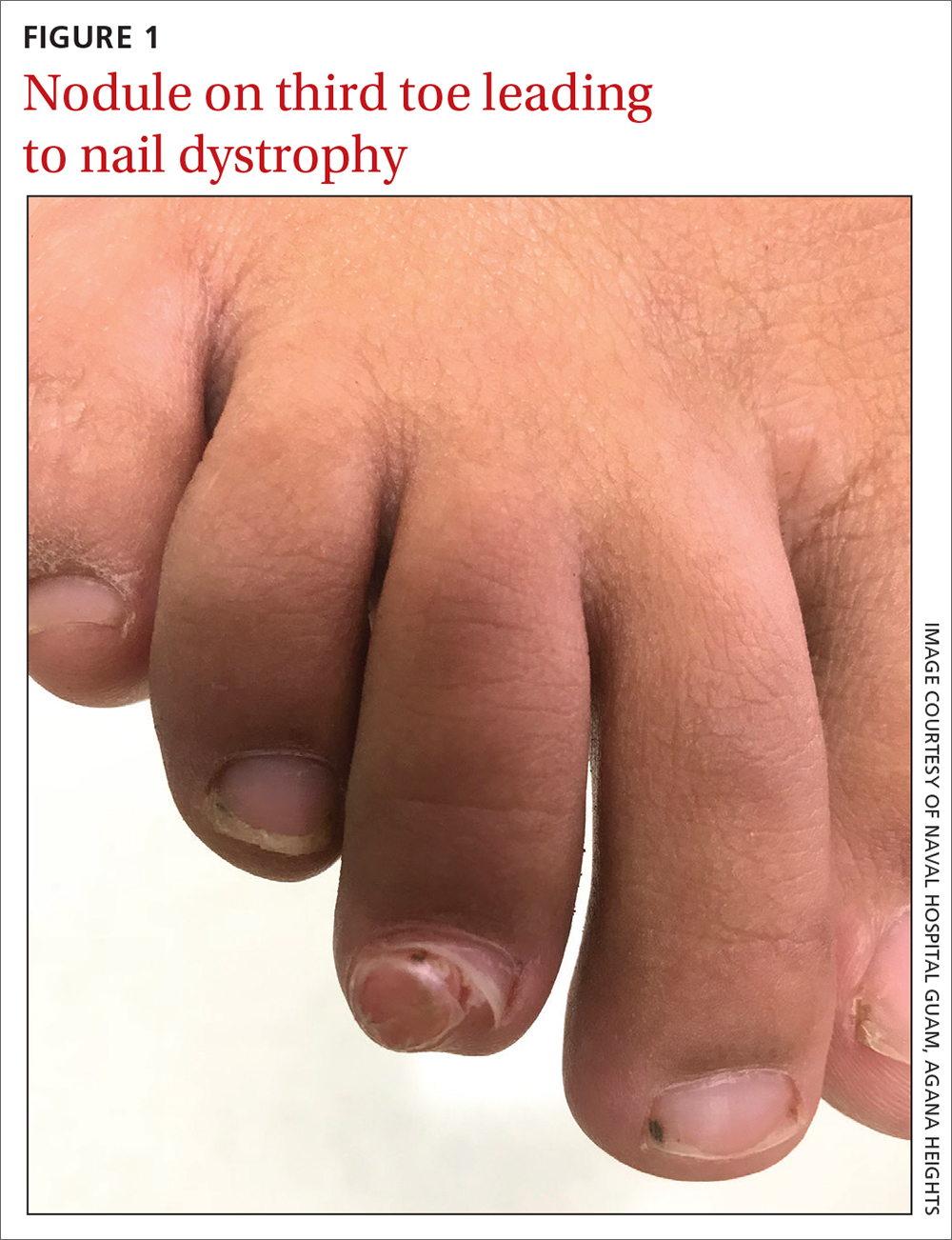

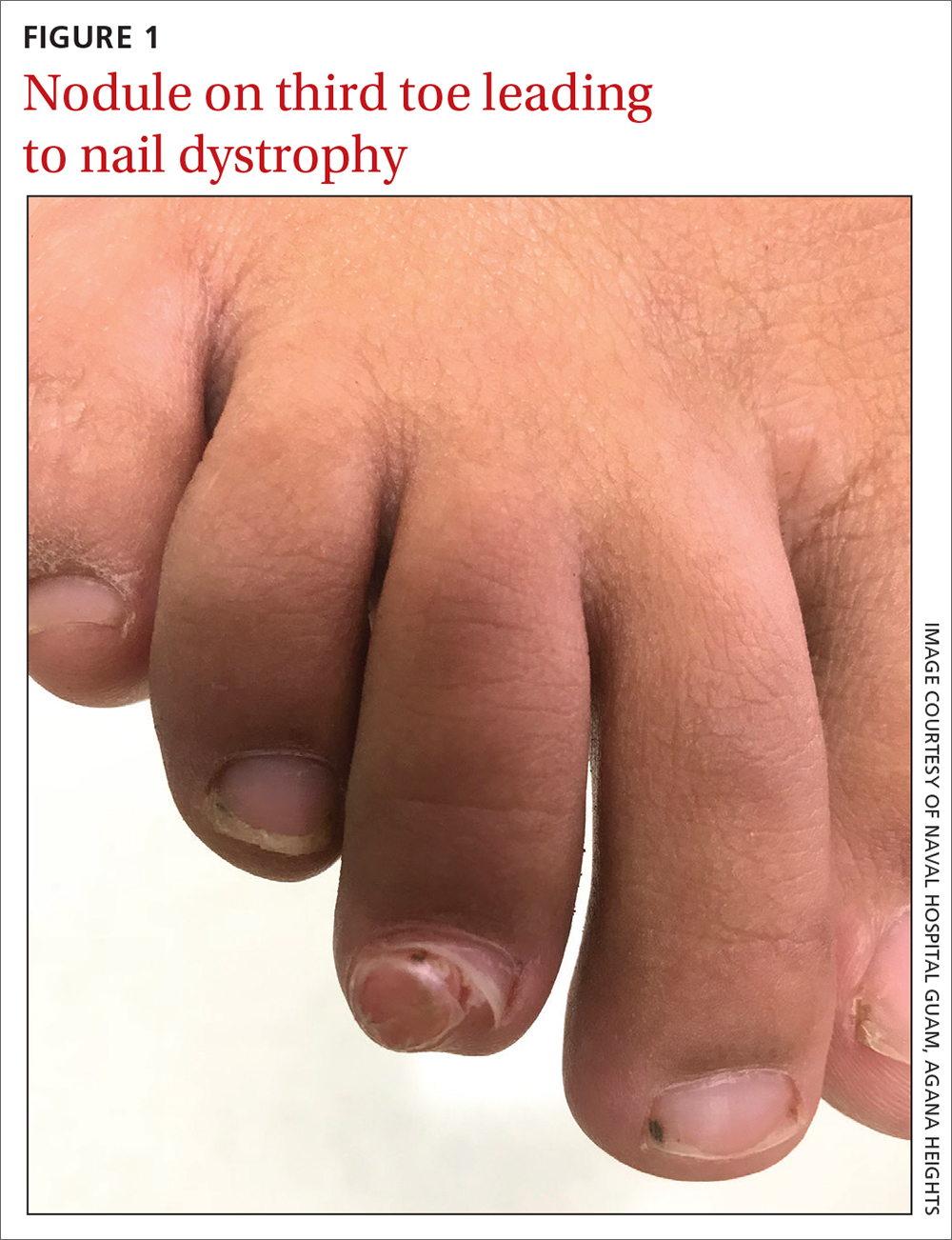

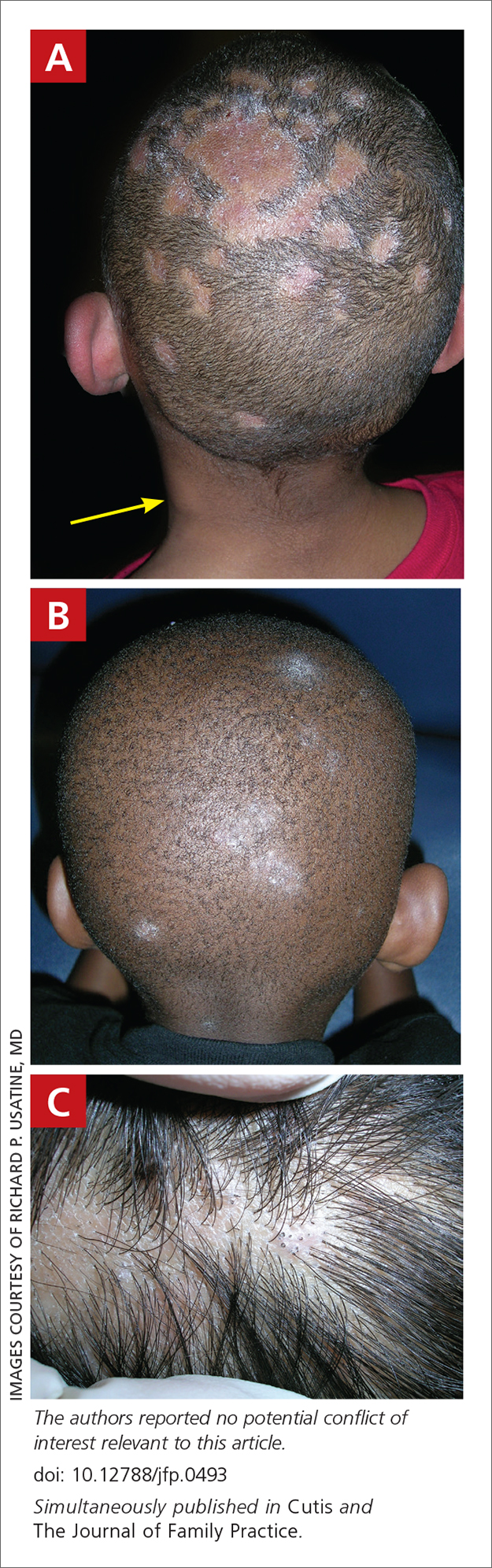

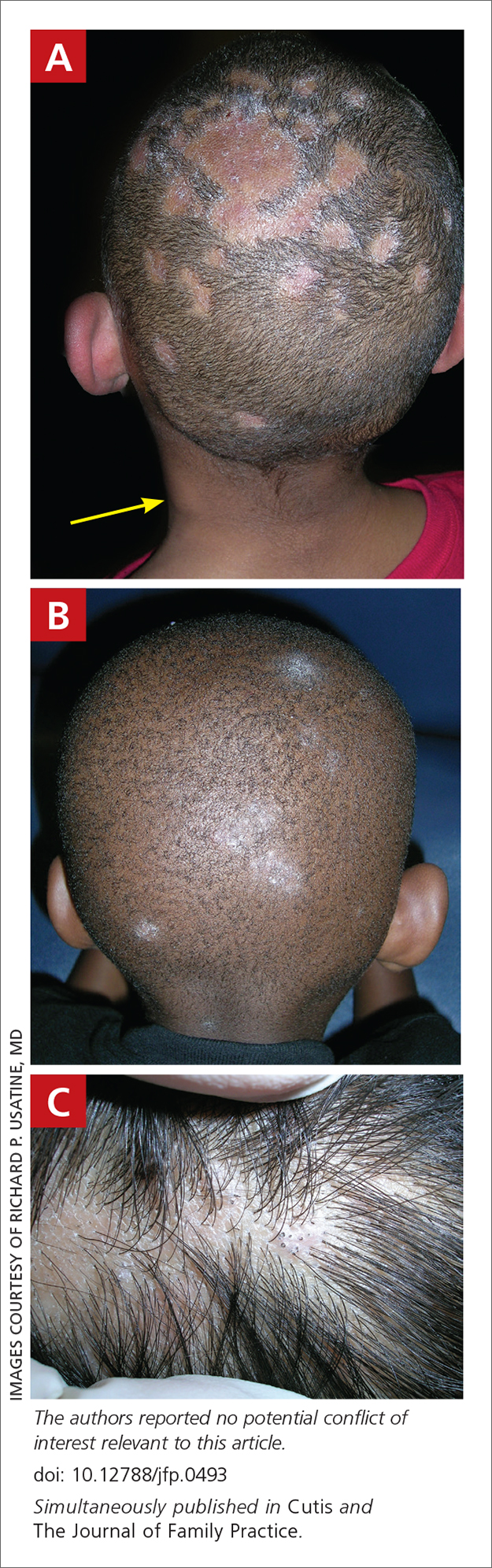

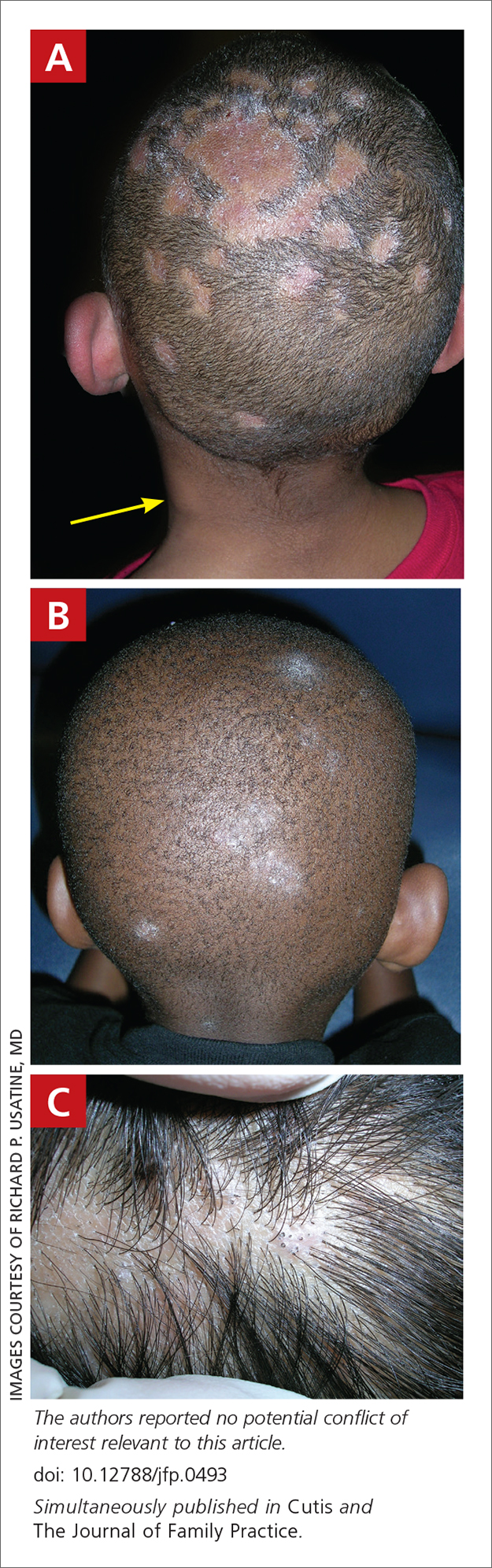

A 13-YEAR-OLD GIRL presented to the clinic with a 1-year history of a slow-growing mass on the third toe of her right foot. As a soccer player, she experienced associated pain when kicking the ball or when wearing tight-fitting shoes. The lesion was otherwise asymptomatic. She denied any overt trauma to the area and indicated that the mass had enlarged over the previous year.

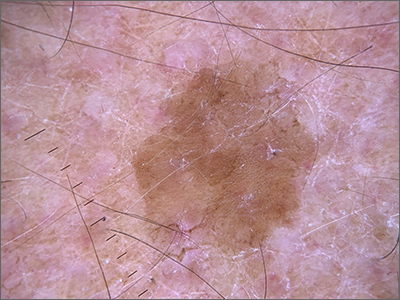

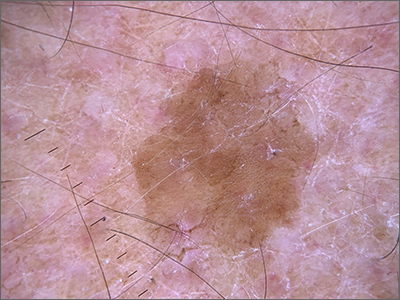

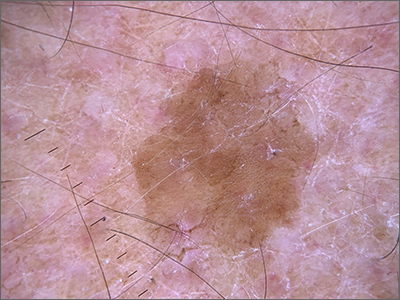

On exam, there was a nontender 8 × 8-mm firm nodule underneath the nail with associated nail dystrophy (FIGURE 1). The toe had full mobility, sensation was intact, and capillary refill time was < 2 seconds.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Subungual exostosis

A plain radiograph of the patient’s foot showed continuity with the bony cortex and medullary space, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis (FIGURE 2).1 An exostosis, or osteochondroma, is a form of benign bone tumor in which trabecular bone overgrows its normal border in a nodular pattern. When this occurs under the nail bed, it is called subungual exostosis.2 Exostosis represents 10% to 15% of all benign bone tumors, making it the most common benign bone tumor.3 Generally, the age of occurrence is 10 to 15 years.3

Repetitive trauma can be a culprit. Up to 8% of exostoses occur in the foot, with the most commonly affected area being the distal medial portion of the big toe.3,4 Repetitive trauma and infection are potential risk factors.3,4 The affected toe may be painful, but that is not always the case.4 Typically, lesions are solitary; however, multiple lesions can occur.4

Most pediatric foot lesions are benign and involve soft tissue

Benign soft-tissue masses make up the overwhelming majority of pediatric foot lesions, accounting for 61% to 87% of all foot lesions.3 Malignancies such as chondrosarcoma can occur and can be difficult to diagnose. Rapid growth, family history, size > 5 cm, heterogenous appearance on magnetic resonance imaging, and poorly defined margins are a few characteristics that should increase suspicion for possible malignancy.5

The differential diagnosis for a growth on the toe similar to the one our patient had would include pyogenic granuloma,

Pyogenic granulomas are benign vascular lesions that occur in patients of all ages. They tend to be dome-shaped and flesh-toned to violaceous red, and they are usually found on the head, neck, and extremities—especially fingers.6 They are associated with trauma and are classically tender with a propensity to bleed.6

Acral fibromyxoma is a benign, slow-growing, predominately painless, firm mass with an affinity for the great toe; the affected area includes the nail in 50% of cases.7 A radiograph may show bony erosion or scalloping due to mass effect; however, there will be no continuity with the bony matrix. (Such continuity would suggest exostosis.)

Periungual fibromas are benign soft-tissue masses, which are pink to red and firm, and emerge from underneath the nails, potentially resulting in dystrophy.8 They can bleed and cause pain, and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis.5

Continue to: Verruca vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris, the common wart, can also manifest in the subungual region as a firm, generally painless mass. It is the most common neoplasm of the hand and fingers.6 Tiny black dots that correspond to thrombosed capillaries are key to identifying this lesion.

Surgical excision when patient reaches maturity

The definitive treatment for subungual exostosis is surgical excision, preferably once the patient has reached skeletal maturity. Surgery at this point is associated with decreased recurrence rates.3,4 That said, excision may need to be performed sooner if the lesion is painful and leading to deformity.3

Our patient’s persistent pain prompted us to recommend surgical excision. She underwent a third digit exostectomy, which she tolerated without any issues. The patient was fitted with a postoperative shoe that she wore until her 2-week follow-up appointment, when her sutures were removed. The patient’s activity level progressed as tolerated. She regained full function and returned to playing soccer, without any pain, 3 months after her surgery.

1. Das PC, Hassan S, Kumar P. Subungual exostosis – clinical, radiological, and histological findings. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:202-203. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_104_18

2. Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257. doi:10.12788/cutis.0380

3. Bouchard B, Bartlett M, Donnan L. Assessment of the pediatric foot mass. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:32-41. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00397

4. DaCambra MP, Gupta SK, Ferri-de-Barros F. Subungual exostosis of the toes: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1251-1259. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4

5. Shah SH, Callahan MJ. Ultrasound evaluation of superficial lumps and bumps of the extremities in children: a 5-year retrospective review. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43 suppl 1:S23-S40. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2590-0

6. Habif, Thomas P. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Mosby/Elsevier, 2016.

7. Ramya C, Nayak C, Tambe S. Superficial acral fibromyxoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:457-459. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.185734

8. Ma D, Darling T, Moss J, et al. Histologic variants of periungual fibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:442-444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.002

A 13-YEAR-OLD GIRL presented to the clinic with a 1-year history of a slow-growing mass on the third toe of her right foot. As a soccer player, she experienced associated pain when kicking the ball or when wearing tight-fitting shoes. The lesion was otherwise asymptomatic. She denied any overt trauma to the area and indicated that the mass had enlarged over the previous year.

On exam, there was a nontender 8 × 8-mm firm nodule underneath the nail with associated nail dystrophy (FIGURE 1). The toe had full mobility, sensation was intact, and capillary refill time was < 2 seconds.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Subungual exostosis

A plain radiograph of the patient’s foot showed continuity with the bony cortex and medullary space, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis (FIGURE 2).1 An exostosis, or osteochondroma, is a form of benign bone tumor in which trabecular bone overgrows its normal border in a nodular pattern. When this occurs under the nail bed, it is called subungual exostosis.2 Exostosis represents 10% to 15% of all benign bone tumors, making it the most common benign bone tumor.3 Generally, the age of occurrence is 10 to 15 years.3

Repetitive trauma can be a culprit. Up to 8% of exostoses occur in the foot, with the most commonly affected area being the distal medial portion of the big toe.3,4 Repetitive trauma and infection are potential risk factors.3,4 The affected toe may be painful, but that is not always the case.4 Typically, lesions are solitary; however, multiple lesions can occur.4

Most pediatric foot lesions are benign and involve soft tissue

Benign soft-tissue masses make up the overwhelming majority of pediatric foot lesions, accounting for 61% to 87% of all foot lesions.3 Malignancies such as chondrosarcoma can occur and can be difficult to diagnose. Rapid growth, family history, size > 5 cm, heterogenous appearance on magnetic resonance imaging, and poorly defined margins are a few characteristics that should increase suspicion for possible malignancy.5

The differential diagnosis for a growth on the toe similar to the one our patient had would include pyogenic granuloma,

Pyogenic granulomas are benign vascular lesions that occur in patients of all ages. They tend to be dome-shaped and flesh-toned to violaceous red, and they are usually found on the head, neck, and extremities—especially fingers.6 They are associated with trauma and are classically tender with a propensity to bleed.6

Acral fibromyxoma is a benign, slow-growing, predominately painless, firm mass with an affinity for the great toe; the affected area includes the nail in 50% of cases.7 A radiograph may show bony erosion or scalloping due to mass effect; however, there will be no continuity with the bony matrix. (Such continuity would suggest exostosis.)

Periungual fibromas are benign soft-tissue masses, which are pink to red and firm, and emerge from underneath the nails, potentially resulting in dystrophy.8 They can bleed and cause pain, and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis.5

Continue to: Verruca vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris, the common wart, can also manifest in the subungual region as a firm, generally painless mass. It is the most common neoplasm of the hand and fingers.6 Tiny black dots that correspond to thrombosed capillaries are key to identifying this lesion.

Surgical excision when patient reaches maturity

The definitive treatment for subungual exostosis is surgical excision, preferably once the patient has reached skeletal maturity. Surgery at this point is associated with decreased recurrence rates.3,4 That said, excision may need to be performed sooner if the lesion is painful and leading to deformity.3

Our patient’s persistent pain prompted us to recommend surgical excision. She underwent a third digit exostectomy, which she tolerated without any issues. The patient was fitted with a postoperative shoe that she wore until her 2-week follow-up appointment, when her sutures were removed. The patient’s activity level progressed as tolerated. She regained full function and returned to playing soccer, without any pain, 3 months after her surgery.

A 13-YEAR-OLD GIRL presented to the clinic with a 1-year history of a slow-growing mass on the third toe of her right foot. As a soccer player, she experienced associated pain when kicking the ball or when wearing tight-fitting shoes. The lesion was otherwise asymptomatic. She denied any overt trauma to the area and indicated that the mass had enlarged over the previous year.

On exam, there was a nontender 8 × 8-mm firm nodule underneath the nail with associated nail dystrophy (FIGURE 1). The toe had full mobility, sensation was intact, and capillary refill time was < 2 seconds.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Subungual exostosis

A plain radiograph of the patient’s foot showed continuity with the bony cortex and medullary space, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis (FIGURE 2).1 An exostosis, or osteochondroma, is a form of benign bone tumor in which trabecular bone overgrows its normal border in a nodular pattern. When this occurs under the nail bed, it is called subungual exostosis.2 Exostosis represents 10% to 15% of all benign bone tumors, making it the most common benign bone tumor.3 Generally, the age of occurrence is 10 to 15 years.3

Repetitive trauma can be a culprit. Up to 8% of exostoses occur in the foot, with the most commonly affected area being the distal medial portion of the big toe.3,4 Repetitive trauma and infection are potential risk factors.3,4 The affected toe may be painful, but that is not always the case.4 Typically, lesions are solitary; however, multiple lesions can occur.4

Most pediatric foot lesions are benign and involve soft tissue

Benign soft-tissue masses make up the overwhelming majority of pediatric foot lesions, accounting for 61% to 87% of all foot lesions.3 Malignancies such as chondrosarcoma can occur and can be difficult to diagnose. Rapid growth, family history, size > 5 cm, heterogenous appearance on magnetic resonance imaging, and poorly defined margins are a few characteristics that should increase suspicion for possible malignancy.5

The differential diagnosis for a growth on the toe similar to the one our patient had would include pyogenic granuloma,

Pyogenic granulomas are benign vascular lesions that occur in patients of all ages. They tend to be dome-shaped and flesh-toned to violaceous red, and they are usually found on the head, neck, and extremities—especially fingers.6 They are associated with trauma and are classically tender with a propensity to bleed.6

Acral fibromyxoma is a benign, slow-growing, predominately painless, firm mass with an affinity for the great toe; the affected area includes the nail in 50% of cases.7 A radiograph may show bony erosion or scalloping due to mass effect; however, there will be no continuity with the bony matrix. (Such continuity would suggest exostosis.)

Periungual fibromas are benign soft-tissue masses, which are pink to red and firm, and emerge from underneath the nails, potentially resulting in dystrophy.8 They can bleed and cause pain, and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis.5

Continue to: Verruca vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris, the common wart, can also manifest in the subungual region as a firm, generally painless mass. It is the most common neoplasm of the hand and fingers.6 Tiny black dots that correspond to thrombosed capillaries are key to identifying this lesion.

Surgical excision when patient reaches maturity

The definitive treatment for subungual exostosis is surgical excision, preferably once the patient has reached skeletal maturity. Surgery at this point is associated with decreased recurrence rates.3,4 That said, excision may need to be performed sooner if the lesion is painful and leading to deformity.3

Our patient’s persistent pain prompted us to recommend surgical excision. She underwent a third digit exostectomy, which she tolerated without any issues. The patient was fitted with a postoperative shoe that she wore until her 2-week follow-up appointment, when her sutures were removed. The patient’s activity level progressed as tolerated. She regained full function and returned to playing soccer, without any pain, 3 months after her surgery.

1. Das PC, Hassan S, Kumar P. Subungual exostosis – clinical, radiological, and histological findings. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:202-203. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_104_18

2. Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257. doi:10.12788/cutis.0380

3. Bouchard B, Bartlett M, Donnan L. Assessment of the pediatric foot mass. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:32-41. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00397

4. DaCambra MP, Gupta SK, Ferri-de-Barros F. Subungual exostosis of the toes: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1251-1259. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4

5. Shah SH, Callahan MJ. Ultrasound evaluation of superficial lumps and bumps of the extremities in children: a 5-year retrospective review. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43 suppl 1:S23-S40. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2590-0

6. Habif, Thomas P. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Mosby/Elsevier, 2016.

7. Ramya C, Nayak C, Tambe S. Superficial acral fibromyxoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:457-459. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.185734

8. Ma D, Darling T, Moss J, et al. Histologic variants of periungual fibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:442-444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.002

1. Das PC, Hassan S, Kumar P. Subungual exostosis – clinical, radiological, and histological findings. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:202-203. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_104_18

2. Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257. doi:10.12788/cutis.0380

3. Bouchard B, Bartlett M, Donnan L. Assessment of the pediatric foot mass. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:32-41. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00397

4. DaCambra MP, Gupta SK, Ferri-de-Barros F. Subungual exostosis of the toes: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1251-1259. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4

5. Shah SH, Callahan MJ. Ultrasound evaluation of superficial lumps and bumps of the extremities in children: a 5-year retrospective review. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43 suppl 1:S23-S40. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2590-0

6. Habif, Thomas P. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Mosby/Elsevier, 2016.

7. Ramya C, Nayak C, Tambe S. Superficial acral fibromyxoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:457-459. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.185734

8. Ma D, Darling T, Moss J, et al. Histologic variants of periungual fibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:442-444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.002

Would your patient benefit from a monoclonal antibody?

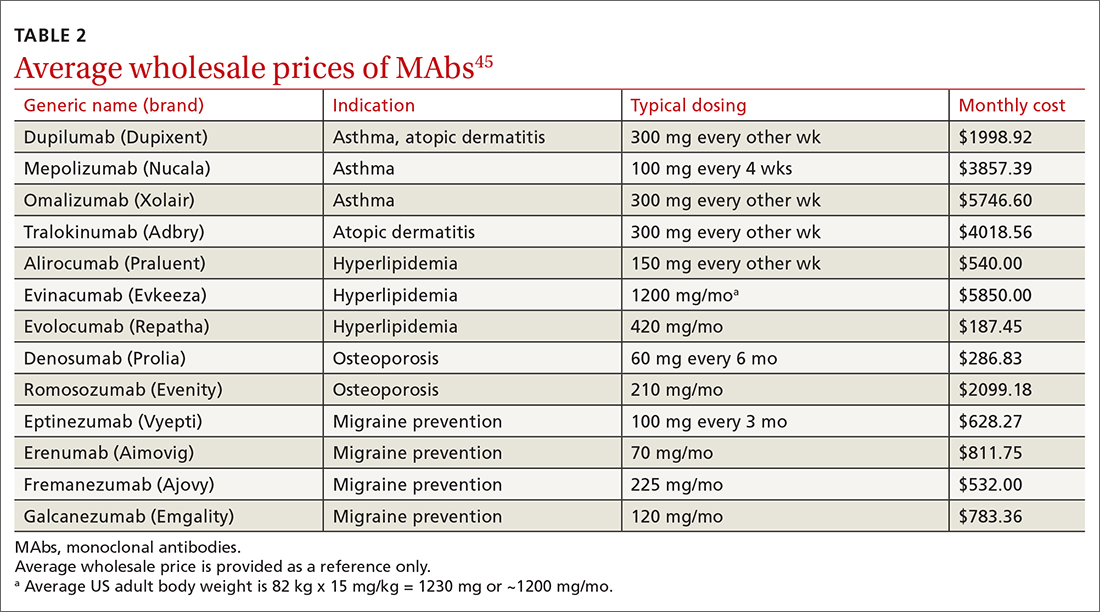

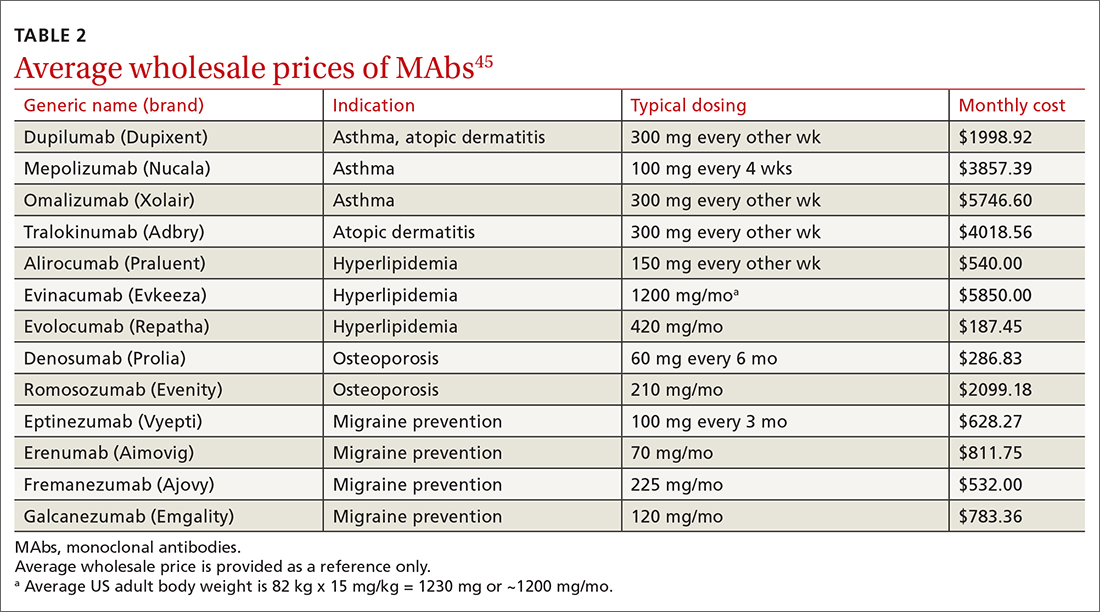

Small-molecule drugs such as aspirin, albuterol, atorvastatin, and lisinopril are the backbone of disease management in family medicine.1 However, large-molecule biological drugs such as monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are increasingly prescribed to treat common conditions. In the past decade, MAbs comprised 20% of all drug approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and today they represent more than half of drugs currently in development.2 Fifteen MAbs have been approved by the FDA over the past decade for asthma, atopic dermatitis (AD), hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, and migraine prevention.3 This review details what makes MAbs unique and what you should know about them.

The uniqueness of monoclonal antibodies

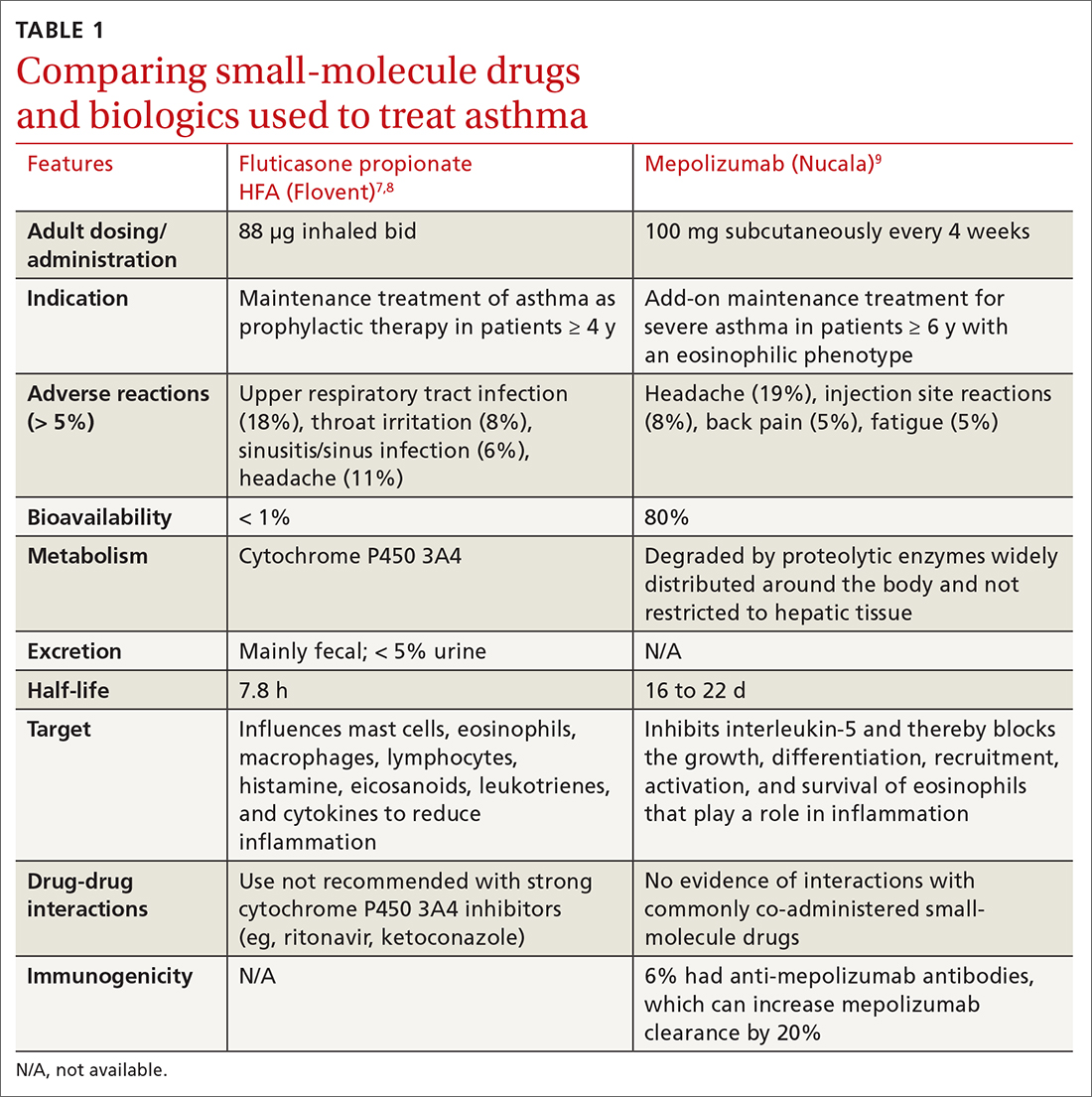

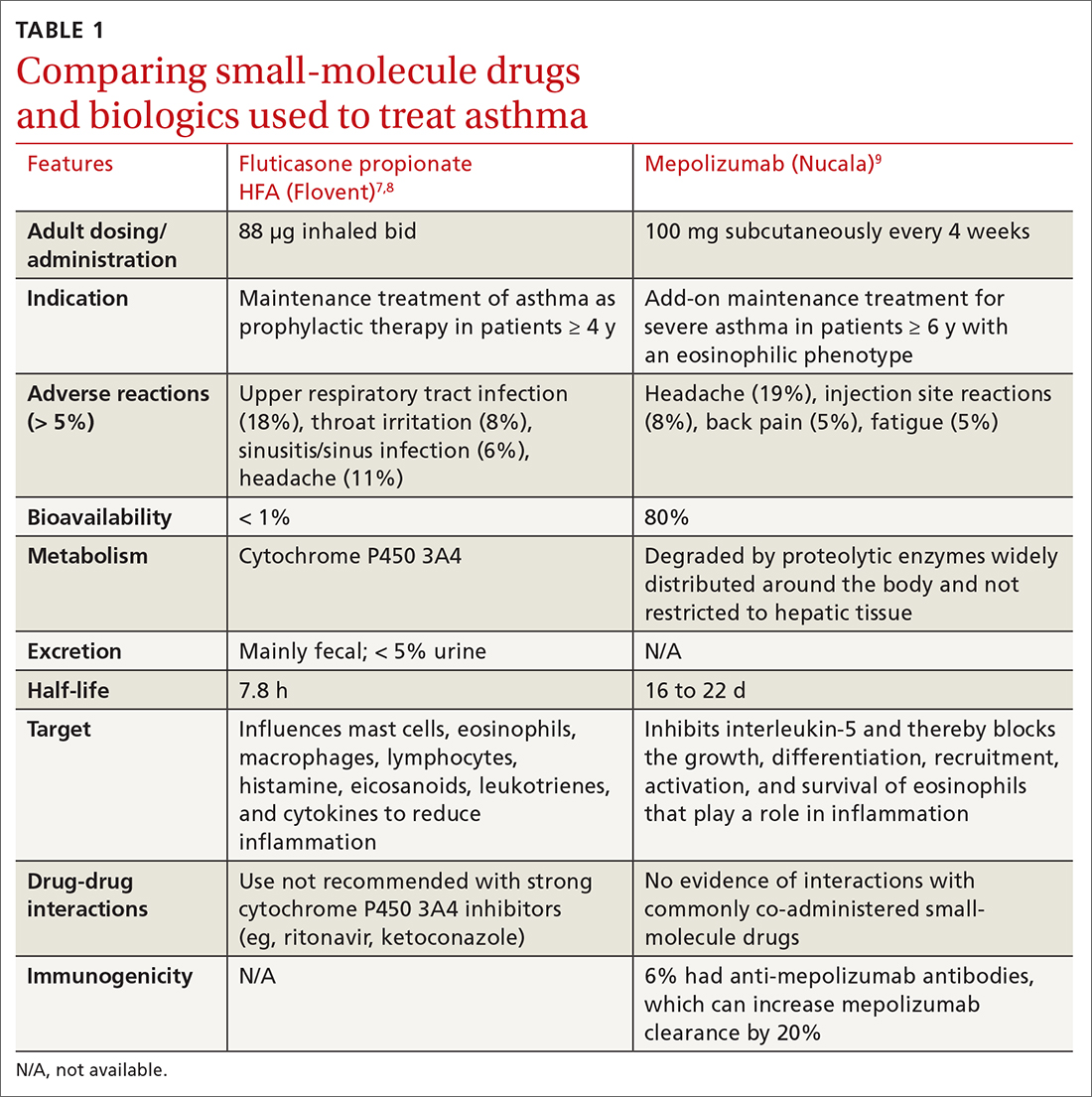

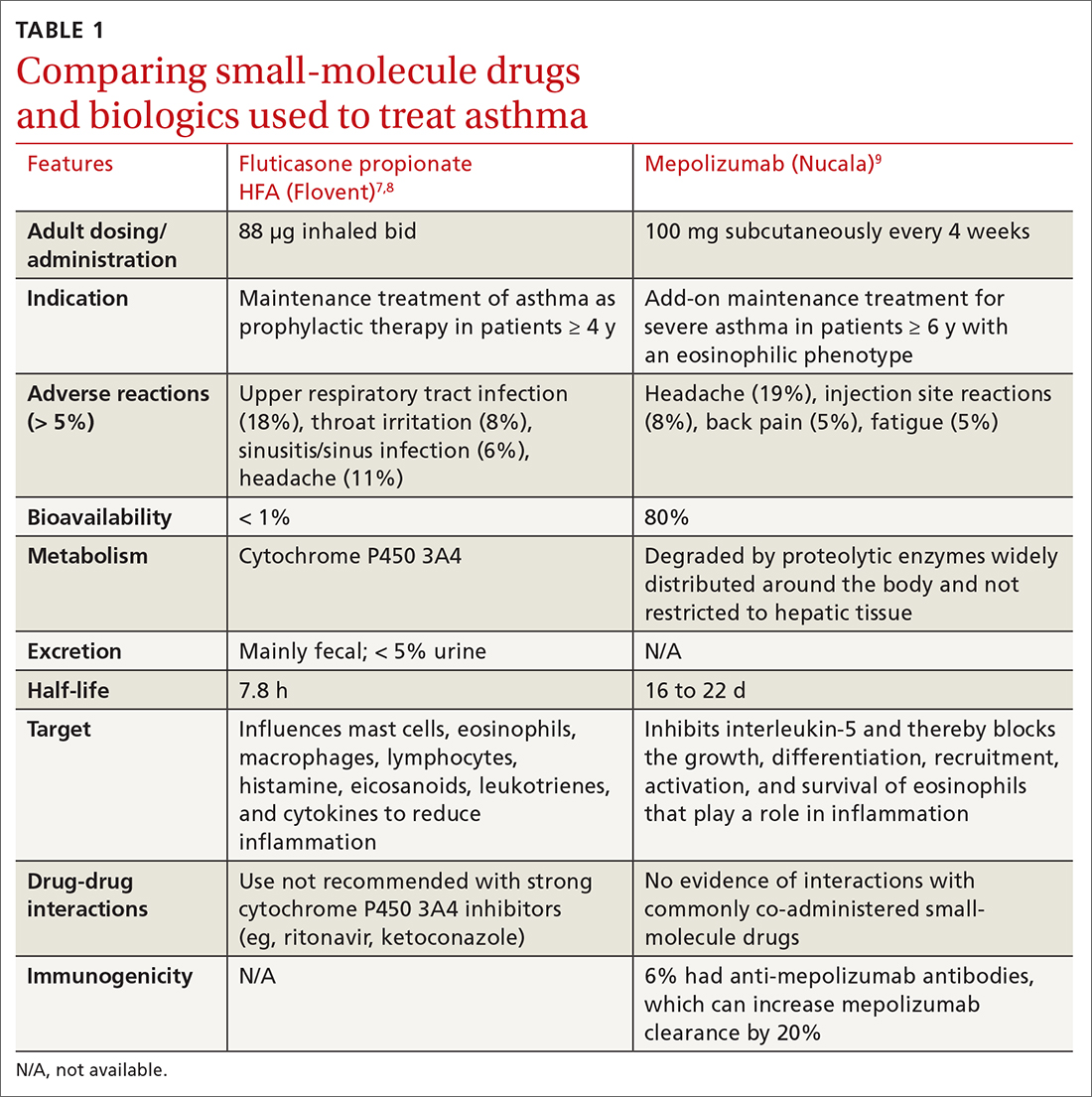

MAbs are biologics, but not all biologics are MAbs—eg, adalimumab (Humira) is a MAb, but etanercept (Enbrel) is not. MAbs are therapeutic proteins made possible by hybridoma technology used to create an antibody with single specificity.4-6 Monoclonal antibodies differ from small-molecule drugs in structure, dosing, route of administration, manufacturing, metabolism, drug interactions, and elimination (TABLE 17-9).

MAbs can be classified as naked, “without any drug or radioactive material attached to them,” or conjugated, “joined to a chemotherapy drug, radioactive isotope, or toxin.”10 MAbs work in several ways, including competitively inhibiting ligand-receptor binding, receptor blockade, or cell elimination from indirect immune system activities such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.11,12

Monoclonal antibody uses in family medicine

Asthma

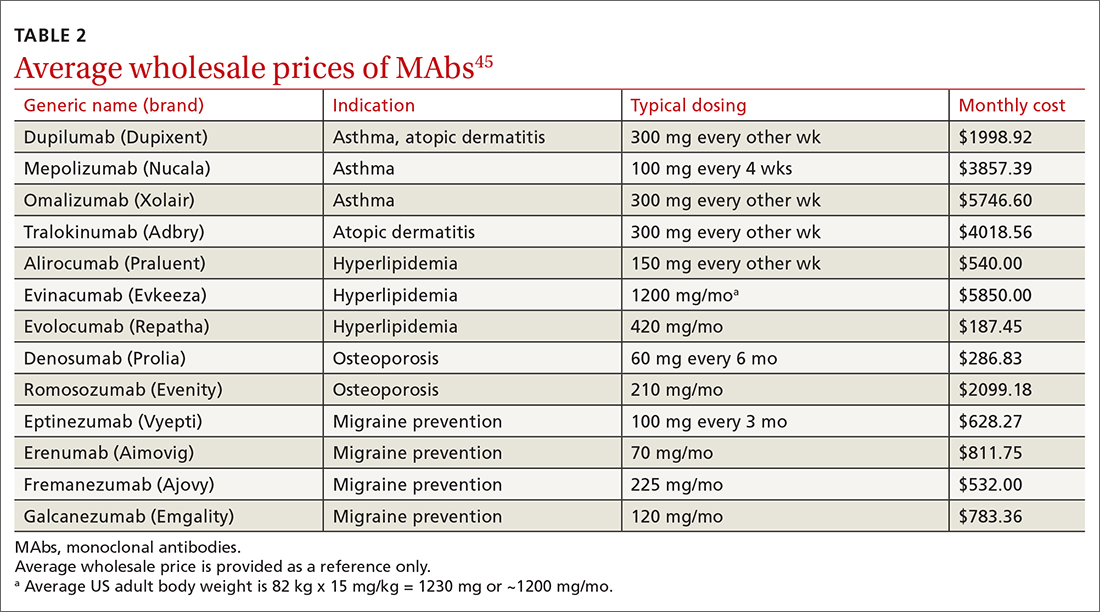

Several MAbs have been approved for use in severe asthma, including but not limited to: omalizumab (Xolair),13 mepolizumab (Nucala),9,14 and dupilumab (Dupixent).15

Omalizumab is a humanized MAb that prevents IgE antibodies from binding to mast cells and basophils, thereby reducing inflammatory mediators.13 A systematic review found that, compared with placebo, omalizumab used in patients with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe asthma led to significantly fewer asthma exacerbations (absolute risk reduction [ARR], 16% vs 26%; odds ratio [OR] = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.42-0.60; number needed to treat [NNT] = 10) and fewer hospitalizations (ARR, 0.5% vs 3%; OR = 0.16; 95% CI, 0.06-0.42; NNT = 40).13

Significantly more patients in the omalizumab group were able to withdraw from, or reduce, the dose of ICS. GINA recommends omalizumab for patients with positive skin sensitization, total serum IgE ≥ 30 IU/mL, weight within 30 kg to 150 kg, history of childhood asthma and recent exacerbations, and blood eosinophils ≥ 260/mcL.16 Omalizumab is also approved for use in chronic spontaneous urticaria and nasal polyps.

Mepolizumab

Continue to: Another trial found that...

Another trial found that mepolizumab reduced total OCS doses in patients with severe asthma by 50% without increasing exacerbations or worsening asthma control.18 All 3 anti-IL-5 drugs—including not only mepolizumab, but also benralizumab (Fasenra) and reslizumab (Cinqair)—appear to yield similar improvements. A 2017 systematic review found all anti-IL-5 treatments reduced rates of clinically significant asthma exacerbations (treatment with OCS for ≥ 3 days) by roughly 50% in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma and a history of ≥ 2 exacerbations in the past year.

Dupilumab is a humanized MAb that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13, which influence multiple cell types involved in inflammation (eg, mast cells, eosinophils) and inflammatory mediators (histamine, leukotrienes, cytokines).15 In a recent study of patients with uncontrolled asthma, dupilumab 200 mg every 2 weeks compared with placebo showed a modest reduction in the annualized rate of severe asthma exacerbations (0.46 exacerbations vs 0.87, respectively). Dupilumab was effective in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥ 150/μL but was ineffective in patients with eosinophil counts < 150/μL.15

For patients ≥ 12 years old with severe eosinophilic asthma, GINA recommends using dupilumab as add-on therapy for an initial trial of 4 months at doses of 200 or 300 mg SC every 2 weeks, with preference for 300 mg SC every 2 weeks for OCS-dependent asthma. Dupilumab is approved for use in AD and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. If a biologic agent is not successful after a 4-month trial, consider a 6- to 12-month trial. If efficacy is still minimal, consider switching to an alternative biologic therapy approved for asthma.16

❯ Asthma: Test your skills

Subjective findings: A 19-year-old man presents to your clinic. He has a history of nasal polyps and allergic asthma. At age 18, he was given a diagnosis of severe persistent asthma. He has shortness of breath during waking hours 4 times per week, and treats each of these episodes with albuterol. He also wakes up about twice a week with shortness of breath and has some limitations in normal activities. He reports missing his prescribed fluticasone/salmeterol 500/50 μg, 1 inhalation bid, only once each month. In the last year, he has had 2 exacerbations requiring oral steroids.

Medications: Albuterol 90 μg, 1-2 inhalations, q6h prn; fluticasone/salmeterol 500/50 μg, 1 inhalation bid; tiotropium 1.25 μg, 2 puffs/d; montelukast 10 mg every morning; prednisone 10 mg/d.

Continue to: Objective data

Objective data: Patient is in no apparent distress and afebrile, and oxygen saturation on room air is 97%. Ht, 70 inches; wt, 75 kg. Labs: IgE, 15 IU/mL; serum eosinophils, 315/μL.

Which MAb would be appropriate for this patient? Given that the patient has a blood eosinophil level ≥ 300/μL and severe exacerbations, adult-onset asthma, nasal polyposis, and maintenance OCS at baseline, it would be reasonable to initiate mepolizumab 100 mg SC every 4 weeks, or dupilumab 600 mg once, then 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. Both agents can be self-administered.

Atopic dermatitis

Two MAbs—dupilumab and tralokinumab (Adbry; inhibits IL-13)—are approved for treatment of AD in adults that is uncontrolled with conventional therapy.15,19 Dupilumab is also approved for children ≥ 6 months old.20 Both MAbs are dosed at 600 mg SC, followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks. Dupilumab was compared with placebo in adult patients who had moderate-to-severe AD inadequately controlled on topical corticosteroids (TCSs), to determine the proportion of patients in each group achieving improvement of either 0 or 1 points or ≥ 2 points in the 5-point Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score from baseline to 16 weeks.21 Thirty-seven percent of patients receiving dupilumab 300 mg SC weekly and 38% of patients receiving dupilumab 300 mg SC every 2 weeks achieved the primary outcome, compared with 10% of those receiving placebo (P < .001).21 Similar IGA scores were reported when dupilumab was combined with TCS, compared with placebo.22

It would be reasonable to consider dupilumab or tralokinumab in patients with: cutaneous atrophy or hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression with TCS, concerns of malignancy with topical calcineurin inhibitors, or problems with the alternative systemic therapies (cyclosporine-induced hypertension, nephrotoxicity, or immunosuppression; azathioprine-induced malignancy; or methotrexate-induced bone marrow suppression, renal impairment, hepatotoxicity, pneumonitis, or gastrointestinal toxicity).23

A distinct advantage of MAbs over other systemic agents in the management of AD is that MAbs do not require frequent monitoring of blood pressure, renal or liver function, complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, or uric acid. Additionally, MAbs have fewer black box warnings and adverse reactions when compared with other systemic agents.

Continue to: Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia

Three MAbs are approved for use in hyperlipidemia: the angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) inhibitor evinacumab (Evkeeza)24 and 2 proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, evolocumab (Repatha)25 and alirocumab (Praluent).26

ANGPTL3 inhibitors block ANGPTL3 and reduce endothelial lipase and lipoprotein lipase activity, which in turn decreases low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglyceride formation. PCSK9 inhibitors prevent PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors, thereby maintaining the number of active LDL receptors and increasing LDL-C removal.

Evinacumab is indicated for homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and is administered intravenously every 4 weeks. Evinacumab has not been evaluated for effects on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Evolocumab 140 mg SC every 2 weeks or 420 mg SC monthly has been studied in patients on statin therapy with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL. Patients on evolocumab experienced significantly less of the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization compared with placebo (9.8% vs 11.3%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.92; NNT = 67.27

Alirocumab 75 mg SC every 2 weeks has also been studied in patients receiving statin therapy with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL. Patients taking alirocumab experienced significantly less of the composite endpoint of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, ischemic stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina compared with placebo (9.5% vs 11.1%; HR = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93; NNT = 63).

Continue to: According to the 2018...

According to the 2018 AHA Cholesterol Guidelines, PCSK9 inhibitors are indicated for patients receiving maximally tolerated LDL-C-lowering therapy (statin and ezetimibe) with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL, if they have had multiple atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events or 1 major ASCVD event with multiple high-risk conditions (eg, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, history of coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention, hypertension, estimated glomerular filtration rate of 15 to 59 mL/min/1.73m2).29 For patients without prior ASCVD events or high-risk conditions who are receiving maximally tolerated LDL-C-lowering therapy (statin and ezetimibe), PCSK9 inhibitors are indicated if the LDL-C remains ≥ 100 mg/dL.

Osteoporosis

The 2 MAbs approved for use in osteoporosis are the receptor activator of nuclear factor kB ligand (RANKL) inhibitor denosumab (Prolia)30 and the sclerostin inhibitor romosozumab (Evenity).31

Denosumab prevents RANKL from binding to the RANK receptor, thereby inhibiting osteoclast formation and decreasing bone resorption. Denosumab is approved for use in women and men who are at high risk of osteoporotic fracture, including those taking OCSs, men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer, and women receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer.

In a 3-year randomized trial, denosumab 60 mg SC every 6 months was compared with placebo in postmenopausal women with T-scores < –2.5, but not < –4.0 at the lumbar spine or total hip. Denosumab significantly reduced new radiographic vertebral fractures (2.3% vs 7.2%; risk ratio [RR] = 0.32; 95% CI, 0.26-0.41; NNT = 21), hip fracture (0.7% vs 1.2%), and nonvertebral fracture (6.5% vs 8.0%).32 Denosumab carries an increased risk of multiple vertebral fractures following discontinuation, skin infections, dermatologic reactions, and severe bone, joint, and muscle pain.

Romosozumab inhibits sclerostin, thereby increasing bone formation and, to a lesser degree, decreasing bone resorption. Romosozumab is approved for use in postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture (ie, those with a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple risk factors for fracture) or in patients who have not benefited from or are intolerant of other therapies. In one study, postmenopausal women with a T-score of –2.5 to –3.5 at the total hip or femoral neck were randomly assigned to receive either romosozumab 210 mg SC or placebo for 12 months, then each group was switched to denosumab 60 mg SC for 12 months. After the first year, prior to initiating denosumab, patients taking romosozumab experienced significantly fewer new vertebral fractures than patients taking placebo (0.5% vs 1.8%; RR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.16-0.47; NNT = 77); however, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups with nonvertebral fractures (HR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.53-1.05).33

Continue to: In another study...

In another study, romosozumab 210 mg SC was compared with alendronate 70 mg weekly, followed by alendronate 70 mg weekly in both groups. Over the first 12 months, patients treated with romosozumab saw a significant reduction in the incidence of new vertebral fractures (4% vs 6.3%; RR = 0.63, P < .003; NNT = 44). Patients treated with romosozumab with alendronate added for another 12 months also saw a significant reduction in new incidence of vertebral fractures (6.2% vs 11.9%; RR = 0.52; P < .001; NNT = 18).34 There was a higher risk of cardiovascular events among patients receiving romosozumab compared with those treated with alendronate, so romosozumab should not be used in individuals who have had an MI or stroke within the previous year.34 Denosumab and romosozumab offer an advantage over some bisphosphonates in that they require less frequent dosing and can be used in patients with renal impairment (creatinine clearance < 35 mL/min, in which zoledronic acid is contraindicated and alendronate is not recommended; < 30 mL/min, in which risedronate and ibandronate are not recommended).

Migraine prevention

Four

Erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab are all available in subcutaneous autoinjectors (or syringe with fremanezumab). Eptinezumab is an intravenous (IV) infusion given every 3 months.

Erenumab is available in both 70-mg and 140-mg dosing options. Fremanezumab can be given as 225 mg monthly or 675 mg quarterly. Galcanezumab has an initial loading dose of 240 mg followed by 120 mg given monthly. Erenumab targets the CGRP receptor; the others target the CGRP ligand. Eptinezumab has 100% bioavailability and reaches maximum serum concentration sooner than the other antagonists (due to its route of administration), but it must be given in an infusion center. Few insurers approve the use of eptinezumab unless a trial of least 1 of the monthly injectables has failed.

There are no head-to-head studies of the medications in this class. Additionally, differing study designs, definitions, statistical analyses, endpoints, and responder-rate calculations make it challenging to compare them directly against one another. At the very least, all of the CGRP MAbs have efficacy comparable to conventional preventive migraine medications such as propranolol, amitriptyline, and topiramate.40

Continue to: The most commonly reported adverse...

The most commonly reported adverse effect for all 4 CGRPs is injection site reaction, which was highest with the quarterly fremanezumab dose (45%).37 Constipation was most notable with the 140-mg dose of erenumab (3%)35; with the other CGRP MAbs it is comparable to that seen with placebo (< 1%).

Erenumab-induced hypertension has been identified in 61 cases reported through the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) as of 2021.41 This was not reported during MAb development programs, nor was it noted during clinical trials. Blood pressure elevation was seen within 1 week of injection in nearly 50% of the cases, and nearly one-third had pre-existing hypertension.41 Due to these findings, the erenumab prescribing information was updated to include hypertension in its warnings and precautions. It is possible that hypertension could be a class effect, although trial data and posthoc studies have yet to bear that out. Since erenumab was the first CGRP antagonist brought to market (May 2018 vs September 2018 for fremanezumab and galcanezumab), it may have accumulated more FAERS reports. Nearly all studies exclude patients with older age, uncontrolled hypertension, and unstable cardiovascular disease, which could impact data.41

Overall, this class of medications is very well tolerated, easy to use (again, excluding eptinezumab), and maintains a low adverse effect profile, giving added value compared with conventional preventive migraine medications.

The American Headache Society recommends a preventive oral therapy for at least 3 months before trying an alternative medication. After treatment failure with at least 2 oral agents, CGRP MAbs are recommended.42 CGRP antagonists offer convenient dosing, bypass gastrointestinal metabolism (which is useful in patients with nausea/vomiting), and have fewer adverse effects than traditional oral medications.

Worth noting. Several newer oral agents have been recently approved for migraine prevention, including atogepant (Qulipta) and rimegepant (Nurtec), which are also CGRP antagonists. Rimegepant is approved for both acute migraine treatment and prevention.

Continue to: Migraine

❯ Migraine: Test your skills

Subjective findings: A 25-year-old woman presents to your clinic for management of episodic migraines with aura. Her baseline average migraine frequency is 9 headache days/month. Her migraines are becoming more frequent despite treatment. She fears IV medication use and avoids hospitals.

History: Hypertension, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), and depression. The patient is not pregnant or trying to get pregnant.

Medications: Current medications (for previous 4 months) include propranolol 40 mg at bedtime, linaclotide 145 μg/d, citalopram 20 mg/d, and sumatriptan 50 mg prn. Past medications include venlafaxine 150 mg po bid for 5 months.