User login

Switching to Disposable Duodenoscopes: Risks and Rewards

- US Food and Drug Administration. Infections associated with reprocessed duodenoscopes. Updated June 30, 2022. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/reprocessing-reusable-medical-devices/infections-associated-reprocessed-duodenoscopes

- Heuvelmans M, Wunderink HF, van der Mei HC, Monkelbaan JF. A narrative review on current duodenoscope reprocessing techniques and novel developments. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10(1):171. doi:10.1186/s13756-021-01037-z

- US Food and Drug Administration. Use duodenoscopes with innovative designs to enhance safety: FDA safety communication. Updated June 30, 2022. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/use-duodenoscopes-innovative-designs-enhance-safety-fda-safety-communication

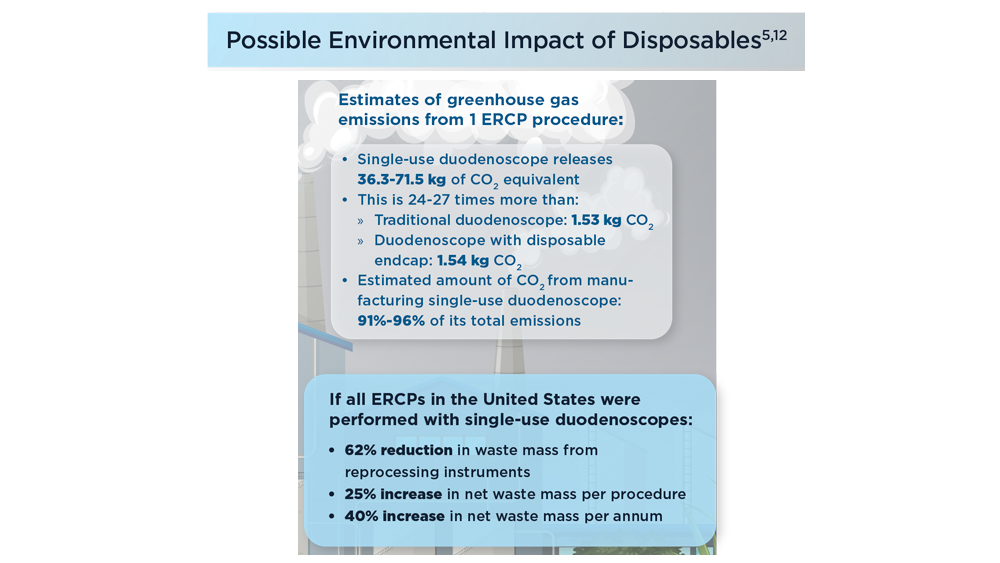

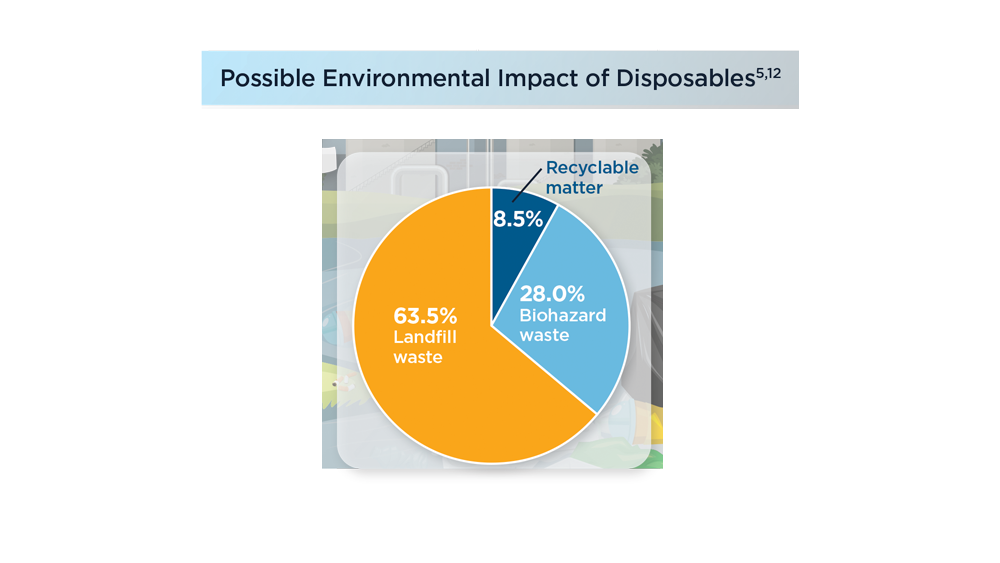

- Pass W. Weighing the pros and cons of disposable duodenoscopes. MDedge News. Published May 19, 2021. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.mdedge.com/gihepnews/article/240339/endoscopy

- Le NNT, Hernandez L, Vakil N, Guda N, Patnode C, Jolliet O. Environmental and health outcomes of single-use versus reusable duodenoscopes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;S0016-5107(22)01765-5. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2022.06.014

- Ridtitid W, Thummongkol T, Chatsuwan T, et al. Bacterial contamination and organic residue after reprocessing in duodenoscopes with disposable distal caps compared to duodenoscopes with fixed distal caps: a randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;S0016-5107(22)01766-7. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2022.06.015

- Naryzhny I, Silas D, Chi K. Impact of ethylene oxide gas sterilization of duodenoscopes after a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae outbreak. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(2):259-262. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.01.055

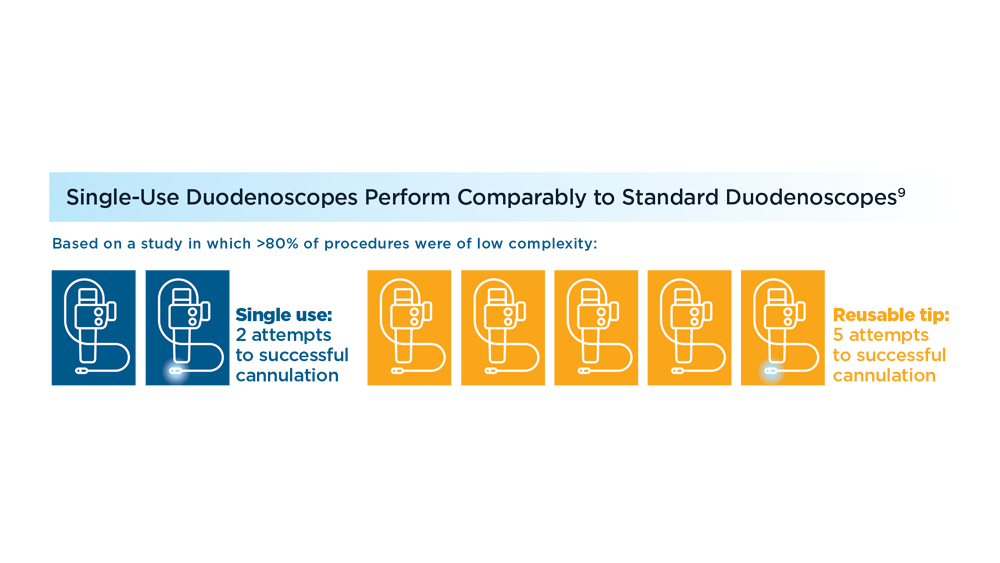

- Muthusamy VR, Bruno MJ, Kozarek RA, et al. Clinical evaluation of a single-use duodenoscope for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):2108-2117.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.10.052

- Bang JY, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Equivalent performance of single-use and reusable duodenoscopes in a randomised trial. Gut. 2021;70(5):838-844. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321836

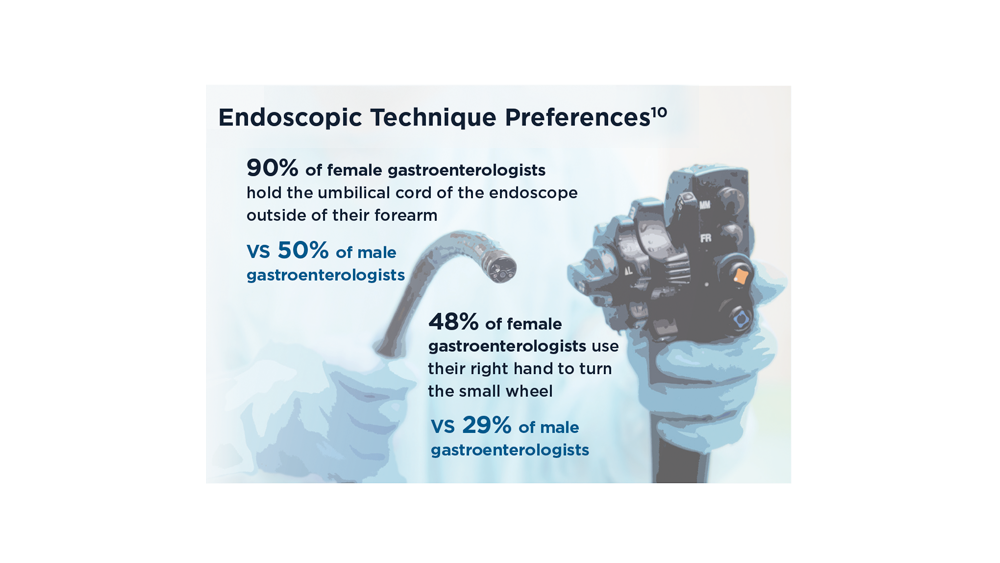

- Bhatt A, Thosani N, Patil P. ID: 3527241. Ergonomic study analyzing differences in endoscopy styles between female and male gastroenterologists [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(6 Suppl):AB42-AB43. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2021.03.148

- Trindade AJ, Copland A, Bhatt A, et al. Single-use duodenoscopes and duodenoscopes with disposable end caps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):997-1005. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.12.033

- Namburar S, von Renteln D, Damianos J, et al. Estimating the environmental impact of disposable endoscopic equipment and endoscopes. Gut. 2022;71(7):1326-1331. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324729

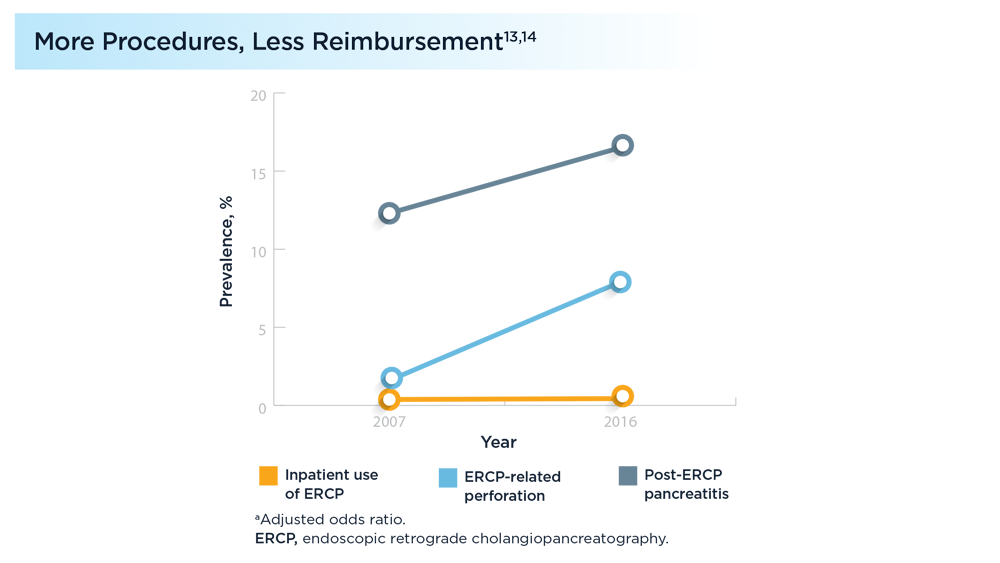

- Kröner PT, Bilal M, Samuel R, et al. Use of ERCP in the United States over the past decade. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8(6):E761-E769. doi:10.1055/a-1134-4873

- Patel K, Lad M, Siddiqui E, Ahlawat S. National trends in reimbursement and utilization of advanced endoscopic procedures in the Medicare population [abstract S0904]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:S465-S466. doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000705664.35696.6e

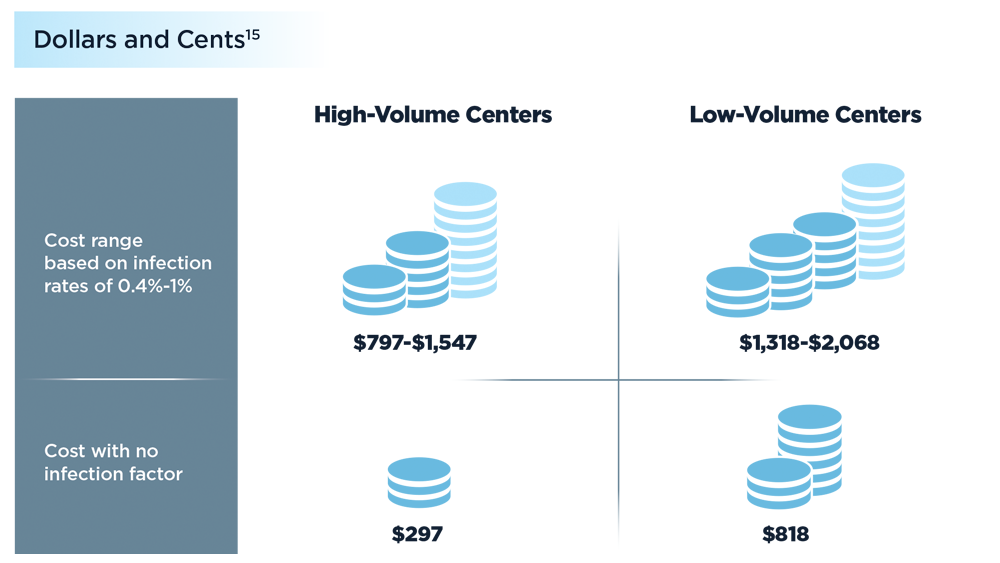

- Bang JY, Sutton B, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Concept of disposable duodenoscope: at what cost? Gut. 2019;68(11):1915-1917. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318227

- US Food and Drug Administration. Infections associated with reprocessed duodenoscopes. Updated June 30, 2022. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/reprocessing-reusable-medical-devices/infections-associated-reprocessed-duodenoscopes

- Heuvelmans M, Wunderink HF, van der Mei HC, Monkelbaan JF. A narrative review on current duodenoscope reprocessing techniques and novel developments. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10(1):171. doi:10.1186/s13756-021-01037-z

- US Food and Drug Administration. Use duodenoscopes with innovative designs to enhance safety: FDA safety communication. Updated June 30, 2022. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/use-duodenoscopes-innovative-designs-enhance-safety-fda-safety-communication

- Pass W. Weighing the pros and cons of disposable duodenoscopes. MDedge News. Published May 19, 2021. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.mdedge.com/gihepnews/article/240339/endoscopy

- Le NNT, Hernandez L, Vakil N, Guda N, Patnode C, Jolliet O. Environmental and health outcomes of single-use versus reusable duodenoscopes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;S0016-5107(22)01765-5. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2022.06.014

- Ridtitid W, Thummongkol T, Chatsuwan T, et al. Bacterial contamination and organic residue after reprocessing in duodenoscopes with disposable distal caps compared to duodenoscopes with fixed distal caps: a randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;S0016-5107(22)01766-7. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2022.06.015

- Naryzhny I, Silas D, Chi K. Impact of ethylene oxide gas sterilization of duodenoscopes after a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae outbreak. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(2):259-262. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.01.055

- Muthusamy VR, Bruno MJ, Kozarek RA, et al. Clinical evaluation of a single-use duodenoscope for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):2108-2117.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.10.052

- Bang JY, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Equivalent performance of single-use and reusable duodenoscopes in a randomised trial. Gut. 2021;70(5):838-844. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321836

- Bhatt A, Thosani N, Patil P. ID: 3527241. Ergonomic study analyzing differences in endoscopy styles between female and male gastroenterologists [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(6 Suppl):AB42-AB43. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2021.03.148

- Trindade AJ, Copland A, Bhatt A, et al. Single-use duodenoscopes and duodenoscopes with disposable end caps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):997-1005. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.12.033

- Namburar S, von Renteln D, Damianos J, et al. Estimating the environmental impact of disposable endoscopic equipment and endoscopes. Gut. 2022;71(7):1326-1331. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324729

- Kröner PT, Bilal M, Samuel R, et al. Use of ERCP in the United States over the past decade. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8(6):E761-E769. doi:10.1055/a-1134-4873

- Patel K, Lad M, Siddiqui E, Ahlawat S. National trends in reimbursement and utilization of advanced endoscopic procedures in the Medicare population [abstract S0904]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:S465-S466. doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000705664.35696.6e

- Bang JY, Sutton B, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Concept of disposable duodenoscope: at what cost? Gut. 2019;68(11):1915-1917. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318227

- US Food and Drug Administration. Infections associated with reprocessed duodenoscopes. Updated June 30, 2022. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/reprocessing-reusable-medical-devices/infections-associated-reprocessed-duodenoscopes

- Heuvelmans M, Wunderink HF, van der Mei HC, Monkelbaan JF. A narrative review on current duodenoscope reprocessing techniques and novel developments. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10(1):171. doi:10.1186/s13756-021-01037-z

- US Food and Drug Administration. Use duodenoscopes with innovative designs to enhance safety: FDA safety communication. Updated June 30, 2022. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/use-duodenoscopes-innovative-designs-enhance-safety-fda-safety-communication

- Pass W. Weighing the pros and cons of disposable duodenoscopes. MDedge News. Published May 19, 2021. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.mdedge.com/gihepnews/article/240339/endoscopy

- Le NNT, Hernandez L, Vakil N, Guda N, Patnode C, Jolliet O. Environmental and health outcomes of single-use versus reusable duodenoscopes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;S0016-5107(22)01765-5. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2022.06.014

- Ridtitid W, Thummongkol T, Chatsuwan T, et al. Bacterial contamination and organic residue after reprocessing in duodenoscopes with disposable distal caps compared to duodenoscopes with fixed distal caps: a randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;S0016-5107(22)01766-7. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2022.06.015

- Naryzhny I, Silas D, Chi K. Impact of ethylene oxide gas sterilization of duodenoscopes after a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae outbreak. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(2):259-262. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.01.055

- Muthusamy VR, Bruno MJ, Kozarek RA, et al. Clinical evaluation of a single-use duodenoscope for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):2108-2117.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.10.052

- Bang JY, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Equivalent performance of single-use and reusable duodenoscopes in a randomised trial. Gut. 2021;70(5):838-844. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321836

- Bhatt A, Thosani N, Patil P. ID: 3527241. Ergonomic study analyzing differences in endoscopy styles between female and male gastroenterologists [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(6 Suppl):AB42-AB43. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2021.03.148

- Trindade AJ, Copland A, Bhatt A, et al. Single-use duodenoscopes and duodenoscopes with disposable end caps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):997-1005. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.12.033

- Namburar S, von Renteln D, Damianos J, et al. Estimating the environmental impact of disposable endoscopic equipment and endoscopes. Gut. 2022;71(7):1326-1331. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324729

- Kröner PT, Bilal M, Samuel R, et al. Use of ERCP in the United States over the past decade. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8(6):E761-E769. doi:10.1055/a-1134-4873

- Patel K, Lad M, Siddiqui E, Ahlawat S. National trends in reimbursement and utilization of advanced endoscopic procedures in the Medicare population [abstract S0904]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:S465-S466. doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000705664.35696.6e

- Bang JY, Sutton B, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Concept of disposable duodenoscope: at what cost? Gut. 2019;68(11):1915-1917. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318227

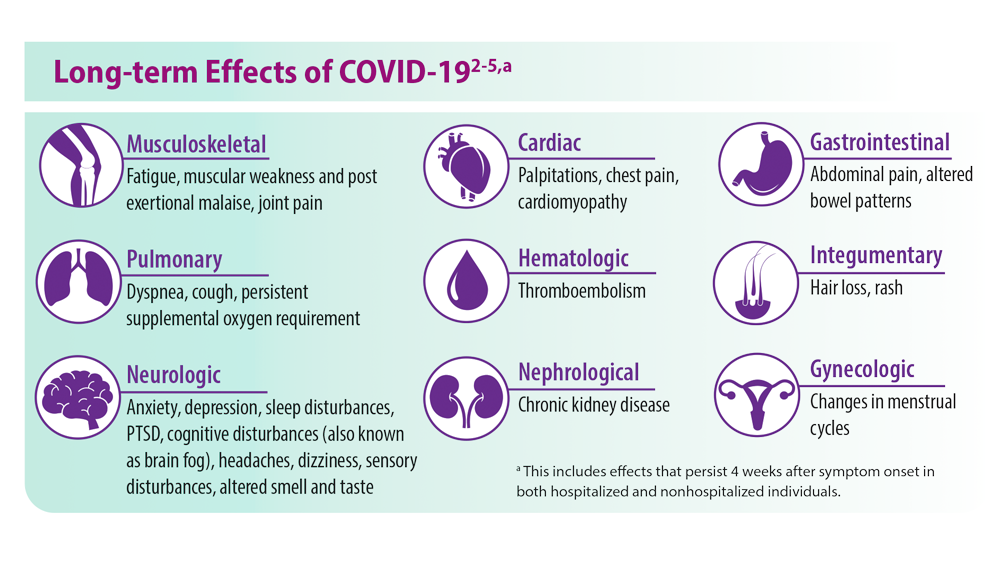

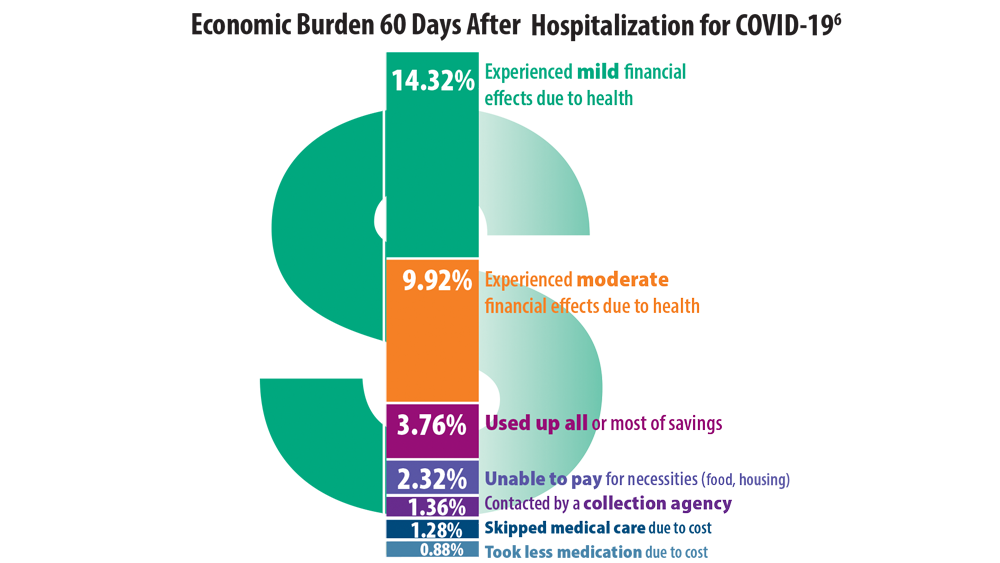

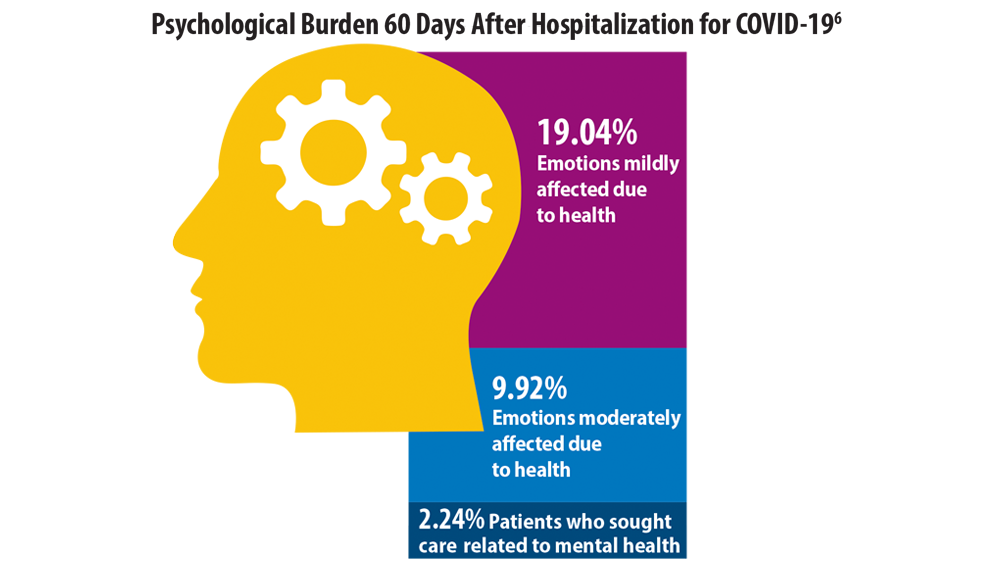

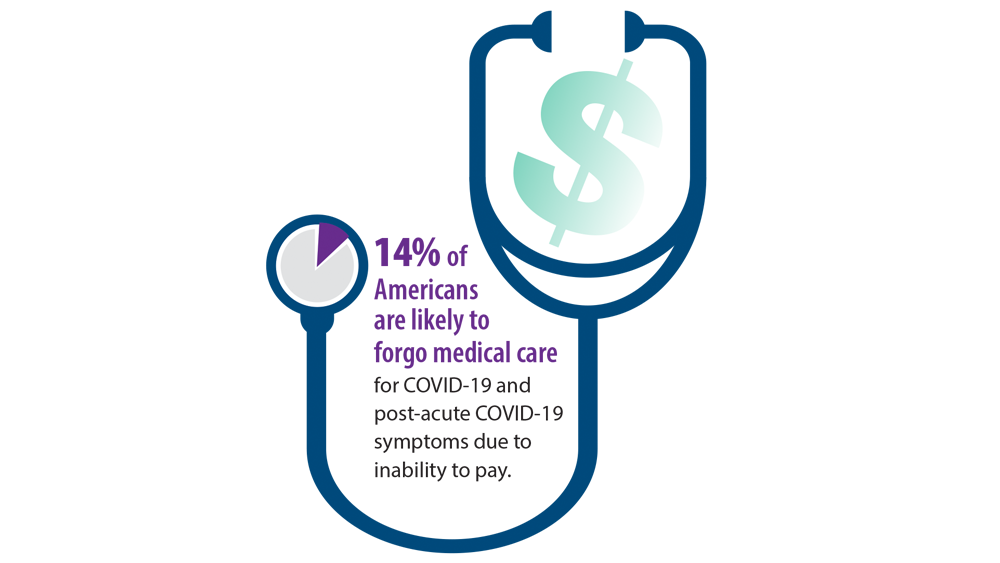

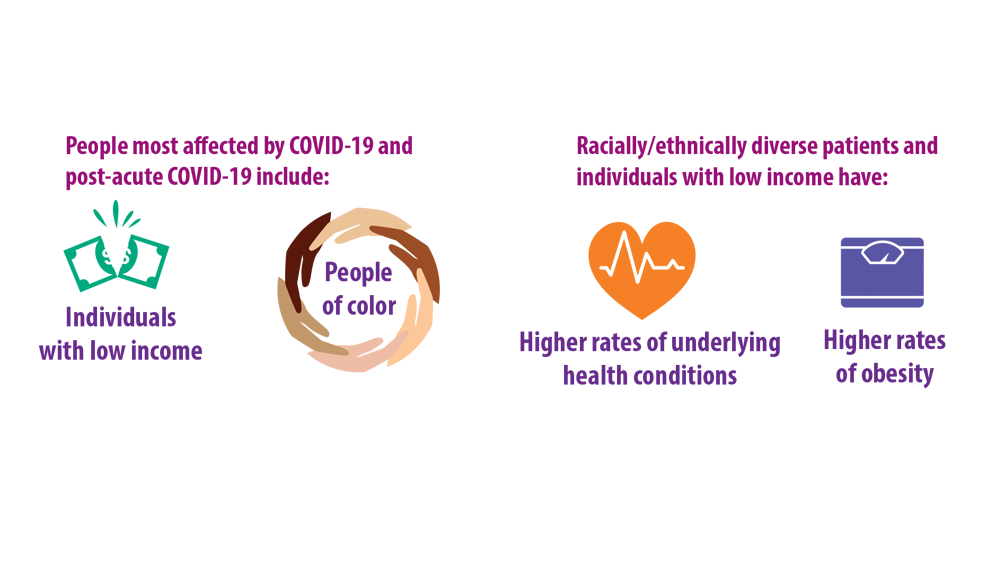

Post-COVID-19 Effects

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. Updated August 19, 2022. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):601-615. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long COVID or post-COVID conditions. Updated May 5, 2022. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-termeffects/index.html

- Ghazanfar H, Kandhi S, Shin D, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the gastrointestinal tract: a clinical review. Cureus. 2022;14(3):e23333. doi:10.7759/cureus.23333

- Khan SM, Shilen A, Heslin KM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent changes in the menstrual cycle among participants in the Arizona CoVHORT study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2):270-273. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.09.016

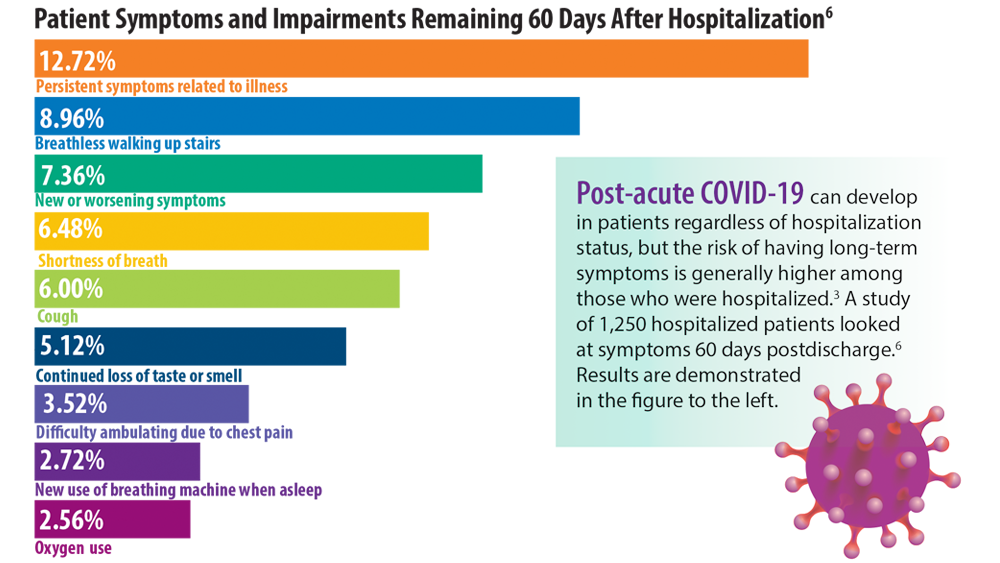

- Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(4):576-578. doi:10.7326/M20-5661

- Jiang DH, McCoy RG. Planning for the post-COVID syndrome: how payers can mitigate long-term complications of the pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3036-3039. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06042-3

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. Updated August 19, 2022. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):601-615. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long COVID or post-COVID conditions. Updated May 5, 2022. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-termeffects/index.html

- Ghazanfar H, Kandhi S, Shin D, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the gastrointestinal tract: a clinical review. Cureus. 2022;14(3):e23333. doi:10.7759/cureus.23333

- Khan SM, Shilen A, Heslin KM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent changes in the menstrual cycle among participants in the Arizona CoVHORT study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2):270-273. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.09.016

- Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(4):576-578. doi:10.7326/M20-5661

- Jiang DH, McCoy RG. Planning for the post-COVID syndrome: how payers can mitigate long-term complications of the pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3036-3039. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06042-3

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. Updated August 19, 2022. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):601-615. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long COVID or post-COVID conditions. Updated May 5, 2022. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-termeffects/index.html

- Ghazanfar H, Kandhi S, Shin D, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the gastrointestinal tract: a clinical review. Cureus. 2022;14(3):e23333. doi:10.7759/cureus.23333

- Khan SM, Shilen A, Heslin KM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent changes in the menstrual cycle among participants in the Arizona CoVHORT study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2):270-273. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.09.016

- Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(4):576-578. doi:10.7326/M20-5661

- Jiang DH, McCoy RG. Planning for the post-COVID syndrome: how payers can mitigate long-term complications of the pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3036-3039. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06042-3

Painful and Pruritic Eruptions on the Entire Body

The Diagnosis: IgA Pemphigus

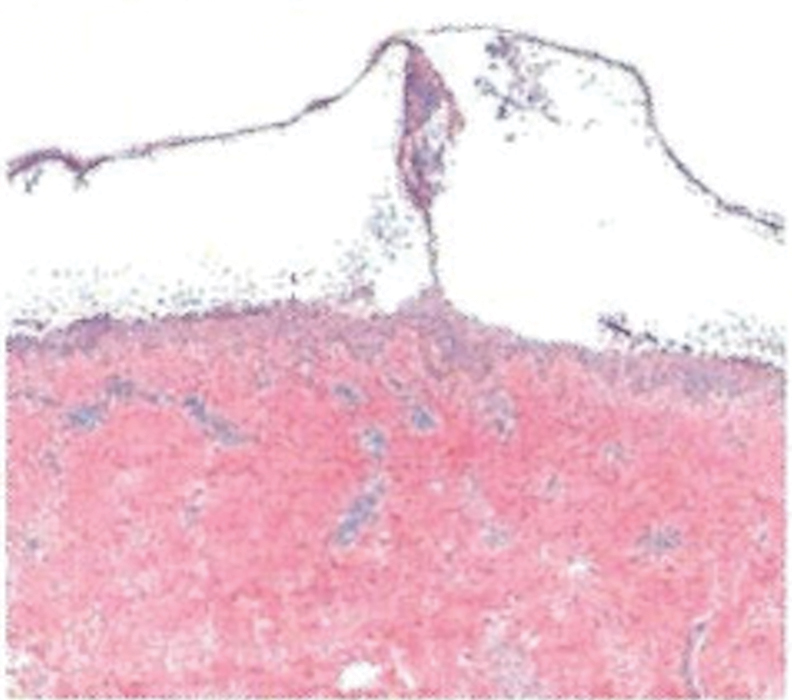

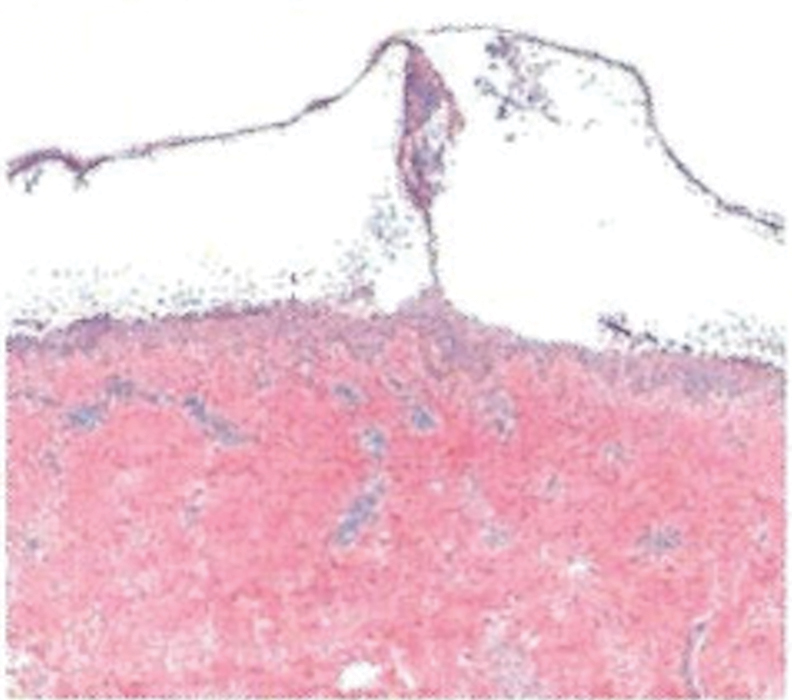

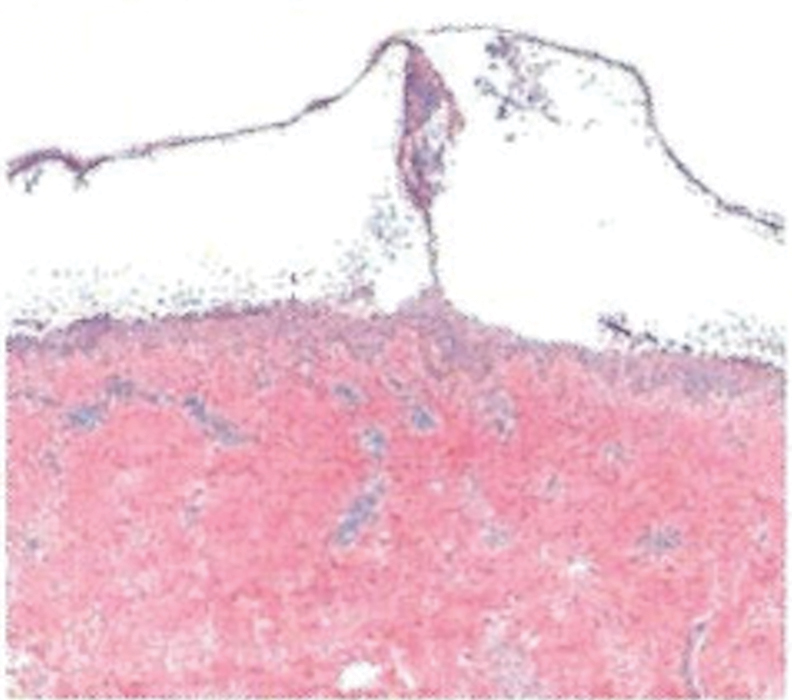

Histopathology revealed a neutrophilic pustule and vesicle formation underlying the corneal layer (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed weak positive staining for IgA within the intercellular keratinocyte in the epithelial compartment and a negative pattern with IgG, IgM, C3, and fibrinogen. The patient received a 40-mg intralesional triamcinolone injection and was placed on an oral prednisone 50-mg taper within 5 days. The plaques, bullae, and pustules began to resolve, but the lesions returned 1 day later. Oral prednisone 10 mg daily was initiated for 1 month, which resulted in full resolution of the lesions.

IgA pemphigus is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the occurrence of painful pruritic blisters caused by circulating IgA antibodies, which react against keratinocyte cellular components responsible for mediating cell-to-cell adherence.1 The etiology of IgA pemphigus presently remains elusive, though it has been reported to occur concomitantly with several chronic malignancies and inflammatory conditions. Although its etiology is unknown, IgA pemphigus most commonly is treated with oral dapsone and corticosteroids.2

IgA pemphigus can be divided into 2 primary subtypes: subcorneal pustular dermatosis and intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis.1,3 The former is characterized by intercellular deposition of IgA that reacts to the glycoprotein desmocollin-1 in the upper layer of the epidermis. Intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis is distinguished by the presence of autoantibodies against the desmoglein members of the cadherin superfamily of proteins. Additionally, unlike subcorneal pustular dermatosis, intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis autoantibody reactivity occurs in the lower epidermis.4

The differential includes dermatitis herpetiformis, which is commonly seen on the elbows, knees, and buttocks, with DIF showing IgA deposition at the dermal papillae. Pemphigus foliaceus is distributed on the scalp, face, and trunk, with DIF showing IgG intercellular deposition. Pustular psoriasis presents as erythematous sterile pustules in a more localized annular pattern. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) has similar clinical and histological findings to IgA pemphigus; however, DIF is negative.

- Kridin K, Patel PM, Jones VA, et al. IgA pemphigus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1386-1392.

- Moreno ACL, Santi CG, Gabbi TVB, et al. IgA pemphigus: case series with emphasis on therapeutic response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:200-201.

- Niimi Y, Kawana S, Kusunoki T. IgA pemphigus: a case report and its characteristic clinical features compared with subcorneal pustular dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:546-549.

- Aslanova M, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. IgA pemphigus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

The Diagnosis: IgA Pemphigus

Histopathology revealed a neutrophilic pustule and vesicle formation underlying the corneal layer (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed weak positive staining for IgA within the intercellular keratinocyte in the epithelial compartment and a negative pattern with IgG, IgM, C3, and fibrinogen. The patient received a 40-mg intralesional triamcinolone injection and was placed on an oral prednisone 50-mg taper within 5 days. The plaques, bullae, and pustules began to resolve, but the lesions returned 1 day later. Oral prednisone 10 mg daily was initiated for 1 month, which resulted in full resolution of the lesions.

IgA pemphigus is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the occurrence of painful pruritic blisters caused by circulating IgA antibodies, which react against keratinocyte cellular components responsible for mediating cell-to-cell adherence.1 The etiology of IgA pemphigus presently remains elusive, though it has been reported to occur concomitantly with several chronic malignancies and inflammatory conditions. Although its etiology is unknown, IgA pemphigus most commonly is treated with oral dapsone and corticosteroids.2

IgA pemphigus can be divided into 2 primary subtypes: subcorneal pustular dermatosis and intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis.1,3 The former is characterized by intercellular deposition of IgA that reacts to the glycoprotein desmocollin-1 in the upper layer of the epidermis. Intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis is distinguished by the presence of autoantibodies against the desmoglein members of the cadherin superfamily of proteins. Additionally, unlike subcorneal pustular dermatosis, intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis autoantibody reactivity occurs in the lower epidermis.4

The differential includes dermatitis herpetiformis, which is commonly seen on the elbows, knees, and buttocks, with DIF showing IgA deposition at the dermal papillae. Pemphigus foliaceus is distributed on the scalp, face, and trunk, with DIF showing IgG intercellular deposition. Pustular psoriasis presents as erythematous sterile pustules in a more localized annular pattern. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) has similar clinical and histological findings to IgA pemphigus; however, DIF is negative.

The Diagnosis: IgA Pemphigus

Histopathology revealed a neutrophilic pustule and vesicle formation underlying the corneal layer (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed weak positive staining for IgA within the intercellular keratinocyte in the epithelial compartment and a negative pattern with IgG, IgM, C3, and fibrinogen. The patient received a 40-mg intralesional triamcinolone injection and was placed on an oral prednisone 50-mg taper within 5 days. The plaques, bullae, and pustules began to resolve, but the lesions returned 1 day later. Oral prednisone 10 mg daily was initiated for 1 month, which resulted in full resolution of the lesions.

IgA pemphigus is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the occurrence of painful pruritic blisters caused by circulating IgA antibodies, which react against keratinocyte cellular components responsible for mediating cell-to-cell adherence.1 The etiology of IgA pemphigus presently remains elusive, though it has been reported to occur concomitantly with several chronic malignancies and inflammatory conditions. Although its etiology is unknown, IgA pemphigus most commonly is treated with oral dapsone and corticosteroids.2

IgA pemphigus can be divided into 2 primary subtypes: subcorneal pustular dermatosis and intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis.1,3 The former is characterized by intercellular deposition of IgA that reacts to the glycoprotein desmocollin-1 in the upper layer of the epidermis. Intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis is distinguished by the presence of autoantibodies against the desmoglein members of the cadherin superfamily of proteins. Additionally, unlike subcorneal pustular dermatosis, intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis autoantibody reactivity occurs in the lower epidermis.4

The differential includes dermatitis herpetiformis, which is commonly seen on the elbows, knees, and buttocks, with DIF showing IgA deposition at the dermal papillae. Pemphigus foliaceus is distributed on the scalp, face, and trunk, with DIF showing IgG intercellular deposition. Pustular psoriasis presents as erythematous sterile pustules in a more localized annular pattern. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) has similar clinical and histological findings to IgA pemphigus; however, DIF is negative.

- Kridin K, Patel PM, Jones VA, et al. IgA pemphigus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1386-1392.

- Moreno ACL, Santi CG, Gabbi TVB, et al. IgA pemphigus: case series with emphasis on therapeutic response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:200-201.

- Niimi Y, Kawana S, Kusunoki T. IgA pemphigus: a case report and its characteristic clinical features compared with subcorneal pustular dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:546-549.

- Aslanova M, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. IgA pemphigus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Kridin K, Patel PM, Jones VA, et al. IgA pemphigus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1386-1392.

- Moreno ACL, Santi CG, Gabbi TVB, et al. IgA pemphigus: case series with emphasis on therapeutic response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:200-201.

- Niimi Y, Kawana S, Kusunoki T. IgA pemphigus: a case report and its characteristic clinical features compared with subcorneal pustular dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:546-549.

- Aslanova M, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. IgA pemphigus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

A 36-year-old man presented with painful tender blisters and rashes on the entire body, including the ears and tongue. The rash began as a few pinpointed red dots on the abdomen, which subsequently increased in size and spread over the last week. He initially felt red and flushed and noticed new lesions appearing throughout the day. He did not attempt any specific treatment for these lesions. The patient tested positive for COVID-19 four months prior to the skin eruption. He denied systemic symptoms, smoking, or recent travel. He had no history of skin cancer, skin disorders, HIV, or hepatitis. He had no known medication allergies. Physical examination revealed multiple disseminated pustules on the ears, superficial ulcerations on the tongue, and blisters on the right lip. Few lesions were tender to the touch and drained clear fluid. Bacterial, viral, HIV, herpes, and rapid plasma reagin culture and laboratory screenings were negative. He was started on valaciclovir and cephalexin; however, no improvement was noticed. Punch biopsies were taken from the blisters on the chest and perilesional area.

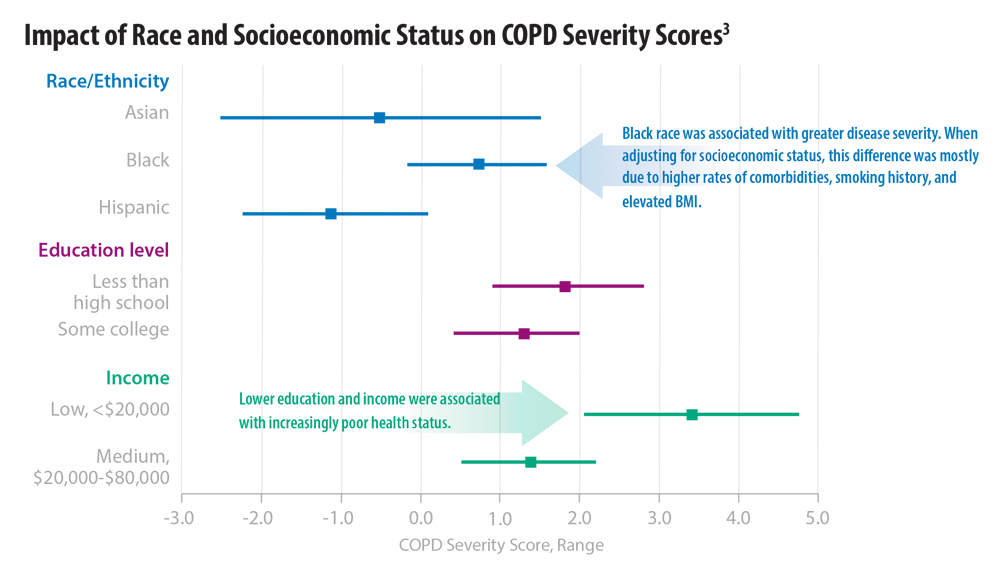

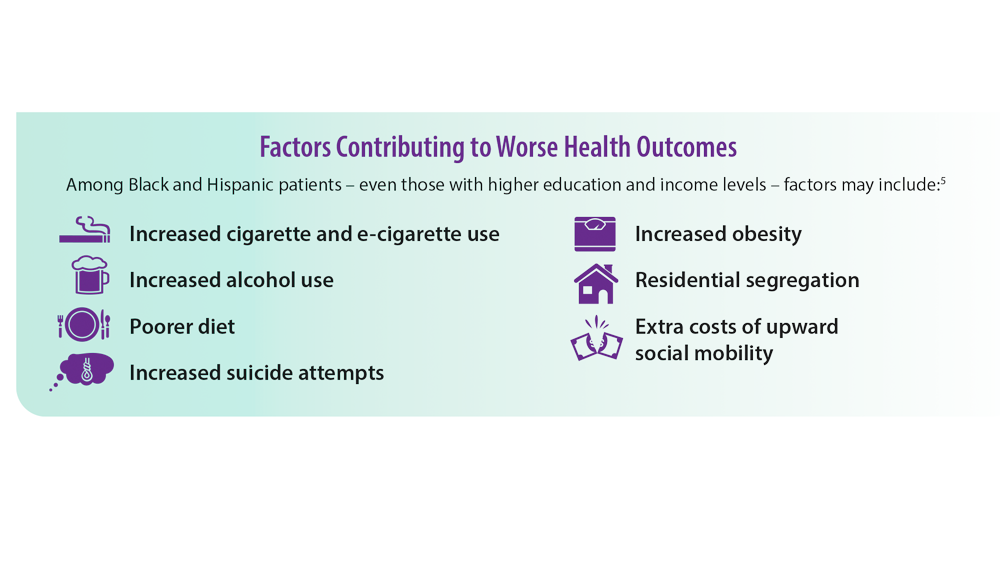

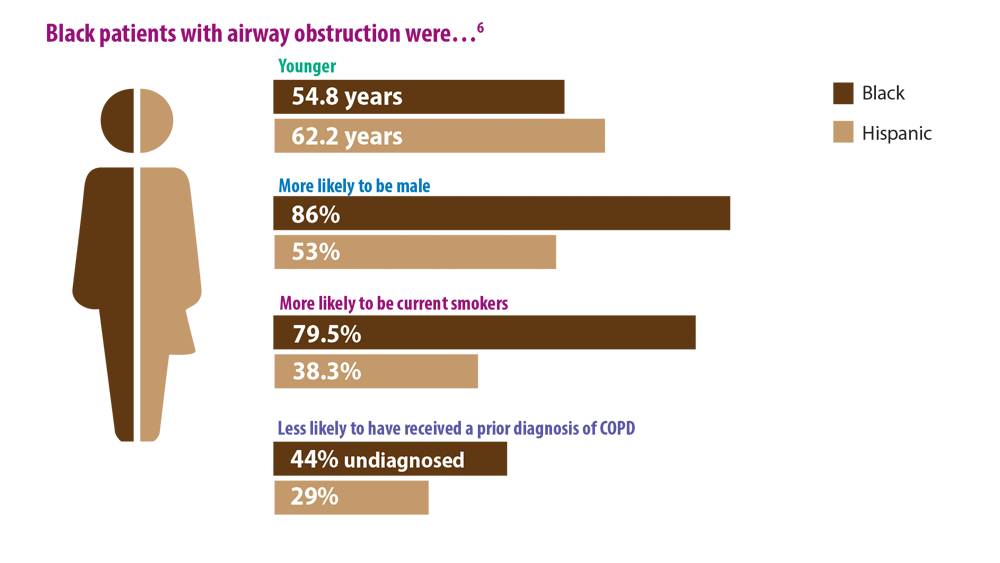

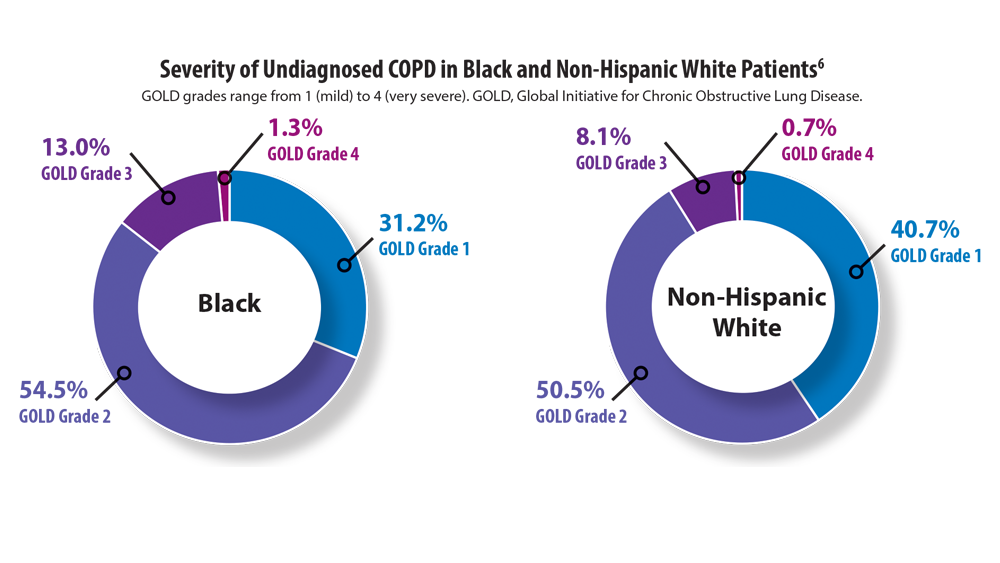

COPD Characteristics and Health Disparities

1. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 22, 2021. Accessed May 30, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/copd/index.html

2. Stellefson M, Wang MQ, Kinder C. Racial disparities in health risk indicators reported by Alabamians diagnosed with COPD. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9662. doi:10.3390/ ijerph18189662

3. Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Omachi TA, et al. Socioeconomic status, race and COPD health outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(1):26-34. doi:10.1136/jech.2009.089722

4. Croft JB, Wheaton AG, Liu Y, et al. Urban-rural county and state differences in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(7):205- 211. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6707a1

5. Assari S, Chalian H, Bazargan M. Race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and chronic lung disease in the U.S. Res Health Sci. 2020;5(1):48-63. doi:10.22158/rhs.v5n1p48

6. Mamary AJ, Stewart JI, Kinney GL, et al. Race and gender disparities are evident in COPD underdiagnoses across all severities of measured airflow obstruction. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;5(3):177-184. doi:10.15326/jcopdf.5.3.2017.0145

7. Woo H, Brigham EP, Allbright K, et al. Racial segregation and respiratory outcomes among urban black residents with and at risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(5):536-545. doi:10.1164/rccm.202009- 3721OC

8. Hosseini M, Almasi-Hashiani A, Sepidarkish M, Maroufizadeh S. Global prevalence of asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):229. doi:10.1186/s12931-019-1198-4

9. Han MK, Agusti A, Celli BR, et al. From GOLD 0 to pre-COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(4):414-423. doi:10.1164/ rccm.202008-3328PP

1. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 22, 2021. Accessed May 30, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/copd/index.html

2. Stellefson M, Wang MQ, Kinder C. Racial disparities in health risk indicators reported by Alabamians diagnosed with COPD. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9662. doi:10.3390/ ijerph18189662

3. Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Omachi TA, et al. Socioeconomic status, race and COPD health outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(1):26-34. doi:10.1136/jech.2009.089722

4. Croft JB, Wheaton AG, Liu Y, et al. Urban-rural county and state differences in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(7):205- 211. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6707a1

5. Assari S, Chalian H, Bazargan M. Race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and chronic lung disease in the U.S. Res Health Sci. 2020;5(1):48-63. doi:10.22158/rhs.v5n1p48

6. Mamary AJ, Stewart JI, Kinney GL, et al. Race and gender disparities are evident in COPD underdiagnoses across all severities of measured airflow obstruction. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;5(3):177-184. doi:10.15326/jcopdf.5.3.2017.0145

7. Woo H, Brigham EP, Allbright K, et al. Racial segregation and respiratory outcomes among urban black residents with and at risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(5):536-545. doi:10.1164/rccm.202009- 3721OC

8. Hosseini M, Almasi-Hashiani A, Sepidarkish M, Maroufizadeh S. Global prevalence of asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):229. doi:10.1186/s12931-019-1198-4

9. Han MK, Agusti A, Celli BR, et al. From GOLD 0 to pre-COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(4):414-423. doi:10.1164/ rccm.202008-3328PP

1. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 22, 2021. Accessed May 30, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/copd/index.html

2. Stellefson M, Wang MQ, Kinder C. Racial disparities in health risk indicators reported by Alabamians diagnosed with COPD. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9662. doi:10.3390/ ijerph18189662

3. Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Omachi TA, et al. Socioeconomic status, race and COPD health outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(1):26-34. doi:10.1136/jech.2009.089722

4. Croft JB, Wheaton AG, Liu Y, et al. Urban-rural county and state differences in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(7):205- 211. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6707a1

5. Assari S, Chalian H, Bazargan M. Race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and chronic lung disease in the U.S. Res Health Sci. 2020;5(1):48-63. doi:10.22158/rhs.v5n1p48

6. Mamary AJ, Stewart JI, Kinney GL, et al. Race and gender disparities are evident in COPD underdiagnoses across all severities of measured airflow obstruction. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;5(3):177-184. doi:10.15326/jcopdf.5.3.2017.0145

7. Woo H, Brigham EP, Allbright K, et al. Racial segregation and respiratory outcomes among urban black residents with and at risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(5):536-545. doi:10.1164/rccm.202009- 3721OC

8. Hosseini M, Almasi-Hashiani A, Sepidarkish M, Maroufizadeh S. Global prevalence of asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):229. doi:10.1186/s12931-019-1198-4

9. Han MK, Agusti A, Celli BR, et al. From GOLD 0 to pre-COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(4):414-423. doi:10.1164/ rccm.202008-3328PP

Early Onset Colorectal Cancer: Trends in Incidence and Screening

- Nfonsam VN, Jecius HC, Janda J, et al. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) promotes cell proliferation in early-onset colon cancer tumorigenesis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(9):3992-3998. doi:10.1007/s00464-019-07185-z

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8):djw322. doi:10.1093/jnci/djw322

- Loomans-Kropp HA, Umar A. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in young adults. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;2019:9841295. doi:10.1155/2019/9841295

- Gausman V, Dornblaser D, Anand S, et al. Risk factors associated with early-onset colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(12):2752-2759.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.10.009

- Use of colorectal cancer screening tests. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 3, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/use-screening-tests-BRFSS.htm

- Lee JK, Lam AY, Jensen CD, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fecal immunochemical testing, colonoscopy services, and colorectal neoplasia detection in a large United States community-based population. Gastroenterology. 2022;S0016-5085(22)00503-0. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.014

- Zhao G, Li H, Yang Z, et al. Multiplex methylated DNA testing in plasma with high sensitivity and specificity for colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Med. 2019;8:5619-5628. doi:10.1002/cam4.2475

- Abualkhair WH, Zhou M, Ahnen D, Yu Q, Wu XC, Karlitz JJ. Trends in incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer in the United States among those approaching screening age. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1920407. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20407

- Burnett-Hartman AN, Lee JK, Demb J, Gupta S. An update on the epidemiology, molecular characterization, diagnosis, and screening strategies for early-onset colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(4):1041-1049. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.068

- Gu J, Li Y, Yu J, et al. A risk scoring system to predict the individual incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):122. doi:10.1186/s12885-022-09238-4

- Lou S, Shaukat A. Noninvasive strategies for colorectal cancer screening: opportunities and limitations. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37(1):44-51. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000688

- Fecal immunochemical test (FIT). MedlinePlus. Updated July 1, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000704.htm

- Colorectal cancer screening tests. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 17, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/basic_info/screening/tests.htm

- Nfonsam VN, Jecius HC, Janda J, et al. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) promotes cell proliferation in early-onset colon cancer tumorigenesis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(9):3992-3998. doi:10.1007/s00464-019-07185-z

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8):djw322. doi:10.1093/jnci/djw322

- Loomans-Kropp HA, Umar A. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in young adults. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;2019:9841295. doi:10.1155/2019/9841295

- Gausman V, Dornblaser D, Anand S, et al. Risk factors associated with early-onset colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(12):2752-2759.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.10.009

- Use of colorectal cancer screening tests. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 3, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/use-screening-tests-BRFSS.htm

- Lee JK, Lam AY, Jensen CD, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fecal immunochemical testing, colonoscopy services, and colorectal neoplasia detection in a large United States community-based population. Gastroenterology. 2022;S0016-5085(22)00503-0. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.014

- Zhao G, Li H, Yang Z, et al. Multiplex methylated DNA testing in plasma with high sensitivity and specificity for colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Med. 2019;8:5619-5628. doi:10.1002/cam4.2475

- Abualkhair WH, Zhou M, Ahnen D, Yu Q, Wu XC, Karlitz JJ. Trends in incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer in the United States among those approaching screening age. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1920407. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20407

- Burnett-Hartman AN, Lee JK, Demb J, Gupta S. An update on the epidemiology, molecular characterization, diagnosis, and screening strategies for early-onset colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(4):1041-1049. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.068

- Gu J, Li Y, Yu J, et al. A risk scoring system to predict the individual incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):122. doi:10.1186/s12885-022-09238-4

- Lou S, Shaukat A. Noninvasive strategies for colorectal cancer screening: opportunities and limitations. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37(1):44-51. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000688

- Fecal immunochemical test (FIT). MedlinePlus. Updated July 1, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000704.htm

- Colorectal cancer screening tests. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 17, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/basic_info/screening/tests.htm

- Nfonsam VN, Jecius HC, Janda J, et al. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) promotes cell proliferation in early-onset colon cancer tumorigenesis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(9):3992-3998. doi:10.1007/s00464-019-07185-z

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8):djw322. doi:10.1093/jnci/djw322

- Loomans-Kropp HA, Umar A. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in young adults. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;2019:9841295. doi:10.1155/2019/9841295

- Gausman V, Dornblaser D, Anand S, et al. Risk factors associated with early-onset colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(12):2752-2759.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.10.009

- Use of colorectal cancer screening tests. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 3, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/use-screening-tests-BRFSS.htm

- Lee JK, Lam AY, Jensen CD, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fecal immunochemical testing, colonoscopy services, and colorectal neoplasia detection in a large United States community-based population. Gastroenterology. 2022;S0016-5085(22)00503-0. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.014

- Zhao G, Li H, Yang Z, et al. Multiplex methylated DNA testing in plasma with high sensitivity and specificity for colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Med. 2019;8:5619-5628. doi:10.1002/cam4.2475

- Abualkhair WH, Zhou M, Ahnen D, Yu Q, Wu XC, Karlitz JJ. Trends in incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer in the United States among those approaching screening age. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1920407. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20407

- Burnett-Hartman AN, Lee JK, Demb J, Gupta S. An update on the epidemiology, molecular characterization, diagnosis, and screening strategies for early-onset colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(4):1041-1049. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.068

- Gu J, Li Y, Yu J, et al. A risk scoring system to predict the individual incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):122. doi:10.1186/s12885-022-09238-4

- Lou S, Shaukat A. Noninvasive strategies for colorectal cancer screening: opportunities and limitations. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37(1):44-51. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000688

- Fecal immunochemical test (FIT). MedlinePlus. Updated July 1, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000704.htm

- Colorectal cancer screening tests. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 17, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/basic_info/screening/tests.htm

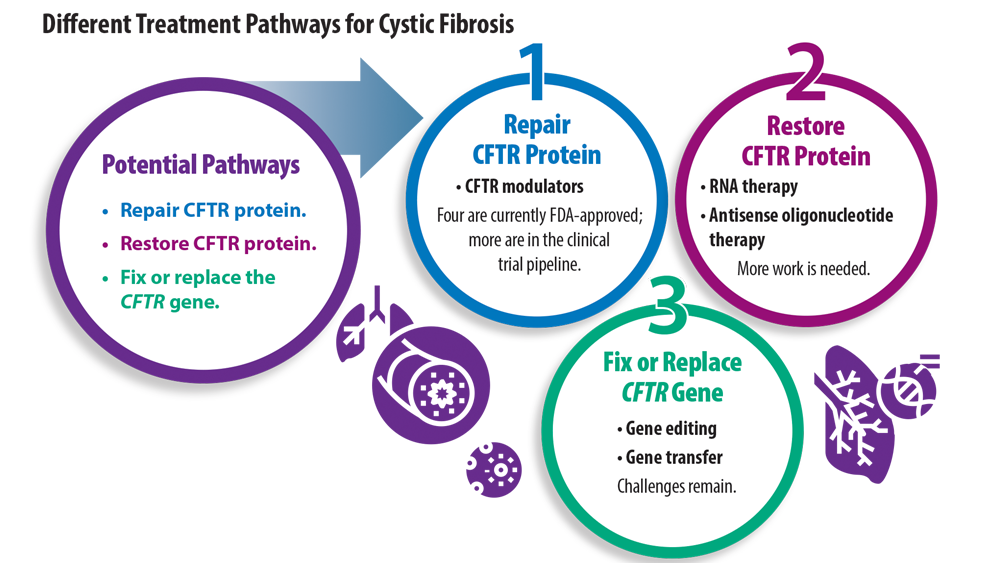

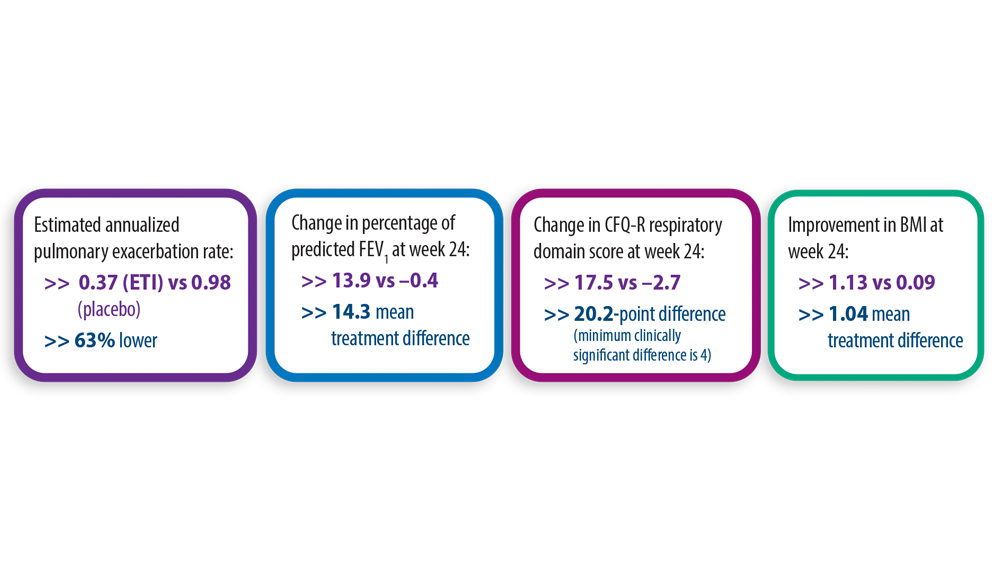

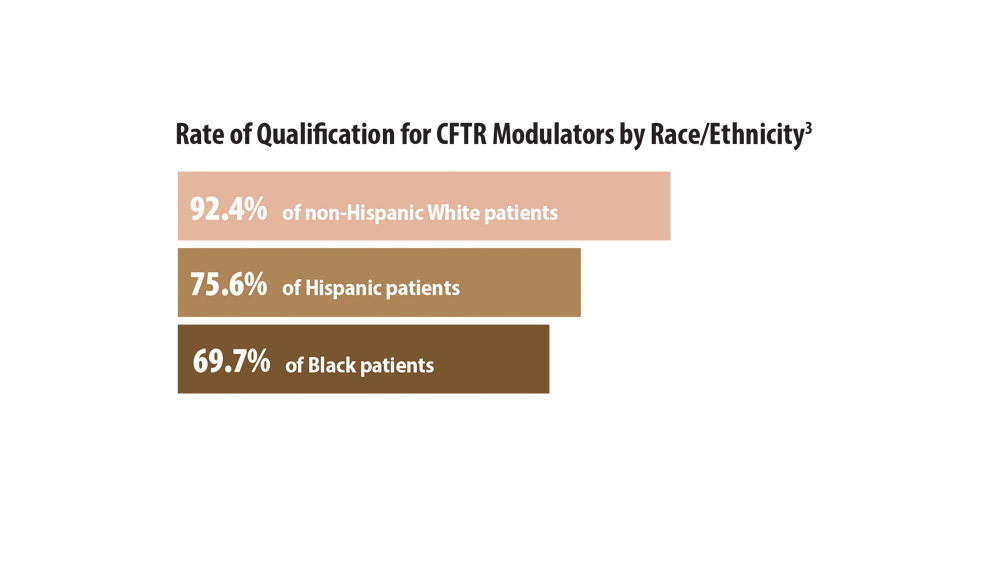

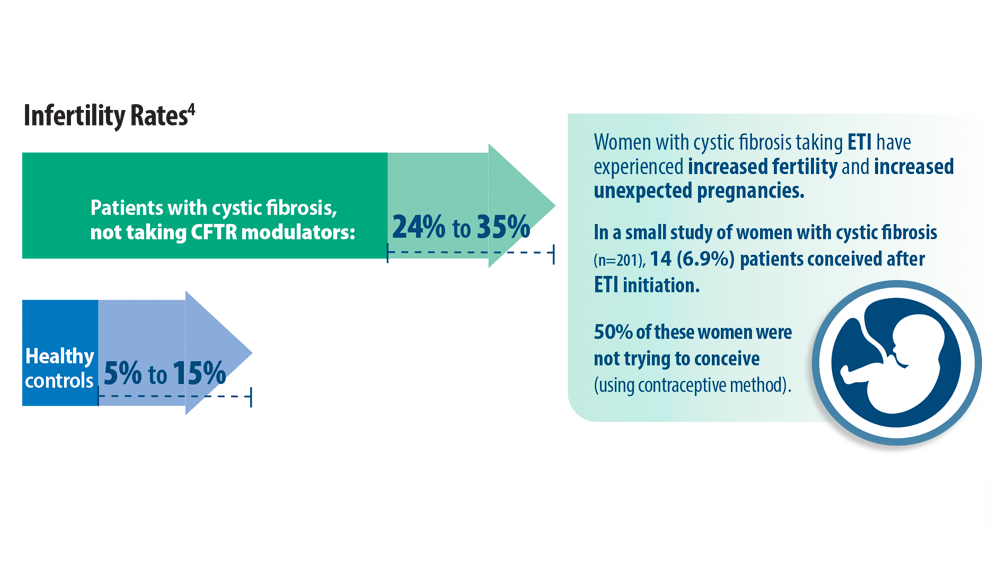

New Treatment Pathways for Cystic Fibrosis

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. What is cystic fibrosis? https://www. cff.org/intro-cf/about-cystic-fibrosis. Accessed June 17, 2022.

- Middleton PG, Mall MA, Dřevínek P, et al. Elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis with a single Phe508del allele. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(19):1809-1819. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908639

- McGarry ME, McColley SA. Cystic fibrosis patients of minority race and ethnicity less likely eligible for CFTR modulators based on CFTR genotype. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(6):1496-1503. doi:10.1002/ppul.25285

- O’Connor KE, Goodwin DL, NeSmith A, et al. Elexacaftor/ tezacaftor/ivacaftor resolves subfertility in females with CF: a two center case series. J Cyst Fibros. 2021;20(3):399-401. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2020.12.011

- Shteinberg M, Taylor-Cousar JL, Durieu I, Cohen-Cymberknoh M. Fertility and Pregnancy in Cystic Fibrosis. Chest. 2021;160(6):2051-2060. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.024

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. What is cystic fibrosis? https://www. cff.org/intro-cf/about-cystic-fibrosis. Accessed June 17, 2022.

- Middleton PG, Mall MA, Dřevínek P, et al. Elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis with a single Phe508del allele. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(19):1809-1819. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908639

- McGarry ME, McColley SA. Cystic fibrosis patients of minority race and ethnicity less likely eligible for CFTR modulators based on CFTR genotype. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(6):1496-1503. doi:10.1002/ppul.25285

- O’Connor KE, Goodwin DL, NeSmith A, et al. Elexacaftor/ tezacaftor/ivacaftor resolves subfertility in females with CF: a two center case series. J Cyst Fibros. 2021;20(3):399-401. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2020.12.011

- Shteinberg M, Taylor-Cousar JL, Durieu I, Cohen-Cymberknoh M. Fertility and Pregnancy in Cystic Fibrosis. Chest. 2021;160(6):2051-2060. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.024

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. What is cystic fibrosis? https://www. cff.org/intro-cf/about-cystic-fibrosis. Accessed June 17, 2022.

- Middleton PG, Mall MA, Dřevínek P, et al. Elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis with a single Phe508del allele. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(19):1809-1819. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908639

- McGarry ME, McColley SA. Cystic fibrosis patients of minority race and ethnicity less likely eligible for CFTR modulators based on CFTR genotype. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(6):1496-1503. doi:10.1002/ppul.25285

- O’Connor KE, Goodwin DL, NeSmith A, et al. Elexacaftor/ tezacaftor/ivacaftor resolves subfertility in females with CF: a two center case series. J Cyst Fibros. 2021;20(3):399-401. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2020.12.011

- Shteinberg M, Taylor-Cousar JL, Durieu I, Cohen-Cymberknoh M. Fertility and Pregnancy in Cystic Fibrosis. Chest. 2021;160(6):2051-2060. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.024

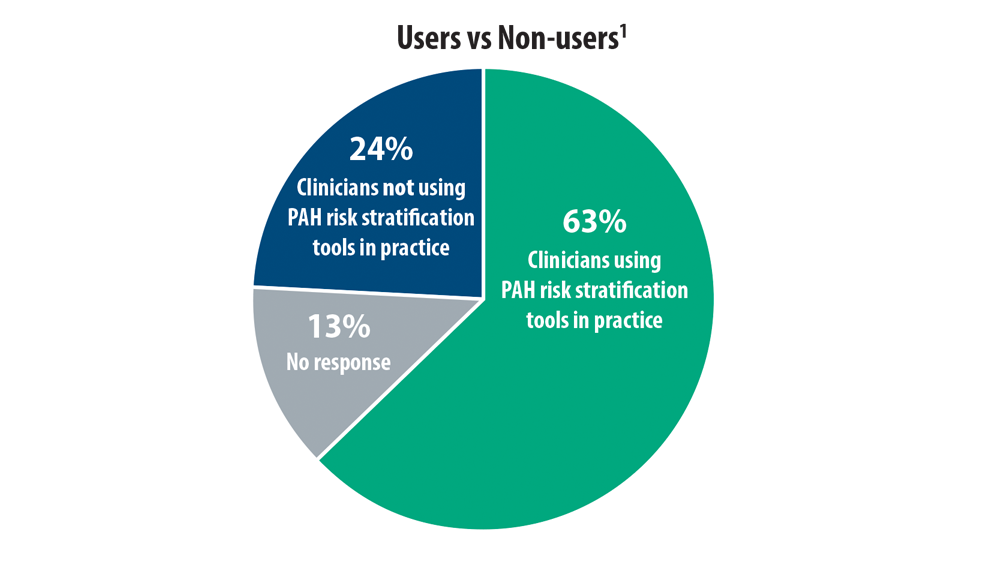

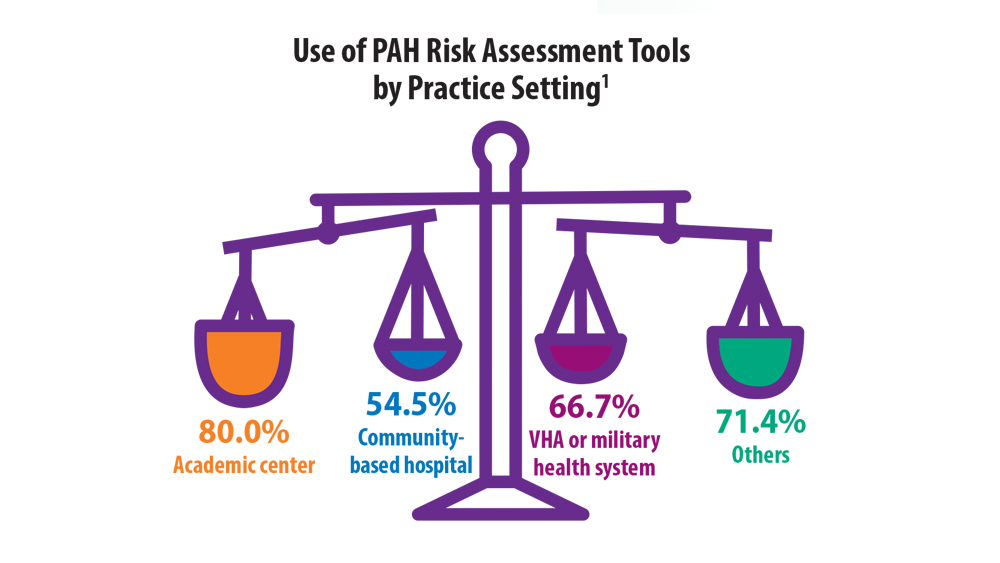

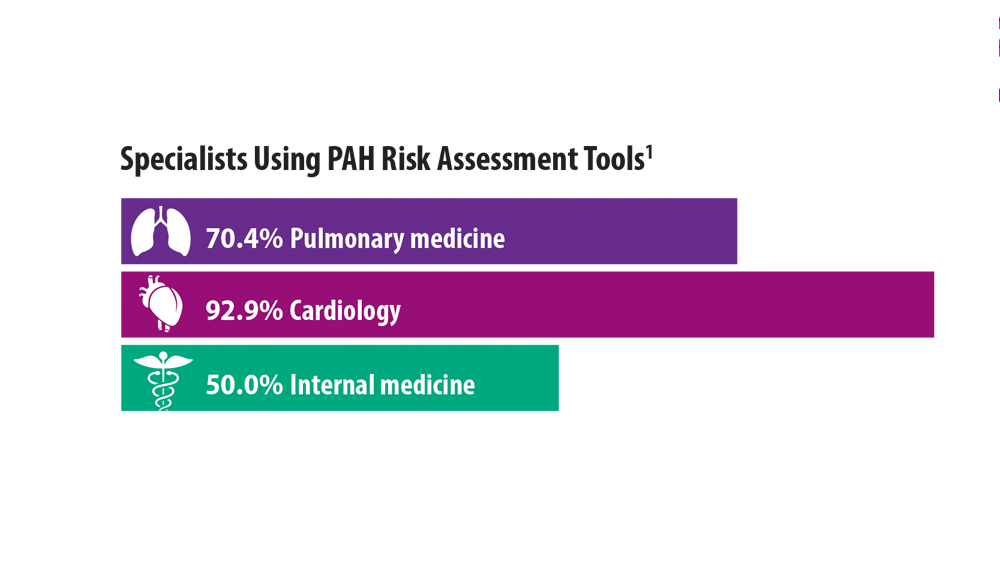

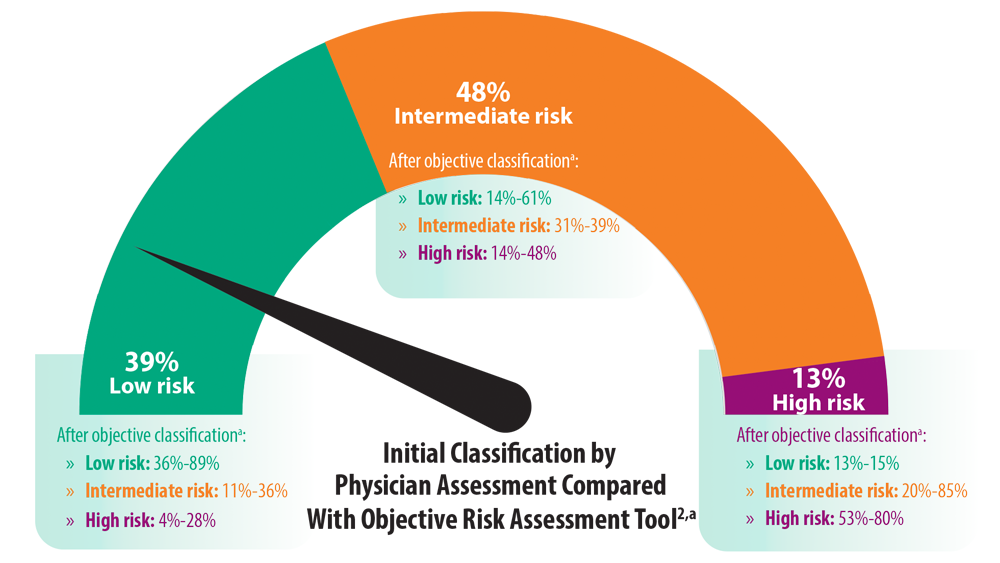

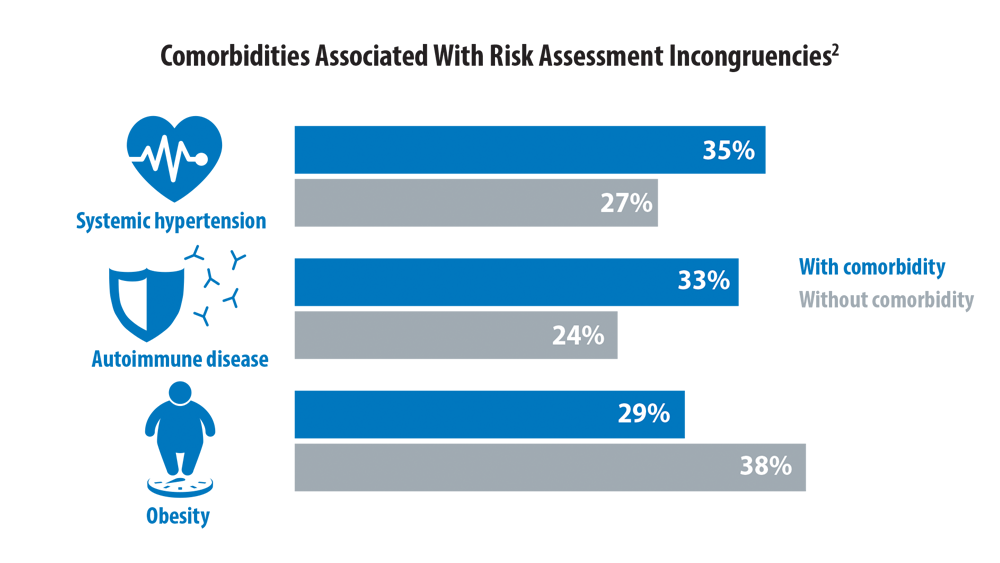

Risk Assessment in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

- Sahay S, Balasubramanian V, Memon H, et al. Utilization of risk assessment tools in management of PAH: a PAH provider survey. Pulm Circ. 2022;12(2):e12057. doi:10.1002/pul2.12057

- Sahay S, Tonelli AR, Selej M, Watson Z, Benza RL. Risk assessment in patients with functional class II pulmonary arterial hypertension: comparison of physician gestalt with ESC/ERS and the REVEAL 2.0 risk score. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241504. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241504

- Galiè N, Channick RN, Frantz RP, et al. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801889. doi:10.1183/13993003.01889-2018

- Boucly A, Weatherald J, Savale L, et al. Risk assessment, prognosis and guideline implementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1700889. doi:10.1183/13993003.00889-2017

- Wilson M, Keeley J, Kingman M, Wang J, Rogers F. Current clinical utilization of risk assessment tools in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a descriptive survey of facilitation strategies, patterns, and barriers to use in the United States. Pulm Circ. 2020;10(3):2045894020950186. doi:10.1177/2045894020950186

- Sahay S, Balasubramanian V, Memon H, et al. Utilization of risk assessment tools in management of PAH: a PAH provider survey. Pulm Circ. 2022;12(2):e12057. doi:10.1002/pul2.12057

- Sahay S, Tonelli AR, Selej M, Watson Z, Benza RL. Risk assessment in patients with functional class II pulmonary arterial hypertension: comparison of physician gestalt with ESC/ERS and the REVEAL 2.0 risk score. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241504. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241504

- Galiè N, Channick RN, Frantz RP, et al. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801889. doi:10.1183/13993003.01889-2018

- Boucly A, Weatherald J, Savale L, et al. Risk assessment, prognosis and guideline implementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1700889. doi:10.1183/13993003.00889-2017

- Wilson M, Keeley J, Kingman M, Wang J, Rogers F. Current clinical utilization of risk assessment tools in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a descriptive survey of facilitation strategies, patterns, and barriers to use in the United States. Pulm Circ. 2020;10(3):2045894020950186. doi:10.1177/2045894020950186

- Sahay S, Balasubramanian V, Memon H, et al. Utilization of risk assessment tools in management of PAH: a PAH provider survey. Pulm Circ. 2022;12(2):e12057. doi:10.1002/pul2.12057

- Sahay S, Tonelli AR, Selej M, Watson Z, Benza RL. Risk assessment in patients with functional class II pulmonary arterial hypertension: comparison of physician gestalt with ESC/ERS and the REVEAL 2.0 risk score. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241504. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241504

- Galiè N, Channick RN, Frantz RP, et al. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801889. doi:10.1183/13993003.01889-2018

- Boucly A, Weatherald J, Savale L, et al. Risk assessment, prognosis and guideline implementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1700889. doi:10.1183/13993003.00889-2017

- Wilson M, Keeley J, Kingman M, Wang J, Rogers F. Current clinical utilization of risk assessment tools in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a descriptive survey of facilitation strategies, patterns, and barriers to use in the United States. Pulm Circ. 2020;10(3):2045894020950186. doi:10.1177/2045894020950186

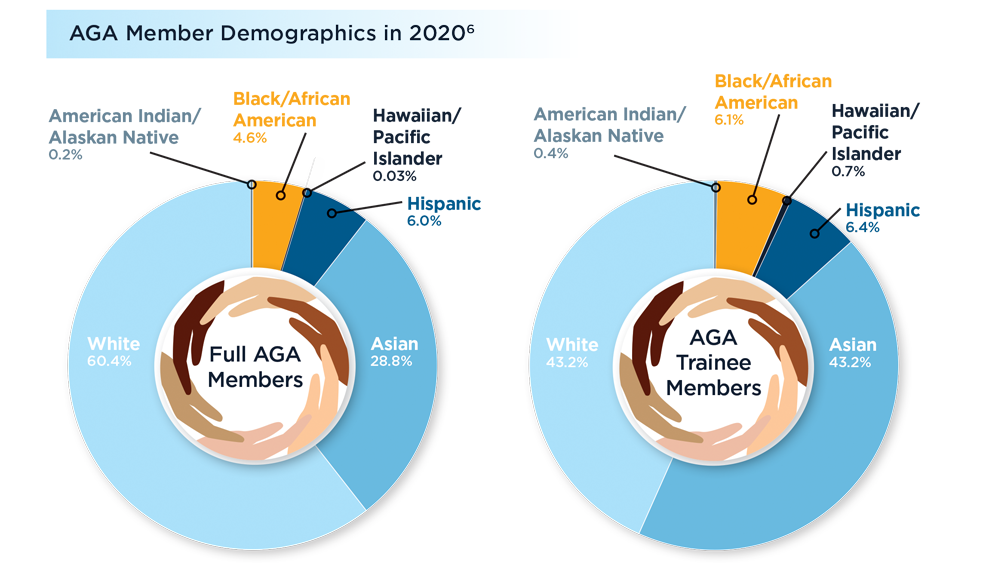

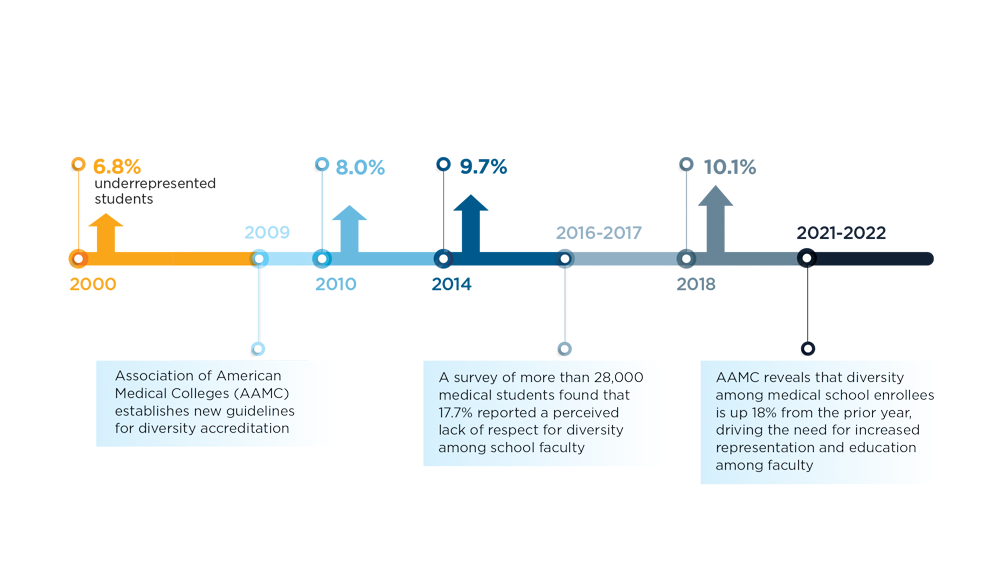

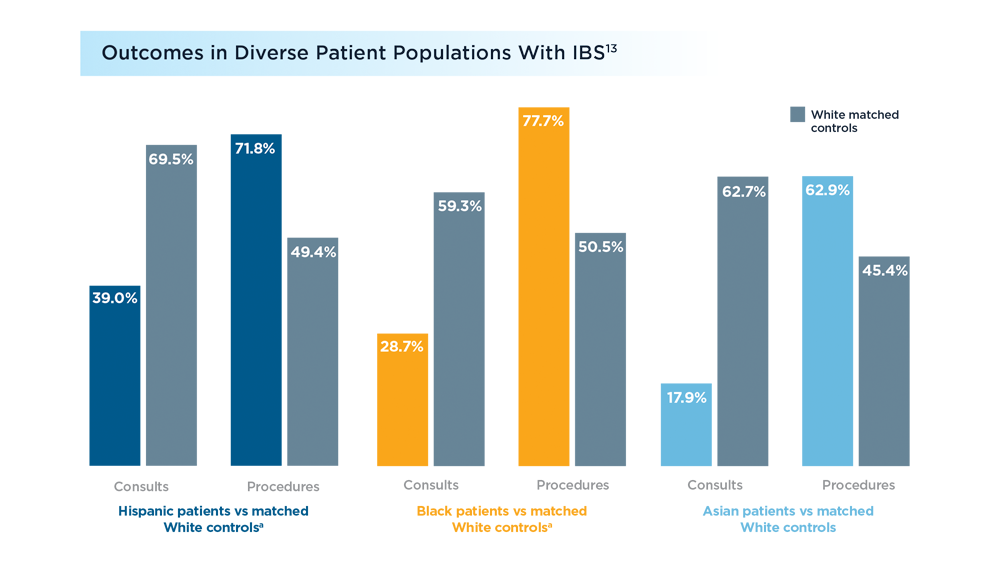

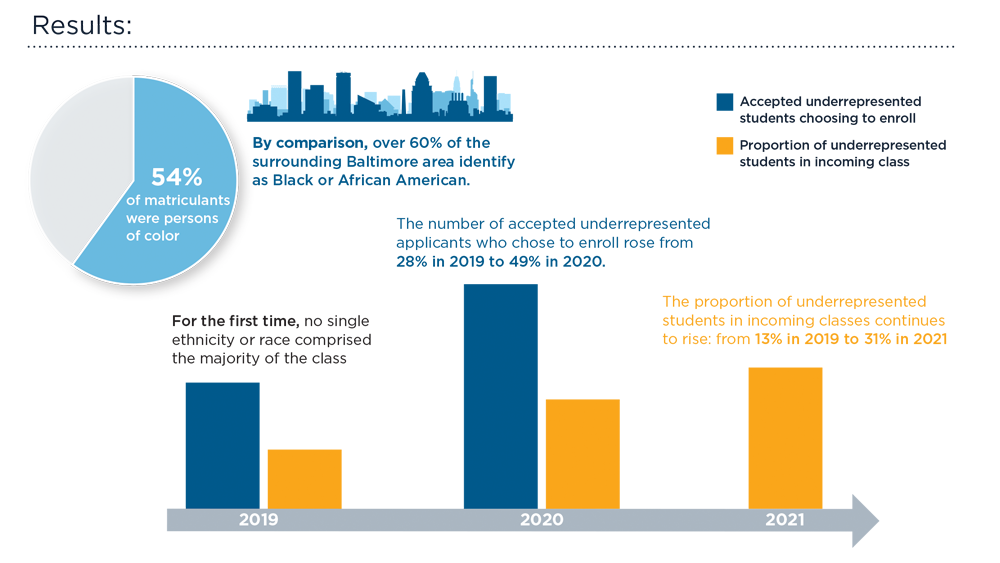

Diversity in the Gastroenterology Workforce and its Implications for Patients

- Welch M. Required curricula in diversity and cross-cultural medicine: the time is now. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 1998;53(3 Suppl):121-3, 130. PMID:17598289.

- Carethers JM. Toward realizing diversity in academic medicine. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(11):5626-5628. doi:10.1172/JCI144527

- Guevara JP, Adanga E, Avakame E, Carthon MB. Minority faculty development programs and underrepresented minority faculty representation at US medical schools. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2297-2304. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.282116

- Guevara JP, Wade R, Aysola J. Racial and ethnic diversity at medical schools – why aren’t we there yet? N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1732-1734. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2105578

- Dill J, Akosionu O, Karbeah JM, Henning-Smith C. Addressing systemic racial inequity in the health care workforce. Health Affairs. September 10, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200908.133196/full/

- Carr RM, Quezada SM, Gangarosa LM, et al; Governing Board of the American Gastroenterological Association. From intention to action: operationalizing AGA diversity policy to combat racism and health disparities in gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(5):1637-1647. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.044

- American Gastroenterological Association. AGA equity project. Accessed July 11, 2022. https://gastro.org/aga-leadership/initiatives-and-programs/aga-equity-project/

- Barnes EL, Loftus EV Jr, Kappelman MD. Effects of race and ethnicity on diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(3):677-689. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.064

- White PM, Iroku U, Carr RM, May FP; Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists Board of Directors. Advancing health equity: The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(7):449-450. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00464-y

- Ogunyemi D, Okekpe CC, Barrientos DR, Bui T, Au MN, Lamba S. United States medical school academic faculty workforce diversity, institutional characteristics, and geographical distributions from 2014-2018. Cureus. 2022;14(2):e22292. doi:10.7759/cureus.22292

- Weiss J, Balasuriya L, Cramer LD, et al. Medical students’ demographic characteristics and their perceptions of faculty role modeling of respect for diversity. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112795. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12795

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Medical school enrollment more diverse in 2021. December 8, 2021. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/medical-school-enrollment-more-diverse-2021

- Silvernale C, Kuo B, Staller K. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with irritable bowel syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;33(5):e14039. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039

- Robinett K, Kareem R, Reavis K, Quezada S. A multi-pronged, antiracist approach to optimize equity in medical school admissions. Med Educ. 2021;55(12):1376-1382. doi:10.1111/medu.14589

- Welch M. Required curricula in diversity and cross-cultural medicine: the time is now. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 1998;53(3 Suppl):121-3, 130. PMID:17598289.

- Carethers JM. Toward realizing diversity in academic medicine. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(11):5626-5628. doi:10.1172/JCI144527

- Guevara JP, Adanga E, Avakame E, Carthon MB. Minority faculty development programs and underrepresented minority faculty representation at US medical schools. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2297-2304. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.282116

- Guevara JP, Wade R, Aysola J. Racial and ethnic diversity at medical schools – why aren’t we there yet? N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1732-1734. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2105578

- Dill J, Akosionu O, Karbeah JM, Henning-Smith C. Addressing systemic racial inequity in the health care workforce. Health Affairs. September 10, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200908.133196/full/

- Carr RM, Quezada SM, Gangarosa LM, et al; Governing Board of the American Gastroenterological Association. From intention to action: operationalizing AGA diversity policy to combat racism and health disparities in gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(5):1637-1647. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.044

- American Gastroenterological Association. AGA equity project. Accessed July 11, 2022. https://gastro.org/aga-leadership/initiatives-and-programs/aga-equity-project/

- Barnes EL, Loftus EV Jr, Kappelman MD. Effects of race and ethnicity on diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(3):677-689. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.064

- White PM, Iroku U, Carr RM, May FP; Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists Board of Directors. Advancing health equity: The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(7):449-450. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00464-y

- Ogunyemi D, Okekpe CC, Barrientos DR, Bui T, Au MN, Lamba S. United States medical school academic faculty workforce diversity, institutional characteristics, and geographical distributions from 2014-2018. Cureus. 2022;14(2):e22292. doi:10.7759/cureus.22292

- Weiss J, Balasuriya L, Cramer LD, et al. Medical students’ demographic characteristics and their perceptions of faculty role modeling of respect for diversity. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112795. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12795

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Medical school enrollment more diverse in 2021. December 8, 2021. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/medical-school-enrollment-more-diverse-2021

- Silvernale C, Kuo B, Staller K. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with irritable bowel syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;33(5):e14039. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039

- Robinett K, Kareem R, Reavis K, Quezada S. A multi-pronged, antiracist approach to optimize equity in medical school admissions. Med Educ. 2021;55(12):1376-1382. doi:10.1111/medu.14589

- Welch M. Required curricula in diversity and cross-cultural medicine: the time is now. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 1998;53(3 Suppl):121-3, 130. PMID:17598289.

- Carethers JM. Toward realizing diversity in academic medicine. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(11):5626-5628. doi:10.1172/JCI144527

- Guevara JP, Adanga E, Avakame E, Carthon MB. Minority faculty development programs and underrepresented minority faculty representation at US medical schools. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2297-2304. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.282116

- Guevara JP, Wade R, Aysola J. Racial and ethnic diversity at medical schools – why aren’t we there yet? N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1732-1734. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2105578

- Dill J, Akosionu O, Karbeah JM, Henning-Smith C. Addressing systemic racial inequity in the health care workforce. Health Affairs. September 10, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200908.133196/full/

- Carr RM, Quezada SM, Gangarosa LM, et al; Governing Board of the American Gastroenterological Association. From intention to action: operationalizing AGA diversity policy to combat racism and health disparities in gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(5):1637-1647. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.044

- American Gastroenterological Association. AGA equity project. Accessed July 11, 2022. https://gastro.org/aga-leadership/initiatives-and-programs/aga-equity-project/

- Barnes EL, Loftus EV Jr, Kappelman MD. Effects of race and ethnicity on diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(3):677-689. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.064

- White PM, Iroku U, Carr RM, May FP; Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists Board of Directors. Advancing health equity: The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(7):449-450. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00464-y

- Ogunyemi D, Okekpe CC, Barrientos DR, Bui T, Au MN, Lamba S. United States medical school academic faculty workforce diversity, institutional characteristics, and geographical distributions from 2014-2018. Cureus. 2022;14(2):e22292. doi:10.7759/cureus.22292

- Weiss J, Balasuriya L, Cramer LD, et al. Medical students’ demographic characteristics and their perceptions of faculty role modeling of respect for diversity. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112795. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12795

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Medical school enrollment more diverse in 2021. December 8, 2021. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/medical-school-enrollment-more-diverse-2021

- Silvernale C, Kuo B, Staller K. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with irritable bowel syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;33(5):e14039. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039

- Robinett K, Kareem R, Reavis K, Quezada S. A multi-pronged, antiracist approach to optimize equity in medical school admissions. Med Educ. 2021;55(12):1376-1382. doi:10.1111/medu.14589

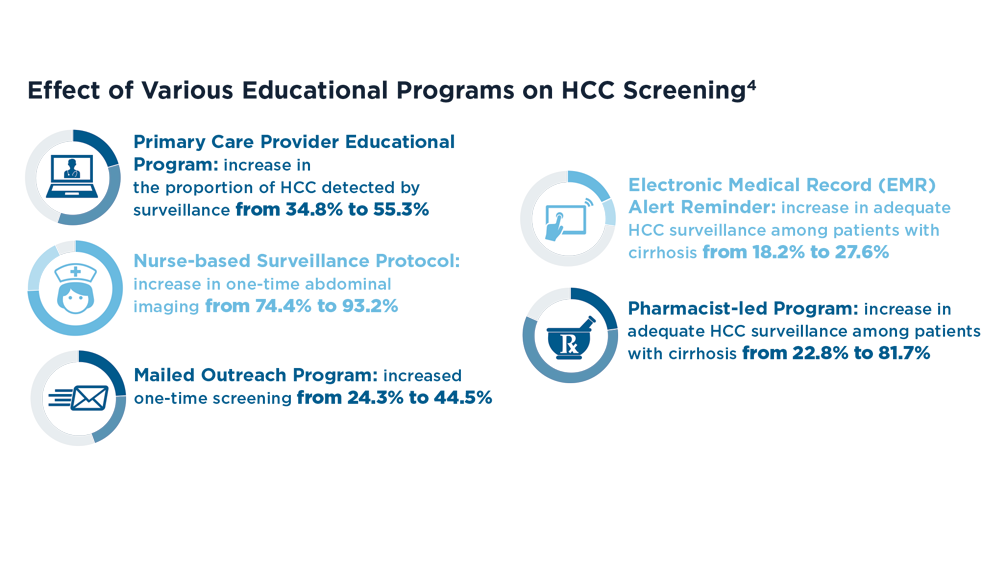

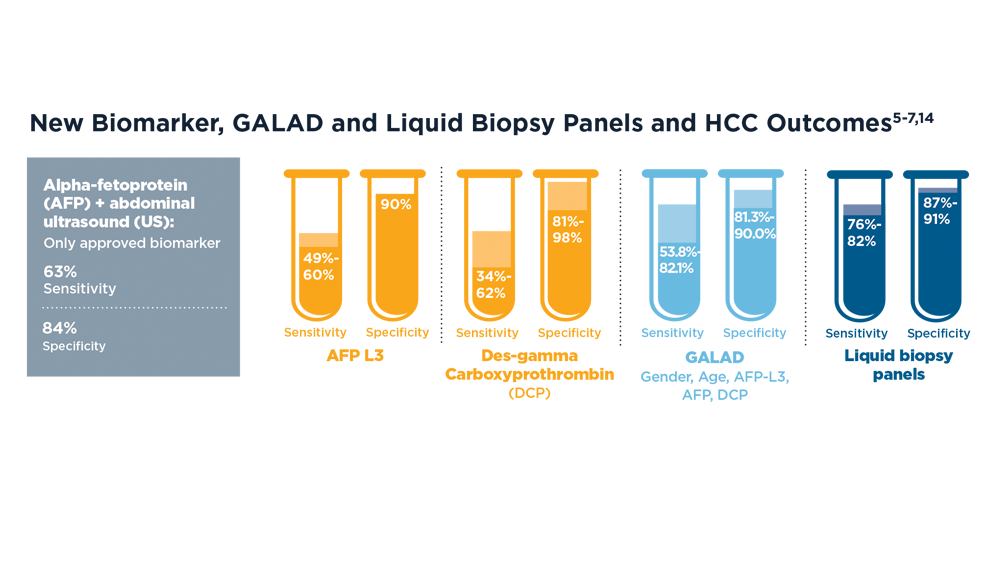

Increasing Surveillance Programs and Expanding Treatment Options in HCC

- Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):6. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3

- Dasgupta P, Henshaw C, Youlden DR, Clark PJ, Aitken JF, Baade PD. Global trends in incidence rates of primary adult liver cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2020;10:171. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.00171

- Lee YT, Wang JJ, Luu M, et al. The mortality and overall survival trends of primary liver cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(11):1531-1541. doi:10.1093/jnci/djab079

- Wolf E, Rich NE, Marrero JA, Parikh ND, Singal AG. Use of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2021;73(2):713-725. doi:10.1002/hep.31309

- Parikh ND, Mehta AS, Singal AG, Block T, Marrero JA, Lok AS. Biomarkers for the early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(12):2495-2503. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0005

- Berhane S, Toyoda H, Tada T, et al. Role of the GALAD and BALAD-2 serologic models in diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma and prediction of survival in patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(6):875-886.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.042

- Lin N, Lin Y, Xu J, et al. A multi-analyte cell-free DNA-based blood test for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6(7):1753-1763. doi:10.1002/hep4.1918

- Del Poggio P, Mazzoleni M, Lazzaroni S, D'Alessio A. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma at the community level: Easier said than done. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(37):6180-6190. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i37.6180

- Byrd K, Alqahtani S, Yopp AC, Singal AG. Role of Multidisciplinary Care in the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2021;41(1):1-8. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1719178

- Mazzaferro V, Citterio D, Bhoori S, et al. Liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma after tumour downstaging (XXL): a randomised, controlled, phase 2b/3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):e373]. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):947-956. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30224-2

- Makary MS, Khandpur U, Cloyd JM, Mumtaz K, Dowell JD. Locoregional therapy approaches for hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advances and management strategies. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(7):1914. doi:10.3390/cancers12071914

- Salem R, Johnson GE, Kim E, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for the treatment of solitary, unresectable HCC: the LEGACY study. Hepatology. 2021;74(5):2342-2352. doi:10.1002/hep.31819

- Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):862-873. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030

- Tzartzeva K, Obi J, Rich NE, et al. Surveillance Imaging and Alpha Fetoprotein for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Cirrhosis: A Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):1706-1718.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.064

- Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):6. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3

- Dasgupta P, Henshaw C, Youlden DR, Clark PJ, Aitken JF, Baade PD. Global trends in incidence rates of primary adult liver cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2020;10:171. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.00171

- Lee YT, Wang JJ, Luu M, et al. The mortality and overall survival trends of primary liver cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(11):1531-1541. doi:10.1093/jnci/djab079

- Wolf E, Rich NE, Marrero JA, Parikh ND, Singal AG. Use of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2021;73(2):713-725. doi:10.1002/hep.31309

- Parikh ND, Mehta AS, Singal AG, Block T, Marrero JA, Lok AS. Biomarkers for the early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(12):2495-2503. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0005

- Berhane S, Toyoda H, Tada T, et al. Role of the GALAD and BALAD-2 serologic models in diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma and prediction of survival in patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(6):875-886.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.042

- Lin N, Lin Y, Xu J, et al. A multi-analyte cell-free DNA-based blood test for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6(7):1753-1763. doi:10.1002/hep4.1918

- Del Poggio P, Mazzoleni M, Lazzaroni S, D'Alessio A. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma at the community level: Easier said than done. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(37):6180-6190. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i37.6180

- Byrd K, Alqahtani S, Yopp AC, Singal AG. Role of Multidisciplinary Care in the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2021;41(1):1-8. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1719178

- Mazzaferro V, Citterio D, Bhoori S, et al. Liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma after tumour downstaging (XXL): a randomised, controlled, phase 2b/3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):e373]. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):947-956. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30224-2

- Makary MS, Khandpur U, Cloyd JM, Mumtaz K, Dowell JD. Locoregional therapy approaches for hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advances and management strategies. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(7):1914. doi:10.3390/cancers12071914

- Salem R, Johnson GE, Kim E, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for the treatment of solitary, unresectable HCC: the LEGACY study. Hepatology. 2021;74(5):2342-2352. doi:10.1002/hep.31819

- Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):862-873. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030

- Tzartzeva K, Obi J, Rich NE, et al. Surveillance Imaging and Alpha Fetoprotein for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Cirrhosis: A Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):1706-1718.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.064

- Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):6. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3

- Dasgupta P, Henshaw C, Youlden DR, Clark PJ, Aitken JF, Baade PD. Global trends in incidence rates of primary adult liver cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2020;10:171. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.00171

- Lee YT, Wang JJ, Luu M, et al. The mortality and overall survival trends of primary liver cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(11):1531-1541. doi:10.1093/jnci/djab079

- Wolf E, Rich NE, Marrero JA, Parikh ND, Singal AG. Use of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2021;73(2):713-725. doi:10.1002/hep.31309

- Parikh ND, Mehta AS, Singal AG, Block T, Marrero JA, Lok AS. Biomarkers for the early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(12):2495-2503. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0005

- Berhane S, Toyoda H, Tada T, et al. Role of the GALAD and BALAD-2 serologic models in diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma and prediction of survival in patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(6):875-886.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.042

- Lin N, Lin Y, Xu J, et al. A multi-analyte cell-free DNA-based blood test for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6(7):1753-1763. doi:10.1002/hep4.1918

- Del Poggio P, Mazzoleni M, Lazzaroni S, D'Alessio A. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma at the community level: Easier said than done. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(37):6180-6190. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i37.6180

- Byrd K, Alqahtani S, Yopp AC, Singal AG. Role of Multidisciplinary Care in the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2021;41(1):1-8. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1719178

- Mazzaferro V, Citterio D, Bhoori S, et al. Liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma after tumour downstaging (XXL): a randomised, controlled, phase 2b/3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):e373]. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):947-956. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30224-2

- Makary MS, Khandpur U, Cloyd JM, Mumtaz K, Dowell JD. Locoregional therapy approaches for hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advances and management strategies. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(7):1914. doi:10.3390/cancers12071914

- Salem R, Johnson GE, Kim E, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for the treatment of solitary, unresectable HCC: the LEGACY study. Hepatology. 2021;74(5):2342-2352. doi:10.1002/hep.31819

- Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):862-873. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030

- Tzartzeva K, Obi J, Rich NE, et al. Surveillance Imaging and Alpha Fetoprotein for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Cirrhosis: A Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):1706-1718.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.064

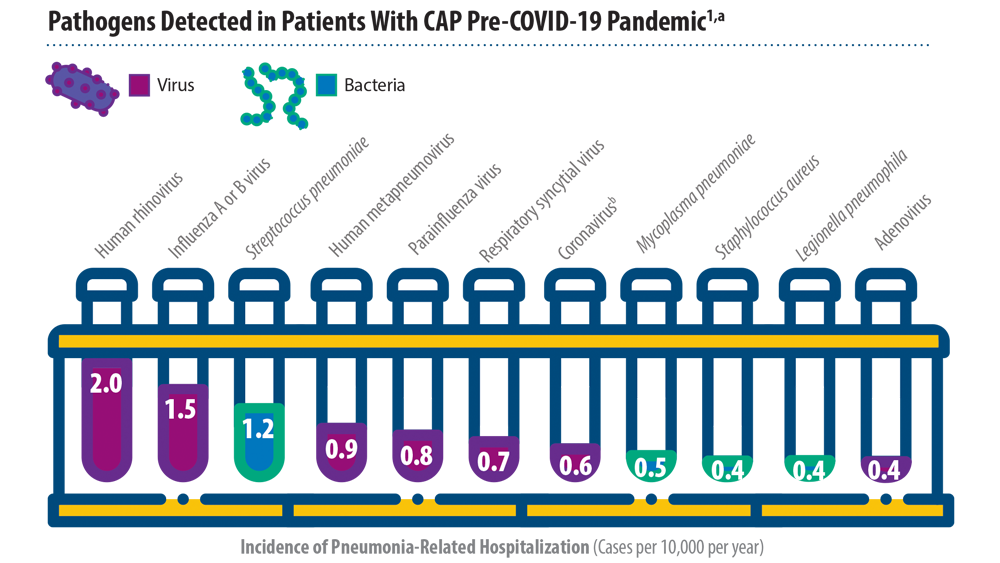

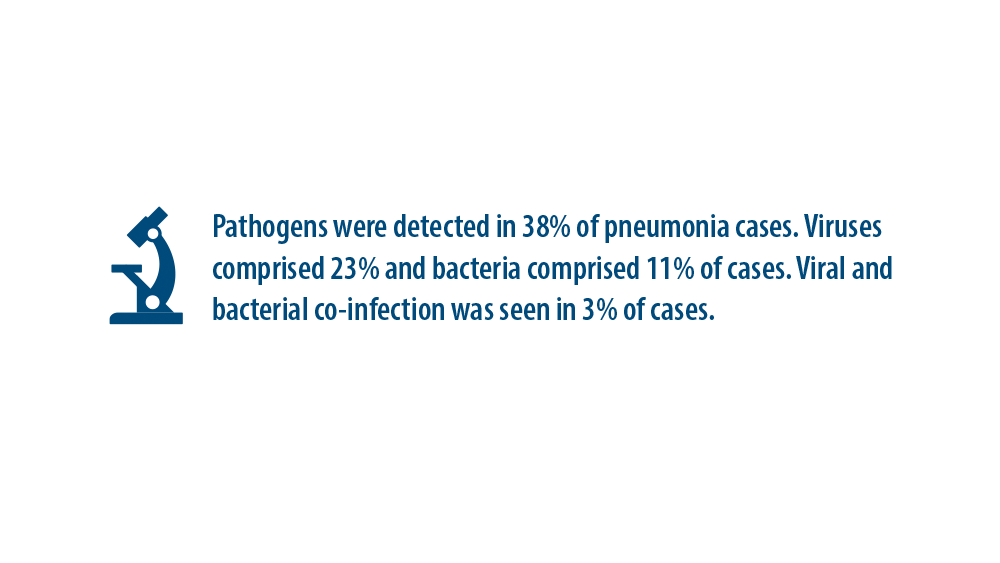

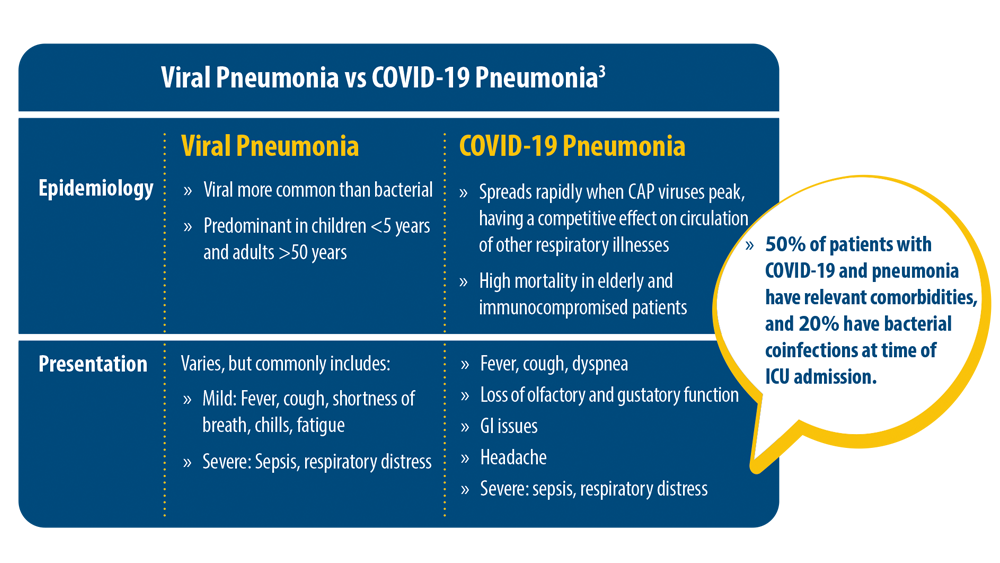

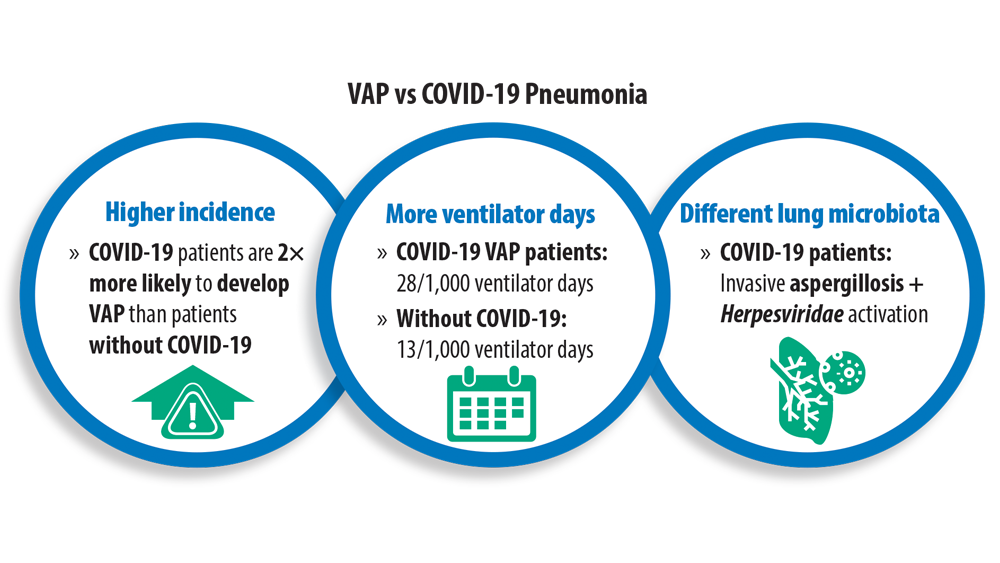

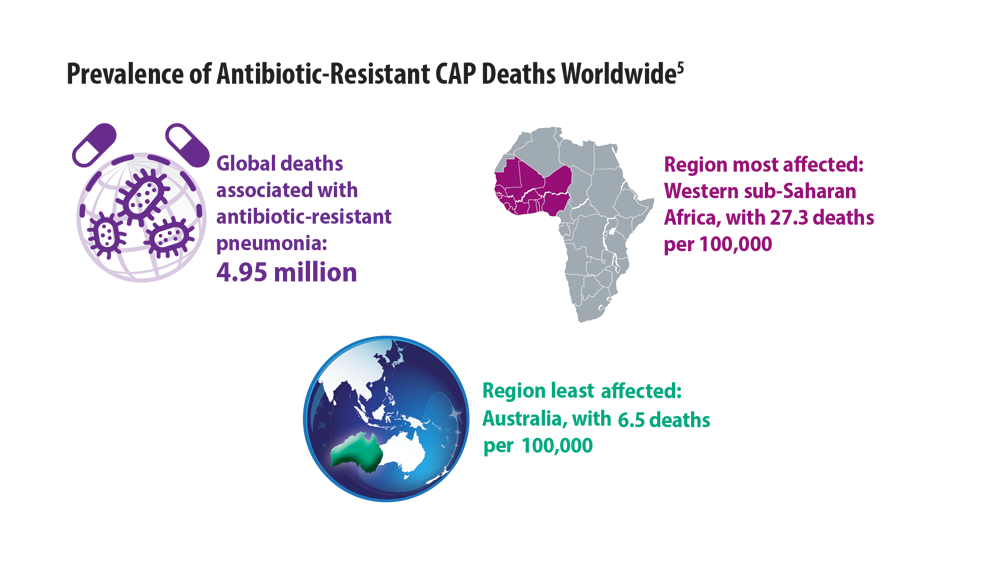

New Pathogens, COVID-19, and Antibiotic Resistance in the Field of Pneumonia

- Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among US adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):415-427. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500245

- Aliberti S, Dela Cruz CS, Amati F, Sotgiu G, Restrepo MI. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet. 2021;398(10303):906-919. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00630-9

- Pagliano P, Sellitto C, Conti V, Ascione T, Esposito S. Characteristics of viral pneumonia in the COVID-19 era: an update. Infection. 2021;49(4):607-616. doi:10.1007/s15010-021-01603-y

- Maes M, Higginson E, Pereira-Dias J, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients with COVID-19 [published correction appears in Crit Care. 2021 Apr 6;25(1):130]. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):25. doi:10.1186/s13054-021-03460-5

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629-655. doi:10.1016/S0140- 6736(21)02724-0

- Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among US adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):415-427. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500245

- Aliberti S, Dela Cruz CS, Amati F, Sotgiu G, Restrepo MI. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet. 2021;398(10303):906-919. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00630-9

- Pagliano P, Sellitto C, Conti V, Ascione T, Esposito S. Characteristics of viral pneumonia in the COVID-19 era: an update. Infection. 2021;49(4):607-616. doi:10.1007/s15010-021-01603-y

- Maes M, Higginson E, Pereira-Dias J, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients with COVID-19 [published correction appears in Crit Care. 2021 Apr 6;25(1):130]. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):25. doi:10.1186/s13054-021-03460-5

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629-655. doi:10.1016/S0140- 6736(21)02724-0

- Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among US adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):415-427. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500245

- Aliberti S, Dela Cruz CS, Amati F, Sotgiu G, Restrepo MI. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet. 2021;398(10303):906-919. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00630-9

- Pagliano P, Sellitto C, Conti V, Ascione T, Esposito S. Characteristics of viral pneumonia in the COVID-19 era: an update. Infection. 2021;49(4):607-616. doi:10.1007/s15010-021-01603-y

- Maes M, Higginson E, Pereira-Dias J, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients with COVID-19 [published correction appears in Crit Care. 2021 Apr 6;25(1):130]. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):25. doi:10.1186/s13054-021-03460-5

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629-655. doi:10.1016/S0140- 6736(21)02724-0