User login

Advances in Lung Cancer Diagnostics and Treatment

1. Cancer facts and figures 2022. American Cancer Society. Accessed June 14, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/ cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancerfacts-and-figures/2022/2022-cancer-facts-and-figures

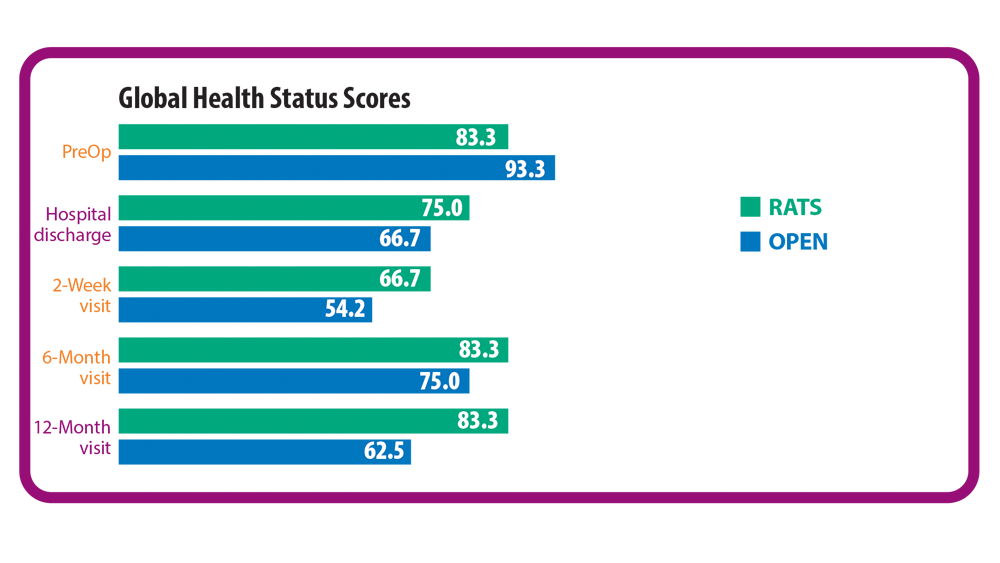

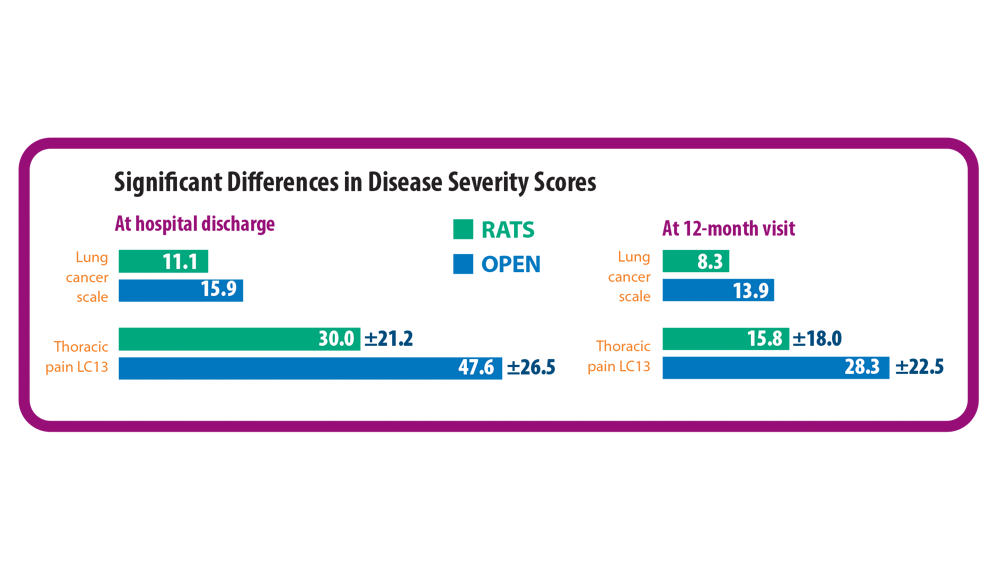

2. Novellis P, Maisonneuve P, Dieci E, et al. Quality of life, postoperative pain, and lymph node dissection in a robotic approach compared to VATS and OPEN for early stage lung cancer. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1687. doi:10.3390/jcm10081687

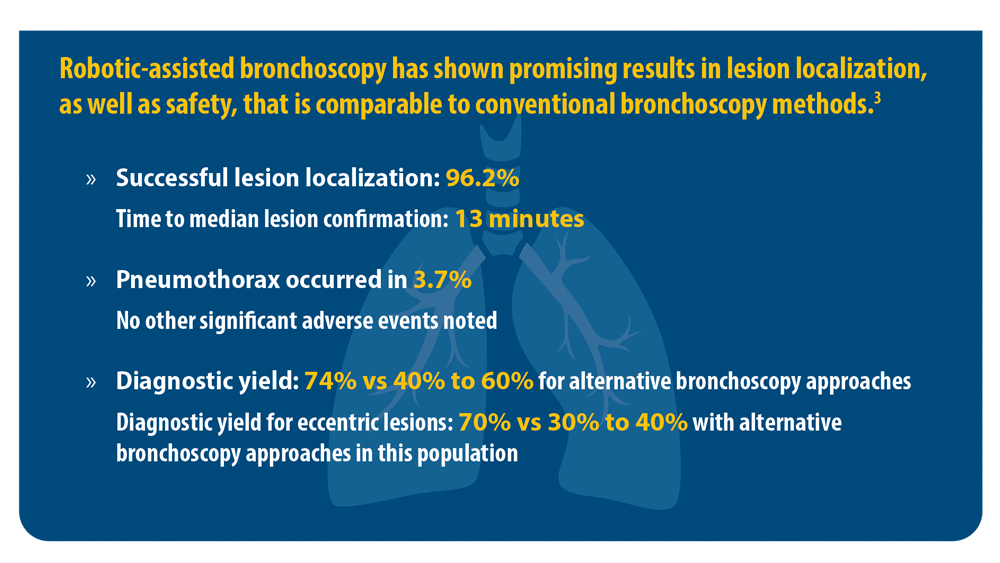

3. Chen AC, Pastis NJ Jr, Mahajan AK, et al. Robotic bronchoscopy for peripheral pulmonary lesions: a multicenter pilot and feasibility study (BENEFIT). Chest. 2021;159(2):845-852. doi:10.1016/j. chest.2020.08.2047

4. Current cigarette smoking among adults in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 17, 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/ data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm

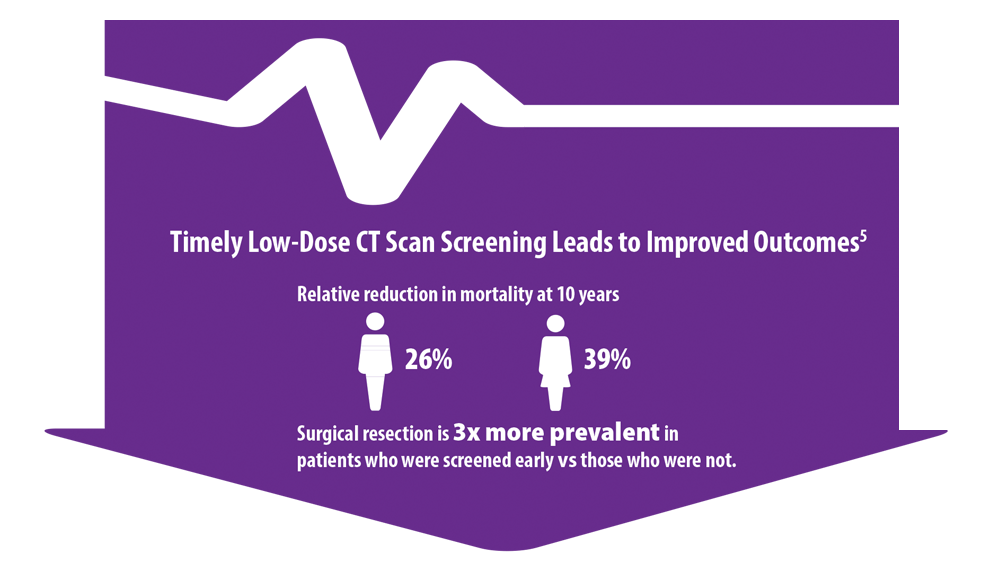

5. Haddad DN, Sandler KL, Henderson LM, Rivera MP, Aldrich MC. Disparities in lung cancer screening: a review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(4):399-405. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201907- 556CME

6. US Preventive Services Task Force issues final recommendation statement on screening for lung cancer. USPSTF Bulletin. Published March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/lung-cancer-newsbulletin.pdf

7. Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Souter LH, et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021;160(5):e427-e494. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

8. Lung cancer screening report. National Cancer Institute Cancer Trends Progress Report. Updated April 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/lung_cancer

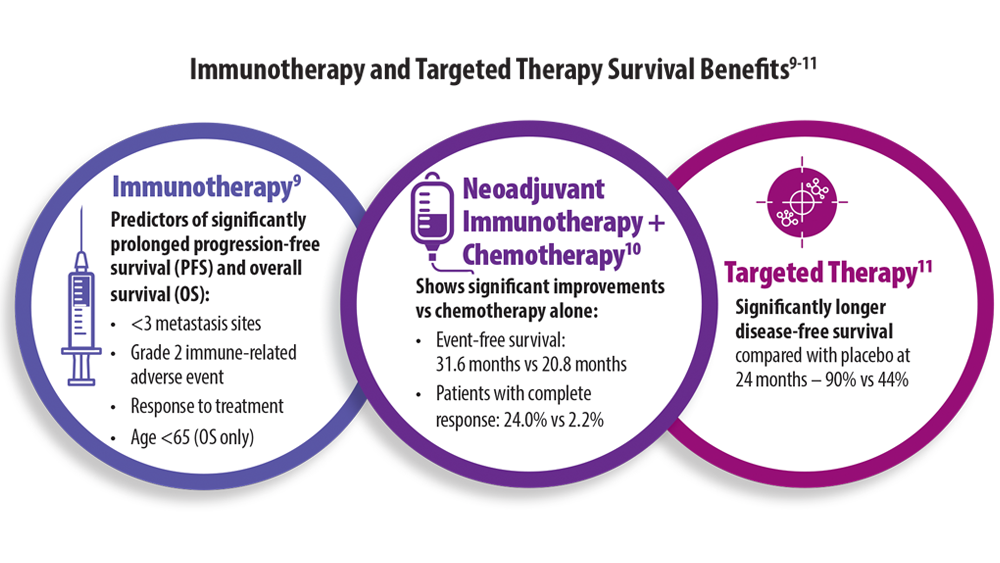

9. Huang L, Li L, Zhou Y, et al. Clinical characteristics correlate with outcomes of immunotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer. 2020;11(24):7137-7145. doi:10.7150/ jca.49213

10. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(21):1973-1985. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2202170

11. Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, et al. Osimertinib in Resected EGFR-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(18):1711-1723. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2027071

1. Cancer facts and figures 2022. American Cancer Society. Accessed June 14, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/ cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancerfacts-and-figures/2022/2022-cancer-facts-and-figures

2. Novellis P, Maisonneuve P, Dieci E, et al. Quality of life, postoperative pain, and lymph node dissection in a robotic approach compared to VATS and OPEN for early stage lung cancer. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1687. doi:10.3390/jcm10081687

3. Chen AC, Pastis NJ Jr, Mahajan AK, et al. Robotic bronchoscopy for peripheral pulmonary lesions: a multicenter pilot and feasibility study (BENEFIT). Chest. 2021;159(2):845-852. doi:10.1016/j. chest.2020.08.2047

4. Current cigarette smoking among adults in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 17, 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/ data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm

5. Haddad DN, Sandler KL, Henderson LM, Rivera MP, Aldrich MC. Disparities in lung cancer screening: a review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(4):399-405. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201907- 556CME

6. US Preventive Services Task Force issues final recommendation statement on screening for lung cancer. USPSTF Bulletin. Published March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/lung-cancer-newsbulletin.pdf

7. Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Souter LH, et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021;160(5):e427-e494. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

8. Lung cancer screening report. National Cancer Institute Cancer Trends Progress Report. Updated April 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/lung_cancer

9. Huang L, Li L, Zhou Y, et al. Clinical characteristics correlate with outcomes of immunotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer. 2020;11(24):7137-7145. doi:10.7150/ jca.49213

10. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(21):1973-1985. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2202170

11. Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, et al. Osimertinib in Resected EGFR-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(18):1711-1723. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2027071

1. Cancer facts and figures 2022. American Cancer Society. Accessed June 14, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/ cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancerfacts-and-figures/2022/2022-cancer-facts-and-figures

2. Novellis P, Maisonneuve P, Dieci E, et al. Quality of life, postoperative pain, and lymph node dissection in a robotic approach compared to VATS and OPEN for early stage lung cancer. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1687. doi:10.3390/jcm10081687

3. Chen AC, Pastis NJ Jr, Mahajan AK, et al. Robotic bronchoscopy for peripheral pulmonary lesions: a multicenter pilot and feasibility study (BENEFIT). Chest. 2021;159(2):845-852. doi:10.1016/j. chest.2020.08.2047

4. Current cigarette smoking among adults in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 17, 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/ data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm

5. Haddad DN, Sandler KL, Henderson LM, Rivera MP, Aldrich MC. Disparities in lung cancer screening: a review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(4):399-405. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201907- 556CME

6. US Preventive Services Task Force issues final recommendation statement on screening for lung cancer. USPSTF Bulletin. Published March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/lung-cancer-newsbulletin.pdf

7. Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Souter LH, et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021;160(5):e427-e494. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

8. Lung cancer screening report. National Cancer Institute Cancer Trends Progress Report. Updated April 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/lung_cancer

9. Huang L, Li L, Zhou Y, et al. Clinical characteristics correlate with outcomes of immunotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer. 2020;11(24):7137-7145. doi:10.7150/ jca.49213

10. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(21):1973-1985. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2202170

11. Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, et al. Osimertinib in Resected EGFR-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(18):1711-1723. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2027071

Botanical Briefs: Toxicodendron Dermatitis

Reactions to poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac, which affect 10 to 50 million Americans a year,1 are classified as Toxicodendron dermatitis; 50% to 75% of US adults are clinically sensitive to these plants.2 Furthermore, people of all ethnicities, skin types, and ages residing in most US geographical regions are at risk.3 Allergenicity is caused by urushiol, which is found in members of the Anacardiaceae family.4 Once absorbed, urushiol causes a type IV hypersensitivity reaction in those who are susceptible.5

Cutaneous Manifestations

Toxicodendron dermatitis presents with an acute eczematous eruption characterized by streaks of intensely pruritic and erythematous papules and vesicles (Figure 1). Areas of involvement are characterized by sharp margins that follow the pattern of contact made by the plant’s leaves, berries, stems, and vines.6 The fluid content of the vesicles is not antigenic and cannot cause subsequent transmission to oneself or others.3 A person with prior contact to the plant who becomes sensitized develops an eruption 24 to 48 hours after subsequent contact with the plant; peak severity manifests 1 to 14 days later.7

When left untreated, the eruption can last 3 weeks. If the plant is burned, urushiol can be aerosolized in smoke, causing respiratory tract inflammation and generalized dermatitis, which has been reported among wildland firefighters.2 Long-term complications from an outbreak are limited but can include postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and secondary bacterial infection.8 Rare reports of nephrotic syndrome also have appeared in the literature.9 Toxicodendron dermatitis can present distinctively as so-called black dot dermatitis.6

Nomenclature

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac are members of the family Anacardiaceae and genus Toxicodendron,6 derived from the Greek words toxikos (poison) and dendron (tree).10

Distribution

Toxicodendron plants characteristically are found in various regions of the United States. Poison ivy is the most common and is comprised of 2 species: Toxicodendron rydbergii and Toxicodendron radicans. Toxicodendron rydbergii is a nonclimbing dwarf shrub typically found in the northern and western United States. Toxicodendron radicans is a climbing vine found in the eastern United States. Poison oak also is comprised of 2 species—Toxicodendron toxicarium and Toxicodendron diversilobum—and is more common in the western United States. Poison sumac (also known as Toxicodendron vernix) is a small shrub that grows in moist swampy areas. It has a predilection for marshes of the eastern and southeastern United States.6,11

Identifying Features

Educating patients on how to identify poison ivy can play a key role in avoidance, which is the most important step in preventing Toxicodendron dermatitis. A challenge in identification of poison ivy is the plant’s variable appearance; it grows as a small shrub, low-lying vine, or vine that climbs other trees.

As the vine matures, it develops tiny, rough, “hairy” rootlets—hence the saying, “Hairy vine, no friend of mine!” Rootlets help the plant attach to trees growing near a water source. Vines can reach a diameter of 3 inches. From mature vines, solitary stems extend 1 to 2 inches with 3 characteristic leaves at the terminus (Figure 2), prompting another classic saying, “Leaves of 3, let it be!”12

Poison oak is characterized by 3 to 5 leaflets. Poison sumac has 7 to 13 pointed, smooth-edged leaves.6

Dermatitis-Inducing Plant Parts

The primary allergenic component of Toxicodendron plants is urushiol, a resinous sap found in stems, roots, leaves, and skins of the fruits. These components must be damaged or bruised to release the allergen; slight contact with an uninjured plant part might not lead to harm.2,13 Some common forms of transmission include skin contact, ingestion, inhalation of smoke from burning plants, and contact with skin through contaminated items, such as clothing, animals, and tools.14

Allergens

The catecholic ring and aliphatic chain of the urushiol molecule are allergenic.15 The degree of saturation and length of the side chains vary with different catechols. Urushiol displays cross-reactivity with poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. Urushiol from these plants differs only slightly in structure; therefore, sensitization to one causes sensitization to all. There also is cross-reactivity between different members of the Anacardiaceae family, including Anacardium occidentale (tropical cashew nut), Mangifera indica (tropical mango tree), Ginkgo biloba (ginkgo tree), and Semecarpus anacardium (Indian marking nut tree).12

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac cause allergic contact dermatitis as a type IV hypersensitivity reaction. First, urushiol binds and penetrates the skin, where it is oxidized to quinone intermediates and bound to haptens. Then, the intermediates bind surface proteins on antigen-presenting cells, specifically Langerhans cells in the epidermis and dermis.5

Presentation of nonpeptide antigens, such as urushiol, to T cells requires expression of langerin (also known as CD207) and CD1a.16 Langerin is a C-type lectin that causes formation of Birbeck granules; CD1a is a major histocompatibility complex class I molecule found in Birbeck granules.5,17 After Langerhans cells internalize and process the urushiol self-hapten neoantigen, it is presented to CD4+ T cells.6 These cells then expand to form circulating activated T-effector and T-memory lymphocytes.18

The molecular link that occurs between the hapten and carrier protein determines the response. When linked by an amino nucleophile, selective induction of T-effector cells ensues, resulting in allergic contact dermatitis. When linked by a sulfhydryl bond, selective induction of suppressor cells occurs, resulting in a reduced allergic contact dermatitis response.19 In the case of activation of T-effector cells, a cell-mediated cytotoxic immune response is generated that destroys epidermal cells and dermal vasculature.2 The incidence and intensity of poison ivy sensitivity decline proportionally with age and the absence of continued exposure.20

Preventive Action—Patients should be counseled that if contact between plant and skin occurs, it is important to remove contaminated clothing or objects and wash them with soap to prevent additional exposure.14,21 Areas of the skin that made contact with the plant should be washed with water as soon as possible; after 30 minutes, urushiol has sufficiently penetrated to cause a reaction.2 Forceful unidirectional washing with a damp washcloth and liquid dishwashing soap is recommended.22

Several barrier creams are commercially available to help prevent absorption or to deactivate the urushiol antigen. These products are used widely by forestry workers and wildland firefighters.23 One such barrier cream is bentoquatam (sold as various trade names), an organoclay compound made of quaternium-18 bentonite that interferes with absorption of the allergen by acting as a physical blocker.24

Treatment

After Toxicodendron dermatitis develops, several treatments are available to help manage symptoms. Calamine lotion can be used to help dry weeping lesions.25,26 Topical steroids can be used to help control pruritus and alleviate inflammation. High-potency topical corticosteroids such as clobetasol and mid-potency steroids such as triamcinolone can be used. Topical anesthetics (eg, benzocaine, pramoxine, benzyl alcohol) might provide symptomatic relief.27,28

Oral antihistamines can allow for better sleep by providing sedation but do not target the pruritus of poison ivy dermatitis, which is not histamine mediated.29,30 Systemic corticosteroids usually are considered in more severe dermatitis—when 20% or more of the body surface area is involved; blistering and itching are severe; or the face, hands, or genitalia are involved.31,32

Clinical Uses

Therapeutic uses for poison ivy have been explored extensively. In 1892, Dakin33 reported that ingestion of leaves by Native Americans reduced the incidence and severity of skin lesions after contact with poison ivy. Consumption of poison ivy was further studied by Epstein and colleagues34 in 1974; they concluded that ingestion of a large amount of urushiol over a period of 3 months or longer may help with hyposensitization—but not complete desensitization—to contact with poison ivy. However, the risk for adverse effects is thought to outweigh benefits because ingestion can cause perianal dermatitis, mucocutaneous sequelae, and systemic contact dermatitis.2

Although the use of Toxicodendron plants in modern-day medicine is limited, development of a vaccine (immunotherapy) against Toxicodendron dermatitis offers an exciting opportunity for further research.

- Pariser DM, Ceilley RI, Lefkovits AM, et al. Poison ivy, oak and sumac. Derm Insights. 2003;4:26-28.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128. doi:10.1580/pr31-05.1

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak/sumac. part II: specific features. Cutis. 1996;58:22-24.

- Cruse JM, Lewis RE. Atlas of Immunology. CRC Press; 2004.

- Valladeau J, Ravel O, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, et al. Langerin, a novel C-type lectin specific to Langerhans cells, is an endocytic receptor that induces the formation of Birbeck granules. Immunity. 2000;12:71-81. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80160-0

- Marks JG. Poison ivy and poison oak allergic contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;9:497-506.

- Williams JV, Light J, Marks JG Jr. Individual variations in allergic contact dermatitis from urushiol. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1002-1003. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.8.1002

- Brook I, Frazier EH, Yeager JK. Microbiology of infected poison ivy dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:943-946. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03475.x

- Rytand DA. Fatal anuria, the nephrotic syndrome and glomerular nephritis as sequels of the dermatitis of poison oak. Am J Med. 1948;5:548-560. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(48)90105-3

- Gledhill D. The Names of Plants. Cambridge University Press; 2008.

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac: how to treat the rash. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/everyday-care/itchy-skin/poison-ivy/treat-rash

- Monroe J. Toxicodendron contact dermatitis: a case report and brief review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(9 suppl 1):S29-S34.

- Marks JG Jr, Anderson BE, DeLeo VA. Contact & Occupational Dermatology. 4th ed. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2016.

- Fisher AA, Mitchell JC. Toxicodendron plants and spices. In: Rietschel RL, Fowler JF Jr, eds. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. 4th ed. Williams and Wilkins; 1995:461-523.

- Dawson CR. The chemistry of poison ivy. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1956;18:427-443. doi:10.1111/j.2164-0947.1956.tb00465.x

- Hunger RE, Sieling PA, Ochoa MT, et al. Langerhans cells utilize CD1a and langerin to efficiently present nonpeptide antigens to T cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:701-708. doi:10.1172/JCI19655

- Hanau D, Fabre M, Schmitt DA, et al. Human epidermal Langerhans cells cointernalize by receptor-mediated endocytosis “non-classical” major histocompatibility complex class Imolecules (T6 antigens) and class II molecules (HLA-DR antigens). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:2901-2905. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.9.2901

- Gayer KD, Burnett JW. Toxicodendron dermatitis. Cutis. 1988;42:99-100.

- Dunn IS, Liberato DJ, Castagnoli N, et al. Contact sensitivity to urushiol: role of covalent bond formation. Cell Immunol. 1982;74:220-233. doi:10.1016/0008-8749(82)90023-5

- Kligman AM. Poison ivy (Rhus) dermatitis; an experimental study. AMA Arch Derm. 1958;77:149-180. doi:10.1001/archderm.1958.01560020001001

- Derraik JGB. Heracleum mantegazzianum and Toxicodendron succedaneum: plants of human health significance in New Zealand and the National Pest Plant Accord. N Z Med J. 2007;120:U2657.

- Neill BC, Neill JA, Brauker J, et al. Postexposure prevention of Toxicodendron dermatitis by early forceful unidirectional washing with liquid dishwashing soap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;81:E25. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.081

- Kim Y, Flamm A, ElSohly MA, et al. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis: what is known and what is new? Dermatitis. 2019;30:183-190. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000472

- Marks JG Jr, Fowler JF Jr, Sheretz EF, et al. Prevention of poison ivy and poison oak allergic contact dermatitis by quaternium-18 bentonite. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:212-216. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90237-6

- Baer RL. Poison ivy dermatitis. Cutis. 1990;46:34-36.

- Williford PM, Sheretz EF. Poison ivy dermatitis. nuances in treatment. Arch Fam Med. 1995;3:184.

- Amrol D, Keitel D, Hagaman D, et al. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of human allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:563-566. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61535-9

- Stephanides SL, Moore C. Toxicodendron poisoning treatment & management. Medscape. Updated June 13, 2022. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/817671-treatment#d11

- Munday J, Bloomfield R, Goldman M, et al. Chlorpheniramine is no more effective than placebo in relieving the symptoms of childhood atopic dermatitis with a nocturnal itching and scratching component. Dermatology. 2002;205:40-45. doi:10.1159/000063138

- Yosipovitch G, Fleischer A. Itch associated with skin disease: advances in pathophysiology and emerging therapies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:617-622. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304090-00004

- Li LY, Cruz PD Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis: pathophysiology applied to future therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:219-223. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04023.x

- Craig K, Meadows SE. What is the best duration of steroid therapy for contact dermatitis (Rhus)? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:166-167.

- Dakin R. Remarks on a cutaneous affection, produced by certain poisonous vegetables. Am J Med Sci. 1829;4:98-100.

- Epstein WL, Baer H, Dawson CR, et al. Poison oak hyposensitization. evaluation of purified urushiol. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:356-360.

Reactions to poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac, which affect 10 to 50 million Americans a year,1 are classified as Toxicodendron dermatitis; 50% to 75% of US adults are clinically sensitive to these plants.2 Furthermore, people of all ethnicities, skin types, and ages residing in most US geographical regions are at risk.3 Allergenicity is caused by urushiol, which is found in members of the Anacardiaceae family.4 Once absorbed, urushiol causes a type IV hypersensitivity reaction in those who are susceptible.5

Cutaneous Manifestations

Toxicodendron dermatitis presents with an acute eczematous eruption characterized by streaks of intensely pruritic and erythematous papules and vesicles (Figure 1). Areas of involvement are characterized by sharp margins that follow the pattern of contact made by the plant’s leaves, berries, stems, and vines.6 The fluid content of the vesicles is not antigenic and cannot cause subsequent transmission to oneself or others.3 A person with prior contact to the plant who becomes sensitized develops an eruption 24 to 48 hours after subsequent contact with the plant; peak severity manifests 1 to 14 days later.7

When left untreated, the eruption can last 3 weeks. If the plant is burned, urushiol can be aerosolized in smoke, causing respiratory tract inflammation and generalized dermatitis, which has been reported among wildland firefighters.2 Long-term complications from an outbreak are limited but can include postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and secondary bacterial infection.8 Rare reports of nephrotic syndrome also have appeared in the literature.9 Toxicodendron dermatitis can present distinctively as so-called black dot dermatitis.6

Nomenclature

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac are members of the family Anacardiaceae and genus Toxicodendron,6 derived from the Greek words toxikos (poison) and dendron (tree).10

Distribution

Toxicodendron plants characteristically are found in various regions of the United States. Poison ivy is the most common and is comprised of 2 species: Toxicodendron rydbergii and Toxicodendron radicans. Toxicodendron rydbergii is a nonclimbing dwarf shrub typically found in the northern and western United States. Toxicodendron radicans is a climbing vine found in the eastern United States. Poison oak also is comprised of 2 species—Toxicodendron toxicarium and Toxicodendron diversilobum—and is more common in the western United States. Poison sumac (also known as Toxicodendron vernix) is a small shrub that grows in moist swampy areas. It has a predilection for marshes of the eastern and southeastern United States.6,11

Identifying Features

Educating patients on how to identify poison ivy can play a key role in avoidance, which is the most important step in preventing Toxicodendron dermatitis. A challenge in identification of poison ivy is the plant’s variable appearance; it grows as a small shrub, low-lying vine, or vine that climbs other trees.

As the vine matures, it develops tiny, rough, “hairy” rootlets—hence the saying, “Hairy vine, no friend of mine!” Rootlets help the plant attach to trees growing near a water source. Vines can reach a diameter of 3 inches. From mature vines, solitary stems extend 1 to 2 inches with 3 characteristic leaves at the terminus (Figure 2), prompting another classic saying, “Leaves of 3, let it be!”12

Poison oak is characterized by 3 to 5 leaflets. Poison sumac has 7 to 13 pointed, smooth-edged leaves.6

Dermatitis-Inducing Plant Parts

The primary allergenic component of Toxicodendron plants is urushiol, a resinous sap found in stems, roots, leaves, and skins of the fruits. These components must be damaged or bruised to release the allergen; slight contact with an uninjured plant part might not lead to harm.2,13 Some common forms of transmission include skin contact, ingestion, inhalation of smoke from burning plants, and contact with skin through contaminated items, such as clothing, animals, and tools.14

Allergens

The catecholic ring and aliphatic chain of the urushiol molecule are allergenic.15 The degree of saturation and length of the side chains vary with different catechols. Urushiol displays cross-reactivity with poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. Urushiol from these plants differs only slightly in structure; therefore, sensitization to one causes sensitization to all. There also is cross-reactivity between different members of the Anacardiaceae family, including Anacardium occidentale (tropical cashew nut), Mangifera indica (tropical mango tree), Ginkgo biloba (ginkgo tree), and Semecarpus anacardium (Indian marking nut tree).12

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac cause allergic contact dermatitis as a type IV hypersensitivity reaction. First, urushiol binds and penetrates the skin, where it is oxidized to quinone intermediates and bound to haptens. Then, the intermediates bind surface proteins on antigen-presenting cells, specifically Langerhans cells in the epidermis and dermis.5

Presentation of nonpeptide antigens, such as urushiol, to T cells requires expression of langerin (also known as CD207) and CD1a.16 Langerin is a C-type lectin that causes formation of Birbeck granules; CD1a is a major histocompatibility complex class I molecule found in Birbeck granules.5,17 After Langerhans cells internalize and process the urushiol self-hapten neoantigen, it is presented to CD4+ T cells.6 These cells then expand to form circulating activated T-effector and T-memory lymphocytes.18

The molecular link that occurs between the hapten and carrier protein determines the response. When linked by an amino nucleophile, selective induction of T-effector cells ensues, resulting in allergic contact dermatitis. When linked by a sulfhydryl bond, selective induction of suppressor cells occurs, resulting in a reduced allergic contact dermatitis response.19 In the case of activation of T-effector cells, a cell-mediated cytotoxic immune response is generated that destroys epidermal cells and dermal vasculature.2 The incidence and intensity of poison ivy sensitivity decline proportionally with age and the absence of continued exposure.20

Preventive Action—Patients should be counseled that if contact between plant and skin occurs, it is important to remove contaminated clothing or objects and wash them with soap to prevent additional exposure.14,21 Areas of the skin that made contact with the plant should be washed with water as soon as possible; after 30 minutes, urushiol has sufficiently penetrated to cause a reaction.2 Forceful unidirectional washing with a damp washcloth and liquid dishwashing soap is recommended.22

Several barrier creams are commercially available to help prevent absorption or to deactivate the urushiol antigen. These products are used widely by forestry workers and wildland firefighters.23 One such barrier cream is bentoquatam (sold as various trade names), an organoclay compound made of quaternium-18 bentonite that interferes with absorption of the allergen by acting as a physical blocker.24

Treatment

After Toxicodendron dermatitis develops, several treatments are available to help manage symptoms. Calamine lotion can be used to help dry weeping lesions.25,26 Topical steroids can be used to help control pruritus and alleviate inflammation. High-potency topical corticosteroids such as clobetasol and mid-potency steroids such as triamcinolone can be used. Topical anesthetics (eg, benzocaine, pramoxine, benzyl alcohol) might provide symptomatic relief.27,28

Oral antihistamines can allow for better sleep by providing sedation but do not target the pruritus of poison ivy dermatitis, which is not histamine mediated.29,30 Systemic corticosteroids usually are considered in more severe dermatitis—when 20% or more of the body surface area is involved; blistering and itching are severe; or the face, hands, or genitalia are involved.31,32

Clinical Uses

Therapeutic uses for poison ivy have been explored extensively. In 1892, Dakin33 reported that ingestion of leaves by Native Americans reduced the incidence and severity of skin lesions after contact with poison ivy. Consumption of poison ivy was further studied by Epstein and colleagues34 in 1974; they concluded that ingestion of a large amount of urushiol over a period of 3 months or longer may help with hyposensitization—but not complete desensitization—to contact with poison ivy. However, the risk for adverse effects is thought to outweigh benefits because ingestion can cause perianal dermatitis, mucocutaneous sequelae, and systemic contact dermatitis.2

Although the use of Toxicodendron plants in modern-day medicine is limited, development of a vaccine (immunotherapy) against Toxicodendron dermatitis offers an exciting opportunity for further research.

Reactions to poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac, which affect 10 to 50 million Americans a year,1 are classified as Toxicodendron dermatitis; 50% to 75% of US adults are clinically sensitive to these plants.2 Furthermore, people of all ethnicities, skin types, and ages residing in most US geographical regions are at risk.3 Allergenicity is caused by urushiol, which is found in members of the Anacardiaceae family.4 Once absorbed, urushiol causes a type IV hypersensitivity reaction in those who are susceptible.5

Cutaneous Manifestations

Toxicodendron dermatitis presents with an acute eczematous eruption characterized by streaks of intensely pruritic and erythematous papules and vesicles (Figure 1). Areas of involvement are characterized by sharp margins that follow the pattern of contact made by the plant’s leaves, berries, stems, and vines.6 The fluid content of the vesicles is not antigenic and cannot cause subsequent transmission to oneself or others.3 A person with prior contact to the plant who becomes sensitized develops an eruption 24 to 48 hours after subsequent contact with the plant; peak severity manifests 1 to 14 days later.7

When left untreated, the eruption can last 3 weeks. If the plant is burned, urushiol can be aerosolized in smoke, causing respiratory tract inflammation and generalized dermatitis, which has been reported among wildland firefighters.2 Long-term complications from an outbreak are limited but can include postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and secondary bacterial infection.8 Rare reports of nephrotic syndrome also have appeared in the literature.9 Toxicodendron dermatitis can present distinctively as so-called black dot dermatitis.6

Nomenclature

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac are members of the family Anacardiaceae and genus Toxicodendron,6 derived from the Greek words toxikos (poison) and dendron (tree).10

Distribution

Toxicodendron plants characteristically are found in various regions of the United States. Poison ivy is the most common and is comprised of 2 species: Toxicodendron rydbergii and Toxicodendron radicans. Toxicodendron rydbergii is a nonclimbing dwarf shrub typically found in the northern and western United States. Toxicodendron radicans is a climbing vine found in the eastern United States. Poison oak also is comprised of 2 species—Toxicodendron toxicarium and Toxicodendron diversilobum—and is more common in the western United States. Poison sumac (also known as Toxicodendron vernix) is a small shrub that grows in moist swampy areas. It has a predilection for marshes of the eastern and southeastern United States.6,11

Identifying Features

Educating patients on how to identify poison ivy can play a key role in avoidance, which is the most important step in preventing Toxicodendron dermatitis. A challenge in identification of poison ivy is the plant’s variable appearance; it grows as a small shrub, low-lying vine, or vine that climbs other trees.

As the vine matures, it develops tiny, rough, “hairy” rootlets—hence the saying, “Hairy vine, no friend of mine!” Rootlets help the plant attach to trees growing near a water source. Vines can reach a diameter of 3 inches. From mature vines, solitary stems extend 1 to 2 inches with 3 characteristic leaves at the terminus (Figure 2), prompting another classic saying, “Leaves of 3, let it be!”12

Poison oak is characterized by 3 to 5 leaflets. Poison sumac has 7 to 13 pointed, smooth-edged leaves.6

Dermatitis-Inducing Plant Parts

The primary allergenic component of Toxicodendron plants is urushiol, a resinous sap found in stems, roots, leaves, and skins of the fruits. These components must be damaged or bruised to release the allergen; slight contact with an uninjured plant part might not lead to harm.2,13 Some common forms of transmission include skin contact, ingestion, inhalation of smoke from burning plants, and contact with skin through contaminated items, such as clothing, animals, and tools.14

Allergens

The catecholic ring and aliphatic chain of the urushiol molecule are allergenic.15 The degree of saturation and length of the side chains vary with different catechols. Urushiol displays cross-reactivity with poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. Urushiol from these plants differs only slightly in structure; therefore, sensitization to one causes sensitization to all. There also is cross-reactivity between different members of the Anacardiaceae family, including Anacardium occidentale (tropical cashew nut), Mangifera indica (tropical mango tree), Ginkgo biloba (ginkgo tree), and Semecarpus anacardium (Indian marking nut tree).12

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac cause allergic contact dermatitis as a type IV hypersensitivity reaction. First, urushiol binds and penetrates the skin, where it is oxidized to quinone intermediates and bound to haptens. Then, the intermediates bind surface proteins on antigen-presenting cells, specifically Langerhans cells in the epidermis and dermis.5

Presentation of nonpeptide antigens, such as urushiol, to T cells requires expression of langerin (also known as CD207) and CD1a.16 Langerin is a C-type lectin that causes formation of Birbeck granules; CD1a is a major histocompatibility complex class I molecule found in Birbeck granules.5,17 After Langerhans cells internalize and process the urushiol self-hapten neoantigen, it is presented to CD4+ T cells.6 These cells then expand to form circulating activated T-effector and T-memory lymphocytes.18

The molecular link that occurs between the hapten and carrier protein determines the response. When linked by an amino nucleophile, selective induction of T-effector cells ensues, resulting in allergic contact dermatitis. When linked by a sulfhydryl bond, selective induction of suppressor cells occurs, resulting in a reduced allergic contact dermatitis response.19 In the case of activation of T-effector cells, a cell-mediated cytotoxic immune response is generated that destroys epidermal cells and dermal vasculature.2 The incidence and intensity of poison ivy sensitivity decline proportionally with age and the absence of continued exposure.20

Preventive Action—Patients should be counseled that if contact between plant and skin occurs, it is important to remove contaminated clothing or objects and wash them with soap to prevent additional exposure.14,21 Areas of the skin that made contact with the plant should be washed with water as soon as possible; after 30 minutes, urushiol has sufficiently penetrated to cause a reaction.2 Forceful unidirectional washing with a damp washcloth and liquid dishwashing soap is recommended.22

Several barrier creams are commercially available to help prevent absorption or to deactivate the urushiol antigen. These products are used widely by forestry workers and wildland firefighters.23 One such barrier cream is bentoquatam (sold as various trade names), an organoclay compound made of quaternium-18 bentonite that interferes with absorption of the allergen by acting as a physical blocker.24

Treatment

After Toxicodendron dermatitis develops, several treatments are available to help manage symptoms. Calamine lotion can be used to help dry weeping lesions.25,26 Topical steroids can be used to help control pruritus and alleviate inflammation. High-potency topical corticosteroids such as clobetasol and mid-potency steroids such as triamcinolone can be used. Topical anesthetics (eg, benzocaine, pramoxine, benzyl alcohol) might provide symptomatic relief.27,28

Oral antihistamines can allow for better sleep by providing sedation but do not target the pruritus of poison ivy dermatitis, which is not histamine mediated.29,30 Systemic corticosteroids usually are considered in more severe dermatitis—when 20% or more of the body surface area is involved; blistering and itching are severe; or the face, hands, or genitalia are involved.31,32

Clinical Uses

Therapeutic uses for poison ivy have been explored extensively. In 1892, Dakin33 reported that ingestion of leaves by Native Americans reduced the incidence and severity of skin lesions after contact with poison ivy. Consumption of poison ivy was further studied by Epstein and colleagues34 in 1974; they concluded that ingestion of a large amount of urushiol over a period of 3 months or longer may help with hyposensitization—but not complete desensitization—to contact with poison ivy. However, the risk for adverse effects is thought to outweigh benefits because ingestion can cause perianal dermatitis, mucocutaneous sequelae, and systemic contact dermatitis.2

Although the use of Toxicodendron plants in modern-day medicine is limited, development of a vaccine (immunotherapy) against Toxicodendron dermatitis offers an exciting opportunity for further research.

- Pariser DM, Ceilley RI, Lefkovits AM, et al. Poison ivy, oak and sumac. Derm Insights. 2003;4:26-28.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128. doi:10.1580/pr31-05.1

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak/sumac. part II: specific features. Cutis. 1996;58:22-24.

- Cruse JM, Lewis RE. Atlas of Immunology. CRC Press; 2004.

- Valladeau J, Ravel O, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, et al. Langerin, a novel C-type lectin specific to Langerhans cells, is an endocytic receptor that induces the formation of Birbeck granules. Immunity. 2000;12:71-81. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80160-0

- Marks JG. Poison ivy and poison oak allergic contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;9:497-506.

- Williams JV, Light J, Marks JG Jr. Individual variations in allergic contact dermatitis from urushiol. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1002-1003. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.8.1002

- Brook I, Frazier EH, Yeager JK. Microbiology of infected poison ivy dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:943-946. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03475.x

- Rytand DA. Fatal anuria, the nephrotic syndrome and glomerular nephritis as sequels of the dermatitis of poison oak. Am J Med. 1948;5:548-560. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(48)90105-3

- Gledhill D. The Names of Plants. Cambridge University Press; 2008.

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac: how to treat the rash. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/everyday-care/itchy-skin/poison-ivy/treat-rash

- Monroe J. Toxicodendron contact dermatitis: a case report and brief review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(9 suppl 1):S29-S34.

- Marks JG Jr, Anderson BE, DeLeo VA. Contact & Occupational Dermatology. 4th ed. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2016.

- Fisher AA, Mitchell JC. Toxicodendron plants and spices. In: Rietschel RL, Fowler JF Jr, eds. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. 4th ed. Williams and Wilkins; 1995:461-523.

- Dawson CR. The chemistry of poison ivy. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1956;18:427-443. doi:10.1111/j.2164-0947.1956.tb00465.x

- Hunger RE, Sieling PA, Ochoa MT, et al. Langerhans cells utilize CD1a and langerin to efficiently present nonpeptide antigens to T cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:701-708. doi:10.1172/JCI19655

- Hanau D, Fabre M, Schmitt DA, et al. Human epidermal Langerhans cells cointernalize by receptor-mediated endocytosis “non-classical” major histocompatibility complex class Imolecules (T6 antigens) and class II molecules (HLA-DR antigens). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:2901-2905. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.9.2901

- Gayer KD, Burnett JW. Toxicodendron dermatitis. Cutis. 1988;42:99-100.

- Dunn IS, Liberato DJ, Castagnoli N, et al. Contact sensitivity to urushiol: role of covalent bond formation. Cell Immunol. 1982;74:220-233. doi:10.1016/0008-8749(82)90023-5

- Kligman AM. Poison ivy (Rhus) dermatitis; an experimental study. AMA Arch Derm. 1958;77:149-180. doi:10.1001/archderm.1958.01560020001001

- Derraik JGB. Heracleum mantegazzianum and Toxicodendron succedaneum: plants of human health significance in New Zealand and the National Pest Plant Accord. N Z Med J. 2007;120:U2657.

- Neill BC, Neill JA, Brauker J, et al. Postexposure prevention of Toxicodendron dermatitis by early forceful unidirectional washing with liquid dishwashing soap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;81:E25. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.081

- Kim Y, Flamm A, ElSohly MA, et al. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis: what is known and what is new? Dermatitis. 2019;30:183-190. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000472

- Marks JG Jr, Fowler JF Jr, Sheretz EF, et al. Prevention of poison ivy and poison oak allergic contact dermatitis by quaternium-18 bentonite. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:212-216. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90237-6

- Baer RL. Poison ivy dermatitis. Cutis. 1990;46:34-36.

- Williford PM, Sheretz EF. Poison ivy dermatitis. nuances in treatment. Arch Fam Med. 1995;3:184.

- Amrol D, Keitel D, Hagaman D, et al. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of human allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:563-566. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61535-9

- Stephanides SL, Moore C. Toxicodendron poisoning treatment & management. Medscape. Updated June 13, 2022. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/817671-treatment#d11

- Munday J, Bloomfield R, Goldman M, et al. Chlorpheniramine is no more effective than placebo in relieving the symptoms of childhood atopic dermatitis with a nocturnal itching and scratching component. Dermatology. 2002;205:40-45. doi:10.1159/000063138

- Yosipovitch G, Fleischer A. Itch associated with skin disease: advances in pathophysiology and emerging therapies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:617-622. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304090-00004

- Li LY, Cruz PD Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis: pathophysiology applied to future therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:219-223. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04023.x

- Craig K, Meadows SE. What is the best duration of steroid therapy for contact dermatitis (Rhus)? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:166-167.

- Dakin R. Remarks on a cutaneous affection, produced by certain poisonous vegetables. Am J Med Sci. 1829;4:98-100.

- Epstein WL, Baer H, Dawson CR, et al. Poison oak hyposensitization. evaluation of purified urushiol. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:356-360.

- Pariser DM, Ceilley RI, Lefkovits AM, et al. Poison ivy, oak and sumac. Derm Insights. 2003;4:26-28.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128. doi:10.1580/pr31-05.1

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak/sumac. part II: specific features. Cutis. 1996;58:22-24.

- Cruse JM, Lewis RE. Atlas of Immunology. CRC Press; 2004.

- Valladeau J, Ravel O, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, et al. Langerin, a novel C-type lectin specific to Langerhans cells, is an endocytic receptor that induces the formation of Birbeck granules. Immunity. 2000;12:71-81. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80160-0

- Marks JG. Poison ivy and poison oak allergic contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;9:497-506.

- Williams JV, Light J, Marks JG Jr. Individual variations in allergic contact dermatitis from urushiol. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1002-1003. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.8.1002

- Brook I, Frazier EH, Yeager JK. Microbiology of infected poison ivy dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:943-946. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03475.x

- Rytand DA. Fatal anuria, the nephrotic syndrome and glomerular nephritis as sequels of the dermatitis of poison oak. Am J Med. 1948;5:548-560. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(48)90105-3

- Gledhill D. The Names of Plants. Cambridge University Press; 2008.

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac: how to treat the rash. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/everyday-care/itchy-skin/poison-ivy/treat-rash

- Monroe J. Toxicodendron contact dermatitis: a case report and brief review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(9 suppl 1):S29-S34.

- Marks JG Jr, Anderson BE, DeLeo VA. Contact & Occupational Dermatology. 4th ed. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2016.

- Fisher AA, Mitchell JC. Toxicodendron plants and spices. In: Rietschel RL, Fowler JF Jr, eds. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. 4th ed. Williams and Wilkins; 1995:461-523.

- Dawson CR. The chemistry of poison ivy. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1956;18:427-443. doi:10.1111/j.2164-0947.1956.tb00465.x

- Hunger RE, Sieling PA, Ochoa MT, et al. Langerhans cells utilize CD1a and langerin to efficiently present nonpeptide antigens to T cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:701-708. doi:10.1172/JCI19655

- Hanau D, Fabre M, Schmitt DA, et al. Human epidermal Langerhans cells cointernalize by receptor-mediated endocytosis “non-classical” major histocompatibility complex class Imolecules (T6 antigens) and class II molecules (HLA-DR antigens). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:2901-2905. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.9.2901

- Gayer KD, Burnett JW. Toxicodendron dermatitis. Cutis. 1988;42:99-100.

- Dunn IS, Liberato DJ, Castagnoli N, et al. Contact sensitivity to urushiol: role of covalent bond formation. Cell Immunol. 1982;74:220-233. doi:10.1016/0008-8749(82)90023-5

- Kligman AM. Poison ivy (Rhus) dermatitis; an experimental study. AMA Arch Derm. 1958;77:149-180. doi:10.1001/archderm.1958.01560020001001

- Derraik JGB. Heracleum mantegazzianum and Toxicodendron succedaneum: plants of human health significance in New Zealand and the National Pest Plant Accord. N Z Med J. 2007;120:U2657.

- Neill BC, Neill JA, Brauker J, et al. Postexposure prevention of Toxicodendron dermatitis by early forceful unidirectional washing with liquid dishwashing soap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;81:E25. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.081

- Kim Y, Flamm A, ElSohly MA, et al. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis: what is known and what is new? Dermatitis. 2019;30:183-190. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000472

- Marks JG Jr, Fowler JF Jr, Sheretz EF, et al. Prevention of poison ivy and poison oak allergic contact dermatitis by quaternium-18 bentonite. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:212-216. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90237-6

- Baer RL. Poison ivy dermatitis. Cutis. 1990;46:34-36.

- Williford PM, Sheretz EF. Poison ivy dermatitis. nuances in treatment. Arch Fam Med. 1995;3:184.

- Amrol D, Keitel D, Hagaman D, et al. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of human allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:563-566. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61535-9

- Stephanides SL, Moore C. Toxicodendron poisoning treatment & management. Medscape. Updated June 13, 2022. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/817671-treatment#d11

- Munday J, Bloomfield R, Goldman M, et al. Chlorpheniramine is no more effective than placebo in relieving the symptoms of childhood atopic dermatitis with a nocturnal itching and scratching component. Dermatology. 2002;205:40-45. doi:10.1159/000063138

- Yosipovitch G, Fleischer A. Itch associated with skin disease: advances in pathophysiology and emerging therapies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:617-622. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304090-00004

- Li LY, Cruz PD Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis: pathophysiology applied to future therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:219-223. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04023.x

- Craig K, Meadows SE. What is the best duration of steroid therapy for contact dermatitis (Rhus)? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:166-167.

- Dakin R. Remarks on a cutaneous affection, produced by certain poisonous vegetables. Am J Med Sci. 1829;4:98-100.

- Epstein WL, Baer H, Dawson CR, et al. Poison oak hyposensitization. evaluation of purified urushiol. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:356-360.

Practice Points

- Toxicodendron dermatitis is a pruritic vesicular eruption in areas of contact with the plant.

- Identification and avoidance are primary methods of preventing Toxicodendron dermatitis.

Dietary Triggers for Atopic Dermatitis in Children

It is unsurprising that food frequently is thought to be the culprit behind an eczema flare, especially in infants. Indeed, it often is said that infants do only 3 things: eat, sleep, and poop.1 For those unfortunate enough to develop the signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD), food quickly emerges as a potential culprit from the tiny pool of suspects, which is against a cultural backdrop of unprecedented focus on foods and food reactions.2 The prevalence of food allergies in children, though admittedly fraught with methodological difficulties, is estimated to have more than doubled from 3.4% in 1999 to 7.6% in 2018.3 As expected, prevalence rates were higher among children with other atopic comorbidities including AD, with up to 50% of children with AD demonstrating convincing food allergy.4 It is easy to imagine a patient conflating these 2 entities and mistaking their correlation for causation. Thus, it follows that more than 90% of parents/guardians have reported that their children have had food-induced AD, and understandably—at least according to one study—75% of parents/guardians were found to have manipulated the diet in an attempt to manage the disease.5,6

Patients and parents/guardians are not the only ones who have suspected food as a driving force in AD. An article in the British Medical Journal from the 1800s beautifully encapsulated the depth and duration of this quandary: “There is probably no subject in which more deeply rooted convictions have been held, not only in the profession but by the laity, than the connection between diet and disease, both as regards the causation and treatment of the latter.”7 Herein, a wide range of food reactions is examined to highlight evidence for the role of diet in AD, which may contradict what patients—and even some clinicians—believe.

No Easy Answers

A definitive statement that food allergy is not the root cause of AD would put this issue to rest, but such simplicity does not reflect the complex reality. First, we must agree on definitions for certain terms. What do we mean by food allergy? A broader category—adverse food reactions—covers a wide range of entities, some immune mediated and some not, including lactose intolerance, irritant contact dermatitis around the mouth, and even dermatitis herpetiformis (the cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease).8 Although the term food allergy often is used synonymously with adverse food reactions, the exact definition of a food allergy is specific: “adverse immune responses to food proteins that result in typical clinical symptoms.”8 The fact that many patients and even health care practitioners seem to frequently misapply this term makes it even more confusing.

The current focus is on foods that could trigger a flare of AD, which clearly is a broader question than food allergy sensu stricto. It seems self-evident, for example, that if an infant with AD were to (messily) eat an acidic food such as an orange, a flare-up of AD around the mouth and on the cheeks and hands would be a forgone conclusion. Similar nonimmunologic scenarios unambiguously can occur with many foods, including citrus; corn; radish; mustard; garlic; onion; pineapple; and many spices, food additives, and preservatives.9 Clearly there are some scenarios whereby food could trigger an AD flare, and yet this more limited vignette generally is not what patients are referring to when suggesting that food is the root cause of their AD.

The Labyrinth of Testing for Food Allergies

Although there is no reliable method for testing for irritant dermatitis, understanding the other types of tests may help guide our thinking. Testing for IgE-mediated food allergies generally is done via an immunoenzymatic serum assay that can document sensitization to a food protein; however, this testing by itself is not sufficient to diagnose a clinical food allergy.10 Similarly, skin prick testing allows for intradermal administration of a food extract to evaluate for an urticarial reaction within 10 to 15 minutes. Although the sensitivity and specificity vary by age, population, and the specific allergen being tested, these are limited to immediate-type reactions and do not reflect the potential to drive an eczematous flare.

The gold standard, if there is one, is likely the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC), ideally with a long enough observation period to capture later-occurring reactions such as an AD flare. However, given the nature of the test—having patients eat the foods of concern and then carefully following them for reactions—it remains time consuming, expensive, and labor intensive.11

To further complicate matters, several unvalidated tests exist such as IgG testing, atopy patch testing, kinesiology, and hair and gastric juice analysis, which remain investigational but continue to be used and may further confuse patients and clinicians.12

Classification of Food Allergies

It is useful to first separate out the classic IgE-mediated food allergy reactions that are common. In these immediate-type reactions, a person sensitized to a food protein will develop characteristic cutaneous and/or extracutaneous reactions such as urticaria, angioedema, and even anaphylaxis, usually within minutes of exposure. Although it is possible that an IgE-mediated reaction could trigger an AD flare—perhaps simply by causing pruritus, which could initiate the itch-scratch cycle—because of the near simultaneity with ingestion of the offending food and the often dramatic clinical presentations, such foods clearly do not represent “hidden” triggers for AD flares.3 The concept of food-triggered AD (FTAD) is crucial for thinking about foods that could result in true eczematous flares, which historically have been classified as early-type (<2 hours after food challenge) and late-type (≥2 hours after food challenge) reactions.13,14

A study of more than 1000 DBPCFCs performed in patients with AD was illustrative.15 Immediate reactions other than AD were fairly common and were observed in 40% of the food challenges compared to only 9% in the placebo group. These reactions included urticaria, angioedema, and gastrointestinal and respiratory tract symptoms. Immediate reactions of AD alone were exceedingly rare at only 0.7% and not significantly elevated compared to placebo. Just over 4% experienced both an immediate AD exacerbation along with other non-AD findings, which was significantly greater than placebo (P<.01). Although intermediate and late reactions manifesting as AD exacerbations did occur after food ingestion, they were rare (2.2% or less) and not significantly different from placebo. The authors concluded that an exacerbation of AD in the absence of other allergic symptoms in children was unlikely to be due to food,15 which is an important finding.

A recent retrospective review of 372 children with AD reported similar results.4 The authors defined FTAD in a different way; instead of showing a flare after a DBPCFC, they looked for “physician-noted sustained improvement in AD upon removal of a food (typically after 2–6-wk follow-up), to which the child was sensitized without any other changes in skin care.” Despite this fundamentally different approach, they similarly concluded that while food allergies were common, FTAD was relatively uncommon—found in 2% of those with mild AD, 6% of those with moderate AD, and 4% of those with severe AD.4

There are other ways that foods could contribute to disease flares, however, and one of the most compelling is that there may be broader concepts at play; perhaps some diets are not specifically driving the AD but rather are affecting inflammation in the body at large. Although somewhat speculative, there is evidence that some foods may simply be proinflammatory, working to exacerbate the disease outside of a specific mechanism, which has been seen in a variety of other conditions such as acne or rheumatoid arthritis.16,17 To speculate further, it is possible that there may be a threshold effect such that when the AD is poorly controlled, certain factors such as inflammatory foods could lead to a flare, while when under better control, these same factors may not cause an effect.

Finally, it is important to also consider the emotional and/or psychological aspects related to food and diet. The power of the placebo in dietary change has been documented in several diseases, though this certainly is not to be dismissive of the patient’s symptoms; it seems reasonable that the very act of changing such a fundamental aspect of daily life could result in a placebo effect.18,19 In the context of relapsing and remitting conditions such as AD, this effect may be magnified. A landmark study by Thompson and Hanifin20 illustrates this possibility. The authors found that in 80% of cases in which patients were convinced that food was a major contributing factor to their AD, such concerns diminished markedly once better control of the eczema was achieved.20

Navigating the Complexity of Dietary Restrictions

This brings us to what to do with an individual patient in the examination room. Because there is such widespread concern and discussion around this topic, it is important to at least briefly address it. If there are known food allergens that are being avoided, it is important to underscore the importance of continuing to avoid those foods, especially when there is actual evidence of true food allergy rather than sensitization alone. Historically, elimination diets often were recommended empirically, though more recent studies, meta-analyses, and guidance documents increasingly have recommended against them.3 In particular, there are major concerns for iatrogenic harm.

First, heavily restricted diets may result in nutritional and/or caloric deficiencies that can be dangerous and lead to poor growth.21 Practices such as drinking unpasteurized milk can expose children to dangerous infections, while feeding them exclusively rice milk can lead to severe malnutrition.22

Second, there is a dawning realization that children with AD placed on elimination diets may actually develop true IgE-mediated allergies, including fatal anaphylaxis, to the excluded foods. In fact, one retrospective review of 298 patients with a history of AD and no prior immediate reactions found that 19% of patients developed new immediate-type hypersensitivity reactions after starting an elimination diet, presumably due to the loss of tolerance to these foods. A striking one-third of these reactions were classified as anaphylaxis, with cow’s milk and egg being the most common offenders.23

It also is crucial to acknowledge that recommending sweeping lifestyle changes is not easy for patients, especially pediatric patients. Onerous dietary restrictions may add considerable stress, ironically a known trigger for AD itself.

Finally, dietary modifications can be a distraction from conventional therapy and may result in treatment delays while the patient continues to experience uncontrolled symptoms of AD.

Final Thoughts

Diet is intimately related to AD. Although the narrative continues to unfold in fascinating domains, such as the skin barrier and the microbiome, it is increasingly clear that these are intertwined and always have been. Despite the rarity of true food-triggered AD, the perception of dietary triggers is so widespread and addressing the topic is important and may help avoid unnecessary harm from unfounded extreme dietary changes. A recent multispecialty workgroup report on AD and food allergy succinctly summarized this as: “AD has many triggers and comorbidities, and food allergy is only one of the potential triggers and comorbid conditions. With regard to AD management, education and skin care are most important.”3 With proper testing, guidance, and both topical and systemic therapies, most AD can be brought under control, and for at least some patients, this may allay concerns about foods triggering their AD.

- Eat, sleep, poop—the top 3 things new parents need to know. John’s Hopkins All Children’s Hospital website. Published May 18, 2019. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.hopkinsallchildrens.org/ACH-News/General-News/Eat-Sleep-Poop-%E2%80%93-The-Top-3-Things-New-Parents-Ne

- Onyimba F, Crowe SE, Johnson S, et al. Food allergies and intolerances: a clinical approach to the diagnosis and management of adverse reactions to food. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2230-2240.e1.

- Singh AM, Anvari S, Hauk P, et al. Atopic dermatitis and food allergy: best practices and knowledge gaps—a work group report from the AAAAI Allergic Skin Diseases Committee and Leadership Institute Project. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:697-706.

- Li JC, Arkin LM, Makhija MM, et al. Prevalence of food allergy diagnosis in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis referred to allergy and/or dermatology subspecialty clinics. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:2469-2471.

- Thompson MM, Tofte SJ, Simpson EL, et al. Patterns of care and referral in children with atopic dermatitis and concern for food allergy. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:91-96.

- Johnston GA, Bilbao RM, Graham-Brown RAC. The use of dietary manipulation by parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1186-1189.

- Mackenzie S. The inaugural address on the advantages to be derived from the study of dermatology: delivered to the Reading Pathological Society. Br Med J. 1896;1:193-197.

- Anvari S, Miller J, Yeh CY, et al. IgE-mediated food allergy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;57:244-260.

- Brancaccio RR, Alvarez MS. Contact allergy to food. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:302-313.

- Robison RG, Singh AM. Controversies in allergy: food testing and dietary avoidance in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:35-39.

- Sicherer SH, Morrow EH, Sampson HA. Dose-response in double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenges in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:582-586.

- Kelso JM. Unproven diagnostic tests for adverse reactions to foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:362-365.

- Heratizadeh A, Wichmann K, Werfel T. Food allergy and atopic dermatitis: how are they connected? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:284-291.

- Breuer K, Heratizadeh A, Wulf A, et al. Late eczematous reactions to food in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:817-824.

- Roerdink EM, Flokstra-de Blok BMJ, Blok JL, et al. Association of food allergy and atopic dermatitis exacerbations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116:334-338.

- Fuglsang G, Madsen G, Halken S, et al. Adverse reactions to food additives in children with atopic symptoms. Allergy. 1994;49:31-37.

- Ehlers I, Worm M, Sterry W, et al. Sugar is not an aggravating factor in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:282-284.

- Staudacher HM, Irving PM, Lomer MCE, et al. The challenges of control groups, placebos and blinding in clinical trials of dietary interventions. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76:203-212.

- Masi A, Lampit A, Glozier N, et al. Predictors of placebo response in pharmacological and dietary supplement treatment trials in pediatric autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:E640.

- Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Effective therapy of childhood atopic dermatitis allays food allergy concerns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 2):S214-S219.

- Meyer R, De Koker C, Dziubak R, et al. The impact of the elimination diet on growth and nutrient intake in children with food protein induced gastrointestinal allergies. Clin Transl Allergy. 2016;6:25.

- Webber SA, Graham-Brown RA, Hutchinson PE, et al. Dietary manipulation in childhood atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:91-98.

- Chang A, Robison R, Cai M, et al. Natural history of food-triggered atopic dermatitis and development of immediate reactions in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:229-236.e1.

It is unsurprising that food frequently is thought to be the culprit behind an eczema flare, especially in infants. Indeed, it often is said that infants do only 3 things: eat, sleep, and poop.1 For those unfortunate enough to develop the signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD), food quickly emerges as a potential culprit from the tiny pool of suspects, which is against a cultural backdrop of unprecedented focus on foods and food reactions.2 The prevalence of food allergies in children, though admittedly fraught with methodological difficulties, is estimated to have more than doubled from 3.4% in 1999 to 7.6% in 2018.3 As expected, prevalence rates were higher among children with other atopic comorbidities including AD, with up to 50% of children with AD demonstrating convincing food allergy.4 It is easy to imagine a patient conflating these 2 entities and mistaking their correlation for causation. Thus, it follows that more than 90% of parents/guardians have reported that their children have had food-induced AD, and understandably—at least according to one study—75% of parents/guardians were found to have manipulated the diet in an attempt to manage the disease.5,6

Patients and parents/guardians are not the only ones who have suspected food as a driving force in AD. An article in the British Medical Journal from the 1800s beautifully encapsulated the depth and duration of this quandary: “There is probably no subject in which more deeply rooted convictions have been held, not only in the profession but by the laity, than the connection between diet and disease, both as regards the causation and treatment of the latter.”7 Herein, a wide range of food reactions is examined to highlight evidence for the role of diet in AD, which may contradict what patients—and even some clinicians—believe.

No Easy Answers

A definitive statement that food allergy is not the root cause of AD would put this issue to rest, but such simplicity does not reflect the complex reality. First, we must agree on definitions for certain terms. What do we mean by food allergy? A broader category—adverse food reactions—covers a wide range of entities, some immune mediated and some not, including lactose intolerance, irritant contact dermatitis around the mouth, and even dermatitis herpetiformis (the cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease).8 Although the term food allergy often is used synonymously with adverse food reactions, the exact definition of a food allergy is specific: “adverse immune responses to food proteins that result in typical clinical symptoms.”8 The fact that many patients and even health care practitioners seem to frequently misapply this term makes it even more confusing.

The current focus is on foods that could trigger a flare of AD, which clearly is a broader question than food allergy sensu stricto. It seems self-evident, for example, that if an infant with AD were to (messily) eat an acidic food such as an orange, a flare-up of AD around the mouth and on the cheeks and hands would be a forgone conclusion. Similar nonimmunologic scenarios unambiguously can occur with many foods, including citrus; corn; radish; mustard; garlic; onion; pineapple; and many spices, food additives, and preservatives.9 Clearly there are some scenarios whereby food could trigger an AD flare, and yet this more limited vignette generally is not what patients are referring to when suggesting that food is the root cause of their AD.

The Labyrinth of Testing for Food Allergies

Although there is no reliable method for testing for irritant dermatitis, understanding the other types of tests may help guide our thinking. Testing for IgE-mediated food allergies generally is done via an immunoenzymatic serum assay that can document sensitization to a food protein; however, this testing by itself is not sufficient to diagnose a clinical food allergy.10 Similarly, skin prick testing allows for intradermal administration of a food extract to evaluate for an urticarial reaction within 10 to 15 minutes. Although the sensitivity and specificity vary by age, population, and the specific allergen being tested, these are limited to immediate-type reactions and do not reflect the potential to drive an eczematous flare.

The gold standard, if there is one, is likely the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC), ideally with a long enough observation period to capture later-occurring reactions such as an AD flare. However, given the nature of the test—having patients eat the foods of concern and then carefully following them for reactions—it remains time consuming, expensive, and labor intensive.11

To further complicate matters, several unvalidated tests exist such as IgG testing, atopy patch testing, kinesiology, and hair and gastric juice analysis, which remain investigational but continue to be used and may further confuse patients and clinicians.12

Classification of Food Allergies

It is useful to first separate out the classic IgE-mediated food allergy reactions that are common. In these immediate-type reactions, a person sensitized to a food protein will develop characteristic cutaneous and/or extracutaneous reactions such as urticaria, angioedema, and even anaphylaxis, usually within minutes of exposure. Although it is possible that an IgE-mediated reaction could trigger an AD flare—perhaps simply by causing pruritus, which could initiate the itch-scratch cycle—because of the near simultaneity with ingestion of the offending food and the often dramatic clinical presentations, such foods clearly do not represent “hidden” triggers for AD flares.3 The concept of food-triggered AD (FTAD) is crucial for thinking about foods that could result in true eczematous flares, which historically have been classified as early-type (<2 hours after food challenge) and late-type (≥2 hours after food challenge) reactions.13,14

A study of more than 1000 DBPCFCs performed in patients with AD was illustrative.15 Immediate reactions other than AD were fairly common and were observed in 40% of the food challenges compared to only 9% in the placebo group. These reactions included urticaria, angioedema, and gastrointestinal and respiratory tract symptoms. Immediate reactions of AD alone were exceedingly rare at only 0.7% and not significantly elevated compared to placebo. Just over 4% experienced both an immediate AD exacerbation along with other non-AD findings, which was significantly greater than placebo (P<.01). Although intermediate and late reactions manifesting as AD exacerbations did occur after food ingestion, they were rare (2.2% or less) and not significantly different from placebo. The authors concluded that an exacerbation of AD in the absence of other allergic symptoms in children was unlikely to be due to food,15 which is an important finding.

A recent retrospective review of 372 children with AD reported similar results.4 The authors defined FTAD in a different way; instead of showing a flare after a DBPCFC, they looked for “physician-noted sustained improvement in AD upon removal of a food (typically after 2–6-wk follow-up), to which the child was sensitized without any other changes in skin care.” Despite this fundamentally different approach, they similarly concluded that while food allergies were common, FTAD was relatively uncommon—found in 2% of those with mild AD, 6% of those with moderate AD, and 4% of those with severe AD.4

There are other ways that foods could contribute to disease flares, however, and one of the most compelling is that there may be broader concepts at play; perhaps some diets are not specifically driving the AD but rather are affecting inflammation in the body at large. Although somewhat speculative, there is evidence that some foods may simply be proinflammatory, working to exacerbate the disease outside of a specific mechanism, which has been seen in a variety of other conditions such as acne or rheumatoid arthritis.16,17 To speculate further, it is possible that there may be a threshold effect such that when the AD is poorly controlled, certain factors such as inflammatory foods could lead to a flare, while when under better control, these same factors may not cause an effect.

Finally, it is important to also consider the emotional and/or psychological aspects related to food and diet. The power of the placebo in dietary change has been documented in several diseases, though this certainly is not to be dismissive of the patient’s symptoms; it seems reasonable that the very act of changing such a fundamental aspect of daily life could result in a placebo effect.18,19 In the context of relapsing and remitting conditions such as AD, this effect may be magnified. A landmark study by Thompson and Hanifin20 illustrates this possibility. The authors found that in 80% of cases in which patients were convinced that food was a major contributing factor to their AD, such concerns diminished markedly once better control of the eczema was achieved.20

Navigating the Complexity of Dietary Restrictions

This brings us to what to do with an individual patient in the examination room. Because there is such widespread concern and discussion around this topic, it is important to at least briefly address it. If there are known food allergens that are being avoided, it is important to underscore the importance of continuing to avoid those foods, especially when there is actual evidence of true food allergy rather than sensitization alone. Historically, elimination diets often were recommended empirically, though more recent studies, meta-analyses, and guidance documents increasingly have recommended against them.3 In particular, there are major concerns for iatrogenic harm.

First, heavily restricted diets may result in nutritional and/or caloric deficiencies that can be dangerous and lead to poor growth.21 Practices such as drinking unpasteurized milk can expose children to dangerous infections, while feeding them exclusively rice milk can lead to severe malnutrition.22

Second, there is a dawning realization that children with AD placed on elimination diets may actually develop true IgE-mediated allergies, including fatal anaphylaxis, to the excluded foods. In fact, one retrospective review of 298 patients with a history of AD and no prior immediate reactions found that 19% of patients developed new immediate-type hypersensitivity reactions after starting an elimination diet, presumably due to the loss of tolerance to these foods. A striking one-third of these reactions were classified as anaphylaxis, with cow’s milk and egg being the most common offenders.23

It also is crucial to acknowledge that recommending sweeping lifestyle changes is not easy for patients, especially pediatric patients. Onerous dietary restrictions may add considerable stress, ironically a known trigger for AD itself.

Finally, dietary modifications can be a distraction from conventional therapy and may result in treatment delays while the patient continues to experience uncontrolled symptoms of AD.

Final Thoughts

Diet is intimately related to AD. Although the narrative continues to unfold in fascinating domains, such as the skin barrier and the microbiome, it is increasingly clear that these are intertwined and always have been. Despite the rarity of true food-triggered AD, the perception of dietary triggers is so widespread and addressing the topic is important and may help avoid unnecessary harm from unfounded extreme dietary changes. A recent multispecialty workgroup report on AD and food allergy succinctly summarized this as: “AD has many triggers and comorbidities, and food allergy is only one of the potential triggers and comorbid conditions. With regard to AD management, education and skin care are most important.”3 With proper testing, guidance, and both topical and systemic therapies, most AD can be brought under control, and for at least some patients, this may allay concerns about foods triggering their AD.