User login

Moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: No increased infection risk with long-term dupilumab use

Key clinical point: In patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD), continuous long-term dupilumab treatment was not associated with an increased risk for overall systemic/cutaneous infections.

Major finding: At 4 years, the overall infection rate was 71.27 number of patients with ≥1 event per 100 patient-years (nP/100 PY), with most infections being mild to moderate in severity, and only a very small number of infections resulted in treatment discontinuation (0.34 nP/100 PY). The rate of total skin infections decreased from 28.10 to 11.48 nP/100 PY from week 16 to year 4.

Study details: Findings are from the analysis of the LIBERTY AD OLE study including 2677 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who received dupilumab, of which 13.1% completed treatment up to week 204.

Disclosures: This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Four authors declared being employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Three authors declared being employees or holding stock options in Sanofi. The other authors reported ties with several sources, including Regeneron and Sanofi.

Source: Blauvelt A et al. No increased risk of overall infection in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis treated for up to 4 years with dupilumab. Adv Ther. 2022 (Nov 1). Doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02322-y

Key clinical point: In patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD), continuous long-term dupilumab treatment was not associated with an increased risk for overall systemic/cutaneous infections.

Major finding: At 4 years, the overall infection rate was 71.27 number of patients with ≥1 event per 100 patient-years (nP/100 PY), with most infections being mild to moderate in severity, and only a very small number of infections resulted in treatment discontinuation (0.34 nP/100 PY). The rate of total skin infections decreased from 28.10 to 11.48 nP/100 PY from week 16 to year 4.

Study details: Findings are from the analysis of the LIBERTY AD OLE study including 2677 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who received dupilumab, of which 13.1% completed treatment up to week 204.

Disclosures: This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Four authors declared being employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Three authors declared being employees or holding stock options in Sanofi. The other authors reported ties with several sources, including Regeneron and Sanofi.

Source: Blauvelt A et al. No increased risk of overall infection in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis treated for up to 4 years with dupilumab. Adv Ther. 2022 (Nov 1). Doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02322-y

Key clinical point: In patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD), continuous long-term dupilumab treatment was not associated with an increased risk for overall systemic/cutaneous infections.

Major finding: At 4 years, the overall infection rate was 71.27 number of patients with ≥1 event per 100 patient-years (nP/100 PY), with most infections being mild to moderate in severity, and only a very small number of infections resulted in treatment discontinuation (0.34 nP/100 PY). The rate of total skin infections decreased from 28.10 to 11.48 nP/100 PY from week 16 to year 4.

Study details: Findings are from the analysis of the LIBERTY AD OLE study including 2677 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who received dupilumab, of which 13.1% completed treatment up to week 204.

Disclosures: This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Four authors declared being employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Three authors declared being employees or holding stock options in Sanofi. The other authors reported ties with several sources, including Regeneron and Sanofi.

Source: Blauvelt A et al. No increased risk of overall infection in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis treated for up to 4 years with dupilumab. Adv Ther. 2022 (Nov 1). Doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02322-y

Exposure to wildfire air pollution increases atopic dermatitis risk in older adults

Key clinical point: Air pollution due to a wildfire increased the rate of clinic visits for atopic dermatitis (AD), especially at a 0-week lag, in adults aged ≥65 years.

Major finding: In adults aged ≥65 years, the adjusted rate of clinic visits for AD during a week with a wildfire was 1.4 (95% CI 1.1-1.9) times the rate during weeks without wildfire and every 1-unit increase in the mean weekly smoke plume density score increased the rate of clinic visits for AD by 1.3 (95% CI 1.1-1.6) times.

Study details: This study analyzed the data of outpatient dermatology visits for AD (5529 visits) and itch (1319 visits).

Disclosures: This study did not report the source of funding. Dr. Grimes declared receiving grants from the University of California, San Francisco.

Source: Fadadu RP et al. Association of exposure to wildfire air pollution with exacerbations of atopic dermatitis and itch among older adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2238594 (Oct 26). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.38594

Key clinical point: Air pollution due to a wildfire increased the rate of clinic visits for atopic dermatitis (AD), especially at a 0-week lag, in adults aged ≥65 years.

Major finding: In adults aged ≥65 years, the adjusted rate of clinic visits for AD during a week with a wildfire was 1.4 (95% CI 1.1-1.9) times the rate during weeks without wildfire and every 1-unit increase in the mean weekly smoke plume density score increased the rate of clinic visits for AD by 1.3 (95% CI 1.1-1.6) times.

Study details: This study analyzed the data of outpatient dermatology visits for AD (5529 visits) and itch (1319 visits).

Disclosures: This study did not report the source of funding. Dr. Grimes declared receiving grants from the University of California, San Francisco.

Source: Fadadu RP et al. Association of exposure to wildfire air pollution with exacerbations of atopic dermatitis and itch among older adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2238594 (Oct 26). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.38594

Key clinical point: Air pollution due to a wildfire increased the rate of clinic visits for atopic dermatitis (AD), especially at a 0-week lag, in adults aged ≥65 years.

Major finding: In adults aged ≥65 years, the adjusted rate of clinic visits for AD during a week with a wildfire was 1.4 (95% CI 1.1-1.9) times the rate during weeks without wildfire and every 1-unit increase in the mean weekly smoke plume density score increased the rate of clinic visits for AD by 1.3 (95% CI 1.1-1.6) times.

Study details: This study analyzed the data of outpatient dermatology visits for AD (5529 visits) and itch (1319 visits).

Disclosures: This study did not report the source of funding. Dr. Grimes declared receiving grants from the University of California, San Francisco.

Source: Fadadu RP et al. Association of exposure to wildfire air pollution with exacerbations of atopic dermatitis and itch among older adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2238594 (Oct 26). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.38594

Atopic dermatitis: Dupilumab serum levels not associated with treatment response or adverse effects

Key clinical point: In patients with atopic dermatitis (AD), serum dupilumab levels at week 16 were not associated with treatment response or adverse effects due to dupilumab during the first year of treatment.

Major finding: Serum dupilumab levels at 16 weeks were not associated with the prediction of treatment response at 52 weeks (≥90% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index; odds ratio [OR] 0.96; P = .34) or adverse events during the first year of treatment (OR 1.01; P = .83).

Study details: Findings are from a prospective clinical cohort study including 295 patients with AD who started dupilumab and had treatment week 16 serum samples available.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie, Eli Lilly, and other sources. The authors declared receiving consulting fees, speaking fees, investigator fees, or research funding from several sources.

Source: Spekhorst LS et al. Association of serum dupilumab levels at 16 weeks with treatment response and adverse effects in patients with atopic dermatitis: A prospective clinical cohort study from the BioDay registry. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Nov 2). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.4639

Key clinical point: In patients with atopic dermatitis (AD), serum dupilumab levels at week 16 were not associated with treatment response or adverse effects due to dupilumab during the first year of treatment.

Major finding: Serum dupilumab levels at 16 weeks were not associated with the prediction of treatment response at 52 weeks (≥90% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index; odds ratio [OR] 0.96; P = .34) or adverse events during the first year of treatment (OR 1.01; P = .83).

Study details: Findings are from a prospective clinical cohort study including 295 patients with AD who started dupilumab and had treatment week 16 serum samples available.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie, Eli Lilly, and other sources. The authors declared receiving consulting fees, speaking fees, investigator fees, or research funding from several sources.

Source: Spekhorst LS et al. Association of serum dupilumab levels at 16 weeks with treatment response and adverse effects in patients with atopic dermatitis: A prospective clinical cohort study from the BioDay registry. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Nov 2). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.4639

Key clinical point: In patients with atopic dermatitis (AD), serum dupilumab levels at week 16 were not associated with treatment response or adverse effects due to dupilumab during the first year of treatment.

Major finding: Serum dupilumab levels at 16 weeks were not associated with the prediction of treatment response at 52 weeks (≥90% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index; odds ratio [OR] 0.96; P = .34) or adverse events during the first year of treatment (OR 1.01; P = .83).

Study details: Findings are from a prospective clinical cohort study including 295 patients with AD who started dupilumab and had treatment week 16 serum samples available.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie, Eli Lilly, and other sources. The authors declared receiving consulting fees, speaking fees, investigator fees, or research funding from several sources.

Source: Spekhorst LS et al. Association of serum dupilumab levels at 16 weeks with treatment response and adverse effects in patients with atopic dermatitis: A prospective clinical cohort study from the BioDay registry. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Nov 2). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.4639

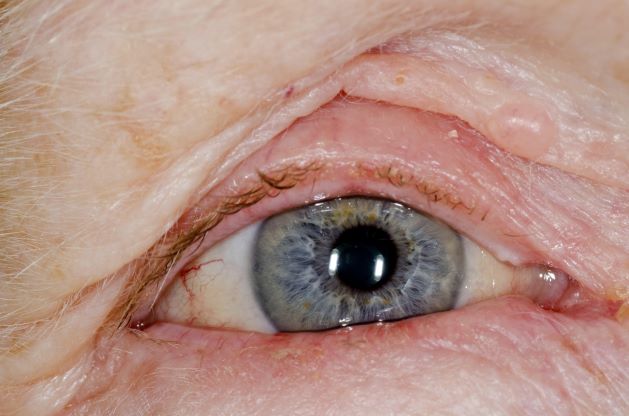

Red swollen eyelids

This patient's symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of blepharitis.

Blepharitis is an inflammatory disorder of the eyelids that is frequently associated with bacterial colonization of the eyelid. Anatomically, it can be categorized as anterior blepharitis or posterior blepharitis. Anterior blepharitis refers to inflammation primarily positioned around the skin, eyelashes, and lash follicles and is usually further divided into staphylococcal and seborrheic variants. Posterior blepharitis involves the meibomian gland orifices, meibomian glands, tarsal plate, and blepharo-conjunctival junction.

Blepharitis can be acute or chronic. It is frequently associated with systemic diseases, such as rosacea, atopy, and seborrheic dermatitis, as well as ocular diseases, such as dry eye syndromes, chalazion, trichiasis, ectropion and entropion, infectious or other inflammatory conjunctivitis, and keratitis. Moreover, high rates of blepharitis have been reported in patients treated with dupilumab for atopic dermatitis.

Eye irritation, itching, erythema of the lids, flaking of the lid margins, and/or changes in the eyelashes are common presenting symptoms in patients with blepharitis. Other symptoms may include:

• Burning

• Watering

• Foreign-body sensation

• Crusting and mattering of the lashes and medial canthus

• Red lids

• Red eyes

• Photophobia

• Pain

• Decreased vision

• Visual fluctuations

• Heat, cold, alcohol, and spicy-food intolerance

The differential diagnosis for blepharitis includes bacterial keratitis, which is a serious ocular disorder that can lead to vision loss if not properly treated. Bacterial keratitis progresses rapidly and can result in corneal destruction within 24-48 hours with some particularly virulent bacteria. Patients with bacterial keratitis typically report rapid onset of pain, photophobia, and decreased vision.

Ocular rosacea should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of blepharitis, and the two conditions can co-occur. Patients with ocular rosacea may experience facial symptoms (eg, recurrent flushing episodes, persistent and/or recurrent midfacial erythema, papular and pustular lesions) in addition to ocular symptoms, which can range from minor irritation, foreign-body sensation, and blurry vision to severe ocular surface disruption and inflammatory keratitis.

Bacterial conjunctivitis involves inflammation of the bulbar and/or palpebral conjunctiva, whereas blepharitis involves inflammation of the eyelids only. Other conditions to consider in the diagnosis of blepharitis can be found here.

Given the unprecedented efficacy seen in clinical trials, dupilumab is emerging as a first-line therapeutic for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. However, clinicians should be alert to ocular complications among their patients with atopic dermatitis who are being treated with dupilumab. In some patients, this may be because of preexisting meibomian gland disease and ocular surface disease. After a diagnosis of ocular complications, the continued use of dupilumab should be jointly evaluated by the ophthalmologist and dermatologist or allergist on the basis of the ocular risk vs systemic benefit. Treatment for blepharitis typically includes strict eyelid hygiene and topical antibiotic ointment; oral antibiotics can be beneficial for refractory disease.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of blepharitis.

Blepharitis is an inflammatory disorder of the eyelids that is frequently associated with bacterial colonization of the eyelid. Anatomically, it can be categorized as anterior blepharitis or posterior blepharitis. Anterior blepharitis refers to inflammation primarily positioned around the skin, eyelashes, and lash follicles and is usually further divided into staphylococcal and seborrheic variants. Posterior blepharitis involves the meibomian gland orifices, meibomian glands, tarsal plate, and blepharo-conjunctival junction.

Blepharitis can be acute or chronic. It is frequently associated with systemic diseases, such as rosacea, atopy, and seborrheic dermatitis, as well as ocular diseases, such as dry eye syndromes, chalazion, trichiasis, ectropion and entropion, infectious or other inflammatory conjunctivitis, and keratitis. Moreover, high rates of blepharitis have been reported in patients treated with dupilumab for atopic dermatitis.

Eye irritation, itching, erythema of the lids, flaking of the lid margins, and/or changes in the eyelashes are common presenting symptoms in patients with blepharitis. Other symptoms may include:

• Burning

• Watering

• Foreign-body sensation

• Crusting and mattering of the lashes and medial canthus

• Red lids

• Red eyes

• Photophobia

• Pain

• Decreased vision

• Visual fluctuations

• Heat, cold, alcohol, and spicy-food intolerance

The differential diagnosis for blepharitis includes bacterial keratitis, which is a serious ocular disorder that can lead to vision loss if not properly treated. Bacterial keratitis progresses rapidly and can result in corneal destruction within 24-48 hours with some particularly virulent bacteria. Patients with bacterial keratitis typically report rapid onset of pain, photophobia, and decreased vision.

Ocular rosacea should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of blepharitis, and the two conditions can co-occur. Patients with ocular rosacea may experience facial symptoms (eg, recurrent flushing episodes, persistent and/or recurrent midfacial erythema, papular and pustular lesions) in addition to ocular symptoms, which can range from minor irritation, foreign-body sensation, and blurry vision to severe ocular surface disruption and inflammatory keratitis.

Bacterial conjunctivitis involves inflammation of the bulbar and/or palpebral conjunctiva, whereas blepharitis involves inflammation of the eyelids only. Other conditions to consider in the diagnosis of blepharitis can be found here.

Given the unprecedented efficacy seen in clinical trials, dupilumab is emerging as a first-line therapeutic for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. However, clinicians should be alert to ocular complications among their patients with atopic dermatitis who are being treated with dupilumab. In some patients, this may be because of preexisting meibomian gland disease and ocular surface disease. After a diagnosis of ocular complications, the continued use of dupilumab should be jointly evaluated by the ophthalmologist and dermatologist or allergist on the basis of the ocular risk vs systemic benefit. Treatment for blepharitis typically includes strict eyelid hygiene and topical antibiotic ointment; oral antibiotics can be beneficial for refractory disease.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of blepharitis.

Blepharitis is an inflammatory disorder of the eyelids that is frequently associated with bacterial colonization of the eyelid. Anatomically, it can be categorized as anterior blepharitis or posterior blepharitis. Anterior blepharitis refers to inflammation primarily positioned around the skin, eyelashes, and lash follicles and is usually further divided into staphylococcal and seborrheic variants. Posterior blepharitis involves the meibomian gland orifices, meibomian glands, tarsal plate, and blepharo-conjunctival junction.

Blepharitis can be acute or chronic. It is frequently associated with systemic diseases, such as rosacea, atopy, and seborrheic dermatitis, as well as ocular diseases, such as dry eye syndromes, chalazion, trichiasis, ectropion and entropion, infectious or other inflammatory conjunctivitis, and keratitis. Moreover, high rates of blepharitis have been reported in patients treated with dupilumab for atopic dermatitis.

Eye irritation, itching, erythema of the lids, flaking of the lid margins, and/or changes in the eyelashes are common presenting symptoms in patients with blepharitis. Other symptoms may include:

• Burning

• Watering

• Foreign-body sensation

• Crusting and mattering of the lashes and medial canthus

• Red lids

• Red eyes

• Photophobia

• Pain

• Decreased vision

• Visual fluctuations

• Heat, cold, alcohol, and spicy-food intolerance

The differential diagnosis for blepharitis includes bacterial keratitis, which is a serious ocular disorder that can lead to vision loss if not properly treated. Bacterial keratitis progresses rapidly and can result in corneal destruction within 24-48 hours with some particularly virulent bacteria. Patients with bacterial keratitis typically report rapid onset of pain, photophobia, and decreased vision.

Ocular rosacea should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of blepharitis, and the two conditions can co-occur. Patients with ocular rosacea may experience facial symptoms (eg, recurrent flushing episodes, persistent and/or recurrent midfacial erythema, papular and pustular lesions) in addition to ocular symptoms, which can range from minor irritation, foreign-body sensation, and blurry vision to severe ocular surface disruption and inflammatory keratitis.

Bacterial conjunctivitis involves inflammation of the bulbar and/or palpebral conjunctiva, whereas blepharitis involves inflammation of the eyelids only. Other conditions to consider in the diagnosis of blepharitis can be found here.

Given the unprecedented efficacy seen in clinical trials, dupilumab is emerging as a first-line therapeutic for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. However, clinicians should be alert to ocular complications among their patients with atopic dermatitis who are being treated with dupilumab. In some patients, this may be because of preexisting meibomian gland disease and ocular surface disease. After a diagnosis of ocular complications, the continued use of dupilumab should be jointly evaluated by the ophthalmologist and dermatologist or allergist on the basis of the ocular risk vs systemic benefit. Treatment for blepharitis typically includes strict eyelid hygiene and topical antibiotic ointment; oral antibiotics can be beneficial for refractory disease.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 71-year-old woman was referred for an ophthalmologic examination by her dermatologist. The patient reports recent onset of red, swollen eyelids; ocular itching; and a burning sensation. Prior medical history includes severe atopic dermatitis, type 2 diabetes, and osteoarthritis. Current medications include metformin 1000 mg/d, celecoxib 200 mg/d, and clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream twice daily. The patient began receiving subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg/once every 2 weeks about 6 weeks earlier.

Right ankle pain and swelling

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic enthesitis.

Enthesitis is a hallmark manifestation of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Approximately 30% of patients with psoriasis are estimated to be affected by PsA, which belongs to the spondyloarthritis (SpA) family of inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

An enthesis is an attachment site of ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules to bone and is a key inflammatory target in SpA. It is a complex structure that dissipates biomechanical stress to preserve homeostasis. Entheses are anatomically and functionally integrated with bursa, fibrocartilage, and synovium in a synovial entheseal complex; biomechanical stress in this area may trigger inflammation. Enthesitis is an early manifestation of PsA that has been associated with radiographic peripheral/axial joint damage and severe disease, as well as reduced quality of life.

Enthesitis can be difficult to diagnose in clinical practice. Symptoms include tenderness, soreness, and pain at entheses on palpation, often without overt clinical evidence of inflammation. In contrast, dactylitis, another hallmark manifestation of PsA, can be recognized by swelling of an entire digit that is different from adjacent digits. Fibromyalgia frequently coexists with enthesitis, and it can be difficult to distinguish the two given the anatomic overlap between the tender points of fibromyalgia and many entheseal sites. Long-lasting morning stiffness and a sustained response to a course of steroids is more suggestive of enthesitis, whereas a higher number of somatoform symptoms is more suggestive of fibromyalgia.

Enthesitis is included in the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) as a hallmark of PsA. While it can be diagnosed clinically, imaging studies may be required, particularly in patients in whom symptoms may be difficult to discern. Evidence of enthesitis by conventional radiography includes bone cortex irregularities, erosions, entheseal soft tissue calcifications, and new bone formation; however, entheseal bone changes detected with conventional radiography appear relatively late in the disease process. Ultrasound is highly sensitive for assessing inflammation and can detect various features of enthesitis, such as increased thickness of tendon insertion, hypoechogenicity, erosions, enthesophytes, and subclinical enthesitis in people with PsA. MRI has the advantage of identifying perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema. Fat-suppressed MRI with or without gadolinium enhancement is a highly sensitive method for visualizing active enthesitis and can identify perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema.

Delayed treatment of PsA can result in irreversible joint damage and reduced quality of life; thus, patients with psoriasis should be closely monitored for early signs of its development, such as enthesitis. A thorough evaluation of the key clinical features of PsA (psoriasis, arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spondylitis), including evaluation of severity of each feature and impact on physical function and quality of life, is encouraged at each clinical encounter. Because patients may not understand the link between psoriasis and joint pain, specific probing questions can be helpful. Screening questionnaires to detect early signs and symptoms of PsA are available, such as the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST), Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) questionnaire, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screening (ToPAS) questionnaire. These and many others may be used to help dermatologists detect early signs and symptoms of PsA. Although these questionnaires all have limitations in sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of PsA, their use can still improve early diagnosis.

The treatment of PsA focuses on achieving the least amount of disease activity and inflammation possible; optimizing functional status, quality of life, and well-being; and preventing structural damage. Treatment decisions are based on the specific domains affected. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroid injections are first-line treatments for enthesitis. Early use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF) (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, infliximab, and golimumab) is recommended. Alternative biologic disease-modifying agents are indicated when these TNF inhibitors provide an inadequate response. They include ustekinumab (dual interleukin [IL]-12 and IL-23 inhibitor), secukinumab (IL-17A inhibitor), and apremilast (phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor) and may be considered for patients with predominantly entheseal manifestations of PsA or dactylitis. Biological disease-modifying agents approved for PsA that have shown efficacy for enthesitis include ixekizumab (which targets IL-17A), abatacept (a T-cell inhibitor), guselkumab (monoclonal antibody), and ustekinumab (monoclonal antibody). Tofacitinib and upadacitinib, both oral Janus kinase inhibitors, may also be considered.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic enthesitis.

Enthesitis is a hallmark manifestation of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Approximately 30% of patients with psoriasis are estimated to be affected by PsA, which belongs to the spondyloarthritis (SpA) family of inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

An enthesis is an attachment site of ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules to bone and is a key inflammatory target in SpA. It is a complex structure that dissipates biomechanical stress to preserve homeostasis. Entheses are anatomically and functionally integrated with bursa, fibrocartilage, and synovium in a synovial entheseal complex; biomechanical stress in this area may trigger inflammation. Enthesitis is an early manifestation of PsA that has been associated with radiographic peripheral/axial joint damage and severe disease, as well as reduced quality of life.

Enthesitis can be difficult to diagnose in clinical practice. Symptoms include tenderness, soreness, and pain at entheses on palpation, often without overt clinical evidence of inflammation. In contrast, dactylitis, another hallmark manifestation of PsA, can be recognized by swelling of an entire digit that is different from adjacent digits. Fibromyalgia frequently coexists with enthesitis, and it can be difficult to distinguish the two given the anatomic overlap between the tender points of fibromyalgia and many entheseal sites. Long-lasting morning stiffness and a sustained response to a course of steroids is more suggestive of enthesitis, whereas a higher number of somatoform symptoms is more suggestive of fibromyalgia.

Enthesitis is included in the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) as a hallmark of PsA. While it can be diagnosed clinically, imaging studies may be required, particularly in patients in whom symptoms may be difficult to discern. Evidence of enthesitis by conventional radiography includes bone cortex irregularities, erosions, entheseal soft tissue calcifications, and new bone formation; however, entheseal bone changes detected with conventional radiography appear relatively late in the disease process. Ultrasound is highly sensitive for assessing inflammation and can detect various features of enthesitis, such as increased thickness of tendon insertion, hypoechogenicity, erosions, enthesophytes, and subclinical enthesitis in people with PsA. MRI has the advantage of identifying perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema. Fat-suppressed MRI with or without gadolinium enhancement is a highly sensitive method for visualizing active enthesitis and can identify perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema.

Delayed treatment of PsA can result in irreversible joint damage and reduced quality of life; thus, patients with psoriasis should be closely monitored for early signs of its development, such as enthesitis. A thorough evaluation of the key clinical features of PsA (psoriasis, arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spondylitis), including evaluation of severity of each feature and impact on physical function and quality of life, is encouraged at each clinical encounter. Because patients may not understand the link between psoriasis and joint pain, specific probing questions can be helpful. Screening questionnaires to detect early signs and symptoms of PsA are available, such as the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST), Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) questionnaire, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screening (ToPAS) questionnaire. These and many others may be used to help dermatologists detect early signs and symptoms of PsA. Although these questionnaires all have limitations in sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of PsA, their use can still improve early diagnosis.

The treatment of PsA focuses on achieving the least amount of disease activity and inflammation possible; optimizing functional status, quality of life, and well-being; and preventing structural damage. Treatment decisions are based on the specific domains affected. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroid injections are first-line treatments for enthesitis. Early use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF) (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, infliximab, and golimumab) is recommended. Alternative biologic disease-modifying agents are indicated when these TNF inhibitors provide an inadequate response. They include ustekinumab (dual interleukin [IL]-12 and IL-23 inhibitor), secukinumab (IL-17A inhibitor), and apremilast (phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor) and may be considered for patients with predominantly entheseal manifestations of PsA or dactylitis. Biological disease-modifying agents approved for PsA that have shown efficacy for enthesitis include ixekizumab (which targets IL-17A), abatacept (a T-cell inhibitor), guselkumab (monoclonal antibody), and ustekinumab (monoclonal antibody). Tofacitinib and upadacitinib, both oral Janus kinase inhibitors, may also be considered.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic enthesitis.

Enthesitis is a hallmark manifestation of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Approximately 30% of patients with psoriasis are estimated to be affected by PsA, which belongs to the spondyloarthritis (SpA) family of inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

An enthesis is an attachment site of ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules to bone and is a key inflammatory target in SpA. It is a complex structure that dissipates biomechanical stress to preserve homeostasis. Entheses are anatomically and functionally integrated with bursa, fibrocartilage, and synovium in a synovial entheseal complex; biomechanical stress in this area may trigger inflammation. Enthesitis is an early manifestation of PsA that has been associated with radiographic peripheral/axial joint damage and severe disease, as well as reduced quality of life.

Enthesitis can be difficult to diagnose in clinical practice. Symptoms include tenderness, soreness, and pain at entheses on palpation, often without overt clinical evidence of inflammation. In contrast, dactylitis, another hallmark manifestation of PsA, can be recognized by swelling of an entire digit that is different from adjacent digits. Fibromyalgia frequently coexists with enthesitis, and it can be difficult to distinguish the two given the anatomic overlap between the tender points of fibromyalgia and many entheseal sites. Long-lasting morning stiffness and a sustained response to a course of steroids is more suggestive of enthesitis, whereas a higher number of somatoform symptoms is more suggestive of fibromyalgia.

Enthesitis is included in the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) as a hallmark of PsA. While it can be diagnosed clinically, imaging studies may be required, particularly in patients in whom symptoms may be difficult to discern. Evidence of enthesitis by conventional radiography includes bone cortex irregularities, erosions, entheseal soft tissue calcifications, and new bone formation; however, entheseal bone changes detected with conventional radiography appear relatively late in the disease process. Ultrasound is highly sensitive for assessing inflammation and can detect various features of enthesitis, such as increased thickness of tendon insertion, hypoechogenicity, erosions, enthesophytes, and subclinical enthesitis in people with PsA. MRI has the advantage of identifying perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema. Fat-suppressed MRI with or without gadolinium enhancement is a highly sensitive method for visualizing active enthesitis and can identify perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema.

Delayed treatment of PsA can result in irreversible joint damage and reduced quality of life; thus, patients with psoriasis should be closely monitored for early signs of its development, such as enthesitis. A thorough evaluation of the key clinical features of PsA (psoriasis, arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spondylitis), including evaluation of severity of each feature and impact on physical function and quality of life, is encouraged at each clinical encounter. Because patients may not understand the link between psoriasis and joint pain, specific probing questions can be helpful. Screening questionnaires to detect early signs and symptoms of PsA are available, such as the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST), Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) questionnaire, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screening (ToPAS) questionnaire. These and many others may be used to help dermatologists detect early signs and symptoms of PsA. Although these questionnaires all have limitations in sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of PsA, their use can still improve early diagnosis.

The treatment of PsA focuses on achieving the least amount of disease activity and inflammation possible; optimizing functional status, quality of life, and well-being; and preventing structural damage. Treatment decisions are based on the specific domains affected. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroid injections are first-line treatments for enthesitis. Early use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF) (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, infliximab, and golimumab) is recommended. Alternative biologic disease-modifying agents are indicated when these TNF inhibitors provide an inadequate response. They include ustekinumab (dual interleukin [IL]-12 and IL-23 inhibitor), secukinumab (IL-17A inhibitor), and apremilast (phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor) and may be considered for patients with predominantly entheseal manifestations of PsA or dactylitis. Biological disease-modifying agents approved for PsA that have shown efficacy for enthesitis include ixekizumab (which targets IL-17A), abatacept (a T-cell inhibitor), guselkumab (monoclonal antibody), and ustekinumab (monoclonal antibody). Tofacitinib and upadacitinib, both oral Janus kinase inhibitors, may also be considered.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 42-year-old woman with a 20-year history of plaque psoriasis presents with complaints of a 3-month history of pain, tenderness, and swelling in her right ankle and foot, of unknown origin. Physical examination reveals active psoriasis, with a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of 6.7 and psoriatic nail dystrophy, including onycholysis, pitting, and hyperkeratosis. Tenderness and swelling are noted at the back of the heel. The patient denies any other complaints. Laboratory tests are normal, including negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear factor. MRI reveals soft tissue and bone marrow edema below the Achilles insertion.

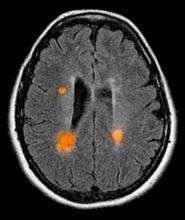

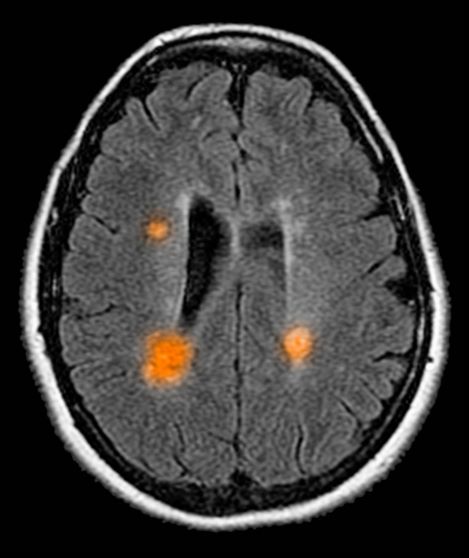

Decline in ambulatory function

Based on this patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). PPMS represents around 10% of MS cases and tends to develop about a decade later than relapsing MS. Unlike other forms of MS, this phenotype progresses steadily instead of in an episodic fashion like relapsing forms of MS. Most patients with PPMS present with gait difficulty because lesions often develop on the spinal cord. While relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is much more common among women than men, men with MS are more likely to have the progressive form.

Although this patient's MRI ultimately points to multiple sclerosis, his functional deficits may initially suggest other conditions in the differential diagnosis. Brainstem gliomas typically manifest in unsteady gait, weakness, double vision, difficulty swallowing, dysarthria, headache, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Transverse myelitis often presents with rapid-onset weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Musculoskeletal and neurologic symptoms are common in Lyme disease. B12 deficiency can present with worsening weakness and a sensory ataxia that can present as balance difficulties, but it would not cause focal lesions on the MRI, nor would it present with bladder symptoms. In addition, the patient's steady decline in function rules out RRMS.

PPMS is diagnosed with confirmation of gradual change in functional ability (often ambulation) over time without remission or relapse. These criteria include 1 full year of worsening neurologic function without asymptomatic periods as well as two of these signs of disease: brain lesion, two or more spinal cord lesions, and oligoclonal bands or elevated Immunoglobulin G index. These timing-specific criteria can delay diagnosis, as seen here.

Ocrelizumab is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy (DMT) proven to alter disease progression in ambulatory patients with PPMS. American Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend ocrelizumab for patients with PPMS who are likely to benefit from this therapy. While it is thought that DMTs are more effective at targeting inflammation in RRMS than nerve degeneration in PPMS, these agents may show benefit for patients with active PPMS (relapse and/or evidence of new MRI activity) rather than inactive disease. A recent PPMS study concluded that among patients with relapse or disease activity, DMTs were associated with a significant reduction of long-term disability risk. Together with immunomodulatory therapy, rehabilitation can help manage symptoms.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on this patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). PPMS represents around 10% of MS cases and tends to develop about a decade later than relapsing MS. Unlike other forms of MS, this phenotype progresses steadily instead of in an episodic fashion like relapsing forms of MS. Most patients with PPMS present with gait difficulty because lesions often develop on the spinal cord. While relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is much more common among women than men, men with MS are more likely to have the progressive form.

Although this patient's MRI ultimately points to multiple sclerosis, his functional deficits may initially suggest other conditions in the differential diagnosis. Brainstem gliomas typically manifest in unsteady gait, weakness, double vision, difficulty swallowing, dysarthria, headache, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Transverse myelitis often presents with rapid-onset weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Musculoskeletal and neurologic symptoms are common in Lyme disease. B12 deficiency can present with worsening weakness and a sensory ataxia that can present as balance difficulties, but it would not cause focal lesions on the MRI, nor would it present with bladder symptoms. In addition, the patient's steady decline in function rules out RRMS.

PPMS is diagnosed with confirmation of gradual change in functional ability (often ambulation) over time without remission or relapse. These criteria include 1 full year of worsening neurologic function without asymptomatic periods as well as two of these signs of disease: brain lesion, two or more spinal cord lesions, and oligoclonal bands or elevated Immunoglobulin G index. These timing-specific criteria can delay diagnosis, as seen here.

Ocrelizumab is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy (DMT) proven to alter disease progression in ambulatory patients with PPMS. American Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend ocrelizumab for patients with PPMS who are likely to benefit from this therapy. While it is thought that DMTs are more effective at targeting inflammation in RRMS than nerve degeneration in PPMS, these agents may show benefit for patients with active PPMS (relapse and/or evidence of new MRI activity) rather than inactive disease. A recent PPMS study concluded that among patients with relapse or disease activity, DMTs were associated with a significant reduction of long-term disability risk. Together with immunomodulatory therapy, rehabilitation can help manage symptoms.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on this patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). PPMS represents around 10% of MS cases and tends to develop about a decade later than relapsing MS. Unlike other forms of MS, this phenotype progresses steadily instead of in an episodic fashion like relapsing forms of MS. Most patients with PPMS present with gait difficulty because lesions often develop on the spinal cord. While relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is much more common among women than men, men with MS are more likely to have the progressive form.

Although this patient's MRI ultimately points to multiple sclerosis, his functional deficits may initially suggest other conditions in the differential diagnosis. Brainstem gliomas typically manifest in unsteady gait, weakness, double vision, difficulty swallowing, dysarthria, headache, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Transverse myelitis often presents with rapid-onset weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Musculoskeletal and neurologic symptoms are common in Lyme disease. B12 deficiency can present with worsening weakness and a sensory ataxia that can present as balance difficulties, but it would not cause focal lesions on the MRI, nor would it present with bladder symptoms. In addition, the patient's steady decline in function rules out RRMS.

PPMS is diagnosed with confirmation of gradual change in functional ability (often ambulation) over time without remission or relapse. These criteria include 1 full year of worsening neurologic function without asymptomatic periods as well as two of these signs of disease: brain lesion, two or more spinal cord lesions, and oligoclonal bands or elevated Immunoglobulin G index. These timing-specific criteria can delay diagnosis, as seen here.

Ocrelizumab is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy (DMT) proven to alter disease progression in ambulatory patients with PPMS. American Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend ocrelizumab for patients with PPMS who are likely to benefit from this therapy. While it is thought that DMTs are more effective at targeting inflammation in RRMS than nerve degeneration in PPMS, these agents may show benefit for patients with active PPMS (relapse and/or evidence of new MRI activity) rather than inactive disease. A recent PPMS study concluded that among patients with relapse or disease activity, DMTs were associated with a significant reduction of long-term disability risk. Together with immunomodulatory therapy, rehabilitation can help manage symptoms.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 59-year-old man presents with worsening decline in ambulatory function and worsening bladder function. He reports "difficulty getting around" for the past year and a half, which he theorized might be because of arthritis, aging, or many years of biking. He presented to his primary care physician 2 months ago and was referred to rheumatology. His height is 5 ft 11 in and his weight is 166 lb (BMI 23.1). The patient subsequently reported a decreased attention span to the rheumatologist. He has no other significant medical or surgical history, though his brother has psoriatic arthritis. MRI shows multiple brain lesions without gadolinium enhancement and multiple spinal cord lesions.

Chest tightness and wheezing

This patient's physical examination and imaging findings are consistent with a diagnosis of acute severe asthma. Agitation, breathlessness during rest, and a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min are some manifestations of an acute severe episode. During severe episodes, accessory muscles of respiration are usually used, and suprasternal retractions are often present. The heart rate is > 120 beats/min and the respiratory rate is > 30 breaths/min. Loud biphasic (expiratory and inspiratory) wheezing can be heard, and pulsus paradoxus is often present (20-40 mm Hg). Oxyhemoglobin saturation with room air is < 91%. As the severity increases, the patient increasingly assumes a hunched-over sitting position with the hands supporting the torso, termed the tripod position.

Asthma is a chronic, heterogenous inflammatory airway disorder characterized by variable expiratory flow; airway wall thickening; respiratory symptoms; and exacerbations, which sometimes require hospitalization. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people in 2019. The presence of airway hyperresponsiveness or bronchial hyperreactivity in asthma is an exaggerated response to various exogenous and endogenous stimuli. Mechanisms implicated in the development of asthma include direct stimulation of airway smooth muscle and indirect stimulation by pharmacologically active substances from mediator-secreting cells, such as mast cells or nonmyelinated sensory neurons. The degree of airway hyperresponsiveness is associated with the clinical severity of asthma.

Acute severe asthma is a life-threatening emergency characterized by severe airflow limitation that is unresponsive to the typical appropriate bronchodilator therapy. As a result of pathophysiologic changes, airflow is severely restricted in severe asthma, leading to premature closure of the airway on expiration; impaired gas exchange; and dynamic hyperinflation, or air-trapping. In such cases, urgent action is essential to thwart serious outcomes, including mechanical ventilation and death.

Asthma severity is defined by the level of treatment required to control a patient's symptoms and exacerbations. According to the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines, a severe asthma exacerbation describes a patient who talks in words (rather than sentences); leans forward; is agitated; uses accessory respiratory muscles; and has a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, heart rate > 120 beats/min, oxygen saturation on air < 90%, and peak expiratory flow ≤ 50% of their best or of predicted value. Given the heterogeneity of asthma, patients with acute severe asthma may present with a variety of signs and symptoms, including dyspnea, chest tightness, cough and wheezing, agitation, drowsiness or signs of confusion, and significant breathlessness at rest.

Exposure to external agents, such as indoor and outdoor allergens, air pollutants, and respiratory tract infections (primarily viral), are the most common causes of asthma exacerbations, which vary in severity. Numerous other factors can trigger an asthma exacerbation, including exercise, weather changes, certain foods, additives, drugs, extreme emotional expressions, rhinitis, sinusitis, polyposis, gastroesophageal reflux, menstruation, and pregnancy. Importantly, a patient with known asthma of any level of severity can experience an asthma exacerbation, including patients with mild or well-controlled asthma.

Patients with a history of poorly controlled asthma or a recent exacerbation are at risk for an acute asthma exacerbation. Other risk factors include poor perception of airflow limitation, regular or overuse of short-acting beta agonists, incorrect inhaler technique, and suboptimal adherence to therapy. Comorbidities associated with risk for an acute asthma exacerbation include obesity, chronic rhinosinusitis, inducible laryngeal obstruction (vocal cord dysfunction), gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, bronchiectasis, cardiac disease, and kyphosis due to osteoporosis (followed by corticosteroid overuse). The lack of a written asthma action plan and socioeconomic factors are also associated with increased risk for a severe exacerbation.

In the emergency department setting, pharmacologic therapy of acute severe asthma should consist of a short-acting beta agonist, ipratropium bromide, systemic corticosteroids (oral or intravenous), and controlled oxygen therapy. Clinicians may also consider intravenous magnesium sulfate and high-dose inhaled corticosteroids. Once stable, patients should be treated with optimal asthma-controlling therapy, as outlined in GINA guidelines. Optimizing patients' inhaler technique and adherence to therapy are imperative, and comorbidities should be appropriately managed. Nonpharmacologic interventions, such as smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, exercise, weight loss, and influenza/COVID-19 vaccination, are also recommended as indicated.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's physical examination and imaging findings are consistent with a diagnosis of acute severe asthma. Agitation, breathlessness during rest, and a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min are some manifestations of an acute severe episode. During severe episodes, accessory muscles of respiration are usually used, and suprasternal retractions are often present. The heart rate is > 120 beats/min and the respiratory rate is > 30 breaths/min. Loud biphasic (expiratory and inspiratory) wheezing can be heard, and pulsus paradoxus is often present (20-40 mm Hg). Oxyhemoglobin saturation with room air is < 91%. As the severity increases, the patient increasingly assumes a hunched-over sitting position with the hands supporting the torso, termed the tripod position.

Asthma is a chronic, heterogenous inflammatory airway disorder characterized by variable expiratory flow; airway wall thickening; respiratory symptoms; and exacerbations, which sometimes require hospitalization. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people in 2019. The presence of airway hyperresponsiveness or bronchial hyperreactivity in asthma is an exaggerated response to various exogenous and endogenous stimuli. Mechanisms implicated in the development of asthma include direct stimulation of airway smooth muscle and indirect stimulation by pharmacologically active substances from mediator-secreting cells, such as mast cells or nonmyelinated sensory neurons. The degree of airway hyperresponsiveness is associated with the clinical severity of asthma.

Acute severe asthma is a life-threatening emergency characterized by severe airflow limitation that is unresponsive to the typical appropriate bronchodilator therapy. As a result of pathophysiologic changes, airflow is severely restricted in severe asthma, leading to premature closure of the airway on expiration; impaired gas exchange; and dynamic hyperinflation, or air-trapping. In such cases, urgent action is essential to thwart serious outcomes, including mechanical ventilation and death.

Asthma severity is defined by the level of treatment required to control a patient's symptoms and exacerbations. According to the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines, a severe asthma exacerbation describes a patient who talks in words (rather than sentences); leans forward; is agitated; uses accessory respiratory muscles; and has a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, heart rate > 120 beats/min, oxygen saturation on air < 90%, and peak expiratory flow ≤ 50% of their best or of predicted value. Given the heterogeneity of asthma, patients with acute severe asthma may present with a variety of signs and symptoms, including dyspnea, chest tightness, cough and wheezing, agitation, drowsiness or signs of confusion, and significant breathlessness at rest.

Exposure to external agents, such as indoor and outdoor allergens, air pollutants, and respiratory tract infections (primarily viral), are the most common causes of asthma exacerbations, which vary in severity. Numerous other factors can trigger an asthma exacerbation, including exercise, weather changes, certain foods, additives, drugs, extreme emotional expressions, rhinitis, sinusitis, polyposis, gastroesophageal reflux, menstruation, and pregnancy. Importantly, a patient with known asthma of any level of severity can experience an asthma exacerbation, including patients with mild or well-controlled asthma.

Patients with a history of poorly controlled asthma or a recent exacerbation are at risk for an acute asthma exacerbation. Other risk factors include poor perception of airflow limitation, regular or overuse of short-acting beta agonists, incorrect inhaler technique, and suboptimal adherence to therapy. Comorbidities associated with risk for an acute asthma exacerbation include obesity, chronic rhinosinusitis, inducible laryngeal obstruction (vocal cord dysfunction), gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, bronchiectasis, cardiac disease, and kyphosis due to osteoporosis (followed by corticosteroid overuse). The lack of a written asthma action plan and socioeconomic factors are also associated with increased risk for a severe exacerbation.

In the emergency department setting, pharmacologic therapy of acute severe asthma should consist of a short-acting beta agonist, ipratropium bromide, systemic corticosteroids (oral or intravenous), and controlled oxygen therapy. Clinicians may also consider intravenous magnesium sulfate and high-dose inhaled corticosteroids. Once stable, patients should be treated with optimal asthma-controlling therapy, as outlined in GINA guidelines. Optimizing patients' inhaler technique and adherence to therapy are imperative, and comorbidities should be appropriately managed. Nonpharmacologic interventions, such as smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, exercise, weight loss, and influenza/COVID-19 vaccination, are also recommended as indicated.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's physical examination and imaging findings are consistent with a diagnosis of acute severe asthma. Agitation, breathlessness during rest, and a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min are some manifestations of an acute severe episode. During severe episodes, accessory muscles of respiration are usually used, and suprasternal retractions are often present. The heart rate is > 120 beats/min and the respiratory rate is > 30 breaths/min. Loud biphasic (expiratory and inspiratory) wheezing can be heard, and pulsus paradoxus is often present (20-40 mm Hg). Oxyhemoglobin saturation with room air is < 91%. As the severity increases, the patient increasingly assumes a hunched-over sitting position with the hands supporting the torso, termed the tripod position.

Asthma is a chronic, heterogenous inflammatory airway disorder characterized by variable expiratory flow; airway wall thickening; respiratory symptoms; and exacerbations, which sometimes require hospitalization. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people in 2019. The presence of airway hyperresponsiveness or bronchial hyperreactivity in asthma is an exaggerated response to various exogenous and endogenous stimuli. Mechanisms implicated in the development of asthma include direct stimulation of airway smooth muscle and indirect stimulation by pharmacologically active substances from mediator-secreting cells, such as mast cells or nonmyelinated sensory neurons. The degree of airway hyperresponsiveness is associated with the clinical severity of asthma.

Acute severe asthma is a life-threatening emergency characterized by severe airflow limitation that is unresponsive to the typical appropriate bronchodilator therapy. As a result of pathophysiologic changes, airflow is severely restricted in severe asthma, leading to premature closure of the airway on expiration; impaired gas exchange; and dynamic hyperinflation, or air-trapping. In such cases, urgent action is essential to thwart serious outcomes, including mechanical ventilation and death.

Asthma severity is defined by the level of treatment required to control a patient's symptoms and exacerbations. According to the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines, a severe asthma exacerbation describes a patient who talks in words (rather than sentences); leans forward; is agitated; uses accessory respiratory muscles; and has a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, heart rate > 120 beats/min, oxygen saturation on air < 90%, and peak expiratory flow ≤ 50% of their best or of predicted value. Given the heterogeneity of asthma, patients with acute severe asthma may present with a variety of signs and symptoms, including dyspnea, chest tightness, cough and wheezing, agitation, drowsiness or signs of confusion, and significant breathlessness at rest.

Exposure to external agents, such as indoor and outdoor allergens, air pollutants, and respiratory tract infections (primarily viral), are the most common causes of asthma exacerbations, which vary in severity. Numerous other factors can trigger an asthma exacerbation, including exercise, weather changes, certain foods, additives, drugs, extreme emotional expressions, rhinitis, sinusitis, polyposis, gastroesophageal reflux, menstruation, and pregnancy. Importantly, a patient with known asthma of any level of severity can experience an asthma exacerbation, including patients with mild or well-controlled asthma.

Patients with a history of poorly controlled asthma or a recent exacerbation are at risk for an acute asthma exacerbation. Other risk factors include poor perception of airflow limitation, regular or overuse of short-acting beta agonists, incorrect inhaler technique, and suboptimal adherence to therapy. Comorbidities associated with risk for an acute asthma exacerbation include obesity, chronic rhinosinusitis, inducible laryngeal obstruction (vocal cord dysfunction), gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, bronchiectasis, cardiac disease, and kyphosis due to osteoporosis (followed by corticosteroid overuse). The lack of a written asthma action plan and socioeconomic factors are also associated with increased risk for a severe exacerbation.

In the emergency department setting, pharmacologic therapy of acute severe asthma should consist of a short-acting beta agonist, ipratropium bromide, systemic corticosteroids (oral or intravenous), and controlled oxygen therapy. Clinicians may also consider intravenous magnesium sulfate and high-dose inhaled corticosteroids. Once stable, patients should be treated with optimal asthma-controlling therapy, as outlined in GINA guidelines. Optimizing patients' inhaler technique and adherence to therapy are imperative, and comorbidities should be appropriately managed. Nonpharmacologic interventions, such as smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, exercise, weight loss, and influenza/COVID-19 vaccination, are also recommended as indicated.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 32-year-old Black man presents to the emergency department with severe dyspnea, chest tightness, and wheezing. The patient is sitting forward in the tripod position and appears agitated and confused. Use of accessory respiratory muscles and suprasternal retractions are noted. He reports an approximate 2-week history of rhinorrhea, cough, and mild fever, for which he has been taking an over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent and cough suppressant. His prior medical history is notable for obesity, type 2 diabetes, allergic rhinitis, mild asthma, and hypercholesterolemia. The patient is a current smoker (17 pack-years). Pertinent physical examination reveals a respiratory rate of 48 breaths/min, heart rate of 135 beats/min, 87% oxygen saturation, and peak expiratory flow of 300 L/min. Low biphasic wheezing can be heard. Rapid antigen and PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 detected by nasopharyngeal swabs both come back negative. Chest radiography is ordered and shows pulmonary hyperinflation with bronchial wall thickening.

New and Improved Devices Add More Therapeutic Options for Treatment of Migraine

Since the mid-2010s, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved or cleared no fewer than 10 migraine treatments in the form of orals, injectables, nasal sprays, and devices. The medical achievements of the last decade in the field of migraine have been nothing less than stunning for physicians and their patients, whether they relied on off-label medications or those sanctioned by the FDA to treat patients living with migraine.

That said, the newer orals and injectables cannot help everyone living with migraine. The small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants) and the monoclonal antibodies that target the CGRP ligand or receptor, while well received by patients and physicians alike, have drawbacks for some patients, including lack of efficacy, slow response rate, and adverse events that prevent some patients from taking them. The gepants, which are oral medications—as opposed to the CGRP monoclonal antibody injectables—can occasionally cause enough nausea, drowsiness, and constipation for patients to choose to discontinue their use.

Certain patients have other reasons to shun orals and injectables. Some cannot swallow pills while others fear or do not tolerate injections. Insurance companies limit the quantity of acute care medications, so some patients cannot treat every migraine attack. Then there are those who have failed so many therapies in the past that they will not try the latest one. Consequently, some lie in bed, vomiting until the pain is gone, and some take too many over-the-counter or migraine-specific products, which make migraine symptoms worse if they develop medication overuse headache. And lastly, there are patients who have never walked through a physician’s door to secure a migraine diagnosis and get appropriate treatment.

Non interventional medical devices cleared by the FDA now allow physicians to offer relief to patients with migraine. They work either through various types of electrical neuromodulation to nerves outside the brain or they apply magnetic stimulation to the back of the brain itself to reach pain-associated pathways. A 2019 report on pain management from the US Department of Health and Human Services noted that some randomized control trials (RCTs) and other studies “have demonstrated that noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation can be effective in ameliorating pain in various types of cluster headaches and migraines.”

At least 3 devices, 1 designed to stimulate both the occipital and trigeminal nerves (eCOT-NS, Relivion, Neurolief Ltd), 1 that stimulates the vagus nerve noninvasively (nVNS, gammaCORE, electroCore), and 1 that stimulates peripheral nerves in the upper arm (remote electrical neuromodulation [REN], Nerivio, Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd), are FDA cleared to treat episodic and chronic migraine. nVNS is also cleared to treat migraine, episodic cluster headache acutely, and chronic cluster acutely in connection with medication.

Real-world studies on all migraine treatments, especially the devices, are flooding PubMed. As for a physician’s observation, we will get to that shortly.

The Devices

Nerivio

Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd makes a REN called Nerivio, which was FDA cleared in January 2021 to treat episodic migraine acutely in adults and adolescents. Studies have shown its effectiveness for chronic migraine patients who are treated acutely, and it has also helped patients with menstrual migraine. The patient wears the device on the upper arm. Sensory fibers, once stimulated in the arm, send an impulse to the brainstem to affect the serotonin- and norepinephrine-modulated descending inhibitory pathway to disrupt incoming pain messaging. Theranica has applied to the FDA for clearance to treat patients with chronic migraine, as well as for prevention.

Relivion

Neurolief Ltd created the external combined occipital and trigeminal nerve stimulation device (eCOT-NS), which stimulates both the occipital and trigeminal nerves. It has multiple output electrodes, which are placed on the forehead to stimulate the trigeminal supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve branches bilaterally, and over the occipital nerves in the back of the head. It is worn like a tiara as it must be in good contact with the forehead and the back of the head simultaneously. It is FDA cleared to treat acute migraine.

gammaCORE

gammaCORE is a nVNS device that is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine in adolescents and adults, and acute and preventive treatment of episodic cluster headache in adults. It is also cleared to treat chronic cluster headache acutely along with medication. The patient applies gel to the device’s 2 electrical contacts and then locates the vagus nerve on the side of the neck and applies the electrodes to the area that will be treated. Patients can adjust the stimulation’s intensity so that they can barely feel the stimulation; it has not been reported to be painful. nVNS is also an FDA cleared treatment for paroxysmal hemicrania and hemicrania continua.

SAVI Dual

The s-TMS (SAVI Dual, formerly called the Spring TMS and the sTMS mini), made by eNeura, is a single-pulse, transcranial magnetic stimulation applied to the back of the head to stimulate the occipital lobes in the brain. It was FDA cleared for acute and preventive care of migraine in adolescents over 12 years and for adults in February 2019. The patient holds a handheld magnetic device against their occiput, and when the tool is discharged, a brief magnetic pulse interrupts the pattern of neuronal firing (probably cortical spreading depression) that can trigger migraine and the visual aura associated with migraine in one-third of patients.

Cefaly

The e-TNS (Cefaly) works by external trigeminal nerve stimulation of the supraorbital and trochlear nerves bilaterally in the forehead. It gradually and automatically increases in intensity and can be controlled by the patient. It is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine, and, unlike the other devices, it is sold over the counter without a prescription. According to the company website, there are 3 devices: 1 is for acute treatment, 1 is for preventive treatment, and 1 device has 2 settings for both acute and preventive treatment.

The Studies

While most of the published studies on devices are company-sponsored, these device makers have underwritten numerous, sometimes very well-designed, studies on their products. A review by VanderPluym et al described those studies and their various risks of bias.

There are at least 10 studies on REN published so far. These include 2 randomized, sham-controlled trials looking at pain freedom and pain relief at 2 hours after stimulation begins. Another study detailed treatment reports from many patients in which 66.5% experienced pain relief at 2 hours post treatment initiation in half of their treatments. A subgroup of 16% of those patients were prescribed REN by their primary care physicians. Of that group, 77.8% experienced pain relief in half their treatments. That figure was very close to another study that found that 23 of 31 (74.2%) of the study patients treated virtually by non headache providers found relief in 50% of their headaches. REN comes with an education and behavioral medicine app that is used during treatment. A study done by the company shows that when a patient uses the relaxation app along with the standard stimulation, they do considerably better than with stimulation alone.

The eCOT-NS has also been tested in an RCT. At 2 hours, the responder rate was twice as high as in the sham group (66.7% vs 32%). Overall headache relief at 2 hours was higher in the responder group (76% vs 31.6%). In a study collecting real-world data on the efficacy of eCOT-NS in the preventive treatment of migraine (abstract data were presented at the American Headache Society meeting in June 2022), there was a 65.3% reduction in monthly migraine days (MMD) from baseline through 6 months. Treatment reduced MMD by 10.0 (from 15.3 to 5.3—a 76.8% reduction), and reduced acute medication use days (12.5 at baseline to 2.9) at 6 months.

Users of nVNS discussed their experiences with the device, which is the size of a large bar of soap, in a patient registry. They reported 192 attacks, with a mean pain score starting at 2.7 and dropping to 1.3 after 30 minutes. The pain levels of 70% of the attacks dropped to either mild or nonexistent. In a multicenter study on nNVS, 48 patients and 44 sham patients with episodic and chronic cluster headache showed no significant difference in the primary endpoint of pain freedom at 15 minutes between the nVNS and sham. There was also no difference in the chronic cluster headache group. But the episodic cluster subgroup showed a difference; nVNS was superior to sham, 48% to 6% (P

The e-TNS device is cleared for treating adults with migraine, acutely and preventively. It received initial clearance in 2017; in 2020, Cefaly Technology received clearance from the FDA to sell its products over the counter. The device, which resembles a large diamond that affixes to the forehead, has received differing reviews between various patient reports (found online at major retailer sites) and study results. In a blinded, intent-to-treat study involving 538 patients, 25.5% of the verum group reported they were pain-free at 2 hours; 18.3% in the sham group reported the same. Additionally, 56.4% of the subjects in the verum group reported they were free of the most bothersome migraine symptoms, as opposed to 42.3% of the sham group.

Adverse Events

The adverse events observed with these devices were, overall, relatively mild, and disappeared once the device was shut off. A few nVNS users said they experienced discomfort at the application site. With REN, 59 of 12,368 patients reported device-related issues; the vast majority were considered mild and consisted mostly of a sensation of warmth under the device. Of the 259 e-TNS users, 8.5% reported minor and reversible occurrences, such as treatment-related discomfort, paresthesia, and burning.

Patients in the Clinic

A few observations from the clinic regarding these devices:

Some devices are easier to use than others. I know this, because at a recent demonstration session in a course for physicians on headache treatment, I agreed to be the person on whom the device was demonstrated. The physician applying the device had difficulty aligning the device’s sensors with the appropriate nerves. Making sure your patients use these devices correctly is essential, and you or your staff should demonstrate their use to the patient. No doubt, this could be time-consuming in some cases, and patients who are reading the device’s instructions while in pain will likely get frustrated if they cannot get the device to work.

Some patients who have failed every medication class can occasionally find partial relief with these devices. One longtime patient of mine came to me severely disabled from chronic migraine and medication overuse headache but was somewhat better with 2 preventive medications. Triptans worked acutely, but she developed nearly every side effect imaginable. I was able to reverse her medication overuse headache, but the gepants, although they worked somewhat, took too long to take effect. We agreed the next step would be to use REN for each migraine attack, combined with acute care medication if necessary. (She uses REN alone for a milder headache and adds a gepant with naproxen if necessary.) She has found using the relaxation module on the REN app increases her chances of eliminating the migraine. She is not pain free all the time, but she appreciates the pain-free intervals.