User login

Anesthetic Choices and Postoperative Delirium Incidence: Propofol vs Sevoflurane

Study 1 Overview (Chang et al)

Objective: To assess the incidence of postoperative delirium (POD) following propofol- vs sevoflurane-based anesthesia in geriatric spine surgery patients.

Design: Retrospective, single-blinded observational study of propofol- and sevoflurane-based anesthesia cohorts.

Setting and participants: Patients eligible for this study were aged 65 years or older admitted to the SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center (Seoul, South Korea). All patients underwent general anesthesia either via intravenous propofol or inhalational sevoflurane for spine surgery between January 2015 and December 2019. Patients were retrospectively identified via electronic medical records. Patient exclusion criteria included preoperative delirium, history of dementia, psychiatric disease, alcoholism, hepatic or renal dysfunction, postoperative mechanical ventilation dependence, other surgery within the recent 6 months, maintenance of intraoperative anesthesia with combined anesthetics, or incomplete medical record.

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome was the incidence of POD after administration of propofol- and sevoflurane-based anesthesia during hospitalization. Patients were screened for POD regularly by attending nurses using the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (disorientation, inappropriate behavior, inappropriate communication, hallucination, and psychomotor retardation) during the entirety of the patient’s hospital stay; if 1 or more screening criteria were met, a psychiatrist was consulted for the proper diagnosis and management of delirium. A psychiatric diagnosis was required for a case to be counted toward the incidence of POD in this study. Secondary outcomes included postoperative 30-day complications (angina, myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack/stroke, pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, acute kidney injury, or infection) and length of postoperative hospital stay.

Main results: POD occurred in 29 patients (10.3%) out of the total cohort of 281. POD was more common in the sevoflurane group than in the propofol group (15.7% vs 5.0%; P = .003). Using multivariable logistic regression, inhalational sevoflurane was associated with an increased risk of POD as compared to propofol-based anesthesia (odds ratio [OR], 4.120; 95% CI, 1.549-10.954; P = .005). There was no association between choice of anesthetic and postoperative 30-day complications or the length of postoperative hospital stay. Both older age (OR, 1.242; 95% CI, 1.130-1.366; P < .001) and higher pain score at postoperative day 1 (OR, 1.338; 95% CI, 1.056-1.696; P = .016) were associated with increased risk of POD.

Conclusion: Propofol-based anesthesia was associated with a lower incidence of and risk for POD than sevoflurane-based anesthesia in older patients undergoing spine surgery.

Study 2 Overview (Mei et al)

Objective: To determine the incidence and duration of POD in older patients after total knee/hip replacement (TKR/THR) under intravenous propofol or inhalational sevoflurane general anesthesia.

Design: Randomized clinical trial of propofol and sevoflurane groups.

Setting and participants: This study was conducted at the Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital and involved 209 participants enrolled between June 2016 and November 2019. All participants were 60 years of age or older, scheduled for TKR/THR surgery under general anesthesia, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class I to III, and assessed to be of normal cognitive function preoperatively via a Mini-Mental State Examination. Participant exclusion criteria included preexisting delirium as assessed by the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), prior diagnosed neurological diseases (eg, Parkinson’s disease), prior diagnosed mental disorders (eg, schizophrenia), or impaired vision or hearing that would influence cognitive assessments. All participants were randomly assigned to either sevoflurane or propofol anesthesia for their surgery via a computer-generated list. Of these, 103 received inhalational sevoflurane and 106 received intravenous propofol. All participants received standardized postoperative care.

Main outcome measures: All participants were interviewed by investigators, who were blinded to the anesthesia regimen, twice daily on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3 using CAM and a CAM-based scoring system (CAM-S) to assess delirium severity. The CAM encapsulated 4 criteria: acute onset and fluctuating course, agitation, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. To diagnose delirium, both the first and second criteria must be met, in addition to either the third or fourth criterion. The averages of the scores across the 3 postoperative days indicated delirium severity, while the incidence and duration of delirium was assessed by the presence of delirium as determined by CAM on any postoperative day.

Main results: All eligible participants (N = 209; mean [SD] age 71.2 [6.7] years; 29.2% male) were included in the final analysis. The incidence of POD was not statistically different between the propofol and sevoflurane groups (33.0% vs 23.3%; P = .119, Chi-square test). It was estimated that 316 participants in each arm of the study were needed to detect statistical differences. The number of days of POD per person were higher with propofol anesthesia as compared to sevoflurane (0.5 [0.8] vs 0.3 [0.5]; P = .049, Student’s t-test).

Conclusion: This underpowered study showed a 9.7% difference in the incidence of POD between older adults who received propofol (33.0%) and sevoflurane (23.3%) after THR/TKR. Further studies with a larger sample size are needed to compare general anesthetics and their role in POD.

Commentary

Delirium is characterized by an acute state of confusion with fluctuating mental status, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. It is often caused by medications and/or their related adverse effects, infections, electrolyte imbalances, and other clinical etiologies. Delirium often manifests in post-surgical settings, disproportionately affecting older patients and leading to increased risk of morbidity, mortality, hospital length of stay, and health care costs.1 Intraoperative risk factors for POD are determined by the degree of operative stress (eg, lower-risk surgeries put the patient at reduced risk for POD as compared to higher-risk surgeries) and are additive to preexisting patient-specific risk factors, such as older age and functional impairment.1 Because operative stress is associated with risk for POD, limiting operative stress in controlled ways, such as through the choice of anesthetic agent administered, may be a pragmatic way to manage operative risks and optimize outcomes, especially when serving a surgically vulnerable population.

In Study 1, Chang et al sought to assess whether 2 commonly utilized general anesthetics, propofol and sevoflurane, in older patients undergoing spine surgery differentially affected the incidence of POD. In this retrospective, single-blinded observational study of 281 geriatric patients, the researchers found that sevoflurane was associated with a higher risk of POD as compared to propofol. However, these anesthetics were not associated with surgical outcomes such as postoperative 30-day complications or the length of postoperative hospital stay. While these findings added new knowledge to this field of research, several limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting this study’s results. For instance, the sample size was relatively small, with all cases selected from a single center utilizing a retrospective analysis. In addition, although a standardized nursing screening tool was used as a method for delirium detection, hypoactive delirium or less symptomatic delirium may have been missed, which in turn would lead to an underestimation of POD incidence. The latter is a common limitation in delirium research.

In Study 2, Mei et al similarly explored the effects of general anesthetics on POD in older surgical patients. Specifically, using a randomized clinical trial design, the investigators compared propofol with sevoflurane in older patients who underwent TKR/THR, and their roles in POD severity and duration. Although the incidence of POD was higher in those who received propofol compared to sevoflurane, this trial was underpowered and the results did not reach statistical significance. In addition, while the duration of POD was slightly longer in the propofol group compared to the sevoflurane group (0.5 vs 0.3 days), it was unclear if this finding was clinically significant. Similar to many research studies in POD, limitations of Study 2 included a small sample size of 209 patients, with all participants enrolled from a single center. On the other hand, this study illustrated the feasibility of a method that allowed reproducible prospective assessment of POD time course using CAM and CAM-S.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

The delineation of risk factors that contribute to delirium after surgery in older patients is key to mitigating risks for POD and improving clinical outcomes. An important step towards a better understanding of these modifiable risk factors is to clearly quantify intraoperative risk of POD attributable to specific anesthetics. While preclinical studies have shown differential neurotoxicity effects of propofol and sevoflurane, their impact on clinically important neurologic outcomes such as delirium and cognitive decline remains poorly understood. Although Studies 1 and 2 both provided head-to-head comparisons of propofol and sevoflurane as risk factors for POD in high-operative-stress surgeries in older patients, the results were inconsistent. That being said, this small incremental increase in knowledge was not unexpected in the course of discovery around a clinically complex research question. Importantly, these studies provided evidence regarding the methodological approaches that could be taken to further this line of research.

The mediating factors of the differences on neurologic outcomes between anesthetic agents are likely pharmacological, biological, and methodological. Pharmacologically, the differences between target receptors, such as GABAA (propofol, etomidate) or NMDA (ketamine), could be a defining feature in the difference in incidence of POD. Additionally, secondary actions of anesthetic agents on glycine, nicotinic, and acetylcholine receptors could play a role as well. Biologically, genes such as CYP2E1, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, GSTP1, UGT1A9, SULT1A1, and NQO1 have all been identified as genetic factors in the metabolism of anesthetics, and variations in such genes could result in different responses to anesthetics.2 Methodologically, routes of anesthetic administration (eg, inhalation vs intravenous), preexisting anatomical structures, or confounding medical conditions (eg, lower respiratory volume due to older age) may influence POD incidence, duration, or severity. Moreover, methodological differences between Studies 1 and 2, such as surgeries performed (spinal vs TKR/THR), patient populations (South Korean vs Chinese), and the diagnosis and monitoring of delirium (retrospective screening and diagnosis vs prospective CAM/CAM-S) may impact delirium outcomes. Thus, these factors should be considered in the design of future clinical trials undertaken to investigate the effects of anesthetics on POD.

Given the high prevalence of delirium and its associated adverse outcomes in the immediate postoperative period in older patients, further research is warranted to determine how anesthetics affect POD in order to optimize perioperative care and mitigate risks in this vulnerable population. Moreover, parallel investigations into how anesthetics differentially impact the development of transient or longer-term cognitive impairment after a surgical procedure (ie, postoperative cognitive dysfunction) in older adults are urgently needed in order to improve their cognitive health.

Practice Points

- Intravenous propofol and inhalational sevoflurane may be differentially associated with incidence, duration, and severity of POD in geriatric surgical patients.

- Further larger-scale studies are warranted to clarify the role of anesthetic choice in POD in order to optimize surgical outcomes in older patients.

–Jared Doan, BS, and Fred Ko, MD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

1. Dasgupta M, Dumbrell AC. Preoperative risk assessment for delirium after noncardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1578-1589. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00893.x

2. Mikstacki A, Skrzypczak-Zielinska M, Tamowicz B, et al. The impact of genetic factors on response to anaesthetics. Adv Med Sci. 2013;58(1):9-14. doi:10.2478/v10039-012-0065-z

Study 1 Overview (Chang et al)

Objective: To assess the incidence of postoperative delirium (POD) following propofol- vs sevoflurane-based anesthesia in geriatric spine surgery patients.

Design: Retrospective, single-blinded observational study of propofol- and sevoflurane-based anesthesia cohorts.

Setting and participants: Patients eligible for this study were aged 65 years or older admitted to the SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center (Seoul, South Korea). All patients underwent general anesthesia either via intravenous propofol or inhalational sevoflurane for spine surgery between January 2015 and December 2019. Patients were retrospectively identified via electronic medical records. Patient exclusion criteria included preoperative delirium, history of dementia, psychiatric disease, alcoholism, hepatic or renal dysfunction, postoperative mechanical ventilation dependence, other surgery within the recent 6 months, maintenance of intraoperative anesthesia with combined anesthetics, or incomplete medical record.

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome was the incidence of POD after administration of propofol- and sevoflurane-based anesthesia during hospitalization. Patients were screened for POD regularly by attending nurses using the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (disorientation, inappropriate behavior, inappropriate communication, hallucination, and psychomotor retardation) during the entirety of the patient’s hospital stay; if 1 or more screening criteria were met, a psychiatrist was consulted for the proper diagnosis and management of delirium. A psychiatric diagnosis was required for a case to be counted toward the incidence of POD in this study. Secondary outcomes included postoperative 30-day complications (angina, myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack/stroke, pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, acute kidney injury, or infection) and length of postoperative hospital stay.

Main results: POD occurred in 29 patients (10.3%) out of the total cohort of 281. POD was more common in the sevoflurane group than in the propofol group (15.7% vs 5.0%; P = .003). Using multivariable logistic regression, inhalational sevoflurane was associated with an increased risk of POD as compared to propofol-based anesthesia (odds ratio [OR], 4.120; 95% CI, 1.549-10.954; P = .005). There was no association between choice of anesthetic and postoperative 30-day complications or the length of postoperative hospital stay. Both older age (OR, 1.242; 95% CI, 1.130-1.366; P < .001) and higher pain score at postoperative day 1 (OR, 1.338; 95% CI, 1.056-1.696; P = .016) were associated with increased risk of POD.

Conclusion: Propofol-based anesthesia was associated with a lower incidence of and risk for POD than sevoflurane-based anesthesia in older patients undergoing spine surgery.

Study 2 Overview (Mei et al)

Objective: To determine the incidence and duration of POD in older patients after total knee/hip replacement (TKR/THR) under intravenous propofol or inhalational sevoflurane general anesthesia.

Design: Randomized clinical trial of propofol and sevoflurane groups.

Setting and participants: This study was conducted at the Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital and involved 209 participants enrolled between June 2016 and November 2019. All participants were 60 years of age or older, scheduled for TKR/THR surgery under general anesthesia, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class I to III, and assessed to be of normal cognitive function preoperatively via a Mini-Mental State Examination. Participant exclusion criteria included preexisting delirium as assessed by the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), prior diagnosed neurological diseases (eg, Parkinson’s disease), prior diagnosed mental disorders (eg, schizophrenia), or impaired vision or hearing that would influence cognitive assessments. All participants were randomly assigned to either sevoflurane or propofol anesthesia for their surgery via a computer-generated list. Of these, 103 received inhalational sevoflurane and 106 received intravenous propofol. All participants received standardized postoperative care.

Main outcome measures: All participants were interviewed by investigators, who were blinded to the anesthesia regimen, twice daily on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3 using CAM and a CAM-based scoring system (CAM-S) to assess delirium severity. The CAM encapsulated 4 criteria: acute onset and fluctuating course, agitation, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. To diagnose delirium, both the first and second criteria must be met, in addition to either the third or fourth criterion. The averages of the scores across the 3 postoperative days indicated delirium severity, while the incidence and duration of delirium was assessed by the presence of delirium as determined by CAM on any postoperative day.

Main results: All eligible participants (N = 209; mean [SD] age 71.2 [6.7] years; 29.2% male) were included in the final analysis. The incidence of POD was not statistically different between the propofol and sevoflurane groups (33.0% vs 23.3%; P = .119, Chi-square test). It was estimated that 316 participants in each arm of the study were needed to detect statistical differences. The number of days of POD per person were higher with propofol anesthesia as compared to sevoflurane (0.5 [0.8] vs 0.3 [0.5]; P = .049, Student’s t-test).

Conclusion: This underpowered study showed a 9.7% difference in the incidence of POD between older adults who received propofol (33.0%) and sevoflurane (23.3%) after THR/TKR. Further studies with a larger sample size are needed to compare general anesthetics and their role in POD.

Commentary

Delirium is characterized by an acute state of confusion with fluctuating mental status, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. It is often caused by medications and/or their related adverse effects, infections, electrolyte imbalances, and other clinical etiologies. Delirium often manifests in post-surgical settings, disproportionately affecting older patients and leading to increased risk of morbidity, mortality, hospital length of stay, and health care costs.1 Intraoperative risk factors for POD are determined by the degree of operative stress (eg, lower-risk surgeries put the patient at reduced risk for POD as compared to higher-risk surgeries) and are additive to preexisting patient-specific risk factors, such as older age and functional impairment.1 Because operative stress is associated with risk for POD, limiting operative stress in controlled ways, such as through the choice of anesthetic agent administered, may be a pragmatic way to manage operative risks and optimize outcomes, especially when serving a surgically vulnerable population.

In Study 1, Chang et al sought to assess whether 2 commonly utilized general anesthetics, propofol and sevoflurane, in older patients undergoing spine surgery differentially affected the incidence of POD. In this retrospective, single-blinded observational study of 281 geriatric patients, the researchers found that sevoflurane was associated with a higher risk of POD as compared to propofol. However, these anesthetics were not associated with surgical outcomes such as postoperative 30-day complications or the length of postoperative hospital stay. While these findings added new knowledge to this field of research, several limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting this study’s results. For instance, the sample size was relatively small, with all cases selected from a single center utilizing a retrospective analysis. In addition, although a standardized nursing screening tool was used as a method for delirium detection, hypoactive delirium or less symptomatic delirium may have been missed, which in turn would lead to an underestimation of POD incidence. The latter is a common limitation in delirium research.

In Study 2, Mei et al similarly explored the effects of general anesthetics on POD in older surgical patients. Specifically, using a randomized clinical trial design, the investigators compared propofol with sevoflurane in older patients who underwent TKR/THR, and their roles in POD severity and duration. Although the incidence of POD was higher in those who received propofol compared to sevoflurane, this trial was underpowered and the results did not reach statistical significance. In addition, while the duration of POD was slightly longer in the propofol group compared to the sevoflurane group (0.5 vs 0.3 days), it was unclear if this finding was clinically significant. Similar to many research studies in POD, limitations of Study 2 included a small sample size of 209 patients, with all participants enrolled from a single center. On the other hand, this study illustrated the feasibility of a method that allowed reproducible prospective assessment of POD time course using CAM and CAM-S.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

The delineation of risk factors that contribute to delirium after surgery in older patients is key to mitigating risks for POD and improving clinical outcomes. An important step towards a better understanding of these modifiable risk factors is to clearly quantify intraoperative risk of POD attributable to specific anesthetics. While preclinical studies have shown differential neurotoxicity effects of propofol and sevoflurane, their impact on clinically important neurologic outcomes such as delirium and cognitive decline remains poorly understood. Although Studies 1 and 2 both provided head-to-head comparisons of propofol and sevoflurane as risk factors for POD in high-operative-stress surgeries in older patients, the results were inconsistent. That being said, this small incremental increase in knowledge was not unexpected in the course of discovery around a clinically complex research question. Importantly, these studies provided evidence regarding the methodological approaches that could be taken to further this line of research.

The mediating factors of the differences on neurologic outcomes between anesthetic agents are likely pharmacological, biological, and methodological. Pharmacologically, the differences between target receptors, such as GABAA (propofol, etomidate) or NMDA (ketamine), could be a defining feature in the difference in incidence of POD. Additionally, secondary actions of anesthetic agents on glycine, nicotinic, and acetylcholine receptors could play a role as well. Biologically, genes such as CYP2E1, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, GSTP1, UGT1A9, SULT1A1, and NQO1 have all been identified as genetic factors in the metabolism of anesthetics, and variations in such genes could result in different responses to anesthetics.2 Methodologically, routes of anesthetic administration (eg, inhalation vs intravenous), preexisting anatomical structures, or confounding medical conditions (eg, lower respiratory volume due to older age) may influence POD incidence, duration, or severity. Moreover, methodological differences between Studies 1 and 2, such as surgeries performed (spinal vs TKR/THR), patient populations (South Korean vs Chinese), and the diagnosis and monitoring of delirium (retrospective screening and diagnosis vs prospective CAM/CAM-S) may impact delirium outcomes. Thus, these factors should be considered in the design of future clinical trials undertaken to investigate the effects of anesthetics on POD.

Given the high prevalence of delirium and its associated adverse outcomes in the immediate postoperative period in older patients, further research is warranted to determine how anesthetics affect POD in order to optimize perioperative care and mitigate risks in this vulnerable population. Moreover, parallel investigations into how anesthetics differentially impact the development of transient or longer-term cognitive impairment after a surgical procedure (ie, postoperative cognitive dysfunction) in older adults are urgently needed in order to improve their cognitive health.

Practice Points

- Intravenous propofol and inhalational sevoflurane may be differentially associated with incidence, duration, and severity of POD in geriatric surgical patients.

- Further larger-scale studies are warranted to clarify the role of anesthetic choice in POD in order to optimize surgical outcomes in older patients.

–Jared Doan, BS, and Fred Ko, MD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Study 1 Overview (Chang et al)

Objective: To assess the incidence of postoperative delirium (POD) following propofol- vs sevoflurane-based anesthesia in geriatric spine surgery patients.

Design: Retrospective, single-blinded observational study of propofol- and sevoflurane-based anesthesia cohorts.

Setting and participants: Patients eligible for this study were aged 65 years or older admitted to the SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center (Seoul, South Korea). All patients underwent general anesthesia either via intravenous propofol or inhalational sevoflurane for spine surgery between January 2015 and December 2019. Patients were retrospectively identified via electronic medical records. Patient exclusion criteria included preoperative delirium, history of dementia, psychiatric disease, alcoholism, hepatic or renal dysfunction, postoperative mechanical ventilation dependence, other surgery within the recent 6 months, maintenance of intraoperative anesthesia with combined anesthetics, or incomplete medical record.

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome was the incidence of POD after administration of propofol- and sevoflurane-based anesthesia during hospitalization. Patients were screened for POD regularly by attending nurses using the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (disorientation, inappropriate behavior, inappropriate communication, hallucination, and psychomotor retardation) during the entirety of the patient’s hospital stay; if 1 or more screening criteria were met, a psychiatrist was consulted for the proper diagnosis and management of delirium. A psychiatric diagnosis was required for a case to be counted toward the incidence of POD in this study. Secondary outcomes included postoperative 30-day complications (angina, myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack/stroke, pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, acute kidney injury, or infection) and length of postoperative hospital stay.

Main results: POD occurred in 29 patients (10.3%) out of the total cohort of 281. POD was more common in the sevoflurane group than in the propofol group (15.7% vs 5.0%; P = .003). Using multivariable logistic regression, inhalational sevoflurane was associated with an increased risk of POD as compared to propofol-based anesthesia (odds ratio [OR], 4.120; 95% CI, 1.549-10.954; P = .005). There was no association between choice of anesthetic and postoperative 30-day complications or the length of postoperative hospital stay. Both older age (OR, 1.242; 95% CI, 1.130-1.366; P < .001) and higher pain score at postoperative day 1 (OR, 1.338; 95% CI, 1.056-1.696; P = .016) were associated with increased risk of POD.

Conclusion: Propofol-based anesthesia was associated with a lower incidence of and risk for POD than sevoflurane-based anesthesia in older patients undergoing spine surgery.

Study 2 Overview (Mei et al)

Objective: To determine the incidence and duration of POD in older patients after total knee/hip replacement (TKR/THR) under intravenous propofol or inhalational sevoflurane general anesthesia.

Design: Randomized clinical trial of propofol and sevoflurane groups.

Setting and participants: This study was conducted at the Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital and involved 209 participants enrolled between June 2016 and November 2019. All participants were 60 years of age or older, scheduled for TKR/THR surgery under general anesthesia, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class I to III, and assessed to be of normal cognitive function preoperatively via a Mini-Mental State Examination. Participant exclusion criteria included preexisting delirium as assessed by the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), prior diagnosed neurological diseases (eg, Parkinson’s disease), prior diagnosed mental disorders (eg, schizophrenia), or impaired vision or hearing that would influence cognitive assessments. All participants were randomly assigned to either sevoflurane or propofol anesthesia for their surgery via a computer-generated list. Of these, 103 received inhalational sevoflurane and 106 received intravenous propofol. All participants received standardized postoperative care.

Main outcome measures: All participants were interviewed by investigators, who were blinded to the anesthesia regimen, twice daily on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3 using CAM and a CAM-based scoring system (CAM-S) to assess delirium severity. The CAM encapsulated 4 criteria: acute onset and fluctuating course, agitation, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. To diagnose delirium, both the first and second criteria must be met, in addition to either the third or fourth criterion. The averages of the scores across the 3 postoperative days indicated delirium severity, while the incidence and duration of delirium was assessed by the presence of delirium as determined by CAM on any postoperative day.

Main results: All eligible participants (N = 209; mean [SD] age 71.2 [6.7] years; 29.2% male) were included in the final analysis. The incidence of POD was not statistically different between the propofol and sevoflurane groups (33.0% vs 23.3%; P = .119, Chi-square test). It was estimated that 316 participants in each arm of the study were needed to detect statistical differences. The number of days of POD per person were higher with propofol anesthesia as compared to sevoflurane (0.5 [0.8] vs 0.3 [0.5]; P = .049, Student’s t-test).

Conclusion: This underpowered study showed a 9.7% difference in the incidence of POD between older adults who received propofol (33.0%) and sevoflurane (23.3%) after THR/TKR. Further studies with a larger sample size are needed to compare general anesthetics and their role in POD.

Commentary

Delirium is characterized by an acute state of confusion with fluctuating mental status, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. It is often caused by medications and/or their related adverse effects, infections, electrolyte imbalances, and other clinical etiologies. Delirium often manifests in post-surgical settings, disproportionately affecting older patients and leading to increased risk of morbidity, mortality, hospital length of stay, and health care costs.1 Intraoperative risk factors for POD are determined by the degree of operative stress (eg, lower-risk surgeries put the patient at reduced risk for POD as compared to higher-risk surgeries) and are additive to preexisting patient-specific risk factors, such as older age and functional impairment.1 Because operative stress is associated with risk for POD, limiting operative stress in controlled ways, such as through the choice of anesthetic agent administered, may be a pragmatic way to manage operative risks and optimize outcomes, especially when serving a surgically vulnerable population.

In Study 1, Chang et al sought to assess whether 2 commonly utilized general anesthetics, propofol and sevoflurane, in older patients undergoing spine surgery differentially affected the incidence of POD. In this retrospective, single-blinded observational study of 281 geriatric patients, the researchers found that sevoflurane was associated with a higher risk of POD as compared to propofol. However, these anesthetics were not associated with surgical outcomes such as postoperative 30-day complications or the length of postoperative hospital stay. While these findings added new knowledge to this field of research, several limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting this study’s results. For instance, the sample size was relatively small, with all cases selected from a single center utilizing a retrospective analysis. In addition, although a standardized nursing screening tool was used as a method for delirium detection, hypoactive delirium or less symptomatic delirium may have been missed, which in turn would lead to an underestimation of POD incidence. The latter is a common limitation in delirium research.

In Study 2, Mei et al similarly explored the effects of general anesthetics on POD in older surgical patients. Specifically, using a randomized clinical trial design, the investigators compared propofol with sevoflurane in older patients who underwent TKR/THR, and their roles in POD severity and duration. Although the incidence of POD was higher in those who received propofol compared to sevoflurane, this trial was underpowered and the results did not reach statistical significance. In addition, while the duration of POD was slightly longer in the propofol group compared to the sevoflurane group (0.5 vs 0.3 days), it was unclear if this finding was clinically significant. Similar to many research studies in POD, limitations of Study 2 included a small sample size of 209 patients, with all participants enrolled from a single center. On the other hand, this study illustrated the feasibility of a method that allowed reproducible prospective assessment of POD time course using CAM and CAM-S.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

The delineation of risk factors that contribute to delirium after surgery in older patients is key to mitigating risks for POD and improving clinical outcomes. An important step towards a better understanding of these modifiable risk factors is to clearly quantify intraoperative risk of POD attributable to specific anesthetics. While preclinical studies have shown differential neurotoxicity effects of propofol and sevoflurane, their impact on clinically important neurologic outcomes such as delirium and cognitive decline remains poorly understood. Although Studies 1 and 2 both provided head-to-head comparisons of propofol and sevoflurane as risk factors for POD in high-operative-stress surgeries in older patients, the results were inconsistent. That being said, this small incremental increase in knowledge was not unexpected in the course of discovery around a clinically complex research question. Importantly, these studies provided evidence regarding the methodological approaches that could be taken to further this line of research.

The mediating factors of the differences on neurologic outcomes between anesthetic agents are likely pharmacological, biological, and methodological. Pharmacologically, the differences between target receptors, such as GABAA (propofol, etomidate) or NMDA (ketamine), could be a defining feature in the difference in incidence of POD. Additionally, secondary actions of anesthetic agents on glycine, nicotinic, and acetylcholine receptors could play a role as well. Biologically, genes such as CYP2E1, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, GSTP1, UGT1A9, SULT1A1, and NQO1 have all been identified as genetic factors in the metabolism of anesthetics, and variations in such genes could result in different responses to anesthetics.2 Methodologically, routes of anesthetic administration (eg, inhalation vs intravenous), preexisting anatomical structures, or confounding medical conditions (eg, lower respiratory volume due to older age) may influence POD incidence, duration, or severity. Moreover, methodological differences between Studies 1 and 2, such as surgeries performed (spinal vs TKR/THR), patient populations (South Korean vs Chinese), and the diagnosis and monitoring of delirium (retrospective screening and diagnosis vs prospective CAM/CAM-S) may impact delirium outcomes. Thus, these factors should be considered in the design of future clinical trials undertaken to investigate the effects of anesthetics on POD.

Given the high prevalence of delirium and its associated adverse outcomes in the immediate postoperative period in older patients, further research is warranted to determine how anesthetics affect POD in order to optimize perioperative care and mitigate risks in this vulnerable population. Moreover, parallel investigations into how anesthetics differentially impact the development of transient or longer-term cognitive impairment after a surgical procedure (ie, postoperative cognitive dysfunction) in older adults are urgently needed in order to improve their cognitive health.

Practice Points

- Intravenous propofol and inhalational sevoflurane may be differentially associated with incidence, duration, and severity of POD in geriatric surgical patients.

- Further larger-scale studies are warranted to clarify the role of anesthetic choice in POD in order to optimize surgical outcomes in older patients.

–Jared Doan, BS, and Fred Ko, MD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

1. Dasgupta M, Dumbrell AC. Preoperative risk assessment for delirium after noncardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1578-1589. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00893.x

2. Mikstacki A, Skrzypczak-Zielinska M, Tamowicz B, et al. The impact of genetic factors on response to anaesthetics. Adv Med Sci. 2013;58(1):9-14. doi:10.2478/v10039-012-0065-z

1. Dasgupta M, Dumbrell AC. Preoperative risk assessment for delirium after noncardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1578-1589. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00893.x

2. Mikstacki A, Skrzypczak-Zielinska M, Tamowicz B, et al. The impact of genetic factors on response to anaesthetics. Adv Med Sci. 2013;58(1):9-14. doi:10.2478/v10039-012-0065-z

Effectiveness of Colonoscopy for Colorectal Cancer Screening in Reducing Cancer-Related Mortality: Interpreting the Results From Two Ongoing Randomized Trials

Study 1 Overview (Bretthauer et al)

Objective: To evaluate the impact of screening colonoscopy on colon cancer–related death.

Design: Randomized trial conducted in 4 European countries.

Setting and participants: Presumptively healthy men and women between the ages of 55 and 64 years were selected from population registries in Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands between 2009 and 2014. Eligible participants had not previously undergone screening. Patients with a diagnosis of colon cancer before trial entry were excluded.

Intervention: Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:2 ratio to undergo colonoscopy screening by invitation or to no invitation and no screening. Participants were randomized using a computer-generated allocation algorithm. Patients were stratified by age, sex, and municipality.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the study was risk of colorectal cancer and related death after a median follow-up of 10 to 15 years. The main secondary endpoint was death from any cause.

Main results: The study reported follow-up data from 84,585 participants (89.1% of all participants originally included in the trial). The remaining participants were either excluded or data could not be included due to lack of follow-up data from the usual-care group. Men (50.1%) and women (49.9%) were equally represented. The median age at entry was 59 years. The median follow-up was 10 years. Characteristics were otherwise balanced. Good bowel preparation was reported in 91% of all participants. Cecal intubation was achieved in 96.8% of all participants. The percentage of patients who underwent screening was 42% for the group, but screening rates varied by country (33%-60%). Colorectal cancer was diagnosed at screening in 62 participants (0.5% of screening group). Adenomas were detected in 30.7% of participants; 15 patients had polypectomy-related major bleeding. There were no perforations.

The risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was 0.98% in the invited-to-screen group and 1.2% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.7-0.93). The reported number needed to invite to prevent 1 case of colon cancer in a 10-year period was 455. The risk of colorectal cancer–related death at 10 years was 0.28% in the invited-to-screen group and 0.31% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). An adjusted per-protocol analysis was performed to account for the estimated effect of screening if all participants assigned to the screening group underwent screening. In this analysis, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was decreased from 1.22% to 0.84% (risk ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.66-0.83).

Conclusion: Based on the results of this European randomized trial, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was lower among those who were invited to undergo screening.

Study 2 Overview (Forsberg et al)

Objective: To investigate the effect of colorectal cancer screening with once-only colonoscopy or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) on colorectal cancer mortality and incidence.

Design: Randomized controlled trial in Sweden utilizing a population registry.

Setting and participants: Patients aged 60 years at the time of entry were identified from a population-based registry from the Swedish Tax Agency.

Intervention: Individuals were assigned by an independent statistician to once-only colonoscopy, 2 rounds of FIT 2 years apart, or a control group in which no intervention was performed. Patients were assigned in a 1:6 ratio for colonoscopy vs control and a 1:2 ratio for FIT vs control.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the trial was colorectal cancer incidence and mortality.

Main results: A total of 278,280 participants were included in the study from March 1, 2014, through December 31, 2020 (31,140 in the colonoscopy group, 60,300 in the FIT group, and 186,840 in the control group). Of those in the colonoscopy group, 35% underwent colonoscopy, and 55% of those in the FIT group participated in testing. Colorectal cancer was detected in 0.16% (49) of people in the colonoscopy group and 0.2% (121) of people in the FIT test group (relative risk, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.56-1.09). The advanced adenoma detection rate was 2.05% in the colonoscopy group and 1.61% in the FIT group (relative risk, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.15-1.41). There were 2 perforations noted in the colonoscopy group and 15 major bleeding events. More right-sided adenomas were detected in the colonoscopy group.

Conclusion: The results of the current study highlight similar detection rates in the colonoscopy and FIT group. Should further follow-up show a benefit in disease-specific mortality, such screening strategies could be translated into population-based screening programs.

Commentary

The first colonoscopy screening recommendations were established in the mid 1990s in the United States, and over the subsequent 2 decades colonoscopy has been the recommended method and main modality for colorectal cancer screening in this country. The advantage of colonoscopy over other screening modalities (sigmoidoscopy and fecal-based testing) is that it can examine the entire large bowel and allow for removal of potential precancerous lesions. However, data to support colonoscopy as a screening modality for colorectal cancer are largely based on cohort studies.1,2 These studies have reported a significant reduction in the incidence of colon cancer. Additionally, colorectal cancer mortality was notably lower in the screened populations. For example, one study among health professionals found a nearly 70% reduction in colorectal cancer mortality in those who underwent at least 1 screening colonoscopy.3

There has been a lack of randomized clinical data to validate the efficacy of colonoscopy screening for reducing colorectal cancer–related deaths. The current study by Bretthauer et al addresses an important need and enhances our understanding of the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening with colonoscopy. In this randomized trial involving more than 84,000 participants from Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands, there was a noted 18% decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer over a 10-year period in the intention-to-screen population. The reduction in the risk of death from colorectal cancer was not statistically significant (risk ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). These results are surprising and certainly raise the question as to whether previous studies overestimated the effectiveness of colonoscopy in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer–related deaths. There are several limitations to the Bretthauer et al study, however.

Perhaps the most important limitation is the fact that only 42% of participants in the invited-to-screen cohort underwent screening colonoscopy. Therefore, this raises the question of whether the efficacy noted is simply due to a lack of participation in the screening protocol. In the adjusted per-protocol analysis, colonoscopy was estimated to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by 31% and the risk of colorectal cancer–related death by around 50%. These findings are more in line with prior published studies regarding the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening. The authors plan to repeat this analysis at 15 years, and it is possible that the risk of colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer–related death can be reduced on subsequent follow-up.

While the results of the Bretthauer et al trial are important, randomized trials that directly compare the effectiveness of different colorectal cancer screening strategies are lacking. The Forsberg et al trial, also an ongoing study, seeks to address this vitally important gap in our current data. The SCREESCO trial is a study that compares the efficacy of colonoscopy with FIT every 2 years or no screening. The currently reported data are preliminary but show a similarly low rate of colonoscopy screening in those invited to do so (35%). This is a similar limitation to that noted in the Bretthauer et al study. Furthermore, there is some question regarding colonoscopy quality in this study, which had a very low reported adenoma detection rate.

While the current studies are important and provide quality randomized data on the effect of colorectal cancer screening, there remain many unanswered questions. Should the results presented by Bretthauer et al represent the current real-world scenario, then colonoscopy screening may not be viewed as an effective screening tool compared to simpler, less-invasive modalities (ie, FIT). Further follow-up from the SCREESCO trial will help shed light on this question. However, there are concerns with this study, including a very low participation rate, which could greatly underestimate the effectiveness of screening. Additional analysis and longer follow-up will be vital to fully understand the benefits of screening colonoscopy. In the meantime, screening remains an important tool for early detection of colorectal cancer and remains a category A recommendation by the United States Preventive Services Task Force.4

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colorectal cancer for persons between 45 and 75 years of age (category B recommendation for those aged 45 to 49 years per the United States Preventive Services Task Force). Stool-based tests and direct visualization tests are both endorsed as screening options. Further follow-up from the presented studies is needed to help shed light on the magnitude of benefit of these modalities.

Practice Points

- Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colon cancer in those aged 45 to 75 years.

- The optimal modality for screening and the impact of screening on cancer-related mortality requires longer- term follow-up from these ongoing studies.

–Daniel Isaac, DO, MS

1. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021 May. Report No.: 20-05271-EF-1.

2. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1978-1998. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4417

3. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1095-1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301969

4. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Colorectal cancer: screening. Published May 18, 2021. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

Study 1 Overview (Bretthauer et al)

Objective: To evaluate the impact of screening colonoscopy on colon cancer–related death.

Design: Randomized trial conducted in 4 European countries.

Setting and participants: Presumptively healthy men and women between the ages of 55 and 64 years were selected from population registries in Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands between 2009 and 2014. Eligible participants had not previously undergone screening. Patients with a diagnosis of colon cancer before trial entry were excluded.

Intervention: Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:2 ratio to undergo colonoscopy screening by invitation or to no invitation and no screening. Participants were randomized using a computer-generated allocation algorithm. Patients were stratified by age, sex, and municipality.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the study was risk of colorectal cancer and related death after a median follow-up of 10 to 15 years. The main secondary endpoint was death from any cause.

Main results: The study reported follow-up data from 84,585 participants (89.1% of all participants originally included in the trial). The remaining participants were either excluded or data could not be included due to lack of follow-up data from the usual-care group. Men (50.1%) and women (49.9%) were equally represented. The median age at entry was 59 years. The median follow-up was 10 years. Characteristics were otherwise balanced. Good bowel preparation was reported in 91% of all participants. Cecal intubation was achieved in 96.8% of all participants. The percentage of patients who underwent screening was 42% for the group, but screening rates varied by country (33%-60%). Colorectal cancer was diagnosed at screening in 62 participants (0.5% of screening group). Adenomas were detected in 30.7% of participants; 15 patients had polypectomy-related major bleeding. There were no perforations.

The risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was 0.98% in the invited-to-screen group and 1.2% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.7-0.93). The reported number needed to invite to prevent 1 case of colon cancer in a 10-year period was 455. The risk of colorectal cancer–related death at 10 years was 0.28% in the invited-to-screen group and 0.31% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). An adjusted per-protocol analysis was performed to account for the estimated effect of screening if all participants assigned to the screening group underwent screening. In this analysis, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was decreased from 1.22% to 0.84% (risk ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.66-0.83).

Conclusion: Based on the results of this European randomized trial, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was lower among those who were invited to undergo screening.

Study 2 Overview (Forsberg et al)

Objective: To investigate the effect of colorectal cancer screening with once-only colonoscopy or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) on colorectal cancer mortality and incidence.

Design: Randomized controlled trial in Sweden utilizing a population registry.

Setting and participants: Patients aged 60 years at the time of entry were identified from a population-based registry from the Swedish Tax Agency.

Intervention: Individuals were assigned by an independent statistician to once-only colonoscopy, 2 rounds of FIT 2 years apart, or a control group in which no intervention was performed. Patients were assigned in a 1:6 ratio for colonoscopy vs control and a 1:2 ratio for FIT vs control.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the trial was colorectal cancer incidence and mortality.

Main results: A total of 278,280 participants were included in the study from March 1, 2014, through December 31, 2020 (31,140 in the colonoscopy group, 60,300 in the FIT group, and 186,840 in the control group). Of those in the colonoscopy group, 35% underwent colonoscopy, and 55% of those in the FIT group participated in testing. Colorectal cancer was detected in 0.16% (49) of people in the colonoscopy group and 0.2% (121) of people in the FIT test group (relative risk, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.56-1.09). The advanced adenoma detection rate was 2.05% in the colonoscopy group and 1.61% in the FIT group (relative risk, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.15-1.41). There were 2 perforations noted in the colonoscopy group and 15 major bleeding events. More right-sided adenomas were detected in the colonoscopy group.

Conclusion: The results of the current study highlight similar detection rates in the colonoscopy and FIT group. Should further follow-up show a benefit in disease-specific mortality, such screening strategies could be translated into population-based screening programs.

Commentary

The first colonoscopy screening recommendations were established in the mid 1990s in the United States, and over the subsequent 2 decades colonoscopy has been the recommended method and main modality for colorectal cancer screening in this country. The advantage of colonoscopy over other screening modalities (sigmoidoscopy and fecal-based testing) is that it can examine the entire large bowel and allow for removal of potential precancerous lesions. However, data to support colonoscopy as a screening modality for colorectal cancer are largely based on cohort studies.1,2 These studies have reported a significant reduction in the incidence of colon cancer. Additionally, colorectal cancer mortality was notably lower in the screened populations. For example, one study among health professionals found a nearly 70% reduction in colorectal cancer mortality in those who underwent at least 1 screening colonoscopy.3

There has been a lack of randomized clinical data to validate the efficacy of colonoscopy screening for reducing colorectal cancer–related deaths. The current study by Bretthauer et al addresses an important need and enhances our understanding of the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening with colonoscopy. In this randomized trial involving more than 84,000 participants from Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands, there was a noted 18% decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer over a 10-year period in the intention-to-screen population. The reduction in the risk of death from colorectal cancer was not statistically significant (risk ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). These results are surprising and certainly raise the question as to whether previous studies overestimated the effectiveness of colonoscopy in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer–related deaths. There are several limitations to the Bretthauer et al study, however.

Perhaps the most important limitation is the fact that only 42% of participants in the invited-to-screen cohort underwent screening colonoscopy. Therefore, this raises the question of whether the efficacy noted is simply due to a lack of participation in the screening protocol. In the adjusted per-protocol analysis, colonoscopy was estimated to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by 31% and the risk of colorectal cancer–related death by around 50%. These findings are more in line with prior published studies regarding the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening. The authors plan to repeat this analysis at 15 years, and it is possible that the risk of colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer–related death can be reduced on subsequent follow-up.

While the results of the Bretthauer et al trial are important, randomized trials that directly compare the effectiveness of different colorectal cancer screening strategies are lacking. The Forsberg et al trial, also an ongoing study, seeks to address this vitally important gap in our current data. The SCREESCO trial is a study that compares the efficacy of colonoscopy with FIT every 2 years or no screening. The currently reported data are preliminary but show a similarly low rate of colonoscopy screening in those invited to do so (35%). This is a similar limitation to that noted in the Bretthauer et al study. Furthermore, there is some question regarding colonoscopy quality in this study, which had a very low reported adenoma detection rate.

While the current studies are important and provide quality randomized data on the effect of colorectal cancer screening, there remain many unanswered questions. Should the results presented by Bretthauer et al represent the current real-world scenario, then colonoscopy screening may not be viewed as an effective screening tool compared to simpler, less-invasive modalities (ie, FIT). Further follow-up from the SCREESCO trial will help shed light on this question. However, there are concerns with this study, including a very low participation rate, which could greatly underestimate the effectiveness of screening. Additional analysis and longer follow-up will be vital to fully understand the benefits of screening colonoscopy. In the meantime, screening remains an important tool for early detection of colorectal cancer and remains a category A recommendation by the United States Preventive Services Task Force.4

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colorectal cancer for persons between 45 and 75 years of age (category B recommendation for those aged 45 to 49 years per the United States Preventive Services Task Force). Stool-based tests and direct visualization tests are both endorsed as screening options. Further follow-up from the presented studies is needed to help shed light on the magnitude of benefit of these modalities.

Practice Points

- Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colon cancer in those aged 45 to 75 years.

- The optimal modality for screening and the impact of screening on cancer-related mortality requires longer- term follow-up from these ongoing studies.

–Daniel Isaac, DO, MS

Study 1 Overview (Bretthauer et al)

Objective: To evaluate the impact of screening colonoscopy on colon cancer–related death.

Design: Randomized trial conducted in 4 European countries.

Setting and participants: Presumptively healthy men and women between the ages of 55 and 64 years were selected from population registries in Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands between 2009 and 2014. Eligible participants had not previously undergone screening. Patients with a diagnosis of colon cancer before trial entry were excluded.

Intervention: Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:2 ratio to undergo colonoscopy screening by invitation or to no invitation and no screening. Participants were randomized using a computer-generated allocation algorithm. Patients were stratified by age, sex, and municipality.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the study was risk of colorectal cancer and related death after a median follow-up of 10 to 15 years. The main secondary endpoint was death from any cause.

Main results: The study reported follow-up data from 84,585 participants (89.1% of all participants originally included in the trial). The remaining participants were either excluded or data could not be included due to lack of follow-up data from the usual-care group. Men (50.1%) and women (49.9%) were equally represented. The median age at entry was 59 years. The median follow-up was 10 years. Characteristics were otherwise balanced. Good bowel preparation was reported in 91% of all participants. Cecal intubation was achieved in 96.8% of all participants. The percentage of patients who underwent screening was 42% for the group, but screening rates varied by country (33%-60%). Colorectal cancer was diagnosed at screening in 62 participants (0.5% of screening group). Adenomas were detected in 30.7% of participants; 15 patients had polypectomy-related major bleeding. There were no perforations.

The risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was 0.98% in the invited-to-screen group and 1.2% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.7-0.93). The reported number needed to invite to prevent 1 case of colon cancer in a 10-year period was 455. The risk of colorectal cancer–related death at 10 years was 0.28% in the invited-to-screen group and 0.31% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). An adjusted per-protocol analysis was performed to account for the estimated effect of screening if all participants assigned to the screening group underwent screening. In this analysis, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was decreased from 1.22% to 0.84% (risk ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.66-0.83).

Conclusion: Based on the results of this European randomized trial, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was lower among those who were invited to undergo screening.

Study 2 Overview (Forsberg et al)

Objective: To investigate the effect of colorectal cancer screening with once-only colonoscopy or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) on colorectal cancer mortality and incidence.

Design: Randomized controlled trial in Sweden utilizing a population registry.

Setting and participants: Patients aged 60 years at the time of entry were identified from a population-based registry from the Swedish Tax Agency.

Intervention: Individuals were assigned by an independent statistician to once-only colonoscopy, 2 rounds of FIT 2 years apart, or a control group in which no intervention was performed. Patients were assigned in a 1:6 ratio for colonoscopy vs control and a 1:2 ratio for FIT vs control.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the trial was colorectal cancer incidence and mortality.

Main results: A total of 278,280 participants were included in the study from March 1, 2014, through December 31, 2020 (31,140 in the colonoscopy group, 60,300 in the FIT group, and 186,840 in the control group). Of those in the colonoscopy group, 35% underwent colonoscopy, and 55% of those in the FIT group participated in testing. Colorectal cancer was detected in 0.16% (49) of people in the colonoscopy group and 0.2% (121) of people in the FIT test group (relative risk, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.56-1.09). The advanced adenoma detection rate was 2.05% in the colonoscopy group and 1.61% in the FIT group (relative risk, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.15-1.41). There were 2 perforations noted in the colonoscopy group and 15 major bleeding events. More right-sided adenomas were detected in the colonoscopy group.

Conclusion: The results of the current study highlight similar detection rates in the colonoscopy and FIT group. Should further follow-up show a benefit in disease-specific mortality, such screening strategies could be translated into population-based screening programs.

Commentary

The first colonoscopy screening recommendations were established in the mid 1990s in the United States, and over the subsequent 2 decades colonoscopy has been the recommended method and main modality for colorectal cancer screening in this country. The advantage of colonoscopy over other screening modalities (sigmoidoscopy and fecal-based testing) is that it can examine the entire large bowel and allow for removal of potential precancerous lesions. However, data to support colonoscopy as a screening modality for colorectal cancer are largely based on cohort studies.1,2 These studies have reported a significant reduction in the incidence of colon cancer. Additionally, colorectal cancer mortality was notably lower in the screened populations. For example, one study among health professionals found a nearly 70% reduction in colorectal cancer mortality in those who underwent at least 1 screening colonoscopy.3

There has been a lack of randomized clinical data to validate the efficacy of colonoscopy screening for reducing colorectal cancer–related deaths. The current study by Bretthauer et al addresses an important need and enhances our understanding of the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening with colonoscopy. In this randomized trial involving more than 84,000 participants from Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands, there was a noted 18% decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer over a 10-year period in the intention-to-screen population. The reduction in the risk of death from colorectal cancer was not statistically significant (risk ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). These results are surprising and certainly raise the question as to whether previous studies overestimated the effectiveness of colonoscopy in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer–related deaths. There are several limitations to the Bretthauer et al study, however.

Perhaps the most important limitation is the fact that only 42% of participants in the invited-to-screen cohort underwent screening colonoscopy. Therefore, this raises the question of whether the efficacy noted is simply due to a lack of participation in the screening protocol. In the adjusted per-protocol analysis, colonoscopy was estimated to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by 31% and the risk of colorectal cancer–related death by around 50%. These findings are more in line with prior published studies regarding the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening. The authors plan to repeat this analysis at 15 years, and it is possible that the risk of colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer–related death can be reduced on subsequent follow-up.

While the results of the Bretthauer et al trial are important, randomized trials that directly compare the effectiveness of different colorectal cancer screening strategies are lacking. The Forsberg et al trial, also an ongoing study, seeks to address this vitally important gap in our current data. The SCREESCO trial is a study that compares the efficacy of colonoscopy with FIT every 2 years or no screening. The currently reported data are preliminary but show a similarly low rate of colonoscopy screening in those invited to do so (35%). This is a similar limitation to that noted in the Bretthauer et al study. Furthermore, there is some question regarding colonoscopy quality in this study, which had a very low reported adenoma detection rate.

While the current studies are important and provide quality randomized data on the effect of colorectal cancer screening, there remain many unanswered questions. Should the results presented by Bretthauer et al represent the current real-world scenario, then colonoscopy screening may not be viewed as an effective screening tool compared to simpler, less-invasive modalities (ie, FIT). Further follow-up from the SCREESCO trial will help shed light on this question. However, there are concerns with this study, including a very low participation rate, which could greatly underestimate the effectiveness of screening. Additional analysis and longer follow-up will be vital to fully understand the benefits of screening colonoscopy. In the meantime, screening remains an important tool for early detection of colorectal cancer and remains a category A recommendation by the United States Preventive Services Task Force.4

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colorectal cancer for persons between 45 and 75 years of age (category B recommendation for those aged 45 to 49 years per the United States Preventive Services Task Force). Stool-based tests and direct visualization tests are both endorsed as screening options. Further follow-up from the presented studies is needed to help shed light on the magnitude of benefit of these modalities.

Practice Points

- Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colon cancer in those aged 45 to 75 years.

- The optimal modality for screening and the impact of screening on cancer-related mortality requires longer- term follow-up from these ongoing studies.

–Daniel Isaac, DO, MS

1. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021 May. Report No.: 20-05271-EF-1.

2. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1978-1998. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4417

3. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1095-1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301969

4. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Colorectal cancer: screening. Published May 18, 2021. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

1. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021 May. Report No.: 20-05271-EF-1.

2. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1978-1998. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4417

3. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1095-1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301969

4. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Colorectal cancer: screening. Published May 18, 2021. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

Safety and Efficacy of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and SGLT2 Inhibitors Among Veterans With Type 2 Diabetes

Selecting the best medication regimen for a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) depends on many factors, such as glycemic control, adherence, adverse effect (AE) profile, and comorbid conditions.1 Selected agents from 2 newer medication classes, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), have demonstrated cardiovascular and renal protective properties, creating a new paradigm in management.

The American Diabetes Association recommends medications with proven benefit in cardiovascular disease (CVD), such as the GLP-1 RAs liraglutide, injectable semaglutide, or dulaglutide, or the SGLT2i empagliflozin or canagliflozin, as second-line after metformin in patients with established atherosclerotic CVD or indicators of high risk to reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).1 SGLT2i are preferred in patients with diabetic kidney disease, and GLP-1 RAs are next in line for selection of agents with proven nephroprotection (liraglutide, injectable semaglutide, dulaglutide). The mechanisms of these benefits are not fully understood but may be due to their extraglycemic effects. The classes likely induce these benefits by different mechanisms: SGLT2i by hemodynamic effects and GLP-1 RAs by anti-inflammatory mechanisms.2 Although there is much interest, evidence is limited regarding the cardiovascular and renal protection benefits of these agents used in combination.

The combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i agents demonstrated greater benefit than separate use in trials with nonveteran populations.3-7 These studies evaluated effects on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, weight loss, blood pressure (BP), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). A meta-analysis of 7 trials found that the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i reduced HbA1c levels, body weight, and systolic blood pressure (SBP).8 All of the changes were statistically significant except for body weight with combination vs SGLT2i alone. Combination therapy was not associated with increased risk of severe hypoglycemia compared with either therapy separately.

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in a real-world, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) population with T2DM.

Methods

This study was a pre-post, retrospective, single-center chart review. Subjects served as their own control. The project was reviewed and approved by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System Institutional Review Board. Subjects prescribed both a GLP-1 RA (semaglutide or liraglutide) and SGLT2i (empagliflozin) between January 1, 2014, and November 10, 2019, were extracted from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) for possible inclusion in the study.

Patients were excluded if they received < 12 weeks of combination GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i therapy or did not have a corresponding 12-week HbA1c level. Patients also were excluded if they had < 12 weeks of monotherapy before starting combination therapy or did not have a baseline HbA1c level, or if the start date of combination therapy was not recorded in the VA electronic health record (EHR). We reviewed data for each patient from 6 months before to 1 year after the second agent was started. Start of the first agent (GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i) was recorded as the date the prescription was picked up in-person or 7 days after release date if mailed to the patient. Start of the second agent (GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i) was defined as baseline and was the date the prescription was picked up in person or 7 days after the release date if mailed.

Baseline measures were taken anytime from 8 weeks after the start of the first agent through 2 weeks after the start of the second agent. Data collected included age, sex, race, height, weight, BP, HbA1c levels, serum creatinine (SCr), eGFR, classes of medications for the treatment of T2DM, and the number of prescribed antihypertensive medications. HbA1c levels, SCr, eGFR, weight, and BP also were collected at 12 weeks (within 8-21 weeks); 26 weeks (within 22-35 weeks); and 52 weeks (within 36-57 weeks) of combination therapy. We reviewed progress notes and laboratory results to determine AEs within 26 weeks before initiating second agent (baseline) and 0 to 26 weeks and 26 to 52 weeks after initiating combination therapy.

The primary objective was to determine the effect on HbA1c levels at 12 weeks when using a GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in combination vs separately. Secondary objectives were to determine change from baseline in mean body weight, BP, SCr, and eGFR at 12, 26, and 52 weeks; change in HbA1c levels at 26 and 52 weeks; and incidence of prespecified adverse drug reactions during combination therapy vs separately.

Statistical Analysis

Assuming a SD of 1, 80% power, significance level of P < .05, 2-sided test, and a correlation between baseline and follow-up of 0.5, we determined that a sample size of 34 subjects was required to detect a 0.5% change in baseline HbA1c level at 12 weeks. A t test (or Wilcoxon signed rank test if outcome not normally distributed) was conducted to examine whether the expected change from baseline was different from 0 for continuous outcomes. Median change from baseline was reported for SCr as a nonparametric t test (Wilcoxon signed rank test) was used.

Results

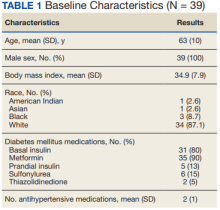

We identified 110 patients for possible study inclusion and 39 met eligibility criteria. After record review, 30 patients were excluded for receiving < 12 weeks of combination therapy or no 12 week HbA1c level; 26 patients were excluded for receiving < 12 weeks of monotherapy before starting combination therapy or no baseline HbA1c level; and 15 patients were excluded for lack of documentation in the VA EHR. Of the 39 patients included, 24 (62%) were prescribed empagliflozin first and then 8 started liraglutide and 16 started semaglutide.

HbA1c levels decreased by 1% after 12 weeks of combination therapy compared with baseline (P < .001), and this reduction was sustained through the duration of the study period (Table 2).

The most common AE during the trial was hypoglycemia, which was mostly mild (level 1) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study evaluated the safety and efficacy of combined use of semaglutide or liraglutide and empagliflozin in a veteran population with T2DM. The retrospective chart review captured real-world practice and outcomes. Combination therapy was associated with a significant reduction in HbA1c levels, body weight, and SBP compared with either agent alone. No significant change was seen in DBP, SCr, or eGFR. Overall, the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i medications demonstrated a good safety profile with most patients reporting no AEs.

Several other studies have assessed the safety and efficacy of using GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in combination. The DURATION 8 trial is the only double-blind trial to randomize subjects to receive either exenatide once weekly, dapagliflozin, or the combination of both for up to 52 weeks.3 Other controlled trials required stable background therapy with either SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA before randomization to receive the other class or placebo and had durations between 18 and 30 weeks.4-7 The AWARD 10 trial studied the combination of canagliflozin and dulaglutide, which both have proven CVD benefit.4 Other studies did not restrict SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA background therapy to agents with proven CVD benefit.5-7 The present study evaluated the combination of empagliflozin plus liraglutide or semaglutide, agents that all have proven CVD benefit.