User login

Lung cancer screening: New evidence, updated guidance

CASE

A 51-year-old man presents to your office to discuss lung cancer screening. He has a history of hypertension and prediabetes. His father died of lung cancer 5 years ago, at age 77. The patient stopped smoking soon thereafter; prior to that, he smoked 1 pack of cigarettes per day for 20 years. He wants to know if he should be screened for lung cancer.

The relative lack of symptoms during the early stages of lung cancer frequently results in a delayed diagnosis. This, and the speed at which the disease progresses, underscores the need for an effective screening modality. More than half of people with lung cancer die within 1 year of diagnosis.1 Excluding skin cancer, lung cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer, and more people die of lung cancer than of colon, breast, and prostate cancers combined.2 In 2022, it was estimated that there would be 236,740 new cases of lung cancer and 130,180 deaths from lung cancer.1,2 The average age at diagnosis is 70 years.2

Screening modalities: Only 1 has demonstrated mortality benefit

In 1968, Wilson and Junger3 outlined the characteristics of the ideal screening test for the World Health Organization: it should limit risk to the patient, be sensitive for detecting the disease early in its course, limit false-positive results, be acceptable to the patient, and be inexpensive to the health system.3 For decades, several screening modalities for lung cancer were trialed to fit the above guidance, but many of them fell short of the most important outcome: the impact on mortality.

Sputum cytology. The use of sputum cytology, either in combination with or without chest radiography, is not recommended. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have failed to demonstrate improved lung cancer detection or mortality reduction in patients screened with this modality.4

Chest radiography (CXR). Several studies have assessed the efficacy of CXR as a screening modality. The best known was the Prostate, Lung, Colon, Ovarian (PLCO) Trial.5 This multicenter RCT enrolled more than 154,000 participants, half of whom received CXR at baseline and then annually for 3 years; the other half continued usual care (no screening). After 13 years of follow-up, there were no significant differences in lung cancer detection or mortality rates between the 2 groups.5

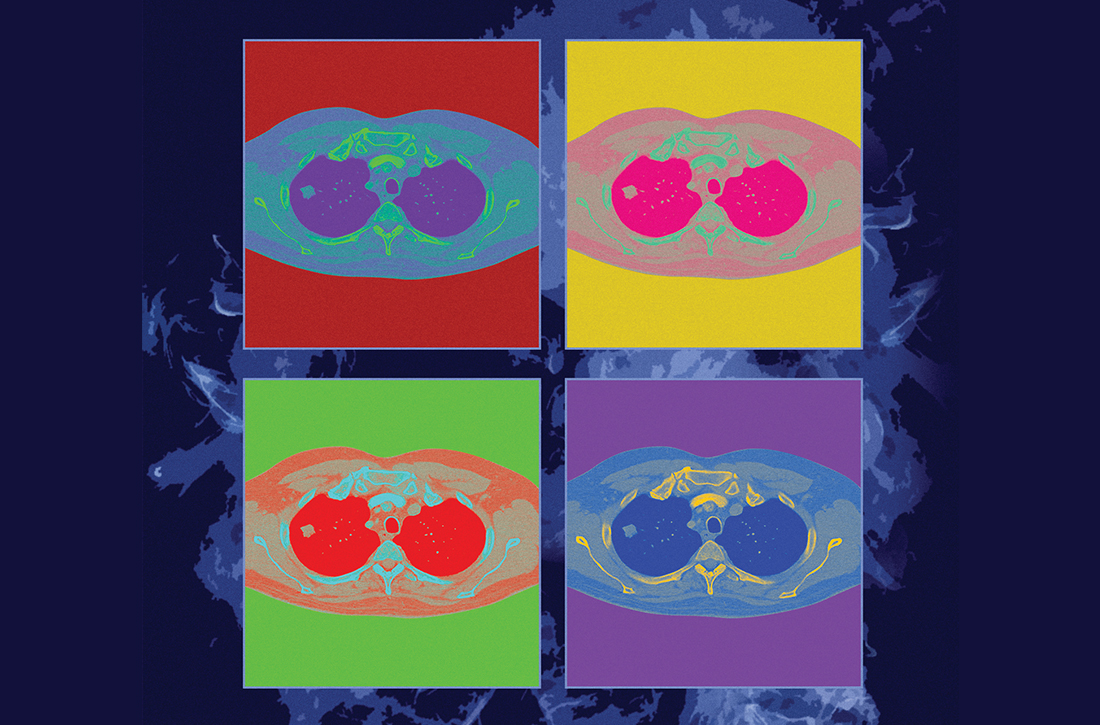

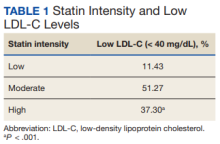

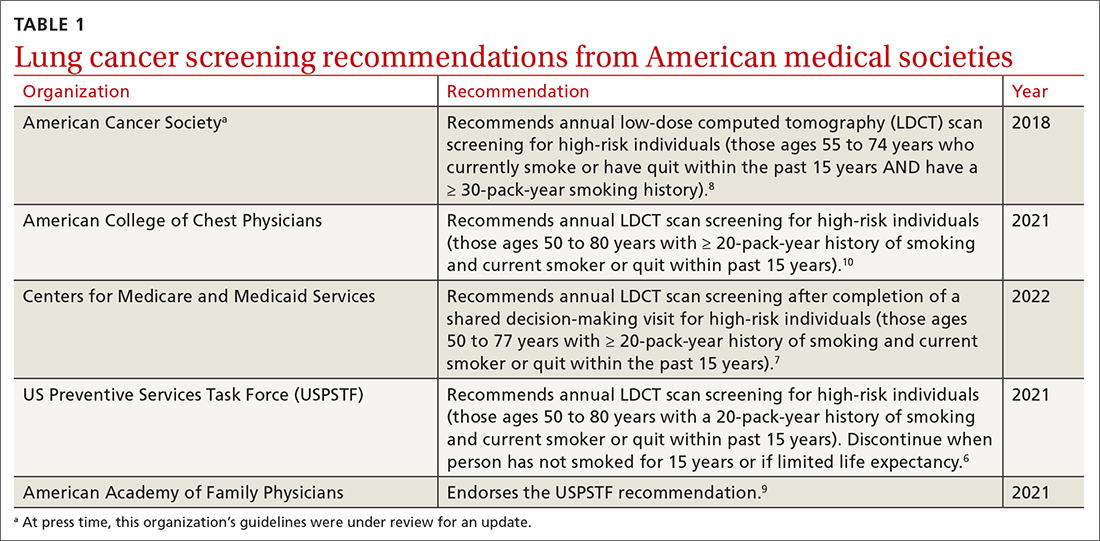

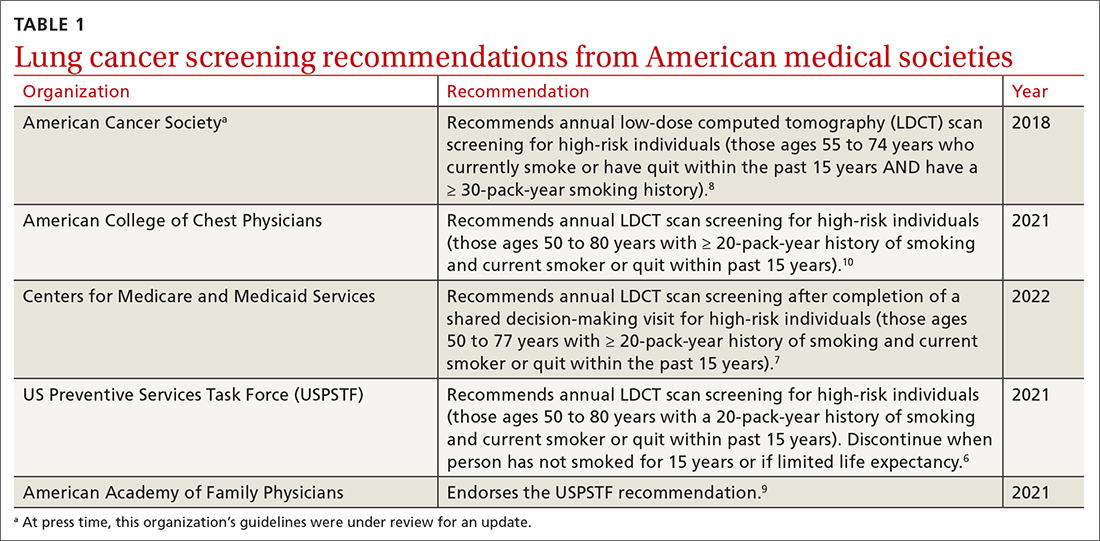

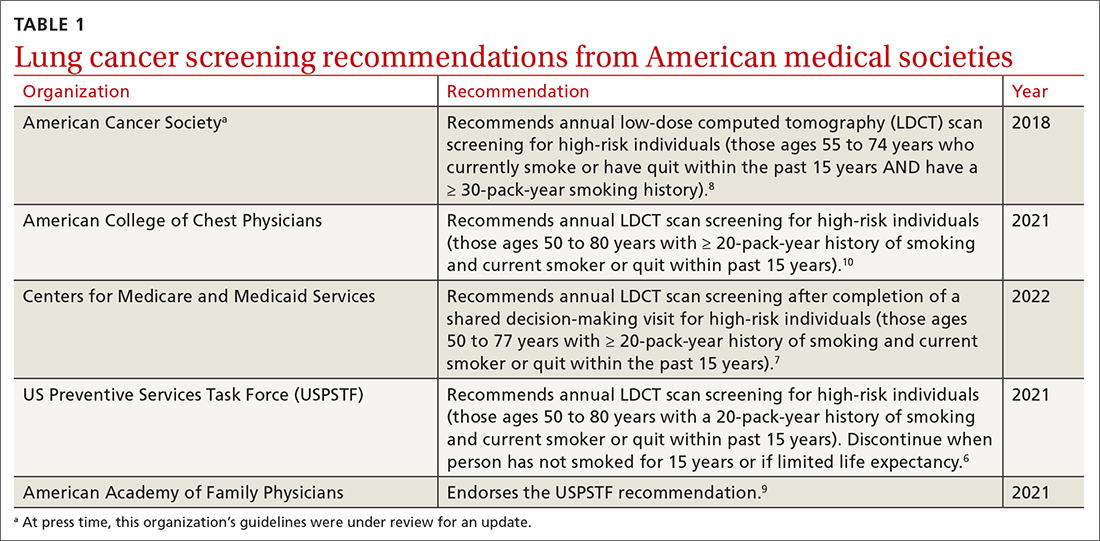

Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT). Several major medical societies recommend LDCT to screen high-risk individuals for lung cancer (TABLE 16-10). Results from 2 major RCTs have guided these recommendations.

The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) was a multicenter RCT comparing 2 screening tests for lung cancer.11 Approximately 54,000 high-risk participants were enrolled between 2002 and 2004 and were randomized to receive annual screening with either LDCT or single-view CXR. The trial was discontinued prematurely when investigators noted a 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality in the LDCT group vs the CXR group.12 This equates to 3 fewer deaths for every 1000 people screened with LDCT vs CXR. There was also a 6% reduction in all-cause mortality noted in the LDCT vs the CXR group.12

Continue to: The NELSON trial...

The NELSON trial, conducted between 2005 and 2015, studied more than 15,000 current or former smokers ages 50 to 74 years and compared LDCT screening at various intervals to no screening.13 After 10 years, lung cancer–related mortality was reduced by 24% (or 1 less death per 1000 person-years) in men who were screened vs their unscreened counterparts.13 In contrast to the NLST, in the NELSON trial, no significant difference in all-cause mortality was observed. Subgroup analysis of the relatively small population of women included in the NELSON trial suggested a 33% reduction in 10-year mortality; however, the difference was nonsignificant between the screened and unscreened groups.13

Each of these landmark studies had characteristics that could limit the results' generalizability to the US population. In the NELSON trial, more than 80% of the study participants were male. In both trials, there was significant underrepresentation of Black, Asian, Hispanic, and other non-White people.12,13 Furthermore, participants in these studies were of higher socioeconomic status than the general US screening-eligible population.

At this time, LDCT is the only lung cancer screening modality that has shown benefit for both disease-related and all-cause mortality, in the populations that were studied. Based on the NLST, the number needed to screen (NNS) with LDCT to prevent 1 lung cancer–related death is 308. The NNS to prevent 1 death from any cause is 219.6

Updated evidence has led to a consensus on screening criteria

Many national societies endorse annual screening with LDCT in high-risk individuals (TABLE 16-10). Risk assessment for the purpose of lung cancer screening includes a detailed review of smoking history and age. The risk of lung cancer increases with advancing age and with cumulative quantity and duration of smoking, but decreases with increasing time since quitting. Therefore, a detailed smoking history should include total number of pack-years, current smoking status, and, if applicable, when smoking cessation occurred.

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) updated their 2013 lung cancer screening recommendations, expanding the screening age range and lowering the smoking history threshold for triggering initiation of screening.6 The impetus for the update was emerging evidence from systematic reviews, RCTs, and the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) that could help to determine the optimal age for screening and identify high-risk groups. For example, the NELSON trial, combined with results from CISNET modeling data, showed an empirical benefit for screening those ages 50 to 55 years.6

Continue to: As a result...

As a result, the USPSTF now recommends annual lung cancer screening with LDCT for any adult ages 50 to 80 years who has a 20-pack-year smoking history and currently smokes or has quit within the past 15 years.6 Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years, develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy, or is not willing to have curative lung surgery.6

Expanding the screening eligibility may also address racial and gender disparities in health care. Black people and women who smoke have a higher risk for lung cancer at a lower intensity of smoking.6

Following the USPSTF update, the American College of Chest Physicians and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services published updated guidance that aligns with USPSTF’s recommendations to lower the age and pack-year qualifications for initiating screening.7,10 The American Cancer Society is currently reviewing its 2018 guidelines on lung cancer screening.14 TABLE 16-10 summarizes the guidance on lung cancer screening from these medical societies.

Effective screening could save lives (and money)

A smoker’s risk for lung cancer is 20 times higher than that of a nonsmoker15,16; 55% of lung cancer deaths in women and 70% in men are attributed to smoking.17 Once diagnosed with lung cancer, more than 50% of people will die within 1 year.1 This underpins the need for a lung cancer screening modality that reduces mortality. Large RCTs, including the NLST and NELSON trials, have shown that screening high-risk individuals with LDCT can significantly reduce lung cancer–related death when compared to no screening or screening with CXR alone.11,13

There is controversy surrounding the cost benefit of implementing a nationwide lung cancer screening program. However, recent use of microsimulation models has shown LDCT to be a cost-effective strategy, with an average cost of $81,000 per quality-adjusted life-year, which is below the threshold of $100,000 to be considered cost effective.18 Expanding the upper age limit for screening leads to a greater reduction in mortality but increases treatment costs and overdiagnosis rates, and overall does not improve quality-adjusted life-years.18

Continue to: Potential harms

Potential harms: False-positives and related complications

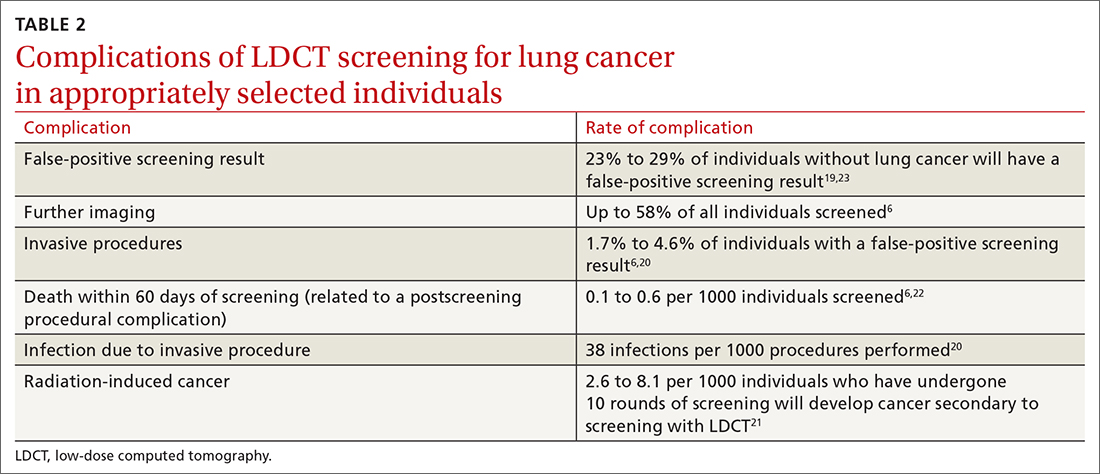

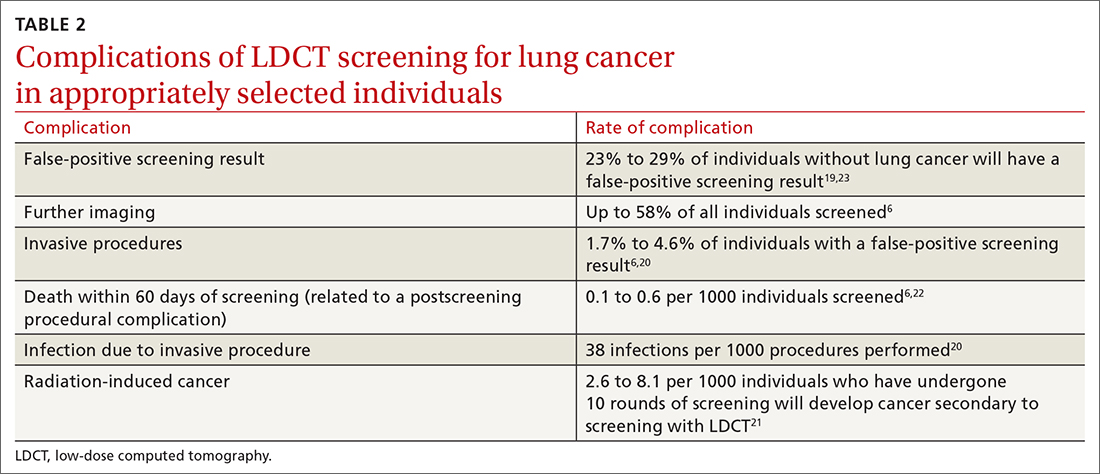

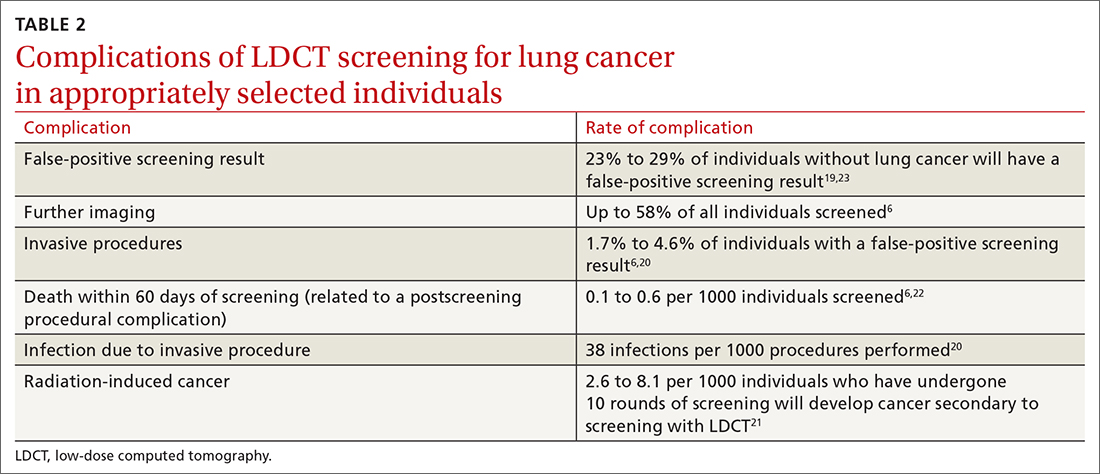

Screening for lung cancer is not without its risks. Harms from screening typically result from false-positive test results leading to overdiagnosis, anxiety and distress, unnecessary invasive tests or procedures, and increased costs.19 TABLE 26,19-23 lists specific complications from lung cancer screening with LDCT.

The false-positive rate is not trivial. For every 1000 patients screened, 250 people will have a positive LDCT finding but will not have lung cancer.19 Furthermore, about 1 in every 2000 individuals who screen positive, but who do not have lung cancer, die as a result of complications from the ensuing work-up.6

Annual LDCT screening increases the risk of radiation-induced cancer by approximately 0.05% over 10 years.21 The absolute risk is generally low but not insignificant. However, the mortality benefits previously outlined are significantly more robust in both absolute and relative terms vs the 10-year risk of radiation-induced cancer.

Lastly, it is important to note that the NELSON trial and NLST included a limited number of LDCT scans. Current guidelines for lung cancer screening with LDCT, including those from the USPSTF, recommend screening annually. We do not know the cumulative harm of annual LDCT over a 20- or 30-year period for those who would qualify (ie, current smokers).

If you screen, you must be able to act on the results

Effective screening programs should extend beyond the LDCT scan itself. The studies that have shown a benefit of LDCT were done at large academic centers that had the appropriate radiologic, pathologic, and surgical infrastructure to interpret and act on results and offer further diagnostic or treatment procedures.

Continue to: Prior to screening...

Prior to screening for lung cancer with LDCT, documentation of shared decision-making between the patient and the clinician is necessary.7 This discussion should include the potential benefits and harms of screening, potential results and likelihood of follow-up diagnostic testing, the false-positive rate of LDCT lung cancer screening, and cumulative radiation exposure. In addition, screening should be considered only if the patient is willing to be screened annually, is willing to pursue follow-up scans and procedures (including lung biopsy) if deemed necessary, and does not have comorbid conditions that significantly limit life expectancy.

Smoking cessation: The most important change to make

Smoking cessation is the single most important risk-modifying behavior to reduce one’s chance of developing lung cancer. At age 40, smokers have a 2-fold increase in all-cause mortality compared to age-matched nonsmokers. This rises to a 3-fold increase by the age of 70.16

Smoking cessation reduces the risk of lung cancer by 20% after 5 years, 30% to 50% after 10 years, and up to 70% after 15 years.24 In its guidelines, the American Thoracic Society recommends varenicline (Chantix) for all smokers to assist with smoking cessation.25

CASE

This 51-year-old patient with at least a 20-pack-year history of smoking should be commended for giving up smoking. Based on the USPSTF recommendations, he should be screened annually with LDCT for the next 10 years.

Screening to save more lives

The results of 2 large multicenter RCTs have led to the recent recommendation for lung cancer screening of high-risk adults with the use of LDCT. Screening with LDCT has been shown to reduce disease-related mortality and likely be cost effective in the long term.

Screening with LDCT should be part of a multidisciplinary system that has the infrastructure not only to perform the screening, but also to diagnose and appropriately follow up and treat patients whose results are concerning. The risk of false-positive results leading to increased anxiety, overdiagnosis, and unnecessary procedures points to the importance of proper patient selection, counseling, and shared decision-making. Smoking cessation remains the most important disease-modifying behavior one can make to reduce their risk for lung cancer.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carlton J. Covey, MD, 101 Bodin Circle, David Grant Medical Center, Travis Air Force Base, Fairfield, CA, 94545; [email protected]

1. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: lung and bronchus cancer. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html

2. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for lung cancer. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

3. Wilson JMG, Junger G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. World Health Organization; 1968:21-25, 100. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37650

4. Humphrey LL, Teutsch S, Johnson M. Lung cancer screening with sputum cytologic examination, chest radiography, and computed tomography: an update for the United States preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:740-753. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-9-200405040-00015

5. Oken MM, Hocking WG, Kvale PA, et al. Screening by chest radiograph and lung cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;306:1865-1873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1591

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325:962-970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1117

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439R). Accessed October 14, 2022. www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncacal-decision-memo.aspx?proposed=N&ncaid=304

8. Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2018: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:297-316. doi: 10.3322/caac.21446

9. American Academy of Family Physicians. AAFP updates recommendation on lung cancer screening. Published April 6, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2022. www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20210406lungcancer.html

10. Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Souter LH, et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. CHEST. 2021;160:E427-E494. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

11. The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

12. The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1980-1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120

13. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:503-513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793

14. American Cancer Society. Lung cancer screening guidelines. Accessed October 14, 2022. www.cancer.org/health-care-professionals/american-cancer-society-prevention-early-detection-guidelines/lung-cancer-screening-guidelines.html

15. Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, et al. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2013;381:133-141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61720-6

16. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE

17. O’Keefe LM, Gemma T, Huxley R, et al. Smoking as a risk factor for lung cancer in women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021611. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021611

18. Criss SD, Pianpian C, Bastani M, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of lung cancer screening in the United States: a comparative modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:796-805. doi: 10.7326/M19-0322

19. Lazris A, Roth RA. Lung cancer screening: pros and cons. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:740-742.

20. Ali MU, Miller J, Peirson L, et al. Screening for lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2016;89:301-314. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.015

21. Rampinelli C, De Marco P, Origgi D, et al. Exposure to low dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening and risk of cancer: secondary analysis of trial data and risk-benefit analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:j347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j347

22. Manser RL, Lethaby A, Irving LB, et al. Screening for lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD001991. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001991.pub3

23. Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Patel S, et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. CHEST. 2018;153:954-985. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.016

24. US Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking. and Health. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555591/

25. Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, et al, on behalf of the American Thoracic Society Assembly on Clinical Problems. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: an official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:e5-e31. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1982ST

CASE

A 51-year-old man presents to your office to discuss lung cancer screening. He has a history of hypertension and prediabetes. His father died of lung cancer 5 years ago, at age 77. The patient stopped smoking soon thereafter; prior to that, he smoked 1 pack of cigarettes per day for 20 years. He wants to know if he should be screened for lung cancer.

The relative lack of symptoms during the early stages of lung cancer frequently results in a delayed diagnosis. This, and the speed at which the disease progresses, underscores the need for an effective screening modality. More than half of people with lung cancer die within 1 year of diagnosis.1 Excluding skin cancer, lung cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer, and more people die of lung cancer than of colon, breast, and prostate cancers combined.2 In 2022, it was estimated that there would be 236,740 new cases of lung cancer and 130,180 deaths from lung cancer.1,2 The average age at diagnosis is 70 years.2

Screening modalities: Only 1 has demonstrated mortality benefit

In 1968, Wilson and Junger3 outlined the characteristics of the ideal screening test for the World Health Organization: it should limit risk to the patient, be sensitive for detecting the disease early in its course, limit false-positive results, be acceptable to the patient, and be inexpensive to the health system.3 For decades, several screening modalities for lung cancer were trialed to fit the above guidance, but many of them fell short of the most important outcome: the impact on mortality.

Sputum cytology. The use of sputum cytology, either in combination with or without chest radiography, is not recommended. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have failed to demonstrate improved lung cancer detection or mortality reduction in patients screened with this modality.4

Chest radiography (CXR). Several studies have assessed the efficacy of CXR as a screening modality. The best known was the Prostate, Lung, Colon, Ovarian (PLCO) Trial.5 This multicenter RCT enrolled more than 154,000 participants, half of whom received CXR at baseline and then annually for 3 years; the other half continued usual care (no screening). After 13 years of follow-up, there were no significant differences in lung cancer detection or mortality rates between the 2 groups.5

Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT). Several major medical societies recommend LDCT to screen high-risk individuals for lung cancer (TABLE 16-10). Results from 2 major RCTs have guided these recommendations.

The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) was a multicenter RCT comparing 2 screening tests for lung cancer.11 Approximately 54,000 high-risk participants were enrolled between 2002 and 2004 and were randomized to receive annual screening with either LDCT or single-view CXR. The trial was discontinued prematurely when investigators noted a 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality in the LDCT group vs the CXR group.12 This equates to 3 fewer deaths for every 1000 people screened with LDCT vs CXR. There was also a 6% reduction in all-cause mortality noted in the LDCT vs the CXR group.12

Continue to: The NELSON trial...

The NELSON trial, conducted between 2005 and 2015, studied more than 15,000 current or former smokers ages 50 to 74 years and compared LDCT screening at various intervals to no screening.13 After 10 years, lung cancer–related mortality was reduced by 24% (or 1 less death per 1000 person-years) in men who were screened vs their unscreened counterparts.13 In contrast to the NLST, in the NELSON trial, no significant difference in all-cause mortality was observed. Subgroup analysis of the relatively small population of women included in the NELSON trial suggested a 33% reduction in 10-year mortality; however, the difference was nonsignificant between the screened and unscreened groups.13

Each of these landmark studies had characteristics that could limit the results' generalizability to the US population. In the NELSON trial, more than 80% of the study participants were male. In both trials, there was significant underrepresentation of Black, Asian, Hispanic, and other non-White people.12,13 Furthermore, participants in these studies were of higher socioeconomic status than the general US screening-eligible population.

At this time, LDCT is the only lung cancer screening modality that has shown benefit for both disease-related and all-cause mortality, in the populations that were studied. Based on the NLST, the number needed to screen (NNS) with LDCT to prevent 1 lung cancer–related death is 308. The NNS to prevent 1 death from any cause is 219.6

Updated evidence has led to a consensus on screening criteria

Many national societies endorse annual screening with LDCT in high-risk individuals (TABLE 16-10). Risk assessment for the purpose of lung cancer screening includes a detailed review of smoking history and age. The risk of lung cancer increases with advancing age and with cumulative quantity and duration of smoking, but decreases with increasing time since quitting. Therefore, a detailed smoking history should include total number of pack-years, current smoking status, and, if applicable, when smoking cessation occurred.

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) updated their 2013 lung cancer screening recommendations, expanding the screening age range and lowering the smoking history threshold for triggering initiation of screening.6 The impetus for the update was emerging evidence from systematic reviews, RCTs, and the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) that could help to determine the optimal age for screening and identify high-risk groups. For example, the NELSON trial, combined with results from CISNET modeling data, showed an empirical benefit for screening those ages 50 to 55 years.6

Continue to: As a result...

As a result, the USPSTF now recommends annual lung cancer screening with LDCT for any adult ages 50 to 80 years who has a 20-pack-year smoking history and currently smokes or has quit within the past 15 years.6 Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years, develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy, or is not willing to have curative lung surgery.6

Expanding the screening eligibility may also address racial and gender disparities in health care. Black people and women who smoke have a higher risk for lung cancer at a lower intensity of smoking.6

Following the USPSTF update, the American College of Chest Physicians and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services published updated guidance that aligns with USPSTF’s recommendations to lower the age and pack-year qualifications for initiating screening.7,10 The American Cancer Society is currently reviewing its 2018 guidelines on lung cancer screening.14 TABLE 16-10 summarizes the guidance on lung cancer screening from these medical societies.

Effective screening could save lives (and money)

A smoker’s risk for lung cancer is 20 times higher than that of a nonsmoker15,16; 55% of lung cancer deaths in women and 70% in men are attributed to smoking.17 Once diagnosed with lung cancer, more than 50% of people will die within 1 year.1 This underpins the need for a lung cancer screening modality that reduces mortality. Large RCTs, including the NLST and NELSON trials, have shown that screening high-risk individuals with LDCT can significantly reduce lung cancer–related death when compared to no screening or screening with CXR alone.11,13

There is controversy surrounding the cost benefit of implementing a nationwide lung cancer screening program. However, recent use of microsimulation models has shown LDCT to be a cost-effective strategy, with an average cost of $81,000 per quality-adjusted life-year, which is below the threshold of $100,000 to be considered cost effective.18 Expanding the upper age limit for screening leads to a greater reduction in mortality but increases treatment costs and overdiagnosis rates, and overall does not improve quality-adjusted life-years.18

Continue to: Potential harms

Potential harms: False-positives and related complications

Screening for lung cancer is not without its risks. Harms from screening typically result from false-positive test results leading to overdiagnosis, anxiety and distress, unnecessary invasive tests or procedures, and increased costs.19 TABLE 26,19-23 lists specific complications from lung cancer screening with LDCT.

The false-positive rate is not trivial. For every 1000 patients screened, 250 people will have a positive LDCT finding but will not have lung cancer.19 Furthermore, about 1 in every 2000 individuals who screen positive, but who do not have lung cancer, die as a result of complications from the ensuing work-up.6

Annual LDCT screening increases the risk of radiation-induced cancer by approximately 0.05% over 10 years.21 The absolute risk is generally low but not insignificant. However, the mortality benefits previously outlined are significantly more robust in both absolute and relative terms vs the 10-year risk of radiation-induced cancer.

Lastly, it is important to note that the NELSON trial and NLST included a limited number of LDCT scans. Current guidelines for lung cancer screening with LDCT, including those from the USPSTF, recommend screening annually. We do not know the cumulative harm of annual LDCT over a 20- or 30-year period for those who would qualify (ie, current smokers).

If you screen, you must be able to act on the results

Effective screening programs should extend beyond the LDCT scan itself. The studies that have shown a benefit of LDCT were done at large academic centers that had the appropriate radiologic, pathologic, and surgical infrastructure to interpret and act on results and offer further diagnostic or treatment procedures.

Continue to: Prior to screening...

Prior to screening for lung cancer with LDCT, documentation of shared decision-making between the patient and the clinician is necessary.7 This discussion should include the potential benefits and harms of screening, potential results and likelihood of follow-up diagnostic testing, the false-positive rate of LDCT lung cancer screening, and cumulative radiation exposure. In addition, screening should be considered only if the patient is willing to be screened annually, is willing to pursue follow-up scans and procedures (including lung biopsy) if deemed necessary, and does not have comorbid conditions that significantly limit life expectancy.

Smoking cessation: The most important change to make

Smoking cessation is the single most important risk-modifying behavior to reduce one’s chance of developing lung cancer. At age 40, smokers have a 2-fold increase in all-cause mortality compared to age-matched nonsmokers. This rises to a 3-fold increase by the age of 70.16

Smoking cessation reduces the risk of lung cancer by 20% after 5 years, 30% to 50% after 10 years, and up to 70% after 15 years.24 In its guidelines, the American Thoracic Society recommends varenicline (Chantix) for all smokers to assist with smoking cessation.25

CASE

This 51-year-old patient with at least a 20-pack-year history of smoking should be commended for giving up smoking. Based on the USPSTF recommendations, he should be screened annually with LDCT for the next 10 years.

Screening to save more lives

The results of 2 large multicenter RCTs have led to the recent recommendation for lung cancer screening of high-risk adults with the use of LDCT. Screening with LDCT has been shown to reduce disease-related mortality and likely be cost effective in the long term.

Screening with LDCT should be part of a multidisciplinary system that has the infrastructure not only to perform the screening, but also to diagnose and appropriately follow up and treat patients whose results are concerning. The risk of false-positive results leading to increased anxiety, overdiagnosis, and unnecessary procedures points to the importance of proper patient selection, counseling, and shared decision-making. Smoking cessation remains the most important disease-modifying behavior one can make to reduce their risk for lung cancer.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carlton J. Covey, MD, 101 Bodin Circle, David Grant Medical Center, Travis Air Force Base, Fairfield, CA, 94545; [email protected]

CASE

A 51-year-old man presents to your office to discuss lung cancer screening. He has a history of hypertension and prediabetes. His father died of lung cancer 5 years ago, at age 77. The patient stopped smoking soon thereafter; prior to that, he smoked 1 pack of cigarettes per day for 20 years. He wants to know if he should be screened for lung cancer.

The relative lack of symptoms during the early stages of lung cancer frequently results in a delayed diagnosis. This, and the speed at which the disease progresses, underscores the need for an effective screening modality. More than half of people with lung cancer die within 1 year of diagnosis.1 Excluding skin cancer, lung cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer, and more people die of lung cancer than of colon, breast, and prostate cancers combined.2 In 2022, it was estimated that there would be 236,740 new cases of lung cancer and 130,180 deaths from lung cancer.1,2 The average age at diagnosis is 70 years.2

Screening modalities: Only 1 has demonstrated mortality benefit

In 1968, Wilson and Junger3 outlined the characteristics of the ideal screening test for the World Health Organization: it should limit risk to the patient, be sensitive for detecting the disease early in its course, limit false-positive results, be acceptable to the patient, and be inexpensive to the health system.3 For decades, several screening modalities for lung cancer were trialed to fit the above guidance, but many of them fell short of the most important outcome: the impact on mortality.

Sputum cytology. The use of sputum cytology, either in combination with or without chest radiography, is not recommended. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have failed to demonstrate improved lung cancer detection or mortality reduction in patients screened with this modality.4

Chest radiography (CXR). Several studies have assessed the efficacy of CXR as a screening modality. The best known was the Prostate, Lung, Colon, Ovarian (PLCO) Trial.5 This multicenter RCT enrolled more than 154,000 participants, half of whom received CXR at baseline and then annually for 3 years; the other half continued usual care (no screening). After 13 years of follow-up, there were no significant differences in lung cancer detection or mortality rates between the 2 groups.5

Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT). Several major medical societies recommend LDCT to screen high-risk individuals for lung cancer (TABLE 16-10). Results from 2 major RCTs have guided these recommendations.

The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) was a multicenter RCT comparing 2 screening tests for lung cancer.11 Approximately 54,000 high-risk participants were enrolled between 2002 and 2004 and were randomized to receive annual screening with either LDCT or single-view CXR. The trial was discontinued prematurely when investigators noted a 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality in the LDCT group vs the CXR group.12 This equates to 3 fewer deaths for every 1000 people screened with LDCT vs CXR. There was also a 6% reduction in all-cause mortality noted in the LDCT vs the CXR group.12

Continue to: The NELSON trial...

The NELSON trial, conducted between 2005 and 2015, studied more than 15,000 current or former smokers ages 50 to 74 years and compared LDCT screening at various intervals to no screening.13 After 10 years, lung cancer–related mortality was reduced by 24% (or 1 less death per 1000 person-years) in men who were screened vs their unscreened counterparts.13 In contrast to the NLST, in the NELSON trial, no significant difference in all-cause mortality was observed. Subgroup analysis of the relatively small population of women included in the NELSON trial suggested a 33% reduction in 10-year mortality; however, the difference was nonsignificant between the screened and unscreened groups.13

Each of these landmark studies had characteristics that could limit the results' generalizability to the US population. In the NELSON trial, more than 80% of the study participants were male. In both trials, there was significant underrepresentation of Black, Asian, Hispanic, and other non-White people.12,13 Furthermore, participants in these studies were of higher socioeconomic status than the general US screening-eligible population.

At this time, LDCT is the only lung cancer screening modality that has shown benefit for both disease-related and all-cause mortality, in the populations that were studied. Based on the NLST, the number needed to screen (NNS) with LDCT to prevent 1 lung cancer–related death is 308. The NNS to prevent 1 death from any cause is 219.6

Updated evidence has led to a consensus on screening criteria

Many national societies endorse annual screening with LDCT in high-risk individuals (TABLE 16-10). Risk assessment for the purpose of lung cancer screening includes a detailed review of smoking history and age. The risk of lung cancer increases with advancing age and with cumulative quantity and duration of smoking, but decreases with increasing time since quitting. Therefore, a detailed smoking history should include total number of pack-years, current smoking status, and, if applicable, when smoking cessation occurred.

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) updated their 2013 lung cancer screening recommendations, expanding the screening age range and lowering the smoking history threshold for triggering initiation of screening.6 The impetus for the update was emerging evidence from systematic reviews, RCTs, and the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) that could help to determine the optimal age for screening and identify high-risk groups. For example, the NELSON trial, combined with results from CISNET modeling data, showed an empirical benefit for screening those ages 50 to 55 years.6

Continue to: As a result...

As a result, the USPSTF now recommends annual lung cancer screening with LDCT for any adult ages 50 to 80 years who has a 20-pack-year smoking history and currently smokes or has quit within the past 15 years.6 Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years, develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy, or is not willing to have curative lung surgery.6

Expanding the screening eligibility may also address racial and gender disparities in health care. Black people and women who smoke have a higher risk for lung cancer at a lower intensity of smoking.6

Following the USPSTF update, the American College of Chest Physicians and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services published updated guidance that aligns with USPSTF’s recommendations to lower the age and pack-year qualifications for initiating screening.7,10 The American Cancer Society is currently reviewing its 2018 guidelines on lung cancer screening.14 TABLE 16-10 summarizes the guidance on lung cancer screening from these medical societies.

Effective screening could save lives (and money)

A smoker’s risk for lung cancer is 20 times higher than that of a nonsmoker15,16; 55% of lung cancer deaths in women and 70% in men are attributed to smoking.17 Once diagnosed with lung cancer, more than 50% of people will die within 1 year.1 This underpins the need for a lung cancer screening modality that reduces mortality. Large RCTs, including the NLST and NELSON trials, have shown that screening high-risk individuals with LDCT can significantly reduce lung cancer–related death when compared to no screening or screening with CXR alone.11,13

There is controversy surrounding the cost benefit of implementing a nationwide lung cancer screening program. However, recent use of microsimulation models has shown LDCT to be a cost-effective strategy, with an average cost of $81,000 per quality-adjusted life-year, which is below the threshold of $100,000 to be considered cost effective.18 Expanding the upper age limit for screening leads to a greater reduction in mortality but increases treatment costs and overdiagnosis rates, and overall does not improve quality-adjusted life-years.18

Continue to: Potential harms

Potential harms: False-positives and related complications

Screening for lung cancer is not without its risks. Harms from screening typically result from false-positive test results leading to overdiagnosis, anxiety and distress, unnecessary invasive tests or procedures, and increased costs.19 TABLE 26,19-23 lists specific complications from lung cancer screening with LDCT.

The false-positive rate is not trivial. For every 1000 patients screened, 250 people will have a positive LDCT finding but will not have lung cancer.19 Furthermore, about 1 in every 2000 individuals who screen positive, but who do not have lung cancer, die as a result of complications from the ensuing work-up.6

Annual LDCT screening increases the risk of radiation-induced cancer by approximately 0.05% over 10 years.21 The absolute risk is generally low but not insignificant. However, the mortality benefits previously outlined are significantly more robust in both absolute and relative terms vs the 10-year risk of radiation-induced cancer.

Lastly, it is important to note that the NELSON trial and NLST included a limited number of LDCT scans. Current guidelines for lung cancer screening with LDCT, including those from the USPSTF, recommend screening annually. We do not know the cumulative harm of annual LDCT over a 20- or 30-year period for those who would qualify (ie, current smokers).

If you screen, you must be able to act on the results

Effective screening programs should extend beyond the LDCT scan itself. The studies that have shown a benefit of LDCT were done at large academic centers that had the appropriate radiologic, pathologic, and surgical infrastructure to interpret and act on results and offer further diagnostic or treatment procedures.

Continue to: Prior to screening...

Prior to screening for lung cancer with LDCT, documentation of shared decision-making between the patient and the clinician is necessary.7 This discussion should include the potential benefits and harms of screening, potential results and likelihood of follow-up diagnostic testing, the false-positive rate of LDCT lung cancer screening, and cumulative radiation exposure. In addition, screening should be considered only if the patient is willing to be screened annually, is willing to pursue follow-up scans and procedures (including lung biopsy) if deemed necessary, and does not have comorbid conditions that significantly limit life expectancy.

Smoking cessation: The most important change to make

Smoking cessation is the single most important risk-modifying behavior to reduce one’s chance of developing lung cancer. At age 40, smokers have a 2-fold increase in all-cause mortality compared to age-matched nonsmokers. This rises to a 3-fold increase by the age of 70.16

Smoking cessation reduces the risk of lung cancer by 20% after 5 years, 30% to 50% after 10 years, and up to 70% after 15 years.24 In its guidelines, the American Thoracic Society recommends varenicline (Chantix) for all smokers to assist with smoking cessation.25

CASE

This 51-year-old patient with at least a 20-pack-year history of smoking should be commended for giving up smoking. Based on the USPSTF recommendations, he should be screened annually with LDCT for the next 10 years.

Screening to save more lives

The results of 2 large multicenter RCTs have led to the recent recommendation for lung cancer screening of high-risk adults with the use of LDCT. Screening with LDCT has been shown to reduce disease-related mortality and likely be cost effective in the long term.

Screening with LDCT should be part of a multidisciplinary system that has the infrastructure not only to perform the screening, but also to diagnose and appropriately follow up and treat patients whose results are concerning. The risk of false-positive results leading to increased anxiety, overdiagnosis, and unnecessary procedures points to the importance of proper patient selection, counseling, and shared decision-making. Smoking cessation remains the most important disease-modifying behavior one can make to reduce their risk for lung cancer.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carlton J. Covey, MD, 101 Bodin Circle, David Grant Medical Center, Travis Air Force Base, Fairfield, CA, 94545; [email protected]

1. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: lung and bronchus cancer. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html

2. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for lung cancer. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

3. Wilson JMG, Junger G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. World Health Organization; 1968:21-25, 100. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37650

4. Humphrey LL, Teutsch S, Johnson M. Lung cancer screening with sputum cytologic examination, chest radiography, and computed tomography: an update for the United States preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:740-753. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-9-200405040-00015

5. Oken MM, Hocking WG, Kvale PA, et al. Screening by chest radiograph and lung cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;306:1865-1873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1591

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325:962-970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1117

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439R). Accessed October 14, 2022. www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncacal-decision-memo.aspx?proposed=N&ncaid=304

8. Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2018: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:297-316. doi: 10.3322/caac.21446

9. American Academy of Family Physicians. AAFP updates recommendation on lung cancer screening. Published April 6, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2022. www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20210406lungcancer.html

10. Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Souter LH, et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. CHEST. 2021;160:E427-E494. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

11. The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

12. The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1980-1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120

13. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:503-513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793

14. American Cancer Society. Lung cancer screening guidelines. Accessed October 14, 2022. www.cancer.org/health-care-professionals/american-cancer-society-prevention-early-detection-guidelines/lung-cancer-screening-guidelines.html

15. Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, et al. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2013;381:133-141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61720-6

16. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE

17. O’Keefe LM, Gemma T, Huxley R, et al. Smoking as a risk factor for lung cancer in women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021611. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021611

18. Criss SD, Pianpian C, Bastani M, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of lung cancer screening in the United States: a comparative modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:796-805. doi: 10.7326/M19-0322

19. Lazris A, Roth RA. Lung cancer screening: pros and cons. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:740-742.

20. Ali MU, Miller J, Peirson L, et al. Screening for lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2016;89:301-314. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.015

21. Rampinelli C, De Marco P, Origgi D, et al. Exposure to low dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening and risk of cancer: secondary analysis of trial data and risk-benefit analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:j347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j347

22. Manser RL, Lethaby A, Irving LB, et al. Screening for lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD001991. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001991.pub3

23. Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Patel S, et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. CHEST. 2018;153:954-985. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.016

24. US Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking. and Health. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555591/

25. Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, et al, on behalf of the American Thoracic Society Assembly on Clinical Problems. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: an official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:e5-e31. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1982ST

1. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: lung and bronchus cancer. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html

2. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for lung cancer. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

3. Wilson JMG, Junger G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. World Health Organization; 1968:21-25, 100. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37650

4. Humphrey LL, Teutsch S, Johnson M. Lung cancer screening with sputum cytologic examination, chest radiography, and computed tomography: an update for the United States preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:740-753. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-9-200405040-00015

5. Oken MM, Hocking WG, Kvale PA, et al. Screening by chest radiograph and lung cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;306:1865-1873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1591

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325:962-970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1117

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439R). Accessed October 14, 2022. www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncacal-decision-memo.aspx?proposed=N&ncaid=304

8. Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2018: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:297-316. doi: 10.3322/caac.21446

9. American Academy of Family Physicians. AAFP updates recommendation on lung cancer screening. Published April 6, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2022. www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20210406lungcancer.html

10. Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Souter LH, et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. CHEST. 2021;160:E427-E494. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

11. The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

12. The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1980-1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120

13. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:503-513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793

14. American Cancer Society. Lung cancer screening guidelines. Accessed October 14, 2022. www.cancer.org/health-care-professionals/american-cancer-society-prevention-early-detection-guidelines/lung-cancer-screening-guidelines.html

15. Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, et al. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2013;381:133-141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61720-6

16. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE

17. O’Keefe LM, Gemma T, Huxley R, et al. Smoking as a risk factor for lung cancer in women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021611. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021611

18. Criss SD, Pianpian C, Bastani M, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of lung cancer screening in the United States: a comparative modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:796-805. doi: 10.7326/M19-0322

19. Lazris A, Roth RA. Lung cancer screening: pros and cons. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:740-742.

20. Ali MU, Miller J, Peirson L, et al. Screening for lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2016;89:301-314. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.015

21. Rampinelli C, De Marco P, Origgi D, et al. Exposure to low dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening and risk of cancer: secondary analysis of trial data and risk-benefit analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:j347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j347

22. Manser RL, Lethaby A, Irving LB, et al. Screening for lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD001991. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001991.pub3

23. Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Patel S, et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. CHEST. 2018;153:954-985. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.016

24. US Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking. and Health. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555591/

25. Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, et al, on behalf of the American Thoracic Society Assembly on Clinical Problems. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: an official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:e5-e31. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1982ST

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Recommend annual lung cancer screening for all highrisk adults ages 50 to 80 years using low-dose computed tomography. A

› Do not pursue lung cancer screening in patients who quit smoking ≥ 15 years ago, have a health problem that limits their life expectancy, or are unwilling to undergo lung surgery. A

› Recommend varenicline as first-line pharmacotherapy for smokers who would like to quit. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

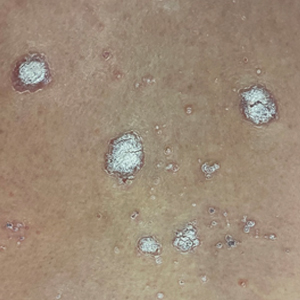

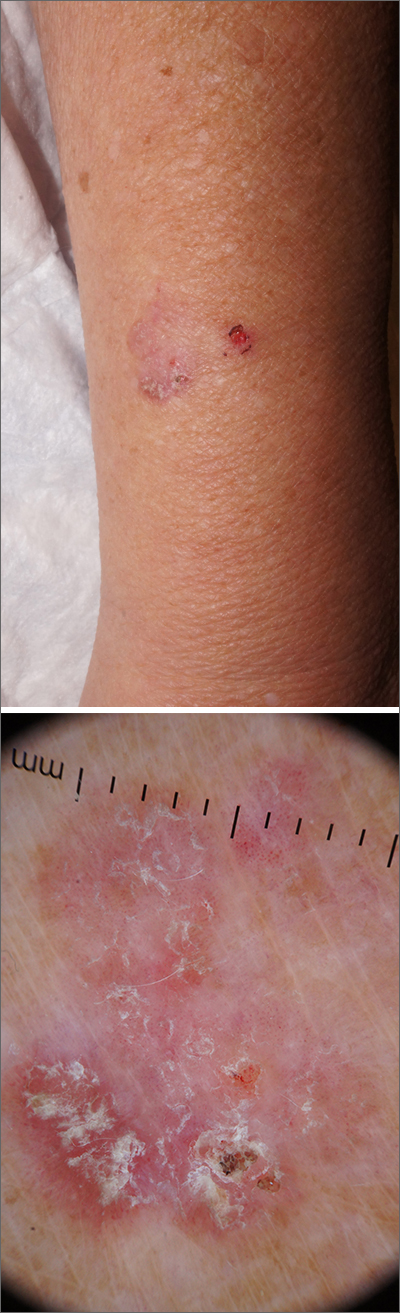

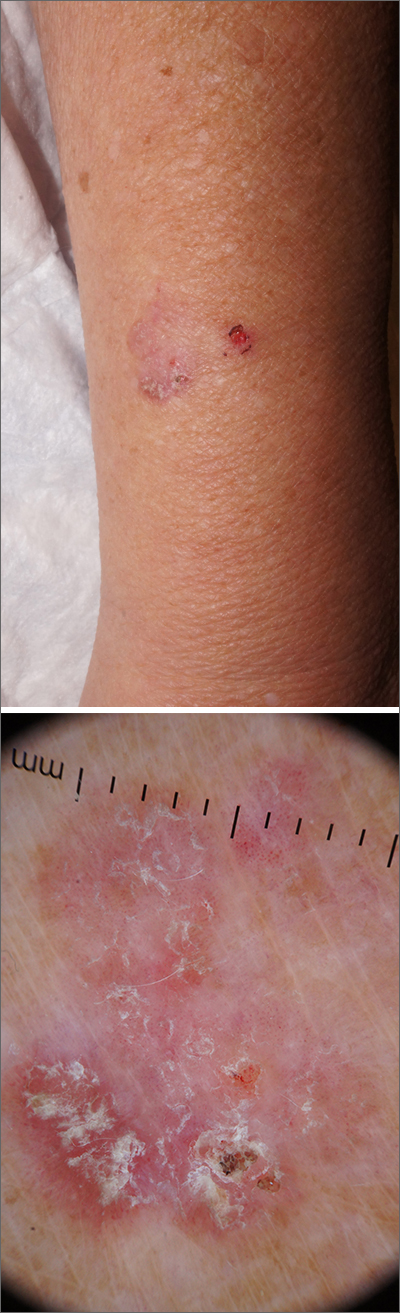

Clear toe lesion

This is a digital mucous cyst, also known as a myxoid cyst. The clear to translucent appearance over a finger or toe joint is usually diagnosed clinically. If uncertain, a biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.

Digital mucous cysts are a type of ganglion cyst that is associated with trauma or arthritis in the toe joint. A microscopic opening in the joint capsule results in a fluid filled cyst in the surrounding tissue. If the cyst is ruptured, thick, gelatinous (sometimes blood-tinged) hyaluronic acid–rich fluid may escape. Sometimes, the cyst applies pressure to the nail matrix, causing a scooped out longitudinal nail deformity.

Digital mucous cysts more commonly affect the fingers than the toes. Although benign, patients may be bothered by the appearance of these cysts and their effect on nails. Observation is a reasonable approach. Rarely, digital mucous cysts resolve spontaneously.

Treatment options include cryotherapy, needle draining and scarification, and surgical excision with flap repair. Surgical excision may be performed quickly in the office and offers the highest cure rate of 95% in 1 study on fingers.1 Cryotherapy is successful in 70% of cases and needle drainage is successful in 39% of cases, but these modalities are quick and require minimal downtime.1

In this case, the patient was not significantly bothered by the lesion and was happy to forego treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Jabbour S, Kechichian E, Haber R, et al. Management of digital mucous cysts: a systematic review and treatment algorithm. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:701-708. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13583

This is a digital mucous cyst, also known as a myxoid cyst. The clear to translucent appearance over a finger or toe joint is usually diagnosed clinically. If uncertain, a biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.

Digital mucous cysts are a type of ganglion cyst that is associated with trauma or arthritis in the toe joint. A microscopic opening in the joint capsule results in a fluid filled cyst in the surrounding tissue. If the cyst is ruptured, thick, gelatinous (sometimes blood-tinged) hyaluronic acid–rich fluid may escape. Sometimes, the cyst applies pressure to the nail matrix, causing a scooped out longitudinal nail deformity.

Digital mucous cysts more commonly affect the fingers than the toes. Although benign, patients may be bothered by the appearance of these cysts and their effect on nails. Observation is a reasonable approach. Rarely, digital mucous cysts resolve spontaneously.

Treatment options include cryotherapy, needle draining and scarification, and surgical excision with flap repair. Surgical excision may be performed quickly in the office and offers the highest cure rate of 95% in 1 study on fingers.1 Cryotherapy is successful in 70% of cases and needle drainage is successful in 39% of cases, but these modalities are quick and require minimal downtime.1

In this case, the patient was not significantly bothered by the lesion and was happy to forego treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

This is a digital mucous cyst, also known as a myxoid cyst. The clear to translucent appearance over a finger or toe joint is usually diagnosed clinically. If uncertain, a biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.

Digital mucous cysts are a type of ganglion cyst that is associated with trauma or arthritis in the toe joint. A microscopic opening in the joint capsule results in a fluid filled cyst in the surrounding tissue. If the cyst is ruptured, thick, gelatinous (sometimes blood-tinged) hyaluronic acid–rich fluid may escape. Sometimes, the cyst applies pressure to the nail matrix, causing a scooped out longitudinal nail deformity.

Digital mucous cysts more commonly affect the fingers than the toes. Although benign, patients may be bothered by the appearance of these cysts and their effect on nails. Observation is a reasonable approach. Rarely, digital mucous cysts resolve spontaneously.

Treatment options include cryotherapy, needle draining and scarification, and surgical excision with flap repair. Surgical excision may be performed quickly in the office and offers the highest cure rate of 95% in 1 study on fingers.1 Cryotherapy is successful in 70% of cases and needle drainage is successful in 39% of cases, but these modalities are quick and require minimal downtime.1

In this case, the patient was not significantly bothered by the lesion and was happy to forego treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Jabbour S, Kechichian E, Haber R, et al. Management of digital mucous cysts: a systematic review and treatment algorithm. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:701-708. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13583

1. Jabbour S, Kechichian E, Haber R, et al. Management of digital mucous cysts: a systematic review and treatment algorithm. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:701-708. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13583

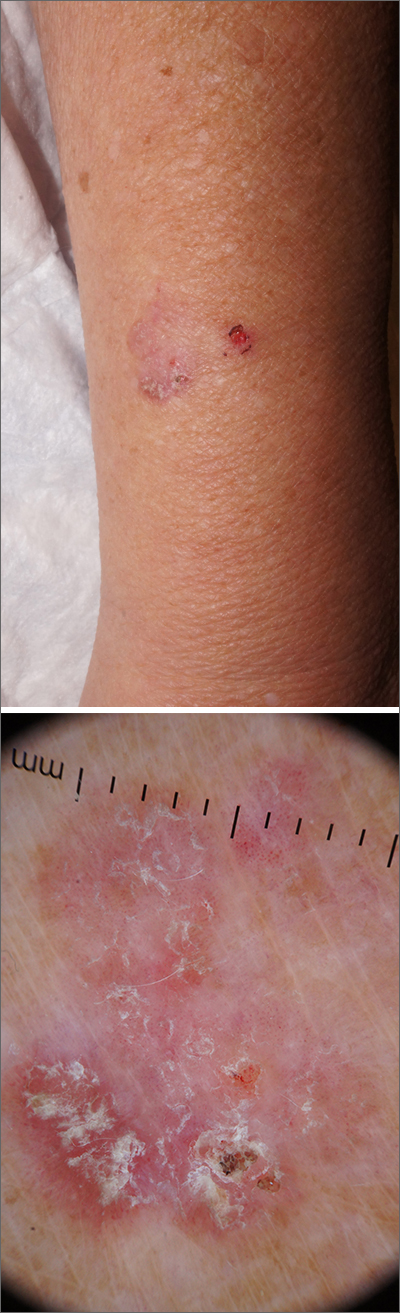

Scaly forearm plaque

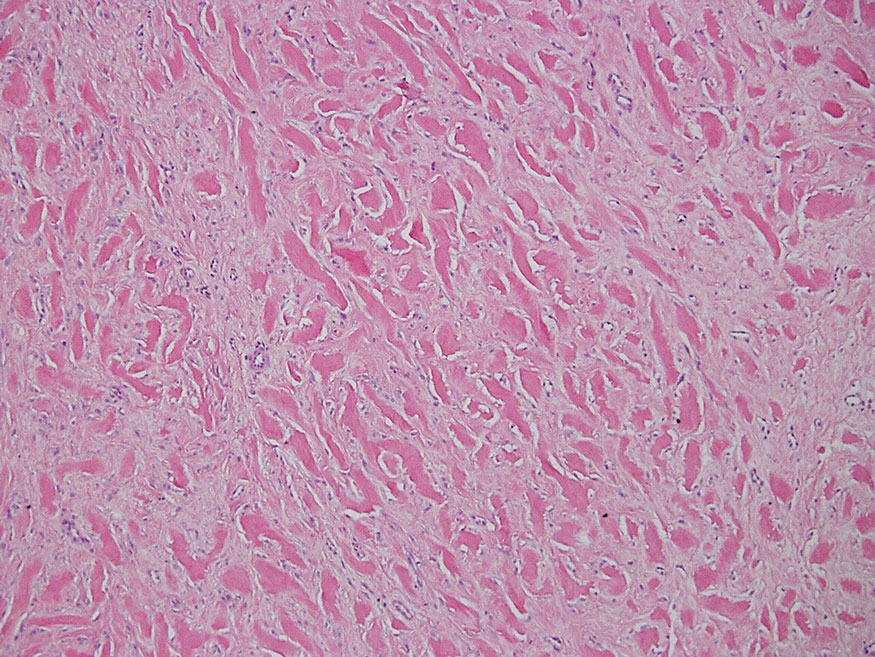

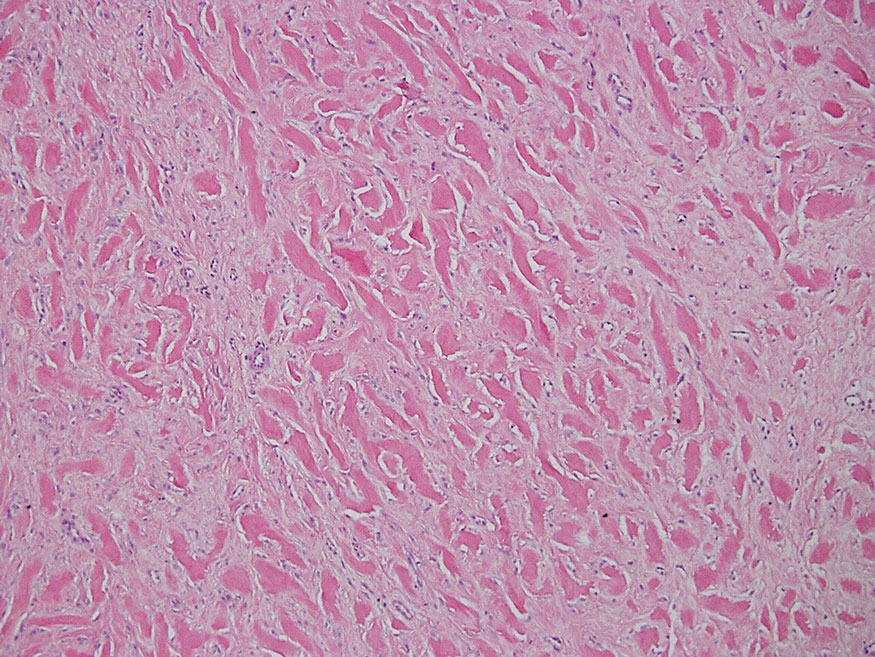

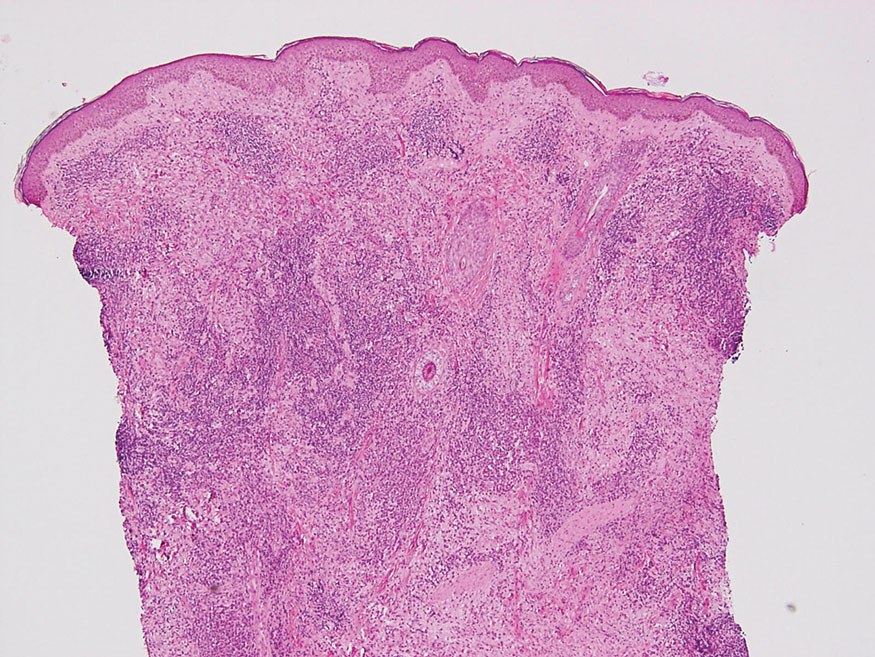

Dermoscopy revealed a keratotic, 2.5-cm scaly plaque with linearly arranged dotted vessels, ulceration, and shiny white lines. A shave biopsy was consistent with a squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCC in situ)—a pre-invasive keratinocyte carcinoma.

SCC in situ, also known as Bowen’s disease, is a very common skin cancer that can be easily treated. Lesions may manifest anywhere on the skin but are most often found on sun-damaged areas. Actinic keratoses are a pre-malignant precursor of SCC in situ; both are characterized by a sandpapery rough surface on a pink or brown background. Histologically, SCC in situ has atypia of keratinocytes over the full thickness of the epidermis, while actinic keratoses have limited atypia of the upper epidermis only. With this in mind, suspect SCC in situ (over actinic keratosis) when a lesion is thicker than 1 mm, larger in diameter than 5 mm, or painful.1

Treatment options include surgical and nonsurgical modalities. Excision and electrodessication and curettage (EDC) are both effective surgical procedures, with cure rates greater than 90%.2 Nonsurgical options include cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy. Treatment with 5FU or imiquimod involves the application of cream to the lesion for 4 to 6 weeks. Marked inflammation during treatment is to be expected.

In the case described here, the patient underwent EDC in the office and was counseled to continue with complete skin exams twice a year for the next 2 years.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Mills KC, Kwatra SG, Feneran AN, et al. Itch and pain in nonmelanoma skin cancer: pain as an important feature of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1422-1423. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.3104

2. Reschly MJ, Shenefelt PD. Controversies in skin surgery: electrodessication and curettage versus excision for low-risk, small, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:773-776.

Dermoscopy revealed a keratotic, 2.5-cm scaly plaque with linearly arranged dotted vessels, ulceration, and shiny white lines. A shave biopsy was consistent with a squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCC in situ)—a pre-invasive keratinocyte carcinoma.

SCC in situ, also known as Bowen’s disease, is a very common skin cancer that can be easily treated. Lesions may manifest anywhere on the skin but are most often found on sun-damaged areas. Actinic keratoses are a pre-malignant precursor of SCC in situ; both are characterized by a sandpapery rough surface on a pink or brown background. Histologically, SCC in situ has atypia of keratinocytes over the full thickness of the epidermis, while actinic keratoses have limited atypia of the upper epidermis only. With this in mind, suspect SCC in situ (over actinic keratosis) when a lesion is thicker than 1 mm, larger in diameter than 5 mm, or painful.1

Treatment options include surgical and nonsurgical modalities. Excision and electrodessication and curettage (EDC) are both effective surgical procedures, with cure rates greater than 90%.2 Nonsurgical options include cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy. Treatment with 5FU or imiquimod involves the application of cream to the lesion for 4 to 6 weeks. Marked inflammation during treatment is to be expected.

In the case described here, the patient underwent EDC in the office and was counseled to continue with complete skin exams twice a year for the next 2 years.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Dermoscopy revealed a keratotic, 2.5-cm scaly plaque with linearly arranged dotted vessels, ulceration, and shiny white lines. A shave biopsy was consistent with a squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCC in situ)—a pre-invasive keratinocyte carcinoma.

SCC in situ, also known as Bowen’s disease, is a very common skin cancer that can be easily treated. Lesions may manifest anywhere on the skin but are most often found on sun-damaged areas. Actinic keratoses are a pre-malignant precursor of SCC in situ; both are characterized by a sandpapery rough surface on a pink or brown background. Histologically, SCC in situ has atypia of keratinocytes over the full thickness of the epidermis, while actinic keratoses have limited atypia of the upper epidermis only. With this in mind, suspect SCC in situ (over actinic keratosis) when a lesion is thicker than 1 mm, larger in diameter than 5 mm, or painful.1

Treatment options include surgical and nonsurgical modalities. Excision and electrodessication and curettage (EDC) are both effective surgical procedures, with cure rates greater than 90%.2 Nonsurgical options include cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy. Treatment with 5FU or imiquimod involves the application of cream to the lesion for 4 to 6 weeks. Marked inflammation during treatment is to be expected.

In the case described here, the patient underwent EDC in the office and was counseled to continue with complete skin exams twice a year for the next 2 years.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Mills KC, Kwatra SG, Feneran AN, et al. Itch and pain in nonmelanoma skin cancer: pain as an important feature of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1422-1423. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.3104

2. Reschly MJ, Shenefelt PD. Controversies in skin surgery: electrodessication and curettage versus excision for low-risk, small, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:773-776.

1. Mills KC, Kwatra SG, Feneran AN, et al. Itch and pain in nonmelanoma skin cancer: pain as an important feature of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1422-1423. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.3104

2. Reschly MJ, Shenefelt PD. Controversies in skin surgery: electrodessication and curettage versus excision for low-risk, small, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:773-776.

Psoriasiform Dermatitis Associated With the Moderna COVID-19 Messenger RNA Vaccine

To the Editor:

The Moderna COVID-19 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine was authorized for use on December 18, 2020, with the second dose beginning on January 15, 2021.1-3 Some individuals who received the Moderna vaccine experienced an intense rash known as “COVID arm,” a harmless but bothersome adverse effect that typically appears within a week and is a localized and transient immunogenic response.4 COVID arm differs from most vaccine adverse effects. The rash emerges not immediately but 5 to 9 days after the initial dose—on average, 1 week later. Apart from being itchy, the rash does not appear to be harmful and is not a reason to hesitate getting vaccinated.

Dermatologists and allergists have been studying this adverse effect, which has been formally termed delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity. Of potential clinical consequence is that the efficacy of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine may be harmed if postvaccination dermal reactions necessitate systemic corticosteroid therapy. Because this vaccine stimulates an immune response as viral RNA integrates in cells secondary to production of the spike protein of the virus, the skin may be affected secondarily and manifestations of any underlying disease may be aggravated.5 We report a patient who developed a psoriasiform dermatitis after the first dose of the Moderna vaccine.

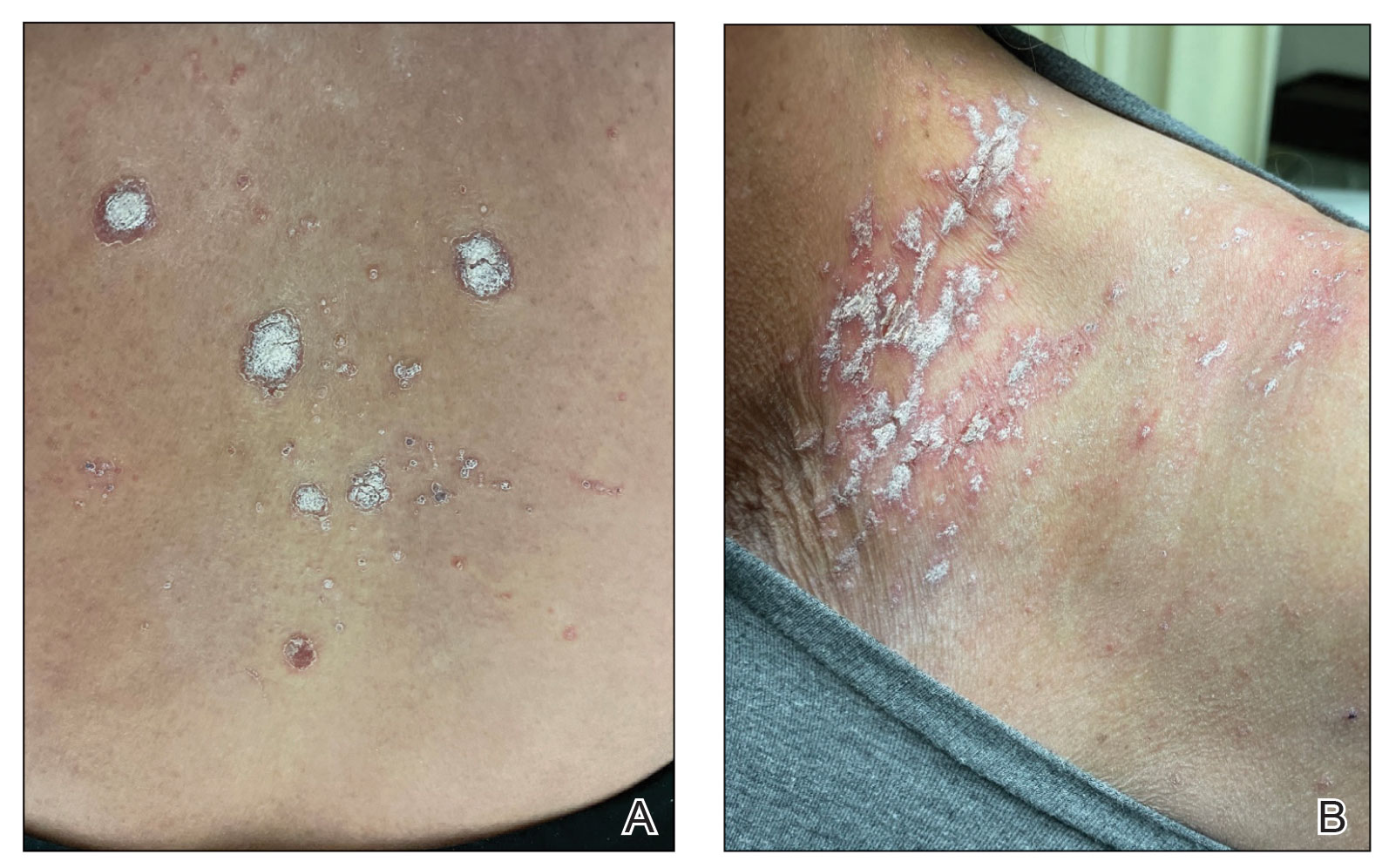

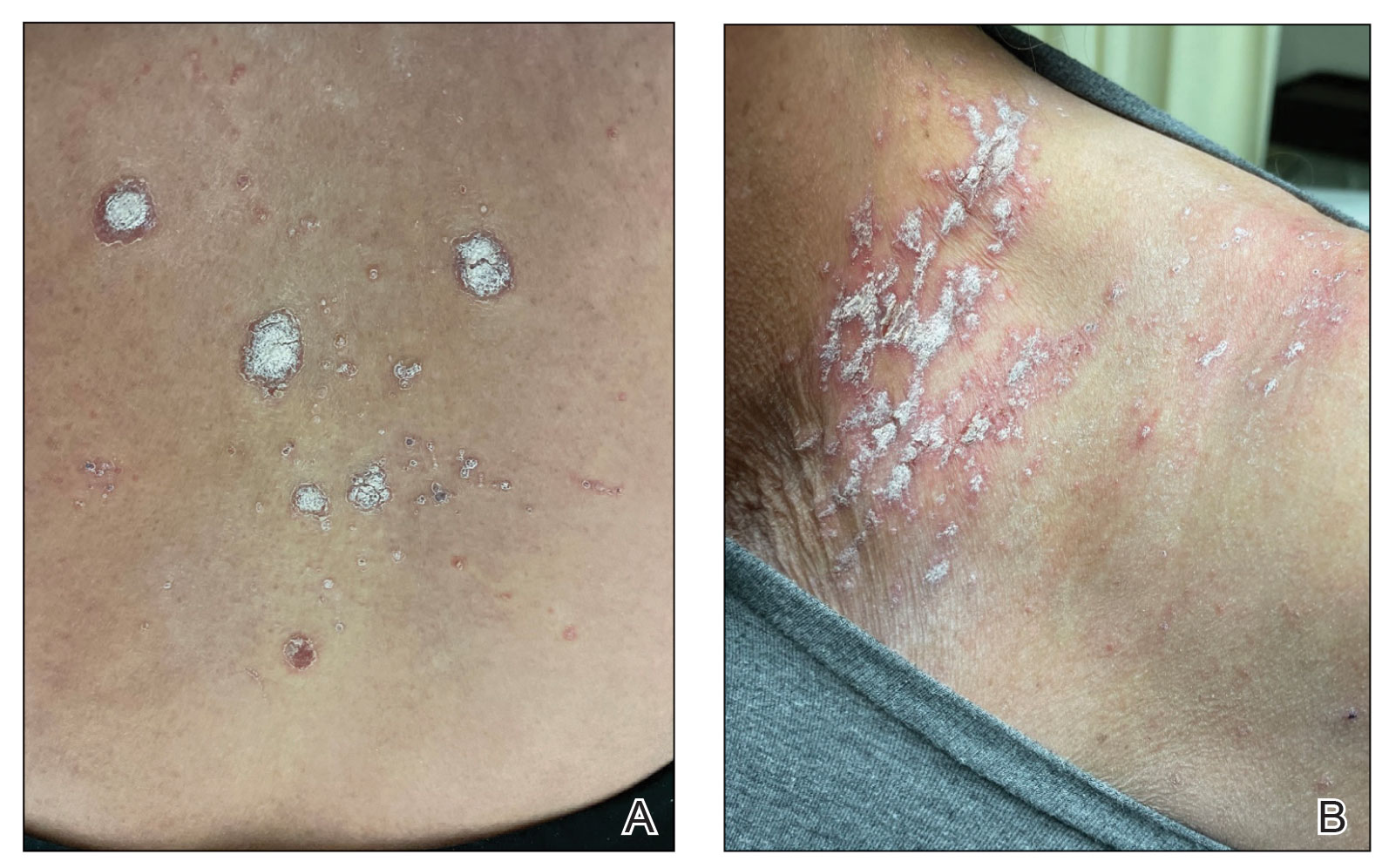

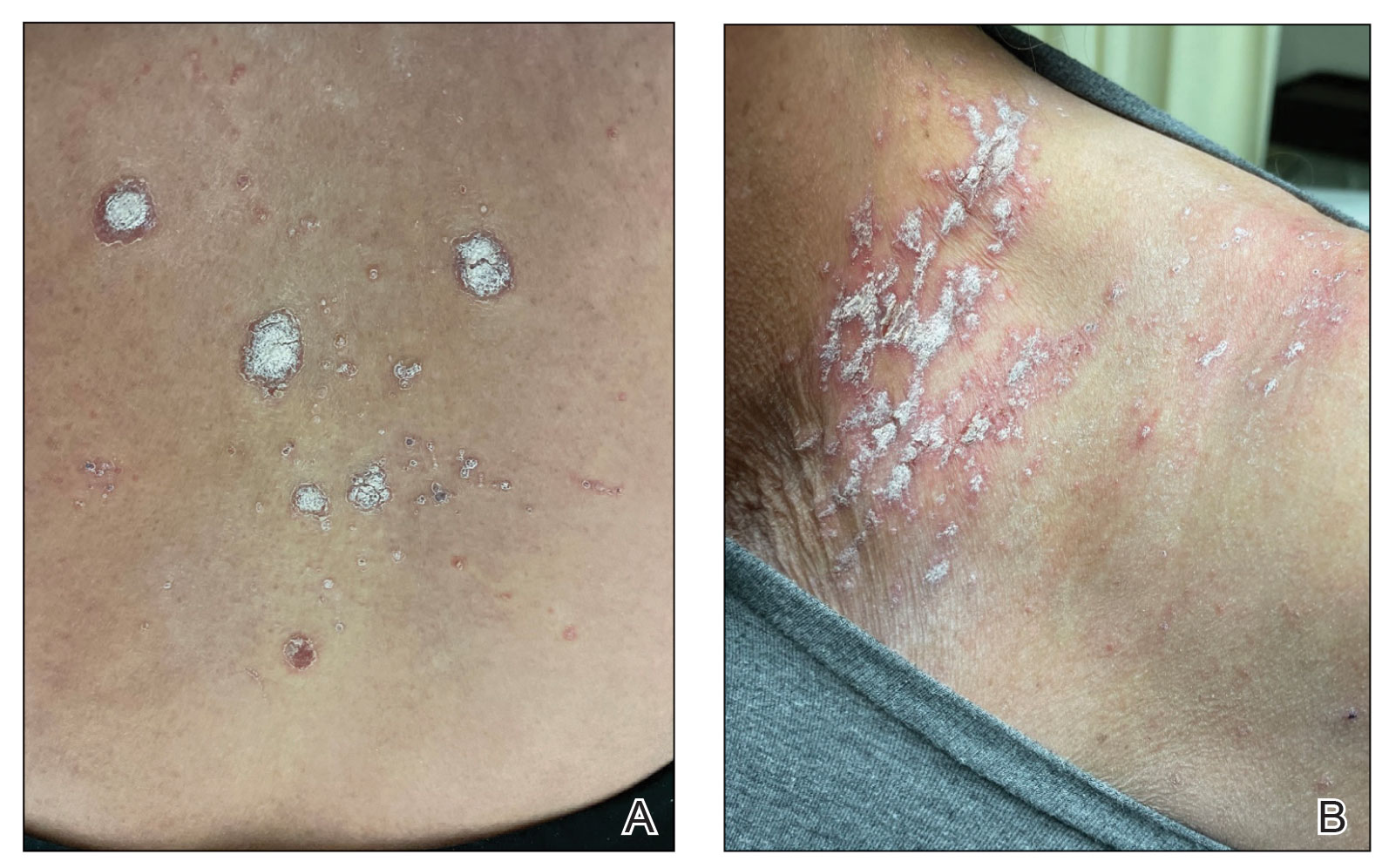

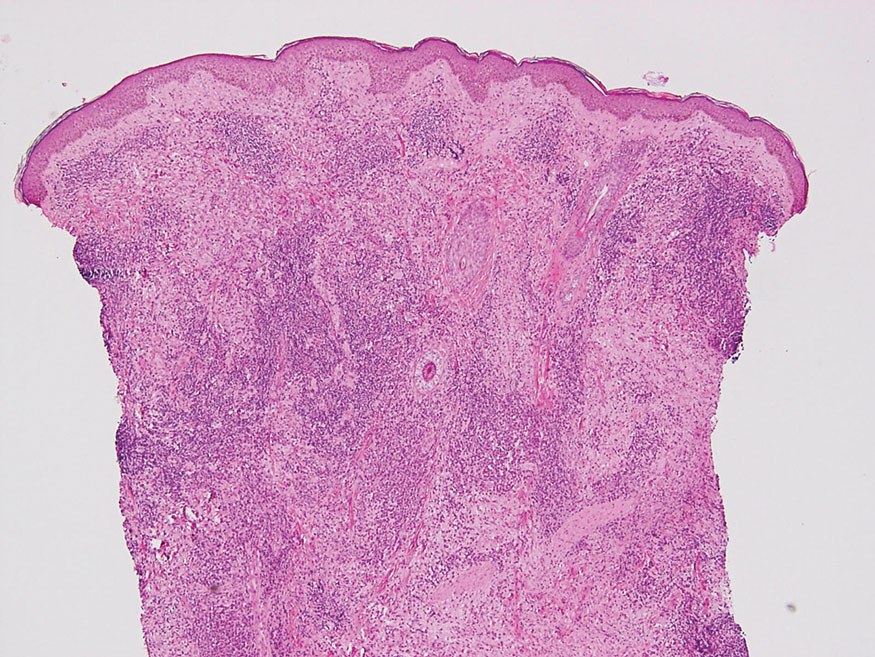

A 65-year-old woman presented to her primary care physician because of the severity of psoriasiform dermatitis that developed 5 days after she received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The patient had a medical history of Sjögren syndrome. Her medication history was negative, and her family history was negative for autoimmune disease. Physical examination by primary care revealed an erythematous scaly rash with plaques and papules on the neck and back (Figure 1). The patient presented again to primary care 2 days later with swollen, painful, discolored digits (Figure 2) and a stiff, sore neck.

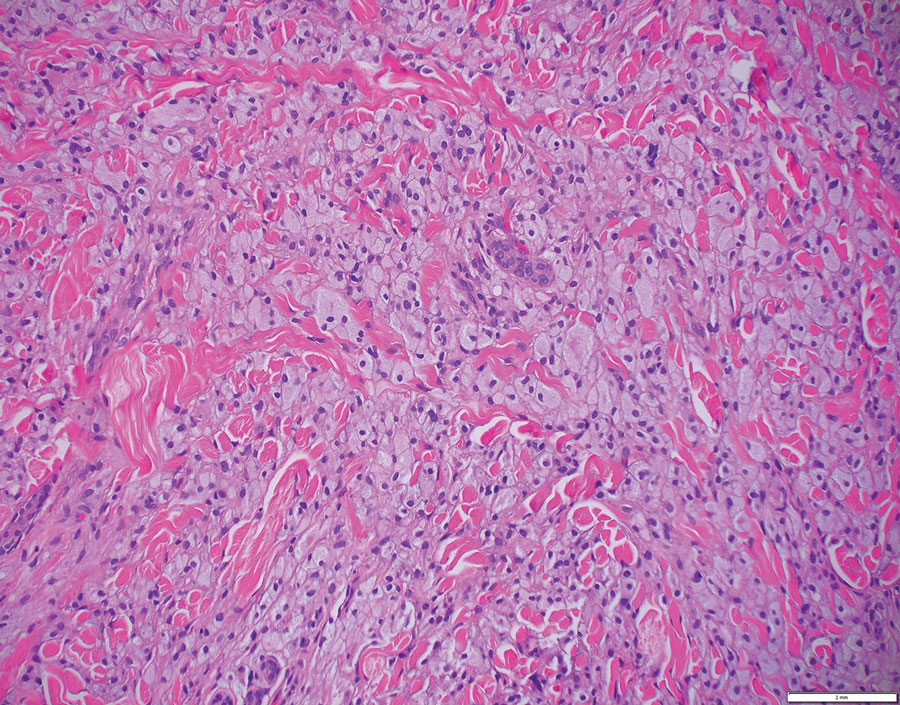

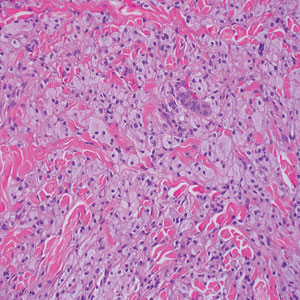

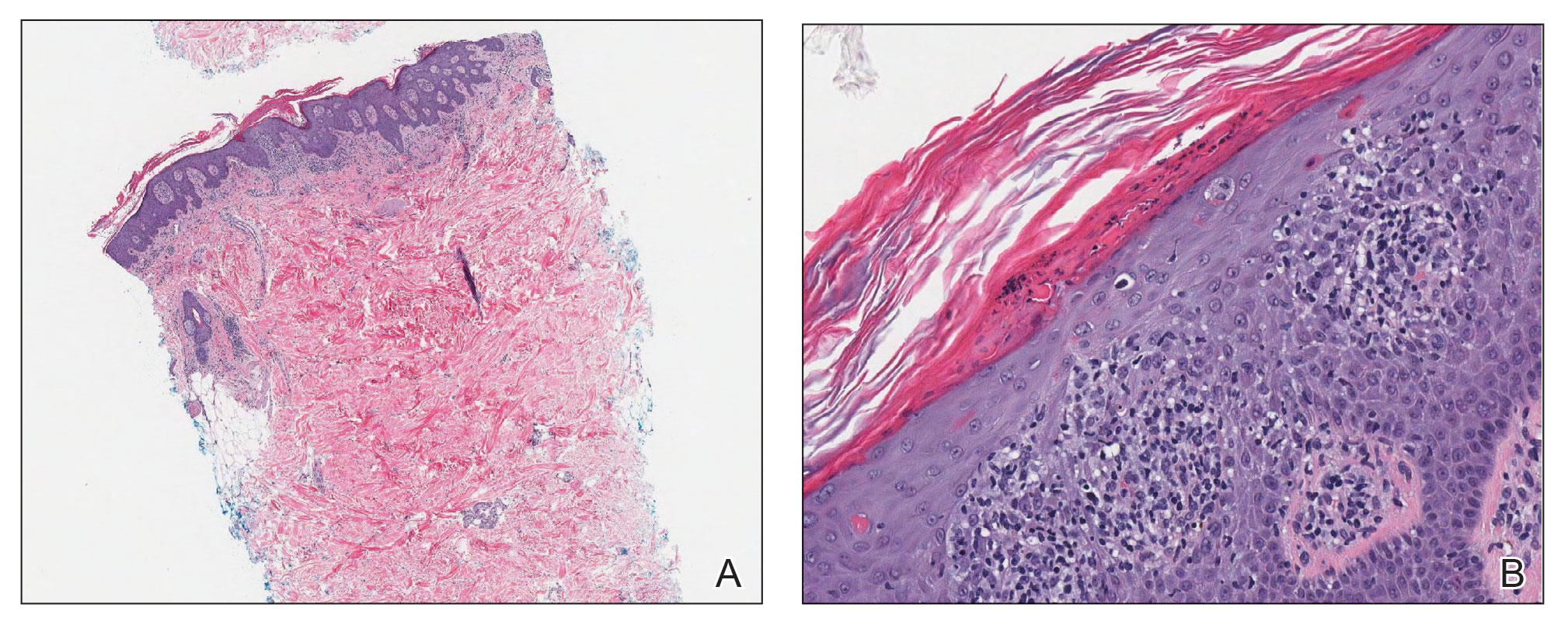

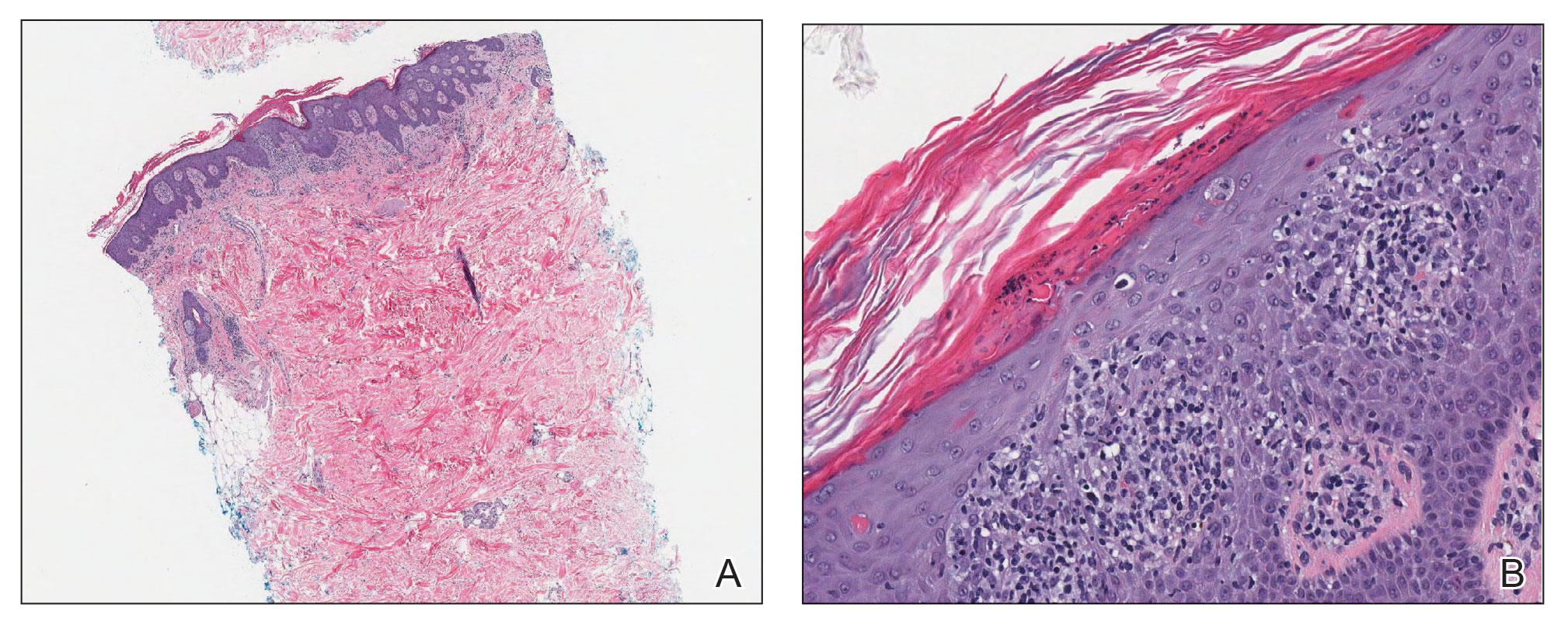

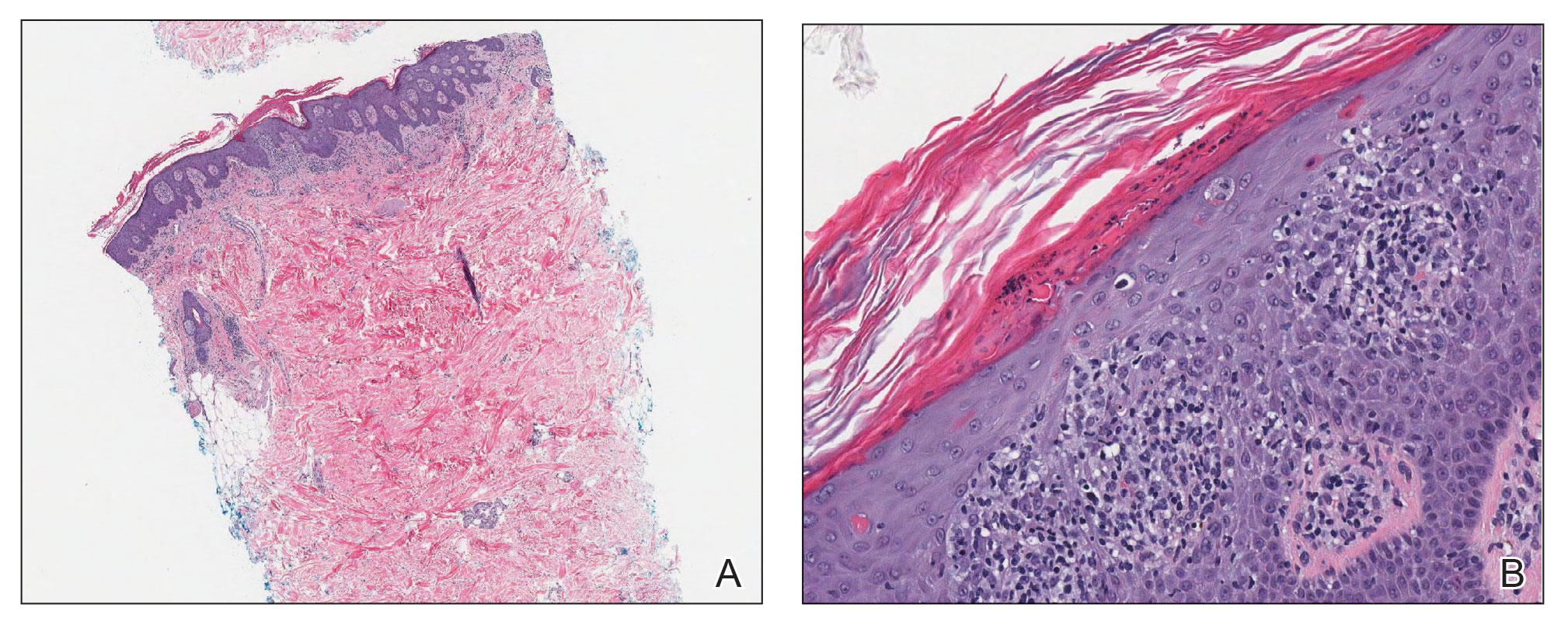

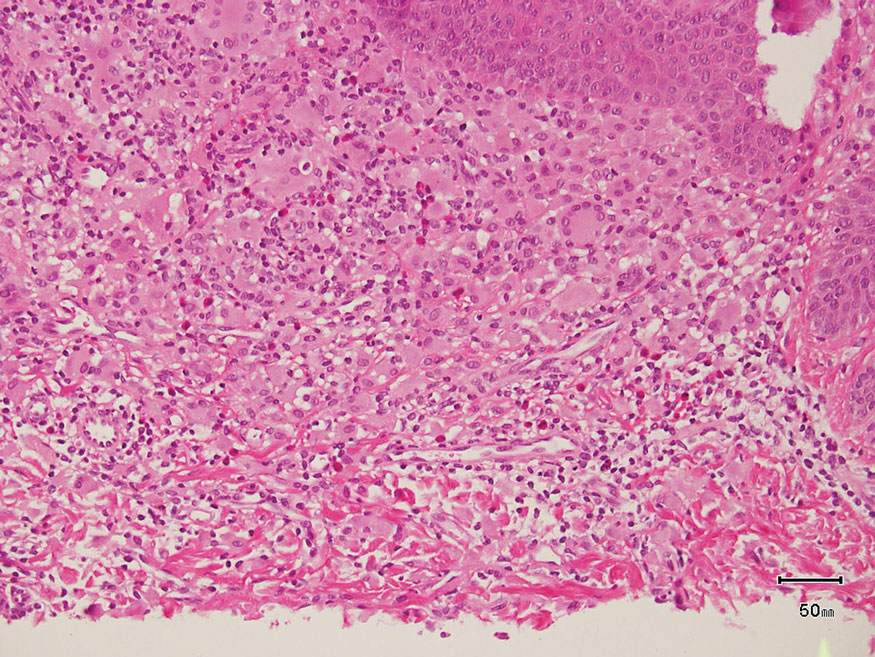

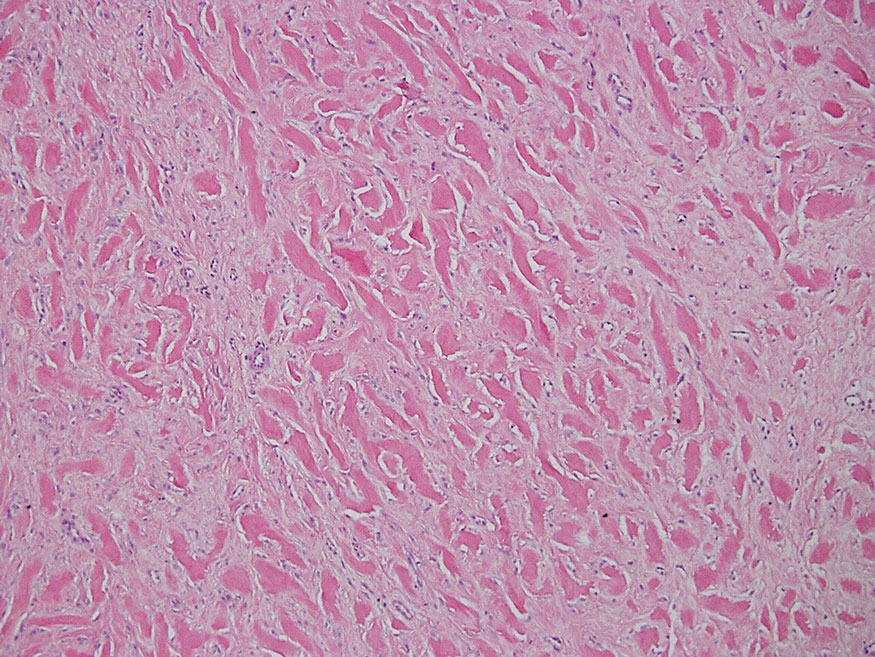

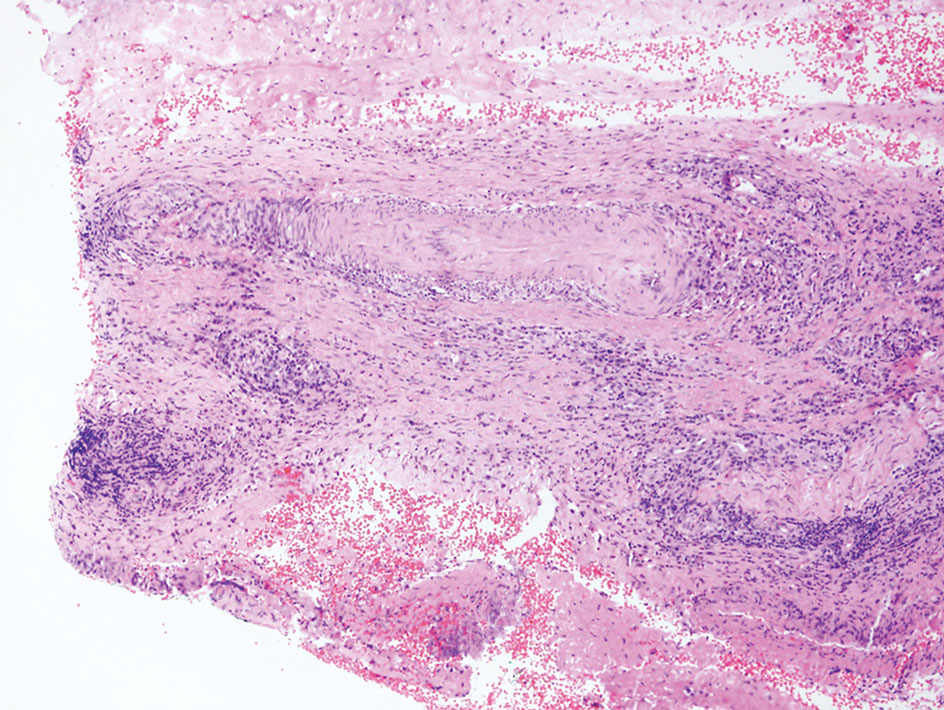

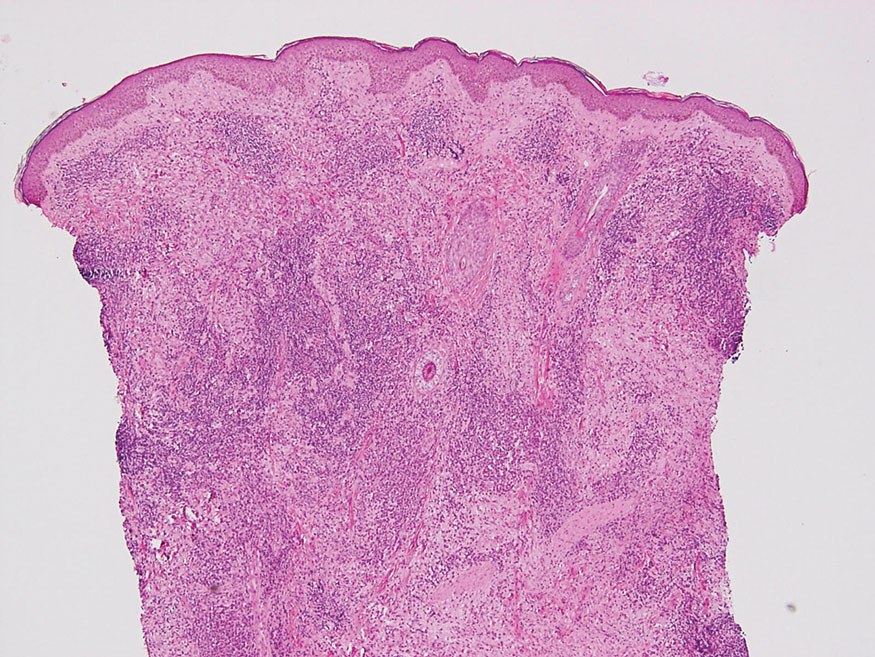

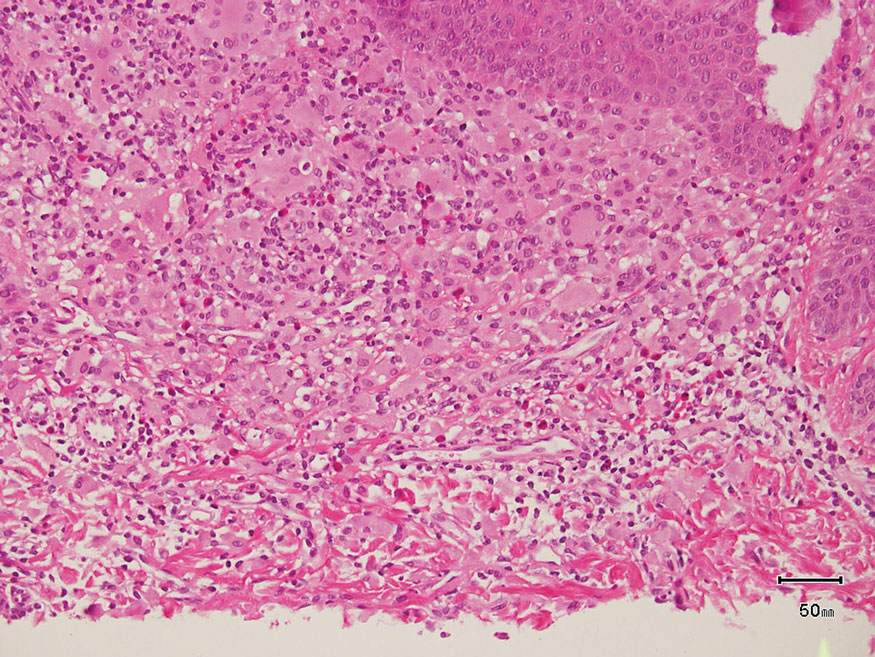

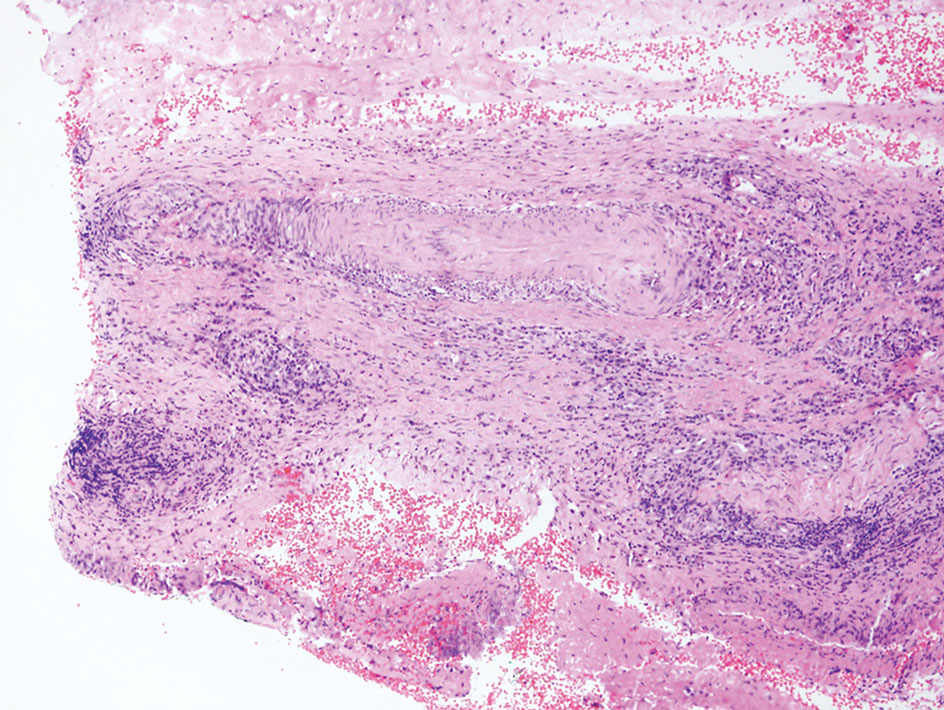

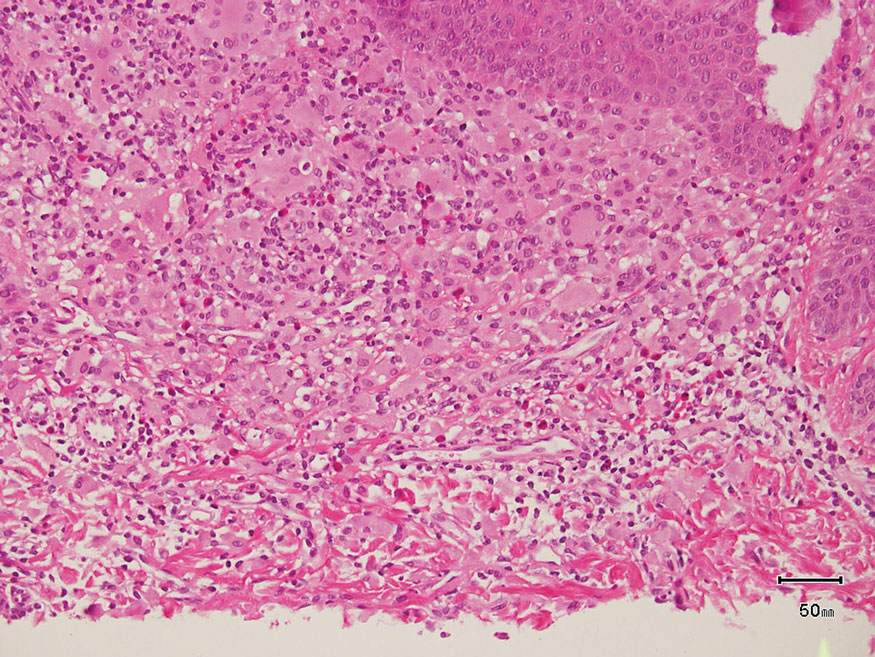

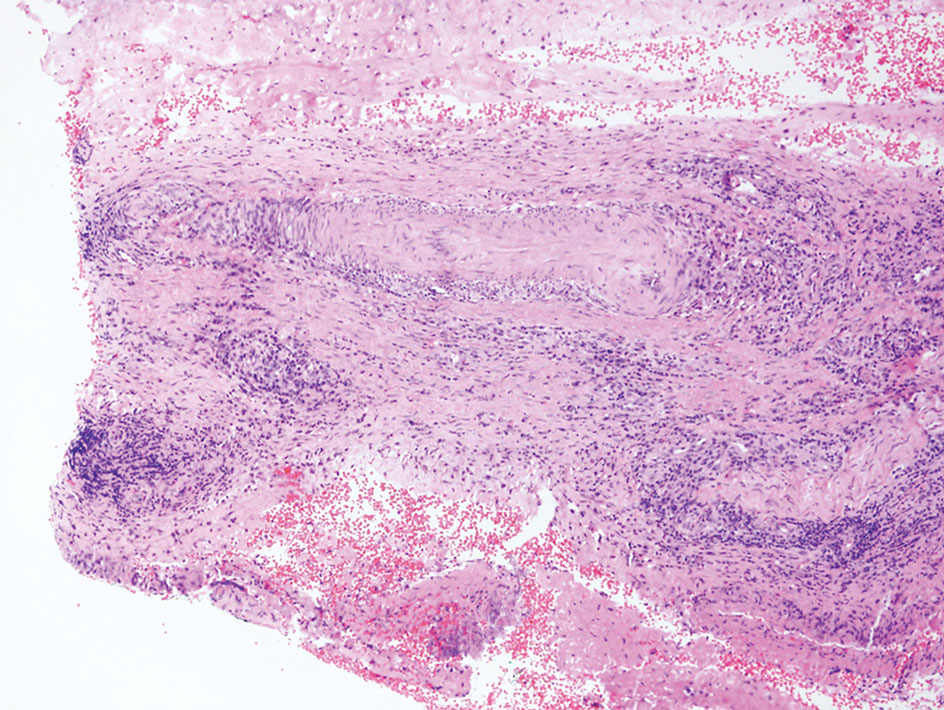

Laboratory results were positive for anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B. A complete blood cell count; comprehensive metabolic panel; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; and assays of rheumatoid factor, C-reactive protein, and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide were within reference range. A biopsy of a lesion on the back showed psoriasiform dermatitis with confluent parakeratosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes. There was superficial perivascular inflammation with rare eosinophils (Figure 3).

The patient was treated with a course of systemic corticosteroids. The rash resolved in 1 week. She did not receive the second dose due to the rash.

Two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines—Pfizer BioNTech and Moderna—have been granted emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration.6 The safety profile of the mRNA-1273 vaccine for the median 2-month follow-up showed no safety concerns.3 Minor localized adverse effects (eg, pain, redness, swelling) have been observed more frequently with the vaccines than with placebo. Systemic symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, headache, and muscle and joint pain, also were seen somewhat more often with the vaccines than with placebo; most such effects occurred 24 to 48 hours after vaccination.3,6,7 The frequency of unsolicited adverse events and serious adverse events reported during the 28-day period after vaccination generally was similar among participants in the vaccine and placebo groups.3

There are 2 types of reactions to COVID-19 vaccination: immediate and delayed. Immediate reactions usually are due to anaphylaxis, requiring prompt recognition and treatment with epinephrine to stop rapid progression of life-threatening symptoms. Delayed reactions include localized reactions, such as urticaria and benign exanthema; serum sickness and serum sickness–like reactions; fever; and rare skin, organ, and neurologic sequelae.1,6-8

Cutaneous manifestations, present in 16% to 50% of patients with Sjögren syndrome, are considered one of the most common extraglandular presentations of the syndrome. They are classified as nonvascular (eg, xerosis, angular cheilitis, eyelid dermatitis, annular erythema) and vascular (eg, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis).9-11 Our patient did not have any of those findings. She had not taken any medications before the rash appeared, thereby ruling out a drug reaction.

The differential for our patient included post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash, which is not typical with Escherichia coli infection but is described with infection with Chlamydia species and Salmonella species. Moreover, post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash appear mostly on the palms and soles. Systemic lupus erythematosus–like rashes have a different histology and appear on sun-exposed areas; our patient’s rash was found mainly on unexposed areas.12

Because our patient received the Moderna vaccine 5 days before the rash appeared and later developed swelling of the digits with morning stiffness, a delayed serum sickness–like reaction secondary to COVID-19 vaccination was possible.3,6

COVID-19 mRNA vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna incorporate a lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system that prevents rapid enzymatic degradation of mRNA and facilitates in vivo delivery of mRNA. This lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system is further stabilized by a polyethylene glycol 2000 lipid conjugate that provides a hydrophilic layer, thus prolonging half-life. The presence of lipid polyethylene glycol 2000 in mRNA vaccines has led to concern that this component could be implicated in anaphylaxis.6

COVID-19 antigens can give rise to varying clinical manifestations that are directly related to viral tissue damage or are indirectly induced by the antiviral immune response.13,14 Hyperactivation of the immune system to eradicate COVID-19 may trigger autoimmunity; several immune-mediated disorders have been described in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. Dermal manifestations include cutaneous rash and vasculitis.13-16 Crucial immunologic steps occur during SARS-CoV-2 infection that may link autoimmunity to COVID-19.13,14 In preliminary published data on the efficacy of the Moderna vaccine on 45 trial enrollees, 3 did not receive the second dose of vaccination, including 1 who developed urticaria on both legs 5 days after the first dose.1

Introduction of viral RNA can induce autoimmunity that can be explained by various phenomena, including epitope spreading, molecular mimicry, cryptic antigen, and bystander activation. Remarkably, more than one-third of immunogenic proteins in SARS-CoV-2 have potentially problematic homology to proteins that are key to the human adaptive immune system.5

Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 seems to induce organ injury through alternative mechanisms beyond direct viral infection, including immunologic injury. In some situations, hyperactivation of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 RNA can result in autoimmune disease. COVID-19 has been associated with immune-mediated systemic or organ-selective manifestations, some of which fulfill the diagnostic or classification criteria of specific autoimmune diseases. It is unclear whether those medical disorders are the result of transitory postinfectious epiphenomena.5

A few studies have shown that patients with rheumatic disease have an incidence and prevalence of COVID-19 that is similar to the general population. A similar pattern has been detected in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates, even among patients with an autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren syndrome.5,17 Furthermore, exacerbation of preexisting rheumatic symptoms may be due to hyperactivation of antiviral pathways in a person with an autoimmune disease.17-19 The findings in our patient suggested a direct role for the vaccine in skin manifestations, rather than for reactivation or development of new systemic autoimmune processes, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination has been described20; however, the case patient did not have a history of psoriasis. The mechanism(s) of such exacerbation remain unclear; COVID-19 vaccine–induced helper T cells (TH17) may play a role.21 Other skin manifestations encountered following COVID-19 vaccination include lichen planus, leukocytoclastic vasculitic rash, erythema multiforme–like rash, and pityriasis rosea–like rash.22-25 The immune mechanisms of these manifestations remain unclear.

The clinical presentation of delayed vaccination reactions can be attributed to the timing of symptoms and, in this case, the immune-mediated background of a psoriasiform reaction. Although adverse reactions to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine are rare, more individuals should be studied after vaccination to confirm and better understand this phenomenon.

- Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, et al; . An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1920-1931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022483

- Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, et al; . Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2427-2438. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028436

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Weise E. ‘COVID arm’ rash seen after Moderna vaccine annoying but harmless, doctors say. USA Today. January 27, 2021. Accessed September 4, 2022. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2021/01/27/covid-arm-moderna-vaccine-rash-harmless-side-effect-doctors-say/4277725001/

- Talotta R, Robertson E. Autoimmunity as the comet tail of COVID-19 pandemic. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:3621-3644. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3621

- Castells MC, Phillips EJ. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:643-649. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2035343

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al; . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2034577

- Dooling K, McClung N, Chamberland M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1857-1859. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1

- Roguedas AM, Misery L, Sassolas B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome are underestimated. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:632-636.

- Katayama I. Dry skin manifestations in Sjögren syndrome and atopic dermatitis related to aberrant sudomotor function in inflammatory allergic skin diseases. Allergol Int. 2018;67:448-454. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2018.07.001

- Generali E, Costanzo A, Mainetti C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:357-370. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8639-y

- Chanprapaph K, Tankunakorn J, Suchonwanit P, et al. Dermatologic manifestations, histologic features and disease progression among cutaneous lupus erythematosus subtypes: a prospective observational study in Asians. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:131-147. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00471-y

- Ortega-Quijano D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Selda-Enriquez G, et al. Algorithm for the classification of COVID-19 rashes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e103-e104. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.034

- Rahimi H, Tehranchinia Z. A comprehensive review of cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID-19. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1236520. doi:10.1155/2020/1236520

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75-81. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011

- Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:739-743. doi:10.1111/ijd.14937

- Dellavance A, Coelho Andrade LE. Immunologic derangement preceding clinical autoimmunity. Lupus. 2014;23:1305-1308. doi:10.1177/0961203314531346

- Parodi A, Gasparini G, Cozzani E. Could antiphospholipid antibodies contribute to coagulopathy in COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e249. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.003

- Zhou Y, Han T, Chen J, et al. Clinical and autoimmune characteristics of severe and critical cases of COVID-19. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13:1077-1086. doi:10.1111/cts.12805

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.812010

- Rouai M, Slimane MB, Sassi W, et al. Pustular rash triggered by Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022:e15465. doi:10.1111/dth.15465

- Altun E, Kuzucular E. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis after COVID-19 vaccination. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15279. doi:10.1111/dth.15279

- Buckley JE, Landis LN, Rapini RP. Pityriasis rosea-like rash after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2022;7:164-168. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.009

- Gökçek GE, Öksüm Solak E, Çölgeçen E. Pityriasis rosea like eruption: a dermatological manifestation of Coronavac-COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15256. doi:10.1111/dth.15256

- Kim MJ, Kim JW, Kim MS, et al. Generalized erythema multiforme-like skin rash following the first dose of COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:e98-e100. doi:10.1111/jdv.17757

To the Editor: