User login

How Well Does the Third Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine Work?

How effective are the COVID-19 vaccines, third time around? Researchers compared 2 large groups of veterans to find out how well a third dose protected against documented infection, symptomatic COVID-19, and COVID-19–related hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and death.

The research, published in Nature, used electronic health records of 65,196 veterans who received BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and 65,196 who received mRNA-1273 (Moderna). They chose to study the 16 weeks between October 20, 2021 and February 8, 2022, which included both Delta- and Omicron-variant waves.

During the follow-up (median, 77 days), 2994 COVID-19 infections were documented, of which 200 were detected as symptomatic, 194 required hospitalization, and 52 required ICU admission. Twenty-two patients died.

In a previous head-to-head trial comparing breakthrough COVID-19 outcomes after the first doses of the 2 vaccines (given when the Alpha and Delta variants were predominant), the researchers had found a low risk of documented infection and severe outcomes, but lower for the Moderna vaccine. They note that few head-to-head comparisons have been made of third-dose effectiveness.

As expected, in this trial, the researchers found a “nearly identical” pattern for the risk of the 2 vaccine groups. Although the risks for all of the measured outcomes over 16 weeks were low for both vaccines ≤ 4% for documented infection and < 0.03% for death in each group—those veterans who received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine had an excess of 45 documented infections and 11 hospitalizations per 10,000 persons, compared with the Moderna group. The Pfizer-BioNTech group also had a higher risk of documented infection over 9 weeks of follow-up, during which an Omicron-variant predominated.

Given the high effectiveness of a third dose of both vaccines, either vaccine is strongly recommended, the researchers conclude. They point to “evidence of clear and comparable benefits” for the most severe outcomes: The difference in estimated 16-week risk of death between the 2 groups was two-thousandths of 1 %.

They add that, while the differences in estimated risk for less severe outcomes between the 2 groups were small on the absolute scale, they may be meaningful when considering the population scale at which these vaccines are deployed.

How effective are the COVID-19 vaccines, third time around? Researchers compared 2 large groups of veterans to find out how well a third dose protected against documented infection, symptomatic COVID-19, and COVID-19–related hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and death.

The research, published in Nature, used electronic health records of 65,196 veterans who received BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and 65,196 who received mRNA-1273 (Moderna). They chose to study the 16 weeks between October 20, 2021 and February 8, 2022, which included both Delta- and Omicron-variant waves.

During the follow-up (median, 77 days), 2994 COVID-19 infections were documented, of which 200 were detected as symptomatic, 194 required hospitalization, and 52 required ICU admission. Twenty-two patients died.

In a previous head-to-head trial comparing breakthrough COVID-19 outcomes after the first doses of the 2 vaccines (given when the Alpha and Delta variants were predominant), the researchers had found a low risk of documented infection and severe outcomes, but lower for the Moderna vaccine. They note that few head-to-head comparisons have been made of third-dose effectiveness.

As expected, in this trial, the researchers found a “nearly identical” pattern for the risk of the 2 vaccine groups. Although the risks for all of the measured outcomes over 16 weeks were low for both vaccines ≤ 4% for documented infection and < 0.03% for death in each group—those veterans who received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine had an excess of 45 documented infections and 11 hospitalizations per 10,000 persons, compared with the Moderna group. The Pfizer-BioNTech group also had a higher risk of documented infection over 9 weeks of follow-up, during which an Omicron-variant predominated.

Given the high effectiveness of a third dose of both vaccines, either vaccine is strongly recommended, the researchers conclude. They point to “evidence of clear and comparable benefits” for the most severe outcomes: The difference in estimated 16-week risk of death between the 2 groups was two-thousandths of 1 %.

They add that, while the differences in estimated risk for less severe outcomes between the 2 groups were small on the absolute scale, they may be meaningful when considering the population scale at which these vaccines are deployed.

How effective are the COVID-19 vaccines, third time around? Researchers compared 2 large groups of veterans to find out how well a third dose protected against documented infection, symptomatic COVID-19, and COVID-19–related hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and death.

The research, published in Nature, used electronic health records of 65,196 veterans who received BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and 65,196 who received mRNA-1273 (Moderna). They chose to study the 16 weeks between October 20, 2021 and February 8, 2022, which included both Delta- and Omicron-variant waves.

During the follow-up (median, 77 days), 2994 COVID-19 infections were documented, of which 200 were detected as symptomatic, 194 required hospitalization, and 52 required ICU admission. Twenty-two patients died.

In a previous head-to-head trial comparing breakthrough COVID-19 outcomes after the first doses of the 2 vaccines (given when the Alpha and Delta variants were predominant), the researchers had found a low risk of documented infection and severe outcomes, but lower for the Moderna vaccine. They note that few head-to-head comparisons have been made of third-dose effectiveness.

As expected, in this trial, the researchers found a “nearly identical” pattern for the risk of the 2 vaccine groups. Although the risks for all of the measured outcomes over 16 weeks were low for both vaccines ≤ 4% for documented infection and < 0.03% for death in each group—those veterans who received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine had an excess of 45 documented infections and 11 hospitalizations per 10,000 persons, compared with the Moderna group. The Pfizer-BioNTech group also had a higher risk of documented infection over 9 weeks of follow-up, during which an Omicron-variant predominated.

Given the high effectiveness of a third dose of both vaccines, either vaccine is strongly recommended, the researchers conclude. They point to “evidence of clear and comparable benefits” for the most severe outcomes: The difference in estimated 16-week risk of death between the 2 groups was two-thousandths of 1 %.

They add that, while the differences in estimated risk for less severe outcomes between the 2 groups were small on the absolute scale, they may be meaningful when considering the population scale at which these vaccines are deployed.

Black Veterans Disproportionately Denied VA Benefits

Black veterans are less likely to have their benefits claims processed and paid than are their White peers because of systemic problems within the US Department of Veterans Affairs, according to a lawsuit filed against the agency.

“A Black veteran who served honorably can walk into the VA, file a disability claim, and be at a significantly higher likelihood of having that claim denied,” said Adam Henderson, a student working with the Yale Law School Veterans Legal Services Clinic, one of several groups connected to the lawsuit.

“The VA has denied countless meritorious applications of Black veterans and thus deprived them and their families of the support that they are entitled to.”

The suit, filed in federal court by the clinic on behalf of Vietnam War veteran Conley Monk Jr., asks for “redress for the harms caused by the failure of VA staff and leaders to administer these benefits programs in a manner free from racial discrimination against Black veterans.”

In a press conference announcing the lawsuit, the effort received backing from Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D, Connecticut) who called it an “unacceptable” situation.

“Black veterans are denied benefits at a very significantly disproportionate rate,” he said. “We know the results. We want to know the reason why.”

The suit stems from an analysis of VA claims records released by the department following an earlier legal action. Between 2001 and 2020, the average denial rate for disability claims filed for Black veterans was 29.5%, significantly above the 24.2% for White veterans.

Attorneys allege the problems date back even further and that VA officials should have known about the racial disparities in the system from previous complaints.

“The negligence of VA leadership, and their failure to train, supervise, monitor and instruct agency officials to take steps to identify and correct racial disparities, led to systematic benefits obstruction for Black veterans,” the suit states.

Monk is a Black disabled Marine Corps veteran who previously sued the military to overturn his less-than-honorable military discharge due to complications from undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder.

He was subsequently granted access to a host of veterans benefits but not to retroactive payouts for claims he was denied in the 1970s.

“They didn’t fully compensate me or my family,” he said. “I wasn’t able to give my kids my educational benefits. We should have been receiving checks while they were growing up.”

Along with potential past benefits for Monk, individuals involved with the lawsuit said the move could force the VA to reassess thousands of other unfairly dismissed cases. “For decades [the US government] has allowed racially discriminatory practices to obstruct Black veterans from easily accessing veterans housing, education, and health care benefits with wide-reaching economic consequences for Black veterans and their families,” said Richard Brookshire, executive director of the Black Veterans Project.

“This lawsuit reckons with the shameful history of racism by the Department of Veteran Affairs and seeks to redress long-standing improprieties reverberating across generations of Black military service.”

In a statement, VA press secretary Terrence Hayes did not directly respond to the lawsuit but noted that “throughout history, there have been unacceptable disparities in both VA benefits decisions and military discharge status due to racism, which have wrongly left Black veterans without access to VA care and benefits.”

“We are actively working to right these wrongs, and we will stop at nothing to ensure that all Black veterans get the VA services they have earned and deserve,” he said. “We are currently studying racial disparities in benefits claims decisions, and we will publish the results of that study as soon as they are available.”

Hayes said the department has already begun targeted outreach to Black veterans to help them with claims and is “taking steps to ensure that our claims process combats institutional racism, rather than perpetuating it.”

Black veterans are less likely to have their benefits claims processed and paid than are their White peers because of systemic problems within the US Department of Veterans Affairs, according to a lawsuit filed against the agency.

“A Black veteran who served honorably can walk into the VA, file a disability claim, and be at a significantly higher likelihood of having that claim denied,” said Adam Henderson, a student working with the Yale Law School Veterans Legal Services Clinic, one of several groups connected to the lawsuit.

“The VA has denied countless meritorious applications of Black veterans and thus deprived them and their families of the support that they are entitled to.”

The suit, filed in federal court by the clinic on behalf of Vietnam War veteran Conley Monk Jr., asks for “redress for the harms caused by the failure of VA staff and leaders to administer these benefits programs in a manner free from racial discrimination against Black veterans.”

In a press conference announcing the lawsuit, the effort received backing from Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D, Connecticut) who called it an “unacceptable” situation.

“Black veterans are denied benefits at a very significantly disproportionate rate,” he said. “We know the results. We want to know the reason why.”

The suit stems from an analysis of VA claims records released by the department following an earlier legal action. Between 2001 and 2020, the average denial rate for disability claims filed for Black veterans was 29.5%, significantly above the 24.2% for White veterans.

Attorneys allege the problems date back even further and that VA officials should have known about the racial disparities in the system from previous complaints.

“The negligence of VA leadership, and their failure to train, supervise, monitor and instruct agency officials to take steps to identify and correct racial disparities, led to systematic benefits obstruction for Black veterans,” the suit states.

Monk is a Black disabled Marine Corps veteran who previously sued the military to overturn his less-than-honorable military discharge due to complications from undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder.

He was subsequently granted access to a host of veterans benefits but not to retroactive payouts for claims he was denied in the 1970s.

“They didn’t fully compensate me or my family,” he said. “I wasn’t able to give my kids my educational benefits. We should have been receiving checks while they were growing up.”

Along with potential past benefits for Monk, individuals involved with the lawsuit said the move could force the VA to reassess thousands of other unfairly dismissed cases. “For decades [the US government] has allowed racially discriminatory practices to obstruct Black veterans from easily accessing veterans housing, education, and health care benefits with wide-reaching economic consequences for Black veterans and their families,” said Richard Brookshire, executive director of the Black Veterans Project.

“This lawsuit reckons with the shameful history of racism by the Department of Veteran Affairs and seeks to redress long-standing improprieties reverberating across generations of Black military service.”

In a statement, VA press secretary Terrence Hayes did not directly respond to the lawsuit but noted that “throughout history, there have been unacceptable disparities in both VA benefits decisions and military discharge status due to racism, which have wrongly left Black veterans without access to VA care and benefits.”

“We are actively working to right these wrongs, and we will stop at nothing to ensure that all Black veterans get the VA services they have earned and deserve,” he said. “We are currently studying racial disparities in benefits claims decisions, and we will publish the results of that study as soon as they are available.”

Hayes said the department has already begun targeted outreach to Black veterans to help them with claims and is “taking steps to ensure that our claims process combats institutional racism, rather than perpetuating it.”

Black veterans are less likely to have their benefits claims processed and paid than are their White peers because of systemic problems within the US Department of Veterans Affairs, according to a lawsuit filed against the agency.

“A Black veteran who served honorably can walk into the VA, file a disability claim, and be at a significantly higher likelihood of having that claim denied,” said Adam Henderson, a student working with the Yale Law School Veterans Legal Services Clinic, one of several groups connected to the lawsuit.

“The VA has denied countless meritorious applications of Black veterans and thus deprived them and their families of the support that they are entitled to.”

The suit, filed in federal court by the clinic on behalf of Vietnam War veteran Conley Monk Jr., asks for “redress for the harms caused by the failure of VA staff and leaders to administer these benefits programs in a manner free from racial discrimination against Black veterans.”

In a press conference announcing the lawsuit, the effort received backing from Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D, Connecticut) who called it an “unacceptable” situation.

“Black veterans are denied benefits at a very significantly disproportionate rate,” he said. “We know the results. We want to know the reason why.”

The suit stems from an analysis of VA claims records released by the department following an earlier legal action. Between 2001 and 2020, the average denial rate for disability claims filed for Black veterans was 29.5%, significantly above the 24.2% for White veterans.

Attorneys allege the problems date back even further and that VA officials should have known about the racial disparities in the system from previous complaints.

“The negligence of VA leadership, and their failure to train, supervise, monitor and instruct agency officials to take steps to identify and correct racial disparities, led to systematic benefits obstruction for Black veterans,” the suit states.

Monk is a Black disabled Marine Corps veteran who previously sued the military to overturn his less-than-honorable military discharge due to complications from undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder.

He was subsequently granted access to a host of veterans benefits but not to retroactive payouts for claims he was denied in the 1970s.

“They didn’t fully compensate me or my family,” he said. “I wasn’t able to give my kids my educational benefits. We should have been receiving checks while they were growing up.”

Along with potential past benefits for Monk, individuals involved with the lawsuit said the move could force the VA to reassess thousands of other unfairly dismissed cases. “For decades [the US government] has allowed racially discriminatory practices to obstruct Black veterans from easily accessing veterans housing, education, and health care benefits with wide-reaching economic consequences for Black veterans and their families,” said Richard Brookshire, executive director of the Black Veterans Project.

“This lawsuit reckons with the shameful history of racism by the Department of Veteran Affairs and seeks to redress long-standing improprieties reverberating across generations of Black military service.”

In a statement, VA press secretary Terrence Hayes did not directly respond to the lawsuit but noted that “throughout history, there have been unacceptable disparities in both VA benefits decisions and military discharge status due to racism, which have wrongly left Black veterans without access to VA care and benefits.”

“We are actively working to right these wrongs, and we will stop at nothing to ensure that all Black veterans get the VA services they have earned and deserve,” he said. “We are currently studying racial disparities in benefits claims decisions, and we will publish the results of that study as soon as they are available.”

Hayes said the department has already begun targeted outreach to Black veterans to help them with claims and is “taking steps to ensure that our claims process combats institutional racism, rather than perpetuating it.”

Exophytic Firm Papulonodule on the Labia in a Patient With Nonspecific Gastrointestinal Symptoms

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

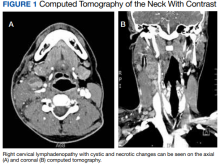

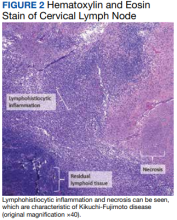

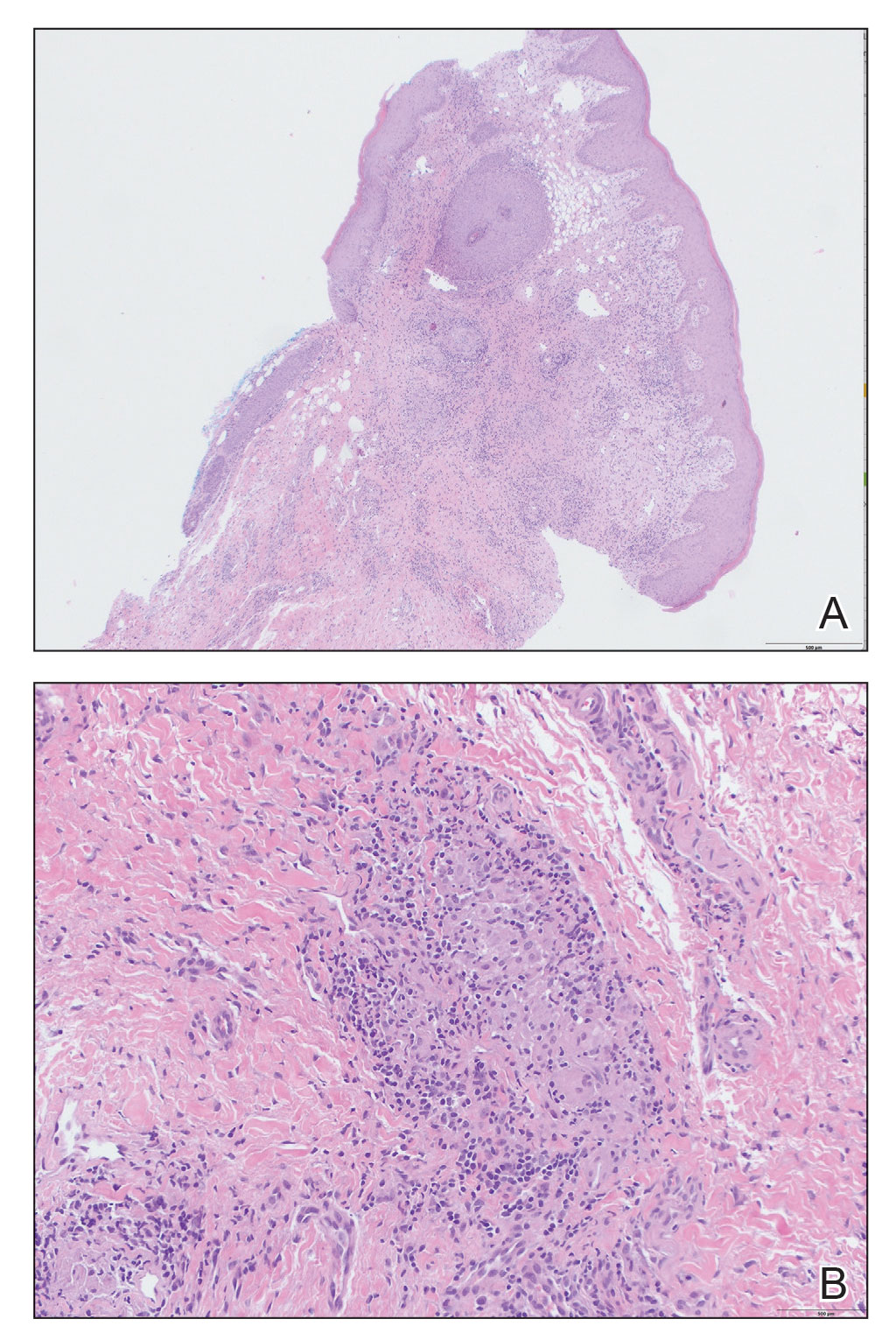

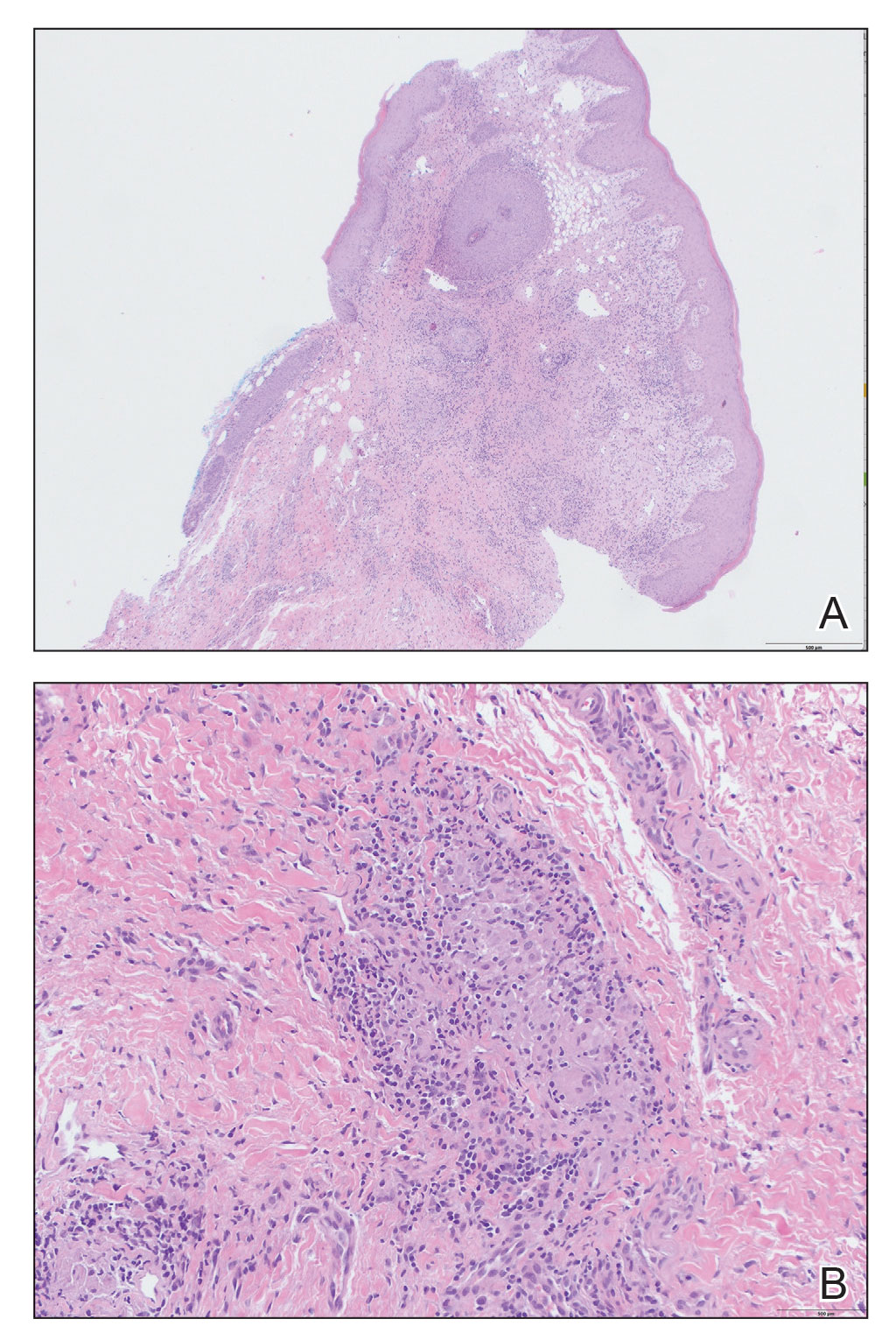

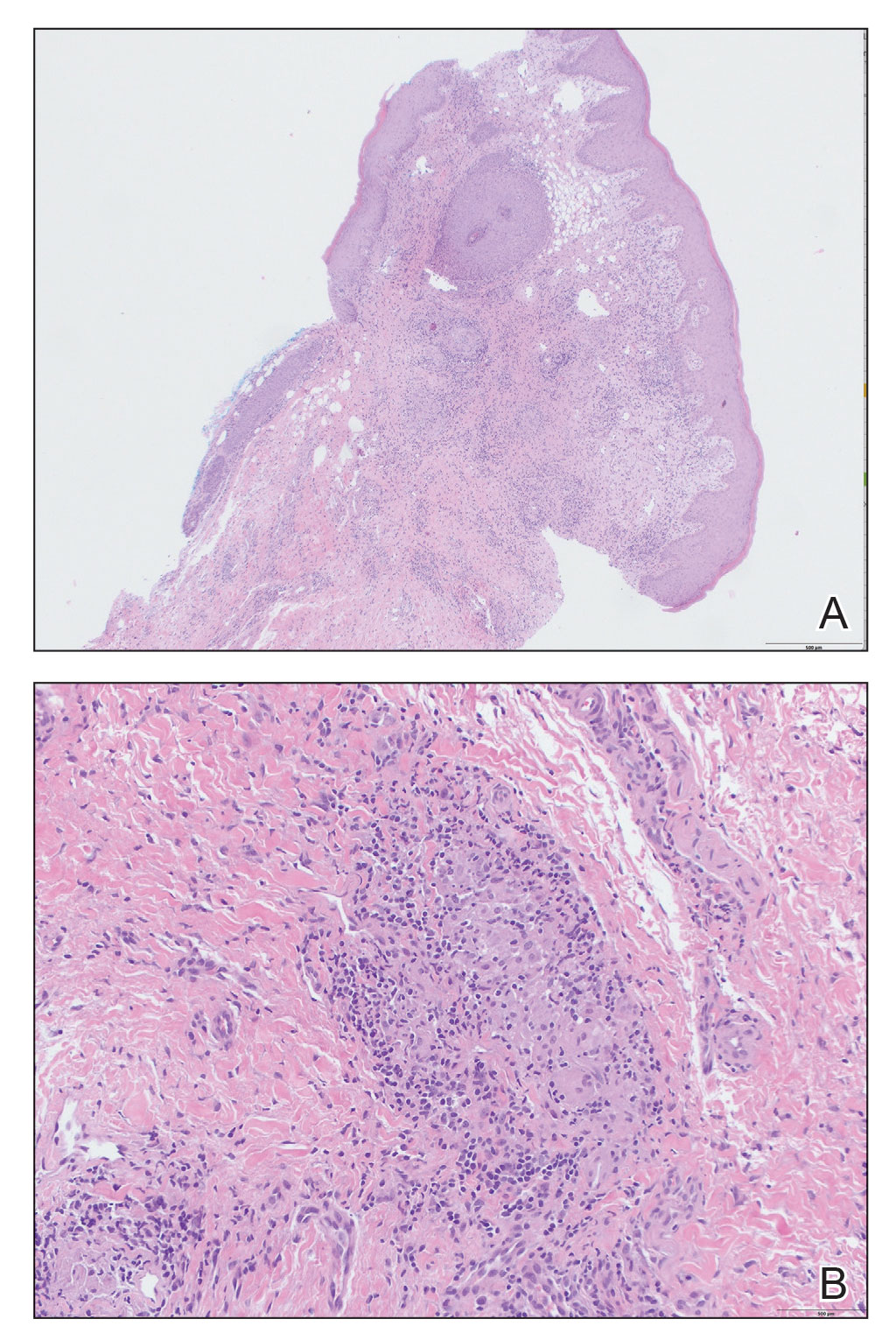

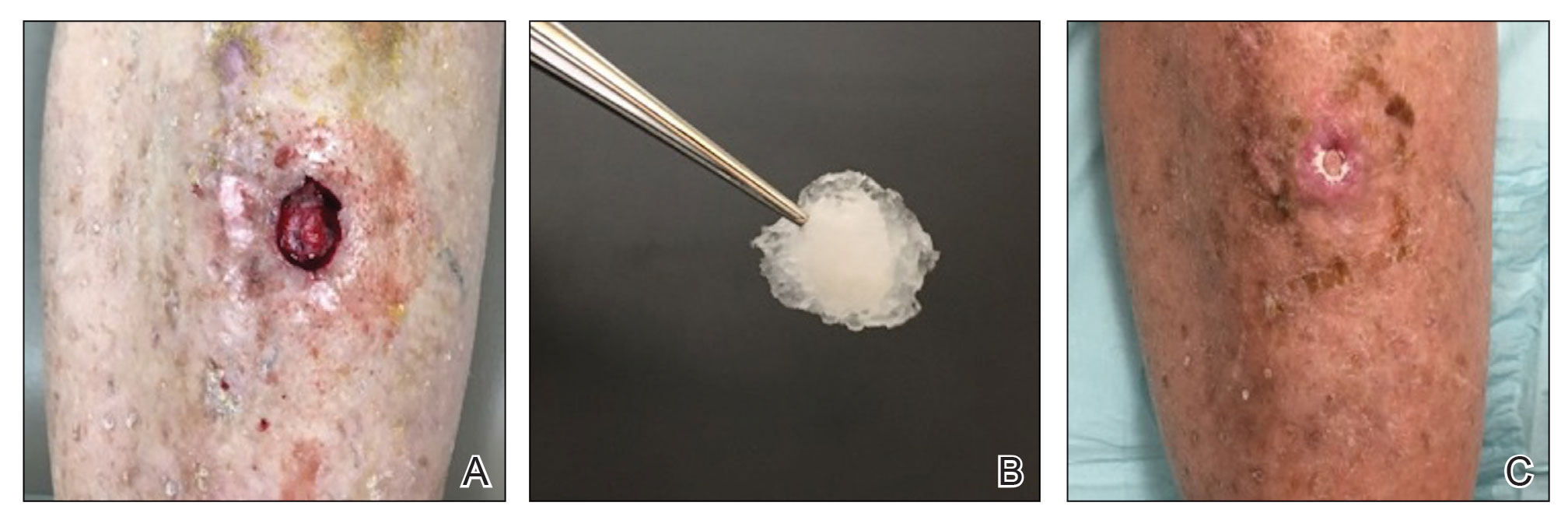

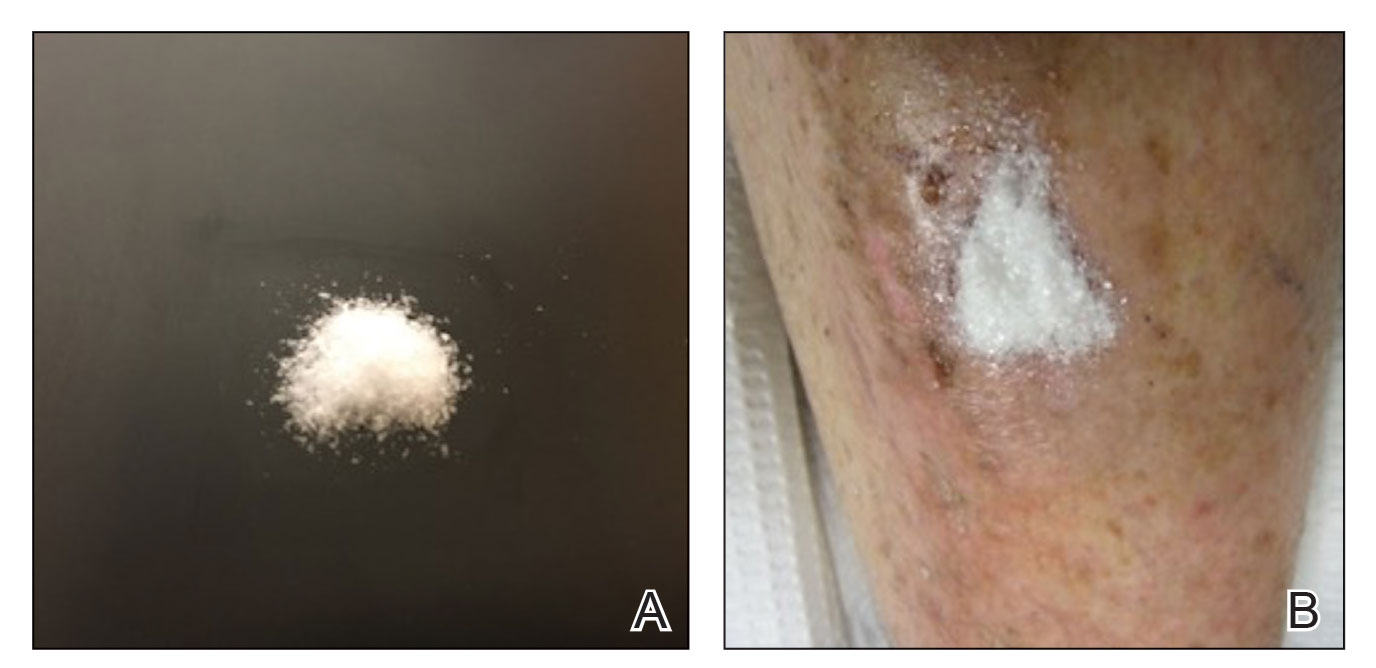

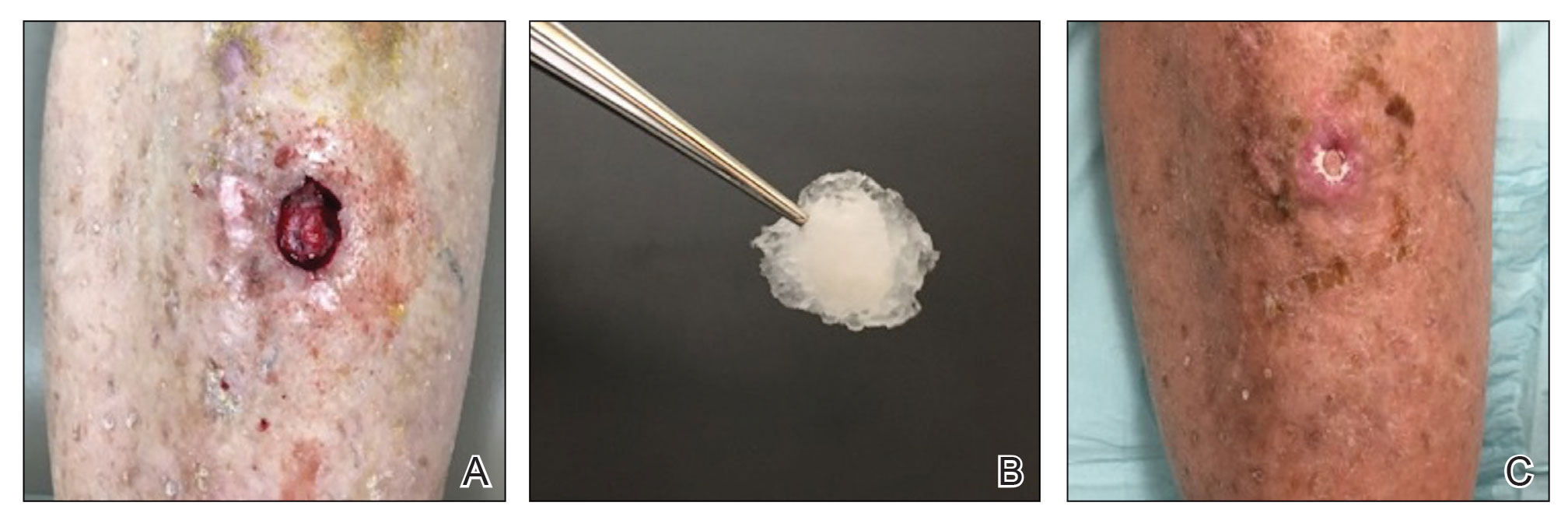

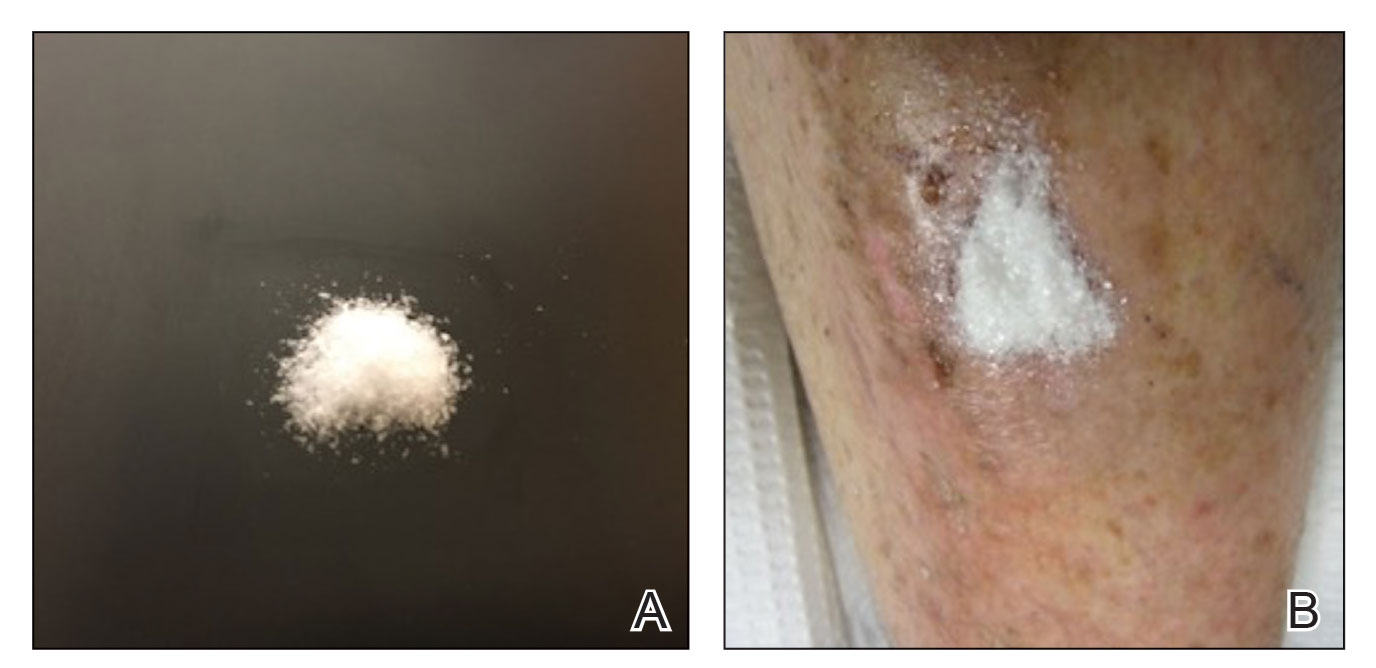

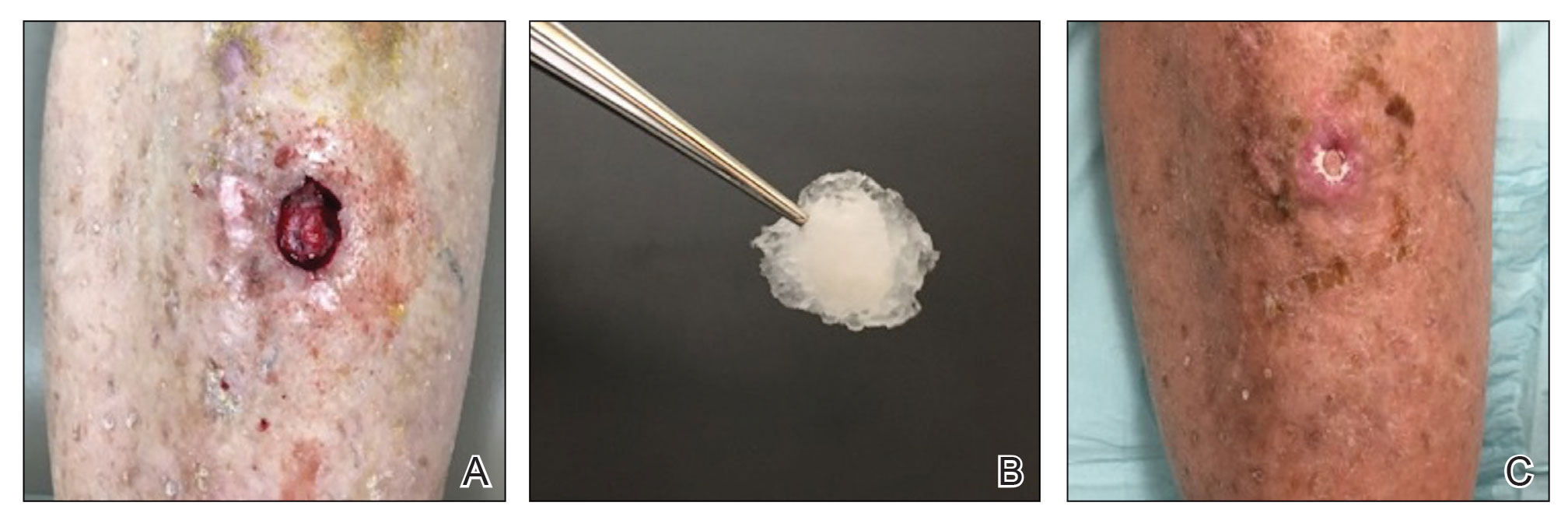

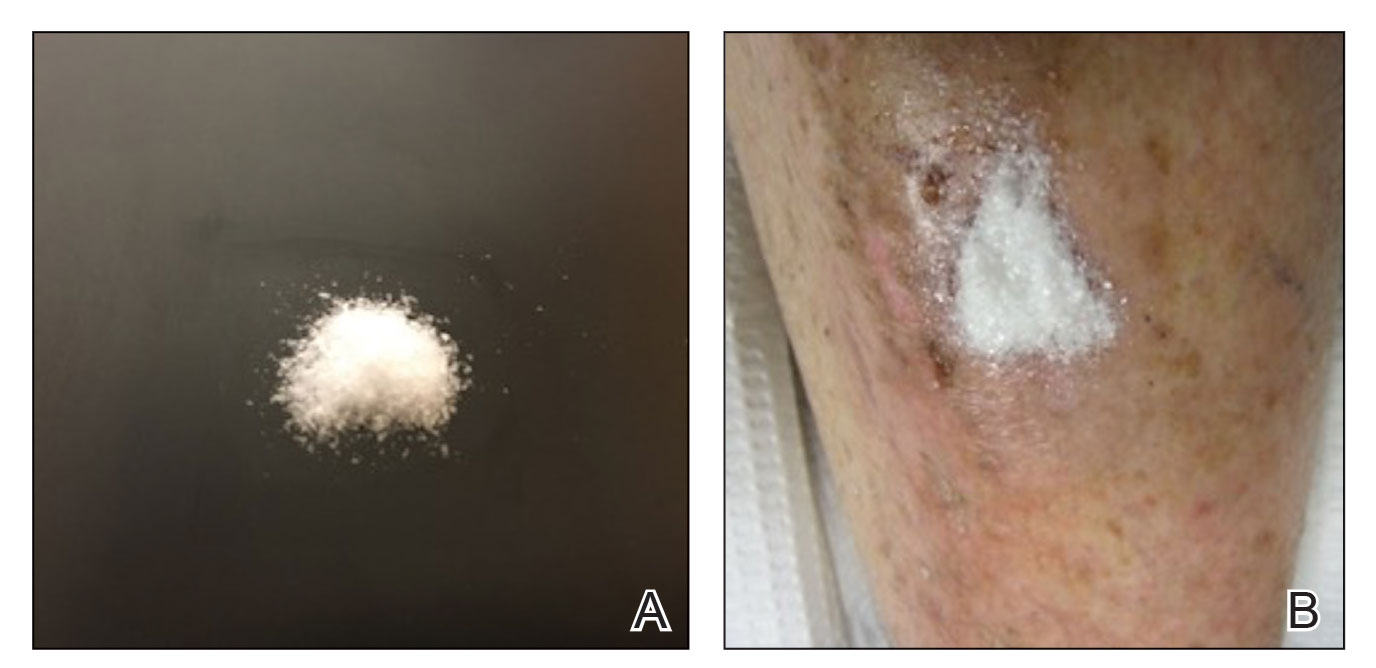

Kinyoun and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the labial biopsy were negative for mycobacteria and fungi, respectively. A complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, celiac disease serologies, stool occult blood, and stool calprotectin laboratory test results were within reference range. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated an anal fissure extending from the anal verge at the 6 o’clock position, abnormal T2 bright signal in the skin of the buttocks and perineum extending to the labia, and mild mucosal enhancement of the rectal and anal mucosa. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and magnetic resonance elastography were unremarkable. Colonoscopy demonstrated scattered superficial erythematous patches and erosions in the rectum. Histologically, there was mild to moderately active colitis in the rectum with no evidence of chronicity. Given our patient’s labial edema and exophytic papulonodule (Figure 1) in the setting of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and granulomatous dermatitis seen on pathology (Figure 2), she was diagnosed with cutaneous Crohn disease (CD).

In our patient, labial biopsy was necessary to definitively diagnose CD. Prior to biopsy of the lesion, our patient was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation leading to an anal fissure and skin tag due to lack of laboratory, imaging, and colonoscopy findings commonly associated with CD. Her biopsy results and gastrointestinal symptoms made these diagnoses, as well as condyloma or a large sentinel skin tag, less likely.

Extraintestinal findings of CD, especially cutaneous manifestations, are relatively frequent and may be present in as many as 44% of patients.1,2 Cutaneous CD often is characterized based on pathogenic mechanisms as either reactive, associated, or CD specific. Reactive cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and oral aphthae. Associated cutaneous manifestations include vitiligo, palmar erythema, and palmoplantar pustulosis.2 Crohn disease–specific manifestations, including genital or extragenital metastatic CD (MCD), fistulas, and oral involvement, are granulomatous in nature, similar to intestinal CD. Genital manifestations of MCD include edema, erythema, fissures, and/or ulceration of the vulva, penis, or scrotum. Labial swelling is the most common presenting symptom of MCD in females in both pediatric and adult age groups.2 Lymphedema, skin tags, and condylomalike growths also can be seen but are relatively less common.2

Given the labial edema, exophytic papulonodule, and granulomatous dermatitis seen on histopathology, our patient likely fit into the MCD category.2 In adults, most instances of MCD arise in the setting of well-established intestinal CD disease,3 whereas in children 86% of cases occur in patients without concurrent intestinal CD.2

Given the nonspecific and variable presentation of MCD, the differential diagnosis is broad. The differential diagnosis could include infectious etiologies such as condyloma acuminatum (human papillomavirus); syphilitic chancre; or mycobacterial, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic vulvovaginitis. Sexual abuse, sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, or hidradenitis suppurativa, among other diagnoses, also should be considered. Diagnostic workup should include biopsy of the lesion with special stains, polarizing microscopy, and tissue cultures.4 A thorough evaluation for gastrointestinal CD should be completed after diagnosis.3

The clinical course of vulvar CD can be unpredictable, with some cases healing spontaneously but most persisting despite treatment and sometimes prompting surgical removal.2,4 Early recognition is crucial, as long-standing MCD lesions can be therapy resistant.5 Due to the rarity of the condition and lack of data, there is a lack of treatment consensus for MCD. In 2014, the American Academy of Dermatology published treatment guidelines recommending superpotent topical steroids or topical tacrolimus as first-line therapy. Next-line therapy includes oral metronidazole, followed by prednisolone if still symptomatic.3 Treatment-resistant disease can warrant treatment with immunomodulators or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. Our patient was started on adalimumab; after just 2 months of therapy, the labial swelling decreased and the exophytic nodule was less firm and smaller.

Metastatic CD is a rare manifestation of cutaneous CD and can be present in the absence of gastrointestinal disease.3 This case demonstrates the importance of recognizing the cutaneous signs of CD and the necessity of lesional biopsy for the diagnosis of MCD, as our patient presented with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and a diagnostic workup, including endoscopies, that proved inconclusive for the diagnosis of CD.

- Antonelli E, Bassotti G, Tramontana M, et al. Dermatological manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1-16. doi:10.3390/JCM10020364

- Schneider SL, Foster K, Patel D, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:566-574. doi:10.1111/PDE.13565

- Kurtzman DJB, Jones T, Lian F, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2014.04.002

- Barret M, De Parades V, Battistella M, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:563-570. doi:10.1016/J.CROHNS.2013.10.009

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder [published online January 3, 2017]. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150. doi:10.1155/2017/8192150

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Kinyoun and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the labial biopsy were negative for mycobacteria and fungi, respectively. A complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, celiac disease serologies, stool occult blood, and stool calprotectin laboratory test results were within reference range. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated an anal fissure extending from the anal verge at the 6 o’clock position, abnormal T2 bright signal in the skin of the buttocks and perineum extending to the labia, and mild mucosal enhancement of the rectal and anal mucosa. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and magnetic resonance elastography were unremarkable. Colonoscopy demonstrated scattered superficial erythematous patches and erosions in the rectum. Histologically, there was mild to moderately active colitis in the rectum with no evidence of chronicity. Given our patient’s labial edema and exophytic papulonodule (Figure 1) in the setting of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and granulomatous dermatitis seen on pathology (Figure 2), she was diagnosed with cutaneous Crohn disease (CD).

In our patient, labial biopsy was necessary to definitively diagnose CD. Prior to biopsy of the lesion, our patient was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation leading to an anal fissure and skin tag due to lack of laboratory, imaging, and colonoscopy findings commonly associated with CD. Her biopsy results and gastrointestinal symptoms made these diagnoses, as well as condyloma or a large sentinel skin tag, less likely.

Extraintestinal findings of CD, especially cutaneous manifestations, are relatively frequent and may be present in as many as 44% of patients.1,2 Cutaneous CD often is characterized based on pathogenic mechanisms as either reactive, associated, or CD specific. Reactive cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and oral aphthae. Associated cutaneous manifestations include vitiligo, palmar erythema, and palmoplantar pustulosis.2 Crohn disease–specific manifestations, including genital or extragenital metastatic CD (MCD), fistulas, and oral involvement, are granulomatous in nature, similar to intestinal CD. Genital manifestations of MCD include edema, erythema, fissures, and/or ulceration of the vulva, penis, or scrotum. Labial swelling is the most common presenting symptom of MCD in females in both pediatric and adult age groups.2 Lymphedema, skin tags, and condylomalike growths also can be seen but are relatively less common.2

Given the labial edema, exophytic papulonodule, and granulomatous dermatitis seen on histopathology, our patient likely fit into the MCD category.2 In adults, most instances of MCD arise in the setting of well-established intestinal CD disease,3 whereas in children 86% of cases occur in patients without concurrent intestinal CD.2

Given the nonspecific and variable presentation of MCD, the differential diagnosis is broad. The differential diagnosis could include infectious etiologies such as condyloma acuminatum (human papillomavirus); syphilitic chancre; or mycobacterial, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic vulvovaginitis. Sexual abuse, sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, or hidradenitis suppurativa, among other diagnoses, also should be considered. Diagnostic workup should include biopsy of the lesion with special stains, polarizing microscopy, and tissue cultures.4 A thorough evaluation for gastrointestinal CD should be completed after diagnosis.3

The clinical course of vulvar CD can be unpredictable, with some cases healing spontaneously but most persisting despite treatment and sometimes prompting surgical removal.2,4 Early recognition is crucial, as long-standing MCD lesions can be therapy resistant.5 Due to the rarity of the condition and lack of data, there is a lack of treatment consensus for MCD. In 2014, the American Academy of Dermatology published treatment guidelines recommending superpotent topical steroids or topical tacrolimus as first-line therapy. Next-line therapy includes oral metronidazole, followed by prednisolone if still symptomatic.3 Treatment-resistant disease can warrant treatment with immunomodulators or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. Our patient was started on adalimumab; after just 2 months of therapy, the labial swelling decreased and the exophytic nodule was less firm and smaller.

Metastatic CD is a rare manifestation of cutaneous CD and can be present in the absence of gastrointestinal disease.3 This case demonstrates the importance of recognizing the cutaneous signs of CD and the necessity of lesional biopsy for the diagnosis of MCD, as our patient presented with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and a diagnostic workup, including endoscopies, that proved inconclusive for the diagnosis of CD.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Kinyoun and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the labial biopsy were negative for mycobacteria and fungi, respectively. A complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, celiac disease serologies, stool occult blood, and stool calprotectin laboratory test results were within reference range. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated an anal fissure extending from the anal verge at the 6 o’clock position, abnormal T2 bright signal in the skin of the buttocks and perineum extending to the labia, and mild mucosal enhancement of the rectal and anal mucosa. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and magnetic resonance elastography were unremarkable. Colonoscopy demonstrated scattered superficial erythematous patches and erosions in the rectum. Histologically, there was mild to moderately active colitis in the rectum with no evidence of chronicity. Given our patient’s labial edema and exophytic papulonodule (Figure 1) in the setting of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and granulomatous dermatitis seen on pathology (Figure 2), she was diagnosed with cutaneous Crohn disease (CD).

In our patient, labial biopsy was necessary to definitively diagnose CD. Prior to biopsy of the lesion, our patient was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation leading to an anal fissure and skin tag due to lack of laboratory, imaging, and colonoscopy findings commonly associated with CD. Her biopsy results and gastrointestinal symptoms made these diagnoses, as well as condyloma or a large sentinel skin tag, less likely.

Extraintestinal findings of CD, especially cutaneous manifestations, are relatively frequent and may be present in as many as 44% of patients.1,2 Cutaneous CD often is characterized based on pathogenic mechanisms as either reactive, associated, or CD specific. Reactive cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and oral aphthae. Associated cutaneous manifestations include vitiligo, palmar erythema, and palmoplantar pustulosis.2 Crohn disease–specific manifestations, including genital or extragenital metastatic CD (MCD), fistulas, and oral involvement, are granulomatous in nature, similar to intestinal CD. Genital manifestations of MCD include edema, erythema, fissures, and/or ulceration of the vulva, penis, or scrotum. Labial swelling is the most common presenting symptom of MCD in females in both pediatric and adult age groups.2 Lymphedema, skin tags, and condylomalike growths also can be seen but are relatively less common.2

Given the labial edema, exophytic papulonodule, and granulomatous dermatitis seen on histopathology, our patient likely fit into the MCD category.2 In adults, most instances of MCD arise in the setting of well-established intestinal CD disease,3 whereas in children 86% of cases occur in patients without concurrent intestinal CD.2

Given the nonspecific and variable presentation of MCD, the differential diagnosis is broad. The differential diagnosis could include infectious etiologies such as condyloma acuminatum (human papillomavirus); syphilitic chancre; or mycobacterial, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic vulvovaginitis. Sexual abuse, sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, or hidradenitis suppurativa, among other diagnoses, also should be considered. Diagnostic workup should include biopsy of the lesion with special stains, polarizing microscopy, and tissue cultures.4 A thorough evaluation for gastrointestinal CD should be completed after diagnosis.3

The clinical course of vulvar CD can be unpredictable, with some cases healing spontaneously but most persisting despite treatment and sometimes prompting surgical removal.2,4 Early recognition is crucial, as long-standing MCD lesions can be therapy resistant.5 Due to the rarity of the condition and lack of data, there is a lack of treatment consensus for MCD. In 2014, the American Academy of Dermatology published treatment guidelines recommending superpotent topical steroids or topical tacrolimus as first-line therapy. Next-line therapy includes oral metronidazole, followed by prednisolone if still symptomatic.3 Treatment-resistant disease can warrant treatment with immunomodulators or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. Our patient was started on adalimumab; after just 2 months of therapy, the labial swelling decreased and the exophytic nodule was less firm and smaller.

Metastatic CD is a rare manifestation of cutaneous CD and can be present in the absence of gastrointestinal disease.3 This case demonstrates the importance of recognizing the cutaneous signs of CD and the necessity of lesional biopsy for the diagnosis of MCD, as our patient presented with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and a diagnostic workup, including endoscopies, that proved inconclusive for the diagnosis of CD.

- Antonelli E, Bassotti G, Tramontana M, et al. Dermatological manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1-16. doi:10.3390/JCM10020364

- Schneider SL, Foster K, Patel D, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:566-574. doi:10.1111/PDE.13565

- Kurtzman DJB, Jones T, Lian F, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2014.04.002

- Barret M, De Parades V, Battistella M, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:563-570. doi:10.1016/J.CROHNS.2013.10.009

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder [published online January 3, 2017]. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150. doi:10.1155/2017/8192150

- Antonelli E, Bassotti G, Tramontana M, et al. Dermatological manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1-16. doi:10.3390/JCM10020364

- Schneider SL, Foster K, Patel D, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:566-574. doi:10.1111/PDE.13565

- Kurtzman DJB, Jones T, Lian F, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2014.04.002

- Barret M, De Parades V, Battistella M, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:563-570. doi:10.1016/J.CROHNS.2013.10.009

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder [published online January 3, 2017]. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150. doi:10.1155/2017/8192150

An 18-year-old woman with chronic constipation presented with an enlarging, painful, and edematous “lump” in the perineum of 1 year’s duration. The lesion became firmer and more painful with bowel movements. Physical examination revealed an enlarged right labia majora, as well as a pink to flesh-colored, exophytic, firm papulonodule in the perineum posterior to the right labia. The patient concomitantly was following with gastroenterology due to abdominal pain that worsened with eating, as well as constipation, nausea, weight loss, and rectal bleeding of 5 years’ duration. The patient denied rash, joint arthralgia, or oral ulcers. A biopsy from the labial lesion was performed.

Recent Developments in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Reflections From ASH 2022

What were the most exciting mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) updates from the recent meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH)?

Dr. Martin: The 2022 ASH meeting reported mostly about MCL research, which is great for the MCL community, because clearly, there is a lot of room for improvement. One of the big trials presented at a plenary session—one which we have been eager to see the results from, but maybe did not expect to see quite so soon—was the European MCL Network TRIANGLE trial. This is a 3-arm trial in which 870 patients were randomized. They had treatment-naive MCL and were younger than 66 years, so they were eligible for more intensive chemotherapy.

Arm A was the standard-of-care arm, defined by the prior European MCL Network TRIANGLE Trial. This was 6 alternating cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin hydrochloride [doxorubicin hydrochloride], vincristine, and prednisone) and R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin) – 3 of each followed by autologous stem cell transplant. Arm B was the same regimen with the addition of the first-in-class Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib to induction followed by 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance. Arm C was the same induction regimen (6 alternating cycles of R-CHOP and R-DHAP plus ibrutinib during induction and maintenance) with no autologous stem cell transplant. Roughly half the patients in the trial, all equally distributed across all arms, received 3 years of maintenance rituximab.

The primary outcome was failure-free survival (FFS). After only 31 months of median follow-up, the trial reported a significant difference in FFS between patients receiving ibrutinib (Arms B and C) and patients who underwent autologous stem cell transplant and did not receive ibrutinib (Arm A).

This clearly shows that 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance significantly improves FFS. FFS was 88% versus 72% (Arm B vs Arm A) at 3 years with a hazard ratio of 0.5. That is a striking hazard ratio, highly statistically significant. Importantly, patients in Arms B and C fared similarly, suggesting that transplant was unnecessary in patients receiving ibrutinib.

What these findings suggest is that in the patient population treated with intensive induction, we are moving beyond autologous stem cell transplant. These results were similar across all subgroups. In fact, outcomes were most striking for patients with higher risk features like high Ki-67 and overexpression of p53.

The patients who need ibrutinib most were those who were most likely to benefit, and that is really encouraging for all of us. There is a clear trend toward an improvement in overall survival with ibrutinib maintenance and there clearly is less toxicity and less treatment-related mortality from avoiding transplant.

It will be important to see this trial published in a peer-reviewed journal with more granular data. But to me, these trial results are groundbreaking. It is a practice-changing trial for sure.

Is there anything else from an investigational approach on the horizon for MCL?

Dr. Martin: Yes. I would like to highlight 2 trials that stand out to me.

First, my colleague Dr. Ruan from Cornell presented on a phase 2 trial of a triplet of acalabrutinib plus lenalidomide plus rituximab with real-time monitoring of minimal residual disease (MRD) in patients with treatment-naive MCL.

This was a small trial with just 24 patients. It was fairly evenly split between low-, medium-, and high-risk MCL international prognostic index (MIPI) scores. All of these patients received the triplet for 1 year of induction followed by an additional year of maintenance with a slightly lower dose of lenalidomide. At the end of 2 years, patients who were in a durable MRD-negative state could stop the oral therapy and just continue with rituximab maintenance.

In a prior trial published in The New England Journal of Medicine, we showed that the lenalidomide plus rituximab regimen has a complete response rate of about 60%. In this new ongoing trial regimen of acalabrutinib plus lenalidomide plus rituximab, we found that at the end of just 1 year of induction treatment, the complete response rate was 83%. With all of the caveats and comparing across trials, this new regimen was clearly active and potentially more active than the prior regimen. It also appeared to be well tolerated without any real significant issues.

I think what this trial plus the TRIANGLE showed us is that BTK inhibitors belong in the front-line setting. That is what patients want. That is what physicians want.

The other trial that I wanted to highlight is an update of something that we saw last year at ASH, specifically a phase 1/2 trial of glofitamab in people with previously treated MCL. The overall response rate was 83% and the complete response rate was 73%. The complete response rate at the first assessment was already almost 50%. These are among patients who have had prior treatment for MCL, including BTK inhibitors.

We are not accustomed to seeing treatments that are so active in the relapsed/refractory MCL patient population, particularly, if they have had a prior BTK inhibitor. So, these results are exciting and promising.

This compares to the ZUMA-2 trial with CAR T-cells. CAR T-cells are also strikingly active in this patient population, but they do have some drawbacks. They have to be administered in a specialized facility and they are associated with fairly high rates of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity.

The rates of grade 3 to 4 cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity with glofitamab were low, but not negligible. All cytokine release syndrome events were manageable, and no patients discontinued treatment because of adverse events. This is, potentially, attractive, because it offers an active therapy to a broader subset of patients with MCL who may not be able to access CAR T-cell therapy as easily. A phase 3 trial is in the planning stages, and it is likely that if that trial has positive results, we will see glofitamab approved in the not-too-distant future for people with MCL, and having more options is always great.

Based on these developments, do you see any shifts in your day-to-day practice in the future?

Dr. Martin: I think what has been interesting to me about MCL over the past decade is this idea that not everybody is the same. That should not come as a surprise statement, but MCL does behave differently in different people.

As a physician who treats a lot of patients with MCL, I have seen all of the different ways in which MCL can behave; combine that with the heterogeneity of humanity as a whole. Having guidelines from the NCCN (National Comprehensive Care Network) are helpful, but those guidelines are broad.

Learning how to take all that heterogeneity and variety into account and match the appropriate treatment to each patient is important. What these front-line trials are telling us is that it is OK to do research that does not involve chemotherapy.

In the past, it might have been considered unethical to give a younger patient a treatment without autologous stem cell transplant. But that is clearly not the case now. I think that in real-life practice in the near future, guidelines may actually start to get a little bit easier to follow as we come up with options that are less intensive.

It may be that patients can access treatments that are a little bit easier, that do not involve a transplant. That would be good for people with MCL from all across the country.

What were the most exciting mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) updates from the recent meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH)?

Dr. Martin: The 2022 ASH meeting reported mostly about MCL research, which is great for the MCL community, because clearly, there is a lot of room for improvement. One of the big trials presented at a plenary session—one which we have been eager to see the results from, but maybe did not expect to see quite so soon—was the European MCL Network TRIANGLE trial. This is a 3-arm trial in which 870 patients were randomized. They had treatment-naive MCL and were younger than 66 years, so they were eligible for more intensive chemotherapy.

Arm A was the standard-of-care arm, defined by the prior European MCL Network TRIANGLE Trial. This was 6 alternating cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin hydrochloride [doxorubicin hydrochloride], vincristine, and prednisone) and R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin) – 3 of each followed by autologous stem cell transplant. Arm B was the same regimen with the addition of the first-in-class Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib to induction followed by 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance. Arm C was the same induction regimen (6 alternating cycles of R-CHOP and R-DHAP plus ibrutinib during induction and maintenance) with no autologous stem cell transplant. Roughly half the patients in the trial, all equally distributed across all arms, received 3 years of maintenance rituximab.

The primary outcome was failure-free survival (FFS). After only 31 months of median follow-up, the trial reported a significant difference in FFS between patients receiving ibrutinib (Arms B and C) and patients who underwent autologous stem cell transplant and did not receive ibrutinib (Arm A).

This clearly shows that 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance significantly improves FFS. FFS was 88% versus 72% (Arm B vs Arm A) at 3 years with a hazard ratio of 0.5. That is a striking hazard ratio, highly statistically significant. Importantly, patients in Arms B and C fared similarly, suggesting that transplant was unnecessary in patients receiving ibrutinib.

What these findings suggest is that in the patient population treated with intensive induction, we are moving beyond autologous stem cell transplant. These results were similar across all subgroups. In fact, outcomes were most striking for patients with higher risk features like high Ki-67 and overexpression of p53.

The patients who need ibrutinib most were those who were most likely to benefit, and that is really encouraging for all of us. There is a clear trend toward an improvement in overall survival with ibrutinib maintenance and there clearly is less toxicity and less treatment-related mortality from avoiding transplant.

It will be important to see this trial published in a peer-reviewed journal with more granular data. But to me, these trial results are groundbreaking. It is a practice-changing trial for sure.

Is there anything else from an investigational approach on the horizon for MCL?

Dr. Martin: Yes. I would like to highlight 2 trials that stand out to me.

First, my colleague Dr. Ruan from Cornell presented on a phase 2 trial of a triplet of acalabrutinib plus lenalidomide plus rituximab with real-time monitoring of minimal residual disease (MRD) in patients with treatment-naive MCL.

This was a small trial with just 24 patients. It was fairly evenly split between low-, medium-, and high-risk MCL international prognostic index (MIPI) scores. All of these patients received the triplet for 1 year of induction followed by an additional year of maintenance with a slightly lower dose of lenalidomide. At the end of 2 years, patients who were in a durable MRD-negative state could stop the oral therapy and just continue with rituximab maintenance.

In a prior trial published in The New England Journal of Medicine, we showed that the lenalidomide plus rituximab regimen has a complete response rate of about 60%. In this new ongoing trial regimen of acalabrutinib plus lenalidomide plus rituximab, we found that at the end of just 1 year of induction treatment, the complete response rate was 83%. With all of the caveats and comparing across trials, this new regimen was clearly active and potentially more active than the prior regimen. It also appeared to be well tolerated without any real significant issues.

I think what this trial plus the TRIANGLE showed us is that BTK inhibitors belong in the front-line setting. That is what patients want. That is what physicians want.

The other trial that I wanted to highlight is an update of something that we saw last year at ASH, specifically a phase 1/2 trial of glofitamab in people with previously treated MCL. The overall response rate was 83% and the complete response rate was 73%. The complete response rate at the first assessment was already almost 50%. These are among patients who have had prior treatment for MCL, including BTK inhibitors.

We are not accustomed to seeing treatments that are so active in the relapsed/refractory MCL patient population, particularly, if they have had a prior BTK inhibitor. So, these results are exciting and promising.

This compares to the ZUMA-2 trial with CAR T-cells. CAR T-cells are also strikingly active in this patient population, but they do have some drawbacks. They have to be administered in a specialized facility and they are associated with fairly high rates of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity.

The rates of grade 3 to 4 cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity with glofitamab were low, but not negligible. All cytokine release syndrome events were manageable, and no patients discontinued treatment because of adverse events. This is, potentially, attractive, because it offers an active therapy to a broader subset of patients with MCL who may not be able to access CAR T-cell therapy as easily. A phase 3 trial is in the planning stages, and it is likely that if that trial has positive results, we will see glofitamab approved in the not-too-distant future for people with MCL, and having more options is always great.

Based on these developments, do you see any shifts in your day-to-day practice in the future?

Dr. Martin: I think what has been interesting to me about MCL over the past decade is this idea that not everybody is the same. That should not come as a surprise statement, but MCL does behave differently in different people.

As a physician who treats a lot of patients with MCL, I have seen all of the different ways in which MCL can behave; combine that with the heterogeneity of humanity as a whole. Having guidelines from the NCCN (National Comprehensive Care Network) are helpful, but those guidelines are broad.

Learning how to take all that heterogeneity and variety into account and match the appropriate treatment to each patient is important. What these front-line trials are telling us is that it is OK to do research that does not involve chemotherapy.

In the past, it might have been considered unethical to give a younger patient a treatment without autologous stem cell transplant. But that is clearly not the case now. I think that in real-life practice in the near future, guidelines may actually start to get a little bit easier to follow as we come up with options that are less intensive.

It may be that patients can access treatments that are a little bit easier, that do not involve a transplant. That would be good for people with MCL from all across the country.

What were the most exciting mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) updates from the recent meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH)?

Dr. Martin: The 2022 ASH meeting reported mostly about MCL research, which is great for the MCL community, because clearly, there is a lot of room for improvement. One of the big trials presented at a plenary session—one which we have been eager to see the results from, but maybe did not expect to see quite so soon—was the European MCL Network TRIANGLE trial. This is a 3-arm trial in which 870 patients were randomized. They had treatment-naive MCL and were younger than 66 years, so they were eligible for more intensive chemotherapy.

Arm A was the standard-of-care arm, defined by the prior European MCL Network TRIANGLE Trial. This was 6 alternating cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin hydrochloride [doxorubicin hydrochloride], vincristine, and prednisone) and R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin) – 3 of each followed by autologous stem cell transplant. Arm B was the same regimen with the addition of the first-in-class Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib to induction followed by 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance. Arm C was the same induction regimen (6 alternating cycles of R-CHOP and R-DHAP plus ibrutinib during induction and maintenance) with no autologous stem cell transplant. Roughly half the patients in the trial, all equally distributed across all arms, received 3 years of maintenance rituximab.

The primary outcome was failure-free survival (FFS). After only 31 months of median follow-up, the trial reported a significant difference in FFS between patients receiving ibrutinib (Arms B and C) and patients who underwent autologous stem cell transplant and did not receive ibrutinib (Arm A).

This clearly shows that 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance significantly improves FFS. FFS was 88% versus 72% (Arm B vs Arm A) at 3 years with a hazard ratio of 0.5. That is a striking hazard ratio, highly statistically significant. Importantly, patients in Arms B and C fared similarly, suggesting that transplant was unnecessary in patients receiving ibrutinib.

What these findings suggest is that in the patient population treated with intensive induction, we are moving beyond autologous stem cell transplant. These results were similar across all subgroups. In fact, outcomes were most striking for patients with higher risk features like high Ki-67 and overexpression of p53.

The patients who need ibrutinib most were those who were most likely to benefit, and that is really encouraging for all of us. There is a clear trend toward an improvement in overall survival with ibrutinib maintenance and there clearly is less toxicity and less treatment-related mortality from avoiding transplant.

It will be important to see this trial published in a peer-reviewed journal with more granular data. But to me, these trial results are groundbreaking. It is a practice-changing trial for sure.

Is there anything else from an investigational approach on the horizon for MCL?

Dr. Martin: Yes. I would like to highlight 2 trials that stand out to me.

First, my colleague Dr. Ruan from Cornell presented on a phase 2 trial of a triplet of acalabrutinib plus lenalidomide plus rituximab with real-time monitoring of minimal residual disease (MRD) in patients with treatment-naive MCL.

This was a small trial with just 24 patients. It was fairly evenly split between low-, medium-, and high-risk MCL international prognostic index (MIPI) scores. All of these patients received the triplet for 1 year of induction followed by an additional year of maintenance with a slightly lower dose of lenalidomide. At the end of 2 years, patients who were in a durable MRD-negative state could stop the oral therapy and just continue with rituximab maintenance.

In a prior trial published in The New England Journal of Medicine, we showed that the lenalidomide plus rituximab regimen has a complete response rate of about 60%. In this new ongoing trial regimen of acalabrutinib plus lenalidomide plus rituximab, we found that at the end of just 1 year of induction treatment, the complete response rate was 83%. With all of the caveats and comparing across trials, this new regimen was clearly active and potentially more active than the prior regimen. It also appeared to be well tolerated without any real significant issues.

I think what this trial plus the TRIANGLE showed us is that BTK inhibitors belong in the front-line setting. That is what patients want. That is what physicians want.

The other trial that I wanted to highlight is an update of something that we saw last year at ASH, specifically a phase 1/2 trial of glofitamab in people with previously treated MCL. The overall response rate was 83% and the complete response rate was 73%. The complete response rate at the first assessment was already almost 50%. These are among patients who have had prior treatment for MCL, including BTK inhibitors.

We are not accustomed to seeing treatments that are so active in the relapsed/refractory MCL patient population, particularly, if they have had a prior BTK inhibitor. So, these results are exciting and promising.

This compares to the ZUMA-2 trial with CAR T-cells. CAR T-cells are also strikingly active in this patient population, but they do have some drawbacks. They have to be administered in a specialized facility and they are associated with fairly high rates of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity.

The rates of grade 3 to 4 cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity with glofitamab were low, but not negligible. All cytokine release syndrome events were manageable, and no patients discontinued treatment because of adverse events. This is, potentially, attractive, because it offers an active therapy to a broader subset of patients with MCL who may not be able to access CAR T-cell therapy as easily. A phase 3 trial is in the planning stages, and it is likely that if that trial has positive results, we will see glofitamab approved in the not-too-distant future for people with MCL, and having more options is always great.

Based on these developments, do you see any shifts in your day-to-day practice in the future?

Dr. Martin: I think what has been interesting to me about MCL over the past decade is this idea that not everybody is the same. That should not come as a surprise statement, but MCL does behave differently in different people.

As a physician who treats a lot of patients with MCL, I have seen all of the different ways in which MCL can behave; combine that with the heterogeneity of humanity as a whole. Having guidelines from the NCCN (National Comprehensive Care Network) are helpful, but those guidelines are broad.

Learning how to take all that heterogeneity and variety into account and match the appropriate treatment to each patient is important. What these front-line trials are telling us is that it is OK to do research that does not involve chemotherapy.

In the past, it might have been considered unethical to give a younger patient a treatment without autologous stem cell transplant. But that is clearly not the case now. I think that in real-life practice in the near future, guidelines may actually start to get a little bit easier to follow as we come up with options that are less intensive.

It may be that patients can access treatments that are a little bit easier, that do not involve a transplant. That would be good for people with MCL from all across the country.

Listeria infection in pregnancy: A potentially serious foodborne illness

CASE Pregnant patient with concerning symptoms of infection

A 28-year-old primigravid woman at 26 weeks’ gestation requests evaluation because of a 3-day history of low-grade fever (38.3 °C), chills, malaise, myalgias, pain in her upper back, nausea, diarrhea, and intermittent uterine contractions. Her symptoms began 2 days after she and her husband dined at a local Mexican restaurant. She specifically recalls eating unpasteurized cheese (queso fresco). Her husband also is experiencing similar symptoms.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What tests should be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

- Does this infection pose a risk to the fetus?

- How should this patient be treated?

Listeriosis, a potentially serious foodborne illness, is an unusual infection in pregnancy. It can cause a number of adverse effects in both the pregnant woman and her fetus, including fetal death in utero. In this article, we review the microbiology and epidemiology of Listeria infection, consider the important steps in diagnosis, and discuss treatment options and prevention measures.

The causative organism in listeriosis

Listeriosis is caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive, non–spore-forming bacillus. The organism is catalase positive and oxidase negative, and it exhibits tumbling motility when grown in culture. It can grow at temperatures less than 4 °C, which facilitates foodborne transmission of the bacterium despite adequate refrigeration. Of the 13 serotypes of L monocytogenes, the 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b are most likely to be associated with human infection. The major virulence factors of L monocytogenes are the internalin surface proteins and the pore-forming listeriolysin O (LLO) cytotoxin. These factors enable the organism to effectively invade host cells.1

The pathogen uses several mechanisms to evade gastrointestinal defenses prior to entry into the bloodstream. It avoids destruction in the stomach by using proton pump inhibitors to elevate the pH of gastric acid. In the duodenum, it survives the antibacterial properties of bile by secreting bile salt hydrolases, which catabolize bile salts. In addition, the cytotoxin listeriolysin S (LLS) disrupts the protective barrier created by the normal gut flora. Once the organism penetrates the gastrointestinal barriers, it disseminates through the blood and lymphatics and then infects other tissues, such as the brain and placenta.1,2

Pathogenesis of infection

The primary reservoir of Listeria is soil and decaying vegetable matter. The organism also has been isolated from animal feed, water, sewage, and many animal species. With rare exceptions, most infections in adults result from inadvertent ingestion of the organism in contaminated food. In certain high-risk occupations, such as veterinary medicine, farming, and laboratory work, infection of the skin or eye can result from direct contact with an infected animal.3

Of note, foodborne illness caused by Listeria has the third highest mortality rate of any foodborne infection, 16% compared with 35% for Vibrio vulnificus and 17% for Clostridium botulinum.2,3 The principal foods that have been linked to listeriosis include:

- soft cheeses, particularly those made from unpasteurized milk

- melon

- hot dogs

- lunch meat, such as bologna

- deli meat, especially chicken

- canned foods, such as smoked seafood, and pâté or meat spreads that are labeled “keep refrigerated”

- unpasteurized milk

- sprouts

- hummus.

In healthy adults, listeriosis is usually a short-lived illness. However, in older adults, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women, the infection can be devastating. Infection in the pregnant woman also poses major danger to the developing fetus because the organism has a special predilection for placental and fetal tissue.1,3,4

Immunity to Listeria infection depends primarily on T-cell lymphokine activation of macrophages. These latter cells are responsible for clearing the bacterium from the blood. As noted above, the principal virulence factor of L monocytogenes is listeriolysin O, a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. This substance induces T-cell receptor unresponsiveness, thus interfering with the host immune response to the invading pathogen.1,3-5

Continue to: Clinical manifestations of listeriosis...

Clinical manifestations of listeriosis

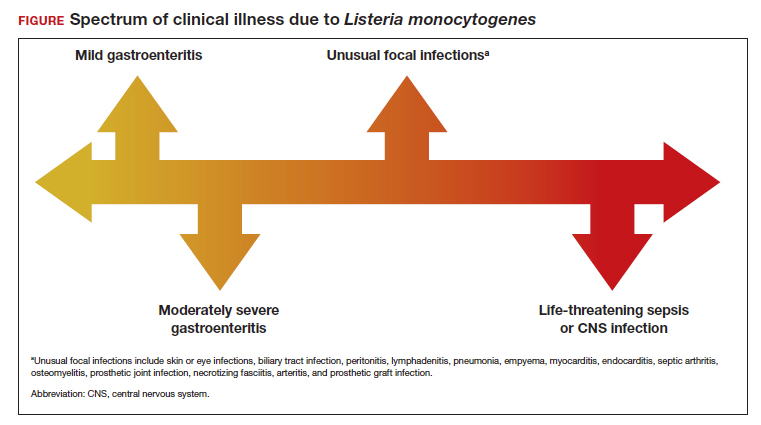

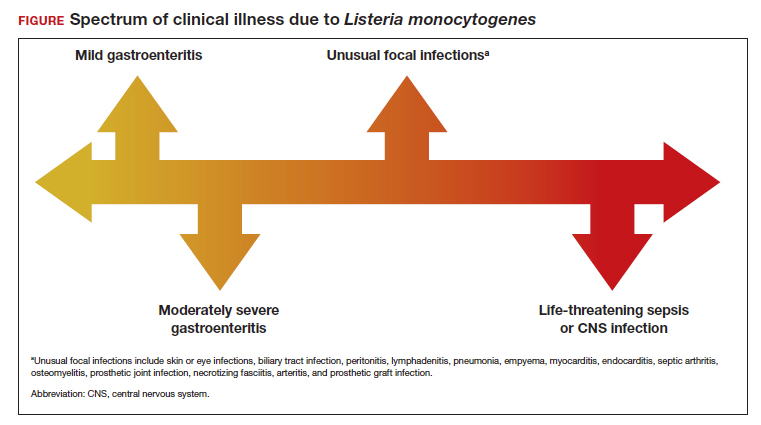

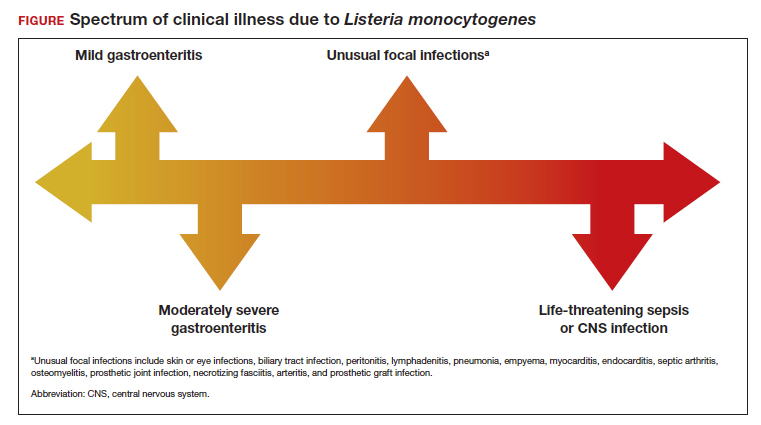

Listeria infections may present with various manifestations, depending on the degree of exposure and the underlying immunocompetence of the host (FIGURE). In its most common and simplest form, listeriosis presents as a mild to moderate gastroenteritis following exposure to contaminated food. Symptoms typically develop within 24 hours of exposure and include fever, myalgias, abdominal or back pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.5

Conversely, in immunocompromised patients, including pregnant women, listeriosis can present as life-threatening sepsis and/or central nervous system (CNS) infection (invasive infection). In this clinical setting, the mean incubation period is 11 days. The manifestations of CNS infection include meningoencephalitis, cerebritis, rhombencephalitis (infection and inflammation of the brain stem), brain abscess, and spinal cord abscess.5

In addition to these 2 clinical presentations, listeriosis can cause unusual focal infections as illustrated in the FIGURE. Some of these infections have unique clinical associations. For example, skin or eye infections may occur as a result of direct inoculation in veterinarians, farmers, and laboratory workers. Listeria peritonitis may occur in patients who are receiving peritoneal dialysis and in those who have cirrhosis. Prosthetic joint and graft infections, of course, may occur in patients who have had invasive procedures for implantation of grafts or prosthetic devices.5

Listeriosis is especially dangerous in pregnancy because it not only can cause serious injury to the mother and even death but it also may pose a major risk to fetal well-being. Possible perinatal complications include fetal death; preterm labor and delivery; and neonatal sepsis, meningitis, and death.5-8

Making the diagnosis

Diagnosis begins with a thorough and focused history to assess for characteristic symptoms and possible Listeria exposure. Exposure should be presumed for patients who report consuming high-risk foods, especially foods recently recalled by the US Food and Drug Administration.

In the asymptomatic pregnant patient, diagnostic testing can be deferred, and the patient should be instructed to return for evaluation if symptoms develop within 2 months of exposure. However, symptomatic, febrile patients require testing. The most valuable testing modality is Gram stain and culture of blood. Gram stain typically will show gram-positive pleomorphic rods with rounded ends. Amniocentesis may be indicated if blood cultures are not definitive. Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid and a positive Gram stain are highly indicative of fetal infection. Cultures of the cerebrospinal fluid are indicated in any individual with focal neurologic findings. Stool cultures are rarely indicated.

When obtaining any of the cultures noted above, the clinician should alert the microbiologist of the concern for listeriosis because L monocytogenes can be confused with common contaminants, such as diphtheroids.5-9

Treatment and follow-up

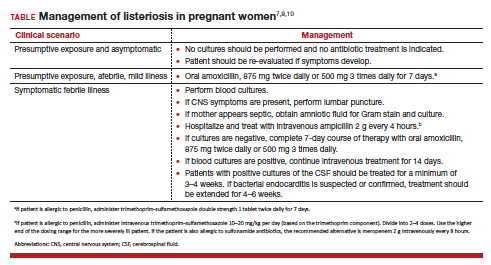

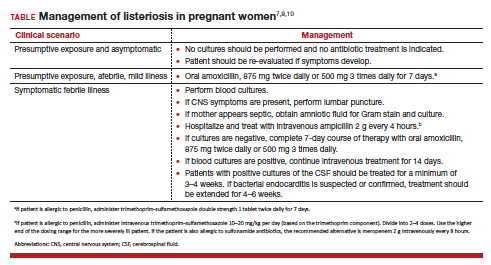

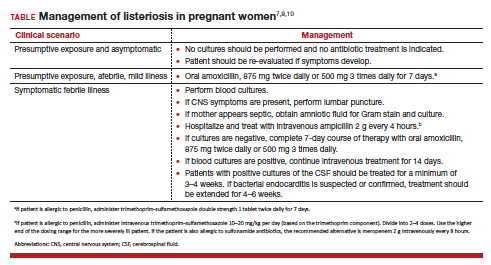

The treatment of listeriosis in pregnancy depends on the severity of the infection and the immune status of the mother. The TABLE offers several different clinical scenarios and the appropriate treatment for each. As noted, several scenarios may require cultures of the blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and amniotic fluid.7,9,10

Following treatment of the mother, serial ultrasound examinations should be performed to monitor fetal growth, CNS anatomy, placental morphology, amniotic fluid volume, and umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry. In the presence of fetal growth restriction, oligohydramnios, or abnormal Doppler velocimetry, biophysical profile testing should be performed. After delivery, the placenta should be examined carefully for histologic evidence of Listeria infection, such as miliary abscesses, and cultured for the bacterium.7-9

Prevention measures

Conservative measures for prevention of Listeria infection in pregnant women include the following7,10-12:

- Refrigerate milk and milk products at 40 °F (4.4 °C).

- Thoroughly cook raw food from animal sources.

- Wash raw vegetables carefully before eating.

- Keep uncooked meats separate from cooked meats and vegetables.

- Do not consume any beverages or foods made from unpasteurized milk.

- After handling uncooked foods, carefully wash all utensils and hands.

- Avoid all soft cheeses, such as Mexican-style feta, Brie, Camembert, and blue cheese, even if they are supposedly made from pasteurized milk.

- Reheat until steaming hot all leftover foods or ready-to-eat foods, such as hot dogs.

- Do not let juice from hot dogs or lunch meat packages drip onto other foods, utensils, or food preparation surfaces.

- Do not store opened hot dog packages in the refrigerator for more than 1 week. Do not store unopened packages for longer than 2 weeks.

- Do not store unopened lunch and deli meat packages in the refrigerator for longer than 2 weeks. Do not store opened packages for longer than 3 to 5 days.

- If other immunosuppressive conditions are present in combination with pregnancy, thoroughly heat cold cuts before eating.

- Do not eat raw or even lightly cooked sprouts of any kind. Cook sprouts thoroughly. Rinsing sprouts will not remove Listeria organisms.

- Do not eat refrigerated pâté or meat spreads from a deli counter or the refrigerated section of a grocery store.

- Canned or shelf-stable pâté and meat spreads are safe to eat, but be sure to refrigerate them after opening the packages.

- Do not eat refrigerated smoked seafood. Canned or shelf-stable seafood, particularly when incorporated into a casserole, is safe to eat.

- Eat cut melon immediately. Refrigerate uneaten melon quickly if not eaten. Discard cut melon that is left at room temperature for more than 4 hours.

CASE Diagnosis made and prompt treatment initiated

The most likely diagnosis in this patient is listeriosis. Because the patient is moderately ill and experiencing uterine contractions, she should be hospitalized and monitored for progressive cervical dilation. Blood cultures should be obtained to identify L monocytogenes. In addition, an amniocentesis should be performed, and the amniotic fluid should be cultured for this microorganism. Stool culture and culture of the cerebrospinal fluid are not indicated. The patient should be treated with intravenous ampicillin, 2 g every 4 hours for 14 days. If she is allergic to penicillin, the alternative drug is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 8 to 10 mg/kg per day in 2 divided doses, for 14 days. Prompt and effective treatment of the mother should prevent infection in the fetus and newborn. ●

- Listeriosis is primarily a foodborne illness caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive bacillus.

- Pregnant women, particularly those who are immunocompromised, are especially susceptible to Listeria infection.

- Foods that pose particular risk of transmitting infection include fresh unpasteurized cheeses, processed meats such as hot dogs, refrigerated pâté and meat spreads, refrigerated smoked seafood, unpasteurized milk, and unwashed raw produce.

- The infection may range from a mild gastroenteritis to life-threatening sepsis and meningitis.

- Listeriosis may cause early and late-onset neonatal infection that presents as either meningitis or sepsis.

- Blood and amniotic fluid cultures are essential to diagnose maternal infection. Stool cultures usually are not indicated.

- Mildly symptomatic but afebrile patients do not require treatment.

- Febrile symptomatic patients should be treated with either intravenous ampicillin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

- Radoshevich L, Cossart P. Listeria monocytogenes: towards a complete picture of its physiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:32-46. doi:10.1038/nnrmicro.2017.126.

- Johnson JE, Mylonakis E. Listeria monocytogenes. In: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2020:2543-2549.

- Gelfand MS, Swamy GK, Thompson JL. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-pathogenesis-of-listeria-monocytogenes-infection?sectionName=CLINICAL%20EPIDEMIOLOGY&topicRef=1277&anchor=H4&source=see_link#H4

- Cherubin CE, Appleman MD, Heseltine PN, et al. Epidemiological spectrum and current treatment of listeriosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:1108-1114.

- Gelfand MS, Swamy GK, Thompson JL. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-listeriamonocytogenes-infection

- Boucher M, Yonekura ML. Perinatal listeriosis (early-onset): correlation of antenatal manifestations and neonatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68:593-597.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 614: management of pregnant women with presumptive exposure to Listeria monocytogenes. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:1241-1244.

- Rouse DJ, Keimig TW, Riley LE, et al. Case 16-2016. A 31-year-old pregnant woman with fever. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2076-2083.

- Craig AM, Dotters-Katz S, Kuller JA, et al. Listeriosis in pregnancy: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2019;74: 362-368.

- Gelfand MS, Thompson JL, Swamy GK. Treatment and prevention of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prevention-of-listeria-monocytogenes-infection?topicRef=1280&source=see_link

- Voetsch AC, Angulo FJ, Jones TF, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emerging Infections Program Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Networking Group. Reduction in the incidence of invasive listeriosis in Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network sites, 1996-2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:513-520.

- MacDonald PDM, Whitwan RE, Boggs JD, et al. Outbreak of listeriosis among Mexican immigrants as a result of consumption of illicitly produced Mexican-style cheese. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:677-682.

CASE Pregnant patient with concerning symptoms of infection

A 28-year-old primigravid woman at 26 weeks’ gestation requests evaluation because of a 3-day history of low-grade fever (38.3 °C), chills, malaise, myalgias, pain in her upper back, nausea, diarrhea, and intermittent uterine contractions. Her symptoms began 2 days after she and her husband dined at a local Mexican restaurant. She specifically recalls eating unpasteurized cheese (queso fresco). Her husband also is experiencing similar symptoms.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What tests should be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

- Does this infection pose a risk to the fetus?

- How should this patient be treated?

Listeriosis, a potentially serious foodborne illness, is an unusual infection in pregnancy. It can cause a number of adverse effects in both the pregnant woman and her fetus, including fetal death in utero. In this article, we review the microbiology and epidemiology of Listeria infection, consider the important steps in diagnosis, and discuss treatment options and prevention measures.

The causative organism in listeriosis

Listeriosis is caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive, non–spore-forming bacillus. The organism is catalase positive and oxidase negative, and it exhibits tumbling motility when grown in culture. It can grow at temperatures less than 4 °C, which facilitates foodborne transmission of the bacterium despite adequate refrigeration. Of the 13 serotypes of L monocytogenes, the 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b are most likely to be associated with human infection. The major virulence factors of L monocytogenes are the internalin surface proteins and the pore-forming listeriolysin O (LLO) cytotoxin. These factors enable the organism to effectively invade host cells.1

The pathogen uses several mechanisms to evade gastrointestinal defenses prior to entry into the bloodstream. It avoids destruction in the stomach by using proton pump inhibitors to elevate the pH of gastric acid. In the duodenum, it survives the antibacterial properties of bile by secreting bile salt hydrolases, which catabolize bile salts. In addition, the cytotoxin listeriolysin S (LLS) disrupts the protective barrier created by the normal gut flora. Once the organism penetrates the gastrointestinal barriers, it disseminates through the blood and lymphatics and then infects other tissues, such as the brain and placenta.1,2

Pathogenesis of infection

The primary reservoir of Listeria is soil and decaying vegetable matter. The organism also has been isolated from animal feed, water, sewage, and many animal species. With rare exceptions, most infections in adults result from inadvertent ingestion of the organism in contaminated food. In certain high-risk occupations, such as veterinary medicine, farming, and laboratory work, infection of the skin or eye can result from direct contact with an infected animal.3

Of note, foodborne illness caused by Listeria has the third highest mortality rate of any foodborne infection, 16% compared with 35% for Vibrio vulnificus and 17% for Clostridium botulinum.2,3 The principal foods that have been linked to listeriosis include:

- soft cheeses, particularly those made from unpasteurized milk

- melon

- hot dogs

- lunch meat, such as bologna

- deli meat, especially chicken

- canned foods, such as smoked seafood, and pâté or meat spreads that are labeled “keep refrigerated”

- unpasteurized milk

- sprouts

- hummus.

In healthy adults, listeriosis is usually a short-lived illness. However, in older adults, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women, the infection can be devastating. Infection in the pregnant woman also poses major danger to the developing fetus because the organism has a special predilection for placental and fetal tissue.1,3,4