User login

Disability in medicine: My experience

What does a doctor look like? Throughout history, this concept has shifted due to societal norms and increased access to medical education. Today, the idea of a physician has expanded to incorporate a myriad of people; however, stigma still exists in medicine regarding mental illness and disability. I would like to share my personal journey through high school, college, medical school, and now residency, and how my identity and struggles have shaped me into the physician I am today. There are few conversations around disability—especially disability and mental health—in medicine, and through my own advocacy, I have met many students with disability who feel that medical school is unattainable. Additionally, I have met many medical students, residents, and pre-health advisors who are happy for the experience to learn more about a marginalized group in medicine. My hope in sharing my story is to offer a space for conversation about intersectionality within medical communities and how physicians and physicians in training can facilitate that change, regardless of their position or specialty. Additionally, I hope to shed light on the unique mental health needs of patients with disabilities and how mental health clinicians can address those needs.

Perceived weaknesses turned into strengths

“Why do you walk like that?” “What is that brace on your leg?” The early years of my childhood were marked by these questions and others like them. I was the kid with the limp, the kid with a brace on his leg, and the kid who disappeared multiple times a week for doctor’s appointments or physical therapy. I learned to deflect these questions or give nebulous answers about an accident or injury. The reality is that I was born with cerebral palsy (CP). My CP manifested as hemiparesis on the left side of my body. I was in aggressive physical therapy throughout childhood, received Botox injections for muscle spasticity, and underwent corrective surgery on my left leg to straighten my foot. In childhood, the diagnosis meant nothing more than 2 words that sounded like they belonged to superheroes in comic books. Even with supportive parents and family, I kept my disability a secret, much like the powers and abilities of my favorite superheroes.

However, like all great origin stories, what I once thought were weaknesses turned out to be strengths that pushed me through college, medical school, and now psychiatry residency. Living with a disability has shaped how I see the world and relate to my patients. My experience has helped me connect to my patients in ways others might not. These properties are important in any physician but vital in psychiatry, where many patients feel neglected or stigmatized; this is another reason there should be more doctors with disabilities in medicine. Unfortunately, systemic barriers are still in place that disincentivize those with a disability from pursuing careers in medicine. Stories like mine are important to inspire a reexamination of what a physician should be and how medicine, patients, and communities benefit from this change.

My experience through medical school

My path to psychiatry and residency was shaped by my early experience with the medical field and treatment. From the early days of my diagnosis at age 4, I was told that my brain was “wired differently” and that, because of this disruption in circuitry, I would have difficulty with physical activity. I grew to appreciate the intricacies of the brain and pathology to understand my body. With greater understanding came the existential realization that I would live with a disability for the rest of my life. Rather than dream of a future where I would be “normal,” I focused on adapting my life to my normal. An unfortunate reality of this normal was that no doctor would be able to relate to me, and my health care would focus on limitations rather than possibilities.

I focused on school as a distraction and slowly warmed to the idea of pursuing medicine as a career. The seed was planted years prior by the numerous doctors’ visits and procedures, and was cultivated by a desire to understand pathologies and offer treatment to patients from the perspective of a patient. When I applied to medical school, I did not know how to address my CP. Living as a person with CP was a core reason for my decision to pursue medicine, but I was afraid that a disclosure of disability would preclude any admission to medical school. Research into programs offered little guidance because most institutions only listed vague “physical expectations” of each student. There were times I doubted if I would be accepted anywhere. Many programs I reached out to about my situation seemed unenthusiastic about the prospect of a student with CP, and when I brought up my CP in interviews, the reaction was often of surprise and an admission that they had forgotten about “that part” of my application. Fortunately, I was accepted to medical school, but still struggled with the fear that one day I would be found out and not allowed to continue. No one in my class or school was like me, and a meeting with an Americans with Disabilities Act coordinator who asked me to reexamine the physical competencies of the school before advancing to clinical clerkships only further reinforced this fear. I decided to fly under the radar and not say anything about my disability to my attendings. I slowly worked my way through clerkships by making do with adapted ways to perform procedures and exams with additional practice and maneuvering at home. I found myself drawn to psychiatry because of the similarities I saw in the patients and myself. I empathized with how the patients struggled with chronic conditions that left them feeling separated from society and how they felt that their diagnosis was something they needed to hide. When medical school ended and I decided to pursue psychiatry, I wanted to share my story to inspire others with a disability to consider medicine as a career given their unique experiences. My experience thus far has been uplifting as my journey has echoed so many others.

A need for greater representation

Disability representation in medicine is needed more than ever. According to the CDC, >60 million adults in the United States (1 in 4) live with a disability.1 Although the physical health disparities are often discussed, there is less conversation surrounding mental health for individuals with disabilities. A 2018 study by Cree et al2 found that approximately 17.4 million adults with disabilities experienced frequent mental distress, defined as reporting ≥14 mentally unhealthy days in the past 30 days. Furthermore, compared to individuals without a disability, those with a disability are statistically more likely to have suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts.3 One way to address this disparity is to recruit medical students with disabilities to become physicians with disabilities. Evidence suggests that physicians who are members of groups that are underrepresented in medicine are more likely to deliver care to underrepresented patients.4 However, medical schools and institutions have been slow to address the disparity. A 2019 survey found an estimated 4.6% of medical students responded “yes” when asked if they had a disability, with most students reporting a psychological or attention/hyperactive disorder.5 Existing barriers include restrictive language surrounding technical standards influenced by long-standing vestiges of what a physician should be.6

An opportunity to connect with patients

I now do not see myself as having a secret identity to hide. Although my CP does not give me any superpowers, it has given me the opportunity to connect with my patients and serve as an example of why medical school recruitment and admissions should expand. Psychiatrists have been on the forefront of change in medicine and can shift the perception of a physician. In doing so, we not only enrich our field but also the lives of our patients who may need it most.

1. Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, et al. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(32):882-887.

2. Cree RA, Okoro CA, Zack MM, et al. Frequent mental distress among adults, by disability status, disability type, and selected characteristics—United States 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1238-1243.

3. Marlow NM, Xie Z, Tanner R, et al. Association between disability and suicide-related outcomes among US adults. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(6):852-862.

4. Thurmond VB, Kirch DG. Impact of minority physicians on health care. South Med J. 1998;91(11):1009-1013.

5. Meeks LM, Case B, Herzer K, et al. Change in prevalence of disabilities and accommodation practices among US medical schools, 2016 vs 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(20):2022-2024.

6. Stauffer C, Case B, Moreland CJ, et al. Technical standards from newly established medical schools: a review of disability inclusive practices. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2022;9:23821205211072763.

What does a doctor look like? Throughout history, this concept has shifted due to societal norms and increased access to medical education. Today, the idea of a physician has expanded to incorporate a myriad of people; however, stigma still exists in medicine regarding mental illness and disability. I would like to share my personal journey through high school, college, medical school, and now residency, and how my identity and struggles have shaped me into the physician I am today. There are few conversations around disability—especially disability and mental health—in medicine, and through my own advocacy, I have met many students with disability who feel that medical school is unattainable. Additionally, I have met many medical students, residents, and pre-health advisors who are happy for the experience to learn more about a marginalized group in medicine. My hope in sharing my story is to offer a space for conversation about intersectionality within medical communities and how physicians and physicians in training can facilitate that change, regardless of their position or specialty. Additionally, I hope to shed light on the unique mental health needs of patients with disabilities and how mental health clinicians can address those needs.

Perceived weaknesses turned into strengths

“Why do you walk like that?” “What is that brace on your leg?” The early years of my childhood were marked by these questions and others like them. I was the kid with the limp, the kid with a brace on his leg, and the kid who disappeared multiple times a week for doctor’s appointments or physical therapy. I learned to deflect these questions or give nebulous answers about an accident or injury. The reality is that I was born with cerebral palsy (CP). My CP manifested as hemiparesis on the left side of my body. I was in aggressive physical therapy throughout childhood, received Botox injections for muscle spasticity, and underwent corrective surgery on my left leg to straighten my foot. In childhood, the diagnosis meant nothing more than 2 words that sounded like they belonged to superheroes in comic books. Even with supportive parents and family, I kept my disability a secret, much like the powers and abilities of my favorite superheroes.

However, like all great origin stories, what I once thought were weaknesses turned out to be strengths that pushed me through college, medical school, and now psychiatry residency. Living with a disability has shaped how I see the world and relate to my patients. My experience has helped me connect to my patients in ways others might not. These properties are important in any physician but vital in psychiatry, where many patients feel neglected or stigmatized; this is another reason there should be more doctors with disabilities in medicine. Unfortunately, systemic barriers are still in place that disincentivize those with a disability from pursuing careers in medicine. Stories like mine are important to inspire a reexamination of what a physician should be and how medicine, patients, and communities benefit from this change.

My experience through medical school

My path to psychiatry and residency was shaped by my early experience with the medical field and treatment. From the early days of my diagnosis at age 4, I was told that my brain was “wired differently” and that, because of this disruption in circuitry, I would have difficulty with physical activity. I grew to appreciate the intricacies of the brain and pathology to understand my body. With greater understanding came the existential realization that I would live with a disability for the rest of my life. Rather than dream of a future where I would be “normal,” I focused on adapting my life to my normal. An unfortunate reality of this normal was that no doctor would be able to relate to me, and my health care would focus on limitations rather than possibilities.

I focused on school as a distraction and slowly warmed to the idea of pursuing medicine as a career. The seed was planted years prior by the numerous doctors’ visits and procedures, and was cultivated by a desire to understand pathologies and offer treatment to patients from the perspective of a patient. When I applied to medical school, I did not know how to address my CP. Living as a person with CP was a core reason for my decision to pursue medicine, but I was afraid that a disclosure of disability would preclude any admission to medical school. Research into programs offered little guidance because most institutions only listed vague “physical expectations” of each student. There were times I doubted if I would be accepted anywhere. Many programs I reached out to about my situation seemed unenthusiastic about the prospect of a student with CP, and when I brought up my CP in interviews, the reaction was often of surprise and an admission that they had forgotten about “that part” of my application. Fortunately, I was accepted to medical school, but still struggled with the fear that one day I would be found out and not allowed to continue. No one in my class or school was like me, and a meeting with an Americans with Disabilities Act coordinator who asked me to reexamine the physical competencies of the school before advancing to clinical clerkships only further reinforced this fear. I decided to fly under the radar and not say anything about my disability to my attendings. I slowly worked my way through clerkships by making do with adapted ways to perform procedures and exams with additional practice and maneuvering at home. I found myself drawn to psychiatry because of the similarities I saw in the patients and myself. I empathized with how the patients struggled with chronic conditions that left them feeling separated from society and how they felt that their diagnosis was something they needed to hide. When medical school ended and I decided to pursue psychiatry, I wanted to share my story to inspire others with a disability to consider medicine as a career given their unique experiences. My experience thus far has been uplifting as my journey has echoed so many others.

A need for greater representation

Disability representation in medicine is needed more than ever. According to the CDC, >60 million adults in the United States (1 in 4) live with a disability.1 Although the physical health disparities are often discussed, there is less conversation surrounding mental health for individuals with disabilities. A 2018 study by Cree et al2 found that approximately 17.4 million adults with disabilities experienced frequent mental distress, defined as reporting ≥14 mentally unhealthy days in the past 30 days. Furthermore, compared to individuals without a disability, those with a disability are statistically more likely to have suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts.3 One way to address this disparity is to recruit medical students with disabilities to become physicians with disabilities. Evidence suggests that physicians who are members of groups that are underrepresented in medicine are more likely to deliver care to underrepresented patients.4 However, medical schools and institutions have been slow to address the disparity. A 2019 survey found an estimated 4.6% of medical students responded “yes” when asked if they had a disability, with most students reporting a psychological or attention/hyperactive disorder.5 Existing barriers include restrictive language surrounding technical standards influenced by long-standing vestiges of what a physician should be.6

An opportunity to connect with patients

I now do not see myself as having a secret identity to hide. Although my CP does not give me any superpowers, it has given me the opportunity to connect with my patients and serve as an example of why medical school recruitment and admissions should expand. Psychiatrists have been on the forefront of change in medicine and can shift the perception of a physician. In doing so, we not only enrich our field but also the lives of our patients who may need it most.

What does a doctor look like? Throughout history, this concept has shifted due to societal norms and increased access to medical education. Today, the idea of a physician has expanded to incorporate a myriad of people; however, stigma still exists in medicine regarding mental illness and disability. I would like to share my personal journey through high school, college, medical school, and now residency, and how my identity and struggles have shaped me into the physician I am today. There are few conversations around disability—especially disability and mental health—in medicine, and through my own advocacy, I have met many students with disability who feel that medical school is unattainable. Additionally, I have met many medical students, residents, and pre-health advisors who are happy for the experience to learn more about a marginalized group in medicine. My hope in sharing my story is to offer a space for conversation about intersectionality within medical communities and how physicians and physicians in training can facilitate that change, regardless of their position or specialty. Additionally, I hope to shed light on the unique mental health needs of patients with disabilities and how mental health clinicians can address those needs.

Perceived weaknesses turned into strengths

“Why do you walk like that?” “What is that brace on your leg?” The early years of my childhood were marked by these questions and others like them. I was the kid with the limp, the kid with a brace on his leg, and the kid who disappeared multiple times a week for doctor’s appointments or physical therapy. I learned to deflect these questions or give nebulous answers about an accident or injury. The reality is that I was born with cerebral palsy (CP). My CP manifested as hemiparesis on the left side of my body. I was in aggressive physical therapy throughout childhood, received Botox injections for muscle spasticity, and underwent corrective surgery on my left leg to straighten my foot. In childhood, the diagnosis meant nothing more than 2 words that sounded like they belonged to superheroes in comic books. Even with supportive parents and family, I kept my disability a secret, much like the powers and abilities of my favorite superheroes.

However, like all great origin stories, what I once thought were weaknesses turned out to be strengths that pushed me through college, medical school, and now psychiatry residency. Living with a disability has shaped how I see the world and relate to my patients. My experience has helped me connect to my patients in ways others might not. These properties are important in any physician but vital in psychiatry, where many patients feel neglected or stigmatized; this is another reason there should be more doctors with disabilities in medicine. Unfortunately, systemic barriers are still in place that disincentivize those with a disability from pursuing careers in medicine. Stories like mine are important to inspire a reexamination of what a physician should be and how medicine, patients, and communities benefit from this change.

My experience through medical school

My path to psychiatry and residency was shaped by my early experience with the medical field and treatment. From the early days of my diagnosis at age 4, I was told that my brain was “wired differently” and that, because of this disruption in circuitry, I would have difficulty with physical activity. I grew to appreciate the intricacies of the brain and pathology to understand my body. With greater understanding came the existential realization that I would live with a disability for the rest of my life. Rather than dream of a future where I would be “normal,” I focused on adapting my life to my normal. An unfortunate reality of this normal was that no doctor would be able to relate to me, and my health care would focus on limitations rather than possibilities.

I focused on school as a distraction and slowly warmed to the idea of pursuing medicine as a career. The seed was planted years prior by the numerous doctors’ visits and procedures, and was cultivated by a desire to understand pathologies and offer treatment to patients from the perspective of a patient. When I applied to medical school, I did not know how to address my CP. Living as a person with CP was a core reason for my decision to pursue medicine, but I was afraid that a disclosure of disability would preclude any admission to medical school. Research into programs offered little guidance because most institutions only listed vague “physical expectations” of each student. There were times I doubted if I would be accepted anywhere. Many programs I reached out to about my situation seemed unenthusiastic about the prospect of a student with CP, and when I brought up my CP in interviews, the reaction was often of surprise and an admission that they had forgotten about “that part” of my application. Fortunately, I was accepted to medical school, but still struggled with the fear that one day I would be found out and not allowed to continue. No one in my class or school was like me, and a meeting with an Americans with Disabilities Act coordinator who asked me to reexamine the physical competencies of the school before advancing to clinical clerkships only further reinforced this fear. I decided to fly under the radar and not say anything about my disability to my attendings. I slowly worked my way through clerkships by making do with adapted ways to perform procedures and exams with additional practice and maneuvering at home. I found myself drawn to psychiatry because of the similarities I saw in the patients and myself. I empathized with how the patients struggled with chronic conditions that left them feeling separated from society and how they felt that their diagnosis was something they needed to hide. When medical school ended and I decided to pursue psychiatry, I wanted to share my story to inspire others with a disability to consider medicine as a career given their unique experiences. My experience thus far has been uplifting as my journey has echoed so many others.

A need for greater representation

Disability representation in medicine is needed more than ever. According to the CDC, >60 million adults in the United States (1 in 4) live with a disability.1 Although the physical health disparities are often discussed, there is less conversation surrounding mental health for individuals with disabilities. A 2018 study by Cree et al2 found that approximately 17.4 million adults with disabilities experienced frequent mental distress, defined as reporting ≥14 mentally unhealthy days in the past 30 days. Furthermore, compared to individuals without a disability, those with a disability are statistically more likely to have suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts.3 One way to address this disparity is to recruit medical students with disabilities to become physicians with disabilities. Evidence suggests that physicians who are members of groups that are underrepresented in medicine are more likely to deliver care to underrepresented patients.4 However, medical schools and institutions have been slow to address the disparity. A 2019 survey found an estimated 4.6% of medical students responded “yes” when asked if they had a disability, with most students reporting a psychological or attention/hyperactive disorder.5 Existing barriers include restrictive language surrounding technical standards influenced by long-standing vestiges of what a physician should be.6

An opportunity to connect with patients

I now do not see myself as having a secret identity to hide. Although my CP does not give me any superpowers, it has given me the opportunity to connect with my patients and serve as an example of why medical school recruitment and admissions should expand. Psychiatrists have been on the forefront of change in medicine and can shift the perception of a physician. In doing so, we not only enrich our field but also the lives of our patients who may need it most.

1. Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, et al. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(32):882-887.

2. Cree RA, Okoro CA, Zack MM, et al. Frequent mental distress among adults, by disability status, disability type, and selected characteristics—United States 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1238-1243.

3. Marlow NM, Xie Z, Tanner R, et al. Association between disability and suicide-related outcomes among US adults. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(6):852-862.

4. Thurmond VB, Kirch DG. Impact of minority physicians on health care. South Med J. 1998;91(11):1009-1013.

5. Meeks LM, Case B, Herzer K, et al. Change in prevalence of disabilities and accommodation practices among US medical schools, 2016 vs 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(20):2022-2024.

6. Stauffer C, Case B, Moreland CJ, et al. Technical standards from newly established medical schools: a review of disability inclusive practices. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2022;9:23821205211072763.

1. Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, et al. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(32):882-887.

2. Cree RA, Okoro CA, Zack MM, et al. Frequent mental distress among adults, by disability status, disability type, and selected characteristics—United States 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1238-1243.

3. Marlow NM, Xie Z, Tanner R, et al. Association between disability and suicide-related outcomes among US adults. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(6):852-862.

4. Thurmond VB, Kirch DG. Impact of minority physicians on health care. South Med J. 1998;91(11):1009-1013.

5. Meeks LM, Case B, Herzer K, et al. Change in prevalence of disabilities and accommodation practices among US medical schools, 2016 vs 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(20):2022-2024.

6. Stauffer C, Case B, Moreland CJ, et al. Technical standards from newly established medical schools: a review of disability inclusive practices. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2022;9:23821205211072763.

Discontinuing a long-acting injectable antipsychotic: What to consider

Mr. R, age 29, was diagnosed with schizophrenia 6 years ago. To manage his disorder, he has been receiving paliperidone palmitate long-acting injectable (LAI) 156 mg once a month for 2 years. Prior to maintenance with paliperidone palmitate, Mr. R was stabilized on oral paliperidone 9 mg/d. Though he was originally initiated on paliperidone palmitate due to nonadherence concerns, Mr. R has been adherent with each injection for 1 year.

At a recent visit, Mr. R says he wants to discontinue the injection because he is not interested in receiving an ongoing injectable medication and is not able to continue monthly clinic visits. He wants to take a daily oral antipsychotic again, despite the availability of longer-acting products.

A paucity of evidence exists regarding the discontinuation of LAI antipsychotics and the next steps that follow in treatment. There is neither a consensus nor recognized guidelines advising how and when to discontinue an LAI and restart an oral antipsychotic. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated different maintenance treatment strategies; however, switching from an LAI antipsychotic to an oral medication was not a focus.1 In this article, we outline a possible approach to discontinuing an LAI antipsychotic and restarting an oral formulation. Before discontinuing an LAI antipsychotic, clinicians should review with the patient the risks and benefits of switching medications, including the risk of decompensation and potential adverse effects.

Switching to an oral antipsychotic

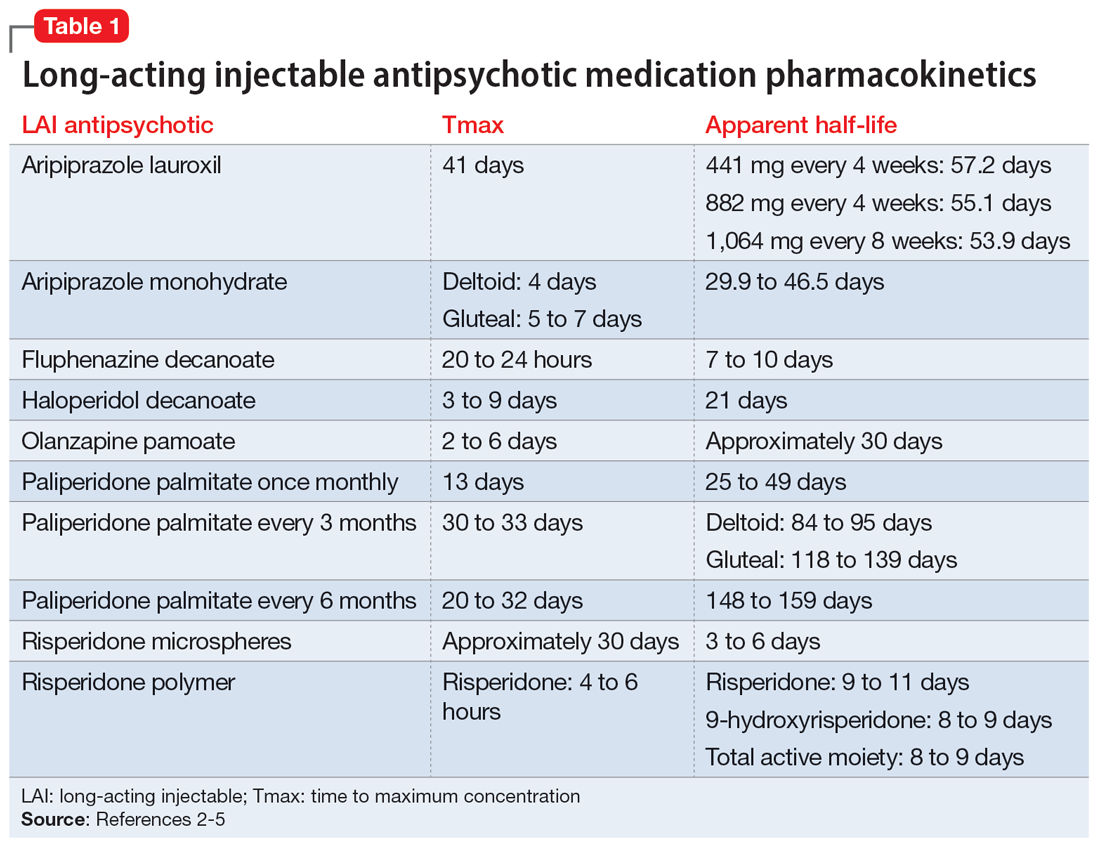

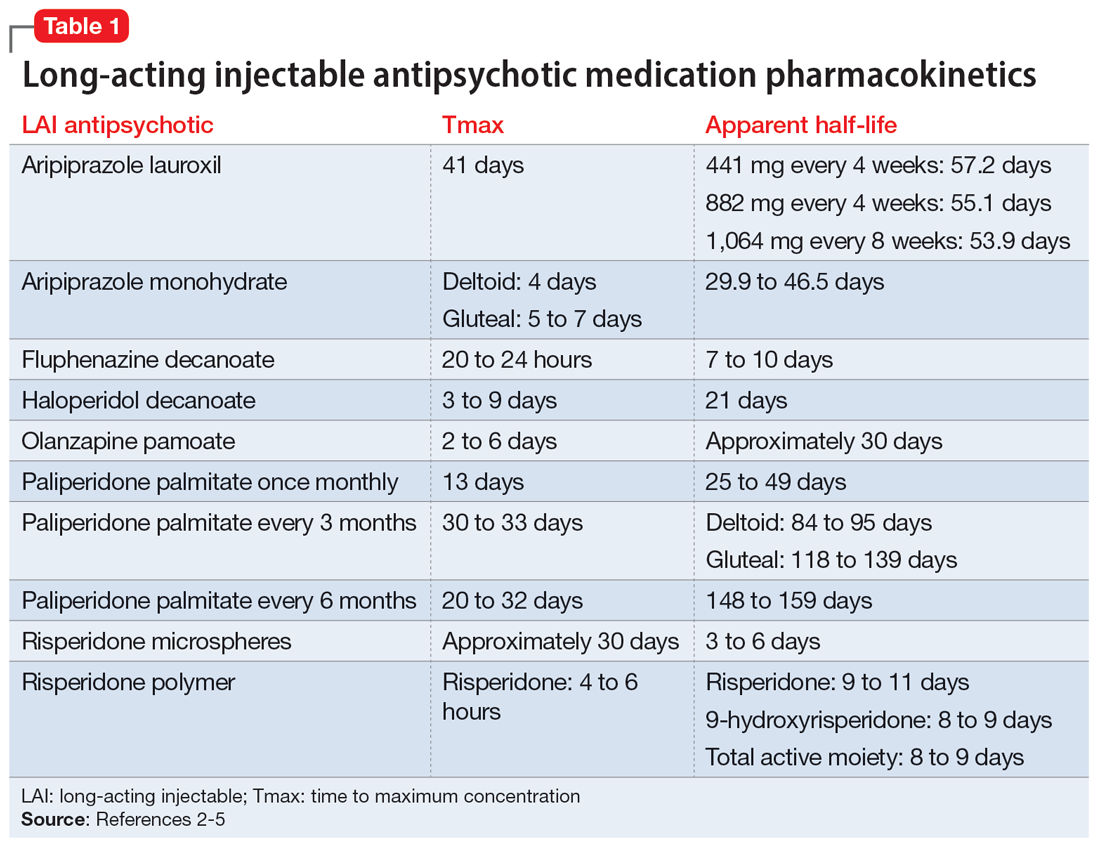

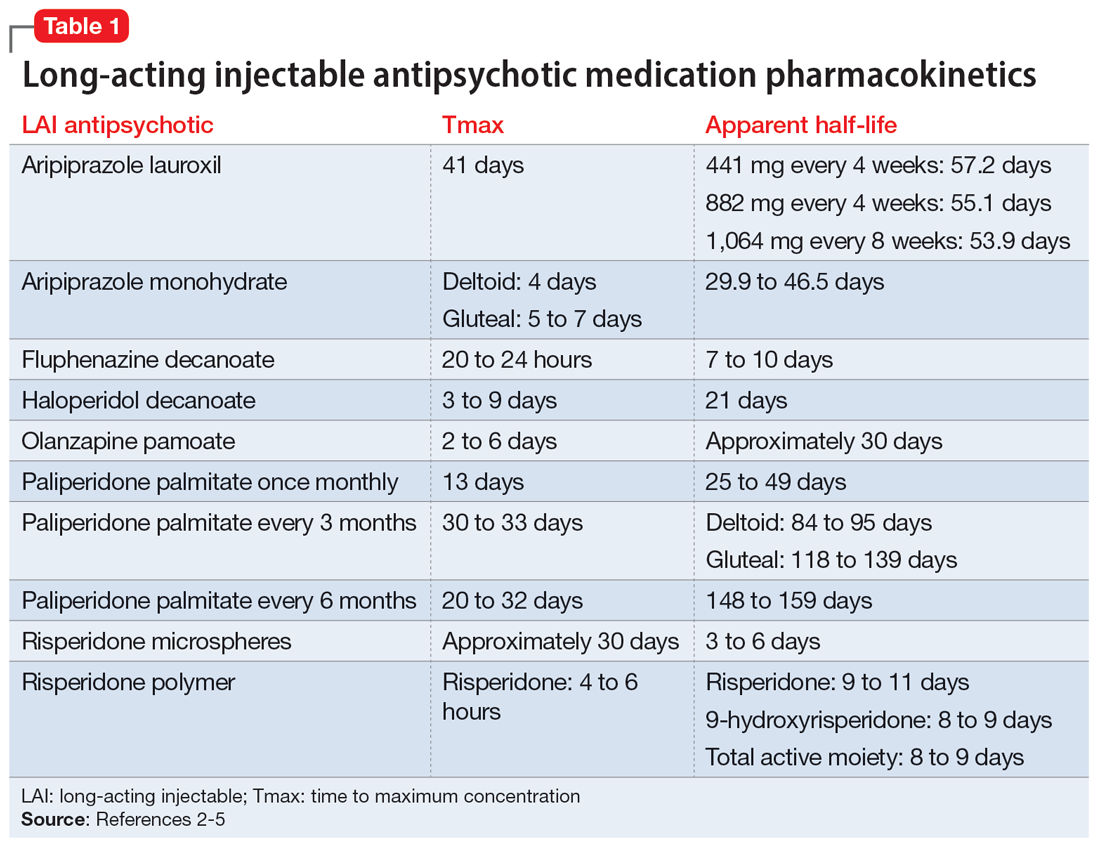

The first step in the discontinuation process is to determine whether the patient will continue the same oral medication as the LAI antipsychotic or if a different oral antipsychotic will be initiated. Next, determining when to initiate the oral medication requires several pieces of information, including the oral dose equivalent of the patient’s current LAI, the half-life of the LAI, and the release mechanism of the LAI (Table 1).2-5 To determine the appropriate time frame for restarting oral treatment, it is also vital to know the date of the last injection.

Based on the date of the next injection, the clinician will utilize the LAI’s half-life and its release mechanism to determine the appropriate time to start a new oral antipsychotic. Research demonstrates that in patients who have achieved steady state with a first-generation antipsychotic, plasma concentrations stay relatively consistent for 6 to 7 weeks after the last injection, which suggests oral medications may not need to be initiated until that time.6-9

For many second-generation LAI antipsychotics, oral medications may be initiated at the date of the next injection. Initiation of an oral antipsychotic may require more time between the last injection dose and the date of administration for oral medication due to the pharmacokinetic profile of risperidone microspheres. Once a patient is at steady state with risperidone microspheres, trough levels are not observed until 3 to 4 weeks after discontinuation.10

Previous pharmacokinetic model–based stimulations of active moiety plasma concentrations of risperidone microspheres demonstrate that 2 weeks after an injection of risperidone microspheres, the concentration of active moiety continued to approximate the steady-state concentration for 3 to 5 weeks.11 This is likely due to the product’s delay in release being 3 weeks from the time of injection to the last release phase. Of note, there was a rapid decline in the active moiety concentration; it reached nearly 0 by Week 5.11 The same pharmacokinetic model–based stimulation demonstrated a steady and slow decline of the concentration of active moiety of paliperidone palmitate after discontinuation of the LAI.11

Continue to: No guidance exists for...

No guidance exists for aripiprazole LAI medications; however, based on the pharmacokinetic data, administration of oral medications should be initiated at the date of next injection. Given the long half-life of aripiprazole, a cross-titration of the LAI with oral medication is reasonable.

Monitoring drug levels

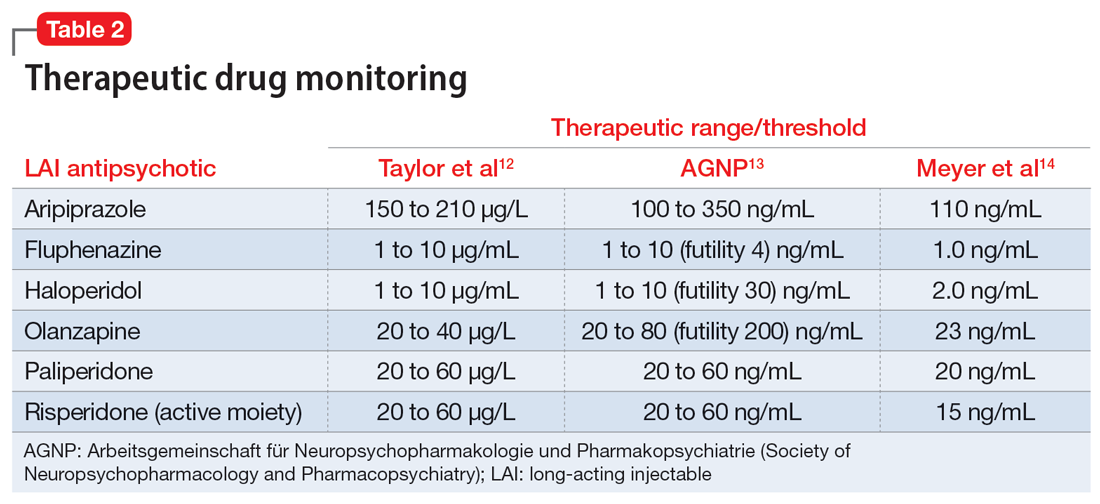

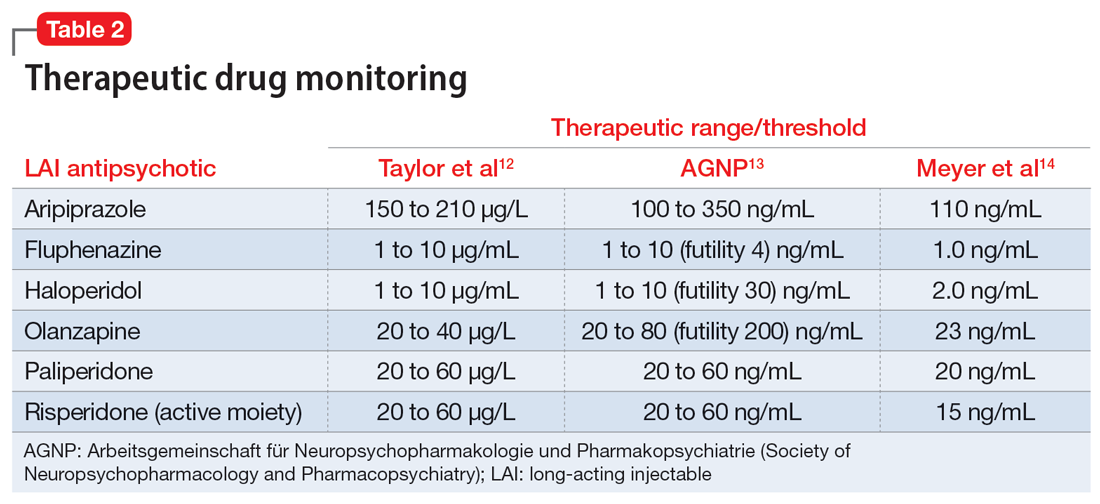

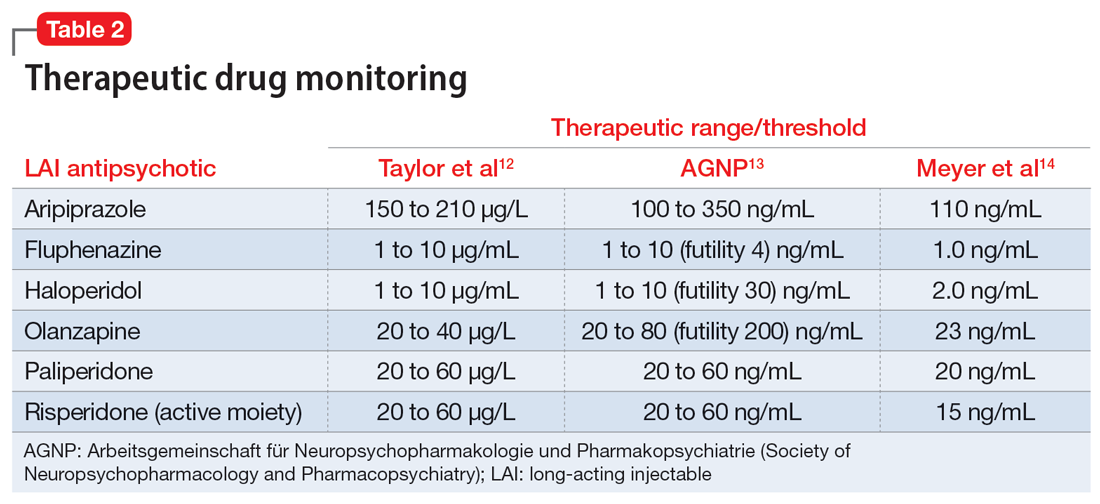

In addition to utilizing the pharmacokinetic data from LAI antipsychotics, therapeutic drug levels can be instrumental in determining the dose of oral medication to use and when to begin titration (Table 2).12-14 Obtaining a drug level on the date of the next injection can provide the clinician with data regarding the release of the medication specific to the patient. Based on the level and the current symptomatology, the clinician could choose to start the oral medication at a lower dose and titrate back to the LAI equivalent oral dose, or initiate the oral dose at the LAI equivalent oral dose. Continued therapeutic drug levels can aid in this determination.

No guidance exists on the appropriate discontinuation of LAI antipsychotics. Utilizing a medication’s half-life and release mechanism, as well as the patient’s previous medication history, date of last injection, and therapeutic drug levels, should be considered when determining the schedule for restarting an oral antipsychotic.

CASE CONTINUED

Based on the current dosing of paliperidone palmitate of 156 mg once a month, Mr. R likely requires 9 mg/d of oral paliperidone upon discontinuation of the LAI. On the date of the next injection, the clinician could decide to initiate a lower dose of paliperidone, such as to 3 mg/d or 6 mg/d, and increase the dose as tolerated over the next 10 to 14 days as the paliperidone palmitate is further metabolized. Additionally, the clinician may consider obtaining a therapeutic drug level to determine the current paliperidone level prior to initiating the oral medication. Each treatment option offers individual risks and benefits. The decision on when and how to initiate the oral medication will be based on the individual patient’s situation and history, as well as the comfort and discretion of the clinician. The clinician should arrange appropriate monitoring for potential increased symptomatology during the transition, and adverse effects should be assessed regularly until steady state is achieved with the targeted oral dose of medication.

Related Resources

- Parmentier BL. Second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics: a practical guide. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):24-32.

- Thippaiah SM, Fargason RE, Birur B. Switching antipsychotics: a guide to dose equivalents. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):13-14. doi:10.12788/cp.0103

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Aripiprazole monohydrate • Maintena

Haloperidol injection • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine pamoate • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate once monthly • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate every 3 months • Invega Trinza

Paliperidone palmitate every 6 months • Invega Hafyera

Risperidone microspheres • Risperdal Consta

Risperidone polymer • Perseris

1. Ostuzzi G, Vita G, Bertolini F, et al. Continuing, reducing, switching, or stopping antipsychotics in individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders who are clinically stable: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(8):614-624.

2. Correll CU, Kim E, Sliwa JK, et al. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia: an overview. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(1):39-59.

3. Spanarello S, La Ferla T. The pharmacokinetics of long-acting antipsychotic medications. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2014;9(3):310-317.

4. Meyer JM. Understanding depot antipsychotics: an illustrated guide to kinetics. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(Suppl 1):58-68.

5. Invega Hafyera [package insert]. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2021.

6. Gitlin MJ, Midha KK, Fogelson D, et al. Persistence of fluphenazine in plasma after decanoate withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988;8(1):53-56.

7. Wistedt B, Jørgensen A, Wiles D. A depot neuroleptic withdrawal study. Plasma concentration of fluphenazine and flupenthixol and relapse frequency. Psychopharmacology. 1982;78(4):301-304.

8. Chang WH, Lin SK, Juang DJ, et al. Prolonged haloperidol and reduced haloperidol plasma concentrations after decanoate withdrawal. Schizophr Res. 1993;9(1):35-40.

9. Eklund K, Forsman A. Minimal effective dose and relapse—double-blind trial: haloperidol decanoate vs. placebo. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1991;1(Suppl 2):S7-S15.

10. Wilson WH. A visual guide to expected blood levels of long-acting injectable risperidone in clinical practice. J Psychiatry Pract. 2004;10(6):393-401.

11. Samtani MN, Sheehan JJ, Fu DJ, et al. Management of antipsychotic treatment discontinuation and interruptions using model-based simulations. Clin Pharmacol. 2012;4:25-40.

12. Taylor D, Barnes TRE, Young AH. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. 13th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2018.

13. Hiemke C, Bergemann N, Clement HW, et al. Consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in neuropsychopharmacology: update 2017. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51(1-2):9-62.

14. Meyer JM, Stahl SM. The Clinical Use of Antipsychotic Plasma Levels. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

Mr. R, age 29, was diagnosed with schizophrenia 6 years ago. To manage his disorder, he has been receiving paliperidone palmitate long-acting injectable (LAI) 156 mg once a month for 2 years. Prior to maintenance with paliperidone palmitate, Mr. R was stabilized on oral paliperidone 9 mg/d. Though he was originally initiated on paliperidone palmitate due to nonadherence concerns, Mr. R has been adherent with each injection for 1 year.

At a recent visit, Mr. R says he wants to discontinue the injection because he is not interested in receiving an ongoing injectable medication and is not able to continue monthly clinic visits. He wants to take a daily oral antipsychotic again, despite the availability of longer-acting products.

A paucity of evidence exists regarding the discontinuation of LAI antipsychotics and the next steps that follow in treatment. There is neither a consensus nor recognized guidelines advising how and when to discontinue an LAI and restart an oral antipsychotic. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated different maintenance treatment strategies; however, switching from an LAI antipsychotic to an oral medication was not a focus.1 In this article, we outline a possible approach to discontinuing an LAI antipsychotic and restarting an oral formulation. Before discontinuing an LAI antipsychotic, clinicians should review with the patient the risks and benefits of switching medications, including the risk of decompensation and potential adverse effects.

Switching to an oral antipsychotic

The first step in the discontinuation process is to determine whether the patient will continue the same oral medication as the LAI antipsychotic or if a different oral antipsychotic will be initiated. Next, determining when to initiate the oral medication requires several pieces of information, including the oral dose equivalent of the patient’s current LAI, the half-life of the LAI, and the release mechanism of the LAI (Table 1).2-5 To determine the appropriate time frame for restarting oral treatment, it is also vital to know the date of the last injection.

Based on the date of the next injection, the clinician will utilize the LAI’s half-life and its release mechanism to determine the appropriate time to start a new oral antipsychotic. Research demonstrates that in patients who have achieved steady state with a first-generation antipsychotic, plasma concentrations stay relatively consistent for 6 to 7 weeks after the last injection, which suggests oral medications may not need to be initiated until that time.6-9

For many second-generation LAI antipsychotics, oral medications may be initiated at the date of the next injection. Initiation of an oral antipsychotic may require more time between the last injection dose and the date of administration for oral medication due to the pharmacokinetic profile of risperidone microspheres. Once a patient is at steady state with risperidone microspheres, trough levels are not observed until 3 to 4 weeks after discontinuation.10

Previous pharmacokinetic model–based stimulations of active moiety plasma concentrations of risperidone microspheres demonstrate that 2 weeks after an injection of risperidone microspheres, the concentration of active moiety continued to approximate the steady-state concentration for 3 to 5 weeks.11 This is likely due to the product’s delay in release being 3 weeks from the time of injection to the last release phase. Of note, there was a rapid decline in the active moiety concentration; it reached nearly 0 by Week 5.11 The same pharmacokinetic model–based stimulation demonstrated a steady and slow decline of the concentration of active moiety of paliperidone palmitate after discontinuation of the LAI.11

Continue to: No guidance exists for...

No guidance exists for aripiprazole LAI medications; however, based on the pharmacokinetic data, administration of oral medications should be initiated at the date of next injection. Given the long half-life of aripiprazole, a cross-titration of the LAI with oral medication is reasonable.

Monitoring drug levels

In addition to utilizing the pharmacokinetic data from LAI antipsychotics, therapeutic drug levels can be instrumental in determining the dose of oral medication to use and when to begin titration (Table 2).12-14 Obtaining a drug level on the date of the next injection can provide the clinician with data regarding the release of the medication specific to the patient. Based on the level and the current symptomatology, the clinician could choose to start the oral medication at a lower dose and titrate back to the LAI equivalent oral dose, or initiate the oral dose at the LAI equivalent oral dose. Continued therapeutic drug levels can aid in this determination.

No guidance exists on the appropriate discontinuation of LAI antipsychotics. Utilizing a medication’s half-life and release mechanism, as well as the patient’s previous medication history, date of last injection, and therapeutic drug levels, should be considered when determining the schedule for restarting an oral antipsychotic.

CASE CONTINUED

Based on the current dosing of paliperidone palmitate of 156 mg once a month, Mr. R likely requires 9 mg/d of oral paliperidone upon discontinuation of the LAI. On the date of the next injection, the clinician could decide to initiate a lower dose of paliperidone, such as to 3 mg/d or 6 mg/d, and increase the dose as tolerated over the next 10 to 14 days as the paliperidone palmitate is further metabolized. Additionally, the clinician may consider obtaining a therapeutic drug level to determine the current paliperidone level prior to initiating the oral medication. Each treatment option offers individual risks and benefits. The decision on when and how to initiate the oral medication will be based on the individual patient’s situation and history, as well as the comfort and discretion of the clinician. The clinician should arrange appropriate monitoring for potential increased symptomatology during the transition, and adverse effects should be assessed regularly until steady state is achieved with the targeted oral dose of medication.

Related Resources

- Parmentier BL. Second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics: a practical guide. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):24-32.

- Thippaiah SM, Fargason RE, Birur B. Switching antipsychotics: a guide to dose equivalents. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):13-14. doi:10.12788/cp.0103

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Aripiprazole monohydrate • Maintena

Haloperidol injection • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine pamoate • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate once monthly • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate every 3 months • Invega Trinza

Paliperidone palmitate every 6 months • Invega Hafyera

Risperidone microspheres • Risperdal Consta

Risperidone polymer • Perseris

Mr. R, age 29, was diagnosed with schizophrenia 6 years ago. To manage his disorder, he has been receiving paliperidone palmitate long-acting injectable (LAI) 156 mg once a month for 2 years. Prior to maintenance with paliperidone palmitate, Mr. R was stabilized on oral paliperidone 9 mg/d. Though he was originally initiated on paliperidone palmitate due to nonadherence concerns, Mr. R has been adherent with each injection for 1 year.

At a recent visit, Mr. R says he wants to discontinue the injection because he is not interested in receiving an ongoing injectable medication and is not able to continue monthly clinic visits. He wants to take a daily oral antipsychotic again, despite the availability of longer-acting products.

A paucity of evidence exists regarding the discontinuation of LAI antipsychotics and the next steps that follow in treatment. There is neither a consensus nor recognized guidelines advising how and when to discontinue an LAI and restart an oral antipsychotic. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated different maintenance treatment strategies; however, switching from an LAI antipsychotic to an oral medication was not a focus.1 In this article, we outline a possible approach to discontinuing an LAI antipsychotic and restarting an oral formulation. Before discontinuing an LAI antipsychotic, clinicians should review with the patient the risks and benefits of switching medications, including the risk of decompensation and potential adverse effects.

Switching to an oral antipsychotic

The first step in the discontinuation process is to determine whether the patient will continue the same oral medication as the LAI antipsychotic or if a different oral antipsychotic will be initiated. Next, determining when to initiate the oral medication requires several pieces of information, including the oral dose equivalent of the patient’s current LAI, the half-life of the LAI, and the release mechanism of the LAI (Table 1).2-5 To determine the appropriate time frame for restarting oral treatment, it is also vital to know the date of the last injection.

Based on the date of the next injection, the clinician will utilize the LAI’s half-life and its release mechanism to determine the appropriate time to start a new oral antipsychotic. Research demonstrates that in patients who have achieved steady state with a first-generation antipsychotic, plasma concentrations stay relatively consistent for 6 to 7 weeks after the last injection, which suggests oral medications may not need to be initiated until that time.6-9

For many second-generation LAI antipsychotics, oral medications may be initiated at the date of the next injection. Initiation of an oral antipsychotic may require more time between the last injection dose and the date of administration for oral medication due to the pharmacokinetic profile of risperidone microspheres. Once a patient is at steady state with risperidone microspheres, trough levels are not observed until 3 to 4 weeks after discontinuation.10

Previous pharmacokinetic model–based stimulations of active moiety plasma concentrations of risperidone microspheres demonstrate that 2 weeks after an injection of risperidone microspheres, the concentration of active moiety continued to approximate the steady-state concentration for 3 to 5 weeks.11 This is likely due to the product’s delay in release being 3 weeks from the time of injection to the last release phase. Of note, there was a rapid decline in the active moiety concentration; it reached nearly 0 by Week 5.11 The same pharmacokinetic model–based stimulation demonstrated a steady and slow decline of the concentration of active moiety of paliperidone palmitate after discontinuation of the LAI.11

Continue to: No guidance exists for...

No guidance exists for aripiprazole LAI medications; however, based on the pharmacokinetic data, administration of oral medications should be initiated at the date of next injection. Given the long half-life of aripiprazole, a cross-titration of the LAI with oral medication is reasonable.

Monitoring drug levels

In addition to utilizing the pharmacokinetic data from LAI antipsychotics, therapeutic drug levels can be instrumental in determining the dose of oral medication to use and when to begin titration (Table 2).12-14 Obtaining a drug level on the date of the next injection can provide the clinician with data regarding the release of the medication specific to the patient. Based on the level and the current symptomatology, the clinician could choose to start the oral medication at a lower dose and titrate back to the LAI equivalent oral dose, or initiate the oral dose at the LAI equivalent oral dose. Continued therapeutic drug levels can aid in this determination.

No guidance exists on the appropriate discontinuation of LAI antipsychotics. Utilizing a medication’s half-life and release mechanism, as well as the patient’s previous medication history, date of last injection, and therapeutic drug levels, should be considered when determining the schedule for restarting an oral antipsychotic.

CASE CONTINUED

Based on the current dosing of paliperidone palmitate of 156 mg once a month, Mr. R likely requires 9 mg/d of oral paliperidone upon discontinuation of the LAI. On the date of the next injection, the clinician could decide to initiate a lower dose of paliperidone, such as to 3 mg/d or 6 mg/d, and increase the dose as tolerated over the next 10 to 14 days as the paliperidone palmitate is further metabolized. Additionally, the clinician may consider obtaining a therapeutic drug level to determine the current paliperidone level prior to initiating the oral medication. Each treatment option offers individual risks and benefits. The decision on when and how to initiate the oral medication will be based on the individual patient’s situation and history, as well as the comfort and discretion of the clinician. The clinician should arrange appropriate monitoring for potential increased symptomatology during the transition, and adverse effects should be assessed regularly until steady state is achieved with the targeted oral dose of medication.

Related Resources

- Parmentier BL. Second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics: a practical guide. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):24-32.

- Thippaiah SM, Fargason RE, Birur B. Switching antipsychotics: a guide to dose equivalents. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):13-14. doi:10.12788/cp.0103

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Aripiprazole monohydrate • Maintena

Haloperidol injection • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine pamoate • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate once monthly • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate every 3 months • Invega Trinza

Paliperidone palmitate every 6 months • Invega Hafyera

Risperidone microspheres • Risperdal Consta

Risperidone polymer • Perseris

1. Ostuzzi G, Vita G, Bertolini F, et al. Continuing, reducing, switching, or stopping antipsychotics in individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders who are clinically stable: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(8):614-624.

2. Correll CU, Kim E, Sliwa JK, et al. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia: an overview. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(1):39-59.

3. Spanarello S, La Ferla T. The pharmacokinetics of long-acting antipsychotic medications. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2014;9(3):310-317.

4. Meyer JM. Understanding depot antipsychotics: an illustrated guide to kinetics. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(Suppl 1):58-68.

5. Invega Hafyera [package insert]. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2021.

6. Gitlin MJ, Midha KK, Fogelson D, et al. Persistence of fluphenazine in plasma after decanoate withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988;8(1):53-56.

7. Wistedt B, Jørgensen A, Wiles D. A depot neuroleptic withdrawal study. Plasma concentration of fluphenazine and flupenthixol and relapse frequency. Psychopharmacology. 1982;78(4):301-304.

8. Chang WH, Lin SK, Juang DJ, et al. Prolonged haloperidol and reduced haloperidol plasma concentrations after decanoate withdrawal. Schizophr Res. 1993;9(1):35-40.

9. Eklund K, Forsman A. Minimal effective dose and relapse—double-blind trial: haloperidol decanoate vs. placebo. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1991;1(Suppl 2):S7-S15.

10. Wilson WH. A visual guide to expected blood levels of long-acting injectable risperidone in clinical practice. J Psychiatry Pract. 2004;10(6):393-401.

11. Samtani MN, Sheehan JJ, Fu DJ, et al. Management of antipsychotic treatment discontinuation and interruptions using model-based simulations. Clin Pharmacol. 2012;4:25-40.

12. Taylor D, Barnes TRE, Young AH. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. 13th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2018.

13. Hiemke C, Bergemann N, Clement HW, et al. Consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in neuropsychopharmacology: update 2017. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51(1-2):9-62.

14. Meyer JM, Stahl SM. The Clinical Use of Antipsychotic Plasma Levels. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

1. Ostuzzi G, Vita G, Bertolini F, et al. Continuing, reducing, switching, or stopping antipsychotics in individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders who are clinically stable: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(8):614-624.

2. Correll CU, Kim E, Sliwa JK, et al. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia: an overview. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(1):39-59.

3. Spanarello S, La Ferla T. The pharmacokinetics of long-acting antipsychotic medications. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2014;9(3):310-317.

4. Meyer JM. Understanding depot antipsychotics: an illustrated guide to kinetics. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(Suppl 1):58-68.

5. Invega Hafyera [package insert]. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2021.

6. Gitlin MJ, Midha KK, Fogelson D, et al. Persistence of fluphenazine in plasma after decanoate withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988;8(1):53-56.

7. Wistedt B, Jørgensen A, Wiles D. A depot neuroleptic withdrawal study. Plasma concentration of fluphenazine and flupenthixol and relapse frequency. Psychopharmacology. 1982;78(4):301-304.

8. Chang WH, Lin SK, Juang DJ, et al. Prolonged haloperidol and reduced haloperidol plasma concentrations after decanoate withdrawal. Schizophr Res. 1993;9(1):35-40.

9. Eklund K, Forsman A. Minimal effective dose and relapse—double-blind trial: haloperidol decanoate vs. placebo. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1991;1(Suppl 2):S7-S15.

10. Wilson WH. A visual guide to expected blood levels of long-acting injectable risperidone in clinical practice. J Psychiatry Pract. 2004;10(6):393-401.

11. Samtani MN, Sheehan JJ, Fu DJ, et al. Management of antipsychotic treatment discontinuation and interruptions using model-based simulations. Clin Pharmacol. 2012;4:25-40.

12. Taylor D, Barnes TRE, Young AH. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. 13th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2018.

13. Hiemke C, Bergemann N, Clement HW, et al. Consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in neuropsychopharmacology: update 2017. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51(1-2):9-62.

14. Meyer JM, Stahl SM. The Clinical Use of Antipsychotic Plasma Levels. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

Medication-induced rhabdomyolysis

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Ms. A, age 32, has a history of anxiety, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder. She is undergoing treatment with lamotrigine 200 mg/d at bedtime, aripiprazole 5 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, clonazepam 0.5 mg twice a day, and hydroxyzine 25 mg twice a day. She presents to the emergency department with myalgia, left upper and lower extremity numbness, and weakness. These symptoms started at approximately 3

Ms. A’s vital signs are hemodynamically stable, but her pulse is 113 bpm. On examination, she appears anxious and has decreased sensation in her upper and lower extremities, with 3/5 strength on the left side. Her laboratory results indicate mild leukocytosis, hyponatremia (129 mmol/L; reference range 136 to 145 mmol/L), and elevations in serum creatinine (3.7 mg/dL; reference range 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (654 U/L; reference range 10 to 42 U/L), alanine transaminase (234 U/L; reference range 10 to 60 U/L), and troponin (2.11 ng/mL; reference range 0 to 0.04 ng/mL). A urinalysis reveals darkly colored urine with large red blood cells.

Neurology and Cardiology consultations are requested to rule out stroke and acute coronary syndromes. A computed tomography scan of the head shows no acute intracranial findings. Her creatinine kinase (CK) level is elevated (>42,670 U/L; reference range 22 to 232 U/L), which prompts a search for causes of rhabdomyolysis, a breakdown of muscle tissue that releases muscle fiber contents into the blood. Ms. A reports no history of recent trauma or strenuous exercise. Infectious, endocrine, and other workups are negative. After a consult to Psychiatry, the treating clinicians suspect that the most likely cause for rhabdomyolysis is aripiprazole.

Ms. A is treated with IV isotonic fluids. Aripiprazole is stopped and her CK levels are closely monitored. CK levels continue to trend down, and by Day 6 of hospitalization her CK level is 1,648 U/L. Her transaminase levels also improve; these elevations are considered likely secondary to rhabdomyolysis. Because there is notable improvement in CK and transaminase levels after stopping aripiprazole, Ms. A is discharged and instructed to follow up with a psychiatrist for further management.

Aripiprazole and rhabdomyolysis

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, an estimated 2.8% of the US population has bipolar disorder and 0.24% to 0.64% has schizophrenia.1,2 Antipsychotics are often used to treat these disorders. The prevalence of antipsychotic use in the general adult population is 1.6%.3 The use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) has increased over recent years with the availability of a variety of formulations, such as immediate-release injectable, long-acting injectable, and orally disintegrating tablets in addition to the customary oral tablets. SGAs can cause several adverse effects, including weight gain, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, QTc prolongation, extrapyramidal side effects, myocarditis, agranulocytosis, cataracts, and sexual adverse effects.4

Antipsychotic use is more commonly associated with serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome than it is with rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis as an adverse effect of antipsychotic use has not been well understood or reported. One study found the prevalence of rhabdomyolysis was approximately 10% among patients who received an antipsychotic medication.5 There have been 4 case reports of clozapine use, 6 of olanzapine use, and 3 of aripiprazole use associated with rhabdomyolysis.6-8 Therefore, this would be the fourth case report to describe aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis.

Aripiprazole is FDA-approved for the treatment of schizophrenia. In this case report, we found that aripiprazole could have led to rhabdomyolysis. Aripiprazole is a quinoline derivative that acts by binding to the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors.9,10 It acts as a partial agonist at 5-HT1A receptors, an antagonist at 5-HT2A receptors, and a partial agonist and stabilizer at the D2 receptor. By binding to the dopamine receptor in its G protein–coupled state, aripiprazole blocks the receptor in the presence of excessive dopamine.11-13 The mechanism of how aripiprazole could cause rhabdomyolysis is unclear. One proposed mechanism is that it can increase the permeability of skeletal muscle by 5-HT2A antagonism. This leads to a decrease in glucose reuptake in the cell and increases the permeability of the cell membrane, leading to elevations in CK levels.14 Another proposed mechanism is that dopamine blockade in the nigrostriatal pathway can result in muscle stiffness, rigidity, parkinsonian-like symptoms, and akathisia, which can result in elevated CK levels.15 There are only 3 other published cases of aripiprazole-induced rhabdomyolysis; we hope this case report will add value to the available literature. More evidence is needed to establish the safety profile of aripiprazole.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of bipolar disorder among adults. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/bipolar-disorder#part_2605

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia#part_2543

3. Dennis JA, Gittner LS, Payne JD, et al. Characteristics of U.S. adults taking prescription antipsychotic medications, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2018. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):483. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02895-4

4. Willner K, Vasan S, Abdijadid S. Atypical antipsychotic agents. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448156/

5. Packard K, Price P, Hanson A. Antipsychotic use and the risk of rhabdomyolysis. J Pharm Pract 2014;27(5):501-512. doi: 10.1177/0897190013516509

6. Wu YF, Chang KY. Aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis in a patient with schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(3):E51.

7. Marzetti E, Bocchino L, Teramo S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis in a patient on aripiprazole with traumatic hip prosthesis luxation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):E40-E41.

8. Zhu X, Hu J, Deng S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and elevated liver enzymes after rapid correction of hyponatremia due to pneumonia and concurrent use of aripiprazole: a case report. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52(2):206. doi:10.1177/0004867417743342

9. Stahl SM. Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Application. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2000.

10. Stahl SM. “Hit-and-run” actions at dopamine receptors, part 1: mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(9):670-671.

11. Leysen JE, Janssen PM, Schotte A, et al. Interaction of antipsychotic drugs with neurotransmitter receptor sites in vitro and in vivo in relation to pharmacological and clinical effects: role of 5HT2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1993;112(1 Suppl):S40-S54.

12. Millan MJ. Improving the treatment of schizophrenia: focus on serotonin (5-HT)(1A) receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295(3):853-861.

13. Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70(2):83-244.

14. Meltzer HY, Cola PA, Parsa M. Marked elevations of serum creatine kinase activity associated with antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15(4):395-405.

15. Devarajan S, Dursun SM. Antipsychotic drugs, serum creatine kinase (CPK) and possible mechanisms. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000;152(1):122.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Ms. A, age 32, has a history of anxiety, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder. She is undergoing treatment with lamotrigine 200 mg/d at bedtime, aripiprazole 5 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, clonazepam 0.5 mg twice a day, and hydroxyzine 25 mg twice a day. She presents to the emergency department with myalgia, left upper and lower extremity numbness, and weakness. These symptoms started at approximately 3

Ms. A’s vital signs are hemodynamically stable, but her pulse is 113 bpm. On examination, she appears anxious and has decreased sensation in her upper and lower extremities, with 3/5 strength on the left side. Her laboratory results indicate mild leukocytosis, hyponatremia (129 mmol/L; reference range 136 to 145 mmol/L), and elevations in serum creatinine (3.7 mg/dL; reference range 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (654 U/L; reference range 10 to 42 U/L), alanine transaminase (234 U/L; reference range 10 to 60 U/L), and troponin (2.11 ng/mL; reference range 0 to 0.04 ng/mL). A urinalysis reveals darkly colored urine with large red blood cells.

Neurology and Cardiology consultations are requested to rule out stroke and acute coronary syndromes. A computed tomography scan of the head shows no acute intracranial findings. Her creatinine kinase (CK) level is elevated (>42,670 U/L; reference range 22 to 232 U/L), which prompts a search for causes of rhabdomyolysis, a breakdown of muscle tissue that releases muscle fiber contents into the blood. Ms. A reports no history of recent trauma or strenuous exercise. Infectious, endocrine, and other workups are negative. After a consult to Psychiatry, the treating clinicians suspect that the most likely cause for rhabdomyolysis is aripiprazole.

Ms. A is treated with IV isotonic fluids. Aripiprazole is stopped and her CK levels are closely monitored. CK levels continue to trend down, and by Day 6 of hospitalization her CK level is 1,648 U/L. Her transaminase levels also improve; these elevations are considered likely secondary to rhabdomyolysis. Because there is notable improvement in CK and transaminase levels after stopping aripiprazole, Ms. A is discharged and instructed to follow up with a psychiatrist for further management.

Aripiprazole and rhabdomyolysis

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, an estimated 2.8% of the US population has bipolar disorder and 0.24% to 0.64% has schizophrenia.1,2 Antipsychotics are often used to treat these disorders. The prevalence of antipsychotic use in the general adult population is 1.6%.3 The use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) has increased over recent years with the availability of a variety of formulations, such as immediate-release injectable, long-acting injectable, and orally disintegrating tablets in addition to the customary oral tablets. SGAs can cause several adverse effects, including weight gain, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, QTc prolongation, extrapyramidal side effects, myocarditis, agranulocytosis, cataracts, and sexual adverse effects.4

Antipsychotic use is more commonly associated with serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome than it is with rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis as an adverse effect of antipsychotic use has not been well understood or reported. One study found the prevalence of rhabdomyolysis was approximately 10% among patients who received an antipsychotic medication.5 There have been 4 case reports of clozapine use, 6 of olanzapine use, and 3 of aripiprazole use associated with rhabdomyolysis.6-8 Therefore, this would be the fourth case report to describe aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis.

Aripiprazole is FDA-approved for the treatment of schizophrenia. In this case report, we found that aripiprazole could have led to rhabdomyolysis. Aripiprazole is a quinoline derivative that acts by binding to the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors.9,10 It acts as a partial agonist at 5-HT1A receptors, an antagonist at 5-HT2A receptors, and a partial agonist and stabilizer at the D2 receptor. By binding to the dopamine receptor in its G protein–coupled state, aripiprazole blocks the receptor in the presence of excessive dopamine.11-13 The mechanism of how aripiprazole could cause rhabdomyolysis is unclear. One proposed mechanism is that it can increase the permeability of skeletal muscle by 5-HT2A antagonism. This leads to a decrease in glucose reuptake in the cell and increases the permeability of the cell membrane, leading to elevations in CK levels.14 Another proposed mechanism is that dopamine blockade in the nigrostriatal pathway can result in muscle stiffness, rigidity, parkinsonian-like symptoms, and akathisia, which can result in elevated CK levels.15 There are only 3 other published cases of aripiprazole-induced rhabdomyolysis; we hope this case report will add value to the available literature. More evidence is needed to establish the safety profile of aripiprazole.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Ms. A, age 32, has a history of anxiety, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder. She is undergoing treatment with lamotrigine 200 mg/d at bedtime, aripiprazole 5 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, clonazepam 0.5 mg twice a day, and hydroxyzine 25 mg twice a day. She presents to the emergency department with myalgia, left upper and lower extremity numbness, and weakness. These symptoms started at approximately 3

Ms. A’s vital signs are hemodynamically stable, but her pulse is 113 bpm. On examination, she appears anxious and has decreased sensation in her upper and lower extremities, with 3/5 strength on the left side. Her laboratory results indicate mild leukocytosis, hyponatremia (129 mmol/L; reference range 136 to 145 mmol/L), and elevations in serum creatinine (3.7 mg/dL; reference range 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (654 U/L; reference range 10 to 42 U/L), alanine transaminase (234 U/L; reference range 10 to 60 U/L), and troponin (2.11 ng/mL; reference range 0 to 0.04 ng/mL). A urinalysis reveals darkly colored urine with large red blood cells.

Neurology and Cardiology consultations are requested to rule out stroke and acute coronary syndromes. A computed tomography scan of the head shows no acute intracranial findings. Her creatinine kinase (CK) level is elevated (>42,670 U/L; reference range 22 to 232 U/L), which prompts a search for causes of rhabdomyolysis, a breakdown of muscle tissue that releases muscle fiber contents into the blood. Ms. A reports no history of recent trauma or strenuous exercise. Infectious, endocrine, and other workups are negative. After a consult to Psychiatry, the treating clinicians suspect that the most likely cause for rhabdomyolysis is aripiprazole.

Ms. A is treated with IV isotonic fluids. Aripiprazole is stopped and her CK levels are closely monitored. CK levels continue to trend down, and by Day 6 of hospitalization her CK level is 1,648 U/L. Her transaminase levels also improve; these elevations are considered likely secondary to rhabdomyolysis. Because there is notable improvement in CK and transaminase levels after stopping aripiprazole, Ms. A is discharged and instructed to follow up with a psychiatrist for further management.

Aripiprazole and rhabdomyolysis

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, an estimated 2.8% of the US population has bipolar disorder and 0.24% to 0.64% has schizophrenia.1,2 Antipsychotics are often used to treat these disorders. The prevalence of antipsychotic use in the general adult population is 1.6%.3 The use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) has increased over recent years with the availability of a variety of formulations, such as immediate-release injectable, long-acting injectable, and orally disintegrating tablets in addition to the customary oral tablets. SGAs can cause several adverse effects, including weight gain, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, QTc prolongation, extrapyramidal side effects, myocarditis, agranulocytosis, cataracts, and sexual adverse effects.4

Antipsychotic use is more commonly associated with serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome than it is with rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis as an adverse effect of antipsychotic use has not been well understood or reported. One study found the prevalence of rhabdomyolysis was approximately 10% among patients who received an antipsychotic medication.5 There have been 4 case reports of clozapine use, 6 of olanzapine use, and 3 of aripiprazole use associated with rhabdomyolysis.6-8 Therefore, this would be the fourth case report to describe aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis.

Aripiprazole is FDA-approved for the treatment of schizophrenia. In this case report, we found that aripiprazole could have led to rhabdomyolysis. Aripiprazole is a quinoline derivative that acts by binding to the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors.9,10 It acts as a partial agonist at 5-HT1A receptors, an antagonist at 5-HT2A receptors, and a partial agonist and stabilizer at the D2 receptor. By binding to the dopamine receptor in its G protein–coupled state, aripiprazole blocks the receptor in the presence of excessive dopamine.11-13 The mechanism of how aripiprazole could cause rhabdomyolysis is unclear. One proposed mechanism is that it can increase the permeability of skeletal muscle by 5-HT2A antagonism. This leads to a decrease in glucose reuptake in the cell and increases the permeability of the cell membrane, leading to elevations in CK levels.14 Another proposed mechanism is that dopamine blockade in the nigrostriatal pathway can result in muscle stiffness, rigidity, parkinsonian-like symptoms, and akathisia, which can result in elevated CK levels.15 There are only 3 other published cases of aripiprazole-induced rhabdomyolysis; we hope this case report will add value to the available literature. More evidence is needed to establish the safety profile of aripiprazole.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of bipolar disorder among adults. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/bipolar-disorder#part_2605

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia#part_2543

3. Dennis JA, Gittner LS, Payne JD, et al. Characteristics of U.S. adults taking prescription antipsychotic medications, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2018. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):483. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02895-4

4. Willner K, Vasan S, Abdijadid S. Atypical antipsychotic agents. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448156/

5. Packard K, Price P, Hanson A. Antipsychotic use and the risk of rhabdomyolysis. J Pharm Pract 2014;27(5):501-512. doi: 10.1177/0897190013516509

6. Wu YF, Chang KY. Aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis in a patient with schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(3):E51.

7. Marzetti E, Bocchino L, Teramo S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis in a patient on aripiprazole with traumatic hip prosthesis luxation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):E40-E41.

8. Zhu X, Hu J, Deng S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and elevated liver enzymes after rapid correction of hyponatremia due to pneumonia and concurrent use of aripiprazole: a case report. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52(2):206. doi:10.1177/0004867417743342

9. Stahl SM. Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Application. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2000.

10. Stahl SM. “Hit-and-run” actions at dopamine receptors, part 1: mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(9):670-671.

11. Leysen JE, Janssen PM, Schotte A, et al. Interaction of antipsychotic drugs with neurotransmitter receptor sites in vitro and in vivo in relation to pharmacological and clinical effects: role of 5HT2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1993;112(1 Suppl):S40-S54.

12. Millan MJ. Improving the treatment of schizophrenia: focus on serotonin (5-HT)(1A) receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295(3):853-861.

13. Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70(2):83-244.

14. Meltzer HY, Cola PA, Parsa M. Marked elevations of serum creatine kinase activity associated with antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15(4):395-405.

15. Devarajan S, Dursun SM. Antipsychotic drugs, serum creatine kinase (CPK) and possible mechanisms. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000;152(1):122.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of bipolar disorder among adults. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/bipolar-disorder#part_2605

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia#part_2543

3. Dennis JA, Gittner LS, Payne JD, et al. Characteristics of U.S. adults taking prescription antipsychotic medications, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2018. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):483. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02895-4

4. Willner K, Vasan S, Abdijadid S. Atypical antipsychotic agents. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448156/

5. Packard K, Price P, Hanson A. Antipsychotic use and the risk of rhabdomyolysis. J Pharm Pract 2014;27(5):501-512. doi: 10.1177/0897190013516509

6. Wu YF, Chang KY. Aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis in a patient with schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(3):E51.

7. Marzetti E, Bocchino L, Teramo S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis in a patient on aripiprazole with traumatic hip prosthesis luxation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):E40-E41.

8. Zhu X, Hu J, Deng S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and elevated liver enzymes after rapid correction of hyponatremia due to pneumonia and concurrent use of aripiprazole: a case report. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52(2):206. doi:10.1177/0004867417743342

9. Stahl SM. Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Application. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2000.

10. Stahl SM. “Hit-and-run” actions at dopamine receptors, part 1: mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(9):670-671.

11. Leysen JE, Janssen PM, Schotte A, et al. Interaction of antipsychotic drugs with neurotransmitter receptor sites in vitro and in vivo in relation to pharmacological and clinical effects: role of 5HT2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1993;112(1 Suppl):S40-S54.

12. Millan MJ. Improving the treatment of schizophrenia: focus on serotonin (5-HT)(1A) receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295(3):853-861.

13. Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70(2):83-244.

14. Meltzer HY, Cola PA, Parsa M. Marked elevations of serum creatine kinase activity associated with antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15(4):395-405.

15. Devarajan S, Dursun SM. Antipsychotic drugs, serum creatine kinase (CPK) and possible mechanisms. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000;152(1):122.

Subtle cognitive decline in a patient with depression and anxiety

CASE Anxious and confused

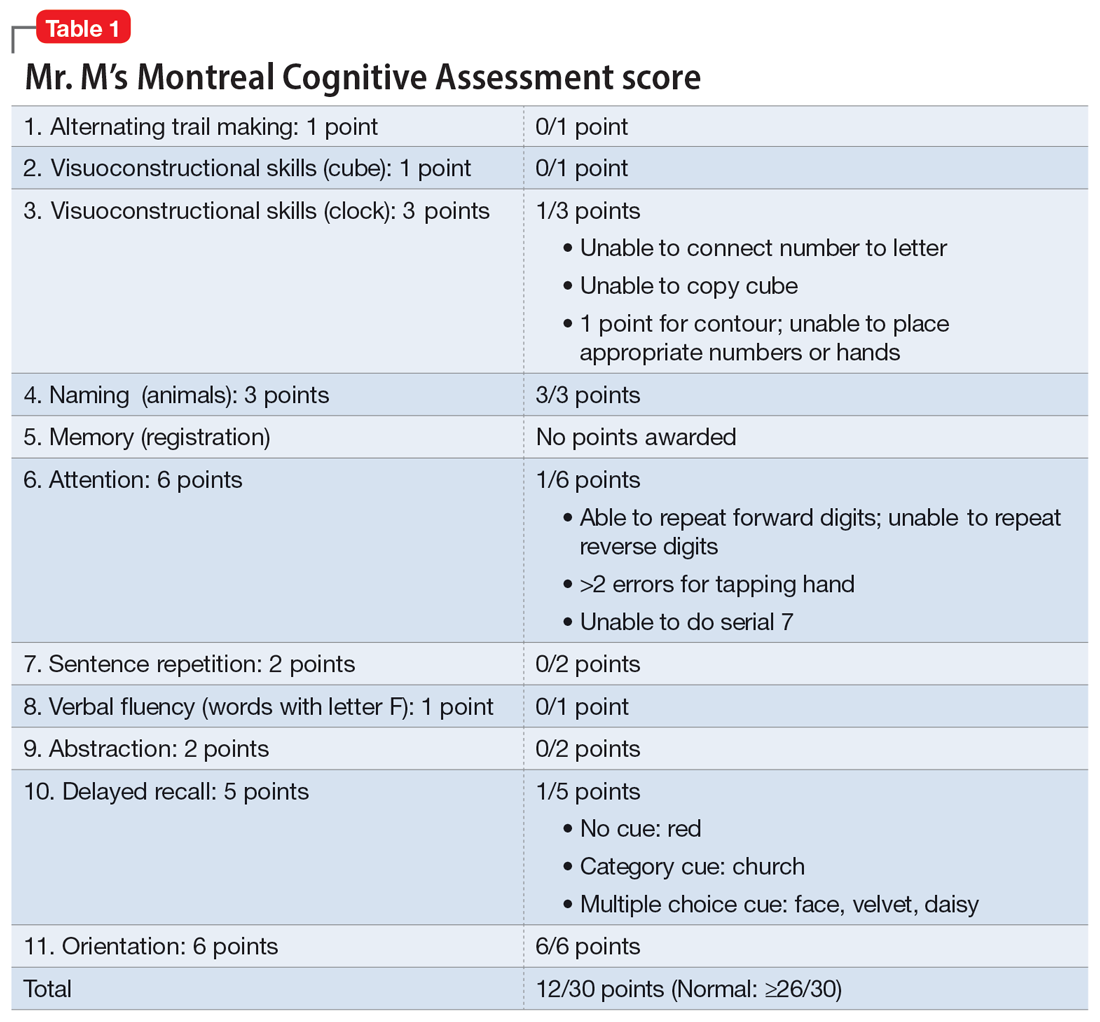

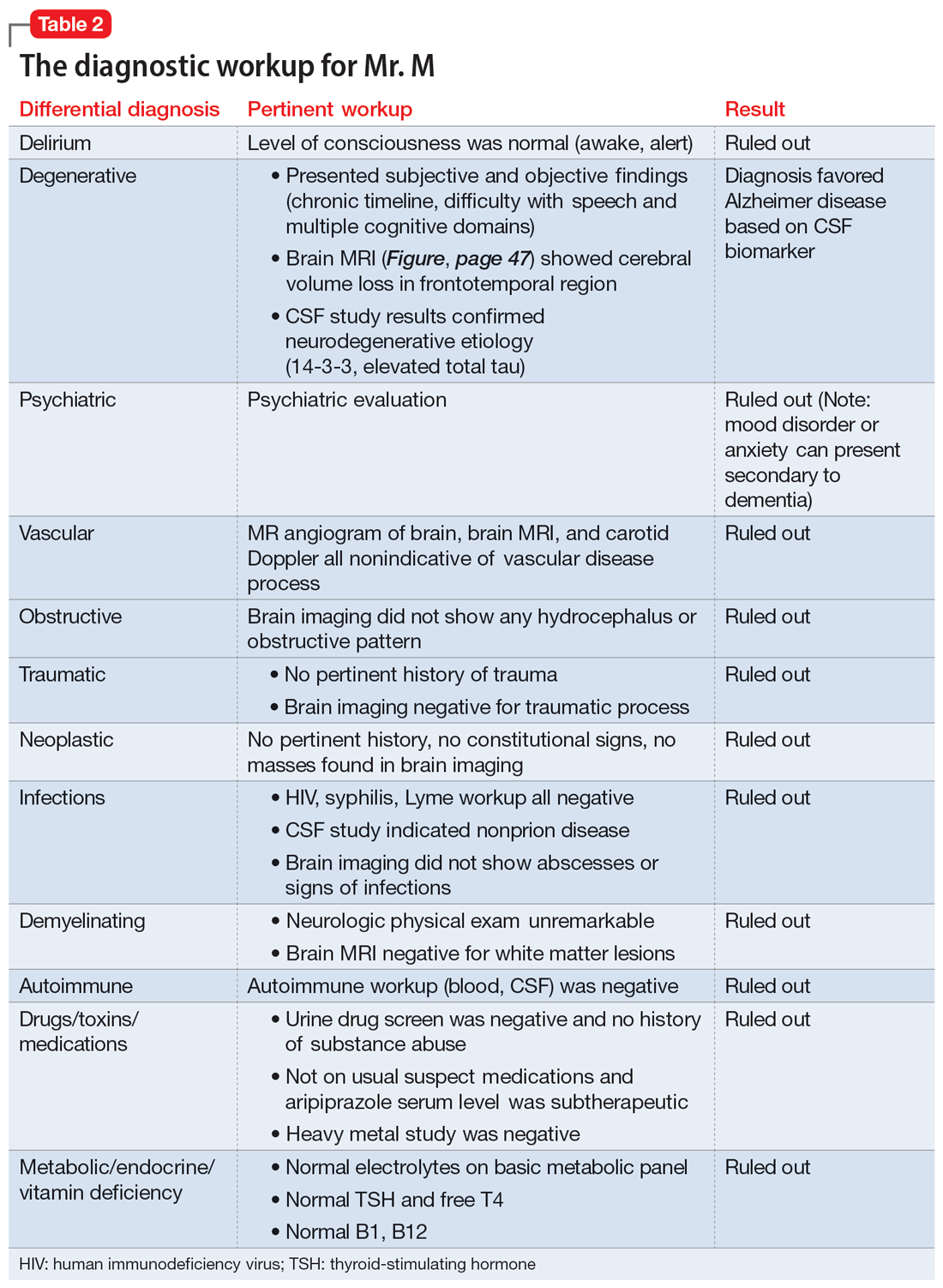

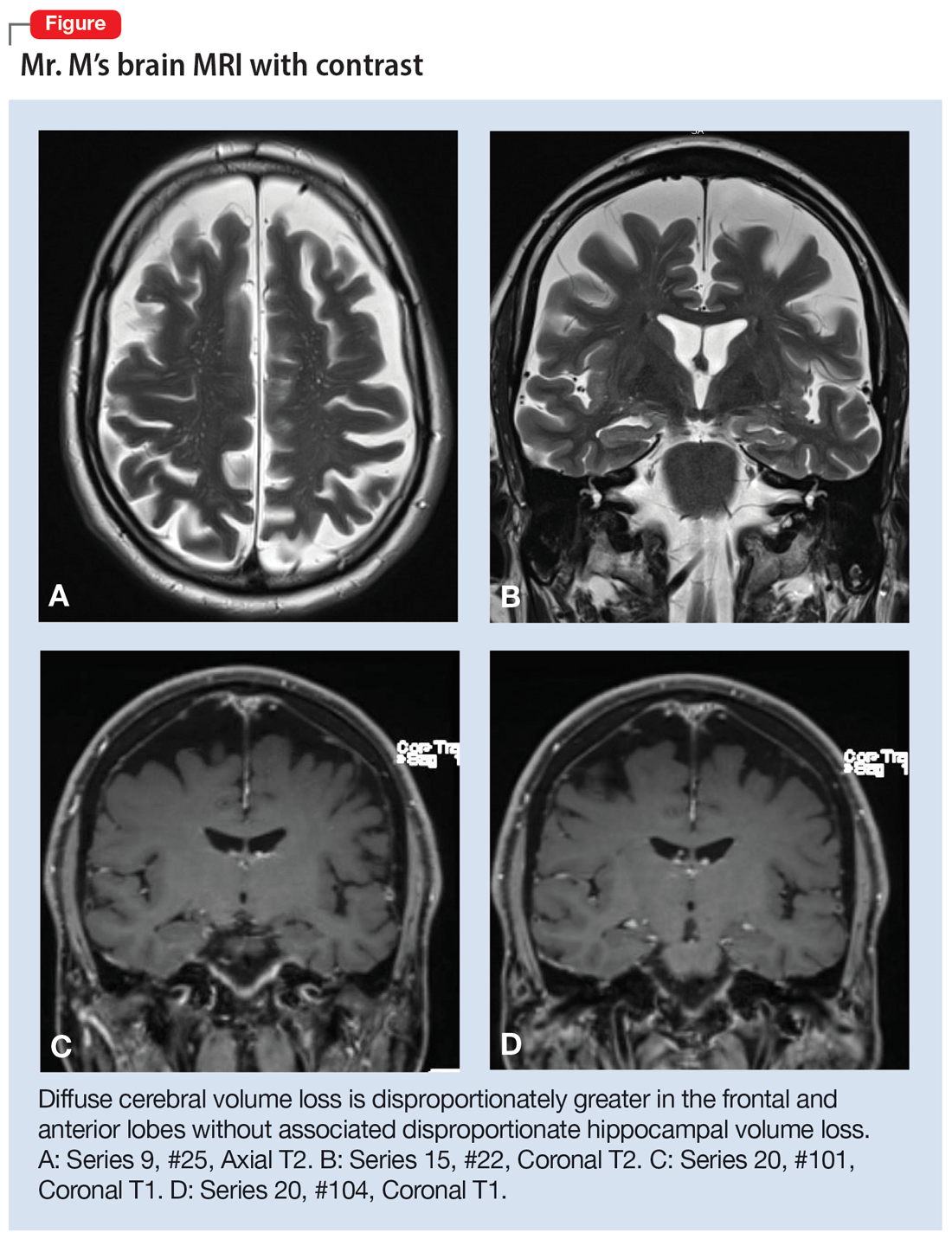

Mr. M, age 53, a surgeon, presents to the emergency department (ED) following a panic attack and concerns from his staff that he appears confused. Specifically, staff members report that in the past 4 months, Mr. M was observed having problems completing some postoperative tasks related to chart documentation. Mr. M has a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes.

HISTORY A long-standing diagnosis of depression