User login

Intranasal zavegepant shows potential as an effective treatment option for acute migraine

Key clinical point: Zavegepant nasal spray was effective in the acute treatment of migraine, with favorable tolerability and safety profiles.

Major finding: At 2 hours post-dose, higher proportions of patients treated with zavegepant vs placebo were free from pain (risk difference 8.8 percentage points; P < .0001) and from their most bothersome symptom (risk difference 8.7 percentage points; P = .0012). Dysgeusia (21% vs 5%), nasal discomfort (4% vs 1%), and nausea (3% vs 1%) were the most common adverse events in the zavegepant vs placebo group.

Study details: Findings are from a phase 3 trial including 1405 patients with ≥1-year history of migraine with or without aura who were randomly assigned to receive zavegepant 10 mg nasal spray (n = 703) or matching placebo (n = 702).

Disclosures: This study was funded by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some authors declared being employees of and holding stocks or stock options in Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some others declared ties with various sources, including Biohaven Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Lipton RB et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of zavegepant 10 mg nasal spray for the acute treatment of migraine in the USA: A phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(3):209-217 (Mar). Doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00517-8

Key clinical point: Zavegepant nasal spray was effective in the acute treatment of migraine, with favorable tolerability and safety profiles.

Major finding: At 2 hours post-dose, higher proportions of patients treated with zavegepant vs placebo were free from pain (risk difference 8.8 percentage points; P < .0001) and from their most bothersome symptom (risk difference 8.7 percentage points; P = .0012). Dysgeusia (21% vs 5%), nasal discomfort (4% vs 1%), and nausea (3% vs 1%) were the most common adverse events in the zavegepant vs placebo group.

Study details: Findings are from a phase 3 trial including 1405 patients with ≥1-year history of migraine with or without aura who were randomly assigned to receive zavegepant 10 mg nasal spray (n = 703) or matching placebo (n = 702).

Disclosures: This study was funded by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some authors declared being employees of and holding stocks or stock options in Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some others declared ties with various sources, including Biohaven Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Lipton RB et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of zavegepant 10 mg nasal spray for the acute treatment of migraine in the USA: A phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(3):209-217 (Mar). Doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00517-8

Key clinical point: Zavegepant nasal spray was effective in the acute treatment of migraine, with favorable tolerability and safety profiles.

Major finding: At 2 hours post-dose, higher proportions of patients treated with zavegepant vs placebo were free from pain (risk difference 8.8 percentage points; P < .0001) and from their most bothersome symptom (risk difference 8.7 percentage points; P = .0012). Dysgeusia (21% vs 5%), nasal discomfort (4% vs 1%), and nausea (3% vs 1%) were the most common adverse events in the zavegepant vs placebo group.

Study details: Findings are from a phase 3 trial including 1405 patients with ≥1-year history of migraine with or without aura who were randomly assigned to receive zavegepant 10 mg nasal spray (n = 703) or matching placebo (n = 702).

Disclosures: This study was funded by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some authors declared being employees of and holding stocks or stock options in Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some others declared ties with various sources, including Biohaven Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Lipton RB et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of zavegepant 10 mg nasal spray for the acute treatment of migraine in the USA: A phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(3):209-217 (Mar). Doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00517-8

Early treatment considerations in RA, April 2023

In evaluating the importance of early aggressive treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), we often look at prognostic factors for severe disease, such as seropositivity, elevated inflammatory markers, and erosions. Eberhard and colleagues looked at the relationship between damage as seen on radiography (including erosions and joint space narrowing) and pain and disability in early RA using an inception cohort with <12 months of symptoms. Over 200 patients in Sweden were followed for 5 years with clinical, laboratory, and radiographic evaluations. Of interest, pain was associated with female sex, tender joint count, and inflammatory markers at various time points but not with radiographic damage. This may reflect that pain is related to current inflammation rather than past joint damage or that pain is related to other factors, such as central sensitization. Radiographic damage was, however, associated with disability and thus remains an important target and outcome measure for assessing treatment effectiveness.

Leon and colleagues also looked at early RA but instead, at the category of difficult-to-treat RA (D2T RA), meaning persistent RA symptoms after a trial of at least two biologic or targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. In order to gain better insight in preventing D2T RA, the authors examined its association with potentially modifiable risk factors early in the course of disease. Of the over 600 patients followed in this inception cohort, only about 6% were classified as having D2T RA. The study found that patients who had D2T RA tended to be younger, with a higher tender joint count, higher pain scores, and a higher initial level of disability. The Disease Activity Score (DAS28) itself was higher in patients with D2T RA, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. The small number of patients (35) in the D2T RA group may have affected the findings as well as their wider applicability. However, it is interesting to consider whether the associations may also reflect the impact of noninflammatory factors, as in the previous study, on the classification of D2T RA.

Park and colleagues evaluated the difference in clinical outcomes in postmenopausal patients with RA who underwent menopause at younger than 45 years or 45 years or older. Among over 2800 patients in Korea, those who underwent early menopause were more likely to be seronegative and have high disease activity and worse patient-reported outcome scores in fatigue, sleep, and health-related quality of life despite comparable treatments and prevalence of erosions. The authors suggest this may be related to lower cumulative estrogen exposure; whether this correlates to inflammatory cytokine signatures is not yet known. However, as with the prior studies, central sensitization and noninflammatory pain may also contribute and should be considered in interpreting response to therapy.

Finally, addressing the potential risk for cancer in patients with RA before or during treatment with immunosuppressive medications, Miyata and colleagues reported a study that screened nearly 2200 patients who underwent CT (from neck to pelvis) and compared them with those who underwent routine screening with physical exam plus radiography. The study found that CT screening enhanced cancer detection, with a large number of cancers detected at an earlier stage with CT screening compared with routine screening. The overall number of cancers detected was low (33), and thus routine screening with neck-to-pelvis CT for all patients with RA may not be a cost-effective practice. However, it bears further examination for potentially higher-risk populations or specific cancers.

In evaluating the importance of early aggressive treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), we often look at prognostic factors for severe disease, such as seropositivity, elevated inflammatory markers, and erosions. Eberhard and colleagues looked at the relationship between damage as seen on radiography (including erosions and joint space narrowing) and pain and disability in early RA using an inception cohort with <12 months of symptoms. Over 200 patients in Sweden were followed for 5 years with clinical, laboratory, and radiographic evaluations. Of interest, pain was associated with female sex, tender joint count, and inflammatory markers at various time points but not with radiographic damage. This may reflect that pain is related to current inflammation rather than past joint damage or that pain is related to other factors, such as central sensitization. Radiographic damage was, however, associated with disability and thus remains an important target and outcome measure for assessing treatment effectiveness.

Leon and colleagues also looked at early RA but instead, at the category of difficult-to-treat RA (D2T RA), meaning persistent RA symptoms after a trial of at least two biologic or targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. In order to gain better insight in preventing D2T RA, the authors examined its association with potentially modifiable risk factors early in the course of disease. Of the over 600 patients followed in this inception cohort, only about 6% were classified as having D2T RA. The study found that patients who had D2T RA tended to be younger, with a higher tender joint count, higher pain scores, and a higher initial level of disability. The Disease Activity Score (DAS28) itself was higher in patients with D2T RA, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. The small number of patients (35) in the D2T RA group may have affected the findings as well as their wider applicability. However, it is interesting to consider whether the associations may also reflect the impact of noninflammatory factors, as in the previous study, on the classification of D2T RA.

Park and colleagues evaluated the difference in clinical outcomes in postmenopausal patients with RA who underwent menopause at younger than 45 years or 45 years or older. Among over 2800 patients in Korea, those who underwent early menopause were more likely to be seronegative and have high disease activity and worse patient-reported outcome scores in fatigue, sleep, and health-related quality of life despite comparable treatments and prevalence of erosions. The authors suggest this may be related to lower cumulative estrogen exposure; whether this correlates to inflammatory cytokine signatures is not yet known. However, as with the prior studies, central sensitization and noninflammatory pain may also contribute and should be considered in interpreting response to therapy.

Finally, addressing the potential risk for cancer in patients with RA before or during treatment with immunosuppressive medications, Miyata and colleagues reported a study that screened nearly 2200 patients who underwent CT (from neck to pelvis) and compared them with those who underwent routine screening with physical exam plus radiography. The study found that CT screening enhanced cancer detection, with a large number of cancers detected at an earlier stage with CT screening compared with routine screening. The overall number of cancers detected was low (33), and thus routine screening with neck-to-pelvis CT for all patients with RA may not be a cost-effective practice. However, it bears further examination for potentially higher-risk populations or specific cancers.

In evaluating the importance of early aggressive treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), we often look at prognostic factors for severe disease, such as seropositivity, elevated inflammatory markers, and erosions. Eberhard and colleagues looked at the relationship between damage as seen on radiography (including erosions and joint space narrowing) and pain and disability in early RA using an inception cohort with <12 months of symptoms. Over 200 patients in Sweden were followed for 5 years with clinical, laboratory, and radiographic evaluations. Of interest, pain was associated with female sex, tender joint count, and inflammatory markers at various time points but not with radiographic damage. This may reflect that pain is related to current inflammation rather than past joint damage or that pain is related to other factors, such as central sensitization. Radiographic damage was, however, associated with disability and thus remains an important target and outcome measure for assessing treatment effectiveness.

Leon and colleagues also looked at early RA but instead, at the category of difficult-to-treat RA (D2T RA), meaning persistent RA symptoms after a trial of at least two biologic or targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. In order to gain better insight in preventing D2T RA, the authors examined its association with potentially modifiable risk factors early in the course of disease. Of the over 600 patients followed in this inception cohort, only about 6% were classified as having D2T RA. The study found that patients who had D2T RA tended to be younger, with a higher tender joint count, higher pain scores, and a higher initial level of disability. The Disease Activity Score (DAS28) itself was higher in patients with D2T RA, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. The small number of patients (35) in the D2T RA group may have affected the findings as well as their wider applicability. However, it is interesting to consider whether the associations may also reflect the impact of noninflammatory factors, as in the previous study, on the classification of D2T RA.

Park and colleagues evaluated the difference in clinical outcomes in postmenopausal patients with RA who underwent menopause at younger than 45 years or 45 years or older. Among over 2800 patients in Korea, those who underwent early menopause were more likely to be seronegative and have high disease activity and worse patient-reported outcome scores in fatigue, sleep, and health-related quality of life despite comparable treatments and prevalence of erosions. The authors suggest this may be related to lower cumulative estrogen exposure; whether this correlates to inflammatory cytokine signatures is not yet known. However, as with the prior studies, central sensitization and noninflammatory pain may also contribute and should be considered in interpreting response to therapy.

Finally, addressing the potential risk for cancer in patients with RA before or during treatment with immunosuppressive medications, Miyata and colleagues reported a study that screened nearly 2200 patients who underwent CT (from neck to pelvis) and compared them with those who underwent routine screening with physical exam plus radiography. The study found that CT screening enhanced cancer detection, with a large number of cancers detected at an earlier stage with CT screening compared with routine screening. The overall number of cancers detected was low (33), and thus routine screening with neck-to-pelvis CT for all patients with RA may not be a cost-effective practice. However, it bears further examination for potentially higher-risk populations or specific cancers.

Commentary: Updates on the Treatment of Mantle Cell Lymphoma, April 2023

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that is clinically heterogeneous, ranging from indolent to aggressive in nature. As with other subtypes of NHL, the treatment landscape is rapidly evolving.

Chemoimmunotherapy remains the standard first-line therapy for younger, fit patients. Although multiple induction regimens are used in this setting, it is typical to use a cytarabine-containing approach. Recently, the long-term analysis of the MCL Younger trial continued to demonstrate improved outcomes with this strategy.1 This phase 3 study included 497 patients aged ≥ 18 to < 66 years with previously untreated MCL who were randomly assigned to R-CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone, rituximab, and vincristine; n = 249) or R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin; n = 248). After a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the R-DHAP vs R-CHOP arm continued to have a significantly longer time to treatment failure (hazard ratio [HR] 0.59; P = .038) and overall survival (Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index + Ki-67–adjusted HR 0.60; P = .0066).

Following chemoimmunotherapy, treatment for this patient population typically consists of consolidation with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and maintenance rituximab.2 Recently, the role of ASCT has been called into question.3 Preliminary data from the phase 3 TRIANGLE study demonstrated improvement in outcomes when the Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib was added to chemoimmunotherapy, regardless of whether patients received ASCT.4 Additional studies evaluating the role of transplantation, particularly among patients who are minimal residual disease negative after chemoimmunotherapy, are ongoing (NCT03267433).

Options continue to expand in the relapsed/refractory setting. The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, brexucabtagene autoleucel (brexu-cel), was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for relapsed/refractory MCL on the basis of the results of the ZUMA-2 study.5 Recently, a multicenter, retrospective study demonstrated promising efficacy in the real world as well (Wang et al). This study was performed across 16 medical centers and included 189 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL who underwent leukapheresis for commercial manufacturing of brexu-cel, of which 168 received brexu-cel infusion. Of all patients receiving leukapheresis, 149 (79%) would not have met the eligibility criteria for ZUMA-2. At a median follow-up of 14.3 months after infusion, the best overall and complete response rates were 90% and 82%, respectively. The 6- and 12-month progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 69% (95% CI 61%-75%) and 59% (95% CI 51%-66%), respectively. This approach, however, was associated with significant toxicity, with a nonrelapse mortality rate of 9.1% at 1 year, primarily because of infections. The grade ≥ 3 cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity rates were 8% and 32%, respectively. Despite risks, this study confirms the role of CAR T-cell therapy for patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.

Other options in the relapsed setting include BTK and anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma (BCL-2) inhibitors. Although venetoclax, a BCL-2 inhibitor, has demonstrated activity in MCL in early-phase clinical trials, the role of this drug in clinical practice remains unclear.6,7 A recent multicenter, retrospective study evaluated the use of venetoclax in 81 adult patients with relapsed/refractory MCL, most of whom were heavily pretreated (median of three prior treatments) and had high-risk features, including high Ki-67 and TP53 alterations, who received venetoclax without (n = 50) or with (n = 31) other agents (Sawalha et al). In this study, venetoclax resulted in a good overall response rate (ORR) but short PFS. At a median follow-up of 16.4 months, patients had a median PFS and overall survival of 3.7 months (95% CI 2.3-5.6) and 12.5 months (95% CI 6.2-28.2), respectively, and an ORR of 40%. Studies of venetoclax in earlier lines of therapy and in combination with other agents are ongoing. There may also be a role for this treatment as a bridge to more definitive therapies, including CAR T-cell therapy or allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Other studies that are evaluating the role of bispecific antibodies and antibody drug conjugates are also underway, suggesting the potential for additional options in this patient population.

Additional References

1. Hermine O, Jiang L, Walewski J, et al. High-dose cytarabine and autologous stem-cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: Long-term follow-up of the randomized Mantle Cell Lymphoma Younger Trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:479-484. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01780

2. Le Gouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, et al. Rituximab after autologous stem-cell transplantation in mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1250-1260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701769

3. Martin P, Cohen JB, Wang M, et al. Treatment outcomes and roles of transplantation and maintenance rituximab in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: Results from large real-world cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:541-554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02698

4. Dreyling M, Doorduijn JK, Gine E, et al. Efficacy and safety of ibrutinib combined with standard first-line treatment or as substitute for autologous stem cell transplantation in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: Results from the randomized Triangle Trial by the European MCL Network. Blood. 2022;140(Suppl 1):1-3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2022-163018

5. Wang M, Munoz J, Goy A, et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-Cell therapy in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1331-1342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914347

6. Davids MS, Roberts AW, Seymour JF, et al. Phase I first-in-human study of venetoclax in patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:826-833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4320

7. Tam CS, Anderson MA, Pott C, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax for the treatment of mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1211-1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715519

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that is clinically heterogeneous, ranging from indolent to aggressive in nature. As with other subtypes of NHL, the treatment landscape is rapidly evolving.

Chemoimmunotherapy remains the standard first-line therapy for younger, fit patients. Although multiple induction regimens are used in this setting, it is typical to use a cytarabine-containing approach. Recently, the long-term analysis of the MCL Younger trial continued to demonstrate improved outcomes with this strategy.1 This phase 3 study included 497 patients aged ≥ 18 to < 66 years with previously untreated MCL who were randomly assigned to R-CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone, rituximab, and vincristine; n = 249) or R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin; n = 248). After a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the R-DHAP vs R-CHOP arm continued to have a significantly longer time to treatment failure (hazard ratio [HR] 0.59; P = .038) and overall survival (Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index + Ki-67–adjusted HR 0.60; P = .0066).

Following chemoimmunotherapy, treatment for this patient population typically consists of consolidation with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and maintenance rituximab.2 Recently, the role of ASCT has been called into question.3 Preliminary data from the phase 3 TRIANGLE study demonstrated improvement in outcomes when the Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib was added to chemoimmunotherapy, regardless of whether patients received ASCT.4 Additional studies evaluating the role of transplantation, particularly among patients who are minimal residual disease negative after chemoimmunotherapy, are ongoing (NCT03267433).

Options continue to expand in the relapsed/refractory setting. The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, brexucabtagene autoleucel (brexu-cel), was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for relapsed/refractory MCL on the basis of the results of the ZUMA-2 study.5 Recently, a multicenter, retrospective study demonstrated promising efficacy in the real world as well (Wang et al). This study was performed across 16 medical centers and included 189 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL who underwent leukapheresis for commercial manufacturing of brexu-cel, of which 168 received brexu-cel infusion. Of all patients receiving leukapheresis, 149 (79%) would not have met the eligibility criteria for ZUMA-2. At a median follow-up of 14.3 months after infusion, the best overall and complete response rates were 90% and 82%, respectively. The 6- and 12-month progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 69% (95% CI 61%-75%) and 59% (95% CI 51%-66%), respectively. This approach, however, was associated with significant toxicity, with a nonrelapse mortality rate of 9.1% at 1 year, primarily because of infections. The grade ≥ 3 cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity rates were 8% and 32%, respectively. Despite risks, this study confirms the role of CAR T-cell therapy for patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.

Other options in the relapsed setting include BTK and anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma (BCL-2) inhibitors. Although venetoclax, a BCL-2 inhibitor, has demonstrated activity in MCL in early-phase clinical trials, the role of this drug in clinical practice remains unclear.6,7 A recent multicenter, retrospective study evaluated the use of venetoclax in 81 adult patients with relapsed/refractory MCL, most of whom were heavily pretreated (median of three prior treatments) and had high-risk features, including high Ki-67 and TP53 alterations, who received venetoclax without (n = 50) or with (n = 31) other agents (Sawalha et al). In this study, venetoclax resulted in a good overall response rate (ORR) but short PFS. At a median follow-up of 16.4 months, patients had a median PFS and overall survival of 3.7 months (95% CI 2.3-5.6) and 12.5 months (95% CI 6.2-28.2), respectively, and an ORR of 40%. Studies of venetoclax in earlier lines of therapy and in combination with other agents are ongoing. There may also be a role for this treatment as a bridge to more definitive therapies, including CAR T-cell therapy or allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Other studies that are evaluating the role of bispecific antibodies and antibody drug conjugates are also underway, suggesting the potential for additional options in this patient population.

Additional References

1. Hermine O, Jiang L, Walewski J, et al. High-dose cytarabine and autologous stem-cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: Long-term follow-up of the randomized Mantle Cell Lymphoma Younger Trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:479-484. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01780

2. Le Gouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, et al. Rituximab after autologous stem-cell transplantation in mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1250-1260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701769

3. Martin P, Cohen JB, Wang M, et al. Treatment outcomes and roles of transplantation and maintenance rituximab in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: Results from large real-world cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:541-554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02698

4. Dreyling M, Doorduijn JK, Gine E, et al. Efficacy and safety of ibrutinib combined with standard first-line treatment or as substitute for autologous stem cell transplantation in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: Results from the randomized Triangle Trial by the European MCL Network. Blood. 2022;140(Suppl 1):1-3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2022-163018

5. Wang M, Munoz J, Goy A, et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-Cell therapy in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1331-1342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914347

6. Davids MS, Roberts AW, Seymour JF, et al. Phase I first-in-human study of venetoclax in patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:826-833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4320

7. Tam CS, Anderson MA, Pott C, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax for the treatment of mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1211-1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715519

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that is clinically heterogeneous, ranging from indolent to aggressive in nature. As with other subtypes of NHL, the treatment landscape is rapidly evolving.

Chemoimmunotherapy remains the standard first-line therapy for younger, fit patients. Although multiple induction regimens are used in this setting, it is typical to use a cytarabine-containing approach. Recently, the long-term analysis of the MCL Younger trial continued to demonstrate improved outcomes with this strategy.1 This phase 3 study included 497 patients aged ≥ 18 to < 66 years with previously untreated MCL who were randomly assigned to R-CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone, rituximab, and vincristine; n = 249) or R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin; n = 248). After a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the R-DHAP vs R-CHOP arm continued to have a significantly longer time to treatment failure (hazard ratio [HR] 0.59; P = .038) and overall survival (Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index + Ki-67–adjusted HR 0.60; P = .0066).

Following chemoimmunotherapy, treatment for this patient population typically consists of consolidation with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and maintenance rituximab.2 Recently, the role of ASCT has been called into question.3 Preliminary data from the phase 3 TRIANGLE study demonstrated improvement in outcomes when the Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib was added to chemoimmunotherapy, regardless of whether patients received ASCT.4 Additional studies evaluating the role of transplantation, particularly among patients who are minimal residual disease negative after chemoimmunotherapy, are ongoing (NCT03267433).

Options continue to expand in the relapsed/refractory setting. The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, brexucabtagene autoleucel (brexu-cel), was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for relapsed/refractory MCL on the basis of the results of the ZUMA-2 study.5 Recently, a multicenter, retrospective study demonstrated promising efficacy in the real world as well (Wang et al). This study was performed across 16 medical centers and included 189 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL who underwent leukapheresis for commercial manufacturing of brexu-cel, of which 168 received brexu-cel infusion. Of all patients receiving leukapheresis, 149 (79%) would not have met the eligibility criteria for ZUMA-2. At a median follow-up of 14.3 months after infusion, the best overall and complete response rates were 90% and 82%, respectively. The 6- and 12-month progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 69% (95% CI 61%-75%) and 59% (95% CI 51%-66%), respectively. This approach, however, was associated with significant toxicity, with a nonrelapse mortality rate of 9.1% at 1 year, primarily because of infections. The grade ≥ 3 cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity rates were 8% and 32%, respectively. Despite risks, this study confirms the role of CAR T-cell therapy for patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.

Other options in the relapsed setting include BTK and anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma (BCL-2) inhibitors. Although venetoclax, a BCL-2 inhibitor, has demonstrated activity in MCL in early-phase clinical trials, the role of this drug in clinical practice remains unclear.6,7 A recent multicenter, retrospective study evaluated the use of venetoclax in 81 adult patients with relapsed/refractory MCL, most of whom were heavily pretreated (median of three prior treatments) and had high-risk features, including high Ki-67 and TP53 alterations, who received venetoclax without (n = 50) or with (n = 31) other agents (Sawalha et al). In this study, venetoclax resulted in a good overall response rate (ORR) but short PFS. At a median follow-up of 16.4 months, patients had a median PFS and overall survival of 3.7 months (95% CI 2.3-5.6) and 12.5 months (95% CI 6.2-28.2), respectively, and an ORR of 40%. Studies of venetoclax in earlier lines of therapy and in combination with other agents are ongoing. There may also be a role for this treatment as a bridge to more definitive therapies, including CAR T-cell therapy or allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Other studies that are evaluating the role of bispecific antibodies and antibody drug conjugates are also underway, suggesting the potential for additional options in this patient population.

Additional References

1. Hermine O, Jiang L, Walewski J, et al. High-dose cytarabine and autologous stem-cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: Long-term follow-up of the randomized Mantle Cell Lymphoma Younger Trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:479-484. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01780

2. Le Gouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, et al. Rituximab after autologous stem-cell transplantation in mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1250-1260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701769

3. Martin P, Cohen JB, Wang M, et al. Treatment outcomes and roles of transplantation and maintenance rituximab in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: Results from large real-world cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:541-554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02698

4. Dreyling M, Doorduijn JK, Gine E, et al. Efficacy and safety of ibrutinib combined with standard first-line treatment or as substitute for autologous stem cell transplantation in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: Results from the randomized Triangle Trial by the European MCL Network. Blood. 2022;140(Suppl 1):1-3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2022-163018

5. Wang M, Munoz J, Goy A, et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-Cell therapy in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1331-1342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914347

6. Davids MS, Roberts AW, Seymour JF, et al. Phase I first-in-human study of venetoclax in patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:826-833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4320

7. Tam CS, Anderson MA, Pott C, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax for the treatment of mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1211-1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715519

Optimal Use of CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Breast Cancer

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors have become integral to the treatment of HR+/HER2- breast cancer. Approved in 2015 for use in the metastatic setting and most recently in the adjuvant setting, CDK4/6 inhibitors have revolutionized treatment in both endocrine-sensitive and endocrine-resistant settings and in pre- and postmenopausal women.

But many questions remain regarding the optimal use of these medications in clinical practice.

In this ReCAP, Dr Virginia Kaklamani from the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in San Antonio, Texas, and Dr Harold Burstein from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, begin their discussion by examining the potential role of adjuvant CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy in early, high-risk breast cancer.

They discuss the three main studies that looked at the role of adjuvant CDK4/6 inhibitors, including the PALLAS and PENELOPE-B trials, in which palbociclib showed no benefit in invasive disease-free survival. In contrast, in the monarchE trial, abemaciclib showed a robust benefit in preventing recurrence, which was sustained after longer follow-up, as reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2022.

Turning to the metastatic setting, the panelists discuss the varied side effect profiles of the three approved CDK4/6 inhibitors, palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib. They also discuss current research into the continuation of these agents beyond progression and whether sequencing of CDK4/6 inhibitors may provide benefit.

--

Virginia Kaklamani, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of Texas Health Sciences Center; Leader, Breast Oncology Program, University of Texas Health MD Anderson Cancer Center, San Antonio, Texas

Virginia Kaklamani, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Gilead; Menarini; Pfizer; Novartis; Lilly; AstraZeneca; Genentech; Daichii; Seagen

Harold J. Burstein, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Medical Oncologist, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts

Harold J. Burstein, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors have become integral to the treatment of HR+/HER2- breast cancer. Approved in 2015 for use in the metastatic setting and most recently in the adjuvant setting, CDK4/6 inhibitors have revolutionized treatment in both endocrine-sensitive and endocrine-resistant settings and in pre- and postmenopausal women.

But many questions remain regarding the optimal use of these medications in clinical practice.

In this ReCAP, Dr Virginia Kaklamani from the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in San Antonio, Texas, and Dr Harold Burstein from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, begin their discussion by examining the potential role of adjuvant CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy in early, high-risk breast cancer.

They discuss the three main studies that looked at the role of adjuvant CDK4/6 inhibitors, including the PALLAS and PENELOPE-B trials, in which palbociclib showed no benefit in invasive disease-free survival. In contrast, in the monarchE trial, abemaciclib showed a robust benefit in preventing recurrence, which was sustained after longer follow-up, as reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2022.

Turning to the metastatic setting, the panelists discuss the varied side effect profiles of the three approved CDK4/6 inhibitors, palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib. They also discuss current research into the continuation of these agents beyond progression and whether sequencing of CDK4/6 inhibitors may provide benefit.

--

Virginia Kaklamani, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of Texas Health Sciences Center; Leader, Breast Oncology Program, University of Texas Health MD Anderson Cancer Center, San Antonio, Texas

Virginia Kaklamani, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Gilead; Menarini; Pfizer; Novartis; Lilly; AstraZeneca; Genentech; Daichii; Seagen

Harold J. Burstein, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Medical Oncologist, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts

Harold J. Burstein, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors have become integral to the treatment of HR+/HER2- breast cancer. Approved in 2015 for use in the metastatic setting and most recently in the adjuvant setting, CDK4/6 inhibitors have revolutionized treatment in both endocrine-sensitive and endocrine-resistant settings and in pre- and postmenopausal women.

But many questions remain regarding the optimal use of these medications in clinical practice.

In this ReCAP, Dr Virginia Kaklamani from the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in San Antonio, Texas, and Dr Harold Burstein from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, begin their discussion by examining the potential role of adjuvant CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy in early, high-risk breast cancer.

They discuss the three main studies that looked at the role of adjuvant CDK4/6 inhibitors, including the PALLAS and PENELOPE-B trials, in which palbociclib showed no benefit in invasive disease-free survival. In contrast, in the monarchE trial, abemaciclib showed a robust benefit in preventing recurrence, which was sustained after longer follow-up, as reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2022.

Turning to the metastatic setting, the panelists discuss the varied side effect profiles of the three approved CDK4/6 inhibitors, palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib. They also discuss current research into the continuation of these agents beyond progression and whether sequencing of CDK4/6 inhibitors may provide benefit.

--

Virginia Kaklamani, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of Texas Health Sciences Center; Leader, Breast Oncology Program, University of Texas Health MD Anderson Cancer Center, San Antonio, Texas

Virginia Kaklamani, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Gilead; Menarini; Pfizer; Novartis; Lilly; AstraZeneca; Genentech; Daichii; Seagen

Harold J. Burstein, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Medical Oncologist, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts

Harold J. Burstein, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Annular Erythematous Plaques With Central Hypopigmentation on Sun-Exposed Skin

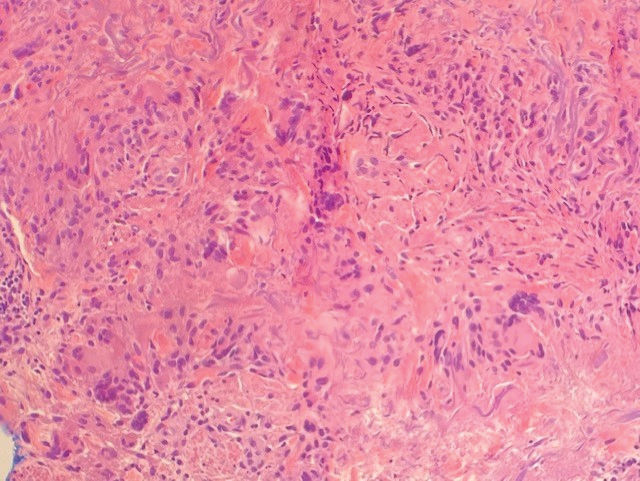

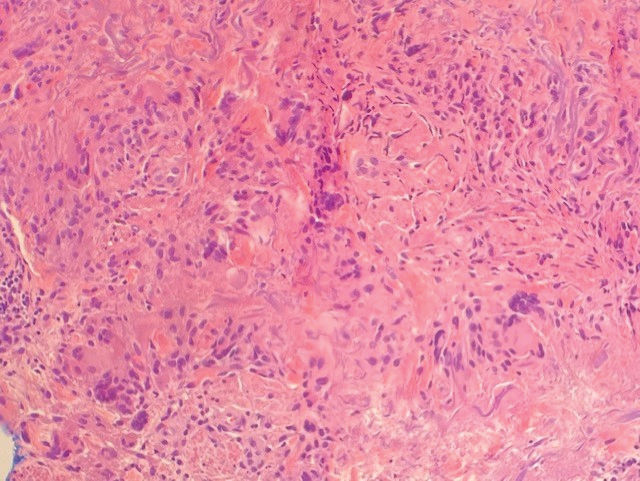

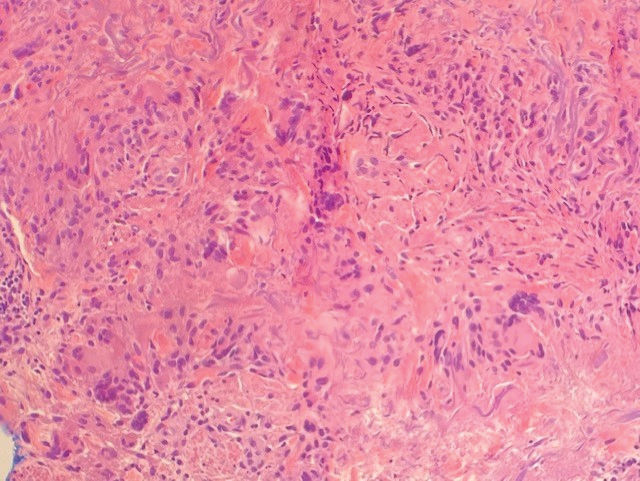

A biopsy showed a markedly elastotic dermis consisting of a palisading granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate and numerous multinucleated histiocytes (Figure). These histopathologic findings along with the clinical presentation confirmed a diagnosis of annular elastolytic granuloma (AEG). Treatment consisting of 3 months of oral minocycline, 2 months of oral doxycycline, and clobetasol ointment all failed. At that point, oral hydroxychloroquine was recommended. Our patient was lost to follow-up by dermatology, then subsequently was placed on hydroxychloroquine by rheumatology to treat both the osteoarthritis and AEG. A follow-up appointment with dermatology was planned for 3 months to monitor hydroxychloroquine treatment and monitor treatment progress; however, she did not follow-up or seek further treatment.

Annular elastolytic granuloma clinically is similar to granuloma annulare (GA), with both presenting as annular plaques surrounded by an elevated border.1 Although AEG clinically is distinct with hypopigmented atrophied plaque centers,2 a biopsy is required to confirm the lack of elastic tissue in zones of atrophy and the presence of multinucleated histiocytes.1,3 Lesions most commonly are seen clinically on sun-exposed areas in middle-aged White women; however, they rarely have been seen on frequently covered skin.4 Our case illustrates the striking photodistribution of AEG, especially on the posterior neck area. The clinical diagnoses of AEG, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma, and GA in sun-exposed areas are synonymous and can be used interchangeably.5,6

Pathologies considered in the diagnosis of AEG include but are not limited to tinea corporis, annular lichen planus, erythema annulare centrifugum, and necrobiosis lipoidica. Scaling typically is absent in AEG, while tinea corporis presents with hyphae within the stratum corneum of the plaques.7 Papules along the periphery of annular lesions are more typical of annular lichen planus than AEG, and they tend to have a more purple hue.8 Erythema annulare centrifugum has annular erythematous plaques similar to those found in AEG but differs with scaling on the inner margins of these plaques. Histopathology presenting with a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding vasculature and no indication of elastolytic degradation would further indicate a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum.9 Histopathology showing necrobiosis, lipid depositions, and vascular wall thickenings is indicative of necrobiosis lipoidica.10

Similar to GA,11 the cause of AEG is idiopathic.2 Annular elastolytic granuloma and GA differ in the fact that elastin degradation is characteristic of AEG compared to collagen degradation in GA. It is suspected that elastin degradation in AEG patients is caused by an immune response triggering phagocytosis of elastin by multinucleated histiocytes.2 Actinic damage also is considered a possible cause of elastin fiber degradation in AEG.12 Granuloma annulare can be ruled out and the diagnosis of AEG confirmed with the absence of elastin fibers and mucin on pathology.13

Although there is no established first-line treatment of AEG, successful treatment has been achieved with antimalarial drugs paired with topical steroids.14 Treatment recommendations for AEG include minocycline, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, tranilast, and oral retinoids, as well as oral and topical steroids. In clinical cases where AEG occurs in the setting of a chronic disease such as diabetes mellitus, vascular occlusion, arthritis, or hypertension, treatment of underlying disease has been shown to resolve AEG symptoms.14

Although light therapy is not common for AEG, UV light radiation has demonstrated success in treating AEG.15,16 One study showed complete clearance of granulomatous papules after narrowband UVB treatment.15 Another study showed that 2 patients treated with psoralen plus UVA therapy reached complete clearance of AEG lasting at least 3 months after treatment.16

1. Lai JH, Murray SJ, Walsh NM. Evolution of granuloma annulare to mid-dermal elastolysis: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:462-468. doi:10.1111/cup.12292 2. Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132 3. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282. doi:10.1111/j.0309-0167.2004.01755.x 4. Revenga F, Rovira I, Pimentel J, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma—actinic granuloma? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:51-53. 5. Hawryluk EB, Izikson L, English JC 3rd. Non-infectious granulomatous diseases of the skin and their associated systemic diseases: an evidence-based update to important clinical questions. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:171-181. doi:10.2165/11530080-000000000-00000 6. Berliner JG, Haemel A, LeBoit PE, et al. The sarcoidal variant of annular elastolytic granuloma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:918-920. doi:10.1111/cup.12237 7. Pflederer RT, Ahmed S, Tonkovic-Capin V, et al. Annular polycyclic plaques on the chest and upper back [published online April 24, 2018]. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:405-407. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.07.022 8. Trayes KP, Savage K, Studdiford JS. Annular lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:283-291. 9. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462. doi:10.1097/00000372-200312000-00001 10. Dowling GB, Jones EW. Atypical (annular) necrobiosis lipoidica of the face and scalp. a report of the clinical and histological features of 7 cases. Dermatologica. 1967;135:11-26. doi:10.1159/000254156 11. Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015 .03.055 12. O’Brien JP, Regan W. Actinically degenerate elastic tissue is the likely antigenic basis of actinic granuloma of the skin and of temporal arteritis [published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000; 42(1 pt 1):148]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2 pt 1):214-222. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70191-x 13. Rencic A, Nousari CH. Other rheumatologic diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2008:600-601. 14. Burlando M, Herzum A, Cozzani E, et al. Can methotrexate be a successful treatment for unresponsive generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma? case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14705. doi:10.1111/dth.14705 15. Takata T, Ikeda M, Kodama H, et al. Regression of papular elastolytic giant cell granuloma using narrow-band UVB irradiation. Dermatology. 2006;212:77-79. doi:10.1159/000089028 16. Pérez-Pérez L, García-Gavín J, Allegue F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralenultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2012.00680.x

A biopsy showed a markedly elastotic dermis consisting of a palisading granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate and numerous multinucleated histiocytes (Figure). These histopathologic findings along with the clinical presentation confirmed a diagnosis of annular elastolytic granuloma (AEG). Treatment consisting of 3 months of oral minocycline, 2 months of oral doxycycline, and clobetasol ointment all failed. At that point, oral hydroxychloroquine was recommended. Our patient was lost to follow-up by dermatology, then subsequently was placed on hydroxychloroquine by rheumatology to treat both the osteoarthritis and AEG. A follow-up appointment with dermatology was planned for 3 months to monitor hydroxychloroquine treatment and monitor treatment progress; however, she did not follow-up or seek further treatment.

Annular elastolytic granuloma clinically is similar to granuloma annulare (GA), with both presenting as annular plaques surrounded by an elevated border.1 Although AEG clinically is distinct with hypopigmented atrophied plaque centers,2 a biopsy is required to confirm the lack of elastic tissue in zones of atrophy and the presence of multinucleated histiocytes.1,3 Lesions most commonly are seen clinically on sun-exposed areas in middle-aged White women; however, they rarely have been seen on frequently covered skin.4 Our case illustrates the striking photodistribution of AEG, especially on the posterior neck area. The clinical diagnoses of AEG, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma, and GA in sun-exposed areas are synonymous and can be used interchangeably.5,6

Pathologies considered in the diagnosis of AEG include but are not limited to tinea corporis, annular lichen planus, erythema annulare centrifugum, and necrobiosis lipoidica. Scaling typically is absent in AEG, while tinea corporis presents with hyphae within the stratum corneum of the plaques.7 Papules along the periphery of annular lesions are more typical of annular lichen planus than AEG, and they tend to have a more purple hue.8 Erythema annulare centrifugum has annular erythematous plaques similar to those found in AEG but differs with scaling on the inner margins of these plaques. Histopathology presenting with a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding vasculature and no indication of elastolytic degradation would further indicate a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum.9 Histopathology showing necrobiosis, lipid depositions, and vascular wall thickenings is indicative of necrobiosis lipoidica.10

Similar to GA,11 the cause of AEG is idiopathic.2 Annular elastolytic granuloma and GA differ in the fact that elastin degradation is characteristic of AEG compared to collagen degradation in GA. It is suspected that elastin degradation in AEG patients is caused by an immune response triggering phagocytosis of elastin by multinucleated histiocytes.2 Actinic damage also is considered a possible cause of elastin fiber degradation in AEG.12 Granuloma annulare can be ruled out and the diagnosis of AEG confirmed with the absence of elastin fibers and mucin on pathology.13

Although there is no established first-line treatment of AEG, successful treatment has been achieved with antimalarial drugs paired with topical steroids.14 Treatment recommendations for AEG include minocycline, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, tranilast, and oral retinoids, as well as oral and topical steroids. In clinical cases where AEG occurs in the setting of a chronic disease such as diabetes mellitus, vascular occlusion, arthritis, or hypertension, treatment of underlying disease has been shown to resolve AEG symptoms.14

Although light therapy is not common for AEG, UV light radiation has demonstrated success in treating AEG.15,16 One study showed complete clearance of granulomatous papules after narrowband UVB treatment.15 Another study showed that 2 patients treated with psoralen plus UVA therapy reached complete clearance of AEG lasting at least 3 months after treatment.16

A biopsy showed a markedly elastotic dermis consisting of a palisading granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate and numerous multinucleated histiocytes (Figure). These histopathologic findings along with the clinical presentation confirmed a diagnosis of annular elastolytic granuloma (AEG). Treatment consisting of 3 months of oral minocycline, 2 months of oral doxycycline, and clobetasol ointment all failed. At that point, oral hydroxychloroquine was recommended. Our patient was lost to follow-up by dermatology, then subsequently was placed on hydroxychloroquine by rheumatology to treat both the osteoarthritis and AEG. A follow-up appointment with dermatology was planned for 3 months to monitor hydroxychloroquine treatment and monitor treatment progress; however, she did not follow-up or seek further treatment.

Annular elastolytic granuloma clinically is similar to granuloma annulare (GA), with both presenting as annular plaques surrounded by an elevated border.1 Although AEG clinically is distinct with hypopigmented atrophied plaque centers,2 a biopsy is required to confirm the lack of elastic tissue in zones of atrophy and the presence of multinucleated histiocytes.1,3 Lesions most commonly are seen clinically on sun-exposed areas in middle-aged White women; however, they rarely have been seen on frequently covered skin.4 Our case illustrates the striking photodistribution of AEG, especially on the posterior neck area. The clinical diagnoses of AEG, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma, and GA in sun-exposed areas are synonymous and can be used interchangeably.5,6

Pathologies considered in the diagnosis of AEG include but are not limited to tinea corporis, annular lichen planus, erythema annulare centrifugum, and necrobiosis lipoidica. Scaling typically is absent in AEG, while tinea corporis presents with hyphae within the stratum corneum of the plaques.7 Papules along the periphery of annular lesions are more typical of annular lichen planus than AEG, and they tend to have a more purple hue.8 Erythema annulare centrifugum has annular erythematous plaques similar to those found in AEG but differs with scaling on the inner margins of these plaques. Histopathology presenting with a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding vasculature and no indication of elastolytic degradation would further indicate a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum.9 Histopathology showing necrobiosis, lipid depositions, and vascular wall thickenings is indicative of necrobiosis lipoidica.10

Similar to GA,11 the cause of AEG is idiopathic.2 Annular elastolytic granuloma and GA differ in the fact that elastin degradation is characteristic of AEG compared to collagen degradation in GA. It is suspected that elastin degradation in AEG patients is caused by an immune response triggering phagocytosis of elastin by multinucleated histiocytes.2 Actinic damage also is considered a possible cause of elastin fiber degradation in AEG.12 Granuloma annulare can be ruled out and the diagnosis of AEG confirmed with the absence of elastin fibers and mucin on pathology.13

Although there is no established first-line treatment of AEG, successful treatment has been achieved with antimalarial drugs paired with topical steroids.14 Treatment recommendations for AEG include minocycline, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, tranilast, and oral retinoids, as well as oral and topical steroids. In clinical cases where AEG occurs in the setting of a chronic disease such as diabetes mellitus, vascular occlusion, arthritis, or hypertension, treatment of underlying disease has been shown to resolve AEG symptoms.14

Although light therapy is not common for AEG, UV light radiation has demonstrated success in treating AEG.15,16 One study showed complete clearance of granulomatous papules after narrowband UVB treatment.15 Another study showed that 2 patients treated with psoralen plus UVA therapy reached complete clearance of AEG lasting at least 3 months after treatment.16

1. Lai JH, Murray SJ, Walsh NM. Evolution of granuloma annulare to mid-dermal elastolysis: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:462-468. doi:10.1111/cup.12292 2. Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132 3. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282. doi:10.1111/j.0309-0167.2004.01755.x 4. Revenga F, Rovira I, Pimentel J, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma—actinic granuloma? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:51-53. 5. Hawryluk EB, Izikson L, English JC 3rd. Non-infectious granulomatous diseases of the skin and their associated systemic diseases: an evidence-based update to important clinical questions. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:171-181. doi:10.2165/11530080-000000000-00000 6. Berliner JG, Haemel A, LeBoit PE, et al. The sarcoidal variant of annular elastolytic granuloma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:918-920. doi:10.1111/cup.12237 7. Pflederer RT, Ahmed S, Tonkovic-Capin V, et al. Annular polycyclic plaques on the chest and upper back [published online April 24, 2018]. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:405-407. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.07.022 8. Trayes KP, Savage K, Studdiford JS. Annular lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:283-291. 9. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462. doi:10.1097/00000372-200312000-00001 10. Dowling GB, Jones EW. Atypical (annular) necrobiosis lipoidica of the face and scalp. a report of the clinical and histological features of 7 cases. Dermatologica. 1967;135:11-26. doi:10.1159/000254156 11. Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015 .03.055 12. O’Brien JP, Regan W. Actinically degenerate elastic tissue is the likely antigenic basis of actinic granuloma of the skin and of temporal arteritis [published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000; 42(1 pt 1):148]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2 pt 1):214-222. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70191-x 13. Rencic A, Nousari CH. Other rheumatologic diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2008:600-601. 14. Burlando M, Herzum A, Cozzani E, et al. Can methotrexate be a successful treatment for unresponsive generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma? case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14705. doi:10.1111/dth.14705 15. Takata T, Ikeda M, Kodama H, et al. Regression of papular elastolytic giant cell granuloma using narrow-band UVB irradiation. Dermatology. 2006;212:77-79. doi:10.1159/000089028 16. Pérez-Pérez L, García-Gavín J, Allegue F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralenultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2012.00680.x

1. Lai JH, Murray SJ, Walsh NM. Evolution of granuloma annulare to mid-dermal elastolysis: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:462-468. doi:10.1111/cup.12292 2. Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132 3. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282. doi:10.1111/j.0309-0167.2004.01755.x 4. Revenga F, Rovira I, Pimentel J, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma—actinic granuloma? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:51-53. 5. Hawryluk EB, Izikson L, English JC 3rd. Non-infectious granulomatous diseases of the skin and their associated systemic diseases: an evidence-based update to important clinical questions. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:171-181. doi:10.2165/11530080-000000000-00000 6. Berliner JG, Haemel A, LeBoit PE, et al. The sarcoidal variant of annular elastolytic granuloma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:918-920. doi:10.1111/cup.12237 7. Pflederer RT, Ahmed S, Tonkovic-Capin V, et al. Annular polycyclic plaques on the chest and upper back [published online April 24, 2018]. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:405-407. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.07.022 8. Trayes KP, Savage K, Studdiford JS. Annular lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:283-291. 9. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462. doi:10.1097/00000372-200312000-00001 10. Dowling GB, Jones EW. Atypical (annular) necrobiosis lipoidica of the face and scalp. a report of the clinical and histological features of 7 cases. Dermatologica. 1967;135:11-26. doi:10.1159/000254156 11. Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015 .03.055 12. O’Brien JP, Regan W. Actinically degenerate elastic tissue is the likely antigenic basis of actinic granuloma of the skin and of temporal arteritis [published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000; 42(1 pt 1):148]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2 pt 1):214-222. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70191-x 13. Rencic A, Nousari CH. Other rheumatologic diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2008:600-601. 14. Burlando M, Herzum A, Cozzani E, et al. Can methotrexate be a successful treatment for unresponsive generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma? case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14705. doi:10.1111/dth.14705 15. Takata T, Ikeda M, Kodama H, et al. Regression of papular elastolytic giant cell granuloma using narrow-band UVB irradiation. Dermatology. 2006;212:77-79. doi:10.1159/000089028 16. Pérez-Pérez L, García-Gavín J, Allegue F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralenultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2012.00680.x

A 67-year-old White woman presented to our dermatology clinic with pruritic annular erythematous plaques with central hypopigmentation on the forearms, dorsal aspect of the hands, neck, and fingers of 3 to 4 months’ duration. The patient rated the severity of pruritus an 8 on a 10-point scale. A review of symptoms was positive for fatigue, joint pain, and headache. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, thyroid disease, and stage 3 renal failure. A punch biopsy from the left forearm was performed.

Commentary: Alisertib, trastuzumab, and treatment timing, April 2023

HER2-positive (HER2+) BC was associated with poor outcomes compared with other BC subtypes. However, the introduction of trastuzumab has drastically changed the treatment paradigm for these patients afflicted with HER2+ BC. The pivotal trials with trastuzumab included only a few patients with lower-risk HER2+ tumors; therefore, it was not clear whether these lower-risk patients can benefit from a de-escalated adjuvant regimen. The phase 2 APT trial prospectively investigated the safety and efficacy of 12 weeks of paclitaxel with trastuzumab, followed by 9 months of trastuzumab monotherapy, in patients with small (≤ 3 cm), node-negative, HER2+ BC. After a median follow-up of 10.8 years, the 10-year invasive disease-free survival was 91.3%, the recurrence-free interval was 96.3%, the overall survival rate was 94.3%, and the BC-specific survival rate was 98.8%.

The researchers also conducted an exploratory analysis in 284 patients using the HER2DX genomic test. This is a single 27-gene expression and clinical feature-based classifier developed for early-stage, HER2+ BC. The tool identified a subset of patients with a high HER2DX score (HERDX score ≥ 32) who might harbor an increased risk for long-term recurrence.

These excellent long-term outcomes from the APT trial support the use of the currently endorsed adjuvant regimen of paclitaxel and trastuzumab in patients with stage I HER2+ BC. Furthermore, the HER2DX risk score, if validated, may provide a promising genomic tool to identify a subset of these patients who are at increased risk for recurrence and therefore may benefit from additional therapy.

Prior studies have noted worse survival outcomes with longer times from BC diagnosis to surgical treatment; however, the specific time interval that is acceptable to wait between diagnosis and surgery is still unclear. A case series study by Weiner and colleagues looked at the association between time from BC diagnosis to primary breast surgery and overall survival. The study looked at 373,334 female patients from the National Cancer Database with stage I-III BC who underwent primary breast surgery. Results showed worse overall survival outcomes when time to surgery was 9 or more weeks compared with surgery between 0 and 4 weeks (hazard ratio 1.15; P < .001). Factors associated with longer times to surgery included younger age, uninsured or Medicaid status, and lower neighborhood household income. On the basis of these findings, surgery before 8 weeks from BC diagnosis appears to be an acceptable time frame to avoid unfavorable survival outcomes and allow for appropriate multidisciplinary care. Furthermore, it is critical to identify potential barriers in a timely manner to prevent prolonged delays in care.

In hormone receptor-positive (HR+) BC, adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) is usually delayed until after adjuvant radiotherapy, although, the optimal sequence of both therapies is still unknown. The aim of the study by Sutton and colleagues was to assess the association between time from surgery to ET initiation and cancer outcomes in high-risk HR+ patients, particularly those with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The study analysed 179 patients with HR+ BC from a multi-institutional database who received adjuvant radiotherapy, of which 68 patients received adjuvant ET before or during radiotherapy and 111 patients received ET after cessation of radiotherapy. Results showed that an interval of >14 weeks between surgery and the receipt of ET was independently associated with worse recurrence-free survival compared with an interval of 14 or less weeks (hazard ratio 3.20; P = .02). Of interest, the study also showed that patients receiving ET before or during radiation were more likely to experience skin and soft tissue late radiation morbidity, and this was nonsignificantly associated with worse radiation-associated complication-free survival (hazard ratio 1.87; P = .06). Although prior studies have reported that the interval from surgery to ET does not affect cancer outcomes, this was not studied in a high-risk cohort who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Further studies in larger prospective cohorts are needed to validate these findings. At this time, the risks and benefits of concurrent ET with radiation need to be assessed prior to making any treatment recommendations.

HER2-positive (HER2+) BC was associated with poor outcomes compared with other BC subtypes. However, the introduction of trastuzumab has drastically changed the treatment paradigm for these patients afflicted with HER2+ BC. The pivotal trials with trastuzumab included only a few patients with lower-risk HER2+ tumors; therefore, it was not clear whether these lower-risk patients can benefit from a de-escalated adjuvant regimen. The phase 2 APT trial prospectively investigated the safety and efficacy of 12 weeks of paclitaxel with trastuzumab, followed by 9 months of trastuzumab monotherapy, in patients with small (≤ 3 cm), node-negative, HER2+ BC. After a median follow-up of 10.8 years, the 10-year invasive disease-free survival was 91.3%, the recurrence-free interval was 96.3%, the overall survival rate was 94.3%, and the BC-specific survival rate was 98.8%.

The researchers also conducted an exploratory analysis in 284 patients using the HER2DX genomic test. This is a single 27-gene expression and clinical feature-based classifier developed for early-stage, HER2+ BC. The tool identified a subset of patients with a high HER2DX score (HERDX score ≥ 32) who might harbor an increased risk for long-term recurrence.

These excellent long-term outcomes from the APT trial support the use of the currently endorsed adjuvant regimen of paclitaxel and trastuzumab in patients with stage I HER2+ BC. Furthermore, the HER2DX risk score, if validated, may provide a promising genomic tool to identify a subset of these patients who are at increased risk for recurrence and therefore may benefit from additional therapy.

Prior studies have noted worse survival outcomes with longer times from BC diagnosis to surgical treatment; however, the specific time interval that is acceptable to wait between diagnosis and surgery is still unclear. A case series study by Weiner and colleagues looked at the association between time from BC diagnosis to primary breast surgery and overall survival. The study looked at 373,334 female patients from the National Cancer Database with stage I-III BC who underwent primary breast surgery. Results showed worse overall survival outcomes when time to surgery was 9 or more weeks compared with surgery between 0 and 4 weeks (hazard ratio 1.15; P < .001). Factors associated with longer times to surgery included younger age, uninsured or Medicaid status, and lower neighborhood household income. On the basis of these findings, surgery before 8 weeks from BC diagnosis appears to be an acceptable time frame to avoid unfavorable survival outcomes and allow for appropriate multidisciplinary care. Furthermore, it is critical to identify potential barriers in a timely manner to prevent prolonged delays in care.

In hormone receptor-positive (HR+) BC, adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) is usually delayed until after adjuvant radiotherapy, although, the optimal sequence of both therapies is still unknown. The aim of the study by Sutton and colleagues was to assess the association between time from surgery to ET initiation and cancer outcomes in high-risk HR+ patients, particularly those with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The study analysed 179 patients with HR+ BC from a multi-institutional database who received adjuvant radiotherapy, of which 68 patients received adjuvant ET before or during radiotherapy and 111 patients received ET after cessation of radiotherapy. Results showed that an interval of >14 weeks between surgery and the receipt of ET was independently associated with worse recurrence-free survival compared with an interval of 14 or less weeks (hazard ratio 3.20; P = .02). Of interest, the study also showed that patients receiving ET before or during radiation were more likely to experience skin and soft tissue late radiation morbidity, and this was nonsignificantly associated with worse radiation-associated complication-free survival (hazard ratio 1.87; P = .06). Although prior studies have reported that the interval from surgery to ET does not affect cancer outcomes, this was not studied in a high-risk cohort who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Further studies in larger prospective cohorts are needed to validate these findings. At this time, the risks and benefits of concurrent ET with radiation need to be assessed prior to making any treatment recommendations.

HER2-positive (HER2+) BC was associated with poor outcomes compared with other BC subtypes. However, the introduction of trastuzumab has drastically changed the treatment paradigm for these patients afflicted with HER2+ BC. The pivotal trials with trastuzumab included only a few patients with lower-risk HER2+ tumors; therefore, it was not clear whether these lower-risk patients can benefit from a de-escalated adjuvant regimen. The phase 2 APT trial prospectively investigated the safety and efficacy of 12 weeks of paclitaxel with trastuzumab, followed by 9 months of trastuzumab monotherapy, in patients with small (≤ 3 cm), node-negative, HER2+ BC. After a median follow-up of 10.8 years, the 10-year invasive disease-free survival was 91.3%, the recurrence-free interval was 96.3%, the overall survival rate was 94.3%, and the BC-specific survival rate was 98.8%.

The researchers also conducted an exploratory analysis in 284 patients using the HER2DX genomic test. This is a single 27-gene expression and clinical feature-based classifier developed for early-stage, HER2+ BC. The tool identified a subset of patients with a high HER2DX score (HERDX score ≥ 32) who might harbor an increased risk for long-term recurrence.

These excellent long-term outcomes from the APT trial support the use of the currently endorsed adjuvant regimen of paclitaxel and trastuzumab in patients with stage I HER2+ BC. Furthermore, the HER2DX risk score, if validated, may provide a promising genomic tool to identify a subset of these patients who are at increased risk for recurrence and therefore may benefit from additional therapy.

Prior studies have noted worse survival outcomes with longer times from BC diagnosis to surgical treatment; however, the specific time interval that is acceptable to wait between diagnosis and surgery is still unclear. A case series study by Weiner and colleagues looked at the association between time from BC diagnosis to primary breast surgery and overall survival. The study looked at 373,334 female patients from the National Cancer Database with stage I-III BC who underwent primary breast surgery. Results showed worse overall survival outcomes when time to surgery was 9 or more weeks compared with surgery between 0 and 4 weeks (hazard ratio 1.15; P < .001). Factors associated with longer times to surgery included younger age, uninsured or Medicaid status, and lower neighborhood household income. On the basis of these findings, surgery before 8 weeks from BC diagnosis appears to be an acceptable time frame to avoid unfavorable survival outcomes and allow for appropriate multidisciplinary care. Furthermore, it is critical to identify potential barriers in a timely manner to prevent prolonged delays in care.

In hormone receptor-positive (HR+) BC, adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) is usually delayed until after adjuvant radiotherapy, although, the optimal sequence of both therapies is still unknown. The aim of the study by Sutton and colleagues was to assess the association between time from surgery to ET initiation and cancer outcomes in high-risk HR+ patients, particularly those with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The study analysed 179 patients with HR+ BC from a multi-institutional database who received adjuvant radiotherapy, of which 68 patients received adjuvant ET before or during radiotherapy and 111 patients received ET after cessation of radiotherapy. Results showed that an interval of >14 weeks between surgery and the receipt of ET was independently associated with worse recurrence-free survival compared with an interval of 14 or less weeks (hazard ratio 3.20; P = .02). Of interest, the study also showed that patients receiving ET before or during radiation were more likely to experience skin and soft tissue late radiation morbidity, and this was nonsignificantly associated with worse radiation-associated complication-free survival (hazard ratio 1.87; P = .06). Although prior studies have reported that the interval from surgery to ET does not affect cancer outcomes, this was not studied in a high-risk cohort who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Further studies in larger prospective cohorts are needed to validate these findings. At this time, the risks and benefits of concurrent ET with radiation need to be assessed prior to making any treatment recommendations.

Commentary: Chemotherapies and gynecologic surgeries relative to breast cancer, April 2023

However, a combined analysis of two other trials (PlanB and SUCCESS C) did not show a benefit with the addition of anthracycline for most patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative early breast cancer.2 Roy and colleagues performed a retrospective study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database, including 1106 women ≥ 66 years of age with node-positive TNBC, of whom 69.3% received adjuvant chemotherapy (N = 767). The use of chemotherapy led to a statistically significant improvement in survival outcomes (3-year cancer-specific survival [CSS] 81.8% vs 71.4%; overall survival 70.7% vs 51.3%). Although the anthracycline/taxane–based therapy did not improve CSS in the overall population vs taxane-based (hazard ratio [HR] 0.94; P = .79), among patients aged ≥ 76 years with four or more positive nodes, there was improvement in CSS with anthracycline/taxane therapy (HR 0.09; P = .02). These data further support the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients when indicated; stimulate consideration of nonanthracycline combinations, particularly now with the use of immunotherapy for early TNBC; and highlight the need for inclusion of older individuals in clinical trials.

Treatment strategies to improve efficacy and minimize toxicity are highly desired for patients with early breast cancer (EBC). As an example, for small, node-negative, HER2-positive tumors, adjuvant systemic therapy with 12 weeks of paclitaxel/trastuzumab followed by continuation of trastuzumab to complete 1 full year has demonstrated excellent survival outcomes at over 10 years of follow-up.3 In the WSG-ADAPT-TP phase 2 trial, 375 patients with hormone receptor–positive , HER2-positive EBC were randomized to receive neoadjuvant T-DM1 (trastuzumab emtansine) with or without endocrine therapy or trastuzumab plus endocrine therapy. Similar 5-year invasive disease-free and overall survival rates were seen between the three arms. Patients who achieved a pathologic complete response (pCR) vs non-pCR had improved 5-year invasive disease-free survival (iDFS) rates (92.7% vs 82.7%; unadjusted HR 0.40). Furthermore, among the 117 patients who achieved pCR, the omission of adjuvant chemotherapy did not compromise survival outcomes (5-year iDFS 93% vs 92.1% for those who had vs those who did not have chemotherapy, respectively; unadjusted HR 1.15) (Harbeck et al). De-escalation approaches should ideally focus on the identification of biomarkers of response and resistance, as well as tools that can help predict patient outcomes and allow modification of therapy in real time. An example of this latter concept is the use of 18F-FDG-PET to identify patients with HER2-positive EBC who were likely to benefit from a chemotherapy-free dual HER2 blockade (trastuzumab/pertuzumab) treatment approach.4