User login

Promising New Approaches for Testicular and Prostate Cancer

- Risk factors for testicular cancer. American Cancer Society. Updated May 17, 2018. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicular-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

- Chovanec M, Cheng L. BMJ. 2022;379:e070499. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-070499

- Tavares NT et al. J Pathol. 2022. doi:10.1002/path.6037

- Bryant AK et al. JAMA Oncol. 2022;e224319. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.4319

- Kabasakal L et al. Nucl Med Commun. 2017;38(2):149-155. doi:10.1097/MNM.0000000000000617

- Sartor O et al; VISION Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(12):1091-1103. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2107322

- Rowe SP et al. Annu Rev Med. 2019;70:461-477. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-062117-073027

- Pomykala KL et al. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;S2588-9311(22)00177-8. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2022.10.007

- Keam SJ. Mol Diagn Ther. 2022;26(4):467-475. doi:10.1007/s40291-022-00594-2

- Lovejoy LA et al. Mil Med. 2022:usac297. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac297

- Smith ZL et al. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(2):251-264. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2017.10.003

- Hohnloser JH et al. Eur J Med Res.1996;1(11):509-514.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine website. Testicular Cancer tumor Markers. Accessed December 2022. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/testicular-cancer/testicular-cancer-tumor-markers

- Webber BJ et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2022;64(1):71-78. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002353

- Risk factors for testicular cancer. American Cancer Society. Updated May 17, 2018. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicular-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

- Chovanec M, Cheng L. BMJ. 2022;379:e070499. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-070499

- Tavares NT et al. J Pathol. 2022. doi:10.1002/path.6037

- Bryant AK et al. JAMA Oncol. 2022;e224319. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.4319

- Kabasakal L et al. Nucl Med Commun. 2017;38(2):149-155. doi:10.1097/MNM.0000000000000617

- Sartor O et al; VISION Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(12):1091-1103. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2107322

- Rowe SP et al. Annu Rev Med. 2019;70:461-477. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-062117-073027

- Pomykala KL et al. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;S2588-9311(22)00177-8. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2022.10.007

- Keam SJ. Mol Diagn Ther. 2022;26(4):467-475. doi:10.1007/s40291-022-00594-2

- Lovejoy LA et al. Mil Med. 2022:usac297. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac297

- Smith ZL et al. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(2):251-264. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2017.10.003

- Hohnloser JH et al. Eur J Med Res.1996;1(11):509-514.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine website. Testicular Cancer tumor Markers. Accessed December 2022. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/testicular-cancer/testicular-cancer-tumor-markers

- Webber BJ et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2022;64(1):71-78. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002353

- Risk factors for testicular cancer. American Cancer Society. Updated May 17, 2018. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicular-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

- Chovanec M, Cheng L. BMJ. 2022;379:e070499. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-070499

- Tavares NT et al. J Pathol. 2022. doi:10.1002/path.6037

- Bryant AK et al. JAMA Oncol. 2022;e224319. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.4319

- Kabasakal L et al. Nucl Med Commun. 2017;38(2):149-155. doi:10.1097/MNM.0000000000000617

- Sartor O et al; VISION Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(12):1091-1103. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2107322

- Rowe SP et al. Annu Rev Med. 2019;70:461-477. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-062117-073027

- Pomykala KL et al. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;S2588-9311(22)00177-8. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2022.10.007

- Keam SJ. Mol Diagn Ther. 2022;26(4):467-475. doi:10.1007/s40291-022-00594-2

- Lovejoy LA et al. Mil Med. 2022:usac297. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac297

- Smith ZL et al. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(2):251-264. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2017.10.003

- Hohnloser JH et al. Eur J Med Res.1996;1(11):509-514.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine website. Testicular Cancer tumor Markers. Accessed December 2022. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/testicular-cancer/testicular-cancer-tumor-markers

- Webber BJ et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2022;64(1):71-78. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002353

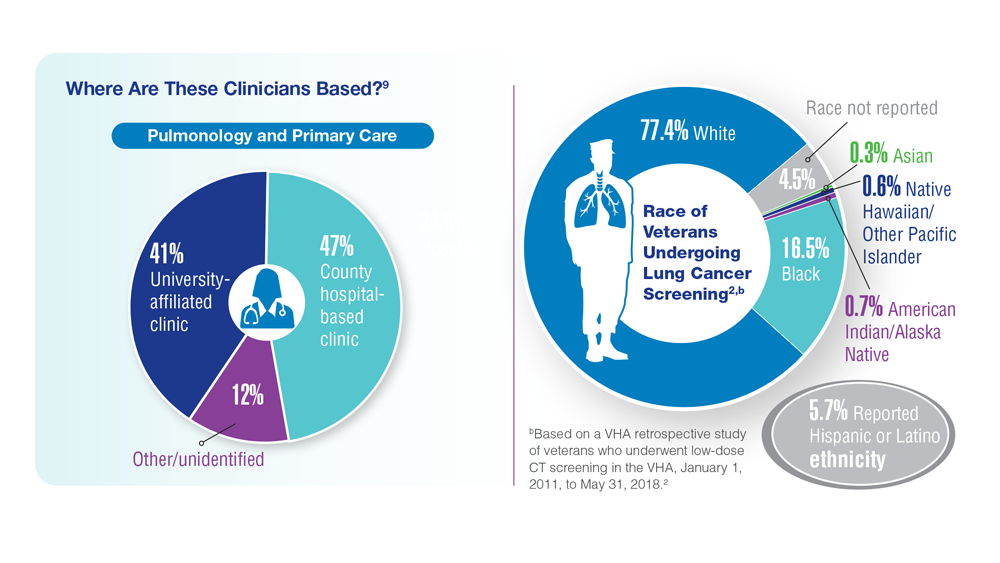

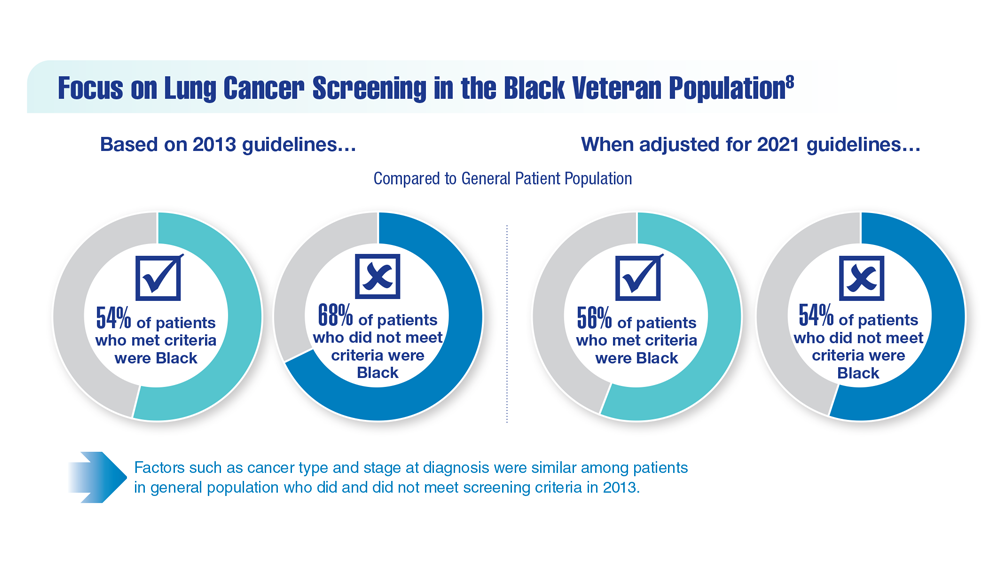

Lung Cancer Screening in Veterans

- Spalluto LB et al. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(6):809-819. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.12.010

- Lewis JA et al. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;4(5):pkaa053. doi:10.1093/jncics/pkaa053

- Wallace C. Largest-ever lung cancer screening study reveals ways to increase screening outreach. Medical University of South Carolina. November 22, 2022. Accessed January 4, 202 https://hollingscancercenter.musc.edu/news/archive/2022/11/22/largest-ever-lung-cancer-screening-study-reveals-ways-to-increase-screening-outreach

- Screening facts & figures. Go2 For Lung Cancer. 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://go2.org/risk-early-detection/screening-facts-figures/

- Dyer O. BMJ. 2021;372:n698. doi:10.1136/bmj.n698

- Boudreau JH et al. Chest. 2021;160(1):358-367. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.02.016

- Maurice NM, Tanner NT. Semin Oncol. 2022;S0093-7754(22)00041-0. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.001

- Rusher TN et al. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 2):S48-S51. doi:10.12788/fp.0269

- Núñez ER et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116233. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16233

- Lake M et al. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):561. doi:1186/s12885-020-06923-0

- Spalluto LB et al. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(6):809-819. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.12.010

- Lewis JA et al. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;4(5):pkaa053. doi:10.1093/jncics/pkaa053

- Wallace C. Largest-ever lung cancer screening study reveals ways to increase screening outreach. Medical University of South Carolina. November 22, 2022. Accessed January 4, 202 https://hollingscancercenter.musc.edu/news/archive/2022/11/22/largest-ever-lung-cancer-screening-study-reveals-ways-to-increase-screening-outreach

- Screening facts & figures. Go2 For Lung Cancer. 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://go2.org/risk-early-detection/screening-facts-figures/

- Dyer O. BMJ. 2021;372:n698. doi:10.1136/bmj.n698

- Boudreau JH et al. Chest. 2021;160(1):358-367. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.02.016

- Maurice NM, Tanner NT. Semin Oncol. 2022;S0093-7754(22)00041-0. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.001

- Rusher TN et al. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 2):S48-S51. doi:10.12788/fp.0269

- Núñez ER et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116233. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16233

- Lake M et al. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):561. doi:1186/s12885-020-06923-0

- Spalluto LB et al. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(6):809-819. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.12.010

- Lewis JA et al. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;4(5):pkaa053. doi:10.1093/jncics/pkaa053

- Wallace C. Largest-ever lung cancer screening study reveals ways to increase screening outreach. Medical University of South Carolina. November 22, 2022. Accessed January 4, 202 https://hollingscancercenter.musc.edu/news/archive/2022/11/22/largest-ever-lung-cancer-screening-study-reveals-ways-to-increase-screening-outreach

- Screening facts & figures. Go2 For Lung Cancer. 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://go2.org/risk-early-detection/screening-facts-figures/

- Dyer O. BMJ. 2021;372:n698. doi:10.1136/bmj.n698

- Boudreau JH et al. Chest. 2021;160(1):358-367. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.02.016

- Maurice NM, Tanner NT. Semin Oncol. 2022;S0093-7754(22)00041-0. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.001

- Rusher TN et al. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 2):S48-S51. doi:10.12788/fp.0269

- Núñez ER et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116233. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16233

- Lake M et al. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):561. doi:1186/s12885-020-06923-0

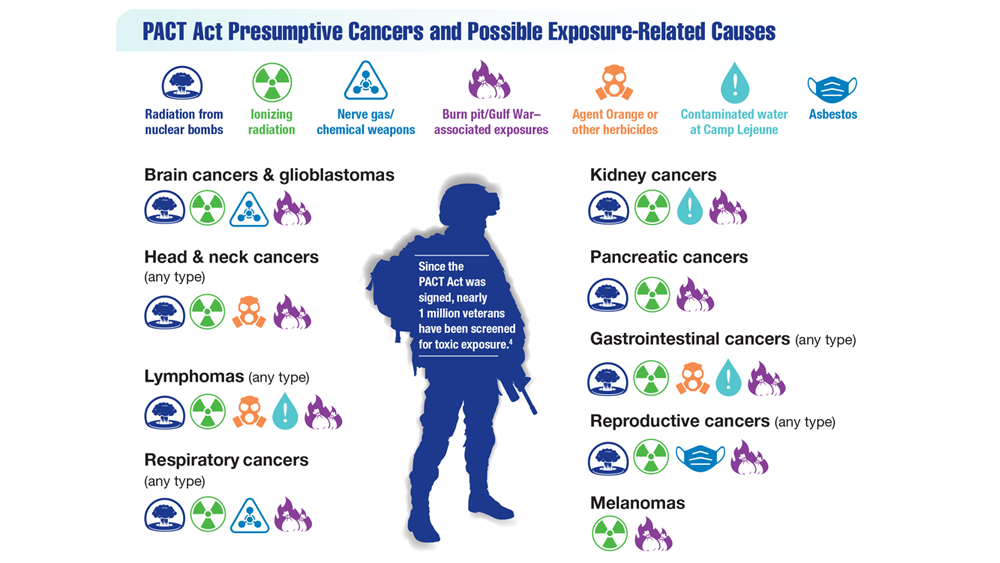

Exposure-Related Cancers: A Look at the PACT Act

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. PACT Act. Updated November 4, 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/benefits/PACT_Act.asp

- The White House. FACT SHEET: President Biden signs the PACT Act and delivers on his promise to America’s veterans. August 10, 202 Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans/

- US House of Representatives. Honoring our promise to address Comprehensive Toxics Act of 2021. Title I – Expansion of health care eligibility for toxic exposed veterans. House report 117-249. February 22, 2022. Accessed January 19, 202 https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CRPT-117hrpt249/html/CRPT-117hrpt249-pt1.htm

- VA News. Cancer Moonshot week of action sees VA deploying new clinical pathways. Updated December 7, 2022. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://news.va.gov/111925/cancer-moonshot-clinical-pathways/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. PACT Act. Updated November 4, 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/benefits/PACT_Act.asp

- The White House. FACT SHEET: President Biden signs the PACT Act and delivers on his promise to America’s veterans. August 10, 202 Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans/

- US House of Representatives. Honoring our promise to address Comprehensive Toxics Act of 2021. Title I – Expansion of health care eligibility for toxic exposed veterans. House report 117-249. February 22, 2022. Accessed January 19, 202 https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CRPT-117hrpt249/html/CRPT-117hrpt249-pt1.htm

- VA News. Cancer Moonshot week of action sees VA deploying new clinical pathways. Updated December 7, 2022. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://news.va.gov/111925/cancer-moonshot-clinical-pathways/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. PACT Act. Updated November 4, 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/benefits/PACT_Act.asp

- The White House. FACT SHEET: President Biden signs the PACT Act and delivers on his promise to America’s veterans. August 10, 202 Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans/

- US House of Representatives. Honoring our promise to address Comprehensive Toxics Act of 2021. Title I – Expansion of health care eligibility for toxic exposed veterans. House report 117-249. February 22, 2022. Accessed January 19, 202 https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CRPT-117hrpt249/html/CRPT-117hrpt249-pt1.htm

- VA News. Cancer Moonshot week of action sees VA deploying new clinical pathways. Updated December 7, 2022. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://news.va.gov/111925/cancer-moonshot-clinical-pathways/

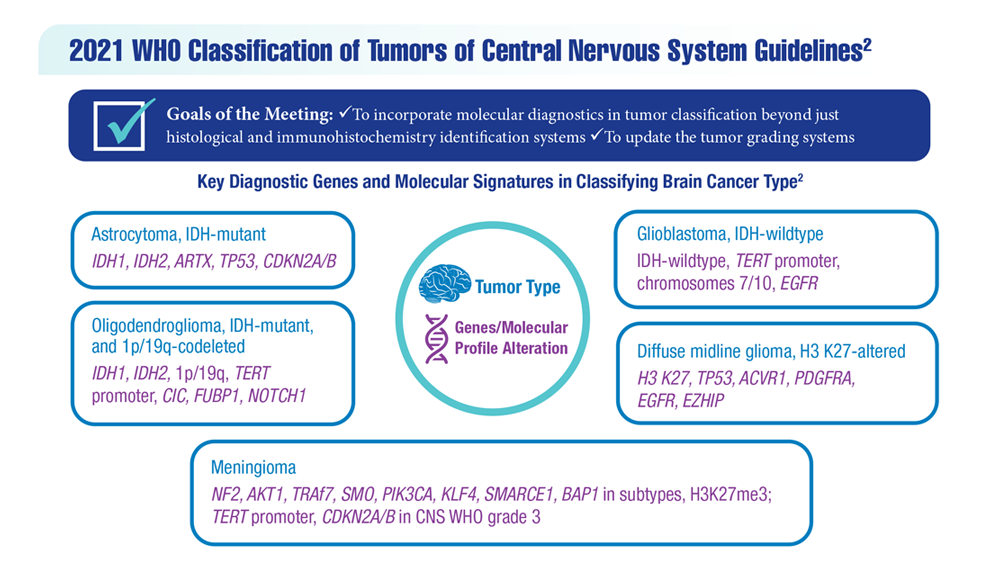

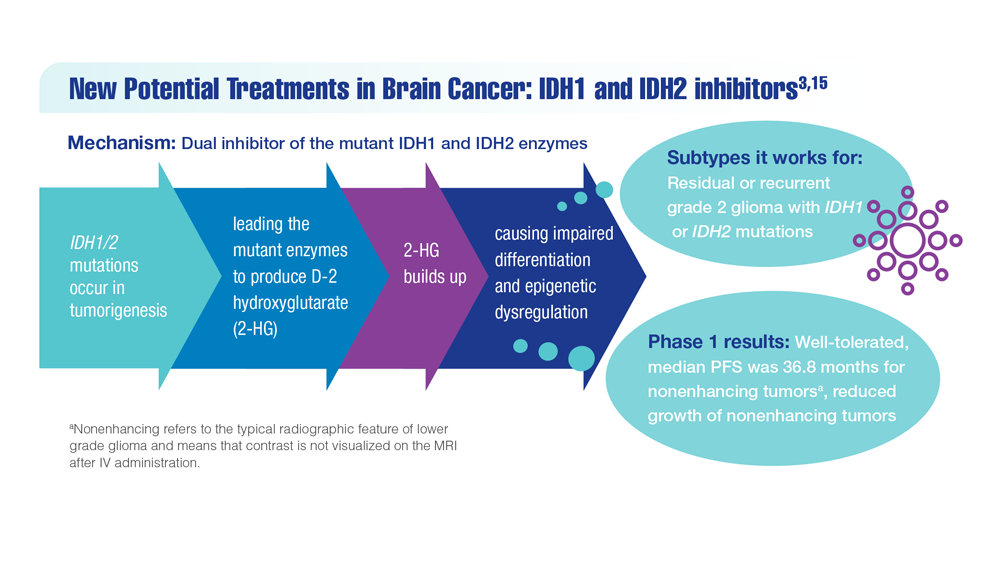

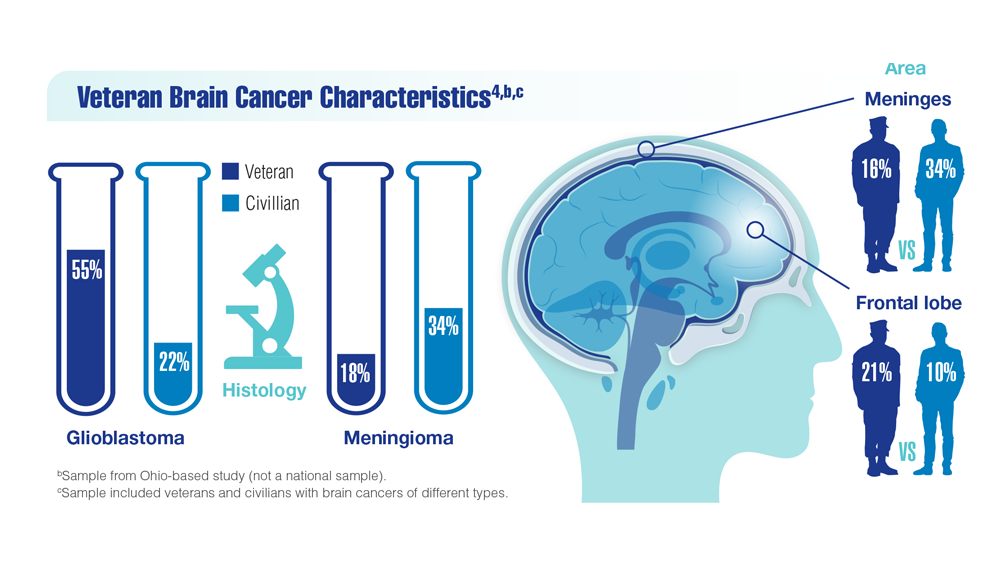

New Classifications and Emerging Treatments in Brain Cancer

- Sokolov AV et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(4):1-32. doi:10.1124/pharmrev.121.000317

- Louis DN et al. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231-1251. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noab106

- Mellinghoff IK et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(16):4491-4499. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0611

- Woo C et al. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2021;5:985-994. doi:10.1200/CCI.21.00052

- Study of vorasidenib (AG-881) in participants with residual or recurrent grade 2 glioma with an IDH1 or IDH2 mutation (INDIGO). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated May 17, 2022. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04164901

- Servier's pivotal phase 3 indigo trial investigating vorasidenib in IDH-mutant low-grade glioma meets primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) and key secondary endpoint of time to next intervention (TTNI) (no date) Servier US. March 14, 2023. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.servier.us/serviers-pivotal-phase-3-indigo-trial-meets-primary-endpoint

- Nehra M et al. J Control Release. 2021;338:224-243. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.027

- Hersh AM et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4920. doi:10.3390/cancers14194920

- Shoaf ML, Desjardins A. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19(6):1818-1831. doi:10.1007/s13311-022-01256-1

- Bagley SJ, O’Rourke DM. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;205:107419. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107419

- Batich KA et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(20):5297-5303. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1082

- Lin J et al. Cancer. 2020;126(13):3053-3060. doi:10.1002/cncr.32884

- Barth SK et al. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50(pt A):22-29. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2017.07.012

- VA and partners hope APOLLO program will be leap forward for precision oncology. US Department of Veteran Affairs. May 1, 2019. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0519-VA-and-partners-hope-APOLLO-program-will-be-leap-forward-for-precision-oncology.cfm

- Konteatis Z et al. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11(2):101-107. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00509

- Sokolov AV et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(4):1-32. doi:10.1124/pharmrev.121.000317

- Louis DN et al. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231-1251. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noab106

- Mellinghoff IK et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(16):4491-4499. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0611

- Woo C et al. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2021;5:985-994. doi:10.1200/CCI.21.00052

- Study of vorasidenib (AG-881) in participants with residual or recurrent grade 2 glioma with an IDH1 or IDH2 mutation (INDIGO). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated May 17, 2022. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04164901

- Servier's pivotal phase 3 indigo trial investigating vorasidenib in IDH-mutant low-grade glioma meets primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) and key secondary endpoint of time to next intervention (TTNI) (no date) Servier US. March 14, 2023. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.servier.us/serviers-pivotal-phase-3-indigo-trial-meets-primary-endpoint

- Nehra M et al. J Control Release. 2021;338:224-243. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.027

- Hersh AM et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4920. doi:10.3390/cancers14194920

- Shoaf ML, Desjardins A. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19(6):1818-1831. doi:10.1007/s13311-022-01256-1

- Bagley SJ, O’Rourke DM. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;205:107419. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107419

- Batich KA et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(20):5297-5303. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1082

- Lin J et al. Cancer. 2020;126(13):3053-3060. doi:10.1002/cncr.32884

- Barth SK et al. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50(pt A):22-29. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2017.07.012

- VA and partners hope APOLLO program will be leap forward for precision oncology. US Department of Veteran Affairs. May 1, 2019. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0519-VA-and-partners-hope-APOLLO-program-will-be-leap-forward-for-precision-oncology.cfm

- Konteatis Z et al. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11(2):101-107. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00509

- Sokolov AV et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(4):1-32. doi:10.1124/pharmrev.121.000317

- Louis DN et al. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231-1251. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noab106

- Mellinghoff IK et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(16):4491-4499. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0611

- Woo C et al. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2021;5:985-994. doi:10.1200/CCI.21.00052

- Study of vorasidenib (AG-881) in participants with residual or recurrent grade 2 glioma with an IDH1 or IDH2 mutation (INDIGO). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated May 17, 2022. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04164901

- Servier's pivotal phase 3 indigo trial investigating vorasidenib in IDH-mutant low-grade glioma meets primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) and key secondary endpoint of time to next intervention (TTNI) (no date) Servier US. March 14, 2023. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.servier.us/serviers-pivotal-phase-3-indigo-trial-meets-primary-endpoint

- Nehra M et al. J Control Release. 2021;338:224-243. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.027

- Hersh AM et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4920. doi:10.3390/cancers14194920

- Shoaf ML, Desjardins A. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19(6):1818-1831. doi:10.1007/s13311-022-01256-1

- Bagley SJ, O’Rourke DM. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;205:107419. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107419

- Batich KA et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(20):5297-5303. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1082

- Lin J et al. Cancer. 2020;126(13):3053-3060. doi:10.1002/cncr.32884

- Barth SK et al. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50(pt A):22-29. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2017.07.012

- VA and partners hope APOLLO program will be leap forward for precision oncology. US Department of Veteran Affairs. May 1, 2019. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0519-VA-and-partners-hope-APOLLO-program-will-be-leap-forward-for-precision-oncology.cfm

- Konteatis Z et al. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11(2):101-107. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00509

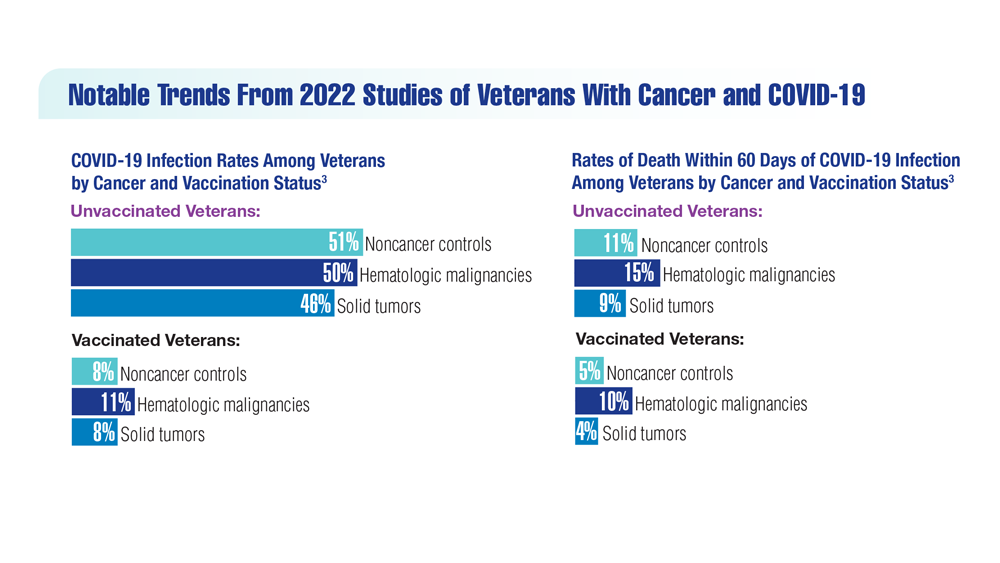

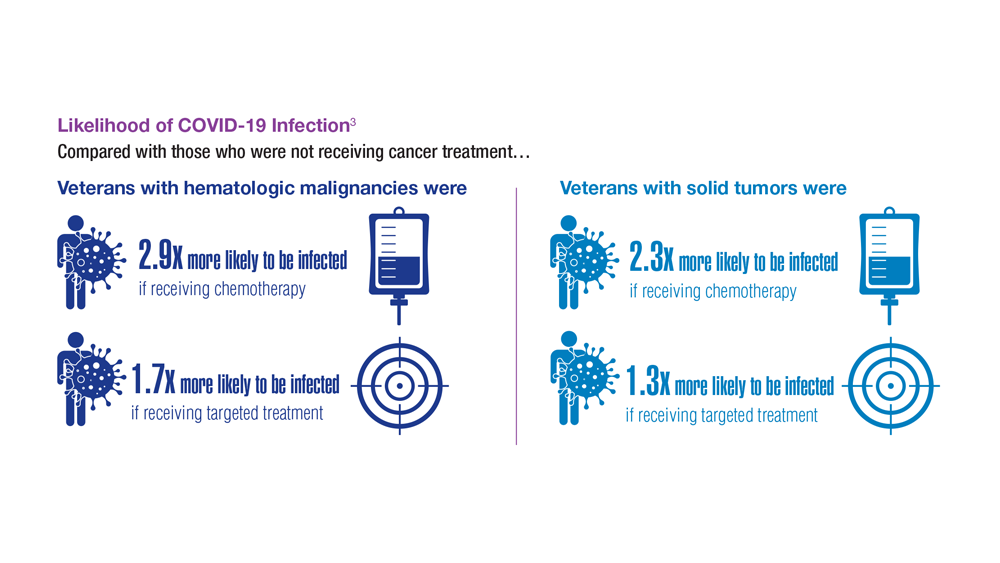

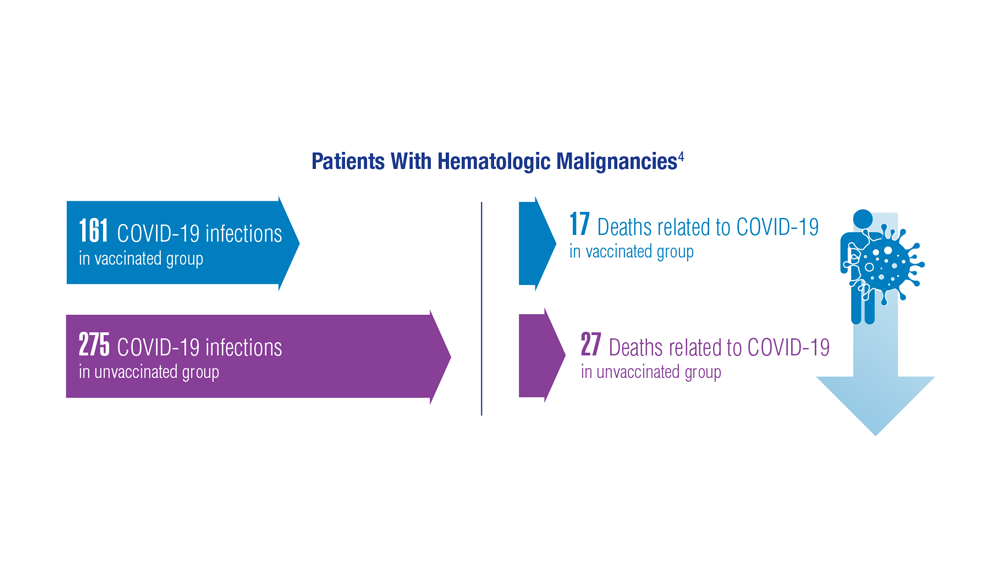

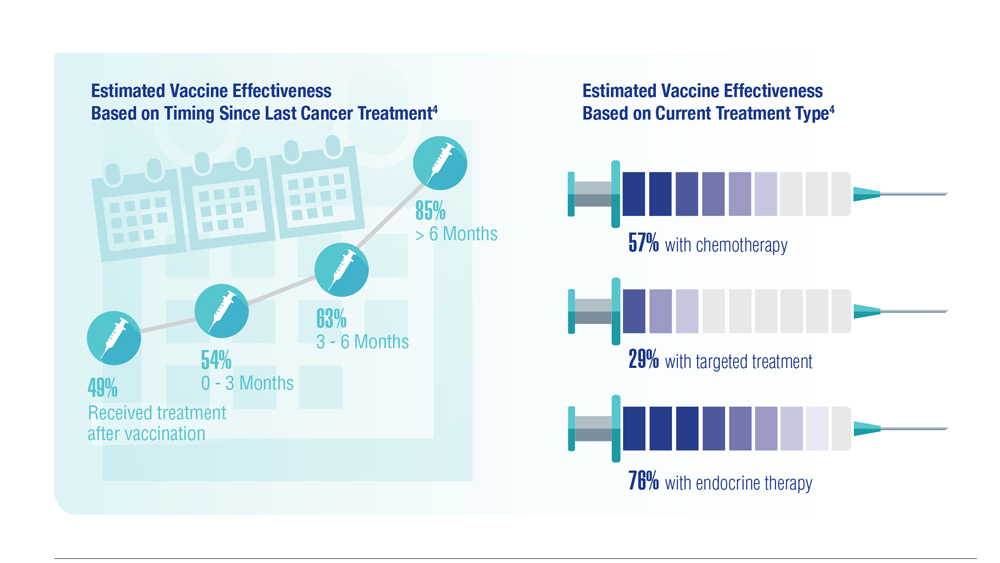

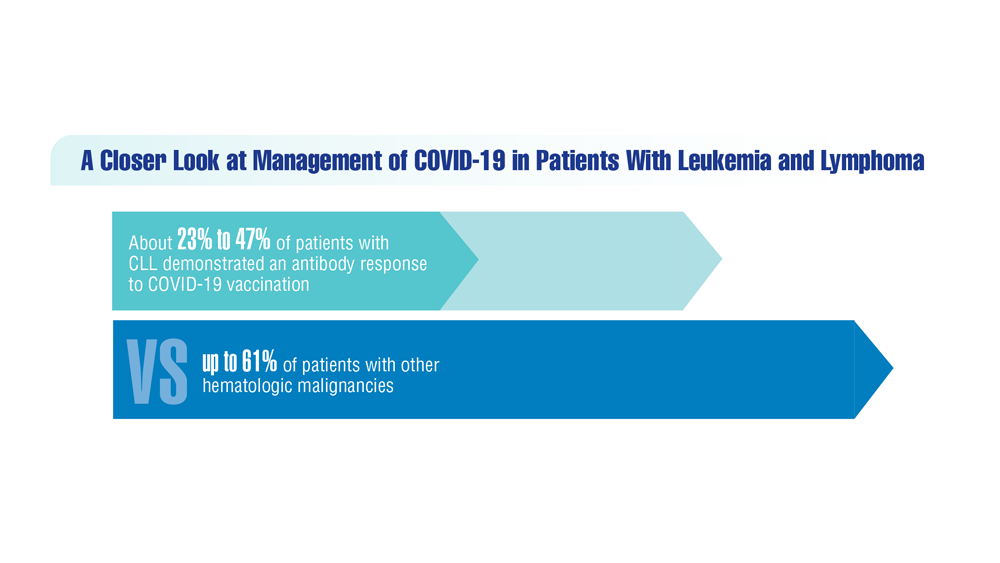

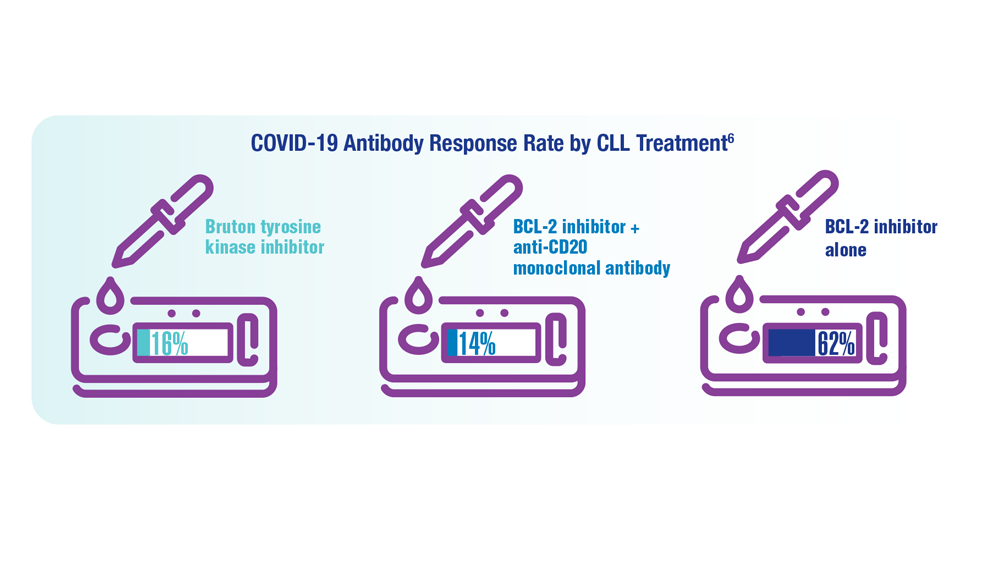

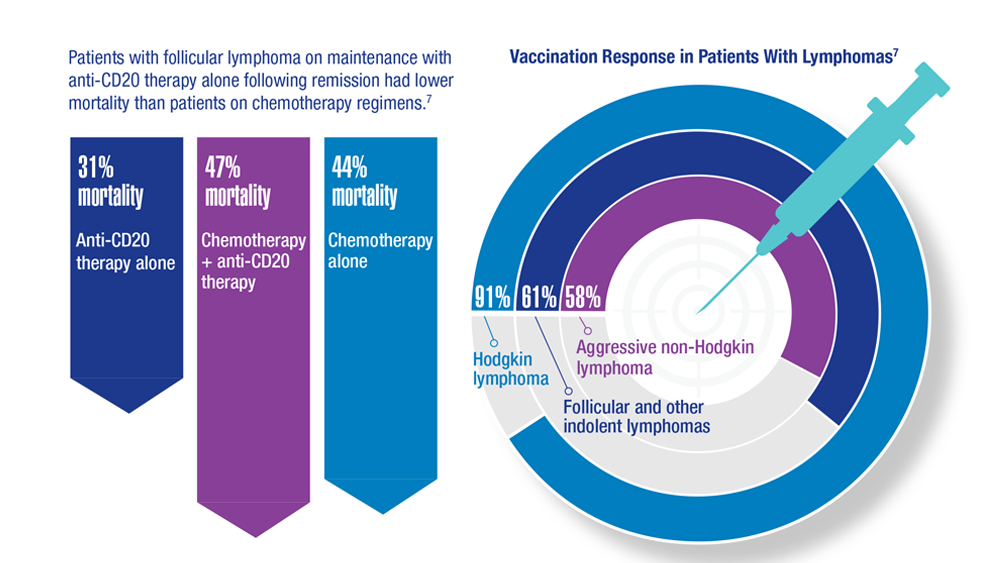

COVID-19 Outcomes in Veterans With Hematologic Malignancies

- Parker S. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(1):2 doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00713-0

- Englum BR et al. Cancer. 2022;128(5):1048-1056. doi:10.1002/cncr.34011

- Leuva H et al. Semin Oncol. 2022:49(5):363-370. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.07.005

- Wu JTY et al. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(2):281-286. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.5771

- Fillmore NR et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(6):691-698. doi:10.1093/jnci/djaa159

- Morawska M. Eur J Haematol. 2022;108(2):91-98. doi:10.1111/ejh.13722

- Passamonti F et al. Hematol Oncol. 2023;41(1):3-15. doi:10.1002/hon.3086

- Parker S. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(1):2 doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00713-0

- Englum BR et al. Cancer. 2022;128(5):1048-1056. doi:10.1002/cncr.34011

- Leuva H et al. Semin Oncol. 2022:49(5):363-370. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.07.005

- Wu JTY et al. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(2):281-286. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.5771

- Fillmore NR et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(6):691-698. doi:10.1093/jnci/djaa159

- Morawska M. Eur J Haematol. 2022;108(2):91-98. doi:10.1111/ejh.13722

- Passamonti F et al. Hematol Oncol. 2023;41(1):3-15. doi:10.1002/hon.3086

- Parker S. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(1):2 doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00713-0

- Englum BR et al. Cancer. 2022;128(5):1048-1056. doi:10.1002/cncr.34011

- Leuva H et al. Semin Oncol. 2022:49(5):363-370. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.07.005

- Wu JTY et al. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(2):281-286. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.5771

- Fillmore NR et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(6):691-698. doi:10.1093/jnci/djaa159

- Morawska M. Eur J Haematol. 2022;108(2):91-98. doi:10.1111/ejh.13722

- Passamonti F et al. Hematol Oncol. 2023;41(1):3-15. doi:10.1002/hon.3086

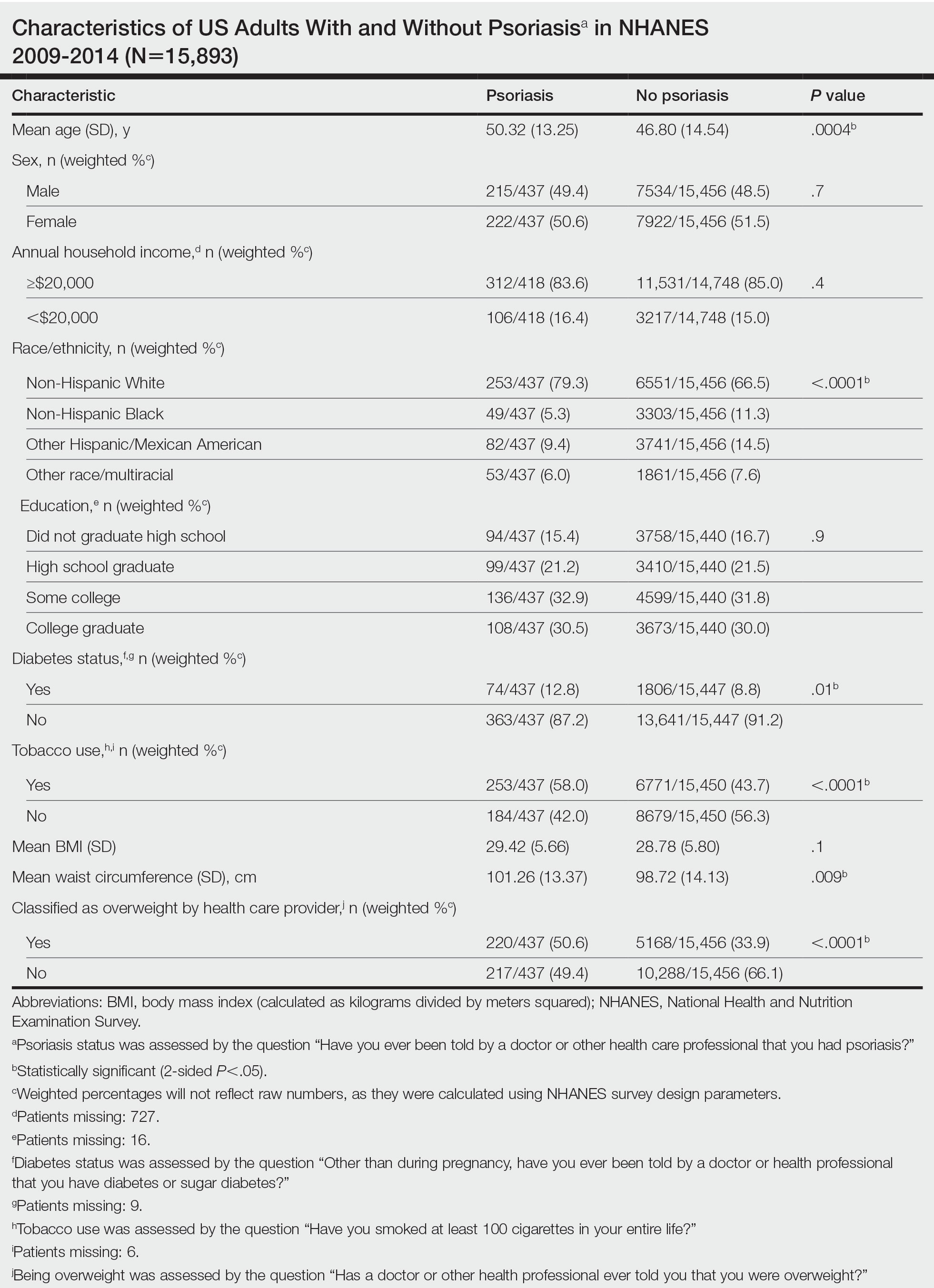

Association Between Psoriasis and Obesity Among US Adults in the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

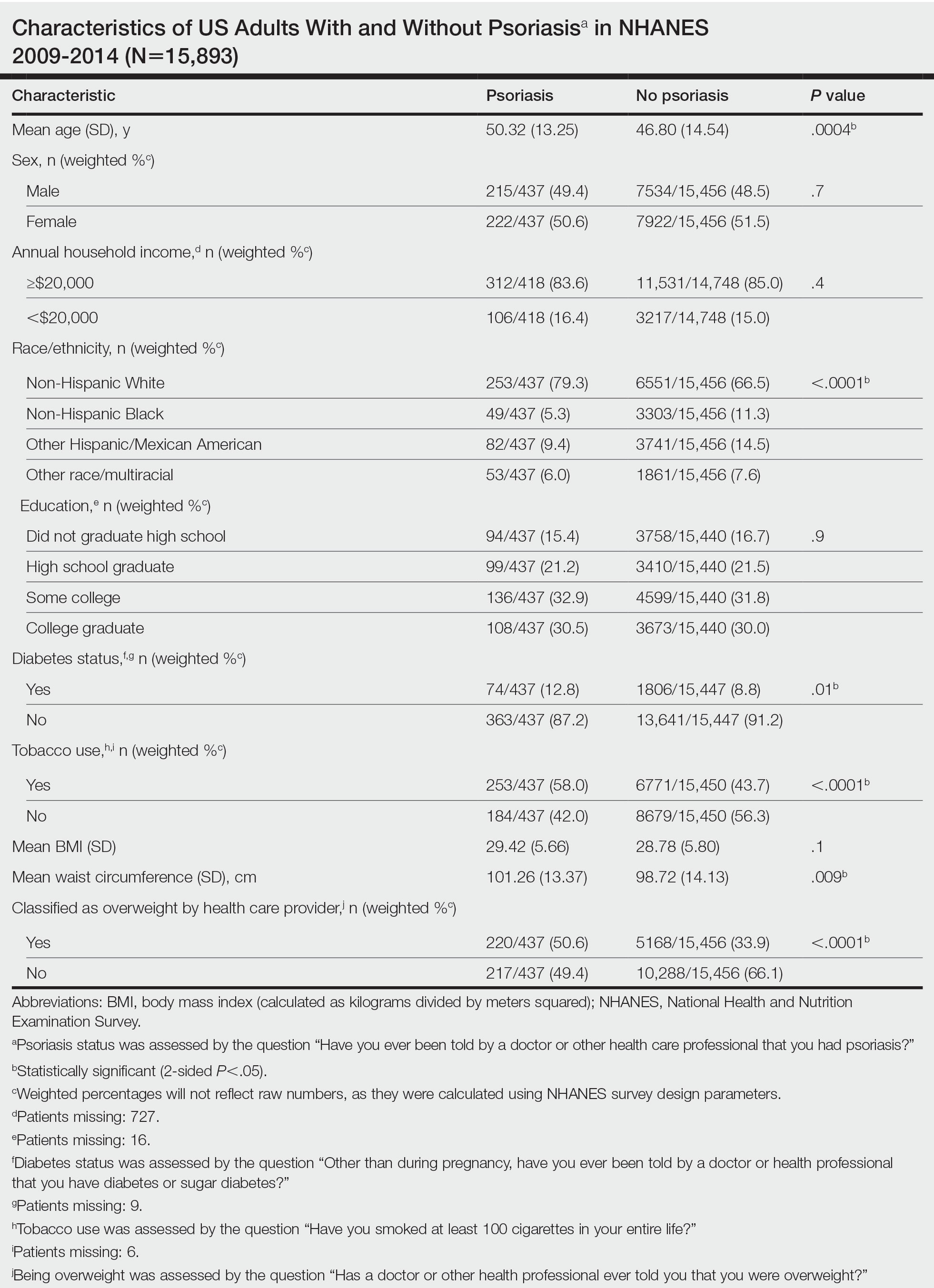

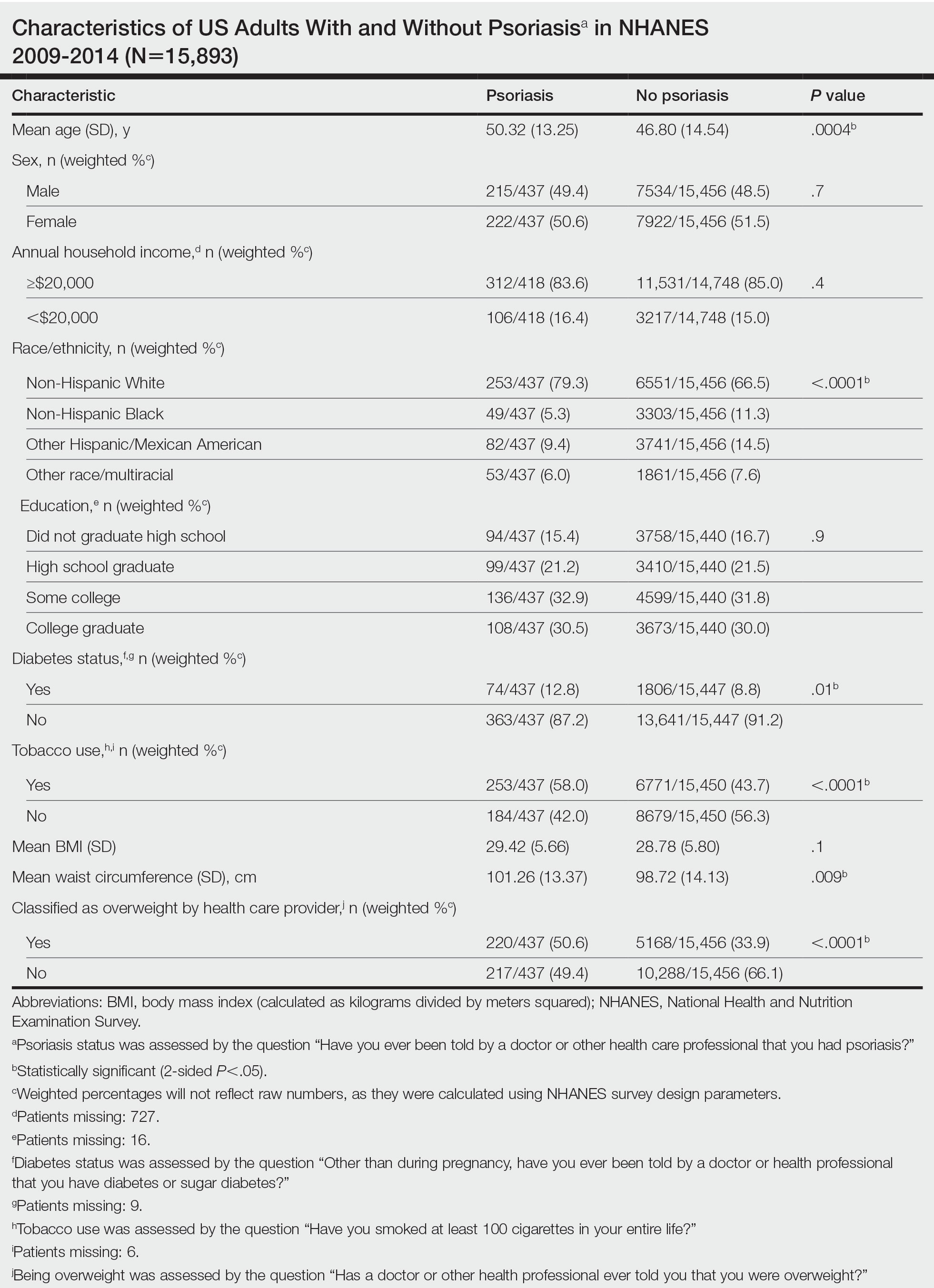

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

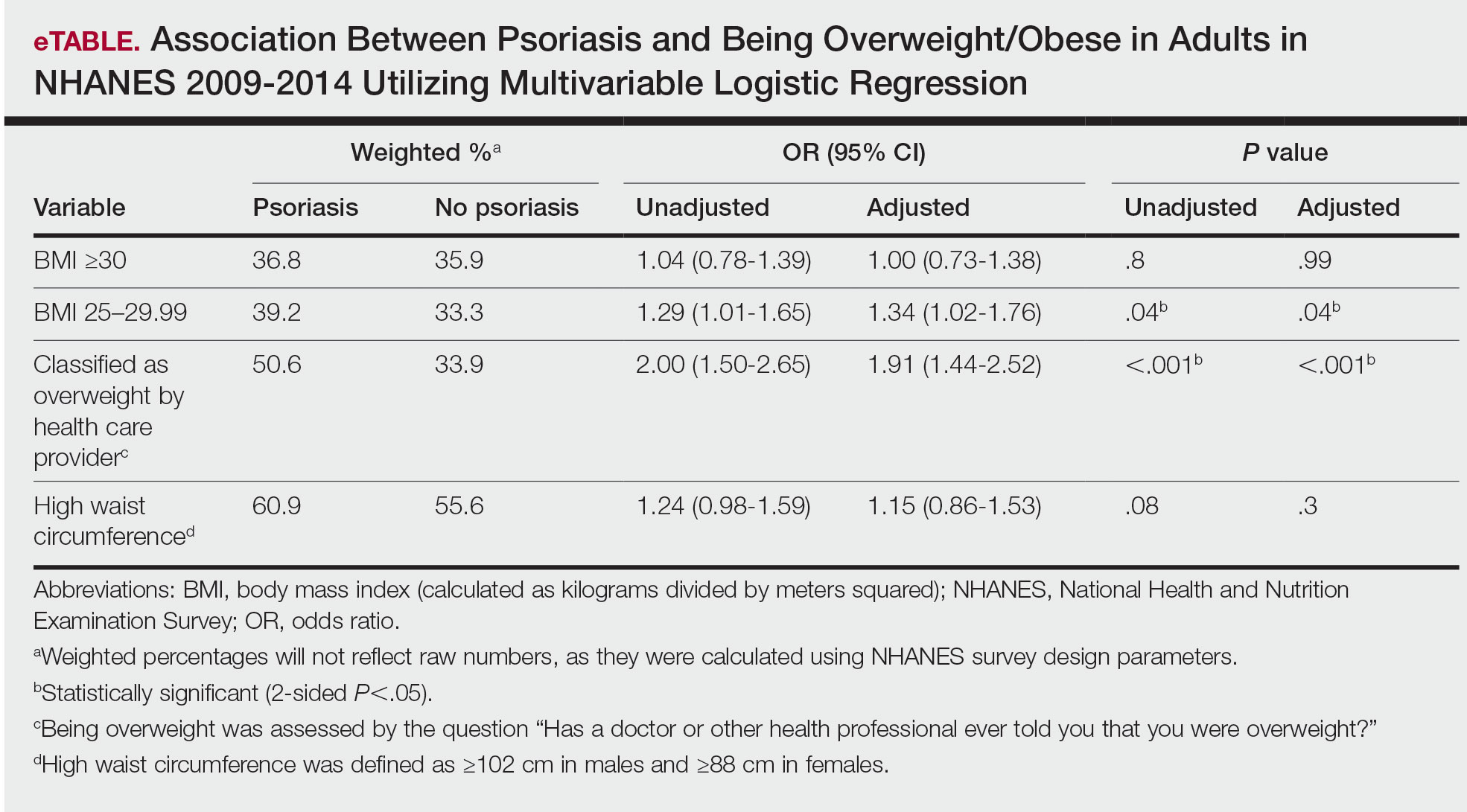

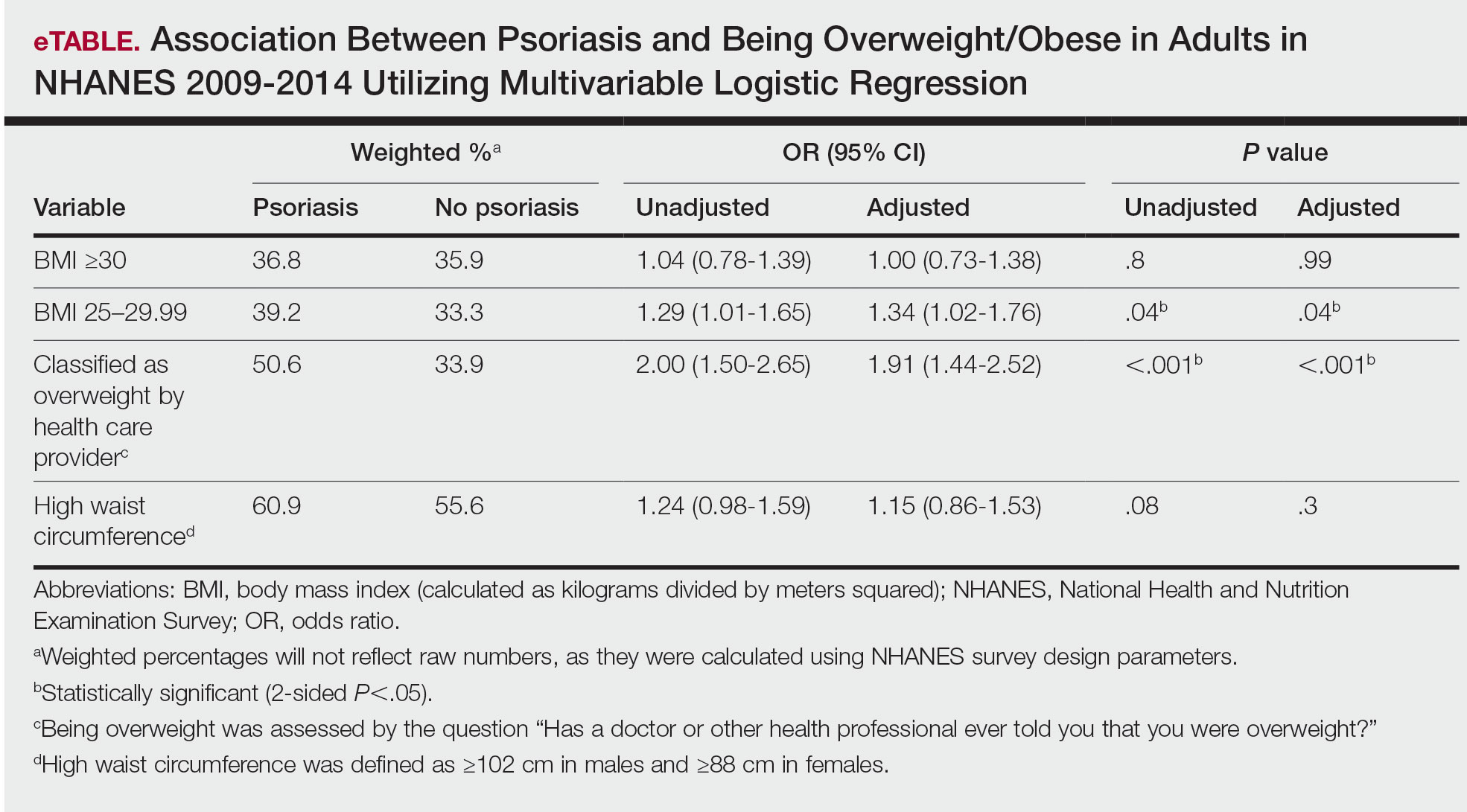

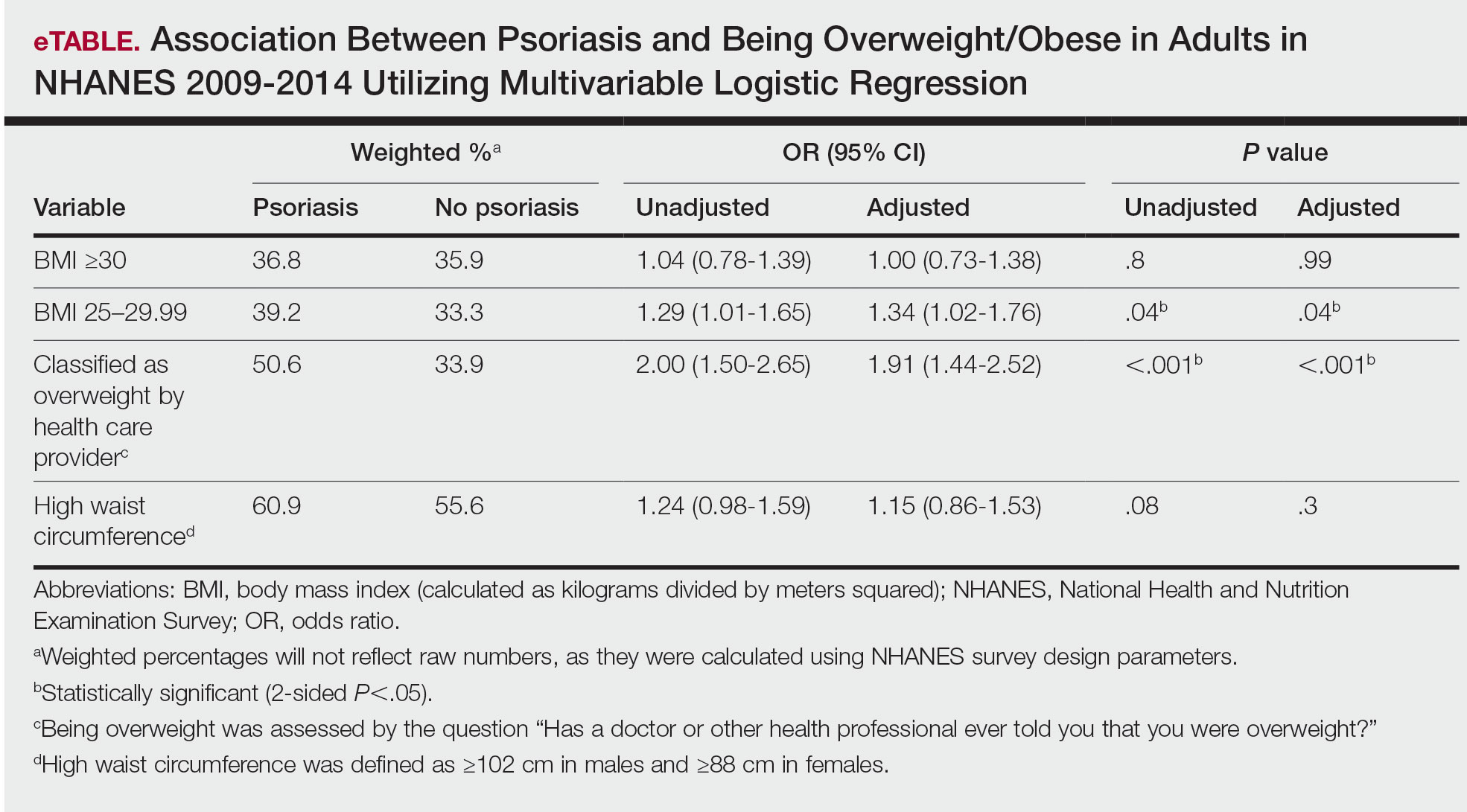

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

Practice Points

- There are many comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis, making it crucial to evaluate for these diseases in patients with psoriasis.

- Obesity may be a contributing factor to psoriasis development due to the role of IL-17 secretion.

Palliative Care: Utilization Patterns in Inpatient Dermatology

Palliative care (PC) is a field of medicine that focuses on improving quality of life by managing physical symptoms as well as mental and spiritual well-being in patients with severe illnesses.1,2 Despite cases of severe dermatologic disease, the use of PC in the field of dermatology is limited, often leaving patients with a range of unmet needs.2,3 In one study that explored PC in patients with melanoma, only one-third of patients with advanced melanoma had a PC consultation.4 Reasons behind the lack of utilization of PC in dermatology include time constraints and limited training in addressing the complex psychosocial needs of patients with severe dermatologic illnesses.1 We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, single-institution study of specific inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period to describe PC utilization among patients who were hospitalized with select severe dermatologic diseases.

Methods

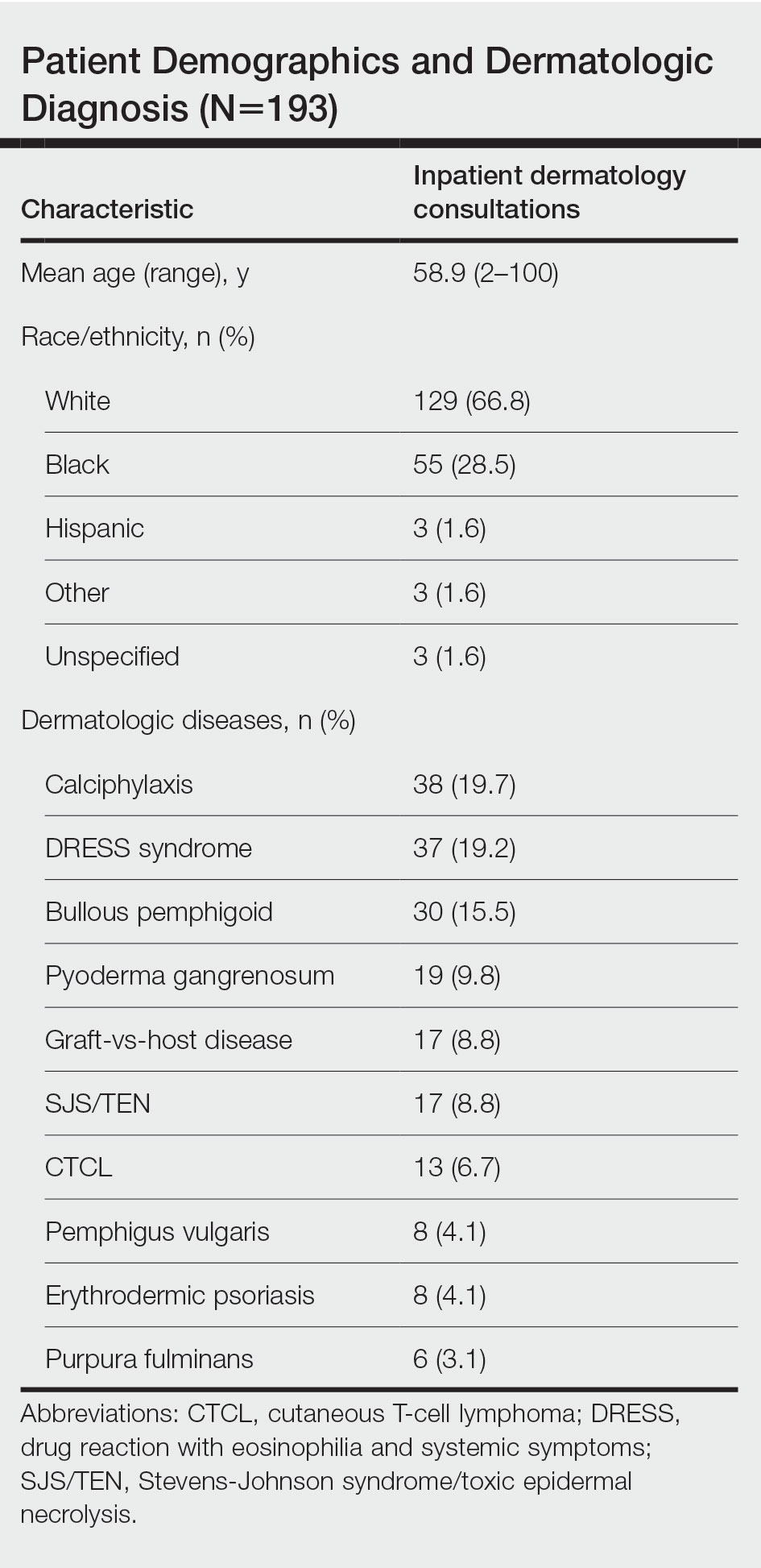

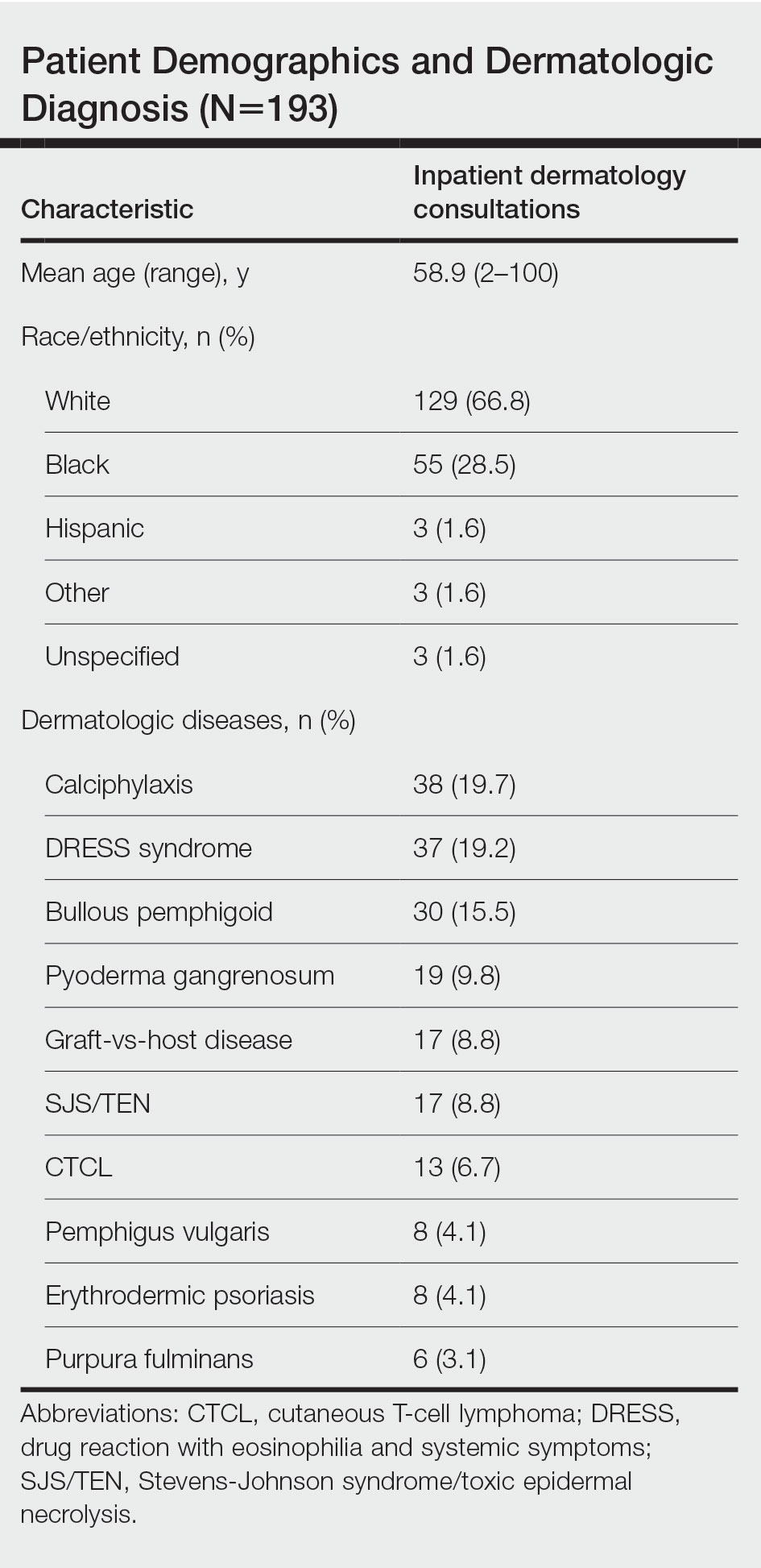

A retrospective, cross-sectional study of inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period (October 2016 to October 2021) was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Patients’ medical records were reviewed if they had one of the following diseases: bullous pemphigoid, calciphylaxis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, erythrodermic psoriasis, graft-vs-host disease, pemphigus vulgaris (PV), purpura fulminans, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. These diseases were selected for inclusion because they have been associated with a documented increase in inpatient mortality and have been described in the published literature on PC in dermatology.2 This study was reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board.

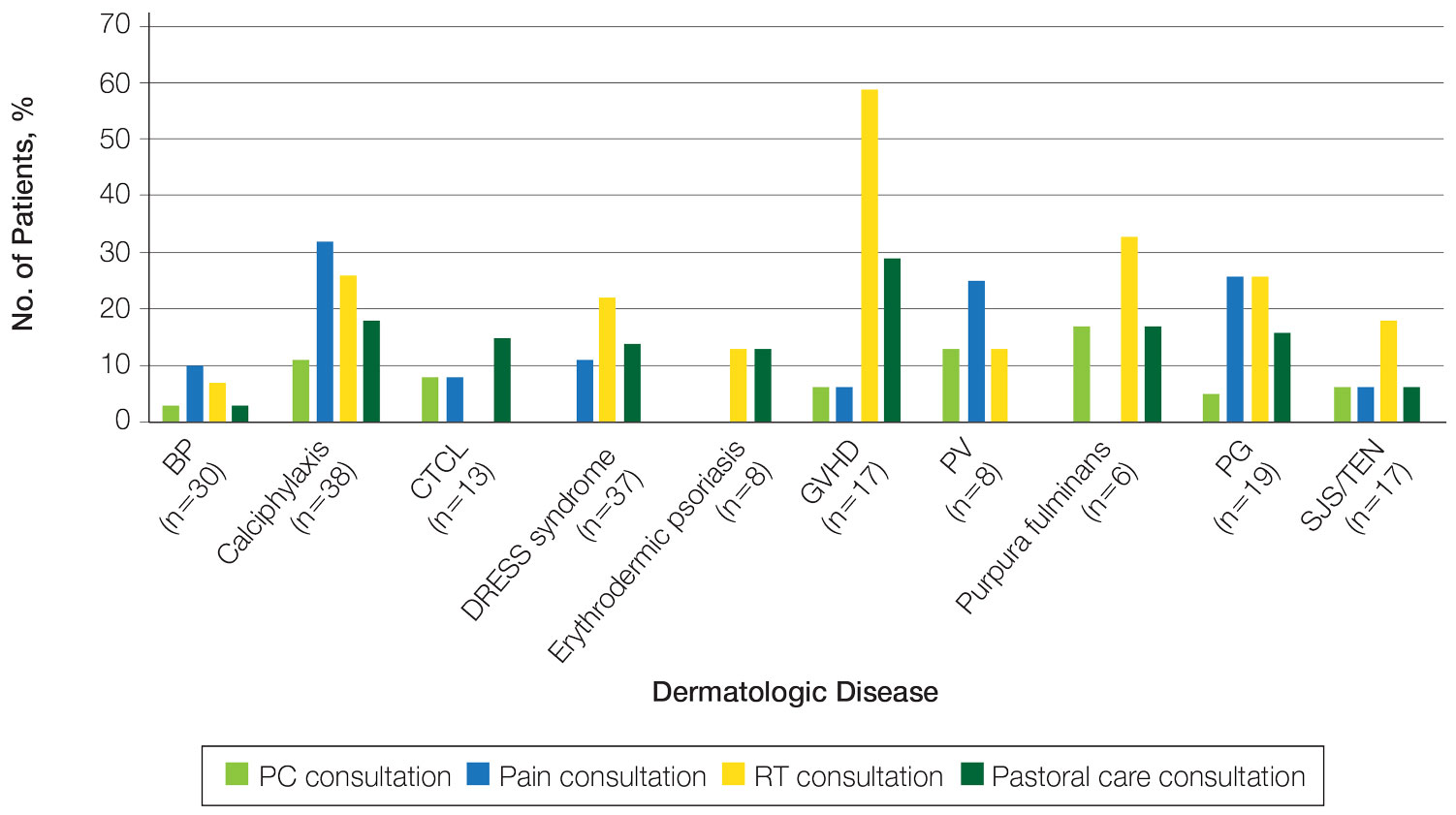

Use of PC consultative services along with other associated consultative care (ie, recreation therapy [RT], acute pain management, pastoral care) was assessed for each patient. Recreation therapy included specific interventions such as music therapy, arts/craft therapy, pet therapy, and other services with the goal of improving patient cognitive, emotional, and social function. For patients with a completed PC consultation, goals for PC intervention were recorded.

Results

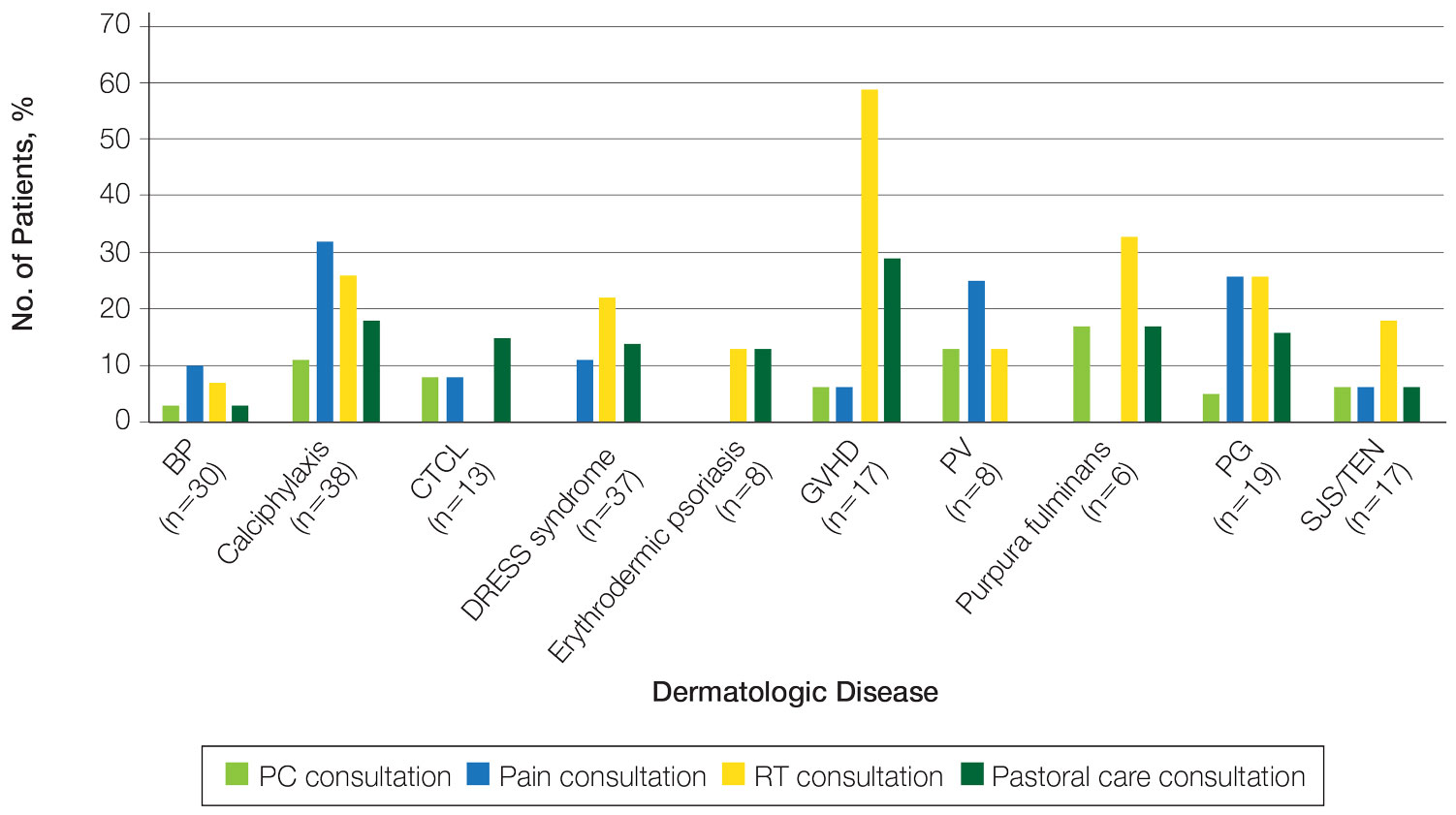

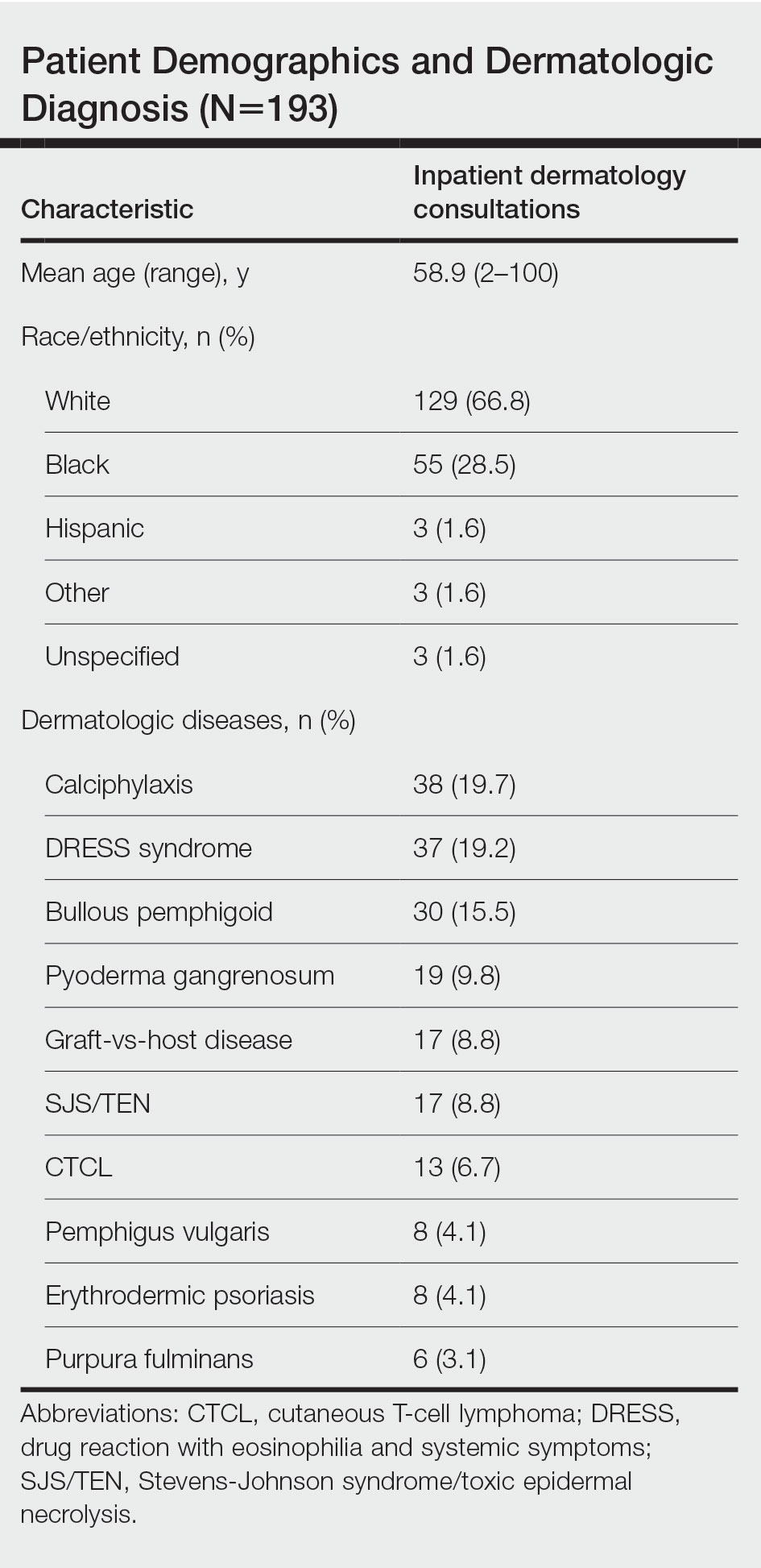

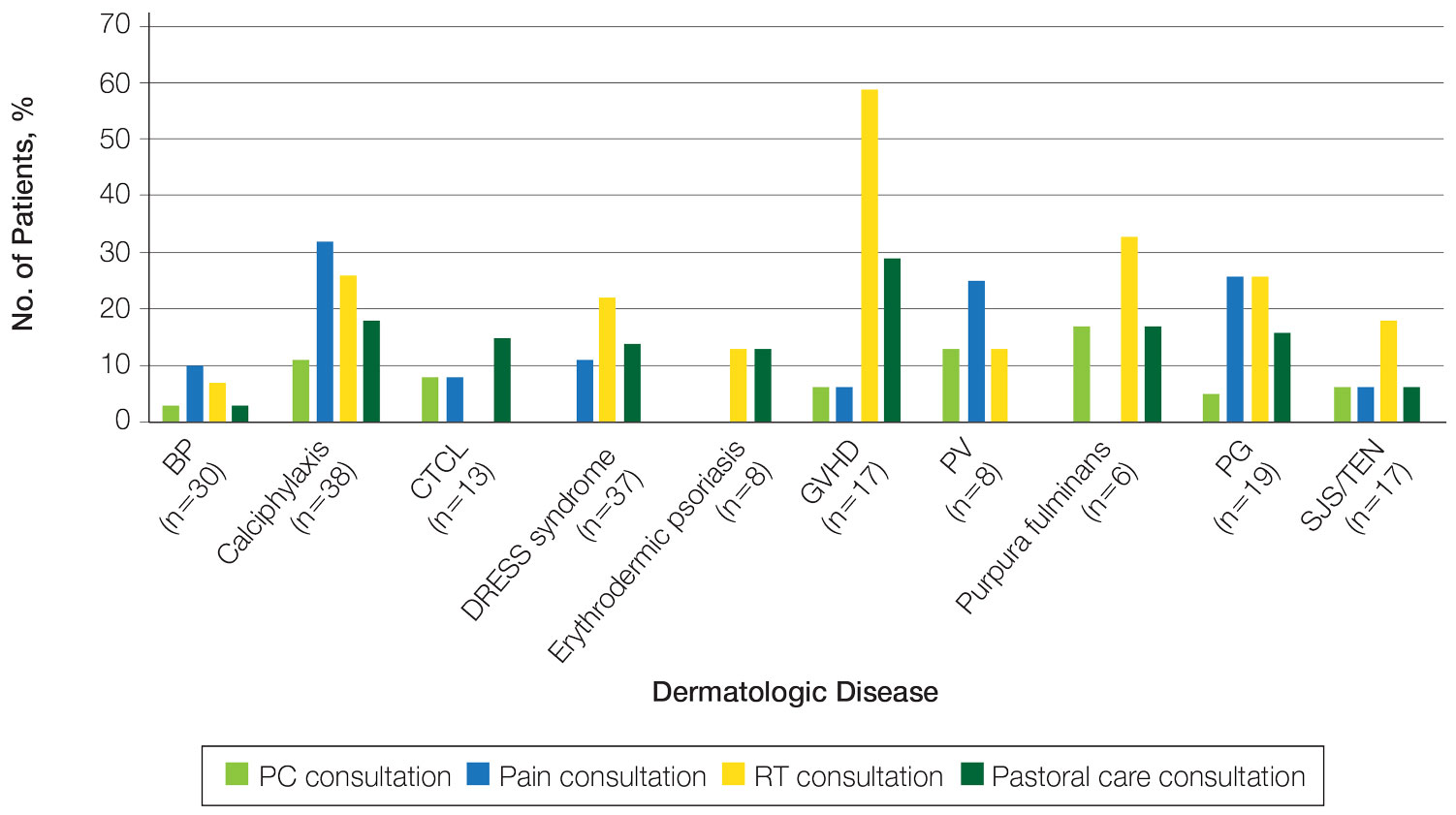

The total study sample included 193 inpatient dermatology consultations. The mean age of the patients was 58.9 years (range, 2–100 years); 66.8% (129/193) were White and 28.5% (55/193) were Black (Table). Palliative care was consulted in 5.7% of cases, with consultations being requested by the primary care team. Reasons for PC consultation included assessment of the patient’s goals of care (4.1% [8/193]), pain management (3.6% [7/193]), non–pain symptom management (2.6% [5/193]), psychosocial support (1.6% [3/193]), and transitions of care (1.0% [2/193]). The average length of patients’ hospital stay prior to PC consultation was 11.5 days(range, 1–32 days). Acute pain management was the reason for consultation in 15.0% of cases (29/193), RT in 21.8% (42/193), and pastoral care in 13.5% (26/193) of cases. Patients with calciphylaxis received the most PC and pain consultations, but fewer than half received these services. Patients with calciphylaxis, PV, purpura fulminans, and CTCL received a higher percentage of PC consultations than the overall cohort, while patients with calciphylaxis, DRESS syndrome, PV, and pyoderma gangrenosum received relatively more pain consultations than the overall cohort (Figure).

Comment

Clinical practice guidelines for quality PC stress the importance of specialists being familiar with these services and the ability to involve PC as part of the treatment plan to achieve better care for patients with serious illnesses.5 Our results demonstrated low rates of PC consultation services for dermatology patients, which supports the existing literature and suggests that PC may be highly underutilized in inpatient settings for patients with serious skin diseases. Use of PC was infrequent and was initiated relatively late in the course of hospital admission, which can negatively impact a patient’s well-being and care experience and can increase the care burden on their caregivers and families.2

Our results suggest a discrepancy in the frequency of formal PC and other palliative consultative services used for dermatologic diseases, with non-PC services including RT, acute pain management, and pastoral care more likely to be utilized. Impacting this finding may be that RT, pastoral care, and acute pain management are provided by nonphysician providers at our institution, not attending faculty staffing PC services. Patients with calciphylaxis were more likely to have PC consultations, potentially due to medicine providers’ familiarity with its morbidity and mortality, as it is commonly associated with end-stage renal disease. Similarly, internal medicine providers may be more familiar with pain classically associated with PG and PV and may be more likely to engage pain experts. Some diseases with notable morbidity and potential mortality were underrepresented including SJS/TEN, erythrodermic psoriasis, CTCL, and GVHD.

Limitations of our study included examination of data from a single institution, as well as the small sample sizes in specific subgroups, which prevented us from making comparisons between diseases. The cross-sectional design also limited our ability to control for confounding variables.

Conclusion

We urge dermatology consultation services to advocate for patients with serious skin diseases andinclude PC consultation as part of their recommendations to primary care teams. Further research should characterize the specific needs of patients that may be addressed by PC services and explore ways dermatologists and others can identify and provide specialty care to hospitalized patients.

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747-755.

- Thompson LL, Chen ST, Lawton A, et al. Palliative care in dermatology: a clinical primer, review of the literature, and needs assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:708-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.029

- Yang CS, Quan VL, Charrow A. The power of a palliative perspective in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:609-610. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1298

- Osagiede O, Colibaseanu DT, Spaulding AC, et al. Palliative care use among patients with solid cancer tumors. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:149-158.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

Palliative care (PC) is a field of medicine that focuses on improving quality of life by managing physical symptoms as well as mental and spiritual well-being in patients with severe illnesses.1,2 Despite cases of severe dermatologic disease, the use of PC in the field of dermatology is limited, often leaving patients with a range of unmet needs.2,3 In one study that explored PC in patients with melanoma, only one-third of patients with advanced melanoma had a PC consultation.4 Reasons behind the lack of utilization of PC in dermatology include time constraints and limited training in addressing the complex psychosocial needs of patients with severe dermatologic illnesses.1 We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, single-institution study of specific inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period to describe PC utilization among patients who were hospitalized with select severe dermatologic diseases.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study of inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period (October 2016 to October 2021) was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Patients’ medical records were reviewed if they had one of the following diseases: bullous pemphigoid, calciphylaxis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, erythrodermic psoriasis, graft-vs-host disease, pemphigus vulgaris (PV), purpura fulminans, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. These diseases were selected for inclusion because they have been associated with a documented increase in inpatient mortality and have been described in the published literature on PC in dermatology.2 This study was reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board.

Use of PC consultative services along with other associated consultative care (ie, recreation therapy [RT], acute pain management, pastoral care) was assessed for each patient. Recreation therapy included specific interventions such as music therapy, arts/craft therapy, pet therapy, and other services with the goal of improving patient cognitive, emotional, and social function. For patients with a completed PC consultation, goals for PC intervention were recorded.

Results

The total study sample included 193 inpatient dermatology consultations. The mean age of the patients was 58.9 years (range, 2–100 years); 66.8% (129/193) were White and 28.5% (55/193) were Black (Table). Palliative care was consulted in 5.7% of cases, with consultations being requested by the primary care team. Reasons for PC consultation included assessment of the patient’s goals of care (4.1% [8/193]), pain management (3.6% [7/193]), non–pain symptom management (2.6% [5/193]), psychosocial support (1.6% [3/193]), and transitions of care (1.0% [2/193]). The average length of patients’ hospital stay prior to PC consultation was 11.5 days(range, 1–32 days). Acute pain management was the reason for consultation in 15.0% of cases (29/193), RT in 21.8% (42/193), and pastoral care in 13.5% (26/193) of cases. Patients with calciphylaxis received the most PC and pain consultations, but fewer than half received these services. Patients with calciphylaxis, PV, purpura fulminans, and CTCL received a higher percentage of PC consultations than the overall cohort, while patients with calciphylaxis, DRESS syndrome, PV, and pyoderma gangrenosum received relatively more pain consultations than the overall cohort (Figure).

Comment

Clinical practice guidelines for quality PC stress the importance of specialists being familiar with these services and the ability to involve PC as part of the treatment plan to achieve better care for patients with serious illnesses.5 Our results demonstrated low rates of PC consultation services for dermatology patients, which supports the existing literature and suggests that PC may be highly underutilized in inpatient settings for patients with serious skin diseases. Use of PC was infrequent and was initiated relatively late in the course of hospital admission, which can negatively impact a patient’s well-being and care experience and can increase the care burden on their caregivers and families.2

Our results suggest a discrepancy in the frequency of formal PC and other palliative consultative services used for dermatologic diseases, with non-PC services including RT, acute pain management, and pastoral care more likely to be utilized. Impacting this finding may be that RT, pastoral care, and acute pain management are provided by nonphysician providers at our institution, not attending faculty staffing PC services. Patients with calciphylaxis were more likely to have PC consultations, potentially due to medicine providers’ familiarity with its morbidity and mortality, as it is commonly associated with end-stage renal disease. Similarly, internal medicine providers may be more familiar with pain classically associated with PG and PV and may be more likely to engage pain experts. Some diseases with notable morbidity and potential mortality were underrepresented including SJS/TEN, erythrodermic psoriasis, CTCL, and GVHD.

Limitations of our study included examination of data from a single institution, as well as the small sample sizes in specific subgroups, which prevented us from making comparisons between diseases. The cross-sectional design also limited our ability to control for confounding variables.

Conclusion

We urge dermatology consultation services to advocate for patients with serious skin diseases andinclude PC consultation as part of their recommendations to primary care teams. Further research should characterize the specific needs of patients that may be addressed by PC services and explore ways dermatologists and others can identify and provide specialty care to hospitalized patients.

Palliative care (PC) is a field of medicine that focuses on improving quality of life by managing physical symptoms as well as mental and spiritual well-being in patients with severe illnesses.1,2 Despite cases of severe dermatologic disease, the use of PC in the field of dermatology is limited, often leaving patients with a range of unmet needs.2,3 In one study that explored PC in patients with melanoma, only one-third of patients with advanced melanoma had a PC consultation.4 Reasons behind the lack of utilization of PC in dermatology include time constraints and limited training in addressing the complex psychosocial needs of patients with severe dermatologic illnesses.1 We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, single-institution study of specific inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period to describe PC utilization among patients who were hospitalized with select severe dermatologic diseases.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study of inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period (October 2016 to October 2021) was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Patients’ medical records were reviewed if they had one of the following diseases: bullous pemphigoid, calciphylaxis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, erythrodermic psoriasis, graft-vs-host disease, pemphigus vulgaris (PV), purpura fulminans, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. These diseases were selected for inclusion because they have been associated with a documented increase in inpatient mortality and have been described in the published literature on PC in dermatology.2 This study was reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board.

Use of PC consultative services along with other associated consultative care (ie, recreation therapy [RT], acute pain management, pastoral care) was assessed for each patient. Recreation therapy included specific interventions such as music therapy, arts/craft therapy, pet therapy, and other services with the goal of improving patient cognitive, emotional, and social function. For patients with a completed PC consultation, goals for PC intervention were recorded.

Results

The total study sample included 193 inpatient dermatology consultations. The mean age of the patients was 58.9 years (range, 2–100 years); 66.8% (129/193) were White and 28.5% (55/193) were Black (Table). Palliative care was consulted in 5.7% of cases, with consultations being requested by the primary care team. Reasons for PC consultation included assessment of the patient’s goals of care (4.1% [8/193]), pain management (3.6% [7/193]), non–pain symptom management (2.6% [5/193]), psychosocial support (1.6% [3/193]), and transitions of care (1.0% [2/193]). The average length of patients’ hospital stay prior to PC consultation was 11.5 days(range, 1–32 days). Acute pain management was the reason for consultation in 15.0% of cases (29/193), RT in 21.8% (42/193), and pastoral care in 13.5% (26/193) of cases. Patients with calciphylaxis received the most PC and pain consultations, but fewer than half received these services. Patients with calciphylaxis, PV, purpura fulminans, and CTCL received a higher percentage of PC consultations than the overall cohort, while patients with calciphylaxis, DRESS syndrome, PV, and pyoderma gangrenosum received relatively more pain consultations than the overall cohort (Figure).

Comment

Clinical practice guidelines for quality PC stress the importance of specialists being familiar with these services and the ability to involve PC as part of the treatment plan to achieve better care for patients with serious illnesses.5 Our results demonstrated low rates of PC consultation services for dermatology patients, which supports the existing literature and suggests that PC may be highly underutilized in inpatient settings for patients with serious skin diseases. Use of PC was infrequent and was initiated relatively late in the course of hospital admission, which can negatively impact a patient’s well-being and care experience and can increase the care burden on their caregivers and families.2

Our results suggest a discrepancy in the frequency of formal PC and other palliative consultative services used for dermatologic diseases, with non-PC services including RT, acute pain management, and pastoral care more likely to be utilized. Impacting this finding may be that RT, pastoral care, and acute pain management are provided by nonphysician providers at our institution, not attending faculty staffing PC services. Patients with calciphylaxis were more likely to have PC consultations, potentially due to medicine providers’ familiarity with its morbidity and mortality, as it is commonly associated with end-stage renal disease. Similarly, internal medicine providers may be more familiar with pain classically associated with PG and PV and may be more likely to engage pain experts. Some diseases with notable morbidity and potential mortality were underrepresented including SJS/TEN, erythrodermic psoriasis, CTCL, and GVHD.

Limitations of our study included examination of data from a single institution, as well as the small sample sizes in specific subgroups, which prevented us from making comparisons between diseases. The cross-sectional design also limited our ability to control for confounding variables.

Conclusion

We urge dermatology consultation services to advocate for patients with serious skin diseases andinclude PC consultation as part of their recommendations to primary care teams. Further research should characterize the specific needs of patients that may be addressed by PC services and explore ways dermatologists and others can identify and provide specialty care to hospitalized patients.

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747-755.

- Thompson LL, Chen ST, Lawton A, et al. Palliative care in dermatology: a clinical primer, review of the literature, and needs assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:708-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.029

- Yang CS, Quan VL, Charrow A. The power of a palliative perspective in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:609-610. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1298

- Osagiede O, Colibaseanu DT, Spaulding AC, et al. Palliative care use among patients with solid cancer tumors. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:149-158.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747-755.

- Thompson LL, Chen ST, Lawton A, et al. Palliative care in dermatology: a clinical primer, review of the literature, and needs assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:708-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.029

- Yang CS, Quan VL, Charrow A. The power of a palliative perspective in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:609-610. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1298

- Osagiede O, Colibaseanu DT, Spaulding AC, et al. Palliative care use among patients with solid cancer tumors. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:149-158.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

Practice Points

- Although severe dermatologic disease negatively impacts patients’ quality of life, palliative care may be underutilized in this population.

- Palliative care should be an integral part of caring for patients who are admitted to the hospital with serious dermatologic illnesses.

Painful, Nonhealing, Violaceus Plaque on the Right Breast

The Diagnosis: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

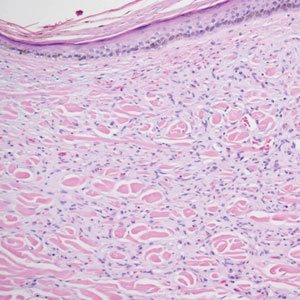

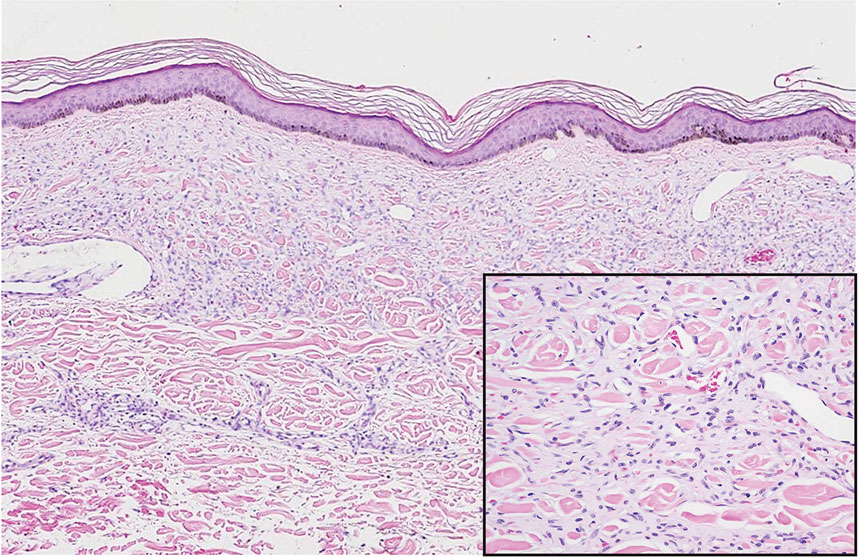

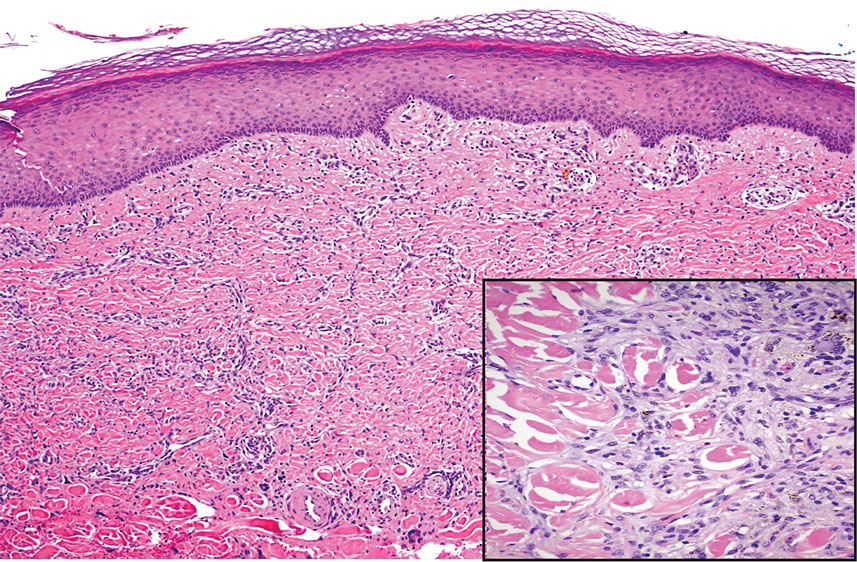

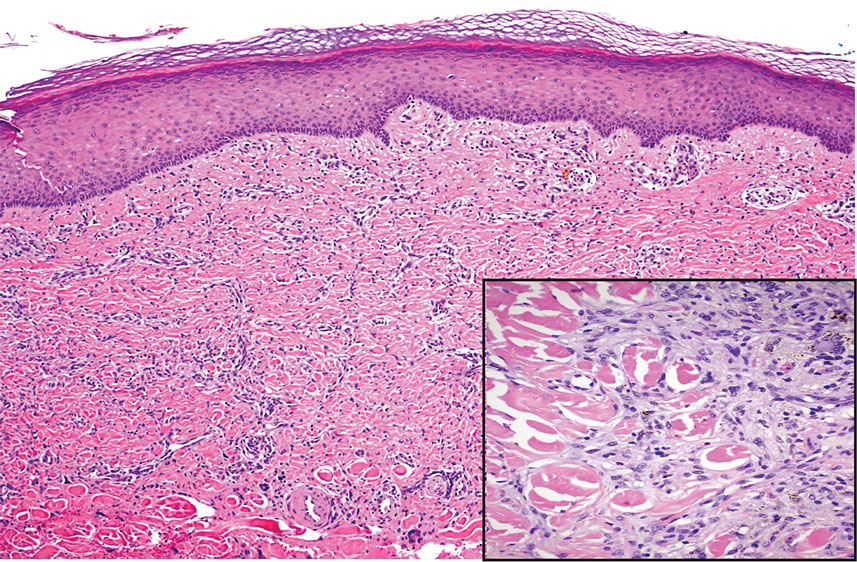

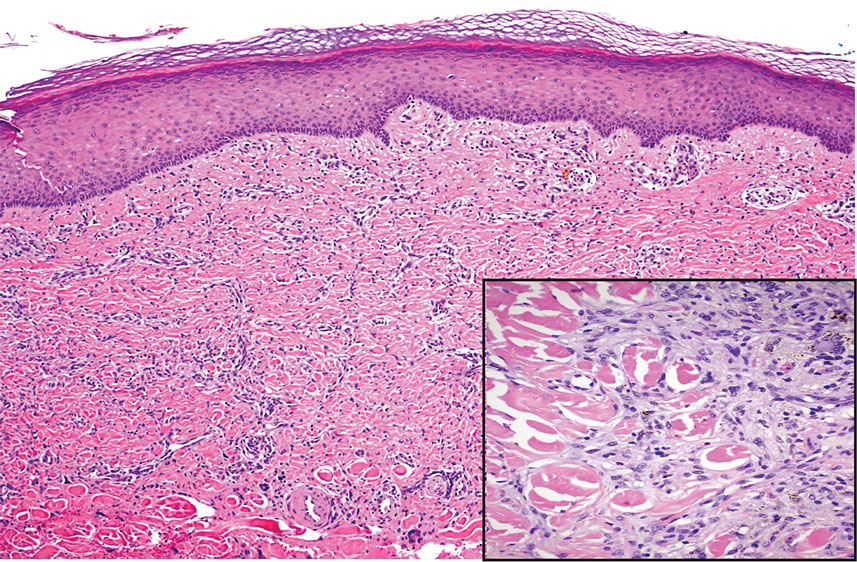

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is an acquired reactive vascular proliferation in the spectrum of cutaneous reactive angioendotheliomatoses. Clinically, DDA presents as violaceous reticulated plaques, often with secondary ulceration and sometimes necrosis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis more commonly presents in patients with a history of severe peripheral vascular disease, coagulopathies, or infection, and it frequently arises on the extremities. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis also has been shown to develop on the breasts, particularly in patients with pendulous breast tissue. Vascular proliferation in DDA is hypothesized to be from ischemia and hypoxia, leading to angiogenesis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized histologically by the presence of a diffuse proliferation of spindled endothelial cells distributed between the collagen bundles throughout the dermis (quiz image and Figure 1). Spindle-shaped endothelial cells exhibit a vacuolated cytoplasm. On immunohistochemistry, these dermal spindle cells classically stain positive for CD31, CD34, and erythroblast transformation specific–related gene (Erg) and stain negative for both human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) and factor XIIIa.

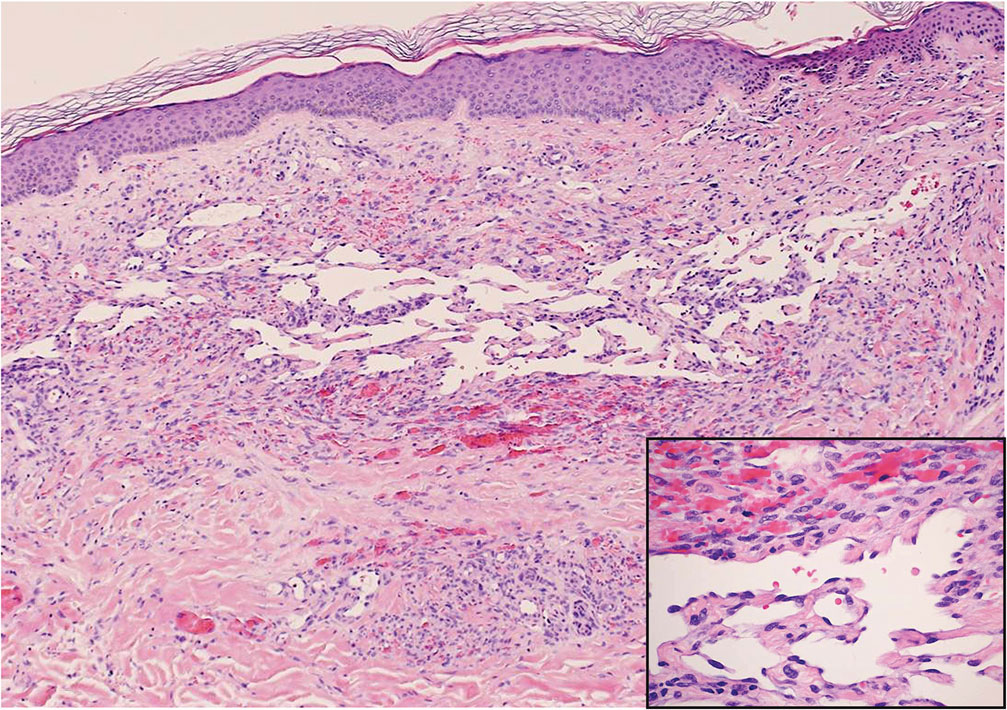

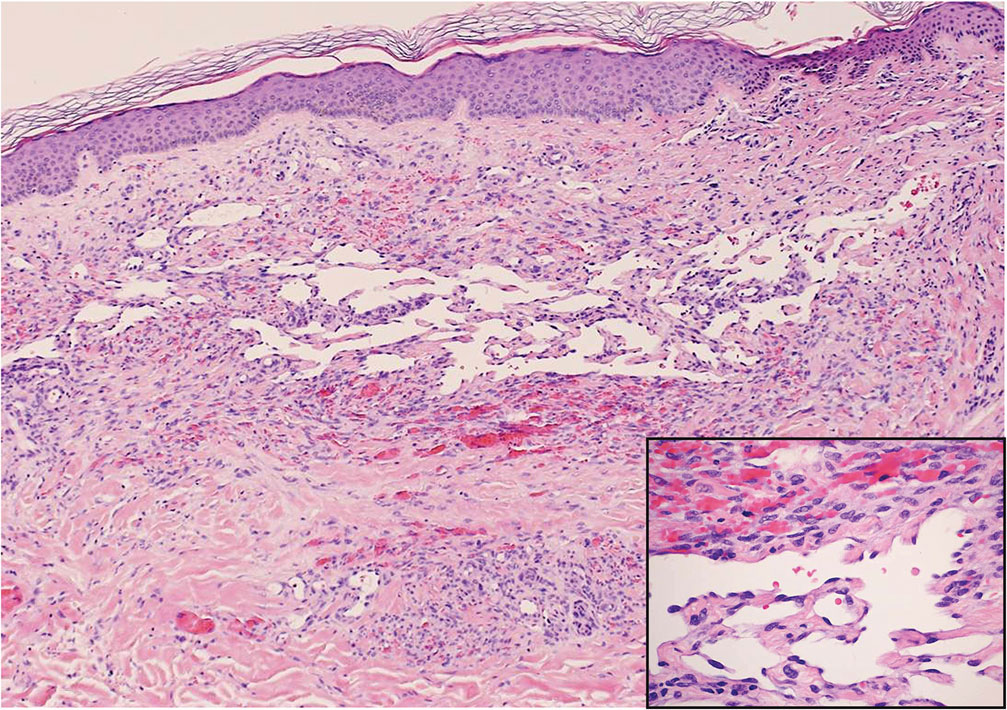

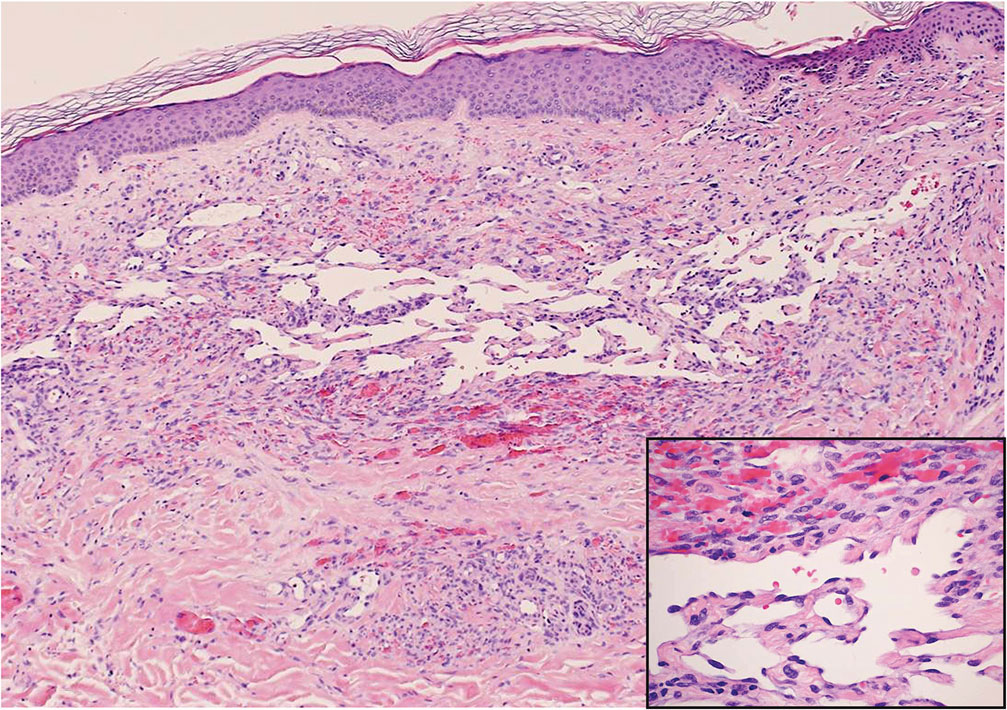

Cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma, more commonly referred to as dermatofibroma, is a common benign lesion that presents clinically as a solitary firm nodule most commonly on the extremities in areas of repetitive trauma or pressure. It classically exhibits dimpling of the overlaying skin with lateral pressure on the lesion, known as the dimple sign.4 Histologically, dermatofibromas share similar features to DDA and demonstrate the presence of bland-appearing spindle cells within the dermis between the collagen bundles, resulting in collagen trapping. However, a distinguishing histologic feature of a dermatofibroma in comparison to DDA is the presence of epidermal hyperplasia overlying the dermatofibroma, leading to tabled rete ridges (Figure 2). Spindle cells in dermatofibromas are fibroblasts and have a distinct immunophenotype that includes factor XIIIa positivity and negative staining for CD31, CD34, and Erg.4,5

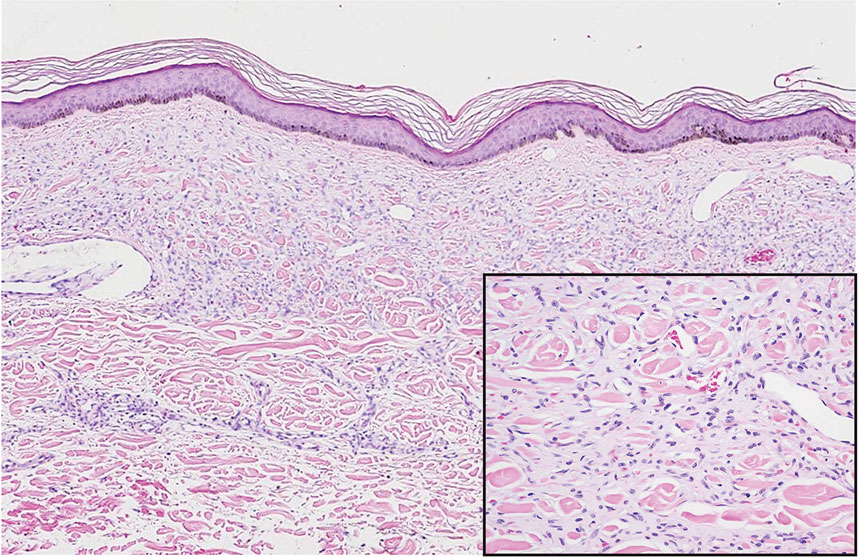

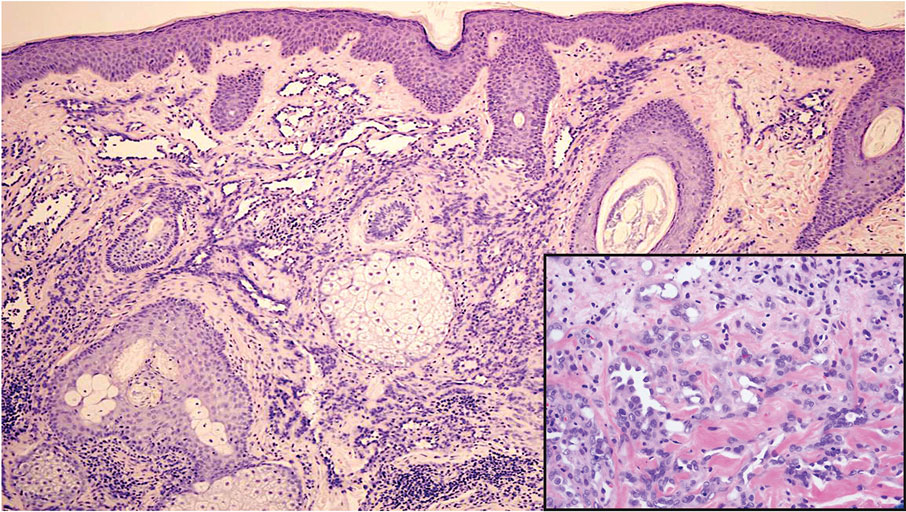

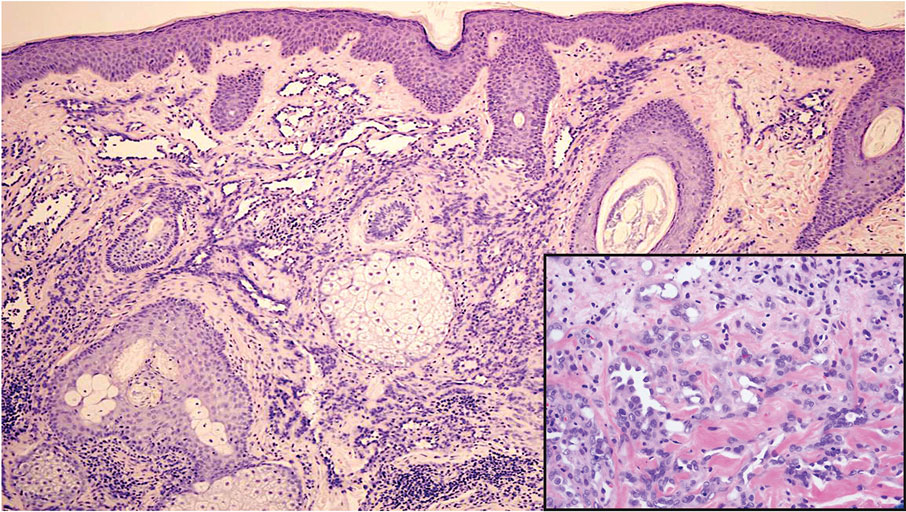

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a rare malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that clinically presents as a firm, flesh-colored, dermal plaque on the trunk, proximal extremities, head, or neck.5 Histologically, DFSP can be distinguished from DDA by the high density of spindle cells that are arranged in a storiform pattern, extending and infiltrating the underlying subcutaneous fat in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 3). Spindle cells in DFSP typically show expression of CD34 but are negative for CD31, Erg, and factor XIIIa.5

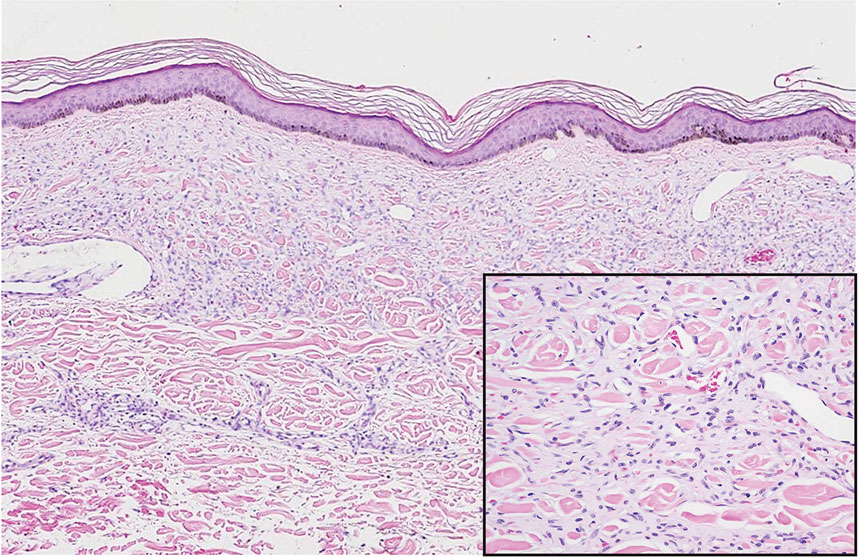

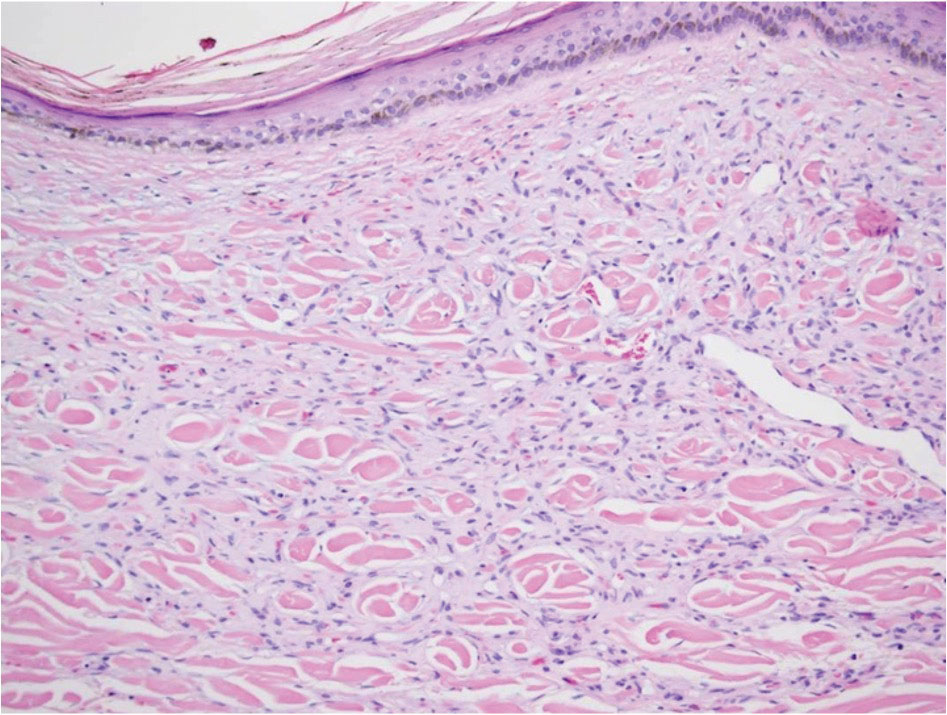

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an endothelial cell–driven angioproliferative neoplasm that is associated with HHV-8 infection.6 The clinical presentation of KS can range from isolated pink or purple papules and patches to more extensive ulcerated plaques or nodules. Histopathology exhibits proliferation of monomorphic spindled endothelial cells within the dermis staining positive for HHV-8, Erg, CD31, and CD34, in conjunction with extravasated erythrocytes arranged within slitlike vascular spaces (Figure 4). Additionally, KS classically exhibits aberrant endothelial cell proliferation and vessel formation around preexisting vessels, which is referred to as the promontory sign (Figure 4).

Angiosarcoma is a rare and highly aggressive vascular tumor arising from endothelial cells lining the blood vessels and lymphatics.7,8 Clinically, angiosarcoma presents as ulcerated violaceous nodules or plaques on the head, neck, or trunk. Histologic evaluation of angiosarcoma reveals a complex and poorly demarcated vascular network dissecting between collagen bundles in the dermis (Figure 5). Multilayering of endothelial cells, papillary projections extending into the vessel lumina, and mitoses frequently are seen. On immunohistochemistry, endothelial cells demonstrate prominent cellular atypia and stain positive with CD31, CD34, and Erg.

- Touloei K, Tongdee E, Smirnov B, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Cutis. 2019;103:181-184.

- Nguyen N, Silfvast-Kaiser AS, Frieder J, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2020;33:273-275.

- Frikha F, Boudaya S, Abid N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with adjacent fat necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1vq114n7.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Cutaneous fibrohistiocytic tumours—an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:148-165.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Etemad SA, Dewan AK. Kaposi sarcoma updates. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:505-517.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Shon W, Billings SD. Cutaneous malignant vascular neoplasms. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:633-646.

The Diagnosis: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is an acquired reactive vascular proliferation in the spectrum of cutaneous reactive angioendotheliomatoses. Clinically, DDA presents as violaceous reticulated plaques, often with secondary ulceration and sometimes necrosis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis more commonly presents in patients with a history of severe peripheral vascular disease, coagulopathies, or infection, and it frequently arises on the extremities. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis also has been shown to develop on the breasts, particularly in patients with pendulous breast tissue. Vascular proliferation in DDA is hypothesized to be from ischemia and hypoxia, leading to angiogenesis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized histologically by the presence of a diffuse proliferation of spindled endothelial cells distributed between the collagen bundles throughout the dermis (quiz image and Figure 1). Spindle-shaped endothelial cells exhibit a vacuolated cytoplasm. On immunohistochemistry, these dermal spindle cells classically stain positive for CD31, CD34, and erythroblast transformation specific–related gene (Erg) and stain negative for both human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) and factor XIIIa.

Cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma, more commonly referred to as dermatofibroma, is a common benign lesion that presents clinically as a solitary firm nodule most commonly on the extremities in areas of repetitive trauma or pressure. It classically exhibits dimpling of the overlaying skin with lateral pressure on the lesion, known as the dimple sign.4 Histologically, dermatofibromas share similar features to DDA and demonstrate the presence of bland-appearing spindle cells within the dermis between the collagen bundles, resulting in collagen trapping. However, a distinguishing histologic feature of a dermatofibroma in comparison to DDA is the presence of epidermal hyperplasia overlying the dermatofibroma, leading to tabled rete ridges (Figure 2). Spindle cells in dermatofibromas are fibroblasts and have a distinct immunophenotype that includes factor XIIIa positivity and negative staining for CD31, CD34, and Erg.4,5

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a rare malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that clinically presents as a firm, flesh-colored, dermal plaque on the trunk, proximal extremities, head, or neck.5 Histologically, DFSP can be distinguished from DDA by the high density of spindle cells that are arranged in a storiform pattern, extending and infiltrating the underlying subcutaneous fat in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 3). Spindle cells in DFSP typically show expression of CD34 but are negative for CD31, Erg, and factor XIIIa.5

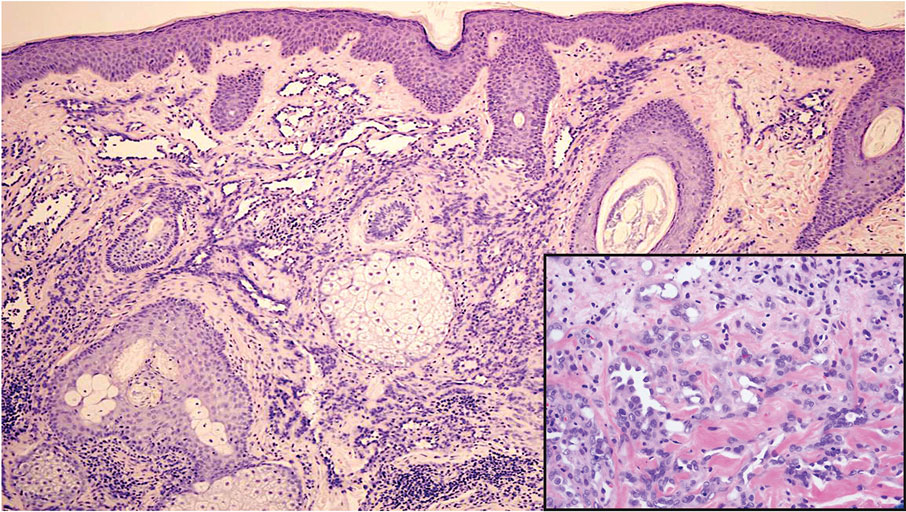

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an endothelial cell–driven angioproliferative neoplasm that is associated with HHV-8 infection.6 The clinical presentation of KS can range from isolated pink or purple papules and patches to more extensive ulcerated plaques or nodules. Histopathology exhibits proliferation of monomorphic spindled endothelial cells within the dermis staining positive for HHV-8, Erg, CD31, and CD34, in conjunction with extravasated erythrocytes arranged within slitlike vascular spaces (Figure 4). Additionally, KS classically exhibits aberrant endothelial cell proliferation and vessel formation around preexisting vessels, which is referred to as the promontory sign (Figure 4).

Angiosarcoma is a rare and highly aggressive vascular tumor arising from endothelial cells lining the blood vessels and lymphatics.7,8 Clinically, angiosarcoma presents as ulcerated violaceous nodules or plaques on the head, neck, or trunk. Histologic evaluation of angiosarcoma reveals a complex and poorly demarcated vascular network dissecting between collagen bundles in the dermis (Figure 5). Multilayering of endothelial cells, papillary projections extending into the vessel lumina, and mitoses frequently are seen. On immunohistochemistry, endothelial cells demonstrate prominent cellular atypia and stain positive with CD31, CD34, and Erg.

The Diagnosis: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is an acquired reactive vascular proliferation in the spectrum of cutaneous reactive angioendotheliomatoses. Clinically, DDA presents as violaceous reticulated plaques, often with secondary ulceration and sometimes necrosis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis more commonly presents in patients with a history of severe peripheral vascular disease, coagulopathies, or infection, and it frequently arises on the extremities. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis also has been shown to develop on the breasts, particularly in patients with pendulous breast tissue. Vascular proliferation in DDA is hypothesized to be from ischemia and hypoxia, leading to angiogenesis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized histologically by the presence of a diffuse proliferation of spindled endothelial cells distributed between the collagen bundles throughout the dermis (quiz image and Figure 1). Spindle-shaped endothelial cells exhibit a vacuolated cytoplasm. On immunohistochemistry, these dermal spindle cells classically stain positive for CD31, CD34, and erythroblast transformation specific–related gene (Erg) and stain negative for both human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) and factor XIIIa.

Cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma, more commonly referred to as dermatofibroma, is a common benign lesion that presents clinically as a solitary firm nodule most commonly on the extremities in areas of repetitive trauma or pressure. It classically exhibits dimpling of the overlaying skin with lateral pressure on the lesion, known as the dimple sign.4 Histologically, dermatofibromas share similar features to DDA and demonstrate the presence of bland-appearing spindle cells within the dermis between the collagen bundles, resulting in collagen trapping. However, a distinguishing histologic feature of a dermatofibroma in comparison to DDA is the presence of epidermal hyperplasia overlying the dermatofibroma, leading to tabled rete ridges (Figure 2). Spindle cells in dermatofibromas are fibroblasts and have a distinct immunophenotype that includes factor XIIIa positivity and negative staining for CD31, CD34, and Erg.4,5

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a rare malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that clinically presents as a firm, flesh-colored, dermal plaque on the trunk, proximal extremities, head, or neck.5 Histologically, DFSP can be distinguished from DDA by the high density of spindle cells that are arranged in a storiform pattern, extending and infiltrating the underlying subcutaneous fat in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 3). Spindle cells in DFSP typically show expression of CD34 but are negative for CD31, Erg, and factor XIIIa.5

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an endothelial cell–driven angioproliferative neoplasm that is associated with HHV-8 infection.6 The clinical presentation of KS can range from isolated pink or purple papules and patches to more extensive ulcerated plaques or nodules. Histopathology exhibits proliferation of monomorphic spindled endothelial cells within the dermis staining positive for HHV-8, Erg, CD31, and CD34, in conjunction with extravasated erythrocytes arranged within slitlike vascular spaces (Figure 4). Additionally, KS classically exhibits aberrant endothelial cell proliferation and vessel formation around preexisting vessels, which is referred to as the promontory sign (Figure 4).

Angiosarcoma is a rare and highly aggressive vascular tumor arising from endothelial cells lining the blood vessels and lymphatics.7,8 Clinically, angiosarcoma presents as ulcerated violaceous nodules or plaques on the head, neck, or trunk. Histologic evaluation of angiosarcoma reveals a complex and poorly demarcated vascular network dissecting between collagen bundles in the dermis (Figure 5). Multilayering of endothelial cells, papillary projections extending into the vessel lumina, and mitoses frequently are seen. On immunohistochemistry, endothelial cells demonstrate prominent cellular atypia and stain positive with CD31, CD34, and Erg.

- Touloei K, Tongdee E, Smirnov B, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Cutis. 2019;103:181-184.

- Nguyen N, Silfvast-Kaiser AS, Frieder J, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2020;33:273-275.

- Frikha F, Boudaya S, Abid N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with adjacent fat necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1vq114n7.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Cutaneous fibrohistiocytic tumours—an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:148-165.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Etemad SA, Dewan AK. Kaposi sarcoma updates. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:505-517.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Shon W, Billings SD. Cutaneous malignant vascular neoplasms. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:633-646.

- Touloei K, Tongdee E, Smirnov B, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Cutis. 2019;103:181-184.

- Nguyen N, Silfvast-Kaiser AS, Frieder J, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2020;33:273-275.

- Frikha F, Boudaya S, Abid N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with adjacent fat necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1vq114n7.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Cutaneous fibrohistiocytic tumours—an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:148-165.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Etemad SA, Dewan AK. Kaposi sarcoma updates. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:505-517.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Shon W, Billings SD. Cutaneous malignant vascular neoplasms. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:633-646.

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of hypertension and smoking tobacco (5 pack years) presented with a painful, nonhealing, violaceous, reticulated plaque with ulceration on the right breast of 3 months’ duration. Histopathology revealed diffuse, interstitial, bland-appearing spindle cells throughout the papillary and reticular dermis that were distributed between the collagen bundles. Dermal interstitial spindle cells were positive for CD31, CD34, and erythroblast transformation specific–related gene immunostains. Factor XIIIa and human herpesvirus 8 immunostaining was negative.

Nails falling off in a 3-year-old

When the nails peel off from the proximal nail folds, the clinical term is onychomadesis and it is important to ask about recent infections or severe metabolic stressors. In children and adults, onychomadesis on multiple fingers may occur after infections and has been associated with hand-foot-mouth disease caused by common viral infections—especially strains of coxsackievirus.1

Because shed nails show evidence of viral infection, one hypothesis for their peeling off is that the tissue of the nail matrix is infected, leading to metabolic changes. As the nail matrix returns to normal function, a new nail is made and ultimately will replace the nail that has come off. In healthy US adults, fingernails grow 3.47 mm per month on average while toenails grow 1.62 mm per month on average.2