User login

Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block: A safe and effective option for treating migraine in elderly

Key clinical point: Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block (SGB) appeared to be safe and effective in reducing pain intensity, headache frequency and duration, and the need for adjunctive anti-migraine medications in elderly patients with migraine.

Major finding: At 3 months after ultrasound-guided SGB treatment, the mean Numerical Rating Scale score reduced from 7.3 at baseline to 3.6 (P < .001), the mean headache frequency per month reduced from 23.1 days at baseline to 14.0 days (P = .001), and the mean headache duration decreased from 22.7 hours at baseline to 14.3 hours (P = .001), with 64% of patients experiencing ≥50% reduction in anti-migraine medication consumption. No procedure-related serious adverse events were reported.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective observational case series study including 52 elderly patients (age ≥ 65 years) with migraine who received ultrasound-guided SGB treatment for headache management.

Disclosures: This study did not disclose the funding source. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yu B et al. Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block for the treatment of migraine in elderly patients: A retrospective and observational study. Headache. 2023;63(6):763-770 (Jun 14). Doi: 10.1111/head.14537

Key clinical point: Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block (SGB) appeared to be safe and effective in reducing pain intensity, headache frequency and duration, and the need for adjunctive anti-migraine medications in elderly patients with migraine.

Major finding: At 3 months after ultrasound-guided SGB treatment, the mean Numerical Rating Scale score reduced from 7.3 at baseline to 3.6 (P < .001), the mean headache frequency per month reduced from 23.1 days at baseline to 14.0 days (P = .001), and the mean headache duration decreased from 22.7 hours at baseline to 14.3 hours (P = .001), with 64% of patients experiencing ≥50% reduction in anti-migraine medication consumption. No procedure-related serious adverse events were reported.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective observational case series study including 52 elderly patients (age ≥ 65 years) with migraine who received ultrasound-guided SGB treatment for headache management.

Disclosures: This study did not disclose the funding source. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yu B et al. Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block for the treatment of migraine in elderly patients: A retrospective and observational study. Headache. 2023;63(6):763-770 (Jun 14). Doi: 10.1111/head.14537

Key clinical point: Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block (SGB) appeared to be safe and effective in reducing pain intensity, headache frequency and duration, and the need for adjunctive anti-migraine medications in elderly patients with migraine.

Major finding: At 3 months after ultrasound-guided SGB treatment, the mean Numerical Rating Scale score reduced from 7.3 at baseline to 3.6 (P < .001), the mean headache frequency per month reduced from 23.1 days at baseline to 14.0 days (P = .001), and the mean headache duration decreased from 22.7 hours at baseline to 14.3 hours (P = .001), with 64% of patients experiencing ≥50% reduction in anti-migraine medication consumption. No procedure-related serious adverse events were reported.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective observational case series study including 52 elderly patients (age ≥ 65 years) with migraine who received ultrasound-guided SGB treatment for headache management.

Disclosures: This study did not disclose the funding source. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yu B et al. Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block for the treatment of migraine in elderly patients: A retrospective and observational study. Headache. 2023;63(6):763-770 (Jun 14). Doi: 10.1111/head.14537

Decrease in visual hypersensitivity predicts clinical response to anti-CGRP mAbs in migraine

Key clinical point: In patients with migraine, treatment with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (anti-CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) reduced visual hypersensitivity, and this reduction was positively associated with a decrease in monthly migraine days (MMD).

Major finding: After 3 months of treatment with anti-CGRP mAb, the mean ictal Leiden Visual Sensitivity Scale (L-VISS) score decreased from 20.1 to 19.2 (P = .042) and the mean interictal L-VISS score decreased from 11.8 to 11.1 (P = .050), and a positive correlation was observed between the reduction in MMD and the decrease in ictal L-VISS (β 0.3; P = .001) and interictal L-VISS (β 0.2; P = .010) scores.

Study details: This prospective follow-up study included 205 patients with migraine who were treated with either erenumab (n = 105) or fremanezumab (n = 100).

Disclosures: This study did not disclose the funding source. Three authors declared receiving consultancy or industry and independent support from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: de Vries Lentsch S et al. Visual hypersensitivity in patients treated with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (receptor) monoclonal antibodies. Headache. 2023;63(7):926-933 (Jun 26). Doi: 10.1111/head.14531

Key clinical point: In patients with migraine, treatment with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (anti-CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) reduced visual hypersensitivity, and this reduction was positively associated with a decrease in monthly migraine days (MMD).

Major finding: After 3 months of treatment with anti-CGRP mAb, the mean ictal Leiden Visual Sensitivity Scale (L-VISS) score decreased from 20.1 to 19.2 (P = .042) and the mean interictal L-VISS score decreased from 11.8 to 11.1 (P = .050), and a positive correlation was observed between the reduction in MMD and the decrease in ictal L-VISS (β 0.3; P = .001) and interictal L-VISS (β 0.2; P = .010) scores.

Study details: This prospective follow-up study included 205 patients with migraine who were treated with either erenumab (n = 105) or fremanezumab (n = 100).

Disclosures: This study did not disclose the funding source. Three authors declared receiving consultancy or industry and independent support from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: de Vries Lentsch S et al. Visual hypersensitivity in patients treated with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (receptor) monoclonal antibodies. Headache. 2023;63(7):926-933 (Jun 26). Doi: 10.1111/head.14531

Key clinical point: In patients with migraine, treatment with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (anti-CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) reduced visual hypersensitivity, and this reduction was positively associated with a decrease in monthly migraine days (MMD).

Major finding: After 3 months of treatment with anti-CGRP mAb, the mean ictal Leiden Visual Sensitivity Scale (L-VISS) score decreased from 20.1 to 19.2 (P = .042) and the mean interictal L-VISS score decreased from 11.8 to 11.1 (P = .050), and a positive correlation was observed between the reduction in MMD and the decrease in ictal L-VISS (β 0.3; P = .001) and interictal L-VISS (β 0.2; P = .010) scores.

Study details: This prospective follow-up study included 205 patients with migraine who were treated with either erenumab (n = 105) or fremanezumab (n = 100).

Disclosures: This study did not disclose the funding source. Three authors declared receiving consultancy or industry and independent support from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: de Vries Lentsch S et al. Visual hypersensitivity in patients treated with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (receptor) monoclonal antibodies. Headache. 2023;63(7):926-933 (Jun 26). Doi: 10.1111/head.14531

Meta-analysis confirms benefits of rimegepant in episodic migraine

Key clinical point: Meta-analysis confirmed better therapeutic efficacy of rimegepant compared with placebo in patients with episodic migraine (EM), along with no significant difference in adverse events.

Major finding: Rimegepant was more effective than placebo in terms of achieving pain freedom and pain relief at 2 hours (odds ratio [OR] 1.84 and 1.80, respectively), 2-24 hours (OR 2.44 and 2.10, respectively), and 2-48 hours (OR 2.27 and 1.92, respectively; all P < .00001) post-dose. The occurrence of adverse events was not significantly different between the rimegepant and control arms (P = .06).

Study details: The data come from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials including 4230 patients with EM.

Disclosures: This study did not declare the source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang Q et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of rimegepant in the treatment of migraine: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1205778 (Jun 20). Doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1205778

Key clinical point: Meta-analysis confirmed better therapeutic efficacy of rimegepant compared with placebo in patients with episodic migraine (EM), along with no significant difference in adverse events.

Major finding: Rimegepant was more effective than placebo in terms of achieving pain freedom and pain relief at 2 hours (odds ratio [OR] 1.84 and 1.80, respectively), 2-24 hours (OR 2.44 and 2.10, respectively), and 2-48 hours (OR 2.27 and 1.92, respectively; all P < .00001) post-dose. The occurrence of adverse events was not significantly different between the rimegepant and control arms (P = .06).

Study details: The data come from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials including 4230 patients with EM.

Disclosures: This study did not declare the source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang Q et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of rimegepant in the treatment of migraine: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1205778 (Jun 20). Doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1205778

Key clinical point: Meta-analysis confirmed better therapeutic efficacy of rimegepant compared with placebo in patients with episodic migraine (EM), along with no significant difference in adverse events.

Major finding: Rimegepant was more effective than placebo in terms of achieving pain freedom and pain relief at 2 hours (odds ratio [OR] 1.84 and 1.80, respectively), 2-24 hours (OR 2.44 and 2.10, respectively), and 2-48 hours (OR 2.27 and 1.92, respectively; all P < .00001) post-dose. The occurrence of adverse events was not significantly different between the rimegepant and control arms (P = .06).

Study details: The data come from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials including 4230 patients with EM.

Disclosures: This study did not declare the source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang Q et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of rimegepant in the treatment of migraine: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1205778 (Jun 20). Doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1205778

Potential moderators of response to behavioral treatment for migraine prophylaxis

Key clinical point: Disability, anxiety, and comorbid mental disorders moderated the long-term effect of migraine-specific cognitive behavioral therapy (miCBT) or relaxation training (RLX) on headache days in patients with migraine, with those having higher and lower burden benefitting more from miCBT and RLX, respectively.

Major finding: Patients with higher headache-related disability (B −0.41; P = .047), anxiety (B −0.66; P = .056), and comorbid mental disorders (B −4.98; P = .053) benefited more from miCBT, whereas those with relatively lower headache-related disability and anxiety and without any comorbid mental disorder benefited more from RLX at 12 months of follow-up.

Study details: This secondary analysis of an open-label randomized controlled trial included 121 patients with migraine who were randomly assigned to the miCBT (n = 40), RLX (n = 41), or waiting-list control (n = 40) group.

Disclosures: This study received no specific funding. C Gaul and E Liesering-Latta declared receiving consulting and lecture honoraria from various sources. C Gaul declared serving as an honorary secretary of the German Migraine and Headache Society. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Klan T et al. Behavioral treatment for migraine prophylaxis in adults: Moderator analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(6) (Jun 8). Doi: 10.1177/03331024231178237

Key clinical point: Disability, anxiety, and comorbid mental disorders moderated the long-term effect of migraine-specific cognitive behavioral therapy (miCBT) or relaxation training (RLX) on headache days in patients with migraine, with those having higher and lower burden benefitting more from miCBT and RLX, respectively.

Major finding: Patients with higher headache-related disability (B −0.41; P = .047), anxiety (B −0.66; P = .056), and comorbid mental disorders (B −4.98; P = .053) benefited more from miCBT, whereas those with relatively lower headache-related disability and anxiety and without any comorbid mental disorder benefited more from RLX at 12 months of follow-up.

Study details: This secondary analysis of an open-label randomized controlled trial included 121 patients with migraine who were randomly assigned to the miCBT (n = 40), RLX (n = 41), or waiting-list control (n = 40) group.

Disclosures: This study received no specific funding. C Gaul and E Liesering-Latta declared receiving consulting and lecture honoraria from various sources. C Gaul declared serving as an honorary secretary of the German Migraine and Headache Society. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Klan T et al. Behavioral treatment for migraine prophylaxis in adults: Moderator analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(6) (Jun 8). Doi: 10.1177/03331024231178237

Key clinical point: Disability, anxiety, and comorbid mental disorders moderated the long-term effect of migraine-specific cognitive behavioral therapy (miCBT) or relaxation training (RLX) on headache days in patients with migraine, with those having higher and lower burden benefitting more from miCBT and RLX, respectively.

Major finding: Patients with higher headache-related disability (B −0.41; P = .047), anxiety (B −0.66; P = .056), and comorbid mental disorders (B −4.98; P = .053) benefited more from miCBT, whereas those with relatively lower headache-related disability and anxiety and without any comorbid mental disorder benefited more from RLX at 12 months of follow-up.

Study details: This secondary analysis of an open-label randomized controlled trial included 121 patients with migraine who were randomly assigned to the miCBT (n = 40), RLX (n = 41), or waiting-list control (n = 40) group.

Disclosures: This study received no specific funding. C Gaul and E Liesering-Latta declared receiving consulting and lecture honoraria from various sources. C Gaul declared serving as an honorary secretary of the German Migraine and Headache Society. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Klan T et al. Behavioral treatment for migraine prophylaxis in adults: Moderator analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(6) (Jun 8). Doi: 10.1177/03331024231178237

Study supports use of BP-lowering medications for prevention of episodic migraine

Key clinical point: A broad category of blood pressure (BP)-lowering medication classes and drugs effectively reduced headache frequency in patients with episodic migraine.

Major finding: Compared with placebo, headache days per month reduced significantly with alpha-blockers (P = .023), angiotensin II receptor blockers (P = .024), beta-blockers (P = .035), and calcium channel blockers (P = .025). Specific BP-lowering drugs, such as clonidine (P = .026), candesartan (P = .001), atenolol (P = .010), bisoprolol (P = .000), propranolol (P = .000), timolol (P = .000), nicardipine (P = .001), and verapamil (P = .016), also effectively reduced the number of headache days per month.

Study details: Findings are from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 studies including 4310 participants.

Disclosures: This study received no specific funding. LR Griffiths reported receiving migraine research funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. AS Zagami declared being an associate editor for Cephalalgia. A Rodgers declared being an inventor for George Health Enterprises. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Carcel C, Haghdoost F, et al. The effect of blood pressure lowering medications on the prevention of episodic migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2023 (Jun 23). Doi: 10.1177/03331024231183166

Key clinical point: A broad category of blood pressure (BP)-lowering medication classes and drugs effectively reduced headache frequency in patients with episodic migraine.

Major finding: Compared with placebo, headache days per month reduced significantly with alpha-blockers (P = .023), angiotensin II receptor blockers (P = .024), beta-blockers (P = .035), and calcium channel blockers (P = .025). Specific BP-lowering drugs, such as clonidine (P = .026), candesartan (P = .001), atenolol (P = .010), bisoprolol (P = .000), propranolol (P = .000), timolol (P = .000), nicardipine (P = .001), and verapamil (P = .016), also effectively reduced the number of headache days per month.

Study details: Findings are from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 studies including 4310 participants.

Disclosures: This study received no specific funding. LR Griffiths reported receiving migraine research funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. AS Zagami declared being an associate editor for Cephalalgia. A Rodgers declared being an inventor for George Health Enterprises. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Carcel C, Haghdoost F, et al. The effect of blood pressure lowering medications on the prevention of episodic migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2023 (Jun 23). Doi: 10.1177/03331024231183166

Key clinical point: A broad category of blood pressure (BP)-lowering medication classes and drugs effectively reduced headache frequency in patients with episodic migraine.

Major finding: Compared with placebo, headache days per month reduced significantly with alpha-blockers (P = .023), angiotensin II receptor blockers (P = .024), beta-blockers (P = .035), and calcium channel blockers (P = .025). Specific BP-lowering drugs, such as clonidine (P = .026), candesartan (P = .001), atenolol (P = .010), bisoprolol (P = .000), propranolol (P = .000), timolol (P = .000), nicardipine (P = .001), and verapamil (P = .016), also effectively reduced the number of headache days per month.

Study details: Findings are from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 studies including 4310 participants.

Disclosures: This study received no specific funding. LR Griffiths reported receiving migraine research funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. AS Zagami declared being an associate editor for Cephalalgia. A Rodgers declared being an inventor for George Health Enterprises. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Carcel C, Haghdoost F, et al. The effect of blood pressure lowering medications on the prevention of episodic migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2023 (Jun 23). Doi: 10.1177/03331024231183166

Migraine elevates risk for ischemic stroke in men and women with migraine

Key clinical point: Migraine increased the risk for premature ischemic stroke similarly among women and men aged ≤60 years; however, the effect of migraine on the risk for premature myocardial infarction (MI) and hemorrhagic stroke was greater only in women but not in men with migraine.

Major finding: Compared with those without migraine, women (adjusted HR [aHR] 1.21) and men (aHR 1.23; both P < .001) with migraine showed a similar increase in the risk for premature ischemic stroke. However, the risk for premature MI (aHR 1.22; 95% CI 1.14-1.31; P < .001) and hemorrhagic stroke (aHR 1.13; 95% CI 1.02-1.24; P = .014) was significantly higher in women with vs without migraine but not in men.

Study details: This nationwide population-based cohort study included 179,680 women and 40,757 men with migraine.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any specific funding. CH Fuglsang declared owning stock in Novo Nordisk, and M Schmidt declared being supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Source: Fuglsang CH et al. Migraine and risk of premature myocardial infarction and stroke among men and women: A Danish population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2023;20(6):e1004238 (Jun 13). Doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004238

Key clinical point: Migraine increased the risk for premature ischemic stroke similarly among women and men aged ≤60 years; however, the effect of migraine on the risk for premature myocardial infarction (MI) and hemorrhagic stroke was greater only in women but not in men with migraine.

Major finding: Compared with those without migraine, women (adjusted HR [aHR] 1.21) and men (aHR 1.23; both P < .001) with migraine showed a similar increase in the risk for premature ischemic stroke. However, the risk for premature MI (aHR 1.22; 95% CI 1.14-1.31; P < .001) and hemorrhagic stroke (aHR 1.13; 95% CI 1.02-1.24; P = .014) was significantly higher in women with vs without migraine but not in men.

Study details: This nationwide population-based cohort study included 179,680 women and 40,757 men with migraine.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any specific funding. CH Fuglsang declared owning stock in Novo Nordisk, and M Schmidt declared being supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Source: Fuglsang CH et al. Migraine and risk of premature myocardial infarction and stroke among men and women: A Danish population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2023;20(6):e1004238 (Jun 13). Doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004238

Key clinical point: Migraine increased the risk for premature ischemic stroke similarly among women and men aged ≤60 years; however, the effect of migraine on the risk for premature myocardial infarction (MI) and hemorrhagic stroke was greater only in women but not in men with migraine.

Major finding: Compared with those without migraine, women (adjusted HR [aHR] 1.21) and men (aHR 1.23; both P < .001) with migraine showed a similar increase in the risk for premature ischemic stroke. However, the risk for premature MI (aHR 1.22; 95% CI 1.14-1.31; P < .001) and hemorrhagic stroke (aHR 1.13; 95% CI 1.02-1.24; P = .014) was significantly higher in women with vs without migraine but not in men.

Study details: This nationwide population-based cohort study included 179,680 women and 40,757 men with migraine.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any specific funding. CH Fuglsang declared owning stock in Novo Nordisk, and M Schmidt declared being supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Source: Fuglsang CH et al. Migraine and risk of premature myocardial infarction and stroke among men and women: A Danish population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2023;20(6):e1004238 (Jun 13). Doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004238

An STI upsurge requires a nimble approach to care

Except for a drop in the number of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) early in the COVID-19 pandemic (March and April 2020), the incidence of STIs has been rising throughout this century.1 In 2018, 1 in 5 people in the United States had an STI; 26 million new cases were reported that year, resulting in direct costs of $16 billion—85% of which was for the care of HIV infection.2 Also that year, infection with Chlamydia trachomatis (chlamydia), Trichomonas vaginalis (trichomoniasis), herpesvirus type 2 (genital herpes), and/or human papillomavirus (condylomata acuminata) constituted 97.6% of all prevalent and 93.1% of all incident STIs.3 Almost half (45.5%) of new cases of STIs occur in people between the ages of 15 and 24 years.3

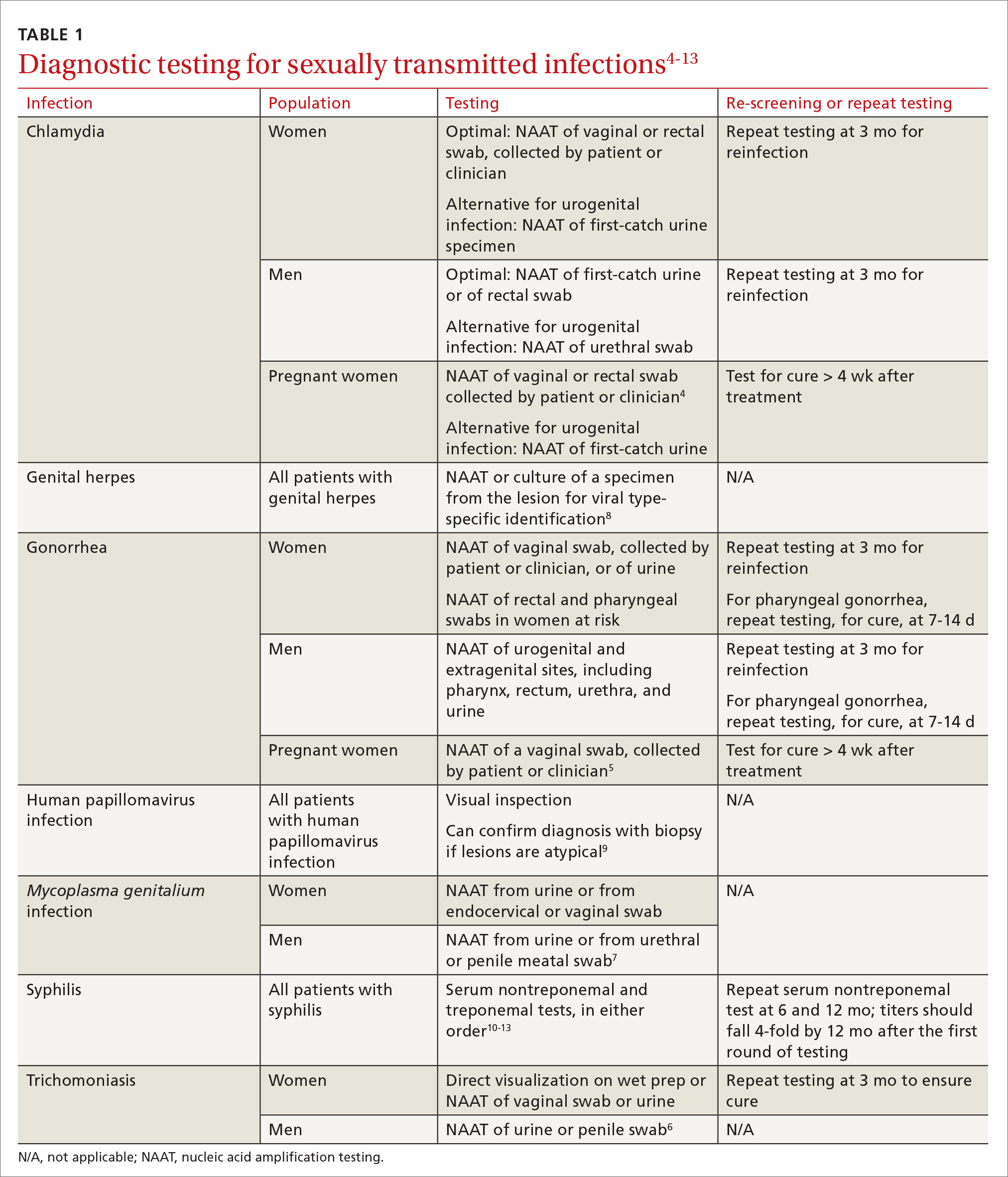

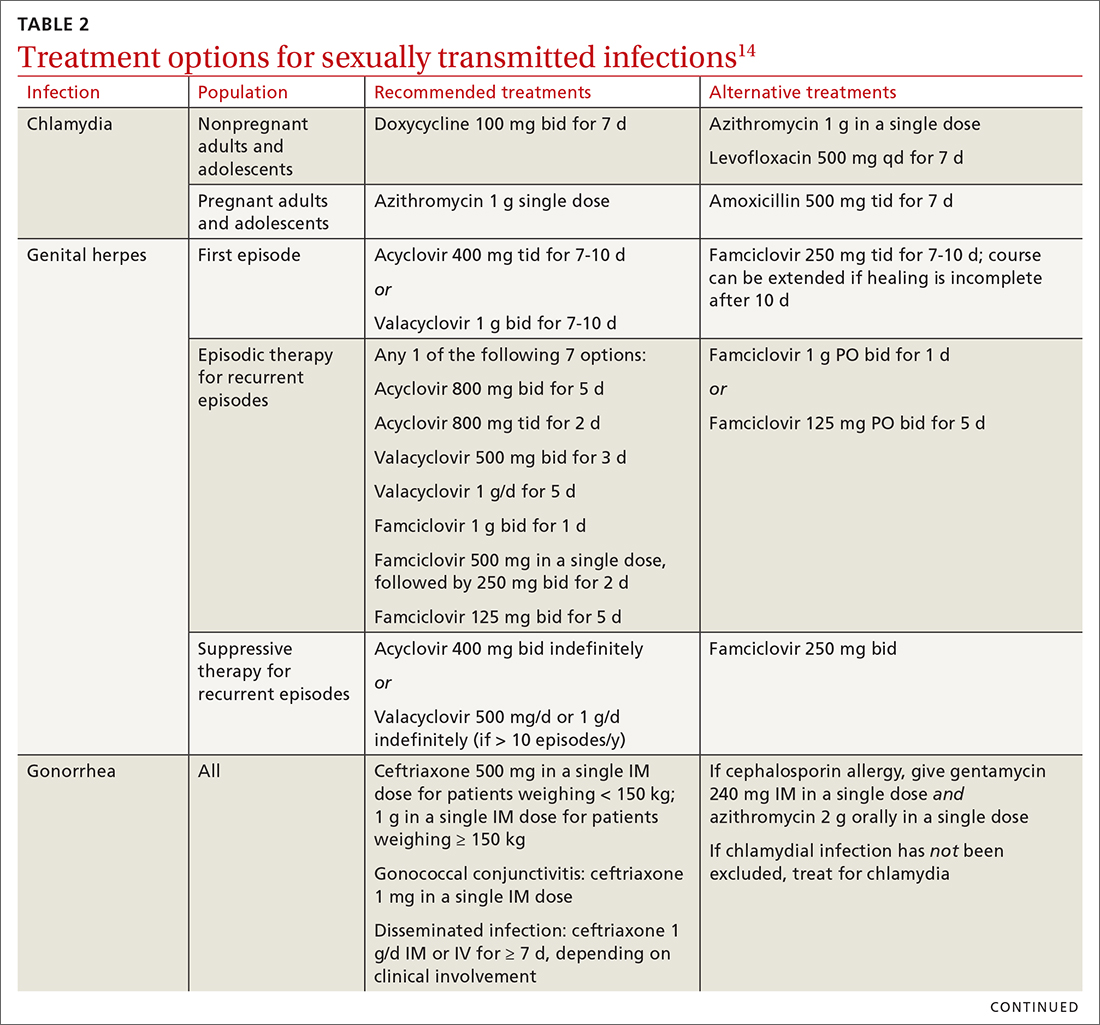

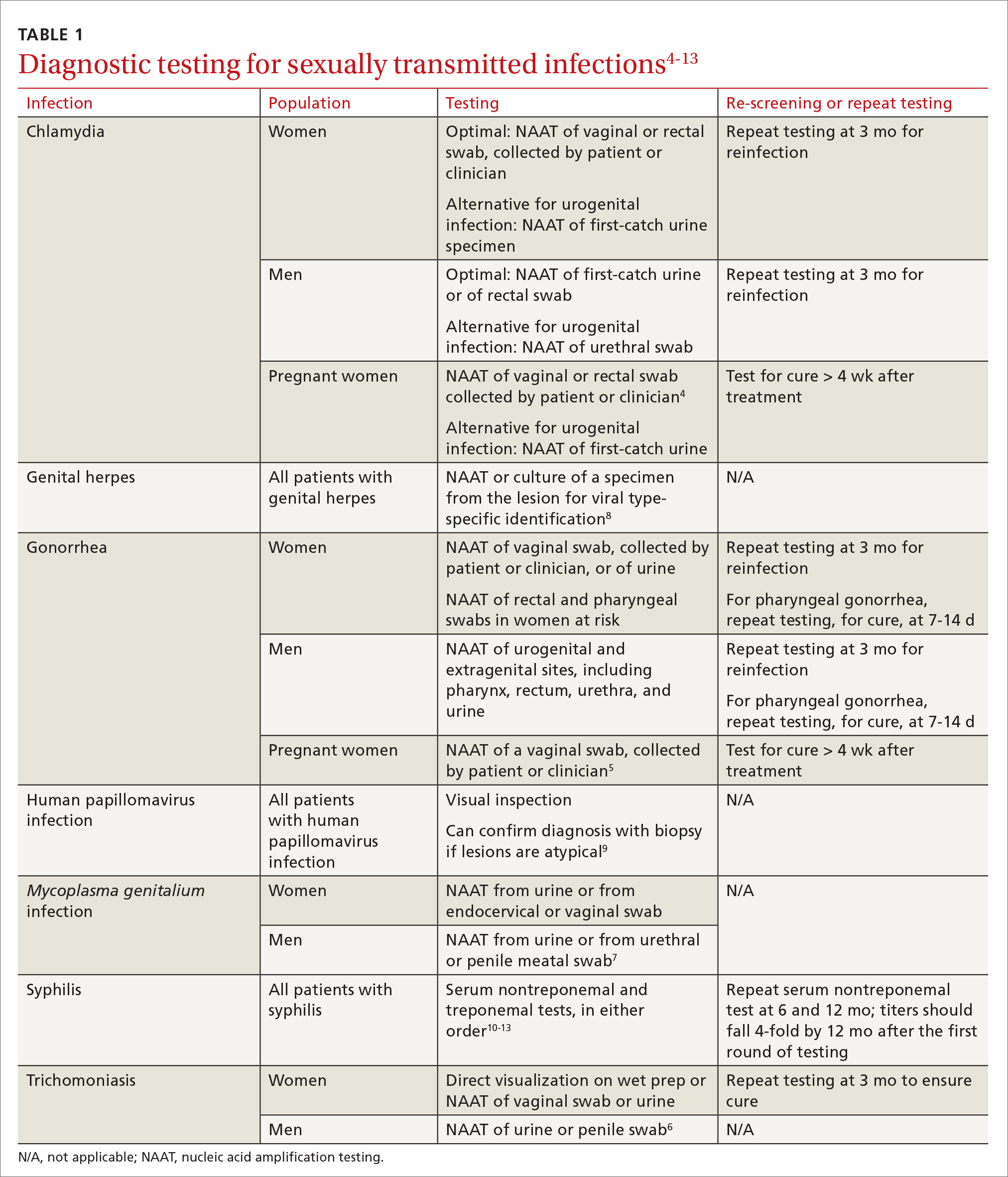

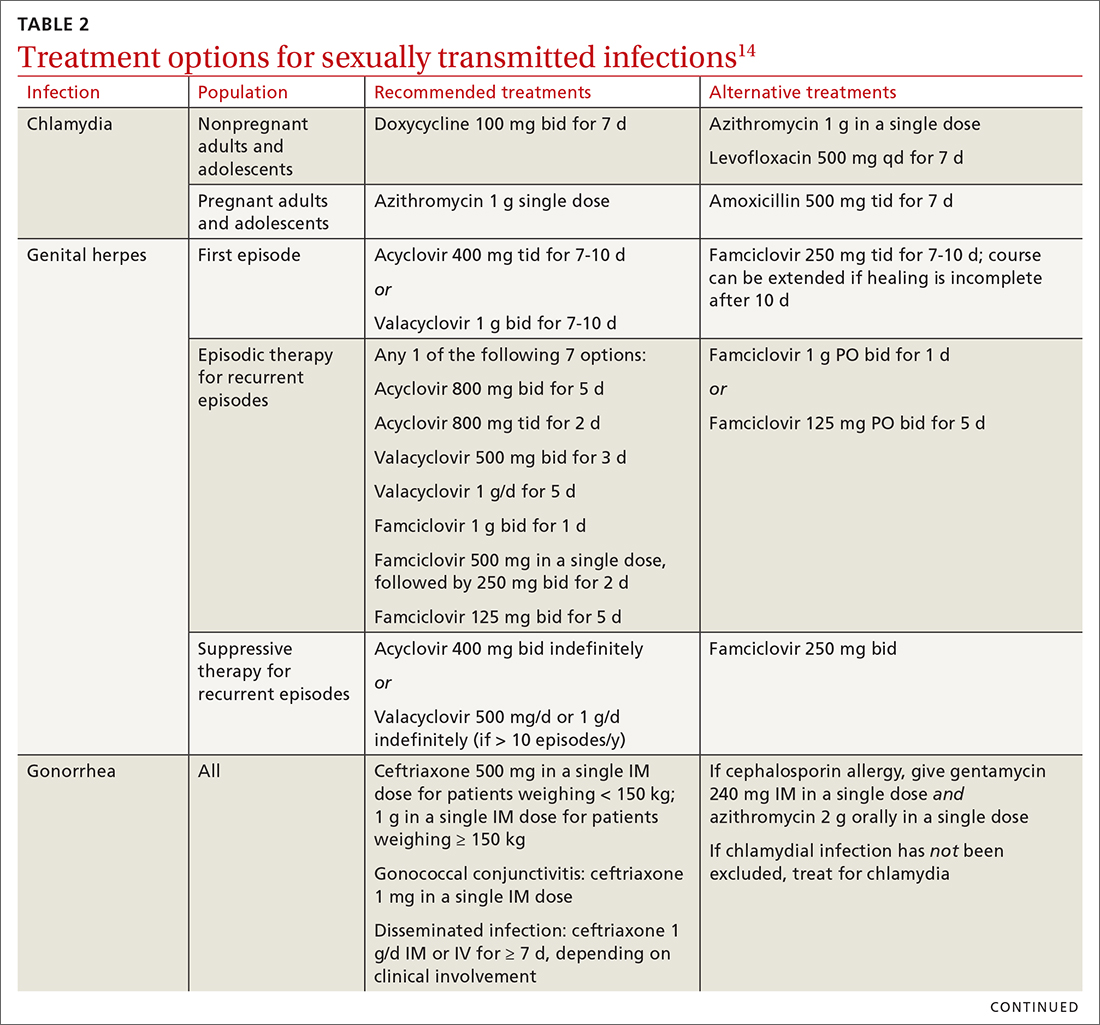

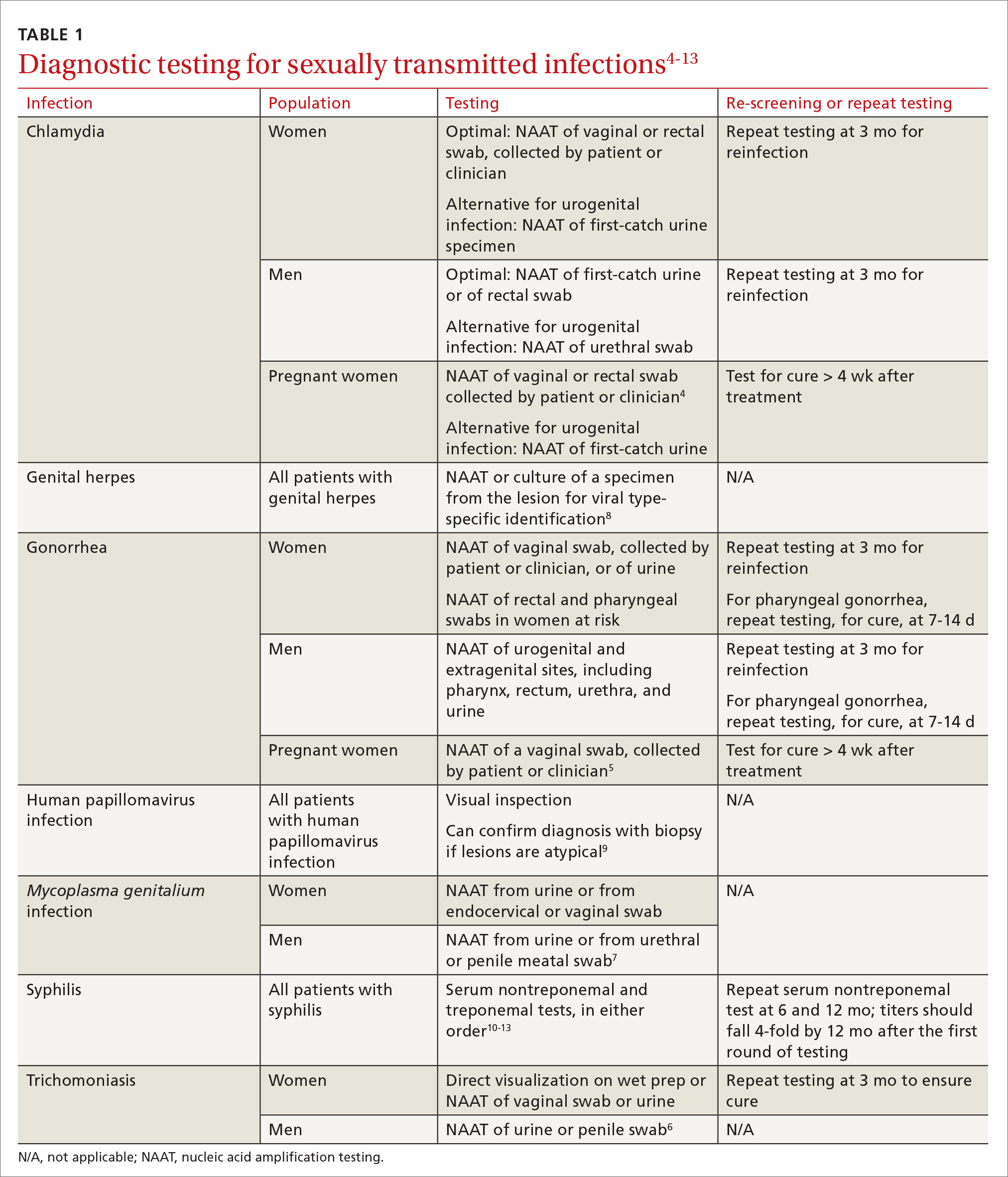

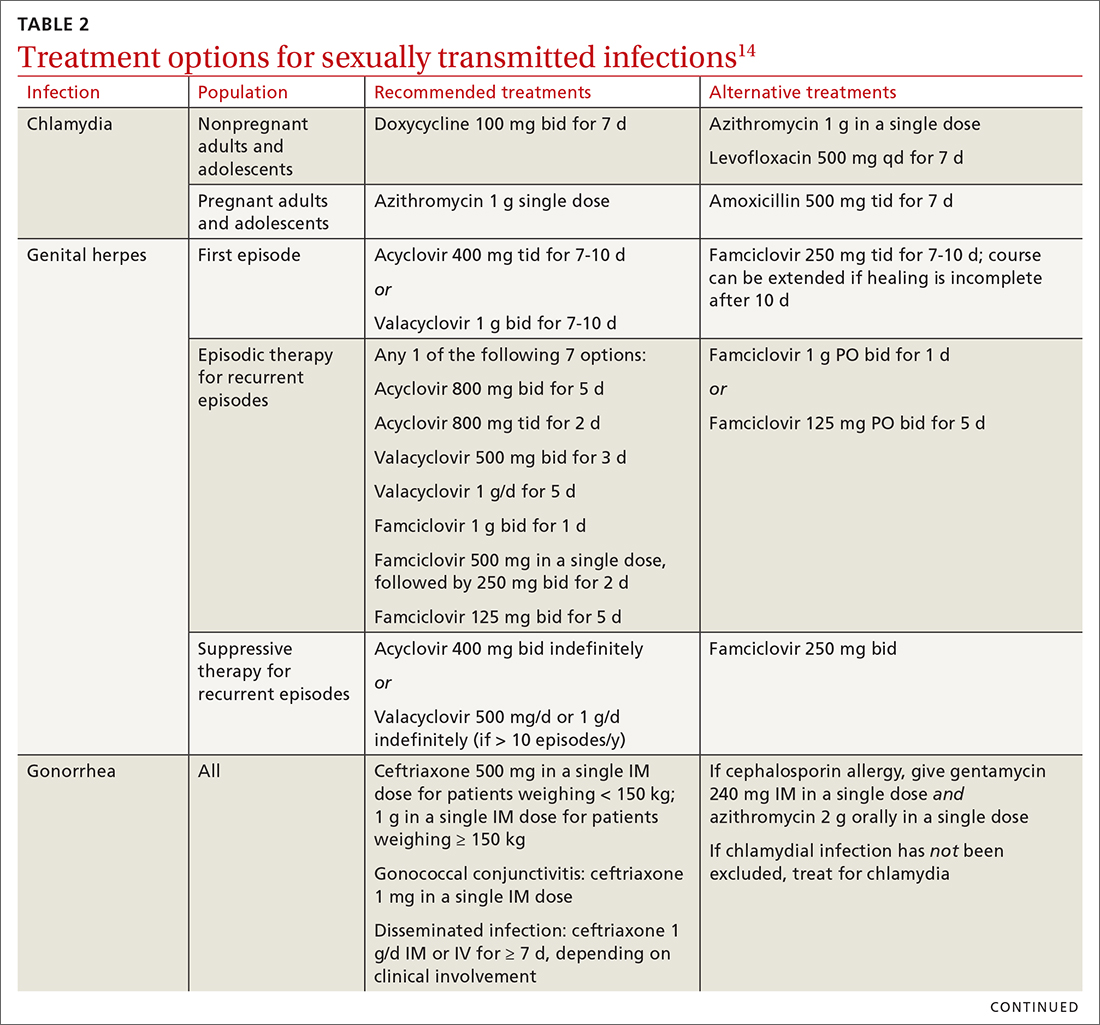

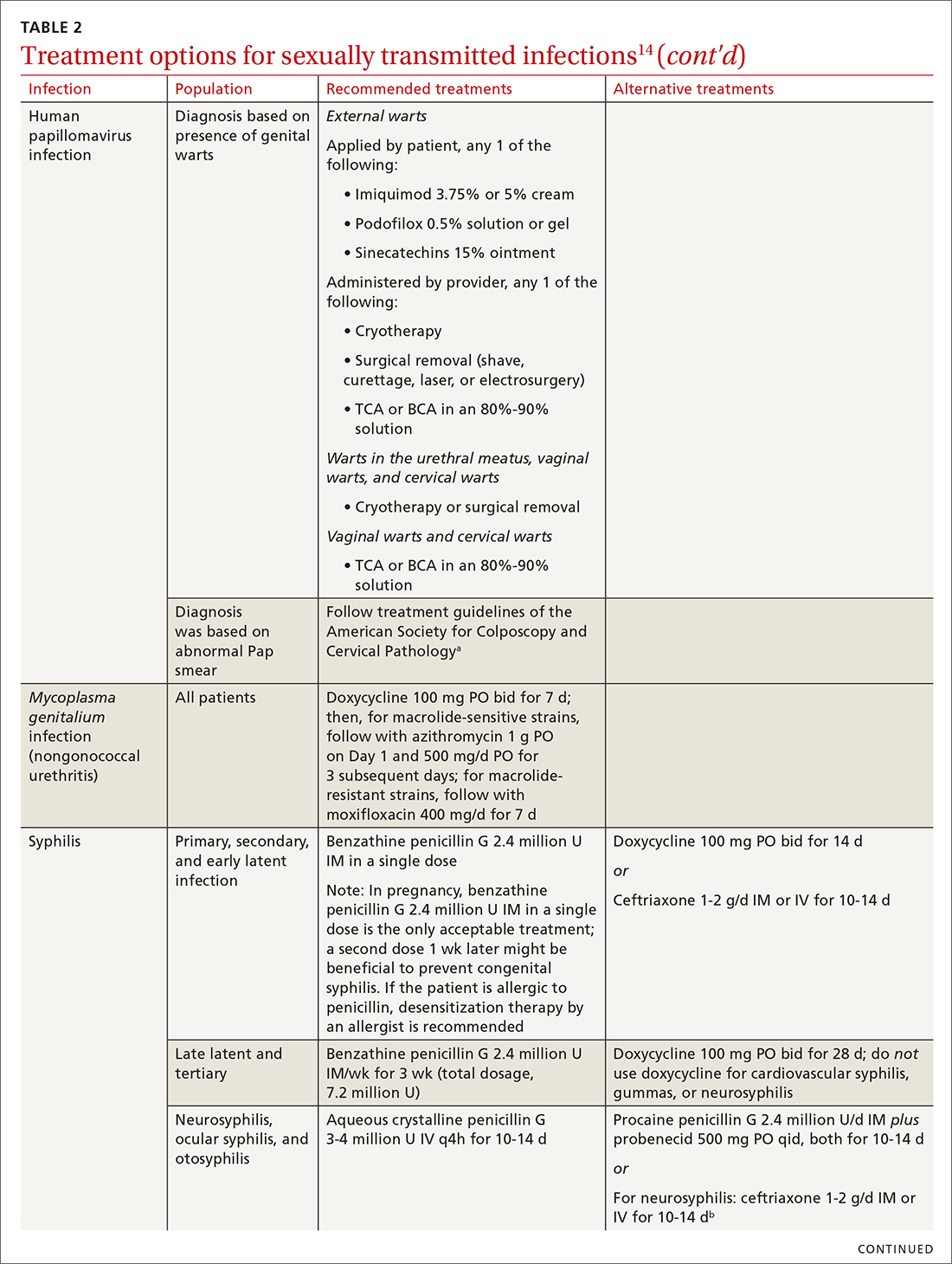

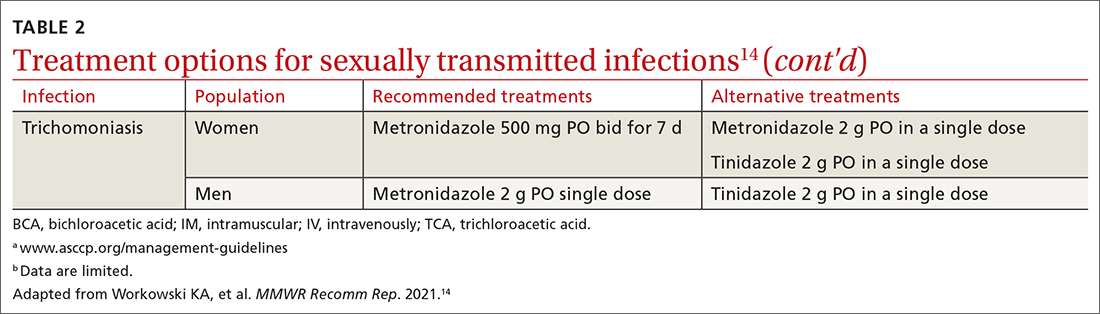

Three factors—changing social patterns, including the increase of social networking; the ability of antiviral therapy to decrease the spread of HIV, leading to a reduction in condom use; and increasing antibiotic resistance—have converged to force changes in screening and treatment recommendations. In this article, we summarize updated guidance for primary care clinicians from several sources—including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)—on diagnosing STIs (TABLE 14-13) and providing guideline-based treatment (Table 214). Because of the breadth and complexity of HIV disease, it is not addressed here.

Chlamydia

Infection with Chlamydia trachomatis—the most commonly reported bacterial STI in the United States—primarily causes cervicitis in women and proctitis in men, and can cause urethritis and pharyngitis in men and women. Prevalence is highest in sexually active people younger than 24 years.15

Because most infected people are asymptomatic and show no signs of illness on physical exam, screening is recommended for all sexually active women younger than 25 years and all men who have sex with men (MSM).4 No studies have established proper screening intervals; a reasonable approach, therefore, is to repeat screening for patients who have a sexual history that confers a new or persistent risk for infection since their last negative result.

Depending on the location of the infection, symptoms of chlamydia can include vaginal or penile irritation or discharge, dysuria, pelvic or rectal pain, and sore throat. Breakthrough bleeding in a patient who is taking an oral contraceptive should raise suspicion for chlamydia.

Untreated chlamydia can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), tubo-ovarian abscess, tubal factor infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain. Infection can be transmitted vertically (mother to baby) antenatally, which can cause ophthalmia neonatorum and pneumonia in these newborns.

Diagnosis. The diagnosis of chlamydia is made using nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT). Specimens can be collected by the clinician or the patient (self collected) using a vaginal, rectal, or oropharyngeal swab, or a combination of these, and can be obtained from urine or liquid-based cytology material.16

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment. Recommendations for treating chlamydia were updated by the CDC in its 2021 treatment guidelines (Table 214). Doxycycline 100 mg bid for 7 days is the preferred regimen; alternative regiments are (1) azithromycin 1 g in a single dose and (2) levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 7 days.4 A meta-analysis17 and a Cochrane review18 showed that the rate of treatment failure was higher among men when they were treated with azithromycin instead of doxycycline; furthermore, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that doxycycline is more effective than azithromycin (cure rate, 100%, compared to 74%) at treating rectal chlamydia in MSM.19

Azithromycin is efficacious for urogenital infection in women; however, there is concern that the 33% to 83% of women who have concomitant rectal infection (despite reporting no receptive anorectal sexual activity) would be insufficiently treated. Outside pregnancy, the CDC does not recommend a test of cure but does recommend follow-up testing for reinfection in 3 months. Patients should abstain from sexual activity until 7 days after all sexual partners have been treated.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT) is the practice of treating sexual partners of patients with known chlamydia (and patients with gonococcal infection). Unless prohibited by law in your state, offer EPT to patients with chlamydia if they cannot ensure that their sexual partners from the past 60 days will seek timely treatment.a

Evidence to support EPT comes from 3 US clinical trials, whose subjects comprised heterosexual men and women with chlamydia or gonorrhea.21-23 The role of EPT for MSM is unclear; data are limited. Shared decision-making is recommended to determine whether EPT should be provided, to ensure that co-infection with other bacterial STIs (eg, syphilis) or HIV is not missed.24-26

a Visit www.cdc.gov/std/ept to read updated information about laws and regulations regarding EPT in your state.20

Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is the second most-reported bacterial communicable disease.5 Infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae causes urethral discharge in men, leading them to seek treatment; infected women, however, are often asymptomatic. Infected men and women might not recognize symptoms until they have transmitted the disease. Women have a slower natural clearance of gonococcal infection, which might explain their higher prevalence.27 Delayed recognition of symptoms can result in complications, including PID.5

Diagnosis. Specimens for NAAT can be obtained from urine, endocervical, vaginal, rectal, pharyngeal, and male urethral specimens. Reported sexual behaviors and exposures of women and transgender or gender-diverse people should be taken into consideration to determine whether rectal or pharyngeal testing, or both, should be performed.28 MSM should be screened annually at sites of contact, including the urethra, rectum, and pharynx.28 All patients with urogenital or rectal gonorrhea should be asked about oral sexual exposure; if reported, pharyngeal testing should be performed.5

NAAT of urine is at least as sensitive as testing of an endocervical specimen; the same specimen can be used to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Patient-collected specimens are a reasonable alternative to clinician-collected swab specimens.29

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment is complicated by the ability of gonorrhea to develop resistance. Intramuscular ceftriaxone 500 mg in a single dose cures 98% to 99% of infections in the United States; however, monitoring local resistance patterns in the community is an important component of treatment.28 (See Table 214 for an alternative regimen for cephalosporin-allergic patients and for treating gonococcal conjunctivitis and disseminated infection.)

In 2007, the CDC identified widespread quinolone-resistant gonococcal strains; therefore, fluoroquinolones no longer are recommended for treating gonorrhea.30 Cefixime has demonstrated only limited success in treating pharyngeal gonorrhea and does not attain a bactericidal level as high as ceftriaxone does; cefixime therefore is recommended only if ceftriaxone is unavailable.28 The national Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project is finding emerging evidence of the reduced susceptibility of N gonorrhoeae to azithromycin—making dual therapy for gonococcal infection no longer a recommendation.28

Patients should abstain from sex until 7 days after all sex partners have been treated for gonorrhea. As with chlamydia, the CDC does not recommend a test of cure for uncomplicated urogenital or rectal gonorrhea unless the patient is pregnant, but does recommend testing for reinfection 3 months after treatment.14 For patients with pharyngeal gonorrhea, a test of cure is recommended 7 to 14 days after initial treatment, due to challenges in treatment and because this site of infection is a potential source of antibiotic resistance.28

Trichomoniasis

T vaginalis, the most common nonviral STI worldwide,31 can manifest as a yellow-green vaginal discharge with or without vaginal discomfort, dysuria, epididymitis, and prostatitis; most cases, however, are asymptomatic. On examination, the cervix might be erythematous with punctate lesions (known as strawberry cervix).

Unlike most STIs, trichomoniasis is as common in women older than 24 years as it is in younger women. Infection is associated with a lower educational level, lower socioeconomic status, and having ≥ 2 sexual partners in the past year.32 Prevalence is approximately 10 times as high in Black women as it is in White women.

T vaginalis infection is associated with an increase in the risk for preterm birth, premature rupture of membranes, cervical cancer, and HIV infection. With a lack of high-quality clinical trials on the efficacy of screening, women with HIV are the only group for whom routine screening is recommended.6

Diagnosis. NAAT for trichomoniasis is now available in conjunction with gonorrhea and chlamydia testing of specimens on vaginal or urethral swabs and of urine specimens and liquid Pap smears.

Continue to: Treatment

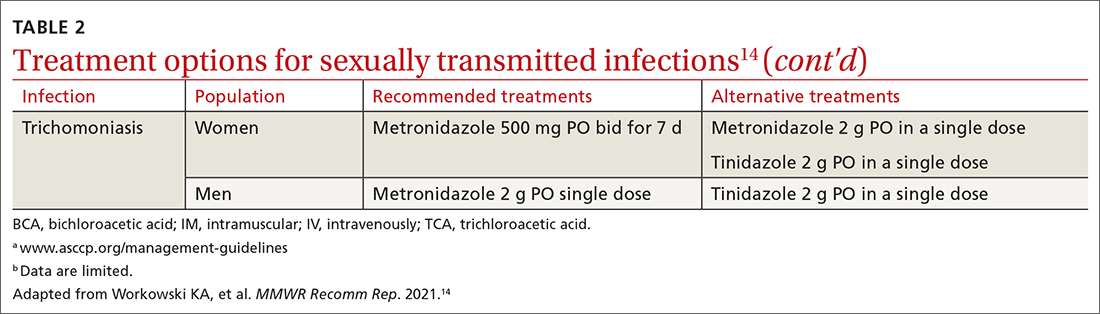

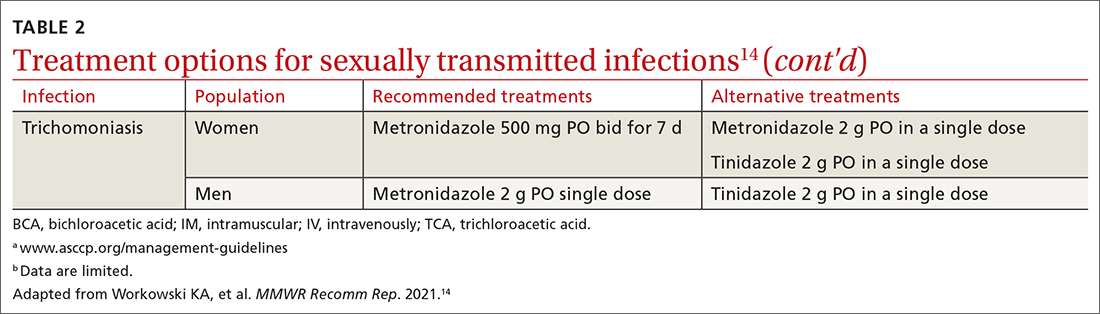

Treatment. Because of greater efficacy, the treatment recommendation for women has changed from a single 2-g dose of oral metronidazole to 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. The 2-g single oral dose is still recommended for men7 (Table 214 lists alternative regimens).

Mycoplasma genitalium

Infection with M genitalium is common and often asymptomatic. The disease causes approximately 20% of all cases of nongonococcal and nonchlamydial urethritis in men and about 40% of persistent or recurrent infections. M genitalium is present in approximately 20% of women with cervicitis and has been associated with PID, preterm delivery, spontaneous abortion, and infertility.

There are limited and conflicting data regarding outcomes in infected patients other than those with persistent or recurrent infection; furthermore, resistance to azithromycin is increasing rapidly, resulting in an increase in treatment failures. Screening therefore is not recommended, and testing is recommended only in men with nongonococcal urethritis.33,34

Diagnosis. NAAT can be performed on urine or on a urethral, penile meatal, endocervical, or vaginal swab; men with recurrent urethritis or women with recurrent cervicitis should be tested. NAAT also can be considered in women with PID. Testing the specimen for the microorganism’s resistance to macrolide antibiotics is recommended (if such testing is available).

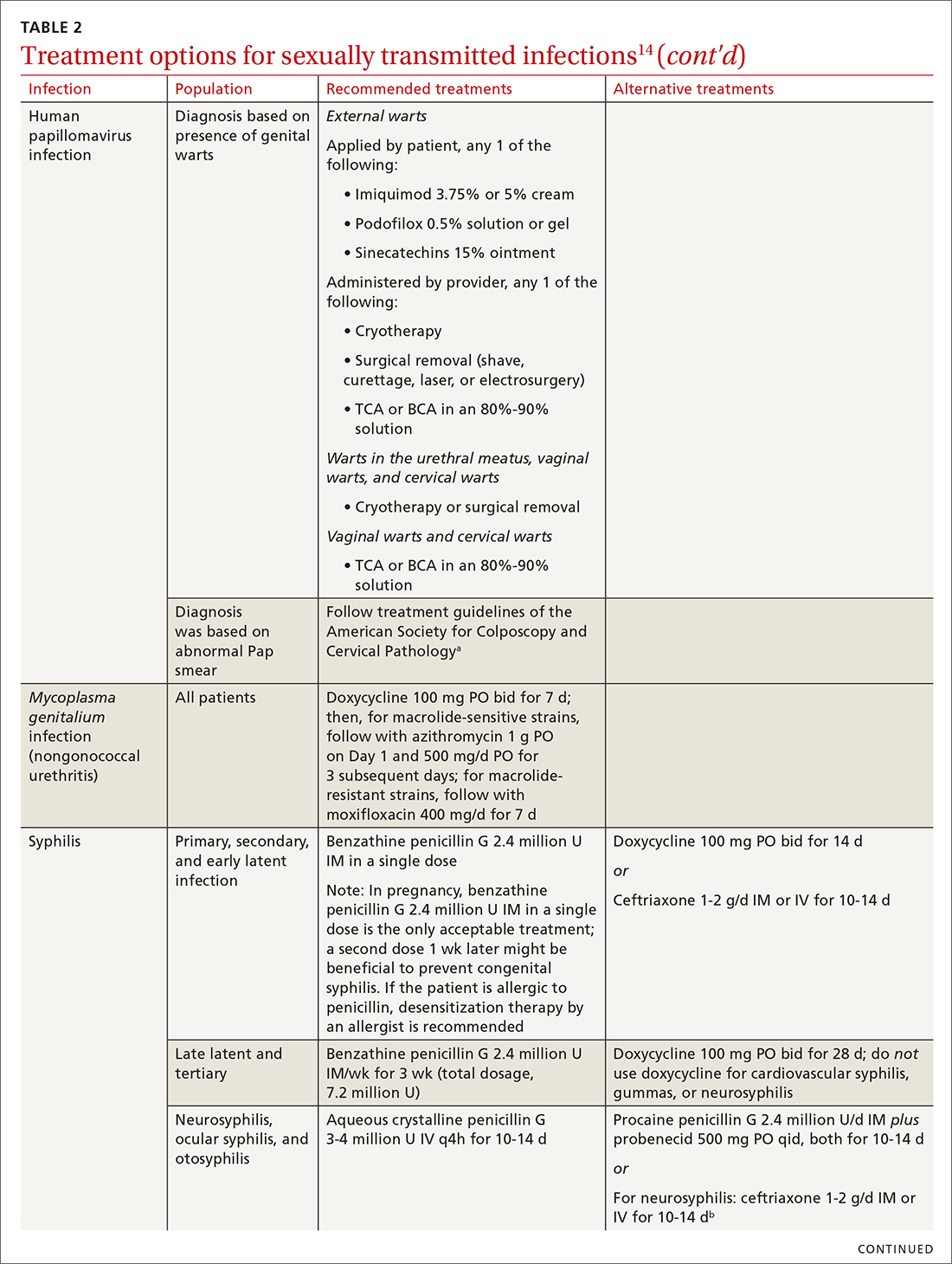

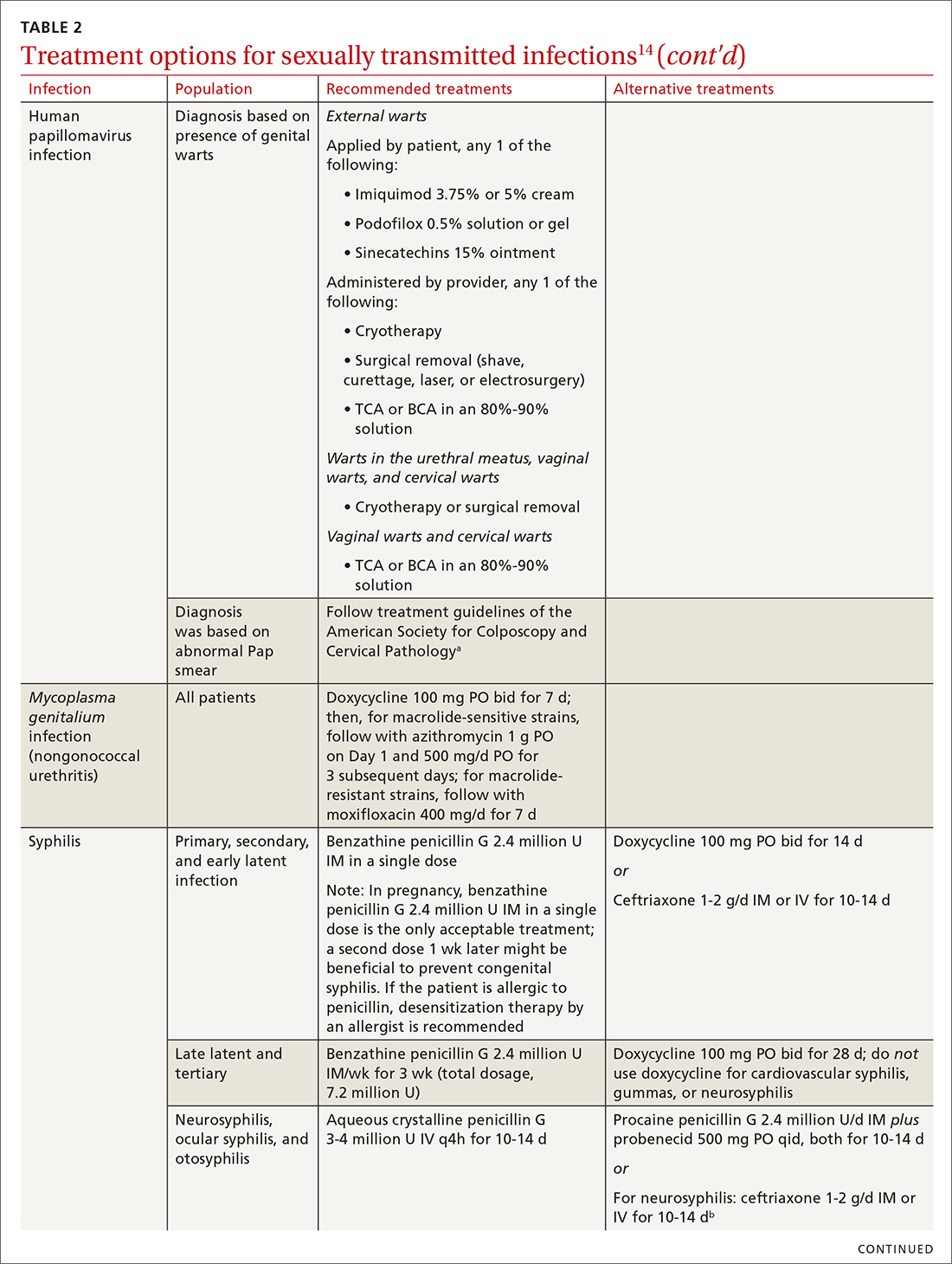

Treatment is initiated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days. If the organism is macrolide sensitive, follow with azithromycin 1 g orally on Day 1, then 500 mg/d for 3 more days. If the organism is macrolide resistant or testing is unavailable, follow doxycycline with oral moxifloxacin 400 mg/d for 7 days.33

Genital herpes (mostly herpesvirus type 2)

Genital herpes, characterized by painful, recurrent outbreaks of genital and anal lesions,35 is a lifelong infection that increases in prevalence with age.8 Because many infected people have disease that is undiagnosed or mild or have unrecognizable symptoms during viral shedding, most genital herpes infections are transmitted by people who are unaware that they are contagious.36 Herpesvirus type 2 (HSV-2) causes most cases of genital herpes, although an increasing percentage of cases are attributed to HSV type 1 (HSV-1) through receptive oral sex from a person who has an oral HSV-1 lesion.

Importantly, HSV-2–infected people are 2 to 3 times more likely to become infected with HIV than people who are not HSV-2 infected.37 This is because CD4+ T cells concentrate at the site of HSV lesions and express a higher level of cell-surface receptors that HIV uses to enter cells. HIV replicates 3 to 5 times more quickly in HSV-infected tissue.38

Continue to: HSV can become disseminated...

HSV can become disseminated, particularly in immunosuppressed people, and can manifest as encephalitis, hepatitis, and pneumonitis. Beyond its significant burden on health, HSV carries significant psychosocial consequences.9

Diagnosis. Clinical diagnosis can be challenging if classic lesions are absent at evaluation. If genital lesions are present, HSV can be identified by NAAT or culture of a specimen of those lesions. False-negative antibody results might be more frequent in early stages of infection; repeating antibody testing 12 weeks after presumed time of acquisition might therefore be indicated, based on clinical judgment. HSV-2 antibody positivity implies anogenital infection because almost all HSV-2 infections are sexually acquired.

HSV-1 antibody positivity alone is more difficult to interpret because this finding does not distinguish between oral and genital lesions, and most HSV-1 seropositivity is acquired during childhood.36 HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of blood should not be performed to diagnose genital herpes infection, except in settings in which there is concern about disseminated infection.

Treatment. Management should address the acute episode and the chronic nature of genital herpes. Antivirals will not eradicate latent

- attenuate current infection

- prevent recurrence

- improve quality of life

- suppress the virus to prevent transmission to sexual partners.

All patients experiencing an initial episode of genital herpes should be treated, regardless of symptoms, due to the potential for prolonged or severe symptoms during recurrent episodes.9 Three drugs—acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir—are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat genital herpes and appear equally effective (TABLE 214).

Antiviral therapy for recurrent genital HSV infection can be administered either as suppressive therapy to reduce the frequency of recurrences or episodically to shorten the duration of lesions:

- Suppressive therapy reduces the frequency of recurrence by 70% to 80% among patients with frequent outbreaks. Long-term safety and efficacy are well established.

- Episodic therapy is most effective if started within 1 day after onset of lesions or during the prodrome.36

There is no specific recommendation for when to choose suppressive over episodic therapy; most patients prefer suppressive therapy because it improves quality of life. Use shared clinical decision-making to determine the best option for an individual patient.

Continue to: Human papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus

Condylomata acuminata (genital warts) are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), most commonly types 6 and 11, which manifest as soft papules or plaques on the external genitalia, perineum, perianal skin, and groin. The warts are usually asymptomatic but can be painful or pruritic, depending on size and location.

Diagnosis is made by visual inspection and can be confirmed by biopsy if lesions are atypical. Lesions can resolve spontaneously, remain unchanged, or grow in size or number.

Treatment. The aim of treatment is relief of symptoms and removal of warts. Treatment does not eradicate HPV infection. Multiple treatments are available that can be applied by the patient as a cream, gel, or ointment or administered by the provider, including cryotherapy, surgical removal, and solutions. The decision on how to treat should be based on the number, size, and

HPV-associated cancers and precancers. This is a broad (and separate) topic. HPV types 16 and 18 cause most cases of cervical, penile, vulvar, vaginal, anal, and oropharyngeal cancer and precancer.39 The USPSTF, the American Cancer Society, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists all have recommendations for cervical cancer screening in the United States.40 Refer to guidelines of the ASCCP for recommendations on abnormal screening tests.41

Prevention of genital warts. The 9-valent HPV vaccine available in the United States is safe and effective and helps protect against viral types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58. Types 6 and 11 are the principal causes of genital warts. Types 16 and 18 cause 66% of cervical cancer. The vaccination series can be started at age 9 years and is recommended for everyone through age 26 years. Only 2 doses are needed if the first dose is given prior to age 15 years; given after that age, a 3-dose series is utilized. Refer to CDC vaccine guidelines42 for details on the exact timing of vaccination.

Vaccination for women ages 27 to 45 years is not universally recommended because most people have been exposed to HPV by that age. However, the vaccine can still be administered, depending on clinical circumstances and the risk for new infection.42

Syphilis

Caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, syphilis manifests across a spectrum—from congenital to tertiary. The inability of medical science to develop a method for culturing the spirochete has confounded diagnosis and treatment.

Continue to: Since reaching a historic...

Since reaching a historic nadir of incidence in 2000 (5979 cases in the United States), there has been an increasingly rapid rise in that number: to 130,000 in 2020. More than 50% of cases are in MSM; however, the number of cases in heterosexual women is rapidly increasing.43

Routine screening for syphilis should be performed in any person who is at risk: all pregnant women in the first trimester (and in the third trimester and at delivery if they are at risk or live in a community where prevalence is high) and annually in sexually active MSM or anyone with HIV infection.10

Diagnosis. Examination by dark-field microscopy, testing by PCR, and direct fluorescent antibody assay for T pallidum from lesion tissue or exudate provide definitive diagnosis for early and congenital syphilis, but are often unavailable.

Presumptive diagnosis requires 2 serologic tests:

- Nontreponemal tests (the VDRL and rapid plasma reagin tests) identify anticardiolipin antibodies released during syphilis infection, although results also can be elevated in autoimmune disease or after certain immunizations, including the COVID-19 vaccine.

- Treponemal tests (the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed assay, T pallidum particulate agglutination assay, enzyme immunoassay, and chemiluminescence immunoassay) are specific antibody tests.

Historically, reactive nontreponemal tests, which are less expensive and easier to perform, were followed by a treponemal test to confirm the presumptive diagnosis. This method continues to be reasonable when screening patients in a low-prevalence population.11 The reverse sequence screening algorithm (ie, begin with a treponemal test) is now frequently used. With this method, a positive treponemal test must be confirmed with a nontreponemal test. If the treponemal test is positive and the nontreponemal test is negative, another treponemal test must be positive to confirm the diagnosis. This algorithm is useful in high-risk populations because it provides earlier detection of recently acquired syphilis and enhanced detection of late latent syphilis.12,13,44 The CDC has not stated a diagnostic preference.

Once the diagnosis is made, a complete history (including a sexual history and a history of syphilis testing and treatment) and a physical exam are necessary to confirm stage of disease.45

Special circumstances. Neurosyphilis, ocular syphilis, and otosyphilis refer to the site of infection and can occur at any stage of disease. The nervous system usually is infected within hours of initial infection, but symptoms might take weeks or years to develop—or might never manifest. Any time a patient develops neurologic, ophthalmologic, or audiologic symptoms, careful neurologic and ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed and the patient should be tested for HIV.

Continue to: Lumbar puncture is warranted...

Lumbar puncture is warranted for evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid if neurologic symptoms are present but is not necessary for isolated ocular syphilis or otosyphilis without neurologic findings. Treatment should not be delayed for test results if ocular syphilis is suspected because permanent blindness can develop. Any patient at high risk for an STI who presents with neurologic or ophthalmologic symptoms should be tested for syphilis and HIV.45

Pregnant women who have a diagnosis of syphilis should be treated with penicillin immediately because treatment ≥ 30 days prior to delivery is likely to prevent most cases of congenital syphilis. However, a course of penicillin might not prevent stillbirth or congenital syphilis in a gravely infected fetus, evidenced by fetal syphilis on a sonogram at the time of treatment. Additional doses of penicillin in pregnant women with early syphilis might be indicated if there is evidence of fetal syphilis on ultrasonography. All women who deliver a stillborn infant (≥ 20 weeks’ gestation) should be tested for syphilis at delivery.46

All patients in whom primary or secondary syphilis has been diagnosed should be tested for HIV at the time of diagnosis and treatment; if the result is negative, they should be offered preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP; discussed shortly). If the incidence of HIV in your community is high, repeat testing for HIV in 3 months. Clinical and serologic evaluation should be performed 6 and 12 months after treatment.47

Treatment. Penicillin remains the standard treatment for syphilis. Primary, secondary, and early tertiary stages (including in pregnancy) are treated with benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscular (IM) in a single dose. For pregnant patients, repeating that dose in 1 week generally is recommended. Patients in the late latent (> 1 year) or tertiary stage receive the same dose of penicillin, which is then repeated weekly, for a total of 3 doses. Doxycycline and ceftriaxone are alternatives, except in pregnancy.

Warn patients of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: fever, headache, and myalgias associated with initiation of treatment in the presence of the high bacterial load seen in early syphilis. Treatment is symptomatic, but the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction can cause fetal distress in pregnancy.

Otosyphilis, ocular syphilis, and neurosyphilis require intravenous (IV) aqueous crystalline penicillin G 3 to 4 million U every 4 hours for 10 to 14 days.45 Alternatively, procaine penicillin G 2.4 million U/d IM can be given daily with oral probenecid 500 mg qid, both for 10 to 14 days (TABLE 214).

Screening andprevention of STIs

Screening recommendations

Follow USPSTF screening guidelines for STIs.10,48-54 Screen annually for:

- gonorrhea and chlamydia in women ages 15 to 24 years and in women older than 25 years if they are at increased risk

- gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and HIV in MSM, and hepatitis C if they are HIV positive

- trichomoniasis in women who are HIV positive.

Continue to: Consider the community in which...

Consider the community in which you practice when determining risk; you might want to consult local public health authorities for information about local epidemiology and guidance on determining which of your patients are at increased risk.

Preexposure prophylaxis

According to the CDC, all sexually active adults and adolescents should be informed about the availability of PrEP to prevent HIV infection. PrEP should be (1) available to anyone who requests it and (2) recommended for anyone who is sexually active and who practices sexual behaviors that place them at substantial risk for exposure to or acquisition of HIV, or both.

The recommended treatment protocol for men and women who have either an HIV-positive partner or inconsistent condom use or who have had a bacterial STI in the previous 6 months is oral emtricitabine 200 mg plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg/d (sold as Truvada-F/TDF). Men and transgender women (ie, assigned male at birth) with at-risk behaviors also can use emtricitabine plus tenofovir alafenamide 25 mg/d (sold as Descovy-F/TAF).

In addition, cabotegravir plus rilpirivine (sold as Cabenuva), IM every 2 months, was approved by the FDA for PrEP in 2021.

Creatinine clearance should be assessed at baseline and yearly (every 6 months for those older than 50 years) in patients taking PrEP. All patients must be tested for HIV at initiation of treatment and every 3 months thereafter (every 4 months for cabotegravir plus rilpirivine). Patients should be screened for bacterial STIs every 6 months (every 3 months for MSM and transgender women); screening for chlamydia should be done yearly. For patients being treated with emtricitabine plus tenofovir alafenamide, weight and a lipid profile (cholesterol and triglycerides) should be assessed annually.55

Postexposure prophylaxis

The sharp rise in the incidence of STIs in the past few years has brought renewed interest in postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for STIs. Although PEP should be standard in cases of sexual assault, this protocol also can be considered in other instances of high-risk exposure.

CDC recommendations for PEP in cases of assault are56:

- ceftriaxone 500 mg IM in a single dose (1 g if weight is ≥ 150 kg) plus

- doxycycline 100 mg bid for 7 days plus

- metronidazole 2 g bid for 7 days (for vaginal exposure)

- pregnancy evaluation and emergency contraception

- hepatitis B risk evaluation and vaccination, with or without hepatitis B immune globulin

- HIV risk evaluation, based on CDC guidelines, and possible HIV prophylaxis (PrEP)

- HPV vaccination for patients ages 9 to 26 years if they are not already fully vaccinated.

CORRESPONDENCE

Belinda Vail, MD, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Mail Stop 4010, Kansas City, KS 66160; [email protected]

1. Pagaoa M, Grey J, Torrone E, et al. Trends in nationally notifiable sexually transmitted disease case reports during the US COVID-19 pandemic, January to December 2020. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48:798-804. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001506

2. Chesson HW, Spicknall IH; Bingham A, et al. The estimated direct lifetime medical costs of sexually transmitted infections acquired in the United States in 2018. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48:215-221. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001380

3. Kreisel KM, Spicknall IH, Gargano JW, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2018. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48:208-214. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001355

4. CDC. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021: Chlamydial infections among adolescents and adults. US Department of Health and Human Services. July 21, 2021. Accessed April 19, 2023. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/chlamydia.htm

5. CDC. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021: Gonococcal infections among adolescents and adults. US Department of Health and Human Services. September 21, 2022. Accessed April 23, 2023. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/gonorrhea-adults.htm

6. Van Gerwen OT, Muzny CA. Recent advances in the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of Trichomonas vaginalis infection. F1000Res. 2019;

7. CDC. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Trichomoniasis. US Department of Health and Human Services. September 21, 2022. Accessed April 23, 2023. December 27, 2021. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/trichomoniasis.htm

8. Spicknall IH, Flagg EW, Torrone EA. Estimates of the prevalence and incidence of genital herpes, United States, 2018. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48:260-265. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001375

9. Mark H, Gilbert L, Nanda J. Psychosocial well-being and quality of life among women newly diagnosed with genital herpes. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs.

10. Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315:2321-2327. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5824

11. Ricco J, Westby A. Syphilis: far from ancient history. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102:91-98.

12. Goza M, Kulwicki B, Akers JM, et al. Syphilis screening: a review of the Syphilis Health Check rapid immunochromatographic test. J Pharm Technol. 2017;33:53-59. doi:10.1177/8755122517691308

13. Henao- AF, Johnson SC. Diagnostic tests for syphilis: new tests and new algorithms. Neurol Clin Pract. 2014;4:114-122. doi: 10.1212/01.CPJ.0000435752.17621.48

14. Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1

15. CDC. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2021. National overview of STDs. US Department of Health and Human Services. April 2023. Accessed May 9, 2023. www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2021/overview.htm#Chlamydia

16. CDC. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae—2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63:1-19.

17. Kong FYS, Tabrizi SN, Law M, et al. Azithromycin versus doxycycline for the treatment of genital chlamydia infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:193-205. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu220

18. Páez-Canro C, Alzate JP, González LM, et al. Antibiotics for treating urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in men and non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD010871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010871.pub2

19. Dombrowski JC, Wierzbicki MR, Newman LM, et al. Doxycycline versus azithromycin for the treatment of rectal chlamydia in men who have sex with men: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:824-831. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab153

20. CDC. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021: Expedited partner therapy. US Department of Health and Human Services. July 22, 2021. Accessed April 19, 2023. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/clinical-EPT.htm

21. Golden MR, Whittington WLH, Handsfield HH, et al. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:676-685. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041681

22. Schillinger JA, Kissinger P, Calvet H, et al. Patient-delivered partner treatment with azithromycin to prevent repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women: a randomized, controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:49-56. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200301000-00011

23. Cameron ST, Glasier A, Scott G, et al. Novel interventions to reduce re-infection in women with chlamydia: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:888-895. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den475

24. McNulty A, Teh MF, Freedman E. Patient delivered partner therapy for chlamydial infection—what would be missed? Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:834-836. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181761993

25. Stekler J, Bachmann L, Brotman RM, et al. Concurrent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in sex partners of patients with selected STIs: implications for patient-delivered partner therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:787-793. doi: 10.1086/428043

26. Schillinger JA, Kissinger P, Calvet H, et al. Patient-delivered partner treatment with azithromycin to prevent repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women: a randomized, controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:49-56. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200301000-00011

27. Stupiansky NW, Van der Pol B, Williams JA, et al. The natural history of incident gonococcal infection in adolescent women. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:750-754. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820ff9a4

28. CDC. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021: Screening recommendations and considerations referenced in treatment guidelines and original sources. US Department of Health and Human Services. June 6, 2022. Accessed May 9, 2023. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/screening-recommen dations.htm

29. Cantor A, Dana T, Griffen JC, et al. Screening for chlamydial and gonococcal infections: a systematic review update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 206. AHRQ Report No. 21-05275-EF-1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. September 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574045

30. CDC. Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:332-336.

31. Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E, et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ. 2019:97:548-562P. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.228486

32. Patel EU, Gaydos CA, Packman ZR, et al. Prevalence and correlates of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among men and women in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:211-217. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy079

33. CDC. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Mycoplasma genitalium. US Department of Health and Human Services. July 22, 2021. Accessed April 23, 2023. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/mycoplasmagenitalium.htm

34. Manhart LE, Broad JM, Bolden MR. Mycoplasma genitalium: should we treat and how? Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(suppl 3):S129-S142. doi:10.1093/cid/cir702.

35. Corey L, Wald A. Genital herpes. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, et al, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2008:399-437.

36. CDC. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021: Genital herpes. US Department of Health and Human Services. September 21, 2022. Accessed April 23, 2023. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/herpes.htm

37. Looker KJ, Elmes JAR, Gottlieb SL, et al. Effect of HSV-2 infection on subsequent HIV acquisition: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1303-1316. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30405-X

38. Rollenhagen C, Lathrop M, Macura SL, et al. Herpes simplex virus type-2 stimulates HIV-1 replication in cervical tissues: implications for HIV-1 transmission and efficacy of anti-HIV-1 microbicides. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:1165-1174. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.3

39. Cogliano V, Baan R, Straif K, et al; WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer. Carcinogenicity of human papillomaviruses. Lancet Oncol.

40. Simon MA, Tseng CW, Wong JB. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10897

41. Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al; . 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24:102-131. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000525

42. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3

43. Schmidt R, Carson PJ, Jansen RJ. Resurgence of syphilis in the United States: an assessment of contributing factors. Infect Dis (Auckl). 2019;12:1178633719883282. doi: 10.1177/1178633719883282

44. Boog GHP, Lopes JVZ, Mahler JV, et al. Diagnostic tools for neurosyphilis: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:568. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06264-8

45. CDC. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Syphilis. US Department of Health and Human Services. April 20, 2023. Accessed April 24, 2023. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm

46. Matthias JM, Rahman MM, Newman DR, et al. Effectiveness of prenatal screening and treatment to prevent congenital syphilis, Louisiana and Florida, 2013-2014. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44:498-502. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000638

47. Clement ME, Okeke NL, Hicks CB. Treatment of syphilis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312:1905-1917. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13259

48. Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;326:949-956. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14081

49. Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;324:2415-2422. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22980

50. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323:970-975. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1123

51. Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Serologic screening for genital herpes infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:2525-2530. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16776

52. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10897

53. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321:2326-2336. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.6587

54. Farley TA, Cohen DA, Elkins W. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases: the case for screening. Prev Med. 2003;36:502-509. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00058-0

55. US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 update. A clinical practice guideline. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed April 24, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf

56. CDC. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021: Sexual assault and abuse and STIs—adolescents and adults, 2021. US Department of Health and Human Services. July 22, 2021. Accessed April 24, 2023. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/sexual-assault-adults.htm

Except for a drop in the number of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) early in the COVID-19 pandemic (March and April 2020), the incidence of STIs has been rising throughout this century.1 In 2018, 1 in 5 people in the United States had an STI; 26 million new cases were reported that year, resulting in direct costs of $16 billion—85% of which was for the care of HIV infection.2 Also that year, infection with Chlamydia trachomatis (chlamydia), Trichomonas vaginalis (trichomoniasis), herpesvirus type 2 (genital herpes), and/or human papillomavirus (condylomata acuminata) constituted 97.6% of all prevalent and 93.1% of all incident STIs.3 Almost half (45.5%) of new cases of STIs occur in people between the ages of 15 and 24 years.3

Three factors—changing social patterns, including the increase of social networking; the ability of antiviral therapy to decrease the spread of HIV, leading to a reduction in condom use; and increasing antibiotic resistance—have converged to force changes in screening and treatment recommendations. In this article, we summarize updated guidance for primary care clinicians from several sources—including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)—on diagnosing STIs (TABLE 14-13) and providing guideline-based treatment (Table 214). Because of the breadth and complexity of HIV disease, it is not addressed here.

Chlamydia

Infection with Chlamydia trachomatis—the most commonly reported bacterial STI in the United States—primarily causes cervicitis in women and proctitis in men, and can cause urethritis and pharyngitis in men and women. Prevalence is highest in sexually active people younger than 24 years.15

Because most infected people are asymptomatic and show no signs of illness on physical exam, screening is recommended for all sexually active women younger than 25 years and all men who have sex with men (MSM).4 No studies have established proper screening intervals; a reasonable approach, therefore, is to repeat screening for patients who have a sexual history that confers a new or persistent risk for infection since their last negative result.

Depending on the location of the infection, symptoms of chlamydia can include vaginal or penile irritation or discharge, dysuria, pelvic or rectal pain, and sore throat. Breakthrough bleeding in a patient who is taking an oral contraceptive should raise suspicion for chlamydia.

Untreated chlamydia can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), tubo-ovarian abscess, tubal factor infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain. Infection can be transmitted vertically (mother to baby) antenatally, which can cause ophthalmia neonatorum and pneumonia in these newborns.

Diagnosis. The diagnosis of chlamydia is made using nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT). Specimens can be collected by the clinician or the patient (self collected) using a vaginal, rectal, or oropharyngeal swab, or a combination of these, and can be obtained from urine or liquid-based cytology material.16

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment. Recommendations for treating chlamydia were updated by the CDC in its 2021 treatment guidelines (Table 214). Doxycycline 100 mg bid for 7 days is the preferred regimen; alternative regiments are (1) azithromycin 1 g in a single dose and (2) levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 7 days.4 A meta-analysis17 and a Cochrane review18 showed that the rate of treatment failure was higher among men when they were treated with azithromycin instead of doxycycline; furthermore, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that doxycycline is more effective than azithromycin (cure rate, 100%, compared to 74%) at treating rectal chlamydia in MSM.19

Azithromycin is efficacious for urogenital infection in women; however, there is concern that the 33% to 83% of women who have concomitant rectal infection (despite reporting no receptive anorectal sexual activity) would be insufficiently treated. Outside pregnancy, the CDC does not recommend a test of cure but does recommend follow-up testing for reinfection in 3 months. Patients should abstain from sexual activity until 7 days after all sexual partners have been treated.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT) is the practice of treating sexual partners of patients with known chlamydia (and patients with gonococcal infection). Unless prohibited by law in your state, offer EPT to patients with chlamydia if they cannot ensure that their sexual partners from the past 60 days will seek timely treatment.a

Evidence to support EPT comes from 3 US clinical trials, whose subjects comprised heterosexual men and women with chlamydia or gonorrhea.21-23 The role of EPT for MSM is unclear; data are limited. Shared decision-making is recommended to determine whether EPT should be provided, to ensure that co-infection with other bacterial STIs (eg, syphilis) or HIV is not missed.24-26

a Visit www.cdc.gov/std/ept to read updated information about laws and regulations regarding EPT in your state.20

Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is the second most-reported bacterial communicable disease.5 Infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae causes urethral discharge in men, leading them to seek treatment; infected women, however, are often asymptomatic. Infected men and women might not recognize symptoms until they have transmitted the disease. Women have a slower natural clearance of gonococcal infection, which might explain their higher prevalence.27 Delayed recognition of symptoms can result in complications, including PID.5

Diagnosis. Specimens for NAAT can be obtained from urine, endocervical, vaginal, rectal, pharyngeal, and male urethral specimens. Reported sexual behaviors and exposures of women and transgender or gender-diverse people should be taken into consideration to determine whether rectal or pharyngeal testing, or both, should be performed.28 MSM should be screened annually at sites of contact, including the urethra, rectum, and pharynx.28 All patients with urogenital or rectal gonorrhea should be asked about oral sexual exposure; if reported, pharyngeal testing should be performed.5

NAAT of urine is at least as sensitive as testing of an endocervical specimen; the same specimen can be used to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Patient-collected specimens are a reasonable alternative to clinician-collected swab specimens.29

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment is complicated by the ability of gonorrhea to develop resistance. Intramuscular ceftriaxone 500 mg in a single dose cures 98% to 99% of infections in the United States; however, monitoring local resistance patterns in the community is an important component of treatment.28 (See Table 214 for an alternative regimen for cephalosporin-allergic patients and for treating gonococcal conjunctivitis and disseminated infection.)

In 2007, the CDC identified widespread quinolone-resistant gonococcal strains; therefore, fluoroquinolones no longer are recommended for treating gonorrhea.30 Cefixime has demonstrated only limited success in treating pharyngeal gonorrhea and does not attain a bactericidal level as high as ceftriaxone does; cefixime therefore is recommended only if ceftriaxone is unavailable.28 The national Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project is finding emerging evidence of the reduced susceptibility of N gonorrhoeae to azithromycin—making dual therapy for gonococcal infection no longer a recommendation.28

Patients should abstain from sex until 7 days after all sex partners have been treated for gonorrhea. As with chlamydia, the CDC does not recommend a test of cure for uncomplicated urogenital or rectal gonorrhea unless the patient is pregnant, but does recommend testing for reinfection 3 months after treatment.14 For patients with pharyngeal gonorrhea, a test of cure is recommended 7 to 14 days after initial treatment, due to challenges in treatment and because this site of infection is a potential source of antibiotic resistance.28

Trichomoniasis

T vaginalis, the most common nonviral STI worldwide,31 can manifest as a yellow-green vaginal discharge with or without vaginal discomfort, dysuria, epididymitis, and prostatitis; most cases, however, are asymptomatic. On examination, the cervix might be erythematous with punctate lesions (known as strawberry cervix).

Unlike most STIs, trichomoniasis is as common in women older than 24 years as it is in younger women. Infection is associated with a lower educational level, lower socioeconomic status, and having ≥ 2 sexual partners in the past year.32 Prevalence is approximately 10 times as high in Black women as it is in White women.

T vaginalis infection is associated with an increase in the risk for preterm birth, premature rupture of membranes, cervical cancer, and HIV infection. With a lack of high-quality clinical trials on the efficacy of screening, women with HIV are the only group for whom routine screening is recommended.6

Diagnosis. NAAT for trichomoniasis is now available in conjunction with gonorrhea and chlamydia testing of specimens on vaginal or urethral swabs and of urine specimens and liquid Pap smears.

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment. Because of greater efficacy, the treatment recommendation for women has changed from a single 2-g dose of oral metronidazole to 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. The 2-g single oral dose is still recommended for men7 (Table 214 lists alternative regimens).

Mycoplasma genitalium

Infection with M genitalium is common and often asymptomatic. The disease causes approximately 20% of all cases of nongonococcal and nonchlamydial urethritis in men and about 40% of persistent or recurrent infections. M genitalium is present in approximately 20% of women with cervicitis and has been associated with PID, preterm delivery, spontaneous abortion, and infertility.

There are limited and conflicting data regarding outcomes in infected patients other than those with persistent or recurrent infection; furthermore, resistance to azithromycin is increasing rapidly, resulting in an increase in treatment failures. Screening therefore is not recommended, and testing is recommended only in men with nongonococcal urethritis.33,34

Diagnosis. NAAT can be performed on urine or on a urethral, penile meatal, endocervical, or vaginal swab; men with recurrent urethritis or women with recurrent cervicitis should be tested. NAAT also can be considered in women with PID. Testing the specimen for the microorganism’s resistance to macrolide antibiotics is recommended (if such testing is available).

Treatment is initiated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days. If the organism is macrolide sensitive, follow with azithromycin 1 g orally on Day 1, then 500 mg/d for 3 more days. If the organism is macrolide resistant or testing is unavailable, follow doxycycline with oral moxifloxacin 400 mg/d for 7 days.33

Genital herpes (mostly herpesvirus type 2)

Genital herpes, characterized by painful, recurrent outbreaks of genital and anal lesions,35 is a lifelong infection that increases in prevalence with age.8 Because many infected people have disease that is undiagnosed or mild or have unrecognizable symptoms during viral shedding, most genital herpes infections are transmitted by people who are unaware that they are contagious.36 Herpesvirus type 2 (HSV-2) causes most cases of genital herpes, although an increasing percentage of cases are attributed to HSV type 1 (HSV-1) through receptive oral sex from a person who has an oral HSV-1 lesion.

Importantly, HSV-2–infected people are 2 to 3 times more likely to become infected with HIV than people who are not HSV-2 infected.37 This is because CD4+ T cells concentrate at the site of HSV lesions and express a higher level of cell-surface receptors that HIV uses to enter cells. HIV replicates 3 to 5 times more quickly in HSV-infected tissue.38

Continue to: HSV can become disseminated...

HSV can become disseminated, particularly in immunosuppressed people, and can manifest as encephalitis, hepatitis, and pneumonitis. Beyond its significant burden on health, HSV carries significant psychosocial consequences.9

Diagnosis. Clinical diagnosis can be challenging if classic lesions are absent at evaluation. If genital lesions are present, HSV can be identified by NAAT or culture of a specimen of those lesions. False-negative antibody results might be more frequent in early stages of infection; repeating antibody testing 12 weeks after presumed time of acquisition might therefore be indicated, based on clinical judgment. HSV-2 antibody positivity implies anogenital infection because almost all HSV-2 infections are sexually acquired.

HSV-1 antibody positivity alone is more difficult to interpret because this finding does not distinguish between oral and genital lesions, and most HSV-1 seropositivity is acquired during childhood.36 HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of blood should not be performed to diagnose genital herpes infection, except in settings in which there is concern about disseminated infection.

Treatment. Management should address the acute episode and the chronic nature of genital herpes. Antivirals will not eradicate latent

- attenuate current infection

- prevent recurrence

- improve quality of life

- suppress the virus to prevent transmission to sexual partners.

All patients experiencing an initial episode of genital herpes should be treated, regardless of symptoms, due to the potential for prolonged or severe symptoms during recurrent episodes.9 Three drugs—acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir—are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat genital herpes and appear equally effective (TABLE 214).

Antiviral therapy for recurrent genital HSV infection can be administered either as suppressive therapy to reduce the frequency of recurrences or episodically to shorten the duration of lesions:

- Suppressive therapy reduces the frequency of recurrence by 70% to 80% among patients with frequent outbreaks. Long-term safety and efficacy are well established.

- Episodic therapy is most effective if started within 1 day after onset of lesions or during the prodrome.36

There is no specific recommendation for when to choose suppressive over episodic therapy; most patients prefer suppressive therapy because it improves quality of life. Use shared clinical decision-making to determine the best option for an individual patient.

Continue to: Human papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus

Condylomata acuminata (genital warts) are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), most commonly types 6 and 11, which manifest as soft papules or plaques on the external genitalia, perineum, perianal skin, and groin. The warts are usually asymptomatic but can be painful or pruritic, depending on size and location.

Diagnosis is made by visual inspection and can be confirmed by biopsy if lesions are atypical. Lesions can resolve spontaneously, remain unchanged, or grow in size or number.

Treatment. The aim of treatment is relief of symptoms and removal of warts. Treatment does not eradicate HPV infection. Multiple treatments are available that can be applied by the patient as a cream, gel, or ointment or administered by the provider, including cryotherapy, surgical removal, and solutions. The decision on how to treat should be based on the number, size, and

HPV-associated cancers and precancers. This is a broad (and separate) topic. HPV types 16 and 18 cause most cases of cervical, penile, vulvar, vaginal, anal, and oropharyngeal cancer and precancer.39 The USPSTF, the American Cancer Society, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists all have recommendations for cervical cancer screening in the United States.40 Refer to guidelines of the ASCCP for recommendations on abnormal screening tests.41

Prevention of genital warts. The 9-valent HPV vaccine available in the United States is safe and effective and helps protect against viral types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58. Types 6 and 11 are the principal causes of genital warts. Types 16 and 18 cause 66% of cervical cancer. The vaccination series can be started at age 9 years and is recommended for everyone through age 26 years. Only 2 doses are needed if the first dose is given prior to age 15 years; given after that age, a 3-dose series is utilized. Refer to CDC vaccine guidelines42 for details on the exact timing of vaccination.

Vaccination for women ages 27 to 45 years is not universally recommended because most people have been exposed to HPV by that age. However, the vaccine can still be administered, depending on clinical circumstances and the risk for new infection.42

Syphilis