User login

Clinical Outcomes of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Based on Hospital Admission Type

Clinical Outcomes of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Based on Hospital Admission Type

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are rare, life-threatening conditions that involve widespread necrosis of the skin and mucous membranes.1 Guidelines for SJS and TEN recommend management in hospitals with access to inpatient dermatology to provide immediate interventions that are necessary for achieving optimal patient outcomes.2 A delay in admission of 5 days or more after onset of symptoms has been associated with increases in overall mortality, bacteremia, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and length of stay.3 Patients who are not directly admitted to specialized facilities and require transfer from other hospitals may experience delays in receiving critical interventions, further increasing the risk for mortality and complications. In this study, we analyzed the clinical outcomes of patients with SJS/TEN in relation to their admission pathway.

Methods

A single-center retrospective chart review was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (AHWFBMC) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Participants were identified using i2b2, an informatics tool compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act for integrating biology and the bedside. Inclusion criteria were having a diagnosis of SJS (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code L51.1; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code 695.13), TEN (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code L51.2; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code 695.15) or Lyell syndrome from January 2012 to December 2024. Patients with erythema multiforme or bullous drug eruption were excluded, as these conditions initially were misdiagnosed as SJS or TEN. Patients with only a reported history of prior SJS or TEN also were excluded.

The following clinical outcomes were assessed: demographics, comorbidities, age at disease onset, outside hospital transfer status, complications during admission, inpatient length of stay in days, age of mortality (if applicable), culprit medications, interventions received, Severity-of-Illness Score for Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (SCORTEN) upon admission, site of admission (eg, floor bed, ICU, medical ICU, burn unit), and length of disease process prior to hospital admission. Patients then were categorized as either direct or transfer admissions based on the initial point of care and admission process. Direct admissions included patients who presented to the AHWFBMC emergency department and were subsequently admitted. Transfer patients included patients who initially presented to an outside hospital and were transferred to AHWFBMC. Data regarding the wait time for Physician Access Line requests and the time elapsed from the initial transfer call to arrival at the tertiary hospital also were collected—this is a method that outside hospitals can use to contact physicians at the tertiary hospital for a possible transfer. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t tests and X2 tests as necessary using GraphPad By Dotmatics Prism.

Results

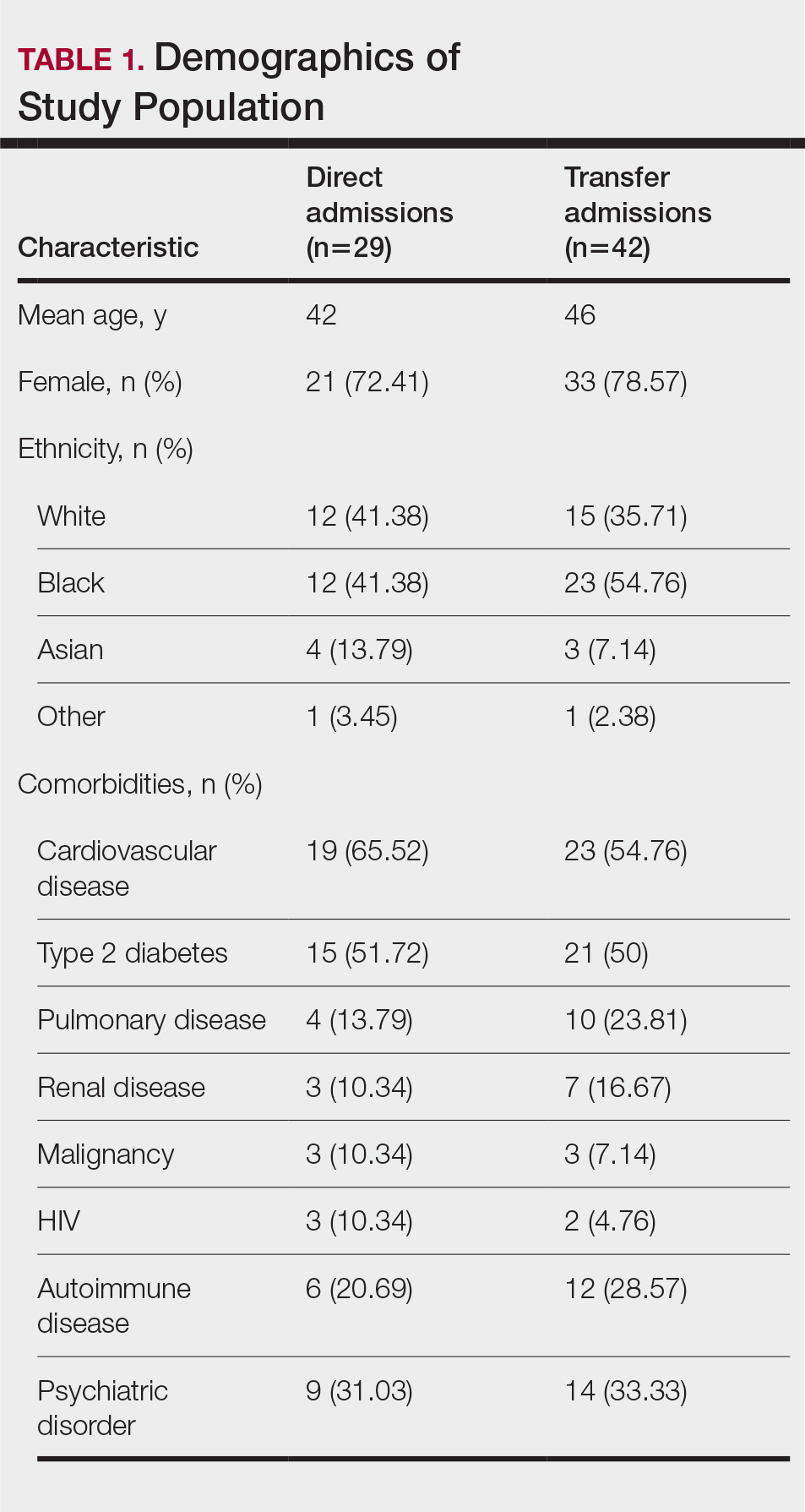

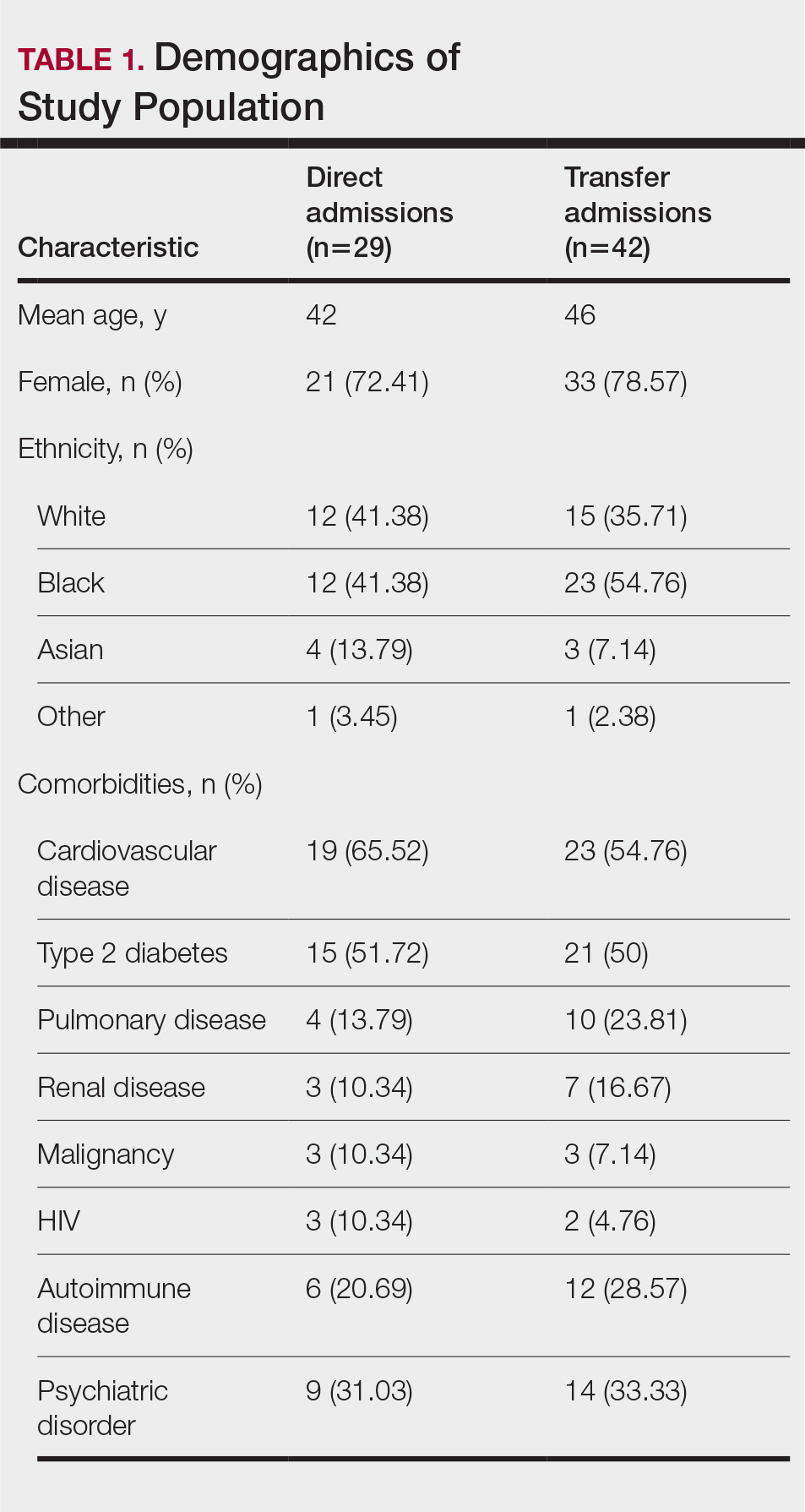

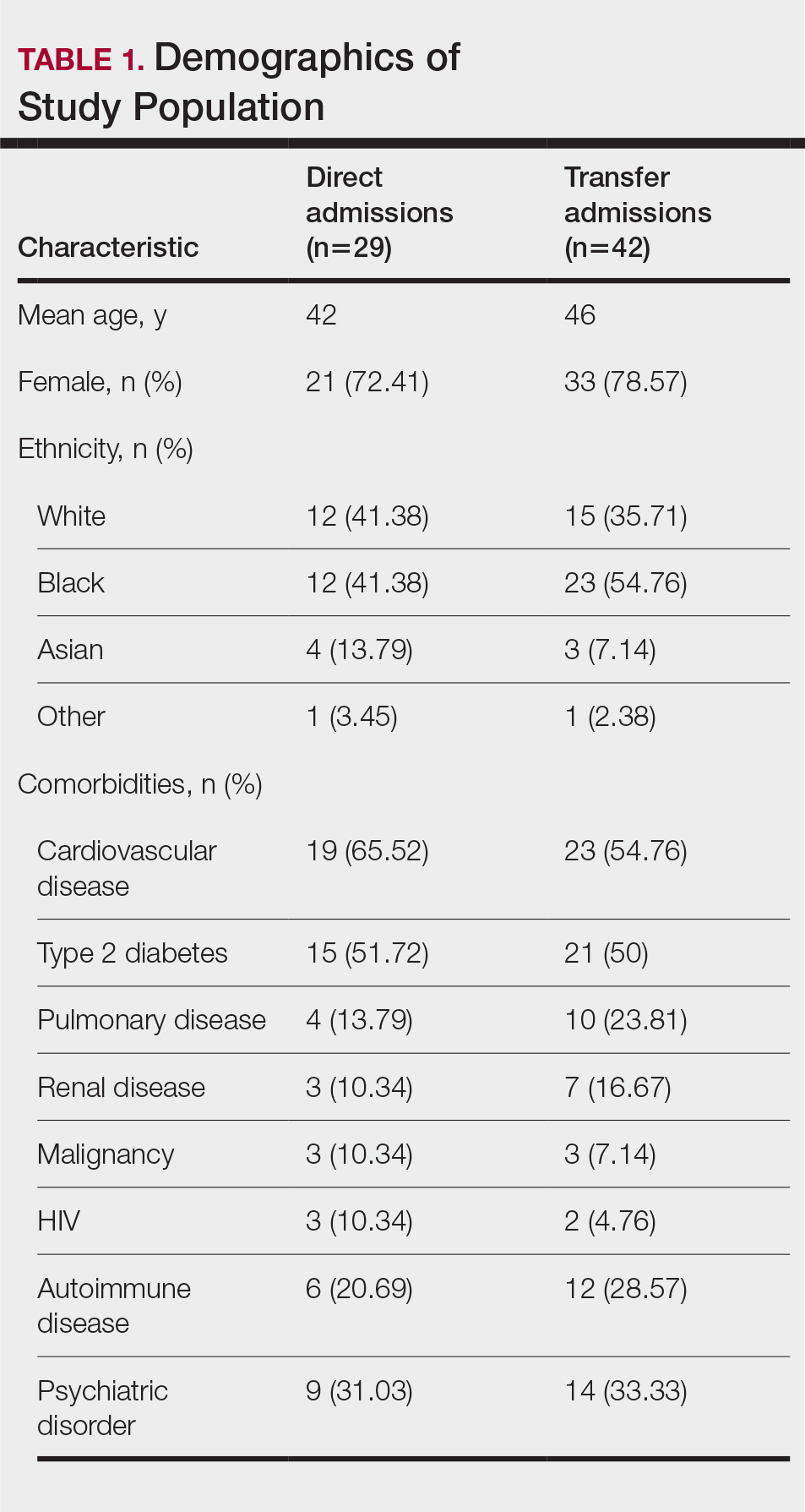

A total of 112 patients were included in the analysis; of these, 71 had a diagnosis with biopsy confirmation of SJS, SJS/TEN overlap, or TEN (Table 1). Forty-one patients were excluded due to having a diagnosis of erythema multiforme or bullous drug eruption or a reported history of prior SJS or TEN without hospitalization. All biopsies were performed at AHWFBMC. Of the 71 confirmed patients with SJS/TEN, 54 (76%) were female with a mean age of 44 years. The majority of patients identified as Black (35 [49%]) or White (27 [38%]), along with Asian (7 [10%]) and other (2 [3%]). The most common comorbidity was cardiovascular disease in 42 (59%) patients, followed by type 2 diabetes in 36 (51%) patients. Among these 71 patients with SJS/TEN, 29 (41%) were directly admitted to the tertiary hospital, while 42 (59%) were transferred from outside hospitals.

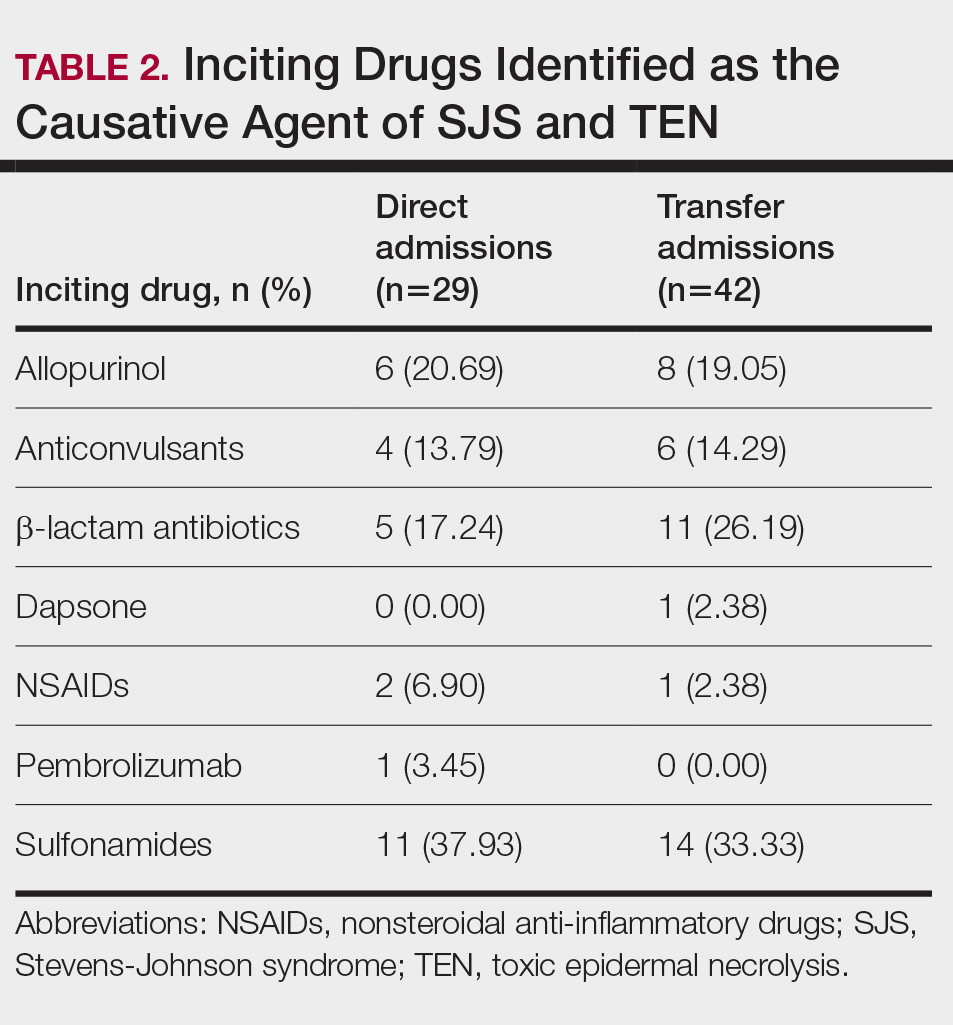

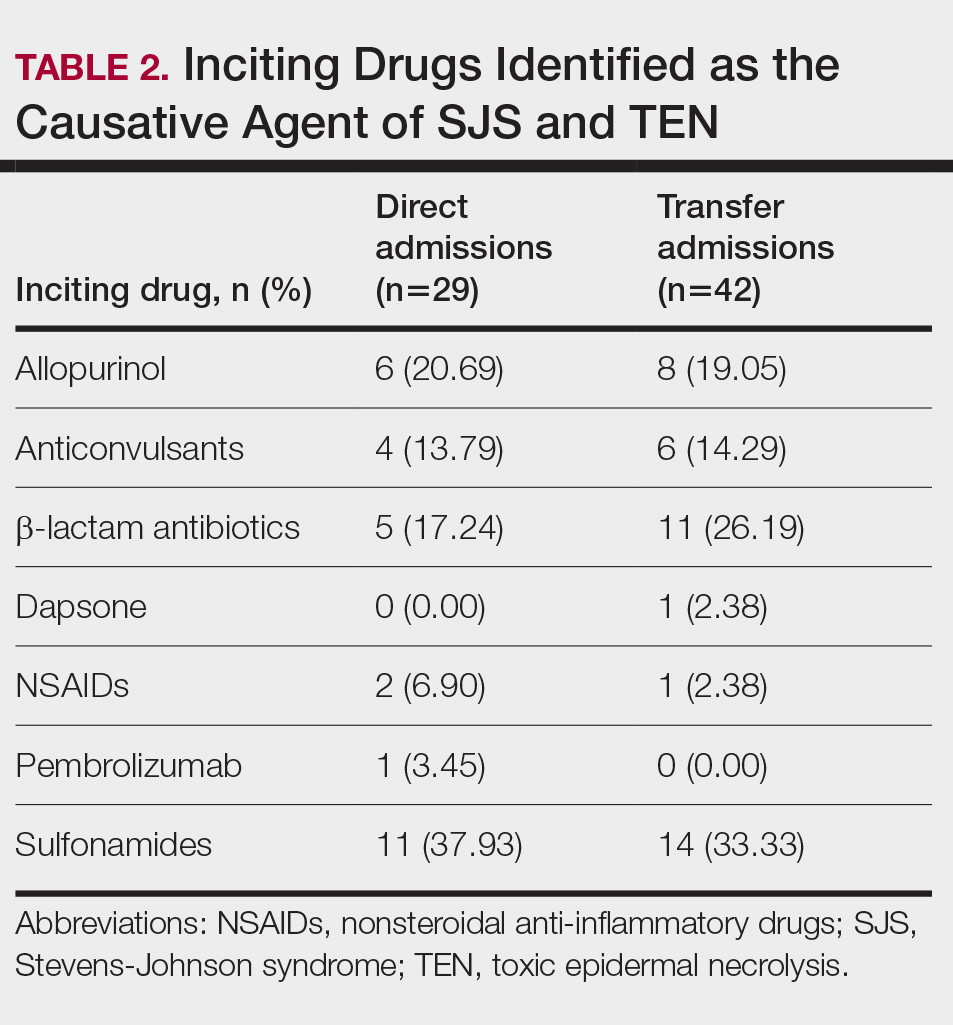

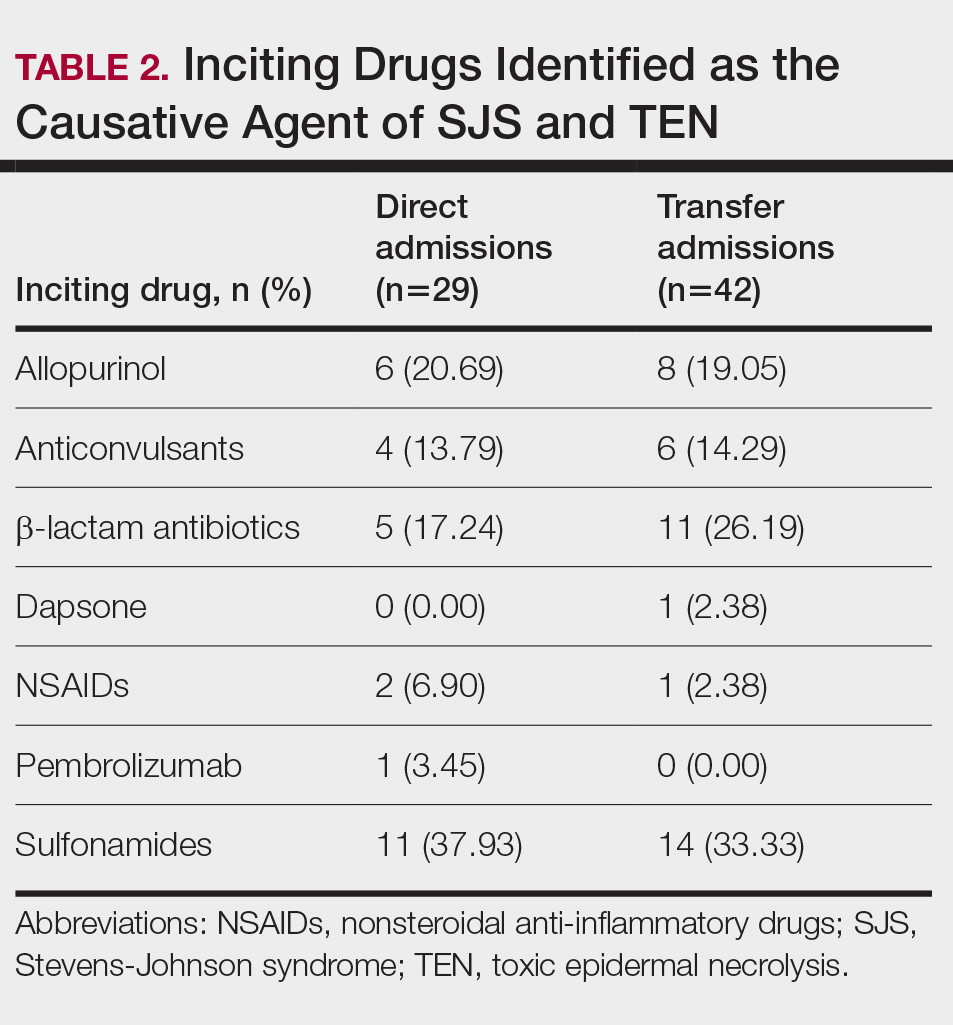

Of the 71 confirmed patients with SJS/TEN, sulfonamides were identified as the most common inciting drug in 25 (41%) patients, followed by beta-lactam antibiotics in 16 (23%) patients (Table 2). This is consistent with previous literature of sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim as the primary causative drug for SJS and TEN in the United States.1

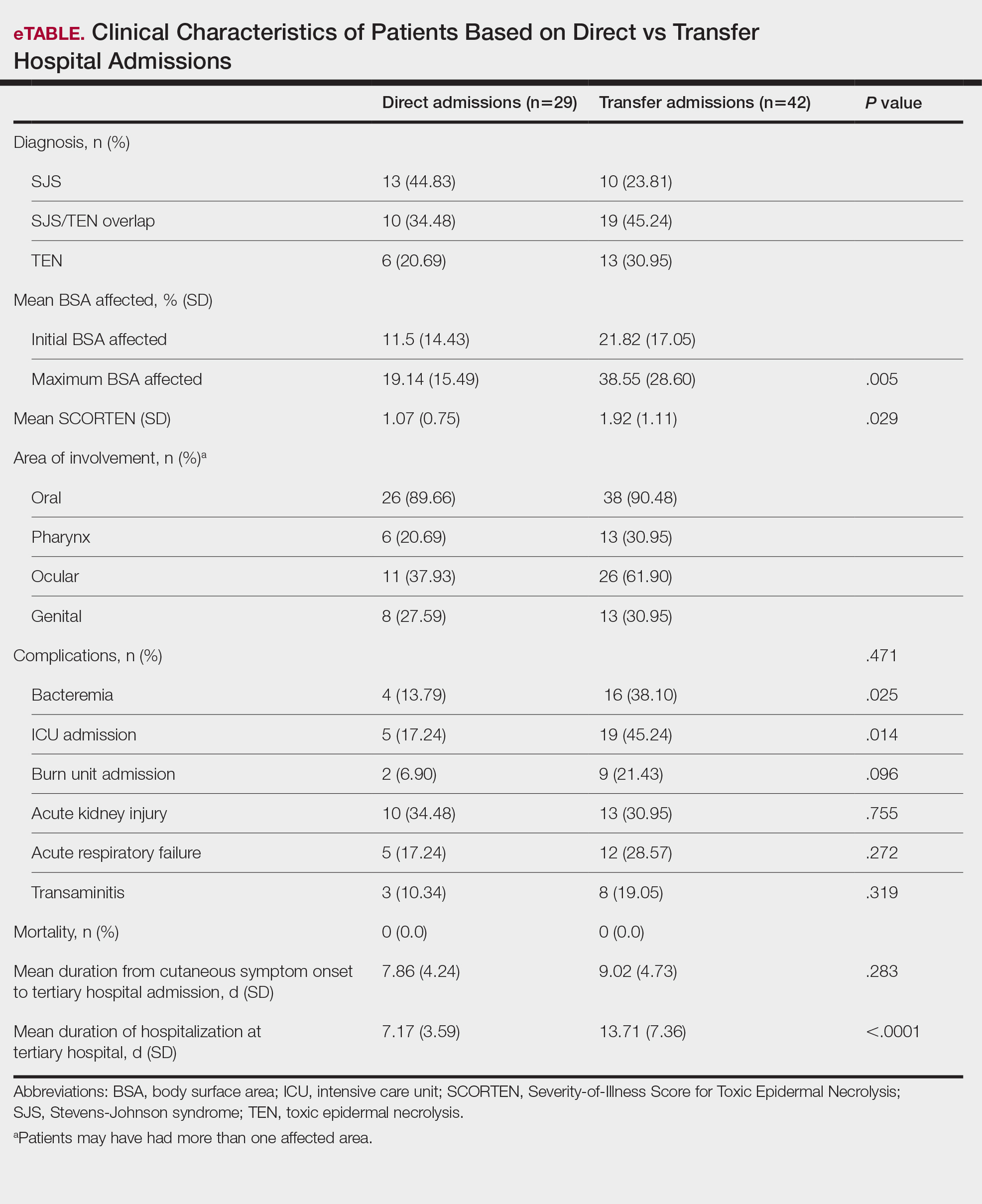

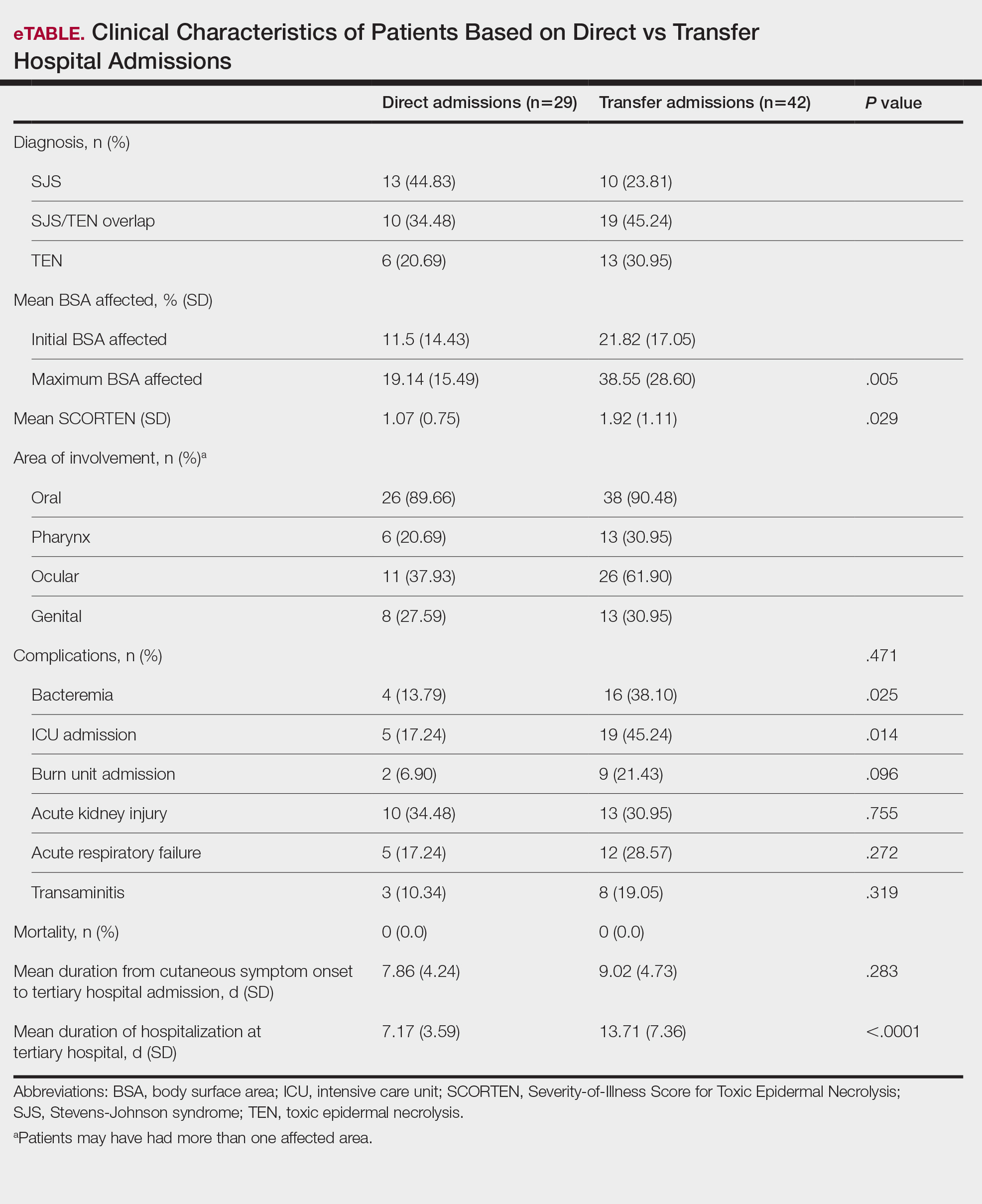

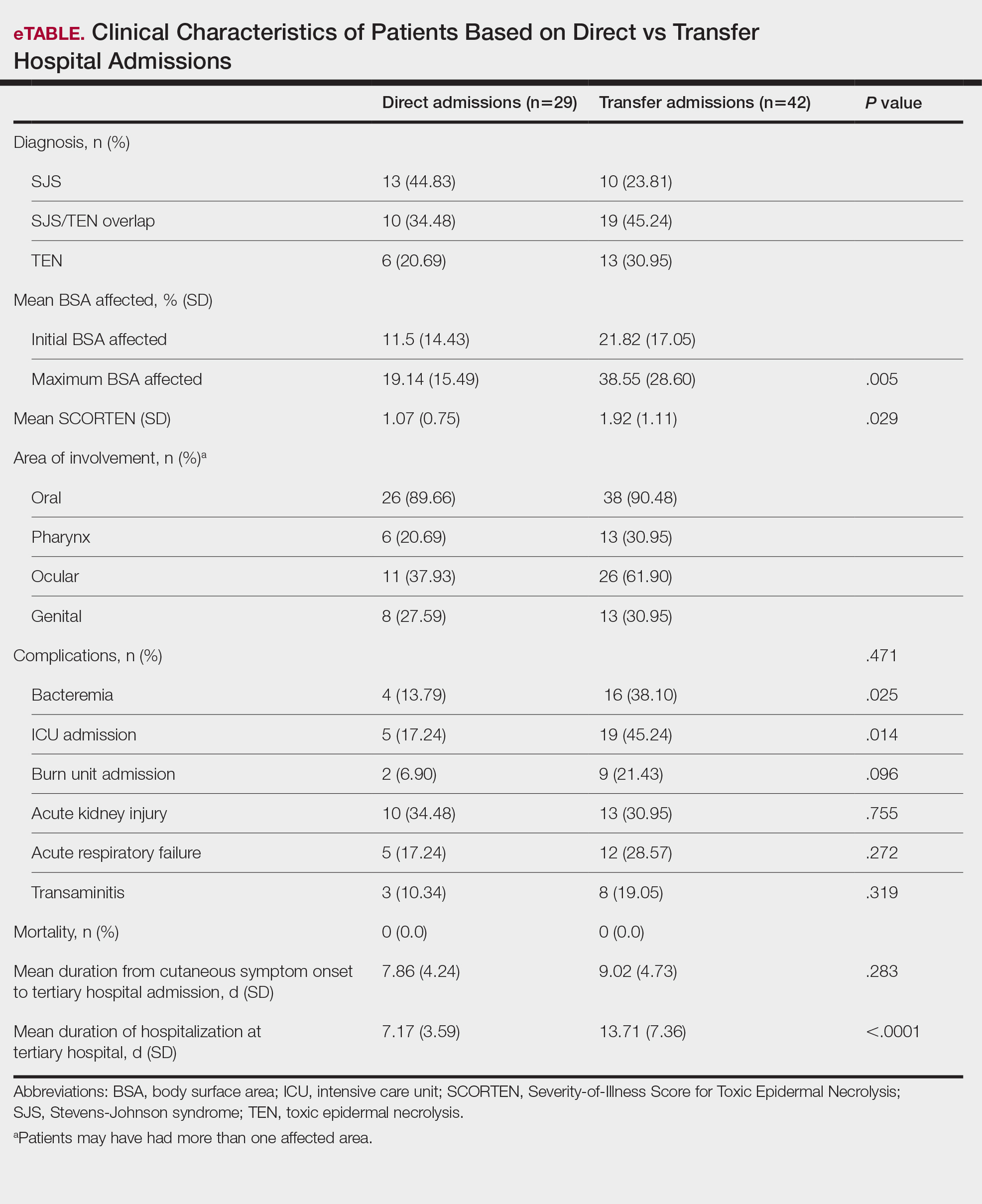

Clinical Outcomes—Of the 71 patients, there were 23 (32%) cases of SJS, 29 (41%) cases of SJS/TEN overlap, and 19 (27%) cases of TEN (eTable). The initial and maximum affected body surface area (BSA) was higher in transfer admissions, with a mean maximum BSA of 38.55% in the transfer group compared to 19.14% in the direct admissions. The mean SCORTEN (range, 0-5) was 1.6 overall, with a higher mean score of 1.92 in the transfer group compared to 1.07 in the direct admissions.

Transfer patients had a longer mean stay at the tertiary hospital (13.71 d) compared to direct admissions (7.17 d). The mean time from symptom onset until tertiary hospital admission was 8.5 days; transfer and direct admission patients had similar mean time from symptom onset of 9.02 days and 7.86 days, respectively. Although the duration of cutaneous symptoms from onset until tertiary hospital admission was similar (P=.283) between direct admissions (7.86 d) and transfer patients (9.02 d), the transfer group presented with greater disease severity at the time of admission. Transfer patients had a higher mean maximum BSA involvement (38.55% vs 19.14% [P=.005]), elevated SCORTEN (1.92 vs 1.07 [P=.029]), and longer mean hospital stays (13.71 d vs 7.17 d [P<.0001]) compared to direct admissions.

Despite the absence of mortality in both groups, transfer patients showed a higher number of ICU admissions (19 vs 5 [P=.014]) and burn unit admissions (9 vs 2 [P=.096]), bacteremia (16 vs 4 [P=.025]), acute kidney injury (13 vs 10 [P=.755]), acute respiratory failure (12 vs 5 [P=.272]), and transaminitis (8 vs 3 [P=.319]).

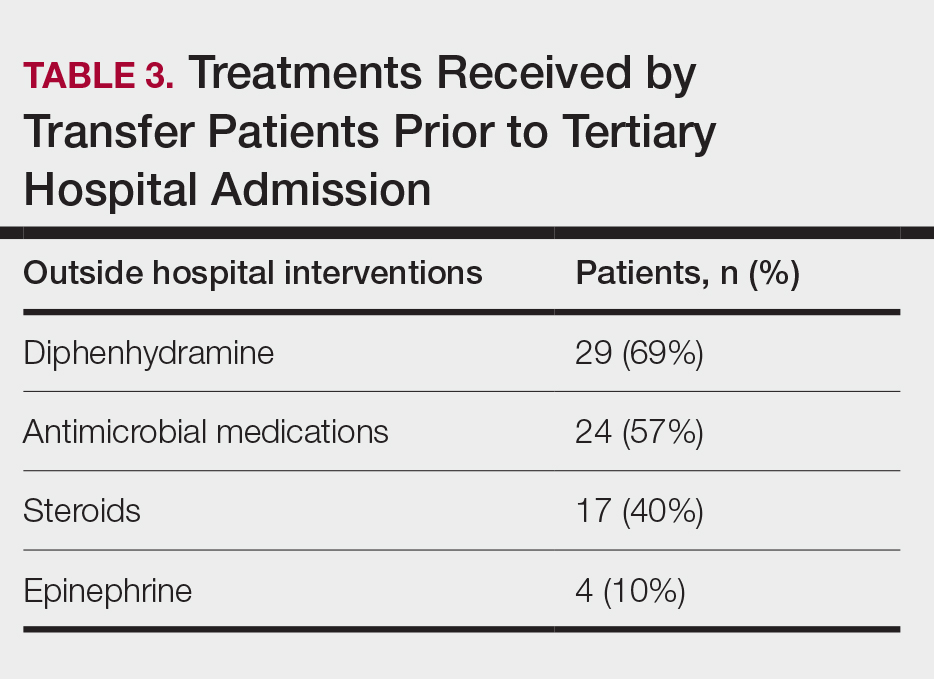

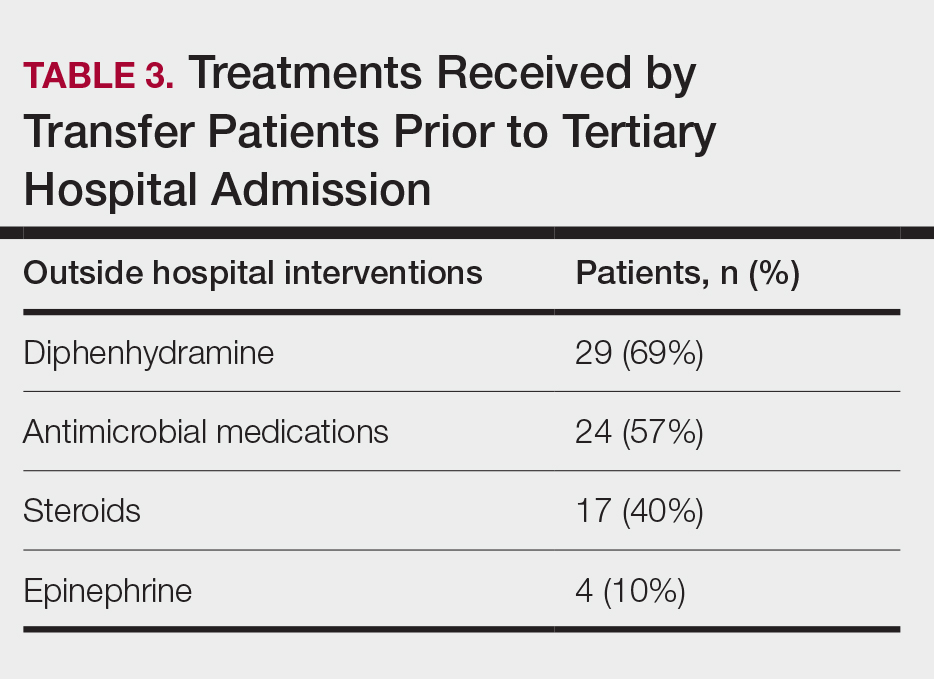

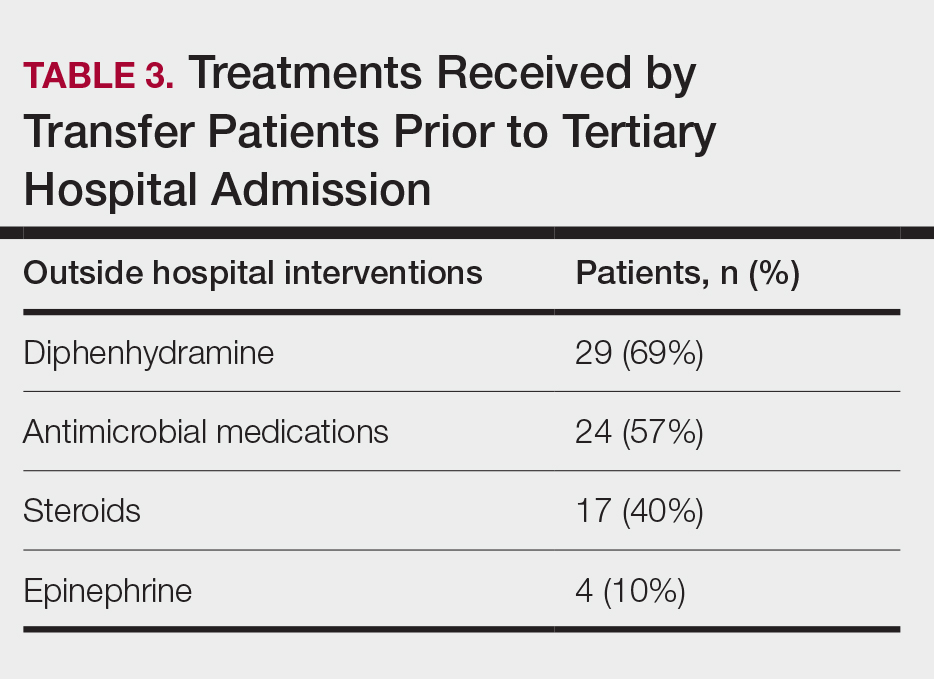

Outside Hospital Treatments—All outside hospitals provided supportive care with intravenous fluids and acetaminophen; however, further care provided at outside hospitals varied (Table 3), with transfer patients most frequently being treated with diphenhydramine (69% [29/42]), antimicrobial medications (57% [24/42]), steroids (40%), and epinephrine (10% [4/42]). Some patients may have received more than one of these treatments. Based on outside hospital treatments, the primary care teams’ main clinical concerns were allergic reactions and infection, as 33 (79%) patients received diphenhydramine (29 [89%]) or epinephrine (4 [12%]) and 24 (52%) received antimicrobial medications. Of the 42 transfer patients, 24 (57%) received or continued these medications before transfer; the medications were promptly discontinued upon tertiary hospital admission.

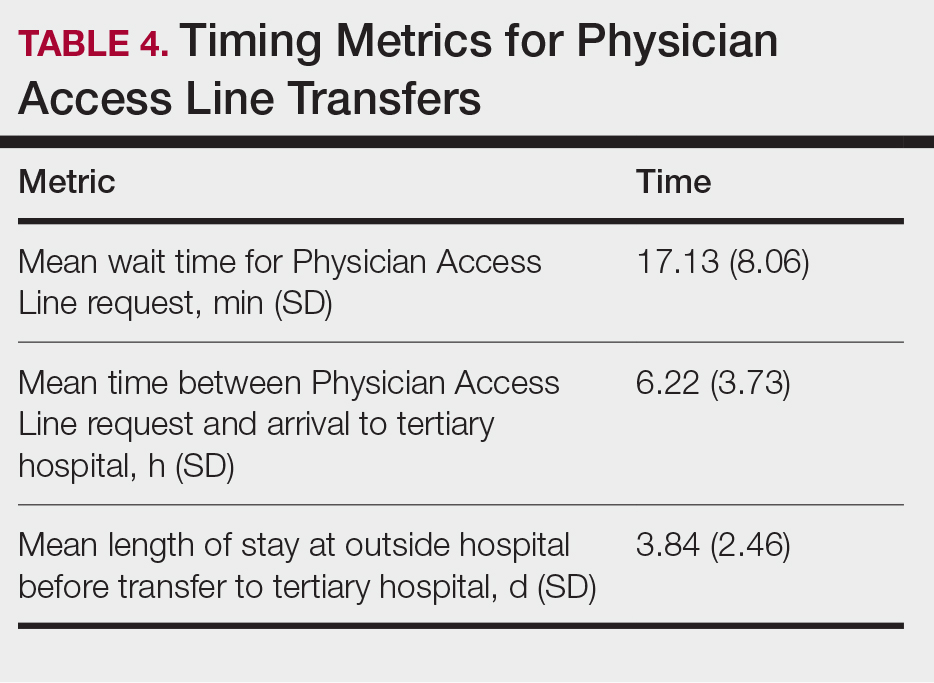

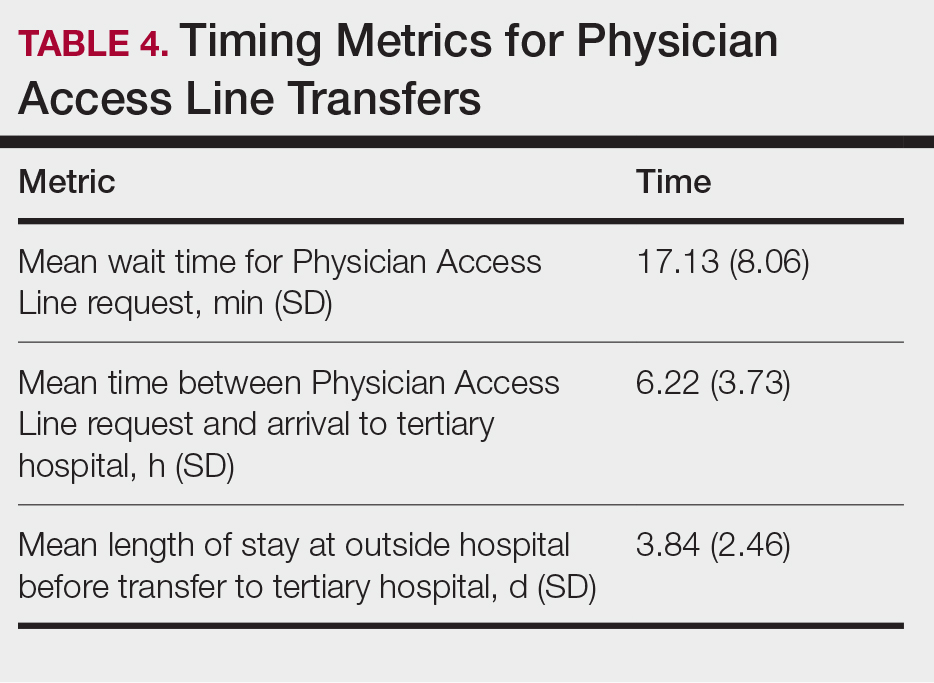

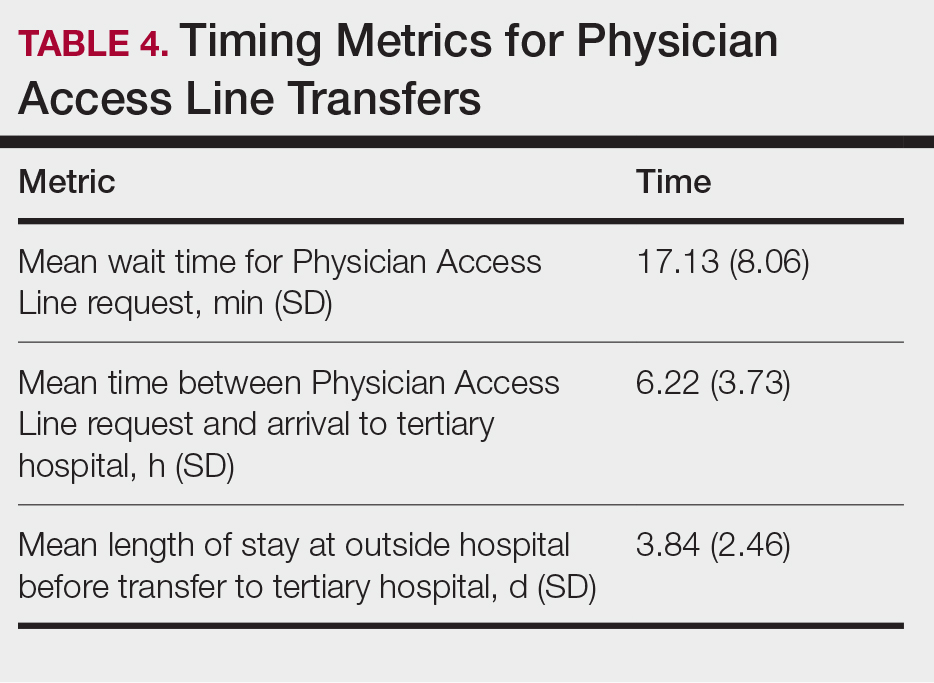

Once the outside hospitals contacted the tertiary hospital for a referral, the mean length of time between the transfer request and Physician Access Line call was 17.13 minutes (Table 4). Following the transfer request, the mean length of time for arrival at the tertiary hospital was 6.22 hours. The mean length of stay at the outside hospital prior to the patient being transferred was 3.84 days.

Comment

This retrospective study examined 71 patients with biopsy-confirmed SJS, SJS/TEN overlap, or TEN to evaluate differences in clinical outcomes between direct and transfer admissions. Transfer patients had a higher mean maximum affected BSA (38.55% vs 19.14% [P=.005]) and elevated SCORTEN (1.92 vs 1.07 [P=.029]); a higher number of transfer patients were admitted to the ICU (19 vs 5 [P=.014]) and burn unit (9 vs 2 [P=.096]), and this group also demonstrated longer hospitalization stays (13.71 vs 7.17 [P<.0001]). There were more complications among transfer patients, including bacteremia (16 vs 4 [P=.025]), which is consistent with findings from the existing literature.3

Once the decision for transfer of the patients included in our study was initiated and accepted, there was a prompt response and transfer of care; the mean length of time for Physician Access Line request was 17.13 minutes, and the mean transfer time to arrive at the tertiary hospital was 6.22 hours; however, patients spent an average of 3.84 days at outside hospitals, reflecting that transfer calls frequently were initiated due to urgent clinical decline of the patient rather than as an early intervention strategy. The management at outside hospitals often included the continuation of antimicrobial medications, which were discontinued upon transfer to AHWFBMC. Causative agents were either previously prescribed for a new medical condition or initiated for the management of suspected infections at outside hospitals. This may reflect the difficulty in correctly diagnosing SJS/TEN and initiating appropriate management at hospital facilities without an inpatient dermatologist.

The presence of inpatient dermatologists can improve the diagnostic accuracy and treatment of various conditions.4,5 Dermatology consultations added or changed 77% of treatment plans for 271 hospitalized patients.4 The impact of this intervention is reflected by the success of early dermatology consultations in reducing the length of hospitalization and use of inappropriate treatments in the care of skin diseases.6-8

Access to dermatologic care has been an identified need in inpatient hospitals that may limit the ability of hospitals to promptly treat serious conditions such as SJS/TEN.9 From an inpatient dermatology study from 2013 through 2019, 98.2% of 782 inpatient dermatologists reside in metropolitan areas, limiting the availability of care for rural patients; this study also found a decreasing number of facilities with inpatient dermatologists.10

The limitations of our study include a small sample size of 71 patients, which restricted the generalizability of our results. Our study also was based at a single tertiary center, which thereby limited the findings to this geographic area. It also was difficult to match patients by their demographic and comorbid conditions. The retrospective study design depended on the accuracy and completeness of medical records, which can introduce information bias. Future studies should compare the clinical outcomes of SJS/TEN based on burn unit and ICU admissions.

Conclusion

Prompt identification of SJS/TEN and rapid transfer to hospitals with inpatient dermatology are essential to optimize patient outcomes. Developing and validating SJS/TEN diagnosis and transfer protocols across multiple institutions may be helpful.

- Kridin K, Brüggen MC, Chua SL, et al. Assessment of treatment approaches and outcomes in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: insights from a pan-European multicenter study. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1182-1190. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3154

- Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski SJ, et al. Society of Dermatology Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1553-1567. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2020.02.066

- Clark AE, Fook-Chong S, Choo K, et al. Delayed admission to a specialist referral center for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis is associated with increased mortality: a retrospective cohort study. JAAD Int. 2021;4:10-12. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.008

- Davila M, Christenson LJ, Sontheimer RD. Epidemiology and outcomes of dermatology in-patient consultations in a Midwestern U.S. university hospital. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:12.

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2440-2

- Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-5-39

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6197

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:523-528. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6130

- Messenger E, Kovarik CL, Lipoff JB. Access to inpatient dermatology care in Pennsylvania hospitals. Cutis. 2016;97:49-51.

- Hydol-Smith JA, Gallardo MA, Korman A, et al. The United States dermatology inpatient workforce between 2013 and 2019: a Medicare analysis reveals contraction of the workforce and vast access desertsa cross-sectional analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:103. doi:10.1007 /s00403-024-02845-0

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are rare, life-threatening conditions that involve widespread necrosis of the skin and mucous membranes.1 Guidelines for SJS and TEN recommend management in hospitals with access to inpatient dermatology to provide immediate interventions that are necessary for achieving optimal patient outcomes.2 A delay in admission of 5 days or more after onset of symptoms has been associated with increases in overall mortality, bacteremia, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and length of stay.3 Patients who are not directly admitted to specialized facilities and require transfer from other hospitals may experience delays in receiving critical interventions, further increasing the risk for mortality and complications. In this study, we analyzed the clinical outcomes of patients with SJS/TEN in relation to their admission pathway.

Methods

A single-center retrospective chart review was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (AHWFBMC) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Participants were identified using i2b2, an informatics tool compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act for integrating biology and the bedside. Inclusion criteria were having a diagnosis of SJS (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code L51.1; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code 695.13), TEN (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code L51.2; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code 695.15) or Lyell syndrome from January 2012 to December 2024. Patients with erythema multiforme or bullous drug eruption were excluded, as these conditions initially were misdiagnosed as SJS or TEN. Patients with only a reported history of prior SJS or TEN also were excluded.

The following clinical outcomes were assessed: demographics, comorbidities, age at disease onset, outside hospital transfer status, complications during admission, inpatient length of stay in days, age of mortality (if applicable), culprit medications, interventions received, Severity-of-Illness Score for Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (SCORTEN) upon admission, site of admission (eg, floor bed, ICU, medical ICU, burn unit), and length of disease process prior to hospital admission. Patients then were categorized as either direct or transfer admissions based on the initial point of care and admission process. Direct admissions included patients who presented to the AHWFBMC emergency department and were subsequently admitted. Transfer patients included patients who initially presented to an outside hospital and were transferred to AHWFBMC. Data regarding the wait time for Physician Access Line requests and the time elapsed from the initial transfer call to arrival at the tertiary hospital also were collected—this is a method that outside hospitals can use to contact physicians at the tertiary hospital for a possible transfer. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t tests and X2 tests as necessary using GraphPad By Dotmatics Prism.

Results

A total of 112 patients were included in the analysis; of these, 71 had a diagnosis with biopsy confirmation of SJS, SJS/TEN overlap, or TEN (Table 1). Forty-one patients were excluded due to having a diagnosis of erythema multiforme or bullous drug eruption or a reported history of prior SJS or TEN without hospitalization. All biopsies were performed at AHWFBMC. Of the 71 confirmed patients with SJS/TEN, 54 (76%) were female with a mean age of 44 years. The majority of patients identified as Black (35 [49%]) or White (27 [38%]), along with Asian (7 [10%]) and other (2 [3%]). The most common comorbidity was cardiovascular disease in 42 (59%) patients, followed by type 2 diabetes in 36 (51%) patients. Among these 71 patients with SJS/TEN, 29 (41%) were directly admitted to the tertiary hospital, while 42 (59%) were transferred from outside hospitals.

Of the 71 confirmed patients with SJS/TEN, sulfonamides were identified as the most common inciting drug in 25 (41%) patients, followed by beta-lactam antibiotics in 16 (23%) patients (Table 2). This is consistent with previous literature of sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim as the primary causative drug for SJS and TEN in the United States.1

Clinical Outcomes—Of the 71 patients, there were 23 (32%) cases of SJS, 29 (41%) cases of SJS/TEN overlap, and 19 (27%) cases of TEN (eTable). The initial and maximum affected body surface area (BSA) was higher in transfer admissions, with a mean maximum BSA of 38.55% in the transfer group compared to 19.14% in the direct admissions. The mean SCORTEN (range, 0-5) was 1.6 overall, with a higher mean score of 1.92 in the transfer group compared to 1.07 in the direct admissions.

Transfer patients had a longer mean stay at the tertiary hospital (13.71 d) compared to direct admissions (7.17 d). The mean time from symptom onset until tertiary hospital admission was 8.5 days; transfer and direct admission patients had similar mean time from symptom onset of 9.02 days and 7.86 days, respectively. Although the duration of cutaneous symptoms from onset until tertiary hospital admission was similar (P=.283) between direct admissions (7.86 d) and transfer patients (9.02 d), the transfer group presented with greater disease severity at the time of admission. Transfer patients had a higher mean maximum BSA involvement (38.55% vs 19.14% [P=.005]), elevated SCORTEN (1.92 vs 1.07 [P=.029]), and longer mean hospital stays (13.71 d vs 7.17 d [P<.0001]) compared to direct admissions.

Despite the absence of mortality in both groups, transfer patients showed a higher number of ICU admissions (19 vs 5 [P=.014]) and burn unit admissions (9 vs 2 [P=.096]), bacteremia (16 vs 4 [P=.025]), acute kidney injury (13 vs 10 [P=.755]), acute respiratory failure (12 vs 5 [P=.272]), and transaminitis (8 vs 3 [P=.319]).

Outside Hospital Treatments—All outside hospitals provided supportive care with intravenous fluids and acetaminophen; however, further care provided at outside hospitals varied (Table 3), with transfer patients most frequently being treated with diphenhydramine (69% [29/42]), antimicrobial medications (57% [24/42]), steroids (40%), and epinephrine (10% [4/42]). Some patients may have received more than one of these treatments. Based on outside hospital treatments, the primary care teams’ main clinical concerns were allergic reactions and infection, as 33 (79%) patients received diphenhydramine (29 [89%]) or epinephrine (4 [12%]) and 24 (52%) received antimicrobial medications. Of the 42 transfer patients, 24 (57%) received or continued these medications before transfer; the medications were promptly discontinued upon tertiary hospital admission.

Once the outside hospitals contacted the tertiary hospital for a referral, the mean length of time between the transfer request and Physician Access Line call was 17.13 minutes (Table 4). Following the transfer request, the mean length of time for arrival at the tertiary hospital was 6.22 hours. The mean length of stay at the outside hospital prior to the patient being transferred was 3.84 days.

Comment

This retrospective study examined 71 patients with biopsy-confirmed SJS, SJS/TEN overlap, or TEN to evaluate differences in clinical outcomes between direct and transfer admissions. Transfer patients had a higher mean maximum affected BSA (38.55% vs 19.14% [P=.005]) and elevated SCORTEN (1.92 vs 1.07 [P=.029]); a higher number of transfer patients were admitted to the ICU (19 vs 5 [P=.014]) and burn unit (9 vs 2 [P=.096]), and this group also demonstrated longer hospitalization stays (13.71 vs 7.17 [P<.0001]). There were more complications among transfer patients, including bacteremia (16 vs 4 [P=.025]), which is consistent with findings from the existing literature.3

Once the decision for transfer of the patients included in our study was initiated and accepted, there was a prompt response and transfer of care; the mean length of time for Physician Access Line request was 17.13 minutes, and the mean transfer time to arrive at the tertiary hospital was 6.22 hours; however, patients spent an average of 3.84 days at outside hospitals, reflecting that transfer calls frequently were initiated due to urgent clinical decline of the patient rather than as an early intervention strategy. The management at outside hospitals often included the continuation of antimicrobial medications, which were discontinued upon transfer to AHWFBMC. Causative agents were either previously prescribed for a new medical condition or initiated for the management of suspected infections at outside hospitals. This may reflect the difficulty in correctly diagnosing SJS/TEN and initiating appropriate management at hospital facilities without an inpatient dermatologist.

The presence of inpatient dermatologists can improve the diagnostic accuracy and treatment of various conditions.4,5 Dermatology consultations added or changed 77% of treatment plans for 271 hospitalized patients.4 The impact of this intervention is reflected by the success of early dermatology consultations in reducing the length of hospitalization and use of inappropriate treatments in the care of skin diseases.6-8

Access to dermatologic care has been an identified need in inpatient hospitals that may limit the ability of hospitals to promptly treat serious conditions such as SJS/TEN.9 From an inpatient dermatology study from 2013 through 2019, 98.2% of 782 inpatient dermatologists reside in metropolitan areas, limiting the availability of care for rural patients; this study also found a decreasing number of facilities with inpatient dermatologists.10

The limitations of our study include a small sample size of 71 patients, which restricted the generalizability of our results. Our study also was based at a single tertiary center, which thereby limited the findings to this geographic area. It also was difficult to match patients by their demographic and comorbid conditions. The retrospective study design depended on the accuracy and completeness of medical records, which can introduce information bias. Future studies should compare the clinical outcomes of SJS/TEN based on burn unit and ICU admissions.

Conclusion

Prompt identification of SJS/TEN and rapid transfer to hospitals with inpatient dermatology are essential to optimize patient outcomes. Developing and validating SJS/TEN diagnosis and transfer protocols across multiple institutions may be helpful.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are rare, life-threatening conditions that involve widespread necrosis of the skin and mucous membranes.1 Guidelines for SJS and TEN recommend management in hospitals with access to inpatient dermatology to provide immediate interventions that are necessary for achieving optimal patient outcomes.2 A delay in admission of 5 days or more after onset of symptoms has been associated with increases in overall mortality, bacteremia, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and length of stay.3 Patients who are not directly admitted to specialized facilities and require transfer from other hospitals may experience delays in receiving critical interventions, further increasing the risk for mortality and complications. In this study, we analyzed the clinical outcomes of patients with SJS/TEN in relation to their admission pathway.

Methods

A single-center retrospective chart review was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (AHWFBMC) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Participants were identified using i2b2, an informatics tool compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act for integrating biology and the bedside. Inclusion criteria were having a diagnosis of SJS (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code L51.1; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code 695.13), TEN (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code L51.2; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code 695.15) or Lyell syndrome from January 2012 to December 2024. Patients with erythema multiforme or bullous drug eruption were excluded, as these conditions initially were misdiagnosed as SJS or TEN. Patients with only a reported history of prior SJS or TEN also were excluded.

The following clinical outcomes were assessed: demographics, comorbidities, age at disease onset, outside hospital transfer status, complications during admission, inpatient length of stay in days, age of mortality (if applicable), culprit medications, interventions received, Severity-of-Illness Score for Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (SCORTEN) upon admission, site of admission (eg, floor bed, ICU, medical ICU, burn unit), and length of disease process prior to hospital admission. Patients then were categorized as either direct or transfer admissions based on the initial point of care and admission process. Direct admissions included patients who presented to the AHWFBMC emergency department and were subsequently admitted. Transfer patients included patients who initially presented to an outside hospital and were transferred to AHWFBMC. Data regarding the wait time for Physician Access Line requests and the time elapsed from the initial transfer call to arrival at the tertiary hospital also were collected—this is a method that outside hospitals can use to contact physicians at the tertiary hospital for a possible transfer. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t tests and X2 tests as necessary using GraphPad By Dotmatics Prism.

Results

A total of 112 patients were included in the analysis; of these, 71 had a diagnosis with biopsy confirmation of SJS, SJS/TEN overlap, or TEN (Table 1). Forty-one patients were excluded due to having a diagnosis of erythema multiforme or bullous drug eruption or a reported history of prior SJS or TEN without hospitalization. All biopsies were performed at AHWFBMC. Of the 71 confirmed patients with SJS/TEN, 54 (76%) were female with a mean age of 44 years. The majority of patients identified as Black (35 [49%]) or White (27 [38%]), along with Asian (7 [10%]) and other (2 [3%]). The most common comorbidity was cardiovascular disease in 42 (59%) patients, followed by type 2 diabetes in 36 (51%) patients. Among these 71 patients with SJS/TEN, 29 (41%) were directly admitted to the tertiary hospital, while 42 (59%) were transferred from outside hospitals.

Of the 71 confirmed patients with SJS/TEN, sulfonamides were identified as the most common inciting drug in 25 (41%) patients, followed by beta-lactam antibiotics in 16 (23%) patients (Table 2). This is consistent with previous literature of sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim as the primary causative drug for SJS and TEN in the United States.1

Clinical Outcomes—Of the 71 patients, there were 23 (32%) cases of SJS, 29 (41%) cases of SJS/TEN overlap, and 19 (27%) cases of TEN (eTable). The initial and maximum affected body surface area (BSA) was higher in transfer admissions, with a mean maximum BSA of 38.55% in the transfer group compared to 19.14% in the direct admissions. The mean SCORTEN (range, 0-5) was 1.6 overall, with a higher mean score of 1.92 in the transfer group compared to 1.07 in the direct admissions.

Transfer patients had a longer mean stay at the tertiary hospital (13.71 d) compared to direct admissions (7.17 d). The mean time from symptom onset until tertiary hospital admission was 8.5 days; transfer and direct admission patients had similar mean time from symptom onset of 9.02 days and 7.86 days, respectively. Although the duration of cutaneous symptoms from onset until tertiary hospital admission was similar (P=.283) between direct admissions (7.86 d) and transfer patients (9.02 d), the transfer group presented with greater disease severity at the time of admission. Transfer patients had a higher mean maximum BSA involvement (38.55% vs 19.14% [P=.005]), elevated SCORTEN (1.92 vs 1.07 [P=.029]), and longer mean hospital stays (13.71 d vs 7.17 d [P<.0001]) compared to direct admissions.

Despite the absence of mortality in both groups, transfer patients showed a higher number of ICU admissions (19 vs 5 [P=.014]) and burn unit admissions (9 vs 2 [P=.096]), bacteremia (16 vs 4 [P=.025]), acute kidney injury (13 vs 10 [P=.755]), acute respiratory failure (12 vs 5 [P=.272]), and transaminitis (8 vs 3 [P=.319]).

Outside Hospital Treatments—All outside hospitals provided supportive care with intravenous fluids and acetaminophen; however, further care provided at outside hospitals varied (Table 3), with transfer patients most frequently being treated with diphenhydramine (69% [29/42]), antimicrobial medications (57% [24/42]), steroids (40%), and epinephrine (10% [4/42]). Some patients may have received more than one of these treatments. Based on outside hospital treatments, the primary care teams’ main clinical concerns were allergic reactions and infection, as 33 (79%) patients received diphenhydramine (29 [89%]) or epinephrine (4 [12%]) and 24 (52%) received antimicrobial medications. Of the 42 transfer patients, 24 (57%) received or continued these medications before transfer; the medications were promptly discontinued upon tertiary hospital admission.

Once the outside hospitals contacted the tertiary hospital for a referral, the mean length of time between the transfer request and Physician Access Line call was 17.13 minutes (Table 4). Following the transfer request, the mean length of time for arrival at the tertiary hospital was 6.22 hours. The mean length of stay at the outside hospital prior to the patient being transferred was 3.84 days.

Comment

This retrospective study examined 71 patients with biopsy-confirmed SJS, SJS/TEN overlap, or TEN to evaluate differences in clinical outcomes between direct and transfer admissions. Transfer patients had a higher mean maximum affected BSA (38.55% vs 19.14% [P=.005]) and elevated SCORTEN (1.92 vs 1.07 [P=.029]); a higher number of transfer patients were admitted to the ICU (19 vs 5 [P=.014]) and burn unit (9 vs 2 [P=.096]), and this group also demonstrated longer hospitalization stays (13.71 vs 7.17 [P<.0001]). There were more complications among transfer patients, including bacteremia (16 vs 4 [P=.025]), which is consistent with findings from the existing literature.3

Once the decision for transfer of the patients included in our study was initiated and accepted, there was a prompt response and transfer of care; the mean length of time for Physician Access Line request was 17.13 minutes, and the mean transfer time to arrive at the tertiary hospital was 6.22 hours; however, patients spent an average of 3.84 days at outside hospitals, reflecting that transfer calls frequently were initiated due to urgent clinical decline of the patient rather than as an early intervention strategy. The management at outside hospitals often included the continuation of antimicrobial medications, which were discontinued upon transfer to AHWFBMC. Causative agents were either previously prescribed for a new medical condition or initiated for the management of suspected infections at outside hospitals. This may reflect the difficulty in correctly diagnosing SJS/TEN and initiating appropriate management at hospital facilities without an inpatient dermatologist.

The presence of inpatient dermatologists can improve the diagnostic accuracy and treatment of various conditions.4,5 Dermatology consultations added or changed 77% of treatment plans for 271 hospitalized patients.4 The impact of this intervention is reflected by the success of early dermatology consultations in reducing the length of hospitalization and use of inappropriate treatments in the care of skin diseases.6-8

Access to dermatologic care has been an identified need in inpatient hospitals that may limit the ability of hospitals to promptly treat serious conditions such as SJS/TEN.9 From an inpatient dermatology study from 2013 through 2019, 98.2% of 782 inpatient dermatologists reside in metropolitan areas, limiting the availability of care for rural patients; this study also found a decreasing number of facilities with inpatient dermatologists.10

The limitations of our study include a small sample size of 71 patients, which restricted the generalizability of our results. Our study also was based at a single tertiary center, which thereby limited the findings to this geographic area. It also was difficult to match patients by their demographic and comorbid conditions. The retrospective study design depended on the accuracy and completeness of medical records, which can introduce information bias. Future studies should compare the clinical outcomes of SJS/TEN based on burn unit and ICU admissions.

Conclusion

Prompt identification of SJS/TEN and rapid transfer to hospitals with inpatient dermatology are essential to optimize patient outcomes. Developing and validating SJS/TEN diagnosis and transfer protocols across multiple institutions may be helpful.

- Kridin K, Brüggen MC, Chua SL, et al. Assessment of treatment approaches and outcomes in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: insights from a pan-European multicenter study. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1182-1190. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3154

- Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski SJ, et al. Society of Dermatology Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1553-1567. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2020.02.066

- Clark AE, Fook-Chong S, Choo K, et al. Delayed admission to a specialist referral center for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis is associated with increased mortality: a retrospective cohort study. JAAD Int. 2021;4:10-12. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.008

- Davila M, Christenson LJ, Sontheimer RD. Epidemiology and outcomes of dermatology in-patient consultations in a Midwestern U.S. university hospital. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:12.

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2440-2

- Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-5-39

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6197

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:523-528. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6130

- Messenger E, Kovarik CL, Lipoff JB. Access to inpatient dermatology care in Pennsylvania hospitals. Cutis. 2016;97:49-51.

- Hydol-Smith JA, Gallardo MA, Korman A, et al. The United States dermatology inpatient workforce between 2013 and 2019: a Medicare analysis reveals contraction of the workforce and vast access desertsa cross-sectional analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:103. doi:10.1007 /s00403-024-02845-0

- Kridin K, Brüggen MC, Chua SL, et al. Assessment of treatment approaches and outcomes in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: insights from a pan-European multicenter study. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1182-1190. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3154

- Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski SJ, et al. Society of Dermatology Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1553-1567. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2020.02.066

- Clark AE, Fook-Chong S, Choo K, et al. Delayed admission to a specialist referral center for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis is associated with increased mortality: a retrospective cohort study. JAAD Int. 2021;4:10-12. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.008

- Davila M, Christenson LJ, Sontheimer RD. Epidemiology and outcomes of dermatology in-patient consultations in a Midwestern U.S. university hospital. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:12.

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2440-2

- Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-5-39

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6197

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:523-528. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6130

- Messenger E, Kovarik CL, Lipoff JB. Access to inpatient dermatology care in Pennsylvania hospitals. Cutis. 2016;97:49-51.

- Hydol-Smith JA, Gallardo MA, Korman A, et al. The United States dermatology inpatient workforce between 2013 and 2019: a Medicare analysis reveals contraction of the workforce and vast access desertsa cross-sectional analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:103. doi:10.1007 /s00403-024-02845-0

Clinical Outcomes of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Based on Hospital Admission Type

Clinical Outcomes of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Based on Hospital Admission Type

PRACTICE POINTS

- Early identification and diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis are essential to improving patient outcomes.

- Patients transferred from outside hospitals often present with more severe disease due to delays in diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment.

- Inpatient dermatology consultation plays a vital role in accurately diagnosing and managing life-threatening dermatologic conditions.

- Establishing timely interhospital transfer protocols may help expedite access to specialized treatment and improve patient outcomes.

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

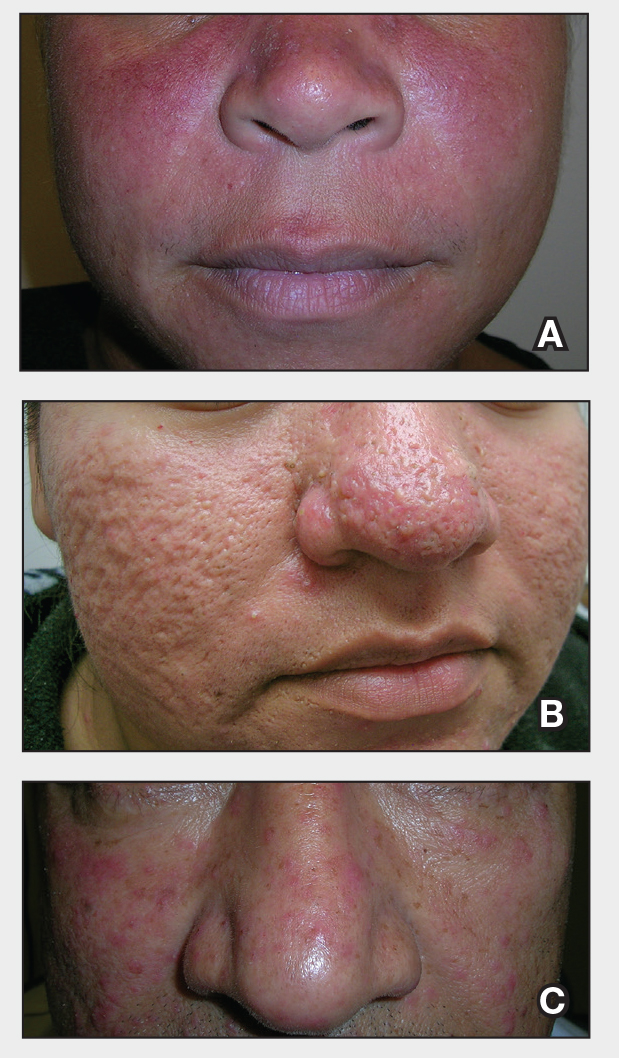

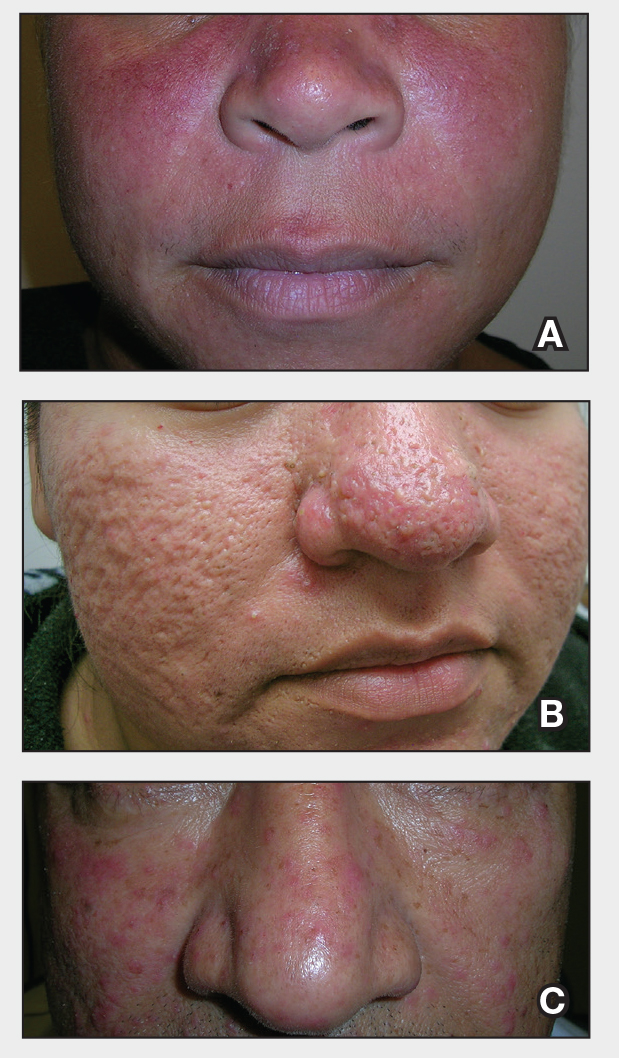

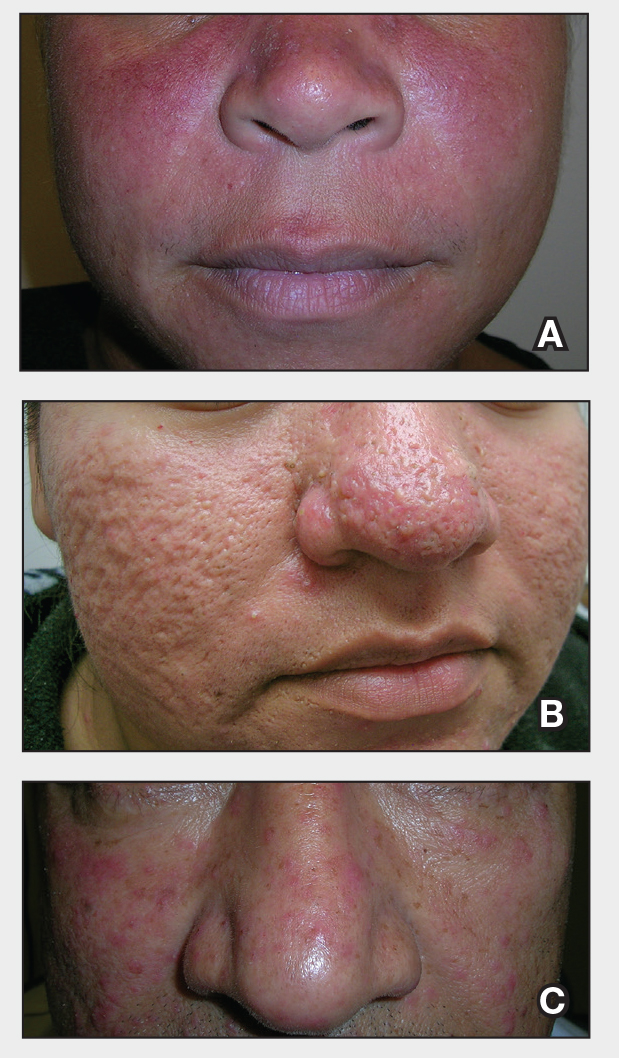

THE COMPARISON:

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

THE COMPARISON:

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

THE COMPARISON:

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

Reddish Nodule on the Left Shoulder

Reddish Nodule on the Left Shoulder

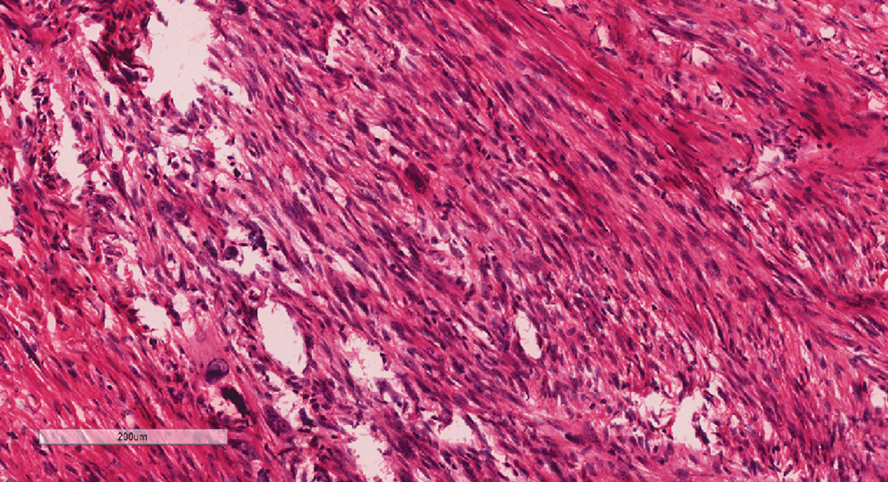

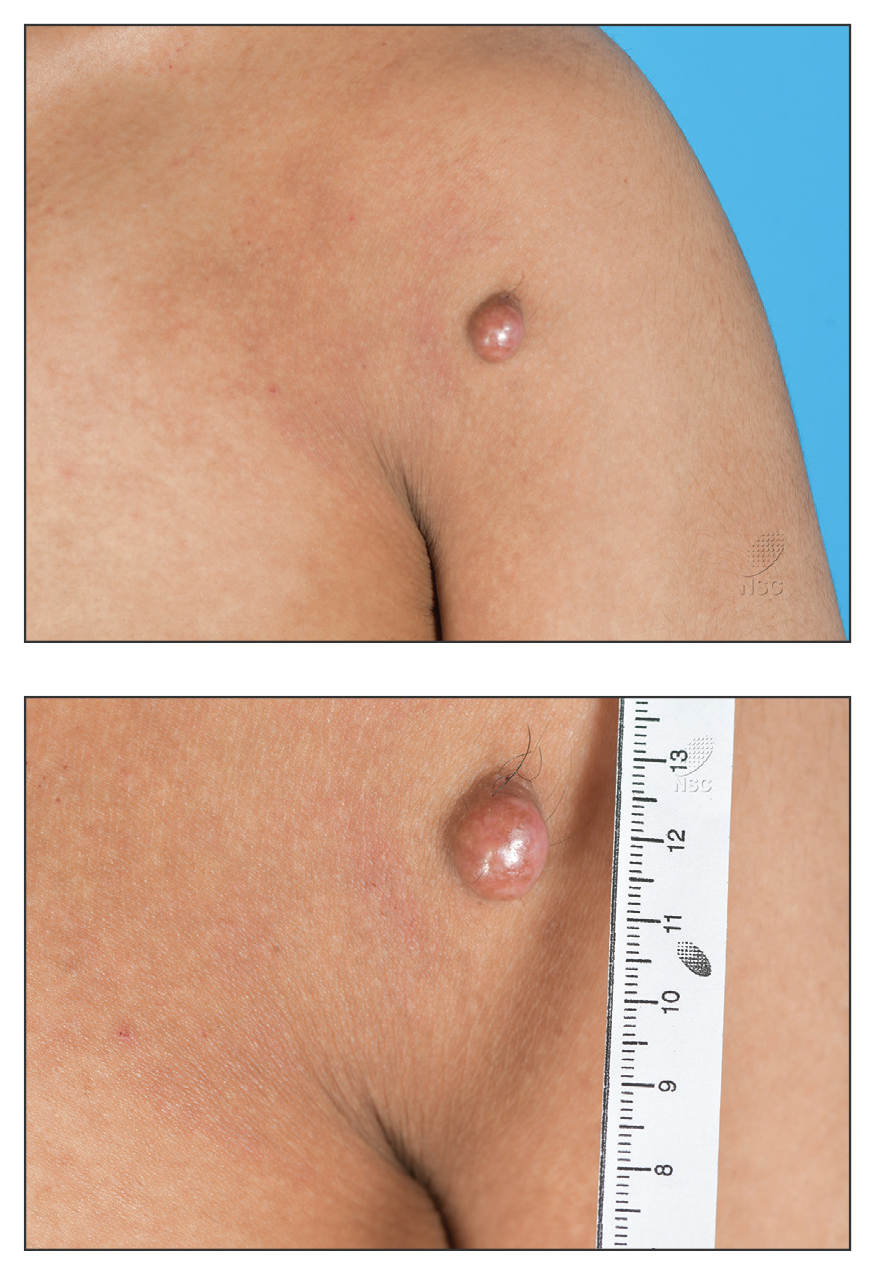

THE DIAGNOSIS: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

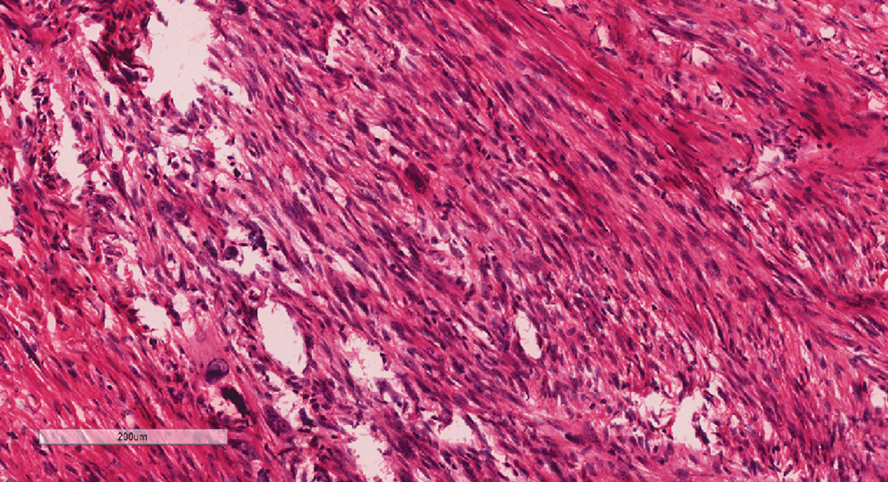

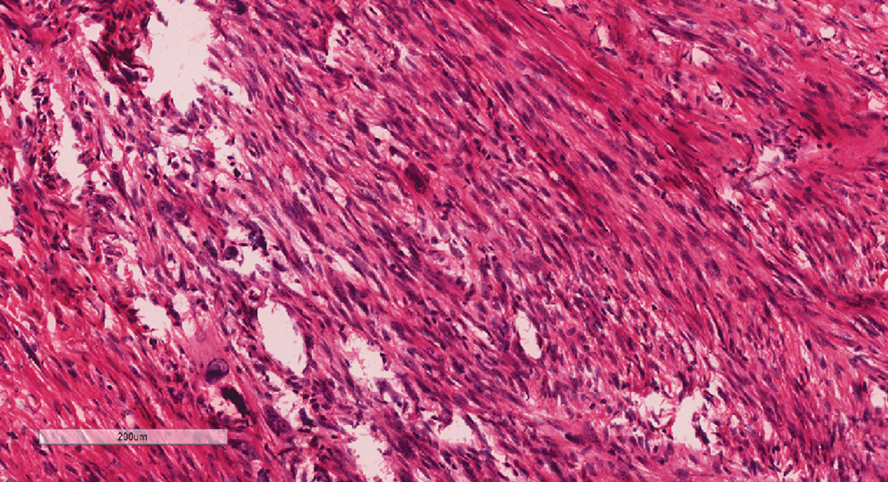

Given the appearance of the nodule and the absence of features of a keloid scar, a soft-tissue or adnexal tumor was suspected. Histology revealed a thin epidermis with loss of rete ridges and a Grenz zone. There was a nodular uncircumscribed dermal proliferation of spindle cells forming interweaving fascicles with elongated ovoid nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Figure). There was moderate cellular and nuclear atypia, and no necrosis was observed. The spindle cells stained positive for CD10 and negative for AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 5/6, S100, melanoma triple marker, Factor XIII 1, ERG, CD31, CD34, desmin, and smooth muscle actin; ERG, CD31, CD34, and SMA highlighted small vessels within the tumor. The histologic diagnosis was an atypical spindle cell tumor favoring atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX). The excisional biopsy margins were clear.

The patient was referred to surgical oncology to consider re-excision of margins after the diagnosis was made. A chest radiograph was clear, and magnetic resonance imaging showed mild skin thickening and image enhancement at the left shoulder—possibly a postsurgical change—with no nodularity suggesting a residual or recurrent tumor. Surgical oncology determined that the patient did not require further excision and placed him on regular follow-up every 2 to 3 months for the next 2 years.

uncertain origin that is considered to be on a spectrum with the more aggressive pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS); it can be distinguished from PDS by histologic features such as nerve or vessel invasion.1 Both entities share oncogenes (eg, tumor protein 53 gene mutations) and are histologically and immunohistochemically similar. Atypical fibroxanthoma largely is viewed as an intermediate-risk tumor that is locally aggressive but rarely metastasizes, with a reported local recurrence rate of 5% to 11% and metastasis risk of 1% to 2%. Conversely, PDS is a more aggressive diagnosis with a high risk for local recurrence and metastasis (7%-69% and 4%-20%, respectively).1

Atypical fibroxanthomas may mimic other entities, both clinically and histologically. It commonly manifests as a flesh-colored to erythematous, sometimes ulcerated nodule on sun-exposed skin in elderly patients, leading to a broad range of clinical differential diagnoses, including other primary cutaneous malignancies (eg, squamous cell carcinoma, amelanotic melanoma), cutaneous sarcomas (eg, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans), adnexal and other tumors (eg, pleomorphic fibroma, pilomatricoma), cutaneous metastases, and even keloid scars. As the differentials can look clinically similar, a skin biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Histologically, AFX tends to show an undifferentiated pleomorphic spindle cell morphology. Notably, histology can be highly variable, with other reported histologic patterns including keloidlike, pleomorphic, epithelioid, rhabdoid, clear-cell, foamy cell, granular cell, bizarre cell, pseudoangiomatous, inflammatory, and osteoclast-rich patterns.2 Thus, the histologic differential diagnosis also is broad, and AFX primarily is a diagnosis of exclusion without specific immunohistochemical markers that serve to exclude other diagnoses. For example, AFX tends to stain positive for CD10 and CD68, though these are not specific markers for AFX. Furthermore, although certain histologic markers may commonly be more positive in AFX than PDS (eg, CD74 stains positive in 20% of AFXs and only 1% of PDSs), this is not reliable enough to be diagnostic.3 As such, AFX is distinguished from PDS primarily by histologic features such as subcutaneous tissue invasion, vascular or perineural invasion, necrosis, or local invasion/ metastases.1 Given the rarity of both tumors, no established management guidelines exist, although excision (wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery) usually is recommended, with some authors suggesting margins of 1 cm for AFX and 2 cm to 3 cm for PDS.1

This atypical case of AFX arising in non–sun-exposed skin in a young man raises questions about whether unknown genetic factors or possibly prior immunosuppression could have contributed to the development of the tumor. A thorough history and physical examination can provide valuable clues for biopsy, including ongoing growth, absence of known prior trauma or acne at the site, and clinical appearance, such as the reddish, solitary, dome-shaped lesion in our patient.

- Ørholt M, Abebe K, Rasmussen LE, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: local recurrence and metastasis in a nationwide population-based cohort of 1118 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:1177-1184. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.08.050

- Agaimy A. The many faces of atypical fibroxanthoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2023;40:306-312. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2023.06.001

- Rapini RP. Practical Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

Given the appearance of the nodule and the absence of features of a keloid scar, a soft-tissue or adnexal tumor was suspected. Histology revealed a thin epidermis with loss of rete ridges and a Grenz zone. There was a nodular uncircumscribed dermal proliferation of spindle cells forming interweaving fascicles with elongated ovoid nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Figure). There was moderate cellular and nuclear atypia, and no necrosis was observed. The spindle cells stained positive for CD10 and negative for AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 5/6, S100, melanoma triple marker, Factor XIII 1, ERG, CD31, CD34, desmin, and smooth muscle actin; ERG, CD31, CD34, and SMA highlighted small vessels within the tumor. The histologic diagnosis was an atypical spindle cell tumor favoring atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX). The excisional biopsy margins were clear.

The patient was referred to surgical oncology to consider re-excision of margins after the diagnosis was made. A chest radiograph was clear, and magnetic resonance imaging showed mild skin thickening and image enhancement at the left shoulder—possibly a postsurgical change—with no nodularity suggesting a residual or recurrent tumor. Surgical oncology determined that the patient did not require further excision and placed him on regular follow-up every 2 to 3 months for the next 2 years.

uncertain origin that is considered to be on a spectrum with the more aggressive pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS); it can be distinguished from PDS by histologic features such as nerve or vessel invasion.1 Both entities share oncogenes (eg, tumor protein 53 gene mutations) and are histologically and immunohistochemically similar. Atypical fibroxanthoma largely is viewed as an intermediate-risk tumor that is locally aggressive but rarely metastasizes, with a reported local recurrence rate of 5% to 11% and metastasis risk of 1% to 2%. Conversely, PDS is a more aggressive diagnosis with a high risk for local recurrence and metastasis (7%-69% and 4%-20%, respectively).1

Atypical fibroxanthomas may mimic other entities, both clinically and histologically. It commonly manifests as a flesh-colored to erythematous, sometimes ulcerated nodule on sun-exposed skin in elderly patients, leading to a broad range of clinical differential diagnoses, including other primary cutaneous malignancies (eg, squamous cell carcinoma, amelanotic melanoma), cutaneous sarcomas (eg, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans), adnexal and other tumors (eg, pleomorphic fibroma, pilomatricoma), cutaneous metastases, and even keloid scars. As the differentials can look clinically similar, a skin biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Histologically, AFX tends to show an undifferentiated pleomorphic spindle cell morphology. Notably, histology can be highly variable, with other reported histologic patterns including keloidlike, pleomorphic, epithelioid, rhabdoid, clear-cell, foamy cell, granular cell, bizarre cell, pseudoangiomatous, inflammatory, and osteoclast-rich patterns.2 Thus, the histologic differential diagnosis also is broad, and AFX primarily is a diagnosis of exclusion without specific immunohistochemical markers that serve to exclude other diagnoses. For example, AFX tends to stain positive for CD10 and CD68, though these are not specific markers for AFX. Furthermore, although certain histologic markers may commonly be more positive in AFX than PDS (eg, CD74 stains positive in 20% of AFXs and only 1% of PDSs), this is not reliable enough to be diagnostic.3 As such, AFX is distinguished from PDS primarily by histologic features such as subcutaneous tissue invasion, vascular or perineural invasion, necrosis, or local invasion/ metastases.1 Given the rarity of both tumors, no established management guidelines exist, although excision (wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery) usually is recommended, with some authors suggesting margins of 1 cm for AFX and 2 cm to 3 cm for PDS.1

This atypical case of AFX arising in non–sun-exposed skin in a young man raises questions about whether unknown genetic factors or possibly prior immunosuppression could have contributed to the development of the tumor. A thorough history and physical examination can provide valuable clues for biopsy, including ongoing growth, absence of known prior trauma or acne at the site, and clinical appearance, such as the reddish, solitary, dome-shaped lesion in our patient.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

Given the appearance of the nodule and the absence of features of a keloid scar, a soft-tissue or adnexal tumor was suspected. Histology revealed a thin epidermis with loss of rete ridges and a Grenz zone. There was a nodular uncircumscribed dermal proliferation of spindle cells forming interweaving fascicles with elongated ovoid nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Figure). There was moderate cellular and nuclear atypia, and no necrosis was observed. The spindle cells stained positive for CD10 and negative for AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 5/6, S100, melanoma triple marker, Factor XIII 1, ERG, CD31, CD34, desmin, and smooth muscle actin; ERG, CD31, CD34, and SMA highlighted small vessels within the tumor. The histologic diagnosis was an atypical spindle cell tumor favoring atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX). The excisional biopsy margins were clear.

The patient was referred to surgical oncology to consider re-excision of margins after the diagnosis was made. A chest radiograph was clear, and magnetic resonance imaging showed mild skin thickening and image enhancement at the left shoulder—possibly a postsurgical change—with no nodularity suggesting a residual or recurrent tumor. Surgical oncology determined that the patient did not require further excision and placed him on regular follow-up every 2 to 3 months for the next 2 years.