User login

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

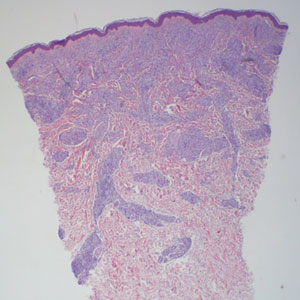

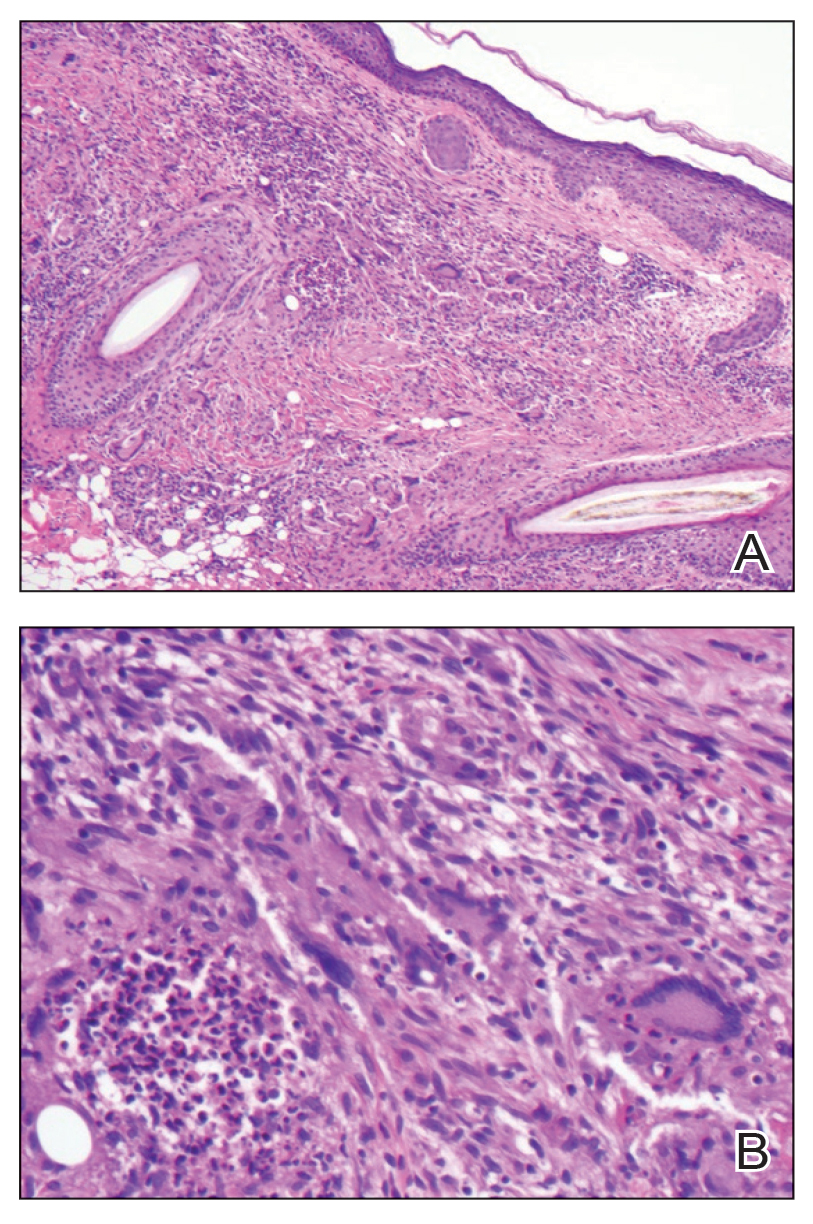

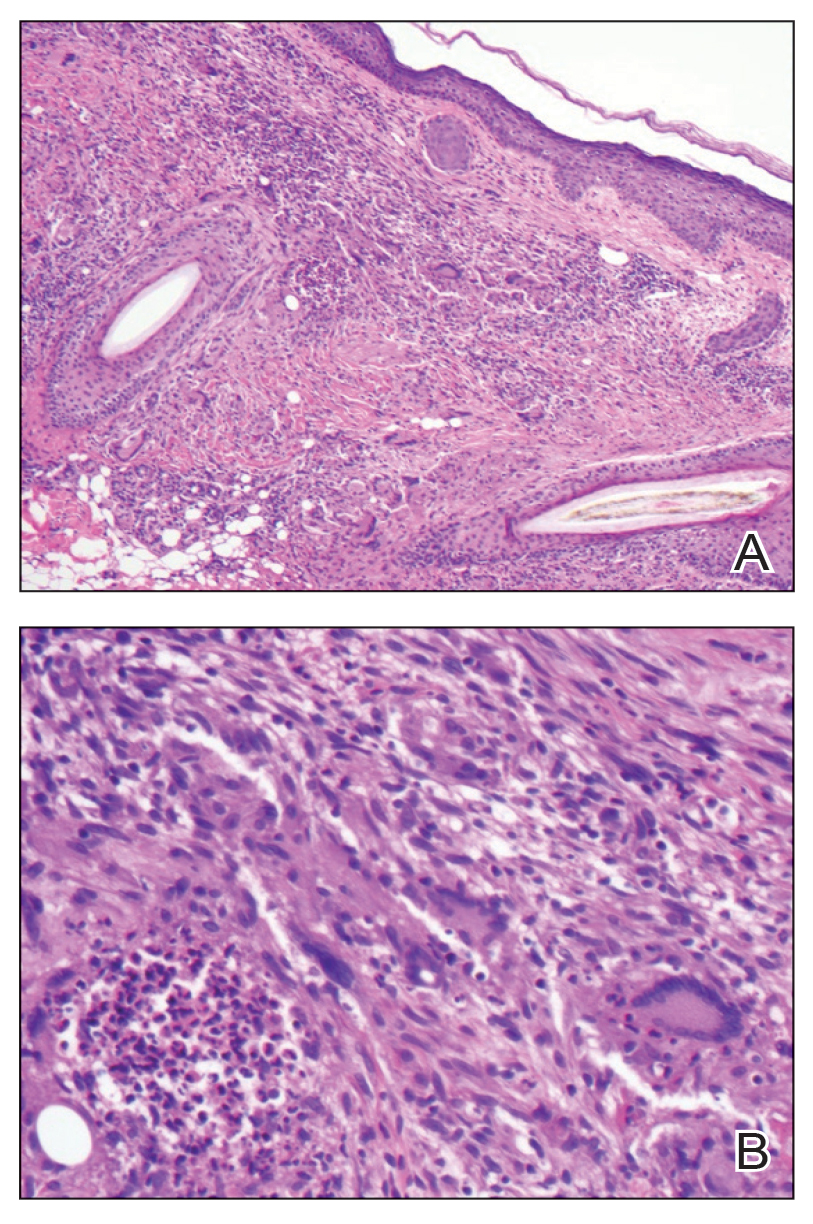

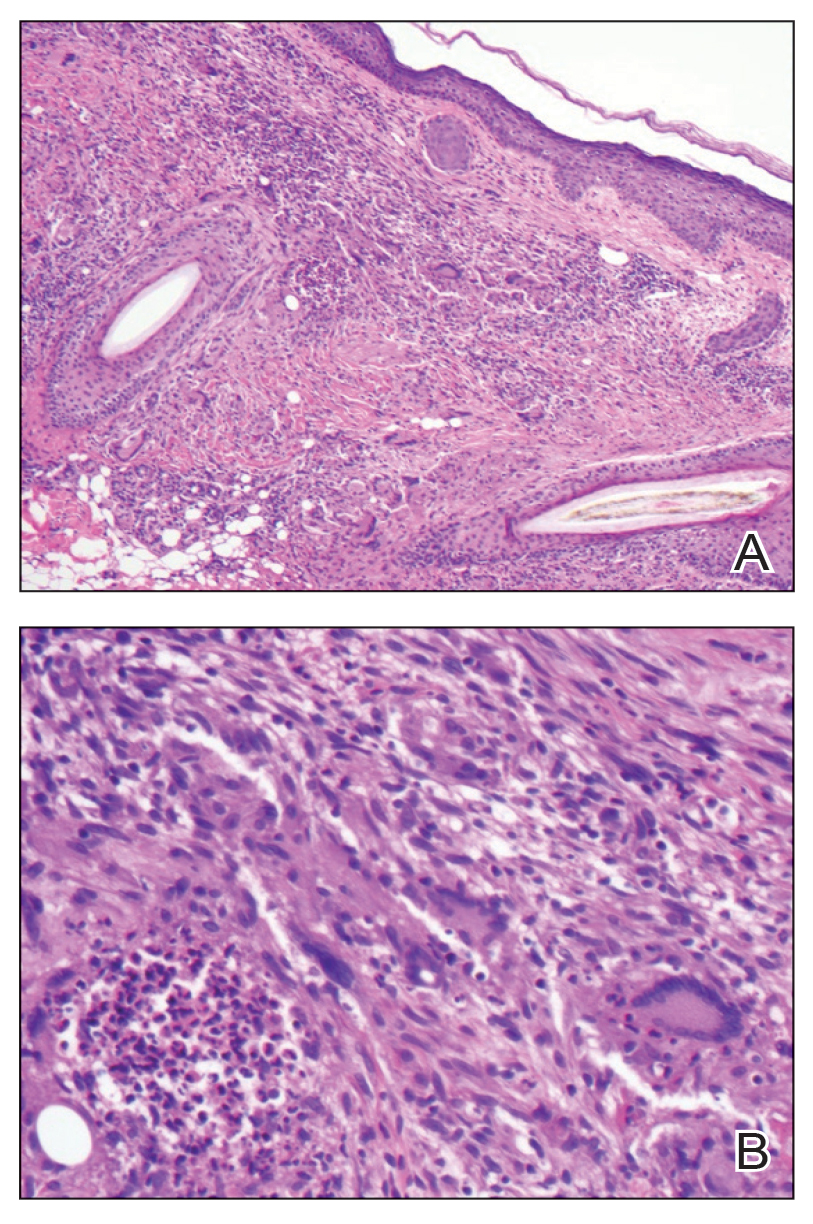

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

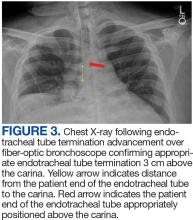

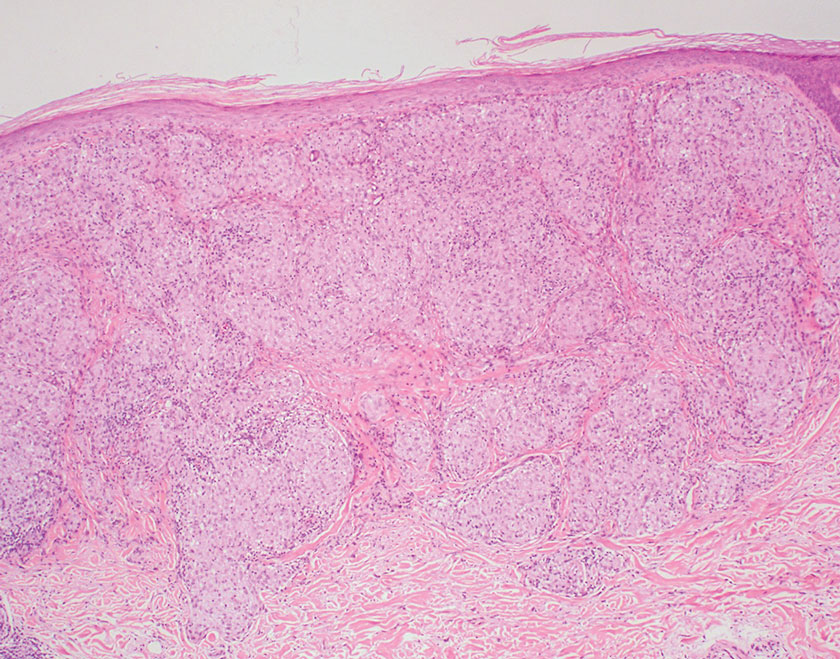

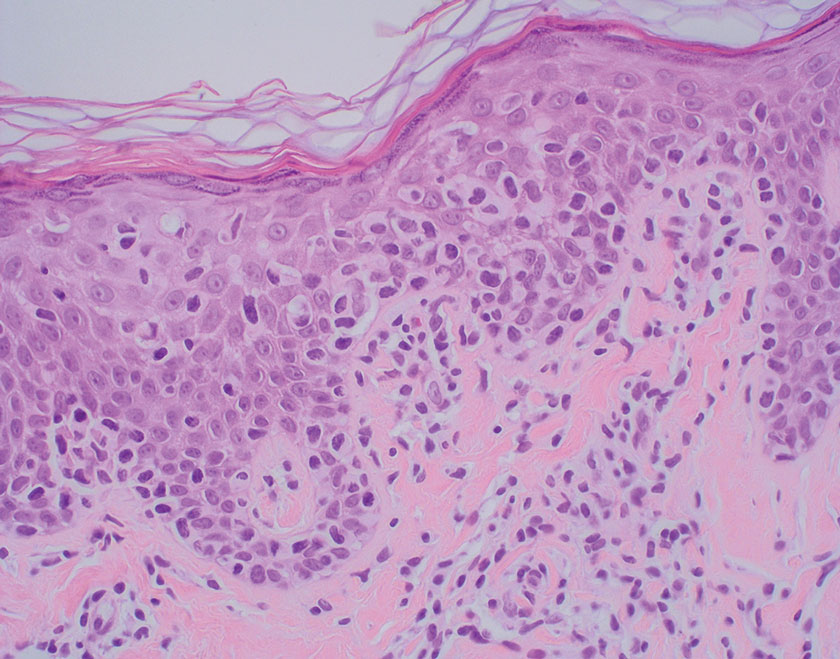

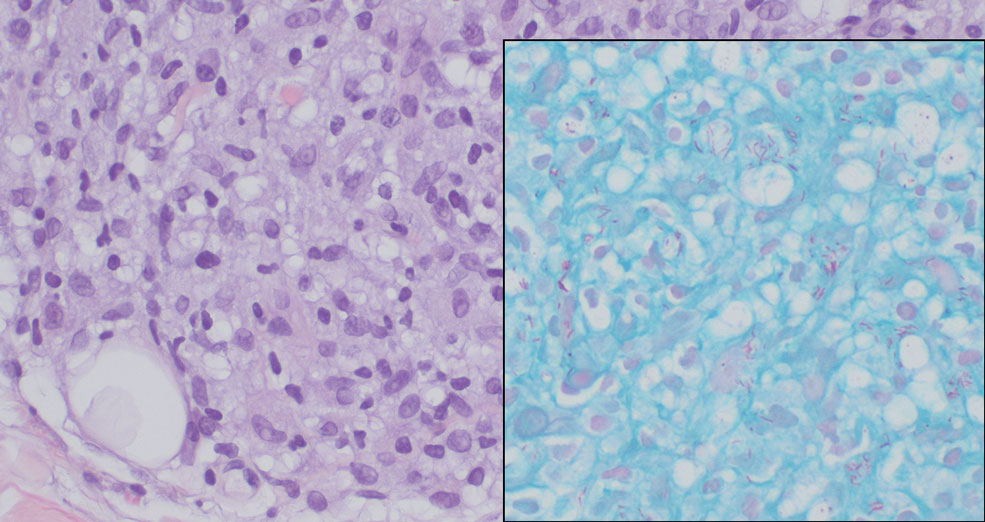

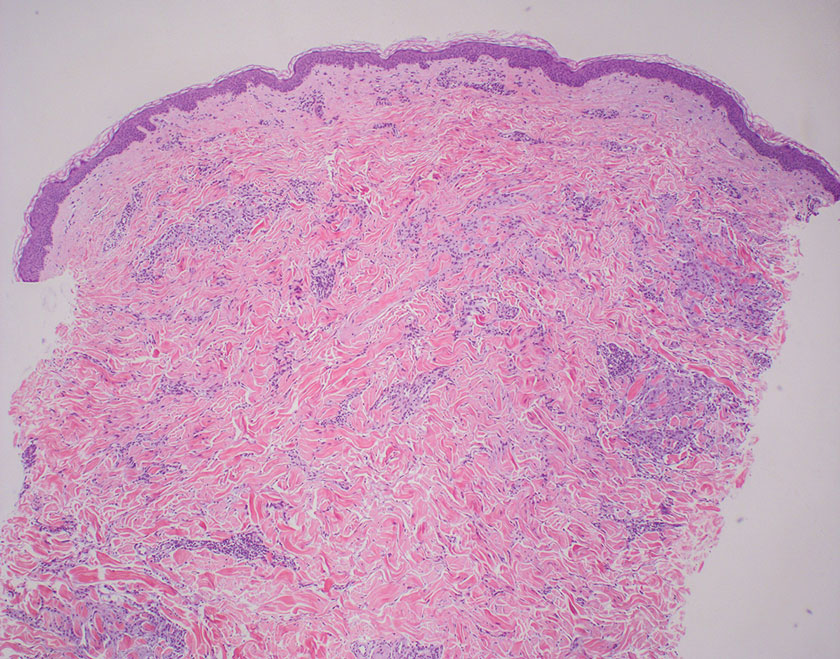

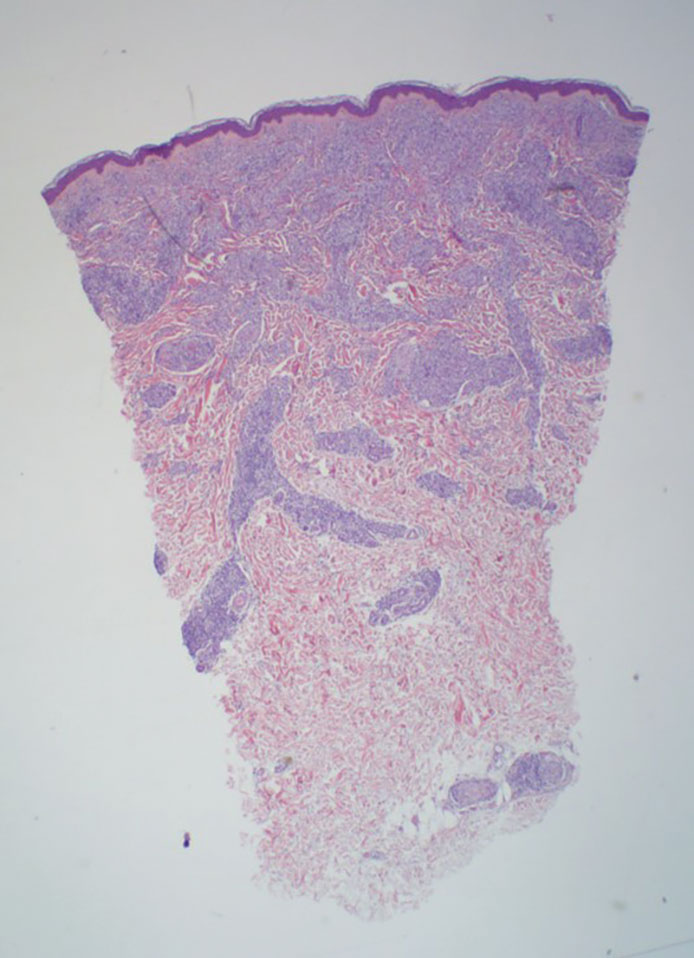

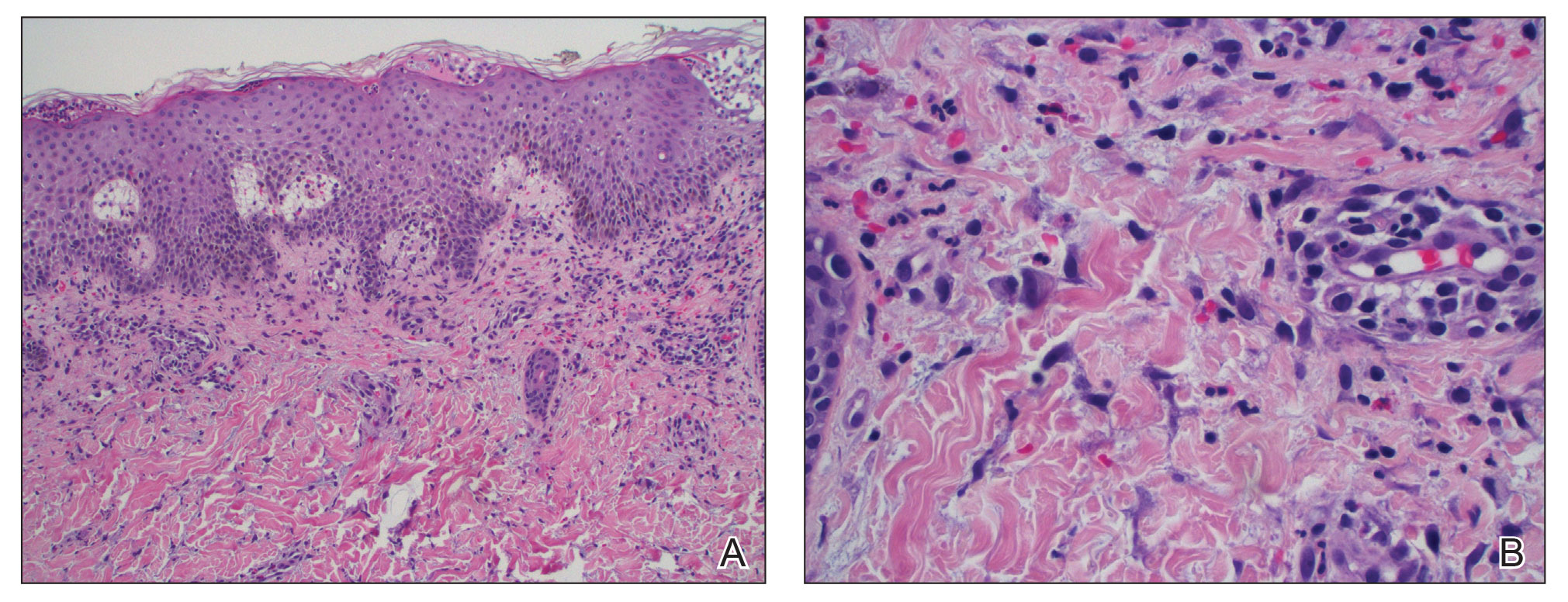

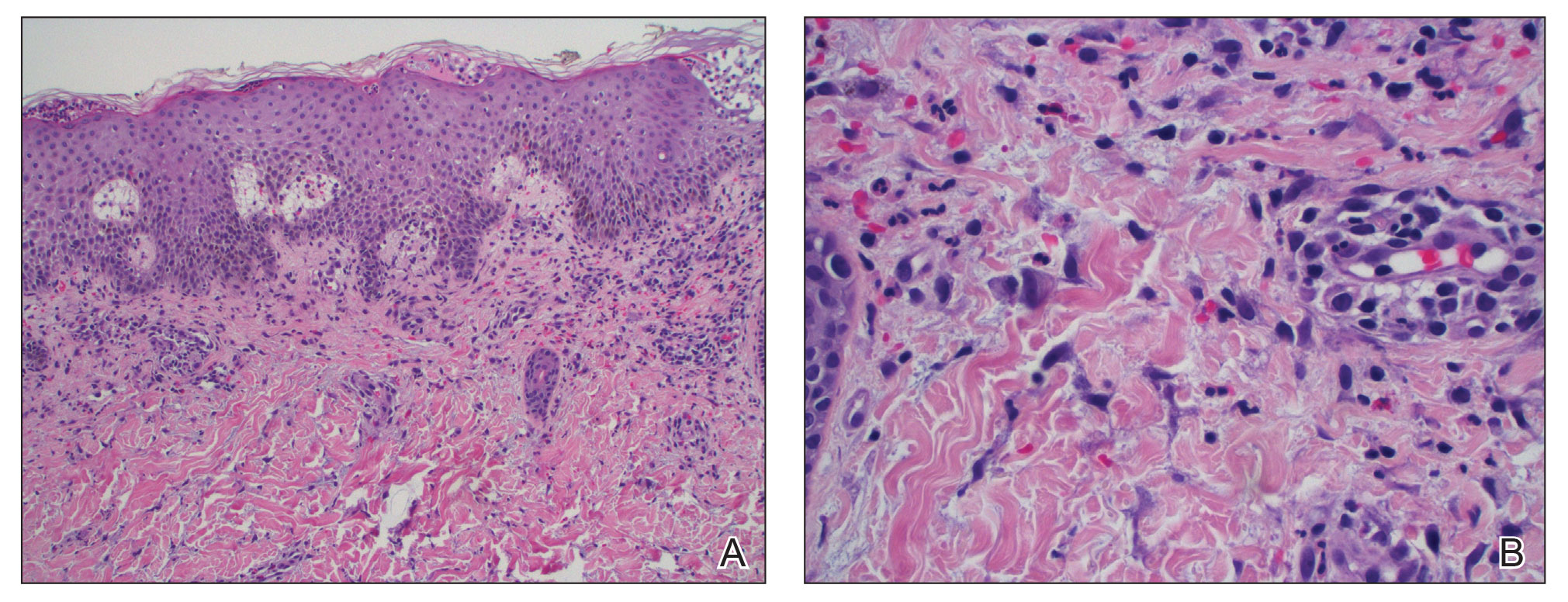

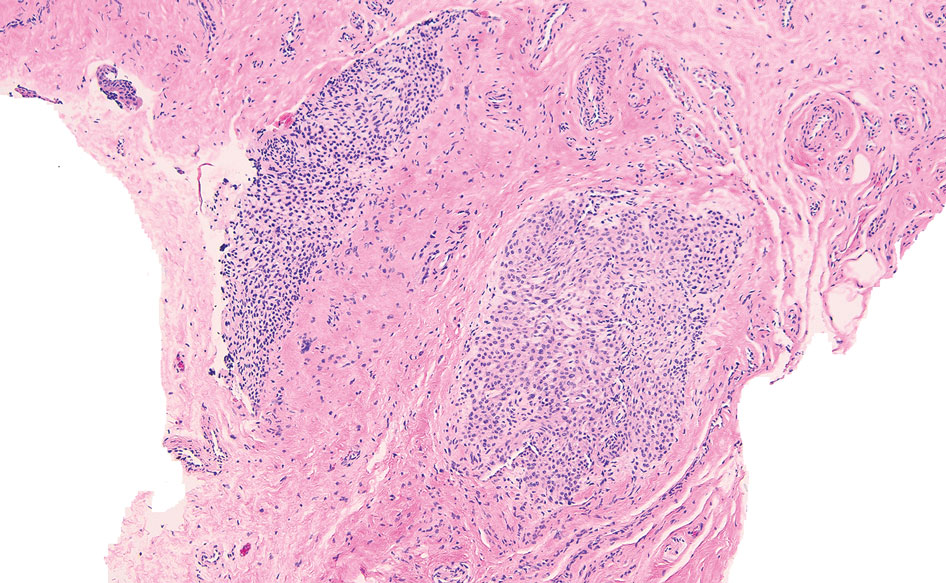

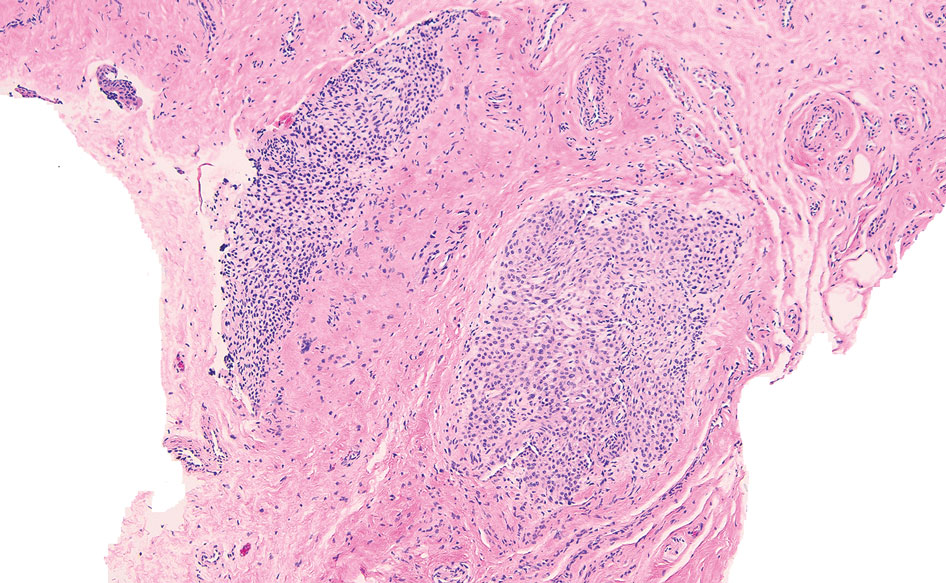

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

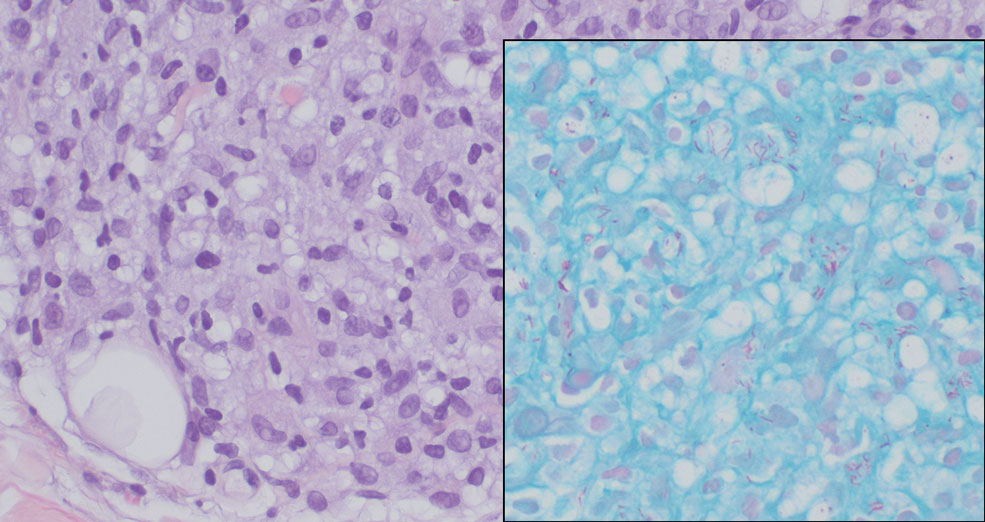

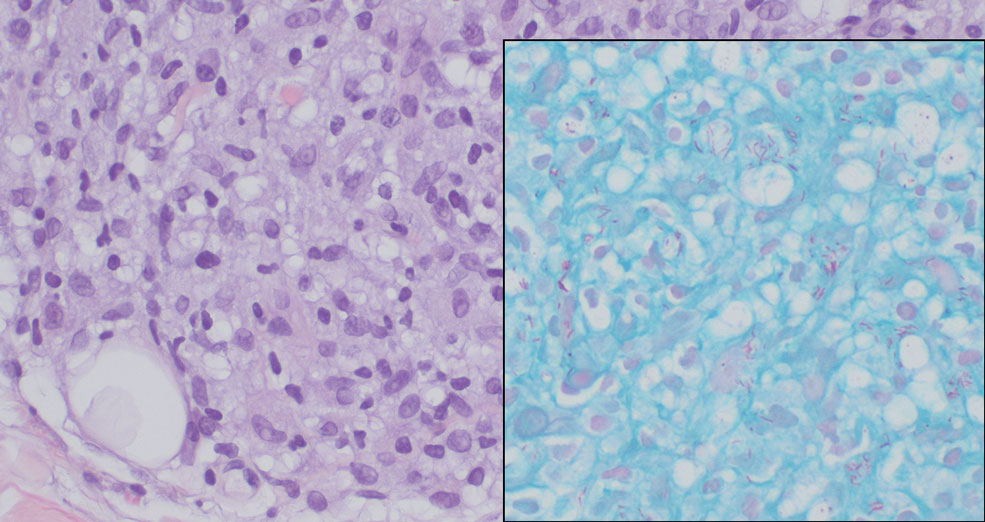

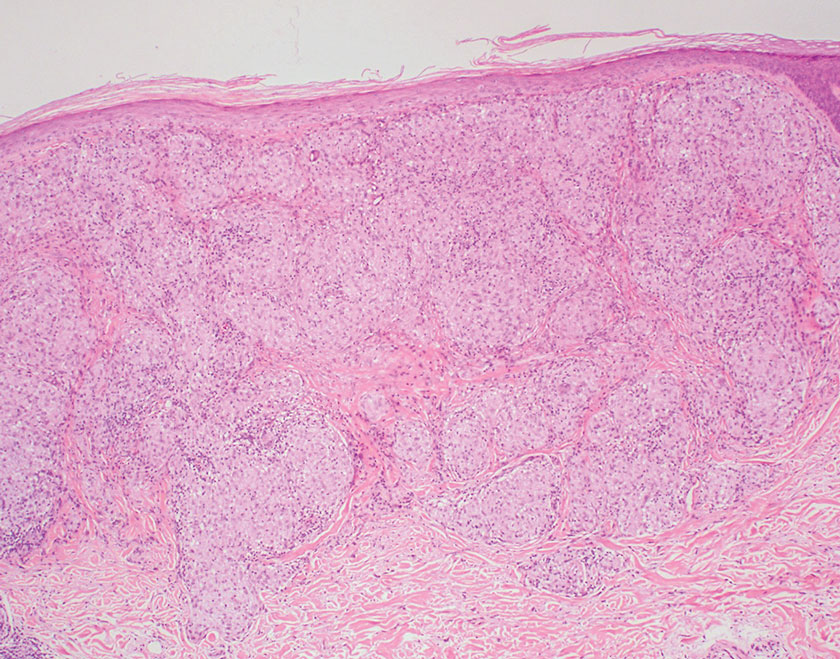

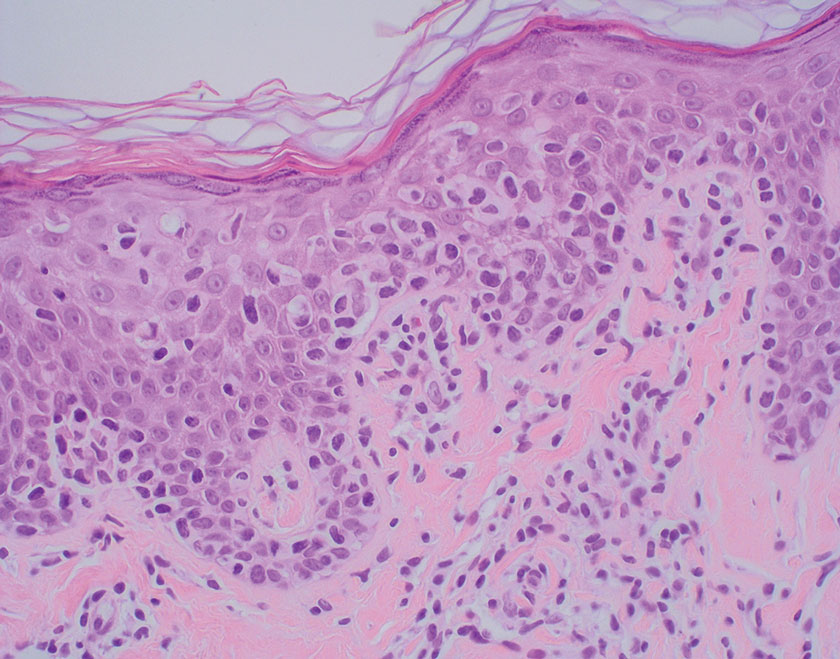

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

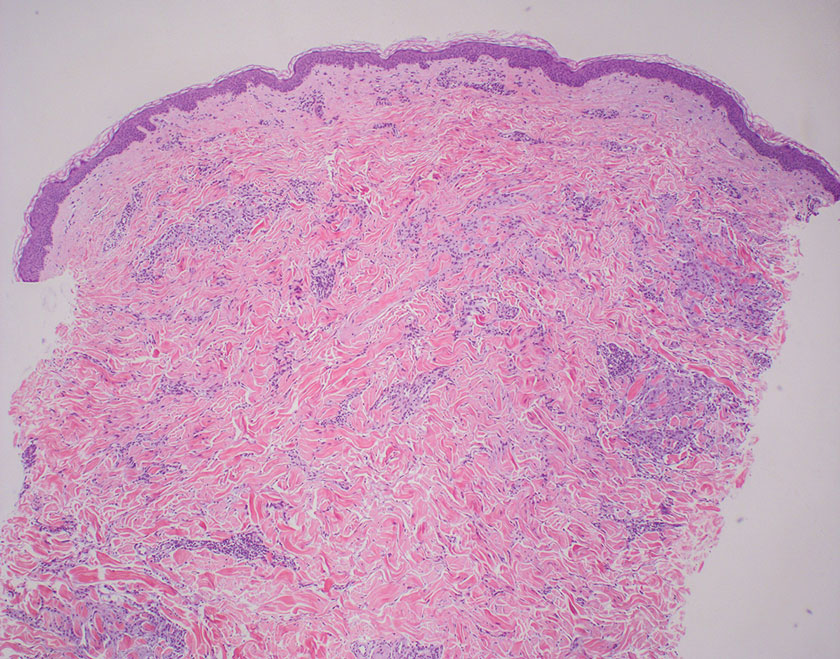

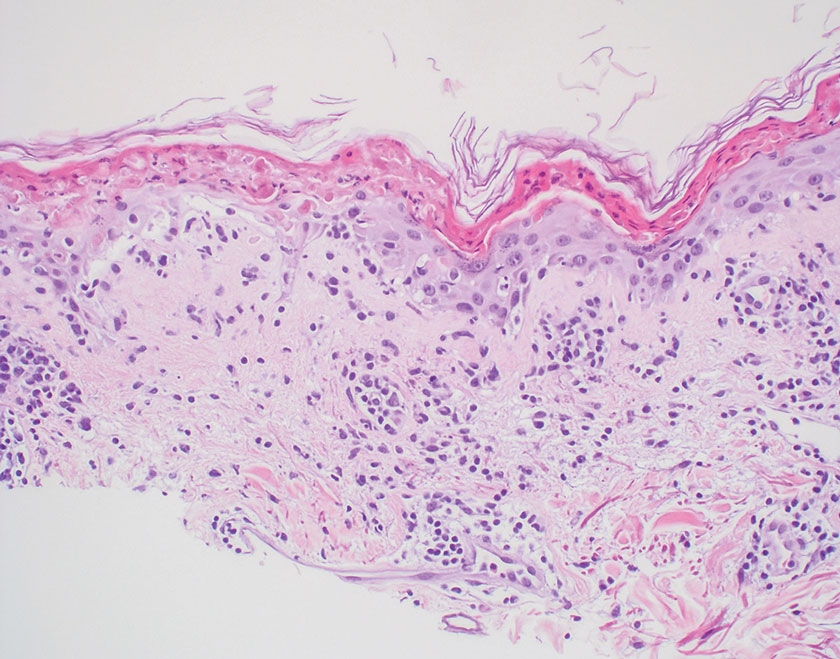

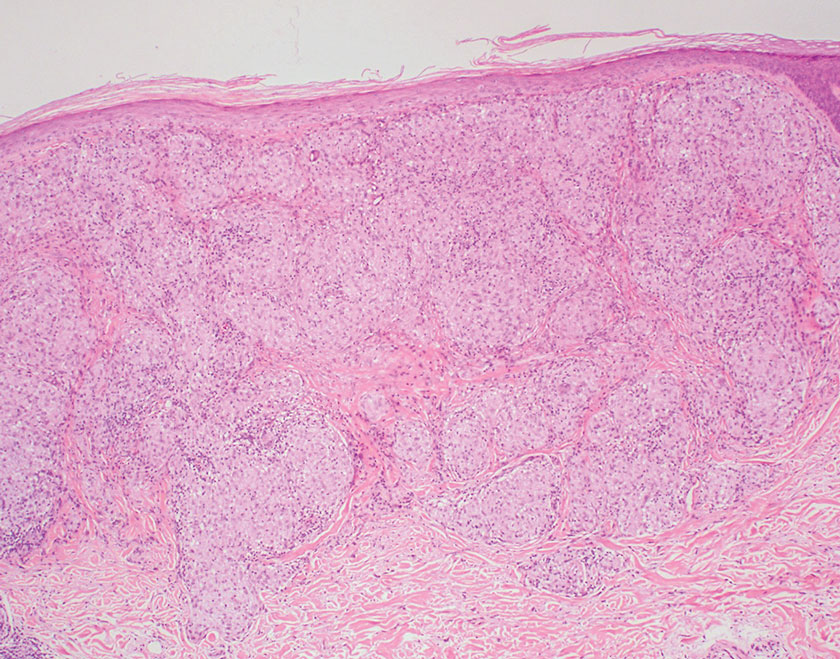

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

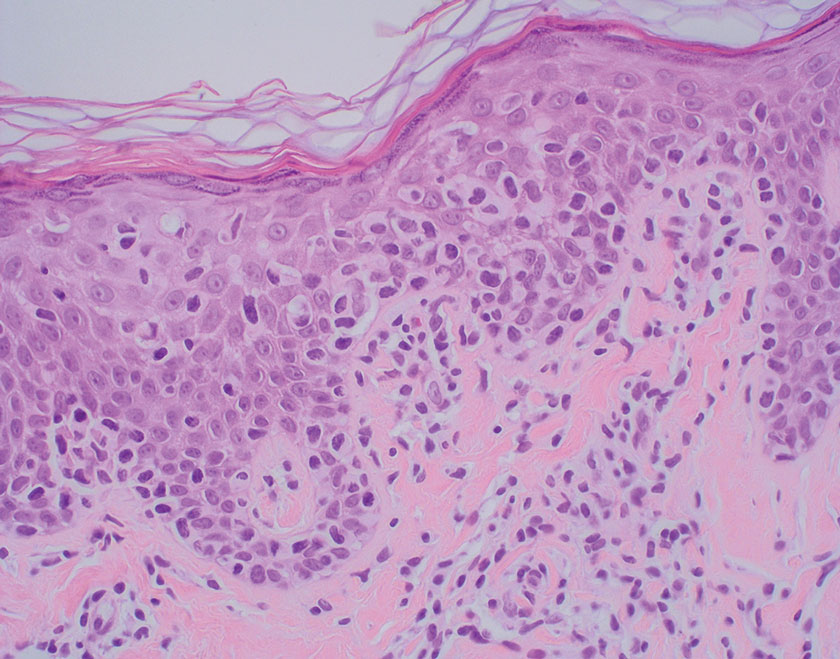

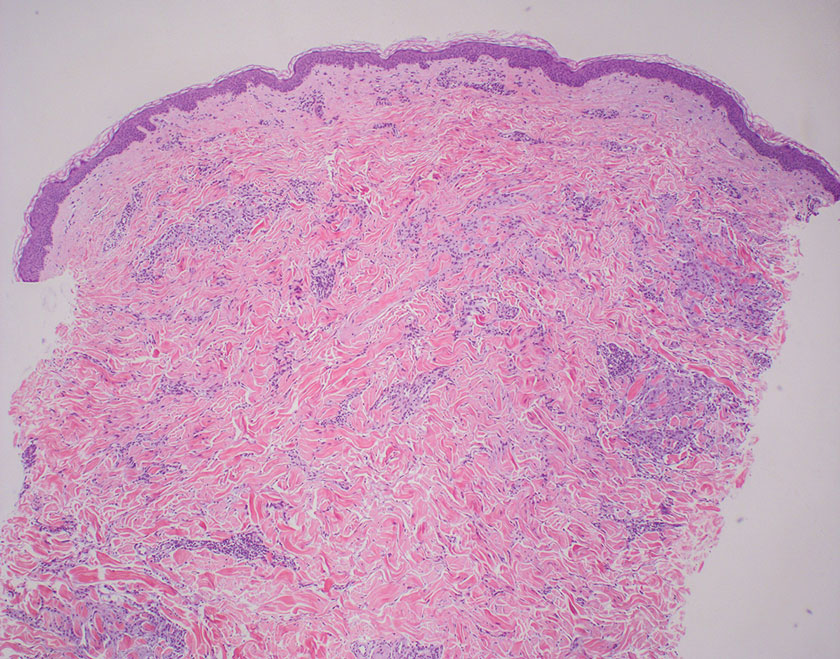

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

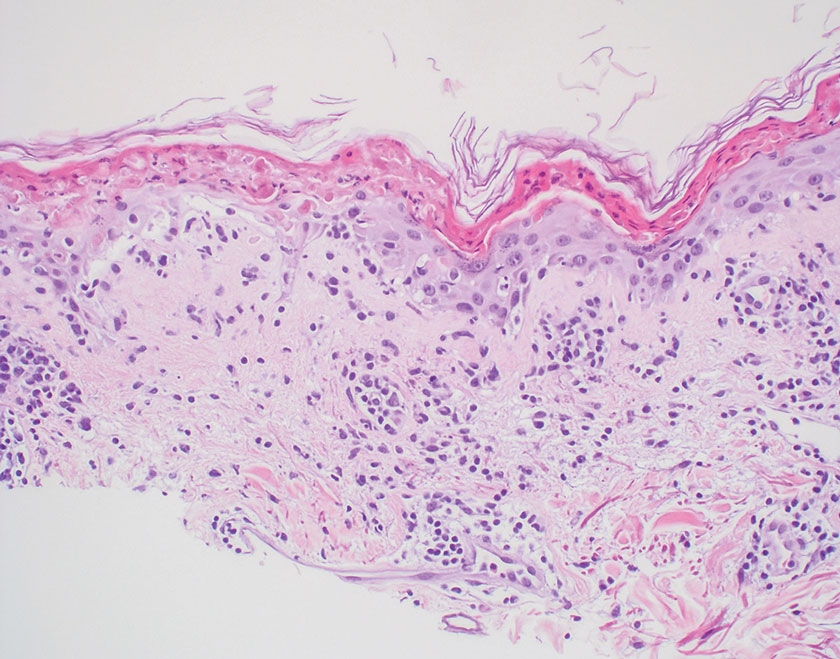

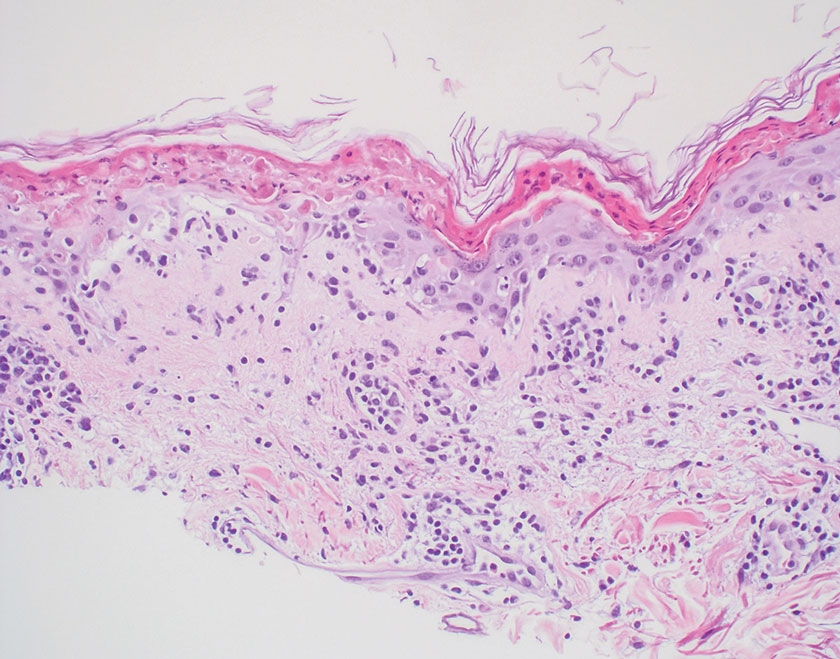

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

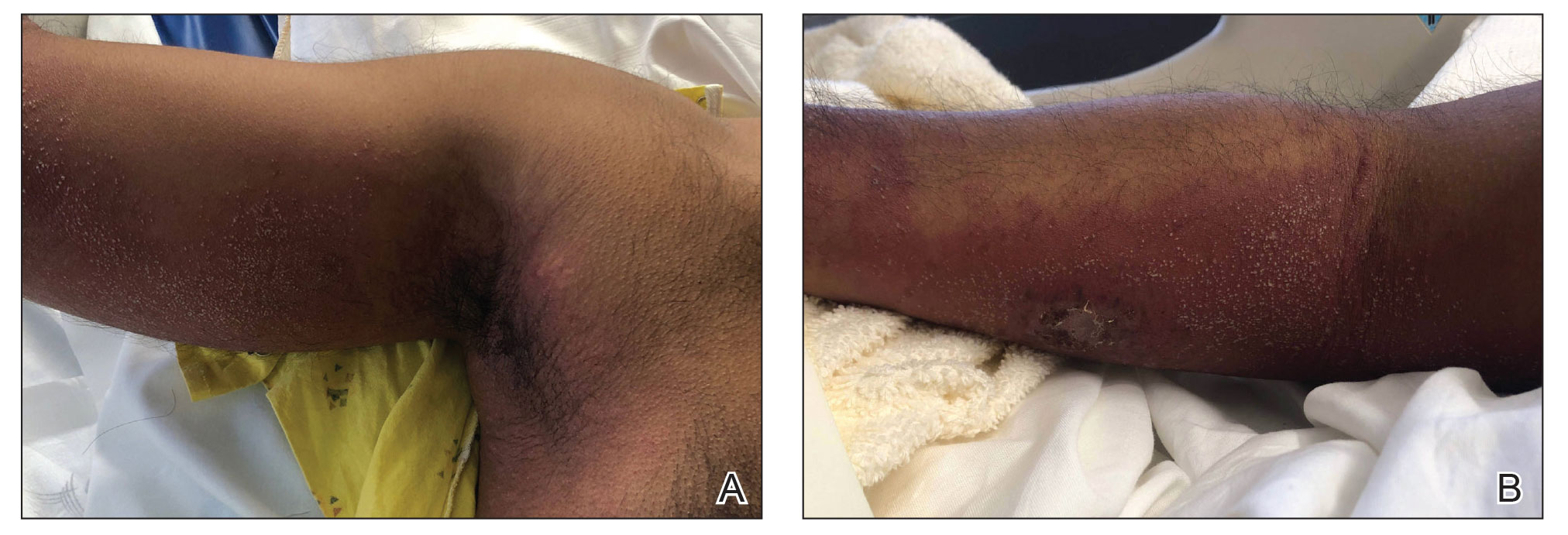

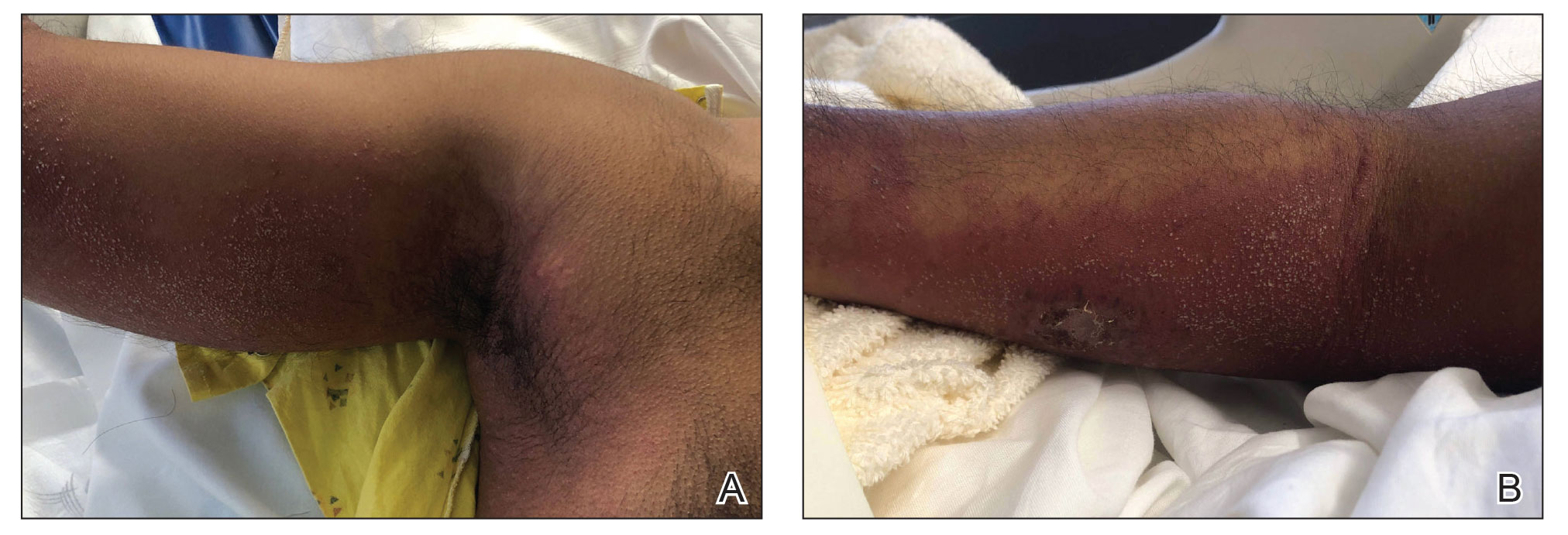

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

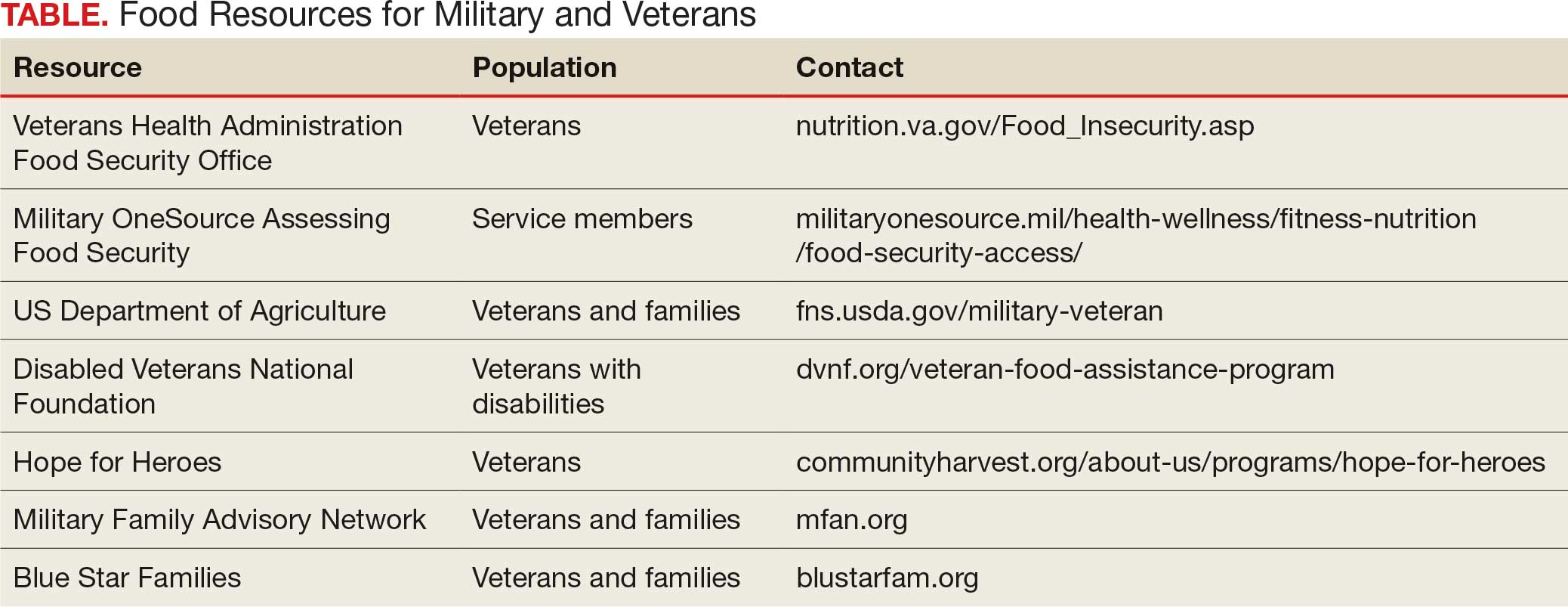

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

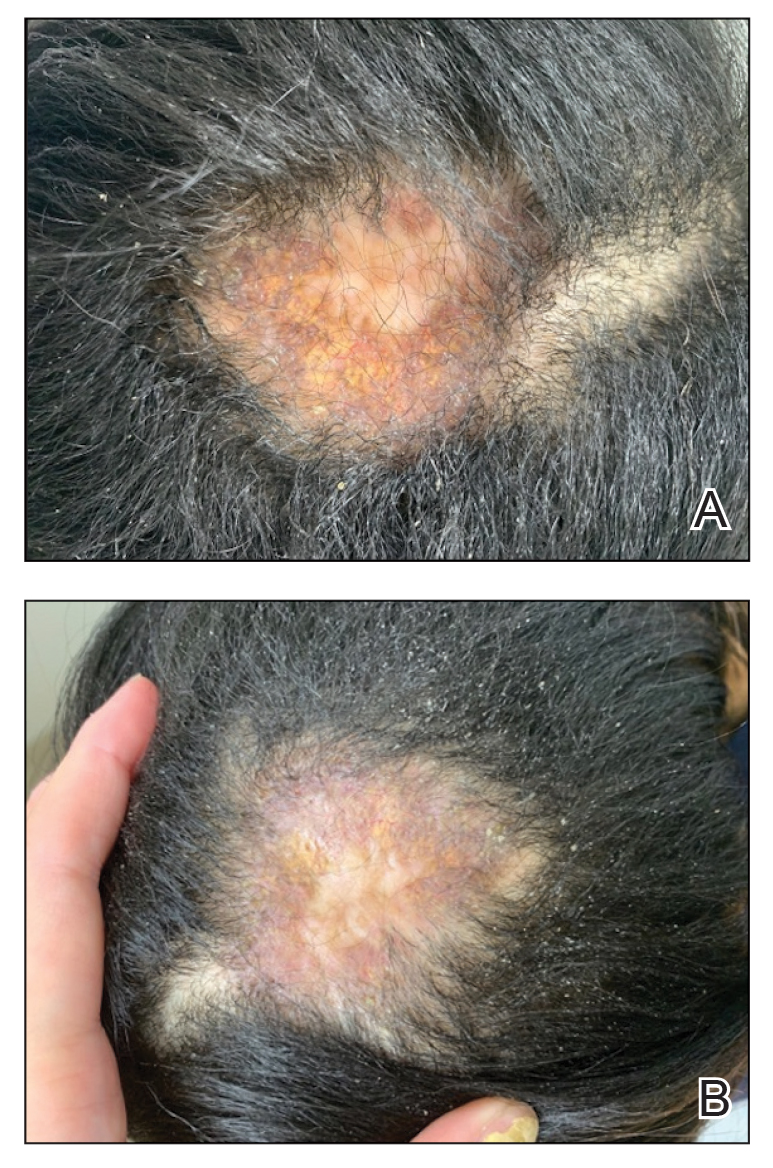

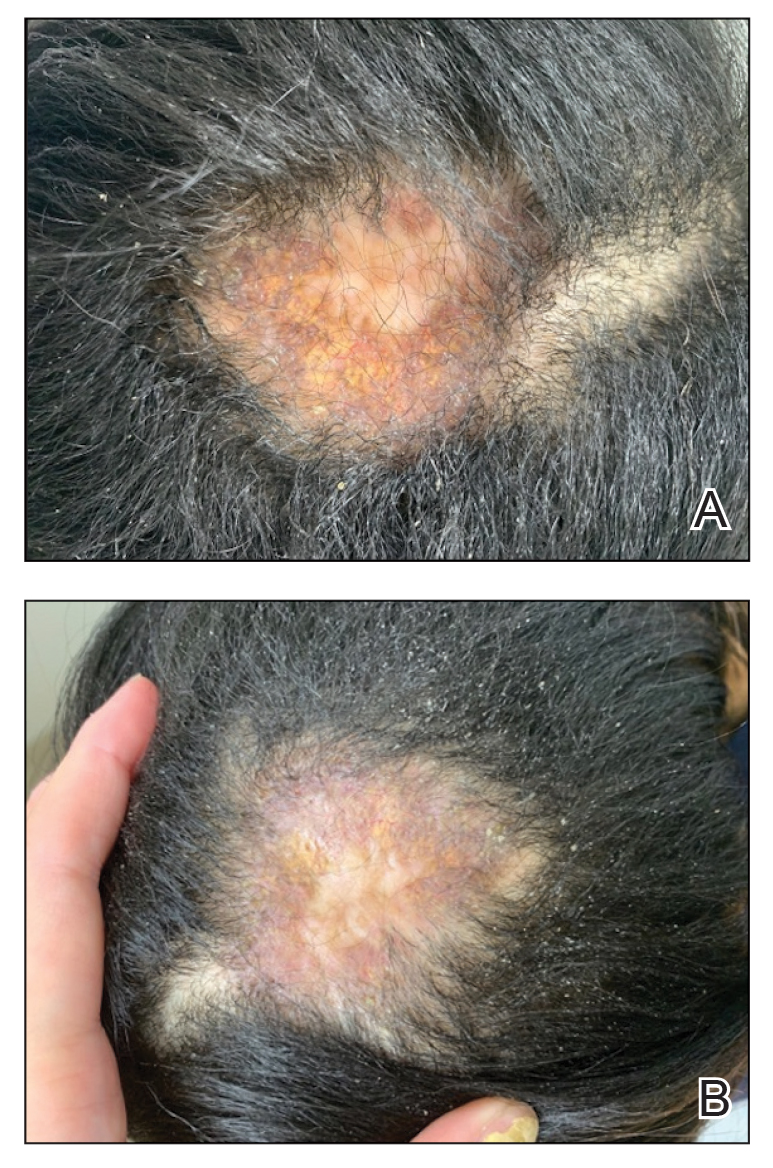

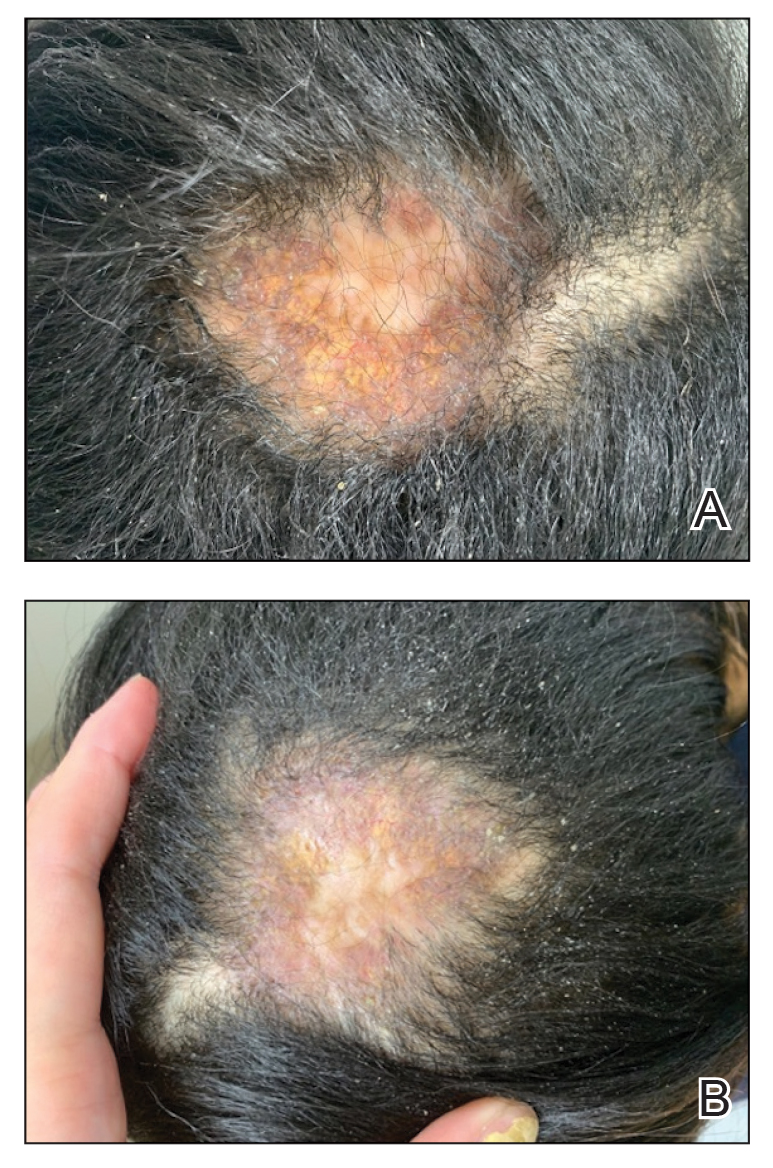

A 44-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a widespread red, itchy, bumpy rash of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination revealed smooth, coalescing, erythematous and edematous plaques on the face (notably the forehead, malar cheeks, and nose), back, arms, and legs. Several plaques on the back had central hypopigmentation. The patient also reported numbness and weakness in the fingers and toes, and hypoesthesia within the lesions was noted. A biopsy of one of the lesions on the left ventral forearm was performed.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

To the Editor:

For many years, topical treatment of plaque psoriasis was limited to steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar products, and anthralin. In recent years, 2 new nonsteroidal treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action, roflumilast 0.3% and tapinarof 1%, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.1 Roflumilast 0.3%, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, was shown in phase 3 clinical trials to reach an Investigator Global Assessment response of 37.5% to 42.2% in 8 weeks using once-daily application with minimal cutaneous adverse effects.1 Furthermore, it has demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas in subset analyses.1 Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation by downregulating IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23.1 In phase 3 clinical trials, 35% to 40% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated improvement in psoriasis compared with 6% who used the vehicle alone.2 In these studies, 18% to 24% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% experienced folliculitis.2

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a nonfollicular pustular drug reaction with systemic symptoms that typically occurs within 2 weeks of exposure to an inciting medication. Systemic antibiotics are the most commonly reported cause of AGEP.3 There are few reports in the literature of AGEP induced by topical agents.4,5 We report a case of AGEP in a young man following the use of tapinarof cream 1%.

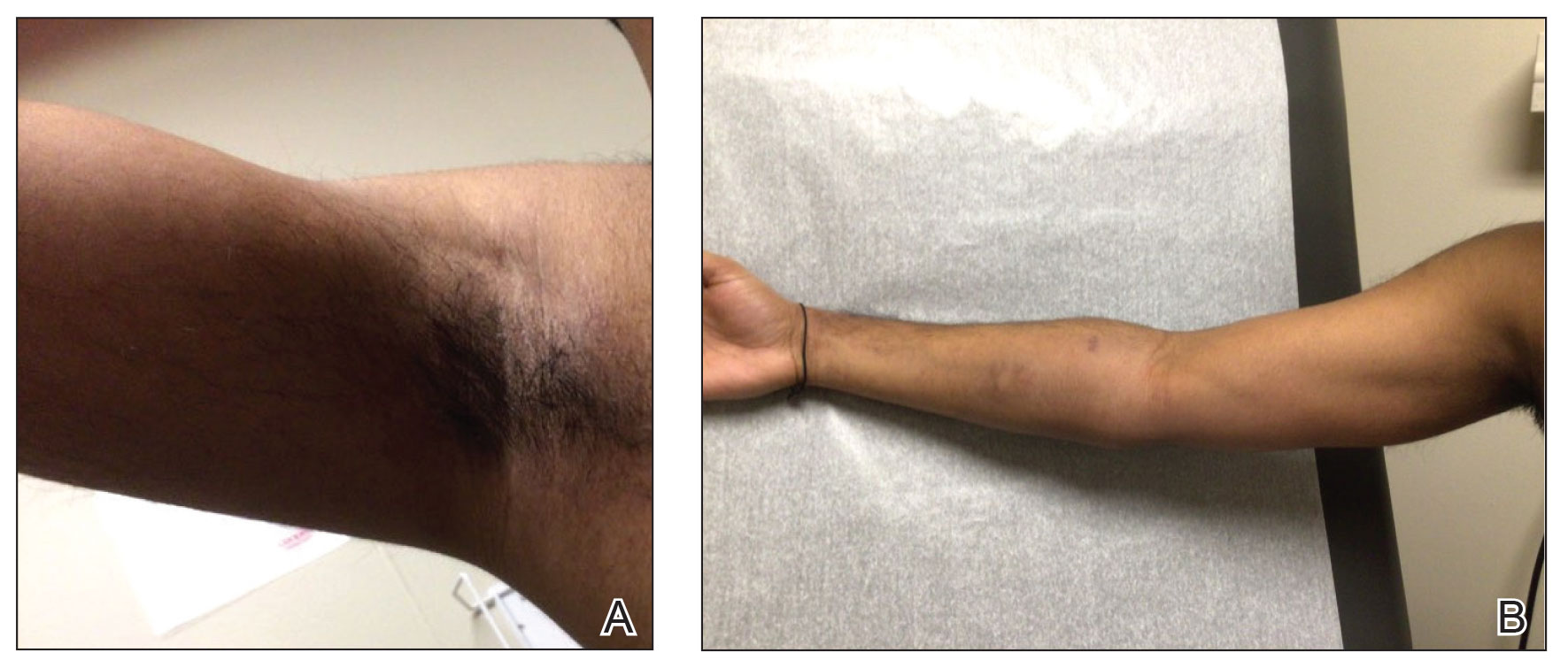

A 23-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to the emergency department with fever and a pustular rash. One week prior to presentation, he developed a pustular eruption around plaques of psoriasis on the arms and legs. The patient had been prescribed tapinarof cream 1% by an outside dermatologist and was applying the medication to the affected areas once daily for 1 month prior to onset of symptoms. He discontinued tapinarof a few days prior to the eruption starting, but the rash progressed centrifugally and was associated with fevers and fatigue despite treatment with a brief course of empiric cephalexin prescribed by his primary care provider.

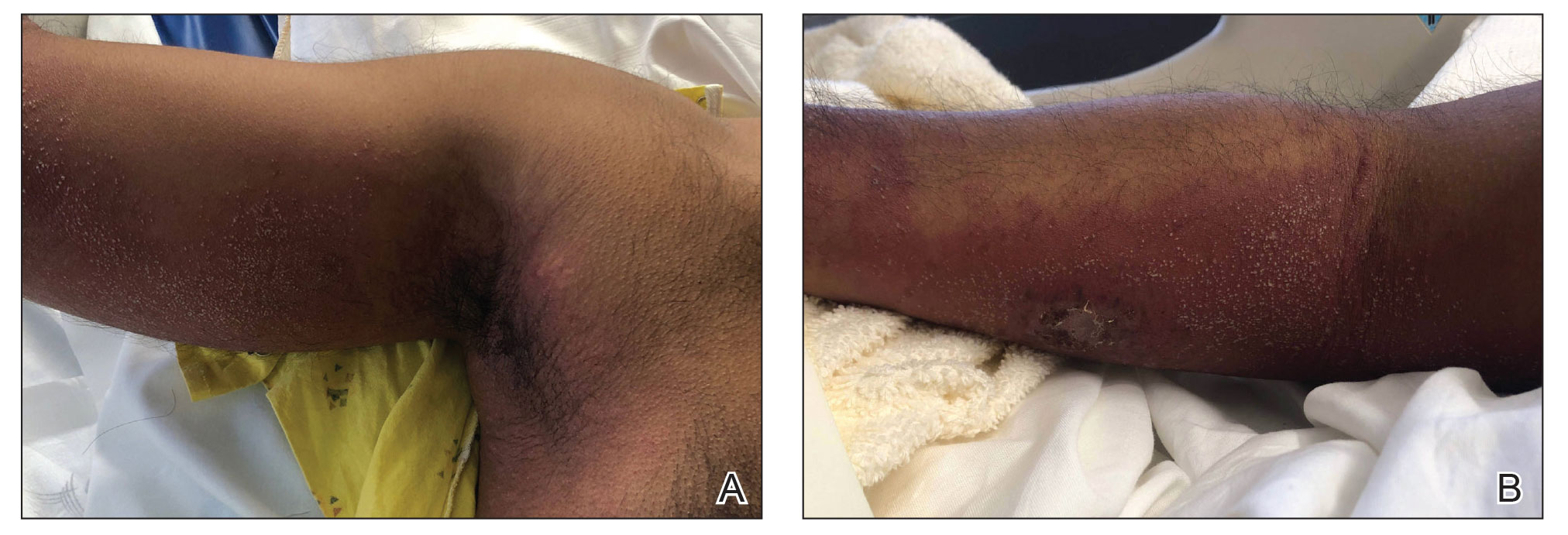

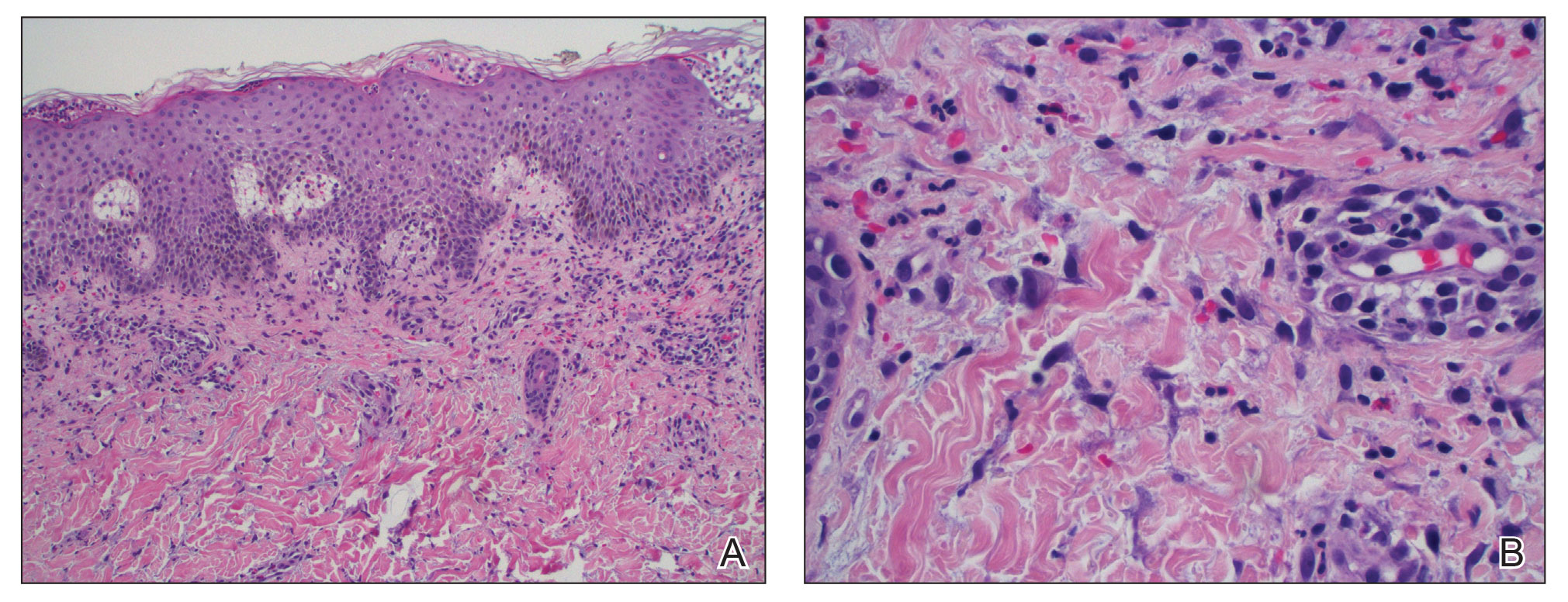

At presentation to our institution, the patient had widespread erythematous patches studded with pustules located on the arms, legs, and flexural areas as well as plaques of psoriasis involving approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Furthermore, the patient was noted to have large noninflammatory bullae along the legs. The new eruption occurred on areas that were both treated and spared from the tapinarof cream 1%. Laboratory evaluation showed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 15.9×103/µL [reference range, 4.0-11.0×103/µL]; absolute neutrophil count, 10.3×103/µL [reference range, 1.5-8.0×103/µL]), absolute eosinophilia (1930/µL [reference range, 0-0.5×103/µL]), hypocalcemia (8.4 mg/dL [reference range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL]), and a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L [reference range, 10-40 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU/L [reference range, 7-56 U/L]). Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules and mixed dermal inflammation containing eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence revealed mild granular staining of C3 at the basement membrane zone.

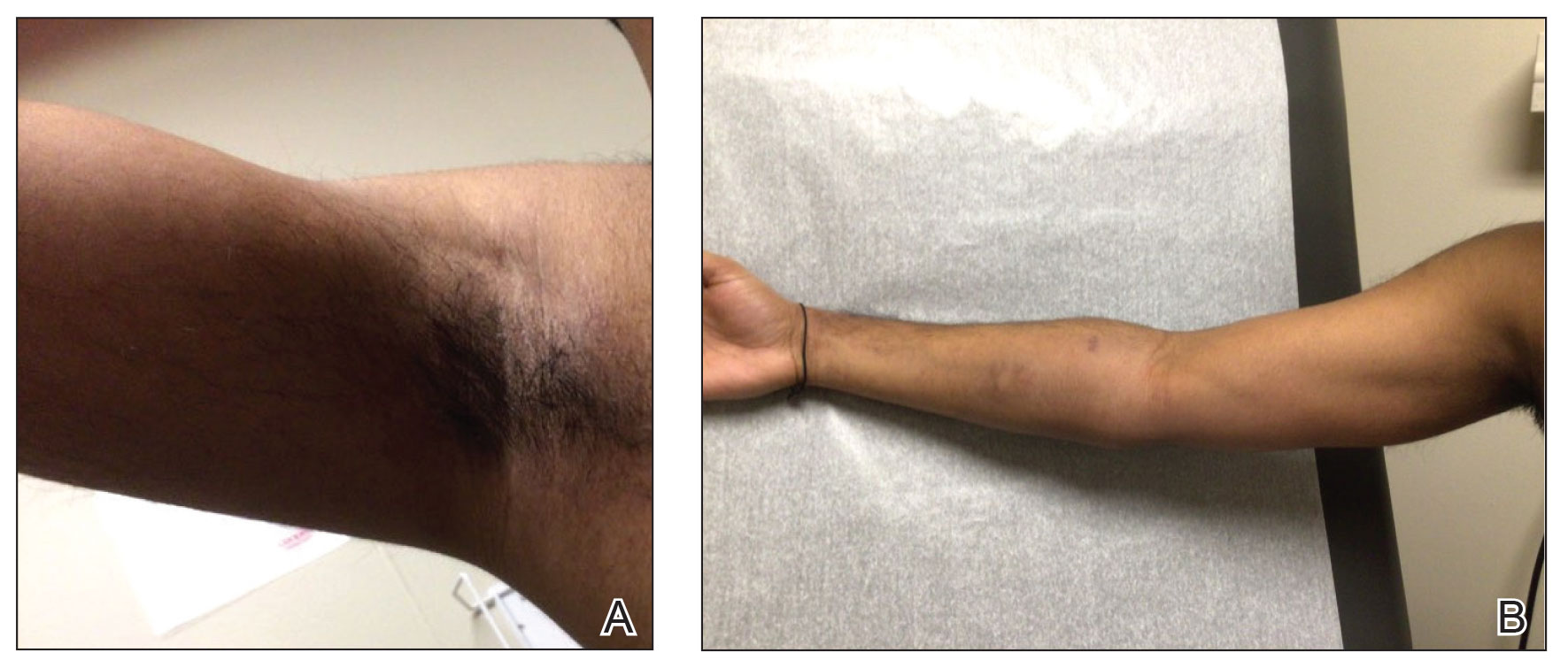

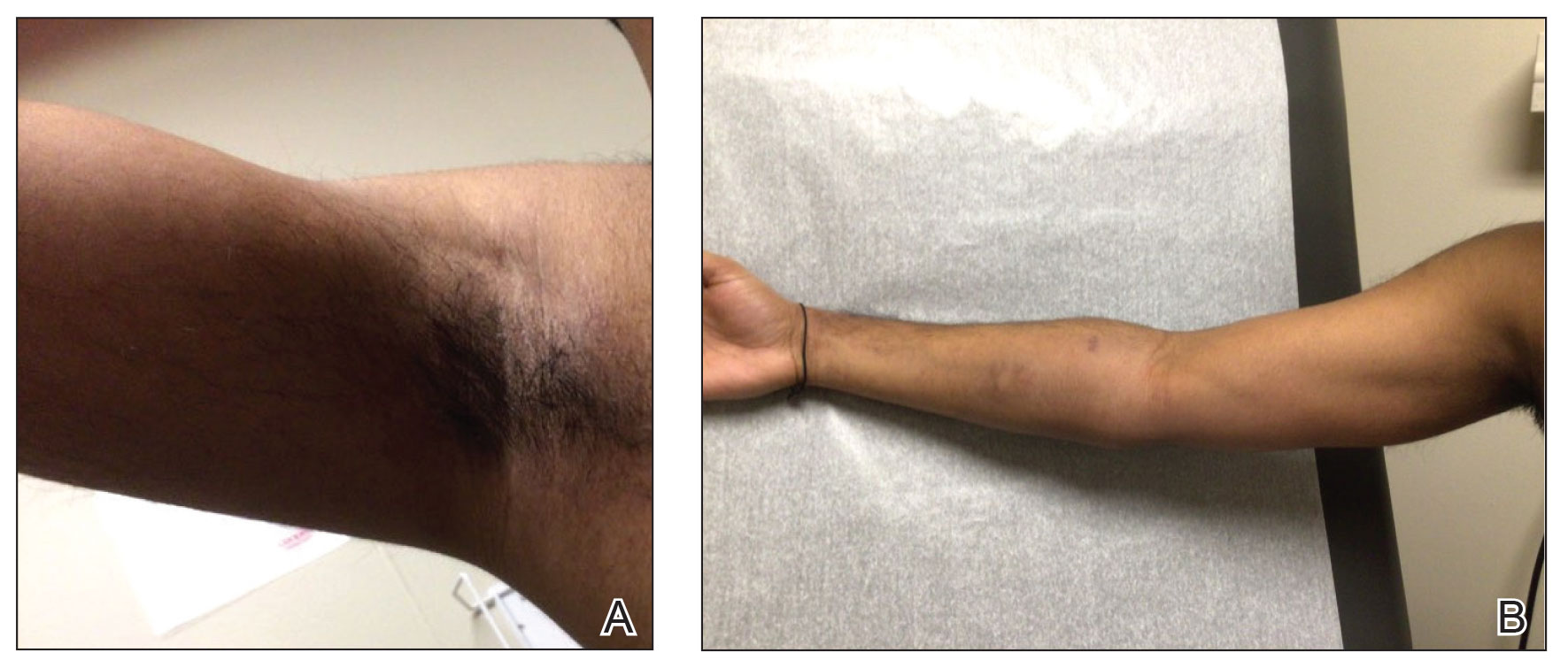

The patient was started on 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 20 days, and he rapidly improved. Alanine aminotransferase levels peaked at 120 IU/L 2 weeks later. At that time, he had complete resolution of the original eruption and was transitioned to topical steroids for continued management of the psoriasis (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis for our patient included AGEP, generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), miliaria pustulosa, generalized cutaneous candidiasis, exuberant allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Based on the clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and histopathologic evaluation, we made the diagnosis of AGEP secondary to tapinarof with systemic absorption. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis has been reported with topical use of morphine and diphenhydramine, among other agents.4,5 To our knowledge, AGEP due to tapinarof cream 1% has not been reported. In the original clinical trials of tapinarof, folliculitis was contained to sites of application.2 Our patient developed pustules at sites distant to areas of application, as well as systemic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, indicating a systemic reaction. It can be difficult to distinguish AGEP clinically and histologically from GPP. Both conditions can manifest with fever, hypocalcemia, and sterile pustules on a background of erythema that favors intertriginous areas.6 Infection, rapid oral steroid withdrawal, pregnancy, and rarely oral medications have been reported causes of GPP.6 Our patient did not have any of these exposures. There is overlap in the histology of AGEP and GPP. One retrospective series compared histologic samples to help distinguish these 2 entities. Reliable markers that favored AGEP over GPP included eosinophilic spongiosis, interface dermatitis, and dermal eosinophilia (>2/mm2).7 In contrast, the presence of CD161 positivity in the dermis with at least 10 cells favored a diagnosis of GPP.7 In our case, the presence of spongiosis with eosinophils in the dermis favored a diagnosis of AGEP over GPP.

Miliaria pustulosa is a benign condition caused by the occlusion of the epidermal portion of eccrine glands related to either high fever or hot and humid environmental conditions. While it can be present in intertriginous areas like AGEP, miliaria pustulosa can be seen extensively on the back, most commonly in immobile hospitalized patients.8 Generalized cutaneous candidiasis usually is caused by the yeast Candida albicans and can take on multiple morphologies, including folliculitis.9 The eruption may be disseminated but often is accentuated in intertriginous areas and the anogenital folds. Predisposing factors include immunosuppression, endocrinopathies, recent use of systemic antibiotics or steroids, chemotherapy, and indwelling catheters.9 Outside of recent antibiotic use, our patient did not have any risk factors for miliaria pustulosa, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Given the presence of overlapping bullae along the lower extremities, an exuberant ACD and LABD were considered. Bullae formation can occur in ACD secondary to robust inflammation and edema leading to acantholysis.10 While a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to topical tapinarof cream 1% was considered given that the patient used the medication for approximately 1 month prior to the onset of symptoms, it would be unlikely for ACD to present with a concomitant pustular eruption. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune blistering disease in which antibodies target bullous pemphigoid antigen 2, and there is characteristically linear deposition of IgA at the dermal-epidermal junction that leads to subepidermal blistering.11 This often manifests clinically as widespread tense vesicles in an annular or string-of-pearls appearance. However, morphologies can vary, and large bullae may be seen. In adults, LABD typically is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or medications, notably vancomycin.11,12 Our patient did not have any of these predisposing factors, and his biopsy for direct immunofluorescence did not reveal the classic pattern described above.

Interestingly, there have been reports in the literature of bullous AGEP in the setting of oral anti-infectives. One report described a 62-year-old woman who developed widespread nonfollicular pustules with multiple tense serous blisters 24 hours after taking oral terbinafine.13 Another case described an 80-year-old woman with a similar presentation following a course of ciprofloxacin (although the timeline of medication administration was not described).14 In this case, patch testing to the culprit medication reproduced the response.14 In both cases, a biopsy revealed subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules with marked dermal edema.13,14 As previously described, spongiosis is a common feature of AGEP. We hypothesize that, similar to these reports, our patient had a robust inflammatory response leading to spongiosis, acantholysis, and blister formation secondary to AGEP.

Dermatologists should be aware of this case of AGEP secondary to tapinarof cream 1%, as reports in the literature are rare and it is a reminder that topical medications can cause serious systemic reactions.

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017

- Ghazawi FM, Colantonio S, Bradshaw S, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical morphine and confirmed by patch testing. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E22-E23. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000573

- Hanafusa T, Igawa K, Azukizawa H, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical diphenhydramine. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:994-995. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1500

- Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, Lee EB, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations,diagnosis, and treatment. Cutis. 2022;110:19-25. doi:10.12788/cutis.0579

- Isom J, Braswell DS, Siroy A, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features differentiating acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and pustular psoriasis: a retrospective series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:265-267. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.015

- Fealey RD, Hebert AA. Disorders of the eccrine sweat glands and sweating. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine.8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:946.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Marchiony Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1329-1363.

- Elmas ÖF, Akdeniz N, Atasoy M, et al. Contact dermatitis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:176-192. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.003

- Hull CM, Zone JZ. Dermatitis herpetiforms and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- Yamagami J, Nakamura Y, Nagao K, et al. Vancomycin mediates IgA autoreactivity in drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1473-1480.

- Bullous acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to oral terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:P115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.468

- Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology. 2005;211:277-280. doi:10.1159/000087024

To the Editor:

For many years, topical treatment of plaque psoriasis was limited to steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar products, and anthralin. In recent years, 2 new nonsteroidal treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action, roflumilast 0.3% and tapinarof 1%, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.1 Roflumilast 0.3%, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, was shown in phase 3 clinical trials to reach an Investigator Global Assessment response of 37.5% to 42.2% in 8 weeks using once-daily application with minimal cutaneous adverse effects.1 Furthermore, it has demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas in subset analyses.1 Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation by downregulating IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23.1 In phase 3 clinical trials, 35% to 40% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated improvement in psoriasis compared with 6% who used the vehicle alone.2 In these studies, 18% to 24% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% experienced folliculitis.2

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a nonfollicular pustular drug reaction with systemic symptoms that typically occurs within 2 weeks of exposure to an inciting medication. Systemic antibiotics are the most commonly reported cause of AGEP.3 There are few reports in the literature of AGEP induced by topical agents.4,5 We report a case of AGEP in a young man following the use of tapinarof cream 1%.

A 23-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to the emergency department with fever and a pustular rash. One week prior to presentation, he developed a pustular eruption around plaques of psoriasis on the arms and legs. The patient had been prescribed tapinarof cream 1% by an outside dermatologist and was applying the medication to the affected areas once daily for 1 month prior to onset of symptoms. He discontinued tapinarof a few days prior to the eruption starting, but the rash progressed centrifugally and was associated with fevers and fatigue despite treatment with a brief course of empiric cephalexin prescribed by his primary care provider.

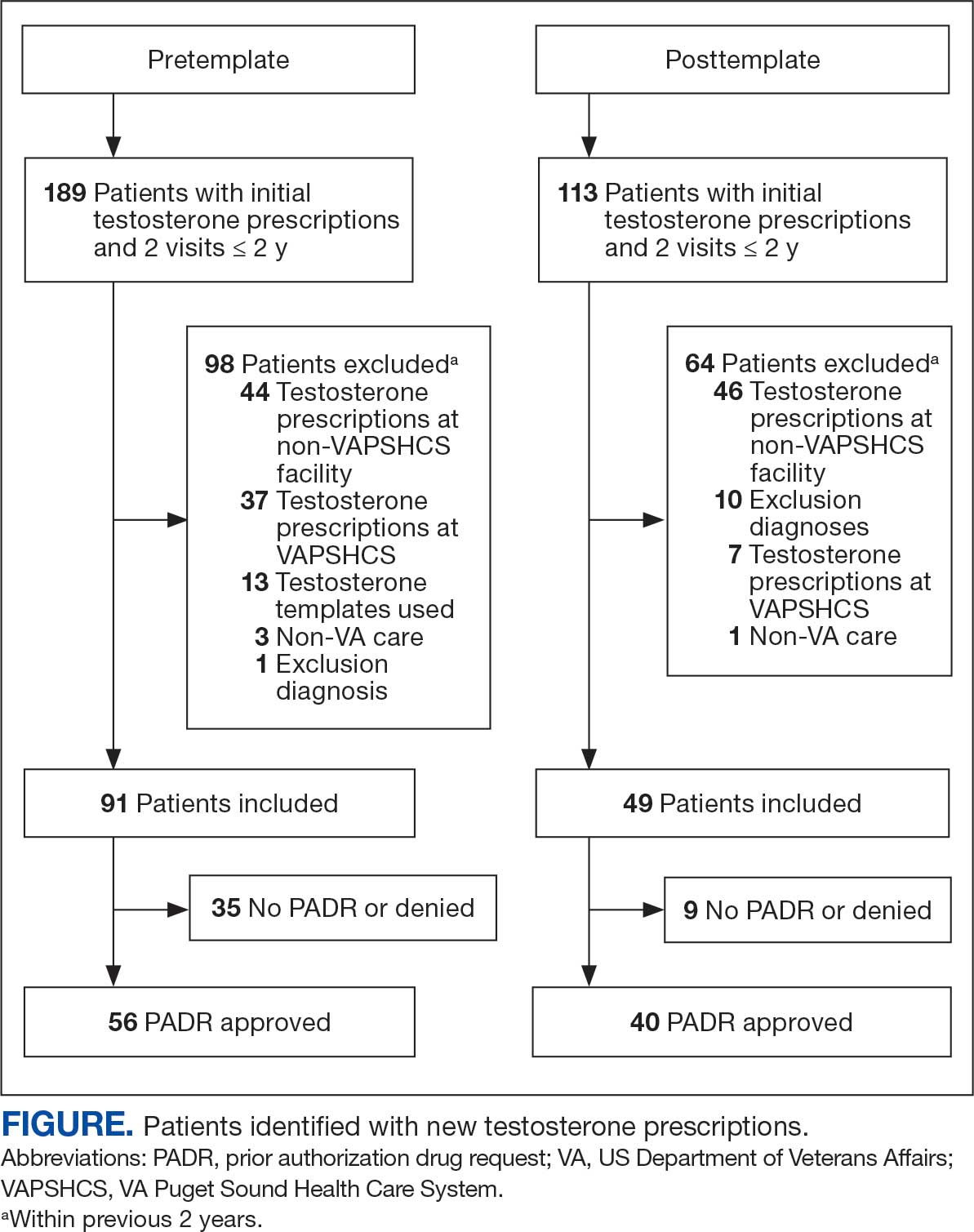

At presentation to our institution, the patient had widespread erythematous patches studded with pustules located on the arms, legs, and flexural areas as well as plaques of psoriasis involving approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Furthermore, the patient was noted to have large noninflammatory bullae along the legs. The new eruption occurred on areas that were both treated and spared from the tapinarof cream 1%. Laboratory evaluation showed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 15.9×103/µL [reference range, 4.0-11.0×103/µL]; absolute neutrophil count, 10.3×103/µL [reference range, 1.5-8.0×103/µL]), absolute eosinophilia (1930/µL [reference range, 0-0.5×103/µL]), hypocalcemia (8.4 mg/dL [reference range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL]), and a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L [reference range, 10-40 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU/L [reference range, 7-56 U/L]). Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules and mixed dermal inflammation containing eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence revealed mild granular staining of C3 at the basement membrane zone.

The patient was started on 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 20 days, and he rapidly improved. Alanine aminotransferase levels peaked at 120 IU/L 2 weeks later. At that time, he had complete resolution of the original eruption and was transitioned to topical steroids for continued management of the psoriasis (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis for our patient included AGEP, generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), miliaria pustulosa, generalized cutaneous candidiasis, exuberant allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Based on the clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and histopathologic evaluation, we made the diagnosis of AGEP secondary to tapinarof with systemic absorption. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis has been reported with topical use of morphine and diphenhydramine, among other agents.4,5 To our knowledge, AGEP due to tapinarof cream 1% has not been reported. In the original clinical trials of tapinarof, folliculitis was contained to sites of application.2 Our patient developed pustules at sites distant to areas of application, as well as systemic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, indicating a systemic reaction. It can be difficult to distinguish AGEP clinically and histologically from GPP. Both conditions can manifest with fever, hypocalcemia, and sterile pustules on a background of erythema that favors intertriginous areas.6 Infection, rapid oral steroid withdrawal, pregnancy, and rarely oral medications have been reported causes of GPP.6 Our patient did not have any of these exposures. There is overlap in the histology of AGEP and GPP. One retrospective series compared histologic samples to help distinguish these 2 entities. Reliable markers that favored AGEP over GPP included eosinophilic spongiosis, interface dermatitis, and dermal eosinophilia (>2/mm2).7 In contrast, the presence of CD161 positivity in the dermis with at least 10 cells favored a diagnosis of GPP.7 In our case, the presence of spongiosis with eosinophils in the dermis favored a diagnosis of AGEP over GPP.

Miliaria pustulosa is a benign condition caused by the occlusion of the epidermal portion of eccrine glands related to either high fever or hot and humid environmental conditions. While it can be present in intertriginous areas like AGEP, miliaria pustulosa can be seen extensively on the back, most commonly in immobile hospitalized patients.8 Generalized cutaneous candidiasis usually is caused by the yeast Candida albicans and can take on multiple morphologies, including folliculitis.9 The eruption may be disseminated but often is accentuated in intertriginous areas and the anogenital folds. Predisposing factors include immunosuppression, endocrinopathies, recent use of systemic antibiotics or steroids, chemotherapy, and indwelling catheters.9 Outside of recent antibiotic use, our patient did not have any risk factors for miliaria pustulosa, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Given the presence of overlapping bullae along the lower extremities, an exuberant ACD and LABD were considered. Bullae formation can occur in ACD secondary to robust inflammation and edema leading to acantholysis.10 While a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to topical tapinarof cream 1% was considered given that the patient used the medication for approximately 1 month prior to the onset of symptoms, it would be unlikely for ACD to present with a concomitant pustular eruption. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune blistering disease in which antibodies target bullous pemphigoid antigen 2, and there is characteristically linear deposition of IgA at the dermal-epidermal junction that leads to subepidermal blistering.11 This often manifests clinically as widespread tense vesicles in an annular or string-of-pearls appearance. However, morphologies can vary, and large bullae may be seen. In adults, LABD typically is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or medications, notably vancomycin.11,12 Our patient did not have any of these predisposing factors, and his biopsy for direct immunofluorescence did not reveal the classic pattern described above.

Interestingly, there have been reports in the literature of bullous AGEP in the setting of oral anti-infectives. One report described a 62-year-old woman who developed widespread nonfollicular pustules with multiple tense serous blisters 24 hours after taking oral terbinafine.13 Another case described an 80-year-old woman with a similar presentation following a course of ciprofloxacin (although the timeline of medication administration was not described).14 In this case, patch testing to the culprit medication reproduced the response.14 In both cases, a biopsy revealed subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules with marked dermal edema.13,14 As previously described, spongiosis is a common feature of AGEP. We hypothesize that, similar to these reports, our patient had a robust inflammatory response leading to spongiosis, acantholysis, and blister formation secondary to AGEP.

Dermatologists should be aware of this case of AGEP secondary to tapinarof cream 1%, as reports in the literature are rare and it is a reminder that topical medications can cause serious systemic reactions.

To the Editor:

For many years, topical treatment of plaque psoriasis was limited to steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar products, and anthralin. In recent years, 2 new nonsteroidal treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action, roflumilast 0.3% and tapinarof 1%, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.1 Roflumilast 0.3%, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, was shown in phase 3 clinical trials to reach an Investigator Global Assessment response of 37.5% to 42.2% in 8 weeks using once-daily application with minimal cutaneous adverse effects.1 Furthermore, it has demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas in subset analyses.1 Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation by downregulating IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23.1 In phase 3 clinical trials, 35% to 40% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated improvement in psoriasis compared with 6% who used the vehicle alone.2 In these studies, 18% to 24% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% experienced folliculitis.2

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a nonfollicular pustular drug reaction with systemic symptoms that typically occurs within 2 weeks of exposure to an inciting medication. Systemic antibiotics are the most commonly reported cause of AGEP.3 There are few reports in the literature of AGEP induced by topical agents.4,5 We report a case of AGEP in a young man following the use of tapinarof cream 1%.

A 23-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to the emergency department with fever and a pustular rash. One week prior to presentation, he developed a pustular eruption around plaques of psoriasis on the arms and legs. The patient had been prescribed tapinarof cream 1% by an outside dermatologist and was applying the medication to the affected areas once daily for 1 month prior to onset of symptoms. He discontinued tapinarof a few days prior to the eruption starting, but the rash progressed centrifugally and was associated with fevers and fatigue despite treatment with a brief course of empiric cephalexin prescribed by his primary care provider.

At presentation to our institution, the patient had widespread erythematous patches studded with pustules located on the arms, legs, and flexural areas as well as plaques of psoriasis involving approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Furthermore, the patient was noted to have large noninflammatory bullae along the legs. The new eruption occurred on areas that were both treated and spared from the tapinarof cream 1%. Laboratory evaluation showed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 15.9×103/µL [reference range, 4.0-11.0×103/µL]; absolute neutrophil count, 10.3×103/µL [reference range, 1.5-8.0×103/µL]), absolute eosinophilia (1930/µL [reference range, 0-0.5×103/µL]), hypocalcemia (8.4 mg/dL [reference range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL]), and a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L [reference range, 10-40 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU/L [reference range, 7-56 U/L]). Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules and mixed dermal inflammation containing eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence revealed mild granular staining of C3 at the basement membrane zone.

The patient was started on 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 20 days, and he rapidly improved. Alanine aminotransferase levels peaked at 120 IU/L 2 weeks later. At that time, he had complete resolution of the original eruption and was transitioned to topical steroids for continued management of the psoriasis (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis for our patient included AGEP, generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), miliaria pustulosa, generalized cutaneous candidiasis, exuberant allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Based on the clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and histopathologic evaluation, we made the diagnosis of AGEP secondary to tapinarof with systemic absorption. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis has been reported with topical use of morphine and diphenhydramine, among other agents.4,5 To our knowledge, AGEP due to tapinarof cream 1% has not been reported. In the original clinical trials of tapinarof, folliculitis was contained to sites of application.2 Our patient developed pustules at sites distant to areas of application, as well as systemic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, indicating a systemic reaction. It can be difficult to distinguish AGEP clinically and histologically from GPP. Both conditions can manifest with fever, hypocalcemia, and sterile pustules on a background of erythema that favors intertriginous areas.6 Infection, rapid oral steroid withdrawal, pregnancy, and rarely oral medications have been reported causes of GPP.6 Our patient did not have any of these exposures. There is overlap in the histology of AGEP and GPP. One retrospective series compared histologic samples to help distinguish these 2 entities. Reliable markers that favored AGEP over GPP included eosinophilic spongiosis, interface dermatitis, and dermal eosinophilia (>2/mm2).7 In contrast, the presence of CD161 positivity in the dermis with at least 10 cells favored a diagnosis of GPP.7 In our case, the presence of spongiosis with eosinophils in the dermis favored a diagnosis of AGEP over GPP.

Miliaria pustulosa is a benign condition caused by the occlusion of the epidermal portion of eccrine glands related to either high fever or hot and humid environmental conditions. While it can be present in intertriginous areas like AGEP, miliaria pustulosa can be seen extensively on the back, most commonly in immobile hospitalized patients.8 Generalized cutaneous candidiasis usually is caused by the yeast Candida albicans and can take on multiple morphologies, including folliculitis.9 The eruption may be disseminated but often is accentuated in intertriginous areas and the anogenital folds. Predisposing factors include immunosuppression, endocrinopathies, recent use of systemic antibiotics or steroids, chemotherapy, and indwelling catheters.9 Outside of recent antibiotic use, our patient did not have any risk factors for miliaria pustulosa, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Given the presence of overlapping bullae along the lower extremities, an exuberant ACD and LABD were considered. Bullae formation can occur in ACD secondary to robust inflammation and edema leading to acantholysis.10 While a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to topical tapinarof cream 1% was considered given that the patient used the medication for approximately 1 month prior to the onset of symptoms, it would be unlikely for ACD to present with a concomitant pustular eruption. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune blistering disease in which antibodies target bullous pemphigoid antigen 2, and there is characteristically linear deposition of IgA at the dermal-epidermal junction that leads to subepidermal blistering.11 This often manifests clinically as widespread tense vesicles in an annular or string-of-pearls appearance. However, morphologies can vary, and large bullae may be seen. In adults, LABD typically is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or medications, notably vancomycin.11,12 Our patient did not have any of these predisposing factors, and his biopsy for direct immunofluorescence did not reveal the classic pattern described above.

Interestingly, there have been reports in the literature of bullous AGEP in the setting of oral anti-infectives. One report described a 62-year-old woman who developed widespread nonfollicular pustules with multiple tense serous blisters 24 hours after taking oral terbinafine.13 Another case described an 80-year-old woman with a similar presentation following a course of ciprofloxacin (although the timeline of medication administration was not described).14 In this case, patch testing to the culprit medication reproduced the response.14 In both cases, a biopsy revealed subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules with marked dermal edema.13,14 As previously described, spongiosis is a common feature of AGEP. We hypothesize that, similar to these reports, our patient had a robust inflammatory response leading to spongiosis, acantholysis, and blister formation secondary to AGEP.

Dermatologists should be aware of this case of AGEP secondary to tapinarof cream 1%, as reports in the literature are rare and it is a reminder that topical medications can cause serious systemic reactions.

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017

- Ghazawi FM, Colantonio S, Bradshaw S, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical morphine and confirmed by patch testing. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E22-E23. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000573

- Hanafusa T, Igawa K, Azukizawa H, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical diphenhydramine. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:994-995. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1500

- Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, Lee EB, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations,diagnosis, and treatment. Cutis. 2022;110:19-25. doi:10.12788/cutis.0579

- Isom J, Braswell DS, Siroy A, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features differentiating acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and pustular psoriasis: a retrospective series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:265-267. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.015

- Fealey RD, Hebert AA. Disorders of the eccrine sweat glands and sweating. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine.8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:946.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Marchiony Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1329-1363.

- Elmas ÖF, Akdeniz N, Atasoy M, et al. Contact dermatitis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:176-192. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.003

- Hull CM, Zone JZ. Dermatitis herpetiforms and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- Yamagami J, Nakamura Y, Nagao K, et al. Vancomycin mediates IgA autoreactivity in drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1473-1480.

- Bullous acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to oral terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:P115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.468

- Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology. 2005;211:277-280. doi:10.1159/000087024

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017

- Ghazawi FM, Colantonio S, Bradshaw S, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical morphine and confirmed by patch testing. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E22-E23. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000573

- Hanafusa T, Igawa K, Azukizawa H, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical diphenhydramine. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:994-995. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1500

- Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, Lee EB, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations,diagnosis, and treatment. Cutis. 2022;110:19-25. doi:10.12788/cutis.0579

- Isom J, Braswell DS, Siroy A, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features differentiating acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and pustular psoriasis: a retrospective series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:265-267. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.015

- Fealey RD, Hebert AA. Disorders of the eccrine sweat glands and sweating. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine.8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:946.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Marchiony Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1329-1363.

- Elmas ÖF, Akdeniz N, Atasoy M, et al. Contact dermatitis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:176-192. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.003

- Hull CM, Zone JZ. Dermatitis herpetiforms and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- Yamagami J, Nakamura Y, Nagao K, et al. Vancomycin mediates IgA autoreactivity in drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1473-1480.

- Bullous acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to oral terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:P115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.468

- Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology. 2005;211:277-280. doi:10.1159/000087024

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

PRACTICE POINTS

- Tapinarof cream 1% can be absorbed systemically and cause acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP).

- Clinical configuration and histology can be useful to distinguish AGEP from mimickers.

- Topical application of drugs in general, particularly over large body surface areas, may lead to systemic drug eruptions.

Longitudinal Erythronychia Manifesting With Pain and Cold Sensitivity

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma

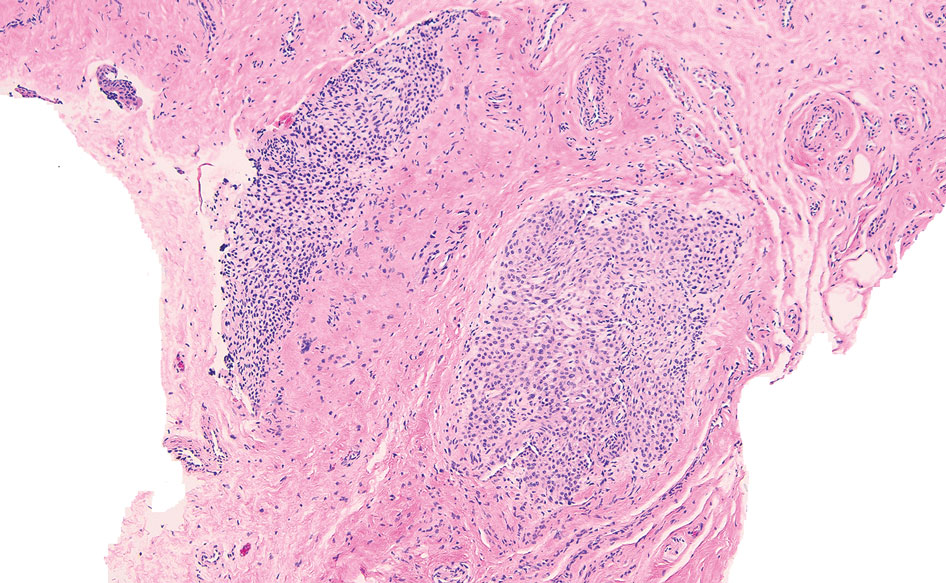

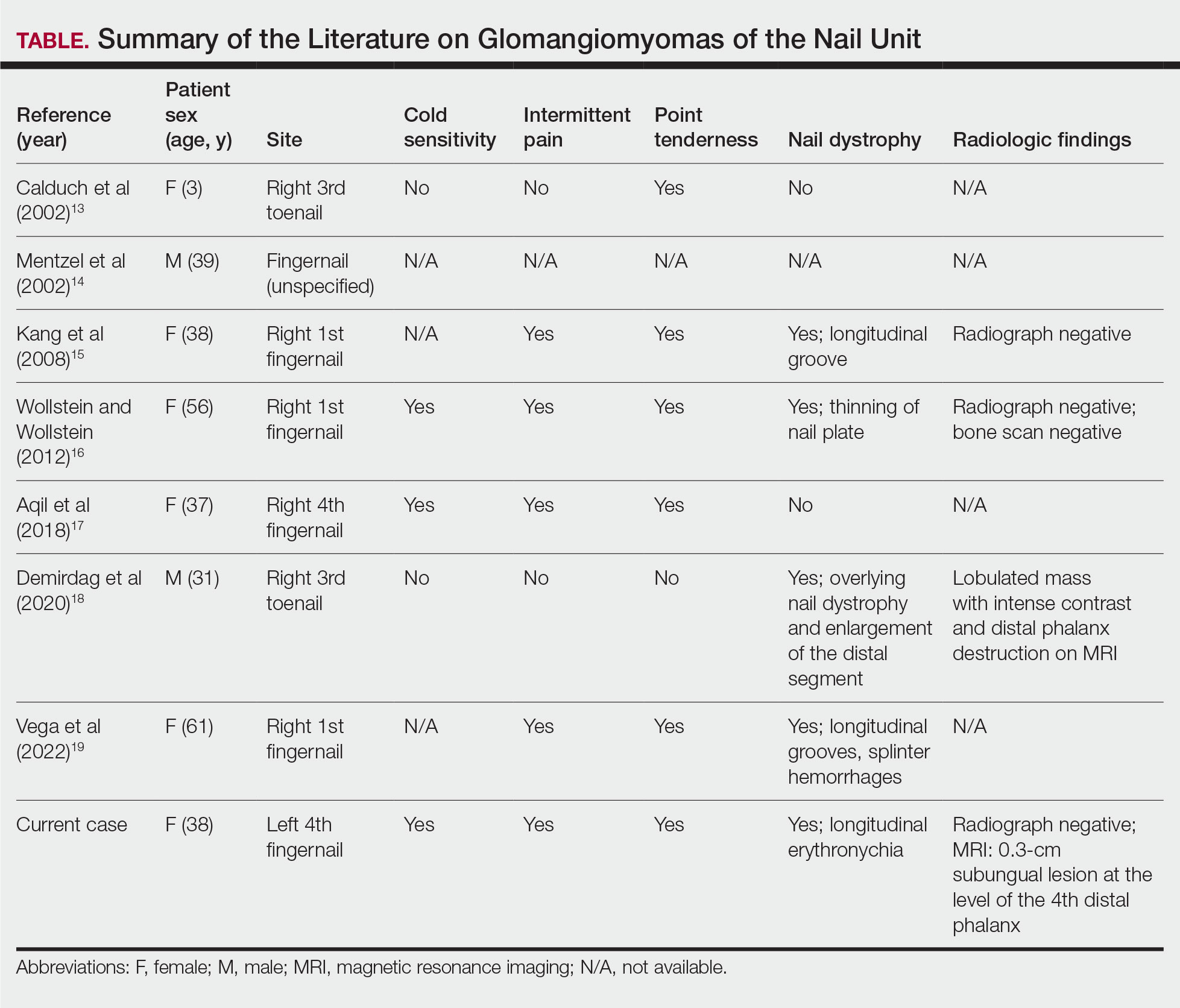

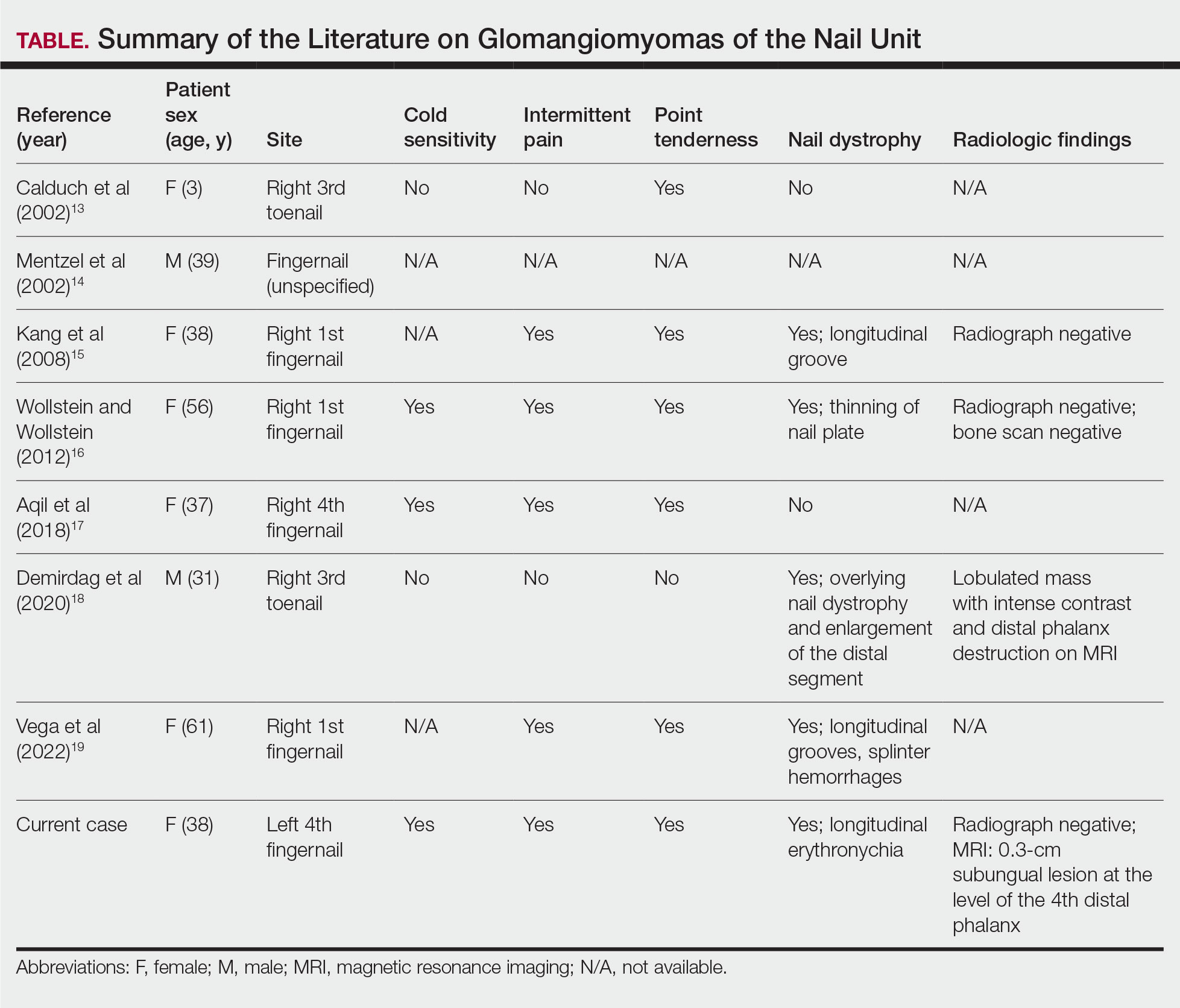

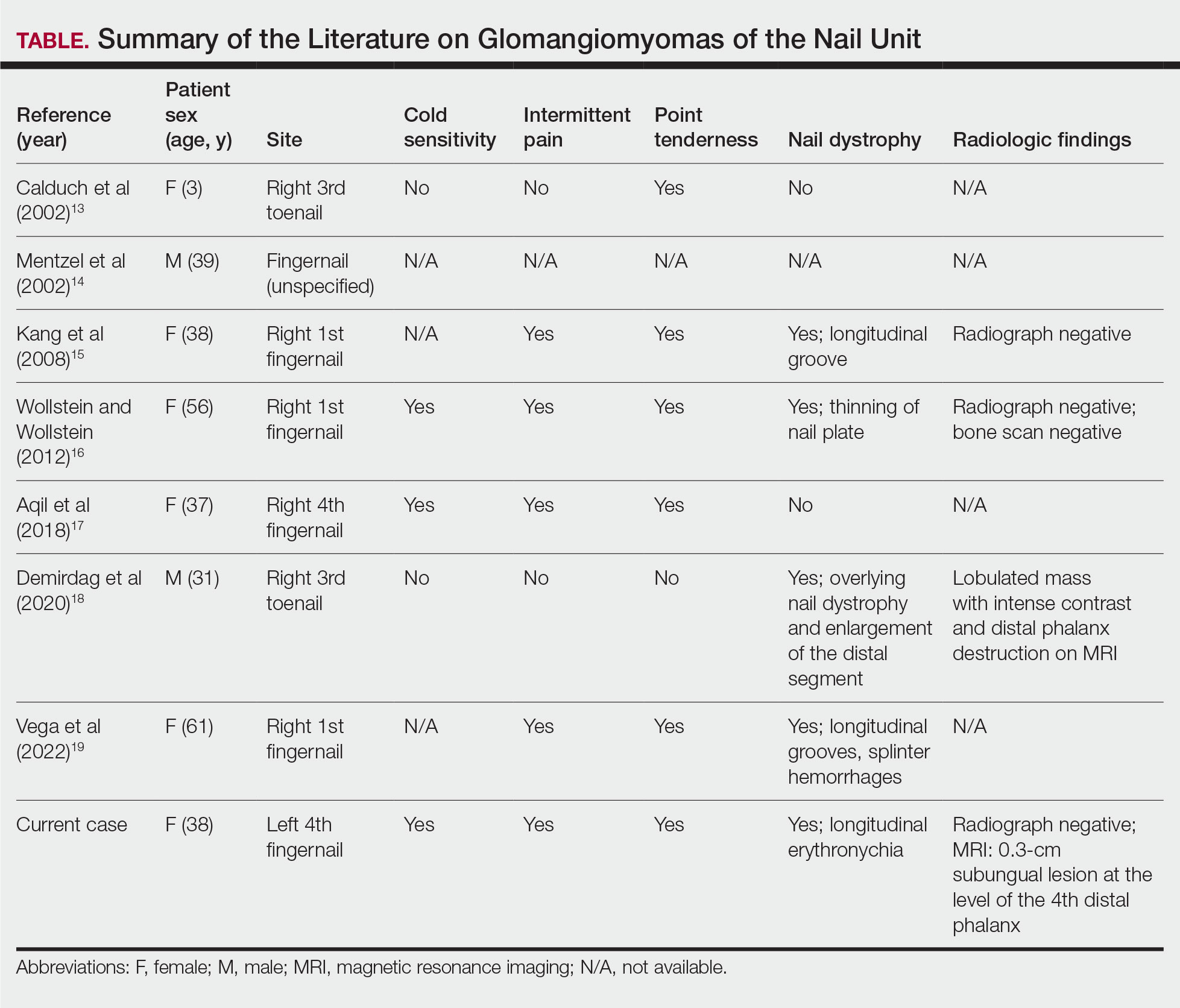

The nail unit excision specimen showed collections of cuboidal cells and spindled cells within the corium that were consistent with a diagnosis of a glomangiomyoma, a rare glomus tumor variant (Figure). Glomus tumors are benign neoplasms comprising glomus bodies, which are arteriovenous anastomoses involved in thermoregulation.1 They develop in areas densely populated by glomus bodies, including the fingers, toes, and subungual areas. Glomus tumors most commonly develop in middle-aged women.2 Clinically, they manifest with a characteristic triad of intense pain, point tenderness, and cold sensitivity and may appear as reddish-pink or blue macules under the nail plate and/or longitudinal erythronychia.2-6 The presence of multiple glomus tumors is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.7

Advanced imaging including ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help confirm the diagnosis but may not be cost effective, as excision with histopathology is needed to relieve symptoms and render a definitive diagnosis. Radiography is highly insensitive in identifying bone erosions associated with glomus tumors.8 With ultrasonography, glomus tumors appear hypoechoic; with Doppler ultrasonography, they appear hypervascular. With MRI, glomus tumors appear as well-defined nodular lesions with hypointense signal intensity on T1-weighted sequence and hyperintense signal intensity on T2-weighted sequence, with strong enhancement using gadolinium-based contrast.9,10 On histopathology, a glomus tumor appears as a nodular tumor with sheets of oval-nucleated cells arranged in multicellular layers surrounding blood vessels and are immunoreactive for α-smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and type IV collagen.11,12

There are several glomus tumor variants. The most common is a solid glomus tumor, which predominantly is composed of glomus cells, followed by glomangioma, which mainly is composed of blood vessels. Glomangiomyoma, which mostly is composed of smooth muscle cells, is the rarest variant.13

While glomus tumors are common in the subungual areas, it is an uncommon location for glomangiomyomas, which have been reported in the nail unit in only 7 prior case reports identified through searches of PubMed and Google Scholar using the terms glomangiomyoma, glomangiomyoma nail, and subungual glomangiomyoma (Table).13-19 Glomangiomyomas more commonly are described in solid organs, including the stomach, kidney, pancreas, and bladder.16 The mean age of patients with subungual glomangiomyomas, including our patient, was 40.4 years (range, 3-61 years), with the majority being female (75.0% [6/8]). Most patients presented with fingernail involvement (75.0% [6/8]), nail dystrophy (eg, nail plate thinning, longitudinal grooves, splinter hemorrhages, longitudinal erythronychia)(62.5% [5/8]), and intermittent pain and/or point tenderness in the affected nail (75.0% [6/8]).13-19 Notably, only our patient had longitudinal erythronychia as a clinical feature, and only one other case described MRI findings, which included a lobulated mass with intense contrast and distal phalanx destruction.18 One patient was a 3-year-old girl with a family history of generalized multiple glomangiomyomas. Although subungual glomangiomyoma was not confirmed on histopathology, the diagnosis in this patient was presumed based on her family history.13 On histopathology, glomangiomyomas are composed of oval-nucleated cells surrounding blood vessels. These oval-nucleated cells then gradually transition to smooth muscle cells.20

A myxoid cyst is composed of a pseudocyst, which lacks a cyst lining, and is a result of synovial fluid from the distal interphalangeal joint entering the pseudocyst space.2 It typically manifests with a longitudinal groove in the nail plate. A flesh-colored nodule may be appreciated between the cuticle and the distal interphalangeal joint.2 The depth of the longitudinal groove may vary depending on the volume of synovial fluid within the myxoid cyst.21 In a series of 35 cases of subungual myxoid cysts, none manifested with longitudinal erythronychia. Due to their composition, myxoid cysts can be distinguished easily from solid tumors of the nail unit via transillumination.22 Pain is a much less common with myxoid cysts vs glomus tumors, as the filling of the pseudocyst space with synovial fluid typically is gradual, allowing the surrounding tissue to accommodate and adapt over time.21 In equivocal cases, MRI or high-resolution ultrasonography may be used to distinguish myxoid cysts and glomus tumors.8 Histopathology shows accumulation of mucin in the dermis with surrounding fibrous stroma.23

Subungual neuromas are painful benign tumors that develop due to disorganized neural proliferation following disruption to peripheral nerves secondary to trauma or surgery. In 3 case reports, subungual neuromas manifested as painful subungual nodules, with proximal nail plate ridging, or onycholysis.24-26 Since neuromas have only rarely been described in the subungual region, reports of MRI and ultrasonography findings are unknown. Histopathology is needed to distinguish neuromas from glomus tumors. Histopathology shows an acapsular structure consisting of disorganized spindle-cell proliferation and nerve fibers arranged in a tangle of fascicles within fibrotic tissue.25 On immunochemistry, spindle cells typically are positive for cellular antigen protein S100.26

Leiomyomas are benign neoplasms derived from smooth muscle, typically localized to the uterus or gastrointestinal tract, and have been described rarely in the nail unit.27,28 It is hypothesized that subungual leiomyomas originate from the vascular smooth muscle in the subcutaneous layer of the nail unit.28 Like glomus tumors, leiomyomas of the subungual region often manifest with pain and longitudinal erythronychia.27-30 Subungual leiomyomas may be distinguished from glomus tumors via advanced imaging techniques, including ultrasonography and MRI. Cutaneous leiomyomas have been described with mild to moderate internal low flow vascularity on Doppler ultrasonography, while glomus tumors typically reveal high internal vascularity.28 Biopsy with histopathology is needed for definitive diagnosis. On histopathology, leiomyomas demonstrate bland-appearing spindle-shaped cells with elongated nuclei arranged in fascicles.27 They typically are positive for α-smooth muscle actin and caldesmon on immunostaining.

Eccrine spiradenomas are benign adnexal tumors likely of apocrine origin with limited case reports in the literature.31,32 Clinically, eccrine spiradenomas involving the nail unit may manifest with longitudinal nail splitting of the nail or as a papule on the proximal nail fold, with associated tenderness.31,32 In a report of a 50-year-old woman with a histopathologically confirmed eccrine spiradenoma manifesting with longitudinal splitting of the nail and pain in the proximal nail fold, the mass appeared hypoechoic on ultrasonography with increased intramass vascularity on Doppler, while MRI showed an intensely enhancing lesion.31 These imaging features, combined with a classically manifesting feature of pain, make eccrine spiradenomas difficult to distinguish from glomus tumors; therefore, histopathologic examination can provide a definitive diagnosis, and surgical excision is used for treatment.31 On histopathology, these tumors are well circumscribed and composed of both small dark basaloid cells with peripheral compact nuclei and larger cells with central pale nuclei, which may be arranged in tubules.31,32

- Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132: 1448-1452. doi:10.5858/2008-132-1448-gt

- Hare AQ, Rich P. Nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:281-292. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.007

- Hazani R, Houle JM, Kasdan ML, et al. Glomus tumors of the hand. Eplasty. 2008;8:E48.

- Hwang JK, Lipner SR. Blue nail discoloration: literature review and diagnostic algorithms. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:419-441. doi:10.1007/s40257-023-00768-6

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Longitudinal erythronychia of the fingernail. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1271-1272. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2747

- Jellinek NJ, Lipner SR. Longitudinal erythronychia: retrospective single-center study evaluating differential diagnosis and the likelihood of malignancy. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:310-319. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000000594

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Subungual glomus tumors: underrecognized clinical findings in neurofibromatosis 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E269. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.129

- Dhami A, Vale SM, Richardson ML, et al. Comparing ultrasound with magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of subungual glomus tumors and subungual myxoid cysts. Skin Appendage Disord. 2023;9:262-267. doi:10.1159/000530397

- Baek HJ, Lee SJ, Cho KH, et al. Subungual tumors: clinicopathologic correlation with US and MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2010;30:1621-1636. doi:10.1148/rg.306105514

- Patel T, Meena V, Meena P. Hand and foot glomus tumors: significance of MRI diagnosis followed by histopathological assessment. Cureus. 2022;14:E30038. doi:10.7759/cureus.30038

- Mravic M, LaChaud G, Nguyen A, et al. Clinical and histopathological diagnosis of glomus tumor: an institutional experience of 138 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23:181-188. doi:10.1177/1066896914567330

- Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1-12. doi:10.1097/00000478-200101000-00001

- Calduch L, Monteagudo C, Martínez-Ruiz E, et al. Familial generalized multiple glomangiomyoma: report of a new family, with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:402-408. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00114.x

- Mentzel T, Hügel H, Kutzner H. CD34-positive glomus tumor: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of six cases with myxoid stromal changes. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:421-425. doi:10.1034 /j.1600-0560.2002.290706.x

- Kang TW, Lee KH, Park CJ. A case of subungual glomangiomyoma with myxoid stromal change. Korean J Dermatol. 2008;46:550-553.

- Wollstein A, Wollstein R. Subungual glomangiomyoma—a case report. Hand Surg. 2012;17:271-273. doi:10.1142/S021881041272032X

- Aqil N, Gallouj S, Moustaide K, et al. Painful tumors in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:319. doi:10.1186/s13256-018-1847-0

- Demirdag HG, Akay BN, Kirmizi A, et al. Subungual glomangiomyoma. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2020;110:Article_13. doi:10.7547/19-051

- Vega SML, Ruiz SJA, Ramírez CS, et al. Subungual glomangiomyoma: a case report. Dermatol Cosmet Med Quir. 2022;20:258-262.

- Chalise S, Jha A, Neupane PR. Glomangiomyoma of uncertain malignant potential in the urinary bladder: a case report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2021;59:719-722. doi:10.31729/jnma.5388

- de Berker D, Goettman S, Baran R. Subungual myxoid cysts: clinical manifestations and response to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:394-398. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.119652

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Transillumination for improved diagnosis of digital myxoid cysts. Cutis. 2020;105:82.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M. Mucin as a diagnostic clue in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1005-1016. doi:10.1111/cup.12782

- Choi R, Kim SR, Glusac EJ, et al. Subungual neuroma masquerading as green nail syndrome. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;20:17-19. doi:10.1016 /j.jdcr.2021.11.025

- Rashid RM, Rashid RM, Thomas V. Subungal traumatic neuroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E7-E8. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.028

- Whitehouse HJ, Urwin R, Stables G. Traumatic subungual neuroma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:65-66. doi:10.1111/ced.13247

- Lipner SR, Ko D, Husain S. Subungual leiyomyoma presenting as erythronychia: case report and review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:465-467.

- Taleb E, Saldías C, Gonzalez S, et al. Sonographic characteristics of leiomyomatous tumors of skin and nail: a case series. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022;12:e2022082. doi:10.5826/dpc.1203a82

- Baran R, Requena L, Drapé JL. Subungual angioleiomyoma masquerading as a glomus tumour. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1239-1241. doi:10.1046/ j.1365-2133.2000.03560.x

- Watabe D, Sakurai E, Mori S, et al. Subungual angioleiomyoma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:74-75. doi:10.4103/0378-6323 .185045

- Jha AK, Sinha R, Kumar A, et al. Spiradenoma causing longitudinal splitting of the nail. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:754-756. doi:10.1111 /ced.12886

- Leach BC, Graham BS. Papular lesion of the proximal nail fold. eccrine spiradenoma. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1003-1008. doi:10.1001 /archderm.140.8.1003-a

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma