User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Obama 2015 budget would extend Medicaid pay bump

Primary care physicians would continue to see higher payments for treating Medicaid patients through the end of 2015, under President Obama’s proposed budget for the upcoming fiscal year.

The budget request submitted to Congress March 4 includes $5.4 billion to extend the Affordable Care Act provisions that pay physicians at the higher Medicare levels for providing certain primary care services to Medicaid patients. The ACA sunsets the pay increase at the end of 2014.

Under the budget proposal, nurse practitioners and physician assistants also would be eligible for the higher payment rates.

"Allowing [the higher rates] to expire would result in a deep, across-the-board cut to primary care physicians who are taking care of the most vulnerable populations, at a time when millions more are becoming eligible for Medicaid," Dr. Molly Cooke, president of the American College of Physicians (ACP), said in a statement. ACP is urging Congress to go further and fund the program for at least 2 more years.

The $1 trillion budget proposed for the Health and Human Services (HHS) department includes $77.1 billion in discretionary spending, down $1.3 billion from 2014. The proposal includes investments in the primary care workforce, expanded mental health services, and continued implementation of the ACA insurance marketplaces.

The president’s budget also calls for Medicare cuts that would save the government more than $400 billion over 10 years. The cost-saving measures, which have been proposed in previous budgets, include reduction in Medicare coverage of hospitals’ bad debts; reductions to indirect graduate medical education payments; payment cuts to critical access hospitals; and payment cuts for inpatient rehabilitation facilities, long-term care hospitals, and home health agencies. In addition, the budget would introduce readmission penalties for skilled nursing facilities and strengthen the controversial Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB).

As have previous budget requests, the fiscal 2015 proposal would require the IPAB to recommend cost-cutting targets to Congress if the Medicare growth rate exceeds gross domestic product plus 0.5 percentage points. Current law sets that level at GDP plus 1 percentage point.

The 2015 budget proposal would increase investment in the primary care workforce. It requests more than $5 billion over the next decade to train 13,000 new residents as part of a new competitive grant program available to teaching hospitals, children’s hospitals, and community-based consortia of teaching hospitals or other health care institutions. In 2015, the program would provide $100 million for pediatric residents in children’s hospitals.

The budget also beefs up funding for the National Health Service Corps. It includes nearly $4 billion in new funding over 6 years to increase the number of health providers in rural areas and federally funded health centers to 15,000. And it would invest $4.6 billion in community health centers in 2015 and another $8.1 billion for the next 3 years.

For mental health services, the budget includes $55 million for Project AWARE, which encourages community and school officials to work together to keep schools safe, refer students to mental health services, and provide mental health "first aid" training so that teachers can detect early signs of mental illness.

The budget request includes $50 million to train about 5,000 new mental health professionals, $20 million to help young adults aged 16-25 years navigate behavioral health services, and $5 million to change attitudes about people who have behavioral health needs in the workplace.

The budget also provides funding for a demonstration project in Medicaid to help reduce the use of psychotropic medications prescribed to children in foster care by improving access to other mental health services.

The release of the president’s budget request comes just weeks before the end of open enrollment in private health plans through the ACA’s marketplaces. The budget includes $1.8 billion in funding for 2015 to cover the cost of running the federally facilitated marketplace. However, most of the funding – $1.2 billion – would be covered by user fees from health plans in the marketplaces. If Congress fails to provide the remaining funds, HHS officials said they could transfer monies from other agency accounts to cover marketplace costs.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Primary care physicians would continue to see higher payments for treating Medicaid patients through the end of 2015, under President Obama’s proposed budget for the upcoming fiscal year.

The budget request submitted to Congress March 4 includes $5.4 billion to extend the Affordable Care Act provisions that pay physicians at the higher Medicare levels for providing certain primary care services to Medicaid patients. The ACA sunsets the pay increase at the end of 2014.

Under the budget proposal, nurse practitioners and physician assistants also would be eligible for the higher payment rates.

"Allowing [the higher rates] to expire would result in a deep, across-the-board cut to primary care physicians who are taking care of the most vulnerable populations, at a time when millions more are becoming eligible for Medicaid," Dr. Molly Cooke, president of the American College of Physicians (ACP), said in a statement. ACP is urging Congress to go further and fund the program for at least 2 more years.

The $1 trillion budget proposed for the Health and Human Services (HHS) department includes $77.1 billion in discretionary spending, down $1.3 billion from 2014. The proposal includes investments in the primary care workforce, expanded mental health services, and continued implementation of the ACA insurance marketplaces.

The president’s budget also calls for Medicare cuts that would save the government more than $400 billion over 10 years. The cost-saving measures, which have been proposed in previous budgets, include reduction in Medicare coverage of hospitals’ bad debts; reductions to indirect graduate medical education payments; payment cuts to critical access hospitals; and payment cuts for inpatient rehabilitation facilities, long-term care hospitals, and home health agencies. In addition, the budget would introduce readmission penalties for skilled nursing facilities and strengthen the controversial Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB).

As have previous budget requests, the fiscal 2015 proposal would require the IPAB to recommend cost-cutting targets to Congress if the Medicare growth rate exceeds gross domestic product plus 0.5 percentage points. Current law sets that level at GDP plus 1 percentage point.

The 2015 budget proposal would increase investment in the primary care workforce. It requests more than $5 billion over the next decade to train 13,000 new residents as part of a new competitive grant program available to teaching hospitals, children’s hospitals, and community-based consortia of teaching hospitals or other health care institutions. In 2015, the program would provide $100 million for pediatric residents in children’s hospitals.

The budget also beefs up funding for the National Health Service Corps. It includes nearly $4 billion in new funding over 6 years to increase the number of health providers in rural areas and federally funded health centers to 15,000. And it would invest $4.6 billion in community health centers in 2015 and another $8.1 billion for the next 3 years.

For mental health services, the budget includes $55 million for Project AWARE, which encourages community and school officials to work together to keep schools safe, refer students to mental health services, and provide mental health "first aid" training so that teachers can detect early signs of mental illness.

The budget request includes $50 million to train about 5,000 new mental health professionals, $20 million to help young adults aged 16-25 years navigate behavioral health services, and $5 million to change attitudes about people who have behavioral health needs in the workplace.

The budget also provides funding for a demonstration project in Medicaid to help reduce the use of psychotropic medications prescribed to children in foster care by improving access to other mental health services.

The release of the president’s budget request comes just weeks before the end of open enrollment in private health plans through the ACA’s marketplaces. The budget includes $1.8 billion in funding for 2015 to cover the cost of running the federally facilitated marketplace. However, most of the funding – $1.2 billion – would be covered by user fees from health plans in the marketplaces. If Congress fails to provide the remaining funds, HHS officials said they could transfer monies from other agency accounts to cover marketplace costs.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Primary care physicians would continue to see higher payments for treating Medicaid patients through the end of 2015, under President Obama’s proposed budget for the upcoming fiscal year.

The budget request submitted to Congress March 4 includes $5.4 billion to extend the Affordable Care Act provisions that pay physicians at the higher Medicare levels for providing certain primary care services to Medicaid patients. The ACA sunsets the pay increase at the end of 2014.

Under the budget proposal, nurse practitioners and physician assistants also would be eligible for the higher payment rates.

"Allowing [the higher rates] to expire would result in a deep, across-the-board cut to primary care physicians who are taking care of the most vulnerable populations, at a time when millions more are becoming eligible for Medicaid," Dr. Molly Cooke, president of the American College of Physicians (ACP), said in a statement. ACP is urging Congress to go further and fund the program for at least 2 more years.

The $1 trillion budget proposed for the Health and Human Services (HHS) department includes $77.1 billion in discretionary spending, down $1.3 billion from 2014. The proposal includes investments in the primary care workforce, expanded mental health services, and continued implementation of the ACA insurance marketplaces.

The president’s budget also calls for Medicare cuts that would save the government more than $400 billion over 10 years. The cost-saving measures, which have been proposed in previous budgets, include reduction in Medicare coverage of hospitals’ bad debts; reductions to indirect graduate medical education payments; payment cuts to critical access hospitals; and payment cuts for inpatient rehabilitation facilities, long-term care hospitals, and home health agencies. In addition, the budget would introduce readmission penalties for skilled nursing facilities and strengthen the controversial Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB).

As have previous budget requests, the fiscal 2015 proposal would require the IPAB to recommend cost-cutting targets to Congress if the Medicare growth rate exceeds gross domestic product plus 0.5 percentage points. Current law sets that level at GDP plus 1 percentage point.

The 2015 budget proposal would increase investment in the primary care workforce. It requests more than $5 billion over the next decade to train 13,000 new residents as part of a new competitive grant program available to teaching hospitals, children’s hospitals, and community-based consortia of teaching hospitals or other health care institutions. In 2015, the program would provide $100 million for pediatric residents in children’s hospitals.

The budget also beefs up funding for the National Health Service Corps. It includes nearly $4 billion in new funding over 6 years to increase the number of health providers in rural areas and federally funded health centers to 15,000. And it would invest $4.6 billion in community health centers in 2015 and another $8.1 billion for the next 3 years.

For mental health services, the budget includes $55 million for Project AWARE, which encourages community and school officials to work together to keep schools safe, refer students to mental health services, and provide mental health "first aid" training so that teachers can detect early signs of mental illness.

The budget request includes $50 million to train about 5,000 new mental health professionals, $20 million to help young adults aged 16-25 years navigate behavioral health services, and $5 million to change attitudes about people who have behavioral health needs in the workplace.

The budget also provides funding for a demonstration project in Medicaid to help reduce the use of psychotropic medications prescribed to children in foster care by improving access to other mental health services.

The release of the president’s budget request comes just weeks before the end of open enrollment in private health plans through the ACA’s marketplaces. The budget includes $1.8 billion in funding for 2015 to cover the cost of running the federally facilitated marketplace. However, most of the funding – $1.2 billion – would be covered by user fees from health plans in the marketplaces. If Congress fails to provide the remaining funds, HHS officials said they could transfer monies from other agency accounts to cover marketplace costs.

On Twitter @maryellenny

CDC sounds alarm on hospital antibiotic use

A scathing new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found ample room for improvement in inpatient antibiotic prescribing.

Findings include continued overuse of antibiotics in hospitals, errors in prescribing, and the lifesaving potential of efforts to reduce antibiotic use:

• Physicians in some hospitals prescribed three times as many antibiotics as doctors in other hospitals, even though patients were being cared for in similar areas of each hospital.

• Antibiotic prescriptions contained an error in 37% of cases involving treatment for urinary tract infections or use of the common and critical drug, vancomycin (Vancocin).

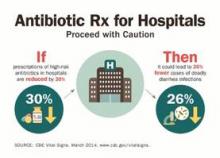

• Models predicted that a 30% decrease in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics would lead to a 26% reduction in Clostridium difficile infections, which kill roughly 14,000 hospitalized patients each year.

"Antibiotics are often lifesaving, and we have to protect them before our medicine chests run empty," CDC director Tom Frieden said during a press conference highlighting the report, released in the CDC’s March 4 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR 2014 March 4;63:1-7).

Dr. Frieden announced that the CDC’s fiscal 2015 budget, part of President Obama’s budget initiative rolled out today, contains a $30 million increase in funds to establish a robust infrastructure in the United States to detect antibiotic threats and protect patients and communities.

The new monies would allow the CDC to extend the "detect and protect" strategy to combat antibiotic resistance outlined last year, help support state and hospital efforts to implement antibiotic stewardship programs, and improve rapid detection of antimicrobial threats and outbreaks.

"One of the things that makes us so focused on antimicrobial resistance is that not only is it a really serious problem, but [also] it’s not too late," Dr. Frieden said.

If funded, he anticipates the CDC and other stakeholders will be able to reverse drug resistance and cut in half the rate of C. difficile and the "nightmare" carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections.

It was noted that robust efforts to improve the use of antibiotics associated with C. difficile in the United Kingdom have resulted in more than a 50% reduction in use of those targeted agents and a roughly 70% reduction in C. difficile infections over the past 6 to 7 years.

The CDC is strongly recommending that every hospital in the United States have an antibiotic stewardship program and is providing a new checklist to help facilities with the task. The checklist contains seven core elements of an effective program: leadership commitment; accountability for outcomes under a single leader; drug expertise under a single pharmacist leader; taking action on at least one prescribing improvement practice; tracking antibiotic prescribing and resistance patterns; reporting regularly to staff about these patterns; and educating staff on antibiotic resistance and improving prescribing practices.

Specific advice was also given to clinicians to order recommended cultures before antibiotics are given and to start drugs promptly; make sure the indication, dose, and expected duration are specified in the patient record; and reassess patients within 48 hours and adjust treatment, if necessary, or stop treatment, if indicated.

Concerns were raised during the briefing over whether voluntary strategies will curb interfacility transmission caused by transfers of patients with multidrug-resistant infections and the failure to report outbreaks between facilities. Dr. John R. Combes, the American Hospital Association’s senior vice president said several groups are working to smooth out these transfers and that the AHA’s "Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence" program provides best practices to facilitate transfers and foster cooperation with surrounding facilities to prevent infections.

The new CDC report is based on a review of data from all 323 hospitals in the MarketScan Hospital Drug Database and from hospitals in the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program.

Antibiotics were prescribed for 55.7% of patients hospitalized in 2010 in the MarketScan Hospital Drug Database, with 30% receiving at least one dose of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

One or more antibiotics were used to treat active infections in 37% of 11,282 patients treated in 2011 at 183 acute care hospitals evaluated by the Emerging Infections Program. Half of the antibiotics were prescribed for one of three scenarios: lower respiratory tract infections (22.2%), urinary tract infections (14%), and suspected drug-resistant Gram-positive infections such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (17.6%).

The CDC previously called on physicians to address antibiotic resistance in its Antibiotic Threats in the United States, 2013 report and the 2013 Get Smart About Antibiotics Week. The issue also will be tackled in the CDC’s forthcoming Transatlantic Taskforce on Antimicrobial Resistance 2013 report, with additional research expected to focus on contributing factors that led to such wide variances in antibiotic use between hospitals.

Dr. Frieden and Dr. Combes reported having no financial disclosures.

|

| Dr. Franklin A. Michota |

Dr. Franklin A. Michota is director of academic affairs, department of hospital medicine, Cleveland Clinic. He reports having no disclosures.

|

| Dr. Franklin A. Michota |

Dr. Franklin A. Michota is director of academic affairs, department of hospital medicine, Cleveland Clinic. He reports having no disclosures.

|

| Dr. Franklin A. Michota |

Dr. Franklin A. Michota is director of academic affairs, department of hospital medicine, Cleveland Clinic. He reports having no disclosures.

A scathing new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found ample room for improvement in inpatient antibiotic prescribing.

Findings include continued overuse of antibiotics in hospitals, errors in prescribing, and the lifesaving potential of efforts to reduce antibiotic use:

• Physicians in some hospitals prescribed three times as many antibiotics as doctors in other hospitals, even though patients were being cared for in similar areas of each hospital.

• Antibiotic prescriptions contained an error in 37% of cases involving treatment for urinary tract infections or use of the common and critical drug, vancomycin (Vancocin).

• Models predicted that a 30% decrease in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics would lead to a 26% reduction in Clostridium difficile infections, which kill roughly 14,000 hospitalized patients each year.

"Antibiotics are often lifesaving, and we have to protect them before our medicine chests run empty," CDC director Tom Frieden said during a press conference highlighting the report, released in the CDC’s March 4 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR 2014 March 4;63:1-7).

Dr. Frieden announced that the CDC’s fiscal 2015 budget, part of President Obama’s budget initiative rolled out today, contains a $30 million increase in funds to establish a robust infrastructure in the United States to detect antibiotic threats and protect patients and communities.

The new monies would allow the CDC to extend the "detect and protect" strategy to combat antibiotic resistance outlined last year, help support state and hospital efforts to implement antibiotic stewardship programs, and improve rapid detection of antimicrobial threats and outbreaks.

"One of the things that makes us so focused on antimicrobial resistance is that not only is it a really serious problem, but [also] it’s not too late," Dr. Frieden said.

If funded, he anticipates the CDC and other stakeholders will be able to reverse drug resistance and cut in half the rate of C. difficile and the "nightmare" carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections.

It was noted that robust efforts to improve the use of antibiotics associated with C. difficile in the United Kingdom have resulted in more than a 50% reduction in use of those targeted agents and a roughly 70% reduction in C. difficile infections over the past 6 to 7 years.

The CDC is strongly recommending that every hospital in the United States have an antibiotic stewardship program and is providing a new checklist to help facilities with the task. The checklist contains seven core elements of an effective program: leadership commitment; accountability for outcomes under a single leader; drug expertise under a single pharmacist leader; taking action on at least one prescribing improvement practice; tracking antibiotic prescribing and resistance patterns; reporting regularly to staff about these patterns; and educating staff on antibiotic resistance and improving prescribing practices.

Specific advice was also given to clinicians to order recommended cultures before antibiotics are given and to start drugs promptly; make sure the indication, dose, and expected duration are specified in the patient record; and reassess patients within 48 hours and adjust treatment, if necessary, or stop treatment, if indicated.

Concerns were raised during the briefing over whether voluntary strategies will curb interfacility transmission caused by transfers of patients with multidrug-resistant infections and the failure to report outbreaks between facilities. Dr. John R. Combes, the American Hospital Association’s senior vice president said several groups are working to smooth out these transfers and that the AHA’s "Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence" program provides best practices to facilitate transfers and foster cooperation with surrounding facilities to prevent infections.

The new CDC report is based on a review of data from all 323 hospitals in the MarketScan Hospital Drug Database and from hospitals in the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program.

Antibiotics were prescribed for 55.7% of patients hospitalized in 2010 in the MarketScan Hospital Drug Database, with 30% receiving at least one dose of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

One or more antibiotics were used to treat active infections in 37% of 11,282 patients treated in 2011 at 183 acute care hospitals evaluated by the Emerging Infections Program. Half of the antibiotics were prescribed for one of three scenarios: lower respiratory tract infections (22.2%), urinary tract infections (14%), and suspected drug-resistant Gram-positive infections such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (17.6%).

The CDC previously called on physicians to address antibiotic resistance in its Antibiotic Threats in the United States, 2013 report and the 2013 Get Smart About Antibiotics Week. The issue also will be tackled in the CDC’s forthcoming Transatlantic Taskforce on Antimicrobial Resistance 2013 report, with additional research expected to focus on contributing factors that led to such wide variances in antibiotic use between hospitals.

Dr. Frieden and Dr. Combes reported having no financial disclosures.

A scathing new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found ample room for improvement in inpatient antibiotic prescribing.

Findings include continued overuse of antibiotics in hospitals, errors in prescribing, and the lifesaving potential of efforts to reduce antibiotic use:

• Physicians in some hospitals prescribed three times as many antibiotics as doctors in other hospitals, even though patients were being cared for in similar areas of each hospital.

• Antibiotic prescriptions contained an error in 37% of cases involving treatment for urinary tract infections or use of the common and critical drug, vancomycin (Vancocin).

• Models predicted that a 30% decrease in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics would lead to a 26% reduction in Clostridium difficile infections, which kill roughly 14,000 hospitalized patients each year.

"Antibiotics are often lifesaving, and we have to protect them before our medicine chests run empty," CDC director Tom Frieden said during a press conference highlighting the report, released in the CDC’s March 4 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR 2014 March 4;63:1-7).

Dr. Frieden announced that the CDC’s fiscal 2015 budget, part of President Obama’s budget initiative rolled out today, contains a $30 million increase in funds to establish a robust infrastructure in the United States to detect antibiotic threats and protect patients and communities.

The new monies would allow the CDC to extend the "detect and protect" strategy to combat antibiotic resistance outlined last year, help support state and hospital efforts to implement antibiotic stewardship programs, and improve rapid detection of antimicrobial threats and outbreaks.

"One of the things that makes us so focused on antimicrobial resistance is that not only is it a really serious problem, but [also] it’s not too late," Dr. Frieden said.

If funded, he anticipates the CDC and other stakeholders will be able to reverse drug resistance and cut in half the rate of C. difficile and the "nightmare" carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections.

It was noted that robust efforts to improve the use of antibiotics associated with C. difficile in the United Kingdom have resulted in more than a 50% reduction in use of those targeted agents and a roughly 70% reduction in C. difficile infections over the past 6 to 7 years.

The CDC is strongly recommending that every hospital in the United States have an antibiotic stewardship program and is providing a new checklist to help facilities with the task. The checklist contains seven core elements of an effective program: leadership commitment; accountability for outcomes under a single leader; drug expertise under a single pharmacist leader; taking action on at least one prescribing improvement practice; tracking antibiotic prescribing and resistance patterns; reporting regularly to staff about these patterns; and educating staff on antibiotic resistance and improving prescribing practices.

Specific advice was also given to clinicians to order recommended cultures before antibiotics are given and to start drugs promptly; make sure the indication, dose, and expected duration are specified in the patient record; and reassess patients within 48 hours and adjust treatment, if necessary, or stop treatment, if indicated.

Concerns were raised during the briefing over whether voluntary strategies will curb interfacility transmission caused by transfers of patients with multidrug-resistant infections and the failure to report outbreaks between facilities. Dr. John R. Combes, the American Hospital Association’s senior vice president said several groups are working to smooth out these transfers and that the AHA’s "Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence" program provides best practices to facilitate transfers and foster cooperation with surrounding facilities to prevent infections.

The new CDC report is based on a review of data from all 323 hospitals in the MarketScan Hospital Drug Database and from hospitals in the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program.

Antibiotics were prescribed for 55.7% of patients hospitalized in 2010 in the MarketScan Hospital Drug Database, with 30% receiving at least one dose of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

One or more antibiotics were used to treat active infections in 37% of 11,282 patients treated in 2011 at 183 acute care hospitals evaluated by the Emerging Infections Program. Half of the antibiotics were prescribed for one of three scenarios: lower respiratory tract infections (22.2%), urinary tract infections (14%), and suspected drug-resistant Gram-positive infections such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (17.6%).

The CDC previously called on physicians to address antibiotic resistance in its Antibiotic Threats in the United States, 2013 report and the 2013 Get Smart About Antibiotics Week. The issue also will be tackled in the CDC’s forthcoming Transatlantic Taskforce on Antimicrobial Resistance 2013 report, with additional research expected to focus on contributing factors that led to such wide variances in antibiotic use between hospitals.

Dr. Frieden and Dr. Combes reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Disclosure programs reduce lawsuits, but bring challenges

Disclosure and apology programs may be one answer to reducing malpractice litigation against physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers.

Pilot efforts in this area by the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, since 2006 have increased adverse event reports from 1,500 per year to 10,000 while decreasing malpractice premiums by $15 million dollars since 2010.

"Through effectively communicating, you can eliminate a whole lot of lawsuits [in which] the patients and families are suing you just because they want answers," said Dr. Tim McDonald, chief safety and risk officer for health affairs for the system. "We think that’s one of the big keys to substantially reducing malpractice costs."

So-called communication and resolution programs (CRPs) involve investigating events in which inappropriate care may have occurred, providing an apology to patients, and offering early compensation if deemed necessary.

Under such programs, physicians or administrators immediately communicate with patients after a poor medical outcome or questionable circumstance and explain that the event is being rapidly investigated.

Once investigation is complete, risk managers or administrators discuss the findings with the patient and the clinician. The team admits any errors and provides an apology to the patient or family if harm was caused. If care was deemed substandard, administrators offer the patient or family appropriate compensation. In the event the care was deemed reasonable, the involved physician and risk manager explain their conclusions and seek understanding, but commit to defending the clinician in court, if necessary.

The CRP program at Illinois was modeled after a similar program at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, which started in late 2001. Since the program began, the average legal expenses per case has been cut at least in half, according to the UM website. In July 2001, the health system had 260 pre-suit claims and lawsuits pending; it now averages about 100/year.

Contributing factors to the success of six early adopters – including the Michigan and Illinois programs – included sufficient resources to fund the ventures, a passionate program advocate, and strong marketing, according to an analysis in the journal Health Affairs.

"The things that really distinguished [the successful early adopters] from the later adopters were they had an incredibly strong champion of the program who made it his job to build the program full time," said Michelle Mello, J.D., Ph.D., director of the law and public health program at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston (Health Aff. 2014;33:120-9).

Ascension Health, a large system of more than 1,900 hospitals in 23 states and the District of Columbia, saw a 52% decrease in the total number of actual and potential liability cases in a demonstration project of an obstetrical CRP (Health Aff. 2014;33:139-45).

The program included the immediate reporting of unexpected events, investigation, documentation and causal analysis, as well as having staff fully disclose unexpected events to patients and families. To do so, each of five hospitals in the pilot created an Obstetrics Event Response Team that consisted of an obstetrician, a neonatologist, an obstetrics nurse manager, a risk manager, and a medical coder.

Following training, the teams became accountable for immediate identification and reporting of any event that resulted in patient harm, expedited investigation of the event, prompt and ongoing disclosure, early resolution of events involving probable liability, and accessing lessons learned from each event to improve patient care.

In just over 3 years after implementation of the demonstration project, the rate of full disclosures more than doubled (221% increase in full disclosures).

"Based on the success of the ... demonstration project, Ascension Health has begun to spread the care model – including electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) and shoulder dystocia e-learning stimulation, TeamSTEPPS training, disclosure and root cause analysis training, and implementation of the Ascension Health shoulder dystocia bundle – as a standard for all obstetrics units throughout the health system," said Ann Hendrich, RN, Ph.D., senior vice president for quality and safety at Ascension Health.

Adoption of CRPs is not without challenges. Participants at five of the six early adoption sites reported practical challenges in educating physicians about the program. Program founders initially struggled to soothe physicians’ skepticism and discomfort with making disclosures to patients. Strong communication by administrators and trust building with physicians was key in overcoming these obstacles, Dr. Mello and her colleagues found.

CRPs would be easier to implement if the current legal and governmental environment supported them, health care experts said (Health Aff. 2014 33:111-19). State laws that prohibit using health care providers’ apologies against them in court would go far to support CRPs. Currently, more than 30 states have some form of apology statute aimed at physicians and other health care providers, but the extent of legal protection differs.

Pennsylvania was the latest state to enact an apology protection law. The statute, which became effective in December 2013, shields any physician action, conduct, or statement that conveys a sense of apology, condolence, explanation, compassion, or commiseration "emanating from humane impulses."

So far, "there have not been any reports or complaints about the new law coming into the medical society," said Chuck Moran, director of media relations and public affairs at the Pennsylvania Medical Society. "That could be a good sign, or it could mean it’s too early to tell."

Disclosure and apology programs may be one answer to reducing malpractice litigation against physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers.

Pilot efforts in this area by the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, since 2006 have increased adverse event reports from 1,500 per year to 10,000 while decreasing malpractice premiums by $15 million dollars since 2010.

"Through effectively communicating, you can eliminate a whole lot of lawsuits [in which] the patients and families are suing you just because they want answers," said Dr. Tim McDonald, chief safety and risk officer for health affairs for the system. "We think that’s one of the big keys to substantially reducing malpractice costs."

So-called communication and resolution programs (CRPs) involve investigating events in which inappropriate care may have occurred, providing an apology to patients, and offering early compensation if deemed necessary.

Under such programs, physicians or administrators immediately communicate with patients after a poor medical outcome or questionable circumstance and explain that the event is being rapidly investigated.

Once investigation is complete, risk managers or administrators discuss the findings with the patient and the clinician. The team admits any errors and provides an apology to the patient or family if harm was caused. If care was deemed substandard, administrators offer the patient or family appropriate compensation. In the event the care was deemed reasonable, the involved physician and risk manager explain their conclusions and seek understanding, but commit to defending the clinician in court, if necessary.

The CRP program at Illinois was modeled after a similar program at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, which started in late 2001. Since the program began, the average legal expenses per case has been cut at least in half, according to the UM website. In July 2001, the health system had 260 pre-suit claims and lawsuits pending; it now averages about 100/year.

Contributing factors to the success of six early adopters – including the Michigan and Illinois programs – included sufficient resources to fund the ventures, a passionate program advocate, and strong marketing, according to an analysis in the journal Health Affairs.

"The things that really distinguished [the successful early adopters] from the later adopters were they had an incredibly strong champion of the program who made it his job to build the program full time," said Michelle Mello, J.D., Ph.D., director of the law and public health program at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston (Health Aff. 2014;33:120-9).

Ascension Health, a large system of more than 1,900 hospitals in 23 states and the District of Columbia, saw a 52% decrease in the total number of actual and potential liability cases in a demonstration project of an obstetrical CRP (Health Aff. 2014;33:139-45).

The program included the immediate reporting of unexpected events, investigation, documentation and causal analysis, as well as having staff fully disclose unexpected events to patients and families. To do so, each of five hospitals in the pilot created an Obstetrics Event Response Team that consisted of an obstetrician, a neonatologist, an obstetrics nurse manager, a risk manager, and a medical coder.

Following training, the teams became accountable for immediate identification and reporting of any event that resulted in patient harm, expedited investigation of the event, prompt and ongoing disclosure, early resolution of events involving probable liability, and accessing lessons learned from each event to improve patient care.

In just over 3 years after implementation of the demonstration project, the rate of full disclosures more than doubled (221% increase in full disclosures).

"Based on the success of the ... demonstration project, Ascension Health has begun to spread the care model – including electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) and shoulder dystocia e-learning stimulation, TeamSTEPPS training, disclosure and root cause analysis training, and implementation of the Ascension Health shoulder dystocia bundle – as a standard for all obstetrics units throughout the health system," said Ann Hendrich, RN, Ph.D., senior vice president for quality and safety at Ascension Health.

Adoption of CRPs is not without challenges. Participants at five of the six early adoption sites reported practical challenges in educating physicians about the program. Program founders initially struggled to soothe physicians’ skepticism and discomfort with making disclosures to patients. Strong communication by administrators and trust building with physicians was key in overcoming these obstacles, Dr. Mello and her colleagues found.

CRPs would be easier to implement if the current legal and governmental environment supported them, health care experts said (Health Aff. 2014 33:111-19). State laws that prohibit using health care providers’ apologies against them in court would go far to support CRPs. Currently, more than 30 states have some form of apology statute aimed at physicians and other health care providers, but the extent of legal protection differs.

Pennsylvania was the latest state to enact an apology protection law. The statute, which became effective in December 2013, shields any physician action, conduct, or statement that conveys a sense of apology, condolence, explanation, compassion, or commiseration "emanating from humane impulses."

So far, "there have not been any reports or complaints about the new law coming into the medical society," said Chuck Moran, director of media relations and public affairs at the Pennsylvania Medical Society. "That could be a good sign, or it could mean it’s too early to tell."

Disclosure and apology programs may be one answer to reducing malpractice litigation against physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers.

Pilot efforts in this area by the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, since 2006 have increased adverse event reports from 1,500 per year to 10,000 while decreasing malpractice premiums by $15 million dollars since 2010.

"Through effectively communicating, you can eliminate a whole lot of lawsuits [in which] the patients and families are suing you just because they want answers," said Dr. Tim McDonald, chief safety and risk officer for health affairs for the system. "We think that’s one of the big keys to substantially reducing malpractice costs."

So-called communication and resolution programs (CRPs) involve investigating events in which inappropriate care may have occurred, providing an apology to patients, and offering early compensation if deemed necessary.

Under such programs, physicians or administrators immediately communicate with patients after a poor medical outcome or questionable circumstance and explain that the event is being rapidly investigated.

Once investigation is complete, risk managers or administrators discuss the findings with the patient and the clinician. The team admits any errors and provides an apology to the patient or family if harm was caused. If care was deemed substandard, administrators offer the patient or family appropriate compensation. In the event the care was deemed reasonable, the involved physician and risk manager explain their conclusions and seek understanding, but commit to defending the clinician in court, if necessary.

The CRP program at Illinois was modeled after a similar program at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, which started in late 2001. Since the program began, the average legal expenses per case has been cut at least in half, according to the UM website. In July 2001, the health system had 260 pre-suit claims and lawsuits pending; it now averages about 100/year.

Contributing factors to the success of six early adopters – including the Michigan and Illinois programs – included sufficient resources to fund the ventures, a passionate program advocate, and strong marketing, according to an analysis in the journal Health Affairs.

"The things that really distinguished [the successful early adopters] from the later adopters were they had an incredibly strong champion of the program who made it his job to build the program full time," said Michelle Mello, J.D., Ph.D., director of the law and public health program at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston (Health Aff. 2014;33:120-9).

Ascension Health, a large system of more than 1,900 hospitals in 23 states and the District of Columbia, saw a 52% decrease in the total number of actual and potential liability cases in a demonstration project of an obstetrical CRP (Health Aff. 2014;33:139-45).

The program included the immediate reporting of unexpected events, investigation, documentation and causal analysis, as well as having staff fully disclose unexpected events to patients and families. To do so, each of five hospitals in the pilot created an Obstetrics Event Response Team that consisted of an obstetrician, a neonatologist, an obstetrics nurse manager, a risk manager, and a medical coder.

Following training, the teams became accountable for immediate identification and reporting of any event that resulted in patient harm, expedited investigation of the event, prompt and ongoing disclosure, early resolution of events involving probable liability, and accessing lessons learned from each event to improve patient care.

In just over 3 years after implementation of the demonstration project, the rate of full disclosures more than doubled (221% increase in full disclosures).

"Based on the success of the ... demonstration project, Ascension Health has begun to spread the care model – including electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) and shoulder dystocia e-learning stimulation, TeamSTEPPS training, disclosure and root cause analysis training, and implementation of the Ascension Health shoulder dystocia bundle – as a standard for all obstetrics units throughout the health system," said Ann Hendrich, RN, Ph.D., senior vice president for quality and safety at Ascension Health.

Adoption of CRPs is not without challenges. Participants at five of the six early adoption sites reported practical challenges in educating physicians about the program. Program founders initially struggled to soothe physicians’ skepticism and discomfort with making disclosures to patients. Strong communication by administrators and trust building with physicians was key in overcoming these obstacles, Dr. Mello and her colleagues found.

CRPs would be easier to implement if the current legal and governmental environment supported them, health care experts said (Health Aff. 2014 33:111-19). State laws that prohibit using health care providers’ apologies against them in court would go far to support CRPs. Currently, more than 30 states have some form of apology statute aimed at physicians and other health care providers, but the extent of legal protection differs.

Pennsylvania was the latest state to enact an apology protection law. The statute, which became effective in December 2013, shields any physician action, conduct, or statement that conveys a sense of apology, condolence, explanation, compassion, or commiseration "emanating from humane impulses."

So far, "there have not been any reports or complaints about the new law coming into the medical society," said Chuck Moran, director of media relations and public affairs at the Pennsylvania Medical Society. "That could be a good sign, or it could mean it’s too early to tell."

New takeaways from the Boston Marathon bombings

NAPLES, FLA. – Without a single life lost at area hospitals, the medical response to the Boston Marathon bombings was by all accounts remarkable. But what if police and other first-responders had tourniquets and were trained in their use?

As it was, advanced topical hemostatic agents and tourniquets were MIA in the field, forcing all but one prehospital tourniquet to be improvised, according to Massachusetts General Hospital trauma surgeon Lt. Col. David King, U. S. Army Reserve.

"It’s abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work," he said. "The fact that every soldier down range has one in his pocket and we couldn’t muster up more than one in the city of Boston is a shame and we need to rectify that."

In all, there were 66 limb injuries, with 29 patients having recognized limb exsanguination at the scene. Of the 27 tourniquets applied, 26 were improvised.

Failure to translate this important lesson from military experience meant that these homemade devices were most likely wildly ineffective and, in some cases, may have even exacerbated blood loss, he said. Surprisingly, there’s no formal protocol for tourniquet application or training paradigm in Massachusetts, such that exists in the Army’s prehospital Tactical Combat Casualty Care handbook.

"If you look across the paramedic medical guidelines, there is no protocol on the right, evidence-based way to put on a tourniquet or what the indications are for a tourniquet," Dr. King said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). "We don’t have it, and we need to" have it nationwide.

EAST is hoping to provide some guidance in this area with the development of practice management guidelines (PMG) for tourniquet use in extremity trauma. Dr. King, who heads this PMG committee, reported at the meeting that the guidelines, due out later this year, will emphasize that commercially made tourniquets should be available in the prehospital setting, improvised tourniquets rarely work and cannot be recommended; essentially all commercially made tourniquets are equieffective; and that nonmedical personnel can be trained to correctly apply a proper tourniquet.

The need for bleeding control equipment and training for the public has not gone unnoticed by other stakeholders and is the central focus of the newest statement from the Hartford Consensus, a collaborative group of trauma surgeons, law enforcement officers, and emergency responders led by the American College of Surgeons (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:467-75).

In dissecting the medical response to the Boston bombings, much has been made of the fact that Boston is home to six Level 1 trauma centers, and that it was race day, a city holiday, 3 p.m., and low-yield devices were used. Dr. King, however, gave high praise to an unsung hero, the Boston EMS loading officer who managed most of the transport destination decisions and smartly distributed critical cases throughout the area’s hospitals.

All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some have argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a "stay-and-play" mentality in the medical tent. The after-action review suggests there probably were enough ambulances to do the job in 30 minutes, said Dr. King, who remarked that the only thing that matters in critical trauma cases is time to surgical hemorrhage control.

"This will remain a controversial issue for Boston, whether staying and playing in the medical tent was a good idea," he said. "I don’t know what the right answer is."

Credit was also given to Massachusetts General, and many of the other city hospitals, for their insistence on regular full-scale drills that allowed quick lock-down of the facility to control access and manage the surge capacity in the emergency department.

"It’s more than just a tabletop exercise," Dr. King said. "When we test the surge capacity, we actually empty the emergency room for real. Usually, it occurs between 5:00 and 7:00 or 4:30 and 7:30 in the morning, but actually doing these things was useful, because when it came time to do it for real, no one was tripping over their own feet."

ED volume on that April afternoon was reduced from 97 patients to just 39 within 1.5 hours. Nontrauma physicians, including psychiatrists, did their part by writing "barebones orders" to get patients transferred to the wards.

Staff at Massachusetts General treated 43 patients, performing nine emergent operations, six amputations, two laparotomies, and one thoracotomy, with two traumatic arrests within the first 72 hours. As with other Boston hospitals, there were no in-hospital deaths, he said.

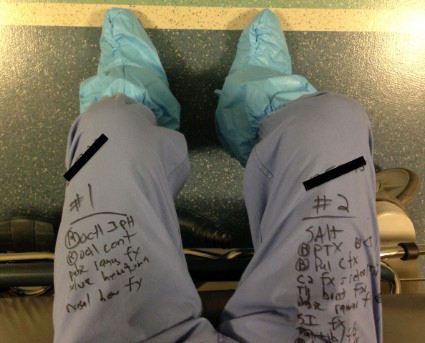

Patients arrived in such rapid succession, however, that it slowed the electronic medical record system and forced staff to use sequential record numbers, which can be dangerous. Registration couldn’t keep up and orders couldn’t be put in fast enough with 43 patients arriving in roughly 35 minutes, Dr. King explained. Workarounds were often old-school, and reminiscent of his days as a green trauma surgeon serving at Ibn Sina Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.

"In the midst of this entire event, I turned to my nurse practitioner and asked for x, y, z information on a particular patient," he said. "She didn’t turn to her tablet or desktop computer in the operating room. She pulled out a piece of paper where she’d written all the relevant information. At the end of the event, I looked down and realized I’d done the same thing. I was keeping track of my patients on my pants with a Sharpie."

King describes this as a failure of technology and translation from the battlefield, but noted that the hospital did use the military’s practice of reviewing a critical event. Once they’d finished in the operating room and achieved hemorrhage and contamination control, the entire trauma team was reassembled. They did detailed tertiary trauma surveys and went back through every single patient to determine what additional studies they needed, what injuries had been missed.

"It was remarkable the number of things that were missed," Dr. King said. "No one was bleeding to death, but tons and tons of [small, non–life threatening] missed injuries [like ruptured ear drums], and to me this was one of the more important events that surrounded our response to the entire bombing – sitting down after the dust had settled and carefully going over every patient’s medical record."

Dr. King reported having no financial disclosures.

Lt. Col. King makes some excellent points. However, despite Dr. King's combat medicine experience, his contribution to this article reveals a gap that still exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

The case against improvised tourniquets

There is no consensus on the definition of an "improvised" tourniquet. Homemade applications such as neckties and sticks are defined as improvised, but the Boston EMS kits (surgical tubing and Kelly clamps) also could be considered improvised. All of these methods may sound primitive since the advent of Combat-Application Tourniquets; however CATS are relatively new to the scene. Should we consider every tourniquet applied prior to their introduction to have been improvised? For the price of one CAT, we can assemble 10 tourniquet kits. And if Dr. King's initial contention was that tourniquets were in short supply, then it is a better system to deploy as many as possible. This point may be moot, however, because since the Boston bombing incident, federal grant money has allowed the purchase of CAT units in great numbers within the Metro-Boston area.

Tourniquet efficacy

"It is abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work." I feel this study had the wrong focus. Rather than ask which tourniquets have a better success rate, the study should have asked whose tourniquets have a better success rate.

Study after study has shown that successful intubation rates have little to do with the level of training of the practitioner, and everything to do with the frequency of intubation. More tubes equal more successful passes. I propose that this applies to tourniquet application as well. Field personnel who do not practice or have the opportunity to apply tourniquets frequently (which is the great majority of us) may not be applying tourniquets properly. This is why we instituted a massive tourniquet training and review program almost immediately following the 2013 bombing at the Boston Marathon.

Another point not addressed in studies is the effectiveness of nonresponder tourniquets. I would contend that an experienced practitioner with a necktie and a stick would be more successful in hemorrhage control that a civilian with a CAT, but those data have not been explored yet either.

The Loading Officer as unsung hero

All our Action Area Officers performed brilliantly (full disclosure, I was the Loading Officer). However the term Loading Officer is a misnomer. Yes, there is a Loading Officer, but there is actually a Loading Team. It consists of staff at the scene who liaise with the treatment areas and the true unsung heroes, the staff in the Operations Division or Dispatch Center. Dispatchers are in constant contact with the hospitals, scene operations, as well as continuing city service. They perform the hospital destination designations because they have a global sense of traffic, while at the scene we have only a worm's-eye view.

The stay-and-play critique

"All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a 'stay-and-play' mentality." I take exception to this assertion. First, the point is contradictory. All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but there was a stay-and-play mentality? Every EMT and paramedic knows that transport times translate into positive results with trauma.

Emergency personnel are taught that what matters most in trauma survival is not basic life support, advance life support, or wheelbarrow, but getting them to the ED fast. Yes, there were slowdowns in the medical tents, but most of delays came from non-EMS personnel who were not well versed in field medicine. We questioned, pleaded, and ultimately ordered some practitioners away from patients as they were attempting to perform procedures that we would never attempt on a trauma patient in the field. This is by no means a condemnation on my part. The staff we worked with was exceptional, and I witnessed true skill, heroism, and compassion. But it also demonstrated to me that a disconnect exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

I see an opportunity here for training to better acclimate responders to working together with our hospital counterparts. We also need hospital personnel to be oriented to realities and limitations of field medicine.

Lt. Brian Pomodoro is a member of the Boston EMS.

Lt. Col. King makes some excellent points. However, despite Dr. King's combat medicine experience, his contribution to this article reveals a gap that still exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

The case against improvised tourniquets

There is no consensus on the definition of an "improvised" tourniquet. Homemade applications such as neckties and sticks are defined as improvised, but the Boston EMS kits (surgical tubing and Kelly clamps) also could be considered improvised. All of these methods may sound primitive since the advent of Combat-Application Tourniquets; however CATS are relatively new to the scene. Should we consider every tourniquet applied prior to their introduction to have been improvised? For the price of one CAT, we can assemble 10 tourniquet kits. And if Dr. King's initial contention was that tourniquets were in short supply, then it is a better system to deploy as many as possible. This point may be moot, however, because since the Boston bombing incident, federal grant money has allowed the purchase of CAT units in great numbers within the Metro-Boston area.

Tourniquet efficacy

"It is abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work." I feel this study had the wrong focus. Rather than ask which tourniquets have a better success rate, the study should have asked whose tourniquets have a better success rate.

Study after study has shown that successful intubation rates have little to do with the level of training of the practitioner, and everything to do with the frequency of intubation. More tubes equal more successful passes. I propose that this applies to tourniquet application as well. Field personnel who do not practice or have the opportunity to apply tourniquets frequently (which is the great majority of us) may not be applying tourniquets properly. This is why we instituted a massive tourniquet training and review program almost immediately following the 2013 bombing at the Boston Marathon.

Another point not addressed in studies is the effectiveness of nonresponder tourniquets. I would contend that an experienced practitioner with a necktie and a stick would be more successful in hemorrhage control that a civilian with a CAT, but those data have not been explored yet either.

The Loading Officer as unsung hero

All our Action Area Officers performed brilliantly (full disclosure, I was the Loading Officer). However the term Loading Officer is a misnomer. Yes, there is a Loading Officer, but there is actually a Loading Team. It consists of staff at the scene who liaise with the treatment areas and the true unsung heroes, the staff in the Operations Division or Dispatch Center. Dispatchers are in constant contact with the hospitals, scene operations, as well as continuing city service. They perform the hospital destination designations because they have a global sense of traffic, while at the scene we have only a worm's-eye view.

The stay-and-play critique

"All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a 'stay-and-play' mentality." I take exception to this assertion. First, the point is contradictory. All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but there was a stay-and-play mentality? Every EMT and paramedic knows that transport times translate into positive results with trauma.

Emergency personnel are taught that what matters most in trauma survival is not basic life support, advance life support, or wheelbarrow, but getting them to the ED fast. Yes, there were slowdowns in the medical tents, but most of delays came from non-EMS personnel who were not well versed in field medicine. We questioned, pleaded, and ultimately ordered some practitioners away from patients as they were attempting to perform procedures that we would never attempt on a trauma patient in the field. This is by no means a condemnation on my part. The staff we worked with was exceptional, and I witnessed true skill, heroism, and compassion. But it also demonstrated to me that a disconnect exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

I see an opportunity here for training to better acclimate responders to working together with our hospital counterparts. We also need hospital personnel to be oriented to realities and limitations of field medicine.

Lt. Brian Pomodoro is a member of the Boston EMS.

Lt. Col. King makes some excellent points. However, despite Dr. King's combat medicine experience, his contribution to this article reveals a gap that still exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

The case against improvised tourniquets

There is no consensus on the definition of an "improvised" tourniquet. Homemade applications such as neckties and sticks are defined as improvised, but the Boston EMS kits (surgical tubing and Kelly clamps) also could be considered improvised. All of these methods may sound primitive since the advent of Combat-Application Tourniquets; however CATS are relatively new to the scene. Should we consider every tourniquet applied prior to their introduction to have been improvised? For the price of one CAT, we can assemble 10 tourniquet kits. And if Dr. King's initial contention was that tourniquets were in short supply, then it is a better system to deploy as many as possible. This point may be moot, however, because since the Boston bombing incident, federal grant money has allowed the purchase of CAT units in great numbers within the Metro-Boston area.

Tourniquet efficacy

"It is abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work." I feel this study had the wrong focus. Rather than ask which tourniquets have a better success rate, the study should have asked whose tourniquets have a better success rate.

Study after study has shown that successful intubation rates have little to do with the level of training of the practitioner, and everything to do with the frequency of intubation. More tubes equal more successful passes. I propose that this applies to tourniquet application as well. Field personnel who do not practice or have the opportunity to apply tourniquets frequently (which is the great majority of us) may not be applying tourniquets properly. This is why we instituted a massive tourniquet training and review program almost immediately following the 2013 bombing at the Boston Marathon.

Another point not addressed in studies is the effectiveness of nonresponder tourniquets. I would contend that an experienced practitioner with a necktie and a stick would be more successful in hemorrhage control that a civilian with a CAT, but those data have not been explored yet either.

The Loading Officer as unsung hero

All our Action Area Officers performed brilliantly (full disclosure, I was the Loading Officer). However the term Loading Officer is a misnomer. Yes, there is a Loading Officer, but there is actually a Loading Team. It consists of staff at the scene who liaise with the treatment areas and the true unsung heroes, the staff in the Operations Division or Dispatch Center. Dispatchers are in constant contact with the hospitals, scene operations, as well as continuing city service. They perform the hospital destination designations because they have a global sense of traffic, while at the scene we have only a worm's-eye view.

The stay-and-play critique

"All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a 'stay-and-play' mentality." I take exception to this assertion. First, the point is contradictory. All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but there was a stay-and-play mentality? Every EMT and paramedic knows that transport times translate into positive results with trauma.

Emergency personnel are taught that what matters most in trauma survival is not basic life support, advance life support, or wheelbarrow, but getting them to the ED fast. Yes, there were slowdowns in the medical tents, but most of delays came from non-EMS personnel who were not well versed in field medicine. We questioned, pleaded, and ultimately ordered some practitioners away from patients as they were attempting to perform procedures that we would never attempt on a trauma patient in the field. This is by no means a condemnation on my part. The staff we worked with was exceptional, and I witnessed true skill, heroism, and compassion. But it also demonstrated to me that a disconnect exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

I see an opportunity here for training to better acclimate responders to working together with our hospital counterparts. We also need hospital personnel to be oriented to realities and limitations of field medicine.

Lt. Brian Pomodoro is a member of the Boston EMS.

NAPLES, FLA. – Without a single life lost at area hospitals, the medical response to the Boston Marathon bombings was by all accounts remarkable. But what if police and other first-responders had tourniquets and were trained in their use?

As it was, advanced topical hemostatic agents and tourniquets were MIA in the field, forcing all but one prehospital tourniquet to be improvised, according to Massachusetts General Hospital trauma surgeon Lt. Col. David King, U. S. Army Reserve.

"It’s abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work," he said. "The fact that every soldier down range has one in his pocket and we couldn’t muster up more than one in the city of Boston is a shame and we need to rectify that."

In all, there were 66 limb injuries, with 29 patients having recognized limb exsanguination at the scene. Of the 27 tourniquets applied, 26 were improvised.

Failure to translate this important lesson from military experience meant that these homemade devices were most likely wildly ineffective and, in some cases, may have even exacerbated blood loss, he said. Surprisingly, there’s no formal protocol for tourniquet application or training paradigm in Massachusetts, such that exists in the Army’s prehospital Tactical Combat Casualty Care handbook.

"If you look across the paramedic medical guidelines, there is no protocol on the right, evidence-based way to put on a tourniquet or what the indications are for a tourniquet," Dr. King said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). "We don’t have it, and we need to" have it nationwide.

EAST is hoping to provide some guidance in this area with the development of practice management guidelines (PMG) for tourniquet use in extremity trauma. Dr. King, who heads this PMG committee, reported at the meeting that the guidelines, due out later this year, will emphasize that commercially made tourniquets should be available in the prehospital setting, improvised tourniquets rarely work and cannot be recommended; essentially all commercially made tourniquets are equieffective; and that nonmedical personnel can be trained to correctly apply a proper tourniquet.

The need for bleeding control equipment and training for the public has not gone unnoticed by other stakeholders and is the central focus of the newest statement from the Hartford Consensus, a collaborative group of trauma surgeons, law enforcement officers, and emergency responders led by the American College of Surgeons (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:467-75).

In dissecting the medical response to the Boston bombings, much has been made of the fact that Boston is home to six Level 1 trauma centers, and that it was race day, a city holiday, 3 p.m., and low-yield devices were used. Dr. King, however, gave high praise to an unsung hero, the Boston EMS loading officer who managed most of the transport destination decisions and smartly distributed critical cases throughout the area’s hospitals.

All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some have argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a "stay-and-play" mentality in the medical tent. The after-action review suggests there probably were enough ambulances to do the job in 30 minutes, said Dr. King, who remarked that the only thing that matters in critical trauma cases is time to surgical hemorrhage control.

"This will remain a controversial issue for Boston, whether staying and playing in the medical tent was a good idea," he said. "I don’t know what the right answer is."

Credit was also given to Massachusetts General, and many of the other city hospitals, for their insistence on regular full-scale drills that allowed quick lock-down of the facility to control access and manage the surge capacity in the emergency department.

"It’s more than just a tabletop exercise," Dr. King said. "When we test the surge capacity, we actually empty the emergency room for real. Usually, it occurs between 5:00 and 7:00 or 4:30 and 7:30 in the morning, but actually doing these things was useful, because when it came time to do it for real, no one was tripping over their own feet."

ED volume on that April afternoon was reduced from 97 patients to just 39 within 1.5 hours. Nontrauma physicians, including psychiatrists, did their part by writing "barebones orders" to get patients transferred to the wards.

Staff at Massachusetts General treated 43 patients, performing nine emergent operations, six amputations, two laparotomies, and one thoracotomy, with two traumatic arrests within the first 72 hours. As with other Boston hospitals, there were no in-hospital deaths, he said.

Patients arrived in such rapid succession, however, that it slowed the electronic medical record system and forced staff to use sequential record numbers, which can be dangerous. Registration couldn’t keep up and orders couldn’t be put in fast enough with 43 patients arriving in roughly 35 minutes, Dr. King explained. Workarounds were often old-school, and reminiscent of his days as a green trauma surgeon serving at Ibn Sina Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.

"In the midst of this entire event, I turned to my nurse practitioner and asked for x, y, z information on a particular patient," he said. "She didn’t turn to her tablet or desktop computer in the operating room. She pulled out a piece of paper where she’d written all the relevant information. At the end of the event, I looked down and realized I’d done the same thing. I was keeping track of my patients on my pants with a Sharpie."

King describes this as a failure of technology and translation from the battlefield, but noted that the hospital did use the military’s practice of reviewing a critical event. Once they’d finished in the operating room and achieved hemorrhage and contamination control, the entire trauma team was reassembled. They did detailed tertiary trauma surveys and went back through every single patient to determine what additional studies they needed, what injuries had been missed.

"It was remarkable the number of things that were missed," Dr. King said. "No one was bleeding to death, but tons and tons of [small, non–life threatening] missed injuries [like ruptured ear drums], and to me this was one of the more important events that surrounded our response to the entire bombing – sitting down after the dust had settled and carefully going over every patient’s medical record."

Dr. King reported having no financial disclosures.

NAPLES, FLA. – Without a single life lost at area hospitals, the medical response to the Boston Marathon bombings was by all accounts remarkable. But what if police and other first-responders had tourniquets and were trained in their use?

As it was, advanced topical hemostatic agents and tourniquets were MIA in the field, forcing all but one prehospital tourniquet to be improvised, according to Massachusetts General Hospital trauma surgeon Lt. Col. David King, U. S. Army Reserve.

"It’s abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work," he said. "The fact that every soldier down range has one in his pocket and we couldn’t muster up more than one in the city of Boston is a shame and we need to rectify that."

In all, there were 66 limb injuries, with 29 patients having recognized limb exsanguination at the scene. Of the 27 tourniquets applied, 26 were improvised.

Failure to translate this important lesson from military experience meant that these homemade devices were most likely wildly ineffective and, in some cases, may have even exacerbated blood loss, he said. Surprisingly, there’s no formal protocol for tourniquet application or training paradigm in Massachusetts, such that exists in the Army’s prehospital Tactical Combat Casualty Care handbook.

"If you look across the paramedic medical guidelines, there is no protocol on the right, evidence-based way to put on a tourniquet or what the indications are for a tourniquet," Dr. King said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). "We don’t have it, and we need to" have it nationwide.

EAST is hoping to provide some guidance in this area with the development of practice management guidelines (PMG) for tourniquet use in extremity trauma. Dr. King, who heads this PMG committee, reported at the meeting that the guidelines, due out later this year, will emphasize that commercially made tourniquets should be available in the prehospital setting, improvised tourniquets rarely work and cannot be recommended; essentially all commercially made tourniquets are equieffective; and that nonmedical personnel can be trained to correctly apply a proper tourniquet.

The need for bleeding control equipment and training for the public has not gone unnoticed by other stakeholders and is the central focus of the newest statement from the Hartford Consensus, a collaborative group of trauma surgeons, law enforcement officers, and emergency responders led by the American College of Surgeons (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:467-75).

In dissecting the medical response to the Boston bombings, much has been made of the fact that Boston is home to six Level 1 trauma centers, and that it was race day, a city holiday, 3 p.m., and low-yield devices were used. Dr. King, however, gave high praise to an unsung hero, the Boston EMS loading officer who managed most of the transport destination decisions and smartly distributed critical cases throughout the area’s hospitals.

All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some have argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a "stay-and-play" mentality in the medical tent. The after-action review suggests there probably were enough ambulances to do the job in 30 minutes, said Dr. King, who remarked that the only thing that matters in critical trauma cases is time to surgical hemorrhage control.

"This will remain a controversial issue for Boston, whether staying and playing in the medical tent was a good idea," he said. "I don’t know what the right answer is."

Credit was also given to Massachusetts General, and many of the other city hospitals, for their insistence on regular full-scale drills that allowed quick lock-down of the facility to control access and manage the surge capacity in the emergency department.

"It’s more than just a tabletop exercise," Dr. King said. "When we test the surge capacity, we actually empty the emergency room for real. Usually, it occurs between 5:00 and 7:00 or 4:30 and 7:30 in the morning, but actually doing these things was useful, because when it came time to do it for real, no one was tripping over their own feet."

ED volume on that April afternoon was reduced from 97 patients to just 39 within 1.5 hours. Nontrauma physicians, including psychiatrists, did their part by writing "barebones orders" to get patients transferred to the wards.

Staff at Massachusetts General treated 43 patients, performing nine emergent operations, six amputations, two laparotomies, and one thoracotomy, with two traumatic arrests within the first 72 hours. As with other Boston hospitals, there were no in-hospital deaths, he said.

Patients arrived in such rapid succession, however, that it slowed the electronic medical record system and forced staff to use sequential record numbers, which can be dangerous. Registration couldn’t keep up and orders couldn’t be put in fast enough with 43 patients arriving in roughly 35 minutes, Dr. King explained. Workarounds were often old-school, and reminiscent of his days as a green trauma surgeon serving at Ibn Sina Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.