User login

Hair loss affects more than half of postmenopausal women

Female-pattern hair loss (FPHL) was identified in 52% of postmenopausal women, and 4% of these cases involved extensive baldness, based on data from 178 individuals.

FPHL can develop at any time from teenage years through and beyond menopause, wrote Sukanya Chaikittisilpa, MD, of Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, and colleagues.

The cause of FPHL remains uncertain, but the presence of estrogen receptors in hair follicles suggests that the hormone changes of menopause may affect hair growth, the researchers said.

In a study published in Menopause, the researchers evaluated 178 postmenopausal women aged 50-65 years for FPHL. FPLH was determined based on photographs and on measures of hormone levels, hair density, and hair diameter.

The overall prevalence of FPHL was 52.2%. The hair loss was divided into three categories indicating mild, moderate, and severe (Ludwig grades I, II, and III) with prevalence of 73.2%, 22.6%, and 4.3%, respectively. The prevalence of FPHL also increased with age and time since menopause. In a simple logistic regression analysis, age 56 years and older and more than 6 years since menopause were significantly associated with FPHL (odds ratios, 3.41 and 1.98, respectively).

However, after adjustment for multiple variables, only a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or higher also was associated with increased prevalence of FPHL (adjusted OR, 2.65).

A total of 60% of the study participants met criteria for low self-esteem, including all the women in the severe hair loss category.

“The postmenopausal women with FPHL in our cohort had lower total hair density, terminal hair density, hair thickness, hair unit density, and average hair per unit than those with normal hair patterns,” although vellus hair density was higher in women with FPHL, the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. This distinction may be caused in part by the shortened hair cycle and reduced anagen phase of velluslike follicles, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the cross-sectional design and the inclusion of only women from a single menopause clinic, which may not reflect FPHL in the general population, as well as the reliance on patients’ recall, the researchers noted. Another limitation was the inability to assess postmenopausal hormone levels, they added.

However, “This study may be the first FPHL study conducted in a menopause clinic that targeted only healthy postmenopausal women,” they wrote. More research is needed to determine the potential role of estrogen and testosterone on FPHL in postmenopausal women, and whether a history of polycystic ovarian syndrome has an effect, they said. Meanwhile, current study results may help clinicians and patients determine the most appropriate menopausal hormone therapies for postmenopausal women with FPHL, they concluded.

Consider lifestyle and self-esteem issues

The current study is important at this time because a larger proportion of women are either reaching menopause or are menopausal, said Constance Bohon, MD, a gynecologist in private practice in Washington, in an interview.

“Whatever we in the medical community can do to help women transition into the menopausal years with the least anxiety is important,” including helping women feel comfortable about their appearance, she said.

“For women in the peri- and postmenopausal years, hair loss is a relatively common concern,” Dr. Bohon said. However, in the current study, “I was surprised that it was associated with low self-esteem and obesity,” she noted. “For these women, it would be interesting to know whether they also had concerns about the appearance of their bodies, or just their hair loss,” she said. The question is whether the hair loss in and of itself caused low self-esteem in the study population, or whether it exacerbated their already poor self-assessment, Dr. Bohon said. “Another consideration is that perhaps these women were already feeling the effects of aging and were trying to change their appearance by using hair dyes, and now they find themselves losing hair as well,” she noted.

The takeaway message for clinicians is that discussions with perimenopausal and postmenopausal women should include the topic of hair loss along with hot flashes and night sweats, said Dr. Bohon.

Women who are experiencing hair loss or concerned about the possibility of hair loss should ask their doctors about possible interventions that may mitigate or prevent further hair loss, she said.

As for additional research, “the most important issue is to determine the factors that are associated with hair loss in the perimenopausal and postmenopausal years,” Dr. Bohon said. Research questions should include impact of dyeing or straightening hair on the likelihood of hair loss, and whether women with more severe hot flashes/night sweats and/or sleeplessness have more hair loss than women who do not experience any of the symptoms as they go through menopause, she emphasized.

Other considerations are whether certain diets or foods are more common among women who have more hair loss, and whether weight loss into a normal range or weight gain into a body mass index greater than 25 kg/m2 affects hair loss, said Dr. Bohon. Also, don’t discount the impact of stress, and whether women who have lost hair identify certain stressful times that preceded their hair loss, as well as what medications could be associated with hair loss, and whether hormone therapy might prevent hair loss, she said.

The study was supported by the Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Bohon had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Ob.Gyn. News.

Female-pattern hair loss (FPHL) was identified in 52% of postmenopausal women, and 4% of these cases involved extensive baldness, based on data from 178 individuals.

FPHL can develop at any time from teenage years through and beyond menopause, wrote Sukanya Chaikittisilpa, MD, of Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, and colleagues.

The cause of FPHL remains uncertain, but the presence of estrogen receptors in hair follicles suggests that the hormone changes of menopause may affect hair growth, the researchers said.

In a study published in Menopause, the researchers evaluated 178 postmenopausal women aged 50-65 years for FPHL. FPLH was determined based on photographs and on measures of hormone levels, hair density, and hair diameter.

The overall prevalence of FPHL was 52.2%. The hair loss was divided into three categories indicating mild, moderate, and severe (Ludwig grades I, II, and III) with prevalence of 73.2%, 22.6%, and 4.3%, respectively. The prevalence of FPHL also increased with age and time since menopause. In a simple logistic regression analysis, age 56 years and older and more than 6 years since menopause were significantly associated with FPHL (odds ratios, 3.41 and 1.98, respectively).

However, after adjustment for multiple variables, only a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or higher also was associated with increased prevalence of FPHL (adjusted OR, 2.65).

A total of 60% of the study participants met criteria for low self-esteem, including all the women in the severe hair loss category.

“The postmenopausal women with FPHL in our cohort had lower total hair density, terminal hair density, hair thickness, hair unit density, and average hair per unit than those with normal hair patterns,” although vellus hair density was higher in women with FPHL, the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. This distinction may be caused in part by the shortened hair cycle and reduced anagen phase of velluslike follicles, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the cross-sectional design and the inclusion of only women from a single menopause clinic, which may not reflect FPHL in the general population, as well as the reliance on patients’ recall, the researchers noted. Another limitation was the inability to assess postmenopausal hormone levels, they added.

However, “This study may be the first FPHL study conducted in a menopause clinic that targeted only healthy postmenopausal women,” they wrote. More research is needed to determine the potential role of estrogen and testosterone on FPHL in postmenopausal women, and whether a history of polycystic ovarian syndrome has an effect, they said. Meanwhile, current study results may help clinicians and patients determine the most appropriate menopausal hormone therapies for postmenopausal women with FPHL, they concluded.

Consider lifestyle and self-esteem issues

The current study is important at this time because a larger proportion of women are either reaching menopause or are menopausal, said Constance Bohon, MD, a gynecologist in private practice in Washington, in an interview.

“Whatever we in the medical community can do to help women transition into the menopausal years with the least anxiety is important,” including helping women feel comfortable about their appearance, she said.

“For women in the peri- and postmenopausal years, hair loss is a relatively common concern,” Dr. Bohon said. However, in the current study, “I was surprised that it was associated with low self-esteem and obesity,” she noted. “For these women, it would be interesting to know whether they also had concerns about the appearance of their bodies, or just their hair loss,” she said. The question is whether the hair loss in and of itself caused low self-esteem in the study population, or whether it exacerbated their already poor self-assessment, Dr. Bohon said. “Another consideration is that perhaps these women were already feeling the effects of aging and were trying to change their appearance by using hair dyes, and now they find themselves losing hair as well,” she noted.

The takeaway message for clinicians is that discussions with perimenopausal and postmenopausal women should include the topic of hair loss along with hot flashes and night sweats, said Dr. Bohon.

Women who are experiencing hair loss or concerned about the possibility of hair loss should ask their doctors about possible interventions that may mitigate or prevent further hair loss, she said.

As for additional research, “the most important issue is to determine the factors that are associated with hair loss in the perimenopausal and postmenopausal years,” Dr. Bohon said. Research questions should include impact of dyeing or straightening hair on the likelihood of hair loss, and whether women with more severe hot flashes/night sweats and/or sleeplessness have more hair loss than women who do not experience any of the symptoms as they go through menopause, she emphasized.

Other considerations are whether certain diets or foods are more common among women who have more hair loss, and whether weight loss into a normal range or weight gain into a body mass index greater than 25 kg/m2 affects hair loss, said Dr. Bohon. Also, don’t discount the impact of stress, and whether women who have lost hair identify certain stressful times that preceded their hair loss, as well as what medications could be associated with hair loss, and whether hormone therapy might prevent hair loss, she said.

The study was supported by the Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Bohon had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Ob.Gyn. News.

Female-pattern hair loss (FPHL) was identified in 52% of postmenopausal women, and 4% of these cases involved extensive baldness, based on data from 178 individuals.

FPHL can develop at any time from teenage years through and beyond menopause, wrote Sukanya Chaikittisilpa, MD, of Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, and colleagues.

The cause of FPHL remains uncertain, but the presence of estrogen receptors in hair follicles suggests that the hormone changes of menopause may affect hair growth, the researchers said.

In a study published in Menopause, the researchers evaluated 178 postmenopausal women aged 50-65 years for FPHL. FPLH was determined based on photographs and on measures of hormone levels, hair density, and hair diameter.

The overall prevalence of FPHL was 52.2%. The hair loss was divided into three categories indicating mild, moderate, and severe (Ludwig grades I, II, and III) with prevalence of 73.2%, 22.6%, and 4.3%, respectively. The prevalence of FPHL also increased with age and time since menopause. In a simple logistic regression analysis, age 56 years and older and more than 6 years since menopause were significantly associated with FPHL (odds ratios, 3.41 and 1.98, respectively).

However, after adjustment for multiple variables, only a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or higher also was associated with increased prevalence of FPHL (adjusted OR, 2.65).

A total of 60% of the study participants met criteria for low self-esteem, including all the women in the severe hair loss category.

“The postmenopausal women with FPHL in our cohort had lower total hair density, terminal hair density, hair thickness, hair unit density, and average hair per unit than those with normal hair patterns,” although vellus hair density was higher in women with FPHL, the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. This distinction may be caused in part by the shortened hair cycle and reduced anagen phase of velluslike follicles, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the cross-sectional design and the inclusion of only women from a single menopause clinic, which may not reflect FPHL in the general population, as well as the reliance on patients’ recall, the researchers noted. Another limitation was the inability to assess postmenopausal hormone levels, they added.

However, “This study may be the first FPHL study conducted in a menopause clinic that targeted only healthy postmenopausal women,” they wrote. More research is needed to determine the potential role of estrogen and testosterone on FPHL in postmenopausal women, and whether a history of polycystic ovarian syndrome has an effect, they said. Meanwhile, current study results may help clinicians and patients determine the most appropriate menopausal hormone therapies for postmenopausal women with FPHL, they concluded.

Consider lifestyle and self-esteem issues

The current study is important at this time because a larger proportion of women are either reaching menopause or are menopausal, said Constance Bohon, MD, a gynecologist in private practice in Washington, in an interview.

“Whatever we in the medical community can do to help women transition into the menopausal years with the least anxiety is important,” including helping women feel comfortable about their appearance, she said.

“For women in the peri- and postmenopausal years, hair loss is a relatively common concern,” Dr. Bohon said. However, in the current study, “I was surprised that it was associated with low self-esteem and obesity,” she noted. “For these women, it would be interesting to know whether they also had concerns about the appearance of their bodies, or just their hair loss,” she said. The question is whether the hair loss in and of itself caused low self-esteem in the study population, or whether it exacerbated their already poor self-assessment, Dr. Bohon said. “Another consideration is that perhaps these women were already feeling the effects of aging and were trying to change their appearance by using hair dyes, and now they find themselves losing hair as well,” she noted.

The takeaway message for clinicians is that discussions with perimenopausal and postmenopausal women should include the topic of hair loss along with hot flashes and night sweats, said Dr. Bohon.

Women who are experiencing hair loss or concerned about the possibility of hair loss should ask their doctors about possible interventions that may mitigate or prevent further hair loss, she said.

As for additional research, “the most important issue is to determine the factors that are associated with hair loss in the perimenopausal and postmenopausal years,” Dr. Bohon said. Research questions should include impact of dyeing or straightening hair on the likelihood of hair loss, and whether women with more severe hot flashes/night sweats and/or sleeplessness have more hair loss than women who do not experience any of the symptoms as they go through menopause, she emphasized.

Other considerations are whether certain diets or foods are more common among women who have more hair loss, and whether weight loss into a normal range or weight gain into a body mass index greater than 25 kg/m2 affects hair loss, said Dr. Bohon. Also, don’t discount the impact of stress, and whether women who have lost hair identify certain stressful times that preceded their hair loss, as well as what medications could be associated with hair loss, and whether hormone therapy might prevent hair loss, she said.

The study was supported by the Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Bohon had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Ob.Gyn. News.

FROM MENOPAUSE

Past spontaneous abortion raises risk for gestational diabetes

Pregnant women with a history of spontaneous abortion had a significantly increased risk of gestational diabetes in subsequent pregnancies, based on data from more than 100,000 women.

Gestational diabetes is associated not only with adverse perinatal outcomes, but also with an increased risk of long-term cardiovascular and metabolic health issues in mothers and children, wrote Yan Zhao, PhD, of Tongji University, Shanghai, and colleagues.

Previous studies also have shown that spontaneous abortion (SAB) is associated with later maternal risk of cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism, the researchers said. The same mechanisms might contribute to the development of gestational diabetes, but the association between abortion history and gestational diabetes risk in subsequent pregnancies remains unclear, they added.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers identified 102,259 pregnant women seen for routine prenatal care at a single hospital in Shanghai between January 2014 and December 2019. The mean age of the women was 29.8 years.

During the study period, 14,579 women experienced SAB (14.3%), 17,935 experienced induced abortion (17.5%), and 4,017 experienced both (11.9%).

In all, 12,153 cases of gestational diabetes were identified, for a prevalence of 11.9%. The relative risk of gestational diabetes was 1.25 for women who experienced SAB and 1.15 for those who experienced both SAB and induced abortion, and the association between SAB and gestational diabetes increased in a number-dependent manner, the researchers said. The increase in relative risk for gestational diabetes in pregnant women with one SAB, two SABs, and three or more SABs was 18%, 41%, and 43%, compared to pregnant women with no SAB history.

However, no association appeared between a history of induced abortion and gestational diabetes, the researchers said. “To date, no study has reported the association of prior induced abortion with gestational diabetes,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on self-reports for history of SAB and therefore possible underreporting, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the lack of data on the timing of SABs; therefore, the time between SAB and gestational diabetes diagnosis could not be included in the analysis, they said. Unknown variables and the inclusion only of women from a single city in China might limit the generalizability of the results, they added.

More research is needed to understand the biological mechanisms behind the association between SAB and gestational diabetes, an association that has potential public health implications, they noted. However, the results suggest that “pregnant women with a history of SAB, especially those with a history of recurrent SAB, should attend more antenatal visits to monitor their blood glucose and implement early prevention and intervention,” such as healthful eating and regular exercise, they wrote.

Findings confirm, not surprise

The diagnosis of gestational diabetes in the current study “was made with a slightly different test than we typically use in the United States – a 1-hour nonfasting glucola followed by a confirmatory 3-hour fasting glucola,” Sarah W. Prager, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview. The current study of both SAB and gestational diabetes is important because both conditions are very common and have been the focus of increased attention in the popular media and in scientific study, she said.

Dr. Prager said she was not surprised by the findings of a link between a history of gestational diabetes and a history of SAB, “but the association is likely that people at risk for gestational diabetes or who have undiagnosed diabetes/glucose intolerance are more likely to experience SAB,” she noted. “I would be surprised if the direction of the association is that SAB puts people at risk for gestational diabetes; more likely undiagnosed diabetes is a risk factor for SAB,” she added. “Perhaps we should be screening for glucose intolerance and other metabolic disorders more frequently in people who have especially recurrent SAB, as the more miscarriages someone had, the more likely they were in this study to be diagnosed with gestational diabetes;” or perhaps those with a history of SAB/recurrent SAB should be screened closer to 24 weeks’ than 28 weeks’ gestation to enable earlier intervention in those more likely to have gestational diabetes, Dr. Prager said.

The study was supported by the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, the Shanghai Municipal Medical and Health Discipline Construction Projects, and the Shanghai Rising-Star Program. The researchers and Dr. Prager had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Prager serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn. News.

Pregnant women with a history of spontaneous abortion had a significantly increased risk of gestational diabetes in subsequent pregnancies, based on data from more than 100,000 women.

Gestational diabetes is associated not only with adverse perinatal outcomes, but also with an increased risk of long-term cardiovascular and metabolic health issues in mothers and children, wrote Yan Zhao, PhD, of Tongji University, Shanghai, and colleagues.

Previous studies also have shown that spontaneous abortion (SAB) is associated with later maternal risk of cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism, the researchers said. The same mechanisms might contribute to the development of gestational diabetes, but the association between abortion history and gestational diabetes risk in subsequent pregnancies remains unclear, they added.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers identified 102,259 pregnant women seen for routine prenatal care at a single hospital in Shanghai between January 2014 and December 2019. The mean age of the women was 29.8 years.

During the study period, 14,579 women experienced SAB (14.3%), 17,935 experienced induced abortion (17.5%), and 4,017 experienced both (11.9%).

In all, 12,153 cases of gestational diabetes were identified, for a prevalence of 11.9%. The relative risk of gestational diabetes was 1.25 for women who experienced SAB and 1.15 for those who experienced both SAB and induced abortion, and the association between SAB and gestational diabetes increased in a number-dependent manner, the researchers said. The increase in relative risk for gestational diabetes in pregnant women with one SAB, two SABs, and three or more SABs was 18%, 41%, and 43%, compared to pregnant women with no SAB history.

However, no association appeared between a history of induced abortion and gestational diabetes, the researchers said. “To date, no study has reported the association of prior induced abortion with gestational diabetes,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on self-reports for history of SAB and therefore possible underreporting, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the lack of data on the timing of SABs; therefore, the time between SAB and gestational diabetes diagnosis could not be included in the analysis, they said. Unknown variables and the inclusion only of women from a single city in China might limit the generalizability of the results, they added.

More research is needed to understand the biological mechanisms behind the association between SAB and gestational diabetes, an association that has potential public health implications, they noted. However, the results suggest that “pregnant women with a history of SAB, especially those with a history of recurrent SAB, should attend more antenatal visits to monitor their blood glucose and implement early prevention and intervention,” such as healthful eating and regular exercise, they wrote.

Findings confirm, not surprise

The diagnosis of gestational diabetes in the current study “was made with a slightly different test than we typically use in the United States – a 1-hour nonfasting glucola followed by a confirmatory 3-hour fasting glucola,” Sarah W. Prager, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview. The current study of both SAB and gestational diabetes is important because both conditions are very common and have been the focus of increased attention in the popular media and in scientific study, she said.

Dr. Prager said she was not surprised by the findings of a link between a history of gestational diabetes and a history of SAB, “but the association is likely that people at risk for gestational diabetes or who have undiagnosed diabetes/glucose intolerance are more likely to experience SAB,” she noted. “I would be surprised if the direction of the association is that SAB puts people at risk for gestational diabetes; more likely undiagnosed diabetes is a risk factor for SAB,” she added. “Perhaps we should be screening for glucose intolerance and other metabolic disorders more frequently in people who have especially recurrent SAB, as the more miscarriages someone had, the more likely they were in this study to be diagnosed with gestational diabetes;” or perhaps those with a history of SAB/recurrent SAB should be screened closer to 24 weeks’ than 28 weeks’ gestation to enable earlier intervention in those more likely to have gestational diabetes, Dr. Prager said.

The study was supported by the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, the Shanghai Municipal Medical and Health Discipline Construction Projects, and the Shanghai Rising-Star Program. The researchers and Dr. Prager had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Prager serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn. News.

Pregnant women with a history of spontaneous abortion had a significantly increased risk of gestational diabetes in subsequent pregnancies, based on data from more than 100,000 women.

Gestational diabetes is associated not only with adverse perinatal outcomes, but also with an increased risk of long-term cardiovascular and metabolic health issues in mothers and children, wrote Yan Zhao, PhD, of Tongji University, Shanghai, and colleagues.

Previous studies also have shown that spontaneous abortion (SAB) is associated with later maternal risk of cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism, the researchers said. The same mechanisms might contribute to the development of gestational diabetes, but the association between abortion history and gestational diabetes risk in subsequent pregnancies remains unclear, they added.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers identified 102,259 pregnant women seen for routine prenatal care at a single hospital in Shanghai between January 2014 and December 2019. The mean age of the women was 29.8 years.

During the study period, 14,579 women experienced SAB (14.3%), 17,935 experienced induced abortion (17.5%), and 4,017 experienced both (11.9%).

In all, 12,153 cases of gestational diabetes were identified, for a prevalence of 11.9%. The relative risk of gestational diabetes was 1.25 for women who experienced SAB and 1.15 for those who experienced both SAB and induced abortion, and the association between SAB and gestational diabetes increased in a number-dependent manner, the researchers said. The increase in relative risk for gestational diabetes in pregnant women with one SAB, two SABs, and three or more SABs was 18%, 41%, and 43%, compared to pregnant women with no SAB history.

However, no association appeared between a history of induced abortion and gestational diabetes, the researchers said. “To date, no study has reported the association of prior induced abortion with gestational diabetes,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on self-reports for history of SAB and therefore possible underreporting, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the lack of data on the timing of SABs; therefore, the time between SAB and gestational diabetes diagnosis could not be included in the analysis, they said. Unknown variables and the inclusion only of women from a single city in China might limit the generalizability of the results, they added.

More research is needed to understand the biological mechanisms behind the association between SAB and gestational diabetes, an association that has potential public health implications, they noted. However, the results suggest that “pregnant women with a history of SAB, especially those with a history of recurrent SAB, should attend more antenatal visits to monitor their blood glucose and implement early prevention and intervention,” such as healthful eating and regular exercise, they wrote.

Findings confirm, not surprise

The diagnosis of gestational diabetes in the current study “was made with a slightly different test than we typically use in the United States – a 1-hour nonfasting glucola followed by a confirmatory 3-hour fasting glucola,” Sarah W. Prager, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview. The current study of both SAB and gestational diabetes is important because both conditions are very common and have been the focus of increased attention in the popular media and in scientific study, she said.

Dr. Prager said she was not surprised by the findings of a link between a history of gestational diabetes and a history of SAB, “but the association is likely that people at risk for gestational diabetes or who have undiagnosed diabetes/glucose intolerance are more likely to experience SAB,” she noted. “I would be surprised if the direction of the association is that SAB puts people at risk for gestational diabetes; more likely undiagnosed diabetes is a risk factor for SAB,” she added. “Perhaps we should be screening for glucose intolerance and other metabolic disorders more frequently in people who have especially recurrent SAB, as the more miscarriages someone had, the more likely they were in this study to be diagnosed with gestational diabetes;” or perhaps those with a history of SAB/recurrent SAB should be screened closer to 24 weeks’ than 28 weeks’ gestation to enable earlier intervention in those more likely to have gestational diabetes, Dr. Prager said.

The study was supported by the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, the Shanghai Municipal Medical and Health Discipline Construction Projects, and the Shanghai Rising-Star Program. The researchers and Dr. Prager had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Prager serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn. News.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

15th Report on Carcinogens Adds to Its List

From environmental tobacco smoke to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, diesel exhaust particulates, lead, and now, chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori (H pylori)—the Report on Carcinogens has regularly updated the list of substances known or “reasonably anticipated” to cause cancer.

The 15th report, which is prepared by the National Toxicology Program (NTP) for the Department of Health and Human Services, has 8 new entries, bringing the number of human carcinogens (eg, metals, pesticides, and drugs) on the list to 256. (The first report, released in 1980, listed 26.) In addition to H pylori infection, this edition adds the flame-retardant chemical antimony trioxide, and 6 haloacetic acids found as water disinfection byproducts.

In 1971, then President Nixon declared “war on cancer” (the second leading cause of death in the US) and signed the National Cancer Act. In 1978, Congress ordered the Report on Carcinogens, to educate the public and health professionals on potential environmental carcinogenic hazards.

Perhaps disheartening to know that even with 256 entries, the list probably understates the number of carcinogens humans and other creatures are exposed to. But things can change with time. Each list goes through a rigorous round of reviews. Sometimes substances are “delisted” after, for instance, litigation or new research. Saccharin, for example, was removed from the ninth edition. It was listed as “reasonably anticipated” in 1981, based on “sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals.” It was removed, however, after extensive review of decades of saccharin use determined that the data were not sufficient to meet current criteria. Further research had revealed, also, that the observed bladder tumors in rats arose from a mechanism not relevant to humans.

Other entries, such as the controversial listing of the cancer drug tamoxifen, walk a fine line between risk and benefit. Tamoxifen, first listed in the ninth report (and still in the 15th report), was included because studies revealed that it could increase the risk of uterine cancer in women. But there also was conclusive evidence that it may prevent or delay breast cancer in women who are at high risk.

Ultimately, the report’s authors make it clear that it is for informative value and guidance, not necessarily a dictate. As one report put it: “Personal decisions concerning voluntary exposures to carcinogenic agents need to be based on additional information that is beyond the scope” of the report.

“As the identification of carcinogens is a key step in cancer prevention,” said Rick Woychik, PhD, director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and NTP, “publication of the report represents an important government activity towards improving public health.”

From environmental tobacco smoke to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, diesel exhaust particulates, lead, and now, chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori (H pylori)—the Report on Carcinogens has regularly updated the list of substances known or “reasonably anticipated” to cause cancer.

The 15th report, which is prepared by the National Toxicology Program (NTP) for the Department of Health and Human Services, has 8 new entries, bringing the number of human carcinogens (eg, metals, pesticides, and drugs) on the list to 256. (The first report, released in 1980, listed 26.) In addition to H pylori infection, this edition adds the flame-retardant chemical antimony trioxide, and 6 haloacetic acids found as water disinfection byproducts.

In 1971, then President Nixon declared “war on cancer” (the second leading cause of death in the US) and signed the National Cancer Act. In 1978, Congress ordered the Report on Carcinogens, to educate the public and health professionals on potential environmental carcinogenic hazards.

Perhaps disheartening to know that even with 256 entries, the list probably understates the number of carcinogens humans and other creatures are exposed to. But things can change with time. Each list goes through a rigorous round of reviews. Sometimes substances are “delisted” after, for instance, litigation or new research. Saccharin, for example, was removed from the ninth edition. It was listed as “reasonably anticipated” in 1981, based on “sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals.” It was removed, however, after extensive review of decades of saccharin use determined that the data were not sufficient to meet current criteria. Further research had revealed, also, that the observed bladder tumors in rats arose from a mechanism not relevant to humans.

Other entries, such as the controversial listing of the cancer drug tamoxifen, walk a fine line between risk and benefit. Tamoxifen, first listed in the ninth report (and still in the 15th report), was included because studies revealed that it could increase the risk of uterine cancer in women. But there also was conclusive evidence that it may prevent or delay breast cancer in women who are at high risk.

Ultimately, the report’s authors make it clear that it is for informative value and guidance, not necessarily a dictate. As one report put it: “Personal decisions concerning voluntary exposures to carcinogenic agents need to be based on additional information that is beyond the scope” of the report.

“As the identification of carcinogens is a key step in cancer prevention,” said Rick Woychik, PhD, director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and NTP, “publication of the report represents an important government activity towards improving public health.”

From environmental tobacco smoke to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, diesel exhaust particulates, lead, and now, chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori (H pylori)—the Report on Carcinogens has regularly updated the list of substances known or “reasonably anticipated” to cause cancer.

The 15th report, which is prepared by the National Toxicology Program (NTP) for the Department of Health and Human Services, has 8 new entries, bringing the number of human carcinogens (eg, metals, pesticides, and drugs) on the list to 256. (The first report, released in 1980, listed 26.) In addition to H pylori infection, this edition adds the flame-retardant chemical antimony trioxide, and 6 haloacetic acids found as water disinfection byproducts.

In 1971, then President Nixon declared “war on cancer” (the second leading cause of death in the US) and signed the National Cancer Act. In 1978, Congress ordered the Report on Carcinogens, to educate the public and health professionals on potential environmental carcinogenic hazards.

Perhaps disheartening to know that even with 256 entries, the list probably understates the number of carcinogens humans and other creatures are exposed to. But things can change with time. Each list goes through a rigorous round of reviews. Sometimes substances are “delisted” after, for instance, litigation or new research. Saccharin, for example, was removed from the ninth edition. It was listed as “reasonably anticipated” in 1981, based on “sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals.” It was removed, however, after extensive review of decades of saccharin use determined that the data were not sufficient to meet current criteria. Further research had revealed, also, that the observed bladder tumors in rats arose from a mechanism not relevant to humans.

Other entries, such as the controversial listing of the cancer drug tamoxifen, walk a fine line between risk and benefit. Tamoxifen, first listed in the ninth report (and still in the 15th report), was included because studies revealed that it could increase the risk of uterine cancer in women. But there also was conclusive evidence that it may prevent or delay breast cancer in women who are at high risk.

Ultimately, the report’s authors make it clear that it is for informative value and guidance, not necessarily a dictate. As one report put it: “Personal decisions concerning voluntary exposures to carcinogenic agents need to be based on additional information that is beyond the scope” of the report.

“As the identification of carcinogens is a key step in cancer prevention,” said Rick Woychik, PhD, director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and NTP, “publication of the report represents an important government activity towards improving public health.”

Early menopause, early dementia risk, study suggests

Earlier menopause appears to be associated with a higher risk of dementia, and earlier onset of dementia, compared with menopause at normal age or later, according to a large study.

“Being aware of this increased risk can help women practice strategies to prevent dementia and to work with their physicians to closely monitor their cognitive status as they age,” study investigator Wenting Hao, MD, with Shandong University, Jinan, China, says in a news release.

The findings were presented in an e-poster March 1 at the Epidemiology, Prevention, Lifestyle & Cardiometabolic Health (EPI|Lifestyle) 2022 conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

UK Biobank data

Dr. Hao and colleagues examined health data for 153,291 women who were 60 years old on average when they became participants in the UK Biobank.

Age at menopause was categorized as premature (younger than age 40), early (40 to 44 years), reference (45 to 51), 52 to 55 years, and 55+ years.

Compared with women who entered menopause around age 50 years (reference), women who experienced premature menopause were 35% more likely to develop some type of dementia later in life (hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.22 to 1.91).

Women with early menopause were also more likely to develop early-onset dementia, that is, before age 65 (HR, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, 1.07 to 1.72).

Women who entered menopause later (at age 52+) had dementia risk similar to women who entered menopause at the average age of 50 to 51 years.

The results were adjusted for relevant cofactors, including age at last exam, race, educational level, cigarette and alcohol use, body mass index, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, income, and leisure and physical activities.

Blame it on estrogen?

Reduced estrogen levels may be a factor in the possible connection between early menopause and dementia, Dr. Hao and her colleagues say.

Estradiol plays a key role in a range of neurological functions, so the reduction of endogenous estrogen at menopause may aggravate brain changes related to neurodegenerative disease and speed up progression of dementia, they explain.

“We know that the lack of estrogen over the long term enhances oxidative stress, which may increase brain aging and lead to cognitive impairment,” Dr. Hao adds.

Limitations of the study include reliance on self-reported information about age at menopause onset.

Also, the researchers did not evaluate dementia rates in women who had a naturally occurring early menopause separate from the women with surgery-induced menopause, which may affect the results.

Finally, the data used for this study included mostly White women living in the U.K. and may not generalize to other populations.

Supportive evidence, critical area of research

The U.K. study supports results of a previously reported Kaiser Permanente study, which showed women who entered menopause at age 45 or younger were at 28% greater dementia risk, compared with women who experienced menopause after age 45.

Reached for comment, Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of medical and scientific relations, noted that nearly two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s are women.

“We know Alzheimer’s and other dementias impact a greater number of women than men, but we don’t know why,” she told this news organization.

“Lifelong differences in women may affect their risk or affect what is contributing to their underlying biology of the disease, and we need more research to better understand what may be these contributing factors,” said Dr. Snyder.

“Reproductive history is one critical area being studied. The physical and hormonal changes that occur during menopause – as well as other hormonal changes throughout life – are considerable, and it’s important to understand what impact, if any, these changes may have on the brain,” Dr. Snyder added.

“The potential link between reproduction history and brain health is intriguing, but much more research in this area is needed to understand these links,” she said.

The study was funded by the Start-up Foundation for Scientific Research at Shandong University. Dr. Hao and Dr. Snyder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Earlier menopause appears to be associated with a higher risk of dementia, and earlier onset of dementia, compared with menopause at normal age or later, according to a large study.

“Being aware of this increased risk can help women practice strategies to prevent dementia and to work with their physicians to closely monitor their cognitive status as they age,” study investigator Wenting Hao, MD, with Shandong University, Jinan, China, says in a news release.

The findings were presented in an e-poster March 1 at the Epidemiology, Prevention, Lifestyle & Cardiometabolic Health (EPI|Lifestyle) 2022 conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

UK Biobank data

Dr. Hao and colleagues examined health data for 153,291 women who were 60 years old on average when they became participants in the UK Biobank.

Age at menopause was categorized as premature (younger than age 40), early (40 to 44 years), reference (45 to 51), 52 to 55 years, and 55+ years.

Compared with women who entered menopause around age 50 years (reference), women who experienced premature menopause were 35% more likely to develop some type of dementia later in life (hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.22 to 1.91).

Women with early menopause were also more likely to develop early-onset dementia, that is, before age 65 (HR, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, 1.07 to 1.72).

Women who entered menopause later (at age 52+) had dementia risk similar to women who entered menopause at the average age of 50 to 51 years.

The results were adjusted for relevant cofactors, including age at last exam, race, educational level, cigarette and alcohol use, body mass index, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, income, and leisure and physical activities.

Blame it on estrogen?

Reduced estrogen levels may be a factor in the possible connection between early menopause and dementia, Dr. Hao and her colleagues say.

Estradiol plays a key role in a range of neurological functions, so the reduction of endogenous estrogen at menopause may aggravate brain changes related to neurodegenerative disease and speed up progression of dementia, they explain.

“We know that the lack of estrogen over the long term enhances oxidative stress, which may increase brain aging and lead to cognitive impairment,” Dr. Hao adds.

Limitations of the study include reliance on self-reported information about age at menopause onset.

Also, the researchers did not evaluate dementia rates in women who had a naturally occurring early menopause separate from the women with surgery-induced menopause, which may affect the results.

Finally, the data used for this study included mostly White women living in the U.K. and may not generalize to other populations.

Supportive evidence, critical area of research

The U.K. study supports results of a previously reported Kaiser Permanente study, which showed women who entered menopause at age 45 or younger were at 28% greater dementia risk, compared with women who experienced menopause after age 45.

Reached for comment, Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of medical and scientific relations, noted that nearly two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s are women.

“We know Alzheimer’s and other dementias impact a greater number of women than men, but we don’t know why,” she told this news organization.

“Lifelong differences in women may affect their risk or affect what is contributing to their underlying biology of the disease, and we need more research to better understand what may be these contributing factors,” said Dr. Snyder.

“Reproductive history is one critical area being studied. The physical and hormonal changes that occur during menopause – as well as other hormonal changes throughout life – are considerable, and it’s important to understand what impact, if any, these changes may have on the brain,” Dr. Snyder added.

“The potential link between reproduction history and brain health is intriguing, but much more research in this area is needed to understand these links,” she said.

The study was funded by the Start-up Foundation for Scientific Research at Shandong University. Dr. Hao and Dr. Snyder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Earlier menopause appears to be associated with a higher risk of dementia, and earlier onset of dementia, compared with menopause at normal age or later, according to a large study.

“Being aware of this increased risk can help women practice strategies to prevent dementia and to work with their physicians to closely monitor their cognitive status as they age,” study investigator Wenting Hao, MD, with Shandong University, Jinan, China, says in a news release.

The findings were presented in an e-poster March 1 at the Epidemiology, Prevention, Lifestyle & Cardiometabolic Health (EPI|Lifestyle) 2022 conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

UK Biobank data

Dr. Hao and colleagues examined health data for 153,291 women who were 60 years old on average when they became participants in the UK Biobank.

Age at menopause was categorized as premature (younger than age 40), early (40 to 44 years), reference (45 to 51), 52 to 55 years, and 55+ years.

Compared with women who entered menopause around age 50 years (reference), women who experienced premature menopause were 35% more likely to develop some type of dementia later in life (hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.22 to 1.91).

Women with early menopause were also more likely to develop early-onset dementia, that is, before age 65 (HR, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, 1.07 to 1.72).

Women who entered menopause later (at age 52+) had dementia risk similar to women who entered menopause at the average age of 50 to 51 years.

The results were adjusted for relevant cofactors, including age at last exam, race, educational level, cigarette and alcohol use, body mass index, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, income, and leisure and physical activities.

Blame it on estrogen?

Reduced estrogen levels may be a factor in the possible connection between early menopause and dementia, Dr. Hao and her colleagues say.

Estradiol plays a key role in a range of neurological functions, so the reduction of endogenous estrogen at menopause may aggravate brain changes related to neurodegenerative disease and speed up progression of dementia, they explain.

“We know that the lack of estrogen over the long term enhances oxidative stress, which may increase brain aging and lead to cognitive impairment,” Dr. Hao adds.

Limitations of the study include reliance on self-reported information about age at menopause onset.

Also, the researchers did not evaluate dementia rates in women who had a naturally occurring early menopause separate from the women with surgery-induced menopause, which may affect the results.

Finally, the data used for this study included mostly White women living in the U.K. and may not generalize to other populations.

Supportive evidence, critical area of research

The U.K. study supports results of a previously reported Kaiser Permanente study, which showed women who entered menopause at age 45 or younger were at 28% greater dementia risk, compared with women who experienced menopause after age 45.

Reached for comment, Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of medical and scientific relations, noted that nearly two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s are women.

“We know Alzheimer’s and other dementias impact a greater number of women than men, but we don’t know why,” she told this news organization.

“Lifelong differences in women may affect their risk or affect what is contributing to their underlying biology of the disease, and we need more research to better understand what may be these contributing factors,” said Dr. Snyder.

“Reproductive history is one critical area being studied. The physical and hormonal changes that occur during menopause – as well as other hormonal changes throughout life – are considerable, and it’s important to understand what impact, if any, these changes may have on the brain,” Dr. Snyder added.

“The potential link between reproduction history and brain health is intriguing, but much more research in this area is needed to understand these links,” she said.

The study was funded by the Start-up Foundation for Scientific Research at Shandong University. Dr. Hao and Dr. Snyder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gestational diabetes: Optimizing Dx and management in primary care

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as new-onset hyperglycemia detected in a pregnant woman after 24 weeks of gestation, affects 4% to 10% of pregnancies in the United States annually1 and is a major challenge for health care professionals.2 During pregnancy, the body’s physiologic responses are altered to support the growing fetus. One of these changes is an increase in insulin resistance, which suggests that pregnancy alone increases the patient’s risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D). However, several other factors also increase this risk, including maternal age, social barriers to care, obesity, poor weight control, and family history.

If not controlled, GDM results in poor health outcomes for the mother, such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and maternal T2D.3-5 For the infant, intrauterine exposure to persistent hyperglycemia is correlated with neonatal macrosomia, hypoglycemia, perinatal complications (eg, preterm delivery, fetal demise), and obesity and insulin resistance later in life.4

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are the patient’s main point of contact prior to pregnancy. This relationship makes PCPs a resource for the patient and specialists during and after pregnancy. In this article, we discuss risk factors and how to screen for GDM, provide an update on practice recommendations for treatment and management of GDM in primary care, and describe the effects of uncontrolled GDM.

Know the key risk factors

Prevention begins with identifying the major risk factors that contribute to the development of GDM. These include maternal age, social barriers to care, family history of prediabetes, and obesity and poor weight control.

Older age. A meta-analysis of 24 studies noted strong positive correlation between GDM risk and maternal age.6 One of the population-based cohort studies in the meta-analysis examined relationships between maternal age and pregnancy outcomes in women living in British Columbia, Canada (n = 203,414). Data suggested that the relative risk of GDM increased linearly with maternal age to 3.2, 4.2, and 4.4 among women ages ≥ 35, ≥ 40, and ≥ 45 years, respectively.7

Social barriers to care. Although the prevalence of GDM has increased over the past few decades,1 from 2011 to 2019 the increase in GDM in individuals at first live birth was significantly higher in non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic/Latina women than in non-Hispanic White women.8 Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention further suggest that diabetes was more prevalent among individuals with a lower socioeconomic status as indicated by their level of education.9 Ogunwole et al10 suggest that racism is the root cause of these disparities and leads to long-term barriers to care (eg, socioeconomic deprivation, lack of health insurance, limited access to care, and poor health literacy), which ultimately contribute to the development of GDM and progression of diabetes. It is important for PCPs and all health professionals to be aware of these barriers so that they may practice mindfulness and deliver culturally sensitive care to patients from marginalized communities.

Family history of prediabetes. In a population-based cohort study (n = 7020), women with prediabetes (A1C, 5.7%-6.4%) were 2.8 times more likely to develop GDM compared with women with normal A1C (< 5.7%).11 Similar results were seen in a retrospective cohort study (n = 2812), in which women with prediabetes were more likely than women with a normal first trimester A1C to have GDM (29.1% vs 13.7%, respectively; adjusted relative risk = 1.48; 95% CI, 1.15-1.89).12 In both studies, prediabetes was not associated with a higher risk for adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes.11,12

Continue to: While there are no current...

While there are no current guidelines for treating prediabetes in pregnancy, women diagnosed with prediabetes in 1 study were found to have significantly less weight gain during pregnancy compared with patients with normal A1C,12 suggesting there may be a benefit in early identification and intervention, although further research is needed.11 In a separate case-control study (n = 345 women with GDM; n = 800 control), high rates of gestational weight gain (> 0.41 kg/wk) were associated with an increased risk of GDM (odds ratio [OR] = 1.74; 95% CI, 1.16-2.60) compared with women with the lowest rate of gestational weight gain (0.27-0.4 kg/wk [OR = 1.43; 95% CI, 0.96-2.14]).13 Thus, it is helpful to have proactive conversations about family planning and adequate weight and glycemic control with high-risk patients to prepare for a healthy pregnancy.

Obesity and weight management. Patients who are overweight (body mass index [BMI], 25-29.9) or obese (BMI > 30) have a substantially increased risk of GDM (adjusted OR = 1.44; 95% CI, 1.04-1.81), as seen in a retrospective cohort study of 1951 pregnant Malaysian women.14 Several factors have been found to contribute to successful weight control, including calorie prescription, a structured meal plan, high physical activity goals (60-90 min/d), daily weighing and monitoring of food intake, behavior therapy, and continued patient–provider contact.15

The safety, efficacy, and sustainability of weight loss with various dietary plans have been studied in individuals who are overweight and obese.16 Ultimately, energy expenditure must be greater than energy intake to promote weight loss. Conventional diets with continuous energy restriction (ie, low-fat, low-carbohydrate, and high-protein diets) have proven to be effective for short-term weight loss but data on long-term weight maintenance are limited.16 The Mediterranean diet, which is comprised mostly of vegetables, fruits, legumes, fish, and grains—with a lower intake of meat and dairy—may reduce gestational weight gain and risk of GDM as suggested by a randomized controlled trial (RCT; n = 1252).17 Although the choice of diet is up to the patient, it is important to be aware of different diets or refer the patient to a registered dietician who can help the patient if needed.

Reduce risk with adequate weight and glycemic control

Prevention of GDM during pregnancy should focus on weight maintenance and optimal glycemic control. Two systematic reviews, one with 8 RCTs (n = 1792) and another with 5 studies (n = 539), assessed the efficacy and safety of energy-restricted dietary intervention on GDM prevention.18 The first review found a significant reduction in gestational weight gain and improved glycemic control without increased risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.18 The second review showed no clear difference between energy-restricted and non–energy-restricted diets on outcomes such as preeclampsia, gestational weight gain, large for gestational age, and macrosomia.18 These data suggest that while energy-restricted dietary interventions made no difference on maternal and fetal complications, they may still be safely used in pregnancy to reduce gestational weight gain and improve glycemic control.18

Once a woman is pregnant, it becomes difficult to lose weight because additional calories are needed to support a growing fetus. It is recommended that patients with healthy pregestational BMI consume an extra 200 to 300 calories/d after the first trimester. However, extra caloric intake in a woman with obesity who is pregnant leads to metabolic impairment and increased risk of diabetes for both the mother and fetus.19 Therefore, it is recommended that patients with obese pregestational BMI not consume additional calories because excess maternal fat is sufficient to support the energy needs of the growing fetus.19

Continue to: Ultimately, earlier intervention...

Ultimately, earlier intervention—prior to conception—helps patients prepare for a healthier pregnancy, resulting in better long-term outcomes. It is helpful to be familiar with the advantages and disadvantages of common approaches to weight management and to be able to refer patients to nutritionists for optimal planning. When establishing a dietary plan, consider patient-specific factors, such as cultural diets, financial and time constraints, and the patient’s readiness to make and maintain these changes. Consistent follow-up and behavioral therapy are necessary to maintain successful weight control.

There are many screening tools, but 1 is preferred in pregnancy

There are several ways to diagnose diabetes in patients who are not pregnant, including A1C, a fasting glucose test, an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or random glucose testing (plus symptoms). However, the preferred method for diagnosing GDM is OGTT because it has a higher sensitivity.20 A1C, while a good measure of hyperglycemic stability, does not register hyperglycemia early enough to diagnose GDM and fasting glucose testing is less sensitive because for most women with GDM, that abnormal postprandial glucose level is the first glycemic abnormality.21

When to screen. Blood glucose levels should be checked in all pregnant women as part of their metabolic panel at the first prenatal visit. A reflex A1C for high glucose levels can be ordered based on the physician’s preference. This may help you to identify patients with prediabetes who are at risk for GDM and implement early behavioral and lifestyle changes. However, further research is needed to determine if intervention early in pregnancy can truly reduce the risk of GDM.11

Screening for GDM should be completed at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation20 because it is likely that this is when the hormonal effects of the placenta that contribute to insulin resistance set the woman up for postprandial hyperglycemia. Currently, there are no evidence-based guidelines for the use of continuous glucose monitoring prior to 24 weeks of gestation to identify GDM.20 If persistent hyperglycemia is present before 24 weeks of gestation, it is considered evidence of a pre-existing metabolic abnormality and is diagnosed as “pregestational diabetes.” Treatment should follow guidelines established for women who had diabetes prior to pregnancy.

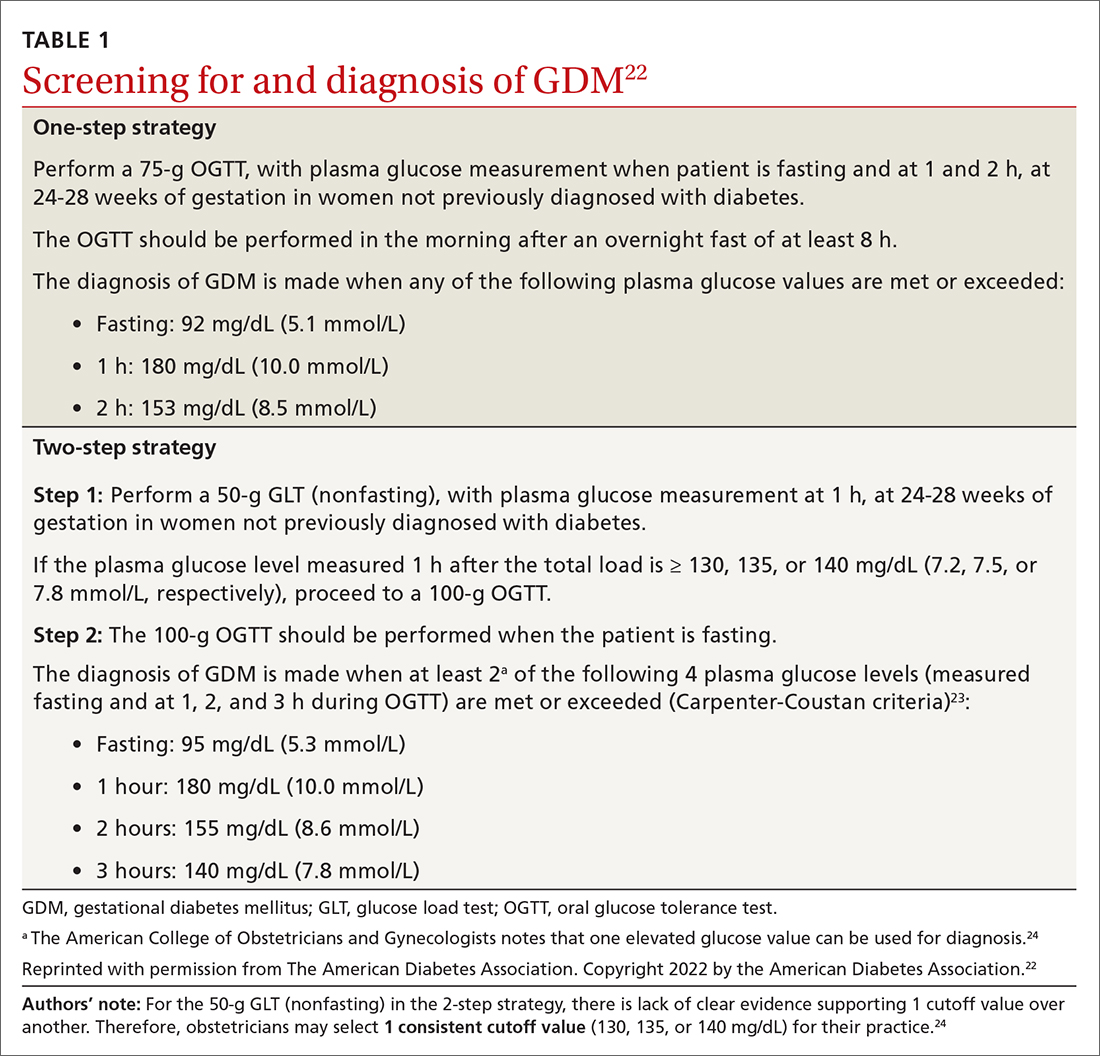

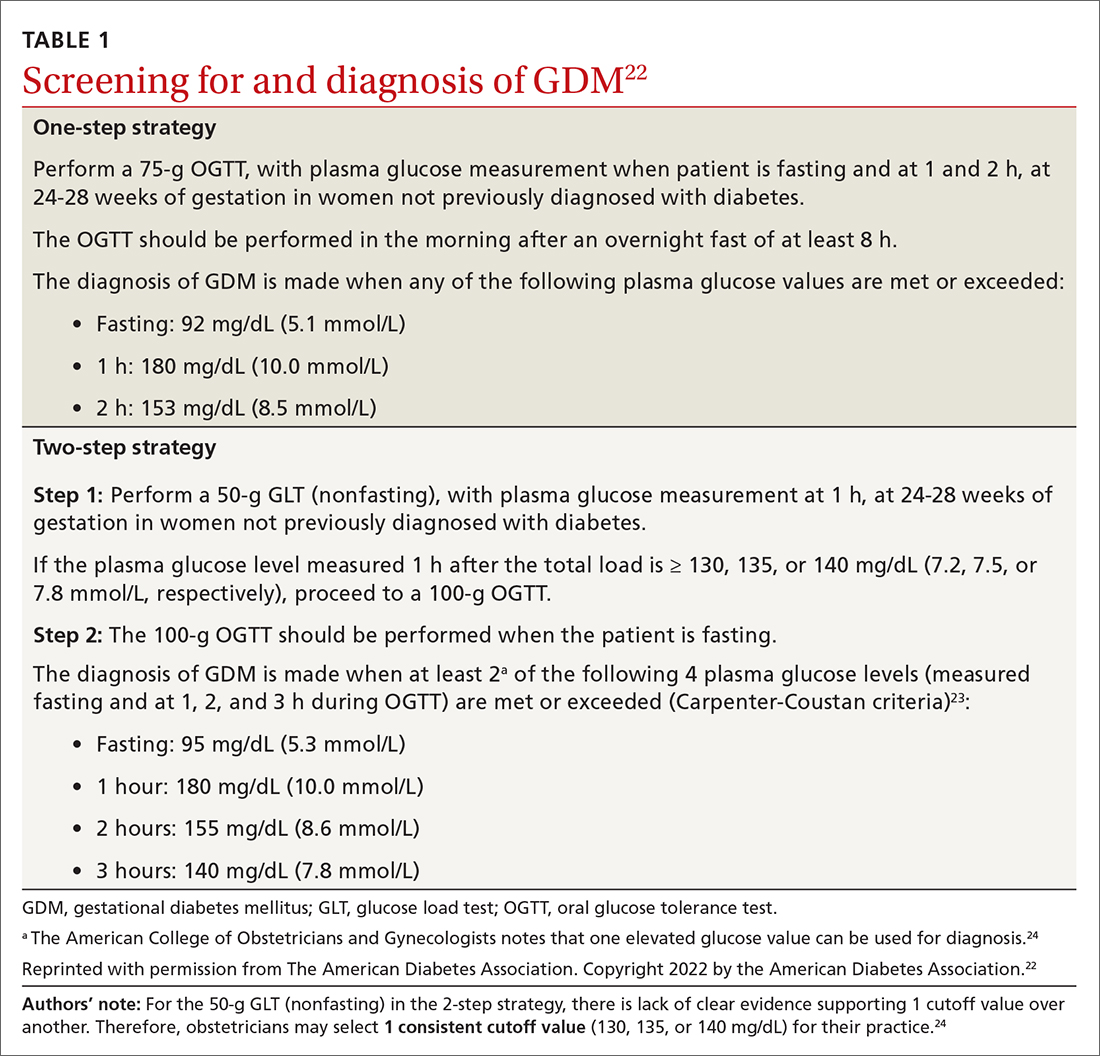

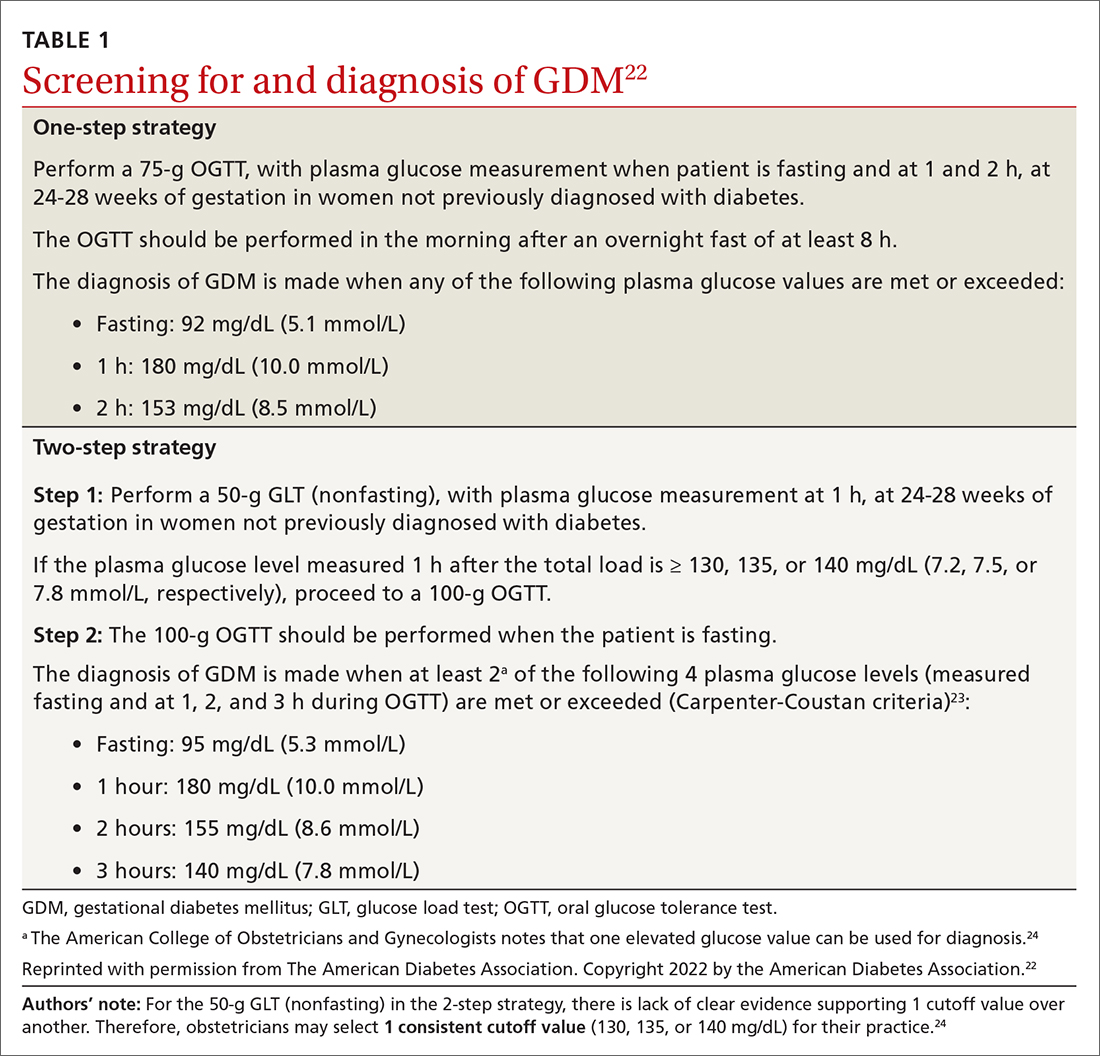

How to screen? There is ongoing discussion about what is the optimal screening method for GDM: a 1-step strategy with a fasting 75-g OGTT only, or a 2-step strategy with a 50-g non-fasting glucose load test followed by a fasting 100-g OGTT in women who do not meet the plasma glucose cutoff (TABLE 1).22-24 Hillier et al25 compared the effectiveness of these strategies in diagnosing GDM and identifying pregnancy complications for the mother and infant. They found that while the 1-step strategy resulted in a 2-fold increase in the diagnosis of GDM, it did not lead to better outcomes for mothers and infants when compared with the 2-step method.25 Currently, the majority of obstetricians (95%) prefer to use the 2-step method.24

Continue to: Manage lifestyle, monitor glucose

Manage lifestyle, monitor glucose

Management of GDM in most women starts with diabetes self-management education and support for therapeutic lifestyle changes, such as nutritional interventions that reduce hyperglycemia and contribute to healthy weight gain during pregnancy.20 This may include medical nutrition therapy that focuses on adequate nutrition for the mother and fetus. Currently, the recommended dietary intake for women who are pregnant (regardless of diabetes) includes a minimum of 175 g of carbohydrates, 71 g of daily protein, and at least 28 g of fiber. Further refinement of dietary intake, including carbohydrate restriction, should be done with guidance from a registered dietitian.20 If the obstetrics team does not include a registered dietitian, a referral to one may be necessary. Regular physical activity should be continued throughout pregnancy as tolerated. Social support, stress reduction, and good sleep hygiene should be encouraged as much as possible.

For successful outcomes, therapeutic lifestyle changes should be coupled with glucose monitoring. The Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus recommends that women with GDM monitor fasting blood glucose and typically 1-hour postprandial glucose. The glucose goals in GDM are as follows26:

- Fasting glucose < 95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L), and either

- 1-hour postprandial glucose < 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L), or

- 2-hour postprandial glucose < 120 mg/dL (6.7 mmol/L).

Importantly, in the second and third trimester, the A1C goal for women with GDM is 6.0%. This is lower than the more traditional A1C goal for 2 reasons: (1) increases in A1C, even within the normal range, increase adverse outcomes; and (2) pregnant women will have an increased red blood cell count turnover, which can lower the A1C.27 In a historical cohort study (n = 27,213), Abell et al28 found that women who have an A1C < 6.0% in the second and third trimester have the lowest risk of giving birth to large-for-gestational-age infants and for having preeclampsia.

Add insulin if glucose targets are not met

Most women who engage in therapeutic lifestyle change (70%-85%) can achieve an A1C < 6% and will not need to take medication to manage GDM.29 If pharmacotherapy is needed to manage glucose, insulin is the preferred treatment for all women with GDM.20 Treatment should be individualized based on the glucose trends the woman is experiencing. Common treatments include bedtime NPH if fasting hyperglycemia is most prominent and analogue insulin at mealtimes for women with prominent postprandial hyperglycemia.

Noninsulin agents such as metformin and sulfonylureas are not currently recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or the American Diabetes Association for use in GDM.20,24 Despite being used for years in women with pregestational diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and polycystic ovary syndrome, there is evidence that metformin crosses the placenta and fetal safety has not yet been established in RCTs. The Metformin in Gestational Diabetes: The Offspring Follow-Up (MiG TOFU) study was a longitudinal follow-up study that evaluated body composition and metabolic outcomes in children (ages 7-9 years) of women with GDM who had received metformin or insulin while pregnant.30 At age 9 years, children who were exposed to metformin weighed more and had a higher waist-to-height ratio and waist circumference than those exposed to insulin.30

Continue to: Sulfonylureas are no longer recommended...

Sulfonylureas are no longer recommended because of the risk of maternal and fetal hypoglycemia and concerns about this medication crossing the placenta.24,31,32 Specifically, in a 2015 meta-analysis and systematic review of 15 articles (n = 2509), glyburide had a higher risk of neonatal hypoglycemia and macrosomia than insulin or metformin.33 For women who cannot manage their glucose with therapeutic lifestyle changes and cannot take insulin, oral therapies may be considered if the risk-benefit ratio is balanced for that person.34

Watch for effects of poor glycemic control on mother, infant

Preeclampsia is defined as new-onset hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation. The correlation between GDM and preeclampsia has partly been explained by their shared overlapping risk factors, including maternal obesity, excessive gestational weight gain, and persistent hyperglycemia.35 On a biochemical level, these risk factors contribute to oxidative stress and systemic vascular dysfunction, which have been hypothesized as the underlying pathophysiology for the development of preeclampsia.35

Neonatal macrosomia, defined as a birth weight ≥ 4000 g, is a common complication that develops in 15% to 45% of infants of mothers with GDM.36 Placental transfer of glucose in mothers with hyperglycemia stimulates the secretion of neonatal insulin and the ultimate storage of the excess glucose as body fat. After delivery, the abrupt discontinuation of placental transfer of glucose to an infant who is actively secreting insulin leads to neonatal hypoglycemia, which if not detected or managed, can lead to long-term neurologic deficits, including recurrent seizures and developmental delays.37 Therefore, it is essential to screen for neonatal hypoglycemia immediately after birth and serially up to 12 hours.38

Postpartum T2D. Poor glycemic control increases the risk of increasing insulin resistance developing into T2D postpartum for mothers.39 It also increases the risk of obesity and insulin resistance later in life for the infant.40 A retrospective cohort study (n = 461) found a positive correlation between exposure to maternal GDM and elevated BMI in children ages 6 to 13 years.41 Kamana et al36 further discussed this correlation and suggested that exposure to maternal hyperglycemia in utero contributes to fetal programming of later adipose deposition. Children may develop without a notable increase in BMI until after puberty.42

Partner with specialists to improve outcomes

Although most women with GDM are managed by specialists (obstetricians, endocrinologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists),43 these patients are still seeking care from their family physicians for other complaints. These visits provide key touchpoints during pregnancy and are opportunities for PCPs to identify a pregnancy-related complication or provide additional education or referral to the obstetrician.

Continue to: Also, if you work in an area...

Also, if you work in an area where specialists are less accessible, you may be the clinician providing the majority of care to a patient with GDM. If this is the case, you’ll want to watch for the following risk factors, which should prompt a referral to specialty care:

- a previous pregnancy with GDM20

- a previous birth of an infant weighing > 4000 g44

- baseline history of hypertension45

- evidence of insulin resistance or polycystic ovary syndrome46,47

- a history of cardiovascular disease20

- a need to treat GDM with pharmacotherapy.48

Ensuring a smooth transition after the birth

Optimal communication and hand-offs throughout pregnancy and after delivery will benefit everyone. When the pregnant patient’s care has been managed by an obstetrician, it is important to address the following issues during the hand-off:

- baseline medical problems

- medical screenings and treatments in pregnancy (retinopathy and nephropathy screening)

- aspirin initiation, if indicated

- management of thyroid abnormalities

- management of mental health conditions

- postpartum glucose management and T2D screening postpartum

- management of complications identified during pregnancy (retinopathy and nephropathy).

Timing and other elements of postpartum care. The first postpartum screen should occur at 4 to 12 weeks postpartum. OGTT is recommended instead of A1C at this time because A1C may still be lowered by the increased red blood cell turnover related to pregnancy and blood loss at delivery. Because women with GDM have a 50% to 75% lifetime risk of T2D,20 patients with normal test results should be re-tested every 1 to 3 years using any of the standard screening methods (A1C, fasting glucose, or OGTT).20

After delivery it may be difficult for women to follow-up with their own personal health care because they are focused on the care of their baby. The increased use of telehealth may make postpartum follow-up visits easier to attend.

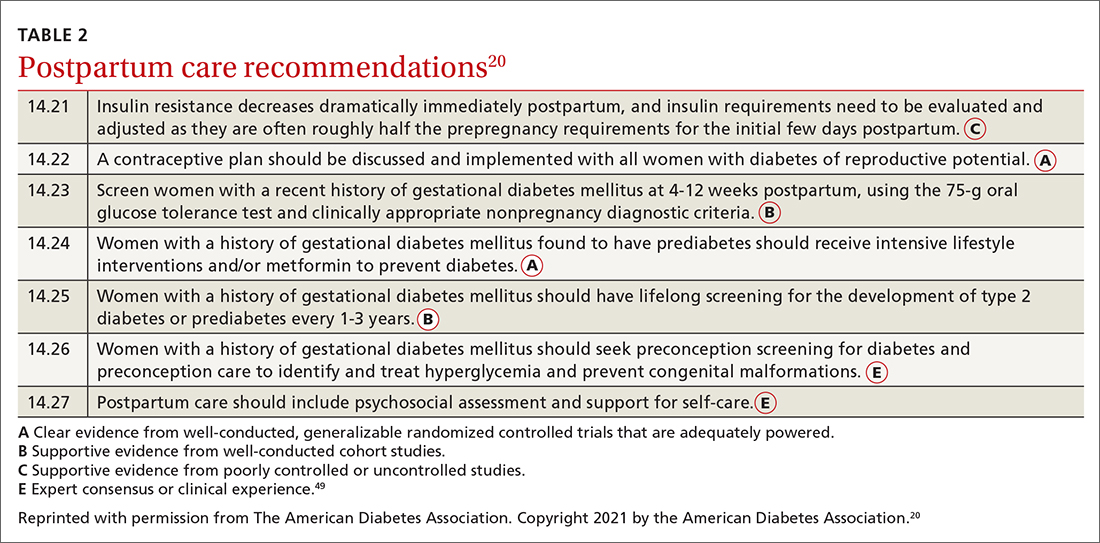

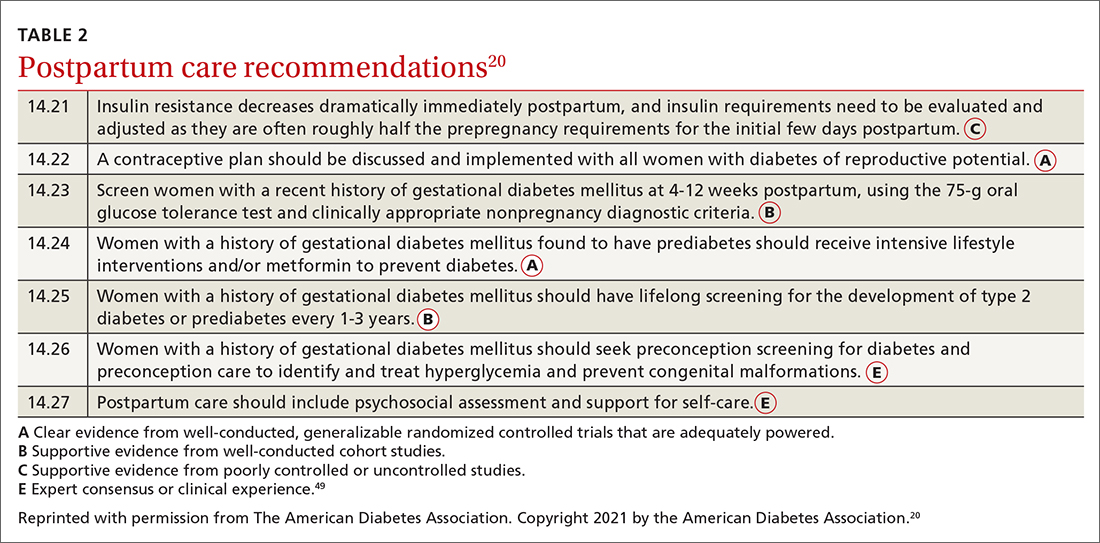

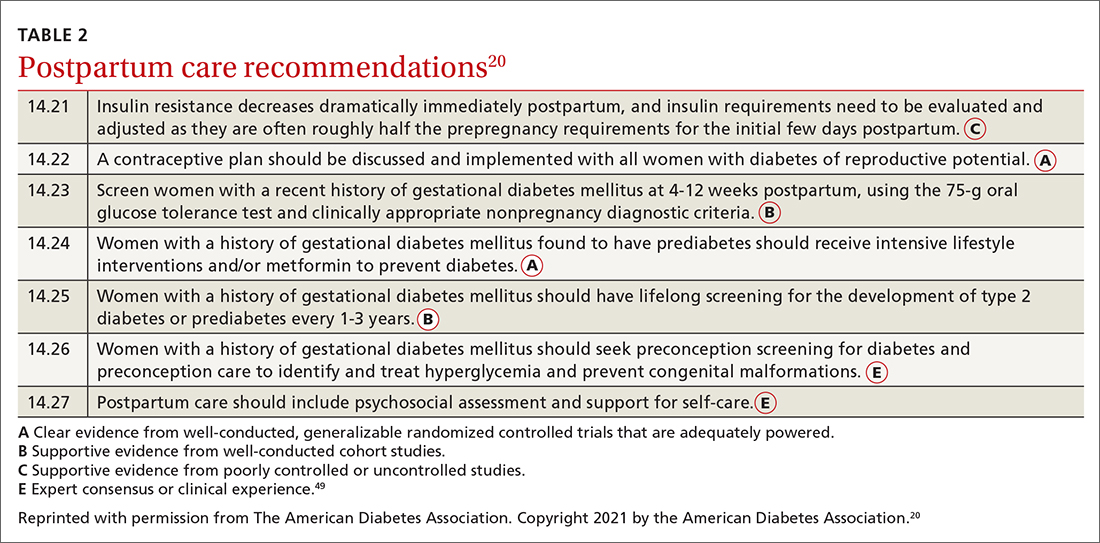

Visits present opportunities. Postpartum visits present another opportunity for PCPs to screen for diabetes and other postpartum complications, including depression and thyroid abnormalities. Visits are also an opportunity to discuss timely contraception so as to prevent an early, unplanned pregnancy. Other important aspects of postpartum care are outlined in TABLE 2.20,49

CORRESPONDENCE

Connie L. Ha, BS, OMS IV, Department of Primary Care, 1310 Club Drive, Touro University California, Vallejo, CA 94592; [email protected]

1. Sheiner E. Gestational diabetes mellitus: long-term consequences for the mother and child grand challenge: how to move on towards secondary prevention? Front Clin Diabetes Healthc. 2020. doi: 10.3389/fcdhc.2020.546256

2. Angueira AR, Ludvik AE, Reddy TE, et al. New insights into gestational glucose metabolism: lessons learned from 21st century approaches. Diabetes. 2015;64:327-334. doi: 10.2337/db14-0877

3. Shou C, Wei Y-M, Wang C, et al. Updates in long-term maternal and fetal adverse effects of gestational diabetes mellitus. Maternal-Fetal Med. 2019;1:91-94. doi: 10.1097/FM9.0000000000000019

4. Plows JF, Stanley JL, Baker PN, et al. The pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3342. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113342

5. Kulshrestha V, Agarwal N. Maternal complications in pregnancy with diabetes. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(9 suppl 1):S74-S77.

6. Li Y, Ren X, He L, et al. Maternal age and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 120 million participants. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108044. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108044

7. Schummers L, Hutcheon JA, Hacker MR, et al. Absolute risks of obstetric outcomes by maternal age at first birth: a population-based cohort. Epidemiology. 2018;29:379-387. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000818

8. Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, et al. Trends in gestational diabetes at first live birth by race and ethnicity in the US, 2011-2019. JAMA. 2021;326:660-669. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7217

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. Accessed February 2, 2022. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

10. Ogunwole SM, Golden SH. Social determinants of health and structural inequities—root causes of diabetes disparities. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:11-13. doi: 10.2337/dci20-0060

11. Chen L, Pocobelli G, Yu O, et al. Early pregnancy hemoglobin A1C and pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36:1045-1053. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1675619

12. Osmundson S, Zhao BS, Kunz L, et al. First trimester hemoglobin A1C prediction of gestational diabetes. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33:977-982. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1581055

13. Hedderson MM, Gunderson EP, Ferrara A. Gestational weight gain and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:1092]. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:597-604. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cfce4f

14. Yong HY, Mohd Shariff Z, Mohd Yusof BN, et al. Independent and combined effects of age, body mass index and gestational weight gain on the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep. 2020;10:8486. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65251-2

15. Phelan S. Windows of opportunity for lifestyle interventions to prevent gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33:1291-1299. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1586504

16. Koliaki C, Spinos T, Spinou M, et al. Defining the optimal dietary approach for safe, effective and sustainable weight loss in overweight and obese adults. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6:73. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6030073

17. Al Wattar BH, Dodds J, Placzek A, et al. Mediterranean-style diet in pregnant women with metabolic risk factors (ESTEEM): a pragmatic multicentre randomised trial. PLOS Med. 2019;16:e1002857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002857

18. Zarogiannis S. Are novel lifestyle approaches to management of type 2 diabetes applicable to prevention and treatment of women with gestational diabetes mellitus? Global Diabetes Open Access J. 2019;1:1-14.

19. Most J, Amant MS, Hsia DS, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for energy intake in pregnant women with obesity. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4682-4690. doi: 10.1172/JCI130341

20. American Diabetes Association. 14. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S200-S210. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S014

21. McIntyre HD, Sacks DA, Barbour LA, et al. Issues with the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in early pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:53-54. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1887

22. American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(suppl 1):S17-S38. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S002

23. Carpenter MW, Coustan DR. Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:768-773. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90349-0

24. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e49-e64. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002501