User login

A 68-year-old man with a blue toe

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

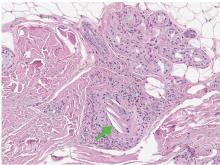

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.

New DES hailed for smallest coronary vessels

Paris – The first multicenter, prospective trial of a drug-eluting stent designed specifically to treat lesions in coronary vessels less than 2.25 mm in diameter showed excellent outcomes, with a 1-year target lesion failure rate of 5% for the Resolute Onyx 2.0 mm diameter zotarolimus-eluting stent.

This result in the pivotal trial easily surpassed the prespecified performance goal of a 19% target lesion failure rate, Matthew J. Price, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

Hemodynamically significant lesions in such small vessels are “not uncommon, particularly in diabetic patients,” Dr. Price said in an interview. Indeed, 47% of patients in the clinical trial had diabetes.

At present, the only ways to treat coronary disease in arteries having a reference vessel diameter less than 2.25 mm are off-label placement of an oversized stent, with its attendant risk of complications; standard balloon angioplasty, which entails a particularly high restenosis rate in this setting; or medical management, the cardiologist noted.

He presented a multicenter, prospective, open-label, single-arm trial of 101 patients with documented ischemia-producing obstructions in coronary arteries having a reference vessel diameter less than 2.25 mm, a lesion length less than 27 mm, and evidence of ischemia attributable to the lesion, typically via fractional flow reserve. The mean diameter by quantitative coronary angiography was 1.91 mm.

The primary endpoint was the rate of target lesion failure at 12 months, a composite comprising cardiac death, target vessel MI, or clinically driven target lesion revascularization. This endpoint occurred in 5% of patients. There was a 3% target vessel MI rate and a 2% target lesion revascularization rate. There were no cardiac deaths.

“Importantly, the stent thrombosis rate in these patients with extremely small vessels was zero,” the cardiologist emphasized.

The mean angiographic in-stent late lumen loss at 13 months was 0.26 mm, which Dr. Price characterized as “quite good.” The in-segment binary angiographic restenosis rate was 20%.

“That’s slightly higher than you would expect to see in vessels with larger reference diameters. I think that’s because of the lack of headroom. You have a very small vessel, and, even with a very small stent, even a small amount of late loss will give you a larger percent diameter restenosis over time,” he explained.

The 19% target lesion failure rate selected as a performance goal in the trial was set somewhat arbitrarily. It wasn’t possible to randomize patients to a comparator arm because there are no approved stents for vessels less than 2.25 mm in diameter. The 19% figure was arrived at in discussion with the Food and Drug Administration on the basis of similarity to the performance goal used in clinical trials to gain approval of 2.25-mm, drug-eluting stents. Because the Onyx 2.0-mm-diameter trial was developed in collaboration with the FDA and the stent aced its primary endpoint and showed excellent clinical outcomes, Dr. Price anticipates the device will readily gain regulatory approval. In April 2017, the FDA approved the Resolute Onyx in sizes of 2.25- to 5.0-mm diameter.

The study met with an enthusiastic reception.

“That was terrific. It’s clearly an incredibly important unmet clinical need,” commented session cochair David R. Holmes Jr., MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Assuming the stent is approved, how should interventionalists put it into practice? he asked.

Dr. Price replied that, first, it’s important to step back and ask if percutaneous coronary intervention of a particular lesion in a very small coronary artery is clinically indicated. The stent itself is readily manipulatable. It is a thin-strut device constructed of a single strand of a cobalt alloy with enhanced radiopacity.

Investigators in the trial used the standard approach to dual antiplatelet therapy – at least 6 months, with 12 months preferable.

The 20% in-segment binary restenosis rate at 13 months provides a clear message for interventionalists, he continued. “What this tells me is that, while this is a very good stent, we can’t forget to treat the patient aggressively with medical therapy to stop the progression of prediabetes, diabetes, and small vessel disease in addition to treating obstructive lesions with a small stent.”

Asked if the lack of headroom in these extra-small arteries warrants liberal use of intraprocedural imaging to make sure the stent is perfectly apposed, Dr. Price replied that he doesn’t think so. He noted that intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography were seldom used in the trial, yet the results were reassuringly excellent.

The study results were published simultaneously with Dr. Price’s presentation (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017 May 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.05.004). The trial was sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Price reported serving as a consultant and paid speaker on behalf of that company, as well as AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, and The Medicines Company.

Paris – The first multicenter, prospective trial of a drug-eluting stent designed specifically to treat lesions in coronary vessels less than 2.25 mm in diameter showed excellent outcomes, with a 1-year target lesion failure rate of 5% for the Resolute Onyx 2.0 mm diameter zotarolimus-eluting stent.

This result in the pivotal trial easily surpassed the prespecified performance goal of a 19% target lesion failure rate, Matthew J. Price, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

Hemodynamically significant lesions in such small vessels are “not uncommon, particularly in diabetic patients,” Dr. Price said in an interview. Indeed, 47% of patients in the clinical trial had diabetes.

At present, the only ways to treat coronary disease in arteries having a reference vessel diameter less than 2.25 mm are off-label placement of an oversized stent, with its attendant risk of complications; standard balloon angioplasty, which entails a particularly high restenosis rate in this setting; or medical management, the cardiologist noted.

He presented a multicenter, prospective, open-label, single-arm trial of 101 patients with documented ischemia-producing obstructions in coronary arteries having a reference vessel diameter less than 2.25 mm, a lesion length less than 27 mm, and evidence of ischemia attributable to the lesion, typically via fractional flow reserve. The mean diameter by quantitative coronary angiography was 1.91 mm.

The primary endpoint was the rate of target lesion failure at 12 months, a composite comprising cardiac death, target vessel MI, or clinically driven target lesion revascularization. This endpoint occurred in 5% of patients. There was a 3% target vessel MI rate and a 2% target lesion revascularization rate. There were no cardiac deaths.

“Importantly, the stent thrombosis rate in these patients with extremely small vessels was zero,” the cardiologist emphasized.

The mean angiographic in-stent late lumen loss at 13 months was 0.26 mm, which Dr. Price characterized as “quite good.” The in-segment binary angiographic restenosis rate was 20%.

“That’s slightly higher than you would expect to see in vessels with larger reference diameters. I think that’s because of the lack of headroom. You have a very small vessel, and, even with a very small stent, even a small amount of late loss will give you a larger percent diameter restenosis over time,” he explained.

The 19% target lesion failure rate selected as a performance goal in the trial was set somewhat arbitrarily. It wasn’t possible to randomize patients to a comparator arm because there are no approved stents for vessels less than 2.25 mm in diameter. The 19% figure was arrived at in discussion with the Food and Drug Administration on the basis of similarity to the performance goal used in clinical trials to gain approval of 2.25-mm, drug-eluting stents. Because the Onyx 2.0-mm-diameter trial was developed in collaboration with the FDA and the stent aced its primary endpoint and showed excellent clinical outcomes, Dr. Price anticipates the device will readily gain regulatory approval. In April 2017, the FDA approved the Resolute Onyx in sizes of 2.25- to 5.0-mm diameter.

The study met with an enthusiastic reception.

“That was terrific. It’s clearly an incredibly important unmet clinical need,” commented session cochair David R. Holmes Jr., MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Assuming the stent is approved, how should interventionalists put it into practice? he asked.

Dr. Price replied that, first, it’s important to step back and ask if percutaneous coronary intervention of a particular lesion in a very small coronary artery is clinically indicated. The stent itself is readily manipulatable. It is a thin-strut device constructed of a single strand of a cobalt alloy with enhanced radiopacity.

Investigators in the trial used the standard approach to dual antiplatelet therapy – at least 6 months, with 12 months preferable.

The 20% in-segment binary restenosis rate at 13 months provides a clear message for interventionalists, he continued. “What this tells me is that, while this is a very good stent, we can’t forget to treat the patient aggressively with medical therapy to stop the progression of prediabetes, diabetes, and small vessel disease in addition to treating obstructive lesions with a small stent.”

Asked if the lack of headroom in these extra-small arteries warrants liberal use of intraprocedural imaging to make sure the stent is perfectly apposed, Dr. Price replied that he doesn’t think so. He noted that intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography were seldom used in the trial, yet the results were reassuringly excellent.

The study results were published simultaneously with Dr. Price’s presentation (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017 May 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.05.004). The trial was sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Price reported serving as a consultant and paid speaker on behalf of that company, as well as AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, and The Medicines Company.

Paris – The first multicenter, prospective trial of a drug-eluting stent designed specifically to treat lesions in coronary vessels less than 2.25 mm in diameter showed excellent outcomes, with a 1-year target lesion failure rate of 5% for the Resolute Onyx 2.0 mm diameter zotarolimus-eluting stent.

This result in the pivotal trial easily surpassed the prespecified performance goal of a 19% target lesion failure rate, Matthew J. Price, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

Hemodynamically significant lesions in such small vessels are “not uncommon, particularly in diabetic patients,” Dr. Price said in an interview. Indeed, 47% of patients in the clinical trial had diabetes.

At present, the only ways to treat coronary disease in arteries having a reference vessel diameter less than 2.25 mm are off-label placement of an oversized stent, with its attendant risk of complications; standard balloon angioplasty, which entails a particularly high restenosis rate in this setting; or medical management, the cardiologist noted.

He presented a multicenter, prospective, open-label, single-arm trial of 101 patients with documented ischemia-producing obstructions in coronary arteries having a reference vessel diameter less than 2.25 mm, a lesion length less than 27 mm, and evidence of ischemia attributable to the lesion, typically via fractional flow reserve. The mean diameter by quantitative coronary angiography was 1.91 mm.

The primary endpoint was the rate of target lesion failure at 12 months, a composite comprising cardiac death, target vessel MI, or clinically driven target lesion revascularization. This endpoint occurred in 5% of patients. There was a 3% target vessel MI rate and a 2% target lesion revascularization rate. There were no cardiac deaths.

“Importantly, the stent thrombosis rate in these patients with extremely small vessels was zero,” the cardiologist emphasized.

The mean angiographic in-stent late lumen loss at 13 months was 0.26 mm, which Dr. Price characterized as “quite good.” The in-segment binary angiographic restenosis rate was 20%.

“That’s slightly higher than you would expect to see in vessels with larger reference diameters. I think that’s because of the lack of headroom. You have a very small vessel, and, even with a very small stent, even a small amount of late loss will give you a larger percent diameter restenosis over time,” he explained.

The 19% target lesion failure rate selected as a performance goal in the trial was set somewhat arbitrarily. It wasn’t possible to randomize patients to a comparator arm because there are no approved stents for vessels less than 2.25 mm in diameter. The 19% figure was arrived at in discussion with the Food and Drug Administration on the basis of similarity to the performance goal used in clinical trials to gain approval of 2.25-mm, drug-eluting stents. Because the Onyx 2.0-mm-diameter trial was developed in collaboration with the FDA and the stent aced its primary endpoint and showed excellent clinical outcomes, Dr. Price anticipates the device will readily gain regulatory approval. In April 2017, the FDA approved the Resolute Onyx in sizes of 2.25- to 5.0-mm diameter.

The study met with an enthusiastic reception.

“That was terrific. It’s clearly an incredibly important unmet clinical need,” commented session cochair David R. Holmes Jr., MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Assuming the stent is approved, how should interventionalists put it into practice? he asked.

Dr. Price replied that, first, it’s important to step back and ask if percutaneous coronary intervention of a particular lesion in a very small coronary artery is clinically indicated. The stent itself is readily manipulatable. It is a thin-strut device constructed of a single strand of a cobalt alloy with enhanced radiopacity.

Investigators in the trial used the standard approach to dual antiplatelet therapy – at least 6 months, with 12 months preferable.

The 20% in-segment binary restenosis rate at 13 months provides a clear message for interventionalists, he continued. “What this tells me is that, while this is a very good stent, we can’t forget to treat the patient aggressively with medical therapy to stop the progression of prediabetes, diabetes, and small vessel disease in addition to treating obstructive lesions with a small stent.”

Asked if the lack of headroom in these extra-small arteries warrants liberal use of intraprocedural imaging to make sure the stent is perfectly apposed, Dr. Price replied that he doesn’t think so. He noted that intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography were seldom used in the trial, yet the results were reassuringly excellent.

The study results were published simultaneously with Dr. Price’s presentation (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017 May 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.05.004). The trial was sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Price reported serving as a consultant and paid speaker on behalf of that company, as well as AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, and The Medicines Company.

AT EUROPCR

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 12 months’ follow-up, the key outcomes were a 3% rate of target vessel MI, a 2% rate of clinically driven target lesion revascularization, no stent thrombosis, and no cardiac deaths.

Data source: A prospective, multicenter, open-label trial in 101 patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention for coronary lesions with a reference vessel diameter of less than 2.25 mm.

Disclosures: The trial was sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Price reported serving as a consultant to and paid speaker on behalf of that company as well as AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, and The Medicines Company.

High readmits after peripheral arterial procedures

WASHINGTON – More than one in six patients who undergo a lower extremity arterial endovascular or surgical procedure are readmitted within 30 days, according to a large national study.

The annual total cost of these early readmissions is high, in excess of $360 million. But because there turned out to be surprisingly little difference in readmission rates between hospitals, 30-day readmissions may not be a rational quality measure on which to base institutional reimbursement or withholding of payment for peripheral arterial interventions, Eric A. Secemsky, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Forty-seven percent of patients had an endovascular procedure, 42% had surgery, and the remainder had hybrid procedures in which both endovascular and surgical interventions took place during the same admission. Patients with hybrid procedures contributed data to both treatment groups.

In-hospital mortality occurred in 2.5% of patients.

Of the patients who survived to discharge, 21,589, or 17.4%, were readmitted within 30 days. The early readmission rate was higher following endovascular procedures, at 18.7%, than the 16.1% rate in the surgical group. The average cost of a readmission was $15,876. Death during readmission occurred in 4.2% of patients.

The median rate ratio – a measure of the amount of variance in readmission rates between hospitals – was 1.12. That’s a low figure.

“If the median rate ratio is lower, like here, it says there’s not a lot of interhospital variability across the country. So overall this burden seems to be pretty uniform across the institutions included in our analysis,” Dr. Secemsky explained.

This observation drew the attention of session comoderator Naomi M. Hamburg, MD.

“It’s interesting that you didn’t see a lot of heterogeneity across hospitals, because we often think of readmissions as a potentially modifiable quality metric. Do you think it’s modifiable, or is this just the nature of the disease?” asked Dr. Hamburg of Boston Medical Center.

It’s the disease process, Dr. Secemsky replied.

“We were surprised by the lack of hospital variation,” he added. None of the institutional characteristics examined, including teaching hospital status, bed size, and procedural volume, had a significant impact on readmission rates.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t opportunities to whittle down those readmissions, according to Dr. Secemsky.

He noted that the high readmission rates were driven by procedural complications such as graft or stent failure. Indeed, procedural complications accounted for 29% of all early readmissions. The procedural complication rate was about 20% following endovascular procedures and 39% after surgery. It’s likely that identification and implementation of best practices could trim those high rates. Unfortunately, however, the nationwide database relies upon ICD-9 codes, which don’t provide the granular level of detail required to home in on specific best practices. That will require further studies, according to Dr. Secemsky.

A distant second on the list of causes of early readmission was peripheral atherosclerosis, meaning persistent claudication or rest pain. This accounted for 8.8% of readmissions. Rounding out the top five causes of readmission were sepsis, which was the reason for 6.7% of readmissions; diabetes with complications, at 4.7%; and heart failure, at 4.6%.

The strongest predictors of readmission included having renal disease at baseline, Medicare rather than private insurance, and discharge to a subacute nursing facility or home with home care.

Dr. Hamburg commented that a focus on reducing readmissions for sepsis as well as for skin and soft tissue infections, which accounted for 2.1% of 30-day hospitalizations, could be fruitful.

Dr. Secemsky reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

WASHINGTON – More than one in six patients who undergo a lower extremity arterial endovascular or surgical procedure are readmitted within 30 days, according to a large national study.

The annual total cost of these early readmissions is high, in excess of $360 million. But because there turned out to be surprisingly little difference in readmission rates between hospitals, 30-day readmissions may not be a rational quality measure on which to base institutional reimbursement or withholding of payment for peripheral arterial interventions, Eric A. Secemsky, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Forty-seven percent of patients had an endovascular procedure, 42% had surgery, and the remainder had hybrid procedures in which both endovascular and surgical interventions took place during the same admission. Patients with hybrid procedures contributed data to both treatment groups.

In-hospital mortality occurred in 2.5% of patients.

Of the patients who survived to discharge, 21,589, or 17.4%, were readmitted within 30 days. The early readmission rate was higher following endovascular procedures, at 18.7%, than the 16.1% rate in the surgical group. The average cost of a readmission was $15,876. Death during readmission occurred in 4.2% of patients.

The median rate ratio – a measure of the amount of variance in readmission rates between hospitals – was 1.12. That’s a low figure.

“If the median rate ratio is lower, like here, it says there’s not a lot of interhospital variability across the country. So overall this burden seems to be pretty uniform across the institutions included in our analysis,” Dr. Secemsky explained.

This observation drew the attention of session comoderator Naomi M. Hamburg, MD.

“It’s interesting that you didn’t see a lot of heterogeneity across hospitals, because we often think of readmissions as a potentially modifiable quality metric. Do you think it’s modifiable, or is this just the nature of the disease?” asked Dr. Hamburg of Boston Medical Center.

It’s the disease process, Dr. Secemsky replied.

“We were surprised by the lack of hospital variation,” he added. None of the institutional characteristics examined, including teaching hospital status, bed size, and procedural volume, had a significant impact on readmission rates.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t opportunities to whittle down those readmissions, according to Dr. Secemsky.

He noted that the high readmission rates were driven by procedural complications such as graft or stent failure. Indeed, procedural complications accounted for 29% of all early readmissions. The procedural complication rate was about 20% following endovascular procedures and 39% after surgery. It’s likely that identification and implementation of best practices could trim those high rates. Unfortunately, however, the nationwide database relies upon ICD-9 codes, which don’t provide the granular level of detail required to home in on specific best practices. That will require further studies, according to Dr. Secemsky.

A distant second on the list of causes of early readmission was peripheral atherosclerosis, meaning persistent claudication or rest pain. This accounted for 8.8% of readmissions. Rounding out the top five causes of readmission were sepsis, which was the reason for 6.7% of readmissions; diabetes with complications, at 4.7%; and heart failure, at 4.6%.

The strongest predictors of readmission included having renal disease at baseline, Medicare rather than private insurance, and discharge to a subacute nursing facility or home with home care.

Dr. Hamburg commented that a focus on reducing readmissions for sepsis as well as for skin and soft tissue infections, which accounted for 2.1% of 30-day hospitalizations, could be fruitful.

Dr. Secemsky reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

WASHINGTON – More than one in six patients who undergo a lower extremity arterial endovascular or surgical procedure are readmitted within 30 days, according to a large national study.

The annual total cost of these early readmissions is high, in excess of $360 million. But because there turned out to be surprisingly little difference in readmission rates between hospitals, 30-day readmissions may not be a rational quality measure on which to base institutional reimbursement or withholding of payment for peripheral arterial interventions, Eric A. Secemsky, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Forty-seven percent of patients had an endovascular procedure, 42% had surgery, and the remainder had hybrid procedures in which both endovascular and surgical interventions took place during the same admission. Patients with hybrid procedures contributed data to both treatment groups.

In-hospital mortality occurred in 2.5% of patients.

Of the patients who survived to discharge, 21,589, or 17.4%, were readmitted within 30 days. The early readmission rate was higher following endovascular procedures, at 18.7%, than the 16.1% rate in the surgical group. The average cost of a readmission was $15,876. Death during readmission occurred in 4.2% of patients.

The median rate ratio – a measure of the amount of variance in readmission rates between hospitals – was 1.12. That’s a low figure.

“If the median rate ratio is lower, like here, it says there’s not a lot of interhospital variability across the country. So overall this burden seems to be pretty uniform across the institutions included in our analysis,” Dr. Secemsky explained.

This observation drew the attention of session comoderator Naomi M. Hamburg, MD.

“It’s interesting that you didn’t see a lot of heterogeneity across hospitals, because we often think of readmissions as a potentially modifiable quality metric. Do you think it’s modifiable, or is this just the nature of the disease?” asked Dr. Hamburg of Boston Medical Center.

It’s the disease process, Dr. Secemsky replied.

“We were surprised by the lack of hospital variation,” he added. None of the institutional characteristics examined, including teaching hospital status, bed size, and procedural volume, had a significant impact on readmission rates.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t opportunities to whittle down those readmissions, according to Dr. Secemsky.

He noted that the high readmission rates were driven by procedural complications such as graft or stent failure. Indeed, procedural complications accounted for 29% of all early readmissions. The procedural complication rate was about 20% following endovascular procedures and 39% after surgery. It’s likely that identification and implementation of best practices could trim those high rates. Unfortunately, however, the nationwide database relies upon ICD-9 codes, which don’t provide the granular level of detail required to home in on specific best practices. That will require further studies, according to Dr. Secemsky.

A distant second on the list of causes of early readmission was peripheral atherosclerosis, meaning persistent claudication or rest pain. This accounted for 8.8% of readmissions. Rounding out the top five causes of readmission were sepsis, which was the reason for 6.7% of readmissions; diabetes with complications, at 4.7%; and heart failure, at 4.6%.

The strongest predictors of readmission included having renal disease at baseline, Medicare rather than private insurance, and discharge to a subacute nursing facility or home with home care.

Dr. Hamburg commented that a focus on reducing readmissions for sepsis as well as for skin and soft tissue infections, which accounted for 2.1% of 30-day hospitalizations, could be fruitful.

Dr. Secemsky reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

AT ACC 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Readmission within 30 days after a peripheral arterial procedure occurred nationally in 17.4% of patients, with little between-hospital variation in rates.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of nearly 124,000 hospital admissions for lower extremity arterial endovascular or surgical procedures.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

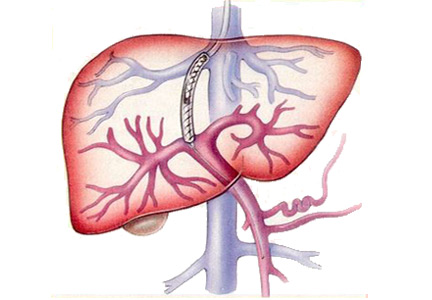

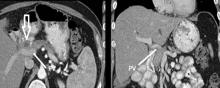

Observation works for most smaller splanchnic artery aneurysms

CHICAGO – Guidelines for the management of splanchnic artery aneurysms have been hard to come by because of their rarity, but investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, have surveyed their 20-year experience to conclude that surveillance is appropriate for most cases of aneurysms smaller than 25 mm, and selective open or endovascular repair is indicated for larger lesions, depending on their location.

“Most of the small splanchnic artery aneurysms (SAAs) of less than 25 mm did not grow or rupture over time and can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years,” Mark F. Conrad, MD, reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

The predominant sites of aneurysm were the splenic artery (95, 36%) and the celiac artery (78, 30%), followed by the hepatic artery (34, 13%), pancreaticoduodenal artery (PDA; 25, 9.6%), superior mesenteric artery (SMA; 17, 6%), gastroduodenal artery (GDA; 11, 4%), jejunal artery (3, 1%) and inferior mesenteric artery (1, 0.4%).

Surveillance consisted of imaging every 3 years. Of the surveillance cohort, 138 patients had longer-term follow-up. The average aneurysm size was 16.3 mm, “so they’re small,” Dr. Conrad said. Of that whole group, only 12 (9%), of SAAs grew in size, and of those, 8 were 25 mm or smaller when they were identified; 8 of the 12 required repair. “The average time to repair was 2 years,” Dr. Conrad said. “There were no ruptures in the surveillance cohort.”

Among the early repair group, 13 (14.7%) had rupture upon presentation, 3 of which (23%) were pseudoaneurysms. The majority of aneurysms in this group were in either the splenic artery, PDA, or GDA. “Their average size was 31 mm – much larger than the patients that we watched,” he said. A total of 70% of all repairs were endovascular in nature, the remainder open, but endovascular comprised a higher percentage of rupture repairs: 10 (77%) vs. 3 (23%) that underwent open procedures.

The outcomes for endovascular and open repair were similar based on the small number of subjects, Dr. Conrad said: 30-day morbidity of 17% for endovascular repair and 22.2% for open; and 30-day mortality of 3.5% and 4.5%, respectively. However, for ruptured lesions, the outcomes were starkly significant: 54% morbidity and 8% mortality at 30 days.

The researchers performed a univariate analysis of predictors for aneurysm. They were aneurysm size with an odds ratio of 1.04 for every 1 mm of growth; PDA or GDA lesions with an OR of 11.2; and Ehlers-Danlos type IV syndrome with an OR of 32.5. The latter included all the three study patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Among patients who had splenic SAAs, 99 (93%) were asymptomatic and 5 (5.3%) had pseudoaneurysm, and almost half (47) went into surveillance. Over a mean observation period of 35 months, six (12.8%) grew in size, comprising half of the growing SAAs in the observation group. Thirty-two had endovascular repair and four open repair, with a 30-day morbidity of 22% and 30-day mortality of 2.7%.

Celiac SAAs proved most problematic in terms of symptomatology; all 78 patients with this variant were asymptomatic, and 12 (15%) had dissection. Sixty patients went into surveillance with a mean time of 43 months, and three (5) had aneurysms that grew in size. Five had intervention, four with open repair, with 30-day morbidity of 20% and no 30-day mortality.

Hepatic SAAs affected 34 study subjects, 29 (85%) of whom were asymptomatic, 4 (15%) who had dissection, and 7 (21%) with pseudoaneurysm. Eleven entered surveillance for an average of 28 months, but none showed any aneurysmal growth. The 16 who had intervention were evenly split between open and endovascular repair with 30-day morbidity of 25% and 30-day morality of 12.5%.

The PDA and GDA aneurysms “are really interesting,” Dr. Conrad said. “I think they’re different in nature than the other aneurysms,” he said, noting that 12 (33%) of these aneurysms were symptomatic and 6 (17%) were pseudoaneurysms. Because of the high rate of rupture of PDA/GDA aneurysms, Dr. Conrad advised repair at diagnosis: “97% of these patients had a celiac stenosis, and of those, two-thirds were atherosclerosis related and one-third related to the median arcuate ligament compression.” The rupture rate was comparatively high – 20%. Twenty cases underwent endovascular repair with a 90% success rate while four cases had open repair. Thirty-day morbidity for intact lesions was 11% with no deaths, and 50% with 14% mortality rate for ruptured lesions.

Of the SMA aneurysms in the study population, only 17% were mycotic with the remainder asymptomatic, Dr. Conrad said. Nine underwent surveillance, with one growing in size over a mean observation period of 28 months, four had open repair, and two endovascular repair. Morbidity was 17% at 30 days with no deaths.

The guidelines Dr. Conrad and his group developed recommend treatment for symptomatic patients and a more nuanced approach for asymptomatic patients, depending on the location and size of SAA. All lesions 25 mm or smaller, except those of the PDA/GDA, can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years, he said; intervention is indicated for all larger lesions. Endovascular repair is in order for all splenic SAAs in pregnancy, liver transplantation, and pseudoaneurysm. For hepatic SAAs, open or endovascular repair is indicated for pseudoaneurysm, but open repair only is indicated for asymptomatic celiac SAAs with pseudoaneurysm. Endovascular intervention can address most SAA aneurysms of the PDA and GDA.

Dr. Conrad disclosed he is a consultant to Medtronic and Volcano and is a member of Bard’s clinical events committee.

CHICAGO – Guidelines for the management of splanchnic artery aneurysms have been hard to come by because of their rarity, but investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, have surveyed their 20-year experience to conclude that surveillance is appropriate for most cases of aneurysms smaller than 25 mm, and selective open or endovascular repair is indicated for larger lesions, depending on their location.

“Most of the small splanchnic artery aneurysms (SAAs) of less than 25 mm did not grow or rupture over time and can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years,” Mark F. Conrad, MD, reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

The predominant sites of aneurysm were the splenic artery (95, 36%) and the celiac artery (78, 30%), followed by the hepatic artery (34, 13%), pancreaticoduodenal artery (PDA; 25, 9.6%), superior mesenteric artery (SMA; 17, 6%), gastroduodenal artery (GDA; 11, 4%), jejunal artery (3, 1%) and inferior mesenteric artery (1, 0.4%).

Surveillance consisted of imaging every 3 years. Of the surveillance cohort, 138 patients had longer-term follow-up. The average aneurysm size was 16.3 mm, “so they’re small,” Dr. Conrad said. Of that whole group, only 12 (9%), of SAAs grew in size, and of those, 8 were 25 mm or smaller when they were identified; 8 of the 12 required repair. “The average time to repair was 2 years,” Dr. Conrad said. “There were no ruptures in the surveillance cohort.”

Among the early repair group, 13 (14.7%) had rupture upon presentation, 3 of which (23%) were pseudoaneurysms. The majority of aneurysms in this group were in either the splenic artery, PDA, or GDA. “Their average size was 31 mm – much larger than the patients that we watched,” he said. A total of 70% of all repairs were endovascular in nature, the remainder open, but endovascular comprised a higher percentage of rupture repairs: 10 (77%) vs. 3 (23%) that underwent open procedures.

The outcomes for endovascular and open repair were similar based on the small number of subjects, Dr. Conrad said: 30-day morbidity of 17% for endovascular repair and 22.2% for open; and 30-day mortality of 3.5% and 4.5%, respectively. However, for ruptured lesions, the outcomes were starkly significant: 54% morbidity and 8% mortality at 30 days.

The researchers performed a univariate analysis of predictors for aneurysm. They were aneurysm size with an odds ratio of 1.04 for every 1 mm of growth; PDA or GDA lesions with an OR of 11.2; and Ehlers-Danlos type IV syndrome with an OR of 32.5. The latter included all the three study patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Among patients who had splenic SAAs, 99 (93%) were asymptomatic and 5 (5.3%) had pseudoaneurysm, and almost half (47) went into surveillance. Over a mean observation period of 35 months, six (12.8%) grew in size, comprising half of the growing SAAs in the observation group. Thirty-two had endovascular repair and four open repair, with a 30-day morbidity of 22% and 30-day mortality of 2.7%.

Celiac SAAs proved most problematic in terms of symptomatology; all 78 patients with this variant were asymptomatic, and 12 (15%) had dissection. Sixty patients went into surveillance with a mean time of 43 months, and three (5) had aneurysms that grew in size. Five had intervention, four with open repair, with 30-day morbidity of 20% and no 30-day mortality.

Hepatic SAAs affected 34 study subjects, 29 (85%) of whom were asymptomatic, 4 (15%) who had dissection, and 7 (21%) with pseudoaneurysm. Eleven entered surveillance for an average of 28 months, but none showed any aneurysmal growth. The 16 who had intervention were evenly split between open and endovascular repair with 30-day morbidity of 25% and 30-day morality of 12.5%.

The PDA and GDA aneurysms “are really interesting,” Dr. Conrad said. “I think they’re different in nature than the other aneurysms,” he said, noting that 12 (33%) of these aneurysms were symptomatic and 6 (17%) were pseudoaneurysms. Because of the high rate of rupture of PDA/GDA aneurysms, Dr. Conrad advised repair at diagnosis: “97% of these patients had a celiac stenosis, and of those, two-thirds were atherosclerosis related and one-third related to the median arcuate ligament compression.” The rupture rate was comparatively high – 20%. Twenty cases underwent endovascular repair with a 90% success rate while four cases had open repair. Thirty-day morbidity for intact lesions was 11% with no deaths, and 50% with 14% mortality rate for ruptured lesions.

Of the SMA aneurysms in the study population, only 17% were mycotic with the remainder asymptomatic, Dr. Conrad said. Nine underwent surveillance, with one growing in size over a mean observation period of 28 months, four had open repair, and two endovascular repair. Morbidity was 17% at 30 days with no deaths.

The guidelines Dr. Conrad and his group developed recommend treatment for symptomatic patients and a more nuanced approach for asymptomatic patients, depending on the location and size of SAA. All lesions 25 mm or smaller, except those of the PDA/GDA, can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years, he said; intervention is indicated for all larger lesions. Endovascular repair is in order for all splenic SAAs in pregnancy, liver transplantation, and pseudoaneurysm. For hepatic SAAs, open or endovascular repair is indicated for pseudoaneurysm, but open repair only is indicated for asymptomatic celiac SAAs with pseudoaneurysm. Endovascular intervention can address most SAA aneurysms of the PDA and GDA.

Dr. Conrad disclosed he is a consultant to Medtronic and Volcano and is a member of Bard’s clinical events committee.

CHICAGO – Guidelines for the management of splanchnic artery aneurysms have been hard to come by because of their rarity, but investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, have surveyed their 20-year experience to conclude that surveillance is appropriate for most cases of aneurysms smaller than 25 mm, and selective open or endovascular repair is indicated for larger lesions, depending on their location.

“Most of the small splanchnic artery aneurysms (SAAs) of less than 25 mm did not grow or rupture over time and can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years,” Mark F. Conrad, MD, reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

The predominant sites of aneurysm were the splenic artery (95, 36%) and the celiac artery (78, 30%), followed by the hepatic artery (34, 13%), pancreaticoduodenal artery (PDA; 25, 9.6%), superior mesenteric artery (SMA; 17, 6%), gastroduodenal artery (GDA; 11, 4%), jejunal artery (3, 1%) and inferior mesenteric artery (1, 0.4%).

Surveillance consisted of imaging every 3 years. Of the surveillance cohort, 138 patients had longer-term follow-up. The average aneurysm size was 16.3 mm, “so they’re small,” Dr. Conrad said. Of that whole group, only 12 (9%), of SAAs grew in size, and of those, 8 were 25 mm or smaller when they were identified; 8 of the 12 required repair. “The average time to repair was 2 years,” Dr. Conrad said. “There were no ruptures in the surveillance cohort.”

Among the early repair group, 13 (14.7%) had rupture upon presentation, 3 of which (23%) were pseudoaneurysms. The majority of aneurysms in this group were in either the splenic artery, PDA, or GDA. “Their average size was 31 mm – much larger than the patients that we watched,” he said. A total of 70% of all repairs were endovascular in nature, the remainder open, but endovascular comprised a higher percentage of rupture repairs: 10 (77%) vs. 3 (23%) that underwent open procedures.

The outcomes for endovascular and open repair were similar based on the small number of subjects, Dr. Conrad said: 30-day morbidity of 17% for endovascular repair and 22.2% for open; and 30-day mortality of 3.5% and 4.5%, respectively. However, for ruptured lesions, the outcomes were starkly significant: 54% morbidity and 8% mortality at 30 days.

The researchers performed a univariate analysis of predictors for aneurysm. They were aneurysm size with an odds ratio of 1.04 for every 1 mm of growth; PDA or GDA lesions with an OR of 11.2; and Ehlers-Danlos type IV syndrome with an OR of 32.5. The latter included all the three study patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Among patients who had splenic SAAs, 99 (93%) were asymptomatic and 5 (5.3%) had pseudoaneurysm, and almost half (47) went into surveillance. Over a mean observation period of 35 months, six (12.8%) grew in size, comprising half of the growing SAAs in the observation group. Thirty-two had endovascular repair and four open repair, with a 30-day morbidity of 22% and 30-day mortality of 2.7%.

Celiac SAAs proved most problematic in terms of symptomatology; all 78 patients with this variant were asymptomatic, and 12 (15%) had dissection. Sixty patients went into surveillance with a mean time of 43 months, and three (5) had aneurysms that grew in size. Five had intervention, four with open repair, with 30-day morbidity of 20% and no 30-day mortality.

Hepatic SAAs affected 34 study subjects, 29 (85%) of whom were asymptomatic, 4 (15%) who had dissection, and 7 (21%) with pseudoaneurysm. Eleven entered surveillance for an average of 28 months, but none showed any aneurysmal growth. The 16 who had intervention were evenly split between open and endovascular repair with 30-day morbidity of 25% and 30-day morality of 12.5%.

The PDA and GDA aneurysms “are really interesting,” Dr. Conrad said. “I think they’re different in nature than the other aneurysms,” he said, noting that 12 (33%) of these aneurysms were symptomatic and 6 (17%) were pseudoaneurysms. Because of the high rate of rupture of PDA/GDA aneurysms, Dr. Conrad advised repair at diagnosis: “97% of these patients had a celiac stenosis, and of those, two-thirds were atherosclerosis related and one-third related to the median arcuate ligament compression.” The rupture rate was comparatively high – 20%. Twenty cases underwent endovascular repair with a 90% success rate while four cases had open repair. Thirty-day morbidity for intact lesions was 11% with no deaths, and 50% with 14% mortality rate for ruptured lesions.

Of the SMA aneurysms in the study population, only 17% were mycotic with the remainder asymptomatic, Dr. Conrad said. Nine underwent surveillance, with one growing in size over a mean observation period of 28 months, four had open repair, and two endovascular repair. Morbidity was 17% at 30 days with no deaths.

The guidelines Dr. Conrad and his group developed recommend treatment for symptomatic patients and a more nuanced approach for asymptomatic patients, depending on the location and size of SAA. All lesions 25 mm or smaller, except those of the PDA/GDA, can be observed with axial imaging every 3 years, he said; intervention is indicated for all larger lesions. Endovascular repair is in order for all splenic SAAs in pregnancy, liver transplantation, and pseudoaneurysm. For hepatic SAAs, open or endovascular repair is indicated for pseudoaneurysm, but open repair only is indicated for asymptomatic celiac SAAs with pseudoaneurysm. Endovascular intervention can address most SAA aneurysms of the PDA and GDA.

Dr. Conrad disclosed he is a consultant to Medtronic and Volcano and is a member of Bard’s clinical events committee.

AT THE NORTHWESTERN VASCULAR SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Surveillance imaging every three years may be adequate to manage splanchnic artery aneurysms (SAA) smaller than 25 mm, because they rarely expand significantly.

Major finding: In the surveillance group that had long-term follow-up, 9% had SAAs that grew in size.

Data source: Analysis of 250 patients with 264 SAAs during 1994-2014 in the Research Patient Data Registry at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Conrad disclosed he is a consultant to Medtronic and Volcano and is a member of Bard’s clinical events committee.

Point/Counterpoint: Is endograft PAA repair durable?

Endovascular repair is durable

Endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysms is vastly superior to all other previous techniques of popliteal aneurysm repair. Half of all popliteal artery aneurysms are bilateral, and 40% are associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm; 1%-2% of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm have a popliteal aneurysm (ANZ J Surg. 2006 Oct;76[10]:912-5). Less than 0.01% of hospitalized patients have popliteal artery aneurysms, and men are 20 times more prone to them than women are.

Traditional treatment involves either bypass with interval ligation or a direct posterior approach with an interposition graft, but surgery is not without its problems. I think of the retired anesthesiologist who came to me with a popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) that his primary care doctor diagnosed. “I’m not having any damn femoral popliteal bypass operation,” he told me. “Every single one of those patients dies.”

Endograft repair is a technique that is reaching its prime, as a growing number of reports have shown – although none of these studies has large numbers because the volume just isn’t available. One recent paper compared 52 open and 23 endovascular PAA repairs (Ann Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;30:253-7) and found both had similarly high rates of reintervention – 50% at 4 years. But it is noteworthy that the endovascular results improved with time.

A University of Pittsburgh study of 186 open and endovascular repairs found that patients with acute presentations of embolization or aneurysm thrombosis did better with open surgery. In addition, while open repair had superior patency initially after surgery, midterm secondary patency and amputation rates of open and endovascular repair were similar (J Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;63[1]:70-6).

A Netherlands study of 72 PAA treated with endografting showed that 84% had primary patency at 1 year, and 74% had assisted primary patency at 3 years (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016 Jul;52[1]:99-104). Among these patients, 13 had late occlusions, 7 were converted to bypass, and 2 required thrombolysis; but none required limb amputation.

A meta-analysis of 540 patients found no statistically significant difference in outcomes between endovascular and open repair for PAA (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50(3):351-9). Another systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies and 514 patients also found no difference in pooled primary and secondary patency at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7).

There certainly are contradictory studies, such as one by Dr. Alik Farber’s group in Boston that showed open repair is superior to endovascular surgery (J Vasc Surg. 2015 Mar;61[3]:663-9); but retrospective database mining certainly has its limitations. Their retrospective study queried the Vascular Quality Initiative database and found that 95% of patients who had open elective popliteal aneurysm repair were free from major adverse limb events, vs. 80% for endovascular treatments.

The best outcomes of open repair happen with autologous vein, but there is precious little of that around now. Emergency patients would probably do better with open surgery, but in elective repair there is no clear differential data.

So, if that’s the case, I’m going to take the small incision.

Peter Rossi, MD, FACS, is an associate professor of surgery and radiology, and the clinical director of vascular surgery, at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. He is also on staff at Clement J. Zablocki Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Milwaukee. Dr. Rossi had no financial relationships to disclose.

Endovascular repair may not be durable

Debating the durability of elective endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysm raises a question: Who determines durability anyway?

Is it the patients who only want the Band-Aid and no incision? I don’t think so. Is it the interventionalist who only does endovascular repairs? I don’t think so. I’m sure it’s not the insurance companies, who only worry about cost containment, either.

So, who should determine durability of endovascular popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) repair?

So, the question is, do we have such data?

There are multiple reports looking at how well open repair works. It has been done for decades. In 2008, a Veterans Affairs study of 583 open PAA repairs reported low death rates and excellent rates of limb salvage at 2 years, even in high-risk patients (J Vasc Surg. 2008 Oct;48[4]:845-51). Open surgical repair has excellent documented durability, and that is not the question at hand.

Endovascular repair has some presumed advantages. It’s less invasive and involves less postoperative pain and a quicker recovery. But it is not without problems – graft thrombosis and occlusion, endoleaks, distal limb ischemia, and stent fractures among them.

Surgery, to be clear, is not perfect, either. One of my patients who years ago presented with an occluded PAA underwent open bypass repair – but then went on later to have a pseudoaneurysm of the proximal anastomosis. I repaired this with an endograft, and he has done quite well. So, we all do endograft repairs, walk out, chest bump the Gore rep, and send the patient home that day.

Is it durable, though?

Most of the data on endovascular repair are from single-center studies dating back to 2003. There’s only one prospective trial comparing endovascular vs. open repair (J Vasc Surg. 2005 Aug;42[2]:185-93), but it was a single-center trial with a severe power limitation, because it involved only 30 patients. It found endovascular repair was comparable to open surgery. Also, I suspect a great deal of selection bias is involved in studies of endovascular repair.

A number of studies have found endovascular repair is not inferior to surgical repair. For example, a study by Dr. Audra Duncan, at Mayo Clinic, and her colleagues found that primary and secondary patency rates of elective and emergent stenting were excellent – but the study results only extended out to 2 years (J Vasc Surg. 2013 May;57[5]:1299-305). I don’t think we could hang our hat on that.

A Swedish study that compared open and endovascular surgery in 592 patients reported that endovascular repair has “significantly inferior results compared with open repair,” particularly in those who present with acute ischemia (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50[3]:342-50). A close look at the data shows that primary patency rates were 89% for open repair and 67.4% for stent graft.

Referencing the systematic review and meta-analysis that Dr. Rossi cited, the primary patency of endovascular repair was only 69% and the secondary patency rate was 77% at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7). As physicians, I submit that we can do better.

A Netherlands study investigated stent fractures, finding that 17% (13 out of 78 cases) had circumferential fractures (J Vasc Surg. 2010 Jun;51[6]:1413-8). This study only included circumferential stent fractures and excluded localized strut fractures. I think these studies show that endovascular repair is not always durable.

I want to remind you that we are vascular surgeons, so it is appropriate for us to embrace surgical bypass and its known durability, especially when the durability of endovascular repair is still not known.

Patrick Muck, MD, is chief of vascular surgery and director of vascular residency and fellowship at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati. He is also on staff at Bethesda North Hospital, Cincinnati, and is affiliated with TriHealth Heart Institute in southwestern Ohio. Dr. Muck had no financial relationships to disclose.

Endovascular repair is durable

Endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysms is vastly superior to all other previous techniques of popliteal aneurysm repair. Half of all popliteal artery aneurysms are bilateral, and 40% are associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm; 1%-2% of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm have a popliteal aneurysm (ANZ J Surg. 2006 Oct;76[10]:912-5). Less than 0.01% of hospitalized patients have popliteal artery aneurysms, and men are 20 times more prone to them than women are.

Traditional treatment involves either bypass with interval ligation or a direct posterior approach with an interposition graft, but surgery is not without its problems. I think of the retired anesthesiologist who came to me with a popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) that his primary care doctor diagnosed. “I’m not having any damn femoral popliteal bypass operation,” he told me. “Every single one of those patients dies.”

Endograft repair is a technique that is reaching its prime, as a growing number of reports have shown – although none of these studies has large numbers because the volume just isn’t available. One recent paper compared 52 open and 23 endovascular PAA repairs (Ann Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;30:253-7) and found both had similarly high rates of reintervention – 50% at 4 years. But it is noteworthy that the endovascular results improved with time.

A University of Pittsburgh study of 186 open and endovascular repairs found that patients with acute presentations of embolization or aneurysm thrombosis did better with open surgery. In addition, while open repair had superior patency initially after surgery, midterm secondary patency and amputation rates of open and endovascular repair were similar (J Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;63[1]:70-6).

A Netherlands study of 72 PAA treated with endografting showed that 84% had primary patency at 1 year, and 74% had assisted primary patency at 3 years (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016 Jul;52[1]:99-104). Among these patients, 13 had late occlusions, 7 were converted to bypass, and 2 required thrombolysis; but none required limb amputation.

A meta-analysis of 540 patients found no statistically significant difference in outcomes between endovascular and open repair for PAA (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50(3):351-9). Another systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies and 514 patients also found no difference in pooled primary and secondary patency at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7).

There certainly are contradictory studies, such as one by Dr. Alik Farber’s group in Boston that showed open repair is superior to endovascular surgery (J Vasc Surg. 2015 Mar;61[3]:663-9); but retrospective database mining certainly has its limitations. Their retrospective study queried the Vascular Quality Initiative database and found that 95% of patients who had open elective popliteal aneurysm repair were free from major adverse limb events, vs. 80% for endovascular treatments.

The best outcomes of open repair happen with autologous vein, but there is precious little of that around now. Emergency patients would probably do better with open surgery, but in elective repair there is no clear differential data.

So, if that’s the case, I’m going to take the small incision.

Peter Rossi, MD, FACS, is an associate professor of surgery and radiology, and the clinical director of vascular surgery, at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. He is also on staff at Clement J. Zablocki Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Milwaukee. Dr. Rossi had no financial relationships to disclose.

Endovascular repair may not be durable

Debating the durability of elective endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysm raises a question: Who determines durability anyway?

Is it the patients who only want the Band-Aid and no incision? I don’t think so. Is it the interventionalist who only does endovascular repairs? I don’t think so. I’m sure it’s not the insurance companies, who only worry about cost containment, either.

So, who should determine durability of endovascular popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) repair?

So, the question is, do we have such data?

There are multiple reports looking at how well open repair works. It has been done for decades. In 2008, a Veterans Affairs study of 583 open PAA repairs reported low death rates and excellent rates of limb salvage at 2 years, even in high-risk patients (J Vasc Surg. 2008 Oct;48[4]:845-51). Open surgical repair has excellent documented durability, and that is not the question at hand.

Endovascular repair has some presumed advantages. It’s less invasive and involves less postoperative pain and a quicker recovery. But it is not without problems – graft thrombosis and occlusion, endoleaks, distal limb ischemia, and stent fractures among them.

Surgery, to be clear, is not perfect, either. One of my patients who years ago presented with an occluded PAA underwent open bypass repair – but then went on later to have a pseudoaneurysm of the proximal anastomosis. I repaired this with an endograft, and he has done quite well. So, we all do endograft repairs, walk out, chest bump the Gore rep, and send the patient home that day.

Is it durable, though?

Most of the data on endovascular repair are from single-center studies dating back to 2003. There’s only one prospective trial comparing endovascular vs. open repair (J Vasc Surg. 2005 Aug;42[2]:185-93), but it was a single-center trial with a severe power limitation, because it involved only 30 patients. It found endovascular repair was comparable to open surgery. Also, I suspect a great deal of selection bias is involved in studies of endovascular repair.

A number of studies have found endovascular repair is not inferior to surgical repair. For example, a study by Dr. Audra Duncan, at Mayo Clinic, and her colleagues found that primary and secondary patency rates of elective and emergent stenting were excellent – but the study results only extended out to 2 years (J Vasc Surg. 2013 May;57[5]:1299-305). I don’t think we could hang our hat on that.

A Swedish study that compared open and endovascular surgery in 592 patients reported that endovascular repair has “significantly inferior results compared with open repair,” particularly in those who present with acute ischemia (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50[3]:342-50). A close look at the data shows that primary patency rates were 89% for open repair and 67.4% for stent graft.

Referencing the systematic review and meta-analysis that Dr. Rossi cited, the primary patency of endovascular repair was only 69% and the secondary patency rate was 77% at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7). As physicians, I submit that we can do better.

A Netherlands study investigated stent fractures, finding that 17% (13 out of 78 cases) had circumferential fractures (J Vasc Surg. 2010 Jun;51[6]:1413-8). This study only included circumferential stent fractures and excluded localized strut fractures. I think these studies show that endovascular repair is not always durable.

I want to remind you that we are vascular surgeons, so it is appropriate for us to embrace surgical bypass and its known durability, especially when the durability of endovascular repair is still not known.

Patrick Muck, MD, is chief of vascular surgery and director of vascular residency and fellowship at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati. He is also on staff at Bethesda North Hospital, Cincinnati, and is affiliated with TriHealth Heart Institute in southwestern Ohio. Dr. Muck had no financial relationships to disclose.

Endovascular repair is durable

Endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysms is vastly superior to all other previous techniques of popliteal aneurysm repair. Half of all popliteal artery aneurysms are bilateral, and 40% are associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm; 1%-2% of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm have a popliteal aneurysm (ANZ J Surg. 2006 Oct;76[10]:912-5). Less than 0.01% of hospitalized patients have popliteal artery aneurysms, and men are 20 times more prone to them than women are.

Traditional treatment involves either bypass with interval ligation or a direct posterior approach with an interposition graft, but surgery is not without its problems. I think of the retired anesthesiologist who came to me with a popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) that his primary care doctor diagnosed. “I’m not having any damn femoral popliteal bypass operation,” he told me. “Every single one of those patients dies.”

Endograft repair is a technique that is reaching its prime, as a growing number of reports have shown – although none of these studies has large numbers because the volume just isn’t available. One recent paper compared 52 open and 23 endovascular PAA repairs (Ann Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;30:253-7) and found both had similarly high rates of reintervention – 50% at 4 years. But it is noteworthy that the endovascular results improved with time.

A University of Pittsburgh study of 186 open and endovascular repairs found that patients with acute presentations of embolization or aneurysm thrombosis did better with open surgery. In addition, while open repair had superior patency initially after surgery, midterm secondary patency and amputation rates of open and endovascular repair were similar (J Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;63[1]:70-6).

A Netherlands study of 72 PAA treated with endografting showed that 84% had primary patency at 1 year, and 74% had assisted primary patency at 3 years (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016 Jul;52[1]:99-104). Among these patients, 13 had late occlusions, 7 were converted to bypass, and 2 required thrombolysis; but none required limb amputation.

A meta-analysis of 540 patients found no statistically significant difference in outcomes between endovascular and open repair for PAA (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50(3):351-9). Another systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies and 514 patients also found no difference in pooled primary and secondary patency at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7).

There certainly are contradictory studies, such as one by Dr. Alik Farber’s group in Boston that showed open repair is superior to endovascular surgery (J Vasc Surg. 2015 Mar;61[3]:663-9); but retrospective database mining certainly has its limitations. Their retrospective study queried the Vascular Quality Initiative database and found that 95% of patients who had open elective popliteal aneurysm repair were free from major adverse limb events, vs. 80% for endovascular treatments.

The best outcomes of open repair happen with autologous vein, but there is precious little of that around now. Emergency patients would probably do better with open surgery, but in elective repair there is no clear differential data.

So, if that’s the case, I’m going to take the small incision.

Peter Rossi, MD, FACS, is an associate professor of surgery and radiology, and the clinical director of vascular surgery, at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. He is also on staff at Clement J. Zablocki Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Milwaukee. Dr. Rossi had no financial relationships to disclose.

Endovascular repair may not be durable

Debating the durability of elective endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysm raises a question: Who determines durability anyway?

Is it the patients who only want the Band-Aid and no incision? I don’t think so. Is it the interventionalist who only does endovascular repairs? I don’t think so. I’m sure it’s not the insurance companies, who only worry about cost containment, either.

So, who should determine durability of endovascular popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) repair?

So, the question is, do we have such data?

There are multiple reports looking at how well open repair works. It has been done for decades. In 2008, a Veterans Affairs study of 583 open PAA repairs reported low death rates and excellent rates of limb salvage at 2 years, even in high-risk patients (J Vasc Surg. 2008 Oct;48[4]:845-51). Open surgical repair has excellent documented durability, and that is not the question at hand.

Endovascular repair has some presumed advantages. It’s less invasive and involves less postoperative pain and a quicker recovery. But it is not without problems – graft thrombosis and occlusion, endoleaks, distal limb ischemia, and stent fractures among them.

Surgery, to be clear, is not perfect, either. One of my patients who years ago presented with an occluded PAA underwent open bypass repair – but then went on later to have a pseudoaneurysm of the proximal anastomosis. I repaired this with an endograft, and he has done quite well. So, we all do endograft repairs, walk out, chest bump the Gore rep, and send the patient home that day.

Is it durable, though?

Most of the data on endovascular repair are from single-center studies dating back to 2003. There’s only one prospective trial comparing endovascular vs. open repair (J Vasc Surg. 2005 Aug;42[2]:185-93), but it was a single-center trial with a severe power limitation, because it involved only 30 patients. It found endovascular repair was comparable to open surgery. Also, I suspect a great deal of selection bias is involved in studies of endovascular repair.

A number of studies have found endovascular repair is not inferior to surgical repair. For example, a study by Dr. Audra Duncan, at Mayo Clinic, and her colleagues found that primary and secondary patency rates of elective and emergent stenting were excellent – but the study results only extended out to 2 years (J Vasc Surg. 2013 May;57[5]:1299-305). I don’t think we could hang our hat on that.

A Swedish study that compared open and endovascular surgery in 592 patients reported that endovascular repair has “significantly inferior results compared with open repair,” particularly in those who present with acute ischemia (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50[3]:342-50). A close look at the data shows that primary patency rates were 89% for open repair and 67.4% for stent graft.

Referencing the systematic review and meta-analysis that Dr. Rossi cited, the primary patency of endovascular repair was only 69% and the secondary patency rate was 77% at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7). As physicians, I submit that we can do better.

A Netherlands study investigated stent fractures, finding that 17% (13 out of 78 cases) had circumferential fractures (J Vasc Surg. 2010 Jun;51[6]:1413-8). This study only included circumferential stent fractures and excluded localized strut fractures. I think these studies show that endovascular repair is not always durable.

I want to remind you that we are vascular surgeons, so it is appropriate for us to embrace surgical bypass and its known durability, especially when the durability of endovascular repair is still not known.