User login

Researchers examine learning curve for gender-affirming vaginoplasty

research suggests. For one surgeon, certain adverse events, including the need for revision surgery, were less likely after 50 cases.

“As surgical programs evolve, the important question becomes: At what case threshold are cases performed safely, efficiently, and with favorable outcomes?” said Cecile A. Ferrando, MD, MPH, program director of the female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellowship at Cleveland Clinic and director of the transgender surgery and medicine program in the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for LGBT Care.

The answer could guide training for future surgeons, Dr. Ferrando said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Future studies should include patient-centered outcomes and data from multiple centers, other doctors said.

Transgender women who opt to surgically transition may undergo vaginoplasty. Although many reports describe surgical techniques, “there is a paucity of evidence-based data as well as few reports on outcomes,” Dr. Ferrando noted.

To describe perioperative adverse events related to vaginoplasty performed for gender affirmation and determine a minimum number of cases needed to reduce their likelihood, Dr. Ferrando performed a retrospective study of 76 patients. The patients underwent surgery between December 2015 and March 2019 and had 6-month postoperative outcomes available. Dr. Ferrando performed the procedures.

Dr. Ferrando evaluated outcomes after increments of 10 cases. After 50 cases, the median surgical time decreased to approximately 180 minutes, which an informal survey of surgeons suggested was efficient, and the rates of adverse events were similar to those in other studies. Dr. Ferrando compared outcomes from the first 50 cases with outcomes from the 26 cases that followed.

Overall, the patients had a mean age of 41 years. The first 50 patients were older on average (44 years vs. 35 years). About 83% underwent full-depth vaginoplasty. The incidence of intraoperative and immediate postoperative events was low and did not differ between the two groups. Rates of delayed postoperative events – those occurring 30 or more days after surgery – did significantly differ between the two groups, however.

After 50 cases, there was a lower incidence of urinary stream abnormalities (7.7% vs. 16.3%), introital stenosis (3.9% vs. 12%), and revision surgery (that is, elective, cosmetic, or functional revision within 6 months; 19.2% vs. 44%), compared with the first 50 cases.

The study did not include patient-centered outcomes and the results may have limited generalizability, Dr. Ferrando noted. “The incidence of serious adverse events related to vaginoplasty is low while minor events are common,” she said. “A 50-case minimum may be an adequate case number target for postgraduate trainees learning how to do this surgery.”

“I learned that the incidence of serious complications, like injuries during the surgery, or serious events immediately after surgery was quite low, which was reassuring,” Dr. Ferrando said in a later interview. “The cosmetic result and detail that is involved with the surgery – something that is very important to patients – that skill set takes time and experience to refine.”

Subsequent studies should include patient-centered outcomes, which may help surgeons understand potential “sources of consternation for patients,” such as persistent corporal tissue, poor aesthetics, vaginal stenosis, urinary meatus location, and clitoral hooding, Joseph J. Pariser, MD, commented in an interview. Dr. Pariser, a urologist who specializes in gender care at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, in 2019 reviewed safety outcomes from published case series.

“In my own practice, precise placement of the urethra, familiarity with landmarks during canal dissection, and rapidity of working through steps of the surgery have all dramatically improved as our experience at University of Minnesota performing primary vaginoplasty has grown,” Dr. Pariser said.

Optimal case thresholds may vary depending on a surgeon’s background, Rachel M. Whynott, MD, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, said in an interview. At the University of Kansas in Kansas City, a multidisciplinary team that includes a gynecologist, a reconstructive urologist, and a plastic surgeon performs the procedure.

Dr. Whynott and colleagues recently published a retrospective study that evaluated surgical aptitude over time in a male-to-female penoscrotal vaginoplasty program . Their analysis of 43 cases identified a learning curve that was reflected in overall time in the operating room and time to neoclitoral sensation.

Investigators are “trying to add to the growing body of literature about this procedure and how we can best go about improving outcomes for our patients and improving this surgery,” Dr. Whynott said. A study that includes data from multiple centers would be useful, she added.

Dr. Ferrando disclosed authorship royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Pariser and Dr. Whynott had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ferrando C. SGS 2020, Abstract 09.

research suggests. For one surgeon, certain adverse events, including the need for revision surgery, were less likely after 50 cases.

“As surgical programs evolve, the important question becomes: At what case threshold are cases performed safely, efficiently, and with favorable outcomes?” said Cecile A. Ferrando, MD, MPH, program director of the female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellowship at Cleveland Clinic and director of the transgender surgery and medicine program in the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for LGBT Care.

The answer could guide training for future surgeons, Dr. Ferrando said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Future studies should include patient-centered outcomes and data from multiple centers, other doctors said.

Transgender women who opt to surgically transition may undergo vaginoplasty. Although many reports describe surgical techniques, “there is a paucity of evidence-based data as well as few reports on outcomes,” Dr. Ferrando noted.

To describe perioperative adverse events related to vaginoplasty performed for gender affirmation and determine a minimum number of cases needed to reduce their likelihood, Dr. Ferrando performed a retrospective study of 76 patients. The patients underwent surgery between December 2015 and March 2019 and had 6-month postoperative outcomes available. Dr. Ferrando performed the procedures.

Dr. Ferrando evaluated outcomes after increments of 10 cases. After 50 cases, the median surgical time decreased to approximately 180 minutes, which an informal survey of surgeons suggested was efficient, and the rates of adverse events were similar to those in other studies. Dr. Ferrando compared outcomes from the first 50 cases with outcomes from the 26 cases that followed.

Overall, the patients had a mean age of 41 years. The first 50 patients were older on average (44 years vs. 35 years). About 83% underwent full-depth vaginoplasty. The incidence of intraoperative and immediate postoperative events was low and did not differ between the two groups. Rates of delayed postoperative events – those occurring 30 or more days after surgery – did significantly differ between the two groups, however.

After 50 cases, there was a lower incidence of urinary stream abnormalities (7.7% vs. 16.3%), introital stenosis (3.9% vs. 12%), and revision surgery (that is, elective, cosmetic, or functional revision within 6 months; 19.2% vs. 44%), compared with the first 50 cases.

The study did not include patient-centered outcomes and the results may have limited generalizability, Dr. Ferrando noted. “The incidence of serious adverse events related to vaginoplasty is low while minor events are common,” she said. “A 50-case minimum may be an adequate case number target for postgraduate trainees learning how to do this surgery.”

“I learned that the incidence of serious complications, like injuries during the surgery, or serious events immediately after surgery was quite low, which was reassuring,” Dr. Ferrando said in a later interview. “The cosmetic result and detail that is involved with the surgery – something that is very important to patients – that skill set takes time and experience to refine.”

Subsequent studies should include patient-centered outcomes, which may help surgeons understand potential “sources of consternation for patients,” such as persistent corporal tissue, poor aesthetics, vaginal stenosis, urinary meatus location, and clitoral hooding, Joseph J. Pariser, MD, commented in an interview. Dr. Pariser, a urologist who specializes in gender care at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, in 2019 reviewed safety outcomes from published case series.

“In my own practice, precise placement of the urethra, familiarity with landmarks during canal dissection, and rapidity of working through steps of the surgery have all dramatically improved as our experience at University of Minnesota performing primary vaginoplasty has grown,” Dr. Pariser said.

Optimal case thresholds may vary depending on a surgeon’s background, Rachel M. Whynott, MD, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, said in an interview. At the University of Kansas in Kansas City, a multidisciplinary team that includes a gynecologist, a reconstructive urologist, and a plastic surgeon performs the procedure.

Dr. Whynott and colleagues recently published a retrospective study that evaluated surgical aptitude over time in a male-to-female penoscrotal vaginoplasty program . Their analysis of 43 cases identified a learning curve that was reflected in overall time in the operating room and time to neoclitoral sensation.

Investigators are “trying to add to the growing body of literature about this procedure and how we can best go about improving outcomes for our patients and improving this surgery,” Dr. Whynott said. A study that includes data from multiple centers would be useful, she added.

Dr. Ferrando disclosed authorship royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Pariser and Dr. Whynott had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ferrando C. SGS 2020, Abstract 09.

research suggests. For one surgeon, certain adverse events, including the need for revision surgery, were less likely after 50 cases.

“As surgical programs evolve, the important question becomes: At what case threshold are cases performed safely, efficiently, and with favorable outcomes?” said Cecile A. Ferrando, MD, MPH, program director of the female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellowship at Cleveland Clinic and director of the transgender surgery and medicine program in the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for LGBT Care.

The answer could guide training for future surgeons, Dr. Ferrando said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Future studies should include patient-centered outcomes and data from multiple centers, other doctors said.

Transgender women who opt to surgically transition may undergo vaginoplasty. Although many reports describe surgical techniques, “there is a paucity of evidence-based data as well as few reports on outcomes,” Dr. Ferrando noted.

To describe perioperative adverse events related to vaginoplasty performed for gender affirmation and determine a minimum number of cases needed to reduce their likelihood, Dr. Ferrando performed a retrospective study of 76 patients. The patients underwent surgery between December 2015 and March 2019 and had 6-month postoperative outcomes available. Dr. Ferrando performed the procedures.

Dr. Ferrando evaluated outcomes after increments of 10 cases. After 50 cases, the median surgical time decreased to approximately 180 minutes, which an informal survey of surgeons suggested was efficient, and the rates of adverse events were similar to those in other studies. Dr. Ferrando compared outcomes from the first 50 cases with outcomes from the 26 cases that followed.

Overall, the patients had a mean age of 41 years. The first 50 patients were older on average (44 years vs. 35 years). About 83% underwent full-depth vaginoplasty. The incidence of intraoperative and immediate postoperative events was low and did not differ between the two groups. Rates of delayed postoperative events – those occurring 30 or more days after surgery – did significantly differ between the two groups, however.

After 50 cases, there was a lower incidence of urinary stream abnormalities (7.7% vs. 16.3%), introital stenosis (3.9% vs. 12%), and revision surgery (that is, elective, cosmetic, or functional revision within 6 months; 19.2% vs. 44%), compared with the first 50 cases.

The study did not include patient-centered outcomes and the results may have limited generalizability, Dr. Ferrando noted. “The incidence of serious adverse events related to vaginoplasty is low while minor events are common,” she said. “A 50-case minimum may be an adequate case number target for postgraduate trainees learning how to do this surgery.”

“I learned that the incidence of serious complications, like injuries during the surgery, or serious events immediately after surgery was quite low, which was reassuring,” Dr. Ferrando said in a later interview. “The cosmetic result and detail that is involved with the surgery – something that is very important to patients – that skill set takes time and experience to refine.”

Subsequent studies should include patient-centered outcomes, which may help surgeons understand potential “sources of consternation for patients,” such as persistent corporal tissue, poor aesthetics, vaginal stenosis, urinary meatus location, and clitoral hooding, Joseph J. Pariser, MD, commented in an interview. Dr. Pariser, a urologist who specializes in gender care at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, in 2019 reviewed safety outcomes from published case series.

“In my own practice, precise placement of the urethra, familiarity with landmarks during canal dissection, and rapidity of working through steps of the surgery have all dramatically improved as our experience at University of Minnesota performing primary vaginoplasty has grown,” Dr. Pariser said.

Optimal case thresholds may vary depending on a surgeon’s background, Rachel M. Whynott, MD, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, said in an interview. At the University of Kansas in Kansas City, a multidisciplinary team that includes a gynecologist, a reconstructive urologist, and a plastic surgeon performs the procedure.

Dr. Whynott and colleagues recently published a retrospective study that evaluated surgical aptitude over time in a male-to-female penoscrotal vaginoplasty program . Their analysis of 43 cases identified a learning curve that was reflected in overall time in the operating room and time to neoclitoral sensation.

Investigators are “trying to add to the growing body of literature about this procedure and how we can best go about improving outcomes for our patients and improving this surgery,” Dr. Whynott said. A study that includes data from multiple centers would be useful, she added.

Dr. Ferrando disclosed authorship royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Pariser and Dr. Whynott had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ferrando C. SGS 2020, Abstract 09.

FROM SGS 2020

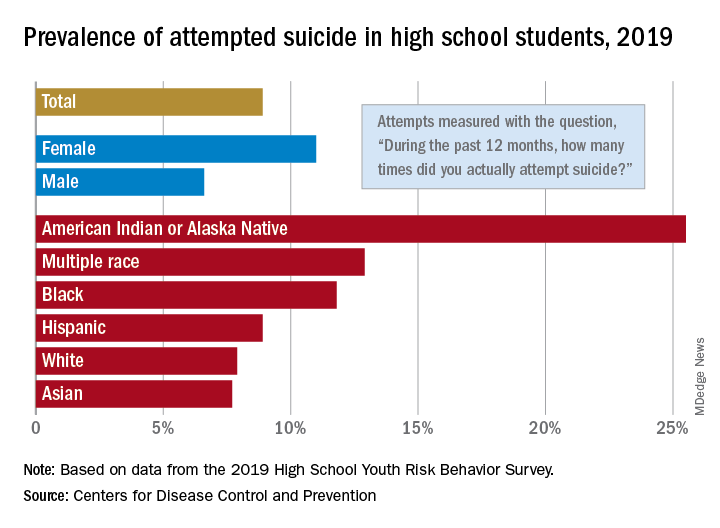

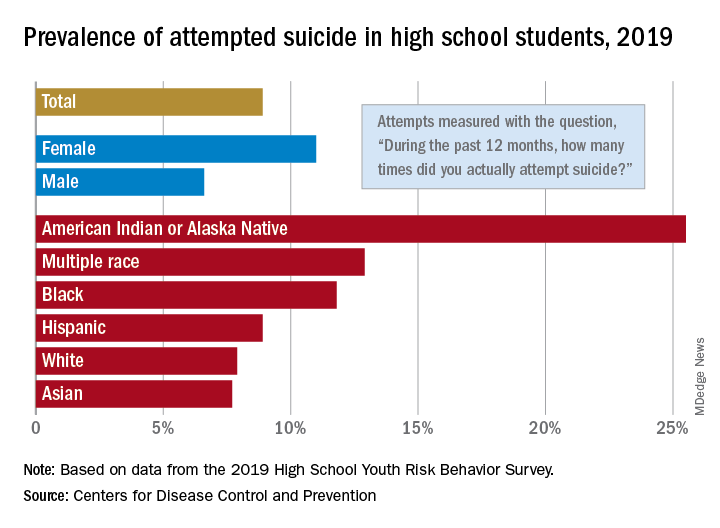

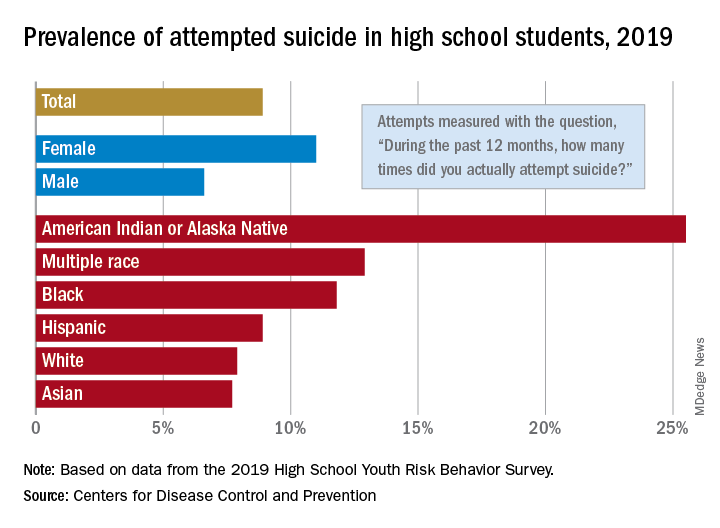

Attempted suicide in high school America, 2019

according to newly released data from the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

The prevalence of attempted suicide during the previous 12 months was 8.9% among the 13,677 students in grades 9-12 who took the survey last year, but the rate was 25.5% for American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) respondents, almost 2.9 times higher, the YRBS data show.

Respondents with multiple races in their backgrounds, at 12.9%, and African Americans, with a prevalence of 11.8%, also were above the high school average for suicide attempts, while Whites (7.9%) and Asians (7.7%) were under it and Hispanics equaled it, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

The number of AI/AN students was insufficient to examine differences by sex, but females in all of the other racial/ethnic groups were more likely than males to have attempted suicide: multiple race (17.8% vs. 7.3%), African American (15.2% vs. 8.5%), Hispanic (11.9% vs. 5.5%), White (9.4% vs. 6.4%), and Asian (8.4% vs. 7.1%), the CDC’s Division of Adolescent and School Health said.

Among all respondents, 11.0% of females had attempted suicide in the 12 months before the survey, a figure that is significantly higher than the 6.6% prevalence in males. Females also were significantly more likely than males to make a plan about how they would attempt suicide (19.9% vs. 11.3%) and to seriously consider an attempt (24.1% vs. 13.3%), CDC investigators said in a separate report.

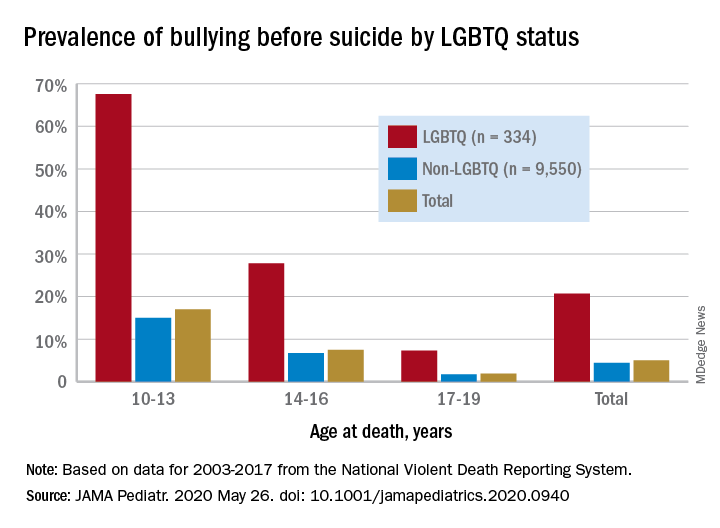

Significant differences also were seen when looking at sexual identity. Suicide attempts were reported by 6.4% of heterosexuals, 16.1% of those who weren’t sure, and 23.4% of lesbians/gays/bisexuals (LGBs). For serious consideration of suicide, the respective numbers were 14.5%, 30.4%, and 46.8%, they reported (MMWR Supp. 2020 Aug 21;69[1]:47-55).

For nonheterosexuals, however, males were slightly more likely (23.8%) than females (23.6%) to have attempted suicide, but females were more likely to seriously consider it (49.0% vs. 40.4%) and to make a plan (42.4% vs. 33.0%), according to the YRBS data.

“Adolescence … represents a time for expanded identity development, with sexual identity development representing a complex, multidimensional, and often stressful process for youths,” the CDC investigators said in the MMWR. “To address the health differences in suicidal ideation and behaviors observed by student demographics and to decrease these outcomes overall, a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention, including programs, practices, and policies based on the best available evidence, is needed.”

according to newly released data from the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

The prevalence of attempted suicide during the previous 12 months was 8.9% among the 13,677 students in grades 9-12 who took the survey last year, but the rate was 25.5% for American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) respondents, almost 2.9 times higher, the YRBS data show.

Respondents with multiple races in their backgrounds, at 12.9%, and African Americans, with a prevalence of 11.8%, also were above the high school average for suicide attempts, while Whites (7.9%) and Asians (7.7%) were under it and Hispanics equaled it, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

The number of AI/AN students was insufficient to examine differences by sex, but females in all of the other racial/ethnic groups were more likely than males to have attempted suicide: multiple race (17.8% vs. 7.3%), African American (15.2% vs. 8.5%), Hispanic (11.9% vs. 5.5%), White (9.4% vs. 6.4%), and Asian (8.4% vs. 7.1%), the CDC’s Division of Adolescent and School Health said.

Among all respondents, 11.0% of females had attempted suicide in the 12 months before the survey, a figure that is significantly higher than the 6.6% prevalence in males. Females also were significantly more likely than males to make a plan about how they would attempt suicide (19.9% vs. 11.3%) and to seriously consider an attempt (24.1% vs. 13.3%), CDC investigators said in a separate report.

Significant differences also were seen when looking at sexual identity. Suicide attempts were reported by 6.4% of heterosexuals, 16.1% of those who weren’t sure, and 23.4% of lesbians/gays/bisexuals (LGBs). For serious consideration of suicide, the respective numbers were 14.5%, 30.4%, and 46.8%, they reported (MMWR Supp. 2020 Aug 21;69[1]:47-55).

For nonheterosexuals, however, males were slightly more likely (23.8%) than females (23.6%) to have attempted suicide, but females were more likely to seriously consider it (49.0% vs. 40.4%) and to make a plan (42.4% vs. 33.0%), according to the YRBS data.

“Adolescence … represents a time for expanded identity development, with sexual identity development representing a complex, multidimensional, and often stressful process for youths,” the CDC investigators said in the MMWR. “To address the health differences in suicidal ideation and behaviors observed by student demographics and to decrease these outcomes overall, a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention, including programs, practices, and policies based on the best available evidence, is needed.”

according to newly released data from the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

The prevalence of attempted suicide during the previous 12 months was 8.9% among the 13,677 students in grades 9-12 who took the survey last year, but the rate was 25.5% for American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) respondents, almost 2.9 times higher, the YRBS data show.

Respondents with multiple races in their backgrounds, at 12.9%, and African Americans, with a prevalence of 11.8%, also were above the high school average for suicide attempts, while Whites (7.9%) and Asians (7.7%) were under it and Hispanics equaled it, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

The number of AI/AN students was insufficient to examine differences by sex, but females in all of the other racial/ethnic groups were more likely than males to have attempted suicide: multiple race (17.8% vs. 7.3%), African American (15.2% vs. 8.5%), Hispanic (11.9% vs. 5.5%), White (9.4% vs. 6.4%), and Asian (8.4% vs. 7.1%), the CDC’s Division of Adolescent and School Health said.

Among all respondents, 11.0% of females had attempted suicide in the 12 months before the survey, a figure that is significantly higher than the 6.6% prevalence in males. Females also were significantly more likely than males to make a plan about how they would attempt suicide (19.9% vs. 11.3%) and to seriously consider an attempt (24.1% vs. 13.3%), CDC investigators said in a separate report.

Significant differences also were seen when looking at sexual identity. Suicide attempts were reported by 6.4% of heterosexuals, 16.1% of those who weren’t sure, and 23.4% of lesbians/gays/bisexuals (LGBs). For serious consideration of suicide, the respective numbers were 14.5%, 30.4%, and 46.8%, they reported (MMWR Supp. 2020 Aug 21;69[1]:47-55).

For nonheterosexuals, however, males were slightly more likely (23.8%) than females (23.6%) to have attempted suicide, but females were more likely to seriously consider it (49.0% vs. 40.4%) and to make a plan (42.4% vs. 33.0%), according to the YRBS data.

“Adolescence … represents a time for expanded identity development, with sexual identity development representing a complex, multidimensional, and often stressful process for youths,” the CDC investigators said in the MMWR. “To address the health differences in suicidal ideation and behaviors observed by student demographics and to decrease these outcomes overall, a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention, including programs, practices, and policies based on the best available evidence, is needed.”

Back to school: How pediatricians can help LGBTQ youth

September every year means one thing to students across the country: Summer break is over, and it is time to go back to school. For LGBTQ youth, this can be both a blessing and a curse. Schools can be a refuge from being stuck at home with unsupportive family, but it also can mean returning to hallways full of harassment from other students and/or staff. Groups such as a gender-sexuality alliance (GSA) or a chapter of the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) can provide a safe space for these students at school. Pediatricians can play an important role in ensuring that their patients know about access to these resources.

Gender-sexuality alliances, or gay-straight alliances as they have been more commonly known, have been around since the late 1980s. The first one was founded at Concord Academy in Massachusetts in 1988 by a straight student who was upset at how her gay classmates were being treated. Today’s GSAs continue this mission to create a welcoming environment for students of all gender identities and sexual orientations to gather, increase awareness on their campus of LGBTQ issues, and make the school environment safer for all students. According to the GSA network, there are over 4,000 active GSAs today in the United States located in 40 states.1

GLSEN was founded in 1990 initially as a network of gay and lesbian educators who wanted to create safer spaces in schools for LGBTQ students. Over the last 30 years, GLSEN continues to support this mission but has expanded into research and advocacy as well. There are currently 43 chapters of GLSEN in 30 states.2 GLSEN sponsors a number of national events throughout the year to raise awareness of LGBTQ issues in schools, including No Name Calling Week and the Day of Silence. Many chapters provide mentoring to local GSAs and volunteering as a mentor can be a great way for pediatricians to become involved in their local schools.

You may be asking yourself, why are GSAs important? According to GLSEN’s 2017 National School Climate Survey, nearly 35% of LGBTQ students missed at least 1 day of school in the previous month because of feeling unsafe, and nearly 57% of students reported hearing homophobic remarks from teachers and staff at their school.3 Around 10% of LGBTQ students reported being physically assaulted based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Those LGBTQ students who experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity were more likely to have lower grade point averages and were more likely to be disciplined than those students who had not experienced discrimination.3 The cumulative effect of these negative experiences at school lead a sizable portion of affected students to drop out of school and possibly not pursue postsecondary education. This then leads to decreased job opportunities or career advancement, which could then lead to unemployment or low-wage jobs. Creating safe spaces for education to take place can have a lasting effect on the lives of LGBTQ students.

The 53% of students who reported having a GSA at their school in the National School Climate survey were less likely to report hearing negative comments about LGBTQ students, were less likely to miss school, experienced lower levels of victimization, and reported higher levels of supportive teachers and staff. All of these factors taken together ensure that LGBTQ students are more likely to complete their high school education. Russell B. Toomey, PhD, and colleagues were able to show that LGBTQ students with a perceived effective GSA were two times more likely than those without an effective GSA to attain a college education.4 Research also has shown that the presence of a GSA can have a beneficial impact on reducing bullying in general for all students, whether they identify as LGBTQ or not.5

What active steps can a pediatrician take to support their LGBTQ students? First, If the families run into trouble from the school, have your social workers help them connect with legal resources, as many court cases have established precedent that public schools cannot have a blanket ban on GSAs solely because they focus on LGBTQ issues. Second, if your patient has a GSA at their school and seems to be struggling with his/her sexual orientation and/or gender identity, encourage that student to consider attending their GSA so that they are able to spend time with other students like themselves. Third, as many schools will be starting virtually this year, you can provide your LGBTQ patients with a list of local online groups that students can participate in virtually if their school’s GSA is not meeting (see my LGBTQ Youth Consult column entitled, “Resources for LGBTQ youth during challenging times” at mdedge.com/pediatrics for a few ideas).* Lastly, be an active advocate in your own local school district for the inclusion of comprehensive nondiscrimination policies and the presence of GSAs for students. These small steps can go a long way to helping your LGBTQ patients thrive and succeed in school.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. Dr. Cooper has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. gsanetwork.org/mission-vision-history/.

2. www.glsen.org/find_chapter?field_chapter_state_target_id=All.

3. live-glsen-website.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2019-10/GLSEN-2017-National-School-Climate-Survey-NSCS-Full-Report.pdf.

4. Appl Dev Sci. 2011 Nov 7;15(4):175-85.

5.www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-08-04/gay-straight-alliances-in-schools-pay-off-for-all-students-study-finds.

*This article was updated 8/17/2020.

September every year means one thing to students across the country: Summer break is over, and it is time to go back to school. For LGBTQ youth, this can be both a blessing and a curse. Schools can be a refuge from being stuck at home with unsupportive family, but it also can mean returning to hallways full of harassment from other students and/or staff. Groups such as a gender-sexuality alliance (GSA) or a chapter of the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) can provide a safe space for these students at school. Pediatricians can play an important role in ensuring that their patients know about access to these resources.

Gender-sexuality alliances, or gay-straight alliances as they have been more commonly known, have been around since the late 1980s. The first one was founded at Concord Academy in Massachusetts in 1988 by a straight student who was upset at how her gay classmates were being treated. Today’s GSAs continue this mission to create a welcoming environment for students of all gender identities and sexual orientations to gather, increase awareness on their campus of LGBTQ issues, and make the school environment safer for all students. According to the GSA network, there are over 4,000 active GSAs today in the United States located in 40 states.1

GLSEN was founded in 1990 initially as a network of gay and lesbian educators who wanted to create safer spaces in schools for LGBTQ students. Over the last 30 years, GLSEN continues to support this mission but has expanded into research and advocacy as well. There are currently 43 chapters of GLSEN in 30 states.2 GLSEN sponsors a number of national events throughout the year to raise awareness of LGBTQ issues in schools, including No Name Calling Week and the Day of Silence. Many chapters provide mentoring to local GSAs and volunteering as a mentor can be a great way for pediatricians to become involved in their local schools.

You may be asking yourself, why are GSAs important? According to GLSEN’s 2017 National School Climate Survey, nearly 35% of LGBTQ students missed at least 1 day of school in the previous month because of feeling unsafe, and nearly 57% of students reported hearing homophobic remarks from teachers and staff at their school.3 Around 10% of LGBTQ students reported being physically assaulted based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Those LGBTQ students who experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity were more likely to have lower grade point averages and were more likely to be disciplined than those students who had not experienced discrimination.3 The cumulative effect of these negative experiences at school lead a sizable portion of affected students to drop out of school and possibly not pursue postsecondary education. This then leads to decreased job opportunities or career advancement, which could then lead to unemployment or low-wage jobs. Creating safe spaces for education to take place can have a lasting effect on the lives of LGBTQ students.

The 53% of students who reported having a GSA at their school in the National School Climate survey were less likely to report hearing negative comments about LGBTQ students, were less likely to miss school, experienced lower levels of victimization, and reported higher levels of supportive teachers and staff. All of these factors taken together ensure that LGBTQ students are more likely to complete their high school education. Russell B. Toomey, PhD, and colleagues were able to show that LGBTQ students with a perceived effective GSA were two times more likely than those without an effective GSA to attain a college education.4 Research also has shown that the presence of a GSA can have a beneficial impact on reducing bullying in general for all students, whether they identify as LGBTQ or not.5

What active steps can a pediatrician take to support their LGBTQ students? First, If the families run into trouble from the school, have your social workers help them connect with legal resources, as many court cases have established precedent that public schools cannot have a blanket ban on GSAs solely because they focus on LGBTQ issues. Second, if your patient has a GSA at their school and seems to be struggling with his/her sexual orientation and/or gender identity, encourage that student to consider attending their GSA so that they are able to spend time with other students like themselves. Third, as many schools will be starting virtually this year, you can provide your LGBTQ patients with a list of local online groups that students can participate in virtually if their school’s GSA is not meeting (see my LGBTQ Youth Consult column entitled, “Resources for LGBTQ youth during challenging times” at mdedge.com/pediatrics for a few ideas).* Lastly, be an active advocate in your own local school district for the inclusion of comprehensive nondiscrimination policies and the presence of GSAs for students. These small steps can go a long way to helping your LGBTQ patients thrive and succeed in school.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. Dr. Cooper has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. gsanetwork.org/mission-vision-history/.

2. www.glsen.org/find_chapter?field_chapter_state_target_id=All.

3. live-glsen-website.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2019-10/GLSEN-2017-National-School-Climate-Survey-NSCS-Full-Report.pdf.

4. Appl Dev Sci. 2011 Nov 7;15(4):175-85.

5.www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-08-04/gay-straight-alliances-in-schools-pay-off-for-all-students-study-finds.

*This article was updated 8/17/2020.

September every year means one thing to students across the country: Summer break is over, and it is time to go back to school. For LGBTQ youth, this can be both a blessing and a curse. Schools can be a refuge from being stuck at home with unsupportive family, but it also can mean returning to hallways full of harassment from other students and/or staff. Groups such as a gender-sexuality alliance (GSA) or a chapter of the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) can provide a safe space for these students at school. Pediatricians can play an important role in ensuring that their patients know about access to these resources.

Gender-sexuality alliances, or gay-straight alliances as they have been more commonly known, have been around since the late 1980s. The first one was founded at Concord Academy in Massachusetts in 1988 by a straight student who was upset at how her gay classmates were being treated. Today’s GSAs continue this mission to create a welcoming environment for students of all gender identities and sexual orientations to gather, increase awareness on their campus of LGBTQ issues, and make the school environment safer for all students. According to the GSA network, there are over 4,000 active GSAs today in the United States located in 40 states.1

GLSEN was founded in 1990 initially as a network of gay and lesbian educators who wanted to create safer spaces in schools for LGBTQ students. Over the last 30 years, GLSEN continues to support this mission but has expanded into research and advocacy as well. There are currently 43 chapters of GLSEN in 30 states.2 GLSEN sponsors a number of national events throughout the year to raise awareness of LGBTQ issues in schools, including No Name Calling Week and the Day of Silence. Many chapters provide mentoring to local GSAs and volunteering as a mentor can be a great way for pediatricians to become involved in their local schools.

You may be asking yourself, why are GSAs important? According to GLSEN’s 2017 National School Climate Survey, nearly 35% of LGBTQ students missed at least 1 day of school in the previous month because of feeling unsafe, and nearly 57% of students reported hearing homophobic remarks from teachers and staff at their school.3 Around 10% of LGBTQ students reported being physically assaulted based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Those LGBTQ students who experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity were more likely to have lower grade point averages and were more likely to be disciplined than those students who had not experienced discrimination.3 The cumulative effect of these negative experiences at school lead a sizable portion of affected students to drop out of school and possibly not pursue postsecondary education. This then leads to decreased job opportunities or career advancement, which could then lead to unemployment or low-wage jobs. Creating safe spaces for education to take place can have a lasting effect on the lives of LGBTQ students.

The 53% of students who reported having a GSA at their school in the National School Climate survey were less likely to report hearing negative comments about LGBTQ students, were less likely to miss school, experienced lower levels of victimization, and reported higher levels of supportive teachers and staff. All of these factors taken together ensure that LGBTQ students are more likely to complete their high school education. Russell B. Toomey, PhD, and colleagues were able to show that LGBTQ students with a perceived effective GSA were two times more likely than those without an effective GSA to attain a college education.4 Research also has shown that the presence of a GSA can have a beneficial impact on reducing bullying in general for all students, whether they identify as LGBTQ or not.5

What active steps can a pediatrician take to support their LGBTQ students? First, If the families run into trouble from the school, have your social workers help them connect with legal resources, as many court cases have established precedent that public schools cannot have a blanket ban on GSAs solely because they focus on LGBTQ issues. Second, if your patient has a GSA at their school and seems to be struggling with his/her sexual orientation and/or gender identity, encourage that student to consider attending their GSA so that they are able to spend time with other students like themselves. Third, as many schools will be starting virtually this year, you can provide your LGBTQ patients with a list of local online groups that students can participate in virtually if their school’s GSA is not meeting (see my LGBTQ Youth Consult column entitled, “Resources for LGBTQ youth during challenging times” at mdedge.com/pediatrics for a few ideas).* Lastly, be an active advocate in your own local school district for the inclusion of comprehensive nondiscrimination policies and the presence of GSAs for students. These small steps can go a long way to helping your LGBTQ patients thrive and succeed in school.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. Dr. Cooper has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. gsanetwork.org/mission-vision-history/.

2. www.glsen.org/find_chapter?field_chapter_state_target_id=All.

3. live-glsen-website.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2019-10/GLSEN-2017-National-School-Climate-Survey-NSCS-Full-Report.pdf.

4. Appl Dev Sci. 2011 Nov 7;15(4):175-85.

5.www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-08-04/gay-straight-alliances-in-schools-pay-off-for-all-students-study-finds.

*This article was updated 8/17/2020.

AAP releases new policy statement on barrier protection for teens

For adolescent patients, routinely take a sexual history, discuss the use of barrier methods, and perform relevant examinations, screenings, and vaccinations, according to a new policy statement on barrier protection use from the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Adolescence.

The policy statement has been expanded to cover multiple types of sexual activity and methods of barrier protection. These include not only traditional condoms, but also internal condoms (available in the United States only by prescription) and dental dams (for use during oral sex) or a latex sheet. “Pediatricians and other clinicians are encouraged to provide barrier methods within their offices and support availability within their communities,” said Laura K. Grubb, MD, MPH, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston, who authored both the policy statement and the technical report.

Counsel adolescents that abstaining from sexual intercourse is the best way to prevent genital sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV infection, and unplanned pregnancy. Also encourage and support consistent, correct barrier method use – in addition to other reliable contraception, if patients are sexually active or are thinking about becoming sexually active – the policy statement notes. Emphasize that all partners share responsibility to prevent STIs and unplanned pregnancies. “Adolescents with intellectual and physical disabilities are an overlooked group when it comes to sexual behavior, but they have similar rates of sexual behaviors when compared with their peers without disabilities,” Dr. Grubb and colleagues emphasized in the policy statement.

This is key because Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017 data showed that in the United States, “456,000 adolescent and young women younger than 20 years became pregnant; 448,000 of those pregnancies were among 15- to 19-year-olds, and 7,400 were among those 14 years of age and younger,” according to the technical report accompanying the policy statement. Also, “new cases of STIs increased 31% in the United States from 2013 to 2017, with half of the 2.3 million new STIs reported each year among young people 15 to 24 years of age.”

Parents may need support and encouragement to talk with their children about sex, sexuality, and the use of barrier methods to prevent STIs. Dr. Grubb and colleagues recommend via the policy statement: “Actively communicate to parents and communities that making barrier methods available to adolescents does not increase the onset or frequency of adolescent sexual activity, and that use of barrier methods can help decrease rates of unintended pregnancy and acquisition of STIs.”

Use Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Fourth Edition, for guidance on supporting parents and adolescents in promoting healthy sexual development and sexuality, including discussions of barrier methods.

Some groups of adolescents may use barrier methods less consistently because they perceive themselves to be lower risk. These include adolescents who use preexposure prophylaxis or nonbarrier contraception, who identify as bisexual or lesbian, or who are in established relationships. Monitor these patients to assess their risk and need for additional counseling. In the technical report, studies are cited finding that barrier methods are used less consistently during oral sex and that condom use is lower among cisgender and transgender females, and among adolescents who self-identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, compared with other groups.

In the policy statement, Dr. Grubb and colleagues call on pediatricians to advocate for more research and better access to barrier methods, especially for higher-risk adolescents and those living in underserved areas. In particular, school education programs on barrier methods can reach large adolescent groups and provide a “comprehensive array of educational and health care resources.”

Katie Brigham, MD, a pediatrician at MassGeneral Hospital for Children in Boston, affirmed the recommendations in the new policy statement (which she did not help write or research). “Even though the pregnancy rate is dropping in the United States, STI rates are increasing, so it is vital that pediatricians and other providers of adolescents and young adults counsel all their patients, regardless of gender and sexual orientation, of the importance of barrier methods when having oral, vaginal, or anal sex,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Brigham praised the technical report, adding that she found no major weaknesses in its methodology. “For future research, it would be interesting to see if there are different rates of pregnancy and STIs in pediatric practices that provide condoms and other barrier methods free to their patients, compared to those that do not.”

No external funding sources were reported. Dr. Grubb and Dr. Brigham reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Grubb LK et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-007237.

For adolescent patients, routinely take a sexual history, discuss the use of barrier methods, and perform relevant examinations, screenings, and vaccinations, according to a new policy statement on barrier protection use from the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Adolescence.

The policy statement has been expanded to cover multiple types of sexual activity and methods of barrier protection. These include not only traditional condoms, but also internal condoms (available in the United States only by prescription) and dental dams (for use during oral sex) or a latex sheet. “Pediatricians and other clinicians are encouraged to provide barrier methods within their offices and support availability within their communities,” said Laura K. Grubb, MD, MPH, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston, who authored both the policy statement and the technical report.

Counsel adolescents that abstaining from sexual intercourse is the best way to prevent genital sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV infection, and unplanned pregnancy. Also encourage and support consistent, correct barrier method use – in addition to other reliable contraception, if patients are sexually active or are thinking about becoming sexually active – the policy statement notes. Emphasize that all partners share responsibility to prevent STIs and unplanned pregnancies. “Adolescents with intellectual and physical disabilities are an overlooked group when it comes to sexual behavior, but they have similar rates of sexual behaviors when compared with their peers without disabilities,” Dr. Grubb and colleagues emphasized in the policy statement.

This is key because Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017 data showed that in the United States, “456,000 adolescent and young women younger than 20 years became pregnant; 448,000 of those pregnancies were among 15- to 19-year-olds, and 7,400 were among those 14 years of age and younger,” according to the technical report accompanying the policy statement. Also, “new cases of STIs increased 31% in the United States from 2013 to 2017, with half of the 2.3 million new STIs reported each year among young people 15 to 24 years of age.”

Parents may need support and encouragement to talk with their children about sex, sexuality, and the use of barrier methods to prevent STIs. Dr. Grubb and colleagues recommend via the policy statement: “Actively communicate to parents and communities that making barrier methods available to adolescents does not increase the onset or frequency of adolescent sexual activity, and that use of barrier methods can help decrease rates of unintended pregnancy and acquisition of STIs.”

Use Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Fourth Edition, for guidance on supporting parents and adolescents in promoting healthy sexual development and sexuality, including discussions of barrier methods.

Some groups of adolescents may use barrier methods less consistently because they perceive themselves to be lower risk. These include adolescents who use preexposure prophylaxis or nonbarrier contraception, who identify as bisexual or lesbian, or who are in established relationships. Monitor these patients to assess their risk and need for additional counseling. In the technical report, studies are cited finding that barrier methods are used less consistently during oral sex and that condom use is lower among cisgender and transgender females, and among adolescents who self-identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, compared with other groups.

In the policy statement, Dr. Grubb and colleagues call on pediatricians to advocate for more research and better access to barrier methods, especially for higher-risk adolescents and those living in underserved areas. In particular, school education programs on barrier methods can reach large adolescent groups and provide a “comprehensive array of educational and health care resources.”

Katie Brigham, MD, a pediatrician at MassGeneral Hospital for Children in Boston, affirmed the recommendations in the new policy statement (which she did not help write or research). “Even though the pregnancy rate is dropping in the United States, STI rates are increasing, so it is vital that pediatricians and other providers of adolescents and young adults counsel all their patients, regardless of gender and sexual orientation, of the importance of barrier methods when having oral, vaginal, or anal sex,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Brigham praised the technical report, adding that she found no major weaknesses in its methodology. “For future research, it would be interesting to see if there are different rates of pregnancy and STIs in pediatric practices that provide condoms and other barrier methods free to their patients, compared to those that do not.”

No external funding sources were reported. Dr. Grubb and Dr. Brigham reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Grubb LK et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-007237.

For adolescent patients, routinely take a sexual history, discuss the use of barrier methods, and perform relevant examinations, screenings, and vaccinations, according to a new policy statement on barrier protection use from the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Adolescence.

The policy statement has been expanded to cover multiple types of sexual activity and methods of barrier protection. These include not only traditional condoms, but also internal condoms (available in the United States only by prescription) and dental dams (for use during oral sex) or a latex sheet. “Pediatricians and other clinicians are encouraged to provide barrier methods within their offices and support availability within their communities,” said Laura K. Grubb, MD, MPH, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston, who authored both the policy statement and the technical report.

Counsel adolescents that abstaining from sexual intercourse is the best way to prevent genital sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV infection, and unplanned pregnancy. Also encourage and support consistent, correct barrier method use – in addition to other reliable contraception, if patients are sexually active or are thinking about becoming sexually active – the policy statement notes. Emphasize that all partners share responsibility to prevent STIs and unplanned pregnancies. “Adolescents with intellectual and physical disabilities are an overlooked group when it comes to sexual behavior, but they have similar rates of sexual behaviors when compared with their peers without disabilities,” Dr. Grubb and colleagues emphasized in the policy statement.

This is key because Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017 data showed that in the United States, “456,000 adolescent and young women younger than 20 years became pregnant; 448,000 of those pregnancies were among 15- to 19-year-olds, and 7,400 were among those 14 years of age and younger,” according to the technical report accompanying the policy statement. Also, “new cases of STIs increased 31% in the United States from 2013 to 2017, with half of the 2.3 million new STIs reported each year among young people 15 to 24 years of age.”

Parents may need support and encouragement to talk with their children about sex, sexuality, and the use of barrier methods to prevent STIs. Dr. Grubb and colleagues recommend via the policy statement: “Actively communicate to parents and communities that making barrier methods available to adolescents does not increase the onset or frequency of adolescent sexual activity, and that use of barrier methods can help decrease rates of unintended pregnancy and acquisition of STIs.”

Use Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Fourth Edition, for guidance on supporting parents and adolescents in promoting healthy sexual development and sexuality, including discussions of barrier methods.

Some groups of adolescents may use barrier methods less consistently because they perceive themselves to be lower risk. These include adolescents who use preexposure prophylaxis or nonbarrier contraception, who identify as bisexual or lesbian, or who are in established relationships. Monitor these patients to assess their risk and need for additional counseling. In the technical report, studies are cited finding that barrier methods are used less consistently during oral sex and that condom use is lower among cisgender and transgender females, and among adolescents who self-identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, compared with other groups.

In the policy statement, Dr. Grubb and colleagues call on pediatricians to advocate for more research and better access to barrier methods, especially for higher-risk adolescents and those living in underserved areas. In particular, school education programs on barrier methods can reach large adolescent groups and provide a “comprehensive array of educational and health care resources.”

Katie Brigham, MD, a pediatrician at MassGeneral Hospital for Children in Boston, affirmed the recommendations in the new policy statement (which she did not help write or research). “Even though the pregnancy rate is dropping in the United States, STI rates are increasing, so it is vital that pediatricians and other providers of adolescents and young adults counsel all their patients, regardless of gender and sexual orientation, of the importance of barrier methods when having oral, vaginal, or anal sex,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Brigham praised the technical report, adding that she found no major weaknesses in its methodology. “For future research, it would be interesting to see if there are different rates of pregnancy and STIs in pediatric practices that provide condoms and other barrier methods free to their patients, compared to those that do not.”

No external funding sources were reported. Dr. Grubb and Dr. Brigham reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Grubb LK et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-007237.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Ignored by doctors, transgender people turn to DIY treatments

For the first 10 months of Christine’s gender transition, a progressive LGBT health clinic in Boston made getting on hormones easy. But after a year or so on estrogen and a testosterone-blocker, she found herself in financial trouble. She had just recently moved to the city, where she was unable to find a job, and her savings were starting to wear thin.

Finding employment as a transgender person, she says, was overwhelmingly difficult: “I was turned down for more jobs than I can count — 20 or 40 different positions in a couple of months.” She would land an interview, then wouldn’t hear back, she says, which she suspects happened because the company noticed she was “not like their other potential hires.”

Christine, a transgender woman, had been enrolled in the state’s Medicaid program, MassHealth, for four months, and her copay for hormone therapy was only $5. But without a job, she found herself torn between food, rent, and medication. For a while, she juggled all three expenses with donations from friends. But after several months, she felt guilty about asking for help and stopped treatment. (Undark has agreed to use only Christine's chosen name because she said she feared both online and in-person harassment for sharing her story.)

At first, Christine didn’t mind being off hormones. She marched in political protests alongside older trans people who assured her that starting and stopping hormones was a normal part of the trans experience. But eventually, Christine felt her body reverting back to the way it had been before her transition; her chest flattened and her fat moved from her hips to her stomach. She stopped wearing dresses and makeup.

“I wasn't looking at myself in the mirror anymore,” she says. “I existed for 10 months, and then I was gone.”

People who are visibly transgender often have trouble finding a job. Nearly a third live in poverty. Many don’t have health insurance, and those who do may have a plan that doesn’t cover hormones. Although testosterone and estrogen only cost $5 to $30 a month for patients with an insurance plan (and typically less than $100 per month for the uninsured), doctors often require consistent therapy and blood work, which ratchets up the cost. Even when trans people have the money, finding doctors willing to treat them can prove impossible. Trans people are also likely to have had bad experiences with the health care system and want to avoid it altogether.

Without access to quality medical care, trans people around the world are seeking hormones from friends or through illegal online markets, even when the cost exceeds what it would through insurance. Although rare, others are resorting to self-surgery by cutting off their own penis and testicles or breasts.

Even with a doctor’s oversight, the health risks of transgender hormone therapy remain unclear, but without formal medical care, the do-it-yourself transition may be downright dangerous. To minimize these risks, some experts suggest health care reforms such as making it easier for primary care physicians to assess trans patients and prescribe hormones or creating specialized clinics where doctors prescribe hormones on demand.

But those solutions aren’t available to most people who are seeking DIY treatments right now. Many doctors aren’t even aware that DIY transitioning exists, although the few experts who are following the community aren’t surprised. Self-treatment is “the reality for most trans people in the world,” says Ayden Scheim, an epidemiologist focusing on transgender health at Drexel University who is trans himself.

After Christine posted about her frustrations on Facebook, a trans friend offered a connection to a store in China that illicitly ships hormones to the United States. Christine didn’t follow up, not wanting to take the legal risk. But as time ticked by and job opportunities came and went, her mind started to change.

“I'm ready to throw all of this away and reach out to anyone — any underground black-market means — of getting what I need,” she thought after moving to the Cape. “If these systems put in place to help me have failed me over and over again, why would I go back to them?”

Transgender is an umbrella term that refers to a person who identifies with a gender that doesn’t match the one they were assigned at birth. For example, someone who has male written on their birth certificate, but who identifies as a woman, is a transgender woman. Many trans people experience distress over how their bodies relate to their gender identity, called gender dysphoria. But gender identity is deeply personal. A five o’clock shadow can spur an intense reaction in some trans women, for instance, while others may be fine with it.

To treat gender dysphoria, some trans people take sex hormones, spurring a sort of second puberty. Trans women — as well as people like Christine, who also identifies as nonbinary, meaning she doesn’t exclusively identify as being either a man or a woman — usually take estrogen with the testosterone-blocker spironolactone. Estrogen comes as a daily pill, by injection, or as a patch (recommended for women above the age of 40). The medications redistribute body fat, spur breast growth, decrease muscle mass, slow body hair growth, and shrink the testicles.

Transgender men and non-binary people who want to appear more traditionally masculine use testosterone, usually in the form of injections, which can be taken weekly, biweekly, or every three months depending on the medication. Others use a daily cream, gel, or patch applied to the skin. Testosterone therapy can redistribute body fat, increase strength, boost body hair growth, deepen the voice, stop menstruation, increase libido, and make the clitoris larger.

Some family members — especially those who are cisgender, which means their gender identity matches what they were assigned at birth — worry that people who are confused about their gender will begin hormones and accumulate permanent bodily changes before they realize they’re actually cisgender.

But many of the changes from taking hormones are reversible, and regret appears to be uncommon. Out of a group of nearly 3,400 trans people in the United Kingdom, only 16 regretted their gender transition, according to research presented at the 2019 biennial conference of the European Professional Association for Transgender Health. And although research on surgical transition is sparse, there are some hints that those who choose it are ultimately happy with the decision. According to a small 2018 study in Istanbul, post-operative trans people report a higher quality of life and fewer concerns about gender discrimination compared to those with dysphoria who haven’t had surgery.

And for trans people with dysphoria, hormones can be medically necessary. The treatments aren’t just cosmetic — transitioning literally saves lives, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. In a 2019 review paper, researchers from the University of San Francisco found that hormone therapy is also linked to a higher quality of life and reduced anxiety and depression.

Despite the growing evidence that medical intervention can help, some trans people are wary of the health care system. According to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, a third of trans people who saw a health care provider experienced mistreatment — from having to educate their doctor about transgender issues to being refused medical treatment to verbal abuse — and 23 percent avoided the doctor’s office because they feared mistreatment.

The health care system has a history of stigmatizing trans identity. Until recently, the World Health Organization and the American Psychiatric Association even considered it a mental disorder. And according to a 2015 study from researchers at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Medical Education Research Group at the Stanford University School of Medicine, less than 35 percent of medical schools teach coursework related to transgender hormone therapy and surgery.

On June 12, the administration of President Donald J. Trump finalized a rule removing protections that had been put in place in 2016 to bar discrimination against transgender people by health care providers. Just three days later, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the 1964 law that bans discrimination in the workplace based on sex, race, national origin, and religion also applies to sexual orientation and gender identity. While not directly touching on the new health care rule, some experts think the Supreme Court's decision may make legal challenges to it more likely to succeed.

Trans-friendly health care providers are rare, and booking an appointment can stretch out over many weeks. In England, for example, the average wait time from the referral to the first appointment is 18 months, according to an investigation by the BBC. Even those with hormone prescriptions face hurdles to get them filled. Scheim, who lived in Canada until recently, knows this firsthand. “As someone who just moved to the U.S., I’m keenly aware of the hoops one has to jump through,” he says.

“Even if it's theoretically possible to get a hormone prescription, and get it filled, and get it paid for, at a certain point people are going to want to go outside the system,” Scheim says. Navigating bureaucracy, being incorrectly identified — or misgendered — and facing outright transphobia from health care providers, he adds, “can just become too much for folks.”

Many of the health care barriers trans people face are amplified when it comes to surgery. Bottom surgery for trans feminine people, for example, costs about $25,000 and isn’t covered by most insurance plans in the U.S.

There are some signs that at least parts of the medical community have been rethinking their stance on transgender patients. “Clearly the medical professionals didn’t do the right thing. But things are changing now,” says Antonio Metastasio, a psychiatrist at the Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust in the U.K.

The Association of American Medical Colleges, for example, released their first curriculum guidelines for treating LGBT patients in 2014. In 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a policy statement on transgender youth, encouraging gender-affirming models of treatment. And in 2019, the American College of Physicians released guidelines for primary care physicians on serving transgender patients.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) — the international authority on transgender health care, according to a summary of clinical evidence on gender reassignment surgery prepared for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services — has also changed its Standards of Care to make access to hormones easier. Previously, WPATH recommended that before a person could receive hormone treatment, they had to have “persistent, well-documented gender dysphoria,” as well as documented, real-life experiences covering at least three months. The newest guidelines, published in 2012, nix these stringent requirements, although they still strongly recommend mental health evaluations before allowing trans people to access gender-affirming medical care and require a referral letter from a mental health professional.

But the shift hasn’t stopped trans people from seeking DIY treatments.

Before Christine moved to Cape Cod, she secured about two weeks of estrogen from a trans friend. But she soon decided to end the DIY treatment and went off hormones for good. “I can only accept help for something like that for so long before I start to feel bad about it,” she says. “At that point, it was just like I gave up.”

But she didn’t give up for long. After the move, Christine tried to get back on hormones through a legitimate health care provider. First, she considered visiting a Planned Parenthood, but the closest one she could find was at least two hours away and she worried her old car couldn’t make the journey. Then she visited a local women’s health clinic. But she says they turned her away, refused to recognize her gender, and wouldn’t direct her to another provider or clinic. Instead of advice, Christine says, “I got ‘no, goodbye.’”

Left with few options and not wanting to take the risks of further DIY treatment, Christine accepted that she would be off hormones for the foreseeable future.

Many trans folks, however, start or extend their hormone use by turning to drugs that aren’t meant for transitioning, like birth control pills. Others buy hormones online, skirting the law to order from overseas pharmacies without a prescription. To figure out how best to take the drugs, people determine dosages from research online — they read academic literature, technical standards written for health care providers, or advice in blog posts and public forums like Reddit.

Then, they medicate themselves.

Metastasio is one of the few scientists who have studied the practice. He learned about it in 2014, when one of his transgender patients admitted they were taking non-prescribed hormones. Metastasio asked his colleagues if they’d heard similar stories, but none had. So he started asking all his trans patients about DIY hormones and tracked those who were involved in the practice, ultimately publishing a report of seven case studies in 2018.

While there isn’t a lot of other existing research on DIY hormone treatment, and some of it may be outdated, the available studies suggest it is fairly common and researchers may in fact be underestimating the prevalence of DIY hormone use because they miss people who avoid the medical system completely. In 2014, researchers in the U.K. found that at the time of their first gender clinic visit, 17 percent of transgender people were already taking hormones that they had bought online or from a friend. In Canada, a quarter of trans people on hormones had self-medicated, according to a 2013 study in the American Journal of Public Health. And in a survey of trans people in Washington, D.C. in 2000, 58 percent said they used non-prescribed hormones.

People cite all sorts of reasons for ordering the drugs online or acquiring them by other means. In addition to distrust of doctors and a lack of insurance or access to health care, some simply don’t want to endure long waits for medications. That’s the case for Emma, a trans woman in college in the Netherlands, where it can take two to three years to receive a physician prescription. (Emma is only using her first name to avoid online harassment, which she says she’s experienced in the past.)

As for surgery, far fewer people turn to DIY versions compared to those who try hormones. A 2012 study in the Journal of Sexual Medicine reported that only 109 cases of self-castration or self-mutilation of the genitals appear in the scientific literature, and not all are related to gender identity. “But one is too many,” Scheim says. “No one should be in a position where they feel like they need to do that.”

The individual cases reveal a practice that is dangerous and devastating. In Hangzhou, China, a 30-year-old transgender woman feared rejection from her family, so she hid her true gender, according to a 2019 Amnesty International report. She also tried to transition in secret. At first, the woman tried putting ice on her genitals to stop them from functioning. When that didn’t work, she booked an appointment with a black-market surgeon, but the doctor was arrested before her session. She attempted surgery on herself, the report says, and after losing a profuse amount of blood, hailed a taxi to the emergency room. There, she asked the doctor to tell her family she had been in an accident.

When it comes to self-surgery, the dangers of DIY transitioning are obvious. The dangers of DIY hormones are more far-ranging, from “not ideal to serious,” Scheim says. Some DIY users take a more-is-better approach, but taking too much testosterone too quickly can fry the vocal cords. Even buying hormones from an online pharmacy is risky. In 2010, more than half of all treatments from illicit websites — not only of hormones, but of any drug — were counterfeit, according to a bulletin from the World Health Organization.

Still, Charley isn’t worried about the legitimacy of the drugs he’s taking. The packaging his estrogen comes in matches what he would get from a pharmacy with a doctor’s prescription, he says. He’s also unconcerned about the side effects. “I just did a metric century” — a 100-kilometer bike ride — “in under four hours and walked away from it feeling great. I’m healthy,” he says. “So, yeah, there might be a few side effects. But I know where the local hospital is.”

Yet waiting to see if a seemingly minor side effect leads to a health emergency may mean a patient gets help too late. “I don’t want to say that the risks are incredibly high and there is a high mortality,” Metastasio says. “I am saying, though, that this is a procedure best to be monitored.” Metastasio and others recommend seeing a doctor regularly to catch any health issues that arise as quickly as possible.

But even when doctors prescribe the drugs, the risks are unclear because of a lack of research on trans health, says Scheim: “There’s so much we don’t know about hormone use.”

Researchers do know a little bit, though. Even when a doctor weighs in on the proper dosages, there is an increased risk of heart attack. Taking testosterone increases the chances of developing acne, headaches and migraines, and anger and irritability, according to the Trans Care Project, a program of the Transcend Transgender Support and Education Society and Vancouver Coastal Health’s Transgender Health Program in Canada. Testosterone also increases the risk of having abnormally high levels of red blood cells, or polycythemia, which thickens the blood and can lead to clotting. Meanwhile, studies suggest estrogen can up the risk for breast cancer, stroke, blood clots, gallstones, and a range of heart issues. And the most common testosterone-blocker, spironolactone, can cause dehydration and weaken the kidneys.

All of these risks make it especially important for trans people to have the support of a medical provider, Metastasio says. Specialists are in short supply, but general practitioners and family doctors should be able to fill the gap. After all, they already sign off on the hormone medications for cisgender people for birth control and conditions such as menopause and male pattern baldness — which come with similar side effects and warnings as when trans people use them.

Some doctors have already realized the connection. “People can increasingly get hormone therapy from their pre-existing family doctor,” Scheim says, “which is really ideal because people should be able to have a sort of continuity of health care.”

Zil Goldstein, associate medical director for transgender and gender non-binary health at the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in New York City, would like to see more of this. Treating gender dysphoria, she says, should be just like treating a patient for any other condition. “It wouldn't be acceptable for someone to come into a primary care provider’s office with diabetes” and for the doctor to say “‘I can't actually treat you. Please leave,’” she says. Primary care providers need to see transgender care, she adds, “as a regular part of their practice.”

Another way to increase access to hormones is through informed consent, a system which received a green light from the newest WPATH guidelines. That’s how Christine received her hormones from Fenway Health before she moved from Boston to Cape Cod. Under informed consent, if someone has a blood test to assess personal health risks of treatment, they can receive a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, sign off on knowing the risks and benefits of hormone therapy, and get a prescription — all in one day.

And Jaime Lynn Gilmour, a trans woman using the full name she chose to match her gender identity, turned to informed consent after struggling to find DIY hormones. In 2017, Jaime realized she was trans while serving in the military, and says she felt she had to keep her gender a secret. When her service ended, she was ready to start taking hormones right away. So she tried to find them online, but her order wouldn’t go through on three different websites. Instead, she visited a Planned Parenthood clinic. After blood work and a few questions, she walked out with three months of estrogen and spironolactone.

But Goldstein says even informed consent doesn’t go far enough: “If I have someone who's diabetic, I don't make them sign a document eliciting their informed consent before starting insulin.”

For trans people, hormone treatments “are life-saving therapies,” Goldstein adds, “and we shouldn’t delay or stigmatize.”

For now Christine still lives with her parents in Cape Cod. She’s also still off hormones. But she found a job. After she stashes a bit more cash in the bank, she plans to move closer to Boston and find a physician.

Despite the positive shifts in her life, it’s been a difficult few months. After moving to Cape Cod, Christine lost most of her social life and support system — particularly since her parents don’t understand or accept her gender identity. Though she has reconnected with a few friends in the past several weeks, she says she’s in a tough place emotionally. In public, she typically dresses and styles herself to look more masculine to avoid rude stares, and she is experiencing self-hatred that she fears won’t go away when she restarts treatment. Transitioning again isn’t going to be easy, as she explained to Undark in a private message on Facebook: “I've been beaten down enough that now I don't wanna get back up most of the time.”

Even worse is the fear that she might not be able to restart treatment at all. Earlier this year, Christine suffered two health emergencies within the span of a week, in which she says her blood pressure spiked, potentially causing organ damage. Christine has had one similar episode in the past and her family has a history of heart issues.

Christine may not be able to get back on estrogen despite the hard work she’s done to be able to afford it, she says, since it can increase the risk of heart attack and stroke. Because she has so far resisted trying DIY treatments again, she may have saved herself from additional health problems.

But Christine doesn’t see it that way. “Even if it was unsafe, even if I risked health concerns making myself a guinea pig, I wish I followed through,” she wrote. “Being off hormones is hell. And now that I face potentially never taking them again, I wish I had.”

Tara Santora is a science journalist based out of Denver. They have written for Psychology Today, Live Science, Fatherly, Audubon, and more.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.