User login

Cachexia affects more than half of lupus patients

Cachexia developed in 56% of adults with systemic lupus erythematosus over a 5-year period, and 18% did not recover their weight, based on data from more than 2,000 patients.

Although weight loss is common in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), cachexia, a disorder of involuntary weight loss, is largely undescribed in SLE patients, wrote George Stojan, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues. Cachexia has been described in a range of disorders, including heart failure, renal disease, and rheumatoid arthritis, they said. “Cachexia has been shown to lead to progressive functional impairment, treatment-related complications, poor quality of life, and increased mortality,” they added.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, consisting of all SLE patients seen at a single center who are followed at least quarterly.

The study population included 2,452 SLE patients older than 18 years who had their weight assessed at each clinic visit. The average follow-up period was 7.75 years, and the average number of weight measurements per patient was nearly 24.

Cachexia was defined as a 5% stable weight loss in 6 months without starvation relative to the average weight in all prior cohort visits; and/or weight loss of more than 2% without starvation relative to the average weight in all prior cohort visits in addition to a body mass index less than 20 kg/m2.

Overall, the risk for cachexia within 5 years of entering the study was significantly higher in patients with a BMI less than 20, current steroid use, vasculitis, lupus nephritis, serositis, hematologic lupus, positive anti-double strand DNA (anti-dsDNA), anti-Smith (anti-Sm), and antiribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP), the researchers noted. After adjustment for prednisone use, cachexia remained significantly associated with lupus nephritis, vasculitis, serositis, and hematologic lupus.

Future organ damage including cataracts, retinal change or optic atrophy, cognitive impairment, cerebrovascular accidents, cranial or peripheral neuropathy, pulmonary hypertension, pleural fibrosis, angina or coronary bypass, bowel infarction or resection, osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, and premature gonadal failure were significantly more likely among patients with intermittent cachexia, compared with those with continuous or no cachexia. Patients with continuous cachexia were significantly more likely to experience an estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 50 mL/min/1.73 m2, proteinuria greater than 3.5 g/day, and end-stage renal disease.

The patients who never developed cachexia were significantly less likely to develop malignancies, diabetes, valvular disease, or cardiomyopathy than were those who did have cachexia, the researchers said.

The mechanisms of action for cachexia in SLE remain unclear, but studies in cancer patients may provide some guidance, the researchers noted. “Tumors secrete a range of procachexia factors thought to be unique to cancer-related cachexia, and colloquially termed the ‘tumor secretome,’ ” they said. “Every single proinflammatory cytokine mentioned as part of the tumor secretome has a role in lupus pathogenesis,” suggesting a possible common pathway to cachexia across different diseases, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, mainly the use of BMI to measure weight “since BMI is a rather poor indicator of percent of body fat,” the researchers noted. “Ideally, cachexia would be defined as sarcopenia based on body composition evaluation with a dual x-ray absorptiometry,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Stojan G et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Aug 2. doi: 10.1002/acr.24395.

Cachexia developed in 56% of adults with systemic lupus erythematosus over a 5-year period, and 18% did not recover their weight, based on data from more than 2,000 patients.

Although weight loss is common in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), cachexia, a disorder of involuntary weight loss, is largely undescribed in SLE patients, wrote George Stojan, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues. Cachexia has been described in a range of disorders, including heart failure, renal disease, and rheumatoid arthritis, they said. “Cachexia has been shown to lead to progressive functional impairment, treatment-related complications, poor quality of life, and increased mortality,” they added.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, consisting of all SLE patients seen at a single center who are followed at least quarterly.

The study population included 2,452 SLE patients older than 18 years who had their weight assessed at each clinic visit. The average follow-up period was 7.75 years, and the average number of weight measurements per patient was nearly 24.

Cachexia was defined as a 5% stable weight loss in 6 months without starvation relative to the average weight in all prior cohort visits; and/or weight loss of more than 2% without starvation relative to the average weight in all prior cohort visits in addition to a body mass index less than 20 kg/m2.

Overall, the risk for cachexia within 5 years of entering the study was significantly higher in patients with a BMI less than 20, current steroid use, vasculitis, lupus nephritis, serositis, hematologic lupus, positive anti-double strand DNA (anti-dsDNA), anti-Smith (anti-Sm), and antiribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP), the researchers noted. After adjustment for prednisone use, cachexia remained significantly associated with lupus nephritis, vasculitis, serositis, and hematologic lupus.

Future organ damage including cataracts, retinal change or optic atrophy, cognitive impairment, cerebrovascular accidents, cranial or peripheral neuropathy, pulmonary hypertension, pleural fibrosis, angina or coronary bypass, bowel infarction or resection, osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, and premature gonadal failure were significantly more likely among patients with intermittent cachexia, compared with those with continuous or no cachexia. Patients with continuous cachexia were significantly more likely to experience an estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 50 mL/min/1.73 m2, proteinuria greater than 3.5 g/day, and end-stage renal disease.

The patients who never developed cachexia were significantly less likely to develop malignancies, diabetes, valvular disease, or cardiomyopathy than were those who did have cachexia, the researchers said.

The mechanisms of action for cachexia in SLE remain unclear, but studies in cancer patients may provide some guidance, the researchers noted. “Tumors secrete a range of procachexia factors thought to be unique to cancer-related cachexia, and colloquially termed the ‘tumor secretome,’ ” they said. “Every single proinflammatory cytokine mentioned as part of the tumor secretome has a role in lupus pathogenesis,” suggesting a possible common pathway to cachexia across different diseases, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, mainly the use of BMI to measure weight “since BMI is a rather poor indicator of percent of body fat,” the researchers noted. “Ideally, cachexia would be defined as sarcopenia based on body composition evaluation with a dual x-ray absorptiometry,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Stojan G et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Aug 2. doi: 10.1002/acr.24395.

Cachexia developed in 56% of adults with systemic lupus erythematosus over a 5-year period, and 18% did not recover their weight, based on data from more than 2,000 patients.

Although weight loss is common in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), cachexia, a disorder of involuntary weight loss, is largely undescribed in SLE patients, wrote George Stojan, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues. Cachexia has been described in a range of disorders, including heart failure, renal disease, and rheumatoid arthritis, they said. “Cachexia has been shown to lead to progressive functional impairment, treatment-related complications, poor quality of life, and increased mortality,” they added.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, consisting of all SLE patients seen at a single center who are followed at least quarterly.

The study population included 2,452 SLE patients older than 18 years who had their weight assessed at each clinic visit. The average follow-up period was 7.75 years, and the average number of weight measurements per patient was nearly 24.

Cachexia was defined as a 5% stable weight loss in 6 months without starvation relative to the average weight in all prior cohort visits; and/or weight loss of more than 2% without starvation relative to the average weight in all prior cohort visits in addition to a body mass index less than 20 kg/m2.

Overall, the risk for cachexia within 5 years of entering the study was significantly higher in patients with a BMI less than 20, current steroid use, vasculitis, lupus nephritis, serositis, hematologic lupus, positive anti-double strand DNA (anti-dsDNA), anti-Smith (anti-Sm), and antiribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP), the researchers noted. After adjustment for prednisone use, cachexia remained significantly associated with lupus nephritis, vasculitis, serositis, and hematologic lupus.

Future organ damage including cataracts, retinal change or optic atrophy, cognitive impairment, cerebrovascular accidents, cranial or peripheral neuropathy, pulmonary hypertension, pleural fibrosis, angina or coronary bypass, bowel infarction or resection, osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, and premature gonadal failure were significantly more likely among patients with intermittent cachexia, compared with those with continuous or no cachexia. Patients with continuous cachexia were significantly more likely to experience an estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 50 mL/min/1.73 m2, proteinuria greater than 3.5 g/day, and end-stage renal disease.

The patients who never developed cachexia were significantly less likely to develop malignancies, diabetes, valvular disease, or cardiomyopathy than were those who did have cachexia, the researchers said.

The mechanisms of action for cachexia in SLE remain unclear, but studies in cancer patients may provide some guidance, the researchers noted. “Tumors secrete a range of procachexia factors thought to be unique to cancer-related cachexia, and colloquially termed the ‘tumor secretome,’ ” they said. “Every single proinflammatory cytokine mentioned as part of the tumor secretome has a role in lupus pathogenesis,” suggesting a possible common pathway to cachexia across different diseases, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, mainly the use of BMI to measure weight “since BMI is a rather poor indicator of percent of body fat,” the researchers noted. “Ideally, cachexia would be defined as sarcopenia based on body composition evaluation with a dual x-ray absorptiometry,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Stojan G et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Aug 2. doi: 10.1002/acr.24395.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Shielding ‘had little effect on rates of COVID-19 in rheumatology patients’

Researchers from the Royal Wolverhampton (England) Hospitals National Health Service Trust say shielding – or taking extra steps to protect oneself against COVID-19 if at high risk – has had little effect on the incidence of COVID-19 in rheumatology patients.

In Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, the team present data from a large rheumatology cohort in the United Kingdom between Feb. 1, 2020, and May 1, 2020. Patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed on April 24, 2020, using the Short Form–12 to assess Physical Component Score (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS) on a 0-100 scale (0 being the lowest score).

Of 1,693 participants, at the time, there were 61 (3.6%) reported COVID-19 infections (eight had confirmatory swab results; three had clinical diagnoses with “false-negative” swab; 50 had clinical diagnosis but were not swabbed in line with U.K. policy at that time).

Seven of the 61 (11.5%) patients were hospitalized, two requiring intensive care. Of this group, 24 were shielding, a similar proportion to the non-COVID cohort (24/61 vs. 768/1,632; P = .24). There was no significant effect of treatment on self-reported COVID-19 incidence.

There were significantly lower MCSs in the infected group, compared with control participants (38.9 vs. 42.2; mean difference: −3.3; 95% CI, −5.2 to 1.4; P < .001). There was no difference in PCS (−0.4; 95% CI, −2.1 to 1.3).

In patients without COVID-19, the ‘shielding’ group had significantly lower MCS (−2.1; 95% CI, −2.9 to 1.4; P < .001) and PCS (−2.2; 95% CI, −3.8 to 2.5; P < .001) than those not shielding.

There were no differences in MCSs between patients on non–biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic DMARDs (0.6; 95% CI, 0.1-2.4).

The findings suggest that overall strict social isolation had little effect on the incidence of COVID-19 infection. Patients who had suffered from the virus had reduced mental but not physical HRQoL scores.

There was an adverse effect on both MCS and PCS reported by patients undergoing shielding,n compared with those not. This has also been shown in previous work from India.

This article originally appeared on Univadis, part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Researchers from the Royal Wolverhampton (England) Hospitals National Health Service Trust say shielding – or taking extra steps to protect oneself against COVID-19 if at high risk – has had little effect on the incidence of COVID-19 in rheumatology patients.

In Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, the team present data from a large rheumatology cohort in the United Kingdom between Feb. 1, 2020, and May 1, 2020. Patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed on April 24, 2020, using the Short Form–12 to assess Physical Component Score (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS) on a 0-100 scale (0 being the lowest score).

Of 1,693 participants, at the time, there were 61 (3.6%) reported COVID-19 infections (eight had confirmatory swab results; three had clinical diagnoses with “false-negative” swab; 50 had clinical diagnosis but were not swabbed in line with U.K. policy at that time).

Seven of the 61 (11.5%) patients were hospitalized, two requiring intensive care. Of this group, 24 were shielding, a similar proportion to the non-COVID cohort (24/61 vs. 768/1,632; P = .24). There was no significant effect of treatment on self-reported COVID-19 incidence.

There were significantly lower MCSs in the infected group, compared with control participants (38.9 vs. 42.2; mean difference: −3.3; 95% CI, −5.2 to 1.4; P < .001). There was no difference in PCS (−0.4; 95% CI, −2.1 to 1.3).

In patients without COVID-19, the ‘shielding’ group had significantly lower MCS (−2.1; 95% CI, −2.9 to 1.4; P < .001) and PCS (−2.2; 95% CI, −3.8 to 2.5; P < .001) than those not shielding.

There were no differences in MCSs between patients on non–biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic DMARDs (0.6; 95% CI, 0.1-2.4).

The findings suggest that overall strict social isolation had little effect on the incidence of COVID-19 infection. Patients who had suffered from the virus had reduced mental but not physical HRQoL scores.

There was an adverse effect on both MCS and PCS reported by patients undergoing shielding,n compared with those not. This has also been shown in previous work from India.

This article originally appeared on Univadis, part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Researchers from the Royal Wolverhampton (England) Hospitals National Health Service Trust say shielding – or taking extra steps to protect oneself against COVID-19 if at high risk – has had little effect on the incidence of COVID-19 in rheumatology patients.

In Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, the team present data from a large rheumatology cohort in the United Kingdom between Feb. 1, 2020, and May 1, 2020. Patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed on April 24, 2020, using the Short Form–12 to assess Physical Component Score (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS) on a 0-100 scale (0 being the lowest score).

Of 1,693 participants, at the time, there were 61 (3.6%) reported COVID-19 infections (eight had confirmatory swab results; three had clinical diagnoses with “false-negative” swab; 50 had clinical diagnosis but were not swabbed in line with U.K. policy at that time).

Seven of the 61 (11.5%) patients were hospitalized, two requiring intensive care. Of this group, 24 were shielding, a similar proportion to the non-COVID cohort (24/61 vs. 768/1,632; P = .24). There was no significant effect of treatment on self-reported COVID-19 incidence.

There were significantly lower MCSs in the infected group, compared with control participants (38.9 vs. 42.2; mean difference: −3.3; 95% CI, −5.2 to 1.4; P < .001). There was no difference in PCS (−0.4; 95% CI, −2.1 to 1.3).

In patients without COVID-19, the ‘shielding’ group had significantly lower MCS (−2.1; 95% CI, −2.9 to 1.4; P < .001) and PCS (−2.2; 95% CI, −3.8 to 2.5; P < .001) than those not shielding.

There were no differences in MCSs between patients on non–biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic DMARDs (0.6; 95% CI, 0.1-2.4).

The findings suggest that overall strict social isolation had little effect on the incidence of COVID-19 infection. Patients who had suffered from the virus had reduced mental but not physical HRQoL scores.

There was an adverse effect on both MCS and PCS reported by patients undergoing shielding,n compared with those not. This has also been shown in previous work from India.

This article originally appeared on Univadis, part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Rheumatologist Lindsey Criswell named new NIAMS director

.

Dr. Criswell, vice chancellor of research at the University of California, San Francisco, will replace acting director Robert H. Carter, MD, who has overseen NIAMS since December 2018, following the unexpected death of longtime director Stephen I. Katz, MD, PhD, who had directed the institute since 1995. She will start her new role in early 2021, according to the NIH.

“Dr. Criswell has rich experience as a clinician, researcher, and administrator. Her ability to oversee the research program of one of the country’s top research-intensive medical schools, and her expertise in autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, make her well-positioned to direct NIAMS,” said NIH director Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, said in an announcement.

Dr. Criswell, who holds the Kenneth H. Fye, M.D., endowed chair in rheumatology and the Jean S. Engleman Distinguished Professorship in Rheumatology at UCSF, spent most of her career at the university, focusing her research on the genetics and epidemiology of human autoimmune disease, particularly rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Using genome-wide association and other genetic studies, her research team contributed to the identification of more than 30 genes linked to these disorders, according to the NIH.

NIAMS has a budget of nearly $625 million and its extramural research program supports scientific studies and research training and career development throughout the country through grants and contracts to research organizations in fields that include rheumatology, muscle biology, orthopedics, bone and mineral metabolism, and dermatology.

.

Dr. Criswell, vice chancellor of research at the University of California, San Francisco, will replace acting director Robert H. Carter, MD, who has overseen NIAMS since December 2018, following the unexpected death of longtime director Stephen I. Katz, MD, PhD, who had directed the institute since 1995. She will start her new role in early 2021, according to the NIH.

“Dr. Criswell has rich experience as a clinician, researcher, and administrator. Her ability to oversee the research program of one of the country’s top research-intensive medical schools, and her expertise in autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, make her well-positioned to direct NIAMS,” said NIH director Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, said in an announcement.

Dr. Criswell, who holds the Kenneth H. Fye, M.D., endowed chair in rheumatology and the Jean S. Engleman Distinguished Professorship in Rheumatology at UCSF, spent most of her career at the university, focusing her research on the genetics and epidemiology of human autoimmune disease, particularly rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Using genome-wide association and other genetic studies, her research team contributed to the identification of more than 30 genes linked to these disorders, according to the NIH.

NIAMS has a budget of nearly $625 million and its extramural research program supports scientific studies and research training and career development throughout the country through grants and contracts to research organizations in fields that include rheumatology, muscle biology, orthopedics, bone and mineral metabolism, and dermatology.

.

Dr. Criswell, vice chancellor of research at the University of California, San Francisco, will replace acting director Robert H. Carter, MD, who has overseen NIAMS since December 2018, following the unexpected death of longtime director Stephen I. Katz, MD, PhD, who had directed the institute since 1995. She will start her new role in early 2021, according to the NIH.

“Dr. Criswell has rich experience as a clinician, researcher, and administrator. Her ability to oversee the research program of one of the country’s top research-intensive medical schools, and her expertise in autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, make her well-positioned to direct NIAMS,” said NIH director Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, said in an announcement.

Dr. Criswell, who holds the Kenneth H. Fye, M.D., endowed chair in rheumatology and the Jean S. Engleman Distinguished Professorship in Rheumatology at UCSF, spent most of her career at the university, focusing her research on the genetics and epidemiology of human autoimmune disease, particularly rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Using genome-wide association and other genetic studies, her research team contributed to the identification of more than 30 genes linked to these disorders, according to the NIH.

NIAMS has a budget of nearly $625 million and its extramural research program supports scientific studies and research training and career development throughout the country through grants and contracts to research organizations in fields that include rheumatology, muscle biology, orthopedics, bone and mineral metabolism, and dermatology.

All NSAIDs raise post-MI risk but some are safer than others: Next chapter

Patients on antithrombotics after an acute MI will face a greater risk for bleeding and secondary cardiovascular (CV) events if they start taking any nonaspirin NSAID, confirms a large observational study.

Like other research before it, the new study suggests those risks will be much lower for some nonaspirin NSAIDs than others. But it may also challenge at least some conventional thinking about the safety of these drugs, and is based solely on a large cohort in South Korea, a group for which such NSAID data has been in short supply.

“It was intriguing that our study presented better safety profiles with celecoxib and meloxicam versus other subtypes of NSAIDs,” noted the report, published online July 27 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Most of the NSAIDs included in the analysis, “including naproxen, conferred a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and bleeding events, compared with celecoxib and meloxicam,” wrote the authors, led by Dong Oh Kang, MD, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, South Korea.

A main contribution of the study “is the thorough and comprehensive evaluation of the Korean population by use of the nationwide prescription claims database that reflects real-world clinical practice,” senior author Cheol Ung Choi, MD, PhD, of the same institution, said in an interview.

“Because we included the largest number of patients of any comparable clinical studies on NSAID treatment after MI thus far, our study may allow the generalizability of the adverse events of NSAIDs to all patients by constituting global evidence encompassing different population groups,” Dr. Choi said.

The analysis has limitations along with its strengths, the authors acknowledged, including its observational design and potential for confounding not addressed in statistical adjustments.

Observers of the study concurred, but some cited evidence pointing to such confounding that is serious enough to question the entire study’s validity.

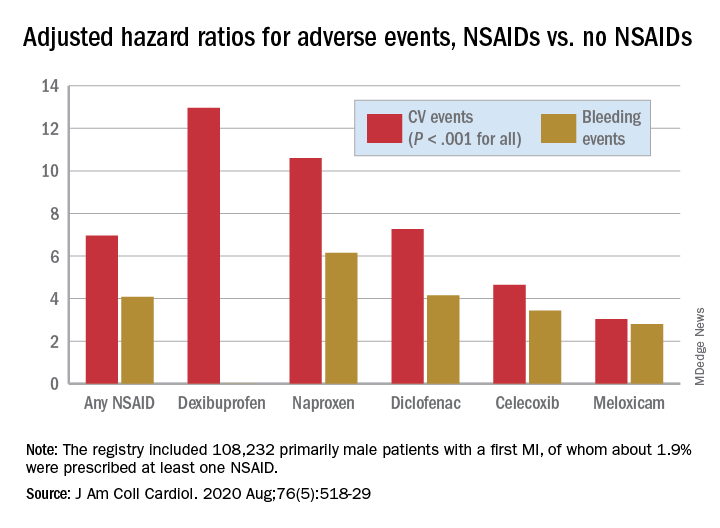

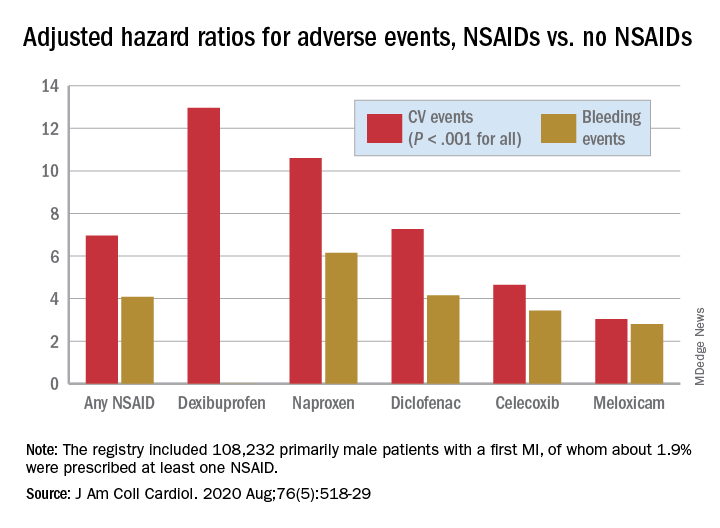

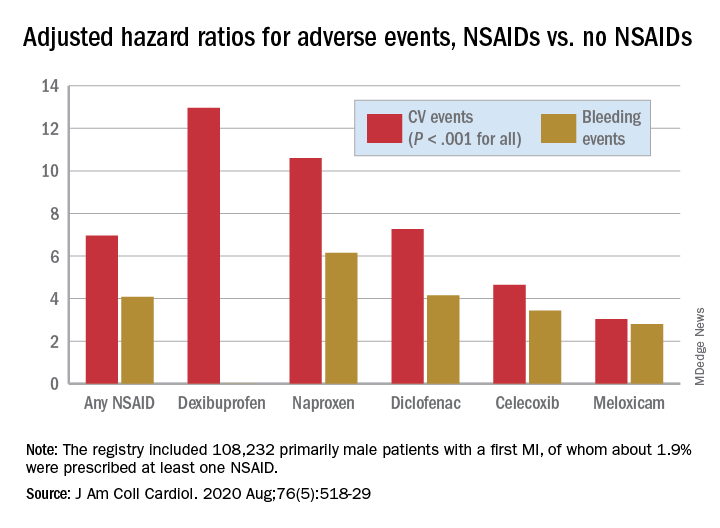

Among the cohort of more than 100,000 patients followed for an average of about 2.3 years after their MI, the adjusted risk of thromboembolic CV events went up almost 7 times for those who took any NSAID for at least 4 consecutive weeks, compared with those who didn’t take NSAIDs, based on prescription records.

Their adjusted risk of bleeding events – which included gastrointestinal, intracranial, respiratory, or urinary tract bleeding or posthemorrhagic anemia, the group writes – was increased 300%.

There was wide variance in the adjusted hazard ratios for outcomes by type of NSAID. The risk of CV events climbed from a low of about 3 with meloxicam and almost 5 for celecoxib to more than 10 and 12 for naproxen and dexibuprofen, respectively.

The hazard ratios for bleeding ranged from about 3 for both meloxicam and celecoxib to more than 6 for naproxen.

Of note, celecoxib and meloxicam both preferentially target the cyclooxygenase type 2 (COX-2) pathway, and naproxen among NSAIDs once had a reputation for relative cardiac safety, although subsequent studies have challenged that notion.

“On the basis of the contemporary guidelines, NSAID treatment should be limited as much as possible after MI; however, our data suggest that celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered possible alternative choices in patients with MI when NSAID prescription is unavoidable,” the group wrote.

They acknowledged some limitations of the analysis, including an observational design and the possibility of unidentified confounders; that mortality outcomes were not available from the National Health Insurance Service database used in the study; and that the 2009-2013 span for the data didn’t allow consideration of more contemporary antiplatelet agents and direct oral anticoagulants.

Also, NSAID use was based on prescriptions without regard to over-the-counter usage. Although use of over-the-counter NSAIDs is common in Korea, “most MI patients in Korea are prescribed most medications, including NSAIDs, in the hospital. So I think that usage of over-the-counter NSAIDs did not change the results,” Dr. Choi said.

“This study breaks new ground by demonstrating cardiovascular safety of meloxicam (and not only of celecoxib), probably because of its higher COX-2 selectivity,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Juan J. Badimon, PhD, and Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, both of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Notably, “this paper rejects the cardiovascular safety of naproxen, which had been suggested classically and in the previous Danish data, but that was not evident in this study.” The finding is consistent with the PRECISION trial, in which both bleeding and CV risk were increased with naproxen versus other NSAIDs, observed Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego.

They agreed with the authors in recommending that, “although NSAID treatment should be avoided in patients with MI, if the use of NSAIDs is inevitable due to comorbidities, the prescription of celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered as alternative options.”

But, “as no study is perfect, this article also presents some limitations,” the editorial agreed, citing some of the same issues noted by Dr. Kang and associates, along with potential confounding by indication and the lack of “clinical information to adjust (e.g., angiographic features, left ventricular function).”

“There’s undoubtedly residual confounding,” James M. Brophy, MD, PhD, a pharmacoepidemiologist at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview.

The 400%-900% relative risks for CV events “are just too far in left field, compared to everything else we know,” he said. “There has never been a class of drugs that have shown this sort of magnitude of effect for adverse events.”

Even in PRECISION with its more than 24,000 high-coronary-risk patients randomized and followed for 5 years, Dr. Brophy observed, relative risks for the different NSAIDs varied by an order of magnitude of only 1-2.

“You should be interpreting things in the context of what is already known,” Dr. Brophy said. “The only conclusion I would draw is the paper is fatally flawed.”

The registry included 108,232 primarily male patients followed from their first diagnosed MI for CV and bleeding events. About 1.9% were prescribed at least one NSAID for 4 or more consecutive weeks during the follow-up period averaging 2.3 years, the group reported.

The most frequently prescribed NSAID was diclofenac, at about 72% of prescribed NSAIDs in the analysis for CV events and about 69% in the bleeding-event analysis.

Adding any NSAID to post-MI antithrombotic therapy led to an adjusted HR of 6.96 (P < .001) for CV events and 4.08 (P < .001) for bleeding events, compared with no NSAID treatment.

The 88% of the cohort who were on dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel showed very nearly the same risk increases for both endpoints.

Further studies are needed to confirm the results “and ensure their generalizability to other populations,” Dr. Choi said. They should be validated especially using the claims data bases of countries near Korea, “such as Japan and Taiwan, to examine the reproducibility of the results in similar ethnic populations.”

That the study focused on a cohort in Korea is a strength, contended the authors as well as Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego, given “that most data about NSAIDs were extracted from Western populations, but the risk of thrombosis/bleeding post-MI varies according to ethnicity,” according to the editorial

Dr. Brophy agreed, but doubted that ethnic differences are responsible for variation in relative risks between the current results and other studies. “There are pharmacogenomic differences between different ethnicities as to how they activate these drugs. But I suspect that sort of difference is really minor. Maybe it leads to a 2% or a 5% difference in risks.”

Dr. Kang and associates, Dr. Badimon, Dr. Santos-Gallego, and Dr. Brophy disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients on antithrombotics after an acute MI will face a greater risk for bleeding and secondary cardiovascular (CV) events if they start taking any nonaspirin NSAID, confirms a large observational study.

Like other research before it, the new study suggests those risks will be much lower for some nonaspirin NSAIDs than others. But it may also challenge at least some conventional thinking about the safety of these drugs, and is based solely on a large cohort in South Korea, a group for which such NSAID data has been in short supply.

“It was intriguing that our study presented better safety profiles with celecoxib and meloxicam versus other subtypes of NSAIDs,” noted the report, published online July 27 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Most of the NSAIDs included in the analysis, “including naproxen, conferred a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and bleeding events, compared with celecoxib and meloxicam,” wrote the authors, led by Dong Oh Kang, MD, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, South Korea.

A main contribution of the study “is the thorough and comprehensive evaluation of the Korean population by use of the nationwide prescription claims database that reflects real-world clinical practice,” senior author Cheol Ung Choi, MD, PhD, of the same institution, said in an interview.

“Because we included the largest number of patients of any comparable clinical studies on NSAID treatment after MI thus far, our study may allow the generalizability of the adverse events of NSAIDs to all patients by constituting global evidence encompassing different population groups,” Dr. Choi said.

The analysis has limitations along with its strengths, the authors acknowledged, including its observational design and potential for confounding not addressed in statistical adjustments.

Observers of the study concurred, but some cited evidence pointing to such confounding that is serious enough to question the entire study’s validity.

Among the cohort of more than 100,000 patients followed for an average of about 2.3 years after their MI, the adjusted risk of thromboembolic CV events went up almost 7 times for those who took any NSAID for at least 4 consecutive weeks, compared with those who didn’t take NSAIDs, based on prescription records.

Their adjusted risk of bleeding events – which included gastrointestinal, intracranial, respiratory, or urinary tract bleeding or posthemorrhagic anemia, the group writes – was increased 300%.

There was wide variance in the adjusted hazard ratios for outcomes by type of NSAID. The risk of CV events climbed from a low of about 3 with meloxicam and almost 5 for celecoxib to more than 10 and 12 for naproxen and dexibuprofen, respectively.

The hazard ratios for bleeding ranged from about 3 for both meloxicam and celecoxib to more than 6 for naproxen.

Of note, celecoxib and meloxicam both preferentially target the cyclooxygenase type 2 (COX-2) pathway, and naproxen among NSAIDs once had a reputation for relative cardiac safety, although subsequent studies have challenged that notion.

“On the basis of the contemporary guidelines, NSAID treatment should be limited as much as possible after MI; however, our data suggest that celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered possible alternative choices in patients with MI when NSAID prescription is unavoidable,” the group wrote.

They acknowledged some limitations of the analysis, including an observational design and the possibility of unidentified confounders; that mortality outcomes were not available from the National Health Insurance Service database used in the study; and that the 2009-2013 span for the data didn’t allow consideration of more contemporary antiplatelet agents and direct oral anticoagulants.

Also, NSAID use was based on prescriptions without regard to over-the-counter usage. Although use of over-the-counter NSAIDs is common in Korea, “most MI patients in Korea are prescribed most medications, including NSAIDs, in the hospital. So I think that usage of over-the-counter NSAIDs did not change the results,” Dr. Choi said.

“This study breaks new ground by demonstrating cardiovascular safety of meloxicam (and not only of celecoxib), probably because of its higher COX-2 selectivity,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Juan J. Badimon, PhD, and Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, both of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Notably, “this paper rejects the cardiovascular safety of naproxen, which had been suggested classically and in the previous Danish data, but that was not evident in this study.” The finding is consistent with the PRECISION trial, in which both bleeding and CV risk were increased with naproxen versus other NSAIDs, observed Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego.

They agreed with the authors in recommending that, “although NSAID treatment should be avoided in patients with MI, if the use of NSAIDs is inevitable due to comorbidities, the prescription of celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered as alternative options.”

But, “as no study is perfect, this article also presents some limitations,” the editorial agreed, citing some of the same issues noted by Dr. Kang and associates, along with potential confounding by indication and the lack of “clinical information to adjust (e.g., angiographic features, left ventricular function).”

“There’s undoubtedly residual confounding,” James M. Brophy, MD, PhD, a pharmacoepidemiologist at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview.

The 400%-900% relative risks for CV events “are just too far in left field, compared to everything else we know,” he said. “There has never been a class of drugs that have shown this sort of magnitude of effect for adverse events.”

Even in PRECISION with its more than 24,000 high-coronary-risk patients randomized and followed for 5 years, Dr. Brophy observed, relative risks for the different NSAIDs varied by an order of magnitude of only 1-2.

“You should be interpreting things in the context of what is already known,” Dr. Brophy said. “The only conclusion I would draw is the paper is fatally flawed.”

The registry included 108,232 primarily male patients followed from their first diagnosed MI for CV and bleeding events. About 1.9% were prescribed at least one NSAID for 4 or more consecutive weeks during the follow-up period averaging 2.3 years, the group reported.

The most frequently prescribed NSAID was diclofenac, at about 72% of prescribed NSAIDs in the analysis for CV events and about 69% in the bleeding-event analysis.

Adding any NSAID to post-MI antithrombotic therapy led to an adjusted HR of 6.96 (P < .001) for CV events and 4.08 (P < .001) for bleeding events, compared with no NSAID treatment.

The 88% of the cohort who were on dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel showed very nearly the same risk increases for both endpoints.

Further studies are needed to confirm the results “and ensure their generalizability to other populations,” Dr. Choi said. They should be validated especially using the claims data bases of countries near Korea, “such as Japan and Taiwan, to examine the reproducibility of the results in similar ethnic populations.”

That the study focused on a cohort in Korea is a strength, contended the authors as well as Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego, given “that most data about NSAIDs were extracted from Western populations, but the risk of thrombosis/bleeding post-MI varies according to ethnicity,” according to the editorial

Dr. Brophy agreed, but doubted that ethnic differences are responsible for variation in relative risks between the current results and other studies. “There are pharmacogenomic differences between different ethnicities as to how they activate these drugs. But I suspect that sort of difference is really minor. Maybe it leads to a 2% or a 5% difference in risks.”

Dr. Kang and associates, Dr. Badimon, Dr. Santos-Gallego, and Dr. Brophy disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients on antithrombotics after an acute MI will face a greater risk for bleeding and secondary cardiovascular (CV) events if they start taking any nonaspirin NSAID, confirms a large observational study.

Like other research before it, the new study suggests those risks will be much lower for some nonaspirin NSAIDs than others. But it may also challenge at least some conventional thinking about the safety of these drugs, and is based solely on a large cohort in South Korea, a group for which such NSAID data has been in short supply.

“It was intriguing that our study presented better safety profiles with celecoxib and meloxicam versus other subtypes of NSAIDs,” noted the report, published online July 27 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Most of the NSAIDs included in the analysis, “including naproxen, conferred a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and bleeding events, compared with celecoxib and meloxicam,” wrote the authors, led by Dong Oh Kang, MD, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, South Korea.

A main contribution of the study “is the thorough and comprehensive evaluation of the Korean population by use of the nationwide prescription claims database that reflects real-world clinical practice,” senior author Cheol Ung Choi, MD, PhD, of the same institution, said in an interview.

“Because we included the largest number of patients of any comparable clinical studies on NSAID treatment after MI thus far, our study may allow the generalizability of the adverse events of NSAIDs to all patients by constituting global evidence encompassing different population groups,” Dr. Choi said.

The analysis has limitations along with its strengths, the authors acknowledged, including its observational design and potential for confounding not addressed in statistical adjustments.

Observers of the study concurred, but some cited evidence pointing to such confounding that is serious enough to question the entire study’s validity.

Among the cohort of more than 100,000 patients followed for an average of about 2.3 years after their MI, the adjusted risk of thromboembolic CV events went up almost 7 times for those who took any NSAID for at least 4 consecutive weeks, compared with those who didn’t take NSAIDs, based on prescription records.

Their adjusted risk of bleeding events – which included gastrointestinal, intracranial, respiratory, or urinary tract bleeding or posthemorrhagic anemia, the group writes – was increased 300%.

There was wide variance in the adjusted hazard ratios for outcomes by type of NSAID. The risk of CV events climbed from a low of about 3 with meloxicam and almost 5 for celecoxib to more than 10 and 12 for naproxen and dexibuprofen, respectively.

The hazard ratios for bleeding ranged from about 3 for both meloxicam and celecoxib to more than 6 for naproxen.

Of note, celecoxib and meloxicam both preferentially target the cyclooxygenase type 2 (COX-2) pathway, and naproxen among NSAIDs once had a reputation for relative cardiac safety, although subsequent studies have challenged that notion.

“On the basis of the contemporary guidelines, NSAID treatment should be limited as much as possible after MI; however, our data suggest that celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered possible alternative choices in patients with MI when NSAID prescription is unavoidable,” the group wrote.

They acknowledged some limitations of the analysis, including an observational design and the possibility of unidentified confounders; that mortality outcomes were not available from the National Health Insurance Service database used in the study; and that the 2009-2013 span for the data didn’t allow consideration of more contemporary antiplatelet agents and direct oral anticoagulants.

Also, NSAID use was based on prescriptions without regard to over-the-counter usage. Although use of over-the-counter NSAIDs is common in Korea, “most MI patients in Korea are prescribed most medications, including NSAIDs, in the hospital. So I think that usage of over-the-counter NSAIDs did not change the results,” Dr. Choi said.

“This study breaks new ground by demonstrating cardiovascular safety of meloxicam (and not only of celecoxib), probably because of its higher COX-2 selectivity,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Juan J. Badimon, PhD, and Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, both of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Notably, “this paper rejects the cardiovascular safety of naproxen, which had been suggested classically and in the previous Danish data, but that was not evident in this study.” The finding is consistent with the PRECISION trial, in which both bleeding and CV risk were increased with naproxen versus other NSAIDs, observed Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego.

They agreed with the authors in recommending that, “although NSAID treatment should be avoided in patients with MI, if the use of NSAIDs is inevitable due to comorbidities, the prescription of celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered as alternative options.”

But, “as no study is perfect, this article also presents some limitations,” the editorial agreed, citing some of the same issues noted by Dr. Kang and associates, along with potential confounding by indication and the lack of “clinical information to adjust (e.g., angiographic features, left ventricular function).”

“There’s undoubtedly residual confounding,” James M. Brophy, MD, PhD, a pharmacoepidemiologist at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview.

The 400%-900% relative risks for CV events “are just too far in left field, compared to everything else we know,” he said. “There has never been a class of drugs that have shown this sort of magnitude of effect for adverse events.”

Even in PRECISION with its more than 24,000 high-coronary-risk patients randomized and followed for 5 years, Dr. Brophy observed, relative risks for the different NSAIDs varied by an order of magnitude of only 1-2.

“You should be interpreting things in the context of what is already known,” Dr. Brophy said. “The only conclusion I would draw is the paper is fatally flawed.”

The registry included 108,232 primarily male patients followed from their first diagnosed MI for CV and bleeding events. About 1.9% were prescribed at least one NSAID for 4 or more consecutive weeks during the follow-up period averaging 2.3 years, the group reported.

The most frequently prescribed NSAID was diclofenac, at about 72% of prescribed NSAIDs in the analysis for CV events and about 69% in the bleeding-event analysis.

Adding any NSAID to post-MI antithrombotic therapy led to an adjusted HR of 6.96 (P < .001) for CV events and 4.08 (P < .001) for bleeding events, compared with no NSAID treatment.

The 88% of the cohort who were on dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel showed very nearly the same risk increases for both endpoints.

Further studies are needed to confirm the results “and ensure their generalizability to other populations,” Dr. Choi said. They should be validated especially using the claims data bases of countries near Korea, “such as Japan and Taiwan, to examine the reproducibility of the results in similar ethnic populations.”

That the study focused on a cohort in Korea is a strength, contended the authors as well as Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego, given “that most data about NSAIDs were extracted from Western populations, but the risk of thrombosis/bleeding post-MI varies according to ethnicity,” according to the editorial

Dr. Brophy agreed, but doubted that ethnic differences are responsible for variation in relative risks between the current results and other studies. “There are pharmacogenomic differences between different ethnicities as to how they activate these drugs. But I suspect that sort of difference is really minor. Maybe it leads to a 2% or a 5% difference in risks.”

Dr. Kang and associates, Dr. Badimon, Dr. Santos-Gallego, and Dr. Brophy disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Fracture risk prediction: No benefit to repeat BMD testing in postmenopausal women

On the basis of the findings, published online in JAMA Internal Medicine, the authors recommend against routine repeat testing in postmenopausal women. Other experts, however, caution that the results may not be so broadly generalizable.

For the investigation, Carolyn J. Crandall, MD, of the division of general internal medicine and health services research at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues analyzed data from 7,419 women enrolled in the prospective Women’s Health Initiative study and who underwent baseline and repeat dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) between 1993 and 2010. The researchers excluded patients who reported using bisphosphonates, calcitonin, or selective estrogen-receptor modulators, those with a history of major osteoporotic fracture, or those who lacked follow-up visits. The mean body mass index (BMI) of the study population was 28.7 kg/m2, and the mean age was 66.1 years.

The mean follow-up after the repeat BMD test was 9.0 years, during which period 732 (9.9%) of the women experienced a major osteoporotic fracture, and 139 (1.9%) experienced hip fractures.

To determine whether repeat testing improved fracture risk discrimination, the researchers calculated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for baseline BMD, absolute change in BMD, and the combination of baseline BMD and change in BMD.

With respect to any major osteoporotic fracture risk, the AUROC values for total hip BMD at baseline, change in total hip BMD at 3 years, and the combination of the two, respectively, were 0.61 (95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.63), 0.53 (95% CI, 0.51-0.55), and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.59-0.63). For hip fracture risk, the respective AUROC values were 0.71 (95% CI, 0.67-0.75), 0.61 (95% CI, 0.56-0.65), and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.69-0.77), the authors reported.

Similar results were observed for femoral neck and lumbar spine BMD measurements. The associations between BMD changes and fracture risk were consistent across age, race, ethnicity, BMI, and baseline BMD T-score subgroups.

Although baseline BMD and change in BMD were independently associated with incident fracture, the association was stronger for lower baseline BMD than the 3-year absolute change in BMD, the authors stated.

The findings, which are consistent with those of previous investigations that involved older adults, are notable because of the age range of the population, according to the authors. “To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study that addressed this issue in a study cohort that included younger postmenopausal U.S. women,” they wrote. “Forty-four percent of our study population was younger than 65 years.”

The authors wrote that, given the lack of benefit associated with repeat BMD testing, such tests should no longer be routinely performed. “Our findings further suggest that resources should be devoted to increasing the underuse of baseline BMD testing among women aged [between] 65 and 85 years, one-quarter of whom do not receive an initial BMD test.”

However, some experts are not comfortable with the broad recommendation to skip repeat testing in the general population. “This is a great study, and it gives important information. However, we know, even in the real world, that patients can lose BMD in this time frame and not really fracture. This does not mean that they will not fracture further down the road,” said Pauline Camacho, MD, director of Loyola University Medical Center’s Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease Center in Chicago,. “The value of doing BMD goes beyond predicting fracture risk. It also helps assess patient compliance and detect the presence of uncorrected secondary causes of osteoporosis that are limiting the response to therapy, including failure to absorb oral bisphosphonates, vitamin D deficiency, or hyperparathyroidism.”

In addition, patients for whom treatment is initiated would want to know whether it’s working. “Seeing the BMD response to therapy is helpful to both clinicians and patients,” Dr. Camacho said in an interview.

Another concern is the study population. “The study was designed to assess the clinical utility of repeating a screening BMD test in a population of low-risk women -- older postmenopausal women with remarkably good BMD on initial testing,” according to E. Michael Lewiecki, MD, vice president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation and director of the New Mexico Clinical Research and Osteoporosis Center in Albuquerque. “Not surprisingly, with what we know about the expected age-related rate of bone loss, there was only a modest decrease in BMD and little clinical utility in repeating DXA in 3 years. However, repeat testing is an important component in the care of many patients seen in clinical practice.”

There are numerous situations in clinical practice in which repeat BMD testing can enhance patient care and potentially improve outcomes, Dr. Lewiecki said in an interview. “Repeating BMD 1-2 years after starting osteoporosis therapy is a useful way to assess response and determine whether the patient is on a pathway to achieving an acceptable level of fracture risk with a strategy called treat to target.”

Additionally, patients starting high-dose glucocorticoids who are at high risk for rapid bone loss may benefit from undergoing baseline BMD testing and having a follow-up test 1 year later or even sooner, he said. Further, for early postmenopausal women, the rate of bone loss may be accelerated and may be faster than age-related bone loss later in life. For this reason, “close monitoring of BMD may be used to determine when a treatment threshold has been crossed and pharmacological therapy is indicated.”

The most important message from this study for clinicians and healthcare policymakers is not the relative value of the repeat BMD testing, Dr. Lewiecki stated. Rather, it is the call to action regarding the underuse of BMD testing. “There is a global crisis in the care of osteoporosis that is characterized by underdiagnosis and undertreatment of patients at risk for fracture. Many patients who could benefit from treatment to reduce fracture risk are not receiving it, resulting in disability and deaths from fractures that might have been prevented. We need more bone density testing in appropriately selected patients to identify high-risk patients and intervene to reduce fracture risk,” he said. “DXA is an inexpensive and highly versatile clinical tool with many applications in clinical practice. When used wisely, it can be extraordinarily useful to identify and monitor high-risk patients, with the goal of reducing the burden of osteoporotic fractures.”

The barriers to performing baseline BMD measurement in this population are poorly understood and not well researched, Dr. Crandall said in an interview. “I expect that they relate to the multiple competing demands on primary care physicians, who are, for example, trying to juggle hypertension, a sprained ankle, diabetes, and complex social situations simultaneously with identifying appropriate candidates for osteoporosis screening and considering numerous other screening guidelines.”

The Women’s Health Initiative is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and the Department of Health & Human Services. The study authors reported relationships with multiple companies, including Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Mithra, Norton Rose Fulbright, TherapeuticsMD, AbbVie, Radius, and Allergan. Dr. Camacho reported relationships with Amgen and Shire. Dr. Lewiecki reported relationships with Amgen, Radius Health, Alexion, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Mereo, and Bindex.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

On the basis of the findings, published online in JAMA Internal Medicine, the authors recommend against routine repeat testing in postmenopausal women. Other experts, however, caution that the results may not be so broadly generalizable.

For the investigation, Carolyn J. Crandall, MD, of the division of general internal medicine and health services research at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues analyzed data from 7,419 women enrolled in the prospective Women’s Health Initiative study and who underwent baseline and repeat dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) between 1993 and 2010. The researchers excluded patients who reported using bisphosphonates, calcitonin, or selective estrogen-receptor modulators, those with a history of major osteoporotic fracture, or those who lacked follow-up visits. The mean body mass index (BMI) of the study population was 28.7 kg/m2, and the mean age was 66.1 years.

The mean follow-up after the repeat BMD test was 9.0 years, during which period 732 (9.9%) of the women experienced a major osteoporotic fracture, and 139 (1.9%) experienced hip fractures.

To determine whether repeat testing improved fracture risk discrimination, the researchers calculated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for baseline BMD, absolute change in BMD, and the combination of baseline BMD and change in BMD.

With respect to any major osteoporotic fracture risk, the AUROC values for total hip BMD at baseline, change in total hip BMD at 3 years, and the combination of the two, respectively, were 0.61 (95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.63), 0.53 (95% CI, 0.51-0.55), and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.59-0.63). For hip fracture risk, the respective AUROC values were 0.71 (95% CI, 0.67-0.75), 0.61 (95% CI, 0.56-0.65), and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.69-0.77), the authors reported.

Similar results were observed for femoral neck and lumbar spine BMD measurements. The associations between BMD changes and fracture risk were consistent across age, race, ethnicity, BMI, and baseline BMD T-score subgroups.

Although baseline BMD and change in BMD were independently associated with incident fracture, the association was stronger for lower baseline BMD than the 3-year absolute change in BMD, the authors stated.

The findings, which are consistent with those of previous investigations that involved older adults, are notable because of the age range of the population, according to the authors. “To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study that addressed this issue in a study cohort that included younger postmenopausal U.S. women,” they wrote. “Forty-four percent of our study population was younger than 65 years.”

The authors wrote that, given the lack of benefit associated with repeat BMD testing, such tests should no longer be routinely performed. “Our findings further suggest that resources should be devoted to increasing the underuse of baseline BMD testing among women aged [between] 65 and 85 years, one-quarter of whom do not receive an initial BMD test.”

However, some experts are not comfortable with the broad recommendation to skip repeat testing in the general population. “This is a great study, and it gives important information. However, we know, even in the real world, that patients can lose BMD in this time frame and not really fracture. This does not mean that they will not fracture further down the road,” said Pauline Camacho, MD, director of Loyola University Medical Center’s Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease Center in Chicago,. “The value of doing BMD goes beyond predicting fracture risk. It also helps assess patient compliance and detect the presence of uncorrected secondary causes of osteoporosis that are limiting the response to therapy, including failure to absorb oral bisphosphonates, vitamin D deficiency, or hyperparathyroidism.”

In addition, patients for whom treatment is initiated would want to know whether it’s working. “Seeing the BMD response to therapy is helpful to both clinicians and patients,” Dr. Camacho said in an interview.

Another concern is the study population. “The study was designed to assess the clinical utility of repeating a screening BMD test in a population of low-risk women -- older postmenopausal women with remarkably good BMD on initial testing,” according to E. Michael Lewiecki, MD, vice president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation and director of the New Mexico Clinical Research and Osteoporosis Center in Albuquerque. “Not surprisingly, with what we know about the expected age-related rate of bone loss, there was only a modest decrease in BMD and little clinical utility in repeating DXA in 3 years. However, repeat testing is an important component in the care of many patients seen in clinical practice.”

There are numerous situations in clinical practice in which repeat BMD testing can enhance patient care and potentially improve outcomes, Dr. Lewiecki said in an interview. “Repeating BMD 1-2 years after starting osteoporosis therapy is a useful way to assess response and determine whether the patient is on a pathway to achieving an acceptable level of fracture risk with a strategy called treat to target.”

Additionally, patients starting high-dose glucocorticoids who are at high risk for rapid bone loss may benefit from undergoing baseline BMD testing and having a follow-up test 1 year later or even sooner, he said. Further, for early postmenopausal women, the rate of bone loss may be accelerated and may be faster than age-related bone loss later in life. For this reason, “close monitoring of BMD may be used to determine when a treatment threshold has been crossed and pharmacological therapy is indicated.”

The most important message from this study for clinicians and healthcare policymakers is not the relative value of the repeat BMD testing, Dr. Lewiecki stated. Rather, it is the call to action regarding the underuse of BMD testing. “There is a global crisis in the care of osteoporosis that is characterized by underdiagnosis and undertreatment of patients at risk for fracture. Many patients who could benefit from treatment to reduce fracture risk are not receiving it, resulting in disability and deaths from fractures that might have been prevented. We need more bone density testing in appropriately selected patients to identify high-risk patients and intervene to reduce fracture risk,” he said. “DXA is an inexpensive and highly versatile clinical tool with many applications in clinical practice. When used wisely, it can be extraordinarily useful to identify and monitor high-risk patients, with the goal of reducing the burden of osteoporotic fractures.”

The barriers to performing baseline BMD measurement in this population are poorly understood and not well researched, Dr. Crandall said in an interview. “I expect that they relate to the multiple competing demands on primary care physicians, who are, for example, trying to juggle hypertension, a sprained ankle, diabetes, and complex social situations simultaneously with identifying appropriate candidates for osteoporosis screening and considering numerous other screening guidelines.”

The Women’s Health Initiative is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and the Department of Health & Human Services. The study authors reported relationships with multiple companies, including Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Mithra, Norton Rose Fulbright, TherapeuticsMD, AbbVie, Radius, and Allergan. Dr. Camacho reported relationships with Amgen and Shire. Dr. Lewiecki reported relationships with Amgen, Radius Health, Alexion, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Mereo, and Bindex.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

On the basis of the findings, published online in JAMA Internal Medicine, the authors recommend against routine repeat testing in postmenopausal women. Other experts, however, caution that the results may not be so broadly generalizable.

For the investigation, Carolyn J. Crandall, MD, of the division of general internal medicine and health services research at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues analyzed data from 7,419 women enrolled in the prospective Women’s Health Initiative study and who underwent baseline and repeat dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) between 1993 and 2010. The researchers excluded patients who reported using bisphosphonates, calcitonin, or selective estrogen-receptor modulators, those with a history of major osteoporotic fracture, or those who lacked follow-up visits. The mean body mass index (BMI) of the study population was 28.7 kg/m2, and the mean age was 66.1 years.

The mean follow-up after the repeat BMD test was 9.0 years, during which period 732 (9.9%) of the women experienced a major osteoporotic fracture, and 139 (1.9%) experienced hip fractures.

To determine whether repeat testing improved fracture risk discrimination, the researchers calculated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for baseline BMD, absolute change in BMD, and the combination of baseline BMD and change in BMD.

With respect to any major osteoporotic fracture risk, the AUROC values for total hip BMD at baseline, change in total hip BMD at 3 years, and the combination of the two, respectively, were 0.61 (95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.63), 0.53 (95% CI, 0.51-0.55), and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.59-0.63). For hip fracture risk, the respective AUROC values were 0.71 (95% CI, 0.67-0.75), 0.61 (95% CI, 0.56-0.65), and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.69-0.77), the authors reported.

Similar results were observed for femoral neck and lumbar spine BMD measurements. The associations between BMD changes and fracture risk were consistent across age, race, ethnicity, BMI, and baseline BMD T-score subgroups.

Although baseline BMD and change in BMD were independently associated with incident fracture, the association was stronger for lower baseline BMD than the 3-year absolute change in BMD, the authors stated.

The findings, which are consistent with those of previous investigations that involved older adults, are notable because of the age range of the population, according to the authors. “To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study that addressed this issue in a study cohort that included younger postmenopausal U.S. women,” they wrote. “Forty-four percent of our study population was younger than 65 years.”

The authors wrote that, given the lack of benefit associated with repeat BMD testing, such tests should no longer be routinely performed. “Our findings further suggest that resources should be devoted to increasing the underuse of baseline BMD testing among women aged [between] 65 and 85 years, one-quarter of whom do not receive an initial BMD test.”

However, some experts are not comfortable with the broad recommendation to skip repeat testing in the general population. “This is a great study, and it gives important information. However, we know, even in the real world, that patients can lose BMD in this time frame and not really fracture. This does not mean that they will not fracture further down the road,” said Pauline Camacho, MD, director of Loyola University Medical Center’s Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease Center in Chicago,. “The value of doing BMD goes beyond predicting fracture risk. It also helps assess patient compliance and detect the presence of uncorrected secondary causes of osteoporosis that are limiting the response to therapy, including failure to absorb oral bisphosphonates, vitamin D deficiency, or hyperparathyroidism.”

In addition, patients for whom treatment is initiated would want to know whether it’s working. “Seeing the BMD response to therapy is helpful to both clinicians and patients,” Dr. Camacho said in an interview.

Another concern is the study population. “The study was designed to assess the clinical utility of repeating a screening BMD test in a population of low-risk women -- older postmenopausal women with remarkably good BMD on initial testing,” according to E. Michael Lewiecki, MD, vice president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation and director of the New Mexico Clinical Research and Osteoporosis Center in Albuquerque. “Not surprisingly, with what we know about the expected age-related rate of bone loss, there was only a modest decrease in BMD and little clinical utility in repeating DXA in 3 years. However, repeat testing is an important component in the care of many patients seen in clinical practice.”

There are numerous situations in clinical practice in which repeat BMD testing can enhance patient care and potentially improve outcomes, Dr. Lewiecki said in an interview. “Repeating BMD 1-2 years after starting osteoporosis therapy is a useful way to assess response and determine whether the patient is on a pathway to achieving an acceptable level of fracture risk with a strategy called treat to target.”

Additionally, patients starting high-dose glucocorticoids who are at high risk for rapid bone loss may benefit from undergoing baseline BMD testing and having a follow-up test 1 year later or even sooner, he said. Further, for early postmenopausal women, the rate of bone loss may be accelerated and may be faster than age-related bone loss later in life. For this reason, “close monitoring of BMD may be used to determine when a treatment threshold has been crossed and pharmacological therapy is indicated.”

The most important message from this study for clinicians and healthcare policymakers is not the relative value of the repeat BMD testing, Dr. Lewiecki stated. Rather, it is the call to action regarding the underuse of BMD testing. “There is a global crisis in the care of osteoporosis that is characterized by underdiagnosis and undertreatment of patients at risk for fracture. Many patients who could benefit from treatment to reduce fracture risk are not receiving it, resulting in disability and deaths from fractures that might have been prevented. We need more bone density testing in appropriately selected patients to identify high-risk patients and intervene to reduce fracture risk,” he said. “DXA is an inexpensive and highly versatile clinical tool with many applications in clinical practice. When used wisely, it can be extraordinarily useful to identify and monitor high-risk patients, with the goal of reducing the burden of osteoporotic fractures.”

The barriers to performing baseline BMD measurement in this population are poorly understood and not well researched, Dr. Crandall said in an interview. “I expect that they relate to the multiple competing demands on primary care physicians, who are, for example, trying to juggle hypertension, a sprained ankle, diabetes, and complex social situations simultaneously with identifying appropriate candidates for osteoporosis screening and considering numerous other screening guidelines.”

The Women’s Health Initiative is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and the Department of Health & Human Services. The study authors reported relationships with multiple companies, including Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Mithra, Norton Rose Fulbright, TherapeuticsMD, AbbVie, Radius, and Allergan. Dr. Camacho reported relationships with Amgen and Shire. Dr. Lewiecki reported relationships with Amgen, Radius Health, Alexion, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Mereo, and Bindex.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Biologics may delay psoriatic arthritis, study finds

(DMARDs), in a single center retrospective analysis in Argentina that followed patients for almost 2 decades.

About 30%-40% of patients with psoriasis go on to develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), usually on average about 10 years after the onset of psoriasis. One potential mechanism of PsA onset is through enthesitis, which has been described at subclinical levels in psoriasis.

“It could be speculated that treatment with biologics in patients with psoriasis could prevent the development of psoriatic arthritis, perhaps by inhibiting the subclinical development of enthesitis,” Luciano Lo Giudice, MD, a rheumatology fellow at Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, said during his presentation at the virtual annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

Although these results do not prove that treatment of the underlying disease delays progression to PsA, it is suggestive, and highlights an emerging field of research, according to Diamant Thaçi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, who led a live discussion following a prerecorded presentation of the results. “We’re going in this direction – how can we prevent psoriatic arthritis, how can we delay it. We are just starting to think about this,” Dr. Thaçi said in an interview.

The researchers examined medical records of 1,626 patients with psoriasis treated at their center between 2000 and 2019, with a total of 15,152 years of follow-up. Of these patients, 1,293 were treated with topical medication, 229 with conventional DMARDs (methotrexate in 77%, cyclosporine in 13%, and both in 10%), and 104 with biologics, including etanercept (34%), secukinumab (20%), adalimumab (20%), ustekinumab (12%), ixekizumab (9%), and infliximab (5%).

They found that 11% in the topical treatment group developed PsA, as did 3.5% in the conventional DMARD group, 1.9% in the biologics group, and 9.1% overall. Treatment with biologics was associated with a significantly lower odds of developing PsA compared with treatment with conventional DMARDs (3 versus 17.2 per 1,000 patient-years; incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.17; P = .0177). There was a trend toward reduced odds of developing PsA among those on biologic therapy compared with those on topicals (3 versus 9.8 per 1,000 patient-years; IRR, 0.3; P = .0588).

The researchers confirmed all medical encounters using electronic medical records and the study had a long follow-up time, but was limited by the single center and its retrospective nature. It also could not associate reduced risk with specific biologics.

The findings probably reflect the presence of subclinical PsA that many clinicians don’t see, according to Dr. Thaçi. While a dermatology practice might find PsA in 2% or 3%, or at most, 10% of patients with psoriasis, “in our department it’s about 50 to 60 percent of patients who have psoriatic arthritis, because we diagnose it early,” he said.

He found the results of the study encouraging. “It looks like some of the biologics, for example IL [interleukin]-17 or even IL-23 [blockers] may have an influence on occurrence or delay the occurrence of psoriatic arthritis.”

Dr. Thaçi noted that early treatment of skin lesions can increase the probability of longer remissions, especially with IL-23 blockers. Still, that’s no guarantee the same would hold true for PsA risk. “Skin is skin and joints are joints,” Dr. Thaçi said.

Dr. Thaçi and Dr. Lo Giudice had no relevant financial disclosures.

(DMARDs), in a single center retrospective analysis in Argentina that followed patients for almost 2 decades.

About 30%-40% of patients with psoriasis go on to develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), usually on average about 10 years after the onset of psoriasis. One potential mechanism of PsA onset is through enthesitis, which has been described at subclinical levels in psoriasis.

“It could be speculated that treatment with biologics in patients with psoriasis could prevent the development of psoriatic arthritis, perhaps by inhibiting the subclinical development of enthesitis,” Luciano Lo Giudice, MD, a rheumatology fellow at Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, said during his presentation at the virtual annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

Although these results do not prove that treatment of the underlying disease delays progression to PsA, it is suggestive, and highlights an emerging field of research, according to Diamant Thaçi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, who led a live discussion following a prerecorded presentation of the results. “We’re going in this direction – how can we prevent psoriatic arthritis, how can we delay it. We are just starting to think about this,” Dr. Thaçi said in an interview.

The researchers examined medical records of 1,626 patients with psoriasis treated at their center between 2000 and 2019, with a total of 15,152 years of follow-up. Of these patients, 1,293 were treated with topical medication, 229 with conventional DMARDs (methotrexate in 77%, cyclosporine in 13%, and both in 10%), and 104 with biologics, including etanercept (34%), secukinumab (20%), adalimumab (20%), ustekinumab (12%), ixekizumab (9%), and infliximab (5%).

They found that 11% in the topical treatment group developed PsA, as did 3.5% in the conventional DMARD group, 1.9% in the biologics group, and 9.1% overall. Treatment with biologics was associated with a significantly lower odds of developing PsA compared with treatment with conventional DMARDs (3 versus 17.2 per 1,000 patient-years; incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.17; P = .0177). There was a trend toward reduced odds of developing PsA among those on biologic therapy compared with those on topicals (3 versus 9.8 per 1,000 patient-years; IRR, 0.3; P = .0588).

The researchers confirmed all medical encounters using electronic medical records and the study had a long follow-up time, but was limited by the single center and its retrospective nature. It also could not associate reduced risk with specific biologics.

The findings probably reflect the presence of subclinical PsA that many clinicians don’t see, according to Dr. Thaçi. While a dermatology practice might find PsA in 2% or 3%, or at most, 10% of patients with psoriasis, “in our department it’s about 50 to 60 percent of patients who have psoriatic arthritis, because we diagnose it early,” he said.

He found the results of the study encouraging. “It looks like some of the biologics, for example IL [interleukin]-17 or even IL-23 [blockers] may have an influence on occurrence or delay the occurrence of psoriatic arthritis.”

Dr. Thaçi noted that early treatment of skin lesions can increase the probability of longer remissions, especially with IL-23 blockers. Still, that’s no guarantee the same would hold true for PsA risk. “Skin is skin and joints are joints,” Dr. Thaçi said.

Dr. Thaçi and Dr. Lo Giudice had no relevant financial disclosures.

(DMARDs), in a single center retrospective analysis in Argentina that followed patients for almost 2 decades.

About 30%-40% of patients with psoriasis go on to develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), usually on average about 10 years after the onset of psoriasis. One potential mechanism of PsA onset is through enthesitis, which has been described at subclinical levels in psoriasis.