User login

Testicular sperm may improve IVF outcomes in some cases

and rates of clinical pregnancy and live birth, a retrospective observational study has found.

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG canceled the meeting and released abstracts for press coverage.

The study, which won the college’s Donald F. Richardson Memorial Prize Research Paper award, evaluated 112 nonazoospermic couples with an average of 2.3 failed in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles (range of 1-8). The couples, patients at Shade Grove Fertility in Washington, underwent 157 total intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles (133 using fresh testicular sperm and 24 using frozen/thawed sperm) and had a total of 101 embryo transfers.

Use of ICSI with testicular sperm compared with prior cycles using ejaculated sperm significantly improved blastocyst development (65% vs. 33%, P < .001), blastocyst conversion rates (67% vs. 35%, P < .001) and the number of embryos available for vitrification (1.6 vs. 0.7, P < .001). Fertilization rates were similar (70% vs. 58%). The clinical pregnancy and live birth rates in couples who used testicular sperm were 44% and 32%, respectively.

The findings suggest improved embryo development and pregnancy rates, and offer more evidence “that this might be something we can offer patients who’ve had multiple failures and no other reason as to why,” M. Blake Evans, DO, clinical fellow in reproductive endocrinology and infertility at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Rockville, Md., said in a interview. “It looks like there is promise, and we need more research to be conducted.”

The integration of the use of testicular sperm at Shady Grove, a private practice fertility center, and the newly completed analysis of outcomes, were driven by studies “showing that testicular sperm has a low DNA fragmentation index and suggesting that it [offers a] better chance of successful IVF outcomes in patients who have had prior failures,” he said.

Almost all of the men who had ICSC using testicular sperm – 105 of the 112 – had a sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF) assessment of their ejaculate sperm. The mean SDF was 32% and of these 105 men, 66 had an SDF greater than 25% (mean of 49%), a value considered abnormal. The outcomes for patients with elevated SDF did not differ significantly from the overall cohort, Dr. Evans and coinvestigators reported in their abstract.

Dr. Evans said that it’s too early to draw any conclusions about the utility of SDF testing, and that the investigators plan to start prospectively evaluating whether levels of sperm DNA damage as reflected in SDF testing correlate with IVF outcomes.

“Right now the evidence is so conflicting as to whether [SDF testing offers] information that all IVF patients or infertility patients should be receiving,” he said. “Is the reason that testicular sperm works better because there’s lower DNA fragmentation? We think so. … But now that we see [that it] appears the outcomes are better [using testicular sperm], we need to take it a step further and look prospectively at the impact of DNA fragmentation, comparing all the outcomes with normal and abnormal DNA [levels].”

Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of Fertility CARE: The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, said in an interview that while “there is increasing evidence – and rather clear evidence – that testicular sperm has less DNA damage,” there has been controversy over available outcomes data, most of which have come from small, retrospective studies. Dr. Trolice was not involved in this study presented at ACOG.

In the case of “very poor outcomes with use of ejaculated sperm and a high SDF index, there seems to be support for the use of testicular sperm on the next IVF cycle,” he said. “But there’s also evidence to support that there’s no significant difference in the outcomes of IUI [intrauterine insemination] or IVF based on the SDF index. So this [study] really took a tremendous leap of faith.”

Dr. Trolice said he looks forward to more research – ideally prospective, randomized studies of men with high SDF levels who proceed with assisted reproductive technologies using ejaculated or testicular sperm.

The research was supported by the division of intramural research at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Evans did not report any relevant financial disclosures. One of his coinvestigators. Micah J. Hill, DO, disclosed having served on the advisory board of Ohana Biosciences. Dr. Trolice reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures. He is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

The abstract was first presented by coauthor Lt. Allison A. Eubanks, MD, of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, at the ACOG Armed Forces District Annual District Meeting in September 2019.

and rates of clinical pregnancy and live birth, a retrospective observational study has found.

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG canceled the meeting and released abstracts for press coverage.

The study, which won the college’s Donald F. Richardson Memorial Prize Research Paper award, evaluated 112 nonazoospermic couples with an average of 2.3 failed in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles (range of 1-8). The couples, patients at Shade Grove Fertility in Washington, underwent 157 total intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles (133 using fresh testicular sperm and 24 using frozen/thawed sperm) and had a total of 101 embryo transfers.

Use of ICSI with testicular sperm compared with prior cycles using ejaculated sperm significantly improved blastocyst development (65% vs. 33%, P < .001), blastocyst conversion rates (67% vs. 35%, P < .001) and the number of embryos available for vitrification (1.6 vs. 0.7, P < .001). Fertilization rates were similar (70% vs. 58%). The clinical pregnancy and live birth rates in couples who used testicular sperm were 44% and 32%, respectively.

The findings suggest improved embryo development and pregnancy rates, and offer more evidence “that this might be something we can offer patients who’ve had multiple failures and no other reason as to why,” M. Blake Evans, DO, clinical fellow in reproductive endocrinology and infertility at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Rockville, Md., said in a interview. “It looks like there is promise, and we need more research to be conducted.”

The integration of the use of testicular sperm at Shady Grove, a private practice fertility center, and the newly completed analysis of outcomes, were driven by studies “showing that testicular sperm has a low DNA fragmentation index and suggesting that it [offers a] better chance of successful IVF outcomes in patients who have had prior failures,” he said.

Almost all of the men who had ICSC using testicular sperm – 105 of the 112 – had a sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF) assessment of their ejaculate sperm. The mean SDF was 32% and of these 105 men, 66 had an SDF greater than 25% (mean of 49%), a value considered abnormal. The outcomes for patients with elevated SDF did not differ significantly from the overall cohort, Dr. Evans and coinvestigators reported in their abstract.

Dr. Evans said that it’s too early to draw any conclusions about the utility of SDF testing, and that the investigators plan to start prospectively evaluating whether levels of sperm DNA damage as reflected in SDF testing correlate with IVF outcomes.

“Right now the evidence is so conflicting as to whether [SDF testing offers] information that all IVF patients or infertility patients should be receiving,” he said. “Is the reason that testicular sperm works better because there’s lower DNA fragmentation? We think so. … But now that we see [that it] appears the outcomes are better [using testicular sperm], we need to take it a step further and look prospectively at the impact of DNA fragmentation, comparing all the outcomes with normal and abnormal DNA [levels].”

Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of Fertility CARE: The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, said in an interview that while “there is increasing evidence – and rather clear evidence – that testicular sperm has less DNA damage,” there has been controversy over available outcomes data, most of which have come from small, retrospective studies. Dr. Trolice was not involved in this study presented at ACOG.

In the case of “very poor outcomes with use of ejaculated sperm and a high SDF index, there seems to be support for the use of testicular sperm on the next IVF cycle,” he said. “But there’s also evidence to support that there’s no significant difference in the outcomes of IUI [intrauterine insemination] or IVF based on the SDF index. So this [study] really took a tremendous leap of faith.”

Dr. Trolice said he looks forward to more research – ideally prospective, randomized studies of men with high SDF levels who proceed with assisted reproductive technologies using ejaculated or testicular sperm.

The research was supported by the division of intramural research at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Evans did not report any relevant financial disclosures. One of his coinvestigators. Micah J. Hill, DO, disclosed having served on the advisory board of Ohana Biosciences. Dr. Trolice reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures. He is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

The abstract was first presented by coauthor Lt. Allison A. Eubanks, MD, of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, at the ACOG Armed Forces District Annual District Meeting in September 2019.

and rates of clinical pregnancy and live birth, a retrospective observational study has found.

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG canceled the meeting and released abstracts for press coverage.

The study, which won the college’s Donald F. Richardson Memorial Prize Research Paper award, evaluated 112 nonazoospermic couples with an average of 2.3 failed in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles (range of 1-8). The couples, patients at Shade Grove Fertility in Washington, underwent 157 total intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles (133 using fresh testicular sperm and 24 using frozen/thawed sperm) and had a total of 101 embryo transfers.

Use of ICSI with testicular sperm compared with prior cycles using ejaculated sperm significantly improved blastocyst development (65% vs. 33%, P < .001), blastocyst conversion rates (67% vs. 35%, P < .001) and the number of embryos available for vitrification (1.6 vs. 0.7, P < .001). Fertilization rates were similar (70% vs. 58%). The clinical pregnancy and live birth rates in couples who used testicular sperm were 44% and 32%, respectively.

The findings suggest improved embryo development and pregnancy rates, and offer more evidence “that this might be something we can offer patients who’ve had multiple failures and no other reason as to why,” M. Blake Evans, DO, clinical fellow in reproductive endocrinology and infertility at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Rockville, Md., said in a interview. “It looks like there is promise, and we need more research to be conducted.”

The integration of the use of testicular sperm at Shady Grove, a private practice fertility center, and the newly completed analysis of outcomes, were driven by studies “showing that testicular sperm has a low DNA fragmentation index and suggesting that it [offers a] better chance of successful IVF outcomes in patients who have had prior failures,” he said.

Almost all of the men who had ICSC using testicular sperm – 105 of the 112 – had a sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF) assessment of their ejaculate sperm. The mean SDF was 32% and of these 105 men, 66 had an SDF greater than 25% (mean of 49%), a value considered abnormal. The outcomes for patients with elevated SDF did not differ significantly from the overall cohort, Dr. Evans and coinvestigators reported in their abstract.

Dr. Evans said that it’s too early to draw any conclusions about the utility of SDF testing, and that the investigators plan to start prospectively evaluating whether levels of sperm DNA damage as reflected in SDF testing correlate with IVF outcomes.

“Right now the evidence is so conflicting as to whether [SDF testing offers] information that all IVF patients or infertility patients should be receiving,” he said. “Is the reason that testicular sperm works better because there’s lower DNA fragmentation? We think so. … But now that we see [that it] appears the outcomes are better [using testicular sperm], we need to take it a step further and look prospectively at the impact of DNA fragmentation, comparing all the outcomes with normal and abnormal DNA [levels].”

Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of Fertility CARE: The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, said in an interview that while “there is increasing evidence – and rather clear evidence – that testicular sperm has less DNA damage,” there has been controversy over available outcomes data, most of which have come from small, retrospective studies. Dr. Trolice was not involved in this study presented at ACOG.

In the case of “very poor outcomes with use of ejaculated sperm and a high SDF index, there seems to be support for the use of testicular sperm on the next IVF cycle,” he said. “But there’s also evidence to support that there’s no significant difference in the outcomes of IUI [intrauterine insemination] or IVF based on the SDF index. So this [study] really took a tremendous leap of faith.”

Dr. Trolice said he looks forward to more research – ideally prospective, randomized studies of men with high SDF levels who proceed with assisted reproductive technologies using ejaculated or testicular sperm.

The research was supported by the division of intramural research at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Evans did not report any relevant financial disclosures. One of his coinvestigators. Micah J. Hill, DO, disclosed having served on the advisory board of Ohana Biosciences. Dr. Trolice reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures. He is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

The abstract was first presented by coauthor Lt. Allison A. Eubanks, MD, of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, at the ACOG Armed Forces District Annual District Meeting in September 2019.

FROM ACOG 2020

Testosterone therapy linked to CV risk in men with HIV

Men with HIV are likely prone to the same cardiovascular risks from testosterone therapy as other men, according to new research.

There’s no reason to think they weren’t, but it hadn’t been demonstrated until now, and men with HIV are already at increased risk for cardiovascular disease. The take-home message is that “it would be prudent for clinicians to monitor closely for cardiovascular risk factors and recommend intervention to lower cardiovascular risk among men with HIV on or considering testosterone therapy,” lead investigator Sabina Haberlen, PhD, an assistant scientist in the infectious disease epidemiology division of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in a poster that was presented as part of the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Testosterone therapy is common among middle-aged and older men with HIV to counter the hypogonadism associated with infection. The investigators turned to the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study – a 30-year, four-city study of HIV-1 infection in men who have sex with men – to gauge its effect.

The 300 men in the study had a baseline coronary CT angiogram in 2010-2013 and a repeat study a mean of 4.5 years later. They had no history of coronary interventions or kidney dysfunction at baseline and were aged 40-70 years, with a median age of 51 years. About 70% reported never using testosterone, 8% were former users before entering the study, 7% started using testosterone between the two CTs, and 15% entered the study on testosterone and stayed on it.

Adjusting for age, race, cardiovascular risk factors, baseline serum testosterone levels, and other potential confounders, the risk of significant coronary artery calcium (CAC) progression was 2 times greater among continuous users (P = .03) and 2.4 times greater among new users (P = .01), compared with former users, who the investigators used as a control group because, at some point, they too had indications for testosterone replacement and so were more medically similar than never users.

The risk of noncalcified plaque volume progression was also more than twice as high among ongoing users, and elevated, although not significantly so, among ongoing users.

In short, “our findings are similar to those on subclinical atherosclerotic progression” in trials of older men in the general population on testosterone replacement, Dr. Haberlen said.

About half the subjects were white, 41% were at high risk for cardiovascular disease, 91% were on antiretroviral therapy, and 81% had undetectable HIV viral loads. Median total testosterone was 606 ng/dL. CAC progression was defined by incident CAC, at least a 10 Agatston unit/year increase if the baseline CAC score was 1-100, and a 10% or more annual increase if the baseline score was above 100.

Lower baseline serum testosterone was also associated with an increased risk of CAC progression, although not progression of noncalcified plaques.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Haberlen didn’t report any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Haberlen S et al. CROI 2020, Abstract 662.

Men with HIV are likely prone to the same cardiovascular risks from testosterone therapy as other men, according to new research.

There’s no reason to think they weren’t, but it hadn’t been demonstrated until now, and men with HIV are already at increased risk for cardiovascular disease. The take-home message is that “it would be prudent for clinicians to monitor closely for cardiovascular risk factors and recommend intervention to lower cardiovascular risk among men with HIV on or considering testosterone therapy,” lead investigator Sabina Haberlen, PhD, an assistant scientist in the infectious disease epidemiology division of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in a poster that was presented as part of the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Testosterone therapy is common among middle-aged and older men with HIV to counter the hypogonadism associated with infection. The investigators turned to the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study – a 30-year, four-city study of HIV-1 infection in men who have sex with men – to gauge its effect.

The 300 men in the study had a baseline coronary CT angiogram in 2010-2013 and a repeat study a mean of 4.5 years later. They had no history of coronary interventions or kidney dysfunction at baseline and were aged 40-70 years, with a median age of 51 years. About 70% reported never using testosterone, 8% were former users before entering the study, 7% started using testosterone between the two CTs, and 15% entered the study on testosterone and stayed on it.

Adjusting for age, race, cardiovascular risk factors, baseline serum testosterone levels, and other potential confounders, the risk of significant coronary artery calcium (CAC) progression was 2 times greater among continuous users (P = .03) and 2.4 times greater among new users (P = .01), compared with former users, who the investigators used as a control group because, at some point, they too had indications for testosterone replacement and so were more medically similar than never users.

The risk of noncalcified plaque volume progression was also more than twice as high among ongoing users, and elevated, although not significantly so, among ongoing users.

In short, “our findings are similar to those on subclinical atherosclerotic progression” in trials of older men in the general population on testosterone replacement, Dr. Haberlen said.

About half the subjects were white, 41% were at high risk for cardiovascular disease, 91% were on antiretroviral therapy, and 81% had undetectable HIV viral loads. Median total testosterone was 606 ng/dL. CAC progression was defined by incident CAC, at least a 10 Agatston unit/year increase if the baseline CAC score was 1-100, and a 10% or more annual increase if the baseline score was above 100.

Lower baseline serum testosterone was also associated with an increased risk of CAC progression, although not progression of noncalcified plaques.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Haberlen didn’t report any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Haberlen S et al. CROI 2020, Abstract 662.

Men with HIV are likely prone to the same cardiovascular risks from testosterone therapy as other men, according to new research.

There’s no reason to think they weren’t, but it hadn’t been demonstrated until now, and men with HIV are already at increased risk for cardiovascular disease. The take-home message is that “it would be prudent for clinicians to monitor closely for cardiovascular risk factors and recommend intervention to lower cardiovascular risk among men with HIV on or considering testosterone therapy,” lead investigator Sabina Haberlen, PhD, an assistant scientist in the infectious disease epidemiology division of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in a poster that was presented as part of the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Testosterone therapy is common among middle-aged and older men with HIV to counter the hypogonadism associated with infection. The investigators turned to the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study – a 30-year, four-city study of HIV-1 infection in men who have sex with men – to gauge its effect.

The 300 men in the study had a baseline coronary CT angiogram in 2010-2013 and a repeat study a mean of 4.5 years later. They had no history of coronary interventions or kidney dysfunction at baseline and were aged 40-70 years, with a median age of 51 years. About 70% reported never using testosterone, 8% were former users before entering the study, 7% started using testosterone between the two CTs, and 15% entered the study on testosterone and stayed on it.

Adjusting for age, race, cardiovascular risk factors, baseline serum testosterone levels, and other potential confounders, the risk of significant coronary artery calcium (CAC) progression was 2 times greater among continuous users (P = .03) and 2.4 times greater among new users (P = .01), compared with former users, who the investigators used as a control group because, at some point, they too had indications for testosterone replacement and so were more medically similar than never users.

The risk of noncalcified plaque volume progression was also more than twice as high among ongoing users, and elevated, although not significantly so, among ongoing users.

In short, “our findings are similar to those on subclinical atherosclerotic progression” in trials of older men in the general population on testosterone replacement, Dr. Haberlen said.

About half the subjects were white, 41% were at high risk for cardiovascular disease, 91% were on antiretroviral therapy, and 81% had undetectable HIV viral loads. Median total testosterone was 606 ng/dL. CAC progression was defined by incident CAC, at least a 10 Agatston unit/year increase if the baseline CAC score was 1-100, and a 10% or more annual increase if the baseline score was above 100.

Lower baseline serum testosterone was also associated with an increased risk of CAC progression, although not progression of noncalcified plaques.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Haberlen didn’t report any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Haberlen S et al. CROI 2020, Abstract 662.

FROM CROI 2020

In gestational diabetes, early postpartum glucose testing is a winner

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Early postpartum glucose tolerance testing for women with gestational diabetes resulted in a 99% adherence rate, with similar sensitivity and specificity as the currently recommended 4- to 12-week postpartum testing schedule.

“Two-day postpartum glucose tolerance testing has similar diagnostic utility as the 4- to 12-week postpartum glucose tolerance test to identify impaired glucose metabolism and diabetes at 1 year postpartum,” said Erika Werner, MD, speaking at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Overall, 29% of women studied had impaired glucose metabolism at 2 days postpartum, as did 25% in the 4- to 12-weeks postpartum window. At 1 year, that figure was 35%. The number of women meeting diagnostic criteria for diabetes held steady at 4% for all three time points.

The findings warrant “consideration for the 2-day postpartum glucose tolerance test (GTT) as the initial postpartum test for women who have gestational diabetes, with repeat testing at 1 year,” said Dr. Werner, a maternal-fetal medicine physician at Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Glucose testing for women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is recommended at 4-12 weeks postpartum by both the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Testing can allow detection and treatment of impaired glucose metabolism, seen in 15%-40% of women with a history of GDM. Up to 1 in 20 women with GDM will receive a postpartum diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

However, fewer than one in five women will actually have postpartum glucose testing, representing a large missed opportunity, said Dr. Werner.

Several factors likely contribute to those screening failures, she added. In addition to the potential for public insurance to lapse at 6 weeks postpartum, the logistical realities and time demands of parenting a newborn are themselves a significant barrier.

“What if we changed the timing?” and shifted glucose testing to the early postpartum days, before hospital discharge, asked Dr. Werner. Several pilot studies had already compared glucose screening in the first few days postpartum with the routine schedule, finding good correlation between the early and routine GTT schedule.

Importantly, the earlier studies achieved an adherence rate of more than 90% for early GTT. By contrast, fewer than half of the participants in the usual-care arms actually returned for postpartum GTT in the 4- to 12-week postpartum window, even under the optimized conditions associated with a medical study.

The single-center prospective cohort study conducted by Dr. Werner and collaborators enrolled 300 women with GDM. Women agreed to participate in glucose tolerance testing as inpatients, at 2 days postpartum, in addition to receiving a GTT between 4 and 12 weeks postpartum, and additional screening that included a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) test at 1 year postpartum.

The investigators obtained postpartum day 2 GTTs for all but four of the patients. A total of 201 patients returned in the 4- to 12-week postpartum window, and 168 of those participants returned for HbA1c testing at 1 year. Of the 95 patients who didn’t come back for the 4- to 12-week test, 33 did return at 1 year for HbA1c testing.

Dr. Werner and her coinvestigators included adult women who spoke either fluent Spanish or English and had GDM diagnosed by the Carpenter-Coustan criteria, or by having a blood glucose level of 200 mg/dL or more in a 1-hour glucose challenge test.

The early GTT results weren’t shared with patients or their health care providers. For outpatient visits, participants were offered financial incentives and received multiple reminder phone calls and the offer of free transportation.

For the purposes of the study, impaired glucose metabolism was defined as fasting blood glucose of 100 mg/dL or greater, a 2-hour GTT blood glucose level of 140 mg/dL or greater, or HbA1c of 5.7% or greater.

Participants were diagnosed with diabetes if they had a fasting blood glucose of 126 mg/dL or greater, a 2-hour GTT blood glucose level of 200 mg/dL or greater, or HbA1c of 6.5% or greater.

Dr. Werner and colleagues conducted two analyses of their results. In the first, they included only women in both arms who had complete data. In the second analysis, they looked at all women who had data for the 1-year postpartum mark, assuming that interval GTTs were negative for women who were missing these values.

The statistical analysis showed that, for women with complete data, both early and later postpartum GTTs were similar in predicting impaired glucose metabolism at 1 year postpartum (areas under the receiver operating curve [AUC], 0.63 and 0.60, respectively).

For identifying diabetes at 1 year, both early and late testing had high negative predictive value (98% and 99%, respectively), but the later testing strategy had higher sensitivity and specificity, yielding an AUC of 0.83, compared with 0.65 for early testing.

Turning to the second analysis that included all women who had 1-year postpartum HbA1c values, negative predictive values for diabetes were similarly high (98%) for both the early and late testing strategies. For identifying impaired glucose metabolism at 1 year in this group, both the positive and negative predictive value of the early and late strategies were similar.

Patients were about 32 years old at baseline, with a mean body mass index of 31.7 kg/m2. More than half of patients (52.3%) had private insurance, and 22% had GDM in a pregnancy prior to the index pregnancy. Black patients made up about 9% of the study population; 54% of participants were white, and 23% Hispanic. About one-third of patients were nulliparous, and two-thirds had education beyond high school.

During their pregnancies, about 44% of patients managed GDM by diet alone, 40% required insulin, with an additional 1% also requiring an oral agent. The remainder required oral agents alone. Patients delivered at a mean 38.3 weeks gestation, with about 40% receiving cesarean deliveries.

Some of the study’s strengths included its prospective nature, the diverse population recruited, and the fact that participants and providers were both blinded to the 2-day GTT results. Although more than half of participants completed the study – besting the previous pilots – 44% of patients still had incomplete data, noted Dr. Werner.

The American Diabetes Association sponsored the study. Dr. Werner reported no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Werner E et al. SMFM 2020. Abstract 72.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Early postpartum glucose tolerance testing for women with gestational diabetes resulted in a 99% adherence rate, with similar sensitivity and specificity as the currently recommended 4- to 12-week postpartum testing schedule.

“Two-day postpartum glucose tolerance testing has similar diagnostic utility as the 4- to 12-week postpartum glucose tolerance test to identify impaired glucose metabolism and diabetes at 1 year postpartum,” said Erika Werner, MD, speaking at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Overall, 29% of women studied had impaired glucose metabolism at 2 days postpartum, as did 25% in the 4- to 12-weeks postpartum window. At 1 year, that figure was 35%. The number of women meeting diagnostic criteria for diabetes held steady at 4% for all three time points.

The findings warrant “consideration for the 2-day postpartum glucose tolerance test (GTT) as the initial postpartum test for women who have gestational diabetes, with repeat testing at 1 year,” said Dr. Werner, a maternal-fetal medicine physician at Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Glucose testing for women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is recommended at 4-12 weeks postpartum by both the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Testing can allow detection and treatment of impaired glucose metabolism, seen in 15%-40% of women with a history of GDM. Up to 1 in 20 women with GDM will receive a postpartum diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

However, fewer than one in five women will actually have postpartum glucose testing, representing a large missed opportunity, said Dr. Werner.

Several factors likely contribute to those screening failures, she added. In addition to the potential for public insurance to lapse at 6 weeks postpartum, the logistical realities and time demands of parenting a newborn are themselves a significant barrier.

“What if we changed the timing?” and shifted glucose testing to the early postpartum days, before hospital discharge, asked Dr. Werner. Several pilot studies had already compared glucose screening in the first few days postpartum with the routine schedule, finding good correlation between the early and routine GTT schedule.

Importantly, the earlier studies achieved an adherence rate of more than 90% for early GTT. By contrast, fewer than half of the participants in the usual-care arms actually returned for postpartum GTT in the 4- to 12-week postpartum window, even under the optimized conditions associated with a medical study.

The single-center prospective cohort study conducted by Dr. Werner and collaborators enrolled 300 women with GDM. Women agreed to participate in glucose tolerance testing as inpatients, at 2 days postpartum, in addition to receiving a GTT between 4 and 12 weeks postpartum, and additional screening that included a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) test at 1 year postpartum.

The investigators obtained postpartum day 2 GTTs for all but four of the patients. A total of 201 patients returned in the 4- to 12-week postpartum window, and 168 of those participants returned for HbA1c testing at 1 year. Of the 95 patients who didn’t come back for the 4- to 12-week test, 33 did return at 1 year for HbA1c testing.

Dr. Werner and her coinvestigators included adult women who spoke either fluent Spanish or English and had GDM diagnosed by the Carpenter-Coustan criteria, or by having a blood glucose level of 200 mg/dL or more in a 1-hour glucose challenge test.

The early GTT results weren’t shared with patients or their health care providers. For outpatient visits, participants were offered financial incentives and received multiple reminder phone calls and the offer of free transportation.

For the purposes of the study, impaired glucose metabolism was defined as fasting blood glucose of 100 mg/dL or greater, a 2-hour GTT blood glucose level of 140 mg/dL or greater, or HbA1c of 5.7% or greater.

Participants were diagnosed with diabetes if they had a fasting blood glucose of 126 mg/dL or greater, a 2-hour GTT blood glucose level of 200 mg/dL or greater, or HbA1c of 6.5% or greater.

Dr. Werner and colleagues conducted two analyses of their results. In the first, they included only women in both arms who had complete data. In the second analysis, they looked at all women who had data for the 1-year postpartum mark, assuming that interval GTTs were negative for women who were missing these values.

The statistical analysis showed that, for women with complete data, both early and later postpartum GTTs were similar in predicting impaired glucose metabolism at 1 year postpartum (areas under the receiver operating curve [AUC], 0.63 and 0.60, respectively).

For identifying diabetes at 1 year, both early and late testing had high negative predictive value (98% and 99%, respectively), but the later testing strategy had higher sensitivity and specificity, yielding an AUC of 0.83, compared with 0.65 for early testing.

Turning to the second analysis that included all women who had 1-year postpartum HbA1c values, negative predictive values for diabetes were similarly high (98%) for both the early and late testing strategies. For identifying impaired glucose metabolism at 1 year in this group, both the positive and negative predictive value of the early and late strategies were similar.

Patients were about 32 years old at baseline, with a mean body mass index of 31.7 kg/m2. More than half of patients (52.3%) had private insurance, and 22% had GDM in a pregnancy prior to the index pregnancy. Black patients made up about 9% of the study population; 54% of participants were white, and 23% Hispanic. About one-third of patients were nulliparous, and two-thirds had education beyond high school.

During their pregnancies, about 44% of patients managed GDM by diet alone, 40% required insulin, with an additional 1% also requiring an oral agent. The remainder required oral agents alone. Patients delivered at a mean 38.3 weeks gestation, with about 40% receiving cesarean deliveries.

Some of the study’s strengths included its prospective nature, the diverse population recruited, and the fact that participants and providers were both blinded to the 2-day GTT results. Although more than half of participants completed the study – besting the previous pilots – 44% of patients still had incomplete data, noted Dr. Werner.

The American Diabetes Association sponsored the study. Dr. Werner reported no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Werner E et al. SMFM 2020. Abstract 72.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Early postpartum glucose tolerance testing for women with gestational diabetes resulted in a 99% adherence rate, with similar sensitivity and specificity as the currently recommended 4- to 12-week postpartum testing schedule.

“Two-day postpartum glucose tolerance testing has similar diagnostic utility as the 4- to 12-week postpartum glucose tolerance test to identify impaired glucose metabolism and diabetes at 1 year postpartum,” said Erika Werner, MD, speaking at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Overall, 29% of women studied had impaired glucose metabolism at 2 days postpartum, as did 25% in the 4- to 12-weeks postpartum window. At 1 year, that figure was 35%. The number of women meeting diagnostic criteria for diabetes held steady at 4% for all three time points.

The findings warrant “consideration for the 2-day postpartum glucose tolerance test (GTT) as the initial postpartum test for women who have gestational diabetes, with repeat testing at 1 year,” said Dr. Werner, a maternal-fetal medicine physician at Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Glucose testing for women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is recommended at 4-12 weeks postpartum by both the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Testing can allow detection and treatment of impaired glucose metabolism, seen in 15%-40% of women with a history of GDM. Up to 1 in 20 women with GDM will receive a postpartum diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

However, fewer than one in five women will actually have postpartum glucose testing, representing a large missed opportunity, said Dr. Werner.

Several factors likely contribute to those screening failures, she added. In addition to the potential for public insurance to lapse at 6 weeks postpartum, the logistical realities and time demands of parenting a newborn are themselves a significant barrier.

“What if we changed the timing?” and shifted glucose testing to the early postpartum days, before hospital discharge, asked Dr. Werner. Several pilot studies had already compared glucose screening in the first few days postpartum with the routine schedule, finding good correlation between the early and routine GTT schedule.

Importantly, the earlier studies achieved an adherence rate of more than 90% for early GTT. By contrast, fewer than half of the participants in the usual-care arms actually returned for postpartum GTT in the 4- to 12-week postpartum window, even under the optimized conditions associated with a medical study.

The single-center prospective cohort study conducted by Dr. Werner and collaborators enrolled 300 women with GDM. Women agreed to participate in glucose tolerance testing as inpatients, at 2 days postpartum, in addition to receiving a GTT between 4 and 12 weeks postpartum, and additional screening that included a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) test at 1 year postpartum.

The investigators obtained postpartum day 2 GTTs for all but four of the patients. A total of 201 patients returned in the 4- to 12-week postpartum window, and 168 of those participants returned for HbA1c testing at 1 year. Of the 95 patients who didn’t come back for the 4- to 12-week test, 33 did return at 1 year for HbA1c testing.

Dr. Werner and her coinvestigators included adult women who spoke either fluent Spanish or English and had GDM diagnosed by the Carpenter-Coustan criteria, or by having a blood glucose level of 200 mg/dL or more in a 1-hour glucose challenge test.

The early GTT results weren’t shared with patients or their health care providers. For outpatient visits, participants were offered financial incentives and received multiple reminder phone calls and the offer of free transportation.

For the purposes of the study, impaired glucose metabolism was defined as fasting blood glucose of 100 mg/dL or greater, a 2-hour GTT blood glucose level of 140 mg/dL or greater, or HbA1c of 5.7% or greater.

Participants were diagnosed with diabetes if they had a fasting blood glucose of 126 mg/dL or greater, a 2-hour GTT blood glucose level of 200 mg/dL or greater, or HbA1c of 6.5% or greater.

Dr. Werner and colleagues conducted two analyses of their results. In the first, they included only women in both arms who had complete data. In the second analysis, they looked at all women who had data for the 1-year postpartum mark, assuming that interval GTTs were negative for women who were missing these values.

The statistical analysis showed that, for women with complete data, both early and later postpartum GTTs were similar in predicting impaired glucose metabolism at 1 year postpartum (areas under the receiver operating curve [AUC], 0.63 and 0.60, respectively).

For identifying diabetes at 1 year, both early and late testing had high negative predictive value (98% and 99%, respectively), but the later testing strategy had higher sensitivity and specificity, yielding an AUC of 0.83, compared with 0.65 for early testing.

Turning to the second analysis that included all women who had 1-year postpartum HbA1c values, negative predictive values for diabetes were similarly high (98%) for both the early and late testing strategies. For identifying impaired glucose metabolism at 1 year in this group, both the positive and negative predictive value of the early and late strategies were similar.

Patients were about 32 years old at baseline, with a mean body mass index of 31.7 kg/m2. More than half of patients (52.3%) had private insurance, and 22% had GDM in a pregnancy prior to the index pregnancy. Black patients made up about 9% of the study population; 54% of participants were white, and 23% Hispanic. About one-third of patients were nulliparous, and two-thirds had education beyond high school.

During their pregnancies, about 44% of patients managed GDM by diet alone, 40% required insulin, with an additional 1% also requiring an oral agent. The remainder required oral agents alone. Patients delivered at a mean 38.3 weeks gestation, with about 40% receiving cesarean deliveries.

Some of the study’s strengths included its prospective nature, the diverse population recruited, and the fact that participants and providers were both blinded to the 2-day GTT results. Although more than half of participants completed the study – besting the previous pilots – 44% of patients still had incomplete data, noted Dr. Werner.

The American Diabetes Association sponsored the study. Dr. Werner reported no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Werner E et al. SMFM 2020. Abstract 72.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Vitamin D supplements in pregnancy boost bone health in offspring

Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy is associated with higher bone mineral content in the offspring, even up to 6 years after birth, research suggests.

“The well-established tracking of bone mineralization from early life throughout childhood and early adulthood is a key factor for the final peak bone mass gained and the subsequent risk of fractures and osteoporosis later in life,” wrote Nicklas Brustad, MD, of the Herlev and Gentofte Hospital at the University of Copenhagen, and coauthors. Their report is in JAMA Pediatrics.This was a secondary analysis of a prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial of high versus standard dose vitamin D supplementation in 623 pregnant Danish women and the outcomes in their 584 children. The women were randomized either to a daily dose of 2,400 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or matching placebo capsules from 24 weeks’ gestation until 1 week after birth. All women were advised to maintain a daily intake of 400 IU of vitamin D3.

The children underwent anthropometric growth assessments regularly up to age 6 years, and underwent whole-body dual-energy radiograph absorptiometry (DXA) scanning at 3 years and 6 years.

At 3 years, children of mothers who received the vitamin D supplements showed significantly higher mean total-body-less-head (TBLH) bone mineral content (BMC) compared with those who received placebo (294 g vs. 289 g) and total-body BMC (526 g vs. 514 g), respectively, after adjustment for age, sex, height, and weight.

The difference in total-body BMC was particularly evident in children of mothers who had insufficient vitamin D levels at baseline, compared with those with sufficient vitamin D levels (538 g vs. 514 g). The study also saw higher head bone mineral density (BMD) in children of mothers with insufficient vitamin D at baseline who received supplementation.

At 6 years, there still were significant differences in BMC between the supplementation and placebo groups. Children in the vitamin D group had an 8-g greater TBLH BMC compared with those in the placebo group, and a 14-g higher total BMC.

Among the children of mothers with insufficient preintervention vitamin D, there was an 18-g higher mean total BMC and 0.0125 g/cm2 greater total BMD, compared with those with sufficient vitamin D at baseline.

Overall, the children of mothers who received high-dose vitamin D supplementation had a mean 8-g higher TBLH BMC, a mean 0.023 g/cm2 higher head BMD, and a mean 12-g higher total BMC.

Dr. Brustad and associates noted that the head could represent the most sensitive compartment for intervention, because 80% of bone mineralization of the skull occurs by the age of 3 years.

The study also showed a seasonal effect, such that mothers who gave birth in winter showed the greatest effects of vitamin D supplementation on head BMC.

There was a nonsignificant trend toward a lower fracture rate among children in the supplementation group, compared with the placebo group.

“We speculate that these intervention effects could be of importance for bone health and osteoporosis risk in adult life, which is supported by our likely underpowered post hoc analysis on fracture risk, suggesting an almost 40% reduced incidence of fractures of the larger bones in the high-dose vitamin D group,” the authors wrote.

Vitamin D supplementation did not appear to affect the children’s growth. At 6 years, there were no significant differences between the two groups in body mass index, height, weight, or waist, head, and thorax circumference.

Neonatologist Carol Wagner, MD, said in an interview that the study provided an absolute reason for vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy.

“At the very least, a study like this argues for much more than is recommended by the European nutrition group or the U.S. group,” said Dr. Wagner, professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. “Here you have a therapy that costs literally pennies a day, and no one should be deficient.”

She also pointed out that the study was able to show significant effects on BMC despite the fact that there would have been considerable variation in postnatal vitamin D intake from breast milk or formula.

Cristina Palacios, PhD, an associate professor in the department of dietetics and nutrition at Florida International University, Miami, said that vitamin D deficiency is increasingly prevalent worldwide, and is associated with a return of rickets – the skeletal disorder caused by vitamin D deficiency – in children.

“If women are deficient during pregnancy, providing vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy may promote bone health in their offspring,” Dr. Palacios said in an interview. “Because vitamin D is such an important component of bone metabolism, this could prevent future rickets in these children.”

Dr. Palacios coauthored a recent Cochrane review that examined the safety of high-dose vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy, and said the analysis found no evidence of safety concerns.

The study was supported by The Lundbeck Foundation, the Ministry of Health, Danish Council for Strategic Research, and the Capital Region Research Foundation. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Brustad N et al. JAMA Pediatrics 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6083.

Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy is associated with higher bone mineral content in the offspring, even up to 6 years after birth, research suggests.

“The well-established tracking of bone mineralization from early life throughout childhood and early adulthood is a key factor for the final peak bone mass gained and the subsequent risk of fractures and osteoporosis later in life,” wrote Nicklas Brustad, MD, of the Herlev and Gentofte Hospital at the University of Copenhagen, and coauthors. Their report is in JAMA Pediatrics.This was a secondary analysis of a prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial of high versus standard dose vitamin D supplementation in 623 pregnant Danish women and the outcomes in their 584 children. The women were randomized either to a daily dose of 2,400 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or matching placebo capsules from 24 weeks’ gestation until 1 week after birth. All women were advised to maintain a daily intake of 400 IU of vitamin D3.

The children underwent anthropometric growth assessments regularly up to age 6 years, and underwent whole-body dual-energy radiograph absorptiometry (DXA) scanning at 3 years and 6 years.

At 3 years, children of mothers who received the vitamin D supplements showed significantly higher mean total-body-less-head (TBLH) bone mineral content (BMC) compared with those who received placebo (294 g vs. 289 g) and total-body BMC (526 g vs. 514 g), respectively, after adjustment for age, sex, height, and weight.

The difference in total-body BMC was particularly evident in children of mothers who had insufficient vitamin D levels at baseline, compared with those with sufficient vitamin D levels (538 g vs. 514 g). The study also saw higher head bone mineral density (BMD) in children of mothers with insufficient vitamin D at baseline who received supplementation.

At 6 years, there still were significant differences in BMC between the supplementation and placebo groups. Children in the vitamin D group had an 8-g greater TBLH BMC compared with those in the placebo group, and a 14-g higher total BMC.

Among the children of mothers with insufficient preintervention vitamin D, there was an 18-g higher mean total BMC and 0.0125 g/cm2 greater total BMD, compared with those with sufficient vitamin D at baseline.

Overall, the children of mothers who received high-dose vitamin D supplementation had a mean 8-g higher TBLH BMC, a mean 0.023 g/cm2 higher head BMD, and a mean 12-g higher total BMC.

Dr. Brustad and associates noted that the head could represent the most sensitive compartment for intervention, because 80% of bone mineralization of the skull occurs by the age of 3 years.

The study also showed a seasonal effect, such that mothers who gave birth in winter showed the greatest effects of vitamin D supplementation on head BMC.

There was a nonsignificant trend toward a lower fracture rate among children in the supplementation group, compared with the placebo group.

“We speculate that these intervention effects could be of importance for bone health and osteoporosis risk in adult life, which is supported by our likely underpowered post hoc analysis on fracture risk, suggesting an almost 40% reduced incidence of fractures of the larger bones in the high-dose vitamin D group,” the authors wrote.

Vitamin D supplementation did not appear to affect the children’s growth. At 6 years, there were no significant differences between the two groups in body mass index, height, weight, or waist, head, and thorax circumference.

Neonatologist Carol Wagner, MD, said in an interview that the study provided an absolute reason for vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy.

“At the very least, a study like this argues for much more than is recommended by the European nutrition group or the U.S. group,” said Dr. Wagner, professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. “Here you have a therapy that costs literally pennies a day, and no one should be deficient.”

She also pointed out that the study was able to show significant effects on BMC despite the fact that there would have been considerable variation in postnatal vitamin D intake from breast milk or formula.

Cristina Palacios, PhD, an associate professor in the department of dietetics and nutrition at Florida International University, Miami, said that vitamin D deficiency is increasingly prevalent worldwide, and is associated with a return of rickets – the skeletal disorder caused by vitamin D deficiency – in children.

“If women are deficient during pregnancy, providing vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy may promote bone health in their offspring,” Dr. Palacios said in an interview. “Because vitamin D is such an important component of bone metabolism, this could prevent future rickets in these children.”

Dr. Palacios coauthored a recent Cochrane review that examined the safety of high-dose vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy, and said the analysis found no evidence of safety concerns.

The study was supported by The Lundbeck Foundation, the Ministry of Health, Danish Council for Strategic Research, and the Capital Region Research Foundation. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Brustad N et al. JAMA Pediatrics 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6083.

Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy is associated with higher bone mineral content in the offspring, even up to 6 years after birth, research suggests.

“The well-established tracking of bone mineralization from early life throughout childhood and early adulthood is a key factor for the final peak bone mass gained and the subsequent risk of fractures and osteoporosis later in life,” wrote Nicklas Brustad, MD, of the Herlev and Gentofte Hospital at the University of Copenhagen, and coauthors. Their report is in JAMA Pediatrics.This was a secondary analysis of a prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial of high versus standard dose vitamin D supplementation in 623 pregnant Danish women and the outcomes in their 584 children. The women were randomized either to a daily dose of 2,400 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or matching placebo capsules from 24 weeks’ gestation until 1 week after birth. All women were advised to maintain a daily intake of 400 IU of vitamin D3.

The children underwent anthropometric growth assessments regularly up to age 6 years, and underwent whole-body dual-energy radiograph absorptiometry (DXA) scanning at 3 years and 6 years.

At 3 years, children of mothers who received the vitamin D supplements showed significantly higher mean total-body-less-head (TBLH) bone mineral content (BMC) compared with those who received placebo (294 g vs. 289 g) and total-body BMC (526 g vs. 514 g), respectively, after adjustment for age, sex, height, and weight.

The difference in total-body BMC was particularly evident in children of mothers who had insufficient vitamin D levels at baseline, compared with those with sufficient vitamin D levels (538 g vs. 514 g). The study also saw higher head bone mineral density (BMD) in children of mothers with insufficient vitamin D at baseline who received supplementation.

At 6 years, there still were significant differences in BMC between the supplementation and placebo groups. Children in the vitamin D group had an 8-g greater TBLH BMC compared with those in the placebo group, and a 14-g higher total BMC.

Among the children of mothers with insufficient preintervention vitamin D, there was an 18-g higher mean total BMC and 0.0125 g/cm2 greater total BMD, compared with those with sufficient vitamin D at baseline.

Overall, the children of mothers who received high-dose vitamin D supplementation had a mean 8-g higher TBLH BMC, a mean 0.023 g/cm2 higher head BMD, and a mean 12-g higher total BMC.

Dr. Brustad and associates noted that the head could represent the most sensitive compartment for intervention, because 80% of bone mineralization of the skull occurs by the age of 3 years.

The study also showed a seasonal effect, such that mothers who gave birth in winter showed the greatest effects of vitamin D supplementation on head BMC.

There was a nonsignificant trend toward a lower fracture rate among children in the supplementation group, compared with the placebo group.

“We speculate that these intervention effects could be of importance for bone health and osteoporosis risk in adult life, which is supported by our likely underpowered post hoc analysis on fracture risk, suggesting an almost 40% reduced incidence of fractures of the larger bones in the high-dose vitamin D group,” the authors wrote.

Vitamin D supplementation did not appear to affect the children’s growth. At 6 years, there were no significant differences between the two groups in body mass index, height, weight, or waist, head, and thorax circumference.

Neonatologist Carol Wagner, MD, said in an interview that the study provided an absolute reason for vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy.

“At the very least, a study like this argues for much more than is recommended by the European nutrition group or the U.S. group,” said Dr. Wagner, professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. “Here you have a therapy that costs literally pennies a day, and no one should be deficient.”

She also pointed out that the study was able to show significant effects on BMC despite the fact that there would have been considerable variation in postnatal vitamin D intake from breast milk or formula.

Cristina Palacios, PhD, an associate professor in the department of dietetics and nutrition at Florida International University, Miami, said that vitamin D deficiency is increasingly prevalent worldwide, and is associated with a return of rickets – the skeletal disorder caused by vitamin D deficiency – in children.

“If women are deficient during pregnancy, providing vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy may promote bone health in their offspring,” Dr. Palacios said in an interview. “Because vitamin D is such an important component of bone metabolism, this could prevent future rickets in these children.”

Dr. Palacios coauthored a recent Cochrane review that examined the safety of high-dose vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy, and said the analysis found no evidence of safety concerns.

The study was supported by The Lundbeck Foundation, the Ministry of Health, Danish Council for Strategic Research, and the Capital Region Research Foundation. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Brustad N et al. JAMA Pediatrics 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6083.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

FDA approves weekly contraceptive patch Twirla

in women whose body mass index is less than 30 kg/m2 and for whom a combined hormonal contraceptive is appropriate.

Applied weekly to the abdomen, buttock, or upper torso (excluding the breasts), Twirla delivers a 30-mcg daily dose of ethinyl estradiol and 120-mcg daily dose of levonorgestrel.

“Twirla is an important addition to available hormonal contraceptive methods, allowing prescribers to now offer appropriate U.S. women a weekly transdermal option that delivers estrogen levels in line with labeled doses of many commonly prescribed oral contraceptives, David Portman, MD, an obstetrician/gynecologist in Columbus, Ohio, and a primary investigator of the SECURE trial, said in a news release issued by the company.

Twirla was evaluated in “a diverse population providing important data to prescribers and to women seeking contraception. It is vital to expand the full range of contraceptive methods and inform the choices that fit an individual’s family planning needs and lifestyle,” Dr. Portman added.

As part of approval, the FDA will require Agile Therapeutics to conduct a long-term, prospective, observational postmarketing study to assess risks for venous thromboembolism and arterial thromboembolism in new users of Twirla, compared with new users of other combined hormonal contraceptives.

Twirla is contraindicated in women at high risk for arterial or venous thrombotic disease, including women with a BMI equal to or greater than 30 kg/m2; women who have headaches with focal neurologic symptoms or migraine with aura; and women older than 35 years who have any migraine headache.

Twirla also should be avoided in women who have liver tumors, acute viral hepatitis, decompensated cirrhosis, liver disease, or undiagnosed abnormal uterine bleeding. It also should be avoided during pregnancy; in women who currently have or who have history of breast cancer or other estrogen- or progestin-sensitive cancer; in women who are hypersensitivity to any components of Twirla; and in women who use hepatitis C drug combinations containing ombitasvir/paraparesis/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir.

Because cigarette smoking increases the risk for serious cardiovascular events from combined hormonal contraceptive use, Twirla also is contraindicated in women older than 35 who smoke.

Twirla will contain a boxed warning that will include these risks about cigarette smoking and the serious cardiovascular events, and it will stipulate that Twirla is contraindicated in women with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in women whose body mass index is less than 30 kg/m2 and for whom a combined hormonal contraceptive is appropriate.

Applied weekly to the abdomen, buttock, or upper torso (excluding the breasts), Twirla delivers a 30-mcg daily dose of ethinyl estradiol and 120-mcg daily dose of levonorgestrel.

“Twirla is an important addition to available hormonal contraceptive methods, allowing prescribers to now offer appropriate U.S. women a weekly transdermal option that delivers estrogen levels in line with labeled doses of many commonly prescribed oral contraceptives, David Portman, MD, an obstetrician/gynecologist in Columbus, Ohio, and a primary investigator of the SECURE trial, said in a news release issued by the company.

Twirla was evaluated in “a diverse population providing important data to prescribers and to women seeking contraception. It is vital to expand the full range of contraceptive methods and inform the choices that fit an individual’s family planning needs and lifestyle,” Dr. Portman added.

As part of approval, the FDA will require Agile Therapeutics to conduct a long-term, prospective, observational postmarketing study to assess risks for venous thromboembolism and arterial thromboembolism in new users of Twirla, compared with new users of other combined hormonal contraceptives.

Twirla is contraindicated in women at high risk for arterial or venous thrombotic disease, including women with a BMI equal to or greater than 30 kg/m2; women who have headaches with focal neurologic symptoms or migraine with aura; and women older than 35 years who have any migraine headache.

Twirla also should be avoided in women who have liver tumors, acute viral hepatitis, decompensated cirrhosis, liver disease, or undiagnosed abnormal uterine bleeding. It also should be avoided during pregnancy; in women who currently have or who have history of breast cancer or other estrogen- or progestin-sensitive cancer; in women who are hypersensitivity to any components of Twirla; and in women who use hepatitis C drug combinations containing ombitasvir/paraparesis/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir.

Because cigarette smoking increases the risk for serious cardiovascular events from combined hormonal contraceptive use, Twirla also is contraindicated in women older than 35 who smoke.

Twirla will contain a boxed warning that will include these risks about cigarette smoking and the serious cardiovascular events, and it will stipulate that Twirla is contraindicated in women with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in women whose body mass index is less than 30 kg/m2 and for whom a combined hormonal contraceptive is appropriate.

Applied weekly to the abdomen, buttock, or upper torso (excluding the breasts), Twirla delivers a 30-mcg daily dose of ethinyl estradiol and 120-mcg daily dose of levonorgestrel.

“Twirla is an important addition to available hormonal contraceptive methods, allowing prescribers to now offer appropriate U.S. women a weekly transdermal option that delivers estrogen levels in line with labeled doses of many commonly prescribed oral contraceptives, David Portman, MD, an obstetrician/gynecologist in Columbus, Ohio, and a primary investigator of the SECURE trial, said in a news release issued by the company.

Twirla was evaluated in “a diverse population providing important data to prescribers and to women seeking contraception. It is vital to expand the full range of contraceptive methods and inform the choices that fit an individual’s family planning needs and lifestyle,” Dr. Portman added.

As part of approval, the FDA will require Agile Therapeutics to conduct a long-term, prospective, observational postmarketing study to assess risks for venous thromboembolism and arterial thromboembolism in new users of Twirla, compared with new users of other combined hormonal contraceptives.

Twirla is contraindicated in women at high risk for arterial or venous thrombotic disease, including women with a BMI equal to or greater than 30 kg/m2; women who have headaches with focal neurologic symptoms or migraine with aura; and women older than 35 years who have any migraine headache.

Twirla also should be avoided in women who have liver tumors, acute viral hepatitis, decompensated cirrhosis, liver disease, or undiagnosed abnormal uterine bleeding. It also should be avoided during pregnancy; in women who currently have or who have history of breast cancer or other estrogen- or progestin-sensitive cancer; in women who are hypersensitivity to any components of Twirla; and in women who use hepatitis C drug combinations containing ombitasvir/paraparesis/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir.

Because cigarette smoking increases the risk for serious cardiovascular events from combined hormonal contraceptive use, Twirla also is contraindicated in women older than 35 who smoke.

Twirla will contain a boxed warning that will include these risks about cigarette smoking and the serious cardiovascular events, and it will stipulate that Twirla is contraindicated in women with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

2020 Update on fertility

Although we are not able to cover all of the important developments in fertility medicine over the past year, there were 3 important articles published in the past 12 months that we highlight here. First, we discuss an American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) committee opinion on genetic carrier screening that was reaffirmed in 2019. Second, we explore an interesting retrospective analysis of time-lapse videos and clinical outcomes of more than 10,000 embryos from 8 IVF clinics, across 4 countries. The authors assessed whether a deep learning model could predict the probability of pregnancy with fetal heart from time-lapse videos in the hopes that their research can improve prioritization of the most viable embryo for single embryo transfer. Last, we consider a review of the data on obstetric and reproductive health effects of preconception and prenatal exposure to several environmental toxicants, including heavy metals, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, pesticides, and air pollution.

Preconception genetic carrier screening: Standardize your counseling approach

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. Committee Opinion No. 690: carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e35-e40.

With the rapid development of advanced and high throughput platforms for DNA sequencing in the past several years, the cost of genetic testing has decreased dramatically. Women's health care providers in general, and fertility specialists in particular, are uniquely positioned to take advantage of these novel and yet affordable technologies by counseling prospective parents during the preconception counseling, or early prenatal period, about the availability of genetic carrier screening and its potential to provide actionable information in a timely manner. The ultimate objective of genetic carrier screening is to enable individuals to make an informed decision regarding their reproductive choices based on their personal values. In a study by Larsen and colleagues, the uptake of genetic carrier screening was significantly higher when offered in the preconception period (68.7%), compared with during pregnancy (35.1%), which highlights the significance of early counseling.1

Based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Birth/Infant Death Data set, birth defects affect 1 in every 33 (about 3%) of all babies born in the United States each year and account for 20% of infant mortality.2 About 20% of birth defects are caused by single-gene (monogenic) disorders, and although some of these are due to dominant conditions or de novo mutations, a significant proportion are due to autosomal recessive, or X-chromosome linked conditions that are commonly assessed by genetic carrier screening.

ACOG published a committee opinion on "Carrier Screening in the Age of Genomic Medicine" in March 2017, which was reaffirmed in 2019.3

Residual risk. Several points discussed in this document are of paramount importance, including the need for pretest and posttest counseling and consent, as well as a discussion of "residual risk." Newer platforms employ sequencing techniques that potentially can detect most, if not all, of the disease-causing variants in the tested genes, such as the gene for cystic fibrosis and, therefore, have a higher detection rate compared with the older PCR-based techniques for a limited number of specific mutations included in the panel. Due to a variety of technical and biological limitations, however, such as allelic dropouts and the occurrence of de novo mutations, the detection rate is not 100%; there is always a residual risk that needs to be estimated and provided to individuals based on the existing knowledge on frequency of gene, penetrance of phenotype, and prevalence of condition in the general and specific ethnic populations.

Continue to: Expanded vs panethnic screening...

Expanded vs panethnic screening. Furthermore, although sequencing technology has made "expanded carrier screening" for several hundred conditions, simultaneous to and independent of ethnicity and family history, more easily available and affordable, ethnic-specific and panethnic screening for a more limited number of conditions are still acceptable approaches. Having said this, when the first partner screened is identified to be a carrier, his/her reproductive partners must be offered next-generation sequencing to identify less common disease-causing variants.4

A cautionary point to consider when expanded carrier screening panels are requested is the significant variability among commercial laboratories with regard to the conditions included in their panels. In addition, consider the absence of a well-defined or predictable phenotype for some of the included conditions.

Perhaps the most important matter when it comes to genetic carrier screening is to have a standard counseling approach that is persistently followed and offers the opportunity for individuals to know about their genetic testing options and available reproductive choices, including the use of donor gametes, preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disease (PGT-M, formerly known as preimplantation genetic diagnosis, or PGD), prenatal testing, and pregnancy management options. For couples and/or individuals who decide to proceed with an affected pregnancy, earlier diagnosis can assist with postnatal management.

Medicolegal responsibility. Genetic carrier screening also is of specific relevance to the field of fertility medicine and assisted reproductive technology (ART) as a potential liability issue. Couples and individuals who are undergoing fertility treatment with in vitro fertilization (IVF) for a variety of medical or personal reasons are a specific group that certainly should be offered genetic carrier screening, as they have the option of "adding on" PGT-M (PGD) to their existing treatment plan at a fraction of the cost and treatment burden that would have otherwise been needed if they were not undergoing IVF. After counseling, some individuals and couples may ultimately opt out of genetic carrier screening. The counseling discussion needs to be clearly documented in the medical chart.

The preconception period is the perfect time to have a discussion about genetic carrier screening; it offers the opportunity for timely interventions if desired by the couples or individuals.

Continue to: Artificial intelligence and embryo selection...

Artificial intelligence and embryo selection

With continued improvements in embryo culture conditions and cryopreservation technology, there has been a tremendous amount of interest in developing better methods for embryo selection. These efforts are aimed at encouraging elective single embryo transfer (eSET) for women of all ages, thereby lowering the risk of multiple pregnancy and its associated adverse neonatal and obstetric outcomes—without compromising the pregnancy rates per transfer or lengthening the time to pregnancy.

One of the most extensively studied methods for this purpose is preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A, formerly known as PGS), but emerging data from large multicenter randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have again cast significant doubt on PGT-A's efficacy and utility.5 Meanwhile, alternative methods for embryo selection are currently under investigation, including noninvasive PGT-A and morphokinetic assessment of embryo development via analysis of images obtained by time-lapse imaging.

The potential of time-lapse imaging

Despite the initial promising results from time-lapse imaging, subsequent RCTs have not shown a significant clinical benefit.6 However, these early methods of morphokinetic assessment are mainly dependent on the embryologists' subjective assessment of individual static frames and "annotation" of observed spatial and temporal features of embryo development. In addition to being a very time-consuming task, this process is subject to significant interobserver and intraobserver variability.

Considering these limitations, even machine-based algorithms that incorporate these annotations along with such other clinical variables as parental age and prior obstetric history, have a low predictive power for the outcome of embryo transfer, with an area under the curve (AUC) of the ROC curve of 0.65 to 0.74. (An AUC of 0.5 represents completely random prediction and an AUC of 1.0 suggests perfect prediction.)7

A recent study by Tran and colleagues has employed a deep learning (neural network) model to analyze the entire raw time-lapse videos in an automated manner without prior annotation by embryologists. After analysis of 10,638 embryos from 8 different IVF clinics in 4 different countries, they have reported an AUC of 0.93 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.94) for prediction of fetal heart rate activity detected at 7 weeks of gestation or beyond. Although these data are very preliminary and have not yet been validated prospectively in larger datasets for live birth, it may herald the beginning of a new era for the automation and standardization of embryo assessment with artificial intelligence—similar to the rapidly increasing role of facial recognition technology for various applications.

Improved standardization of noninvasive embryo selection with growing use of artificial intelligence is a promising new tool to improve the safety and efficacy of ART.

Continue to: Environmental toxicants: The hidden danger...

Environmental toxicants: The hidden danger

Segal TR, Giudice LC. Before the beginning: environmental exposures and reproductive and obstetrical outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:613-621.

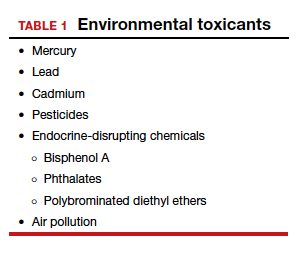

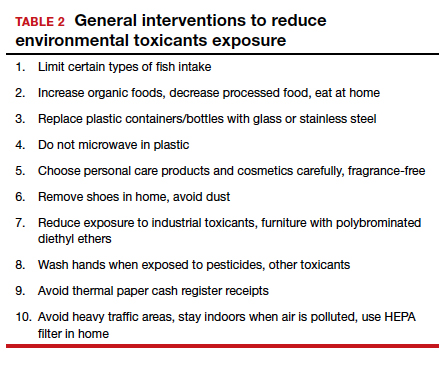

We receive news daily about the existential risk to humans of climate change. However, a risk that is likely as serious goes almost unseen by the public and most health care providers. That risk is environmental toxicants.8