User login

Microplastics permeate human placentas

Researchers in Italy have identified microplastic (MP) fragments in four human placentas that were donated for study after delivery.

“The presence of MPs in the placenta tissue requires the reconsideration of the immunological mechanism of self-tolerance,” wrote Antonio Ragusa, MD, of San Giovanni Calibita Fatebenefratelli Hospital, Rome, and colleagues. “Placenta represents the interface between the fetus and the environment.”

In a pilot observational study published in Environment International, the researchers used Raman microspectroscopy to analyze placentas from six women with physiological pregnancies for the presence of MPs. MPs were defined as particles smaller than 5 mm resulting from the degradation of plastic in the environment, such as plastic objects, coatings, adhesives, paints, and personal care products. Data from previous studies have shown that MPs can move into living organisms, but this study is the first to identify MPs in human placentas, the researchers said.

Polypropylene and pigments identified

A total of 12 microplastic fragments were identified in tissue from the placentas of four women; 5 in the fetal side, 4 in the maternal side, and 3 in the chorioamniotic membranes, which suggests that MPs can reach all levels of placental tissue, the researchers said. Most of the MPs were approximately 10 mcm in size, but two were roughly 5 mcm.

All 12 of the MPs were pigmented; of these, 3 were identified as stained polypropylene and the other 9 contained pigments used in a variety of items including coatings, paints, adhesives, plasters, finger paints, polymers and cosmetics, and personal care products. The researchers used a software program to analyze the pigments and matched them with information from the European Chemical Agency for identification of the commercial name, chemical formula, International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry name, and Color Index Constitution Number.

The mechanism by which MPs may enter the bloodstream and access the placenta remains unclear, the researchers said. “The most probable transport route for MPs is a mechanism of particle uptake and translocation, already described for the internalization from the gastrointestinal tract. Once MPs have reached the maternal surface of the placenta, as other exogenous materials, they can invade the tissue in depth by several transport mechanisms, both active and passive, that are not clearly understood yet.”

The range in location and characteristics of the particles found in the study suggest that passage of MPs into the placenta may be affected by physiological conditions and genetics, as well as food and lifestyle habits of the patients, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size and observational study design.

However, the presence of MPs in the placenta could affect the pregnancy in various ways, including immunity, growth factor signaling, maternal-fetal communication, and trafficking of various cell types and macrophages, the researchers wrote. In addition, MPs could have a transgenerational effect on metabolism and reproduction.

“Further studies need to be performed to assess if the presence of MPs in human placenta may trigger immune responses or may lead to the release of toxic contaminants, resulting harmful for pregnancy,” they concluded.

Cause for concern, but research gaps remain

“Microplastics are ubiquitous in the environment and are detectable in tissues of humans and wildlife,” Andrea C. Gore, PhD, of the University of Texas, Austin, said in an interview. “To my knowledge, this was never previously shown in the placenta.

“There are two reasons why detection of microplastics in placenta would be concerning,” Dr. Gore explained. “First, microplastics may be endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), or they may concentrate other chemicals that are EDCs. Second, the developing fetus is exquisitely sensitive to natural hormones, and disruptions by EDCs may lead to both immediate as well as latent health problems.

“Clinicians should be concerned about particulate matter in the placenta, “although the number of particles was very small,” said Dr. Gore. “Out of six women, four had particles in their placentas (total of 12) of which one was confirmed to be a plastic (polypropylene). For the other 11 particles, only the pigments could be identified, so more work is needed to confirm whether they were plastics.

“If I were a clinician discussing this article with my patients, I would point out that, although it is concerning that microparticles are present in placenta, few of them were found, and it is not known whether any chemical is released from the particles or actually reaches the fetal circulation,” Dr. Gore said. “I would use it as a starting point for a conversation about lifestyle during pregnancy and encouraging pregnant women to avoid eating foods stored and/or prepared in plastics.”

The limitations of the study include not only the small sample size, but also that “the type of chemicals in the microplastics is for the most part unknown, making it difficult to assess which (if any) might be EDCs,” Dr. Gore emphasized. In addition, “lifestyle and diet can greatly affect exposures to chemicals, so this needs to be carefully factored into the analysis.” Also, “most of the detected particles are pigments, so connections to plastics (other than the one polypropylene particle) need to be strengthened,” she explained.

“The pathways by which microplastics might get into tissues are still rather speculative, and the mechanisms proposed by the authors (endocytosis, paracellular diffusion, entry via airways) need to be demonstrated,” Dr. Gore concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gore had no conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Ragusa A et al. Environ Int. 2020 Dec 2. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106274.

Researchers in Italy have identified microplastic (MP) fragments in four human placentas that were donated for study after delivery.

“The presence of MPs in the placenta tissue requires the reconsideration of the immunological mechanism of self-tolerance,” wrote Antonio Ragusa, MD, of San Giovanni Calibita Fatebenefratelli Hospital, Rome, and colleagues. “Placenta represents the interface between the fetus and the environment.”

In a pilot observational study published in Environment International, the researchers used Raman microspectroscopy to analyze placentas from six women with physiological pregnancies for the presence of MPs. MPs were defined as particles smaller than 5 mm resulting from the degradation of plastic in the environment, such as plastic objects, coatings, adhesives, paints, and personal care products. Data from previous studies have shown that MPs can move into living organisms, but this study is the first to identify MPs in human placentas, the researchers said.

Polypropylene and pigments identified

A total of 12 microplastic fragments were identified in tissue from the placentas of four women; 5 in the fetal side, 4 in the maternal side, and 3 in the chorioamniotic membranes, which suggests that MPs can reach all levels of placental tissue, the researchers said. Most of the MPs were approximately 10 mcm in size, but two were roughly 5 mcm.

All 12 of the MPs were pigmented; of these, 3 were identified as stained polypropylene and the other 9 contained pigments used in a variety of items including coatings, paints, adhesives, plasters, finger paints, polymers and cosmetics, and personal care products. The researchers used a software program to analyze the pigments and matched them with information from the European Chemical Agency for identification of the commercial name, chemical formula, International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry name, and Color Index Constitution Number.

The mechanism by which MPs may enter the bloodstream and access the placenta remains unclear, the researchers said. “The most probable transport route for MPs is a mechanism of particle uptake and translocation, already described for the internalization from the gastrointestinal tract. Once MPs have reached the maternal surface of the placenta, as other exogenous materials, they can invade the tissue in depth by several transport mechanisms, both active and passive, that are not clearly understood yet.”

The range in location and characteristics of the particles found in the study suggest that passage of MPs into the placenta may be affected by physiological conditions and genetics, as well as food and lifestyle habits of the patients, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size and observational study design.

However, the presence of MPs in the placenta could affect the pregnancy in various ways, including immunity, growth factor signaling, maternal-fetal communication, and trafficking of various cell types and macrophages, the researchers wrote. In addition, MPs could have a transgenerational effect on metabolism and reproduction.

“Further studies need to be performed to assess if the presence of MPs in human placenta may trigger immune responses or may lead to the release of toxic contaminants, resulting harmful for pregnancy,” they concluded.

Cause for concern, but research gaps remain

“Microplastics are ubiquitous in the environment and are detectable in tissues of humans and wildlife,” Andrea C. Gore, PhD, of the University of Texas, Austin, said in an interview. “To my knowledge, this was never previously shown in the placenta.

“There are two reasons why detection of microplastics in placenta would be concerning,” Dr. Gore explained. “First, microplastics may be endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), or they may concentrate other chemicals that are EDCs. Second, the developing fetus is exquisitely sensitive to natural hormones, and disruptions by EDCs may lead to both immediate as well as latent health problems.

“Clinicians should be concerned about particulate matter in the placenta, “although the number of particles was very small,” said Dr. Gore. “Out of six women, four had particles in their placentas (total of 12) of which one was confirmed to be a plastic (polypropylene). For the other 11 particles, only the pigments could be identified, so more work is needed to confirm whether they were plastics.

“If I were a clinician discussing this article with my patients, I would point out that, although it is concerning that microparticles are present in placenta, few of them were found, and it is not known whether any chemical is released from the particles or actually reaches the fetal circulation,” Dr. Gore said. “I would use it as a starting point for a conversation about lifestyle during pregnancy and encouraging pregnant women to avoid eating foods stored and/or prepared in plastics.”

The limitations of the study include not only the small sample size, but also that “the type of chemicals in the microplastics is for the most part unknown, making it difficult to assess which (if any) might be EDCs,” Dr. Gore emphasized. In addition, “lifestyle and diet can greatly affect exposures to chemicals, so this needs to be carefully factored into the analysis.” Also, “most of the detected particles are pigments, so connections to plastics (other than the one polypropylene particle) need to be strengthened,” she explained.

“The pathways by which microplastics might get into tissues are still rather speculative, and the mechanisms proposed by the authors (endocytosis, paracellular diffusion, entry via airways) need to be demonstrated,” Dr. Gore concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gore had no conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Ragusa A et al. Environ Int. 2020 Dec 2. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106274.

Researchers in Italy have identified microplastic (MP) fragments in four human placentas that were donated for study after delivery.

“The presence of MPs in the placenta tissue requires the reconsideration of the immunological mechanism of self-tolerance,” wrote Antonio Ragusa, MD, of San Giovanni Calibita Fatebenefratelli Hospital, Rome, and colleagues. “Placenta represents the interface between the fetus and the environment.”

In a pilot observational study published in Environment International, the researchers used Raman microspectroscopy to analyze placentas from six women with physiological pregnancies for the presence of MPs. MPs were defined as particles smaller than 5 mm resulting from the degradation of plastic in the environment, such as plastic objects, coatings, adhesives, paints, and personal care products. Data from previous studies have shown that MPs can move into living organisms, but this study is the first to identify MPs in human placentas, the researchers said.

Polypropylene and pigments identified

A total of 12 microplastic fragments were identified in tissue from the placentas of four women; 5 in the fetal side, 4 in the maternal side, and 3 in the chorioamniotic membranes, which suggests that MPs can reach all levels of placental tissue, the researchers said. Most of the MPs were approximately 10 mcm in size, but two were roughly 5 mcm.

All 12 of the MPs were pigmented; of these, 3 were identified as stained polypropylene and the other 9 contained pigments used in a variety of items including coatings, paints, adhesives, plasters, finger paints, polymers and cosmetics, and personal care products. The researchers used a software program to analyze the pigments and matched them with information from the European Chemical Agency for identification of the commercial name, chemical formula, International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry name, and Color Index Constitution Number.

The mechanism by which MPs may enter the bloodstream and access the placenta remains unclear, the researchers said. “The most probable transport route for MPs is a mechanism of particle uptake and translocation, already described for the internalization from the gastrointestinal tract. Once MPs have reached the maternal surface of the placenta, as other exogenous materials, they can invade the tissue in depth by several transport mechanisms, both active and passive, that are not clearly understood yet.”

The range in location and characteristics of the particles found in the study suggest that passage of MPs into the placenta may be affected by physiological conditions and genetics, as well as food and lifestyle habits of the patients, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size and observational study design.

However, the presence of MPs in the placenta could affect the pregnancy in various ways, including immunity, growth factor signaling, maternal-fetal communication, and trafficking of various cell types and macrophages, the researchers wrote. In addition, MPs could have a transgenerational effect on metabolism and reproduction.

“Further studies need to be performed to assess if the presence of MPs in human placenta may trigger immune responses or may lead to the release of toxic contaminants, resulting harmful for pregnancy,” they concluded.

Cause for concern, but research gaps remain

“Microplastics are ubiquitous in the environment and are detectable in tissues of humans and wildlife,” Andrea C. Gore, PhD, of the University of Texas, Austin, said in an interview. “To my knowledge, this was never previously shown in the placenta.

“There are two reasons why detection of microplastics in placenta would be concerning,” Dr. Gore explained. “First, microplastics may be endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), or they may concentrate other chemicals that are EDCs. Second, the developing fetus is exquisitely sensitive to natural hormones, and disruptions by EDCs may lead to both immediate as well as latent health problems.

“Clinicians should be concerned about particulate matter in the placenta, “although the number of particles was very small,” said Dr. Gore. “Out of six women, four had particles in their placentas (total of 12) of which one was confirmed to be a plastic (polypropylene). For the other 11 particles, only the pigments could be identified, so more work is needed to confirm whether they were plastics.

“If I were a clinician discussing this article with my patients, I would point out that, although it is concerning that microparticles are present in placenta, few of them were found, and it is not known whether any chemical is released from the particles or actually reaches the fetal circulation,” Dr. Gore said. “I would use it as a starting point for a conversation about lifestyle during pregnancy and encouraging pregnant women to avoid eating foods stored and/or prepared in plastics.”

The limitations of the study include not only the small sample size, but also that “the type of chemicals in the microplastics is for the most part unknown, making it difficult to assess which (if any) might be EDCs,” Dr. Gore emphasized. In addition, “lifestyle and diet can greatly affect exposures to chemicals, so this needs to be carefully factored into the analysis.” Also, “most of the detected particles are pigments, so connections to plastics (other than the one polypropylene particle) need to be strengthened,” she explained.

“The pathways by which microplastics might get into tissues are still rather speculative, and the mechanisms proposed by the authors (endocytosis, paracellular diffusion, entry via airways) need to be demonstrated,” Dr. Gore concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gore had no conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Ragusa A et al. Environ Int. 2020 Dec 2. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106274.

FROM ENVIRONMENT INTERNATIONAL

One in five gestational carriers do not meet ASRM criteria

About 20% of gestational carriers at one institution did not meet recommended criteria developed by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, according to a retrospective study of 194 patients.

The University of California, San Francisco, offers additional, stricter recommendations, including that gestational carriers have a body mass index less than 35. Under these stricter criteria, about 30% of the gestational carriers did not meet recommendations, Brett Stark, MD, MPH, reported at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2020 annual meeting, held virtually this year.

Deviating from BMI or age recommendations may be associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion, the analysis suggested. In addition, elements of a gestational carrier’s obstetric history not described in current guidelines, such as prior preterm birth, may influence gestational surrogacy outcomes.

The study was limited by incomplete information for some patients, the retrospective design, and the reliance on a relatively small cohort at a single center. Nevertheless, the findings potentially could inform discussions with patients, said Dr. Stark, a 3rd-year obstetrics and gynecology resident at the university.

Investigators aim to enroll patients in a longitudinal cohort study to further examine these questions, he said.

Protecting intended parents and carriers

“Gestational surrogacy has become an increasingly common form of third-party reproduction,” Dr. Stark said at the virtual meeting. The number of cases of in vitro fertilization (IVF) with gestational carriers increased from approximately 700 in 1999 to more than 5,500 in 2016, according to data from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. “Despite the increasing prevalence of gestational carrier utilization, there remains limited guidance with regard to optimizing outcomes for both the intended parents and gestational carriers.”

ASRM and UCSF recommendations are based on expert opinion and include surprisingly little discussion about the prior pregnancy outcomes of potential gestational carriers, Dr. Stark said.

“It is important for all parties involved that we generate research and data that can help drive the development of the guidelines,” he said. Such evidence may help intended parents understand characteristics of gestational carriers that may lead to live births. “For the gestational carriers, it is important that we have information on safety so that they know they are making appropriate decisions for their family and their life.”

Gestational carrier characteristics in the present study that deviated from 2017 ASRM recommendations included age less than 21 years or greater than 45 years, mental health conditions, and having more than five prior deliveries.

“ASRM guidelines focused on criteria for gestational carriers are meant to protect infertile couples, the carrier, as well as the supporting agency,” Alan Penzias, MD, chair of ASRM’s Practice Committee who is in private practice in Boston, said in a society news release that highlighted Dr. Stark’s study. “It is important that gestational carriers have a complete medical history and examination, in addition to a psychological session with a mental health professional to ensure there are no reasons for the carrier to not move forward with pregnancy.”

A retrospective study by Kate Swanson, MD, and associates found that nonadherence to ASRM guidelines was associated with increased rates of cesarean delivery, neonatal morbidity, and preterm birth.

To examine how adherence to ASRM and UCSF recommendations relates to pregnancy outcomes and maternal and neonatal morbidity and death, Dr. Stark and colleagues assessed births from gestational carrier pregnancies at UCSF between 2008 and 2019.

Of 194 gestational carriers included in the analysis, 98.9% had a prior term pregnancy, 11.9% had a prior preterm pregnancy, and 17.5% had a prior spontaneous abortion.

Indications for use of gestational surrogates included serious medical condition of intended parent (25%), uterine factor infertility (23%), recurrent pregnancy loss (10%), and same-sex male couples (8%).

When the researchers compared pregnancy outcomes for gestational carriers who met ASRM guidelines with outcomes for 38 gestational carriers who did not meet ASRM guidelines, there were no statistically significant differences. Antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum complication rates and cesarean delivery rates did not significantly differ based on ASRM guideline adherence.

Nonadherence to the stricter UCSF guidelines, however, was associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion. In all, 23.7% of the 59 gestational carriers who were nonadherent to UCSF guidelines had a pregnancy end in a spontaneous abortion, compared with 6.7% of gestational carriers who were adherent to the UCSF recommendations (odds ratio, 4.35).

An analysis of individual criteria and poor pregnancy outcomes found that BMI greater than 35 was associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion (OR, 4.29), as was age less than 21 years or greater than 45 years (OR, 3.37).

Prior spontaneous abortion was associated with increased likelihood of a biochemical pregnancy (OR, 3.2), and prior preterm birth was associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion (OR, 3.19), previable delivery (OR, 25.2), cesarean delivery (OR, 2.59), and antepartum complications (OR, 3.56).

The role of agencies

About 76% of the gestational carriers had pregnancies mediated through a gestational surrogacy agency. Surrogates from agencies were about three times more likely than surrogates who were family, friends, or from private surrogacy arrangements to adhere to ASRM and UCSF guidelines.

Even after hearing about gestational carrier recommendations, patients may prefer to work with someone they know. “We want to provide our patients with evidence-based information if possible, but ultimately it is their decision to make,” Dr. Stark said. “And we just need to make sure that they are making an informed decision.”

Dr. Stark had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Penzias helped develop the ASRM committee opinion. He had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Stark B et al. ASRM 2020, Abstract O-251.

About 20% of gestational carriers at one institution did not meet recommended criteria developed by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, according to a retrospective study of 194 patients.

The University of California, San Francisco, offers additional, stricter recommendations, including that gestational carriers have a body mass index less than 35. Under these stricter criteria, about 30% of the gestational carriers did not meet recommendations, Brett Stark, MD, MPH, reported at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2020 annual meeting, held virtually this year.

Deviating from BMI or age recommendations may be associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion, the analysis suggested. In addition, elements of a gestational carrier’s obstetric history not described in current guidelines, such as prior preterm birth, may influence gestational surrogacy outcomes.

The study was limited by incomplete information for some patients, the retrospective design, and the reliance on a relatively small cohort at a single center. Nevertheless, the findings potentially could inform discussions with patients, said Dr. Stark, a 3rd-year obstetrics and gynecology resident at the university.

Investigators aim to enroll patients in a longitudinal cohort study to further examine these questions, he said.

Protecting intended parents and carriers

“Gestational surrogacy has become an increasingly common form of third-party reproduction,” Dr. Stark said at the virtual meeting. The number of cases of in vitro fertilization (IVF) with gestational carriers increased from approximately 700 in 1999 to more than 5,500 in 2016, according to data from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. “Despite the increasing prevalence of gestational carrier utilization, there remains limited guidance with regard to optimizing outcomes for both the intended parents and gestational carriers.”

ASRM and UCSF recommendations are based on expert opinion and include surprisingly little discussion about the prior pregnancy outcomes of potential gestational carriers, Dr. Stark said.

“It is important for all parties involved that we generate research and data that can help drive the development of the guidelines,” he said. Such evidence may help intended parents understand characteristics of gestational carriers that may lead to live births. “For the gestational carriers, it is important that we have information on safety so that they know they are making appropriate decisions for their family and their life.”

Gestational carrier characteristics in the present study that deviated from 2017 ASRM recommendations included age less than 21 years or greater than 45 years, mental health conditions, and having more than five prior deliveries.

“ASRM guidelines focused on criteria for gestational carriers are meant to protect infertile couples, the carrier, as well as the supporting agency,” Alan Penzias, MD, chair of ASRM’s Practice Committee who is in private practice in Boston, said in a society news release that highlighted Dr. Stark’s study. “It is important that gestational carriers have a complete medical history and examination, in addition to a psychological session with a mental health professional to ensure there are no reasons for the carrier to not move forward with pregnancy.”

A retrospective study by Kate Swanson, MD, and associates found that nonadherence to ASRM guidelines was associated with increased rates of cesarean delivery, neonatal morbidity, and preterm birth.

To examine how adherence to ASRM and UCSF recommendations relates to pregnancy outcomes and maternal and neonatal morbidity and death, Dr. Stark and colleagues assessed births from gestational carrier pregnancies at UCSF between 2008 and 2019.

Of 194 gestational carriers included in the analysis, 98.9% had a prior term pregnancy, 11.9% had a prior preterm pregnancy, and 17.5% had a prior spontaneous abortion.

Indications for use of gestational surrogates included serious medical condition of intended parent (25%), uterine factor infertility (23%), recurrent pregnancy loss (10%), and same-sex male couples (8%).

When the researchers compared pregnancy outcomes for gestational carriers who met ASRM guidelines with outcomes for 38 gestational carriers who did not meet ASRM guidelines, there were no statistically significant differences. Antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum complication rates and cesarean delivery rates did not significantly differ based on ASRM guideline adherence.

Nonadherence to the stricter UCSF guidelines, however, was associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion. In all, 23.7% of the 59 gestational carriers who were nonadherent to UCSF guidelines had a pregnancy end in a spontaneous abortion, compared with 6.7% of gestational carriers who were adherent to the UCSF recommendations (odds ratio, 4.35).

An analysis of individual criteria and poor pregnancy outcomes found that BMI greater than 35 was associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion (OR, 4.29), as was age less than 21 years or greater than 45 years (OR, 3.37).

Prior spontaneous abortion was associated with increased likelihood of a biochemical pregnancy (OR, 3.2), and prior preterm birth was associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion (OR, 3.19), previable delivery (OR, 25.2), cesarean delivery (OR, 2.59), and antepartum complications (OR, 3.56).

The role of agencies

About 76% of the gestational carriers had pregnancies mediated through a gestational surrogacy agency. Surrogates from agencies were about three times more likely than surrogates who were family, friends, or from private surrogacy arrangements to adhere to ASRM and UCSF guidelines.

Even after hearing about gestational carrier recommendations, patients may prefer to work with someone they know. “We want to provide our patients with evidence-based information if possible, but ultimately it is their decision to make,” Dr. Stark said. “And we just need to make sure that they are making an informed decision.”

Dr. Stark had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Penzias helped develop the ASRM committee opinion. He had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Stark B et al. ASRM 2020, Abstract O-251.

About 20% of gestational carriers at one institution did not meet recommended criteria developed by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, according to a retrospective study of 194 patients.

The University of California, San Francisco, offers additional, stricter recommendations, including that gestational carriers have a body mass index less than 35. Under these stricter criteria, about 30% of the gestational carriers did not meet recommendations, Brett Stark, MD, MPH, reported at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2020 annual meeting, held virtually this year.

Deviating from BMI or age recommendations may be associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion, the analysis suggested. In addition, elements of a gestational carrier’s obstetric history not described in current guidelines, such as prior preterm birth, may influence gestational surrogacy outcomes.

The study was limited by incomplete information for some patients, the retrospective design, and the reliance on a relatively small cohort at a single center. Nevertheless, the findings potentially could inform discussions with patients, said Dr. Stark, a 3rd-year obstetrics and gynecology resident at the university.

Investigators aim to enroll patients in a longitudinal cohort study to further examine these questions, he said.

Protecting intended parents and carriers

“Gestational surrogacy has become an increasingly common form of third-party reproduction,” Dr. Stark said at the virtual meeting. The number of cases of in vitro fertilization (IVF) with gestational carriers increased from approximately 700 in 1999 to more than 5,500 in 2016, according to data from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. “Despite the increasing prevalence of gestational carrier utilization, there remains limited guidance with regard to optimizing outcomes for both the intended parents and gestational carriers.”

ASRM and UCSF recommendations are based on expert opinion and include surprisingly little discussion about the prior pregnancy outcomes of potential gestational carriers, Dr. Stark said.

“It is important for all parties involved that we generate research and data that can help drive the development of the guidelines,” he said. Such evidence may help intended parents understand characteristics of gestational carriers that may lead to live births. “For the gestational carriers, it is important that we have information on safety so that they know they are making appropriate decisions for their family and their life.”

Gestational carrier characteristics in the present study that deviated from 2017 ASRM recommendations included age less than 21 years or greater than 45 years, mental health conditions, and having more than five prior deliveries.

“ASRM guidelines focused on criteria for gestational carriers are meant to protect infertile couples, the carrier, as well as the supporting agency,” Alan Penzias, MD, chair of ASRM’s Practice Committee who is in private practice in Boston, said in a society news release that highlighted Dr. Stark’s study. “It is important that gestational carriers have a complete medical history and examination, in addition to a psychological session with a mental health professional to ensure there are no reasons for the carrier to not move forward with pregnancy.”

A retrospective study by Kate Swanson, MD, and associates found that nonadherence to ASRM guidelines was associated with increased rates of cesarean delivery, neonatal morbidity, and preterm birth.

To examine how adherence to ASRM and UCSF recommendations relates to pregnancy outcomes and maternal and neonatal morbidity and death, Dr. Stark and colleagues assessed births from gestational carrier pregnancies at UCSF between 2008 and 2019.

Of 194 gestational carriers included in the analysis, 98.9% had a prior term pregnancy, 11.9% had a prior preterm pregnancy, and 17.5% had a prior spontaneous abortion.

Indications for use of gestational surrogates included serious medical condition of intended parent (25%), uterine factor infertility (23%), recurrent pregnancy loss (10%), and same-sex male couples (8%).

When the researchers compared pregnancy outcomes for gestational carriers who met ASRM guidelines with outcomes for 38 gestational carriers who did not meet ASRM guidelines, there were no statistically significant differences. Antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum complication rates and cesarean delivery rates did not significantly differ based on ASRM guideline adherence.

Nonadherence to the stricter UCSF guidelines, however, was associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion. In all, 23.7% of the 59 gestational carriers who were nonadherent to UCSF guidelines had a pregnancy end in a spontaneous abortion, compared with 6.7% of gestational carriers who were adherent to the UCSF recommendations (odds ratio, 4.35).

An analysis of individual criteria and poor pregnancy outcomes found that BMI greater than 35 was associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion (OR, 4.29), as was age less than 21 years or greater than 45 years (OR, 3.37).

Prior spontaneous abortion was associated with increased likelihood of a biochemical pregnancy (OR, 3.2), and prior preterm birth was associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous abortion (OR, 3.19), previable delivery (OR, 25.2), cesarean delivery (OR, 2.59), and antepartum complications (OR, 3.56).

The role of agencies

About 76% of the gestational carriers had pregnancies mediated through a gestational surrogacy agency. Surrogates from agencies were about three times more likely than surrogates who were family, friends, or from private surrogacy arrangements to adhere to ASRM and UCSF guidelines.

Even after hearing about gestational carrier recommendations, patients may prefer to work with someone they know. “We want to provide our patients with evidence-based information if possible, but ultimately it is their decision to make,” Dr. Stark said. “And we just need to make sure that they are making an informed decision.”

Dr. Stark had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Penzias helped develop the ASRM committee opinion. He had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Stark B et al. ASRM 2020, Abstract O-251.

FROM ASRM 2020

Reproductive Rounds: Fertility preservation options for cancer patients

What is more stressful in the mind of a patient – a diagnosis of cancer or infertility? An infertile woman’s anxiety and depression scores are equivalent to one with cancer (J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1993;14 Suppl:45-52). These two diseases intersect in the burgeoning field of oncofertility, the collaboration of oncology with reproductive endocrinology to offer patients the option of fertility preservation. The term oncofertility was first coined by Teresa Woodruff, PhD, in 2005 during her invited lecture at the University of Calgary symposium called “Pushing the Boundaries – Advances that Will Change the World in 20 Years.” Her prediction has reached its fruition. This article will review fertility preservation options for female oncology patients.

The ability for oncofertility to exist is the result of improved cancer survival rates and advances in reproductive medicine. Improvements in the treatment of cancer enable many young women to survive and focus on the potential of having a family. Malignancies striking young people, particularly breast, lymphoma, and melanoma, have encouraging 5-year survival rates. If invasive cancer is located only in the breast (affecting 62% of women diagnosed), the 5-year survival rate is 99%. For all with Hodgkin lymphoma, the 5-year survival is 87%, increasing to 92% if the cancer is found in its earliest stages. Among all people with melanoma of the skin, from the time of initial diagnosis, the 5-year survival is 92%.

Long-term survival is expected for 80% of children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer (Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116: 1171-83).

Iatrogenic effects

The reproductive risk of cancer treatment is gonadotoxicity and the subsequent iatrogenic primary ovarian insufficiency (POI, prior termed premature ovarian failure) or infertility.

Chemotherapy with alkylating agents, such as cyclophosphamide, is associated with the greatest chance of amenorrhea (Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:113-28). Chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5 fluorouracil (CMF – commonly used for the treatment of breast cancer) will usually result in loss of ovarian function in 33% of women under age 30, 50% of women aged 30-35, 75% of women aged 35-40, and 95% of women over age 40 (J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5769-79).

The dose at which 50% of oocytes are lost due to radiation is under 2 Gy (Hum Reprod. 2003;18:117-21). Unfortunately, the minimum dose decreases with advancing age of the woman, contributed by natural diminishing reserve and an increase in radiosensitivity of oocytes. Age, proximity of the radiation field to the ovaries, and total dose are important factors determining risk of POI. For brain tumors, cranial irradiation may result in hypothalamic amenorrhea.

Protection

The use of GnRH agonist for 6 months during chemotherapy has been controversial with mixed results in avoiding ovarian failure. A recent study suggests a GnRH agonist does reduce the prevalence of POI (J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1981-90) in women treated for breast cancer but the subsequent ovarian reserve is low (Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1811-6). There are not enough data now to consider this the sole viable option for all patients to preserve fertility.

Patients requiring local pelvic radiation treatment may benefit from transposition of the ovaries to sites away from maximal radiation exposure.

Oocyte cryopreservation (OC) and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC)

Since 2012, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine lifted the experimental designation on OC and, last year, the society removed the same label for OTC, providing an additional fertility preservation option.

Ovarian stimulation and egg retrieval for OC can now occur literally within 2 weeks because of a random start protocol whereby women are stimulated any day in their cycle, pre- and post ovulation. Studies have shown equivalent yield of oocytes.

OC followed by thawing for subsequent fertilization and embryo transfer is employed as a routine matter with egg donation cycles. While there remains debate over whether live birth rates using frozen eggs are inferior to fresh eggs, a learning curve with the new technology may be the important factor (Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:709-16).

When urgent cancer treatment precludes ovarian stimulation for OC, then OTC is a viable option. Another population that could benefit from OTC are prepubertal girls facing gonadotoxic therapy. More research is required to determine the quality of eggs obtained through ovarian stimulation in adolescent and young adult patients. While leukemic patients are eligible for OTC, there is concern about reseeding malignant cells with future autologous transplantation of tissue.

OTC involves obtaining ovarian cortical tissue, dissecting the tissue into small fragments, and cryopreserving it using either a slow-cool technique or vitrification. Orthotopic transplantation has been the most successful method for using ovarian tissue in humans. To date, live birth rates are modest (Fertil Steril. 2015;104:1097-8).

Recent research has combined the freezing of both mature and immature eggs, the latter undergoing IVM (in-vitro maturation) to maximize the potential for fertilizable eggs. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome and certain cancers or medical conditions that warrant avoiding supraphysiologic levels of estradiol from ovarian stimulation, may benefit from the retrieval of immature eggs from unstimulated ovaries.

Pregnancy outcomes using embryos created from ovaries recently exposed to chemotherapy in humans are not known but animal studies suggest there may be higher rates of miscarriage and birth defects.

Breast cancer – a special scenario

With every breast cancer patient, I review the theoretical concern over increasing estradiol levels during an IVF stimulation cycle with the potential impact on her cancer prognosis. Fortunately, the literature has not demonstrated an increased risk of breast cancer or recurrence after undergoing an IVF cycle. Currently, the use of aromatase inhibitors with gonadotropins along with a GnRH-antagonist is the protocol to maintain a lower estradiol level during stimulation, which may be of benefit for breast cancer prognosis. The use of aromatase inhibitors is an off-label indication for fertility with no definitive evidence of teratogenicity. Preimplantation genetic testing of embryos is available and approved by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine for BRCA gene mutation patients.

Oncofertility is an exciting field to allow cancer survivors the option for a biological child. We recommend all our cancer patients meet with our reproductive psychologist to assist in coping with the overwhelming information presented in a short time frame.

Dr. Trolice is director of Fertility CARE – The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

What is more stressful in the mind of a patient – a diagnosis of cancer or infertility? An infertile woman’s anxiety and depression scores are equivalent to one with cancer (J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1993;14 Suppl:45-52). These two diseases intersect in the burgeoning field of oncofertility, the collaboration of oncology with reproductive endocrinology to offer patients the option of fertility preservation. The term oncofertility was first coined by Teresa Woodruff, PhD, in 2005 during her invited lecture at the University of Calgary symposium called “Pushing the Boundaries – Advances that Will Change the World in 20 Years.” Her prediction has reached its fruition. This article will review fertility preservation options for female oncology patients.

The ability for oncofertility to exist is the result of improved cancer survival rates and advances in reproductive medicine. Improvements in the treatment of cancer enable many young women to survive and focus on the potential of having a family. Malignancies striking young people, particularly breast, lymphoma, and melanoma, have encouraging 5-year survival rates. If invasive cancer is located only in the breast (affecting 62% of women diagnosed), the 5-year survival rate is 99%. For all with Hodgkin lymphoma, the 5-year survival is 87%, increasing to 92% if the cancer is found in its earliest stages. Among all people with melanoma of the skin, from the time of initial diagnosis, the 5-year survival is 92%.

Long-term survival is expected for 80% of children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer (Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116: 1171-83).

Iatrogenic effects

The reproductive risk of cancer treatment is gonadotoxicity and the subsequent iatrogenic primary ovarian insufficiency (POI, prior termed premature ovarian failure) or infertility.

Chemotherapy with alkylating agents, such as cyclophosphamide, is associated with the greatest chance of amenorrhea (Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:113-28). Chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5 fluorouracil (CMF – commonly used for the treatment of breast cancer) will usually result in loss of ovarian function in 33% of women under age 30, 50% of women aged 30-35, 75% of women aged 35-40, and 95% of women over age 40 (J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5769-79).

The dose at which 50% of oocytes are lost due to radiation is under 2 Gy (Hum Reprod. 2003;18:117-21). Unfortunately, the minimum dose decreases with advancing age of the woman, contributed by natural diminishing reserve and an increase in radiosensitivity of oocytes. Age, proximity of the radiation field to the ovaries, and total dose are important factors determining risk of POI. For brain tumors, cranial irradiation may result in hypothalamic amenorrhea.

Protection

The use of GnRH agonist for 6 months during chemotherapy has been controversial with mixed results in avoiding ovarian failure. A recent study suggests a GnRH agonist does reduce the prevalence of POI (J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1981-90) in women treated for breast cancer but the subsequent ovarian reserve is low (Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1811-6). There are not enough data now to consider this the sole viable option for all patients to preserve fertility.

Patients requiring local pelvic radiation treatment may benefit from transposition of the ovaries to sites away from maximal radiation exposure.

Oocyte cryopreservation (OC) and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC)

Since 2012, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine lifted the experimental designation on OC and, last year, the society removed the same label for OTC, providing an additional fertility preservation option.

Ovarian stimulation and egg retrieval for OC can now occur literally within 2 weeks because of a random start protocol whereby women are stimulated any day in their cycle, pre- and post ovulation. Studies have shown equivalent yield of oocytes.

OC followed by thawing for subsequent fertilization and embryo transfer is employed as a routine matter with egg donation cycles. While there remains debate over whether live birth rates using frozen eggs are inferior to fresh eggs, a learning curve with the new technology may be the important factor (Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:709-16).

When urgent cancer treatment precludes ovarian stimulation for OC, then OTC is a viable option. Another population that could benefit from OTC are prepubertal girls facing gonadotoxic therapy. More research is required to determine the quality of eggs obtained through ovarian stimulation in adolescent and young adult patients. While leukemic patients are eligible for OTC, there is concern about reseeding malignant cells with future autologous transplantation of tissue.

OTC involves obtaining ovarian cortical tissue, dissecting the tissue into small fragments, and cryopreserving it using either a slow-cool technique or vitrification. Orthotopic transplantation has been the most successful method for using ovarian tissue in humans. To date, live birth rates are modest (Fertil Steril. 2015;104:1097-8).

Recent research has combined the freezing of both mature and immature eggs, the latter undergoing IVM (in-vitro maturation) to maximize the potential for fertilizable eggs. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome and certain cancers or medical conditions that warrant avoiding supraphysiologic levels of estradiol from ovarian stimulation, may benefit from the retrieval of immature eggs from unstimulated ovaries.

Pregnancy outcomes using embryos created from ovaries recently exposed to chemotherapy in humans are not known but animal studies suggest there may be higher rates of miscarriage and birth defects.

Breast cancer – a special scenario

With every breast cancer patient, I review the theoretical concern over increasing estradiol levels during an IVF stimulation cycle with the potential impact on her cancer prognosis. Fortunately, the literature has not demonstrated an increased risk of breast cancer or recurrence after undergoing an IVF cycle. Currently, the use of aromatase inhibitors with gonadotropins along with a GnRH-antagonist is the protocol to maintain a lower estradiol level during stimulation, which may be of benefit for breast cancer prognosis. The use of aromatase inhibitors is an off-label indication for fertility with no definitive evidence of teratogenicity. Preimplantation genetic testing of embryos is available and approved by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine for BRCA gene mutation patients.

Oncofertility is an exciting field to allow cancer survivors the option for a biological child. We recommend all our cancer patients meet with our reproductive psychologist to assist in coping with the overwhelming information presented in a short time frame.

Dr. Trolice is director of Fertility CARE – The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

What is more stressful in the mind of a patient – a diagnosis of cancer or infertility? An infertile woman’s anxiety and depression scores are equivalent to one with cancer (J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1993;14 Suppl:45-52). These two diseases intersect in the burgeoning field of oncofertility, the collaboration of oncology with reproductive endocrinology to offer patients the option of fertility preservation. The term oncofertility was first coined by Teresa Woodruff, PhD, in 2005 during her invited lecture at the University of Calgary symposium called “Pushing the Boundaries – Advances that Will Change the World in 20 Years.” Her prediction has reached its fruition. This article will review fertility preservation options for female oncology patients.

The ability for oncofertility to exist is the result of improved cancer survival rates and advances in reproductive medicine. Improvements in the treatment of cancer enable many young women to survive and focus on the potential of having a family. Malignancies striking young people, particularly breast, lymphoma, and melanoma, have encouraging 5-year survival rates. If invasive cancer is located only in the breast (affecting 62% of women diagnosed), the 5-year survival rate is 99%. For all with Hodgkin lymphoma, the 5-year survival is 87%, increasing to 92% if the cancer is found in its earliest stages. Among all people with melanoma of the skin, from the time of initial diagnosis, the 5-year survival is 92%.

Long-term survival is expected for 80% of children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer (Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116: 1171-83).

Iatrogenic effects

The reproductive risk of cancer treatment is gonadotoxicity and the subsequent iatrogenic primary ovarian insufficiency (POI, prior termed premature ovarian failure) or infertility.

Chemotherapy with alkylating agents, such as cyclophosphamide, is associated with the greatest chance of amenorrhea (Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:113-28). Chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5 fluorouracil (CMF – commonly used for the treatment of breast cancer) will usually result in loss of ovarian function in 33% of women under age 30, 50% of women aged 30-35, 75% of women aged 35-40, and 95% of women over age 40 (J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5769-79).

The dose at which 50% of oocytes are lost due to radiation is under 2 Gy (Hum Reprod. 2003;18:117-21). Unfortunately, the minimum dose decreases with advancing age of the woman, contributed by natural diminishing reserve and an increase in radiosensitivity of oocytes. Age, proximity of the radiation field to the ovaries, and total dose are important factors determining risk of POI. For brain tumors, cranial irradiation may result in hypothalamic amenorrhea.

Protection

The use of GnRH agonist for 6 months during chemotherapy has been controversial with mixed results in avoiding ovarian failure. A recent study suggests a GnRH agonist does reduce the prevalence of POI (J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1981-90) in women treated for breast cancer but the subsequent ovarian reserve is low (Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1811-6). There are not enough data now to consider this the sole viable option for all patients to preserve fertility.

Patients requiring local pelvic radiation treatment may benefit from transposition of the ovaries to sites away from maximal radiation exposure.

Oocyte cryopreservation (OC) and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC)

Since 2012, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine lifted the experimental designation on OC and, last year, the society removed the same label for OTC, providing an additional fertility preservation option.

Ovarian stimulation and egg retrieval for OC can now occur literally within 2 weeks because of a random start protocol whereby women are stimulated any day in their cycle, pre- and post ovulation. Studies have shown equivalent yield of oocytes.

OC followed by thawing for subsequent fertilization and embryo transfer is employed as a routine matter with egg donation cycles. While there remains debate over whether live birth rates using frozen eggs are inferior to fresh eggs, a learning curve with the new technology may be the important factor (Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:709-16).

When urgent cancer treatment precludes ovarian stimulation for OC, then OTC is a viable option. Another population that could benefit from OTC are prepubertal girls facing gonadotoxic therapy. More research is required to determine the quality of eggs obtained through ovarian stimulation in adolescent and young adult patients. While leukemic patients are eligible for OTC, there is concern about reseeding malignant cells with future autologous transplantation of tissue.

OTC involves obtaining ovarian cortical tissue, dissecting the tissue into small fragments, and cryopreserving it using either a slow-cool technique or vitrification. Orthotopic transplantation has been the most successful method for using ovarian tissue in humans. To date, live birth rates are modest (Fertil Steril. 2015;104:1097-8).

Recent research has combined the freezing of both mature and immature eggs, the latter undergoing IVM (in-vitro maturation) to maximize the potential for fertilizable eggs. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome and certain cancers or medical conditions that warrant avoiding supraphysiologic levels of estradiol from ovarian stimulation, may benefit from the retrieval of immature eggs from unstimulated ovaries.

Pregnancy outcomes using embryos created from ovaries recently exposed to chemotherapy in humans are not known but animal studies suggest there may be higher rates of miscarriage and birth defects.

Breast cancer – a special scenario

With every breast cancer patient, I review the theoretical concern over increasing estradiol levels during an IVF stimulation cycle with the potential impact on her cancer prognosis. Fortunately, the literature has not demonstrated an increased risk of breast cancer or recurrence after undergoing an IVF cycle. Currently, the use of aromatase inhibitors with gonadotropins along with a GnRH-antagonist is the protocol to maintain a lower estradiol level during stimulation, which may be of benefit for breast cancer prognosis. The use of aromatase inhibitors is an off-label indication for fertility with no definitive evidence of teratogenicity. Preimplantation genetic testing of embryos is available and approved by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine for BRCA gene mutation patients.

Oncofertility is an exciting field to allow cancer survivors the option for a biological child. We recommend all our cancer patients meet with our reproductive psychologist to assist in coping with the overwhelming information presented in a short time frame.

Dr. Trolice is director of Fertility CARE – The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

Endocrine-disrupting plastics pose growing health threat

Many types of plastics pose an unrecognized threat to human health by leaching endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and a new report from the Endocrine Society and the International Pollutants Elimination Network presents their dangers and risks.

Written in a consumer-friendly form designed to guide public interest groups and policy makers, the report also can be used by clinicians to inform discussions with patients about the potential dangers of plastics and how they can reduce their exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

The report, Plastics, EDCs, & Health, defines endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) as “an exogenous chemical, or mixture of chemicals, that interferes with any aspect of hormone action.” Hormones in the body must be released at specific times, and therefore interference with their normal activity can have profound effects on health in areas including growth and reproductive development, according to the report.

The available data show “more and more information about the different chemicals and the different effects they are having,” said lead author, Jodi Flaws, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in a virtual press conference accompanying the release of the report.

Although numerous EDCs have been identified, a recent study suggested that many potentially dangerous chemical additives remain unknown because they are identified as confidential or simply not well described, the report authors said. In addition, creation of more plastic products will likely lead to increased exposure to EDCs and make health problems worse, said report coauthor Pauliina Damdimopoulou, PhD, of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm.

Lesser-known EDCs populate consumer products

Most consumers are aware of bisphenol A and phthalates as known EDCs, said Dr. Flaws, but the report identifies other lesser-known EDCs including per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), dioxins, flame retardants, and UV stabilizers.

For example, PFAS have been used for decades in a range of consumer products including stain resistant clothes, fast food wrappers, carpet and furniture treatments, cookware, and firefighting foams, according to the report. Consequently, PFAS have become common in many water sources including surface water, drinking water, and ground water because of how they are disposed. “Consumption of fish and other aquatic creatures caught in waterways contaminated with PFAS also poses heightened risks due to bioaccumulation of persistent chemicals in these animals,” the report authors noted. Human exposures to PFAS have been documented in urine, serum, plasma, placenta, umbilical cord, breast milk, and fetal tissues, they added.

Brominated flame retardants are another lesser-known EDC highlighted in the report. These chemical additives are used in plastics such as electronics cases to reduce the spread of fire, as well as in furniture foam and other building materials, the authors wrote. UV stabilizers, which also have been linked to health problems, often are used in manufacturing cars and other machinery.

Microplastics create large risk

Microplastics, defined as plastic particles less than 5 mm in diameter, are another source of exposure to EDCs that is not well publicized, according to the report. Plastic waste disposal often leads to the release of microplastics, which can infiltrate soil and water. Plastic waste is often dumped or burned; outdoor burning of plastic causes emission of dioxins into the air and ground.

“Not only do microplastics contain endogenous chemical additives, which are not bound to the microplastic and can leach out of the microplastic and expose the population, they can also bind and accumulate toxic chemicals from the surrounding environment such as sea water and sediment,” the report authors said.

Recycling is not an easy answer, either. Often more chemicals are created and released during the process of using plastics to make other plastics, according to the report.

Overall, more awareness of the potential for increased exposure to EDCs and support of strategies to seek out alternatives to hazardous chemicals is needed at the global level, the authors wrote. For example, the European Union has proposed a chemicals strategy that includes improved classification of EDCs and banning identified EDCs in consumer products.

New data support ongoing dangers

“It was important to produce the report at this time because several new studies came out on the effects of EDCs from plastics on human health,” Dr. Flaws said in an interview. “Further, there was not previously a single source that brought together all the information in a manner that was targeted towards the public, policy makers, and others,” she said.

Dr. Flaws said that what has surprised her most in the recent research is the fact that plastics contain such a range of chemicals and EDCs.

“A good take-home message [from the report] is that plastics can contain endocrine-disrupting chemicals that can interfere with normal hormones and lead to adverse health outcomes,” she said. “I suggest limiting the use of plastics as much as possible. I know this is very hard to do, so if someone needs to use plastic, they should not heat food or drink in plastic containers,” she emphasized. Individuals also can limit reuse of plastics over and over,” she said. “Heating and repeated use/washing often causes plastics to leach EDCs into food and drink that we then get into our bodies.”

Additional research is needed to understand the mechanisms by which EDCs from plastics cause damage, Dr. Flaws emphasized. “Given that it is not possible to eliminate plastics at this time, if we understood mechanisms of action, we could develop ways to prevent toxicity or treat EDC-induced adverse health outcomes,” she said. “We also need research designed to develop plastics or ‘green materials’ that do not contain endocrine disruptors and do not cause health problems or damage the environment,” she noted.

The report was produced as a joint effort of the Endocrine Society and International Pollutants Elimination Network. The report authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Many types of plastics pose an unrecognized threat to human health by leaching endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and a new report from the Endocrine Society and the International Pollutants Elimination Network presents their dangers and risks.

Written in a consumer-friendly form designed to guide public interest groups and policy makers, the report also can be used by clinicians to inform discussions with patients about the potential dangers of plastics and how they can reduce their exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

The report, Plastics, EDCs, & Health, defines endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) as “an exogenous chemical, or mixture of chemicals, that interferes with any aspect of hormone action.” Hormones in the body must be released at specific times, and therefore interference with their normal activity can have profound effects on health in areas including growth and reproductive development, according to the report.

The available data show “more and more information about the different chemicals and the different effects they are having,” said lead author, Jodi Flaws, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in a virtual press conference accompanying the release of the report.

Although numerous EDCs have been identified, a recent study suggested that many potentially dangerous chemical additives remain unknown because they are identified as confidential or simply not well described, the report authors said. In addition, creation of more plastic products will likely lead to increased exposure to EDCs and make health problems worse, said report coauthor Pauliina Damdimopoulou, PhD, of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm.

Lesser-known EDCs populate consumer products

Most consumers are aware of bisphenol A and phthalates as known EDCs, said Dr. Flaws, but the report identifies other lesser-known EDCs including per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), dioxins, flame retardants, and UV stabilizers.

For example, PFAS have been used for decades in a range of consumer products including stain resistant clothes, fast food wrappers, carpet and furniture treatments, cookware, and firefighting foams, according to the report. Consequently, PFAS have become common in many water sources including surface water, drinking water, and ground water because of how they are disposed. “Consumption of fish and other aquatic creatures caught in waterways contaminated with PFAS also poses heightened risks due to bioaccumulation of persistent chemicals in these animals,” the report authors noted. Human exposures to PFAS have been documented in urine, serum, plasma, placenta, umbilical cord, breast milk, and fetal tissues, they added.

Brominated flame retardants are another lesser-known EDC highlighted in the report. These chemical additives are used in plastics such as electronics cases to reduce the spread of fire, as well as in furniture foam and other building materials, the authors wrote. UV stabilizers, which also have been linked to health problems, often are used in manufacturing cars and other machinery.

Microplastics create large risk

Microplastics, defined as plastic particles less than 5 mm in diameter, are another source of exposure to EDCs that is not well publicized, according to the report. Plastic waste disposal often leads to the release of microplastics, which can infiltrate soil and water. Plastic waste is often dumped or burned; outdoor burning of plastic causes emission of dioxins into the air and ground.

“Not only do microplastics contain endogenous chemical additives, which are not bound to the microplastic and can leach out of the microplastic and expose the population, they can also bind and accumulate toxic chemicals from the surrounding environment such as sea water and sediment,” the report authors said.

Recycling is not an easy answer, either. Often more chemicals are created and released during the process of using plastics to make other plastics, according to the report.

Overall, more awareness of the potential for increased exposure to EDCs and support of strategies to seek out alternatives to hazardous chemicals is needed at the global level, the authors wrote. For example, the European Union has proposed a chemicals strategy that includes improved classification of EDCs and banning identified EDCs in consumer products.

New data support ongoing dangers

“It was important to produce the report at this time because several new studies came out on the effects of EDCs from plastics on human health,” Dr. Flaws said in an interview. “Further, there was not previously a single source that brought together all the information in a manner that was targeted towards the public, policy makers, and others,” she said.

Dr. Flaws said that what has surprised her most in the recent research is the fact that plastics contain such a range of chemicals and EDCs.

“A good take-home message [from the report] is that plastics can contain endocrine-disrupting chemicals that can interfere with normal hormones and lead to adverse health outcomes,” she said. “I suggest limiting the use of plastics as much as possible. I know this is very hard to do, so if someone needs to use plastic, they should not heat food or drink in plastic containers,” she emphasized. Individuals also can limit reuse of plastics over and over,” she said. “Heating and repeated use/washing often causes plastics to leach EDCs into food and drink that we then get into our bodies.”

Additional research is needed to understand the mechanisms by which EDCs from plastics cause damage, Dr. Flaws emphasized. “Given that it is not possible to eliminate plastics at this time, if we understood mechanisms of action, we could develop ways to prevent toxicity or treat EDC-induced adverse health outcomes,” she said. “We also need research designed to develop plastics or ‘green materials’ that do not contain endocrine disruptors and do not cause health problems or damage the environment,” she noted.

The report was produced as a joint effort of the Endocrine Society and International Pollutants Elimination Network. The report authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Many types of plastics pose an unrecognized threat to human health by leaching endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and a new report from the Endocrine Society and the International Pollutants Elimination Network presents their dangers and risks.

Written in a consumer-friendly form designed to guide public interest groups and policy makers, the report also can be used by clinicians to inform discussions with patients about the potential dangers of plastics and how they can reduce their exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

The report, Plastics, EDCs, & Health, defines endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) as “an exogenous chemical, or mixture of chemicals, that interferes with any aspect of hormone action.” Hormones in the body must be released at specific times, and therefore interference with their normal activity can have profound effects on health in areas including growth and reproductive development, according to the report.

The available data show “more and more information about the different chemicals and the different effects they are having,” said lead author, Jodi Flaws, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in a virtual press conference accompanying the release of the report.

Although numerous EDCs have been identified, a recent study suggested that many potentially dangerous chemical additives remain unknown because they are identified as confidential or simply not well described, the report authors said. In addition, creation of more plastic products will likely lead to increased exposure to EDCs and make health problems worse, said report coauthor Pauliina Damdimopoulou, PhD, of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm.

Lesser-known EDCs populate consumer products

Most consumers are aware of bisphenol A and phthalates as known EDCs, said Dr. Flaws, but the report identifies other lesser-known EDCs including per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), dioxins, flame retardants, and UV stabilizers.

For example, PFAS have been used for decades in a range of consumer products including stain resistant clothes, fast food wrappers, carpet and furniture treatments, cookware, and firefighting foams, according to the report. Consequently, PFAS have become common in many water sources including surface water, drinking water, and ground water because of how they are disposed. “Consumption of fish and other aquatic creatures caught in waterways contaminated with PFAS also poses heightened risks due to bioaccumulation of persistent chemicals in these animals,” the report authors noted. Human exposures to PFAS have been documented in urine, serum, plasma, placenta, umbilical cord, breast milk, and fetal tissues, they added.

Brominated flame retardants are another lesser-known EDC highlighted in the report. These chemical additives are used in plastics such as electronics cases to reduce the spread of fire, as well as in furniture foam and other building materials, the authors wrote. UV stabilizers, which also have been linked to health problems, often are used in manufacturing cars and other machinery.

Microplastics create large risk

Microplastics, defined as plastic particles less than 5 mm in diameter, are another source of exposure to EDCs that is not well publicized, according to the report. Plastic waste disposal often leads to the release of microplastics, which can infiltrate soil and water. Plastic waste is often dumped or burned; outdoor burning of plastic causes emission of dioxins into the air and ground.

“Not only do microplastics contain endogenous chemical additives, which are not bound to the microplastic and can leach out of the microplastic and expose the population, they can also bind and accumulate toxic chemicals from the surrounding environment such as sea water and sediment,” the report authors said.

Recycling is not an easy answer, either. Often more chemicals are created and released during the process of using plastics to make other plastics, according to the report.

Overall, more awareness of the potential for increased exposure to EDCs and support of strategies to seek out alternatives to hazardous chemicals is needed at the global level, the authors wrote. For example, the European Union has proposed a chemicals strategy that includes improved classification of EDCs and banning identified EDCs in consumer products.

New data support ongoing dangers

“It was important to produce the report at this time because several new studies came out on the effects of EDCs from plastics on human health,” Dr. Flaws said in an interview. “Further, there was not previously a single source that brought together all the information in a manner that was targeted towards the public, policy makers, and others,” she said.

Dr. Flaws said that what has surprised her most in the recent research is the fact that plastics contain such a range of chemicals and EDCs.

“A good take-home message [from the report] is that plastics can contain endocrine-disrupting chemicals that can interfere with normal hormones and lead to adverse health outcomes,” she said. “I suggest limiting the use of plastics as much as possible. I know this is very hard to do, so if someone needs to use plastic, they should not heat food or drink in plastic containers,” she emphasized. Individuals also can limit reuse of plastics over and over,” she said. “Heating and repeated use/washing often causes plastics to leach EDCs into food and drink that we then get into our bodies.”

Additional research is needed to understand the mechanisms by which EDCs from plastics cause damage, Dr. Flaws emphasized. “Given that it is not possible to eliminate plastics at this time, if we understood mechanisms of action, we could develop ways to prevent toxicity or treat EDC-induced adverse health outcomes,” she said. “We also need research designed to develop plastics or ‘green materials’ that do not contain endocrine disruptors and do not cause health problems or damage the environment,” she noted.

The report was produced as a joint effort of the Endocrine Society and International Pollutants Elimination Network. The report authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The pill toolbox: How to choose a combined oral contraceptive

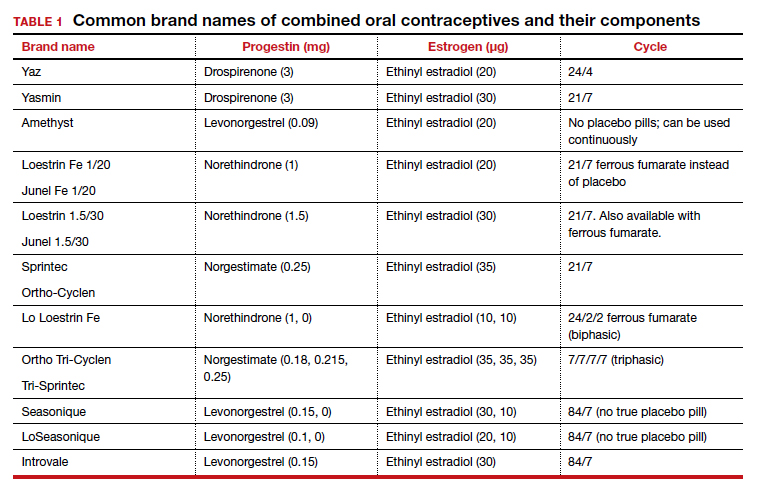

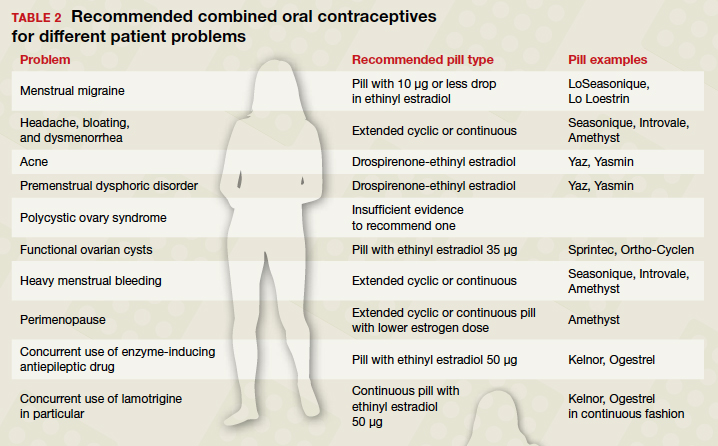

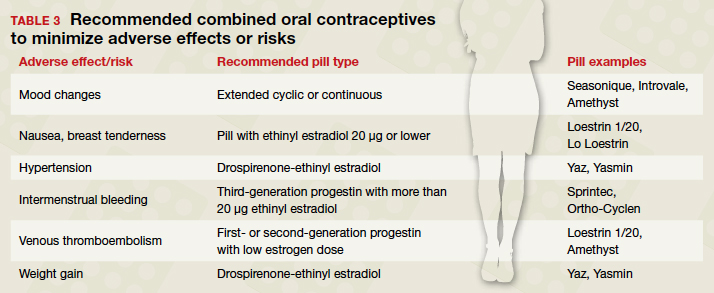

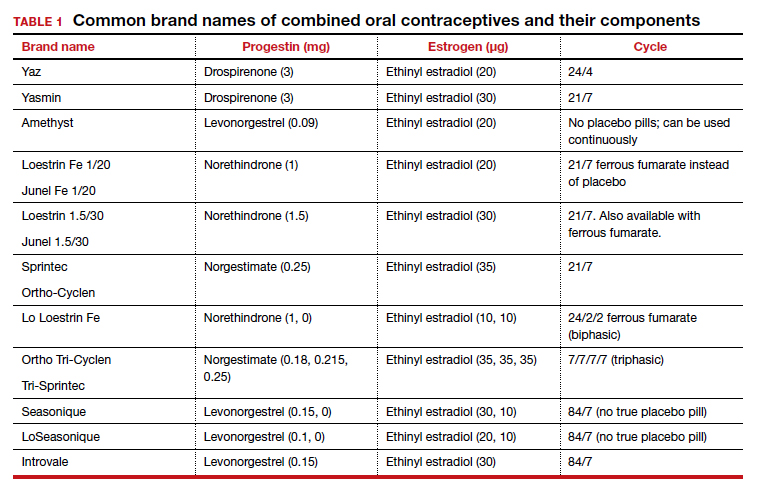

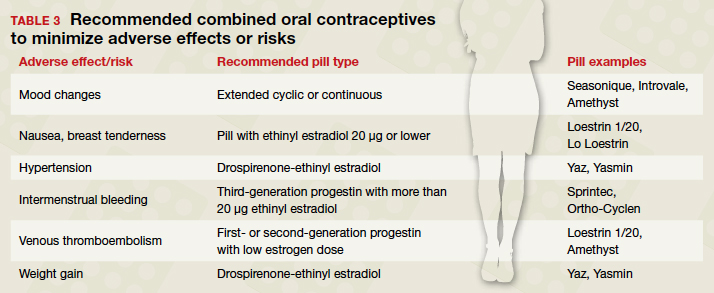

In the era of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), the pill can seem obsolete. However, it is still the second most commonly used birth control method in the United States, chosen by 19% of female contraceptive users as of 2015–2017.1 It also has noncontraceptive benefits, so it is important that obstetrician-gynecologists are well-versed in its uses. In this article, I will focus on combined oral contraceptives (COCs; TABLE 1), reviewing the major risks, benefits, and adverse effects of COCs before focusing on recommendations for particular formulations of COCs for various patient populations.

Benefits and risks

There are numerous noncontraceptive benefits of COCs, including menstrual cycle regulation; reduced risk of ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancer; and treatment of menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, acne, menstrual migraine, premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder, pelvic pain due to endometriosis, and hirsutism.

Common patient concerns

In terms of adverse effects, there are more potential unwanted effects of concern to women than there are ones validated in the literature. Accepted adverse effects include nausea, breast tenderness, and decreased libido. However, one of the most common concerns voiced during contraceptive counseling is that COCs will cause weight gain. A 2014 Cochrane review identified 49 trials studying the weight gain question.2 Of those, only 4 had a placebo or nonintervention group. Of these 4, there was no significant difference in weight change between the COC-receiving group and the control group. When patients bring up their concerns, it may help to remind them that women tend to gain weight over time whether or not they are taking a COC.