User login

Are you SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitant?

When the pandemic was just emerging from its infancy and we were just beginning to think about social distancing, I was sitting around enjoying an adult beverage and some gluten free (not my choice) snacks with some friends. A retired nurse who had just celebrated her 80th birthday said, “I can’t wait until they’ve developed a vaccine.” A former electrical engineer sitting just short of 2 meters to her left responded, “Don’t save me a place near the front of the line for something that is being developed in a program called Warp Speed.”

How do you feel about the potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine? Are you going to roll up your sleeve as soon as the vaccine becomes available in your community? What are you going to suggest to your patients, your children? I suspect many of you will answer, “It depends.”

Will it make any difference to you which biochemical-immune-bending strategy is being used to make the vaccine? All of them will probably be the result of a clever sounding but novel technique, all of them with a track record that is measured in months and not years. Will you be swayed by how large the trials were? Or how long the follow-up lasted? How effective must the vaccine be to convince you that it is worth receiving or recommending? Do you have the tools and experience to make a decision like that? I know I don’t. And should you and I even be put in a position to make that decision?

In the past, you and I may have relied on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for advice. But given the somewhat murky and stormy relationship between the CDC and the president, the vaccine recommendation may be issued by the White House and not the CDC.

For those of us who were practicing medicine during the Swine Flu fiasco of 1976, the pace and the politics surrounding the development of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine has a discomforting déjà vu quality about it. The fact that like this year 1976 was an election year that infused the development process with a sense of urgency above and beyond any of the concerns about the pandemic that never happened. Although causality was never proven, there was a surge in Guillain-Barré syndrome cases that had been linked temporally to the vaccine.

Of course, our pandemic is real, and it would be imprudent to wait a year or more to watch for long-term vaccine sequelae. However, I am more than a little concerned that fast tracking the development process may result in unfortunate consequences in the short term that could have been avoided with a more measured approach to trialing the vaccines.

The sad reality is that as a nation we tend to be impatient. We are drawn to quick fixes that come in a vial or a capsule. We are learning that simple measures like mask wearing and social distancing can make a difference in slowing the spread of the virus. It would be tragic to rush a vaccine into production that at best turns out to simply be an expensive alternative to the measures that we know work or at worst injures more of us than it saves.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

When the pandemic was just emerging from its infancy and we were just beginning to think about social distancing, I was sitting around enjoying an adult beverage and some gluten free (not my choice) snacks with some friends. A retired nurse who had just celebrated her 80th birthday said, “I can’t wait until they’ve developed a vaccine.” A former electrical engineer sitting just short of 2 meters to her left responded, “Don’t save me a place near the front of the line for something that is being developed in a program called Warp Speed.”

How do you feel about the potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine? Are you going to roll up your sleeve as soon as the vaccine becomes available in your community? What are you going to suggest to your patients, your children? I suspect many of you will answer, “It depends.”

Will it make any difference to you which biochemical-immune-bending strategy is being used to make the vaccine? All of them will probably be the result of a clever sounding but novel technique, all of them with a track record that is measured in months and not years. Will you be swayed by how large the trials were? Or how long the follow-up lasted? How effective must the vaccine be to convince you that it is worth receiving or recommending? Do you have the tools and experience to make a decision like that? I know I don’t. And should you and I even be put in a position to make that decision?

In the past, you and I may have relied on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for advice. But given the somewhat murky and stormy relationship between the CDC and the president, the vaccine recommendation may be issued by the White House and not the CDC.

For those of us who were practicing medicine during the Swine Flu fiasco of 1976, the pace and the politics surrounding the development of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine has a discomforting déjà vu quality about it. The fact that like this year 1976 was an election year that infused the development process with a sense of urgency above and beyond any of the concerns about the pandemic that never happened. Although causality was never proven, there was a surge in Guillain-Barré syndrome cases that had been linked temporally to the vaccine.

Of course, our pandemic is real, and it would be imprudent to wait a year or more to watch for long-term vaccine sequelae. However, I am more than a little concerned that fast tracking the development process may result in unfortunate consequences in the short term that could have been avoided with a more measured approach to trialing the vaccines.

The sad reality is that as a nation we tend to be impatient. We are drawn to quick fixes that come in a vial or a capsule. We are learning that simple measures like mask wearing and social distancing can make a difference in slowing the spread of the virus. It would be tragic to rush a vaccine into production that at best turns out to simply be an expensive alternative to the measures that we know work or at worst injures more of us than it saves.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

When the pandemic was just emerging from its infancy and we were just beginning to think about social distancing, I was sitting around enjoying an adult beverage and some gluten free (not my choice) snacks with some friends. A retired nurse who had just celebrated her 80th birthday said, “I can’t wait until they’ve developed a vaccine.” A former electrical engineer sitting just short of 2 meters to her left responded, “Don’t save me a place near the front of the line for something that is being developed in a program called Warp Speed.”

How do you feel about the potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine? Are you going to roll up your sleeve as soon as the vaccine becomes available in your community? What are you going to suggest to your patients, your children? I suspect many of you will answer, “It depends.”

Will it make any difference to you which biochemical-immune-bending strategy is being used to make the vaccine? All of them will probably be the result of a clever sounding but novel technique, all of them with a track record that is measured in months and not years. Will you be swayed by how large the trials were? Or how long the follow-up lasted? How effective must the vaccine be to convince you that it is worth receiving or recommending? Do you have the tools and experience to make a decision like that? I know I don’t. And should you and I even be put in a position to make that decision?

In the past, you and I may have relied on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for advice. But given the somewhat murky and stormy relationship between the CDC and the president, the vaccine recommendation may be issued by the White House and not the CDC.

For those of us who were practicing medicine during the Swine Flu fiasco of 1976, the pace and the politics surrounding the development of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine has a discomforting déjà vu quality about it. The fact that like this year 1976 was an election year that infused the development process with a sense of urgency above and beyond any of the concerns about the pandemic that never happened. Although causality was never proven, there was a surge in Guillain-Barré syndrome cases that had been linked temporally to the vaccine.

Of course, our pandemic is real, and it would be imprudent to wait a year or more to watch for long-term vaccine sequelae. However, I am more than a little concerned that fast tracking the development process may result in unfortunate consequences in the short term that could have been avoided with a more measured approach to trialing the vaccines.

The sad reality is that as a nation we tend to be impatient. We are drawn to quick fixes that come in a vial or a capsule. We are learning that simple measures like mask wearing and social distancing can make a difference in slowing the spread of the virus. It would be tragic to rush a vaccine into production that at best turns out to simply be an expensive alternative to the measures that we know work or at worst injures more of us than it saves.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

MIS-C is a serious immune-mediated response to COVID-19 infection

One of the take-away messages from a review of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is that clinicians treating this condition “need to be comfortable with uncertainty,” Melissa Hazen, MD, said at a synthesis of multiple published case series and personal experience summarized at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

She emphasized MIS-C patient care “requires flexibility,” and she advised clinicians managing these patients to open the lines of communication with the many specialists who often are required to deal with complications affecting an array of organ systems.

MIS-C might best be understood as the most serious manifestation of an immune-mediated response to COVID-19 infection that ranges from transient mild symptoms to the life-threatening multiple organ involvement that characterizes this newly recognized threat. Although “most children who encounter this pathogen only develop mild disease,” the spectrum of the disease can move in a subset of patients to a “Kawasaki-like illness” without hemodynamic instability and then to MIS-C “with highly elevated systemic inflammatory markers and multiple organ involvement,” explained Dr. Hazen, an attending physician in the rheumatology program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

most of which have only recently reached publication, according to Dr. Hazen. In general, the description of the most common symptoms and their course has been relatively consistent.

In 186 cases of MIS-C collected in a study funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 148 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 90 patients (48%) received vasoactive support, 37 (20%) received mechanical ventilation, and 4 (2%) died.1 The median age was 8 years (range, 3-13 years) in this study. The case definition was fever for at least 24 hours, laboratory evidence of inflammation, multisystem organ involvement, and evidence of COVID-19 infection. In this cohort of 186 children, 92% had gastrointestinal, 80% had cardiovascular, 76% had hematologic, and 70% had respiratory system involvement.

In a different series of 95 cases collected in New York State, 79 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 61 (62%) received vasoactive support, 10 (10%) received mechanical ventilation, 4 (4%) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and 2 (2%) died. 2 Thirty-one percent patients were aged 0-5 years, 42% were 6-12 years, and 26% were 13-20 years of age. In that series, for which the case definition was elevation of two or more inflammatory markers, virologic evidence of COVID-19 infection, 80% had gastrointestinal system involvement, and 53% had evidence of myocarditis.

In both of these series, as well as others published and unpublished, the peak in MIS-C cases has occurred about 3 to 4 weeks after peak COVID-19 activity, according to Diana Lee, MD, a pediatrician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. This pattern, reported by others, was observed in New York State, where 230 cases of MIS-C were collected from the beginning of May until the end of June, which reflected this 3- to 4-week delay in peak incidence.

“This does seem to be a rare syndrome since this [group of] 230 cases is amongst the entire population of children in New York State. So, yes, we should be keeping this in mind in our differential, but we should not forget all the other reasons that children can have a fever,” she said.

Both Dr. Hazen and Dr. Lee cautioned that MIS-C, despite a general consistency among published studies, remains a moving target in regard to how it is being characterized. In a 2-day period in May, the CDC, the World Health Organization, and New York State all issued descriptions of MIS-C, employing compatible but slightly different terminology and diagnostic criteria. Many questions regarding optimal methods of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up remain unanswered.

Questions regarding the risk to the cardiovascular system, one of the organs most commonly affected in MIS-C, are among the most urgent. It is not now clear how best to monitor cardiovascular involvement, how to intervene, and how to follow patients in the postinfection period, according to Kevin G. Friedman, MD, a pediatrician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and an attending physician in the department of cardiology at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“The most frequent complication we have seen is ventricular dysfunction, which occurs in about half of these patients,” he reported. “Usually it is in the mild to moderate range, but occasionally patients have an ejection fraction of less than 40%.”

Coronary abnormalities, typically in the form of dilations or small aneurysms, occur in 10%-20% of children with MIS-C, according to Dr. Friedman. Giant aneurysms have been reported.

“Some of these findings can progress including in both the acute phase and, particularly for the coronary aneurysms, in the subacute phase. We recommend echocardiograms and EKGs at diagnosis and at 1-2 weeks to recheck coronary size or sooner if there are clinical indications,” Dr. Friedman advised.

Protocols like these are constantly under review as more information becomes available. There are as yet no guidelines, and practice differs across institutions, according to the investigators summarizing this information.

None of the speakers had any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Feldstein LR et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334-46.

2. Dufort EM et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med 2020;383:347-58.

One of the take-away messages from a review of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is that clinicians treating this condition “need to be comfortable with uncertainty,” Melissa Hazen, MD, said at a synthesis of multiple published case series and personal experience summarized at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

She emphasized MIS-C patient care “requires flexibility,” and she advised clinicians managing these patients to open the lines of communication with the many specialists who often are required to deal with complications affecting an array of organ systems.

MIS-C might best be understood as the most serious manifestation of an immune-mediated response to COVID-19 infection that ranges from transient mild symptoms to the life-threatening multiple organ involvement that characterizes this newly recognized threat. Although “most children who encounter this pathogen only develop mild disease,” the spectrum of the disease can move in a subset of patients to a “Kawasaki-like illness” without hemodynamic instability and then to MIS-C “with highly elevated systemic inflammatory markers and multiple organ involvement,” explained Dr. Hazen, an attending physician in the rheumatology program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

most of which have only recently reached publication, according to Dr. Hazen. In general, the description of the most common symptoms and their course has been relatively consistent.

In 186 cases of MIS-C collected in a study funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 148 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 90 patients (48%) received vasoactive support, 37 (20%) received mechanical ventilation, and 4 (2%) died.1 The median age was 8 years (range, 3-13 years) in this study. The case definition was fever for at least 24 hours, laboratory evidence of inflammation, multisystem organ involvement, and evidence of COVID-19 infection. In this cohort of 186 children, 92% had gastrointestinal, 80% had cardiovascular, 76% had hematologic, and 70% had respiratory system involvement.

In a different series of 95 cases collected in New York State, 79 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 61 (62%) received vasoactive support, 10 (10%) received mechanical ventilation, 4 (4%) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and 2 (2%) died. 2 Thirty-one percent patients were aged 0-5 years, 42% were 6-12 years, and 26% were 13-20 years of age. In that series, for which the case definition was elevation of two or more inflammatory markers, virologic evidence of COVID-19 infection, 80% had gastrointestinal system involvement, and 53% had evidence of myocarditis.

In both of these series, as well as others published and unpublished, the peak in MIS-C cases has occurred about 3 to 4 weeks after peak COVID-19 activity, according to Diana Lee, MD, a pediatrician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. This pattern, reported by others, was observed in New York State, where 230 cases of MIS-C were collected from the beginning of May until the end of June, which reflected this 3- to 4-week delay in peak incidence.

“This does seem to be a rare syndrome since this [group of] 230 cases is amongst the entire population of children in New York State. So, yes, we should be keeping this in mind in our differential, but we should not forget all the other reasons that children can have a fever,” she said.

Both Dr. Hazen and Dr. Lee cautioned that MIS-C, despite a general consistency among published studies, remains a moving target in regard to how it is being characterized. In a 2-day period in May, the CDC, the World Health Organization, and New York State all issued descriptions of MIS-C, employing compatible but slightly different terminology and diagnostic criteria. Many questions regarding optimal methods of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up remain unanswered.

Questions regarding the risk to the cardiovascular system, one of the organs most commonly affected in MIS-C, are among the most urgent. It is not now clear how best to monitor cardiovascular involvement, how to intervene, and how to follow patients in the postinfection period, according to Kevin G. Friedman, MD, a pediatrician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and an attending physician in the department of cardiology at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“The most frequent complication we have seen is ventricular dysfunction, which occurs in about half of these patients,” he reported. “Usually it is in the mild to moderate range, but occasionally patients have an ejection fraction of less than 40%.”

Coronary abnormalities, typically in the form of dilations or small aneurysms, occur in 10%-20% of children with MIS-C, according to Dr. Friedman. Giant aneurysms have been reported.

“Some of these findings can progress including in both the acute phase and, particularly for the coronary aneurysms, in the subacute phase. We recommend echocardiograms and EKGs at diagnosis and at 1-2 weeks to recheck coronary size or sooner if there are clinical indications,” Dr. Friedman advised.

Protocols like these are constantly under review as more information becomes available. There are as yet no guidelines, and practice differs across institutions, according to the investigators summarizing this information.

None of the speakers had any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Feldstein LR et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334-46.

2. Dufort EM et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med 2020;383:347-58.

One of the take-away messages from a review of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is that clinicians treating this condition “need to be comfortable with uncertainty,” Melissa Hazen, MD, said at a synthesis of multiple published case series and personal experience summarized at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

She emphasized MIS-C patient care “requires flexibility,” and she advised clinicians managing these patients to open the lines of communication with the many specialists who often are required to deal with complications affecting an array of organ systems.

MIS-C might best be understood as the most serious manifestation of an immune-mediated response to COVID-19 infection that ranges from transient mild symptoms to the life-threatening multiple organ involvement that characterizes this newly recognized threat. Although “most children who encounter this pathogen only develop mild disease,” the spectrum of the disease can move in a subset of patients to a “Kawasaki-like illness” without hemodynamic instability and then to MIS-C “with highly elevated systemic inflammatory markers and multiple organ involvement,” explained Dr. Hazen, an attending physician in the rheumatology program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

most of which have only recently reached publication, according to Dr. Hazen. In general, the description of the most common symptoms and their course has been relatively consistent.

In 186 cases of MIS-C collected in a study funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 148 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 90 patients (48%) received vasoactive support, 37 (20%) received mechanical ventilation, and 4 (2%) died.1 The median age was 8 years (range, 3-13 years) in this study. The case definition was fever for at least 24 hours, laboratory evidence of inflammation, multisystem organ involvement, and evidence of COVID-19 infection. In this cohort of 186 children, 92% had gastrointestinal, 80% had cardiovascular, 76% had hematologic, and 70% had respiratory system involvement.

In a different series of 95 cases collected in New York State, 79 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 61 (62%) received vasoactive support, 10 (10%) received mechanical ventilation, 4 (4%) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and 2 (2%) died. 2 Thirty-one percent patients were aged 0-5 years, 42% were 6-12 years, and 26% were 13-20 years of age. In that series, for which the case definition was elevation of two or more inflammatory markers, virologic evidence of COVID-19 infection, 80% had gastrointestinal system involvement, and 53% had evidence of myocarditis.

In both of these series, as well as others published and unpublished, the peak in MIS-C cases has occurred about 3 to 4 weeks after peak COVID-19 activity, according to Diana Lee, MD, a pediatrician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. This pattern, reported by others, was observed in New York State, where 230 cases of MIS-C were collected from the beginning of May until the end of June, which reflected this 3- to 4-week delay in peak incidence.

“This does seem to be a rare syndrome since this [group of] 230 cases is amongst the entire population of children in New York State. So, yes, we should be keeping this in mind in our differential, but we should not forget all the other reasons that children can have a fever,” she said.

Both Dr. Hazen and Dr. Lee cautioned that MIS-C, despite a general consistency among published studies, remains a moving target in regard to how it is being characterized. In a 2-day period in May, the CDC, the World Health Organization, and New York State all issued descriptions of MIS-C, employing compatible but slightly different terminology and diagnostic criteria. Many questions regarding optimal methods of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up remain unanswered.

Questions regarding the risk to the cardiovascular system, one of the organs most commonly affected in MIS-C, are among the most urgent. It is not now clear how best to monitor cardiovascular involvement, how to intervene, and how to follow patients in the postinfection period, according to Kevin G. Friedman, MD, a pediatrician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and an attending physician in the department of cardiology at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“The most frequent complication we have seen is ventricular dysfunction, which occurs in about half of these patients,” he reported. “Usually it is in the mild to moderate range, but occasionally patients have an ejection fraction of less than 40%.”

Coronary abnormalities, typically in the form of dilations or small aneurysms, occur in 10%-20% of children with MIS-C, according to Dr. Friedman. Giant aneurysms have been reported.

“Some of these findings can progress including in both the acute phase and, particularly for the coronary aneurysms, in the subacute phase. We recommend echocardiograms and EKGs at diagnosis and at 1-2 weeks to recheck coronary size or sooner if there are clinical indications,” Dr. Friedman advised.

Protocols like these are constantly under review as more information becomes available. There are as yet no guidelines, and practice differs across institutions, according to the investigators summarizing this information.

None of the speakers had any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Feldstein LR et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334-46.

2. Dufort EM et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med 2020;383:347-58.

FROM PHM20 VIRTUAL

Small NY study: Mother-baby transmission of COVID-19 not seen

according to a study out of New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

“It is suggested in the cumulative data that the virus does not confer additional risk to the fetus during labor or during the early postnatal period in both preterm and term infants,” concluded Jeffrey Perlman, MB ChB, and colleagues in Pediatrics.

But other experts suggest substantial gaps remain in our understanding of maternal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

“Much more needs to be known,” Munish Gupta, MD, and colleagues from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an accompanying editorial.

The prospective study is the first to describe a cohort of U.S. COVID-19–related deliveries, with the prior neonatal impact of COVID-19 “almost exclusively” reported from China, noted the authors. They included a cohort of 326 women who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 on admission to labor and delivery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital between March 22 and April 15th, 2020. Of the 31 (10%) mothers who tested positive, 15 (48%) were asymptomatic and 16 (52%) were symptomatic.

Two babies were born prematurely (one by Cesarean) and were isolated in negative pressure rooms with continuous positive airway pressure. Both were moved out of isolation after two negative test results and “have exhibited an unremarkable clinical course,” the authors reported.

The other 29 term babies were cared for in their mothers’ rooms, with breastfeeding allowed, if desired. These babies and their mothers were discharged from the hospital between 24 and 48 hours after delivery.

“Visitor restriction for mothers who were positive for COVID-19 included 14 days of no visitation from the start of symptoms,” noted the team.

They added “since the prepublication release there have been a total of 47 mothers positive for COVID-19, resulting in 47 infants; 4 have been admitted to neonatal intensive care. In addition, 32 other infants have been tested for a variety of indications within the unit. All infants test results have been negative.”

The brief report outlined the institution’s checklist for delivery preparedness in either the operating room or labor delivery room, including personal protective equipment, resuscitation, transportation to the neonatal intensive care unit, and early postresuscitation care. “Suspected or confirmed COVID-19 alone in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy is not an indication for the resuscitation team or the neonatal fellow,” they noted, adding delivery room preparation and management should include contact precautions. “With scrupulous attention to infectious precautions, horizontal viral transmission should be minimized,” they advised.

Dr. Perlman and associates emphasized that rapid turnaround SARSCoV-2 testing is “crucial to minimize the likelihood of a provider becoming infected and/or infecting the infant.”

Although the findings are “clearly reassuring,” Dr. Gupta and colleagues have reservations. “To what extent does this report address concerns for infection risk with a rooming-in approach to care?” they asked in their accompanying editorial. “The answer is likely some, but not much.”

Many questions remain, they said, including: “What precautions were used to minimize infection risk during the postbirth hospital course? What was the approach to skin-to-skin care and direct mother-newborn contact? Were restrictions placed on family members? Were changes made to routine interventions such as hearing screens or circumcisions? What practices were in place around environmental cleaning? Most important, how did the newborns do after discharge?”

The current uncertainty around neonatal COVID-19 infection risk has led to “disparate” variations in care recommendations, they pointed out. Whereas China’s consensus guidelines recommend a 14-day separation of COVID-19–positive mothers from their healthy infants, a practice supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics “when possible,” the Italian Society of Neonatology, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and the Canadian Paediatric Society advise “rooming-in and breastfeeding with appropriate infection prevention measures.”

Dr. Gupta and colleagues pointed to the following as at least three “critical and time-sensitive needs for research around neonatal care and outcomes related to COVID-19”:

- Studies need to have much larger sample sizes and include diverse populations. This will allow for reliable measurement of outcomes.

- Descriptions of care practices must be in detail, especially about infection prevention; these should be presented in a way to compare the efficacy of different approaches.

- There needs to be follow-up information on outcomes of both the mother and the neonate after the birth hospitalization.

Asked to comment, Lillian Beard, MD, of George Washington University in Washington welcomed the data as “good news.”

“Although small, the study was done during a 3-week peak period at the hottest spot of the pandemic in the United States during that period. It illustrates how delivery room preparedness, adequate personal protective equipment, and carefully planned infection control precautions can positively impact outcomes even during a seemingly impossible period,” she said.

“Although there are many uncertainties about maternal COVID-19 transmission and neonatal infection risks ... in my opinion, during the after birth hospitalization, the inherent benefits of rooming in for breast feeding and the opportunities for the demonstration and teaching of infection prevention practices for the family home, far outweigh the risks of disease transmission,” said Dr. Beard, who was not involved with the study.

The study and the commentary emphasize the likely low risk of vertical transmission of the virus, with horizontal transmission being the greater risk. However, cases of transplacental transmission have been reported, and the lead investigator of one recent placental study cautions against complacency.

“Neonates can get infected in both ways. The majority of cases seem to be horizontal, but those who have been infected or highly suspected to be vertically infected are not a small percentage either,” said Daniele de Luca, MD, PhD, president-elect of the European Society for Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) and a neonatologist at Antoine Béclère Hospital in Clamart, France.

“Perlman’s data are interesting and consistent with other reports around the world. However, two things must be remembered,” he said in an interview. “First, newborn infants are at relatively low risk from SARS-CoV-2 infections, but this is very far from zero risk. Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infections do exist and have been described around the world. While they have a mild course in the majority of cases, neonatologists should not forget them and should be prepared to offer the best care to these babies.”

“Second, how this can be balanced with the need to promote breastfeeding and avoid overtreatment or separation from the mother is a question far from being answered. Gupta et al. in their commentary are right in saying that we have more questions than answers. While waiting for the results of large initiatives (such as the ESPNIC EPICENTRE Registry that they cite) to answer these open points, the best we can do is to provide a personalised case by case approach, transparent information to parents, and an open counselling informing clinical decisions.”

The study received no external funding. Dr. Perlman and associates had no financial disclosures. Dr. Gupta and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Neither Dr. Beard nor Dr. de Luca had any relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Perlman J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2):e20201567.

according to a study out of New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

“It is suggested in the cumulative data that the virus does not confer additional risk to the fetus during labor or during the early postnatal period in both preterm and term infants,” concluded Jeffrey Perlman, MB ChB, and colleagues in Pediatrics.

But other experts suggest substantial gaps remain in our understanding of maternal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

“Much more needs to be known,” Munish Gupta, MD, and colleagues from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an accompanying editorial.

The prospective study is the first to describe a cohort of U.S. COVID-19–related deliveries, with the prior neonatal impact of COVID-19 “almost exclusively” reported from China, noted the authors. They included a cohort of 326 women who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 on admission to labor and delivery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital between March 22 and April 15th, 2020. Of the 31 (10%) mothers who tested positive, 15 (48%) were asymptomatic and 16 (52%) were symptomatic.

Two babies were born prematurely (one by Cesarean) and were isolated in negative pressure rooms with continuous positive airway pressure. Both were moved out of isolation after two negative test results and “have exhibited an unremarkable clinical course,” the authors reported.

The other 29 term babies were cared for in their mothers’ rooms, with breastfeeding allowed, if desired. These babies and their mothers were discharged from the hospital between 24 and 48 hours after delivery.

“Visitor restriction for mothers who were positive for COVID-19 included 14 days of no visitation from the start of symptoms,” noted the team.

They added “since the prepublication release there have been a total of 47 mothers positive for COVID-19, resulting in 47 infants; 4 have been admitted to neonatal intensive care. In addition, 32 other infants have been tested for a variety of indications within the unit. All infants test results have been negative.”

The brief report outlined the institution’s checklist for delivery preparedness in either the operating room or labor delivery room, including personal protective equipment, resuscitation, transportation to the neonatal intensive care unit, and early postresuscitation care. “Suspected or confirmed COVID-19 alone in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy is not an indication for the resuscitation team or the neonatal fellow,” they noted, adding delivery room preparation and management should include contact precautions. “With scrupulous attention to infectious precautions, horizontal viral transmission should be minimized,” they advised.

Dr. Perlman and associates emphasized that rapid turnaround SARSCoV-2 testing is “crucial to minimize the likelihood of a provider becoming infected and/or infecting the infant.”

Although the findings are “clearly reassuring,” Dr. Gupta and colleagues have reservations. “To what extent does this report address concerns for infection risk with a rooming-in approach to care?” they asked in their accompanying editorial. “The answer is likely some, but not much.”

Many questions remain, they said, including: “What precautions were used to minimize infection risk during the postbirth hospital course? What was the approach to skin-to-skin care and direct mother-newborn contact? Were restrictions placed on family members? Were changes made to routine interventions such as hearing screens or circumcisions? What practices were in place around environmental cleaning? Most important, how did the newborns do after discharge?”

The current uncertainty around neonatal COVID-19 infection risk has led to “disparate” variations in care recommendations, they pointed out. Whereas China’s consensus guidelines recommend a 14-day separation of COVID-19–positive mothers from their healthy infants, a practice supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics “when possible,” the Italian Society of Neonatology, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and the Canadian Paediatric Society advise “rooming-in and breastfeeding with appropriate infection prevention measures.”

Dr. Gupta and colleagues pointed to the following as at least three “critical and time-sensitive needs for research around neonatal care and outcomes related to COVID-19”:

- Studies need to have much larger sample sizes and include diverse populations. This will allow for reliable measurement of outcomes.

- Descriptions of care practices must be in detail, especially about infection prevention; these should be presented in a way to compare the efficacy of different approaches.

- There needs to be follow-up information on outcomes of both the mother and the neonate after the birth hospitalization.

Asked to comment, Lillian Beard, MD, of George Washington University in Washington welcomed the data as “good news.”

“Although small, the study was done during a 3-week peak period at the hottest spot of the pandemic in the United States during that period. It illustrates how delivery room preparedness, adequate personal protective equipment, and carefully planned infection control precautions can positively impact outcomes even during a seemingly impossible period,” she said.

“Although there are many uncertainties about maternal COVID-19 transmission and neonatal infection risks ... in my opinion, during the after birth hospitalization, the inherent benefits of rooming in for breast feeding and the opportunities for the demonstration and teaching of infection prevention practices for the family home, far outweigh the risks of disease transmission,” said Dr. Beard, who was not involved with the study.

The study and the commentary emphasize the likely low risk of vertical transmission of the virus, with horizontal transmission being the greater risk. However, cases of transplacental transmission have been reported, and the lead investigator of one recent placental study cautions against complacency.

“Neonates can get infected in both ways. The majority of cases seem to be horizontal, but those who have been infected or highly suspected to be vertically infected are not a small percentage either,” said Daniele de Luca, MD, PhD, president-elect of the European Society for Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) and a neonatologist at Antoine Béclère Hospital in Clamart, France.

“Perlman’s data are interesting and consistent with other reports around the world. However, two things must be remembered,” he said in an interview. “First, newborn infants are at relatively low risk from SARS-CoV-2 infections, but this is very far from zero risk. Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infections do exist and have been described around the world. While they have a mild course in the majority of cases, neonatologists should not forget them and should be prepared to offer the best care to these babies.”

“Second, how this can be balanced with the need to promote breastfeeding and avoid overtreatment or separation from the mother is a question far from being answered. Gupta et al. in their commentary are right in saying that we have more questions than answers. While waiting for the results of large initiatives (such as the ESPNIC EPICENTRE Registry that they cite) to answer these open points, the best we can do is to provide a personalised case by case approach, transparent information to parents, and an open counselling informing clinical decisions.”

The study received no external funding. Dr. Perlman and associates had no financial disclosures. Dr. Gupta and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Neither Dr. Beard nor Dr. de Luca had any relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Perlman J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2):e20201567.

according to a study out of New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

“It is suggested in the cumulative data that the virus does not confer additional risk to the fetus during labor or during the early postnatal period in both preterm and term infants,” concluded Jeffrey Perlman, MB ChB, and colleagues in Pediatrics.

But other experts suggest substantial gaps remain in our understanding of maternal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

“Much more needs to be known,” Munish Gupta, MD, and colleagues from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an accompanying editorial.

The prospective study is the first to describe a cohort of U.S. COVID-19–related deliveries, with the prior neonatal impact of COVID-19 “almost exclusively” reported from China, noted the authors. They included a cohort of 326 women who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 on admission to labor and delivery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital between March 22 and April 15th, 2020. Of the 31 (10%) mothers who tested positive, 15 (48%) were asymptomatic and 16 (52%) were symptomatic.

Two babies were born prematurely (one by Cesarean) and were isolated in negative pressure rooms with continuous positive airway pressure. Both were moved out of isolation after two negative test results and “have exhibited an unremarkable clinical course,” the authors reported.

The other 29 term babies were cared for in their mothers’ rooms, with breastfeeding allowed, if desired. These babies and their mothers were discharged from the hospital between 24 and 48 hours after delivery.

“Visitor restriction for mothers who were positive for COVID-19 included 14 days of no visitation from the start of symptoms,” noted the team.

They added “since the prepublication release there have been a total of 47 mothers positive for COVID-19, resulting in 47 infants; 4 have been admitted to neonatal intensive care. In addition, 32 other infants have been tested for a variety of indications within the unit. All infants test results have been negative.”

The brief report outlined the institution’s checklist for delivery preparedness in either the operating room or labor delivery room, including personal protective equipment, resuscitation, transportation to the neonatal intensive care unit, and early postresuscitation care. “Suspected or confirmed COVID-19 alone in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy is not an indication for the resuscitation team or the neonatal fellow,” they noted, adding delivery room preparation and management should include contact precautions. “With scrupulous attention to infectious precautions, horizontal viral transmission should be minimized,” they advised.

Dr. Perlman and associates emphasized that rapid turnaround SARSCoV-2 testing is “crucial to minimize the likelihood of a provider becoming infected and/or infecting the infant.”

Although the findings are “clearly reassuring,” Dr. Gupta and colleagues have reservations. “To what extent does this report address concerns for infection risk with a rooming-in approach to care?” they asked in their accompanying editorial. “The answer is likely some, but not much.”

Many questions remain, they said, including: “What precautions were used to minimize infection risk during the postbirth hospital course? What was the approach to skin-to-skin care and direct mother-newborn contact? Were restrictions placed on family members? Were changes made to routine interventions such as hearing screens or circumcisions? What practices were in place around environmental cleaning? Most important, how did the newborns do after discharge?”

The current uncertainty around neonatal COVID-19 infection risk has led to “disparate” variations in care recommendations, they pointed out. Whereas China’s consensus guidelines recommend a 14-day separation of COVID-19–positive mothers from their healthy infants, a practice supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics “when possible,” the Italian Society of Neonatology, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and the Canadian Paediatric Society advise “rooming-in and breastfeeding with appropriate infection prevention measures.”

Dr. Gupta and colleagues pointed to the following as at least three “critical and time-sensitive needs for research around neonatal care and outcomes related to COVID-19”:

- Studies need to have much larger sample sizes and include diverse populations. This will allow for reliable measurement of outcomes.

- Descriptions of care practices must be in detail, especially about infection prevention; these should be presented in a way to compare the efficacy of different approaches.

- There needs to be follow-up information on outcomes of both the mother and the neonate after the birth hospitalization.

Asked to comment, Lillian Beard, MD, of George Washington University in Washington welcomed the data as “good news.”

“Although small, the study was done during a 3-week peak period at the hottest spot of the pandemic in the United States during that period. It illustrates how delivery room preparedness, adequate personal protective equipment, and carefully planned infection control precautions can positively impact outcomes even during a seemingly impossible period,” she said.

“Although there are many uncertainties about maternal COVID-19 transmission and neonatal infection risks ... in my opinion, during the after birth hospitalization, the inherent benefits of rooming in for breast feeding and the opportunities for the demonstration and teaching of infection prevention practices for the family home, far outweigh the risks of disease transmission,” said Dr. Beard, who was not involved with the study.

The study and the commentary emphasize the likely low risk of vertical transmission of the virus, with horizontal transmission being the greater risk. However, cases of transplacental transmission have been reported, and the lead investigator of one recent placental study cautions against complacency.

“Neonates can get infected in both ways. The majority of cases seem to be horizontal, but those who have been infected or highly suspected to be vertically infected are not a small percentage either,” said Daniele de Luca, MD, PhD, president-elect of the European Society for Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) and a neonatologist at Antoine Béclère Hospital in Clamart, France.

“Perlman’s data are interesting and consistent with other reports around the world. However, two things must be remembered,” he said in an interview. “First, newborn infants are at relatively low risk from SARS-CoV-2 infections, but this is very far from zero risk. Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infections do exist and have been described around the world. While they have a mild course in the majority of cases, neonatologists should not forget them and should be prepared to offer the best care to these babies.”

“Second, how this can be balanced with the need to promote breastfeeding and avoid overtreatment or separation from the mother is a question far from being answered. Gupta et al. in their commentary are right in saying that we have more questions than answers. While waiting for the results of large initiatives (such as the ESPNIC EPICENTRE Registry that they cite) to answer these open points, the best we can do is to provide a personalised case by case approach, transparent information to parents, and an open counselling informing clinical decisions.”

The study received no external funding. Dr. Perlman and associates had no financial disclosures. Dr. Gupta and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Neither Dr. Beard nor Dr. de Luca had any relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Perlman J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2):e20201567.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Internists’ use of ultrasound can reduce radiology referrals

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

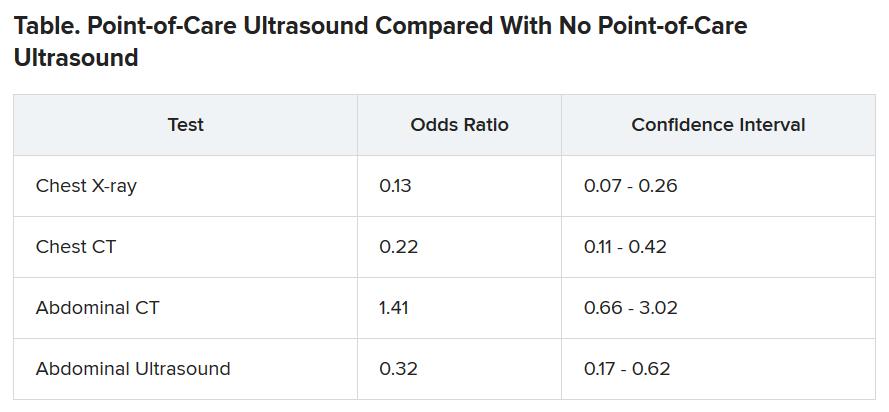

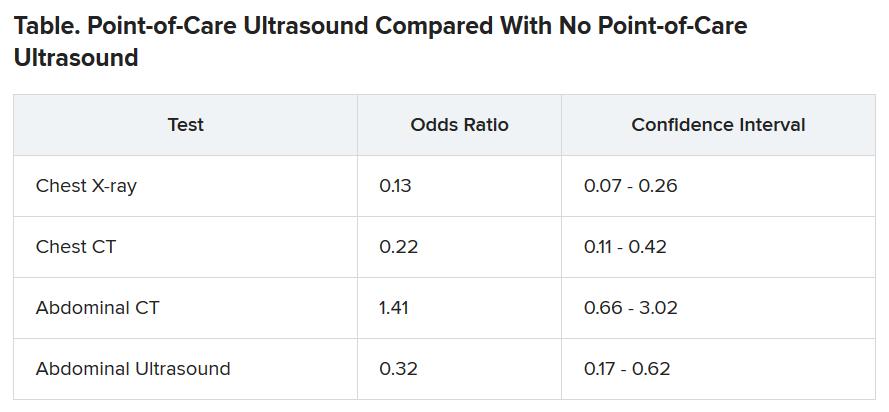

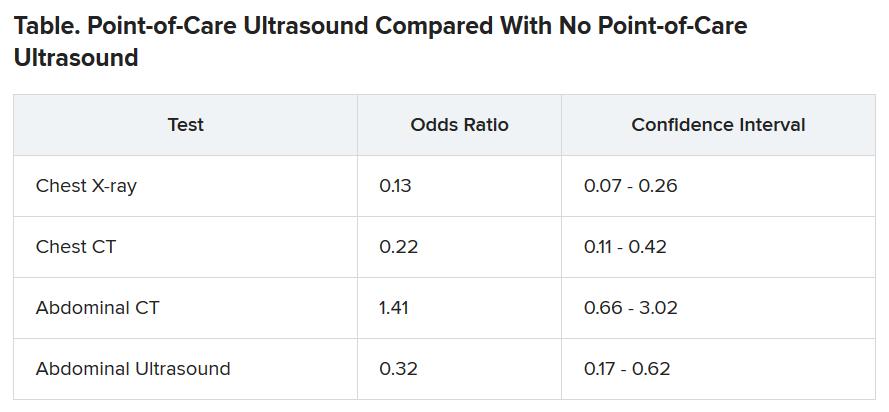

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Ob.gyns. struggle to keep pace with changing COVID-19 knowledge

In early April, Maura Quinlan, MD, was working nights on the labor and delivery unit at Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago. At the time, hospital policy was to test only patients with known COVID-19 symptoms for SARS-CoV-2. Women in labor wore N95 masks, but only while pushing – and practitioners didn’t always don proper protection in time.

Babies came and families rejoiced. But Dr. Quinlan looks back on those weeks with a degree of horror. “We were laboring a bunch of patients that probably had COVID,” she said, and they were doing so without proper protection.

She’s probably right. According to one study in the New England Journal of Medicine, 13.7% of 211 women who came into the labor and delivery unit at one New York City hospital between March 22 and April 2 were asymptomatic but infected, potentially putting staff and doctors at risk.

Dr. Quinlan already knew she and her fellow ob.gyns. had been walking a thin line and, upon seeing that research, her heart sank. In the middle of a pandemic, they had been racing to keep up with the reality of delivering babies. But despite their efforts to protect both practitioners and patients, some aspects slipped through the cracks. Today, every laboring patient admitted to Northwestern is now tested for the novel coronavirus.

Across the country, hospital labor and delivery wards have been working to find a careful and informed balance among multiple competing interests: the safety of their health care workers, the health of tiny and vulnerable new humans, and the stability of a birthing mother. Each hospital has been making the best decisions it can based on available data. The result is a patchwork of policies, but all of them center around rapid testing and appropriate protection.

Shifting recommendations

One case study of women in a New York City hospital during the height of the city’s surge found that, of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive patients, two were asymptomatic upon admission to the obstetrical service, and these same two patients ultimately required unplanned ICU admission. The women’s care prior to their positive diagnosis had exposed multiple health care workers, all of whom lacked appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), the study authors wrote. “Further, five of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive women were afebrile on initial screen, and four did not first report a cough. In some locations where testing availability remains limited, the minimal symptoms reported for some of these cases might have been insufficient to prompt COVID-19 testing.”

As studies like this pour in, societies continue to update their recommendations accordingly. The latest guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists came on July 1. The group suggests testing all labor and delivery patients, particularly in high-prevalence areas. If tests are in short supply, it recommends prioritizing testing pregnant women with suspected COVID-19 and those who develop symptoms during admission.

At Northwestern, the hospital requests patients stay home and quarantine for the weeks leading up to their delivery date. Then, they rapidly test every patient who comes in for delivery and aim to have results available within a few hours.

The hospital’s 30-room labor and delivery wing remains reserved for patients who test negative. Those with positive COVID-19 results are sent to a 6-bed COVID labor and delivery unit elsewhere in the hospital. “We were lucky we had the space to do that, because smaller community hospitals wouldn’t have a separate unused unit where they could put these women,” Dr. Quinlan said.

In the COVID unit, women deliver without a support person – no partner, doula, or family member can join. Doctors and nurses wear full PPE and work only in that ward. And because some research shows that pregnant women who are asymptomatic or presymptomatic may develop symptoms quickly after starting labor with no measurable illness, Dr. Quinlan must decide on a case-by-case basis what to do, if anything at all.

Delaying an induction could allow the infection to resolve or it could result in her patient moving from presymptomatic disease to full-blown pneumonia. Accelerating labor could bring on symptoms or it could allow a mother to deliver safely and get out of the hospital as quickly as possible. “There is an advantage to having the baby now if you feel okay – even if it’s alone – and getting home,” Dr. Quinlan said.

The hospital also tests the partners of women who are COVID-19 positive. Those with negative results can take the newborn home and try to maintain distance until the mother is no longer symptomatic.

In different parts of the country, hospitals have developed different approaches. Southern California is experiencing its own surge, but at the Ronald Reagan University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center there still haven’t been enough COVID-19 patients to warrant a separate labor and delivery unit.

At UCLA, staff swab patients when they enter the labor and delivery ward — those who test positive have specific room designations. For both COVID-19–positive patients and women who progress faster than test results can be returned, the goals are the same, said Rashmi Rao, MD, an ob.gyn. at UCLA: Deliver in the safest way possible for both mother and baby.

All women, positive or negative, must wear masks during labor – as much as they can tolerate, at least. For patients who are only mildly ill or asymptomatic, the only difference is that everyone wears protective gear. But if a patient’s oxygen levels dip, or her baby is in distress, the team moves more quickly to a cesarean delivery than they’d do with a healthy patient.

Just as hospital policies have been evolving, rules for visitors have been constantly changing too. Initially, UCLA allowed a support person to be present during delivery but had to leave immediately following. Now, each new mother is allowed one visitor for the duration of their stay. And the hospital suggests that patients who are COVID-19 positive recover in separate rooms from their babies and encourages them to maintain distance from their infants, except when breastfeeding.

“We respect and understand that this is a joyous occasion and we’re trying to keep families together as much as possible,” Dr. Rao said.

Care conundrums

How hospitals protect their smallest charges keeps changing too. Reports have been circulating about newborns being taken away from COVID-19-positive mothers, especially in marginalized communities. The stories have led many to worry they’d be forcibly separated from their babies. Most hospitals, however, leave it up to the woman and her doctors to decide how much separation is needed. “After delivery, it depends on how someone is feeling,” Dr. Rao said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that mothers who are COVID-19–positive pump breast milk and have a healthy caregiver use that milk, or formula, to bottle-feed the baby, with the new mother remaining 6 feet away from the child as much as she can. If that’s not possible, she should wear gloves and a mask while breastfeeding until she has been naturally afebrile for 72 hours and at least 1 week removed from the first appearance of her symptoms.

“It’s tragically hard,” said Dr. Quinlan, to keep a COVID-19–positive mother even 6 feet away from her newborn baby. “If a mother declines separation, we ask the acting pediatric team to discuss the theoretical risks and paucity of data.”

Until recently, research indicated that SARS-CoV-2 wasn’t being transmitted through the uterus from mothers to their babies. And despite a recent case study reporting transplacental transmission between a mother and her fetus in France, researchers still say that the risk of transference is low. To ensure newborn risk remains as low as possible, UCLA’s policy is to swab the baby when he/she is 24 hours old and keep watch for signs of infection: increased lethargy, difficulty waking, or gastrointestinal symptoms like vomiting.

Transmission via breast milk has also, to date, proven relatively unlikely. One study in The Lancet detected the novel coronavirus in breast milk, although it’s not clear that the virus can be passed on in the fluid, says Christina Chambers, PhD, a professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Chambers is studying breast milk to see if the virus or antibodies to it are present. She is also investigating how infection with SARS-CoV-2 impacts women at different times in pregnancy, something that’s still an open question.

“[In] pregnant women with a deteriorating infection, the decisions are the same you would make with any delivery: Save the mom and save the baby,” Dr. Chambers said. “Beyond that, I am encouraged to see that pregnant women are prioritized to being tested,” something that will help researchers understand prevalence of disease in order to better understand whether some symptoms are more dangerous than others.

The situation is evolving so quickly that hospitals and providers are simply trying to stay abreast of the flood of new research. In the absence of definitive answers, they are using the information available and adjusting on the fly. “We are cautiously waiting for more data,” said Dr. Rao. “With the information we have we are doing the best we can to keep our patients safe. And we’re just going to keep at it.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In early April, Maura Quinlan, MD, was working nights on the labor and delivery unit at Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago. At the time, hospital policy was to test only patients with known COVID-19 symptoms for SARS-CoV-2. Women in labor wore N95 masks, but only while pushing – and practitioners didn’t always don proper protection in time.

Babies came and families rejoiced. But Dr. Quinlan looks back on those weeks with a degree of horror. “We were laboring a bunch of patients that probably had COVID,” she said, and they were doing so without proper protection.

She’s probably right. According to one study in the New England Journal of Medicine, 13.7% of 211 women who came into the labor and delivery unit at one New York City hospital between March 22 and April 2 were asymptomatic but infected, potentially putting staff and doctors at risk.

Dr. Quinlan already knew she and her fellow ob.gyns. had been walking a thin line and, upon seeing that research, her heart sank. In the middle of a pandemic, they had been racing to keep up with the reality of delivering babies. But despite their efforts to protect both practitioners and patients, some aspects slipped through the cracks. Today, every laboring patient admitted to Northwestern is now tested for the novel coronavirus.

Across the country, hospital labor and delivery wards have been working to find a careful and informed balance among multiple competing interests: the safety of their health care workers, the health of tiny and vulnerable new humans, and the stability of a birthing mother. Each hospital has been making the best decisions it can based on available data. The result is a patchwork of policies, but all of them center around rapid testing and appropriate protection.

Shifting recommendations

One case study of women in a New York City hospital during the height of the city’s surge found that, of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive patients, two were asymptomatic upon admission to the obstetrical service, and these same two patients ultimately required unplanned ICU admission. The women’s care prior to their positive diagnosis had exposed multiple health care workers, all of whom lacked appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), the study authors wrote. “Further, five of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive women were afebrile on initial screen, and four did not first report a cough. In some locations where testing availability remains limited, the minimal symptoms reported for some of these cases might have been insufficient to prompt COVID-19 testing.”

As studies like this pour in, societies continue to update their recommendations accordingly. The latest guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists came on July 1. The group suggests testing all labor and delivery patients, particularly in high-prevalence areas. If tests are in short supply, it recommends prioritizing testing pregnant women with suspected COVID-19 and those who develop symptoms during admission.

At Northwestern, the hospital requests patients stay home and quarantine for the weeks leading up to their delivery date. Then, they rapidly test every patient who comes in for delivery and aim to have results available within a few hours.

The hospital’s 30-room labor and delivery wing remains reserved for patients who test negative. Those with positive COVID-19 results are sent to a 6-bed COVID labor and delivery unit elsewhere in the hospital. “We were lucky we had the space to do that, because smaller community hospitals wouldn’t have a separate unused unit where they could put these women,” Dr. Quinlan said.

In the COVID unit, women deliver without a support person – no partner, doula, or family member can join. Doctors and nurses wear full PPE and work only in that ward. And because some research shows that pregnant women who are asymptomatic or presymptomatic may develop symptoms quickly after starting labor with no measurable illness, Dr. Quinlan must decide on a case-by-case basis what to do, if anything at all.