User login

Guideline-concordant treatment still unlikely in nonchildren’s hospitals for pediatric CAP

according to new research.

“This gap is concerning because approximately 70% of children hospitalized with pneumonia receive care in nonchildren’s hospitals,” wrote Alison C. Tribble, MD, of C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her associates. The report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

Data were collected from the Pediatric Health Information System (children’s hospitals) and Premier Perspectives (all hospitals) databases and included a total of 120,238 children aged 1-17 years diagnosed with CAP between Jan. 1, 2009, and Sept. 30, 2015. Before the publication of the new guideline in October 2011, the probability of receiving what would become guideline-concordant antibiotics was 0.25 in children’s hospitals and 0.06 in nonchildren’s hospitals.

By the end of the study period, the probability of receiving guideline-concordant antibiotics for pediatric CAP was 0.61 in children’s hospitals and 0.27 in nonchildren’s hospitals. Without the interventions, the probabilities would have been 0.31 and 0.08, respectively. The rate of growth over the 4-year postintervention period was similar in both children’s and nonchildren’s hospitals.

“Studies in children’s hospitals have suggested that local implementation efforts may be important in facilitating guideline uptake. Nonchildren’s hospitals likely have fewer resources to lead pediatric-specific efforts, and care may be influenced by adult CAP guidelines,” the authors noted.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Tribble AC et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Dec 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4270.

according to new research.

“This gap is concerning because approximately 70% of children hospitalized with pneumonia receive care in nonchildren’s hospitals,” wrote Alison C. Tribble, MD, of C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her associates. The report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

Data were collected from the Pediatric Health Information System (children’s hospitals) and Premier Perspectives (all hospitals) databases and included a total of 120,238 children aged 1-17 years diagnosed with CAP between Jan. 1, 2009, and Sept. 30, 2015. Before the publication of the new guideline in October 2011, the probability of receiving what would become guideline-concordant antibiotics was 0.25 in children’s hospitals and 0.06 in nonchildren’s hospitals.

By the end of the study period, the probability of receiving guideline-concordant antibiotics for pediatric CAP was 0.61 in children’s hospitals and 0.27 in nonchildren’s hospitals. Without the interventions, the probabilities would have been 0.31 and 0.08, respectively. The rate of growth over the 4-year postintervention period was similar in both children’s and nonchildren’s hospitals.

“Studies in children’s hospitals have suggested that local implementation efforts may be important in facilitating guideline uptake. Nonchildren’s hospitals likely have fewer resources to lead pediatric-specific efforts, and care may be influenced by adult CAP guidelines,” the authors noted.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Tribble AC et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Dec 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4270.

according to new research.

“This gap is concerning because approximately 70% of children hospitalized with pneumonia receive care in nonchildren’s hospitals,” wrote Alison C. Tribble, MD, of C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her associates. The report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

Data were collected from the Pediatric Health Information System (children’s hospitals) and Premier Perspectives (all hospitals) databases and included a total of 120,238 children aged 1-17 years diagnosed with CAP between Jan. 1, 2009, and Sept. 30, 2015. Before the publication of the new guideline in October 2011, the probability of receiving what would become guideline-concordant antibiotics was 0.25 in children’s hospitals and 0.06 in nonchildren’s hospitals.

By the end of the study period, the probability of receiving guideline-concordant antibiotics for pediatric CAP was 0.61 in children’s hospitals and 0.27 in nonchildren’s hospitals. Without the interventions, the probabilities would have been 0.31 and 0.08, respectively. The rate of growth over the 4-year postintervention period was similar in both children’s and nonchildren’s hospitals.

“Studies in children’s hospitals have suggested that local implementation efforts may be important in facilitating guideline uptake. Nonchildren’s hospitals likely have fewer resources to lead pediatric-specific efforts, and care may be influenced by adult CAP guidelines,” the authors noted.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Tribble AC et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Dec 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4270.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

ICU-acquired pneumonia mortality risk may be underestimated

In a large prospectively collected database, the risk of death at 30 days in ICU patients was far greater in those with hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) than in those with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) even after adjustment for prognostic factors, according to a large study that compared mortality risk for these complications.

The data for this newly published study were drawn from an evaluation of 14,212 patients treated at 23 ICUs participating in a collaborative French network OUTCOMEREA and published Critical Care Medicine.

HAP in ICU patients “was associated with an 82% increase in the risk of death at day 30,” reported a team of investigators led by Wafa Ibn Saied, MD, of the Université Paris Diderot. Although VAP and HAP were independent risk factors (P both less than .0001) for death at 30 days, VAP increased risk by 38%, less than half of HAP, which increased risk by 82%.

From an observational but prospective database initiated in 1997, this study evaluated 7,735 ICU patients at risk for VAP and 9,747 at risk for HAP. Of those at risk, defined by several factors including an ICU stay of more than 48 hours, HAP developed in 8% and VAP developed in 1%.

The 30-day mortality rates at 30 days after pneumonia were 23.9% for HAP and 28.4% for VAP. The greater risk of death by HR was identified after an analysis that adjusted for mortality risk factors, the adequacy of initial treatment, and other factors, such as prior history of pneumonia.

In HAP patients, the rate of mortality at 30 days was 32% in the 75 who were reintubated but only 16% in the 101 who were not. Adequate empirical therapy within the first 24 hours for HAP was not associated with a reduction in the risk of death.

As in the HAP patients, mortality was not significantly higher in VAP patients who received inadequate empirical therapy, compared with those who did, according to the authors.

Previous studies have suggested that both HAP and VAP increase risk of death in ICU patients, but the authors of this study believe that the relative risk of HAP “is underappreciated.” They asserted, based on these most recent data as well as on previously published analyses, that nonventilated HAP results in “significant increases in cost, length of stay, and mortality.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Saied WI et al. Crit Care Med. 2018 Nov 7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003553.

In a large prospectively collected database, the risk of death at 30 days in ICU patients was far greater in those with hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) than in those with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) even after adjustment for prognostic factors, according to a large study that compared mortality risk for these complications.

The data for this newly published study were drawn from an evaluation of 14,212 patients treated at 23 ICUs participating in a collaborative French network OUTCOMEREA and published Critical Care Medicine.

HAP in ICU patients “was associated with an 82% increase in the risk of death at day 30,” reported a team of investigators led by Wafa Ibn Saied, MD, of the Université Paris Diderot. Although VAP and HAP were independent risk factors (P both less than .0001) for death at 30 days, VAP increased risk by 38%, less than half of HAP, which increased risk by 82%.

From an observational but prospective database initiated in 1997, this study evaluated 7,735 ICU patients at risk for VAP and 9,747 at risk for HAP. Of those at risk, defined by several factors including an ICU stay of more than 48 hours, HAP developed in 8% and VAP developed in 1%.

The 30-day mortality rates at 30 days after pneumonia were 23.9% for HAP and 28.4% for VAP. The greater risk of death by HR was identified after an analysis that adjusted for mortality risk factors, the adequacy of initial treatment, and other factors, such as prior history of pneumonia.

In HAP patients, the rate of mortality at 30 days was 32% in the 75 who were reintubated but only 16% in the 101 who were not. Adequate empirical therapy within the first 24 hours for HAP was not associated with a reduction in the risk of death.

As in the HAP patients, mortality was not significantly higher in VAP patients who received inadequate empirical therapy, compared with those who did, according to the authors.

Previous studies have suggested that both HAP and VAP increase risk of death in ICU patients, but the authors of this study believe that the relative risk of HAP “is underappreciated.” They asserted, based on these most recent data as well as on previously published analyses, that nonventilated HAP results in “significant increases in cost, length of stay, and mortality.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Saied WI et al. Crit Care Med. 2018 Nov 7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003553.

In a large prospectively collected database, the risk of death at 30 days in ICU patients was far greater in those with hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) than in those with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) even after adjustment for prognostic factors, according to a large study that compared mortality risk for these complications.

The data for this newly published study were drawn from an evaluation of 14,212 patients treated at 23 ICUs participating in a collaborative French network OUTCOMEREA and published Critical Care Medicine.

HAP in ICU patients “was associated with an 82% increase in the risk of death at day 30,” reported a team of investigators led by Wafa Ibn Saied, MD, of the Université Paris Diderot. Although VAP and HAP were independent risk factors (P both less than .0001) for death at 30 days, VAP increased risk by 38%, less than half of HAP, which increased risk by 82%.

From an observational but prospective database initiated in 1997, this study evaluated 7,735 ICU patients at risk for VAP and 9,747 at risk for HAP. Of those at risk, defined by several factors including an ICU stay of more than 48 hours, HAP developed in 8% and VAP developed in 1%.

The 30-day mortality rates at 30 days after pneumonia were 23.9% for HAP and 28.4% for VAP. The greater risk of death by HR was identified after an analysis that adjusted for mortality risk factors, the adequacy of initial treatment, and other factors, such as prior history of pneumonia.

In HAP patients, the rate of mortality at 30 days was 32% in the 75 who were reintubated but only 16% in the 101 who were not. Adequate empirical therapy within the first 24 hours for HAP was not associated with a reduction in the risk of death.

As in the HAP patients, mortality was not significantly higher in VAP patients who received inadequate empirical therapy, compared with those who did, according to the authors.

Previous studies have suggested that both HAP and VAP increase risk of death in ICU patients, but the authors of this study believe that the relative risk of HAP “is underappreciated.” They asserted, based on these most recent data as well as on previously published analyses, that nonventilated HAP results in “significant increases in cost, length of stay, and mortality.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Saied WI et al. Crit Care Med. 2018 Nov 7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003553.

FROM CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Hospital-acquired pneumonia poses a greater risk of death in the ICU than ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Major finding: After prognostic adjustment, the mortality hazard ratios were 1.82 and 1.38 for HAP and VAP, respectively.

Study details: Observational cohort study.

Disclosures: The researchers had no disclosures.

Source: Saied WI et al. Crit Care Med. 2018 Nov 7; doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003553.

Adjuvanted flu vaccine reduces hospitalizations in oldest old

SAN FRANCISCO – presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“It’s one thing to say you have a more immunogenic vaccine, it’s another thing to be able to say it offers clinical benefit, especially in the oldest old and the frailest frail,” says Stefan Gravenstein, MD, professor of medicine and health services, policy and practice at the Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, R.I. Dr. Gravenstein presented a poster outlying a randomized, clinical trial of the Fluad vaccine in nursing homes.

The study randomized the nursing homes so that some facilities would offer Fluad as part of their standard of care. The design helped address the problem of consent. Any clinical trial that requires individual consent would likely exclude many of the frailest patients, leading to an unrepresentative sample. “So if you want to have a generalizable result, you’d like to have it applied to the population the way you would in the real world, so randomizing the nursing homes rather than the people makes a lot of sense,” said Dr. Gravenstein.

Dr. Gravenstein chose to test the vaccine in nursing home residents, hoping to see a signal in a population in which flu complications are more common. “If you can get a difference in a nursing home population, that’s clinically important, that gives you hope that you can see it in all the other populations, too,” he said.

SOURCE: Gravenstein S et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 996.

SAN FRANCISCO – presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“It’s one thing to say you have a more immunogenic vaccine, it’s another thing to be able to say it offers clinical benefit, especially in the oldest old and the frailest frail,” says Stefan Gravenstein, MD, professor of medicine and health services, policy and practice at the Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, R.I. Dr. Gravenstein presented a poster outlying a randomized, clinical trial of the Fluad vaccine in nursing homes.

The study randomized the nursing homes so that some facilities would offer Fluad as part of their standard of care. The design helped address the problem of consent. Any clinical trial that requires individual consent would likely exclude many of the frailest patients, leading to an unrepresentative sample. “So if you want to have a generalizable result, you’d like to have it applied to the population the way you would in the real world, so randomizing the nursing homes rather than the people makes a lot of sense,” said Dr. Gravenstein.

Dr. Gravenstein chose to test the vaccine in nursing home residents, hoping to see a signal in a population in which flu complications are more common. “If you can get a difference in a nursing home population, that’s clinically important, that gives you hope that you can see it in all the other populations, too,” he said.

SOURCE: Gravenstein S et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 996.

SAN FRANCISCO – presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“It’s one thing to say you have a more immunogenic vaccine, it’s another thing to be able to say it offers clinical benefit, especially in the oldest old and the frailest frail,” says Stefan Gravenstein, MD, professor of medicine and health services, policy and practice at the Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, R.I. Dr. Gravenstein presented a poster outlying a randomized, clinical trial of the Fluad vaccine in nursing homes.

The study randomized the nursing homes so that some facilities would offer Fluad as part of their standard of care. The design helped address the problem of consent. Any clinical trial that requires individual consent would likely exclude many of the frailest patients, leading to an unrepresentative sample. “So if you want to have a generalizable result, you’d like to have it applied to the population the way you would in the real world, so randomizing the nursing homes rather than the people makes a lot of sense,” said Dr. Gravenstein.

Dr. Gravenstein chose to test the vaccine in nursing home residents, hoping to see a signal in a population in which flu complications are more common. “If you can get a difference in a nursing home population, that’s clinically important, that gives you hope that you can see it in all the other populations, too,” he said.

SOURCE: Gravenstein S et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 996.

REPORTING FROM ID WEEK 2018

FDA approves omadacycline for pneumonia and skin infections

The, for treating community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in adults, the manufacturer, Paratek, announced in a press release.

The company expects that omadacycline will be available in the first quarter of 2019. Administered once-daily in either oral or IV formulations, the antibiotic was effective and well tolerated across multiple trials, which altogether included almost 2,000 patients, according to Paratek. As part of the approval, the company has agreed to conduct postmarketing studies, specifically, more studies in CABP and in pediatric populations. “To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Nuzyra and other antibacterial drugs, Nuzyra should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria,” according to a statement in the indications section of the prescribing information.

Omadacycline is contraindicated for patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or any members of the tetracycline class of antibacterial drugs; hypersensitivity reactions have been observed, so use should be discontinued if one is suspected. Use of this drug during later stages of pregnancy can lead to irreversible discoloration of the infant’s teeth and inhibition of bone growth; it should also not be used during breastfeeding.

Because omadacycline is structurally similar to tetracycline class drugs, some adverse reactions to those drugs may be seen with this one, such as photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri, and antianabolic action. Adverse reactions known to have an association with omadacycline include nausea, vomiting, hypertension, insomnia, diarrhea, constipation, and increases of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Drug interactions may occur with anticoagulants, so dosage of those drugs may need to be reduced while treating with omadacycline. Antacids also are believed to have a drug interaction – specifically, impairing absorption of omadacycline

The, for treating community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in adults, the manufacturer, Paratek, announced in a press release.

The company expects that omadacycline will be available in the first quarter of 2019. Administered once-daily in either oral or IV formulations, the antibiotic was effective and well tolerated across multiple trials, which altogether included almost 2,000 patients, according to Paratek. As part of the approval, the company has agreed to conduct postmarketing studies, specifically, more studies in CABP and in pediatric populations. “To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Nuzyra and other antibacterial drugs, Nuzyra should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria,” according to a statement in the indications section of the prescribing information.

Omadacycline is contraindicated for patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or any members of the tetracycline class of antibacterial drugs; hypersensitivity reactions have been observed, so use should be discontinued if one is suspected. Use of this drug during later stages of pregnancy can lead to irreversible discoloration of the infant’s teeth and inhibition of bone growth; it should also not be used during breastfeeding.

Because omadacycline is structurally similar to tetracycline class drugs, some adverse reactions to those drugs may be seen with this one, such as photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri, and antianabolic action. Adverse reactions known to have an association with omadacycline include nausea, vomiting, hypertension, insomnia, diarrhea, constipation, and increases of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Drug interactions may occur with anticoagulants, so dosage of those drugs may need to be reduced while treating with omadacycline. Antacids also are believed to have a drug interaction – specifically, impairing absorption of omadacycline

The, for treating community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in adults, the manufacturer, Paratek, announced in a press release.

The company expects that omadacycline will be available in the first quarter of 2019. Administered once-daily in either oral or IV formulations, the antibiotic was effective and well tolerated across multiple trials, which altogether included almost 2,000 patients, according to Paratek. As part of the approval, the company has agreed to conduct postmarketing studies, specifically, more studies in CABP and in pediatric populations. “To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Nuzyra and other antibacterial drugs, Nuzyra should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria,” according to a statement in the indications section of the prescribing information.

Omadacycline is contraindicated for patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or any members of the tetracycline class of antibacterial drugs; hypersensitivity reactions have been observed, so use should be discontinued if one is suspected. Use of this drug during later stages of pregnancy can lead to irreversible discoloration of the infant’s teeth and inhibition of bone growth; it should also not be used during breastfeeding.

Because omadacycline is structurally similar to tetracycline class drugs, some adverse reactions to those drugs may be seen with this one, such as photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri, and antianabolic action. Adverse reactions known to have an association with omadacycline include nausea, vomiting, hypertension, insomnia, diarrhea, constipation, and increases of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Drug interactions may occur with anticoagulants, so dosage of those drugs may need to be reduced while treating with omadacycline. Antacids also are believed to have a drug interaction – specifically, impairing absorption of omadacycline

PCV13 moderately effective in older adults

ATLANTA – (IPD) caused by PCV13 vaccine serotypes in adults aged 65 years and older, according to a case-control study involving Medicare beneficiaries.

Conversely, the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) showed limited effectiveness against serotypes unique to that vaccine in the study, which included 699 cases and more than 10,000 controls, Olivia Almendares, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Vaccine efficacy against PCV13 [plus 6C type, which has cross-reactivity with serotype 6A] was 47% in those who received PCV13 vaccine only,” Ms. Almendares said in an interview, noting that efficacy was 26% against serotype 3 and 67% against other PCV13 serotypes (plus 6C). “Vaccine efficacy against PPSV23-unique types was 36% for those who received only PPSV23.”

Neither vaccine showed effectiveness against serotypes not included in the respective vaccines, she said.

The findings are timely given that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is reevaluating its PCV13 recommendation for adults aged 65 years and older, she added.

“Specifically, ACIP is addressing whether PCV13 should be recommended routinely for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 and older given sustained indirect effects,” she said, explaining that, in 2014 when ACIP recommended routine use of the vaccine in series with PPSV23 for adults aged 65 years and older, the committee recognized that herd immunity effects from PCV13 use in children might eventually limit the utility of this recommendation, and therefore it proposed reevaluation and revision as needed after 4 years.

For the current study, she and her colleagues linked IPD cases in persons aged 65 years and older, which were identified through Active Bacterial Core surveillance during 2015-2016, to records for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) beneficiaries. Vaccination and medical histories were obtained through medical records, and vaccine effectiveness was estimated as one minus the odds ratio for vaccination with PCV13 only or PPSV23 only versus neither vaccine using conditional logistic regression, with adjustment for sex and underlying medical conditions.

Of 2,246 IPD cases, 1,017 (45%) were matched to Medicare beneficiaries, and 699 were included in the analysis after those with noncontinuous enrollment in Medicare, long-term care residence, and missing census tract data were excluded. The cases were matched based on age, census tract of residence, and length of Medicare enrollment to 10,152 matched controls identified through CMS.

IPD associated with PCV13 (plus type 6C) accounted for 164 (23% of cases), of which 88 (12% of cases) involved serotype 3, and invasive pneumococcal disease associated with PPSV23 accounted for 350 cases (50%), she said.

PCV13 vaccine was given alone in 14% and 18% of cases and controls, respectively; PPSV23 alone was given in 22% and 21% of case patients and controls, respectively; and both vaccines were given in 8% of cases and controls.

Compared with controls, case patients were more likely to be of nonwhite race (16% vs. 11%), to have more than one chronic medical condition (88% vs. 58%), and to have one or more immunocompromising conditions (54% vs. 32%), she and her colleagues reported.

“PCV13 showed moderate overall effectiveness in preventing IPD caused by PCV13 (including 6C), but effectiveness may be lower for serotype 3 than for other PCV13 types,” she said.

“These results are in agreement with those from CAPiTA – a large clinical trial conducted in the Netherlands, which showed PCV13 to be effective against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older,” she noted. “Additionally, data from CDC surveillance suggest that PCV13-serotype [invasive pneumococcal disease] among children and adults aged 65 and older has declined dramatically following PCV13 introduction for children in 2010, as predicted.”

In fact, among adults aged 65 years and older, PCV13-serotype invasive pneumococcal disease declined by 40% after the vaccine was introduced in children. This corresponds to a change in the annual PCV13-serotype incidence from 14 cases per 100,000 population in 2010 to five cases per 100,000 population in 2014, she said; she added that IPD incidence plateaued in 2014-2016 with vaccine serotypes contributing to a small proportion of overall IPD burden among adults aged 65 years and older.

ACIP’s reevaluation of the PCV13 recommendation is ongoing and will be addressed at upcoming meetings.

“As part of the review process, we look at changes in disease incidence focusing primarily on invasive pneumococcal disease and noninvasive pneumonia, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, and vaccine safety,” she said. She noted that ACIP currently has no plans to consider revising PCV13 recommendations for adults who have immunocompromising conditions, for whom PCV13 has been recommended since 2012.

Ms. Almendares reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Almendares O et al. ICEID 2018, Board 376.

ATLANTA – (IPD) caused by PCV13 vaccine serotypes in adults aged 65 years and older, according to a case-control study involving Medicare beneficiaries.

Conversely, the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) showed limited effectiveness against serotypes unique to that vaccine in the study, which included 699 cases and more than 10,000 controls, Olivia Almendares, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Vaccine efficacy against PCV13 [plus 6C type, which has cross-reactivity with serotype 6A] was 47% in those who received PCV13 vaccine only,” Ms. Almendares said in an interview, noting that efficacy was 26% against serotype 3 and 67% against other PCV13 serotypes (plus 6C). “Vaccine efficacy against PPSV23-unique types was 36% for those who received only PPSV23.”

Neither vaccine showed effectiveness against serotypes not included in the respective vaccines, she said.

The findings are timely given that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is reevaluating its PCV13 recommendation for adults aged 65 years and older, she added.

“Specifically, ACIP is addressing whether PCV13 should be recommended routinely for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 and older given sustained indirect effects,” she said, explaining that, in 2014 when ACIP recommended routine use of the vaccine in series with PPSV23 for adults aged 65 years and older, the committee recognized that herd immunity effects from PCV13 use in children might eventually limit the utility of this recommendation, and therefore it proposed reevaluation and revision as needed after 4 years.

For the current study, she and her colleagues linked IPD cases in persons aged 65 years and older, which were identified through Active Bacterial Core surveillance during 2015-2016, to records for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) beneficiaries. Vaccination and medical histories were obtained through medical records, and vaccine effectiveness was estimated as one minus the odds ratio for vaccination with PCV13 only or PPSV23 only versus neither vaccine using conditional logistic regression, with adjustment for sex and underlying medical conditions.

Of 2,246 IPD cases, 1,017 (45%) were matched to Medicare beneficiaries, and 699 were included in the analysis after those with noncontinuous enrollment in Medicare, long-term care residence, and missing census tract data were excluded. The cases were matched based on age, census tract of residence, and length of Medicare enrollment to 10,152 matched controls identified through CMS.

IPD associated with PCV13 (plus type 6C) accounted for 164 (23% of cases), of which 88 (12% of cases) involved serotype 3, and invasive pneumococcal disease associated with PPSV23 accounted for 350 cases (50%), she said.

PCV13 vaccine was given alone in 14% and 18% of cases and controls, respectively; PPSV23 alone was given in 22% and 21% of case patients and controls, respectively; and both vaccines were given in 8% of cases and controls.

Compared with controls, case patients were more likely to be of nonwhite race (16% vs. 11%), to have more than one chronic medical condition (88% vs. 58%), and to have one or more immunocompromising conditions (54% vs. 32%), she and her colleagues reported.

“PCV13 showed moderate overall effectiveness in preventing IPD caused by PCV13 (including 6C), but effectiveness may be lower for serotype 3 than for other PCV13 types,” she said.

“These results are in agreement with those from CAPiTA – a large clinical trial conducted in the Netherlands, which showed PCV13 to be effective against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older,” she noted. “Additionally, data from CDC surveillance suggest that PCV13-serotype [invasive pneumococcal disease] among children and adults aged 65 and older has declined dramatically following PCV13 introduction for children in 2010, as predicted.”

In fact, among adults aged 65 years and older, PCV13-serotype invasive pneumococcal disease declined by 40% after the vaccine was introduced in children. This corresponds to a change in the annual PCV13-serotype incidence from 14 cases per 100,000 population in 2010 to five cases per 100,000 population in 2014, she said; she added that IPD incidence plateaued in 2014-2016 with vaccine serotypes contributing to a small proportion of overall IPD burden among adults aged 65 years and older.

ACIP’s reevaluation of the PCV13 recommendation is ongoing and will be addressed at upcoming meetings.

“As part of the review process, we look at changes in disease incidence focusing primarily on invasive pneumococcal disease and noninvasive pneumonia, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, and vaccine safety,” she said. She noted that ACIP currently has no plans to consider revising PCV13 recommendations for adults who have immunocompromising conditions, for whom PCV13 has been recommended since 2012.

Ms. Almendares reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Almendares O et al. ICEID 2018, Board 376.

ATLANTA – (IPD) caused by PCV13 vaccine serotypes in adults aged 65 years and older, according to a case-control study involving Medicare beneficiaries.

Conversely, the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) showed limited effectiveness against serotypes unique to that vaccine in the study, which included 699 cases and more than 10,000 controls, Olivia Almendares, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Vaccine efficacy against PCV13 [plus 6C type, which has cross-reactivity with serotype 6A] was 47% in those who received PCV13 vaccine only,” Ms. Almendares said in an interview, noting that efficacy was 26% against serotype 3 and 67% against other PCV13 serotypes (plus 6C). “Vaccine efficacy against PPSV23-unique types was 36% for those who received only PPSV23.”

Neither vaccine showed effectiveness against serotypes not included in the respective vaccines, she said.

The findings are timely given that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is reevaluating its PCV13 recommendation for adults aged 65 years and older, she added.

“Specifically, ACIP is addressing whether PCV13 should be recommended routinely for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 and older given sustained indirect effects,” she said, explaining that, in 2014 when ACIP recommended routine use of the vaccine in series with PPSV23 for adults aged 65 years and older, the committee recognized that herd immunity effects from PCV13 use in children might eventually limit the utility of this recommendation, and therefore it proposed reevaluation and revision as needed after 4 years.

For the current study, she and her colleagues linked IPD cases in persons aged 65 years and older, which were identified through Active Bacterial Core surveillance during 2015-2016, to records for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) beneficiaries. Vaccination and medical histories were obtained through medical records, and vaccine effectiveness was estimated as one minus the odds ratio for vaccination with PCV13 only or PPSV23 only versus neither vaccine using conditional logistic regression, with adjustment for sex and underlying medical conditions.

Of 2,246 IPD cases, 1,017 (45%) were matched to Medicare beneficiaries, and 699 were included in the analysis after those with noncontinuous enrollment in Medicare, long-term care residence, and missing census tract data were excluded. The cases were matched based on age, census tract of residence, and length of Medicare enrollment to 10,152 matched controls identified through CMS.

IPD associated with PCV13 (plus type 6C) accounted for 164 (23% of cases), of which 88 (12% of cases) involved serotype 3, and invasive pneumococcal disease associated with PPSV23 accounted for 350 cases (50%), she said.

PCV13 vaccine was given alone in 14% and 18% of cases and controls, respectively; PPSV23 alone was given in 22% and 21% of case patients and controls, respectively; and both vaccines were given in 8% of cases and controls.

Compared with controls, case patients were more likely to be of nonwhite race (16% vs. 11%), to have more than one chronic medical condition (88% vs. 58%), and to have one or more immunocompromising conditions (54% vs. 32%), she and her colleagues reported.

“PCV13 showed moderate overall effectiveness in preventing IPD caused by PCV13 (including 6C), but effectiveness may be lower for serotype 3 than for other PCV13 types,” she said.

“These results are in agreement with those from CAPiTA – a large clinical trial conducted in the Netherlands, which showed PCV13 to be effective against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older,” she noted. “Additionally, data from CDC surveillance suggest that PCV13-serotype [invasive pneumococcal disease] among children and adults aged 65 and older has declined dramatically following PCV13 introduction for children in 2010, as predicted.”

In fact, among adults aged 65 years and older, PCV13-serotype invasive pneumococcal disease declined by 40% after the vaccine was introduced in children. This corresponds to a change in the annual PCV13-serotype incidence from 14 cases per 100,000 population in 2010 to five cases per 100,000 population in 2014, she said; she added that IPD incidence plateaued in 2014-2016 with vaccine serotypes contributing to a small proportion of overall IPD burden among adults aged 65 years and older.

ACIP’s reevaluation of the PCV13 recommendation is ongoing and will be addressed at upcoming meetings.

“As part of the review process, we look at changes in disease incidence focusing primarily on invasive pneumococcal disease and noninvasive pneumonia, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, and vaccine safety,” she said. She noted that ACIP currently has no plans to consider revising PCV13 recommendations for adults who have immunocompromising conditions, for whom PCV13 has been recommended since 2012.

Ms. Almendares reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Almendares O et al. ICEID 2018, Board 376.

REPORTING FROM ICEID 2018

Most in-hospital pneumonia deaths may not be preventable

Most in-hospital deaths from community-acquired pneumonia are not preventable with current medical therapy, according to an analysis of deaths at five U.S. hospitals with expertise in pneumonia care.

Adults who are hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) are at high risk for short-term mortality but it is unclear whether an improvement in care could lower this risk, noted the study authors led by Grant W. Waterer, MBBS, PhD, of Northwestern University, Chicago.

“Understanding the circumstances in which CAP patients die could facilitate improvements in the management of CAP by enabling future improvement efforts to focus on common preventable causes of death,” they wrote. Their report was published in CHEST®.

They therefore performed a secondary analysis of the Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study involving adults hospitalized with CAP between January 2010 and June 2012 across five tertiary-care hospitals in the United States.

The clinical characteristics of patients who died in the hospital were compared with those of patients who survived to hospital discharge. Chronic heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, chronic liver disease, cerebrovascular disease, cancer (excluding skin cancer), and diabetes were considered as severe chronic comorbidities based on their association with increased mortality and ICU admission in CAP severity scores.

Deaths caused by septic shock, respiratory failure, multisystem organ failure, cardiopulmonary arrest prior to stabilization of CAP, and endocarditis, were considered to be directly related to CAP.

Conversely, causes of death indirectly related to CAP included acute cardiovascular disease, stroke, acute renal failure, and secondary infections developed after hospitalization. Deaths caused by cancer, cirrhosis, and chronic neurologic conditions were considered unrelated to CAP.

Medical notes were assessed to determine whether the patient received management consistent with current recommendations; for example, antibiotics consistent with guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

End-of-life limitations in care, such as patient/family decision not to proceed with full medical treatment, also were considered by the research team.

Results showed that among the 2,320 patients with radiographically confirmed CAP, 52 died during initial hospitalization, 33 of whom were aged 65 years or older, and 32 of whom had two or more chronic comorbidities.

Most of the in-hospital deaths occurred early in the hospitalization: 35 within the first 10 days of admission, and 5 after 30 days in hospital.

CAP was judged by an expert physician review panel to be the direct cause of death in 27 of the patients, 10 with CAP having an indirect role with major contribution, 9 with CAP having an indirect role with minor contribution, and 6 with CAP having no role in death.

Do-not-resuscitate orders were present at the time of death for 21 of the patients.

Forty-five of the patients were admitted to an ICU, with 37 dying in the ICU. The eight patients who died on the ward after transfer out of the ICU had end-of-life limitations of care in place.

The researchers noted that the number of patients dying in the ICU was greater in the United States, possibly because in Europe fewer patients are admitted to an ICU.

“This discrepancy likely reflects cultural differences between the U.S. and Europe in the role of intensive care for patients with advanced age and/or advanced comorbid conditions,” they noted.

Overall, the physician review panel identified nine patients who had a lapse in quality of in-hospital CAP care, with four of the deaths potentially linked to this lapse in care.

However, two of the patients had end-of-life limitations of care in place, which according to the authors meant that “only two patients undergoing full medical treatment without end-of-life limitations of care had an identified lapse in quality of in-hospital pneumonia care potentially contributing to in-hospital death, including one with a delay in antibiotics for over an hour in the presence of shock and one with initial antibiotics not consistent with IDSA/ATS guidelines.”

The research team concluded that most in-hospital deaths among adult patients admitted with CAP in their study would not have been preventable with higher quality in-hospital pneumonia care.

“Many of the in-hospital deaths among patients admitted with CAP occurred in older patients with severe comorbidities and end-of-life limitations in care,” they noted.

They said the influence of end-of-life limitations on care short of full palliation was an important finding, with all patients who died outside the ICU having end-of-life limitations in care.

“Current diagnostic related group (DRG) and international classification of diseases (ICD) coding systems do not have the necessary nuances to capture these limitations of care, yet they are clearly important factors in determining whether patients experience in-hospital death,” they added.

Dr. Waterer reported no conflicts. Two coauthors reported potential conflicts of interest in relation to consulting fees from several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Waterer G. et al. CHEST 2018;154(3):628-35. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.05.021.

Most in-hospital deaths from community-acquired pneumonia are not preventable with current medical therapy, according to an analysis of deaths at five U.S. hospitals with expertise in pneumonia care.

Adults who are hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) are at high risk for short-term mortality but it is unclear whether an improvement in care could lower this risk, noted the study authors led by Grant W. Waterer, MBBS, PhD, of Northwestern University, Chicago.

“Understanding the circumstances in which CAP patients die could facilitate improvements in the management of CAP by enabling future improvement efforts to focus on common preventable causes of death,” they wrote. Their report was published in CHEST®.

They therefore performed a secondary analysis of the Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study involving adults hospitalized with CAP between January 2010 and June 2012 across five tertiary-care hospitals in the United States.

The clinical characteristics of patients who died in the hospital were compared with those of patients who survived to hospital discharge. Chronic heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, chronic liver disease, cerebrovascular disease, cancer (excluding skin cancer), and diabetes were considered as severe chronic comorbidities based on their association with increased mortality and ICU admission in CAP severity scores.

Deaths caused by septic shock, respiratory failure, multisystem organ failure, cardiopulmonary arrest prior to stabilization of CAP, and endocarditis, were considered to be directly related to CAP.

Conversely, causes of death indirectly related to CAP included acute cardiovascular disease, stroke, acute renal failure, and secondary infections developed after hospitalization. Deaths caused by cancer, cirrhosis, and chronic neurologic conditions were considered unrelated to CAP.

Medical notes were assessed to determine whether the patient received management consistent with current recommendations; for example, antibiotics consistent with guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

End-of-life limitations in care, such as patient/family decision not to proceed with full medical treatment, also were considered by the research team.

Results showed that among the 2,320 patients with radiographically confirmed CAP, 52 died during initial hospitalization, 33 of whom were aged 65 years or older, and 32 of whom had two or more chronic comorbidities.

Most of the in-hospital deaths occurred early in the hospitalization: 35 within the first 10 days of admission, and 5 after 30 days in hospital.

CAP was judged by an expert physician review panel to be the direct cause of death in 27 of the patients, 10 with CAP having an indirect role with major contribution, 9 with CAP having an indirect role with minor contribution, and 6 with CAP having no role in death.

Do-not-resuscitate orders were present at the time of death for 21 of the patients.

Forty-five of the patients were admitted to an ICU, with 37 dying in the ICU. The eight patients who died on the ward after transfer out of the ICU had end-of-life limitations of care in place.

The researchers noted that the number of patients dying in the ICU was greater in the United States, possibly because in Europe fewer patients are admitted to an ICU.

“This discrepancy likely reflects cultural differences between the U.S. and Europe in the role of intensive care for patients with advanced age and/or advanced comorbid conditions,” they noted.

Overall, the physician review panel identified nine patients who had a lapse in quality of in-hospital CAP care, with four of the deaths potentially linked to this lapse in care.

However, two of the patients had end-of-life limitations of care in place, which according to the authors meant that “only two patients undergoing full medical treatment without end-of-life limitations of care had an identified lapse in quality of in-hospital pneumonia care potentially contributing to in-hospital death, including one with a delay in antibiotics for over an hour in the presence of shock and one with initial antibiotics not consistent with IDSA/ATS guidelines.”

The research team concluded that most in-hospital deaths among adult patients admitted with CAP in their study would not have been preventable with higher quality in-hospital pneumonia care.

“Many of the in-hospital deaths among patients admitted with CAP occurred in older patients with severe comorbidities and end-of-life limitations in care,” they noted.

They said the influence of end-of-life limitations on care short of full palliation was an important finding, with all patients who died outside the ICU having end-of-life limitations in care.

“Current diagnostic related group (DRG) and international classification of diseases (ICD) coding systems do not have the necessary nuances to capture these limitations of care, yet they are clearly important factors in determining whether patients experience in-hospital death,” they added.

Dr. Waterer reported no conflicts. Two coauthors reported potential conflicts of interest in relation to consulting fees from several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Waterer G. et al. CHEST 2018;154(3):628-35. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.05.021.

Most in-hospital deaths from community-acquired pneumonia are not preventable with current medical therapy, according to an analysis of deaths at five U.S. hospitals with expertise in pneumonia care.

Adults who are hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) are at high risk for short-term mortality but it is unclear whether an improvement in care could lower this risk, noted the study authors led by Grant W. Waterer, MBBS, PhD, of Northwestern University, Chicago.

“Understanding the circumstances in which CAP patients die could facilitate improvements in the management of CAP by enabling future improvement efforts to focus on common preventable causes of death,” they wrote. Their report was published in CHEST®.

They therefore performed a secondary analysis of the Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study involving adults hospitalized with CAP between January 2010 and June 2012 across five tertiary-care hospitals in the United States.

The clinical characteristics of patients who died in the hospital were compared with those of patients who survived to hospital discharge. Chronic heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, chronic liver disease, cerebrovascular disease, cancer (excluding skin cancer), and diabetes were considered as severe chronic comorbidities based on their association with increased mortality and ICU admission in CAP severity scores.

Deaths caused by septic shock, respiratory failure, multisystem organ failure, cardiopulmonary arrest prior to stabilization of CAP, and endocarditis, were considered to be directly related to CAP.

Conversely, causes of death indirectly related to CAP included acute cardiovascular disease, stroke, acute renal failure, and secondary infections developed after hospitalization. Deaths caused by cancer, cirrhosis, and chronic neurologic conditions were considered unrelated to CAP.

Medical notes were assessed to determine whether the patient received management consistent with current recommendations; for example, antibiotics consistent with guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

End-of-life limitations in care, such as patient/family decision not to proceed with full medical treatment, also were considered by the research team.

Results showed that among the 2,320 patients with radiographically confirmed CAP, 52 died during initial hospitalization, 33 of whom were aged 65 years or older, and 32 of whom had two or more chronic comorbidities.

Most of the in-hospital deaths occurred early in the hospitalization: 35 within the first 10 days of admission, and 5 after 30 days in hospital.

CAP was judged by an expert physician review panel to be the direct cause of death in 27 of the patients, 10 with CAP having an indirect role with major contribution, 9 with CAP having an indirect role with minor contribution, and 6 with CAP having no role in death.

Do-not-resuscitate orders were present at the time of death for 21 of the patients.

Forty-five of the patients were admitted to an ICU, with 37 dying in the ICU. The eight patients who died on the ward after transfer out of the ICU had end-of-life limitations of care in place.

The researchers noted that the number of patients dying in the ICU was greater in the United States, possibly because in Europe fewer patients are admitted to an ICU.

“This discrepancy likely reflects cultural differences between the U.S. and Europe in the role of intensive care for patients with advanced age and/or advanced comorbid conditions,” they noted.

Overall, the physician review panel identified nine patients who had a lapse in quality of in-hospital CAP care, with four of the deaths potentially linked to this lapse in care.

However, two of the patients had end-of-life limitations of care in place, which according to the authors meant that “only two patients undergoing full medical treatment without end-of-life limitations of care had an identified lapse in quality of in-hospital pneumonia care potentially contributing to in-hospital death, including one with a delay in antibiotics for over an hour in the presence of shock and one with initial antibiotics not consistent with IDSA/ATS guidelines.”

The research team concluded that most in-hospital deaths among adult patients admitted with CAP in their study would not have been preventable with higher quality in-hospital pneumonia care.

“Many of the in-hospital deaths among patients admitted with CAP occurred in older patients with severe comorbidities and end-of-life limitations in care,” they noted.

They said the influence of end-of-life limitations on care short of full palliation was an important finding, with all patients who died outside the ICU having end-of-life limitations in care.

“Current diagnostic related group (DRG) and international classification of diseases (ICD) coding systems do not have the necessary nuances to capture these limitations of care, yet they are clearly important factors in determining whether patients experience in-hospital death,” they added.

Dr. Waterer reported no conflicts. Two coauthors reported potential conflicts of interest in relation to consulting fees from several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Waterer G. et al. CHEST 2018;154(3):628-35. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.05.021.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Most in-hospital deaths from community-acquired pneumonia are not preventable with current medical therapy.

Major finding: Two out of 52 patients who died in-hospital from community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) who were undergoing full medical treatment without end-of-life limitations of care had an identified lapse in quality of in-hospital pneumonia care that potentially contributed to their death.

Study details: A secondary analysis of the prospective multicenter Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study involving 2,320 adults with radiographically confirmed CAP.

Disclosures: Dr. Waterer reported no conflicts. Two coauthors reported potential conflicts of interest in relation to consulting fees from several pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Waterer G. et al. CHEST 2018;154(3):628-35.

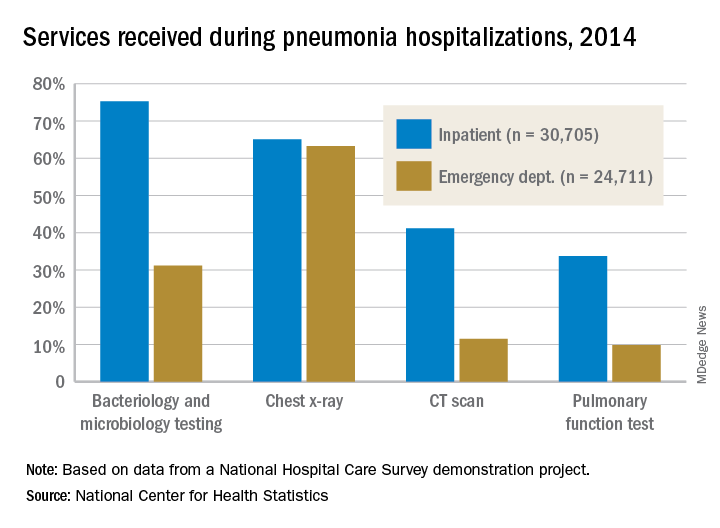

Service, please: Hospital setting matters for pneumonia

the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reported.

The percentages were not as close, however, for other diagnostic services. Inpatient stays were much more likely than ED encounters to involve bacteriology and microbiology testing (75.3% vs. 31.2%), CT scans (41.2% vs. 11.5%), and pulmonary function tests (33.7% vs. 9.8%), investigators from the NCHS said.

The age distribution of the two patient populations also were quite different, with those aged 65 years and older making up the largest share (46%) of pneumonia inpatients and the 15-and-under group representing the largest proportion (47%) of ED visits. For the inpatient setting, the smallest age group was those aged 15-44 years (10%), and for the ED it was those aged 65 years and older (14%), they reported.

The National Hospital Care Survey “is not yet nationally representative,” the NCHS investigators wrote – the overall sample for 2014 consisted of 581 hospitals – but “the number of encounters and the inclusion of [personally identifiable information] allow an example of analysis that was not previously possible.”

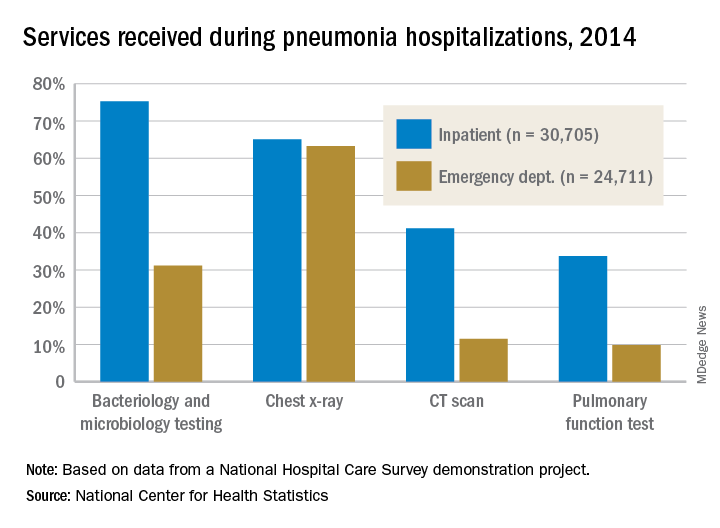

the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reported.

The percentages were not as close, however, for other diagnostic services. Inpatient stays were much more likely than ED encounters to involve bacteriology and microbiology testing (75.3% vs. 31.2%), CT scans (41.2% vs. 11.5%), and pulmonary function tests (33.7% vs. 9.8%), investigators from the NCHS said.

The age distribution of the two patient populations also were quite different, with those aged 65 years and older making up the largest share (46%) of pneumonia inpatients and the 15-and-under group representing the largest proportion (47%) of ED visits. For the inpatient setting, the smallest age group was those aged 15-44 years (10%), and for the ED it was those aged 65 years and older (14%), they reported.

The National Hospital Care Survey “is not yet nationally representative,” the NCHS investigators wrote – the overall sample for 2014 consisted of 581 hospitals – but “the number of encounters and the inclusion of [personally identifiable information] allow an example of analysis that was not previously possible.”

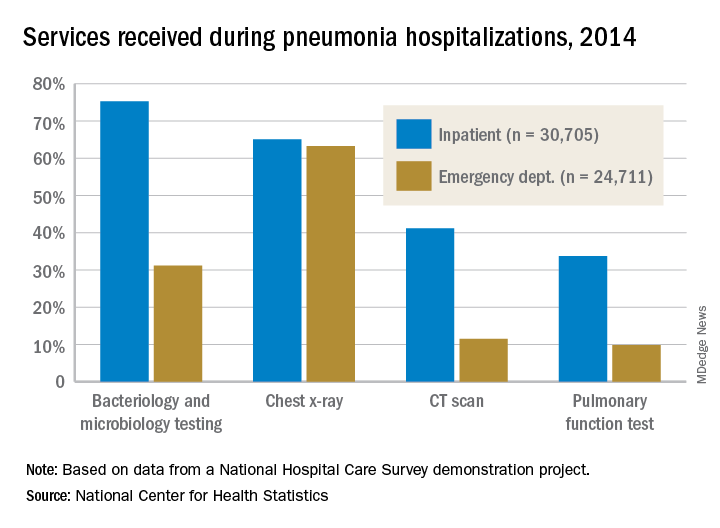

the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reported.

The percentages were not as close, however, for other diagnostic services. Inpatient stays were much more likely than ED encounters to involve bacteriology and microbiology testing (75.3% vs. 31.2%), CT scans (41.2% vs. 11.5%), and pulmonary function tests (33.7% vs. 9.8%), investigators from the NCHS said.

The age distribution of the two patient populations also were quite different, with those aged 65 years and older making up the largest share (46%) of pneumonia inpatients and the 15-and-under group representing the largest proportion (47%) of ED visits. For the inpatient setting, the smallest age group was those aged 15-44 years (10%), and for the ED it was those aged 65 years and older (14%), they reported.

The National Hospital Care Survey “is not yet nationally representative,” the NCHS investigators wrote – the overall sample for 2014 consisted of 581 hospitals – but “the number of encounters and the inclusion of [personally identifiable information] allow an example of analysis that was not previously possible.”

Negative chest x-ray to rule out pediatric pneumonia

, researchers say.

In a paper published in the September issue of Pediatrics, researchers report the results of a prospective cohort study in 683 children – with a median age of 3.1 years – presenting to emergency departments with suspected pneumonia.

Dr. Susan C. Lipsett, from the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and co-authors, wrote that the use of chest radiograph to diagnose pneumonia is thought to have limitations such as its inability to distinguish between bacteria and viral infection, and the possible absence of radiographic presentations early in the disease in patients with dehydration.

In this study, 457 (72.8%) of the children had negative chest radiographs. Of these, 44 were clinically diagnosed with pneumonia, despite the radiograph results, and prescribed antibiotics. These children were more likely to have rales or respiratory distress and less likely to have wheezing compared with the children with negative radiographs who were not initially diagnosed with pneumonia.

Among the remaining 411 children with negative radiographs – who were not prescribed antibiotics – five (1.2%) were subsequently diagnosed with pneumonia within 2 weeks of the radiograph. These five children were all under 3 years of age, but none had been treated with intravenous fluids for dehydration. Only one had radiographic findings of pneumonia on a follow-up visit.

Counting the 44 children diagnosed with pneumonia despite the negative x-ray, chest radiography showed a negative predictive value of 89.2% (95% confidence interval, 85.9%-91.9%). Without those children, the negative predictive value was 98.8% (95% CI, 97%-99.6%).

There were also 113 children (16.5%) with positive chest radiographs, and 72 (10.7%) with equivocal radiographs.

The authors said their results showed that most children with negative chest radiograph would recover fully without needing antibiotics, and argued there was a place for chest radiography in the diagnostic process, to rule out bacterial pneumonia.

“Most clinicians caring for children in the outpatient setting rely on clinical signs and symptoms to determine whether to prescribe an antibiotic for the treatment of pneumonia,” they wrote. “However, given recent literature in which the poor reliability and validity of physical examination findings are cited, reliance on physical examination alone may lead to the overdiagnosis of pneumonia.”

They acknowledged that the lack of a universally accepted gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children was a significant limitation of the research. In addition, the lack of systematic radiographs meant some children who initially had a negative result and recovered without antibiotics may have shown a positive result on a second scan.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lipsett S et al. Pediatrics 2018 142(3):e20180236.

While the results of this study offer reassurance that chest radiograph for suspected pneumonia in children has a high negative predictive value, perhaps a more important question is the accuracy of chest radiography at ruling in bacterial pneumonia – its positive predictive value.

There are reasons to suspect that the positive predictive value of chest radiography may not be as high as the negative predictive value found in this study. This is particularly important given that questions have been raised about the utility of antibiotic therapy in treating Mycoplasma pneumonia infection in children.

Leaving out chest radiography altogether in children with a low clinical suspicion for pneumonia would decreased radi-ation use, cost, and perhaps also unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.

Matthew D. Garber, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville and Ricardo A. Quinonez, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics 2018, 142(3): e20182025. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2025). No conflicts of interest were declared.

While the results of this study offer reassurance that chest radiograph for suspected pneumonia in children has a high negative predictive value, perhaps a more important question is the accuracy of chest radiography at ruling in bacterial pneumonia – its positive predictive value.

There are reasons to suspect that the positive predictive value of chest radiography may not be as high as the negative predictive value found in this study. This is particularly important given that questions have been raised about the utility of antibiotic therapy in treating Mycoplasma pneumonia infection in children.

Leaving out chest radiography altogether in children with a low clinical suspicion for pneumonia would decreased radi-ation use, cost, and perhaps also unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.

Matthew D. Garber, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville and Ricardo A. Quinonez, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics 2018, 142(3): e20182025. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2025). No conflicts of interest were declared.

While the results of this study offer reassurance that chest radiograph for suspected pneumonia in children has a high negative predictive value, perhaps a more important question is the accuracy of chest radiography at ruling in bacterial pneumonia – its positive predictive value.

There are reasons to suspect that the positive predictive value of chest radiography may not be as high as the negative predictive value found in this study. This is particularly important given that questions have been raised about the utility of antibiotic therapy in treating Mycoplasma pneumonia infection in children.

Leaving out chest radiography altogether in children with a low clinical suspicion for pneumonia would decreased radi-ation use, cost, and perhaps also unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.

Matthew D. Garber, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville and Ricardo A. Quinonez, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics 2018, 142(3): e20182025. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2025). No conflicts of interest were declared.

, researchers say.

In a paper published in the September issue of Pediatrics, researchers report the results of a prospective cohort study in 683 children – with a median age of 3.1 years – presenting to emergency departments with suspected pneumonia.

Dr. Susan C. Lipsett, from the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and co-authors, wrote that the use of chest radiograph to diagnose pneumonia is thought to have limitations such as its inability to distinguish between bacteria and viral infection, and the possible absence of radiographic presentations early in the disease in patients with dehydration.

In this study, 457 (72.8%) of the children had negative chest radiographs. Of these, 44 were clinically diagnosed with pneumonia, despite the radiograph results, and prescribed antibiotics. These children were more likely to have rales or respiratory distress and less likely to have wheezing compared with the children with negative radiographs who were not initially diagnosed with pneumonia.

Among the remaining 411 children with negative radiographs – who were not prescribed antibiotics – five (1.2%) were subsequently diagnosed with pneumonia within 2 weeks of the radiograph. These five children were all under 3 years of age, but none had been treated with intravenous fluids for dehydration. Only one had radiographic findings of pneumonia on a follow-up visit.

Counting the 44 children diagnosed with pneumonia despite the negative x-ray, chest radiography showed a negative predictive value of 89.2% (95% confidence interval, 85.9%-91.9%). Without those children, the negative predictive value was 98.8% (95% CI, 97%-99.6%).

There were also 113 children (16.5%) with positive chest radiographs, and 72 (10.7%) with equivocal radiographs.

The authors said their results showed that most children with negative chest radiograph would recover fully without needing antibiotics, and argued there was a place for chest radiography in the diagnostic process, to rule out bacterial pneumonia.

“Most clinicians caring for children in the outpatient setting rely on clinical signs and symptoms to determine whether to prescribe an antibiotic for the treatment of pneumonia,” they wrote. “However, given recent literature in which the poor reliability and validity of physical examination findings are cited, reliance on physical examination alone may lead to the overdiagnosis of pneumonia.”

They acknowledged that the lack of a universally accepted gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children was a significant limitation of the research. In addition, the lack of systematic radiographs meant some children who initially had a negative result and recovered without antibiotics may have shown a positive result on a second scan.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lipsett S et al. Pediatrics 2018 142(3):e20180236.

, researchers say.

In a paper published in the September issue of Pediatrics, researchers report the results of a prospective cohort study in 683 children – with a median age of 3.1 years – presenting to emergency departments with suspected pneumonia.

Dr. Susan C. Lipsett, from the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and co-authors, wrote that the use of chest radiograph to diagnose pneumonia is thought to have limitations such as its inability to distinguish between bacteria and viral infection, and the possible absence of radiographic presentations early in the disease in patients with dehydration.

In this study, 457 (72.8%) of the children had negative chest radiographs. Of these, 44 were clinically diagnosed with pneumonia, despite the radiograph results, and prescribed antibiotics. These children were more likely to have rales or respiratory distress and less likely to have wheezing compared with the children with negative radiographs who were not initially diagnosed with pneumonia.

Among the remaining 411 children with negative radiographs – who were not prescribed antibiotics – five (1.2%) were subsequently diagnosed with pneumonia within 2 weeks of the radiograph. These five children were all under 3 years of age, but none had been treated with intravenous fluids for dehydration. Only one had radiographic findings of pneumonia on a follow-up visit.

Counting the 44 children diagnosed with pneumonia despite the negative x-ray, chest radiography showed a negative predictive value of 89.2% (95% confidence interval, 85.9%-91.9%). Without those children, the negative predictive value was 98.8% (95% CI, 97%-99.6%).

There were also 113 children (16.5%) with positive chest radiographs, and 72 (10.7%) with equivocal radiographs.

The authors said their results showed that most children with negative chest radiograph would recover fully without needing antibiotics, and argued there was a place for chest radiography in the diagnostic process, to rule out bacterial pneumonia.

“Most clinicians caring for children in the outpatient setting rely on clinical signs and symptoms to determine whether to prescribe an antibiotic for the treatment of pneumonia,” they wrote. “However, given recent literature in which the poor reliability and validity of physical examination findings are cited, reliance on physical examination alone may lead to the overdiagnosis of pneumonia.”

They acknowledged that the lack of a universally accepted gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children was a significant limitation of the research. In addition, the lack of systematic radiographs meant some children who initially had a negative result and recovered without antibiotics may have shown a positive result on a second scan.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lipsett S et al. Pediatrics 2018 142(3):e20180236.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Negative chest radiograph can rule out pneumonia in children.

Major finding: Chest radiograph has a negative predictive value of 89.2% in children with suspected pneumonia.

Study details: Prospective cohort study in 683 children with suspected pneumonia.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Lipsett S et al. Pediatrics 2018 142(3):e20180236. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0236.