User login

Osteonecrosis of jaw in mRCC higher with denosumab/antiangiogenics

The combination of a targeted antiangiogenic agent and denosumab (Xgeva) appears to significantly increase the risk for osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), French investigators cautioned.

Among 41 patients with RCC metastatic to bone treated with an antiangiogenic agent and denosumab, 7 (17%) developed osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ). All seven received the combination in the first line, reported Aline Guillot, MD, from the Institut de cancérologie Lucien Neuwirth in Saint-Priest-en-Jarez, France, and her colleagues.

“The incidence of ONJ was high in this real-life population of patients with mRCC treated with antiangiogenic therapies combined with denosumab. This toxicity signal should warn physicians about this combination in the mRCC population,” they wrote in Clinical Genitourinary Cancer.

Previous studies have shown that the combination of another bone-targeted therapy – zoledronic acid – with antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as sunitinib (Sutent) is associated with increased risk for ONJ. In addition, ONJ with the combination of denosumab and antiangiogenic therapies “has been noticed but never estimated,” the authors noted.

To evaluate the incidence of hypocalcemia and ONJ in patients with RCC metastatic to bone treated with denosumab and a TKI or mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, the investigators gathered data retrospectively from 10 French centers.

They identified 25 men and 16 women with a median age of 62 years (range, 54-68 years). Of this group, 40 received denosumab in the first line in combination with either sunitinib (31 patients), pazopanib (6), everolimus (Afinitor and generics; 2), and temsirolimus (Torisel and generics; 1). The median duration of first-line therapy was 12 months.

Denosumab was given in the second line with axitinib (Inlyta) to nine patients, with everolimus to nine, and with sunitinib to three patients. The median duration of second-line therapy was 3 months.

Skeletal-related events occurred in 41% of patients prior to receiving denosumab and in 61% (25 patients) after denosumab. The events included clinical fracture, bone pain requiring radiation, and spinal compression.

Of the seven patients who developed ONJ, six received denosumab and sunitinib in the first line and one received denosumab plus temsirolimus, with a median duration of treatment of 11.8 months. Three of these patients also received denosumab in the second line with either axitinib, everolimus, or sunitinib, with a median duration of 9.8 months. Data on second-line therapy for the remaining four patients with ONJ were not available.

The investigators noted that the 17% incidence of ONJ was higher than the 10% rate seen in a study of patients with mRCC treated with a TKI and a bisphosphonate (Acta Clin Belg. 2018 Apr;73(2):100-9), and the 1.8% incidence seen in an analysis of three phase 3 trials in cancer patients with bone metastases (Ann Oncol. 2012 May;23(5):1341-7).

Although the etiology of ONJ is unknown, patient education and oral hygiene may reduce the risk in patients treated with denosumab and a TKI.

“The benefit of denosumab in this setting in regard [to] toxicity needs to be demonstrated in a prospective trial,” they wrote.

No conflicts of interest or disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Guillot A et al. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.08.006.

The combination of a targeted antiangiogenic agent and denosumab (Xgeva) appears to significantly increase the risk for osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), French investigators cautioned.

Among 41 patients with RCC metastatic to bone treated with an antiangiogenic agent and denosumab, 7 (17%) developed osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ). All seven received the combination in the first line, reported Aline Guillot, MD, from the Institut de cancérologie Lucien Neuwirth in Saint-Priest-en-Jarez, France, and her colleagues.

“The incidence of ONJ was high in this real-life population of patients with mRCC treated with antiangiogenic therapies combined with denosumab. This toxicity signal should warn physicians about this combination in the mRCC population,” they wrote in Clinical Genitourinary Cancer.

Previous studies have shown that the combination of another bone-targeted therapy – zoledronic acid – with antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as sunitinib (Sutent) is associated with increased risk for ONJ. In addition, ONJ with the combination of denosumab and antiangiogenic therapies “has been noticed but never estimated,” the authors noted.

To evaluate the incidence of hypocalcemia and ONJ in patients with RCC metastatic to bone treated with denosumab and a TKI or mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, the investigators gathered data retrospectively from 10 French centers.

They identified 25 men and 16 women with a median age of 62 years (range, 54-68 years). Of this group, 40 received denosumab in the first line in combination with either sunitinib (31 patients), pazopanib (6), everolimus (Afinitor and generics; 2), and temsirolimus (Torisel and generics; 1). The median duration of first-line therapy was 12 months.

Denosumab was given in the second line with axitinib (Inlyta) to nine patients, with everolimus to nine, and with sunitinib to three patients. The median duration of second-line therapy was 3 months.

Skeletal-related events occurred in 41% of patients prior to receiving denosumab and in 61% (25 patients) after denosumab. The events included clinical fracture, bone pain requiring radiation, and spinal compression.

Of the seven patients who developed ONJ, six received denosumab and sunitinib in the first line and one received denosumab plus temsirolimus, with a median duration of treatment of 11.8 months. Three of these patients also received denosumab in the second line with either axitinib, everolimus, or sunitinib, with a median duration of 9.8 months. Data on second-line therapy for the remaining four patients with ONJ were not available.

The investigators noted that the 17% incidence of ONJ was higher than the 10% rate seen in a study of patients with mRCC treated with a TKI and a bisphosphonate (Acta Clin Belg. 2018 Apr;73(2):100-9), and the 1.8% incidence seen in an analysis of three phase 3 trials in cancer patients with bone metastases (Ann Oncol. 2012 May;23(5):1341-7).

Although the etiology of ONJ is unknown, patient education and oral hygiene may reduce the risk in patients treated with denosumab and a TKI.

“The benefit of denosumab in this setting in regard [to] toxicity needs to be demonstrated in a prospective trial,” they wrote.

No conflicts of interest or disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Guillot A et al. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.08.006.

The combination of a targeted antiangiogenic agent and denosumab (Xgeva) appears to significantly increase the risk for osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), French investigators cautioned.

Among 41 patients with RCC metastatic to bone treated with an antiangiogenic agent and denosumab, 7 (17%) developed osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ). All seven received the combination in the first line, reported Aline Guillot, MD, from the Institut de cancérologie Lucien Neuwirth in Saint-Priest-en-Jarez, France, and her colleagues.

“The incidence of ONJ was high in this real-life population of patients with mRCC treated with antiangiogenic therapies combined with denosumab. This toxicity signal should warn physicians about this combination in the mRCC population,” they wrote in Clinical Genitourinary Cancer.

Previous studies have shown that the combination of another bone-targeted therapy – zoledronic acid – with antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as sunitinib (Sutent) is associated with increased risk for ONJ. In addition, ONJ with the combination of denosumab and antiangiogenic therapies “has been noticed but never estimated,” the authors noted.

To evaluate the incidence of hypocalcemia and ONJ in patients with RCC metastatic to bone treated with denosumab and a TKI or mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, the investigators gathered data retrospectively from 10 French centers.

They identified 25 men and 16 women with a median age of 62 years (range, 54-68 years). Of this group, 40 received denosumab in the first line in combination with either sunitinib (31 patients), pazopanib (6), everolimus (Afinitor and generics; 2), and temsirolimus (Torisel and generics; 1). The median duration of first-line therapy was 12 months.

Denosumab was given in the second line with axitinib (Inlyta) to nine patients, with everolimus to nine, and with sunitinib to three patients. The median duration of second-line therapy was 3 months.

Skeletal-related events occurred in 41% of patients prior to receiving denosumab and in 61% (25 patients) after denosumab. The events included clinical fracture, bone pain requiring radiation, and spinal compression.

Of the seven patients who developed ONJ, six received denosumab and sunitinib in the first line and one received denosumab plus temsirolimus, with a median duration of treatment of 11.8 months. Three of these patients also received denosumab in the second line with either axitinib, everolimus, or sunitinib, with a median duration of 9.8 months. Data on second-line therapy for the remaining four patients with ONJ were not available.

The investigators noted that the 17% incidence of ONJ was higher than the 10% rate seen in a study of patients with mRCC treated with a TKI and a bisphosphonate (Acta Clin Belg. 2018 Apr;73(2):100-9), and the 1.8% incidence seen in an analysis of three phase 3 trials in cancer patients with bone metastases (Ann Oncol. 2012 May;23(5):1341-7).

Although the etiology of ONJ is unknown, patient education and oral hygiene may reduce the risk in patients treated with denosumab and a TKI.

“The benefit of denosumab in this setting in regard [to] toxicity needs to be demonstrated in a prospective trial,” they wrote.

No conflicts of interest or disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Guillot A et al. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.08.006.

FROM CLINICAL GENITOURINARY CANCER

Key clinical point: The combination of denosumab and an antiangiogenic agent is associated with increased risk for osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), a serious and debilitating side effect.

Major finding: Of 41 patients treated with denosumab and a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the front line, 7 developed ONJ.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of data on 41 patients with mRCC treated with denosumab and an antiangiogenic agent at 10 cancer centers in France.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest or disclosures were reported.

Source: Guillot A et al. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.08.006.

Skin signs may be good omens during cancer therapy

Signs of efficacy of anti-cancer therapies may be only skin deep, results of a retrospective review indicate.

Cutaneous toxicities such as vitiligo, rash, alopecia, and nail toxicities may be early signs of efficacy of targeted therapies, immunotherapy, or cytotoxic chemotherapy, according to Alexandra K. Rzepecki, of the University of Michigan, and her coauthors from Albert Einstein Medical College in the Bronx, New York.

“Because cutaneous toxicities are a clinically visible parameter, they may alert clinicians to the possibility of treatment success or failure in a rapid, cost-effective, and noninvasive manner,” they wrote. The report is in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The investigators reviewed the medical literature for clinical studies of three major classes of anti-cancer therapies that included data on associations between cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes such progression-free survival (PFS) overall survival (OS).

The drug classes and their associations with cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes were as follows:

- Targeted therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) such as cetuximab (Erbitux) and erlotinib (Tarceva), and multikinase targeted agents such as sorafenib (Nexavar) and sunitinib (Sutent). Toxicities associated with clinical benefit from EGFR inhibitors include rash, xerosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, paronychia, and pruritus, whereas skin toxicities associated with the multikinase inhibitors trended toward the hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction.

- Immunotherapies included blockers of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4) such as ipilimumab (Yervoy) and inhibitors of programmed death 1 protein (PD-1) and its ligand 1 (PD-L1) such as nivolumab (Opdivo), pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and atezolizumab (Tecentriq). In studies of pembrolizumab for various malignancies, rash or vitiligo was an independent prognostic factor for longer OS, a higher proportion of objective responses, and longer PFS. Similar associations were seen with nivolumab, with the additional association of hair repigmentation among patients with non–small-cell lung cancer being associated with stable disease responses or better. Among patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab, hair depigmentation correlated with durable responses.

- Cytotoxic chemotherapy agents included the anthracycline doxorubicin, taxanes such as paclitaxel and docetaxel, platinum agents (cisplatin and carboplatin), and fluoropyrimidines such as capecitabine. Patients treated for various cancers with doxorubicin who had alopecia were significantly more likely to have clinical remissions than were patients who did not lose their hair, and patients treated with this agent who developed hand-foot syndrome had significantly longer PFS. For patients treated with docetaxel, severity of nail changes and/or development of nail alterations were associated with both improved OS and PFS. Patients treated with the combination of paclitaxel and a platinum agent who developed grade 2 or greater alopecia up to cycle 3 had significantly longer OS than did patients who had hair loss later in the course of therapy. Patients treated with capecitabine who developed had hand-foot skin reactions had improved progression-free and disease-free survival.

“Although further studies are needed to better evaluate these promising associations, vigilant monitoring of cutaneous toxicities should be a priority, as their development may indicate a favorable response to treatment. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to collaborate with oncologists to help identify and manage these toxicities, thereby allowing patients to receive life-prolonging anticancer therapy while minimizing dose reduction or interruption of their treatment,” the authors wrote.

They reported no study funding source and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rzepecki A, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:545-555.

Signs of efficacy of anti-cancer therapies may be only skin deep, results of a retrospective review indicate.

Cutaneous toxicities such as vitiligo, rash, alopecia, and nail toxicities may be early signs of efficacy of targeted therapies, immunotherapy, or cytotoxic chemotherapy, according to Alexandra K. Rzepecki, of the University of Michigan, and her coauthors from Albert Einstein Medical College in the Bronx, New York.

“Because cutaneous toxicities are a clinically visible parameter, they may alert clinicians to the possibility of treatment success or failure in a rapid, cost-effective, and noninvasive manner,” they wrote. The report is in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The investigators reviewed the medical literature for clinical studies of three major classes of anti-cancer therapies that included data on associations between cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes such progression-free survival (PFS) overall survival (OS).

The drug classes and their associations with cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes were as follows:

- Targeted therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) such as cetuximab (Erbitux) and erlotinib (Tarceva), and multikinase targeted agents such as sorafenib (Nexavar) and sunitinib (Sutent). Toxicities associated with clinical benefit from EGFR inhibitors include rash, xerosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, paronychia, and pruritus, whereas skin toxicities associated with the multikinase inhibitors trended toward the hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction.

- Immunotherapies included blockers of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4) such as ipilimumab (Yervoy) and inhibitors of programmed death 1 protein (PD-1) and its ligand 1 (PD-L1) such as nivolumab (Opdivo), pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and atezolizumab (Tecentriq). In studies of pembrolizumab for various malignancies, rash or vitiligo was an independent prognostic factor for longer OS, a higher proportion of objective responses, and longer PFS. Similar associations were seen with nivolumab, with the additional association of hair repigmentation among patients with non–small-cell lung cancer being associated with stable disease responses or better. Among patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab, hair depigmentation correlated with durable responses.

- Cytotoxic chemotherapy agents included the anthracycline doxorubicin, taxanes such as paclitaxel and docetaxel, platinum agents (cisplatin and carboplatin), and fluoropyrimidines such as capecitabine. Patients treated for various cancers with doxorubicin who had alopecia were significantly more likely to have clinical remissions than were patients who did not lose their hair, and patients treated with this agent who developed hand-foot syndrome had significantly longer PFS. For patients treated with docetaxel, severity of nail changes and/or development of nail alterations were associated with both improved OS and PFS. Patients treated with the combination of paclitaxel and a platinum agent who developed grade 2 or greater alopecia up to cycle 3 had significantly longer OS than did patients who had hair loss later in the course of therapy. Patients treated with capecitabine who developed had hand-foot skin reactions had improved progression-free and disease-free survival.

“Although further studies are needed to better evaluate these promising associations, vigilant monitoring of cutaneous toxicities should be a priority, as their development may indicate a favorable response to treatment. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to collaborate with oncologists to help identify and manage these toxicities, thereby allowing patients to receive life-prolonging anticancer therapy while minimizing dose reduction or interruption of their treatment,” the authors wrote.

They reported no study funding source and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rzepecki A, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:545-555.

Signs of efficacy of anti-cancer therapies may be only skin deep, results of a retrospective review indicate.

Cutaneous toxicities such as vitiligo, rash, alopecia, and nail toxicities may be early signs of efficacy of targeted therapies, immunotherapy, or cytotoxic chemotherapy, according to Alexandra K. Rzepecki, of the University of Michigan, and her coauthors from Albert Einstein Medical College in the Bronx, New York.

“Because cutaneous toxicities are a clinically visible parameter, they may alert clinicians to the possibility of treatment success or failure in a rapid, cost-effective, and noninvasive manner,” they wrote. The report is in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The investigators reviewed the medical literature for clinical studies of three major classes of anti-cancer therapies that included data on associations between cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes such progression-free survival (PFS) overall survival (OS).

The drug classes and their associations with cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes were as follows:

- Targeted therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) such as cetuximab (Erbitux) and erlotinib (Tarceva), and multikinase targeted agents such as sorafenib (Nexavar) and sunitinib (Sutent). Toxicities associated with clinical benefit from EGFR inhibitors include rash, xerosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, paronychia, and pruritus, whereas skin toxicities associated with the multikinase inhibitors trended toward the hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction.

- Immunotherapies included blockers of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4) such as ipilimumab (Yervoy) and inhibitors of programmed death 1 protein (PD-1) and its ligand 1 (PD-L1) such as nivolumab (Opdivo), pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and atezolizumab (Tecentriq). In studies of pembrolizumab for various malignancies, rash or vitiligo was an independent prognostic factor for longer OS, a higher proportion of objective responses, and longer PFS. Similar associations were seen with nivolumab, with the additional association of hair repigmentation among patients with non–small-cell lung cancer being associated with stable disease responses or better. Among patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab, hair depigmentation correlated with durable responses.

- Cytotoxic chemotherapy agents included the anthracycline doxorubicin, taxanes such as paclitaxel and docetaxel, platinum agents (cisplatin and carboplatin), and fluoropyrimidines such as capecitabine. Patients treated for various cancers with doxorubicin who had alopecia were significantly more likely to have clinical remissions than were patients who did not lose their hair, and patients treated with this agent who developed hand-foot syndrome had significantly longer PFS. For patients treated with docetaxel, severity of nail changes and/or development of nail alterations were associated with both improved OS and PFS. Patients treated with the combination of paclitaxel and a platinum agent who developed grade 2 or greater alopecia up to cycle 3 had significantly longer OS than did patients who had hair loss later in the course of therapy. Patients treated with capecitabine who developed had hand-foot skin reactions had improved progression-free and disease-free survival.

“Although further studies are needed to better evaluate these promising associations, vigilant monitoring of cutaneous toxicities should be a priority, as their development may indicate a favorable response to treatment. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to collaborate with oncologists to help identify and manage these toxicities, thereby allowing patients to receive life-prolonging anticancer therapy while minimizing dose reduction or interruption of their treatment,” the authors wrote.

They reported no study funding source and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rzepecki A, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:545-555.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Cutaneous adverse events may be early signs of drug efficacy in patients treated for various cancers.

Major finding: Cutaneous toxicities with targeted therapies, immunotherapy, and cytotoxic drugs were associated in multiple studies with improved outcomes, including progression-free and overall survival.

Study details: Retrospective review of medical literature for clinical studies reporting associations between cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes of cancer therapy.

Disclosures: The authors reported no study funding source and no conflicts of interest.

Source: Rzepecki A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Sep;79[3]:545-55.

AACR: New cancer cases predicted to rise above 2.3 million by 2035

during the last 12 months.

Among the advances outlined in the AACR Cancer Progress Report 2018 are “revolutionary new immunotherapeutics called CAR T–cell therapies, exciting new targeted radiotherapeutics, and numerous new targeted therapeutics that are expanding the scope of precision medicine,” the AACR said in a written statement.

Despite this progress, however, cancer continues to pose immense public health challenges.

The number of new cancer cases in the United States is predicted to increase from more than 1.7 million in 2018 to almost 2.4 million in 2035, due in large part to the rising number of people age 65 and older, according to the report.

AACR calls on elected officials to:

- Maintain “robust, sustained, and predictable growth” of the National Institutes of Health budget, increasing it at least $2 billion in fiscal year (FY) 2019, for a total funding level of at least $39.1 billion.

- Make sure that the $711 million in funding provided through the 21st Century Cures Act for targeted initiatives – including the National Cancer Moonshot – “is fully appropriated in FY 2019 and is supplemental to the healthy increase for the NIH’s base budget.”

- Raise the Food and Drug Administration’s base budget in FY 2019 to $3.1 billion – a $308 million increase above its FY 2018 level – to secure support for regulatory science and speed the development of medical products, ones that are safe and effective. Particularly, in FY 2019, the AACR backs a funding level of $20 million for the FDA Oncology Center of Excellence.

- Provide the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cancer Prevention and Control Programs with total funding of at least $517 million. This would include funding for “comprehensive cancer control, cancer registries, and screening and awareness programs for specific cancers.”

Read the full report and watch video stories from patients here.

during the last 12 months.

Among the advances outlined in the AACR Cancer Progress Report 2018 are “revolutionary new immunotherapeutics called CAR T–cell therapies, exciting new targeted radiotherapeutics, and numerous new targeted therapeutics that are expanding the scope of precision medicine,” the AACR said in a written statement.

Despite this progress, however, cancer continues to pose immense public health challenges.

The number of new cancer cases in the United States is predicted to increase from more than 1.7 million in 2018 to almost 2.4 million in 2035, due in large part to the rising number of people age 65 and older, according to the report.

AACR calls on elected officials to:

- Maintain “robust, sustained, and predictable growth” of the National Institutes of Health budget, increasing it at least $2 billion in fiscal year (FY) 2019, for a total funding level of at least $39.1 billion.

- Make sure that the $711 million in funding provided through the 21st Century Cures Act for targeted initiatives – including the National Cancer Moonshot – “is fully appropriated in FY 2019 and is supplemental to the healthy increase for the NIH’s base budget.”

- Raise the Food and Drug Administration’s base budget in FY 2019 to $3.1 billion – a $308 million increase above its FY 2018 level – to secure support for regulatory science and speed the development of medical products, ones that are safe and effective. Particularly, in FY 2019, the AACR backs a funding level of $20 million for the FDA Oncology Center of Excellence.

- Provide the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cancer Prevention and Control Programs with total funding of at least $517 million. This would include funding for “comprehensive cancer control, cancer registries, and screening and awareness programs for specific cancers.”

Read the full report and watch video stories from patients here.

during the last 12 months.

Among the advances outlined in the AACR Cancer Progress Report 2018 are “revolutionary new immunotherapeutics called CAR T–cell therapies, exciting new targeted radiotherapeutics, and numerous new targeted therapeutics that are expanding the scope of precision medicine,” the AACR said in a written statement.

Despite this progress, however, cancer continues to pose immense public health challenges.

The number of new cancer cases in the United States is predicted to increase from more than 1.7 million in 2018 to almost 2.4 million in 2035, due in large part to the rising number of people age 65 and older, according to the report.

AACR calls on elected officials to:

- Maintain “robust, sustained, and predictable growth” of the National Institutes of Health budget, increasing it at least $2 billion in fiscal year (FY) 2019, for a total funding level of at least $39.1 billion.

- Make sure that the $711 million in funding provided through the 21st Century Cures Act for targeted initiatives – including the National Cancer Moonshot – “is fully appropriated in FY 2019 and is supplemental to the healthy increase for the NIH’s base budget.”

- Raise the Food and Drug Administration’s base budget in FY 2019 to $3.1 billion – a $308 million increase above its FY 2018 level – to secure support for regulatory science and speed the development of medical products, ones that are safe and effective. Particularly, in FY 2019, the AACR backs a funding level of $20 million for the FDA Oncology Center of Excellence.

- Provide the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cancer Prevention and Control Programs with total funding of at least $517 million. This would include funding for “comprehensive cancer control, cancer registries, and screening and awareness programs for specific cancers.”

Read the full report and watch video stories from patients here.

ASCO updates guidance on prophylaxis for adults with cancer-related immunosuppression

Fluoroquinolones are recommended for adults with cancer-related immunosuppression if they are at high risk of infection, according to an updated clinical practice guideline on antimicrobial prophylaxis.

By contrast, patients with solid tumors are not routinely recommended to receive antibiotic prophylaxis, according to the guideline, developed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) with the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

The guideline includes antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral prophylaxis recommendations, along with additional precautions such as hand hygiene that may reduce infection risk.

Released in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, the updated guidelines were developed by an expert panel cochaired by Christopher R. Flowers, MD of Emory University, Atlanta, and Randy A. Taplitz, MD of the University of California, San Diego, Health.

For the most part, the panel endorsed the previous ASCO recommendations, published in 2013. However, the panel considered six new high-quality studies and six new or updated meta-analyses to make modifications and add some new recommendations.

Fluoroquinolones, in the 2013 guideline, were recommended over trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole because of fewer adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation. Panelists for the new guidelines said they continued to support that recommendation, based on an updated literature review.

That review showed significant reductions in both febrile neutropenia incidence and all-cause mortality, not only for patients at high risk of febrile neutropenia or profound, protracted neutropenia but also for lower-risk patients with solid tumors, they said.

However, the benefits did not sufficiently outweigh the harms to justify recommending fluoroquinolone prophylaxis for all patients with solid tumors or lymphoma, according to the report from the expert panel.

Those harms could include antibiotic-associated adverse effects, emergence of resistance, and Clostridium difficile infections, they said.

Accordingly, they recommended fluoroquinolone prophylaxis for the high-risk patients, including most patients with acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromes (AML/MDS) or those undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT).

Similarly, the panel recommended that high-risk patients should receive antifungal prophylaxis with an oral triazole or parenteral echinocandin, while prophylaxis would not be routinely recommended for solid tumor patients.

By contrast, all patients undergoing chemotherapy for malignancy should receive yearly influenza vaccination with an inactivated quadrivalent vaccine, the panel said in its antiviral prophylaxis recommendations.

Family members, household contacts, and health care providers also should receive influenza vaccinations, said the panel, endorsing recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that were also cited in the 2013 ASCO guidelines.

Health care workers should follow hand hygiene and respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette to reduce risk of pathogen transmission, the panel said, endorsing CDC recommendations cited in the previous guideline.

However, the panel said they recommend against interventions such as neutropenic diet, footwear exchange, nutritional supplements, and surgical masks.

“Evidence of clinical benefit is lacking” for those interventions, they said.

Participants in the expert panel disclosed potential conflicts of interest related to Merck, Chimerix, GlyPharma Therapeutic, Pfizer, Cidara Therapeutics, Celgene, Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, and Allergan, among other entities.

SOURCE: Taplitz RA et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00374.

Fluoroquinolones are recommended for adults with cancer-related immunosuppression if they are at high risk of infection, according to an updated clinical practice guideline on antimicrobial prophylaxis.

By contrast, patients with solid tumors are not routinely recommended to receive antibiotic prophylaxis, according to the guideline, developed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) with the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

The guideline includes antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral prophylaxis recommendations, along with additional precautions such as hand hygiene that may reduce infection risk.

Released in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, the updated guidelines were developed by an expert panel cochaired by Christopher R. Flowers, MD of Emory University, Atlanta, and Randy A. Taplitz, MD of the University of California, San Diego, Health.

For the most part, the panel endorsed the previous ASCO recommendations, published in 2013. However, the panel considered six new high-quality studies and six new or updated meta-analyses to make modifications and add some new recommendations.

Fluoroquinolones, in the 2013 guideline, were recommended over trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole because of fewer adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation. Panelists for the new guidelines said they continued to support that recommendation, based on an updated literature review.

That review showed significant reductions in both febrile neutropenia incidence and all-cause mortality, not only for patients at high risk of febrile neutropenia or profound, protracted neutropenia but also for lower-risk patients with solid tumors, they said.

However, the benefits did not sufficiently outweigh the harms to justify recommending fluoroquinolone prophylaxis for all patients with solid tumors or lymphoma, according to the report from the expert panel.

Those harms could include antibiotic-associated adverse effects, emergence of resistance, and Clostridium difficile infections, they said.

Accordingly, they recommended fluoroquinolone prophylaxis for the high-risk patients, including most patients with acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromes (AML/MDS) or those undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT).

Similarly, the panel recommended that high-risk patients should receive antifungal prophylaxis with an oral triazole or parenteral echinocandin, while prophylaxis would not be routinely recommended for solid tumor patients.

By contrast, all patients undergoing chemotherapy for malignancy should receive yearly influenza vaccination with an inactivated quadrivalent vaccine, the panel said in its antiviral prophylaxis recommendations.

Family members, household contacts, and health care providers also should receive influenza vaccinations, said the panel, endorsing recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that were also cited in the 2013 ASCO guidelines.

Health care workers should follow hand hygiene and respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette to reduce risk of pathogen transmission, the panel said, endorsing CDC recommendations cited in the previous guideline.

However, the panel said they recommend against interventions such as neutropenic diet, footwear exchange, nutritional supplements, and surgical masks.

“Evidence of clinical benefit is lacking” for those interventions, they said.

Participants in the expert panel disclosed potential conflicts of interest related to Merck, Chimerix, GlyPharma Therapeutic, Pfizer, Cidara Therapeutics, Celgene, Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, and Allergan, among other entities.

SOURCE: Taplitz RA et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00374.

Fluoroquinolones are recommended for adults with cancer-related immunosuppression if they are at high risk of infection, according to an updated clinical practice guideline on antimicrobial prophylaxis.

By contrast, patients with solid tumors are not routinely recommended to receive antibiotic prophylaxis, according to the guideline, developed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) with the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

The guideline includes antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral prophylaxis recommendations, along with additional precautions such as hand hygiene that may reduce infection risk.

Released in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, the updated guidelines were developed by an expert panel cochaired by Christopher R. Flowers, MD of Emory University, Atlanta, and Randy A. Taplitz, MD of the University of California, San Diego, Health.

For the most part, the panel endorsed the previous ASCO recommendations, published in 2013. However, the panel considered six new high-quality studies and six new or updated meta-analyses to make modifications and add some new recommendations.

Fluoroquinolones, in the 2013 guideline, were recommended over trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole because of fewer adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation. Panelists for the new guidelines said they continued to support that recommendation, based on an updated literature review.

That review showed significant reductions in both febrile neutropenia incidence and all-cause mortality, not only for patients at high risk of febrile neutropenia or profound, protracted neutropenia but also for lower-risk patients with solid tumors, they said.

However, the benefits did not sufficiently outweigh the harms to justify recommending fluoroquinolone prophylaxis for all patients with solid tumors or lymphoma, according to the report from the expert panel.

Those harms could include antibiotic-associated adverse effects, emergence of resistance, and Clostridium difficile infections, they said.

Accordingly, they recommended fluoroquinolone prophylaxis for the high-risk patients, including most patients with acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromes (AML/MDS) or those undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT).

Similarly, the panel recommended that high-risk patients should receive antifungal prophylaxis with an oral triazole or parenteral echinocandin, while prophylaxis would not be routinely recommended for solid tumor patients.

By contrast, all patients undergoing chemotherapy for malignancy should receive yearly influenza vaccination with an inactivated quadrivalent vaccine, the panel said in its antiviral prophylaxis recommendations.

Family members, household contacts, and health care providers also should receive influenza vaccinations, said the panel, endorsing recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that were also cited in the 2013 ASCO guidelines.

Health care workers should follow hand hygiene and respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette to reduce risk of pathogen transmission, the panel said, endorsing CDC recommendations cited in the previous guideline.

However, the panel said they recommend against interventions such as neutropenic diet, footwear exchange, nutritional supplements, and surgical masks.

“Evidence of clinical benefit is lacking” for those interventions, they said.

Participants in the expert panel disclosed potential conflicts of interest related to Merck, Chimerix, GlyPharma Therapeutic, Pfizer, Cidara Therapeutics, Celgene, Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, and Allergan, among other entities.

SOURCE: Taplitz RA et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00374.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

ESMO scale offers guidance on cancer targets

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has published a proposed scale that would rank molecular targets for various cancers by how well they can be treated with new or emerging drugs.

The ESMO Scale of Clinical Actionability for Molecular Targets is designed to “harmonize and standardize the reporting and interpretation of clinically relevant genomics data,” according to Joaquin Mateo, MD, PhD, from the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, Spain, and his fellow members of the ESMO Translational Research and Precision Medicine Working Group.

“A major challenge for oncologists in the clinic is to distinguish between findings that represent proven clinical value or potential value based on preliminary clinical or preclinical evidence from hypothetical gene-drug matches and findings that are currently irrelevant for clinical practice,” they wrote in Annals of Oncology.

The scale groups targets into one of six tiers based on levels of evidence ranging from the gold standard of prospective, randomized clinical trials to targets for which there are no evidence and only hypothetical actionability. The primary goal is to help oncologists assign priority to potential targets when they review results of gene-sequencing panels for individual patients, according to the developers.

Briefly, the six tiers are:

Tier I includes targets that are agreed to be suitable for routine use and a recommended specific drug when a specific molecular alteration is detected. Examples include trastuzumab for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer, and inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in patients with non–small cell lung cancer positive for EGFR mutations.

Tier II includes “investigational targets that likely define a patient population that benefits from a targeted drug but additional data are needed.” This tier includes agents that work in the phosphatidylinostiol 3-kinase pathway.

Tier III is similar to Tier II, in that it includes investigational targets that define a patient population with proven benefit from a targeted therapy, but in this case the target is detected in a different tumor type that has not previously been studied. For example, the targeted agent vemurafenib (Zelboraf), which extends survival of patients with metastatic melanomas carrying the BRAF V600E mutation, has only limited activity against BRAF-mutated colorectal cancers.

Tier IV includes targets with preclinical evidence of actionability.

Tier V includes targets with “evidence of relevant antitumor activity, not resulting in clinical meaningful benefit as single treatment but supporting development of cotargeting approaches.” The authors cite the example of PIK3CA inhibitors in patients with estrogen receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancers who also have PIK3CA activating mutations. In clinical trials, this strategy led to objective responses but not change outcomes.

The final tier is not Tier VI, as might be expected, but Tier X, with the X in this case being the unknown – that is, alterations/mutations for which there is neither preclinical nor clinical evidence to support their hypothetical use as a drug target.

“This clinical benefit–centered classification system offers a common language for all the actors involved in clinical cancer drug development. Its implementation in sequencing reports, tumor boards, and scientific communication can enable precise treatment decisions and facilitate discussions with patients about novel therapeutic options,” Dr. Mateo and his associates wrote in their conclusion.

The development process was supported by ESMO. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with various companies as well as grants/support from other foundations or charities.

SOURCE: Mateo J et al. Ann Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy263.

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has published a proposed scale that would rank molecular targets for various cancers by how well they can be treated with new or emerging drugs.

The ESMO Scale of Clinical Actionability for Molecular Targets is designed to “harmonize and standardize the reporting and interpretation of clinically relevant genomics data,” according to Joaquin Mateo, MD, PhD, from the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, Spain, and his fellow members of the ESMO Translational Research and Precision Medicine Working Group.

“A major challenge for oncologists in the clinic is to distinguish between findings that represent proven clinical value or potential value based on preliminary clinical or preclinical evidence from hypothetical gene-drug matches and findings that are currently irrelevant for clinical practice,” they wrote in Annals of Oncology.

The scale groups targets into one of six tiers based on levels of evidence ranging from the gold standard of prospective, randomized clinical trials to targets for which there are no evidence and only hypothetical actionability. The primary goal is to help oncologists assign priority to potential targets when they review results of gene-sequencing panels for individual patients, according to the developers.

Briefly, the six tiers are:

Tier I includes targets that are agreed to be suitable for routine use and a recommended specific drug when a specific molecular alteration is detected. Examples include trastuzumab for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer, and inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in patients with non–small cell lung cancer positive for EGFR mutations.

Tier II includes “investigational targets that likely define a patient population that benefits from a targeted drug but additional data are needed.” This tier includes agents that work in the phosphatidylinostiol 3-kinase pathway.

Tier III is similar to Tier II, in that it includes investigational targets that define a patient population with proven benefit from a targeted therapy, but in this case the target is detected in a different tumor type that has not previously been studied. For example, the targeted agent vemurafenib (Zelboraf), which extends survival of patients with metastatic melanomas carrying the BRAF V600E mutation, has only limited activity against BRAF-mutated colorectal cancers.

Tier IV includes targets with preclinical evidence of actionability.

Tier V includes targets with “evidence of relevant antitumor activity, not resulting in clinical meaningful benefit as single treatment but supporting development of cotargeting approaches.” The authors cite the example of PIK3CA inhibitors in patients with estrogen receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancers who also have PIK3CA activating mutations. In clinical trials, this strategy led to objective responses but not change outcomes.

The final tier is not Tier VI, as might be expected, but Tier X, with the X in this case being the unknown – that is, alterations/mutations for which there is neither preclinical nor clinical evidence to support their hypothetical use as a drug target.

“This clinical benefit–centered classification system offers a common language for all the actors involved in clinical cancer drug development. Its implementation in sequencing reports, tumor boards, and scientific communication can enable precise treatment decisions and facilitate discussions with patients about novel therapeutic options,” Dr. Mateo and his associates wrote in their conclusion.

The development process was supported by ESMO. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with various companies as well as grants/support from other foundations or charities.

SOURCE: Mateo J et al. Ann Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy263.

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has published a proposed scale that would rank molecular targets for various cancers by how well they can be treated with new or emerging drugs.

The ESMO Scale of Clinical Actionability for Molecular Targets is designed to “harmonize and standardize the reporting and interpretation of clinically relevant genomics data,” according to Joaquin Mateo, MD, PhD, from the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, Spain, and his fellow members of the ESMO Translational Research and Precision Medicine Working Group.

“A major challenge for oncologists in the clinic is to distinguish between findings that represent proven clinical value or potential value based on preliminary clinical or preclinical evidence from hypothetical gene-drug matches and findings that are currently irrelevant for clinical practice,” they wrote in Annals of Oncology.

The scale groups targets into one of six tiers based on levels of evidence ranging from the gold standard of prospective, randomized clinical trials to targets for which there are no evidence and only hypothetical actionability. The primary goal is to help oncologists assign priority to potential targets when they review results of gene-sequencing panels for individual patients, according to the developers.

Briefly, the six tiers are:

Tier I includes targets that are agreed to be suitable for routine use and a recommended specific drug when a specific molecular alteration is detected. Examples include trastuzumab for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer, and inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in patients with non–small cell lung cancer positive for EGFR mutations.

Tier II includes “investigational targets that likely define a patient population that benefits from a targeted drug but additional data are needed.” This tier includes agents that work in the phosphatidylinostiol 3-kinase pathway.

Tier III is similar to Tier II, in that it includes investigational targets that define a patient population with proven benefit from a targeted therapy, but in this case the target is detected in a different tumor type that has not previously been studied. For example, the targeted agent vemurafenib (Zelboraf), which extends survival of patients with metastatic melanomas carrying the BRAF V600E mutation, has only limited activity against BRAF-mutated colorectal cancers.

Tier IV includes targets with preclinical evidence of actionability.

Tier V includes targets with “evidence of relevant antitumor activity, not resulting in clinical meaningful benefit as single treatment but supporting development of cotargeting approaches.” The authors cite the example of PIK3CA inhibitors in patients with estrogen receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancers who also have PIK3CA activating mutations. In clinical trials, this strategy led to objective responses but not change outcomes.

The final tier is not Tier VI, as might be expected, but Tier X, with the X in this case being the unknown – that is, alterations/mutations for which there is neither preclinical nor clinical evidence to support their hypothetical use as a drug target.

“This clinical benefit–centered classification system offers a common language for all the actors involved in clinical cancer drug development. Its implementation in sequencing reports, tumor boards, and scientific communication can enable precise treatment decisions and facilitate discussions with patients about novel therapeutic options,” Dr. Mateo and his associates wrote in their conclusion.

The development process was supported by ESMO. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with various companies as well as grants/support from other foundations or charities.

SOURCE: Mateo J et al. Ann Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy263.

FROM ANNALS OF ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: The scale is intended to standardize reporting and interpretation of cancer gene panel results to help oncologists plan treatment.

Major finding: The scale divides current and future therapeutic targets into tiers based on levels of clinical and preclinical evidence.

Study details: Proposed guiding principles for a classification system developed by the Translational Research and Precision Medicine Working Group of the European Society of Medical Oncology.

Disclosures: The development process was supported by ESMO. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with various companies as well as grants/support from other foundations or charities.

Source: Mateo J et al. Ann Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy263.

When is the right time to stop treatment?

Martha Boxer (not her real name) had mentally prepared herself that this could happen, but the news still hit hard. Her doctors on the leukemia service broke the facts as gently as we could: The chemotherapy she had been suffering through for the last 2 weeks hadn’t worked. The results of her latest bone marrow biopsy showed it remained packed with cancer cells.

As Martha absorbed the news quietly, her son, sitting next to her bedside with his hand on hers, spoke first. “What now?”

I looked at my attending and nodded, as we were fully ready to answer this question. From the outset, we knew that Martha’s leukemia carried a genetic mutation that unfortunately put her in a high-risk category. The chances of her cancer responding to the first round of chemotherapy were low. When this happens, what we typically do next is reinduction, we explained. It’s a different combination of chemotherapy drugs, with a somewhat different side effect profile. But it would give her the best chance of response, we believed. We could start the new chemotherapy as early as today, we said.

Martha took this in. “Okay,” she said pensively. “I’ve been thinking. And I think maybe … I won’t do chemotherapy anymore.”

Her words caught me off guard because, frankly, they seemed premature. Her leukemia had not budged with the first round of treatment. But we still had an option B, and then an option C. It was usually at a later, more dire stage – when multiple lines of treatment had not worked, and instead had only caused harm – or, when the decision was forced by the medical system’s admission that we had nothing left to offer – that I’d heard patients express similar preferences. It was then that I’d seen patients and their loved ones flip a mental switch and choose to focus the time they had left on what really mattered to them.

It didn’t feel like we were at that point.

And so, as we debriefed outside her room, my first instinct was to convince her otherwise.

However, Martha had other priorities, as I would come to learn. Above all else, she hated the hospital. She hated feeling trapped in a strange room that wasn’t hers; she hated how the chemotherapy stole her energy and made her feel too weak to even shower. She wanted to be in her own home. She wanted to eat her own food, sleep in her own bed, and be surrounded by what she recognized.

But, she also wanted to live. Two paths lay ahead of her. It was a trade-off of more suffering with a small chance at remission, versus accepting no chance of cure but feeling well for as long as she could. She soon clarified that she wasn’t definitely against chemotherapy. She couldn’t decide. She needed more information from us to make this decision, the hardest of her life.

Over the next few days, I watched as our attending physician expertly provided just that. There were actually three options, she laid out. There was aggressive chemotherapy, entailing at least 3 more weeks in the hospital and coming with significant risk of infection, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. The chances of inducing a remission were about one in three to one in two, and that remission would likely last between several months and 2 years before the leukemia would relapse. The second option was a chemotherapy pill she could take at home, an option with fewer side effects but no longer aimed at cure. The third option was home hospice support, focused on symptoms, without any anticancer medication.

I noticed a few things during those conversations. I noticed how my attending took a navigator role, not pushing Martha in one direction or another, but rather imparting all the relevant information to empower Martha to decide for herself. I noticed how she provided realistic estimates, not hedging away from numbers, but giving the honest, nitty-gritty facts, as best as she could predict. I noticed how she took the time and never rushed, even in spite of external pressures to discharge the patient from the hospital.

There was no right or wrong answer. I no longer felt that we had something in our grasp – a clear-cut, best decision – to persuade Martha toward. Is one in three good odds, or bad odds? Is 2 years a long period of time, or a short one? Of course, there is no actual answer to these questions; the answer is as elusive and personal as if we had asked Martha: What do you think?

What I learned from Martha is that, with a devastating diagnosis, there isn’t a right time to make this decision. There isn’t one defining moment where we flip a switch and change course. It isn’t only when we run out of treatment options that the choice to forgo it makes sense. That option is on a flexible line, different for every person and priority. As my attending later said, with Martha’s diagnosis and her values, it wouldn’t have been unreasonable to decide against chemotherapy from the start.

The language we use can sometimes mask that reality. As doctors, we may casually slip in words like “need” and “have to” in response to patients’ questions about what to do next. “You need more chemotherapy,” we might say. “We’d have to treat it.” We have “treatment,” after all, and so we go down the line of offering what’s next in the medical algorithm. That word, too, can be deceivingly tempting, enticing down a road that makes it seem like the obvious answer – or the only one. If the choices are treatment versus not, who wouldn’t want the treatment? But the details are where things get murky. What does that treatment involve? What are the chances it will work, and for how long?

Surreptitiously missing from this language is the fact that there’s a choice. There’s always a choice, and it’s on the table at any point. You can start chemotherapy without committing to stick it out until the end. You can go home, if that is what’s important to you. The best treatment option is the one the patient wants.

After 4 days, Martha decided to go home with palliative chemotherapy and a bridge to hospice. Each member of our team hugged her goodbye and wished her luck. She was nervous. But she packed her hospital room, and she left.

I recently pulled up her medical chart, bracing myself for bad news. But the interesting thing about hospice is that even though the focus is no longer on prolonging life, people sometimes live longer.

She felt well, the most recent palliative note said. She was spending her time writing, getting her finances in order, and finishing a legacy project for her grandchildren.

For Martha, it seemed to be the right choice.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

Martha Boxer (not her real name) had mentally prepared herself that this could happen, but the news still hit hard. Her doctors on the leukemia service broke the facts as gently as we could: The chemotherapy she had been suffering through for the last 2 weeks hadn’t worked. The results of her latest bone marrow biopsy showed it remained packed with cancer cells.

As Martha absorbed the news quietly, her son, sitting next to her bedside with his hand on hers, spoke first. “What now?”

I looked at my attending and nodded, as we were fully ready to answer this question. From the outset, we knew that Martha’s leukemia carried a genetic mutation that unfortunately put her in a high-risk category. The chances of her cancer responding to the first round of chemotherapy were low. When this happens, what we typically do next is reinduction, we explained. It’s a different combination of chemotherapy drugs, with a somewhat different side effect profile. But it would give her the best chance of response, we believed. We could start the new chemotherapy as early as today, we said.

Martha took this in. “Okay,” she said pensively. “I’ve been thinking. And I think maybe … I won’t do chemotherapy anymore.”

Her words caught me off guard because, frankly, they seemed premature. Her leukemia had not budged with the first round of treatment. But we still had an option B, and then an option C. It was usually at a later, more dire stage – when multiple lines of treatment had not worked, and instead had only caused harm – or, when the decision was forced by the medical system’s admission that we had nothing left to offer – that I’d heard patients express similar preferences. It was then that I’d seen patients and their loved ones flip a mental switch and choose to focus the time they had left on what really mattered to them.

It didn’t feel like we were at that point.

And so, as we debriefed outside her room, my first instinct was to convince her otherwise.

However, Martha had other priorities, as I would come to learn. Above all else, she hated the hospital. She hated feeling trapped in a strange room that wasn’t hers; she hated how the chemotherapy stole her energy and made her feel too weak to even shower. She wanted to be in her own home. She wanted to eat her own food, sleep in her own bed, and be surrounded by what she recognized.

But, she also wanted to live. Two paths lay ahead of her. It was a trade-off of more suffering with a small chance at remission, versus accepting no chance of cure but feeling well for as long as she could. She soon clarified that she wasn’t definitely against chemotherapy. She couldn’t decide. She needed more information from us to make this decision, the hardest of her life.

Over the next few days, I watched as our attending physician expertly provided just that. There were actually three options, she laid out. There was aggressive chemotherapy, entailing at least 3 more weeks in the hospital and coming with significant risk of infection, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. The chances of inducing a remission were about one in three to one in two, and that remission would likely last between several months and 2 years before the leukemia would relapse. The second option was a chemotherapy pill she could take at home, an option with fewer side effects but no longer aimed at cure. The third option was home hospice support, focused on symptoms, without any anticancer medication.

I noticed a few things during those conversations. I noticed how my attending took a navigator role, not pushing Martha in one direction or another, but rather imparting all the relevant information to empower Martha to decide for herself. I noticed how she provided realistic estimates, not hedging away from numbers, but giving the honest, nitty-gritty facts, as best as she could predict. I noticed how she took the time and never rushed, even in spite of external pressures to discharge the patient from the hospital.

There was no right or wrong answer. I no longer felt that we had something in our grasp – a clear-cut, best decision – to persuade Martha toward. Is one in three good odds, or bad odds? Is 2 years a long period of time, or a short one? Of course, there is no actual answer to these questions; the answer is as elusive and personal as if we had asked Martha: What do you think?

What I learned from Martha is that, with a devastating diagnosis, there isn’t a right time to make this decision. There isn’t one defining moment where we flip a switch and change course. It isn’t only when we run out of treatment options that the choice to forgo it makes sense. That option is on a flexible line, different for every person and priority. As my attending later said, with Martha’s diagnosis and her values, it wouldn’t have been unreasonable to decide against chemotherapy from the start.

The language we use can sometimes mask that reality. As doctors, we may casually slip in words like “need” and “have to” in response to patients’ questions about what to do next. “You need more chemotherapy,” we might say. “We’d have to treat it.” We have “treatment,” after all, and so we go down the line of offering what’s next in the medical algorithm. That word, too, can be deceivingly tempting, enticing down a road that makes it seem like the obvious answer – or the only one. If the choices are treatment versus not, who wouldn’t want the treatment? But the details are where things get murky. What does that treatment involve? What are the chances it will work, and for how long?

Surreptitiously missing from this language is the fact that there’s a choice. There’s always a choice, and it’s on the table at any point. You can start chemotherapy without committing to stick it out until the end. You can go home, if that is what’s important to you. The best treatment option is the one the patient wants.

After 4 days, Martha decided to go home with palliative chemotherapy and a bridge to hospice. Each member of our team hugged her goodbye and wished her luck. She was nervous. But she packed her hospital room, and she left.

I recently pulled up her medical chart, bracing myself for bad news. But the interesting thing about hospice is that even though the focus is no longer on prolonging life, people sometimes live longer.

She felt well, the most recent palliative note said. She was spending her time writing, getting her finances in order, and finishing a legacy project for her grandchildren.

For Martha, it seemed to be the right choice.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

Martha Boxer (not her real name) had mentally prepared herself that this could happen, but the news still hit hard. Her doctors on the leukemia service broke the facts as gently as we could: The chemotherapy she had been suffering through for the last 2 weeks hadn’t worked. The results of her latest bone marrow biopsy showed it remained packed with cancer cells.

As Martha absorbed the news quietly, her son, sitting next to her bedside with his hand on hers, spoke first. “What now?”

I looked at my attending and nodded, as we were fully ready to answer this question. From the outset, we knew that Martha’s leukemia carried a genetic mutation that unfortunately put her in a high-risk category. The chances of her cancer responding to the first round of chemotherapy were low. When this happens, what we typically do next is reinduction, we explained. It’s a different combination of chemotherapy drugs, with a somewhat different side effect profile. But it would give her the best chance of response, we believed. We could start the new chemotherapy as early as today, we said.

Martha took this in. “Okay,” she said pensively. “I’ve been thinking. And I think maybe … I won’t do chemotherapy anymore.”

Her words caught me off guard because, frankly, they seemed premature. Her leukemia had not budged with the first round of treatment. But we still had an option B, and then an option C. It was usually at a later, more dire stage – when multiple lines of treatment had not worked, and instead had only caused harm – or, when the decision was forced by the medical system’s admission that we had nothing left to offer – that I’d heard patients express similar preferences. It was then that I’d seen patients and their loved ones flip a mental switch and choose to focus the time they had left on what really mattered to them.

It didn’t feel like we were at that point.

And so, as we debriefed outside her room, my first instinct was to convince her otherwise.

However, Martha had other priorities, as I would come to learn. Above all else, she hated the hospital. She hated feeling trapped in a strange room that wasn’t hers; she hated how the chemotherapy stole her energy and made her feel too weak to even shower. She wanted to be in her own home. She wanted to eat her own food, sleep in her own bed, and be surrounded by what she recognized.

But, she also wanted to live. Two paths lay ahead of her. It was a trade-off of more suffering with a small chance at remission, versus accepting no chance of cure but feeling well for as long as she could. She soon clarified that she wasn’t definitely against chemotherapy. She couldn’t decide. She needed more information from us to make this decision, the hardest of her life.

Over the next few days, I watched as our attending physician expertly provided just that. There were actually three options, she laid out. There was aggressive chemotherapy, entailing at least 3 more weeks in the hospital and coming with significant risk of infection, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. The chances of inducing a remission were about one in three to one in two, and that remission would likely last between several months and 2 years before the leukemia would relapse. The second option was a chemotherapy pill she could take at home, an option with fewer side effects but no longer aimed at cure. The third option was home hospice support, focused on symptoms, without any anticancer medication.

I noticed a few things during those conversations. I noticed how my attending took a navigator role, not pushing Martha in one direction or another, but rather imparting all the relevant information to empower Martha to decide for herself. I noticed how she provided realistic estimates, not hedging away from numbers, but giving the honest, nitty-gritty facts, as best as she could predict. I noticed how she took the time and never rushed, even in spite of external pressures to discharge the patient from the hospital.

There was no right or wrong answer. I no longer felt that we had something in our grasp – a clear-cut, best decision – to persuade Martha toward. Is one in three good odds, or bad odds? Is 2 years a long period of time, or a short one? Of course, there is no actual answer to these questions; the answer is as elusive and personal as if we had asked Martha: What do you think?

What I learned from Martha is that, with a devastating diagnosis, there isn’t a right time to make this decision. There isn’t one defining moment where we flip a switch and change course. It isn’t only when we run out of treatment options that the choice to forgo it makes sense. That option is on a flexible line, different for every person and priority. As my attending later said, with Martha’s diagnosis and her values, it wouldn’t have been unreasonable to decide against chemotherapy from the start.

The language we use can sometimes mask that reality. As doctors, we may casually slip in words like “need” and “have to” in response to patients’ questions about what to do next. “You need more chemotherapy,” we might say. “We’d have to treat it.” We have “treatment,” after all, and so we go down the line of offering what’s next in the medical algorithm. That word, too, can be deceivingly tempting, enticing down a road that makes it seem like the obvious answer – or the only one. If the choices are treatment versus not, who wouldn’t want the treatment? But the details are where things get murky. What does that treatment involve? What are the chances it will work, and for how long?

Surreptitiously missing from this language is the fact that there’s a choice. There’s always a choice, and it’s on the table at any point. You can start chemotherapy without committing to stick it out until the end. You can go home, if that is what’s important to you. The best treatment option is the one the patient wants.

After 4 days, Martha decided to go home with palliative chemotherapy and a bridge to hospice. Each member of our team hugged her goodbye and wished her luck. She was nervous. But she packed her hospital room, and she left.

I recently pulled up her medical chart, bracing myself for bad news. But the interesting thing about hospice is that even though the focus is no longer on prolonging life, people sometimes live longer.

She felt well, the most recent palliative note said. She was spending her time writing, getting her finances in order, and finishing a legacy project for her grandchildren.

For Martha, it seemed to be the right choice.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

Immunotherapy-related adverse effects: how to identify and treat them in the emergency department

DR HENRY I am pleased to be talking with Dr Maura Sammon, an emergency department (ED) physician, about identifying and treating immunotherapy-related side effects in the ED. This is a hot topic in oncology, and I was very interested in having an ED physician talk about what happens when treating oncologists send their patients to the ED, because a physician may think it is chemotherapy when it is immunotherapy. Let’s start with the example of an oncology patient going to the ED with some symptoms, and the ED physician asks the patient what they’re being treated with. The patient may or may not say the right thing – that is, inform you whether they are being treated with chemotherapy or immunotherapy. How do you morph over into knowing that they are not getting chemotherapy?

DR SAMMON Yes, that’s a big problem in the ED. Patients come to the ED and say they’re being treated for cancer. They say they’re on chemotherapy, when they’re actually on immunotherapy, and it can really send the treatment team down the wrong path. I have a metaphor to explain this. They say that Great Britain and the United States are two nations separated by a common language. For example, when a British person talks about football, they mean something very different than when an American talks about football. If someone in Great Britain asks you to come play football, you might show up with shoulder pads and a helmet rather than shin guards, and you’re left without having the right tools to participate in the game.

How this sometimes plays out with immunotherapy, unfortunately, is that a patient will present to the ED and say they’re having a cough and that they’re on chemotherapy for melanoma. Usually, this patient would be worked up for being in a potentially immunosuppressed state. You might get a white blood cell count. You might get a chest X-ray. You might see what looks to you like a new infiltrate on this chest X-ray and then start going down the path of treating someone whom you think is immunosuppressed with pneumonia and giving them antibiotics rather than what could be life-saving steroids, as would be the case if the patient were on immunotherapy.

It’s a real problem, because you have one word that patients may use meaning two very different things. It can get you into trouble if you are treating someone for potentially infectious causes rather than immunotherapy-related adverse reactions, which are much more similar to graft-versus-host disease than in the case of traditional chemotherapy.

DR HENRY That’s a very good point. I think, as we in oncology use these immunotherapies/checkpoint inhibitors more often, you will see them more often in the ED. Let’s get right into that. You’ve identified this patient as not getting a traditional chemotherapy – hopefully, all our records on these patients are available. You’ve decided to follow onto what might be a side effect of the immunotherapy, so I’m going to name the side effects that always occur to me: lung, gastrointestinal (GI) – which could be loose bowels or liver function – rash, endocrine problems. Let’s start with lung symptoms. You see the patient is short of breath and you identified immunotherapy. What’s your next step?

DR SAMMON That’s a great example, because the problem is that you see these patients with cough or shortness of breath and pulmonary complications, and pulmonary complications of immunotherapy, while rare, are potentially life threatening if they’re not identified quickly.

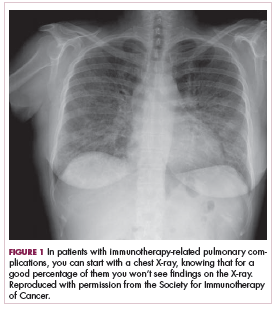

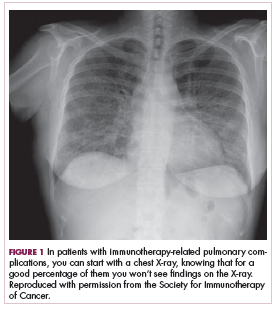

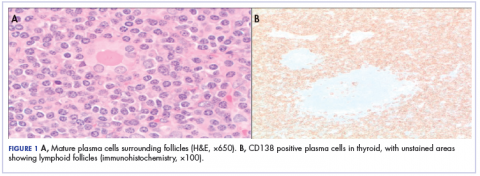

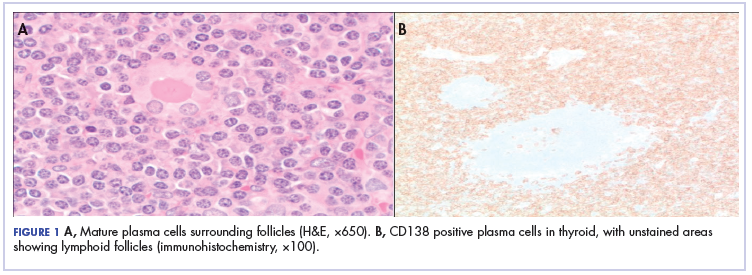

You can start with a chest X-ray on these patients knowing, however, that for a good percentage of them you won’t see findings on their chest X-ray (Figure 1, from Sammon M, Tobin T. Identification and management of immune-related adverse events in the emergency setting. Presented at: Advances in Cancer Immunotherapy – Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC); August 4, 2017; Philadelphia, PA). You need to proceed to computed tomography (CT), because the issue is that you can have protean findings on the CT related to immunotherapy treatment/adverse reactions. You need to have a very high index of suspicion regardless of what abnormal findings you’re seeing on this CT and erring toward withholding the drugs, starting treatment, and being more aggressive with this type of finding.

DR HENRY I’ve heard you talk at a conference about a patient with metastatic lung cancer, or some other tumor that may have existing disease in lung. The patient is aware of that, and the chart reflects that. Then you have this difficulty where the CT scan shows a pneumonitis, and it may not be tumor progression at all – it may be the drug. How do you work through that? Of course, your additional problem is you don’t have a whole lot of time. You must decide to whether you’re going to keep them in the ED, admit them, or send them home.