User login

More biosimilars reach the market in efforts to improve access and cut costs

Biosimilars are copies of FDA-approved biologic drugs (those generally derived from a living organism) that cannot be identical to the reference drug but demonstrate a high similarity to it. As patents on the reference drugs expire, biosimilars are being developed to increase competition in the marketplace to reduce costs and improve patient access to therapy. Although the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has no regulatory power over drug prices, it recently announced efforts to streamline the biosimilar approval process to facilitate access to therapies and curb the associated skyrocketing costs.

Several biosimilars have been approved by the agency in recent years, and earlier this year they were joined by 2 more: the approval in May of epoetin alfa-epbx (Retacrit; Hospira, a Pfizer company) for all indications of the reference product (epoetin alfa; Epogen/Procrit, Amgen), including the treatment of anemia caused by myelosuppressive chemotherapy, when there is a minimum of 2 additional months of planned chemotherapy;1 and the June approval of pegfilgrastim-jmdb (Fulphila, Mylan and Biocon) for the treatment of patients undergoing myelosuppressive chemotherapy to help reduce the chance of infection as suggested by febrile neutropenia (fever, often with other signs of infection, associated with an abnormally low number of infection-fighting white blood cells).2 The reference product for pegfilgrastim-jmdb is pegfilgrastim (Neulasta, Amgen).

The approval of both biosimilars was based on a review of a body of evidence that included structural and functional characterization, animal study data, human pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) data, clinical immunogenicity data, and other clinical safety and efficacy data. This evidence established that the biosimilars were highly similar to the already FDA-approved reference products, with no clinically relevant differences.

Biocon and Mylan-GmBH, which jointly developed pegfilgrastim-jmdb, originally filed for approval in 2017; and Hospira Inc, a Pfizer company that developed epoetin alfa-epbx, filed for the first time in 2015. They subsequently received complete response letters from the FDA, twice in the case of the epoetin alfa biosimilar, rejecting their approval. For pegfilgrastim-jmdb, the complete response letter was related to a pending update of the Biologic License Application as the result of requalification activities taken because of modifications at their manufacturing plant. For epoetin alfa-epbx, the FDA expressed concerns relating to a manufacturing facility. The companies addressed the concerns in the complete response letters and submitted corrective and preventive action plans.3,4

Pegfilgrastim-jmdb

The results from a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind parallel-group trial of pegfilgrastim-jmdb compared with European Union-approved pegfilgrastim were published in 2016. Chemotherapy and radiation-naïve patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer (n = 194) received the biosimilar or reference product every 3 weeks for 6 cycles. The primary endpoint was duration of severe neutropenia in cycle 1, defined as days with absolute neutrophil count <0.5 x 109/L. The mean standard deviation was 1.2 [0.93] in the pegfilgrastim-jmdb arm and 1.2 [1.10] in the EU-pegfilgrastim arm, and the 95% confidence interval of least squares means differences was within the -1 day, +1 day range, indicating equivalency.5

A characterization and similarity assessment of pegfilgrastim-jmdb compared with US- and EU-approved pegfilgrastim was presented at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR) binding was assessed by surface plasmon resonance and potency was measured by in vitro stimulated proliferation in a mouse myelogenous leukemia cell line. In vivo rodent studies were also performed and included a PD study with a single dose of up to 3 mg/kg.6

There was high similarity in the structure, molecular mass, impurities and functional activity of the biosimilar and reference products, as well as similar G-CSFR binding and equivalent relative potency. Neutrophil and leukocyte counts were increased to a similar degree, and toxicology and drug kinetics were also comparable.

The recommended dose of pegfilgrastim-jmdb is a 6 mg/0.6 ml injection in a single-dose prefilled syringe for manual use only, administered subcutaneously once per chemotherapy cycle. The prescribing information also has dosing guidelines for administration in pediatric patients who weigh less than 45 kg. Pegfilgrastim-jmdb should not be administered between 14 days before and 24 hours after administration of chemotherapy.

The prescribing information details warnings and precautions relating to splenic rupture, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), serious allergic reactions, potential for severe/fatal sickle cell crises in patients with sickle cell disorders, glomerulonephritis, leukocytosis, capillary leak syndrome, and the potential for tumor growth or recurrence.7

Patients should be evaluated for an enlarged spleen or splenic rupture if they report upper left abdominal or shoulder pain. Patients who develop fever and lung infiltrates or respiratory distress should be evaluated for ARDS and treatment discontinued if a diagnosis is confirmed. Pegfilgrastim-jmdb should be permanently discontinued in patients who develop serious allergic reactions and should not be used in patients with a history of serious allergic reactions to pegfilgrastim or filgrastim products.

Dose-reduction or interruption should be considered in patients who develop glomerulonephritis. Complete blood counts should be monitored throughout treatment. Patients should be monitored closely for capillary leak syndrome and treated with standard therapy. Pegfilgrastim-jmdb is marketed as Fulphila.

Epoetin alfa-epbx

Epoetin alfa-epbx was evaluated in 2 clinical trials in healthy individuals. The EPOE-12-02 trial established the PK and PD following a single subcutaneous dose of 100 U/kg in 81 participants. The EPOE-14-1 study was designed to determine the PK and PD of multiple doses of subcutaneous 100 U/kg 3 times weekly for 3 weeks in 129 participants. Both studies met prespecified criteria

Evidence of efficacy and safety were also evaluated using pooled data from EPOE-10-13 and EPOE-10-01, conducted in patients with chronic kidney disease, which was considered the most sensitive population in which to evaluate clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar and reference product.8,9

There were no clinically meaningful differences in efficacy and a similar adverse event profile. The most common side effects include high blood pressure, joint pain, muscle spasm, fever, dizziness, respiratory infection, and cough, among others.

The recommended dose of epoetin alfa-epbx, which is marketed as Retacrit, is 40,000 Units weekly or 150 U/kg 3 times weekly in adults and 600 U/kg intravenously weekly in pediatric patients aged 5 years or younger. Epoetin alfa-epbx comes with a boxed warning to alert health care providers to the increased risks of death, heart problems, stroke, and tumor growth, or recurrence. The prescribing information also details warnings and precautions relating to these risks, as well as hypertension, seizures, lack or loss of hemoglobin response, pure red cell aplasia, serious allergic reactions, and severe cutaneous reactions.9

Blood pressure should be appropriately controlled before treatment initiation, treatment should be reduced or withheld if it becomes uncontrollable, and patients should be advised of the importance of compliance with anti-hypertensive medication and dietary restrictions. Patients should be monitored closely for premonitory neurologic symptoms and advised to contact their provider in the event of new-onset seizures, premonitory symptoms, or change in seizure frequency.

The prescribing information has dosing recommendations for lack or loss of hemoglobin response to epoetin alfa-epbx. If severe anemia or low reticulocyte count occur, treatment should be withheld and patients evaluated for neutralizing antibodies to erythropoietin and, in the event that PRCA is confirmed, treatment should be permanently discontinued. Treatment should be immediately and permanently discontinued for serious allergic reactions or severe cutaneous reactions.

1. US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA approves first epoetin alfa biosimilar for the treatment of anemia. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm607703.htm. Updated May 15, 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

2. US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA approves first biosimilar to Neulasta to help reduce the risk of infection during cancer treatment. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm609805.htm. Updated June 4, 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

3. Reuters. BRIEF – Biocon says US FDA issues complete response letter for proposed biosimilar pegfilgrastim. https://www.reuters.com/article/brief-biocon-says-us-fda-issued-complete/brief-biocon-says-us-fda-issued-complete-response-letter-for-proposed-biosimilar-pegfilgrastim-idUSFWN1MK0Q1. Updated October 9, 2017. Accessed June 22, 2018.

4. FiercePharma. Pfizer, on third try, wins nod for biosimilar of blockbuster epogen/procrit. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/pfizer-third-try-wins-fda-nod-for-biosimilar-blockbuster-epogen-procrit. Updated May 15, 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

5. Waller CF, Blakeley C, Pennella E. Phase 3 efficacy and safety trial of proposed pegfilgrastim biosimilar MYL-1401H vs EU-neulasta in the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl_6):1433O.

6. Sankaran PV, Palanivelu DV, Nair R, et al. Characterization and similarity assessment of a pegfilgrastim biosimilar MYL-1401H. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(suppl; abstr e19028).

7. Fulphila (pegfilgrastim-jmdb) injection, for subcutaneous use. Prescribing information. Mylan GmBH. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761075s000lbl.pdf. Released June 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

8. US Food and Drug Administration website. ‘Epoetin Hospira,’ a proposed biosimilar to US-licensed Epogen/Procrit. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/OncologicDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM559962.pdf. Updated May 25, 2017. Accessed June 22, 2018.

9. Retacrit (epoetin alfa-epbx) injection, for intravenous or subcutaneous use. Prescribing information. Pfizer. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125545s000lbl.pdf. Released May 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

Biosimilars are copies of FDA-approved biologic drugs (those generally derived from a living organism) that cannot be identical to the reference drug but demonstrate a high similarity to it. As patents on the reference drugs expire, biosimilars are being developed to increase competition in the marketplace to reduce costs and improve patient access to therapy. Although the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has no regulatory power over drug prices, it recently announced efforts to streamline the biosimilar approval process to facilitate access to therapies and curb the associated skyrocketing costs.

Several biosimilars have been approved by the agency in recent years, and earlier this year they were joined by 2 more: the approval in May of epoetin alfa-epbx (Retacrit; Hospira, a Pfizer company) for all indications of the reference product (epoetin alfa; Epogen/Procrit, Amgen), including the treatment of anemia caused by myelosuppressive chemotherapy, when there is a minimum of 2 additional months of planned chemotherapy;1 and the June approval of pegfilgrastim-jmdb (Fulphila, Mylan and Biocon) for the treatment of patients undergoing myelosuppressive chemotherapy to help reduce the chance of infection as suggested by febrile neutropenia (fever, often with other signs of infection, associated with an abnormally low number of infection-fighting white blood cells).2 The reference product for pegfilgrastim-jmdb is pegfilgrastim (Neulasta, Amgen).

The approval of both biosimilars was based on a review of a body of evidence that included structural and functional characterization, animal study data, human pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) data, clinical immunogenicity data, and other clinical safety and efficacy data. This evidence established that the biosimilars were highly similar to the already FDA-approved reference products, with no clinically relevant differences.

Biocon and Mylan-GmBH, which jointly developed pegfilgrastim-jmdb, originally filed for approval in 2017; and Hospira Inc, a Pfizer company that developed epoetin alfa-epbx, filed for the first time in 2015. They subsequently received complete response letters from the FDA, twice in the case of the epoetin alfa biosimilar, rejecting their approval. For pegfilgrastim-jmdb, the complete response letter was related to a pending update of the Biologic License Application as the result of requalification activities taken because of modifications at their manufacturing plant. For epoetin alfa-epbx, the FDA expressed concerns relating to a manufacturing facility. The companies addressed the concerns in the complete response letters and submitted corrective and preventive action plans.3,4

Pegfilgrastim-jmdb

The results from a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind parallel-group trial of pegfilgrastim-jmdb compared with European Union-approved pegfilgrastim were published in 2016. Chemotherapy and radiation-naïve patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer (n = 194) received the biosimilar or reference product every 3 weeks for 6 cycles. The primary endpoint was duration of severe neutropenia in cycle 1, defined as days with absolute neutrophil count <0.5 x 109/L. The mean standard deviation was 1.2 [0.93] in the pegfilgrastim-jmdb arm and 1.2 [1.10] in the EU-pegfilgrastim arm, and the 95% confidence interval of least squares means differences was within the -1 day, +1 day range, indicating equivalency.5

A characterization and similarity assessment of pegfilgrastim-jmdb compared with US- and EU-approved pegfilgrastim was presented at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR) binding was assessed by surface plasmon resonance and potency was measured by in vitro stimulated proliferation in a mouse myelogenous leukemia cell line. In vivo rodent studies were also performed and included a PD study with a single dose of up to 3 mg/kg.6

There was high similarity in the structure, molecular mass, impurities and functional activity of the biosimilar and reference products, as well as similar G-CSFR binding and equivalent relative potency. Neutrophil and leukocyte counts were increased to a similar degree, and toxicology and drug kinetics were also comparable.

The recommended dose of pegfilgrastim-jmdb is a 6 mg/0.6 ml injection in a single-dose prefilled syringe for manual use only, administered subcutaneously once per chemotherapy cycle. The prescribing information also has dosing guidelines for administration in pediatric patients who weigh less than 45 kg. Pegfilgrastim-jmdb should not be administered between 14 days before and 24 hours after administration of chemotherapy.

The prescribing information details warnings and precautions relating to splenic rupture, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), serious allergic reactions, potential for severe/fatal sickle cell crises in patients with sickle cell disorders, glomerulonephritis, leukocytosis, capillary leak syndrome, and the potential for tumor growth or recurrence.7

Patients should be evaluated for an enlarged spleen or splenic rupture if they report upper left abdominal or shoulder pain. Patients who develop fever and lung infiltrates or respiratory distress should be evaluated for ARDS and treatment discontinued if a diagnosis is confirmed. Pegfilgrastim-jmdb should be permanently discontinued in patients who develop serious allergic reactions and should not be used in patients with a history of serious allergic reactions to pegfilgrastim or filgrastim products.

Dose-reduction or interruption should be considered in patients who develop glomerulonephritis. Complete blood counts should be monitored throughout treatment. Patients should be monitored closely for capillary leak syndrome and treated with standard therapy. Pegfilgrastim-jmdb is marketed as Fulphila.

Epoetin alfa-epbx

Epoetin alfa-epbx was evaluated in 2 clinical trials in healthy individuals. The EPOE-12-02 trial established the PK and PD following a single subcutaneous dose of 100 U/kg in 81 participants. The EPOE-14-1 study was designed to determine the PK and PD of multiple doses of subcutaneous 100 U/kg 3 times weekly for 3 weeks in 129 participants. Both studies met prespecified criteria

Evidence of efficacy and safety were also evaluated using pooled data from EPOE-10-13 and EPOE-10-01, conducted in patients with chronic kidney disease, which was considered the most sensitive population in which to evaluate clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar and reference product.8,9

There were no clinically meaningful differences in efficacy and a similar adverse event profile. The most common side effects include high blood pressure, joint pain, muscle spasm, fever, dizziness, respiratory infection, and cough, among others.

The recommended dose of epoetin alfa-epbx, which is marketed as Retacrit, is 40,000 Units weekly or 150 U/kg 3 times weekly in adults and 600 U/kg intravenously weekly in pediatric patients aged 5 years or younger. Epoetin alfa-epbx comes with a boxed warning to alert health care providers to the increased risks of death, heart problems, stroke, and tumor growth, or recurrence. The prescribing information also details warnings and precautions relating to these risks, as well as hypertension, seizures, lack or loss of hemoglobin response, pure red cell aplasia, serious allergic reactions, and severe cutaneous reactions.9

Blood pressure should be appropriately controlled before treatment initiation, treatment should be reduced or withheld if it becomes uncontrollable, and patients should be advised of the importance of compliance with anti-hypertensive medication and dietary restrictions. Patients should be monitored closely for premonitory neurologic symptoms and advised to contact their provider in the event of new-onset seizures, premonitory symptoms, or change in seizure frequency.

The prescribing information has dosing recommendations for lack or loss of hemoglobin response to epoetin alfa-epbx. If severe anemia or low reticulocyte count occur, treatment should be withheld and patients evaluated for neutralizing antibodies to erythropoietin and, in the event that PRCA is confirmed, treatment should be permanently discontinued. Treatment should be immediately and permanently discontinued for serious allergic reactions or severe cutaneous reactions.

Biosimilars are copies of FDA-approved biologic drugs (those generally derived from a living organism) that cannot be identical to the reference drug but demonstrate a high similarity to it. As patents on the reference drugs expire, biosimilars are being developed to increase competition in the marketplace to reduce costs and improve patient access to therapy. Although the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has no regulatory power over drug prices, it recently announced efforts to streamline the biosimilar approval process to facilitate access to therapies and curb the associated skyrocketing costs.

Several biosimilars have been approved by the agency in recent years, and earlier this year they were joined by 2 more: the approval in May of epoetin alfa-epbx (Retacrit; Hospira, a Pfizer company) for all indications of the reference product (epoetin alfa; Epogen/Procrit, Amgen), including the treatment of anemia caused by myelosuppressive chemotherapy, when there is a minimum of 2 additional months of planned chemotherapy;1 and the June approval of pegfilgrastim-jmdb (Fulphila, Mylan and Biocon) for the treatment of patients undergoing myelosuppressive chemotherapy to help reduce the chance of infection as suggested by febrile neutropenia (fever, often with other signs of infection, associated with an abnormally low number of infection-fighting white blood cells).2 The reference product for pegfilgrastim-jmdb is pegfilgrastim (Neulasta, Amgen).

The approval of both biosimilars was based on a review of a body of evidence that included structural and functional characterization, animal study data, human pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) data, clinical immunogenicity data, and other clinical safety and efficacy data. This evidence established that the biosimilars were highly similar to the already FDA-approved reference products, with no clinically relevant differences.

Biocon and Mylan-GmBH, which jointly developed pegfilgrastim-jmdb, originally filed for approval in 2017; and Hospira Inc, a Pfizer company that developed epoetin alfa-epbx, filed for the first time in 2015. They subsequently received complete response letters from the FDA, twice in the case of the epoetin alfa biosimilar, rejecting their approval. For pegfilgrastim-jmdb, the complete response letter was related to a pending update of the Biologic License Application as the result of requalification activities taken because of modifications at their manufacturing plant. For epoetin alfa-epbx, the FDA expressed concerns relating to a manufacturing facility. The companies addressed the concerns in the complete response letters and submitted corrective and preventive action plans.3,4

Pegfilgrastim-jmdb

The results from a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind parallel-group trial of pegfilgrastim-jmdb compared with European Union-approved pegfilgrastim were published in 2016. Chemotherapy and radiation-naïve patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer (n = 194) received the biosimilar or reference product every 3 weeks for 6 cycles. The primary endpoint was duration of severe neutropenia in cycle 1, defined as days with absolute neutrophil count <0.5 x 109/L. The mean standard deviation was 1.2 [0.93] in the pegfilgrastim-jmdb arm and 1.2 [1.10] in the EU-pegfilgrastim arm, and the 95% confidence interval of least squares means differences was within the -1 day, +1 day range, indicating equivalency.5

A characterization and similarity assessment of pegfilgrastim-jmdb compared with US- and EU-approved pegfilgrastim was presented at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR) binding was assessed by surface plasmon resonance and potency was measured by in vitro stimulated proliferation in a mouse myelogenous leukemia cell line. In vivo rodent studies were also performed and included a PD study with a single dose of up to 3 mg/kg.6

There was high similarity in the structure, molecular mass, impurities and functional activity of the biosimilar and reference products, as well as similar G-CSFR binding and equivalent relative potency. Neutrophil and leukocyte counts were increased to a similar degree, and toxicology and drug kinetics were also comparable.

The recommended dose of pegfilgrastim-jmdb is a 6 mg/0.6 ml injection in a single-dose prefilled syringe for manual use only, administered subcutaneously once per chemotherapy cycle. The prescribing information also has dosing guidelines for administration in pediatric patients who weigh less than 45 kg. Pegfilgrastim-jmdb should not be administered between 14 days before and 24 hours after administration of chemotherapy.

The prescribing information details warnings and precautions relating to splenic rupture, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), serious allergic reactions, potential for severe/fatal sickle cell crises in patients with sickle cell disorders, glomerulonephritis, leukocytosis, capillary leak syndrome, and the potential for tumor growth or recurrence.7

Patients should be evaluated for an enlarged spleen or splenic rupture if they report upper left abdominal or shoulder pain. Patients who develop fever and lung infiltrates or respiratory distress should be evaluated for ARDS and treatment discontinued if a diagnosis is confirmed. Pegfilgrastim-jmdb should be permanently discontinued in patients who develop serious allergic reactions and should not be used in patients with a history of serious allergic reactions to pegfilgrastim or filgrastim products.

Dose-reduction or interruption should be considered in patients who develop glomerulonephritis. Complete blood counts should be monitored throughout treatment. Patients should be monitored closely for capillary leak syndrome and treated with standard therapy. Pegfilgrastim-jmdb is marketed as Fulphila.

Epoetin alfa-epbx

Epoetin alfa-epbx was evaluated in 2 clinical trials in healthy individuals. The EPOE-12-02 trial established the PK and PD following a single subcutaneous dose of 100 U/kg in 81 participants. The EPOE-14-1 study was designed to determine the PK and PD of multiple doses of subcutaneous 100 U/kg 3 times weekly for 3 weeks in 129 participants. Both studies met prespecified criteria

Evidence of efficacy and safety were also evaluated using pooled data from EPOE-10-13 and EPOE-10-01, conducted in patients with chronic kidney disease, which was considered the most sensitive population in which to evaluate clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar and reference product.8,9

There were no clinically meaningful differences in efficacy and a similar adverse event profile. The most common side effects include high blood pressure, joint pain, muscle spasm, fever, dizziness, respiratory infection, and cough, among others.

The recommended dose of epoetin alfa-epbx, which is marketed as Retacrit, is 40,000 Units weekly or 150 U/kg 3 times weekly in adults and 600 U/kg intravenously weekly in pediatric patients aged 5 years or younger. Epoetin alfa-epbx comes with a boxed warning to alert health care providers to the increased risks of death, heart problems, stroke, and tumor growth, or recurrence. The prescribing information also details warnings and precautions relating to these risks, as well as hypertension, seizures, lack or loss of hemoglobin response, pure red cell aplasia, serious allergic reactions, and severe cutaneous reactions.9

Blood pressure should be appropriately controlled before treatment initiation, treatment should be reduced or withheld if it becomes uncontrollable, and patients should be advised of the importance of compliance with anti-hypertensive medication and dietary restrictions. Patients should be monitored closely for premonitory neurologic symptoms and advised to contact their provider in the event of new-onset seizures, premonitory symptoms, or change in seizure frequency.

The prescribing information has dosing recommendations for lack or loss of hemoglobin response to epoetin alfa-epbx. If severe anemia or low reticulocyte count occur, treatment should be withheld and patients evaluated for neutralizing antibodies to erythropoietin and, in the event that PRCA is confirmed, treatment should be permanently discontinued. Treatment should be immediately and permanently discontinued for serious allergic reactions or severe cutaneous reactions.

1. US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA approves first epoetin alfa biosimilar for the treatment of anemia. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm607703.htm. Updated May 15, 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

2. US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA approves first biosimilar to Neulasta to help reduce the risk of infection during cancer treatment. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm609805.htm. Updated June 4, 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

3. Reuters. BRIEF – Biocon says US FDA issues complete response letter for proposed biosimilar pegfilgrastim. https://www.reuters.com/article/brief-biocon-says-us-fda-issued-complete/brief-biocon-says-us-fda-issued-complete-response-letter-for-proposed-biosimilar-pegfilgrastim-idUSFWN1MK0Q1. Updated October 9, 2017. Accessed June 22, 2018.

4. FiercePharma. Pfizer, on third try, wins nod for biosimilar of blockbuster epogen/procrit. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/pfizer-third-try-wins-fda-nod-for-biosimilar-blockbuster-epogen-procrit. Updated May 15, 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

5. Waller CF, Blakeley C, Pennella E. Phase 3 efficacy and safety trial of proposed pegfilgrastim biosimilar MYL-1401H vs EU-neulasta in the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl_6):1433O.

6. Sankaran PV, Palanivelu DV, Nair R, et al. Characterization and similarity assessment of a pegfilgrastim biosimilar MYL-1401H. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(suppl; abstr e19028).

7. Fulphila (pegfilgrastim-jmdb) injection, for subcutaneous use. Prescribing information. Mylan GmBH. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761075s000lbl.pdf. Released June 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

8. US Food and Drug Administration website. ‘Epoetin Hospira,’ a proposed biosimilar to US-licensed Epogen/Procrit. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/OncologicDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM559962.pdf. Updated May 25, 2017. Accessed June 22, 2018.

9. Retacrit (epoetin alfa-epbx) injection, for intravenous or subcutaneous use. Prescribing information. Pfizer. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125545s000lbl.pdf. Released May 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

1. US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA approves first epoetin alfa biosimilar for the treatment of anemia. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm607703.htm. Updated May 15, 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

2. US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA approves first biosimilar to Neulasta to help reduce the risk of infection during cancer treatment. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm609805.htm. Updated June 4, 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

3. Reuters. BRIEF – Biocon says US FDA issues complete response letter for proposed biosimilar pegfilgrastim. https://www.reuters.com/article/brief-biocon-says-us-fda-issued-complete/brief-biocon-says-us-fda-issued-complete-response-letter-for-proposed-biosimilar-pegfilgrastim-idUSFWN1MK0Q1. Updated October 9, 2017. Accessed June 22, 2018.

4. FiercePharma. Pfizer, on third try, wins nod for biosimilar of blockbuster epogen/procrit. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/pfizer-third-try-wins-fda-nod-for-biosimilar-blockbuster-epogen-procrit. Updated May 15, 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

5. Waller CF, Blakeley C, Pennella E. Phase 3 efficacy and safety trial of proposed pegfilgrastim biosimilar MYL-1401H vs EU-neulasta in the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl_6):1433O.

6. Sankaran PV, Palanivelu DV, Nair R, et al. Characterization and similarity assessment of a pegfilgrastim biosimilar MYL-1401H. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(suppl; abstr e19028).

7. Fulphila (pegfilgrastim-jmdb) injection, for subcutaneous use. Prescribing information. Mylan GmBH. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761075s000lbl.pdf. Released June 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

8. US Food and Drug Administration website. ‘Epoetin Hospira,’ a proposed biosimilar to US-licensed Epogen/Procrit. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/OncologicDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM559962.pdf. Updated May 25, 2017. Accessed June 22, 2018.

9. Retacrit (epoetin alfa-epbx) injection, for intravenous or subcutaneous use. Prescribing information. Pfizer. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125545s000lbl.pdf. Released May 2018. Accessed June 22, 2018.

Finding your practice home base

As summer winds down and we begin to gear up to return to school or work, I was thinking about new and returning hem-onc residents, fellows, and young attendings and a question I routinely get from them: what should I do next in my career? I always answer by holding up 3 fingers and telling them that they can practice 1, at a university hospital; 2, at a university teaching affiliate; or 3, at a community hospital or practice with a little or no university affiliation. These days, trainees in hematology-oncology are often advised to be highly specialty-specific when they plan their long-term careers and to focus on a particular cancer or hematologic disorder. That is fine if you want to remain in an academic or university-based practice, but not if community practice is your preference. So, what are the differences among these 3 options?

Option 1, to remain in a university setting where you can be highly focused and specialized in a single narrowly defined area, could be satisfying, but keep in mind that the institution expects results! You will be carefully monitored for research output and teaching and administration commitments, and your interaction with patients could add up to less than 50% of your time. Publication and grant renewal will also play a role and therefore take up your time.

If you are considering option 2 – to work at a university teaching affiliate hospital – you need to bear in mind that you likely will see a patient population with a much broader range of diagnoses than would be the case with the first option. Patient care for option 2 will take up more than 50% of your time, so it might be a little more challenging to stay current, but perhaps more refreshing if you enjoy contact with patients. Teaching, research, and administration will surely be available, and publication and grant renewal will play as big or small a role as you want.

Option 3 would be to join a community hospital or practice where the primary focus is on patient care and the diagnoses will span the hematology and oncology spectrum. This type of practice can be very demanding of one’s time, but as rewarding as the other options, especially if you value contact with patients. With this option, one is more likely to practice as a generalist, perhaps with an emphasis in one of the hem-onc specialties, but able to treat a cluster of different types of cancer as well.

I always advise trainees to be sure they ask physicians practicing in each of these options to give examples of what their best and worst days are like so that they can get some idea of what the daily humdrum and challenges would encompass. What did I choose? I have always gone with option 2 and have been very happy in that setting.

In this issue…

More biosimilars head our way. Turning to the current issue of the journal, on page e181, Dr Jane de Lartigue discusses 2 new biosimilars recently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – epoetin alfa-epbx (Retacrit; Hospira, a Pfizer company) for chemotherapy-induced anemia (CIA), and pegfilgrastim-jmdb (Fulphila; Mylan and Biocon) for prevention of febrile neutropenia. As Dr de Lartigue notes, biosimilars are copies of FDA-approved biologic drugs that cannot be identical to the reference drug but demonstrate a high similarity to it. In this case, the reference drug for epoetin alfa-epbx is epoetin alfa (Epogen/Procrit, Amgen) and for pegfilgrastim-jmdb, it is pegfilgrastim (Neulasta, Amgen). As the reference drugs’ patents expire, biosimilars are being developed to increase competition in the marketplace in an effort to reduce costs and improve patient access to these therapies. Indeed, the FDA is working to streamline the biosimilar approval process to facilitate that access.

Reading this article got me thinking about something I often have to consider in the course of my work: transfusion versus erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs)? Recombinant erythropoietin drugs such as the biosimilar, epoetin alfa-epbx, and its reference drug are grouped together as ESAs, and have been used to treat CIA since the late 1980s. However, there were a few trials that used higher-dose ESA or set high hemoglobin targets, and their findings suggested that ESAs may shorten survival in patients with cancer or increase tumor growth, or both. The use of ESAs took a nosedive after the 2007 decision by the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee to rein in their use for a hard start of ESA treatment at less than 10 g/dL hemoglobin, and not higher. Subsequent trials addressed the concerns about survival and tumor growth. A meta-analysis of 60 randomized, placebo-controlled trials of ESAs in CIA found that there was no difference in overall survival between the study and control groups.1 Likewise, findings from an FDA-mandated trial with epoetin alfa (Procrit) in patients with metastatic breast cancer have reported that there was no significant difference in overall survival between the study and control groups.2 The results of a second FDA-mandated trial with darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp, Amgen) in patients with metastatic lung cancer are expected to be released soon. The FDA lifted the ESA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy based on those findings. However, many practitioners, both young and old, continue to shy away from using ESAs because of the FDA black box warning that remains in place despite the latest data.3The use of transfusion ticked up reciprocally with the decline in ESA use, but perhaps we should re-evaluate the use of these agents in our practice, especially now that the less costly, equally safe and effective biosimilars are becoming available and we have the new survival data. Transfusions are time consuming and have side effects, including allergic reaction and infection risk, whereas ESAs are easily administered by injection, which patients might find preferable.

Malignancies in patients with HIV-AIDS. On page e188, Koppaka and colleagues report on a study in India of the patterns of malignancies in patients with HIV-AIDS. I began my career just as the first reports of what became known as HIV-AIDS emerged, and we were all mystified by what was killing these patients and the curious hematologic and oncologic problems they developed. Back then, the patients were profoundly immunosuppressed, and the immunosuppression cancers of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, usually higher grade, and Kaposi sarcoma were most prevalent and today are collectively labeled AIDS-defining malignancies (ADMs).

Fast forward to present day, and we have extremely effective antiretroviral therapies that have resulted in a significant reduction in mortality among HIV-infected individuals who are now living long enough to get what we call non–AIDS-defining malignancies (NADMs) such as anal or cervical cancers, hepatoma (hepatocellular carcinoma), Hodgkin lymphoma, and lung cancer. Of note is that these NADMs are all highly viral associated, with anal and cervical cancers linked to infection with the human papillomavirus; hepatoma linked to the hepatitis B/C viruses; Hodgkin lymphoma to the Epstein-Barr virus; and lung cancer, possibly also HPV. Fortunately, these days we can use standard-dose chemoradiation therapy for all HIV-related cancers because the patients’ immune systems are much better reconstituted and the modern-day antiretroviral therapies have much less drug–drug interaction thanks to the advent of the integrase inhibitors. The researchers give an excellent breakdown of the occurrence of these malignancies, as well as an analysis of the correlation between CD4 counts and the different malignancies.

Immunotherapy-related side effects in the ED. What happens when our patients who are on immunotherapy end up in the emergency department (ED) with therapy-related symptoms? And what can the treating oncologist do to help the ED physician achieve the best possible outcome for the patient? I spoke to Dr Maura Sammon, an ED physician, about some of the more common of these side effects – lung, gastrointestinal, rash, and endocrine-related problems – and she describes in detail how physicians in the ED would triage and treat the patient. Dr Sammon also emphasizes the importance of communication: first, between the treating oncologist and patient, about the differences between chemotherapy and immunotherapy; and second, between the ED physician and the treating oncologist as soon as possible after the patient has presented to ensure a good outcome. The interview is part of The JCSO Interview series. It is jam-packed with useful, how-to information, and you can read a transcript of it on page e216 of this issue, or you can listen to it online.4

We round off the issue with a selection of Case Reports (pp. e200-e209), an original report on the characteristics of urgent palliative cancer care consultations encountered by radiation oncologists (p. e193), and a New Therapies feature, also by Dr de Lartigue, focusing on the rarity and complexities of sarcomas (p. e210).

Those are my dog-day-of-summer thoughts as we head toward another Labor Day and a new academic year. Since we are all online now, we encourage you to listen to my bimonthly podcast of each issue on our website at www.jcso-online.com, and of course, follow us on Twitter (@jcs_onc) and Instagram (@jcsoncology) and like us on Facebook.

1. Glaspy J, Crawford J, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in oncology: a study-level meta-analysis of survival and other safety outcomes. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(2):301-315.

2. Leyland-Jones B, Bondarenko I, Nemsadze G, et al. A randomized, open-label, multicenter, phase III study of epoetin alfa versus best standard of care in anemic patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving standard chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1197-1207.

3. US Food and Drug Administration release. Information on erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) epoetin alfa (marketed as Procrit, Epogen), darbepoetin alfa (marketed as Aranesp). https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm109375.htm. Last updated April 13, 2017. Accessed August 20, 2018.

4. Henry D, Sammon M. Treating immunotherapy-related AEs in the emergency department [Audio]. https://www.mdedge.com/jcso/article/171966/patient-survivor-care/treating-immunotherapy-related-aes-emergency-department. Published August 6, 2018.

As summer winds down and we begin to gear up to return to school or work, I was thinking about new and returning hem-onc residents, fellows, and young attendings and a question I routinely get from them: what should I do next in my career? I always answer by holding up 3 fingers and telling them that they can practice 1, at a university hospital; 2, at a university teaching affiliate; or 3, at a community hospital or practice with a little or no university affiliation. These days, trainees in hematology-oncology are often advised to be highly specialty-specific when they plan their long-term careers and to focus on a particular cancer or hematologic disorder. That is fine if you want to remain in an academic or university-based practice, but not if community practice is your preference. So, what are the differences among these 3 options?

Option 1, to remain in a university setting where you can be highly focused and specialized in a single narrowly defined area, could be satisfying, but keep in mind that the institution expects results! You will be carefully monitored for research output and teaching and administration commitments, and your interaction with patients could add up to less than 50% of your time. Publication and grant renewal will also play a role and therefore take up your time.

If you are considering option 2 – to work at a university teaching affiliate hospital – you need to bear in mind that you likely will see a patient population with a much broader range of diagnoses than would be the case with the first option. Patient care for option 2 will take up more than 50% of your time, so it might be a little more challenging to stay current, but perhaps more refreshing if you enjoy contact with patients. Teaching, research, and administration will surely be available, and publication and grant renewal will play as big or small a role as you want.

Option 3 would be to join a community hospital or practice where the primary focus is on patient care and the diagnoses will span the hematology and oncology spectrum. This type of practice can be very demanding of one’s time, but as rewarding as the other options, especially if you value contact with patients. With this option, one is more likely to practice as a generalist, perhaps with an emphasis in one of the hem-onc specialties, but able to treat a cluster of different types of cancer as well.

I always advise trainees to be sure they ask physicians practicing in each of these options to give examples of what their best and worst days are like so that they can get some idea of what the daily humdrum and challenges would encompass. What did I choose? I have always gone with option 2 and have been very happy in that setting.

In this issue…

More biosimilars head our way. Turning to the current issue of the journal, on page e181, Dr Jane de Lartigue discusses 2 new biosimilars recently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – epoetin alfa-epbx (Retacrit; Hospira, a Pfizer company) for chemotherapy-induced anemia (CIA), and pegfilgrastim-jmdb (Fulphila; Mylan and Biocon) for prevention of febrile neutropenia. As Dr de Lartigue notes, biosimilars are copies of FDA-approved biologic drugs that cannot be identical to the reference drug but demonstrate a high similarity to it. In this case, the reference drug for epoetin alfa-epbx is epoetin alfa (Epogen/Procrit, Amgen) and for pegfilgrastim-jmdb, it is pegfilgrastim (Neulasta, Amgen). As the reference drugs’ patents expire, biosimilars are being developed to increase competition in the marketplace in an effort to reduce costs and improve patient access to these therapies. Indeed, the FDA is working to streamline the biosimilar approval process to facilitate that access.

Reading this article got me thinking about something I often have to consider in the course of my work: transfusion versus erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs)? Recombinant erythropoietin drugs such as the biosimilar, epoetin alfa-epbx, and its reference drug are grouped together as ESAs, and have been used to treat CIA since the late 1980s. However, there were a few trials that used higher-dose ESA or set high hemoglobin targets, and their findings suggested that ESAs may shorten survival in patients with cancer or increase tumor growth, or both. The use of ESAs took a nosedive after the 2007 decision by the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee to rein in their use for a hard start of ESA treatment at less than 10 g/dL hemoglobin, and not higher. Subsequent trials addressed the concerns about survival and tumor growth. A meta-analysis of 60 randomized, placebo-controlled trials of ESAs in CIA found that there was no difference in overall survival between the study and control groups.1 Likewise, findings from an FDA-mandated trial with epoetin alfa (Procrit) in patients with metastatic breast cancer have reported that there was no significant difference in overall survival between the study and control groups.2 The results of a second FDA-mandated trial with darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp, Amgen) in patients with metastatic lung cancer are expected to be released soon. The FDA lifted the ESA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy based on those findings. However, many practitioners, both young and old, continue to shy away from using ESAs because of the FDA black box warning that remains in place despite the latest data.3The use of transfusion ticked up reciprocally with the decline in ESA use, but perhaps we should re-evaluate the use of these agents in our practice, especially now that the less costly, equally safe and effective biosimilars are becoming available and we have the new survival data. Transfusions are time consuming and have side effects, including allergic reaction and infection risk, whereas ESAs are easily administered by injection, which patients might find preferable.

Malignancies in patients with HIV-AIDS. On page e188, Koppaka and colleagues report on a study in India of the patterns of malignancies in patients with HIV-AIDS. I began my career just as the first reports of what became known as HIV-AIDS emerged, and we were all mystified by what was killing these patients and the curious hematologic and oncologic problems they developed. Back then, the patients were profoundly immunosuppressed, and the immunosuppression cancers of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, usually higher grade, and Kaposi sarcoma were most prevalent and today are collectively labeled AIDS-defining malignancies (ADMs).

Fast forward to present day, and we have extremely effective antiretroviral therapies that have resulted in a significant reduction in mortality among HIV-infected individuals who are now living long enough to get what we call non–AIDS-defining malignancies (NADMs) such as anal or cervical cancers, hepatoma (hepatocellular carcinoma), Hodgkin lymphoma, and lung cancer. Of note is that these NADMs are all highly viral associated, with anal and cervical cancers linked to infection with the human papillomavirus; hepatoma linked to the hepatitis B/C viruses; Hodgkin lymphoma to the Epstein-Barr virus; and lung cancer, possibly also HPV. Fortunately, these days we can use standard-dose chemoradiation therapy for all HIV-related cancers because the patients’ immune systems are much better reconstituted and the modern-day antiretroviral therapies have much less drug–drug interaction thanks to the advent of the integrase inhibitors. The researchers give an excellent breakdown of the occurrence of these malignancies, as well as an analysis of the correlation between CD4 counts and the different malignancies.

Immunotherapy-related side effects in the ED. What happens when our patients who are on immunotherapy end up in the emergency department (ED) with therapy-related symptoms? And what can the treating oncologist do to help the ED physician achieve the best possible outcome for the patient? I spoke to Dr Maura Sammon, an ED physician, about some of the more common of these side effects – lung, gastrointestinal, rash, and endocrine-related problems – and she describes in detail how physicians in the ED would triage and treat the patient. Dr Sammon also emphasizes the importance of communication: first, between the treating oncologist and patient, about the differences between chemotherapy and immunotherapy; and second, between the ED physician and the treating oncologist as soon as possible after the patient has presented to ensure a good outcome. The interview is part of The JCSO Interview series. It is jam-packed with useful, how-to information, and you can read a transcript of it on page e216 of this issue, or you can listen to it online.4

We round off the issue with a selection of Case Reports (pp. e200-e209), an original report on the characteristics of urgent palliative cancer care consultations encountered by radiation oncologists (p. e193), and a New Therapies feature, also by Dr de Lartigue, focusing on the rarity and complexities of sarcomas (p. e210).

Those are my dog-day-of-summer thoughts as we head toward another Labor Day and a new academic year. Since we are all online now, we encourage you to listen to my bimonthly podcast of each issue on our website at www.jcso-online.com, and of course, follow us on Twitter (@jcs_onc) and Instagram (@jcsoncology) and like us on Facebook.

As summer winds down and we begin to gear up to return to school or work, I was thinking about new and returning hem-onc residents, fellows, and young attendings and a question I routinely get from them: what should I do next in my career? I always answer by holding up 3 fingers and telling them that they can practice 1, at a university hospital; 2, at a university teaching affiliate; or 3, at a community hospital or practice with a little or no university affiliation. These days, trainees in hematology-oncology are often advised to be highly specialty-specific when they plan their long-term careers and to focus on a particular cancer or hematologic disorder. That is fine if you want to remain in an academic or university-based practice, but not if community practice is your preference. So, what are the differences among these 3 options?

Option 1, to remain in a university setting where you can be highly focused and specialized in a single narrowly defined area, could be satisfying, but keep in mind that the institution expects results! You will be carefully monitored for research output and teaching and administration commitments, and your interaction with patients could add up to less than 50% of your time. Publication and grant renewal will also play a role and therefore take up your time.

If you are considering option 2 – to work at a university teaching affiliate hospital – you need to bear in mind that you likely will see a patient population with a much broader range of diagnoses than would be the case with the first option. Patient care for option 2 will take up more than 50% of your time, so it might be a little more challenging to stay current, but perhaps more refreshing if you enjoy contact with patients. Teaching, research, and administration will surely be available, and publication and grant renewal will play as big or small a role as you want.

Option 3 would be to join a community hospital or practice where the primary focus is on patient care and the diagnoses will span the hematology and oncology spectrum. This type of practice can be very demanding of one’s time, but as rewarding as the other options, especially if you value contact with patients. With this option, one is more likely to practice as a generalist, perhaps with an emphasis in one of the hem-onc specialties, but able to treat a cluster of different types of cancer as well.

I always advise trainees to be sure they ask physicians practicing in each of these options to give examples of what their best and worst days are like so that they can get some idea of what the daily humdrum and challenges would encompass. What did I choose? I have always gone with option 2 and have been very happy in that setting.

In this issue…

More biosimilars head our way. Turning to the current issue of the journal, on page e181, Dr Jane de Lartigue discusses 2 new biosimilars recently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – epoetin alfa-epbx (Retacrit; Hospira, a Pfizer company) for chemotherapy-induced anemia (CIA), and pegfilgrastim-jmdb (Fulphila; Mylan and Biocon) for prevention of febrile neutropenia. As Dr de Lartigue notes, biosimilars are copies of FDA-approved biologic drugs that cannot be identical to the reference drug but demonstrate a high similarity to it. In this case, the reference drug for epoetin alfa-epbx is epoetin alfa (Epogen/Procrit, Amgen) and for pegfilgrastim-jmdb, it is pegfilgrastim (Neulasta, Amgen). As the reference drugs’ patents expire, biosimilars are being developed to increase competition in the marketplace in an effort to reduce costs and improve patient access to these therapies. Indeed, the FDA is working to streamline the biosimilar approval process to facilitate that access.

Reading this article got me thinking about something I often have to consider in the course of my work: transfusion versus erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs)? Recombinant erythropoietin drugs such as the biosimilar, epoetin alfa-epbx, and its reference drug are grouped together as ESAs, and have been used to treat CIA since the late 1980s. However, there were a few trials that used higher-dose ESA or set high hemoglobin targets, and their findings suggested that ESAs may shorten survival in patients with cancer or increase tumor growth, or both. The use of ESAs took a nosedive after the 2007 decision by the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee to rein in their use for a hard start of ESA treatment at less than 10 g/dL hemoglobin, and not higher. Subsequent trials addressed the concerns about survival and tumor growth. A meta-analysis of 60 randomized, placebo-controlled trials of ESAs in CIA found that there was no difference in overall survival between the study and control groups.1 Likewise, findings from an FDA-mandated trial with epoetin alfa (Procrit) in patients with metastatic breast cancer have reported that there was no significant difference in overall survival between the study and control groups.2 The results of a second FDA-mandated trial with darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp, Amgen) in patients with metastatic lung cancer are expected to be released soon. The FDA lifted the ESA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy based on those findings. However, many practitioners, both young and old, continue to shy away from using ESAs because of the FDA black box warning that remains in place despite the latest data.3The use of transfusion ticked up reciprocally with the decline in ESA use, but perhaps we should re-evaluate the use of these agents in our practice, especially now that the less costly, equally safe and effective biosimilars are becoming available and we have the new survival data. Transfusions are time consuming and have side effects, including allergic reaction and infection risk, whereas ESAs are easily administered by injection, which patients might find preferable.

Malignancies in patients with HIV-AIDS. On page e188, Koppaka and colleagues report on a study in India of the patterns of malignancies in patients with HIV-AIDS. I began my career just as the first reports of what became known as HIV-AIDS emerged, and we were all mystified by what was killing these patients and the curious hematologic and oncologic problems they developed. Back then, the patients were profoundly immunosuppressed, and the immunosuppression cancers of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, usually higher grade, and Kaposi sarcoma were most prevalent and today are collectively labeled AIDS-defining malignancies (ADMs).

Fast forward to present day, and we have extremely effective antiretroviral therapies that have resulted in a significant reduction in mortality among HIV-infected individuals who are now living long enough to get what we call non–AIDS-defining malignancies (NADMs) such as anal or cervical cancers, hepatoma (hepatocellular carcinoma), Hodgkin lymphoma, and lung cancer. Of note is that these NADMs are all highly viral associated, with anal and cervical cancers linked to infection with the human papillomavirus; hepatoma linked to the hepatitis B/C viruses; Hodgkin lymphoma to the Epstein-Barr virus; and lung cancer, possibly also HPV. Fortunately, these days we can use standard-dose chemoradiation therapy for all HIV-related cancers because the patients’ immune systems are much better reconstituted and the modern-day antiretroviral therapies have much less drug–drug interaction thanks to the advent of the integrase inhibitors. The researchers give an excellent breakdown of the occurrence of these malignancies, as well as an analysis of the correlation between CD4 counts and the different malignancies.

Immunotherapy-related side effects in the ED. What happens when our patients who are on immunotherapy end up in the emergency department (ED) with therapy-related symptoms? And what can the treating oncologist do to help the ED physician achieve the best possible outcome for the patient? I spoke to Dr Maura Sammon, an ED physician, about some of the more common of these side effects – lung, gastrointestinal, rash, and endocrine-related problems – and she describes in detail how physicians in the ED would triage and treat the patient. Dr Sammon also emphasizes the importance of communication: first, between the treating oncologist and patient, about the differences between chemotherapy and immunotherapy; and second, between the ED physician and the treating oncologist as soon as possible after the patient has presented to ensure a good outcome. The interview is part of The JCSO Interview series. It is jam-packed with useful, how-to information, and you can read a transcript of it on page e216 of this issue, or you can listen to it online.4

We round off the issue with a selection of Case Reports (pp. e200-e209), an original report on the characteristics of urgent palliative cancer care consultations encountered by radiation oncologists (p. e193), and a New Therapies feature, also by Dr de Lartigue, focusing on the rarity and complexities of sarcomas (p. e210).

Those are my dog-day-of-summer thoughts as we head toward another Labor Day and a new academic year. Since we are all online now, we encourage you to listen to my bimonthly podcast of each issue on our website at www.jcso-online.com, and of course, follow us on Twitter (@jcs_onc) and Instagram (@jcsoncology) and like us on Facebook.

1. Glaspy J, Crawford J, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in oncology: a study-level meta-analysis of survival and other safety outcomes. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(2):301-315.

2. Leyland-Jones B, Bondarenko I, Nemsadze G, et al. A randomized, open-label, multicenter, phase III study of epoetin alfa versus best standard of care in anemic patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving standard chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1197-1207.

3. US Food and Drug Administration release. Information on erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) epoetin alfa (marketed as Procrit, Epogen), darbepoetin alfa (marketed as Aranesp). https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm109375.htm. Last updated April 13, 2017. Accessed August 20, 2018.

4. Henry D, Sammon M. Treating immunotherapy-related AEs in the emergency department [Audio]. https://www.mdedge.com/jcso/article/171966/patient-survivor-care/treating-immunotherapy-related-aes-emergency-department. Published August 6, 2018.

1. Glaspy J, Crawford J, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in oncology: a study-level meta-analysis of survival and other safety outcomes. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(2):301-315.

2. Leyland-Jones B, Bondarenko I, Nemsadze G, et al. A randomized, open-label, multicenter, phase III study of epoetin alfa versus best standard of care in anemic patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving standard chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1197-1207.

3. US Food and Drug Administration release. Information on erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) epoetin alfa (marketed as Procrit, Epogen), darbepoetin alfa (marketed as Aranesp). https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm109375.htm. Last updated April 13, 2017. Accessed August 20, 2018.

4. Henry D, Sammon M. Treating immunotherapy-related AEs in the emergency department [Audio]. https://www.mdedge.com/jcso/article/171966/patient-survivor-care/treating-immunotherapy-related-aes-emergency-department. Published August 6, 2018.

Carcinoma of the colon in a child

Colon cancer is not common in childhood even though cases have been reported in children and adolescents.1,2 Although it is sporadic, it can arise in the setting of predisposing illnesses such as familial polyposis syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease.2-5 Only 1 or 2 cases per million children are reported globally each year, but the incidence has been noted to be on the rise.2 The nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and anemia as features of the disease could also be seen in other common childhood ailments, such as helminthiasis in our region in West Africa. As a result, unless there is a high index of suspicion at the outset, there is a risk that colon cancer will be diagnosed at a late stage, especially in children with no apparent predisposing factor.

In this case, an 11-year-old girl presented to our institution with abdominal pain, melena, abdominal swelling, and iron deficiency anemia. A positive family history of colon cancer in the mother and a brain tumor in an elder sibling prompted a search for and subsequent diagnosis of colon cancer. Her case highlights the importance of a high index of suspicion in making an early diagnosis to achieve the best possible outcomes. This case is being reported in line with the SCARE guidelines.6

Case summary and presentation

An 11-year-old girl presented to our facilty with recurrent abdominal pain of 8 months duration, a 4-month history of progressive paleness of the palms, and a month-long fever. There was an associated change in bowel habit to about 2-3 times per day, weight loss despite a preserved appetite, and black, tarry stools. A month before she presented, she developed low-grade pyrexia, dysuria, and pica. She was treated for iron deficiency anemia at a peripheral hospital where she first sought for care with oral iron, folic acid, and vitamin C, but with no improvement in symptoms.

She was the youngest of 8 children born to parents who were first cousins. Her father had died in a car accident when she was a year old, and her mother had died 6 years later after being diagnosed with and treated for colon cancer. An elder sibling died of a brain tumor at the age of 9 years.

On admission to our institution, the girl looked acutely ill. She was severely pale, but afebrile and anicteric. She had no petechial or purpuric skin rashes, but had glossitis with areas of papules on the anterior two-thirds of the dorsum of the tongue. She had no gingival hypertrophy, but had significant peripheral lymphadenopathy and weighed 67% of the weight for her age. In addition, she had generalized abdominal pain and a soft, well-circumscribed tender mass located at the right iliac fossa was palpated and estimated to be 8 cm x 6 cm.

A full blood count showed severe hypochromic microcytic anemia, with a red blood cell count of 2.53 x 1012/L, packed cell volume of 9%, white blood cell count 9.4 x109/L, platelet cell count of 453 x 109/L, mean corpuscular volume of 48.6 fl, and a red cell distribution width of 23.7%. Iron studies could not be done because we lacked the facilities, but a bone marrow aspiration biopsy showed reduced bone marrow iron stores. A fecal occult blood test was positive for blood, but negative for culture, ova, or cysts. An abdominopelvic ultrasound showed the well-circumscribed mass at the right iliac fossa, and that was confirmed by a computed-tomographic scan (Figure 1).

An upper endoscopy revealed fundal and prepyloric erosions and reflux eosophagitis. Although findings from a sigmoidoscopy were normal, a histology of biopsied tissues showed features of chronic inflammation.

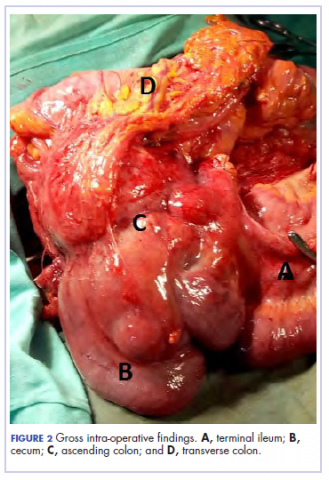

There was a delay in arriving at the final diagnosis because the patient’s family faced financial difficulties and some of the imaging procedures were not available at our institution. Other diagnoses that were entertained and managed in this case were iron deficiency anemia from peptic ulcer disease. Six weeks after her initial presentation to our institution, the patient had an exploratory laparotomy. The findings intra-operatively were those of a huge tumor involving the ascending colon measuring 16 x14 cm and extending to involve the cecum and mesenteric lymph nodes (Figure 2).

Kidneys, liver and spleen were macroscopically normal. An assessment of Duke’s stage 3C colon cancer was made and she had an extended radical hemicolectomy with anastomosis.

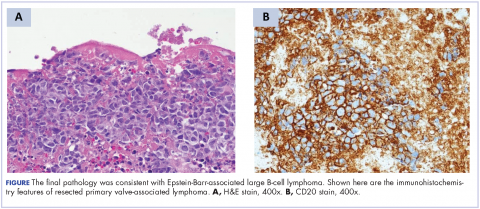

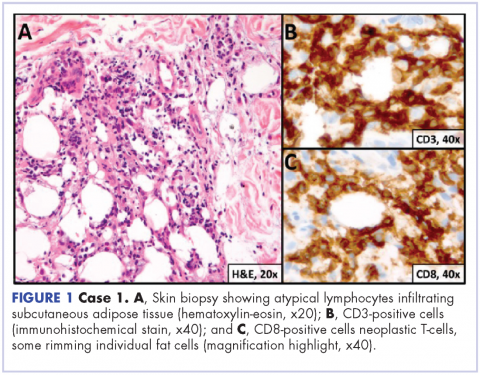

A 44.5-cm long right hemicolectomy segment comprising a 17-cm ileal segment, a 6-cm cecum, 21.5-cm ascending colon, and an 8-cm appendix was removed. The tumor was located in the ascending colon at 7.5 cm from the distal resection margin and extending 1 cm into the cecum. It had a circumference of 27 cm with fibrinous exudates on its peritoneal surface. Dissection revealed uneven circumferential thickening of the bowel wall, luminal dilatation, marked mucosal ulcerations, and liquid content made up of fecal material and necrotic debris. The tumor cut surface was solid white. We also removed 4 lymph nodes. Other uninvolved areas showed focal mucosal hyperemia, but no polyps were observed. Histology showed moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (pT4) with ¼ nodal involvement (Figure 3).

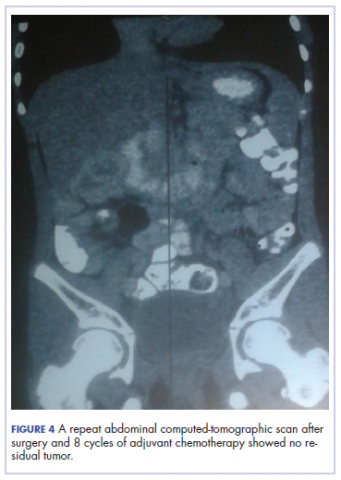

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and she had adjuvant chemotherapy with oral capecitabine and intravenous oxaliplatin. She completed the 8-cycle protocol with excellent clinical response and minimal adverse events were recorded. A repeat abdominal CT scan showed no residual tumor (Figure 4), and her full blood count showed normal hematological profile with no evidence of iron deficiency.

She is presently on follow up 2 years after confirmation of the diagnosis. (Her histological diagnosis was made June 2016, and her last clinic follow-up was March 2018.

Discussion

Our patient presented with symptoms of abdominal pain, dysuria, melena, and pallor as in other case reports.7-10 A diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia was initially entertained in view of the hematologic profile, and for which management was instituted. The findings of gastric and duodenal erosions on endoscopy further supported the assumption for and treatment of peptic ulcer disease. Iron deficiency in this patient was owing to chronic blood loss from a tumour located at the upper parts of the. Vague and nonspecific symptoms are associated with delayed diagnosis and poor prognosis.1-5,11 Nonspecificity of symptoms is typical feature of colon cancer as reported in other studies.1,11-13 However, the strong family history of colon cancer heightened suspicion in this case, otherwise the diagnosis of an ascending colon tumor could have been delayed until much later and with graver consequences.

The diagnosis of colon cancer in this child was made about a year after her initial symptoms, and 3 months after her presentation to us. Ascending and transverse colon cancers are usually diagnosed late because the symptoms of intestinal obstruction – frank bleeding – will not present until the illness is substantially advanced. Ameh and Nmadu reported a case series of 8 patients from our facility with rectosigmoid tumor, of whom 6 had mucinous adenocarcinaoma and 5 of those 6 had stage 3C disease. Although the patient in the present case had an advanced disease at diagnosis, she had a moderately differentiated histology in contrast to the 6 previously reported cases, who had mucinous histology.14

Previous studies have shown that colorectal carcinoma is a rare disease worldwide, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 0.38 people/million.1,2 When it occurs in the young, familial or hereditary predisposition should be highly suspected.1-3 To date, there is scant literature on children younger than 16 years in Nigeria.15 Various studies have found a relationship between patients with early-stage colon cancer and inherited genetic predisposition to the disease.2,5 Familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the development of polyps during the first decade of life, extensive polyposis in the second decade, and transformation into frank carcinoma in early adulthood.1-5

Although our patient’s mother was diagnosed with and died of colon cancer, the type of which could not be ascertained because her records could not be traced. However, the operative and histological findings in this patient did not suggest the presence of polyposis. The clinical phenotype for the autosomal recessive mismatch repair deficiency includes susceptibity to glioma, leukemia, lymphoma, and colorectal carcinoma in children and young adults.1,5 Screening for genetic markers in the child in the present case might have identified the genetic abnormalities involved and would have been invaluable in the evaluation of her 6 surviving siblings and further management of this family. In conclusion. A high index of suspicion should prompt inclusion of colon cancer in the differential diagnosis of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms associated with colon cancer in children.

Acknowledg

The authors obtained written informed consent from the patient and her elder sibling before writing this report. In addition, the authors thank all the staff involved in the management of this child in the pediatric medical and surgical wards.

1. Sultan I, Rodriguez-Galindo C, El-Taani H, Pastore G, Casanova M, Gallino G, Ferrari A. Distinct features of colorectal cancer in children and adolescents. A population-based study of 159 cases. Cancer. 2010;1;116(3):758-65.

2. Ferrari A. Intestinal carcinomas. In: Schneider DT, Brecht IB, Olson TA, Ferrari A (eds). Rare tumors in children and adolescents. 1st ed. Copyright, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg; 2012; chap 32.

3. Hill DA, Furman WL, Bilups CA, Riedly SE, Cain AM, Rao BN. Colorectal carcinoma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathological review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5808-5814.

4. Saab OKR, Furman WL. Epidemiology and management options for colorectal cancer in children. Paediatr Drugs. 2008;10(3):177-192.

5. Bertario L, Signoroni S. Gastrointestinal cancer predisposition syndromes. In: Schneider DT, Brecht IB, Olson TA, Ferrari A (eds). Rare tumors in children and adolescents. Copyright, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg; 2012; chap 30.

6. Agha RA, Fowler AJ, Saetta A, et al, for the SCARE Group. The SCARE Statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int J Surg. 2016;34:180-186.

7. Tricoli JV, Seibel NL, Blair DG, Albritton K, Hayes-Lattin B. Unique characteristics of adolescent and young adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia, breast cancer, and colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(8):628-635.

8. Begum M, Khan ZJ, Hassan K, Karim S. Carcinoma colon of a child presenting with abdominal pain. Bangaladesh J Child Health. 2014;38(1):44-47.

9. Woods R, Larkin JO, Muldoon C, Kennedy MJ, Mehigan B, McCormick P. Metastatic paediatric colorectal carcinoma. Ir Med J. 2012;105(3):88-89.

10. Bjoernsen LP, Lindsay MB. An unusual case of pediatric abdominal pain. CJEM. 2011;13(2):133-138.

11. Takalkar UV, Asegaonkar SB, Kulkarni U, Jadhav A, Advani S, Reddy DN. Carcinoma of colon in an adolescent: a case report with review of literature. Int J Sci Rep 2015;1(2):151-3.

12. Zamir N, Ahmad S, Akhtar J. Mucinous adenocarcinoma of colon. APSP J Case Rep. 2010;1(2):20.

13. Al-Tonbary Y, Darwish A, El-Hussein A, Fouda A. Adenocarcinoma of the colon in children: case series and mini-review of the literature. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2013;6(1):29-33.

14. Ameh EA, Nmadu PT. Colorectal adenocarcinoma in children and adolescents: a report of 8 patients from Zaria, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2000;19(4):273-276.

15. Ibrahim, AE, Afolayan KA, Adeniji OM, Buhari KB. Colorectal carcinoma in children and young adults in Ilorin, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2011;30(3):202-205.

Colon cancer is not common in childhood even though cases have been reported in children and adolescents.1,2 Although it is sporadic, it can arise in the setting of predisposing illnesses such as familial polyposis syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease.2-5 Only 1 or 2 cases per million children are reported globally each year, but the incidence has been noted to be on the rise.2 The nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and anemia as features of the disease could also be seen in other common childhood ailments, such as helminthiasis in our region in West Africa. As a result, unless there is a high index of suspicion at the outset, there is a risk that colon cancer will be diagnosed at a late stage, especially in children with no apparent predisposing factor.

In this case, an 11-year-old girl presented to our institution with abdominal pain, melena, abdominal swelling, and iron deficiency anemia. A positive family history of colon cancer in the mother and a brain tumor in an elder sibling prompted a search for and subsequent diagnosis of colon cancer. Her case highlights the importance of a high index of suspicion in making an early diagnosis to achieve the best possible outcomes. This case is being reported in line with the SCARE guidelines.6

Case summary and presentation

An 11-year-old girl presented to our facilty with recurrent abdominal pain of 8 months duration, a 4-month history of progressive paleness of the palms, and a month-long fever. There was an associated change in bowel habit to about 2-3 times per day, weight loss despite a preserved appetite, and black, tarry stools. A month before she presented, she developed low-grade pyrexia, dysuria, and pica. She was treated for iron deficiency anemia at a peripheral hospital where she first sought for care with oral iron, folic acid, and vitamin C, but with no improvement in symptoms.

She was the youngest of 8 children born to parents who were first cousins. Her father had died in a car accident when she was a year old, and her mother had died 6 years later after being diagnosed with and treated for colon cancer. An elder sibling died of a brain tumor at the age of 9 years.

On admission to our institution, the girl looked acutely ill. She was severely pale, but afebrile and anicteric. She had no petechial or purpuric skin rashes, but had glossitis with areas of papules on the anterior two-thirds of the dorsum of the tongue. She had no gingival hypertrophy, but had significant peripheral lymphadenopathy and weighed 67% of the weight for her age. In addition, she had generalized abdominal pain and a soft, well-circumscribed tender mass located at the right iliac fossa was palpated and estimated to be 8 cm x 6 cm.

A full blood count showed severe hypochromic microcytic anemia, with a red blood cell count of 2.53 x 1012/L, packed cell volume of 9%, white blood cell count 9.4 x109/L, platelet cell count of 453 x 109/L, mean corpuscular volume of 48.6 fl, and a red cell distribution width of 23.7%. Iron studies could not be done because we lacked the facilities, but a bone marrow aspiration biopsy showed reduced bone marrow iron stores. A fecal occult blood test was positive for blood, but negative for culture, ova, or cysts. An abdominopelvic ultrasound showed the well-circumscribed mass at the right iliac fossa, and that was confirmed by a computed-tomographic scan (Figure 1).

An upper endoscopy revealed fundal and prepyloric erosions and reflux eosophagitis. Although findings from a sigmoidoscopy were normal, a histology of biopsied tissues showed features of chronic inflammation.