User login

Unavoidable, random DNA replication errors are the most common cancer drivers

Up to two-thirds of the mutations that drive human cancers may be due to DNA replication errors in normally dividing stem cells, not by inherited or environmentally induced mutations, according to a mathematical modeling study.

The proportion of replication error-driven mutations varied widely among 17 cancers analyzed, but the overall attributable risk of these errors was remarkably consistent among 69 countries included in the study, said Cristian Tomasetti, PhD, a coauthor of the paper and a biostatistician at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The findings should be a game-changer in the cancer field, Dr. Tomasetti said during a press briefing sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Research dogma has long held that most cancers are related to lifestyle and environmental exposure, with a few primarily due to genetic factors.

“We have now determined that there is a third factor, and that it causes most of the mutations that drive cancer,” Dr. Tomasetti said. “We cannot ignore it and pretend it doesn’t exist. This is a complete paradigm shift in how we think of cancer and what causes it.”

The finding that 66% of cancer-driving mutations are based on unavoidable replication errors doesn’t challenge well-established epidemiology, said Dr. Tomasetti and his coauthor, Bert Vogelstein, MD. Rather, it fits perfectly with several key understandings of cancer: that about 40% of cases are preventable, that rapidly dividing tissues are more prone to develop cancers, and that cancer incidence rises exponentially as humans age.

“If we have as our starting point the assumption that 42% of cancers are preventable, we are completely consistent with that,” in finding that about 60% of cancers are unavoidable, Dr. Tomasetti said. “Those two numbers go perfectly together.”

The study also found that replication-error mutations (R) were most likely to drive cancers in tissues with rapid turnover, such as colorectal tissue. This makes intuitive sense, given that basal mutation rates hover at about three errors per cell replication cycle regardless of tissue type.

“The basal mutation rate in all cells is pretty even,” said Dr. Vogelstein, the Clayton Professor of Oncology and Pathology at John Hopkins University, Baltimore. “The difference is the number of stem cells. The more cells, the more divisions, and the more mistakes.”

R-mutations also contribute to age-related cancer incidence. As a person ages, more cell divisions accumulate, thus increasing the risk of a cancer-driving R-error. But these mutations also occur in children, who have rapid cell division in all their tissues. In fact, the colleagues suspect that R-errors are the main drivers of almost all pediatric cancers.

The new study bolsters the duo’s controversial 2015 work.

The theory sparked controversy among scholars and researchers. They challenged it on a number of technical fronts, from stem cell counts and division rates to charges that it didn’t adequately assess the interaction between R-mutations and environmental risks.

Some commentators, perceiving nihilism in the paper, expressed concern that clinicians and patients would get the idea that cancer prevention strategies were useless, since most cancers were simply a case of “bad luck.”

A pervading theme of these counter arguments was one familiar to any researcher: Correlation does not equal causation. The new study was an attempt to expand upon and strengthen the original findings, Dr. Tomasetti said.

“There are well-known environmental risk variations across the world, and there was a question of how our findings might change if we did this analysis in a different country. This paper is also the very first time that someone has ever looked at the proportions of mutations in each cancer type and assigned them to these factors.”

The new study employed a similar mathematical model, but comprised data from 423 cancer registries in 69 countries. The researchers examined the relationship between the lifetime risk of 17 cancers (including breast and prostate, which were not included in the 2015 study) and lifetime stem cell divisions for each tissue. The median correlation coefficient was 0.80; 89% of the countries examined had a correlation of greater than 0.70. This was “remarkably similar” to the correlation determined in the 2015 U.S.-only study.

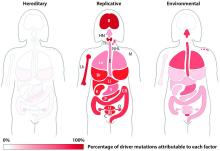

The team’s next step was to determine what fraction of cancer-driving mutations arose from R-errors, from environmental factors (E), and from hereditary factors (H). They examined these proportions in 32 different cancers in which environmental, lifestyle, and genetic factors have been thoroughly studied. Overall, 29% of the driver mutations were due to environment, 5% to heredity, and 66% to R-errors.

The proportions of these drivers did vary widely between the cancer types, the team noted. For example, lung and esophageal cancers and melanoma were primarily driven by environmental factors (more than 60% each). However, they wrote, “even in lung adenocarcinomas, R contributes a third of the total mutations, with tobacco smoke [including secondhand smoke], diet, radiation, and occupational exposures contributing the remainder. In cancers that are less strongly associated with environmental factors, such as those of the pancreas, brain, bone, or prostate, the majority of the mutations are attributable to R.”

During the press briefing, Dr. Tomasetti and Dr. Vogelstein stressed that most of the inevitable R-errors don’t precipitate cancer – and that even if they do increase risk, that risk may not ever trip the disease process.

“Most of the time these replicative mutations do no harm,” Dr Vogelstein said. “They occur in junk DNA genes, or in areas that are unimportant with respect to cancer. That’s the good luck. Occasionally, they occur in a cancer driver gene, and that is bad luck.”

But even a dose of bad luck isn’t enough to cause cancer. Most cancers require multiple hits to develop – which makes primary prevention strategies more important than ever, Dr. Tomasetti said.

“In the case of lung cancer, for instance, three or more mutations are needed. We showed that these mutations are caused by a combination of environment and R-errors. In theory, then, all of these cancers are preventable because if we can prevent even one of the environmentally caused mutations, then that patient won’t develop cancer.”

However, he said, some cancers do appear to be entirely driven by E-errors and, thus, appear entirely unavoidable. This is an extremely difficult area for clinicians and patients to navigate, said Dr. Vogelstein, a former pediatrician.

“We hope that understanding this will offer some comfort to the literally millions of patients who develop cancer despite having lead a near-perfect life,” in terms of managing risk factors. “Cancer develops in people who haven’t smoked, who avoided the sun and wore sunscreen, who eat perfectly healthy diets and exercise regularly. This is a particularly important concept for parents of children who have cancer, who think ‘I either transmitted a bad gene or unknowingly exposed my child to an environmental agent that caused their cancer.’ They need to understand that these cancers would have occurred no matter what they did.”

Dr. Tomasetti had no disclosures. Dr. Vogelstein is on the scientific advisory boards of Morphotek, Exelixis GP, and Sysmex Inostics, and is a founder of PapGene and Personal Genome Diagnostics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

Up to two-thirds of the mutations that drive human cancers may be due to DNA replication errors in normally dividing stem cells, not by inherited or environmentally induced mutations, according to a mathematical modeling study.

The proportion of replication error-driven mutations varied widely among 17 cancers analyzed, but the overall attributable risk of these errors was remarkably consistent among 69 countries included in the study, said Cristian Tomasetti, PhD, a coauthor of the paper and a biostatistician at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The findings should be a game-changer in the cancer field, Dr. Tomasetti said during a press briefing sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Research dogma has long held that most cancers are related to lifestyle and environmental exposure, with a few primarily due to genetic factors.

“We have now determined that there is a third factor, and that it causes most of the mutations that drive cancer,” Dr. Tomasetti said. “We cannot ignore it and pretend it doesn’t exist. This is a complete paradigm shift in how we think of cancer and what causes it.”

The finding that 66% of cancer-driving mutations are based on unavoidable replication errors doesn’t challenge well-established epidemiology, said Dr. Tomasetti and his coauthor, Bert Vogelstein, MD. Rather, it fits perfectly with several key understandings of cancer: that about 40% of cases are preventable, that rapidly dividing tissues are more prone to develop cancers, and that cancer incidence rises exponentially as humans age.

“If we have as our starting point the assumption that 42% of cancers are preventable, we are completely consistent with that,” in finding that about 60% of cancers are unavoidable, Dr. Tomasetti said. “Those two numbers go perfectly together.”

The study also found that replication-error mutations (R) were most likely to drive cancers in tissues with rapid turnover, such as colorectal tissue. This makes intuitive sense, given that basal mutation rates hover at about three errors per cell replication cycle regardless of tissue type.

“The basal mutation rate in all cells is pretty even,” said Dr. Vogelstein, the Clayton Professor of Oncology and Pathology at John Hopkins University, Baltimore. “The difference is the number of stem cells. The more cells, the more divisions, and the more mistakes.”

R-mutations also contribute to age-related cancer incidence. As a person ages, more cell divisions accumulate, thus increasing the risk of a cancer-driving R-error. But these mutations also occur in children, who have rapid cell division in all their tissues. In fact, the colleagues suspect that R-errors are the main drivers of almost all pediatric cancers.

The new study bolsters the duo’s controversial 2015 work.

The theory sparked controversy among scholars and researchers. They challenged it on a number of technical fronts, from stem cell counts and division rates to charges that it didn’t adequately assess the interaction between R-mutations and environmental risks.

Some commentators, perceiving nihilism in the paper, expressed concern that clinicians and patients would get the idea that cancer prevention strategies were useless, since most cancers were simply a case of “bad luck.”

A pervading theme of these counter arguments was one familiar to any researcher: Correlation does not equal causation. The new study was an attempt to expand upon and strengthen the original findings, Dr. Tomasetti said.

“There are well-known environmental risk variations across the world, and there was a question of how our findings might change if we did this analysis in a different country. This paper is also the very first time that someone has ever looked at the proportions of mutations in each cancer type and assigned them to these factors.”

The new study employed a similar mathematical model, but comprised data from 423 cancer registries in 69 countries. The researchers examined the relationship between the lifetime risk of 17 cancers (including breast and prostate, which were not included in the 2015 study) and lifetime stem cell divisions for each tissue. The median correlation coefficient was 0.80; 89% of the countries examined had a correlation of greater than 0.70. This was “remarkably similar” to the correlation determined in the 2015 U.S.-only study.

The team’s next step was to determine what fraction of cancer-driving mutations arose from R-errors, from environmental factors (E), and from hereditary factors (H). They examined these proportions in 32 different cancers in which environmental, lifestyle, and genetic factors have been thoroughly studied. Overall, 29% of the driver mutations were due to environment, 5% to heredity, and 66% to R-errors.

The proportions of these drivers did vary widely between the cancer types, the team noted. For example, lung and esophageal cancers and melanoma were primarily driven by environmental factors (more than 60% each). However, they wrote, “even in lung adenocarcinomas, R contributes a third of the total mutations, with tobacco smoke [including secondhand smoke], diet, radiation, and occupational exposures contributing the remainder. In cancers that are less strongly associated with environmental factors, such as those of the pancreas, brain, bone, or prostate, the majority of the mutations are attributable to R.”

During the press briefing, Dr. Tomasetti and Dr. Vogelstein stressed that most of the inevitable R-errors don’t precipitate cancer – and that even if they do increase risk, that risk may not ever trip the disease process.

“Most of the time these replicative mutations do no harm,” Dr Vogelstein said. “They occur in junk DNA genes, or in areas that are unimportant with respect to cancer. That’s the good luck. Occasionally, they occur in a cancer driver gene, and that is bad luck.”

But even a dose of bad luck isn’t enough to cause cancer. Most cancers require multiple hits to develop – which makes primary prevention strategies more important than ever, Dr. Tomasetti said.

“In the case of lung cancer, for instance, three or more mutations are needed. We showed that these mutations are caused by a combination of environment and R-errors. In theory, then, all of these cancers are preventable because if we can prevent even one of the environmentally caused mutations, then that patient won’t develop cancer.”

However, he said, some cancers do appear to be entirely driven by E-errors and, thus, appear entirely unavoidable. This is an extremely difficult area for clinicians and patients to navigate, said Dr. Vogelstein, a former pediatrician.

“We hope that understanding this will offer some comfort to the literally millions of patients who develop cancer despite having lead a near-perfect life,” in terms of managing risk factors. “Cancer develops in people who haven’t smoked, who avoided the sun and wore sunscreen, who eat perfectly healthy diets and exercise regularly. This is a particularly important concept for parents of children who have cancer, who think ‘I either transmitted a bad gene or unknowingly exposed my child to an environmental agent that caused their cancer.’ They need to understand that these cancers would have occurred no matter what they did.”

Dr. Tomasetti had no disclosures. Dr. Vogelstein is on the scientific advisory boards of Morphotek, Exelixis GP, and Sysmex Inostics, and is a founder of PapGene and Personal Genome Diagnostics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

Up to two-thirds of the mutations that drive human cancers may be due to DNA replication errors in normally dividing stem cells, not by inherited or environmentally induced mutations, according to a mathematical modeling study.

The proportion of replication error-driven mutations varied widely among 17 cancers analyzed, but the overall attributable risk of these errors was remarkably consistent among 69 countries included in the study, said Cristian Tomasetti, PhD, a coauthor of the paper and a biostatistician at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The findings should be a game-changer in the cancer field, Dr. Tomasetti said during a press briefing sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Research dogma has long held that most cancers are related to lifestyle and environmental exposure, with a few primarily due to genetic factors.

“We have now determined that there is a third factor, and that it causes most of the mutations that drive cancer,” Dr. Tomasetti said. “We cannot ignore it and pretend it doesn’t exist. This is a complete paradigm shift in how we think of cancer and what causes it.”

The finding that 66% of cancer-driving mutations are based on unavoidable replication errors doesn’t challenge well-established epidemiology, said Dr. Tomasetti and his coauthor, Bert Vogelstein, MD. Rather, it fits perfectly with several key understandings of cancer: that about 40% of cases are preventable, that rapidly dividing tissues are more prone to develop cancers, and that cancer incidence rises exponentially as humans age.

“If we have as our starting point the assumption that 42% of cancers are preventable, we are completely consistent with that,” in finding that about 60% of cancers are unavoidable, Dr. Tomasetti said. “Those two numbers go perfectly together.”

The study also found that replication-error mutations (R) were most likely to drive cancers in tissues with rapid turnover, such as colorectal tissue. This makes intuitive sense, given that basal mutation rates hover at about three errors per cell replication cycle regardless of tissue type.

“The basal mutation rate in all cells is pretty even,” said Dr. Vogelstein, the Clayton Professor of Oncology and Pathology at John Hopkins University, Baltimore. “The difference is the number of stem cells. The more cells, the more divisions, and the more mistakes.”

R-mutations also contribute to age-related cancer incidence. As a person ages, more cell divisions accumulate, thus increasing the risk of a cancer-driving R-error. But these mutations also occur in children, who have rapid cell division in all their tissues. In fact, the colleagues suspect that R-errors are the main drivers of almost all pediatric cancers.

The new study bolsters the duo’s controversial 2015 work.

The theory sparked controversy among scholars and researchers. They challenged it on a number of technical fronts, from stem cell counts and division rates to charges that it didn’t adequately assess the interaction between R-mutations and environmental risks.

Some commentators, perceiving nihilism in the paper, expressed concern that clinicians and patients would get the idea that cancer prevention strategies were useless, since most cancers were simply a case of “bad luck.”

A pervading theme of these counter arguments was one familiar to any researcher: Correlation does not equal causation. The new study was an attempt to expand upon and strengthen the original findings, Dr. Tomasetti said.

“There are well-known environmental risk variations across the world, and there was a question of how our findings might change if we did this analysis in a different country. This paper is also the very first time that someone has ever looked at the proportions of mutations in each cancer type and assigned them to these factors.”

The new study employed a similar mathematical model, but comprised data from 423 cancer registries in 69 countries. The researchers examined the relationship between the lifetime risk of 17 cancers (including breast and prostate, which were not included in the 2015 study) and lifetime stem cell divisions for each tissue. The median correlation coefficient was 0.80; 89% of the countries examined had a correlation of greater than 0.70. This was “remarkably similar” to the correlation determined in the 2015 U.S.-only study.

The team’s next step was to determine what fraction of cancer-driving mutations arose from R-errors, from environmental factors (E), and from hereditary factors (H). They examined these proportions in 32 different cancers in which environmental, lifestyle, and genetic factors have been thoroughly studied. Overall, 29% of the driver mutations were due to environment, 5% to heredity, and 66% to R-errors.

The proportions of these drivers did vary widely between the cancer types, the team noted. For example, lung and esophageal cancers and melanoma were primarily driven by environmental factors (more than 60% each). However, they wrote, “even in lung adenocarcinomas, R contributes a third of the total mutations, with tobacco smoke [including secondhand smoke], diet, radiation, and occupational exposures contributing the remainder. In cancers that are less strongly associated with environmental factors, such as those of the pancreas, brain, bone, or prostate, the majority of the mutations are attributable to R.”

During the press briefing, Dr. Tomasetti and Dr. Vogelstein stressed that most of the inevitable R-errors don’t precipitate cancer – and that even if they do increase risk, that risk may not ever trip the disease process.

“Most of the time these replicative mutations do no harm,” Dr Vogelstein said. “They occur in junk DNA genes, or in areas that are unimportant with respect to cancer. That’s the good luck. Occasionally, they occur in a cancer driver gene, and that is bad luck.”

But even a dose of bad luck isn’t enough to cause cancer. Most cancers require multiple hits to develop – which makes primary prevention strategies more important than ever, Dr. Tomasetti said.

“In the case of lung cancer, for instance, three or more mutations are needed. We showed that these mutations are caused by a combination of environment and R-errors. In theory, then, all of these cancers are preventable because if we can prevent even one of the environmentally caused mutations, then that patient won’t develop cancer.”

However, he said, some cancers do appear to be entirely driven by E-errors and, thus, appear entirely unavoidable. This is an extremely difficult area for clinicians and patients to navigate, said Dr. Vogelstein, a former pediatrician.

“We hope that understanding this will offer some comfort to the literally millions of patients who develop cancer despite having lead a near-perfect life,” in terms of managing risk factors. “Cancer develops in people who haven’t smoked, who avoided the sun and wore sunscreen, who eat perfectly healthy diets and exercise regularly. This is a particularly important concept for parents of children who have cancer, who think ‘I either transmitted a bad gene or unknowingly exposed my child to an environmental agent that caused their cancer.’ They need to understand that these cancers would have occurred no matter what they did.”

Dr. Tomasetti had no disclosures. Dr. Vogelstein is on the scientific advisory boards of Morphotek, Exelixis GP, and Sysmex Inostics, and is a founder of PapGene and Personal Genome Diagnostics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Two-thirds (66%) of cancer drivers are replication errors, 29% are environmentally induced, and 5% are hereditary.

Data source: The researchers examined cancer mutation drivers in two cohorts that spanned 69 countries.

Disclosures: Dr. Tomasetti had no disclosures. Dr. Vogelstein is on the scientific advisory boards of Morphotek, Exelixis GP, and Sysmex Inostics, and is a founder of PapGene and Personal Genome Diagnostics.

Cardiovascular disease most common cause of death in CRC survivors

SEATTLE – Improvements in diagnosis and treatment have lengthened the survival time of patients with colorectal cancer, but the majority of deaths from CRC occur within the first 5 years.

According to new findings presented at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium, CRC as a cause of death is surpassed by cardiovascular disease (CVD) and second primary cancers as time goes on.

Dr. Lewis explained that CRC as a cause of death begins to plateau over time and other causes become more important.

“As time goes on, colorectal cancer becomes less prominent, and by year 8, cardiovascular death surpasses it. By year 10, colorectal cancer is surpassed by second cancers and neurologic diseases.”

Information about long-term health problems in long-term colorectal cancer survivors is limited. To address this, Dr. Lewis and his colleagues sought to understand the trends and causes of death over time.

They analyzed causes of death in CRC patients who have survived 5 years and longer using the California Cancer Registry (2000-2011) that is linked to inpatient records. From this database, 139,743 patients with CRC were identified, with 97,604 (69.8%) having been treated for disease originating from the colon and 42,139 (30.2%) from the rectum.

The median age of the patients at the time of presentation was 68 years; at 5 years after diagnosis, 70 years; and at 10 years, 74 years. The 5-year overall survival was 59.1%, and it was during that 5 years that 95% of cancer-specific deaths occurred.

During the first 5 years, the major cause of death was CRC, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the mortality (n = 38,992, 65.4%). This was followed by cardiovascular disease (n = 7,140, 12.0%), second primary cancer (n = 3,775, 6.3%), neurologic disease (n = 2,329, 3.9%), and pulmonary disease (n = 2,307, 3.9%).

The most common second primary malignancies affecting CRC survivors were lung and hematologic cancers, followed by pancreatic and liver cancers.

Overall, in long-term survivors, cardiovascular disease was the major cause of death (n = 2,163, 24.0%) although nearly as many deaths were due to CRC (2,094, 23.2%). This was followed by neurologic disease (n = 1,174, 13.0%), secondary primary cancer (n = 1,146, 12.7%), and pulmonary disease (n = 765, 8.5%).

There was no funding source disclosed in the abstract. Dr. Lewis had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Improvements in diagnosis and treatment have lengthened the survival time of patients with colorectal cancer, but the majority of deaths from CRC occur within the first 5 years.

According to new findings presented at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium, CRC as a cause of death is surpassed by cardiovascular disease (CVD) and second primary cancers as time goes on.

Dr. Lewis explained that CRC as a cause of death begins to plateau over time and other causes become more important.

“As time goes on, colorectal cancer becomes less prominent, and by year 8, cardiovascular death surpasses it. By year 10, colorectal cancer is surpassed by second cancers and neurologic diseases.”

Information about long-term health problems in long-term colorectal cancer survivors is limited. To address this, Dr. Lewis and his colleagues sought to understand the trends and causes of death over time.

They analyzed causes of death in CRC patients who have survived 5 years and longer using the California Cancer Registry (2000-2011) that is linked to inpatient records. From this database, 139,743 patients with CRC were identified, with 97,604 (69.8%) having been treated for disease originating from the colon and 42,139 (30.2%) from the rectum.

The median age of the patients at the time of presentation was 68 years; at 5 years after diagnosis, 70 years; and at 10 years, 74 years. The 5-year overall survival was 59.1%, and it was during that 5 years that 95% of cancer-specific deaths occurred.

During the first 5 years, the major cause of death was CRC, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the mortality (n = 38,992, 65.4%). This was followed by cardiovascular disease (n = 7,140, 12.0%), second primary cancer (n = 3,775, 6.3%), neurologic disease (n = 2,329, 3.9%), and pulmonary disease (n = 2,307, 3.9%).

The most common second primary malignancies affecting CRC survivors were lung and hematologic cancers, followed by pancreatic and liver cancers.

Overall, in long-term survivors, cardiovascular disease was the major cause of death (n = 2,163, 24.0%) although nearly as many deaths were due to CRC (2,094, 23.2%). This was followed by neurologic disease (n = 1,174, 13.0%), secondary primary cancer (n = 1,146, 12.7%), and pulmonary disease (n = 765, 8.5%).

There was no funding source disclosed in the abstract. Dr. Lewis had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Improvements in diagnosis and treatment have lengthened the survival time of patients with colorectal cancer, but the majority of deaths from CRC occur within the first 5 years.

According to new findings presented at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium, CRC as a cause of death is surpassed by cardiovascular disease (CVD) and second primary cancers as time goes on.

Dr. Lewis explained that CRC as a cause of death begins to plateau over time and other causes become more important.

“As time goes on, colorectal cancer becomes less prominent, and by year 8, cardiovascular death surpasses it. By year 10, colorectal cancer is surpassed by second cancers and neurologic diseases.”

Information about long-term health problems in long-term colorectal cancer survivors is limited. To address this, Dr. Lewis and his colleagues sought to understand the trends and causes of death over time.

They analyzed causes of death in CRC patients who have survived 5 years and longer using the California Cancer Registry (2000-2011) that is linked to inpatient records. From this database, 139,743 patients with CRC were identified, with 97,604 (69.8%) having been treated for disease originating from the colon and 42,139 (30.2%) from the rectum.

The median age of the patients at the time of presentation was 68 years; at 5 years after diagnosis, 70 years; and at 10 years, 74 years. The 5-year overall survival was 59.1%, and it was during that 5 years that 95% of cancer-specific deaths occurred.

During the first 5 years, the major cause of death was CRC, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the mortality (n = 38,992, 65.4%). This was followed by cardiovascular disease (n = 7,140, 12.0%), second primary cancer (n = 3,775, 6.3%), neurologic disease (n = 2,329, 3.9%), and pulmonary disease (n = 2,307, 3.9%).

The most common second primary malignancies affecting CRC survivors were lung and hematologic cancers, followed by pancreatic and liver cancers.

Overall, in long-term survivors, cardiovascular disease was the major cause of death (n = 2,163, 24.0%) although nearly as many deaths were due to CRC (2,094, 23.2%). This was followed by neurologic disease (n = 1,174, 13.0%), secondary primary cancer (n = 1,146, 12.7%), and pulmonary disease (n = 765, 8.5%).

There was no funding source disclosed in the abstract. Dr. Lewis had no disclosures.

AT SSO 2017

Key clinical point: Long-term colorectal cancer survivors generally will die from other causes.

Major finding: By year 8, cardiovascular disease surpasses colorectal cancer in survivors, as the leading cause of death.

Data source: Large cancer registry with almost 140,000 colorectal cancer patients.

Disclosures: There was no funding source disclosed in the abstract. Dr. Lewis had no disclosures.

Portfolio of physician-led measures nets better quality of care

ORLANDO – A multifaceted portfolio of physician-led measures with feedback and financial incentives can dramatically improve the quality of care provided at cancer centers, suggests the experience of Stanford (Calif.) Health Care.

Physician leaders of 13 disease-specific cancer care programs (CCPs) identified measures of care that were meaningful to their team and patients, spanning the spectrum from new diagnosis through end of life and survivorship care. Quality and analytics teams developed 16 corresponding metrics and performance reports used for feedback. Programs were also given a financial incentive to meet jointly set targets.

After a year, the CCPs had improved on 12 of the metrics and maintained high baseline levels of performance on the other 4 metrics, investigators reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. For example, they got better at entering staging information in a dedicated field in the electronic health record (+50% absolute increase), recording hand and foot pain (+34%), performing hepatitis B testing before rituximab use (+17%), and referring patients with ovarian cancer for genetic counseling (+43%).

“The main drivers, I would argue, besides the Hawthorne effect, were a high level of physician engagement in the selection, management, and improvement of the metrics, and these metrics excited the care teams, which also provided some motivation,” she said. “We provided real-time, high-quality feedback of performance. And last but probably not least was a financial incentive for the CCP as a team, not part of any individual compensation.”

The investigators plan to continue measuring the metrics, to expand them to other sites in their network, and to add new metrics that are common across the programs to minimize measurement burden, according to Ms. Porter. “We also plan to build cohorts for value-based care and unplanned care like ED visits and unplanned admissions. Finally, we want to keep momentum going and capitalize upon a provider engagement in value measurement and improvement,” she said.

“Based on this work and prior abstracts, … there are many validated metrics to be used. So, to choose those metrics and to choose them through local leadership support, most importantly, engaging frontline staff and having their buy-in of the measures that you are collecting are important,” commented invited discussant Jessica A. Zerillo, MD, MPH, of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “And this can include using incentives that drive such stakeholders, whether they be financial or simply pride with public reporting.”

Study details

“In the summer of 2015, we were starting to feel a lot of pressure to prepare for evolving reimbursement models,” Ms. Porter said, explaining the initiative’s genesis. “Mainly, how do we define our value, and how can we measure and improve on that value of the care we deliver? One answer, of course, is to measure and reduce unnecessary variation. And we knew, to be successful, we had to increase our physician engagement and leadership in the selection and improvement of our metrics.”

Physician leaders of the CCPs were asked to choose quality measures that met three criteria: they were meaningful and important to both the care team and patients, they had pertinent data elements already available in existing databases (to reduce documentation burden), and they were multidisciplinary in nature, reflecting the care provided by the whole program. The measures ultimately selected included a variety of those put forth by American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative and the American Society for Radiation Oncology. CCPs were offered a financial incentive for meeting targets ranging from $75,000 to $125,000 that was based on number of providers and patient volume, rather than on the impact of improved metric. “This was really meant for reinvestment back into their quality programs,” Ms. Porter said. “I would argue this was really a culture-building year for us, and we hope that next year there might be a little bit more tangible value with the metrics.”

The quality team gave CCPs monthly or quarterly performance reports with unblinded physician- and patient-level details that were ultimately disseminated to all the other CCPs. They also investigated any missing data for individual metrics.

Study results showed that half of the 16 measures the physician leaders chose pertained to the diagnosis and treatment planning phase of care, according to Ms. Porter. “It was important to many of our CCPs to ensure that specific testing was done, which would then, in turn, drive treatment planning decisions,” she commented.

At the end of the year, each metric was assessed among 13 to 2,406 patients. “All CCPs met their predetermined target and earned their financial incentive award for the year,” Ms. Porter reported.

Improvement was most marked, with a 50% absolute increase, for the metric of completing a staging module, which required conversion of staging information (historically embedded in progress notes) into a structured format in a dedicated field in the electronic health record within 45 days of a patient’s first cancer treatment. This practice enables ready identification of stage cohorts in which value of care can be assessed, she noted.

There were also sizable absolute increases in relevant CCPs in the proportion of blood and marrow transplant recipients referred to survivorship care by day 100 (+20%) and visiting that service by day 180 (+13%), recording of hand and foot pain (+34%) and radiation dermatitis (+21%), mismatch repair testing in patients with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer (+10%), referral of patients with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer for genetic counseling (+43%), cytogenetic testing in patients with newly diagnosed hematologic malignancies (+17%), hepatitis B testing before rituximab administration (+17%), and allowance of at least 2 nights for treatment plan physics–quality assurance before the start of a nonemergent radiation oncology treatment (+14%).

Meanwhile, there were decreases, considered favorable changes, in chemotherapy use in the last 2 weeks of life among neuro-oncology patients (–9%) and in patients’ receipt of more than 10 fractions of radiation therapy for palliation of bone metastases (–9%).

Finally, there was no change in several metrics of quality that were already at very high or low levels, as appropriate, at baseline: molecular testing in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (stable at 95%), hospice enrollment at the time of death for neuro-oncology patients (stable at 100%), chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life for patients with sarcoma (stable at 0%), and epidermal growth factor receptor testing in patients with newly diagnosed lung adenocarcinoma (stable at 98%).

ORLANDO – A multifaceted portfolio of physician-led measures with feedback and financial incentives can dramatically improve the quality of care provided at cancer centers, suggests the experience of Stanford (Calif.) Health Care.

Physician leaders of 13 disease-specific cancer care programs (CCPs) identified measures of care that were meaningful to their team and patients, spanning the spectrum from new diagnosis through end of life and survivorship care. Quality and analytics teams developed 16 corresponding metrics and performance reports used for feedback. Programs were also given a financial incentive to meet jointly set targets.

After a year, the CCPs had improved on 12 of the metrics and maintained high baseline levels of performance on the other 4 metrics, investigators reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. For example, they got better at entering staging information in a dedicated field in the electronic health record (+50% absolute increase), recording hand and foot pain (+34%), performing hepatitis B testing before rituximab use (+17%), and referring patients with ovarian cancer for genetic counseling (+43%).

“The main drivers, I would argue, besides the Hawthorne effect, were a high level of physician engagement in the selection, management, and improvement of the metrics, and these metrics excited the care teams, which also provided some motivation,” she said. “We provided real-time, high-quality feedback of performance. And last but probably not least was a financial incentive for the CCP as a team, not part of any individual compensation.”

The investigators plan to continue measuring the metrics, to expand them to other sites in their network, and to add new metrics that are common across the programs to minimize measurement burden, according to Ms. Porter. “We also plan to build cohorts for value-based care and unplanned care like ED visits and unplanned admissions. Finally, we want to keep momentum going and capitalize upon a provider engagement in value measurement and improvement,” she said.

“Based on this work and prior abstracts, … there are many validated metrics to be used. So, to choose those metrics and to choose them through local leadership support, most importantly, engaging frontline staff and having their buy-in of the measures that you are collecting are important,” commented invited discussant Jessica A. Zerillo, MD, MPH, of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “And this can include using incentives that drive such stakeholders, whether they be financial or simply pride with public reporting.”

Study details

“In the summer of 2015, we were starting to feel a lot of pressure to prepare for evolving reimbursement models,” Ms. Porter said, explaining the initiative’s genesis. “Mainly, how do we define our value, and how can we measure and improve on that value of the care we deliver? One answer, of course, is to measure and reduce unnecessary variation. And we knew, to be successful, we had to increase our physician engagement and leadership in the selection and improvement of our metrics.”

Physician leaders of the CCPs were asked to choose quality measures that met three criteria: they were meaningful and important to both the care team and patients, they had pertinent data elements already available in existing databases (to reduce documentation burden), and they were multidisciplinary in nature, reflecting the care provided by the whole program. The measures ultimately selected included a variety of those put forth by American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative and the American Society for Radiation Oncology. CCPs were offered a financial incentive for meeting targets ranging from $75,000 to $125,000 that was based on number of providers and patient volume, rather than on the impact of improved metric. “This was really meant for reinvestment back into their quality programs,” Ms. Porter said. “I would argue this was really a culture-building year for us, and we hope that next year there might be a little bit more tangible value with the metrics.”

The quality team gave CCPs monthly or quarterly performance reports with unblinded physician- and patient-level details that were ultimately disseminated to all the other CCPs. They also investigated any missing data for individual metrics.

Study results showed that half of the 16 measures the physician leaders chose pertained to the diagnosis and treatment planning phase of care, according to Ms. Porter. “It was important to many of our CCPs to ensure that specific testing was done, which would then, in turn, drive treatment planning decisions,” she commented.

At the end of the year, each metric was assessed among 13 to 2,406 patients. “All CCPs met their predetermined target and earned their financial incentive award for the year,” Ms. Porter reported.

Improvement was most marked, with a 50% absolute increase, for the metric of completing a staging module, which required conversion of staging information (historically embedded in progress notes) into a structured format in a dedicated field in the electronic health record within 45 days of a patient’s first cancer treatment. This practice enables ready identification of stage cohorts in which value of care can be assessed, she noted.

There were also sizable absolute increases in relevant CCPs in the proportion of blood and marrow transplant recipients referred to survivorship care by day 100 (+20%) and visiting that service by day 180 (+13%), recording of hand and foot pain (+34%) and radiation dermatitis (+21%), mismatch repair testing in patients with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer (+10%), referral of patients with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer for genetic counseling (+43%), cytogenetic testing in patients with newly diagnosed hematologic malignancies (+17%), hepatitis B testing before rituximab administration (+17%), and allowance of at least 2 nights for treatment plan physics–quality assurance before the start of a nonemergent radiation oncology treatment (+14%).

Meanwhile, there were decreases, considered favorable changes, in chemotherapy use in the last 2 weeks of life among neuro-oncology patients (–9%) and in patients’ receipt of more than 10 fractions of radiation therapy for palliation of bone metastases (–9%).

Finally, there was no change in several metrics of quality that were already at very high or low levels, as appropriate, at baseline: molecular testing in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (stable at 95%), hospice enrollment at the time of death for neuro-oncology patients (stable at 100%), chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life for patients with sarcoma (stable at 0%), and epidermal growth factor receptor testing in patients with newly diagnosed lung adenocarcinoma (stable at 98%).

ORLANDO – A multifaceted portfolio of physician-led measures with feedback and financial incentives can dramatically improve the quality of care provided at cancer centers, suggests the experience of Stanford (Calif.) Health Care.

Physician leaders of 13 disease-specific cancer care programs (CCPs) identified measures of care that were meaningful to their team and patients, spanning the spectrum from new diagnosis through end of life and survivorship care. Quality and analytics teams developed 16 corresponding metrics and performance reports used for feedback. Programs were also given a financial incentive to meet jointly set targets.

After a year, the CCPs had improved on 12 of the metrics and maintained high baseline levels of performance on the other 4 metrics, investigators reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. For example, they got better at entering staging information in a dedicated field in the electronic health record (+50% absolute increase), recording hand and foot pain (+34%), performing hepatitis B testing before rituximab use (+17%), and referring patients with ovarian cancer for genetic counseling (+43%).

“The main drivers, I would argue, besides the Hawthorne effect, were a high level of physician engagement in the selection, management, and improvement of the metrics, and these metrics excited the care teams, which also provided some motivation,” she said. “We provided real-time, high-quality feedback of performance. And last but probably not least was a financial incentive for the CCP as a team, not part of any individual compensation.”

The investigators plan to continue measuring the metrics, to expand them to other sites in their network, and to add new metrics that are common across the programs to minimize measurement burden, according to Ms. Porter. “We also plan to build cohorts for value-based care and unplanned care like ED visits and unplanned admissions. Finally, we want to keep momentum going and capitalize upon a provider engagement in value measurement and improvement,” she said.

“Based on this work and prior abstracts, … there are many validated metrics to be used. So, to choose those metrics and to choose them through local leadership support, most importantly, engaging frontline staff and having their buy-in of the measures that you are collecting are important,” commented invited discussant Jessica A. Zerillo, MD, MPH, of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “And this can include using incentives that drive such stakeholders, whether they be financial or simply pride with public reporting.”

Study details

“In the summer of 2015, we were starting to feel a lot of pressure to prepare for evolving reimbursement models,” Ms. Porter said, explaining the initiative’s genesis. “Mainly, how do we define our value, and how can we measure and improve on that value of the care we deliver? One answer, of course, is to measure and reduce unnecessary variation. And we knew, to be successful, we had to increase our physician engagement and leadership in the selection and improvement of our metrics.”

Physician leaders of the CCPs were asked to choose quality measures that met three criteria: they were meaningful and important to both the care team and patients, they had pertinent data elements already available in existing databases (to reduce documentation burden), and they were multidisciplinary in nature, reflecting the care provided by the whole program. The measures ultimately selected included a variety of those put forth by American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative and the American Society for Radiation Oncology. CCPs were offered a financial incentive for meeting targets ranging from $75,000 to $125,000 that was based on number of providers and patient volume, rather than on the impact of improved metric. “This was really meant for reinvestment back into their quality programs,” Ms. Porter said. “I would argue this was really a culture-building year for us, and we hope that next year there might be a little bit more tangible value with the metrics.”

The quality team gave CCPs monthly or quarterly performance reports with unblinded physician- and patient-level details that were ultimately disseminated to all the other CCPs. They also investigated any missing data for individual metrics.

Study results showed that half of the 16 measures the physician leaders chose pertained to the diagnosis and treatment planning phase of care, according to Ms. Porter. “It was important to many of our CCPs to ensure that specific testing was done, which would then, in turn, drive treatment planning decisions,” she commented.

At the end of the year, each metric was assessed among 13 to 2,406 patients. “All CCPs met their predetermined target and earned their financial incentive award for the year,” Ms. Porter reported.

Improvement was most marked, with a 50% absolute increase, for the metric of completing a staging module, which required conversion of staging information (historically embedded in progress notes) into a structured format in a dedicated field in the electronic health record within 45 days of a patient’s first cancer treatment. This practice enables ready identification of stage cohorts in which value of care can be assessed, she noted.

There were also sizable absolute increases in relevant CCPs in the proportion of blood and marrow transplant recipients referred to survivorship care by day 100 (+20%) and visiting that service by day 180 (+13%), recording of hand and foot pain (+34%) and radiation dermatitis (+21%), mismatch repair testing in patients with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer (+10%), referral of patients with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer for genetic counseling (+43%), cytogenetic testing in patients with newly diagnosed hematologic malignancies (+17%), hepatitis B testing before rituximab administration (+17%), and allowance of at least 2 nights for treatment plan physics–quality assurance before the start of a nonemergent radiation oncology treatment (+14%).

Meanwhile, there were decreases, considered favorable changes, in chemotherapy use in the last 2 weeks of life among neuro-oncology patients (–9%) and in patients’ receipt of more than 10 fractions of radiation therapy for palliation of bone metastases (–9%).

Finally, there was no change in several metrics of quality that were already at very high or low levels, as appropriate, at baseline: molecular testing in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (stable at 95%), hospice enrollment at the time of death for neuro-oncology patients (stable at 100%), chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life for patients with sarcoma (stable at 0%), and epidermal growth factor receptor testing in patients with newly diagnosed lung adenocarcinoma (stable at 98%).

AT THE QUALITY CARE SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Over a 1-year period, the center saw improvements in practices such as completion of staging modules (+50%), recording of hand and foot pain (+34%), hepatitis B testing before rituximab use (+17%), and referral of patients with ovarian cancer for genetic counseling (+43%).

Data source: An initiative targeting 16 quality metrics undertaken by 13 cancer care programs at Stanford Health Care.

Disclosures: Ms. Porter disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Decision support tool appears to safely reduce CSF use

ORLANDO – A decision support tool safely reduces use of colony-stimulating factors (CSFs) in patients undergoing chemotherapy for lung cancer, suggests a retrospective claims-based cohort study of nearly 3,500 patients across the country.

The rate of CSF use fell among patients treated in the nine states that implemented the tool – a library of chemotherapy regimens and their expected FN risk that uses preauthorization and an algorithm to promote risk-appropriate, guideline-adherent use – but it remained unchanged in the 39 states and the District of Columbia, where usual practice continued, investigators reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and simultaneously published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 March 4. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.020867). The adjusted difference was nearly 9%.

“Decision support programs like the one highlighted here could be one way, definitely not the only way, of achieving guideline-adherent CSF use and reducing practice variation across the country,” commented coinvestigator Abiy Agiro, PhD, associate director of payer and provider research at HealthCore, a subsidiary of Anthem, in Wilmington, Delaware.

“Such efforts could also have unintended consequences, so it’s important to study relevant patient outcomes,” he added. “In this case, although it appears that the incidence of febrile neutropenia rising does not seem to relate with the program, the study does not establish the safety of CSF use reduction in lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. So, we should take the results with that caveat.”

Parsing the findings

Although the United States makes up just 4% of the world’s population, it uses nearly 80% of CSFs sold by a leading manufacturer, according to invited discussant Thomas J. Smith, MD, a professor of oncology and palliative medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“When we rewrote the ASCO [American Society of Clinical Oncology] guidelines on CSF use in 2015, there were some specific indications: dose-intense chemo for adjuvant breast cancer and uroepithelial cancer and ... when the risk of febrile neutropenia is about 20% and dose reduction is not an appropriate strategy. We were quick to point out that most regimens have a risk of febrile neutropenia much less than that,” he noted.

Dr. Agiro and his colleagues’ findings are valid, real, and reproducible, Dr. Smith maintained. However, it is unclear to what extent the observed levels of CSF use represented overuse.

“In lung cancer, there are very few regimens that have a febrile neutropenia rate close to 20%,” he elaborated. “What we don’t know is how much of this [use] was actually justified. I would suspect it is 10% or 15%, rather than 40%.”

CSF use, as guided by the new tool, “might not support increased dose density [of chemotherapy], but I would challenge anybody in the audience to show me data in normal solid tumor patients that [show that] dose density maintained by CSFs makes a difference in overall survival,” he said.

Questions yet to be addressed include the difficulty and cost of using the decision support tool and the possible negative impact on practices’ finances, according to Dr. Smith.

“When ESAs [erythropoiesis-stimulating agents] came off being used so much, some of my friends’ practices took a 15% to 20% drop in their revenue, and this is an important source of revenue for a lot of practices,” he explained. “So, I hope that when we take this revenue away, that we are cognizant of that and realize that it’s just another stress on practices, many of which are under significant stress already.”

Study details

An estimated 26% of uses of CSFs in patients with lung cancer are not in accordance with the ASCO practice guidelines, according to Dr. Agiro. “Such variations from recommendations are sometimes the reason why different stakeholders take actions” to improve care, such as ASCO’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) and the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely initiative (J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:338-43).

The decision support tool evaluated in the study uses preauthorization before delivery of care and, therefore, differs from point-of-care interventions, he noted.

“The tool allows access to a library of chemotherapy regimens and their associated, expected febrile neutropenia risk based on the myelotoxicity of the planned regimens as indicated in published trials. The tool is accessible online and provides real-time recommendations that are tailored based on disease- and patient-specific factors for either the use of CSF or not,” he elaborated.

According to the tool’s algorithm, use is recommended for patients who are given a regimen with a high risk of febrile neutropenia (greater than 20%) and is not recommended for those given a low-risk regimen (less than 10%). It is tailored according to the presence of additional risk factors for the intermediate-risk group.

Oncologists use the tool only for patients starting a new chemotherapy and only in the first cycle, when the risk of febrile neutropenia is highest, according to Dr. Agiro. “Once the approval is given in the first cycle, it remains in effect for the next 6 months, so they don’t have to use it again and again in additional cycles,” he explained.

The decision support tool was implemented in nine states starting in July 2014. In the study, which was funded by Anthem, the investigators analyzed administrative claims data from commercially insured adult patients starting chemotherapy for lung cancer, assessing changes in outcomes between a preimplementation period (April 2013 to Dec. 2013) and a postimplementation period (July 2014 to March 2015).

Analyses were based on 1,857 patients in the states that implemented the tool and 1,610 patients in the states that did not.

The percentage of patients receiving CSFs in the 6 months after starting chemotherapy fell in states that implemented the decision support tool (from 48.4% to 35.6%) but remained stable in states that did not (43.2% and 44.4%), Dr. Agiro reported. The adjusted difference in differences was –8.7% (P less than .001).

Meanwhile, the percentage of patients admitted for febrile neutropenia or experiencing this outcome while hospitalized increased in both states implementing the tool (from 2.8% to 4.3%) and those not implementing it (from 3.1% to 5.1%). Although the magnitude of increase was smaller in the former (+1.5% vs. +2.0%), the difference was not significant. Findings were essentially the same among the subset of patients aged 65 years and older.

“It’s important to study both intended and unintended consequences of such interventions,” Dr. Agiro noted. “Our study goes beyond financial considerations by looking at unintended outcomes: in this case, focusing on the incidence of febrile neutropenia, an outcome that is of prime interest to patients and oncologists and payers alike.”

The study may have missed some cases of febrile neutropenia, he acknowledged. “Also, there are other important outcomes of concern. For example, were there any delays in chemotherapy administration or immune recovery that could have been triggered by the implementation of the decision support program?”

The impact, both intended and unintended, on practices warrants evaluation as well, he further noted. “An important question could be, ‘Does it take less time to use this decision support tool compared to the time taken with normal care processes?’ ”

Dr. Agiro disclosed that he is employed by, has stock or other ownership interests in, and receives research funding from Anthem.

ORLANDO – A decision support tool safely reduces use of colony-stimulating factors (CSFs) in patients undergoing chemotherapy for lung cancer, suggests a retrospective claims-based cohort study of nearly 3,500 patients across the country.

The rate of CSF use fell among patients treated in the nine states that implemented the tool – a library of chemotherapy regimens and their expected FN risk that uses preauthorization and an algorithm to promote risk-appropriate, guideline-adherent use – but it remained unchanged in the 39 states and the District of Columbia, where usual practice continued, investigators reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and simultaneously published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 March 4. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.020867). The adjusted difference was nearly 9%.

“Decision support programs like the one highlighted here could be one way, definitely not the only way, of achieving guideline-adherent CSF use and reducing practice variation across the country,” commented coinvestigator Abiy Agiro, PhD, associate director of payer and provider research at HealthCore, a subsidiary of Anthem, in Wilmington, Delaware.

“Such efforts could also have unintended consequences, so it’s important to study relevant patient outcomes,” he added. “In this case, although it appears that the incidence of febrile neutropenia rising does not seem to relate with the program, the study does not establish the safety of CSF use reduction in lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. So, we should take the results with that caveat.”

Parsing the findings

Although the United States makes up just 4% of the world’s population, it uses nearly 80% of CSFs sold by a leading manufacturer, according to invited discussant Thomas J. Smith, MD, a professor of oncology and palliative medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“When we rewrote the ASCO [American Society of Clinical Oncology] guidelines on CSF use in 2015, there were some specific indications: dose-intense chemo for adjuvant breast cancer and uroepithelial cancer and ... when the risk of febrile neutropenia is about 20% and dose reduction is not an appropriate strategy. We were quick to point out that most regimens have a risk of febrile neutropenia much less than that,” he noted.

Dr. Agiro and his colleagues’ findings are valid, real, and reproducible, Dr. Smith maintained. However, it is unclear to what extent the observed levels of CSF use represented overuse.

“In lung cancer, there are very few regimens that have a febrile neutropenia rate close to 20%,” he elaborated. “What we don’t know is how much of this [use] was actually justified. I would suspect it is 10% or 15%, rather than 40%.”

CSF use, as guided by the new tool, “might not support increased dose density [of chemotherapy], but I would challenge anybody in the audience to show me data in normal solid tumor patients that [show that] dose density maintained by CSFs makes a difference in overall survival,” he said.

Questions yet to be addressed include the difficulty and cost of using the decision support tool and the possible negative impact on practices’ finances, according to Dr. Smith.

“When ESAs [erythropoiesis-stimulating agents] came off being used so much, some of my friends’ practices took a 15% to 20% drop in their revenue, and this is an important source of revenue for a lot of practices,” he explained. “So, I hope that when we take this revenue away, that we are cognizant of that and realize that it’s just another stress on practices, many of which are under significant stress already.”

Study details

An estimated 26% of uses of CSFs in patients with lung cancer are not in accordance with the ASCO practice guidelines, according to Dr. Agiro. “Such variations from recommendations are sometimes the reason why different stakeholders take actions” to improve care, such as ASCO’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) and the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely initiative (J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:338-43).

The decision support tool evaluated in the study uses preauthorization before delivery of care and, therefore, differs from point-of-care interventions, he noted.

“The tool allows access to a library of chemotherapy regimens and their associated, expected febrile neutropenia risk based on the myelotoxicity of the planned regimens as indicated in published trials. The tool is accessible online and provides real-time recommendations that are tailored based on disease- and patient-specific factors for either the use of CSF or not,” he elaborated.

According to the tool’s algorithm, use is recommended for patients who are given a regimen with a high risk of febrile neutropenia (greater than 20%) and is not recommended for those given a low-risk regimen (less than 10%). It is tailored according to the presence of additional risk factors for the intermediate-risk group.

Oncologists use the tool only for patients starting a new chemotherapy and only in the first cycle, when the risk of febrile neutropenia is highest, according to Dr. Agiro. “Once the approval is given in the first cycle, it remains in effect for the next 6 months, so they don’t have to use it again and again in additional cycles,” he explained.

The decision support tool was implemented in nine states starting in July 2014. In the study, which was funded by Anthem, the investigators analyzed administrative claims data from commercially insured adult patients starting chemotherapy for lung cancer, assessing changes in outcomes between a preimplementation period (April 2013 to Dec. 2013) and a postimplementation period (July 2014 to March 2015).

Analyses were based on 1,857 patients in the states that implemented the tool and 1,610 patients in the states that did not.

The percentage of patients receiving CSFs in the 6 months after starting chemotherapy fell in states that implemented the decision support tool (from 48.4% to 35.6%) but remained stable in states that did not (43.2% and 44.4%), Dr. Agiro reported. The adjusted difference in differences was –8.7% (P less than .001).

Meanwhile, the percentage of patients admitted for febrile neutropenia or experiencing this outcome while hospitalized increased in both states implementing the tool (from 2.8% to 4.3%) and those not implementing it (from 3.1% to 5.1%). Although the magnitude of increase was smaller in the former (+1.5% vs. +2.0%), the difference was not significant. Findings were essentially the same among the subset of patients aged 65 years and older.

“It’s important to study both intended and unintended consequences of such interventions,” Dr. Agiro noted. “Our study goes beyond financial considerations by looking at unintended outcomes: in this case, focusing on the incidence of febrile neutropenia, an outcome that is of prime interest to patients and oncologists and payers alike.”

The study may have missed some cases of febrile neutropenia, he acknowledged. “Also, there are other important outcomes of concern. For example, were there any delays in chemotherapy administration or immune recovery that could have been triggered by the implementation of the decision support program?”

The impact, both intended and unintended, on practices warrants evaluation as well, he further noted. “An important question could be, ‘Does it take less time to use this decision support tool compared to the time taken with normal care processes?’ ”

Dr. Agiro disclosed that he is employed by, has stock or other ownership interests in, and receives research funding from Anthem.

ORLANDO – A decision support tool safely reduces use of colony-stimulating factors (CSFs) in patients undergoing chemotherapy for lung cancer, suggests a retrospective claims-based cohort study of nearly 3,500 patients across the country.

The rate of CSF use fell among patients treated in the nine states that implemented the tool – a library of chemotherapy regimens and their expected FN risk that uses preauthorization and an algorithm to promote risk-appropriate, guideline-adherent use – but it remained unchanged in the 39 states and the District of Columbia, where usual practice continued, investigators reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and simultaneously published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 March 4. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.020867). The adjusted difference was nearly 9%.

“Decision support programs like the one highlighted here could be one way, definitely not the only way, of achieving guideline-adherent CSF use and reducing practice variation across the country,” commented coinvestigator Abiy Agiro, PhD, associate director of payer and provider research at HealthCore, a subsidiary of Anthem, in Wilmington, Delaware.

“Such efforts could also have unintended consequences, so it’s important to study relevant patient outcomes,” he added. “In this case, although it appears that the incidence of febrile neutropenia rising does not seem to relate with the program, the study does not establish the safety of CSF use reduction in lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. So, we should take the results with that caveat.”

Parsing the findings

Although the United States makes up just 4% of the world’s population, it uses nearly 80% of CSFs sold by a leading manufacturer, according to invited discussant Thomas J. Smith, MD, a professor of oncology and palliative medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“When we rewrote the ASCO [American Society of Clinical Oncology] guidelines on CSF use in 2015, there were some specific indications: dose-intense chemo for adjuvant breast cancer and uroepithelial cancer and ... when the risk of febrile neutropenia is about 20% and dose reduction is not an appropriate strategy. We were quick to point out that most regimens have a risk of febrile neutropenia much less than that,” he noted.

Dr. Agiro and his colleagues’ findings are valid, real, and reproducible, Dr. Smith maintained. However, it is unclear to what extent the observed levels of CSF use represented overuse.

“In lung cancer, there are very few regimens that have a febrile neutropenia rate close to 20%,” he elaborated. “What we don’t know is how much of this [use] was actually justified. I would suspect it is 10% or 15%, rather than 40%.”

CSF use, as guided by the new tool, “might not support increased dose density [of chemotherapy], but I would challenge anybody in the audience to show me data in normal solid tumor patients that [show that] dose density maintained by CSFs makes a difference in overall survival,” he said.

Questions yet to be addressed include the difficulty and cost of using the decision support tool and the possible negative impact on practices’ finances, according to Dr. Smith.

“When ESAs [erythropoiesis-stimulating agents] came off being used so much, some of my friends’ practices took a 15% to 20% drop in their revenue, and this is an important source of revenue for a lot of practices,” he explained. “So, I hope that when we take this revenue away, that we are cognizant of that and realize that it’s just another stress on practices, many of which are under significant stress already.”

Study details

An estimated 26% of uses of CSFs in patients with lung cancer are not in accordance with the ASCO practice guidelines, according to Dr. Agiro. “Such variations from recommendations are sometimes the reason why different stakeholders take actions” to improve care, such as ASCO’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) and the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely initiative (J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:338-43).

The decision support tool evaluated in the study uses preauthorization before delivery of care and, therefore, differs from point-of-care interventions, he noted.

“The tool allows access to a library of chemotherapy regimens and their associated, expected febrile neutropenia risk based on the myelotoxicity of the planned regimens as indicated in published trials. The tool is accessible online and provides real-time recommendations that are tailored based on disease- and patient-specific factors for either the use of CSF or not,” he elaborated.

According to the tool’s algorithm, use is recommended for patients who are given a regimen with a high risk of febrile neutropenia (greater than 20%) and is not recommended for those given a low-risk regimen (less than 10%). It is tailored according to the presence of additional risk factors for the intermediate-risk group.

Oncologists use the tool only for patients starting a new chemotherapy and only in the first cycle, when the risk of febrile neutropenia is highest, according to Dr. Agiro. “Once the approval is given in the first cycle, it remains in effect for the next 6 months, so they don’t have to use it again and again in additional cycles,” he explained.

The decision support tool was implemented in nine states starting in July 2014. In the study, which was funded by Anthem, the investigators analyzed administrative claims data from commercially insured adult patients starting chemotherapy for lung cancer, assessing changes in outcomes between a preimplementation period (April 2013 to Dec. 2013) and a postimplementation period (July 2014 to March 2015).

Analyses were based on 1,857 patients in the states that implemented the tool and 1,610 patients in the states that did not.

The percentage of patients receiving CSFs in the 6 months after starting chemotherapy fell in states that implemented the decision support tool (from 48.4% to 35.6%) but remained stable in states that did not (43.2% and 44.4%), Dr. Agiro reported. The adjusted difference in differences was –8.7% (P less than .001).

Meanwhile, the percentage of patients admitted for febrile neutropenia or experiencing this outcome while hospitalized increased in both states implementing the tool (from 2.8% to 4.3%) and those not implementing it (from 3.1% to 5.1%). Although the magnitude of increase was smaller in the former (+1.5% vs. +2.0%), the difference was not significant. Findings were essentially the same among the subset of patients aged 65 years and older.

“It’s important to study both intended and unintended consequences of such interventions,” Dr. Agiro noted. “Our study goes beyond financial considerations by looking at unintended outcomes: in this case, focusing on the incidence of febrile neutropenia, an outcome that is of prime interest to patients and oncologists and payers alike.”

The study may have missed some cases of febrile neutropenia, he acknowledged. “Also, there are other important outcomes of concern. For example, were there any delays in chemotherapy administration or immune recovery that could have been triggered by the implementation of the decision support program?”

The impact, both intended and unintended, on practices warrants evaluation as well, he further noted. “An important question could be, ‘Does it take less time to use this decision support tool compared to the time taken with normal care processes?’ ”

Dr. Agiro disclosed that he is employed by, has stock or other ownership interests in, and receives research funding from Anthem.

AT THE QUALITY CARE SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The percentage of patients receiving CSFs fell in states that used the tool, versus those that did not (difference in differences, –8.7%), but changes in admissions for febrile neutropenia did not differ significantly.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 3,467 patients from 48 states starting chemotherapy for lung cancer.

Disclosures: Dr. Agiro disclosed that he is employed by, has stock or other ownership interests in, and receives research funding from Anthem. The study was funded by Anthem.

VIDEO: Sexuality, fertility are focus of cancer education website

MIAMI BEACH – Often people living with cancer hesitate to ask their providers about sensitive and important issues surrounding sexuality and fertility. At the same time, some clinicians remain uncomfortable raising questions regarding sexual function or simply lack the time to appropriately address the issues during a patient encounter.

A new online resource aims to solve both problems simultaneously, giving both patients and providers the tools to meaningfully address sexuality and fertility issues, Leslie R. Schover, PhD, said in a video interview at the annual Miami Breast Cancer Conference, held by Physicians’ Education Resource.

The Will2love.com site features first-person patient account videos from women and men who faced similar concerns, said Dr. Schover, founder of the Will2Love digital health company based in Houston. In addition, vignettes with actors inform patients and also model how oncologists, oncology nurses, and other staff could effectively communicate with concerned patients. A professional portal offers online skills training for clinicians.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MIAMI BEACH – Often people living with cancer hesitate to ask their providers about sensitive and important issues surrounding sexuality and fertility. At the same time, some clinicians remain uncomfortable raising questions regarding sexual function or simply lack the time to appropriately address the issues during a patient encounter.

A new online resource aims to solve both problems simultaneously, giving both patients and providers the tools to meaningfully address sexuality and fertility issues, Leslie R. Schover, PhD, said in a video interview at the annual Miami Breast Cancer Conference, held by Physicians’ Education Resource.

The Will2love.com site features first-person patient account videos from women and men who faced similar concerns, said Dr. Schover, founder of the Will2Love digital health company based in Houston. In addition, vignettes with actors inform patients and also model how oncologists, oncology nurses, and other staff could effectively communicate with concerned patients. A professional portal offers online skills training for clinicians.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MIAMI BEACH – Often people living with cancer hesitate to ask their providers about sensitive and important issues surrounding sexuality and fertility. At the same time, some clinicians remain uncomfortable raising questions regarding sexual function or simply lack the time to appropriately address the issues during a patient encounter.