User login

Evidence for medical marijuana largely up in smoke

SAN DIEGO – Despite the popularity of medical marijuana, robust evidence for its use is limited or nonexistent for most medical conditions.

“This is a tough subject to study,” Ellie Grossman, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “There is federal money that can only be used in very limited ways to study it. Our science is way behind the times in terms of what our patients are doing and using.”

Typical limitations of marijuana studies include self-report of quantity/duration used and the fact that biochemical/quantifiable measures are lacking. “For inhaled marijuana, there is variability in how much is inhaled and how deeply it’s being inhaled,” said Dr. Grossman, an internist who practices in Somerville, Mass.

Then there’s the issue of recall bias and the question as to whether oral cannabinoids equate to the plant-derived forms of medical marijuana that patients obtain from their local dispensaries.

That matters, because the majority of published studies on the topic have evaluated oral cannabinoids, not the plant form. “So, what we’re studying is vastly different from what our patients are using,” she said.

The most solid indication clinicians have for recommending medical marijuana is for chronic pain, and the most common condition studied has been neuropathy.

“Most evidence compares cannabinoid to placebo,” said Dr. Grossman, primary care lead for behavioral health integration at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance. “There’s almost nothing out there comparing cannabinoid to any other pain-relieving agent that a patient might choose to use.

“A lot of the literature comes from oral synthesized agents,” she continued. “There’s a little bit of science about inhaled forms, but a lot of this is very different from what my patient got last week in a medical marijuana dispensary in Massachusetts.”

Results from a systematic review of 79 studies of cannabinoids for medical use in 6,462 study participants showed that, compared with placebo, cannabinoids were associated with a greater average number of patients showing a complete nausea and vomiting response (47% vs. 20%; odds ratio, 3.82), reduction in pain (37% vs. 31%; OR, 1.41), a greater average reduction in numerical rating scale pain assessment (on a 0- to 10-point scale; weighted mean difference of –0.46), and average reduction in the Ashworth spasticity scale (–0.36) (JAMA 2015 Jun 23-30;313[24]:2456-73).

A separate meta-analysis of studies compared inhaled cannabis sativa to placebo for chronic painful neuropathy. The researchers found that those patients who used inhaled cannabis sativa were 3.2 times more likely to achieve a 30% or greater reduction in pain, compared with those in the placebo group (J. Pain 2015 Dec;16[12]:1221-32).

However, Dr. Grossman cautioned that the number of patients studied was fewer than 200, “so, you could argue that this is a body of knowledge where the jury is still out.”

According to a 2017 report from the National Academy of Sciences titled, “The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids,” another area in which the knowledge base is less solid is the use of oral cannabinoids for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

“There’s a reasonable amount of evidence showing that some of these are better than placebo for relief of these symptoms,” Dr. Grossman said. “That said, the jury’s out as to whether they are any better than our other antiemetic agents. And there are no studies comparing them to neurokinin-1 inhibitors, which are the newest class of drug often used by oncologists for this indication. There is also no good evidence about inhaled plant cannabis.”

Studies of oral cannabinoids for multiple-sclerosis–related spasticity have demonstrated a small improvement on patient-reported spasticity (less than 1 point on a 10-point scale), but there was no improvement in clinician-reported outcomes. At the same time, their use for weight loss/anorexia in HIV “is very limited, and there are no studies of plant-derived cannabis,” Dr. Grossman said.

According to the National Academy of Sciences report, some evidence supports the use of oral cannabinoids for short-term sleep outcomes in patients with chronic diseases such as fibromyalgia and MS. One small study of oral cannabinoid for anxiety found that it improved social anxiety symptoms on the public speaking test, but there have been no studies using inhaled cannabinoids/marijuana.

The health risks of medical marijuana are largely unknown, Dr. Grossman said, noting that most evidence on longer‐term health risks comes from epidemiologic studies of recreational cannabis users.

“Medical marijuana users tend to be older and tend to be sicker,” she said. “We don’t know anything about the long-term effects in that sicker population.”

Among healthier people, Dr. Grossman continued, cannabis use is associated with increased risk of cough, wheeze, and sputum/phlegm. “There’s also an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents,” she said. “That is certainly a concern in places where they’re legalizing marijuana.”

Cannabis use is associated with lower neonatal birth weight, case reports/series of unintentional pediatric ingestions, and a possible increase in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

“The evidence is very limited regarding associations with myocardial infarction, stroke, COPD, and mortality,” she added. “We don’t really know.”

Dr. Grossman reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Despite the popularity of medical marijuana, robust evidence for its use is limited or nonexistent for most medical conditions.

“This is a tough subject to study,” Ellie Grossman, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “There is federal money that can only be used in very limited ways to study it. Our science is way behind the times in terms of what our patients are doing and using.”

Typical limitations of marijuana studies include self-report of quantity/duration used and the fact that biochemical/quantifiable measures are lacking. “For inhaled marijuana, there is variability in how much is inhaled and how deeply it’s being inhaled,” said Dr. Grossman, an internist who practices in Somerville, Mass.

Then there’s the issue of recall bias and the question as to whether oral cannabinoids equate to the plant-derived forms of medical marijuana that patients obtain from their local dispensaries.

That matters, because the majority of published studies on the topic have evaluated oral cannabinoids, not the plant form. “So, what we’re studying is vastly different from what our patients are using,” she said.

The most solid indication clinicians have for recommending medical marijuana is for chronic pain, and the most common condition studied has been neuropathy.

“Most evidence compares cannabinoid to placebo,” said Dr. Grossman, primary care lead for behavioral health integration at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance. “There’s almost nothing out there comparing cannabinoid to any other pain-relieving agent that a patient might choose to use.

“A lot of the literature comes from oral synthesized agents,” she continued. “There’s a little bit of science about inhaled forms, but a lot of this is very different from what my patient got last week in a medical marijuana dispensary in Massachusetts.”

Results from a systematic review of 79 studies of cannabinoids for medical use in 6,462 study participants showed that, compared with placebo, cannabinoids were associated with a greater average number of patients showing a complete nausea and vomiting response (47% vs. 20%; odds ratio, 3.82), reduction in pain (37% vs. 31%; OR, 1.41), a greater average reduction in numerical rating scale pain assessment (on a 0- to 10-point scale; weighted mean difference of –0.46), and average reduction in the Ashworth spasticity scale (–0.36) (JAMA 2015 Jun 23-30;313[24]:2456-73).

A separate meta-analysis of studies compared inhaled cannabis sativa to placebo for chronic painful neuropathy. The researchers found that those patients who used inhaled cannabis sativa were 3.2 times more likely to achieve a 30% or greater reduction in pain, compared with those in the placebo group (J. Pain 2015 Dec;16[12]:1221-32).

However, Dr. Grossman cautioned that the number of patients studied was fewer than 200, “so, you could argue that this is a body of knowledge where the jury is still out.”

According to a 2017 report from the National Academy of Sciences titled, “The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids,” another area in which the knowledge base is less solid is the use of oral cannabinoids for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

“There’s a reasonable amount of evidence showing that some of these are better than placebo for relief of these symptoms,” Dr. Grossman said. “That said, the jury’s out as to whether they are any better than our other antiemetic agents. And there are no studies comparing them to neurokinin-1 inhibitors, which are the newest class of drug often used by oncologists for this indication. There is also no good evidence about inhaled plant cannabis.”

Studies of oral cannabinoids for multiple-sclerosis–related spasticity have demonstrated a small improvement on patient-reported spasticity (less than 1 point on a 10-point scale), but there was no improvement in clinician-reported outcomes. At the same time, their use for weight loss/anorexia in HIV “is very limited, and there are no studies of plant-derived cannabis,” Dr. Grossman said.

According to the National Academy of Sciences report, some evidence supports the use of oral cannabinoids for short-term sleep outcomes in patients with chronic diseases such as fibromyalgia and MS. One small study of oral cannabinoid for anxiety found that it improved social anxiety symptoms on the public speaking test, but there have been no studies using inhaled cannabinoids/marijuana.

The health risks of medical marijuana are largely unknown, Dr. Grossman said, noting that most evidence on longer‐term health risks comes from epidemiologic studies of recreational cannabis users.

“Medical marijuana users tend to be older and tend to be sicker,” she said. “We don’t know anything about the long-term effects in that sicker population.”

Among healthier people, Dr. Grossman continued, cannabis use is associated with increased risk of cough, wheeze, and sputum/phlegm. “There’s also an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents,” she said. “That is certainly a concern in places where they’re legalizing marijuana.”

Cannabis use is associated with lower neonatal birth weight, case reports/series of unintentional pediatric ingestions, and a possible increase in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

“The evidence is very limited regarding associations with myocardial infarction, stroke, COPD, and mortality,” she added. “We don’t really know.”

Dr. Grossman reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Despite the popularity of medical marijuana, robust evidence for its use is limited or nonexistent for most medical conditions.

“This is a tough subject to study,” Ellie Grossman, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “There is federal money that can only be used in very limited ways to study it. Our science is way behind the times in terms of what our patients are doing and using.”

Typical limitations of marijuana studies include self-report of quantity/duration used and the fact that biochemical/quantifiable measures are lacking. “For inhaled marijuana, there is variability in how much is inhaled and how deeply it’s being inhaled,” said Dr. Grossman, an internist who practices in Somerville, Mass.

Then there’s the issue of recall bias and the question as to whether oral cannabinoids equate to the plant-derived forms of medical marijuana that patients obtain from their local dispensaries.

That matters, because the majority of published studies on the topic have evaluated oral cannabinoids, not the plant form. “So, what we’re studying is vastly different from what our patients are using,” she said.

The most solid indication clinicians have for recommending medical marijuana is for chronic pain, and the most common condition studied has been neuropathy.

“Most evidence compares cannabinoid to placebo,” said Dr. Grossman, primary care lead for behavioral health integration at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance. “There’s almost nothing out there comparing cannabinoid to any other pain-relieving agent that a patient might choose to use.

“A lot of the literature comes from oral synthesized agents,” she continued. “There’s a little bit of science about inhaled forms, but a lot of this is very different from what my patient got last week in a medical marijuana dispensary in Massachusetts.”

Results from a systematic review of 79 studies of cannabinoids for medical use in 6,462 study participants showed that, compared with placebo, cannabinoids were associated with a greater average number of patients showing a complete nausea and vomiting response (47% vs. 20%; odds ratio, 3.82), reduction in pain (37% vs. 31%; OR, 1.41), a greater average reduction in numerical rating scale pain assessment (on a 0- to 10-point scale; weighted mean difference of –0.46), and average reduction in the Ashworth spasticity scale (–0.36) (JAMA 2015 Jun 23-30;313[24]:2456-73).

A separate meta-analysis of studies compared inhaled cannabis sativa to placebo for chronic painful neuropathy. The researchers found that those patients who used inhaled cannabis sativa were 3.2 times more likely to achieve a 30% or greater reduction in pain, compared with those in the placebo group (J. Pain 2015 Dec;16[12]:1221-32).

However, Dr. Grossman cautioned that the number of patients studied was fewer than 200, “so, you could argue that this is a body of knowledge where the jury is still out.”

According to a 2017 report from the National Academy of Sciences titled, “The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids,” another area in which the knowledge base is less solid is the use of oral cannabinoids for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

“There’s a reasonable amount of evidence showing that some of these are better than placebo for relief of these symptoms,” Dr. Grossman said. “That said, the jury’s out as to whether they are any better than our other antiemetic agents. And there are no studies comparing them to neurokinin-1 inhibitors, which are the newest class of drug often used by oncologists for this indication. There is also no good evidence about inhaled plant cannabis.”

Studies of oral cannabinoids for multiple-sclerosis–related spasticity have demonstrated a small improvement on patient-reported spasticity (less than 1 point on a 10-point scale), but there was no improvement in clinician-reported outcomes. At the same time, their use for weight loss/anorexia in HIV “is very limited, and there are no studies of plant-derived cannabis,” Dr. Grossman said.

According to the National Academy of Sciences report, some evidence supports the use of oral cannabinoids for short-term sleep outcomes in patients with chronic diseases such as fibromyalgia and MS. One small study of oral cannabinoid for anxiety found that it improved social anxiety symptoms on the public speaking test, but there have been no studies using inhaled cannabinoids/marijuana.

The health risks of medical marijuana are largely unknown, Dr. Grossman said, noting that most evidence on longer‐term health risks comes from epidemiologic studies of recreational cannabis users.

“Medical marijuana users tend to be older and tend to be sicker,” she said. “We don’t know anything about the long-term effects in that sicker population.”

Among healthier people, Dr. Grossman continued, cannabis use is associated with increased risk of cough, wheeze, and sputum/phlegm. “There’s also an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents,” she said. “That is certainly a concern in places where they’re legalizing marijuana.”

Cannabis use is associated with lower neonatal birth weight, case reports/series of unintentional pediatric ingestions, and a possible increase in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

“The evidence is very limited regarding associations with myocardial infarction, stroke, COPD, and mortality,” she added. “We don’t really know.”

Dr. Grossman reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT ACP INTERNAL MEDICINE

Off-the-shelf T cells an option for post-HCT viral infections

ORLANDO – Infusions of banked multivirus-specific T lymphocytes were associated with complete or partial responses in 93% of 42 patients who had undergone hematopoietic cell transplants and had drug-refractory viral illnesses. Further, these patients experienced minimal new or reactivated graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Viral infections cause nearly 40% of deaths after alternative donor hematopoietic cell transfer (HCT), Ifigeneia Tzannou, MD, said at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Banked, “off-the-shelf” donor virus-resistant T cells can be an alternative to antiviral drugs, which are far from universally effective and may have serious side effects.

“Traditionally, we have generated T cells for infusion from the stem cell donor” by isolating and then stimulating and expanding the peripheral blood mononuclear cells for about 10 days ex vivo, said Dr. Tzannou. At that point, the clonal multivirus-resistant T cells can then be transferred to the recipient.

Donor-derived T cells have been used to prevent and treat Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus (AdV), BK virus (BKV), and human herpes virus 6 (HHV6) infections. The approach has been safe, reconstituting antiviral immunity and clearing disease effectively, with a 94% response rate reported in one recent study. However, said Dr. Tzannou, donor-derived virus-specific T cells (VSTs) have their limitations. Donors are increasingly younger and cord blood is being used more commonly, so there are growing numbers of donors who are seronegative for pathogenic viruses. In addition, the 10 days of production time and the additional week or 10 days required for release means that donor-derived VSTs can’t be urgently used.

The concept of banked third party VST therapy came about to address those limitations, said Dr. Tzannou of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

In a banked VST scenario, donor T cells with specific multiviral immunity are human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typed, expanded, and cryopreserved. A post-HCT patient with drug-refractory viral illness can receive T cells that are partially matched at HLA –A, HLA-B, or HLA-DR. Dr. Tzannou said that her group has now generated a bank of 59 VST lines to use in clinical testing of the third party approach.

In the study, Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues included both pediatric and adult post-allo-HCT patients with refractory EBV, CMV, AdV, BKV, and/or HHV6 infections. All had either failed a 14-day trial of antiviral therapy or could not tolerate antivirals. Patients could not be on more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone; they had to have an absolute neutrophil count above 500 per microliter and hemoglobin greater than 8 g/dL. Patients were excluded if they had acute GVHD of grade 2 or higher. There had to be a compatible VST line available that matched both the patient’s illness and HLA typing.

Patients initially received 20,000,000 VST cells per square meter of body surface area. If the investigators saw a partial response, patients could receive additional VST doses every 2 weeks.

Of the 42 patients infused, 23 received one infusion and 19 required two or more infusions. Seven study participants had two viral infections; 18 had CMV, 2 had EBV, 9 had AdV, 17 had BKV, and 3 had HHV6.

Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues tracked the virus-specific T cells and viral load for particular viruses. Virus-specific peripheral T cell counts also rose measurably and viral load plummeted within 2 weeks of VST infusions for most patients.

Overall, 93% of patients met the primary outcome measure of achieving complete or partial response; a partial response was defined as a 50% or better decrease in the viral load and/or clinical improvement.

All of the 17 BKV patients treated to date had tissue disease; 15 had hemorrhagic cystitis and 2 had nephritis. All responded to VSTs, and all of those with hemorrhagic cystitis had symptomatic improvement or resolution.

Overall, the safety profile for VST was good, said Dr. Tzannou. Four patients developed grade 1 acute cutaneous GVHD within 45 days of infusion; one of these developed de novo, but resolved with topical steroids. Another patient had a flare of gastrointestinal GVHD when immunosuppresion was being tapered. One more patient had a transient fever post infusion that resolved spontaneously, said Dr. Tzannou.

Next steps include a multicenter registration study, said Dr. Tzannou, who reports being a consultant for ViraCyte, which helped fund the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

ORLANDO – Infusions of banked multivirus-specific T lymphocytes were associated with complete or partial responses in 93% of 42 patients who had undergone hematopoietic cell transplants and had drug-refractory viral illnesses. Further, these patients experienced minimal new or reactivated graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Viral infections cause nearly 40% of deaths after alternative donor hematopoietic cell transfer (HCT), Ifigeneia Tzannou, MD, said at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Banked, “off-the-shelf” donor virus-resistant T cells can be an alternative to antiviral drugs, which are far from universally effective and may have serious side effects.

“Traditionally, we have generated T cells for infusion from the stem cell donor” by isolating and then stimulating and expanding the peripheral blood mononuclear cells for about 10 days ex vivo, said Dr. Tzannou. At that point, the clonal multivirus-resistant T cells can then be transferred to the recipient.

Donor-derived T cells have been used to prevent and treat Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus (AdV), BK virus (BKV), and human herpes virus 6 (HHV6) infections. The approach has been safe, reconstituting antiviral immunity and clearing disease effectively, with a 94% response rate reported in one recent study. However, said Dr. Tzannou, donor-derived virus-specific T cells (VSTs) have their limitations. Donors are increasingly younger and cord blood is being used more commonly, so there are growing numbers of donors who are seronegative for pathogenic viruses. In addition, the 10 days of production time and the additional week or 10 days required for release means that donor-derived VSTs can’t be urgently used.

The concept of banked third party VST therapy came about to address those limitations, said Dr. Tzannou of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

In a banked VST scenario, donor T cells with specific multiviral immunity are human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typed, expanded, and cryopreserved. A post-HCT patient with drug-refractory viral illness can receive T cells that are partially matched at HLA –A, HLA-B, or HLA-DR. Dr. Tzannou said that her group has now generated a bank of 59 VST lines to use in clinical testing of the third party approach.

In the study, Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues included both pediatric and adult post-allo-HCT patients with refractory EBV, CMV, AdV, BKV, and/or HHV6 infections. All had either failed a 14-day trial of antiviral therapy or could not tolerate antivirals. Patients could not be on more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone; they had to have an absolute neutrophil count above 500 per microliter and hemoglobin greater than 8 g/dL. Patients were excluded if they had acute GVHD of grade 2 or higher. There had to be a compatible VST line available that matched both the patient’s illness and HLA typing.

Patients initially received 20,000,000 VST cells per square meter of body surface area. If the investigators saw a partial response, patients could receive additional VST doses every 2 weeks.

Of the 42 patients infused, 23 received one infusion and 19 required two or more infusions. Seven study participants had two viral infections; 18 had CMV, 2 had EBV, 9 had AdV, 17 had BKV, and 3 had HHV6.

Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues tracked the virus-specific T cells and viral load for particular viruses. Virus-specific peripheral T cell counts also rose measurably and viral load plummeted within 2 weeks of VST infusions for most patients.

Overall, 93% of patients met the primary outcome measure of achieving complete or partial response; a partial response was defined as a 50% or better decrease in the viral load and/or clinical improvement.

All of the 17 BKV patients treated to date had tissue disease; 15 had hemorrhagic cystitis and 2 had nephritis. All responded to VSTs, and all of those with hemorrhagic cystitis had symptomatic improvement or resolution.

Overall, the safety profile for VST was good, said Dr. Tzannou. Four patients developed grade 1 acute cutaneous GVHD within 45 days of infusion; one of these developed de novo, but resolved with topical steroids. Another patient had a flare of gastrointestinal GVHD when immunosuppresion was being tapered. One more patient had a transient fever post infusion that resolved spontaneously, said Dr. Tzannou.

Next steps include a multicenter registration study, said Dr. Tzannou, who reports being a consultant for ViraCyte, which helped fund the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

ORLANDO – Infusions of banked multivirus-specific T lymphocytes were associated with complete or partial responses in 93% of 42 patients who had undergone hematopoietic cell transplants and had drug-refractory viral illnesses. Further, these patients experienced minimal new or reactivated graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Viral infections cause nearly 40% of deaths after alternative donor hematopoietic cell transfer (HCT), Ifigeneia Tzannou, MD, said at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Banked, “off-the-shelf” donor virus-resistant T cells can be an alternative to antiviral drugs, which are far from universally effective and may have serious side effects.

“Traditionally, we have generated T cells for infusion from the stem cell donor” by isolating and then stimulating and expanding the peripheral blood mononuclear cells for about 10 days ex vivo, said Dr. Tzannou. At that point, the clonal multivirus-resistant T cells can then be transferred to the recipient.

Donor-derived T cells have been used to prevent and treat Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus (AdV), BK virus (BKV), and human herpes virus 6 (HHV6) infections. The approach has been safe, reconstituting antiviral immunity and clearing disease effectively, with a 94% response rate reported in one recent study. However, said Dr. Tzannou, donor-derived virus-specific T cells (VSTs) have their limitations. Donors are increasingly younger and cord blood is being used more commonly, so there are growing numbers of donors who are seronegative for pathogenic viruses. In addition, the 10 days of production time and the additional week or 10 days required for release means that donor-derived VSTs can’t be urgently used.

The concept of banked third party VST therapy came about to address those limitations, said Dr. Tzannou of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

In a banked VST scenario, donor T cells with specific multiviral immunity are human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typed, expanded, and cryopreserved. A post-HCT patient with drug-refractory viral illness can receive T cells that are partially matched at HLA –A, HLA-B, or HLA-DR. Dr. Tzannou said that her group has now generated a bank of 59 VST lines to use in clinical testing of the third party approach.

In the study, Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues included both pediatric and adult post-allo-HCT patients with refractory EBV, CMV, AdV, BKV, and/or HHV6 infections. All had either failed a 14-day trial of antiviral therapy or could not tolerate antivirals. Patients could not be on more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone; they had to have an absolute neutrophil count above 500 per microliter and hemoglobin greater than 8 g/dL. Patients were excluded if they had acute GVHD of grade 2 or higher. There had to be a compatible VST line available that matched both the patient’s illness and HLA typing.

Patients initially received 20,000,000 VST cells per square meter of body surface area. If the investigators saw a partial response, patients could receive additional VST doses every 2 weeks.

Of the 42 patients infused, 23 received one infusion and 19 required two or more infusions. Seven study participants had two viral infections; 18 had CMV, 2 had EBV, 9 had AdV, 17 had BKV, and 3 had HHV6.

Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues tracked the virus-specific T cells and viral load for particular viruses. Virus-specific peripheral T cell counts also rose measurably and viral load plummeted within 2 weeks of VST infusions for most patients.

Overall, 93% of patients met the primary outcome measure of achieving complete or partial response; a partial response was defined as a 50% or better decrease in the viral load and/or clinical improvement.

All of the 17 BKV patients treated to date had tissue disease; 15 had hemorrhagic cystitis and 2 had nephritis. All responded to VSTs, and all of those with hemorrhagic cystitis had symptomatic improvement or resolution.

Overall, the safety profile for VST was good, said Dr. Tzannou. Four patients developed grade 1 acute cutaneous GVHD within 45 days of infusion; one of these developed de novo, but resolved with topical steroids. Another patient had a flare of gastrointestinal GVHD when immunosuppresion was being tapered. One more patient had a transient fever post infusion that resolved spontaneously, said Dr. Tzannou.

Next steps include a multicenter registration study, said Dr. Tzannou, who reports being a consultant for ViraCyte, which helped fund the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE 2017 BMT TANDEM MEETINGS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: With banked multivirus-specific T cells, viral illnesses either improved or resolved in 93% of 42 patients.

Data source: Clinical trial of 42 postallogeneic hematopoietic cell transfer patients who had any of five viral illnesses and had either failed a 14-day trial of antiviral therapy or could not tolerate antivirals.

Disclosures: Dr. Tzannou is a consultant for Incyte, which partially funded the trial and is developing third-party VSTs.

Tocilizumab shows promise for GVHD prevention

ORLANDO – Tocilizumab plus standard immune suppression appears to drive down the risk for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to results from a phase II study of 35 adults undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplants.

The effect was particularly pronounced for prevention of GVHD in the colon, William Drobyski, MD, reported at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

The incidence rate of grades II-IV and III-IV acute GVHD was 12% at day 100 in patients given standard prophylaxis of tacrolimus/methotrexate (Tac/MTX) and 3% in patients given Tac/MTX plus 8 mg/kg of tocilizumab (Toc, capped at 800 mg), said Dr. Drobyski of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

To provide further context to the results, Dr. Drobyski and his colleagues performed a matched case-control analysis using contemporary controls in the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research from 2000 to 2014. The same eligibility criteria used for the trial were applied to the matched controls except for the use of Tac/MTX as GVHD prophylaxis. Patients were otherwise matched based on age, performance score, disease, and donor type.

The incidence of grades II-IV acute GVHD at day 100 was significantly lower in the Toc/Tac/MTX group than in the Tac/MTX control population (12% vs. 41%). The incidence of grades III-IV acute GVHD was slightly lower with tocilizumab, but the difference between the groups was not statistically significant, Dr. Drobyski said.

The probability of grade II-IV acute GVHD–free survival, which was the primary endpoint of the study, was significantly higher in the Toc/Tac/MTX group (79% vs 52%), he said.

Five patients developed grade 2 acute GVHD of the skin or upper GI tract, and one patient died of grade 4 acute GVHD of the skin in the first 100 days. Notably, there were no cases of acute GVHD of the lower GI tract during that time, although two cases did occur between days 130 and 180, he said.

“There was no difference in transplant-related mortality, relapse, disease-free survival, or overall survival,” he said, adding that preliminary data suggest there were no differences in chronic GVHD between the groups.

Causes of death also were similar between the two cohorts with respect to disease- and transplant-related complications.

Patients in the tocilizumab study were enrolled between January 2015 and June 2016; the median age was 66 years. Diseases represented in the cohort included de novo acute myeloid leukemia (13 patients), AML (6 patients), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (6 patients), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (4 patients), myelodysplastic syndrome (3 patients), and T-cell lymphoma, chronic myeloid leukemia, and NK/T cell lymphoma (in 1 patient each). Most patients were classified as high risk (9 patients) or intermediate risk (22 patients) by the disease risk index.

Conditioning was entirely busulfan based. Myeloablative conditioning was with busulfan and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) in 5 patients, or fludarabine and 4 days of busulfan in 10 patients, and reduced-intensity conditioning was with fludarabine and 2 days of busulfan in 18 patients. Transplants were with either HLA-matched related or unrelated donor grafts. Most patients (29 of 35) received peripheral stem cell grafts.

Tocilizumab, an interleuken-6 receptor blocker that is approved for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, was administered after completion of conditioning and on the day prior to stem cell infusion.

In a pilot clinical trial of tocilizumab for the treatment of steroid-resistant acute GVHD in patients who had primarily had lower GI tract disease, “we were able to demonstrate responses in a majority of these patients,” Dr. Drobyski said, noting that a recent study presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology also showed efficacy in the treatment of lower tract GI GVHD, “providing evidence that tocilizumab had activity in acute GVHD, and perhaps in the treatment of steroid-refractory lower GI GVHD.”

Elevated IL-6 levels in the peripheral blood are correlated with an increased incidence and severity of GVHD; administration of an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody has been shown in preclinical studies to protect mice from lethal GVHD. The current open-label study was performed to “try to advance this concept” by assessing whether inhibition of IL-6 signaling could also prevent acute GVHD.

The findings confirm those of a 2014 study by Kennedy et al. in Lancet Oncology (2014;15:1451-9), and imply that tocilizumab warrants a randomized trial as prophylaxis for acute GVHD, he concluded.

Dr. Drobyski reported having no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Tocilizumab plus standard immune suppression appears to drive down the risk for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to results from a phase II study of 35 adults undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplants.

The effect was particularly pronounced for prevention of GVHD in the colon, William Drobyski, MD, reported at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

The incidence rate of grades II-IV and III-IV acute GVHD was 12% at day 100 in patients given standard prophylaxis of tacrolimus/methotrexate (Tac/MTX) and 3% in patients given Tac/MTX plus 8 mg/kg of tocilizumab (Toc, capped at 800 mg), said Dr. Drobyski of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

To provide further context to the results, Dr. Drobyski and his colleagues performed a matched case-control analysis using contemporary controls in the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research from 2000 to 2014. The same eligibility criteria used for the trial were applied to the matched controls except for the use of Tac/MTX as GVHD prophylaxis. Patients were otherwise matched based on age, performance score, disease, and donor type.

The incidence of grades II-IV acute GVHD at day 100 was significantly lower in the Toc/Tac/MTX group than in the Tac/MTX control population (12% vs. 41%). The incidence of grades III-IV acute GVHD was slightly lower with tocilizumab, but the difference between the groups was not statistically significant, Dr. Drobyski said.

The probability of grade II-IV acute GVHD–free survival, which was the primary endpoint of the study, was significantly higher in the Toc/Tac/MTX group (79% vs 52%), he said.

Five patients developed grade 2 acute GVHD of the skin or upper GI tract, and one patient died of grade 4 acute GVHD of the skin in the first 100 days. Notably, there were no cases of acute GVHD of the lower GI tract during that time, although two cases did occur between days 130 and 180, he said.

“There was no difference in transplant-related mortality, relapse, disease-free survival, or overall survival,” he said, adding that preliminary data suggest there were no differences in chronic GVHD between the groups.

Causes of death also were similar between the two cohorts with respect to disease- and transplant-related complications.

Patients in the tocilizumab study were enrolled between January 2015 and June 2016; the median age was 66 years. Diseases represented in the cohort included de novo acute myeloid leukemia (13 patients), AML (6 patients), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (6 patients), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (4 patients), myelodysplastic syndrome (3 patients), and T-cell lymphoma, chronic myeloid leukemia, and NK/T cell lymphoma (in 1 patient each). Most patients were classified as high risk (9 patients) or intermediate risk (22 patients) by the disease risk index.

Conditioning was entirely busulfan based. Myeloablative conditioning was with busulfan and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) in 5 patients, or fludarabine and 4 days of busulfan in 10 patients, and reduced-intensity conditioning was with fludarabine and 2 days of busulfan in 18 patients. Transplants were with either HLA-matched related or unrelated donor grafts. Most patients (29 of 35) received peripheral stem cell grafts.

Tocilizumab, an interleuken-6 receptor blocker that is approved for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, was administered after completion of conditioning and on the day prior to stem cell infusion.

In a pilot clinical trial of tocilizumab for the treatment of steroid-resistant acute GVHD in patients who had primarily had lower GI tract disease, “we were able to demonstrate responses in a majority of these patients,” Dr. Drobyski said, noting that a recent study presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology also showed efficacy in the treatment of lower tract GI GVHD, “providing evidence that tocilizumab had activity in acute GVHD, and perhaps in the treatment of steroid-refractory lower GI GVHD.”

Elevated IL-6 levels in the peripheral blood are correlated with an increased incidence and severity of GVHD; administration of an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody has been shown in preclinical studies to protect mice from lethal GVHD. The current open-label study was performed to “try to advance this concept” by assessing whether inhibition of IL-6 signaling could also prevent acute GVHD.

The findings confirm those of a 2014 study by Kennedy et al. in Lancet Oncology (2014;15:1451-9), and imply that tocilizumab warrants a randomized trial as prophylaxis for acute GVHD, he concluded.

Dr. Drobyski reported having no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Tocilizumab plus standard immune suppression appears to drive down the risk for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to results from a phase II study of 35 adults undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplants.

The effect was particularly pronounced for prevention of GVHD in the colon, William Drobyski, MD, reported at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

The incidence rate of grades II-IV and III-IV acute GVHD was 12% at day 100 in patients given standard prophylaxis of tacrolimus/methotrexate (Tac/MTX) and 3% in patients given Tac/MTX plus 8 mg/kg of tocilizumab (Toc, capped at 800 mg), said Dr. Drobyski of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

To provide further context to the results, Dr. Drobyski and his colleagues performed a matched case-control analysis using contemporary controls in the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research from 2000 to 2014. The same eligibility criteria used for the trial were applied to the matched controls except for the use of Tac/MTX as GVHD prophylaxis. Patients were otherwise matched based on age, performance score, disease, and donor type.

The incidence of grades II-IV acute GVHD at day 100 was significantly lower in the Toc/Tac/MTX group than in the Tac/MTX control population (12% vs. 41%). The incidence of grades III-IV acute GVHD was slightly lower with tocilizumab, but the difference between the groups was not statistically significant, Dr. Drobyski said.

The probability of grade II-IV acute GVHD–free survival, which was the primary endpoint of the study, was significantly higher in the Toc/Tac/MTX group (79% vs 52%), he said.

Five patients developed grade 2 acute GVHD of the skin or upper GI tract, and one patient died of grade 4 acute GVHD of the skin in the first 100 days. Notably, there were no cases of acute GVHD of the lower GI tract during that time, although two cases did occur between days 130 and 180, he said.

“There was no difference in transplant-related mortality, relapse, disease-free survival, or overall survival,” he said, adding that preliminary data suggest there were no differences in chronic GVHD between the groups.

Causes of death also were similar between the two cohorts with respect to disease- and transplant-related complications.

Patients in the tocilizumab study were enrolled between January 2015 and June 2016; the median age was 66 years. Diseases represented in the cohort included de novo acute myeloid leukemia (13 patients), AML (6 patients), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (6 patients), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (4 patients), myelodysplastic syndrome (3 patients), and T-cell lymphoma, chronic myeloid leukemia, and NK/T cell lymphoma (in 1 patient each). Most patients were classified as high risk (9 patients) or intermediate risk (22 patients) by the disease risk index.

Conditioning was entirely busulfan based. Myeloablative conditioning was with busulfan and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) in 5 patients, or fludarabine and 4 days of busulfan in 10 patients, and reduced-intensity conditioning was with fludarabine and 2 days of busulfan in 18 patients. Transplants were with either HLA-matched related or unrelated donor grafts. Most patients (29 of 35) received peripheral stem cell grafts.

Tocilizumab, an interleuken-6 receptor blocker that is approved for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, was administered after completion of conditioning and on the day prior to stem cell infusion.

In a pilot clinical trial of tocilizumab for the treatment of steroid-resistant acute GVHD in patients who had primarily had lower GI tract disease, “we were able to demonstrate responses in a majority of these patients,” Dr. Drobyski said, noting that a recent study presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology also showed efficacy in the treatment of lower tract GI GVHD, “providing evidence that tocilizumab had activity in acute GVHD, and perhaps in the treatment of steroid-refractory lower GI GVHD.”

Elevated IL-6 levels in the peripheral blood are correlated with an increased incidence and severity of GVHD; administration of an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody has been shown in preclinical studies to protect mice from lethal GVHD. The current open-label study was performed to “try to advance this concept” by assessing whether inhibition of IL-6 signaling could also prevent acute GVHD.

The findings confirm those of a 2014 study by Kennedy et al. in Lancet Oncology (2014;15:1451-9), and imply that tocilizumab warrants a randomized trial as prophylaxis for acute GVHD, he concluded.

Dr. Drobyski reported having no disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The probability of grade II-IV acute GVHD-free survival was 79% vs. 52% in the tocilizumab group vs. age-matched controls.

Data source: An open-label phase II study of 35 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Drobyski reported having no disclosures.

Demystifying the diagnosis and classification of lymphoma: a guide to the hematopathologist’s galaxy

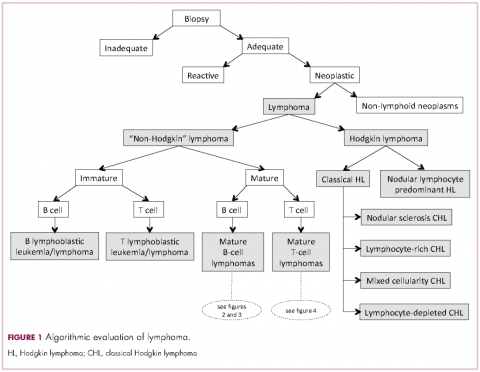

Lymphomas constitute a very heterogeneous group of neoplasms with diverse clinical presentations, prognoses, and responses to therapy. Approximately 80,500 new cases of lymphoma are expected to be diagnosed in the United States in 2017, of which about one quarter will lead to the death of the patient.1 Perhaps more so than any other group of neoplasms, the diagnosis of lymphoma involves the integration of a multiplicity of clinical, histologic and immunophenotypic findings and, on occasion, cytogenetic and molecular results as well. An accurate diagnosis of lymphoma, usually rendered by hematopathologists, allows hematologists/oncologists to treat patients appropriately. Herein we will describe a simplified approach to the diagnosis and classification of lymphomas (Figure 1).

Lymphoma classification

Lymphomas are clonal neoplasms characterized by the expansion of abnormal lymphoid cells that may develop in any organ but commonly involve lymph nodes. The fourth edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid tissues, published in 2008, is the official and most current guideline used for diagnosis of lymphoid neoplasms.2 The WHO scheme classifies lymphomas according to the type of cell from which they are derived (mature and immature B cells, T cells, or natural killer (NK) cells, findings determined by their morphology and immunophenotype) and their clinical, cytogenetic, and/or molecular features. This official classification is currently being updated3 and is expected to be published in full in 2017, at which time it is anticipated to include definitions for more than 70 distinct neoplasms.

Lymphomas are broadly and informally classified as Hodgkin lymphomas (HLs) and non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), based on the differences these two groups show in their clinical presentation, treatment, prognosis, and proportion of neoplastic cells, among others. NHLs are by far the most common type of lymphomas, accounting for approximately 90% of all new cases of lymphoma in the United States and 70% worldwide.1,2 NHLs are a very heterogeneous group of B-, T-, or NK-cell neoplasms that, in turn, can also be informally subclassified as low-grade (or indolent) or high-grade (or aggressive) according to their predicted clinical behavior. HLs are comparatively rare, less heterogeneous, uniformly of B-cell origin and, in the case of classical Hodgkin lymphoma, highly curable.1,2 It is beyond the scope of this manuscript to outline the features of each of the >70 specific entities, but the reader is referred elsewhere for more detail and encouraged to become familiarized with the complexity, challenges, and beauty of lymphoma diagnosis.2,3

Biopsy procedure

A correct diagnosis begins with an adequate biopsy procedure. It is essential that biopsy specimens for lymphoma evaluation be submitted fresh and unfixed, because some crucial analyses such as flow cytometry or conventional cytogenetics can only be performed on fresh tissue. Indeed, it is important for the hematologist/oncologist and/or surgeon and/or interventional radiologist to converse with the hematopathologist prior to and even during some procedures to ensure the correct processing of the specimen. Also, it is important to limit the compression of the specimen and the excessive use of cauterization during the biopsy procedure, both of which cause artifacts that may render impossible the interpretation of the histopathologic findings.

Given that the diagnosis of lymphoma is based not only on the cytologic details of the lymphoma cells but also on the architectural pattern with which they infiltrate an organ, the larger the biopsy specimen, the easier it will be for a hematopathologist to identify the pattern. In addition, excisional biopsies frequently contain more diagnostic tissue than needle core biopsies and this provides pathologists with the option to submit tissue fragments for ancillary tests that require unfixed tissue as noted above. Needle core biopsies of lymph nodes are increasingly being used because of their association with fewer complications and lower cost than excisional biopsies. However, needle core biopsies provide only a glimpse of the pattern of infiltration and may not be completely representative of the architecture. Therefore, excisional lymph node biopsies of lymph nodes are preferred over needle core biopsies, recognizing that in the setting of deeply seated lymph nodes, needle core biopsies may be the only or the best surgical option.

Clinical presentation

Accurate diagnosis of lymphoma cannot take place in a vacuum. The hematopathologist’s initial approach to the diagnosis of lymphoid processes in tissue biopsies should begin with a thorough review of the clinical history, although some pathology laboratories may not have immediate access to this information. The hematopathologist should evaluate factors such as age, gender, location of the tumor, symptomatology, medications, serology, and prior history of malignancy, immunosuppression or immunodeficiency in every case. Other important but frequently omitted parts of the clinical history are the patient’s occupation, history of exposure to animals, and the presence of tattoos, which may be associated with certain reactive lymphadenopathies.

Histomorphologic evaluation

Despite the plethora of new and increasingly sophisticated tools, histologic and morphologic analysis still remains the cornerstone of diagnosis in hematopathology. However, for the characterization of an increasing number of reactive and neoplastic lymphoid processes, hematopathologists may also require immunophenotypic, molecular, and cytogenetic tests for an accurate diagnosis. Upon review of the clinical information, a microscopic evaluation of the tissue submitted for processing by the histology laboratory will be performed. The results of concurrent flow cytometric evaluation (performed on fresh unfixed material) should also be available in most if not all cases before the H&E-stained slides are available for review. Upon receipt of H&E-stained slides, the hematopathologist will evaluate the quality of the submitted specimen, since many diagnostic difficulties stem from suboptimal techniques related to the biopsy procedure, fixation, processing, cutting, or staining (Figure 1). If deemed suitable for accurate diagnosis, a search for signs of preservation or disruption of the organ that was biopsied will follow. The identification of certain morphologic patterns aids the hematopathologist in answering the first question: “what organ is this and is this consistent with what is indicated on the requisition?” This is usually immediately followed by “is this sufficient and adequate material for a diagnosis?” and “is there any normal architecture?” If the architecture is not normal, “is this alteration due to a reactive or a neoplastic process?” If neoplastic, “is it lymphoma or a non-hematolymphoid neoplasm?”

Both reactive and neoplastic processes have variably unique morphologic features that if properly recognized, guide the subsequent testing. However, some reactive and neoplastic processes can present with overlapping features, and even after extensive immunophenotypic evaluation and the performance of ancillary studies, it may not be possible to conclusively determine its nature. If the lymph node architecture is altered or effaced, the predominant pattern of infiltration (eg, nodular, diffuse, interfollicular, intrasinusoidal) and the degree of alteration of the normal architecture is evaluated, usually at low magnification. When the presence of an infiltrate is recognized, its components must be characterized. If the infiltrate is composed of a homogeneous expansion of lymphoid cells that disrupts or replaces the normal lymphoid architecture, a lymphoma will be suspected or diagnosed. The pattern of distribution of the cells along with their individual morphologic characteristics (ie, size, nuclear shape, chromatin configuration, nucleoli, amount and hue of cytoplasm) are key factors for the diagnosis and classification of the lymphoma that will guide subsequent testing. The immunophenotypic analysis (by immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry or a combination of both) may confirm the reactive or neoplastic nature of the process, and its subclassification. B-cell lymphomas, in particular have variable and distinctive histologic features: as a diffuse infiltrate of large mature lymphoid cells (eg, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), an expansion of immature lymphoid cells (lymphoblastic lymphoma), and a nodular infiltrate of small, intermediate and/or mature large B cells (eg, follicular lymphoma).

Mature T-cell lymphomas may display similar histologic, features but they can be quite heterogeneous with an infiltrate composed of one predominant cell type or a mixture of small, medium-sized, and large atypical lymphoid cells (on occasion with abundant clear cytoplasm) and a variable number of eosinophils, plasma cells, macrophages (including granulomas), and B cells. HLs most commonly efface the lymph node architecture with a nodular or diffuse infiltrate variably composed of reactive lymphocytes, granulocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells and usually a minority of large neoplastic cells (Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells and/or lymphocyte predominant cells).

Once the H&E-stained slides are evaluated and a diagnosis of lymphoma is suspected or established, the hematopathologist will attempt to determine whether it has mature or immature features, and whether low- or high-grade morphologic characteristics are present. The maturity of lymphoid cells is generally determined by the nature of the chromatin, which if “fine” and homogeneous (with or without a conspicuous nucleolus) will usually, but not always, be considered immature, whereas clumped, vesicular or hyperchromatic chromatin is generally, but not always, associated with maturity. If the chromatin displays immature features, the differential diagnosis will mainly include B- and T-lymphoblastic lymphomas, but also blastoid variants of mature neoplasm such as mantle cell lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma, as well as high-grade B-cell lymphomas. Features associated with low-grade lymphomas (eg, follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia, marginal zone lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma) include small cell morphology, mature chromatin, absence of a significant number of mitoses or apoptotic cells, and a low proliferation index as shown by immunohistochemistry for Ki67. High-grade lymphomas, such as lymphoblastic lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, or certain large B-cell lymphomas tend to show opposite features, and some of the mature entities are frequently associated with MYC rearrangements. Of note, immature lymphomas tend to be clinically high grade, but not all clinically high-grade lymphomas are immature. Conversely, the majority of low-grade lymphomas are usually mature.

Immunophenotypic evaluation

Immunophenotypic evaluation is essential because the lineage of lymphoma cells cannot be determined by morphology alone. The immunophenotype is the combination of proteins/markers (eg, CD20, CD3, TdT) expressed by cells. Usually, it is evaluated by immunohistochemistry and/or flow cytometry, which help determine the proportion of lymphoid cells that express a certain marker and its location and intensity within the cells. While immunohistochemistry is normally performed on formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue, flow cytometry can be evaluated only on fresh unfixed tissue. Flow cytometry has the advantage over immunohistochemistry of being faster and better at simultaneously identifying coexpression of multiple markers on multiple cell populations. However, certain markers can only be evaluated by immunohistochemistry.

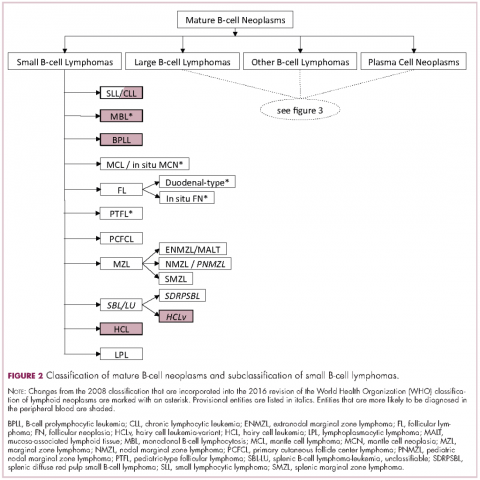

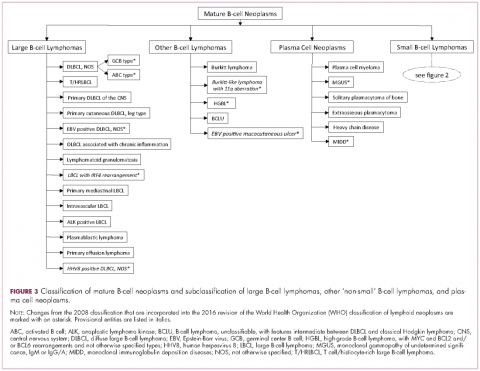

The immunophenotypic analysis will in most cases reveal whether the lymphomas is of B-, T- or NK-cell origin, and whether a lymphoma subtype associated immunophenotype is present. Typical pan B-cell antigens include PAX5, CD19, and CD79a (CD20 is less broadly expressed throughout B-cell differentiation, although it is usually evident in most mature B-cell lymphomas), and typical pan T-cell antigens include CD2, CD5, and CD7. The immature or mature nature of a lymphoma can also be confirmed by evaluation of the immunophenotype. Immature lymphomas commonly express one or more of TdT, CD10, or CD34; T-lymphoblastic lymphoma cells may also coexpress CD1a. The majority of NHLs and all HLs are derived from (or reflect) B cells at different stages of maturation. Mature B-cell lymphomas are the most common type of lymphoma and typically, but not always, express pan B-cell markers as well as surface membrane immunoglobulin, with the latter also most useful in assessing clonality via a determination of light chain restriction. Some mature B-cell lymphomas tend to acquire markers that are either never physiologically expressed by normal mature B cells (eg, cyclin D1 in mantle cell lymphoma, or BCL2 in germinal center B cells in follicular lymphoma) or only expressed in a minor fraction (eg, CD5 that is characteristically expressed in small lymphocytic and mantle cell lymphoma). The most common mature B-cell lymphomas include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Figures 2 and 3). Classical HLs are also lymphomas of B-cell origin that demonstrate diminished preservation of their B-cell immunophenotype (as evidenced by the dim expression of PAX5 but absence of most other pan B-cell antigens), expression of CD30, variable expression of CD15, and loss of CD45 (Figure 1). In contrast, nodular lymphocyte predominant HL shows a preserved B-cell immunophenotypic program and expression of CD45, typically without CD30 and CD15. Of note, the evaluation of the immunophenotype of the neoplastic cells in HL is routinely assessed by immunohistochemistry because most flow cytometry laboratories cannot reliably detect and characterize the low numbers of these cells.

Mature T-cell lymphomas generally express one or more T-cell markers, and tend to display a T-helper (CD4-positive) or cytotoxic (CD8-positive) immunophenotype and may show loss of markers expressed by most normal T-cells (eg, CD5, CD7; Figure 4). However, a subset of them may express markers not commonly detected in normal T cells, such as ALK. NK-cell lymphomas lack surface CD3 (expressing only cytoplasmic CD3) and CD5 but express some pan T-cell antigens (such as CD2 and CD7) as well as CD16 and/or CD56.

Patients with primary or acquired immune dysfunction are at risk for development of lymphoma and other less clearly defined lymphoproliferative disorders, the majority of which are associated with infection of the lymphoid cells with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Therefore, evaluation with chromogenic in situ hybridization for an EBV-encoded early RNA (EBER1) is routinely performed in these cases; it is thus essential that the hematopathologist be informed of the altered immune system of the patient. If lymphoma develops, they may be morphologically similar to those that appear in immunocompetent patients, which specifically in the post-transplant setting are known as monomorphic post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD). If the PTLD does not meet the criteria for any of the recognized types of lymphoma, it may be best characterized as a polymorphic PTLD.

Once the lineage (B-, T-, or NK-cell) of the mature lymphoma has been established, the sum (and on occasion the gestalt) of the clinical, morphologic, immunophenotypic and other findings will be considered for the subclassification of the neoplasm.

Cytogenetic and molecular evaluation

If the morphologic and immunophenotypic analysis is inconclusive or nondiagnostic, then molecular and/or cytogenetic testing may further aid in the characterization of the process. Some of available molecular tests include analyses for the rearrangements of the variable region of the immunoglobulin (IG) or T-cell receptor (TCR) genes and for mutations on specific genes. The identification of specific mutations not only confirms the clonal nature of the process but, on occasion, it may also help subclassify the lymphoma, whereas IG or TCR rearrangement studies are used to establish whether a lymphoid expansion is polyclonal or monoclonal. The molecular findings should not be evaluated in isolation, because not all monoclonal rearrangements are diagnostic of lymphoma, and not all lymphomas will show a monoclonal rearrangement. Other methodologies that can aid in the identification of a clonal process or specific genetic abnormalities include metaphase cytogenetics (karyotyping) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). If any cytogenetic abnormalities are found in sufficient numbers (and constitutional abnormalities are excluded), their identification indicates the presence of a clonal process. Also, some cytogenetic abnormalities are characteristic of certain lymphomas. However, they may be neither 100% diagnostically sensitive nor diagnostically specific, for example, the hallmark t(14;18)/IGH-BCL2 is not present in all follicular lymphomas and not all lymphomas with this translocation are follicular lymphomas. Whereas FISH is generally performed on a minimum of 200 cells, compared with typically 20 metaphase by “conventional” karyotyping, and is therefore considered to have higher analytical sensitivity, it evaluates only for the presence or absence of the abnormality being investigated with a given set of probes, and therefore other abnormalities, if present, will not be identified. The value of FISH cytogenetic studies is perhaps best illustrated in the need to diagnose double hit lymphomas, amongst other scenarios. The detection of certain mutations can aid in the diagnosis of certain lymphomas, such as MYD88 in lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, prognosis of others, such as in follicular lymphoma and identify pathways that may be precisely therapeutically targeted.

Final remarks

The diagnosis of lymphoma can be complex and usually requires the hematopathologist to integrate multiple parameters. The classification of lymphomas is not static, and new entities or variants are continuously described, and the facets of well-known ones refined. While such changes are often to the chagrin of hematologists/oncologists and hematopathologists alike, we should embrace the incorporation of nascent and typically cool data into our practice, as more therapeutically relevant entities are molded.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017 ;67(1):7-30.

2. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. In: Bosman FT, Jaffe ES, Lakhani SR, Ohgaki H, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC; 2008.

3. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016 ;127(20):2375-2390.

Lymphomas constitute a very heterogeneous group of neoplasms with diverse clinical presentations, prognoses, and responses to therapy. Approximately 80,500 new cases of lymphoma are expected to be diagnosed in the United States in 2017, of which about one quarter will lead to the death of the patient.1 Perhaps more so than any other group of neoplasms, the diagnosis of lymphoma involves the integration of a multiplicity of clinical, histologic and immunophenotypic findings and, on occasion, cytogenetic and molecular results as well. An accurate diagnosis of lymphoma, usually rendered by hematopathologists, allows hematologists/oncologists to treat patients appropriately. Herein we will describe a simplified approach to the diagnosis and classification of lymphomas (Figure 1).

Lymphoma classification

Lymphomas are clonal neoplasms characterized by the expansion of abnormal lymphoid cells that may develop in any organ but commonly involve lymph nodes. The fourth edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid tissues, published in 2008, is the official and most current guideline used for diagnosis of lymphoid neoplasms.2 The WHO scheme classifies lymphomas according to the type of cell from which they are derived (mature and immature B cells, T cells, or natural killer (NK) cells, findings determined by their morphology and immunophenotype) and their clinical, cytogenetic, and/or molecular features. This official classification is currently being updated3 and is expected to be published in full in 2017, at which time it is anticipated to include definitions for more than 70 distinct neoplasms.

Lymphomas are broadly and informally classified as Hodgkin lymphomas (HLs) and non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), based on the differences these two groups show in their clinical presentation, treatment, prognosis, and proportion of neoplastic cells, among others. NHLs are by far the most common type of lymphomas, accounting for approximately 90% of all new cases of lymphoma in the United States and 70% worldwide.1,2 NHLs are a very heterogeneous group of B-, T-, or NK-cell neoplasms that, in turn, can also be informally subclassified as low-grade (or indolent) or high-grade (or aggressive) according to their predicted clinical behavior. HLs are comparatively rare, less heterogeneous, uniformly of B-cell origin and, in the case of classical Hodgkin lymphoma, highly curable.1,2 It is beyond the scope of this manuscript to outline the features of each of the >70 specific entities, but the reader is referred elsewhere for more detail and encouraged to become familiarized with the complexity, challenges, and beauty of lymphoma diagnosis.2,3

Biopsy procedure

A correct diagnosis begins with an adequate biopsy procedure. It is essential that biopsy specimens for lymphoma evaluation be submitted fresh and unfixed, because some crucial analyses such as flow cytometry or conventional cytogenetics can only be performed on fresh tissue. Indeed, it is important for the hematologist/oncologist and/or surgeon and/or interventional radiologist to converse with the hematopathologist prior to and even during some procedures to ensure the correct processing of the specimen. Also, it is important to limit the compression of the specimen and the excessive use of cauterization during the biopsy procedure, both of which cause artifacts that may render impossible the interpretation of the histopathologic findings.

Given that the diagnosis of lymphoma is based not only on the cytologic details of the lymphoma cells but also on the architectural pattern with which they infiltrate an organ, the larger the biopsy specimen, the easier it will be for a hematopathologist to identify the pattern. In addition, excisional biopsies frequently contain more diagnostic tissue than needle core biopsies and this provides pathologists with the option to submit tissue fragments for ancillary tests that require unfixed tissue as noted above. Needle core biopsies of lymph nodes are increasingly being used because of their association with fewer complications and lower cost than excisional biopsies. However, needle core biopsies provide only a glimpse of the pattern of infiltration and may not be completely representative of the architecture. Therefore, excisional lymph node biopsies of lymph nodes are preferred over needle core biopsies, recognizing that in the setting of deeply seated lymph nodes, needle core biopsies may be the only or the best surgical option.

Clinical presentation

Accurate diagnosis of lymphoma cannot take place in a vacuum. The hematopathologist’s initial approach to the diagnosis of lymphoid processes in tissue biopsies should begin with a thorough review of the clinical history, although some pathology laboratories may not have immediate access to this information. The hematopathologist should evaluate factors such as age, gender, location of the tumor, symptomatology, medications, serology, and prior history of malignancy, immunosuppression or immunodeficiency in every case. Other important but frequently omitted parts of the clinical history are the patient’s occupation, history of exposure to animals, and the presence of tattoos, which may be associated with certain reactive lymphadenopathies.

Histomorphologic evaluation

Despite the plethora of new and increasingly sophisticated tools, histologic and morphologic analysis still remains the cornerstone of diagnosis in hematopathology. However, for the characterization of an increasing number of reactive and neoplastic lymphoid processes, hematopathologists may also require immunophenotypic, molecular, and cytogenetic tests for an accurate diagnosis. Upon review of the clinical information, a microscopic evaluation of the tissue submitted for processing by the histology laboratory will be performed. The results of concurrent flow cytometric evaluation (performed on fresh unfixed material) should also be available in most if not all cases before the H&E-stained slides are available for review. Upon receipt of H&E-stained slides, the hematopathologist will evaluate the quality of the submitted specimen, since many diagnostic difficulties stem from suboptimal techniques related to the biopsy procedure, fixation, processing, cutting, or staining (Figure 1). If deemed suitable for accurate diagnosis, a search for signs of preservation or disruption of the organ that was biopsied will follow. The identification of certain morphologic patterns aids the hematopathologist in answering the first question: “what organ is this and is this consistent with what is indicated on the requisition?” This is usually immediately followed by “is this sufficient and adequate material for a diagnosis?” and “is there any normal architecture?” If the architecture is not normal, “is this alteration due to a reactive or a neoplastic process?” If neoplastic, “is it lymphoma or a non-hematolymphoid neoplasm?”

Both reactive and neoplastic processes have variably unique morphologic features that if properly recognized, guide the subsequent testing. However, some reactive and neoplastic processes can present with overlapping features, and even after extensive immunophenotypic evaluation and the performance of ancillary studies, it may not be possible to conclusively determine its nature. If the lymph node architecture is altered or effaced, the predominant pattern of infiltration (eg, nodular, diffuse, interfollicular, intrasinusoidal) and the degree of alteration of the normal architecture is evaluated, usually at low magnification. When the presence of an infiltrate is recognized, its components must be characterized. If the infiltrate is composed of a homogeneous expansion of lymphoid cells that disrupts or replaces the normal lymphoid architecture, a lymphoma will be suspected or diagnosed. The pattern of distribution of the cells along with their individual morphologic characteristics (ie, size, nuclear shape, chromatin configuration, nucleoli, amount and hue of cytoplasm) are key factors for the diagnosis and classification of the lymphoma that will guide subsequent testing. The immunophenotypic analysis (by immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry or a combination of both) may confirm the reactive or neoplastic nature of the process, and its subclassification. B-cell lymphomas, in particular have variable and distinctive histologic features: as a diffuse infiltrate of large mature lymphoid cells (eg, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), an expansion of immature lymphoid cells (lymphoblastic lymphoma), and a nodular infiltrate of small, intermediate and/or mature large B cells (eg, follicular lymphoma).

Mature T-cell lymphomas may display similar histologic, features but they can be quite heterogeneous with an infiltrate composed of one predominant cell type or a mixture of small, medium-sized, and large atypical lymphoid cells (on occasion with abundant clear cytoplasm) and a variable number of eosinophils, plasma cells, macrophages (including granulomas), and B cells. HLs most commonly efface the lymph node architecture with a nodular or diffuse infiltrate variably composed of reactive lymphocytes, granulocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells and usually a minority of large neoplastic cells (Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells and/or lymphocyte predominant cells).

Once the H&E-stained slides are evaluated and a diagnosis of lymphoma is suspected or established, the hematopathologist will attempt to determine whether it has mature or immature features, and whether low- or high-grade morphologic characteristics are present. The maturity of lymphoid cells is generally determined by the nature of the chromatin, which if “fine” and homogeneous (with or without a conspicuous nucleolus) will usually, but not always, be considered immature, whereas clumped, vesicular or hyperchromatic chromatin is generally, but not always, associated with maturity. If the chromatin displays immature features, the differential diagnosis will mainly include B- and T-lymphoblastic lymphomas, but also blastoid variants of mature neoplasm such as mantle cell lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma, as well as high-grade B-cell lymphomas. Features associated with low-grade lymphomas (eg, follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia, marginal zone lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma) include small cell morphology, mature chromatin, absence of a significant number of mitoses or apoptotic cells, and a low proliferation index as shown by immunohistochemistry for Ki67. High-grade lymphomas, such as lymphoblastic lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, or certain large B-cell lymphomas tend to show opposite features, and some of the mature entities are frequently associated with MYC rearrangements. Of note, immature lymphomas tend to be clinically high grade, but not all clinically high-grade lymphomas are immature. Conversely, the majority of low-grade lymphomas are usually mature.

Immunophenotypic evaluation

Immunophenotypic evaluation is essential because the lineage of lymphoma cells cannot be determined by morphology alone. The immunophenotype is the combination of proteins/markers (eg, CD20, CD3, TdT) expressed by cells. Usually, it is evaluated by immunohistochemistry and/or flow cytometry, which help determine the proportion of lymphoid cells that express a certain marker and its location and intensity within the cells. While immunohistochemistry is normally performed on formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue, flow cytometry can be evaluated only on fresh unfixed tissue. Flow cytometry has the advantage over immunohistochemistry of being faster and better at simultaneously identifying coexpression of multiple markers on multiple cell populations. However, certain markers can only be evaluated by immunohistochemistry.