User login

Isolated ocular metastases from lung cancer

Non–small cell lung cancer constitutes 80%-85% of lung cancers, and 40% of NSCLC are adenocarcinoma. It is rare to find intraocular metastasis from lung cancer. In this article, we present the case of a patient who presented with complaints of diminished vision redness of the eye and was found to have intra-ocular metastases from lung cancer.

Case presentation and summary

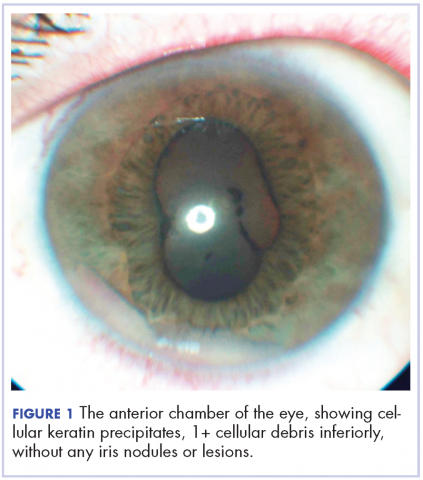

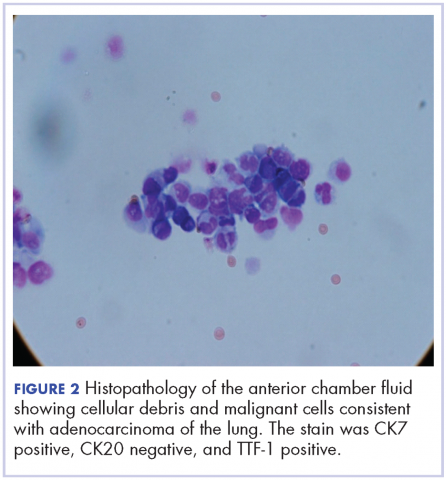

A 60-year-old man with a 40-pack per year history of smoking presented to multiple ophthalmologists with complaints of decreased vision and redness of the left eye. He was eventually evaluated by an ophthalmologist who performed a biopsy of the anterior chamber of the eye. Histologic findings were consistent with adenocarcinoma of lung primary (Figures 1 and 2).

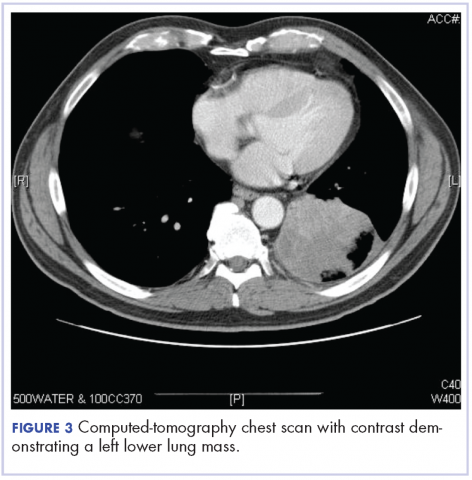

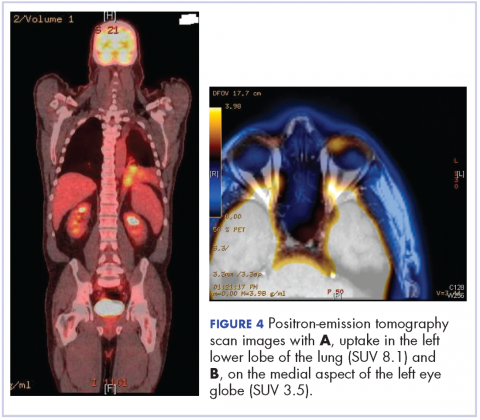

After the diagnosis, a chest X-ray showed that the patient had a left lower lung mass. The results of his physical exam were all within normal limits, with the exception of decreased visual acuity in the left eye. The results of his laboratory studies, including complete blood count and serum chemistries, were also within normal limits. Imaging studies – including a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and a full-body positron-emission tomography–CT scan – showed a hypermetabolic left lower lobe mass 4.5 cm and right lower paratracheal lymph node metastasis 2 cm with a small focus of increased uptake alone the medial aspect of the left globe (Figures 3 and 4).

An MRI orbit was performed in an attempt to better characterize the left eye mass, but no optic lesion was identified. A biopsy of the left lower lung mass was consistent with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Aside from the isolated left eye metastases, the patient did not have evidence of other distant metastatic involvement.

He was started on palliative chemotherapy on a clinical trial and received intravenous carboplatin AUC 6, pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, and bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks. He received 1 dose intraocular bevacizumab injection before initiation of systemic chemotherapy as he was symptomatic from the intraocular metastases. Within 2 weeks after intravitreal bevacizumab was administered, the patient had subjective improvement in vision. Mutational analysis to identify if the patient would benefit from targeted therapy showed no presence of EGFR mutation and ALK gene rearrangement, and that the patient was K-RAS mutant.

After treatment initiation, interval imaging studies (a computed-tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, pelvis; and magnetic-resonance imaging of the brain) after 3 cycles showed no evidence of disease progression, and after 4 cycles of chemotherapy with these drugs, the patient was started on maintenance chemotherapy with bevacizumab 15 mg/kg and pemetrexed 500 mg/m2.

Discussion

Choroidal metastasis is the most common site of intraocular tumor. In an autopsy study of 230 patients with carcinoma, 12% of cases demonstrated histologic evidence of ocular metastasis.1 A retrospective series of patients with malignant involvement of the eye, 66% of patients had a known history of primary cancer and in 34% of patients the ocular tumor was the first sign of cancer.2 The most common cancers that were found to have ocular metastasis were lung and breast cancer.2 Adenocarcinoma was the most common histologic type of lung cancer to result in ocular metastases and was seen in 41% of patients.3

Decreased or blurred vision with redness as the primary complaint of NSCLC is rare. Only a few case reports are available. Abundo and colleagues reported that 0.7%-12% of patients with lung cancer develop ocular metastases.4 Therefore, routine ophthalmologic screening for ocular metastases in patients with cancer has not been pursued in asymptomatic patients.5 Ophthalmological evaluation is recommended in symptomatic patients.

Metastatic involvement of two or more other organs was found to be a risk factor for development of choroidal metastasis in patients with lung cancer though in our patient no evidence of other organ involvement was found.5 The most common site of metastases in patients with NSCLC with ocular metastases was found to be the liver. Choroidal metastases was reported to be the sixth common site of metastases in patients with lung cancer.5

Treatment of ocular manifestations has been generally confined to surgical resection or radiation therapy, but advances in chemotherapy and development of novel targeted agents have shown promising results.7 Median life expectancy after a diagnosis of uveal metastases was reported to be 12 months in a retrospective study, which is similar to the reported median survival in metastatic NSCLC.8

Our patient was enrolled in a clinical trial and was treated with a regimen of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab. On presentation, he had significant impairment of vision with pain. He was treated with intravitreal bevacizumab yielding improvement in his visual symptoms. Bevacizumab is a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody approved for use in patients with metastatic lung cancer. Other pathways that have been reported in development of lung cancer involve the ALK gene translocation, and EGFR and K-RAS mutations, and targeted therapy has shown good results in cancer patients with these molecular defects. Randomized clinical trials in patients with advanced NSCLC and an EGFR mutation have shown significant improvement in overall survival with the use of erlotinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor.9 Similarly, crizotinib has shown promising results in patients with metastatic NSCLC who have ELM-ALK rearrangement.10 As our patient’s tumor did not have either of these mutations, he was initiated on chemotherapy with bevacizumab. The presence of a K-RAS mutation in this patient further supported the use of front-line chemotherapy given that it may confer resistance against agents that target the EGFR pathway.

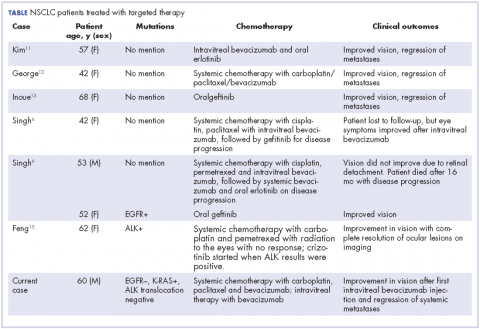

In our review of the literature, we found cases of patients with ocular metastases who responded well to therapy with targeted agents (Table).

Singh and colleagues did a systematic review of 55 cases of patients with lung cancer and choroidal metastases and found that the type of therapy depended on when the diagnosis had been made in relation to the advent of targeted therapy: cases diagnosed before targeted therapy had received radiation therapy or enucleation.6 As far as we could ascertain, there have been no randomized studies evaluating the impact of various targeted therapies or systemic chemotherapy on ocular metastases, although case reports have documented improvement in vision and regression of metastases with such therapy.

Conclusion

The goal of therapy in metastatic lung cancer is palliation of symptoms and improvement in patient quality of life with prolongation in overall survival. The newer targeted chemotherapeutic agents assist in achieving these goals and may decrease the morbidity associated from radiation or surgery with improvement in vision and regression of ocular metastatic lesions. Targeted therapies should be considered in the treatment of patients with ocular metastases from NSCLC.

1. Bloch RS, Gartner S. The incidence of ocular metastatic carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol-Chic. 1971;85(6):673-675.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA, Gross NE, Schwartz GP, Lally SE. Survey of 520 eyes with uveal metastases. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(8):1265-1276.

3. Kreusel KM, Bechrakis NE, Wiegel T, Krause L, Foerster MH. Incidence and clinical characteristics of symptomatic choroidal metastasis from lung cancer. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(5):515-519.

4. Abundo RE, Orenic CJ, Anderson SF, Townsend JC. Choroidal metastases resulting from carcinoma of the lung. J Am Optom Assoc. 1997;68(2):95-108.

5. Kreusel KM, Wiegel T, Stange M, Bornfeld N, Hinkelbein W, Foerster MH. Choroidal metastasis in disseminated lung cancer: frequency and risk factors. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134(3):445-447.

6. Singh N, Kulkarni P, Aggarwal AN, et al. Choroidal metastasis as a presenting manifestation of lung cancer: a report of 3 cases and systematic review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91(4):179-194.

7. Chen CJ, McCoy AN, Brahmer J, Handa JT. Emerging treatments for choroidal metastases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56(6):511-521.

8. Shah SU, Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, et al. Uveal metastasis from lung cancer: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in 194 patients. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):352-357.

9. Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123-132.

10. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385-2394.

11. Kim SW, Kim MJ, Huh K, Oh J. Complete regression of choroidal metastasis secondary to non-small-cell lung cancer with intravitreal bevacizumab and oral erlotinib combination therapy. Ophthalmologica. 2009;223(6):411-413.

12. George B, Wirostko WJ, Connor TB, Choong NW. Complete and durable response of choroid metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer with systemic bevacizumab and chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):661-662.

13. Inoue M, Watanabe Y, Yamane S, et al. Choroidal metastasis with adenocarcinoma of the lung treated with gefitinib. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(5):963-965.

14. Shimomura I, Tada Y, Miura G, et al. Choroidal metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer that responded to gefitinib. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/criopm/2013/213124/. Published 2013. Accessed May 4, 2017.

15. Feng Y, Singh AD, Lanigan C, Tubbs RR, Ma PC. Choroidal metastases responsive to crizotinib therapy in a lung adenocarcinoma patient with ALK 2p23 fusion identified by ALK immunohistochemistry. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(12):e109-111.

Non–small cell lung cancer constitutes 80%-85% of lung cancers, and 40% of NSCLC are adenocarcinoma. It is rare to find intraocular metastasis from lung cancer. In this article, we present the case of a patient who presented with complaints of diminished vision redness of the eye and was found to have intra-ocular metastases from lung cancer.

Case presentation and summary

A 60-year-old man with a 40-pack per year history of smoking presented to multiple ophthalmologists with complaints of decreased vision and redness of the left eye. He was eventually evaluated by an ophthalmologist who performed a biopsy of the anterior chamber of the eye. Histologic findings were consistent with adenocarcinoma of lung primary (Figures 1 and 2).

After the diagnosis, a chest X-ray showed that the patient had a left lower lung mass. The results of his physical exam were all within normal limits, with the exception of decreased visual acuity in the left eye. The results of his laboratory studies, including complete blood count and serum chemistries, were also within normal limits. Imaging studies – including a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and a full-body positron-emission tomography–CT scan – showed a hypermetabolic left lower lobe mass 4.5 cm and right lower paratracheal lymph node metastasis 2 cm with a small focus of increased uptake alone the medial aspect of the left globe (Figures 3 and 4).

An MRI orbit was performed in an attempt to better characterize the left eye mass, but no optic lesion was identified. A biopsy of the left lower lung mass was consistent with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Aside from the isolated left eye metastases, the patient did not have evidence of other distant metastatic involvement.

He was started on palliative chemotherapy on a clinical trial and received intravenous carboplatin AUC 6, pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, and bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks. He received 1 dose intraocular bevacizumab injection before initiation of systemic chemotherapy as he was symptomatic from the intraocular metastases. Within 2 weeks after intravitreal bevacizumab was administered, the patient had subjective improvement in vision. Mutational analysis to identify if the patient would benefit from targeted therapy showed no presence of EGFR mutation and ALK gene rearrangement, and that the patient was K-RAS mutant.

After treatment initiation, interval imaging studies (a computed-tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, pelvis; and magnetic-resonance imaging of the brain) after 3 cycles showed no evidence of disease progression, and after 4 cycles of chemotherapy with these drugs, the patient was started on maintenance chemotherapy with bevacizumab 15 mg/kg and pemetrexed 500 mg/m2.

Discussion

Choroidal metastasis is the most common site of intraocular tumor. In an autopsy study of 230 patients with carcinoma, 12% of cases demonstrated histologic evidence of ocular metastasis.1 A retrospective series of patients with malignant involvement of the eye, 66% of patients had a known history of primary cancer and in 34% of patients the ocular tumor was the first sign of cancer.2 The most common cancers that were found to have ocular metastasis were lung and breast cancer.2 Adenocarcinoma was the most common histologic type of lung cancer to result in ocular metastases and was seen in 41% of patients.3

Decreased or blurred vision with redness as the primary complaint of NSCLC is rare. Only a few case reports are available. Abundo and colleagues reported that 0.7%-12% of patients with lung cancer develop ocular metastases.4 Therefore, routine ophthalmologic screening for ocular metastases in patients with cancer has not been pursued in asymptomatic patients.5 Ophthalmological evaluation is recommended in symptomatic patients.

Metastatic involvement of two or more other organs was found to be a risk factor for development of choroidal metastasis in patients with lung cancer though in our patient no evidence of other organ involvement was found.5 The most common site of metastases in patients with NSCLC with ocular metastases was found to be the liver. Choroidal metastases was reported to be the sixth common site of metastases in patients with lung cancer.5

Treatment of ocular manifestations has been generally confined to surgical resection or radiation therapy, but advances in chemotherapy and development of novel targeted agents have shown promising results.7 Median life expectancy after a diagnosis of uveal metastases was reported to be 12 months in a retrospective study, which is similar to the reported median survival in metastatic NSCLC.8

Our patient was enrolled in a clinical trial and was treated with a regimen of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab. On presentation, he had significant impairment of vision with pain. He was treated with intravitreal bevacizumab yielding improvement in his visual symptoms. Bevacizumab is a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody approved for use in patients with metastatic lung cancer. Other pathways that have been reported in development of lung cancer involve the ALK gene translocation, and EGFR and K-RAS mutations, and targeted therapy has shown good results in cancer patients with these molecular defects. Randomized clinical trials in patients with advanced NSCLC and an EGFR mutation have shown significant improvement in overall survival with the use of erlotinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor.9 Similarly, crizotinib has shown promising results in patients with metastatic NSCLC who have ELM-ALK rearrangement.10 As our patient’s tumor did not have either of these mutations, he was initiated on chemotherapy with bevacizumab. The presence of a K-RAS mutation in this patient further supported the use of front-line chemotherapy given that it may confer resistance against agents that target the EGFR pathway.

In our review of the literature, we found cases of patients with ocular metastases who responded well to therapy with targeted agents (Table).

Singh and colleagues did a systematic review of 55 cases of patients with lung cancer and choroidal metastases and found that the type of therapy depended on when the diagnosis had been made in relation to the advent of targeted therapy: cases diagnosed before targeted therapy had received radiation therapy or enucleation.6 As far as we could ascertain, there have been no randomized studies evaluating the impact of various targeted therapies or systemic chemotherapy on ocular metastases, although case reports have documented improvement in vision and regression of metastases with such therapy.

Conclusion

The goal of therapy in metastatic lung cancer is palliation of symptoms and improvement in patient quality of life with prolongation in overall survival. The newer targeted chemotherapeutic agents assist in achieving these goals and may decrease the morbidity associated from radiation or surgery with improvement in vision and regression of ocular metastatic lesions. Targeted therapies should be considered in the treatment of patients with ocular metastases from NSCLC.

Non–small cell lung cancer constitutes 80%-85% of lung cancers, and 40% of NSCLC are adenocarcinoma. It is rare to find intraocular metastasis from lung cancer. In this article, we present the case of a patient who presented with complaints of diminished vision redness of the eye and was found to have intra-ocular metastases from lung cancer.

Case presentation and summary

A 60-year-old man with a 40-pack per year history of smoking presented to multiple ophthalmologists with complaints of decreased vision and redness of the left eye. He was eventually evaluated by an ophthalmologist who performed a biopsy of the anterior chamber of the eye. Histologic findings were consistent with adenocarcinoma of lung primary (Figures 1 and 2).

After the diagnosis, a chest X-ray showed that the patient had a left lower lung mass. The results of his physical exam were all within normal limits, with the exception of decreased visual acuity in the left eye. The results of his laboratory studies, including complete blood count and serum chemistries, were also within normal limits. Imaging studies – including a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and a full-body positron-emission tomography–CT scan – showed a hypermetabolic left lower lobe mass 4.5 cm and right lower paratracheal lymph node metastasis 2 cm with a small focus of increased uptake alone the medial aspect of the left globe (Figures 3 and 4).

An MRI orbit was performed in an attempt to better characterize the left eye mass, but no optic lesion was identified. A biopsy of the left lower lung mass was consistent with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Aside from the isolated left eye metastases, the patient did not have evidence of other distant metastatic involvement.

He was started on palliative chemotherapy on a clinical trial and received intravenous carboplatin AUC 6, pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, and bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks. He received 1 dose intraocular bevacizumab injection before initiation of systemic chemotherapy as he was symptomatic from the intraocular metastases. Within 2 weeks after intravitreal bevacizumab was administered, the patient had subjective improvement in vision. Mutational analysis to identify if the patient would benefit from targeted therapy showed no presence of EGFR mutation and ALK gene rearrangement, and that the patient was K-RAS mutant.

After treatment initiation, interval imaging studies (a computed-tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, pelvis; and magnetic-resonance imaging of the brain) after 3 cycles showed no evidence of disease progression, and after 4 cycles of chemotherapy with these drugs, the patient was started on maintenance chemotherapy with bevacizumab 15 mg/kg and pemetrexed 500 mg/m2.

Discussion

Choroidal metastasis is the most common site of intraocular tumor. In an autopsy study of 230 patients with carcinoma, 12% of cases demonstrated histologic evidence of ocular metastasis.1 A retrospective series of patients with malignant involvement of the eye, 66% of patients had a known history of primary cancer and in 34% of patients the ocular tumor was the first sign of cancer.2 The most common cancers that were found to have ocular metastasis were lung and breast cancer.2 Adenocarcinoma was the most common histologic type of lung cancer to result in ocular metastases and was seen in 41% of patients.3

Decreased or blurred vision with redness as the primary complaint of NSCLC is rare. Only a few case reports are available. Abundo and colleagues reported that 0.7%-12% of patients with lung cancer develop ocular metastases.4 Therefore, routine ophthalmologic screening for ocular metastases in patients with cancer has not been pursued in asymptomatic patients.5 Ophthalmological evaluation is recommended in symptomatic patients.

Metastatic involvement of two or more other organs was found to be a risk factor for development of choroidal metastasis in patients with lung cancer though in our patient no evidence of other organ involvement was found.5 The most common site of metastases in patients with NSCLC with ocular metastases was found to be the liver. Choroidal metastases was reported to be the sixth common site of metastases in patients with lung cancer.5

Treatment of ocular manifestations has been generally confined to surgical resection or radiation therapy, but advances in chemotherapy and development of novel targeted agents have shown promising results.7 Median life expectancy after a diagnosis of uveal metastases was reported to be 12 months in a retrospective study, which is similar to the reported median survival in metastatic NSCLC.8

Our patient was enrolled in a clinical trial and was treated with a regimen of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab. On presentation, he had significant impairment of vision with pain. He was treated with intravitreal bevacizumab yielding improvement in his visual symptoms. Bevacizumab is a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody approved for use in patients with metastatic lung cancer. Other pathways that have been reported in development of lung cancer involve the ALK gene translocation, and EGFR and K-RAS mutations, and targeted therapy has shown good results in cancer patients with these molecular defects. Randomized clinical trials in patients with advanced NSCLC and an EGFR mutation have shown significant improvement in overall survival with the use of erlotinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor.9 Similarly, crizotinib has shown promising results in patients with metastatic NSCLC who have ELM-ALK rearrangement.10 As our patient’s tumor did not have either of these mutations, he was initiated on chemotherapy with bevacizumab. The presence of a K-RAS mutation in this patient further supported the use of front-line chemotherapy given that it may confer resistance against agents that target the EGFR pathway.

In our review of the literature, we found cases of patients with ocular metastases who responded well to therapy with targeted agents (Table).

Singh and colleagues did a systematic review of 55 cases of patients with lung cancer and choroidal metastases and found that the type of therapy depended on when the diagnosis had been made in relation to the advent of targeted therapy: cases diagnosed before targeted therapy had received radiation therapy or enucleation.6 As far as we could ascertain, there have been no randomized studies evaluating the impact of various targeted therapies or systemic chemotherapy on ocular metastases, although case reports have documented improvement in vision and regression of metastases with such therapy.

Conclusion

The goal of therapy in metastatic lung cancer is palliation of symptoms and improvement in patient quality of life with prolongation in overall survival. The newer targeted chemotherapeutic agents assist in achieving these goals and may decrease the morbidity associated from radiation or surgery with improvement in vision and regression of ocular metastatic lesions. Targeted therapies should be considered in the treatment of patients with ocular metastases from NSCLC.

1. Bloch RS, Gartner S. The incidence of ocular metastatic carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol-Chic. 1971;85(6):673-675.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA, Gross NE, Schwartz GP, Lally SE. Survey of 520 eyes with uveal metastases. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(8):1265-1276.

3. Kreusel KM, Bechrakis NE, Wiegel T, Krause L, Foerster MH. Incidence and clinical characteristics of symptomatic choroidal metastasis from lung cancer. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(5):515-519.

4. Abundo RE, Orenic CJ, Anderson SF, Townsend JC. Choroidal metastases resulting from carcinoma of the lung. J Am Optom Assoc. 1997;68(2):95-108.

5. Kreusel KM, Wiegel T, Stange M, Bornfeld N, Hinkelbein W, Foerster MH. Choroidal metastasis in disseminated lung cancer: frequency and risk factors. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134(3):445-447.

6. Singh N, Kulkarni P, Aggarwal AN, et al. Choroidal metastasis as a presenting manifestation of lung cancer: a report of 3 cases and systematic review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91(4):179-194.

7. Chen CJ, McCoy AN, Brahmer J, Handa JT. Emerging treatments for choroidal metastases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56(6):511-521.

8. Shah SU, Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, et al. Uveal metastasis from lung cancer: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in 194 patients. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):352-357.

9. Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123-132.

10. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385-2394.

11. Kim SW, Kim MJ, Huh K, Oh J. Complete regression of choroidal metastasis secondary to non-small-cell lung cancer with intravitreal bevacizumab and oral erlotinib combination therapy. Ophthalmologica. 2009;223(6):411-413.

12. George B, Wirostko WJ, Connor TB, Choong NW. Complete and durable response of choroid metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer with systemic bevacizumab and chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):661-662.

13. Inoue M, Watanabe Y, Yamane S, et al. Choroidal metastasis with adenocarcinoma of the lung treated with gefitinib. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(5):963-965.

14. Shimomura I, Tada Y, Miura G, et al. Choroidal metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer that responded to gefitinib. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/criopm/2013/213124/. Published 2013. Accessed May 4, 2017.

15. Feng Y, Singh AD, Lanigan C, Tubbs RR, Ma PC. Choroidal metastases responsive to crizotinib therapy in a lung adenocarcinoma patient with ALK 2p23 fusion identified by ALK immunohistochemistry. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(12):e109-111.

1. Bloch RS, Gartner S. The incidence of ocular metastatic carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol-Chic. 1971;85(6):673-675.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA, Gross NE, Schwartz GP, Lally SE. Survey of 520 eyes with uveal metastases. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(8):1265-1276.

3. Kreusel KM, Bechrakis NE, Wiegel T, Krause L, Foerster MH. Incidence and clinical characteristics of symptomatic choroidal metastasis from lung cancer. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(5):515-519.

4. Abundo RE, Orenic CJ, Anderson SF, Townsend JC. Choroidal metastases resulting from carcinoma of the lung. J Am Optom Assoc. 1997;68(2):95-108.

5. Kreusel KM, Wiegel T, Stange M, Bornfeld N, Hinkelbein W, Foerster MH. Choroidal metastasis in disseminated lung cancer: frequency and risk factors. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134(3):445-447.

6. Singh N, Kulkarni P, Aggarwal AN, et al. Choroidal metastasis as a presenting manifestation of lung cancer: a report of 3 cases and systematic review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91(4):179-194.

7. Chen CJ, McCoy AN, Brahmer J, Handa JT. Emerging treatments for choroidal metastases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56(6):511-521.

8. Shah SU, Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, et al. Uveal metastasis from lung cancer: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in 194 patients. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):352-357.

9. Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123-132.

10. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385-2394.

11. Kim SW, Kim MJ, Huh K, Oh J. Complete regression of choroidal metastasis secondary to non-small-cell lung cancer with intravitreal bevacizumab and oral erlotinib combination therapy. Ophthalmologica. 2009;223(6):411-413.

12. George B, Wirostko WJ, Connor TB, Choong NW. Complete and durable response of choroid metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer with systemic bevacizumab and chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):661-662.

13. Inoue M, Watanabe Y, Yamane S, et al. Choroidal metastasis with adenocarcinoma of the lung treated with gefitinib. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(5):963-965.

14. Shimomura I, Tada Y, Miura G, et al. Choroidal metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer that responded to gefitinib. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/criopm/2013/213124/. Published 2013. Accessed May 4, 2017.

15. Feng Y, Singh AD, Lanigan C, Tubbs RR, Ma PC. Choroidal metastases responsive to crizotinib therapy in a lung adenocarcinoma patient with ALK 2p23 fusion identified by ALK immunohistochemistry. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(12):e109-111.

Resolution of refractory pruritus with aprepitant in a patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma

Substance P is an important neurotransmitter implicated in itch pathways.1 After binding to its receptor, neurokinin-1 (NK-1), substance P induces release of factors including histamine, which may cause pruritus.2 Recent literature has reported successful use of aprepitant, an NK-1 antagonist that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, for treatment of pruritus. We report here the case of a patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) who presented with refractory pruritus and who had rapid and complete resolution of itch after administration of aprepitant.

Case presentation and summary

A 73-year-old man presented with a 12-year history of a small nodule on his philtrum, which had been increasing in size. He subsequently developed upper-lip numbness and nasal induration. He complained of 2.5 months of severe, debilitating, full-body pruritus. His symptoms were refractory to treatment with prednisone, gabapentin, doxycycline, doxepin, antihistamines, and topical steroids. At the time of consultation, he was being treated with hydroxyzine and topical pramocaine lotion with minimal relief.

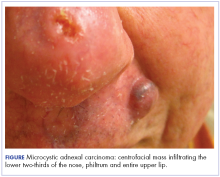

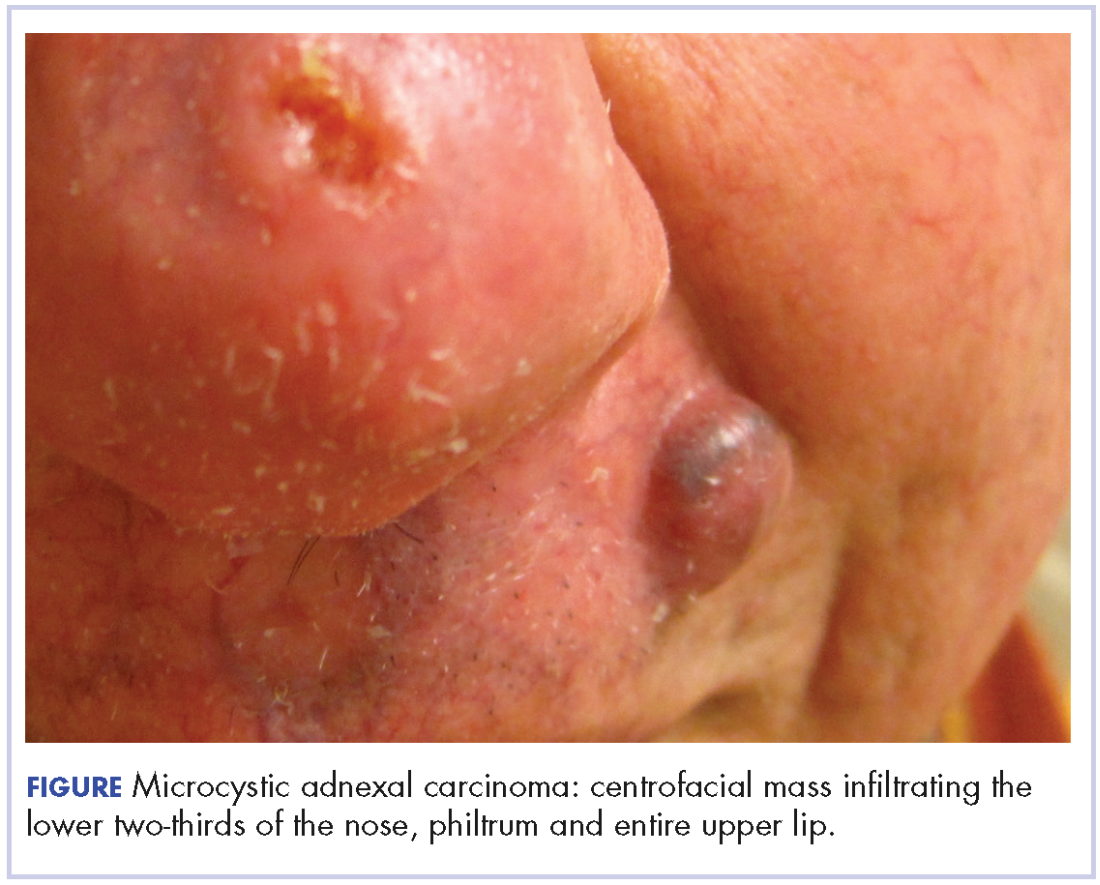

At initial dermatologic evaluation, his tumor involved the lower two-thirds of the nose and entire upper cutaneous lip. There was a 4-mm rolled ulcer on the nasal tip and a 1-cm exophytic, smooth nodule on the left upper lip with palpable 4-cm submandibular adenopathy (Figure). Skin examination otherwise revealed linear excoriations on the upper back with no additional primary lesions. The nodule was biopsied, and the patient was diagnosed with MAC with gross nodal involvement. Laboratory findings including serum chemistries, blood urea nitrogen, complete blood cell count, thyroid, and liver function were normal. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging was negative for distant metastases.

Treatment was initiated with oral aprepitant – 125 mg on day 1, 80 mg on day 2, and 80 mg on day 3 –with concomitant weekly carboplatin (AUC 1.5) and paclitaxel (30 mg/m2) as well as radiation. Within hours after the first dose of aprepitant, the patient reported a notable cessation in his pruritus. He reported that after 5 hours, his skin “finally turned off” and over the hour that followed, he had complete resolution of symptoms. He completed chemoradiation with a significant disease response. Despite persistent MAC confined to the philtrum, he has been followed for over 2 years without recurrence of itch.

Discussion

MAC is an uncommon cutaneous malignancy of sweat and eccrine gland differentiation. In all, 700 cases of MAC have been described in the literature; a 2008 review estimated the incidence of metastasis at around 2.1%.3 Though metastasis is exceedingly rare, the tumor is locally aggressive and there are reports of invasion into the muscle, perichondrium, periosteum, bone marrow, as well as perineural spaces and vascular adventitia.4

The clinical presentation of MAC includes smooth, flesh-colored or yellow papules, nodules, or plaques.3 Patients often present with numbness, paresthesia, and burning in the area of involvement because of neural infiltration with tumor. Despite the rarity of MAC, pruritus has been reported as a presenting symptom in 1 other case in the literature.4 Our case represents the first report of MAC presenting with a grossly enlarging centrofacial mass, lymph node involvement, and severe full-body pruritus. Our patient responded completely, and within hours, to treatment with aprepitant after experiencing months of failure with conventional antipruritus treatments and without recurrence in symptoms in more than 2 years of follow-up.

Aprepitant blocks the binding of substance P to its receptor NK-1 and has been approved as an anti-emetic for chemotherapy patients. Substance P has been shown to be important in both nausea and itch pathways. The largest prospective study to date on aprepitant for the indication of pruritus in 45 patients with metastatic solid tumors demonstrated a 91% response rate, defined by >50% reduction in pruritus intensity, and 13% recurrence rate that occurred at a median of 7 weeks after initial treatment.5 Aprepitant treatment has been used with success for pruritus associated with both malignant and nonmalignant conditions in at least 74 patients,6 among whom the malignant conditions included cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and metastatic solid tumors.5-7 Aprepitant has also been used for erlotinib- and nivolumab-induced pruritus in non–small cell lung cancer, which suggests a possible future role for aprepitant in the treatment of pruritus secondary to novel cancer therapies, perhaps including immune checkpoint inhibitors.8-10

However, despite those reports, and likely owing to the multifactorial nature of pruritus, aprepitant is not unviversally effective. Mechanisms of malignancy-associated itch are yet to be elucidated, and optimal patient selection for aprepitant use needs to be determined. However, our patient’s notable response supports the increasing evidence that substance P is a key mediator of pruritus and that disruption of binding to its receptor may result in significant improvement in symptoms in certain patients. It remains to be seen whether the cell type or the tendency toward neural invasion plays a role. Large, randomized studies are needed to guide patient selection and confirm the findings reported here and in the literature, with careful documentation of and close attention paid to timing of pruritus relief and improvement in patient quality of life. Aprepitant might be an important therapeutic tool for refractory, malignancy-associated pruritus, in which patient quality of life is especially critical.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the Multinational Association of Supportive Care and Cancer Meeting, in Miami Florida, June 26-28, 2014. The authors are indebted to Saajar Jadeja for his assistance preparing the manuscript.

1. Wallengren J. Neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of itch. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(4):292-303.

2. Kulka M, Sheen CH, Tancowny BP, Grammer LC, Schleimer RP. Neuropeptides activate human mast cell degranulation and chemokine production. Immunology. 2008;123(3):398-410.

3. Wetter R, Goldstein GD. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(6):452-458.

4. Adamson T. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Nurs. 2004;16(4):365.

5. Santini D, Vincenzi B, Guida FM, et al. Aprepitant for management of severe pruritus related to biological cancer treatments: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):1020-1024.

6. Song JS, Tawa M, Chau NG, Kupper TS, LeBoeuf NR. Aprepitant for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-associated pruritus: 4 cases and a review of the literature. BMC Cancer. 2017;17.

7. Villafranca JJA, Siles MG, Casanova M, Goitia BT, Domínguez AR. Paraneoplastic pruritus presenting with Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2014;8:300.

8. Ito J, Fujimoto D, Nakamura A, et al. Aprepitant for refractory nivolumab-induced pruritus. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2017;109:58-61.

9. Levêque D. Aprepitant for erlotinib-induced pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1680-1681; author reply 1681.

10. Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Homey B. More on aprepitant for erlotinib-induced pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):486-487.

Substance P is an important neurotransmitter implicated in itch pathways.1 After binding to its receptor, neurokinin-1 (NK-1), substance P induces release of factors including histamine, which may cause pruritus.2 Recent literature has reported successful use of aprepitant, an NK-1 antagonist that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, for treatment of pruritus. We report here the case of a patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) who presented with refractory pruritus and who had rapid and complete resolution of itch after administration of aprepitant.

Case presentation and summary

A 73-year-old man presented with a 12-year history of a small nodule on his philtrum, which had been increasing in size. He subsequently developed upper-lip numbness and nasal induration. He complained of 2.5 months of severe, debilitating, full-body pruritus. His symptoms were refractory to treatment with prednisone, gabapentin, doxycycline, doxepin, antihistamines, and topical steroids. At the time of consultation, he was being treated with hydroxyzine and topical pramocaine lotion with minimal relief.

At initial dermatologic evaluation, his tumor involved the lower two-thirds of the nose and entire upper cutaneous lip. There was a 4-mm rolled ulcer on the nasal tip and a 1-cm exophytic, smooth nodule on the left upper lip with palpable 4-cm submandibular adenopathy (Figure). Skin examination otherwise revealed linear excoriations on the upper back with no additional primary lesions. The nodule was biopsied, and the patient was diagnosed with MAC with gross nodal involvement. Laboratory findings including serum chemistries, blood urea nitrogen, complete blood cell count, thyroid, and liver function were normal. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging was negative for distant metastases.

Treatment was initiated with oral aprepitant – 125 mg on day 1, 80 mg on day 2, and 80 mg on day 3 –with concomitant weekly carboplatin (AUC 1.5) and paclitaxel (30 mg/m2) as well as radiation. Within hours after the first dose of aprepitant, the patient reported a notable cessation in his pruritus. He reported that after 5 hours, his skin “finally turned off” and over the hour that followed, he had complete resolution of symptoms. He completed chemoradiation with a significant disease response. Despite persistent MAC confined to the philtrum, he has been followed for over 2 years without recurrence of itch.

Discussion

MAC is an uncommon cutaneous malignancy of sweat and eccrine gland differentiation. In all, 700 cases of MAC have been described in the literature; a 2008 review estimated the incidence of metastasis at around 2.1%.3 Though metastasis is exceedingly rare, the tumor is locally aggressive and there are reports of invasion into the muscle, perichondrium, periosteum, bone marrow, as well as perineural spaces and vascular adventitia.4

The clinical presentation of MAC includes smooth, flesh-colored or yellow papules, nodules, or plaques.3 Patients often present with numbness, paresthesia, and burning in the area of involvement because of neural infiltration with tumor. Despite the rarity of MAC, pruritus has been reported as a presenting symptom in 1 other case in the literature.4 Our case represents the first report of MAC presenting with a grossly enlarging centrofacial mass, lymph node involvement, and severe full-body pruritus. Our patient responded completely, and within hours, to treatment with aprepitant after experiencing months of failure with conventional antipruritus treatments and without recurrence in symptoms in more than 2 years of follow-up.

Aprepitant blocks the binding of substance P to its receptor NK-1 and has been approved as an anti-emetic for chemotherapy patients. Substance P has been shown to be important in both nausea and itch pathways. The largest prospective study to date on aprepitant for the indication of pruritus in 45 patients with metastatic solid tumors demonstrated a 91% response rate, defined by >50% reduction in pruritus intensity, and 13% recurrence rate that occurred at a median of 7 weeks after initial treatment.5 Aprepitant treatment has been used with success for pruritus associated with both malignant and nonmalignant conditions in at least 74 patients,6 among whom the malignant conditions included cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and metastatic solid tumors.5-7 Aprepitant has also been used for erlotinib- and nivolumab-induced pruritus in non–small cell lung cancer, which suggests a possible future role for aprepitant in the treatment of pruritus secondary to novel cancer therapies, perhaps including immune checkpoint inhibitors.8-10

However, despite those reports, and likely owing to the multifactorial nature of pruritus, aprepitant is not unviversally effective. Mechanisms of malignancy-associated itch are yet to be elucidated, and optimal patient selection for aprepitant use needs to be determined. However, our patient’s notable response supports the increasing evidence that substance P is a key mediator of pruritus and that disruption of binding to its receptor may result in significant improvement in symptoms in certain patients. It remains to be seen whether the cell type or the tendency toward neural invasion plays a role. Large, randomized studies are needed to guide patient selection and confirm the findings reported here and in the literature, with careful documentation of and close attention paid to timing of pruritus relief and improvement in patient quality of life. Aprepitant might be an important therapeutic tool for refractory, malignancy-associated pruritus, in which patient quality of life is especially critical.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the Multinational Association of Supportive Care and Cancer Meeting, in Miami Florida, June 26-28, 2014. The authors are indebted to Saajar Jadeja for his assistance preparing the manuscript.

Substance P is an important neurotransmitter implicated in itch pathways.1 After binding to its receptor, neurokinin-1 (NK-1), substance P induces release of factors including histamine, which may cause pruritus.2 Recent literature has reported successful use of aprepitant, an NK-1 antagonist that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, for treatment of pruritus. We report here the case of a patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) who presented with refractory pruritus and who had rapid and complete resolution of itch after administration of aprepitant.

Case presentation and summary

A 73-year-old man presented with a 12-year history of a small nodule on his philtrum, which had been increasing in size. He subsequently developed upper-lip numbness and nasal induration. He complained of 2.5 months of severe, debilitating, full-body pruritus. His symptoms were refractory to treatment with prednisone, gabapentin, doxycycline, doxepin, antihistamines, and topical steroids. At the time of consultation, he was being treated with hydroxyzine and topical pramocaine lotion with minimal relief.

At initial dermatologic evaluation, his tumor involved the lower two-thirds of the nose and entire upper cutaneous lip. There was a 4-mm rolled ulcer on the nasal tip and a 1-cm exophytic, smooth nodule on the left upper lip with palpable 4-cm submandibular adenopathy (Figure). Skin examination otherwise revealed linear excoriations on the upper back with no additional primary lesions. The nodule was biopsied, and the patient was diagnosed with MAC with gross nodal involvement. Laboratory findings including serum chemistries, blood urea nitrogen, complete blood cell count, thyroid, and liver function were normal. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging was negative for distant metastases.

Treatment was initiated with oral aprepitant – 125 mg on day 1, 80 mg on day 2, and 80 mg on day 3 –with concomitant weekly carboplatin (AUC 1.5) and paclitaxel (30 mg/m2) as well as radiation. Within hours after the first dose of aprepitant, the patient reported a notable cessation in his pruritus. He reported that after 5 hours, his skin “finally turned off” and over the hour that followed, he had complete resolution of symptoms. He completed chemoradiation with a significant disease response. Despite persistent MAC confined to the philtrum, he has been followed for over 2 years without recurrence of itch.

Discussion

MAC is an uncommon cutaneous malignancy of sweat and eccrine gland differentiation. In all, 700 cases of MAC have been described in the literature; a 2008 review estimated the incidence of metastasis at around 2.1%.3 Though metastasis is exceedingly rare, the tumor is locally aggressive and there are reports of invasion into the muscle, perichondrium, periosteum, bone marrow, as well as perineural spaces and vascular adventitia.4

The clinical presentation of MAC includes smooth, flesh-colored or yellow papules, nodules, or plaques.3 Patients often present with numbness, paresthesia, and burning in the area of involvement because of neural infiltration with tumor. Despite the rarity of MAC, pruritus has been reported as a presenting symptom in 1 other case in the literature.4 Our case represents the first report of MAC presenting with a grossly enlarging centrofacial mass, lymph node involvement, and severe full-body pruritus. Our patient responded completely, and within hours, to treatment with aprepitant after experiencing months of failure with conventional antipruritus treatments and without recurrence in symptoms in more than 2 years of follow-up.

Aprepitant blocks the binding of substance P to its receptor NK-1 and has been approved as an anti-emetic for chemotherapy patients. Substance P has been shown to be important in both nausea and itch pathways. The largest prospective study to date on aprepitant for the indication of pruritus in 45 patients with metastatic solid tumors demonstrated a 91% response rate, defined by >50% reduction in pruritus intensity, and 13% recurrence rate that occurred at a median of 7 weeks after initial treatment.5 Aprepitant treatment has been used with success for pruritus associated with both malignant and nonmalignant conditions in at least 74 patients,6 among whom the malignant conditions included cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and metastatic solid tumors.5-7 Aprepitant has also been used for erlotinib- and nivolumab-induced pruritus in non–small cell lung cancer, which suggests a possible future role for aprepitant in the treatment of pruritus secondary to novel cancer therapies, perhaps including immune checkpoint inhibitors.8-10

However, despite those reports, and likely owing to the multifactorial nature of pruritus, aprepitant is not unviversally effective. Mechanisms of malignancy-associated itch are yet to be elucidated, and optimal patient selection for aprepitant use needs to be determined. However, our patient’s notable response supports the increasing evidence that substance P is a key mediator of pruritus and that disruption of binding to its receptor may result in significant improvement in symptoms in certain patients. It remains to be seen whether the cell type or the tendency toward neural invasion plays a role. Large, randomized studies are needed to guide patient selection and confirm the findings reported here and in the literature, with careful documentation of and close attention paid to timing of pruritus relief and improvement in patient quality of life. Aprepitant might be an important therapeutic tool for refractory, malignancy-associated pruritus, in which patient quality of life is especially critical.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the Multinational Association of Supportive Care and Cancer Meeting, in Miami Florida, June 26-28, 2014. The authors are indebted to Saajar Jadeja for his assistance preparing the manuscript.

1. Wallengren J. Neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of itch. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(4):292-303.

2. Kulka M, Sheen CH, Tancowny BP, Grammer LC, Schleimer RP. Neuropeptides activate human mast cell degranulation and chemokine production. Immunology. 2008;123(3):398-410.

3. Wetter R, Goldstein GD. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(6):452-458.

4. Adamson T. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Nurs. 2004;16(4):365.

5. Santini D, Vincenzi B, Guida FM, et al. Aprepitant for management of severe pruritus related to biological cancer treatments: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):1020-1024.

6. Song JS, Tawa M, Chau NG, Kupper TS, LeBoeuf NR. Aprepitant for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-associated pruritus: 4 cases and a review of the literature. BMC Cancer. 2017;17.

7. Villafranca JJA, Siles MG, Casanova M, Goitia BT, Domínguez AR. Paraneoplastic pruritus presenting with Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2014;8:300.

8. Ito J, Fujimoto D, Nakamura A, et al. Aprepitant for refractory nivolumab-induced pruritus. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2017;109:58-61.

9. Levêque D. Aprepitant for erlotinib-induced pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1680-1681; author reply 1681.

10. Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Homey B. More on aprepitant for erlotinib-induced pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):486-487.

1. Wallengren J. Neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of itch. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(4):292-303.

2. Kulka M, Sheen CH, Tancowny BP, Grammer LC, Schleimer RP. Neuropeptides activate human mast cell degranulation and chemokine production. Immunology. 2008;123(3):398-410.

3. Wetter R, Goldstein GD. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(6):452-458.

4. Adamson T. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Nurs. 2004;16(4):365.

5. Santini D, Vincenzi B, Guida FM, et al. Aprepitant for management of severe pruritus related to biological cancer treatments: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):1020-1024.

6. Song JS, Tawa M, Chau NG, Kupper TS, LeBoeuf NR. Aprepitant for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-associated pruritus: 4 cases and a review of the literature. BMC Cancer. 2017;17.

7. Villafranca JJA, Siles MG, Casanova M, Goitia BT, Domínguez AR. Paraneoplastic pruritus presenting with Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2014;8:300.

8. Ito J, Fujimoto D, Nakamura A, et al. Aprepitant for refractory nivolumab-induced pruritus. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2017;109:58-61.

9. Levêque D. Aprepitant for erlotinib-induced pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1680-1681; author reply 1681.

10. Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Homey B. More on aprepitant for erlotinib-induced pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):486-487.

Rare paraneoplastic dermatomyositis secondary to high-grade bladder cancer

The clinical presentation of bladder cancer typically presents with hematuria; changes in voiding habits such as urgency, frequency, and pain; or less commonly, obstructive symptoms. Rarely does bladder cancer first present as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome with an inflammatory myopathy. Inflammatory myopathies such as dermatomyositis have been known to be associated with malignancy, however, in a meta-analysis by Yang and colleagues of 449 patients with dermatomyositis and malignancy there were only 8 cases reported of bladder cancer.1 Herein, we report a paraneoplastic dermatomyositis in the setting of a bladder cancer.

Case presentation and summary

A 65-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension and alcohol use presented to the emergency department with worsening pain, stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and inability to lift his arms above his shoulders. During the physical exam, an erythematous purple rash was noted over his chest, neck, and arms. Upon further evaluation, his creatine phosphokinase was 3,500 U/L (reference range 52-336 U/L) suggesting muscle breakdown and possible inflammatory myopathy. A biopsy of the left deltoid and quadriceps muscles was performed and yielded a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. He was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily for his inflammatory myopathy. The patient also reported an unintentional weight loss of 20 lbs. and increasing weakness and inability to swallow, which caused aspiration events without developing pneumonia.

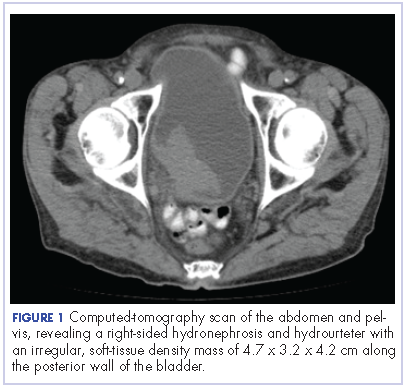

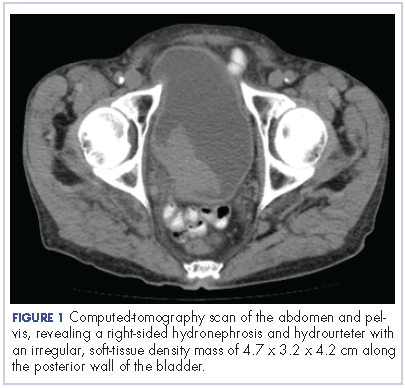

The patient’s symptoms worsened while he was on steroids, and we became concerned about the possibility of a primary malignancy, which led to further work-up. The results of a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed right-sided hydronephrosis and hydrourteter with an irregular, soft-tissue density mass of 4.7 x 3.2 x 4.2 cm along the posterior wall of the bladder (Figure 1).

A cystoscopy was performed with transurethral resection of a bladder tumor that was more than 8 cm in diameter. Because the mass was not fully resectable, only 25% of the tumor burden was removed. The pathology report revealed an invasive, high-grade urothelial cell carcinoma (Figure 2, see PDF). Further imaging ruled out metastatic spread. The patient was continued on steroids. He was not a candidate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy because of his comorbidities and cisplatin ineligibility owing to his significant bilateral hearing deficiencies. Members of a multidisciplinary tumor board decided to move forward with definitive surgery. The patient underwent a robotic-assisted laparoscoptic cystoprostatectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and open ileal conduit urinary diversion. Staging of tumor was determined as pT3b N1 (1/30) M0, LVI+. After the surgery, the patient had resolution of his rash and significant improvement in his muscle weakness with the ability to raise his arms over his head and climb stairs. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not given since he was cisplatin ineligible as a result of his hearing loss. Active surveillance was preferred.

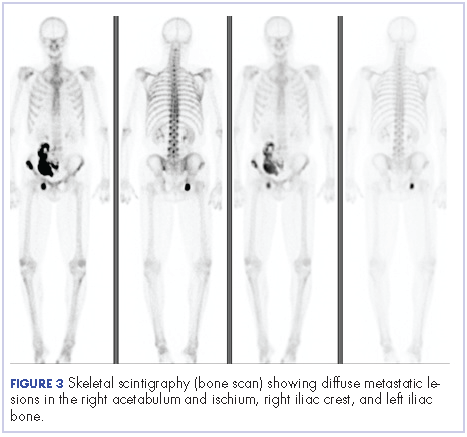

Four months after his cystoprostatectomy, he experienced new-onset hip pain and further imaging, including a bone scan, was performed. It showed metastatic disease in the ischium and iliac crest (Figure 3).

The patient decided to forgo any palliative chemotherapy and to have palliative radiation for pain and enroll in hospice. He died nine months after the initial diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma.

Discussion

Dermatomyositis is one of the inflammatory myopathies with a clinical presentation of proximal muscle weakness and characteristic skin findings of Gottron papules and heliotrope eruption. The most common subgroups of inflammatory myopathies are dermatomyositis, polymyositis, necrotizing autoimmune myopathy, and inclusion body myopathy. The pathogenesis of inflammatory myopathies is not well understood; however, some theories have been described, including: type 1 interferon signaling causing myofiber injury and antibody-complement mediated processes causing ischemia resulting in myofiber injury. 2,3 The diagnoses of inflammatory myopathies may be suggested based on history, physical examination findings, laboratory values showing muscle injury (creatine kinase, aldolase, ALT, AST, LDH), myositis-specific antibodies (antisynthetase autoantibodies), electromyogram, and magnetic-resonance imaging. However, muscle biopsy remains the gold standard.4

The initial treatment of inflammatory myopathies begins with glucocorticoid therapy at 0.5-1.0 mg/kg. This regimen may be titrated down over 6 weeks to a level adequate to control symptoms. Even while on glucocorticoid therapy, this patient’s symptoms continued, along with the development of dysphagia. Dysphagia is another notable symptom of dermatomyositis that may result in aspiration pneumonia with fatal outcomes.5,6,7 Not only did this patient initially respond poorly to corticosteroids, but the unintentional weight loss was another alarming feature prompting further evaluation. That led to the diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma, which was causing the paraneoplastic syndrome.

A paraneoplastic syndrome is a collection of symptoms that are observed in organ systems separate from the primary disease. This process is mostly caused by an autoimmune response to the tumor and nervous system.8 Inflammatory myopathies, such as dermatomyositis, have been shown to be associated with a variety of malignancies as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome. The most common cancers associated with dermatomyositis are ovarian, lung, pancreatic, stomach, colorectal, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.9 Although an association between dermatomyositis and bladder cancer has been established, very few cases have been reported in the literature. In the Yang meta-analysis, the relative risk of malignancy for patients with dermatomyositis was 5.5%, and of the 449 patients with dermatomyositis who had malignancy, only 8 cases of bladder cancer were reported.1

After a patient has been diagnosed with an inflammatory myopathy, there should be further evaluation for an underling malignancy causing a paraneoplastic process. The risk of these patients having a malignancy overall is 4.5 times higher than patients without dermatomyositis.1 Definite screening recommendations have not been established, but screening should be based on patient’s age, gender, and clinical scenario. The European Federation of Neurological Societies formed a task force to focus on malignancy screening of paraneoplastic neurological syndromes and included dermatomyositis as one of the signs.10 Patients should have a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Women should have a mammogram and a pelvis ultrasound. Men younger than 50 years should consider testes ultrasound, and patients older than 50 years should undergo usual colonoscopy screening.

The risk of malignancy is highest in the first year after diagnosis, but may extend to 5 years after the diagnosis, so repeat screening should be performed 3-6 months after diagnosis, followed with biannual testing for 4 years. If a malignancy is present, then treatment should be tailored to the neoplasm to improve symptoms of myositis; however, response is generally worse than it would be with dermatomyositis in the absence of malignancy. In the present case with bladder cancer, therapies may include platinum-based-chemotherapy, resection, and radiation. Dermatomyositis as a result of a bladder cancer paraneoplastic syndrome is associated with a poor prognosis as demonstrated in the case of this patient and others reported in the literature.11

Even though dermatomyositis is usually a chronic disease process, 87% of patients respond initially to corticosteroid treatment.12 Therefore, treatment should be escalated with an agent such as azathioprine or methotrexate, or, like in this case, an underlying malignancy should be suspected. This case emphasizes the importance of screening patients appropriately for malignancy in patients with an inflammatory myopathy and reveals the poor prognosis associated with this disease.

1. Yang Z, Lin F, Qin B, Liang Y, Zhong R. Polymyositis/dermatomyositis and malignancy risk: a metaanalysis study. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(2):282-291.

2. Greenberg, SA. Dermatomyositis and type 1 interferons. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(3):198-203.

3. Dalakas, MC, Hohlfeld, R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362(9388):971-982.

4. Malik A, Hayat G, Kalia JS, Guzman MA. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: clinical approach and management. Front Neurol. 2016;7:64.

5. Sabio JM, Vargas-Hitos JA, Jiménez-Alonso J. Paraneoplastic dermatomyositis associated with bladder cancer. Lupus. 2006;15(9):619-620.

6. Mallon E, Osborne G, Dinneen M, Lane RJ, Glaser M, Bunker CB. Dermatomyositis in association with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24(2):94-96.

7. Hafejee A, Coulson IH. Dysphagia in dermatomyositis secondary to bladder cancer: rapid response to combined immunoglobulin and methylprednisolone. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30(1):93-94.

8. Dalmau J, Gultekin HS, Posner JB. Paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes: pathogenesis and physiopathology. Brain Pathol. 1999;9(2):275-284.

9. Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigureirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357(9250):96-100.

10. Titulaer, MJ, Soffietti R, Dalmau J, et al. Screening for tumours in paraneoplastic syndromes: report of an EFNS Task Force. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18(1):19-e3.

11. Xu R, Zhong Z, Jiang H, Zhang L, Zhao X. A rare paraneoplastic dermatomyositis in bladder cancer with fatal outcome. Urol J. 2013;10(1):815-817.

12. Troyanov Y, Targoff IN, Tremblay JL, Goulet JR, Raymond Y, Senecal JL. Novel classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies based on overlap syndrome features and autoantibodies: analysis of 100 French Canadian patients. Medicine (Baltimore), 2005;84(4):231-249.

The clinical presentation of bladder cancer typically presents with hematuria; changes in voiding habits such as urgency, frequency, and pain; or less commonly, obstructive symptoms. Rarely does bladder cancer first present as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome with an inflammatory myopathy. Inflammatory myopathies such as dermatomyositis have been known to be associated with malignancy, however, in a meta-analysis by Yang and colleagues of 449 patients with dermatomyositis and malignancy there were only 8 cases reported of bladder cancer.1 Herein, we report a paraneoplastic dermatomyositis in the setting of a bladder cancer.

Case presentation and summary

A 65-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension and alcohol use presented to the emergency department with worsening pain, stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and inability to lift his arms above his shoulders. During the physical exam, an erythematous purple rash was noted over his chest, neck, and arms. Upon further evaluation, his creatine phosphokinase was 3,500 U/L (reference range 52-336 U/L) suggesting muscle breakdown and possible inflammatory myopathy. A biopsy of the left deltoid and quadriceps muscles was performed and yielded a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. He was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily for his inflammatory myopathy. The patient also reported an unintentional weight loss of 20 lbs. and increasing weakness and inability to swallow, which caused aspiration events without developing pneumonia.

The patient’s symptoms worsened while he was on steroids, and we became concerned about the possibility of a primary malignancy, which led to further work-up. The results of a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed right-sided hydronephrosis and hydrourteter with an irregular, soft-tissue density mass of 4.7 x 3.2 x 4.2 cm along the posterior wall of the bladder (Figure 1).

A cystoscopy was performed with transurethral resection of a bladder tumor that was more than 8 cm in diameter. Because the mass was not fully resectable, only 25% of the tumor burden was removed. The pathology report revealed an invasive, high-grade urothelial cell carcinoma (Figure 2, see PDF). Further imaging ruled out metastatic spread. The patient was continued on steroids. He was not a candidate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy because of his comorbidities and cisplatin ineligibility owing to his significant bilateral hearing deficiencies. Members of a multidisciplinary tumor board decided to move forward with definitive surgery. The patient underwent a robotic-assisted laparoscoptic cystoprostatectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and open ileal conduit urinary diversion. Staging of tumor was determined as pT3b N1 (1/30) M0, LVI+. After the surgery, the patient had resolution of his rash and significant improvement in his muscle weakness with the ability to raise his arms over his head and climb stairs. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not given since he was cisplatin ineligible as a result of his hearing loss. Active surveillance was preferred.

Four months after his cystoprostatectomy, he experienced new-onset hip pain and further imaging, including a bone scan, was performed. It showed metastatic disease in the ischium and iliac crest (Figure 3).

The patient decided to forgo any palliative chemotherapy and to have palliative radiation for pain and enroll in hospice. He died nine months after the initial diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma.

Discussion

Dermatomyositis is one of the inflammatory myopathies with a clinical presentation of proximal muscle weakness and characteristic skin findings of Gottron papules and heliotrope eruption. The most common subgroups of inflammatory myopathies are dermatomyositis, polymyositis, necrotizing autoimmune myopathy, and inclusion body myopathy. The pathogenesis of inflammatory myopathies is not well understood; however, some theories have been described, including: type 1 interferon signaling causing myofiber injury and antibody-complement mediated processes causing ischemia resulting in myofiber injury. 2,3 The diagnoses of inflammatory myopathies may be suggested based on history, physical examination findings, laboratory values showing muscle injury (creatine kinase, aldolase, ALT, AST, LDH), myositis-specific antibodies (antisynthetase autoantibodies), electromyogram, and magnetic-resonance imaging. However, muscle biopsy remains the gold standard.4

The initial treatment of inflammatory myopathies begins with glucocorticoid therapy at 0.5-1.0 mg/kg. This regimen may be titrated down over 6 weeks to a level adequate to control symptoms. Even while on glucocorticoid therapy, this patient’s symptoms continued, along with the development of dysphagia. Dysphagia is another notable symptom of dermatomyositis that may result in aspiration pneumonia with fatal outcomes.5,6,7 Not only did this patient initially respond poorly to corticosteroids, but the unintentional weight loss was another alarming feature prompting further evaluation. That led to the diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma, which was causing the paraneoplastic syndrome.

A paraneoplastic syndrome is a collection of symptoms that are observed in organ systems separate from the primary disease. This process is mostly caused by an autoimmune response to the tumor and nervous system.8 Inflammatory myopathies, such as dermatomyositis, have been shown to be associated with a variety of malignancies as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome. The most common cancers associated with dermatomyositis are ovarian, lung, pancreatic, stomach, colorectal, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.9 Although an association between dermatomyositis and bladder cancer has been established, very few cases have been reported in the literature. In the Yang meta-analysis, the relative risk of malignancy for patients with dermatomyositis was 5.5%, and of the 449 patients with dermatomyositis who had malignancy, only 8 cases of bladder cancer were reported.1

After a patient has been diagnosed with an inflammatory myopathy, there should be further evaluation for an underling malignancy causing a paraneoplastic process. The risk of these patients having a malignancy overall is 4.5 times higher than patients without dermatomyositis.1 Definite screening recommendations have not been established, but screening should be based on patient’s age, gender, and clinical scenario. The European Federation of Neurological Societies formed a task force to focus on malignancy screening of paraneoplastic neurological syndromes and included dermatomyositis as one of the signs.10 Patients should have a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Women should have a mammogram and a pelvis ultrasound. Men younger than 50 years should consider testes ultrasound, and patients older than 50 years should undergo usual colonoscopy screening.

The risk of malignancy is highest in the first year after diagnosis, but may extend to 5 years after the diagnosis, so repeat screening should be performed 3-6 months after diagnosis, followed with biannual testing for 4 years. If a malignancy is present, then treatment should be tailored to the neoplasm to improve symptoms of myositis; however, response is generally worse than it would be with dermatomyositis in the absence of malignancy. In the present case with bladder cancer, therapies may include platinum-based-chemotherapy, resection, and radiation. Dermatomyositis as a result of a bladder cancer paraneoplastic syndrome is associated with a poor prognosis as demonstrated in the case of this patient and others reported in the literature.11

Even though dermatomyositis is usually a chronic disease process, 87% of patients respond initially to corticosteroid treatment.12 Therefore, treatment should be escalated with an agent such as azathioprine or methotrexate, or, like in this case, an underlying malignancy should be suspected. This case emphasizes the importance of screening patients appropriately for malignancy in patients with an inflammatory myopathy and reveals the poor prognosis associated with this disease.

The clinical presentation of bladder cancer typically presents with hematuria; changes in voiding habits such as urgency, frequency, and pain; or less commonly, obstructive symptoms. Rarely does bladder cancer first present as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome with an inflammatory myopathy. Inflammatory myopathies such as dermatomyositis have been known to be associated with malignancy, however, in a meta-analysis by Yang and colleagues of 449 patients with dermatomyositis and malignancy there were only 8 cases reported of bladder cancer.1 Herein, we report a paraneoplastic dermatomyositis in the setting of a bladder cancer.

Case presentation and summary

A 65-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension and alcohol use presented to the emergency department with worsening pain, stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and inability to lift his arms above his shoulders. During the physical exam, an erythematous purple rash was noted over his chest, neck, and arms. Upon further evaluation, his creatine phosphokinase was 3,500 U/L (reference range 52-336 U/L) suggesting muscle breakdown and possible inflammatory myopathy. A biopsy of the left deltoid and quadriceps muscles was performed and yielded a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. He was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily for his inflammatory myopathy. The patient also reported an unintentional weight loss of 20 lbs. and increasing weakness and inability to swallow, which caused aspiration events without developing pneumonia.

The patient’s symptoms worsened while he was on steroids, and we became concerned about the possibility of a primary malignancy, which led to further work-up. The results of a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed right-sided hydronephrosis and hydrourteter with an irregular, soft-tissue density mass of 4.7 x 3.2 x 4.2 cm along the posterior wall of the bladder (Figure 1).

A cystoscopy was performed with transurethral resection of a bladder tumor that was more than 8 cm in diameter. Because the mass was not fully resectable, only 25% of the tumor burden was removed. The pathology report revealed an invasive, high-grade urothelial cell carcinoma (Figure 2, see PDF). Further imaging ruled out metastatic spread. The patient was continued on steroids. He was not a candidate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy because of his comorbidities and cisplatin ineligibility owing to his significant bilateral hearing deficiencies. Members of a multidisciplinary tumor board decided to move forward with definitive surgery. The patient underwent a robotic-assisted laparoscoptic cystoprostatectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and open ileal conduit urinary diversion. Staging of tumor was determined as pT3b N1 (1/30) M0, LVI+. After the surgery, the patient had resolution of his rash and significant improvement in his muscle weakness with the ability to raise his arms over his head and climb stairs. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not given since he was cisplatin ineligible as a result of his hearing loss. Active surveillance was preferred.

Four months after his cystoprostatectomy, he experienced new-onset hip pain and further imaging, including a bone scan, was performed. It showed metastatic disease in the ischium and iliac crest (Figure 3).

The patient decided to forgo any palliative chemotherapy and to have palliative radiation for pain and enroll in hospice. He died nine months after the initial diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma.

Discussion

Dermatomyositis is one of the inflammatory myopathies with a clinical presentation of proximal muscle weakness and characteristic skin findings of Gottron papules and heliotrope eruption. The most common subgroups of inflammatory myopathies are dermatomyositis, polymyositis, necrotizing autoimmune myopathy, and inclusion body myopathy. The pathogenesis of inflammatory myopathies is not well understood; however, some theories have been described, including: type 1 interferon signaling causing myofiber injury and antibody-complement mediated processes causing ischemia resulting in myofiber injury. 2,3 The diagnoses of inflammatory myopathies may be suggested based on history, physical examination findings, laboratory values showing muscle injury (creatine kinase, aldolase, ALT, AST, LDH), myositis-specific antibodies (antisynthetase autoantibodies), electromyogram, and magnetic-resonance imaging. However, muscle biopsy remains the gold standard.4

The initial treatment of inflammatory myopathies begins with glucocorticoid therapy at 0.5-1.0 mg/kg. This regimen may be titrated down over 6 weeks to a level adequate to control symptoms. Even while on glucocorticoid therapy, this patient’s symptoms continued, along with the development of dysphagia. Dysphagia is another notable symptom of dermatomyositis that may result in aspiration pneumonia with fatal outcomes.5,6,7 Not only did this patient initially respond poorly to corticosteroids, but the unintentional weight loss was another alarming feature prompting further evaluation. That led to the diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma, which was causing the paraneoplastic syndrome.

A paraneoplastic syndrome is a collection of symptoms that are observed in organ systems separate from the primary disease. This process is mostly caused by an autoimmune response to the tumor and nervous system.8 Inflammatory myopathies, such as dermatomyositis, have been shown to be associated with a variety of malignancies as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome. The most common cancers associated with dermatomyositis are ovarian, lung, pancreatic, stomach, colorectal, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.9 Although an association between dermatomyositis and bladder cancer has been established, very few cases have been reported in the literature. In the Yang meta-analysis, the relative risk of malignancy for patients with dermatomyositis was 5.5%, and of the 449 patients with dermatomyositis who had malignancy, only 8 cases of bladder cancer were reported.1

After a patient has been diagnosed with an inflammatory myopathy, there should be further evaluation for an underling malignancy causing a paraneoplastic process. The risk of these patients having a malignancy overall is 4.5 times higher than patients without dermatomyositis.1 Definite screening recommendations have not been established, but screening should be based on patient’s age, gender, and clinical scenario. The European Federation of Neurological Societies formed a task force to focus on malignancy screening of paraneoplastic neurological syndromes and included dermatomyositis as one of the signs.10 Patients should have a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Women should have a mammogram and a pelvis ultrasound. Men younger than 50 years should consider testes ultrasound, and patients older than 50 years should undergo usual colonoscopy screening.

The risk of malignancy is highest in the first year after diagnosis, but may extend to 5 years after the diagnosis, so repeat screening should be performed 3-6 months after diagnosis, followed with biannual testing for 4 years. If a malignancy is present, then treatment should be tailored to the neoplasm to improve symptoms of myositis; however, response is generally worse than it would be with dermatomyositis in the absence of malignancy. In the present case with bladder cancer, therapies may include platinum-based-chemotherapy, resection, and radiation. Dermatomyositis as a result of a bladder cancer paraneoplastic syndrome is associated with a poor prognosis as demonstrated in the case of this patient and others reported in the literature.11

Even though dermatomyositis is usually a chronic disease process, 87% of patients respond initially to corticosteroid treatment.12 Therefore, treatment should be escalated with an agent such as azathioprine or methotrexate, or, like in this case, an underlying malignancy should be suspected. This case emphasizes the importance of screening patients appropriately for malignancy in patients with an inflammatory myopathy and reveals the poor prognosis associated with this disease.

1. Yang Z, Lin F, Qin B, Liang Y, Zhong R. Polymyositis/dermatomyositis and malignancy risk: a metaanalysis study. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(2):282-291.

2. Greenberg, SA. Dermatomyositis and type 1 interferons. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(3):198-203.

3. Dalakas, MC, Hohlfeld, R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362(9388):971-982.

4. Malik A, Hayat G, Kalia JS, Guzman MA. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: clinical approach and management. Front Neurol. 2016;7:64.

5. Sabio JM, Vargas-Hitos JA, Jiménez-Alonso J. Paraneoplastic dermatomyositis associated with bladder cancer. Lupus. 2006;15(9):619-620.