User login

Marijuana: Most oncologists are having the conversation

The vast majority of oncologists discuss medical marijuana use with their patients, and around one-half recommend it to patients, yet many also say they do not feel equipped to make clinical recommendations on its use, new research has found.

A survey on medical marijuana was mailed to a nationally-representative, random sample of 400 medical oncologists and had a response rate of 63%; results from the 237 responders revealed that 79.8% had discussed medical marijuana use with patients or their families and 45.9% had recommended medical marijuana for cancer-related issues to at least one patient in the previous year.

Oncologists in the western United States were significantly more likely to recommend medical marijuana use, compared with those in the south of the country (84.2% vs. 34.7%, respectively; P less than .001), Ilana M. Braun, MD, and her associates reported in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Doctors who practiced outside a hospital setting were also significantly more likely to recommend medical marijuana to their patients, as were medical oncologists with higher practice volumes.

Among the oncologists who reported discussing medical marijuana use with patients, 78% said these conversations were more likely to be initiated by the patient and their family than by the oncologist themselves.

However only 29.4% of oncologists surveyed said they felt “sufficiently knowledgeable” to make recommendations to patients about medical marijuana. Even among those who said they had recommended medical marijuana to a patient in the past year, 56.2% said they didn’t feel they had enough knowledge to make a recommendation.

Overall, oncologists had mixed views about medical marijuana. About one-third viewed it as equal to or more effective than standard pain treatments, one-third viewed it as less effective, and one-third said they did not know. However two-thirds viewed medical marijuana as a useful adjunct to standard pain therapies.

Two-thirds of oncologists surveyed believed medical marijuana was as good as or better than standard treatments for poor appetite or cachexia, but less than half felt it was equal to or better than standard antinausea therapies.

The data revealed a “clinically problematic discrepancy” between medical oncologists’ their perceived knowledge about medical marijuana use and their actual beliefs and practices, said Dr. Braun of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and her associates.

“Although our survey could not determine why oncologists recommend medical marijuana, it may be because they regard medical marijuana as an alternative therapy that is difficult to evaluate given sparse randomized, controlled trial data,” they wrote.

“[The results] highlight a crucial need for expedited clinical trials exploring marijuana’s potential medicinal effects in oncology (e.g. as an adjunctive pain management strategy or as a treatment of anorexia/cachexia) and the need for educational programs about medical marijuana to inform oncologists who frequently confront questions regarding medical marijuana in daily practice.”

No funding was declared. Two authors declared royalties and honoraria from medical publishing and a research institute, and one declared fees for expert testimony.

SOURCE: Braun I et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.1221.

The vast majority of oncologists discuss medical marijuana use with their patients, and around one-half recommend it to patients, yet many also say they do not feel equipped to make clinical recommendations on its use, new research has found.

A survey on medical marijuana was mailed to a nationally-representative, random sample of 400 medical oncologists and had a response rate of 63%; results from the 237 responders revealed that 79.8% had discussed medical marijuana use with patients or their families and 45.9% had recommended medical marijuana for cancer-related issues to at least one patient in the previous year.

Oncologists in the western United States were significantly more likely to recommend medical marijuana use, compared with those in the south of the country (84.2% vs. 34.7%, respectively; P less than .001), Ilana M. Braun, MD, and her associates reported in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Doctors who practiced outside a hospital setting were also significantly more likely to recommend medical marijuana to their patients, as were medical oncologists with higher practice volumes.

Among the oncologists who reported discussing medical marijuana use with patients, 78% said these conversations were more likely to be initiated by the patient and their family than by the oncologist themselves.

However only 29.4% of oncologists surveyed said they felt “sufficiently knowledgeable” to make recommendations to patients about medical marijuana. Even among those who said they had recommended medical marijuana to a patient in the past year, 56.2% said they didn’t feel they had enough knowledge to make a recommendation.

Overall, oncologists had mixed views about medical marijuana. About one-third viewed it as equal to or more effective than standard pain treatments, one-third viewed it as less effective, and one-third said they did not know. However two-thirds viewed medical marijuana as a useful adjunct to standard pain therapies.

Two-thirds of oncologists surveyed believed medical marijuana was as good as or better than standard treatments for poor appetite or cachexia, but less than half felt it was equal to or better than standard antinausea therapies.

The data revealed a “clinically problematic discrepancy” between medical oncologists’ their perceived knowledge about medical marijuana use and their actual beliefs and practices, said Dr. Braun of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and her associates.

“Although our survey could not determine why oncologists recommend medical marijuana, it may be because they regard medical marijuana as an alternative therapy that is difficult to evaluate given sparse randomized, controlled trial data,” they wrote.

“[The results] highlight a crucial need for expedited clinical trials exploring marijuana’s potential medicinal effects in oncology (e.g. as an adjunctive pain management strategy or as a treatment of anorexia/cachexia) and the need for educational programs about medical marijuana to inform oncologists who frequently confront questions regarding medical marijuana in daily practice.”

No funding was declared. Two authors declared royalties and honoraria from medical publishing and a research institute, and one declared fees for expert testimony.

SOURCE: Braun I et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.1221.

The vast majority of oncologists discuss medical marijuana use with their patients, and around one-half recommend it to patients, yet many also say they do not feel equipped to make clinical recommendations on its use, new research has found.

A survey on medical marijuana was mailed to a nationally-representative, random sample of 400 medical oncologists and had a response rate of 63%; results from the 237 responders revealed that 79.8% had discussed medical marijuana use with patients or their families and 45.9% had recommended medical marijuana for cancer-related issues to at least one patient in the previous year.

Oncologists in the western United States were significantly more likely to recommend medical marijuana use, compared with those in the south of the country (84.2% vs. 34.7%, respectively; P less than .001), Ilana M. Braun, MD, and her associates reported in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Doctors who practiced outside a hospital setting were also significantly more likely to recommend medical marijuana to their patients, as were medical oncologists with higher practice volumes.

Among the oncologists who reported discussing medical marijuana use with patients, 78% said these conversations were more likely to be initiated by the patient and their family than by the oncologist themselves.

However only 29.4% of oncologists surveyed said they felt “sufficiently knowledgeable” to make recommendations to patients about medical marijuana. Even among those who said they had recommended medical marijuana to a patient in the past year, 56.2% said they didn’t feel they had enough knowledge to make a recommendation.

Overall, oncologists had mixed views about medical marijuana. About one-third viewed it as equal to or more effective than standard pain treatments, one-third viewed it as less effective, and one-third said they did not know. However two-thirds viewed medical marijuana as a useful adjunct to standard pain therapies.

Two-thirds of oncologists surveyed believed medical marijuana was as good as or better than standard treatments for poor appetite or cachexia, but less than half felt it was equal to or better than standard antinausea therapies.

The data revealed a “clinically problematic discrepancy” between medical oncologists’ their perceived knowledge about medical marijuana use and their actual beliefs and practices, said Dr. Braun of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and her associates.

“Although our survey could not determine why oncologists recommend medical marijuana, it may be because they regard medical marijuana as an alternative therapy that is difficult to evaluate given sparse randomized, controlled trial data,” they wrote.

“[The results] highlight a crucial need for expedited clinical trials exploring marijuana’s potential medicinal effects in oncology (e.g. as an adjunctive pain management strategy or as a treatment of anorexia/cachexia) and the need for educational programs about medical marijuana to inform oncologists who frequently confront questions regarding medical marijuana in daily practice.”

No funding was declared. Two authors declared royalties and honoraria from medical publishing and a research institute, and one declared fees for expert testimony.

SOURCE: Braun I et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.1221.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: The majority of medical oncologists discuss medical marijuana use with their patients, though few feel knowledgeable on the subject.

Major finding: Nearly 80% of medical oncologists have discussed medical marijuana use with their patients, but only 29.4% of those surveyed felt sufficiently knowledgeable.

Study details: Survey of 237 medical oncologists.

Disclosures: No funding was declared. Two authors declared royalties and honoraria from medical publishing and a research institute, and one declared fees for expert testimony.

Source: Braun I et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.1221.

Patients with CF at increased risk for GI cancers

Patients with cystic fibrosis have a significantly greater risk for developing cancers of the gastrointestinal tract compared with the general population, results of a systematic review and meta-analysis indicate.

Among persons with cystic fibrosis (CF) the standardized incidence ratio (SIR) for any gastrointestinal cancer compared with the general population was 8.13 (P less than .0001). Patients with CF were at significantly elevated risk for cancers of the small bowel, colon, biliary tract, and pancreas, reported Atsushi Sakuraba, MD, PhD, of the University of Chicago, and his colleagues.

“Additionally, our findings suggest that patients who had an organ transplant have a higher risk of developing gastrointestinal cancer than those who did not. Although further studies are needed to monitor gastrointestinal cancer incidence over time in patients with cystic fibrosis, the development of a screening strategy for gastrointestinal cancer in these patients is warranted,” they wrote in Lancet Oncology.

As patients with CF live longer because of improvements in therapies and management of comorbidities, their risks for cancer and other diseases will increase, the authors noted.

To get a more accurate estimate of the degree of risk than what smaller cohort studies could provide, the investigators conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis. They narrowed their search to six cohort studies including 99,925 patients with CF followed for a total of 5,444,695 person-years.

As noted, patients with CF overall had an eightfold higher risk for gastrointestinal cancers compared with the general population, and for the subgroup of patients who had undergone a lung transplant, the SIR was 21.13 compared with 4.18 for those with CF but no lung transplant (P less than .0001).

- The SIRs for site-specific gastrointestinal cancers were as follows:

- Small bowel: SIR= 18.94 (P less than .0001).

- Colon: SIR = 10.91 (P less than .0001).

- Biliary tract: SIR = 17.87 (P less than .0001).

- Pancreas: SIR = 6.18 (P = .022).

The investigators recommend screening for gastrointestinal cancers in patients with CF in general, and especially for patients who have undergone lung transplantation and are receiving immunosuppressive therapies.

Because of the elevated risk of pancreatic and biliary tract cancers, the authors propose a screening program including magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound, or abdominal ultrasound and measurement of cancer antigen 19-9.

The authors reported that the study had no funding source, and they declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Yamada A et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr 26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30188-8.

The emergence of gastrointestinal cancer as a clinical complication in adults with cystic fibrosis is a consequence of the substantial improvement in life expectancy. Novel CFTR modulator therapies, which correct the malfunctioning protein and increase its expression at the apical surface, might decrease the incidence of gastrointestinal cancers in patients with cystic fibrosis.

In conclusion, the meta-analysis by Yamada and colleagues shows that cystic fibrosis can be considered a gastrointestinal cancer syndrome, for which screening and surveillance protocols should be implemented. Oncologists and gastroenterologists managing patients with cystic fibrosis should consider the best methods for screening of the small bowel, biliary tract, pancreas, and colon to prevent gastrointestinal malignancies in these patients.

Mordechai Slae, MD, and Michael Wilschanski, MD, are with the Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. These comments are condensed from their editorial in The Lancet Oncology.

The emergence of gastrointestinal cancer as a clinical complication in adults with cystic fibrosis is a consequence of the substantial improvement in life expectancy. Novel CFTR modulator therapies, which correct the malfunctioning protein and increase its expression at the apical surface, might decrease the incidence of gastrointestinal cancers in patients with cystic fibrosis.

In conclusion, the meta-analysis by Yamada and colleagues shows that cystic fibrosis can be considered a gastrointestinal cancer syndrome, for which screening and surveillance protocols should be implemented. Oncologists and gastroenterologists managing patients with cystic fibrosis should consider the best methods for screening of the small bowel, biliary tract, pancreas, and colon to prevent gastrointestinal malignancies in these patients.

Mordechai Slae, MD, and Michael Wilschanski, MD, are with the Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. These comments are condensed from their editorial in The Lancet Oncology.

The emergence of gastrointestinal cancer as a clinical complication in adults with cystic fibrosis is a consequence of the substantial improvement in life expectancy. Novel CFTR modulator therapies, which correct the malfunctioning protein and increase its expression at the apical surface, might decrease the incidence of gastrointestinal cancers in patients with cystic fibrosis.

In conclusion, the meta-analysis by Yamada and colleagues shows that cystic fibrosis can be considered a gastrointestinal cancer syndrome, for which screening and surveillance protocols should be implemented. Oncologists and gastroenterologists managing patients with cystic fibrosis should consider the best methods for screening of the small bowel, biliary tract, pancreas, and colon to prevent gastrointestinal malignancies in these patients.

Mordechai Slae, MD, and Michael Wilschanski, MD, are with the Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. These comments are condensed from their editorial in The Lancet Oncology.

Patients with cystic fibrosis have a significantly greater risk for developing cancers of the gastrointestinal tract compared with the general population, results of a systematic review and meta-analysis indicate.

Among persons with cystic fibrosis (CF) the standardized incidence ratio (SIR) for any gastrointestinal cancer compared with the general population was 8.13 (P less than .0001). Patients with CF were at significantly elevated risk for cancers of the small bowel, colon, biliary tract, and pancreas, reported Atsushi Sakuraba, MD, PhD, of the University of Chicago, and his colleagues.

“Additionally, our findings suggest that patients who had an organ transplant have a higher risk of developing gastrointestinal cancer than those who did not. Although further studies are needed to monitor gastrointestinal cancer incidence over time in patients with cystic fibrosis, the development of a screening strategy for gastrointestinal cancer in these patients is warranted,” they wrote in Lancet Oncology.

As patients with CF live longer because of improvements in therapies and management of comorbidities, their risks for cancer and other diseases will increase, the authors noted.

To get a more accurate estimate of the degree of risk than what smaller cohort studies could provide, the investigators conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis. They narrowed their search to six cohort studies including 99,925 patients with CF followed for a total of 5,444,695 person-years.

As noted, patients with CF overall had an eightfold higher risk for gastrointestinal cancers compared with the general population, and for the subgroup of patients who had undergone a lung transplant, the SIR was 21.13 compared with 4.18 for those with CF but no lung transplant (P less than .0001).

- The SIRs for site-specific gastrointestinal cancers were as follows:

- Small bowel: SIR= 18.94 (P less than .0001).

- Colon: SIR = 10.91 (P less than .0001).

- Biliary tract: SIR = 17.87 (P less than .0001).

- Pancreas: SIR = 6.18 (P = .022).

The investigators recommend screening for gastrointestinal cancers in patients with CF in general, and especially for patients who have undergone lung transplantation and are receiving immunosuppressive therapies.

Because of the elevated risk of pancreatic and biliary tract cancers, the authors propose a screening program including magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound, or abdominal ultrasound and measurement of cancer antigen 19-9.

The authors reported that the study had no funding source, and they declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Yamada A et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr 26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30188-8.

Patients with cystic fibrosis have a significantly greater risk for developing cancers of the gastrointestinal tract compared with the general population, results of a systematic review and meta-analysis indicate.

Among persons with cystic fibrosis (CF) the standardized incidence ratio (SIR) for any gastrointestinal cancer compared with the general population was 8.13 (P less than .0001). Patients with CF were at significantly elevated risk for cancers of the small bowel, colon, biliary tract, and pancreas, reported Atsushi Sakuraba, MD, PhD, of the University of Chicago, and his colleagues.

“Additionally, our findings suggest that patients who had an organ transplant have a higher risk of developing gastrointestinal cancer than those who did not. Although further studies are needed to monitor gastrointestinal cancer incidence over time in patients with cystic fibrosis, the development of a screening strategy for gastrointestinal cancer in these patients is warranted,” they wrote in Lancet Oncology.

As patients with CF live longer because of improvements in therapies and management of comorbidities, their risks for cancer and other diseases will increase, the authors noted.

To get a more accurate estimate of the degree of risk than what smaller cohort studies could provide, the investigators conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis. They narrowed their search to six cohort studies including 99,925 patients with CF followed for a total of 5,444,695 person-years.

As noted, patients with CF overall had an eightfold higher risk for gastrointestinal cancers compared with the general population, and for the subgroup of patients who had undergone a lung transplant, the SIR was 21.13 compared with 4.18 for those with CF but no lung transplant (P less than .0001).

- The SIRs for site-specific gastrointestinal cancers were as follows:

- Small bowel: SIR= 18.94 (P less than .0001).

- Colon: SIR = 10.91 (P less than .0001).

- Biliary tract: SIR = 17.87 (P less than .0001).

- Pancreas: SIR = 6.18 (P = .022).

The investigators recommend screening for gastrointestinal cancers in patients with CF in general, and especially for patients who have undergone lung transplantation and are receiving immunosuppressive therapies.

Because of the elevated risk of pancreatic and biliary tract cancers, the authors propose a screening program including magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound, or abdominal ultrasound and measurement of cancer antigen 19-9.

The authors reported that the study had no funding source, and they declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Yamada A et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr 26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30188-8.

FROM THE LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Patients with cystic fibrosis, especially those who have received a lung transplant, are at increased risk for gastrointestinal tract cancers.

Major finding: The standard incidence ratio for GI cancers among patients with CF was 8.13 compared with the general population.

Study details: Systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies including 99,925 patients with CF followed for 5,444,695 person-years.

Disclosures: The authors reported that the study had no funding source, and they declared no competing interests.

Source: Yamada A et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Apr 26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30188-8.

Novel targeted cancer drugs cause fewer arrhythmias

ORLANDO – Not all oncology drugs are equal when it comes to their risk of treatment-induced cardiac arrhythmias.

Indeed, compared with anthracycline-based regimens, long the workhorse in treating many forms of cancer, the novel targeted agents – tyrosine kinase inhibitors, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies – were 40% less likely to result in a new arrhythmia diagnosis within 6 months of treatment initiation, in a large, single-center retrospective study reported by Andrew Nickel at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Overall, 14% of cancer patients developed a first-ever cardiac arrhythmia within the first 6 months after treatment began. In a Cox multivariate analysis, treatment with a targeted cancer agent was independently associated with a 40% lower risk of arrhythmia, compared with anthracycline-containing therapy. Of note, the incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation was closely similar in the two groups.

Several patient factors emerged as independent predictors of increased risk of cancer treatment–induced arrhythmia in the multivariate analysis: male sex, with a 1.2-fold increased risk; baseline heart failure, with a 2.2-fold risk; and hypertension, which conferred a 1.6-fold increased risk. These are patient groups in which the novel targeted cancer treatments are a particularly attractive option from the standpoint of mitigating arrhythmia risk, provided their use would be appropriate, he observed.

Mr. Nickel reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Nickel A et al. ACC 18. Abstract 900-06.

ORLANDO – Not all oncology drugs are equal when it comes to their risk of treatment-induced cardiac arrhythmias.

Indeed, compared with anthracycline-based regimens, long the workhorse in treating many forms of cancer, the novel targeted agents – tyrosine kinase inhibitors, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies – were 40% less likely to result in a new arrhythmia diagnosis within 6 months of treatment initiation, in a large, single-center retrospective study reported by Andrew Nickel at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Overall, 14% of cancer patients developed a first-ever cardiac arrhythmia within the first 6 months after treatment began. In a Cox multivariate analysis, treatment with a targeted cancer agent was independently associated with a 40% lower risk of arrhythmia, compared with anthracycline-containing therapy. Of note, the incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation was closely similar in the two groups.

Several patient factors emerged as independent predictors of increased risk of cancer treatment–induced arrhythmia in the multivariate analysis: male sex, with a 1.2-fold increased risk; baseline heart failure, with a 2.2-fold risk; and hypertension, which conferred a 1.6-fold increased risk. These are patient groups in which the novel targeted cancer treatments are a particularly attractive option from the standpoint of mitigating arrhythmia risk, provided their use would be appropriate, he observed.

Mr. Nickel reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Nickel A et al. ACC 18. Abstract 900-06.

ORLANDO – Not all oncology drugs are equal when it comes to their risk of treatment-induced cardiac arrhythmias.

Indeed, compared with anthracycline-based regimens, long the workhorse in treating many forms of cancer, the novel targeted agents – tyrosine kinase inhibitors, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies – were 40% less likely to result in a new arrhythmia diagnosis within 6 months of treatment initiation, in a large, single-center retrospective study reported by Andrew Nickel at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Overall, 14% of cancer patients developed a first-ever cardiac arrhythmia within the first 6 months after treatment began. In a Cox multivariate analysis, treatment with a targeted cancer agent was independently associated with a 40% lower risk of arrhythmia, compared with anthracycline-containing therapy. Of note, the incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation was closely similar in the two groups.

Several patient factors emerged as independent predictors of increased risk of cancer treatment–induced arrhythmia in the multivariate analysis: male sex, with a 1.2-fold increased risk; baseline heart failure, with a 2.2-fold risk; and hypertension, which conferred a 1.6-fold increased risk. These are patient groups in which the novel targeted cancer treatments are a particularly attractive option from the standpoint of mitigating arrhythmia risk, provided their use would be appropriate, he observed.

Mr. Nickel reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Nickel A et al. ACC 18. Abstract 900-06.

REPORTING FROM ACC 2018

Key clinical point: The novel targeted cancer therapies cause markedly fewer cardiac arrhythmias.

Major finding: Cancer patients treated with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, immune checkpoint inhibitor, or another of the novel targeted therapies were 40% less likely than were those on anthracycline-based therapy to develop a treatment-induced cardiac arrhythmia up to 6 months after treatment initiation.

Study details: This was a retrospective single-center study including more than 5,000 cancer patients.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Source: Nickel A et al. ACC 18, Abstract #900-06.

Reduced intensity conditioning doesn’t protect fertility

SALT LAKE CITY – Both male and female recipients of childhood hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) were very likely to have severely decreased fertility potential, even in the setting of preserved puberty, according to a recent study of adolescent and young adult HSCT recipients.

A reduced intensity conditioning regimen did not protect this cohort from decreased fertility, a finding that surprised the study’s lead author.

“We had hypothesized that, as compared to myeloablative conditioning, reduced intensity conditioning in children who received HSCT would lower the risk of infertility and lessen gonadal failure,” said Helen Oquendo del Toro, MD. In fact, Dr. Oquendo del Toro and her collaborators found that more than 90% of semen samples available for analysis had results that indicated infertility or severely impaired fertility, regardless of the type of pretransplant conditioning the patient had received.

The study highlights the need for fertility preservation when possible before HSCT, and makes clear that “normal puberty does not equate to normal fertility,” said Dr. Oquendo del Toro, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Oquendo del Toro presented results of an observational cohort study of late effects of HSCT that included individuals aged 1-40 years old who received a single HSCT at, or after, 1 year of age.

Twenty-one males in the study had semen available for analysis. Of the 10 males who received myeloablative conditioning (MAC), 8 had azoospermia, and 2 more had oligoteratospermia (low sperm count with abnormal morphology). For the 11 males who received reduced intensity conditioning (RIC), eight had azoospermia, two had semen samples that showed oligoteratospermia, and one had a normal semen analysis.

The median age at transplant for these males was 14.5 years, and patients were a median of 19 years old at follow-up, Dr. Oquendo del Toro said at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

For females in the study, low levels of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) – generally considered the best surrogate lab value for ovarian reserve – were nearly as common. Of 14 females receiving MAC, 13 (93%) had low AMH, as did 6 of 8 (75%) female patients who received RIC.

Individuals with more than one HSCT were excluded, as were those with Fanconi anemia, which itself carries a risk of gonadal failure. The study’s two aims were to investigate gonadal function as well as fertility potential after receipt of either RIC or MAC for HSCT.

Patients were seen by an endocrinologist who assessed testicular volume and assigned a Tanner stage. At age 11 and older, patients’ gonadal function was assessed on an annual basis by obtaining levels of luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone for all patients; female estradiol levels were tracked, as were male testosterone levels.

Assessment of fertility potential required additional laboratory testing: For females, the investigators obtained AMH levels, while for males, semen analysis was coupled with serum levels of inhibin B, an indicator of Sertoli cell function.

A total of 72 males were more than 1 year post-HSCT in the cohort, and of these, 41 were at least 11 years old and had achieved pubertal status according to laboratory evaluation. In all, 22 of the male patients received RIC, and 19 received MAC.

Males receiving MAC were a median 20 years old at their follow-up evaluation, and a median 6 years post-HSCT, while the RIC group were a median of 18.5 years old and 5.5 years out from their transplant.

Of the 50 females who were more than 1 year post-HSCT, 25 were pubertal and 11 years old or older. Nine of the female patients received RIC, and 16 received MAC.

Females who received MAC were a median 12.1 years old and 4.1 years post-HSCT at their follow-up evaluation. Females receiving RIC were a median 16 years old, and 6.5 years post-HSCT at the time of evaluation.

Patients received their transplants for a variety of malignant and nonmalignant conditions.

“We saw relatively normal gonadotropins after both reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning in males,” Dr. Oquendo del Toro said. Of the MAC group, 4 of 15 (27%) had elevated follicle stimulating hormone levels, as did 2 of 17 (12%) of the RIC group. Elevated luteinizing hormone levels were seen in 2 of 15 (13%) of the MAC group and 1 of 17 (6%) of the RIC group. Four patients in each group had abnormally low testosterone levels.

However, when the investigators looked at inhibin B levels in males, they found abnormally low levels in 9 of 15 (60%) of those who received MAC, and in 6 of 15 (40%) of those who received RIC. These results meshed with the severely abnormal semen analyses investigators found from those participants for whom a sample was available, Dr. Oquendo del Toro said.

For females, estradiol levels were significantly lower for those who had received MAC, with 7 of 11 (64%) of that group having abnormally low estradiol levels. The levels approached 0 pg/mL for many, said Dr. Oquendo del Toro. None of the eight patients who had received RIC had abnormally low estradiol levels (P = .0008).

“Male puberty is relatively well preserved after both myeloablative and reduced intensity conditioning, but there is a greater than 90% risk of male infertility associated with both reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning for HSCT,” Dr. Oquendo del Toro said.

For females, the study paints a different picture. “We saw decreased premature ovarian failure after reduced intensity conditioning … but the fertility potential as assessed by anti-Müllerian hormone was decreased” after both conditioning regimens, she said.

Dr. Oquendo del Toro reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Oquendo del Toro H et al. The 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings, Abstract 88.

SALT LAKE CITY – Both male and female recipients of childhood hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) were very likely to have severely decreased fertility potential, even in the setting of preserved puberty, according to a recent study of adolescent and young adult HSCT recipients.

A reduced intensity conditioning regimen did not protect this cohort from decreased fertility, a finding that surprised the study’s lead author.

“We had hypothesized that, as compared to myeloablative conditioning, reduced intensity conditioning in children who received HSCT would lower the risk of infertility and lessen gonadal failure,” said Helen Oquendo del Toro, MD. In fact, Dr. Oquendo del Toro and her collaborators found that more than 90% of semen samples available for analysis had results that indicated infertility or severely impaired fertility, regardless of the type of pretransplant conditioning the patient had received.

The study highlights the need for fertility preservation when possible before HSCT, and makes clear that “normal puberty does not equate to normal fertility,” said Dr. Oquendo del Toro, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Oquendo del Toro presented results of an observational cohort study of late effects of HSCT that included individuals aged 1-40 years old who received a single HSCT at, or after, 1 year of age.

Twenty-one males in the study had semen available for analysis. Of the 10 males who received myeloablative conditioning (MAC), 8 had azoospermia, and 2 more had oligoteratospermia (low sperm count with abnormal morphology). For the 11 males who received reduced intensity conditioning (RIC), eight had azoospermia, two had semen samples that showed oligoteratospermia, and one had a normal semen analysis.

The median age at transplant for these males was 14.5 years, and patients were a median of 19 years old at follow-up, Dr. Oquendo del Toro said at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

For females in the study, low levels of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) – generally considered the best surrogate lab value for ovarian reserve – were nearly as common. Of 14 females receiving MAC, 13 (93%) had low AMH, as did 6 of 8 (75%) female patients who received RIC.

Individuals with more than one HSCT were excluded, as were those with Fanconi anemia, which itself carries a risk of gonadal failure. The study’s two aims were to investigate gonadal function as well as fertility potential after receipt of either RIC or MAC for HSCT.

Patients were seen by an endocrinologist who assessed testicular volume and assigned a Tanner stage. At age 11 and older, patients’ gonadal function was assessed on an annual basis by obtaining levels of luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone for all patients; female estradiol levels were tracked, as were male testosterone levels.

Assessment of fertility potential required additional laboratory testing: For females, the investigators obtained AMH levels, while for males, semen analysis was coupled with serum levels of inhibin B, an indicator of Sertoli cell function.

A total of 72 males were more than 1 year post-HSCT in the cohort, and of these, 41 were at least 11 years old and had achieved pubertal status according to laboratory evaluation. In all, 22 of the male patients received RIC, and 19 received MAC.

Males receiving MAC were a median 20 years old at their follow-up evaluation, and a median 6 years post-HSCT, while the RIC group were a median of 18.5 years old and 5.5 years out from their transplant.

Of the 50 females who were more than 1 year post-HSCT, 25 were pubertal and 11 years old or older. Nine of the female patients received RIC, and 16 received MAC.

Females who received MAC were a median 12.1 years old and 4.1 years post-HSCT at their follow-up evaluation. Females receiving RIC were a median 16 years old, and 6.5 years post-HSCT at the time of evaluation.

Patients received their transplants for a variety of malignant and nonmalignant conditions.

“We saw relatively normal gonadotropins after both reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning in males,” Dr. Oquendo del Toro said. Of the MAC group, 4 of 15 (27%) had elevated follicle stimulating hormone levels, as did 2 of 17 (12%) of the RIC group. Elevated luteinizing hormone levels were seen in 2 of 15 (13%) of the MAC group and 1 of 17 (6%) of the RIC group. Four patients in each group had abnormally low testosterone levels.

However, when the investigators looked at inhibin B levels in males, they found abnormally low levels in 9 of 15 (60%) of those who received MAC, and in 6 of 15 (40%) of those who received RIC. These results meshed with the severely abnormal semen analyses investigators found from those participants for whom a sample was available, Dr. Oquendo del Toro said.

For females, estradiol levels were significantly lower for those who had received MAC, with 7 of 11 (64%) of that group having abnormally low estradiol levels. The levels approached 0 pg/mL for many, said Dr. Oquendo del Toro. None of the eight patients who had received RIC had abnormally low estradiol levels (P = .0008).

“Male puberty is relatively well preserved after both myeloablative and reduced intensity conditioning, but there is a greater than 90% risk of male infertility associated with both reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning for HSCT,” Dr. Oquendo del Toro said.

For females, the study paints a different picture. “We saw decreased premature ovarian failure after reduced intensity conditioning … but the fertility potential as assessed by anti-Müllerian hormone was decreased” after both conditioning regimens, she said.

Dr. Oquendo del Toro reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Oquendo del Toro H et al. The 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings, Abstract 88.

SALT LAKE CITY – Both male and female recipients of childhood hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) were very likely to have severely decreased fertility potential, even in the setting of preserved puberty, according to a recent study of adolescent and young adult HSCT recipients.

A reduced intensity conditioning regimen did not protect this cohort from decreased fertility, a finding that surprised the study’s lead author.

“We had hypothesized that, as compared to myeloablative conditioning, reduced intensity conditioning in children who received HSCT would lower the risk of infertility and lessen gonadal failure,” said Helen Oquendo del Toro, MD. In fact, Dr. Oquendo del Toro and her collaborators found that more than 90% of semen samples available for analysis had results that indicated infertility or severely impaired fertility, regardless of the type of pretransplant conditioning the patient had received.

The study highlights the need for fertility preservation when possible before HSCT, and makes clear that “normal puberty does not equate to normal fertility,” said Dr. Oquendo del Toro, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Oquendo del Toro presented results of an observational cohort study of late effects of HSCT that included individuals aged 1-40 years old who received a single HSCT at, or after, 1 year of age.

Twenty-one males in the study had semen available for analysis. Of the 10 males who received myeloablative conditioning (MAC), 8 had azoospermia, and 2 more had oligoteratospermia (low sperm count with abnormal morphology). For the 11 males who received reduced intensity conditioning (RIC), eight had azoospermia, two had semen samples that showed oligoteratospermia, and one had a normal semen analysis.

The median age at transplant for these males was 14.5 years, and patients were a median of 19 years old at follow-up, Dr. Oquendo del Toro said at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

For females in the study, low levels of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) – generally considered the best surrogate lab value for ovarian reserve – were nearly as common. Of 14 females receiving MAC, 13 (93%) had low AMH, as did 6 of 8 (75%) female patients who received RIC.

Individuals with more than one HSCT were excluded, as were those with Fanconi anemia, which itself carries a risk of gonadal failure. The study’s two aims were to investigate gonadal function as well as fertility potential after receipt of either RIC or MAC for HSCT.

Patients were seen by an endocrinologist who assessed testicular volume and assigned a Tanner stage. At age 11 and older, patients’ gonadal function was assessed on an annual basis by obtaining levels of luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone for all patients; female estradiol levels were tracked, as were male testosterone levels.

Assessment of fertility potential required additional laboratory testing: For females, the investigators obtained AMH levels, while for males, semen analysis was coupled with serum levels of inhibin B, an indicator of Sertoli cell function.

A total of 72 males were more than 1 year post-HSCT in the cohort, and of these, 41 were at least 11 years old and had achieved pubertal status according to laboratory evaluation. In all, 22 of the male patients received RIC, and 19 received MAC.

Males receiving MAC were a median 20 years old at their follow-up evaluation, and a median 6 years post-HSCT, while the RIC group were a median of 18.5 years old and 5.5 years out from their transplant.

Of the 50 females who were more than 1 year post-HSCT, 25 were pubertal and 11 years old or older. Nine of the female patients received RIC, and 16 received MAC.

Females who received MAC were a median 12.1 years old and 4.1 years post-HSCT at their follow-up evaluation. Females receiving RIC were a median 16 years old, and 6.5 years post-HSCT at the time of evaluation.

Patients received their transplants for a variety of malignant and nonmalignant conditions.

“We saw relatively normal gonadotropins after both reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning in males,” Dr. Oquendo del Toro said. Of the MAC group, 4 of 15 (27%) had elevated follicle stimulating hormone levels, as did 2 of 17 (12%) of the RIC group. Elevated luteinizing hormone levels were seen in 2 of 15 (13%) of the MAC group and 1 of 17 (6%) of the RIC group. Four patients in each group had abnormally low testosterone levels.

However, when the investigators looked at inhibin B levels in males, they found abnormally low levels in 9 of 15 (60%) of those who received MAC, and in 6 of 15 (40%) of those who received RIC. These results meshed with the severely abnormal semen analyses investigators found from those participants for whom a sample was available, Dr. Oquendo del Toro said.

For females, estradiol levels were significantly lower for those who had received MAC, with 7 of 11 (64%) of that group having abnormally low estradiol levels. The levels approached 0 pg/mL for many, said Dr. Oquendo del Toro. None of the eight patients who had received RIC had abnormally low estradiol levels (P = .0008).

“Male puberty is relatively well preserved after both myeloablative and reduced intensity conditioning, but there is a greater than 90% risk of male infertility associated with both reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning for HSCT,” Dr. Oquendo del Toro said.

For females, the study paints a different picture. “We saw decreased premature ovarian failure after reduced intensity conditioning … but the fertility potential as assessed by anti-Müllerian hormone was decreased” after both conditioning regimens, she said.

Dr. Oquendo del Toro reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Oquendo del Toro H et al. The 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings, Abstract 88.

REPORTING FROM THE 2018 BMT TANDEM MEETINGS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 21 males receiving reduced intensity conditioning or myeloablative conditioning, all but one had azoospermia or oligoteratospermia.

Study details: Observational cohort study of 41 males and 25 females receiving pediatric HSCT.

Disclosures: Dr. Oquendo del Toro reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Oquendo del Toro H et al. The 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings, Abstract 88.

Prompt palliative care cut hospital costs in pooled study

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Average cost savings per admission were $3,237 overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P-values less than .001).

Study details: Systematic review and meta-analysis of six cohort studies of 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease.

Disclosures: Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

Qualitative assessment of organizational barriers to optimal lung cancer care in a community hospital setting in the United States

Lung cancer is a major public health challenge in the United States. It is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States, accounting for 27% of all cancer deaths, and it has an aggregate 5-year survival rate of 18%.1 Advances in diagnostic and treatment options are rapidly increasing the complexity of lung cancer care delivery, which involves multiple specialty providers and often cuts across health care institutions.2-4 Navigating the process of care while coping with the complexities of the illness can be overwhelming for both the patient and the caregiver.5 With increasing regulations and cost-cutting measures, the health care system in the United States can pose many challenges, especially for those dealing with catastrophic and life-threatening illnesses. Any barrier to accessing care often increases anxiety in patients, who are already trying to cope with the management of their disease.6-8

The concept of barriers to quality care (such as the receipt of timely and appropriate diagnostic and staging work-up and treatment selection according to evidence-based guidelines) is generally used in the context of improving health care management or prevention programs.9-13 Barriers might include high costs, transportation, distance, underinsurance, limited hours for access to care, patient sharing by physicians, and a lack of access to information about physicians’ recommendations.10,14-16 Such barriers have been categorized as organizational (leadership and workforce), structural (process of care), clinical (provider-patient encounter), and macro (policy and population).17,18 Organizational barriers are defined as impediments encountered within the medical system and health care organizations when accessing, receiving, and delivering care.12 Several organizational barriers have been identified in the literature based on characteristics of the targeted population (eg, race, ethnicity, type of illness), key stakeholder views, and aspects of care (eg, screening, preventive practice, care, and treatment).

In a systematic review, Betancourt and colleagues reported provider-patient interactions, processes of care, and language as some of the barriers to receiving quality care.17 Although cancer screening has been shown to reduce mortality in the adult population for several types of cancer,19-21 barriers that impede access to services have been identified as emanating not only from the macro level (eg, age of screening, reimbursement problems, screening guidelines) or inter- and intra-individual levels (eg, awareness of screening, various perspectives on life and cancer, comorbidities, social support), but also from the organization (organizational infrastructure that inhibits screening because of limited participation in research trials) and provider levels (impaired communication regarding screening between patient and physician, low commitment to shared decision-making, provider’s awareness of screening and screening guidelines).18 Other organizational barriers, such as difficulty navigating the health care system, poor interaction between patients and medical staff, and language barriers, have been identified in a systematic review of breast cancer screening in immigrant and minority women.22

Other barriers to quality cancer care reported by patients include knowledge about the disease and treatment, poor communication with providers, lack of coordination and timeliness of care, and lack of attention to care. Providers have identified other barriers to quality care, which include a lack of access to care, reimbursement problems, poor psychosocial support services, accountability of care, provider workload, and inadequate patient education.23 Few qualitative studies have been conducted to understand the organizational barriers that lung cancer patients and their caregivers face within the health care system.

Through the use of focus groups, we sought the perspectives of lung cancer patients and their caregivers on the organizational barriers that they experience while navigating the health care system. Identifying and understanding these barriers can help health care professionals work with patients and their caregivers to alleviate these stressors in an already difficult time.3,24 In addition, a more thorough understanding of patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives on organizational barriers may help improve health care delivery and, thus, patient satisfaction.

Methods

With the approval of the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Memphis and the Baptist Memorial Health Care Corporation, we conducted focus groups with lung cancer patients and their informal caregivers to understand the challenges they encounter while navigating the health care system during their illness. The Baptist Memorial Health Care system is centered in the Mid-South region of the United States, which has some of the highest US lung cancer incidence rates.25

Research staff identified potential participants from a roster of patients provided by treatment clinics within the system. Patients eligible for this study had received care for suspected lung cancer within a community-based health care system within 6 months preceding the date of the focus group. Eligible patients were approached by the research staff by cold calling or in-person contact during clinic visits for their consent to participate in the study. From a compiled list of 219 patients, 89 received initial contact to gauge interest. Of those, 42 patients were formally approached and asked to participate; 22 agreed to participate, and 20 did not participate for reasons including illness, previous participation in other forms of patient feedback, lack of interest, failure to show up to focus group sessions, change of mind, lack of transportation, or other commitments. Patients identified their informal caregivers to form patient-caregiver dyads. All patients and caregivers provided written informed consent before participating in the focus groups.

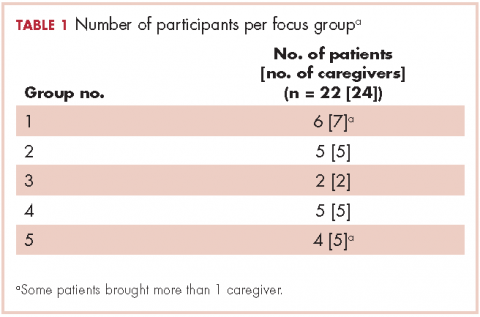

We conducted 10 focus groups during March 2013 through January 2014 – 5 with 22 patients and 5 with 24 caregivers (Table 1). Eight of the focus groups were conducted in Memphis, Tennessee, and to obtain the perspectives of patients from a rural setting, we conducted 2 focus groups in Grenada, Mississippi. All of the focus groups were facilitated by a medical anthropologist (SK) and a clinical psychologist (KDW), neither of whom was affiliated with the health care system. Each facilitator was accompanied by a note-taker. Patient-caregiver dyads came to the designated location together. Two focus groups (one for patients, the other for caregivers) were then conducted simultaneously in 2 separate rooms. The facilitators used a pilot-tested focus group interview guide during each session. The items in the focus group guide revolved around experience with the health care system in diagnosis and treatment; timeliness with appointments and procedures for diagnosis and subsequent care; physician communication in being informed about the disease, treatment, and getting questions answered; coordination of care; other challenges in receiving quality care; and suggestions for improving the patient and caregiver experience with the health care system.

The focus group sessions lasted 1 to 2 hours and were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. The data were analyzed by using Dedoose software version 5.0.11 (Sociocultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, California). Data collection and analysis were conducted concurrently to achieve theoretical saturation. Creswell’s 7-step analysis framework was used as a guide to code and interpret the data.26 The process involved collecting raw data, preparing and organizing transcripts, reading the transcripts, coding the data with the help of qualitative software, analyzing the data for themes and subthemes, interpreting the themes, and devising the meaning of the themes.26 Initial codes were categorized and compared to determine recurrent themes. Three members of the research team independently reviewed the transcripts, extensively discussed the content, and developed consensus around the identified themes. Critical and rigorous steps were taken throughout data collection and analysis to ensure the credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the qualitative data.27-29 In addition, elements of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist were used to strengthen the data collection, analysis, and reporting process.30

Results

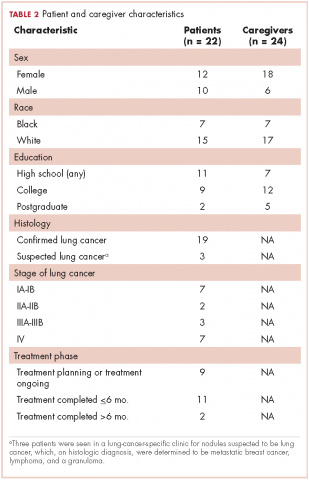

The 10 focus groups included 46 participants: 22 patients and 24 caregivers (some patients brought multiple caregivers). Of the 22 patients, 12 were women and 7 were black. An equal proportion of patients had at least a high school education as had a college or postgraduate degree. Although all of the patients had had a lung lesion suspicious for lung cancer, 19 eventually had a histologic diagnosis of lung cancer. The remaining 3 patients were all evaluated in a thoracic oncology clinic but were eventually found to have metastatic breast cancer, lymphoma, and a granuloma. Nine patients were either currently in the treatment decision-making process or actively receiving treatment, 11 had completed treatment within the preceding 6 months, and 2 had completed treatment more than 6 months previously. Treatment covered the spectrum from curative intent to palliative care. Of the 24 caregivers, 18 were women and 7 were black; 12 caregivers had at least a college education, of whom 2 had postgraduate degrees (Table 2).

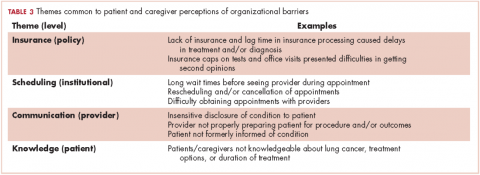

Based on participants’ feedback, we identified 4 main levels within the system where barriers to optimal care occurred: policy, institutional, provider, and patient. From our qualitative analyses, we identified a central theme associated with each level, around which the barriers coalesced. The themes were insurance, scheduling, provider communication, and patient knowledge. At the policy level, medical insurance was perceived to affect the timeliness of care and to be a deterrent to timely diagnosis and quality treatment. Lack of insurance was a daunting obstacle for indigent patients. However, even those who were insured felt that dealing with insurance companies was a significant barrier to care. At the institutional level, appointment scheduling caused problems for both patients and their caregivers. At the health care provider level, communication was perceived as a major problem. And finally, at the patient level, both patient and caregiver lack of knowledge of lung cancer and the processes inherent in lung cancer treatment were barriers for optimal diagnosis and treatment (Table 3).

Insurance barriers

At the policy level, health insurance was reported as a significant barrier to accessing health care. Patients and caregivers reported delays in diagnosis and/or treatment because of either lack of insurance or lag time in insurance processing of clinician requests. Insurance restrictions on tests, procedures, and office visits presented difficulties in getting additional opinions from providers regarding diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment plans. Some patients were no longer able to see providers after they had met the test or office visit limit allotted by insurance providers. One patient shared the following experience with office visits leading up to their lung cancer diagnosis:

Patient … with my insurance I just had only 12 office visits … and I had already maxed those out.

In other instances, insurers would not cover hospital or clinic visits if certain logistic protocols were not met. This would sometimes leave patients stranded for a period of time without receiving any care.

Caretaker … went home and went to one of those minor emergency clinics and they sent her to [xx hospital in another city]. There they did nothing. That was then over the weekend, and my son wanted to get her out of there to get her into practice because they weren’t doing anything. They said, ‘No. Your insurance won’t pay for it unless you stay here till we sign the papers to be transferred.’ … It was a bandage. Period.

Some insurers would not cover certain health services outside of routine testing protocols for the patients’ conditions. This lack of coverage caused patients to pay out of pocket for needed care.

Patient Nothing in the lymph nodes, but if it hadn’t been for me going ahead with this [coronary] calcium score, the insurance wasn’t gonna pay anything. If it wouldn’t been for the 79 bucks or the family situation, I wouldn’t be sitting [here] today.

Individuals who had not yet met the age requirement for Medicare reported being without insurance for a period of time, which contributed to delays in accessing care.

Caregiver [xx patient] probably … could’ve been diagnosed maybe even months ago, but she is in that in-between where she gets Social Security but she’s not 65 until November, so she has no insurance.

Scheduling barriers

At the institutional level, patients and caregivers reported problems with appointment scheduling. Logistic problems with adjusting work schedules and arranging for transportation as well as long wait times before evaluation by a provider were recurrent themes expressed by both patients and caregivers. Many had become resigned to the expectation of long wait times during appointments.

Patient I have to call the month before to make the appointment because they don’t take appointments so far—‘Oh, we’re not working on that yet.’ I find that very annoying ....

Caregiver The last time I was there I waited four hours.

Caregiver … your appointment at 9:00 and you get called back at 9:30 or 10:00 and you get to see the doctor by 11:00, but that’s not any different than anywhere, unfortunately ….

Rescheduled appointments also posed a problem for participants. Constant rescheduling was an inconvenience for both patients and caregivers. Many were unhappy with rescheduling because both patients and caregivers had prepared mentally and physically for an appointment, only to be told that they would have to reschedule, which caused delays in the care process.

Patient I think every single visit I had with him gets rescheduled at least twice ....

Caregiver Three times this week we’ve been geared up, ready to have chemo and they keep changing it.

Patient Everything was fine with me, but they keep cancelling my appointments ....

Some participants perceived that the popularity of physicians might explain the difficulty with scheduling. Patients suggested that it is challenging to get appointments with better-known physicians, so they are more accepting of appointments at any time, even if the time is inconvenient for them.

Caregiver Of course, … if you have a popular doctor, sometimes you don’t always get the appointment you want …

Participants also expressed frustration with the way appointments were rescheduled. They felt as though the physicians were not concerned about their lives outside of office visits.

Patient … patients actually have lives. Many of them have jobs or families or responsibilities.

Communication barriers

At the provider level, poor communication between health care providers and patients was perceived as a major impediment to the quality of care patients received. Both patients and caregivers emphasized the importance of open patient-provider interactions and that there was a lack of such open communications in many instances. There was concern regarding the way diagnoses or prognoses were relayed to patients. Many times, physicians were insensitive and disregarded the sentiments of the patients and caregivers when delivering news about the patients’ condition, as one caregiver shared,

Caregiver … the pulmonary man came … in the room and said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about your lungs. Something else will get you first,’ which was a very, very bad thing to say.

Participants also expressed concerns that they were not properly prepared for treatments by their physicians because vital information was not discussed. They felt as if physicians were not realistic about potential outcomes. This resulted in patients and caregivers being too optimistic and later disappointed when the outcome was not what they had originally expected.

Patient Until I got to this office, I was totally oversold on everything. I was told surgery … robotic, not invasive. Day one, surgery. Day two, tubes out. Day three, go home. I expected to be home on Sunday night, stir-frying vegetables, and making dinner, feeding my cat. I was in ICU four days … I went home with oxygen. I mean I thought I was just gonna walk outta there…. You take a little thing out and you put a Band-Aid on, and you go home.

Data also revealed that patients were unsure of their condition, even following treatment. Information was not communicated to patients about the specifics of their disease, either because of miscommunication or minimal patient-provider time spent during office visits. This lack of communication between patients and providers often left patients and caregivers uncertain about exactly what condition they had or what they were being treated for.

Patient I just can’t have the time with Dr. xx, cuz he’s so busy...

Patient … I didn’t understand. Which exactly what type of cancer did I have, cuz I’m—really to tell you the truth—I’m still wondering.

Knowledge barriers

Patients and caregivers also identified a lack of education and knowledge about lung cancer diagnosis and treatment as a barrier to their care. Patients and caregivers were not always fully knowledgeable about lung cancer, treatment options, or the duration of treatments. They relied on the provider to disclose such information or direct them to credible sources. In many instances, patients were misinformed about the causes of lung cancer. There were misconceptions that lung cancer was only caused by a history of smoking or genetic predisposition. Patients who did not smoke or did not have a family history of lung cancer were often confused and dismayed by the diagnosis.

Patient I was trying to figure out, why do I have lung cancer. Never smoked a day in my life.

Patients were often unaware of treatment options or side effects of various treatments. They relied on physicians to relay information and make decisions for them about treatment plans.

Patient I was told chemo would probably be the best thing for me, and I just had faith that Dr. xx knows more about it than me.

Patient I’m doing chemo but it’s — what I’m doing is different. Of course, I don’t know anything about it actually either. It’s what I hear from other people.

Other patients relied on their own sources for information about their condition, either through the Internet, from family members and/or friends, or from preconceived notions.

Patient Well — of course in the meantime, I read — because they said it was a small cell, very aggressive, so I felt like everything I read — that’s the deal. I think we’ve become where we can get on the internet and look up so much, that to me, I was gonna be gone.

Patient When he said, ‘Cancer,’ I said, ‘Well, I thought cancer was a heredity thing? That you have to have somebody in your family that has it…’

Discussion

Organizational barriers are an important consideration in the delivery and receipt of high-quality, patient-centered lung cancer care. This qualitative study of patients being treated for lung cancer and their informal caregivers revealed several common perceived organizational barriers to receiving care, including health insurance coverage restrictions, appointment scheduling difficulties, quality of communication with physicians, and failure to properly educate the patient and family about the disease and what to expect of the treatment process.

The provider communication and patient knowledge barriers seem to reinforce each other and could be improved through focused efforts on the quality of communication between patients and their caregivers and clinical care providers. Patients expect, but are often deprived of, open and active dialogue with their providers. Improved communication can be helpful in educating patients and their caregivers about their disease, prognosis, and treatment goals. Although communication ranks highly as a patient and caregiver priority, there is often a disconnect between patients and caregivers and their physicians.31 Patients and caregivers often want to be more involved in the decision-making process, and effective communication between physicians and patients has been linked to the patient’s ability to understand, and also receive high-quality care.32,33 Failure to communicate effectively and educate patients on key aspects of their condition strips them of their autonomy in decision-making.

The involvement of a navigator for patients being treated for lung cancer could be pivotal in relieving the communication and scheduling barriers. The nurse navigator assists with coordinating effective communication and providing needed information between providers and patients and their caregivers. A navigator also serves as a single point of contact for patients and caregivers to communicate questions outside of physician visits or concerns that may not be urgent enough to warrant immediate physician response.34 The navigator coordinates patients’ appointment schedules and physician referrals and communicates the details of the next steps in the care-delivery process. This helps remove the barriers to care and improve patient outcomes and the quality of health care delivery, especially for patients and caregivers dealing with a life-threatening illness within a complex referral process.35

Multidisciplinary care, a much-recommended alternative care-delivery model, should, in theory, promote connectivity of providers and collaboration between providers, patients, and family members. This model could help reduce barriers for patients and caregivers.3,24,36 A network of connected providers can better coordinate treatment plans, easily share test results, and provide built-in second opinions. Given the increasingly multimodal approach to the diagnosis, staging, and treatment of lung cancer, the multidisciplinary model could allow physicians to consider multiple perspectives and care-delivery options and, ideally, develop consensus around the optimal approach for each individual patient in one setting. This can shorten the length of time before treatment and establish a plan that is tailored to the patient’s needs.24