User login

Dolutegravir passes late pregnancy test

SEATTLE – In HIV-positive pregnant women who had not previously been on antiretroviral therapy (ART), initiation of treatment with dolutegravir during the third trimester led to lower viral loads at delivery and reduced HIV transmission to offspring compared to treatment with efavirenz. The result comes from a study conducted in South Africa and Uganda. Both drugs were combined with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs).

ART-naive women who start ART during the third trimester often do not achieve sufficient reduction of viral load, and the researchers believed that integrase inhibitors like dolutegravir may lead to greater success because they can lead to viral clearance faster than other classes of drugs, which aren’t powerful enough to get viral loads to undetectable levels by the time of delivery. In fact, women who start therapy in the third trimester are at a 600% higher risk of transmitting the virus to offspring, and infant mortality is doubled in the first year of life, according to Saye Khoo, MD, professor of molecular and clinical pharmacology at the University of Liverpool (England).

“Clearly the viral load and undetectable viral load at the time of delivery is the best proxy for the lowest risk of mother to child transmission,” Dr. Khoo said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections. “This study clearly showed that there were big differences between dolutegravir and efavirenz. Viral load was undetectable in 74% in the dolutegravir group compared to 43% in efavirenz, which was highly significant.”

In the open-label DolPHIN-2 study, 268 women were randomized after week 28 of their pregnancy (median, 31 weeks) to receive dolutegravir or efavirenz plus two NRTIs. The dolutegravir group was more likely to achieve viral load less than 50 copies/mL at delivery (74% vs. 43%; adjusted risk ratio, 1.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.09). The trend occurred across subanalyses that included baseline viral load, baseline CD4 count, and gestation at initiation. 93% of the women in the dolutegravir group had a viral load less than 1,000 copies/mL, compared with 83% in the efavirenz group (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.00-1.23).

There were no differences between the two groups with respect to frequency of severe adverse events, organ class of severe adverse events, gestational age at delivery, births earlier than 34 weeks, or births earlier than 37 weeks.

Four stillbirths occurred in the dolutegravir arm, and none in the efavirenz group. “Each of these was examined in great detail, as you might imagine. There were clear explanations for the cause of death, and it was related to maternal infection in two cases and obstetric complications in the other two,” said Dr. Khoo. There were no observations of neural tube defects – a concern that has been raised in the use of dolutegravir at the time of conception.

“I think we did see clear differences in virologic response in the arms, and so that would argue that dolutegravir certainly could be considered in these high-risk scenarios,” said Dr. Khoo.

The study was funded by the University of Liverpool. Dr. Khoo reported consulting for and receiving research funding from ViiV.

SOURCE: Khoo S et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 40 LB.

SEATTLE – In HIV-positive pregnant women who had not previously been on antiretroviral therapy (ART), initiation of treatment with dolutegravir during the third trimester led to lower viral loads at delivery and reduced HIV transmission to offspring compared to treatment with efavirenz. The result comes from a study conducted in South Africa and Uganda. Both drugs were combined with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs).

ART-naive women who start ART during the third trimester often do not achieve sufficient reduction of viral load, and the researchers believed that integrase inhibitors like dolutegravir may lead to greater success because they can lead to viral clearance faster than other classes of drugs, which aren’t powerful enough to get viral loads to undetectable levels by the time of delivery. In fact, women who start therapy in the third trimester are at a 600% higher risk of transmitting the virus to offspring, and infant mortality is doubled in the first year of life, according to Saye Khoo, MD, professor of molecular and clinical pharmacology at the University of Liverpool (England).

“Clearly the viral load and undetectable viral load at the time of delivery is the best proxy for the lowest risk of mother to child transmission,” Dr. Khoo said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections. “This study clearly showed that there were big differences between dolutegravir and efavirenz. Viral load was undetectable in 74% in the dolutegravir group compared to 43% in efavirenz, which was highly significant.”

In the open-label DolPHIN-2 study, 268 women were randomized after week 28 of their pregnancy (median, 31 weeks) to receive dolutegravir or efavirenz plus two NRTIs. The dolutegravir group was more likely to achieve viral load less than 50 copies/mL at delivery (74% vs. 43%; adjusted risk ratio, 1.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.09). The trend occurred across subanalyses that included baseline viral load, baseline CD4 count, and gestation at initiation. 93% of the women in the dolutegravir group had a viral load less than 1,000 copies/mL, compared with 83% in the efavirenz group (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.00-1.23).

There were no differences between the two groups with respect to frequency of severe adverse events, organ class of severe adverse events, gestational age at delivery, births earlier than 34 weeks, or births earlier than 37 weeks.

Four stillbirths occurred in the dolutegravir arm, and none in the efavirenz group. “Each of these was examined in great detail, as you might imagine. There were clear explanations for the cause of death, and it was related to maternal infection in two cases and obstetric complications in the other two,” said Dr. Khoo. There were no observations of neural tube defects – a concern that has been raised in the use of dolutegravir at the time of conception.

“I think we did see clear differences in virologic response in the arms, and so that would argue that dolutegravir certainly could be considered in these high-risk scenarios,” said Dr. Khoo.

The study was funded by the University of Liverpool. Dr. Khoo reported consulting for and receiving research funding from ViiV.

SOURCE: Khoo S et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 40 LB.

SEATTLE – In HIV-positive pregnant women who had not previously been on antiretroviral therapy (ART), initiation of treatment with dolutegravir during the third trimester led to lower viral loads at delivery and reduced HIV transmission to offspring compared to treatment with efavirenz. The result comes from a study conducted in South Africa and Uganda. Both drugs were combined with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs).

ART-naive women who start ART during the third trimester often do not achieve sufficient reduction of viral load, and the researchers believed that integrase inhibitors like dolutegravir may lead to greater success because they can lead to viral clearance faster than other classes of drugs, which aren’t powerful enough to get viral loads to undetectable levels by the time of delivery. In fact, women who start therapy in the third trimester are at a 600% higher risk of transmitting the virus to offspring, and infant mortality is doubled in the first year of life, according to Saye Khoo, MD, professor of molecular and clinical pharmacology at the University of Liverpool (England).

“Clearly the viral load and undetectable viral load at the time of delivery is the best proxy for the lowest risk of mother to child transmission,” Dr. Khoo said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections. “This study clearly showed that there were big differences between dolutegravir and efavirenz. Viral load was undetectable in 74% in the dolutegravir group compared to 43% in efavirenz, which was highly significant.”

In the open-label DolPHIN-2 study, 268 women were randomized after week 28 of their pregnancy (median, 31 weeks) to receive dolutegravir or efavirenz plus two NRTIs. The dolutegravir group was more likely to achieve viral load less than 50 copies/mL at delivery (74% vs. 43%; adjusted risk ratio, 1.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.09). The trend occurred across subanalyses that included baseline viral load, baseline CD4 count, and gestation at initiation. 93% of the women in the dolutegravir group had a viral load less than 1,000 copies/mL, compared with 83% in the efavirenz group (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.00-1.23).

There were no differences between the two groups with respect to frequency of severe adverse events, organ class of severe adverse events, gestational age at delivery, births earlier than 34 weeks, or births earlier than 37 weeks.

Four stillbirths occurred in the dolutegravir arm, and none in the efavirenz group. “Each of these was examined in great detail, as you might imagine. There were clear explanations for the cause of death, and it was related to maternal infection in two cases and obstetric complications in the other two,” said Dr. Khoo. There were no observations of neural tube defects – a concern that has been raised in the use of dolutegravir at the time of conception.

“I think we did see clear differences in virologic response in the arms, and so that would argue that dolutegravir certainly could be considered in these high-risk scenarios,” said Dr. Khoo.

The study was funded by the University of Liverpool. Dr. Khoo reported consulting for and receiving research funding from ViiV.

SOURCE: Khoo S et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 40 LB.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

First-of-its-kind study looks at pregnancies in prison

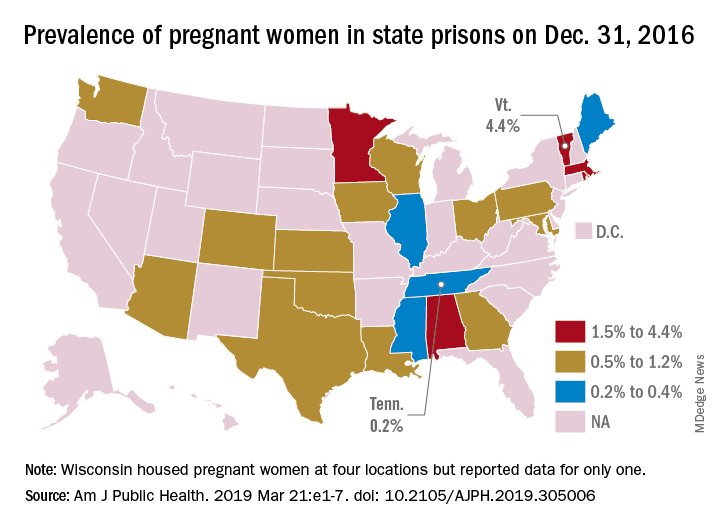

according to a systematic study believed to be the first of its kind.

That works out to 0.6% of the 56,262 women housed in the 23 prison systems on Dec. 31, 2016, Carolyn Sufrin, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her associates wrote in the American Journal of Public Health.

Nearly 1,400 pregnant women were admitted to the 26 federal prisons that house women and 22 state prison systems over a 1-year period in 2016-2017. The prisons involved in the study represent 57% of all women incarcerated in the United States, they noted.

Among the pregnancies completed while women were in prison, there were 753 live births: 685 at state facilities and 68 at federal sites. About 6% of those births were preterm, compared with almost 10% nationally in 2016, and 32% were cesarean deliveries, Dr. Sufrin and her associates reported.

All but six births occurred in a hospital; three “were attributable to precipitous labor with prison nurses or paramedics in attendance, and details were not available for the others,” they wrote. Of the 8% of non–live birth pregnancies, 6% were miscarriages, 1% were abortions, and the remainder were stillbirths or ectopic pregnancies. There were three newborn deaths and no maternal deaths.

“That prison pregnancy data have previously not been systematically collected or reported signals a glaring disregard for the health and well-being of incarcerated pregnant women. The Bureau of Justice Statistics collects data on deaths during custody but not births during custody. Despite this marginalization, it is important to recognize that incarcerated women are still members of broader society, that most of them will be released, and that some will give birth while in custody; therefore, their pregnancies must be counted,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development. The investigators had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Sufrin C et al. Am J Public Health. 2019 Mar 21:e1-7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305006.

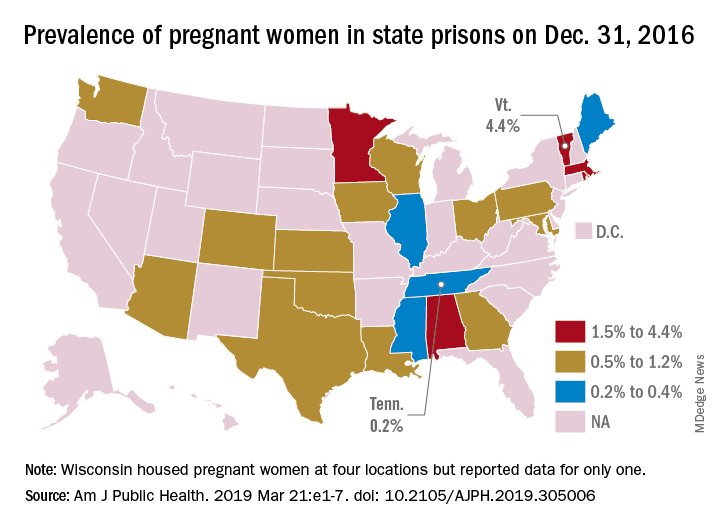

according to a systematic study believed to be the first of its kind.

That works out to 0.6% of the 56,262 women housed in the 23 prison systems on Dec. 31, 2016, Carolyn Sufrin, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her associates wrote in the American Journal of Public Health.

Nearly 1,400 pregnant women were admitted to the 26 federal prisons that house women and 22 state prison systems over a 1-year period in 2016-2017. The prisons involved in the study represent 57% of all women incarcerated in the United States, they noted.

Among the pregnancies completed while women were in prison, there were 753 live births: 685 at state facilities and 68 at federal sites. About 6% of those births were preterm, compared with almost 10% nationally in 2016, and 32% were cesarean deliveries, Dr. Sufrin and her associates reported.

All but six births occurred in a hospital; three “were attributable to precipitous labor with prison nurses or paramedics in attendance, and details were not available for the others,” they wrote. Of the 8% of non–live birth pregnancies, 6% were miscarriages, 1% were abortions, and the remainder were stillbirths or ectopic pregnancies. There were three newborn deaths and no maternal deaths.

“That prison pregnancy data have previously not been systematically collected or reported signals a glaring disregard for the health and well-being of incarcerated pregnant women. The Bureau of Justice Statistics collects data on deaths during custody but not births during custody. Despite this marginalization, it is important to recognize that incarcerated women are still members of broader society, that most of them will be released, and that some will give birth while in custody; therefore, their pregnancies must be counted,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development. The investigators had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Sufrin C et al. Am J Public Health. 2019 Mar 21:e1-7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305006.

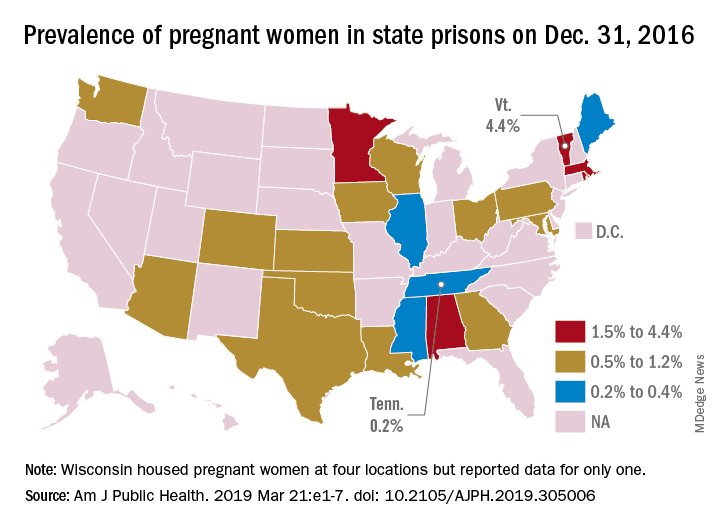

according to a systematic study believed to be the first of its kind.

That works out to 0.6% of the 56,262 women housed in the 23 prison systems on Dec. 31, 2016, Carolyn Sufrin, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her associates wrote in the American Journal of Public Health.

Nearly 1,400 pregnant women were admitted to the 26 federal prisons that house women and 22 state prison systems over a 1-year period in 2016-2017. The prisons involved in the study represent 57% of all women incarcerated in the United States, they noted.

Among the pregnancies completed while women were in prison, there were 753 live births: 685 at state facilities and 68 at federal sites. About 6% of those births were preterm, compared with almost 10% nationally in 2016, and 32% were cesarean deliveries, Dr. Sufrin and her associates reported.

All but six births occurred in a hospital; three “were attributable to precipitous labor with prison nurses or paramedics in attendance, and details were not available for the others,” they wrote. Of the 8% of non–live birth pregnancies, 6% were miscarriages, 1% were abortions, and the remainder were stillbirths or ectopic pregnancies. There were three newborn deaths and no maternal deaths.

“That prison pregnancy data have previously not been systematically collected or reported signals a glaring disregard for the health and well-being of incarcerated pregnant women. The Bureau of Justice Statistics collects data on deaths during custody but not births during custody. Despite this marginalization, it is important to recognize that incarcerated women are still members of broader society, that most of them will be released, and that some will give birth while in custody; therefore, their pregnancies must be counted,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development. The investigators had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Sufrin C et al. Am J Public Health. 2019 Mar 21:e1-7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305006.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Women with FXI deficiency face hemorrhage risk with gyn surgery

Women with factor XI (FXI) deficiency, particularly those with a history of bleeding and low plasmatic FXI levels, are at risk of experiencing obstetric and gynecologic hemorrhage, according to a retrospective analysis.

“[W]hile spontaneous bleeding episodes are unusual, FXI-deficient patients tend to bleed excessively after trauma or surgery, especially when highly fibrinolytic tissues are involved, such as rhino/oropharyngeal and genitourinary mucosa,” wrote Carlos Bravo-Perez, MD, of Universidad de Murcia in Spain, along with his colleagues. The report is in Medicina Clínica. “Menstruation, pregnancy and birth labour constitute intrinsic haemostatic challenges for FXI deficient women,” they noted.

The researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of 95 women with FXI deficiency. Cohort data was collected over a period of 20 years (1994 to 2014) from the city of Yecla, Spain.

Clinical information obtained included blood group, age, sex, aPTT ratio, and FXI coagulant levels, among others. The team completed a comprehensive molecular and biochemical analysis on all study patients.

“Surgical interventions and postoperative bleeding were recorded, as well as the use of antihemorrhagic prophylaxis or treatment,” the researchers wrote.

Bleeding occurred in 27.4% of women with FXI deficiency, with the majority of events being a single episode. The team reported that 52.5% of hemorrhagic events were provoked by surgical, obstetric, or dental procedures, while 47.5% were spontaneous bleeding events.

Among women who experienced bleeding events, 73.1% were gynecologic or obstetric hemorrhagic episodes. These included abnormal uterine bleeding, postpartum hemorrhage, excessive bleeding after a miscarriage, and bleeding after gynecologic surgery.

Overall, the proportion of abnormal uterine bleeding was 12.6%, the proportion of postpartum hemorrhage was 6.6%, and the proportion of gynecologic postoperative hemorrhage was 16%.

While the proportion of these bleeding events is higher than what has been observed in the general population, it is lower than what has been reported in other reviews for women with FXI deficiency, the researchers noted.

They also found that a positive history of bleeding and low plasmatic FXI levels were associated with a higher prevalence of gynecologic or obstetric bleeding.

The study was funded by Fundación Española de Trombosis y Hemostasia and Sociedad Española de Hematología y Hemoterapia in Spain. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bravo-Perez C et al. Med Clin (Barc). 2019 Mar 26. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2019.01.029.

Women with factor XI (FXI) deficiency, particularly those with a history of bleeding and low plasmatic FXI levels, are at risk of experiencing obstetric and gynecologic hemorrhage, according to a retrospective analysis.

“[W]hile spontaneous bleeding episodes are unusual, FXI-deficient patients tend to bleed excessively after trauma or surgery, especially when highly fibrinolytic tissues are involved, such as rhino/oropharyngeal and genitourinary mucosa,” wrote Carlos Bravo-Perez, MD, of Universidad de Murcia in Spain, along with his colleagues. The report is in Medicina Clínica. “Menstruation, pregnancy and birth labour constitute intrinsic haemostatic challenges for FXI deficient women,” they noted.

The researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of 95 women with FXI deficiency. Cohort data was collected over a period of 20 years (1994 to 2014) from the city of Yecla, Spain.

Clinical information obtained included blood group, age, sex, aPTT ratio, and FXI coagulant levels, among others. The team completed a comprehensive molecular and biochemical analysis on all study patients.

“Surgical interventions and postoperative bleeding were recorded, as well as the use of antihemorrhagic prophylaxis or treatment,” the researchers wrote.

Bleeding occurred in 27.4% of women with FXI deficiency, with the majority of events being a single episode. The team reported that 52.5% of hemorrhagic events were provoked by surgical, obstetric, or dental procedures, while 47.5% were spontaneous bleeding events.

Among women who experienced bleeding events, 73.1% were gynecologic or obstetric hemorrhagic episodes. These included abnormal uterine bleeding, postpartum hemorrhage, excessive bleeding after a miscarriage, and bleeding after gynecologic surgery.

Overall, the proportion of abnormal uterine bleeding was 12.6%, the proportion of postpartum hemorrhage was 6.6%, and the proportion of gynecologic postoperative hemorrhage was 16%.

While the proportion of these bleeding events is higher than what has been observed in the general population, it is lower than what has been reported in other reviews for women with FXI deficiency, the researchers noted.

They also found that a positive history of bleeding and low plasmatic FXI levels were associated with a higher prevalence of gynecologic or obstetric bleeding.

The study was funded by Fundación Española de Trombosis y Hemostasia and Sociedad Española de Hematología y Hemoterapia in Spain. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bravo-Perez C et al. Med Clin (Barc). 2019 Mar 26. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2019.01.029.

Women with factor XI (FXI) deficiency, particularly those with a history of bleeding and low plasmatic FXI levels, are at risk of experiencing obstetric and gynecologic hemorrhage, according to a retrospective analysis.

“[W]hile spontaneous bleeding episodes are unusual, FXI-deficient patients tend to bleed excessively after trauma or surgery, especially when highly fibrinolytic tissues are involved, such as rhino/oropharyngeal and genitourinary mucosa,” wrote Carlos Bravo-Perez, MD, of Universidad de Murcia in Spain, along with his colleagues. The report is in Medicina Clínica. “Menstruation, pregnancy and birth labour constitute intrinsic haemostatic challenges for FXI deficient women,” they noted.

The researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of 95 women with FXI deficiency. Cohort data was collected over a period of 20 years (1994 to 2014) from the city of Yecla, Spain.

Clinical information obtained included blood group, age, sex, aPTT ratio, and FXI coagulant levels, among others. The team completed a comprehensive molecular and biochemical analysis on all study patients.

“Surgical interventions and postoperative bleeding were recorded, as well as the use of antihemorrhagic prophylaxis or treatment,” the researchers wrote.

Bleeding occurred in 27.4% of women with FXI deficiency, with the majority of events being a single episode. The team reported that 52.5% of hemorrhagic events were provoked by surgical, obstetric, or dental procedures, while 47.5% were spontaneous bleeding events.

Among women who experienced bleeding events, 73.1% were gynecologic or obstetric hemorrhagic episodes. These included abnormal uterine bleeding, postpartum hemorrhage, excessive bleeding after a miscarriage, and bleeding after gynecologic surgery.

Overall, the proportion of abnormal uterine bleeding was 12.6%, the proportion of postpartum hemorrhage was 6.6%, and the proportion of gynecologic postoperative hemorrhage was 16%.

While the proportion of these bleeding events is higher than what has been observed in the general population, it is lower than what has been reported in other reviews for women with FXI deficiency, the researchers noted.

They also found that a positive history of bleeding and low plasmatic FXI levels were associated with a higher prevalence of gynecologic or obstetric bleeding.

The study was funded by Fundación Española de Trombosis y Hemostasia and Sociedad Española de Hematología y Hemoterapia in Spain. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bravo-Perez C et al. Med Clin (Barc). 2019 Mar 26. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2019.01.029.

FROM MEDICINA CLÍNICA

Is Routine 39-Week Induction of Labor in Healthy Pregnancy a Reasonable Course?

In this supplement to OBG Management a panel of experts discuss the risks and benefits of routine induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks. The panelists examine the findings from the ARRIVE trial and the potential impact on real-world practice. The experts also describe their own approach to IOL at 39 weeks and what they see for the future.

Panelists

- Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, MBA (Moderator)

- Aaron B. Caughey, MD, PhD

- John T. Repke, MD

- Sindhu K. Srinivas, MD, MSCE

In this supplement to OBG Management a panel of experts discuss the risks and benefits of routine induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks. The panelists examine the findings from the ARRIVE trial and the potential impact on real-world practice. The experts also describe their own approach to IOL at 39 weeks and what they see for the future.

Panelists

- Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, MBA (Moderator)

- Aaron B. Caughey, MD, PhD

- John T. Repke, MD

- Sindhu K. Srinivas, MD, MSCE

In this supplement to OBG Management a panel of experts discuss the risks and benefits of routine induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks. The panelists examine the findings from the ARRIVE trial and the potential impact on real-world practice. The experts also describe their own approach to IOL at 39 weeks and what they see for the future.

Panelists

- Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, MBA (Moderator)

- Aaron B. Caughey, MD, PhD

- John T. Repke, MD

- Sindhu K. Srinivas, MD, MSCE

Expert gives tips on timing, managing lupus pregnancies

SAN FRANCISCO – Not that many years ago, women with systemic lupus erythematosus were told not to get pregnant. It was just one more lupus heartbreak.

Times have changed, according to Lisa Sammaritano, MD, a lupus specialist and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

While lupus certainly complicates pregnancy, it by no means rules it out these days. With careful management, the dream of motherhood can become a reality for many women. Dr. Sammaritano shared her insights about timing and treatment at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

It’s important that the disease is under control as much as possible; that means that timing – and contraception – are key. Antiphospholipid antibodies, common in lupus, complicate matters, but there are workarounds, she said.

SAN FRANCISCO – Not that many years ago, women with systemic lupus erythematosus were told not to get pregnant. It was just one more lupus heartbreak.

Times have changed, according to Lisa Sammaritano, MD, a lupus specialist and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

While lupus certainly complicates pregnancy, it by no means rules it out these days. With careful management, the dream of motherhood can become a reality for many women. Dr. Sammaritano shared her insights about timing and treatment at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

It’s important that the disease is under control as much as possible; that means that timing – and contraception – are key. Antiphospholipid antibodies, common in lupus, complicate matters, but there are workarounds, she said.

SAN FRANCISCO – Not that many years ago, women with systemic lupus erythematosus were told not to get pregnant. It was just one more lupus heartbreak.

Times have changed, according to Lisa Sammaritano, MD, a lupus specialist and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

While lupus certainly complicates pregnancy, it by no means rules it out these days. With careful management, the dream of motherhood can become a reality for many women. Dr. Sammaritano shared her insights about timing and treatment at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

It’s important that the disease is under control as much as possible; that means that timing – and contraception – are key. Antiphospholipid antibodies, common in lupus, complicate matters, but there are workarounds, she said.

AT LUPUS 2019

2019 Update on prenatal exome sequencing

Prenatal diagnosis of genetic anomalies is important for diagnosing lethal genetic conditions before birth. It can provide information for parents regarding pregnancy options and allow for recurrence risk counseling and the potential use of preimplantation genetic testing in the next pregnancy. For decades, a karyotype was used to analyze amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling specimens; in recent years, chromosomal microarray analysis provides more information about significant chromosomal abnormalities, including microdeletions and microduplications. However, microarrays also have limitations, as they do not identify base pair changes associated with single-gene disorders.

The advent of next-generation sequencing has substantially reduced the cost of DNA sequencing. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) can sequence the entire genome— both the coding (exonic) and noncoding (intronic) regions—while exome sequencing analyzes only the protein-coding exons, which make up 1% to 2% of the genome and about 85% of the protein-coding genes associated with known human disease. Exome sequencing increasingly is used in cases of suspected genetic disorders when other tests have been unrevealing.

In this Update, we review recent reports of prenatal exome sequencing, including studies exploring the yield in fetuses with structural anomalies; the importance of prenatal phenotyping; the perspectives of parents and health care professionals who were involved in prenatal exome sequencing studies; and a summary of a joint position statement from 3 societies regarding prenatal sequencing.

Prenatal whole exome sequencing has potential utility, with some limitations

Petrovski S, Aggarwal V, Giordano JL, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in the evaluation of fetal structural anomalies: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393:758-767.

Lord J, McMullan DJ, Eberhardt RY, et al; for the Prenatal Assessment of Genomes and Exomes Consortium. Prenatal exome sequencing analysis in fetal structural anomalies detected by ultrasonography (PAGE): a cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393:747-757.

Exome sequencing has been shown to identify an underlying genetic cause in 25% to 30% of children with an undiagnosed suspected genetic disorder. Two studies recently published in the Lancet sought to determine the incremental diagnostic yield of prenatal whole exome sequencing (WES) in the setting of fetal structural anomalies when karyotype and microarray results were normal.

Continue to: Details of the studies...

Details of the studies

In a prospective cohort study by Petrovski and colleagues, DNA samples from 234 fetuses with a structural anomaly (identified on ultrasonography) and both parents (parent-fetus "trios") were used for analysis. WES identified diagnostic genetic variants in 24 trios (10%). An additional 46 (20%) had variants that indicated pathogenicity but without sufficient evidence to be considered diagnostic.

The anomalies with the highest frequency of a genetic diagnosis were lymphatic, 24%; skeletal, 24%; central nervous system, 22%; and renal, 16%; while cardiac anomalies had the lowest yield at 5%.

In another prospective cohort study, known as the Prenatal Assessment of Genomes and Exomes (PAGE), Lord and colleagues sequenced DNA samples from 610 parent-fetus trios, but they restricted sequencing to a predefined list of 1,628 genes. Diagnostic genetic variants were identified in 52 fetuses (8.5%), while 24 (3.9%) had a variant of uncertain significance that was thought to be of potential clinical usefulness.

Fetuses with multiple anomalies had the highest genetic yield (15.4%), followed by skeletal (15.4%) and cardiac anomalies (11.1%), with the lowest yield in fetuses with isolated increased nuchal translucency (3.2%).

Diagnostic yield is high, but prenatal utility is limited

Both studies showed a clinically significant diagnostic yield of 8% to 10% for prenatal exome sequencing in cases of fetal structural anomalies with normal karyotype and microarray testing. While this yield demonstrates the utility of prenatal exome sequencing, it is significantly lower than what has been reported in postnatal studies. One of the reasons for this is the inherent limitation of prenatal phenotyping (discussed below).

The cohort studies by both Petrovski and Lord and their colleagues show the feasibility and potential diagnostic utility of exome sequencing in cases of fetal structural anomalies where karyotype and microarray are not diagnostic. However, the lower yield found in these studies compared with those in postnatal studies highlights in part the limitations of prenatal phenotyping.

The importance of prenatal phenotyping

Aarabi M, Sniezek O, Jiang H, et al. Importance of complete phenotyping in prenatal whole exome sequencing. Hum Genet. 2018;137:175-181.

In postnatal exome sequencing, the physical exam, imaging findings, and laboratory results are components of the phenotype that are used to interpret the sequencing data. Prenatal phenotyping, however, is limited to the use of fetal ultrasonography and, occasionally, the addition of magnetic resonance imaging. Prenatal phenotyping is without the benefit of an exam to detect more subtle anomalies or functional status, such as developmental delay, seizures, or failure to thrive.

When a structural anomaly is identified on prenatal ultrasonography, it is especially important that detailed imaging be undertaken to detect other anomalies, including more subtle facial features and dysmorphology.

Value of reanalyzing exome sequencing data

Aarabi and colleagues conducted a retrospective study of 20 fetuses with structural anomalies and normal karyotype and microarray. They performed trio exome sequencing first using information available only prenatally and then conducted a reanalysis using information available after delivery.

With prenatal phenotyping only, the investigators identified no pathogenic, or likely pathogenic, variants. On reanalysis of combined prenatal and postnatal findings, however, they identified pathogenic variants in 20% of cases.

Significance of the findings

This study highlights both the importance of a careful, detailed fetal ultrasonography study and the possible additional benefit of a postnatal examination (such as an autopsy) in order to yield improved results. In addition, the authors noted that the development of a prenatal phenotype-genotype database would significantly help exome sequencing interpretation in the prenatal setting.

Careful prenatal ultrasonography is crucial to help in the interpretation of prenatal exome sequencing. Patients who have undergone prenatal clinical exome sequencing may benefit from reanalysis of the genetic data based on detailed postnatal findings.

Social impact of WES: Parent and provider perspectives

Wou K, Weitz T, McCormack C, et al. Parental perceptions of prenatal whole exome sequencing (PPPWES) study. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38:801-811.

Horn R, Parker M. Health professionals' and researchers' perspectives on prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing: 'We can't shut the door now, the genie's out, we need to refine it.' PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204158.

As health care providers enter a new era of prenatal genetic testing with exome sequencing, it is crucial to the path forward that we obtain perspectives from the parents and providers who participated in these studies. Notably, in both of the previously discussed Lancet reports, the authors interviewed the participants to discuss the challenges involved and identify strategies for improving future testing.

Continue to: What parents want...

What parents want

To ascertain the perceptions of couples who underwent prenatal WES, Wou and colleagues conducted semi-structured interviews with participants from the Fetal Sequencing Study regarding their experience. They interviewed 29 parents from 17 pregnancies, including a mix of those who had pathogenic prenatal results, terminated prior to receiving the results, and had normal results.

Expressed feelings and desires. Parents recalled feelings of anxiety and stress around the time of diagnosis and the need for help with coping while awaiting results. The majority of parents reported that they would like to be told about uncertain results, but that desire decreased as the certainty of results decreased.

Parents were overall satisfied with the prenatal genetic testing experience, but they added that they would have liked to receive written materials beforehand and a written report of the test results (including negative cases). They also would like to have connected with other families with similar experiences, to have received results sooner, and to have an in-person meeting after telephone disclosure of the results.

Health professionals articulate complexity of prenatal genomics

In a qualitative interview study to explore critical issues involved in the clinical practice use of prenatal genomics, Horn and Parker conducted interviews with 20 health care professionals who were involved in the previously described PAGE trial. Patient recruiters, midwives, genetic counselors, research assistants, and laboratory staff were included.

Interviewees cited numerous challenges involved in their day-to-day work with prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing, including:

- the complexity of achieving valid parental consent at a time of vulnerability

- management of parent expectations

- transmitting and comprehending complex information

- the usefulness of information

- the difficulty of a long turnaround time for study results.

All the interviewees agreed that prenatal exome sequencing studies contribute to knowledge generation and the advancement of technology.

The authors concluded that an appropriate next step would be the development of appropriate guidelines for good ethical practice that address the concerns encountered in genomics clinical practice.

The prenatal experience can be overwhelming for parents. Pretest and posttest counseling on genetic testing and results are of the utmost importance, as is finding ways to help support parents through this anxious time.

Societies offer guidance on using genome and exome sequencing

International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis, Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine, Perinatal Quality Foundation. Joint Position Statement from the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis (ISPD), the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine (SMFM), and the Perinatal Quality Foundation (PQF) on the use of genome-wide sequencing for fetal diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38:6-9.

In response to the rapid integration of exome sequencing for genetic diagnosis, several professional societies—the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis, Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, and Perinatal Quality Foundation—issued a joint statement addressing the clinical use of prenatal diagnostic genome wide sequencing, including exome sequencing.

Continue to: Guidance at a glance...

Guidance at a glance

The societies' recommendations are summarized as follows:

- Exome sequencing is best done as a trio analysis, with fetal and both parental samples sequenced and analyzed together.

- Extensive pretest education, counseling, and informed consent, as well as posttest counseling, are essential. This should include:

—the types of results to be conveyed (variants that are pathogenic, likely pathogenic, of uncertain significance, likely benign, and benign)

—the possibility that results will not be obtained or may not be available before the birth of the fetus

—realistic expectations regarding the likelihood that a significant result will be obtained

—the timeframe to results

—the option to include or exclude in the results incidental or secondary findings (such as an unexpected childhood disorder, cancer susceptibility genes, adult-onset disorders)

—the possibility of uncovering nonpaternity or consanguinity

—the potential reanalysis of results over time

—how data are stored, who has access, and for what purpose.

- Fetal sequencing may be beneficial in the following scenarios:

—multiple fetal anomalies or a single major anomaly suggestive of a genetic disorder, when the microarray is negative

—no microarray result is available, but the fetus exhibits a pattern of anomalies strongly suggestive of a single-gene disorder

—a prior undiagnosed fetus (or child) with anomalies suggestive of a genetic etiology, and with similar anomalies in the current pregnancy, with normal karyotype or microarray. Providers also can consider sequencing samples from both parents prior to preimplantation genetic testing to check for shared carrier status for autosomal recessive mutations, although obtaining exome sequencing from the prior affected fetus (or child) is ideal.

—history of recurrent stillbirths of unknown etiology, with a recurrent pattern of anomalies in the current pregnancy, with normal karyotype or microarray.

- Interpretation of results should be done using a multidisciplinary team-based approach, including clinical scientists, geneticists, genetic counselors, and experts in prenatal diagnosis.

- Where possible and after informed consent, reanalysis of results should be undertaken if a future pregnancy is planned or ongoing, and a significant amount of time has elapsed since the time the result was last reported.

- Parents should be given a written report of test results.

Three professional societies have convened to issue consensus opinion that includes current indications for prenatal exome sequencing and important factors to include in the consent process. We follow these guidelines in our own practice.

Summary

Exome sequencing is increasingly becoming mainstream in postnatal genetic testing, and it is emerging as the newest diagnostic frontier in prenatal genetic testing. However, there are limitations to prenatal exome sequencing, including issues with consent at a vulnerable time for parents, limited information available regarding the phenotype, and results that may not be available before the birth of a fetus. Providers should be familiar with the indications for testing, the possible results, the limitations of prenatal phenotyping, and the implications for future pregnancies.

Prenatal diagnosis of genetic anomalies is important for diagnosing lethal genetic conditions before birth. It can provide information for parents regarding pregnancy options and allow for recurrence risk counseling and the potential use of preimplantation genetic testing in the next pregnancy. For decades, a karyotype was used to analyze amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling specimens; in recent years, chromosomal microarray analysis provides more information about significant chromosomal abnormalities, including microdeletions and microduplications. However, microarrays also have limitations, as they do not identify base pair changes associated with single-gene disorders.

The advent of next-generation sequencing has substantially reduced the cost of DNA sequencing. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) can sequence the entire genome— both the coding (exonic) and noncoding (intronic) regions—while exome sequencing analyzes only the protein-coding exons, which make up 1% to 2% of the genome and about 85% of the protein-coding genes associated with known human disease. Exome sequencing increasingly is used in cases of suspected genetic disorders when other tests have been unrevealing.

In this Update, we review recent reports of prenatal exome sequencing, including studies exploring the yield in fetuses with structural anomalies; the importance of prenatal phenotyping; the perspectives of parents and health care professionals who were involved in prenatal exome sequencing studies; and a summary of a joint position statement from 3 societies regarding prenatal sequencing.

Prenatal whole exome sequencing has potential utility, with some limitations

Petrovski S, Aggarwal V, Giordano JL, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in the evaluation of fetal structural anomalies: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393:758-767.

Lord J, McMullan DJ, Eberhardt RY, et al; for the Prenatal Assessment of Genomes and Exomes Consortium. Prenatal exome sequencing analysis in fetal structural anomalies detected by ultrasonography (PAGE): a cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393:747-757.

Exome sequencing has been shown to identify an underlying genetic cause in 25% to 30% of children with an undiagnosed suspected genetic disorder. Two studies recently published in the Lancet sought to determine the incremental diagnostic yield of prenatal whole exome sequencing (WES) in the setting of fetal structural anomalies when karyotype and microarray results were normal.

Continue to: Details of the studies...

Details of the studies

In a prospective cohort study by Petrovski and colleagues, DNA samples from 234 fetuses with a structural anomaly (identified on ultrasonography) and both parents (parent-fetus "trios") were used for analysis. WES identified diagnostic genetic variants in 24 trios (10%). An additional 46 (20%) had variants that indicated pathogenicity but without sufficient evidence to be considered diagnostic.

The anomalies with the highest frequency of a genetic diagnosis were lymphatic, 24%; skeletal, 24%; central nervous system, 22%; and renal, 16%; while cardiac anomalies had the lowest yield at 5%.

In another prospective cohort study, known as the Prenatal Assessment of Genomes and Exomes (PAGE), Lord and colleagues sequenced DNA samples from 610 parent-fetus trios, but they restricted sequencing to a predefined list of 1,628 genes. Diagnostic genetic variants were identified in 52 fetuses (8.5%), while 24 (3.9%) had a variant of uncertain significance that was thought to be of potential clinical usefulness.

Fetuses with multiple anomalies had the highest genetic yield (15.4%), followed by skeletal (15.4%) and cardiac anomalies (11.1%), with the lowest yield in fetuses with isolated increased nuchal translucency (3.2%).

Diagnostic yield is high, but prenatal utility is limited

Both studies showed a clinically significant diagnostic yield of 8% to 10% for prenatal exome sequencing in cases of fetal structural anomalies with normal karyotype and microarray testing. While this yield demonstrates the utility of prenatal exome sequencing, it is significantly lower than what has been reported in postnatal studies. One of the reasons for this is the inherent limitation of prenatal phenotyping (discussed below).

The cohort studies by both Petrovski and Lord and their colleagues show the feasibility and potential diagnostic utility of exome sequencing in cases of fetal structural anomalies where karyotype and microarray are not diagnostic. However, the lower yield found in these studies compared with those in postnatal studies highlights in part the limitations of prenatal phenotyping.

The importance of prenatal phenotyping

Aarabi M, Sniezek O, Jiang H, et al. Importance of complete phenotyping in prenatal whole exome sequencing. Hum Genet. 2018;137:175-181.

In postnatal exome sequencing, the physical exam, imaging findings, and laboratory results are components of the phenotype that are used to interpret the sequencing data. Prenatal phenotyping, however, is limited to the use of fetal ultrasonography and, occasionally, the addition of magnetic resonance imaging. Prenatal phenotyping is without the benefit of an exam to detect more subtle anomalies or functional status, such as developmental delay, seizures, or failure to thrive.

When a structural anomaly is identified on prenatal ultrasonography, it is especially important that detailed imaging be undertaken to detect other anomalies, including more subtle facial features and dysmorphology.

Value of reanalyzing exome sequencing data

Aarabi and colleagues conducted a retrospective study of 20 fetuses with structural anomalies and normal karyotype and microarray. They performed trio exome sequencing first using information available only prenatally and then conducted a reanalysis using information available after delivery.

With prenatal phenotyping only, the investigators identified no pathogenic, or likely pathogenic, variants. On reanalysis of combined prenatal and postnatal findings, however, they identified pathogenic variants in 20% of cases.

Significance of the findings

This study highlights both the importance of a careful, detailed fetal ultrasonography study and the possible additional benefit of a postnatal examination (such as an autopsy) in order to yield improved results. In addition, the authors noted that the development of a prenatal phenotype-genotype database would significantly help exome sequencing interpretation in the prenatal setting.

Careful prenatal ultrasonography is crucial to help in the interpretation of prenatal exome sequencing. Patients who have undergone prenatal clinical exome sequencing may benefit from reanalysis of the genetic data based on detailed postnatal findings.

Social impact of WES: Parent and provider perspectives

Wou K, Weitz T, McCormack C, et al. Parental perceptions of prenatal whole exome sequencing (PPPWES) study. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38:801-811.

Horn R, Parker M. Health professionals' and researchers' perspectives on prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing: 'We can't shut the door now, the genie's out, we need to refine it.' PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204158.

As health care providers enter a new era of prenatal genetic testing with exome sequencing, it is crucial to the path forward that we obtain perspectives from the parents and providers who participated in these studies. Notably, in both of the previously discussed Lancet reports, the authors interviewed the participants to discuss the challenges involved and identify strategies for improving future testing.

Continue to: What parents want...

What parents want

To ascertain the perceptions of couples who underwent prenatal WES, Wou and colleagues conducted semi-structured interviews with participants from the Fetal Sequencing Study regarding their experience. They interviewed 29 parents from 17 pregnancies, including a mix of those who had pathogenic prenatal results, terminated prior to receiving the results, and had normal results.

Expressed feelings and desires. Parents recalled feelings of anxiety and stress around the time of diagnosis and the need for help with coping while awaiting results. The majority of parents reported that they would like to be told about uncertain results, but that desire decreased as the certainty of results decreased.

Parents were overall satisfied with the prenatal genetic testing experience, but they added that they would have liked to receive written materials beforehand and a written report of the test results (including negative cases). They also would like to have connected with other families with similar experiences, to have received results sooner, and to have an in-person meeting after telephone disclosure of the results.

Health professionals articulate complexity of prenatal genomics

In a qualitative interview study to explore critical issues involved in the clinical practice use of prenatal genomics, Horn and Parker conducted interviews with 20 health care professionals who were involved in the previously described PAGE trial. Patient recruiters, midwives, genetic counselors, research assistants, and laboratory staff were included.

Interviewees cited numerous challenges involved in their day-to-day work with prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing, including:

- the complexity of achieving valid parental consent at a time of vulnerability

- management of parent expectations

- transmitting and comprehending complex information

- the usefulness of information

- the difficulty of a long turnaround time for study results.

All the interviewees agreed that prenatal exome sequencing studies contribute to knowledge generation and the advancement of technology.

The authors concluded that an appropriate next step would be the development of appropriate guidelines for good ethical practice that address the concerns encountered in genomics clinical practice.

The prenatal experience can be overwhelming for parents. Pretest and posttest counseling on genetic testing and results are of the utmost importance, as is finding ways to help support parents through this anxious time.

Societies offer guidance on using genome and exome sequencing

International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis, Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine, Perinatal Quality Foundation. Joint Position Statement from the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis (ISPD), the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine (SMFM), and the Perinatal Quality Foundation (PQF) on the use of genome-wide sequencing for fetal diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38:6-9.

In response to the rapid integration of exome sequencing for genetic diagnosis, several professional societies—the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis, Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, and Perinatal Quality Foundation—issued a joint statement addressing the clinical use of prenatal diagnostic genome wide sequencing, including exome sequencing.

Continue to: Guidance at a glance...

Guidance at a glance

The societies' recommendations are summarized as follows:

- Exome sequencing is best done as a trio analysis, with fetal and both parental samples sequenced and analyzed together.

- Extensive pretest education, counseling, and informed consent, as well as posttest counseling, are essential. This should include:

—the types of results to be conveyed (variants that are pathogenic, likely pathogenic, of uncertain significance, likely benign, and benign)

—the possibility that results will not be obtained or may not be available before the birth of the fetus

—realistic expectations regarding the likelihood that a significant result will be obtained

—the timeframe to results

—the option to include or exclude in the results incidental or secondary findings (such as an unexpected childhood disorder, cancer susceptibility genes, adult-onset disorders)

—the possibility of uncovering nonpaternity or consanguinity

—the potential reanalysis of results over time

—how data are stored, who has access, and for what purpose.

- Fetal sequencing may be beneficial in the following scenarios:

—multiple fetal anomalies or a single major anomaly suggestive of a genetic disorder, when the microarray is negative

—no microarray result is available, but the fetus exhibits a pattern of anomalies strongly suggestive of a single-gene disorder

—a prior undiagnosed fetus (or child) with anomalies suggestive of a genetic etiology, and with similar anomalies in the current pregnancy, with normal karyotype or microarray. Providers also can consider sequencing samples from both parents prior to preimplantation genetic testing to check for shared carrier status for autosomal recessive mutations, although obtaining exome sequencing from the prior affected fetus (or child) is ideal.

—history of recurrent stillbirths of unknown etiology, with a recurrent pattern of anomalies in the current pregnancy, with normal karyotype or microarray.

- Interpretation of results should be done using a multidisciplinary team-based approach, including clinical scientists, geneticists, genetic counselors, and experts in prenatal diagnosis.

- Where possible and after informed consent, reanalysis of results should be undertaken if a future pregnancy is planned or ongoing, and a significant amount of time has elapsed since the time the result was last reported.

- Parents should be given a written report of test results.

Three professional societies have convened to issue consensus opinion that includes current indications for prenatal exome sequencing and important factors to include in the consent process. We follow these guidelines in our own practice.

Summary

Exome sequencing is increasingly becoming mainstream in postnatal genetic testing, and it is emerging as the newest diagnostic frontier in prenatal genetic testing. However, there are limitations to prenatal exome sequencing, including issues with consent at a vulnerable time for parents, limited information available regarding the phenotype, and results that may not be available before the birth of a fetus. Providers should be familiar with the indications for testing, the possible results, the limitations of prenatal phenotyping, and the implications for future pregnancies.

Prenatal diagnosis of genetic anomalies is important for diagnosing lethal genetic conditions before birth. It can provide information for parents regarding pregnancy options and allow for recurrence risk counseling and the potential use of preimplantation genetic testing in the next pregnancy. For decades, a karyotype was used to analyze amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling specimens; in recent years, chromosomal microarray analysis provides more information about significant chromosomal abnormalities, including microdeletions and microduplications. However, microarrays also have limitations, as they do not identify base pair changes associated with single-gene disorders.

The advent of next-generation sequencing has substantially reduced the cost of DNA sequencing. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) can sequence the entire genome— both the coding (exonic) and noncoding (intronic) regions—while exome sequencing analyzes only the protein-coding exons, which make up 1% to 2% of the genome and about 85% of the protein-coding genes associated with known human disease. Exome sequencing increasingly is used in cases of suspected genetic disorders when other tests have been unrevealing.

In this Update, we review recent reports of prenatal exome sequencing, including studies exploring the yield in fetuses with structural anomalies; the importance of prenatal phenotyping; the perspectives of parents and health care professionals who were involved in prenatal exome sequencing studies; and a summary of a joint position statement from 3 societies regarding prenatal sequencing.

Prenatal whole exome sequencing has potential utility, with some limitations

Petrovski S, Aggarwal V, Giordano JL, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in the evaluation of fetal structural anomalies: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393:758-767.

Lord J, McMullan DJ, Eberhardt RY, et al; for the Prenatal Assessment of Genomes and Exomes Consortium. Prenatal exome sequencing analysis in fetal structural anomalies detected by ultrasonography (PAGE): a cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393:747-757.

Exome sequencing has been shown to identify an underlying genetic cause in 25% to 30% of children with an undiagnosed suspected genetic disorder. Two studies recently published in the Lancet sought to determine the incremental diagnostic yield of prenatal whole exome sequencing (WES) in the setting of fetal structural anomalies when karyotype and microarray results were normal.

Continue to: Details of the studies...

Details of the studies

In a prospective cohort study by Petrovski and colleagues, DNA samples from 234 fetuses with a structural anomaly (identified on ultrasonography) and both parents (parent-fetus "trios") were used for analysis. WES identified diagnostic genetic variants in 24 trios (10%). An additional 46 (20%) had variants that indicated pathogenicity but without sufficient evidence to be considered diagnostic.

The anomalies with the highest frequency of a genetic diagnosis were lymphatic, 24%; skeletal, 24%; central nervous system, 22%; and renal, 16%; while cardiac anomalies had the lowest yield at 5%.

In another prospective cohort study, known as the Prenatal Assessment of Genomes and Exomes (PAGE), Lord and colleagues sequenced DNA samples from 610 parent-fetus trios, but they restricted sequencing to a predefined list of 1,628 genes. Diagnostic genetic variants were identified in 52 fetuses (8.5%), while 24 (3.9%) had a variant of uncertain significance that was thought to be of potential clinical usefulness.

Fetuses with multiple anomalies had the highest genetic yield (15.4%), followed by skeletal (15.4%) and cardiac anomalies (11.1%), with the lowest yield in fetuses with isolated increased nuchal translucency (3.2%).

Diagnostic yield is high, but prenatal utility is limited

Both studies showed a clinically significant diagnostic yield of 8% to 10% for prenatal exome sequencing in cases of fetal structural anomalies with normal karyotype and microarray testing. While this yield demonstrates the utility of prenatal exome sequencing, it is significantly lower than what has been reported in postnatal studies. One of the reasons for this is the inherent limitation of prenatal phenotyping (discussed below).

The cohort studies by both Petrovski and Lord and their colleagues show the feasibility and potential diagnostic utility of exome sequencing in cases of fetal structural anomalies where karyotype and microarray are not diagnostic. However, the lower yield found in these studies compared with those in postnatal studies highlights in part the limitations of prenatal phenotyping.

The importance of prenatal phenotyping

Aarabi M, Sniezek O, Jiang H, et al. Importance of complete phenotyping in prenatal whole exome sequencing. Hum Genet. 2018;137:175-181.

In postnatal exome sequencing, the physical exam, imaging findings, and laboratory results are components of the phenotype that are used to interpret the sequencing data. Prenatal phenotyping, however, is limited to the use of fetal ultrasonography and, occasionally, the addition of magnetic resonance imaging. Prenatal phenotyping is without the benefit of an exam to detect more subtle anomalies or functional status, such as developmental delay, seizures, or failure to thrive.

When a structural anomaly is identified on prenatal ultrasonography, it is especially important that detailed imaging be undertaken to detect other anomalies, including more subtle facial features and dysmorphology.

Value of reanalyzing exome sequencing data

Aarabi and colleagues conducted a retrospective study of 20 fetuses with structural anomalies and normal karyotype and microarray. They performed trio exome sequencing first using information available only prenatally and then conducted a reanalysis using information available after delivery.

With prenatal phenotyping only, the investigators identified no pathogenic, or likely pathogenic, variants. On reanalysis of combined prenatal and postnatal findings, however, they identified pathogenic variants in 20% of cases.

Significance of the findings

This study highlights both the importance of a careful, detailed fetal ultrasonography study and the possible additional benefit of a postnatal examination (such as an autopsy) in order to yield improved results. In addition, the authors noted that the development of a prenatal phenotype-genotype database would significantly help exome sequencing interpretation in the prenatal setting.

Careful prenatal ultrasonography is crucial to help in the interpretation of prenatal exome sequencing. Patients who have undergone prenatal clinical exome sequencing may benefit from reanalysis of the genetic data based on detailed postnatal findings.

Social impact of WES: Parent and provider perspectives

Wou K, Weitz T, McCormack C, et al. Parental perceptions of prenatal whole exome sequencing (PPPWES) study. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38:801-811.

Horn R, Parker M. Health professionals' and researchers' perspectives on prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing: 'We can't shut the door now, the genie's out, we need to refine it.' PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204158.

As health care providers enter a new era of prenatal genetic testing with exome sequencing, it is crucial to the path forward that we obtain perspectives from the parents and providers who participated in these studies. Notably, in both of the previously discussed Lancet reports, the authors interviewed the participants to discuss the challenges involved and identify strategies for improving future testing.

Continue to: What parents want...

What parents want

To ascertain the perceptions of couples who underwent prenatal WES, Wou and colleagues conducted semi-structured interviews with participants from the Fetal Sequencing Study regarding their experience. They interviewed 29 parents from 17 pregnancies, including a mix of those who had pathogenic prenatal results, terminated prior to receiving the results, and had normal results.

Expressed feelings and desires. Parents recalled feelings of anxiety and stress around the time of diagnosis and the need for help with coping while awaiting results. The majority of parents reported that they would like to be told about uncertain results, but that desire decreased as the certainty of results decreased.

Parents were overall satisfied with the prenatal genetic testing experience, but they added that they would have liked to receive written materials beforehand and a written report of the test results (including negative cases). They also would like to have connected with other families with similar experiences, to have received results sooner, and to have an in-person meeting after telephone disclosure of the results.

Health professionals articulate complexity of prenatal genomics

In a qualitative interview study to explore critical issues involved in the clinical practice use of prenatal genomics, Horn and Parker conducted interviews with 20 health care professionals who were involved in the previously described PAGE trial. Patient recruiters, midwives, genetic counselors, research assistants, and laboratory staff were included.

Interviewees cited numerous challenges involved in their day-to-day work with prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing, including:

- the complexity of achieving valid parental consent at a time of vulnerability

- management of parent expectations

- transmitting and comprehending complex information

- the usefulness of information

- the difficulty of a long turnaround time for study results.

All the interviewees agreed that prenatal exome sequencing studies contribute to knowledge generation and the advancement of technology.

The authors concluded that an appropriate next step would be the development of appropriate guidelines for good ethical practice that address the concerns encountered in genomics clinical practice.

The prenatal experience can be overwhelming for parents. Pretest and posttest counseling on genetic testing and results are of the utmost importance, as is finding ways to help support parents through this anxious time.

Societies offer guidance on using genome and exome sequencing

International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis, Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine, Perinatal Quality Foundation. Joint Position Statement from the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis (ISPD), the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine (SMFM), and the Perinatal Quality Foundation (PQF) on the use of genome-wide sequencing for fetal diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38:6-9.

In response to the rapid integration of exome sequencing for genetic diagnosis, several professional societies—the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis, Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, and Perinatal Quality Foundation—issued a joint statement addressing the clinical use of prenatal diagnostic genome wide sequencing, including exome sequencing.

Continue to: Guidance at a glance...

Guidance at a glance

The societies' recommendations are summarized as follows:

- Exome sequencing is best done as a trio analysis, with fetal and both parental samples sequenced and analyzed together.

- Extensive pretest education, counseling, and informed consent, as well as posttest counseling, are essential. This should include:

—the types of results to be conveyed (variants that are pathogenic, likely pathogenic, of uncertain significance, likely benign, and benign)

—the possibility that results will not be obtained or may not be available before the birth of the fetus

—realistic expectations regarding the likelihood that a significant result will be obtained

—the timeframe to results

—the option to include or exclude in the results incidental or secondary findings (such as an unexpected childhood disorder, cancer susceptibility genes, adult-onset disorders)

—the possibility of uncovering nonpaternity or consanguinity

—the potential reanalysis of results over time

—how data are stored, who has access, and for what purpose.

- Fetal sequencing may be beneficial in the following scenarios:

—multiple fetal anomalies or a single major anomaly suggestive of a genetic disorder, when the microarray is negative

—no microarray result is available, but the fetus exhibits a pattern of anomalies strongly suggestive of a single-gene disorder

—a prior undiagnosed fetus (or child) with anomalies suggestive of a genetic etiology, and with similar anomalies in the current pregnancy, with normal karyotype or microarray. Providers also can consider sequencing samples from both parents prior to preimplantation genetic testing to check for shared carrier status for autosomal recessive mutations, although obtaining exome sequencing from the prior affected fetus (or child) is ideal.

—history of recurrent stillbirths of unknown etiology, with a recurrent pattern of anomalies in the current pregnancy, with normal karyotype or microarray.

- Interpretation of results should be done using a multidisciplinary team-based approach, including clinical scientists, geneticists, genetic counselors, and experts in prenatal diagnosis.

- Where possible and after informed consent, reanalysis of results should be undertaken if a future pregnancy is planned or ongoing, and a significant amount of time has elapsed since the time the result was last reported.

- Parents should be given a written report of test results.

Three professional societies have convened to issue consensus opinion that includes current indications for prenatal exome sequencing and important factors to include in the consent process. We follow these guidelines in our own practice.

Summary

Exome sequencing is increasingly becoming mainstream in postnatal genetic testing, and it is emerging as the newest diagnostic frontier in prenatal genetic testing. However, there are limitations to prenatal exome sequencing, including issues with consent at a vulnerable time for parents, limited information available regarding the phenotype, and results that may not be available before the birth of a fetus. Providers should be familiar with the indications for testing, the possible results, the limitations of prenatal phenotyping, and the implications for future pregnancies.

Screening and counseling interventions to prevent peripartum depression: A practical approach

Perinatal depression is an episode of major or minor depression that occurs during pregnancy or in the 12 months after birth; it affects about 10% of new mothers.1 Perinatal depression adversely impacts mothers, children, and their families. Pregnant women with depression are at increased risk for preterm birth and low birth weight.2 Infants of mothers with postpartum depression have reduced bonding, lower rates of breastfeeding, delayed cognitive and social development, and an increased risk of future mental health issues.3 Timely treatment of perinatal depression can improve health outcomes for the woman, her children, and their family.

Clinicians follow current screening recommendations

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently recommends that ObGynsscreen all pregnant women for depression and anxiety symptoms at least once during the perinatal period.1 Many practices use the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) during pregnancy and postpartum. Women who screen positive are referred to mental health clinicians or have treatment initiated by their primary obstetrician.

Clinicians have been phenomenally successful in screening for perinatal depression. In a recent study from Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 98% of pregnant women were screened for perinatal depression, and a diagnosis of depression was made in 12%.4 Of note, only 47% of women who screened positive for depression initiated treatment, although 82% of women with the most severe symptoms initiated treatment. These data demonstrate that ObGyns consistently screen pregnant women for depression but, due to patient and system issues, treatment of all screen-positive women remains a yet unattained goal.5,6

New USPSTF guideline: Identify women at risk for perinatal depression and refer for counseling

In 2016 the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended that pregnant and postpartum women be screened for depression with adequate systems in place to ensure diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up.7 The 2016 USPSTF recommendation was consistent with prior guidelines from both the American Academy of Pediatrics in 20108 and ACOG in 2015.9

Now, the USPSTF is making a bold new recommendation, jumping ahead of professional societies: screen pregnant women to identify those at risk for perinatal depression and refer them for counseling (B recommendation; net benefit is moderate).10,11 The USPSTF recommendation is based on growing literature that shows counseling women at risk for perinatal depression reduces the risk of having an episode of major depression by 40%.11 Both interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy have been reported to be effective for preventing perinatal depression.12,13

As an example of the relevant literature, in one trial performed in Rhode Island, women who were 20 to 35 weeks pregnant with a high score (≥27) on the Cooper Survey Questionnaire and on public assistance were randomized to counseling or usual care. The counseling intervention involved 4 small group (2 to 5 women) sessions of 90 minutes and one individual session of 50 minutes.14 The treatment focused on managing the transition to motherhood, developing a support system, improving communication skills to manage conflict, goal setting, and identifying psychosocial supports for new mothers. At 6 months after birth, a depressive episode had occurred in 31% of the control women and 16% of the women who had experienced the intervention (P = .041). At 12 months after birth, a depressive episode had occurred in 40% of control women and 26% of women in the intervention group (P = .052).

Of note, most cases of postpartum depression were diagnosed more than 3 months after birth, a time when new mothers generally no longer are receiving regular postpartum care by an obstetrician. The timing of the diagnosis of perinatal depression indicates that an effective handoff between the obstetrician and primary care and/or mental health clinicians is of great importance. The investigators concluded that pregnant women at very high risk for perinatal depression who receive interpersonal therapy have a lower rate of a postpartum depressive episode than women receiving usual care.14

Pregnancy, delivery, and the first year following birth are stressful for many women and their families. Women who are young, poor, and with minimal social supports are at especially high risk for developing perinatal depression. However, it will be challenging for obstetric practices to rapidly implement the new USPSTF recommendations because there is no professional consensus on how to screen women to identify those at high risk for perinatal depression, and mental health resources to care for the screen-positive women are not sufficient.

Continue to: Challenges to implementing new USPSTF guideline...

Challenges to implementing new USPSTF guideline

Obstetricians have had great success in screening for perinatal depression because validated screening tools are available. Professional societies need to reach a consensus on recommending a specific screening tool for perinatal depression risk that can be used in all obstetric practices.

- personal history of depression

- current depressive symptoms that do not reach a diagnostic threshold

- low income

- all adolescents

- all single mothers

- recent exposure to intimate partner violence

- elevated anxiety symptoms

- a history of significant negative life events.

For many obstetricians, most of their pregnant patients meet the USPSTF criteria for being at high risk for perinatal depression and, per the guideline, these women should have a counseling intervention.

For many health systems, the resources available to provide mental health services are very limited. If most pregnant women need a counseling intervention, the health system must evolve to meet this need. In addition, risk factors for perinatal depression are also risk factors for having difficulty in participating in mental health interventions due to limitations, such as lack of transportation, social support, and money.4

Fortunately, clinicians from many backgrounds, including psychologists, social workers, nurse practitioners, and public health workers have the experience and/or training to provide the counseling interventions that have been shown to reduce the risk of perinatal depression. Health systems will need to tap all these resources to accommodate the large numbers of pregnant women who will be referred for counseling interventions. Pilot projects using electronic interventions, including telephone counseling, smartphone apps, and internet programs show promise.15,16 Electronic interventions have the potential to reach many pregnant women without over-taxing limited mental health resources.

A practical approach