User login

Does the use of frankincense make sense in dermatology?

The Boswellia serrata exudate or gum (known in India as “guggulu”) that forms an aromatic resin traditionally used as incense – and known as frankincense (especially when retrieved from Boswellia species found in Eritrea and Somalia but also from the Indian variety) – has been considered for thousands of years to possess therapeutic properties. It is used in Ayurvedic medicine, as well as in traditional medicine in China and the Middle East, particularly for its anti-inflammatory effects to treat chronic conditions.1-8 In fact, such essential oils have been used since 2800 BC to treat various inflammatory conditions, including skin sores and wounds, as well as in perfumes and incense.2,9 In the West, use of frankincense dates back to thousands of years as well, more often found in the form of incense for religious and cultural ceremonies.7 Over the past 2 decades, .3 This column focuses on some of the emerging data on this ancient botanical agent.

Chemical constituents

Terpenoids and essential oils are the primary components of frankincense and are known to impart anti-inflammatory and anticancer activity. The same is true for myrrh, which has been combined with frankincense in traditional Chinese medicine as a single medication for millennia, with the two acting synergistically and considered still to be a potent combination in conferring various biological benefits.7

In 2010, in a systematic review of the anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of Boswellia species and their chemical ingredients, Efferth and Oesch found that frankincense blocks the production of leukotrienes, cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 and 2, as well as 5-lipoxygenase; and oxidative stress. It also contributes to regulation of immune cells from the innate and acquired immune systems and exerts anticancer activity by influencing signaling transduction responsible for cell cycle arrest, as well as inhibition of proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. The investigators also reported on clinical trial results that have found efficacy of frankincense and its constituents in ameliorating symptoms of psoriasis and erythematous eczema, among other disorders.3

Anti-inflammatory activity

Li et al. completed a study in 2016 to identify the active ingredients responsible for the anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of frankincense. They found that alpha-pinene, linalool, and 1-octanol were key contributors. These constituents were noted for suppressing COX-2 overexpression in mice, as well as nociceptive stimulus-induced inflammatory infiltrates.10

Noting the increasing popularity of frankincense essential oil in skin care, despite a paucity of data, in 2017, Han et al. evaluated the biological activities of the essential oil in pre-inflamed human dermal fibroblasts using 17 key protein biomarkers. Frankincense essential oil displayed significant antiproliferative activity and suppressed collagen III, interferon gamma-induced protein 10, and intracellular adhesion molecule 1. The investigators referred to the overall encouraging potential of frankincense essential oil to exert influence over inflammation and tissue remodeling in human skin and called for additional research into its mechanisms of action and active constituents.11

Anticancer activity

The main active ingredient in frankincense, boswellic acid, has been shown to promote apoptosis, suppress matrix metalloproteinase secretion, and hinder migration in metastatic melanoma cell lines in mice.6,12

In 2019, Hakkim et al. demonstrated that frankincense essential oil yielded substantial antimelanoma activity in vitro and in vivo and ameliorated hepatotoxicity caused by acetaminophen.13

There is one case report in the literature on the use of frankincense as a treatment for skin cancer. A 56-year-old man received frankincense oil multiple times a day for 4 months to treat a nodular basal cell carcinoma on one arm (which resolved) and an infiltrative BCC on the chest (some focal residual tumor remained).6,14 Topical frankincense or boswellic acid has been given a grade D recommendation for treating skin cancer, however, because of only one level-of-evidence-5 study.6

Antimicrobial activity

In 2012, de Rapper et al. collected samples of three essential oils of frankincense (Boswellia rivae, Boswellia neglecta, and Boswellia papyrifera) and two essential oil samples of myrrh and sweet myrrh from different regions of Ethiopia to study their anti-infective properties alone and in combination. The investigators observed synergistic and additive effects, particularly between B. papyrifera and Commiphora myrrha. While noting the long history of the combined use of frankincense and myrrh essential oils since 1500 BC, the investigators highlighted their study as the first antimicrobial work to verify the effectiveness of this combination, validating the use of this combination to thwart particular pathogens.15

Just 2 years ago, Ljaljević Grbić et al. evaluated the in vitro antimicrobial potential of the liquid and vapor phases of B. carteri and C. myrrha (frankincense and myrrh, respectively) essential oils, finding that frankincense demonstrated marked capacity to act as a natural antimicrobial agent.9

Transdermal delivery

In 2017, Zhu et al. showed that frankincense and myrrh essential oils promoted the permeability of the Chinese herb Chuanxiong and may facilitate drug elimination from the epidermis via dermal capillaries by dint of improved cutaneous blood flow, thereby augmenting transdermal drug delivery.16 The same team also showed that frankincense and myrrh essential oils, by fostering permeation by enhancing drug delivery across the stratum corneum, can also alter the structure of the stratum corneum.17

Conclusion

The use of frankincense in traditional medicine has a long and impressive track record. Recent research provides reason for optimism, and further investigating the possible incorporation of this botanical agent into modern dermatologic therapies appears warranted. Clearly, however, much more research is needed.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Kimmatkar N et al. Phytomedicine. 2003 Jan;10(1):3-7.

2. Ammon HP. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2002;152(15-16):373-8.

3. Efferth T & Oesch F. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020 Feb 4;S1044-579X(20)30034-1.

4. Banno N et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006 Sep 19;107(2):249-53.

5. Poeckel D & Werz O. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13(28):3359-69.

6. Li JY, Kampp JT. Dermatol Surg. 2019 Jan;45(1):58-67.

7. Cao B et al. Molecules. 2019 Aug 24;24(17): 3076.

8. Mertens M et al. Flavour Fragr J. 2009;24:279-300.

9. Ljaljević Grbić M et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018 Jun 12;219:1-14.

10. Li XJ et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016 Feb 17;179:22-6.

11. Han X et al. Biochim Open. 2017 Feb 3;4:31-5.

12. Zhao W et al. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:67-75.

13. Hakkim FL et al. Oncotarget. 2019 May 28;10(37):3472-90.

14. Fung K et al. OA Altern Med 2013;1:14.

15. de Rapper S et al. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2012 Apr;54(4):352-8.

16. Zhu XF et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2017 Feb;42(4):680-5.

17. Guan YM et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2017 Sep;42(17):3350-5.

The Boswellia serrata exudate or gum (known in India as “guggulu”) that forms an aromatic resin traditionally used as incense – and known as frankincense (especially when retrieved from Boswellia species found in Eritrea and Somalia but also from the Indian variety) – has been considered for thousands of years to possess therapeutic properties. It is used in Ayurvedic medicine, as well as in traditional medicine in China and the Middle East, particularly for its anti-inflammatory effects to treat chronic conditions.1-8 In fact, such essential oils have been used since 2800 BC to treat various inflammatory conditions, including skin sores and wounds, as well as in perfumes and incense.2,9 In the West, use of frankincense dates back to thousands of years as well, more often found in the form of incense for religious and cultural ceremonies.7 Over the past 2 decades, .3 This column focuses on some of the emerging data on this ancient botanical agent.

Chemical constituents

Terpenoids and essential oils are the primary components of frankincense and are known to impart anti-inflammatory and anticancer activity. The same is true for myrrh, which has been combined with frankincense in traditional Chinese medicine as a single medication for millennia, with the two acting synergistically and considered still to be a potent combination in conferring various biological benefits.7

In 2010, in a systematic review of the anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of Boswellia species and their chemical ingredients, Efferth and Oesch found that frankincense blocks the production of leukotrienes, cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 and 2, as well as 5-lipoxygenase; and oxidative stress. It also contributes to regulation of immune cells from the innate and acquired immune systems and exerts anticancer activity by influencing signaling transduction responsible for cell cycle arrest, as well as inhibition of proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. The investigators also reported on clinical trial results that have found efficacy of frankincense and its constituents in ameliorating symptoms of psoriasis and erythematous eczema, among other disorders.3

Anti-inflammatory activity

Li et al. completed a study in 2016 to identify the active ingredients responsible for the anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of frankincense. They found that alpha-pinene, linalool, and 1-octanol were key contributors. These constituents were noted for suppressing COX-2 overexpression in mice, as well as nociceptive stimulus-induced inflammatory infiltrates.10

Noting the increasing popularity of frankincense essential oil in skin care, despite a paucity of data, in 2017, Han et al. evaluated the biological activities of the essential oil in pre-inflamed human dermal fibroblasts using 17 key protein biomarkers. Frankincense essential oil displayed significant antiproliferative activity and suppressed collagen III, interferon gamma-induced protein 10, and intracellular adhesion molecule 1. The investigators referred to the overall encouraging potential of frankincense essential oil to exert influence over inflammation and tissue remodeling in human skin and called for additional research into its mechanisms of action and active constituents.11

Anticancer activity

The main active ingredient in frankincense, boswellic acid, has been shown to promote apoptosis, suppress matrix metalloproteinase secretion, and hinder migration in metastatic melanoma cell lines in mice.6,12

In 2019, Hakkim et al. demonstrated that frankincense essential oil yielded substantial antimelanoma activity in vitro and in vivo and ameliorated hepatotoxicity caused by acetaminophen.13

There is one case report in the literature on the use of frankincense as a treatment for skin cancer. A 56-year-old man received frankincense oil multiple times a day for 4 months to treat a nodular basal cell carcinoma on one arm (which resolved) and an infiltrative BCC on the chest (some focal residual tumor remained).6,14 Topical frankincense or boswellic acid has been given a grade D recommendation for treating skin cancer, however, because of only one level-of-evidence-5 study.6

Antimicrobial activity

In 2012, de Rapper et al. collected samples of three essential oils of frankincense (Boswellia rivae, Boswellia neglecta, and Boswellia papyrifera) and two essential oil samples of myrrh and sweet myrrh from different regions of Ethiopia to study their anti-infective properties alone and in combination. The investigators observed synergistic and additive effects, particularly between B. papyrifera and Commiphora myrrha. While noting the long history of the combined use of frankincense and myrrh essential oils since 1500 BC, the investigators highlighted their study as the first antimicrobial work to verify the effectiveness of this combination, validating the use of this combination to thwart particular pathogens.15

Just 2 years ago, Ljaljević Grbić et al. evaluated the in vitro antimicrobial potential of the liquid and vapor phases of B. carteri and C. myrrha (frankincense and myrrh, respectively) essential oils, finding that frankincense demonstrated marked capacity to act as a natural antimicrobial agent.9

Transdermal delivery

In 2017, Zhu et al. showed that frankincense and myrrh essential oils promoted the permeability of the Chinese herb Chuanxiong and may facilitate drug elimination from the epidermis via dermal capillaries by dint of improved cutaneous blood flow, thereby augmenting transdermal drug delivery.16 The same team also showed that frankincense and myrrh essential oils, by fostering permeation by enhancing drug delivery across the stratum corneum, can also alter the structure of the stratum corneum.17

Conclusion

The use of frankincense in traditional medicine has a long and impressive track record. Recent research provides reason for optimism, and further investigating the possible incorporation of this botanical agent into modern dermatologic therapies appears warranted. Clearly, however, much more research is needed.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Kimmatkar N et al. Phytomedicine. 2003 Jan;10(1):3-7.

2. Ammon HP. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2002;152(15-16):373-8.

3. Efferth T & Oesch F. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020 Feb 4;S1044-579X(20)30034-1.

4. Banno N et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006 Sep 19;107(2):249-53.

5. Poeckel D & Werz O. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13(28):3359-69.

6. Li JY, Kampp JT. Dermatol Surg. 2019 Jan;45(1):58-67.

7. Cao B et al. Molecules. 2019 Aug 24;24(17): 3076.

8. Mertens M et al. Flavour Fragr J. 2009;24:279-300.

9. Ljaljević Grbić M et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018 Jun 12;219:1-14.

10. Li XJ et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016 Feb 17;179:22-6.

11. Han X et al. Biochim Open. 2017 Feb 3;4:31-5.

12. Zhao W et al. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:67-75.

13. Hakkim FL et al. Oncotarget. 2019 May 28;10(37):3472-90.

14. Fung K et al. OA Altern Med 2013;1:14.

15. de Rapper S et al. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2012 Apr;54(4):352-8.

16. Zhu XF et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2017 Feb;42(4):680-5.

17. Guan YM et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2017 Sep;42(17):3350-5.

The Boswellia serrata exudate or gum (known in India as “guggulu”) that forms an aromatic resin traditionally used as incense – and known as frankincense (especially when retrieved from Boswellia species found in Eritrea and Somalia but also from the Indian variety) – has been considered for thousands of years to possess therapeutic properties. It is used in Ayurvedic medicine, as well as in traditional medicine in China and the Middle East, particularly for its anti-inflammatory effects to treat chronic conditions.1-8 In fact, such essential oils have been used since 2800 BC to treat various inflammatory conditions, including skin sores and wounds, as well as in perfumes and incense.2,9 In the West, use of frankincense dates back to thousands of years as well, more often found in the form of incense for religious and cultural ceremonies.7 Over the past 2 decades, .3 This column focuses on some of the emerging data on this ancient botanical agent.

Chemical constituents

Terpenoids and essential oils are the primary components of frankincense and are known to impart anti-inflammatory and anticancer activity. The same is true for myrrh, which has been combined with frankincense in traditional Chinese medicine as a single medication for millennia, with the two acting synergistically and considered still to be a potent combination in conferring various biological benefits.7

In 2010, in a systematic review of the anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of Boswellia species and their chemical ingredients, Efferth and Oesch found that frankincense blocks the production of leukotrienes, cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 and 2, as well as 5-lipoxygenase; and oxidative stress. It also contributes to regulation of immune cells from the innate and acquired immune systems and exerts anticancer activity by influencing signaling transduction responsible for cell cycle arrest, as well as inhibition of proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. The investigators also reported on clinical trial results that have found efficacy of frankincense and its constituents in ameliorating symptoms of psoriasis and erythematous eczema, among other disorders.3

Anti-inflammatory activity

Li et al. completed a study in 2016 to identify the active ingredients responsible for the anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of frankincense. They found that alpha-pinene, linalool, and 1-octanol were key contributors. These constituents were noted for suppressing COX-2 overexpression in mice, as well as nociceptive stimulus-induced inflammatory infiltrates.10

Noting the increasing popularity of frankincense essential oil in skin care, despite a paucity of data, in 2017, Han et al. evaluated the biological activities of the essential oil in pre-inflamed human dermal fibroblasts using 17 key protein biomarkers. Frankincense essential oil displayed significant antiproliferative activity and suppressed collagen III, interferon gamma-induced protein 10, and intracellular adhesion molecule 1. The investigators referred to the overall encouraging potential of frankincense essential oil to exert influence over inflammation and tissue remodeling in human skin and called for additional research into its mechanisms of action and active constituents.11

Anticancer activity

The main active ingredient in frankincense, boswellic acid, has been shown to promote apoptosis, suppress matrix metalloproteinase secretion, and hinder migration in metastatic melanoma cell lines in mice.6,12

In 2019, Hakkim et al. demonstrated that frankincense essential oil yielded substantial antimelanoma activity in vitro and in vivo and ameliorated hepatotoxicity caused by acetaminophen.13

There is one case report in the literature on the use of frankincense as a treatment for skin cancer. A 56-year-old man received frankincense oil multiple times a day for 4 months to treat a nodular basal cell carcinoma on one arm (which resolved) and an infiltrative BCC on the chest (some focal residual tumor remained).6,14 Topical frankincense or boswellic acid has been given a grade D recommendation for treating skin cancer, however, because of only one level-of-evidence-5 study.6

Antimicrobial activity

In 2012, de Rapper et al. collected samples of three essential oils of frankincense (Boswellia rivae, Boswellia neglecta, and Boswellia papyrifera) and two essential oil samples of myrrh and sweet myrrh from different regions of Ethiopia to study their anti-infective properties alone and in combination. The investigators observed synergistic and additive effects, particularly between B. papyrifera and Commiphora myrrha. While noting the long history of the combined use of frankincense and myrrh essential oils since 1500 BC, the investigators highlighted their study as the first antimicrobial work to verify the effectiveness of this combination, validating the use of this combination to thwart particular pathogens.15

Just 2 years ago, Ljaljević Grbić et al. evaluated the in vitro antimicrobial potential of the liquid and vapor phases of B. carteri and C. myrrha (frankincense and myrrh, respectively) essential oils, finding that frankincense demonstrated marked capacity to act as a natural antimicrobial agent.9

Transdermal delivery

In 2017, Zhu et al. showed that frankincense and myrrh essential oils promoted the permeability of the Chinese herb Chuanxiong and may facilitate drug elimination from the epidermis via dermal capillaries by dint of improved cutaneous blood flow, thereby augmenting transdermal drug delivery.16 The same team also showed that frankincense and myrrh essential oils, by fostering permeation by enhancing drug delivery across the stratum corneum, can also alter the structure of the stratum corneum.17

Conclusion

The use of frankincense in traditional medicine has a long and impressive track record. Recent research provides reason for optimism, and further investigating the possible incorporation of this botanical agent into modern dermatologic therapies appears warranted. Clearly, however, much more research is needed.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Kimmatkar N et al. Phytomedicine. 2003 Jan;10(1):3-7.

2. Ammon HP. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2002;152(15-16):373-8.

3. Efferth T & Oesch F. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020 Feb 4;S1044-579X(20)30034-1.

4. Banno N et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006 Sep 19;107(2):249-53.

5. Poeckel D & Werz O. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13(28):3359-69.

6. Li JY, Kampp JT. Dermatol Surg. 2019 Jan;45(1):58-67.

7. Cao B et al. Molecules. 2019 Aug 24;24(17): 3076.

8. Mertens M et al. Flavour Fragr J. 2009;24:279-300.

9. Ljaljević Grbić M et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018 Jun 12;219:1-14.

10. Li XJ et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016 Feb 17;179:22-6.

11. Han X et al. Biochim Open. 2017 Feb 3;4:31-5.

12. Zhao W et al. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:67-75.

13. Hakkim FL et al. Oncotarget. 2019 May 28;10(37):3472-90.

14. Fung K et al. OA Altern Med 2013;1:14.

15. de Rapper S et al. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2012 Apr;54(4):352-8.

16. Zhu XF et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2017 Feb;42(4):680-5.

17. Guan YM et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2017 Sep;42(17):3350-5.

Early Pilomatrix Carcinoma: A Case Report With Emphasis on Molecular Pathology and Review of the Literature

Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare adnexal tumor with origin from the germinative matrical cells of the hair follicle. Clinically, it presents as a solitary lesion commonly found in the head and neck region as well as the upper back. The tumors cannot be distinguished by their clinical appearance only and frequently are mistaken for cysts. Histopathologic examination provides the definitive diagnosis in most cases. These carcinomas are aggressive neoplasms with a high probability of local recurrence and distant metastasis. Assessment of the Wnt signaling pathway components such as β-catenin, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF-1), and caudal-related homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX-2) potentially can be used for diagnostic purposes and targeted therapy.

We report a rare and unique case of early pilomatrix carcinoma with intralesional melanocytes. We review the molecular pathology and pathogenesis of these carcinomas as well as the significance of early diagnosis.

Case Report

A 73-year-old man with a history of extensive sun exposure presented with a 1-cm, raised, rapidly growing, slightly irregular, purple lesion on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration with tendency to bleed. He did not have a history of skin cancers and was otherwise healthy. Excision was recommended due to the progressive and rapid growth of the lesion.

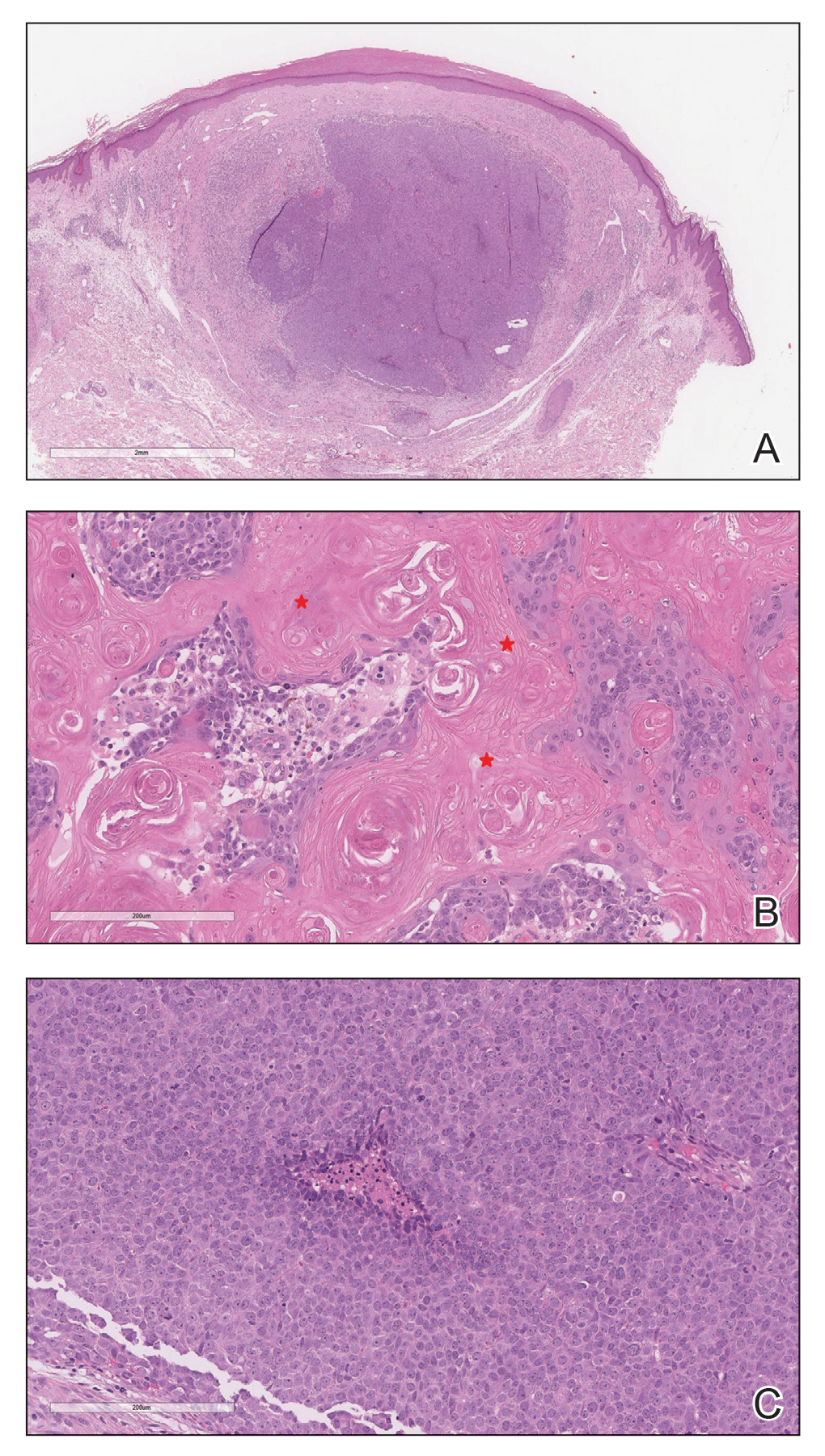

Histopathologic Findings—Gross examination revealed a 0.9×0.7-cm, raised, slightly irregular lesion located 1 mm away from the closest peripheral margin. Histologically, the lesion was a relatively circumscribed, dermal-based basaloid neoplasm with slightly ill-defined edges involving the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). The neoplasm was formed predominantly of sheets of basaloid cells and small nests of ghost cells, in addition to some squamoid and transitional cells (Figure 1B). The basaloid cells exhibited severe nuclear atypia, pleomorphism, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1C), minimal to moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and coarse chromatin pattern. Abundant mitotic activity and apoptotic bodies were present as well as focal area of central necrosis (Figure 1C). Also, melanophages and a multinucleated giant cell reaction was noted. Elastic trichrome special stain highlighted focal infiltration of the neoplastic cells into the adjacent desmoplastic stroma. Melanin stain was negative for melanin pigment within the neoplasm. Given the presence of severely atypical basaloid cells along with ghost cells indicating matrical differentiation, a diagnosis of pilomatrix carcinoma was rendered.

Immunohistochemistry—The neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for p63, CDX-2 (Figure 2A), β-catenin (Figure 2B), and CD10 (Figure 2C), and focally and weakly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5, BerEP4 (staining the tumor periphery), androgen receptor, and CK18 (a low-molecular-weight keratin). They were negative for monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, CK7, CK20, CD34, SOX-10, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin. Cytokeratin 14 was positive in the squamoid cells but negative in the basaloid cells. SOX-10 and melanoma cocktail immunostains demonstrated few intralesional dendritic melanocytes.

Comment

Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasm with origin from the germinative matrix of the hair bulb region of hair follicles. Pilomatrix carcinoma was first reported in 1980.1,2 These tumors are characterized by rapid growth and aggressive behavior. Their benign counterpart, pilomatrixoma, is a slow-growing, dermal or subcutaneous tumor that rarely recurs after complete excision.

As with pilomatrixoma, pilomatrix carcinomas are asymptomatic and present as solitary dermal or subcutaneous masses3,4 that most commonly are found in the posterior neck, upper back, and preauricular regions of middle-aged or elderly adults with male predominance.5 They range in size from 0.5 to 20 cm with a mean of 4 cm that is slightly larger than pilomatrixoma. Pilomatrix carcinomas predominantly are firm tumors with or without cystic components, and they exhibit a high probability of recurrence and have risk for distant metastasis.6-15

The differential diagnosis includes epidermal cysts, pilomatrixoma, basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation, trichoblastoma/trichoblastic carcinoma, and trichilemmal carcinoma. Pilomatrix carcinomas frequently are mistaken for epidermal cysts on clinical examination. Such a distinction can be easily resolved by histopathologic evaluation. The more challenging differential diagnosis is with pilomatrixoma. Histologically, pilomatrixomas consist of a distinct population of cells including basaloid, squamoid, transitional, and shadow cells in variable proportions. The basaloid cells transition to shadow cells in an organized zonal fashion.16 Compared to pilomatrixomas, pilomatrix carcinomas often show predominance of the basaloid cells; marked cytologic atypia and pleomorphism; numerous mitotic figures; deep infiltrative pattern into subcutaneous fat, fascia, and skeletal muscle; stromal desmoplasia; necrosis; and neurovascular invasion (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, the shadow cells tend to form a small nested pattern in pilomatrix carcinoma instead of the flat sheetlike pattern usually observed in pilomatrixoma.16 Basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation can pose a diagnostic challenge in the differential diagnosis; basal cell carcinoma usually exhibits a peripheral palisade of the basaloid cells accompanied by retraction spaces separating the tumor from the stroma. Trichoblastoma/trichoblastic carcinoma with matrical differentiation can be distinguished by its exuberant stroma, prominent primitive hair follicles, and papillary mesenchymal bodies. Trichilemmal carcinomas are recognized by their connection to the overlying epidermis, peripheral palisading, and presence of clear cells, while pilomatrix carcinoma lacks connection to the surface epithelium.

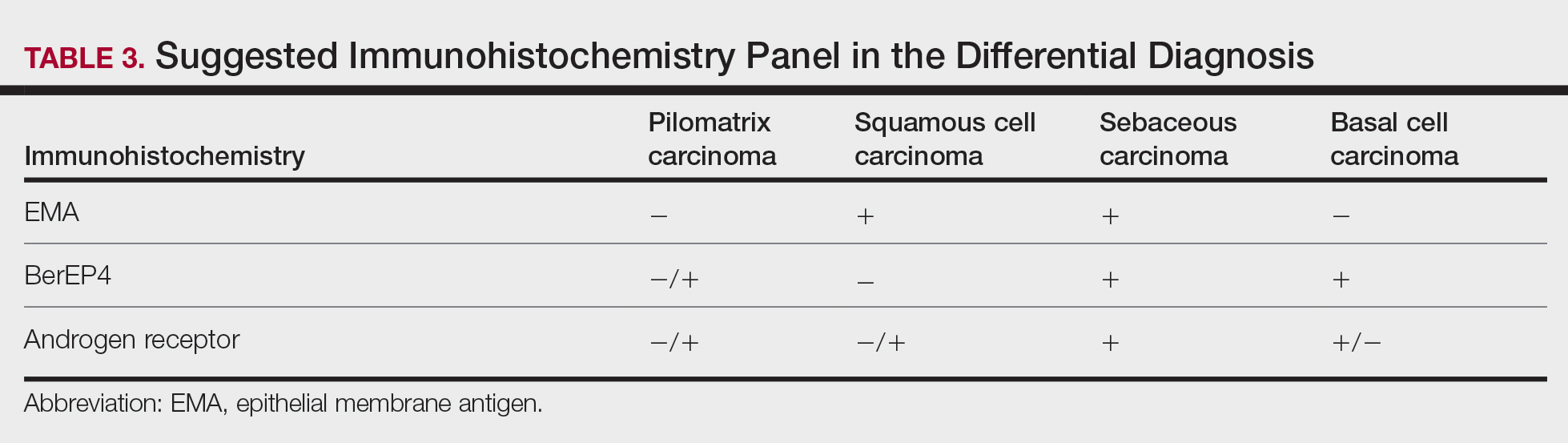

Immunohistochemical stains have little to no role in the differential diagnosis, and morphology is the mainstay in making the diagnosis. Rarely, pilomatrix carcinoma can be confused with poorly differentiated sebaceous carcinoma and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Although careful scrutiny of the histologic features may help identify mature sebocytes in sebaceous carcinoma, evidence of keratinization in squamous cell carcinoma and ghost cells in pilomatrix carcinoma, using a panel of immunohistochemical stains can be helpful in reaching the final diagnosis (Table 3).

The development of hair matrix tumors have been known to harbor mutations in exon 3 of the catenin beta-1 gene, CTNNB1, that encodes for β-catenin, a downstream effector in the Wnt signaling pathway responsible for differentiation, proliferation, and adhesion of epithelial stem cells.17-21 In a study conducted by Kazakov et al,22 DNA was extracted from 86 lesions: 4 were pilomatrixomas and 1 was a pilomatrix carcinoma. A polymerase chain reaction assay revealed 8 pathogenic variants of the β-catenin gene. D32Y (CTNNB1):c.94G>T (p.Asp32Tyr) and G34R (CTNNB1):c.100G>C (p.Gly34Arg) were the mutations present in pilomatrixoma and pilomatrix carcinoma, respectively.22 In addition, there are several proteins that are part of the Wnt pathway in addition to β-catenin—LEF-1 and CDX-2.

Tumminello and Hosler23 found that pilomatrixomas and pilomatrix carcinomas were positive for CDX-2, β-catenin, and LEF-1 by immunohistochemistry. These downstream molecules in the Wnt signaling pathway could have the potential to be used as diagnostic and prognostic markers.2,13,15,23

Although the pathogenesis is unclear, there are 2 possible mechanisms by which pilomatrix carcinomas develop. They can either arise as de novo tumors, or it is possible that initial mutations in β-catenin result in the formation of pilomatrixomas at an early age that may undergo malignant transformation in elderly patients over time with additional mutations.2

Our case was strongly and diffusely positive for β-catenin in a nuclear and cytoplasmic pattern and CDX-2 in a nuclear pattern, supporting the role of the Wnt signaling pathway in such tumors. Furthermore, our case demonstrated the presence of few intralesional normal dendritic melanocytes, a rare finding1,24,25 but not unexpected, as melanocytes normally are present within the hair follicle matrix.

Pilomatrix carcinomas are aggressive tumors with a high risk for local recurrence and tendency for metastasis. In a study of 13 cases of pilomatrix carcinomas, Herrmann et al13 found that metastasis was significantly associated with local tumor recurrence (P<.0413). They concluded that the combination of overall high local recurrence and metastatic rates of pilomatrix carcinoma as well as documented tumor-related deaths would warrant continued patient follow-up, especially for recurrent tumors.13 Rapid growth of a tumor, either de novo or following several months of stable size, should alert physicians to perform a diagnostic biopsy.

Management options of pilomatrix carcinoma include surgery or radiation with close follow-up. The most widely reported treatment of pilomatrix carcinoma is wide local excision with histologically confirmed clear margins. Mohs micrographic surgery is an excellent treatment option.2,13-15 Adjuvant radiation therapy may be necessary following excision. Currently there is no consensus on surgical management, and standard excisional margins have not been defined.26 Jones et al2 concluded that complete excision with wide margins likely is curative, with decreased rates of recurrence, and better awareness of this carcinoma would lead to appropriate treatment while avoiding unnecessary diagnostic tests.2

Conclusion

We report an exceptionally unique case of early pilomatrix carcinoma with a discussion on the pathogenesis and molecular pathology of hair matrix tumors. A large cohort of patients with longer follow-up periods and better molecular characterization is essential in drawing accurate information about their prognosis, identifying molecular markers that can be used as therapeutic targets, and determining ideal management strategy.

- Jani P, Chetty R, Ghazarian DM. An unusual composite pilomatrix carcinoma with intralesional melanocytes: differential diagnosis, immunohistochemical evaluation, and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:174-177.

- Jones C, Twoon M, Ho W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 12-year experience and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:33-38.

- Forbis R, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606.

- Elder D, Elenitsas R, Ragsdale BD. Tumors of epidermal appendages. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Lippincott Raven; 1997:757-759.

- Aherne NJ, Fitzpatrick DA, Gibbons D, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma presenting as an extra axial mass: clinicopathological features. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:47.

- Papadakis M, de Bree E, Floros N, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: more malignant biological behavior than was considered in the past. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:415-418.

- LeBoit PE, Parslow TG, Choy SH. Hair matrix differentiation: occurrence in lesions other than pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1987;9:399-405.

- Campoy F, Stiefel P, Stiefel E, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: role played by MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 1989;31:196-198.

- Tateyama H, Eimoto T, Tada T, et al. Malignant pilomatricoma: an immunohistochemical study with antihair keratin antibody. Cancer. 1992;69:127-132.

- O’Donovan DG, Freemont AJ, Adams JE, et al. Malignant pilomatrixoma with bone metastasis. Histopathology. 1993;23:385-386.

- Cross P, Richmond I, Wells S, et al. Malignant pilomatrixoma with bone metastasis. Histopathology. 1994;24:499-500.

- Niedermeyer HP, Peris K, Höfler H. Pilomatrix carcinoma with multiple visceral metastases: report of a case. Cancer. 1996;77:1311-1314.

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.

- Xing L, Marzolf SA, Vandergriff T, et al. Facial pilomatrix carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:253-255.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Sarcomatoid pilomatrix carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:508-514.

- Sau P, Lupton GP, Graham JH. Pilomatrix carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:2491-2498.

- Chan E, Gat U, McNiff JM, et al. A common human skin tumour is caused by activating mutations in β-catenin. Nat Genet. 1999;21:410-413.

- Huelsken J, Vogel R, Erdmann B, et al. β-catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell. 2001;105:533-545.

- Kikuchi A. Tumor formation by genetic mutations in the components of the Wnt signaling pathway. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:225-229.

- Durand M, Moles J. Beta-catenin mutations in a common skin cancer: pilomatricoma. Bull Cancer. 1999;86:725-726.

- Lazar AJF, Calonje E, Grayson W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinomas contain mutations in CTNNB1, the gene encoding beta-catenin. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:148-157.

- Kazakov DV, Sima R, Vanecek T, et al. Mutations in exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene (β-catenin gene) in cutaneous adnexal tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:248-255.

- Tumminello K, Hosler GA. CDX2 and LEF-1 expression in pilomatrical tumors and their utility in the diagnosis of pilomatrical carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:318-324.

- Rodic´ N, Taube JM, Manson P, et al Locally invasive dermal squamomelanocytic tumor with matrical differentiation: a peculiar case with review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E72-E76.

- Perez C, Debbaneh M, Cassarino D. Preference for the term pilomatrical carcinoma with melanocytic hyperplasia: letter to the editor. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:655-657.

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.

Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare adnexal tumor with origin from the germinative matrical cells of the hair follicle. Clinically, it presents as a solitary lesion commonly found in the head and neck region as well as the upper back. The tumors cannot be distinguished by their clinical appearance only and frequently are mistaken for cysts. Histopathologic examination provides the definitive diagnosis in most cases. These carcinomas are aggressive neoplasms with a high probability of local recurrence and distant metastasis. Assessment of the Wnt signaling pathway components such as β-catenin, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF-1), and caudal-related homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX-2) potentially can be used for diagnostic purposes and targeted therapy.

We report a rare and unique case of early pilomatrix carcinoma with intralesional melanocytes. We review the molecular pathology and pathogenesis of these carcinomas as well as the significance of early diagnosis.

Case Report

A 73-year-old man with a history of extensive sun exposure presented with a 1-cm, raised, rapidly growing, slightly irregular, purple lesion on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration with tendency to bleed. He did not have a history of skin cancers and was otherwise healthy. Excision was recommended due to the progressive and rapid growth of the lesion.

Histopathologic Findings—Gross examination revealed a 0.9×0.7-cm, raised, slightly irregular lesion located 1 mm away from the closest peripheral margin. Histologically, the lesion was a relatively circumscribed, dermal-based basaloid neoplasm with slightly ill-defined edges involving the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). The neoplasm was formed predominantly of sheets of basaloid cells and small nests of ghost cells, in addition to some squamoid and transitional cells (Figure 1B). The basaloid cells exhibited severe nuclear atypia, pleomorphism, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1C), minimal to moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and coarse chromatin pattern. Abundant mitotic activity and apoptotic bodies were present as well as focal area of central necrosis (Figure 1C). Also, melanophages and a multinucleated giant cell reaction was noted. Elastic trichrome special stain highlighted focal infiltration of the neoplastic cells into the adjacent desmoplastic stroma. Melanin stain was negative for melanin pigment within the neoplasm. Given the presence of severely atypical basaloid cells along with ghost cells indicating matrical differentiation, a diagnosis of pilomatrix carcinoma was rendered.

Immunohistochemistry—The neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for p63, CDX-2 (Figure 2A), β-catenin (Figure 2B), and CD10 (Figure 2C), and focally and weakly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5, BerEP4 (staining the tumor periphery), androgen receptor, and CK18 (a low-molecular-weight keratin). They were negative for monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, CK7, CK20, CD34, SOX-10, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin. Cytokeratin 14 was positive in the squamoid cells but negative in the basaloid cells. SOX-10 and melanoma cocktail immunostains demonstrated few intralesional dendritic melanocytes.

Comment

Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasm with origin from the germinative matrix of the hair bulb region of hair follicles. Pilomatrix carcinoma was first reported in 1980.1,2 These tumors are characterized by rapid growth and aggressive behavior. Their benign counterpart, pilomatrixoma, is a slow-growing, dermal or subcutaneous tumor that rarely recurs after complete excision.

As with pilomatrixoma, pilomatrix carcinomas are asymptomatic and present as solitary dermal or subcutaneous masses3,4 that most commonly are found in the posterior neck, upper back, and preauricular regions of middle-aged or elderly adults with male predominance.5 They range in size from 0.5 to 20 cm with a mean of 4 cm that is slightly larger than pilomatrixoma. Pilomatrix carcinomas predominantly are firm tumors with or without cystic components, and they exhibit a high probability of recurrence and have risk for distant metastasis.6-15

The differential diagnosis includes epidermal cysts, pilomatrixoma, basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation, trichoblastoma/trichoblastic carcinoma, and trichilemmal carcinoma. Pilomatrix carcinomas frequently are mistaken for epidermal cysts on clinical examination. Such a distinction can be easily resolved by histopathologic evaluation. The more challenging differential diagnosis is with pilomatrixoma. Histologically, pilomatrixomas consist of a distinct population of cells including basaloid, squamoid, transitional, and shadow cells in variable proportions. The basaloid cells transition to shadow cells in an organized zonal fashion.16 Compared to pilomatrixomas, pilomatrix carcinomas often show predominance of the basaloid cells; marked cytologic atypia and pleomorphism; numerous mitotic figures; deep infiltrative pattern into subcutaneous fat, fascia, and skeletal muscle; stromal desmoplasia; necrosis; and neurovascular invasion (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, the shadow cells tend to form a small nested pattern in pilomatrix carcinoma instead of the flat sheetlike pattern usually observed in pilomatrixoma.16 Basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation can pose a diagnostic challenge in the differential diagnosis; basal cell carcinoma usually exhibits a peripheral palisade of the basaloid cells accompanied by retraction spaces separating the tumor from the stroma. Trichoblastoma/trichoblastic carcinoma with matrical differentiation can be distinguished by its exuberant stroma, prominent primitive hair follicles, and papillary mesenchymal bodies. Trichilemmal carcinomas are recognized by their connection to the overlying epidermis, peripheral palisading, and presence of clear cells, while pilomatrix carcinoma lacks connection to the surface epithelium.

Immunohistochemical stains have little to no role in the differential diagnosis, and morphology is the mainstay in making the diagnosis. Rarely, pilomatrix carcinoma can be confused with poorly differentiated sebaceous carcinoma and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Although careful scrutiny of the histologic features may help identify mature sebocytes in sebaceous carcinoma, evidence of keratinization in squamous cell carcinoma and ghost cells in pilomatrix carcinoma, using a panel of immunohistochemical stains can be helpful in reaching the final diagnosis (Table 3).

The development of hair matrix tumors have been known to harbor mutations in exon 3 of the catenin beta-1 gene, CTNNB1, that encodes for β-catenin, a downstream effector in the Wnt signaling pathway responsible for differentiation, proliferation, and adhesion of epithelial stem cells.17-21 In a study conducted by Kazakov et al,22 DNA was extracted from 86 lesions: 4 were pilomatrixomas and 1 was a pilomatrix carcinoma. A polymerase chain reaction assay revealed 8 pathogenic variants of the β-catenin gene. D32Y (CTNNB1):c.94G>T (p.Asp32Tyr) and G34R (CTNNB1):c.100G>C (p.Gly34Arg) were the mutations present in pilomatrixoma and pilomatrix carcinoma, respectively.22 In addition, there are several proteins that are part of the Wnt pathway in addition to β-catenin—LEF-1 and CDX-2.

Tumminello and Hosler23 found that pilomatrixomas and pilomatrix carcinomas were positive for CDX-2, β-catenin, and LEF-1 by immunohistochemistry. These downstream molecules in the Wnt signaling pathway could have the potential to be used as diagnostic and prognostic markers.2,13,15,23

Although the pathogenesis is unclear, there are 2 possible mechanisms by which pilomatrix carcinomas develop. They can either arise as de novo tumors, or it is possible that initial mutations in β-catenin result in the formation of pilomatrixomas at an early age that may undergo malignant transformation in elderly patients over time with additional mutations.2

Our case was strongly and diffusely positive for β-catenin in a nuclear and cytoplasmic pattern and CDX-2 in a nuclear pattern, supporting the role of the Wnt signaling pathway in such tumors. Furthermore, our case demonstrated the presence of few intralesional normal dendritic melanocytes, a rare finding1,24,25 but not unexpected, as melanocytes normally are present within the hair follicle matrix.

Pilomatrix carcinomas are aggressive tumors with a high risk for local recurrence and tendency for metastasis. In a study of 13 cases of pilomatrix carcinomas, Herrmann et al13 found that metastasis was significantly associated with local tumor recurrence (P<.0413). They concluded that the combination of overall high local recurrence and metastatic rates of pilomatrix carcinoma as well as documented tumor-related deaths would warrant continued patient follow-up, especially for recurrent tumors.13 Rapid growth of a tumor, either de novo or following several months of stable size, should alert physicians to perform a diagnostic biopsy.

Management options of pilomatrix carcinoma include surgery or radiation with close follow-up. The most widely reported treatment of pilomatrix carcinoma is wide local excision with histologically confirmed clear margins. Mohs micrographic surgery is an excellent treatment option.2,13-15 Adjuvant radiation therapy may be necessary following excision. Currently there is no consensus on surgical management, and standard excisional margins have not been defined.26 Jones et al2 concluded that complete excision with wide margins likely is curative, with decreased rates of recurrence, and better awareness of this carcinoma would lead to appropriate treatment while avoiding unnecessary diagnostic tests.2

Conclusion

We report an exceptionally unique case of early pilomatrix carcinoma with a discussion on the pathogenesis and molecular pathology of hair matrix tumors. A large cohort of patients with longer follow-up periods and better molecular characterization is essential in drawing accurate information about their prognosis, identifying molecular markers that can be used as therapeutic targets, and determining ideal management strategy.

Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare adnexal tumor with origin from the germinative matrical cells of the hair follicle. Clinically, it presents as a solitary lesion commonly found in the head and neck region as well as the upper back. The tumors cannot be distinguished by their clinical appearance only and frequently are mistaken for cysts. Histopathologic examination provides the definitive diagnosis in most cases. These carcinomas are aggressive neoplasms with a high probability of local recurrence and distant metastasis. Assessment of the Wnt signaling pathway components such as β-catenin, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF-1), and caudal-related homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX-2) potentially can be used for diagnostic purposes and targeted therapy.

We report a rare and unique case of early pilomatrix carcinoma with intralesional melanocytes. We review the molecular pathology and pathogenesis of these carcinomas as well as the significance of early diagnosis.

Case Report

A 73-year-old man with a history of extensive sun exposure presented with a 1-cm, raised, rapidly growing, slightly irregular, purple lesion on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration with tendency to bleed. He did not have a history of skin cancers and was otherwise healthy. Excision was recommended due to the progressive and rapid growth of the lesion.

Histopathologic Findings—Gross examination revealed a 0.9×0.7-cm, raised, slightly irregular lesion located 1 mm away from the closest peripheral margin. Histologically, the lesion was a relatively circumscribed, dermal-based basaloid neoplasm with slightly ill-defined edges involving the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). The neoplasm was formed predominantly of sheets of basaloid cells and small nests of ghost cells, in addition to some squamoid and transitional cells (Figure 1B). The basaloid cells exhibited severe nuclear atypia, pleomorphism, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1C), minimal to moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and coarse chromatin pattern. Abundant mitotic activity and apoptotic bodies were present as well as focal area of central necrosis (Figure 1C). Also, melanophages and a multinucleated giant cell reaction was noted. Elastic trichrome special stain highlighted focal infiltration of the neoplastic cells into the adjacent desmoplastic stroma. Melanin stain was negative for melanin pigment within the neoplasm. Given the presence of severely atypical basaloid cells along with ghost cells indicating matrical differentiation, a diagnosis of pilomatrix carcinoma was rendered.

Immunohistochemistry—The neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for p63, CDX-2 (Figure 2A), β-catenin (Figure 2B), and CD10 (Figure 2C), and focally and weakly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5, BerEP4 (staining the tumor periphery), androgen receptor, and CK18 (a low-molecular-weight keratin). They were negative for monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, CK7, CK20, CD34, SOX-10, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin. Cytokeratin 14 was positive in the squamoid cells but negative in the basaloid cells. SOX-10 and melanoma cocktail immunostains demonstrated few intralesional dendritic melanocytes.

Comment

Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasm with origin from the germinative matrix of the hair bulb region of hair follicles. Pilomatrix carcinoma was first reported in 1980.1,2 These tumors are characterized by rapid growth and aggressive behavior. Their benign counterpart, pilomatrixoma, is a slow-growing, dermal or subcutaneous tumor that rarely recurs after complete excision.

As with pilomatrixoma, pilomatrix carcinomas are asymptomatic and present as solitary dermal or subcutaneous masses3,4 that most commonly are found in the posterior neck, upper back, and preauricular regions of middle-aged or elderly adults with male predominance.5 They range in size from 0.5 to 20 cm with a mean of 4 cm that is slightly larger than pilomatrixoma. Pilomatrix carcinomas predominantly are firm tumors with or without cystic components, and they exhibit a high probability of recurrence and have risk for distant metastasis.6-15

The differential diagnosis includes epidermal cysts, pilomatrixoma, basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation, trichoblastoma/trichoblastic carcinoma, and trichilemmal carcinoma. Pilomatrix carcinomas frequently are mistaken for epidermal cysts on clinical examination. Such a distinction can be easily resolved by histopathologic evaluation. The more challenging differential diagnosis is with pilomatrixoma. Histologically, pilomatrixomas consist of a distinct population of cells including basaloid, squamoid, transitional, and shadow cells in variable proportions. The basaloid cells transition to shadow cells in an organized zonal fashion.16 Compared to pilomatrixomas, pilomatrix carcinomas often show predominance of the basaloid cells; marked cytologic atypia and pleomorphism; numerous mitotic figures; deep infiltrative pattern into subcutaneous fat, fascia, and skeletal muscle; stromal desmoplasia; necrosis; and neurovascular invasion (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, the shadow cells tend to form a small nested pattern in pilomatrix carcinoma instead of the flat sheetlike pattern usually observed in pilomatrixoma.16 Basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation can pose a diagnostic challenge in the differential diagnosis; basal cell carcinoma usually exhibits a peripheral palisade of the basaloid cells accompanied by retraction spaces separating the tumor from the stroma. Trichoblastoma/trichoblastic carcinoma with matrical differentiation can be distinguished by its exuberant stroma, prominent primitive hair follicles, and papillary mesenchymal bodies. Trichilemmal carcinomas are recognized by their connection to the overlying epidermis, peripheral palisading, and presence of clear cells, while pilomatrix carcinoma lacks connection to the surface epithelium.

Immunohistochemical stains have little to no role in the differential diagnosis, and morphology is the mainstay in making the diagnosis. Rarely, pilomatrix carcinoma can be confused with poorly differentiated sebaceous carcinoma and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Although careful scrutiny of the histologic features may help identify mature sebocytes in sebaceous carcinoma, evidence of keratinization in squamous cell carcinoma and ghost cells in pilomatrix carcinoma, using a panel of immunohistochemical stains can be helpful in reaching the final diagnosis (Table 3).

The development of hair matrix tumors have been known to harbor mutations in exon 3 of the catenin beta-1 gene, CTNNB1, that encodes for β-catenin, a downstream effector in the Wnt signaling pathway responsible for differentiation, proliferation, and adhesion of epithelial stem cells.17-21 In a study conducted by Kazakov et al,22 DNA was extracted from 86 lesions: 4 were pilomatrixomas and 1 was a pilomatrix carcinoma. A polymerase chain reaction assay revealed 8 pathogenic variants of the β-catenin gene. D32Y (CTNNB1):c.94G>T (p.Asp32Tyr) and G34R (CTNNB1):c.100G>C (p.Gly34Arg) were the mutations present in pilomatrixoma and pilomatrix carcinoma, respectively.22 In addition, there are several proteins that are part of the Wnt pathway in addition to β-catenin—LEF-1 and CDX-2.

Tumminello and Hosler23 found that pilomatrixomas and pilomatrix carcinomas were positive for CDX-2, β-catenin, and LEF-1 by immunohistochemistry. These downstream molecules in the Wnt signaling pathway could have the potential to be used as diagnostic and prognostic markers.2,13,15,23

Although the pathogenesis is unclear, there are 2 possible mechanisms by which pilomatrix carcinomas develop. They can either arise as de novo tumors, or it is possible that initial mutations in β-catenin result in the formation of pilomatrixomas at an early age that may undergo malignant transformation in elderly patients over time with additional mutations.2

Our case was strongly and diffusely positive for β-catenin in a nuclear and cytoplasmic pattern and CDX-2 in a nuclear pattern, supporting the role of the Wnt signaling pathway in such tumors. Furthermore, our case demonstrated the presence of few intralesional normal dendritic melanocytes, a rare finding1,24,25 but not unexpected, as melanocytes normally are present within the hair follicle matrix.

Pilomatrix carcinomas are aggressive tumors with a high risk for local recurrence and tendency for metastasis. In a study of 13 cases of pilomatrix carcinomas, Herrmann et al13 found that metastasis was significantly associated with local tumor recurrence (P<.0413). They concluded that the combination of overall high local recurrence and metastatic rates of pilomatrix carcinoma as well as documented tumor-related deaths would warrant continued patient follow-up, especially for recurrent tumors.13 Rapid growth of a tumor, either de novo or following several months of stable size, should alert physicians to perform a diagnostic biopsy.

Management options of pilomatrix carcinoma include surgery or radiation with close follow-up. The most widely reported treatment of pilomatrix carcinoma is wide local excision with histologically confirmed clear margins. Mohs micrographic surgery is an excellent treatment option.2,13-15 Adjuvant radiation therapy may be necessary following excision. Currently there is no consensus on surgical management, and standard excisional margins have not been defined.26 Jones et al2 concluded that complete excision with wide margins likely is curative, with decreased rates of recurrence, and better awareness of this carcinoma would lead to appropriate treatment while avoiding unnecessary diagnostic tests.2

Conclusion

We report an exceptionally unique case of early pilomatrix carcinoma with a discussion on the pathogenesis and molecular pathology of hair matrix tumors. A large cohort of patients with longer follow-up periods and better molecular characterization is essential in drawing accurate information about their prognosis, identifying molecular markers that can be used as therapeutic targets, and determining ideal management strategy.

- Jani P, Chetty R, Ghazarian DM. An unusual composite pilomatrix carcinoma with intralesional melanocytes: differential diagnosis, immunohistochemical evaluation, and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:174-177.

- Jones C, Twoon M, Ho W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 12-year experience and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:33-38.

- Forbis R, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606.

- Elder D, Elenitsas R, Ragsdale BD. Tumors of epidermal appendages. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Lippincott Raven; 1997:757-759.

- Aherne NJ, Fitzpatrick DA, Gibbons D, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma presenting as an extra axial mass: clinicopathological features. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:47.

- Papadakis M, de Bree E, Floros N, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: more malignant biological behavior than was considered in the past. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:415-418.

- LeBoit PE, Parslow TG, Choy SH. Hair matrix differentiation: occurrence in lesions other than pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1987;9:399-405.

- Campoy F, Stiefel P, Stiefel E, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: role played by MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 1989;31:196-198.

- Tateyama H, Eimoto T, Tada T, et al. Malignant pilomatricoma: an immunohistochemical study with antihair keratin antibody. Cancer. 1992;69:127-132.

- O’Donovan DG, Freemont AJ, Adams JE, et al. Malignant pilomatrixoma with bone metastasis. Histopathology. 1993;23:385-386.

- Cross P, Richmond I, Wells S, et al. Malignant pilomatrixoma with bone metastasis. Histopathology. 1994;24:499-500.

- Niedermeyer HP, Peris K, Höfler H. Pilomatrix carcinoma with multiple visceral metastases: report of a case. Cancer. 1996;77:1311-1314.

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.

- Xing L, Marzolf SA, Vandergriff T, et al. Facial pilomatrix carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:253-255.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Sarcomatoid pilomatrix carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:508-514.

- Sau P, Lupton GP, Graham JH. Pilomatrix carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:2491-2498.

- Chan E, Gat U, McNiff JM, et al. A common human skin tumour is caused by activating mutations in β-catenin. Nat Genet. 1999;21:410-413.

- Huelsken J, Vogel R, Erdmann B, et al. β-catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell. 2001;105:533-545.

- Kikuchi A. Tumor formation by genetic mutations in the components of the Wnt signaling pathway. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:225-229.

- Durand M, Moles J. Beta-catenin mutations in a common skin cancer: pilomatricoma. Bull Cancer. 1999;86:725-726.

- Lazar AJF, Calonje E, Grayson W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinomas contain mutations in CTNNB1, the gene encoding beta-catenin. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:148-157.

- Kazakov DV, Sima R, Vanecek T, et al. Mutations in exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene (β-catenin gene) in cutaneous adnexal tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:248-255.

- Tumminello K, Hosler GA. CDX2 and LEF-1 expression in pilomatrical tumors and their utility in the diagnosis of pilomatrical carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:318-324.

- Rodic´ N, Taube JM, Manson P, et al Locally invasive dermal squamomelanocytic tumor with matrical differentiation: a peculiar case with review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E72-E76.

- Perez C, Debbaneh M, Cassarino D. Preference for the term pilomatrical carcinoma with melanocytic hyperplasia: letter to the editor. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:655-657.

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.

- Jani P, Chetty R, Ghazarian DM. An unusual composite pilomatrix carcinoma with intralesional melanocytes: differential diagnosis, immunohistochemical evaluation, and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:174-177.

- Jones C, Twoon M, Ho W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 12-year experience and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:33-38.

- Forbis R, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606.

- Elder D, Elenitsas R, Ragsdale BD. Tumors of epidermal appendages. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Lippincott Raven; 1997:757-759.

- Aherne NJ, Fitzpatrick DA, Gibbons D, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma presenting as an extra axial mass: clinicopathological features. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:47.

- Papadakis M, de Bree E, Floros N, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: more malignant biological behavior than was considered in the past. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:415-418.

- LeBoit PE, Parslow TG, Choy SH. Hair matrix differentiation: occurrence in lesions other than pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1987;9:399-405.

- Campoy F, Stiefel P, Stiefel E, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: role played by MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 1989;31:196-198.

- Tateyama H, Eimoto T, Tada T, et al. Malignant pilomatricoma: an immunohistochemical study with antihair keratin antibody. Cancer. 1992;69:127-132.

- O’Donovan DG, Freemont AJ, Adams JE, et al. Malignant pilomatrixoma with bone metastasis. Histopathology. 1993;23:385-386.

- Cross P, Richmond I, Wells S, et al. Malignant pilomatrixoma with bone metastasis. Histopathology. 1994;24:499-500.

- Niedermeyer HP, Peris K, Höfler H. Pilomatrix carcinoma with multiple visceral metastases: report of a case. Cancer. 1996;77:1311-1314.

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.

- Xing L, Marzolf SA, Vandergriff T, et al. Facial pilomatrix carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:253-255.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Sarcomatoid pilomatrix carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:508-514.

- Sau P, Lupton GP, Graham JH. Pilomatrix carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:2491-2498.

- Chan E, Gat U, McNiff JM, et al. A common human skin tumour is caused by activating mutations in β-catenin. Nat Genet. 1999;21:410-413.

- Huelsken J, Vogel R, Erdmann B, et al. β-catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell. 2001;105:533-545.

- Kikuchi A. Tumor formation by genetic mutations in the components of the Wnt signaling pathway. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:225-229.

- Durand M, Moles J. Beta-catenin mutations in a common skin cancer: pilomatricoma. Bull Cancer. 1999;86:725-726.

- Lazar AJF, Calonje E, Grayson W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinomas contain mutations in CTNNB1, the gene encoding beta-catenin. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:148-157.

- Kazakov DV, Sima R, Vanecek T, et al. Mutations in exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene (β-catenin gene) in cutaneous adnexal tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:248-255.

- Tumminello K, Hosler GA. CDX2 and LEF-1 expression in pilomatrical tumors and their utility in the diagnosis of pilomatrical carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:318-324.

- Rodic´ N, Taube JM, Manson P, et al Locally invasive dermal squamomelanocytic tumor with matrical differentiation: a peculiar case with review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E72-E76.

- Perez C, Debbaneh M, Cassarino D. Preference for the term pilomatrical carcinoma with melanocytic hyperplasia: letter to the editor. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:655-657.

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.

Practice Points

- Clinicians and pathologists should be aware of pilomatrix carcinoma to facilitate early detection.

- Early diagnosis and prompt treatment of pilomatrix carcinoma is crucial in lowering recurrence rate and avoiding a poor outcome.

- Caudal-related homeobox transcription factor 2 and β-catenin components of the Wnt signaling pathway play an important role in the pathogenesis of pilomatrix carcinoma.

- Although controversial, wide local excision is the treatment of choice for pilomatrix carcinoma.

TANS Syndrome: Tanorexia, Anorexia, and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

The term tanorexia describes compulsive use of a tanning bed, a disorder often identified in White patients. This compulsion is driven by underlying psychological distress that typically correlates with another psychiatric disorder, such as anxiety, body dysmorphic disorder, or an eating disorder. 1 Severe anorexia combined with excessive indoor tanning led to a notable burden of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas in one of our patients. We discuss the management and approach to patient care in this difficult situation, which we have coined TANS syndrome (for T anorexia, A norexia, and N onmelanoma s kin cancer).

A Patient With TANS Syndrome

A 35-year-old cachectic woman, who appeared much older than her chronologic age, presented for management of numerous painful bleeding skin lesions. Diffuse, erythematous, tender nodules with central keratotic cores, some several centimeters in diameter, were scattered on the abdomen, chest, and extremities (Figure 1); similar lesions were noted on the neck (Figure 2). Numerous erythematous scaly papules and plaques consistent with actinic keratoses were noted throughout the body.

The patient reported that the cutaneous SCCs presented over the last few years, whereas her eating disorder began in adolescence and persisted despite multiple intensive outpatient and inpatient programs. The patient adamantly refused repeat hospitalization, against repeated suggestions by health care providers and her family. Comorbidities related to her anorexia included severe renal insufficiency, iron deficiency anemia, hypertriglyceridemia, kwashiorkor, and pellagra.

Within the last year, the patient had several biopsies showing SCC, keratoacanthoma type. The largest tumors had been treated by Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation or curettage. Adjuvant therapy over the last 2 years consisted of tazarotene cream 0.1%, imiquimod cream 5%, oral nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily, and acitretin 10 to 20 mg daily. Human papillomavirus 9-valent vaccine, recombinant, also had been tried as a chemopreventive and treatment, based on a published report of 2 patients in whom keratinocytic carcinomas decreased after such vaccination.2 The dose of acitretin was kept low because of the patient’s severe renal insufficiency and lack of supporting data for its use in this setting. Despite these modalities, our patient continued to develop new cutaneous SCCs.

We considered starting intralesional methotrexate but deferred this course of action, given the patient’s deteriorating renal function. Our plan was to initiate intralesional 5-fluorouracil; however, the patient was admitted to the hospital and subsequently died due to cardiovascular complications of anorexia.

UV Radiation in the Setting of Immune Compromise

Habitual tanning bed use has been recognized as a psychologic addiction.3,4 After exposure to UV radiation, damaged DNA upregulates pro-opiomelanocortin, which posttranslationally generates β-endorphins to elevate mood.3,5

Tanning beds deliver a higher dose of UVA radiation than UVB radiation and cause darkening of pigmentation by oxidation of preformed melanin and redistribution of melanosomes.3 UVA radiation (320–400 nm) emitted from a tanning bed is 10- to 15-times higher than the radiation emitted by the midday sun and causes DNA damage through generation of reactive oxygen species. UVA penetrates the dermis; its harmful effect on DNA contributes to the pathogenesis of melanoma.

UVB radiation (290–320 nm) is mainly restricted to the epidermis and is largely responsible for erythema of the skin. UVB specifically causes direct damage to DNA by forming pyrimidine dimers, superficially causing sunburn. Excessive exposure to UVB radiation increases the risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer.6

Severe starvation and chronic malnutrition, as seen in anorexia nervosa, also are known to lead to immunosuppression.7 Exposure to UV radiation has been shown to impair the function of antigen-presenting cells, cytokines, and suppressor T cells, and is classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization.3,8 Combining a compromised immune system in anorexia with DNA damage from frequent indoor tanning provides a dangerous milieu for carcinogenesis.8 Without immune surveillance, as occurs with adequate nutrition, treatment of cutaneous SCC is, at best, challenging.

Primary care physicians, dermatologists, psychiatrists, nutritionists, and public health officials should educate high-risk patients to prevent TANS syndrome.

- Petit A, Karila L, Chalmin F, et al. Phenomenology and psychopathology of excessive indoor tanning. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:664-672. doi:10.1111/ijd.12336

- Nichols AJ, Allen AH, Shareef S, et al. Association of human papillomavirus vaccine with the development of keratinocyte carcinomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:571-574. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5703

- Madigan LM, Lim HW. Tanning beds: impact on health, and recent regulations. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:640-648. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.05.016

- Schwebel DC. Adolescent tanning, disordered eating, and risk taking. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35:225-227. doi:10.1097/DBP.0000000000000045

- Friedman B, English JC 3rd, Ferris LK. Indoor tanning, skin cancer and the young female patient: a review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28:275-283. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2014.07.015

- Armstrong BK, Kricker A. Epidemiology of UV induced skin cancer. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;63:8-18. doi:10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00198-1

- Hanachi M, Bohem V, Bemer P, et al. Negative role of malnutrition in cell-mediated immune response: Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) in a severely malnourished, HIV-negative patient with anorexia nervosa. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;25:163-165. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.03.121

- Schwarz T, Beissert S. Milestones in photoimmunology. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:E7-E10. doi:10.1038/skinbio.2013.177

The term tanorexia describes compulsive use of a tanning bed, a disorder often identified in White patients. This compulsion is driven by underlying psychological distress that typically correlates with another psychiatric disorder, such as anxiety, body dysmorphic disorder, or an eating disorder. 1 Severe anorexia combined with excessive indoor tanning led to a notable burden of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas in one of our patients. We discuss the management and approach to patient care in this difficult situation, which we have coined TANS syndrome (for T anorexia, A norexia, and N onmelanoma s kin cancer).

A Patient With TANS Syndrome

A 35-year-old cachectic woman, who appeared much older than her chronologic age, presented for management of numerous painful bleeding skin lesions. Diffuse, erythematous, tender nodules with central keratotic cores, some several centimeters in diameter, were scattered on the abdomen, chest, and extremities (Figure 1); similar lesions were noted on the neck (Figure 2). Numerous erythematous scaly papules and plaques consistent with actinic keratoses were noted throughout the body.

The patient reported that the cutaneous SCCs presented over the last few years, whereas her eating disorder began in adolescence and persisted despite multiple intensive outpatient and inpatient programs. The patient adamantly refused repeat hospitalization, against repeated suggestions by health care providers and her family. Comorbidities related to her anorexia included severe renal insufficiency, iron deficiency anemia, hypertriglyceridemia, kwashiorkor, and pellagra.

Within the last year, the patient had several biopsies showing SCC, keratoacanthoma type. The largest tumors had been treated by Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation or curettage. Adjuvant therapy over the last 2 years consisted of tazarotene cream 0.1%, imiquimod cream 5%, oral nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily, and acitretin 10 to 20 mg daily. Human papillomavirus 9-valent vaccine, recombinant, also had been tried as a chemopreventive and treatment, based on a published report of 2 patients in whom keratinocytic carcinomas decreased after such vaccination.2 The dose of acitretin was kept low because of the patient’s severe renal insufficiency and lack of supporting data for its use in this setting. Despite these modalities, our patient continued to develop new cutaneous SCCs.

We considered starting intralesional methotrexate but deferred this course of action, given the patient’s deteriorating renal function. Our plan was to initiate intralesional 5-fluorouracil; however, the patient was admitted to the hospital and subsequently died due to cardiovascular complications of anorexia.

UV Radiation in the Setting of Immune Compromise

Habitual tanning bed use has been recognized as a psychologic addiction.3,4 After exposure to UV radiation, damaged DNA upregulates pro-opiomelanocortin, which posttranslationally generates β-endorphins to elevate mood.3,5

Tanning beds deliver a higher dose of UVA radiation than UVB radiation and cause darkening of pigmentation by oxidation of preformed melanin and redistribution of melanosomes.3 UVA radiation (320–400 nm) emitted from a tanning bed is 10- to 15-times higher than the radiation emitted by the midday sun and causes DNA damage through generation of reactive oxygen species. UVA penetrates the dermis; its harmful effect on DNA contributes to the pathogenesis of melanoma.

UVB radiation (290–320 nm) is mainly restricted to the epidermis and is largely responsible for erythema of the skin. UVB specifically causes direct damage to DNA by forming pyrimidine dimers, superficially causing sunburn. Excessive exposure to UVB radiation increases the risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer.6

Severe starvation and chronic malnutrition, as seen in anorexia nervosa, also are known to lead to immunosuppression.7 Exposure to UV radiation has been shown to impair the function of antigen-presenting cells, cytokines, and suppressor T cells, and is classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization.3,8 Combining a compromised immune system in anorexia with DNA damage from frequent indoor tanning provides a dangerous milieu for carcinogenesis.8 Without immune surveillance, as occurs with adequate nutrition, treatment of cutaneous SCC is, at best, challenging.

Primary care physicians, dermatologists, psychiatrists, nutritionists, and public health officials should educate high-risk patients to prevent TANS syndrome.

The term tanorexia describes compulsive use of a tanning bed, a disorder often identified in White patients. This compulsion is driven by underlying psychological distress that typically correlates with another psychiatric disorder, such as anxiety, body dysmorphic disorder, or an eating disorder. 1 Severe anorexia combined with excessive indoor tanning led to a notable burden of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas in one of our patients. We discuss the management and approach to patient care in this difficult situation, which we have coined TANS syndrome (for T anorexia, A norexia, and N onmelanoma s kin cancer).

A Patient With TANS Syndrome

A 35-year-old cachectic woman, who appeared much older than her chronologic age, presented for management of numerous painful bleeding skin lesions. Diffuse, erythematous, tender nodules with central keratotic cores, some several centimeters in diameter, were scattered on the abdomen, chest, and extremities (Figure 1); similar lesions were noted on the neck (Figure 2). Numerous erythematous scaly papules and plaques consistent with actinic keratoses were noted throughout the body.