User login

For MD-IQ use only

Coronavirus impact on medical education: Thoughts from two GI fellows’ perspectives

Introduction

We are living in an unprecedented time. During March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) outbreak, our institution removed all medical students from rotations with direct patient contact to prioritize their safety and well-being, following recommendations made by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).1 Similarly, we as gastroenterology fellows experienced an upheaval in our usual schedules and routines. Some of us were redeployed to other areas of the hospital, such as inpatient wards and emergency departments, to meet the needs of our patients and our health system. These changes were difficult, not only because we were practicing in different roles, but also because unknown situations commonly incite fear and anxiety.

Among the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic were the changes thrust upon medical students who suddenly found themselves without clinical exposure (both on core clerkships and electives) for the duration of the academic year.2 We too lost many of our educational and teaching opportunities as we adapted to our changing circumstances and new reality. Therefore, . We used the lessons we learned because of the changes in our own medical education to anticipate the best ways to provide learning opportunities for our students.

GI fellows’ experiences

The changes to our schedules and lack of in-person educational conferences seemingly happened overnight – the shock of being pulled from clinics, consults, and endoscopy left us feeling scared and lonely. We were quickly transitioned from knowing our roles and responsibilities as GI providers to taking over care for hospitalist patients as the “primary team,” working in the COVID emergency department (ED), and losing our clinic space. Redeployment to other clinical environments was anxiety-provoking. Self-doubt and fear were the most cited concerns as we asked ourselves: Do I remember enough general medicine to be an effective hospitalist? How do I place admission orders or perform a medication reconciliation on discharge? What can I expect in the COVID ED? Will I have to intubate someone? What about possible PPE shortages? Are my family members safe at home? Should I stay in a hotel? Do we have estimates on how long this will last?

Clinical schedules were reconfigured to consolidate the use of inpatient fellows and allow for reserves of fellows to be redeployed if needed. Schedules for the following 7 days were made just 48 hours prior to the start of each workweek. The anticipation and fear of the unknown were perhaps the hardest parts of the changes in our clinical learning environment. Little time was provided to make child care arrangements, coordinate with the schedules of significant others, or review topics and skills we might need in the next week that had gone unused for some time.

Our conference schedule was pared down considerably as fellows and attendings adjusted to their new responsibilities and a virtual platform for fellows’ education. While the transition to online lectures was seamless, the spirit of conference certainly changed. Impromptu questions and conversations that oftentimes arise organically during case conferences no longer occurred as virtual meetings do not offer the same space to foster these discussions as we awkwardly muted and unmuted ourselves. Participation in lectures seemed disjointed, which translated in some ways to less effective learning opportunities. Our involvement in endoscopy was also removed as only urgent cases were being performed and PPE conservation was of the utmost priority. This was especially concerning for third-year fellows on the cusp of graduation who would soon be independent practitioners without recent procedural practice. In general, the fellowship felt isolated and uncertain, which our program director addressed with weekly virtual COVID-19 “happy hour” updates.

GI fellows’ contribution

As our program encouraged us to come together during this time to support each other, we realized that while our clinical duties may look different during the COVID-19 crisis, our responsibility to learners was more important than ever. At many academic institutions, GI fellows are referred to as “the face of the division” owed in large part to our consistent presence on consult services and roles as teachers for medical students and residents who rotate with us. In an effort to assist the medical school’s charge to rapidly generate at-home curriculum for our students, we created an online curriculum for medical students to complete during the time they were previously scheduled to rotate with us on consults either as third- or fourth-year students.

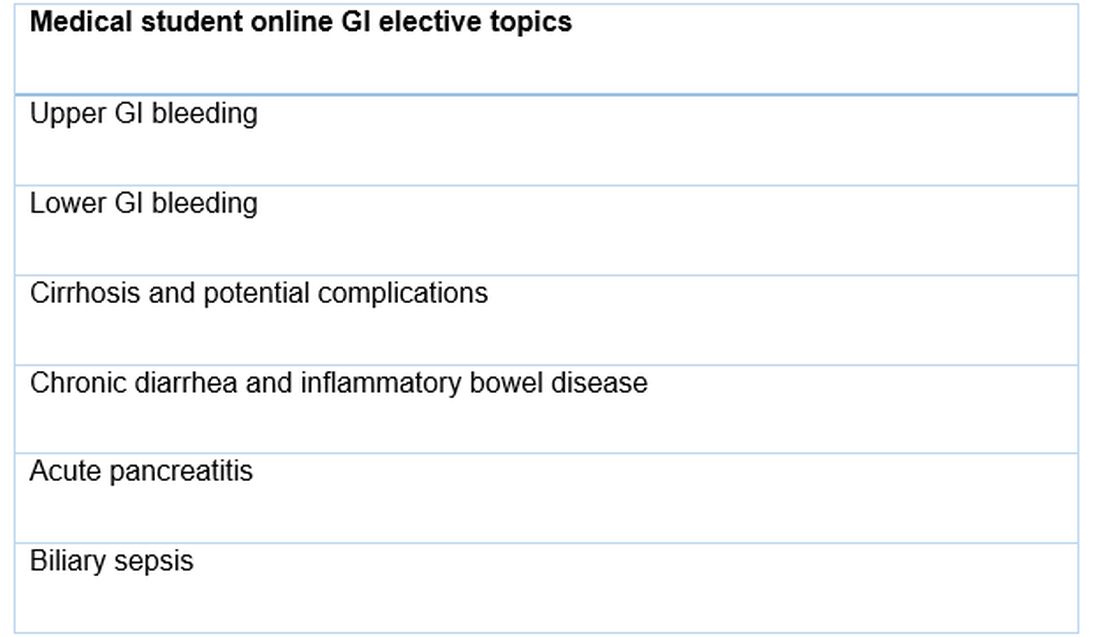

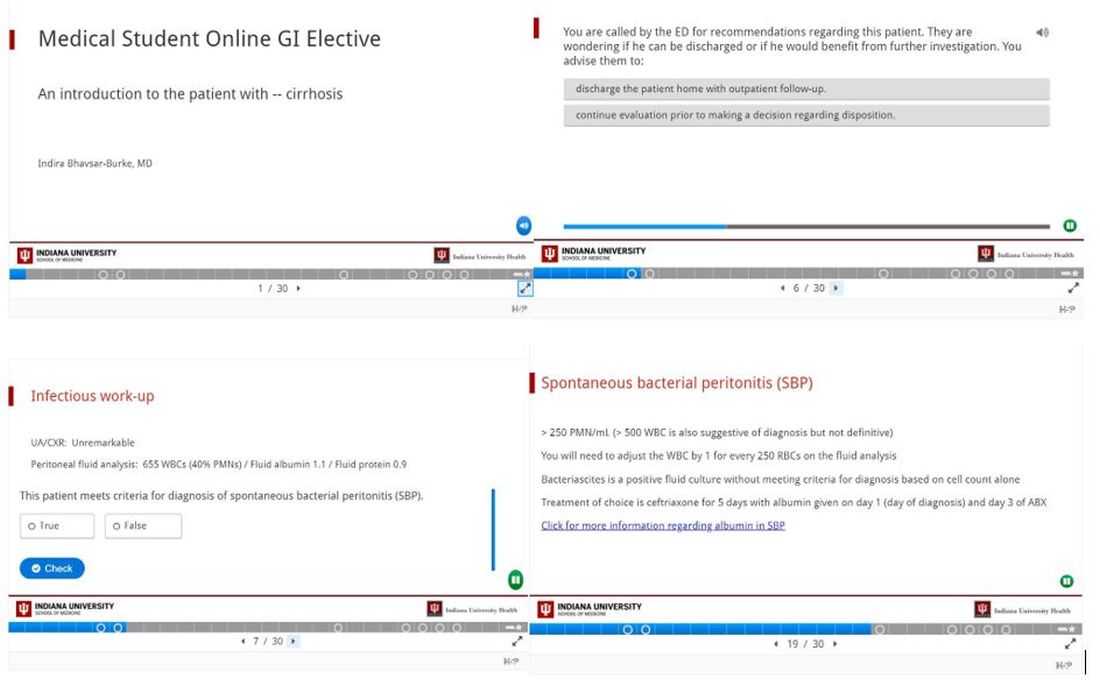

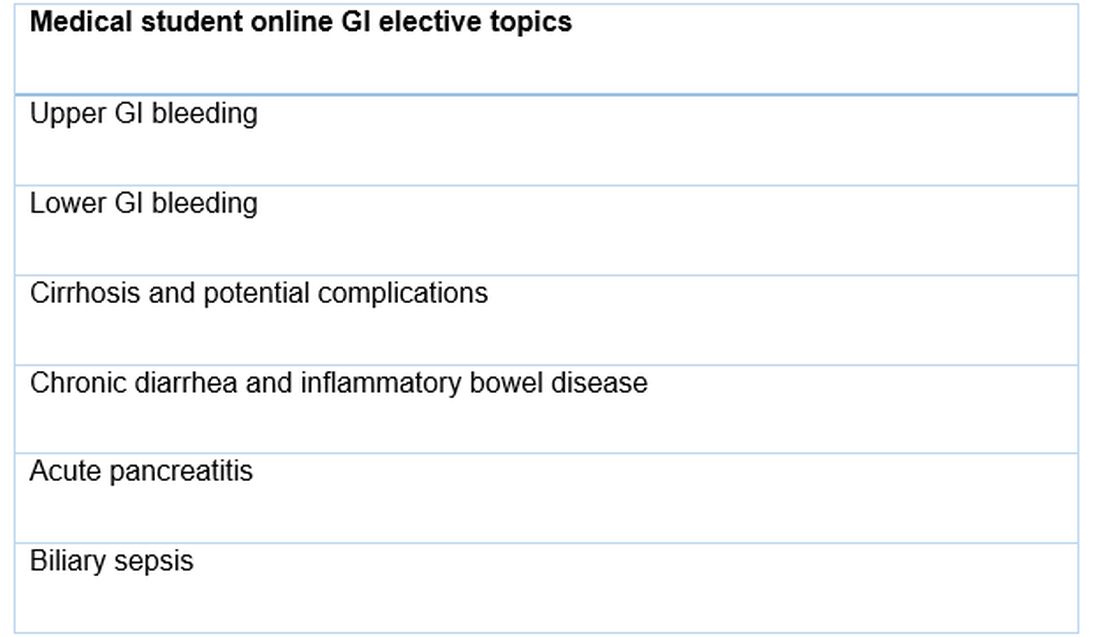

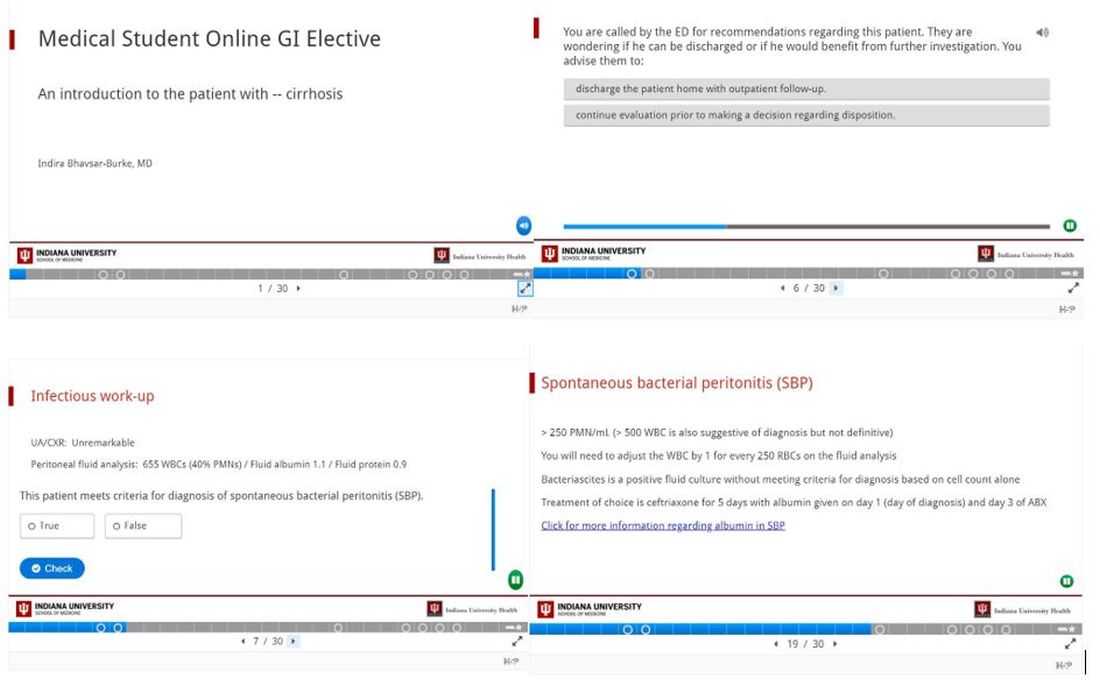

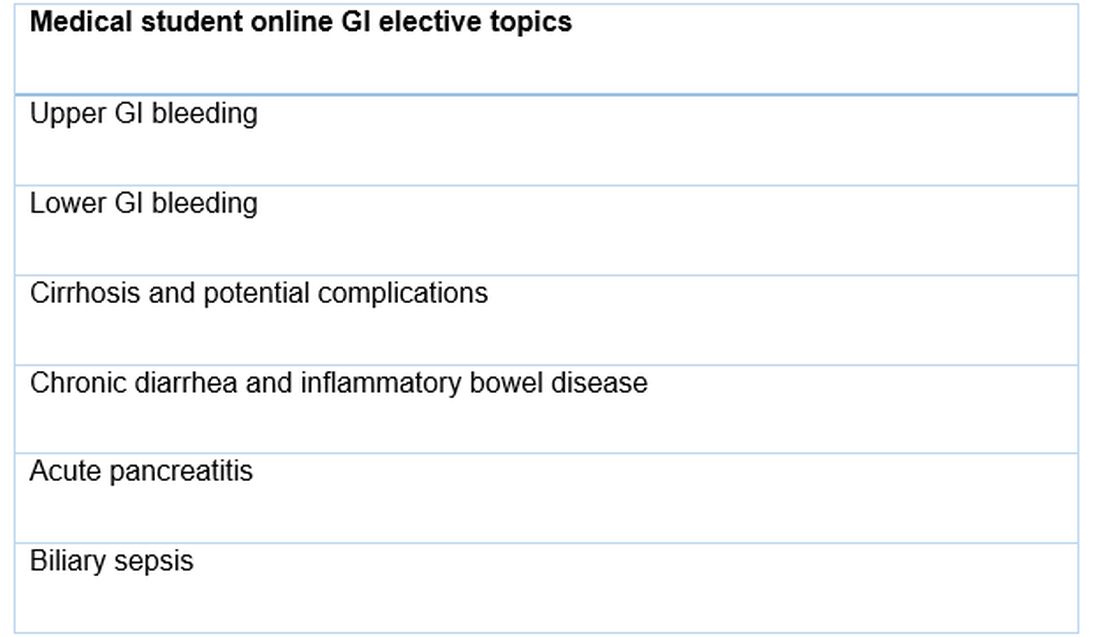

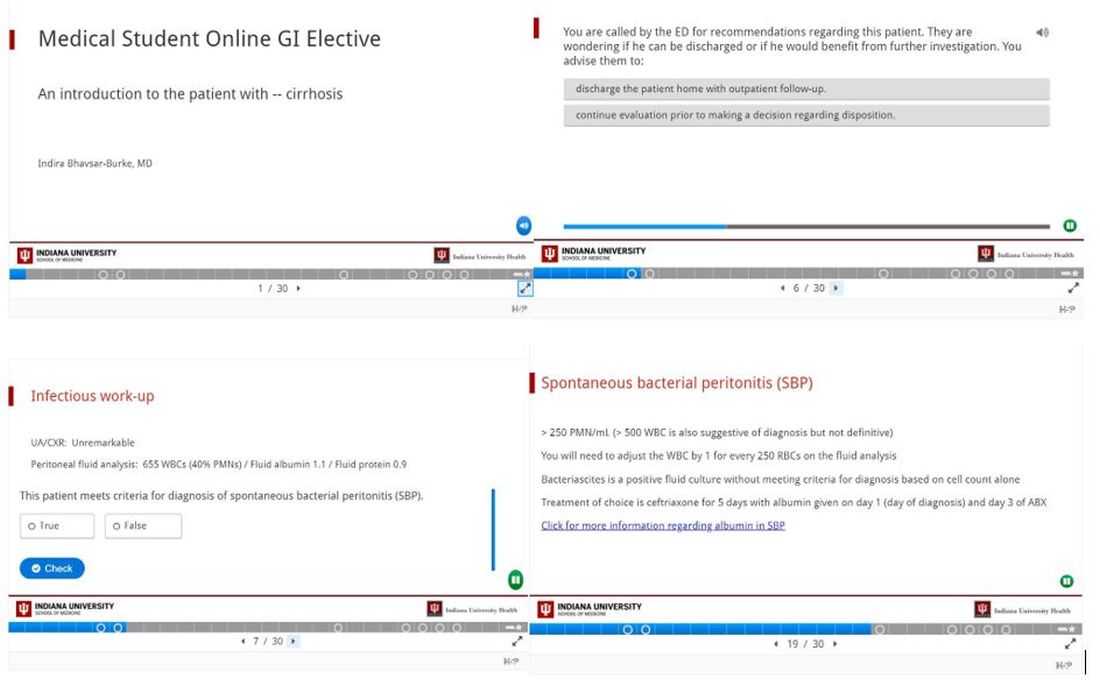

We designed a series of interactive podcasts covering six topics that are commonly encountered issues on the GI consult service: upper GI bleeding, lower GI bleeding, biliary sepsis, acute pancreatitis, chronic diarrhea with a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, as well as cirrhosis and its associated complications.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant change in the daily activities of GI fellows including new responsibilities and a great need for adaptation. We hope that the lessons the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us – to think of others and make our talents available to those who need them, to look for ways to adapt to challenges, to live in the present but focus on the future, and to spread creativity when able – will continue long after the curve has flattened.

References

1. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/online-learning-during-covid-19-tips-help-med-students. Apr 3, 2020.

2. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-how-virus-impacting-medical-schools. Mar 20, 2020.

3. “H5P: Create, share and reuse interactive HTML5 content in your browser.” H5P website. https://h5p.org.

Dr. Bhavsar-Burke and Dr. Jansson-Knodell are GI fellows in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Introduction

We are living in an unprecedented time. During March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) outbreak, our institution removed all medical students from rotations with direct patient contact to prioritize their safety and well-being, following recommendations made by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).1 Similarly, we as gastroenterology fellows experienced an upheaval in our usual schedules and routines. Some of us were redeployed to other areas of the hospital, such as inpatient wards and emergency departments, to meet the needs of our patients and our health system. These changes were difficult, not only because we were practicing in different roles, but also because unknown situations commonly incite fear and anxiety.

Among the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic were the changes thrust upon medical students who suddenly found themselves without clinical exposure (both on core clerkships and electives) for the duration of the academic year.2 We too lost many of our educational and teaching opportunities as we adapted to our changing circumstances and new reality. Therefore, . We used the lessons we learned because of the changes in our own medical education to anticipate the best ways to provide learning opportunities for our students.

GI fellows’ experiences

The changes to our schedules and lack of in-person educational conferences seemingly happened overnight – the shock of being pulled from clinics, consults, and endoscopy left us feeling scared and lonely. We were quickly transitioned from knowing our roles and responsibilities as GI providers to taking over care for hospitalist patients as the “primary team,” working in the COVID emergency department (ED), and losing our clinic space. Redeployment to other clinical environments was anxiety-provoking. Self-doubt and fear were the most cited concerns as we asked ourselves: Do I remember enough general medicine to be an effective hospitalist? How do I place admission orders or perform a medication reconciliation on discharge? What can I expect in the COVID ED? Will I have to intubate someone? What about possible PPE shortages? Are my family members safe at home? Should I stay in a hotel? Do we have estimates on how long this will last?

Clinical schedules were reconfigured to consolidate the use of inpatient fellows and allow for reserves of fellows to be redeployed if needed. Schedules for the following 7 days were made just 48 hours prior to the start of each workweek. The anticipation and fear of the unknown were perhaps the hardest parts of the changes in our clinical learning environment. Little time was provided to make child care arrangements, coordinate with the schedules of significant others, or review topics and skills we might need in the next week that had gone unused for some time.

Our conference schedule was pared down considerably as fellows and attendings adjusted to their new responsibilities and a virtual platform for fellows’ education. While the transition to online lectures was seamless, the spirit of conference certainly changed. Impromptu questions and conversations that oftentimes arise organically during case conferences no longer occurred as virtual meetings do not offer the same space to foster these discussions as we awkwardly muted and unmuted ourselves. Participation in lectures seemed disjointed, which translated in some ways to less effective learning opportunities. Our involvement in endoscopy was also removed as only urgent cases were being performed and PPE conservation was of the utmost priority. This was especially concerning for third-year fellows on the cusp of graduation who would soon be independent practitioners without recent procedural practice. In general, the fellowship felt isolated and uncertain, which our program director addressed with weekly virtual COVID-19 “happy hour” updates.

GI fellows’ contribution

As our program encouraged us to come together during this time to support each other, we realized that while our clinical duties may look different during the COVID-19 crisis, our responsibility to learners was more important than ever. At many academic institutions, GI fellows are referred to as “the face of the division” owed in large part to our consistent presence on consult services and roles as teachers for medical students and residents who rotate with us. In an effort to assist the medical school’s charge to rapidly generate at-home curriculum for our students, we created an online curriculum for medical students to complete during the time they were previously scheduled to rotate with us on consults either as third- or fourth-year students.

We designed a series of interactive podcasts covering six topics that are commonly encountered issues on the GI consult service: upper GI bleeding, lower GI bleeding, biliary sepsis, acute pancreatitis, chronic diarrhea with a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, as well as cirrhosis and its associated complications.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant change in the daily activities of GI fellows including new responsibilities and a great need for adaptation. We hope that the lessons the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us – to think of others and make our talents available to those who need them, to look for ways to adapt to challenges, to live in the present but focus on the future, and to spread creativity when able – will continue long after the curve has flattened.

References

1. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/online-learning-during-covid-19-tips-help-med-students. Apr 3, 2020.

2. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-how-virus-impacting-medical-schools. Mar 20, 2020.

3. “H5P: Create, share and reuse interactive HTML5 content in your browser.” H5P website. https://h5p.org.

Dr. Bhavsar-Burke and Dr. Jansson-Knodell are GI fellows in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Introduction

We are living in an unprecedented time. During March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) outbreak, our institution removed all medical students from rotations with direct patient contact to prioritize their safety and well-being, following recommendations made by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).1 Similarly, we as gastroenterology fellows experienced an upheaval in our usual schedules and routines. Some of us were redeployed to other areas of the hospital, such as inpatient wards and emergency departments, to meet the needs of our patients and our health system. These changes were difficult, not only because we were practicing in different roles, but also because unknown situations commonly incite fear and anxiety.

Among the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic were the changes thrust upon medical students who suddenly found themselves without clinical exposure (both on core clerkships and electives) for the duration of the academic year.2 We too lost many of our educational and teaching opportunities as we adapted to our changing circumstances and new reality. Therefore, . We used the lessons we learned because of the changes in our own medical education to anticipate the best ways to provide learning opportunities for our students.

GI fellows’ experiences

The changes to our schedules and lack of in-person educational conferences seemingly happened overnight – the shock of being pulled from clinics, consults, and endoscopy left us feeling scared and lonely. We were quickly transitioned from knowing our roles and responsibilities as GI providers to taking over care for hospitalist patients as the “primary team,” working in the COVID emergency department (ED), and losing our clinic space. Redeployment to other clinical environments was anxiety-provoking. Self-doubt and fear were the most cited concerns as we asked ourselves: Do I remember enough general medicine to be an effective hospitalist? How do I place admission orders or perform a medication reconciliation on discharge? What can I expect in the COVID ED? Will I have to intubate someone? What about possible PPE shortages? Are my family members safe at home? Should I stay in a hotel? Do we have estimates on how long this will last?

Clinical schedules were reconfigured to consolidate the use of inpatient fellows and allow for reserves of fellows to be redeployed if needed. Schedules for the following 7 days were made just 48 hours prior to the start of each workweek. The anticipation and fear of the unknown were perhaps the hardest parts of the changes in our clinical learning environment. Little time was provided to make child care arrangements, coordinate with the schedules of significant others, or review topics and skills we might need in the next week that had gone unused for some time.

Our conference schedule was pared down considerably as fellows and attendings adjusted to their new responsibilities and a virtual platform for fellows’ education. While the transition to online lectures was seamless, the spirit of conference certainly changed. Impromptu questions and conversations that oftentimes arise organically during case conferences no longer occurred as virtual meetings do not offer the same space to foster these discussions as we awkwardly muted and unmuted ourselves. Participation in lectures seemed disjointed, which translated in some ways to less effective learning opportunities. Our involvement in endoscopy was also removed as only urgent cases were being performed and PPE conservation was of the utmost priority. This was especially concerning for third-year fellows on the cusp of graduation who would soon be independent practitioners without recent procedural practice. In general, the fellowship felt isolated and uncertain, which our program director addressed with weekly virtual COVID-19 “happy hour” updates.

GI fellows’ contribution

As our program encouraged us to come together during this time to support each other, we realized that while our clinical duties may look different during the COVID-19 crisis, our responsibility to learners was more important than ever. At many academic institutions, GI fellows are referred to as “the face of the division” owed in large part to our consistent presence on consult services and roles as teachers for medical students and residents who rotate with us. In an effort to assist the medical school’s charge to rapidly generate at-home curriculum for our students, we created an online curriculum for medical students to complete during the time they were previously scheduled to rotate with us on consults either as third- or fourth-year students.

We designed a series of interactive podcasts covering six topics that are commonly encountered issues on the GI consult service: upper GI bleeding, lower GI bleeding, biliary sepsis, acute pancreatitis, chronic diarrhea with a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, as well as cirrhosis and its associated complications.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant change in the daily activities of GI fellows including new responsibilities and a great need for adaptation. We hope that the lessons the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us – to think of others and make our talents available to those who need them, to look for ways to adapt to challenges, to live in the present but focus on the future, and to spread creativity when able – will continue long after the curve has flattened.

References

1. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/online-learning-during-covid-19-tips-help-med-students. Apr 3, 2020.

2. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-how-virus-impacting-medical-schools. Mar 20, 2020.

3. “H5P: Create, share and reuse interactive HTML5 content in your browser.” H5P website. https://h5p.org.

Dr. Bhavsar-Burke and Dr. Jansson-Knodell are GI fellows in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Dermatology News welcomes new advisory board member

at University Hospital Saint-Louis in Paris, in the inflammatory diseases outpatient clinic, where he treats patients with severe psoriasis and other inflammatory chronic skin diseases.

He is a member of several dermatology specialty organizations, including the Société Française de Dermatologie, the European Academy of Dermatology, as well as the American Academy of Dermatology. His research interests are in immunology and inflammatory diseases; he also has a passion for art and history.

at University Hospital Saint-Louis in Paris, in the inflammatory diseases outpatient clinic, where he treats patients with severe psoriasis and other inflammatory chronic skin diseases.

He is a member of several dermatology specialty organizations, including the Société Française de Dermatologie, the European Academy of Dermatology, as well as the American Academy of Dermatology. His research interests are in immunology and inflammatory diseases; he also has a passion for art and history.

at University Hospital Saint-Louis in Paris, in the inflammatory diseases outpatient clinic, where he treats patients with severe psoriasis and other inflammatory chronic skin diseases.

He is a member of several dermatology specialty organizations, including the Société Française de Dermatologie, the European Academy of Dermatology, as well as the American Academy of Dermatology. His research interests are in immunology and inflammatory diseases; he also has a passion for art and history.

Choosing a career in health equity and health care policy

Dr. Anyane-Yeboa is a Commonwealth Fund Fellow in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University and a recent graduate of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She previously completed her gastroenterology fellowship at the University of Chicago. She will be an academic gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital starting in the fall of 2020.

How did your career pathway lead you to a career in health equity and policy?

I have been passionate about issues related to health equity, workforce diversity, and care of vulnerable populations since the early years of my career. For instance, as undergraduates my friends and I received a grant to start a program to provide mentorship for endangered youth in Boston. During my residency and chief residency, I advocated for increased resident diversity and created programs for underrepresented minority medical students to increase minority representation in medicine. During my gastroenterology fellowship, I remained passionate about the care of minority and underserved populations. During my second year of fellowship, I looked for advanced training opportunities where I could learn the skills to tackle health disparities in minority communities, and almost serendipitously came across the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy. When I decided to apply for the fellowship, I knew that this would be a nontraditional path for most gastroenterology fellows, but the right path for me.

About the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship

The purpose of the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University is to train the next generation of leaders in health care. The program is based at Harvard Medical School and supported by the Commonwealth Fund whose mission is to “provide affordable quality health care for all.” To date, the fellowship has trained more than 130 physicians who are advancing health care across the nation as leaders in public health, academic medicine, and health policy.

The fellowship is a year-long, full-time, degree-granting program. Fellows are eligible for a master’s in public health with a concentration in health management or health policy from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health or a master’s in public administration from the Harvard Kennedy School.

The fellowship program and experiences have been transformative for me. The structure of the program consists of visits to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Boston Public Health Commission, and the Commonwealth Fund, as well as lectures, seminars, and journal club sessions with national leaders in public health, health policy, and health care delivery reform. Additional opportunities include one-on-one shadowing experiences with leaders in hospital administration at academic institutions in Boston and private meetings with leaders and staff at several government agencies in Washington, including the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services, the Office of Minority Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the National Institutes of Health.

The program has given me an opportunity to meet and learn from physicians who have chosen a variety of different career paths. Through the program I have had exposure to physicians in academic medicine, health care administration, health policy, and public service as well as those who have chosen a combination of clinical practice with any of the above. This experience has opened my eyes to the different possibilities for physician careers and has encouraged me to be open if new opportunities should arise.

As part of the fellowship, we also have regular meetings with Joan Reede, MD, MPH, who is the director of the fellowship and has been with the program since its inception; she is also the Dean of Diversity and Inclusion at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Reede is an incredibly wise, insightful, and caring mentor, but also a powerhouse in issues surrounding workforce diversity, mentorship, policy, care of underserved communities, and being an advocate for change. To have access to such a powerful individual who has dedicated her career to the mentorship of individuals like myself, who cares deeply about the impact of our careers, and who genuinely values each fellow almost as her own child is a unique gift that is hard to describe in words.

The Commonwealth Fund Fellowship also provides a large network of mentors and advisers. My direct mentor for the program is Monica Bharel, MD, MPH, who is a former Commonwealth Fund fellow and the current Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. However, I also have a wealth of other mentors and advisers in the alumni fellows, including Darrell Gray II, MD, MPH, a former fellow and gastroenterologist at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, as well as the other faculty associated with the program. I never imagined that I would have access to leaders in so many different sectors of health care and policy who are genuinely and passionately rooting for my success. In addition, my cofellows and I have created a uniquely special bond, and they will likely continue as my close network of peer advisers as I move forward throughout my career.

After the fellowship

I have no doubt that the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship will alter the trajectory of my career. It has already affected my career path in ways that I could not have anticipated years ago. The knowledge that I have gained in health care policy, innovation, and equity, as well as the networks that I have access to as a fellow, will be invaluable as I move forward. In terms of next steps, I will be working as an academic gastroenterologist; I will continue to lead initiatives, perform research, and participate in projects to elevate the voices of underserved communities and work toward health equity in gastroenterology. I am particularly passionate about ending disparities in colorectal cancer in minority communities and increasing awareness around minorities with inflammatory bowel disease.

I plan to work with health centers, city- and state-level organizations, and community partners to raise awareness around issues of equity in gastroenterology and develop interventions to create change. I will also work with local legislators and community-based organizations to advocate for policies that remove barriers to screening both locally and nationally. Further down the line, I am open to exploring careers in the public sector or health care administration if that is where my career takes me. The exposure that I had to these fields as part of the fellowship has shown me that it is possible to be a practicing gastroenterologist and simultaneously work in the public sector, health policy, or health care administration. If you are interested in applying to the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University, please feel free to contact me at [email protected]. More information about the program and how to apply can be found at https://cff.hms.harvard.edu/.

Dr. Anyane-Yeboa is a Commonwealth Fund Fellow in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University and a recent graduate of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She previously completed her gastroenterology fellowship at the University of Chicago. She will be an academic gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital starting in the fall of 2020.

How did your career pathway lead you to a career in health equity and policy?

I have been passionate about issues related to health equity, workforce diversity, and care of vulnerable populations since the early years of my career. For instance, as undergraduates my friends and I received a grant to start a program to provide mentorship for endangered youth in Boston. During my residency and chief residency, I advocated for increased resident diversity and created programs for underrepresented minority medical students to increase minority representation in medicine. During my gastroenterology fellowship, I remained passionate about the care of minority and underserved populations. During my second year of fellowship, I looked for advanced training opportunities where I could learn the skills to tackle health disparities in minority communities, and almost serendipitously came across the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy. When I decided to apply for the fellowship, I knew that this would be a nontraditional path for most gastroenterology fellows, but the right path for me.

About the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship

The purpose of the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University is to train the next generation of leaders in health care. The program is based at Harvard Medical School and supported by the Commonwealth Fund whose mission is to “provide affordable quality health care for all.” To date, the fellowship has trained more than 130 physicians who are advancing health care across the nation as leaders in public health, academic medicine, and health policy.

The fellowship is a year-long, full-time, degree-granting program. Fellows are eligible for a master’s in public health with a concentration in health management or health policy from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health or a master’s in public administration from the Harvard Kennedy School.

The fellowship program and experiences have been transformative for me. The structure of the program consists of visits to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Boston Public Health Commission, and the Commonwealth Fund, as well as lectures, seminars, and journal club sessions with national leaders in public health, health policy, and health care delivery reform. Additional opportunities include one-on-one shadowing experiences with leaders in hospital administration at academic institutions in Boston and private meetings with leaders and staff at several government agencies in Washington, including the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services, the Office of Minority Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the National Institutes of Health.

The program has given me an opportunity to meet and learn from physicians who have chosen a variety of different career paths. Through the program I have had exposure to physicians in academic medicine, health care administration, health policy, and public service as well as those who have chosen a combination of clinical practice with any of the above. This experience has opened my eyes to the different possibilities for physician careers and has encouraged me to be open if new opportunities should arise.

As part of the fellowship, we also have regular meetings with Joan Reede, MD, MPH, who is the director of the fellowship and has been with the program since its inception; she is also the Dean of Diversity and Inclusion at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Reede is an incredibly wise, insightful, and caring mentor, but also a powerhouse in issues surrounding workforce diversity, mentorship, policy, care of underserved communities, and being an advocate for change. To have access to such a powerful individual who has dedicated her career to the mentorship of individuals like myself, who cares deeply about the impact of our careers, and who genuinely values each fellow almost as her own child is a unique gift that is hard to describe in words.

The Commonwealth Fund Fellowship also provides a large network of mentors and advisers. My direct mentor for the program is Monica Bharel, MD, MPH, who is a former Commonwealth Fund fellow and the current Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. However, I also have a wealth of other mentors and advisers in the alumni fellows, including Darrell Gray II, MD, MPH, a former fellow and gastroenterologist at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, as well as the other faculty associated with the program. I never imagined that I would have access to leaders in so many different sectors of health care and policy who are genuinely and passionately rooting for my success. In addition, my cofellows and I have created a uniquely special bond, and they will likely continue as my close network of peer advisers as I move forward throughout my career.

After the fellowship

I have no doubt that the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship will alter the trajectory of my career. It has already affected my career path in ways that I could not have anticipated years ago. The knowledge that I have gained in health care policy, innovation, and equity, as well as the networks that I have access to as a fellow, will be invaluable as I move forward. In terms of next steps, I will be working as an academic gastroenterologist; I will continue to lead initiatives, perform research, and participate in projects to elevate the voices of underserved communities and work toward health equity in gastroenterology. I am particularly passionate about ending disparities in colorectal cancer in minority communities and increasing awareness around minorities with inflammatory bowel disease.

I plan to work with health centers, city- and state-level organizations, and community partners to raise awareness around issues of equity in gastroenterology and develop interventions to create change. I will also work with local legislators and community-based organizations to advocate for policies that remove barriers to screening both locally and nationally. Further down the line, I am open to exploring careers in the public sector or health care administration if that is where my career takes me. The exposure that I had to these fields as part of the fellowship has shown me that it is possible to be a practicing gastroenterologist and simultaneously work in the public sector, health policy, or health care administration. If you are interested in applying to the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University, please feel free to contact me at [email protected]. More information about the program and how to apply can be found at https://cff.hms.harvard.edu/.

Dr. Anyane-Yeboa is a Commonwealth Fund Fellow in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University and a recent graduate of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She previously completed her gastroenterology fellowship at the University of Chicago. She will be an academic gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital starting in the fall of 2020.

How did your career pathway lead you to a career in health equity and policy?

I have been passionate about issues related to health equity, workforce diversity, and care of vulnerable populations since the early years of my career. For instance, as undergraduates my friends and I received a grant to start a program to provide mentorship for endangered youth in Boston. During my residency and chief residency, I advocated for increased resident diversity and created programs for underrepresented minority medical students to increase minority representation in medicine. During my gastroenterology fellowship, I remained passionate about the care of minority and underserved populations. During my second year of fellowship, I looked for advanced training opportunities where I could learn the skills to tackle health disparities in minority communities, and almost serendipitously came across the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy. When I decided to apply for the fellowship, I knew that this would be a nontraditional path for most gastroenterology fellows, but the right path for me.

About the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship

The purpose of the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University is to train the next generation of leaders in health care. The program is based at Harvard Medical School and supported by the Commonwealth Fund whose mission is to “provide affordable quality health care for all.” To date, the fellowship has trained more than 130 physicians who are advancing health care across the nation as leaders in public health, academic medicine, and health policy.

The fellowship is a year-long, full-time, degree-granting program. Fellows are eligible for a master’s in public health with a concentration in health management or health policy from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health or a master’s in public administration from the Harvard Kennedy School.

The fellowship program and experiences have been transformative for me. The structure of the program consists of visits to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Boston Public Health Commission, and the Commonwealth Fund, as well as lectures, seminars, and journal club sessions with national leaders in public health, health policy, and health care delivery reform. Additional opportunities include one-on-one shadowing experiences with leaders in hospital administration at academic institutions in Boston and private meetings with leaders and staff at several government agencies in Washington, including the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services, the Office of Minority Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the National Institutes of Health.

The program has given me an opportunity to meet and learn from physicians who have chosen a variety of different career paths. Through the program I have had exposure to physicians in academic medicine, health care administration, health policy, and public service as well as those who have chosen a combination of clinical practice with any of the above. This experience has opened my eyes to the different possibilities for physician careers and has encouraged me to be open if new opportunities should arise.

As part of the fellowship, we also have regular meetings with Joan Reede, MD, MPH, who is the director of the fellowship and has been with the program since its inception; she is also the Dean of Diversity and Inclusion at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Reede is an incredibly wise, insightful, and caring mentor, but also a powerhouse in issues surrounding workforce diversity, mentorship, policy, care of underserved communities, and being an advocate for change. To have access to such a powerful individual who has dedicated her career to the mentorship of individuals like myself, who cares deeply about the impact of our careers, and who genuinely values each fellow almost as her own child is a unique gift that is hard to describe in words.

The Commonwealth Fund Fellowship also provides a large network of mentors and advisers. My direct mentor for the program is Monica Bharel, MD, MPH, who is a former Commonwealth Fund fellow and the current Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. However, I also have a wealth of other mentors and advisers in the alumni fellows, including Darrell Gray II, MD, MPH, a former fellow and gastroenterologist at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, as well as the other faculty associated with the program. I never imagined that I would have access to leaders in so many different sectors of health care and policy who are genuinely and passionately rooting for my success. In addition, my cofellows and I have created a uniquely special bond, and they will likely continue as my close network of peer advisers as I move forward throughout my career.

After the fellowship

I have no doubt that the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship will alter the trajectory of my career. It has already affected my career path in ways that I could not have anticipated years ago. The knowledge that I have gained in health care policy, innovation, and equity, as well as the networks that I have access to as a fellow, will be invaluable as I move forward. In terms of next steps, I will be working as an academic gastroenterologist; I will continue to lead initiatives, perform research, and participate in projects to elevate the voices of underserved communities and work toward health equity in gastroenterology. I am particularly passionate about ending disparities in colorectal cancer in minority communities and increasing awareness around minorities with inflammatory bowel disease.

I plan to work with health centers, city- and state-level organizations, and community partners to raise awareness around issues of equity in gastroenterology and develop interventions to create change. I will also work with local legislators and community-based organizations to advocate for policies that remove barriers to screening both locally and nationally. Further down the line, I am open to exploring careers in the public sector or health care administration if that is where my career takes me. The exposure that I had to these fields as part of the fellowship has shown me that it is possible to be a practicing gastroenterologist and simultaneously work in the public sector, health policy, or health care administration. If you are interested in applying to the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University, please feel free to contact me at [email protected]. More information about the program and how to apply can be found at https://cff.hms.harvard.edu/.

Severe Gingival Swelling and Erythema

The Diagnosis: Plasma Cell Gingivitis

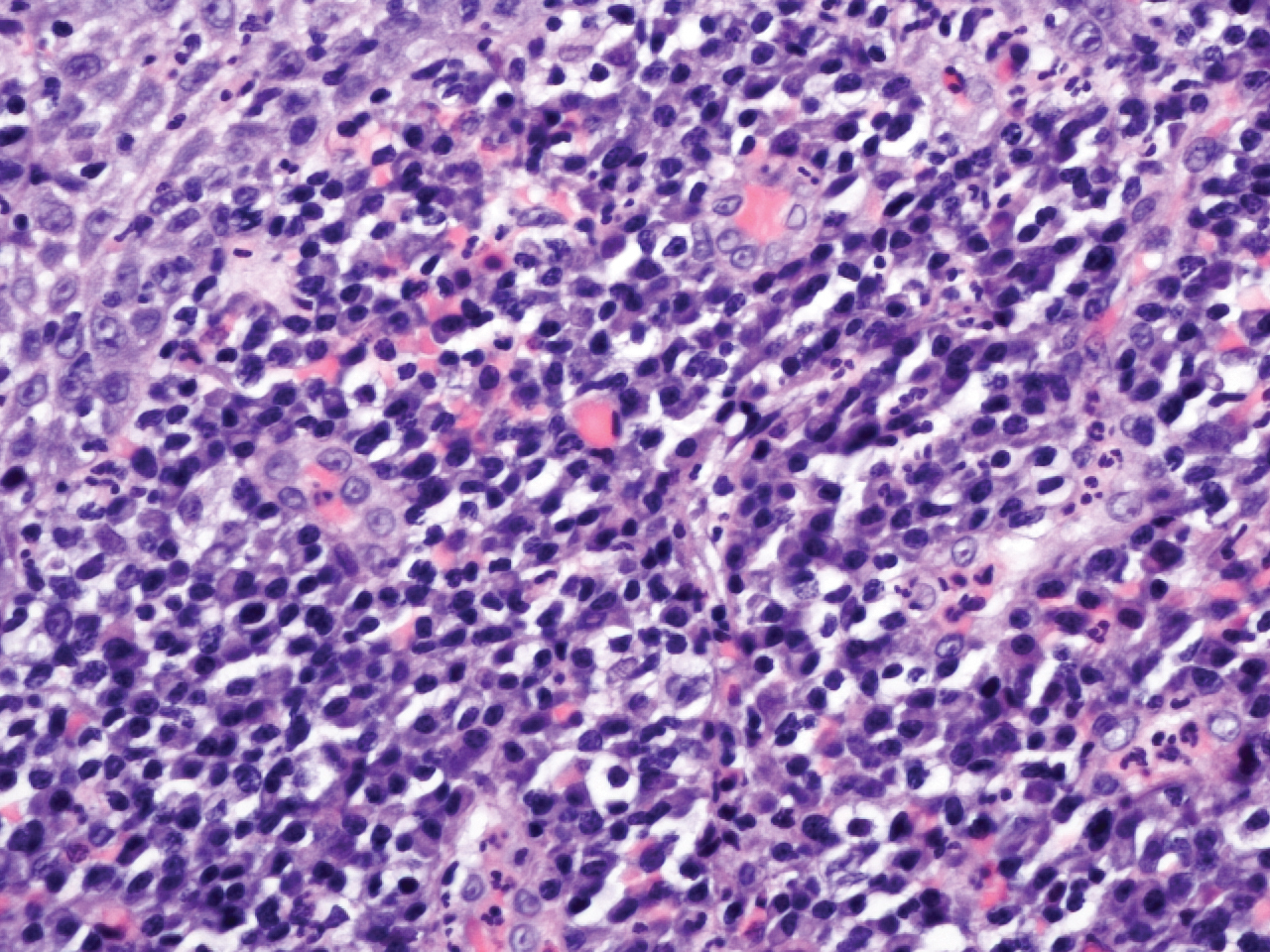

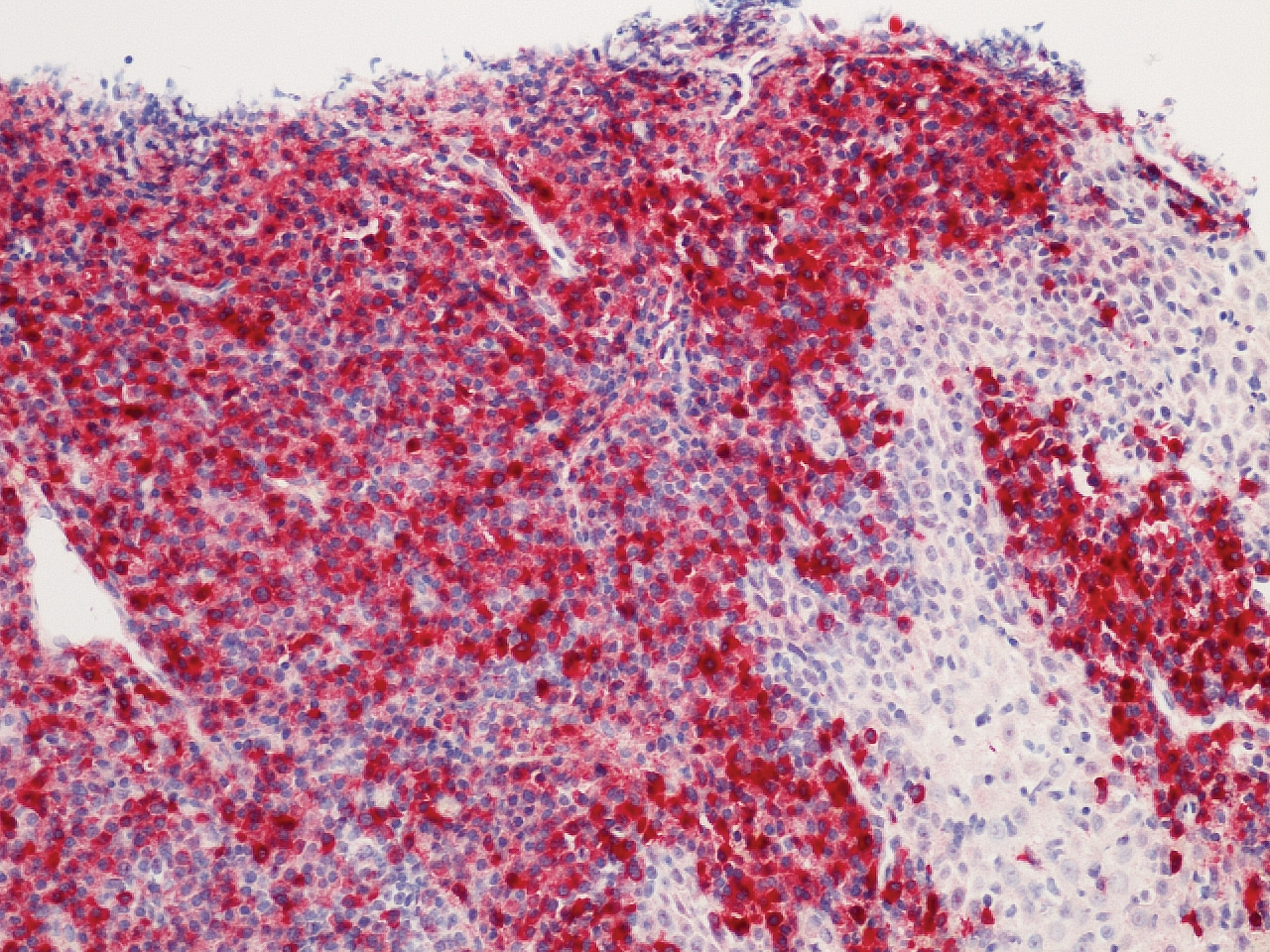

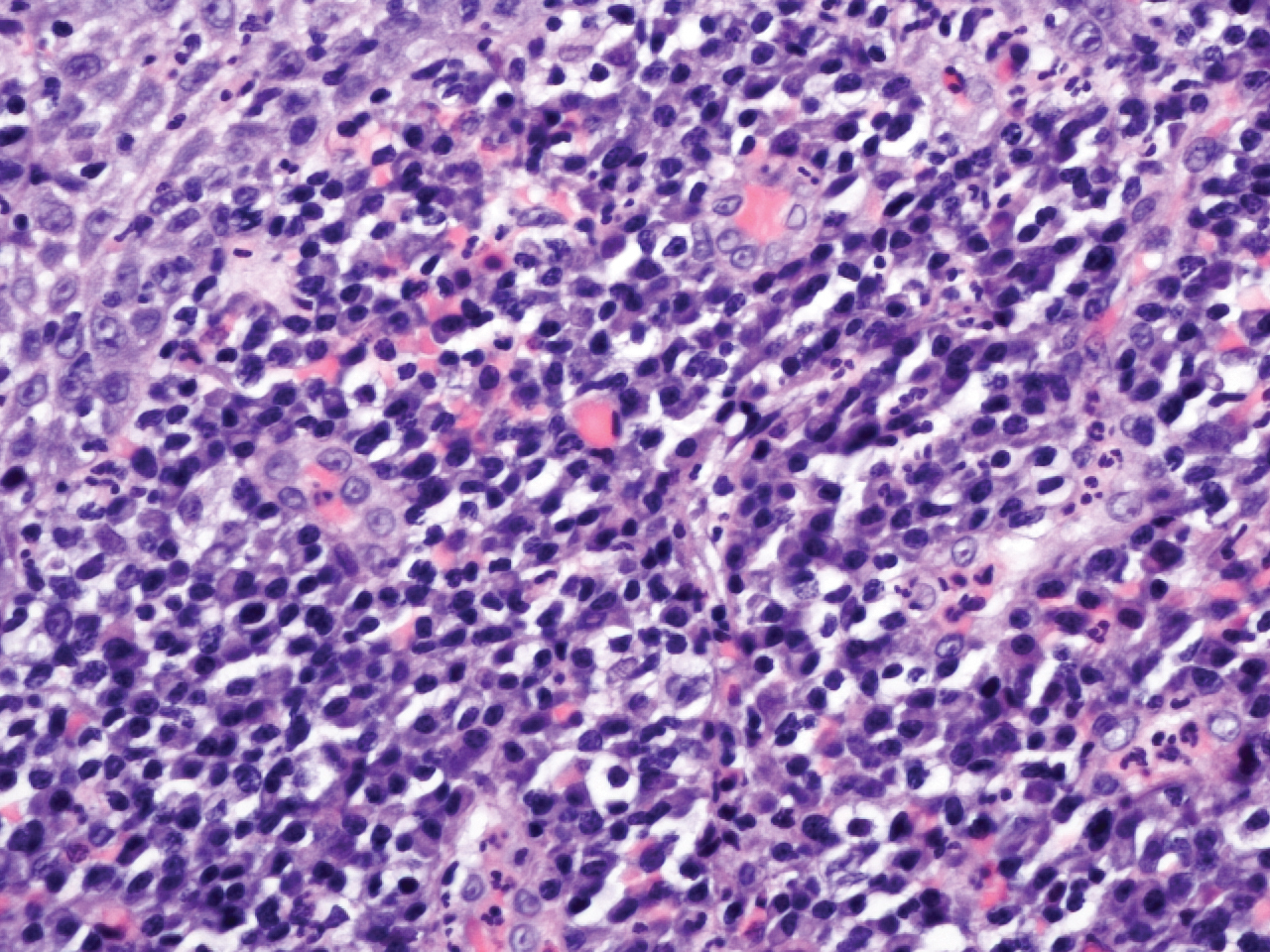

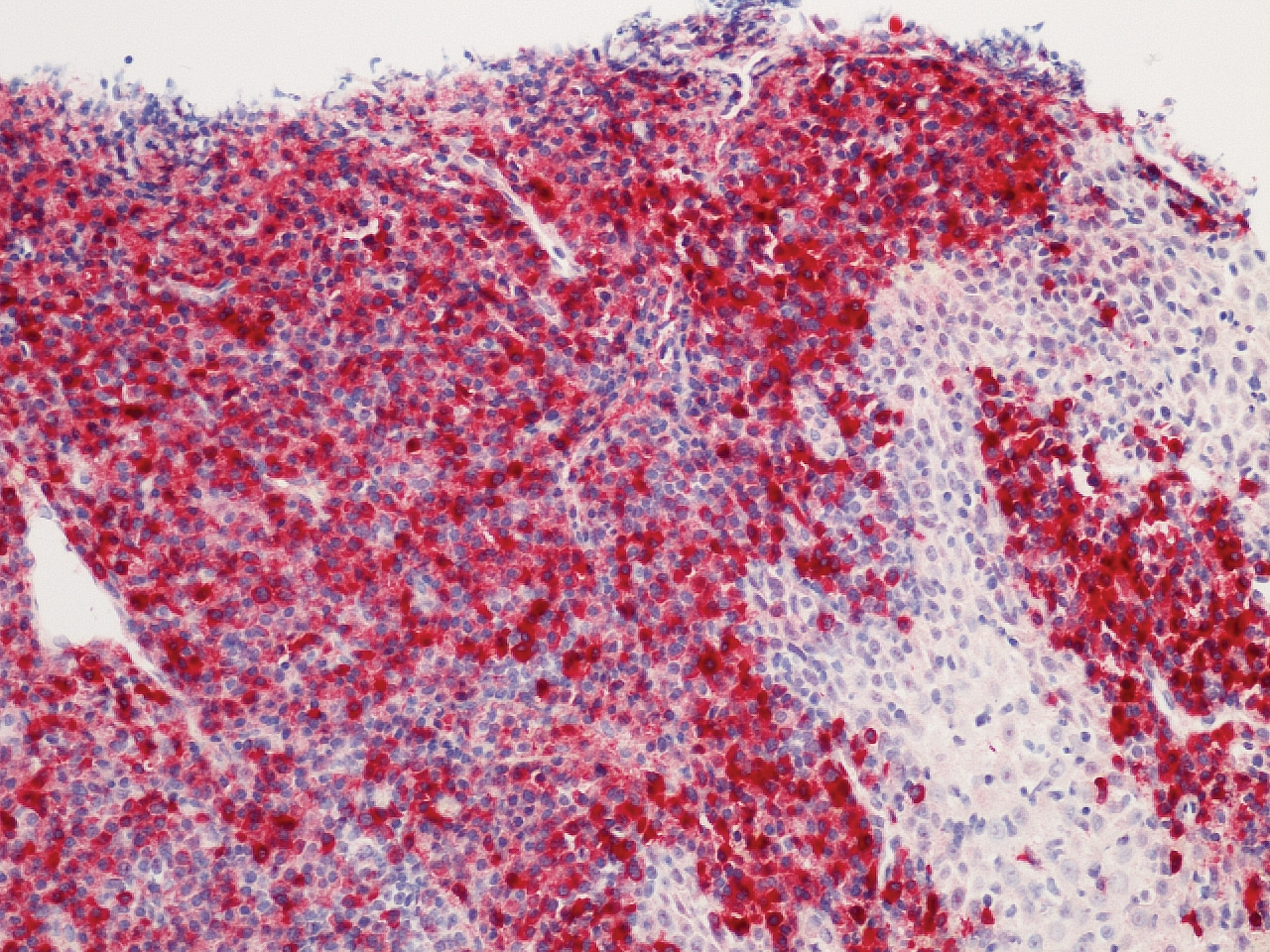

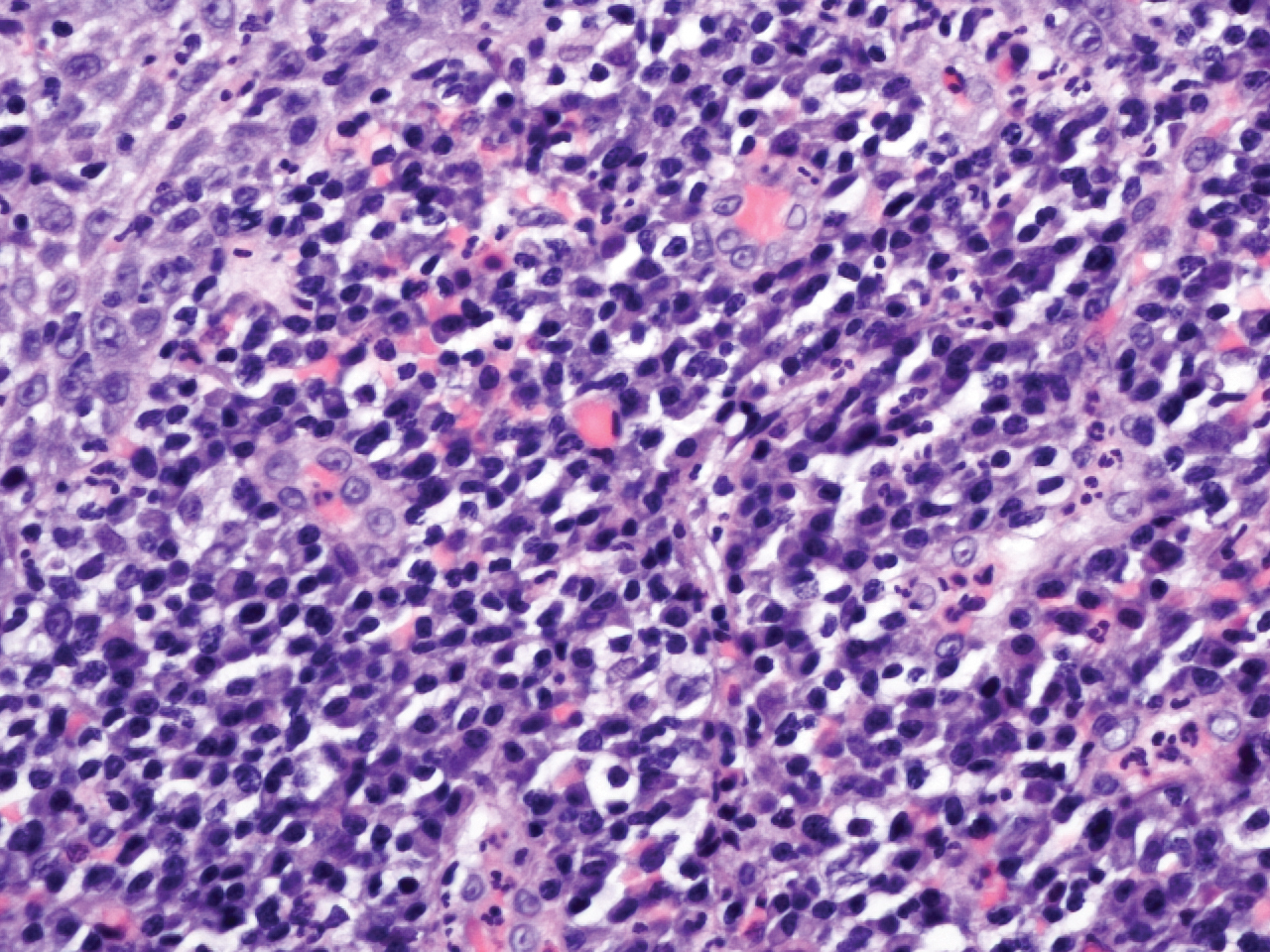

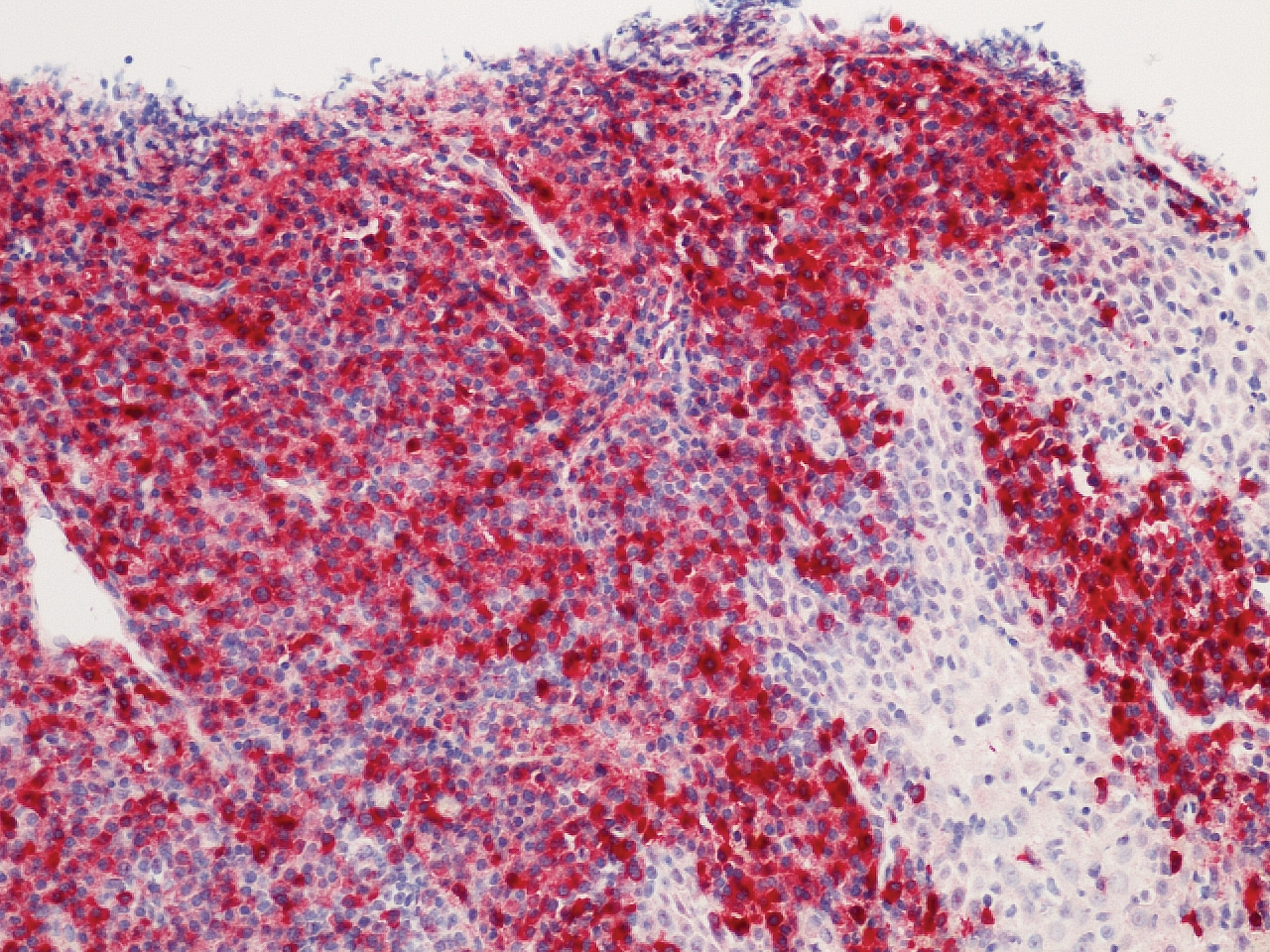

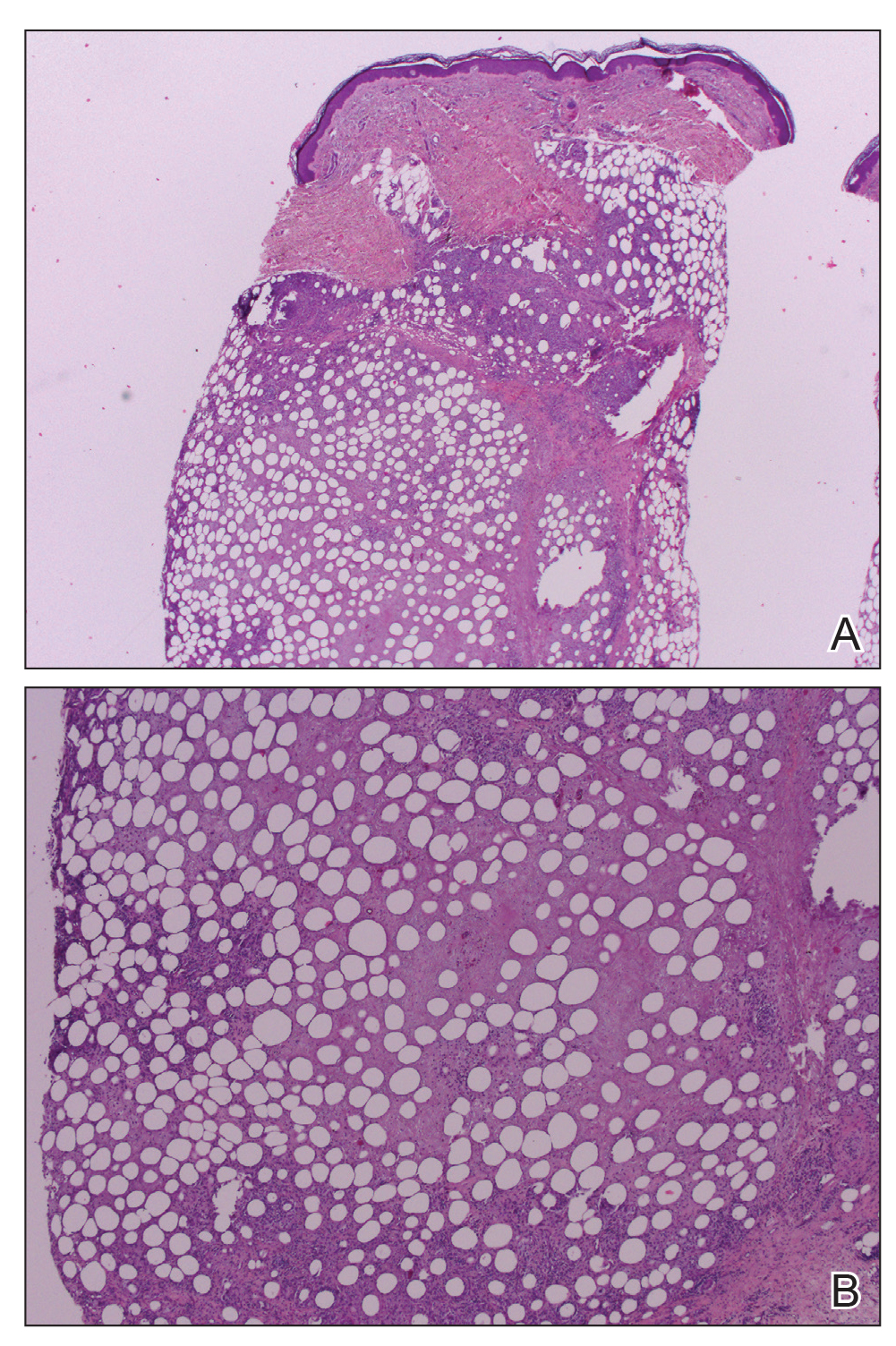

Microscopic analysis demonstrated an acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium with an edematous fibrous stroma containing dense perivascular infiltrates of plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical analysis with kappa, lambda, and CD79a immunostains indicated a polyclonal proliferation of plasma cells that excluded monoclonal plasma cell neoplasia (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative. Serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for bullous pemphigoid 180 and 230 antibodies as well as desmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies was normal. The cumulative findings were consistent with plasma cell gingivitis (PCG). It was recommended that the patient avoid possible foods (eg, citrus) and oral hygiene products (eg, mint-flavored toothpaste) that could trigger PCG. With patient compliance to an elimination diet for 3 months, the condition resolved (Figure 3).

Plasma cell gingivitis is a rare condition characterized by generalized edema and erythema of the attached gingiva. It was described in the 1960s and classified into 3 types based on etiology: (1) hypersensitivity (most common), (2) neoplastic, and (3) PCG of unknown origin.1,2 Spices, herbs, and flavoring agents are implicated as potential triggers of hypersensitivity PCG, while neoplastic PCG is associated with monoclonal plasma cell neoplasms, such as multiple myeloma and extramedullary plasmacytoma.2,3 Histologically, a diffuse subepithelial infiltrate of a polyclonal mixture of plasma cells typically is observed in hypersensitivity PCG.3 The plasma cell infiltration in hypersensitivity PCG is a benign reactive process without known risk for development of plasma cell malignancy, but the presence of a notable number of plasma cells may require special tissue staining to rule out the possibility of associated neoplasia.2,3 There are no standardized protocols for management of PCG.4 Elimination of potential allergens, including flavored oral hygiene products, may result in resolution of hypersensitivity PCG lesions, as exemplified in our patient.1 Neoplastic PCG responds to treatment of the underlying malignancy.5 Topical, intralesional, and/or systemic steroids may be considered in symptomatic cases of PCG.4

Clinical presentation of PCG can mimic immune-mediated mucocutaneous diseases such as mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), pemphigus vulgaris (PV), and oral lichen planus; microscopic analysis is needed to establish the diagnosis.6 Mucous membrane pemphigoid is a chronic autoimmune blistering disease involving the mucous membranes with possible cutaneous involvement. It is characterized by a complement-mediated autoantibody process against one or several antigens in the epithelial basement membrane. The oral mucosa is involved in 85% of MMP patients, and 65% of patients experience complications involving the ocular conjunctiva. Intraorally, MMP typically manifests as painful erosions, ulcerations, desquamative gingivitis, and/or occasionally intact blisters. Ocular complications include conjunctivitis and corneal erosions that often scar, resulting in blindness in approximately 15% of patients with ocular involvement. Microscopic features of MMP classically exhibit subepithelial separation with a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate on routine analysis and linear deposition of IgG, IgA, or C3 within the basement membrane zone on DIF. Treatment of MMP involves topical or systemic immunosuppressants to control symptoms, minimize complications, and alter disease progression.6

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune vesiculobullous disease that affects the oral mucosa with or without cutaneous involvement.7 Desmogleins 1 and 3, transmembrane glycoproteins of desmosomes that convene cell-to-cell adhesion, are identified as antigens in PV. Antibodies against these desmoglein proteins result in intraepithelial separation, which leads to blister formation.7 Oral manifestations of PV include mucosal erosions and ulcerations as well as desquamative gingivitis. Bullae rarely are seen in the oral cavity, as they tend to rupture, leaving nonhealing ulcerations.8 Histologically, PV is characterized by acantholysis of the suprabasal cell layers with an intact basement membrane zone on routine examination. The distinctive microscopic feature of PV is the detection of cell surface-bound IgG within the epidermis on DIF.7 Treatment of PV may include topical and/or systemic corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody, has been successful in the management of PV.8

Oral lichen planus is a T-cell mediated autoimmune condition that leads to subepithelial lymphocytic infiltration and excessive keratinocyte apoptosis.9 Women typically are affected more often than men, and 75% of patients also have cutaneous manifestations of the condition. Desquamation and/or erythema of the gingiva may be the initial manifestation of oral lichen planus.9 Other commonly involved sites include the buccal mucosa, tongue, and palate. Biopsy of affected tissues typically demonstrates degeneration of the basal cell layer with subjacent bandlike lymphocytic infiltration on routine staining. Linear fibrinogen at the basement membrane zone usually is observed on DIF. Topical corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy, but systemic therapy including corticosteroids, steroid-sparing agents, or immunomodulators may be used in severe cases.9

There are 3 variants of plasma cell neoplasms including multiple myeloma, medullary plasmacytoma (also known as solitary bone plasmacytoma), and extramedullary plasmacytoma (EMP).10 Extramedullary plasmacytoma, sometimes referred to as extraosseous plasmacytoma, is described as a solitary or multiple plasma cell neoplasm contained in the soft tissue. Its occurrence is rare, accounting for only 3% of plasma cell neoplasms. Approximately 90% of EMPs affect the head and neck region, and males are affected 4 times more often than females. The oral cavity is one of the sites of clinical presentation; the gingival tissue infrequently is affected. When EMP affects the gingiva, it can mimic any form of gingivitis as well as other benign inflammatory conditions, such as pyogenic granuloma. Biopsy is the gold standard diagnostic method for differentiating EMP from other conditions, and specific immunohistochemical stains are essential for the diagnosis. Extramedullary plasmacytoma has the best prognosis among plasma cell neoplasms, despite the risk for progression to multiple myeloma. Extramedullary plasmacytoma lesions are very sensitive to radiotherapy, and the 10-year survival rate is approximately 70%.10

- Sollecito TP, Greenberg MS. Plasma cell gingivitis: report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:690-693.

- Gargiulo AV, Ladone JA, Ladone PA, et al. Case report: plasma cell gingivitis A. CDS Rev. 1995;88:22-23.

- Abhishek K, Rashmi J. Plasma cell gingivitis associated with inflammatory cheilitis: a report on a rare case. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013;23:183-187.

- Arduino PG, D'Aiuto F, Cavallito C, et al. Professional oral hygiene as a therapeutic option for pediatric patients with plasma cell gingivitis: preliminary results of a prospective case series. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1670-1675.

- Nayak A, Nayak MT. Multiple myeloma with an unusual oral presentation. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2016;11:199-206.

- Xu HH, Werth VP, Parisi E, et al. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:611-630.

- Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of disease: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Ann Rev Pathol. 2016;11:75-97.

- Cizenski JD, Michel P, Watson IT, et al. Spectrum of orocutaneous disease associations: immune-mediated conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:795-806.

- Stoopler ET, Sollecito TP. Recurrent gingival and oral mucosal lesions. JAMA. 2014;312:1794-1795.

- Nair SK, Faizuddin M, Jayanthi D, et al. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of gingiva and soft tissue in neck. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZD16-ZD18.

The Diagnosis: Plasma Cell Gingivitis

Microscopic analysis demonstrated an acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium with an edematous fibrous stroma containing dense perivascular infiltrates of plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical analysis with kappa, lambda, and CD79a immunostains indicated a polyclonal proliferation of plasma cells that excluded monoclonal plasma cell neoplasia (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative. Serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for bullous pemphigoid 180 and 230 antibodies as well as desmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies was normal. The cumulative findings were consistent with plasma cell gingivitis (PCG). It was recommended that the patient avoid possible foods (eg, citrus) and oral hygiene products (eg, mint-flavored toothpaste) that could trigger PCG. With patient compliance to an elimination diet for 3 months, the condition resolved (Figure 3).

Plasma cell gingivitis is a rare condition characterized by generalized edema and erythema of the attached gingiva. It was described in the 1960s and classified into 3 types based on etiology: (1) hypersensitivity (most common), (2) neoplastic, and (3) PCG of unknown origin.1,2 Spices, herbs, and flavoring agents are implicated as potential triggers of hypersensitivity PCG, while neoplastic PCG is associated with monoclonal plasma cell neoplasms, such as multiple myeloma and extramedullary plasmacytoma.2,3 Histologically, a diffuse subepithelial infiltrate of a polyclonal mixture of plasma cells typically is observed in hypersensitivity PCG.3 The plasma cell infiltration in hypersensitivity PCG is a benign reactive process without known risk for development of plasma cell malignancy, but the presence of a notable number of plasma cells may require special tissue staining to rule out the possibility of associated neoplasia.2,3 There are no standardized protocols for management of PCG.4 Elimination of potential allergens, including flavored oral hygiene products, may result in resolution of hypersensitivity PCG lesions, as exemplified in our patient.1 Neoplastic PCG responds to treatment of the underlying malignancy.5 Topical, intralesional, and/or systemic steroids may be considered in symptomatic cases of PCG.4

Clinical presentation of PCG can mimic immune-mediated mucocutaneous diseases such as mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), pemphigus vulgaris (PV), and oral lichen planus; microscopic analysis is needed to establish the diagnosis.6 Mucous membrane pemphigoid is a chronic autoimmune blistering disease involving the mucous membranes with possible cutaneous involvement. It is characterized by a complement-mediated autoantibody process against one or several antigens in the epithelial basement membrane. The oral mucosa is involved in 85% of MMP patients, and 65% of patients experience complications involving the ocular conjunctiva. Intraorally, MMP typically manifests as painful erosions, ulcerations, desquamative gingivitis, and/or occasionally intact blisters. Ocular complications include conjunctivitis and corneal erosions that often scar, resulting in blindness in approximately 15% of patients with ocular involvement. Microscopic features of MMP classically exhibit subepithelial separation with a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate on routine analysis and linear deposition of IgG, IgA, or C3 within the basement membrane zone on DIF. Treatment of MMP involves topical or systemic immunosuppressants to control symptoms, minimize complications, and alter disease progression.6

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune vesiculobullous disease that affects the oral mucosa with or without cutaneous involvement.7 Desmogleins 1 and 3, transmembrane glycoproteins of desmosomes that convene cell-to-cell adhesion, are identified as antigens in PV. Antibodies against these desmoglein proteins result in intraepithelial separation, which leads to blister formation.7 Oral manifestations of PV include mucosal erosions and ulcerations as well as desquamative gingivitis. Bullae rarely are seen in the oral cavity, as they tend to rupture, leaving nonhealing ulcerations.8 Histologically, PV is characterized by acantholysis of the suprabasal cell layers with an intact basement membrane zone on routine examination. The distinctive microscopic feature of PV is the detection of cell surface-bound IgG within the epidermis on DIF.7 Treatment of PV may include topical and/or systemic corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody, has been successful in the management of PV.8

Oral lichen planus is a T-cell mediated autoimmune condition that leads to subepithelial lymphocytic infiltration and excessive keratinocyte apoptosis.9 Women typically are affected more often than men, and 75% of patients also have cutaneous manifestations of the condition. Desquamation and/or erythema of the gingiva may be the initial manifestation of oral lichen planus.9 Other commonly involved sites include the buccal mucosa, tongue, and palate. Biopsy of affected tissues typically demonstrates degeneration of the basal cell layer with subjacent bandlike lymphocytic infiltration on routine staining. Linear fibrinogen at the basement membrane zone usually is observed on DIF. Topical corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy, but systemic therapy including corticosteroids, steroid-sparing agents, or immunomodulators may be used in severe cases.9

There are 3 variants of plasma cell neoplasms including multiple myeloma, medullary plasmacytoma (also known as solitary bone plasmacytoma), and extramedullary plasmacytoma (EMP).10 Extramedullary plasmacytoma, sometimes referred to as extraosseous plasmacytoma, is described as a solitary or multiple plasma cell neoplasm contained in the soft tissue. Its occurrence is rare, accounting for only 3% of plasma cell neoplasms. Approximately 90% of EMPs affect the head and neck region, and males are affected 4 times more often than females. The oral cavity is one of the sites of clinical presentation; the gingival tissue infrequently is affected. When EMP affects the gingiva, it can mimic any form of gingivitis as well as other benign inflammatory conditions, such as pyogenic granuloma. Biopsy is the gold standard diagnostic method for differentiating EMP from other conditions, and specific immunohistochemical stains are essential for the diagnosis. Extramedullary plasmacytoma has the best prognosis among plasma cell neoplasms, despite the risk for progression to multiple myeloma. Extramedullary plasmacytoma lesions are very sensitive to radiotherapy, and the 10-year survival rate is approximately 70%.10

The Diagnosis: Plasma Cell Gingivitis

Microscopic analysis demonstrated an acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium with an edematous fibrous stroma containing dense perivascular infiltrates of plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical analysis with kappa, lambda, and CD79a immunostains indicated a polyclonal proliferation of plasma cells that excluded monoclonal plasma cell neoplasia (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative. Serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for bullous pemphigoid 180 and 230 antibodies as well as desmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies was normal. The cumulative findings were consistent with plasma cell gingivitis (PCG). It was recommended that the patient avoid possible foods (eg, citrus) and oral hygiene products (eg, mint-flavored toothpaste) that could trigger PCG. With patient compliance to an elimination diet for 3 months, the condition resolved (Figure 3).

Plasma cell gingivitis is a rare condition characterized by generalized edema and erythema of the attached gingiva. It was described in the 1960s and classified into 3 types based on etiology: (1) hypersensitivity (most common), (2) neoplastic, and (3) PCG of unknown origin.1,2 Spices, herbs, and flavoring agents are implicated as potential triggers of hypersensitivity PCG, while neoplastic PCG is associated with monoclonal plasma cell neoplasms, such as multiple myeloma and extramedullary plasmacytoma.2,3 Histologically, a diffuse subepithelial infiltrate of a polyclonal mixture of plasma cells typically is observed in hypersensitivity PCG.3 The plasma cell infiltration in hypersensitivity PCG is a benign reactive process without known risk for development of plasma cell malignancy, but the presence of a notable number of plasma cells may require special tissue staining to rule out the possibility of associated neoplasia.2,3 There are no standardized protocols for management of PCG.4 Elimination of potential allergens, including flavored oral hygiene products, may result in resolution of hypersensitivity PCG lesions, as exemplified in our patient.1 Neoplastic PCG responds to treatment of the underlying malignancy.5 Topical, intralesional, and/or systemic steroids may be considered in symptomatic cases of PCG.4

Clinical presentation of PCG can mimic immune-mediated mucocutaneous diseases such as mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), pemphigus vulgaris (PV), and oral lichen planus; microscopic analysis is needed to establish the diagnosis.6 Mucous membrane pemphigoid is a chronic autoimmune blistering disease involving the mucous membranes with possible cutaneous involvement. It is characterized by a complement-mediated autoantibody process against one or several antigens in the epithelial basement membrane. The oral mucosa is involved in 85% of MMP patients, and 65% of patients experience complications involving the ocular conjunctiva. Intraorally, MMP typically manifests as painful erosions, ulcerations, desquamative gingivitis, and/or occasionally intact blisters. Ocular complications include conjunctivitis and corneal erosions that often scar, resulting in blindness in approximately 15% of patients with ocular involvement. Microscopic features of MMP classically exhibit subepithelial separation with a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate on routine analysis and linear deposition of IgG, IgA, or C3 within the basement membrane zone on DIF. Treatment of MMP involves topical or systemic immunosuppressants to control symptoms, minimize complications, and alter disease progression.6

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune vesiculobullous disease that affects the oral mucosa with or without cutaneous involvement.7 Desmogleins 1 and 3, transmembrane glycoproteins of desmosomes that convene cell-to-cell adhesion, are identified as antigens in PV. Antibodies against these desmoglein proteins result in intraepithelial separation, which leads to blister formation.7 Oral manifestations of PV include mucosal erosions and ulcerations as well as desquamative gingivitis. Bullae rarely are seen in the oral cavity, as they tend to rupture, leaving nonhealing ulcerations.8 Histologically, PV is characterized by acantholysis of the suprabasal cell layers with an intact basement membrane zone on routine examination. The distinctive microscopic feature of PV is the detection of cell surface-bound IgG within the epidermis on DIF.7 Treatment of PV may include topical and/or systemic corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody, has been successful in the management of PV.8

Oral lichen planus is a T-cell mediated autoimmune condition that leads to subepithelial lymphocytic infiltration and excessive keratinocyte apoptosis.9 Women typically are affected more often than men, and 75% of patients also have cutaneous manifestations of the condition. Desquamation and/or erythema of the gingiva may be the initial manifestation of oral lichen planus.9 Other commonly involved sites include the buccal mucosa, tongue, and palate. Biopsy of affected tissues typically demonstrates degeneration of the basal cell layer with subjacent bandlike lymphocytic infiltration on routine staining. Linear fibrinogen at the basement membrane zone usually is observed on DIF. Topical corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy, but systemic therapy including corticosteroids, steroid-sparing agents, or immunomodulators may be used in severe cases.9

There are 3 variants of plasma cell neoplasms including multiple myeloma, medullary plasmacytoma (also known as solitary bone plasmacytoma), and extramedullary plasmacytoma (EMP).10 Extramedullary plasmacytoma, sometimes referred to as extraosseous plasmacytoma, is described as a solitary or multiple plasma cell neoplasm contained in the soft tissue. Its occurrence is rare, accounting for only 3% of plasma cell neoplasms. Approximately 90% of EMPs affect the head and neck region, and males are affected 4 times more often than females. The oral cavity is one of the sites of clinical presentation; the gingival tissue infrequently is affected. When EMP affects the gingiva, it can mimic any form of gingivitis as well as other benign inflammatory conditions, such as pyogenic granuloma. Biopsy is the gold standard diagnostic method for differentiating EMP from other conditions, and specific immunohistochemical stains are essential for the diagnosis. Extramedullary plasmacytoma has the best prognosis among plasma cell neoplasms, despite the risk for progression to multiple myeloma. Extramedullary plasmacytoma lesions are very sensitive to radiotherapy, and the 10-year survival rate is approximately 70%.10

- Sollecito TP, Greenberg MS. Plasma cell gingivitis: report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:690-693.

- Gargiulo AV, Ladone JA, Ladone PA, et al. Case report: plasma cell gingivitis A. CDS Rev. 1995;88:22-23.

- Abhishek K, Rashmi J. Plasma cell gingivitis associated with inflammatory cheilitis: a report on a rare case. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013;23:183-187.

- Arduino PG, D'Aiuto F, Cavallito C, et al. Professional oral hygiene as a therapeutic option for pediatric patients with plasma cell gingivitis: preliminary results of a prospective case series. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1670-1675.

- Nayak A, Nayak MT. Multiple myeloma with an unusual oral presentation. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2016;11:199-206.

- Xu HH, Werth VP, Parisi E, et al. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:611-630.

- Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of disease: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Ann Rev Pathol. 2016;11:75-97.

- Cizenski JD, Michel P, Watson IT, et al. Spectrum of orocutaneous disease associations: immune-mediated conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:795-806.

- Stoopler ET, Sollecito TP. Recurrent gingival and oral mucosal lesions. JAMA. 2014;312:1794-1795.

- Nair SK, Faizuddin M, Jayanthi D, et al. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of gingiva and soft tissue in neck. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZD16-ZD18.

- Sollecito TP, Greenberg MS. Plasma cell gingivitis: report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:690-693.

- Gargiulo AV, Ladone JA, Ladone PA, et al. Case report: plasma cell gingivitis A. CDS Rev. 1995;88:22-23.

- Abhishek K, Rashmi J. Plasma cell gingivitis associated with inflammatory cheilitis: a report on a rare case. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013;23:183-187.

- Arduino PG, D'Aiuto F, Cavallito C, et al. Professional oral hygiene as a therapeutic option for pediatric patients with plasma cell gingivitis: preliminary results of a prospective case series. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1670-1675.

- Nayak A, Nayak MT. Multiple myeloma with an unusual oral presentation. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2016;11:199-206.

- Xu HH, Werth VP, Parisi E, et al. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:611-630.

- Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of disease: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Ann Rev Pathol. 2016;11:75-97.

- Cizenski JD, Michel P, Watson IT, et al. Spectrum of orocutaneous disease associations: immune-mediated conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:795-806.

- Stoopler ET, Sollecito TP. Recurrent gingival and oral mucosal lesions. JAMA. 2014;312:1794-1795.

- Nair SK, Faizuddin M, Jayanthi D, et al. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of gingiva and soft tissue in neck. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZD16-ZD18.

A 62-year-old man presented to an oral medicine specialist with gingival inflammation of at least 1 year's duration. He reported mild discomfort when consuming spicy foods and denied associated extraoral lesions. His medical history revealed hypertension, hypothyroidism, and psoriasis. Medications included lisinopril 10 mg and levothyroxine 100 µg daily. No known drug allergies were reported. His family and social history were noncontributory, and a detailed review of systems was unremarkable. Extraoral examination revealed no lymphadenopathy, salivary gland enlargement, or thyromegaly. Intraoral examination revealed diffuse enlargement of the maxillary and mandibular gingiva accompanied by severe erythema and bleeding on provocation. A 3-mm punch biopsy of the gingiva was performed for routine analysis and direct immunofluorescence.

Disseminated Erythema Induratum in a Patient With a History of Tuberculosis

To the Editor:

Erythema induratum, also known as nodular vasculitis, is a panniculitis that usually affects the lower extremities in middle-aged women. Classically, it has been described as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, also known as a tuberculid.1,2 Other infections, however, also have been implicated as causes of erythema induratum, including bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, which commonly is used for tuberculosis vaccination. Medications also may cause erythema induratum. The characteristic distribution of the nodules on the posterior calves helps to distinguish erythema induratum from other panniculitides. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term disseminated erythema induratum revealed few case reports documenting nodules on the arms, thighs, or chest, and only 1 case report of disseminated erythema induratum.3-8 We describe a rare combination of disseminated erythema induratum in a patient with remote exposure to tuberculosis and recent BCG exposure.

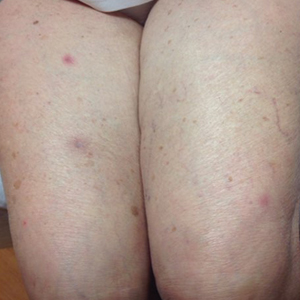

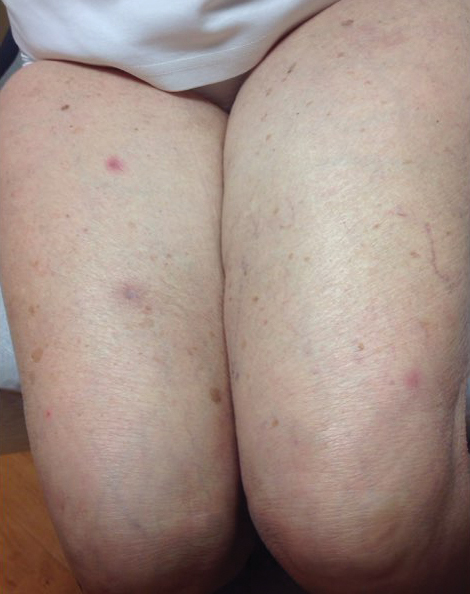

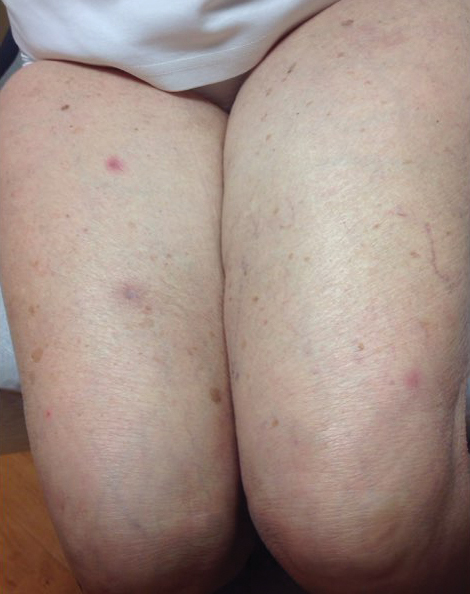

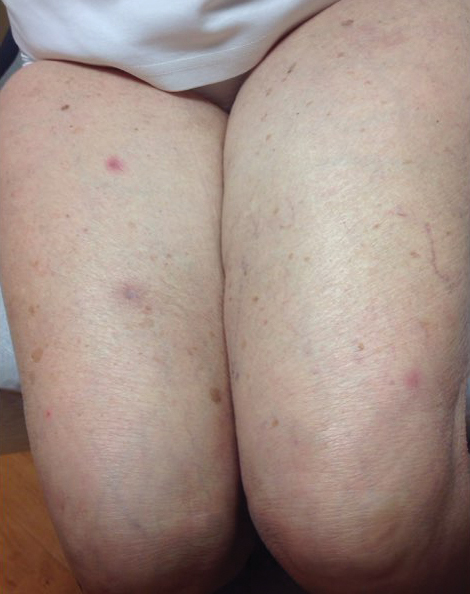

An 88-year-old woman presented for evaluation of violaceous, minimally tender, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodules on the legs, arms, and trunk of several weeks’ duration (Figure 1). She had a remote history of tuberculosis as a child, prior to the advent of modern antituberculosis regimens. Her medical history also included hypertension, breast cancer treated with lymph node dissection, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and bladder cancer treated with intravesical BCG 10 years prior to the onset of the nodules. She reported minimal coughing and a 25-lb weight loss over the last year, but she denied night sweats, fever, or chills.

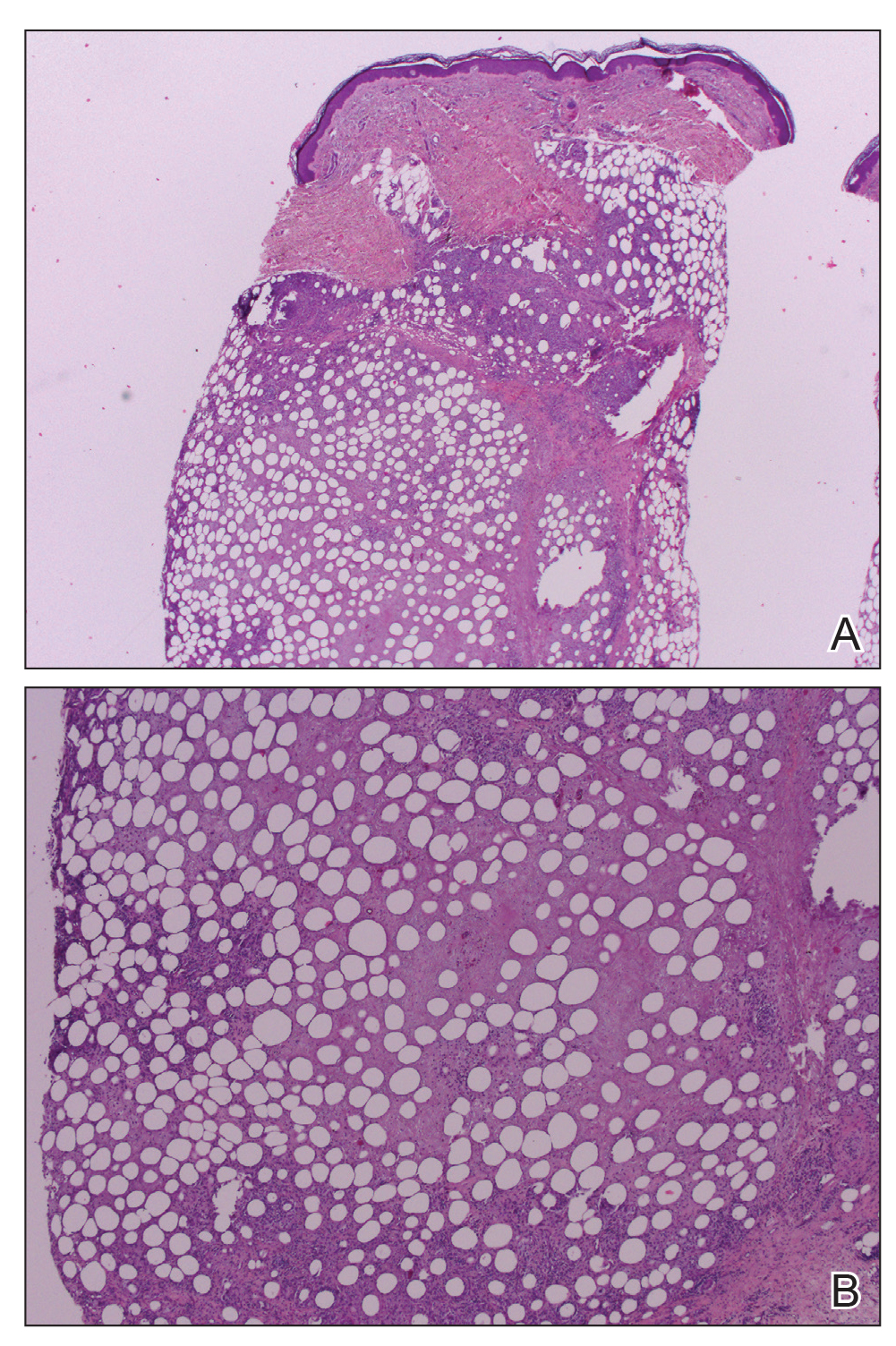

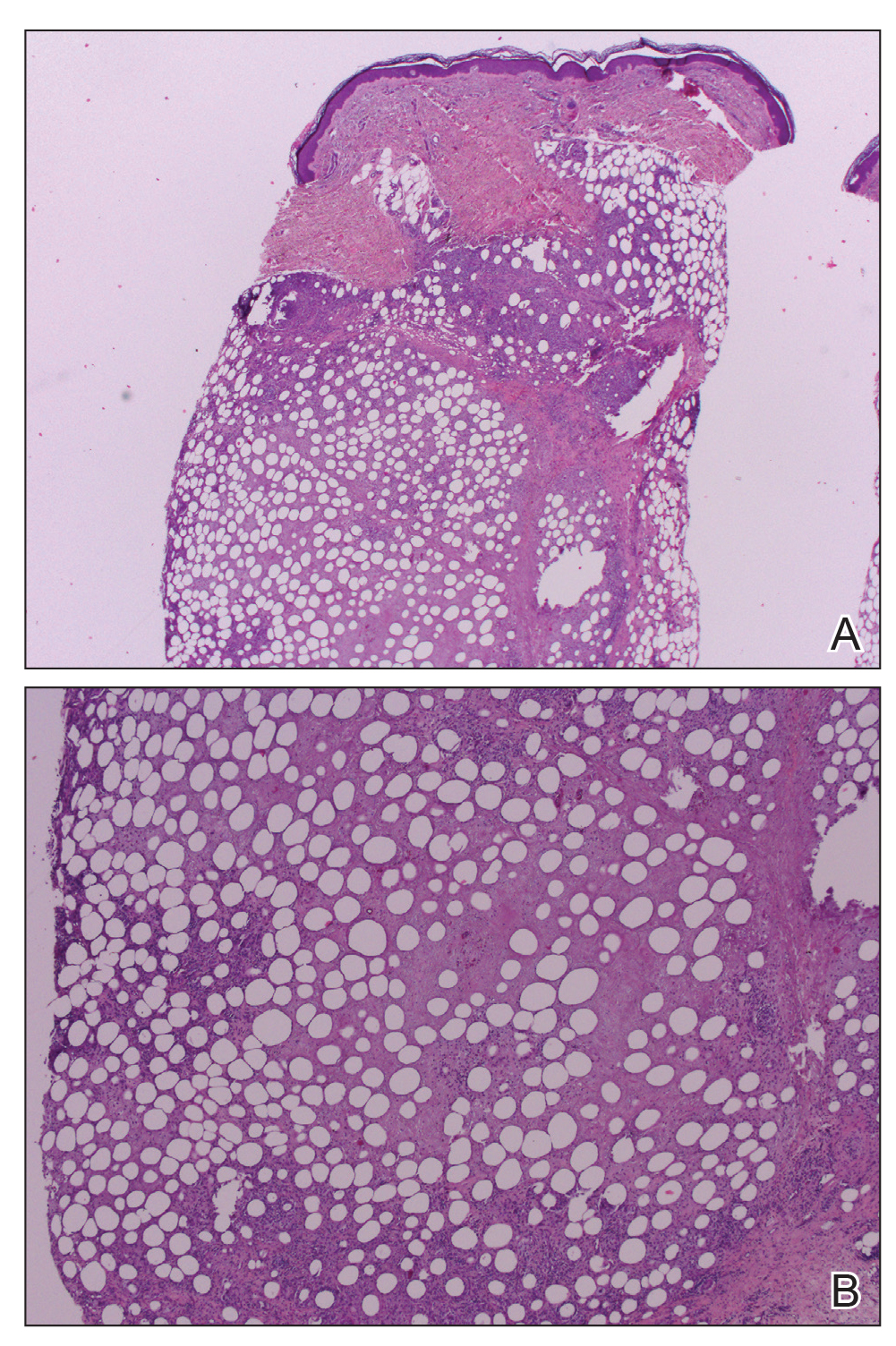

Workup included a biopsy, which showed a dense inflammatory infiltrate within the septae and lobules of the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2A). Foci of necrosis were seen within the fat lobules (Figure 2B). The histologic diagnosis was erythema induratum. Tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative. Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis also was negative. An IFN-γ release assay test was positive for infection with M tuberculosis, suggesting that the erythema induratum was due to tuberculosis rather than BCG exposure. A chest radiograph demonstrated a 22-mm nodule in the left lung (unchanged from a prior film) and a new 10-mm nodule in the left upper lobe.

The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred that the erythema induratum and the new lung nodule likely represented a reactivation of tuberculosis. Sputum samples were found to be smear and culture negative for mycobacteria, but due to high clinical suspicion, she was started on a 4-drug tuberculosis regimen of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Some lesions had started to improve prior to the institution of therapy; after initiation of treatment, all lesions resolved within 4 weeks of starting treatment without recurrence.

Erythema induratum was first described by Bazin9 in 1861. The disorder usually occurs in middle-aged women and is characterized by violaceous ulcerative plaques that classically present on the lower extremities, especially the calves. When the eruption occurs due to a nontuberculous etiology, the term nodular vasculitis is used.1,5 The distinction largely is historical, as most dermatologists today recognize erythema induratum and nodular vasculitis to be the same entity. Examples of nontuberculous causes include infections such as Nocardia, Pseudomonas, Fusarium, or other Mycobacterium species.10 Medications such as propylthiouracil also have been implicated.11 The classification of erythema induratum as a tuberculid suggests that the nodules are a reaction pattern rather than a primary infection, though the term tuberculid may be imprecise. The differential diagnosis of violaceous nodules on the lower extremities and trunk is broad and includes erythema nodosum, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, pancreatic panniculitis, subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and lupus profundus.1,11,12

Histologically, lesions classically demonstrate a mostly lobular panniculitis with varying degrees of septal fibrosis and focal necrosis. Neutrophils may predominate early, while adipocyte necrosis, epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes may be found in older lesions. The presence of vasculitis as a requisite diagnostic criterion remains controversial.1,12

The incidence of erythema induratum has decreased since multidrug tuberculosis treatment has become more widespread.3 Our case displayed the disseminated variant of erythema induratum, an even rarer clinical entity.8 Interestingly, our patient had a history of tuberculosis and exposure to BCG prior to the development of lesions. Case reports have documented erythema induratum after BCG exposure but less frequently than in cases associated with tuberculosis.3,13

The use of BCG vaccines has necessitated the need for a more precise method of determining tuberculosis activity. The tuberculin skin test reacts positively with a history of BCG exposure, rendering it an inadequate test in a patient who is suspected of having an active or latent M tuberculosis infection.13,14 IFN-γ release assays are more specific in detecting latent or active tuberculosis than the tuberculin skin test. Such assays use early secretory antigenic target 6 and cultured filtrate protein 10 as antigens to determine sensitization to M tuberculosis.13,15 These antigens are not produced by BCG or Mycobacterium avium; however, other mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium marinum, Mycobacterium kansasii, and some strains of M bovis produce the aforementioned antigens, and exposure to these microbes may be confounding.13 Importantly, positive IFN-γ release assay results also have been documented after BCG exposure but occur at a much lower frequency than for tuberculosis.15 Thus, the combination of the positive IFN-γ release assay and new chest radiograph nodule in our patient provided strong evidence of reactivated tuberculosis as the precipitating cause of her skin disease.

Despite her negative PCR study, our patient’s presentation remains consistent with the diagnosis of disseminated erythema induratum.13,15 The value of PCR studies in establishing the diagnosis remains to be determined. Case reports have described positive PCR results detecting M tuberculosis in panniculitic nodules, suggesting that trace amounts of the organism are present in lesional tissue despite the negative culture result and immunostains.1 Tuberculid reactions, including lichen scrofulosorum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and erythema induratum, historically are defined by the lack of positive cultures and immunostains, making positive PCR results difficult to reconcile pathophysiologically.1,13 Therefore, use of the term tuberculid altogether as a descriptor for pathogenesis of this disease may need to be avoided.16 Postulated explanations for the relationship of tuberculid diseases and negative cultures and immunostains include the presence of a small number of bacilli that escape routine laboratory detection, early destruction of organisms, or a reaction to circulating M tuberculosis fragments.2 Regardless, until the pathophysiology of erythema induratum has been fully elucidated, the value of PCR remains unclear.

Disseminated erythema induratum, an exceptionally rare variant of panniculitis, may be seen in patients with a remote history of M tuberculosis exposure and/or recent therapeutic BCG exposure. It is imperative to rule out active tuberculosis, especially in elderly patients whose disease predated the advent of modern antituberculosis therapy. Using an IFN-γ release assay in addition to chest radiographs and other clinical stigmata allows differentiation of the etiology of erythema induratum in those patients with tuberculosis who also were treated with BCG.

- Mascaro JM, Basalga E. Erythema induratum of Bazin. Dermatol Clin. 2008;28:439-445.

- Lighter J, Tse DB, Li Y, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin in a child: evidence for a cell-mediated hyper-response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:326-328.

- Inoue T, Fukumoto T, Ansai S, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin in an infant after bacilli Calmette-Guerin vaccination. J Dermatol. 2006;33:268-272.

- Degonda Halter M, Nebiker P, Hug B, et al. Atypical erythema induratum Bazin with tuberculous osteomyelitis. Internist. 2006;47:853-856.

- Gilchrist H, Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum and erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis): diagnosis and management. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:320-327.

- Sharma S, Sehgal VN, Bhattacharya SN, et al. Clinicopathologic spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis: a retrospective analysis of 165 Indians. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:444-450.

- Sethuraman G, Ramesh V. Cutaneous tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:7-16.

- Teramura K, Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, et al. Disseminated erythema induratum of Bazin. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:697-698.

- Bazin E. Extrait des Lecons Théoretiques et Cliniques sur le Scrofule. 2nd ed. Paris, France: Delhaye; 1861.

- Campbell SM, Winkelmann RR, Sammons DL. Erythema induratum caused by Mycobacterium chelonei in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-40.

- Patterson JW. Panniculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Barcelona, Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:1641-1662.

- Segura S, Pujol R, Trinidade F, et al. Vasculitis in erythema induratum of Bazin: a histopathologic study of 101 biopsy specimens from 86 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:839-851.

- Vera-Kellet C, Peters L, Elwood K, et al. Usefulness of interferon-γ release assays in the diagnosis of erythema induratum. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:949-952.

- Prajapati V, Steed M, Grewal P, et al. Erythema induratum: case series illustrating the utility of the interferon-γ release assay in determining the association with tuberculosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:S6-S11.

- Sim JH, Whang KU. Application of the QuantiFERON-Gold TB test in erythema induratum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:260-263.

- Wiebels D, Turnbull K, Steinkraus V, et al. Erythema induratum Bazin.”tuberculid” or tuberculosis? [in German]. Hautarzt. 2007;58:237-240.

To the Editor:

Erythema induratum, also known as nodular vasculitis, is a panniculitis that usually affects the lower extremities in middle-aged women. Classically, it has been described as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, also known as a tuberculid.1,2 Other infections, however, also have been implicated as causes of erythema induratum, including bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, which commonly is used for tuberculosis vaccination. Medications also may cause erythema induratum. The characteristic distribution of the nodules on the posterior calves helps to distinguish erythema induratum from other panniculitides. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term disseminated erythema induratum revealed few case reports documenting nodules on the arms, thighs, or chest, and only 1 case report of disseminated erythema induratum.3-8 We describe a rare combination of disseminated erythema induratum in a patient with remote exposure to tuberculosis and recent BCG exposure.

An 88-year-old woman presented for evaluation of violaceous, minimally tender, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodules on the legs, arms, and trunk of several weeks’ duration (Figure 1). She had a remote history of tuberculosis as a child, prior to the advent of modern antituberculosis regimens. Her medical history also included hypertension, breast cancer treated with lymph node dissection, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and bladder cancer treated with intravesical BCG 10 years prior to the onset of the nodules. She reported minimal coughing and a 25-lb weight loss over the last year, but she denied night sweats, fever, or chills.