User login

For MD-IQ use only

December 2020 - Quick Quiz Question 2

Q2. Correct answer: D

Rationale

Deficient intake of fiber and folate may originate in the food choice of the individual, whereas some deficiencies of intake, such as thiamine, appear to be celiac specific. The provider should encourage intake of nutrient-dense foods including wholegrain foods, enriched if possible, legumes, fruits, vegetables, lean meat, fish, chicken, and eggs. It is not necessary to prioritize micronutrient supplements over achieving nutritional adequacy through dietary intake. Iron deficiency is an effect of untreated celiac disease.

Reference

1. Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. J Human Nutr Dietet. 2012;26:349-58.

Q2. Correct answer: D

Rationale

Deficient intake of fiber and folate may originate in the food choice of the individual, whereas some deficiencies of intake, such as thiamine, appear to be celiac specific. The provider should encourage intake of nutrient-dense foods including wholegrain foods, enriched if possible, legumes, fruits, vegetables, lean meat, fish, chicken, and eggs. It is not necessary to prioritize micronutrient supplements over achieving nutritional adequacy through dietary intake. Iron deficiency is an effect of untreated celiac disease.

Reference

1. Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. J Human Nutr Dietet. 2012;26:349-58.

Q2. Correct answer: D

Rationale

Deficient intake of fiber and folate may originate in the food choice of the individual, whereas some deficiencies of intake, such as thiamine, appear to be celiac specific. The provider should encourage intake of nutrient-dense foods including wholegrain foods, enriched if possible, legumes, fruits, vegetables, lean meat, fish, chicken, and eggs. It is not necessary to prioritize micronutrient supplements over achieving nutritional adequacy through dietary intake. Iron deficiency is an effect of untreated celiac disease.

Reference

1. Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. J Human Nutr Dietet. 2012;26:349-58.

Question 2

December 2020 - Quick Quiz Question 1

Correct answer: C

Rationale

According to the Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, colonoscopy should be performed 1 year after resection, and again 3 years later, in order to decrease the risk of metachronous colorectal cancer.

Reference

1. Kahi CJ, Boland CR, Dominitz JA. Gastroenterology. 2016. 150(3):758-68.e11.

Correct answer: C

Rationale

According to the Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, colonoscopy should be performed 1 year after resection, and again 3 years later, in order to decrease the risk of metachronous colorectal cancer.

Reference

1. Kahi CJ, Boland CR, Dominitz JA. Gastroenterology. 2016. 150(3):758-68.e11.

Correct answer: C

Rationale

According to the Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, colonoscopy should be performed 1 year after resection, and again 3 years later, in order to decrease the risk of metachronous colorectal cancer.

Reference

1. Kahi CJ, Boland CR, Dominitz JA. Gastroenterology. 2016. 150(3):758-68.e11.

You perform a colonoscopy for a patient who underwent sigmoid resection for stage 2 colorectal cancer 1 year ago. The colonoscopy reveals one diminutive adenoma in the cecum, which you remove with a cold snare.

Pigment traits, sun sensitivity associated with risk of non-Hodgkin lymphomas and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Risk factors for keratinocyte carcinomas, primarily pigment traits and sun sensitivity, were associated with the risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in an analysis of 92,097 women in France.

The presence of “many or very many nevi [moles]” was particularly associated with the risk of CLL among individuals in the E3N cohort, according to a report published online in Cancer Medicine. E3N is a prospective cohort of French women aged 40-65 years at inclusion in 1990. Researchers collected cancer data at baseline and every 2-3 years.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between patients pigmentary traits and sun exposure and their risk for CLL/NHL were estimated using Cox models, according to study author Louis-Marie Garcin, MD, of the Université Paris-Saclay, Villejuif, and colleagues.

Common etiology?

Among the 92,097 women included in the study, 622 incident cases of CLL/NHL were observed over a median of 24-years’ follow-up.

The presence of nevi was associated with CLL/NHL risk. The HR for “many or very many nevi” relative to “no nevi” was 1.56. The association with number of nevi was strongest for the risk of CLL, with an HR for “many or very many nevi” of 3.00 vs. 1.32 for NHL. In addition, the researchers found that women whose skin was highly sensitive to sunburn also had a higher risk of CLL (HR, 1.96), while no increased risk of NHL was observed. All HR values were within their respective 95% confidence intervals.

Relevant characteristics that were found to not be associated with added CLL/NHL risk were skin or hair color, number of freckles, and average daily UV dose during spring and summer in the location of residence at birth or at inclusion.

These observations suggest that CLL in particular may share some constitutional risk factors with keratinocyte cancers, according to the researchers.

“We report an association between nevi frequency and CLL/NHL risk, suggesting a partly common genetic etiology of these tumors. Future research should investigate common pathophysiological pathways that could promote the development of both skin carcinoma and CLL/NHL,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the French government. The authors stated that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garcin L-M et al. Cancer Med. 2020. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3586.

Risk factors for keratinocyte carcinomas, primarily pigment traits and sun sensitivity, were associated with the risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in an analysis of 92,097 women in France.

The presence of “many or very many nevi [moles]” was particularly associated with the risk of CLL among individuals in the E3N cohort, according to a report published online in Cancer Medicine. E3N is a prospective cohort of French women aged 40-65 years at inclusion in 1990. Researchers collected cancer data at baseline and every 2-3 years.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between patients pigmentary traits and sun exposure and their risk for CLL/NHL were estimated using Cox models, according to study author Louis-Marie Garcin, MD, of the Université Paris-Saclay, Villejuif, and colleagues.

Common etiology?

Among the 92,097 women included in the study, 622 incident cases of CLL/NHL were observed over a median of 24-years’ follow-up.

The presence of nevi was associated with CLL/NHL risk. The HR for “many or very many nevi” relative to “no nevi” was 1.56. The association with number of nevi was strongest for the risk of CLL, with an HR for “many or very many nevi” of 3.00 vs. 1.32 for NHL. In addition, the researchers found that women whose skin was highly sensitive to sunburn also had a higher risk of CLL (HR, 1.96), while no increased risk of NHL was observed. All HR values were within their respective 95% confidence intervals.

Relevant characteristics that were found to not be associated with added CLL/NHL risk were skin or hair color, number of freckles, and average daily UV dose during spring and summer in the location of residence at birth or at inclusion.

These observations suggest that CLL in particular may share some constitutional risk factors with keratinocyte cancers, according to the researchers.

“We report an association between nevi frequency and CLL/NHL risk, suggesting a partly common genetic etiology of these tumors. Future research should investigate common pathophysiological pathways that could promote the development of both skin carcinoma and CLL/NHL,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the French government. The authors stated that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garcin L-M et al. Cancer Med. 2020. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3586.

Risk factors for keratinocyte carcinomas, primarily pigment traits and sun sensitivity, were associated with the risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in an analysis of 92,097 women in France.

The presence of “many or very many nevi [moles]” was particularly associated with the risk of CLL among individuals in the E3N cohort, according to a report published online in Cancer Medicine. E3N is a prospective cohort of French women aged 40-65 years at inclusion in 1990. Researchers collected cancer data at baseline and every 2-3 years.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between patients pigmentary traits and sun exposure and their risk for CLL/NHL were estimated using Cox models, according to study author Louis-Marie Garcin, MD, of the Université Paris-Saclay, Villejuif, and colleagues.

Common etiology?

Among the 92,097 women included in the study, 622 incident cases of CLL/NHL were observed over a median of 24-years’ follow-up.

The presence of nevi was associated with CLL/NHL risk. The HR for “many or very many nevi” relative to “no nevi” was 1.56. The association with number of nevi was strongest for the risk of CLL, with an HR for “many or very many nevi” of 3.00 vs. 1.32 for NHL. In addition, the researchers found that women whose skin was highly sensitive to sunburn also had a higher risk of CLL (HR, 1.96), while no increased risk of NHL was observed. All HR values were within their respective 95% confidence intervals.

Relevant characteristics that were found to not be associated with added CLL/NHL risk were skin or hair color, number of freckles, and average daily UV dose during spring and summer in the location of residence at birth or at inclusion.

These observations suggest that CLL in particular may share some constitutional risk factors with keratinocyte cancers, according to the researchers.

“We report an association between nevi frequency and CLL/NHL risk, suggesting a partly common genetic etiology of these tumors. Future research should investigate common pathophysiological pathways that could promote the development of both skin carcinoma and CLL/NHL,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the French government. The authors stated that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garcin L-M et al. Cancer Med. 2020. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3586.

FROM CANCER MEDICINE

Photosensitivity diagnosis made simple

of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“When a patient comes in who makes you suspect a photosensitivity, there will be two different presentations,” he said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In some cases, the patient presents with a reaction they believe is sun related, although they don’t have a rash currently, he said. In other cases, “you as a good clinician suspect photosensitivity because the eruption is in a photo distribution,” although the patient may or may not relate it to sun exposure, he added.

Dr. DeLeo noted a few key points to include when taking the history in patients with likely photosensitivity, whether or not they present with a rash.

“I always ask patients when did the episode occur? Is it chronic?” Also ask about timing: Does the reaction occur in the sun, or later? Does it occur quickly and go away within hours, or occur within days or weeks of exposure?

“Always take a good drug history, as photosensitivity can often be related to drugs,” Dr. DeLeo noted. For example, approximately 50% of individuals on amiodarone will have some type of photosensitivity, he said.

Other drug-induced photosensitive conditions include drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus and pseudoporphyria from NSAIDs, as well as hyperpigmentation from diltiazem, which most often occurs in Black women, he said.

“Photodrug reactions are usually related to UVA radiation, and that is important because you can develop it through the window while driving in your car”: The car windows do not protect against UVA, Dr. DeLeo said. If you have a patient who tells you about a photosensitivity or has a rash and they are on a photosensitizing drug, first rule out connective tissue disease, then discontinue the drug in collaboration with the patient’s internist and wait for the reaction to disappear, and it should, he said.

Some photosensitivity rashes have characteristic patterns, notably connective tissue disease patterns in lupus and dermatomyositis patients, bullous eruptions in cases of porphyria or phototoxic contact dermatitis, and eczematous eruptions, Dr. DeLeo noted.

Patients who present without a rash, but report a history of a reaction that they believe is related to sun exposure, fall into two categories: some had a rash that occurred while in the sun and disappeared quickly, and some had one that occurred hours or days after exposure and lasted a few days to weeks, said Dr. DeLeo.

The differential diagnosis in the patient with immediate photosensitivity is fairly clear: These patients usually have solar urticaria, he said. However, some lupus patients may report this reaction so it is important to rule out connective tissue disease. The diagnosis can be made with phototesting or do a simple test by having the patient sit out in the sunshine, he said.

For the patient who has a delayed reactivity after sun exposure, and doesn’t have the reaction when they come to the office, the differential diagnosis in a simply applied way is that, if the reaction spared the face, it is likely polymorphous light eruption (PMLE); but if the face is involved, the patient likely has photoallergic contact dermatitis, Dr. DeLeo explained. However, always consider the alternatives of connective tissue disease, drug reactions, and contact dermatitis that is not photoallergic, he noted.

PMLE “is the most common photosensitivity reaction that we see in the United States,” and it almost always occurs when people are away from home, usually on vacation, said Dr. DeLeo. The differential diagnosis for patients with recurrent or delayed rash involving the face could be photoallergic contact dermatitis, but rule out airborne contact dermatitis, personal care product contact dermatitis, and chronic actinic dermatitis, he said. A work-up for these patients could include a photo test, photopatch test, or patch test.

Dr. DeLeo disclosed serving as a consultant for Estee Lauder.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“When a patient comes in who makes you suspect a photosensitivity, there will be two different presentations,” he said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In some cases, the patient presents with a reaction they believe is sun related, although they don’t have a rash currently, he said. In other cases, “you as a good clinician suspect photosensitivity because the eruption is in a photo distribution,” although the patient may or may not relate it to sun exposure, he added.

Dr. DeLeo noted a few key points to include when taking the history in patients with likely photosensitivity, whether or not they present with a rash.

“I always ask patients when did the episode occur? Is it chronic?” Also ask about timing: Does the reaction occur in the sun, or later? Does it occur quickly and go away within hours, or occur within days or weeks of exposure?

“Always take a good drug history, as photosensitivity can often be related to drugs,” Dr. DeLeo noted. For example, approximately 50% of individuals on amiodarone will have some type of photosensitivity, he said.

Other drug-induced photosensitive conditions include drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus and pseudoporphyria from NSAIDs, as well as hyperpigmentation from diltiazem, which most often occurs in Black women, he said.

“Photodrug reactions are usually related to UVA radiation, and that is important because you can develop it through the window while driving in your car”: The car windows do not protect against UVA, Dr. DeLeo said. If you have a patient who tells you about a photosensitivity or has a rash and they are on a photosensitizing drug, first rule out connective tissue disease, then discontinue the drug in collaboration with the patient’s internist and wait for the reaction to disappear, and it should, he said.

Some photosensitivity rashes have characteristic patterns, notably connective tissue disease patterns in lupus and dermatomyositis patients, bullous eruptions in cases of porphyria or phototoxic contact dermatitis, and eczematous eruptions, Dr. DeLeo noted.

Patients who present without a rash, but report a history of a reaction that they believe is related to sun exposure, fall into two categories: some had a rash that occurred while in the sun and disappeared quickly, and some had one that occurred hours or days after exposure and lasted a few days to weeks, said Dr. DeLeo.

The differential diagnosis in the patient with immediate photosensitivity is fairly clear: These patients usually have solar urticaria, he said. However, some lupus patients may report this reaction so it is important to rule out connective tissue disease. The diagnosis can be made with phototesting or do a simple test by having the patient sit out in the sunshine, he said.

For the patient who has a delayed reactivity after sun exposure, and doesn’t have the reaction when they come to the office, the differential diagnosis in a simply applied way is that, if the reaction spared the face, it is likely polymorphous light eruption (PMLE); but if the face is involved, the patient likely has photoallergic contact dermatitis, Dr. DeLeo explained. However, always consider the alternatives of connective tissue disease, drug reactions, and contact dermatitis that is not photoallergic, he noted.

PMLE “is the most common photosensitivity reaction that we see in the United States,” and it almost always occurs when people are away from home, usually on vacation, said Dr. DeLeo. The differential diagnosis for patients with recurrent or delayed rash involving the face could be photoallergic contact dermatitis, but rule out airborne contact dermatitis, personal care product contact dermatitis, and chronic actinic dermatitis, he said. A work-up for these patients could include a photo test, photopatch test, or patch test.

Dr. DeLeo disclosed serving as a consultant for Estee Lauder.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“When a patient comes in who makes you suspect a photosensitivity, there will be two different presentations,” he said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In some cases, the patient presents with a reaction they believe is sun related, although they don’t have a rash currently, he said. In other cases, “you as a good clinician suspect photosensitivity because the eruption is in a photo distribution,” although the patient may or may not relate it to sun exposure, he added.

Dr. DeLeo noted a few key points to include when taking the history in patients with likely photosensitivity, whether or not they present with a rash.

“I always ask patients when did the episode occur? Is it chronic?” Also ask about timing: Does the reaction occur in the sun, or later? Does it occur quickly and go away within hours, or occur within days or weeks of exposure?

“Always take a good drug history, as photosensitivity can often be related to drugs,” Dr. DeLeo noted. For example, approximately 50% of individuals on amiodarone will have some type of photosensitivity, he said.

Other drug-induced photosensitive conditions include drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus and pseudoporphyria from NSAIDs, as well as hyperpigmentation from diltiazem, which most often occurs in Black women, he said.

“Photodrug reactions are usually related to UVA radiation, and that is important because you can develop it through the window while driving in your car”: The car windows do not protect against UVA, Dr. DeLeo said. If you have a patient who tells you about a photosensitivity or has a rash and they are on a photosensitizing drug, first rule out connective tissue disease, then discontinue the drug in collaboration with the patient’s internist and wait for the reaction to disappear, and it should, he said.

Some photosensitivity rashes have characteristic patterns, notably connective tissue disease patterns in lupus and dermatomyositis patients, bullous eruptions in cases of porphyria or phototoxic contact dermatitis, and eczematous eruptions, Dr. DeLeo noted.

Patients who present without a rash, but report a history of a reaction that they believe is related to sun exposure, fall into two categories: some had a rash that occurred while in the sun and disappeared quickly, and some had one that occurred hours or days after exposure and lasted a few days to weeks, said Dr. DeLeo.

The differential diagnosis in the patient with immediate photosensitivity is fairly clear: These patients usually have solar urticaria, he said. However, some lupus patients may report this reaction so it is important to rule out connective tissue disease. The diagnosis can be made with phototesting or do a simple test by having the patient sit out in the sunshine, he said.

For the patient who has a delayed reactivity after sun exposure, and doesn’t have the reaction when they come to the office, the differential diagnosis in a simply applied way is that, if the reaction spared the face, it is likely polymorphous light eruption (PMLE); but if the face is involved, the patient likely has photoallergic contact dermatitis, Dr. DeLeo explained. However, always consider the alternatives of connective tissue disease, drug reactions, and contact dermatitis that is not photoallergic, he noted.

PMLE “is the most common photosensitivity reaction that we see in the United States,” and it almost always occurs when people are away from home, usually on vacation, said Dr. DeLeo. The differential diagnosis for patients with recurrent or delayed rash involving the face could be photoallergic contact dermatitis, but rule out airborne contact dermatitis, personal care product contact dermatitis, and chronic actinic dermatitis, he said. A work-up for these patients could include a photo test, photopatch test, or patch test.

Dr. DeLeo disclosed serving as a consultant for Estee Lauder.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Scalp Arteriovenous Fistula With Intracranial Communication

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old man presented with a nodule on the vertex of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. The lesion had become soft and tender during the week prior to presentation. He noted that he was experiencing headaches and a buzzing sound in his head. He denied all other neurologic symptoms. The patient was given amoxicillin from a primary care physician and was referred to our institution for evaluation of a presumed inflamed cyst.

The patient’s medical history included an intracranial arteriovenous fistula (AVF) treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to presentation, 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness, essential hypertension, and an aortic aneurysm. His medications included amlodipine, lisinopril, amoxicillin, a multivitamin, and grape seed extract.

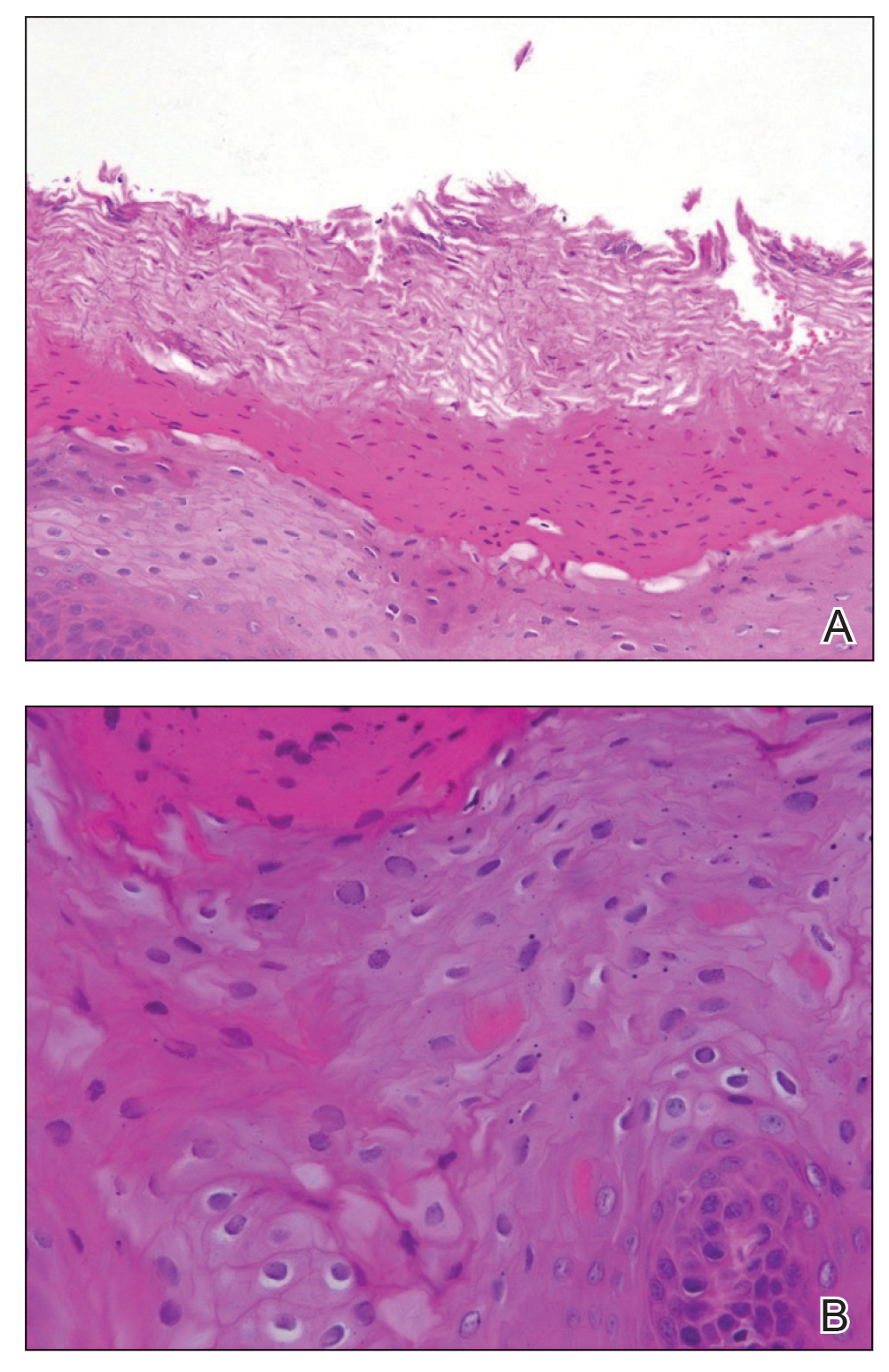

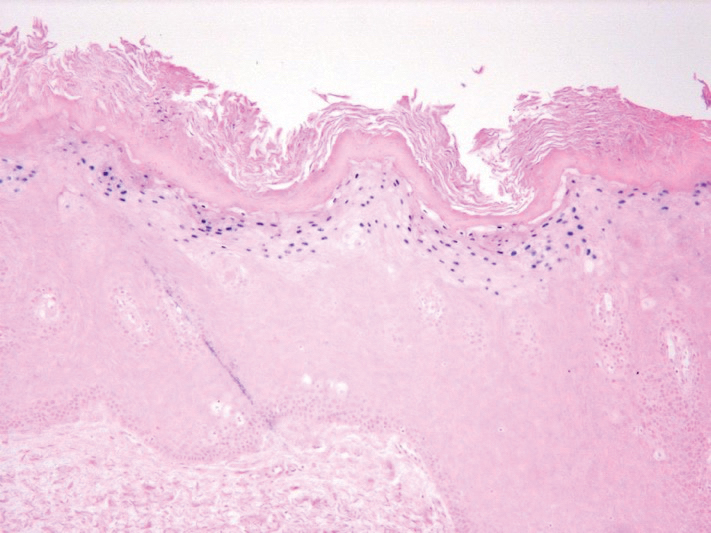

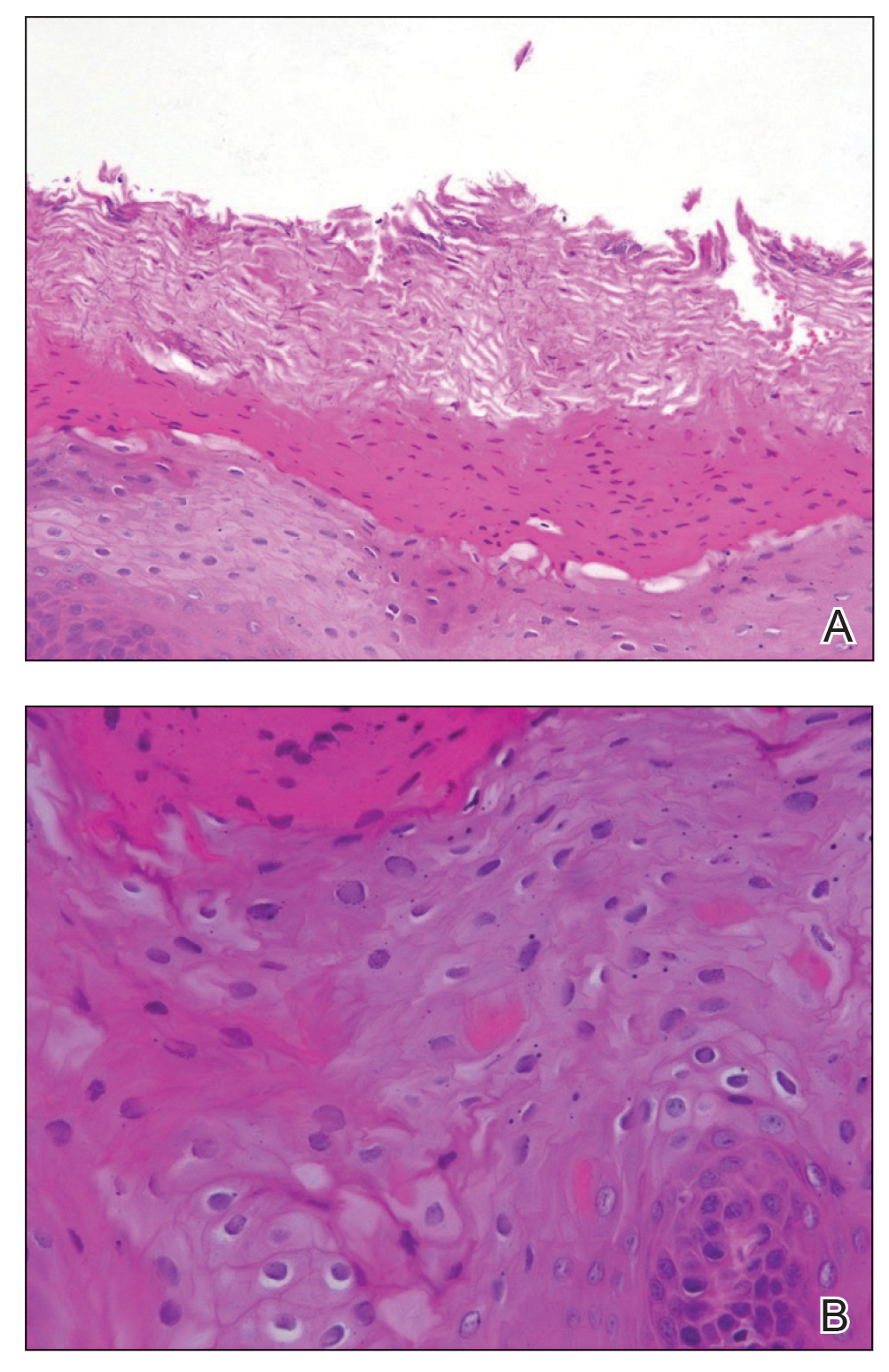

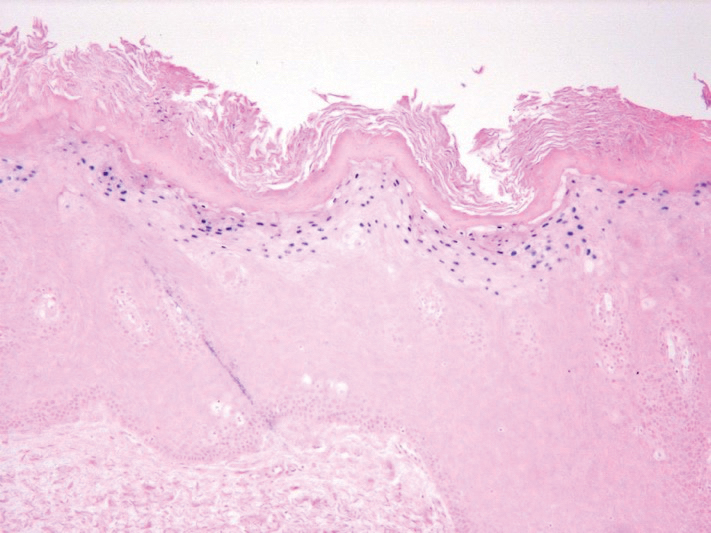

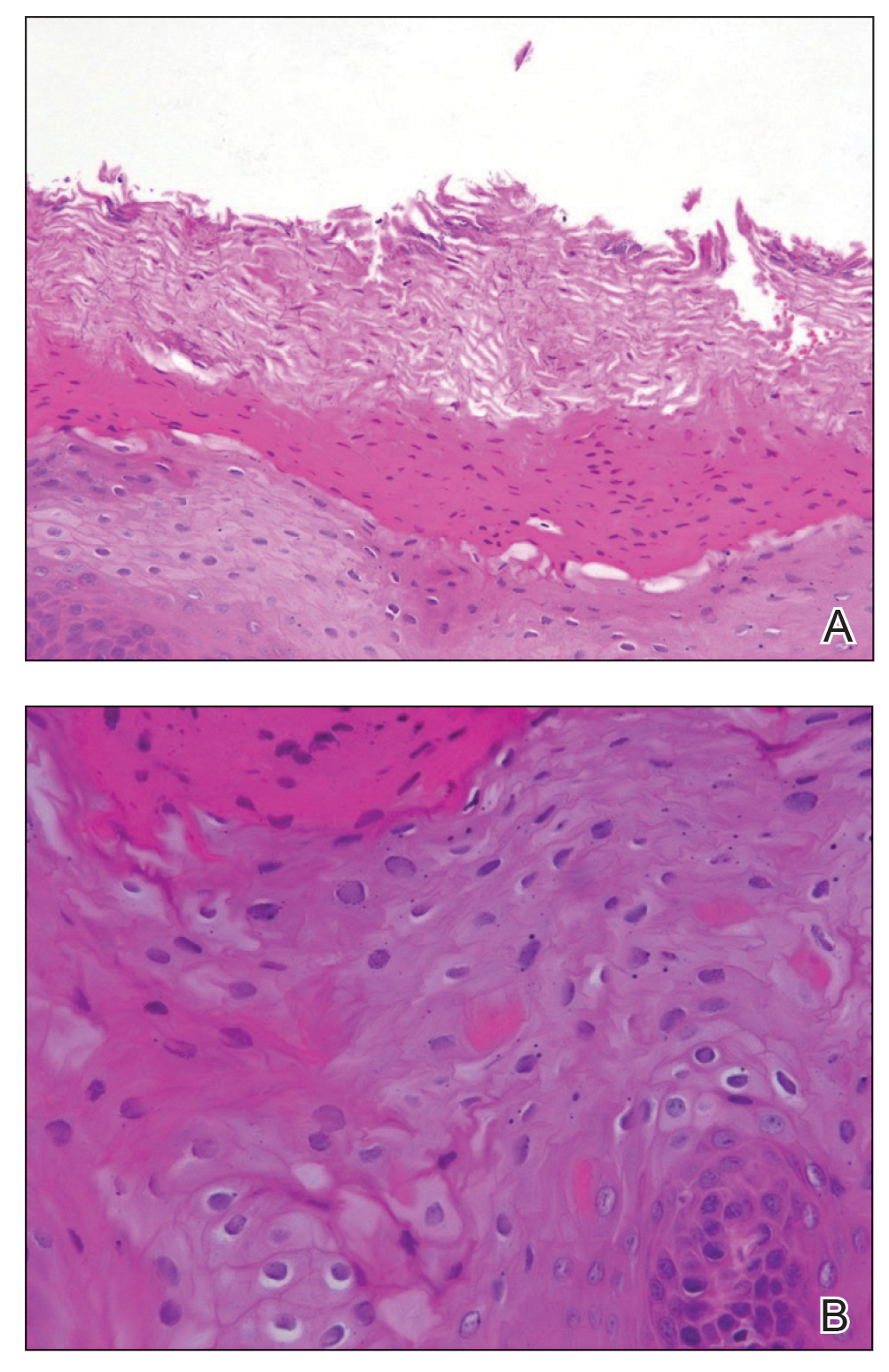

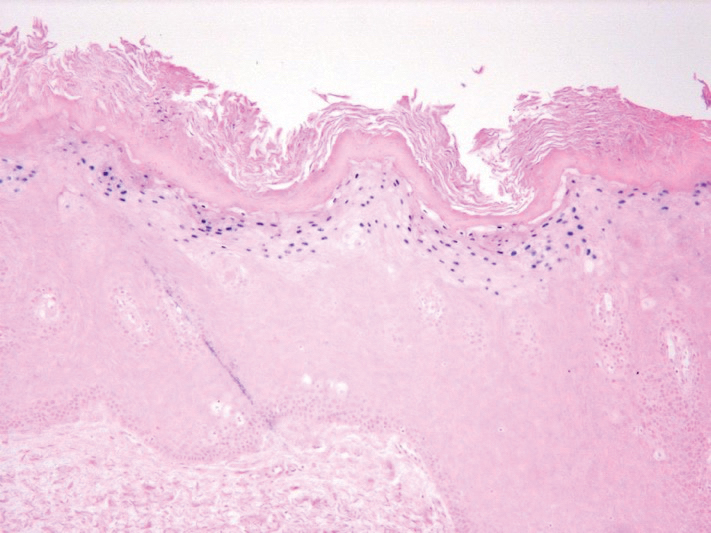

Physical examination revealed a 2-cm, pink, somewhat rubbery, subcutaneous, nonmobile nodule on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 1). The lesion was not consistent with a common pilar cyst, and an excisional biopsy was performed to exclude malignancy. Upon superficial incision, the lesion bled moderately, and the procedure was immediately discontinued. Hemostasis was obtained, and the patient was sent for ultrasonography of the lesion.

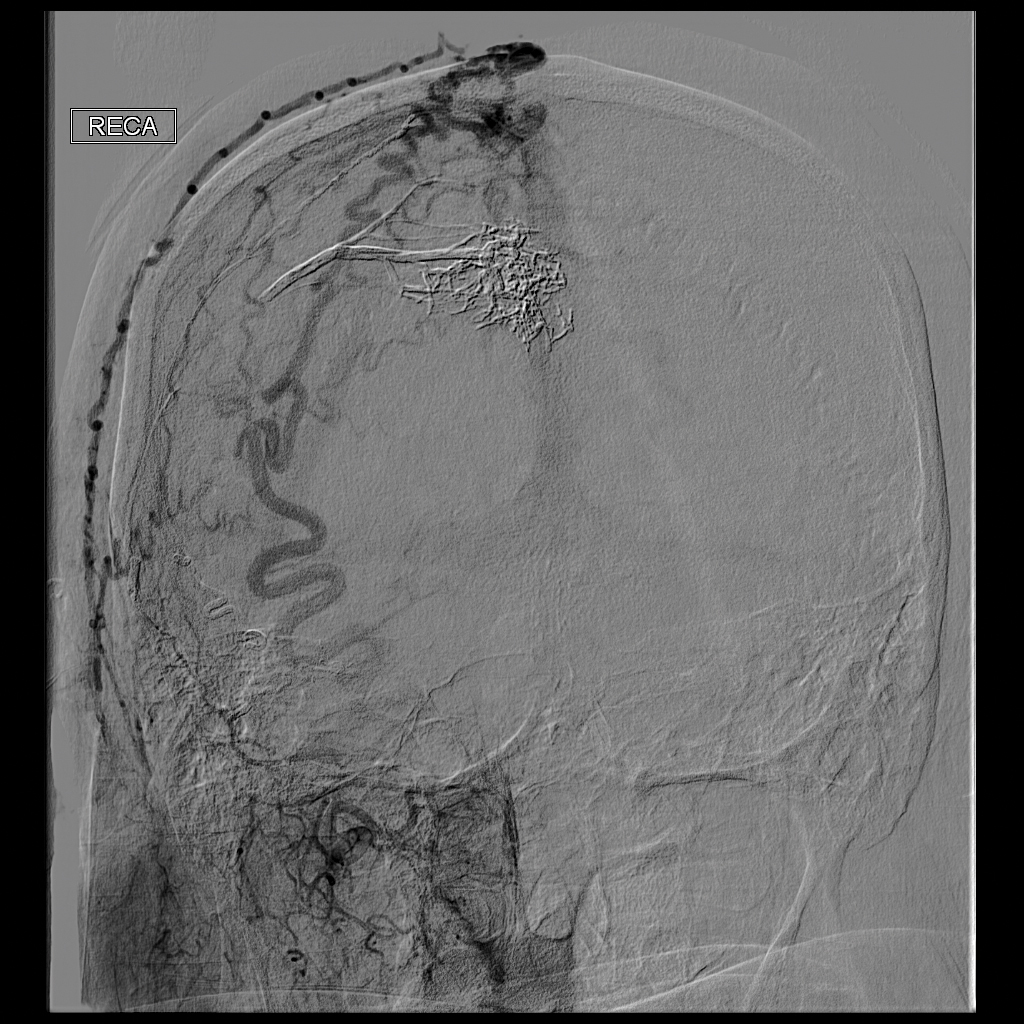

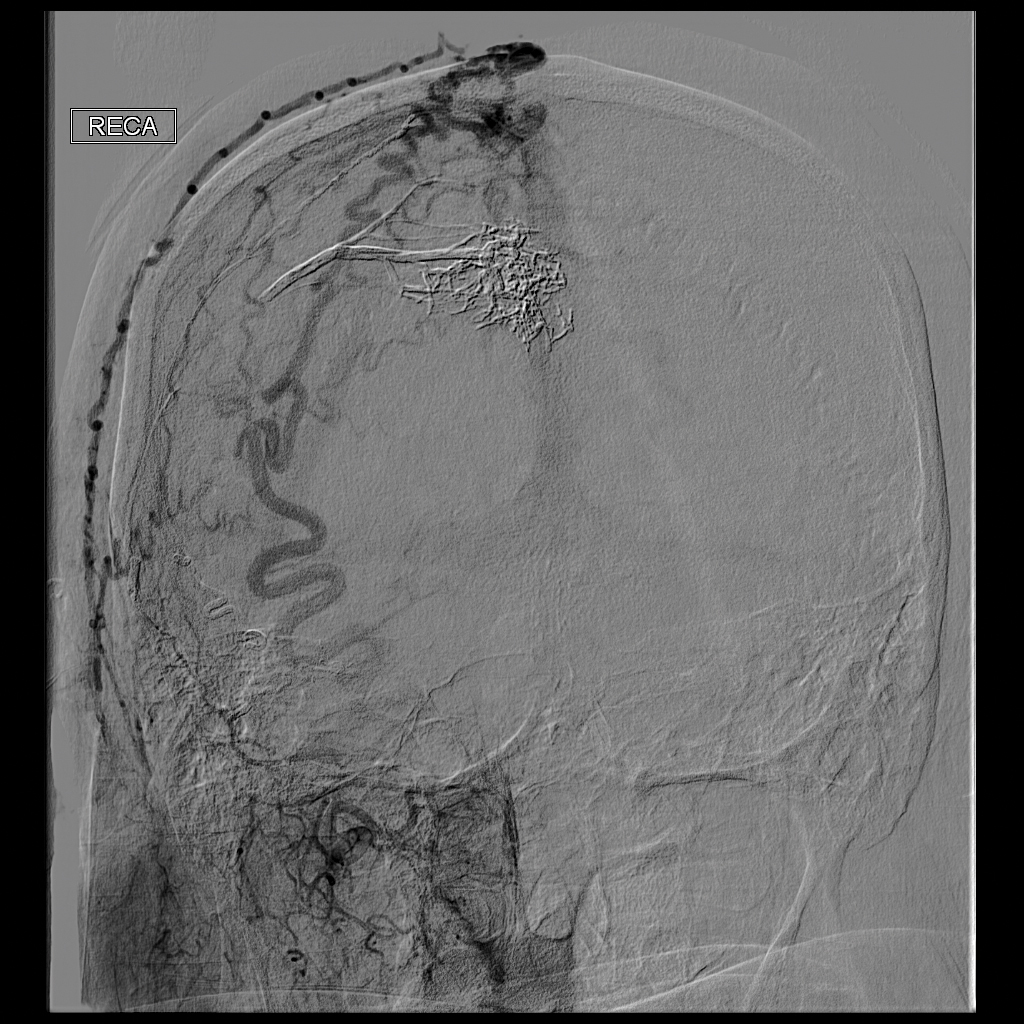

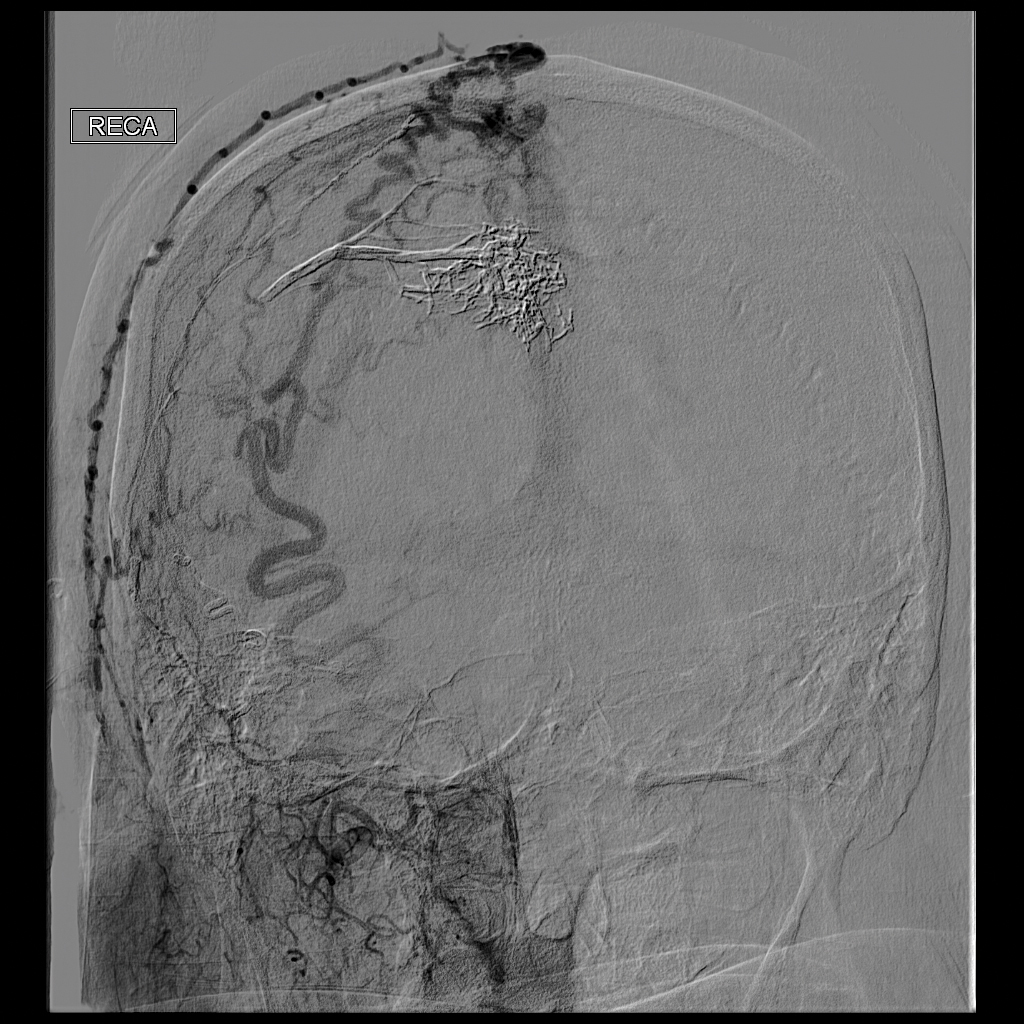

Ultrasonography demonstrated a small hypoechoic nodule measuring up to 0.5 cm containing a tangle of vessels in the subcutaneous soft tissue corresponding to the palpable abnormality. A cerebral angiogram demonstrated a dural AVF of the superior sagittal sinus with multifocal supply that connected with this scalp nodule (Figure 2). The patient was treated by interventional neuroradiology with endovascular embolization, which resulted in complete resolution of the scalp nodule.

Scalp arteriovenous fistulas (S-AVFs) are characterized by abnormal connections between supplying arteries and draining veins in the subcutaneous plane of the scalp.1,2 The veins of an S-AVF undergo progressive aneurysmal dilatation from abnormal hemodynamics.1-3 Scalp arteriovenous fistulas are rare and may present as either an innocuous-looking scalp nodule or a progressively enlarging pulsatile mass on the scalp.2-4 Associated symptoms often include headache, local pain, bruits, tinnitus, and thrill.1,3,4 Recurrent hemorrhage, scalp necrosis, congestive heart failure, epilepsy, mental retardation, and intracranial ischemia also may occur.4

Scalp AVFs may occur with or without intracranial communication.4 Spontaneous S-AVFs with intracranial communication are uncommon, and their etiology is unclear. They may form as congenital malformations or may be idiopathic. Factors increasing circulation through the S-AVF such as trauma, pregnancy, hormonal changes, and inflammation prompt the development of symptoms.4 Scalp AVFs also may be caused by trauma.3 Scalp AVFs without intracranial communication have been reported following hair transplantation.1 Scalp AVFs with intracranial communication have been reported months to years after skull fracture or craniotomy.2 True spontaneous S-AVFs are difficult to differentiate from traumatic S-AVFs other than by history alone.2

Increased venous pressure has been shown to generate AVFs in rats.5 It has been suggested that S-AVFs can become enlarged by capturing subcutaneous or intracranial feeder vessels and that the consequent hemodynamic stress may induce de novo aneurysms in S-AVFs. Additionally, intracranial AVFs may alter the intracranial hemodynamics, leading to increased venous pressure in the superior sagittal sinus and the formation of communicating S-AVFs.5 Interestingly, our patient had an intracranial AVF treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to the formation of the S-AVF. An angiogram at the time of this embolization procedure did not demonstrate any S-AVFs. Furthermore, our patient has a history of 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness. Perhaps these traumas initiated a channel through the cranium where an S-AVF with intracranial communication was able to form and may have only become clinically or radiographically detectable once it enlarged due to the altered hemodynamics caused by the intracranial AVF 1 year prior.

The diagnosis of an S-AVF is confirmed with imaging studies. Doppler ultrasonography initially will help to detect that a lesion is vascular in nature. Intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography is the gold-standard imaging technique and is necessary to delineate the feeding arteries and the draining channels as well as possible communication with intracranial vasculature.1,2 There is controversy regarding the appropriate treatment of S-AVFs.2 Each S-AVF possesses unique anatomic features that dictate appropriate management. The prognosis for an S-AVF is extremely variable, and the decision to treat is based on the patient’s symptoms and risk for exsanguinating hemorrhage.2,4 Neurosurgical approaches include ligation of the feeding arteries, surgical resection, electrothrombosis, direct intralesional injection of sclerosing agents, and endovascular embolization. Endovascular intervention increasingly is utilized as a primary treatment or as a preoperative adjunct to surgery.2,4 Large S-AVFs have a high risk for recurrence after treatment with endovascular embolization alone. In cases with intracranial communication, the intracranial component is treated first.2

This case emphasizes the importance of including S-AVFs on the dermatologic differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule, especially in patients with any history of intracranial AVF. A thorough history, detailed intake of potential signs and symptoms of AVF, and palpation for bruits is recommended as part of the surgical evaluation of a scalp nodule. Imaging of scalp nodules also should be considered for patients with any history of intracranial AVF; S-AVFs should be referred to neurosurgery or interventional neuroradiology for evaluation and possible treatment.

- Bernstein J, Podnos S, Leavitt M. Arteriovenous fistula following hair transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:873-875.

- Kumar R, Sharma G, Sharma BS. Management of scalp arterio-venous malformation: case series and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26:371-377.

- Gurkanlar D, Gonul M, Solmaz I, et al. Cirsoid aneurysms of the scalp. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:208-212.

- Senoglu M, Yasim A, Gokce M, et al. Nontraumatic scalp arteriovenous fistula in an adult: technical report on an illustrative case. Surg Neurol. 2008;70:194-197.

- Lanzino G, Passacantilli E, Lemole G, et al. Scalp arteriovenous malformation draining into the superior sagittal sinus associated with an intracranial arteriovenous malformation: just a coincidence? case report. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:440-443.

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old man presented with a nodule on the vertex of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. The lesion had become soft and tender during the week prior to presentation. He noted that he was experiencing headaches and a buzzing sound in his head. He denied all other neurologic symptoms. The patient was given amoxicillin from a primary care physician and was referred to our institution for evaluation of a presumed inflamed cyst.

The patient’s medical history included an intracranial arteriovenous fistula (AVF) treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to presentation, 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness, essential hypertension, and an aortic aneurysm. His medications included amlodipine, lisinopril, amoxicillin, a multivitamin, and grape seed extract.

Physical examination revealed a 2-cm, pink, somewhat rubbery, subcutaneous, nonmobile nodule on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 1). The lesion was not consistent with a common pilar cyst, and an excisional biopsy was performed to exclude malignancy. Upon superficial incision, the lesion bled moderately, and the procedure was immediately discontinued. Hemostasis was obtained, and the patient was sent for ultrasonography of the lesion.

Ultrasonography demonstrated a small hypoechoic nodule measuring up to 0.5 cm containing a tangle of vessels in the subcutaneous soft tissue corresponding to the palpable abnormality. A cerebral angiogram demonstrated a dural AVF of the superior sagittal sinus with multifocal supply that connected with this scalp nodule (Figure 2). The patient was treated by interventional neuroradiology with endovascular embolization, which resulted in complete resolution of the scalp nodule.

Scalp arteriovenous fistulas (S-AVFs) are characterized by abnormal connections between supplying arteries and draining veins in the subcutaneous plane of the scalp.1,2 The veins of an S-AVF undergo progressive aneurysmal dilatation from abnormal hemodynamics.1-3 Scalp arteriovenous fistulas are rare and may present as either an innocuous-looking scalp nodule or a progressively enlarging pulsatile mass on the scalp.2-4 Associated symptoms often include headache, local pain, bruits, tinnitus, and thrill.1,3,4 Recurrent hemorrhage, scalp necrosis, congestive heart failure, epilepsy, mental retardation, and intracranial ischemia also may occur.4

Scalp AVFs may occur with or without intracranial communication.4 Spontaneous S-AVFs with intracranial communication are uncommon, and their etiology is unclear. They may form as congenital malformations or may be idiopathic. Factors increasing circulation through the S-AVF such as trauma, pregnancy, hormonal changes, and inflammation prompt the development of symptoms.4 Scalp AVFs also may be caused by trauma.3 Scalp AVFs without intracranial communication have been reported following hair transplantation.1 Scalp AVFs with intracranial communication have been reported months to years after skull fracture or craniotomy.2 True spontaneous S-AVFs are difficult to differentiate from traumatic S-AVFs other than by history alone.2

Increased venous pressure has been shown to generate AVFs in rats.5 It has been suggested that S-AVFs can become enlarged by capturing subcutaneous or intracranial feeder vessels and that the consequent hemodynamic stress may induce de novo aneurysms in S-AVFs. Additionally, intracranial AVFs may alter the intracranial hemodynamics, leading to increased venous pressure in the superior sagittal sinus and the formation of communicating S-AVFs.5 Interestingly, our patient had an intracranial AVF treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to the formation of the S-AVF. An angiogram at the time of this embolization procedure did not demonstrate any S-AVFs. Furthermore, our patient has a history of 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness. Perhaps these traumas initiated a channel through the cranium where an S-AVF with intracranial communication was able to form and may have only become clinically or radiographically detectable once it enlarged due to the altered hemodynamics caused by the intracranial AVF 1 year prior.

The diagnosis of an S-AVF is confirmed with imaging studies. Doppler ultrasonography initially will help to detect that a lesion is vascular in nature. Intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography is the gold-standard imaging technique and is necessary to delineate the feeding arteries and the draining channels as well as possible communication with intracranial vasculature.1,2 There is controversy regarding the appropriate treatment of S-AVFs.2 Each S-AVF possesses unique anatomic features that dictate appropriate management. The prognosis for an S-AVF is extremely variable, and the decision to treat is based on the patient’s symptoms and risk for exsanguinating hemorrhage.2,4 Neurosurgical approaches include ligation of the feeding arteries, surgical resection, electrothrombosis, direct intralesional injection of sclerosing agents, and endovascular embolization. Endovascular intervention increasingly is utilized as a primary treatment or as a preoperative adjunct to surgery.2,4 Large S-AVFs have a high risk for recurrence after treatment with endovascular embolization alone. In cases with intracranial communication, the intracranial component is treated first.2

This case emphasizes the importance of including S-AVFs on the dermatologic differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule, especially in patients with any history of intracranial AVF. A thorough history, detailed intake of potential signs and symptoms of AVF, and palpation for bruits is recommended as part of the surgical evaluation of a scalp nodule. Imaging of scalp nodules also should be considered for patients with any history of intracranial AVF; S-AVFs should be referred to neurosurgery or interventional neuroradiology for evaluation and possible treatment.

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old man presented with a nodule on the vertex of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. The lesion had become soft and tender during the week prior to presentation. He noted that he was experiencing headaches and a buzzing sound in his head. He denied all other neurologic symptoms. The patient was given amoxicillin from a primary care physician and was referred to our institution for evaluation of a presumed inflamed cyst.

The patient’s medical history included an intracranial arteriovenous fistula (AVF) treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to presentation, 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness, essential hypertension, and an aortic aneurysm. His medications included amlodipine, lisinopril, amoxicillin, a multivitamin, and grape seed extract.

Physical examination revealed a 2-cm, pink, somewhat rubbery, subcutaneous, nonmobile nodule on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 1). The lesion was not consistent with a common pilar cyst, and an excisional biopsy was performed to exclude malignancy. Upon superficial incision, the lesion bled moderately, and the procedure was immediately discontinued. Hemostasis was obtained, and the patient was sent for ultrasonography of the lesion.

Ultrasonography demonstrated a small hypoechoic nodule measuring up to 0.5 cm containing a tangle of vessels in the subcutaneous soft tissue corresponding to the palpable abnormality. A cerebral angiogram demonstrated a dural AVF of the superior sagittal sinus with multifocal supply that connected with this scalp nodule (Figure 2). The patient was treated by interventional neuroradiology with endovascular embolization, which resulted in complete resolution of the scalp nodule.

Scalp arteriovenous fistulas (S-AVFs) are characterized by abnormal connections between supplying arteries and draining veins in the subcutaneous plane of the scalp.1,2 The veins of an S-AVF undergo progressive aneurysmal dilatation from abnormal hemodynamics.1-3 Scalp arteriovenous fistulas are rare and may present as either an innocuous-looking scalp nodule or a progressively enlarging pulsatile mass on the scalp.2-4 Associated symptoms often include headache, local pain, bruits, tinnitus, and thrill.1,3,4 Recurrent hemorrhage, scalp necrosis, congestive heart failure, epilepsy, mental retardation, and intracranial ischemia also may occur.4

Scalp AVFs may occur with or without intracranial communication.4 Spontaneous S-AVFs with intracranial communication are uncommon, and their etiology is unclear. They may form as congenital malformations or may be idiopathic. Factors increasing circulation through the S-AVF such as trauma, pregnancy, hormonal changes, and inflammation prompt the development of symptoms.4 Scalp AVFs also may be caused by trauma.3 Scalp AVFs without intracranial communication have been reported following hair transplantation.1 Scalp AVFs with intracranial communication have been reported months to years after skull fracture or craniotomy.2 True spontaneous S-AVFs are difficult to differentiate from traumatic S-AVFs other than by history alone.2

Increased venous pressure has been shown to generate AVFs in rats.5 It has been suggested that S-AVFs can become enlarged by capturing subcutaneous or intracranial feeder vessels and that the consequent hemodynamic stress may induce de novo aneurysms in S-AVFs. Additionally, intracranial AVFs may alter the intracranial hemodynamics, leading to increased venous pressure in the superior sagittal sinus and the formation of communicating S-AVFs.5 Interestingly, our patient had an intracranial AVF treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to the formation of the S-AVF. An angiogram at the time of this embolization procedure did not demonstrate any S-AVFs. Furthermore, our patient has a history of 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness. Perhaps these traumas initiated a channel through the cranium where an S-AVF with intracranial communication was able to form and may have only become clinically or radiographically detectable once it enlarged due to the altered hemodynamics caused by the intracranial AVF 1 year prior.

The diagnosis of an S-AVF is confirmed with imaging studies. Doppler ultrasonography initially will help to detect that a lesion is vascular in nature. Intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography is the gold-standard imaging technique and is necessary to delineate the feeding arteries and the draining channels as well as possible communication with intracranial vasculature.1,2 There is controversy regarding the appropriate treatment of S-AVFs.2 Each S-AVF possesses unique anatomic features that dictate appropriate management. The prognosis for an S-AVF is extremely variable, and the decision to treat is based on the patient’s symptoms and risk for exsanguinating hemorrhage.2,4 Neurosurgical approaches include ligation of the feeding arteries, surgical resection, electrothrombosis, direct intralesional injection of sclerosing agents, and endovascular embolization. Endovascular intervention increasingly is utilized as a primary treatment or as a preoperative adjunct to surgery.2,4 Large S-AVFs have a high risk for recurrence after treatment with endovascular embolization alone. In cases with intracranial communication, the intracranial component is treated first.2

This case emphasizes the importance of including S-AVFs on the dermatologic differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule, especially in patients with any history of intracranial AVF. A thorough history, detailed intake of potential signs and symptoms of AVF, and palpation for bruits is recommended as part of the surgical evaluation of a scalp nodule. Imaging of scalp nodules also should be considered for patients with any history of intracranial AVF; S-AVFs should be referred to neurosurgery or interventional neuroradiology for evaluation and possible treatment.

- Bernstein J, Podnos S, Leavitt M. Arteriovenous fistula following hair transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:873-875.

- Kumar R, Sharma G, Sharma BS. Management of scalp arterio-venous malformation: case series and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26:371-377.

- Gurkanlar D, Gonul M, Solmaz I, et al. Cirsoid aneurysms of the scalp. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:208-212.

- Senoglu M, Yasim A, Gokce M, et al. Nontraumatic scalp arteriovenous fistula in an adult: technical report on an illustrative case. Surg Neurol. 2008;70:194-197.

- Lanzino G, Passacantilli E, Lemole G, et al. Scalp arteriovenous malformation draining into the superior sagittal sinus associated with an intracranial arteriovenous malformation: just a coincidence? case report. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:440-443.

- Bernstein J, Podnos S, Leavitt M. Arteriovenous fistula following hair transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:873-875.

- Kumar R, Sharma G, Sharma BS. Management of scalp arterio-venous malformation: case series and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26:371-377.

- Gurkanlar D, Gonul M, Solmaz I, et al. Cirsoid aneurysms of the scalp. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:208-212.

- Senoglu M, Yasim A, Gokce M, et al. Nontraumatic scalp arteriovenous fistula in an adult: technical report on an illustrative case. Surg Neurol. 2008;70:194-197.

- Lanzino G, Passacantilli E, Lemole G, et al. Scalp arteriovenous malformation draining into the superior sagittal sinus associated with an intracranial arteriovenous malformation: just a coincidence? case report. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:440-443.

Practice Points

- Scalp arteriovenous fistulas may be traumatic or spontaneous and present as either an innocuous-looking scalp nodule or as a progressively enlarging pulsatile mass on the scalp.

- Clinical detection followed by appropriate imaging and referral to neurosurgery or interventional neuroradiology is vital to patient safety.

@GiJournal: An online platform to discuss the latest gastroenterology and hepatology publications

The last decade has seen an increased focus on the use of social media for medical education. Twitter, with over 330 million active users, is the most popular social media platform for medical education. We describe here our recent initiative to establish a weekly online gastroenterology-focused journal club on Twitter.

How was the idea conceived?

Sultan Mahmood, MD (@SultanMahmoodMD)

I joined #GITwitter at the end of 2019 and started following some of the leading experts in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology. It was a pleasant surprise to see how easy it was to engage with them and get expert opinions from across the world in real time. #MondayNightIBD, led by Aline Charabaty, MD, had become a phenomenon in the GI community and changed the perception of medical education in the digital world. There were online journal clubs for different medical subspecialties, including #NephroJC, #HOJournalClub, and #DermJC, but none for gastroenterology. Realizing this opportunity, and with guidance from Dr. Charabaty, we started @GiJournal in December of 2019 with weekly discussions.

@GiJournal started off as an informal discussion in which we would post a summary of the article and invite an expert in the field to comment. However, the interest in the journal club quickly took off as we gained more followers and a worldwide audience joined our journal club discussions on a weekly basis. As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold and endoscopy suites around the word closed, interest in online medical education grew. @GIJournal provided a platform for trainees and practicing physicians alike to stay up to date with the latest publications from the comfort of their homes. Needless to say, the journal club has evolved since its inception in that we now work with a team of experts and trainees who run the journal club on a rotating basis.

How does @GiJournal work?

Ijlal Akbar Ali, MD (@IjlalAkbar)

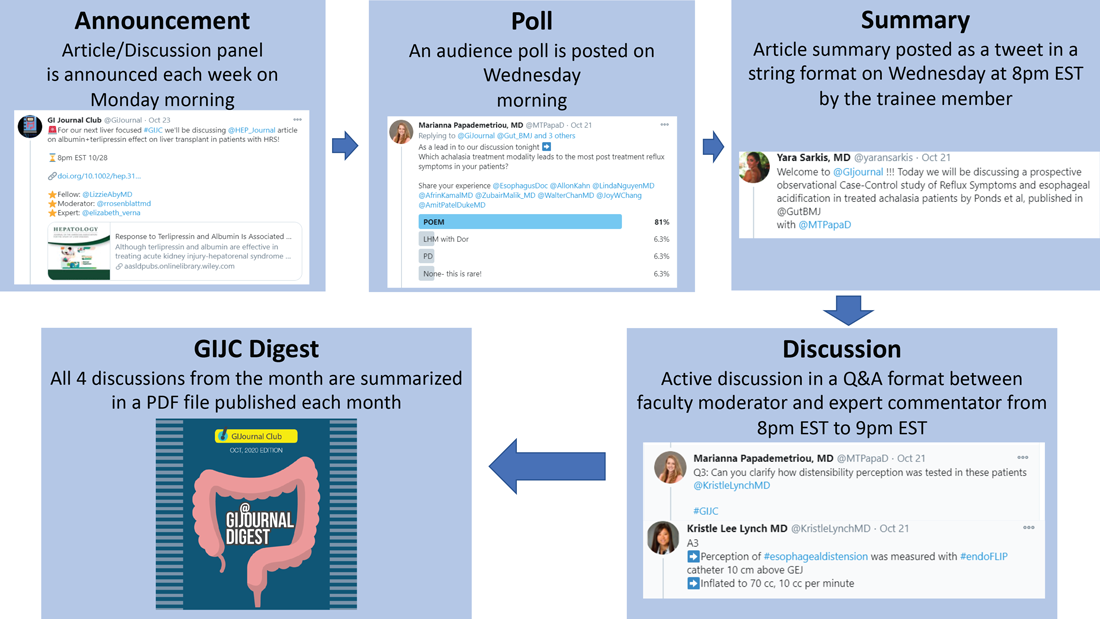

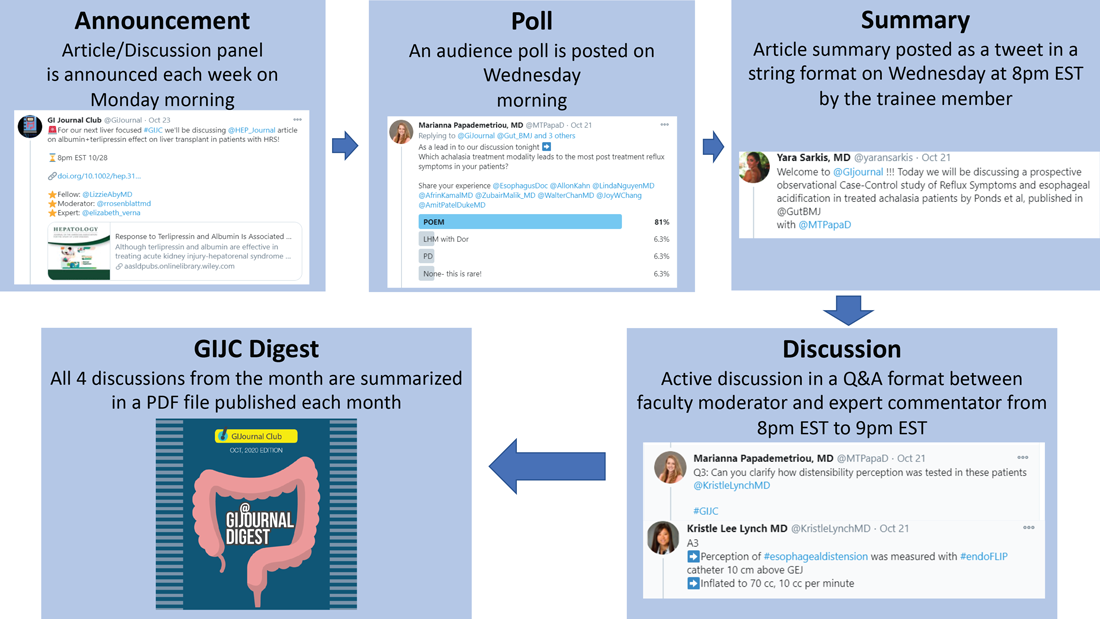

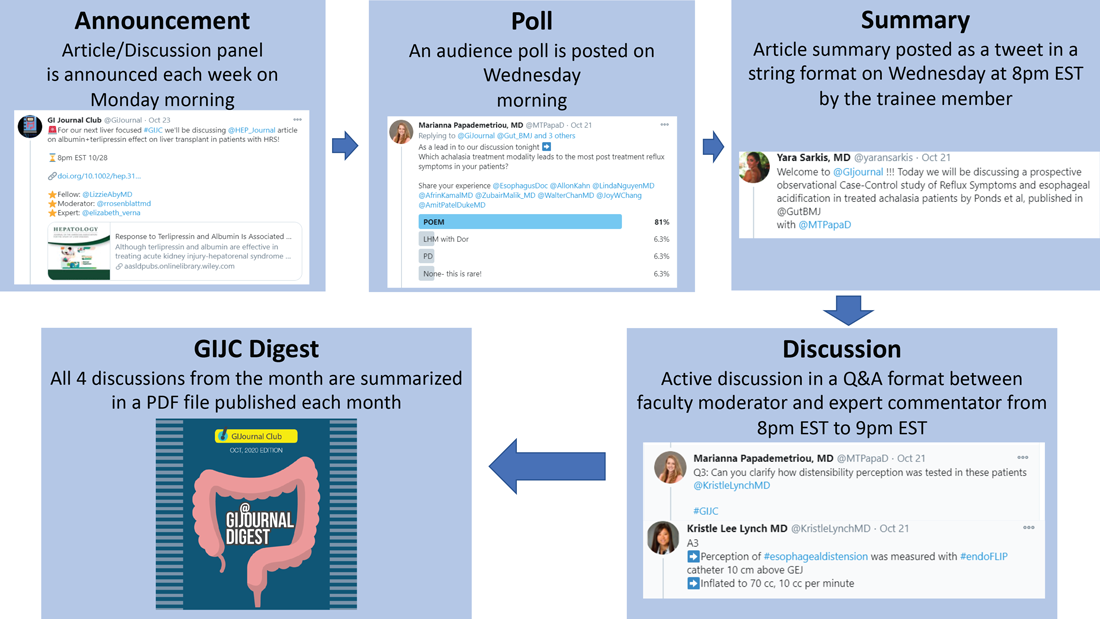

We have a large editorial board with volunteer faculty and trainees, all divided into four special interest groups (general GI/inflammatory bowel disease, interventional endoscopy/bariatric endoscopy, hepatology, and esophageal/motility disorders). Each week, a faculty member and a trainee pick a recently published article from a high-impact GI-focused journal. We also try to invite an expert of international repute (often the authors of the article themselves!) to engage as well. The faculty moderator and invited expert then work with the trainee to plan the session content. We post the topic and article on Monday. At 8 p.m. EST on Wednesday, the trainee posts a series of six to eight tweets summarizing the article. The faculty then asks the invited expert (and audience at large) a series of predetermined questions. Anyone can respond, share their opinion, and direct their own questions toward the moderator and expert who continually check their notifications and respond in real time. This brews into an hour-long discussion which covers not only the methodologic aspects of the article, but clinical practice in general. Discussions often trickle into the next day as people from different time zones participate. Everyone uses #GIJC at the end of their tweets which assists those following the article and facilitates indexing for future review. For those who miss or want to review sessions, we conveniently summarize all articles and corresponding discussions in a monthly publication, @GiJournal Digest, that is posted on Twitter for anyone to download, read and enjoy (Figure 1).

How is this different from any other journal club?

Atoosa Rabiee, MD (@AtoosaRabiee)

@GiJournal is unique in that it provides trainees and practicing gastroenterologists access to interactive discussions with both authors and world-renowned experts in the field. Online journal clubs operate with a flattened hierarchy; as such, they inherently break down access barriers to both the researchers who performed the study and key opinion leaders who commonly participate. There is no boundary as far as institutions or even countries. As a result, our platform has uncovered an unexpected degree of interest in live online discussion, and we have enjoyed collaborating and learning from experts from all over the world. @GiJournal also differs from conventional journal clubs by allowing trainees the opportunity to collaborate and engage with mentors from other institutions. As such, trainees develop relationships with experts in the field outside their home institutions, experts with whom they may not have had contact otherwise.

Although worldwide participation is a key strength of the online @GiJournal platform, it may be challenging for some members to attend the live discussion based on time difference. We account for this in two ways. First, participants are encouraged to continue with comments and questions afterward at their convenience, which allows experts and moderators to continue the conversation, often for several days. Second, to promote inclusivity, we have created a unique, customized publication to summarize and present the key points of conversation for each session. This asynchronous access is a quality not found in more traditional journal club formats. Finally, studies have shown that articles shared on social media tend to have increased citations and higher Altmetric scores.

What are the opportunities for trainees and recent graduates?

Sunil Amin, MD, MPH (@SunilAminMD)

Our surveys have shown that 30%-45% of the @GiJournal discussion participants are trainees. Both gastroenterology fellows and internal medicine residents from around the world are an integral part of each specialty panel for the weekly @GIjournal discussions. Trainees are paired up with a specific faculty mentor and together they choose an article for discussion, create a summary, informal twitter poll, and questions for the discussion. This direct access provides an opportunity for trainees to interact, ask questions, and learn from faculty in an informal atmosphere.

We have heard from multiple trainees who have developed long-term relationships with the experts and faculty mentors they worked with and are now also working on research projects. Additionally, trainees can bring the expertise they have now acquired back to their home institutions to pick articles, add specific teaching points, and enrich their local journal club discussions. Finally, trainees who present on the @GiJournal platform are given unique visibility to the many faculty members and opinion leaders participating in each discussion. This may facilitate future networking opportunities and enhance their CVs for future fellowship or employment applications.

Plans for the future?

Allon Kahn, MD (@AllonKahn)

Despite significant evolution and growth in @GiJournal over the past year, we are still actively working to expand our platform. Modes of online medical education, specifically Twitter-based GI journal club discussions, remain in their infancy. We see this @GiJournal as an opportunity for innovation as we plan for the year ahead. Our top priority for the upcoming year includes obtaining CME approval, which we are currently developing with Integrity CE (an Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education–accredited provider of CME for health care professionals). This will give an opportunity for the participants to be awarded CME credit when they participate in our weekly discussions. Other options being explored include starting a podcast and translation of @GiJournal Digest in different languages to reach a wider international audience. Furthermore, with the continued expansion of GI leaders and experts joining and engaging in Twitter, our options for unique and multidisciplinary discussion topics will continue to grow.

How can you join the @GiJournal discussions?

@SultanMahmoodMD

Joining the journal club discussion is easy. Just follow the @GiJournal handle on Twitter and turn on the notifications icon. Although we encourage everyone to “actively” participate in the discussion by asking questions or sharing your personal experience, joining the discussion as an “observer” is also a great way to learn. The discussion starts at 8 p.m. EST every Wednesday. Follow the #GIJC and the @GiJournal handle as questions are posted by the faculty moderator and answered by the experts. Even if you miss the discussion, the @GiJournal Digest is a great way to recap the discussions in an easy-to-read PDF format. The @GiJournal Digest is a monthly publication that archives the four @GiJournal club discussions in the previous month. Follow the link below to access the recent publications: http://ow.ly/uu2550C3RXX

Conclusion

In summary, we believe Twitter-based journal clubs offer an engaging way of virtual learning from the comfort of one’s home and a convenient way to directly interact with the experts. The success of @GiJournal highlights the importance of social media for medical education in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology and we look forward to developing this endeavor further.

Dr. Mahmood is clinical assistant professor of medicine, co–program director of the GI fellowship program, UB division of gastroenterology, hepatology & nutrition, State University of New York at Buffalo; Dr. Rabiee is assistant professor of medicine, director of hepatology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Washington DC VA Medical Center, Washington; Dr. Amin is assistant professor of medicine, director of endoscopy, The Lennar Foundation Medical Center, division of digestive health and liver disease, department of medicine, University of Miami; Dr. Kahn is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Dr. Akbar Ali is a gastroenterology fellow in the division of digestive diseases and nutrition, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

The last decade has seen an increased focus on the use of social media for medical education. Twitter, with over 330 million active users, is the most popular social media platform for medical education. We describe here our recent initiative to establish a weekly online gastroenterology-focused journal club on Twitter.

How was the idea conceived?

Sultan Mahmood, MD (@SultanMahmoodMD)

I joined #GITwitter at the end of 2019 and started following some of the leading experts in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology. It was a pleasant surprise to see how easy it was to engage with them and get expert opinions from across the world in real time. #MondayNightIBD, led by Aline Charabaty, MD, had become a phenomenon in the GI community and changed the perception of medical education in the digital world. There were online journal clubs for different medical subspecialties, including #NephroJC, #HOJournalClub, and #DermJC, but none for gastroenterology. Realizing this opportunity, and with guidance from Dr. Charabaty, we started @GiJournal in December of 2019 with weekly discussions.

@GiJournal started off as an informal discussion in which we would post a summary of the article and invite an expert in the field to comment. However, the interest in the journal club quickly took off as we gained more followers and a worldwide audience joined our journal club discussions on a weekly basis. As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold and endoscopy suites around the word closed, interest in online medical education grew. @GIJournal provided a platform for trainees and practicing physicians alike to stay up to date with the latest publications from the comfort of their homes. Needless to say, the journal club has evolved since its inception in that we now work with a team of experts and trainees who run the journal club on a rotating basis.

How does @GiJournal work?

Ijlal Akbar Ali, MD (@IjlalAkbar)

We have a large editorial board with volunteer faculty and trainees, all divided into four special interest groups (general GI/inflammatory bowel disease, interventional endoscopy/bariatric endoscopy, hepatology, and esophageal/motility disorders). Each week, a faculty member and a trainee pick a recently published article from a high-impact GI-focused journal. We also try to invite an expert of international repute (often the authors of the article themselves!) to engage as well. The faculty moderator and invited expert then work with the trainee to plan the session content. We post the topic and article on Monday. At 8 p.m. EST on Wednesday, the trainee posts a series of six to eight tweets summarizing the article. The faculty then asks the invited expert (and audience at large) a series of predetermined questions. Anyone can respond, share their opinion, and direct their own questions toward the moderator and expert who continually check their notifications and respond in real time. This brews into an hour-long discussion which covers not only the methodologic aspects of the article, but clinical practice in general. Discussions often trickle into the next day as people from different time zones participate. Everyone uses #GIJC at the end of their tweets which assists those following the article and facilitates indexing for future review. For those who miss or want to review sessions, we conveniently summarize all articles and corresponding discussions in a monthly publication, @GiJournal Digest, that is posted on Twitter for anyone to download, read and enjoy (Figure 1).

How is this different from any other journal club?

Atoosa Rabiee, MD (@AtoosaRabiee)

@GiJournal is unique in that it provides trainees and practicing gastroenterologists access to interactive discussions with both authors and world-renowned experts in the field. Online journal clubs operate with a flattened hierarchy; as such, they inherently break down access barriers to both the researchers who performed the study and key opinion leaders who commonly participate. There is no boundary as far as institutions or even countries. As a result, our platform has uncovered an unexpected degree of interest in live online discussion, and we have enjoyed collaborating and learning from experts from all over the world. @GiJournal also differs from conventional journal clubs by allowing trainees the opportunity to collaborate and engage with mentors from other institutions. As such, trainees develop relationships with experts in the field outside their home institutions, experts with whom they may not have had contact otherwise.

Although worldwide participation is a key strength of the online @GiJournal platform, it may be challenging for some members to attend the live discussion based on time difference. We account for this in two ways. First, participants are encouraged to continue with comments and questions afterward at their convenience, which allows experts and moderators to continue the conversation, often for several days. Second, to promote inclusivity, we have created a unique, customized publication to summarize and present the key points of conversation for each session. This asynchronous access is a quality not found in more traditional journal club formats. Finally, studies have shown that articles shared on social media tend to have increased citations and higher Altmetric scores.

What are the opportunities for trainees and recent graduates?

Sunil Amin, MD, MPH (@SunilAminMD)

Our surveys have shown that 30%-45% of the @GiJournal discussion participants are trainees. Both gastroenterology fellows and internal medicine residents from around the world are an integral part of each specialty panel for the weekly @GIjournal discussions. Trainees are paired up with a specific faculty mentor and together they choose an article for discussion, create a summary, informal twitter poll, and questions for the discussion. This direct access provides an opportunity for trainees to interact, ask questions, and learn from faculty in an informal atmosphere.

We have heard from multiple trainees who have developed long-term relationships with the experts and faculty mentors they worked with and are now also working on research projects. Additionally, trainees can bring the expertise they have now acquired back to their home institutions to pick articles, add specific teaching points, and enrich their local journal club discussions. Finally, trainees who present on the @GiJournal platform are given unique visibility to the many faculty members and opinion leaders participating in each discussion. This may facilitate future networking opportunities and enhance their CVs for future fellowship or employment applications.

Plans for the future?

Allon Kahn, MD (@AllonKahn)

Despite significant evolution and growth in @GiJournal over the past year, we are still actively working to expand our platform. Modes of online medical education, specifically Twitter-based GI journal club discussions, remain in their infancy. We see this @GiJournal as an opportunity for innovation as we plan for the year ahead. Our top priority for the upcoming year includes obtaining CME approval, which we are currently developing with Integrity CE (an Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education–accredited provider of CME for health care professionals). This will give an opportunity for the participants to be awarded CME credit when they participate in our weekly discussions. Other options being explored include starting a podcast and translation of @GiJournal Digest in different languages to reach a wider international audience. Furthermore, with the continued expansion of GI leaders and experts joining and engaging in Twitter, our options for unique and multidisciplinary discussion topics will continue to grow.

How can you join the @GiJournal discussions?

@SultanMahmoodMD

Joining the journal club discussion is easy. Just follow the @GiJournal handle on Twitter and turn on the notifications icon. Although we encourage everyone to “actively” participate in the discussion by asking questions or sharing your personal experience, joining the discussion as an “observer” is also a great way to learn. The discussion starts at 8 p.m. EST every Wednesday. Follow the #GIJC and the @GiJournal handle as questions are posted by the faculty moderator and answered by the experts. Even if you miss the discussion, the @GiJournal Digest is a great way to recap the discussions in an easy-to-read PDF format. The @GiJournal Digest is a monthly publication that archives the four @GiJournal club discussions in the previous month. Follow the link below to access the recent publications: http://ow.ly/uu2550C3RXX

Conclusion

In summary, we believe Twitter-based journal clubs offer an engaging way of virtual learning from the comfort of one’s home and a convenient way to directly interact with the experts. The success of @GiJournal highlights the importance of social media for medical education in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology and we look forward to developing this endeavor further.

Dr. Mahmood is clinical assistant professor of medicine, co–program director of the GI fellowship program, UB division of gastroenterology, hepatology & nutrition, State University of New York at Buffalo; Dr. Rabiee is assistant professor of medicine, director of hepatology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Washington DC VA Medical Center, Washington; Dr. Amin is assistant professor of medicine, director of endoscopy, The Lennar Foundation Medical Center, division of digestive health and liver disease, department of medicine, University of Miami; Dr. Kahn is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Dr. Akbar Ali is a gastroenterology fellow in the division of digestive diseases and nutrition, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

The last decade has seen an increased focus on the use of social media for medical education. Twitter, with over 330 million active users, is the most popular social media platform for medical education. We describe here our recent initiative to establish a weekly online gastroenterology-focused journal club on Twitter.

How was the idea conceived?

Sultan Mahmood, MD (@SultanMahmoodMD)

I joined #GITwitter at the end of 2019 and started following some of the leading experts in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology. It was a pleasant surprise to see how easy it was to engage with them and get expert opinions from across the world in real time. #MondayNightIBD, led by Aline Charabaty, MD, had become a phenomenon in the GI community and changed the perception of medical education in the digital world. There were online journal clubs for different medical subspecialties, including #NephroJC, #HOJournalClub, and #DermJC, but none for gastroenterology. Realizing this opportunity, and with guidance from Dr. Charabaty, we started @GiJournal in December of 2019 with weekly discussions.

@GiJournal started off as an informal discussion in which we would post a summary of the article and invite an expert in the field to comment. However, the interest in the journal club quickly took off as we gained more followers and a worldwide audience joined our journal club discussions on a weekly basis. As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold and endoscopy suites around the word closed, interest in online medical education grew. @GIJournal provided a platform for trainees and practicing physicians alike to stay up to date with the latest publications from the comfort of their homes. Needless to say, the journal club has evolved since its inception in that we now work with a team of experts and trainees who run the journal club on a rotating basis.

How does @GiJournal work?

Ijlal Akbar Ali, MD (@IjlalAkbar)

We have a large editorial board with volunteer faculty and trainees, all divided into four special interest groups (general GI/inflammatory bowel disease, interventional endoscopy/bariatric endoscopy, hepatology, and esophageal/motility disorders). Each week, a faculty member and a trainee pick a recently published article from a high-impact GI-focused journal. We also try to invite an expert of international repute (often the authors of the article themselves!) to engage as well. The faculty moderator and invited expert then work with the trainee to plan the session content. We post the topic and article on Monday. At 8 p.m. EST on Wednesday, the trainee posts a series of six to eight tweets summarizing the article. The faculty then asks the invited expert (and audience at large) a series of predetermined questions. Anyone can respond, share their opinion, and direct their own questions toward the moderator and expert who continually check their notifications and respond in real time. This brews into an hour-long discussion which covers not only the methodologic aspects of the article, but clinical practice in general. Discussions often trickle into the next day as people from different time zones participate. Everyone uses #GIJC at the end of their tweets which assists those following the article and facilitates indexing for future review. For those who miss or want to review sessions, we conveniently summarize all articles and corresponding discussions in a monthly publication, @GiJournal Digest, that is posted on Twitter for anyone to download, read and enjoy (Figure 1).

How is this different from any other journal club?

Atoosa Rabiee, MD (@AtoosaRabiee)

@GiJournal is unique in that it provides trainees and practicing gastroenterologists access to interactive discussions with both authors and world-renowned experts in the field. Online journal clubs operate with a flattened hierarchy; as such, they inherently break down access barriers to both the researchers who performed the study and key opinion leaders who commonly participate. There is no boundary as far as institutions or even countries. As a result, our platform has uncovered an unexpected degree of interest in live online discussion, and we have enjoyed collaborating and learning from experts from all over the world. @GiJournal also differs from conventional journal clubs by allowing trainees the opportunity to collaborate and engage with mentors from other institutions. As such, trainees develop relationships with experts in the field outside their home institutions, experts with whom they may not have had contact otherwise.

Although worldwide participation is a key strength of the online @GiJournal platform, it may be challenging for some members to attend the live discussion based on time difference. We account for this in two ways. First, participants are encouraged to continue with comments and questions afterward at their convenience, which allows experts and moderators to continue the conversation, often for several days. Second, to promote inclusivity, we have created a unique, customized publication to summarize and present the key points of conversation for each session. This asynchronous access is a quality not found in more traditional journal club formats. Finally, studies have shown that articles shared on social media tend to have increased citations and higher Altmetric scores.

What are the opportunities for trainees and recent graduates?

Sunil Amin, MD, MPH (@SunilAminMD)

Our surveys have shown that 30%-45% of the @GiJournal discussion participants are trainees. Both gastroenterology fellows and internal medicine residents from around the world are an integral part of each specialty panel for the weekly @GIjournal discussions. Trainees are paired up with a specific faculty mentor and together they choose an article for discussion, create a summary, informal twitter poll, and questions for the discussion. This direct access provides an opportunity for trainees to interact, ask questions, and learn from faculty in an informal atmosphere.

We have heard from multiple trainees who have developed long-term relationships with the experts and faculty mentors they worked with and are now also working on research projects. Additionally, trainees can bring the expertise they have now acquired back to their home institutions to pick articles, add specific teaching points, and enrich their local journal club discussions. Finally, trainees who present on the @GiJournal platform are given unique visibility to the many faculty members and opinion leaders participating in each discussion. This may facilitate future networking opportunities and enhance their CVs for future fellowship or employment applications.

Plans for the future?

Allon Kahn, MD (@AllonKahn)

Despite significant evolution and growth in @GiJournal over the past year, we are still actively working to expand our platform. Modes of online medical education, specifically Twitter-based GI journal club discussions, remain in their infancy. We see this @GiJournal as an opportunity for innovation as we plan for the year ahead. Our top priority for the upcoming year includes obtaining CME approval, which we are currently developing with Integrity CE (an Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education–accredited provider of CME for health care professionals). This will give an opportunity for the participants to be awarded CME credit when they participate in our weekly discussions. Other options being explored include starting a podcast and translation of @GiJournal Digest in different languages to reach a wider international audience. Furthermore, with the continued expansion of GI leaders and experts joining and engaging in Twitter, our options for unique and multidisciplinary discussion topics will continue to grow.

How can you join the @GiJournal discussions?

@SultanMahmoodMD

Joining the journal club discussion is easy. Just follow the @GiJournal handle on Twitter and turn on the notifications icon. Although we encourage everyone to “actively” participate in the discussion by asking questions or sharing your personal experience, joining the discussion as an “observer” is also a great way to learn. The discussion starts at 8 p.m. EST every Wednesday. Follow the #GIJC and the @GiJournal handle as questions are posted by the faculty moderator and answered by the experts. Even if you miss the discussion, the @GiJournal Digest is a great way to recap the discussions in an easy-to-read PDF format. The @GiJournal Digest is a monthly publication that archives the four @GiJournal club discussions in the previous month. Follow the link below to access the recent publications: http://ow.ly/uu2550C3RXX

Conclusion

In summary, we believe Twitter-based journal clubs offer an engaging way of virtual learning from the comfort of one’s home and a convenient way to directly interact with the experts. The success of @GiJournal highlights the importance of social media for medical education in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology and we look forward to developing this endeavor further.

Dr. Mahmood is clinical assistant professor of medicine, co–program director of the GI fellowship program, UB division of gastroenterology, hepatology & nutrition, State University of New York at Buffalo; Dr. Rabiee is assistant professor of medicine, director of hepatology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Washington DC VA Medical Center, Washington; Dr. Amin is assistant professor of medicine, director of endoscopy, The Lennar Foundation Medical Center, division of digestive health and liver disease, department of medicine, University of Miami; Dr. Kahn is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Dr. Akbar Ali is a gastroenterology fellow in the division of digestive diseases and nutrition, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

Abnormal anal paps in people with HIV can go more than a year without follow-up

That delay “revealed missed opportunities for a better experience on the patient, clinic, and provider level,” Jessica Wells, PhD, research assistant professor at the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. After all, “a lot can happen in that 1 year,” including early development of human papillomavirus (HPV)–associated anal cancer.

Although it’s too soon to say how significant that delay is with respect to the natural history of anal cancer, Dr. Wells said the data are a potential signal of disparities.

“The findings from my study may foreshadow potential disparities if we don’t have the necessary resources in place to promote follow-up care after an abnormal Pap test, similar to the disparities that we see in cervical cancer,” she said during the virtual Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2020 Annual Meeting.

Single-center study

In the United States, people living with HIV are 19 times more likely to develop anal cancer than the general population, according to a 2018 article in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. Another single-center study from Yale University found that, in minority communities, anal cancer rates were 75% higher than in White communities. Anal cancer rates were 72% higher in communities with greater poverty. As a result, many clinics are beginning to administer Pap tests to determine early signs of HPV infection and associated changes.

In Dr. Wells’ study, which was conducted from 2012 to 2015, 150 adults with HIV who were aged 21 and older were recruited from Grady Ponce De Leon Center in Atlanta. According to a 2018 study from that center, a large minority of participants had late-stage HIV and suppressed immune systems.

All participants had been referred for HRA after a recent abnormal anal Pap test. Participants filled out questionnaires on sociodemographics, internalized HIV-related stigma, depression, risk behaviors, social support, and knowledge about HPV and anal cancer.

Participants were disproportionately older (mean age, 50.9 years); cisgender (86.7%), Black (78%); and gay, lesbian, or bisexual (84.3%). Slightly more than 1 in 10 participants (11.3%) were transgender women.

Although for 6% of participants, Pap test results indicated high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), an additional 8% had atypical Pap findings that couldn’t exclude HSIL – the kinds of results that are one step away from a cancer diagnosis. More than 80% of participants had low-grade or inconclusive results. Nearly half (44%) of participants’ Pap tests revealed low-grade squamous cell intraepithelial cell lesions (LSIL); 42% indicated atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance.

When Dr. Wells looked at how long participants had waited to undergo HRA, she found something that surprised her: although some participants underwent follow-up assessment in 17 days, for many, it took much longer. The longest wait was 2,350 days – more than 6 years.

“There were quite a few patients who had follow-up beyond 1,000-plus days,” Dr. Wells said in an interview. “I didn›t think the delays were that long — at most, I would say that patients will get scheduled and come back within a few weeks or months.”

What’s more, she discovered through the HPV knowledge questionnaire that many participants did not understand why they were having a follow-up appointment. Anecdotally, some confused HPV with HIV.

“There’s education to be done to inform this target population that those living with HIV are more prone or at increased risk of this virus causing cancer later,” she said. “There are a lot of campaigns around women living with HIV, that they need to do cervical cancer screening. I think we need to really expand this campaign to include that HPV can also cause anal cancer.”

Dr. Wells had planned to primarily investigate the impact of psychosocial factors on wait time to follow-up, but none of those factors were associated with longer wait times.

Systems-level factors

That led Ann Gakumo, PhD, chair of nursing at the College of Nursing and Health Sciences of the University of Massachusetts, Boston, to ask what other factors could account for the delay.

There were several, Dr. Wells said. Precarious housing, for example, could have influenced this lag in follow-up. About one in four participants were in transient housing, and one participant reported having been incarcerated. She gathered street addresses and plans to analyze that data to see whether the cases occurred in clusters in specific neighborhoods, as the Yale data indicated.

In addition, the anoscopy clinic was only available to receive patients one day a week and was staffed with only one clinician who was trained to perform HRA. Wait times could stretch for hours. Sometimes, participants had to leave the clinic to attend to other business, and their appointments needed to be rescheduled, Wells said.

In addition to the sometimes poor understanding of the importance of the follow-up test, Dr. Wells said, “we start to see a layering of these barriers. That’s where we start seeing breakdowns. So I’m hoping in a larger study I can address some of these barriers on a multilevel approach.”

This resonated with Dr. Gakumo.