User login

Barbers have role in encouraging diabetes screening in black men

Shave and a haircut … and a blood glucose test? A study shows that barbershops owned by black proprietors can play a role in encouraging black men to get screened for diabetes.

In research letter published in the Jan. 27 edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, Marcela Osorio, BA, from New York University and coauthors wrote that black men with diabetes have disproportionately high rates of diabetes complications and lower survival rates. Their diagnosis is often delayed, particularly among men without regular primary health care.

“In barbershops, which are places of trust among black men, community-based interventions have been successful in identifying and treating men with hypertension,” they wrote.

In this study, the researchers approached customers in eight barbershops in Brooklyn, in areas associated with a high prevalence of individuals with poor glycemic control, to encourage them to get tested for diabetes. All barbershops were owned by black individuals.

Around one-third of the 895 black men who were asked to participate in the study agreed to be screened, and 290 (32.4%) were successfully tested using point-of-care hemoglobin A1c testing.

The screening revealed that 9% of those tested had an HbA1c level of 6.5% or higher, and 16 of these individuals were obese. Three men had an HbA1c level of 7.5% or higher. The investigators noted that this prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was much higher than the 3.6% estimated prevalence among New York City residents.

The highest HbA1c level recorded during testing was 7.8%, and 28.3% of those tested had a level between 5.7% and 6.4%, which meets the criteria for a diagnosis of prediabetes.

“We also found that barbers were important health advocates; although we do not have exact numbers, some customers (who initially declined testing) agreed after encouragement from their barber,” the authors wrote.

Of the 583 men who declined to participate, around one-quarter did so on the grounds that they already knew their health status or had been checked by their doctor, one-third (35.3%) said they were healthy or didn’t have the time or interest, or didn’t want to know the results. There were also 26 individuals who reported being scared of needles.

“Black men who live in urban areas of the United States may face socioeconomic barriers to good health, including poor food environments and difficulty in obtaining primary care,” the authors wrote. “Our findings suggest that community-based diabetes screening in barbershops owned by black individuals may play a role in the timely diagnosis of diabetes and may help to identify black men who need appropriate care for their newly diagnosed diabetes.”

The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two authors declared grants from the institute during the study, and one also reported grants from other research foundations outside the study.

SOURCE: Osorio M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6867.

Shave and a haircut … and a blood glucose test? A study shows that barbershops owned by black proprietors can play a role in encouraging black men to get screened for diabetes.

In research letter published in the Jan. 27 edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, Marcela Osorio, BA, from New York University and coauthors wrote that black men with diabetes have disproportionately high rates of diabetes complications and lower survival rates. Their diagnosis is often delayed, particularly among men without regular primary health care.

“In barbershops, which are places of trust among black men, community-based interventions have been successful in identifying and treating men with hypertension,” they wrote.

In this study, the researchers approached customers in eight barbershops in Brooklyn, in areas associated with a high prevalence of individuals with poor glycemic control, to encourage them to get tested for diabetes. All barbershops were owned by black individuals.

Around one-third of the 895 black men who were asked to participate in the study agreed to be screened, and 290 (32.4%) were successfully tested using point-of-care hemoglobin A1c testing.

The screening revealed that 9% of those tested had an HbA1c level of 6.5% or higher, and 16 of these individuals were obese. Three men had an HbA1c level of 7.5% or higher. The investigators noted that this prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was much higher than the 3.6% estimated prevalence among New York City residents.

The highest HbA1c level recorded during testing was 7.8%, and 28.3% of those tested had a level between 5.7% and 6.4%, which meets the criteria for a diagnosis of prediabetes.

“We also found that barbers were important health advocates; although we do not have exact numbers, some customers (who initially declined testing) agreed after encouragement from their barber,” the authors wrote.

Of the 583 men who declined to participate, around one-quarter did so on the grounds that they already knew their health status or had been checked by their doctor, one-third (35.3%) said they were healthy or didn’t have the time or interest, or didn’t want to know the results. There were also 26 individuals who reported being scared of needles.

“Black men who live in urban areas of the United States may face socioeconomic barriers to good health, including poor food environments and difficulty in obtaining primary care,” the authors wrote. “Our findings suggest that community-based diabetes screening in barbershops owned by black individuals may play a role in the timely diagnosis of diabetes and may help to identify black men who need appropriate care for their newly diagnosed diabetes.”

The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two authors declared grants from the institute during the study, and one also reported grants from other research foundations outside the study.

SOURCE: Osorio M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6867.

Shave and a haircut … and a blood glucose test? A study shows that barbershops owned by black proprietors can play a role in encouraging black men to get screened for diabetes.

In research letter published in the Jan. 27 edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, Marcela Osorio, BA, from New York University and coauthors wrote that black men with diabetes have disproportionately high rates of diabetes complications and lower survival rates. Their diagnosis is often delayed, particularly among men without regular primary health care.

“In barbershops, which are places of trust among black men, community-based interventions have been successful in identifying and treating men with hypertension,” they wrote.

In this study, the researchers approached customers in eight barbershops in Brooklyn, in areas associated with a high prevalence of individuals with poor glycemic control, to encourage them to get tested for diabetes. All barbershops were owned by black individuals.

Around one-third of the 895 black men who were asked to participate in the study agreed to be screened, and 290 (32.4%) were successfully tested using point-of-care hemoglobin A1c testing.

The screening revealed that 9% of those tested had an HbA1c level of 6.5% or higher, and 16 of these individuals were obese. Three men had an HbA1c level of 7.5% or higher. The investigators noted that this prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was much higher than the 3.6% estimated prevalence among New York City residents.

The highest HbA1c level recorded during testing was 7.8%, and 28.3% of those tested had a level between 5.7% and 6.4%, which meets the criteria for a diagnosis of prediabetes.

“We also found that barbers were important health advocates; although we do not have exact numbers, some customers (who initially declined testing) agreed after encouragement from their barber,” the authors wrote.

Of the 583 men who declined to participate, around one-quarter did so on the grounds that they already knew their health status or had been checked by their doctor, one-third (35.3%) said they were healthy or didn’t have the time or interest, or didn’t want to know the results. There were also 26 individuals who reported being scared of needles.

“Black men who live in urban areas of the United States may face socioeconomic barriers to good health, including poor food environments and difficulty in obtaining primary care,” the authors wrote. “Our findings suggest that community-based diabetes screening in barbershops owned by black individuals may play a role in the timely diagnosis of diabetes and may help to identify black men who need appropriate care for their newly diagnosed diabetes.”

The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two authors declared grants from the institute during the study, and one also reported grants from other research foundations outside the study.

SOURCE: Osorio M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6867.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Barbershops could offer a way to encourage diabetes screening among black men.

Major finding: HbA1c testing in barbershops identified a significant number of individuals with undiagnosed diabetes.

Study details: Study involving 895 black men attending eight barbershops in Brooklyn.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two authors declared grants from the institute during the study, and one also reported grants from other research foundations outside the study.

Source: Osorio M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6867.

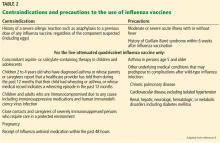

A quick guide to PrEP: Steps to take & insurance coverage changes to watch for

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2016. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2019;24. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published February 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 update: a clinical practice guideline. CDC Web Site. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Published March 2018. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: preexposure prophylaxis. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Published June 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- Campos-Outcalt D. A look at new guidelines for HIV treatment and prevention. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:768-772.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2016. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2019;24. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published February 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 update: a clinical practice guideline. CDC Web Site. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Published March 2018. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: preexposure prophylaxis. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Published June 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- Campos-Outcalt D. A look at new guidelines for HIV treatment and prevention. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:768-772.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2016. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2019;24. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published February 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 update: a clinical practice guideline. CDC Web Site. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Published March 2018. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: preexposure prophylaxis. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Published June 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- Campos-Outcalt D. A look at new guidelines for HIV treatment and prevention. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:768-772.

Testosterone gel increases LV mass in older men

PHILADELPHIA – Testosterone gel for treatment of hypogonadism in older men boosted their left ventricular mass by 3.5% in a single year in the multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial, although the clinical implications of this impressive increase remain unclear, Elizabeth Hutchins, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“I do think these results should be considered as part of the safety profile for testosterone gel and also represent an interesting and understudied area for future research,” said Dr. Hutchins, a hospitalist affiliated with the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Center at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

The Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial was one of seven coordinated placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials of the impact of raising serum testosterone levels in older men with low testosterone. Some results of what are known as the TTrials have previously been reported (Endocr Rev. 2018 Jun 1;39[3]:369-86).

Dr. Hutchins presented new findings on the effect of treatment with 1% topical testosterone gel on body surface area–indexed left ventricular mass. The trial utilized a widely prescribed, commercially available product known as AndroGel. The study included 123 men over age 65 with low serum testosterone and coronary CT angiography images obtained at baseline and again after 1 year of double-blind testosterone gel or placebo. More than 80% of the men were above age 75, half were obese, more than two-thirds had hypertension, and 30% had diabetes.

The men initially applied 5 g of the testosterone gel daily, providing 15 mg/day of testosterone, with subsequent dosing adjustments as needed based on serum testosterone levels measured at a central laboratory. Participants were evaluated in office visits with serum testosterone measurements every 3 months. Testosterone levels in the men assigned to active treatment quickly rose to normal range and stayed there for the full 12 months, while the placebo-treated controls continued to have below-normal testosterone throughout the trial.

The key study finding was that LV mass indexed to body surface area rose significantly in the testosterone gel group, from an average of 71.5 g/m2 at baseline to 74.8 g/m2 at 1 year. That’s a statistically significant 3.5% increase. In contrast, LV mass remained flat across the year in controls: 73.8 g/m2 at baseline and 73.3 g/m2 at 12 months.

There was, however, no change over time in left or right atrial or ventricular chamber volumes in the testosterone gel recipients, nor in the controls.

Session comoderator Eric D. Peterson, MD, professor of medicine and a cardiologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C., said that “this is a very important topic,” then posed a provocative question to Dr. Hutchins: “If the intervention had been running instead of testosterone gel, would the results have looked similar, and would you be concluding that there should be a warning around the use of running?”

Dr. Hutchins replied that she’s given that question much thought.

“Of course, exercise leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that to be good muscle, and high blood pressure leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that bad muscle. So which one is it in this case? From what I can find in the literature, it seems that incremental increases in LV mass in the absence of being an athlete are deleterious. But I think we would need outcomes-based research to really answer that question,” she said.

Dr. Hutchins noted that this was the first-ever randomized controlled trial to measure the effect of testosterone therapy on LV mass in humans. The documented increase achieved with 1 year of testosterone gel doesn’t come close to reaching the threshold of LV hypertrophy, which is about 125 g/m2 for men. But evidence from animal and observational human studies suggests that even in the absence of LV hypertrophy, increases in LV mass are associated with increased mortality, she added.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Hutchins E. AHA 2019, Session FS.AOS.04.

PHILADELPHIA – Testosterone gel for treatment of hypogonadism in older men boosted their left ventricular mass by 3.5% in a single year in the multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial, although the clinical implications of this impressive increase remain unclear, Elizabeth Hutchins, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“I do think these results should be considered as part of the safety profile for testosterone gel and also represent an interesting and understudied area for future research,” said Dr. Hutchins, a hospitalist affiliated with the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Center at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

The Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial was one of seven coordinated placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials of the impact of raising serum testosterone levels in older men with low testosterone. Some results of what are known as the TTrials have previously been reported (Endocr Rev. 2018 Jun 1;39[3]:369-86).

Dr. Hutchins presented new findings on the effect of treatment with 1% topical testosterone gel on body surface area–indexed left ventricular mass. The trial utilized a widely prescribed, commercially available product known as AndroGel. The study included 123 men over age 65 with low serum testosterone and coronary CT angiography images obtained at baseline and again after 1 year of double-blind testosterone gel or placebo. More than 80% of the men were above age 75, half were obese, more than two-thirds had hypertension, and 30% had diabetes.

The men initially applied 5 g of the testosterone gel daily, providing 15 mg/day of testosterone, with subsequent dosing adjustments as needed based on serum testosterone levels measured at a central laboratory. Participants were evaluated in office visits with serum testosterone measurements every 3 months. Testosterone levels in the men assigned to active treatment quickly rose to normal range and stayed there for the full 12 months, while the placebo-treated controls continued to have below-normal testosterone throughout the trial.

The key study finding was that LV mass indexed to body surface area rose significantly in the testosterone gel group, from an average of 71.5 g/m2 at baseline to 74.8 g/m2 at 1 year. That’s a statistically significant 3.5% increase. In contrast, LV mass remained flat across the year in controls: 73.8 g/m2 at baseline and 73.3 g/m2 at 12 months.

There was, however, no change over time in left or right atrial or ventricular chamber volumes in the testosterone gel recipients, nor in the controls.

Session comoderator Eric D. Peterson, MD, professor of medicine and a cardiologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C., said that “this is a very important topic,” then posed a provocative question to Dr. Hutchins: “If the intervention had been running instead of testosterone gel, would the results have looked similar, and would you be concluding that there should be a warning around the use of running?”

Dr. Hutchins replied that she’s given that question much thought.

“Of course, exercise leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that to be good muscle, and high blood pressure leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that bad muscle. So which one is it in this case? From what I can find in the literature, it seems that incremental increases in LV mass in the absence of being an athlete are deleterious. But I think we would need outcomes-based research to really answer that question,” she said.

Dr. Hutchins noted that this was the first-ever randomized controlled trial to measure the effect of testosterone therapy on LV mass in humans. The documented increase achieved with 1 year of testosterone gel doesn’t come close to reaching the threshold of LV hypertrophy, which is about 125 g/m2 for men. But evidence from animal and observational human studies suggests that even in the absence of LV hypertrophy, increases in LV mass are associated with increased mortality, she added.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Hutchins E. AHA 2019, Session FS.AOS.04.

PHILADELPHIA – Testosterone gel for treatment of hypogonadism in older men boosted their left ventricular mass by 3.5% in a single year in the multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial, although the clinical implications of this impressive increase remain unclear, Elizabeth Hutchins, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“I do think these results should be considered as part of the safety profile for testosterone gel and also represent an interesting and understudied area for future research,” said Dr. Hutchins, a hospitalist affiliated with the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Center at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

The Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial was one of seven coordinated placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials of the impact of raising serum testosterone levels in older men with low testosterone. Some results of what are known as the TTrials have previously been reported (Endocr Rev. 2018 Jun 1;39[3]:369-86).

Dr. Hutchins presented new findings on the effect of treatment with 1% topical testosterone gel on body surface area–indexed left ventricular mass. The trial utilized a widely prescribed, commercially available product known as AndroGel. The study included 123 men over age 65 with low serum testosterone and coronary CT angiography images obtained at baseline and again after 1 year of double-blind testosterone gel or placebo. More than 80% of the men were above age 75, half were obese, more than two-thirds had hypertension, and 30% had diabetes.

The men initially applied 5 g of the testosterone gel daily, providing 15 mg/day of testosterone, with subsequent dosing adjustments as needed based on serum testosterone levels measured at a central laboratory. Participants were evaluated in office visits with serum testosterone measurements every 3 months. Testosterone levels in the men assigned to active treatment quickly rose to normal range and stayed there for the full 12 months, while the placebo-treated controls continued to have below-normal testosterone throughout the trial.

The key study finding was that LV mass indexed to body surface area rose significantly in the testosterone gel group, from an average of 71.5 g/m2 at baseline to 74.8 g/m2 at 1 year. That’s a statistically significant 3.5% increase. In contrast, LV mass remained flat across the year in controls: 73.8 g/m2 at baseline and 73.3 g/m2 at 12 months.

There was, however, no change over time in left or right atrial or ventricular chamber volumes in the testosterone gel recipients, nor in the controls.

Session comoderator Eric D. Peterson, MD, professor of medicine and a cardiologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C., said that “this is a very important topic,” then posed a provocative question to Dr. Hutchins: “If the intervention had been running instead of testosterone gel, would the results have looked similar, and would you be concluding that there should be a warning around the use of running?”

Dr. Hutchins replied that she’s given that question much thought.

“Of course, exercise leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that to be good muscle, and high blood pressure leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that bad muscle. So which one is it in this case? From what I can find in the literature, it seems that incremental increases in LV mass in the absence of being an athlete are deleterious. But I think we would need outcomes-based research to really answer that question,” she said.

Dr. Hutchins noted that this was the first-ever randomized controlled trial to measure the effect of testosterone therapy on LV mass in humans. The documented increase achieved with 1 year of testosterone gel doesn’t come close to reaching the threshold of LV hypertrophy, which is about 125 g/m2 for men. But evidence from animal and observational human studies suggests that even in the absence of LV hypertrophy, increases in LV mass are associated with increased mortality, she added.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Hutchins E. AHA 2019, Session FS.AOS.04.

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

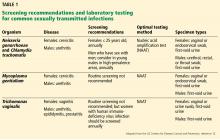

Provide appropriate sexual, reproductive health care for transgender patients

I recently was on a panel of experts discussing how to prevent HIV among transgender youth. Preventing HIV among transgender youth, especially transgender youth of color, remains a challenge for multiple reasons – racism, poverty, stigma, marginalization, and discrimination play a role in the HIV epidemic. A barrier to preventing HIV infections among transgender youth is a lack of knowledge on how to provide them with comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care. Here are some tips and resources that can help you ensure that transgender youth are safe and healthy.

One of the challenges of obtaining a sexual history is asking the right questions For example, if you have a transgender male assigned female at birth, ask whether their partners produce sperm instead of asking about the sex of their partners. A transgender male’s partner may identify as female but is assigned male at birth and uses her penis during sex. Furthermore, a transgender male may be on testosterone, but he still can get pregnant. Asking how they use their organs is just as important. A transgender male who has condomless penile-vaginal sex with multiple partners is at a higher risk for HIV infection than is a transgender male who shares sex toys with his only partner.

Normalizing that you ask a comprehensive sexual history to all your patients regardless of gender identity may put the patient at ease. Many transgender people are reluctant to disclose their gender identity to their provider because they are afraid that the provider may fixate on their sexuality once they do. Stating that you ask sexual health questions to all your patients may prevent the transgender patient from feeling singled out.

Finally, you don’t have to ask a sexual history with every transgender patient, just as you wouldn’t for your cisgender patients. If a patient is complaining of a sprained ankle, a sexual history may not be helpful, compared with obtaining one when a patient comes in with pelvic pain. Many transgender patients avoid care because they are frequently asked about their sexual history or gender identity when these are not relevant to their chief complaint.

Here are some helpful questions to ask when taking a sexual history, according to the University of California, San Francisco, Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines.1

- Are you having sex? How many sex partners have you had in the past year?

- Who are you having sex with? What types of sex are you having? What parts of your anatomy do you use for sex?

- How do you protect yourself from STIs?

- What STIs have you had in the past, if any? When were you last tested for STIs?

- Has your partner(s) ever been diagnosed with any STIs?

- Do you use alcohol or any drugs when you have sex?

- Do you exchange sex for money, drugs, or a place to stay?

Also, use a trauma-informed approach when working with transgender patients. Many have been victims of sexual trauma. Always have a chaperone accompany you during the exam, explain to the patient what you plan to do and why it is necessary, and allow them to decline (and document their declining the physical exam). Also consider having your patient self-swab for STI screening if appropriate.1

Like obtaining a sexual history, routine screenings for certain types of cancers will be based on the organs the patient has. For example, a transgender woman assigned male at birth will not need a cervical cancer screening, but a transgender man assigned female at birth may need one – if the patient still has a cervix. Cervical cancer screening guidelines are similar for transgender men as it is for nontransgender women, and one should use the same guidelines endorsed by the American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathologists, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the World Health Organization.2-4

Cervical screenings should never be a requirement for testosterone therapy, and no transgender male under the age of 21 years will need cervical screening. The University of California guidelines offers tips on how to make transgender men more comfortable during cervical cancer screening.5

Contraception and menstrual management also are important for transgender patients. Testosterone can induce amenorrhea for transgender men, but it is not good birth control. If a transgender male patient has sex with partners that produce sperm, then the physician should discuss effective birth control options. There is no ideal birth control option for transgender men. One must consider multiple factors including the patient’s desire for pregnancy, desire to cease periods, ease of administration, and risk for thrombosis.

Most transgender men may balk at the idea of taking estrogen-containing contraception, but it is more effective than oral progestin-only pills. Intrauterine devices are highly effective in pregnancy prevention and can achieve amenorrhea in 50% of users within 1 year,but some transmen may become dysphoric with the procedure. 6 The etonogestrel implants also are highly effective birth control, but irregular periods are common, leading to discontinuation. Depot medroxyprogesterone is highly effective in preventing pregnancy and can induce amenorrhea in 70% of users within 1 year and 80% of users in 2 years, but also is associated with weight gain in one-third of users.7 Finally, pubertal blockers can rapidly stop periods for transmen who are severely dysphoric from their menses; however, before achieving amenorrhea, a flare bleed can occur 4-6 weeks after administration.8 Support from a mental health therapist during this time is critical. Pubertal blockers, nevertheless, are not suitable birth control.

When providing affirming sexual and reproductive health care for transgender patients, key principles include focusing on organs and activities over identity. Additionally, screening for certain types of cancers also is dependent on organs. Finally, do not neglect the importance of contraception among transgender men. Taking these principles in consideration will help you provide excellent care for transgender youth.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Transgender people and sexually transmitted infections (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/stis).

2. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72.

3. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880-91.

4. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries: Report of a WHO consultation. 2002. World Health Organization, Geneva.

5. Screening for cervical cancer for transgender men (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/cervical-cancer).

6. Contraception. 2002 Feb;65(2):129-32.

7. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011 Jun;12(2):93-106.

8. Int J Womens Health. 2014 Jun 23;6:631-7.

Resources

Breast cancer screening in transgender men. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-men).

Screening for breast cancer in transgender women. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-women).

Transgender health and HIV (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/hiv).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and Transgender People (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html).

I recently was on a panel of experts discussing how to prevent HIV among transgender youth. Preventing HIV among transgender youth, especially transgender youth of color, remains a challenge for multiple reasons – racism, poverty, stigma, marginalization, and discrimination play a role in the HIV epidemic. A barrier to preventing HIV infections among transgender youth is a lack of knowledge on how to provide them with comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care. Here are some tips and resources that can help you ensure that transgender youth are safe and healthy.

One of the challenges of obtaining a sexual history is asking the right questions For example, if you have a transgender male assigned female at birth, ask whether their partners produce sperm instead of asking about the sex of their partners. A transgender male’s partner may identify as female but is assigned male at birth and uses her penis during sex. Furthermore, a transgender male may be on testosterone, but he still can get pregnant. Asking how they use their organs is just as important. A transgender male who has condomless penile-vaginal sex with multiple partners is at a higher risk for HIV infection than is a transgender male who shares sex toys with his only partner.

Normalizing that you ask a comprehensive sexual history to all your patients regardless of gender identity may put the patient at ease. Many transgender people are reluctant to disclose their gender identity to their provider because they are afraid that the provider may fixate on their sexuality once they do. Stating that you ask sexual health questions to all your patients may prevent the transgender patient from feeling singled out.

Finally, you don’t have to ask a sexual history with every transgender patient, just as you wouldn’t for your cisgender patients. If a patient is complaining of a sprained ankle, a sexual history may not be helpful, compared with obtaining one when a patient comes in with pelvic pain. Many transgender patients avoid care because they are frequently asked about their sexual history or gender identity when these are not relevant to their chief complaint.

Here are some helpful questions to ask when taking a sexual history, according to the University of California, San Francisco, Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines.1

- Are you having sex? How many sex partners have you had in the past year?

- Who are you having sex with? What types of sex are you having? What parts of your anatomy do you use for sex?

- How do you protect yourself from STIs?

- What STIs have you had in the past, if any? When were you last tested for STIs?

- Has your partner(s) ever been diagnosed with any STIs?

- Do you use alcohol or any drugs when you have sex?

- Do you exchange sex for money, drugs, or a place to stay?

Also, use a trauma-informed approach when working with transgender patients. Many have been victims of sexual trauma. Always have a chaperone accompany you during the exam, explain to the patient what you plan to do and why it is necessary, and allow them to decline (and document their declining the physical exam). Also consider having your patient self-swab for STI screening if appropriate.1

Like obtaining a sexual history, routine screenings for certain types of cancers will be based on the organs the patient has. For example, a transgender woman assigned male at birth will not need a cervical cancer screening, but a transgender man assigned female at birth may need one – if the patient still has a cervix. Cervical cancer screening guidelines are similar for transgender men as it is for nontransgender women, and one should use the same guidelines endorsed by the American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathologists, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the World Health Organization.2-4

Cervical screenings should never be a requirement for testosterone therapy, and no transgender male under the age of 21 years will need cervical screening. The University of California guidelines offers tips on how to make transgender men more comfortable during cervical cancer screening.5

Contraception and menstrual management also are important for transgender patients. Testosterone can induce amenorrhea for transgender men, but it is not good birth control. If a transgender male patient has sex with partners that produce sperm, then the physician should discuss effective birth control options. There is no ideal birth control option for transgender men. One must consider multiple factors including the patient’s desire for pregnancy, desire to cease periods, ease of administration, and risk for thrombosis.

Most transgender men may balk at the idea of taking estrogen-containing contraception, but it is more effective than oral progestin-only pills. Intrauterine devices are highly effective in pregnancy prevention and can achieve amenorrhea in 50% of users within 1 year,but some transmen may become dysphoric with the procedure. 6 The etonogestrel implants also are highly effective birth control, but irregular periods are common, leading to discontinuation. Depot medroxyprogesterone is highly effective in preventing pregnancy and can induce amenorrhea in 70% of users within 1 year and 80% of users in 2 years, but also is associated with weight gain in one-third of users.7 Finally, pubertal blockers can rapidly stop periods for transmen who are severely dysphoric from their menses; however, before achieving amenorrhea, a flare bleed can occur 4-6 weeks after administration.8 Support from a mental health therapist during this time is critical. Pubertal blockers, nevertheless, are not suitable birth control.

When providing affirming sexual and reproductive health care for transgender patients, key principles include focusing on organs and activities over identity. Additionally, screening for certain types of cancers also is dependent on organs. Finally, do not neglect the importance of contraception among transgender men. Taking these principles in consideration will help you provide excellent care for transgender youth.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Transgender people and sexually transmitted infections (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/stis).

2. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72.

3. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880-91.

4. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries: Report of a WHO consultation. 2002. World Health Organization, Geneva.

5. Screening for cervical cancer for transgender men (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/cervical-cancer).

6. Contraception. 2002 Feb;65(2):129-32.

7. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011 Jun;12(2):93-106.

8. Int J Womens Health. 2014 Jun 23;6:631-7.

Resources

Breast cancer screening in transgender men. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-men).

Screening for breast cancer in transgender women. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-women).

Transgender health and HIV (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/hiv).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and Transgender People (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html).

I recently was on a panel of experts discussing how to prevent HIV among transgender youth. Preventing HIV among transgender youth, especially transgender youth of color, remains a challenge for multiple reasons – racism, poverty, stigma, marginalization, and discrimination play a role in the HIV epidemic. A barrier to preventing HIV infections among transgender youth is a lack of knowledge on how to provide them with comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care. Here are some tips and resources that can help you ensure that transgender youth are safe and healthy.

One of the challenges of obtaining a sexual history is asking the right questions For example, if you have a transgender male assigned female at birth, ask whether their partners produce sperm instead of asking about the sex of their partners. A transgender male’s partner may identify as female but is assigned male at birth and uses her penis during sex. Furthermore, a transgender male may be on testosterone, but he still can get pregnant. Asking how they use their organs is just as important. A transgender male who has condomless penile-vaginal sex with multiple partners is at a higher risk for HIV infection than is a transgender male who shares sex toys with his only partner.

Normalizing that you ask a comprehensive sexual history to all your patients regardless of gender identity may put the patient at ease. Many transgender people are reluctant to disclose their gender identity to their provider because they are afraid that the provider may fixate on their sexuality once they do. Stating that you ask sexual health questions to all your patients may prevent the transgender patient from feeling singled out.

Finally, you don’t have to ask a sexual history with every transgender patient, just as you wouldn’t for your cisgender patients. If a patient is complaining of a sprained ankle, a sexual history may not be helpful, compared with obtaining one when a patient comes in with pelvic pain. Many transgender patients avoid care because they are frequently asked about their sexual history or gender identity when these are not relevant to their chief complaint.

Here are some helpful questions to ask when taking a sexual history, according to the University of California, San Francisco, Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines.1

- Are you having sex? How many sex partners have you had in the past year?

- Who are you having sex with? What types of sex are you having? What parts of your anatomy do you use for sex?

- How do you protect yourself from STIs?

- What STIs have you had in the past, if any? When were you last tested for STIs?

- Has your partner(s) ever been diagnosed with any STIs?

- Do you use alcohol or any drugs when you have sex?

- Do you exchange sex for money, drugs, or a place to stay?

Also, use a trauma-informed approach when working with transgender patients. Many have been victims of sexual trauma. Always have a chaperone accompany you during the exam, explain to the patient what you plan to do and why it is necessary, and allow them to decline (and document their declining the physical exam). Also consider having your patient self-swab for STI screening if appropriate.1

Like obtaining a sexual history, routine screenings for certain types of cancers will be based on the organs the patient has. For example, a transgender woman assigned male at birth will not need a cervical cancer screening, but a transgender man assigned female at birth may need one – if the patient still has a cervix. Cervical cancer screening guidelines are similar for transgender men as it is for nontransgender women, and one should use the same guidelines endorsed by the American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathologists, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the World Health Organization.2-4

Cervical screenings should never be a requirement for testosterone therapy, and no transgender male under the age of 21 years will need cervical screening. The University of California guidelines offers tips on how to make transgender men more comfortable during cervical cancer screening.5

Contraception and menstrual management also are important for transgender patients. Testosterone can induce amenorrhea for transgender men, but it is not good birth control. If a transgender male patient has sex with partners that produce sperm, then the physician should discuss effective birth control options. There is no ideal birth control option for transgender men. One must consider multiple factors including the patient’s desire for pregnancy, desire to cease periods, ease of administration, and risk for thrombosis.

Most transgender men may balk at the idea of taking estrogen-containing contraception, but it is more effective than oral progestin-only pills. Intrauterine devices are highly effective in pregnancy prevention and can achieve amenorrhea in 50% of users within 1 year,but some transmen may become dysphoric with the procedure. 6 The etonogestrel implants also are highly effective birth control, but irregular periods are common, leading to discontinuation. Depot medroxyprogesterone is highly effective in preventing pregnancy and can induce amenorrhea in 70% of users within 1 year and 80% of users in 2 years, but also is associated with weight gain in one-third of users.7 Finally, pubertal blockers can rapidly stop periods for transmen who are severely dysphoric from their menses; however, before achieving amenorrhea, a flare bleed can occur 4-6 weeks after administration.8 Support from a mental health therapist during this time is critical. Pubertal blockers, nevertheless, are not suitable birth control.

When providing affirming sexual and reproductive health care for transgender patients, key principles include focusing on organs and activities over identity. Additionally, screening for certain types of cancers also is dependent on organs. Finally, do not neglect the importance of contraception among transgender men. Taking these principles in consideration will help you provide excellent care for transgender youth.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Transgender people and sexually transmitted infections (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/stis).

2. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72.

3. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880-91.

4. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries: Report of a WHO consultation. 2002. World Health Organization, Geneva.

5. Screening for cervical cancer for transgender men (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/cervical-cancer).

6. Contraception. 2002 Feb;65(2):129-32.

7. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011 Jun;12(2):93-106.

8. Int J Womens Health. 2014 Jun 23;6:631-7.

Resources

Breast cancer screening in transgender men. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-men).

Screening for breast cancer in transgender women. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-women).

Transgender health and HIV (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/hiv).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and Transgender People (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html).

New guideline for testosterone treatment in men with ‘low T’

The American College of Physicians has released new clinical guidelines providing practical recommendations for testosterone therapy in adult men with age-related low testosterone.

The evidence-based recommendations target all clinicians and were published online January 6, 2020, in Annals of Internal Medicine, highlighting data from a systematic review of evidence on the efficacy and safety of testosterone treatment in adult men with age-related low testosterone.

Serum testosterone levels drop as men age, starting in their mid-30s, and approximately 20% of American men older than 60 years have low testosterone.

However, no widely accepted testosterone threshold level exists that represents a measure below which symptoms of androgen deficiency and adverse health outcomes occur.

In addition, the role of testosterone therapy in managing this patient population is controversial.

“The purpose of this American College of Physicians guideline is to present recommendations based on the best available evidence on the benefits, harms, and costs of testosterone treatment in adult men with age-related low testosterone,” write Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA, from the American College of Physicians, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“This guideline does not address screening or diagnosis of hypogonadism or monitoring of testosterone levels,” the authors note.

In particular, the recommendations suggest that clinicians should initiate testosterone treatment in these patients only to help them improve their sexual function.

According to the authors, moderate-certainty evidence from seven trials involving testosterone treatment in adult men with age-related low testosterone showed a small improvement in global sexual function, whereas low-certainty evidence from seven trials showed a small improvement in erectile function.

By contrast, the guideline emphasizes that clinicians should avoid prescribing testosterone treatment for any other concern in this population. Available evidence demonstrates little to no improvement in physical function, depressive symptoms, energy and vitality, or cognition among these men after receiving testosterone treatment, the authors stress.

ACP recommends that clinicians should reassess men’s symptoms within 12 months of testosterone treatment initiation, with regular reevaluations during subsequent follow up. Clinicians should discontinue treatment in men if sexual function fails to improve.

The guideline also recommends using intramuscular formulations of testosterone treatment for this patient population instead of transdermal ones, because intramuscular formulations cost less and have similar clinical effectiveness and harms.

“The annual cost in 2016 per beneficiary for TRT [testosterone replacement therapy] was $2,135.32 for the transdermal and $156.24 for the intramuscular formulation, according to paid pharmaceutical claims provided in the 2016 Medicare Part D Drug Claims data,” the authors write.

In an accompanying editorial, E. Victor Adlin, MD, of Temple University, Philadelphia, notes that these new ACP guidelines mostly mirror those recently proposed by both the Endocrine Society and the American Urological Association.

However, he predicts that many clinicians will question the ACP’s recommendation to favor use of intramuscular over transdermal formulations of testosterone.

Although Dr. Adlin acknowledges the lower cost of intramuscular preparations as a major consideration, he explains that “the need for an intramuscular injection every 1-4 weeks is a potential barrier to adherence, and some patients require visits to a health care facility for the injections, which may add to the expense.”

Fluctuating blood testosterone levels after each injection may also result in irregular symptom relief and difficulty achieving the desired blood level, he adds. “Individual preference may vary widely in the choice of testosterone therapy.”

Overall, Dr. Adlin stresses that a patient-clinician discussion should serve as the foundation for starting testosterone therapy in men with age-related low testosterone, with the patient playing a central role in treatment decision making.

This guideline was developed with financial support from the American College of Physicians’ operating budget. Study author Carrie Horwitch reports serving as a fiduciary officer for the Washington State Medical Association. Jennifer S. Lin, a member of the ACP Clinical Guidelines Committee, reports being an employee of Kaiser Permanente. Robert McLean, another member of the committee, reports being an employee of Northeast Medical Group. The remaining authors and the editorialist have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this story appeared on Medscape.com.

The American College of Physicians has released new clinical guidelines providing practical recommendations for testosterone therapy in adult men with age-related low testosterone.

The evidence-based recommendations target all clinicians and were published online January 6, 2020, in Annals of Internal Medicine, highlighting data from a systematic review of evidence on the efficacy and safety of testosterone treatment in adult men with age-related low testosterone.

Serum testosterone levels drop as men age, starting in their mid-30s, and approximately 20% of American men older than 60 years have low testosterone.

However, no widely accepted testosterone threshold level exists that represents a measure below which symptoms of androgen deficiency and adverse health outcomes occur.

In addition, the role of testosterone therapy in managing this patient population is controversial.

“The purpose of this American College of Physicians guideline is to present recommendations based on the best available evidence on the benefits, harms, and costs of testosterone treatment in adult men with age-related low testosterone,” write Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA, from the American College of Physicians, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“This guideline does not address screening or diagnosis of hypogonadism or monitoring of testosterone levels,” the authors note.

In particular, the recommendations suggest that clinicians should initiate testosterone treatment in these patients only to help them improve their sexual function.

According to the authors, moderate-certainty evidence from seven trials involving testosterone treatment in adult men with age-related low testosterone showed a small improvement in global sexual function, whereas low-certainty evidence from seven trials showed a small improvement in erectile function.

By contrast, the guideline emphasizes that clinicians should avoid prescribing testosterone treatment for any other concern in this population. Available evidence demonstrates little to no improvement in physical function, depressive symptoms, energy and vitality, or cognition among these men after receiving testosterone treatment, the authors stress.

ACP recommends that clinicians should reassess men’s symptoms within 12 months of testosterone treatment initiation, with regular reevaluations during subsequent follow up. Clinicians should discontinue treatment in men if sexual function fails to improve.

The guideline also recommends using intramuscular formulations of testosterone treatment for this patient population instead of transdermal ones, because intramuscular formulations cost less and have similar clinical effectiveness and harms.

“The annual cost in 2016 per beneficiary for TRT [testosterone replacement therapy] was $2,135.32 for the transdermal and $156.24 for the intramuscular formulation, according to paid pharmaceutical claims provided in the 2016 Medicare Part D Drug Claims data,” the authors write.

In an accompanying editorial, E. Victor Adlin, MD, of Temple University, Philadelphia, notes that these new ACP guidelines mostly mirror those recently proposed by both the Endocrine Society and the American Urological Association.

However, he predicts that many clinicians will question the ACP’s recommendation to favor use of intramuscular over transdermal formulations of testosterone.

Although Dr. Adlin acknowledges the lower cost of intramuscular preparations as a major consideration, he explains that “the need for an intramuscular injection every 1-4 weeks is a potential barrier to adherence, and some patients require visits to a health care facility for the injections, which may add to the expense.”

Fluctuating blood testosterone levels after each injection may also result in irregular symptom relief and difficulty achieving the desired blood level, he adds. “Individual preference may vary widely in the choice of testosterone therapy.”

Overall, Dr. Adlin stresses that a patient-clinician discussion should serve as the foundation for starting testosterone therapy in men with age-related low testosterone, with the patient playing a central role in treatment decision making.

This guideline was developed with financial support from the American College of Physicians’ operating budget. Study author Carrie Horwitch reports serving as a fiduciary officer for the Washington State Medical Association. Jennifer S. Lin, a member of the ACP Clinical Guidelines Committee, reports being an employee of Kaiser Permanente. Robert McLean, another member of the committee, reports being an employee of Northeast Medical Group. The remaining authors and the editorialist have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this story appeared on Medscape.com.

The American College of Physicians has released new clinical guidelines providing practical recommendations for testosterone therapy in adult men with age-related low testosterone.

The evidence-based recommendations target all clinicians and were published online January 6, 2020, in Annals of Internal Medicine, highlighting data from a systematic review of evidence on the efficacy and safety of testosterone treatment in adult men with age-related low testosterone.

Serum testosterone levels drop as men age, starting in their mid-30s, and approximately 20% of American men older than 60 years have low testosterone.

However, no widely accepted testosterone threshold level exists that represents a measure below which symptoms of androgen deficiency and adverse health outcomes occur.

In addition, the role of testosterone therapy in managing this patient population is controversial.

“The purpose of this American College of Physicians guideline is to present recommendations based on the best available evidence on the benefits, harms, and costs of testosterone treatment in adult men with age-related low testosterone,” write Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA, from the American College of Physicians, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“This guideline does not address screening or diagnosis of hypogonadism or monitoring of testosterone levels,” the authors note.

In particular, the recommendations suggest that clinicians should initiate testosterone treatment in these patients only to help them improve their sexual function.

According to the authors, moderate-certainty evidence from seven trials involving testosterone treatment in adult men with age-related low testosterone showed a small improvement in global sexual function, whereas low-certainty evidence from seven trials showed a small improvement in erectile function.

By contrast, the guideline emphasizes that clinicians should avoid prescribing testosterone treatment for any other concern in this population. Available evidence demonstrates little to no improvement in physical function, depressive symptoms, energy and vitality, or cognition among these men after receiving testosterone treatment, the authors stress.

ACP recommends that clinicians should reassess men’s symptoms within 12 months of testosterone treatment initiation, with regular reevaluations during subsequent follow up. Clinicians should discontinue treatment in men if sexual function fails to improve.

The guideline also recommends using intramuscular formulations of testosterone treatment for this patient population instead of transdermal ones, because intramuscular formulations cost less and have similar clinical effectiveness and harms.

“The annual cost in 2016 per beneficiary for TRT [testosterone replacement therapy] was $2,135.32 for the transdermal and $156.24 for the intramuscular formulation, according to paid pharmaceutical claims provided in the 2016 Medicare Part D Drug Claims data,” the authors write.

In an accompanying editorial, E. Victor Adlin, MD, of Temple University, Philadelphia, notes that these new ACP guidelines mostly mirror those recently proposed by both the Endocrine Society and the American Urological Association.

However, he predicts that many clinicians will question the ACP’s recommendation to favor use of intramuscular over transdermal formulations of testosterone.

Although Dr. Adlin acknowledges the lower cost of intramuscular preparations as a major consideration, he explains that “the need for an intramuscular injection every 1-4 weeks is a potential barrier to adherence, and some patients require visits to a health care facility for the injections, which may add to the expense.”

Fluctuating blood testosterone levels after each injection may also result in irregular symptom relief and difficulty achieving the desired blood level, he adds. “Individual preference may vary widely in the choice of testosterone therapy.”

Overall, Dr. Adlin stresses that a patient-clinician discussion should serve as the foundation for starting testosterone therapy in men with age-related low testosterone, with the patient playing a central role in treatment decision making.

This guideline was developed with financial support from the American College of Physicians’ operating budget. Study author Carrie Horwitch reports serving as a fiduciary officer for the Washington State Medical Association. Jennifer S. Lin, a member of the ACP Clinical Guidelines Committee, reports being an employee of Kaiser Permanente. Robert McLean, another member of the committee, reports being an employee of Northeast Medical Group. The remaining authors and the editorialist have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this story appeared on Medscape.com.

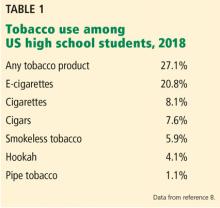

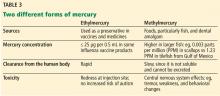

Vaping: The new wave of nicotine addiction

Electronic cigarettes and other “vaping” devices have been increasing in popularity among youth and adults since their introduction in the US market in 2007.1 This increase is partially driven by a public perception that vaping is harmless, or at least less harmful than cigarette smoking.2 Vaping fans also argue that current smokers can use vaping as nicotine replacement therapy to help them quit smoking.3

We disagree. Research on the health effects of vaping, though still limited, is accumulating rapidly and making it increasingly clear that this habit is far from harmless. For youth, it is a gateway to addiction to nicotine and other substances. Whether it can help people quit smoking remains to be seen. And recent months have seen reports of serious respiratory illnesses and even deaths linked to vaping.4

In December 2016, the US Surgeon General warned that e-cigarette use among youth and young adults in the United States represents a “major public health concern,”5 and that more adolescents and young adults are now vaping than smoking conventional tobacco products.

This article reviews the issue of vaping in the United States, as well as available evidence regarding its safety.

YOUTH AT RISK

Retail sales of e-cigarettes and vaping devices approach an annual $7 billion.6 A 2014–2015 survey found that 2.4% of the general US population were current users of e-cigarettes, and 8.5% had tried them at least once.3

In 2014, for the first time, e-cigarette use became more common among US youth than traditional cigarettes.5

The odds of taking up vaping are higher among minority youth in the United States, particularly Hispanics.9 This trend is particularly worrisome because several longitudinal studies have shown that adolescents who use e-cigarettes are 3 times as likely to eventually become smokers of traditional cigarettes compared with adolescents who do not use e-cigarettes.10–12

If US youth continue smoking at the current rate, 5.6 million of the current population under age 18, or 1 of every 13, will die early of a smoking-related illness.13

RECENT OUTBREAK OF VAPING-ASSOCIATED LUNG INJURY

As of November 5, 2019, there had been 2,051 cases of vaping-associated lung injury in 49 states (all except Alaska), the District of Columbia, and 1 US territory reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with 39 confirmed deaths.4 The reported cases include respiratory injury including acute eosinophilic pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis.14

Most of these patients had been vaping tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), though many used both nicotine- and THC-containing products, and others used products containing nicotine exclusively.4 Thus, it is difficult to identify the exact substance or substances that may be contributing to this sudden outbreak among vape users, and many different product sources are currently under investigation.

One substance that may be linked to the epidemic is vitamin E acetate, which the New York State Department of Health has detected in high levels in cannabis vaping cartridges used by patients who developed lung injury.15 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is continuing to analyze vape cartridge samples submitted by affected patients to look for other chemicals that can contribute to the development of serious pulmonary illness.

WHAT IS AN E-CIGARETTE? WHAT IS A VAPE PEN?

Vape pens consist of similar elements but are not necessarily similar in appearance to a conventional cigarette, and may look more like a pen or a USB flash drive. In fact, the Juul device is recharged by plugging it into a USB port.

Vaping devices have many street names, including e-cigs, e-hookahs, vape pens, mods, vapes, and tank systems.

The first US patent application for a device resembling a modern e-cigarette was filed in 1963, but the product never made it to the market.16 Instead, the first commercially successful e-cigarette was created in Beijing in 2003 and introduced to US markets in 2007.

Newer-generation devices have larger batteries and can heat the liquid to higher temperatures, releasing more nicotine and forming additional toxicants such as formaldehyde. Devices lack standardization in terms of design, capacity for safely holding e-liquid, packaging of the e-liquid, and features designed to minimize hazards of use.

Not just nicotine

Many devices are designed for use with other drugs, including THC.17 In a 2018 study, 10.9% of college students reported vaping marijuana in the past 30 days, up from 5.2% in 2017.18

Other substances are being vaped as well.19 In theory, any heat-stable psychoactive recreational drug could be aerosolized and vaped. There are increasing reports of e-liquids containing recreational drugs such as synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists, crack cocaine, LSD, and methamphetamine.17

Freedom, rebellion, glamour

Sales have risen rapidly since 2007 with widespread advertising on television and in print publications for popular brands, often featuring celebrities.20 Spending on advertising for e-cigarettes and vape devices rose from $6.4 million in 2011 to $115 million in 2014—and that was before the advent of Juul (see below).21

Marketing campaigns for vaping devices mimic the themes previously used successfully by the tobacco industry, eg, freedom, rebellion, and glamour. They also make unsubstantiated claims about health benefits and smoking cessation, though initial websites contained endorsements from physicians, similar to the strategies of tobacco companies in old cigarette ads. Cigarette ads have been prohibited since 1971—but not e-cigarette ads. Moreover, vaping products appear as product placements in television shows and movies, with advocacy groups on social media.22

By law, buyers have to be 18 or 21

Vaping devices can be purchased at vape shops, convenience stores, gas stations, and over the Internet; up to 50% of sales are conducted online.24

Fruit flavors are popular

Zhu et al25 estimated that 7,700 unique vaping flavors exist, with fruit and candy flavors predominating. The most popular flavors are tobacco and mint, followed by fruit, dessert and candy flavors, alcoholic flavors (strawberry daiquiri, margarita), and food flavors.25 These flavors have been associated with higher usage in youth, leading to increased risk of nicotine addiction.26

WHAT IS JUUL?

The Juul device (Juul Labs, www.juul.com) was developed in 2015 by 2 Stanford University graduates. Their goal was to produce a more satisfying and cigarette-like vaping experience, specifically by increasing the amount of nicotine delivered while maintaining smooth and pleasant inhalation. They created an e-liquid that could be vaporized effectively at lower temperatures.27

While more than 400 brands of vaping devices are currently available in the United States,3 Juul has held the largest market share since 2017,28 an estimated 72.1% as of August 2018.29 The surge in popularity of this particular brand is attributed to its trendy design that is similar in size and appearance to a USB flash drive,29 and its offering of sweet flavors such as “crème brûlée” and “cool mint.”

On April 24, 2018, in view of growing concern about the popularity of Juul products among youth, the FDA requested that the company submit documents regarding its marketing tactics, as well as research on the effects of this marketing on product design and public health impact, and information about adverse experiences and complaints.30 The company was forced to change its marketing to appeal less to youth. Now it offers only 3 flavors: “Virginia tobacco,” “classic tobacco,” and “menthol,” although off-brand pods containing a variety of flavors are still available. And some pods are refillable, so users can essentially vape any substance they want.

Although the Juul device delivers a strong dose of nicotine, it is small and therefore easy to hide from parents and teachers, and widespread use has been reported among youth in middle and high schools. Hoodies, hemp jewelry, and backpacks have been designed to hide the devices and allow for easy, hands-free use. YouTube searches for terms such as “Juul,” “hiding Juul at school,” and “Juul in class,” yield thousands of results.31 A 2017 survey reported that 8% of Americans age 15 to 24 had used Juul in the month prior to the survey.32 “To juul” has become a verb.

Each Juul starter kit contains the rechargeable inhalation device plus 4 flavored pods. In the United States, each Juul pod contains nearly as much nicotine as 1 pack of 20 cigarettes in a concentration of 3% or 5%. (Israel and Europe have forced the company to replace the 5% nicotine pods with 1.7% nicotine pods.33) A starter kit costs $49.99, and additional packs of 4 flavored liquid cartridges or pods cost $15.99.34 Other brands of vape pens cost between $15 and $35, and 10-mL bottles of e-liquid cost approximately $7.

What is ‘dripping’?

Hard-core vapers seeking a more intense experience are taking their vaping devices apart and modifying them for “dripping,” ie, directly dripping vape liquids onto the heated coils for inhalation. In a survey, 1 in 4 high school students using vape devices also used them for dripping, citing desires for a thicker cloud of vapor, more intense flavor, “a stronger throat hit,” curiosity, and other reasons.35 Dripping involves higher temperatures, which leads to higher amounts of nicotine delivered, along with more formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acetone (see below).36

BAD THINGS IN E-LIQUID AEROSOL

Studies of vape liquids consistently confirm the presence of toxic substances in the resulting vape aerosol.37–40 Depending on the combination of flavorings and solvents in a given e-liquid, a variety of chemicals can be detected in the aerosol from various vaping devices. Chemicals that may be detected include known irritants of respiratory mucosa, as well as various carcinogens. The list includes:

- Organic volatile compounds such as propylene glycol, glycerin, and toluene

- Aldehydes such as formaldehyde (released when propylene glycol is heated to high temperatures), acetaldehyde, and benzaldehyde

- Acetone and acrolein

- Carcinogenic nitrosamines

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- Particulate matter

- Metals including chromium, cadmium, nickel, and lead; and particles of copper, nickel, and silver have been found in electronic nicotine delivery system aerosol in higher levels than in conventional cigarette smoke.41

The specific chemicals detected can vary greatly between brands, even when the flavoring and nicotine content are equivalent, which frequently results in inconsistent and conflicting study findings. The chemicals detected also vary with the voltage or power used to generate the aerosol. Different flavors may carry varying levels of risk; for example, mint- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes were shown to expose users to dangerous levels of pulegone, a carcinogenic compound banned as a food additive in 2018.42 The concentrations of some of these chemicals are sufficiently high to be of toxicologic concern; for example, one study reported the presence of benzaldehyde in e-cigarette aerosol at twice the workplace exposure limit.43

Biologic effects

In an in vitro study,44 57% of e-liquids studied were found to be cytotoxic to human pulmonary fibroblasts, lung epithelial cells, and human embryonic stem cells. Fruit-flavored e-liquids in particular caused a significant increase in DNA fragmentation. Cell cultures treated with e-cigarette liquids showed increased oxidative stress, reduced cell proliferation, and increased DNA damage,44 which may have implications for carcinogenic risk.

In another study,45 exposure to e-cigarette aerosol as well as conventional cigarette smoke resulted in suppression of genes related to immune and inflammatory response in respiratory epithelial cells. All genes with decreased expression after exposure to conventional cigarette smoke also showed decreased expression with exposure to e-cigarette smoke, which the study authors suggested could lead to immune suppression at the level of the nasal mucosa. Diacetyl and acetoin, chemicals found in certain flavorings, have been linked to bronchiolitis obliterans, or “popcorn lung.”46

Nicotine is not benign

The nicotine itself in many vaping liquids should also not be underestimated. Nicotine has harmful neurocognitive effects and addictive properties, particularly in the developing brains of adolescents and young adults.47 Nicotine exposure during adolescence negatively affects memory, attention, and emotional regulation,48 as well as executive functioning, reward processing, and learning.49

The brain undergoes major structural remodeling in adolescence, and nicotine acetylcholine receptors regulate neural maturation. Early exposure to nicotine disrupts this process, leading to poor executive functioning, difficulty learning, decreased memory, and issues with reward processing.

Fetal exposure, if nicotine products are used during pregnancy, has also been linked to adverse consequences such as deficits in attention and cognition, behavioral effects, and sudden infant death syndrome.5

Much to learn about toxicity

Partly because vaping devices have been available to US consumers only since 2007, limited evidence is available regarding the long-term effects of exposure to the aerosol from these devices in humans.1 Many of the studies mentioned above were in vitro studies or conducted in mouse models. Differences in device design and the composition of the e-liquid among device brands pose a challenge for developing well-designed studies of the long-term health effects of e-cigarette and vape use. Additionally, devices may have different health impacts when used to vape cannabis or other drugs besides nicotine, which requires further investigation.

E-CIGARETTES AND SMOKING CESSATION

Conventional cigarette smoking is a major public health threat, as tobacco use is responsible for 480,000 deaths annually in the United States.50

And smoking is extremely difficult to quit: as many as 80% of smokers who attempt to quit resume smoking within the first month.51 The chance of successfully quitting improves by over 50% if the individual undergoes nicotine replacement therapy, and it improves even more with counseling.50

There are currently 5 types of FDA-approved nicotine replacement therapy products (gum, patch, lozenge, inhaler, nasal spray) to help with smoking cessation. In addition, 2 non-nicotine prescription drugs (varenicline and bupropion) have been approved for treating tobacco dependence.

Can vaping devices be added to the list of nicotine replacement therapy products? Although some manufacturers try to brand their devices as smoking cessation aids, in one study,52 one-third of e-cigarette users said they had either never used conventional cigarettes or had formerly smoked them.

Bullen et al53 randomized smokers interested in quitting to receive either e-cigarettes, nicotine patches, or placebo (nicotine-free) e-cigarettes and followed them for 6 months. Rates of tobacco cessation were less than predicted for the entire study population, resulting in insufficient power to determine the superiority of any single method, but the study authors concluded that nicotine e-cigarettes were “modestly effective” at helping smokers quit, and that abstinence rates may be similar to those with nicotine patches.53

Hajek et al54 randomized 886 smokers to e-cigarette or nicotine replacement products of their choice. After 1 year, 18% of e-cigarette users had stopped smoking, compared with 9.9% of nicotine replacement product users. However, 80% of the e-cigarette users were still using e-cigarettes after 1 year, while only 9% of nicotine replacement product users were still using nicotine replacement therapy products after 1 year.