User login

New mobile app assists clinicians in assessing menopausal patients

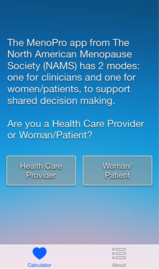

A new mobile app for iPhone and iPad enables both clinicians and patients to make decisions about menopausal therapies for moderate to severe hot flashes, night sweats, and/or genitourinary symptoms. The app also aids in assessing the patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and fracture.

|

|

|

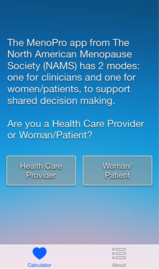

The MenoPro app, developed in association with the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), is available free of charge from Apple. The app is designed to aid in the assessment and management of bothersome menopausal symptoms in women aged 45 and older.

Designed for both clinician and patient

A novel feature of the app is its two modes—one for the clinician and another for the patient. The clinician mode enables risk assessment and decision-making to determine whether hormonal therapy might be indicated and to determine the formulation and dosage of the therapy selected. It also features assessment of the patient’s 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease, her risk of breast cancer using the Gail model, and her fracture risk using the FRAX tool. When hormonal therapies are not appropriate, the app steers the clinician to nonhormonal options.

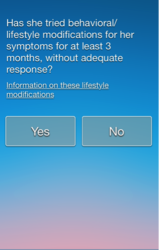

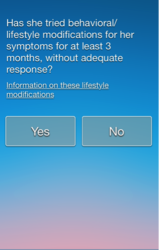

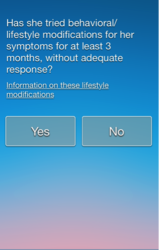

The patient can make use of the app to learn about her different treatment options, including lifestyle modifications. The app guides her through a self-assessment to gauge how far along she is in the menopausal transition, the severity of her symptoms, and her interest in hormonal or nonhormonal therapy. The app begins by recommending lifestyle changes and behavioral factors that can reduce menopausal symptoms. After a 3-month trial of these modifications, the patient is prompted to visit her health-care provider if further relief is needed.

Only FDA-approved drugs are recommended

“The app is completely up to date in terms of information about the newest medications that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration,” says JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, current chair of the NAMS Scientific Program and a past president of NAMS. Dr. Manson is Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She also is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health at Harvard Medical School.

“The app focuses on FDA-approved medications, including off-label use of medications that may be commonly prescribed in practice to treat hot flashes, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs),” she says.

“I think another big advantage is that very often clinicians who are managing patients during the menopausal transition or in early menopause may not be thinking that much about cardiovascular risk or even know how to evaluate it or make use of a 10-year risk score. So the app really helps them to become very familiar with the evaluation of cardiovascular risk, breast cancer risk, and fracture risk, and provides them with the resources to make use of the information.”

An algorithm is available within the app

The app is based on an algorithm that can be accessed within the app by choosing the “About” button. Another feature: the clinician can email a summary of the patient’s assessment directly to her, along with links to resources on a variety of relevant topics.

“In the future, there is a plan to have the app available for other mobile phones and tablet devices in addition to the iPhone and iPad,” says Dr. Manson. “We also hope to have it incorporated into electronic health records, where it could be used for clinical decision-making within the record.”

The app is not intended to replace clinical judgment, she adds. “I think clinicians are really familiar with the concept that, when you’re using an app, clinical judgment remains paramount. The app is not going to replace the clinician’s own discernment of what is going on with the patient.”

For detailed information, see an article on the app in the journal Menopause, available at http://www.menopause.org/docs/default-source/professional/our-new-paper.pdf

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A new mobile app for iPhone and iPad enables both clinicians and patients to make decisions about menopausal therapies for moderate to severe hot flashes, night sweats, and/or genitourinary symptoms. The app also aids in assessing the patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and fracture.

|

|

|

The MenoPro app, developed in association with the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), is available free of charge from Apple. The app is designed to aid in the assessment and management of bothersome menopausal symptoms in women aged 45 and older.

Designed for both clinician and patient

A novel feature of the app is its two modes—one for the clinician and another for the patient. The clinician mode enables risk assessment and decision-making to determine whether hormonal therapy might be indicated and to determine the formulation and dosage of the therapy selected. It also features assessment of the patient’s 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease, her risk of breast cancer using the Gail model, and her fracture risk using the FRAX tool. When hormonal therapies are not appropriate, the app steers the clinician to nonhormonal options.

The patient can make use of the app to learn about her different treatment options, including lifestyle modifications. The app guides her through a self-assessment to gauge how far along she is in the menopausal transition, the severity of her symptoms, and her interest in hormonal or nonhormonal therapy. The app begins by recommending lifestyle changes and behavioral factors that can reduce menopausal symptoms. After a 3-month trial of these modifications, the patient is prompted to visit her health-care provider if further relief is needed.

Only FDA-approved drugs are recommended

“The app is completely up to date in terms of information about the newest medications that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration,” says JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, current chair of the NAMS Scientific Program and a past president of NAMS. Dr. Manson is Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She also is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health at Harvard Medical School.

“The app focuses on FDA-approved medications, including off-label use of medications that may be commonly prescribed in practice to treat hot flashes, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs),” she says.

“I think another big advantage is that very often clinicians who are managing patients during the menopausal transition or in early menopause may not be thinking that much about cardiovascular risk or even know how to evaluate it or make use of a 10-year risk score. So the app really helps them to become very familiar with the evaluation of cardiovascular risk, breast cancer risk, and fracture risk, and provides them with the resources to make use of the information.”

An algorithm is available within the app

The app is based on an algorithm that can be accessed within the app by choosing the “About” button. Another feature: the clinician can email a summary of the patient’s assessment directly to her, along with links to resources on a variety of relevant topics.

“In the future, there is a plan to have the app available for other mobile phones and tablet devices in addition to the iPhone and iPad,” says Dr. Manson. “We also hope to have it incorporated into electronic health records, where it could be used for clinical decision-making within the record.”

The app is not intended to replace clinical judgment, she adds. “I think clinicians are really familiar with the concept that, when you’re using an app, clinical judgment remains paramount. The app is not going to replace the clinician’s own discernment of what is going on with the patient.”

For detailed information, see an article on the app in the journal Menopause, available at http://www.menopause.org/docs/default-source/professional/our-new-paper.pdf

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A new mobile app for iPhone and iPad enables both clinicians and patients to make decisions about menopausal therapies for moderate to severe hot flashes, night sweats, and/or genitourinary symptoms. The app also aids in assessing the patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and fracture.

|

|

|

The MenoPro app, developed in association with the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), is available free of charge from Apple. The app is designed to aid in the assessment and management of bothersome menopausal symptoms in women aged 45 and older.

Designed for both clinician and patient

A novel feature of the app is its two modes—one for the clinician and another for the patient. The clinician mode enables risk assessment and decision-making to determine whether hormonal therapy might be indicated and to determine the formulation and dosage of the therapy selected. It also features assessment of the patient’s 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease, her risk of breast cancer using the Gail model, and her fracture risk using the FRAX tool. When hormonal therapies are not appropriate, the app steers the clinician to nonhormonal options.

The patient can make use of the app to learn about her different treatment options, including lifestyle modifications. The app guides her through a self-assessment to gauge how far along she is in the menopausal transition, the severity of her symptoms, and her interest in hormonal or nonhormonal therapy. The app begins by recommending lifestyle changes and behavioral factors that can reduce menopausal symptoms. After a 3-month trial of these modifications, the patient is prompted to visit her health-care provider if further relief is needed.

Only FDA-approved drugs are recommended

“The app is completely up to date in terms of information about the newest medications that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration,” says JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, current chair of the NAMS Scientific Program and a past president of NAMS. Dr. Manson is Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She also is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health at Harvard Medical School.

“The app focuses on FDA-approved medications, including off-label use of medications that may be commonly prescribed in practice to treat hot flashes, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs),” she says.

“I think another big advantage is that very often clinicians who are managing patients during the menopausal transition or in early menopause may not be thinking that much about cardiovascular risk or even know how to evaluate it or make use of a 10-year risk score. So the app really helps them to become very familiar with the evaluation of cardiovascular risk, breast cancer risk, and fracture risk, and provides them with the resources to make use of the information.”

An algorithm is available within the app

The app is based on an algorithm that can be accessed within the app by choosing the “About” button. Another feature: the clinician can email a summary of the patient’s assessment directly to her, along with links to resources on a variety of relevant topics.

“In the future, there is a plan to have the app available for other mobile phones and tablet devices in addition to the iPhone and iPad,” says Dr. Manson. “We also hope to have it incorporated into electronic health records, where it could be used for clinical decision-making within the record.”

The app is not intended to replace clinical judgment, she adds. “I think clinicians are really familiar with the concept that, when you’re using an app, clinical judgment remains paramount. The app is not going to replace the clinician’s own discernment of what is going on with the patient.”

For detailed information, see an article on the app in the journal Menopause, available at http://www.menopause.org/docs/default-source/professional/our-new-paper.pdf

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Conjugated estrogen plus bazedoxifene—a new approach to estrogen therapy

In this special installment of Cases in Menopause, I interview series contributor and menopause expert JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD. We discuss a fairly new therapy: the combination conjugated estrogen and bazedoxifene (CE/BZA; Duavee) for the treatment of moderate to severe hot flashes due to menopause and the prevention of menopausal osteoporosis.

Much of my practice has focused on the treatment of menopausal women, but which of my patients can benefit from this particular combination of CE 0.45 mg plus BZA 20 mg? I asked Dr. Pinkerton this question, and more.

Which patients can benefit most?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA was tested in healthy postmenopausal women with a uterus at risk for bone loss who were reporting 50 or more moderate to severe hot flashes per week. The combination of CE and BZA is a good choice for women who have bothersome menopausal symptoms: hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruption or symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)—although it’s not approved for VVA.

Efficacy and safety data show that compared with placebo:

- CE/BZA decreases the frequency and severity of hot flashes at 12 weeks, and those decreases are maintained at 12 months.1,2

- Women taking CE/BZA have greater improvements in sleep, with both decreased sleep disturbance and time to fall asleep.3

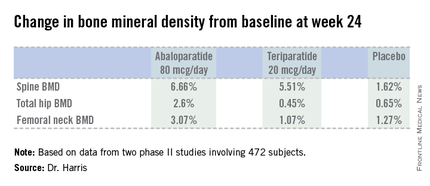

- CE/BZA maintained or prevented lumbar spine and hip bone loss in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis. 1,4,5

Although fracture data were not captured and the drug was not tested in osteoporotic women, study results showed bone loss prevention at 12 months, which was sustained at 24 months. The improvement in bone mineral density from baseline was about 1% to 1.5%. This was compared with a bone loss of 1.8% in women taking placebo (P<.01).

In clinical studies, women taking CE/BZA versus placebo also have reported a lower incidence of painful intercourse,6 and some improvement in health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction.7,8

In short, CE/BZA is a good option for symptomatic menopausal women with a uterus who have bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruptions and want to prevent bone loss.

What about adverse effects?

Dr. Pinkerton In general, CE/BZA has a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with an overall incidence of adverse events similar to placebo. The rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, cancers (breast, endometrial, and ovarian), and mortality are comparable to placebo in 2-year trials. These data are limited; studies have been conducted in healthy postmenopausal women. Future studies need to define the full risk profile, particularly among overweight or obese women and different ethnic groups and for longer-term use.

Is there a role among women with breast cancer?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has not been tested in women at risk for or with prior breast cancer. In preclinical trials of up to 2 years, involving healthy postmenopausal women, the rates for breast cancer with CE/BZA were similar to placebo. There are no long-term data, however, and there are no data in women at risk for breast cancer. I recommend that women who have or are at high risk for breast cancer consider nonhormonal treatment options.9–11

Has there been an associated increase in breast density with CE/BZA?

Dr. Pinkerton No. Data from two randomized clinical trials showed that the breast density changes with 12-month CE/BZA treatment was similar to placebo—which is markedly different from comparisons of placebo and combination estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT), where EPT increased breast density. If indeed this lack of an association translates into fewer breast cancers, it would be wonderful, but we do not have long-term data. We can tell our patients that using CE/BZA has not been shown to increase the risk of breast cancer, at least up to 2 years.

What makes CE/BZA different from traditional EPT?

Dr. Pinkerton There are two exciting differences:

- The incidences of breast pain and tenderness were found to be similar to placebo, and were significantly less than those with the comparator EPT (conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate [CE/MPA] 1.5 mg).9,10,12

- Bleeding and spotting rates were significantly less than those found with CE/MPA.13

In addition, high rates of amenorrhea have been found—comparable to placebo.13

CE/BZA is similar to traditional EPT in several ways. For instance, compared with placebo, at 2 years, CE/BZA was not found to increase the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial thickness (increase from baseline was <1 mm and comparable to placebo), or endometrial cancers.14 Lastly, similar to EPT, there is probably a twofold risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with BZA 20 mg alone.15 Importantly, there has been no additive effect on VTE risk when combining CE with BZA; however, we will need longer studies, in older women, to fully evaluate this risk.1

Overall, in symptomatic postmenopausal women with a uterus, randomized controlled data show the same improvement with CE/BZA as that seen with traditional oral EPTs, with improvements in hot flashes; night sweats, with fewer sleep disruptions; and prevention of bone loss. In addition, the changes in cholesterol (an increase in triglyceride levels) and effect on the vagina are the same. Yet, CE/BZA appears to have a neutral effect on the breast and protects against endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer without causing bleeding.9,10 CE/BZA’s VTE and stroke risks are expected to be similar to traditional oral EPT.

Therefore, the major benefit of CE/BZA for women who have a uterus is the lack of significant breast tenderness, lack of changes in breast density, and lack of vaginal bleeding that is often seen with traditional EPT.12

Then, is progestogen the harmful agent in traditional HT options?

Dr. Pinkerton There is evidence that estrogen plus progestogen therapy has more risk for breast cancer than estrogen alone. But in women who have a uterus, you need to protect against uterine cancer so, up until now, the only option was to add progestogen. Some studies suggest the risk of breast cancer may differ depending on the type of progestogen. So it’s a laudable goal to try to protect the endometrium without using a progestogen.

Given its safety profile, do you see CE/BZA being indicated for women without a uterus?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has been tested only in women with a uterus; there is no indication for using it in hysterectomized women. In the future, unless trial data show a benefit to hysterectomized women—by a reduction in breast cancer compared with estrogen alone—there would be no reason to add BZA to the CE for these women. You would just use CE or another type of estrogen alone.

Do you anticipate BZA being used alone?

Dr. Pinkerton For treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased fracture risk, BZA alone has greater benefits than risks. It is approved in other countries to prevent or treat osteoporosis. In 2008, Wyeth received an approval letter from the US Food and Drug Administration for BZA alone but, for whatever reason, the drug was not brought to market. BZA reduces the number of new lumbar spine fractures by 4% (vs 2% for placebo), with efficacy better in those with a higher risk of fractures. Like raloxifene, it has not been shown effective at reducing nonvertebral fractures, although it maintains spinal bone density.16

BZA available as monotherapy could tempt clinicians to pair it with other estrogens. We must recognize that the combination of the specific estrogen and BZA dose and type need to be balanced to provide endometrial hyperplasia protection. It would not be safe or effective to take BZA as a selective estrogen-receptor modulator and pair it with any other untested systemic estrogen. I do not anticipate, in this country, that BZA will become available as monotherapy.

New options are welcome

Dr. Moore Novel strategies for clinicians to optimally treat menopausal symptoms are always welcome. I look forward to more data from the SMART trials on CE/BZA and to moving forward as we gain experience with using this new treatment option.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic bone parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

2. Pinkerton JV, Utian WH, Constantine GD, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Relief of vasomotor symptoms with the tissue-selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2009;16:(6)1116–1124.

3. Pinkerton JV, Pan K, Abraham L, et al. Sleep parameters and health-related quality of life with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2014;21(3):252–259.

4. Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, Pickar JH, Constantine G. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1045–1052.

5. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

6. Kagan R, Williams RS, Pan K, Mirkin S, Pickar JH. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(2):281–289.

7. Utian W, Yu H, Bobula J, Mirkin S, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2009;63:(4)329–335.

8. Abraham L, Pinkerton JV, Messig M, Ryan KA, Komm BS, Mirkin S. Menopause-specific quality of life across varying menopausal populations with conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene. Maturitas. 2014;78(3):212–218.

9. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20:(2)138–145.

10. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

11. Kaunitz AM. When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):59–65.

12. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15:(5)411–418.

13. Archer DF, Lewis V, Carr BR, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE): incidence of uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1039–1044.

14. Pickar JH, Yeh I-T, Bachmann G, Speroff L. Endometrial effects of a tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a menopausal therapy. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3):1018–1024.

15. Mirkin S, Komm BS. Tissue-selective estrogen complexes for postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2013;76(3):213–220.

16. Ellis AG, Reginster JY, Luo X, et al. Bazedoxifene versus oral bisphosphonates for the prevention of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at higher risk of fracture. Value Health. 2014;17(4):424–432.

In this special installment of Cases in Menopause, I interview series contributor and menopause expert JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD. We discuss a fairly new therapy: the combination conjugated estrogen and bazedoxifene (CE/BZA; Duavee) for the treatment of moderate to severe hot flashes due to menopause and the prevention of menopausal osteoporosis.

Much of my practice has focused on the treatment of menopausal women, but which of my patients can benefit from this particular combination of CE 0.45 mg plus BZA 20 mg? I asked Dr. Pinkerton this question, and more.

Which patients can benefit most?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA was tested in healthy postmenopausal women with a uterus at risk for bone loss who were reporting 50 or more moderate to severe hot flashes per week. The combination of CE and BZA is a good choice for women who have bothersome menopausal symptoms: hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruption or symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)—although it’s not approved for VVA.

Efficacy and safety data show that compared with placebo:

- CE/BZA decreases the frequency and severity of hot flashes at 12 weeks, and those decreases are maintained at 12 months.1,2

- Women taking CE/BZA have greater improvements in sleep, with both decreased sleep disturbance and time to fall asleep.3

- CE/BZA maintained or prevented lumbar spine and hip bone loss in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis. 1,4,5

Although fracture data were not captured and the drug was not tested in osteoporotic women, study results showed bone loss prevention at 12 months, which was sustained at 24 months. The improvement in bone mineral density from baseline was about 1% to 1.5%. This was compared with a bone loss of 1.8% in women taking placebo (P<.01).

In clinical studies, women taking CE/BZA versus placebo also have reported a lower incidence of painful intercourse,6 and some improvement in health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction.7,8

In short, CE/BZA is a good option for symptomatic menopausal women with a uterus who have bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruptions and want to prevent bone loss.

What about adverse effects?

Dr. Pinkerton In general, CE/BZA has a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with an overall incidence of adverse events similar to placebo. The rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, cancers (breast, endometrial, and ovarian), and mortality are comparable to placebo in 2-year trials. These data are limited; studies have been conducted in healthy postmenopausal women. Future studies need to define the full risk profile, particularly among overweight or obese women and different ethnic groups and for longer-term use.

Is there a role among women with breast cancer?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has not been tested in women at risk for or with prior breast cancer. In preclinical trials of up to 2 years, involving healthy postmenopausal women, the rates for breast cancer with CE/BZA were similar to placebo. There are no long-term data, however, and there are no data in women at risk for breast cancer. I recommend that women who have or are at high risk for breast cancer consider nonhormonal treatment options.9–11

Has there been an associated increase in breast density with CE/BZA?

Dr. Pinkerton No. Data from two randomized clinical trials showed that the breast density changes with 12-month CE/BZA treatment was similar to placebo—which is markedly different from comparisons of placebo and combination estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT), where EPT increased breast density. If indeed this lack of an association translates into fewer breast cancers, it would be wonderful, but we do not have long-term data. We can tell our patients that using CE/BZA has not been shown to increase the risk of breast cancer, at least up to 2 years.

What makes CE/BZA different from traditional EPT?

Dr. Pinkerton There are two exciting differences:

- The incidences of breast pain and tenderness were found to be similar to placebo, and were significantly less than those with the comparator EPT (conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate [CE/MPA] 1.5 mg).9,10,12

- Bleeding and spotting rates were significantly less than those found with CE/MPA.13

In addition, high rates of amenorrhea have been found—comparable to placebo.13

CE/BZA is similar to traditional EPT in several ways. For instance, compared with placebo, at 2 years, CE/BZA was not found to increase the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial thickness (increase from baseline was <1 mm and comparable to placebo), or endometrial cancers.14 Lastly, similar to EPT, there is probably a twofold risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with BZA 20 mg alone.15 Importantly, there has been no additive effect on VTE risk when combining CE with BZA; however, we will need longer studies, in older women, to fully evaluate this risk.1

Overall, in symptomatic postmenopausal women with a uterus, randomized controlled data show the same improvement with CE/BZA as that seen with traditional oral EPTs, with improvements in hot flashes; night sweats, with fewer sleep disruptions; and prevention of bone loss. In addition, the changes in cholesterol (an increase in triglyceride levels) and effect on the vagina are the same. Yet, CE/BZA appears to have a neutral effect on the breast and protects against endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer without causing bleeding.9,10 CE/BZA’s VTE and stroke risks are expected to be similar to traditional oral EPT.

Therefore, the major benefit of CE/BZA for women who have a uterus is the lack of significant breast tenderness, lack of changes in breast density, and lack of vaginal bleeding that is often seen with traditional EPT.12

Then, is progestogen the harmful agent in traditional HT options?

Dr. Pinkerton There is evidence that estrogen plus progestogen therapy has more risk for breast cancer than estrogen alone. But in women who have a uterus, you need to protect against uterine cancer so, up until now, the only option was to add progestogen. Some studies suggest the risk of breast cancer may differ depending on the type of progestogen. So it’s a laudable goal to try to protect the endometrium without using a progestogen.

Given its safety profile, do you see CE/BZA being indicated for women without a uterus?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has been tested only in women with a uterus; there is no indication for using it in hysterectomized women. In the future, unless trial data show a benefit to hysterectomized women—by a reduction in breast cancer compared with estrogen alone—there would be no reason to add BZA to the CE for these women. You would just use CE or another type of estrogen alone.

Do you anticipate BZA being used alone?

Dr. Pinkerton For treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased fracture risk, BZA alone has greater benefits than risks. It is approved in other countries to prevent or treat osteoporosis. In 2008, Wyeth received an approval letter from the US Food and Drug Administration for BZA alone but, for whatever reason, the drug was not brought to market. BZA reduces the number of new lumbar spine fractures by 4% (vs 2% for placebo), with efficacy better in those with a higher risk of fractures. Like raloxifene, it has not been shown effective at reducing nonvertebral fractures, although it maintains spinal bone density.16

BZA available as monotherapy could tempt clinicians to pair it with other estrogens. We must recognize that the combination of the specific estrogen and BZA dose and type need to be balanced to provide endometrial hyperplasia protection. It would not be safe or effective to take BZA as a selective estrogen-receptor modulator and pair it with any other untested systemic estrogen. I do not anticipate, in this country, that BZA will become available as monotherapy.

New options are welcome

Dr. Moore Novel strategies for clinicians to optimally treat menopausal symptoms are always welcome. I look forward to more data from the SMART trials on CE/BZA and to moving forward as we gain experience with using this new treatment option.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this special installment of Cases in Menopause, I interview series contributor and menopause expert JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD. We discuss a fairly new therapy: the combination conjugated estrogen and bazedoxifene (CE/BZA; Duavee) for the treatment of moderate to severe hot flashes due to menopause and the prevention of menopausal osteoporosis.

Much of my practice has focused on the treatment of menopausal women, but which of my patients can benefit from this particular combination of CE 0.45 mg plus BZA 20 mg? I asked Dr. Pinkerton this question, and more.

Which patients can benefit most?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA was tested in healthy postmenopausal women with a uterus at risk for bone loss who were reporting 50 or more moderate to severe hot flashes per week. The combination of CE and BZA is a good choice for women who have bothersome menopausal symptoms: hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruption or symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)—although it’s not approved for VVA.

Efficacy and safety data show that compared with placebo:

- CE/BZA decreases the frequency and severity of hot flashes at 12 weeks, and those decreases are maintained at 12 months.1,2

- Women taking CE/BZA have greater improvements in sleep, with both decreased sleep disturbance and time to fall asleep.3

- CE/BZA maintained or prevented lumbar spine and hip bone loss in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis. 1,4,5

Although fracture data were not captured and the drug was not tested in osteoporotic women, study results showed bone loss prevention at 12 months, which was sustained at 24 months. The improvement in bone mineral density from baseline was about 1% to 1.5%. This was compared with a bone loss of 1.8% in women taking placebo (P<.01).

In clinical studies, women taking CE/BZA versus placebo also have reported a lower incidence of painful intercourse,6 and some improvement in health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction.7,8

In short, CE/BZA is a good option for symptomatic menopausal women with a uterus who have bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruptions and want to prevent bone loss.

What about adverse effects?

Dr. Pinkerton In general, CE/BZA has a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with an overall incidence of adverse events similar to placebo. The rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, cancers (breast, endometrial, and ovarian), and mortality are comparable to placebo in 2-year trials. These data are limited; studies have been conducted in healthy postmenopausal women. Future studies need to define the full risk profile, particularly among overweight or obese women and different ethnic groups and for longer-term use.

Is there a role among women with breast cancer?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has not been tested in women at risk for or with prior breast cancer. In preclinical trials of up to 2 years, involving healthy postmenopausal women, the rates for breast cancer with CE/BZA were similar to placebo. There are no long-term data, however, and there are no data in women at risk for breast cancer. I recommend that women who have or are at high risk for breast cancer consider nonhormonal treatment options.9–11

Has there been an associated increase in breast density with CE/BZA?

Dr. Pinkerton No. Data from two randomized clinical trials showed that the breast density changes with 12-month CE/BZA treatment was similar to placebo—which is markedly different from comparisons of placebo and combination estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT), where EPT increased breast density. If indeed this lack of an association translates into fewer breast cancers, it would be wonderful, but we do not have long-term data. We can tell our patients that using CE/BZA has not been shown to increase the risk of breast cancer, at least up to 2 years.

What makes CE/BZA different from traditional EPT?

Dr. Pinkerton There are two exciting differences:

- The incidences of breast pain and tenderness were found to be similar to placebo, and were significantly less than those with the comparator EPT (conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate [CE/MPA] 1.5 mg).9,10,12

- Bleeding and spotting rates were significantly less than those found with CE/MPA.13

In addition, high rates of amenorrhea have been found—comparable to placebo.13

CE/BZA is similar to traditional EPT in several ways. For instance, compared with placebo, at 2 years, CE/BZA was not found to increase the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial thickness (increase from baseline was <1 mm and comparable to placebo), or endometrial cancers.14 Lastly, similar to EPT, there is probably a twofold risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with BZA 20 mg alone.15 Importantly, there has been no additive effect on VTE risk when combining CE with BZA; however, we will need longer studies, in older women, to fully evaluate this risk.1

Overall, in symptomatic postmenopausal women with a uterus, randomized controlled data show the same improvement with CE/BZA as that seen with traditional oral EPTs, with improvements in hot flashes; night sweats, with fewer sleep disruptions; and prevention of bone loss. In addition, the changes in cholesterol (an increase in triglyceride levels) and effect on the vagina are the same. Yet, CE/BZA appears to have a neutral effect on the breast and protects against endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer without causing bleeding.9,10 CE/BZA’s VTE and stroke risks are expected to be similar to traditional oral EPT.

Therefore, the major benefit of CE/BZA for women who have a uterus is the lack of significant breast tenderness, lack of changes in breast density, and lack of vaginal bleeding that is often seen with traditional EPT.12

Then, is progestogen the harmful agent in traditional HT options?

Dr. Pinkerton There is evidence that estrogen plus progestogen therapy has more risk for breast cancer than estrogen alone. But in women who have a uterus, you need to protect against uterine cancer so, up until now, the only option was to add progestogen. Some studies suggest the risk of breast cancer may differ depending on the type of progestogen. So it’s a laudable goal to try to protect the endometrium without using a progestogen.

Given its safety profile, do you see CE/BZA being indicated for women without a uterus?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has been tested only in women with a uterus; there is no indication for using it in hysterectomized women. In the future, unless trial data show a benefit to hysterectomized women—by a reduction in breast cancer compared with estrogen alone—there would be no reason to add BZA to the CE for these women. You would just use CE or another type of estrogen alone.

Do you anticipate BZA being used alone?

Dr. Pinkerton For treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased fracture risk, BZA alone has greater benefits than risks. It is approved in other countries to prevent or treat osteoporosis. In 2008, Wyeth received an approval letter from the US Food and Drug Administration for BZA alone but, for whatever reason, the drug was not brought to market. BZA reduces the number of new lumbar spine fractures by 4% (vs 2% for placebo), with efficacy better in those with a higher risk of fractures. Like raloxifene, it has not been shown effective at reducing nonvertebral fractures, although it maintains spinal bone density.16

BZA available as monotherapy could tempt clinicians to pair it with other estrogens. We must recognize that the combination of the specific estrogen and BZA dose and type need to be balanced to provide endometrial hyperplasia protection. It would not be safe or effective to take BZA as a selective estrogen-receptor modulator and pair it with any other untested systemic estrogen. I do not anticipate, in this country, that BZA will become available as monotherapy.

New options are welcome

Dr. Moore Novel strategies for clinicians to optimally treat menopausal symptoms are always welcome. I look forward to more data from the SMART trials on CE/BZA and to moving forward as we gain experience with using this new treatment option.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic bone parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

2. Pinkerton JV, Utian WH, Constantine GD, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Relief of vasomotor symptoms with the tissue-selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2009;16:(6)1116–1124.

3. Pinkerton JV, Pan K, Abraham L, et al. Sleep parameters and health-related quality of life with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2014;21(3):252–259.

4. Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, Pickar JH, Constantine G. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1045–1052.

5. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

6. Kagan R, Williams RS, Pan K, Mirkin S, Pickar JH. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(2):281–289.

7. Utian W, Yu H, Bobula J, Mirkin S, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2009;63:(4)329–335.

8. Abraham L, Pinkerton JV, Messig M, Ryan KA, Komm BS, Mirkin S. Menopause-specific quality of life across varying menopausal populations with conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene. Maturitas. 2014;78(3):212–218.

9. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20:(2)138–145.

10. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

11. Kaunitz AM. When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):59–65.

12. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15:(5)411–418.

13. Archer DF, Lewis V, Carr BR, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE): incidence of uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1039–1044.

14. Pickar JH, Yeh I-T, Bachmann G, Speroff L. Endometrial effects of a tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a menopausal therapy. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3):1018–1024.

15. Mirkin S, Komm BS. Tissue-selective estrogen complexes for postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2013;76(3):213–220.

16. Ellis AG, Reginster JY, Luo X, et al. Bazedoxifene versus oral bisphosphonates for the prevention of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at higher risk of fracture. Value Health. 2014;17(4):424–432.

1. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic bone parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

2. Pinkerton JV, Utian WH, Constantine GD, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Relief of vasomotor symptoms with the tissue-selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2009;16:(6)1116–1124.

3. Pinkerton JV, Pan K, Abraham L, et al. Sleep parameters and health-related quality of life with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2014;21(3):252–259.

4. Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, Pickar JH, Constantine G. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1045–1052.

5. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

6. Kagan R, Williams RS, Pan K, Mirkin S, Pickar JH. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(2):281–289.

7. Utian W, Yu H, Bobula J, Mirkin S, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2009;63:(4)329–335.

8. Abraham L, Pinkerton JV, Messig M, Ryan KA, Komm BS, Mirkin S. Menopause-specific quality of life across varying menopausal populations with conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene. Maturitas. 2014;78(3):212–218.

9. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20:(2)138–145.

10. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

11. Kaunitz AM. When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):59–65.

12. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15:(5)411–418.

13. Archer DF, Lewis V, Carr BR, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE): incidence of uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1039–1044.

14. Pickar JH, Yeh I-T, Bachmann G, Speroff L. Endometrial effects of a tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a menopausal therapy. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3):1018–1024.

15. Mirkin S, Komm BS. Tissue-selective estrogen complexes for postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2013;76(3):213–220.

16. Ellis AG, Reginster JY, Luo X, et al. Bazedoxifene versus oral bisphosphonates for the prevention of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at higher risk of fracture. Value Health. 2014;17(4):424–432.

After 3-year stumble, new weight-loss drug wins FDA approval

After a delay of more than 3 years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved the nation’s third weight-loss drug, a combination of naltrexone and bupropion.

The extended release tablets (Contrave; Orexigen and Takeda) are approved for use in adults who have a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, or those with a BMI of at least 27 kg/m2 and at least one additional weight-related condition such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia. The agency recommended that Contrave be used in addition to caloric restriction and increased physical activity.

Dr. Timothy Garvey, chair of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ scientific committee, lauded the approval.

"We have a new tool now to treat obesity – and that is very good news," he said in an interview.

He said Contrave will be a valuable addition to the existing weight-loss medications: the phentermine/topiramate combo (Qsymia; Vivus) and lorcaserin (Belviq; Arena).

"There are no head-to-head trials with the other drugs, so we really can’t say much about relative efficacy," said Dr. Garvey. "But when you look at the placebo-subtracted weight loss in all the phase III data, it looks like Contrave is in the middle, with about a 6% loss over lifestyle interventions alone. So it’s not as effective as the topiramate combination, but more effective than lorcaserin."

In the pivotal, 56-week phase III trials, those taking Contrave lost 5%-8% of their baseline body weight, compared with a loss of 1%-2% in those on placebo. The proportion of those who lost at least 5% of their baseline body weight ranged from 45%-56% of those on the proposed dose, compared with 16%-43% of those on placebo.

The FDA guidance on weight-loss drugs suggests a 12-week efficacy evaluation – if the patient has not lost at least 5% of total body weight by then, the drug should be discontinued and another started.

It’s not possible to predict who will respond best to which drug, although there are some things to consider when choosing, said Dr. Garvey, who is chair of the department of nutrition at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

"For example, women of childbearing age need to take precautions against becoming pregnant if they take the topiramate combination, and should stop it right away if they do become pregnant. And since lorcaserin is a serotonergic drug, it has to be used very cautiously in patients who are on other serotonergic medications. We definitely need more safety data there."

Additionally, none of the weight-loss drugs should be used in children or teens until more studies confirm their safety for those patients, "All of the companies are planning these trials, and we hope they will complete them expeditiously," Dr. Garvey said. "Childhood and adolescent obesity is a huge problem, and we really need some good treatment options there."

Because it contains bupropion, an antidepressant that has been associated with an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and actions, the drug carries a black box warning. Bupropion is also known to lower seizure threshold, so the drug should not be used in patients with seizure disorders. If a seizure occurs while taking on the medication, it should be permanently discontinued. Nor should it be used in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Orexigen and Takeda originally brought the drug forward in December 2011. It was not approved at that time because of concerns about its effect on blood pressure – an unexpected move, and one that Orexigen management called "a big setback."

About a quarter of those in the 56-week pivotal phase III trial experienced significant blood pressure increases of at least 10% above their baseline, compared with about 20% of those in the control arm. Increases of diastolic blood pressure of at least 5 mm Hg over baseline occurred in 37% of those on the combination, compared with 29% of those on placebo. About a quarter in the active arm also had heart rate increases of at least 10 beats per minute, compared with 19% of those taking placebo.

Because of these concerns, the FDA required the drug companies to conduct a large, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to investigate the risk of major cardiovascular events. Takeda and Orexigen then launched the 4-year, 8,900 patient Light study, which is still ongoing. Endpoints are major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke) in overweight and obese subjects who have concomitant diabetes and/or other cardiovascular risk factors.

In June, citing encouraging preliminary results, Takeda and Orexigen brought Contrave to the FDA once more – only to be shot down again, at least temporarily. The agency required a review extension in order to come to agreement on the final form of postmarketing surveillance, said Denise Powell, a spokeswoman for Orexigen.

"At that time, FDA said the data looked good," she said in an interview. "We just needed more time to work out the postmarketing requirements."

Those will include:

• A cardiovascular outcomes trial to assess the cardiovascular risk associated with Contrave use.

• Two efficacy, safety, and clinical pharmacology studies in pediatric patients (one in patients 12-17 years old, and one in patients 7-11 years old).

• A juvenile animal toxicity study with a particular focus on growth and development as well as behavior, learning, and memory.

• A cardiac conduction study.

• Clinical trials to evaluate dosing in patients with hepatic or renal impairment.

• A clinical trial to evaluate the potential for interactions between the medication and other drugs.

Contrave contains an extended-release formulation of 8 mg naltrexone and 90 mg bupropion. It is to be administered in an in a 4-week upward titration schedule, with a single morning tablet during week 1; a single tablet at morning and evening during week 2; two tablets in the morning and one in the evening during week 3; and two tablets both morning and evening from week 4 and onward.

Dr. Garvey is a consultant for Daiichi Sankyo, LipoScience, Takeda, Vivus, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Eisai, and Novo Nordisk. He has received research funding from Merck, AstraZeneca, Weight Watchers, Eisai, and Sanofi.

On Twitter @alz_gal

After a delay of more than 3 years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved the nation’s third weight-loss drug, a combination of naltrexone and bupropion.

The extended release tablets (Contrave; Orexigen and Takeda) are approved for use in adults who have a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, or those with a BMI of at least 27 kg/m2 and at least one additional weight-related condition such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia. The agency recommended that Contrave be used in addition to caloric restriction and increased physical activity.

Dr. Timothy Garvey, chair of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ scientific committee, lauded the approval.

"We have a new tool now to treat obesity – and that is very good news," he said in an interview.

He said Contrave will be a valuable addition to the existing weight-loss medications: the phentermine/topiramate combo (Qsymia; Vivus) and lorcaserin (Belviq; Arena).

"There are no head-to-head trials with the other drugs, so we really can’t say much about relative efficacy," said Dr. Garvey. "But when you look at the placebo-subtracted weight loss in all the phase III data, it looks like Contrave is in the middle, with about a 6% loss over lifestyle interventions alone. So it’s not as effective as the topiramate combination, but more effective than lorcaserin."

In the pivotal, 56-week phase III trials, those taking Contrave lost 5%-8% of their baseline body weight, compared with a loss of 1%-2% in those on placebo. The proportion of those who lost at least 5% of their baseline body weight ranged from 45%-56% of those on the proposed dose, compared with 16%-43% of those on placebo.

The FDA guidance on weight-loss drugs suggests a 12-week efficacy evaluation – if the patient has not lost at least 5% of total body weight by then, the drug should be discontinued and another started.

It’s not possible to predict who will respond best to which drug, although there are some things to consider when choosing, said Dr. Garvey, who is chair of the department of nutrition at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

"For example, women of childbearing age need to take precautions against becoming pregnant if they take the topiramate combination, and should stop it right away if they do become pregnant. And since lorcaserin is a serotonergic drug, it has to be used very cautiously in patients who are on other serotonergic medications. We definitely need more safety data there."

Additionally, none of the weight-loss drugs should be used in children or teens until more studies confirm their safety for those patients, "All of the companies are planning these trials, and we hope they will complete them expeditiously," Dr. Garvey said. "Childhood and adolescent obesity is a huge problem, and we really need some good treatment options there."

Because it contains bupropion, an antidepressant that has been associated with an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and actions, the drug carries a black box warning. Bupropion is also known to lower seizure threshold, so the drug should not be used in patients with seizure disorders. If a seizure occurs while taking on the medication, it should be permanently discontinued. Nor should it be used in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Orexigen and Takeda originally brought the drug forward in December 2011. It was not approved at that time because of concerns about its effect on blood pressure – an unexpected move, and one that Orexigen management called "a big setback."

About a quarter of those in the 56-week pivotal phase III trial experienced significant blood pressure increases of at least 10% above their baseline, compared with about 20% of those in the control arm. Increases of diastolic blood pressure of at least 5 mm Hg over baseline occurred in 37% of those on the combination, compared with 29% of those on placebo. About a quarter in the active arm also had heart rate increases of at least 10 beats per minute, compared with 19% of those taking placebo.

Because of these concerns, the FDA required the drug companies to conduct a large, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to investigate the risk of major cardiovascular events. Takeda and Orexigen then launched the 4-year, 8,900 patient Light study, which is still ongoing. Endpoints are major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke) in overweight and obese subjects who have concomitant diabetes and/or other cardiovascular risk factors.

In June, citing encouraging preliminary results, Takeda and Orexigen brought Contrave to the FDA once more – only to be shot down again, at least temporarily. The agency required a review extension in order to come to agreement on the final form of postmarketing surveillance, said Denise Powell, a spokeswoman for Orexigen.

"At that time, FDA said the data looked good," she said in an interview. "We just needed more time to work out the postmarketing requirements."

Those will include:

• A cardiovascular outcomes trial to assess the cardiovascular risk associated with Contrave use.

• Two efficacy, safety, and clinical pharmacology studies in pediatric patients (one in patients 12-17 years old, and one in patients 7-11 years old).

• A juvenile animal toxicity study with a particular focus on growth and development as well as behavior, learning, and memory.

• A cardiac conduction study.

• Clinical trials to evaluate dosing in patients with hepatic or renal impairment.

• A clinical trial to evaluate the potential for interactions between the medication and other drugs.

Contrave contains an extended-release formulation of 8 mg naltrexone and 90 mg bupropion. It is to be administered in an in a 4-week upward titration schedule, with a single morning tablet during week 1; a single tablet at morning and evening during week 2; two tablets in the morning and one in the evening during week 3; and two tablets both morning and evening from week 4 and onward.

Dr. Garvey is a consultant for Daiichi Sankyo, LipoScience, Takeda, Vivus, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Eisai, and Novo Nordisk. He has received research funding from Merck, AstraZeneca, Weight Watchers, Eisai, and Sanofi.

On Twitter @alz_gal

After a delay of more than 3 years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved the nation’s third weight-loss drug, a combination of naltrexone and bupropion.

The extended release tablets (Contrave; Orexigen and Takeda) are approved for use in adults who have a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, or those with a BMI of at least 27 kg/m2 and at least one additional weight-related condition such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia. The agency recommended that Contrave be used in addition to caloric restriction and increased physical activity.

Dr. Timothy Garvey, chair of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ scientific committee, lauded the approval.

"We have a new tool now to treat obesity – and that is very good news," he said in an interview.

He said Contrave will be a valuable addition to the existing weight-loss medications: the phentermine/topiramate combo (Qsymia; Vivus) and lorcaserin (Belviq; Arena).

"There are no head-to-head trials with the other drugs, so we really can’t say much about relative efficacy," said Dr. Garvey. "But when you look at the placebo-subtracted weight loss in all the phase III data, it looks like Contrave is in the middle, with about a 6% loss over lifestyle interventions alone. So it’s not as effective as the topiramate combination, but more effective than lorcaserin."

In the pivotal, 56-week phase III trials, those taking Contrave lost 5%-8% of their baseline body weight, compared with a loss of 1%-2% in those on placebo. The proportion of those who lost at least 5% of their baseline body weight ranged from 45%-56% of those on the proposed dose, compared with 16%-43% of those on placebo.

The FDA guidance on weight-loss drugs suggests a 12-week efficacy evaluation – if the patient has not lost at least 5% of total body weight by then, the drug should be discontinued and another started.

It’s not possible to predict who will respond best to which drug, although there are some things to consider when choosing, said Dr. Garvey, who is chair of the department of nutrition at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

"For example, women of childbearing age need to take precautions against becoming pregnant if they take the topiramate combination, and should stop it right away if they do become pregnant. And since lorcaserin is a serotonergic drug, it has to be used very cautiously in patients who are on other serotonergic medications. We definitely need more safety data there."

Additionally, none of the weight-loss drugs should be used in children or teens until more studies confirm their safety for those patients, "All of the companies are planning these trials, and we hope they will complete them expeditiously," Dr. Garvey said. "Childhood and adolescent obesity is a huge problem, and we really need some good treatment options there."

Because it contains bupropion, an antidepressant that has been associated with an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and actions, the drug carries a black box warning. Bupropion is also known to lower seizure threshold, so the drug should not be used in patients with seizure disorders. If a seizure occurs while taking on the medication, it should be permanently discontinued. Nor should it be used in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Orexigen and Takeda originally brought the drug forward in December 2011. It was not approved at that time because of concerns about its effect on blood pressure – an unexpected move, and one that Orexigen management called "a big setback."

About a quarter of those in the 56-week pivotal phase III trial experienced significant blood pressure increases of at least 10% above their baseline, compared with about 20% of those in the control arm. Increases of diastolic blood pressure of at least 5 mm Hg over baseline occurred in 37% of those on the combination, compared with 29% of those on placebo. About a quarter in the active arm also had heart rate increases of at least 10 beats per minute, compared with 19% of those taking placebo.

Because of these concerns, the FDA required the drug companies to conduct a large, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to investigate the risk of major cardiovascular events. Takeda and Orexigen then launched the 4-year, 8,900 patient Light study, which is still ongoing. Endpoints are major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke) in overweight and obese subjects who have concomitant diabetes and/or other cardiovascular risk factors.

In June, citing encouraging preliminary results, Takeda and Orexigen brought Contrave to the FDA once more – only to be shot down again, at least temporarily. The agency required a review extension in order to come to agreement on the final form of postmarketing surveillance, said Denise Powell, a spokeswoman for Orexigen.

"At that time, FDA said the data looked good," she said in an interview. "We just needed more time to work out the postmarketing requirements."

Those will include:

• A cardiovascular outcomes trial to assess the cardiovascular risk associated with Contrave use.

• Two efficacy, safety, and clinical pharmacology studies in pediatric patients (one in patients 12-17 years old, and one in patients 7-11 years old).

• A juvenile animal toxicity study with a particular focus on growth and development as well as behavior, learning, and memory.

• A cardiac conduction study.

• Clinical trials to evaluate dosing in patients with hepatic or renal impairment.

• A clinical trial to evaluate the potential for interactions between the medication and other drugs.

Contrave contains an extended-release formulation of 8 mg naltrexone and 90 mg bupropion. It is to be administered in an in a 4-week upward titration schedule, with a single morning tablet during week 1; a single tablet at morning and evening during week 2; two tablets in the morning and one in the evening during week 3; and two tablets both morning and evening from week 4 and onward.

Dr. Garvey is a consultant for Daiichi Sankyo, LipoScience, Takeda, Vivus, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Eisai, and Novo Nordisk. He has received research funding from Merck, AstraZeneca, Weight Watchers, Eisai, and Sanofi.

On Twitter @alz_gal

2014 Update on sexual dysfunction

Since the last installment of this Update on Sexual Dysfunction, three new drugs have been added to the armamentarium for menopausal symptoms and dyspareunia:

- paroxetine 7.5 mg (Brisdelle)

- conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene (Duavee)

- ospemifene (Osphena).

In this article, I present a case-based approach to incorporating these drugs into practice and restoring sexual function in the setting of vulvovaginal atrophy and dyspareunia. As is often the case, decision-making requires sifting through multiple layers of information.

How to “tease out” the problem and help the patient regain sexual function

Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

Conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene (Duavee) for menopausal symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2014;56(1441):33–34.

DeGregorio MW, Zerbe RL, Wurz GT. Ospemifene: a first-in-class, non-hormonal selective estrogen receptor modulator approved for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy [published online ahead of print August 1, 2014]. Steroids. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2014.07.012.

Goldstein SR, Archer DF, Simon JA, Constantine G. Endometrial safety of ospemifene and the ability of transvaginal ultrasonography to detect small changes in endometrial thickness. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):96S–97S.

CASE: LOW DESIRE AND DISCOMFORT DURING INTERCOURSE

Your 58-year-old patient, G2P2, mentions during her annual visit that she’s not that interested in sex anymore. Her children are grown, she’s been happily married for 28 years, and she enjoys her job and denies any symptoms of depression. She says her relationship with her husband is good and, aside from her low desire, she has no worries about the marriage. Her only medication is paroxetine 7.5 mg/day (Brisdelle) for management of her moderate hot flashes, which she initiated at her last annual visit. She reports improvement in her sleep and menopausal symptoms as a result. She has an intact uterus.

You perform a pelvic exam and find atrophic vulva and vagina with mild erythema, and thinned epithelium. When you ask if she has experienced any discomfort, she reports that she needs to use lubrication for intercourse and that, even with lubrication, she has pain upon penetration and a burning sensation that continues throughout intercourse. She also reports that it seems to take her much longer to achieve arousal than in the past, and she often fails to reach orgasm.

How would you manage this patient?

As always, begin with the history

The transition to menopause creates multiple layers of potential symptoms and problems for our patients, and sometimes medical therapy can generate additional ones.

In a patient reporting the onset of low desire and dyspareunia, you would want to first consider her medication history, despite the clear evidence of vaginal atrophy. Begin by asking whether she is taking any new medications prescribed by another provider. In some cases, antihypertensive drugs, psychotropic agents, and other medications can affect sexual function.

This patient has been taking Brisdelle for 1 year and is happy with its effect on her sleep and hot flashes. Simon and colleagues found this nonhormonal agent for moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms to produce no notable effects in weight, libido, or sleep, compared with placebo.

Nevertheless, in this case, because selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as paroxetine can affect arousal and orgasm, it is unclear whether the ultra-low dose of paroxetine she is taking is contributing to her problems. If you were to discontinue the drug to find out, her vasomotor symptoms and sleep disruption would likely recur.

Your decision-making is important here and should involve the patient in an extensive discussion. If there is not enough time for this discussion at the current visit, schedule a follow-up to address her issues fully.

Vulvovaginal atrophy has its own timeline

In many cases, vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes occur years before the skin begins to atrophy in the vulva and vagina, particularly in women who enter menopause naturally. Among menopausal women who continue to have intercourse on a regular basis, however, these skin changes often are much less troublesome than they are for women who have sex more rarely.

In this patient, one possible scenario is that paroxetine caused a slight reduction in sexual interest, and the frequency of intercourse went down as a result. In women who have little or no intercourse, the vagina begins to shrink and the tissues lose elasticity. This patient may have been undergoing the natural process of menopause, and that process may have been compounded by a decrease in the frequency of sex.

If you were to discontinue the paroxetine, it would still be necessary to treat the vulvovaginal skin and work on manual techniques to gently dilate the introitus.

Option 1: Systemic hormone therapy

Systemic estrogen is the most effective treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms, reducing hot flashes by 50% to 100% within 4 weeks of initiation. However, because our patient has an intact uterus, any systemic estrogen she opts to use must be opposed by a progestin for safety reasons.

In terms of estrogen, her options are oral or nonoral formulations. Not only would estrogen manage our patient’s hot flashes but, over time, it would improve her sexual problems and atrophy, which might or might not improve her current complaint of low desire. You likely would need to add a short regimen of topical estrogen and perhaps even a dilator to restore her sexual function completely, however.

Since our patient chose the nonhormonal agent Brisdelle to manage her menopausal symptoms, she may be worried about the increased risk of breast cancer associated with use of a progestin in combination with estrogen. One hormonal option now available that eliminates the need for a progestin is conjugated estrogens and bazedoxefine (Duavee). Bazedoxefine is a third-

generation selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). This drug has estrogen-like effects on bone and antiestrogen effects on the uterus.

Duavee is indicated for use in women with a uterus for treatment of:

- moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms of menopause

- prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Among the risks are an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and stroke. It is not approved specifically for the treatment of dyspareunia.

Another hormonal option is ospemifene (Osphena), an estrogen agonist/antagonist indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia in menopausal women. Among the drugs in its class, such as tamoxifen and raloxifene, ospemifene is the only agent that maintains a full estrogenic effect on vaginal tissues. Its risks include VTE and stroke.

Although the labeling includes a warning about the risk of endometrial hyperplasia associated with its use, Goldstein and colleagues found no significant difference in the rate of endometrial thickening greater than 5 mm between women taking ospemifene and those taking placebo after 1 year of daily oral treatment. No carcinomas were found in either group.

Option 2: Local estrogen

If our patient declines all systemic hormone therapy, the topical approach should resolve her vulvovaginal symptoms, and she could continue taking Brisdelle for her menopausal symptoms. Vaginal estrogen would address the skin problems, provided the patient applies it correctly. Many women are afraid to use estrogen creams and compensate by applying them only to the vulva, thinking that, by limiting their use to external tissues, they are avoiding any associated risks.

If she opts for the local approach, this patient should be encouraged to use transvaginal estrogen in small doses to increase the elasticity of the vulvovaginal tissue, even though it may require daily use for a week or two to improve her symptoms, after which once- or twice-weekly administration should suffice.

The use of low-dose vaginal cream for a short duration is unlikely to increase her risks in any way.

Local estrogen is available as a tablet, cream, or ring.

Option 3: A nonhormonal approach

If the patient refuses any hormonal agent—even topical estrogen—I would recommend the use of silicone-based lubricants and a dilator and prescribe more frequent penetration to increase elasticity and reduce pain.

Brisdelle could be continued to address her menopausal symptoms.

Don’t overlook behavioral techniques

Before this patient leaves your office with the option of her choice, a bit of counseling is necessary to instruct her about methods of restoring full sexual function.

Pain is a powerful aversive stimulus. This patient clearly states that she has had less frequent intercourse as a result of dyspareunia. It is not unusual for patients to develop a “habit” of avoidance in response to the behavior that causes their pain.

One recommendation is to talk to this patient about putting sex back into her life by encouraging her to increase sexual activity without penetration until she begins to arouse easily again. Arousal produces physiologic effects, increasing the caliber and length of the vagina as well as lubrication. The use of fingers or dilators may help restore caliber.

The patient can be encouraged to engage in snuggling and cuddling to regain those activities without the fear of pain associated with penetration. Follow-up after 2 weeks of this therapy can confirm the restoration of tissue elasticity, and the green light can be given for penetration to begin again. Couples can be encouraged to plan a “honeymoon weekend” and put some fun back into their sex lives so that this phase of healing doesn’t become an onerous task.

CASE RESOLVED After a discussion of her options, the patient chooses to stick with Brisdelle and use behavioral therapy alone to resolve her dyspareunia. At her follow-up visit 2 weeks later, she reports that she has enjoyed the period of pain-free “sex” and feels ready to add penetration into her activities.

You encourage her to continue sexual intercourse on a regular, relatively frequent basis to prevent a recurrence of dyspareunia. She continues to use silicone-based lubricants.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Since the last installment of this Update on Sexual Dysfunction, three new drugs have been added to the armamentarium for menopausal symptoms and dyspareunia:

- paroxetine 7.5 mg (Brisdelle)

- conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene (Duavee)

- ospemifene (Osphena).

In this article, I present a case-based approach to incorporating these drugs into practice and restoring sexual function in the setting of vulvovaginal atrophy and dyspareunia. As is often the case, decision-making requires sifting through multiple layers of information.

How to “tease out” the problem and help the patient regain sexual function

Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

Conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene (Duavee) for menopausal symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2014;56(1441):33–34.

DeGregorio MW, Zerbe RL, Wurz GT. Ospemifene: a first-in-class, non-hormonal selective estrogen receptor modulator approved for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy [published online ahead of print August 1, 2014]. Steroids. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2014.07.012.

Goldstein SR, Archer DF, Simon JA, Constantine G. Endometrial safety of ospemifene and the ability of transvaginal ultrasonography to detect small changes in endometrial thickness. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):96S–97S.

CASE: LOW DESIRE AND DISCOMFORT DURING INTERCOURSE