User login

Laparoscopic myomectomy with enclosed transvaginal tissue extraction

Ceana Nezhat, MD, and Erica Dun, MD, of the Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, present this surgical case of a 41-year-old G0 with radiating lower abdominal pain and mennorhagia who desired removal of her symptomatic myomas. Preoperative transvaginal ultrasound revealed a 4-cm posterior pedunculated myoma and 5-cm fundal intramural myoma.

Ceana Nezhat, MD, and Erica Dun, MD, of the Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, present this surgical case of a 41-year-old G0 with radiating lower abdominal pain and mennorhagia who desired removal of her symptomatic myomas. Preoperative transvaginal ultrasound revealed a 4-cm posterior pedunculated myoma and 5-cm fundal intramural myoma.

Ceana Nezhat, MD, and Erica Dun, MD, of the Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, present this surgical case of a 41-year-old G0 with radiating lower abdominal pain and mennorhagia who desired removal of her symptomatic myomas. Preoperative transvaginal ultrasound revealed a 4-cm posterior pedunculated myoma and 5-cm fundal intramural myoma.

Early low-dose menopausal hormone therapy did not affect atherosclerosis

Two low-dose menopausal hormone regimens improved some cardiovascular parameters in healthy women but did not affect atherosclerosis progression, even when started early and continued for up to 4 years, investigators reported online July 28 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Neither of the low-dose menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) regimens used in the study affected blood pressure, but both relieved hot flushes, added Dr. S. Mitchell Harman of the Phoenix Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Arizona and his associates.

Follow-up analyses of Women’s Health Initiative data had suggested that MHT might have cardiovascular benefits if started early enough or in younger women, the researchers noted.

To further explore the association, the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) enrolled 727 healthy women aged 42-58 years who were considered low risk for cardiovascular disease and were within 36 months of their last menses (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014 July 28 [doi: 10.7326/M14-0353]). The women were randomized in a double-blinded fashion to oral progesterone (200 mg for 12 days per month), plus either oral estrogen (conjugated equine estrogen, 0.45 mg per day) or transdermal estrogen (17-beta-estradiol, 50 mcg per day), or to a placebo, the researchers said.

Vascular ultrasonography at baseline and after up to 4 years of treatment revealed no effect of MHT on the progression of atherosclerosis, the researchers said. Average increases in carotid artery intima-media thickness were 0.0076 mm per year and were similar across treatment groups, as were increases in coronary artery calcium scores (17.4% for the oral estrogen group, 18.9% for the transdermal estrogen group, and 21.0% for the placebo group), they reported.

Neither hormone therapy regimen led to changes in blood pressure or interleukin-6 levels, although vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes) improved with both regimens, the investigators said. Lipoprotein cholesterol levels also improved in both treatment groups, and the oral estrogen group had improvements in C-reactive protein and sex hormone–binding globulin. The transdermal estrogen group had improvements in insulin sensitivity.

The study was inadequately powered to allow comparison of clinical events, and power for the coronary artery calcium score also was limited, the researchers noted. The results also might not be generalizable to women who have substantial cardiovascular risk factors, they added.

The Aurora Foundation funded the research, and Abbott Laboratories and Bayer Healthcare donated study medications. Dr. Harman reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Two low-dose menopausal hormone regimens improved some cardiovascular parameters in healthy women but did not affect atherosclerosis progression, even when started early and continued for up to 4 years, investigators reported online July 28 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Neither of the low-dose menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) regimens used in the study affected blood pressure, but both relieved hot flushes, added Dr. S. Mitchell Harman of the Phoenix Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Arizona and his associates.

Follow-up analyses of Women’s Health Initiative data had suggested that MHT might have cardiovascular benefits if started early enough or in younger women, the researchers noted.

To further explore the association, the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) enrolled 727 healthy women aged 42-58 years who were considered low risk for cardiovascular disease and were within 36 months of their last menses (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014 July 28 [doi: 10.7326/M14-0353]). The women were randomized in a double-blinded fashion to oral progesterone (200 mg for 12 days per month), plus either oral estrogen (conjugated equine estrogen, 0.45 mg per day) or transdermal estrogen (17-beta-estradiol, 50 mcg per day), or to a placebo, the researchers said.

Vascular ultrasonography at baseline and after up to 4 years of treatment revealed no effect of MHT on the progression of atherosclerosis, the researchers said. Average increases in carotid artery intima-media thickness were 0.0076 mm per year and were similar across treatment groups, as were increases in coronary artery calcium scores (17.4% for the oral estrogen group, 18.9% for the transdermal estrogen group, and 21.0% for the placebo group), they reported.

Neither hormone therapy regimen led to changes in blood pressure or interleukin-6 levels, although vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes) improved with both regimens, the investigators said. Lipoprotein cholesterol levels also improved in both treatment groups, and the oral estrogen group had improvements in C-reactive protein and sex hormone–binding globulin. The transdermal estrogen group had improvements in insulin sensitivity.

The study was inadequately powered to allow comparison of clinical events, and power for the coronary artery calcium score also was limited, the researchers noted. The results also might not be generalizable to women who have substantial cardiovascular risk factors, they added.

The Aurora Foundation funded the research, and Abbott Laboratories and Bayer Healthcare donated study medications. Dr. Harman reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Two low-dose menopausal hormone regimens improved some cardiovascular parameters in healthy women but did not affect atherosclerosis progression, even when started early and continued for up to 4 years, investigators reported online July 28 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Neither of the low-dose menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) regimens used in the study affected blood pressure, but both relieved hot flushes, added Dr. S. Mitchell Harman of the Phoenix Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Arizona and his associates.

Follow-up analyses of Women’s Health Initiative data had suggested that MHT might have cardiovascular benefits if started early enough or in younger women, the researchers noted.

To further explore the association, the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) enrolled 727 healthy women aged 42-58 years who were considered low risk for cardiovascular disease and were within 36 months of their last menses (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014 July 28 [doi: 10.7326/M14-0353]). The women were randomized in a double-blinded fashion to oral progesterone (200 mg for 12 days per month), plus either oral estrogen (conjugated equine estrogen, 0.45 mg per day) or transdermal estrogen (17-beta-estradiol, 50 mcg per day), or to a placebo, the researchers said.

Vascular ultrasonography at baseline and after up to 4 years of treatment revealed no effect of MHT on the progression of atherosclerosis, the researchers said. Average increases in carotid artery intima-media thickness were 0.0076 mm per year and were similar across treatment groups, as were increases in coronary artery calcium scores (17.4% for the oral estrogen group, 18.9% for the transdermal estrogen group, and 21.0% for the placebo group), they reported.

Neither hormone therapy regimen led to changes in blood pressure or interleukin-6 levels, although vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes) improved with both regimens, the investigators said. Lipoprotein cholesterol levels also improved in both treatment groups, and the oral estrogen group had improvements in C-reactive protein and sex hormone–binding globulin. The transdermal estrogen group had improvements in insulin sensitivity.

The study was inadequately powered to allow comparison of clinical events, and power for the coronary artery calcium score also was limited, the researchers noted. The results also might not be generalizable to women who have substantial cardiovascular risk factors, they added.

The Aurora Foundation funded the research, and Abbott Laboratories and Bayer Healthcare donated study medications. Dr. Harman reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Low-dose menopausal hormone therapy did not affect the progression of atherosclerosis, even when started early and continued for up to 4 years.

Major finding: Average increases in carotid artery intima-media thickness were 0.0076 mm per year and were similar across treatment groups, as were average changes in coronary artery calcium scores (17.4% for the oral estrogen group, 18.9% for the transdermal estrogen group, and 21.0% for the placebo group).

Data source: Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of 727 healthy women within 36 months of their last menses. Women were randomized to oral conjugated equine estrogens (0.45 mg per day) and oral progesterone (200 mg for 12 days per month); the same dose of oral progesterone plus transdermal 17-beta-estradiol (50 mcg per day); or placebo.

Disclosures: The Aurora Foundation funded the research, and Abbott Laboratories and Bayer Healthcare donated study medications. Dr. Harman reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

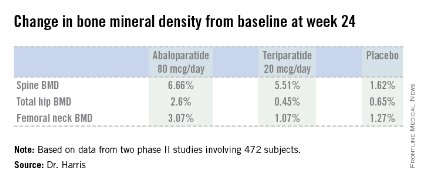

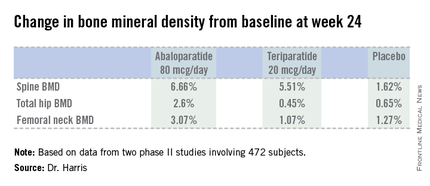

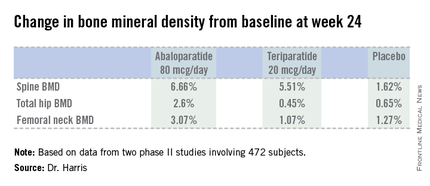

New agent builds bone bigger, faster

CHICAGO – Abaloparatide, a synthetic analog of human parathyroid hormone–related peptide, displayed jaw-dropping superiority to teriparatide in boosting bone mineral density at multiple anatomic sites in a head-to-head, placebo-controlled phase II study.

"Given the consistency of these increases in BMD [bone mineral density] seen in the phase II studies, abaloparatide may emerge as an important therapeutic agent in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis," Dr. Alan G. Harris observed in presenting the results of two separate phase II abaloparatide studies at the joint meeting of the International Congress of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society.

"There is an unmet need for anabolic agents that preferentially increase bone formation as opposed to decreasing bone resorption. There is also a challenge we’re faced with in clinical practice: that is, the lack of early hip BMD increase with teriparatide," added Dr. Harris, chief medical officer at Radius Health of Cambridge, Mass., which is developing the agent.

The phase II data suggest abaloparatide at 80 mcg by once-daily subcutaneous injection meets both needs, he added.

Indeed, based upon the highly positive phase II work, a phase III, placebo- and teriparatide-controlled clinical trial with fracture endpoints is well underway. The 18-month trial involving more than 2,400 patients is due to be completed later this year.

Separately, Gary Hattersley, Ph.D., presented encouraging results from a 231-patient, 24-week, phase-II, dose-ranging study of abaloparatide delivered by transdermal patch.

"We look at this as being a strong proof-of-concept study demonstrating that this simple transdermal patch with only a 5-minute wear time is able to deliver meaningful amounts of abaloparatide through the skin without the need for a subcutaneous injection in order to achieve meaningful increases in BMD," said Dr. Hattersley, chief scientific officer at Radius Health.

"We recognize that there’s really a significant opportunity for an alternative to daily subcutaneous injection. This has the potential to improve both patient convenience as well as patient compliance," he added.

The increases in BMD with the patch – a 2.95% increase from baseline at the spine with the 150-mcg patch and a 1.49% rise in total hip BMD – were not as robust as in controls assigned to once-daily abaloparatide at 80 mcg, which is the optimal injectable dose also being used in the ongoing phase III trial. But Dr. Hattersley said he believes that higher-dose patches now under study will achieve substantially bigger increases in BMD.

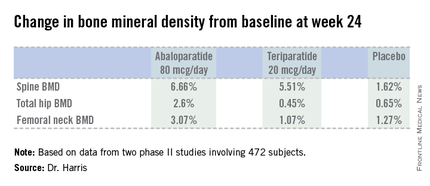

Dr. Harris presented data from two phase II studies on a total of 472 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. In one, subjects were randomized to subcutaneous abaloparatide, teriparatide (Forteo) at its approved dose of 20 mcg by daily subcutaneous injection, or placebo. Although the primary endpoints in this study were assessed at 24 weeks, in an extension out to 48 weeks the increase in lumbar spine BMD over baseline was 12.9% with abaloparatide 80 mcg, 8.6% with teriparatide, and 0.7% with placebo.

In the other study, patients were randomized to abaloparatide or placebo. In this trial, patients on abaloparatide at 80 mcg showed a 5.8% increase over baseline in spine BMD at 24 weeks, along with a 2.74% increase in total hip BMD and a 2.76% increase in femoral neck BMD, as compared with a 0.44% increase in spine BMD with placebo and net BMD losses of less than 1% at each of the other two sites.

In both studies, side effects of abaloparatide were similar in type and incidence to placebo. Of note, the incidence of mild, transient hypercalcemia in abaloparatide-treated patients was half that of the teriparatide group.

Asked why the subcutaneous abaloparatide at 80 mcg is so much more effective at increasing BMD than teriparatide is at its approved dose, Dr. Harris replied, "They’re different peptides." In monkey studies, abaloparatide showed less increase in cortical bone porosity than in studies done using teriparatide. And in the head-to-head phase II study, the increase in bone turnover markers related to resorption was substantially greater with teriparatide. So abaloparatide’s greater BMD-building efficacy is because of greater selectivity for increased bone formation and less bone resorption relative to teriparatide, he suggested.

The abaloparatide patch utilizes proprietary technology developed by 3M. The dime-size patch contains 316 spearlike microprojections, each 500 mcm (micrometers) long. The tip of each microprojection is coated with abaloparatide. When the patch is applied to periumbilical skin, the microprojections penetrate the skin to a depth of about 250 mcm, putting the tip into the upper dermis. Patch application was painless and without side effects in the phase II study, according to Dr. Harris.

These phase II studies were funded by Radius Health.

CHICAGO – Abaloparatide, a synthetic analog of human parathyroid hormone–related peptide, displayed jaw-dropping superiority to teriparatide in boosting bone mineral density at multiple anatomic sites in a head-to-head, placebo-controlled phase II study.

"Given the consistency of these increases in BMD [bone mineral density] seen in the phase II studies, abaloparatide may emerge as an important therapeutic agent in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis," Dr. Alan G. Harris observed in presenting the results of two separate phase II abaloparatide studies at the joint meeting of the International Congress of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society.

"There is an unmet need for anabolic agents that preferentially increase bone formation as opposed to decreasing bone resorption. There is also a challenge we’re faced with in clinical practice: that is, the lack of early hip BMD increase with teriparatide," added Dr. Harris, chief medical officer at Radius Health of Cambridge, Mass., which is developing the agent.

The phase II data suggest abaloparatide at 80 mcg by once-daily subcutaneous injection meets both needs, he added.

Indeed, based upon the highly positive phase II work, a phase III, placebo- and teriparatide-controlled clinical trial with fracture endpoints is well underway. The 18-month trial involving more than 2,400 patients is due to be completed later this year.

Separately, Gary Hattersley, Ph.D., presented encouraging results from a 231-patient, 24-week, phase-II, dose-ranging study of abaloparatide delivered by transdermal patch.

"We look at this as being a strong proof-of-concept study demonstrating that this simple transdermal patch with only a 5-minute wear time is able to deliver meaningful amounts of abaloparatide through the skin without the need for a subcutaneous injection in order to achieve meaningful increases in BMD," said Dr. Hattersley, chief scientific officer at Radius Health.

"We recognize that there’s really a significant opportunity for an alternative to daily subcutaneous injection. This has the potential to improve both patient convenience as well as patient compliance," he added.

The increases in BMD with the patch – a 2.95% increase from baseline at the spine with the 150-mcg patch and a 1.49% rise in total hip BMD – were not as robust as in controls assigned to once-daily abaloparatide at 80 mcg, which is the optimal injectable dose also being used in the ongoing phase III trial. But Dr. Hattersley said he believes that higher-dose patches now under study will achieve substantially bigger increases in BMD.

Dr. Harris presented data from two phase II studies on a total of 472 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. In one, subjects were randomized to subcutaneous abaloparatide, teriparatide (Forteo) at its approved dose of 20 mcg by daily subcutaneous injection, or placebo. Although the primary endpoints in this study were assessed at 24 weeks, in an extension out to 48 weeks the increase in lumbar spine BMD over baseline was 12.9% with abaloparatide 80 mcg, 8.6% with teriparatide, and 0.7% with placebo.

In the other study, patients were randomized to abaloparatide or placebo. In this trial, patients on abaloparatide at 80 mcg showed a 5.8% increase over baseline in spine BMD at 24 weeks, along with a 2.74% increase in total hip BMD and a 2.76% increase in femoral neck BMD, as compared with a 0.44% increase in spine BMD with placebo and net BMD losses of less than 1% at each of the other two sites.

In both studies, side effects of abaloparatide were similar in type and incidence to placebo. Of note, the incidence of mild, transient hypercalcemia in abaloparatide-treated patients was half that of the teriparatide group.

Asked why the subcutaneous abaloparatide at 80 mcg is so much more effective at increasing BMD than teriparatide is at its approved dose, Dr. Harris replied, "They’re different peptides." In monkey studies, abaloparatide showed less increase in cortical bone porosity than in studies done using teriparatide. And in the head-to-head phase II study, the increase in bone turnover markers related to resorption was substantially greater with teriparatide. So abaloparatide’s greater BMD-building efficacy is because of greater selectivity for increased bone formation and less bone resorption relative to teriparatide, he suggested.

The abaloparatide patch utilizes proprietary technology developed by 3M. The dime-size patch contains 316 spearlike microprojections, each 500 mcm (micrometers) long. The tip of each microprojection is coated with abaloparatide. When the patch is applied to periumbilical skin, the microprojections penetrate the skin to a depth of about 250 mcm, putting the tip into the upper dermis. Patch application was painless and without side effects in the phase II study, according to Dr. Harris.

These phase II studies were funded by Radius Health.

CHICAGO – Abaloparatide, a synthetic analog of human parathyroid hormone–related peptide, displayed jaw-dropping superiority to teriparatide in boosting bone mineral density at multiple anatomic sites in a head-to-head, placebo-controlled phase II study.

"Given the consistency of these increases in BMD [bone mineral density] seen in the phase II studies, abaloparatide may emerge as an important therapeutic agent in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis," Dr. Alan G. Harris observed in presenting the results of two separate phase II abaloparatide studies at the joint meeting of the International Congress of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society.

"There is an unmet need for anabolic agents that preferentially increase bone formation as opposed to decreasing bone resorption. There is also a challenge we’re faced with in clinical practice: that is, the lack of early hip BMD increase with teriparatide," added Dr. Harris, chief medical officer at Radius Health of Cambridge, Mass., which is developing the agent.

The phase II data suggest abaloparatide at 80 mcg by once-daily subcutaneous injection meets both needs, he added.

Indeed, based upon the highly positive phase II work, a phase III, placebo- and teriparatide-controlled clinical trial with fracture endpoints is well underway. The 18-month trial involving more than 2,400 patients is due to be completed later this year.

Separately, Gary Hattersley, Ph.D., presented encouraging results from a 231-patient, 24-week, phase-II, dose-ranging study of abaloparatide delivered by transdermal patch.

"We look at this as being a strong proof-of-concept study demonstrating that this simple transdermal patch with only a 5-minute wear time is able to deliver meaningful amounts of abaloparatide through the skin without the need for a subcutaneous injection in order to achieve meaningful increases in BMD," said Dr. Hattersley, chief scientific officer at Radius Health.

"We recognize that there’s really a significant opportunity for an alternative to daily subcutaneous injection. This has the potential to improve both patient convenience as well as patient compliance," he added.

The increases in BMD with the patch – a 2.95% increase from baseline at the spine with the 150-mcg patch and a 1.49% rise in total hip BMD – were not as robust as in controls assigned to once-daily abaloparatide at 80 mcg, which is the optimal injectable dose also being used in the ongoing phase III trial. But Dr. Hattersley said he believes that higher-dose patches now under study will achieve substantially bigger increases in BMD.

Dr. Harris presented data from two phase II studies on a total of 472 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. In one, subjects were randomized to subcutaneous abaloparatide, teriparatide (Forteo) at its approved dose of 20 mcg by daily subcutaneous injection, or placebo. Although the primary endpoints in this study were assessed at 24 weeks, in an extension out to 48 weeks the increase in lumbar spine BMD over baseline was 12.9% with abaloparatide 80 mcg, 8.6% with teriparatide, and 0.7% with placebo.

In the other study, patients were randomized to abaloparatide or placebo. In this trial, patients on abaloparatide at 80 mcg showed a 5.8% increase over baseline in spine BMD at 24 weeks, along with a 2.74% increase in total hip BMD and a 2.76% increase in femoral neck BMD, as compared with a 0.44% increase in spine BMD with placebo and net BMD losses of less than 1% at each of the other two sites.

In both studies, side effects of abaloparatide were similar in type and incidence to placebo. Of note, the incidence of mild, transient hypercalcemia in abaloparatide-treated patients was half that of the teriparatide group.

Asked why the subcutaneous abaloparatide at 80 mcg is so much more effective at increasing BMD than teriparatide is at its approved dose, Dr. Harris replied, "They’re different peptides." In monkey studies, abaloparatide showed less increase in cortical bone porosity than in studies done using teriparatide. And in the head-to-head phase II study, the increase in bone turnover markers related to resorption was substantially greater with teriparatide. So abaloparatide’s greater BMD-building efficacy is because of greater selectivity for increased bone formation and less bone resorption relative to teriparatide, he suggested.

The abaloparatide patch utilizes proprietary technology developed by 3M. The dime-size patch contains 316 spearlike microprojections, each 500 mcm (micrometers) long. The tip of each microprojection is coated with abaloparatide. When the patch is applied to periumbilical skin, the microprojections penetrate the skin to a depth of about 250 mcm, putting the tip into the upper dermis. Patch application was painless and without side effects in the phase II study, according to Dr. Harris.

These phase II studies were funded by Radius Health.

AT ICE/ENDO 2014

Key clinical point: A novel anabolic agent being developed for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis increased BMD faster and to a greater extent than did teriparatide.

Major finding: Total hip bone mineral density increased by 2.6% over baseline after 24 weeks of abaloparatide at 80 mcg daily, compared with 0.45% with teriparatide at 20 mcg daily and 0.65% with placebo.

Data source: This phase II randomized trial included 222 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Radius Health. The presenter is the company’s chief medical officer.

Systemwide disparities seen in diagnosis, care of women with heart disease

MELBOURNE – Women with heart disease are frequently underdiagnosed, undertreated, and underrepresented in clinical trials, and experience poorer outcomes both from inpatient and outpatient care.

Furthermore, while women have a tremendous amount of cardiovascular risk, they themselves are failing to recognize that heart disease is their No. 1 killer, Dr. Joanne M. Foody of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said at the World Congress of Cardiology 2014.

"The challenge is to ensure that women understand their risk, that the health care provider taking care of them understand their risk, and only by doing that can we really then impact their risk factors and treat them appropriately," said Dr. Foody, also director of the Pollin Cardiovascular Wellness Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Heart disease often presents differently in women than in men, with symptoms such as fatigue and breathlessness, which many women themselves would likely dismiss as just being part of a busy life.

While men tend to develop more focal plaques and narrowing of the arteries, women have smaller coronary arteries, even after body size is adjusted for, and therefore often have a more diffuse distribution of atherosclerosis.

"Women tend not to get that acute heart attack; they tend to have symptoms more related to small vessel disease which can lead to heart failure–like symptoms," she said.

Dr. Foody said that while the same cardiovascular risk factors apply to women and men, hormonal changes with menopause have a significant impact that is frequently underestimated by women and health care providers.

"Women undergo significant changes in their cholesterol levels, their blood pressure, and even their insulin resistance as they go through perimenopause and menopause, so it puts women at a unique transition point," Dr. Foody said. "Unfortunately, in women who were completely healthy and had no risk factors, that can change dramatically within the course of a couple of years."

Dr. Foody said that given the differences in presentation and treatment of heart disease in women, it is hardly surprising that women are more likely to die in the hospital, are more likely to experience reinfarction, and have a higher risk of heart failure, stroke, bleeding, and transfusion.

Women are also less likely to have an ECG performed within 10 minutes of hospital presentation, less likely to receive care from a cardiologist, and less likely to undergo diagnostic catheterization and revascularization procedures.

"These differences in care and in treatment can easily explain at least part of the disparities we see in outcomes for women," Dr. Foody said at the conference, which was sponsored by the World Heart Federation.

However, women themselves are also often more wary or skeptical of medication, Dr. Foody said, with evidence suggesting that married men are the most adherent to medication while married women are the least adherent.

Recent initiatives such as the global Go Red for Women and U.S.-based Screen Us campaigns were both aimed at raising awareness of heart disease among women and health care providers, but Dr. Foody said a system-level approach is required.

"That has to be coupled though with comparable programs that help inform health care providers, that help really put funding into appropriate screenings as well as appropriate research."

Dr. Foody said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

MELBOURNE – Women with heart disease are frequently underdiagnosed, undertreated, and underrepresented in clinical trials, and experience poorer outcomes both from inpatient and outpatient care.

Furthermore, while women have a tremendous amount of cardiovascular risk, they themselves are failing to recognize that heart disease is their No. 1 killer, Dr. Joanne M. Foody of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said at the World Congress of Cardiology 2014.

"The challenge is to ensure that women understand their risk, that the health care provider taking care of them understand their risk, and only by doing that can we really then impact their risk factors and treat them appropriately," said Dr. Foody, also director of the Pollin Cardiovascular Wellness Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Heart disease often presents differently in women than in men, with symptoms such as fatigue and breathlessness, which many women themselves would likely dismiss as just being part of a busy life.

While men tend to develop more focal plaques and narrowing of the arteries, women have smaller coronary arteries, even after body size is adjusted for, and therefore often have a more diffuse distribution of atherosclerosis.

"Women tend not to get that acute heart attack; they tend to have symptoms more related to small vessel disease which can lead to heart failure–like symptoms," she said.

Dr. Foody said that while the same cardiovascular risk factors apply to women and men, hormonal changes with menopause have a significant impact that is frequently underestimated by women and health care providers.

"Women undergo significant changes in their cholesterol levels, their blood pressure, and even their insulin resistance as they go through perimenopause and menopause, so it puts women at a unique transition point," Dr. Foody said. "Unfortunately, in women who were completely healthy and had no risk factors, that can change dramatically within the course of a couple of years."

Dr. Foody said that given the differences in presentation and treatment of heart disease in women, it is hardly surprising that women are more likely to die in the hospital, are more likely to experience reinfarction, and have a higher risk of heart failure, stroke, bleeding, and transfusion.

Women are also less likely to have an ECG performed within 10 minutes of hospital presentation, less likely to receive care from a cardiologist, and less likely to undergo diagnostic catheterization and revascularization procedures.

"These differences in care and in treatment can easily explain at least part of the disparities we see in outcomes for women," Dr. Foody said at the conference, which was sponsored by the World Heart Federation.

However, women themselves are also often more wary or skeptical of medication, Dr. Foody said, with evidence suggesting that married men are the most adherent to medication while married women are the least adherent.

Recent initiatives such as the global Go Red for Women and U.S.-based Screen Us campaigns were both aimed at raising awareness of heart disease among women and health care providers, but Dr. Foody said a system-level approach is required.

"That has to be coupled though with comparable programs that help inform health care providers, that help really put funding into appropriate screenings as well as appropriate research."

Dr. Foody said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

MELBOURNE – Women with heart disease are frequently underdiagnosed, undertreated, and underrepresented in clinical trials, and experience poorer outcomes both from inpatient and outpatient care.

Furthermore, while women have a tremendous amount of cardiovascular risk, they themselves are failing to recognize that heart disease is their No. 1 killer, Dr. Joanne M. Foody of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said at the World Congress of Cardiology 2014.

"The challenge is to ensure that women understand their risk, that the health care provider taking care of them understand their risk, and only by doing that can we really then impact their risk factors and treat them appropriately," said Dr. Foody, also director of the Pollin Cardiovascular Wellness Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Heart disease often presents differently in women than in men, with symptoms such as fatigue and breathlessness, which many women themselves would likely dismiss as just being part of a busy life.

While men tend to develop more focal plaques and narrowing of the arteries, women have smaller coronary arteries, even after body size is adjusted for, and therefore often have a more diffuse distribution of atherosclerosis.

"Women tend not to get that acute heart attack; they tend to have symptoms more related to small vessel disease which can lead to heart failure–like symptoms," she said.

Dr. Foody said that while the same cardiovascular risk factors apply to women and men, hormonal changes with menopause have a significant impact that is frequently underestimated by women and health care providers.

"Women undergo significant changes in their cholesterol levels, their blood pressure, and even their insulin resistance as they go through perimenopause and menopause, so it puts women at a unique transition point," Dr. Foody said. "Unfortunately, in women who were completely healthy and had no risk factors, that can change dramatically within the course of a couple of years."

Dr. Foody said that given the differences in presentation and treatment of heart disease in women, it is hardly surprising that women are more likely to die in the hospital, are more likely to experience reinfarction, and have a higher risk of heart failure, stroke, bleeding, and transfusion.

Women are also less likely to have an ECG performed within 10 minutes of hospital presentation, less likely to receive care from a cardiologist, and less likely to undergo diagnostic catheterization and revascularization procedures.

"These differences in care and in treatment can easily explain at least part of the disparities we see in outcomes for women," Dr. Foody said at the conference, which was sponsored by the World Heart Federation.

However, women themselves are also often more wary or skeptical of medication, Dr. Foody said, with evidence suggesting that married men are the most adherent to medication while married women are the least adherent.

Recent initiatives such as the global Go Red for Women and U.S.-based Screen Us campaigns were both aimed at raising awareness of heart disease among women and health care providers, but Dr. Foody said a system-level approach is required.

"That has to be coupled though with comparable programs that help inform health care providers, that help really put funding into appropriate screenings as well as appropriate research."

Dr. Foody said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCC 2014

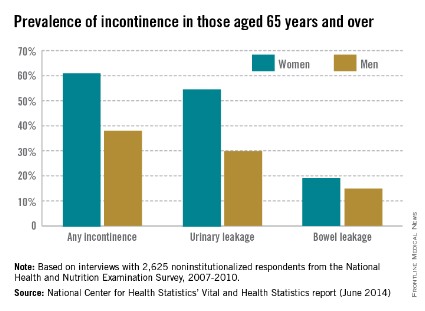

More than half of older women have experienced incontinence

Among noninstitutionalized Americans aged 65 years and older, 61.2% of women and 38% of men experience at least occasional urinary or bowel incontinence, the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

Data from the 2007-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show that 54.8% of women and 29.9% of men had urinary leakage at least a few times a month, while 19.2% of women and 14.9% of men had accidental bowel leakage of mucus, liquid stool, or solid stool at least one to three times a month, according to the NCHS (Vital Health Stat. 2014;3[36]).

Among women aged 65-74 years, 60.6% had some type of incontinence, compared with 61.9% of women aged 75 years and over. The difference was larger for men, however, with 34.1% of those aged 65-74 years reporting incontinence, compared with 42.4% of men aged 75 years and over, the report showed.

The NHANES data are based on in-home interviews with a nationally representative sample of 2,625 respondents.

Among noninstitutionalized Americans aged 65 years and older, 61.2% of women and 38% of men experience at least occasional urinary or bowel incontinence, the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

Data from the 2007-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show that 54.8% of women and 29.9% of men had urinary leakage at least a few times a month, while 19.2% of women and 14.9% of men had accidental bowel leakage of mucus, liquid stool, or solid stool at least one to three times a month, according to the NCHS (Vital Health Stat. 2014;3[36]).

Among women aged 65-74 years, 60.6% had some type of incontinence, compared with 61.9% of women aged 75 years and over. The difference was larger for men, however, with 34.1% of those aged 65-74 years reporting incontinence, compared with 42.4% of men aged 75 years and over, the report showed.

The NHANES data are based on in-home interviews with a nationally representative sample of 2,625 respondents.

Among noninstitutionalized Americans aged 65 years and older, 61.2% of women and 38% of men experience at least occasional urinary or bowel incontinence, the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

Data from the 2007-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show that 54.8% of women and 29.9% of men had urinary leakage at least a few times a month, while 19.2% of women and 14.9% of men had accidental bowel leakage of mucus, liquid stool, or solid stool at least one to three times a month, according to the NCHS (Vital Health Stat. 2014;3[36]).

Among women aged 65-74 years, 60.6% had some type of incontinence, compared with 61.9% of women aged 75 years and over. The difference was larger for men, however, with 34.1% of those aged 65-74 years reporting incontinence, compared with 42.4% of men aged 75 years and over, the report showed.

The NHANES data are based on in-home interviews with a nationally representative sample of 2,625 respondents.

Denosumab's benefits persist through 8 years

CHICAGO – Postmenopausal women on denosumab for 8 years straight showed a continued near-linear increase in bone mineral density at the lumbar spine as well as persistent reduction of bone turnover markers and a sustained low incidence of new vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in the ongoing FREEDOM open-label extension study.

Moreover, no new safety signals have emerged during 5 years of additional denosumab (Prolia) on top of an initial 3 years occurring in the pivotal, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled FREEDOM (Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis Every 6 Months) trial.

Importantly, the overall risk of adverse events has not increased over time, and rates of malignancies, serious infections, eczema, hypocalcemia, and other adverse events in denosumab-treated patients remain comparable to rates seen in placebo-treated controls in the earlier double-blind phase, Dr. E. Michael Lewiecki reported at the joint meeting of the International Congress of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society.

"The benefit/risk profile for denosumab remains favorable," declared Dr. Lewiecki, director of the New Mexico Clinical Research and Osteoporosis Center, Albuquerque.

The FREEDOM open-label extension is designed to assess the efficacy and safety of up to 10 years of denosumab therapy. Dr. Lewiecki presented the latest update, based on 8 years of treatment, or 5 years for patients in the original placebo arm who later elected to crossover to denosumab upon completing the 3-year double-blind phase. His report included 2,243 women on denosumab at 60 mg by subcutaneous injection every 6 months continuously for 8 years and another 2,207 on the drug for 5 years.

Five cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw have occurred in the long-term therapy group, as well as three cases among those who crossed over to the drug. In addition, there has been one atypical femoral fracture during 8 consecutive years on denosumab and one case in the crossover group.

Impressively, lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) has increased by 18.4% over baseline with 8 years of denosumab and by 13.7% with 5 years of active therapy.

"The near-linear slope of increase is unchanged over the course of the study. A similar slope is seen in the crossover group," the endocrinologist observed.

Total hip BMD increased by 8.3% with 8 years of denosumab and 4.9% with 5 years of therapy.

In the pivotal phase III FREEDOM trial, 3 years of denosumab reduced the risk of vertebral fractures by 68% compared to placebo, hip fractures by 40%, and nonvertebral fractures by 20% (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:756-65).

The yearly incidence of new vertebral fractures was 0.7%-1.1% in denosumab-treated patients during years 1-3 and 1.1%-1.3% annually in open-label years 4-8. The annual incidence of new nonvertebral fractures in the denosumab group was 2.1%-2.6% in the first 3 years of double-blind therapy and has trended lower since then: 1.5% in year 4, 1.2% in year 5, 1.8% in year 6, 1.6% in year 7, and 0.7% in year 8.

"There’s a suggestion of a further reduction in the risk of nonvertebral fractures out to the 8-year time point. It’ll be fascinating to look at the data for years 9 and 10 to see if that’s just a statistical aberrance or that very low risk of nonvertebral fractures persists," Dr. Lewiecki commented.

Levels of the bone turnover markers serum C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen and procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide quickly dropped upon initiation of denosumab and have remained low through 8 years.

Asked about the mechanism underlying the continued linear increase in lumbar spine BMD seen through 8 years of denosumab, in sharp contrast to the bisphosphonates, where BMD plateaus, Dr. Lewiecki confessed that "Many of us are scratching our heads about this and trying to come up with an explanation."

"I don’t know the reason why, but there are several hypotheses worth considering," he continued. "One is that the effects on cortical bone appear to be different with denosumab than with bisphosphonates. We see a reduction in cortical porosity and a larger improvement in bone mineral density at cortical skeletal sites. Secondly, there’s a possible parathyroid hormone effect that may play a role here: There is a larger and longer-lasting increase in parathyroid hormone with denosumab as compared with bisphosphonates. And finally, there’s animal data in monkeys showing ongoing bone modeling taking place with denosumab; it’s possible that may also play a role."

Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B (RANK) ligand.

The FREEDOM study is supported by Amgen. Dr. Lewiecki reported serving as a consultant to that company as well as to AgNovos Healthcare, Lilly, Merck, and Radius Health.

CHICAGO – Postmenopausal women on denosumab for 8 years straight showed a continued near-linear increase in bone mineral density at the lumbar spine as well as persistent reduction of bone turnover markers and a sustained low incidence of new vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in the ongoing FREEDOM open-label extension study.

Moreover, no new safety signals have emerged during 5 years of additional denosumab (Prolia) on top of an initial 3 years occurring in the pivotal, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled FREEDOM (Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis Every 6 Months) trial.

Importantly, the overall risk of adverse events has not increased over time, and rates of malignancies, serious infections, eczema, hypocalcemia, and other adverse events in denosumab-treated patients remain comparable to rates seen in placebo-treated controls in the earlier double-blind phase, Dr. E. Michael Lewiecki reported at the joint meeting of the International Congress of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society.

"The benefit/risk profile for denosumab remains favorable," declared Dr. Lewiecki, director of the New Mexico Clinical Research and Osteoporosis Center, Albuquerque.

The FREEDOM open-label extension is designed to assess the efficacy and safety of up to 10 years of denosumab therapy. Dr. Lewiecki presented the latest update, based on 8 years of treatment, or 5 years for patients in the original placebo arm who later elected to crossover to denosumab upon completing the 3-year double-blind phase. His report included 2,243 women on denosumab at 60 mg by subcutaneous injection every 6 months continuously for 8 years and another 2,207 on the drug for 5 years.

Five cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw have occurred in the long-term therapy group, as well as three cases among those who crossed over to the drug. In addition, there has been one atypical femoral fracture during 8 consecutive years on denosumab and one case in the crossover group.

Impressively, lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) has increased by 18.4% over baseline with 8 years of denosumab and by 13.7% with 5 years of active therapy.

"The near-linear slope of increase is unchanged over the course of the study. A similar slope is seen in the crossover group," the endocrinologist observed.

Total hip BMD increased by 8.3% with 8 years of denosumab and 4.9% with 5 years of therapy.

In the pivotal phase III FREEDOM trial, 3 years of denosumab reduced the risk of vertebral fractures by 68% compared to placebo, hip fractures by 40%, and nonvertebral fractures by 20% (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:756-65).

The yearly incidence of new vertebral fractures was 0.7%-1.1% in denosumab-treated patients during years 1-3 and 1.1%-1.3% annually in open-label years 4-8. The annual incidence of new nonvertebral fractures in the denosumab group was 2.1%-2.6% in the first 3 years of double-blind therapy and has trended lower since then: 1.5% in year 4, 1.2% in year 5, 1.8% in year 6, 1.6% in year 7, and 0.7% in year 8.

"There’s a suggestion of a further reduction in the risk of nonvertebral fractures out to the 8-year time point. It’ll be fascinating to look at the data for years 9 and 10 to see if that’s just a statistical aberrance or that very low risk of nonvertebral fractures persists," Dr. Lewiecki commented.

Levels of the bone turnover markers serum C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen and procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide quickly dropped upon initiation of denosumab and have remained low through 8 years.

Asked about the mechanism underlying the continued linear increase in lumbar spine BMD seen through 8 years of denosumab, in sharp contrast to the bisphosphonates, where BMD plateaus, Dr. Lewiecki confessed that "Many of us are scratching our heads about this and trying to come up with an explanation."

"I don’t know the reason why, but there are several hypotheses worth considering," he continued. "One is that the effects on cortical bone appear to be different with denosumab than with bisphosphonates. We see a reduction in cortical porosity and a larger improvement in bone mineral density at cortical skeletal sites. Secondly, there’s a possible parathyroid hormone effect that may play a role here: There is a larger and longer-lasting increase in parathyroid hormone with denosumab as compared with bisphosphonates. And finally, there’s animal data in monkeys showing ongoing bone modeling taking place with denosumab; it’s possible that may also play a role."

Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B (RANK) ligand.

The FREEDOM study is supported by Amgen. Dr. Lewiecki reported serving as a consultant to that company as well as to AgNovos Healthcare, Lilly, Merck, and Radius Health.

CHICAGO – Postmenopausal women on denosumab for 8 years straight showed a continued near-linear increase in bone mineral density at the lumbar spine as well as persistent reduction of bone turnover markers and a sustained low incidence of new vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in the ongoing FREEDOM open-label extension study.

Moreover, no new safety signals have emerged during 5 years of additional denosumab (Prolia) on top of an initial 3 years occurring in the pivotal, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled FREEDOM (Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis Every 6 Months) trial.

Importantly, the overall risk of adverse events has not increased over time, and rates of malignancies, serious infections, eczema, hypocalcemia, and other adverse events in denosumab-treated patients remain comparable to rates seen in placebo-treated controls in the earlier double-blind phase, Dr. E. Michael Lewiecki reported at the joint meeting of the International Congress of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society.

"The benefit/risk profile for denosumab remains favorable," declared Dr. Lewiecki, director of the New Mexico Clinical Research and Osteoporosis Center, Albuquerque.

The FREEDOM open-label extension is designed to assess the efficacy and safety of up to 10 years of denosumab therapy. Dr. Lewiecki presented the latest update, based on 8 years of treatment, or 5 years for patients in the original placebo arm who later elected to crossover to denosumab upon completing the 3-year double-blind phase. His report included 2,243 women on denosumab at 60 mg by subcutaneous injection every 6 months continuously for 8 years and another 2,207 on the drug for 5 years.

Five cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw have occurred in the long-term therapy group, as well as three cases among those who crossed over to the drug. In addition, there has been one atypical femoral fracture during 8 consecutive years on denosumab and one case in the crossover group.

Impressively, lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) has increased by 18.4% over baseline with 8 years of denosumab and by 13.7% with 5 years of active therapy.

"The near-linear slope of increase is unchanged over the course of the study. A similar slope is seen in the crossover group," the endocrinologist observed.

Total hip BMD increased by 8.3% with 8 years of denosumab and 4.9% with 5 years of therapy.

In the pivotal phase III FREEDOM trial, 3 years of denosumab reduced the risk of vertebral fractures by 68% compared to placebo, hip fractures by 40%, and nonvertebral fractures by 20% (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:756-65).

The yearly incidence of new vertebral fractures was 0.7%-1.1% in denosumab-treated patients during years 1-3 and 1.1%-1.3% annually in open-label years 4-8. The annual incidence of new nonvertebral fractures in the denosumab group was 2.1%-2.6% in the first 3 years of double-blind therapy and has trended lower since then: 1.5% in year 4, 1.2% in year 5, 1.8% in year 6, 1.6% in year 7, and 0.7% in year 8.

"There’s a suggestion of a further reduction in the risk of nonvertebral fractures out to the 8-year time point. It’ll be fascinating to look at the data for years 9 and 10 to see if that’s just a statistical aberrance or that very low risk of nonvertebral fractures persists," Dr. Lewiecki commented.

Levels of the bone turnover markers serum C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen and procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide quickly dropped upon initiation of denosumab and have remained low through 8 years.

Asked about the mechanism underlying the continued linear increase in lumbar spine BMD seen through 8 years of denosumab, in sharp contrast to the bisphosphonates, where BMD plateaus, Dr. Lewiecki confessed that "Many of us are scratching our heads about this and trying to come up with an explanation."

"I don’t know the reason why, but there are several hypotheses worth considering," he continued. "One is that the effects on cortical bone appear to be different with denosumab than with bisphosphonates. We see a reduction in cortical porosity and a larger improvement in bone mineral density at cortical skeletal sites. Secondly, there’s a possible parathyroid hormone effect that may play a role here: There is a larger and longer-lasting increase in parathyroid hormone with denosumab as compared with bisphosphonates. And finally, there’s animal data in monkeys showing ongoing bone modeling taking place with denosumab; it’s possible that may also play a role."

Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B (RANK) ligand.

The FREEDOM study is supported by Amgen. Dr. Lewiecki reported serving as a consultant to that company as well as to AgNovos Healthcare, Lilly, Merck, and Radius Health.

AT ICE/ENDO 2014

Key clinical point: An ongoing major study provides reassurance regarding the long-term safety and effectiveness of denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Major finding: Eight years of denosumab was associated with sustained low fracture rates, steadily increasing bone mineral density, persistent reduction of bone turnover, and no increase in adverse events over time.

Data source: The FREEDOM trial open-label extension includes 4,450 women on denosumab for either 5 or 8 years and counting.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Amgen. The presenter serves as a consultant to the company.

Hormone therapy for menopausal vasomotor symptoms

Estrogen therapy is highly effective in the treatment of hot flashes among postmenopausal women. For postmenopausal women with a uterus, estrogen treatment for hot flashes is almost always combined with a progestin to reduce the risk of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. For instance, in the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions Trial, 62% of the women with a uterus treated with conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily without a progestin developed endometrial hyperplasia.1

In the United States, the most commonly prescribed progestin for hormone therapy has been medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Provera). However, data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials indicate that MPA, when combined with CEE, may have adverse health effects among postmenopausal women.

Let’s examine the WHI data

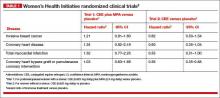

Among women 50 to 59 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a trend toward an increased risk of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction.2 In contrast, among women 50 to 59 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction (TABLE 1).

Among women 50 to 79 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.53; P = .04).2 In contrast, among women 50 to 79 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of breast cancer (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61–1.02, P = .07).2

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

When the analysis was limited to women consistently adherent to their CEE monotherapy, the estrogen treatment significantly decreased the risk of invasive breast cancer (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.97; P = .03).3

The addition of MPA to CEE appears to reverse some of the health benefits of CEE monotherapy, although the biological mechanisms are unclear. This observation should prompt us to explore alternative and novel treatments of vasomotor symptoms that do not utilize MPA. Some options for MPA-free hormone therapy include:

- transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone

- CEE plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

- bazedoxifene plus CEE.

In addition, nonhormonal treatment of hot flashes is an option, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Related article: Is one oral estrogen formulation safer than another for menopausal women? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; January 2014)

MPA-free hormone therapy for hot flashes

Estrogen plus micronized progesterone

When using an estrogen plus progestin regimen to treat hot flashes, many experts favor a combination of low-dose transdermal estradiol and oral micronized progesterone (Prometrium). This combination is believed by some experts to result in a lower risk of venous thromboembolism, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer than an estrogen-MPA combination.4–7

When prescribing transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone for a woman within 1 to 2 years of her last menses, a cyclic regimen can help reduce episodes of irregular, unscheduled uterine bleeding. I often use this cyclic regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus cyclic oral micronized progesterone 200 mg prior to bedtime for calendar days 1 to 12.

When using transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone in a woman more than 2 years from her last menses, a continuous regimen is often prescribed. I often use this continuous regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus continuous oral micronized progesterone 100 mg daily prior to bedtime.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Estrogen plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systemThe levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; 20 µg daily; Mirena) is frequently used in Europe to protect the endometrium against the adverse effects of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. In a meta-analysis of five clinical trials involving postmenopausal women, the LNG-IUS provided excellent protection against endometrial hyperplasia, compared with MPA.8

One caution about using the LNG-IUS system with estrogen in postmenopausal women is that an observational study of all women with breast cancer in Finland from 1995 through 2007 reported a significantly increased risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women using an LNG-IUS compared with women who did not use hormones or used only estrogen because they had a hysterectomy (TABLE 2).9 This study was not a randomized clinical trial and patients at higher baseline risk for breast cancer, including women with a high body mass index, may have been preferentially treated with an LNG-IUS. More information is needed to better understand the relationship between the LNG-IUS and breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Related article: What we’ve learned from 2 decades’ experience with the LNG-IUS. Q&A with Oskari Heikinheimo, MD, PhD (February 2011)

Progestin-free hormone treatment, bazedoxifene plus CEE

The main reason for adding a progestin to estrogen therapy for vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women with a uterus is to prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. A major innovation in hormone therapy is the discovery that third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as bazedoxifene (BZA), can prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer but do not interfere with the efficacy of estrogen in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms.

BZA is an estrogen agonist in bone and an estrogen antagonist in the endometrium.10–12 The combination of BZA (20 mg daily) plus CEE (0.45 mg daily) (Duavee) is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis.13–15 Over 24 months of therapy, various doses of BZA plus CEE reduced reported daily hot flashes by 52% to 86%.16 In the same study, placebo treatment was associated with a 17% reduction in hot flashes.16

The main adverse effect of BZA/CEE is an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis. Therefore, BZA/CEE is contraindicated in women with a known thrombophilia or a personal history of hormone-induced deep venous thrombosis. The effect of BZA/CEE on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer is not known; over 52 weeks of therapy it did not increase breast density on mammogram.17,18

BZA/CEE is a remarkable advance in hormone therapy. It is progestin-free, uses estrogen to treat vasomotor symptoms, and uses BZA to protect the endometrium against estrogen-induced hyperplasia.

Related article: New option for treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms receives FDA approval. (News for your Practice; October 2013)

Nonhormone treatment of vasomotor symptoms Paroxetine mesylateFor postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms who cannot take estrogen, SSRIs are modestly effective in reducing moderate to severe hot flashes. The US Food and Drug Administration recently approved paroxetine mesylate (Brisdelle) for the treatment of postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms. The approved dose is 7.5 mg daily taken at bedtime.

Data supporting the efficacy of paroxetine mesylate are available from two studies involving 1,184 menopausal women with vasomotor symptoms randomly assigned to receive paroxetine 7.5 mg daily or placebo for 12 weeks of treatment.19-22 In one of the two clinical trials, women treated with paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg daily had 5.6 fewer moderate to severe hot flashes daily after 12 weeks of treatment compared with 3.9 fewer hot flashes with placebo (median treatment difference, 1.7; P<.001).21

Paroxetine can block the metabolism of tamoxifen to its highly potent metabolite, endoxifen. Consequently, paroxetine may reduce the effectiveness of tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer and should be used with caution in postmenopausal women with breast cancer being treated with tamoxifen.

Related article: Paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg found to be a safe alternative to hormone therapy for menopausal women with hot flashes. (News for your Practice; June 2014)

Escitalopram

Gynecologists are familiar with the use of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, clonidine, citalopram, sertraline, and fluoxetine for the treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes. Recently, escitalopram (Lexapro) at doses of 10 to 20 mg daily has been shown to be more effective than placebo in the treatment of hot flashes and sleep disturbances in postmenopausal women.23,24 In one trial of escitalopram 10 to 20 mg daily versus placebo in 205 postmenopausal women averaging 9.8 hot flashes daily at baseline, escitalopram and placebo reduced mean daily hot flashes by 4.6 and 3.2, respectively (P<.001), after 8 weeks of treatment.

In a meta-analysis of SSRIs for the treatment of hot flashes, data from a mixed-treatment comparison analysis indicated that the rank order from most to least effective therapy for hot flashes was: escitalopram > paroxetine > sertraline > citalopram > fluoxetine.25 Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine, two serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors that are effective in the treatment of hot flashes, were not included in the mixed-treatment comparison.

Use of alternatives to MPA could mean fewer health risks for women on a wide scale

Substantial data indicate that MPA is not an optimal progestin to combine with estrogen for hormone therapy. Currently, many health insurance plans and Medicare use pharmacy management formularies that prioritize dispensing MPA for postmenopausal hormone therapy. Dispensing an alternative to MPA, such as micronized progesterone, often requires the patient to make a significant copayment.

Hopefully, health insurance companies, Medicare, and their affiliated pharmacy management administrators will soon stop their current policy of using financial incentives to favor dispensing MPA when hormone therapy is prescribed because alternatives to MPA appear to be associated with fewer health risks for postmenopausal women.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on endometrial histology in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. JAMA. 1996;275(5):370–375.

2. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefnick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

3. Stefanick ML, Anderson GL, Margolis KL, et al; WHI Investigators. Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA. 2006;295(14):1647–1657.

4. Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? [published online head of print January 6, 2014]. Menopause. PMID: 24398406.

5. Manson JE. Current recommendations: What is the clinician to do? Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):916–921.

6. Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: Results from the E3N cohort study [published correction appears in Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):307–308]. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(1):103–111.

7. Renoux C, Dell’aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: A nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519.

8. Somboonpom W, Panna S, Temtanakitpaisan T, Kaewrudee S, Soontrapa S. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system plus estrogen therapy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1060–1066.

9. Lyytinen HK, Dyba T, Ylikorkala O, Pukkala EI. A case-control study on hormone therapy as a risk factor for breast cancer in Finland: Intrauterine system carries a risk as well. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):483–489.

10. Komm BS, Mirkin S. An overview of current and emerging SERMs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;143C:207–222.

11. Ethun KF, Wood CE, Cline JM, Register TC, Appt SE, Clarkson TB. Endometrial profile of bazedoxifene acetate alone and in combination with conjugated equine estrogens in a primate model. Menopause. 2013;20(7):777–784.

12. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: A randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

13. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

14. Pinkerton JV, Abraham L, Bushmakin AG, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for secondary outcomes including vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women by years since menopause in the Selective estrogens, Menopause and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(1):18–28.

15. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

16. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

17. Harvey JA, Holm MK, Ranganath R, Guse PA, Trott EA, Helzner E. The effects of bazedoxifene on mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Menopause. 2009;16(6):1193–1196.

18. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20(2):138–145.

19. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: Two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1035.

20. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

21. Orleans RJ, Li L, Kim MJ, et al. FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flashes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1777–1779.

22. Paroxetine (Brisdelle) for hot flashes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55(1428):85–86.

23. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in health menopausal women. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267–274.

24. Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19(8):848–855.

25. Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):204–213.

Estrogen therapy is highly effective in the treatment of hot flashes among postmenopausal women. For postmenopausal women with a uterus, estrogen treatment for hot flashes is almost always combined with a progestin to reduce the risk of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. For instance, in the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions Trial, 62% of the women with a uterus treated with conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily without a progestin developed endometrial hyperplasia.1

In the United States, the most commonly prescribed progestin for hormone therapy has been medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Provera). However, data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials indicate that MPA, when combined with CEE, may have adverse health effects among postmenopausal women.

Let’s examine the WHI data

Among women 50 to 59 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a trend toward an increased risk of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction.2 In contrast, among women 50 to 59 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction (TABLE 1).

Among women 50 to 79 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.53; P = .04).2 In contrast, among women 50 to 79 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of breast cancer (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61–1.02, P = .07).2

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

When the analysis was limited to women consistently adherent to their CEE monotherapy, the estrogen treatment significantly decreased the risk of invasive breast cancer (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.97; P = .03).3

The addition of MPA to CEE appears to reverse some of the health benefits of CEE monotherapy, although the biological mechanisms are unclear. This observation should prompt us to explore alternative and novel treatments of vasomotor symptoms that do not utilize MPA. Some options for MPA-free hormone therapy include:

- transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone

- CEE plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

- bazedoxifene plus CEE.

In addition, nonhormonal treatment of hot flashes is an option, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Related article: Is one oral estrogen formulation safer than another for menopausal women? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; January 2014)

MPA-free hormone therapy for hot flashes

Estrogen plus micronized progesterone

When using an estrogen plus progestin regimen to treat hot flashes, many experts favor a combination of low-dose transdermal estradiol and oral micronized progesterone (Prometrium). This combination is believed by some experts to result in a lower risk of venous thromboembolism, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer than an estrogen-MPA combination.4–7

When prescribing transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone for a woman within 1 to 2 years of her last menses, a cyclic regimen can help reduce episodes of irregular, unscheduled uterine bleeding. I often use this cyclic regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus cyclic oral micronized progesterone 200 mg prior to bedtime for calendar days 1 to 12.

When using transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone in a woman more than 2 years from her last menses, a continuous regimen is often prescribed. I often use this continuous regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus continuous oral micronized progesterone 100 mg daily prior to bedtime.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Estrogen plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systemThe levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; 20 µg daily; Mirena) is frequently used in Europe to protect the endometrium against the adverse effects of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. In a meta-analysis of five clinical trials involving postmenopausal women, the LNG-IUS provided excellent protection against endometrial hyperplasia, compared with MPA.8

One caution about using the LNG-IUS system with estrogen in postmenopausal women is that an observational study of all women with breast cancer in Finland from 1995 through 2007 reported a significantly increased risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women using an LNG-IUS compared with women who did not use hormones or used only estrogen because they had a hysterectomy (TABLE 2).9 This study was not a randomized clinical trial and patients at higher baseline risk for breast cancer, including women with a high body mass index, may have been preferentially treated with an LNG-IUS. More information is needed to better understand the relationship between the LNG-IUS and breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Related article: What we’ve learned from 2 decades’ experience with the LNG-IUS. Q&A with Oskari Heikinheimo, MD, PhD (February 2011)

Progestin-free hormone treatment, bazedoxifene plus CEE

The main reason for adding a progestin to estrogen therapy for vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women with a uterus is to prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. A major innovation in hormone therapy is the discovery that third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as bazedoxifene (BZA), can prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer but do not interfere with the efficacy of estrogen in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms.

BZA is an estrogen agonist in bone and an estrogen antagonist in the endometrium.10–12 The combination of BZA (20 mg daily) plus CEE (0.45 mg daily) (Duavee) is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis.13–15 Over 24 months of therapy, various doses of BZA plus CEE reduced reported daily hot flashes by 52% to 86%.16 In the same study, placebo treatment was associated with a 17% reduction in hot flashes.16

The main adverse effect of BZA/CEE is an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis. Therefore, BZA/CEE is contraindicated in women with a known thrombophilia or a personal history of hormone-induced deep venous thrombosis. The effect of BZA/CEE on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer is not known; over 52 weeks of therapy it did not increase breast density on mammogram.17,18

BZA/CEE is a remarkable advance in hormone therapy. It is progestin-free, uses estrogen to treat vasomotor symptoms, and uses BZA to protect the endometrium against estrogen-induced hyperplasia.

Related article: New option for treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms receives FDA approval. (News for your Practice; October 2013)

Nonhormone treatment of vasomotor symptoms Paroxetine mesylateFor postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms who cannot take estrogen, SSRIs are modestly effective in reducing moderate to severe hot flashes. The US Food and Drug Administration recently approved paroxetine mesylate (Brisdelle) for the treatment of postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms. The approved dose is 7.5 mg daily taken at bedtime.

Data supporting the efficacy of paroxetine mesylate are available from two studies involving 1,184 menopausal women with vasomotor symptoms randomly assigned to receive paroxetine 7.5 mg daily or placebo for 12 weeks of treatment.19-22 In one of the two clinical trials, women treated with paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg daily had 5.6 fewer moderate to severe hot flashes daily after 12 weeks of treatment compared with 3.9 fewer hot flashes with placebo (median treatment difference, 1.7; P<.001).21

Paroxetine can block the metabolism of tamoxifen to its highly potent metabolite, endoxifen. Consequently, paroxetine may reduce the effectiveness of tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer and should be used with caution in postmenopausal women with breast cancer being treated with tamoxifen.

Related article: Paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg found to be a safe alternative to hormone therapy for menopausal women with hot flashes. (News for your Practice; June 2014)

Escitalopram