User login

Adverse skin effects of cancer immunotherapy reviewed

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have unquestionably revolutionized the care of patients with malignant melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and other types of cancer.

, according to members of a European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) task force.

“The desirable, immune-mediated oncologic response is often achieved at the cost of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) that may potentially affect any organ system,” they write in a position statement on the management of ICI-derived dermatologic adverse events.

Recommendations from the EADV “Dermatology for Cancer Patients” task force have been published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Task force members developed the recommendations based on clinical experience from published data and came up with specific recommendations for treating cutaneous toxicities associated with dermatologic immune-related adverse events (dirAEs) that occur in patients receiving immunotherapy with an ICI.

ICIs include the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor ipilimumab (Yervoy, Bristol Myers Squibb), and inhibitors of programmed death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1), including nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol Myers Squibb), pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck), and other agents.

“The basic principle of management is that the interventions should be tailored to serve the equilibrium between patients’ relief from the symptoms and signs of skin toxicity and the preservation of an unimpeded oncologic treatment,” they write.

The recommendations are in line with those included in a 2021 update of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines on the management of irAEs in patients treated with ICIs across the whole range of organ systems, said Milan J. Anadkat, MD, professor of dermatology and director of dermatology clinical trials at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Anadkat was a coauthor of the ASCO guideline update.

Although the European recommendations focus only on dermatologic side effects of ICIs in patients with cancer, “that doesn’t diminish their importance. They do a good job of summarizing how to approach and how to manage it depending on the severity of the toxicities and the various types of toxicities,” he told this news organization.

Having a paper focused exclusively on the dermatologic side effects of ICIs allows the inclusion of photographs that can help clinicians identify specific conditions that may require referral to a dermatologist, he said.

Both Dr. Anadkat and the authors of the European recommendations noted that dermatologic irAEs are more common with CTLA-4 inhibition than with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition.

“It has to do with where the target is,” Dr. Anadkat said. “CTLA-4 inhibition works on a central aspect of the immune system, so it’s a much less specific site, whereas PD-1 affects an interaction at the site of the tumor cell itself, so it’s a little more specific.”

Pruritus

ICI-induced pruritus can occur without apparent skin changes, they write, noting that in a recent study of patients with dirAEs, about one-third had isolated pruritus.

The task force members cite a meta-analysis indicating a pruritus incidence of 13.2% for patients treated with nivolumab and 20.2% for patients treated with pembrolizumab but respective grade 3 pruritus rates of only 0.5% and 2.3%. The reported incidence of pruritus with ipilimumab was 47% in a different study.

Recommended treatments include topical moisturizers with or without medium-to-high potency corticosteroids for grade 1 reactions, non-sedating histamines and/or GABA agonists such as pregabalin, or gabapentin for grade 2 pruritus, and suspension of ICIs until pruritus improves in patients with grade 3 pruritus.

Maculopapular rash

Maculopapular or eczema-like rashes may occur in up to 68% of patients who receive a CTLA-4 inhibitor and up to 20% of those who receive a PD1/PD-L1 inhibitor, the authors note. Rashes commonly appear within 3-6 weeks of initiating therapy.

“The clinical presentation is nonspecific and consists of a rapid onset of multiple minimally scaly, erythematous macules and papules, congregating into plaques. Lesions are mostly located on trunk and extensor surfaces of the extremities and the face is generally spared,” they write.

Maculopapular rashes are typically accompanied by itching but could be asymptomatic, they noted.

Mild (grade 1) rashes may respond to moisturizers and topical potent or super-potent corticosteroids. Patients with grade 2 rash should also receive oral antihistamines. Systemic corticosteroids may be considered for patients with grade 3 rashes but only after other dirAEs that may require specific management, such as psoriasis, are ruled out.

Psoriasis-like rash

The most common form of psoriasis seen in patients treated with ICIs is psoriasis vulgaris with plaques, but other clinical variants are also seen, the authors note.

“Topical agents (corticosteroids, Vitamin D analogues) are prescribed in Grades 1/2 and supplementary” to systemic treatment for patients with grade 3 or recalcitrant lesions, they write. “If skin-directed therapies fail to provide symptomatic control,” systemic treatment and narrow band UVB phototherapy “should be considered,” they add.

Evidence regarding the use of systemic therapies to treat psoriasis-like rash associated with ICIs is sparse. Acitretin can be safely used in patients with cancer. Low-dose methotrexate is also safe to use except in patients with non-melanoma skin cancers. Cyclosporine, however, should be avoided because of the potential for tumor-promoting effects, they emphasized.

The recommendations also cover treatment of lichen planus-like and vitiligo-like rashes, as well as hair and nail changes, autoimmune bullous disorders, and oral mucosal dirAEs.

In addition, the recommendations cover severe cutaneous adverse reactions as well as serious, potentially life-threatening dirAEs, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms/drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DRESS/DIHS).

“The dose of corticosteroids may be adapted to the severity of DRESS. The therapeutic benefit of systemic corticosteroids in the management of SJS/TEN remains controversial, and some authors favor treatment with cyclosporine. However, the use of corticosteroids in this context of ICI treatment appears reasonable and should be proposed. Short courses of steroids seem also effective in AGEP,” the task force members write.

The recommendations did not have outside funding. Of the 19 authors, 6 disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Leo Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, and/or Janssen. Dr. Anadkat disclosed previous relationships with Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, and current relationships with others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have unquestionably revolutionized the care of patients with malignant melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and other types of cancer.

, according to members of a European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) task force.

“The desirable, immune-mediated oncologic response is often achieved at the cost of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) that may potentially affect any organ system,” they write in a position statement on the management of ICI-derived dermatologic adverse events.

Recommendations from the EADV “Dermatology for Cancer Patients” task force have been published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Task force members developed the recommendations based on clinical experience from published data and came up with specific recommendations for treating cutaneous toxicities associated with dermatologic immune-related adverse events (dirAEs) that occur in patients receiving immunotherapy with an ICI.

ICIs include the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor ipilimumab (Yervoy, Bristol Myers Squibb), and inhibitors of programmed death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1), including nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol Myers Squibb), pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck), and other agents.

“The basic principle of management is that the interventions should be tailored to serve the equilibrium between patients’ relief from the symptoms and signs of skin toxicity and the preservation of an unimpeded oncologic treatment,” they write.

The recommendations are in line with those included in a 2021 update of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines on the management of irAEs in patients treated with ICIs across the whole range of organ systems, said Milan J. Anadkat, MD, professor of dermatology and director of dermatology clinical trials at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Anadkat was a coauthor of the ASCO guideline update.

Although the European recommendations focus only on dermatologic side effects of ICIs in patients with cancer, “that doesn’t diminish their importance. They do a good job of summarizing how to approach and how to manage it depending on the severity of the toxicities and the various types of toxicities,” he told this news organization.

Having a paper focused exclusively on the dermatologic side effects of ICIs allows the inclusion of photographs that can help clinicians identify specific conditions that may require referral to a dermatologist, he said.

Both Dr. Anadkat and the authors of the European recommendations noted that dermatologic irAEs are more common with CTLA-4 inhibition than with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition.

“It has to do with where the target is,” Dr. Anadkat said. “CTLA-4 inhibition works on a central aspect of the immune system, so it’s a much less specific site, whereas PD-1 affects an interaction at the site of the tumor cell itself, so it’s a little more specific.”

Pruritus

ICI-induced pruritus can occur without apparent skin changes, they write, noting that in a recent study of patients with dirAEs, about one-third had isolated pruritus.

The task force members cite a meta-analysis indicating a pruritus incidence of 13.2% for patients treated with nivolumab and 20.2% for patients treated with pembrolizumab but respective grade 3 pruritus rates of only 0.5% and 2.3%. The reported incidence of pruritus with ipilimumab was 47% in a different study.

Recommended treatments include topical moisturizers with or without medium-to-high potency corticosteroids for grade 1 reactions, non-sedating histamines and/or GABA agonists such as pregabalin, or gabapentin for grade 2 pruritus, and suspension of ICIs until pruritus improves in patients with grade 3 pruritus.

Maculopapular rash

Maculopapular or eczema-like rashes may occur in up to 68% of patients who receive a CTLA-4 inhibitor and up to 20% of those who receive a PD1/PD-L1 inhibitor, the authors note. Rashes commonly appear within 3-6 weeks of initiating therapy.

“The clinical presentation is nonspecific and consists of a rapid onset of multiple minimally scaly, erythematous macules and papules, congregating into plaques. Lesions are mostly located on trunk and extensor surfaces of the extremities and the face is generally spared,” they write.

Maculopapular rashes are typically accompanied by itching but could be asymptomatic, they noted.

Mild (grade 1) rashes may respond to moisturizers and topical potent or super-potent corticosteroids. Patients with grade 2 rash should also receive oral antihistamines. Systemic corticosteroids may be considered for patients with grade 3 rashes but only after other dirAEs that may require specific management, such as psoriasis, are ruled out.

Psoriasis-like rash

The most common form of psoriasis seen in patients treated with ICIs is psoriasis vulgaris with plaques, but other clinical variants are also seen, the authors note.

“Topical agents (corticosteroids, Vitamin D analogues) are prescribed in Grades 1/2 and supplementary” to systemic treatment for patients with grade 3 or recalcitrant lesions, they write. “If skin-directed therapies fail to provide symptomatic control,” systemic treatment and narrow band UVB phototherapy “should be considered,” they add.

Evidence regarding the use of systemic therapies to treat psoriasis-like rash associated with ICIs is sparse. Acitretin can be safely used in patients with cancer. Low-dose methotrexate is also safe to use except in patients with non-melanoma skin cancers. Cyclosporine, however, should be avoided because of the potential for tumor-promoting effects, they emphasized.

The recommendations also cover treatment of lichen planus-like and vitiligo-like rashes, as well as hair and nail changes, autoimmune bullous disorders, and oral mucosal dirAEs.

In addition, the recommendations cover severe cutaneous adverse reactions as well as serious, potentially life-threatening dirAEs, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms/drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DRESS/DIHS).

“The dose of corticosteroids may be adapted to the severity of DRESS. The therapeutic benefit of systemic corticosteroids in the management of SJS/TEN remains controversial, and some authors favor treatment with cyclosporine. However, the use of corticosteroids in this context of ICI treatment appears reasonable and should be proposed. Short courses of steroids seem also effective in AGEP,” the task force members write.

The recommendations did not have outside funding. Of the 19 authors, 6 disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Leo Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, and/or Janssen. Dr. Anadkat disclosed previous relationships with Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, and current relationships with others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have unquestionably revolutionized the care of patients with malignant melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and other types of cancer.

, according to members of a European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) task force.

“The desirable, immune-mediated oncologic response is often achieved at the cost of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) that may potentially affect any organ system,” they write in a position statement on the management of ICI-derived dermatologic adverse events.

Recommendations from the EADV “Dermatology for Cancer Patients” task force have been published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Task force members developed the recommendations based on clinical experience from published data and came up with specific recommendations for treating cutaneous toxicities associated with dermatologic immune-related adverse events (dirAEs) that occur in patients receiving immunotherapy with an ICI.

ICIs include the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor ipilimumab (Yervoy, Bristol Myers Squibb), and inhibitors of programmed death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1), including nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol Myers Squibb), pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck), and other agents.

“The basic principle of management is that the interventions should be tailored to serve the equilibrium between patients’ relief from the symptoms and signs of skin toxicity and the preservation of an unimpeded oncologic treatment,” they write.

The recommendations are in line with those included in a 2021 update of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines on the management of irAEs in patients treated with ICIs across the whole range of organ systems, said Milan J. Anadkat, MD, professor of dermatology and director of dermatology clinical trials at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Anadkat was a coauthor of the ASCO guideline update.

Although the European recommendations focus only on dermatologic side effects of ICIs in patients with cancer, “that doesn’t diminish their importance. They do a good job of summarizing how to approach and how to manage it depending on the severity of the toxicities and the various types of toxicities,” he told this news organization.

Having a paper focused exclusively on the dermatologic side effects of ICIs allows the inclusion of photographs that can help clinicians identify specific conditions that may require referral to a dermatologist, he said.

Both Dr. Anadkat and the authors of the European recommendations noted that dermatologic irAEs are more common with CTLA-4 inhibition than with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition.

“It has to do with where the target is,” Dr. Anadkat said. “CTLA-4 inhibition works on a central aspect of the immune system, so it’s a much less specific site, whereas PD-1 affects an interaction at the site of the tumor cell itself, so it’s a little more specific.”

Pruritus

ICI-induced pruritus can occur without apparent skin changes, they write, noting that in a recent study of patients with dirAEs, about one-third had isolated pruritus.

The task force members cite a meta-analysis indicating a pruritus incidence of 13.2% for patients treated with nivolumab and 20.2% for patients treated with pembrolizumab but respective grade 3 pruritus rates of only 0.5% and 2.3%. The reported incidence of pruritus with ipilimumab was 47% in a different study.

Recommended treatments include topical moisturizers with or without medium-to-high potency corticosteroids for grade 1 reactions, non-sedating histamines and/or GABA agonists such as pregabalin, or gabapentin for grade 2 pruritus, and suspension of ICIs until pruritus improves in patients with grade 3 pruritus.

Maculopapular rash

Maculopapular or eczema-like rashes may occur in up to 68% of patients who receive a CTLA-4 inhibitor and up to 20% of those who receive a PD1/PD-L1 inhibitor, the authors note. Rashes commonly appear within 3-6 weeks of initiating therapy.

“The clinical presentation is nonspecific and consists of a rapid onset of multiple minimally scaly, erythematous macules and papules, congregating into plaques. Lesions are mostly located on trunk and extensor surfaces of the extremities and the face is generally spared,” they write.

Maculopapular rashes are typically accompanied by itching but could be asymptomatic, they noted.

Mild (grade 1) rashes may respond to moisturizers and topical potent or super-potent corticosteroids. Patients with grade 2 rash should also receive oral antihistamines. Systemic corticosteroids may be considered for patients with grade 3 rashes but only after other dirAEs that may require specific management, such as psoriasis, are ruled out.

Psoriasis-like rash

The most common form of psoriasis seen in patients treated with ICIs is psoriasis vulgaris with plaques, but other clinical variants are also seen, the authors note.

“Topical agents (corticosteroids, Vitamin D analogues) are prescribed in Grades 1/2 and supplementary” to systemic treatment for patients with grade 3 or recalcitrant lesions, they write. “If skin-directed therapies fail to provide symptomatic control,” systemic treatment and narrow band UVB phototherapy “should be considered,” they add.

Evidence regarding the use of systemic therapies to treat psoriasis-like rash associated with ICIs is sparse. Acitretin can be safely used in patients with cancer. Low-dose methotrexate is also safe to use except in patients with non-melanoma skin cancers. Cyclosporine, however, should be avoided because of the potential for tumor-promoting effects, they emphasized.

The recommendations also cover treatment of lichen planus-like and vitiligo-like rashes, as well as hair and nail changes, autoimmune bullous disorders, and oral mucosal dirAEs.

In addition, the recommendations cover severe cutaneous adverse reactions as well as serious, potentially life-threatening dirAEs, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms/drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DRESS/DIHS).

“The dose of corticosteroids may be adapted to the severity of DRESS. The therapeutic benefit of systemic corticosteroids in the management of SJS/TEN remains controversial, and some authors favor treatment with cyclosporine. However, the use of corticosteroids in this context of ICI treatment appears reasonable and should be proposed. Short courses of steroids seem also effective in AGEP,” the task force members write.

The recommendations did not have outside funding. Of the 19 authors, 6 disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Leo Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, and/or Janssen. Dr. Anadkat disclosed previous relationships with Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, and current relationships with others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ways to lessen toxic effects of chemo in older adults

Age-related changes that potentiate adverse drug reactions include alterations in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. As such, older patients often require adjustments in medications to optimize safety and use. Medication adjustment is especially important for older patients on complex medication regimens for multiple conditions, such as those undergoing cancer treatment. Three recent high-quality randomized trials evaluated the use of geriatric assessment (GA) in older adults with cancer.1-3

Interdisciplinary GA can identify aging-related conditions associated with poor outcomes in older patients with cancer (e.g., toxic effects of chemotherapy) and provide recommendations aimed at improving health outcomes. The results of these trials suggest that interdisciplinary GA can improve care outcomes and oncologists’ communication for older adults with cancer, and should be considered an emerging standard of care.

Geriatric assessment and chemotherapy-related toxic effects

A cluster randomized trial1 at City of Hope National Medical Center conducted between August 2015 and February 2019 enrolled 613 participants and randomly assigned them to receive a GA-guided intervention or usual standard of care in a 2-to-1 ratio. Participants were eligible for the study if they were aged ≥65 years; had a diagnosis of solid malignant neoplasm of any stage; were starting a new chemotherapy regimen; and were fluent in English, Spanish, or Chinese.

The intervention included a GA at baseline followed by assessments focused on six common areas: sleep problems, problems with eating and feeding, incontinence, confusion, evidence of falls, and skin breakdown. An interdisciplinary team (oncologist, nurse practitioner, pharmacist, physical therapist, occupational therapist, social worker, and nutritionist) performed the assessment and developed a plan of care. Interventions were multifactorial and could include referral to specialists; recommendations for medication changes; symptom management; nutritional intervention with diet recommendations and supplementation; and interventions targeting social, spiritual, and functional well-being. Follow-up by a nurse practitioner continued until completion of chemotherapy or 6 months after starting chemotherapy, whichever was earlier.

The primary outcome was grade 3 or higher chemotherapy-related toxic effects using National Cancer Institute criteria, and secondary outcomes were advance directive completion, emergency room visits and unplanned hospitalizations, and survival up to 12 months. Results showed a 10% absolute reduction in the incidence of grade 3 or higher toxic effects (P = .02), with a number needed to treat of 10. Advance directive completion also increased by 15%, but no differences were observed for other outcomes. This study offers high-quality evidence that a GA-based intervention can reduce toxic effects of chemotherapy regimens for older adults with cancer.

Geriatric assessment in community oncology practices

A recent study by Supriya G. Mohile, MD, and colleagues2 is the first nationwide multicenter clinical trial to demonstrate the effects of GA and GA-guided management. This study was conducted in 40 oncology practices from the University of Rochester National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program network. Centers were randomly assigned to intervention or usual care (362 patients treated by 68 oncologists in the intervention group and 371 patients treated by 91 oncologists in the usual-care group). Eligibility criteria were age ≥70 years; impairment in at least one GA domain other than polypharmacy; incurable advanced solid tumor or lymphoma with a plan to start new cancer treatment with a high risk for toxic effects within 4 weeks; and English language fluency. Both study groups underwent a baseline GA that assessed patients’ physical performance, functional status, comorbidity, cognition, nutrition, social support, polypharmacy, and psychological status. For the intervention group, a summary and management recommendations were provided to the treating oncologists.

The primary outcome was grade 3 or higher toxic effects within 3 months of starting a new regimen; secondary outcomes included treatment intensity and survival and GA outcomes within 3 months. A smaller proportion of patients in the intervention group experienced toxicity (51% vs. 71%), with an absolute risk reduction of 20%. Patients in the intervention group also had fewer falls and a greater reduction in medications used; there were no other differences in secondary outcomes. This study offers very strong and generalizable evidence that incorporating GA in the care of older adults with cancer at risk for toxicity can reduce toxicity as well as improve other outcomes, such as falls and polypharmacy.

Geriatric assessment and oncologist-patient communication

A secondary analysis3 of data from Dr. Mohile and colleagues2 evaluated the effect of GA-guided recommendations on oncologist-patient communication regarding comorbidities. Patients (n = 541) included in this analysis were 76.6 years of age on average and had 3.2 (standard deviation, 1.9) comorbid conditions. All patients underwent GA, but only oncologists in the intervention arm received GA-based recommendations. Clinical encounters between oncologist and patient immediately following the GA were audio recorded and analyzed to examine communication between oncologists and participants as it relates to chronic comorbid conditions.

In the intervention arm, more discussions regarding comorbidities took place, and more participants’ concerns about comorbidities were acknowledged. More importantly, participants in the intervention group were 2.4 times more likely to have their concerns about comorbidities addressed through referral or education, compared with the usual-care group (P = .004). Moreover, 41% of oncologists in the intervention arm modified dosage or cancer treatment schedule because of concern about tolerability or comorbidities. This study demonstrates beneficial effects of GA in increasing communication and perhaps consideration of comorbidities of older adults when planning cancer treatment.

Dr. Hung is professor of geriatrics and palliative care at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Li D et al. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:e214158.

2. Mohile SG et al. Lancet. 2021;398:1894-1904.

3. Kleckner AS et al. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:e9-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Age-related changes that potentiate adverse drug reactions include alterations in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. As such, older patients often require adjustments in medications to optimize safety and use. Medication adjustment is especially important for older patients on complex medication regimens for multiple conditions, such as those undergoing cancer treatment. Three recent high-quality randomized trials evaluated the use of geriatric assessment (GA) in older adults with cancer.1-3

Interdisciplinary GA can identify aging-related conditions associated with poor outcomes in older patients with cancer (e.g., toxic effects of chemotherapy) and provide recommendations aimed at improving health outcomes. The results of these trials suggest that interdisciplinary GA can improve care outcomes and oncologists’ communication for older adults with cancer, and should be considered an emerging standard of care.

Geriatric assessment and chemotherapy-related toxic effects

A cluster randomized trial1 at City of Hope National Medical Center conducted between August 2015 and February 2019 enrolled 613 participants and randomly assigned them to receive a GA-guided intervention or usual standard of care in a 2-to-1 ratio. Participants were eligible for the study if they were aged ≥65 years; had a diagnosis of solid malignant neoplasm of any stage; were starting a new chemotherapy regimen; and were fluent in English, Spanish, or Chinese.

The intervention included a GA at baseline followed by assessments focused on six common areas: sleep problems, problems with eating and feeding, incontinence, confusion, evidence of falls, and skin breakdown. An interdisciplinary team (oncologist, nurse practitioner, pharmacist, physical therapist, occupational therapist, social worker, and nutritionist) performed the assessment and developed a plan of care. Interventions were multifactorial and could include referral to specialists; recommendations for medication changes; symptom management; nutritional intervention with diet recommendations and supplementation; and interventions targeting social, spiritual, and functional well-being. Follow-up by a nurse practitioner continued until completion of chemotherapy or 6 months after starting chemotherapy, whichever was earlier.

The primary outcome was grade 3 or higher chemotherapy-related toxic effects using National Cancer Institute criteria, and secondary outcomes were advance directive completion, emergency room visits and unplanned hospitalizations, and survival up to 12 months. Results showed a 10% absolute reduction in the incidence of grade 3 or higher toxic effects (P = .02), with a number needed to treat of 10. Advance directive completion also increased by 15%, but no differences were observed for other outcomes. This study offers high-quality evidence that a GA-based intervention can reduce toxic effects of chemotherapy regimens for older adults with cancer.

Geriatric assessment in community oncology practices

A recent study by Supriya G. Mohile, MD, and colleagues2 is the first nationwide multicenter clinical trial to demonstrate the effects of GA and GA-guided management. This study was conducted in 40 oncology practices from the University of Rochester National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program network. Centers were randomly assigned to intervention or usual care (362 patients treated by 68 oncologists in the intervention group and 371 patients treated by 91 oncologists in the usual-care group). Eligibility criteria were age ≥70 years; impairment in at least one GA domain other than polypharmacy; incurable advanced solid tumor or lymphoma with a plan to start new cancer treatment with a high risk for toxic effects within 4 weeks; and English language fluency. Both study groups underwent a baseline GA that assessed patients’ physical performance, functional status, comorbidity, cognition, nutrition, social support, polypharmacy, and psychological status. For the intervention group, a summary and management recommendations were provided to the treating oncologists.

The primary outcome was grade 3 or higher toxic effects within 3 months of starting a new regimen; secondary outcomes included treatment intensity and survival and GA outcomes within 3 months. A smaller proportion of patients in the intervention group experienced toxicity (51% vs. 71%), with an absolute risk reduction of 20%. Patients in the intervention group also had fewer falls and a greater reduction in medications used; there were no other differences in secondary outcomes. This study offers very strong and generalizable evidence that incorporating GA in the care of older adults with cancer at risk for toxicity can reduce toxicity as well as improve other outcomes, such as falls and polypharmacy.

Geriatric assessment and oncologist-patient communication

A secondary analysis3 of data from Dr. Mohile and colleagues2 evaluated the effect of GA-guided recommendations on oncologist-patient communication regarding comorbidities. Patients (n = 541) included in this analysis were 76.6 years of age on average and had 3.2 (standard deviation, 1.9) comorbid conditions. All patients underwent GA, but only oncologists in the intervention arm received GA-based recommendations. Clinical encounters between oncologist and patient immediately following the GA were audio recorded and analyzed to examine communication between oncologists and participants as it relates to chronic comorbid conditions.

In the intervention arm, more discussions regarding comorbidities took place, and more participants’ concerns about comorbidities were acknowledged. More importantly, participants in the intervention group were 2.4 times more likely to have their concerns about comorbidities addressed through referral or education, compared with the usual-care group (P = .004). Moreover, 41% of oncologists in the intervention arm modified dosage or cancer treatment schedule because of concern about tolerability or comorbidities. This study demonstrates beneficial effects of GA in increasing communication and perhaps consideration of comorbidities of older adults when planning cancer treatment.

Dr. Hung is professor of geriatrics and palliative care at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Li D et al. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:e214158.

2. Mohile SG et al. Lancet. 2021;398:1894-1904.

3. Kleckner AS et al. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:e9-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Age-related changes that potentiate adverse drug reactions include alterations in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. As such, older patients often require adjustments in medications to optimize safety and use. Medication adjustment is especially important for older patients on complex medication regimens for multiple conditions, such as those undergoing cancer treatment. Three recent high-quality randomized trials evaluated the use of geriatric assessment (GA) in older adults with cancer.1-3

Interdisciplinary GA can identify aging-related conditions associated with poor outcomes in older patients with cancer (e.g., toxic effects of chemotherapy) and provide recommendations aimed at improving health outcomes. The results of these trials suggest that interdisciplinary GA can improve care outcomes and oncologists’ communication for older adults with cancer, and should be considered an emerging standard of care.

Geriatric assessment and chemotherapy-related toxic effects

A cluster randomized trial1 at City of Hope National Medical Center conducted between August 2015 and February 2019 enrolled 613 participants and randomly assigned them to receive a GA-guided intervention or usual standard of care in a 2-to-1 ratio. Participants were eligible for the study if they were aged ≥65 years; had a diagnosis of solid malignant neoplasm of any stage; were starting a new chemotherapy regimen; and were fluent in English, Spanish, or Chinese.

The intervention included a GA at baseline followed by assessments focused on six common areas: sleep problems, problems with eating and feeding, incontinence, confusion, evidence of falls, and skin breakdown. An interdisciplinary team (oncologist, nurse practitioner, pharmacist, physical therapist, occupational therapist, social worker, and nutritionist) performed the assessment and developed a plan of care. Interventions were multifactorial and could include referral to specialists; recommendations for medication changes; symptom management; nutritional intervention with diet recommendations and supplementation; and interventions targeting social, spiritual, and functional well-being. Follow-up by a nurse practitioner continued until completion of chemotherapy or 6 months after starting chemotherapy, whichever was earlier.

The primary outcome was grade 3 or higher chemotherapy-related toxic effects using National Cancer Institute criteria, and secondary outcomes were advance directive completion, emergency room visits and unplanned hospitalizations, and survival up to 12 months. Results showed a 10% absolute reduction in the incidence of grade 3 or higher toxic effects (P = .02), with a number needed to treat of 10. Advance directive completion also increased by 15%, but no differences were observed for other outcomes. This study offers high-quality evidence that a GA-based intervention can reduce toxic effects of chemotherapy regimens for older adults with cancer.

Geriatric assessment in community oncology practices

A recent study by Supriya G. Mohile, MD, and colleagues2 is the first nationwide multicenter clinical trial to demonstrate the effects of GA and GA-guided management. This study was conducted in 40 oncology practices from the University of Rochester National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program network. Centers were randomly assigned to intervention or usual care (362 patients treated by 68 oncologists in the intervention group and 371 patients treated by 91 oncologists in the usual-care group). Eligibility criteria were age ≥70 years; impairment in at least one GA domain other than polypharmacy; incurable advanced solid tumor or lymphoma with a plan to start new cancer treatment with a high risk for toxic effects within 4 weeks; and English language fluency. Both study groups underwent a baseline GA that assessed patients’ physical performance, functional status, comorbidity, cognition, nutrition, social support, polypharmacy, and psychological status. For the intervention group, a summary and management recommendations were provided to the treating oncologists.

The primary outcome was grade 3 or higher toxic effects within 3 months of starting a new regimen; secondary outcomes included treatment intensity and survival and GA outcomes within 3 months. A smaller proportion of patients in the intervention group experienced toxicity (51% vs. 71%), with an absolute risk reduction of 20%. Patients in the intervention group also had fewer falls and a greater reduction in medications used; there were no other differences in secondary outcomes. This study offers very strong and generalizable evidence that incorporating GA in the care of older adults with cancer at risk for toxicity can reduce toxicity as well as improve other outcomes, such as falls and polypharmacy.

Geriatric assessment and oncologist-patient communication

A secondary analysis3 of data from Dr. Mohile and colleagues2 evaluated the effect of GA-guided recommendations on oncologist-patient communication regarding comorbidities. Patients (n = 541) included in this analysis were 76.6 years of age on average and had 3.2 (standard deviation, 1.9) comorbid conditions. All patients underwent GA, but only oncologists in the intervention arm received GA-based recommendations. Clinical encounters between oncologist and patient immediately following the GA were audio recorded and analyzed to examine communication between oncologists and participants as it relates to chronic comorbid conditions.

In the intervention arm, more discussions regarding comorbidities took place, and more participants’ concerns about comorbidities were acknowledged. More importantly, participants in the intervention group were 2.4 times more likely to have their concerns about comorbidities addressed through referral or education, compared with the usual-care group (P = .004). Moreover, 41% of oncologists in the intervention arm modified dosage or cancer treatment schedule because of concern about tolerability or comorbidities. This study demonstrates beneficial effects of GA in increasing communication and perhaps consideration of comorbidities of older adults when planning cancer treatment.

Dr. Hung is professor of geriatrics and palliative care at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Li D et al. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:e214158.

2. Mohile SG et al. Lancet. 2021;398:1894-1904.

3. Kleckner AS et al. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:e9-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Complex link between gut microbiome and immunotherapy response in advanced melanoma

A large-scale than previously thought.

Overall, researchers identified a panel of species, including Roseburia spp. and Akkermansia muciniphila, associated with responses to ICI therapy. However, no single species was a “fully consistent biomarker” across the studies, the authors explain.

This “machine learning analysis confirmed the link between the microbiome and overall response rates (ORRs) and progression-free survival (PFS) with ICIs but also revealed limited reproducibility of microbiome-based signatures across cohorts,” Karla A. Lee, PhD, a clinical research fellow at King’s College London, and colleagues report. The results suggest that “the microbiome is predictive of response in some, but not all, cohorts.”

The findings were published online Feb. 28 in Nature Medicine.

Despite recent advances in targeted therapies for melanoma, less than half of the those who receive a single-agent ICI respond, and those who receive combination ICI therapy often suffer from severe drug toxicity problems. That is why finding patients more likely to respond to a single-agent ICI has become a priority.

Previous studies have identified the gut microbiome as “a potential biomarker of response, as well as a therapeutic target” in melanoma and other malignancies, but “little consensus exists on which microbiome characteristics are associated with treatment responses in the human setting,” the authors explain.

To further clarify the microbiome–immunotherapy relationship, the researchers performed metagenomic sequencing of stool samples collected from 165 ICI-naive patients with unresectable stage III or IV cutaneous melanoma from 5 observational cohorts in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, and Spain. These data were integrated with 147 samples from publicly available datasets.

First, the authors highlighted the variability in findings across these observational studies. For instance, they analyzed stool samples from one UK-based observational study of patients with melanoma (PRIMM-UK) and found a small but statistically significant difference in the microbiome composition of immunotherapy responders versus nonresponders (P = .05) but did not find such an association in a parallel study in the Netherlands (PRIMM-NL, P = .61).

The investigators also explored biomarkers of response across different cohorts and found several standouts. In trials using ORR as an endpoint, two uncultivated Roseburia species (CAG:182 and CAG:471) were associated with responses to ICIs. For patients with available PFS data, Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens and Lactobacillus vaginalis were “enriched in responders” across 7 datasets and significant in 3 of the 8 meta-analysis approaches. A muciniphila and Dorea formicigenerans were also associated with ORR and PFS at 12 months in several meta-analyses.

However, “no single bacterium was a fully consistent biomarker of response across all datasets,” the authors wrote.

Still, the findings could have important implications for the more than 50% of patients with advanced melanoma who don’t respond to single-agent ICI therapy.

“Our study shows that studying the microbiome is important to improve and personalize immunotherapy treatments for melanoma,” study coauthor Nicola Segata, PhD, principal investigator in the Laboratory of Computational Metagenomics, University of Trento, Italy, said in a press release. “However, it also suggests that because of the person-to-person variability of the gut microbiome, even larger studies must be carried out to understand the specific gut microbial features that are more likely to lead to a positive response to immunotherapy.”

Coauthor Tim Spector, PhD, head of the Department of Twin Research & Genetic Epidemiology at King’s College London, added that “the ultimate goal is to identify which specific features of the microbiome are directly influencing the clinical benefits of immunotherapy to exploit these features in new personalized approaches to support cancer immunotherapy.”

In the meantime, he said, “this study highlights the potential impact of good diet and gut health on chances of survival in patients undergoing immunotherapy.”

This study was coordinated by King’s College London, CIBIO Department of the University of Trento and European Institute of Oncology in Italy, and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and was funded by the Seerave Foundation. Dr. Lee, Dr. Segata, and Dr. Spector have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A large-scale than previously thought.

Overall, researchers identified a panel of species, including Roseburia spp. and Akkermansia muciniphila, associated with responses to ICI therapy. However, no single species was a “fully consistent biomarker” across the studies, the authors explain.

This “machine learning analysis confirmed the link between the microbiome and overall response rates (ORRs) and progression-free survival (PFS) with ICIs but also revealed limited reproducibility of microbiome-based signatures across cohorts,” Karla A. Lee, PhD, a clinical research fellow at King’s College London, and colleagues report. The results suggest that “the microbiome is predictive of response in some, but not all, cohorts.”

The findings were published online Feb. 28 in Nature Medicine.

Despite recent advances in targeted therapies for melanoma, less than half of the those who receive a single-agent ICI respond, and those who receive combination ICI therapy often suffer from severe drug toxicity problems. That is why finding patients more likely to respond to a single-agent ICI has become a priority.

Previous studies have identified the gut microbiome as “a potential biomarker of response, as well as a therapeutic target” in melanoma and other malignancies, but “little consensus exists on which microbiome characteristics are associated with treatment responses in the human setting,” the authors explain.

To further clarify the microbiome–immunotherapy relationship, the researchers performed metagenomic sequencing of stool samples collected from 165 ICI-naive patients with unresectable stage III or IV cutaneous melanoma from 5 observational cohorts in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, and Spain. These data were integrated with 147 samples from publicly available datasets.

First, the authors highlighted the variability in findings across these observational studies. For instance, they analyzed stool samples from one UK-based observational study of patients with melanoma (PRIMM-UK) and found a small but statistically significant difference in the microbiome composition of immunotherapy responders versus nonresponders (P = .05) but did not find such an association in a parallel study in the Netherlands (PRIMM-NL, P = .61).

The investigators also explored biomarkers of response across different cohorts and found several standouts. In trials using ORR as an endpoint, two uncultivated Roseburia species (CAG:182 and CAG:471) were associated with responses to ICIs. For patients with available PFS data, Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens and Lactobacillus vaginalis were “enriched in responders” across 7 datasets and significant in 3 of the 8 meta-analysis approaches. A muciniphila and Dorea formicigenerans were also associated with ORR and PFS at 12 months in several meta-analyses.

However, “no single bacterium was a fully consistent biomarker of response across all datasets,” the authors wrote.

Still, the findings could have important implications for the more than 50% of patients with advanced melanoma who don’t respond to single-agent ICI therapy.

“Our study shows that studying the microbiome is important to improve and personalize immunotherapy treatments for melanoma,” study coauthor Nicola Segata, PhD, principal investigator in the Laboratory of Computational Metagenomics, University of Trento, Italy, said in a press release. “However, it also suggests that because of the person-to-person variability of the gut microbiome, even larger studies must be carried out to understand the specific gut microbial features that are more likely to lead to a positive response to immunotherapy.”

Coauthor Tim Spector, PhD, head of the Department of Twin Research & Genetic Epidemiology at King’s College London, added that “the ultimate goal is to identify which specific features of the microbiome are directly influencing the clinical benefits of immunotherapy to exploit these features in new personalized approaches to support cancer immunotherapy.”

In the meantime, he said, “this study highlights the potential impact of good diet and gut health on chances of survival in patients undergoing immunotherapy.”

This study was coordinated by King’s College London, CIBIO Department of the University of Trento and European Institute of Oncology in Italy, and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and was funded by the Seerave Foundation. Dr. Lee, Dr. Segata, and Dr. Spector have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A large-scale than previously thought.

Overall, researchers identified a panel of species, including Roseburia spp. and Akkermansia muciniphila, associated with responses to ICI therapy. However, no single species was a “fully consistent biomarker” across the studies, the authors explain.

This “machine learning analysis confirmed the link between the microbiome and overall response rates (ORRs) and progression-free survival (PFS) with ICIs but also revealed limited reproducibility of microbiome-based signatures across cohorts,” Karla A. Lee, PhD, a clinical research fellow at King’s College London, and colleagues report. The results suggest that “the microbiome is predictive of response in some, but not all, cohorts.”

The findings were published online Feb. 28 in Nature Medicine.

Despite recent advances in targeted therapies for melanoma, less than half of the those who receive a single-agent ICI respond, and those who receive combination ICI therapy often suffer from severe drug toxicity problems. That is why finding patients more likely to respond to a single-agent ICI has become a priority.

Previous studies have identified the gut microbiome as “a potential biomarker of response, as well as a therapeutic target” in melanoma and other malignancies, but “little consensus exists on which microbiome characteristics are associated with treatment responses in the human setting,” the authors explain.

To further clarify the microbiome–immunotherapy relationship, the researchers performed metagenomic sequencing of stool samples collected from 165 ICI-naive patients with unresectable stage III or IV cutaneous melanoma from 5 observational cohorts in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, and Spain. These data were integrated with 147 samples from publicly available datasets.

First, the authors highlighted the variability in findings across these observational studies. For instance, they analyzed stool samples from one UK-based observational study of patients with melanoma (PRIMM-UK) and found a small but statistically significant difference in the microbiome composition of immunotherapy responders versus nonresponders (P = .05) but did not find such an association in a parallel study in the Netherlands (PRIMM-NL, P = .61).

The investigators also explored biomarkers of response across different cohorts and found several standouts. In trials using ORR as an endpoint, two uncultivated Roseburia species (CAG:182 and CAG:471) were associated with responses to ICIs. For patients with available PFS data, Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens and Lactobacillus vaginalis were “enriched in responders” across 7 datasets and significant in 3 of the 8 meta-analysis approaches. A muciniphila and Dorea formicigenerans were also associated with ORR and PFS at 12 months in several meta-analyses.

However, “no single bacterium was a fully consistent biomarker of response across all datasets,” the authors wrote.

Still, the findings could have important implications for the more than 50% of patients with advanced melanoma who don’t respond to single-agent ICI therapy.

“Our study shows that studying the microbiome is important to improve and personalize immunotherapy treatments for melanoma,” study coauthor Nicola Segata, PhD, principal investigator in the Laboratory of Computational Metagenomics, University of Trento, Italy, said in a press release. “However, it also suggests that because of the person-to-person variability of the gut microbiome, even larger studies must be carried out to understand the specific gut microbial features that are more likely to lead to a positive response to immunotherapy.”

Coauthor Tim Spector, PhD, head of the Department of Twin Research & Genetic Epidemiology at King’s College London, added that “the ultimate goal is to identify which specific features of the microbiome are directly influencing the clinical benefits of immunotherapy to exploit these features in new personalized approaches to support cancer immunotherapy.”

In the meantime, he said, “this study highlights the potential impact of good diet and gut health on chances of survival in patients undergoing immunotherapy.”

This study was coordinated by King’s College London, CIBIO Department of the University of Trento and European Institute of Oncology in Italy, and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and was funded by the Seerave Foundation. Dr. Lee, Dr. Segata, and Dr. Spector have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

At-Home Treatment of Pigmented Lesions With a Zinc Chloride Preparation

To the Editor:

Zinc chloride originally was used by Dr. Frederic Mohs as an in vivo tissue fixative during the early phases of Mohs micrographic surgery.1 Although this technique has since been replaced with fresh frozen tissue fixation, zinc chloride still is found in topical preparations that are readily available to patients. Specifically, black salve describes variably composed topical preparations that share the common ingredients zinc chloride and Sanguinaria canadensis (bloodroot).2 Patients self-treat with these unregulated compounds, but the majority do not have their lesions evaluated by a clinician prior to use and are unaware of the potential risks.3-5 Products containing zinc chloride and S canadensis that are not marketed as black salve present a new problem for the dermatology community.

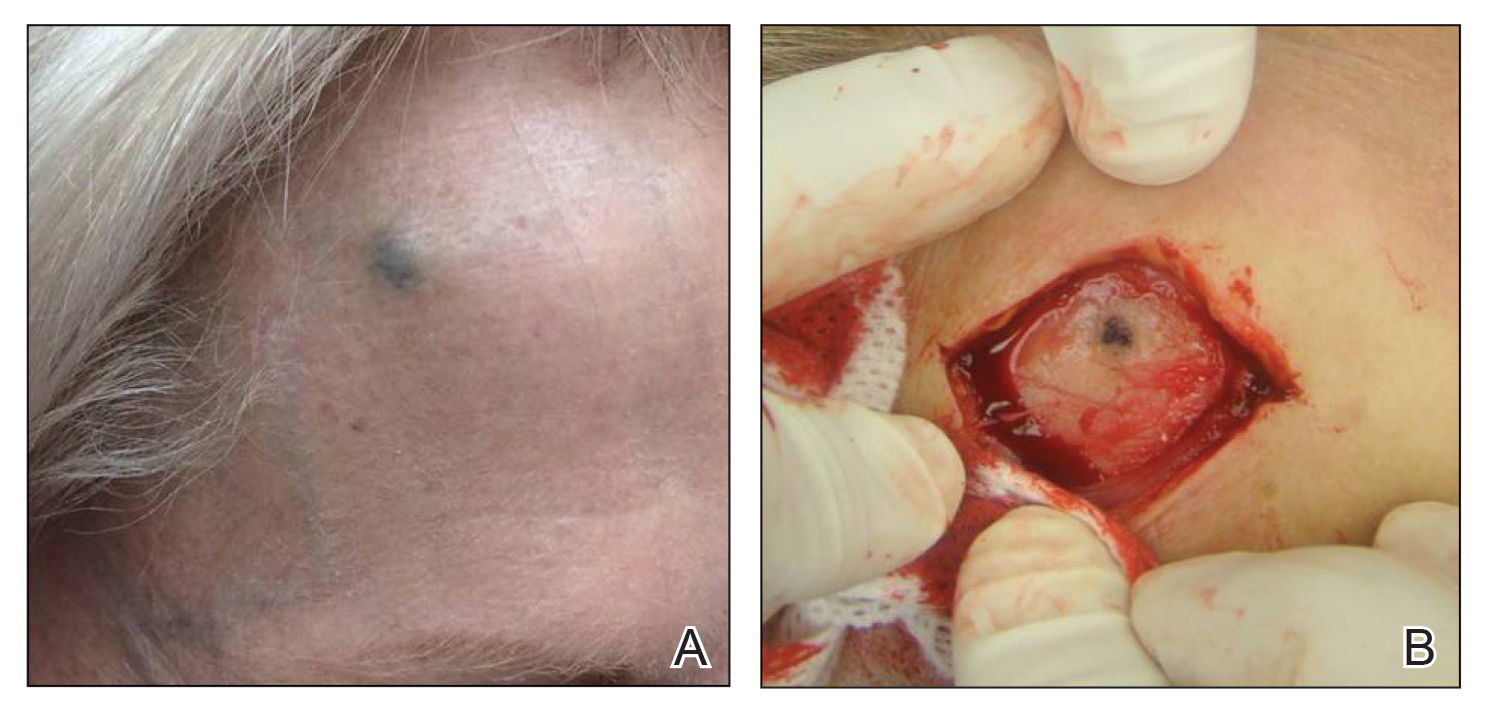

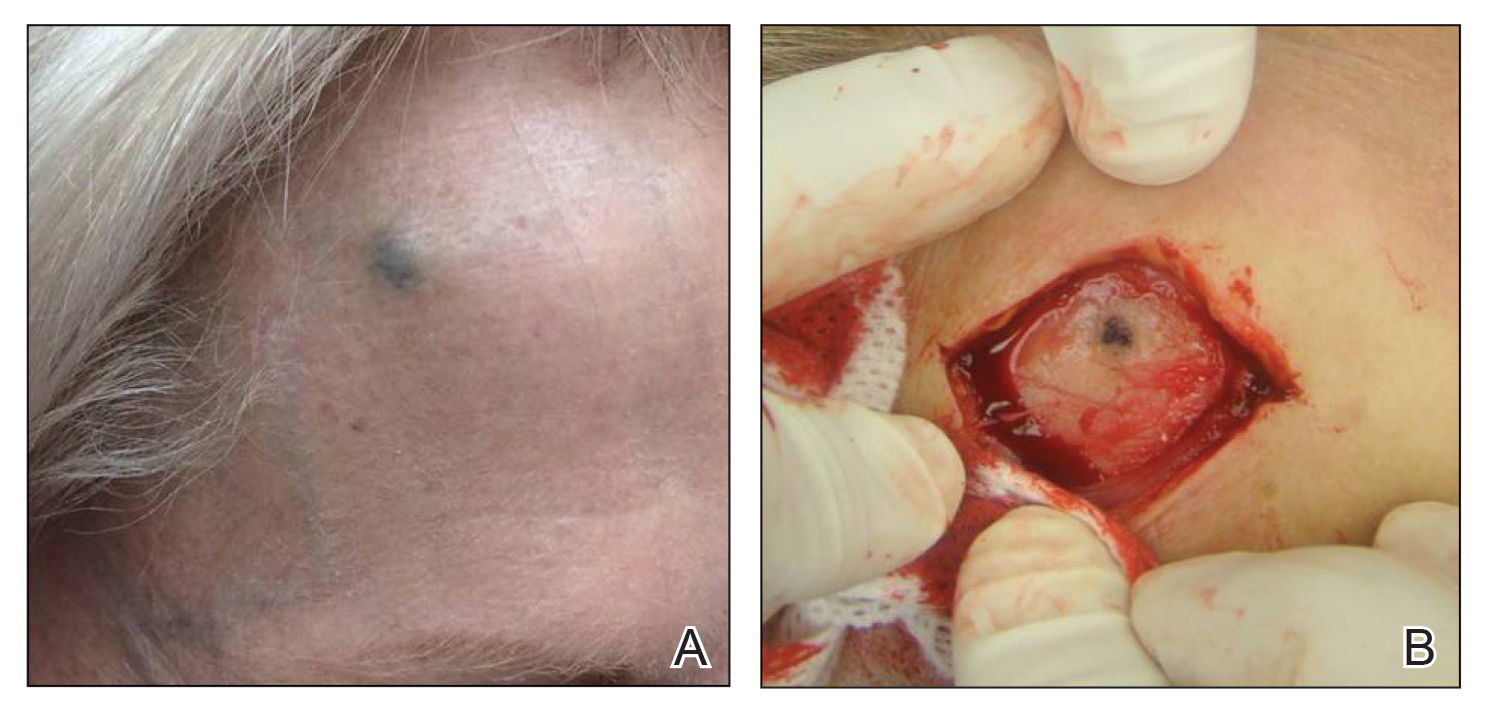

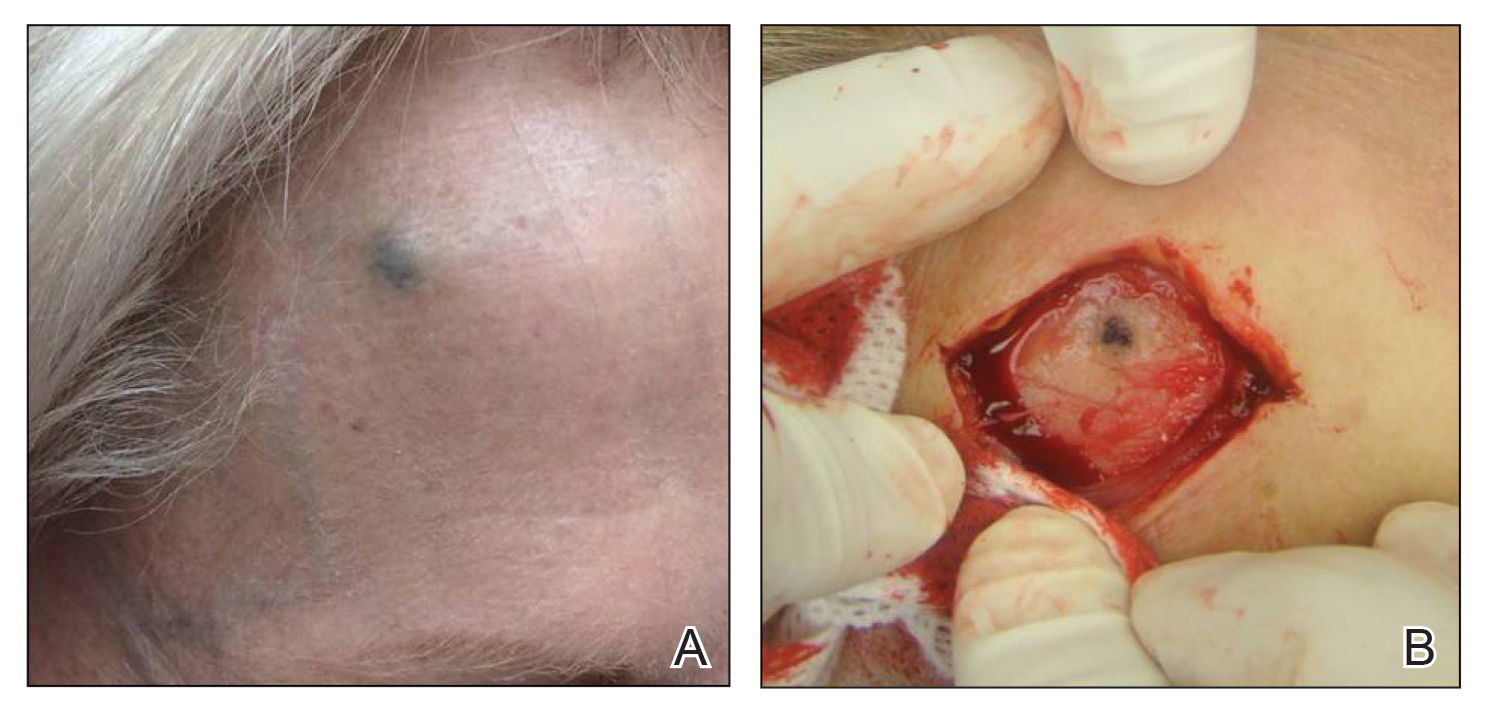

A 73-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic for the focused evaluation of scaly lesions on the face and nose. At this visit, it was recommended he undergo a total-body skin examination for skin cancer screening given his age and substantial photodamage.

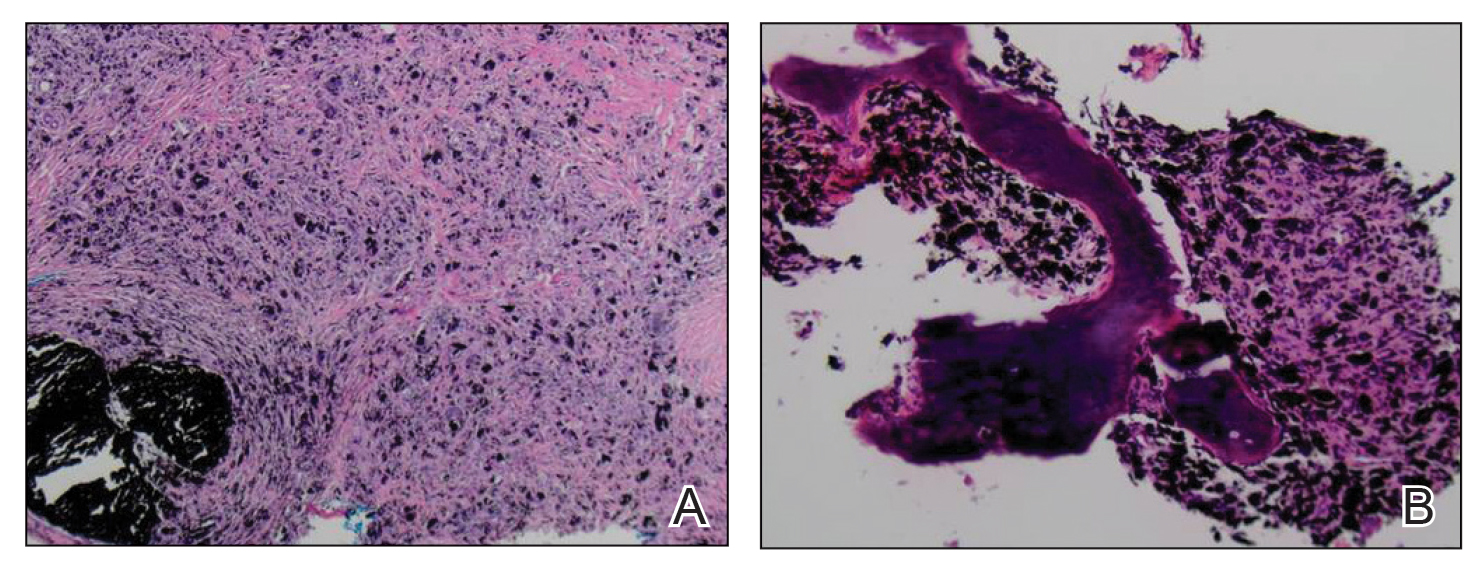

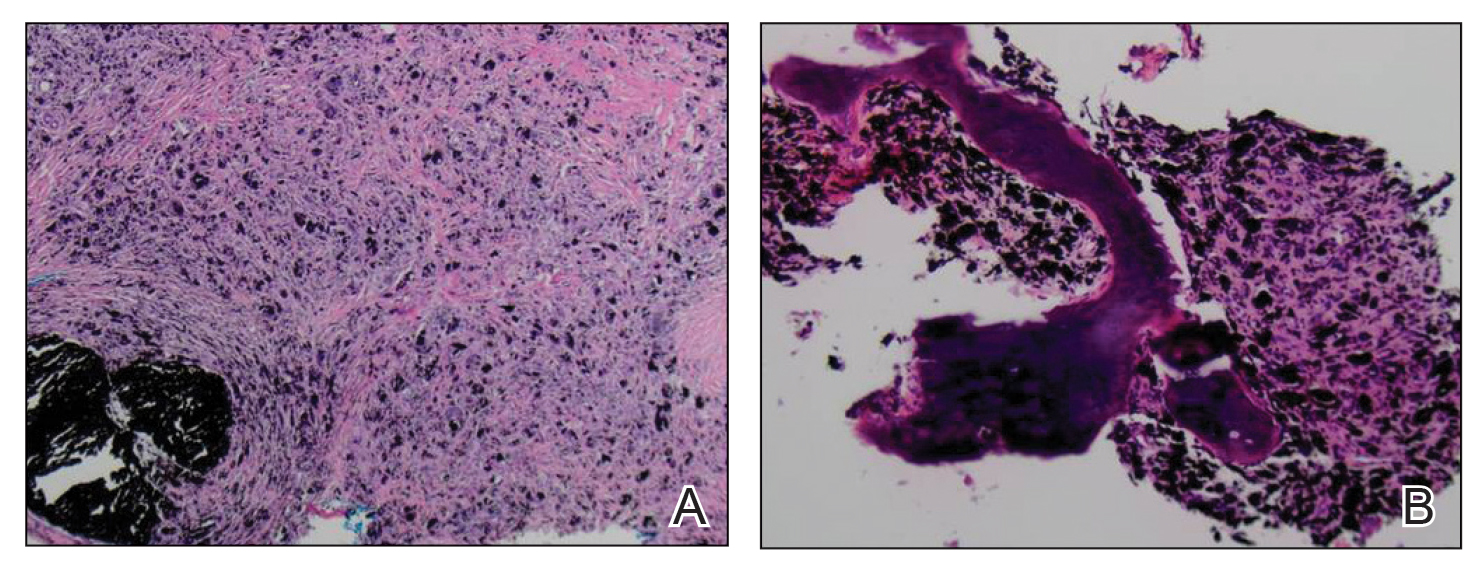

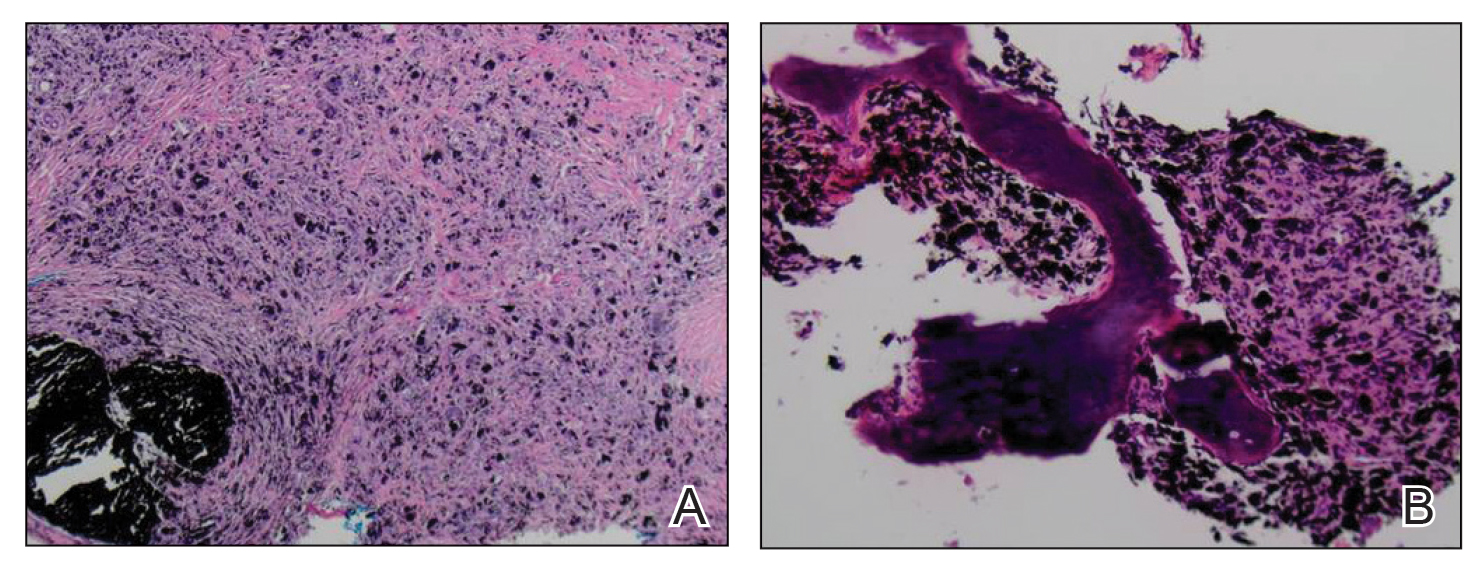

Physical examination revealed more than 20 superficial, 3- to 10-mm scars predominantly over the trunk. One scar over the left mid-back had a large, 1.2-cm peripheral rim of dark brown pigment that was clinically concerning for a melanocytic neoplasm. Shave removal of this lesion was performed. Histologic examination showed melanoma in situ with a central scar. The central scar spanned the depth of the dermis, and the melanocytic component was absent in this area, raising the question if prior biopsy or treatment had been performed on this lesion. During a discussion of the results with the patient, he was questioned about prior biopsy or treatment of this lesion. He reported prior use of a topical all-natural cream containing zinc chloride and S canadensis that he purchased online, which he had used to treat this lesion as well as numerous presumed moles.

The trend of at-home mole removal products containing the traditional ingredients in black salve seems to be one of rapidly shifting product availability as well as a departure from marketing items as black salve. Many prior black salve products are no longer available.4 The product that our patient used is a topical cream marketed as a treatment for moles and skin tags.6 Despite not being marketed as black salve, it does contain zinc chloride and S canadensis. The product’s website highlights these ingredients as being a safe and effective treatment for mole removal, with claims that the product will remove the mole or skin tag without irritating the surrounding skin and can be safely used anywhere on the body without scarring.6 A Google search at the time this article was written using the term skin tag remover revealed similar products marketed as all-natural “skin tag remover and mole corrector creams.” These similar products containing zinc chloride and S canadensis were available in the United States at the time of our initial research but have since been removed and only are available outside of the United States.7

Prior reports of melanoma masked by zinc chloride and S canadensis described the use of topical agents marketed as black salve. This new wave of products marketed as all-natural creams makes continued education on the available products and their associated risks necessary for clinicians. The lack of US Food and Drug Administration oversight for these products and their frequent introduction and discontinuation in the market makes keeping updated even more challenging. Because many patients self-treat without prior evaluation by a health care provider, treatment with these products can lead to a delay in diagnosis or inaccurate staging due to scars from the chemical destruction, both of which may have occurred in our patient.5 Until these products become regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, it is imperative that clinicians continue to educate their patients on the lack of documented benefit and clear risks of their use as well as remain up-to-date on product trends.

- Cohen DK. Mohs micrographic surgery: past, present, and future. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:329-339. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001701

- Eastman KL. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:284-289. doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0377

- Sivyer GW, Rosendahl C. Application of black salve to a thin melanoma that subsequently progressed to metastatic melanoma: a case study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:77-80. doi:10.5826/dpc.0403a16

- McDaniel S. Consequences of using escharotic agents as primary treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1593-1596.

- Clark JJ. Community perceptions about the use of black salve. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1021-1023. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.016

- Skinprov Cream. Skinprov. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://skinprov.net

- HaloDerm. HaloDerm Inc. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://haloderm.com/

To the Editor:

Zinc chloride originally was used by Dr. Frederic Mohs as an in vivo tissue fixative during the early phases of Mohs micrographic surgery.1 Although this technique has since been replaced with fresh frozen tissue fixation, zinc chloride still is found in topical preparations that are readily available to patients. Specifically, black salve describes variably composed topical preparations that share the common ingredients zinc chloride and Sanguinaria canadensis (bloodroot).2 Patients self-treat with these unregulated compounds, but the majority do not have their lesions evaluated by a clinician prior to use and are unaware of the potential risks.3-5 Products containing zinc chloride and S canadensis that are not marketed as black salve present a new problem for the dermatology community.

A 73-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic for the focused evaluation of scaly lesions on the face and nose. At this visit, it was recommended he undergo a total-body skin examination for skin cancer screening given his age and substantial photodamage.

Physical examination revealed more than 20 superficial, 3- to 10-mm scars predominantly over the trunk. One scar over the left mid-back had a large, 1.2-cm peripheral rim of dark brown pigment that was clinically concerning for a melanocytic neoplasm. Shave removal of this lesion was performed. Histologic examination showed melanoma in situ with a central scar. The central scar spanned the depth of the dermis, and the melanocytic component was absent in this area, raising the question if prior biopsy or treatment had been performed on this lesion. During a discussion of the results with the patient, he was questioned about prior biopsy or treatment of this lesion. He reported prior use of a topical all-natural cream containing zinc chloride and S canadensis that he purchased online, which he had used to treat this lesion as well as numerous presumed moles.

The trend of at-home mole removal products containing the traditional ingredients in black salve seems to be one of rapidly shifting product availability as well as a departure from marketing items as black salve. Many prior black salve products are no longer available.4 The product that our patient used is a topical cream marketed as a treatment for moles and skin tags.6 Despite not being marketed as black salve, it does contain zinc chloride and S canadensis. The product’s website highlights these ingredients as being a safe and effective treatment for mole removal, with claims that the product will remove the mole or skin tag without irritating the surrounding skin and can be safely used anywhere on the body without scarring.6 A Google search at the time this article was written using the term skin tag remover revealed similar products marketed as all-natural “skin tag remover and mole corrector creams.” These similar products containing zinc chloride and S canadensis were available in the United States at the time of our initial research but have since been removed and only are available outside of the United States.7

Prior reports of melanoma masked by zinc chloride and S canadensis described the use of topical agents marketed as black salve. This new wave of products marketed as all-natural creams makes continued education on the available products and their associated risks necessary for clinicians. The lack of US Food and Drug Administration oversight for these products and their frequent introduction and discontinuation in the market makes keeping updated even more challenging. Because many patients self-treat without prior evaluation by a health care provider, treatment with these products can lead to a delay in diagnosis or inaccurate staging due to scars from the chemical destruction, both of which may have occurred in our patient.5 Until these products become regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, it is imperative that clinicians continue to educate their patients on the lack of documented benefit and clear risks of their use as well as remain up-to-date on product trends.

To the Editor:

Zinc chloride originally was used by Dr. Frederic Mohs as an in vivo tissue fixative during the early phases of Mohs micrographic surgery.1 Although this technique has since been replaced with fresh frozen tissue fixation, zinc chloride still is found in topical preparations that are readily available to patients. Specifically, black salve describes variably composed topical preparations that share the common ingredients zinc chloride and Sanguinaria canadensis (bloodroot).2 Patients self-treat with these unregulated compounds, but the majority do not have their lesions evaluated by a clinician prior to use and are unaware of the potential risks.3-5 Products containing zinc chloride and S canadensis that are not marketed as black salve present a new problem for the dermatology community.

A 73-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic for the focused evaluation of scaly lesions on the face and nose. At this visit, it was recommended he undergo a total-body skin examination for skin cancer screening given his age and substantial photodamage.

Physical examination revealed more than 20 superficial, 3- to 10-mm scars predominantly over the trunk. One scar over the left mid-back had a large, 1.2-cm peripheral rim of dark brown pigment that was clinically concerning for a melanocytic neoplasm. Shave removal of this lesion was performed. Histologic examination showed melanoma in situ with a central scar. The central scar spanned the depth of the dermis, and the melanocytic component was absent in this area, raising the question if prior biopsy or treatment had been performed on this lesion. During a discussion of the results with the patient, he was questioned about prior biopsy or treatment of this lesion. He reported prior use of a topical all-natural cream containing zinc chloride and S canadensis that he purchased online, which he had used to treat this lesion as well as numerous presumed moles.

The trend of at-home mole removal products containing the traditional ingredients in black salve seems to be one of rapidly shifting product availability as well as a departure from marketing items as black salve. Many prior black salve products are no longer available.4 The product that our patient used is a topical cream marketed as a treatment for moles and skin tags.6 Despite not being marketed as black salve, it does contain zinc chloride and S canadensis. The product’s website highlights these ingredients as being a safe and effective treatment for mole removal, with claims that the product will remove the mole or skin tag without irritating the surrounding skin and can be safely used anywhere on the body without scarring.6 A Google search at the time this article was written using the term skin tag remover revealed similar products marketed as all-natural “skin tag remover and mole corrector creams.” These similar products containing zinc chloride and S canadensis were available in the United States at the time of our initial research but have since been removed and only are available outside of the United States.7

Prior reports of melanoma masked by zinc chloride and S canadensis described the use of topical agents marketed as black salve. This new wave of products marketed as all-natural creams makes continued education on the available products and their associated risks necessary for clinicians. The lack of US Food and Drug Administration oversight for these products and their frequent introduction and discontinuation in the market makes keeping updated even more challenging. Because many patients self-treat without prior evaluation by a health care provider, treatment with these products can lead to a delay in diagnosis or inaccurate staging due to scars from the chemical destruction, both of which may have occurred in our patient.5 Until these products become regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, it is imperative that clinicians continue to educate their patients on the lack of documented benefit and clear risks of their use as well as remain up-to-date on product trends.

- Cohen DK. Mohs micrographic surgery: past, present, and future. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:329-339. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001701

- Eastman KL. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:284-289. doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0377

- Sivyer GW, Rosendahl C. Application of black salve to a thin melanoma that subsequently progressed to metastatic melanoma: a case study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:77-80. doi:10.5826/dpc.0403a16

- McDaniel S. Consequences of using escharotic agents as primary treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1593-1596.

- Clark JJ. Community perceptions about the use of black salve. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1021-1023. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.016

- Skinprov Cream. Skinprov. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://skinprov.net

- HaloDerm. HaloDerm Inc. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://haloderm.com/

- Cohen DK. Mohs micrographic surgery: past, present, and future. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:329-339. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001701

- Eastman KL. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:284-289. doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0377

- Sivyer GW, Rosendahl C. Application of black salve to a thin melanoma that subsequently progressed to metastatic melanoma: a case study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:77-80. doi:10.5826/dpc.0403a16

- McDaniel S. Consequences of using escharotic agents as primary treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1593-1596.

- Clark JJ. Community perceptions about the use of black salve. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1021-1023. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.016

- Skinprov Cream. Skinprov. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://skinprov.net

- HaloDerm. HaloDerm Inc. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://haloderm.com/

Practice Points

- Zinc chloride preparations are readily available over the counter and unregulated.

- Patients may attempt to self-treat pigmented lesions based on claims they see online.

- When asking patients about prior treatments, it may be prudent to specifically ask about over-the-counter products and their ingredients.

High early recurrence rates with Merkel cell carcinoma

, and more than half of all patients with stage IV disease will have a recurrence within 1 year of definitive therapy, results of a new study show.

A study of 618 patients with MCC who were enrolled in a Seattle-based data repository shows that among all patients the 5-year recurrence rate was 40%. The risk of recurrence within the first year was 11% for patients with pathologic stage I disease, 33% for those with stage IIA/IIB disease, 45% for those with stage IIIB disease, and 58% for patients with pathologic stage IV MCC.

Approximately 95% of all recurrences happened within 3 years of the initial diagnosis, report Aubriana McEvoy, MD, from the University of Washington in Seattle, and colleagues.

“This cohort study indicates that the highest yield (and likely most cost-effective) time period for detecting MCC recurrence is 1-3 years after diagnosis,” they write in a study published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The estimated annual incidence of MCC in the United States in 2018 was 2,000 according to the American Cancer Society. The annual incidence rate is rising rapidly, however, and is estimated to reach 3,284 by 2025, McEvoy and colleagues write.

Although MCC is known to have high recurrence rates and is associated with a higher mortality rate than malignant melanoma, recurrence rate data are not captured by either the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database or by the National Cancer Database. As a result, estimates of recurrence rates with MCC have been all over the map, ranging from 27% to 77%, depending on the population studied.

But as senior author Paul Nghiem, MD, PhD, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization, recurrence rates over time in their study were remarkably consistent.

“The biggest surprise to me was that, when we broke our nearly 20-year cohort into three 5- or 6-year chunks, every one of the groups had a 40% recurrence rate, within 1%. So we feel really confident that’s the right number,” he said.

Dr. Nghiem and colleagues report that, in contrast to patients with MCC, approximately 19% of patients with melanoma will have a recurrence, as will an estimated 5%-9% of patients with squamous cell carcinoma and 1%-10% of patients with basal cell carcinoma.

The fact that recurrence rates of MCC have remained stable over time despite presumed improvements in definitive therapy is disappointing, Dr. Nghiem acknowledged. He noted that it’s still unclear whether immunotherapy will have the same dramatic effect on survival rates for patients with MCC as it has for patients with malignant melanoma.

The high recurrence rates following definitive therapy for patients with early-stage disease was a novel finding, commented Shawn Demehri, MD, PhD, director of the high-risk skin cancer clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“When you’re looking at patients with stage I or stage II, and they have definitive surgery but still have recurrences at a higher rate than melanoma, it brings home the point that these are among the most aggressive tumors of the skin,” he said in an interview.

The high recurrence rates seen with MCC are attributable to a variety of factors.

“This is a rare cancer of mostly older individuals with a lot of comorbidities, and also a cancer that, even though it is a primary cancer, might be detected a little later than even a melanoma primary tumor, just because of the nature of the neuroendocrine tumor cells,” he said.

Dr. Demehri was not involved in the study.

Prospective cohort

The study cohort consisted of 618 patients with MCC. The median age of the patients was 69, and 227 (37%) were women. The patients were enrolled within 6 months of their diagnosis in the prospective data repository from 2003 through 2019. Of this group, 223 had a recurrence of MCC.

As noted, there was a high risk of recurrence within 1 year, ranging from 11% for patients with pathologic stage I tumors to 58% for those with stage IV disease, and 95% of all recurrences occurred within 3 years of definitive therapy.

To get a better picture of the natural history of MCC recurrence, the investigators studied a cohort of patients with pathologically confirmed MCC who were prospectively enrolled from January 2003 through April 2019 in a data repository maintained at the University of Washington.

In addition to disease stage, factors associated with increased recurrence risk in univariable analyses include immunosuppression (hazard ratio, 2.4; P < .001), male sex (HR, 1.9; P < .001), known primary lesion among patients with clinically detectable nodal disease (HR, 2.3; P = .001), and older age (HR, 1.1, P = .06 for each 10-year increase).

Of the 187 patients in the cohort who died during the study, 121 died from MCC. At 4 years after diagnosis, MCC-specific survival rates were 95% for patients with pathologic stage I, 84% with stage IIA/IIB, 80% with stage IIIA, 58% with stage IIIB, and 41% with stage IV.

Evidence supports close monitoring within the first 3 years for patients with stage I-II MCC. Local recurrence within or adjacent to the primary tumor scar was associated with a 5-year MCC-specific survival rate of 85%, compared with 88% of patients with stage I or II disease who did not have recurrences.

“Because more than 90% of MCC recurrences arise within 3 years, it is appropriate to adjust surveillance intensity accordingly. Stage- and time-specific recurrence data can assist in appropriately focusing surveillance resources on patients and time intervals in which recurrence risk is highest,” the authors wrote.

“If you’re a patient who has not had your cancer come back for 3, 4, or 5 years, you can really cut down on the intensity of your follow-up and scans,” Dr. Nghiem said.

“We do now have two excellent blood tests that are working very well, and we have really good ways to detect the cancer coming back early, and that’s important, because we have potentially curative therapies that tend to work better if you catch the cancer early,” he said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Nghiem reported personal fees and institutional support outside the study from several companies and patents for Merkel cell therapies with the University of Washington and University of Denmark. Dr. Demehri has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, and more than half of all patients with stage IV disease will have a recurrence within 1 year of definitive therapy, results of a new study show.

A study of 618 patients with MCC who were enrolled in a Seattle-based data repository shows that among all patients the 5-year recurrence rate was 40%. The risk of recurrence within the first year was 11% for patients with pathologic stage I disease, 33% for those with stage IIA/IIB disease, 45% for those with stage IIIB disease, and 58% for patients with pathologic stage IV MCC.

Approximately 95% of all recurrences happened within 3 years of the initial diagnosis, report Aubriana McEvoy, MD, from the University of Washington in Seattle, and colleagues.

“This cohort study indicates that the highest yield (and likely most cost-effective) time period for detecting MCC recurrence is 1-3 years after diagnosis,” they write in a study published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The estimated annual incidence of MCC in the United States in 2018 was 2,000 according to the American Cancer Society. The annual incidence rate is rising rapidly, however, and is estimated to reach 3,284 by 2025, McEvoy and colleagues write.

Although MCC is known to have high recurrence rates and is associated with a higher mortality rate than malignant melanoma, recurrence rate data are not captured by either the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database or by the National Cancer Database. As a result, estimates of recurrence rates with MCC have been all over the map, ranging from 27% to 77%, depending on the population studied.

But as senior author Paul Nghiem, MD, PhD, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization, recurrence rates over time in their study were remarkably consistent.

“The biggest surprise to me was that, when we broke our nearly 20-year cohort into three 5- or 6-year chunks, every one of the groups had a 40% recurrence rate, within 1%. So we feel really confident that’s the right number,” he said.