User login

The Burden of Skin Cancer in the Military Health System, 2017-2022

This retrospective observational study investigates skin cancer prevalence and care patterns within the Military Health System (MHS) from 2017 to 2022. Utilizing the MHS Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (most commonly called M2), we analyzed more than 5 million patient encounters and documented skin cancer prevalence in the MHS beneficiary population utilizing available demographic data. Notable findings included an increased prevalence of skin cancer in the military population compared with the civilian population, a substantial decline in direct care (DC) visits at military treatment facilities compared with civilian purchased care (PC) visits, and a decreased total number of visits during COVID-19 restrictions.

The Military Health System (MHS) is a worldwide health care delivery system that serves 9.6 million beneficiaries, including military service members, retirees, and their families.1 Its mission is 2-fold: provide a medically ready force, and provide a medical benefit in keeping with the service and sacrifice of active-duty personnel, military retirees, and their families. For fiscal year (FY) 2022, active-duty service members and their families comprised 16.7% and 19.9% of beneficiaries, respectively, while retired service members and their families comprised 27% and 32% of beneficiaries, respectively.

The MHS operates under the authority of the Department of Defense (DoD) and is supported by an annual budget of approximately $50 billion.1 Health care provision within the MHS is managed by TRICARE regional networks.2 Within these networks, MHS beneficiaries may receive health care in 2 categories: direct care (DC) and purchased care (PC). Direct care is rendered in military treatment facilities by military or civilian providers contracted by the DoD, and PC is administered by civilian providers at civilian health care facilities within the TRICARE network, which is comprised of individual providers, clinics, and hospitals that have agreed to accept TRICARE beneficiaries.1 Purchased care is fee-for-service and paid for by the MHS. Of note, the MHS differs from the Veterans Affairs health care system in that the MHS through DC and PC sees only active-duty service members, active-duty dependents, retirees, and retirees’ dependents (primarily spouses), whereas Veterans Affairs sees only veterans (not necessarily retirees) discharged from military service with compensable medical conditions or disabilities.

Skin cancer presents a notable concern for the US Military, as the risk for skin cancer is thought to be higher than in the general population.3,4 This elevated risk is attributed to numerous factors inherent to active-duty service, including time spent in tropical environments, increased exposure to UV radiation, time spent at high altitudes, and decreased rates of sun-protective behaviors.3 Although numerous studies have explored the mechanisms that contribute to service members’ increased skin cancer risk, there are few (if any) that discuss the burden of skin cancer on the MHS and where its beneficiaries receive their skin cancer care. This study evaluated the burden of skin cancer within the MHS, as demonstrated by the period prevalence of skin cancer among its beneficiaries and the number and distribution of patient visits for skin cancer across both DC and PC from 2017 to 2022.

Methods

Data Collection—This retrospective observational study was designed to describe trends in outpatient visits with a skin cancer diagnosis and annual prevalence of skin cancer types in the MHS. Data are from all MHS beneficiaries who were eligible or enrolled in the analysis year. Our data source was the MHS Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (most commonly called M2), a query tool that contains the current and most recent 5 full FYs of Defense Health Agency corporate health care data including aggregated FY and calendar-year counts of MHS beneficiaries from 2017 to 2022 using encounter and claims data tables from both DC and PC. Data in M2 are coded using a pseudo-person identification number, and queries performed for this study were limited to de-identified visit and patient counts.

Skin cancer diagnoses were defined by relevant International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes recorded from outpatient visits in DC and PC. The M2 database was queried to find aggregate counts of visits and unique MHS beneficiaries with one or more diagnoses of a skin cancer type of interest (defined by relevant ICD-10-CM code) over the study period stratified by year and by patient demographic characteristics. Skin cancer types by ICD-10-CM code group included basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), malignant melanoma (MM), and other (including Merkel cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma). Demographic strata included age, sex, military status (active duty, dependents of active duty, retired, or all others), sponsor military rank, and sponsor branch (army, air force, marine corps, or navy). Visit counts included diagnoses from any ICD position (for encounters that contained multiple ICD codes) to describe the total volume of care that addressed a diagnosed skin cancer. Counts of unique patients in prevalence analyses included relevant diagnoses in the primary ICD position only to increase the specificity of prevalence estimates.

Data Analysis—Descriptive analyses included the total number of outpatient visits with a skin cancer diagnosis in DC and PC over the study period, with percentages of total visits by year and by demographic strata. Separate analyses estimated annual prevalences of skin cancer types in the MHS by study year and within 2022 by demographic strata. Numerators in prevalence analyses were defined as the number of unique individuals with one or more relevant ICD codes in the analysis year. Denominators were defined as the total number of MHS beneficiaries in the analysis year and resulting period prevalences reported. Observed prevalences were qualitatively described, and trends were compared with prevalences in nonmilitary populations reported in the literature.

Ethics—This study was conducted as part of a study using secondary analyses of de-identified data from the M2 database. The study was reviewed and approved by the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center institutional review board.

Results

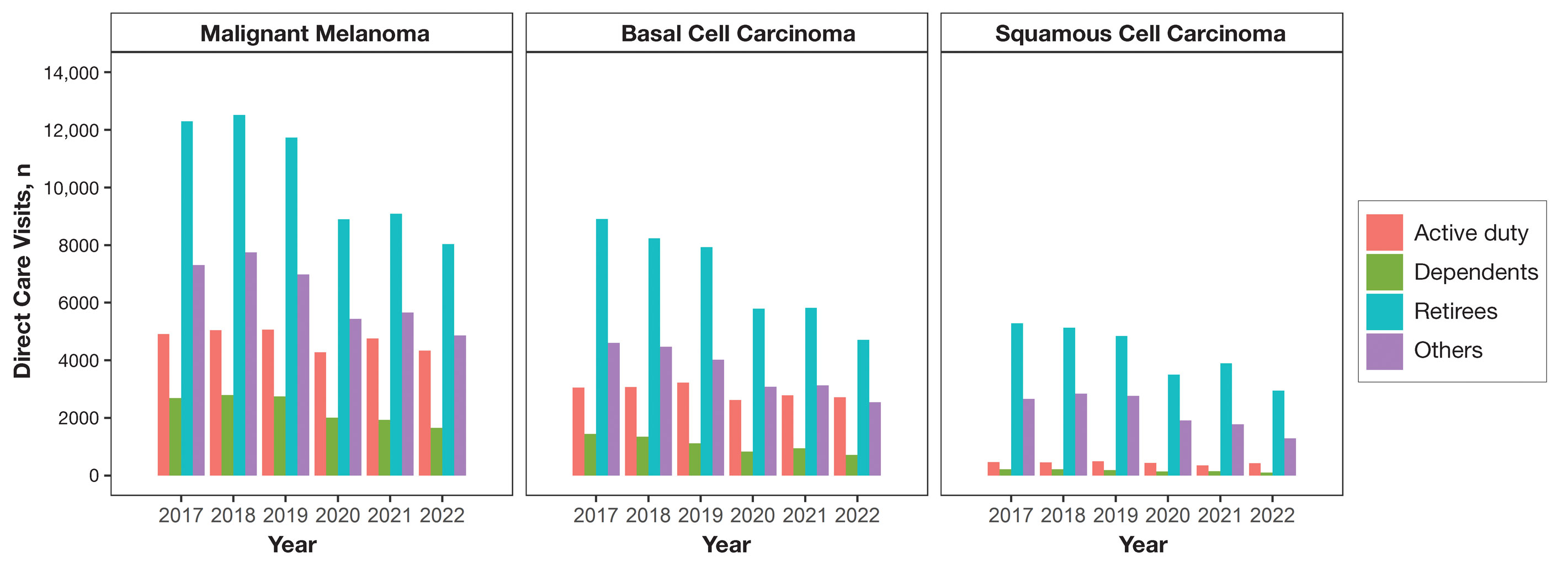

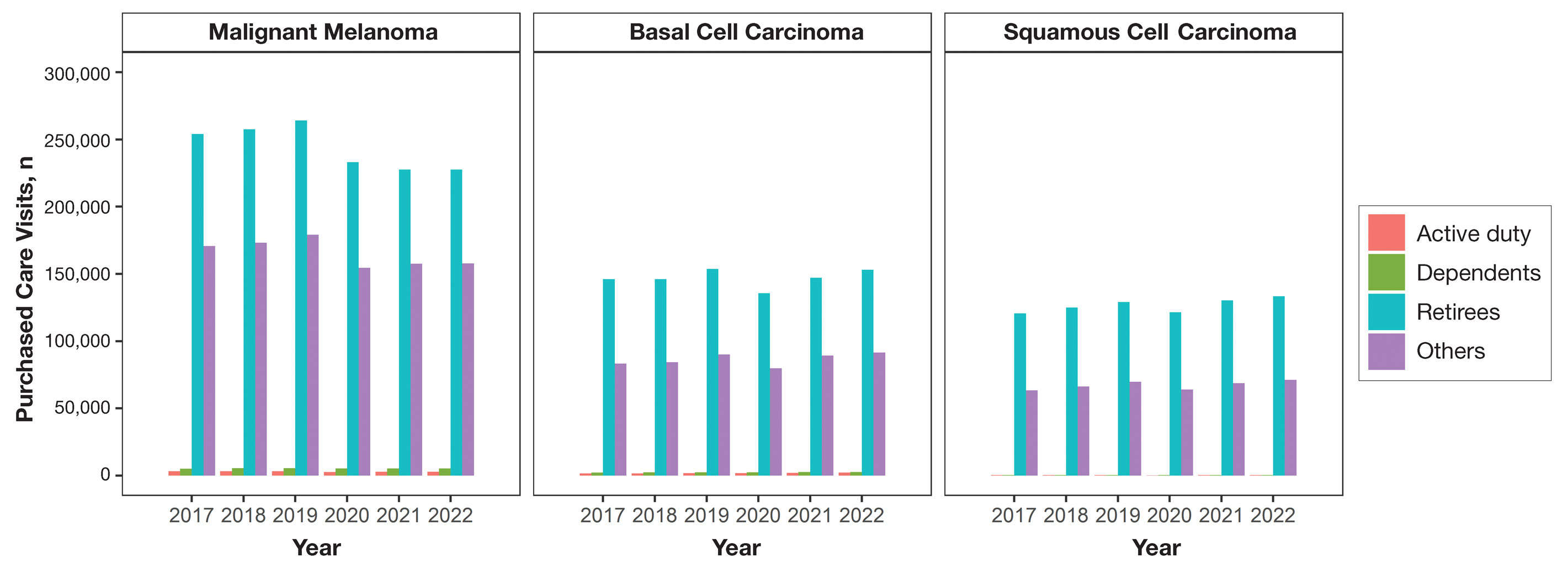

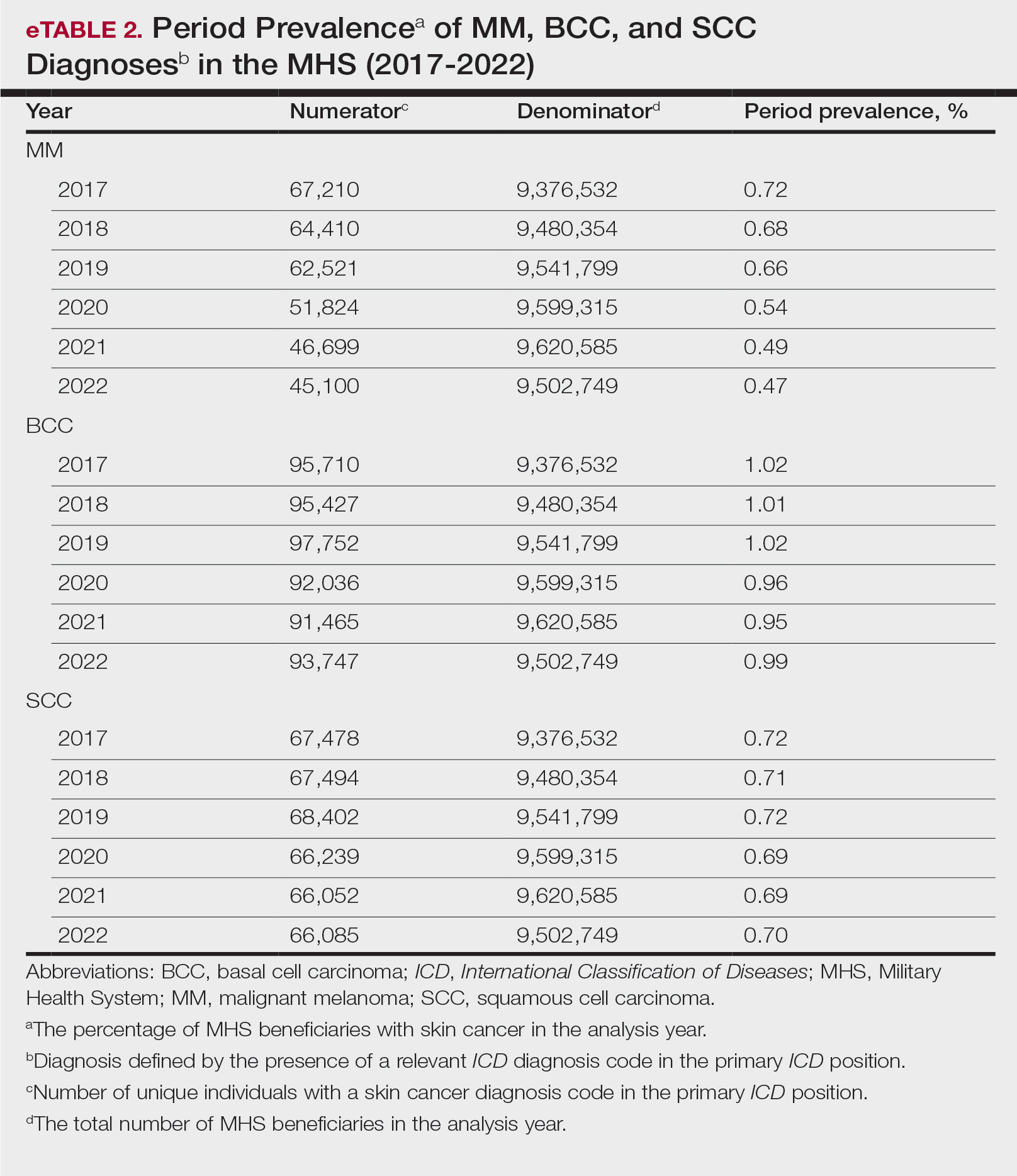

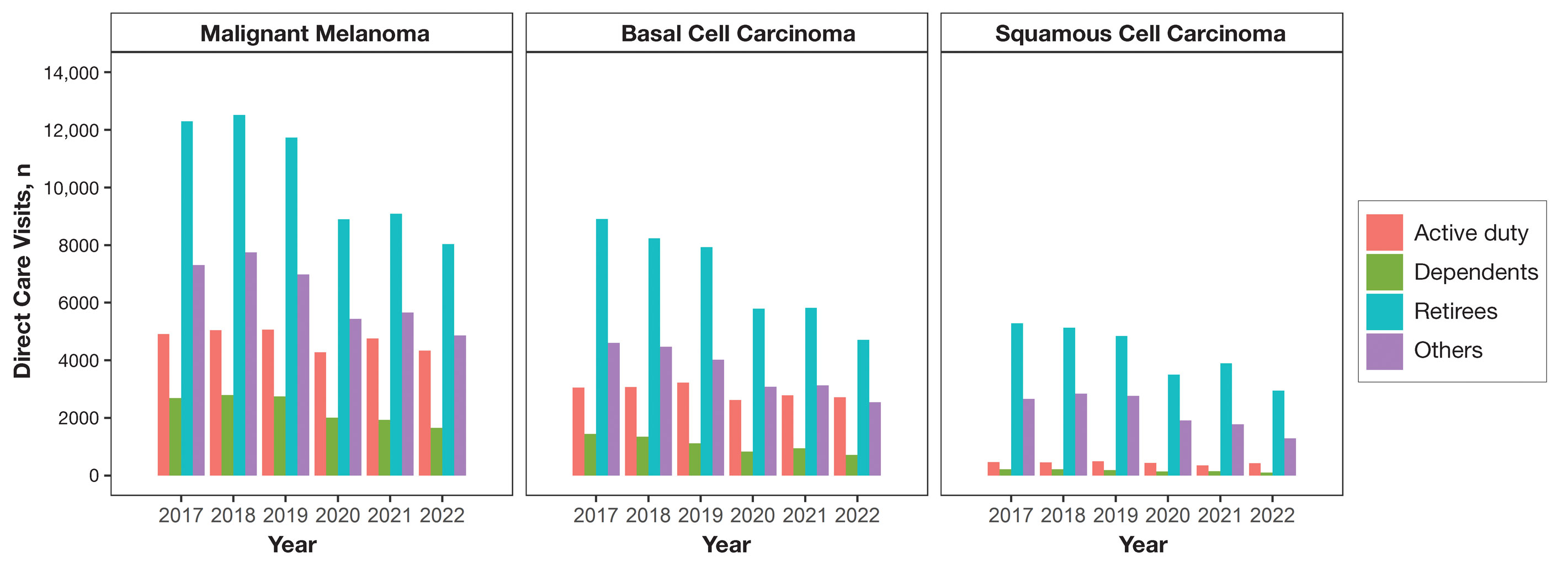

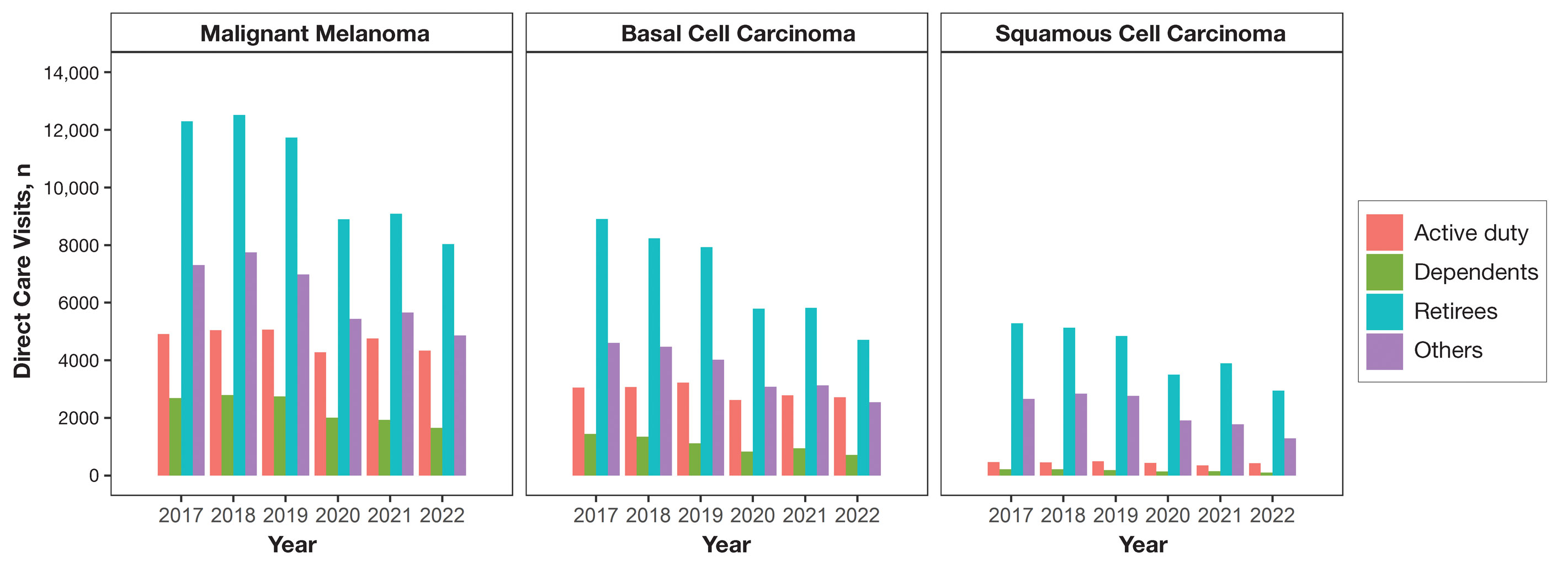

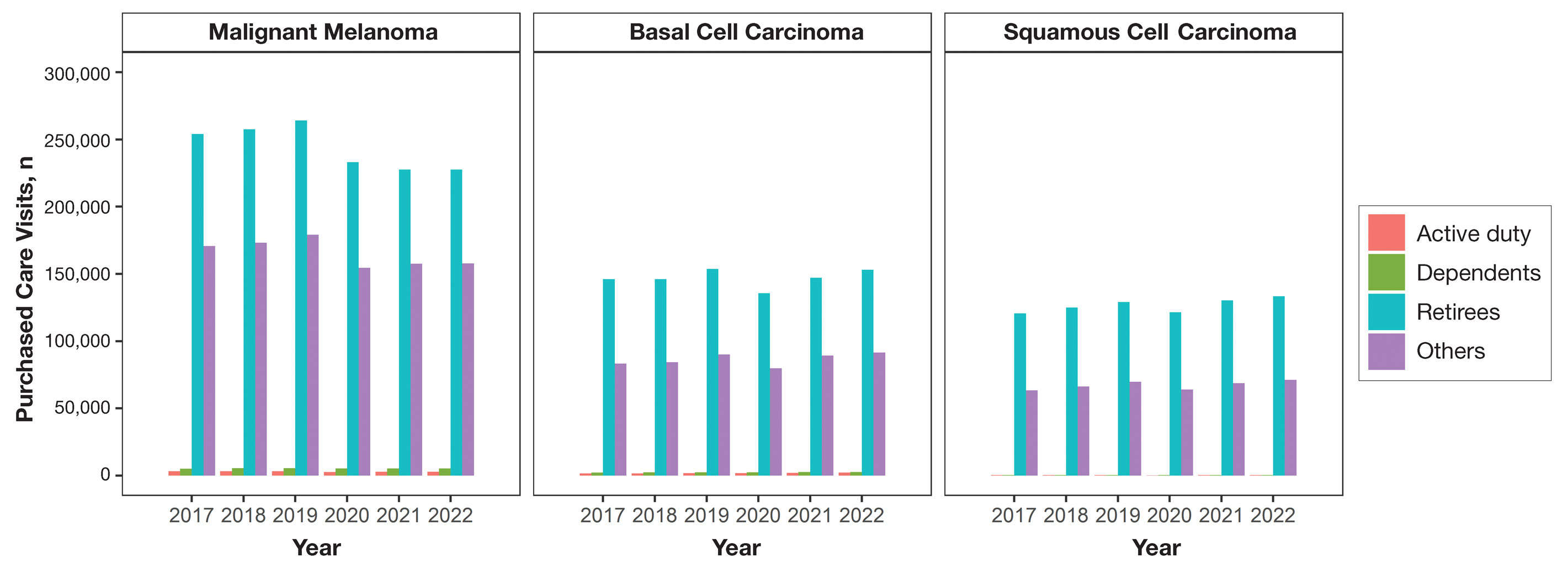

Encounter data were analyzed from a total of 5,374,348 visits between DC and PC over the study period for each cancer type of interest. Figures 1 and 2 show temporal trends in DC visits compared with PC visits in each beneficiary category. The percentage of total DC visits subsequently declined each year throughout the study period, with percentage decreases from 2017 to 2022 of 1.45% or 8200 fewer visits for MM, 3.41% or 7280 fewer visits for BCC, and 2.26% or 3673 fewer visits for SCC.

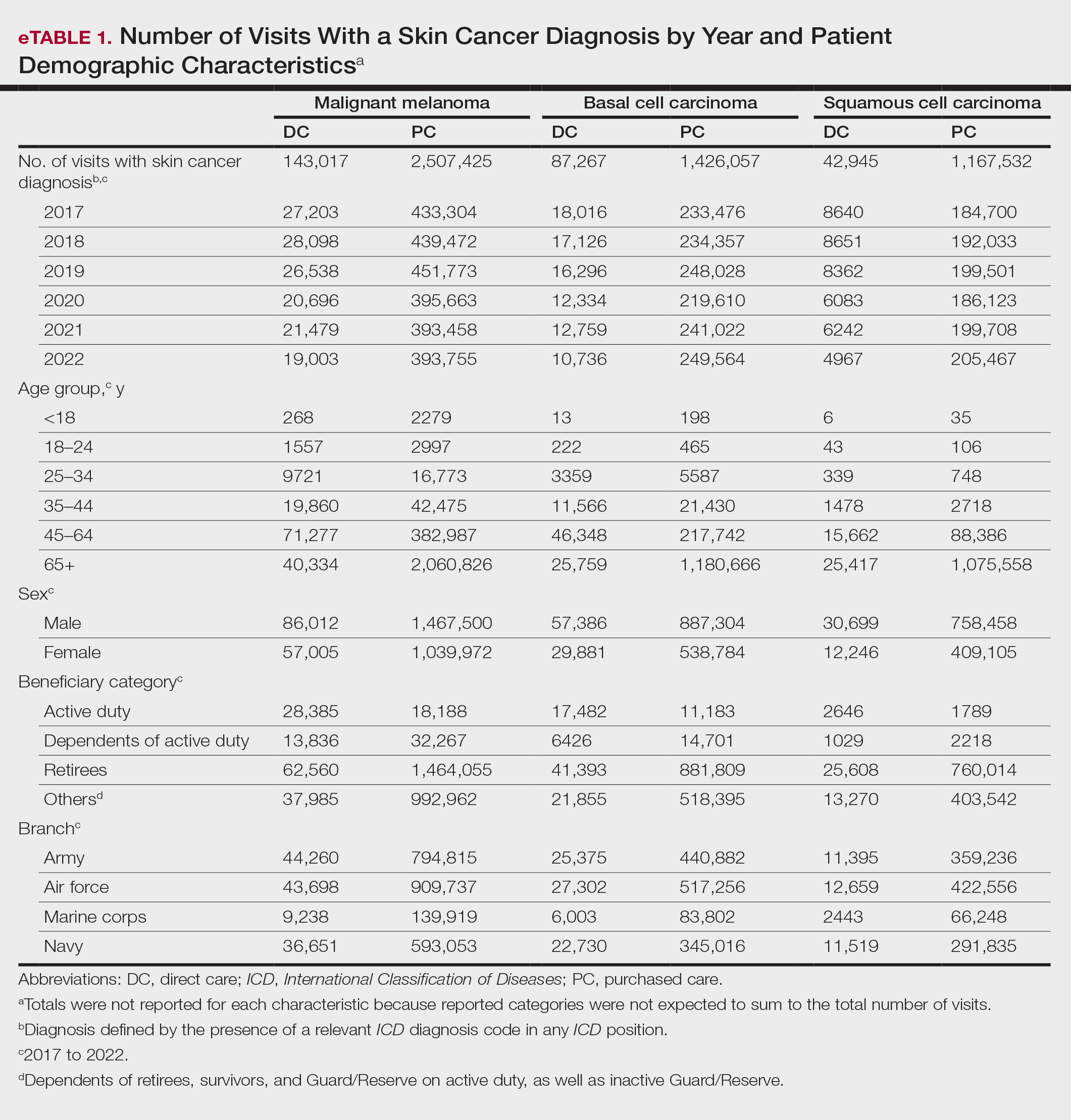

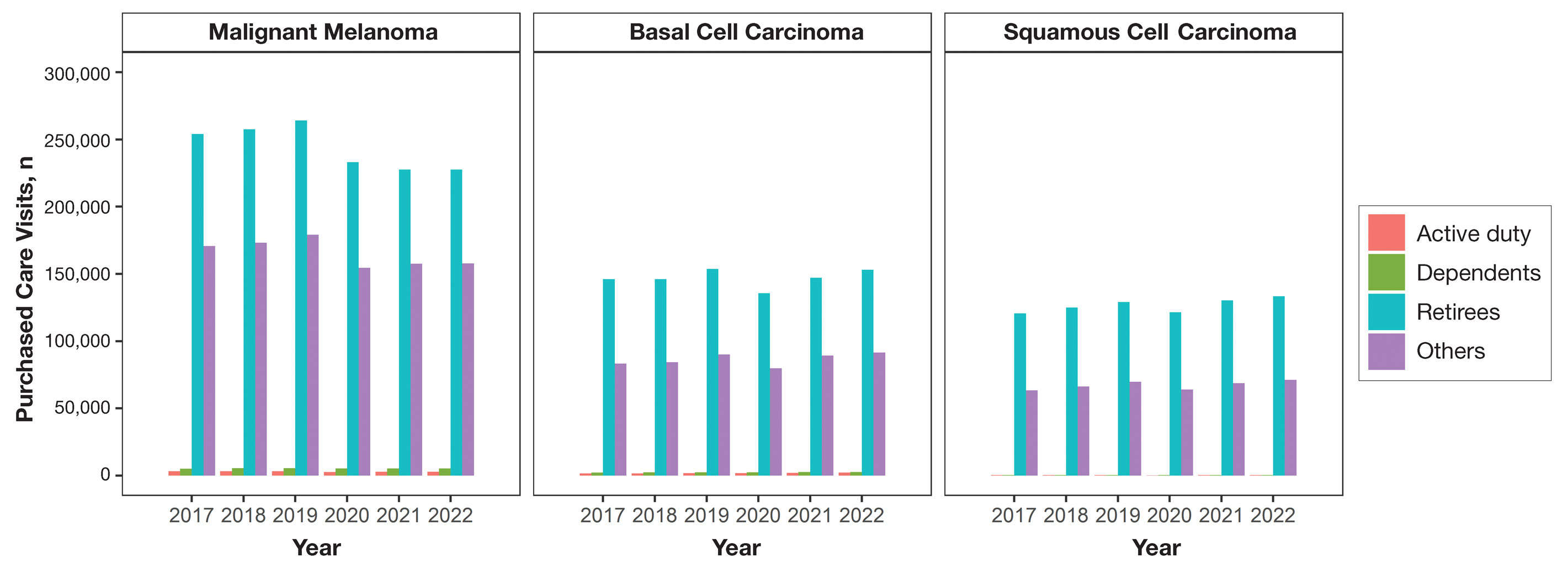

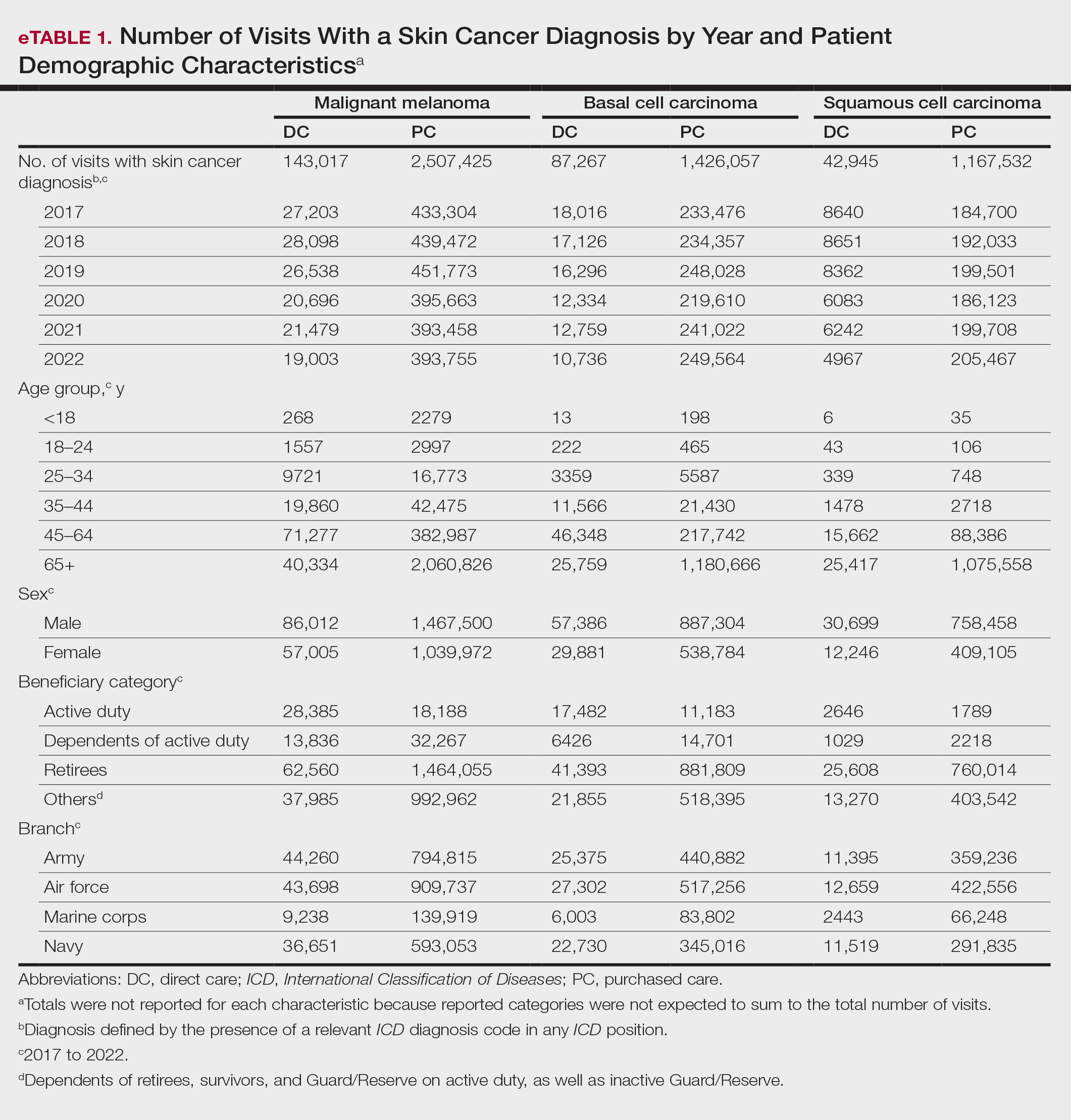

When stratified by beneficiary category, this trend remained consistent among dependents and retirees, with the most notable annual percentage decrease from 2019 to 2020. A higher proportion of younger adults and active-duty beneficiaries was seen in DC relative to PC, in which most visits were among retirees and others (primarily dependents of retirees, survivors, and Guard/Reserve on active duty, as well as inactive Guard/Reserve). No linear trends over time were apparent for active duty in DC and for dependents and retirees in PC. eTable 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of MHS beneficiaries being seen in DC and PC over the study period for each cancer type of interest.

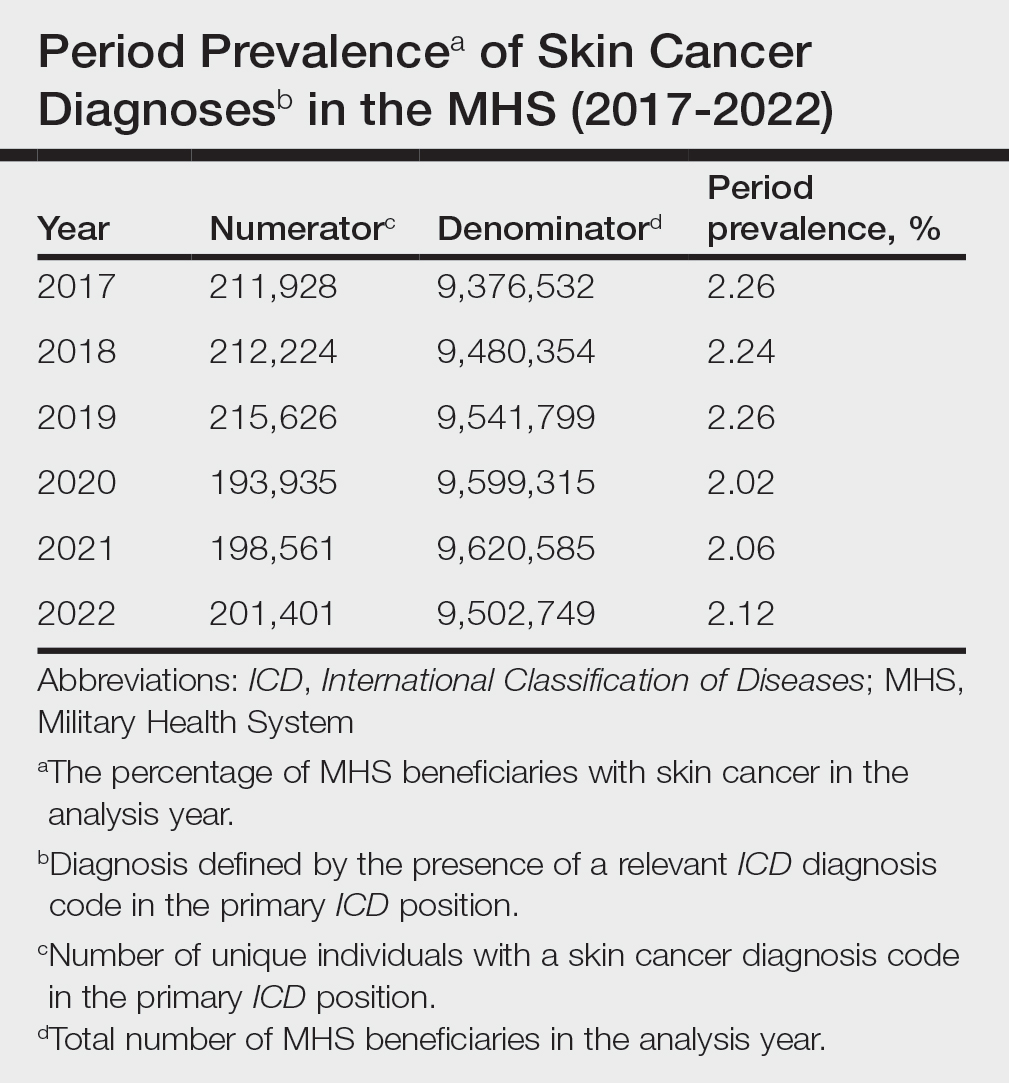

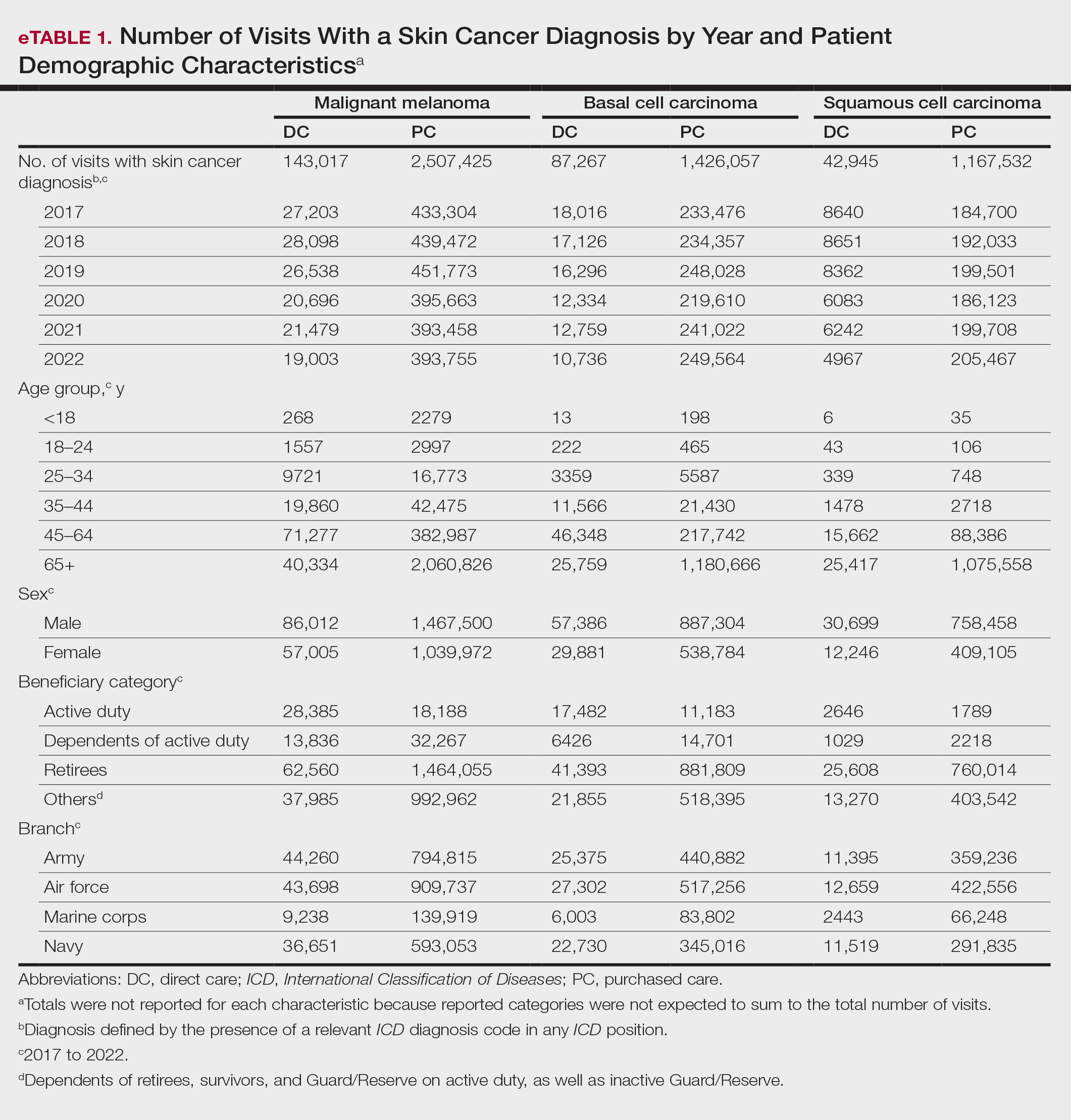

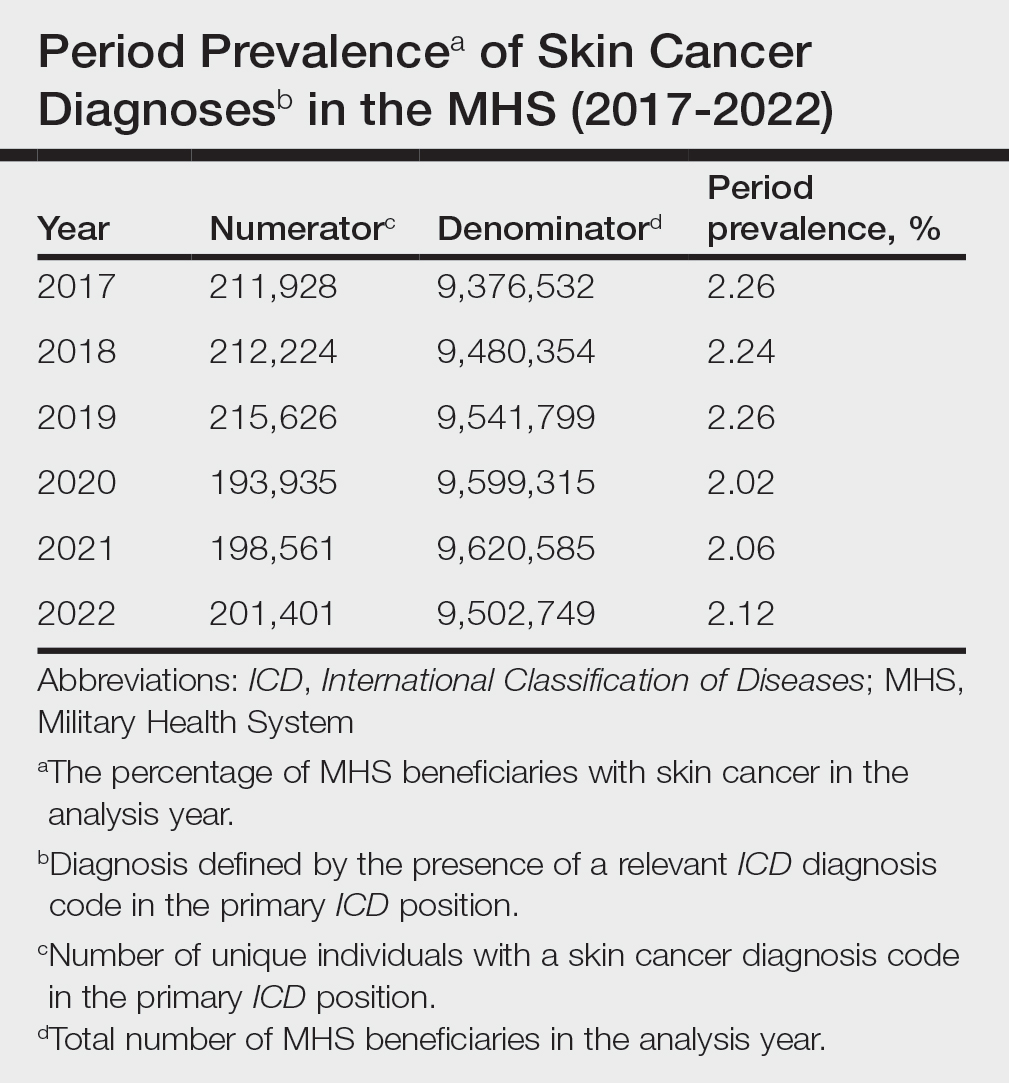

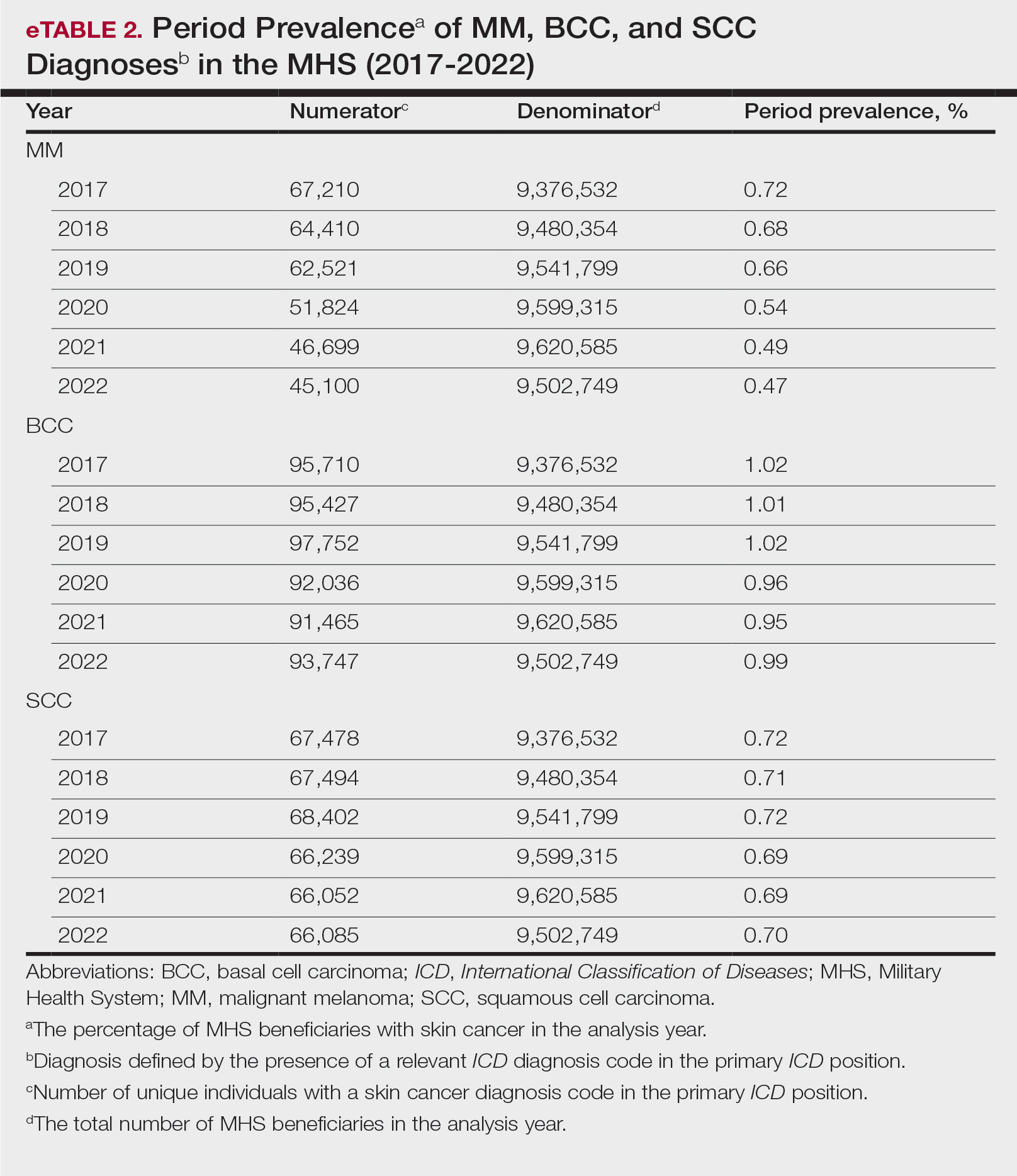

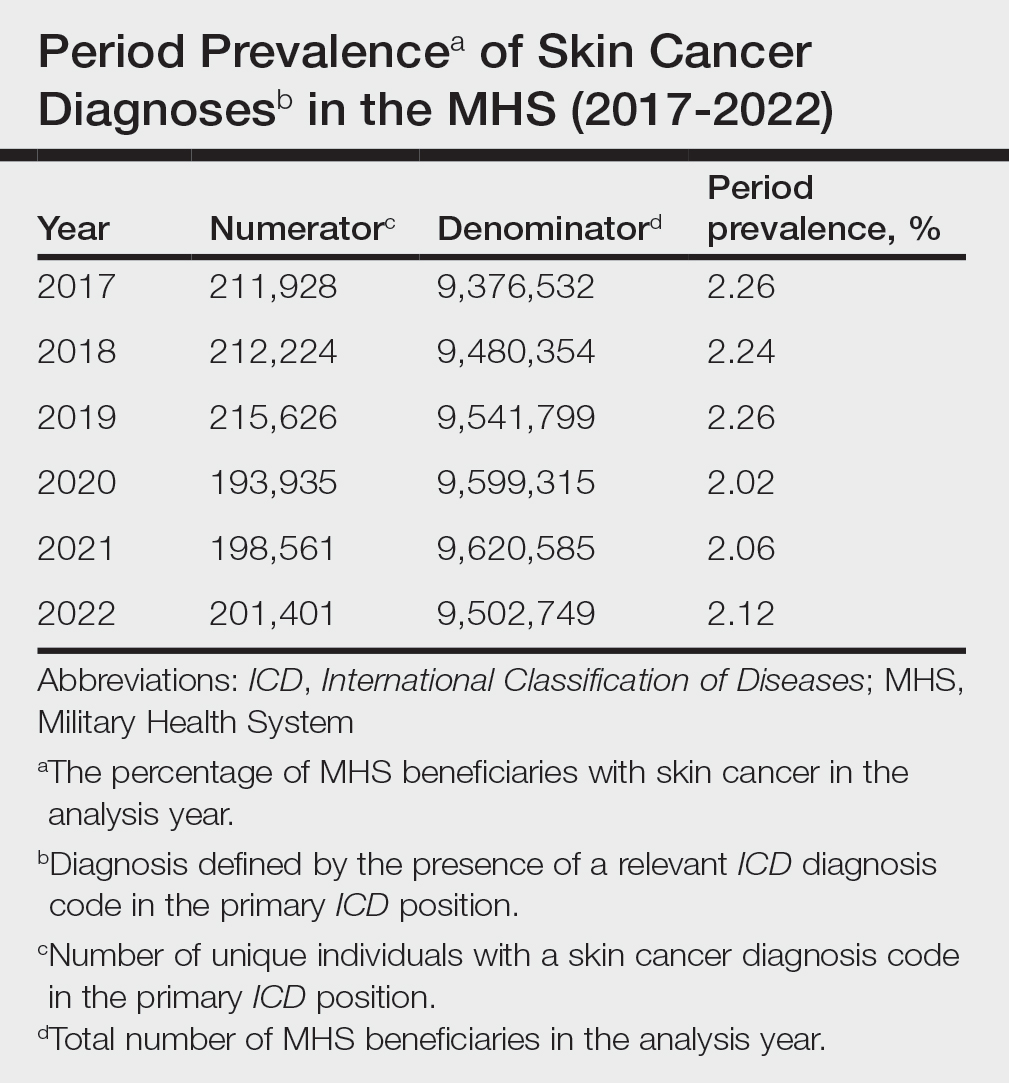

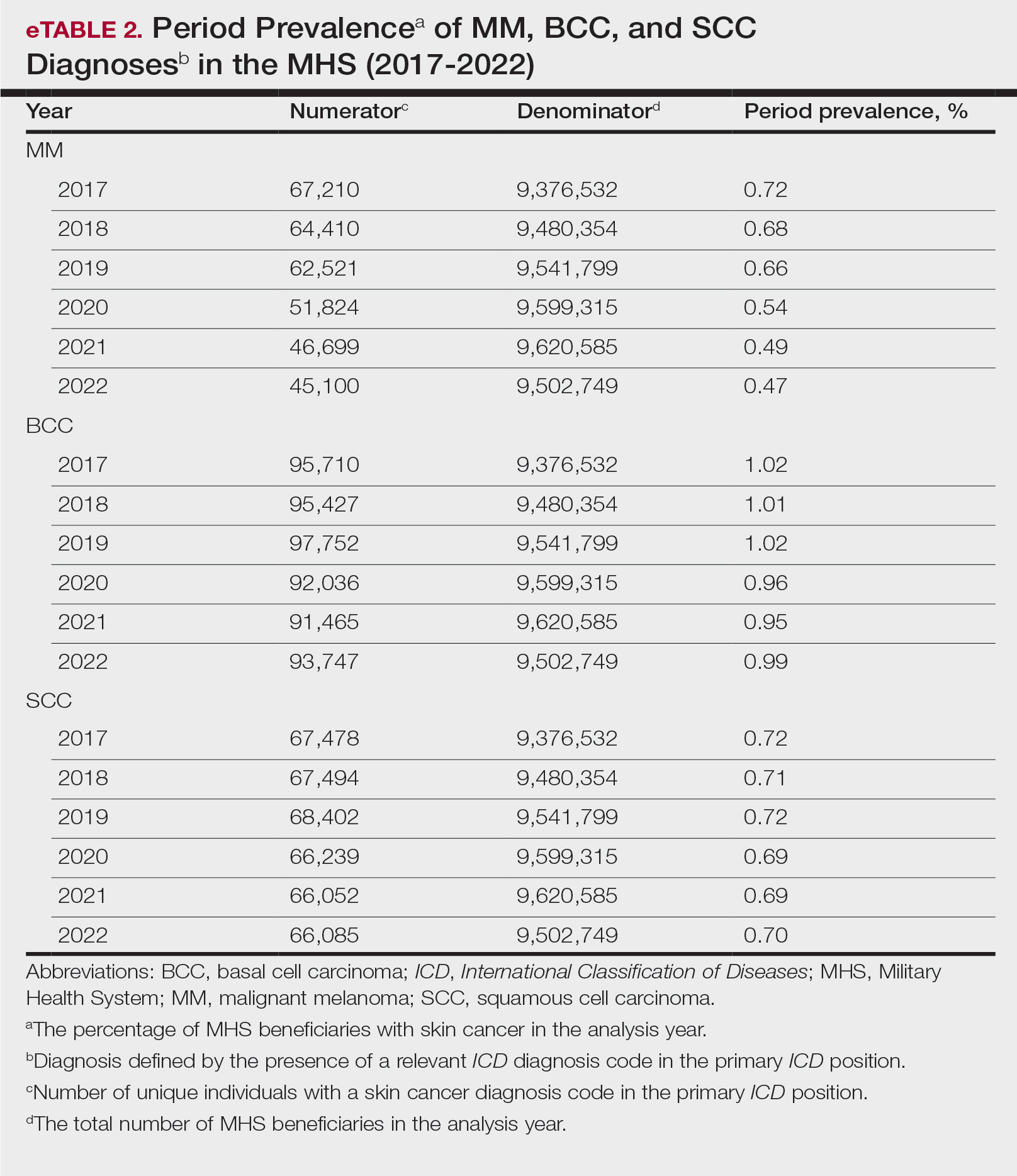

The Table shows the period prevalence of skin cancer diagnoses within the MHS beneficiary population from 2017 to 2022. These data were further analyzed by MM, BCC, and SCC (eTable 2) and demographics of interest for the year 2022. By beneficiary category, the period prevalence of MM was 0.08% in active duty, 0.06% in dependents, 0.48% in others, and 1.10% in retirees; the period prevalence of BCC was 0.12% in active duty, 0.07% in dependents, 0.91% in others, and 2.50% in retirees; and the period prevalence of SCC was 0.02% in active duty, 0.01% in dependents, 0.63% in others, and 1.87% in retirees. By sponsor branch, the period prevalence of MM was 0.35% in the army, 0.62% in the air force, 0.35% in the marine corps, and 0.65% in the navy; the period prevalence of BCC was 0.74% in the army, 1.30% in the air force, 0.74% in the marine corps, and 1.36% in the navy; and the period prevalence of SCC was 0.52% in the army, 0.92% in the air force, 0.51% in the marine corps, and 0.97% in the navy.

Comment

This study aimed to provide insight into the burden of skin cancer within the MHS beneficiary population and to identify temporal trends in where these beneficiaries receive their care. We examined patient encounter data from more than 9.6 million MHS beneficiaries.

The utilization of ICD codes from patient encounters to estimate the prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) has demonstrated a high positive predictive value. In one study, NMSC cases were confirmed in 96.5% of ICD code–identified patients.5 We presented an extensive collection of epidemiologic data on BCC and SCC, which posed unique challenges for tracking, as they are not reported to or monitored by cancer registries such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.6

MHS Compared to the US Population—A study using the Global Burden of Disease 2019 database revealed an increasing trend in the incidence and prevalence of NMSC and melanoma since 1990. The same study found the period prevalence in 2019 of MM, SCC, and BCC in the general US population to be 0.13%, 0.31%, and 0.05%, respectively.7 In contrast, among MHS beneficiaries, we observed a higher prevalence in the same year, with figures of 0.66% for MM, 0.72% for SCC, and 1.02% for BCC. According to the SEER database, the period prevalence of MM within the general US population in 2020 was 0.4%.8 That same year, we identified a higher period prevalence of MM—0.54%—within the MHS beneficiary population. Specifically, within the MHS retiree population, the prevalence in 2022 was double that of the general MHS population, with a rate of 1.10%, underscoring the importance of skin cancer screening in older, at-risk adult populations. Prior studies similarly found increased rates of skin cancer within the military beneficiary population. Further studies are needed to compare age-adjusted rates in the MHS vs US population.9-11

COVID-19 Trends—Our data showed an overall decreasing prevalence of skin cancer in the MHS from 2019 to 2021. We suspect that the apparent decrease in skin cancer prevalence may be attributed to underdiagnosis from COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. During that time, many dermatology clinics at military treatment facilities underwent temporary closures, and some dermatologists were sent on nondermatologic utilization tours. Likewise, a US multi-institutional study described declining rates of new melanomas from 2020 to 2021, with an increased proportion of patient presentations with advanced melanoma, suggesting an underdiagnosis of melanoma cases during pandemic restrictions. That study also noted an increased rate of patient-identified melanomas and a decreased rate of provider-identified melanomas during that time.12 Contributing factors may include excess hospital demand, increased patient complexity and acute care needs, and long outpatient clinic backlogs during this time.13Financial Burden—Over our 5-year study period, there were 5,374,348 patient encounters addressing skin cancer, both in DC and PC (Figures 1 and 2; eTable 1). In 2016 to 2018, the average annual cost of treating skin cancer in the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population was $1243 for NMSC (BCC and SCC) and $2430 for melanoma.6 Using this metric, the estimated total cost of care rendered in the MHS in 2018 for NMSC and melanoma was $202,510,803 and $156,516,300, respectively.

Trends in DC vs PC—In the years examined, we found a notable decrease in the number of beneficiaries receiving treatment for MM, BCC, and SCC in DC. Simultaneously, there has been an increase in the number of beneficiaries receiving PC for BCC and SCC, though this trend was not apparent for MM.

Our data provided interesting insights into the percentage of PC compared with DC offered within the MHS. Importantly, our findings suggested that the majority of skin cancer in active-duty service members is managed with DC within the military treatment facility setting (61% DC management over the period analyzed). This finding was true across all years of data analyzed, suggesting that the COVID-19 pandemic did not result in a quantifiable shift in care of skin cancer within the active-duty component to outside providers. One of the critical roles of dermatologists in the MHS is to diagnose and treat skin cancer, and our study suggested that the current global manning and staffing for MHS dermatologists may not be sufficient to meet the burden of skin cancers encountered within our active-duty troops, as only 61% are managed with DC. In particular, service members in more austere and/or overseas locations may not have ready access to a dermatologist.

The burden of skin cancer shifts dramatically when analyzing care of all other populations included in these data, including dependents of active-duty service members, retirees, and the category of “other” (ie, principally dependents of retirees). Within these populations, the rate of DC falls to 30%, with 70% of active-duty dependent care being deferred to network. The findings are even more noticeable for retirees and others within these 2 cohorts in all types of skin cancer analyzed, where DC only accounted for 5.2% of those skin cancers encountered and managed across TRICARE-eligible beneficiaries. For MM, BCC, and SCC, percentages of DC were 5.4%, 5.8%, and 3.5%, respectively. Although it is interesting to note the lower percentage of SCC managed via DC, our data did not allow for extrapolation as to why more SCC cases may be deferred to network. The shift to PC may align with DoD initiatives to increase the private sector’s involvement in military medicine and transition to civilianizing the MHS.14 In the end, the findings are remarkable, with approximately 95% of skin cancer care and management provided overall via PC.

These findings differ from previously published data regarding DC and PC from other specialty areas. Results from an analysis of DC vs PC for plastic surgery for the entire MHS from 2016 to 2019 found 83.2% of cases were deferred to network.15 A similar publication in the orthopedics literature examined TRICARE claims for patients who underwent total hip or knee arthroplasties between 2006 and 2019 and found 84.6% of cases were referred for PC. Notably, the authors utilized generalized linear models for cost analysis and found that DC was more expensive than PC, though this likely was a result of higher rates of hospital readmission within DC cases.16 Lastly, an article on the DC vs PC disposition of MHS patients with breast cancer from 2003 to 2008 found 46% of cases managed with DC vs 26.% with PC and 27.8% receiving a combination. In this case, the authors found a reduced cost associated with DC vs PC.17

Little additional literature exists regarding the costs of DC vs PC. An article published in 2016 designed to assess costs of DC vs PC showed that almost all military treatment facilities have higher costs than their private sector counterparts, with a few exceptions.18 This does not assess the costs of specific procedures, however, and only the overall cost to maintain a treatment facility. Importantly, this study was based on data from FY 2014 and has not been updated to reflect complex changes within the MHS system and the private health care system. Indeed, a US Government Accountability Office FY 2023 study highlighted staffing and efficiency issues within this transition to civilian medicine; subsequently, the 2024 President’s Budget suspended all planned clinical medical military end strength divestitures, underscoring the potential ineffectiveness of a civilianized MHS at meeting the health care needs of its beneficiaries.19,20 Future research on a national scale will be necessary to see if there is a reversal of this trend to PC and if doing so has any impact on access to DC for active-duty troops or active-duty dependents.

In addition to PC vs DC trends, we also can get a sense of the impact of the COVID pandemic restrictions on access to DC vs PC by assessing the change in rates seen in the data from the pre-COVID years (2017-2019) to the “post-COVID” years (2020-2022) included. Overall, rates of DC decreased uniformly from their already low percentages. In our study, rates of DC decreased from 5.8% in 2019 to 4.8% in 2022 for MM, from 6.6% to 4.3% for BCC, and from 4.2% to 2.9% for SCC. Although these changes seem small at first, they represent a 30.6% overall decrease in DC for BCC and an overall decrease of 55.4% in DC for SCC. Although our data do not allow us to extrapolate the real cost of this reduction across a nationwide health care system and more than 5 million care encounters, the financial and personal (ie, lost man-hours) costs of this decrease in DC likely are substantial.

In addition to costs, qualitative aspects that contribute to the burden of skin cancer include treatment-related morbidity, such as scarring, pain, and time spent away from family, work, and hobbies, as well as overall patient satisfaction with the quality of care they receive.21 Future work is critical to assess the real cost of this immense burden of PC for the treatment and management of skin cancers within the DoD beneficiary population.

Limitations—This study is limited by its observational nature. Given the mechanism of our data collection, we may have underestimated disease prevalence, as not all patients are seen for their diagnosis annually. Furthermore, reported demographic strata (eg, age, sex) were limited to those available and valid in the M2 reporting system. Finally, our study only collected data from those service members or former service members seen within the MHS and does not reflect any care rendered to those who are no longer active duty but did not officially retire from the military (ie, nonretired service members receiving care in the Veterans Affairs system for skin cancer).

Conclusion

We describe the annual burden of care for skin cancer in the MHS beneficiary population. Noteworthy findings observed were an overall decrease in beneficiaries being treated for skin cancer through DC; a decreasing annual prevalence of skin cancer diagnosis between 2019 and 2021, which may represent underdiagnosis or decreased follow-up in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic; and a higher rate of skin cancer in the military beneficiary population compared to the civilian population.

- US Department of Defense. Military health. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/

- Wooten NR, Brittingham JA, Pitner RO, et al. Purchased behavioral health care received by Military Health System beneficiaries in civilian medical facilities, 2000-2014. Mil Med. 2018;183:E278-E290. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx101

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- American Academy of Dermatology. Skin cancer. Updated April 22, 2022. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Eide MJ, Krajenta R, Johnson D, et al. Identification of patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer using health maintenance organization claims data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:123-128. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp352

- Kao SYZ, Ekwueme DU, Holman DM, et al. Economic burden of skin cancer treatment in the USA: an analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Data, 2012-2018. Cancer Causes Control. 2023;34:205-212. doi:10.1007/s10552-022-01644-0

- Aggarwal P, Knabel P, Fleischer AB. United States burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer from 1990 to 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:388-395. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.109

- SEER*Explorer. SEER Incidence Data, November 2023 Submission (1975-2021). National Cancer Institute; 2024. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html?site=53&data_type=1&graph_type=1&compareBy=sex&chk_sex_1=1&chk_sex_3=3&chk_sex_2=2&rate_type=2&race=1&age_range=1&advopt_precision=1&advopt_show_ci=on&hdn_view=1&advopt_show_apc=on&advopt_display=1

- Brown J, Kopf AW, Rigel DS, et al. Malignant melanoma in World War II veterans. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:661-663. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1984.tb01228.x

- Page WF, Whiteman D, Murphy M. A comparison of melanoma mortality among WWII veterans of the Pacific and European theaters. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:192-195. doi:10.1016/s1047-2797(99)00050-2

- Ramani ML, Bennett RG. High prevalence of skin cancer in World War II servicemen stationed in the Pacific theater. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:733-737. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70102-Y

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Gibbs A. COVID-19 shutdowns caused delays in melanoma diagnoses, study finds. OHSU News. August 4, 2022. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://news.ohsu.edu/2022/08/04/covid-19-shutdowns-caused-delays-in-melanoma-diagnoses-study-finds

- Kime P. Pentagon budget calls for ‘civilianizing’ military hospitals. Military Times. Published February 10, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2020/02/10/pentagon-budget-calls-for-civilianizing-military-hospitals/

- O’Reilly EB, Norris E, Ortiz-Pomales YT, et al. A comparison of direct care at military medical treatment facilities with purchased care in plastic surgery operative volume. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10(10 suppl):124-125. doi:10.1097/01.GOX.0000898976.03344.62

- Haag A, Hosein S, Lyon S, et al. Outcomes for arthroplasties in military health: a retrospective analysis of direct versus purchased care. Mil Med. 2023;188(suppl 6):45-51. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac441

- Eaglehouse YL, Georg MW, Richard P, et al. Cost-efficiency of breast cancer care in the US Military Health System: an economic evaluation in direct and purchased care. Mil Med. 2019;184:e494-e501. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz025

- Lurie PM. Comparing the cost of military treatment facilities with private sector care. Institute for Defense Analyses; February 2016. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.ida.org/research-and-publications/publications/all/c/co/comparing-the-costs-of-military-treatment-facilities-with-private-sector-care

- Defense Health Program. Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 President’s Budget: Operation and Maintenance Procurement Research, Development, Test and Evaluation. Department of Defense; March 2023. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2024/budget_justification/pdfs/09_Defense_Health_Program/00-DHP_Vols_I_II_and_III_PB24.pdf

- US Government Accountability Office. Defense Health Care. DOD should reevaluate market structure for military medical treatment facility management. Published August 21, 2023. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105441

- Rosenberg A, Cho S. We can do better at protecting our service members from skin cancer. Mil Med. 2022;187:311-313. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac198

This retrospective observational study investigates skin cancer prevalence and care patterns within the Military Health System (MHS) from 2017 to 2022. Utilizing the MHS Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (most commonly called M2), we analyzed more than 5 million patient encounters and documented skin cancer prevalence in the MHS beneficiary population utilizing available demographic data. Notable findings included an increased prevalence of skin cancer in the military population compared with the civilian population, a substantial decline in direct care (DC) visits at military treatment facilities compared with civilian purchased care (PC) visits, and a decreased total number of visits during COVID-19 restrictions.

The Military Health System (MHS) is a worldwide health care delivery system that serves 9.6 million beneficiaries, including military service members, retirees, and their families.1 Its mission is 2-fold: provide a medically ready force, and provide a medical benefit in keeping with the service and sacrifice of active-duty personnel, military retirees, and their families. For fiscal year (FY) 2022, active-duty service members and their families comprised 16.7% and 19.9% of beneficiaries, respectively, while retired service members and their families comprised 27% and 32% of beneficiaries, respectively.

The MHS operates under the authority of the Department of Defense (DoD) and is supported by an annual budget of approximately $50 billion.1 Health care provision within the MHS is managed by TRICARE regional networks.2 Within these networks, MHS beneficiaries may receive health care in 2 categories: direct care (DC) and purchased care (PC). Direct care is rendered in military treatment facilities by military or civilian providers contracted by the DoD, and PC is administered by civilian providers at civilian health care facilities within the TRICARE network, which is comprised of individual providers, clinics, and hospitals that have agreed to accept TRICARE beneficiaries.1 Purchased care is fee-for-service and paid for by the MHS. Of note, the MHS differs from the Veterans Affairs health care system in that the MHS through DC and PC sees only active-duty service members, active-duty dependents, retirees, and retirees’ dependents (primarily spouses), whereas Veterans Affairs sees only veterans (not necessarily retirees) discharged from military service with compensable medical conditions or disabilities.

Skin cancer presents a notable concern for the US Military, as the risk for skin cancer is thought to be higher than in the general population.3,4 This elevated risk is attributed to numerous factors inherent to active-duty service, including time spent in tropical environments, increased exposure to UV radiation, time spent at high altitudes, and decreased rates of sun-protective behaviors.3 Although numerous studies have explored the mechanisms that contribute to service members’ increased skin cancer risk, there are few (if any) that discuss the burden of skin cancer on the MHS and where its beneficiaries receive their skin cancer care. This study evaluated the burden of skin cancer within the MHS, as demonstrated by the period prevalence of skin cancer among its beneficiaries and the number and distribution of patient visits for skin cancer across both DC and PC from 2017 to 2022.

Methods

Data Collection—This retrospective observational study was designed to describe trends in outpatient visits with a skin cancer diagnosis and annual prevalence of skin cancer types in the MHS. Data are from all MHS beneficiaries who were eligible or enrolled in the analysis year. Our data source was the MHS Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (most commonly called M2), a query tool that contains the current and most recent 5 full FYs of Defense Health Agency corporate health care data including aggregated FY and calendar-year counts of MHS beneficiaries from 2017 to 2022 using encounter and claims data tables from both DC and PC. Data in M2 are coded using a pseudo-person identification number, and queries performed for this study were limited to de-identified visit and patient counts.

Skin cancer diagnoses were defined by relevant International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes recorded from outpatient visits in DC and PC. The M2 database was queried to find aggregate counts of visits and unique MHS beneficiaries with one or more diagnoses of a skin cancer type of interest (defined by relevant ICD-10-CM code) over the study period stratified by year and by patient demographic characteristics. Skin cancer types by ICD-10-CM code group included basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), malignant melanoma (MM), and other (including Merkel cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma). Demographic strata included age, sex, military status (active duty, dependents of active duty, retired, or all others), sponsor military rank, and sponsor branch (army, air force, marine corps, or navy). Visit counts included diagnoses from any ICD position (for encounters that contained multiple ICD codes) to describe the total volume of care that addressed a diagnosed skin cancer. Counts of unique patients in prevalence analyses included relevant diagnoses in the primary ICD position only to increase the specificity of prevalence estimates.

Data Analysis—Descriptive analyses included the total number of outpatient visits with a skin cancer diagnosis in DC and PC over the study period, with percentages of total visits by year and by demographic strata. Separate analyses estimated annual prevalences of skin cancer types in the MHS by study year and within 2022 by demographic strata. Numerators in prevalence analyses were defined as the number of unique individuals with one or more relevant ICD codes in the analysis year. Denominators were defined as the total number of MHS beneficiaries in the analysis year and resulting period prevalences reported. Observed prevalences were qualitatively described, and trends were compared with prevalences in nonmilitary populations reported in the literature.

Ethics—This study was conducted as part of a study using secondary analyses of de-identified data from the M2 database. The study was reviewed and approved by the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center institutional review board.

Results

Encounter data were analyzed from a total of 5,374,348 visits between DC and PC over the study period for each cancer type of interest. Figures 1 and 2 show temporal trends in DC visits compared with PC visits in each beneficiary category. The percentage of total DC visits subsequently declined each year throughout the study period, with percentage decreases from 2017 to 2022 of 1.45% or 8200 fewer visits for MM, 3.41% or 7280 fewer visits for BCC, and 2.26% or 3673 fewer visits for SCC.

When stratified by beneficiary category, this trend remained consistent among dependents and retirees, with the most notable annual percentage decrease from 2019 to 2020. A higher proportion of younger adults and active-duty beneficiaries was seen in DC relative to PC, in which most visits were among retirees and others (primarily dependents of retirees, survivors, and Guard/Reserve on active duty, as well as inactive Guard/Reserve). No linear trends over time were apparent for active duty in DC and for dependents and retirees in PC. eTable 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of MHS beneficiaries being seen in DC and PC over the study period for each cancer type of interest.

The Table shows the period prevalence of skin cancer diagnoses within the MHS beneficiary population from 2017 to 2022. These data were further analyzed by MM, BCC, and SCC (eTable 2) and demographics of interest for the year 2022. By beneficiary category, the period prevalence of MM was 0.08% in active duty, 0.06% in dependents, 0.48% in others, and 1.10% in retirees; the period prevalence of BCC was 0.12% in active duty, 0.07% in dependents, 0.91% in others, and 2.50% in retirees; and the period prevalence of SCC was 0.02% in active duty, 0.01% in dependents, 0.63% in others, and 1.87% in retirees. By sponsor branch, the period prevalence of MM was 0.35% in the army, 0.62% in the air force, 0.35% in the marine corps, and 0.65% in the navy; the period prevalence of BCC was 0.74% in the army, 1.30% in the air force, 0.74% in the marine corps, and 1.36% in the navy; and the period prevalence of SCC was 0.52% in the army, 0.92% in the air force, 0.51% in the marine corps, and 0.97% in the navy.

Comment

This study aimed to provide insight into the burden of skin cancer within the MHS beneficiary population and to identify temporal trends in where these beneficiaries receive their care. We examined patient encounter data from more than 9.6 million MHS beneficiaries.

The utilization of ICD codes from patient encounters to estimate the prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) has demonstrated a high positive predictive value. In one study, NMSC cases were confirmed in 96.5% of ICD code–identified patients.5 We presented an extensive collection of epidemiologic data on BCC and SCC, which posed unique challenges for tracking, as they are not reported to or monitored by cancer registries such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.6

MHS Compared to the US Population—A study using the Global Burden of Disease 2019 database revealed an increasing trend in the incidence and prevalence of NMSC and melanoma since 1990. The same study found the period prevalence in 2019 of MM, SCC, and BCC in the general US population to be 0.13%, 0.31%, and 0.05%, respectively.7 In contrast, among MHS beneficiaries, we observed a higher prevalence in the same year, with figures of 0.66% for MM, 0.72% for SCC, and 1.02% for BCC. According to the SEER database, the period prevalence of MM within the general US population in 2020 was 0.4%.8 That same year, we identified a higher period prevalence of MM—0.54%—within the MHS beneficiary population. Specifically, within the MHS retiree population, the prevalence in 2022 was double that of the general MHS population, with a rate of 1.10%, underscoring the importance of skin cancer screening in older, at-risk adult populations. Prior studies similarly found increased rates of skin cancer within the military beneficiary population. Further studies are needed to compare age-adjusted rates in the MHS vs US population.9-11

COVID-19 Trends—Our data showed an overall decreasing prevalence of skin cancer in the MHS from 2019 to 2021. We suspect that the apparent decrease in skin cancer prevalence may be attributed to underdiagnosis from COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. During that time, many dermatology clinics at military treatment facilities underwent temporary closures, and some dermatologists were sent on nondermatologic utilization tours. Likewise, a US multi-institutional study described declining rates of new melanomas from 2020 to 2021, with an increased proportion of patient presentations with advanced melanoma, suggesting an underdiagnosis of melanoma cases during pandemic restrictions. That study also noted an increased rate of patient-identified melanomas and a decreased rate of provider-identified melanomas during that time.12 Contributing factors may include excess hospital demand, increased patient complexity and acute care needs, and long outpatient clinic backlogs during this time.13Financial Burden—Over our 5-year study period, there were 5,374,348 patient encounters addressing skin cancer, both in DC and PC (Figures 1 and 2; eTable 1). In 2016 to 2018, the average annual cost of treating skin cancer in the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population was $1243 for NMSC (BCC and SCC) and $2430 for melanoma.6 Using this metric, the estimated total cost of care rendered in the MHS in 2018 for NMSC and melanoma was $202,510,803 and $156,516,300, respectively.

Trends in DC vs PC—In the years examined, we found a notable decrease in the number of beneficiaries receiving treatment for MM, BCC, and SCC in DC. Simultaneously, there has been an increase in the number of beneficiaries receiving PC for BCC and SCC, though this trend was not apparent for MM.

Our data provided interesting insights into the percentage of PC compared with DC offered within the MHS. Importantly, our findings suggested that the majority of skin cancer in active-duty service members is managed with DC within the military treatment facility setting (61% DC management over the period analyzed). This finding was true across all years of data analyzed, suggesting that the COVID-19 pandemic did not result in a quantifiable shift in care of skin cancer within the active-duty component to outside providers. One of the critical roles of dermatologists in the MHS is to diagnose and treat skin cancer, and our study suggested that the current global manning and staffing for MHS dermatologists may not be sufficient to meet the burden of skin cancers encountered within our active-duty troops, as only 61% are managed with DC. In particular, service members in more austere and/or overseas locations may not have ready access to a dermatologist.

The burden of skin cancer shifts dramatically when analyzing care of all other populations included in these data, including dependents of active-duty service members, retirees, and the category of “other” (ie, principally dependents of retirees). Within these populations, the rate of DC falls to 30%, with 70% of active-duty dependent care being deferred to network. The findings are even more noticeable for retirees and others within these 2 cohorts in all types of skin cancer analyzed, where DC only accounted for 5.2% of those skin cancers encountered and managed across TRICARE-eligible beneficiaries. For MM, BCC, and SCC, percentages of DC were 5.4%, 5.8%, and 3.5%, respectively. Although it is interesting to note the lower percentage of SCC managed via DC, our data did not allow for extrapolation as to why more SCC cases may be deferred to network. The shift to PC may align with DoD initiatives to increase the private sector’s involvement in military medicine and transition to civilianizing the MHS.14 In the end, the findings are remarkable, with approximately 95% of skin cancer care and management provided overall via PC.

These findings differ from previously published data regarding DC and PC from other specialty areas. Results from an analysis of DC vs PC for plastic surgery for the entire MHS from 2016 to 2019 found 83.2% of cases were deferred to network.15 A similar publication in the orthopedics literature examined TRICARE claims for patients who underwent total hip or knee arthroplasties between 2006 and 2019 and found 84.6% of cases were referred for PC. Notably, the authors utilized generalized linear models for cost analysis and found that DC was more expensive than PC, though this likely was a result of higher rates of hospital readmission within DC cases.16 Lastly, an article on the DC vs PC disposition of MHS patients with breast cancer from 2003 to 2008 found 46% of cases managed with DC vs 26.% with PC and 27.8% receiving a combination. In this case, the authors found a reduced cost associated with DC vs PC.17

Little additional literature exists regarding the costs of DC vs PC. An article published in 2016 designed to assess costs of DC vs PC showed that almost all military treatment facilities have higher costs than their private sector counterparts, with a few exceptions.18 This does not assess the costs of specific procedures, however, and only the overall cost to maintain a treatment facility. Importantly, this study was based on data from FY 2014 and has not been updated to reflect complex changes within the MHS system and the private health care system. Indeed, a US Government Accountability Office FY 2023 study highlighted staffing and efficiency issues within this transition to civilian medicine; subsequently, the 2024 President’s Budget suspended all planned clinical medical military end strength divestitures, underscoring the potential ineffectiveness of a civilianized MHS at meeting the health care needs of its beneficiaries.19,20 Future research on a national scale will be necessary to see if there is a reversal of this trend to PC and if doing so has any impact on access to DC for active-duty troops or active-duty dependents.

In addition to PC vs DC trends, we also can get a sense of the impact of the COVID pandemic restrictions on access to DC vs PC by assessing the change in rates seen in the data from the pre-COVID years (2017-2019) to the “post-COVID” years (2020-2022) included. Overall, rates of DC decreased uniformly from their already low percentages. In our study, rates of DC decreased from 5.8% in 2019 to 4.8% in 2022 for MM, from 6.6% to 4.3% for BCC, and from 4.2% to 2.9% for SCC. Although these changes seem small at first, they represent a 30.6% overall decrease in DC for BCC and an overall decrease of 55.4% in DC for SCC. Although our data do not allow us to extrapolate the real cost of this reduction across a nationwide health care system and more than 5 million care encounters, the financial and personal (ie, lost man-hours) costs of this decrease in DC likely are substantial.

In addition to costs, qualitative aspects that contribute to the burden of skin cancer include treatment-related morbidity, such as scarring, pain, and time spent away from family, work, and hobbies, as well as overall patient satisfaction with the quality of care they receive.21 Future work is critical to assess the real cost of this immense burden of PC for the treatment and management of skin cancers within the DoD beneficiary population.

Limitations—This study is limited by its observational nature. Given the mechanism of our data collection, we may have underestimated disease prevalence, as not all patients are seen for their diagnosis annually. Furthermore, reported demographic strata (eg, age, sex) were limited to those available and valid in the M2 reporting system. Finally, our study only collected data from those service members or former service members seen within the MHS and does not reflect any care rendered to those who are no longer active duty but did not officially retire from the military (ie, nonretired service members receiving care in the Veterans Affairs system for skin cancer).

Conclusion

We describe the annual burden of care for skin cancer in the MHS beneficiary population. Noteworthy findings observed were an overall decrease in beneficiaries being treated for skin cancer through DC; a decreasing annual prevalence of skin cancer diagnosis between 2019 and 2021, which may represent underdiagnosis or decreased follow-up in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic; and a higher rate of skin cancer in the military beneficiary population compared to the civilian population.

This retrospective observational study investigates skin cancer prevalence and care patterns within the Military Health System (MHS) from 2017 to 2022. Utilizing the MHS Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (most commonly called M2), we analyzed more than 5 million patient encounters and documented skin cancer prevalence in the MHS beneficiary population utilizing available demographic data. Notable findings included an increased prevalence of skin cancer in the military population compared with the civilian population, a substantial decline in direct care (DC) visits at military treatment facilities compared with civilian purchased care (PC) visits, and a decreased total number of visits during COVID-19 restrictions.

The Military Health System (MHS) is a worldwide health care delivery system that serves 9.6 million beneficiaries, including military service members, retirees, and their families.1 Its mission is 2-fold: provide a medically ready force, and provide a medical benefit in keeping with the service and sacrifice of active-duty personnel, military retirees, and their families. For fiscal year (FY) 2022, active-duty service members and their families comprised 16.7% and 19.9% of beneficiaries, respectively, while retired service members and their families comprised 27% and 32% of beneficiaries, respectively.

The MHS operates under the authority of the Department of Defense (DoD) and is supported by an annual budget of approximately $50 billion.1 Health care provision within the MHS is managed by TRICARE regional networks.2 Within these networks, MHS beneficiaries may receive health care in 2 categories: direct care (DC) and purchased care (PC). Direct care is rendered in military treatment facilities by military or civilian providers contracted by the DoD, and PC is administered by civilian providers at civilian health care facilities within the TRICARE network, which is comprised of individual providers, clinics, and hospitals that have agreed to accept TRICARE beneficiaries.1 Purchased care is fee-for-service and paid for by the MHS. Of note, the MHS differs from the Veterans Affairs health care system in that the MHS through DC and PC sees only active-duty service members, active-duty dependents, retirees, and retirees’ dependents (primarily spouses), whereas Veterans Affairs sees only veterans (not necessarily retirees) discharged from military service with compensable medical conditions or disabilities.

Skin cancer presents a notable concern for the US Military, as the risk for skin cancer is thought to be higher than in the general population.3,4 This elevated risk is attributed to numerous factors inherent to active-duty service, including time spent in tropical environments, increased exposure to UV radiation, time spent at high altitudes, and decreased rates of sun-protective behaviors.3 Although numerous studies have explored the mechanisms that contribute to service members’ increased skin cancer risk, there are few (if any) that discuss the burden of skin cancer on the MHS and where its beneficiaries receive their skin cancer care. This study evaluated the burden of skin cancer within the MHS, as demonstrated by the period prevalence of skin cancer among its beneficiaries and the number and distribution of patient visits for skin cancer across both DC and PC from 2017 to 2022.

Methods

Data Collection—This retrospective observational study was designed to describe trends in outpatient visits with a skin cancer diagnosis and annual prevalence of skin cancer types in the MHS. Data are from all MHS beneficiaries who were eligible or enrolled in the analysis year. Our data source was the MHS Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (most commonly called M2), a query tool that contains the current and most recent 5 full FYs of Defense Health Agency corporate health care data including aggregated FY and calendar-year counts of MHS beneficiaries from 2017 to 2022 using encounter and claims data tables from both DC and PC. Data in M2 are coded using a pseudo-person identification number, and queries performed for this study were limited to de-identified visit and patient counts.

Skin cancer diagnoses were defined by relevant International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes recorded from outpatient visits in DC and PC. The M2 database was queried to find aggregate counts of visits and unique MHS beneficiaries with one or more diagnoses of a skin cancer type of interest (defined by relevant ICD-10-CM code) over the study period stratified by year and by patient demographic characteristics. Skin cancer types by ICD-10-CM code group included basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), malignant melanoma (MM), and other (including Merkel cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma). Demographic strata included age, sex, military status (active duty, dependents of active duty, retired, or all others), sponsor military rank, and sponsor branch (army, air force, marine corps, or navy). Visit counts included diagnoses from any ICD position (for encounters that contained multiple ICD codes) to describe the total volume of care that addressed a diagnosed skin cancer. Counts of unique patients in prevalence analyses included relevant diagnoses in the primary ICD position only to increase the specificity of prevalence estimates.

Data Analysis—Descriptive analyses included the total number of outpatient visits with a skin cancer diagnosis in DC and PC over the study period, with percentages of total visits by year and by demographic strata. Separate analyses estimated annual prevalences of skin cancer types in the MHS by study year and within 2022 by demographic strata. Numerators in prevalence analyses were defined as the number of unique individuals with one or more relevant ICD codes in the analysis year. Denominators were defined as the total number of MHS beneficiaries in the analysis year and resulting period prevalences reported. Observed prevalences were qualitatively described, and trends were compared with prevalences in nonmilitary populations reported in the literature.

Ethics—This study was conducted as part of a study using secondary analyses of de-identified data from the M2 database. The study was reviewed and approved by the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center institutional review board.

Results

Encounter data were analyzed from a total of 5,374,348 visits between DC and PC over the study period for each cancer type of interest. Figures 1 and 2 show temporal trends in DC visits compared with PC visits in each beneficiary category. The percentage of total DC visits subsequently declined each year throughout the study period, with percentage decreases from 2017 to 2022 of 1.45% or 8200 fewer visits for MM, 3.41% or 7280 fewer visits for BCC, and 2.26% or 3673 fewer visits for SCC.

When stratified by beneficiary category, this trend remained consistent among dependents and retirees, with the most notable annual percentage decrease from 2019 to 2020. A higher proportion of younger adults and active-duty beneficiaries was seen in DC relative to PC, in which most visits were among retirees and others (primarily dependents of retirees, survivors, and Guard/Reserve on active duty, as well as inactive Guard/Reserve). No linear trends over time were apparent for active duty in DC and for dependents and retirees in PC. eTable 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of MHS beneficiaries being seen in DC and PC over the study period for each cancer type of interest.

The Table shows the period prevalence of skin cancer diagnoses within the MHS beneficiary population from 2017 to 2022. These data were further analyzed by MM, BCC, and SCC (eTable 2) and demographics of interest for the year 2022. By beneficiary category, the period prevalence of MM was 0.08% in active duty, 0.06% in dependents, 0.48% in others, and 1.10% in retirees; the period prevalence of BCC was 0.12% in active duty, 0.07% in dependents, 0.91% in others, and 2.50% in retirees; and the period prevalence of SCC was 0.02% in active duty, 0.01% in dependents, 0.63% in others, and 1.87% in retirees. By sponsor branch, the period prevalence of MM was 0.35% in the army, 0.62% in the air force, 0.35% in the marine corps, and 0.65% in the navy; the period prevalence of BCC was 0.74% in the army, 1.30% in the air force, 0.74% in the marine corps, and 1.36% in the navy; and the period prevalence of SCC was 0.52% in the army, 0.92% in the air force, 0.51% in the marine corps, and 0.97% in the navy.

Comment

This study aimed to provide insight into the burden of skin cancer within the MHS beneficiary population and to identify temporal trends in where these beneficiaries receive their care. We examined patient encounter data from more than 9.6 million MHS beneficiaries.

The utilization of ICD codes from patient encounters to estimate the prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) has demonstrated a high positive predictive value. In one study, NMSC cases were confirmed in 96.5% of ICD code–identified patients.5 We presented an extensive collection of epidemiologic data on BCC and SCC, which posed unique challenges for tracking, as they are not reported to or monitored by cancer registries such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.6

MHS Compared to the US Population—A study using the Global Burden of Disease 2019 database revealed an increasing trend in the incidence and prevalence of NMSC and melanoma since 1990. The same study found the period prevalence in 2019 of MM, SCC, and BCC in the general US population to be 0.13%, 0.31%, and 0.05%, respectively.7 In contrast, among MHS beneficiaries, we observed a higher prevalence in the same year, with figures of 0.66% for MM, 0.72% for SCC, and 1.02% for BCC. According to the SEER database, the period prevalence of MM within the general US population in 2020 was 0.4%.8 That same year, we identified a higher period prevalence of MM—0.54%—within the MHS beneficiary population. Specifically, within the MHS retiree population, the prevalence in 2022 was double that of the general MHS population, with a rate of 1.10%, underscoring the importance of skin cancer screening in older, at-risk adult populations. Prior studies similarly found increased rates of skin cancer within the military beneficiary population. Further studies are needed to compare age-adjusted rates in the MHS vs US population.9-11

COVID-19 Trends—Our data showed an overall decreasing prevalence of skin cancer in the MHS from 2019 to 2021. We suspect that the apparent decrease in skin cancer prevalence may be attributed to underdiagnosis from COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. During that time, many dermatology clinics at military treatment facilities underwent temporary closures, and some dermatologists were sent on nondermatologic utilization tours. Likewise, a US multi-institutional study described declining rates of new melanomas from 2020 to 2021, with an increased proportion of patient presentations with advanced melanoma, suggesting an underdiagnosis of melanoma cases during pandemic restrictions. That study also noted an increased rate of patient-identified melanomas and a decreased rate of provider-identified melanomas during that time.12 Contributing factors may include excess hospital demand, increased patient complexity and acute care needs, and long outpatient clinic backlogs during this time.13Financial Burden—Over our 5-year study period, there were 5,374,348 patient encounters addressing skin cancer, both in DC and PC (Figures 1 and 2; eTable 1). In 2016 to 2018, the average annual cost of treating skin cancer in the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population was $1243 for NMSC (BCC and SCC) and $2430 for melanoma.6 Using this metric, the estimated total cost of care rendered in the MHS in 2018 for NMSC and melanoma was $202,510,803 and $156,516,300, respectively.

Trends in DC vs PC—In the years examined, we found a notable decrease in the number of beneficiaries receiving treatment for MM, BCC, and SCC in DC. Simultaneously, there has been an increase in the number of beneficiaries receiving PC for BCC and SCC, though this trend was not apparent for MM.

Our data provided interesting insights into the percentage of PC compared with DC offered within the MHS. Importantly, our findings suggested that the majority of skin cancer in active-duty service members is managed with DC within the military treatment facility setting (61% DC management over the period analyzed). This finding was true across all years of data analyzed, suggesting that the COVID-19 pandemic did not result in a quantifiable shift in care of skin cancer within the active-duty component to outside providers. One of the critical roles of dermatologists in the MHS is to diagnose and treat skin cancer, and our study suggested that the current global manning and staffing for MHS dermatologists may not be sufficient to meet the burden of skin cancers encountered within our active-duty troops, as only 61% are managed with DC. In particular, service members in more austere and/or overseas locations may not have ready access to a dermatologist.

The burden of skin cancer shifts dramatically when analyzing care of all other populations included in these data, including dependents of active-duty service members, retirees, and the category of “other” (ie, principally dependents of retirees). Within these populations, the rate of DC falls to 30%, with 70% of active-duty dependent care being deferred to network. The findings are even more noticeable for retirees and others within these 2 cohorts in all types of skin cancer analyzed, where DC only accounted for 5.2% of those skin cancers encountered and managed across TRICARE-eligible beneficiaries. For MM, BCC, and SCC, percentages of DC were 5.4%, 5.8%, and 3.5%, respectively. Although it is interesting to note the lower percentage of SCC managed via DC, our data did not allow for extrapolation as to why more SCC cases may be deferred to network. The shift to PC may align with DoD initiatives to increase the private sector’s involvement in military medicine and transition to civilianizing the MHS.14 In the end, the findings are remarkable, with approximately 95% of skin cancer care and management provided overall via PC.

These findings differ from previously published data regarding DC and PC from other specialty areas. Results from an analysis of DC vs PC for plastic surgery for the entire MHS from 2016 to 2019 found 83.2% of cases were deferred to network.15 A similar publication in the orthopedics literature examined TRICARE claims for patients who underwent total hip or knee arthroplasties between 2006 and 2019 and found 84.6% of cases were referred for PC. Notably, the authors utilized generalized linear models for cost analysis and found that DC was more expensive than PC, though this likely was a result of higher rates of hospital readmission within DC cases.16 Lastly, an article on the DC vs PC disposition of MHS patients with breast cancer from 2003 to 2008 found 46% of cases managed with DC vs 26.% with PC and 27.8% receiving a combination. In this case, the authors found a reduced cost associated with DC vs PC.17

Little additional literature exists regarding the costs of DC vs PC. An article published in 2016 designed to assess costs of DC vs PC showed that almost all military treatment facilities have higher costs than their private sector counterparts, with a few exceptions.18 This does not assess the costs of specific procedures, however, and only the overall cost to maintain a treatment facility. Importantly, this study was based on data from FY 2014 and has not been updated to reflect complex changes within the MHS system and the private health care system. Indeed, a US Government Accountability Office FY 2023 study highlighted staffing and efficiency issues within this transition to civilian medicine; subsequently, the 2024 President’s Budget suspended all planned clinical medical military end strength divestitures, underscoring the potential ineffectiveness of a civilianized MHS at meeting the health care needs of its beneficiaries.19,20 Future research on a national scale will be necessary to see if there is a reversal of this trend to PC and if doing so has any impact on access to DC for active-duty troops or active-duty dependents.

In addition to PC vs DC trends, we also can get a sense of the impact of the COVID pandemic restrictions on access to DC vs PC by assessing the change in rates seen in the data from the pre-COVID years (2017-2019) to the “post-COVID” years (2020-2022) included. Overall, rates of DC decreased uniformly from their already low percentages. In our study, rates of DC decreased from 5.8% in 2019 to 4.8% in 2022 for MM, from 6.6% to 4.3% for BCC, and from 4.2% to 2.9% for SCC. Although these changes seem small at first, they represent a 30.6% overall decrease in DC for BCC and an overall decrease of 55.4% in DC for SCC. Although our data do not allow us to extrapolate the real cost of this reduction across a nationwide health care system and more than 5 million care encounters, the financial and personal (ie, lost man-hours) costs of this decrease in DC likely are substantial.

In addition to costs, qualitative aspects that contribute to the burden of skin cancer include treatment-related morbidity, such as scarring, pain, and time spent away from family, work, and hobbies, as well as overall patient satisfaction with the quality of care they receive.21 Future work is critical to assess the real cost of this immense burden of PC for the treatment and management of skin cancers within the DoD beneficiary population.

Limitations—This study is limited by its observational nature. Given the mechanism of our data collection, we may have underestimated disease prevalence, as not all patients are seen for their diagnosis annually. Furthermore, reported demographic strata (eg, age, sex) were limited to those available and valid in the M2 reporting system. Finally, our study only collected data from those service members or former service members seen within the MHS and does not reflect any care rendered to those who are no longer active duty but did not officially retire from the military (ie, nonretired service members receiving care in the Veterans Affairs system for skin cancer).

Conclusion

We describe the annual burden of care for skin cancer in the MHS beneficiary population. Noteworthy findings observed were an overall decrease in beneficiaries being treated for skin cancer through DC; a decreasing annual prevalence of skin cancer diagnosis between 2019 and 2021, which may represent underdiagnosis or decreased follow-up in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic; and a higher rate of skin cancer in the military beneficiary population compared to the civilian population.

- US Department of Defense. Military health. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/

- Wooten NR, Brittingham JA, Pitner RO, et al. Purchased behavioral health care received by Military Health System beneficiaries in civilian medical facilities, 2000-2014. Mil Med. 2018;183:E278-E290. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx101

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- American Academy of Dermatology. Skin cancer. Updated April 22, 2022. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Eide MJ, Krajenta R, Johnson D, et al. Identification of patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer using health maintenance organization claims data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:123-128. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp352

- Kao SYZ, Ekwueme DU, Holman DM, et al. Economic burden of skin cancer treatment in the USA: an analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Data, 2012-2018. Cancer Causes Control. 2023;34:205-212. doi:10.1007/s10552-022-01644-0

- Aggarwal P, Knabel P, Fleischer AB. United States burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer from 1990 to 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:388-395. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.109

- SEER*Explorer. SEER Incidence Data, November 2023 Submission (1975-2021). National Cancer Institute; 2024. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html?site=53&data_type=1&graph_type=1&compareBy=sex&chk_sex_1=1&chk_sex_3=3&chk_sex_2=2&rate_type=2&race=1&age_range=1&advopt_precision=1&advopt_show_ci=on&hdn_view=1&advopt_show_apc=on&advopt_display=1

- Brown J, Kopf AW, Rigel DS, et al. Malignant melanoma in World War II veterans. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:661-663. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1984.tb01228.x

- Page WF, Whiteman D, Murphy M. A comparison of melanoma mortality among WWII veterans of the Pacific and European theaters. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:192-195. doi:10.1016/s1047-2797(99)00050-2

- Ramani ML, Bennett RG. High prevalence of skin cancer in World War II servicemen stationed in the Pacific theater. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:733-737. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70102-Y

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Gibbs A. COVID-19 shutdowns caused delays in melanoma diagnoses, study finds. OHSU News. August 4, 2022. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://news.ohsu.edu/2022/08/04/covid-19-shutdowns-caused-delays-in-melanoma-diagnoses-study-finds

- Kime P. Pentagon budget calls for ‘civilianizing’ military hospitals. Military Times. Published February 10, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2020/02/10/pentagon-budget-calls-for-civilianizing-military-hospitals/

- O’Reilly EB, Norris E, Ortiz-Pomales YT, et al. A comparison of direct care at military medical treatment facilities with purchased care in plastic surgery operative volume. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10(10 suppl):124-125. doi:10.1097/01.GOX.0000898976.03344.62

- Haag A, Hosein S, Lyon S, et al. Outcomes for arthroplasties in military health: a retrospective analysis of direct versus purchased care. Mil Med. 2023;188(suppl 6):45-51. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac441

- Eaglehouse YL, Georg MW, Richard P, et al. Cost-efficiency of breast cancer care in the US Military Health System: an economic evaluation in direct and purchased care. Mil Med. 2019;184:e494-e501. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz025

- Lurie PM. Comparing the cost of military treatment facilities with private sector care. Institute for Defense Analyses; February 2016. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.ida.org/research-and-publications/publications/all/c/co/comparing-the-costs-of-military-treatment-facilities-with-private-sector-care

- Defense Health Program. Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 President’s Budget: Operation and Maintenance Procurement Research, Development, Test and Evaluation. Department of Defense; March 2023. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2024/budget_justification/pdfs/09_Defense_Health_Program/00-DHP_Vols_I_II_and_III_PB24.pdf

- US Government Accountability Office. Defense Health Care. DOD should reevaluate market structure for military medical treatment facility management. Published August 21, 2023. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105441

- Rosenberg A, Cho S. We can do better at protecting our service members from skin cancer. Mil Med. 2022;187:311-313. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac198

- US Department of Defense. Military health. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/

- Wooten NR, Brittingham JA, Pitner RO, et al. Purchased behavioral health care received by Military Health System beneficiaries in civilian medical facilities, 2000-2014. Mil Med. 2018;183:E278-E290. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx101

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- American Academy of Dermatology. Skin cancer. Updated April 22, 2022. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Eide MJ, Krajenta R, Johnson D, et al. Identification of patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer using health maintenance organization claims data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:123-128. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp352

- Kao SYZ, Ekwueme DU, Holman DM, et al. Economic burden of skin cancer treatment in the USA: an analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Data, 2012-2018. Cancer Causes Control. 2023;34:205-212. doi:10.1007/s10552-022-01644-0

- Aggarwal P, Knabel P, Fleischer AB. United States burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer from 1990 to 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:388-395. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.109

- SEER*Explorer. SEER Incidence Data, November 2023 Submission (1975-2021). National Cancer Institute; 2024. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html?site=53&data_type=1&graph_type=1&compareBy=sex&chk_sex_1=1&chk_sex_3=3&chk_sex_2=2&rate_type=2&race=1&age_range=1&advopt_precision=1&advopt_show_ci=on&hdn_view=1&advopt_show_apc=on&advopt_display=1

- Brown J, Kopf AW, Rigel DS, et al. Malignant melanoma in World War II veterans. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:661-663. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1984.tb01228.x

- Page WF, Whiteman D, Murphy M. A comparison of melanoma mortality among WWII veterans of the Pacific and European theaters. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:192-195. doi:10.1016/s1047-2797(99)00050-2

- Ramani ML, Bennett RG. High prevalence of skin cancer in World War II servicemen stationed in the Pacific theater. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:733-737. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70102-Y

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Gibbs A. COVID-19 shutdowns caused delays in melanoma diagnoses, study finds. OHSU News. August 4, 2022. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://news.ohsu.edu/2022/08/04/covid-19-shutdowns-caused-delays-in-melanoma-diagnoses-study-finds

- Kime P. Pentagon budget calls for ‘civilianizing’ military hospitals. Military Times. Published February 10, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2020/02/10/pentagon-budget-calls-for-civilianizing-military-hospitals/

- O’Reilly EB, Norris E, Ortiz-Pomales YT, et al. A comparison of direct care at military medical treatment facilities with purchased care in plastic surgery operative volume. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10(10 suppl):124-125. doi:10.1097/01.GOX.0000898976.03344.62

- Haag A, Hosein S, Lyon S, et al. Outcomes for arthroplasties in military health: a retrospective analysis of direct versus purchased care. Mil Med. 2023;188(suppl 6):45-51. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac441

- Eaglehouse YL, Georg MW, Richard P, et al. Cost-efficiency of breast cancer care in the US Military Health System: an economic evaluation in direct and purchased care. Mil Med. 2019;184:e494-e501. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz025

- Lurie PM. Comparing the cost of military treatment facilities with private sector care. Institute for Defense Analyses; February 2016. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.ida.org/research-and-publications/publications/all/c/co/comparing-the-costs-of-military-treatment-facilities-with-private-sector-care

- Defense Health Program. Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 President’s Budget: Operation and Maintenance Procurement Research, Development, Test and Evaluation. Department of Defense; March 2023. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2024/budget_justification/pdfs/09_Defense_Health_Program/00-DHP_Vols_I_II_and_III_PB24.pdf

- US Government Accountability Office. Defense Health Care. DOD should reevaluate market structure for military medical treatment facility management. Published August 21, 2023. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105441

- Rosenberg A, Cho S. We can do better at protecting our service members from skin cancer. Mil Med. 2022;187:311-313. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac198

PRACTICE POINTS

- Study data showed an overall decreasing prevalence of skin cancer in the Military Health System (MHS) from 2019 to 2021, possibly attributable to underdiagnosis resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Providers should be mindful of this trend when screening patients who have experienced interruptions in care.

- An overall increased prevalence of skin cancer was noted in the military beneficiary population compared with publicly available civilian data—and thus this diagnosis should be given special consideration within this population.

The Clinical Utility of Teledermatology in Triaging and Diagnosing Skin Malignancies: Case Series

With the increasing utilization of telemedicine since the COVID-19 pandemic, it is critical that clinicians have an appropriate understanding of the application of virtual care resources, including teledermatology. We present a case series of 3 patients to demonstrate the clinical utility of teledermatology in reducing the time to diagnosis of various rare and/or aggressive cutaneous malignancies, including Merkel cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, and atypical fibroxanthoma. Cases were obtained from one large Midwestern medical center during the month of July 2021. Each case presented includes a description of the initial teledermatology presentation and reviews the clinical timeline from initial consultation submission to in-person clinic visit with lesion biopsy. This case series demonstrates real-world examples of how teledermatology can be utilized to expedite the care of specific vulnerable patient populations.

Teledermatology is a rapidly growing digital resource with specific utility in triaging patients to determine those requiring in-person evaluation for early and accurate detection of skin malignancies. Approximately one-third of teledermatology consultations result in face-to-face clinical encounters, with malignant neoplasms being the leading cause for biopsy.1,2 For specific populations, such as geriatric and immunocompromised patients, teledermatology may serve as a valuable tool, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, telemedicine may aid in addressing health disparities within the field of medicine and ultimately may improve access to care for vulnerable populations.3 Along with increasing access to specific subspecialty expertise, the use of teledermatology may reduce health care costs and improve the overall quality of care delivered to patients.4,5

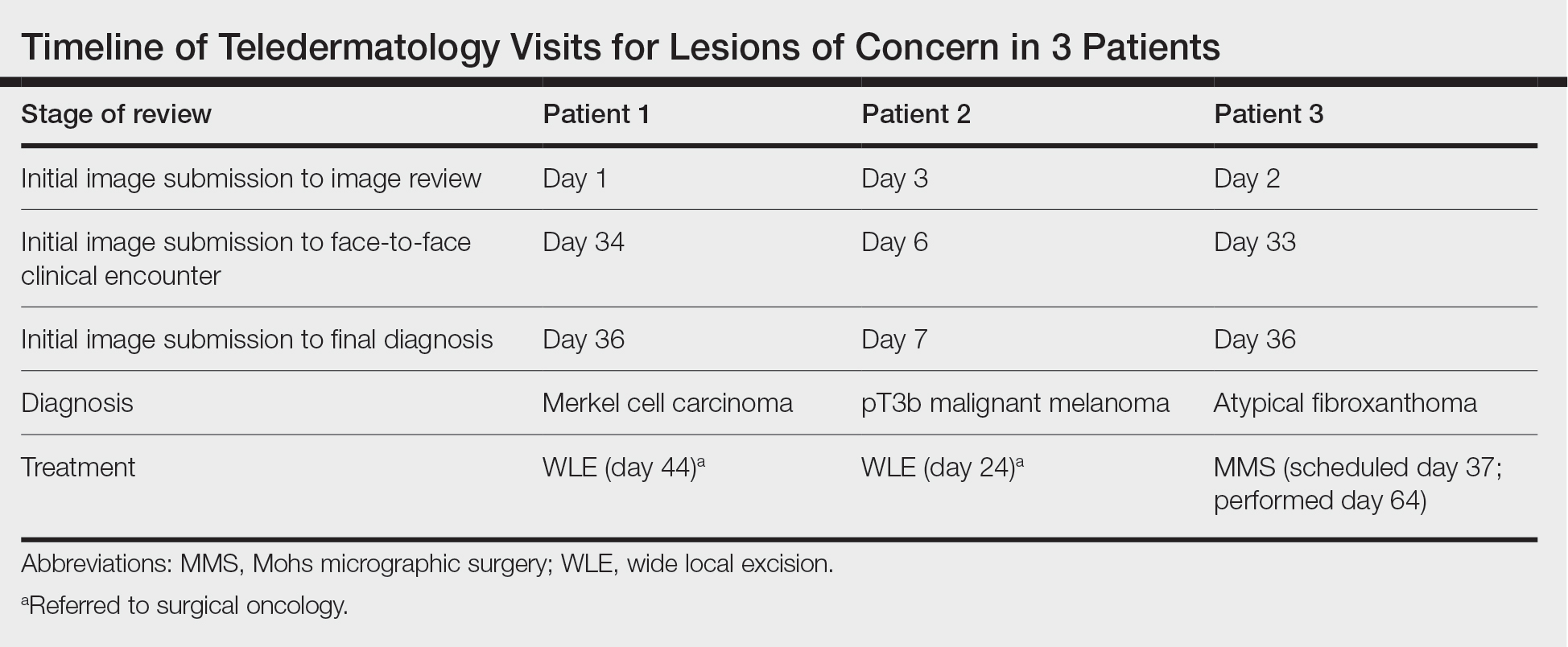

We describe the clinical utility of teledermatology in triaging and diagnosing skin malignancies through a series of 3 cases obtained from digital image review at one large Midwestern medical center during the month of July 2021. Three unique cases with a final diagnosis of a rare or aggressive skin cancer were selected as examples, including a 75-year-old man with Merkle cell carcinoma, a 55-year-old man with aggressive pT3b malignant melanoma, and a 72-year-old man with an atypical fibroxanthoma. A clinical timeline of each case is presented, including the time intervals from initial image submission to image review, image submission to face-to-face clinical encounter, and image submission to final diagnosis. In all cases, the primary care provider submitted an order for teledermatology, and the teledermatology team obtained the images.

Case Series

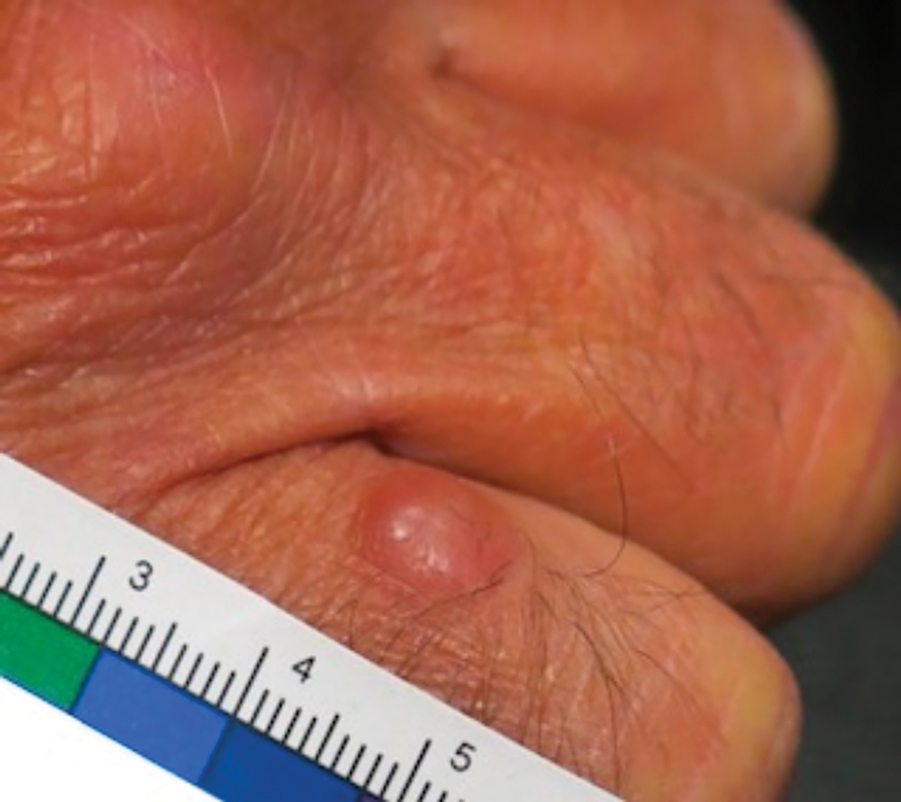

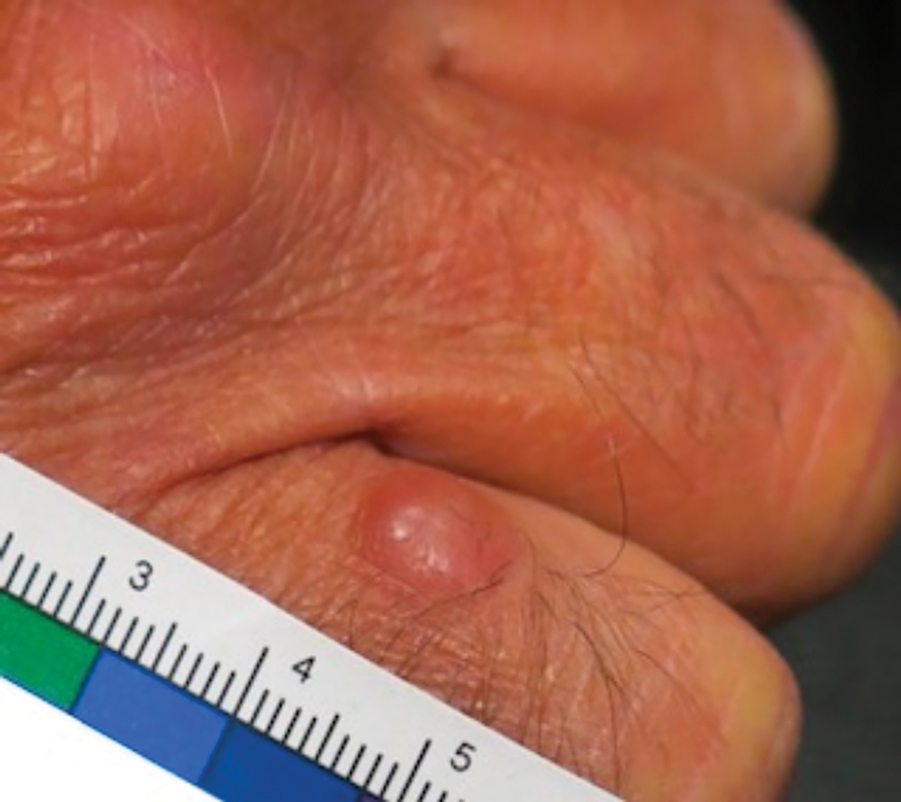

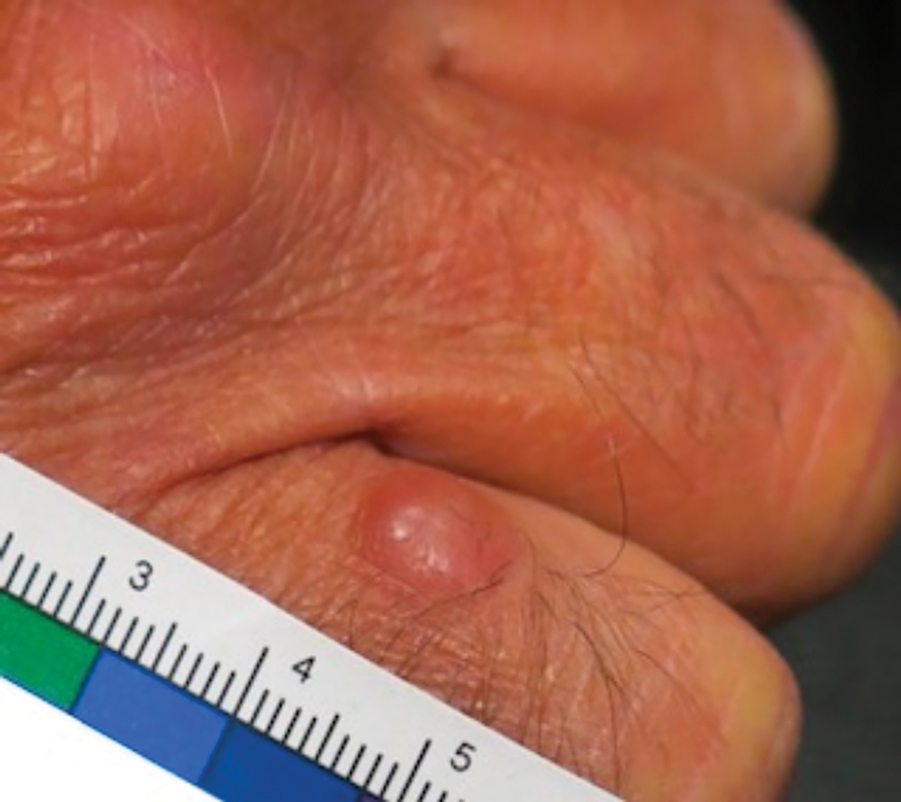

Patient 1—Images of the right hand of a 75-year-old man with a medical history of basal cell carcinoma were submitted for teledermatology consultation utilizing store-and-forward image-capturing technology (day 1). The patient history provided with image submission indicated that the lesion had been present for 6 months and there were no associated symptoms. Clinical imaging demonstrated a pink-red pearly papule located on the proximal fourth digit of the dorsal aspect of the right hand (Figure 1). One day following the teledermatology request (day 2), the patient’s case was reviewed and triaged for an in-person visit. The patient was brought to clinic on day 34, and a biopsy was performed. On day 36, dermatopathology results indicated a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma. On day 37, the patient was referred to surgical oncology, and on day 44, the patient underwent an initial surgical oncology visit with a plan for wide local excision of the right fourth digit with right axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Patient 2—Images of the left flank of a 55-year-old man were submitted for teledermatology consultation via store-and-forward technology (day 1). A patient history provided with the image indicated that the lesion had been present for months to years and there were no associated symptoms, but the lesion recently had changed in color and size. Teledermatology images were reviewed on day 3 and demonstrated a 2- to 3-cm brown plaque on the left flank with color variegation and a prominent red papule protruding centrally (Figure 2). The patient was scheduled for an urgent in-person visit with biopsy. On day 6, the patient presented to clinic and an excision biopsy was performed. Dermatopathology was ordered with a RUSH indication, with results on day 7 revealing a pT3b malignant melanoma. An urgent consultation to surgical oncology was placed on the same day, and the patient underwent an initial surgical oncology visit on day 24 with a plan for wide local excision with left axillary and inguinal sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Patient 3—Images of the left ear of a 72-year-old man were submitted for teledermatology consultation utilizing review via store-and-forward technology (day 1). A patient history indicated that the lesion had been present for 3 months with associated bleeding. Image review demonstrated a solitary pearly pink papule located on the crura of the antihelix (Figure 3). Initial teledermatology consultation was reviewed on day 2 with notification of the need for in-person evaluation. The patient presented to clinic on day 33 for a biopsy, with dermatopathology results on day 36 consistent with an atypical fibroxanthoma. The patient was scheduled for Mohs micrographic surgery on day 37 and underwent surgical treatment on day 64.

Comment

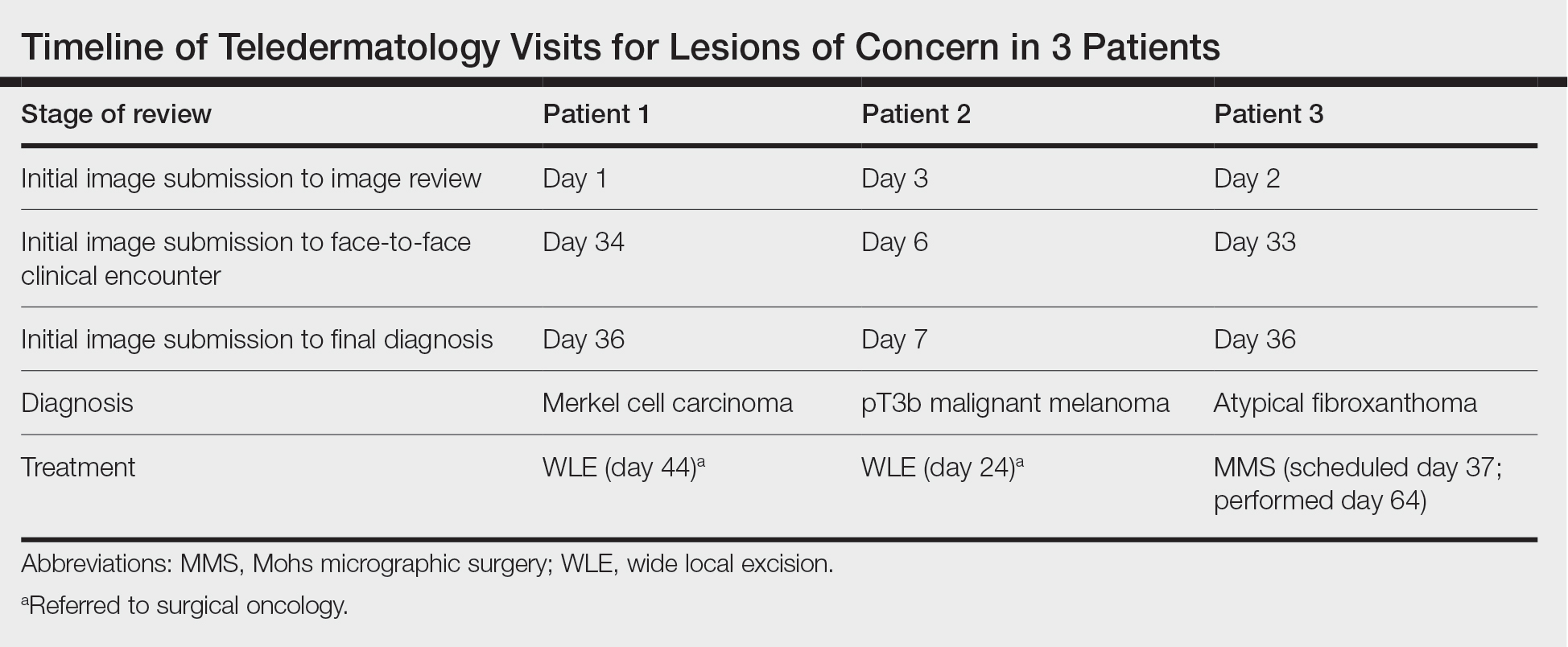

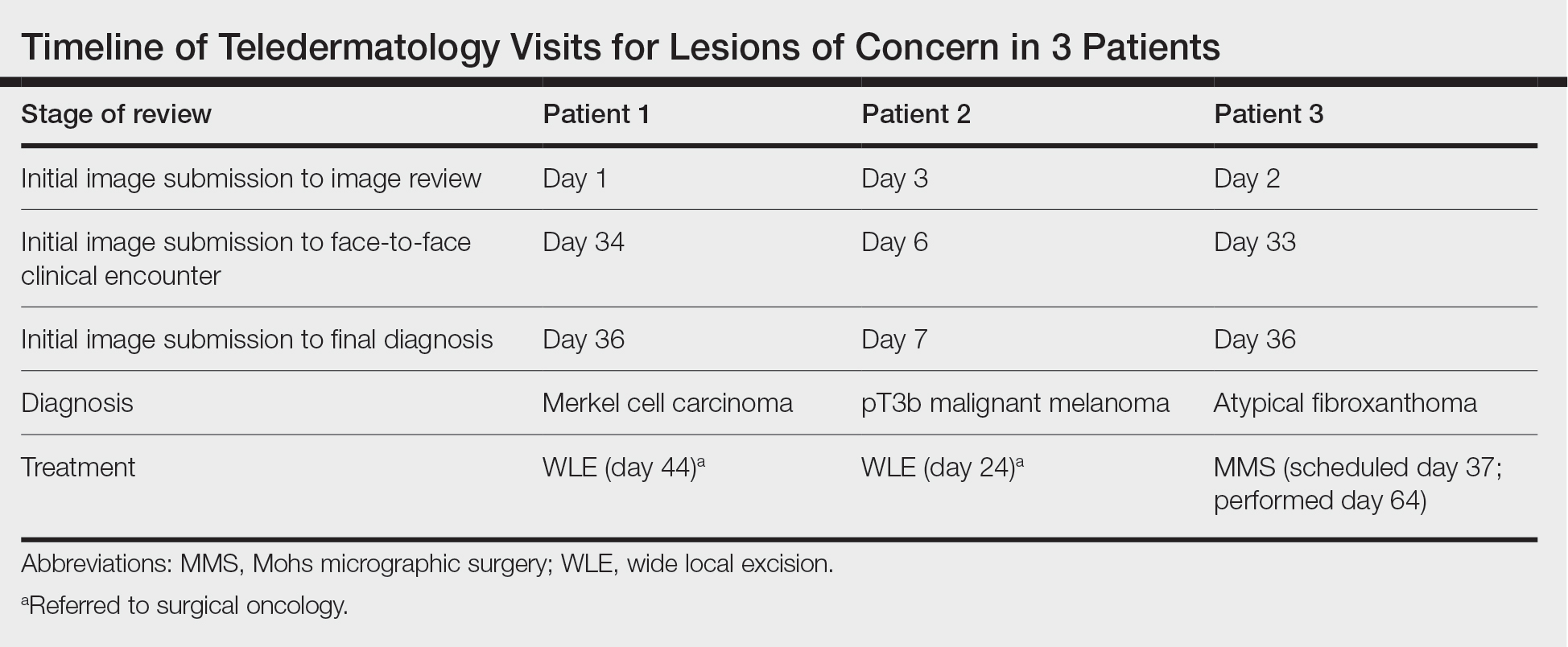

Teledermatology consultations from all patients demonstrated adequate image quality to be able to evaluate the lesion of concern and yielded a request for in-person evaluation with possible biopsy (Table). In this case series, the average time interval from teledermatology consultation placement to teledermatology image report was 2 days (range, 1–3 days). The average time from teledermatology consultation placement to face-to-face encounter with biopsy was 24.3 days for the 3 cases presented in this series (range, 6–34 days). The initial surgical oncology visits took place an average of 34 days after the initial teledermatology consultation was placed for the 2 patients requiring referral (44 days for patient 1; 24 days for patient 2). For patient 3, Mohs micrographic surgery was required for treatment, which was scheduled by day 37 and subsequently performed on day 64.