User login

U.S. flu activity increases slightly

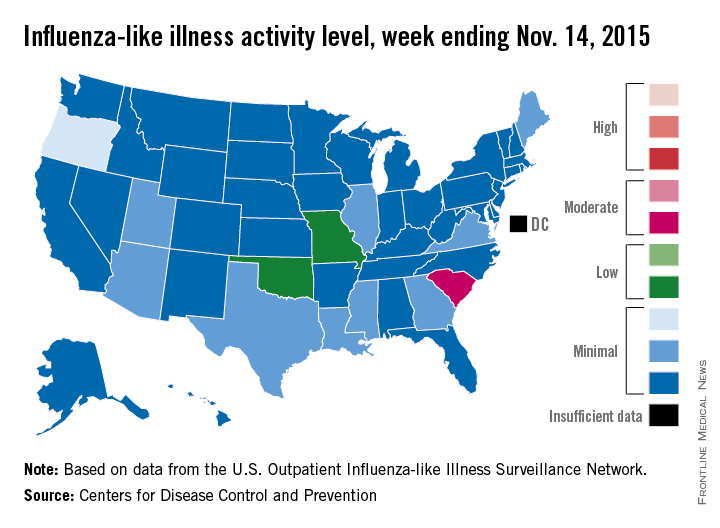

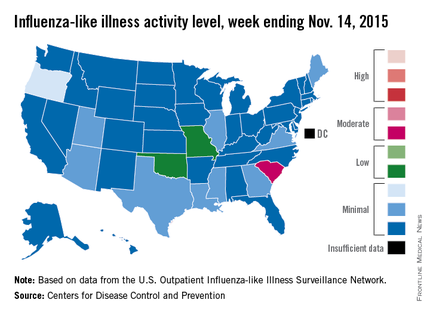

Activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) “increased slightly in the United States” during week 5 of the 2015-2016 influenza season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Nov. 20.

Thirteen states were above level-1 activity as of Nov. 14, 2015, compared with seven the week before. South Carolina jumped all the way up to “moderate” activity (level 6) and Missouri and Oklahoma moved into the low-activity category (level 4). Oregon remained at a still-minimal level 3, while Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Texas, Utah, and Virginia are at level 2, according to the CDC.

The first influenza-associated pediatric death was reported this week, although it actually occurred during week 4 (the week ending Nov. 7), the CDC said. There has been an average of 143 flu-associated pediatric deaths over the last three flu seasons.

ILI is defined as fever (temperature of 100° F or greater) and cough and/or sore throat. Activity level within a state is the proportion of outpatient visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness.

That proportion for the United States overall was 1.6%, which is up from last week’s 1.4% but still below the national baseline of 2.1%, the CDC said.

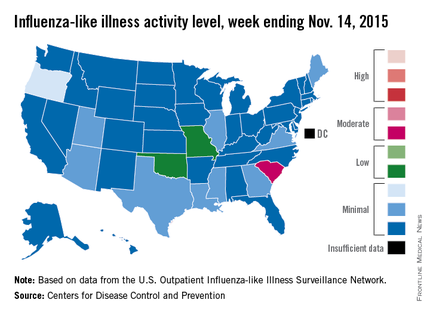

Activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) “increased slightly in the United States” during week 5 of the 2015-2016 influenza season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Nov. 20.

Thirteen states were above level-1 activity as of Nov. 14, 2015, compared with seven the week before. South Carolina jumped all the way up to “moderate” activity (level 6) and Missouri and Oklahoma moved into the low-activity category (level 4). Oregon remained at a still-minimal level 3, while Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Texas, Utah, and Virginia are at level 2, according to the CDC.

The first influenza-associated pediatric death was reported this week, although it actually occurred during week 4 (the week ending Nov. 7), the CDC said. There has been an average of 143 flu-associated pediatric deaths over the last three flu seasons.

ILI is defined as fever (temperature of 100° F or greater) and cough and/or sore throat. Activity level within a state is the proportion of outpatient visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness.

That proportion for the United States overall was 1.6%, which is up from last week’s 1.4% but still below the national baseline of 2.1%, the CDC said.

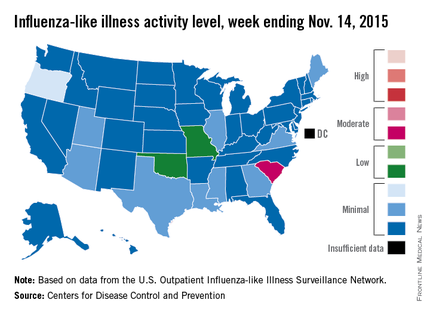

Activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) “increased slightly in the United States” during week 5 of the 2015-2016 influenza season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Nov. 20.

Thirteen states were above level-1 activity as of Nov. 14, 2015, compared with seven the week before. South Carolina jumped all the way up to “moderate” activity (level 6) and Missouri and Oklahoma moved into the low-activity category (level 4). Oregon remained at a still-minimal level 3, while Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Texas, Utah, and Virginia are at level 2, according to the CDC.

The first influenza-associated pediatric death was reported this week, although it actually occurred during week 4 (the week ending Nov. 7), the CDC said. There has been an average of 143 flu-associated pediatric deaths over the last three flu seasons.

ILI is defined as fever (temperature of 100° F or greater) and cough and/or sore throat. Activity level within a state is the proportion of outpatient visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness.

That proportion for the United States overall was 1.6%, which is up from last week’s 1.4% but still below the national baseline of 2.1%, the CDC said.

Prime-boost flu vaccination strategy effective in children

A prime-boost flu vaccination strategy proved effective in children and adolescents in an open-label phase III trial conducted by the vaccine manufacturer and reported online in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.

This proof-of-concept result suggests that at the outbreak of the next flu pandemic, immediate priming with two doses of a subtype-matched flu vaccine, followed by boosting once a strain-matched vaccine becomes available, will offer the pediatric population better protection than simply waiting for adequate quantities of the strain-matched vaccine to be developed and marketed.

It is impossible to predict which specific viral strain will cause the next flu pandemic, but H5N1 is considered a likely candidate virus, “to the extent that vaccine manufacturers and regulatory authorities are actively developing H5N1 vaccines” for all age groups, said Dr. Patricia Izurieta of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Belgium, and her associates.

Waiting for a pandemic to begin and then producing strain-specific vaccines could take as long as 6 months, and even then supplies probably would be limited. Experts have theorized that preemptive “priming” with already stockpiled H5N1 vaccines immediately after a pandemic begins may provide broad cross-protection that could mitigate the intensity of the subsequent pandemic, potentially reducing morbidity, mortality, and viral transmission.

To test this theory, Dr. Izurieta and her associates mimicked a potential flu pandemic by priming children and adolescents with two doses of an H5N1-AS03 vaccine, giving a booster dose of a specific H5N1 strain at 6 months, and assessing antibody response to all the vaccinations through 12 months. (Assessing actual vaccine efficacy was impossible because it would be unethical to determine this by exposing children to a flu virus.)

A total of 520 participants at a single medical center in the Philippines who were aged 3-18 years (mean age, 9 years) were assigned to two intervention groups and two control groups. Approximately half of these children and adolescents received the intervention – two priming doses of A/Indonesia/05/2005/H5N1-AS03B vaccine – while the control subjects received a single dose of hepatitis A vaccine. At day 182, half of the primed and half of the unprimed participants then received a booster dose of A/turkey/Turkey/01/2005-H5N1-As03B, while the remainder received the hepatitis A vaccine.

Compared with no priming, priming afforded superior seroconversion and putative seroprotection against the second, specific strain of H5N1. This robust protective effect was seen within 10 days after vaccination, occurred across all ages, and persisted through 12 months of follow-up, the investigators said (Ped Infect Dis J. 2015 Nov 6. [doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000968]).

Adverse events within 7 days of the priming vaccinations developed in 68%-76% of the intervention group, compared with only 37%-64% of the control group. Adverse events within 7 days of the booster vaccinations developed in 69% of the intervention group, compared with only 40% of the control group. The most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection (20% vs 14%), nasopharyngitis (4% vs 3%), and rhinitis (3% in both study groups). The most serious adverse events affected two children and were classified as grade 3.

The study results suggest that a prime-boost strategy can induce broad and long-lasting immunity and could be effectively employed in this age group in the prepandemic setting, Dr. Izurieta and her associates reported.

This trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, which also was involved in the design and conduct of the study, the data analysis, and the writing and publishing of the report. Dr. Izurieta and two of her associates are employed by GSK.

A prime-boost flu vaccination strategy proved effective in children and adolescents in an open-label phase III trial conducted by the vaccine manufacturer and reported online in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.

This proof-of-concept result suggests that at the outbreak of the next flu pandemic, immediate priming with two doses of a subtype-matched flu vaccine, followed by boosting once a strain-matched vaccine becomes available, will offer the pediatric population better protection than simply waiting for adequate quantities of the strain-matched vaccine to be developed and marketed.

It is impossible to predict which specific viral strain will cause the next flu pandemic, but H5N1 is considered a likely candidate virus, “to the extent that vaccine manufacturers and regulatory authorities are actively developing H5N1 vaccines” for all age groups, said Dr. Patricia Izurieta of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Belgium, and her associates.

Waiting for a pandemic to begin and then producing strain-specific vaccines could take as long as 6 months, and even then supplies probably would be limited. Experts have theorized that preemptive “priming” with already stockpiled H5N1 vaccines immediately after a pandemic begins may provide broad cross-protection that could mitigate the intensity of the subsequent pandemic, potentially reducing morbidity, mortality, and viral transmission.

To test this theory, Dr. Izurieta and her associates mimicked a potential flu pandemic by priming children and adolescents with two doses of an H5N1-AS03 vaccine, giving a booster dose of a specific H5N1 strain at 6 months, and assessing antibody response to all the vaccinations through 12 months. (Assessing actual vaccine efficacy was impossible because it would be unethical to determine this by exposing children to a flu virus.)

A total of 520 participants at a single medical center in the Philippines who were aged 3-18 years (mean age, 9 years) were assigned to two intervention groups and two control groups. Approximately half of these children and adolescents received the intervention – two priming doses of A/Indonesia/05/2005/H5N1-AS03B vaccine – while the control subjects received a single dose of hepatitis A vaccine. At day 182, half of the primed and half of the unprimed participants then received a booster dose of A/turkey/Turkey/01/2005-H5N1-As03B, while the remainder received the hepatitis A vaccine.

Compared with no priming, priming afforded superior seroconversion and putative seroprotection against the second, specific strain of H5N1. This robust protective effect was seen within 10 days after vaccination, occurred across all ages, and persisted through 12 months of follow-up, the investigators said (Ped Infect Dis J. 2015 Nov 6. [doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000968]).

Adverse events within 7 days of the priming vaccinations developed in 68%-76% of the intervention group, compared with only 37%-64% of the control group. Adverse events within 7 days of the booster vaccinations developed in 69% of the intervention group, compared with only 40% of the control group. The most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection (20% vs 14%), nasopharyngitis (4% vs 3%), and rhinitis (3% in both study groups). The most serious adverse events affected two children and were classified as grade 3.

The study results suggest that a prime-boost strategy can induce broad and long-lasting immunity and could be effectively employed in this age group in the prepandemic setting, Dr. Izurieta and her associates reported.

This trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, which also was involved in the design and conduct of the study, the data analysis, and the writing and publishing of the report. Dr. Izurieta and two of her associates are employed by GSK.

A prime-boost flu vaccination strategy proved effective in children and adolescents in an open-label phase III trial conducted by the vaccine manufacturer and reported online in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.

This proof-of-concept result suggests that at the outbreak of the next flu pandemic, immediate priming with two doses of a subtype-matched flu vaccine, followed by boosting once a strain-matched vaccine becomes available, will offer the pediatric population better protection than simply waiting for adequate quantities of the strain-matched vaccine to be developed and marketed.

It is impossible to predict which specific viral strain will cause the next flu pandemic, but H5N1 is considered a likely candidate virus, “to the extent that vaccine manufacturers and regulatory authorities are actively developing H5N1 vaccines” for all age groups, said Dr. Patricia Izurieta of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Belgium, and her associates.

Waiting for a pandemic to begin and then producing strain-specific vaccines could take as long as 6 months, and even then supplies probably would be limited. Experts have theorized that preemptive “priming” with already stockpiled H5N1 vaccines immediately after a pandemic begins may provide broad cross-protection that could mitigate the intensity of the subsequent pandemic, potentially reducing morbidity, mortality, and viral transmission.

To test this theory, Dr. Izurieta and her associates mimicked a potential flu pandemic by priming children and adolescents with two doses of an H5N1-AS03 vaccine, giving a booster dose of a specific H5N1 strain at 6 months, and assessing antibody response to all the vaccinations through 12 months. (Assessing actual vaccine efficacy was impossible because it would be unethical to determine this by exposing children to a flu virus.)

A total of 520 participants at a single medical center in the Philippines who were aged 3-18 years (mean age, 9 years) were assigned to two intervention groups and two control groups. Approximately half of these children and adolescents received the intervention – two priming doses of A/Indonesia/05/2005/H5N1-AS03B vaccine – while the control subjects received a single dose of hepatitis A vaccine. At day 182, half of the primed and half of the unprimed participants then received a booster dose of A/turkey/Turkey/01/2005-H5N1-As03B, while the remainder received the hepatitis A vaccine.

Compared with no priming, priming afforded superior seroconversion and putative seroprotection against the second, specific strain of H5N1. This robust protective effect was seen within 10 days after vaccination, occurred across all ages, and persisted through 12 months of follow-up, the investigators said (Ped Infect Dis J. 2015 Nov 6. [doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000968]).

Adverse events within 7 days of the priming vaccinations developed in 68%-76% of the intervention group, compared with only 37%-64% of the control group. Adverse events within 7 days of the booster vaccinations developed in 69% of the intervention group, compared with only 40% of the control group. The most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection (20% vs 14%), nasopharyngitis (4% vs 3%), and rhinitis (3% in both study groups). The most serious adverse events affected two children and were classified as grade 3.

The study results suggest that a prime-boost strategy can induce broad and long-lasting immunity and could be effectively employed in this age group in the prepandemic setting, Dr. Izurieta and her associates reported.

This trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, which also was involved in the design and conduct of the study, the data analysis, and the writing and publishing of the report. Dr. Izurieta and two of her associates are employed by GSK.

FROM THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASE JOURNAL

Key clinical point: A prime-boost flu vaccination strategy was found effective in children and adolescents.

Major finding: Compared with no priming, priming afforded superior seroconversion and putative seroprotection against the second, specific strain of H5N1.

Data source: An industry-sponsored, single-center, open-label phase III trial involving 520 participants aged 3-18 years followed for 1 year.

Disclosures: This trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, which also was involved in the design and conduct of the study, the data analysis, and the writing and publishing of the report. Dr. Izurieta and two of her associates are employed by GSK.

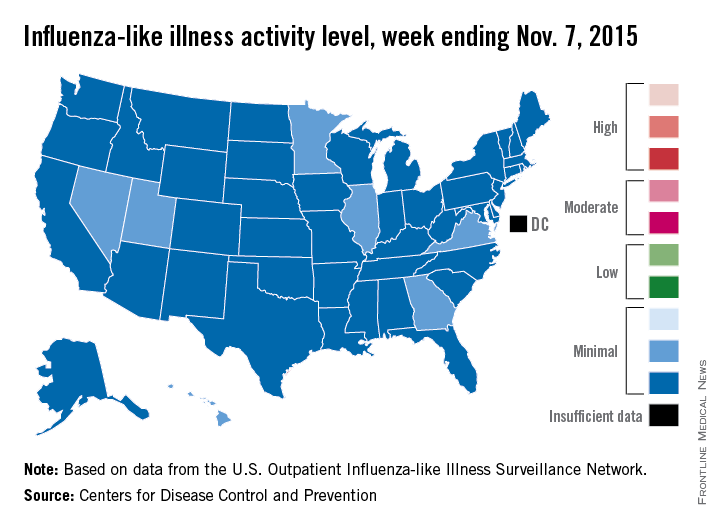

U.S. influenza activity minimal so far

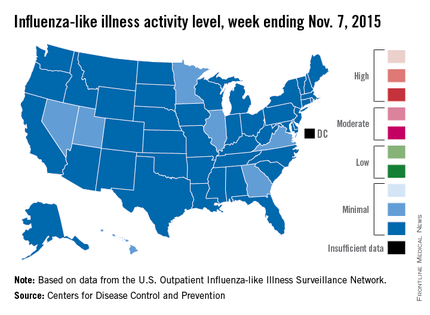

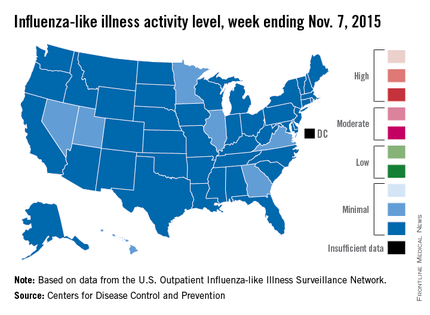

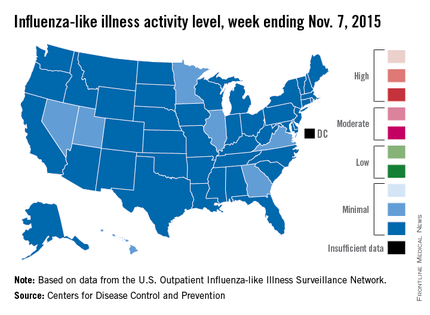

Four weeks into the 2015-2016 flu season, activity levels of influenza-like illness (ILI) are minimal in all 50 states, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Nov. 13.

Seven states – Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Minnesota, Nevada, Utah, and Virginia – had level 2 activity for the week ending Nov. 7, 2015, which, although still minimal, was higher than the level 1 activity in the other 43 states. There was a moderate level of influenza-like illness activity (level 7) in Puerto Rico, which was up from level 6 the week before, and there were insufficient data to determine flu activity in the District of Columbia, according to the CDC.

ILI is defined as fever (temperature of 100° F or greater) and cough and/or sore throat. Activity level within a state is the proportion of outpatient visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness.

For the country overall, the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI was 1.4%, which is below the national baseline of 2.1% for week 4 of the flu season, the CDC noted.

Four weeks into the 2015-2016 flu season, activity levels of influenza-like illness (ILI) are minimal in all 50 states, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Nov. 13.

Seven states – Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Minnesota, Nevada, Utah, and Virginia – had level 2 activity for the week ending Nov. 7, 2015, which, although still minimal, was higher than the level 1 activity in the other 43 states. There was a moderate level of influenza-like illness activity (level 7) in Puerto Rico, which was up from level 6 the week before, and there were insufficient data to determine flu activity in the District of Columbia, according to the CDC.

ILI is defined as fever (temperature of 100° F or greater) and cough and/or sore throat. Activity level within a state is the proportion of outpatient visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness.

For the country overall, the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI was 1.4%, which is below the national baseline of 2.1% for week 4 of the flu season, the CDC noted.

Four weeks into the 2015-2016 flu season, activity levels of influenza-like illness (ILI) are minimal in all 50 states, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Nov. 13.

Seven states – Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Minnesota, Nevada, Utah, and Virginia – had level 2 activity for the week ending Nov. 7, 2015, which, although still minimal, was higher than the level 1 activity in the other 43 states. There was a moderate level of influenza-like illness activity (level 7) in Puerto Rico, which was up from level 6 the week before, and there were insufficient data to determine flu activity in the District of Columbia, according to the CDC.

ILI is defined as fever (temperature of 100° F or greater) and cough and/or sore throat. Activity level within a state is the proportion of outpatient visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness.

For the country overall, the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI was 1.4%, which is below the national baseline of 2.1% for week 4 of the flu season, the CDC noted.

CHEST: Oral solithromycin shows pneumonia pivotal-trial efficacy

MONTREAL – A new, next-generation macrolide, solithromycin, showed safety and efficacy as a once-daily oral agent that was noninferior to the comparator oral antibiotic, the fluoroquinolone moxifloxacin, in a phase III trial.

Macrolide resistance among strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae that cause many U.S. cases of severe community-acquired pneumonia has become common, complicating treatment of this common infection with a macrolide, Dr. Carlos M. Barrera explained at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The SOLITAIRE-ORAL (Efficacy and Safety Study of Oral Solithromycin [CEM-101] Compared to Oral Moxifloxacin in Treatment of Patients With Community-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia) trial enrolled 860 patients with moderate to moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia.

About half of the patients enrolled in the trial underwent microbiologic assessment of their infecting pathogen, and about 40% of cases in each treatment arm had infections caused by S. pneumoniae. In this subgroup, the 5-day regimen of solithromycin tested in the study succeeded in clearing the infection in 89% of patients, comparable to the 83% success rate achieved with a 7-day course of moxifloxacin (Avelox), said Dr. Barrera, a pulmonologist who practices in Miami.

The study’s primary endpoint for Food and Drug Administration approval of solithromycin was early clinical response, defined as an improvement in at least two listed symptoms at 72 hours after onset of treatment. That endpoint occurred in 78% of patients enrolled in each of the two arms of the study.

The data make solithromycin look like a promising way to once again have a macrolide available for empiric oral treatment of more severe community-acquired pneumonia, pending full peer review of the data, commented Dr. Muthiah P. Muthiah, a pulmonologist at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis.

“A couple of decades ago, you could comfortably treat a patient with severe community-acquired pneumonia with a macrolide, but you can’t do that anymore,” Dr. Muthiah said in an interview.

If the newly reported data on oral solithromycin hold up under further review, it would mean that solithromycin was as effective as a potent quinolone, which remains an effective monotherapy for community-acquired pneumonia in patients who do not require treatment in an intensive care unit, Dr. Muthiah noted.

A companion study, SOLITAIRE-IV, is a phase III pivotal trial assessing the safety and efficacy of solithromycin when begun intravenously for treating community-acquired pneumonia, followed by a switch to oral dosing, in comparison with intravenous followed by oral treatment with moxifloxacin.

Once those data are fully collected and analyzed, the company will submit the information from both trials to the FDA, said Dr. David Oldach, chief medical officer for Cempra.

Results from the intravenous trial, reported in a preliminary way by Cempra Oct. 16 in a press release, showed that the solithromycin treatment regimen tested in SOLITAIRE-IV met its noninferiority targets, compared with moxifloxacin. The safety results, however, showed that solithromycin produced a higher number of patients with a liver-enzyme elevation, compared with patients treated with moxifloxacin.

In SOLITAIRE-IV, Cempra reported that grade 3 increase in levels of alanine transaminase (ALT) occurred in 8% of patients on solithromycin and in 3% of patients on moxifloxacin. Grade 4 increases in ALT occurred in less than 1% of patients in both treatment arms.

In the current, orally administered trial, grade 3 ALT increases occurred in 5% of patients treated with solithromycin and in 2% of patients treated with moxifloxacin, Dr. Barrera reported. Grade 4 ALT increases occurred in 0.5% of patients treated with solithromycin and in 1.2% of those treated with moxifloxacin. No patients in either arm developed an elevation of both ALT and bilirubin, and the ALT increases seen were reversible and asymptomatic, Dr. Barrera said.

By other assessments, the safety profiles of solithromycin and moxifloxacin were similar: 7% of patients on solithromycin and 6% on moxifloxacin had a serious adverse event, and 4% of patients in each study arm discontinued treatment because of an adverse event.

SOLITAIRE-ORAL was sponsored by Cempra, the company developing solithromycin. Dr. Barrera has received research funding from Cempra. Dr. Muthiah had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – A new, next-generation macrolide, solithromycin, showed safety and efficacy as a once-daily oral agent that was noninferior to the comparator oral antibiotic, the fluoroquinolone moxifloxacin, in a phase III trial.

Macrolide resistance among strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae that cause many U.S. cases of severe community-acquired pneumonia has become common, complicating treatment of this common infection with a macrolide, Dr. Carlos M. Barrera explained at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The SOLITAIRE-ORAL (Efficacy and Safety Study of Oral Solithromycin [CEM-101] Compared to Oral Moxifloxacin in Treatment of Patients With Community-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia) trial enrolled 860 patients with moderate to moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia.

About half of the patients enrolled in the trial underwent microbiologic assessment of their infecting pathogen, and about 40% of cases in each treatment arm had infections caused by S. pneumoniae. In this subgroup, the 5-day regimen of solithromycin tested in the study succeeded in clearing the infection in 89% of patients, comparable to the 83% success rate achieved with a 7-day course of moxifloxacin (Avelox), said Dr. Barrera, a pulmonologist who practices in Miami.

The study’s primary endpoint for Food and Drug Administration approval of solithromycin was early clinical response, defined as an improvement in at least two listed symptoms at 72 hours after onset of treatment. That endpoint occurred in 78% of patients enrolled in each of the two arms of the study.

The data make solithromycin look like a promising way to once again have a macrolide available for empiric oral treatment of more severe community-acquired pneumonia, pending full peer review of the data, commented Dr. Muthiah P. Muthiah, a pulmonologist at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis.

“A couple of decades ago, you could comfortably treat a patient with severe community-acquired pneumonia with a macrolide, but you can’t do that anymore,” Dr. Muthiah said in an interview.

If the newly reported data on oral solithromycin hold up under further review, it would mean that solithromycin was as effective as a potent quinolone, which remains an effective monotherapy for community-acquired pneumonia in patients who do not require treatment in an intensive care unit, Dr. Muthiah noted.

A companion study, SOLITAIRE-IV, is a phase III pivotal trial assessing the safety and efficacy of solithromycin when begun intravenously for treating community-acquired pneumonia, followed by a switch to oral dosing, in comparison with intravenous followed by oral treatment with moxifloxacin.

Once those data are fully collected and analyzed, the company will submit the information from both trials to the FDA, said Dr. David Oldach, chief medical officer for Cempra.

Results from the intravenous trial, reported in a preliminary way by Cempra Oct. 16 in a press release, showed that the solithromycin treatment regimen tested in SOLITAIRE-IV met its noninferiority targets, compared with moxifloxacin. The safety results, however, showed that solithromycin produced a higher number of patients with a liver-enzyme elevation, compared with patients treated with moxifloxacin.

In SOLITAIRE-IV, Cempra reported that grade 3 increase in levels of alanine transaminase (ALT) occurred in 8% of patients on solithromycin and in 3% of patients on moxifloxacin. Grade 4 increases in ALT occurred in less than 1% of patients in both treatment arms.

In the current, orally administered trial, grade 3 ALT increases occurred in 5% of patients treated with solithromycin and in 2% of patients treated with moxifloxacin, Dr. Barrera reported. Grade 4 ALT increases occurred in 0.5% of patients treated with solithromycin and in 1.2% of those treated with moxifloxacin. No patients in either arm developed an elevation of both ALT and bilirubin, and the ALT increases seen were reversible and asymptomatic, Dr. Barrera said.

By other assessments, the safety profiles of solithromycin and moxifloxacin were similar: 7% of patients on solithromycin and 6% on moxifloxacin had a serious adverse event, and 4% of patients in each study arm discontinued treatment because of an adverse event.

SOLITAIRE-ORAL was sponsored by Cempra, the company developing solithromycin. Dr. Barrera has received research funding from Cempra. Dr. Muthiah had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – A new, next-generation macrolide, solithromycin, showed safety and efficacy as a once-daily oral agent that was noninferior to the comparator oral antibiotic, the fluoroquinolone moxifloxacin, in a phase III trial.

Macrolide resistance among strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae that cause many U.S. cases of severe community-acquired pneumonia has become common, complicating treatment of this common infection with a macrolide, Dr. Carlos M. Barrera explained at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The SOLITAIRE-ORAL (Efficacy and Safety Study of Oral Solithromycin [CEM-101] Compared to Oral Moxifloxacin in Treatment of Patients With Community-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia) trial enrolled 860 patients with moderate to moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia.

About half of the patients enrolled in the trial underwent microbiologic assessment of their infecting pathogen, and about 40% of cases in each treatment arm had infections caused by S. pneumoniae. In this subgroup, the 5-day regimen of solithromycin tested in the study succeeded in clearing the infection in 89% of patients, comparable to the 83% success rate achieved with a 7-day course of moxifloxacin (Avelox), said Dr. Barrera, a pulmonologist who practices in Miami.

The study’s primary endpoint for Food and Drug Administration approval of solithromycin was early clinical response, defined as an improvement in at least two listed symptoms at 72 hours after onset of treatment. That endpoint occurred in 78% of patients enrolled in each of the two arms of the study.

The data make solithromycin look like a promising way to once again have a macrolide available for empiric oral treatment of more severe community-acquired pneumonia, pending full peer review of the data, commented Dr. Muthiah P. Muthiah, a pulmonologist at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis.

“A couple of decades ago, you could comfortably treat a patient with severe community-acquired pneumonia with a macrolide, but you can’t do that anymore,” Dr. Muthiah said in an interview.

If the newly reported data on oral solithromycin hold up under further review, it would mean that solithromycin was as effective as a potent quinolone, which remains an effective monotherapy for community-acquired pneumonia in patients who do not require treatment in an intensive care unit, Dr. Muthiah noted.

A companion study, SOLITAIRE-IV, is a phase III pivotal trial assessing the safety and efficacy of solithromycin when begun intravenously for treating community-acquired pneumonia, followed by a switch to oral dosing, in comparison with intravenous followed by oral treatment with moxifloxacin.

Once those data are fully collected and analyzed, the company will submit the information from both trials to the FDA, said Dr. David Oldach, chief medical officer for Cempra.

Results from the intravenous trial, reported in a preliminary way by Cempra Oct. 16 in a press release, showed that the solithromycin treatment regimen tested in SOLITAIRE-IV met its noninferiority targets, compared with moxifloxacin. The safety results, however, showed that solithromycin produced a higher number of patients with a liver-enzyme elevation, compared with patients treated with moxifloxacin.

In SOLITAIRE-IV, Cempra reported that grade 3 increase in levels of alanine transaminase (ALT) occurred in 8% of patients on solithromycin and in 3% of patients on moxifloxacin. Grade 4 increases in ALT occurred in less than 1% of patients in both treatment arms.

In the current, orally administered trial, grade 3 ALT increases occurred in 5% of patients treated with solithromycin and in 2% of patients treated with moxifloxacin, Dr. Barrera reported. Grade 4 ALT increases occurred in 0.5% of patients treated with solithromycin and in 1.2% of those treated with moxifloxacin. No patients in either arm developed an elevation of both ALT and bilirubin, and the ALT increases seen were reversible and asymptomatic, Dr. Barrera said.

By other assessments, the safety profiles of solithromycin and moxifloxacin were similar: 7% of patients on solithromycin and 6% on moxifloxacin had a serious adverse event, and 4% of patients in each study arm discontinued treatment because of an adverse event.

SOLITAIRE-ORAL was sponsored by Cempra, the company developing solithromycin. Dr. Barrera has received research funding from Cempra. Dr. Muthiah had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT CHEST 2015

Key clinical point: A next-generation, orally administered macrolide, solithromycin, showed efficacy that was noninferior to moxifloxacin against moderate to moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia in a phase III pivotal trial.

Major finding: Both solithromycin and moxifloxacin produced a 78% early clinical response rate, the study’s primary endpoint for Food and Drug Administration approval.

Data source: SOLITAIRE-ORAL, a multicenter, international phase III trial involving 860 patients with community-acquired pneumonia.

Disclosures: SOLITAIRE-ORAL was sponsored by Cempra, the company developing solithromycin. Dr. Barrera has received research funding from Cempra. Dr. Muthiah had no disclosures.

No flu vaccine for patients with egg allergy?

A 35-year-old woman with asthma presents for a follow-up visit in October. You recommend that she receive the influenza vaccine. She tells you that she cannot take the influenza vaccine because she is allergic to eggs.

What do you recommend?

A. Give her the influenza vaccine.

B. Give her an oseltamivir prescription, and have her start it if any flu-like symptoms appear.

C. Give her the nasal influenza vaccine.

D. Give her the cell-based influenza vaccine.

The clinic I work in asks all patients if they have allergy to eggs before giving the influenza vaccine. If the patient replies yes, then the vaccine is not given and the physician is consulted.

For many years, allergy to egg was considered a contraindication to receiving the influenza vaccine. This contraindication was based on the fear that administering a vaccine that was grown in eggs and could contain egg protein might cause anaphylaxis in patients with immunoglobulin E antibodies against egg proteins.

Fortunately, there is a good evidence base that shows that administering influenza vaccine to patients with egg allergy is safe.

This is extremely important information, because it is estimated that there are about 200,000-300,000 hospitalizations annually because of influenza. For the 2012-2013 influenza season, the CDC estimated that the flu vaccine prevented 6.6 million cases of influenza, 3.2 million doctor visits, and 79,000 hospitalizations. There were 170 pediatric deaths from the flu during the 2012-2013 influenza season (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Dec 13;62[49]:997-1000). The need for widespread vaccination is great, and decreasing the number of people unable to receive the vaccine is an important goal.

There are many studies in children and adults that show that those with egg allergy can be safely vaccinated with influenza vaccine. Dr. John M. James and colleagues reported a study of mostly children with egg allergy confirmed with skin testing (average age of the study group was 3 years) receiving influenza vaccine (J Pediatr. 1998 Nov;133[5]:624-8). A total of 83 patients with egg allergy received the vaccine (including 27 patients with a history of anaphylaxis or severe reactions after egg ingestion). No patients suffered severe reactions with the vaccine, with only four patients having mild, self-limited symptoms.

In another study, Dr. Anne Des Roches and colleagues performed a prospective, cohort study recruiting and vaccinating egg-allergic patients with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine between 2010 and 2012 (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Nov;130[5]:1213-1216.e1). In the second year of the study, the focus was on recruiting patients with a history of anaphylaxis or severe cardiopulmonary symptoms upon egg ingestion. In addition, a retrospective study of all egg-allergic patients who had received an influenza vaccine between 2007 and 2010 was included.

A total of 457 doses of vaccine were administered to 367 patients with egg allergy, of whom 132 had a history of severe allergy. No patients developed anaphylaxis, and 13 patients developed mild allergiclike symptoms in the 24 hours after vaccination.

In an authoritative review on the subject of influenza vaccination in egg-allergic patients, Dr. John Kelso reported on 28 studies with a total of 4,315 patients with egg allergy, including 656 with history of anaphylaxis with egg ingestion (Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014 Aug;13[8]:1049-57). None of these patients developed a serious reaction when they received influenza vaccine.

Dr. Des Roches and colleagues reported on a prospective, cohort study in which 68 children with previous egg allergy received intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccine (J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015 Jan-Feb;3[1]:138-9). No patients had anaphylaxis or a severe allergic reaction. There were more adverse reactions in the patients with egg (7 patients) than in the control group (1 patient), but these were mild and nonspecific (abdominal pain, nasal congestion, headache, and cough).

The 2012 adverse reactions to vaccines practice parameter update recommended that patients with egg allergy should receive influenza vaccinations (trivalent influenza vaccine), because the risks of vaccinating are outweighed by the risks of not vaccinating (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Jul;130[1]:25-43).

A subsequent recommendation takes this a step further, recommending that all patients with egg allergy of any severity should receive inactivated influenza vaccine annually, using any age-approved brand (Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013 Oct;111[4]:301-2). In addition, there are no special waiting periods after vaccination of egg allergic patients beyond what is standard practice for any vaccine.

I think that we have plenty of evidence now to immunize all patients who report egg allergy, and to do so in the primary care setting.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 35-year-old woman with asthma presents for a follow-up visit in October. You recommend that she receive the influenza vaccine. She tells you that she cannot take the influenza vaccine because she is allergic to eggs.

What do you recommend?

A. Give her the influenza vaccine.

B. Give her an oseltamivir prescription, and have her start it if any flu-like symptoms appear.

C. Give her the nasal influenza vaccine.

D. Give her the cell-based influenza vaccine.

The clinic I work in asks all patients if they have allergy to eggs before giving the influenza vaccine. If the patient replies yes, then the vaccine is not given and the physician is consulted.

For many years, allergy to egg was considered a contraindication to receiving the influenza vaccine. This contraindication was based on the fear that administering a vaccine that was grown in eggs and could contain egg protein might cause anaphylaxis in patients with immunoglobulin E antibodies against egg proteins.

Fortunately, there is a good evidence base that shows that administering influenza vaccine to patients with egg allergy is safe.

This is extremely important information, because it is estimated that there are about 200,000-300,000 hospitalizations annually because of influenza. For the 2012-2013 influenza season, the CDC estimated that the flu vaccine prevented 6.6 million cases of influenza, 3.2 million doctor visits, and 79,000 hospitalizations. There were 170 pediatric deaths from the flu during the 2012-2013 influenza season (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Dec 13;62[49]:997-1000). The need for widespread vaccination is great, and decreasing the number of people unable to receive the vaccine is an important goal.

There are many studies in children and adults that show that those with egg allergy can be safely vaccinated with influenza vaccine. Dr. John M. James and colleagues reported a study of mostly children with egg allergy confirmed with skin testing (average age of the study group was 3 years) receiving influenza vaccine (J Pediatr. 1998 Nov;133[5]:624-8). A total of 83 patients with egg allergy received the vaccine (including 27 patients with a history of anaphylaxis or severe reactions after egg ingestion). No patients suffered severe reactions with the vaccine, with only four patients having mild, self-limited symptoms.

In another study, Dr. Anne Des Roches and colleagues performed a prospective, cohort study recruiting and vaccinating egg-allergic patients with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine between 2010 and 2012 (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Nov;130[5]:1213-1216.e1). In the second year of the study, the focus was on recruiting patients with a history of anaphylaxis or severe cardiopulmonary symptoms upon egg ingestion. In addition, a retrospective study of all egg-allergic patients who had received an influenza vaccine between 2007 and 2010 was included.

A total of 457 doses of vaccine were administered to 367 patients with egg allergy, of whom 132 had a history of severe allergy. No patients developed anaphylaxis, and 13 patients developed mild allergiclike symptoms in the 24 hours after vaccination.

In an authoritative review on the subject of influenza vaccination in egg-allergic patients, Dr. John Kelso reported on 28 studies with a total of 4,315 patients with egg allergy, including 656 with history of anaphylaxis with egg ingestion (Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014 Aug;13[8]:1049-57). None of these patients developed a serious reaction when they received influenza vaccine.

Dr. Des Roches and colleagues reported on a prospective, cohort study in which 68 children with previous egg allergy received intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccine (J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015 Jan-Feb;3[1]:138-9). No patients had anaphylaxis or a severe allergic reaction. There were more adverse reactions in the patients with egg (7 patients) than in the control group (1 patient), but these were mild and nonspecific (abdominal pain, nasal congestion, headache, and cough).

The 2012 adverse reactions to vaccines practice parameter update recommended that patients with egg allergy should receive influenza vaccinations (trivalent influenza vaccine), because the risks of vaccinating are outweighed by the risks of not vaccinating (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Jul;130[1]:25-43).

A subsequent recommendation takes this a step further, recommending that all patients with egg allergy of any severity should receive inactivated influenza vaccine annually, using any age-approved brand (Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013 Oct;111[4]:301-2). In addition, there are no special waiting periods after vaccination of egg allergic patients beyond what is standard practice for any vaccine.

I think that we have plenty of evidence now to immunize all patients who report egg allergy, and to do so in the primary care setting.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 35-year-old woman with asthma presents for a follow-up visit in October. You recommend that she receive the influenza vaccine. She tells you that she cannot take the influenza vaccine because she is allergic to eggs.

What do you recommend?

A. Give her the influenza vaccine.

B. Give her an oseltamivir prescription, and have her start it if any flu-like symptoms appear.

C. Give her the nasal influenza vaccine.

D. Give her the cell-based influenza vaccine.

The clinic I work in asks all patients if they have allergy to eggs before giving the influenza vaccine. If the patient replies yes, then the vaccine is not given and the physician is consulted.

For many years, allergy to egg was considered a contraindication to receiving the influenza vaccine. This contraindication was based on the fear that administering a vaccine that was grown in eggs and could contain egg protein might cause anaphylaxis in patients with immunoglobulin E antibodies against egg proteins.

Fortunately, there is a good evidence base that shows that administering influenza vaccine to patients with egg allergy is safe.

This is extremely important information, because it is estimated that there are about 200,000-300,000 hospitalizations annually because of influenza. For the 2012-2013 influenza season, the CDC estimated that the flu vaccine prevented 6.6 million cases of influenza, 3.2 million doctor visits, and 79,000 hospitalizations. There were 170 pediatric deaths from the flu during the 2012-2013 influenza season (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Dec 13;62[49]:997-1000). The need for widespread vaccination is great, and decreasing the number of people unable to receive the vaccine is an important goal.

There are many studies in children and adults that show that those with egg allergy can be safely vaccinated with influenza vaccine. Dr. John M. James and colleagues reported a study of mostly children with egg allergy confirmed with skin testing (average age of the study group was 3 years) receiving influenza vaccine (J Pediatr. 1998 Nov;133[5]:624-8). A total of 83 patients with egg allergy received the vaccine (including 27 patients with a history of anaphylaxis or severe reactions after egg ingestion). No patients suffered severe reactions with the vaccine, with only four patients having mild, self-limited symptoms.

In another study, Dr. Anne Des Roches and colleagues performed a prospective, cohort study recruiting and vaccinating egg-allergic patients with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine between 2010 and 2012 (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Nov;130[5]:1213-1216.e1). In the second year of the study, the focus was on recruiting patients with a history of anaphylaxis or severe cardiopulmonary symptoms upon egg ingestion. In addition, a retrospective study of all egg-allergic patients who had received an influenza vaccine between 2007 and 2010 was included.

A total of 457 doses of vaccine were administered to 367 patients with egg allergy, of whom 132 had a history of severe allergy. No patients developed anaphylaxis, and 13 patients developed mild allergiclike symptoms in the 24 hours after vaccination.

In an authoritative review on the subject of influenza vaccination in egg-allergic patients, Dr. John Kelso reported on 28 studies with a total of 4,315 patients with egg allergy, including 656 with history of anaphylaxis with egg ingestion (Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014 Aug;13[8]:1049-57). None of these patients developed a serious reaction when they received influenza vaccine.

Dr. Des Roches and colleagues reported on a prospective, cohort study in which 68 children with previous egg allergy received intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccine (J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015 Jan-Feb;3[1]:138-9). No patients had anaphylaxis or a severe allergic reaction. There were more adverse reactions in the patients with egg (7 patients) than in the control group (1 patient), but these were mild and nonspecific (abdominal pain, nasal congestion, headache, and cough).

The 2012 adverse reactions to vaccines practice parameter update recommended that patients with egg allergy should receive influenza vaccinations (trivalent influenza vaccine), because the risks of vaccinating are outweighed by the risks of not vaccinating (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Jul;130[1]:25-43).

A subsequent recommendation takes this a step further, recommending that all patients with egg allergy of any severity should receive inactivated influenza vaccine annually, using any age-approved brand (Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013 Oct;111[4]:301-2). In addition, there are no special waiting periods after vaccination of egg allergic patients beyond what is standard practice for any vaccine.

I think that we have plenty of evidence now to immunize all patients who report egg allergy, and to do so in the primary care setting.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

VIDEO: Flu shot lowered hospitalization risk for influenza pneumonia

Getting a flu shot may be a highly effective method to prevent hospitalization for influenza-associated pneumonia.

That’s according to researchers who found that patients hospitalized with influenza-associated pneumonia were more likely to not have been vaccinated than patients whose pneumonia was due to other causes.

In video interviews, Dr. Kathryn M. Edwards and Dr. Carlos G. Grijalva of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, discussed their study of patients admitted through the emergency department for pneumonia and the benefits of flu vaccination in preventing hospitalization for influenza pneumonia.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Getting a flu shot may be a highly effective method to prevent hospitalization for influenza-associated pneumonia.

That’s according to researchers who found that patients hospitalized with influenza-associated pneumonia were more likely to not have been vaccinated than patients whose pneumonia was due to other causes.

In video interviews, Dr. Kathryn M. Edwards and Dr. Carlos G. Grijalva of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, discussed their study of patients admitted through the emergency department for pneumonia and the benefits of flu vaccination in preventing hospitalization for influenza pneumonia.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Getting a flu shot may be a highly effective method to prevent hospitalization for influenza-associated pneumonia.

That’s according to researchers who found that patients hospitalized with influenza-associated pneumonia were more likely to not have been vaccinated than patients whose pneumonia was due to other causes.

In video interviews, Dr. Kathryn M. Edwards and Dr. Carlos G. Grijalva of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, discussed their study of patients admitted through the emergency department for pneumonia and the benefits of flu vaccination in preventing hospitalization for influenza pneumonia.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

FROM JAMA

Peramivir effective against most flu viruses circulating globally

SAN DIEGO – The neuraminidase inhibitor peramivir inhibited about 99% of seasonal influenza A and B viruses circulating globally during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons, a large analysis demonstrated.

“The frequency of H1N1pdm09 viruses carrying neuraminidase (NA) H275Y remained low during both seasons; this mutation confers resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir,” said Margaret Okomo-Adhiambo, Ph.D., at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. In addition, “a small proportion of viruses contained other neuraminidase changes that affect binding of peramivir to viral enzymes and may decrease virus susceptibility. These changes need to be closely monitored.”

Approved by the FDA in December of 2014, peramivir (Rapivab) is the only antiviral agent for influenza treatment to come to market in nearly 20 years. Approved for intravenous administration as a single dose, it is indicated for adults with acute uncomplicated influenza who may have trouble taking orally administered or inhaled neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors. Other NA inhibitors approved by the FDA for influenza infection include oseltamivir, which is orally administered, and zanamivir, which is inhaled.

For the current analysis, Dr. Okomo-Adhiambo of the influenza division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates tested influenza virus susceptibility to peramivir during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons as part of the World Health Organization Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System. A total of 8,426 viruses were tested, 75% of which were circulating in the United States.

Dr. Okomo-Adhiambo reported that during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons, about 99% of influenza type A and B viruses were inhibited by peramivir, except for a few viruses belonging to subtype A(H1N1)pdm09 (1.5%), subtype A(H3N2) (0.2%), and type B (0.4%). In addition, NA activity of type A viruses was five to six times more sensitive to inhibition by peramivir, compared with type B NA.

She concluded her presentation by noting that studies “are needed to establish molecular markers of clinically relevant resistance to peramivir.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The neuraminidase inhibitor peramivir inhibited about 99% of seasonal influenza A and B viruses circulating globally during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons, a large analysis demonstrated.

“The frequency of H1N1pdm09 viruses carrying neuraminidase (NA) H275Y remained low during both seasons; this mutation confers resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir,” said Margaret Okomo-Adhiambo, Ph.D., at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. In addition, “a small proportion of viruses contained other neuraminidase changes that affect binding of peramivir to viral enzymes and may decrease virus susceptibility. These changes need to be closely monitored.”

Approved by the FDA in December of 2014, peramivir (Rapivab) is the only antiviral agent for influenza treatment to come to market in nearly 20 years. Approved for intravenous administration as a single dose, it is indicated for adults with acute uncomplicated influenza who may have trouble taking orally administered or inhaled neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors. Other NA inhibitors approved by the FDA for influenza infection include oseltamivir, which is orally administered, and zanamivir, which is inhaled.

For the current analysis, Dr. Okomo-Adhiambo of the influenza division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates tested influenza virus susceptibility to peramivir during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons as part of the World Health Organization Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System. A total of 8,426 viruses were tested, 75% of which were circulating in the United States.

Dr. Okomo-Adhiambo reported that during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons, about 99% of influenza type A and B viruses were inhibited by peramivir, except for a few viruses belonging to subtype A(H1N1)pdm09 (1.5%), subtype A(H3N2) (0.2%), and type B (0.4%). In addition, NA activity of type A viruses was five to six times more sensitive to inhibition by peramivir, compared with type B NA.

She concluded her presentation by noting that studies “are needed to establish molecular markers of clinically relevant resistance to peramivir.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The neuraminidase inhibitor peramivir inhibited about 99% of seasonal influenza A and B viruses circulating globally during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons, a large analysis demonstrated.

“The frequency of H1N1pdm09 viruses carrying neuraminidase (NA) H275Y remained low during both seasons; this mutation confers resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir,” said Margaret Okomo-Adhiambo, Ph.D., at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. In addition, “a small proportion of viruses contained other neuraminidase changes that affect binding of peramivir to viral enzymes and may decrease virus susceptibility. These changes need to be closely monitored.”

Approved by the FDA in December of 2014, peramivir (Rapivab) is the only antiviral agent for influenza treatment to come to market in nearly 20 years. Approved for intravenous administration as a single dose, it is indicated for adults with acute uncomplicated influenza who may have trouble taking orally administered or inhaled neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors. Other NA inhibitors approved by the FDA for influenza infection include oseltamivir, which is orally administered, and zanamivir, which is inhaled.

For the current analysis, Dr. Okomo-Adhiambo of the influenza division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates tested influenza virus susceptibility to peramivir during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons as part of the World Health Organization Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System. A total of 8,426 viruses were tested, 75% of which were circulating in the United States.

Dr. Okomo-Adhiambo reported that during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons, about 99% of influenza type A and B viruses were inhibited by peramivir, except for a few viruses belonging to subtype A(H1N1)pdm09 (1.5%), subtype A(H3N2) (0.2%), and type B (0.4%). In addition, NA activity of type A viruses was five to six times more sensitive to inhibition by peramivir, compared with type B NA.

She concluded her presentation by noting that studies “are needed to establish molecular markers of clinically relevant resistance to peramivir.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ICAAC 2015

Key clinical point: Peramivir is potently effective against seasonal influenza viruses circulating globally.

Major finding: During the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons, about 99% of influenza type A and B viruses were inhibited by peramivir.

Data source: An analysis of 8,426 influenza viruses that were tested during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 influenza seasons as part of the World Health Organization Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System.

Disclosures: The researchers reporting having no financial disclosures.

Flu shot linked to lower risk of hospitalization for influenza pneumonia

Patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed, influenza-associated pneumonia had a 57% lower odds of having received the influenza vaccine than controls whose pneumonia was due to other causes, investigators reported Oct. 5 in JAMA.

The findings could be used in future studies to estimate the number of hospitalizations prevented by influenza vaccination, according to Dr. Carlos Grijalva of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and his associates.

Seasonal influenza causes about 226,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 to 49,000 deaths every year in the United States. Observational studies show that influenza vaccination helps prevent hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness, but whether it also cuts the odds of hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia is unknown, the investigators wrote.

To explore this question, they conducted an observational, multicenter study of 2,767 patients who had been hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia over 3 consecutive influenza seasons at four sites in the United States. Patients were at least 6 months old, were not severely immunosuppressed, and had not been recently hospitalized or resided in a long-term care facility (JAMA. 2015 Oct 5, doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12160.).

In all, 162 (6%) patients had laboratory-confirmed influenza, including 17% who had received the influenza vaccine, the researchers wrote. In contrast, 29% of controls had received the vaccine, for an adjusted odds ratio of 0.43 (95% confidence interval, 0.28 to 0.68) after controlling for demographic characteristics, comorbidities, influenza season, study site, and time of disease onset. The estimated vaccine effectiveness was 57%.

The test-positive case, test-negative control design is widely used to study vaccine effectiveness and is better than comparing hospitalized cases with population controls, because it “implicitly” accounts for the risk of hospitalization, the researchers wrote. But “despite enrollment over 3 consecutive seasons, a relatively small number of influenza-associated pneumonia cases met eligibility criteria, resulting in limited precision for some subgroup analyses,” they added. “Thus, the association between influenza vaccines and pneumonia among older adults remains controversial, and additional studies in this group are needed.”

Dr. Grijalva reported having served as a consultant to Pfizer. Several coauthors reported having received grant and other support from the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medscape, MedImmune, Roche, Abbvie, and a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed, influenza-associated pneumonia had a 57% lower odds of having received the influenza vaccine than controls whose pneumonia was due to other causes, investigators reported Oct. 5 in JAMA.

The findings could be used in future studies to estimate the number of hospitalizations prevented by influenza vaccination, according to Dr. Carlos Grijalva of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and his associates.

Seasonal influenza causes about 226,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 to 49,000 deaths every year in the United States. Observational studies show that influenza vaccination helps prevent hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness, but whether it also cuts the odds of hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia is unknown, the investigators wrote.

To explore this question, they conducted an observational, multicenter study of 2,767 patients who had been hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia over 3 consecutive influenza seasons at four sites in the United States. Patients were at least 6 months old, were not severely immunosuppressed, and had not been recently hospitalized or resided in a long-term care facility (JAMA. 2015 Oct 5, doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12160.).

In all, 162 (6%) patients had laboratory-confirmed influenza, including 17% who had received the influenza vaccine, the researchers wrote. In contrast, 29% of controls had received the vaccine, for an adjusted odds ratio of 0.43 (95% confidence interval, 0.28 to 0.68) after controlling for demographic characteristics, comorbidities, influenza season, study site, and time of disease onset. The estimated vaccine effectiveness was 57%.

The test-positive case, test-negative control design is widely used to study vaccine effectiveness and is better than comparing hospitalized cases with population controls, because it “implicitly” accounts for the risk of hospitalization, the researchers wrote. But “despite enrollment over 3 consecutive seasons, a relatively small number of influenza-associated pneumonia cases met eligibility criteria, resulting in limited precision for some subgroup analyses,” they added. “Thus, the association between influenza vaccines and pneumonia among older adults remains controversial, and additional studies in this group are needed.”

Dr. Grijalva reported having served as a consultant to Pfizer. Several coauthors reported having received grant and other support from the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medscape, MedImmune, Roche, Abbvie, and a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed, influenza-associated pneumonia had a 57% lower odds of having received the influenza vaccine than controls whose pneumonia was due to other causes, investigators reported Oct. 5 in JAMA.

The findings could be used in future studies to estimate the number of hospitalizations prevented by influenza vaccination, according to Dr. Carlos Grijalva of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and his associates.

Seasonal influenza causes about 226,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 to 49,000 deaths every year in the United States. Observational studies show that influenza vaccination helps prevent hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness, but whether it also cuts the odds of hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia is unknown, the investigators wrote.

To explore this question, they conducted an observational, multicenter study of 2,767 patients who had been hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia over 3 consecutive influenza seasons at four sites in the United States. Patients were at least 6 months old, were not severely immunosuppressed, and had not been recently hospitalized or resided in a long-term care facility (JAMA. 2015 Oct 5, doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12160.).

In all, 162 (6%) patients had laboratory-confirmed influenza, including 17% who had received the influenza vaccine, the researchers wrote. In contrast, 29% of controls had received the vaccine, for an adjusted odds ratio of 0.43 (95% confidence interval, 0.28 to 0.68) after controlling for demographic characteristics, comorbidities, influenza season, study site, and time of disease onset. The estimated vaccine effectiveness was 57%.

The test-positive case, test-negative control design is widely used to study vaccine effectiveness and is better than comparing hospitalized cases with population controls, because it “implicitly” accounts for the risk of hospitalization, the researchers wrote. But “despite enrollment over 3 consecutive seasons, a relatively small number of influenza-associated pneumonia cases met eligibility criteria, resulting in limited precision for some subgroup analyses,” they added. “Thus, the association between influenza vaccines and pneumonia among older adults remains controversial, and additional studies in this group are needed.”

Dr. Grijalva reported having served as a consultant to Pfizer. Several coauthors reported having received grant and other support from the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medscape, MedImmune, Roche, Abbvie, and a number of pharmaceutical companies.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Hospitalized patients with laboratory-confirmed, influenza-associated pneumonia were less likely to have been vaccinated against influenza than hospitalized controls with non-influenza pneumonia.

Major finding: Influenza-associated pneumonia patients had a 57% lower odds of having been vaccinated against influenza than controls (adjusted odds ratio, 0.43).

Data source: An observational, multicenter study of 2,767 hospitalizations for community-acquired pneumonia at four sites in the United States.

Disclosures: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Grijalva reported having served as a consultant to Pfizer. Several coauthors reported having received grant and other support from the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medscape, MedImmune, Roche, Abbvie, and a number of pharmaceutical companies.

HHS funds experimental flu drug for hospital patients

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) will provide “technical assistance and funding” to Janssen Pharmaceuticals for the development of an influenza antiviral drug that could be more potent and have a longer treatment window than do existing influenza drugs, according a statement from HHS.

The experimental drug, which Janssen intends to use to treat hospitalized patients with influenza, is called JNJ-872, also known as VX787, and may be the first in an entirely new class of influenza antivirals.

ASPR’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) specifically will provide up to $103.5 million over the next 4 years and 3 months to Janssen, and the contract leaves open the possibility of BARDA providing additional funding, capped at $131 million, for this project. BARDA’s contribution is part of its program for “advanced research and development, innovation, acquisition, and manufacturing of vaccines, drugs, diagnostic tools, and nonpharmaceutical products for public health emergency threats.”

Janssen will use the funds to conduct late stage clinical development of JNJ-872, which includes phase III studies in high-risk populations and hospitalized patients, and the final development of a validated commercial-scale manufacturing process. The pharmaceutical company will also explore the feasibility of an innovative approach to manufacturing, which allows for the continuous flow of materials throughout the manufacturing process, unlike the traditional manufacturing process, which is riddled with interruptions.

“BARDA’s goal for supporting JNJ-872 is development of a product that can be used not only to treat hospitalized influenza patients but also to treat patients for whom influenza poses high risks, such as the elderly, pediatrics, and those with chronic conditions such as COPD and heart disease ...,” the statement indicated.

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) will provide “technical assistance and funding” to Janssen Pharmaceuticals for the development of an influenza antiviral drug that could be more potent and have a longer treatment window than do existing influenza drugs, according a statement from HHS.

The experimental drug, which Janssen intends to use to treat hospitalized patients with influenza, is called JNJ-872, also known as VX787, and may be the first in an entirely new class of influenza antivirals.

ASPR’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) specifically will provide up to $103.5 million over the next 4 years and 3 months to Janssen, and the contract leaves open the possibility of BARDA providing additional funding, capped at $131 million, for this project. BARDA’s contribution is part of its program for “advanced research and development, innovation, acquisition, and manufacturing of vaccines, drugs, diagnostic tools, and nonpharmaceutical products for public health emergency threats.”

Janssen will use the funds to conduct late stage clinical development of JNJ-872, which includes phase III studies in high-risk populations and hospitalized patients, and the final development of a validated commercial-scale manufacturing process. The pharmaceutical company will also explore the feasibility of an innovative approach to manufacturing, which allows for the continuous flow of materials throughout the manufacturing process, unlike the traditional manufacturing process, which is riddled with interruptions.

“BARDA’s goal for supporting JNJ-872 is development of a product that can be used not only to treat hospitalized influenza patients but also to treat patients for whom influenza poses high risks, such as the elderly, pediatrics, and those with chronic conditions such as COPD and heart disease ...,” the statement indicated.

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) will provide “technical assistance and funding” to Janssen Pharmaceuticals for the development of an influenza antiviral drug that could be more potent and have a longer treatment window than do existing influenza drugs, according a statement from HHS.

The experimental drug, which Janssen intends to use to treat hospitalized patients with influenza, is called JNJ-872, also known as VX787, and may be the first in an entirely new class of influenza antivirals.

ASPR’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) specifically will provide up to $103.5 million over the next 4 years and 3 months to Janssen, and the contract leaves open the possibility of BARDA providing additional funding, capped at $131 million, for this project. BARDA’s contribution is part of its program for “advanced research and development, innovation, acquisition, and manufacturing of vaccines, drugs, diagnostic tools, and nonpharmaceutical products for public health emergency threats.”

Janssen will use the funds to conduct late stage clinical development of JNJ-872, which includes phase III studies in high-risk populations and hospitalized patients, and the final development of a validated commercial-scale manufacturing process. The pharmaceutical company will also explore the feasibility of an innovative approach to manufacturing, which allows for the continuous flow of materials throughout the manufacturing process, unlike the traditional manufacturing process, which is riddled with interruptions.

“BARDA’s goal for supporting JNJ-872 is development of a product that can be used not only to treat hospitalized influenza patients but also to treat patients for whom influenza poses high risks, such as the elderly, pediatrics, and those with chronic conditions such as COPD and heart disease ...,” the statement indicated.

Send patients reminders for flu vaccines, study says

ATLANTA – Mobile reminders from health care providers to their patients, notifying them to get influenza vaccinations, significantly increases the likelihood that those patients will get vaccinated, according to a study by Dr. Katherine A. Benedict and coinvestigators in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Benedict presented findings of the research at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The researchers used data from the March 2012 National Flu Survey, a CDC “random digit dial telephone survey” of influenza vaccination trends in adults 18 years of age and older. They analyzed the data to determine whether or not patients received reminders, recommendations, or offers for influenza vaccinations from their health care providers since July 1, 2011. They did a logistic regression analysis to determine if there was any relationship between influenza vaccination rates and receipt of recommendations from health care providers.

Almost 73% of adults reported visiting a physician at least once since July 1, 2011, the start of data collection for the March 2012 study cycle, with 17.2% reporting that they received a reminder from their doctors to get a flu vaccine. Overall, 45.5% of adults ultimately got vaccinated, with 75.6% of those who reported receiving a reminder saying that they also were offered vaccinations by their doctors.

Adults who received recommendations for influenza vaccination from their health care providers were most likely to get vaccinated, and had an unadjusted prevalence ratio of 2.09. Next likely were those who received vaccination offers (PR = 1.90), and those who simply received reminders (PR = 1.33). Furthermore, those between 50 and 64 years old were found more likely to receive a recommendation or offer – PR = 1.23 and PR = 1.09, respectively – than were those in the 18- to 49-year age range (PR = 1.06 for recommendation, PR = 0.99 for offer).

The takeaway from this, according to the investigators, is that reminders should be sent at least once at the beginning of each influenza season. Prevalence ratios were consistently higher for patients with more frequent visits to their health care providers, meaning that continued interaction with and communication from doctors increases the likelihood of vaccination. Dr. Benedict also recommended sending additional reminders throughout the season, and that patients should either seek out or be referred to doctors who offer influenza vaccinations themselves.

Dr. Benedict did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Mobile reminders from health care providers to their patients, notifying them to get influenza vaccinations, significantly increases the likelihood that those patients will get vaccinated, according to a study by Dr. Katherine A. Benedict and coinvestigators in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Benedict presented findings of the research at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The researchers used data from the March 2012 National Flu Survey, a CDC “random digit dial telephone survey” of influenza vaccination trends in adults 18 years of age and older. They analyzed the data to determine whether or not patients received reminders, recommendations, or offers for influenza vaccinations from their health care providers since July 1, 2011. They did a logistic regression analysis to determine if there was any relationship between influenza vaccination rates and receipt of recommendations from health care providers.

Almost 73% of adults reported visiting a physician at least once since July 1, 2011, the start of data collection for the March 2012 study cycle, with 17.2% reporting that they received a reminder from their doctors to get a flu vaccine. Overall, 45.5% of adults ultimately got vaccinated, with 75.6% of those who reported receiving a reminder saying that they also were offered vaccinations by their doctors.

Adults who received recommendations for influenza vaccination from their health care providers were most likely to get vaccinated, and had an unadjusted prevalence ratio of 2.09. Next likely were those who received vaccination offers (PR = 1.90), and those who simply received reminders (PR = 1.33). Furthermore, those between 50 and 64 years old were found more likely to receive a recommendation or offer – PR = 1.23 and PR = 1.09, respectively – than were those in the 18- to 49-year age range (PR = 1.06 for recommendation, PR = 0.99 for offer).