User login

Shortage reported of antibiotic commonly used for children

The liquid form of the antibiotic amoxicillin often used to treat ear infections and strep throat in children is in short supply, just as Americans head into the season when they use the bacteria-fighting drug the most.

The FDA officially listed the shortage Oct. 28, but pharmacists, hospitals, and a supply tracking database sounded alarms earlier this month.

“The scary part is, we’re coming into the time of the year where you have the greatest need,” independent pharmacy owner Hugh Chancy, PharmD, of Georgia, told NBC News.

Thus far, reports indicate the impact of the shortages is not widespread but does affect some pharmacies, and at least one hospital has published an algorithm for offering treatment alternatives.

CVS told Bloomberg News that some stores are experiencing shortages of certain doses of amoxicillin, but a Walmart spokesperson said its diverse supply chain meant none of its pharmacies were affected.

“Hypothetically, if amoxicillin doesn’t come into stock for some time, then we’re potentially having to use less effective antibiotics with more side effects,” said Ohio pediatrician Sean Gallagher, MD, according to Bloomberg.

The shortage impacts three of the four largest amoxicillin manufacturers worldwide, according to the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota. The FDA listed the reason for the shortage as “demand increase for drug,” except in the case of manufacturer Sandoz, for which the reason listed read “information pending.”

A company spokesperson told Bloomberg the reasons were complex.

“The combination in rapid succession of the pandemic impact and consequent demand swings, manufacturing capacity constraints, scarcity of raw materials, and the current energy crisis means we face a uniquely difficult situation in the short term,” Sandoz spokesperson Leslie Pott told Bloomberg.

According to Bloomberg, other major manufacturers are still delivering the product, but limiting new orders.

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists issued an alert for the shortage last week via its real time drug shortage database.

“Amoxicillin comes in many forms – including capsules, powders and chewable tablets – but the most common type children take is the liquid form, which makes up at least 19 products that are part of the” shortage, Becker’s Hospital Review summarized of the database reports.

The pediatric health system Children’s Minnesota told CIDRAP that supplies are low and that alternatives are being prescribed “when appropriate.”

“As a final step, we temporarily discontinued our standard procedure of dispensing the entire bottle of amoxicillin (which comes in multiple sizes),” a spokesperson told CIDRAP. “We are instead mixing and pouring the exact amount for each course of therapy, to eliminate waste.”

The Minnesota pediatric clinic and others are particularly on alert because of the surge nationwide of a respiratory virus that particularly impacts children known as RSV.

“We have certainly observed an increase in recent use most likely correlating with the surge in RSV and other respiratory viruses with concern for superimposed bacterial infection in our critically ill and hospitalized patient population,” Laura Bio, PharmD, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health told CIDRAP.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The liquid form of the antibiotic amoxicillin often used to treat ear infections and strep throat in children is in short supply, just as Americans head into the season when they use the bacteria-fighting drug the most.

The FDA officially listed the shortage Oct. 28, but pharmacists, hospitals, and a supply tracking database sounded alarms earlier this month.

“The scary part is, we’re coming into the time of the year where you have the greatest need,” independent pharmacy owner Hugh Chancy, PharmD, of Georgia, told NBC News.

Thus far, reports indicate the impact of the shortages is not widespread but does affect some pharmacies, and at least one hospital has published an algorithm for offering treatment alternatives.

CVS told Bloomberg News that some stores are experiencing shortages of certain doses of amoxicillin, but a Walmart spokesperson said its diverse supply chain meant none of its pharmacies were affected.

“Hypothetically, if amoxicillin doesn’t come into stock for some time, then we’re potentially having to use less effective antibiotics with more side effects,” said Ohio pediatrician Sean Gallagher, MD, according to Bloomberg.

The shortage impacts three of the four largest amoxicillin manufacturers worldwide, according to the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota. The FDA listed the reason for the shortage as “demand increase for drug,” except in the case of manufacturer Sandoz, for which the reason listed read “information pending.”

A company spokesperson told Bloomberg the reasons were complex.

“The combination in rapid succession of the pandemic impact and consequent demand swings, manufacturing capacity constraints, scarcity of raw materials, and the current energy crisis means we face a uniquely difficult situation in the short term,” Sandoz spokesperson Leslie Pott told Bloomberg.

According to Bloomberg, other major manufacturers are still delivering the product, but limiting new orders.

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists issued an alert for the shortage last week via its real time drug shortage database.

“Amoxicillin comes in many forms – including capsules, powders and chewable tablets – but the most common type children take is the liquid form, which makes up at least 19 products that are part of the” shortage, Becker’s Hospital Review summarized of the database reports.

The pediatric health system Children’s Minnesota told CIDRAP that supplies are low and that alternatives are being prescribed “when appropriate.”

“As a final step, we temporarily discontinued our standard procedure of dispensing the entire bottle of amoxicillin (which comes in multiple sizes),” a spokesperson told CIDRAP. “We are instead mixing and pouring the exact amount for each course of therapy, to eliminate waste.”

The Minnesota pediatric clinic and others are particularly on alert because of the surge nationwide of a respiratory virus that particularly impacts children known as RSV.

“We have certainly observed an increase in recent use most likely correlating with the surge in RSV and other respiratory viruses with concern for superimposed bacterial infection in our critically ill and hospitalized patient population,” Laura Bio, PharmD, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health told CIDRAP.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The liquid form of the antibiotic amoxicillin often used to treat ear infections and strep throat in children is in short supply, just as Americans head into the season when they use the bacteria-fighting drug the most.

The FDA officially listed the shortage Oct. 28, but pharmacists, hospitals, and a supply tracking database sounded alarms earlier this month.

“The scary part is, we’re coming into the time of the year where you have the greatest need,” independent pharmacy owner Hugh Chancy, PharmD, of Georgia, told NBC News.

Thus far, reports indicate the impact of the shortages is not widespread but does affect some pharmacies, and at least one hospital has published an algorithm for offering treatment alternatives.

CVS told Bloomberg News that some stores are experiencing shortages of certain doses of amoxicillin, but a Walmart spokesperson said its diverse supply chain meant none of its pharmacies were affected.

“Hypothetically, if amoxicillin doesn’t come into stock for some time, then we’re potentially having to use less effective antibiotics with more side effects,” said Ohio pediatrician Sean Gallagher, MD, according to Bloomberg.

The shortage impacts three of the four largest amoxicillin manufacturers worldwide, according to the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota. The FDA listed the reason for the shortage as “demand increase for drug,” except in the case of manufacturer Sandoz, for which the reason listed read “information pending.”

A company spokesperson told Bloomberg the reasons were complex.

“The combination in rapid succession of the pandemic impact and consequent demand swings, manufacturing capacity constraints, scarcity of raw materials, and the current energy crisis means we face a uniquely difficult situation in the short term,” Sandoz spokesperson Leslie Pott told Bloomberg.

According to Bloomberg, other major manufacturers are still delivering the product, but limiting new orders.

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists issued an alert for the shortage last week via its real time drug shortage database.

“Amoxicillin comes in many forms – including capsules, powders and chewable tablets – but the most common type children take is the liquid form, which makes up at least 19 products that are part of the” shortage, Becker’s Hospital Review summarized of the database reports.

The pediatric health system Children’s Minnesota told CIDRAP that supplies are low and that alternatives are being prescribed “when appropriate.”

“As a final step, we temporarily discontinued our standard procedure of dispensing the entire bottle of amoxicillin (which comes in multiple sizes),” a spokesperson told CIDRAP. “We are instead mixing and pouring the exact amount for each course of therapy, to eliminate waste.”

The Minnesota pediatric clinic and others are particularly on alert because of the surge nationwide of a respiratory virus that particularly impacts children known as RSV.

“We have certainly observed an increase in recent use most likely correlating with the surge in RSV and other respiratory viruses with concern for superimposed bacterial infection in our critically ill and hospitalized patient population,” Laura Bio, PharmD, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health told CIDRAP.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Mid-October flulike illness cases higher than past 5 years

Outpatient visits for influenzalike illness (ILI), which includes influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and RSV, were higher after 3 weeks than for any of the previous five flu seasons: 3.3% of visits reported through the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network involved ILI as of Oct. 22. The highest comparable rate in the previous 5 years was the 1.9% recorded in late October of 2021, shortly after the definition of ILI was changed to also include illnesses other than influenza.

This season’s higher flu activity is in contrast to the previous two, which were unusually mild. The change, however, is not unexpected, as William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert and professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University, recently told CNN.

“Here we are in the middle of October – not the middle of November – we’re already seeing scattered influenza cases, even hospitalized influenza cases, around the country,” he said. “So we know that this virus is now spreading out in the community already. It’s gathering speed already. It looks to me to be about a month early.”

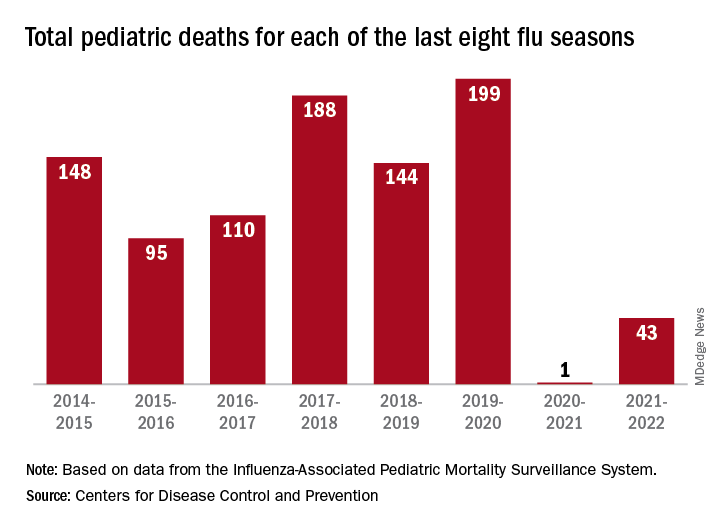

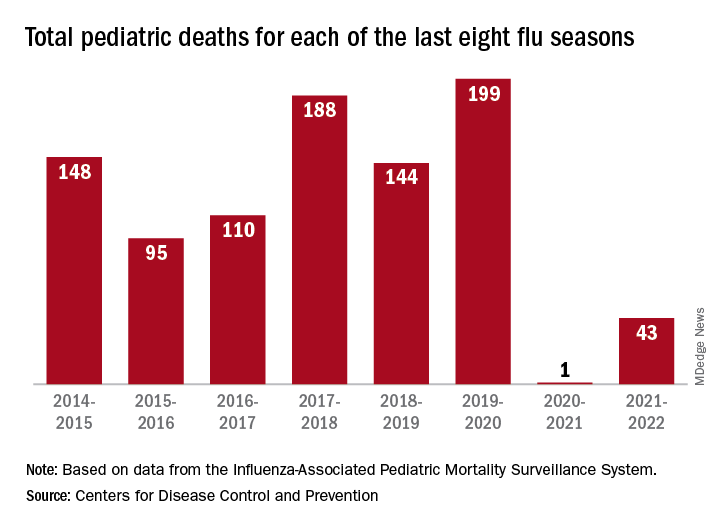

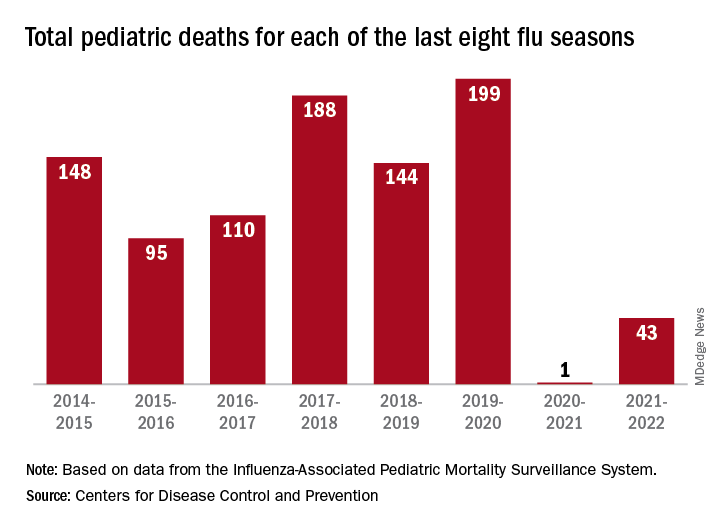

One indication of the mildness of the previous two flu seasons was the number of deaths, both pediatric and overall. Influenza-associated pediatric deaths had averaged about 110 per season over the previous eight seasons, compared with just 1 for 2020-2021 and 43 in 2021-2022. Overall flu deaths never reached 1% of all weekly deaths for either season, well below baseline levels for the flu, which range from 5.5% to 6.8%, CDC data show.

Other indicators of early severity

This season’s early rise in viral activity also can be seen in hospitalizations. The cumulative rate of flu-related admissions was 1.5 per 100,000 population as of Oct. 22, higher than the rate observed in the comparable week of previous seasons going back to 2010-2011, according to the CDC’s Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network.

A look at state reports of ILI outpatient visit rates shows that the District of Columbia and South Carolina are already in the very high range of the CDC’s severity scale, while 11 states are in the high range. Again going back to 2010-2011, no jurisdiction has ever been in the very high range this early in the season, based on data from the Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network.

Outpatient visits for influenzalike illness (ILI), which includes influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and RSV, were higher after 3 weeks than for any of the previous five flu seasons: 3.3% of visits reported through the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network involved ILI as of Oct. 22. The highest comparable rate in the previous 5 years was the 1.9% recorded in late October of 2021, shortly after the definition of ILI was changed to also include illnesses other than influenza.

This season’s higher flu activity is in contrast to the previous two, which were unusually mild. The change, however, is not unexpected, as William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert and professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University, recently told CNN.

“Here we are in the middle of October – not the middle of November – we’re already seeing scattered influenza cases, even hospitalized influenza cases, around the country,” he said. “So we know that this virus is now spreading out in the community already. It’s gathering speed already. It looks to me to be about a month early.”

One indication of the mildness of the previous two flu seasons was the number of deaths, both pediatric and overall. Influenza-associated pediatric deaths had averaged about 110 per season over the previous eight seasons, compared with just 1 for 2020-2021 and 43 in 2021-2022. Overall flu deaths never reached 1% of all weekly deaths for either season, well below baseline levels for the flu, which range from 5.5% to 6.8%, CDC data show.

Other indicators of early severity

This season’s early rise in viral activity also can be seen in hospitalizations. The cumulative rate of flu-related admissions was 1.5 per 100,000 population as of Oct. 22, higher than the rate observed in the comparable week of previous seasons going back to 2010-2011, according to the CDC’s Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network.

A look at state reports of ILI outpatient visit rates shows that the District of Columbia and South Carolina are already in the very high range of the CDC’s severity scale, while 11 states are in the high range. Again going back to 2010-2011, no jurisdiction has ever been in the very high range this early in the season, based on data from the Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network.

Outpatient visits for influenzalike illness (ILI), which includes influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and RSV, were higher after 3 weeks than for any of the previous five flu seasons: 3.3% of visits reported through the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network involved ILI as of Oct. 22. The highest comparable rate in the previous 5 years was the 1.9% recorded in late October of 2021, shortly after the definition of ILI was changed to also include illnesses other than influenza.

This season’s higher flu activity is in contrast to the previous two, which were unusually mild. The change, however, is not unexpected, as William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert and professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University, recently told CNN.

“Here we are in the middle of October – not the middle of November – we’re already seeing scattered influenza cases, even hospitalized influenza cases, around the country,” he said. “So we know that this virus is now spreading out in the community already. It’s gathering speed already. It looks to me to be about a month early.”

One indication of the mildness of the previous two flu seasons was the number of deaths, both pediatric and overall. Influenza-associated pediatric deaths had averaged about 110 per season over the previous eight seasons, compared with just 1 for 2020-2021 and 43 in 2021-2022. Overall flu deaths never reached 1% of all weekly deaths for either season, well below baseline levels for the flu, which range from 5.5% to 6.8%, CDC data show.

Other indicators of early severity

This season’s early rise in viral activity also can be seen in hospitalizations. The cumulative rate of flu-related admissions was 1.5 per 100,000 population as of Oct. 22, higher than the rate observed in the comparable week of previous seasons going back to 2010-2011, according to the CDC’s Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network.

A look at state reports of ILI outpatient visit rates shows that the District of Columbia and South Carolina are already in the very high range of the CDC’s severity scale, while 11 states are in the high range. Again going back to 2010-2011, no jurisdiction has ever been in the very high range this early in the season, based on data from the Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network.

‘Unappreciated’ ties between COVID and gut dysbiosis

(BSIs), new research suggests.

“Collectively, these results reveal an unappreciated link between SARS-CoV-2 infection, gut microbiome dysbiosis, and a severe complication of COVID-19, BSIs,” the study team reported in Nature Communications.

“Our findings suggest that coronavirus infection directly interferes with the healthy balance of microbes in the gut, further endangering patients in the process,” microbiologist and co–senior author Ken Cadwell, PhD, New York University, added in a news release. “Now that we have uncovered the source of this bacterial imbalance, physicians can better identify those coronavirus patients most at risk of a secondary bloodstream infection.”

In a mouse model, the researchers first demonstrated that the SARS-CoV-2 infection alone induces gut microbiome dysbiosis and gut epithelial cell alterations, which correlate with markers of gut barrier permeability.

Next, they analyzed the bacterial composition of stool samples from 96 adults hospitalized with COVID-19 in 2020 in New York and New Haven, Conn.

In line with their observations in mice, they found that the SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with “severe microbiome injury,” characterized by the loss of gut microbiome diversity.

They also observed an increase in populations of several microbes known to include antibiotic-resistant species. An analysis of stool samples paired with blood cultures found that antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the gut migrated to the bloodstream in 20% of patients.

This migration could be caused by a combination of the immune-compromising effects of the viral infection and the antibiotic-driven depletion of commensal gut microbes, the researchers said.

However, COVID-19 patients are also uniquely exposed to other potential factors predisposing them to bacteremia, including immunosuppressive drugs, long hospital stays, and catheters, the investigators noted. The study is limited in its ability to investigate the individual effects of these factors.

“Our findings support a scenario in which gut-to-blood translocation of microorganisms following microbiome dysbiosis leads to dangerous BSIs during COVID-19, a complication seen in other immunocompromised patients, including patients with cancer, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and in ICU patients receiving probiotics,” the researchers wrote.

Investigating the underlying mechanism behind their observations could help inform “the judicious application of antibiotics and immunosuppressives in patients with respiratory viral infections and increase our resilience to pandemics,” they added.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the Yale School of Public Health, and numerous other sources. Dr. Cadwell has received research support from Pfizer, Takeda, Pacific Biosciences, Genentech, and AbbVie; consulted for or received an honoraria from PureTech Health, Genentech, and AbbVie; and is named as an inventor on US patent 10,722,600 and provisional patents 62/935,035 and 63/157,225.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(BSIs), new research suggests.

“Collectively, these results reveal an unappreciated link between SARS-CoV-2 infection, gut microbiome dysbiosis, and a severe complication of COVID-19, BSIs,” the study team reported in Nature Communications.

“Our findings suggest that coronavirus infection directly interferes with the healthy balance of microbes in the gut, further endangering patients in the process,” microbiologist and co–senior author Ken Cadwell, PhD, New York University, added in a news release. “Now that we have uncovered the source of this bacterial imbalance, physicians can better identify those coronavirus patients most at risk of a secondary bloodstream infection.”

In a mouse model, the researchers first demonstrated that the SARS-CoV-2 infection alone induces gut microbiome dysbiosis and gut epithelial cell alterations, which correlate with markers of gut barrier permeability.

Next, they analyzed the bacterial composition of stool samples from 96 adults hospitalized with COVID-19 in 2020 in New York and New Haven, Conn.

In line with their observations in mice, they found that the SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with “severe microbiome injury,” characterized by the loss of gut microbiome diversity.

They also observed an increase in populations of several microbes known to include antibiotic-resistant species. An analysis of stool samples paired with blood cultures found that antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the gut migrated to the bloodstream in 20% of patients.

This migration could be caused by a combination of the immune-compromising effects of the viral infection and the antibiotic-driven depletion of commensal gut microbes, the researchers said.

However, COVID-19 patients are also uniquely exposed to other potential factors predisposing them to bacteremia, including immunosuppressive drugs, long hospital stays, and catheters, the investigators noted. The study is limited in its ability to investigate the individual effects of these factors.

“Our findings support a scenario in which gut-to-blood translocation of microorganisms following microbiome dysbiosis leads to dangerous BSIs during COVID-19, a complication seen in other immunocompromised patients, including patients with cancer, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and in ICU patients receiving probiotics,” the researchers wrote.

Investigating the underlying mechanism behind their observations could help inform “the judicious application of antibiotics and immunosuppressives in patients with respiratory viral infections and increase our resilience to pandemics,” they added.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the Yale School of Public Health, and numerous other sources. Dr. Cadwell has received research support from Pfizer, Takeda, Pacific Biosciences, Genentech, and AbbVie; consulted for or received an honoraria from PureTech Health, Genentech, and AbbVie; and is named as an inventor on US patent 10,722,600 and provisional patents 62/935,035 and 63/157,225.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(BSIs), new research suggests.

“Collectively, these results reveal an unappreciated link between SARS-CoV-2 infection, gut microbiome dysbiosis, and a severe complication of COVID-19, BSIs,” the study team reported in Nature Communications.

“Our findings suggest that coronavirus infection directly interferes with the healthy balance of microbes in the gut, further endangering patients in the process,” microbiologist and co–senior author Ken Cadwell, PhD, New York University, added in a news release. “Now that we have uncovered the source of this bacterial imbalance, physicians can better identify those coronavirus patients most at risk of a secondary bloodstream infection.”

In a mouse model, the researchers first demonstrated that the SARS-CoV-2 infection alone induces gut microbiome dysbiosis and gut epithelial cell alterations, which correlate with markers of gut barrier permeability.

Next, they analyzed the bacterial composition of stool samples from 96 adults hospitalized with COVID-19 in 2020 in New York and New Haven, Conn.

In line with their observations in mice, they found that the SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with “severe microbiome injury,” characterized by the loss of gut microbiome diversity.

They also observed an increase in populations of several microbes known to include antibiotic-resistant species. An analysis of stool samples paired with blood cultures found that antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the gut migrated to the bloodstream in 20% of patients.

This migration could be caused by a combination of the immune-compromising effects of the viral infection and the antibiotic-driven depletion of commensal gut microbes, the researchers said.

However, COVID-19 patients are also uniquely exposed to other potential factors predisposing them to bacteremia, including immunosuppressive drugs, long hospital stays, and catheters, the investigators noted. The study is limited in its ability to investigate the individual effects of these factors.

“Our findings support a scenario in which gut-to-blood translocation of microorganisms following microbiome dysbiosis leads to dangerous BSIs during COVID-19, a complication seen in other immunocompromised patients, including patients with cancer, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and in ICU patients receiving probiotics,” the researchers wrote.

Investigating the underlying mechanism behind their observations could help inform “the judicious application of antibiotics and immunosuppressives in patients with respiratory viral infections and increase our resilience to pandemics,” they added.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the Yale School of Public Health, and numerous other sources. Dr. Cadwell has received research support from Pfizer, Takeda, Pacific Biosciences, Genentech, and AbbVie; consulted for or received an honoraria from PureTech Health, Genentech, and AbbVie; and is named as an inventor on US patent 10,722,600 and provisional patents 62/935,035 and 63/157,225.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

Mycetomalike Skin Infection Due to Gordonia bronchialis in an Immunocompetent Patient

Mycetoma is a chronic subcutaneous infection due to fungal (eumycetoma) or aerobic actinomycetes (actinomycetoma) organisms. Clinical lesions develop from a granulomatous infiltrate organizing around the infectious organism. Patients can present with extensive subcutaneous nodularity and draining sinuses that can lead to deformation of the affected extremity. These infections are rare in developed countries, and the prevalence and incidence remain unknown. It has been reported that actinomycetes represent 60% of mycetoma cases worldwide, with the majority of cases in Central America from Nocardia (86%) and Actinomadura madurae (10%). 1Gordonia species are aerobic, partially acid-fast, gram-positive actinobacteria that may comprise a notable minority of actinomycete isolates. 2 The species Gordonia bronchialis is of particular interest as a human pathogen because of increasing reports of nosocomial infections. 3,4 We describe a case of a mycetomalike infection due to G bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient with complete resolution after 3 months of antibiotics.

Case Report

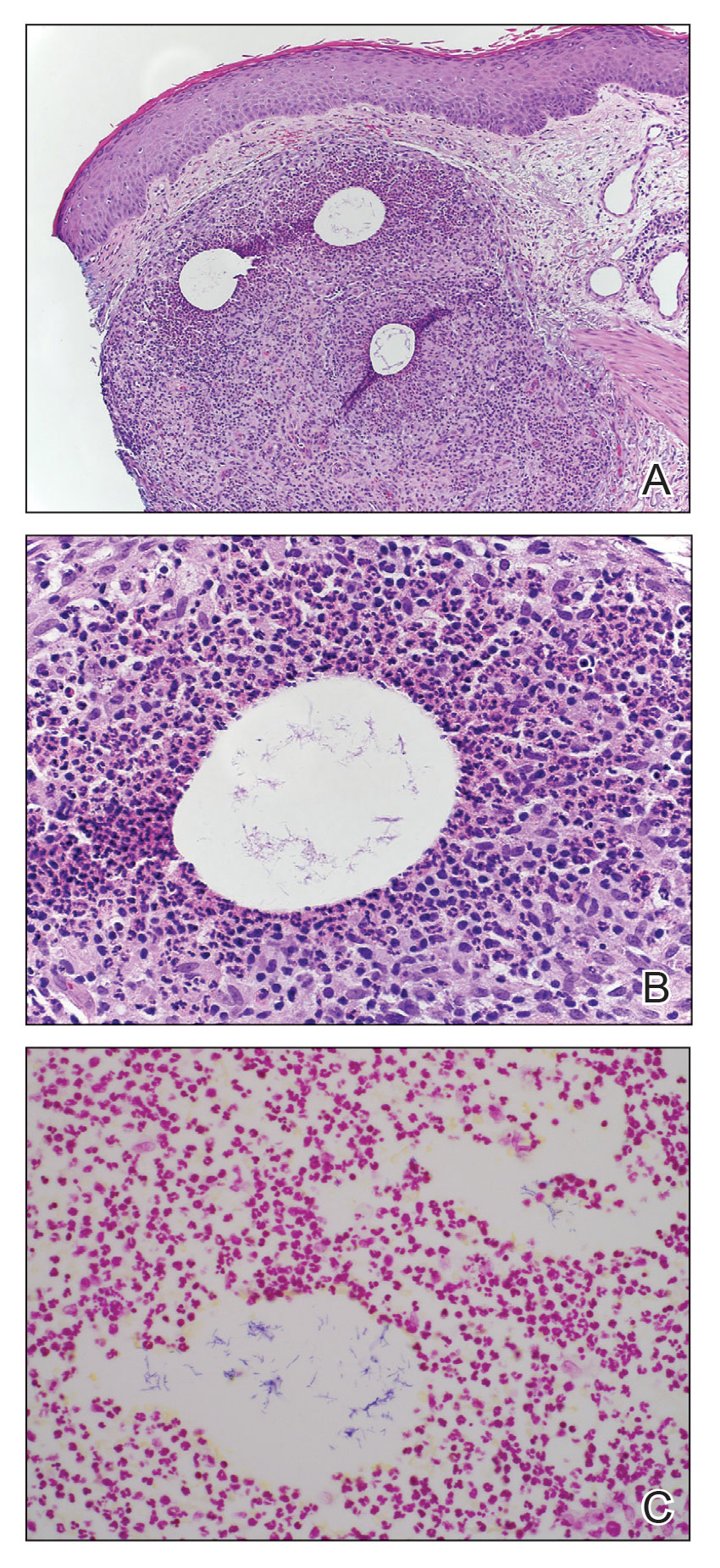

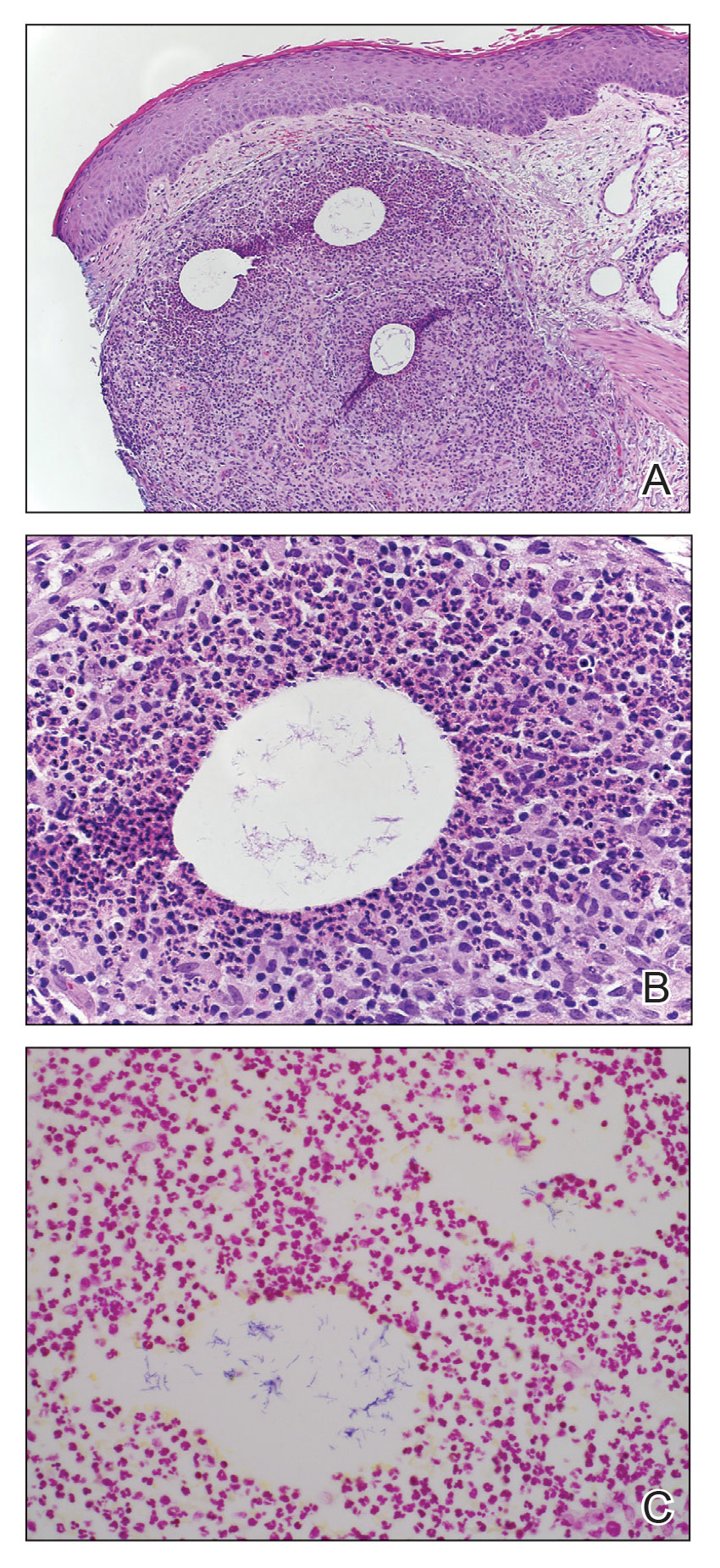

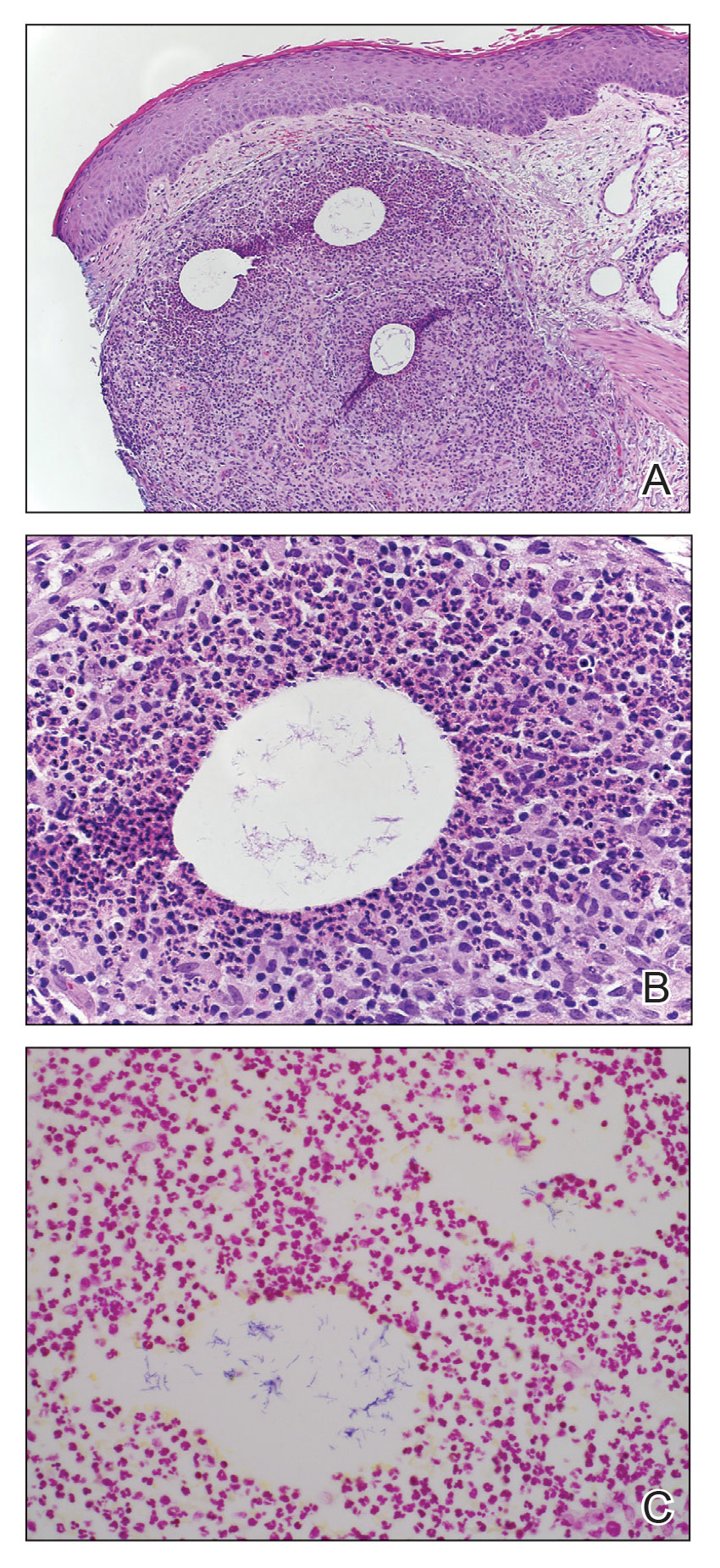

An 86-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a pruritic rash on the right forearm. He had a history of chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and inverse psoriasis complicated by steroid atrophy. He reported trauma to the right antecubital fossa approximately 1 to 2 months prior from a car door; he received wound care over several weeks at an outside hospital. The initial wound healed completely, but he subsequently noticed erythema spreading down the forearm. At the current presentation, he was empirically treated with mid-potency topical steroids and cefuroxime for 7 days. Initial laboratory results were notable for a white blood cell count of 5.7×103 cells/μL (reference range,3.7–8.4×103 cells/μL) and a creatinine level of 1.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.57–1.25 mg/dL). The patient returned to the emergency department 2 weeks later with spreading of the initial rash and worsening pruritus. Dermatologic evaluation revealed the patient was afebrile and had violaceous papules and nodules that coalesced into plaques on the right arm, with the largest measuring approximately 15 cm. Areas of superficial erosion and crusting were noted (Figure 1A). The patient denied constitutional symptoms and had no axillary or cervical lymphadenopathy. The differential initially included an atypical infection vs a neoplasm. Two 5-mm punch biopsies were performed, which demonstrated a suppurative granulomatous infiltrate in the dermis with extension into the subcutis (Figure 2A). Focal vacuolations within the dermis demonstrated aggregates of gram-positive pseudofilamentous organisms (Figures 2B and 2C). Aerobic tissue cultures grew G bronchialis that was susceptible to all antibiotics tested and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Fungal and mycobacterial cultures were negative. The patient was placed on amoxicillin 875 mg–clavulanate 125 mg twice daily for 3 weeks. However, he demonstrated progression of the rash, with increased induration and confluence of plaques on the forearm (Figure 1B). A repeat excisional biopsy was performed, and a tissue sample was sent for 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing identification. However, neither conventional cultures nor sequencing demonstrated evidence of G bronchialis or any other pathogen. Additionally, bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial blood cultures were negative. Amoxicillin-clavulanate was stopped, and he was placed on trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 2 weeks, then changed to linezolid (600 mg twice daily) due to continued lack of improvement of the rash. After 2 weeks of linezolid, the rash was slightly improved, but the patient had notable side effects (eg, nausea, mucositis). Therefore, he was switched back to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for another 6 weeks. Antibiotic therapy was discontinued after there was notable regression of indurated plaques (Figure 1C); he received more than 3 months of antibiotics in all. At 1 month after completion of antibiotic therapy, the patient had no evidence of recurrence.

Comment

Microbiology of Gordonia Species—Gordonia bronchialis originally was isolated in 1971 by Tsukamura et al5 from the sputum of patients with cavitary tuberculosis and bronchiectasis in Japan. Other Gordonia species (formerly Rhodococcus or Gordona) later were identified in soil, seawater, sediment, and wastewater. Gordonia bronchialis is a gram-positive aerobic actinomycete short rod that organizes in cordlike compact groups. It is weakly acid fast, nonmotile, and nonsporulating. Colonies exhibit pinkish-brown pigmentation. Our understanding of the clinical significance of this organism continues to evolve, and it is not always clearly pathogenic. Because Gordonia isolates may be dismissed as commensals or misidentified as Nocardia or Rhodococcus by routine biochemical tests, it is possible that infections may go undetected. Speciation requires gene sequencing; as our utilization of molecular methods has increased, the identification of clinically relevant aerobic actinomycetes, including Gordonia, has improved,6 and the following species have been recognized as pathogens: Gordonia araii, G bronchialis, Gordonia effusa, Gordonia otitidis, Gordonia polyisoprenivorans, Gordonia rubirpertincta, Gordonia sputi, and Gordonia terrae.7

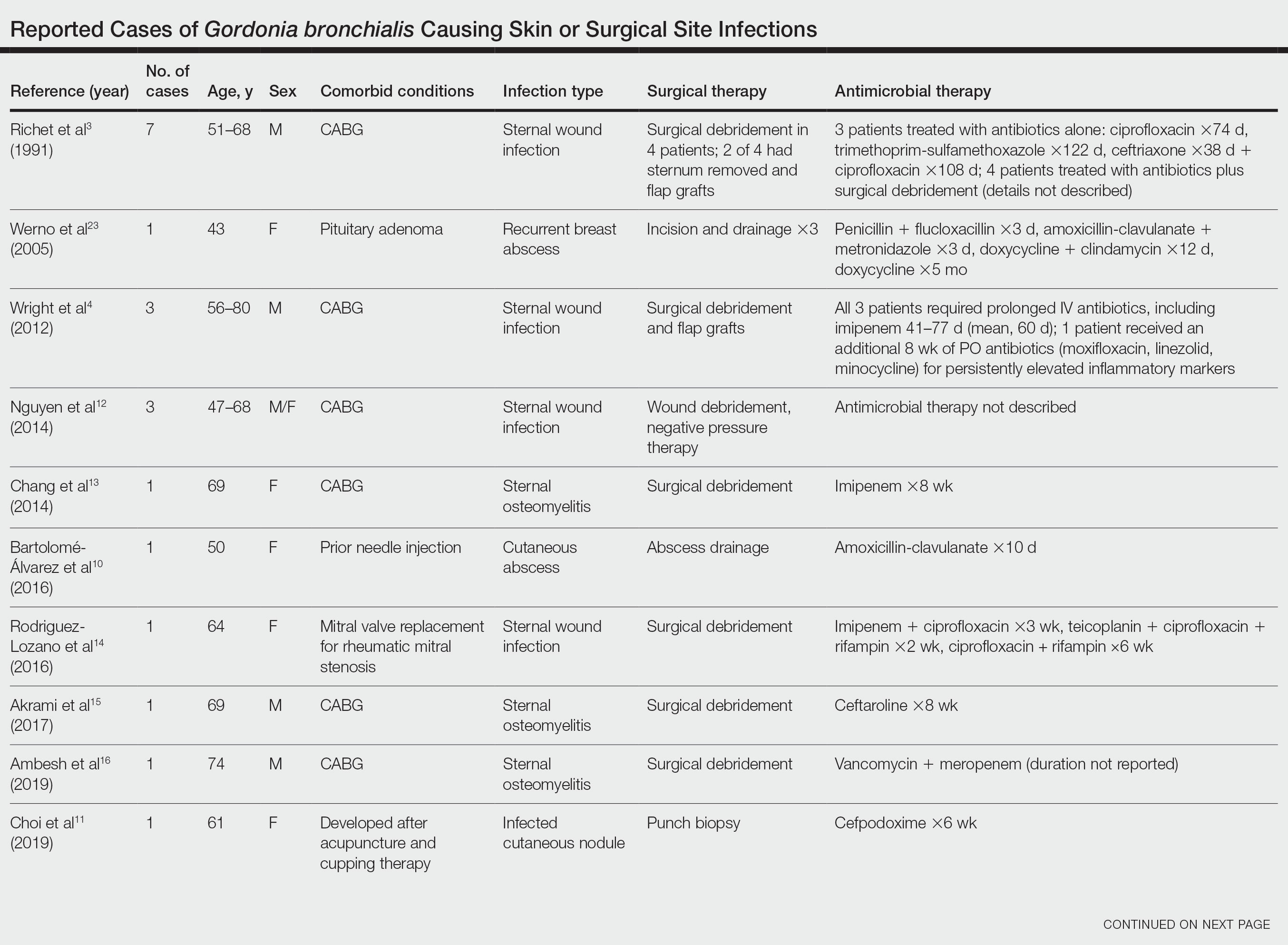

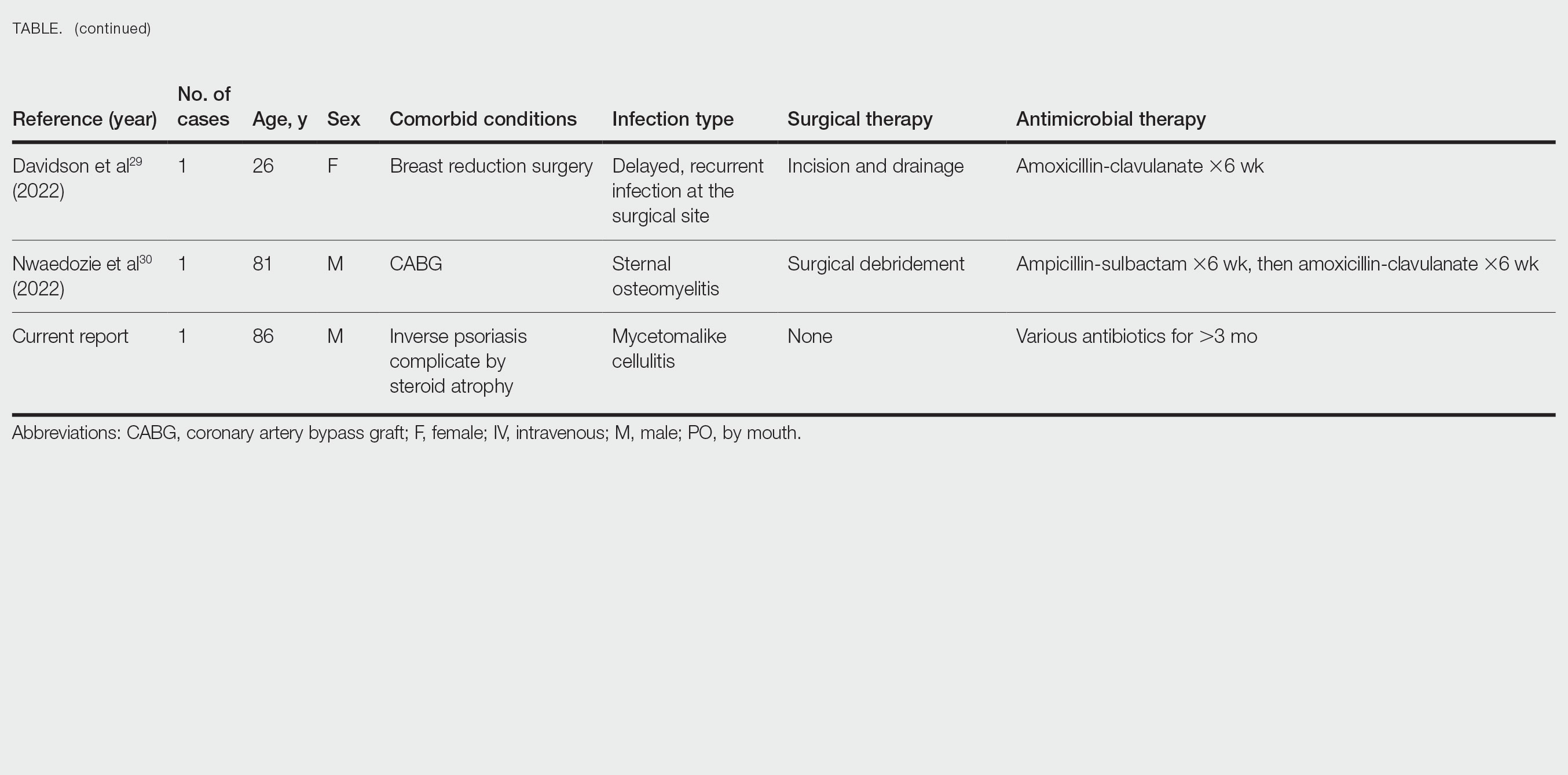

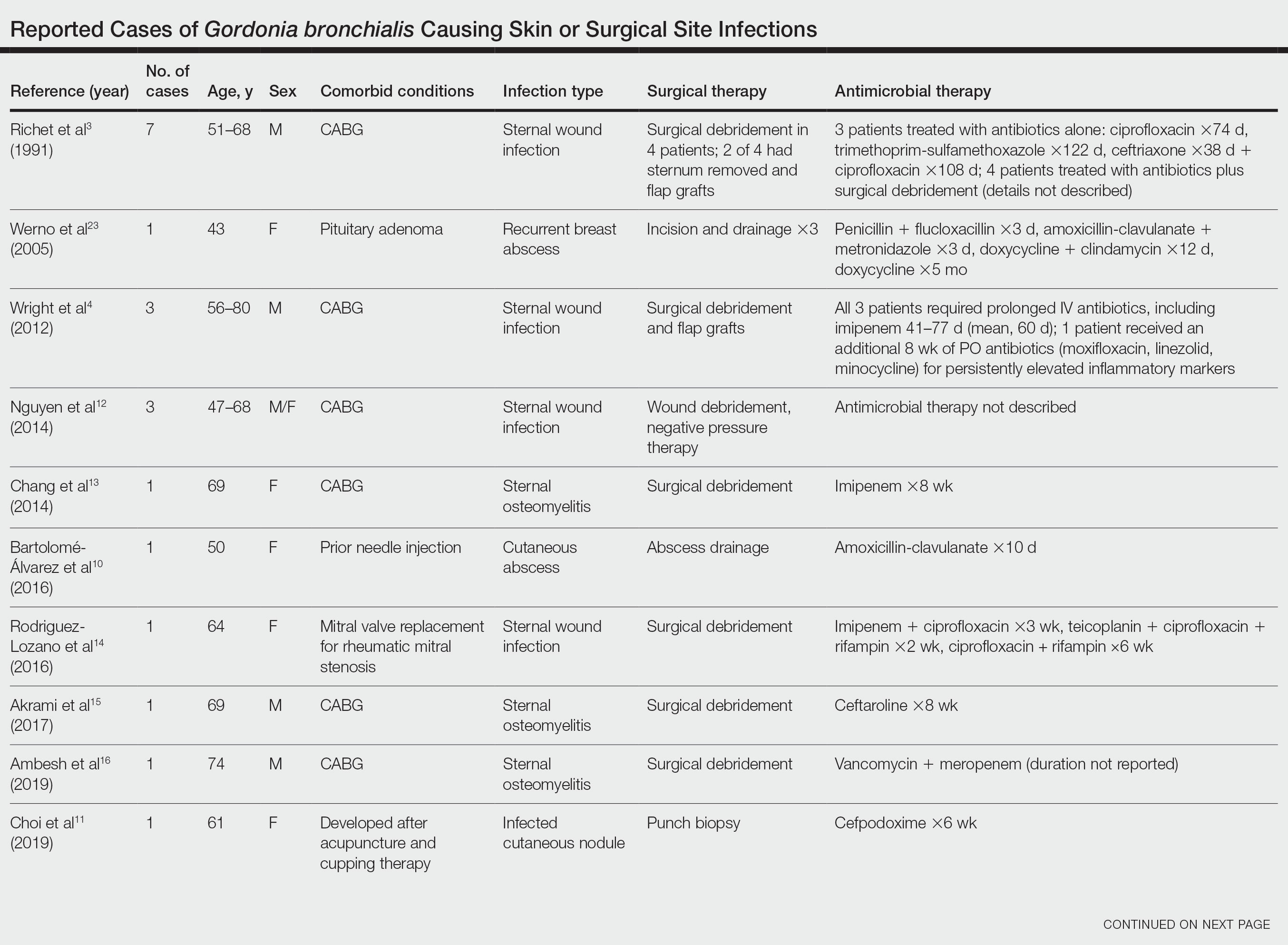

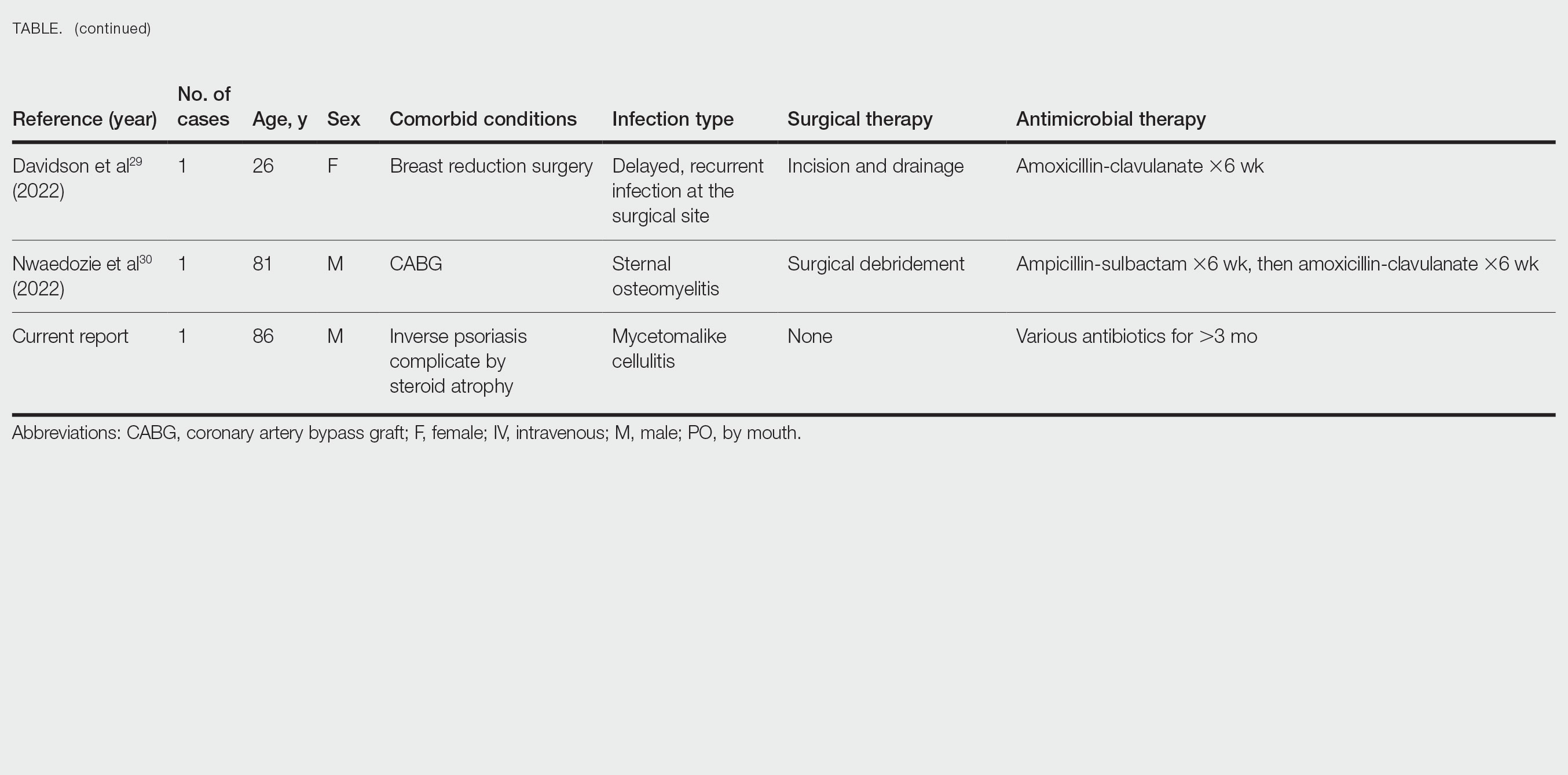

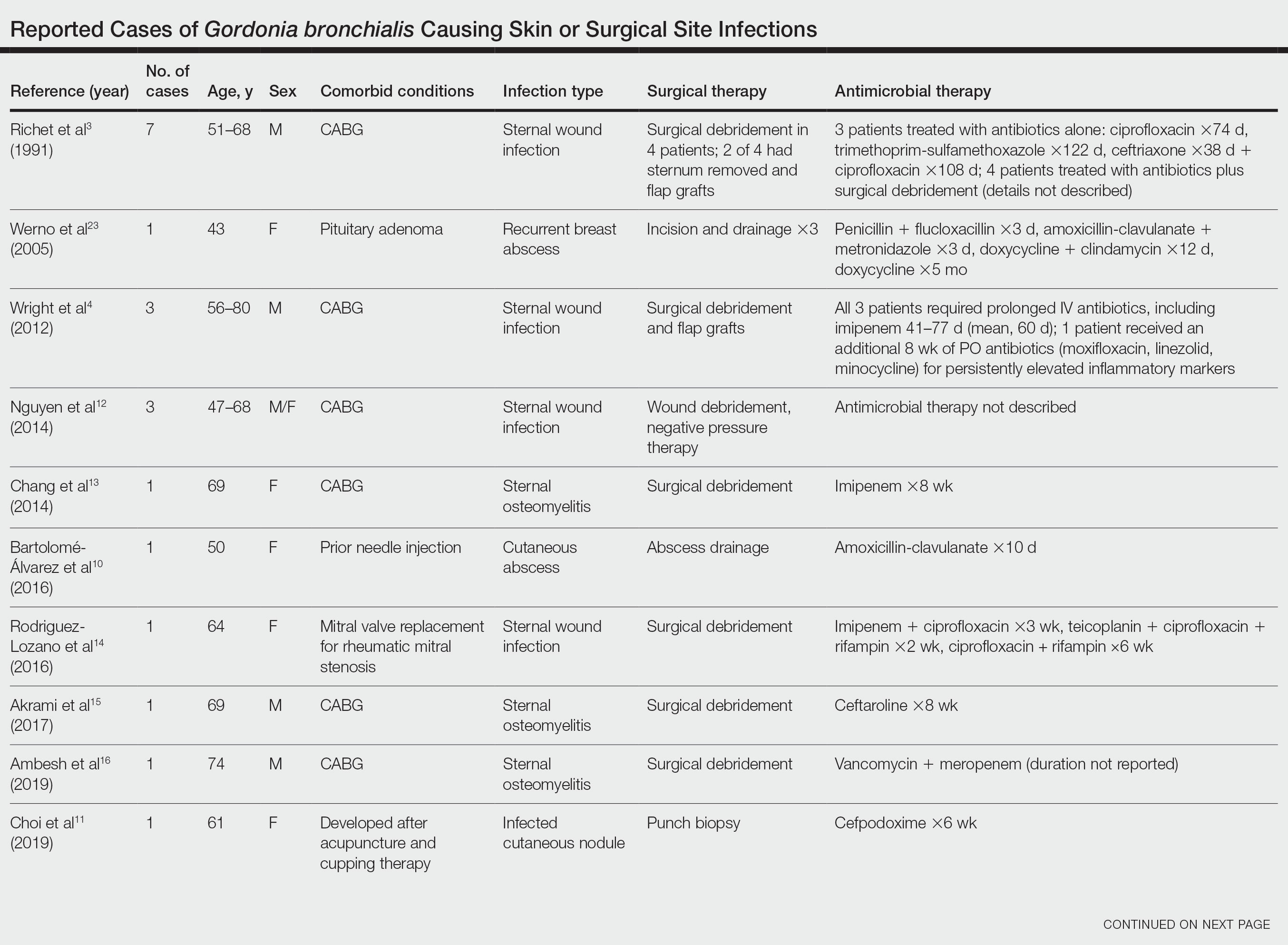

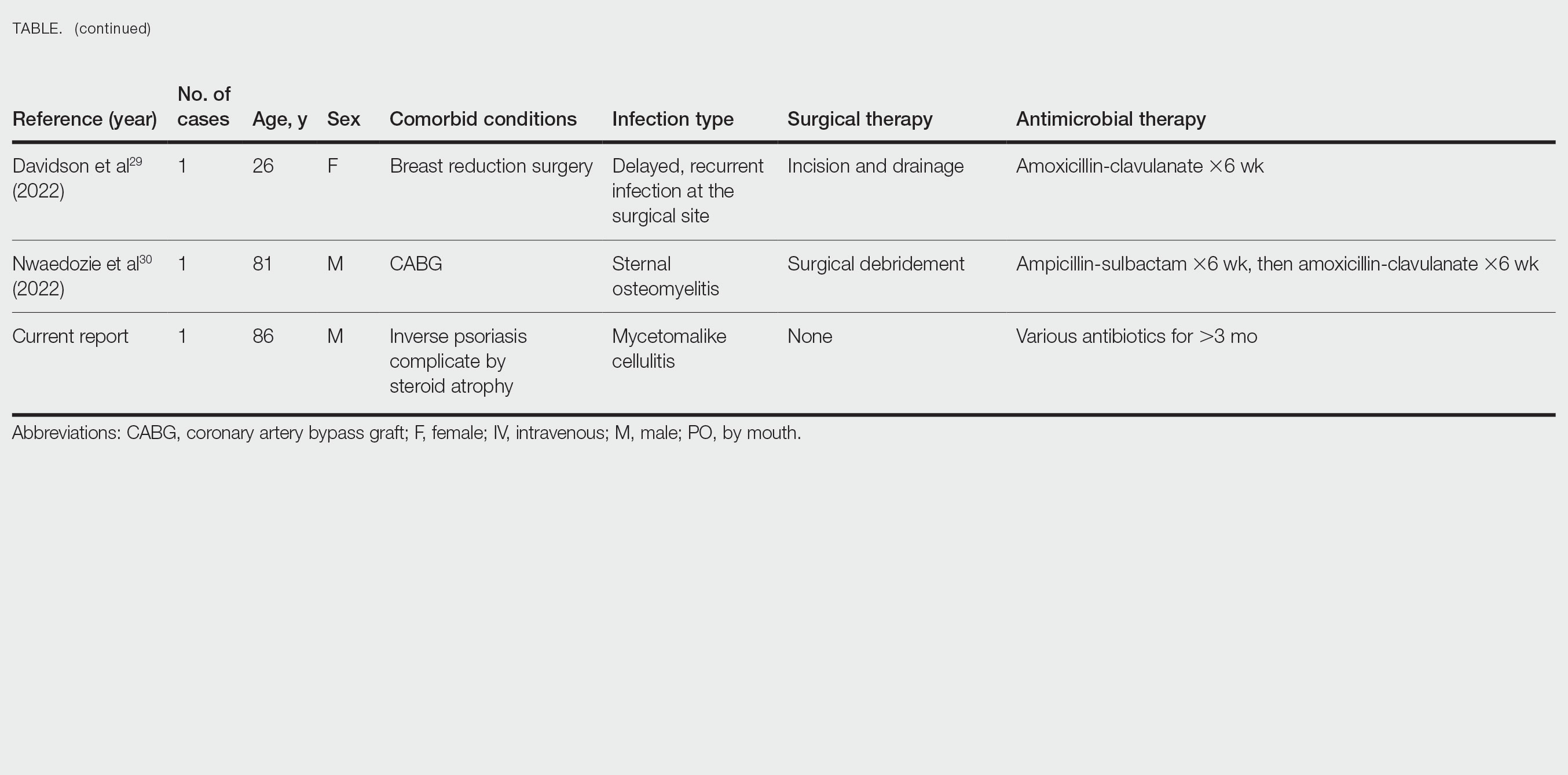

Cases Reported in the Literature—A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term Gordonia bronchialis yielded 35 previously reported human cases of G bronchialis infection, most often associated with medical devices or procedures.8-31 Eighteen of these cases were sternal surgical site infections in patients with a history of cardiac surgery,3,4,12-16,30 including 2 outbreaks following coronary artery bypass grafting that were thought to be related to intraoperative transmission from a nurse.3,4 Of the remaining cases, 12 were linked to a procedure or an indwelling catheter: 4 cases of peritonitis in the setting of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis17,18,26,27; 3 cases of skin and soft tissue infection (1 at the site of a prior needle injection,10 1 after acupuncture,11 and 1 after breast reduction surgery29); 1 case of ventriculitis in a premature neonate with an underlying intraventricular shunt19; 2 cases of pacemaker-induced endocarditis20,28; 1 case of tibial osteomyelitis related to a bioresorbable polymer screw21; and 1 case of chronic endophthalmitis with underlying intraocular lens implants.22 The Table lists all cases of G bronchialis skin or surgical site infections encountered in our literature search as well as the treatment provided in each case.

Only 4 of these 35 cases of G bronchialis infections were skin and soft tissue infections. All 4 occurred in immunocompetent hosts, and 3 were associated with needle punctures or surgery. The fourth case involved a recurrent breast abscess that occurred in a patient without known risk factors or recent procedures.23 Other Gordonia species have been associated with cutaneous infections, including Gordonia amicalis, G terrae, and recently Gordonia westfalica, with the latter 2 demonstrating actinomycetoma formation.32-34 Our case is remarkable in that it represents actinomycetoma due to G bronchialis. Of note, our patient was immunocompetent and did not have any radiation or chronic lymphedema involving the affected extremity. However, his history of steroid-induced skin atrophy may have predisposed him to this rare infection.

Clinical Presentation—Classic mycetoma demonstrate organismal granules within the dermis, surrounded by a neutrophilic infiltrate, which is in turn surrounded by histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Periodic acid–Schiff and silver stains can identify fungal organisms, while Gram stain helps to elucidate bacterial etiologies.1 In our patient, a biopsy revealed several dermal aggregates of pseudofilamentous gram-positive organisms surrounded by a neutrophilic and histiocytic infiltrate.8 Because this case presented over weeks to months rather than months to years, it progressed more rapidly than a classic mycetoma. However, the dermatologic and histologic features were consistent with mycetoma.

Management—General treatment of actinomycetoma requires identification of the causative organism and prolonged administration of antibiotics, typically in combination.35-37 Most G bronchialis infections associated with surgical intervention or implants in the literature required surgical debridement and removal of contaminated material for clinical cure, with the exception of 3 cases of sternal wound infection and 1 case of peritonitis that recovered with antimicrobial therapy alone.3,17 Combination therapy often was used, but monotherapy, particularly with a fluoroquinolone, has been reported. Susceptibility data are limited, but in general, Gordonia species appear susceptible to imipenem, ciprofloxacin, amikacin, gentamicin, and linezolid, with variable susceptibility to vancomycin (89% of isolates), third-generation cephalosporins (80%–90% of isolates), tetracyclines (≤85% of isolates), penicillin (≤70% of isolates), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (≤65% of isolates).7,10,19,38-40 Although there are no standardized recommendations for the treatment of these infections, the most commonly used drugs to treat Gordonia are carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, with or without an aminoglycoside, followed by third-generation cephalosporins and vancomycin, depending on susceptibilities. Additional antibiotics (alone or in combination) that have previously been used with favorable outcomes include amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate, piperacillin-tazobactam, rifampicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, doxycycline, and daptomycin.

Our patient received amoxicillin-clavulanate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid. We considered combination therapy but decided against it due to concern for toxicity, given his age and poor renal function. The antibiotic that was most important to his recovery was unclear; the patient insisted that his body, not antibiotics, deserved most of the credit for healing his arm. Although cultures and polymerase chain reaction assays were negative after 3 weeks of amoxicillin-clavulanate, the patient did not show clinical improvement—reasons could be because the antibiotic reduced but did not eliminate the bacterial burden, sampling error of the biopsy, or it takes much longer for the body to heal than it takes to kill the bacteria. Most likely a combination of factors was at play.

Conclusion

Gordonia bronchialis is an emerging cause of human infections typically occurring after trauma, inoculation, or surgery. Most infections are localized; however, the present case highlights the ability of this species to form a massive cutaneous infection. Treatment should be tailored to susceptibility, with close follow-up to ensure improvement and resolution. For clinicians encountering a similar case, we encourage biopsy prior to empiric antibiotics, as antibiotic therapy can decrease the yield of subsequent testing. Treatment should be guided by the clinical course and may need to last weeks to months. Combination therapy for Gordonia infections should be considered in severe cases, in cases presenting as actinomycetoma, in those not responding to therapy, or when the susceptibility profile is unknown or unreliable.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank this veteran for allowing us to participate in his care and to learn from his experience. He gave his consent for us to share his story and the photographs of the arm.

- Arenas R, Fernandez Martinez RF, Torres-Guerrero E, et al. Actinomycetoma: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Cutis. 2017;99:E11-E15.

- Poonwan N, Mekha N, Yazawa K, et al. Characterization of clinical isolates of pathogenic Nocardia strains and related actinomycetes in Thailand from 1996 to 2003. Mycopathologia. 2005;159:361-368.

- Richet HM, Craven PC, Brown JM, et al. A cluster of Rhodococcus (Gordona) bronchialis sternal-wound infections after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:104-109.

- Wright SN, Gerry JS, Busowski MT, et al. Gordonia bronchialis sternal wound infection in 3 patients following open heart surgery: intraoperative transmission from a healthcare worker. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1238-1241.

- Tsukamura M. Proposal of a new genus, Gordona, for slightly acid-fast organisms occurring in sputa of patients with pulmonary disease and in soil. J Gen Microbiol. 1971;68:15-26.

- Wang T, Kong F, Chen S, et al. Improved identification of Gordonia, Rhodococcus and Tsukamurella species by 5′-end 16s rRNA gene sequencing. Pathology. 2011;43:58-63.

- Aoyama K, Kang Y, Yazawa K, et al. Characterization of clinical isolates of Gordonia species in Japanese clinical samples during 1998-2008. Mycopathologia. 2009;168:175-183.

- Ivanova N, Sikorski J, Jando M, et al. Complete genome sequence of Gordonia bronchialis type strain (3410 T). Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;2:19-28.

- Johnson JA, Onderdonk AB, Cosimi LA, et al. Gordonia bronchialis bacteremia and pleural infection: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1662-1666.

- Bartolomé-Álvarez J, Sáez-Nieto JA, Escudero-Jiménez A, et al. Cutaneous abscess due to Gordonia bronchialis: case report and literature review. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2016;29:170-173.

- Choi ME, Jung CJ, Won CH, et al. Case report of cutaneous nodule caused by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient after receiving acupuncture. J Dermatol. 2019;46:343-346.

- Nguyen DB, Gupta N, Abou-Daoud A, et al. A polymicrobial outbreak of surgical site infections following cardiac surgery at a community hospital in Florida, 2011-2012. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:432-435.

- Chang JH, Ji M, Hong HL, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis caused byGordonia bronchialis after open-heart surgery. Infect Chemother. 2014;46:110-114.

- Rodriguez-Lozano J, Pérez-Llantada E, Agüero J, et al. Sternal wound infection caused by Gordonia bronchialis: identification by MALDI-TOF MS. JMM Case Rep. 2016;3:e005067.

- Akrami K, Coletta J, Mehta S, et al. Gordonia sternal wound infection treated with ceftaroline: case report and literature review. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4:e005113.

- Ambesh P, Kapoor A, Kazmi D, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient after open heart surgery. Ann Card Anaesth. 2019;22:221-224.

- Ma TKW, Chow KM, Kwan BCH, et al. Peritoneal-dialysis related peritonitis caused by Gordonia species: report of four cases and literature review. Nephrology. 2014;19:379-383.

- Lam JYW, Wu AKL, Leung WS, et al. Gordonia species as emerging causes of continuous-ambulatory-peritoneal-dialysis-related peritonitis identified by 16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequencing and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:671-676.

- Blaschke AJ, Bender J, Byington CL, et al. Gordonia species: emerging pathogens in pediatric patients that are identified by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:483-486.

- Titécat M, Loïez C, Courcol RJ, et al. Difficulty with Gordonia bronchialis identification by Microflex mass spectrometer in a pacemaker‐induced endocarditis. JMM Case Rep. 2014;1:E003681.

- Siddiqui N, Toumeh A, Georgescu C. Tibial osteomyelitis caused by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3119-3121.

- Choi R, Strnad L, Flaxel CJ, et al. Gordonia bronchialis–associated endophthalmitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:1017-1019.

- Werno AM, Anderson TP, Chambers ST, et al. Recurrent breast abscess caused by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3009-3010.

- Sng LH, Koh TH, Toney SR, et al. Bacteremia caused by Gordonia bronchialis in a patient with sequestrated lung. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2870-2871.

- Ramanan P, Deziel PJ, Wengenack NL. Gordonia bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:3443-3447.

- Sukackiene D, Rimsevicius L, Kiveryte S, et al. A case of successfully treated relapsing peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis caused by Gordonia bronchialis in a farmer. Nephrol Ther. 2018;14:109-111.

- Bruno V, Tjon J, Lin S, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis caused by Gordonia bronchialis: first pediatric report. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;37:217-220. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-05313-3

- Mormeneo Bayo S, Palacián Ruíz MP, Asin Samper U, et al. Pacemaker-induced endocarditis by Gordonia bronchialis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed). 2022;40:255-257.

- Davidson AL, Driscoll CR, Luther VP, et al. Recurrent skin and soft tissue infection following breast reduction surgery caused by Gordonia bronchialis: a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10:E4395.

- Nwaedozie S, Mojarrab JN, Gopinath P, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis caused by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient following coronary artery bypass surgery. IDCases. 2022;29:E01548.

- Nakahama H, Hanada S, Takada K, et al. Obstructive pneumonia caused by Gordonia bronchialis with a bronchial foreign body. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;124:157-158. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.09.028

- Lai CC, Hsieh JH, Tsai HY, et al. Cutaneous infection caused by Gordonia amicalis after a traumatic injury. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1821-1822.

- Bakker XR, Spauwen PHM, Dolmans WMV. Mycetoma of the hand caused by Gordona terrae: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29:188-190.

- Gueneau R, Blanchet D, Rodriguez-Nava V, et al. Actinomycetoma caused by Gordonia westfalica: first reported case of human infection. New Microbes New Infect. 2020;34:100658.

- Auwaerter PG, ed. The Johns Hopkins POC-IT ABX Guide. Johns Hopkins Medicine; 2021.

- Welsh O, Sauceda E, Gonzalez J, et al. Amikacin alone andin combination with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of actinomycotic mycetoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:443-448.

- Zijlstra EE, van de Sande WWJ, Welsh O, et al. Mycetoma: a unique neglected tropical disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:100-112.

- Pham AS, Dé I, Rolston KV, et al. Catheter-related bacteremia caused by the nocardioform actinomycete Gordonia terrae. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:524-527.

- Renvoise A, Harle JR, Raoult D, et al. Gordonia sputi bacteremia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1535-1537.

- Moser BD, Pellegrini GJ, Lasker BA, et al. Pattern of antimicrobial susceptibility obtained from blood isolates of a rare but emerging human pathogen, Gordonia polyisoprenivorans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4991-4993.

Mycetoma is a chronic subcutaneous infection due to fungal (eumycetoma) or aerobic actinomycetes (actinomycetoma) organisms. Clinical lesions develop from a granulomatous infiltrate organizing around the infectious organism. Patients can present with extensive subcutaneous nodularity and draining sinuses that can lead to deformation of the affected extremity. These infections are rare in developed countries, and the prevalence and incidence remain unknown. It has been reported that actinomycetes represent 60% of mycetoma cases worldwide, with the majority of cases in Central America from Nocardia (86%) and Actinomadura madurae (10%). 1Gordonia species are aerobic, partially acid-fast, gram-positive actinobacteria that may comprise a notable minority of actinomycete isolates. 2 The species Gordonia bronchialis is of particular interest as a human pathogen because of increasing reports of nosocomial infections. 3,4 We describe a case of a mycetomalike infection due to G bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient with complete resolution after 3 months of antibiotics.

Case Report

An 86-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a pruritic rash on the right forearm. He had a history of chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and inverse psoriasis complicated by steroid atrophy. He reported trauma to the right antecubital fossa approximately 1 to 2 months prior from a car door; he received wound care over several weeks at an outside hospital. The initial wound healed completely, but he subsequently noticed erythema spreading down the forearm. At the current presentation, he was empirically treated with mid-potency topical steroids and cefuroxime for 7 days. Initial laboratory results were notable for a white blood cell count of 5.7×103 cells/μL (reference range,3.7–8.4×103 cells/μL) and a creatinine level of 1.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.57–1.25 mg/dL). The patient returned to the emergency department 2 weeks later with spreading of the initial rash and worsening pruritus. Dermatologic evaluation revealed the patient was afebrile and had violaceous papules and nodules that coalesced into plaques on the right arm, with the largest measuring approximately 15 cm. Areas of superficial erosion and crusting were noted (Figure 1A). The patient denied constitutional symptoms and had no axillary or cervical lymphadenopathy. The differential initially included an atypical infection vs a neoplasm. Two 5-mm punch biopsies were performed, which demonstrated a suppurative granulomatous infiltrate in the dermis with extension into the subcutis (Figure 2A). Focal vacuolations within the dermis demonstrated aggregates of gram-positive pseudofilamentous organisms (Figures 2B and 2C). Aerobic tissue cultures grew G bronchialis that was susceptible to all antibiotics tested and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Fungal and mycobacterial cultures were negative. The patient was placed on amoxicillin 875 mg–clavulanate 125 mg twice daily for 3 weeks. However, he demonstrated progression of the rash, with increased induration and confluence of plaques on the forearm (Figure 1B). A repeat excisional biopsy was performed, and a tissue sample was sent for 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing identification. However, neither conventional cultures nor sequencing demonstrated evidence of G bronchialis or any other pathogen. Additionally, bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial blood cultures were negative. Amoxicillin-clavulanate was stopped, and he was placed on trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 2 weeks, then changed to linezolid (600 mg twice daily) due to continued lack of improvement of the rash. After 2 weeks of linezolid, the rash was slightly improved, but the patient had notable side effects (eg, nausea, mucositis). Therefore, he was switched back to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for another 6 weeks. Antibiotic therapy was discontinued after there was notable regression of indurated plaques (Figure 1C); he received more than 3 months of antibiotics in all. At 1 month after completion of antibiotic therapy, the patient had no evidence of recurrence.

Comment

Microbiology of Gordonia Species—Gordonia bronchialis originally was isolated in 1971 by Tsukamura et al5 from the sputum of patients with cavitary tuberculosis and bronchiectasis in Japan. Other Gordonia species (formerly Rhodococcus or Gordona) later were identified in soil, seawater, sediment, and wastewater. Gordonia bronchialis is a gram-positive aerobic actinomycete short rod that organizes in cordlike compact groups. It is weakly acid fast, nonmotile, and nonsporulating. Colonies exhibit pinkish-brown pigmentation. Our understanding of the clinical significance of this organism continues to evolve, and it is not always clearly pathogenic. Because Gordonia isolates may be dismissed as commensals or misidentified as Nocardia or Rhodococcus by routine biochemical tests, it is possible that infections may go undetected. Speciation requires gene sequencing; as our utilization of molecular methods has increased, the identification of clinically relevant aerobic actinomycetes, including Gordonia, has improved,6 and the following species have been recognized as pathogens: Gordonia araii, G bronchialis, Gordonia effusa, Gordonia otitidis, Gordonia polyisoprenivorans, Gordonia rubirpertincta, Gordonia sputi, and Gordonia terrae.7

Cases Reported in the Literature—A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term Gordonia bronchialis yielded 35 previously reported human cases of G bronchialis infection, most often associated with medical devices or procedures.8-31 Eighteen of these cases were sternal surgical site infections in patients with a history of cardiac surgery,3,4,12-16,30 including 2 outbreaks following coronary artery bypass grafting that were thought to be related to intraoperative transmission from a nurse.3,4 Of the remaining cases, 12 were linked to a procedure or an indwelling catheter: 4 cases of peritonitis in the setting of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis17,18,26,27; 3 cases of skin and soft tissue infection (1 at the site of a prior needle injection,10 1 after acupuncture,11 and 1 after breast reduction surgery29); 1 case of ventriculitis in a premature neonate with an underlying intraventricular shunt19; 2 cases of pacemaker-induced endocarditis20,28; 1 case of tibial osteomyelitis related to a bioresorbable polymer screw21; and 1 case of chronic endophthalmitis with underlying intraocular lens implants.22 The Table lists all cases of G bronchialis skin or surgical site infections encountered in our literature search as well as the treatment provided in each case.

Only 4 of these 35 cases of G bronchialis infections were skin and soft tissue infections. All 4 occurred in immunocompetent hosts, and 3 were associated with needle punctures or surgery. The fourth case involved a recurrent breast abscess that occurred in a patient without known risk factors or recent procedures.23 Other Gordonia species have been associated with cutaneous infections, including Gordonia amicalis, G terrae, and recently Gordonia westfalica, with the latter 2 demonstrating actinomycetoma formation.32-34 Our case is remarkable in that it represents actinomycetoma due to G bronchialis. Of note, our patient was immunocompetent and did not have any radiation or chronic lymphedema involving the affected extremity. However, his history of steroid-induced skin atrophy may have predisposed him to this rare infection.

Clinical Presentation—Classic mycetoma demonstrate organismal granules within the dermis, surrounded by a neutrophilic infiltrate, which is in turn surrounded by histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Periodic acid–Schiff and silver stains can identify fungal organisms, while Gram stain helps to elucidate bacterial etiologies.1 In our patient, a biopsy revealed several dermal aggregates of pseudofilamentous gram-positive organisms surrounded by a neutrophilic and histiocytic infiltrate.8 Because this case presented over weeks to months rather than months to years, it progressed more rapidly than a classic mycetoma. However, the dermatologic and histologic features were consistent with mycetoma.

Management—General treatment of actinomycetoma requires identification of the causative organism and prolonged administration of antibiotics, typically in combination.35-37 Most G bronchialis infections associated with surgical intervention or implants in the literature required surgical debridement and removal of contaminated material for clinical cure, with the exception of 3 cases of sternal wound infection and 1 case of peritonitis that recovered with antimicrobial therapy alone.3,17 Combination therapy often was used, but monotherapy, particularly with a fluoroquinolone, has been reported. Susceptibility data are limited, but in general, Gordonia species appear susceptible to imipenem, ciprofloxacin, amikacin, gentamicin, and linezolid, with variable susceptibility to vancomycin (89% of isolates), third-generation cephalosporins (80%–90% of isolates), tetracyclines (≤85% of isolates), penicillin (≤70% of isolates), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (≤65% of isolates).7,10,19,38-40 Although there are no standardized recommendations for the treatment of these infections, the most commonly used drugs to treat Gordonia are carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, with or without an aminoglycoside, followed by third-generation cephalosporins and vancomycin, depending on susceptibilities. Additional antibiotics (alone or in combination) that have previously been used with favorable outcomes include amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate, piperacillin-tazobactam, rifampicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, doxycycline, and daptomycin.

Our patient received amoxicillin-clavulanate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid. We considered combination therapy but decided against it due to concern for toxicity, given his age and poor renal function. The antibiotic that was most important to his recovery was unclear; the patient insisted that his body, not antibiotics, deserved most of the credit for healing his arm. Although cultures and polymerase chain reaction assays were negative after 3 weeks of amoxicillin-clavulanate, the patient did not show clinical improvement—reasons could be because the antibiotic reduced but did not eliminate the bacterial burden, sampling error of the biopsy, or it takes much longer for the body to heal than it takes to kill the bacteria. Most likely a combination of factors was at play.

Conclusion

Gordonia bronchialis is an emerging cause of human infections typically occurring after trauma, inoculation, or surgery. Most infections are localized; however, the present case highlights the ability of this species to form a massive cutaneous infection. Treatment should be tailored to susceptibility, with close follow-up to ensure improvement and resolution. For clinicians encountering a similar case, we encourage biopsy prior to empiric antibiotics, as antibiotic therapy can decrease the yield of subsequent testing. Treatment should be guided by the clinical course and may need to last weeks to months. Combination therapy for Gordonia infections should be considered in severe cases, in cases presenting as actinomycetoma, in those not responding to therapy, or when the susceptibility profile is unknown or unreliable.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank this veteran for allowing us to participate in his care and to learn from his experience. He gave his consent for us to share his story and the photographs of the arm.

Mycetoma is a chronic subcutaneous infection due to fungal (eumycetoma) or aerobic actinomycetes (actinomycetoma) organisms. Clinical lesions develop from a granulomatous infiltrate organizing around the infectious organism. Patients can present with extensive subcutaneous nodularity and draining sinuses that can lead to deformation of the affected extremity. These infections are rare in developed countries, and the prevalence and incidence remain unknown. It has been reported that actinomycetes represent 60% of mycetoma cases worldwide, with the majority of cases in Central America from Nocardia (86%) and Actinomadura madurae (10%). 1Gordonia species are aerobic, partially acid-fast, gram-positive actinobacteria that may comprise a notable minority of actinomycete isolates. 2 The species Gordonia bronchialis is of particular interest as a human pathogen because of increasing reports of nosocomial infections. 3,4 We describe a case of a mycetomalike infection due to G bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient with complete resolution after 3 months of antibiotics.

Case Report

An 86-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a pruritic rash on the right forearm. He had a history of chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and inverse psoriasis complicated by steroid atrophy. He reported trauma to the right antecubital fossa approximately 1 to 2 months prior from a car door; he received wound care over several weeks at an outside hospital. The initial wound healed completely, but he subsequently noticed erythema spreading down the forearm. At the current presentation, he was empirically treated with mid-potency topical steroids and cefuroxime for 7 days. Initial laboratory results were notable for a white blood cell count of 5.7×103 cells/μL (reference range,3.7–8.4×103 cells/μL) and a creatinine level of 1.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.57–1.25 mg/dL). The patient returned to the emergency department 2 weeks later with spreading of the initial rash and worsening pruritus. Dermatologic evaluation revealed the patient was afebrile and had violaceous papules and nodules that coalesced into plaques on the right arm, with the largest measuring approximately 15 cm. Areas of superficial erosion and crusting were noted (Figure 1A). The patient denied constitutional symptoms and had no axillary or cervical lymphadenopathy. The differential initially included an atypical infection vs a neoplasm. Two 5-mm punch biopsies were performed, which demonstrated a suppurative granulomatous infiltrate in the dermis with extension into the subcutis (Figure 2A). Focal vacuolations within the dermis demonstrated aggregates of gram-positive pseudofilamentous organisms (Figures 2B and 2C). Aerobic tissue cultures grew G bronchialis that was susceptible to all antibiotics tested and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Fungal and mycobacterial cultures were negative. The patient was placed on amoxicillin 875 mg–clavulanate 125 mg twice daily for 3 weeks. However, he demonstrated progression of the rash, with increased induration and confluence of plaques on the forearm (Figure 1B). A repeat excisional biopsy was performed, and a tissue sample was sent for 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing identification. However, neither conventional cultures nor sequencing demonstrated evidence of G bronchialis or any other pathogen. Additionally, bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial blood cultures were negative. Amoxicillin-clavulanate was stopped, and he was placed on trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 2 weeks, then changed to linezolid (600 mg twice daily) due to continued lack of improvement of the rash. After 2 weeks of linezolid, the rash was slightly improved, but the patient had notable side effects (eg, nausea, mucositis). Therefore, he was switched back to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for another 6 weeks. Antibiotic therapy was discontinued after there was notable regression of indurated plaques (Figure 1C); he received more than 3 months of antibiotics in all. At 1 month after completion of antibiotic therapy, the patient had no evidence of recurrence.

Comment

Microbiology of Gordonia Species—Gordonia bronchialis originally was isolated in 1971 by Tsukamura et al5 from the sputum of patients with cavitary tuberculosis and bronchiectasis in Japan. Other Gordonia species (formerly Rhodococcus or Gordona) later were identified in soil, seawater, sediment, and wastewater. Gordonia bronchialis is a gram-positive aerobic actinomycete short rod that organizes in cordlike compact groups. It is weakly acid fast, nonmotile, and nonsporulating. Colonies exhibit pinkish-brown pigmentation. Our understanding of the clinical significance of this organism continues to evolve, and it is not always clearly pathogenic. Because Gordonia isolates may be dismissed as commensals or misidentified as Nocardia or Rhodococcus by routine biochemical tests, it is possible that infections may go undetected. Speciation requires gene sequencing; as our utilization of molecular methods has increased, the identification of clinically relevant aerobic actinomycetes, including Gordonia, has improved,6 and the following species have been recognized as pathogens: Gordonia araii, G bronchialis, Gordonia effusa, Gordonia otitidis, Gordonia polyisoprenivorans, Gordonia rubirpertincta, Gordonia sputi, and Gordonia terrae.7

Cases Reported in the Literature—A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term Gordonia bronchialis yielded 35 previously reported human cases of G bronchialis infection, most often associated with medical devices or procedures.8-31 Eighteen of these cases were sternal surgical site infections in patients with a history of cardiac surgery,3,4,12-16,30 including 2 outbreaks following coronary artery bypass grafting that were thought to be related to intraoperative transmission from a nurse.3,4 Of the remaining cases, 12 were linked to a procedure or an indwelling catheter: 4 cases of peritonitis in the setting of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis17,18,26,27; 3 cases of skin and soft tissue infection (1 at the site of a prior needle injection,10 1 after acupuncture,11 and 1 after breast reduction surgery29); 1 case of ventriculitis in a premature neonate with an underlying intraventricular shunt19; 2 cases of pacemaker-induced endocarditis20,28; 1 case of tibial osteomyelitis related to a bioresorbable polymer screw21; and 1 case of chronic endophthalmitis with underlying intraocular lens implants.22 The Table lists all cases of G bronchialis skin or surgical site infections encountered in our literature search as well as the treatment provided in each case.

Only 4 of these 35 cases of G bronchialis infections were skin and soft tissue infections. All 4 occurred in immunocompetent hosts, and 3 were associated with needle punctures or surgery. The fourth case involved a recurrent breast abscess that occurred in a patient without known risk factors or recent procedures.23 Other Gordonia species have been associated with cutaneous infections, including Gordonia amicalis, G terrae, and recently Gordonia westfalica, with the latter 2 demonstrating actinomycetoma formation.32-34 Our case is remarkable in that it represents actinomycetoma due to G bronchialis. Of note, our patient was immunocompetent and did not have any radiation or chronic lymphedema involving the affected extremity. However, his history of steroid-induced skin atrophy may have predisposed him to this rare infection.

Clinical Presentation—Classic mycetoma demonstrate organismal granules within the dermis, surrounded by a neutrophilic infiltrate, which is in turn surrounded by histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Periodic acid–Schiff and silver stains can identify fungal organisms, while Gram stain helps to elucidate bacterial etiologies.1 In our patient, a biopsy revealed several dermal aggregates of pseudofilamentous gram-positive organisms surrounded by a neutrophilic and histiocytic infiltrate.8 Because this case presented over weeks to months rather than months to years, it progressed more rapidly than a classic mycetoma. However, the dermatologic and histologic features were consistent with mycetoma.

Management—General treatment of actinomycetoma requires identification of the causative organism and prolonged administration of antibiotics, typically in combination.35-37 Most G bronchialis infections associated with surgical intervention or implants in the literature required surgical debridement and removal of contaminated material for clinical cure, with the exception of 3 cases of sternal wound infection and 1 case of peritonitis that recovered with antimicrobial therapy alone.3,17 Combination therapy often was used, but monotherapy, particularly with a fluoroquinolone, has been reported. Susceptibility data are limited, but in general, Gordonia species appear susceptible to imipenem, ciprofloxacin, amikacin, gentamicin, and linezolid, with variable susceptibility to vancomycin (89% of isolates), third-generation cephalosporins (80%–90% of isolates), tetracyclines (≤85% of isolates), penicillin (≤70% of isolates), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (≤65% of isolates).7,10,19,38-40 Although there are no standardized recommendations for the treatment of these infections, the most commonly used drugs to treat Gordonia are carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, with or without an aminoglycoside, followed by third-generation cephalosporins and vancomycin, depending on susceptibilities. Additional antibiotics (alone or in combination) that have previously been used with favorable outcomes include amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate, piperacillin-tazobactam, rifampicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, doxycycline, and daptomycin.

Our patient received amoxicillin-clavulanate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid. We considered combination therapy but decided against it due to concern for toxicity, given his age and poor renal function. The antibiotic that was most important to his recovery was unclear; the patient insisted that his body, not antibiotics, deserved most of the credit for healing his arm. Although cultures and polymerase chain reaction assays were negative after 3 weeks of amoxicillin-clavulanate, the patient did not show clinical improvement—reasons could be because the antibiotic reduced but did not eliminate the bacterial burden, sampling error of the biopsy, or it takes much longer for the body to heal than it takes to kill the bacteria. Most likely a combination of factors was at play.

Conclusion

Gordonia bronchialis is an emerging cause of human infections typically occurring after trauma, inoculation, or surgery. Most infections are localized; however, the present case highlights the ability of this species to form a massive cutaneous infection. Treatment should be tailored to susceptibility, with close follow-up to ensure improvement and resolution. For clinicians encountering a similar case, we encourage biopsy prior to empiric antibiotics, as antibiotic therapy can decrease the yield of subsequent testing. Treatment should be guided by the clinical course and may need to last weeks to months. Combination therapy for Gordonia infections should be considered in severe cases, in cases presenting as actinomycetoma, in those not responding to therapy, or when the susceptibility profile is unknown or unreliable.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank this veteran for allowing us to participate in his care and to learn from his experience. He gave his consent for us to share his story and the photographs of the arm.

- Arenas R, Fernandez Martinez RF, Torres-Guerrero E, et al. Actinomycetoma: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Cutis. 2017;99:E11-E15.

- Poonwan N, Mekha N, Yazawa K, et al. Characterization of clinical isolates of pathogenic Nocardia strains and related actinomycetes in Thailand from 1996 to 2003. Mycopathologia. 2005;159:361-368.

- Richet HM, Craven PC, Brown JM, et al. A cluster of Rhodococcus (Gordona) bronchialis sternal-wound infections after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:104-109.

- Wright SN, Gerry JS, Busowski MT, et al. Gordonia bronchialis sternal wound infection in 3 patients following open heart surgery: intraoperative transmission from a healthcare worker. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1238-1241.

- Tsukamura M. Proposal of a new genus, Gordona, for slightly acid-fast organisms occurring in sputa of patients with pulmonary disease and in soil. J Gen Microbiol. 1971;68:15-26.

- Wang T, Kong F, Chen S, et al. Improved identification of Gordonia, Rhodococcus and Tsukamurella species by 5′-end 16s rRNA gene sequencing. Pathology. 2011;43:58-63.

- Aoyama K, Kang Y, Yazawa K, et al. Characterization of clinical isolates of Gordonia species in Japanese clinical samples during 1998-2008. Mycopathologia. 2009;168:175-183.

- Ivanova N, Sikorski J, Jando M, et al. Complete genome sequence of Gordonia bronchialis type strain (3410 T). Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;2:19-28.

- Johnson JA, Onderdonk AB, Cosimi LA, et al. Gordonia bronchialis bacteremia and pleural infection: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1662-1666.

- Bartolomé-Álvarez J, Sáez-Nieto JA, Escudero-Jiménez A, et al. Cutaneous abscess due to Gordonia bronchialis: case report and literature review. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2016;29:170-173.

- Choi ME, Jung CJ, Won CH, et al. Case report of cutaneous nodule caused by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient after receiving acupuncture. J Dermatol. 2019;46:343-346.

- Nguyen DB, Gupta N, Abou-Daoud A, et al. A polymicrobial outbreak of surgical site infections following cardiac surgery at a community hospital in Florida, 2011-2012. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:432-435.

- Chang JH, Ji M, Hong HL, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis caused byGordonia bronchialis after open-heart surgery. Infect Chemother. 2014;46:110-114.

- Rodriguez-Lozano J, Pérez-Llantada E, Agüero J, et al. Sternal wound infection caused by Gordonia bronchialis: identification by MALDI-TOF MS. JMM Case Rep. 2016;3:e005067.

- Akrami K, Coletta J, Mehta S, et al. Gordonia sternal wound infection treated with ceftaroline: case report and literature review. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4:e005113.

- Ambesh P, Kapoor A, Kazmi D, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient after open heart surgery. Ann Card Anaesth. 2019;22:221-224.

- Ma TKW, Chow KM, Kwan BCH, et al. Peritoneal-dialysis related peritonitis caused by Gordonia species: report of four cases and literature review. Nephrology. 2014;19:379-383.

- Lam JYW, Wu AKL, Leung WS, et al. Gordonia species as emerging causes of continuous-ambulatory-peritoneal-dialysis-related peritonitis identified by 16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequencing and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:671-676.

- Blaschke AJ, Bender J, Byington CL, et al. Gordonia species: emerging pathogens in pediatric patients that are identified by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:483-486.

- Titécat M, Loïez C, Courcol RJ, et al. Difficulty with Gordonia bronchialis identification by Microflex mass spectrometer in a pacemaker‐induced endocarditis. JMM Case Rep. 2014;1:E003681.

- Siddiqui N, Toumeh A, Georgescu C. Tibial osteomyelitis caused by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3119-3121.

- Choi R, Strnad L, Flaxel CJ, et al. Gordonia bronchialis–associated endophthalmitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:1017-1019.

- Werno AM, Anderson TP, Chambers ST, et al. Recurrent breast abscess caused by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3009-3010.

- Sng LH, Koh TH, Toney SR, et al. Bacteremia caused by Gordonia bronchialis in a patient with sequestrated lung. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2870-2871.

- Ramanan P, Deziel PJ, Wengenack NL. Gordonia bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:3443-3447.

- Sukackiene D, Rimsevicius L, Kiveryte S, et al. A case of successfully treated relapsing peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis caused by Gordonia bronchialis in a farmer. Nephrol Ther. 2018;14:109-111.

- Bruno V, Tjon J, Lin S, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis caused by Gordonia bronchialis: first pediatric report. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;37:217-220. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-05313-3

- Mormeneo Bayo S, Palacián Ruíz MP, Asin Samper U, et al. Pacemaker-induced endocarditis by Gordonia bronchialis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed). 2022;40:255-257.

- Davidson AL, Driscoll CR, Luther VP, et al. Recurrent skin and soft tissue infection following breast reduction surgery caused by Gordonia bronchialis: a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10:E4395.

- Nwaedozie S, Mojarrab JN, Gopinath P, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis caused by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient following coronary artery bypass surgery. IDCases. 2022;29:E01548.

- Nakahama H, Hanada S, Takada K, et al. Obstructive pneumonia caused by Gordonia bronchialis with a bronchial foreign body. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;124:157-158. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.09.028

- Lai CC, Hsieh JH, Tsai HY, et al. Cutaneous infection caused by Gordonia amicalis after a traumatic injury. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1821-1822.

- Bakker XR, Spauwen PHM, Dolmans WMV. Mycetoma of the hand caused by Gordona terrae: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29:188-190.

- Gueneau R, Blanchet D, Rodriguez-Nava V, et al. Actinomycetoma caused by Gordonia westfalica: first reported case of human infection. New Microbes New Infect. 2020;34:100658.

- Auwaerter PG, ed. The Johns Hopkins POC-IT ABX Guide. Johns Hopkins Medicine; 2021.

- Welsh O, Sauceda E, Gonzalez J, et al. Amikacin alone andin combination with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of actinomycotic mycetoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:443-448.

- Zijlstra EE, van de Sande WWJ, Welsh O, et al. Mycetoma: a unique neglected tropical disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:100-112.

- Pham AS, Dé I, Rolston KV, et al. Catheter-related bacteremia caused by the nocardioform actinomycete Gordonia terrae. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:524-527.

- Renvoise A, Harle JR, Raoult D, et al. Gordonia sputi bacteremia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1535-1537.

- Moser BD, Pellegrini GJ, Lasker BA, et al. Pattern of antimicrobial susceptibility obtained from blood isolates of a rare but emerging human pathogen, Gordonia polyisoprenivorans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4991-4993.

- Arenas R, Fernandez Martinez RF, Torres-Guerrero E, et al. Actinomycetoma: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Cutis. 2017;99:E11-E15.

- Poonwan N, Mekha N, Yazawa K, et al. Characterization of clinical isolates of pathogenic Nocardia strains and related actinomycetes in Thailand from 1996 to 2003. Mycopathologia. 2005;159:361-368.

- Richet HM, Craven PC, Brown JM, et al. A cluster of Rhodococcus (Gordona) bronchialis sternal-wound infections after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:104-109.

- Wright SN, Gerry JS, Busowski MT, et al. Gordonia bronchialis sternal wound infection in 3 patients following open heart surgery: intraoperative transmission from a healthcare worker. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1238-1241.

- Tsukamura M. Proposal of a new genus, Gordona, for slightly acid-fast organisms occurring in sputa of patients with pulmonary disease and in soil. J Gen Microbiol. 1971;68:15-26.

- Wang T, Kong F, Chen S, et al. Improved identification of Gordonia, Rhodococcus and Tsukamurella species by 5′-end 16s rRNA gene sequencing. Pathology. 2011;43:58-63.

- Aoyama K, Kang Y, Yazawa K, et al. Characterization of clinical isolates of Gordonia species in Japanese clinical samples during 1998-2008. Mycopathologia. 2009;168:175-183.

- Ivanova N, Sikorski J, Jando M, et al. Complete genome sequence of Gordonia bronchialis type strain (3410 T). Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;2:19-28.

- Johnson JA, Onderdonk AB, Cosimi LA, et al. Gordonia bronchialis bacteremia and pleural infection: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1662-1666.

- Bartolomé-Álvarez J, Sáez-Nieto JA, Escudero-Jiménez A, et al. Cutaneous abscess due to Gordonia bronchialis: case report and literature review. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2016;29:170-173.

- Choi ME, Jung CJ, Won CH, et al. Case report of cutaneous nodule caused by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient after receiving acupuncture. J Dermatol. 2019;46:343-346.

- Nguyen DB, Gupta N, Abou-Daoud A, et al. A polymicrobial outbreak of surgical site infections following cardiac surgery at a community hospital in Florida, 2011-2012. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:432-435.

- Chang JH, Ji M, Hong HL, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis caused byGordonia bronchialis after open-heart surgery. Infect Chemother. 2014;46:110-114.

- Rodriguez-Lozano J, Pérez-Llantada E, Agüero J, et al. Sternal wound infection caused by Gordonia bronchialis: identification by MALDI-TOF MS. JMM Case Rep. 2016;3:e005067.

- Akrami K, Coletta J, Mehta S, et al. Gordonia sternal wound infection treated with ceftaroline: case report and literature review. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4:e005113.

- Ambesh P, Kapoor A, Kazmi D, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient after open heart surgery. Ann Card Anaesth. 2019;22:221-224.

- Ma TKW, Chow KM, Kwan BCH, et al. Peritoneal-dialysis related peritonitis caused by Gordonia species: report of four cases and literature review. Nephrology. 2014;19:379-383.