User login

Love them or hate them, masks in schools work

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No benefit of rivaroxaban in COVID outpatients: PREVENT-HD

A new U.S. randomized trial has failed to show benefit of a 35-day course of oral anticoagulation with rivaroxaban for the prevention of thrombotic events in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19.

The PREVENT-HD trial was presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions by Gregory Piazza, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“With the caveat that the trial was underpowered to provide a definitive conclusion, these data do not support routine antithrombotic prophylaxis in nonhospitalized patients with symptomatic COVID-19,” Dr. Piazza concluded.

PREVENT-HD is the largest randomized study to look at anticoagulation in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients and joins a long list of smaller trials that have also shown no benefit with this approach.

However, anticoagulation is recommended in patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19.

Dr. Piazza noted that the issue of anticoagulation in COVID-19 has focused mainly on hospitalized patients, but most COVID-19 cases are treated as outpatients, who are also suspected to be at risk for venous and arterial thrombotic events, especially if they have additional risk factors. Histopathological evidence also suggests that at least part of the deterioration in lung function leading to hospitalization may be attributable to in situ pulmonary artery thrombosis.

The PREVENT-HD trial explored the question of whether early initiation of thromboprophylaxis dosing of rivaroxaban in higher-risk outpatients with COVID-19 may lower the incidence of venous and arterial thrombotic events, reduce in situ pulmonary thrombosis and the worsening of pulmonary function that may lead to hospitalization, and reduce all-cause mortality.

The trial included 1,284 outpatients with a positive test for COVID-19 and who were within 14 days of symptom onset. They also had to have at least one of the following additional risk factors: age over 60 years; prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE), thrombophilia, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, cardiovascular disease or ischemic stroke, cancer, diabetes, heart failure, obesity (body mass index ≥ 35 kg/m2) or D-dimer > upper limit of normal. Around 35% of the study population had two or more of these risk factors.

Patients were randomized to rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 35 days or placebo.

The primary efficacy endpoint was time to first occurrence of a composite of symptomatic VTE, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, acute limb ischemia, non–central nervous system systemic embolization, all-cause hospitalization, and all-cause mortality up to day 35.

The primary safety endpoint was time to first occurrence of International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) critical-site and fatal bleeding.

A modified intention-to-treat analysis (all participants taking at least one dose of study intervention) was also planned.

The trial was stopped early in April this year because of a lower than expected event incidence (3.2%), compared with the planned rate (8.5%), giving a very low likelihood of being able to achieve the required number of events.

Dr. Piazza said reasons contributing to the low event rate included a falling COVID-19 death and hospitalization rate nationwide, and increased use of effective vaccines.

Results of the main intention-to-treat analysis (in 1,284 patients) showed no significant difference in the primary efficacy composite endpoint, which occurred in 3.4% of the rivaroxaban group versus 3.0% of the placebo group.

In the modified intention-to-treat analysis (which included 1,197 patients who actually took at least one dose of the study medication) there was shift in the directionality of the point estimate (rivaroxaban 2.0% vs. placebo 2.7%), which Dr. Piazza said was related to a higher number of patients hospitalized before receiving study drug in the rivaroxaban group. However, the difference was still nonsignificant.

The first major secondary outcome of symptomatic VTE, arterial thrombotic events, and all-cause mortality occurred in 0.3% of rivaroxaban patients versus 1.1% of placebo patients, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

However, a post hoc exploratory analysis did show a significant reduction in the outcome of symptomatic VTE and arterial thrombotic events.

In terms of safety, there were no fatal critical-site bleeding events, and there was no difference in ISTH major bleeding, which occurred in one patient in the rivaroxaban group versus no patients in the placebo group.

There was, however, a significant increase in nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding with rivaroxaban, which occurred in nine patients (1.5%) versus one patient (0.2%) in the placebo group.

Trivial bleeding was also increased in the rivaroxaban group, occurring in 17 patients (2.8%) versus 5 patients (0.8%) in the placebo group.

Discussant for the study, Renato Lopes, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., noted that the relationship between COVID-19 and thrombosis has been an important issue since the beginning of the pandemic, with many proposed mechanisms to explain the COVID-19–associated coagulopathy, which is a major cause of death and disability.

While observational data at the beginning of the pandemic suggested patients with COVID-19 might benefit from anticoagulation, looking at all the different randomized trials that have tested anticoagulation in COVID-19 outpatients, there is no treatment effect on the various different primary outcomes in those studies and also no effect on all-cause mortality, Dr. Lopes said.

He pointed out that PREVENT-HD was stopped prematurely with only about one-third of the planned number of patients enrolled, “just like every other outpatient COVID-19 trial.”

He also drew attention to the low rates of vaccination in the trial population, which does not reflect the current vaccination rate in the United States, and said the different direction of the results between the main intention-to-treat and modified intention-to-treat analyses deserve further investigation.

However, Dr. Lopes concluded, “The results of this trial, in line with the body of evidence in this field, do not support the routine use of any antithrombotic therapy for outpatients with COVID-19.”

The PREVENT-HD trial was sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Piazza has reported receiving research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Bayer, Janssen, Alexion, Amgen, and Boston Scientific, and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Boston Scientific, Janssen, NAMSA, Prairie Education and Research Cooperative, Boston Clinical Research Institute, and Amgen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new U.S. randomized trial has failed to show benefit of a 35-day course of oral anticoagulation with rivaroxaban for the prevention of thrombotic events in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19.

The PREVENT-HD trial was presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions by Gregory Piazza, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“With the caveat that the trial was underpowered to provide a definitive conclusion, these data do not support routine antithrombotic prophylaxis in nonhospitalized patients with symptomatic COVID-19,” Dr. Piazza concluded.

PREVENT-HD is the largest randomized study to look at anticoagulation in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients and joins a long list of smaller trials that have also shown no benefit with this approach.

However, anticoagulation is recommended in patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19.

Dr. Piazza noted that the issue of anticoagulation in COVID-19 has focused mainly on hospitalized patients, but most COVID-19 cases are treated as outpatients, who are also suspected to be at risk for venous and arterial thrombotic events, especially if they have additional risk factors. Histopathological evidence also suggests that at least part of the deterioration in lung function leading to hospitalization may be attributable to in situ pulmonary artery thrombosis.

The PREVENT-HD trial explored the question of whether early initiation of thromboprophylaxis dosing of rivaroxaban in higher-risk outpatients with COVID-19 may lower the incidence of venous and arterial thrombotic events, reduce in situ pulmonary thrombosis and the worsening of pulmonary function that may lead to hospitalization, and reduce all-cause mortality.

The trial included 1,284 outpatients with a positive test for COVID-19 and who were within 14 days of symptom onset. They also had to have at least one of the following additional risk factors: age over 60 years; prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE), thrombophilia, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, cardiovascular disease or ischemic stroke, cancer, diabetes, heart failure, obesity (body mass index ≥ 35 kg/m2) or D-dimer > upper limit of normal. Around 35% of the study population had two or more of these risk factors.

Patients were randomized to rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 35 days or placebo.

The primary efficacy endpoint was time to first occurrence of a composite of symptomatic VTE, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, acute limb ischemia, non–central nervous system systemic embolization, all-cause hospitalization, and all-cause mortality up to day 35.

The primary safety endpoint was time to first occurrence of International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) critical-site and fatal bleeding.

A modified intention-to-treat analysis (all participants taking at least one dose of study intervention) was also planned.

The trial was stopped early in April this year because of a lower than expected event incidence (3.2%), compared with the planned rate (8.5%), giving a very low likelihood of being able to achieve the required number of events.

Dr. Piazza said reasons contributing to the low event rate included a falling COVID-19 death and hospitalization rate nationwide, and increased use of effective vaccines.

Results of the main intention-to-treat analysis (in 1,284 patients) showed no significant difference in the primary efficacy composite endpoint, which occurred in 3.4% of the rivaroxaban group versus 3.0% of the placebo group.

In the modified intention-to-treat analysis (which included 1,197 patients who actually took at least one dose of the study medication) there was shift in the directionality of the point estimate (rivaroxaban 2.0% vs. placebo 2.7%), which Dr. Piazza said was related to a higher number of patients hospitalized before receiving study drug in the rivaroxaban group. However, the difference was still nonsignificant.

The first major secondary outcome of symptomatic VTE, arterial thrombotic events, and all-cause mortality occurred in 0.3% of rivaroxaban patients versus 1.1% of placebo patients, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

However, a post hoc exploratory analysis did show a significant reduction in the outcome of symptomatic VTE and arterial thrombotic events.

In terms of safety, there were no fatal critical-site bleeding events, and there was no difference in ISTH major bleeding, which occurred in one patient in the rivaroxaban group versus no patients in the placebo group.

There was, however, a significant increase in nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding with rivaroxaban, which occurred in nine patients (1.5%) versus one patient (0.2%) in the placebo group.

Trivial bleeding was also increased in the rivaroxaban group, occurring in 17 patients (2.8%) versus 5 patients (0.8%) in the placebo group.

Discussant for the study, Renato Lopes, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., noted that the relationship between COVID-19 and thrombosis has been an important issue since the beginning of the pandemic, with many proposed mechanisms to explain the COVID-19–associated coagulopathy, which is a major cause of death and disability.

While observational data at the beginning of the pandemic suggested patients with COVID-19 might benefit from anticoagulation, looking at all the different randomized trials that have tested anticoagulation in COVID-19 outpatients, there is no treatment effect on the various different primary outcomes in those studies and also no effect on all-cause mortality, Dr. Lopes said.

He pointed out that PREVENT-HD was stopped prematurely with only about one-third of the planned number of patients enrolled, “just like every other outpatient COVID-19 trial.”

He also drew attention to the low rates of vaccination in the trial population, which does not reflect the current vaccination rate in the United States, and said the different direction of the results between the main intention-to-treat and modified intention-to-treat analyses deserve further investigation.

However, Dr. Lopes concluded, “The results of this trial, in line with the body of evidence in this field, do not support the routine use of any antithrombotic therapy for outpatients with COVID-19.”

The PREVENT-HD trial was sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Piazza has reported receiving research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Bayer, Janssen, Alexion, Amgen, and Boston Scientific, and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Boston Scientific, Janssen, NAMSA, Prairie Education and Research Cooperative, Boston Clinical Research Institute, and Amgen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new U.S. randomized trial has failed to show benefit of a 35-day course of oral anticoagulation with rivaroxaban for the prevention of thrombotic events in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19.

The PREVENT-HD trial was presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions by Gregory Piazza, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“With the caveat that the trial was underpowered to provide a definitive conclusion, these data do not support routine antithrombotic prophylaxis in nonhospitalized patients with symptomatic COVID-19,” Dr. Piazza concluded.

PREVENT-HD is the largest randomized study to look at anticoagulation in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients and joins a long list of smaller trials that have also shown no benefit with this approach.

However, anticoagulation is recommended in patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19.

Dr. Piazza noted that the issue of anticoagulation in COVID-19 has focused mainly on hospitalized patients, but most COVID-19 cases are treated as outpatients, who are also suspected to be at risk for venous and arterial thrombotic events, especially if they have additional risk factors. Histopathological evidence also suggests that at least part of the deterioration in lung function leading to hospitalization may be attributable to in situ pulmonary artery thrombosis.

The PREVENT-HD trial explored the question of whether early initiation of thromboprophylaxis dosing of rivaroxaban in higher-risk outpatients with COVID-19 may lower the incidence of venous and arterial thrombotic events, reduce in situ pulmonary thrombosis and the worsening of pulmonary function that may lead to hospitalization, and reduce all-cause mortality.

The trial included 1,284 outpatients with a positive test for COVID-19 and who were within 14 days of symptom onset. They also had to have at least one of the following additional risk factors: age over 60 years; prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE), thrombophilia, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, cardiovascular disease or ischemic stroke, cancer, diabetes, heart failure, obesity (body mass index ≥ 35 kg/m2) or D-dimer > upper limit of normal. Around 35% of the study population had two or more of these risk factors.

Patients were randomized to rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 35 days or placebo.

The primary efficacy endpoint was time to first occurrence of a composite of symptomatic VTE, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, acute limb ischemia, non–central nervous system systemic embolization, all-cause hospitalization, and all-cause mortality up to day 35.

The primary safety endpoint was time to first occurrence of International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) critical-site and fatal bleeding.

A modified intention-to-treat analysis (all participants taking at least one dose of study intervention) was also planned.

The trial was stopped early in April this year because of a lower than expected event incidence (3.2%), compared with the planned rate (8.5%), giving a very low likelihood of being able to achieve the required number of events.

Dr. Piazza said reasons contributing to the low event rate included a falling COVID-19 death and hospitalization rate nationwide, and increased use of effective vaccines.

Results of the main intention-to-treat analysis (in 1,284 patients) showed no significant difference in the primary efficacy composite endpoint, which occurred in 3.4% of the rivaroxaban group versus 3.0% of the placebo group.

In the modified intention-to-treat analysis (which included 1,197 patients who actually took at least one dose of the study medication) there was shift in the directionality of the point estimate (rivaroxaban 2.0% vs. placebo 2.7%), which Dr. Piazza said was related to a higher number of patients hospitalized before receiving study drug in the rivaroxaban group. However, the difference was still nonsignificant.

The first major secondary outcome of symptomatic VTE, arterial thrombotic events, and all-cause mortality occurred in 0.3% of rivaroxaban patients versus 1.1% of placebo patients, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

However, a post hoc exploratory analysis did show a significant reduction in the outcome of symptomatic VTE and arterial thrombotic events.

In terms of safety, there were no fatal critical-site bleeding events, and there was no difference in ISTH major bleeding, which occurred in one patient in the rivaroxaban group versus no patients in the placebo group.

There was, however, a significant increase in nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding with rivaroxaban, which occurred in nine patients (1.5%) versus one patient (0.2%) in the placebo group.

Trivial bleeding was also increased in the rivaroxaban group, occurring in 17 patients (2.8%) versus 5 patients (0.8%) in the placebo group.

Discussant for the study, Renato Lopes, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., noted that the relationship between COVID-19 and thrombosis has been an important issue since the beginning of the pandemic, with many proposed mechanisms to explain the COVID-19–associated coagulopathy, which is a major cause of death and disability.

While observational data at the beginning of the pandemic suggested patients with COVID-19 might benefit from anticoagulation, looking at all the different randomized trials that have tested anticoagulation in COVID-19 outpatients, there is no treatment effect on the various different primary outcomes in those studies and also no effect on all-cause mortality, Dr. Lopes said.

He pointed out that PREVENT-HD was stopped prematurely with only about one-third of the planned number of patients enrolled, “just like every other outpatient COVID-19 trial.”

He also drew attention to the low rates of vaccination in the trial population, which does not reflect the current vaccination rate in the United States, and said the different direction of the results between the main intention-to-treat and modified intention-to-treat analyses deserve further investigation.

However, Dr. Lopes concluded, “The results of this trial, in line with the body of evidence in this field, do not support the routine use of any antithrombotic therapy for outpatients with COVID-19.”

The PREVENT-HD trial was sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Piazza has reported receiving research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Bayer, Janssen, Alexion, Amgen, and Boston Scientific, and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Boston Scientific, Janssen, NAMSA, Prairie Education and Research Cooperative, Boston Clinical Research Institute, and Amgen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AHA 2022

Children from poorer ZIP codes often untreated for ear infections

Children from socially disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to be treated for middle ear infections and are likely to experience serious complications from the condition – potentially with lifelong economic consequences – researchers have found.

Problems such as hearing loss and chronic ear infections were more common for children who lived in areas marked by difficult socioeconomic circumstances, according to the researchers, who linked the complications to a lack of adequate treatment in this population.

“We are treating socially disadvantaged kids differently than we are treating more advantaged kids,” said Jason Qian, MD, a resident in otolaryngology and head and neck surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University, who helped conduct the new study. “We have to think about social inequalities so we can ensure all kids are receiving the same level and type of care.”

In the United States, 80% of children will experience otitis media during their lifetime. Untreated ear infections can lead to symptoms ranging from mild discharge from the ear to life-threatening conditions like mastoiditis and intracranial abscesses.

For the new study, published online in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, Dr. Qian and colleagues looked at 4.8 million children with private health insurance across the United States using a database with information on inpatient and outpatient visits and medication use. The researchers identified patients between January 2003 and March 2021 who received treatment for recurrent and suppurative otitis media, those who received tympanostomy tubes, and children who experienced severe complications from undertreated ear infections.

Social disadvantage was assessed using the Social Deprivation Index (SDI), a tool used to measure indicators of poverty throughout the United States based on seven demographic factors including level of educational attainment, the number of single-parent households, the share of people living in overcrowded homes, and other factors.

Every point increase in the SDI score was associated with a 14% lower likelihood of being treated for recurrent ear infections despite having them and a 28% greater chance of being hospitalized for severe ear infections, according to the researchers.

Previous research established that children with government health insurance or no coverage have more difficulty receiving proper treatment for ear infections. Although people with commercial insurance are generally wealthier than those without private coverage, Dr. Qian said, the new data indicate that significant social disparities in care exist even within this group.

Although some studies have found that wealthier children are more likely to develop otitis media, Dr. Qian’s group said that association likely reflects the better access to health care money affords.

“We found that socially disadvantaged children not only have a higher burden of otitis media but are also undertreated both medically and surgically for [ear infections]. Because chronic and complicated forms of otitis media can cause childhood hearing loss, which in turn limits academic and economic potential, undertreatment of [otitis media] in socially disadvantaged populations can contribute to generational cycles of poverty, unemployment, and low pay,” they write.

“The biggest take home is that we are not treating children equitably when it comes to ear infections,” Dr. Qian added. “In order to give children equal access to care, we as health care providers need to find strategies to do better.”

The study was supported by the Stanford Center for Population Health Science Data Core, which is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health and internal funding. Dr. Qian has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children from socially disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to be treated for middle ear infections and are likely to experience serious complications from the condition – potentially with lifelong economic consequences – researchers have found.

Problems such as hearing loss and chronic ear infections were more common for children who lived in areas marked by difficult socioeconomic circumstances, according to the researchers, who linked the complications to a lack of adequate treatment in this population.

“We are treating socially disadvantaged kids differently than we are treating more advantaged kids,” said Jason Qian, MD, a resident in otolaryngology and head and neck surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University, who helped conduct the new study. “We have to think about social inequalities so we can ensure all kids are receiving the same level and type of care.”

In the United States, 80% of children will experience otitis media during their lifetime. Untreated ear infections can lead to symptoms ranging from mild discharge from the ear to life-threatening conditions like mastoiditis and intracranial abscesses.

For the new study, published online in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, Dr. Qian and colleagues looked at 4.8 million children with private health insurance across the United States using a database with information on inpatient and outpatient visits and medication use. The researchers identified patients between January 2003 and March 2021 who received treatment for recurrent and suppurative otitis media, those who received tympanostomy tubes, and children who experienced severe complications from undertreated ear infections.

Social disadvantage was assessed using the Social Deprivation Index (SDI), a tool used to measure indicators of poverty throughout the United States based on seven demographic factors including level of educational attainment, the number of single-parent households, the share of people living in overcrowded homes, and other factors.

Every point increase in the SDI score was associated with a 14% lower likelihood of being treated for recurrent ear infections despite having them and a 28% greater chance of being hospitalized for severe ear infections, according to the researchers.

Previous research established that children with government health insurance or no coverage have more difficulty receiving proper treatment for ear infections. Although people with commercial insurance are generally wealthier than those without private coverage, Dr. Qian said, the new data indicate that significant social disparities in care exist even within this group.

Although some studies have found that wealthier children are more likely to develop otitis media, Dr. Qian’s group said that association likely reflects the better access to health care money affords.

“We found that socially disadvantaged children not only have a higher burden of otitis media but are also undertreated both medically and surgically for [ear infections]. Because chronic and complicated forms of otitis media can cause childhood hearing loss, which in turn limits academic and economic potential, undertreatment of [otitis media] in socially disadvantaged populations can contribute to generational cycles of poverty, unemployment, and low pay,” they write.

“The biggest take home is that we are not treating children equitably when it comes to ear infections,” Dr. Qian added. “In order to give children equal access to care, we as health care providers need to find strategies to do better.”

The study was supported by the Stanford Center for Population Health Science Data Core, which is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health and internal funding. Dr. Qian has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children from socially disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to be treated for middle ear infections and are likely to experience serious complications from the condition – potentially with lifelong economic consequences – researchers have found.

Problems such as hearing loss and chronic ear infections were more common for children who lived in areas marked by difficult socioeconomic circumstances, according to the researchers, who linked the complications to a lack of adequate treatment in this population.

“We are treating socially disadvantaged kids differently than we are treating more advantaged kids,” said Jason Qian, MD, a resident in otolaryngology and head and neck surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University, who helped conduct the new study. “We have to think about social inequalities so we can ensure all kids are receiving the same level and type of care.”

In the United States, 80% of children will experience otitis media during their lifetime. Untreated ear infections can lead to symptoms ranging from mild discharge from the ear to life-threatening conditions like mastoiditis and intracranial abscesses.

For the new study, published online in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, Dr. Qian and colleagues looked at 4.8 million children with private health insurance across the United States using a database with information on inpatient and outpatient visits and medication use. The researchers identified patients between January 2003 and March 2021 who received treatment for recurrent and suppurative otitis media, those who received tympanostomy tubes, and children who experienced severe complications from undertreated ear infections.

Social disadvantage was assessed using the Social Deprivation Index (SDI), a tool used to measure indicators of poverty throughout the United States based on seven demographic factors including level of educational attainment, the number of single-parent households, the share of people living in overcrowded homes, and other factors.

Every point increase in the SDI score was associated with a 14% lower likelihood of being treated for recurrent ear infections despite having them and a 28% greater chance of being hospitalized for severe ear infections, according to the researchers.

Previous research established that children with government health insurance or no coverage have more difficulty receiving proper treatment for ear infections. Although people with commercial insurance are generally wealthier than those without private coverage, Dr. Qian said, the new data indicate that significant social disparities in care exist even within this group.

Although some studies have found that wealthier children are more likely to develop otitis media, Dr. Qian’s group said that association likely reflects the better access to health care money affords.

“We found that socially disadvantaged children not only have a higher burden of otitis media but are also undertreated both medically and surgically for [ear infections]. Because chronic and complicated forms of otitis media can cause childhood hearing loss, which in turn limits academic and economic potential, undertreatment of [otitis media] in socially disadvantaged populations can contribute to generational cycles of poverty, unemployment, and low pay,” they write.

“The biggest take home is that we are not treating children equitably when it comes to ear infections,” Dr. Qian added. “In order to give children equal access to care, we as health care providers need to find strategies to do better.”

The study was supported by the Stanford Center for Population Health Science Data Core, which is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health and internal funding. Dr. Qian has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Monkeypox in children appears rare and relatively mild

Monkeypox virus infections in children and adolescents in the United States are rare, and young patients with known infections have all recovered, according to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In addition, evidence suggests that secondary transmission in schools or childcare facilities may be unlikely.

The study was the first comprehensive study on the impact of monkeypox on children during the 2022 outbreak, according to a statement emailed to this news organization from the California Department of Public Health, one of the state health departments that partnered with the CDC to share information.

News of low infection rates and relatively mild disease was welcome to clinicians, who had braced for severe findings on the basis of sparse prior data, according to Peter Chin-Hong, MD, a professor of medicine and an infectious diseases physician at the University of California, San Francisco.

“We were on heightened alert that kids may do poorly,” said Dr. Chin-Hong, who was not involved in the study but who cared for monkeypox patients during the outbreak. “I think this study is reassuring.

“The other silver lining about it is that most of the kids got infected in the household setting from ways that you would expect them to get [infected],” Dr. Chin-Hong said in an interview.

However, Black and Hispanic children were more likely to contract the disease, underscoring troubling inequities.

“Early on, individuals of color were much less likely to be able to successfully access vaccination,” said first author Ian Hennessee, PhD, MPH, an epidemic intelligence service officer with the CDC and a member of the Special Case Investigation Unit of the Multinational Monkeypox Response Team at the CDC. “We think those kinds of structural inequities really trickled down towards the children and adolescents that have been affected by this outbreak.”

The study was published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

A nationwide look at the data

The researchers discussed 83 children and adolescents with monkeypox who came to the CDC’s attention between May 17 and Sept. 24, 2022.

The 83 cases represent 0.3% of the 25,038 reported monkeypox cases in the United States over that period. Of the 28 children aged 12 years or younger, 18 (64%) were boys. Sixteen children were younger than 4 years.

Exposure data were available for 20 (71%) of those aged 0-12. In that group, 19 were exposed at home; 17 cases were due to routine skin-to-skin contact with a household caregiver; and one case was suspected to be caused by fomites (such as a shared towel). Exposure information was unavailable for the remaining case.

Most of the children experienced lesions on the trunk. No lesions were anogenital. Two patients in the youngest age group were hospitalized because of widespread rash that involved the eyelids, and a patient in the 5- to 12-year-old group was hospitalized because of periorbital cellulitis and conjunctivitis.

Among those aged 13-17, there were 55 cases. Of these patients, 89% were boys. Exposure data were available for 35 (64%). In 32 of these patients, the infection occurred from presumed sexual contact. Twenty-three of those adolescents reported male-to-male sexual contact. No case was found to be connected with sexual abuse.

Lesions in the adolescents were mostly truncal or anogenital. Six in this group were hospitalized, and all of them recovered. One adolescent was found to be HIV positive.

Black and Hispanic children accounted for 47% and 35% of all cases, respectively.

Eleven percent of all the children and adolescents were hospitalized, and none received intensive care.

Treatments, when given, included the antiviral drug tecovirimat, intravenous vaccinia immune globulin, and topical trifluridine. There were no deaths.

Ten symptomatic patients attended school or daycare. Among these patients, no secondary transmissions were found to have occurred. Some contacts were offered the JYNNEOS monkeypox vaccine as postexposure prophylaxis.

Limitations of the study included potentially overlooked cases. Data were collected through routine surveillance, children frequently experience rashes, and access to testing has been a challenge, Dr. Hennessee explained.

In addition, data on exposure characteristics were missing for some children.

Inequities and the risks of being judged

The outbreak in the United States has eased in recent months. However, though uncommon in children, monkeypox has affected some racial groups disproportionately.

“Especially in the later course of the outbreak, the majority of cases were among Black and Hispanic individuals,” said co-author Rachel E. Harold, MD, an infectious diseases specialist and supervisory medical officer with the District of Columbia Department of Health’s HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STDs, and TB Administration.

“Unfortunately, the pediatric cases do reflect the outbreak overall,” she told this news organization.

Dr. Harold noted there have been efforts in D.C. and other jurisdictions, as well as by the White House monkeypox response team, to reach populations at greatest risk and that they were “really trying to make vaccine available to people of color.”

Vaccination clinics often popped up in unexpected locations at short notice, and that made it hard for some people to get to them, Dr. Chin-Hong pointed out.

Another factor was “the public aspect of accessing diagnostics and vaccines and the way that that’s linked to potential judgment or sexual risk,” he added.

“Not everybody’s out,” Dr. Chin-Hong said, referring to members of the LGBTQ community. “In many communities of color, going to get a test or going to get a vaccine essentially means that you’re out.”

For clinicians who suspect monkeypox in a child, Dr. Harold suggests keeping a broad differential diagnosis, looking for an epidemiologic link, and contacting the CDC for assistance. Infected children should be encouraged to avoid touching their own eyes or mucous membranes, she added.

In addition, she said, tecovirimat is a reasonable treatment and is well tolerated by pediatric monkeypox patients with eczema, an underlying condition that could lead to severe disease.

For infected caregivers, Dr. Hennessee said, measures to prevent infecting children at home include isolation, contact precautions, and in some cases, postexposure prophylaxis via vaccination.

For sexually active adolescents, he advised that clinicians offer vaccination, education on sexual health, and testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

“It’s important to remember that adolescents may be sexually active, and clinicians should do a thorough and nonjudgmental sexual history,” Dr. Harold added. “That is always true, but especially if there is concern for [monkeypox].”

Dr. Hennessee, Dr. Chin-Hong, and Dr. Harold have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Monkeypox virus infections in children and adolescents in the United States are rare, and young patients with known infections have all recovered, according to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In addition, evidence suggests that secondary transmission in schools or childcare facilities may be unlikely.

The study was the first comprehensive study on the impact of monkeypox on children during the 2022 outbreak, according to a statement emailed to this news organization from the California Department of Public Health, one of the state health departments that partnered with the CDC to share information.

News of low infection rates and relatively mild disease was welcome to clinicians, who had braced for severe findings on the basis of sparse prior data, according to Peter Chin-Hong, MD, a professor of medicine and an infectious diseases physician at the University of California, San Francisco.

“We were on heightened alert that kids may do poorly,” said Dr. Chin-Hong, who was not involved in the study but who cared for monkeypox patients during the outbreak. “I think this study is reassuring.

“The other silver lining about it is that most of the kids got infected in the household setting from ways that you would expect them to get [infected],” Dr. Chin-Hong said in an interview.

However, Black and Hispanic children were more likely to contract the disease, underscoring troubling inequities.

“Early on, individuals of color were much less likely to be able to successfully access vaccination,” said first author Ian Hennessee, PhD, MPH, an epidemic intelligence service officer with the CDC and a member of the Special Case Investigation Unit of the Multinational Monkeypox Response Team at the CDC. “We think those kinds of structural inequities really trickled down towards the children and adolescents that have been affected by this outbreak.”

The study was published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

A nationwide look at the data

The researchers discussed 83 children and adolescents with monkeypox who came to the CDC’s attention between May 17 and Sept. 24, 2022.

The 83 cases represent 0.3% of the 25,038 reported monkeypox cases in the United States over that period. Of the 28 children aged 12 years or younger, 18 (64%) were boys. Sixteen children were younger than 4 years.

Exposure data were available for 20 (71%) of those aged 0-12. In that group, 19 were exposed at home; 17 cases were due to routine skin-to-skin contact with a household caregiver; and one case was suspected to be caused by fomites (such as a shared towel). Exposure information was unavailable for the remaining case.

Most of the children experienced lesions on the trunk. No lesions were anogenital. Two patients in the youngest age group were hospitalized because of widespread rash that involved the eyelids, and a patient in the 5- to 12-year-old group was hospitalized because of periorbital cellulitis and conjunctivitis.

Among those aged 13-17, there were 55 cases. Of these patients, 89% were boys. Exposure data were available for 35 (64%). In 32 of these patients, the infection occurred from presumed sexual contact. Twenty-three of those adolescents reported male-to-male sexual contact. No case was found to be connected with sexual abuse.

Lesions in the adolescents were mostly truncal or anogenital. Six in this group were hospitalized, and all of them recovered. One adolescent was found to be HIV positive.

Black and Hispanic children accounted for 47% and 35% of all cases, respectively.

Eleven percent of all the children and adolescents were hospitalized, and none received intensive care.

Treatments, when given, included the antiviral drug tecovirimat, intravenous vaccinia immune globulin, and topical trifluridine. There were no deaths.

Ten symptomatic patients attended school or daycare. Among these patients, no secondary transmissions were found to have occurred. Some contacts were offered the JYNNEOS monkeypox vaccine as postexposure prophylaxis.

Limitations of the study included potentially overlooked cases. Data were collected through routine surveillance, children frequently experience rashes, and access to testing has been a challenge, Dr. Hennessee explained.

In addition, data on exposure characteristics were missing for some children.

Inequities and the risks of being judged

The outbreak in the United States has eased in recent months. However, though uncommon in children, monkeypox has affected some racial groups disproportionately.

“Especially in the later course of the outbreak, the majority of cases were among Black and Hispanic individuals,” said co-author Rachel E. Harold, MD, an infectious diseases specialist and supervisory medical officer with the District of Columbia Department of Health’s HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STDs, and TB Administration.

“Unfortunately, the pediatric cases do reflect the outbreak overall,” she told this news organization.

Dr. Harold noted there have been efforts in D.C. and other jurisdictions, as well as by the White House monkeypox response team, to reach populations at greatest risk and that they were “really trying to make vaccine available to people of color.”

Vaccination clinics often popped up in unexpected locations at short notice, and that made it hard for some people to get to them, Dr. Chin-Hong pointed out.

Another factor was “the public aspect of accessing diagnostics and vaccines and the way that that’s linked to potential judgment or sexual risk,” he added.

“Not everybody’s out,” Dr. Chin-Hong said, referring to members of the LGBTQ community. “In many communities of color, going to get a test or going to get a vaccine essentially means that you’re out.”

For clinicians who suspect monkeypox in a child, Dr. Harold suggests keeping a broad differential diagnosis, looking for an epidemiologic link, and contacting the CDC for assistance. Infected children should be encouraged to avoid touching their own eyes or mucous membranes, she added.

In addition, she said, tecovirimat is a reasonable treatment and is well tolerated by pediatric monkeypox patients with eczema, an underlying condition that could lead to severe disease.

For infected caregivers, Dr. Hennessee said, measures to prevent infecting children at home include isolation, contact precautions, and in some cases, postexposure prophylaxis via vaccination.

For sexually active adolescents, he advised that clinicians offer vaccination, education on sexual health, and testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

“It’s important to remember that adolescents may be sexually active, and clinicians should do a thorough and nonjudgmental sexual history,” Dr. Harold added. “That is always true, but especially if there is concern for [monkeypox].”

Dr. Hennessee, Dr. Chin-Hong, and Dr. Harold have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Monkeypox virus infections in children and adolescents in the United States are rare, and young patients with known infections have all recovered, according to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In addition, evidence suggests that secondary transmission in schools or childcare facilities may be unlikely.

The study was the first comprehensive study on the impact of monkeypox on children during the 2022 outbreak, according to a statement emailed to this news organization from the California Department of Public Health, one of the state health departments that partnered with the CDC to share information.

News of low infection rates and relatively mild disease was welcome to clinicians, who had braced for severe findings on the basis of sparse prior data, according to Peter Chin-Hong, MD, a professor of medicine and an infectious diseases physician at the University of California, San Francisco.

“We were on heightened alert that kids may do poorly,” said Dr. Chin-Hong, who was not involved in the study but who cared for monkeypox patients during the outbreak. “I think this study is reassuring.

“The other silver lining about it is that most of the kids got infected in the household setting from ways that you would expect them to get [infected],” Dr. Chin-Hong said in an interview.

However, Black and Hispanic children were more likely to contract the disease, underscoring troubling inequities.

“Early on, individuals of color were much less likely to be able to successfully access vaccination,” said first author Ian Hennessee, PhD, MPH, an epidemic intelligence service officer with the CDC and a member of the Special Case Investigation Unit of the Multinational Monkeypox Response Team at the CDC. “We think those kinds of structural inequities really trickled down towards the children and adolescents that have been affected by this outbreak.”

The study was published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

A nationwide look at the data

The researchers discussed 83 children and adolescents with monkeypox who came to the CDC’s attention between May 17 and Sept. 24, 2022.

The 83 cases represent 0.3% of the 25,038 reported monkeypox cases in the United States over that period. Of the 28 children aged 12 years or younger, 18 (64%) were boys. Sixteen children were younger than 4 years.

Exposure data were available for 20 (71%) of those aged 0-12. In that group, 19 were exposed at home; 17 cases were due to routine skin-to-skin contact with a household caregiver; and one case was suspected to be caused by fomites (such as a shared towel). Exposure information was unavailable for the remaining case.

Most of the children experienced lesions on the trunk. No lesions were anogenital. Two patients in the youngest age group were hospitalized because of widespread rash that involved the eyelids, and a patient in the 5- to 12-year-old group was hospitalized because of periorbital cellulitis and conjunctivitis.

Among those aged 13-17, there were 55 cases. Of these patients, 89% were boys. Exposure data were available for 35 (64%). In 32 of these patients, the infection occurred from presumed sexual contact. Twenty-three of those adolescents reported male-to-male sexual contact. No case was found to be connected with sexual abuse.

Lesions in the adolescents were mostly truncal or anogenital. Six in this group were hospitalized, and all of them recovered. One adolescent was found to be HIV positive.

Black and Hispanic children accounted for 47% and 35% of all cases, respectively.

Eleven percent of all the children and adolescents were hospitalized, and none received intensive care.

Treatments, when given, included the antiviral drug tecovirimat, intravenous vaccinia immune globulin, and topical trifluridine. There were no deaths.

Ten symptomatic patients attended school or daycare. Among these patients, no secondary transmissions were found to have occurred. Some contacts were offered the JYNNEOS monkeypox vaccine as postexposure prophylaxis.

Limitations of the study included potentially overlooked cases. Data were collected through routine surveillance, children frequently experience rashes, and access to testing has been a challenge, Dr. Hennessee explained.

In addition, data on exposure characteristics were missing for some children.

Inequities and the risks of being judged

The outbreak in the United States has eased in recent months. However, though uncommon in children, monkeypox has affected some racial groups disproportionately.

“Especially in the later course of the outbreak, the majority of cases were among Black and Hispanic individuals,” said co-author Rachel E. Harold, MD, an infectious diseases specialist and supervisory medical officer with the District of Columbia Department of Health’s HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STDs, and TB Administration.

“Unfortunately, the pediatric cases do reflect the outbreak overall,” she told this news organization.

Dr. Harold noted there have been efforts in D.C. and other jurisdictions, as well as by the White House monkeypox response team, to reach populations at greatest risk and that they were “really trying to make vaccine available to people of color.”

Vaccination clinics often popped up in unexpected locations at short notice, and that made it hard for some people to get to them, Dr. Chin-Hong pointed out.

Another factor was “the public aspect of accessing diagnostics and vaccines and the way that that’s linked to potential judgment or sexual risk,” he added.

“Not everybody’s out,” Dr. Chin-Hong said, referring to members of the LGBTQ community. “In many communities of color, going to get a test or going to get a vaccine essentially means that you’re out.”

For clinicians who suspect monkeypox in a child, Dr. Harold suggests keeping a broad differential diagnosis, looking for an epidemiologic link, and contacting the CDC for assistance. Infected children should be encouraged to avoid touching their own eyes or mucous membranes, she added.

In addition, she said, tecovirimat is a reasonable treatment and is well tolerated by pediatric monkeypox patients with eczema, an underlying condition that could lead to severe disease.

For infected caregivers, Dr. Hennessee said, measures to prevent infecting children at home include isolation, contact precautions, and in some cases, postexposure prophylaxis via vaccination.

For sexually active adolescents, he advised that clinicians offer vaccination, education on sexual health, and testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

“It’s important to remember that adolescents may be sexually active, and clinicians should do a thorough and nonjudgmental sexual history,” Dr. Harold added. “That is always true, but especially if there is concern for [monkeypox].”

Dr. Hennessee, Dr. Chin-Hong, and Dr. Harold have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

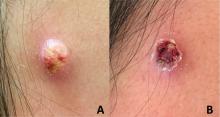

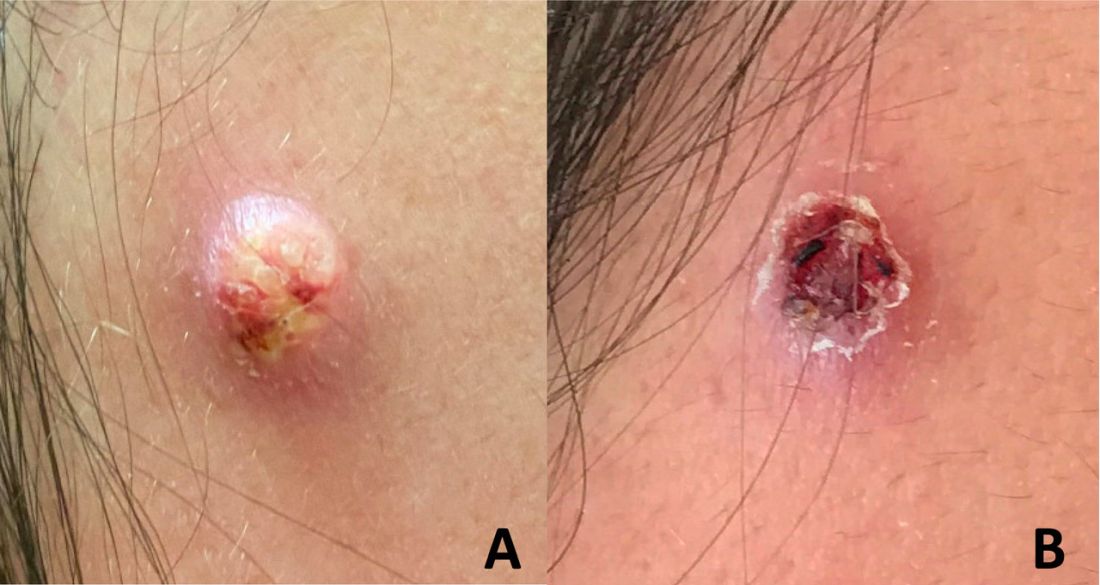

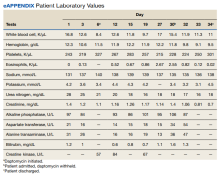

An adolescent male presents with an eroded bump on the temple

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References

1. Brown J et al. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;45(2):93-9.

2. Hanson D and Diven DG. Dermatol Online J. 2003 Mar;9(2).

3. Badri T and Gandhi GR. Molluscum contagiosum. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing.

4. Schwartz JJ and Myskowski PL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct 1;27(4):583-8.

5. Antonov NK et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Apr 5;5(4):342-5.

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References

1. Brown J et al. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;45(2):93-9.

2. Hanson D and Diven DG. Dermatol Online J. 2003 Mar;9(2).

3. Badri T and Gandhi GR. Molluscum contagiosum. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing.

4. Schwartz JJ and Myskowski PL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct 1;27(4):583-8.

5. Antonov NK et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Apr 5;5(4):342-5.

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.