User login

Methotrexate relieves pain of Chikungunya-associated arthritis

Methotrexate is effective for the control of pain produced by arthritis associated with Chikungunya virus infection, according to a retrospective review of outcomes in a series of 50 patients.

Joint pain and joint inflammation are commonly seen in the approximately 60% of patients who progress to the chronic phase of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection, but there is no current consensus about how best to manage this complication, according to first author J. Kennedy Amaral, MD, of the department of infectious diseases and tropical medicine at the University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and his colleagues, who published their experience in 50 patients in the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology.

In this study, the primary measure of efficacy was pain control because not all CHIKV infection patients with rheumatic symptoms demonstrate synovitis on radiological examination. The 50 patients included in this series all had joint symptoms persisting more than 12 weeks after onset of CHIKV infection.

All but four of the patients in this series were women. The mean age was 61.9 years. At baseline, 28 had a musculoskeletal disorder defined by presence of arthralgia, 11 had rheumatoid arthritis, seven had fibromyalgia, and four had undifferentiated polyarthritis.

On a 0-10 visual analog scale (VAS), the mean pain score at baseline was 7.7. All patients were initiated on a 4-week course of 7.5 mg of methotrexate administered with folic acid.

Four patients not examined after 4 weeks of treatment were excluded from analysis. Of those evaluated, 80% had achieved at least a 2-point reduction in VAS score, which is considered clinically meaningful. The mean reduction in VAS pain score at 4 weeks was 4.3 points (P less than .0001 vs. baseline). In 12 patients, symptoms were resolved, and they were not further evaluated.

Those with inadequate pain control at 4 weeks were permitted to begin a higher dose of methotrexate and to receive additional therapies. At 8 weeks, the reduction in VAS pain score was only modestly increased, reaching a mean 4.5-point reduction from baseline on a mean methotrexate dose of 9.2 mg/week. A substantial proportion of patients had added other medications, such as prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

Only 20 patients had joint swelling and frank arthritis at baseline. In these, the mean swollen joint count decreased from 7.15 to 2.89 (P less than .0001). There was no further reduction at 8 weeks.

Over the course of the study, there was no evidence that methotrexate exacerbated CHIKV infection.

The data were collected retrospectively, and there was no control group, but the findings inform practitioners of the “possible benefit of low-dose methotrexate to treat both arthralgia and arthritis” in chronic CHIK-associated arthritis, according to Dr. Amaral and his coinvestigators.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Amaral JK et al. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000943.

Methotrexate is effective for the control of pain produced by arthritis associated with Chikungunya virus infection, according to a retrospective review of outcomes in a series of 50 patients.

Joint pain and joint inflammation are commonly seen in the approximately 60% of patients who progress to the chronic phase of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection, but there is no current consensus about how best to manage this complication, according to first author J. Kennedy Amaral, MD, of the department of infectious diseases and tropical medicine at the University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and his colleagues, who published their experience in 50 patients in the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology.

In this study, the primary measure of efficacy was pain control because not all CHIKV infection patients with rheumatic symptoms demonstrate synovitis on radiological examination. The 50 patients included in this series all had joint symptoms persisting more than 12 weeks after onset of CHIKV infection.

All but four of the patients in this series were women. The mean age was 61.9 years. At baseline, 28 had a musculoskeletal disorder defined by presence of arthralgia, 11 had rheumatoid arthritis, seven had fibromyalgia, and four had undifferentiated polyarthritis.

On a 0-10 visual analog scale (VAS), the mean pain score at baseline was 7.7. All patients were initiated on a 4-week course of 7.5 mg of methotrexate administered with folic acid.

Four patients not examined after 4 weeks of treatment were excluded from analysis. Of those evaluated, 80% had achieved at least a 2-point reduction in VAS score, which is considered clinically meaningful. The mean reduction in VAS pain score at 4 weeks was 4.3 points (P less than .0001 vs. baseline). In 12 patients, symptoms were resolved, and they were not further evaluated.

Those with inadequate pain control at 4 weeks were permitted to begin a higher dose of methotrexate and to receive additional therapies. At 8 weeks, the reduction in VAS pain score was only modestly increased, reaching a mean 4.5-point reduction from baseline on a mean methotrexate dose of 9.2 mg/week. A substantial proportion of patients had added other medications, such as prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

Only 20 patients had joint swelling and frank arthritis at baseline. In these, the mean swollen joint count decreased from 7.15 to 2.89 (P less than .0001). There was no further reduction at 8 weeks.

Over the course of the study, there was no evidence that methotrexate exacerbated CHIKV infection.

The data were collected retrospectively, and there was no control group, but the findings inform practitioners of the “possible benefit of low-dose methotrexate to treat both arthralgia and arthritis” in chronic CHIK-associated arthritis, according to Dr. Amaral and his coinvestigators.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Amaral JK et al. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000943.

Methotrexate is effective for the control of pain produced by arthritis associated with Chikungunya virus infection, according to a retrospective review of outcomes in a series of 50 patients.

Joint pain and joint inflammation are commonly seen in the approximately 60% of patients who progress to the chronic phase of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection, but there is no current consensus about how best to manage this complication, according to first author J. Kennedy Amaral, MD, of the department of infectious diseases and tropical medicine at the University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and his colleagues, who published their experience in 50 patients in the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology.

In this study, the primary measure of efficacy was pain control because not all CHIKV infection patients with rheumatic symptoms demonstrate synovitis on radiological examination. The 50 patients included in this series all had joint symptoms persisting more than 12 weeks after onset of CHIKV infection.

All but four of the patients in this series were women. The mean age was 61.9 years. At baseline, 28 had a musculoskeletal disorder defined by presence of arthralgia, 11 had rheumatoid arthritis, seven had fibromyalgia, and four had undifferentiated polyarthritis.

On a 0-10 visual analog scale (VAS), the mean pain score at baseline was 7.7. All patients were initiated on a 4-week course of 7.5 mg of methotrexate administered with folic acid.

Four patients not examined after 4 weeks of treatment were excluded from analysis. Of those evaluated, 80% had achieved at least a 2-point reduction in VAS score, which is considered clinically meaningful. The mean reduction in VAS pain score at 4 weeks was 4.3 points (P less than .0001 vs. baseline). In 12 patients, symptoms were resolved, and they were not further evaluated.

Those with inadequate pain control at 4 weeks were permitted to begin a higher dose of methotrexate and to receive additional therapies. At 8 weeks, the reduction in VAS pain score was only modestly increased, reaching a mean 4.5-point reduction from baseline on a mean methotrexate dose of 9.2 mg/week. A substantial proportion of patients had added other medications, such as prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

Only 20 patients had joint swelling and frank arthritis at baseline. In these, the mean swollen joint count decreased from 7.15 to 2.89 (P less than .0001). There was no further reduction at 8 weeks.

Over the course of the study, there was no evidence that methotrexate exacerbated CHIKV infection.

The data were collected retrospectively, and there was no control group, but the findings inform practitioners of the “possible benefit of low-dose methotrexate to treat both arthralgia and arthritis” in chronic CHIK-associated arthritis, according to Dr. Amaral and his coinvestigators.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Amaral JK et al. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000943.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: On a 10-point visual analog scale, the pain reduction from baseline on methotrexate at 8 weeks was 4.5 (P less than .0001).

Study details: Retrospective observational study.

Disclosures: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Amaral JK et al. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000943

Non-TB mycobacteria infections rising in COPD patients

Veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have seen a sharp increase since 2012 in rates of non-TB mycobacteria infections, which carry a significantly higher risk of death in COPD patients, according to findings from a nationwide study.

For their research, published in Frontiers of Medicine, Fahim Pyarali, MD, and colleagues at the University of Miami, reviewed data from Veterans Affairs hospitals to identify non-TB mycobacteria (NTM) infections among more than 2 million COPD patients seen between 2000 and 2015. Incidence of NTM infections was 34.2 per 100,000 COPD patients in 2001, a rate that remained steady until 2012, when it began climbing sharply through 2015 to reach 70.3 per 100,000 (P = .035). Dr. Pyarali and colleagues also found that, during the study period, prevalence of NTM climbed from 93.1 infections per 100,000 population in 2001 to 277.6 per 100,000 in 2015.

Hotspots for NTM infections included Puerto Rico, which had the highest prevalence seen in the study at 370 infections per 100,000 COPD population; Florida, with 351 per 100,000; and Washington, D.C., with 309 per 100,000. Additional hotspots were identified around Lake Michigan, in coastal Louisiana, and in parts of the Southwest.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted that the geographical concentration of cases near oceans and lakes was “supported by previous findings that warmer temperatures, lower dissolved oxygen, and lower pH in the soils and waters provide a major environmental source for NTM organisms;” however, the study is the first to identify Puerto Rico as having exceptionally high prevalence. The reasons for this should be extensively investigated, the investigators argued.

The mortality risk was 43% higher among NTM-infected patients than in COPD patients without an NTM diagnosis (95% confidence interval, 1.31-1.58; P less than .001), independent of other comorbidities.

Though rates of NTM infection were seen rising steeply in men and women alike, Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted as a limitation of their study its use of an overwhelmingly male population, writing that this may obscure “the true reach of NTM disease and mortality” in the general population. The average age of NTM diagnosis remained steady throughout the study period, suggesting that rising incidence is not attributable to earlier diagnosis.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues reported no outside sources of funding or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pyarali F et al. Front Med. 2018 Nov 6. doi: 10.3389/fmed2018.00311.

Veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have seen a sharp increase since 2012 in rates of non-TB mycobacteria infections, which carry a significantly higher risk of death in COPD patients, according to findings from a nationwide study.

For their research, published in Frontiers of Medicine, Fahim Pyarali, MD, and colleagues at the University of Miami, reviewed data from Veterans Affairs hospitals to identify non-TB mycobacteria (NTM) infections among more than 2 million COPD patients seen between 2000 and 2015. Incidence of NTM infections was 34.2 per 100,000 COPD patients in 2001, a rate that remained steady until 2012, when it began climbing sharply through 2015 to reach 70.3 per 100,000 (P = .035). Dr. Pyarali and colleagues also found that, during the study period, prevalence of NTM climbed from 93.1 infections per 100,000 population in 2001 to 277.6 per 100,000 in 2015.

Hotspots for NTM infections included Puerto Rico, which had the highest prevalence seen in the study at 370 infections per 100,000 COPD population; Florida, with 351 per 100,000; and Washington, D.C., with 309 per 100,000. Additional hotspots were identified around Lake Michigan, in coastal Louisiana, and in parts of the Southwest.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted that the geographical concentration of cases near oceans and lakes was “supported by previous findings that warmer temperatures, lower dissolved oxygen, and lower pH in the soils and waters provide a major environmental source for NTM organisms;” however, the study is the first to identify Puerto Rico as having exceptionally high prevalence. The reasons for this should be extensively investigated, the investigators argued.

The mortality risk was 43% higher among NTM-infected patients than in COPD patients without an NTM diagnosis (95% confidence interval, 1.31-1.58; P less than .001), independent of other comorbidities.

Though rates of NTM infection were seen rising steeply in men and women alike, Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted as a limitation of their study its use of an overwhelmingly male population, writing that this may obscure “the true reach of NTM disease and mortality” in the general population. The average age of NTM diagnosis remained steady throughout the study period, suggesting that rising incidence is not attributable to earlier diagnosis.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues reported no outside sources of funding or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pyarali F et al. Front Med. 2018 Nov 6. doi: 10.3389/fmed2018.00311.

Veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have seen a sharp increase since 2012 in rates of non-TB mycobacteria infections, which carry a significantly higher risk of death in COPD patients, according to findings from a nationwide study.

For their research, published in Frontiers of Medicine, Fahim Pyarali, MD, and colleagues at the University of Miami, reviewed data from Veterans Affairs hospitals to identify non-TB mycobacteria (NTM) infections among more than 2 million COPD patients seen between 2000 and 2015. Incidence of NTM infections was 34.2 per 100,000 COPD patients in 2001, a rate that remained steady until 2012, when it began climbing sharply through 2015 to reach 70.3 per 100,000 (P = .035). Dr. Pyarali and colleagues also found that, during the study period, prevalence of NTM climbed from 93.1 infections per 100,000 population in 2001 to 277.6 per 100,000 in 2015.

Hotspots for NTM infections included Puerto Rico, which had the highest prevalence seen in the study at 370 infections per 100,000 COPD population; Florida, with 351 per 100,000; and Washington, D.C., with 309 per 100,000. Additional hotspots were identified around Lake Michigan, in coastal Louisiana, and in parts of the Southwest.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted that the geographical concentration of cases near oceans and lakes was “supported by previous findings that warmer temperatures, lower dissolved oxygen, and lower pH in the soils and waters provide a major environmental source for NTM organisms;” however, the study is the first to identify Puerto Rico as having exceptionally high prevalence. The reasons for this should be extensively investigated, the investigators argued.

The mortality risk was 43% higher among NTM-infected patients than in COPD patients without an NTM diagnosis (95% confidence interval, 1.31-1.58; P less than .001), independent of other comorbidities.

Though rates of NTM infection were seen rising steeply in men and women alike, Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted as a limitation of their study its use of an overwhelmingly male population, writing that this may obscure “the true reach of NTM disease and mortality” in the general population. The average age of NTM diagnosis remained steady throughout the study period, suggesting that rising incidence is not attributable to earlier diagnosis.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues reported no outside sources of funding or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pyarali F et al. Front Med. 2018 Nov 6. doi: 10.3389/fmed2018.00311.

FROM FRONTIERS IN MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Incidence and prevalence of non-TB mycobacteria infections rose sharply in a national veterans population with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after 2012.

Major finding: Incidence of non-TB mycobacteria infections doubled in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients between 2001 and 2015, with most of the increase seen after 2012

Study details: A retrospective, cross-sectional study using records from over 2 million, mostly male chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in a Veterans Affairs database.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no outside sources of funding or financial conflicts of interest.

Source: Pyarali F et al. Front Med. 2018 Nov 6. doi: 10.3389/fmed2018.00311.

Primary Cutaneous Cryptococcosis in an Immunocompetent Iraq War Veteran

To the Editor:

Disseminated cryptococcosis is a well-known opportunistic infection in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, but it is not frequently seen as a primary infection of the skin in immunocompetent hosts. We report a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) of the lower legs in an immunocompetent Iraq War veteran.

A 28-year-old female service member presented to the dermatology clinic with progressively enlarging plaquelike lesions on the shins of 6 months’ duration. The patient had resided and worked as a deployed soldier in the lower level of a bullet hole–laden, pigeon-infested observation tower in southern Iraq 9 months prior to the current presentation. During her 7-month deployment, she reported daily exposure to pigeon excreta on equipment and frequently sustained superficial abrasions and lacerations to the legs due to the cramped and hazardous working environment. The patient noticed intensely pruritic, bugbitelike papular lesions on the shins and calves 1 month after residing in the observation tower. She sought medical treatment and was given hydrocortisone cream 1% and calamine lotion for a presumed irritant dermatitis. Over the ensuing 3 months, the pruritus worsened, and the primary lesions coalesced into annular erythematous plaques (Figure).

After returning to the United States, the patient presented again for medical care and was given ketoconazole cream 1% for presumed tinea corporis, which resulted in no improvement. A dermatologic consultation and evaluation ensued with subsequent microbial workup showing no bacterial growth on wound culture and no fungal elements on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining did not demonstrate any organisms. Tissue cultures for bacteria and acid-fast bacilli showed no growth. A fungal tissue culture ultimately confirmed the presence of Cryptococcus neoformans. A lumbar puncture showed no evidence of Cryptococcus on DNA probe testing. Serologic testing for HIV was negative, and brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no lesions. Sputum culture and staining showed no fungal elements, and a chest radiograph was normal. A diagnosis of PCC was made and therapy with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated, with the intention of completing a 6-month course. During the treatment, the pruritus resolved within 3 weeks and the lesions involuted over 3 months. From the time of onset of the lesions throughout treatment, the patient showed no pulmonary, neurologic, or other systemic symptoms. She currently is healthy with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis mainly affects individuals with underlying immunosuppression, most commonly due to advanced HIV, prolonged treatment with immunosuppressive medications, or organ transplantation.1 The most common route of inoculation is by inhalation of Cryptococcus spores with subsequent hematogenous dissemination.2 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis with skin lesions and no concomitant systemic involvement has rarely been reported, and

Due to the worldwide deployment of US military service members, exotic cutaneous infectious diseases such as PCC may be encountered in dermatology practice. Prompt clinical and histologic diagnosis is imperative to assess for systemic disease and avoid cutaneous spread and morbidity in US service members and travelers returning home from the Middle East.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789-94.

- Kielstein P, Hotzel H, Schmalreck A, et al. Occurrence of Cryptococcus spp. in excreta of pigeons and pet birds. Mycoses. 2000;43:7-15.

- Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host [published online October 28, 2010]. Med Mycol. 2011;49:352-355.

- Zorman JV, Zupanc TL, Parac Z, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses. 2010;53:535-537.

To the Editor:

Disseminated cryptococcosis is a well-known opportunistic infection in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, but it is not frequently seen as a primary infection of the skin in immunocompetent hosts. We report a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) of the lower legs in an immunocompetent Iraq War veteran.

A 28-year-old female service member presented to the dermatology clinic with progressively enlarging plaquelike lesions on the shins of 6 months’ duration. The patient had resided and worked as a deployed soldier in the lower level of a bullet hole–laden, pigeon-infested observation tower in southern Iraq 9 months prior to the current presentation. During her 7-month deployment, she reported daily exposure to pigeon excreta on equipment and frequently sustained superficial abrasions and lacerations to the legs due to the cramped and hazardous working environment. The patient noticed intensely pruritic, bugbitelike papular lesions on the shins and calves 1 month after residing in the observation tower. She sought medical treatment and was given hydrocortisone cream 1% and calamine lotion for a presumed irritant dermatitis. Over the ensuing 3 months, the pruritus worsened, and the primary lesions coalesced into annular erythematous plaques (Figure).

After returning to the United States, the patient presented again for medical care and was given ketoconazole cream 1% for presumed tinea corporis, which resulted in no improvement. A dermatologic consultation and evaluation ensued with subsequent microbial workup showing no bacterial growth on wound culture and no fungal elements on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining did not demonstrate any organisms. Tissue cultures for bacteria and acid-fast bacilli showed no growth. A fungal tissue culture ultimately confirmed the presence of Cryptococcus neoformans. A lumbar puncture showed no evidence of Cryptococcus on DNA probe testing. Serologic testing for HIV was negative, and brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no lesions. Sputum culture and staining showed no fungal elements, and a chest radiograph was normal. A diagnosis of PCC was made and therapy with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated, with the intention of completing a 6-month course. During the treatment, the pruritus resolved within 3 weeks and the lesions involuted over 3 months. From the time of onset of the lesions throughout treatment, the patient showed no pulmonary, neurologic, or other systemic symptoms. She currently is healthy with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis mainly affects individuals with underlying immunosuppression, most commonly due to advanced HIV, prolonged treatment with immunosuppressive medications, or organ transplantation.1 The most common route of inoculation is by inhalation of Cryptococcus spores with subsequent hematogenous dissemination.2 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis with skin lesions and no concomitant systemic involvement has rarely been reported, and

Due to the worldwide deployment of US military service members, exotic cutaneous infectious diseases such as PCC may be encountered in dermatology practice. Prompt clinical and histologic diagnosis is imperative to assess for systemic disease and avoid cutaneous spread and morbidity in US service members and travelers returning home from the Middle East.

To the Editor:

Disseminated cryptococcosis is a well-known opportunistic infection in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, but it is not frequently seen as a primary infection of the skin in immunocompetent hosts. We report a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) of the lower legs in an immunocompetent Iraq War veteran.

A 28-year-old female service member presented to the dermatology clinic with progressively enlarging plaquelike lesions on the shins of 6 months’ duration. The patient had resided and worked as a deployed soldier in the lower level of a bullet hole–laden, pigeon-infested observation tower in southern Iraq 9 months prior to the current presentation. During her 7-month deployment, she reported daily exposure to pigeon excreta on equipment and frequently sustained superficial abrasions and lacerations to the legs due to the cramped and hazardous working environment. The patient noticed intensely pruritic, bugbitelike papular lesions on the shins and calves 1 month after residing in the observation tower. She sought medical treatment and was given hydrocortisone cream 1% and calamine lotion for a presumed irritant dermatitis. Over the ensuing 3 months, the pruritus worsened, and the primary lesions coalesced into annular erythematous plaques (Figure).

After returning to the United States, the patient presented again for medical care and was given ketoconazole cream 1% for presumed tinea corporis, which resulted in no improvement. A dermatologic consultation and evaluation ensued with subsequent microbial workup showing no bacterial growth on wound culture and no fungal elements on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining did not demonstrate any organisms. Tissue cultures for bacteria and acid-fast bacilli showed no growth. A fungal tissue culture ultimately confirmed the presence of Cryptococcus neoformans. A lumbar puncture showed no evidence of Cryptococcus on DNA probe testing. Serologic testing for HIV was negative, and brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no lesions. Sputum culture and staining showed no fungal elements, and a chest radiograph was normal. A diagnosis of PCC was made and therapy with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated, with the intention of completing a 6-month course. During the treatment, the pruritus resolved within 3 weeks and the lesions involuted over 3 months. From the time of onset of the lesions throughout treatment, the patient showed no pulmonary, neurologic, or other systemic symptoms. She currently is healthy with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis mainly affects individuals with underlying immunosuppression, most commonly due to advanced HIV, prolonged treatment with immunosuppressive medications, or organ transplantation.1 The most common route of inoculation is by inhalation of Cryptococcus spores with subsequent hematogenous dissemination.2 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis with skin lesions and no concomitant systemic involvement has rarely been reported, and

Due to the worldwide deployment of US military service members, exotic cutaneous infectious diseases such as PCC may be encountered in dermatology practice. Prompt clinical and histologic diagnosis is imperative to assess for systemic disease and avoid cutaneous spread and morbidity in US service members and travelers returning home from the Middle East.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789-94.

- Kielstein P, Hotzel H, Schmalreck A, et al. Occurrence of Cryptococcus spp. in excreta of pigeons and pet birds. Mycoses. 2000;43:7-15.

- Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host [published online October 28, 2010]. Med Mycol. 2011;49:352-355.

- Zorman JV, Zupanc TL, Parac Z, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses. 2010;53:535-537.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789-94.

- Kielstein P, Hotzel H, Schmalreck A, et al. Occurrence of Cryptococcus spp. in excreta of pigeons and pet birds. Mycoses. 2000;43:7-15.

- Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host [published online October 28, 2010]. Med Mycol. 2011;49:352-355.

- Zorman JV, Zupanc TL, Parac Z, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses. 2010;53:535-537.

Practice Points

- Disseminated cryptococcosis is not commonly seen as a primary cutaneous infection in immunocompetent hosts.

- When encountered, primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) usually is associated with environments that predispose patients to skin wounds with simultaneous exposure to soil or vegetative debris contaminated with bird excreta.

- The variable presentation of PCC can cause clinical confusion and diagnostic delay; therefore, a high index of suspicion is required for timely diagnosis, particularly in US service members and travelers returning home from endemic areas.

Erythematous Pruritic Plaque on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

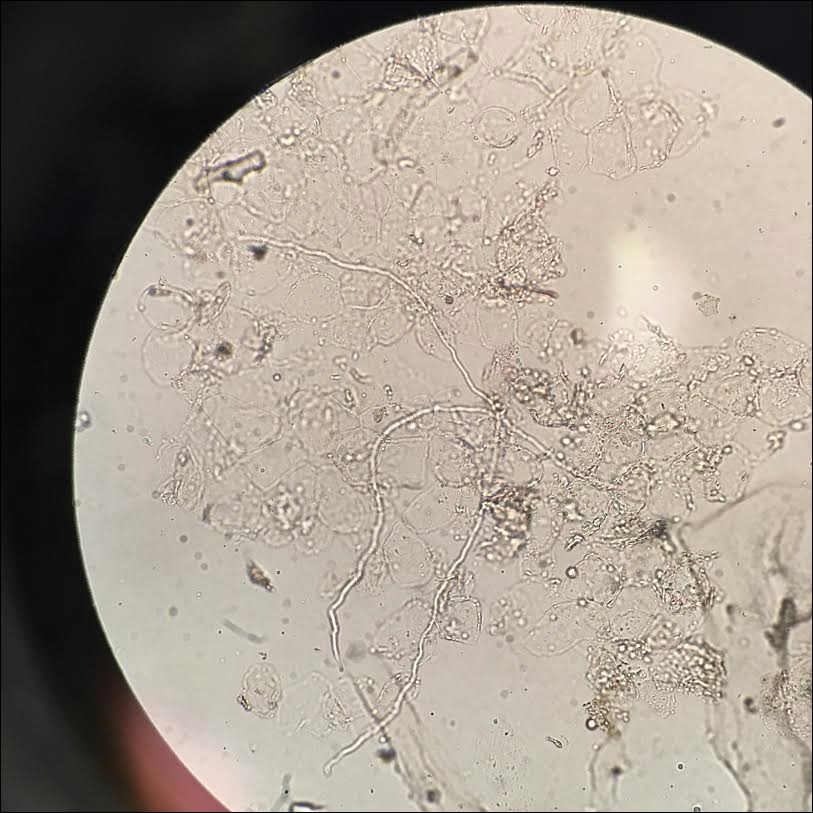

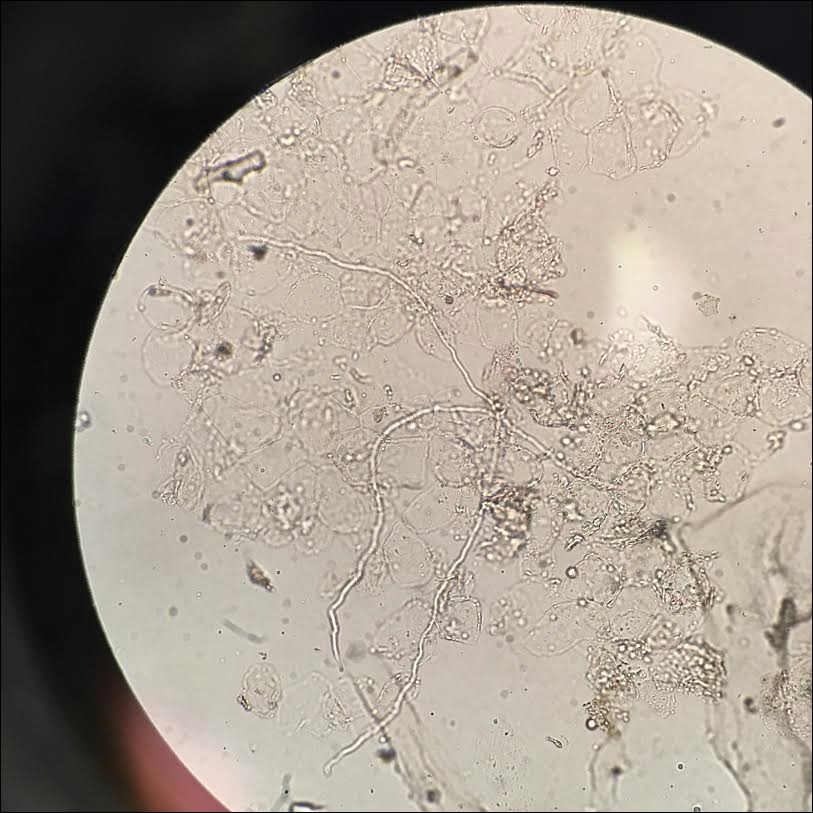

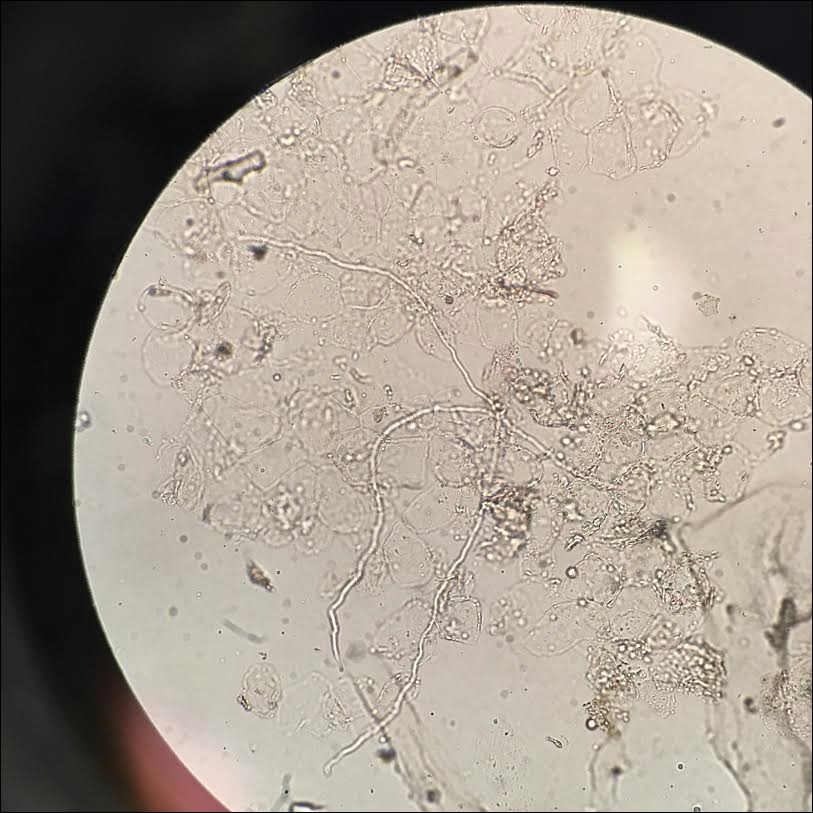

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

A 19-year-old man with a medical history of keloids presented with a slowly enlarging, red, itchy plaque on the left cheek of 1 year's duration that first began to develop during basic training in the military. The patient denied other pain, pruritus, or separate dermatitis. He initially was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which he used for 8 days prior to referral to the dermatology department. The patient denied other acute concerns. On physical examination, multiple erythematous papules coalescing into a large, 10-cm, papulosquamous, arciform plaque were noted on the left preauricular cheek.

ICU-acquired pneumonia mortality risk may be underestimated

In a large prospectively collected database, the risk of death at 30 days in ICU patients was far greater in those with hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) than in those with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) even after adjustment for prognostic factors, according to a large study that compared mortality risk for these complications.

The data for this newly published study were drawn from an evaluation of 14,212 patients treated at 23 ICUs participating in a collaborative French network OUTCOMEREA and published Critical Care Medicine.

HAP in ICU patients “was associated with an 82% increase in the risk of death at day 30,” reported a team of investigators led by Wafa Ibn Saied, MD, of the Université Paris Diderot. Although VAP and HAP were independent risk factors (P both less than .0001) for death at 30 days, VAP increased risk by 38%, less than half of HAP, which increased risk by 82%.

From an observational but prospective database initiated in 1997, this study evaluated 7,735 ICU patients at risk for VAP and 9,747 at risk for HAP. Of those at risk, defined by several factors including an ICU stay of more than 48 hours, HAP developed in 8% and VAP developed in 1%.

The 30-day mortality rates at 30 days after pneumonia were 23.9% for HAP and 28.4% for VAP. The greater risk of death by HR was identified after an analysis that adjusted for mortality risk factors, the adequacy of initial treatment, and other factors, such as prior history of pneumonia.

In HAP patients, the rate of mortality at 30 days was 32% in the 75 who were reintubated but only 16% in the 101 who were not. Adequate empirical therapy within the first 24 hours for HAP was not associated with a reduction in the risk of death.

As in the HAP patients, mortality was not significantly higher in VAP patients who received inadequate empirical therapy, compared with those who did, according to the authors.

Previous studies have suggested that both HAP and VAP increase risk of death in ICU patients, but the authors of this study believe that the relative risk of HAP “is underappreciated.” They asserted, based on these most recent data as well as on previously published analyses, that nonventilated HAP results in “significant increases in cost, length of stay, and mortality.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Saied WI et al. Crit Care Med. 2018 Nov 7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003553.

In a large prospectively collected database, the risk of death at 30 days in ICU patients was far greater in those with hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) than in those with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) even after adjustment for prognostic factors, according to a large study that compared mortality risk for these complications.

The data for this newly published study were drawn from an evaluation of 14,212 patients treated at 23 ICUs participating in a collaborative French network OUTCOMEREA and published Critical Care Medicine.

HAP in ICU patients “was associated with an 82% increase in the risk of death at day 30,” reported a team of investigators led by Wafa Ibn Saied, MD, of the Université Paris Diderot. Although VAP and HAP were independent risk factors (P both less than .0001) for death at 30 days, VAP increased risk by 38%, less than half of HAP, which increased risk by 82%.

From an observational but prospective database initiated in 1997, this study evaluated 7,735 ICU patients at risk for VAP and 9,747 at risk for HAP. Of those at risk, defined by several factors including an ICU stay of more than 48 hours, HAP developed in 8% and VAP developed in 1%.

The 30-day mortality rates at 30 days after pneumonia were 23.9% for HAP and 28.4% for VAP. The greater risk of death by HR was identified after an analysis that adjusted for mortality risk factors, the adequacy of initial treatment, and other factors, such as prior history of pneumonia.

In HAP patients, the rate of mortality at 30 days was 32% in the 75 who were reintubated but only 16% in the 101 who were not. Adequate empirical therapy within the first 24 hours for HAP was not associated with a reduction in the risk of death.

As in the HAP patients, mortality was not significantly higher in VAP patients who received inadequate empirical therapy, compared with those who did, according to the authors.

Previous studies have suggested that both HAP and VAP increase risk of death in ICU patients, but the authors of this study believe that the relative risk of HAP “is underappreciated.” They asserted, based on these most recent data as well as on previously published analyses, that nonventilated HAP results in “significant increases in cost, length of stay, and mortality.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Saied WI et al. Crit Care Med. 2018 Nov 7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003553.

In a large prospectively collected database, the risk of death at 30 days in ICU patients was far greater in those with hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) than in those with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) even after adjustment for prognostic factors, according to a large study that compared mortality risk for these complications.

The data for this newly published study were drawn from an evaluation of 14,212 patients treated at 23 ICUs participating in a collaborative French network OUTCOMEREA and published Critical Care Medicine.

HAP in ICU patients “was associated with an 82% increase in the risk of death at day 30,” reported a team of investigators led by Wafa Ibn Saied, MD, of the Université Paris Diderot. Although VAP and HAP were independent risk factors (P both less than .0001) for death at 30 days, VAP increased risk by 38%, less than half of HAP, which increased risk by 82%.

From an observational but prospective database initiated in 1997, this study evaluated 7,735 ICU patients at risk for VAP and 9,747 at risk for HAP. Of those at risk, defined by several factors including an ICU stay of more than 48 hours, HAP developed in 8% and VAP developed in 1%.

The 30-day mortality rates at 30 days after pneumonia were 23.9% for HAP and 28.4% for VAP. The greater risk of death by HR was identified after an analysis that adjusted for mortality risk factors, the adequacy of initial treatment, and other factors, such as prior history of pneumonia.

In HAP patients, the rate of mortality at 30 days was 32% in the 75 who were reintubated but only 16% in the 101 who were not. Adequate empirical therapy within the first 24 hours for HAP was not associated with a reduction in the risk of death.

As in the HAP patients, mortality was not significantly higher in VAP patients who received inadequate empirical therapy, compared with those who did, according to the authors.

Previous studies have suggested that both HAP and VAP increase risk of death in ICU patients, but the authors of this study believe that the relative risk of HAP “is underappreciated.” They asserted, based on these most recent data as well as on previously published analyses, that nonventilated HAP results in “significant increases in cost, length of stay, and mortality.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Saied WI et al. Crit Care Med. 2018 Nov 7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003553.

FROM CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Hospital-acquired pneumonia poses a greater risk of death in the ICU than ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Major finding: After prognostic adjustment, the mortality hazard ratios were 1.82 and 1.38 for HAP and VAP, respectively.

Study details: Observational cohort study.

Disclosures: The researchers had no disclosures.

Source: Saied WI et al. Crit Care Med. 2018 Nov 7; doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003553.

Oral Bowenoid Papulosis

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old Somali woman presented to our institution with oral lesions of 2 years’ duration. The lesions started as small papules in the corners of the mouth that gradually continued to spread to the mucosal lips and gums. The lesions did not drain any material. The patient reported that they were not painful and had not regressed. She was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient believed the lesions had developed from working in a chicken factory and was concerned that they appeared possibly due to contact with a substance in the factory. Additionally, she noted that her voice had become hoarse. She was otherwise healthy and denied any sexual contact or ever having a blood transfusion.

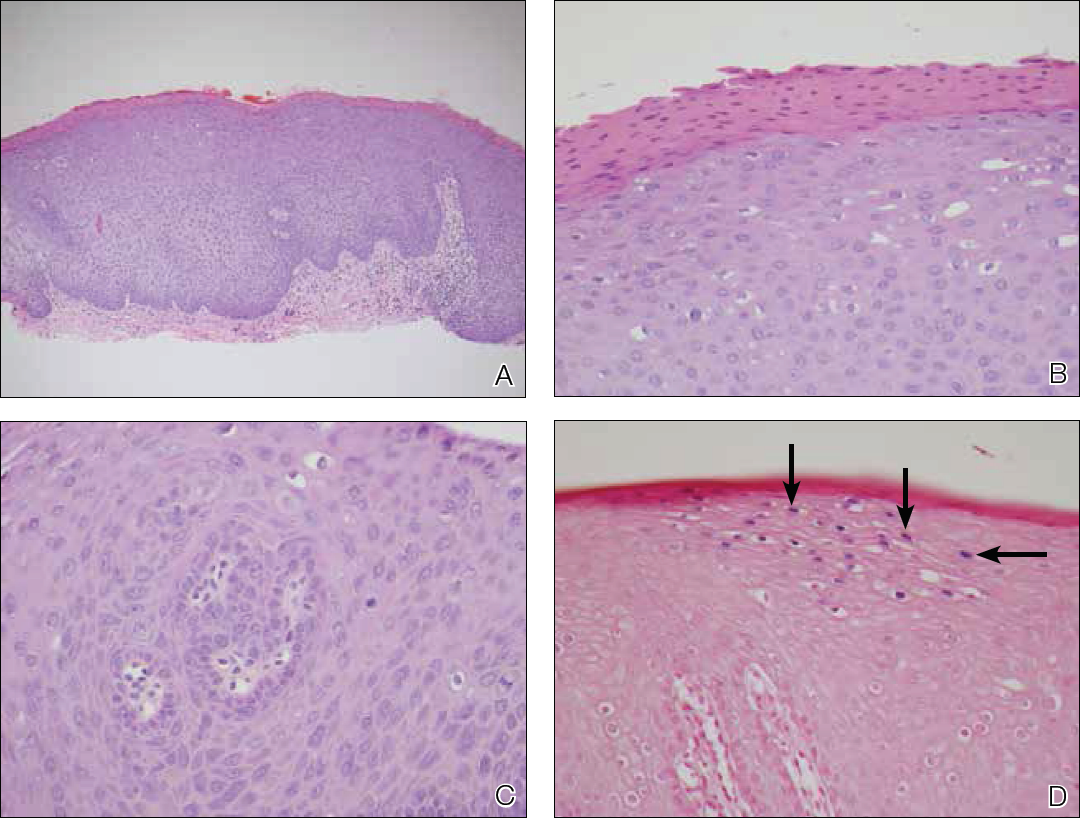

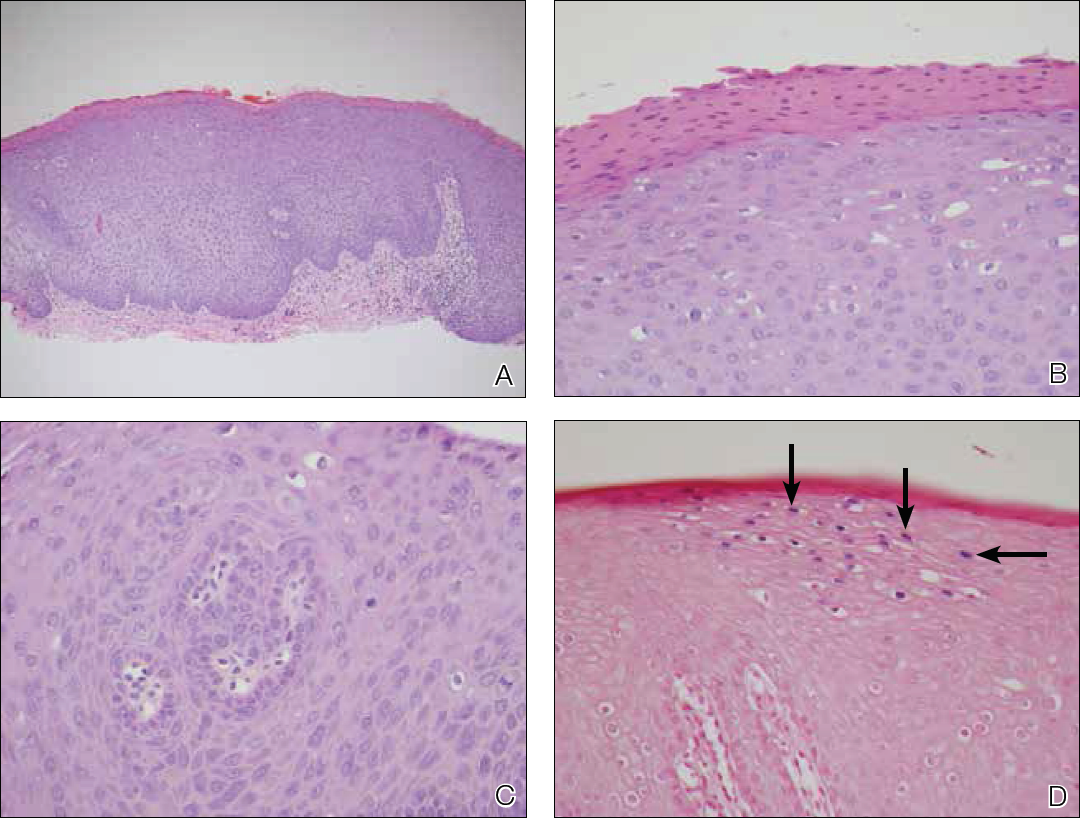

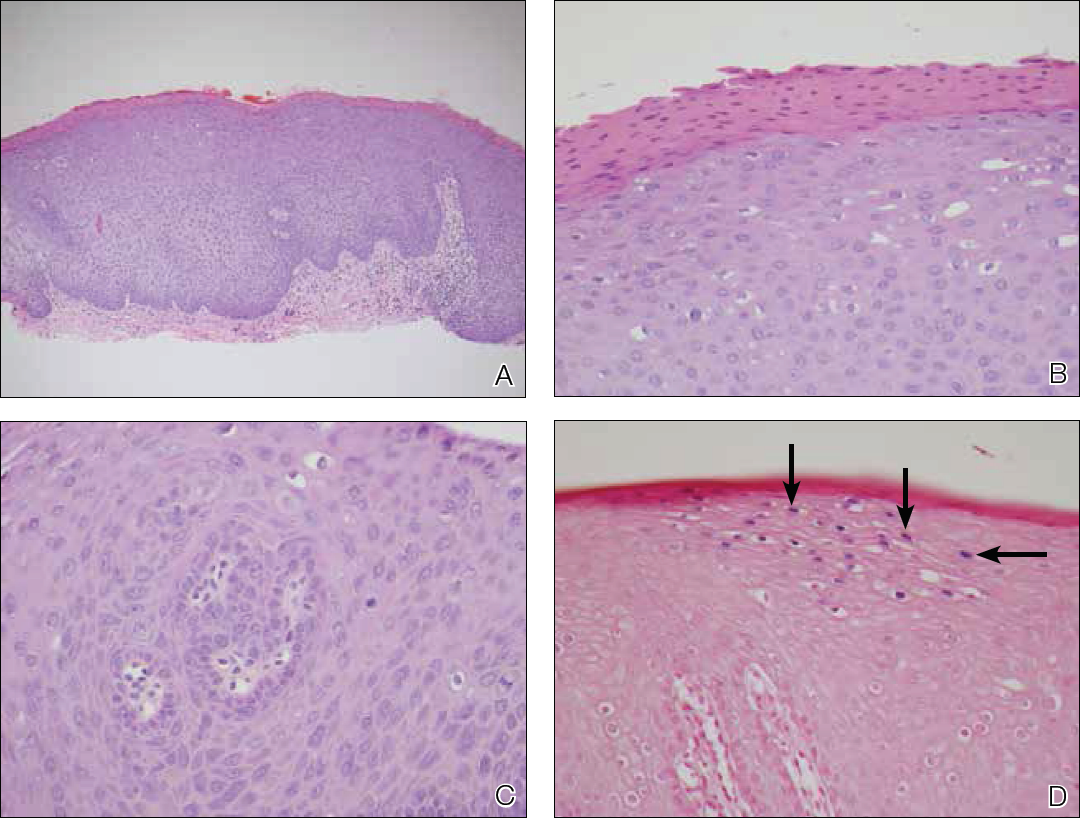

Physical examination revealed 10 to 15 flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter on the vermilion, mucosal surfaces of the lips, and upper and lower gingivae (Figure 1). No lesions were seen on the hard and soft palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, or posterior pharynx.

Skin biopsy of the left lower mucosal lip revealed parakeratosis, acanthosis, superficial koilocytes, and atypical keratinocytes with frequent mitoses (Figures 2A–2C). In situ hybridization testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) was negative for low-risk types 6 and 11 but positive for high-risk types 16 and 18 (Figure 2D). Laboratory investigations including complete blood cell count, electrolyte panel, and liver function studies were normal, and serum was negative for syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies.

The combined clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic of oral bowenoid papulosis. Gynecologic evaluation showed that the patient had undergone female circumcision, and she had a normal Papanicolaou test. The patient was referred to both the ear, nose, and throat clinic as well as the dermatologic surgery department to discuss treatment options, but she was lost to follow-up.

Bowenoid papulosis is triggered by HPV infection and manifests clinically as solitary or multiple verrucous papules and plaques that are usually located on the genitalia.1 Only a few cases of bowenoid papulosis have been reported in the oral cavity.1-5 Because this disease is sexually transmitted, the mean age of onset of bowenoid papulosis is 31 years.2 There is a small risk (2%–3%) of developing invasive carcinoma in bowenoid papulosis.1-3,6 Most lesions are associated with HPV type 16; however, bowenoid papulosis also has been associated with HPV types 18, 31, 32, 35, and 39.2

Some investigators consider bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease (a type of squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] in situ) to be histologically identical1,6; however, some histologic differences have been reported.1-3,6 Bowenoid papulosis has more dilated and tortuous dermal capillaries and less atypia and dyskeratosis than Bowen disease.1,6 In contrast to bowenoid papulosis, Bowen disease is characterized clinically as well-defined scaly plaques on sun-exposed areas of the skin in older adults. Invasive SCC can be seen in 5% of skin lesions and 30% of penile lesions associated with Bowen disease.2 Risk factors for Bowen disease include sun exposure; arsenic poisoning; and infection with HPV types 2, 16, 18, 31, 33, 52, and 67.1,6

Oral bowenoid papulosis is rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term oral bowenoid papulosis yielded 7 additional cases, which are summarized in the Table. In 1987 Lookingbill et al2 described one of the first reported cases of oral disease in a 33-year-old immunosuppressed man receiving prednisone therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus who had both mouth and genital lesions. All lesions were positive for HPV type 16. The patient subsequently developed SCC of the tongue.2

The risk for progression of oral bowenoid papulosis to invasive SCC is not known. Our search yielded only 1 case of this occurrence.2

Two of 3 cases of solitary lip lesions in oral bowenoid papulosis were treated with surgical excision.1 Other treatment options include CO2 laser therapy, cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, intralesional interferon alfa, and imiquimod.1-3,5,6

Our case represents a rare report of oral bowenoid papulosis. Recognition of this unusual presentation is important for the diagnosis and management of this disease.

- Daley T, Birek C, Wysocki GP. Oral bowenoid lesions: differential diagnosis and pathogenetic insights. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:466-473.

- Lookingbill DP, Kreider JW, Howett MK, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 in bowenoid papulosis, intraoral papillomas, and squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:363-368.

- Kratochvil FJ, Cioffi GA, Auclair PL, et al. Virus-associated dysplasia (bowenoid papulosis?) of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:312-316.

- Degener AM, Latino L, Pierangeli A, et al. Human papilloma virus-32-positive extragenital bowenoid papulosis in a HIV patient with typical genital bowenoid papulosis localization. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:619-622.

- Rinaggio J, Glick M, Lambert WC. Oral bowenoid papulosis in an HIV-positive male [published online October 14, 2005]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:328-332.

- Regezi JA, Dekker NP, Ramos DM, et al. Proliferation and invasion factors in HIV-associated dysplastic and nondysplastic oral warts and in oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and RT-PCR evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:724-731.

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old Somali woman presented to our institution with oral lesions of 2 years’ duration. The lesions started as small papules in the corners of the mouth that gradually continued to spread to the mucosal lips and gums. The lesions did not drain any material. The patient reported that they were not painful and had not regressed. She was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient believed the lesions had developed from working in a chicken factory and was concerned that they appeared possibly due to contact with a substance in the factory. Additionally, she noted that her voice had become hoarse. She was otherwise healthy and denied any sexual contact or ever having a blood transfusion.

Physical examination revealed 10 to 15 flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter on the vermilion, mucosal surfaces of the lips, and upper and lower gingivae (Figure 1). No lesions were seen on the hard and soft palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, or posterior pharynx.

Skin biopsy of the left lower mucosal lip revealed parakeratosis, acanthosis, superficial koilocytes, and atypical keratinocytes with frequent mitoses (Figures 2A–2C). In situ hybridization testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) was negative for low-risk types 6 and 11 but positive for high-risk types 16 and 18 (Figure 2D). Laboratory investigations including complete blood cell count, electrolyte panel, and liver function studies were normal, and serum was negative for syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies.

The combined clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic of oral bowenoid papulosis. Gynecologic evaluation showed that the patient had undergone female circumcision, and she had a normal Papanicolaou test. The patient was referred to both the ear, nose, and throat clinic as well as the dermatologic surgery department to discuss treatment options, but she was lost to follow-up.

Bowenoid papulosis is triggered by HPV infection and manifests clinically as solitary or multiple verrucous papules and plaques that are usually located on the genitalia.1 Only a few cases of bowenoid papulosis have been reported in the oral cavity.1-5 Because this disease is sexually transmitted, the mean age of onset of bowenoid papulosis is 31 years.2 There is a small risk (2%–3%) of developing invasive carcinoma in bowenoid papulosis.1-3,6 Most lesions are associated with HPV type 16; however, bowenoid papulosis also has been associated with HPV types 18, 31, 32, 35, and 39.2

Some investigators consider bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease (a type of squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] in situ) to be histologically identical1,6; however, some histologic differences have been reported.1-3,6 Bowenoid papulosis has more dilated and tortuous dermal capillaries and less atypia and dyskeratosis than Bowen disease.1,6 In contrast to bowenoid papulosis, Bowen disease is characterized clinically as well-defined scaly plaques on sun-exposed areas of the skin in older adults. Invasive SCC can be seen in 5% of skin lesions and 30% of penile lesions associated with Bowen disease.2 Risk factors for Bowen disease include sun exposure; arsenic poisoning; and infection with HPV types 2, 16, 18, 31, 33, 52, and 67.1,6

Oral bowenoid papulosis is rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term oral bowenoid papulosis yielded 7 additional cases, which are summarized in the Table. In 1987 Lookingbill et al2 described one of the first reported cases of oral disease in a 33-year-old immunosuppressed man receiving prednisone therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus who had both mouth and genital lesions. All lesions were positive for HPV type 16. The patient subsequently developed SCC of the tongue.2

The risk for progression of oral bowenoid papulosis to invasive SCC is not known. Our search yielded only 1 case of this occurrence.2

Two of 3 cases of solitary lip lesions in oral bowenoid papulosis were treated with surgical excision.1 Other treatment options include CO2 laser therapy, cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, intralesional interferon alfa, and imiquimod.1-3,5,6

Our case represents a rare report of oral bowenoid papulosis. Recognition of this unusual presentation is important for the diagnosis and management of this disease.

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old Somali woman presented to our institution with oral lesions of 2 years’ duration. The lesions started as small papules in the corners of the mouth that gradually continued to spread to the mucosal lips and gums. The lesions did not drain any material. The patient reported that they were not painful and had not regressed. She was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient believed the lesions had developed from working in a chicken factory and was concerned that they appeared possibly due to contact with a substance in the factory. Additionally, she noted that her voice had become hoarse. She was otherwise healthy and denied any sexual contact or ever having a blood transfusion.

Physical examination revealed 10 to 15 flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter on the vermilion, mucosal surfaces of the lips, and upper and lower gingivae (Figure 1). No lesions were seen on the hard and soft palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, or posterior pharynx.

Skin biopsy of the left lower mucosal lip revealed parakeratosis, acanthosis, superficial koilocytes, and atypical keratinocytes with frequent mitoses (Figures 2A–2C). In situ hybridization testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) was negative for low-risk types 6 and 11 but positive for high-risk types 16 and 18 (Figure 2D). Laboratory investigations including complete blood cell count, electrolyte panel, and liver function studies were normal, and serum was negative for syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies.

The combined clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic of oral bowenoid papulosis. Gynecologic evaluation showed that the patient had undergone female circumcision, and she had a normal Papanicolaou test. The patient was referred to both the ear, nose, and throat clinic as well as the dermatologic surgery department to discuss treatment options, but she was lost to follow-up.

Bowenoid papulosis is triggered by HPV infection and manifests clinically as solitary or multiple verrucous papules and plaques that are usually located on the genitalia.1 Only a few cases of bowenoid papulosis have been reported in the oral cavity.1-5 Because this disease is sexually transmitted, the mean age of onset of bowenoid papulosis is 31 years.2 There is a small risk (2%–3%) of developing invasive carcinoma in bowenoid papulosis.1-3,6 Most lesions are associated with HPV type 16; however, bowenoid papulosis also has been associated with HPV types 18, 31, 32, 35, and 39.2

Some investigators consider bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease (a type of squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] in situ) to be histologically identical1,6; however, some histologic differences have been reported.1-3,6 Bowenoid papulosis has more dilated and tortuous dermal capillaries and less atypia and dyskeratosis than Bowen disease.1,6 In contrast to bowenoid papulosis, Bowen disease is characterized clinically as well-defined scaly plaques on sun-exposed areas of the skin in older adults. Invasive SCC can be seen in 5% of skin lesions and 30% of penile lesions associated with Bowen disease.2 Risk factors for Bowen disease include sun exposure; arsenic poisoning; and infection with HPV types 2, 16, 18, 31, 33, 52, and 67.1,6

Oral bowenoid papulosis is rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term oral bowenoid papulosis yielded 7 additional cases, which are summarized in the Table. In 1987 Lookingbill et al2 described one of the first reported cases of oral disease in a 33-year-old immunosuppressed man receiving prednisone therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus who had both mouth and genital lesions. All lesions were positive for HPV type 16. The patient subsequently developed SCC of the tongue.2

The risk for progression of oral bowenoid papulosis to invasive SCC is not known. Our search yielded only 1 case of this occurrence.2

Two of 3 cases of solitary lip lesions in oral bowenoid papulosis were treated with surgical excision.1 Other treatment options include CO2 laser therapy, cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, intralesional interferon alfa, and imiquimod.1-3,5,6

Our case represents a rare report of oral bowenoid papulosis. Recognition of this unusual presentation is important for the diagnosis and management of this disease.

- Daley T, Birek C, Wysocki GP. Oral bowenoid lesions: differential diagnosis and pathogenetic insights. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:466-473.

- Lookingbill DP, Kreider JW, Howett MK, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 in bowenoid papulosis, intraoral papillomas, and squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:363-368.

- Kratochvil FJ, Cioffi GA, Auclair PL, et al. Virus-associated dysplasia (bowenoid papulosis?) of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:312-316.

- Degener AM, Latino L, Pierangeli A, et al. Human papilloma virus-32-positive extragenital bowenoid papulosis in a HIV patient with typical genital bowenoid papulosis localization. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:619-622.

- Rinaggio J, Glick M, Lambert WC. Oral bowenoid papulosis in an HIV-positive male [published online October 14, 2005]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:328-332.

- Regezi JA, Dekker NP, Ramos DM, et al. Proliferation and invasion factors in HIV-associated dysplastic and nondysplastic oral warts and in oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and RT-PCR evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:724-731.

- Daley T, Birek C, Wysocki GP. Oral bowenoid lesions: differential diagnosis and pathogenetic insights. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:466-473.

- Lookingbill DP, Kreider JW, Howett MK, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 in bowenoid papulosis, intraoral papillomas, and squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:363-368.

- Kratochvil FJ, Cioffi GA, Auclair PL, et al. Virus-associated dysplasia (bowenoid papulosis?) of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:312-316.

- Degener AM, Latino L, Pierangeli A, et al. Human papilloma virus-32-positive extragenital bowenoid papulosis in a HIV patient with typical genital bowenoid papulosis localization. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:619-622.

- Rinaggio J, Glick M, Lambert WC. Oral bowenoid papulosis in an HIV-positive male [published online October 14, 2005]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:328-332.

- Regezi JA, Dekker NP, Ramos DM, et al. Proliferation and invasion factors in HIV-associated dysplastic and nondysplastic oral warts and in oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and RT-PCR evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:724-731.

Practice Points

- Bowenoid papulosis is triggered by human papillomavirus infection and manifests clinically as solitary or multiple verrucous papules and plaques that usually are located on the genitalia.

- Oral bowenoid papulosis is rare, and recognition of this unusual presentation is important for the diagnosis and management of this disease.

Vitamin D–binding protein polymorphisms affect HCV susceptibility

Two specific polymorphisms within the vitamin D–binding protein (VDBP) gene may contribute to susceptibility to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in a high-risk Chinese Han population, according to the results of a case-control study published in Gene.

Previous research has indicated that vitamin D deficiency may have an impact on the antiviral response in chronic HCV, and VDBP has been shown to transport vitamin D and its metabolites, thereby influencing vitamin D status. This made VDBP a valid candidate for study as to its effects on HCV infection.

The current study initially recruited around 2,500 Chinese subjects over the period October 2008 to January 2016. The majority were women, and the average age of the subjects was 49-50 years.

The researchers genotyped seven genetic variants in the VDBP gene in 886 patients with HCV persistent infection, 539 subjects with spontaneous clearance, and 1,081 uninfected controls, according to Chao-Nan Xie of the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, Nanjing (China) Medical University, and colleagues.

The researchers found that two variants (rs7041-G and rs3733359-T alleles) were significantly associated with an increased susceptibility of HCV infection. In addition, the combined effect of having the two unfavorable alleles was related to an elevated risk of HCV infection in a locus-dosage manner (P = .000816).

Haplotype analysis suggested that the GT haplotype showed an increased risk effect of HCV infection (odds ratio, 1.464), compared with the most frequent TC haplotype.

“Taken together, polymorphisms within the VDBP gene (rs4588 and rs3733359) may contribute to susceptibility to HCV infection in a high-risk Chinese Han population, which implicates a role of VDR genetic polymorphisms and vitamin D levels in the immune regulation and course of HCV infection,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Xie C-N et al. Gene 2018;679:405-11.

Two specific polymorphisms within the vitamin D–binding protein (VDBP) gene may contribute to susceptibility to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in a high-risk Chinese Han population, according to the results of a case-control study published in Gene.

Previous research has indicated that vitamin D deficiency may have an impact on the antiviral response in chronic HCV, and VDBP has been shown to transport vitamin D and its metabolites, thereby influencing vitamin D status. This made VDBP a valid candidate for study as to its effects on HCV infection.

The current study initially recruited around 2,500 Chinese subjects over the period October 2008 to January 2016. The majority were women, and the average age of the subjects was 49-50 years.

The researchers genotyped seven genetic variants in the VDBP gene in 886 patients with HCV persistent infection, 539 subjects with spontaneous clearance, and 1,081 uninfected controls, according to Chao-Nan Xie of the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, Nanjing (China) Medical University, and colleagues.

The researchers found that two variants (rs7041-G and rs3733359-T alleles) were significantly associated with an increased susceptibility of HCV infection. In addition, the combined effect of having the two unfavorable alleles was related to an elevated risk of HCV infection in a locus-dosage manner (P = .000816).

Haplotype analysis suggested that the GT haplotype showed an increased risk effect of HCV infection (odds ratio, 1.464), compared with the most frequent TC haplotype.

“Taken together, polymorphisms within the VDBP gene (rs4588 and rs3733359) may contribute to susceptibility to HCV infection in a high-risk Chinese Han population, which implicates a role of VDR genetic polymorphisms and vitamin D levels in the immune regulation and course of HCV infection,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Xie C-N et al. Gene 2018;679:405-11.

Two specific polymorphisms within the vitamin D–binding protein (VDBP) gene may contribute to susceptibility to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in a high-risk Chinese Han population, according to the results of a case-control study published in Gene.

Previous research has indicated that vitamin D deficiency may have an impact on the antiviral response in chronic HCV, and VDBP has been shown to transport vitamin D and its metabolites, thereby influencing vitamin D status. This made VDBP a valid candidate for study as to its effects on HCV infection.

The current study initially recruited around 2,500 Chinese subjects over the period October 2008 to January 2016. The majority were women, and the average age of the subjects was 49-50 years.

The researchers genotyped seven genetic variants in the VDBP gene in 886 patients with HCV persistent infection, 539 subjects with spontaneous clearance, and 1,081 uninfected controls, according to Chao-Nan Xie of the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, Nanjing (China) Medical University, and colleagues.

The researchers found that two variants (rs7041-G and rs3733359-T alleles) were significantly associated with an increased susceptibility of HCV infection. In addition, the combined effect of having the two unfavorable alleles was related to an elevated risk of HCV infection in a locus-dosage manner (P = .000816).

Haplotype analysis suggested that the GT haplotype showed an increased risk effect of HCV infection (odds ratio, 1.464), compared with the most frequent TC haplotype.

“Taken together, polymorphisms within the VDBP gene (rs4588 and rs3733359) may contribute to susceptibility to HCV infection in a high-risk Chinese Han population, which implicates a role of VDR genetic polymorphisms and vitamin D levels in the immune regulation and course of HCV infection,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Xie C-N et al. Gene 2018;679:405-11.

FROM GENE

Key clinical point: VDBP alleles influence susceptibility to HCV infection in a Chinese population.

Major finding: The GT haplotype showed an increased risk effect of HCV infection (odds ratio 1.464) compared to the most frequent TC haplotype.

Study details: Case-control study of 886 HIV-infected, 539 spontaneously cleared, and 1,081 control patients.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Xie C-N et al. Gene. 2018;679:405-11.

It’s time for universal HCV screening in the ED

SAN FRANCISCO – Emergency departments are the ideal place to screen for hepatitis C infection, according to investigators from Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Current recommendations call for screening baby boomers born from 1945 to 1965 and patients with risk factors, especially injection drug use. The problem is that the guidelines don’t say, exactly, how and where that should be done, so uptake has been spotty. Also, people aren’t exactly forthcoming when it comes to admitting IV drug use.

Enter universal screening in the ED. Vanderbilt is one of several academic centers that have adopted the approach, and others are following suit. Across the board, they’ve found that HCV infection is more common than projections based on baby boomer and risk factor demographics suggest, and, even more importantly, the boomer/risk factor strategy misses a large number of active cases, said Cody A. Chastain, MD, assistant professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt, who led the ED screening initiative.

In short, universal screening in the ED would keep people from falling through the cracks.

From April 2017 to March 2018, every adult who had blood drawn at Vanderbilt’s tertiary care ED was asked by a nurse if they’d also like to be checked for HCV, so long as they were alert enough for the conversation. If they agreed, an additional phlebotomy tube was added to the draw, and sent off for testing. Fewer than 5% of patients opted out.

Antibody positive samples were automatically screened for active disease by HCV RNA. Results were entered into the medical record and shared with patients at discharge. Active cases were counseled and offered linkage to care, regardless of insurance status.

The initiative screened 11,637 patients; 1,008 (8.7%) were antibody positive, of whom 488 (48%) were RNA positive. Thirty-seven percent of the active cases were in non–baby boomers – most born after 1965 – with no known injection drug use. The baby boomer/risk factor model would have missed most of them.

Also, spontaneous clearance – antibody positive, RNA negative without HCV treatment – “is dramatically higher” than what’s thought. “The historic estimate of 20% clearly is not reflected” in the Vanderbilt results, nor in similar universal screening studies; “spontaneous clearance is about 50% or so,” Dr. Chastain said.

Even so, “virtually every study published in this space finds more cases of infection than traditional screening would find. [Our work] is just one more piece of data” to indicate the usefulness of the approach. “Emergency departments [are] ideal for hepatitis C screening,” he said at IDWeek, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases, where he presented the findings.

“This is well trodden territory; we’ve already addressed it with HIV. We recognized that HIV screening had a stigma and was a challenge, [so we] moved to universal screening” of all adults, at least once. It “drastically improved screening rates. I don’t see a rational reason” not to do this for hepatitis C. “There are very well-meaning people who engage in the cost effectiveness side of this discussion, but I don’t think it helps us in our efforts to control this epidemic from a public health standpoint,” Dr. Chastain said.

Vanderbilt continues to screen for HCV in the ED; the next step is to see how well efforts to link active cases with care are working. Many times during the study, Dr. Chastain said positive patients eventually revealed that they already knew they had HCV, but had been told there was nothing they could do about it, so they didn’t get care. Maybe they were told that because they didn’t have insurance.

Vanderbilt has dropped screening ED patients born before 1945 because the odds of picking up an unknown HCV infection proved to be tiny, and, in any case, patients are generally too comorbid for treatment. It’s made screening more efficient.