User login

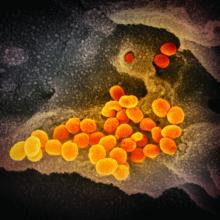

COVID-19: Time to ‘take the risk of scaring people’

It’s past time to call the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, a pandemic and “time to push people to prepare, and guide their prep,” according to risk communication experts.

Medical messaging about containing or stopping the spread of the virus is doing more harm than good, write Peter Sandman, PhD, and Jody Lanard, MD, both based in New York City, in a recent blog post.

“We are near-certain that the desperate-sounding last-ditch containment messaging of recent days is contributing to a massive global misperception,” they warn.

“The most crucial (and overdue) risk communication task … is to help people visualize their communities when ‘keeping it out’ – containment – is no longer relevant.”

That message is embraced by several experts who spoke to Medscape Medical News.

“I’m jealous of what [they] have written: It is so clear, so correct, and so practical,” said David Fisman, MD, MPH, professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto, Canada. “I think WHO [World Health Organization] is shying away from the P word,” he continued, referring to the organization’s continuing decision not to call the outbreak a pandemic.

“I fully support exactly what [Sandman and Lanard] are saying,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, MPH, professor of environmental health sciences and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Sandman and Lanard write. “Hardly any officials are telling civil society and the general public how to get ready for this pandemic.”

Effective communication should inform people of what to expect now, they continue: “[T]he end of most quarantines, travel restrictions, contact tracing, and other measures designed to keep ‘them’ from infecting ‘us,’ and the switch to measures like canceling mass events designed to keep us from infecting each other.”

Among the new messages that should be delivered are things like:

- Stockpiling nonperishable food and prescription meds.

- Considering care of sick family members.

- Cross-training work personnel so one person’s absence won’t derail an organization’s ability to function.

“We hope that governments and healthcare institutions are using this time wisely,” Sandman and Lanard continue. “We know that ordinary citizens are not being asked to do so. In most countries … ordinary citizens have not been asked to prepare. Instead, they have been led to expect that their governments will keep the virus from their doors.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s past time to call the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, a pandemic and “time to push people to prepare, and guide their prep,” according to risk communication experts.

Medical messaging about containing or stopping the spread of the virus is doing more harm than good, write Peter Sandman, PhD, and Jody Lanard, MD, both based in New York City, in a recent blog post.

“We are near-certain that the desperate-sounding last-ditch containment messaging of recent days is contributing to a massive global misperception,” they warn.

“The most crucial (and overdue) risk communication task … is to help people visualize their communities when ‘keeping it out’ – containment – is no longer relevant.”

That message is embraced by several experts who spoke to Medscape Medical News.

“I’m jealous of what [they] have written: It is so clear, so correct, and so practical,” said David Fisman, MD, MPH, professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto, Canada. “I think WHO [World Health Organization] is shying away from the P word,” he continued, referring to the organization’s continuing decision not to call the outbreak a pandemic.

“I fully support exactly what [Sandman and Lanard] are saying,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, MPH, professor of environmental health sciences and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Sandman and Lanard write. “Hardly any officials are telling civil society and the general public how to get ready for this pandemic.”

Effective communication should inform people of what to expect now, they continue: “[T]he end of most quarantines, travel restrictions, contact tracing, and other measures designed to keep ‘them’ from infecting ‘us,’ and the switch to measures like canceling mass events designed to keep us from infecting each other.”

Among the new messages that should be delivered are things like:

- Stockpiling nonperishable food and prescription meds.

- Considering care of sick family members.

- Cross-training work personnel so one person’s absence won’t derail an organization’s ability to function.

“We hope that governments and healthcare institutions are using this time wisely,” Sandman and Lanard continue. “We know that ordinary citizens are not being asked to do so. In most countries … ordinary citizens have not been asked to prepare. Instead, they have been led to expect that their governments will keep the virus from their doors.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s past time to call the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, a pandemic and “time to push people to prepare, and guide their prep,” according to risk communication experts.

Medical messaging about containing or stopping the spread of the virus is doing more harm than good, write Peter Sandman, PhD, and Jody Lanard, MD, both based in New York City, in a recent blog post.

“We are near-certain that the desperate-sounding last-ditch containment messaging of recent days is contributing to a massive global misperception,” they warn.

“The most crucial (and overdue) risk communication task … is to help people visualize their communities when ‘keeping it out’ – containment – is no longer relevant.”

That message is embraced by several experts who spoke to Medscape Medical News.

“I’m jealous of what [they] have written: It is so clear, so correct, and so practical,” said David Fisman, MD, MPH, professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto, Canada. “I think WHO [World Health Organization] is shying away from the P word,” he continued, referring to the organization’s continuing decision not to call the outbreak a pandemic.

“I fully support exactly what [Sandman and Lanard] are saying,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, MPH, professor of environmental health sciences and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Sandman and Lanard write. “Hardly any officials are telling civil society and the general public how to get ready for this pandemic.”

Effective communication should inform people of what to expect now, they continue: “[T]he end of most quarantines, travel restrictions, contact tracing, and other measures designed to keep ‘them’ from infecting ‘us,’ and the switch to measures like canceling mass events designed to keep us from infecting each other.”

Among the new messages that should be delivered are things like:

- Stockpiling nonperishable food and prescription meds.

- Considering care of sick family members.

- Cross-training work personnel so one person’s absence won’t derail an organization’s ability to function.

“We hope that governments and healthcare institutions are using this time wisely,” Sandman and Lanard continue. “We know that ordinary citizens are not being asked to do so. In most countries … ordinary citizens have not been asked to prepare. Instead, they have been led to expect that their governments will keep the virus from their doors.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC expects eventual community spread of coronavirus in U.S.

“We have for many weeks been saying that, while we hope this is not going to be severe, we are planning as if it is,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC, said during a Feb. 25, 2020, telebriefing with reporters. “The data over the last week and the spread in other countries has certainly raised our level of concern and raised our level expectation that we are going to have community spread here.”

Dr. Messonnier noted that the coronavirus is now showing signs of community spread without a known source of exposure in a number of countries, including in Hong Kong, Iran, Italy, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand. This has now raised the belief that there will be more widespread outbreaks in the United States.

“What we still don’t know is what that will look like,” she said. “As many of you know, we can have community spread in the United States and have it be reasonably mild. We can have community spread in the U.S. and have it be very severe. That is what we don’t completely know yet and we certainly also don’t exactly know when it is going to happen.”

She reiterated the number of actions being taken to slow the potential spread in the United States, including detecting, tracking, and isolating all cases, as well as restricting travel into the United States and issuing travel advisories for countries where coronavirus outbreaks are known.

“We are doing this with the goal of slowing the introduction of this new virus into the U.S. and buying us more time to prepare,” Dr. Messonnier said, noting the containment strategies have been largely successful, though it will be more difficult as more countries experience community spread of the virus.

Dr. Messonnier also reiterated that at this time there are no vaccines and no medicines to treat the coronavirus. She stressed the need to adhere to nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), as they will be “the most important tools in our response to this virus.”

She said the NPIs will vary based on the severity of the outbreak in any given local community and include personal protective measures that individuals can take every day (many of which mirror the recommendations for preventing the spread of the seasonal flu virus), community NPIs that involve social distancing measures designed to keep people away from others, and environmental NPIs such as surface cleaning measures.

CDC’s latest warning comes as parent agency the Department of Health & Human Services is seeking $2.5 billion in funds from Congress to address the coronavirus outbreak.

During a separate press conference on the same day, HHS Secretary Alex Azar noted that there are five major priorities related to those funds, which would be used in the current year, including expansion of surveillance work within the influenza surveillance network; supporting public health preparedness and response for state and local governments; support the development of therapeutics and the development of vaccines; and the purchase of personal protective equipment for national stockpiles.

Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease at the National Institutes of Health, added during the press conference that vaccine work is in progress and could be ready for phase 1 testing within a month and a half. If all goes well, it would still be at least 12 - 18 months following the completion of a phase 2 trial before it could be produced for mass consumption.

“It is certainly conceivable that this issue with this coronavirus will go well beyond this season into next season,” Dr. Fauci said. “So a vaccine may not solve the problems of the next couple of months, but it certainly would be an important tool that we would have and we will keep you posted on that.”

He also mentioned that NIAID is looking at a number of candidates for therapeutic treatment of coronavirus. He highlighted Gilead’s remdesivir, a nucleotide analog, as one which undergoing two trials – a randomized controlled trial in China and a copy of that trial in Nebraska among patients with the coronavirus who were taken from the Diamond Princess cruise line in Japan.

“I am optimistic that we will at least get an answer if we do have do have a therapy that really is a gamechanger because then we could do something from the standpoint of intervention for those who are sick,” Dr. Fauci said.

UPDATE: This story was updated 2/25 at 4:51 p.m. ET

“We have for many weeks been saying that, while we hope this is not going to be severe, we are planning as if it is,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC, said during a Feb. 25, 2020, telebriefing with reporters. “The data over the last week and the spread in other countries has certainly raised our level of concern and raised our level expectation that we are going to have community spread here.”

Dr. Messonnier noted that the coronavirus is now showing signs of community spread without a known source of exposure in a number of countries, including in Hong Kong, Iran, Italy, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand. This has now raised the belief that there will be more widespread outbreaks in the United States.

“What we still don’t know is what that will look like,” she said. “As many of you know, we can have community spread in the United States and have it be reasonably mild. We can have community spread in the U.S. and have it be very severe. That is what we don’t completely know yet and we certainly also don’t exactly know when it is going to happen.”

She reiterated the number of actions being taken to slow the potential spread in the United States, including detecting, tracking, and isolating all cases, as well as restricting travel into the United States and issuing travel advisories for countries where coronavirus outbreaks are known.

“We are doing this with the goal of slowing the introduction of this new virus into the U.S. and buying us more time to prepare,” Dr. Messonnier said, noting the containment strategies have been largely successful, though it will be more difficult as more countries experience community spread of the virus.

Dr. Messonnier also reiterated that at this time there are no vaccines and no medicines to treat the coronavirus. She stressed the need to adhere to nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), as they will be “the most important tools in our response to this virus.”

She said the NPIs will vary based on the severity of the outbreak in any given local community and include personal protective measures that individuals can take every day (many of which mirror the recommendations for preventing the spread of the seasonal flu virus), community NPIs that involve social distancing measures designed to keep people away from others, and environmental NPIs such as surface cleaning measures.

CDC’s latest warning comes as parent agency the Department of Health & Human Services is seeking $2.5 billion in funds from Congress to address the coronavirus outbreak.

During a separate press conference on the same day, HHS Secretary Alex Azar noted that there are five major priorities related to those funds, which would be used in the current year, including expansion of surveillance work within the influenza surveillance network; supporting public health preparedness and response for state and local governments; support the development of therapeutics and the development of vaccines; and the purchase of personal protective equipment for national stockpiles.

Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease at the National Institutes of Health, added during the press conference that vaccine work is in progress and could be ready for phase 1 testing within a month and a half. If all goes well, it would still be at least 12 - 18 months following the completion of a phase 2 trial before it could be produced for mass consumption.

“It is certainly conceivable that this issue with this coronavirus will go well beyond this season into next season,” Dr. Fauci said. “So a vaccine may not solve the problems of the next couple of months, but it certainly would be an important tool that we would have and we will keep you posted on that.”

He also mentioned that NIAID is looking at a number of candidates for therapeutic treatment of coronavirus. He highlighted Gilead’s remdesivir, a nucleotide analog, as one which undergoing two trials – a randomized controlled trial in China and a copy of that trial in Nebraska among patients with the coronavirus who were taken from the Diamond Princess cruise line in Japan.

“I am optimistic that we will at least get an answer if we do have do have a therapy that really is a gamechanger because then we could do something from the standpoint of intervention for those who are sick,” Dr. Fauci said.

UPDATE: This story was updated 2/25 at 4:51 p.m. ET

“We have for many weeks been saying that, while we hope this is not going to be severe, we are planning as if it is,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC, said during a Feb. 25, 2020, telebriefing with reporters. “The data over the last week and the spread in other countries has certainly raised our level of concern and raised our level expectation that we are going to have community spread here.”

Dr. Messonnier noted that the coronavirus is now showing signs of community spread without a known source of exposure in a number of countries, including in Hong Kong, Iran, Italy, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand. This has now raised the belief that there will be more widespread outbreaks in the United States.

“What we still don’t know is what that will look like,” she said. “As many of you know, we can have community spread in the United States and have it be reasonably mild. We can have community spread in the U.S. and have it be very severe. That is what we don’t completely know yet and we certainly also don’t exactly know when it is going to happen.”

She reiterated the number of actions being taken to slow the potential spread in the United States, including detecting, tracking, and isolating all cases, as well as restricting travel into the United States and issuing travel advisories for countries where coronavirus outbreaks are known.

“We are doing this with the goal of slowing the introduction of this new virus into the U.S. and buying us more time to prepare,” Dr. Messonnier said, noting the containment strategies have been largely successful, though it will be more difficult as more countries experience community spread of the virus.

Dr. Messonnier also reiterated that at this time there are no vaccines and no medicines to treat the coronavirus. She stressed the need to adhere to nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), as they will be “the most important tools in our response to this virus.”

She said the NPIs will vary based on the severity of the outbreak in any given local community and include personal protective measures that individuals can take every day (many of which mirror the recommendations for preventing the spread of the seasonal flu virus), community NPIs that involve social distancing measures designed to keep people away from others, and environmental NPIs such as surface cleaning measures.

CDC’s latest warning comes as parent agency the Department of Health & Human Services is seeking $2.5 billion in funds from Congress to address the coronavirus outbreak.

During a separate press conference on the same day, HHS Secretary Alex Azar noted that there are five major priorities related to those funds, which would be used in the current year, including expansion of surveillance work within the influenza surveillance network; supporting public health preparedness and response for state and local governments; support the development of therapeutics and the development of vaccines; and the purchase of personal protective equipment for national stockpiles.

Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease at the National Institutes of Health, added during the press conference that vaccine work is in progress and could be ready for phase 1 testing within a month and a half. If all goes well, it would still be at least 12 - 18 months following the completion of a phase 2 trial before it could be produced for mass consumption.

“It is certainly conceivable that this issue with this coronavirus will go well beyond this season into next season,” Dr. Fauci said. “So a vaccine may not solve the problems of the next couple of months, but it certainly would be an important tool that we would have and we will keep you posted on that.”

He also mentioned that NIAID is looking at a number of candidates for therapeutic treatment of coronavirus. He highlighted Gilead’s remdesivir, a nucleotide analog, as one which undergoing two trials – a randomized controlled trial in China and a copy of that trial in Nebraska among patients with the coronavirus who were taken from the Diamond Princess cruise line in Japan.

“I am optimistic that we will at least get an answer if we do have do have a therapy that really is a gamechanger because then we could do something from the standpoint of intervention for those who are sick,” Dr. Fauci said.

UPDATE: This story was updated 2/25 at 4:51 p.m. ET

HBV: Rethink the free pass for immune tolerant patients

MAUI, HAWAII – There might well be a cure for hepatitis B in coming years, just like there is now for hepatitis C, according to Norah Terrault, MD, chief of the division of GI and liver at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“We are going to have a laundry list of new drugs” that are in the pipeline now. Phase 2 results “look encouraging. You will hear much more about this in the years ahead,” said Dr. Terrault, lead author of the 2018 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) hepatitis B guidance.

For now, though, the field is largely limited to the nucleoside analogues tenofovir and entecavir. Treatment is often indefinite because, although hepatitis B virus (HBV) e-antigen is cleared, it usually doesn’t clear the HBV surface antigen, which is linked to liver cancer. “Even with e-antigen–negative patients, we feel that indefinite therapy is really the way to go,” Dr. Terrault said at the Gastroenterology Updates, IBD, Liver Disease Conference.

One of the biggest problems with that strategy is what to do when HBV does not seem to be much of a problem for carriers. Such patients are referred to as immune tolerant.

A newly recognized cancer risk

Immune tolerant patients tend to be young and have extremely high viral loads but no apparent ill effects, with normal ALT levels, normal histology, and no sign of cirrhosis. Although the AASLD recommends not treating these patients until they are 40 years old, waiting makes people nervous. “You have a hammer, you want to hit a nail,” Dr. Terrault said.

A recent review (Gut. 2018 May;67[5]:945-52) suggests that hitting the nail might be the way to go. South Korean investigators found that 413 untreated immune tolerate patients with a mean age of 38 years had more than twice the risk of liver cancer over 10 years than did almost 1,500 treated patients with active disease.

The study investigators concluded that “unnecessary deaths could be prevented through earlier antiviral intervention in select [immune tolerate] patients.”

This finding is one reason “we [AASLD] are rethinking the mantra of not treating the immune tolerant. There is a group that is transitioning” to active disease. “I’m thinking we should really [lower] the age cutoff” to 30 years, as some other groups [European Association for the Study of the Liver and Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver] have done, plus “patients feel really good when they know the virus is controlled, and so do physicians,” Dr. Terrault said.

Entecavir versus tenofovir

Meanwhile, recent studies have raised the question of whether tenofovir is better than entecavir at preventing liver cancer.

A JAMA Oncology (JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jan 1;5[1]:30-6) study of some 25,000 patients in South Korea found a 32% lower risk of liver cancer when they were treated with tenofovir instead of entecavir. “This led to a lot of concern that maybe we should be moving all our patients to tenofovir,” she said.

Another study, a meta-analysis published earlier this year (Hepatol Int. 2020 Jan;14[1]:105-14), confirmed the difference in cancer risk when it combined those findings with other research. After adjustment for potential confounders, including disease stage and length of follow-up, “the difference disappeared” (hazard ration, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-1.04), authors of the meta-analysis reported.

Study patients who received entecavir tended to be “treated many years ago and tended to have more severe [baseline] disease,” Dr. Terrault said.

So “while we see this difference, there’s not enough data yet for us to make a recommendation for our patients to switch from” entecavir to tenofovir. “Until a randomized controlled trial is done, this may remain an issue,” she said.

A drug holiday?

Dr. Terrault also reviewed research that suggests nucleoside analogue treatment can be stopped in e-antigen–negative patients after at least 3 years.

“The evidence is increasing that a finite NA [nucleoside analogue] treatment approach leads to higher HBsAg [hepatitis B surface antigen] loss rates, compared with the current long-term NA strategy, and can be considered a rational strategy to induce a functional cure in selected HBeAg-negative patients without cirrhosis who are willing to comply with close follow-up monitoring. ... The current observed functional cure rates” – perhaps about 40% – “would be well worth the effort,” editorialists commenting on the research concluded (Hepatology. 2018 Aug;68[2]:397-400).

It’s an interesting idea, Dr. Terrault said, but the virus will flare 8-12 weeks after treatment withdrawal, which is why it shouldn’t be considered in patients with cirrhosis.

Dr. Terrault is a consultant for AbbVie, Merck, Gilead, and other companies and disclosed grants from those companies and others.

MAUI, HAWAII – There might well be a cure for hepatitis B in coming years, just like there is now for hepatitis C, according to Norah Terrault, MD, chief of the division of GI and liver at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“We are going to have a laundry list of new drugs” that are in the pipeline now. Phase 2 results “look encouraging. You will hear much more about this in the years ahead,” said Dr. Terrault, lead author of the 2018 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) hepatitis B guidance.

For now, though, the field is largely limited to the nucleoside analogues tenofovir and entecavir. Treatment is often indefinite because, although hepatitis B virus (HBV) e-antigen is cleared, it usually doesn’t clear the HBV surface antigen, which is linked to liver cancer. “Even with e-antigen–negative patients, we feel that indefinite therapy is really the way to go,” Dr. Terrault said at the Gastroenterology Updates, IBD, Liver Disease Conference.

One of the biggest problems with that strategy is what to do when HBV does not seem to be much of a problem for carriers. Such patients are referred to as immune tolerant.

A newly recognized cancer risk

Immune tolerant patients tend to be young and have extremely high viral loads but no apparent ill effects, with normal ALT levels, normal histology, and no sign of cirrhosis. Although the AASLD recommends not treating these patients until they are 40 years old, waiting makes people nervous. “You have a hammer, you want to hit a nail,” Dr. Terrault said.

A recent review (Gut. 2018 May;67[5]:945-52) suggests that hitting the nail might be the way to go. South Korean investigators found that 413 untreated immune tolerate patients with a mean age of 38 years had more than twice the risk of liver cancer over 10 years than did almost 1,500 treated patients with active disease.

The study investigators concluded that “unnecessary deaths could be prevented through earlier antiviral intervention in select [immune tolerate] patients.”

This finding is one reason “we [AASLD] are rethinking the mantra of not treating the immune tolerant. There is a group that is transitioning” to active disease. “I’m thinking we should really [lower] the age cutoff” to 30 years, as some other groups [European Association for the Study of the Liver and Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver] have done, plus “patients feel really good when they know the virus is controlled, and so do physicians,” Dr. Terrault said.

Entecavir versus tenofovir

Meanwhile, recent studies have raised the question of whether tenofovir is better than entecavir at preventing liver cancer.

A JAMA Oncology (JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jan 1;5[1]:30-6) study of some 25,000 patients in South Korea found a 32% lower risk of liver cancer when they were treated with tenofovir instead of entecavir. “This led to a lot of concern that maybe we should be moving all our patients to tenofovir,” she said.

Another study, a meta-analysis published earlier this year (Hepatol Int. 2020 Jan;14[1]:105-14), confirmed the difference in cancer risk when it combined those findings with other research. After adjustment for potential confounders, including disease stage and length of follow-up, “the difference disappeared” (hazard ration, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-1.04), authors of the meta-analysis reported.

Study patients who received entecavir tended to be “treated many years ago and tended to have more severe [baseline] disease,” Dr. Terrault said.

So “while we see this difference, there’s not enough data yet for us to make a recommendation for our patients to switch from” entecavir to tenofovir. “Until a randomized controlled trial is done, this may remain an issue,” she said.

A drug holiday?

Dr. Terrault also reviewed research that suggests nucleoside analogue treatment can be stopped in e-antigen–negative patients after at least 3 years.

“The evidence is increasing that a finite NA [nucleoside analogue] treatment approach leads to higher HBsAg [hepatitis B surface antigen] loss rates, compared with the current long-term NA strategy, and can be considered a rational strategy to induce a functional cure in selected HBeAg-negative patients without cirrhosis who are willing to comply with close follow-up monitoring. ... The current observed functional cure rates” – perhaps about 40% – “would be well worth the effort,” editorialists commenting on the research concluded (Hepatology. 2018 Aug;68[2]:397-400).

It’s an interesting idea, Dr. Terrault said, but the virus will flare 8-12 weeks after treatment withdrawal, which is why it shouldn’t be considered in patients with cirrhosis.

Dr. Terrault is a consultant for AbbVie, Merck, Gilead, and other companies and disclosed grants from those companies and others.

MAUI, HAWAII – There might well be a cure for hepatitis B in coming years, just like there is now for hepatitis C, according to Norah Terrault, MD, chief of the division of GI and liver at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“We are going to have a laundry list of new drugs” that are in the pipeline now. Phase 2 results “look encouraging. You will hear much more about this in the years ahead,” said Dr. Terrault, lead author of the 2018 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) hepatitis B guidance.

For now, though, the field is largely limited to the nucleoside analogues tenofovir and entecavir. Treatment is often indefinite because, although hepatitis B virus (HBV) e-antigen is cleared, it usually doesn’t clear the HBV surface antigen, which is linked to liver cancer. “Even with e-antigen–negative patients, we feel that indefinite therapy is really the way to go,” Dr. Terrault said at the Gastroenterology Updates, IBD, Liver Disease Conference.

One of the biggest problems with that strategy is what to do when HBV does not seem to be much of a problem for carriers. Such patients are referred to as immune tolerant.

A newly recognized cancer risk

Immune tolerant patients tend to be young and have extremely high viral loads but no apparent ill effects, with normal ALT levels, normal histology, and no sign of cirrhosis. Although the AASLD recommends not treating these patients until they are 40 years old, waiting makes people nervous. “You have a hammer, you want to hit a nail,” Dr. Terrault said.

A recent review (Gut. 2018 May;67[5]:945-52) suggests that hitting the nail might be the way to go. South Korean investigators found that 413 untreated immune tolerate patients with a mean age of 38 years had more than twice the risk of liver cancer over 10 years than did almost 1,500 treated patients with active disease.

The study investigators concluded that “unnecessary deaths could be prevented through earlier antiviral intervention in select [immune tolerate] patients.”

This finding is one reason “we [AASLD] are rethinking the mantra of not treating the immune tolerant. There is a group that is transitioning” to active disease. “I’m thinking we should really [lower] the age cutoff” to 30 years, as some other groups [European Association for the Study of the Liver and Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver] have done, plus “patients feel really good when they know the virus is controlled, and so do physicians,” Dr. Terrault said.

Entecavir versus tenofovir

Meanwhile, recent studies have raised the question of whether tenofovir is better than entecavir at preventing liver cancer.

A JAMA Oncology (JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jan 1;5[1]:30-6) study of some 25,000 patients in South Korea found a 32% lower risk of liver cancer when they were treated with tenofovir instead of entecavir. “This led to a lot of concern that maybe we should be moving all our patients to tenofovir,” she said.

Another study, a meta-analysis published earlier this year (Hepatol Int. 2020 Jan;14[1]:105-14), confirmed the difference in cancer risk when it combined those findings with other research. After adjustment for potential confounders, including disease stage and length of follow-up, “the difference disappeared” (hazard ration, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-1.04), authors of the meta-analysis reported.

Study patients who received entecavir tended to be “treated many years ago and tended to have more severe [baseline] disease,” Dr. Terrault said.

So “while we see this difference, there’s not enough data yet for us to make a recommendation for our patients to switch from” entecavir to tenofovir. “Until a randomized controlled trial is done, this may remain an issue,” she said.

A drug holiday?

Dr. Terrault also reviewed research that suggests nucleoside analogue treatment can be stopped in e-antigen–negative patients after at least 3 years.

“The evidence is increasing that a finite NA [nucleoside analogue] treatment approach leads to higher HBsAg [hepatitis B surface antigen] loss rates, compared with the current long-term NA strategy, and can be considered a rational strategy to induce a functional cure in selected HBeAg-negative patients without cirrhosis who are willing to comply with close follow-up monitoring. ... The current observed functional cure rates” – perhaps about 40% – “would be well worth the effort,” editorialists commenting on the research concluded (Hepatology. 2018 Aug;68[2]:397-400).

It’s an interesting idea, Dr. Terrault said, but the virus will flare 8-12 weeks after treatment withdrawal, which is why it shouldn’t be considered in patients with cirrhosis.

Dr. Terrault is a consultant for AbbVie, Merck, Gilead, and other companies and disclosed grants from those companies and others.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM GUILD 2020

Not So Classic, Classic Kaposi Sarcoma

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a lymphatic endothelial cell neoplasm that frequently presents as multiple vascular cutaneous and mucosal nodules.1 The classic KS variant typically is described as the presentation of KS in otherwise healthy elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.2 We present 2 cases of classic KS presenting in Mexican women living in Los Angeles County, California, with atypical clinical features.

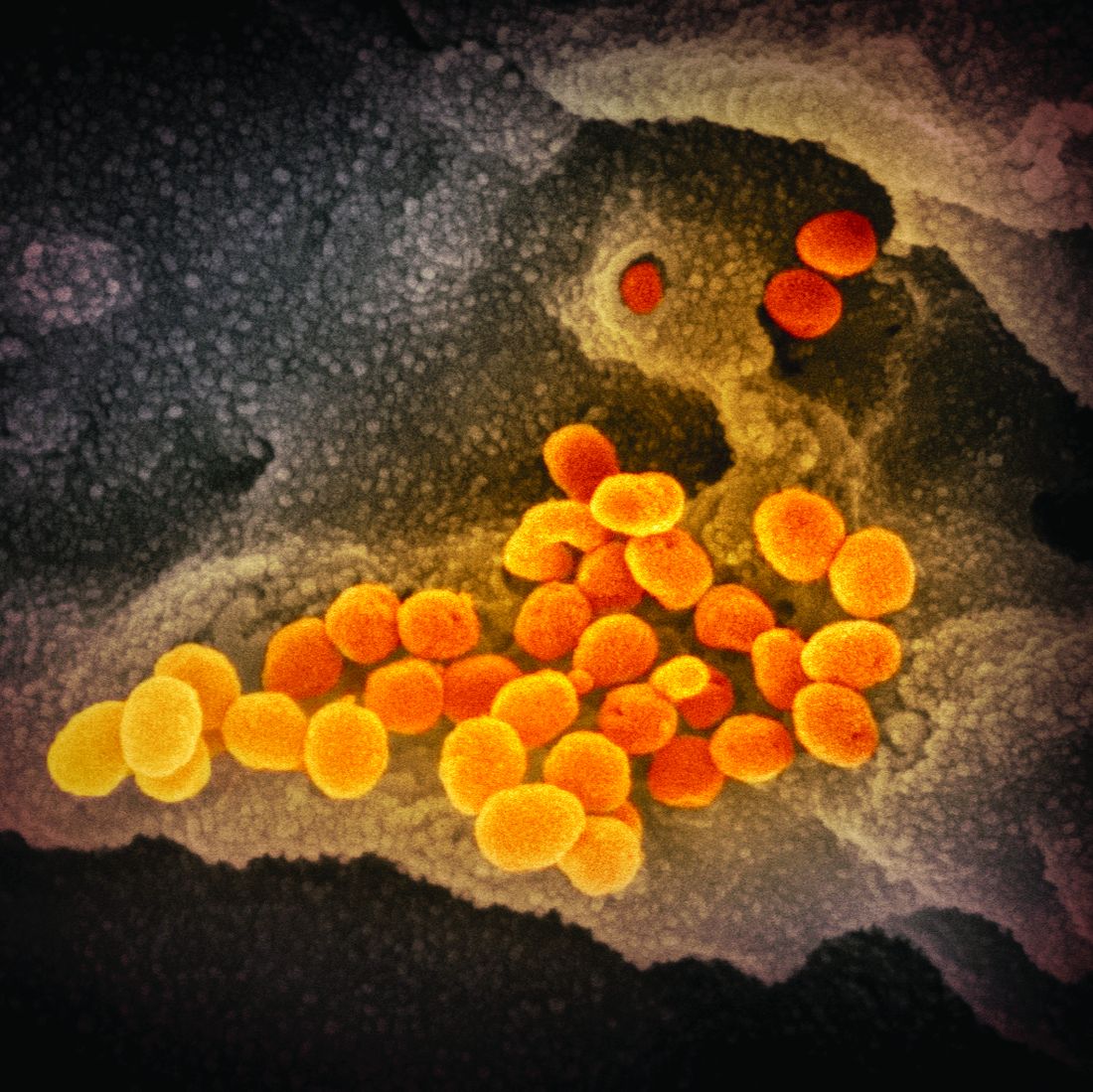

A 65-year-old woman of Mexican descent presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of an asymptomatic growth on the right ventral forearm of 4 months’ duration. Biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a spindle cell proliferation suspicious for KS. Physical examination several months following the initial biopsy revealed a mildly indurated scar on the right ventral forearm with an adjacent faintly erythematous papule (Figure 1A). Repeat biopsy revealed a dermal spindle cell proliferation suggestive of KS (Figures 1B and 1C). S-100 and cytokeratin stains were negative, but a latent nuclear antigen 1 stain for human herpesvirus 8 was positive. Human immunodeficiency virus screening also was negative. Given the isolated findings, the oncology service determined that observation alone was the most appropriate management. Over time, the patient developed several similar scattered erythematous papules, and treatment with imiquimod cream 5% was initiated for 1 month without improvement. She was subsequently given a trial of alitretinoin ointment 0.1% twice daily. The lesions improved, and she continues to be well controlled on this topical therapy alone.

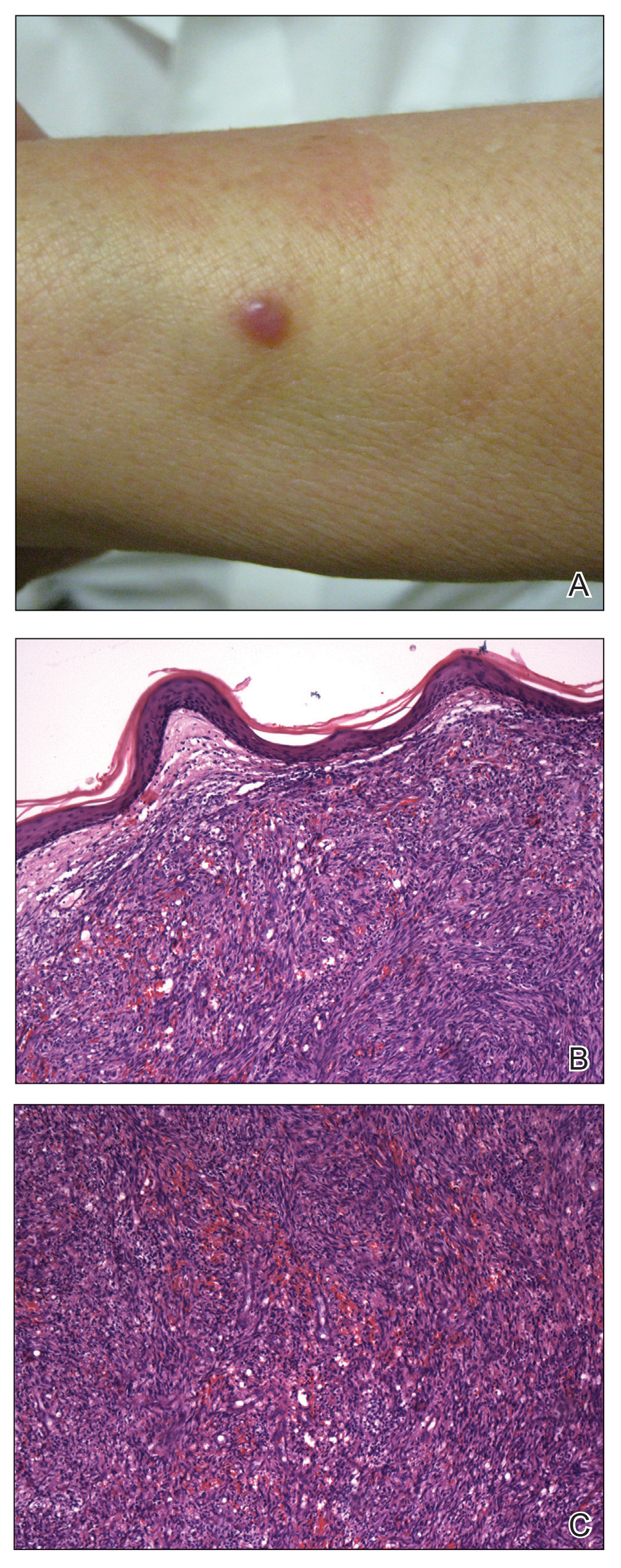

A 62-year-old woman of Mexican descent with end-stage cryptogenic cirrhosis was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of transplant candidacy. Dermatology was consulted to assess a 5×3-cm, asymptomatic, solitary, violaceous plaque on the right plantar foot (Figure 2A) with no palpable lymph nodes. Biopsy revealed a dermal proliferation of slit-like vascular channels infiltrating through the collagen and surrounding preexisting vascular spaces and adnexal structures (Figure 2B). Extravasation of erythrocytes and plasma cells also was appreciated. Latent nuclear antigen 1 staining showed strong nuclear positivity consistent with KS (Figure 2C), and a human immunodeficiency virus test and workup for underlying immunosuppression were negative. The patient had no history of treatment with immunosuppressive medications. Further workup revealed involvement of the lymphatic system. The patient was removed from the transplant list and was not a candidate for chemotherapy due to liver failure.

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8. It typically presents as erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques on the extremities.1 At least 10 morphologic variants of KS have been identified.3 The indolent classic variant of KS most commonly is found in immunocompetent individuals and has been reported to primarily affect elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.

Epidemiologic analyses of this disease in the South American population are rare. More than 250 cases have been published from South American countries with the largest series published from patients in Argentina, Peru, and Colombia.4 The incidence of classic KS in Peru is 2.54 per 10,000 individuals,5 and the disease has been diagnosed in 1 of 1000 malignant neoplasms at the National Cancer Institute of Colombia.6

A search of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Soft Tissue Pathology registry for classic KS patients (1980-2000) showed that 18% of 438 cases of classic KS were diagnosed in South American Hispanics,7 a percentage that nearly approximates the proportion of patients with KS of Mediterranean descent. Interestingly, in an analysis conducted within Los Angeles County, classic KS was most frequently diagnosed in Jewish, Eastern European–born men who were 55 years or older, followed by European-born women. In this study, white, Spanish, and black populations were diagnosed with classic KS with equal frequency.8

Our 2 cases of classic KS from Los Angeles County had several notable features. Both patients were women from Mexico, a demographic not previously associated with classic KS,8 and they did not have risk factors commonly associated with classic KS. We emphasize that classic KS likely is underreported and understudied in the Mexican and South American populations with need for further epidemiological and clinical analyses.

- Kaposi M. Idiopathisches multiples Pigmentsarkom der Haut. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1872;4:265-272.

- Akasbi Y, Awada A, Arifi S, et al. Non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review and therapeutic perspectives. Bull Cancer. 2012;99:92-99.

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:2392-2350.

- Mohanna S, Ferrufino JC, Sanchez J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma in Peru. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:435-441.

- García A, Olivella F, Valderrama S, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Colombia. Cancer. 1989;64:2393-2398.

- Hiatt KM, Nelson AM, Lichy JH, et al. Classic Kaposi Sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:572-582.

- Ross RK, Casagrande JT, Dworsky RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Los Angeles, California. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:1011-1015.

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a lymphatic endothelial cell neoplasm that frequently presents as multiple vascular cutaneous and mucosal nodules.1 The classic KS variant typically is described as the presentation of KS in otherwise healthy elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.2 We present 2 cases of classic KS presenting in Mexican women living in Los Angeles County, California, with atypical clinical features.

A 65-year-old woman of Mexican descent presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of an asymptomatic growth on the right ventral forearm of 4 months’ duration. Biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a spindle cell proliferation suspicious for KS. Physical examination several months following the initial biopsy revealed a mildly indurated scar on the right ventral forearm with an adjacent faintly erythematous papule (Figure 1A). Repeat biopsy revealed a dermal spindle cell proliferation suggestive of KS (Figures 1B and 1C). S-100 and cytokeratin stains were negative, but a latent nuclear antigen 1 stain for human herpesvirus 8 was positive. Human immunodeficiency virus screening also was negative. Given the isolated findings, the oncology service determined that observation alone was the most appropriate management. Over time, the patient developed several similar scattered erythematous papules, and treatment with imiquimod cream 5% was initiated for 1 month without improvement. She was subsequently given a trial of alitretinoin ointment 0.1% twice daily. The lesions improved, and she continues to be well controlled on this topical therapy alone.

A 62-year-old woman of Mexican descent with end-stage cryptogenic cirrhosis was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of transplant candidacy. Dermatology was consulted to assess a 5×3-cm, asymptomatic, solitary, violaceous plaque on the right plantar foot (Figure 2A) with no palpable lymph nodes. Biopsy revealed a dermal proliferation of slit-like vascular channels infiltrating through the collagen and surrounding preexisting vascular spaces and adnexal structures (Figure 2B). Extravasation of erythrocytes and plasma cells also was appreciated. Latent nuclear antigen 1 staining showed strong nuclear positivity consistent with KS (Figure 2C), and a human immunodeficiency virus test and workup for underlying immunosuppression were negative. The patient had no history of treatment with immunosuppressive medications. Further workup revealed involvement of the lymphatic system. The patient was removed from the transplant list and was not a candidate for chemotherapy due to liver failure.

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8. It typically presents as erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques on the extremities.1 At least 10 morphologic variants of KS have been identified.3 The indolent classic variant of KS most commonly is found in immunocompetent individuals and has been reported to primarily affect elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.

Epidemiologic analyses of this disease in the South American population are rare. More than 250 cases have been published from South American countries with the largest series published from patients in Argentina, Peru, and Colombia.4 The incidence of classic KS in Peru is 2.54 per 10,000 individuals,5 and the disease has been diagnosed in 1 of 1000 malignant neoplasms at the National Cancer Institute of Colombia.6

A search of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Soft Tissue Pathology registry for classic KS patients (1980-2000) showed that 18% of 438 cases of classic KS were diagnosed in South American Hispanics,7 a percentage that nearly approximates the proportion of patients with KS of Mediterranean descent. Interestingly, in an analysis conducted within Los Angeles County, classic KS was most frequently diagnosed in Jewish, Eastern European–born men who were 55 years or older, followed by European-born women. In this study, white, Spanish, and black populations were diagnosed with classic KS with equal frequency.8

Our 2 cases of classic KS from Los Angeles County had several notable features. Both patients were women from Mexico, a demographic not previously associated with classic KS,8 and they did not have risk factors commonly associated with classic KS. We emphasize that classic KS likely is underreported and understudied in the Mexican and South American populations with need for further epidemiological and clinical analyses.

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a lymphatic endothelial cell neoplasm that frequently presents as multiple vascular cutaneous and mucosal nodules.1 The classic KS variant typically is described as the presentation of KS in otherwise healthy elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.2 We present 2 cases of classic KS presenting in Mexican women living in Los Angeles County, California, with atypical clinical features.

A 65-year-old woman of Mexican descent presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of an asymptomatic growth on the right ventral forearm of 4 months’ duration. Biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a spindle cell proliferation suspicious for KS. Physical examination several months following the initial biopsy revealed a mildly indurated scar on the right ventral forearm with an adjacent faintly erythematous papule (Figure 1A). Repeat biopsy revealed a dermal spindle cell proliferation suggestive of KS (Figures 1B and 1C). S-100 and cytokeratin stains were negative, but a latent nuclear antigen 1 stain for human herpesvirus 8 was positive. Human immunodeficiency virus screening also was negative. Given the isolated findings, the oncology service determined that observation alone was the most appropriate management. Over time, the patient developed several similar scattered erythematous papules, and treatment with imiquimod cream 5% was initiated for 1 month without improvement. She was subsequently given a trial of alitretinoin ointment 0.1% twice daily. The lesions improved, and she continues to be well controlled on this topical therapy alone.

A 62-year-old woman of Mexican descent with end-stage cryptogenic cirrhosis was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of transplant candidacy. Dermatology was consulted to assess a 5×3-cm, asymptomatic, solitary, violaceous plaque on the right plantar foot (Figure 2A) with no palpable lymph nodes. Biopsy revealed a dermal proliferation of slit-like vascular channels infiltrating through the collagen and surrounding preexisting vascular spaces and adnexal structures (Figure 2B). Extravasation of erythrocytes and plasma cells also was appreciated. Latent nuclear antigen 1 staining showed strong nuclear positivity consistent with KS (Figure 2C), and a human immunodeficiency virus test and workup for underlying immunosuppression were negative. The patient had no history of treatment with immunosuppressive medications. Further workup revealed involvement of the lymphatic system. The patient was removed from the transplant list and was not a candidate for chemotherapy due to liver failure.

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8. It typically presents as erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques on the extremities.1 At least 10 morphologic variants of KS have been identified.3 The indolent classic variant of KS most commonly is found in immunocompetent individuals and has been reported to primarily affect elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.

Epidemiologic analyses of this disease in the South American population are rare. More than 250 cases have been published from South American countries with the largest series published from patients in Argentina, Peru, and Colombia.4 The incidence of classic KS in Peru is 2.54 per 10,000 individuals,5 and the disease has been diagnosed in 1 of 1000 malignant neoplasms at the National Cancer Institute of Colombia.6

A search of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Soft Tissue Pathology registry for classic KS patients (1980-2000) showed that 18% of 438 cases of classic KS were diagnosed in South American Hispanics,7 a percentage that nearly approximates the proportion of patients with KS of Mediterranean descent. Interestingly, in an analysis conducted within Los Angeles County, classic KS was most frequently diagnosed in Jewish, Eastern European–born men who were 55 years or older, followed by European-born women. In this study, white, Spanish, and black populations were diagnosed with classic KS with equal frequency.8

Our 2 cases of classic KS from Los Angeles County had several notable features. Both patients were women from Mexico, a demographic not previously associated with classic KS,8 and they did not have risk factors commonly associated with classic KS. We emphasize that classic KS likely is underreported and understudied in the Mexican and South American populations with need for further epidemiological and clinical analyses.

- Kaposi M. Idiopathisches multiples Pigmentsarkom der Haut. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1872;4:265-272.

- Akasbi Y, Awada A, Arifi S, et al. Non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review and therapeutic perspectives. Bull Cancer. 2012;99:92-99.

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:2392-2350.

- Mohanna S, Ferrufino JC, Sanchez J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma in Peru. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:435-441.

- García A, Olivella F, Valderrama S, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Colombia. Cancer. 1989;64:2393-2398.

- Hiatt KM, Nelson AM, Lichy JH, et al. Classic Kaposi Sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:572-582.

- Ross RK, Casagrande JT, Dworsky RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Los Angeles, California. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:1011-1015.

- Kaposi M. Idiopathisches multiples Pigmentsarkom der Haut. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1872;4:265-272.

- Akasbi Y, Awada A, Arifi S, et al. Non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review and therapeutic perspectives. Bull Cancer. 2012;99:92-99.

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:2392-2350.

- Mohanna S, Ferrufino JC, Sanchez J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma in Peru. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:435-441.

- García A, Olivella F, Valderrama S, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Colombia. Cancer. 1989;64:2393-2398.

- Hiatt KM, Nelson AM, Lichy JH, et al. Classic Kaposi Sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:572-582.

- Ross RK, Casagrande JT, Dworsky RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Los Angeles, California. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:1011-1015.

Practice Points

- Classic Kaposi sarcoma is an indolent neoplasm that can be diagnosed in immunocompetent females of Mexican descent.

- Common diagnoses appearing in skin of color may appear morphologically disparate, and a high index of suspicion is needed for correct diagnosis.

Opioid use disorder up in sepsis hospitalizations

ORLANDO –

The prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) has significantly increased over the past 15 years, the analysis further shows.

Results of the study, presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, further suggested that OUD disproportionately contributes to sepsis deaths in younger, healthier patients.

Together, these findings underscore the importance of ongoing efforts to address the opioid epidemic in the United States, according to researcher Mohammad Alrawashdeh, PhD, MSN, a postdoctoral research fellow with Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

“In addition to ongoing efforts to combat the opioid crisis, future public health interventions should focus on increasing awareness, recognition, and aggressive treatment of sepsis in this population,” Dr. Alrawashdeh said in an oral presentation of the study.

This study fills an important knowledge gap regarding the connection between OUD and sepsis, according to Greg S. Martin, MD, MS, FCCM, professor of medicine in pulmonary critical care at Emory University, Atlanta, and secretary for the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“We’ve not really ever been able to piece together the relationship between opioid use disorders and sepsis,” Dr. Martin said in an interview. “It’s not that people wouldn’t suspect that there’s a connection – it’s more that we have simply not been able to get the kind of data that you can use, like they’ve done here, that really helps you to answer that question.”

The study suggests not only that OUD and sepsis are linked, Dr. Martin added, but that health care providers need to be prepared to potentially see further increases in the number of patients with OUD seen in the intensive care unit.

“Both of those are things that we certainly need to be aware of, both from the individual practitioner perspective and also the public health planning perspective,” he said.

The retrospective study by Dr. Alrawashdeh and coinvestigators focused on electronic health record data for adults admitted to 373 hospitals in the United States between 2009 and 2015, including 375,479 who had sepsis.

Over time, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of OUD among those hospitalized for sepsis, from less than 2.0% in 2009 to more than 3% in 2015, representing a significant 77.3% increase. In general, the prevalence of sepsis was significantly higher among hospitalized patients with OUD compared with patients without the disorder, at 7.2% and 5.6%, respectively.

The sepsis patients with OUD tended to be younger, healthier, and more likely to be white compared with patients without OUD, according to the report. Moreover, the sepsis patients with OUD more often had endocarditis and gram-positive and fungal bloodstream infections. They also required more mechanical ventilation and had more ICU admissions, with longer stays in both the ICU and hospital.

The OUD patients accounted for 2.1% of sepsis-associated deaths overall, but 3.3% of those deaths in healthy patients, and 7.1% of deaths among younger patients, according to the report.

Those findings provide some clues that could help guide clinical practice, according to Dr. Martin. For example, the data show a nearly fivefold increased risk of endocarditis with OUD (3.9% versus 0.7%), which may inform screening practices.

“While we don’t necessarily screen every sepsis patient for endocarditis, if it’s an opioid use disorder patient – particularly one with a bloodstream infection – then that’s almost certainly something you should be doing,” Dr. Martin said.

The data suggest gram-positive bacterial and fungal infections will more likely be encountered among these patients, which could guide empiric treatment, he said.

Providers specializing in OUD should have a heightened awareness of the potential for infection and sepsis among those patients, and perhaps be more attuned to fever and other signs of infection that might warrant a referral or additional care, Dr. Martin added.

Dr. Alrawashdeh reported no disclosures related to the study.

SOURCE: Alrawashdeh M et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 Jan;48(1):28. Abstract 56.

ORLANDO –

The prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) has significantly increased over the past 15 years, the analysis further shows.

Results of the study, presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, further suggested that OUD disproportionately contributes to sepsis deaths in younger, healthier patients.

Together, these findings underscore the importance of ongoing efforts to address the opioid epidemic in the United States, according to researcher Mohammad Alrawashdeh, PhD, MSN, a postdoctoral research fellow with Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

“In addition to ongoing efforts to combat the opioid crisis, future public health interventions should focus on increasing awareness, recognition, and aggressive treatment of sepsis in this population,” Dr. Alrawashdeh said in an oral presentation of the study.

This study fills an important knowledge gap regarding the connection between OUD and sepsis, according to Greg S. Martin, MD, MS, FCCM, professor of medicine in pulmonary critical care at Emory University, Atlanta, and secretary for the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“We’ve not really ever been able to piece together the relationship between opioid use disorders and sepsis,” Dr. Martin said in an interview. “It’s not that people wouldn’t suspect that there’s a connection – it’s more that we have simply not been able to get the kind of data that you can use, like they’ve done here, that really helps you to answer that question.”

The study suggests not only that OUD and sepsis are linked, Dr. Martin added, but that health care providers need to be prepared to potentially see further increases in the number of patients with OUD seen in the intensive care unit.

“Both of those are things that we certainly need to be aware of, both from the individual practitioner perspective and also the public health planning perspective,” he said.

The retrospective study by Dr. Alrawashdeh and coinvestigators focused on electronic health record data for adults admitted to 373 hospitals in the United States between 2009 and 2015, including 375,479 who had sepsis.

Over time, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of OUD among those hospitalized for sepsis, from less than 2.0% in 2009 to more than 3% in 2015, representing a significant 77.3% increase. In general, the prevalence of sepsis was significantly higher among hospitalized patients with OUD compared with patients without the disorder, at 7.2% and 5.6%, respectively.

The sepsis patients with OUD tended to be younger, healthier, and more likely to be white compared with patients without OUD, according to the report. Moreover, the sepsis patients with OUD more often had endocarditis and gram-positive and fungal bloodstream infections. They also required more mechanical ventilation and had more ICU admissions, with longer stays in both the ICU and hospital.

The OUD patients accounted for 2.1% of sepsis-associated deaths overall, but 3.3% of those deaths in healthy patients, and 7.1% of deaths among younger patients, according to the report.

Those findings provide some clues that could help guide clinical practice, according to Dr. Martin. For example, the data show a nearly fivefold increased risk of endocarditis with OUD (3.9% versus 0.7%), which may inform screening practices.

“While we don’t necessarily screen every sepsis patient for endocarditis, if it’s an opioid use disorder patient – particularly one with a bloodstream infection – then that’s almost certainly something you should be doing,” Dr. Martin said.

The data suggest gram-positive bacterial and fungal infections will more likely be encountered among these patients, which could guide empiric treatment, he said.

Providers specializing in OUD should have a heightened awareness of the potential for infection and sepsis among those patients, and perhaps be more attuned to fever and other signs of infection that might warrant a referral or additional care, Dr. Martin added.

Dr. Alrawashdeh reported no disclosures related to the study.

SOURCE: Alrawashdeh M et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 Jan;48(1):28. Abstract 56.

ORLANDO –

The prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) has significantly increased over the past 15 years, the analysis further shows.

Results of the study, presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, further suggested that OUD disproportionately contributes to sepsis deaths in younger, healthier patients.

Together, these findings underscore the importance of ongoing efforts to address the opioid epidemic in the United States, according to researcher Mohammad Alrawashdeh, PhD, MSN, a postdoctoral research fellow with Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

“In addition to ongoing efforts to combat the opioid crisis, future public health interventions should focus on increasing awareness, recognition, and aggressive treatment of sepsis in this population,” Dr. Alrawashdeh said in an oral presentation of the study.

This study fills an important knowledge gap regarding the connection between OUD and sepsis, according to Greg S. Martin, MD, MS, FCCM, professor of medicine in pulmonary critical care at Emory University, Atlanta, and secretary for the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“We’ve not really ever been able to piece together the relationship between opioid use disorders and sepsis,” Dr. Martin said in an interview. “It’s not that people wouldn’t suspect that there’s a connection – it’s more that we have simply not been able to get the kind of data that you can use, like they’ve done here, that really helps you to answer that question.”

The study suggests not only that OUD and sepsis are linked, Dr. Martin added, but that health care providers need to be prepared to potentially see further increases in the number of patients with OUD seen in the intensive care unit.

“Both of those are things that we certainly need to be aware of, both from the individual practitioner perspective and also the public health planning perspective,” he said.

The retrospective study by Dr. Alrawashdeh and coinvestigators focused on electronic health record data for adults admitted to 373 hospitals in the United States between 2009 and 2015, including 375,479 who had sepsis.

Over time, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of OUD among those hospitalized for sepsis, from less than 2.0% in 2009 to more than 3% in 2015, representing a significant 77.3% increase. In general, the prevalence of sepsis was significantly higher among hospitalized patients with OUD compared with patients without the disorder, at 7.2% and 5.6%, respectively.

The sepsis patients with OUD tended to be younger, healthier, and more likely to be white compared with patients without OUD, according to the report. Moreover, the sepsis patients with OUD more often had endocarditis and gram-positive and fungal bloodstream infections. They also required more mechanical ventilation and had more ICU admissions, with longer stays in both the ICU and hospital.

The OUD patients accounted for 2.1% of sepsis-associated deaths overall, but 3.3% of those deaths in healthy patients, and 7.1% of deaths among younger patients, according to the report.

Those findings provide some clues that could help guide clinical practice, according to Dr. Martin. For example, the data show a nearly fivefold increased risk of endocarditis with OUD (3.9% versus 0.7%), which may inform screening practices.

“While we don’t necessarily screen every sepsis patient for endocarditis, if it’s an opioid use disorder patient – particularly one with a bloodstream infection – then that’s almost certainly something you should be doing,” Dr. Martin said.

The data suggest gram-positive bacterial and fungal infections will more likely be encountered among these patients, which could guide empiric treatment, he said.

Providers specializing in OUD should have a heightened awareness of the potential for infection and sepsis among those patients, and perhaps be more attuned to fever and other signs of infection that might warrant a referral or additional care, Dr. Martin added.

Dr. Alrawashdeh reported no disclosures related to the study.

SOURCE: Alrawashdeh M et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 Jan;48(1):28. Abstract 56.

REPORTING FROM CCC49

Drop in flu activity suggests season may have peaked

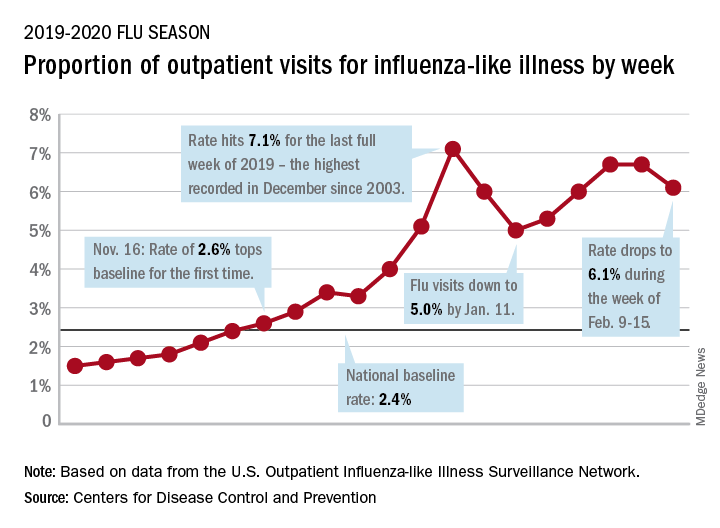

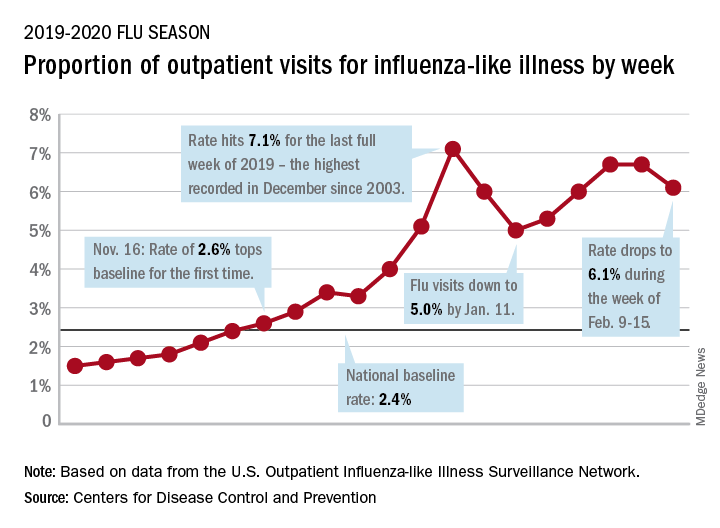

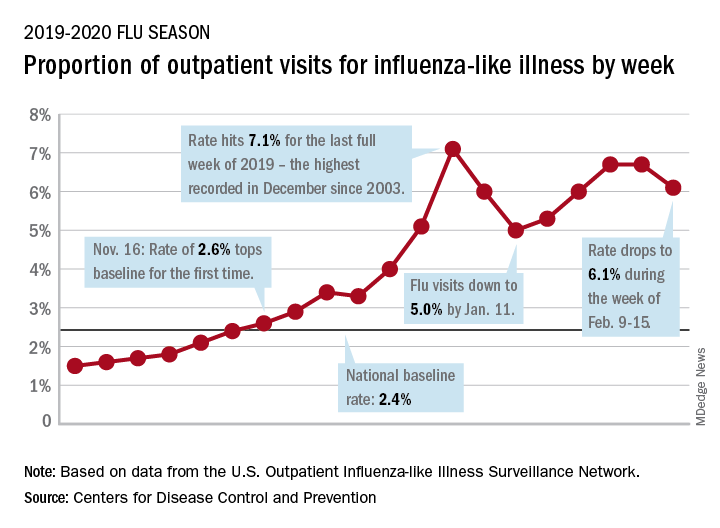

Influenza activity dropped during the week ending Feb. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That decline, along with revised data from the 2 previous weeks, suggests that the 2019-2020 season has peaked for the second time. The rate of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) came in at 6.1% for the week ending Feb. 15, after two straight weeks at 6.7%, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 21.

The rates for those 2 earlier weeks had previously been reported at 6.8% (Feb. 8) and 6.6% (Feb. 1), which means that there have now been 2 consecutive weeks without an increase in national ILI activity.

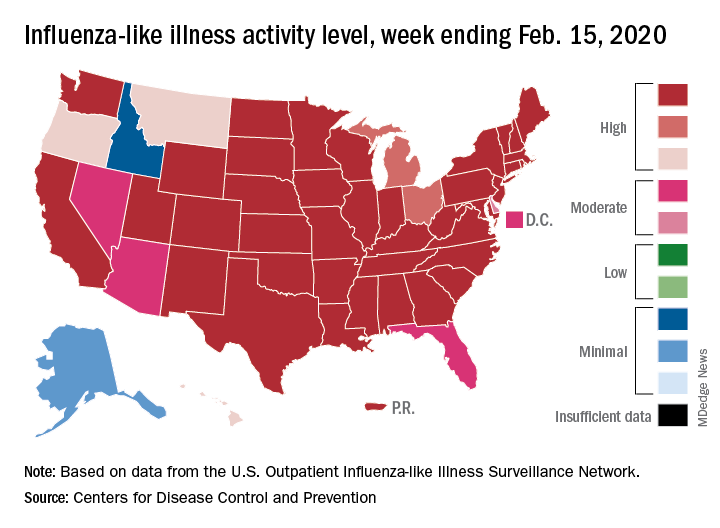

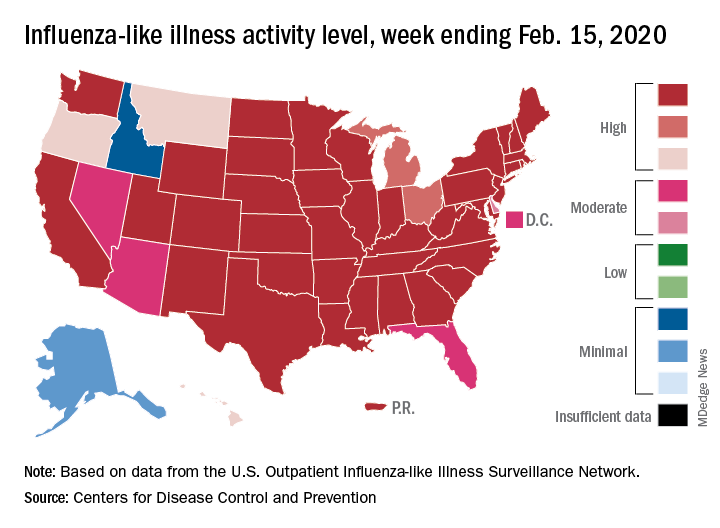

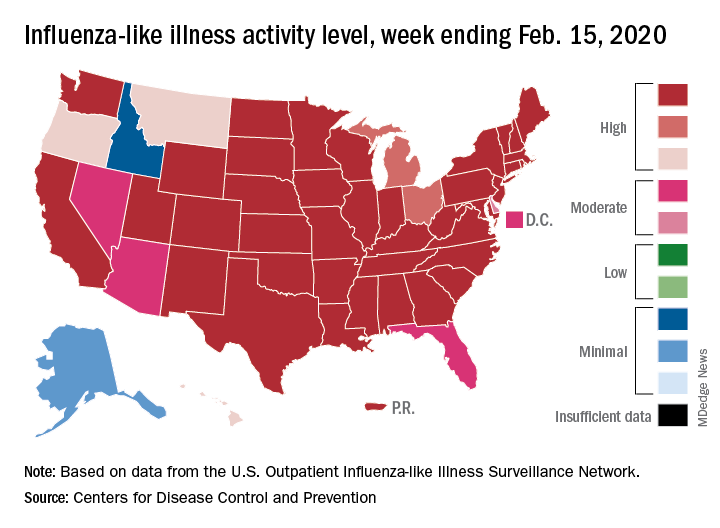

State-level activity was down slightly as well. For the week ending Feb. 15, there were 39 states and Puerto Rico at the highest level of activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, compared with 41 states and Puerto Rico the week before. The number of states in the “high” range, which includes levels 8 and 9, went from 44 to 45, however, CDC data show.

Laboratory measures also dropped a bit. For the week, 29.6% of respiratory specimens tested positive for influenza, compared with 30.3% the previous week. The predominance of influenza A continued to increase, as type A went from 59.4% to 63.5% of positive specimens and type B dropped from 40.6% to 36.5%, the influenza division said.

In a separate report, the CDC announced interim flu vaccine effectiveness estimates.For the 2019-2020 season so far, “flu vaccines are reducing doctor’s visits for flu illness by almost half (45%). This is consistent with estimates of flu vaccine effectiveness (VE) from previous flu seasons that ranged from 40% to 60% when flu vaccine viruses were similar to circulating influenza viruses,” the CDC said.

Although VE among children aged 6 months to 17 years is even higher, at 55%, this season “has been especially bad for children. Flu hospitalization rates among children are higher than at this time in other recent seasons, including the 2017-18 season,” the CDC noted.

The number of pediatric flu deaths for 2019-2020 – now up to 105 – is “higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, with the exception of the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC added.

Interim VE estimates for other age groups are 25% for adults aged 18-49 and 43% for those 50 years and older. “The lower VE point estimates observed among adults 18-49 years appear to be associated with a trend suggesting lower VE in this age group against A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses,” the CDC said.

Influenza activity dropped during the week ending Feb. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That decline, along with revised data from the 2 previous weeks, suggests that the 2019-2020 season has peaked for the second time. The rate of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) came in at 6.1% for the week ending Feb. 15, after two straight weeks at 6.7%, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 21.

The rates for those 2 earlier weeks had previously been reported at 6.8% (Feb. 8) and 6.6% (Feb. 1), which means that there have now been 2 consecutive weeks without an increase in national ILI activity.

State-level activity was down slightly as well. For the week ending Feb. 15, there were 39 states and Puerto Rico at the highest level of activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, compared with 41 states and Puerto Rico the week before. The number of states in the “high” range, which includes levels 8 and 9, went from 44 to 45, however, CDC data show.

Laboratory measures also dropped a bit. For the week, 29.6% of respiratory specimens tested positive for influenza, compared with 30.3% the previous week. The predominance of influenza A continued to increase, as type A went from 59.4% to 63.5% of positive specimens and type B dropped from 40.6% to 36.5%, the influenza division said.

In a separate report, the CDC announced interim flu vaccine effectiveness estimates.For the 2019-2020 season so far, “flu vaccines are reducing doctor’s visits for flu illness by almost half (45%). This is consistent with estimates of flu vaccine effectiveness (VE) from previous flu seasons that ranged from 40% to 60% when flu vaccine viruses were similar to circulating influenza viruses,” the CDC said.

Although VE among children aged 6 months to 17 years is even higher, at 55%, this season “has been especially bad for children. Flu hospitalization rates among children are higher than at this time in other recent seasons, including the 2017-18 season,” the CDC noted.

The number of pediatric flu deaths for 2019-2020 – now up to 105 – is “higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, with the exception of the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC added.

Interim VE estimates for other age groups are 25% for adults aged 18-49 and 43% for those 50 years and older. “The lower VE point estimates observed among adults 18-49 years appear to be associated with a trend suggesting lower VE in this age group against A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses,” the CDC said.

Influenza activity dropped during the week ending Feb. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That decline, along with revised data from the 2 previous weeks, suggests that the 2019-2020 season has peaked for the second time. The rate of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) came in at 6.1% for the week ending Feb. 15, after two straight weeks at 6.7%, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 21.

The rates for those 2 earlier weeks had previously been reported at 6.8% (Feb. 8) and 6.6% (Feb. 1), which means that there have now been 2 consecutive weeks without an increase in national ILI activity.

State-level activity was down slightly as well. For the week ending Feb. 15, there were 39 states and Puerto Rico at the highest level of activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, compared with 41 states and Puerto Rico the week before. The number of states in the “high” range, which includes levels 8 and 9, went from 44 to 45, however, CDC data show.

Laboratory measures also dropped a bit. For the week, 29.6% of respiratory specimens tested positive for influenza, compared with 30.3% the previous week. The predominance of influenza A continued to increase, as type A went from 59.4% to 63.5% of positive specimens and type B dropped from 40.6% to 36.5%, the influenza division said.

In a separate report, the CDC announced interim flu vaccine effectiveness estimates.For the 2019-2020 season so far, “flu vaccines are reducing doctor’s visits for flu illness by almost half (45%). This is consistent with estimates of flu vaccine effectiveness (VE) from previous flu seasons that ranged from 40% to 60% when flu vaccine viruses were similar to circulating influenza viruses,” the CDC said.

Although VE among children aged 6 months to 17 years is even higher, at 55%, this season “has been especially bad for children. Flu hospitalization rates among children are higher than at this time in other recent seasons, including the 2017-18 season,” the CDC noted.

The number of pediatric flu deaths for 2019-2020 – now up to 105 – is “higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, with the exception of the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC added.

Interim VE estimates for other age groups are 25% for adults aged 18-49 and 43% for those 50 years and older. “The lower VE point estimates observed among adults 18-49 years appear to be associated with a trend suggesting lower VE in this age group against A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses,” the CDC said.

FROM THE CDC

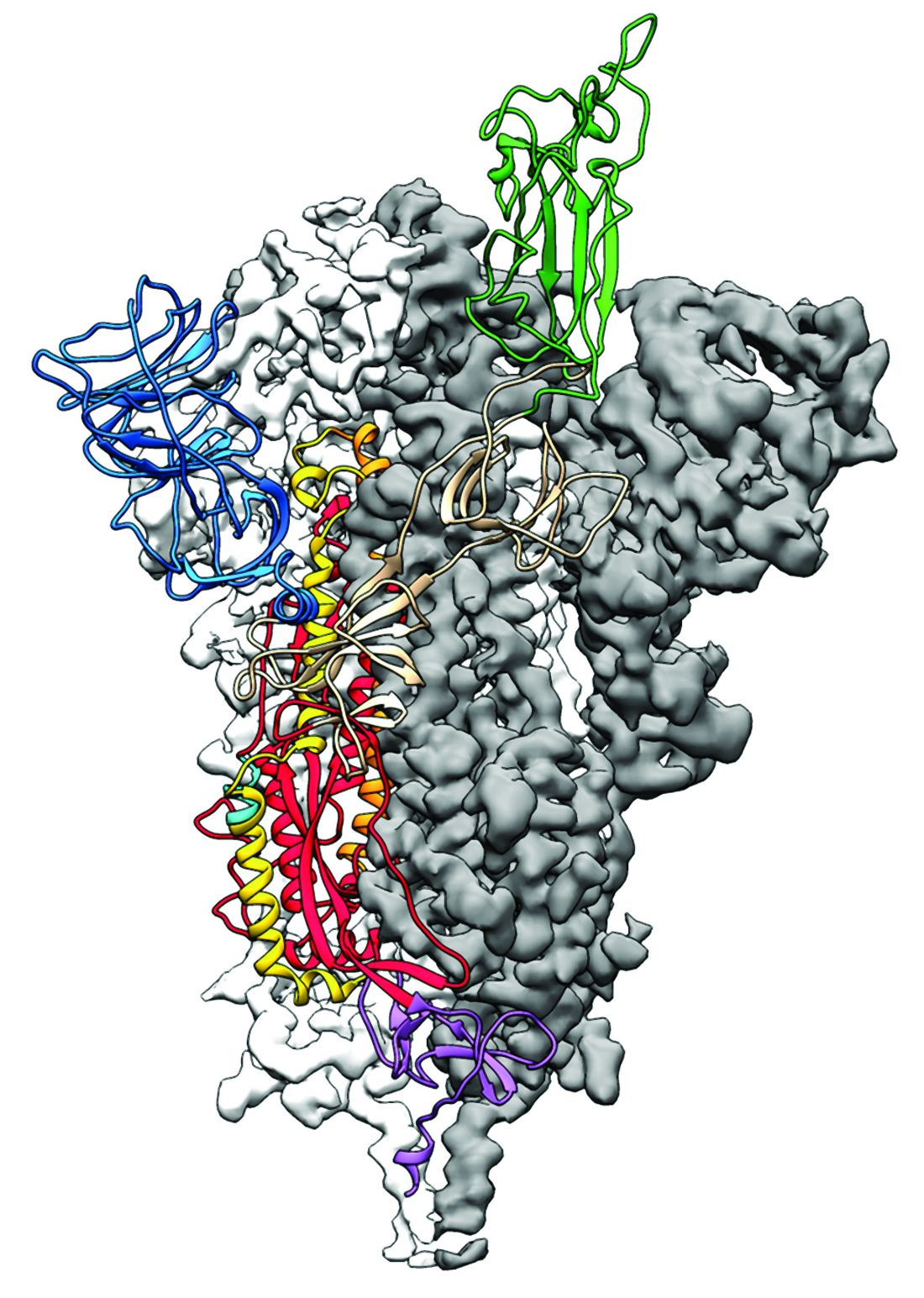

2019-nCoV: Structure, characteristics of key potential therapy target determined

Researchers have identified the structure of a protein that could turn out to be a potential vaccine target for the 2019-nCoV.

As is typical of other coronaviruses, 2019-nCoV makes use of a densely glycosylated spike protein to gain entry into host cells. The spike protein is a trimeric class I fusion protein that exists in a metastable prefusion conformation that undergoes a dramatic structural rearrangement to fuse the viral membrane with the host-cell membrane, according to Daniel Wrapp of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

The researchers performed a study to synthesize and determine the 3-D structure of the spike protein because it is a logical target for vaccine development and for the development of targeted therapeutics for COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

“As soon as we knew this was a coronavirus, we felt we had to jump at it,” senior author Jason S. McLellan, PhD, associate professor of molecular science, said in a press release from the University, “because we could be one of the first ones to get this structure. We knew exactly what mutations to put into this because we’ve already shown these mutations work for a bunch of other coronaviruses.”

Because recent reports by other researchers demonstrated that 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV spike proteins share the same functional host-cell receptor–angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), Dr. McLellan and his colleagues examined the relation between the two viruses. They found biophysical and structural evidence that the 2019-nCoV spike protein binds ACE2 with higher affinity than the closely related SARS-CoV spike protein. “The high affinity of 2019-nCoV S for human ACE2 may contribute to the apparent ease with which 2019-nCoV can spread from human-to-human; however, additional studies are needed to investigate this possibility,” the researchers wrote.

Focusing their attention on the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the 2019-nCoV spike protein, they tested several published SARS-CoV RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies against it and found that these antibodies showed no appreciable binding to 2019-nCoV spike protein, which suggests limited antibody cross-reactivity. For this reason, they suggested that future antibody isolation and therapeutic design efforts will benefit from specifically using 2019-nCoV spike proteins as probes.

“This information will support precision vaccine design and discovery of anti-viral therapeutics, accelerating medical countermeasure development,” they concluded.

The research was supported in part by an National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Four authors are inventors on US patent application No. 62/412,703 (Prefusion Coronavirus Spike Proteins and Their Use) and all are inventors on US patent application No. 62/972,886 (2019-nCoV Vaccine).

SOURCE: Wrapp D et al. Science. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507.

Researchers have identified the structure of a protein that could turn out to be a potential vaccine target for the 2019-nCoV.

As is typical of other coronaviruses, 2019-nCoV makes use of a densely glycosylated spike protein to gain entry into host cells. The spike protein is a trimeric class I fusion protein that exists in a metastable prefusion conformation that undergoes a dramatic structural rearrangement to fuse the viral membrane with the host-cell membrane, according to Daniel Wrapp of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

The researchers performed a study to synthesize and determine the 3-D structure of the spike protein because it is a logical target for vaccine development and for the development of targeted therapeutics for COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

“As soon as we knew this was a coronavirus, we felt we had to jump at it,” senior author Jason S. McLellan, PhD, associate professor of molecular science, said in a press release from the University, “because we could be one of the first ones to get this structure. We knew exactly what mutations to put into this because we’ve already shown these mutations work for a bunch of other coronaviruses.”

Because recent reports by other researchers demonstrated that 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV spike proteins share the same functional host-cell receptor–angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), Dr. McLellan and his colleagues examined the relation between the two viruses. They found biophysical and structural evidence that the 2019-nCoV spike protein binds ACE2 with higher affinity than the closely related SARS-CoV spike protein. “The high affinity of 2019-nCoV S for human ACE2 may contribute to the apparent ease with which 2019-nCoV can spread from human-to-human; however, additional studies are needed to investigate this possibility,” the researchers wrote.