User login

Injection beats pill for long-lasting HIV prevention

Injections of cabotegravir (ViiV Healthcare) given every other month are more effective in blocking HIV transmission than is the once-a-day combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine (Truvada, Gilead Science), new data from the HPTN 083 trial show.

The findings “could transform the HIV prevention landscape for so many people,” said Megan Coleman, DNP, from Whitman-Walker Health in Washington, DC, who regularly prescribes Truvada as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

At Whitman-Walker alone, about 3000 people were taking the pill in early 2020, but “for some people, taking a pill every day just isn’t a viable option,” said Coleman. “To have something that can support a patient’s choice and a patient’s ability to reduce their own risk of HIV is amazing.”

Final results from the trial — which looked at the drug in cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men — were presented at the International AIDS Conference 2020.

Early Study Termination

Half of the 4566 study participants — from 43 sites in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the United States — were younger than 30 years, 12.4% were transgender women, 29.7% were black, and 46.1% were Hispanic.

By design, ViiV Healthcare, the study sponsor, required that 50% of American participants be black to reflect the population at risk for HIV in the United States, said Raphael Landovitz, MD, from the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine in Los Angeles, who is protocol chair for HPTN 083. In fact, 49.7% of the American cohort was black and 17.8% was Hispanic.

Patients randomized to the cabotegravir group received daily oral cabotegravir plus daily oral placebo for 5 weeks, to assess safety, followed by a cabotegravir injection at weeks 5 and 9 and every 2 months thereafter out to week 153 plus daily oral placebo. Patients randomized to the Truvada group received daily oral Truvada plus daily oral placebo for 5 weeks, followed by daily oral Truvada plus placebo injection, on the same schedule, out to week 153.

After the final injection, all participants continued on daily oral Truvada for 48 weeks.

The researchers expected to wait until 172 participants acquired HIV; they decided at the outset that this number would be sufficient to power a decision on whether or not cabotegravir injections are better than daily oral Truvada. But by May 2020, when 52 of the study participants had acquired HIV, the results were so lopsided in favor of cabotegravir that the trial was stopped. At that point, all participants were offered cabotegravir injections every 2 months.

Thirty-nine of the 52 (75%) new HIV infections occurred in the Truvada group. In fact, (hazard ratio, 0.34).

“This definitively establishes the superiority of cabotegravir,” said Landovitz.

He and his colleagues had been legitimately concerned that HIV acquisition would be so low in the trial that they wouldn’t be able to show how effective the injectable was. The success of Truvada PrEP has made it difficult to design prevention trials.

“We know that Truvada works extremely well, so the fact that we were able to show that cabotegravir in this population works better” is a powerful observation, said Landovitz. This is especially true because the rates of sexually transmitted infections — which are thought to increase risk for HIV transmission — were so high. Overall, 16.5% of the participants tested positive for syphilis during the trial, 13.3% tested positive for gonorrhea, and 21.1% tested positive for Chlamydia.

Five Surprising Seroconversions

Eleven of the 15 HIV infections in the cabotegravir group occurred in people who had received at least one injection. Three of these infections actually occurred during the first 5 weeks of the study when participants were taking oral cabotegravir, two occurred when participants chose to discontinue the injection and return to daily oral Truvada, and one occurred after a participant missed the injection for a prolonged period of time.

But five of the transmissions occurred in participants who appeared to be perfectly adherent.

Landovitz offered a number of possible reasons for this surprising finding.

“Number one could be that there’s something about these five particular individuals such that they grind up and eliminate the cabotegravir faster than other people, so an 8-week interval is too long for them,” he explained. “Another possibility, although pretty rare, is that there is a rare circulating virus that is intrinsically resistant to cabotegravir.”

Breakthrough HIV transmissions have been rare in people taking oral PrEP.

Disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have meant that the researchers don’t yet have the data on drug-resistant mutations or drug levels for these five participants, but they will.

“I suspect the truth is that there will never be a 100% failsafe HIV prevention mechanism,” said Landovitz.

“Impressive” Findings

The findings were greeted with excitement, although questions remain.

They are “impressive,” especially the data on black and Hispanic participants, said Paul Sax, MD, medical director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

However, he said he is interested in the data showing that although participants in both groups gained weight during the study, there was early weight loss in the Truvada group, meaning that those in the cabotegravir group weighed more at the end of the study than those in the Truvada group.

“I’ve been watching the data on weight with integrase inhibitors,” he explained, including weight data specific to Truvada and to the combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide (Descovy, Gilead). It looks like Truvada “has some sort of weight-suppressive effects. That’s going to be a thing we’re going to have to watch.”

Coleman said she is already thinking about patients at Whitman-Walker who might do well on cabotegravir and those who can start PrEP for the first time with this option.

“Not only would people probably switch to this option, but maybe people would be interested in starting a biomedical prevention approach that isn’t a pill every day,” she said. “It’s just exciting to have another option. Hopefully, in a few years, we’ll have implantable devices and rings; I can’t even imagine what all those brilliant minds are coming up with.”

But that’s still a ways off. First, cabotegravir has yet to be approved for HIV prevention, and ideally, eventually, there will be a way to determine if cabotegravir is safe for each patient that doesn’t involve a month of daily pills.

“We need to solve that problem because it’s so complicated to do an oral lead-in for a month or so,” said Carl Dieffenbach, PhD, director of the Division of AIDS at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. “Otherwise it’s not going to be feasible.”

We need to make sure this gets licensed for men and women and transgender individuals.

Even with these positive data, Dieffenbach and other officials are not keen to have ViiV apply for licensing right away. Last October, Descovy was the second oral PrEP pill approved for HIV prevention, but only for use by gay men and transgender women — it hadn’t been well studied in cisgender women — causing an outcry. Now, officials are suggesting that ViiV not make the same mistake.

They are urging the company to hold off until data from the sister study of the medication in women — HPTN 084 — is completed in 2022.

“We need to make sure this gets licensed for men and women and transgender individuals,” Dieffenbach told Medscape Medical News. “We just need to give this a little more time and then build a plan with contingencies, so that if something happens, we still have collected all the safety data in women so we can say it’s safe.”

ViiV seems to be making such a plan.

“Our goal is to seek approval across all genders and we will work with the FDA and other regulatory agencies to map out a plan to achieve this goal,” said Kimberly Smith, MD, head of research and development at ViiV Healthcare.

The World Health Organization (WHO), meanwhile, doesn’t expect to change its guidelines on HIV prevention medications until data from HPTN 084 are reported.

“What’s important when we look at guidelines is that we also look across populations,” said Meg Doherty, coordinator of treatment and care in the Department of HIV/AIDS at WHO. “We’re waiting to know more about how cabotegravir works in women, because we certainly want to have prevention drugs that can be used in men and women at different age ranges and, ideally, during pregnancy.”

International AIDS Conference 2020: Abstracts OAXLB01. Presented July 8, 2020.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Injections of cabotegravir (ViiV Healthcare) given every other month are more effective in blocking HIV transmission than is the once-a-day combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine (Truvada, Gilead Science), new data from the HPTN 083 trial show.

The findings “could transform the HIV prevention landscape for so many people,” said Megan Coleman, DNP, from Whitman-Walker Health in Washington, DC, who regularly prescribes Truvada as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

At Whitman-Walker alone, about 3000 people were taking the pill in early 2020, but “for some people, taking a pill every day just isn’t a viable option,” said Coleman. “To have something that can support a patient’s choice and a patient’s ability to reduce their own risk of HIV is amazing.”

Final results from the trial — which looked at the drug in cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men — were presented at the International AIDS Conference 2020.

Early Study Termination

Half of the 4566 study participants — from 43 sites in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the United States — were younger than 30 years, 12.4% were transgender women, 29.7% were black, and 46.1% were Hispanic.

By design, ViiV Healthcare, the study sponsor, required that 50% of American participants be black to reflect the population at risk for HIV in the United States, said Raphael Landovitz, MD, from the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine in Los Angeles, who is protocol chair for HPTN 083. In fact, 49.7% of the American cohort was black and 17.8% was Hispanic.

Patients randomized to the cabotegravir group received daily oral cabotegravir plus daily oral placebo for 5 weeks, to assess safety, followed by a cabotegravir injection at weeks 5 and 9 and every 2 months thereafter out to week 153 plus daily oral placebo. Patients randomized to the Truvada group received daily oral Truvada plus daily oral placebo for 5 weeks, followed by daily oral Truvada plus placebo injection, on the same schedule, out to week 153.

After the final injection, all participants continued on daily oral Truvada for 48 weeks.

The researchers expected to wait until 172 participants acquired HIV; they decided at the outset that this number would be sufficient to power a decision on whether or not cabotegravir injections are better than daily oral Truvada. But by May 2020, when 52 of the study participants had acquired HIV, the results were so lopsided in favor of cabotegravir that the trial was stopped. At that point, all participants were offered cabotegravir injections every 2 months.

Thirty-nine of the 52 (75%) new HIV infections occurred in the Truvada group. In fact, (hazard ratio, 0.34).

“This definitively establishes the superiority of cabotegravir,” said Landovitz.

He and his colleagues had been legitimately concerned that HIV acquisition would be so low in the trial that they wouldn’t be able to show how effective the injectable was. The success of Truvada PrEP has made it difficult to design prevention trials.

“We know that Truvada works extremely well, so the fact that we were able to show that cabotegravir in this population works better” is a powerful observation, said Landovitz. This is especially true because the rates of sexually transmitted infections — which are thought to increase risk for HIV transmission — were so high. Overall, 16.5% of the participants tested positive for syphilis during the trial, 13.3% tested positive for gonorrhea, and 21.1% tested positive for Chlamydia.

Five Surprising Seroconversions

Eleven of the 15 HIV infections in the cabotegravir group occurred in people who had received at least one injection. Three of these infections actually occurred during the first 5 weeks of the study when participants were taking oral cabotegravir, two occurred when participants chose to discontinue the injection and return to daily oral Truvada, and one occurred after a participant missed the injection for a prolonged period of time.

But five of the transmissions occurred in participants who appeared to be perfectly adherent.

Landovitz offered a number of possible reasons for this surprising finding.

“Number one could be that there’s something about these five particular individuals such that they grind up and eliminate the cabotegravir faster than other people, so an 8-week interval is too long for them,” he explained. “Another possibility, although pretty rare, is that there is a rare circulating virus that is intrinsically resistant to cabotegravir.”

Breakthrough HIV transmissions have been rare in people taking oral PrEP.

Disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have meant that the researchers don’t yet have the data on drug-resistant mutations or drug levels for these five participants, but they will.

“I suspect the truth is that there will never be a 100% failsafe HIV prevention mechanism,” said Landovitz.

“Impressive” Findings

The findings were greeted with excitement, although questions remain.

They are “impressive,” especially the data on black and Hispanic participants, said Paul Sax, MD, medical director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

However, he said he is interested in the data showing that although participants in both groups gained weight during the study, there was early weight loss in the Truvada group, meaning that those in the cabotegravir group weighed more at the end of the study than those in the Truvada group.

“I’ve been watching the data on weight with integrase inhibitors,” he explained, including weight data specific to Truvada and to the combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide (Descovy, Gilead). It looks like Truvada “has some sort of weight-suppressive effects. That’s going to be a thing we’re going to have to watch.”

Coleman said she is already thinking about patients at Whitman-Walker who might do well on cabotegravir and those who can start PrEP for the first time with this option.

“Not only would people probably switch to this option, but maybe people would be interested in starting a biomedical prevention approach that isn’t a pill every day,” she said. “It’s just exciting to have another option. Hopefully, in a few years, we’ll have implantable devices and rings; I can’t even imagine what all those brilliant minds are coming up with.”

But that’s still a ways off. First, cabotegravir has yet to be approved for HIV prevention, and ideally, eventually, there will be a way to determine if cabotegravir is safe for each patient that doesn’t involve a month of daily pills.

“We need to solve that problem because it’s so complicated to do an oral lead-in for a month or so,” said Carl Dieffenbach, PhD, director of the Division of AIDS at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. “Otherwise it’s not going to be feasible.”

We need to make sure this gets licensed for men and women and transgender individuals.

Even with these positive data, Dieffenbach and other officials are not keen to have ViiV apply for licensing right away. Last October, Descovy was the second oral PrEP pill approved for HIV prevention, but only for use by gay men and transgender women — it hadn’t been well studied in cisgender women — causing an outcry. Now, officials are suggesting that ViiV not make the same mistake.

They are urging the company to hold off until data from the sister study of the medication in women — HPTN 084 — is completed in 2022.

“We need to make sure this gets licensed for men and women and transgender individuals,” Dieffenbach told Medscape Medical News. “We just need to give this a little more time and then build a plan with contingencies, so that if something happens, we still have collected all the safety data in women so we can say it’s safe.”

ViiV seems to be making such a plan.

“Our goal is to seek approval across all genders and we will work with the FDA and other regulatory agencies to map out a plan to achieve this goal,” said Kimberly Smith, MD, head of research and development at ViiV Healthcare.

The World Health Organization (WHO), meanwhile, doesn’t expect to change its guidelines on HIV prevention medications until data from HPTN 084 are reported.

“What’s important when we look at guidelines is that we also look across populations,” said Meg Doherty, coordinator of treatment and care in the Department of HIV/AIDS at WHO. “We’re waiting to know more about how cabotegravir works in women, because we certainly want to have prevention drugs that can be used in men and women at different age ranges and, ideally, during pregnancy.”

International AIDS Conference 2020: Abstracts OAXLB01. Presented July 8, 2020.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Injections of cabotegravir (ViiV Healthcare) given every other month are more effective in blocking HIV transmission than is the once-a-day combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine (Truvada, Gilead Science), new data from the HPTN 083 trial show.

The findings “could transform the HIV prevention landscape for so many people,” said Megan Coleman, DNP, from Whitman-Walker Health in Washington, DC, who regularly prescribes Truvada as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

At Whitman-Walker alone, about 3000 people were taking the pill in early 2020, but “for some people, taking a pill every day just isn’t a viable option,” said Coleman. “To have something that can support a patient’s choice and a patient’s ability to reduce their own risk of HIV is amazing.”

Final results from the trial — which looked at the drug in cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men — were presented at the International AIDS Conference 2020.

Early Study Termination

Half of the 4566 study participants — from 43 sites in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the United States — were younger than 30 years, 12.4% were transgender women, 29.7% were black, and 46.1% were Hispanic.

By design, ViiV Healthcare, the study sponsor, required that 50% of American participants be black to reflect the population at risk for HIV in the United States, said Raphael Landovitz, MD, from the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine in Los Angeles, who is protocol chair for HPTN 083. In fact, 49.7% of the American cohort was black and 17.8% was Hispanic.

Patients randomized to the cabotegravir group received daily oral cabotegravir plus daily oral placebo for 5 weeks, to assess safety, followed by a cabotegravir injection at weeks 5 and 9 and every 2 months thereafter out to week 153 plus daily oral placebo. Patients randomized to the Truvada group received daily oral Truvada plus daily oral placebo for 5 weeks, followed by daily oral Truvada plus placebo injection, on the same schedule, out to week 153.

After the final injection, all participants continued on daily oral Truvada for 48 weeks.

The researchers expected to wait until 172 participants acquired HIV; they decided at the outset that this number would be sufficient to power a decision on whether or not cabotegravir injections are better than daily oral Truvada. But by May 2020, when 52 of the study participants had acquired HIV, the results were so lopsided in favor of cabotegravir that the trial was stopped. At that point, all participants were offered cabotegravir injections every 2 months.

Thirty-nine of the 52 (75%) new HIV infections occurred in the Truvada group. In fact, (hazard ratio, 0.34).

“This definitively establishes the superiority of cabotegravir,” said Landovitz.

He and his colleagues had been legitimately concerned that HIV acquisition would be so low in the trial that they wouldn’t be able to show how effective the injectable was. The success of Truvada PrEP has made it difficult to design prevention trials.

“We know that Truvada works extremely well, so the fact that we were able to show that cabotegravir in this population works better” is a powerful observation, said Landovitz. This is especially true because the rates of sexually transmitted infections — which are thought to increase risk for HIV transmission — were so high. Overall, 16.5% of the participants tested positive for syphilis during the trial, 13.3% tested positive for gonorrhea, and 21.1% tested positive for Chlamydia.

Five Surprising Seroconversions

Eleven of the 15 HIV infections in the cabotegravir group occurred in people who had received at least one injection. Three of these infections actually occurred during the first 5 weeks of the study when participants were taking oral cabotegravir, two occurred when participants chose to discontinue the injection and return to daily oral Truvada, and one occurred after a participant missed the injection for a prolonged period of time.

But five of the transmissions occurred in participants who appeared to be perfectly adherent.

Landovitz offered a number of possible reasons for this surprising finding.

“Number one could be that there’s something about these five particular individuals such that they grind up and eliminate the cabotegravir faster than other people, so an 8-week interval is too long for them,” he explained. “Another possibility, although pretty rare, is that there is a rare circulating virus that is intrinsically resistant to cabotegravir.”

Breakthrough HIV transmissions have been rare in people taking oral PrEP.

Disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have meant that the researchers don’t yet have the data on drug-resistant mutations or drug levels for these five participants, but they will.

“I suspect the truth is that there will never be a 100% failsafe HIV prevention mechanism,” said Landovitz.

“Impressive” Findings

The findings were greeted with excitement, although questions remain.

They are “impressive,” especially the data on black and Hispanic participants, said Paul Sax, MD, medical director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

However, he said he is interested in the data showing that although participants in both groups gained weight during the study, there was early weight loss in the Truvada group, meaning that those in the cabotegravir group weighed more at the end of the study than those in the Truvada group.

“I’ve been watching the data on weight with integrase inhibitors,” he explained, including weight data specific to Truvada and to the combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide (Descovy, Gilead). It looks like Truvada “has some sort of weight-suppressive effects. That’s going to be a thing we’re going to have to watch.”

Coleman said she is already thinking about patients at Whitman-Walker who might do well on cabotegravir and those who can start PrEP for the first time with this option.

“Not only would people probably switch to this option, but maybe people would be interested in starting a biomedical prevention approach that isn’t a pill every day,” she said. “It’s just exciting to have another option. Hopefully, in a few years, we’ll have implantable devices and rings; I can’t even imagine what all those brilliant minds are coming up with.”

But that’s still a ways off. First, cabotegravir has yet to be approved for HIV prevention, and ideally, eventually, there will be a way to determine if cabotegravir is safe for each patient that doesn’t involve a month of daily pills.

“We need to solve that problem because it’s so complicated to do an oral lead-in for a month or so,” said Carl Dieffenbach, PhD, director of the Division of AIDS at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. “Otherwise it’s not going to be feasible.”

We need to make sure this gets licensed for men and women and transgender individuals.

Even with these positive data, Dieffenbach and other officials are not keen to have ViiV apply for licensing right away. Last October, Descovy was the second oral PrEP pill approved for HIV prevention, but only for use by gay men and transgender women — it hadn’t been well studied in cisgender women — causing an outcry. Now, officials are suggesting that ViiV not make the same mistake.

They are urging the company to hold off until data from the sister study of the medication in women — HPTN 084 — is completed in 2022.

“We need to make sure this gets licensed for men and women and transgender individuals,” Dieffenbach told Medscape Medical News. “We just need to give this a little more time and then build a plan with contingencies, so that if something happens, we still have collected all the safety data in women so we can say it’s safe.”

ViiV seems to be making such a plan.

“Our goal is to seek approval across all genders and we will work with the FDA and other regulatory agencies to map out a plan to achieve this goal,” said Kimberly Smith, MD, head of research and development at ViiV Healthcare.

The World Health Organization (WHO), meanwhile, doesn’t expect to change its guidelines on HIV prevention medications until data from HPTN 084 are reported.

“What’s important when we look at guidelines is that we also look across populations,” said Meg Doherty, coordinator of treatment and care in the Department of HIV/AIDS at WHO. “We’re waiting to know more about how cabotegravir works in women, because we certainly want to have prevention drugs that can be used in men and women at different age ranges and, ideally, during pregnancy.”

International AIDS Conference 2020: Abstracts OAXLB01. Presented July 8, 2020.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

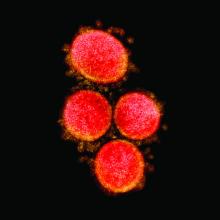

Children rarely transmit SARS-CoV-2 within households

“Unlike with other viral respiratory infections, children do not seem to be a major vector of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission, with most pediatric cases described inside familial clusters and no documentation of child-to-child or child-to-adult transmission,” said Klara M. Posfay-Barbe, MD, of the University of Geneva, Switzerland, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers analyzed data from all COVID-19 patients younger than 16 years who were identified between March 10, 2020, and April 10, 2020, through a hospital surveillance network. Parents and household contacts were called for contact tracing.

In 31 of 39 (79%) households, at least one adult family member had a suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection before onset of symptoms in the child. These findings support data from previous studies suggesting that children mainly become infected from adult family members rather than transmitting the virus to them, the researchers said

In only 3 of 39 (8%) households was the study child the first to develop symptoms. “Surprisingly, in 33% of households, symptomatic HHCs [household contacts] tested negative despite belonging to a familial cluster with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases, suggesting an underreporting of cases,” Dr. Posfay-Barbe and associates noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including potential underreporting of cases because those with mild or atypical presentations may not have sought medical care, and the inability to confirm child-to-adult transmission. The results were strengthened by the extensive contact tracing and very few individuals lost to follow-up, they said; however, more diagnostic screening and contact tracing are needed to improve understanding of household transmission of SARS-CoV-2, they concluded.

Resolving the issue of how much children contribute to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is essential to making informed decisions about public health, including how to structure schools and child-care facility reopening, Benjamin Lee, MD, and William V. Raszka Jr., MD, both of the University of Vermont, Burlington, said in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds/2020-004879).

The data in the current study support other studies of transmission among household contacts in China suggesting that, in most cases of childhood infections, “the child was not the source of infection and that children most frequently acquire COVID-19 from adults, rather than transmitting it to them,” they wrote.

In addition, the limited data on transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by children outside of the household show few cases of secondary infection from children identified with SARS-CoV-2 in school settings in studies from France and Australia, Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka noted.

the editorialists wrote. “This would be another manner by which SARS-CoV2 differs drastically from influenza, for which school-based transmission is well recognized as a significant driver of epidemic disease and forms the basis for most evidence regarding school closures as public health strategy.”

“Therefore, serious consideration should be paid toward strategies that allow schools to remain open, even during periods of COVID-19 spread,” the editorialists concluded. “In doing so, we could minimize the potentially profound adverse social, developmental, and health costs that our children will continue to suffer until an effective treatment or vaccine can be developed and distributed or, failing that, until we reach herd immunity,” Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka emphasized.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Posfay-Barbe KM et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1576.

“Unlike with other viral respiratory infections, children do not seem to be a major vector of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission, with most pediatric cases described inside familial clusters and no documentation of child-to-child or child-to-adult transmission,” said Klara M. Posfay-Barbe, MD, of the University of Geneva, Switzerland, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers analyzed data from all COVID-19 patients younger than 16 years who were identified between March 10, 2020, and April 10, 2020, through a hospital surveillance network. Parents and household contacts were called for contact tracing.

In 31 of 39 (79%) households, at least one adult family member had a suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection before onset of symptoms in the child. These findings support data from previous studies suggesting that children mainly become infected from adult family members rather than transmitting the virus to them, the researchers said

In only 3 of 39 (8%) households was the study child the first to develop symptoms. “Surprisingly, in 33% of households, symptomatic HHCs [household contacts] tested negative despite belonging to a familial cluster with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases, suggesting an underreporting of cases,” Dr. Posfay-Barbe and associates noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including potential underreporting of cases because those with mild or atypical presentations may not have sought medical care, and the inability to confirm child-to-adult transmission. The results were strengthened by the extensive contact tracing and very few individuals lost to follow-up, they said; however, more diagnostic screening and contact tracing are needed to improve understanding of household transmission of SARS-CoV-2, they concluded.

Resolving the issue of how much children contribute to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is essential to making informed decisions about public health, including how to structure schools and child-care facility reopening, Benjamin Lee, MD, and William V. Raszka Jr., MD, both of the University of Vermont, Burlington, said in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds/2020-004879).

The data in the current study support other studies of transmission among household contacts in China suggesting that, in most cases of childhood infections, “the child was not the source of infection and that children most frequently acquire COVID-19 from adults, rather than transmitting it to them,” they wrote.

In addition, the limited data on transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by children outside of the household show few cases of secondary infection from children identified with SARS-CoV-2 in school settings in studies from France and Australia, Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka noted.

the editorialists wrote. “This would be another manner by which SARS-CoV2 differs drastically from influenza, for which school-based transmission is well recognized as a significant driver of epidemic disease and forms the basis for most evidence regarding school closures as public health strategy.”

“Therefore, serious consideration should be paid toward strategies that allow schools to remain open, even during periods of COVID-19 spread,” the editorialists concluded. “In doing so, we could minimize the potentially profound adverse social, developmental, and health costs that our children will continue to suffer until an effective treatment or vaccine can be developed and distributed or, failing that, until we reach herd immunity,” Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka emphasized.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Posfay-Barbe KM et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1576.

“Unlike with other viral respiratory infections, children do not seem to be a major vector of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission, with most pediatric cases described inside familial clusters and no documentation of child-to-child or child-to-adult transmission,” said Klara M. Posfay-Barbe, MD, of the University of Geneva, Switzerland, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers analyzed data from all COVID-19 patients younger than 16 years who were identified between March 10, 2020, and April 10, 2020, through a hospital surveillance network. Parents and household contacts were called for contact tracing.

In 31 of 39 (79%) households, at least one adult family member had a suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection before onset of symptoms in the child. These findings support data from previous studies suggesting that children mainly become infected from adult family members rather than transmitting the virus to them, the researchers said

In only 3 of 39 (8%) households was the study child the first to develop symptoms. “Surprisingly, in 33% of households, symptomatic HHCs [household contacts] tested negative despite belonging to a familial cluster with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases, suggesting an underreporting of cases,” Dr. Posfay-Barbe and associates noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including potential underreporting of cases because those with mild or atypical presentations may not have sought medical care, and the inability to confirm child-to-adult transmission. The results were strengthened by the extensive contact tracing and very few individuals lost to follow-up, they said; however, more diagnostic screening and contact tracing are needed to improve understanding of household transmission of SARS-CoV-2, they concluded.

Resolving the issue of how much children contribute to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is essential to making informed decisions about public health, including how to structure schools and child-care facility reopening, Benjamin Lee, MD, and William V. Raszka Jr., MD, both of the University of Vermont, Burlington, said in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds/2020-004879).

The data in the current study support other studies of transmission among household contacts in China suggesting that, in most cases of childhood infections, “the child was not the source of infection and that children most frequently acquire COVID-19 from adults, rather than transmitting it to them,” they wrote.

In addition, the limited data on transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by children outside of the household show few cases of secondary infection from children identified with SARS-CoV-2 in school settings in studies from France and Australia, Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka noted.

the editorialists wrote. “This would be another manner by which SARS-CoV2 differs drastically from influenza, for which school-based transmission is well recognized as a significant driver of epidemic disease and forms the basis for most evidence regarding school closures as public health strategy.”

“Therefore, serious consideration should be paid toward strategies that allow schools to remain open, even during periods of COVID-19 spread,” the editorialists concluded. “In doing so, we could minimize the potentially profound adverse social, developmental, and health costs that our children will continue to suffer until an effective treatment or vaccine can be developed and distributed or, failing that, until we reach herd immunity,” Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka emphasized.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Posfay-Barbe KM et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1576.

FROM PEDIATRICS

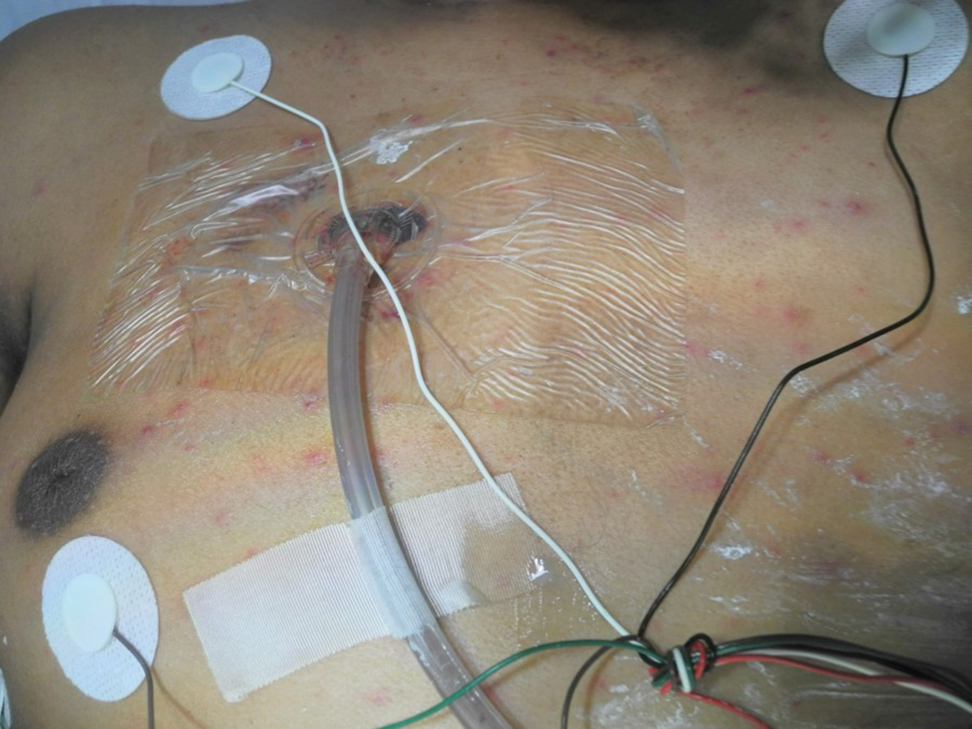

Risky business: Longer-course prophylactic perioperative antimicrobials

Background: National guidelines recommend that surgical prophylactic antimicrobials be initiated within 1 hour prior to incision and discontinued 24 hours postoperatively. However, the risks and benefits of longer duration of antimicrobials are uncertain.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Veterans Affairs hospitals.

Synopsis: After stratification by type of surgery and adjustment for covariates, antibiotic prophylaxis greater than 24 hours was not associated with lower SSI risk.

However, the odds of postoperative AKI increased with each additional day of prophylaxis (adjusted odds ratios, 1.82; 95% confidence interval,1.54-2.16 and aOR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.27-2.53) with longer than 72 hours prophylaxis for cardiac and noncardiac surgery, respectively). Similarly, C. difficile infections increased with each additional day beyond 24 hours (aOR, 3.65; 95% CI, 2.40-5.55 with more than 72 hours of use).

Bottom line: Each day of perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis beyond 24 hours increases the risk for postoperative AKI or C. difficile infection without reducing the risk of surgical site infection.

Citation: Branch-Elliman W et al. Association of duration and type of surgical prophylaxis with antimicrobial-associated adverse events. JAMA Surg. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0569.

Dr. Miller is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: National guidelines recommend that surgical prophylactic antimicrobials be initiated within 1 hour prior to incision and discontinued 24 hours postoperatively. However, the risks and benefits of longer duration of antimicrobials are uncertain.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Veterans Affairs hospitals.

Synopsis: After stratification by type of surgery and adjustment for covariates, antibiotic prophylaxis greater than 24 hours was not associated with lower SSI risk.

However, the odds of postoperative AKI increased with each additional day of prophylaxis (adjusted odds ratios, 1.82; 95% confidence interval,1.54-2.16 and aOR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.27-2.53) with longer than 72 hours prophylaxis for cardiac and noncardiac surgery, respectively). Similarly, C. difficile infections increased with each additional day beyond 24 hours (aOR, 3.65; 95% CI, 2.40-5.55 with more than 72 hours of use).

Bottom line: Each day of perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis beyond 24 hours increases the risk for postoperative AKI or C. difficile infection without reducing the risk of surgical site infection.

Citation: Branch-Elliman W et al. Association of duration and type of surgical prophylaxis with antimicrobial-associated adverse events. JAMA Surg. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0569.

Dr. Miller is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: National guidelines recommend that surgical prophylactic antimicrobials be initiated within 1 hour prior to incision and discontinued 24 hours postoperatively. However, the risks and benefits of longer duration of antimicrobials are uncertain.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Veterans Affairs hospitals.

Synopsis: After stratification by type of surgery and adjustment for covariates, antibiotic prophylaxis greater than 24 hours was not associated with lower SSI risk.

However, the odds of postoperative AKI increased with each additional day of prophylaxis (adjusted odds ratios, 1.82; 95% confidence interval,1.54-2.16 and aOR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.27-2.53) with longer than 72 hours prophylaxis for cardiac and noncardiac surgery, respectively). Similarly, C. difficile infections increased with each additional day beyond 24 hours (aOR, 3.65; 95% CI, 2.40-5.55 with more than 72 hours of use).

Bottom line: Each day of perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis beyond 24 hours increases the risk for postoperative AKI or C. difficile infection without reducing the risk of surgical site infection.

Citation: Branch-Elliman W et al. Association of duration and type of surgical prophylaxis with antimicrobial-associated adverse events. JAMA Surg. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0569.

Dr. Miller is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Even a few days of steroids may be risky, new study suggests

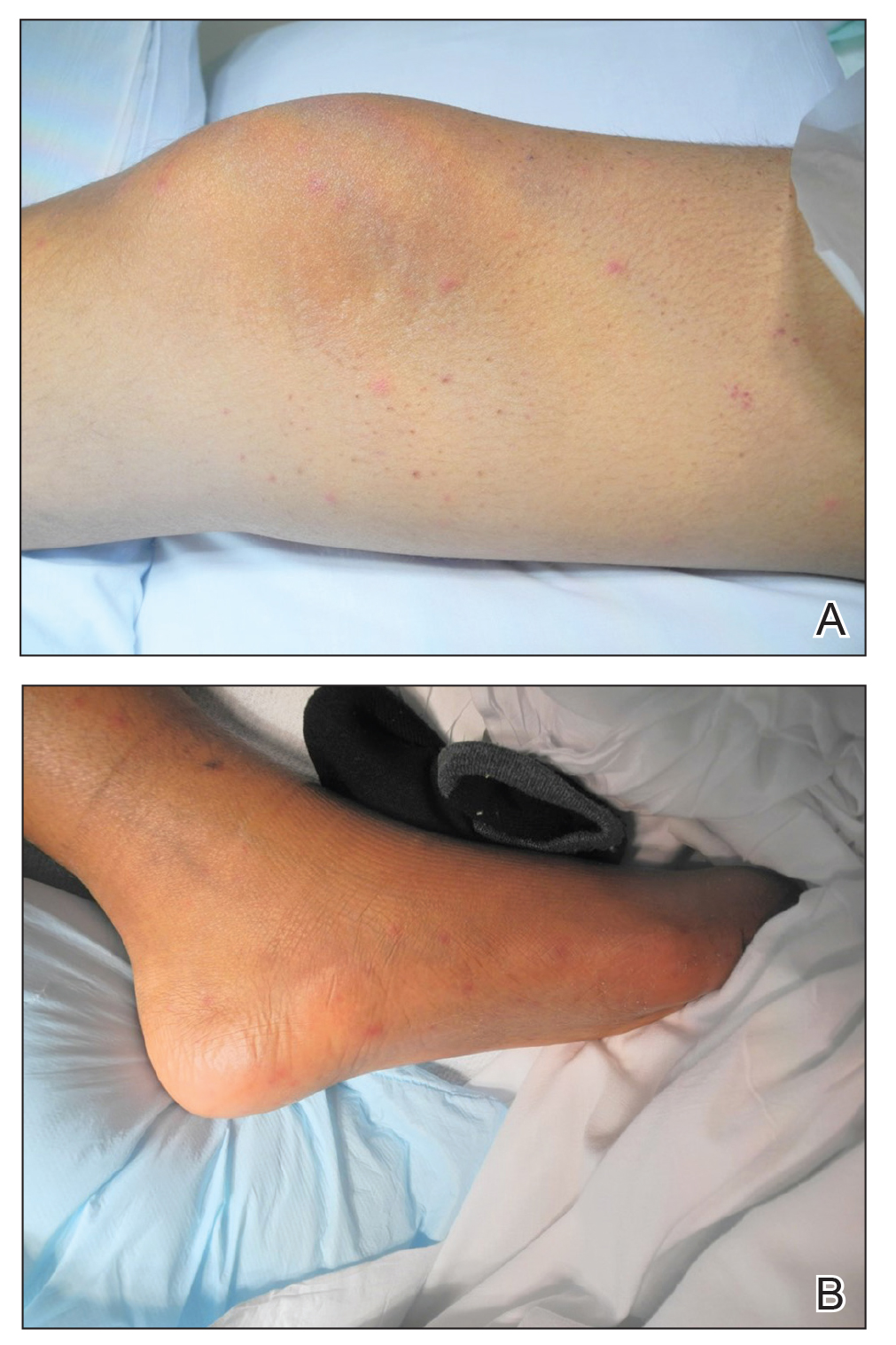

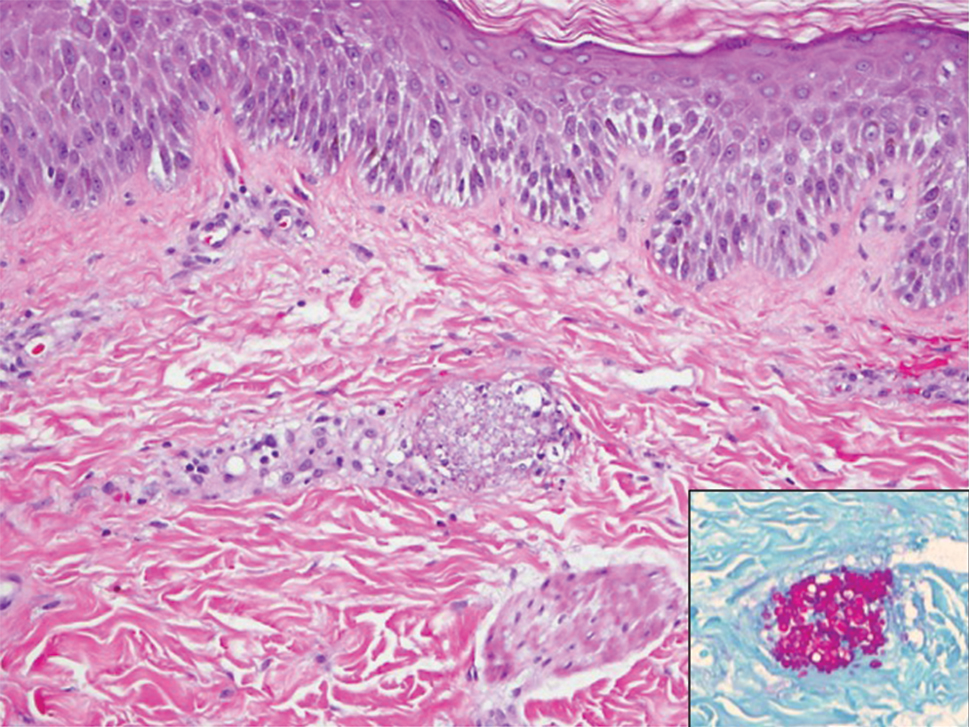

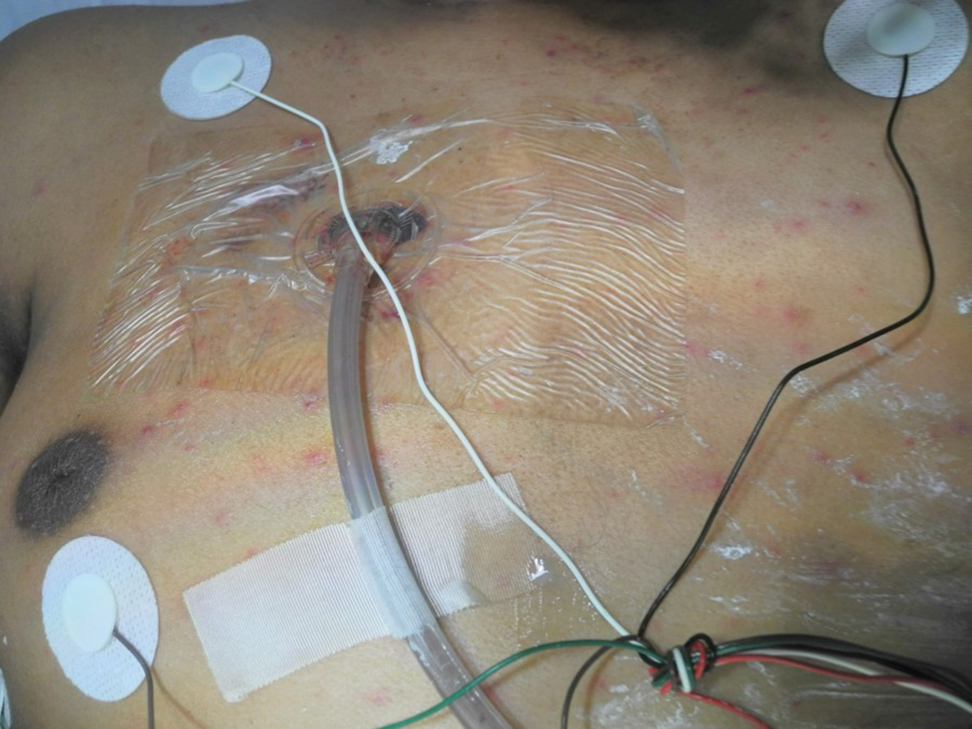

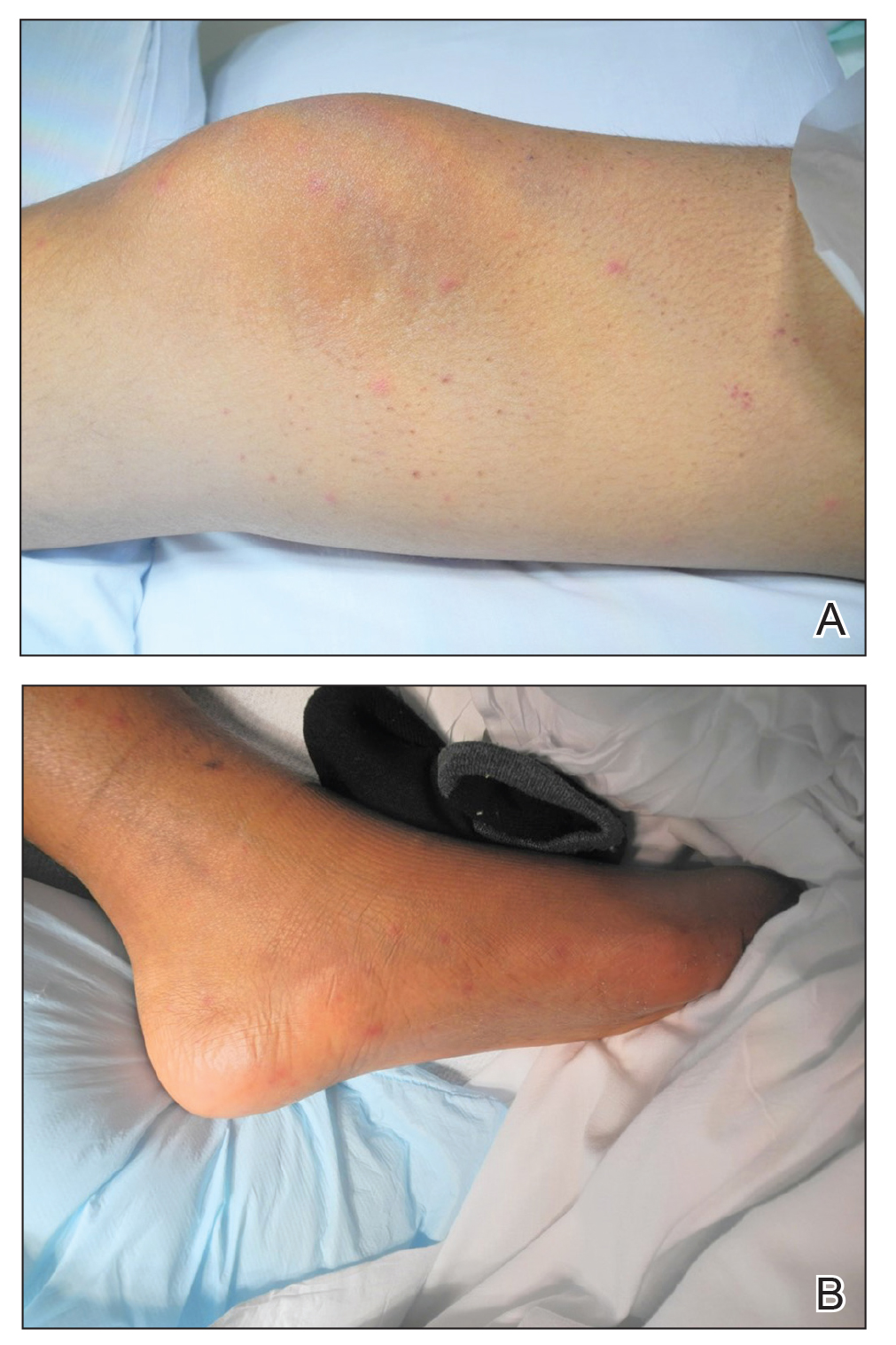

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.

Given the findings, physicians should weigh the benefits against the risks of rare but potentially serious consequences of these anti-inflammatory drugs, according to the authors.

“After initiating patients on oral steroid bursts, physicians should be on the lookout for these severe adverse events, particularly within the first month after initiation of steroid therapy,” Dr. Yao said in an interview.

The findings were published online July 6 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Of the 15,859,129 adult Asians in the Taiwanese database, the study included 2,623,327 adults aged 20-64 years who received single steroid bursts (14 days or less) between Jan. 1, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2015.

Almost 60% of the indications were for skin disorders, such as eczema and urticaria, and for respiratory tract infections, such as sinusitis and acute pharyngitis. Among specialties, dermatology, otolaryngology, family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics accounted for 88% of prescriptions.

“Our findings are important for physicians and guideline developers because short-term use of oral corticosteroids is common and the real-world safety of this approach remains unclear,” the authors wrote. They acknowledged that the database did not provide information on such potential confounders as disease severity and lifestyle factors, nor did it include children and vulnerable individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the results.

The findings echo those of a 2017 cohort study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That study, by Akbar K. Waljee, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues, included data on more than 1.5 million privately insured U.S. adults. The researchers included somewhat longer steroid bursts of up to 30 days’ duration and found that use of the drugs was associated with a greater than fivefold increased risk for sepsis, a more than threefold increased risk for venous thromboembolism, and a nearly twofold increased risk for fracture within 30 days of starting treatment.

Furthermore, the elevated risk persisted at prednisone-equivalent doses of less than 20 mg/d (IRR, 4.02 for sepsis, 3.61 for venous thromboembolism, and 1.83 for fracture; all P < .001).

The U.S. study also found that during the 3-year period from 2012 to 2014, more than 20% of patients were prescribed short-term oral corticosteroids.

“Both studies indicate that these short-term regimens are more common in the real world than was previously thought and are not risk free,” Dr. Yao said.

Recognition that corticosteroids are associated with adverse events has been building for decades, according to the authors of an editorial that accompanies the new study.

“However, we commonly use short corticosteroid ‘bursts’ for minor ailments despite a lack of evidence for meaningful benefit. We are now learning that bursts as short as 3 days may increase risk for serious AEs, even in young and healthy people,” wrote editorialists Beth I. Wallace, MD, of the Center for Clinical Management Research at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Waljee, who led the 2017 study.

Dr. Wallace and Dr. Waljee drew parallels between corticosteroid bursts and other short-term regimens, such as of antibiotics and opiates, in which prescriber preference and sometimes patient pressure play a role. “All of these treatments have well-defined indications but can cause net harm when used. We can thus conceive of a corticosteroid stewardship model of targeted interventions that aims to reduce inappropriate prescribing,” they wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Wallace, a rheumatologist who prescribes oral steroids fairly frequently, noted that the Taiwan study is the first to investigate steroid bursts. “Up till now, these very short courses have flown under the radar. Clinicians very commonly prescribe short courses to help relieve symptoms of self-limited conditions like bronchitis, and we assume that because the exposure duration is short, the risks are low, especially for patients who are otherwise healthy.”

She warned that the data in the current study indicate that these short bursts – even at the lower end of the 1- to 2-week courses American physicians prescribe most often – carry small but real increases in risk for serious AEs. “And these increases were seen in young, healthy people, not just in people with preexisting conditions,” she said. “So, we might need to start thinking harder about how we are prescribing even these very short courses of steroids and try to use steroids only when their meaningful benefits really outweigh the risk.”

She noted that a patient with a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit substantially from short-term steroids to treat a disease flare. In that specific case, the benefits of short-term steroids may outweigh the risks, Dr. Wallace said.

But not everyone thinks a new strategy is needed. For Whitney A. High, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pathology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, the overprescribing of short-term corticosteroids is not a problem, and dermatologists are already exercising caution.

“I only prescribe these drugs short term to, at a guess, about 1 in 40 patients and only when a patient is miserable and quality of life is being seriously affected,” he said in an interview. “And that’s something that can’t be measured in a database study like the one from Taiwan but only in a risk-benefit analysis,” he said.

Furthermore, dermatologists have other drugs and technologies in their armamentarium, including topical steroids with occlusion or with wet wraps, phototherapy, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcipotriene, methotrexate and other immunosuppressive agents, and biologics. “In fact, many of these agents are specifically referred to as steroid-sparing,” Dr. High said.

Nor does he experience much pressure from patients to prescribe these drugs. “While occasionally I may encounter a patient who places pressure on me for oral steroids, it’s probably not nearly as frequently as providers in other fields are pressured to prescribe antibiotics or narcotics,” he said.

According to the Taiwanese researchers, the next step is to conduct more studies, including clinical trials, to determine optimal use of corticosteroids by monitoring adverse events. In the meantime, for practitioners such as Dr. Wallace and Dr. High, there is ample evidence from several recent studies of the harms of short-term corticosteroids, whereas the benefits for patients with self-limiting conditions remain uncertain. “This and other studies like it quite appropriately remind providers to avoid oral steroids when they’re not necessary and to seek alternatives where possible,” Dr. High said.

The study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan, the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, the Chang Gung Medical Foundation, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Yao has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wu has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. The editorialists and Dr. High have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace received an NIH grant during the writing of the editorial.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.

Given the findings, physicians should weigh the benefits against the risks of rare but potentially serious consequences of these anti-inflammatory drugs, according to the authors.

“After initiating patients on oral steroid bursts, physicians should be on the lookout for these severe adverse events, particularly within the first month after initiation of steroid therapy,” Dr. Yao said in an interview.

The findings were published online July 6 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Of the 15,859,129 adult Asians in the Taiwanese database, the study included 2,623,327 adults aged 20-64 years who received single steroid bursts (14 days or less) between Jan. 1, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2015.

Almost 60% of the indications were for skin disorders, such as eczema and urticaria, and for respiratory tract infections, such as sinusitis and acute pharyngitis. Among specialties, dermatology, otolaryngology, family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics accounted for 88% of prescriptions.

“Our findings are important for physicians and guideline developers because short-term use of oral corticosteroids is common and the real-world safety of this approach remains unclear,” the authors wrote. They acknowledged that the database did not provide information on such potential confounders as disease severity and lifestyle factors, nor did it include children and vulnerable individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the results.

The findings echo those of a 2017 cohort study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That study, by Akbar K. Waljee, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues, included data on more than 1.5 million privately insured U.S. adults. The researchers included somewhat longer steroid bursts of up to 30 days’ duration and found that use of the drugs was associated with a greater than fivefold increased risk for sepsis, a more than threefold increased risk for venous thromboembolism, and a nearly twofold increased risk for fracture within 30 days of starting treatment.

Furthermore, the elevated risk persisted at prednisone-equivalent doses of less than 20 mg/d (IRR, 4.02 for sepsis, 3.61 for venous thromboembolism, and 1.83 for fracture; all P < .001).

The U.S. study also found that during the 3-year period from 2012 to 2014, more than 20% of patients were prescribed short-term oral corticosteroids.

“Both studies indicate that these short-term regimens are more common in the real world than was previously thought and are not risk free,” Dr. Yao said.

Recognition that corticosteroids are associated with adverse events has been building for decades, according to the authors of an editorial that accompanies the new study.

“However, we commonly use short corticosteroid ‘bursts’ for minor ailments despite a lack of evidence for meaningful benefit. We are now learning that bursts as short as 3 days may increase risk for serious AEs, even in young and healthy people,” wrote editorialists Beth I. Wallace, MD, of the Center for Clinical Management Research at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Waljee, who led the 2017 study.

Dr. Wallace and Dr. Waljee drew parallels between corticosteroid bursts and other short-term regimens, such as of antibiotics and opiates, in which prescriber preference and sometimes patient pressure play a role. “All of these treatments have well-defined indications but can cause net harm when used. We can thus conceive of a corticosteroid stewardship model of targeted interventions that aims to reduce inappropriate prescribing,” they wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Wallace, a rheumatologist who prescribes oral steroids fairly frequently, noted that the Taiwan study is the first to investigate steroid bursts. “Up till now, these very short courses have flown under the radar. Clinicians very commonly prescribe short courses to help relieve symptoms of self-limited conditions like bronchitis, and we assume that because the exposure duration is short, the risks are low, especially for patients who are otherwise healthy.”

She warned that the data in the current study indicate that these short bursts – even at the lower end of the 1- to 2-week courses American physicians prescribe most often – carry small but real increases in risk for serious AEs. “And these increases were seen in young, healthy people, not just in people with preexisting conditions,” she said. “So, we might need to start thinking harder about how we are prescribing even these very short courses of steroids and try to use steroids only when their meaningful benefits really outweigh the risk.”

She noted that a patient with a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit substantially from short-term steroids to treat a disease flare. In that specific case, the benefits of short-term steroids may outweigh the risks, Dr. Wallace said.

But not everyone thinks a new strategy is needed. For Whitney A. High, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pathology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, the overprescribing of short-term corticosteroids is not a problem, and dermatologists are already exercising caution.

“I only prescribe these drugs short term to, at a guess, about 1 in 40 patients and only when a patient is miserable and quality of life is being seriously affected,” he said in an interview. “And that’s something that can’t be measured in a database study like the one from Taiwan but only in a risk-benefit analysis,” he said.

Furthermore, dermatologists have other drugs and technologies in their armamentarium, including topical steroids with occlusion or with wet wraps, phototherapy, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcipotriene, methotrexate and other immunosuppressive agents, and biologics. “In fact, many of these agents are specifically referred to as steroid-sparing,” Dr. High said.

Nor does he experience much pressure from patients to prescribe these drugs. “While occasionally I may encounter a patient who places pressure on me for oral steroids, it’s probably not nearly as frequently as providers in other fields are pressured to prescribe antibiotics or narcotics,” he said.

According to the Taiwanese researchers, the next step is to conduct more studies, including clinical trials, to determine optimal use of corticosteroids by monitoring adverse events. In the meantime, for practitioners such as Dr. Wallace and Dr. High, there is ample evidence from several recent studies of the harms of short-term corticosteroids, whereas the benefits for patients with self-limiting conditions remain uncertain. “This and other studies like it quite appropriately remind providers to avoid oral steroids when they’re not necessary and to seek alternatives where possible,” Dr. High said.

The study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan, the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, the Chang Gung Medical Foundation, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Yao has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wu has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. The editorialists and Dr. High have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace received an NIH grant during the writing of the editorial.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.

Given the findings, physicians should weigh the benefits against the risks of rare but potentially serious consequences of these anti-inflammatory drugs, according to the authors.

“After initiating patients on oral steroid bursts, physicians should be on the lookout for these severe adverse events, particularly within the first month after initiation of steroid therapy,” Dr. Yao said in an interview.

The findings were published online July 6 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Of the 15,859,129 adult Asians in the Taiwanese database, the study included 2,623,327 adults aged 20-64 years who received single steroid bursts (14 days or less) between Jan. 1, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2015.

Almost 60% of the indications were for skin disorders, such as eczema and urticaria, and for respiratory tract infections, such as sinusitis and acute pharyngitis. Among specialties, dermatology, otolaryngology, family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics accounted for 88% of prescriptions.

“Our findings are important for physicians and guideline developers because short-term use of oral corticosteroids is common and the real-world safety of this approach remains unclear,” the authors wrote. They acknowledged that the database did not provide information on such potential confounders as disease severity and lifestyle factors, nor did it include children and vulnerable individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the results.

The findings echo those of a 2017 cohort study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That study, by Akbar K. Waljee, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues, included data on more than 1.5 million privately insured U.S. adults. The researchers included somewhat longer steroid bursts of up to 30 days’ duration and found that use of the drugs was associated with a greater than fivefold increased risk for sepsis, a more than threefold increased risk for venous thromboembolism, and a nearly twofold increased risk for fracture within 30 days of starting treatment.

Furthermore, the elevated risk persisted at prednisone-equivalent doses of less than 20 mg/d (IRR, 4.02 for sepsis, 3.61 for venous thromboembolism, and 1.83 for fracture; all P < .001).

The U.S. study also found that during the 3-year period from 2012 to 2014, more than 20% of patients were prescribed short-term oral corticosteroids.

“Both studies indicate that these short-term regimens are more common in the real world than was previously thought and are not risk free,” Dr. Yao said.

Recognition that corticosteroids are associated with adverse events has been building for decades, according to the authors of an editorial that accompanies the new study.

“However, we commonly use short corticosteroid ‘bursts’ for minor ailments despite a lack of evidence for meaningful benefit. We are now learning that bursts as short as 3 days may increase risk for serious AEs, even in young and healthy people,” wrote editorialists Beth I. Wallace, MD, of the Center for Clinical Management Research at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Waljee, who led the 2017 study.

Dr. Wallace and Dr. Waljee drew parallels between corticosteroid bursts and other short-term regimens, such as of antibiotics and opiates, in which prescriber preference and sometimes patient pressure play a role. “All of these treatments have well-defined indications but can cause net harm when used. We can thus conceive of a corticosteroid stewardship model of targeted interventions that aims to reduce inappropriate prescribing,” they wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Wallace, a rheumatologist who prescribes oral steroids fairly frequently, noted that the Taiwan study is the first to investigate steroid bursts. “Up till now, these very short courses have flown under the radar. Clinicians very commonly prescribe short courses to help relieve symptoms of self-limited conditions like bronchitis, and we assume that because the exposure duration is short, the risks are low, especially for patients who are otherwise healthy.”

She warned that the data in the current study indicate that these short bursts – even at the lower end of the 1- to 2-week courses American physicians prescribe most often – carry small but real increases in risk for serious AEs. “And these increases were seen in young, healthy people, not just in people with preexisting conditions,” she said. “So, we might need to start thinking harder about how we are prescribing even these very short courses of steroids and try to use steroids only when their meaningful benefits really outweigh the risk.”

She noted that a patient with a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit substantially from short-term steroids to treat a disease flare. In that specific case, the benefits of short-term steroids may outweigh the risks, Dr. Wallace said.

But not everyone thinks a new strategy is needed. For Whitney A. High, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pathology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, the overprescribing of short-term corticosteroids is not a problem, and dermatologists are already exercising caution.

“I only prescribe these drugs short term to, at a guess, about 1 in 40 patients and only when a patient is miserable and quality of life is being seriously affected,” he said in an interview. “And that’s something that can’t be measured in a database study like the one from Taiwan but only in a risk-benefit analysis,” he said.

Furthermore, dermatologists have other drugs and technologies in their armamentarium, including topical steroids with occlusion or with wet wraps, phototherapy, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcipotriene, methotrexate and other immunosuppressive agents, and biologics. “In fact, many of these agents are specifically referred to as steroid-sparing,” Dr. High said.

Nor does he experience much pressure from patients to prescribe these drugs. “While occasionally I may encounter a patient who places pressure on me for oral steroids, it’s probably not nearly as frequently as providers in other fields are pressured to prescribe antibiotics or narcotics,” he said.

According to the Taiwanese researchers, the next step is to conduct more studies, including clinical trials, to determine optimal use of corticosteroids by monitoring adverse events. In the meantime, for practitioners such as Dr. Wallace and Dr. High, there is ample evidence from several recent studies of the harms of short-term corticosteroids, whereas the benefits for patients with self-limiting conditions remain uncertain. “This and other studies like it quite appropriately remind providers to avoid oral steroids when they’re not necessary and to seek alternatives where possible,” Dr. High said.

The study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan, the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, the Chang Gung Medical Foundation, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Yao has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wu has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. The editorialists and Dr. High have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace received an NIH grant during the writing of the editorial.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Retreatment of Hepatitis C Infection With Direct-Acting Antivirals

An estimated 3.5 million people in the US have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and between 10% and 20% of those developed cirrhosis over 20 to 30 years.1 There are at least 6 genotypes (GTs) of HCV, with GT1 being the most common in the US and previously one of the most difficult to treat.2,3 The goal of treatment is to achieve viral cure, called sustained virologic response (SVR) when HCV viral load remains undetectable several weeks after therapy completion. In the 2000s, pegylated interferon (pegIFN) and ribavirin (RBV) were the standard of care.2 For patients with GT1 infections, an SVR of 40 to 50% was commonly seen after 48 weeks of pegIFN/RBV regimens compared with 70 to 80% SVR for GT2 or GT3 after 24 weeks of pegIFN/RBV therapy.2 However, treatment has evolved rapidly (Table 1).2-17

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the protease inhibitors (PIs) boceprevir and telaprevir, which added a new class of agents with increased SVR for patients with GT1 infection; however, pegIFN and RBV were still needed for treatment.4 In addition, both PIs required multiple doses per day and strict adherence to an 8-hour schedule.4 Boceprevir required treatment with RBV and pegIFN for 48 weeks unless futility rule was met at 24 weeks of treatment (ie, viral load still detectable).4 The SVR in patients with GT1 infection improved to > 65% for patients in clinical trials.2 FDA approval of the direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) sofosbuvir and simeprevir in late 2013 decreased the usual duration of therapy to only 12 weeks with improved SVR rates 12 weeks posttherapy (SVR12) to 90% or higher.2,6,10

FDA approval of ledipasvir (LDV)/sofosbuvir (SOF) in October 2014 resulted in the first interferon-free all-oral regimen indicated for HCV GT1 infection.11 In December 2014, FDA approved a combination of paritaprevir, ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir (PrOD).12 In 2015 GT-specific approvals were issued for daclastavir to be used with SOV for GT1 and GT3 and a combination similar to PrOD without dasabuvir (PrO) for GT4.13 In 2016, a combination of elbasvir (ERB) and grazoprevir (GZP) was approved for GT1 and GT4.14

In 2016, a pangenotypic DAA of SOF and velpatasvir (VEL) was approved.15 Most recently, combinations of SOF, VEL, and voxilaprevir (VOX), and glecaprevir (GLE) and pibrentasvir (PIB) were approved for patients with previous DAA treatment failures.7, 8,16,17 These oral regimens avoided the significant adverse events (AEs) associated with pegIFN and RBV (eg, thrombocytopenia, depression), were expected to improve treatment adherence and shorten duration of therapy.

The West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs has had a nurse practitioner (NP)-based HCV treatment clinic since the late 1990s. When PIs became available, a CPS started reviewing patient electronic health records (EHRs) and monitored response to therapy along with the NP to ensure discontinuation of therapy if futility criteria were met.7 Our unpublished experience showed SVR > 60% with both boceprevir and SOF regimens and > 90% with oral DAA regimens.

This review will provide the SVR rates for patients that needed retreatment for HCV infection since 2015 until December 2019. We treated all willing patients, beginning with the patients who had experienced failures with previous regimens. Patients first received education on HCV infection and treatment options in a group class then they were seen by the NP individually for specific education on treatment. The CPS reviewed the patient’s medical record to assess for appropriate therapy, possible drug-drug interactions and contraindications to therapy. In addition, patient outcomes (eg, viral load, AEs) were documented by the CPS in collaboration with the NP throughout treatment until viral load for SVR evaluation was obtained.

Methods

A retrospective EHR review of patients retreated from January 2015 to December 2019 was conducted. Data collected included age, sex, HCV GT, previous therapy, new medications prescribed, creatinine clearance, and achievement of SVR12. This retrospective review was approved by the facility’s scientific advisory committee as part of performance improvement efforts. Descriptive statistics are provided.

Results

Boceprevir

We treated 31 patients with boceprevir of which 3 met futility rule and 28 completed therapy. Eighteen of 28 responded (64%) to the treatment. The 10 patients who failed treatment were retreated with LDV/SOF, and all achieved SVR.

Sofosbuvir

A total of 53 patients were treated with SOF, RBV, and pegIFN for 12 weeks. Forty-one achieved SVR (77%). Of the 12 who failed therapy, all have been retreated and achieved SVR (Table 2).

Interferon-Free DAA Oral Regimens

More than 900 patients have been treated with interferon-free regimens since 2015 and outcomes were documented for > 800 patients. The SVR rates by GT were as follows: GT1 639 of 676 (95%); GT2 76 of 79 (96%); GT3 40 of 48 (83%); and GT4 6 of 6 (100%). Eighty-four percent of patients had GT1 infection. The median age of patient was 62 years, 72% were treatment naïve, and 35% having cirrhosis (based on liver biopsy or FIB4 score).18

Of 48 treatment failures, 30 patients were retreated; the rest of the patients were lost to follow-up (n = 9) or unable to receive retreatment (n = 9) mainly due to decompensated cirrhosis or liver cancer and short life expectancy. The median age of patient in this retreatment group was 62 years, 62% had cirrhosis, and most were infected with GT1. The average creatinine clearance was 73 mL/min. Twenty-two patients who failed therapy with ledipasvir/SOF were retreated (Table 3). A total of 13 patients out of the 19 tested eventually achieved SVR (68%). Four of the patients who had treatment failure again had GT1 infection and the other 2 GT3. All had cirrhosis.

Thirty-five patients were treated with PrOD, and 32 achieved SVR (91%). All 3 patients were retreated. One patient each achieved SVR with ERB/GZP, SOF/VEL and SOF/VEL/VOX. Fifty patients were treated with ERB/GZP and 45 achieved SVR (90%). All 5 treatment failures were retreated. Four achieved SVR and 1 was lost to follow-up (Table 4). Overall, of 30 patients who were retreated after failure with an all-oral DAA regimen, 27 patients had SVR values available and 21 achieved it (78%).

Discussion

Overall SVR was very high for patients who received oral treatment for HCV infection. A low number of patients failed therapy and were retreated. Patients who failed therapy again were similar in age but were more likely to have cirrhosis when compared with the overall interferon-free treated group. Thus, prompt treatment after HCV detection and before disease progression may improve treatment outcomes. Achieving SVR has been shown to improve fibrosis, portal hypertension, splenomegaly and cirrhosis, and reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by 70% and liver-related mortality by 90%.19-21/

Patients who failed therapy primarily had GT1—the most prevalent GT treated. A higher prevalence of GT1 is expected since it is the most common GT in the US.6 However, disease progression occurs more rapidly in those with GT3 and is more difficult to treat.22 The overall response rate was lower with this GT (83%) in this report, with only 1 of 3 patients retreated achieving an SVR.

Similar results are documented in retreatment trials.23 In the POLARIS-1 trial, treatment with SOF/VEL/VOX resulted in an overall response rate of 96% but only 91% for patients with GT3, compared with 95 to 100% for GTs 1, 2, or 4.23 In the current report, only 1 patient (GT1) failed retreatment with SOF/VEL/VOX. At this time, there are no clear treatment options for this patient. However, patients who fail GLE/PIB (none so far in the current report) may be able to receive SOF/VEL/VOX.24 In a small study, 29 of 31 patients achieved SVR with SOF/VEL/VOX after GLE/PIB failure (12 of 13 GT1 and 17 of 18 GT3).24

Limitations

This review was an observational, nonrandomized design, and only 1 medical center was involved. These results may not be applicable to other patient populations without a clinic set up with routine follow-ups to encourage adherence and completion of therapy.

Conclusions

Treatment of HCV infection has improved significantly over the past 10 years. Use of DAAs results in SVR for > 90% of patients, especially if the disease had not progressed to cirrhosis. Failure after retreatment for HCV infection was rare as well. Given that cirrhosis seems to increase the chance of treatment failure, it is imperative to identify candidates for treatment before the infection has progressed to cirrhosis. Patients infected with GT3 in particular should be more aggressively identified and treated.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nick P. Becky, PharmD, for his contributions to the identification of patients needing treatment for their HCV infection and review of initial manuscript information.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis: hepatitis C information. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/index.htm. Reviewed April 14, 2020. Accessed June 16, 2020.

2. American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. https://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed June 16, 2020.

3. Lingala S, Ghany MG. Natural history of hepatitis C. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2015;44(4):717-734. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2015.07.003