User login

COVID-19 child case count now over 400,000

according to a new report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

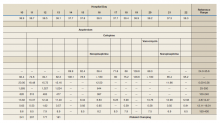

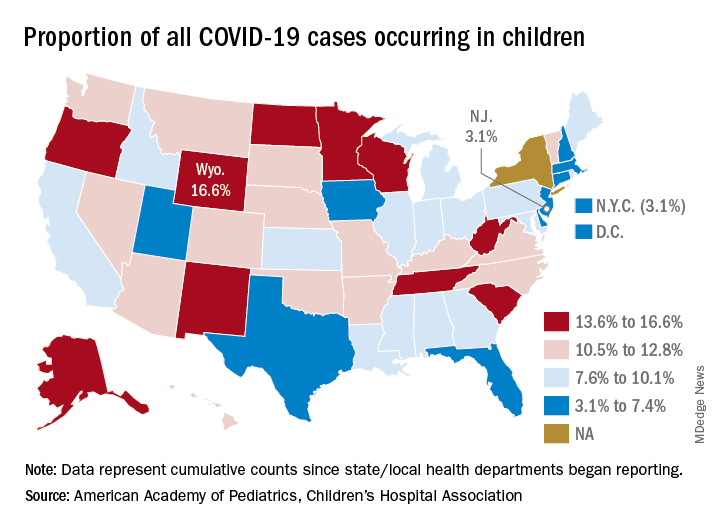

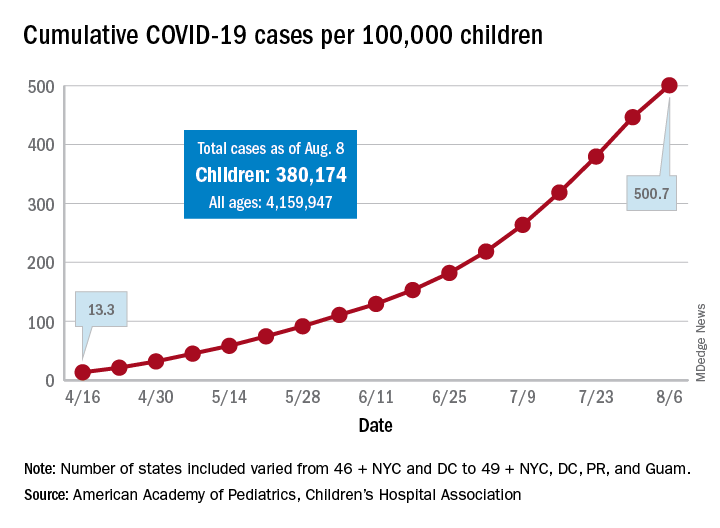

The 406,000 children who have tested positive for COVID-19 represent 9.1% of all cases reported so far by 49 states (New York does not provide age distribution), New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Since the proportion of child cases also was 9.1% on Aug. 6, the most recent week is the first without an increase since tracking began in mid-April, the report shows.

State-level data show that Wyoming has the highest percentage of child cases (16.6%) after Alabama changed its “definition of child case from 0-24 to 0-17 years, resulting in a downward revision of cumulative child cases,” the AAP and the CHA said. Alabama’s proportion of such cases dropped from 22.5% to 9.0%.

New Jersey had the lowest rate (3.1%) again this week, along with New York City, but both were up slightly from the week before, when New Jersey was at 2.9% and N.Y.C. was 3.0%. The only states, other than Alabama, that saw declines over the last week were Arkansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, South Dakota, Texas, and West Virginia. Texas, however, has reported age for only 8% of its confirmed cases, the report noted.

The overall rate of child COVID-19 cases as of Aug. 13 was 538 per 100,000 children, up from 500.7 per 100,000 a week earlier. Arizona was again highest among the states with a rate of 1,254 per 100,000 (up from 1,206) and Vermont was lowest at 121, although Puerto Rico (114) and Guam (88) were lower still, the AAP/CHA data indicate.

For the nine states that report testing information for children, Arizona has the highest positivity rate at 18.3% and West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%. Data on hospitalizations – available from 21 states and N.Y.C. – show that 3,849 children have been admitted, with rates varying from 0.2% of children in Hawaii to 8.8% in the Big Apple, according to the report.

More specific information on child cases, such as symptoms or underlying conditions, is not being provided by states at this time, the AAP and CHA pointed out.

according to a new report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

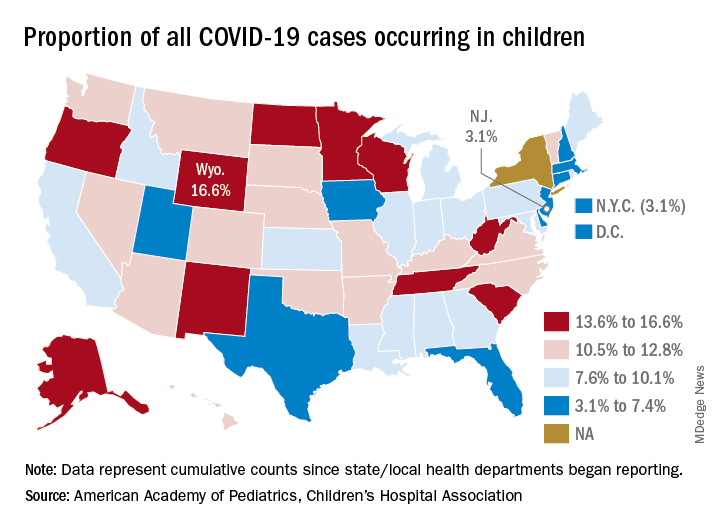

The 406,000 children who have tested positive for COVID-19 represent 9.1% of all cases reported so far by 49 states (New York does not provide age distribution), New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Since the proportion of child cases also was 9.1% on Aug. 6, the most recent week is the first without an increase since tracking began in mid-April, the report shows.

State-level data show that Wyoming has the highest percentage of child cases (16.6%) after Alabama changed its “definition of child case from 0-24 to 0-17 years, resulting in a downward revision of cumulative child cases,” the AAP and the CHA said. Alabama’s proportion of such cases dropped from 22.5% to 9.0%.

New Jersey had the lowest rate (3.1%) again this week, along with New York City, but both were up slightly from the week before, when New Jersey was at 2.9% and N.Y.C. was 3.0%. The only states, other than Alabama, that saw declines over the last week were Arkansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, South Dakota, Texas, and West Virginia. Texas, however, has reported age for only 8% of its confirmed cases, the report noted.

The overall rate of child COVID-19 cases as of Aug. 13 was 538 per 100,000 children, up from 500.7 per 100,000 a week earlier. Arizona was again highest among the states with a rate of 1,254 per 100,000 (up from 1,206) and Vermont was lowest at 121, although Puerto Rico (114) and Guam (88) were lower still, the AAP/CHA data indicate.

For the nine states that report testing information for children, Arizona has the highest positivity rate at 18.3% and West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%. Data on hospitalizations – available from 21 states and N.Y.C. – show that 3,849 children have been admitted, with rates varying from 0.2% of children in Hawaii to 8.8% in the Big Apple, according to the report.

More specific information on child cases, such as symptoms or underlying conditions, is not being provided by states at this time, the AAP and CHA pointed out.

according to a new report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 406,000 children who have tested positive for COVID-19 represent 9.1% of all cases reported so far by 49 states (New York does not provide age distribution), New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Since the proportion of child cases also was 9.1% on Aug. 6, the most recent week is the first without an increase since tracking began in mid-April, the report shows.

State-level data show that Wyoming has the highest percentage of child cases (16.6%) after Alabama changed its “definition of child case from 0-24 to 0-17 years, resulting in a downward revision of cumulative child cases,” the AAP and the CHA said. Alabama’s proportion of such cases dropped from 22.5% to 9.0%.

New Jersey had the lowest rate (3.1%) again this week, along with New York City, but both were up slightly from the week before, when New Jersey was at 2.9% and N.Y.C. was 3.0%. The only states, other than Alabama, that saw declines over the last week were Arkansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, South Dakota, Texas, and West Virginia. Texas, however, has reported age for only 8% of its confirmed cases, the report noted.

The overall rate of child COVID-19 cases as of Aug. 13 was 538 per 100,000 children, up from 500.7 per 100,000 a week earlier. Arizona was again highest among the states with a rate of 1,254 per 100,000 (up from 1,206) and Vermont was lowest at 121, although Puerto Rico (114) and Guam (88) were lower still, the AAP/CHA data indicate.

For the nine states that report testing information for children, Arizona has the highest positivity rate at 18.3% and West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%. Data on hospitalizations – available from 21 states and N.Y.C. – show that 3,849 children have been admitted, with rates varying from 0.2% of children in Hawaii to 8.8% in the Big Apple, according to the report.

More specific information on child cases, such as symptoms or underlying conditions, is not being provided by states at this time, the AAP and CHA pointed out.

COVID-19: A Dermatologist’s Experience From the US Epicenter

The 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic was the most severe pandemic in recent history. Fifty to 100 million individuals died worldwide, with approximately 675,000 deaths in the United States.1-3 The fatality rate was approximately 2% and was highest during the second and third waves of the disease.4 At that time, there were no diagnostic tests for influenza infection, influenza vaccines, antiviral drugs, antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections, or mechanical ventilation. Some cities decided to close schools, limit public gatherings, self-isolate, and issue quarantine orders; the federal government took no central role.

The 1918 influenza pandemic seems far away in history, but my mother often tells me stories about her own grandmother who disliked shaking anyone’s hands and would worry when people coughed or sneezed around her. It sounded like she was overreacting. Now, we can better relate to her concerns. Life has changed dramatically.

In mid-February 2020, news spread that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) had spread from Wuhan, China, to a number of countries in Asia and the Middle East. I was following the news with great sadness for those affected countries, especially for Iran, my country of origin, which had become an epicenter of COVID-19. We were not worried for ourselves in the United States. These infections seemed far away. However, once Italy became the new epicenter of COVID-19 with alarmingly high death rates, I grasped the inevitable reality: The novel coronavirus would not spare the United States and would not spare New York.

Then the virus arrived in New York City. On March 10, 2020, our hospital recommended using teledermatology instead of in-person visits in an attempt to keep patients safe in their own homes. Cases of COVID-19 were escalating, hospitals were filling up, health care workers were falling ill, and there was a shortage of health care staff and personal protective equipment (PPE). Dermatologists at various hospitals were asked to retrain to help care for COVID-19 patients.

On March 13, flights from Europe to the United States were suspended. A statewide stay-at-home order subsequently went into effect on March 22. It felt surreal. From March 23 on, various specialty physicians and nurses in our hospital volunteered to work as frontline staff in the newly prepared annex where patients with possible COVID-19 would arrive. My dermatology co-residents and I started working as frontline physicians. Everything we had heard from the countries affected first had become our reality. Our hospital, part of the largest public health care system in the nation, became a dedicated COVID-19 treatment center.

Large numbers of scared patients with symptoms of COVID-19 flooded the annex. We sent the majority of them home, unable to offer them even a diagnostic test, and advised them to stay isolated. We only had the capacity to test those who required hospital admission.

It broke my heart even more when my colleagues became patients. We often felt helpless, not being able to help every patient and not being able to help our infected colleagues.

Elective surgeries were suspended. Inpatient beds, including specialized intensive care unit beds, rapidly filled up with COVID-19 patients. To help with the surge of patients, our hospital added medical and intensive care unit beds. The hospital became surreal, the corridors eerily empty and silent while every bed was filled, and health care workers were rushing around the inpatient units.

Life quickly became filled with fears—worries about how sick the patients would be, how much we would be able to help them, whether we would have enough PPE, who among our friends or family might be infected next, and whether we might ourselves be next. As PPE became scarce, I desperately searched for some form of protective equipment. I hunted for protective masks, face shields, eye protection, and gowns. We had to reuse disposable N95 masks and face shields multiple times and disinfect them as best we could. Our attendings ordered any protective gear they could find for us. Nearly everything was sold out; the very few items remaining would not for arrive for months. I could have never imagined that I would be afraid of going to work, of not having the appropriate protective gear, and that any day might be my last because of my profession.

New York City had become the epicenter of COVID-19. The city, the country, and the world were in chaos. Hospitals were overflowing, and makeshift morgues were appearing outside of hospitals. Those who could fled the city. Despite warnings from experts, we were not prepared. The number of deaths was climbing rapidly. There was no clarity on who could be tested or how to get it done. It felt like a nightmare.

Social distancing was in place, nonessential businesses were shut down, street vendors disappeared, and people were advised to wear face coverings. People were afraid of each other, afraid of getting too close and catching the virus. New York City—The City That Never Sleeps—went into deep sleep. Every day brought ever greater numbers of infected patients and more deaths.

Every day at 7:00

After around 2 months of lockdown, New York City passed its peak, and the epicenter moved on. The current death toll (ie, confirmed deaths due to COVID-19) in New York stands at 18,836, while the reported death toll in the United States is 143,868, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New York City has started a phased reopening to a new normal. Elective care has resumed, and people are leaving their homes again, eager to bring some sense of normalcy back into their lives.

I fear for those who will contract the virus in the next wave. I wonder what we will have learned.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to thank Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his friendship and invaluable assistance with the conception and editing of this manuscript.

- Taubenberger JK. The origin and virulence of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus. Proc Am Philos Soc. 2006;150:86-112.

- Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. The mother of all pandemics is 100 years old (and going strong)! Am J Public Health. 2018;108:1449-1454.

- Johnson NPAS, Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Bull Hist Med. 2002;76:105-115.

- Morens DM, Fauci AS. The 1918 influenza pandemic: insights for the 21st century. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1018-1028.

The 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic was the most severe pandemic in recent history. Fifty to 100 million individuals died worldwide, with approximately 675,000 deaths in the United States.1-3 The fatality rate was approximately 2% and was highest during the second and third waves of the disease.4 At that time, there were no diagnostic tests for influenza infection, influenza vaccines, antiviral drugs, antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections, or mechanical ventilation. Some cities decided to close schools, limit public gatherings, self-isolate, and issue quarantine orders; the federal government took no central role.

The 1918 influenza pandemic seems far away in history, but my mother often tells me stories about her own grandmother who disliked shaking anyone’s hands and would worry when people coughed or sneezed around her. It sounded like she was overreacting. Now, we can better relate to her concerns. Life has changed dramatically.

In mid-February 2020, news spread that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) had spread from Wuhan, China, to a number of countries in Asia and the Middle East. I was following the news with great sadness for those affected countries, especially for Iran, my country of origin, which had become an epicenter of COVID-19. We were not worried for ourselves in the United States. These infections seemed far away. However, once Italy became the new epicenter of COVID-19 with alarmingly high death rates, I grasped the inevitable reality: The novel coronavirus would not spare the United States and would not spare New York.

Then the virus arrived in New York City. On March 10, 2020, our hospital recommended using teledermatology instead of in-person visits in an attempt to keep patients safe in their own homes. Cases of COVID-19 were escalating, hospitals were filling up, health care workers were falling ill, and there was a shortage of health care staff and personal protective equipment (PPE). Dermatologists at various hospitals were asked to retrain to help care for COVID-19 patients.

On March 13, flights from Europe to the United States were suspended. A statewide stay-at-home order subsequently went into effect on March 22. It felt surreal. From March 23 on, various specialty physicians and nurses in our hospital volunteered to work as frontline staff in the newly prepared annex where patients with possible COVID-19 would arrive. My dermatology co-residents and I started working as frontline physicians. Everything we had heard from the countries affected first had become our reality. Our hospital, part of the largest public health care system in the nation, became a dedicated COVID-19 treatment center.

Large numbers of scared patients with symptoms of COVID-19 flooded the annex. We sent the majority of them home, unable to offer them even a diagnostic test, and advised them to stay isolated. We only had the capacity to test those who required hospital admission.

It broke my heart even more when my colleagues became patients. We often felt helpless, not being able to help every patient and not being able to help our infected colleagues.

Elective surgeries were suspended. Inpatient beds, including specialized intensive care unit beds, rapidly filled up with COVID-19 patients. To help with the surge of patients, our hospital added medical and intensive care unit beds. The hospital became surreal, the corridors eerily empty and silent while every bed was filled, and health care workers were rushing around the inpatient units.

Life quickly became filled with fears—worries about how sick the patients would be, how much we would be able to help them, whether we would have enough PPE, who among our friends or family might be infected next, and whether we might ourselves be next. As PPE became scarce, I desperately searched for some form of protective equipment. I hunted for protective masks, face shields, eye protection, and gowns. We had to reuse disposable N95 masks and face shields multiple times and disinfect them as best we could. Our attendings ordered any protective gear they could find for us. Nearly everything was sold out; the very few items remaining would not for arrive for months. I could have never imagined that I would be afraid of going to work, of not having the appropriate protective gear, and that any day might be my last because of my profession.

New York City had become the epicenter of COVID-19. The city, the country, and the world were in chaos. Hospitals were overflowing, and makeshift morgues were appearing outside of hospitals. Those who could fled the city. Despite warnings from experts, we were not prepared. The number of deaths was climbing rapidly. There was no clarity on who could be tested or how to get it done. It felt like a nightmare.

Social distancing was in place, nonessential businesses were shut down, street vendors disappeared, and people were advised to wear face coverings. People were afraid of each other, afraid of getting too close and catching the virus. New York City—The City That Never Sleeps—went into deep sleep. Every day brought ever greater numbers of infected patients and more deaths.

Every day at 7:00

After around 2 months of lockdown, New York City passed its peak, and the epicenter moved on. The current death toll (ie, confirmed deaths due to COVID-19) in New York stands at 18,836, while the reported death toll in the United States is 143,868, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New York City has started a phased reopening to a new normal. Elective care has resumed, and people are leaving their homes again, eager to bring some sense of normalcy back into their lives.

I fear for those who will contract the virus in the next wave. I wonder what we will have learned.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to thank Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his friendship and invaluable assistance with the conception and editing of this manuscript.

The 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic was the most severe pandemic in recent history. Fifty to 100 million individuals died worldwide, with approximately 675,000 deaths in the United States.1-3 The fatality rate was approximately 2% and was highest during the second and third waves of the disease.4 At that time, there were no diagnostic tests for influenza infection, influenza vaccines, antiviral drugs, antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections, or mechanical ventilation. Some cities decided to close schools, limit public gatherings, self-isolate, and issue quarantine orders; the federal government took no central role.

The 1918 influenza pandemic seems far away in history, but my mother often tells me stories about her own grandmother who disliked shaking anyone’s hands and would worry when people coughed or sneezed around her. It sounded like she was overreacting. Now, we can better relate to her concerns. Life has changed dramatically.

In mid-February 2020, news spread that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) had spread from Wuhan, China, to a number of countries in Asia and the Middle East. I was following the news with great sadness for those affected countries, especially for Iran, my country of origin, which had become an epicenter of COVID-19. We were not worried for ourselves in the United States. These infections seemed far away. However, once Italy became the new epicenter of COVID-19 with alarmingly high death rates, I grasped the inevitable reality: The novel coronavirus would not spare the United States and would not spare New York.

Then the virus arrived in New York City. On March 10, 2020, our hospital recommended using teledermatology instead of in-person visits in an attempt to keep patients safe in their own homes. Cases of COVID-19 were escalating, hospitals were filling up, health care workers were falling ill, and there was a shortage of health care staff and personal protective equipment (PPE). Dermatologists at various hospitals were asked to retrain to help care for COVID-19 patients.

On March 13, flights from Europe to the United States were suspended. A statewide stay-at-home order subsequently went into effect on March 22. It felt surreal. From March 23 on, various specialty physicians and nurses in our hospital volunteered to work as frontline staff in the newly prepared annex where patients with possible COVID-19 would arrive. My dermatology co-residents and I started working as frontline physicians. Everything we had heard from the countries affected first had become our reality. Our hospital, part of the largest public health care system in the nation, became a dedicated COVID-19 treatment center.

Large numbers of scared patients with symptoms of COVID-19 flooded the annex. We sent the majority of them home, unable to offer them even a diagnostic test, and advised them to stay isolated. We only had the capacity to test those who required hospital admission.

It broke my heart even more when my colleagues became patients. We often felt helpless, not being able to help every patient and not being able to help our infected colleagues.

Elective surgeries were suspended. Inpatient beds, including specialized intensive care unit beds, rapidly filled up with COVID-19 patients. To help with the surge of patients, our hospital added medical and intensive care unit beds. The hospital became surreal, the corridors eerily empty and silent while every bed was filled, and health care workers were rushing around the inpatient units.

Life quickly became filled with fears—worries about how sick the patients would be, how much we would be able to help them, whether we would have enough PPE, who among our friends or family might be infected next, and whether we might ourselves be next. As PPE became scarce, I desperately searched for some form of protective equipment. I hunted for protective masks, face shields, eye protection, and gowns. We had to reuse disposable N95 masks and face shields multiple times and disinfect them as best we could. Our attendings ordered any protective gear they could find for us. Nearly everything was sold out; the very few items remaining would not for arrive for months. I could have never imagined that I would be afraid of going to work, of not having the appropriate protective gear, and that any day might be my last because of my profession.

New York City had become the epicenter of COVID-19. The city, the country, and the world were in chaos. Hospitals were overflowing, and makeshift morgues were appearing outside of hospitals. Those who could fled the city. Despite warnings from experts, we were not prepared. The number of deaths was climbing rapidly. There was no clarity on who could be tested or how to get it done. It felt like a nightmare.

Social distancing was in place, nonessential businesses were shut down, street vendors disappeared, and people were advised to wear face coverings. People were afraid of each other, afraid of getting too close and catching the virus. New York City—The City That Never Sleeps—went into deep sleep. Every day brought ever greater numbers of infected patients and more deaths.

Every day at 7:00

After around 2 months of lockdown, New York City passed its peak, and the epicenter moved on. The current death toll (ie, confirmed deaths due to COVID-19) in New York stands at 18,836, while the reported death toll in the United States is 143,868, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New York City has started a phased reopening to a new normal. Elective care has resumed, and people are leaving their homes again, eager to bring some sense of normalcy back into their lives.

I fear for those who will contract the virus in the next wave. I wonder what we will have learned.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to thank Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his friendship and invaluable assistance with the conception and editing of this manuscript.

- Taubenberger JK. The origin and virulence of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus. Proc Am Philos Soc. 2006;150:86-112.

- Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. The mother of all pandemics is 100 years old (and going strong)! Am J Public Health. 2018;108:1449-1454.

- Johnson NPAS, Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Bull Hist Med. 2002;76:105-115.

- Morens DM, Fauci AS. The 1918 influenza pandemic: insights for the 21st century. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1018-1028.

- Taubenberger JK. The origin and virulence of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus. Proc Am Philos Soc. 2006;150:86-112.

- Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. The mother of all pandemics is 100 years old (and going strong)! Am J Public Health. 2018;108:1449-1454.

- Johnson NPAS, Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Bull Hist Med. 2002;76:105-115.

- Morens DM, Fauci AS. The 1918 influenza pandemic: insights for the 21st century. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1018-1028.

Practice Points

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) can spread quickly, creating chaos in the health care system and leading to critical supply shortages within a short amount of time.

- Social distancing, quarantine, and isolation appear to be powerful tools in reducing the spread of COVID-19.

Severe obesity ups risk for death in younger men with COVID-19

In a large California health care plan, among patients with COVID-19, men aged 60 years and younger had a much higher risk of dying within 3 weeks of diagnosis if they had severe obesity as opposed to being of normal weight, independently of other risk factors.

reported Sara Y. Tartof, PhD, MPH, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, Calif., and coauthors.

The data “highlight the leading role of severe obesity over correlated risk factors, providing a target for early intervention,” they concluded in an article published online Aug. 12 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

This work adds to nearly 300 articles that have shown that severe obesity is associated with an increased risk for morbidity and mortality from COVID-19.

In an accompanying editorial, David A. Kass, MD, said: “Consistency of this new study and prior research should put to rest the contention that obesity is common in severe COVID-19 because it is common in the population.”

Rather, these findings show that “obesity is an important independent risk factor for serious COVID-19 disease,” he pointed out.

On the basis of this evidence, “arguably the hardest question to answer is: What is to be done?” wondered Kass, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Although data consistently show that a body mass index >35 kg/m2 is predictive of major health risks, “weight reduction at that level of obesity is difficult and certainly is not achieved rapidly,” Dr. Kass stressed.

“Therefore ... social distancing; altering behaviors to reduce viral exposure and transmission, such as wearing masks; and instituting policies and health care approaches that recognize the potential effects of obesity should be implemented,” he emphasized. “These actions should help and are certainly doable.”

Similarly, Dr. Tartof and colleagues said their “findings also reveal the distressing collision of two pandemics: COVID-19 and obesity.

“As COVID-19 continues to spread unabated, we must focus our immediate efforts on containing the crisis at hand,” they urged.

However, the findings also “underscore the need for future collective efforts to combat the equally devastating, and potentially synergistic, force of the obesity epidemic.”

COVID-19 pandemic collides with obesity epidemic

Previous studies of obesity and COVID-19 were small, did not adjust for multiple confounders, or did not include nonhospitalized patients, Dr. Tartof and coauthors wrote.

Their study included 6,916 members of the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health care plan who were diagnosed with COVID-19 from Feb. 13 to May 2, 2020.

The researchers calculated the risk for death at 21 days after a COVID-19 diagnosis; findings were corrected for age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking, myocardial infarction, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, renal disease, metastatic tumor or malignancy, other immune disease, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, asthma, organ transplant, and diabetes status.

On the basis of BMI, the patients were classified as being underweight, of normal weight, overweight, or as having class 1, 2, or 3 obesity. BMI of 18.5 to 24 kg/m2 is defined as normal weight.

Class 3 obesity, also called severe obesity, included moderately severe obesity (BMI, 40-44 kg/m2) and extremely severe obesity (≥45 kg/m2).

A little more than half of the patients were women (55%), and more than 50% were Hispanic (54%).

A total of 206 patients (3%) died within 21 days of being diagnosed with COVID-19; of these, 67% had been hospitalized, and 43% had been intubated.

Overall, the COVID-19 patients with moderately severe or extremely severe obesity had a 2.7-fold and 4.2-fold increased risk for death, respectively, within 3 weeks compared with patients of normal weight.

Patients in the other BMI categories did not have a significantly higher risk of dying during follow-up.

However, each decade of increasing age after age 40 was associated with a stepwise increased risk for death within 3 weeks of the COVID-19 diagnosis.

Risk stratified by age and sex

Further analysis showed that, “most strikingly,” among patients aged 60 and younger, those with moderately severe obesity and extremely severe obesity had significant 17-fold and 12-fold higher risks of dying during follow-up, respectively, compared with patients of normal weight, the researchers reported.

In patients older than 60, moderately severe obesity did not confer a significant increased risk for imminent death from COVID-19; extremely severe obesity conferred a smaller, threefold increased risk for this.

“Our finding that severe obesity, particularly among younger patients, eclipses the mortality risk posed by other obesity-related conditions, such as history of myocardial infarction (MI), diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia, suggests a significant pathophysiologic link between excess adiposity and severe COVID-19 illness,” the researchers noted.

This independent increased risk for death with severe obesity was seen in men but not in women.

Men with moderately severe and extremely severe obesity had significant 4.8-fold and 10-fold higher risks of dying within 3 weeks, respectively, compared with men of normal weight.

“That the risks are higher in younger patients is probably not because obesity is particularly damaging in this age group; it is more likely that other serious comorbidities that evolve later in life take over as dominant risk factors,” Dr. Kass suggested in his editorial.

“That males are particularly affected may reflect their greater visceral adiposity over females, given that this fat is notably proinflammatory and contributes to metabolic and vascular disease,” he added.

“As a cardiologist who studies heart failure,” Dr. Kass wrote, “I am struck by how many of the mechanisms that are mentioned in reviews of obesity risk and heart disease are also mentioned in reviews of obesity and COVID-19.”

The study was funded by Roche-Genentech. Kass has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures of the authors are listed in the article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large California health care plan, among patients with COVID-19, men aged 60 years and younger had a much higher risk of dying within 3 weeks of diagnosis if they had severe obesity as opposed to being of normal weight, independently of other risk factors.

reported Sara Y. Tartof, PhD, MPH, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, Calif., and coauthors.

The data “highlight the leading role of severe obesity over correlated risk factors, providing a target for early intervention,” they concluded in an article published online Aug. 12 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

This work adds to nearly 300 articles that have shown that severe obesity is associated with an increased risk for morbidity and mortality from COVID-19.

In an accompanying editorial, David A. Kass, MD, said: “Consistency of this new study and prior research should put to rest the contention that obesity is common in severe COVID-19 because it is common in the population.”

Rather, these findings show that “obesity is an important independent risk factor for serious COVID-19 disease,” he pointed out.

On the basis of this evidence, “arguably the hardest question to answer is: What is to be done?” wondered Kass, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Although data consistently show that a body mass index >35 kg/m2 is predictive of major health risks, “weight reduction at that level of obesity is difficult and certainly is not achieved rapidly,” Dr. Kass stressed.

“Therefore ... social distancing; altering behaviors to reduce viral exposure and transmission, such as wearing masks; and instituting policies and health care approaches that recognize the potential effects of obesity should be implemented,” he emphasized. “These actions should help and are certainly doable.”

Similarly, Dr. Tartof and colleagues said their “findings also reveal the distressing collision of two pandemics: COVID-19 and obesity.

“As COVID-19 continues to spread unabated, we must focus our immediate efforts on containing the crisis at hand,” they urged.

However, the findings also “underscore the need for future collective efforts to combat the equally devastating, and potentially synergistic, force of the obesity epidemic.”

COVID-19 pandemic collides with obesity epidemic

Previous studies of obesity and COVID-19 were small, did not adjust for multiple confounders, or did not include nonhospitalized patients, Dr. Tartof and coauthors wrote.

Their study included 6,916 members of the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health care plan who were diagnosed with COVID-19 from Feb. 13 to May 2, 2020.

The researchers calculated the risk for death at 21 days after a COVID-19 diagnosis; findings were corrected for age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking, myocardial infarction, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, renal disease, metastatic tumor or malignancy, other immune disease, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, asthma, organ transplant, and diabetes status.

On the basis of BMI, the patients were classified as being underweight, of normal weight, overweight, or as having class 1, 2, or 3 obesity. BMI of 18.5 to 24 kg/m2 is defined as normal weight.

Class 3 obesity, also called severe obesity, included moderately severe obesity (BMI, 40-44 kg/m2) and extremely severe obesity (≥45 kg/m2).

A little more than half of the patients were women (55%), and more than 50% were Hispanic (54%).

A total of 206 patients (3%) died within 21 days of being diagnosed with COVID-19; of these, 67% had been hospitalized, and 43% had been intubated.

Overall, the COVID-19 patients with moderately severe or extremely severe obesity had a 2.7-fold and 4.2-fold increased risk for death, respectively, within 3 weeks compared with patients of normal weight.

Patients in the other BMI categories did not have a significantly higher risk of dying during follow-up.

However, each decade of increasing age after age 40 was associated with a stepwise increased risk for death within 3 weeks of the COVID-19 diagnosis.

Risk stratified by age and sex

Further analysis showed that, “most strikingly,” among patients aged 60 and younger, those with moderately severe obesity and extremely severe obesity had significant 17-fold and 12-fold higher risks of dying during follow-up, respectively, compared with patients of normal weight, the researchers reported.

In patients older than 60, moderately severe obesity did not confer a significant increased risk for imminent death from COVID-19; extremely severe obesity conferred a smaller, threefold increased risk for this.

“Our finding that severe obesity, particularly among younger patients, eclipses the mortality risk posed by other obesity-related conditions, such as history of myocardial infarction (MI), diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia, suggests a significant pathophysiologic link between excess adiposity and severe COVID-19 illness,” the researchers noted.

This independent increased risk for death with severe obesity was seen in men but not in women.

Men with moderately severe and extremely severe obesity had significant 4.8-fold and 10-fold higher risks of dying within 3 weeks, respectively, compared with men of normal weight.

“That the risks are higher in younger patients is probably not because obesity is particularly damaging in this age group; it is more likely that other serious comorbidities that evolve later in life take over as dominant risk factors,” Dr. Kass suggested in his editorial.

“That males are particularly affected may reflect their greater visceral adiposity over females, given that this fat is notably proinflammatory and contributes to metabolic and vascular disease,” he added.

“As a cardiologist who studies heart failure,” Dr. Kass wrote, “I am struck by how many of the mechanisms that are mentioned in reviews of obesity risk and heart disease are also mentioned in reviews of obesity and COVID-19.”

The study was funded by Roche-Genentech. Kass has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures of the authors are listed in the article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large California health care plan, among patients with COVID-19, men aged 60 years and younger had a much higher risk of dying within 3 weeks of diagnosis if they had severe obesity as opposed to being of normal weight, independently of other risk factors.

reported Sara Y. Tartof, PhD, MPH, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, Calif., and coauthors.

The data “highlight the leading role of severe obesity over correlated risk factors, providing a target for early intervention,” they concluded in an article published online Aug. 12 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

This work adds to nearly 300 articles that have shown that severe obesity is associated with an increased risk for morbidity and mortality from COVID-19.

In an accompanying editorial, David A. Kass, MD, said: “Consistency of this new study and prior research should put to rest the contention that obesity is common in severe COVID-19 because it is common in the population.”

Rather, these findings show that “obesity is an important independent risk factor for serious COVID-19 disease,” he pointed out.

On the basis of this evidence, “arguably the hardest question to answer is: What is to be done?” wondered Kass, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Although data consistently show that a body mass index >35 kg/m2 is predictive of major health risks, “weight reduction at that level of obesity is difficult and certainly is not achieved rapidly,” Dr. Kass stressed.

“Therefore ... social distancing; altering behaviors to reduce viral exposure and transmission, such as wearing masks; and instituting policies and health care approaches that recognize the potential effects of obesity should be implemented,” he emphasized. “These actions should help and are certainly doable.”

Similarly, Dr. Tartof and colleagues said their “findings also reveal the distressing collision of two pandemics: COVID-19 and obesity.

“As COVID-19 continues to spread unabated, we must focus our immediate efforts on containing the crisis at hand,” they urged.

However, the findings also “underscore the need for future collective efforts to combat the equally devastating, and potentially synergistic, force of the obesity epidemic.”

COVID-19 pandemic collides with obesity epidemic

Previous studies of obesity and COVID-19 were small, did not adjust for multiple confounders, or did not include nonhospitalized patients, Dr. Tartof and coauthors wrote.

Their study included 6,916 members of the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health care plan who were diagnosed with COVID-19 from Feb. 13 to May 2, 2020.

The researchers calculated the risk for death at 21 days after a COVID-19 diagnosis; findings were corrected for age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking, myocardial infarction, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, renal disease, metastatic tumor or malignancy, other immune disease, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, asthma, organ transplant, and diabetes status.

On the basis of BMI, the patients were classified as being underweight, of normal weight, overweight, or as having class 1, 2, or 3 obesity. BMI of 18.5 to 24 kg/m2 is defined as normal weight.

Class 3 obesity, also called severe obesity, included moderately severe obesity (BMI, 40-44 kg/m2) and extremely severe obesity (≥45 kg/m2).

A little more than half of the patients were women (55%), and more than 50% were Hispanic (54%).

A total of 206 patients (3%) died within 21 days of being diagnosed with COVID-19; of these, 67% had been hospitalized, and 43% had been intubated.

Overall, the COVID-19 patients with moderately severe or extremely severe obesity had a 2.7-fold and 4.2-fold increased risk for death, respectively, within 3 weeks compared with patients of normal weight.

Patients in the other BMI categories did not have a significantly higher risk of dying during follow-up.

However, each decade of increasing age after age 40 was associated with a stepwise increased risk for death within 3 weeks of the COVID-19 diagnosis.

Risk stratified by age and sex

Further analysis showed that, “most strikingly,” among patients aged 60 and younger, those with moderately severe obesity and extremely severe obesity had significant 17-fold and 12-fold higher risks of dying during follow-up, respectively, compared with patients of normal weight, the researchers reported.

In patients older than 60, moderately severe obesity did not confer a significant increased risk for imminent death from COVID-19; extremely severe obesity conferred a smaller, threefold increased risk for this.

“Our finding that severe obesity, particularly among younger patients, eclipses the mortality risk posed by other obesity-related conditions, such as history of myocardial infarction (MI), diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia, suggests a significant pathophysiologic link between excess adiposity and severe COVID-19 illness,” the researchers noted.

This independent increased risk for death with severe obesity was seen in men but not in women.

Men with moderately severe and extremely severe obesity had significant 4.8-fold and 10-fold higher risks of dying within 3 weeks, respectively, compared with men of normal weight.

“That the risks are higher in younger patients is probably not because obesity is particularly damaging in this age group; it is more likely that other serious comorbidities that evolve later in life take over as dominant risk factors,” Dr. Kass suggested in his editorial.

“That males are particularly affected may reflect their greater visceral adiposity over females, given that this fat is notably proinflammatory and contributes to metabolic and vascular disease,” he added.

“As a cardiologist who studies heart failure,” Dr. Kass wrote, “I am struck by how many of the mechanisms that are mentioned in reviews of obesity risk and heart disease are also mentioned in reviews of obesity and COVID-19.”

The study was funded by Roche-Genentech. Kass has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures of the authors are listed in the article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Pooled COVID-19 testing feasible, greatly reduces supply use

‘Straightforward, cost effective, and efficient’

Combining specimens from several low-risk inpatients in a single test for SARS-CoV-2 infection allowed hospital staff to stretch testing supplies and provide test results quickly for many more patients than they might have otherwise, researchers found.

“We believe this strategy conserved [personal protective equipment (PPE)], led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care,” wrote David Mastrianni, MD, and colleagues from Saratoga Hospital in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. “Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community.”

The researchers published their findings July 20 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“What was really important about this study was they were actually able to implement pooled testing after communication with the [Food and Drug Administration],” Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, SFHM, the journal’s editor-in-chief, said in an interview.

“Pooled testing combines samples from multiple people within a single test. The benefit is, if the test is negative [you know that] everyone whose sample was combined … is negative. So you’ve effectively tested anywhere from three to five people with the resources required for only one test,” Dr. Shah continued.

The challenge is that, if the test is positive, everyone in that testing group must be retested individually because one or more of them has the infection, said Dr. Shah, director of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Mastrianni said early in the pandemic they started getting the “New York surge” at their hospital, located approximately 3 hours from New York City. They wanted to test all of the inpatients at their hospital for COVID-19 and they had a rapid in-house test that worked well, “but we just didn’t have enough cartridges, and we couldn’t get deliveries, and we started pooling.” In fact, they ran out of testing supplies at one point during the study but were able to replenish their supply in about a day, he noted.

For the current study, all patients admitted to the hospital, including those admitted for observation, underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2. Staff in the emergency department designated patients as low risk if they had no symptoms or other clinical evidence of COVID-19; those patients underwent pooled testing.

Patients with clinical evidence of COVID-19, such as respiratory symptoms or laboratory or radiographic findings consistent with infection, were considered high risk and were tested on an individual basis and thus excluded from the current analysis.

The pooled testing strategy required some patients to be held in the emergency department until there were three available for pooled testing. On several occasions when this was not practical, specimens from two patients were pooled.

Between April 17 and May 11, clinicians tested 530 patients via pooled testing using 179 cartridges (172 with swabs from three patients and 7 with swabs from two patients). There were four positive pooled tests, which necessitated the use of an additional 11 cartridges. Overall, the testing used 190 cartridges, which is 340 fewer than would have been used if all patients had been tested individually.

Among the low-risk patients, the positive rate was 0.8% (4/530). No patients from pools that were negative tested positive later during their hospitalization or developed evidence of the infection.

Team effort, flexibility needed

Dr. Mastrianni said he expected their study to find that pooled testing saved testing resources, but he “was surprised by the complexity of the logistics in the hospital, and how it really required getting everybody to work together. …There were a lot of details, and it really took a lot of teamwork.”

The nursing supervisor in the emergency department was in charge of the batch and coordinated with the laboratory, he explained. There were many moving parts to manage, including monitoring how many patients were being admitted, what their conditions were, whether they were high or low risk, and where they would house those patients as the emergency department became increasingly busy. “It’s a lot for them, but they’ve adapted really well,” Dr. Mastrianni said.

Pooling tests seems to work best for three to five patients at a time; larger batches increase the chance of having a positive test, and thus identifying the sick individual(s) becomes more challenging and expensive, Dr. Shah said.

“It’s a fine line between having a pool large enough that you save on testing supplies and testing costs but not having the pool so large that you dramatically increase your likelihood of having a positive test,” Dr. Shah said.

Hospitals will likely need to be flexible and adapt as the local positivity rate changes and supply levels vary, according to the authors.

“Pooled testing is mainly dependent on the COVID-19 positive rate in the population of interest in addition to the sensitivity of the [reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)] method used for COVID-19 testing,” said Baha Abdalhamid, MD, PhD, of the department of pathology and microbiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha.

“Each laboratory and hospital needs to do their own validation testing because it is dependent on the positive rate of COVID-19,” added Dr. Abdalhamid, who was not involved in the current study.

It’s important for clinicians to “do a good history to find who’s high risk and who’s low risk,” Dr. Mastrianni said. Clinicians also need to remember that, although a patient may test negative initially, they may still have COVID-19, he warned. That test reflects a single point in time, and a patient could be infected and not yet be ill, so clinicians need to be alert to a change in the patient’s status.

Best for settings with low-risk individuals

“Pooled COVID-19 testing is a straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient approach,” Dr. Abdalhamid said. He and his colleagues found pooled testing could increase testing capability by 69% or more when the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is 10% or lower.

He said the approach would be helpful in other settings “as long as the positive rate is equal to or less than 10%. Asymptomatic population or surveillance groups such as students, athletes, and military service members are [an] interesting population to test using pooling testing because we expect these populations to have low positive rates, which makes pooled testing ideal.”

Benefit outweighs risk

“There is risk of missing specimens with low concentration of the virus,” Dr. Abdalhamid cautioned. “These specimens might be missed due to the dilution factor of pooling [false-negative specimens]. We did not have a single false-negative specimen in our proof-of-concept study. In addition, there are practical approaches to deal with false-negative pooled specimens.

“The benefit definitely outweighs the risk of false-negative specimens because false-negative results rarely occur, if any. In addition, there is significant saving of time, reagents, and supplies in [a] pooled specimens approach as well as expansion of the test for higher number of patients,” Dr. Abdalhamid continued.

Dr. Mastrianni’s hospital currently has enough testing cartridges, but they are continuing to conduct pooled testing to conserve resources for the benefit of their own hospital and for the nation as a whole, he said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abdalhamid and Dr. Shah have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Straightforward, cost effective, and efficient’

‘Straightforward, cost effective, and efficient’

Combining specimens from several low-risk inpatients in a single test for SARS-CoV-2 infection allowed hospital staff to stretch testing supplies and provide test results quickly for many more patients than they might have otherwise, researchers found.

“We believe this strategy conserved [personal protective equipment (PPE)], led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care,” wrote David Mastrianni, MD, and colleagues from Saratoga Hospital in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. “Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community.”

The researchers published their findings July 20 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“What was really important about this study was they were actually able to implement pooled testing after communication with the [Food and Drug Administration],” Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, SFHM, the journal’s editor-in-chief, said in an interview.

“Pooled testing combines samples from multiple people within a single test. The benefit is, if the test is negative [you know that] everyone whose sample was combined … is negative. So you’ve effectively tested anywhere from three to five people with the resources required for only one test,” Dr. Shah continued.

The challenge is that, if the test is positive, everyone in that testing group must be retested individually because one or more of them has the infection, said Dr. Shah, director of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Mastrianni said early in the pandemic they started getting the “New York surge” at their hospital, located approximately 3 hours from New York City. They wanted to test all of the inpatients at their hospital for COVID-19 and they had a rapid in-house test that worked well, “but we just didn’t have enough cartridges, and we couldn’t get deliveries, and we started pooling.” In fact, they ran out of testing supplies at one point during the study but were able to replenish their supply in about a day, he noted.

For the current study, all patients admitted to the hospital, including those admitted for observation, underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2. Staff in the emergency department designated patients as low risk if they had no symptoms or other clinical evidence of COVID-19; those patients underwent pooled testing.

Patients with clinical evidence of COVID-19, such as respiratory symptoms or laboratory or radiographic findings consistent with infection, were considered high risk and were tested on an individual basis and thus excluded from the current analysis.

The pooled testing strategy required some patients to be held in the emergency department until there were three available for pooled testing. On several occasions when this was not practical, specimens from two patients were pooled.

Between April 17 and May 11, clinicians tested 530 patients via pooled testing using 179 cartridges (172 with swabs from three patients and 7 with swabs from two patients). There were four positive pooled tests, which necessitated the use of an additional 11 cartridges. Overall, the testing used 190 cartridges, which is 340 fewer than would have been used if all patients had been tested individually.

Among the low-risk patients, the positive rate was 0.8% (4/530). No patients from pools that were negative tested positive later during their hospitalization or developed evidence of the infection.

Team effort, flexibility needed

Dr. Mastrianni said he expected their study to find that pooled testing saved testing resources, but he “was surprised by the complexity of the logistics in the hospital, and how it really required getting everybody to work together. …There were a lot of details, and it really took a lot of teamwork.”

The nursing supervisor in the emergency department was in charge of the batch and coordinated with the laboratory, he explained. There were many moving parts to manage, including monitoring how many patients were being admitted, what their conditions were, whether they were high or low risk, and where they would house those patients as the emergency department became increasingly busy. “It’s a lot for them, but they’ve adapted really well,” Dr. Mastrianni said.

Pooling tests seems to work best for three to five patients at a time; larger batches increase the chance of having a positive test, and thus identifying the sick individual(s) becomes more challenging and expensive, Dr. Shah said.

“It’s a fine line between having a pool large enough that you save on testing supplies and testing costs but not having the pool so large that you dramatically increase your likelihood of having a positive test,” Dr. Shah said.

Hospitals will likely need to be flexible and adapt as the local positivity rate changes and supply levels vary, according to the authors.

“Pooled testing is mainly dependent on the COVID-19 positive rate in the population of interest in addition to the sensitivity of the [reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)] method used for COVID-19 testing,” said Baha Abdalhamid, MD, PhD, of the department of pathology and microbiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha.

“Each laboratory and hospital needs to do their own validation testing because it is dependent on the positive rate of COVID-19,” added Dr. Abdalhamid, who was not involved in the current study.

It’s important for clinicians to “do a good history to find who’s high risk and who’s low risk,” Dr. Mastrianni said. Clinicians also need to remember that, although a patient may test negative initially, they may still have COVID-19, he warned. That test reflects a single point in time, and a patient could be infected and not yet be ill, so clinicians need to be alert to a change in the patient’s status.

Best for settings with low-risk individuals

“Pooled COVID-19 testing is a straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient approach,” Dr. Abdalhamid said. He and his colleagues found pooled testing could increase testing capability by 69% or more when the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is 10% or lower.

He said the approach would be helpful in other settings “as long as the positive rate is equal to or less than 10%. Asymptomatic population or surveillance groups such as students, athletes, and military service members are [an] interesting population to test using pooling testing because we expect these populations to have low positive rates, which makes pooled testing ideal.”

Benefit outweighs risk

“There is risk of missing specimens with low concentration of the virus,” Dr. Abdalhamid cautioned. “These specimens might be missed due to the dilution factor of pooling [false-negative specimens]. We did not have a single false-negative specimen in our proof-of-concept study. In addition, there are practical approaches to deal with false-negative pooled specimens.

“The benefit definitely outweighs the risk of false-negative specimens because false-negative results rarely occur, if any. In addition, there is significant saving of time, reagents, and supplies in [a] pooled specimens approach as well as expansion of the test for higher number of patients,” Dr. Abdalhamid continued.

Dr. Mastrianni’s hospital currently has enough testing cartridges, but they are continuing to conduct pooled testing to conserve resources for the benefit of their own hospital and for the nation as a whole, he said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abdalhamid and Dr. Shah have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Combining specimens from several low-risk inpatients in a single test for SARS-CoV-2 infection allowed hospital staff to stretch testing supplies and provide test results quickly for many more patients than they might have otherwise, researchers found.

“We believe this strategy conserved [personal protective equipment (PPE)], led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care,” wrote David Mastrianni, MD, and colleagues from Saratoga Hospital in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. “Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community.”

The researchers published their findings July 20 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“What was really important about this study was they were actually able to implement pooled testing after communication with the [Food and Drug Administration],” Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, SFHM, the journal’s editor-in-chief, said in an interview.

“Pooled testing combines samples from multiple people within a single test. The benefit is, if the test is negative [you know that] everyone whose sample was combined … is negative. So you’ve effectively tested anywhere from three to five people with the resources required for only one test,” Dr. Shah continued.

The challenge is that, if the test is positive, everyone in that testing group must be retested individually because one or more of them has the infection, said Dr. Shah, director of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Mastrianni said early in the pandemic they started getting the “New York surge” at their hospital, located approximately 3 hours from New York City. They wanted to test all of the inpatients at their hospital for COVID-19 and they had a rapid in-house test that worked well, “but we just didn’t have enough cartridges, and we couldn’t get deliveries, and we started pooling.” In fact, they ran out of testing supplies at one point during the study but were able to replenish their supply in about a day, he noted.

For the current study, all patients admitted to the hospital, including those admitted for observation, underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2. Staff in the emergency department designated patients as low risk if they had no symptoms or other clinical evidence of COVID-19; those patients underwent pooled testing.

Patients with clinical evidence of COVID-19, such as respiratory symptoms or laboratory or radiographic findings consistent with infection, were considered high risk and were tested on an individual basis and thus excluded from the current analysis.

The pooled testing strategy required some patients to be held in the emergency department until there were three available for pooled testing. On several occasions when this was not practical, specimens from two patients were pooled.

Between April 17 and May 11, clinicians tested 530 patients via pooled testing using 179 cartridges (172 with swabs from three patients and 7 with swabs from two patients). There were four positive pooled tests, which necessitated the use of an additional 11 cartridges. Overall, the testing used 190 cartridges, which is 340 fewer than would have been used if all patients had been tested individually.

Among the low-risk patients, the positive rate was 0.8% (4/530). No patients from pools that were negative tested positive later during their hospitalization or developed evidence of the infection.

Team effort, flexibility needed

Dr. Mastrianni said he expected their study to find that pooled testing saved testing resources, but he “was surprised by the complexity of the logistics in the hospital, and how it really required getting everybody to work together. …There were a lot of details, and it really took a lot of teamwork.”

The nursing supervisor in the emergency department was in charge of the batch and coordinated with the laboratory, he explained. There were many moving parts to manage, including monitoring how many patients were being admitted, what their conditions were, whether they were high or low risk, and where they would house those patients as the emergency department became increasingly busy. “It’s a lot for them, but they’ve adapted really well,” Dr. Mastrianni said.

Pooling tests seems to work best for three to five patients at a time; larger batches increase the chance of having a positive test, and thus identifying the sick individual(s) becomes more challenging and expensive, Dr. Shah said.

“It’s a fine line between having a pool large enough that you save on testing supplies and testing costs but not having the pool so large that you dramatically increase your likelihood of having a positive test,” Dr. Shah said.

Hospitals will likely need to be flexible and adapt as the local positivity rate changes and supply levels vary, according to the authors.

“Pooled testing is mainly dependent on the COVID-19 positive rate in the population of interest in addition to the sensitivity of the [reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)] method used for COVID-19 testing,” said Baha Abdalhamid, MD, PhD, of the department of pathology and microbiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha.

“Each laboratory and hospital needs to do their own validation testing because it is dependent on the positive rate of COVID-19,” added Dr. Abdalhamid, who was not involved in the current study.

It’s important for clinicians to “do a good history to find who’s high risk and who’s low risk,” Dr. Mastrianni said. Clinicians also need to remember that, although a patient may test negative initially, they may still have COVID-19, he warned. That test reflects a single point in time, and a patient could be infected and not yet be ill, so clinicians need to be alert to a change in the patient’s status.

Best for settings with low-risk individuals

“Pooled COVID-19 testing is a straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient approach,” Dr. Abdalhamid said. He and his colleagues found pooled testing could increase testing capability by 69% or more when the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is 10% or lower.

He said the approach would be helpful in other settings “as long as the positive rate is equal to or less than 10%. Asymptomatic population or surveillance groups such as students, athletes, and military service members are [an] interesting population to test using pooling testing because we expect these populations to have low positive rates, which makes pooled testing ideal.”

Benefit outweighs risk

“There is risk of missing specimens with low concentration of the virus,” Dr. Abdalhamid cautioned. “These specimens might be missed due to the dilution factor of pooling [false-negative specimens]. We did not have a single false-negative specimen in our proof-of-concept study. In addition, there are practical approaches to deal with false-negative pooled specimens.

“The benefit definitely outweighs the risk of false-negative specimens because false-negative results rarely occur, if any. In addition, there is significant saving of time, reagents, and supplies in [a] pooled specimens approach as well as expansion of the test for higher number of patients,” Dr. Abdalhamid continued.

Dr. Mastrianni’s hospital currently has enough testing cartridges, but they are continuing to conduct pooled testing to conserve resources for the benefit of their own hospital and for the nation as a whole, he said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abdalhamid and Dr. Shah have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Pan-Pseudothrombocytopenia in COVID-19: A Harbinger for Lethal Arterial Thrombosis?

In late 2019 a new pandemic started in Wuhan, China, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) due to its similarities with the virus responsible for the SARS outbreak of 2003. The disease manifestations are named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1

Pseudothrombocytopenia, or platelet clumping, visualized on the peripheral blood smear, is a common cause for artificial thrombocytopenia laboratory reporting and is frequently attributed to laboratory artifact. In this case presentation, a critically ill patient with COVID-19 developed pan-pseudothrombocytopenia (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], sodium citrate, and heparin tubes) just prior to his death from a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in the setting of therapeutic anticoagulation during a prolonged hospitalization. This case raises the possibility that pseudothrombocytopenia in the setting of COVID-19 critical illness may represent an ominous feature of COVID-19-associated coagulopathy (CAC). Furthermore, it prompts the question whether pseudothrombocytopenia in this setting is representative of increased platelet aggregation activity in vivo.

Case Presentation

A 50-year-old African American man who was diagnosed with COVID-19 3 days prior to admission presented to the emergency department of the W.G. (Bill) Hefner VA Medical Center in Salisbury, North Carolina, with worsening dyspnea and fever. His primary chronic medical problems included obesity (body mass index, 33), type 2 diabetes mellitus (hemoglobin A1c 2 months prior of 6.6%), migraine headaches, and obstructive sleep apnea. Shortly after presentation, his respiratory status declined, requiring intubation. He was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for further management.

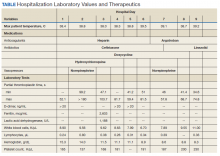

Notable findings at admission included > 20 mcg/mL FEU D-dimer (normal range, 0-0.56 mcg/mL FEU), 20.4 mg/dL C-reactive protein (normal range, < 1 mg/dL), 30 mm/h erythrocyte sedimentation rate (normal range, 0-25 mm/h), and 3.56 ng/mL procalcitonin (normal range, 0.05-1.99 ng/mL). Patient’s hemoglobin and platelet counts were normal. Empiric antimicrobial therapy was initiated with ceftriaxone (2 g IV daily) and doxycycline (100 mg IV twice daily) due to concern of superimposed infection in the setting of an elevated procalcitonin.

A heparin infusion was initiated (5,000 U IV bolus followed by continuous infusion with goal partial thromboplastin time [PTT] of 1.5x the upper limit of normal) on admission to treat CAC. Renal function worsened requiring intermittent renal replacement therapy on day 3. His lactate dehydrogenase was elevated to 1,188 U/L (normal range: 100-240 U/L) and ferritin was elevated to 2,603 ng/mL (normal range: 25-350 ng/mL) (Table). Initial neuromuscular blockade and prone positioning maneuvers were instituted to optimize oxygenation based on the latest literature for respiratory distress in the COVID-19 management.2

Intermittent norepinephrine infusion (5 mcg/min with a 2 mcg/min titration every 5 minutes as needed to maintain mean arterial pressure of > 65 mm Hg) was required for hemodynamic support throughout the patient’s course. Several therapies for COVID-19 were considered and were a reflection of the rapidly evolving literature during the care of patients with this disease. The patient originally received hydroxychloroquine (200 mg by mouth twice daily) in accordance with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) institutional protocol between day 2 and day 4; however, hydroxychloroquine was stopped due to concerns of QTc prolongation. The patient also received 1 unit of convalescent plasma on day 6 after being enrolled in the expanded access program.3 The patient was not a candidate for remdesivir due to his unstable renal function and need for vasopressors. Finally, interleukin-6 inhibitors also were considered; however, the risk of superimposed infection precluded its use.

On day 7 antimicrobial therapy was transitioned to linezolid (600 mg IV twice daily) due to the persistence of fever and a portable chest radiograph revealing diffuse infiltrates throughout the bilateral lungs, worse compared with prior radiograph on day 5, suggesting a worsening of pneumonia. On day 12, the patient was transitioned to cefepime (1 gram IV daily) to broaden antimicrobial coverage and was continued thereafter. Blood cultures were negative throughout his hospitalization.

Given his worsening clinical scenario there was a question about whether or not the patient was still shedding virus for prognostic and therapeutic implications. Therefore, his SARS-CoV-2 test by polymerase chain reaction nasopharyngeal was positive again on day 18. On day 20, the patient developed leukocytosis, his fever persisted, and a portable chest radiograph revealed extensive bilateral pulmonary opacities with focal worsening in left lower base. Due to this constellation of findings, a vancomycin IV (1,500 mg once) was started for empirical treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Sputum samples obtained on day 20 revealed Staphylococcus aureus on subsequent days.

From a hematologic perspective, on day 9 due to challenges to maintain a therapeutic level of anticoagulation with heparin infusion thought to be related to antithrombin deficiency, anticoagulation was changed to argatroban infusion (0.5 mcg/kg/min targeting a PTT of 70-105 seconds) for ongoing management of CAC. Although D-dimer was > 20 mcg/mL FEU on admission and on days 4 and 5, D-dimer trended down to 12.5 mcg/mL FEU on day 16.

Throughout the patient’s hospital stay, no significant bleeding was seen. Hemoglobin was 15.2 g/dL on admission, but anemia developed with a nadir of 6.5 g/dL, warranting transfusion of red blood cells on day 22. Platelet count was 165,000 per microliter on admission and remained within normal limits until platelet clumping was noted on day 15 laboratory collection.

Hematology was consulted on day 20 to obtain an accurate platelet count. A peripheral blood smear from a sodium citrate containing tube was remarkable for prominent platelet clumping, particularly at the periphery of the slide (Figure 1). Platelet clumping was reproduced in samples containing EDTA and heparin. Other features of the peripheral blood smear included the presence of echinocytes with rare schistocytes. To investigate for presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation on day 22, fibrinogen was found to be mildly elevated at 538 mg/dL (normal range: 243-517 mg/dL) and a D-dimer value of 11.96 mcg/mL FEU.

On day 22, the patient’s ventilator requirements escalated to requiring 100% FiO2 and 10 cm H20 of positive end-expiratory pressure with mean arterial pressures in the 50 to 60 mm Hg range. Within 30 minutes an electrocardiogram (EKG) obtained revealed a STEMI (Figure 2). Troponin was measured at 0.65 ng/mL (normal range: 0.02-0.06 ng/mL). Just after an EKG was performed, the patient developed a ventricular fibrillation arrest and was unable to obtain return of spontaneous circulation. The patient was pronounced dead. The family declined an autopsy.

Discussion

Pseudothrombocytopenia, or platelet clumping (agglutination), is estimated to be present in up to 2% of hospitalized patients.4 Pseudothrombocytopenia was found to be the root cause of thrombocytopenia hematology consultations in up to 4% of hospitalized patients.5 The etiology is commonly ascribed to EDTA inducing a conformational change in the GpIIb-IIIa platelet complex, rendering it susceptible to binding of autoantibodies, which cause subsequent platelet agglutination.6 In most cases (83%), the use of a non-EDTA anticoagulant, such as sodium citrate, resolves the platelet agglutination and allows for accurate platelet count reporting.4 Pseudothrombocytopenia in most cases is considered an in vitro finding without clinical relevance.7 However, in this patient’s case, his pan-pseudothrombocytopenia was temporally associated with an arterial occlusive event (STEMI) leading to his demise despite therapeutic anticoagulation in the setting of CAC. This temporal association raises the possibility that pseudothrombocytopenia seen on the peripheral blood smear is an accurate representation of in vivo activity.

Pseudothrombocytopenia has been associated with sepsis from bacterial and viral causes as well as autoimmune and medication effect.4,8-10 Li and colleagues reported transient EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient with COVID-19 infection; however, platelet clumping resolved with use of a citrate tube, and the EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia phenomenon resolved with patient recovery.11 The frequency of COVID-19-related pseudothrombocytopenia is currently unknown.

Although the understanding of COVID-19-associated CAC continues to evolve, it seems that initial reports support the idea that hemostatic dysfunction tends to more thrombosis than to bleeding.12 Rather than overt disseminated intravascular coagulation with reduced fibrinogen and bleeding, CAC is more closely associated with blood clotting, as demonstrated by autopsy studies revealing microvascular thrombosis in the lungs.13 The D-dimer test has been identified as the most useful biomarker by the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis to screen for CAC and stratify patients who warrant admission or closer monitoring.12 Other identified features of CAC include prolonged prothrombin time and thrombocytopenia.12

There have been varying clinical approaches to CAC management. A retrospective review found that prophylactic heparin doses were associated with improved mortality in those with elevated D-dimer > 3.0 mg/L.14 There continues to be a diversity of varying clinical approaches with many medical centers advocating for an intensified prophylactic twice daily low molecular-weight heparin compared with others advocating for full therapeutic dose anticoagulation for patients with elevated D-dimer.15 This patient was treated aggressively with full-dose anticoagulation, and despite his having a down-trend in D-dimer, he suffered a lethal arterial thrombosis in the form of a STEMI.

Varatharajah and Rajah

Conclusions