User login

ACIP releases new dengue vaccine recommendations

The vaccine is only to be used for children aged 9-16 who live in endemic areas and who have evidence with a specific diagnostic test of prior dengue infection.

Dengue is a mosquito-borne virus found throughout the world, primarily in tropical or subtropical climates. Cases had steadily been increasing to 5.2 million in 2019, and the geographic distribution of cases is broadening with climate change and urbanization. About half of the world’s population is now at risk.

The dengue virus has four serotypes. The first infection may be mild or asymptomatic, but the second one can be life-threatening because of a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement.

The lead author of the new recommendations is Gabriela Paz-Bailey, MD, PhD, division of vector-borne diseases, dengue branch, CDC. She told this news organization that, during the second infection, when there are “low levels of antibodies from that first infection, the antibodies help the virus get inside the cells. There the virus is not killed, and that results in increased viral load, and then that can result in more severe disease and the plasma leakage” syndrome, which can lead to shock, severe bleeding, and organ failure. The death rate for severe dengue is up to 13%.

Previous infection with Zika virus, common in the same areas where dengue is endemic, can also increase the risk for symptomatic and severe dengue for subsequent infections.

In the United States, Puerto Rico is the main focus of control efforts because 95% of domestic dengue cases originate there – almost 30,000 cases between 2010 and 2020, with 11,000 cases and 4,000 hospitalizations occurring in children between the ages of 10 and 19.

Because Aedes aegypti, the primary mosquito vector transmitting dengue, is resistant to all commonly used insecticides in Puerto Rico, preventive efforts have shifted from insecticides to vaccination.

Antibody tests prevaccination

The main concern with the Sanofi’s dengue vaccine is that it could act as an asymptomatic primary dengue infection, in effect priming the body for a severe reaction from antibody-dependent enhancement with a subsequent infection. That is why it’s critical that the vaccine only be given to children with evidence of prior disease.

Dr. Paz-Bailey said: “The CDC came up with recommendations of what the performance of the test used for prevaccination screening should be. And it was 98% specificity and 75% sensitivity. ... But no test by itself was found to have a specificity of 98%, and this is why we’re recommending the two-test algorithm,” in which two different assays are run off the same blood sample, drawn at a prevaccination visit.

If the child has evidence of prior dengue, they can proceed with vaccination to protect against recurrent infection. Dengvaxia is given as a series of three shots over 6 months. Vaccine efficacy is 82% – so not everyone is protected, and additionally, that protection declines over time.

There is concern that it will be difficult to achieve compliance with such a complex regimen. Dr. Paz-Bailey said, “But I think that the trust in vaccines that is highly prevalent for [Puerto] Rico and trusting the health care system, and sort of the importance that is assigned to dengue by providers and by parents because of previous outbreaks and previous experiences is going to help us.” She added, “I think that the COVID experience has been very revealing. And what we have learned is that Puerto Rico has a very strong health care system, a very strong network of vaccine providers. ... Coverage for COVID vaccine is higher than in other parts of the U.S.”

One of the interesting things about dengue is that the first infection can range from asymptomatic to life-threatening. The second infection is generally worse because of this antibody-dependent enhancement phenomenon. Eng Eong Ooi, MD, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology, National University of Singapore, told this news organization, “After you have two infections, you seem to be protected quite well against the remaining two [serotypes]. The vaccine serves as another episode of infection in those who had prior dengue, so then any natural infections after the vaccination in the seropositive become like the outcome of a third or fourth infection.”

Vaccination alone will not solve dengue. Dr. Ooi said, “There’s not one method that would fully control dengue. You need both vaccines as well as control measures, whether it’s Wolbachia or something else. At the same time, I think we need antiviral drugs, because hitting this virus in just one part of its life cycle wouldn’t make a huge, lasting impact.” Dr. Ooi added that as “the spread of the virus and the population immunity drops, you’re actually now more vulnerable to dengue outbreaks when they do get introduced. So, suppressing transmission alone isn’t the answer. You also have to keep herd immunity levels high. So if we can reduce the virus transmission by controlling either mosquito population or transmission and at the same time vaccinate to keep the immunity levels high, then I think we have a chance of controlling dengue.”

Dr. Paz-Bailey concluded: “I do want to emphasize that we are excited about having these tools, because for years and years, we have had really limited options to prevent and control dengue. It’s an important addition to have the vaccine be approved to be used within the U.S., and it’s going to pave the road for future vaccines.”

Dr. Paz-Bailey and Dr. Ooi reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vaccine is only to be used for children aged 9-16 who live in endemic areas and who have evidence with a specific diagnostic test of prior dengue infection.

Dengue is a mosquito-borne virus found throughout the world, primarily in tropical or subtropical climates. Cases had steadily been increasing to 5.2 million in 2019, and the geographic distribution of cases is broadening with climate change and urbanization. About half of the world’s population is now at risk.

The dengue virus has four serotypes. The first infection may be mild or asymptomatic, but the second one can be life-threatening because of a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement.

The lead author of the new recommendations is Gabriela Paz-Bailey, MD, PhD, division of vector-borne diseases, dengue branch, CDC. She told this news organization that, during the second infection, when there are “low levels of antibodies from that first infection, the antibodies help the virus get inside the cells. There the virus is not killed, and that results in increased viral load, and then that can result in more severe disease and the plasma leakage” syndrome, which can lead to shock, severe bleeding, and organ failure. The death rate for severe dengue is up to 13%.

Previous infection with Zika virus, common in the same areas where dengue is endemic, can also increase the risk for symptomatic and severe dengue for subsequent infections.

In the United States, Puerto Rico is the main focus of control efforts because 95% of domestic dengue cases originate there – almost 30,000 cases between 2010 and 2020, with 11,000 cases and 4,000 hospitalizations occurring in children between the ages of 10 and 19.

Because Aedes aegypti, the primary mosquito vector transmitting dengue, is resistant to all commonly used insecticides in Puerto Rico, preventive efforts have shifted from insecticides to vaccination.

Antibody tests prevaccination

The main concern with the Sanofi’s dengue vaccine is that it could act as an asymptomatic primary dengue infection, in effect priming the body for a severe reaction from antibody-dependent enhancement with a subsequent infection. That is why it’s critical that the vaccine only be given to children with evidence of prior disease.

Dr. Paz-Bailey said: “The CDC came up with recommendations of what the performance of the test used for prevaccination screening should be. And it was 98% specificity and 75% sensitivity. ... But no test by itself was found to have a specificity of 98%, and this is why we’re recommending the two-test algorithm,” in which two different assays are run off the same blood sample, drawn at a prevaccination visit.

If the child has evidence of prior dengue, they can proceed with vaccination to protect against recurrent infection. Dengvaxia is given as a series of three shots over 6 months. Vaccine efficacy is 82% – so not everyone is protected, and additionally, that protection declines over time.

There is concern that it will be difficult to achieve compliance with such a complex regimen. Dr. Paz-Bailey said, “But I think that the trust in vaccines that is highly prevalent for [Puerto] Rico and trusting the health care system, and sort of the importance that is assigned to dengue by providers and by parents because of previous outbreaks and previous experiences is going to help us.” She added, “I think that the COVID experience has been very revealing. And what we have learned is that Puerto Rico has a very strong health care system, a very strong network of vaccine providers. ... Coverage for COVID vaccine is higher than in other parts of the U.S.”

One of the interesting things about dengue is that the first infection can range from asymptomatic to life-threatening. The second infection is generally worse because of this antibody-dependent enhancement phenomenon. Eng Eong Ooi, MD, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology, National University of Singapore, told this news organization, “After you have two infections, you seem to be protected quite well against the remaining two [serotypes]. The vaccine serves as another episode of infection in those who had prior dengue, so then any natural infections after the vaccination in the seropositive become like the outcome of a third or fourth infection.”

Vaccination alone will not solve dengue. Dr. Ooi said, “There’s not one method that would fully control dengue. You need both vaccines as well as control measures, whether it’s Wolbachia or something else. At the same time, I think we need antiviral drugs, because hitting this virus in just one part of its life cycle wouldn’t make a huge, lasting impact.” Dr. Ooi added that as “the spread of the virus and the population immunity drops, you’re actually now more vulnerable to dengue outbreaks when they do get introduced. So, suppressing transmission alone isn’t the answer. You also have to keep herd immunity levels high. So if we can reduce the virus transmission by controlling either mosquito population or transmission and at the same time vaccinate to keep the immunity levels high, then I think we have a chance of controlling dengue.”

Dr. Paz-Bailey concluded: “I do want to emphasize that we are excited about having these tools, because for years and years, we have had really limited options to prevent and control dengue. It’s an important addition to have the vaccine be approved to be used within the U.S., and it’s going to pave the road for future vaccines.”

Dr. Paz-Bailey and Dr. Ooi reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vaccine is only to be used for children aged 9-16 who live in endemic areas and who have evidence with a specific diagnostic test of prior dengue infection.

Dengue is a mosquito-borne virus found throughout the world, primarily in tropical or subtropical climates. Cases had steadily been increasing to 5.2 million in 2019, and the geographic distribution of cases is broadening with climate change and urbanization. About half of the world’s population is now at risk.

The dengue virus has four serotypes. The first infection may be mild or asymptomatic, but the second one can be life-threatening because of a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement.

The lead author of the new recommendations is Gabriela Paz-Bailey, MD, PhD, division of vector-borne diseases, dengue branch, CDC. She told this news organization that, during the second infection, when there are “low levels of antibodies from that first infection, the antibodies help the virus get inside the cells. There the virus is not killed, and that results in increased viral load, and then that can result in more severe disease and the plasma leakage” syndrome, which can lead to shock, severe bleeding, and organ failure. The death rate for severe dengue is up to 13%.

Previous infection with Zika virus, common in the same areas where dengue is endemic, can also increase the risk for symptomatic and severe dengue for subsequent infections.

In the United States, Puerto Rico is the main focus of control efforts because 95% of domestic dengue cases originate there – almost 30,000 cases between 2010 and 2020, with 11,000 cases and 4,000 hospitalizations occurring in children between the ages of 10 and 19.

Because Aedes aegypti, the primary mosquito vector transmitting dengue, is resistant to all commonly used insecticides in Puerto Rico, preventive efforts have shifted from insecticides to vaccination.

Antibody tests prevaccination

The main concern with the Sanofi’s dengue vaccine is that it could act as an asymptomatic primary dengue infection, in effect priming the body for a severe reaction from antibody-dependent enhancement with a subsequent infection. That is why it’s critical that the vaccine only be given to children with evidence of prior disease.

Dr. Paz-Bailey said: “The CDC came up with recommendations of what the performance of the test used for prevaccination screening should be. And it was 98% specificity and 75% sensitivity. ... But no test by itself was found to have a specificity of 98%, and this is why we’re recommending the two-test algorithm,” in which two different assays are run off the same blood sample, drawn at a prevaccination visit.

If the child has evidence of prior dengue, they can proceed with vaccination to protect against recurrent infection. Dengvaxia is given as a series of three shots over 6 months. Vaccine efficacy is 82% – so not everyone is protected, and additionally, that protection declines over time.

There is concern that it will be difficult to achieve compliance with such a complex regimen. Dr. Paz-Bailey said, “But I think that the trust in vaccines that is highly prevalent for [Puerto] Rico and trusting the health care system, and sort of the importance that is assigned to dengue by providers and by parents because of previous outbreaks and previous experiences is going to help us.” She added, “I think that the COVID experience has been very revealing. And what we have learned is that Puerto Rico has a very strong health care system, a very strong network of vaccine providers. ... Coverage for COVID vaccine is higher than in other parts of the U.S.”

One of the interesting things about dengue is that the first infection can range from asymptomatic to life-threatening. The second infection is generally worse because of this antibody-dependent enhancement phenomenon. Eng Eong Ooi, MD, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology, National University of Singapore, told this news organization, “After you have two infections, you seem to be protected quite well against the remaining two [serotypes]. The vaccine serves as another episode of infection in those who had prior dengue, so then any natural infections after the vaccination in the seropositive become like the outcome of a third or fourth infection.”

Vaccination alone will not solve dengue. Dr. Ooi said, “There’s not one method that would fully control dengue. You need both vaccines as well as control measures, whether it’s Wolbachia or something else. At the same time, I think we need antiviral drugs, because hitting this virus in just one part of its life cycle wouldn’t make a huge, lasting impact.” Dr. Ooi added that as “the spread of the virus and the population immunity drops, you’re actually now more vulnerable to dengue outbreaks when they do get introduced. So, suppressing transmission alone isn’t the answer. You also have to keep herd immunity levels high. So if we can reduce the virus transmission by controlling either mosquito population or transmission and at the same time vaccinate to keep the immunity levels high, then I think we have a chance of controlling dengue.”

Dr. Paz-Bailey concluded: “I do want to emphasize that we are excited about having these tools, because for years and years, we have had really limited options to prevent and control dengue. It’s an important addition to have the vaccine be approved to be used within the U.S., and it’s going to pave the road for future vaccines.”

Dr. Paz-Bailey and Dr. Ooi reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MMWR RECOMMENDATIONS AND REPORTS

Clinician experience, life stressors drive HIV adherence, retention in new patients

A novel twist on the concept of “meeting people where they are” may hold the key to retaining new HIV patients, and even bringing the elusive goal of ending the AIDS epidemic a bit closer. While the concept commonly refers to community outreach and engagement, understanding patient experiences and expectations and personal life stressors in the actual clinic setting may improve overall outcomes, according to new research.

In fact,

“Medical science is not necessarily [at the forefront] of where we want to focus our efforts right now,” Emmanuel Guajardo, MD, lead study author and instructor of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, told this news organization.

Rather, “we need to focus on retention in care and adherence to medications. Doubling down on these efforts could really go a long way toward ending the HIV epidemic,” he said.

Study findings were published online Jan. 5, 2022, in AIDS and Behavior.

First time’s a charm

A total of 450 patients attending an HIV clinic in Houston were asked to complete a postvisit survey detailing their experience with the HIV clinician, as well as personal life stressors in the preceding 6 months. Study participants were predominantly non-Hispanic Black (54.2%) or Hispanic (30.7%) and mostly men who have sex with men (MSM), populations that mimic the patients seen at Dr. Guajardo’s clinic. Patients were given the option of survey completion while awaiting discharge, within 2 weeks at the clinic, or (as a last resort) by phone.

Overall scores were based on a composite of validated scales: patient experience scores were defined dichotomously (best experience, most positive experience vs. not the best experience), and life stressor events (death, relationship, economic) were assigned weighted scores based on life change impact (for example, death of a spouse received a score of 100 while moved/changed living location was assigned a score of 25).

“We found that patients who reported better initial experiences with their provider at the first visit were less likely to be lost to follow-up at 6 and 12 months,” explained Dr. Guajardo. “Having fewer life stressors at the first visit [was] also [protective].”

At 6 months, mean overall patient experience scores were 8.60 for those LTFU versus and 8.98 for those not LTFU (P = .011); corresponding mean scores at 12 months were 8.43 and 8.98 respectively (P = .001).

For the dichotomized scoring, patients reporting the best experience with the health care professional were significantly less likely to be LTFU at 6 months (adjusted odd ratio, 0.866; P = .038) and 12 months (aOR, 1.263; P = .029) versus those not reporting the best experience.

Mean life change scores appeared to portend patient drop-off; patients reporting more stressful life events were likelier to be LTFU at 6 months (mean life change score, 129 vs. 100 for those retained in care) and at 12 months (126 vs. 101).

Corresponding multivariate logistic regression models controlling for age, baseline CD4 cell count less than 200, and diagnosis of at least 3 months showed that patients with higher life stressor burdens were significantly more likely to be LTFU at both 6 months (aOR, 1.232, P = .037) and 12 months (aOR, 1.263, P = .029).

Approach matters

“The [study] really hits the nail on the head in terms of identifying a couple of these very salient issues that affect people’s care, especially concerning HIV,” Philip A. Chan, MD, infectious disease specialist and associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I, told this news organization.

“It highlights things that we see on the ground that can interfere with HIV care or [pre-exposure prophylaxis] care, just health care in general, certainly one’s relationship with the physician or provider, and also, you know, real-life stressors,” said Dr. Chan, who was not involved with the study.

Relationship building is especially important for historically underserved populations, a point that’s hardly lost on either Dr. Chan or Dr. Guajardo, who both pointed to higher levels of mistrust among certain patient populations because of their mistreatment by the health care system. The answer? Let the patient lead the initial discussion, allow them to feel comfortable and participate in their care in ways that are most beneficial to them.

“There’s so much miscommunication, misunderstanding, and stigma related to HIV out in the community. So, it’s important to really open the floor for whatever they want to talk about first, before I push any agenda on a new patient.” Dr. Guajardo said. Thereafter, he relies on open-ended questions such as ‘tell me about your sexual partners?’ or ‘what sort of sexual practices do you engage in?’

“At the end of the day, you just need someone dedicated, who can be respectful and listening and caring, and dedicate time to patients to help keep them in care, to listen, and to navigate our incredibly, incredibly complex health care system,” Dr. Chan added.

This study was partly supported by use of the facilities and resources of the Houston Veterans Affairs Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety and Harris Health System. Support for the study was also provided by the National Institute of Mental Health and the University of Texas MD Anderson Foundation Chair at Baylor College of Medicine. Dr. Guajardo and Dr. Chan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel twist on the concept of “meeting people where they are” may hold the key to retaining new HIV patients, and even bringing the elusive goal of ending the AIDS epidemic a bit closer. While the concept commonly refers to community outreach and engagement, understanding patient experiences and expectations and personal life stressors in the actual clinic setting may improve overall outcomes, according to new research.

In fact,

“Medical science is not necessarily [at the forefront] of where we want to focus our efforts right now,” Emmanuel Guajardo, MD, lead study author and instructor of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, told this news organization.

Rather, “we need to focus on retention in care and adherence to medications. Doubling down on these efforts could really go a long way toward ending the HIV epidemic,” he said.

Study findings were published online Jan. 5, 2022, in AIDS and Behavior.

First time’s a charm

A total of 450 patients attending an HIV clinic in Houston were asked to complete a postvisit survey detailing their experience with the HIV clinician, as well as personal life stressors in the preceding 6 months. Study participants were predominantly non-Hispanic Black (54.2%) or Hispanic (30.7%) and mostly men who have sex with men (MSM), populations that mimic the patients seen at Dr. Guajardo’s clinic. Patients were given the option of survey completion while awaiting discharge, within 2 weeks at the clinic, or (as a last resort) by phone.

Overall scores were based on a composite of validated scales: patient experience scores were defined dichotomously (best experience, most positive experience vs. not the best experience), and life stressor events (death, relationship, economic) were assigned weighted scores based on life change impact (for example, death of a spouse received a score of 100 while moved/changed living location was assigned a score of 25).

“We found that patients who reported better initial experiences with their provider at the first visit were less likely to be lost to follow-up at 6 and 12 months,” explained Dr. Guajardo. “Having fewer life stressors at the first visit [was] also [protective].”

At 6 months, mean overall patient experience scores were 8.60 for those LTFU versus and 8.98 for those not LTFU (P = .011); corresponding mean scores at 12 months were 8.43 and 8.98 respectively (P = .001).

For the dichotomized scoring, patients reporting the best experience with the health care professional were significantly less likely to be LTFU at 6 months (adjusted odd ratio, 0.866; P = .038) and 12 months (aOR, 1.263; P = .029) versus those not reporting the best experience.

Mean life change scores appeared to portend patient drop-off; patients reporting more stressful life events were likelier to be LTFU at 6 months (mean life change score, 129 vs. 100 for those retained in care) and at 12 months (126 vs. 101).

Corresponding multivariate logistic regression models controlling for age, baseline CD4 cell count less than 200, and diagnosis of at least 3 months showed that patients with higher life stressor burdens were significantly more likely to be LTFU at both 6 months (aOR, 1.232, P = .037) and 12 months (aOR, 1.263, P = .029).

Approach matters

“The [study] really hits the nail on the head in terms of identifying a couple of these very salient issues that affect people’s care, especially concerning HIV,” Philip A. Chan, MD, infectious disease specialist and associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I, told this news organization.

“It highlights things that we see on the ground that can interfere with HIV care or [pre-exposure prophylaxis] care, just health care in general, certainly one’s relationship with the physician or provider, and also, you know, real-life stressors,” said Dr. Chan, who was not involved with the study.

Relationship building is especially important for historically underserved populations, a point that’s hardly lost on either Dr. Chan or Dr. Guajardo, who both pointed to higher levels of mistrust among certain patient populations because of their mistreatment by the health care system. The answer? Let the patient lead the initial discussion, allow them to feel comfortable and participate in their care in ways that are most beneficial to them.

“There’s so much miscommunication, misunderstanding, and stigma related to HIV out in the community. So, it’s important to really open the floor for whatever they want to talk about first, before I push any agenda on a new patient.” Dr. Guajardo said. Thereafter, he relies on open-ended questions such as ‘tell me about your sexual partners?’ or ‘what sort of sexual practices do you engage in?’

“At the end of the day, you just need someone dedicated, who can be respectful and listening and caring, and dedicate time to patients to help keep them in care, to listen, and to navigate our incredibly, incredibly complex health care system,” Dr. Chan added.

This study was partly supported by use of the facilities and resources of the Houston Veterans Affairs Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety and Harris Health System. Support for the study was also provided by the National Institute of Mental Health and the University of Texas MD Anderson Foundation Chair at Baylor College of Medicine. Dr. Guajardo and Dr. Chan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel twist on the concept of “meeting people where they are” may hold the key to retaining new HIV patients, and even bringing the elusive goal of ending the AIDS epidemic a bit closer. While the concept commonly refers to community outreach and engagement, understanding patient experiences and expectations and personal life stressors in the actual clinic setting may improve overall outcomes, according to new research.

In fact,

“Medical science is not necessarily [at the forefront] of where we want to focus our efforts right now,” Emmanuel Guajardo, MD, lead study author and instructor of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, told this news organization.

Rather, “we need to focus on retention in care and adherence to medications. Doubling down on these efforts could really go a long way toward ending the HIV epidemic,” he said.

Study findings were published online Jan. 5, 2022, in AIDS and Behavior.

First time’s a charm

A total of 450 patients attending an HIV clinic in Houston were asked to complete a postvisit survey detailing their experience with the HIV clinician, as well as personal life stressors in the preceding 6 months. Study participants were predominantly non-Hispanic Black (54.2%) or Hispanic (30.7%) and mostly men who have sex with men (MSM), populations that mimic the patients seen at Dr. Guajardo’s clinic. Patients were given the option of survey completion while awaiting discharge, within 2 weeks at the clinic, or (as a last resort) by phone.

Overall scores were based on a composite of validated scales: patient experience scores were defined dichotomously (best experience, most positive experience vs. not the best experience), and life stressor events (death, relationship, economic) were assigned weighted scores based on life change impact (for example, death of a spouse received a score of 100 while moved/changed living location was assigned a score of 25).

“We found that patients who reported better initial experiences with their provider at the first visit were less likely to be lost to follow-up at 6 and 12 months,” explained Dr. Guajardo. “Having fewer life stressors at the first visit [was] also [protective].”

At 6 months, mean overall patient experience scores were 8.60 for those LTFU versus and 8.98 for those not LTFU (P = .011); corresponding mean scores at 12 months were 8.43 and 8.98 respectively (P = .001).

For the dichotomized scoring, patients reporting the best experience with the health care professional were significantly less likely to be LTFU at 6 months (adjusted odd ratio, 0.866; P = .038) and 12 months (aOR, 1.263; P = .029) versus those not reporting the best experience.

Mean life change scores appeared to portend patient drop-off; patients reporting more stressful life events were likelier to be LTFU at 6 months (mean life change score, 129 vs. 100 for those retained in care) and at 12 months (126 vs. 101).

Corresponding multivariate logistic regression models controlling for age, baseline CD4 cell count less than 200, and diagnosis of at least 3 months showed that patients with higher life stressor burdens were significantly more likely to be LTFU at both 6 months (aOR, 1.232, P = .037) and 12 months (aOR, 1.263, P = .029).

Approach matters

“The [study] really hits the nail on the head in terms of identifying a couple of these very salient issues that affect people’s care, especially concerning HIV,” Philip A. Chan, MD, infectious disease specialist and associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I, told this news organization.

“It highlights things that we see on the ground that can interfere with HIV care or [pre-exposure prophylaxis] care, just health care in general, certainly one’s relationship with the physician or provider, and also, you know, real-life stressors,” said Dr. Chan, who was not involved with the study.

Relationship building is especially important for historically underserved populations, a point that’s hardly lost on either Dr. Chan or Dr. Guajardo, who both pointed to higher levels of mistrust among certain patient populations because of their mistreatment by the health care system. The answer? Let the patient lead the initial discussion, allow them to feel comfortable and participate in their care in ways that are most beneficial to them.

“There’s so much miscommunication, misunderstanding, and stigma related to HIV out in the community. So, it’s important to really open the floor for whatever they want to talk about first, before I push any agenda on a new patient.” Dr. Guajardo said. Thereafter, he relies on open-ended questions such as ‘tell me about your sexual partners?’ or ‘what sort of sexual practices do you engage in?’

“At the end of the day, you just need someone dedicated, who can be respectful and listening and caring, and dedicate time to patients to help keep them in care, to listen, and to navigate our incredibly, incredibly complex health care system,” Dr. Chan added.

This study was partly supported by use of the facilities and resources of the Houston Veterans Affairs Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety and Harris Health System. Support for the study was also provided by the National Institute of Mental Health and the University of Texas MD Anderson Foundation Chair at Baylor College of Medicine. Dr. Guajardo and Dr. Chan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AIDS AND BEHAVIOR

Common cold could protect against COVID-19, study says

, according to a small study published Jan. 10 in Nature Communications.

Previous studies have shown that T cells created from other coronaviruses can recognize SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In the new study, researchers at Imperial College London found that the presence of these T cells at the time of COVID-19 exposure could reduce the chance of getting infected.

The findings could provide a blueprint for a second-generation, universal vaccine to prevent infection from COVID-19 variants, including Omicron and ones that crop up later.

“Being exposed to SARS-CoV-2 virus doesn’t always result in infection, and we’ve been keen to understand why,” Rhia Kundu, PhD, the lead study author from Imperial’s National Heart and Lung Institute, said in a statement.

People with higher levels of T cells from the common cold were less likely to become infected with COVID-19, the researchers found.

“While this is an important discovery, it is only one form of protection, and I would stress that no one should rely on this alone,” Dr. Kundu said. “Instead, the best way to protect yourself against COVID-19 is to be fully vaccinated, including getting your booster dose.”

For the study, Dr. Kundu and colleagues analyzed blood samples from 52 people who lived with someone with confirmed COVID-19 in September 2020. Among the 26 people who didn’t contract COVID-19, there were “significantly higher levels” of preexisting T cells from common cold coronaviruses, as compared with the 26 people who did become infected.

The T cells researched in the study are considered “cross-reactive” and can recognize the proteins of SARS-CoV-2. They offer protection by targeting proteins inside the SARS-CoV-2 virus, rather than the spike proteins on the surface that allow the virus to invade cells.

The current COVID-19 vaccines target the spike proteins, which are more likely to mutate than internal proteins, the researchers wrote. The Omicron variant, for instance, has numerous mutations on spike proteins that may allow it to evade vaccines.

The data suggest that the next step of COVID-19 vaccine development could focus on internal proteins, the researchers said, which could provide lasting protection because T-cell responses persist longer than antibody responses that fade within a few months of vaccination.

“New vaccines that include these conserved, internal proteins would therefore induce broadly protective T-cell responses that should protect against current and future SARS-CoV-2 variants,” Ajit Lalvani, MD, the senior study author and director of Imperial’s respiratory infections health protection research unit, said in the statement.

But more research is needed, the authors said, noting that the study had a small sample size and lacked ethnic diversity, which puts limits on the research.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com

, according to a small study published Jan. 10 in Nature Communications.

Previous studies have shown that T cells created from other coronaviruses can recognize SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In the new study, researchers at Imperial College London found that the presence of these T cells at the time of COVID-19 exposure could reduce the chance of getting infected.

The findings could provide a blueprint for a second-generation, universal vaccine to prevent infection from COVID-19 variants, including Omicron and ones that crop up later.

“Being exposed to SARS-CoV-2 virus doesn’t always result in infection, and we’ve been keen to understand why,” Rhia Kundu, PhD, the lead study author from Imperial’s National Heart and Lung Institute, said in a statement.

People with higher levels of T cells from the common cold were less likely to become infected with COVID-19, the researchers found.

“While this is an important discovery, it is only one form of protection, and I would stress that no one should rely on this alone,” Dr. Kundu said. “Instead, the best way to protect yourself against COVID-19 is to be fully vaccinated, including getting your booster dose.”

For the study, Dr. Kundu and colleagues analyzed blood samples from 52 people who lived with someone with confirmed COVID-19 in September 2020. Among the 26 people who didn’t contract COVID-19, there were “significantly higher levels” of preexisting T cells from common cold coronaviruses, as compared with the 26 people who did become infected.

The T cells researched in the study are considered “cross-reactive” and can recognize the proteins of SARS-CoV-2. They offer protection by targeting proteins inside the SARS-CoV-2 virus, rather than the spike proteins on the surface that allow the virus to invade cells.

The current COVID-19 vaccines target the spike proteins, which are more likely to mutate than internal proteins, the researchers wrote. The Omicron variant, for instance, has numerous mutations on spike proteins that may allow it to evade vaccines.

The data suggest that the next step of COVID-19 vaccine development could focus on internal proteins, the researchers said, which could provide lasting protection because T-cell responses persist longer than antibody responses that fade within a few months of vaccination.

“New vaccines that include these conserved, internal proteins would therefore induce broadly protective T-cell responses that should protect against current and future SARS-CoV-2 variants,” Ajit Lalvani, MD, the senior study author and director of Imperial’s respiratory infections health protection research unit, said in the statement.

But more research is needed, the authors said, noting that the study had a small sample size and lacked ethnic diversity, which puts limits on the research.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com

, according to a small study published Jan. 10 in Nature Communications.

Previous studies have shown that T cells created from other coronaviruses can recognize SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In the new study, researchers at Imperial College London found that the presence of these T cells at the time of COVID-19 exposure could reduce the chance of getting infected.

The findings could provide a blueprint for a second-generation, universal vaccine to prevent infection from COVID-19 variants, including Omicron and ones that crop up later.

“Being exposed to SARS-CoV-2 virus doesn’t always result in infection, and we’ve been keen to understand why,” Rhia Kundu, PhD, the lead study author from Imperial’s National Heart and Lung Institute, said in a statement.

People with higher levels of T cells from the common cold were less likely to become infected with COVID-19, the researchers found.

“While this is an important discovery, it is only one form of protection, and I would stress that no one should rely on this alone,” Dr. Kundu said. “Instead, the best way to protect yourself against COVID-19 is to be fully vaccinated, including getting your booster dose.”

For the study, Dr. Kundu and colleagues analyzed blood samples from 52 people who lived with someone with confirmed COVID-19 in September 2020. Among the 26 people who didn’t contract COVID-19, there were “significantly higher levels” of preexisting T cells from common cold coronaviruses, as compared with the 26 people who did become infected.

The T cells researched in the study are considered “cross-reactive” and can recognize the proteins of SARS-CoV-2. They offer protection by targeting proteins inside the SARS-CoV-2 virus, rather than the spike proteins on the surface that allow the virus to invade cells.

The current COVID-19 vaccines target the spike proteins, which are more likely to mutate than internal proteins, the researchers wrote. The Omicron variant, for instance, has numerous mutations on spike proteins that may allow it to evade vaccines.

The data suggest that the next step of COVID-19 vaccine development could focus on internal proteins, the researchers said, which could provide lasting protection because T-cell responses persist longer than antibody responses that fade within a few months of vaccination.

“New vaccines that include these conserved, internal proteins would therefore induce broadly protective T-cell responses that should protect against current and future SARS-CoV-2 variants,” Ajit Lalvani, MD, the senior study author and director of Imperial’s respiratory infections health protection research unit, said in the statement.

But more research is needed, the authors said, noting that the study had a small sample size and lacked ethnic diversity, which puts limits on the research.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com

Ranking seven COVID-19 antigen tests by ease of use: Report

Some COVID-19 rapid antigen home test kits are much easier to use than others, according to an analysis by ECRI, an independent, nonprofit patient safety organization.

None of the tests were rated as “excellent” in terms of usability and some had “noteworthy” usability concerns, the company said.

If a test is hard to use, “chances are that you may miss a step or not follow the right order, or contaminate the testing area and that can definitely influence the accuracy of the test and lead to a wrong test result,” Marcus Schabacker, MD, PhD, president and CEO of ECRI, told this news organization.

To gauge usability, ECRI used the “industry-standard” system usability scale (SUS), which rates products on a scale of 0 to 100 with 100 being the easiest to use.

More than 30 points separated the top and bottom tests analyzed. The top performer was On/Go, followed by CareStart and Flowflex.

ECRI analysts found that some tests require particularly fine motor skills or have instructions with extremely small font size that may make it hard for older adults or people with complex health conditions to use the tests correctly.

“If you have a tremor from Parkinson’s, for example, or anything which won’t allow you to handle small items, you will have difficulties to do that test by yourself. That is the No. 1 concern we have,” Dr. Schabacker said.

“The second concern is readability, as all of these tests have relatively small instructions. One of them actually has doesn’t even have instructions – you have to download an app,” he noted.

Given demand and supply issues, Dr. Schabacker acknowledged that consumers might not have a choice in which test to use and may have to rely on whatever is available.

These tests are a “hot commodity right now,” he said. “If you have a choice, people should use the ones which are easiest to use, which is the On/Go, the CareStart, or the Flowflex.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some COVID-19 rapid antigen home test kits are much easier to use than others, according to an analysis by ECRI, an independent, nonprofit patient safety organization.

None of the tests were rated as “excellent” in terms of usability and some had “noteworthy” usability concerns, the company said.

If a test is hard to use, “chances are that you may miss a step or not follow the right order, or contaminate the testing area and that can definitely influence the accuracy of the test and lead to a wrong test result,” Marcus Schabacker, MD, PhD, president and CEO of ECRI, told this news organization.

To gauge usability, ECRI used the “industry-standard” system usability scale (SUS), which rates products on a scale of 0 to 100 with 100 being the easiest to use.

More than 30 points separated the top and bottom tests analyzed. The top performer was On/Go, followed by CareStart and Flowflex.

ECRI analysts found that some tests require particularly fine motor skills or have instructions with extremely small font size that may make it hard for older adults or people with complex health conditions to use the tests correctly.

“If you have a tremor from Parkinson’s, for example, or anything which won’t allow you to handle small items, you will have difficulties to do that test by yourself. That is the No. 1 concern we have,” Dr. Schabacker said.

“The second concern is readability, as all of these tests have relatively small instructions. One of them actually has doesn’t even have instructions – you have to download an app,” he noted.

Given demand and supply issues, Dr. Schabacker acknowledged that consumers might not have a choice in which test to use and may have to rely on whatever is available.

These tests are a “hot commodity right now,” he said. “If you have a choice, people should use the ones which are easiest to use, which is the On/Go, the CareStart, or the Flowflex.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some COVID-19 rapid antigen home test kits are much easier to use than others, according to an analysis by ECRI, an independent, nonprofit patient safety organization.

None of the tests were rated as “excellent” in terms of usability and some had “noteworthy” usability concerns, the company said.

If a test is hard to use, “chances are that you may miss a step or not follow the right order, or contaminate the testing area and that can definitely influence the accuracy of the test and lead to a wrong test result,” Marcus Schabacker, MD, PhD, president and CEO of ECRI, told this news organization.

To gauge usability, ECRI used the “industry-standard” system usability scale (SUS), which rates products on a scale of 0 to 100 with 100 being the easiest to use.

More than 30 points separated the top and bottom tests analyzed. The top performer was On/Go, followed by CareStart and Flowflex.

ECRI analysts found that some tests require particularly fine motor skills or have instructions with extremely small font size that may make it hard for older adults or people with complex health conditions to use the tests correctly.

“If you have a tremor from Parkinson’s, for example, or anything which won’t allow you to handle small items, you will have difficulties to do that test by yourself. That is the No. 1 concern we have,” Dr. Schabacker said.

“The second concern is readability, as all of these tests have relatively small instructions. One of them actually has doesn’t even have instructions – you have to download an app,” he noted.

Given demand and supply issues, Dr. Schabacker acknowledged that consumers might not have a choice in which test to use and may have to rely on whatever is available.

These tests are a “hot commodity right now,” he said. “If you have a choice, people should use the ones which are easiest to use, which is the On/Go, the CareStart, or the Flowflex.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The etiology of acute otitis media in young children in recent years

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, pediatricians have been seeing fewer cases of all respiratory illnesses, including acute otitis media (AOM). However, as I prepare this column, an uptick has commenced and likely will continue in an upward trajectory as we emerge from the pandemic into an endemic coronavirus era. Our group in Rochester, N.Y., has continued prospective studies of AOM throughout the pandemic. We found that nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis remained prevalent in our study cohort of children aged 6-36 months. However, with all the precautions of masking, social distancing, hand washing, and quick exclusion from day care when illness occurred, the frequency of detecting these common otopathogens decreased, as one might expect.1

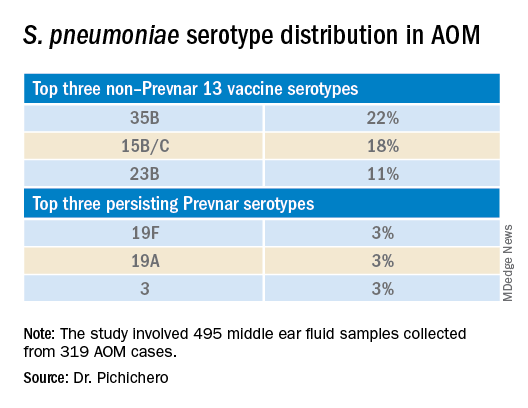

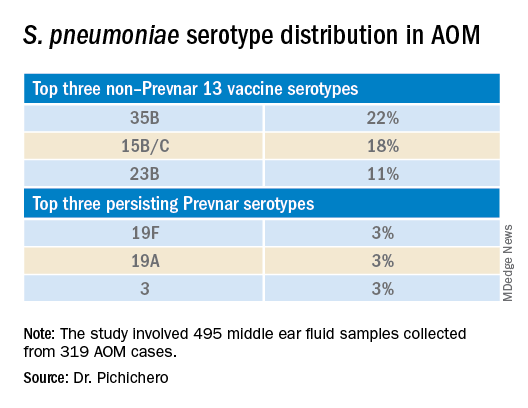

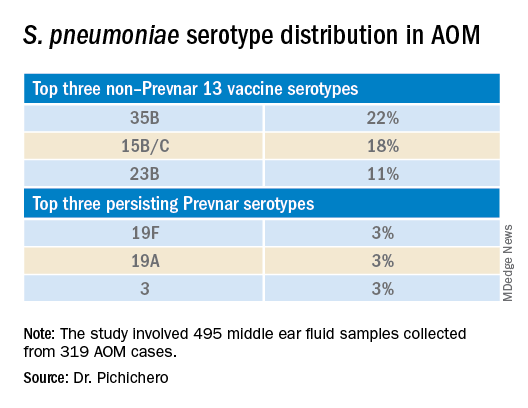

Leading up to the pandemic, we had an abundance of data to characterize AOM etiology and found that the cause of AOM continues to change following the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar 13). Our most recent report on otopathogen distribution and antibiotic susceptibility covered the years 2015-2019.2 A total of 589 children were enrolled prospectively and we collected 495 middle ear fluid samples (MEF) from 319 AOM cases using tympanocentesis. The frequency of isolates was H. influenzae (34%), pneumococcus (24%), and M. catarrhalis (15%). Beta-lactamase–positive H. influenzae strains were identified among 49% of the isolates, rendering them resistant to amoxicillin. PCV13 serotypes were infrequently isolated. However, we did isolate vaccine types (VTs) in some children from MEF, notably serotypes 19F, 19A, and 3. Non-PCV13 pneumococcus serotypes 35B, 23B, and 15B/C emerged as the most common serotypes. Amoxicillin resistance was identified among 25% of pneumococcal strains. Out of 16 antibiotics tested, 9 (56%) showed a significant increase in nonsusceptibility among pneumococcal isolates. 100% of M. catarrhalis isolates were beta-lactamase producers and therefore resistant to amoxicillin.

PCV13 has resulted in a decline in both invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal infections caused by strains expressing the 13 capsular serotypes included in the vaccine. However, the emergence of replacement serotypes occurred after introduction of PCV73,4 and continues to occur during the PCV13 era, as shown from the results presented here. Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for more than 90% of MEF isolates during 2015-2019, with 35B, 21 and 23B being the most commonly isolated. Other emergent serotypes of potential importance were nonvaccine serotypes 15A, 15B, 15C, 23A and 11A. This is highly relevant because forthcoming higher-valency PCVs – PCV15 (manufactured by Merck) and PCV20 (manufactured by Pfizer) will not include many of the dominant capsular serotypes of pneumococcus strains causing AOM. Consequently, the impact of higher-valency PCVs on AOM will not be as great as was observed with the introduction of PCV7 or PCV13.

Of special interest, 22% of pneumococcus isolates from MEF were serotype 35B, making it the most prevalent. Recently we reported a significant rise in antibiotic nonsusceptibility in Spn isolates, contributed mainly by serotype 35B5 and we have been studying how 35B strains transitioned from commensal to otopathogen in children.6 Because serotype 35B strains are increasingly prevalent and often antibiotic resistant, absence of this serotype from PCV15 and PCV20 is cause for concern.

The frequency of isolation of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis has remained stable across the PCV13 era as the No. 1 and No. 3 pathogens. Similarly, the production of beta-lactamase among strains causing AOM has remained stable at close to 50% and 100%, respectively. Use of amoxicillin, either high dose or standard dose, would not be expected to kill these bacteria.

Our study design has limitations. The population is derived from a predominantly middle-class, suburban population of children in upstate New York and may not be representative of other types of populations in the United States. The children are 6-36 months old, the age when most AOM occurs. MEF samples that were culture negative for bacteria were not further tested by polymerase chain reaction methods.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:722483.

2. Kaur R et al. Euro J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44

3. Pelton SI et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2004;23:1015-22.

4. Farrell DJ et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2007;26:123-8..

5. Kaur R et al. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(5):797-805.

6. Fuji N et al. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:744742.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, pediatricians have been seeing fewer cases of all respiratory illnesses, including acute otitis media (AOM). However, as I prepare this column, an uptick has commenced and likely will continue in an upward trajectory as we emerge from the pandemic into an endemic coronavirus era. Our group in Rochester, N.Y., has continued prospective studies of AOM throughout the pandemic. We found that nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis remained prevalent in our study cohort of children aged 6-36 months. However, with all the precautions of masking, social distancing, hand washing, and quick exclusion from day care when illness occurred, the frequency of detecting these common otopathogens decreased, as one might expect.1

Leading up to the pandemic, we had an abundance of data to characterize AOM etiology and found that the cause of AOM continues to change following the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar 13). Our most recent report on otopathogen distribution and antibiotic susceptibility covered the years 2015-2019.2 A total of 589 children were enrolled prospectively and we collected 495 middle ear fluid samples (MEF) from 319 AOM cases using tympanocentesis. The frequency of isolates was H. influenzae (34%), pneumococcus (24%), and M. catarrhalis (15%). Beta-lactamase–positive H. influenzae strains were identified among 49% of the isolates, rendering them resistant to amoxicillin. PCV13 serotypes were infrequently isolated. However, we did isolate vaccine types (VTs) in some children from MEF, notably serotypes 19F, 19A, and 3. Non-PCV13 pneumococcus serotypes 35B, 23B, and 15B/C emerged as the most common serotypes. Amoxicillin resistance was identified among 25% of pneumococcal strains. Out of 16 antibiotics tested, 9 (56%) showed a significant increase in nonsusceptibility among pneumococcal isolates. 100% of M. catarrhalis isolates were beta-lactamase producers and therefore resistant to amoxicillin.

PCV13 has resulted in a decline in both invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal infections caused by strains expressing the 13 capsular serotypes included in the vaccine. However, the emergence of replacement serotypes occurred after introduction of PCV73,4 and continues to occur during the PCV13 era, as shown from the results presented here. Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for more than 90% of MEF isolates during 2015-2019, with 35B, 21 and 23B being the most commonly isolated. Other emergent serotypes of potential importance were nonvaccine serotypes 15A, 15B, 15C, 23A and 11A. This is highly relevant because forthcoming higher-valency PCVs – PCV15 (manufactured by Merck) and PCV20 (manufactured by Pfizer) will not include many of the dominant capsular serotypes of pneumococcus strains causing AOM. Consequently, the impact of higher-valency PCVs on AOM will not be as great as was observed with the introduction of PCV7 or PCV13.

Of special interest, 22% of pneumococcus isolates from MEF were serotype 35B, making it the most prevalent. Recently we reported a significant rise in antibiotic nonsusceptibility in Spn isolates, contributed mainly by serotype 35B5 and we have been studying how 35B strains transitioned from commensal to otopathogen in children.6 Because serotype 35B strains are increasingly prevalent and often antibiotic resistant, absence of this serotype from PCV15 and PCV20 is cause for concern.

The frequency of isolation of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis has remained stable across the PCV13 era as the No. 1 and No. 3 pathogens. Similarly, the production of beta-lactamase among strains causing AOM has remained stable at close to 50% and 100%, respectively. Use of amoxicillin, either high dose or standard dose, would not be expected to kill these bacteria.

Our study design has limitations. The population is derived from a predominantly middle-class, suburban population of children in upstate New York and may not be representative of other types of populations in the United States. The children are 6-36 months old, the age when most AOM occurs. MEF samples that were culture negative for bacteria were not further tested by polymerase chain reaction methods.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:722483.

2. Kaur R et al. Euro J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44

3. Pelton SI et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2004;23:1015-22.

4. Farrell DJ et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2007;26:123-8..

5. Kaur R et al. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(5):797-805.

6. Fuji N et al. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:744742.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, pediatricians have been seeing fewer cases of all respiratory illnesses, including acute otitis media (AOM). However, as I prepare this column, an uptick has commenced and likely will continue in an upward trajectory as we emerge from the pandemic into an endemic coronavirus era. Our group in Rochester, N.Y., has continued prospective studies of AOM throughout the pandemic. We found that nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis remained prevalent in our study cohort of children aged 6-36 months. However, with all the precautions of masking, social distancing, hand washing, and quick exclusion from day care when illness occurred, the frequency of detecting these common otopathogens decreased, as one might expect.1

Leading up to the pandemic, we had an abundance of data to characterize AOM etiology and found that the cause of AOM continues to change following the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar 13). Our most recent report on otopathogen distribution and antibiotic susceptibility covered the years 2015-2019.2 A total of 589 children were enrolled prospectively and we collected 495 middle ear fluid samples (MEF) from 319 AOM cases using tympanocentesis. The frequency of isolates was H. influenzae (34%), pneumococcus (24%), and M. catarrhalis (15%). Beta-lactamase–positive H. influenzae strains were identified among 49% of the isolates, rendering them resistant to amoxicillin. PCV13 serotypes were infrequently isolated. However, we did isolate vaccine types (VTs) in some children from MEF, notably serotypes 19F, 19A, and 3. Non-PCV13 pneumococcus serotypes 35B, 23B, and 15B/C emerged as the most common serotypes. Amoxicillin resistance was identified among 25% of pneumococcal strains. Out of 16 antibiotics tested, 9 (56%) showed a significant increase in nonsusceptibility among pneumococcal isolates. 100% of M. catarrhalis isolates were beta-lactamase producers and therefore resistant to amoxicillin.

PCV13 has resulted in a decline in both invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal infections caused by strains expressing the 13 capsular serotypes included in the vaccine. However, the emergence of replacement serotypes occurred after introduction of PCV73,4 and continues to occur during the PCV13 era, as shown from the results presented here. Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for more than 90% of MEF isolates during 2015-2019, with 35B, 21 and 23B being the most commonly isolated. Other emergent serotypes of potential importance were nonvaccine serotypes 15A, 15B, 15C, 23A and 11A. This is highly relevant because forthcoming higher-valency PCVs – PCV15 (manufactured by Merck) and PCV20 (manufactured by Pfizer) will not include many of the dominant capsular serotypes of pneumococcus strains causing AOM. Consequently, the impact of higher-valency PCVs on AOM will not be as great as was observed with the introduction of PCV7 or PCV13.

Of special interest, 22% of pneumococcus isolates from MEF were serotype 35B, making it the most prevalent. Recently we reported a significant rise in antibiotic nonsusceptibility in Spn isolates, contributed mainly by serotype 35B5 and we have been studying how 35B strains transitioned from commensal to otopathogen in children.6 Because serotype 35B strains are increasingly prevalent and often antibiotic resistant, absence of this serotype from PCV15 and PCV20 is cause for concern.

The frequency of isolation of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis has remained stable across the PCV13 era as the No. 1 and No. 3 pathogens. Similarly, the production of beta-lactamase among strains causing AOM has remained stable at close to 50% and 100%, respectively. Use of amoxicillin, either high dose or standard dose, would not be expected to kill these bacteria.

Our study design has limitations. The population is derived from a predominantly middle-class, suburban population of children in upstate New York and may not be representative of other types of populations in the United States. The children are 6-36 months old, the age when most AOM occurs. MEF samples that were culture negative for bacteria were not further tested by polymerase chain reaction methods.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:722483.

2. Kaur R et al. Euro J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44

3. Pelton SI et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2004;23:1015-22.

4. Farrell DJ et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2007;26:123-8..

5. Kaur R et al. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(5):797-805.

6. Fuji N et al. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:744742.

Children and COVID: New cases and hospital admissions skyrocket

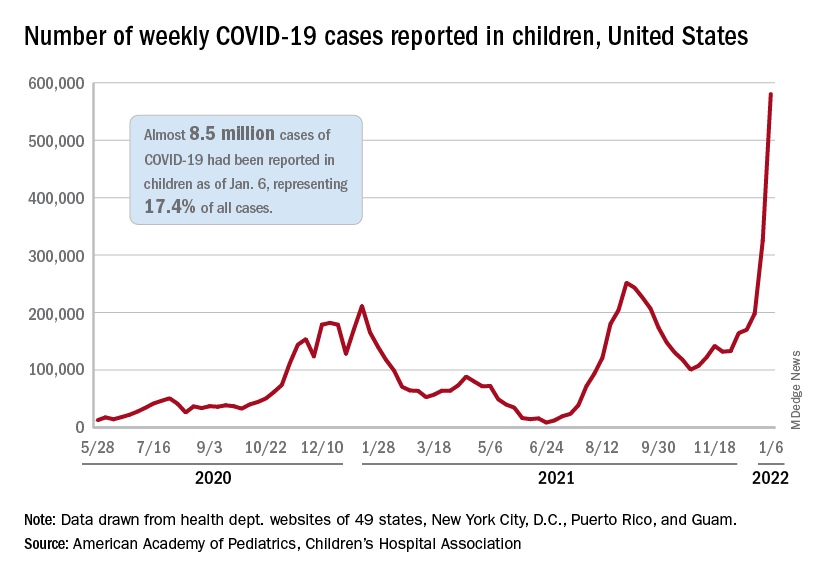

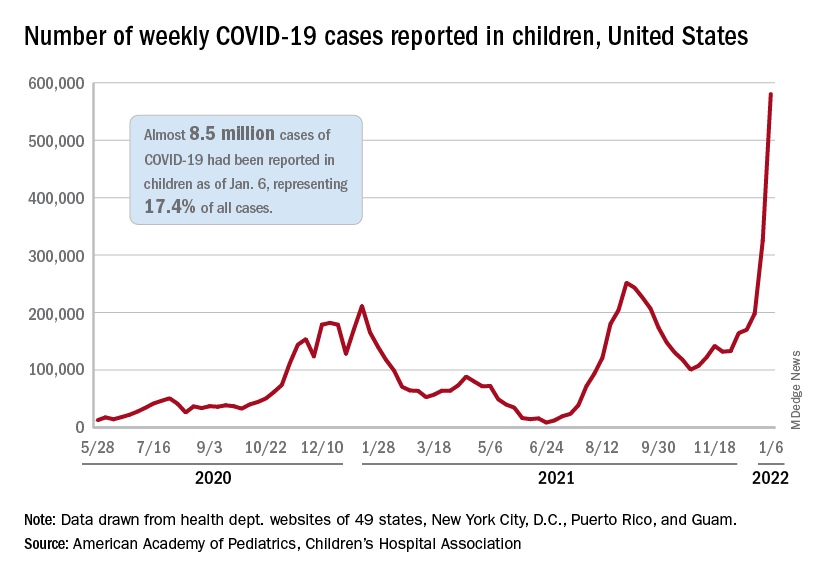

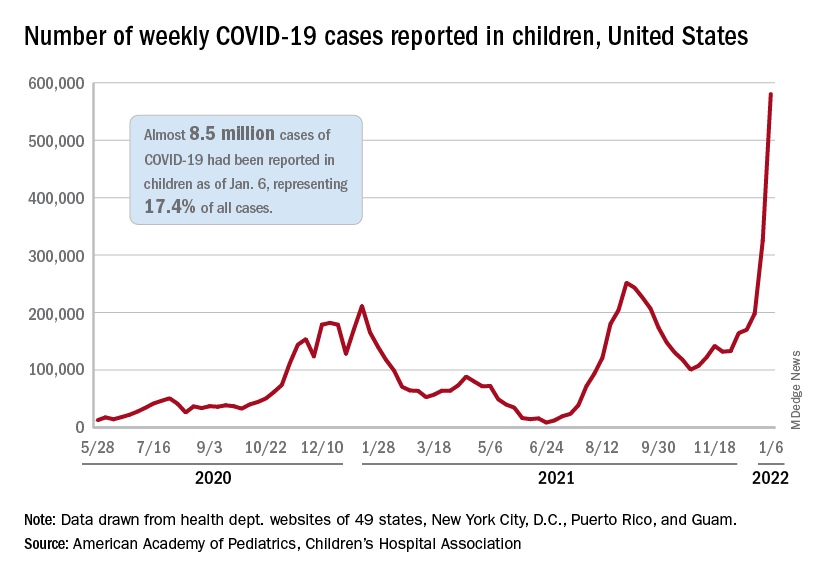

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total for the week of Dec. 31 to Jan. 6 – the highest since the pandemic began – was an increase of 78% over the previous week (325,000) and 192% higher than just 2 weeks before (199,000), the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. No region of the country was spared, as all four saw at least 50,000 more cases than the week before, but the increase was largest in the West and smallest in the Midwest.

“Nearly 8.5 million children have tested positive for COVID-19 since the onset of the pandemic; nearly 11% of these cases have been added in the past 2 weeks,” the AAP said.

The situation is the same for hospitalizations. On Dec. 15, the daily rate of new admissions for children aged 0-17 years was 0.26 per 100,000, and by Jan. 7 it had more than quadrupled to 1.15 per 100,000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported. Before Omicron, the highest rate was 0.47 per 100,000 on Sept. 4, 2021.

The number of children occupying inpatient beds who had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 went from 2,343 on Jan. 2 to 3,476 on Jan. 9, a jump of more than 48% in just 1 week. Texas had more hospitalized children (392) than any other state on Jan. 9, with California (339) and New York (313) the only other states over 300, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

For vaccinations. however, the situation is definitely not the same. The number of children added to the ranks of those with at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine was down in early 2022 (Jan. 3-9) for both 5- to 11-year-olds (–8.2%) and 16- to 17-year-olds (–12.2%) but higher among those aged 12-15 (12.2%), compared with the previous week (Dec. 27 to Jan. 2), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Cumulative figures show that 26.3% of all children aged 5-11 had received at least one dose of vaccine and 17.2% were fully vaccinated as of Jan. 10, compared with 62.2% and 52.0% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 68.5% and 58.1% of those aged 16-17. Altogether, over 23.8 million children in those three age groups have received at least one dose and almost 18.6 million are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total for the week of Dec. 31 to Jan. 6 – the highest since the pandemic began – was an increase of 78% over the previous week (325,000) and 192% higher than just 2 weeks before (199,000), the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. No region of the country was spared, as all four saw at least 50,000 more cases than the week before, but the increase was largest in the West and smallest in the Midwest.

“Nearly 8.5 million children have tested positive for COVID-19 since the onset of the pandemic; nearly 11% of these cases have been added in the past 2 weeks,” the AAP said.

The situation is the same for hospitalizations. On Dec. 15, the daily rate of new admissions for children aged 0-17 years was 0.26 per 100,000, and by Jan. 7 it had more than quadrupled to 1.15 per 100,000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported. Before Omicron, the highest rate was 0.47 per 100,000 on Sept. 4, 2021.

The number of children occupying inpatient beds who had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 went from 2,343 on Jan. 2 to 3,476 on Jan. 9, a jump of more than 48% in just 1 week. Texas had more hospitalized children (392) than any other state on Jan. 9, with California (339) and New York (313) the only other states over 300, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

For vaccinations. however, the situation is definitely not the same. The number of children added to the ranks of those with at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine was down in early 2022 (Jan. 3-9) for both 5- to 11-year-olds (–8.2%) and 16- to 17-year-olds (–12.2%) but higher among those aged 12-15 (12.2%), compared with the previous week (Dec. 27 to Jan. 2), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Cumulative figures show that 26.3% of all children aged 5-11 had received at least one dose of vaccine and 17.2% were fully vaccinated as of Jan. 10, compared with 62.2% and 52.0% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 68.5% and 58.1% of those aged 16-17. Altogether, over 23.8 million children in those three age groups have received at least one dose and almost 18.6 million are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total for the week of Dec. 31 to Jan. 6 – the highest since the pandemic began – was an increase of 78% over the previous week (325,000) and 192% higher than just 2 weeks before (199,000), the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. No region of the country was spared, as all four saw at least 50,000 more cases than the week before, but the increase was largest in the West and smallest in the Midwest.

“Nearly 8.5 million children have tested positive for COVID-19 since the onset of the pandemic; nearly 11% of these cases have been added in the past 2 weeks,” the AAP said.

The situation is the same for hospitalizations. On Dec. 15, the daily rate of new admissions for children aged 0-17 years was 0.26 per 100,000, and by Jan. 7 it had more than quadrupled to 1.15 per 100,000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported. Before Omicron, the highest rate was 0.47 per 100,000 on Sept. 4, 2021.

The number of children occupying inpatient beds who had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 went from 2,343 on Jan. 2 to 3,476 on Jan. 9, a jump of more than 48% in just 1 week. Texas had more hospitalized children (392) than any other state on Jan. 9, with California (339) and New York (313) the only other states over 300, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

For vaccinations. however, the situation is definitely not the same. The number of children added to the ranks of those with at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine was down in early 2022 (Jan. 3-9) for both 5- to 11-year-olds (–8.2%) and 16- to 17-year-olds (–12.2%) but higher among those aged 12-15 (12.2%), compared with the previous week (Dec. 27 to Jan. 2), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Cumulative figures show that 26.3% of all children aged 5-11 had received at least one dose of vaccine and 17.2% were fully vaccinated as of Jan. 10, compared with 62.2% and 52.0% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 68.5% and 58.1% of those aged 16-17. Altogether, over 23.8 million children in those three age groups have received at least one dose and almost 18.6 million are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

CDC: More kids hospitalized with COVID since pandemic began

Hospital admissions of U.S. children younger than 5 – the only group ineligible for vaccination – have reached their peak since the start of the pandemic, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said the higher numbers show the importance of vaccination for all eligible groups.

“This is the highest number of pediatric hospitalizations we’ve seen throughout the pandemic, which we said about Delta until now,” she said at a CDC briefing Friday. “This very well may be that there are just more cases out there, and our children are more vulnerable when they have more cases surrounding them.”

Despite the skyrocketing admissions, hospitalizations are still relatively low for children, she said. The hospitalization rate for children under 5 is 4 in 100,000, and it’s about 1 in 100,000 in children 5-17.

Dr. Walensky said not all children are being hospitalized for COVID-19 – some are admitted for unrelated issues and test positive but don’t have symptoms.

“We are still learning more about the severity of Omicron in children,” she said, noting that just over 50% of children 12-18 are fully vaccinated, while only 16% of those ages 5-11 are fully vaccinated.

Friday’s teleconference was the first CDC briefing in several months and comes on the heels of recent guideline updates for testing and isolation that have left the American public dumbfounded. When asked why the briefing was held, Dr. Walensky said there had been interest in hearing more from the CDC, saying, “I anticipate this will be the first of many briefings.”

She also defended the confusing guideline changes, saying, “We’re in an unprecedented time with the speed of Omicron cases rising. … This is hard, and I am committed to continuing to improve as we learn more about the science and communicate that to you.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Hospital admissions of U.S. children younger than 5 – the only group ineligible for vaccination – have reached their peak since the start of the pandemic, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said the higher numbers show the importance of vaccination for all eligible groups.

“This is the highest number of pediatric hospitalizations we’ve seen throughout the pandemic, which we said about Delta until now,” she said at a CDC briefing Friday. “This very well may be that there are just more cases out there, and our children are more vulnerable when they have more cases surrounding them.”

Despite the skyrocketing admissions, hospitalizations are still relatively low for children, she said. The hospitalization rate for children under 5 is 4 in 100,000, and it’s about 1 in 100,000 in children 5-17.

Dr. Walensky said not all children are being hospitalized for COVID-19 – some are admitted for unrelated issues and test positive but don’t have symptoms.

“We are still learning more about the severity of Omicron in children,” she said, noting that just over 50% of children 12-18 are fully vaccinated, while only 16% of those ages 5-11 are fully vaccinated.

Friday’s teleconference was the first CDC briefing in several months and comes on the heels of recent guideline updates for testing and isolation that have left the American public dumbfounded. When asked why the briefing was held, Dr. Walensky said there had been interest in hearing more from the CDC, saying, “I anticipate this will be the first of many briefings.”

She also defended the confusing guideline changes, saying, “We’re in an unprecedented time with the speed of Omicron cases rising. … This is hard, and I am committed to continuing to improve as we learn more about the science and communicate that to you.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Hospital admissions of U.S. children younger than 5 – the only group ineligible for vaccination – have reached their peak since the start of the pandemic, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said the higher numbers show the importance of vaccination for all eligible groups.

“This is the highest number of pediatric hospitalizations we’ve seen throughout the pandemic, which we said about Delta until now,” she said at a CDC briefing Friday. “This very well may be that there are just more cases out there, and our children are more vulnerable when they have more cases surrounding them.”

Despite the skyrocketing admissions, hospitalizations are still relatively low for children, she said. The hospitalization rate for children under 5 is 4 in 100,000, and it’s about 1 in 100,000 in children 5-17.

Dr. Walensky said not all children are being hospitalized for COVID-19 – some are admitted for unrelated issues and test positive but don’t have symptoms.

“We are still learning more about the severity of Omicron in children,” she said, noting that just over 50% of children 12-18 are fully vaccinated, while only 16% of those ages 5-11 are fully vaccinated.

Friday’s teleconference was the first CDC briefing in several months and comes on the heels of recent guideline updates for testing and isolation that have left the American public dumbfounded. When asked why the briefing was held, Dr. Walensky said there had been interest in hearing more from the CDC, saying, “I anticipate this will be the first of many briefings.”

She also defended the confusing guideline changes, saying, “We’re in an unprecedented time with the speed of Omicron cases rising. … This is hard, and I am committed to continuing to improve as we learn more about the science and communicate that to you.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Pediatric antibiotic prescriptions plummeted in pandemic

Antibiotic prescribing in pediatric primary care decreased dramatically when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and new research indicates that drop was sustained through June of 2021.

Lauren Dutcher, MD, with the division of infectious diseases at Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, led a study of 27 pediatric primary care practices in the United States. Encounters from Jan. 1, 2018, through June 30, 2021, were included.

Researchers found a 72.7% drop in antibiotic prescriptions when they compared prepandemic April 2019 through December 2019 with the same period in 2020.

Prescriptions remained at the lower levels, primarily driven by reductions in respiratory tract infection (RTI) encounters, and began to rise only in April of 2021, the authors write.

Findings were published online Jan. 11 in Pediatrics.

Researchers report there were 69,327 antibiotic prescriptions from April through December in 2019 and 18,935 antibiotic prescriptions during the same months in 2020.

“The reduction in prescriptions at visits for respiratory tract infection (RTI) accounted for 87.3% of this decrease,” the authors write.

Both prescribing and acute non–COVID-19 respiratory tract infection diagnoses decreased.

Researchers conclude reductions in viral RTI transmission likely played a large role in reduced RTI pediatric visits and antibiotic prescriptions.

Dr. Dutcher told this publication the reduction was likely caused by a combination of less viral transmission of respiratory infections, helped in part by masking and distancing, but also avoidance of health care in the pandemic.

She said the data reinforce the need for appropriate prescribing.

“Antibiotic prescribing is really heavily driven by respiratory infections so this should continue to clue providers in on how frequently that can be unnecessary,“ she said.

Dr. Dutcher said there was probably a reduction in secondary bacterial infections as well as the viral infections.

The research is more comprehensive than some other previous studies, the authors write.

“Although other studies demonstrated early reductions in RTIs and antibiotic prescribing during the COVID-19 pandemic, to our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate a sustained decrease in antibiotic prescribing in pediatric primary care throughout 2020 and early 2021,” they write.

The findings also suggest benefits of preventive measures during the pandemic, the authors say.

“Our data suggest that reducing community viral RTI transmission through social distancing and masking corresponds with a reduction in antibiotic prescribing,” they write.

Kao-Ping Chua, MD, a pediatrician and an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said the reductions indicate one of two things is happening: either children aren’t getting sick as often during the pandemic or they are getting sick, but not coming in.